Abstract

Aims

To provide data on prevalence and trends in the use of different types of e‐cigarettes (disposable, pod, tank) in Germany (a country with high smoking prevalence of approximately 30%) from 2016 to 2023, and to analyse the characteristics and smoking behaviours of users of these types.

Design

A series of nationally representative cross‐sectional face‐to‐face household surveys.

Setting

General population of Germany, 2016–2023.

Participants

A total of 92 327 people (aged ≥14 years) of which 1398 reported current use of e‐cigarettes.

Measurements

Type of e‐cigarette usually used (single choice: disposable, pod, or tank), person characteristics, and smoking/vaping behaviour.

Findings

E‐cigarette use in the population of Germany has increased from 1.6% (95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.1,2.2) in 2016 to 2.2% (95% CI = 1.6,3.0) at the end of 2023. Disposable e‐cigarette use has increased in this period from 0.1% (95% CI = 0.0,0.3) to 0.8% (95% CI = 0.4,1.8). Pod type use exhibited the most stable trend, with a steady rise to 0.6% (95% CI = 0.4,0.9) in 2023. Tank e‐cigarette use peaked at 1.6% (95% CI = 1.3,1.9) in November 2017, declined to 0.7% (95% CI = 0.6,0.9) in December 2020, and has since remained constant at 0.8% (95% CI = 0.6,1.0). Disposable e‐cigarette users were on average 3.5 and 4.1 years younger than tank and pod users, respectively. They were more likely than tank users to be female, non‐daily users, and dual users of tobacco. In the subgroup of dual users, there were no significant differences with regard to urges to smoke, cigarettes smoked per day, motivation to stop, and attempts to stop smoking between users of disposables and other types.

Conclusions

The use of e‐cigarettes has increased in Germany from 2016 to 2023, especially that of disposable e‐cigarettes, which are now the most commonly used type with a prevalence rate of 0.8%. However, the use of e‐cigarettes is still much lower compared with tobacco smoking.

Keywords: disposable, e‐cigarettes, population survey, tobacco smokers, trends, Germany

INTRODUCTION

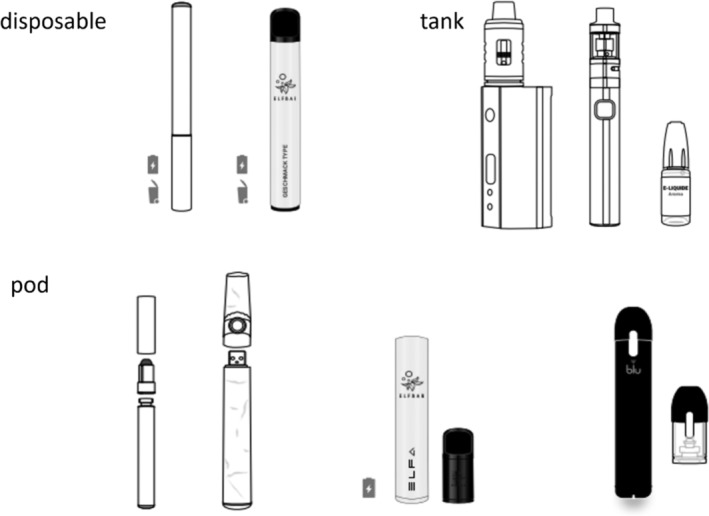

E‐cigarette liquids mainly consist of propylene glycol, glycerine and flavourings [1], which vary from fruity, such as apple, to spicy, such as pepper [2]. In recent years, there have been substantial advancements in their design and functionality, including increased capacity, stronger batteries and exchangeable components. E‐cigarettes can be divided into three main types: devices which are disposable, with exchangeable pods and with refillable tanks [3, 4] (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

The three different types of e‐cigarettes (in Germany).

Current evidence on the health effects of e‐cigarette use (‘vaping’) is limited because of a lack of long‐term data (≥12 months), and because users are often current and former tobacco smokers. However, it has been confirmed to date that people who vape are exposed to lower levels of toxicants associated with the risk of cancer, respiratory diseases and other health outcomes compared to those who smoke tobacco [5]. Regarding inflammation and oxidative stress among e‐cigarette users compared to smokers and non‐users, current evidence does not indicate a consistent relationship [5]. It has been shown that the inhalation of both nicotine and non‐nicotine‐containing products can have a detrimental impact on brain maturation and cognitive functions, and predisposes individuals to substance use in later life [6], which poses a significant risk especially for adolescents and young adults. Although tobacco smokers who completely switch to e‐cigarettes may experience health benefits because of lower toxicity of vapour than cigarette smoke [7, 8], widespread dual use of e‐cigarettes and tobacco results in continued health risks from tobacco and may also result in increased overall nicotine consumption [9].

Global e‐cigarette use has been on the rise [10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16], but insights into trends among users of different types are limited. Although pod systems dominated middle and high school students' e‐cigarette use in the United States (US) in 2020, disposables took precedence in 2021 among current users (prevalence high school = 55.8%, middle school = 43.8%) [17, 18]. United Kingdom (UK) data from 2016 onward revealed a preference for tank types among current or recent tobacco smokers, but a shift occurred in 2021, with a notable increase in disposable e‐cigarette use and a decline in tank types [13]. Data from the International Tobacco Control Youth Tobacco and Vaping Survey conducted in Canada, the United Kingdom and the United States also revealed an increase in the usage of disposable e‐cigarettes among the 16‐to‐19 age group. In the United Kingdom and the United States, disposable e‐cigarettes were the most commonly used type by youth who vaped in 2022. They were used by 67%, 52% and 34% of vapers in the United Kingdom, United States and Canada, respectively [19]. Unfortunately, no data are currently available regarding the prevalence of different types of e‐cigarettes in Germany.

Furthermore, limited research has examined associations between the characteristics of users of different types of e‐cigarettes. A study from the United States showed that disposables were favoured by younger people (15–20 year olds), whereas those age 21 or older leaned toward tank types [20]. Tank users vaped on average on more days a month than disposable and pod‐users [20]. Another study from the United States found that users of disposable pods were younger, used higher nicotine concentrations, were less likely to have ever smoked cigarettes and were less likely to use e‐cigarettes daily, compared to users of refillable pods and other non‐pod e‐cigarette devices [21]. Furthermore, a study from the United States showed that adolescents using JUUL and pod mod systems reported increased addiction symptoms, adjusted for current smoking status [22]. Again, comparable data from Germany are lacking.

The present study aims to provide data on the prevalence and trends in the use of different types of e‐cigarettes in Germany over the last few years. Germany is a country with a high prevalence of tobacco smoking (~30% at the present time; for trend information, see Supplement 1). Notably, young adults age 18 to 25 exhibit a high prevalence of smoking, reaching 29.8% in 2021 [23]. Furthermore, we aim to analyse the characteristics and smoking behaviour of users of different types of e‐cigarettes in detail. Such information is crucial for evaluating the potential public health impact of e‐cigarette use. More information about the regulation of e‐cigarettes in Germany can be found in Supplement 2. The specific research questions were:

What has been the prevalence of disposable (and other types of) e‐cigarette usage over the period 2016 to 2023 in the general German population age 14 years and older?

How do current e‐cigarette users of the three main types of e‐cigarettes (disposable, pod and tank) differ in terms of age, sex, starting age of e‐cigarette use, 30‐day‐use of e‐cigarettes, number of units used per day, nicotine concentration in e‐cigarette liquid and dual‐use of tobacco products?

In the subgroup of current dual‐users of e‐cigarettes and smoked tobacco products: do users of the three main types of e‐cigarettes (disposable, pod and tank) differ regarding the number of cigarettes smoked per day, motivation to stop smoking, time spent with urges to smoke, strength of urges to smoke and attempts to stop smoking tobacco in the past year?

METHODS

Pre‐registration

The study protocol with the analysis plan was pre‐registered on the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/45xpq).

Study design

We used data from the German Study on Tobacco Use (DEBRA: ‘Deutsche Befragung zum Rauchverhalten’), an ongoing representative survey that collects data every other month through computer‐assisted face‐to‐face household interviews in representative samples of ~2000 people age 14 or older residing in Germany [24]. Respondents are selected by random stratified sampling (50%) and quota sampling (50%, details: https://osf.io/s2wxc). For the present study, we used data from June/July 2016 (the first wave of DEBRA) to November 2023 (wave 45). A total of 92 327 people were interviewed during this period.

Measures

The general DEBRA survey with all questions and response options is openly accessible (https://osf.io/snm3p).

Prevalence of e‐cigarette use

After a brief introductory text on the topic of e‐cigarettes we asked: ‘Have you ever used an e‐cigarette or a similar product (e.g. ELFBAR, Blu, e‐shisha, or e‐cigar)?’ Response options were: (1) ‘Yes, I have used them until today’ (defines current e‐cigarette users), (2) ‘Yes, I used them regularly in the past, but don't use them anymore’, (3) ‘Yes, I tried them earlier, but don't use them anymore’, or (4) ‘No, I have never used them’.

Types of e‐cigarettes

Current e‐cigarette users were asked: ‘What type of e‐cigarette do you usually use?’ Response options were: (1) ‘A disposable e‐cigarette’, (2) ‘An e‐cigarette with replaceable, pre‐filled cartridges or pods’, (3) ‘An e‐cigarette with tank which one can fill with liquid oneself’, (4) ‘A different type, namely: <free text>’, or (5) ‘No response’. Groups (4) and (5) were not included in the current analyses.

Dual use of e‐cigarettes and smoked tobacco

Dual users of e‐cigarettes and smoked tobacco were defined as all respondents who were current e‐cigarette users (see above) as well as current tobacco smokers (defined as people who [1] ‘(…) smoke cigarettes every day’, [2] ‘(…) smoke cigarettes, but not every day’, [3] ‘(…) do not smoke cigarettes at all, but [..] do smoke tobacco of some kind (e.g. pipe or cigar)’).

Demographic characteristics

Age was categorized (14–17, 18–24, 25–39, 40+) for the sample description and used as a continuous variable for the statistical analyses. Gender was self‐reported as male or female (20 respondents with diverse gender were excluded from the analyses).

E‐cigarette usage behaviour

The starting age of e‐cigarette usage was categorized (10–13, 14–17, 18–24, 25+) for the sample description and used as a continuous variable for the statistical analyses. Thirty‐day use of e‐cigarettes was assessed with the question ‘What do you think on how many of the past 30 days have you used e‐cigarettes?’ (0–30 days). We dichotomised this variable into daily (all 30 days) and non‐daily use (0–29 days). We asked tank users how many millilitres (mL) of liquid they currently consume on average per day. We asked users of disposable e‐cigarettes and pod e‐cigarettes how many disposables and pods they currently use on average per day and converted these amounts into mL per day (details can be found in the study protocol). The nicotine concentration in liquids was assessed by asking ‘What is the concentration of nicotine in the disposable e‐cigarettes, cartridges, pods, or liquid you use?’ Respondents were asked to give the number in milligrams per mL. Further response options were ‘I use e‐cigarettes without nicotine’ or ‘Do not know.’

Tobacco smoking behaviour

Cigarette smokers were asked about the number of cigarettes smoked per day. All current smokers were asked about their level of motivation to stop smoking using the validated Motivation To Stop Scale [25, 26], ranging from the lowest level [1] ‘I don't want to stop smoking’ to the highest level [7] ‘I really want to stop smoking and intend to in the next month’. We dichotomised this variable into not motivated (levels 1–2) and motivated [3, 4, 5, 6, 7]. All past‐year smokers were asked about their urges to smoke using the following two validated items [27]: time spent with urges to smoke in the last 24 hours ranging from [1] ‘not at all’ to [6] ‘all the time’ and strength of urges to smoke ranging from (0) ‘none’ to [5] ‘extremely strong’. For the analyses, we used both variables as continuous variables. We also asked about serious attempts to stop smoking in the past year (dichotomised into no attempt and one attempt or more).

Statistical analyses

To address research question 1 (prevalence of e‐cigarette type usage), we plotted prevalences (in %) over time for the total number of 92 327 respondents, along with pointwise 95% CI (Clopper‐Pearson method). This was done both with all types combined and stratified by e‐cigarette type using weighted data. Weighting aimed to approximate the sample to the German population in terms of age, gender, household size, level of education and region (details: https://osf.io/zp7c6). To model trends, we used binomial logistic regression models with a random effect for wave, using restricted cubic spline terms for wave with knot positions at years 2018, 2020 and 2022. This analysis was conducted both for all e‐cigarette types combined and separately for each e‐cigarette type: disposable, pod and tank. The fit of the spline model was compared with a linear trend model, which in turn was compared with a model of no trend via likelihood ratio tests.

To address research question 2 (associations of e‐cigarette type with person characteristics), we conducted multilevel analyses with wave as random effect and e‐cigarette type as categorical predictor. * Dichotomous outcomes (sex, dual‐use and 30‐day‐use of e‐cigarettes) were assessed using logistic mixed‐effects models, whereas continuous outcomes (age, starting age of e‐cigarette use, mL of e‐cigarette use per day and nicotine concentration) were analysed using linear mixed‐effects models. The starting age of e‐cigarette use, mL of e‐cigarette use per day and nicotine concentration were log‐transformed because of excessive right‐skewness. Following the omnibus test (χ2 test with 2 degrees of freedom), pairwise tests were performed. Estimated mean values of the log‐transformed variables were back‐transformed (with , where , and are estimates of the mean, error variance and random effect variance, respectively) for better interpretability [28].

To address research question 3 (associations of e‐cigarette type with smoking behaviour), we conducted multilevel analyses as described above, but within the subgroup of dual users of e‐cigarettes and smoked tobacco. Logistic mixed‐effects models were used for dichotomous outcomes (attempts to stop smoking in the past year, motivation to stop smoking), linear mixed‐effects models for continuous outcomes (time spent with urges to smoke and strength of urges to smoke), and a Poisson mixed‐effects model for cigarettes smoked per day (with a random effect for persons added to account for potential overdispersion). After the omnibus test, pairwise tests followed.

RESULTS

Of the 92 327 participants interviewed between 2016 and 2023, 1475 reported current vaping. We excluded 77 participants who could not be assigned to one of the three e‐cigarette types under analysis (47 who reported using different types, such as heated tobacco products, which are not e‐cigarettes, and 30 who did not provide a response), leaving a final sample of 1398 people (1.5% of 92 327; weighted numbers: 1.6% [1405 of 89 998]) currently vaping at the time of the interview: 166 usually used disposable e‐cigarettes, 331 pods and 901 tanks. A total of 1086 people (77.7% of 1398) used e‐cigarettes and tobacco (dual use). The number of non‐respondents was 388 (0.4% of 92 327) regarding e‐cigarette use and 573 (0.6% of 92 327) regarding tobacco smoking.

People who usually used disposables were on average younger than those who used pods or tanks (Table 1). The proportion of people aged <25 years was 27.7% (n = 46) in users of disposables compared with 17.5% (n = 58) in pod and 18.9% (n = 170) in tank users. Dual use was higher among users of disposables (90.4%, n = 150) than among users of pods (84.0%, n = 278) and tanks (73.0%, n = 658). Daily use of e‐cigarettes was lower among users of disposables (21.1%, n = 35) than among users of pods (34.4%, n = 114) and tanks (47.8%, n = 431).

TABLE 1.

Sample characteristics, stratified by e‐cigarette type (unweighted data).

| Total a (n = 1398) | E‐cigarette type | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disposable (n = 166) | Pod (n = 331) | Tank (n = 901) | ||

| Age (y) | ||||

| 14–17 | 3.2 (45) | 4.8 (8) | 3.9 (13) | 2.7 (24) |

| 18–24 | 16.4 (229) | 22.9 (38) | 13.6 (45) | 16.2 (146) |

| 25–39 | 36.2 (506) | 36.1 (60) | 35.0 (116) | 36.6 (330) |

| 40+ | 44.2 (618) | 36.1 (60) | 47.4 (157) | 44.5 (401) |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 58.7 (820) | 47.0 (78) | 49.2 (163) | 64.3 (579) |

| Female | 41.3 (578) | 53.0 (88) | 50.8 (168) | 35.7 (322) |

| Tobacco smoking status | ||||

| Current smoker | 77.7 (1086) | 90.4 (150) | 84.0 (278) | 73.0 (658) |

| Ex‐smoker | 15.8 (221) | 3.6 (6) | 11.2 (37) | 19.8 (178) |

| Never smoker | 5.5 (77) | 4.8 (8) | 4.8 (16) | 5.9 (53) |

| Starting age of e‐cigarette use (y) | ||||

| 10–13 | 1.0 (14) | 1.8 (3) | 1.2 (4) | 0.8 (7) |

| 14–17 | 7.9 (110) | 13.3 (22) | 10.3 (34) | 6.0 (54) |

| 18–24 | 18.1 (253) | 21.7 (36) | 14.2 (47) | 18.9 (170) |

| 25+ | 65.2 (912) | 47.6 (79) | 66.5 (220) | 68.0 (613) |

| Frequency of vaping during last 30 days | ||||

| Daily | 41.5 (580) | 21.1 (35) | 34.4 (114) | 47.8 (431) |

| Not daily | 55.2 (772) | 71.1 (118) | 61.6 (204) | 49.9 (450) |

| Liquid used per day (mL), median (interquartile range) b | 2.0 (5.7) | 1.4 (5.7) | 0.6 (4.4) | 3.0 (5.3) |

| Nicotine concentration of liquid (mg/mL) c , median (interquartile range) | 4.0 (6.1) | 2.0 (7.8) | 6.0 (6.7) | 4.0 (5.7) |

Note: Unless stated otherwise, data are presented as column percentages (absolute numbers); sum below 100% because of missing values.

Total sample of people who reported current use of disposable, pod or tank e‐cigarettes.

For this variable, only 70.0% of the total sample (n = 1270) could be included. Missing data was because of people responding ‘do not know’ (21.2%), or ‘no response’ (8.8%).

For this variable, only 60.3% of the total sample (n = 1290) could be included in the analysis. Missing data was because of people responding ‘do not know’ (total = 35.9%; in the subgroup of: disposable users = 53.1%, pod user = 53.0%, tank user = 25.8%) or ‘no response’ (total = 3.8%; in the subgroup of: disposable users = 5.0%, pod users = 5.7%, tank users = 2.8%).

Prevalence of e‐cigarette type usage

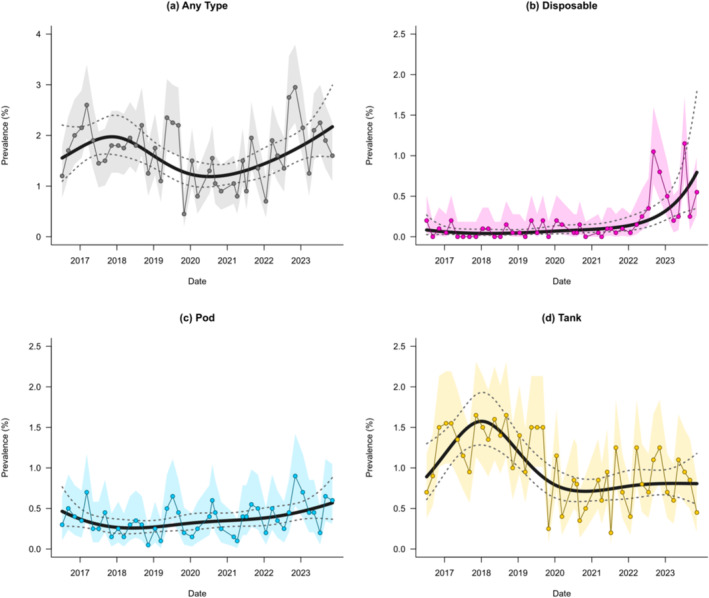

Figure 2 shows the trends in prevalence of e‐cigarette type usage in the total population since 2016 (see Supplement 3 for the results of the comparisons of the spline, linear trend and no trend models). After an initial estimated peak at 2.0% (95% CI = 1.6–2.4) in late 2017, the prevalence decreased until the first half of 2020. Since then, the prevalence has steadily increased, reaching a new estimated high at 2.2% (95% CI = 1.6–3.0) at the end of 2023 (Figure 2(a)). Disposable e‐cigarette usage has slowly increased since the second half of 2020, with a steep rise starting in the first half of 2022, peaking at an estimated 0.8% (95% CI = 0.4–1.8) by the end of 2023 (Figure 2(b)). Pod usage prevalence has steadily increased since 2019, reaching a peak at an estimated 0.6% (95% CI = 0.4–0.9) by the end of 2023 (Figure 2(c)). Tank usage had an estimated peak at 1.6% (95% CI = 1.3–1.9) by the end of 2017, then steeply declined until the second half of 2020, remaining fairly constant at ~0.8% (95% CI = 0.6–1.0) since then (Figure 2(d)).

FIGURE 2.

Trends in prevalence of e‐cigarette type usage in the German population between 2016 and 2023.

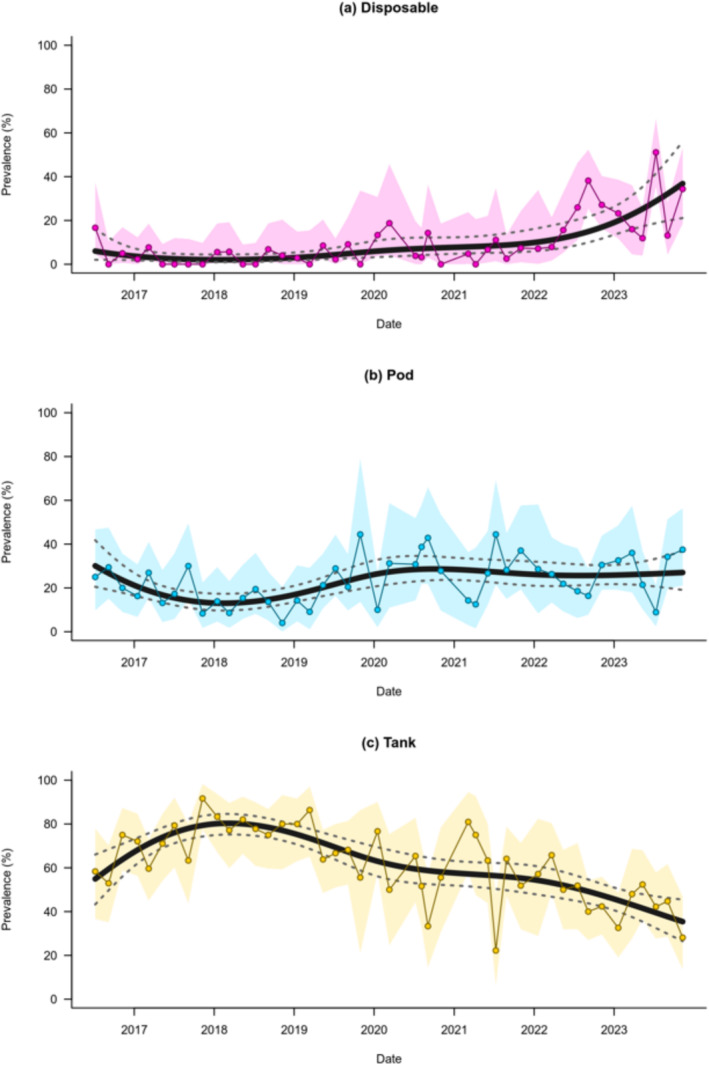

Figure 3 shows the trends in prevalence of e‐cigarette type usage in the subgroup of current e‐cigarette users. Disposable e‐cigarette usage has slowly increased since the second half of 2020, with a steep increase starting in the first half of 2022, reaching an estimated peak at 36.8% (95% CI = 21.1–56.0) by the end of 2023 (Figure 3(a)). Pod usage prevalence decreased from an estimated 30.1% (95% CI = 20.5–41.8) in July 2016 to 13.0% (95% CI = 9.7–17.3) in February 2018, then increased until the first half of 2020 and has remained fairly stable at ~28.0% (95% CI = 22.4–34.4) since then (Figure 3(b)). Tank usage prevalence has steadily decreased from its estimated peak at 80.1% (95% CI = 75.1–84.3) in May 2018 to 35.4% (95% CI = 26.5–45.5) at the end of 2023 (Figure 3(c)).

FIGURE 3.

Trends in prevalence of e‐cigarette type usage in current e‐cigarette user between 2016 and 2023.

Associations of e‐cigarette type with person characteristics

The odds of using tank e‐cigarettes versus disposables were 50% lower among females than among males (OR = 0.50, 95% CI = 0.33–0.74) (Table 2). † Disposable users were on average 4.1 years younger than pod users and 3.5 years younger than tank users (Table 3). This pattern corresponds with the mean age of initiation: users of disposable initiated their use on average 4.9 years earlier than users of pods, and 4.8 years earlier than users of tanks (Table 3). The odds of using tanks versus disposables were 73% lower in smokers (i.e. dual users) than in non‐smokers (OR = 0.27, 95% CI = 0.14–0.52) (Table 2). Additionally, the odds of using tanks versus disposables was more than three times higher among people who used e‐cigarettes daily than among non‐daily users (OR = 3.23, 95% CI = 2.00–5.22). Significant differences were observed in the amount of e‐liquid consumed per day among the three groups, with disposable users consuming on average 5.85 mL e‐liquid per day, which is 2.15 mL more than pod users, but 3.68 mL less than tank users. Regarding nicotine concentration, users of disposables did not differ significantly from users of pods or tanks.

TABLE 2.

Associations of e‐cigarette type with user characteristics—binary outcomes (unweighted data).

| Current e‐cigarette user (n = 1398) a | Test statistic | E‐cigarette type | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pod vs. disposable | Tank vs. disposable | Pod vs. tank | |||

| χ2 | P | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Sex | 31.85 | <0.001 | |||

| Female vs. male | 0.92 (0.59–1.43) | 0.50 (0.33–0.74) | 1.85 (1.36–2.51) | ||

| 30‐day‐use | 41.33 | <0.001 | |||

| Daily vs. not daily | 1.89 (1.12–3.18) | 3.23 (2.00–5.22) | 0.58 (0.42–0.80) | ||

| Use of tobacco | 30.53 | <0.001 | |||

| Dual‐use vs. no dual‐use | 0.49 (0.23–1.02) | 0.27 (0.14–0.52) | 1.84 (1.25–2.72) | ||

| Dual user (n = 1086) b | |||||

| Motivation to stop smoking | 12.38 | 0.002 | |||

| Motivated vs. not motivated | 0.69 (0.40–1.18) | 1.21 (0.75–1.96) | 0.57 (0.39–0.83) | ||

| Attempts to stop smoking c | 5.08 | 0.079 | |||

| At least one attempt vs. no attempt | 1.04 (0.55–1.96) | 1.47 (0.83–2.61) | 0.71 (0.46–1.08) | ||

Note: Logistic mixed‐effects model; bold indicates statistically significant difference; greyed out indicates test statistic (omnibus test) not significant.

Refers to research question 2.

Dual user = subgroup of current e‐cigarette user, who are also current tobacco smoker (refers to research question 3).

Quit attempts in the last 12 months.

TABLE 3.

Associations of e‐cigarette type with user characteristics—continuous outcomes (unweighted data).

| Current e‐cig user (n = 1398) a | Test statistic | E‐cigarette type | Difference in estimated means | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D | P | T | P vs. D | T vs. D | P vs. T | ||||||

| χ2 | P | Estimated mean (95% CI) | Estimated mean (95% CI) | Estimated mean (95% CI) | Dif. | P | Dif. | P | Dif. | P | |

| Age | 9.20 | 0.010 | 35.81 (33.04–38.57) | 39.93 (37.97–41.89) | 39.28 (38.10–40.47) | 4.12 | 0.003 | 3.48 | 0.005 | 0.65 | 0.502 |

| Starting age of e‐cigarette use | 13.23 | 0.001 | 31.24 (28.56–34.17) | 36.17 (34.03–38.44) | 36.03 (34.70–37.41) | 4.93 | 0.005 | 4.79 | <0.001 | −0.14 | <0.001 |

| E‐liquid used per day (in mL) | 54.91 | <0.001 | 5.85 (4.03–8.48) | 3.70 (2.86–4.78) | 9.53 (7.95–11.43) | −2.15 | 0.014 | 3.68 | 0.004 | −5.83 | <0.001 |

| Nicotine concentration (in mg/mL) | 0.63 | 0.729 | 5.80 (4.05–8.15) | 6.12 (4.71–7.83) | 6.43 (5.50–7.49) | 0.32 | 0.744 | 0.31 | 0.478 | −0.31 | 0.632 |

| Dual user (n = 1086) b | |||||||||||

| Time spent with urges to smoke c | 3.49 | 0.175 | 3.18 (2.95–3.40) | 3.39 (3.23–3.55) | 3.30 (3.20–3.41) | 0.21 | 0.063 | 0.13 | 0.222 | 0.08 | 0.280 |

| Strengths of urges to smoke d | 2.13 | 0.344 | 1.99 (1.79–2.18) | 2.09 (1.95–2.24) | 2.00 (1.91–2.09) | 0.11 | 0.278 | 0.01 | 0.907 | 0.10 | 0.165 |

| Cigarettes smoked per day e | 1.70 | 0.427 | 9.54 (8.11–11.21) | 10.50 (9.39–11.74) | 10.47 (9.71–11.29) | 0.96 | 0.240 | 0.93 | 0.210 | 0.03 | 0.954 |

Note: Linear mixed effects model; bold indicates statistically significant difference; greyed out indicates test statistic (omnibus test) not significant.

Abbreviations: D, disposable; P, pod; T, tank.

Refers to research question 2.

Dual user = subgroup of current e‐cigarette user, who are also current tobacco smoker (refers to research question 3).

Time spent with urges to smoke in the last 24 hours ranging from (1) ‘not at all’ to (6) ‘all the time’.

Strength of urges to smoke ranging from (0) ‘none’ to (5) ‘extremely strong’.

Analysed with Poisson mixed‐effects model.

Associations of e‐cigarette type with smoking behaviour

In the subgroup of dual users of e‐cigarettes and tobacco, users of disposables did not differ significantly from users of pods or tanks regarding the number of tobacco cigarettes smoked per day, urges to smoke, attempts to stop smoking in the past year and motivation to stop smoking (Tables 2 and 3).

DISCUSSION

The prevalence of e‐cigarette users in Germany has risen to an estimated 2.2% by the end of 2023. This increase may be driven by the growing popularity of disposable e‐cigarettes, which are now the most commonly used type of e‐cigarette in Germany.

We found that the prevalence of current e‐cigarette use in the German population age 14 years or older averaged 1.6% over the years 2016 to 2023, which is slightly below the European Union average of 2.0% in 2020 [12]. Similar to our findings, evidence from studies conducted in Canada, the United States, the United Kingdom, Europe and China suggests that the prevalence of e‐cigarette use has increased globally over the past decade [15, 16].

The shift we observed in the use of disposable, pod and tank e‐cigarettes in Germany in recent years is similar to trends observed in the United Kingdom. We found that the use of disposable e‐cigarettes has shown a steep increase, particularly since the year 2022, whereas the use of tank types has been declining since 2018 and remained relatively stable over time for pods. In the United Kingdom, 7.2% of e‐cigarette users used disposables and 57.4% tanks in 2021, whereas in 2023, 41.6% used disposables and 33.9% tanks [13]. In the United States between February 2020 and February 2022, sales of disposable e‐cigarettes surged from 2.8 million to 8.8 million units, with the market share escalating from 18.8% to 38.9% [29]. Conversely, the market share of e‐cigarettes with prefilled cartridges decreased from 81.1% to 61.1% during the same period [29].

As in other studies, we also observe a higher prevalence (59%) of male e‐cigarette users in our data [30]. Notably, there is a significant gender difference among users of different e‐cigarette types, with a higher share of males (65%) among tank users and a lower share (47%) among disposable users. Our data, as well as data from a cohort study of 15 to 35‐year‐olds in the United States, indicate an age difference among users of different e‐cigarette types [20]. In line with other studies, there is evidence indicating a significant increase in sales and usage of disposables particularly among younger age groups in the last few years [17, 31, 32]. Users of disposable e‐cigarettes tend to be younger, possibly because of targeted promotion and widespread availability for younger individuals [14, 33, 34, 35]. Regarding the frequency of use in the last 30 days, only one in five users of disposable e‐cigarettes reported daily use, in contrast to pod and tank users, where every second user claimed using them daily. This aligns with other studies reporting non‐daily consumption among users of disposable e‐cigarettes [20, 21]. Disposable e‐cigarettes may be used more frequently on specific occasions, such as going to a club or bar, or when meeting friends.

The proportion of dual user (using both e‐cigarettes and smoked tobacco) was higher among disposable e‐cigarette than tank user. An explanation may be that tank types are more commonly used by individuals attempting and succeeding in smoking cessation, which is indicated by the relatively high percentage of former smokers among tank users (20% compared with 4% among disposable users). A higher prevalence of former smokers among tank users was also found in data from the United Kingdom [13]. A US study on cigarette smoking cessation behaviours in dual users revealed that the type of e‐cigarette used is associated with the intention to quit smoking, with tank users showing a more concrete contemplation of smoking cessation compared to users of disposable e‐cigarettes [36].

Strengths and limitations

Our study has several limitations, starting with a limited sample size because of the relatively low prevalence of e‐cigarette users in Germany. This limits the possibility to assess trends in use of different e‐cigarette types in relevant strata of the population (e.g. in specific age groups). Conducting a more fine‐grained, year‐by‐year analysis was not possible because of the limited sample size (~180 current vapers per year) and was not the primary focus of our paper. Second, the classification of devices into three broad types (disposable, pod and tank) is broad and not accurately reflects the technical diversity of e‐cigarettes from 2016 to 2023. We potentially underestimated the absolute prevalence of each type, because it is likely that people use different types of e‐cigarettes at the same time or at different time points. Hence, our study did not reflect the complete evolution of usage of different e‐cigarette types across time. Third, social desirability bias may have led to underreporting of vaping, particularly among young people, given the legal restrictions on vaping for those under 18. Fourth, the aggregated analysis spanning 2016 to 2023 provides a broad overview, but person characteristics and associations may have changed over time. Fifth, statements about the average nicotine concentration should be interpreted with caution, because there was great uncertainty among respondents (e.g. 50% of disposable and pod users did not know the concentration of their products). Finally, unit values from disposable and pod users were converted to a comparable mL unit for tank users, introducing approximation and potential variation from actual values.

Strengths of this study include the use of nationally representative samples and nearly 8 years of bi‐monthly data collection, providing a substantial data set for exploring changes over time. The detailed data collection on various e‐cigarette types (disposable, pod and tank) and multiple factors related to e‐cigarette and tobacco consumption, as well as socio‐economic and socio‐demographic factors, allows for a nuanced exploration of e‐cigarette use in Germany. Additionally, the use of face‐to‐face interviews minimizes missing data, and visual aids help respondents clearly distinguish between different types, enhancing the reliability of the findings.

CONCLUSION

The use of e‐cigarettes has increased in Germany in recent years especially that of disposable e‐cigarettes, which are now the most commonly used type with a prevalence of 0.8%. This trend should be continuously monitored, particularly because disposable e‐cigarettes are the type primarily consumed by younger people. However, the use of e‐cigarettes is much lower compared to the use of tobacco (prevalence rate ~30%), despite its potential for smoking cessation.

Police options such as banning flavours that are particularly attractive to adolescents, imposing higher taxes on disposable e‐cigarettes and restricting the sale of e‐cigarettes to licensed stores are needed to limit consumption, especially among younger people. For future research, it is recommended to conduct qualitative interviews as they can offer valuable insights into the consumption motives of various e‐cigarette user types, contributing to a more comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon. Additionally, investigating the reasons behind the lack of knowledge regarding nicotine concentration among users of disposables and tanks could provide further clarity and inform targeted educational interventions.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Stephanie Klosterhalfen: Coordinates the study, co‐analysed and interpreted the data and drafted and co‐visualized the manuscript. Wolfgang Viechtbauer: Analysed and co‐interpreted the data and co‐visualized the manuscript. Daniel Kotz: Conceived the study, contributed to the study design, co‐interpreted the data and contriubted to the writing of the manuscript.

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

None to declare.

Supporting information

Figure S1: Prevalence and trend of current tobacco smoking in the German population between 2016 and –‐2023.

Figure S2: E‐cigarette regulation in Germany.

Table S1: P‐values for model comparisons.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We extend our appreciation to the market research institute Cerner Enviza (an Oracle company) for their contribution to data collection, with special acknowledgment to Constanze Cholmakow‐Bodechtel and Marvin Krämer. Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Klosterhalfen S, Viechtbauer W, Kotz D. Disposable e‐cigarettes: Prevalence of use in Germany from 2016 to 2023 and associated user characteristics. Addiction. 2025;120(3):557–567. 10.1111/add.16675

Funding information The DEBRA study was funded from 2016 to 2019 (waves 1‐18) by the Ministry of Innovation, Science and Research of the German State of North Rhine–Westphalia (MIWF) in the context of the “NRW Rückkehrprogramm” (the North Rhine–Westphalian postdoc return program). Since 2019 (wave 19 onward), the study has been funded by the German Federal Ministry of Health.

Clinical trial registration details: German Clinical Trials Register (registration numbers DRKS00011322, DRKS00017157 and DRKS00028054).

Footnotes

Based on the request of the Statistics and Methodology Editor, we have rerun analyses 2 and 3 including crossed random effects for state (16 levels) and “BIK region” (10 levels). None of the conclusions have changed. The output of the analyses can be viewed at: https://osf.io/q7xts.

Equivalently, it could also be stated that “The odds of being female were 50% lower among users of tank e‐cigarettes compared to users of disposables”. However, for linguistic reasons, we have chosen the wording as used in the text.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Schaller K, Kahnert S, Graen L, Mons U, Ouédraogo N. Tobacco Atlas [Tabakatlas] Deutschland 2020 [Internet]. 1. Auflage. Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum, editor Lengerich: Pabst Science Publishers; 2020. Retrieved 01.12.2022 from: https://www.dkfz.de/de/tabakkontrolle/download/Publikationen/sonstVeroeffentlichungen/Tabakatlas-Deutschland-2020_dp.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Krüsemann EJZ, Boesveldt S, de Graaf K, Talhout R. An E‐liquid flavor wheel: a shared vocabulary based on systematically reviewing E‐liquid flavor classifications in literature. Nicotine Tob Res. 2019;21(10):1310–1319. 10.1093/ntr/nty101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. National Academies of science engineering and medicine (NASEM) . Public health consequences of E‐cigarettes Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) . E‐cigarette, or vaping, products visual dictionary [Internet] U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2019. Retrieved 02.10.2023 from: https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/pdfs/ecigarette-or-vaping-products-visual-dictionary-508.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 5. McNeill A, Simonavicius E, Brose L, Taylor E, East K, Zuikova E, et al. Nicotine vaping in England: an evidence update including health risks and perceptions, September 2022 [internet] London: Office for Health Improvement and Disparities; 2022. p. 1468 Retrieved 20.04.2024 from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1107701/Nicotine-vaping-in-England-2022-report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nasr SZ, Nasrallah AI, Abdulghani M, Sweet SC. The impact of conventional and nonconventional inhalants on children and adolescents. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2018;53(4):391–399. 10.1002/ppul.23836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bundesinstitut für Risikobewertung . E‐cigarettes – anything but harmless [E‐Zigaretten ‐ alles andere als harmlos] [Internet]. Retrieved 28.10.2023 from: https://www.bfr.bund.de/cm/343/e-zigaretten-alles-andere-als-harmlos.pdf

- 8. George J, Hussain M, Vadiveloo T, Ireland S, Hopkinson P, Struthers AD, et al. Cardiovascular effects of switching from tobacco cigarettes to electronic cigarettes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74(25):3112–3120. 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.09.067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Martínez Ú, Martínez‐Loredo V, Simmons VN, Meltzer LR, Drobes DJ, Brandon KO, et al. How does smoking and nicotine dependence change after onset of vaping? A retrospective analysis of dual users. Nicotine Tob Res. 2020;22(5):764–770. 10.1093/ntr/ntz043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cornelius ME, Wang TW, Jamal A, Loretan CG, Neff LJ. Tobacco product use among adults — United States, 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(46):1736–1742. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6946a4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. East KA, Reid JL, Hammond D. Smoking and vaping among Canadian youth and adults in 2017 and 2019. Tob Control. 2023;32(2):259–262. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2021-056605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Eurobarameter . Special Eurpobarameter 506 Attitude of Europeans towards tobacco and electronic cigarettes [Internet]. 2021. Retrieved 01.10.2022 from: https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/2240 [Google Scholar]

- 13. Smoking in England [Internet] . The smoking toolkit study ‐ Prevalence of e‐cigarette and heated tobacco product use. Retrieved 09.11.2023 from: https://smokinginengland.info/graphs/e-cigarettes-latest-trends [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wang TW, Gentzke AS, Creamer MR, Cullen KA, Holder‐Hayes E, Sawdey MD, et al. Tobacco product use and associated factors among middle and high school students — United States, 2019. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2019;68(12):1–22. 10.15585/mmwr.ss6812a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Xiao L, Yin X, Di X, Nan Y, Lyu T, Wu Y, et al. Awareness and prevalence of e‐cigarette use among Chinese adults: policy implications. Tob Control. 2022;31(4):498–504. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2020-056114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lyzwinski LN, Naslund JA, Miller CJ, Eisenberg MJ. Global youth vaping and respiratory health: epidemiology, interventions, and policies. Npj Prim Care Respir Med. 2022;32(1):14. 10.1038/s41533-022-00277-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wang TW, Neff LJ, Park‐Lee E, Ren C, Cullen KA, King BA. E‐cigarette use among middle and high school students — United States, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(37):1310–1312. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6937e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gentzke AS, Wang TW, Cornelius M, Park‐Lee E, Ren C, Sawdey MD, et al. Tobacco product use and associated factors among middle and high school students — National Youth Tobacco Survey, United States, 2021. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2022;71(5):1–29. 10.15585/mmwr.ss7105a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hammond D, Reid J, Burkhalter R, Hong D. Trends in smoking and vaping among young people: findings from the ITC youth survey [internet] University of Waterloo; 2023. Retrieved 01.02.2024 from: https://davidhammond.ca/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/2023-ITC-Youth-Report-Final.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Do EK, Aarvig K, Donovan EM, Barrington‐Trimis JL, Vallone DM, Hair EC. E‐cigarette device type, source, and use behaviors of youth and young adults: findings from the truth longitudinal cohort (2020–2021). Subst Use Misuse. 2023;58(6):796–803. 10.1080/10826084.2023.2188555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Galimov A, Leventhal A, Meza L, Unger JB, Huh J, Baezconde‐Garbanati L, et al. Prevalence of disposable pod use and consumer preference for e‐cigarette product characteristics among vape shop customers in Southern California: a cross‐sectional study. BMJ Open. 2021;11(10):e049604. 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-049604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tackett AP, Hébert ET, Smith CE, Wallace SW, Barrington‐Trimis JL, Norris JE, et al. Youth use of e‐cigarettes: does dependence vary by device type? Addict Behav. 2021;119:106918. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2021.106918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Orth B, Merkel C. Substance use among adolescents and young adults in Germany. Results of the 2021 Alcohol Survey on alcohol, smoking, cannabis, and trends. BZgA Research Report [Der Substanzkonsum Jugendlicher und junger Erwachsener in Deutschland. Ergebnisse des Alkoholsurveys 2021 zu Alkohol, Rauchen, Cannabis und Trends. BZgA‐Forschungsbericht] [Internet]. 2022. Retrieved 04.03.2024 from: https://www.bzga.de/forschung/studien/abgeschlossene-studien/studien-ab-1997/suchtpraevention/der-substanzkonsum-jugendlicher-und-junger-erwachsener-in-deutschland/ [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kastaun S, Brown J, Brose LS, Ratschen E, Raupach T, Nowak D, et al. Study protocol of the German study on tobacco use (DEBRA): a national household survey of smoking behaviour and cessation. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):378. 10.1186/s12889-017-4328-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kotz D, Brown J, West R. Predictive validity of the motivation to stop scale (MTSS): a single‐item measure of motivation to stop smoking. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;128(1–2):15–19. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.07.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pashutina Y, Kastaun S, Ratschen E, Shahab L, Kotz D. External validation of a single‐item scale to measure motivation to quit smoking: results of a representative population survey (DEBRA study) [Externe Validierung einer single‐item Skala zur Erfassung der motivation zum Rauchstopp: Ergebnisse einer repräsentativen Bevölkerungsbefragung (DEBRA Studie)]. SUCHT. 2021;67(4):171–180. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fidler JA, Shahab L, West R. Strength of urges to smoke as a measure of severity of cigarette dependence: comparison with the Fagerström test for nicotine dependence and its components. Addiction. 2011;106(3):631–638. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03226.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gromping U. A note on fitting a marginal model to mixed effects log‐linear regression data via GEE. Biometrics. 1996;52(1):280–285. 10.2307/2533162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Foundation (CDC) . Monitoring U. S E‐Cigarette Sales: National Trend [Internet]. 2022. Retrieved 23.01.2024 from: https://www.cdcfoundation.org/National-E-CigaretteSales-DataBrief-2022-Feb20?inline [Google Scholar]

- 30. Surís JC, Berchtold A, Akre C. Reasons to use e‐cigarettes and associations with other substances among adolescents in Switzerland. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;153:140–144. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.05.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Park‐Lee E, Ren C, Sawdey MD, Gentzke AS, Cornelius M, Jamal A, et al. Notes from the field: E‐cigarette use among middle and high school students — National Youth Tobacco Survey, United States, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(39):1387–1389. 10.15585/mmwr.mm7039a4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Leventhal AM, Dai H, Barrington‐Trimis JL, Tackett AP, Pedersen ER, Tran DD. Disposable E‐cigarette use prevalence, correlates, and associations with previous tobacco product use in young adults. Nicotine Tob Res. 2022;24(3):372–379. 10.1093/ntr/ntab165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Smith MJ, Buckton C, Patterson C, Hilton S. User‐generated content and influencer marketing involving e‐cigarettes on social media: a scoping review and content analysis of YouTube and Instagram. BMC Public Health. 2023;23(1):530. 10.1186/s12889-023-15389-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Padon AA, Lochbuehler K, Maloney EK, Cappella JN. A randomized trial of the effect of youth appealing E‐cigarette advertising on susceptibility to use E‐cigarettes among youth. Nicotine Tob Res. 2018;20(8):954–961. 10.1093/ntr/ntx155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Collins L, Glasser AM, Abudayyeh H, Pearson JL, Villanti AC. E‐cigarette marketing and communication: how E‐cigarette companies market E‐cigarettes and the public engages with E‐cigarette information. Nicotine Tob Res. 2019;21(1):14–24. 10.1093/ntr/ntx284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zavala‐Arciniega L, Hirschtick JL, Meza R, Fleischer NL. E‐cigarette characteristics and cigarette smoking cessation behaviors among U.S. Adult dual users of cigarettes and e‐cigarettes. Prev Med Rep. 2022;26:101748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1: Prevalence and trend of current tobacco smoking in the German population between 2016 and –‐2023.

Figure S2: E‐cigarette regulation in Germany.

Table S1: P‐values for model comparisons.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.