Abstract

Colic and diarrhea are common gastrointestinal (GI) disorders in captive Asian elephants, which can severely impact health and lead to mortality. Gut dysbiosis, indicated by alterations in gut microbiome composition, can be observed in individuals with GI disorders. However, changes in gut microbial profiles of elephants with GI disorders have never been investigated. Thus, this study aimed to elucidate the profiles of gut microbiota in captive elephants with different GI symptoms. Fecal samples were collected from eighteen elephants in Chiang Mai, Thailand, including seven healthy individuals, seven with impaction colic, and four with diarrhea. The samples were subjected to DNA extraction and amplification targeting the V3-V4 region of 16S rRNA gene for next-generation sequencing analysis. Elephants with GI symptoms exhibited a decreased microbial stability, as characterized by a significant reduction in microbiota diversity within individual guts and notable differences in microbial community composition when compared with healthy elephants. These changes included a decrease in the relative abundance of specific bacterial taxa, in elephants with GI symptoms such as a reduction in genera Rubrobacter, Rokubacteria, UBA1819, Nitrospira, and MND1. Conversely, an increase in genera Lysinibacillus, Bacteroidetes_BD2-2, and the family Marinifilaceae was observed when, compared with the healthy group. Variations in taxa of gut microbiota among elephants with GI disorders indicated diverse microbial characteristics associated with different GI symptoms. This study suggests that exploring gut microbiota dynamics in elephant health and GI disorders can lead to a better understanding of food and water management for maintaining a healthy gut and ensuring the longevity of the elephants.

Keywords: Gut microbiome, Elephants, Captive, Gastrointestinal disorder, Colic, Diarrhea

Subject terms: Microbiology, Molecular biology, Zoology, Health care

Introduction

The gut microbiota, which comprises of millions of microorganisms, plays a crucial and central role in various functions within the host. Gut microbiota maintain the integrity of intestinal-endothelial cell barrier, regulate host immune nutrient metabolism, modulate the immune system, and provide defense against pathogens1,2. An imbalance in microbiome homeostasis may arise from alterations in the relative abundance of microorganisms due to certain diseases, leading to changes in the microbiome composition, a condition referred to as dysbiosis3,4. Gastrointestinal (GI) disorders are the most common symptoms found in elephants, and these disorders can be significant and life threatening for animals. According to reports from the National Elephant Institute in Thailand, GI disorders showed a prevalence of 25%5, while those in the Myanmar Timber Enterprise in Myanmar reported an 18.9% incidence rate6. These disorders accounted for 9.8% of overall causes of death in Asian Elephants (Elephas maximus)7.

Colic and diarrhea are common GI symptoms in elephants and can be life-threatening for these animals. Both conditions can present as acute or subacute clinical signs and can be caused by either infection or non-infection factors. Suspected causes of GI discomfort include dietary changes (especially the source of hay), eating novel food items, ingestion of sand and/or rocks, and decreased exercise8. Colic is a broad clinical term that refers to abdominal pain with associated clinical signs such as restlessness, stretching, rolling, and abdominal distension9. This condition can be classified into two types: spasmodic colic and obstructive colic. Spasmodic colic describes a condition where bowel becomes overactive, leading to spasms. In horses, this condition has often been linked to intestinal tapeworm infestation10. Fortunately, spasmodic colic can usually be effectively managed with pain relief and antispasmodic medication11. On the other hand, obstructive colic results from intestinal tract obstruction, often induced by feed impaction, dental problems and/or inadequate chewing12, as well as and or foreign body ingestion13, which impedes normal passage through the intestinal tract. In their natural habitats, impaction colic may be attributed to heavy intestinal helminth infestations14,15. Diarrhea is characterized by loose, watery stools during bowel movements and is closely associated with an altered composition of gut microbiota. In humans and animals, diarrhea often occurs with disruptions in gut microbiota, and infections can also trigger diarrhea16,17. Infection-related diarrhea in elephants is caused by various factors, including bacteria such as Salmonella18, Clostridium19,20, and Escherichia21; protozoa such as Balantidium coli22; and viruses such as elephant endotheliotropic herpesvirus (EEHV)23. These infections can cause enteritis, resulting in inflammation of the intestines. This inflammation leads to severe symptoms such as diarrhea, dehydration, electrolyte disturbance, and metabolic acidosis, potentially resulting in death if prompt treatment was not performed24.

Metagenomics serves as a crucial tool for studying alterations in the gut microbiota in the context of diseases. Previous studies indicated a correlation between changes in specific bacterial groups, which were crucial for maintaining a healthy GI tract, and the occurrence of colic and diarrhea in equines25–27. However, there is limited information available about the gut microbiota of elephants, and even fewer studies have explored its composition and structure under different GI health conditions. Therefore, the goal of this study is to examine and compare the gut microbial composition in healthy elephants and those with GI symptoms, with the goal of filling the gap in understanding the elephant gut microbiota and providing insights into its role in GI health and disease.

Results

Analysis of microbial diversity in healthy elephants and elephants with GI symptoms

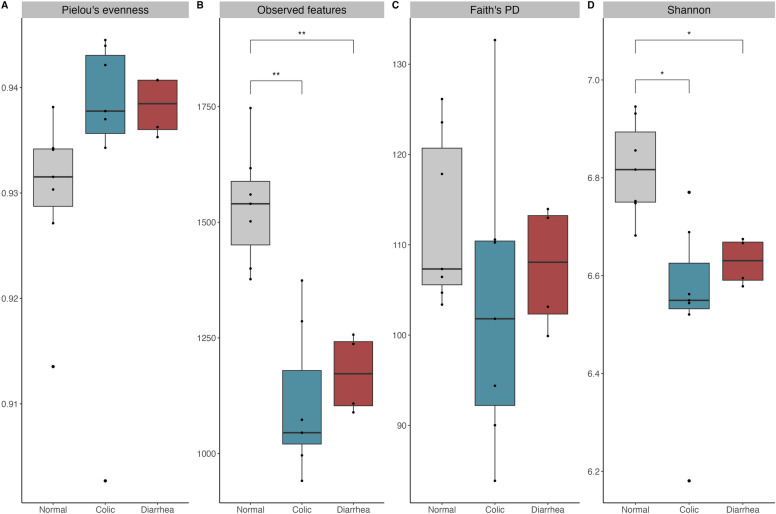

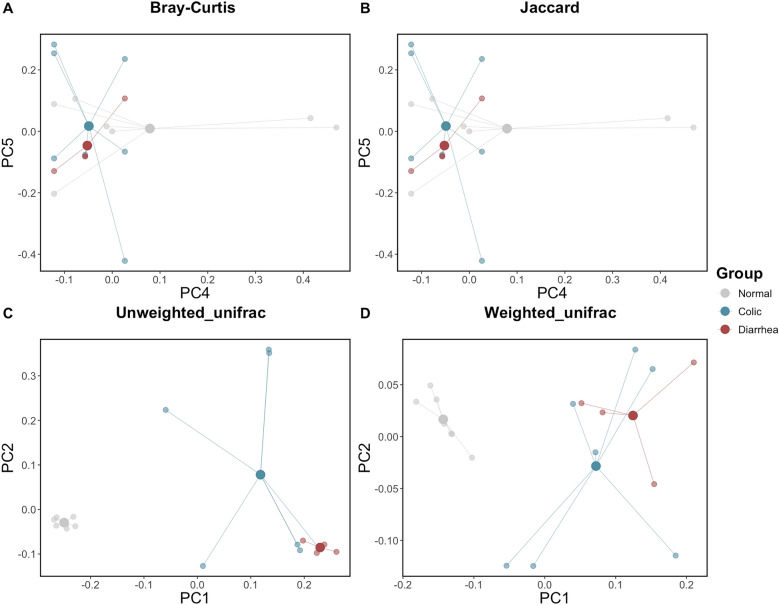

The differences in alpha diversity between gut microbiota of healthy elephants and those experiencing GI disorders (i.e. colic and diarrhea) were examined using of Pielou’s evenness, Observed features, Faith’s PD, and Shannon’s index to estimate species richness and evenness (Fig. 1). Alpha diversity, measured by Observed features and Shannon’s index, was significantly lower in elephants with colic and diarrhea than in healthy elephants (q < 0.05), with comparisons of colic and healthy yielding adjusted p-values of 0.006 and 0.01, respectively, and comparisons of diarrhea and healthy yielding adjusted p-values of 0.009 and 0.01, respectively (Fig. 1B,D, Supplementary Table 1). Meanwhile, alpha diversity analyses, including Pielou’s evenness (Fig. 1A) and Faith’s PD (Fig. 1C), showed no significant differences among the health groups. These findings suggested that GI disorders in elephants have an impact on the alpha diversity of their gut microbiota. In contrast, there was no difference in alpha diversity between elephants with colic and those with diarrhea. The compositional similarities of gut microbiota among distinct groups were assessed through beta diversity and represented via principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) plots, using of Bray–Curtis, Jaccard, Unweighted UniFrac, and Weighted UniFrac (Fig. 2). The Bray–Curtis (Fig. 2A) and Jaccard (Fig. 2B) analyses indicated no statistically significant differences in gut microbiota composition between healthy elephants and those with GI disorders. However, both Unweighted (Fig. 2C) and Weighted UniFrac (Fig. 2D) analyses revealed a statistically significant distinction between these groups, with a q-value < 0.05 in the pairwise PERMANOVA test. Specifically, comparisons of normal and colic yielding q-values of 0.003 and 0.003, respectively, and comparisons of normal and diarrhea yielding q-values of 0.006 and 0.003, respectively (Supplementary Table 2).

Fig. 1.

Alpha diversity of gut microbiota of captive infant Asian elephants categorized by GI status. Alpha diversity with (A) Pielou’s evenness, (B) Observed features, (C) Faith’s PD, (D) Shannon’s index, by Kruskal–Wallis test with significance threshold of * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01.

Fig. 2.

Beta diversity of gut microbiota of infant captive elephants in Northern Thailand categorized GI status. Beta diversity including (A) Bray–Curtis, (B) Jaccard, (C) Unweighted UniFra, and (D) Weighted UniFrac.

Composition analysis of the gut microbial community in healthy elephants and elephants with GI symptoms

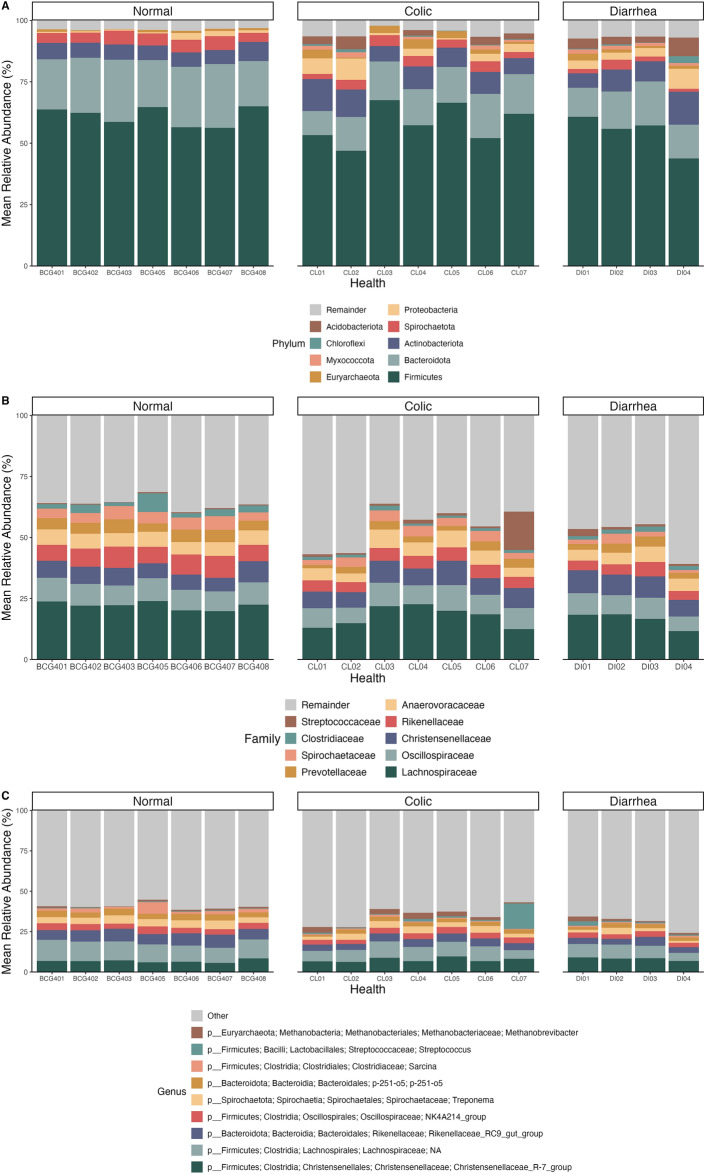

The taxonomy of gut microbiota was determined based on the data from the hypervariable region V3-V4 of the 16S rRNA gene. A total of forty-one phyla and 792 genera of gut microflora were identified within the complete set of elephant fecal samples, and specific details regarding the phyla, families and genera were described in Table 1. The relative abundance of gut microbiota at the phylum, family, and genus levels across all age groups is presented in Fig. 3.

Table 1.

The abundance of elephant gut microbiota at the phylum, family, and genus levels, categorized by health condition.

| Group | Phylum | Family | Genus |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | 19 | 99 | 191 |

| Colic | 27 | 162 | 262 |

| Diarrhea | 34 | 186 | 302 |

Fig. 3.

Comparison of the relative abundance of elephant gut microbiota at the (A) phylum, (B) family, and (C) genus levels. Elephants categorized by GI status included normal elephants, elephants with colic, and elephants with diarrhea.

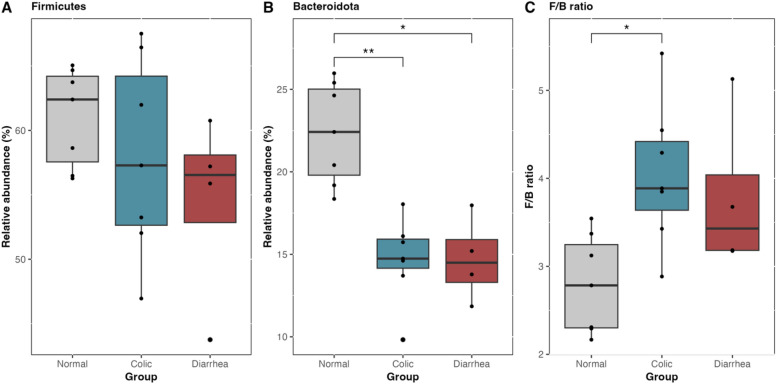

Compositional analysis revealed that the gut microbiota of healthy elephants was predominantly composed of the phylum Firmicutes (61%), followed by Bacteroidota (22%), Actinobacteria (6%), Spirochaetota (4.7%), Proteobacteria (1%), and Euryarchaeota (0.7%), in descending order of abundance (Fig. 3A). Elephants with GI symptoms exhibited a gut microbiota composition predominantly dominated by Firmicutes (57% in colic cases and 54% in diarrhea cases) (Fig. 4A), accompanied by a significant reduction in the relative abundance of Bacteroidota, which was 14% in both colic and diarrhea groups (Fig. 4B). Accordingly, the Firmicutes/Bacteroidota (F/B) ratio in elephants afflicted with GI disorders increased to 4.04 ± 0.815 and 3.79 ± 0.922 for colic and diarrhea, respectively. Notably, the F/B ratio in elephants with colic was significantly higher than that in healthy elephants, which had a ratio of 2.79 ± 0.560 (p < 0.01) (Fig. 4C). Moreover, increases in the abundances of Proteobacteria and Acidobacteriota, and the emergence of Euryarchaeota were observed, alongside the presence of Myxococcota and Chloroflexi, in elephants afflicted with GI disorders (Fig. 3A). A comprehensive list of relative abundances is provided in Supplementary Table 3.

Fig. 4.

The number of relative abundance (%) of major gut microbiota phyla: (A) Firmicutes, (B) Bacteroidota, and (C) Firmicutes to Bacteroidota (F/B) ratio, compared among health status groups by Kruskal–Wallis test with significance threshold of * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01.

In elephants with normal GI health, the gut microbiota was predominantly composed of families such as Lachnospiraceae, Oscillospiraceae, Rikenellaceae, Christensenellaceae, Anaerovoracaceae, Prevotellaceae, Spirochaetaceae, Clostridiaceae, and Streptococcaceae. However, in elephants experiencing GI disorders, the relative abundance of these families varied significantly across individuals, indicating fluctuations in microbial composition associated with GI disturbances (Fig. 3B). At the genus level, Christensenellaceae_R-7_group, an unidentified genus of the family Lachnospiraceae, Rikenellaceae_RC9_gut_group, NK4A214_group of family Oscillospiraceae, Treponema, p-251-o5 of order Bacteroidales, Sarcina, and Methanobrevibacter were predominant in the gut microbiota composition of healthy elephants (Fig. 3C). Meanwhile, elephants with GI problems showed a decrease in these genera proportion but exhibited increase in the abundance Methanobrevibacter (Fig. 3C). Interestingly, in one elephant afflicted with colic, there was a noticeable increase in the Streptococcus genus from the Streptococcaceae family (Fig. 3B,C).

Elephants with GI disorders exhibited a markedly distinct composition of gut microbiota in comparison to healthy elephants

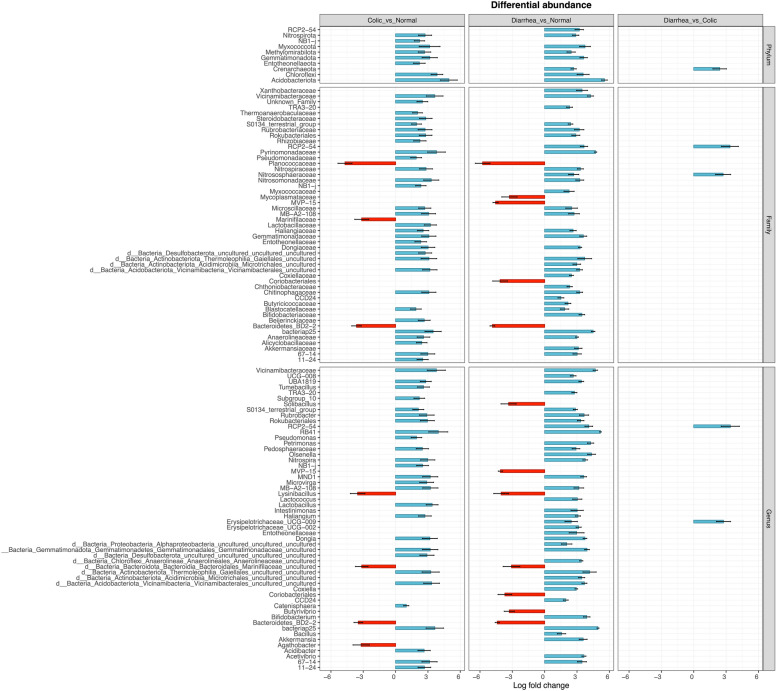

Differential abundance analyses were carried out employing the Analysis of Composition of Microbiomes with Bias Correction (ANCOM-BC) method to ascertain phyla, families, and genera exhibiting notable differences in abundance across varying health statuses. The results detailing significantly disparate taxa at each level of fecal microbiota are illustrated in Fig. 5, whereas exhaustive information regarding all statistically significant taxa is available in Supplementary Table 4. Normal GI elephants were utilized as the reference group for comparison.

Fig. 5.

The differential abundance of gut microbiota of captive elephants categorized by their GI status: normal elephants, elephants experiencing colic, and elephants suffering from diarrhea. The data are presented through Log fold change, with healthy elephants serving as the reference group. Only log fold changes exceeding 0.5 are visualized in this figure. Full lists of significant differential abundances are provided in Supplementary Table 4.

In elephants afflicted with GI disorders, the abundances of the phyla Nitrospirota, Myxococcota, Methylomirabilota, Gemmatimonadota, Chloroflexi, and Acidobacteriota were lower than those observed in elephants with healthy GI tracts. Additionally, the abundances of the phyla NB1-j and Entotheonellaeota decreased only in elephants that experienced colic, whereas those of the phyla RCP2-54 and Crenarchaeota were notably lower only in elephants afflicted with diarrhea than in those with normal GI function (Fig. 5).

Taxa from the families including Vicinamibacteraceae, S0134_terrestrial_group, Rubrobacteriaceae, Rokubacteriales, Pyrinomonadaceae, Nitrospiraceae, Nitrosomonadaceae, Microscillaceae, MB-A2-108, Haliangiaceae, Gemmatimonadaceae, Dongiaceae, uncultured taxa of order Gaiellales, uncultured taxa of order Vicinamibacterales, Chitinophagaceae, Blastocatellaceae, bacteriap25, Anaerolineaceae, and 67–14 of order Solirubrobacterales presented lower abundances in elephants suffering from GI disorders. Conversely, the abundances of the families Planococcaceae and Bacteroidetes_BD2-2 in elephants with GI symptoms were greater than those in elephants with normal GI health (Fig. 5).

At the genus level, Vicinamibacteraceae, UBA1819, S0134_terrestrial_group, Rubrobacter, Rokubacteriales, RB41, Pedosphaeraceae, Nitrospira, MND1, MB-A2-108, Haliangium, Dongia, uncultured taxa of the families Gemmatimonadaceae, uncultured of the order Vicinamibacterales, bacteriap25, and 67-14 of the order Solirubrobacterales presented a decreased abundance in elephants with GI symptoms compared to those with healthy GI tracts. In contrast, taxa from the genera including Lysinibacillus of the family Planococcaceae, uncultured taxa of the family Marinifilaceae, and Bacteroidetes_BD2 - 2 of the family Bacteroidetes_BD2 - 2 in elephants afflicted with GI disorders were found to be more abundant in elephants afflicted with GI disorders than in their healthy counterparts. Moreover, the genus Agathobacter was more abundant solely in elephants suffering from colic, whereas the genera Solibacillus, MVP-15, Coriobacteriales, and Butyrivibrio were significantly more abundant only in elephants with diarrhea than in those with healthy GI tracts (Fig. 5).

Noticeable variations in gut microbiota composition were noted between individuals presenting with colic and those presenting with diarrhea. Specifically, elephants that experienced diarrhea presented a decrease abundance of phylum Crenarchaeota, the families Pyrinomonadaceae and Nitrososphaeraceae, as well as the genera Rokubacteriales and Erysipelotrichaceae_UCG-009, compared with elephants that experienced colic (Fig. 5).

Prediction functions of elephant gut microbiota in healthy elephants and elephants with GI symptoms

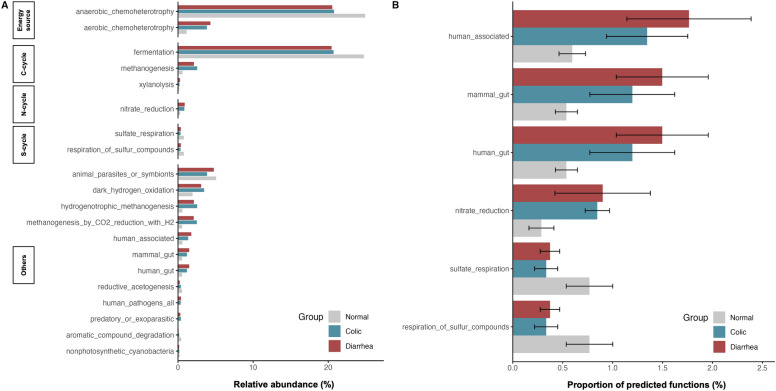

Functional Annotation of Prokaryotic Taxa (FAPROTAX) was employed to investigate the metabolic functions of microbial communities based on their taxonomic composition. This analysis provided insights into how shifts in microbial communities are associated with GI disorders in elephants. The gut microbiota in elephants primarily engaged in anaerobic chemoheterotrophy and fermentation processes (Fig. 6A).

Fig. 6.

Barplot of predicted microbial functions derived from the FAPROTAX database. (A) Relative abundance (%) of the top 20 predicted functional categories. (B) Predicted functional categories presenting mean values and error bars representing standard error (SE). Statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) were determined using one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction.

Significant differences were observed in the predicted functional categories among the normal, colic, and diarrhea elephants. Elephants with GI disorders showed an increase in functions related to human gut function, human-associated functions, and mammalian gut functions compared to healthy elephants. This finding suggests a potential enrichment of pathogenic or dysbiotic taxa in these groups. Conversely, functions related to sulfate respiration and the metabolism of sulfur compounds were significantly reduced in the colic and diarrhea groups compared to the healthy elephants, indicating a disruption in sulfur metabolism under diseased conditions (Fig. 6B). This suggests that acute GI symptoms can significantly impact the functional profile of elephants’ gut microbiota.

Discussion

Recent advances in metagenomics have brought significant attention to the investigation of the gut microbiota in Asian elephants. Previous studies have highlighted a strong association between GI disorders and alterations in gut microbiota in both humans and horses28–30. Our study is the first to characterize and compare the gut microbiota composition in healthy Asian elephants and those afflicted with colic and diarrhea, utilizing high-throughput sequencing to analyze the fecal microbiome. We found that the bacterial community structures in elephants with GI disorders differed significantly from those in healthy elephants. Healthy elephants presented a relatively uniform bacterial composition, suggesting a balanced microbial community in the intestines. However, elephants with GI disorders presented changes in the abundance of certain bacterial species. Additionally, noticeable variations in gut microbiota were observed between elephants suffering from impaction colic and those suffering from diarrhea. Specifically, elephants with GI symptoms exhibited reduced gut bacterial diversity, with lower species richness and variable evenness compared to healthy elephants.

As expected, elephants with GI disorders presented a prompt decrease in alpha diversity in their microbiota compared with those with normal GI function. Additionally, significant differences were observed in phylogenetic relationships and the relative abundances of microbial species in the guts of elephants with GI symptoms compared with healthy elephants, as indicated by both the Unweighted and Weighted UniFrac measures. These findings suggest a less diverse and potentially less healthy gut microbiota in elephants with GI symptoms, similar to the findings from prior research on captive elephants with colic31. The reduction in diversity might result in dysbiosis, characterized by an imbalance in gut microbiome composition32,33. The factors that influenced these changes vary depending on the specific disease context. Similar reductions in gut microbiota diversity were observed in humans with GI disorders such as acute diarrheal disease34, and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)35. Interestingly, a study by Keady, et al.36 revealed that captive African elephants with recent GI disorders exhibit lower bacterial richness compared to those without, a pattern not observed in Asian elephants. The shorter GI tract of African elephants may contribute to a higher sensitivity to dietary changes37,38 and a greater predisposition to IG issues, supporting observations that GI discomfort is more common in captive African elephants36. In equines, which share anatomical similarities in their GI tracts with elephants, a previous study demonstrated lower alpha diversity in diarrheic horses than in their healthy counterparts27. However, study by Costa, et al.39, suggested that equine colitis might not be consistently correlated with decreased diversity and richness. Changes in the abundance of specific bacterial groups within the gut microbiota of horses experiencing colic and diarrhea highlighted their critical role in maintaining GI health9,40–42.

The gut microbiota of elephants with normal GI function was primarily composed of phylum Firmicutes, followed by Bacteroidota, Actinobacteriota, and Spirochaetota, respectively. In this study, elephants that succumbed to colic and diarrhea exhibited reduced levels of the Bacteroidota phylum compared to healthy elephants, leading to an increase of F/B ratio in afflicted elephants. The phylum Bacteroidota is widely acknowledged as a predominant component of the healthy GI tract in humans43 and various mammalian species44,45. Therefore, a decrease in its relative abundance has been associated with chronic diarrhea in humans46. The F/B ratio is widely recognized as an indicator of intestinal equilibrium. An elevation or decrease in the F/B ratio indicates dysbiosis, commonly associated with obesity and IBD in humans47,48. Additionally, an increased F/B ratio has been reported in herbivorous animals, such as horses with hindgut fermentation, where those with intestinal diseases showed higher ratios compared to healthy horses49. However, relying solely on the F/B ratio for disease assessment is considered inadequate due to its inconsistent and limited systematic changes.

Recent studies found that the gut microbiota of captive and wild Asian elephants predominantly harbors hemicellulose-degrading hydrolases rather than cellulose-degrading ones, indicating a potential source of novel, efficient lignocellulose-degrading enzymes50,51. However, elephants with colic and diarrhea experience disruptions in the delicate balance of commensal microorganisms in the GI tract. Specifically, Rubrobacter spp., associated with lignin degradation52, were less abundant in symptomatic elephants, further reflecting the impact of GI disorders on microbial composition. Rokubacteria spp., non-methanotrophic bacteria positively correlated with pH and total nitrogen content53, were less abundant in symptomatic elephants compared to those with healthy GI tracts. Elephants with GI symptoms also showed a reduction in UBA1819 spp., butyrate-producing bacteria from the family Ruminococcaceae54,55 which are important for gut motility by stimulating the release of gut hormones such as glucagon-like peptide-1 and peptide YY55. These hormones were essential for regulating GI transit time56,57. Consequently, a decrease in these beneficial bacteria could impair digestive efficiency and nutrient absorption, worsening GI symptoms and affecting overall health. In addition to the bacterial genera Nitrospira and MND1, was reduced in elephants with GI disorders. Previous pyrosequencing studies had detected Nitrospira bacteria in pediatric patients with irritable bowel syndrome58, highlighting their potential role as indicators of GI disorders.

Compared to healthy group, elephants with GI disorders showed an increased relative abundance of certain bacterial taxa, including the genus Lysinibacillus (family Planococcaceae), an uncultured genus belonging to the family Marinifilaceae, and the genus Bacteroidetes_BD2-2. The genus Lysinibacillus is known for its beneficial properties, such as inhibiting pathogenic bacteria and promoting beneficial bacteria, thereby enhancing microbial diversity59. In elephants with GI disorders, increased levels of Marinifilaceae, known for their nitrogen-fixing capabilities60,61, may represent an adaptive response aimed at stabilizing nitrogen balance and supporting the gut’s nitrogen cycle amid dysbiotic conditions. In contrast, human studies associate lower levels of Marinifilaceae with IBD62, where increased nitric oxide and reactive nitrogen species create a hostile gut environment that disrupts microbial diversity and function60,63. The contrasting abundance of the family Marinifilaceae between elephants with GI disorders and humans IBD highlights potential differences in gut microbiome adaptations across species. The observed differences suggest that in some elephants with food impaction, higher proportions of Marinifilaceae might offer temporary benefits by buffering the nitrogen cycle in response to nitrate-rich diets, as they may have ingested grass grown in areas close to fertilized crops, potentially leading to elevated nitrate levels in their feed. While these bacteria may contribute to nitrogen metabolism and resilience against dysbiosis, their elevated levels in a disrupted gut environment could also exacerbate microbial imbalances, thus playing a dual role in gut health.

The function prediction analysis revealed significant metabolic shifts in elephants with GI disorders. Both healthy and elephants with GI disorders showed bacterial functional groups primarily involved in energy generation and fermentation. However, elephants with GI disorders exhibited an increase in functions associated with human gut activity, human-associated processes, and mammalian gut functions compared to healthy elephants. These findings suggest that the altered gut environment in elephants with GI disorders promotes the growth of microbial species commonly found in human and mammalian guts. The enrichment of these functions may reflect a shift toward microbial communities typically associated with dysbiosis in elephants. Additionally, the increased presence of nitrate-reducing bacteria (NRB) in the gut of sick elephants might reflect a response to altered nitrate levels caused by dietary changes or a disrupted gut environment60. NRB convert nitrate to nitrite, producing nitric oxide, which can enhance blood flow, contribute to hypoxic signaling, and reduce inflammation60,64. This response might be compensatory, as elevated nitrate levels in GI disorders likely promoted NRB proliferation, potentially mitigating some adverse effects while contributing to dysbiosis.

The reduction of sulfate-reducing bacteria (SRB) in elephants with GI disorders likely results from disturbances in the gut environment, reflecting distinct dietary and physiological differences between humans and elephants. SRB typically thrived in neutral pH conditions, but GI disorders might have created more acidic environments65. In humans, sulfur is primarily sourced from animal-based proteins66, contributing to essential processes like protein synthesis and metabolism of bile acids67. In IBD sulfur metabolites, especially hydrogen sulfide (H₂S)68,69, are elevated and exacerbate inflammation and dysbiosis70. Elephants, however, consume a fiber-rich diet where sulfur comes mainly from plant-derived amino acids like cysteine and methionine71. In diseased states, elephants show a reduction in sulfate respiration and sulfur metabolism, indicating a suppression rather than an intensification of sulfur processing. Plants also defend themselves from herbivory using sulfur-containing compounds that become toxic upon tissue damage, which may impact herbivores’ gut environments71,72. Thus, while sulfur metabolism amplifies inflammation in human GI disorders, its disruption in elephants may reflect a distinct vulnerability tied to their high-fiber diet and reliance on microbial sulfur metabolism. In GI disorders, altered gut conditions may shift the microbial community structure, leading to changes in NRB and SRB activity and impacting overall gut health. Understanding these dynamics was crucial for developing therapeutic strategies that modulated microbial activity and gut health. Future metagenomic studies will be vital for distinguishing core microbial functions across species and improving our understanding of gut microbiota interactions with host health.

Comparative analysis of gut microbiota diversity between elephants with colic and those with diarrhea showed no significant differences in either alpha-diversity or beta-diversity. However, differences in specific bacterial taxa were observed between elephants afflicted with colic and those with diarrhea. Elephants with colic showed reduced abundance of the families Pyrinomonadaceae and Nitrospiraceae, and the genera RCP2-54 and Erysipelotrichaceae_UCG-009, compared to those with diarrhea. These findings suggest that colic and diarrhea are associated with distinct microbial signatures, likely reflecting differences in their underlying causes. Diarrhea might result from bacterial infections or dietary factors, whereas colic can stem from conditions such as impaction colic or constipation, each impacting the elephant gut microbiota differently. Nevertheless, notable fluctuations in microbial taxa were observed in one elephant afflicted with food impaction colic, characterized by a marked increase in the relative abundance of the Streptococcus genus. Streptococcus spp., commonly found in the normal enteric flora, was frequently associated with opportunistic infections and lactic acid production in horses73. An overabundance of the Streptococcus genus has been reported in horses with both large and small intestinal colic49,74, and strongly linked to high-concentrate forage diets73. This elephant was fed a dietary supplement, including feed pellets, alongside its usual roughage diet, which may have contributed to the overgrowth of Streptococcus spp. However, the observed discrepancies could be age-related, as the affected elephant was a juvenile while the others were adults. Age-related differences can significantly impact gut microbiota composition75,76, potentially complicating interpretation of the results. Future research is needed to comprehensively understand the extent of this influence.

In captivity, wild animals are exposed to environments and lifestyles that differ drastically from their natural habitats due to extensive human manipulation of their surroundings, diet, healthcare, and social interactions77. Previous studies have linked captivity to various health issues, including weight loss, immune system alterations, reduced reproductive capacity78,79, and induced microbiome alterations in captive Asian elephants80. Emerging research across multiple biological fields underscores the microbiome’s potential role in mediating these health conditions in captivity78. Diet and water management also play critical roles in GI health. Variations in diet, such as changes in forage type, hay sources, or novel foods, may contribute to dysbiosis, influencing the gut microbiota and GI symptoms in elephants8,81. High-fiber diets are recommended to prevent colic and support GI health82. Therefore, it is crucial to explore new methods to enhance animal welfare in captivity. Focusing microbiome research and interventions on a species-specific basis, while comprehensively consideration of immune, behavioral, reproductive, and metabolic health, can lead to more effective management and conservation strategies78.

This study faced several limitations, including the age and sex of the elephants, which are known to influence gut microbiota composition. Additionally, the variability in disease etiology among the subjects, including bacterial or viral infections, parasitic infestations, toxic ingestion, and other underlying health conditions, introduced significant heterogeneity into the study population. This variability makes it challenging to attribute observed changes in the microbiota solely to specific disease conditions. Future research should aim to control for these variables to better understand the relationship between the intestinal microbiota and GI disorders in elephants.

Conclusion

This study significantly enhances our understanding of the gut microbiota in Asian elephants, particularly those with GI disorders. Utilizing high-throughput sequencing, we observed distinct microbial profiles in healthy elephants compared with those succumbed from colic and diarrhea, indicating dysbiosis in afflicted animals. While healthy elephants exhibited a relatively uniform bacterial composition, those with GI disorders presented notable changes and unique patterns in the abundances of specific bacterial taxa. The observed increase in certain beneficial bacteria in ill elephants warrants further investigation to understand their potential role in the pathogenesis and their interactions with other gut microbes. Future research should focus on larger sample sizes and more homogenous study populations to address current limitations and provide deeper insights into the relationship between gut microbiota and GI health in elephants. Such research could pave the way for developing targeted interventions aimed at improving the well-being of these animals.

Methods

Animals and sample collection

This study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai, Thailand (FVM-ACUC; R3/2563) and all experiments were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. All methods used in this study are reported in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines.

A total of unrelated 18 elephants were included in this study, comprising of seven healthy captive elephants, seven that were diagnosed with food impaction colic, and four exhibiting diarrhea. Among the four diarrheic elephants, one was found to have intestinal parasites, another was affected by geophagia, and the etiology of the other two cases was undetermined. Comprehensive information regarding the cause of disease for each elephant is detailed in Table 2. The elephants in this study were housed in elephant tourist camps in Chiang Mai, Thailand, where they regularly interacted with their mahouts and tourists. They were managed under consistent conditions, including diet and housing. The primary diet of most elephants consisted of Napier grass (Pennisetum purpureum), with only one individual primarily fed corn stalks (Zea mays L.) supplemented with elephant feed pellets. Seasonal supplements, including banana, sugarcane, mango, tamarind, watermelon, and corn, were also provided. Comprehensive details of dietary management for each elephant are presented in Table 3. Clinical health was assessed by veterinarians specializing in elephants through comprehensive historical and clinical examinations. Healthy elephants had no reported GI symptoms and had not been exposed to antibiotics or other drugs for at least six months prior to the study. Elephants with colic exhibited symptoms such as rapid abdominal bloating, abdominal discomfort, absence of defecation for 12 h, and decreased alertness. Those with diarrhea exhibited a decrease in appetite, sudden watery stools, and lethargy, without fever. Importantly, these elephants had been feeding normally on roughage until the evening before the onset of symptoms. Samples from elephants with GI symptoms were collected before treatment began, preferably before the administration of antibiotics.

Table 2.

Elephant characteristics, GI problem etiology, and camp locations.

| Elephant ID | Age (years) | Sex | GI status | Causes of GI problems | Elephant camp |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BCG401 | 15 | Female | Normal | – | Mae Taeng district, Chiang Mai, Thailand |

| BCG402 | 20 | Female | Normal | – | Mae Taeng district, Chiang Mai, Thailand |

| BCG403 | 20 | Female | Normal | – | Mae Taeng district, Chiang Mai, Thailand |

| BCG405 | 20 | Male | Normal | – | Mae Taeng district, Chiang Mai, Thailand |

| BCG406 | 40 | Female | Normal | – | Mae Taeng district, Chiang Mai, Thailand |

| BCG407 | 40 | Female | Normal | – | Mae Taeng district, Chiang Mai, Thailand |

| CL01 | 45 | Female | Colic | Food impaction | Mae Taeng district, Chiang Mai, Thailand |

| CL02 | 22 | Female | Colic | Food impaction | Mae Sa district, Chiang Mai, Thailand |

| CL03 | 19 | Female | Colic | Food impaction | Mae Taeng district, Chiang Mai, Thailand |

| CL04 | 14 | Female | Colic | Food impaction | Mae Taeng district, Chiang Mai, Thailand |

| CL05 | 17 | Female | Colic | Food impaction | Mae Taeng district, Chiang Mai, Thailand |

| CL06 | 23 | Male | Colic | Food impaction | Mae Taeng district, Chiang Mai, Thailand |

| CL07 | 5 | Male | Colic | Food impaction | Mae Wang district, Chiang Mai, Thailand |

| DI01 | 3 | Male | Diarrhea | Unknown | Mae Taeng district, Chiang Mai, Thailand |

| DI02 | 42 | Male | Diarrhea | Intestinal parasite | Mae Sa district, Chiang Mai, Thailand |

| DL03 | 4 | Female | Diarrhea | Geophagy | Mae Taeng district, Chiang Mai, Thailand |

| DL04 | 1 | Female | Diarrhea | Unknown | Mae Taeng district, Chiang Mai, Thailand |

Table 3.

Diet management and feed types for elephants in this study.

| Elephant ID | Diet volume (kg/day) | Feeding time** (meal per Day) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Roughage type | Supplementary | |||||||||

| Napier grass | Corn stalk | Banana | Sugarcane | Mango | Tamarind | Water melon | Corn | Feed pellets* | ||

| BCG401 | 160 | 0 | 10 | 8 | 2 | 0.5 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 3 |

| BCG402 | 200 | 0 | 10 | 8 | 2 | 0.5 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 4 |

| BCG403 | 200 | 0 | 10 | 8 | 2 | 0.5 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 4 |

| BCG405 | 200 | 0 | 10 | 8 | 2 | 0.5 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 4 |

| BCG406 | 200 | 0 | 10 | 8 | 2 | 0.5 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 4 |

| BCG407 | 200 | 0 | 10 | 8 | 2 | 0.5 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 4 |

| CL01 | 200 | 0 | 5 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| CL02 | 210 | 0 | 10 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| CL03 | 180 | 0 | 10 | 8 | 2 | 0.5 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 4 |

| CL04 | 140 | 0 | 10 | 8 | 2 | 0.5 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 4 |

| CL05 | 180 | 0 | 10 | 8 | 2 | 0.5 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 4 |

| CL06 | 200 | 0 | 10 | 8 | 2 | 0.5 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 4 |

| CL07 | 80 | 0 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| DI01 | 60 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| DI02 | 240 | 0 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Ad libitum |

| DL03 | 0 | 80 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 3 |

| DL04 | 0 | 40 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

*Elephant feed pellet (Erawan, Charoen Pokphand Foods, Thailand) (contained more than 8% protein, 2% fat, and not more than 20% roughage).

**Feeding time was defined as follows: 3 meals per day at 08:00, 12:00, and 16:00; 4 meals per day at 08:00, 12:00, 16:00, and 20:00.

Fresh fecal samples (approximately 50 g) were collected directly from the rectum or immediately post-defecation and promptly stored in a cooler box at 4℃ and transported to the laboratory within 3 h. Once in the laboratory, the samples were immediately transferred to a freezer at − 20℃ until DNA extraction, which employed a commercial genomic DNA isolation kit, specifically the QIAamp PowerFecal Pro DNA Kit by QIAGEN (Germany). To analyse changes in the gut bacterial community, bacterial genomic DNA was amplified, targeting the hypervariable region V3-V4 of the 16S rRNA gene using specific primers (F 5′-CCTAYGGGRBGCASCAG-3′, R 5′-GGACTACNNGGGTATCTAAT-3′). This was followed by sequencing using paired-end reads method on an Illumina MiSeq platform. The processes of DNA amplification, data quality control, and sequencing were meticulously carried out by Novogene Inc (Singapore City, Singapore). Employing a double-blind study design with systematically categorized samples was instrumental in mitigating potential biases.

Bioinformatics and data analysis

The initial data from Illumina MiSeq sequencing were performed a quality assessment to obtain effective data. DNA sequence data from NGS were processed using the Quantitative Insights Into Microbial Ecology 2 (QIIME 2 version 2023.2.0) open-source software83. The raw datasets containing pair-ended reads and quality scores were merged, denoised, trimmed according to quality scores, and assigned to amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) by using q2‐dada2 plugin version 2023.2.084. A feature table including the number of each ASV per sample was also generated85. The ASVs were aligned with MAFFT and used to generate a phylogenetic tree for further analysis86,87. The diversity analyses were conducted with rarefication at the sequencing depth of 23,000 as this is the minimum reads to retain all the samples in this study88. The alpha diversity measures, including Observed features, Pielou’s evenness89, Faith’s PD90, and Shannon’s index91 were calculated and analysed using Kruskal–Wallis test in QIIME2. The beta diversity including Bray Curtis, Jaccard, unweighted UniFrac92, and weighted UniFrac93 distance matrices were analyzed and were illustrated as (PCoA). The taxonomy was assigned to ASVs by using q2‐feature‐classifier classify‐sklearn naïve Bayes taxonomy classifier94 by using the data reference from SILVA database version 13895. For visualization of population structure and relative abundance, taxonomical bar plots indicating the relative abundance at the phylum, class, and genus levels of each sample from the different age groups were generated. The differences in taxon abundance between categories and the associations between taxa were estimated with a statistical framework: analysis of the composition of microbiomes with Bias Correction (ANCOM-BC)96. The data visualization was conducted through R version 4.4 by using ‘qiime2R’ package. Functional capabilities of the microbial community were predicted using FAPROTAX based on 16S rRNA gene data and nd KEGG functional databases. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni correction (p < 0.05) was performed using R software.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to the Center of Excellence in Cardiac Electrophysiology Research, Faculty of Medicine; the Center of Elephant and Wildlife Health Animal Hospital, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine; and the Erawan HPC Project, Information Technology Service Center (ITSC), Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai, Thailand for their support. We also appreciate the elephant camp owners, their managers, and the mahouts for providing samples and data.

Author contributions

S.Kl., N.C., S.C.C., and C.T. conceptualized the idea and designed the research. S.Kl. and S.Ke. handled the preparation of materials and conducted the measurements. S.Kl., C.K., and S.S. analyzed and investigated the data. S.Kl. wrote the original draft manuscript. S.Kl., C.K., N.C., S.C.C., and C.T. reviewed and edited the manuscript. N.C., S.C.C., and C.T. secured the funding. N.C., S.C.C., and C.T. supervised the research.

Funding

This study was supported by the Thailand Research Fund (C.T.), the CMU Presidential Scholarship and Chiang Mai University (grant number 59/2565 to S.Kl.), the Distinguished Research Professor Grant from the National Research Council of Thailand (N42A660301 to S.C.C.); the Research Chair Grant from the National Research Council of Thailand (N42A670594 to N.C.); and a Chiang Mai University Center of Excellence Award (N.C., C.T.)

Data availability

The raw 16S rRNA gene sequence data and metadata files in this study are available in the NCBI sequence read archive under the accession number PRJNA1144818.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Siriporn C. Chattipakorn, Email: siriporn.c@cmu.ac.th

Chatchote Thitaram, Email: chatchote.thitaram@cmu.ac.th.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-85495-0.

References

- 1.Rooks, M. G. & Garrett, W. S. Gut microbiota, metabolites and host immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol.16, 341–352. 10.1038/nri.2016.42 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Esser, D. et al. Functions of the microbiota for the physiology of animal metaorganisms. J. Innate Immun.11, 393–404. 10.1159/000495115 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Das, B. & Nair, G. B. Homeostasis and dysbiosis of the gut microbiome in health and disease. J. Biosci.44, 117 (2019). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Belizário, J. E. & Faintuch, J. Metabolic Interaction in Infection (Springer, 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Angkawanish, T. et al. Elephant health status in Thailand: the role of mobile elephant clinic and elephant hospital. Gajah31, 15–20 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oo, Z. M. Health issues of captive Asian elephants in Myanmar. Gajah36, 21–22 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miller, D. et al. Elephant (Elephas maximus) health and management in Asia: variations in veterinary perspectives. Vet. Med. Int.10.1155/2015/614690 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Edwards, K. L., Miller, M. A., Carlstead, K. & Brown, J. L. Relationships between housing and management factors and clinical health events in elephants in North American zoos. PLoS ONE14, e0217774. 10.1371/journal.pone.0217774 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Worku, Y., Wondimagegn, W., Aklilu, N., Assefa, Z. & Gizachew, A. Equine colic: clinical epidemiology and associated risk factors in and around Debre Zeit. Trop. Anim. Health Prod.49, 959–965. 10.1007/s11250-017-1283-y (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Proudman, C., French, N. & Trees, A. Tapeworm infection is a significant risk factor for spasmodic colic and ileal impaction colic in the horse. Equine Vet. J.30, 194–199. 10.1111/j.2042-3306.1998.tb04487.x (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greene, W., Dierenfeld, E. S. & Mikota, S. A review of Asian and African elephant gastrointestinal anatomy, physiology, and pharmacology: elephant gastrointestinal anatomy, physiology, and pharmacology. J. Zoo Aquar. Res.7, 1–14. 10.19227/jzar.v7i1.329 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheeran, J. V. & Chandrasekharan, K. Biology, Medicine, and Surgery of Elephants (Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 2006). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Teodoro, T. G. W. et al. Colonic sand impaction with cecal rupture and peritonitis in an adult African savanna elephant, and review of noninfectious causes of gastrointestinal disease in elephants. J. Vet. Diagn. Invest.35, 47–52. 10.1177/10406387221130024 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Obanda, V., Mutinda, N. M., Gakuya, F. & Iwaki, T. Gastrointestinal parasites and associated pathological lesions in starving free-ranging African elephants: research article. S. Afr. J. Wildl. Res.41, 167–172. 10.10520/EJC117379 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuruwita, V. & Vasanthathilake, V. Gastro-intestinal [sic] nematode parasites occurring in free-ranging Elephants (Elephas maximus ceylonicus) in Sri Lanka. Sri Lanka Vet. J.40, 15–23 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carroll, I. M., Ringel-Kulka, T., Siddle, J. P. & Ringel, Y. Alterations in composition and diversity of the intestinal microbiota in patients with diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Neurogastroenterol. Motil.24, 521-e248 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arroyo, L. G. et al. Luminal and mucosal microbiota of the cecum and large colon of healthy and diarrheic horses. Animals10, 1403. 10.3390/ani10081403 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Janssen, D., Karesh, W., Cosgrove, G. & Oosterhuis, J. Salmonellosis in a herd of captive elephants. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc.185, 1450–1 (1984). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bacciarini, L., Gröne, A., Pagan, O. & Frey, J. Clostridium perfringensβ2-toxin in an African elephant (Loxodonta Africana) with ulcerative enteritis. Vet. Rec.149, 618–620. 10.1136/vr.149.20.618 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bojesen, A. M., Olsen, K. E. & Bertelsen, M. F. Fatal enterocolitis in Asian elephants (Elephas maximus) caused by Clostridium difficile. Vet. Microbiol.116, 329–335. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2006.04.025 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mahato, G. et al. First report of isolation of enteropathogenic Escherichia Fergusonii from the faeces of elephantcalf (Elephas Maximus). Explor. Anim. Med. Res.13, 178–183 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thakur, N., Suresh, R., Chethan, G. E. & Mahendran, K. Balantidiasis in an Asiatic elephant and its therapeutic management. J. Parasit. Dis.43, 186–189. 10.1007/s12639-018-1072-1 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garner, M. et al. Clinico-pathologic features of fatal disease attributed to new variants of endotheliotropic herpesviruses in two Asian elephants (Elephas maximus). Vet. Pathol.46, 97–104. 10.1354/vp.46-1-97 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Elliott, E. J. Acute gastroenteritis in children. BMJ334, 35–40. 10.1136/bmj.39036.406169.80 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Costa, M. C. & Weese, J. S. Understanding the intestinal microbiome in health and disease. Vet. Clin. North Am. Equine Pract.34, 1–12. 10.1016/j.cveq.2017.11.005 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salem, S. E. et al. Variation in faecal microbiota in a group of horses managed at pasture over a 12-month period. Sci. Rep.8, 8510. 10.1038/s41598-018-26930-3 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li, Y., Lan, Y., Zhang, S. & Wang, X. Comparative analysis of gut microbiota between healthy and diarrheic horses. Front. Vet. Sci.9, 882423. 10.3389/fvets.2022.882423 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aziz, Q., Doré, J., Emmanuel, A., Guarner, F. & Quigley, E. Gut microbiota and gastrointestinal health: current concepts and future directions. J. Neurogastroenterol. Motil.25, 4–15. 10.1111/nmo.12046 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nagao-Kitamoto, H., Kitamoto, S., Kuffa, P. & Kamada, N. Pathogenic role of the gut microbiota in gastrointestinal diseases. Intest. Res.14, 127 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chaucheyras-Durand, F., Sacy, A., Karges, K. & Apper, E. Gastro-intestinal microbiota in equines and its role in health and disease: The black box opens. Microorganisms10, 2517. 10.3390/microorganisms10122517 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bo, T. et al. Mechanism of inulin in colic and gut microbiota of captive Asian elephant. Microbiome11, 148. 10.1186/s40168-023-01581-3 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Scher, J. U. et al. Decreased bacterial diversity characterizes the altered gut microbiota in patients with psoriatic arthritis, resembling dysbiosis in inflammatory bowel disease. Arthritis Rheumatol.67, 128–139. 10.1002/art.38892 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johnson, K.V.-A. Gut microbiome composition and diversity are related to human personality traits. Hum. Microb. J.15, 100069. 10.1016/j.humic.2019.100069 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.David, L. A. et al. Gut microbial succession follows acute secretory diarrhea in humans. mBio6, e00381-00315. 10.1128/mBio.00381-15 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kabeerdoss, J., Sankaran, V., Pugazhendhi, S. & Ramakrishna, B. S. Clostridium leptum group bacteria abundance and diversity in the fecal microbiota of patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a case–control study in India. BMC Gastroenterol.13, 20. 10.1186/1471-230X-13-20 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Keady, M. M. et al. Clinical health issues, reproductive hormones, and metabolic hormones associated with gut microbiome structure in African and Asian elephants. Anim. Microbiome3, 85. 10.1186/s42523-021-00146-9 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Clauss, M. et al. Observations on the length of the intestinal tract of African Loxodonta africana (Blumenbach 1797) and Asian elephants Elephas maximus (Linné 1735). Eur. J. Wildl. Res.53, 68–72 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Amato, K. R. et al. Using the gut microbiota as a novel tool for examining colobine primate GI health. Glob. Ecol. Conserv.7, 225–237 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Costa, M. C. et al. Comparison of the fecal microbiota of healthy horses and horses with colitis by high throughput sequencing of the V3–V5 region of the 16S rRNA gene. PLoS ONE7, e41484. 10.1371/journal.pone.0041484 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Niwa, H. et al. Postoperative Clostridium difficile infection with PCR ribotype 078 strain identified at necropsy in five Thoroughbred racehorses. Vet. Rec.173, 607–607. 10.1136/vr.101960 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schoster, A. et al. Prevalence of Clostridium difficile and Clostridium perfringens in Swiss horses with and without gastrointestinal disease and microbiota composition in relation to Clostridium difficile shedding. Vet. Microbiol.239, 108433. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2019.108433 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Venable, E., Kerley, M. & Raub, R. Assessment of equine fecal microbial profiles during and after a colic episode using pyrosequencing. J. Equine Vet. Sci.5, 347–348. 10.1016/j.jevs.2013.03.066 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ley, R. E., Turnbaugh, P. J., Klein, S. & Gordon, J. I. Human gut microbes associated with obesity. Nature444, 1022–1023. 10.1038/4441022a (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.de Jonge, N., Carlsen, B., Christensen, M. H., Pertoldi, C. & Nielsen, J. L. The gut microbiome of 54 mammalian species. Front. Microbiol.13, 886252. 10.3389/fmicb.2022.886252 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.O’Donnell, M. M., Harris, H. M., Ross, R. P. & O’Toole, P. W. Core fecal microbiota of domesticated herbivorous ruminant, hindgut fermenters, and monogastric animals. Microbiologyopen6, e00509. 10.1002/mbo3.509 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Khoruts, A., Dicksved, J., Jansson, J. K. & Sadowsky, M. J. Changes in the composition of the human fecal microbiome after bacteriotherapy for recurrent Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea. J. Clin. Gastroenterol.44, 354–360. 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181c87e02 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stojanov, S., Berlec, A. & Štrukelj, B. The influence of probiotics on the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio in the treatment of obesity and inflammatory bowel disease. Microorganisms8, 1715. 10.3390/microorganisms8111715 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Magne, F. et al. The Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio: a relevant marker of gut dysbiosis in obese patients?. Nutrients10.3390/nu12051474 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Park, T. et al. Comparison of the fecal microbiota of horses with intestinal disease and their healthy counterparts. Vet. Sci.8, 113. 10.3390/vetsci8060113 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang, C., Xu, B., Lu, T. & Huang, Z. Metagenomic analysis of the fecal microbiomes of wild Asian elephants reveals microflora and enzymes that mainly digest hemicellulose. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol.29, 1255–1265. 10.4014/jmb.1904.04033 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang, Y. et al. Exploring the gut microbiota of healthy captive Asian elephants from various locations in Yunnan, China. Front. Microbiol.15, 1403930 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ceballos, S. J. et al. Development and characterization of a thermophilic, lignin degrading microbiota. Process. Biochem.63, 193–203. 10.1016/j.procbio.2017.08.018 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ivanova, A. A. et al. Rokubacteria in northern peatlands: habitat preferences and diversity patterns. Microorganisms10, 11. 10.3390/microorganisms10010011 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Quesada-Vázquez, S. et al. Microbiota dysbiosis and gut barrier dysfunction associated with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease are modulated by a specific metabolic cofactors’ combination. Int. J. Mol. Sci.23, 13675. 10.3390/ijms232213675 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhou, J. et al. Peptide YY and proglucagon mRNA expression patterns and regulation in the gut. Obesity14, 683–689. 10.1038/oby.2006.77 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dumoulin, V. et al. Peptide YY, glucagon-like peptide-1, and neurotensin responses to luminal factors in the isolated vascularly perfused rat ileum. Endocrinology139, 3780–3786. 10.1210/endo.139.9.6202 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Barreto, S. G. & Windsor, J. A. Does the ileal brake contribute to delayed gastric emptying after pancreatoduodenectomy?. Dig. Dis. Sci.62, 319–335. 10.1007/s10620-016-4402-0 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rajilić-Stojanović, M. & De Vos, W. M. The first 1000 cultured species of the human gastrointestinal microbiota. FEMS Microbiol. Rev.38, 996–1047. 10.1111/1574-6976.12075 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zeng, Z. et al. Effect of Lysinibacillus isolated from environment on probiotic properties and gut microbiota in mice. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf.258, 114952. 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2023.114952 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Liu, H. et al. From nitrate to NO: potential effects of nitrate-reducing bacteria on systemic health and disease. Eur. J. Med. Res.28, 425. 10.1186/s40001-023-01413-y (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Li, J., Dong, C., Lai, Q., Wang, G. & Shao, Z. Frequent occurrence and metabolic versatility of Marinifilaceae bacteria as key players in organic matter mineralization in global deep seas. mSystems10.1128/msystems.00864-22 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Teofani, A. et al. Intestinal taxa abundance and diversity in inflammatory bowel disease patients: An analysis including covariates and confounders. Nutrients14, 260. 10.3390/nu14020260 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kamalian, A. et al. Interventions of natural and synthetic agents in inflammatory bowel disease, modulation of nitric oxide pathways. World J. Gastroenterol.26, 3365–3400. 10.3748/wjg.v26.i24.3365 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lundberg, J. O., Weitzberg, E. & Gladwin, M. T. The nitrate–nitrite–nitric oxide pathway in physiology and therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov.7, 156–167. 10.1038/nrd2466 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kushkevych, I. et al. The sulfate-reducing microbial communities and meta-analysis of their occurrence during diseases of small-large intestine axis. J. Clin. Med.8, 1656. 10.3390/jcm8101656 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Barton, L. L., Ritz, N. L., Fauque, G. D. & Lin, H. C. Sulfur cycling and the intestinal microbiome. Dig. Dis. Sci.62, 2241–2257. 10.1007/s10620-017-4689-5 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lambert, I. H., Kristensen, D. M., Holm, J. B. & Mortensen, O. H. Physiological role of taurine–from organism to organelle. Acta Physiol. (Oxford)213, 191–212. 10.1111/apha.12365 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kushkevych, I. et al. Recent advances in metabolic pathways of sulfate reduction in intestinal bacteria. Cells10.3390/cells9030698 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mutuyemungu, E., Singh, M., Liu, S. & Rose, D. J. Intestinal gas production by the gut microbiota: A review. J. Funct. Foods100, 105367. 10.1016/j.jff.2022.105367 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 70.Walker, A. & Schmitt-Kopplin, P. The role of fecal sulfur metabolome in inflammatory bowel diseases. Int. J. Med. Microbiol.311, 151513. 10.1016/j.ijmm.2021.151513 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Takahashi, H., Kopriva, S., Giordano, M., Saito, K. & Hell, R. Sulfur assimilation in photosynthetic organisms: molecular functions and regulations of transporters and assimilatory enzymes. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol.62, 157–184. 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042110-103921 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Jacoby, R. P., Koprivova, A. & Kopriva, S. Pinpointing secondary metabolites that shape the composition and function of the plant microbiome. J. Exp. Bot.72, 57–69. 10.1093/jxb/eraa424 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Garber, A., Hastie, P. & Murray, J.-A. Factors influencing equine gut microbiota: Current knowledge. J. Equine Vet. Sci.88, 102943. 10.1016/j.jevs.2020.102943 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Stewart, H. L. et al. Differences in the equine faecal microbiota between horses presenting to a tertiary referral hospital for colic compared with an elective surgical procedure. Equine Vet. J.51, 336–342. 10.1111/evj.13010 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Klinhom, S. et al. Characteristics of gut microbiota in captive Asian elephants (Elephas maximus) from infant to elderly. Sci. Rep.13, 23027. 10.1038/s41598-023-50429-1 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Klinsawat, W. et al. Microbiome variations among age classes and diets of captive Asian elephants (Elephas maximus) in Thailand using full-length 16S rRNA nanopore sequencing. Sci. Rep.13, 17685. 10.1038/s41598-023-44981-z (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Carthey, A. J., Blumstein, D. T., Gallagher, R. V., Tetu, S. G. & Gillings, M. R. Conserving the holobiont. Funct. Ecol.34, 764–776. 10.1111/1365-2435.13504 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 78.Diaz, J. & Reese, A. T. Possibilities and limits for using the gut microbiome to improve captive animal health. Anim. Microbiome3, 89. 10.1186/s42523-021-00155-8 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Fischer, C. P. & Romero, L. M. Chronic captivity stress in wild animals is highly species-specific. Conserv. Physiol.10.1093/conphys/coz093 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Moustafa, M. A. M. et al. Anthropogenic interferences lead to gut microbiome dysbiosis in Asian elephants and may alter adaptation processes to surrounding environments. Sci. Rep.11, 741. 10.1038/s41598-020-80537-1 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mikota, S. K., Sargent, E. L. & Ranglack, G. Medical Management of the Elephant (Indira Publishing House, 1994). [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hatt, J. M. & Clauss, M. Feeding Asian and African elephants Elephas maximus and Loxodonta africana in captivity. Int. Zoo Yearb.40, 88–95 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bolyen, E. et al. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol.37, 852–857. 10.1038/s41587-019-0209-9 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Callahan, B. J. et al. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods13, 581–583. 10.1038/nmeth.3869 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.McDonald, D. et al. An improved Greengenes taxonomy with explicit ranks for ecological and evolutionary analyses of bacteria and archaea. ISME J.6, 610–618. 10.1038/ismej.2011.139 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Katoh, K. & Standley, D. M. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol.30, 772–780. 10.1093/molbev/mst010 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Price, M. N., Dehal, P. S. & Arkin, A. P. FastTree 2–approximately maximum-likelihood trees for large alignments. PloS ONE5, e9490 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Weiss, S. et al. Normalization and microbial differential abundance strategies depend upon data characteristics. Microbiome5, 1–18 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Pielou, E. C. The measurement of diversity in different types of biological collections. J. Theor. Biol.13, 131–144 (1966). [Google Scholar]

- 90.Faith, D. P. Conservation evaluation and phylogenetic diversity. Biol. Conserv.61, 1–10 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- 91.Shannon, C. E. A mathematical theory of communication. Bell Syst. Tech. J.27, 379–423. 10.1002/j.1538-7305.1948.tb01338.x (1948). [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lozupone, C. & Knight, R. UniFrac: a new phylogenetic method for comparing microbial communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol.71, 8228–8235. 10.1128/AEM.71.12.8228-8235.2005 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lozupone, C. A., Hamady, M., Kelley, S. T. & Knight, R. Quantitative and qualitative β diversity measures lead to different insights into factors that structure microbial communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol.73, 1576–1585. 10.1128/AEM.01996-06 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Bokulich, N. A. et al. Optimizing taxonomic classification of marker-gene amplicon sequences with QIIME 2’s q2-feature-classifier plugin. Microbiome6, 1–17. 10.1186/s40168-018-0470-z (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Quast, C. et al. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res.10.1093/nar/gks1219 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lin, H. & Peddada, S. D. Analysis of compositions of microbiomes with bias correction. Nat. Commun.11, 1–11. 10.1038/s41467-020-17041-7 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The raw 16S rRNA gene sequence data and metadata files in this study are available in the NCBI sequence read archive under the accession number PRJNA1144818.