Abstract

This study aims to analyze the trends in the burden of depression among adolescents aged 10 to 24 years globally from 1990 to 2021, with a focus on the impact of COVID-19 on adolescent depression and health inequalities. Using data from the 2021 Global Burden of Disease Study, we examined age-standardized prevalence, incidence, and disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for depression among adolescents aged 10–24 years. Estimated annual percentage change (EAPC) was used to assess temporal trends. Age-period-cohort (APC) analysis estimated age, period, and cohort effects. Bayesian APC (BAPC) analysis projected future trends. Decomposition analysis further explored drivers of changes in depression burden. Slope Index of Inequality (SII) and Concentration Index (CI) were calculated to assess health inequalities across regions and countries. From 1990 to 2021, the global incidence, prevalence and DALY rates of adolescent depression remained stable. Depression incidence and prevalence increased with age, with the 20–24 age group showing the highest rates. The burden of depression was higher in females than in males. The COVID-19 pandemic significantly impacted adolescent depression, with reported prevalence, incidence, and DALY rates in 2020 and 2021 far exceeding predicted values, and the burden of depression is expected to continue rising. Health inequalities between adolescents in high- and low-income regions have widened, particularly following the pandemic. The COVID-19 pandemic significantly exacerbated the burden of depression and intensified health inequalities.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-84843-w.

Keywords: Adolescents, Depression, Epidemiology, Global burden of Disease Study, Mental Health

Subject terms: Epidemiology, Paediatric research, Depression

Introduction

Depression, a major contributor to the global disease burden related to mental health, affected approximately 563 million individuals worldwide in 20211. Beyond its direct impact, depression is also associated with premature mortality due to comorbidity with other diseases and with suicide, amplifying its public health significance1. In the adolescent population, the burden of depression is particularly concerning. Adolescents, defined as individuals aged 10–24 years, are in a critical developmental stage marked by rapid physical, emotional, and social changes2. These changes make them particularly vulnerable to mental health problems, including depression. Depression in this age group can lead to severe consequences, including academic failure, substance abuse, and an increased risk of suicide, which is a leading cause of death among adolescents3.The urgency to study depression in adolescents stems from the potential long-term consequences of untreated depression. For instance, numerous longitudinal studies have demonstrated that early-life experiences of depression are associated with an array of negative outcomes in adulthood, including substance abuse, violent behaviors, and criminal offenses4–6. Despite the increasing recognition of this issue, there has been limited comprehensive global analysis on the trends and burden of adolescent depression.

In recent years, several studies have explored the burden of depression among adolescents. For example, the latest research based on the GBD 2021 database indicates a significant increase in the incidence of major depressive disorder during the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly in high-income countries7. Additionally, earlier studies have highlighted disparities in depression burden across various demographic factors, including region, age, gender, and the sociodemographic index8–11. However, these studies often focus on specific disorders, limited geographic areas, or outdated datasets, lacking comprehensive and up-to-date analyses of cross-regional dynamic trends. Moreover, while the pandemic has further exacerbated mental health challenges among adolescents, systematic assessments of its impact on the burden of adolescent depression remain scarce.

This study aims to analyze the burden of depression among adolescents aged 10–24 years using the data from the GBD 2021 database. Our analysis not only examines the disparities in disease burden across different demographic groups-such as gender, age, and geographic regions-but also delves into how these disparities have evolved in the context of the pandemic, with a specific focus on the changes in health inequalities over time.

Methods

Overview

The study utilized data from the GBD 2021, which comprehensively assessed health loss across 204 countries and regions from 1990 to 2021. The GBD study provides detailed estimates of the prevalence, incidence, mortality, and disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for various health conditions across different populations and time periods. Detailed descriptions of the original GBD data and methods can be found in previous publications12,13. Based on previous studies, this study adopted a broad age definition of adolescence, ranging from 10 to 24 years, which is further divided into early adolescence (10–14 years), mid-adolescence (15–19 years), and late adolescence (20–24 years)8–10,14,15, reflecting distinct phases of growth and maturation. Cases that meet the diagnostic criteria for MDD and Dysthymia, according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) and the International Classification of Diseases (ICD), are included in the GBD study’s disease models16. Each step in the analysis of the GBD database adhered to the Guidelines for Accurate and Transparent Health Estimates Reporting (GATHER), which have been previously described in detail13,17.

Statistical analysis

We described the changes in burden of depression across 204 countries in 21 different regions during the study period. The key metrics analyzed include prevalence, incidence, and disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), differentiated by sex, age, region, and country. These data are presented as both numbers and age-standardized rates (ASR), which includes age- standardized incidence rate (ASIR), the age- standardized prevalence rate (ASPR), and the age- standardized DALY rate (ASDR), each accompanied by 95% uncertainty intervals (UI). The formula for calculating the ASR has been detailed in previous publications7,16. Additionally, to analyze the temporal changes in incidence, prevalence, and DALYs, we calculated the estimated annual percentage change (EAPC) rate. The calculation of EAPC and its 95% confidence interval (CI) can be referenced in previous literature8,18.

The Age-Period-Cohort (APC) model is used to disentangle and analyze the impact of three different time-related factors on specific outcomes or trends: age effects, period effects, and cohort effects9,19. To ensure accuracy, we organized the data into 5-year age intervals corresponding to 5-year periods from 1992 to 2021. Additionally, we constructed eight overlapping 5-year birth cohorts, ranging from those born in 1970 to those born in 2009. This structure allows for a thorough examination of the effects of age, period, and birth cohort on depression trends. The APC model determines the overall time trend, or “net drift,” which is the annual percentage change in the disease burden, reflecting the combined effect of time progression and successive birth cohorts. Conversely, “local drift,” or the specific time trend for each age group, indicates the annual percentage change within each age group. We used the Wald χ1 test to assess the statistical significance of these trends.

Our study conducted a decomposition analysis to understand the factors influencing the burden of depression from 1990 to 2021. This involved examining changes in population size, age distribution, and epidemiological trends. The methodology for these analyses is detailed in a previously published article, which provides an in-depth reference to the techniques used20.

The Bayesian Age-Period-Cohort (BAPC) model, based on Bayesian statistical theory, is used to analyze and interpret trends in individual attributes across age, period, and birth cohorts in a population21. Using the standard age structure from the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study and population projections from the World Health Organization (WHO), we applied a Bayesian Age-Period-Cohort (BAPC) model to predict data for 2020 and 2021 based on data from 1990 to 2019. We then compared these predicted values with the actual reported data. Additionally, we projected the prevalence and incidence of depression for the next 15 years using data from 1990 to 2021 to understand potential future trends in the disease’s progression.

Our study amassed data on total DALYs crude rates for the analysis of health inequalities. In accordance with recommendations from the World Health Organization, the Slope Index of Inequality (SII) and the Concentration Index (CI) were employed to assess absolute and relative inequalities related to income between countries. These indices are well-established metrics for evaluating absolute and relative inequality gradients8,9. All statistical analysis and graphical representations were conducted using R software (version 4.3.1).

Ethical approval

As our study involves secondary analysis of aggregated, anonymized data from the 2021 Global Burden of Disease Study, separate ethical approval was not required.

Results

Global disease burden of depression in adolescents

In 2021, the number of adolescents with depression was 57,488,802 cases (95% UI 44,127,193–73,889,612), representing a 49.41% increase since 1990. The incidence was 73,809,681 cases (95% UI 53,637,291–97,618,586), reflecting a 54.61% increase from 1990. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) reached 10,718,195 (95% UI 6,792,136–15,633,301), marking a 52.57% increase compared to 1990 (Table 1; Fig. 1). From 1990 to 2021, there were no significant changes observed in the ASPR (EAPC = 0.15, 95% CI -0.03 to 0.33), ASIR (EAPC = 0.11, 95% CI -0.12 to 0.34), or ASDR (EAPC = 0.14, 95% CI -0.06 to 0.35) for adolescent depression. Although females consistently had higher ASPR, ASIR, and ASDR than males, no significant changes were observed for either gender from 1990 to 2021 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Prevalence, incidence and disability-adjusted life years of depression in adolescents aged 10–24 years, from 1990 to 2021.

| Type | 1990 | 2021 | EAPC (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number (95% UI) | ASR per 105 (95% UI) | Number (95% UI) | ASR per 105 (95% UI) | ||

| Prevalence | |||||

| Global | 38,476,683 (30133092–48956768) | 2472.56 (1851.75,3289.02) | 57,488,802 (44127193–73889612) | 3045.32 (2237.13,4136.26) | 0.15 (-0.03-0.33) |

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 23,837,058 (18701859–30260321) | 3103.49 (2323.61,4129.39) | 34,754,077 (26764453–44365663) | 3766.2 (2770.39,5112.54) | 0.06 (-0.18-0.3) |

| Male | 14,639,626 (11461147–18545713) | 1857.83 (1388.04,2465.31) | 22,734,724 (17366672–29386129) | 2356.54 (1720.11,3191.64) | 0.12 (-0.09-0.32) |

| Sociodemographic index | |||||

| Low SDI | 4,264,370 (3253225–5574347) | 2909.01 (2115.36,3978.8) | 11,480,881 (8605718–14945077) | 3227.73 (2316.85,4424.11) | -0.08 (-0.21-0.05) |

| Low-middle SDI | 9,016,206 (6911491–11692495) | 2596.2 (1907.43,3495.49) | 16,653,939 (12699262–21849251) | 3006.28 (2185.94,4102.15) | -0.11 (-0.3-0.08) |

| Middle SDI | 11,802,941 (9207771–15031549) | 2111.22 (1575.67,2797) | 13,868,382 (10700016–17740211) | 2497.36 (1839.05,3387.98) | 0 (-0.19-0.19) |

| High-middle SDI | 6,867,077 (5463194–8596651) | 2331.26 (1763.87,3037.86) | 6,224,704 (4783419–7980205) | 2730.92 (1968.89,3721.78) | 0.03 (-0.16-0.22) |

| High SDI | 6,493,809 (5219198–7985654) | 3187.01 (2439.23,4107.74) | 9,218,396 (7279862–11459503) | 4843.56 (3647.19,6397.1) | 0.81 (0.6–1.02) |

| Region | |||||

| Andean Latin America | 231,300 (173370–299750) | 1941.97 (1393.85,2642.46) | 464,565 (335422–644553) | 2634.44 (1812.14,3731.57) | 0.17 (-0.19-0.53) |

| Australasia | 241,426 (186798–301929) | 4853.85 (3580.2,6369.15) | 314,196 (231364–417414) | 5383.29 (3821.79,7605.54) | 0.28 (0.18–0.38) |

| Caribbean | 302,398 (226013–396442) | 2783.65 (1994.91,3776.07) | 352,084 (256979–485037) | 3036.83 (2090.53,4381.6) | -0.32 (-0.56–0.08) |

| Central Asia | 452,556 (341994–589588) | 2316.79 (1677.6,3151.33) | 611,802 (449929–836854) | 2808.08 (1958.24,3895.19) | 0.13 (-0.05-0.31) |

| Central Europe | 542,181 (418463–695428) | 1878.16 (1376.55,2515.96) | 426,636 (324819–549507) | 2325.83 (1675.82,3173.71) | -0.11 (-0.37-0.15) |

| Central Latin America | 1,014,764 (788682–1316548) | 1926.77 (1427.17,2591.19) | 1,840,650 (1406901–2417143) | 2775.81 (2011.65,3793.94) | 0.62 (0.39–0.85) |

| Central Sub-Saharan Africa | 715,746 (509796–969232) | 4356.24 (3010.45,6171.92) | 1,978,244 (1405135–2780617) | 4657.82 (3143.29,6729.64) | -0.04 (-0.17-0.08) |

| East Asia | 7,130,559 (5660934–9075408) | 1773.69 (1338.7,2295.87) | 3,097,322 (2477477–3879073) | 1286.32 (969.57,1676.94) | -1.14 (-1.25–1.04) |

| Eastern Europe | 1,058,075 (821241–1382226) | 2233.82 (1659.72,3012.83) | 949,918 (725828–1244711) | 2960.96 (2133.04,4043.6) | -0.01 (-0.26-0.24) |

| Eastern Sub-Saharan Africa | 1,879,518 (1456493–2429974) | 3231.79 (2372.41,4382.34) | 5,085,287 (3820003–6769075) | 3621.58 (2602.13,4958.09) | -0.17 (-0.32–0.02) |

| High-income Asia Pacific | 911,585 (730954–1127125) | 2084.06 (1606.26,2671.99) | 750,688 (582986–949791) | 2728.3 (2042.51,3572.49) | 0.54 (0.4–0.67) |

| High-income North America | 2,523,593 (2007330–3102030) | 3986.13 (3022.44,5153.42) | 5,015,588 (4009520–6089667) | 6898.34 (5324.92,8856.85) | 1.04 (0.77–1.31) |

| North Africa and Middle East | 3,967,975 (2974437–5177617) | 3758.65 (2672.54,5220.98) | 7,308,837 (5292502–9824858) | 4541.51 (3117.93,6428.28) | 0.28 (0.1–0.45) |

| Oceania | 47,676 (35170–65261) | 2353.67 (1660.71,3298.39) | 98,102 (71151–137263) | 2467.23 (1696.05,3522.23) | -0.12 (-0.18–0.05) |

| South Asia | 7,774,724 (6107780–10031373) | 2409.95 (1811.24,3204.49) | 14,594,747 (11408747–18638166) | 2732.87 (2026.46,3689.84) | -0.24 (-0.44–0.03) |

| Southeast Asia | 2,729,909 (2115243–3500397) | 1872.87 (1366.87,2529.34) | 3,983,318 (3046488–5215615) | 2298.39 (1643.88,3155.86) | 0.14 (-0.07-0.34) |

| Southern Latin America | 440,214 (344883–553647) | 3362.25 (2516.68,4443.96) | 666,737 (498696–855657) | 4246.63 (3023.63,5731.77) | 0.09 (-0.17-0.36) |

| Southern Sub-Saharan Africa | 446,255 (352131–561668) | 2686.78 (2024.94,3523.34) | 778,715 (593451–995024) | 3606.4 (2639.25,4807.06) | 0.46 (0.23–0.68) |

| Tropical Latin America | 1,255,863 (980155–1618236) | 2694.82 (2005.93,3588) | 1,685,936 (1291883–2199642) | 3175.67 (2353.84,4291.85) | -0.38 (-0.85-0.1) |

| Western Europe | 3,332,524 (2730989–4092627) | 3859.37 (2997.21,4943.84) | 3,415,977 (2546202–4435448) | 4651.69 (3280.83,6468.23) | 0.06 (-0.18-0.29) |

| Western Sub-Saharan Africa | 1,477,842 (1138417–1951156) | 2598.03 (1886.75,3504.74) | 4,069,453 (3136028–5308433) | 2648.01 (1888.22,3611.59) | -0.07 (-0.17-0.03) |

| Incidence | |||||

| Global | 47,739,042 (35706347–63520938) | 3069.49 (2183.96,4243) | 73,809,681 (53637291–97618586) | 3909.88 (2722.04,5501.78) | 0.11 (-0.12-0.34) |

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 29,932,178 (22537815–39742261) | 3901.73 (2785.81,5404.82) | 44,867,009 (32872250–58705832) | 4865.35 (3397,6861.84) | 0.05 (-0.23-0.33) |

| Male | 17,806,864 (13239024–23692258) | 2259.62 (1594.84,3131.24) | 28,942,672 (20852925–38491309) | 2998.21 (2072.5,4219.33) | 0.07 (-0.19-0.32) |

| Sociodemographic index | |||||

| Low SDI | 5,221,225 (3673134–7084885) | 3524.88 (2386.37,5084.11) | 14,398,342 (10007286–19592572) | 4014.8 (2654.99,5796.91) | -0.13 (-0.3-0.04) |

| Low-middle SDI | 11,291,507 (8331776–15362090) | 3233.21 (2254.39,4594.71) | 21,250,480 (15232171–28609514) | 3836.59 (2618.9,5469.75) | -0.22 (-0.47-0.04) |

| Middle SDI | 14,609,672 (10911915–19541306) | 2618.82 (1851.19,3626.36) | 17,617,056 (13056072–23397245) | 3175.56 (2206.1,4472) | -0.09 (-0.33-0.16) |

| High-middle SDI | 8,501,874 (6542527–11043421) | 2906.05 (2105.76,3935.6) | 7,977,472 (5895769–10454887) | 3510.9 (2386.87,4955.29) | 0 (-0.24-0.23) |

| High SDI | 8,074,817 (6279238–10288948) | 3999.67 (2934,5312.94) | 12,511,299 (9407431–15996313) | 6631.59 (4793.39,8897.78) | 1 (0.75–1.25) |

| Region | |||||

| Andean Latin America | 280,214 (199824–380608) | 2339.8 (1586.35,3349.76) | 604,570 (411299–867257) | 3444.14 (2222.82,5094.55) | 0.2 (-0.26-0.65) |

| Australasia | 323,548 (241386–416322) | 6537.24 (4617.19,8815.27) | 428,706 (299787–584185) | 7382.63 (4902.7,10563.42) | 0.31 (0.2–0.43) |

| Caribbean | 397,964 (283916–539008) | 3665.86 (2482.56,5192.24) | 471,217 (325337–670524) | 4079.67 (2651.1,6138.74) | -0.38 (-0.68–0.09) |

| Central Asia | 544,999 (385807–733041) | 2780.23 (1878.27,3935.37) | 776,936 (540712–1085239) | 3560.52 (2346.49,5235.24) | 0.17 (-0.06-0.4) |

| Central Europe | 610,705 (446867–820500) | 2109.65 (1461.67,2953.57) | 515,528 (370550–709804) | 2820.32 (1891.5,4078.63) | -0.17 (-0.54-0.2) |

| Central Latin America | 1,254,360 (926977–1684641) | 2370.13 (1655.16,3311.11) | 2,469,993 (1814447–3336508) | 3733.11 (2607.79,5258.79) | 0.79 (0.5–1.07) |

| Central Sub-Saharan Africa | 964,729 (651094–1367890) | 5830.39 (3774.83,8623.27) | 2,703,093 (1773498–3895034) | 6310.5 (3961.44,9542.85) | -0.05 (-0.2-0.1) |

| East Asia | 8,670,892 (6558652–11470919) | 2177.75 (1567.3,2994.09) | 3,397,308 (2547414–4427705) | 1409.59 (997.24,1942.51) | -1.56 (-1.7–1.43) |

| Eastern Europe | 1,288,899 (948264–1731985) | 2721.26 (1865.15,3849.98) | 1,254,429 (905921–1697740) | 3894.61 (2605.83,5472.76) | -0.02 (-0.34-0.3) |

| Eastern Sub-Saharan Africa | 2,254,637 (1612156–3034495) | 3826.45 (2589.72,5482.51) | 6,321,964 (4356705–8663916) | 4465.2 (2950.66,6481.42) | -0.21 (-0.41–0.01) |

| High-income Asia Pacific | 1,119,774 (843789–1436710) | 2568.09 (1855.77,3461.75) | 976,061 (719517–1295670) | 3584.46 (2518.34,4870.14) | 0.69 (0.53–0.85) |

| High-income North America | 3,137,300 (2404609–4037578) | 5008.86 (3638.71,6696.01) | 7,045,511 (5513507–8913319) | 9758.81 (7270.02,12770.1) | 1.3 (0.96–1.64) |

| North Africa and Middle East | 5,198,201 (3691130–6997012) | 4888.01 (3301.77,7015.52) | 9,842,270 (6780495–13664266) | 6103.99 (3929.65,8971.48) | 0.3 (0.1–0.51) |

| Oceania | 61,134 (42795–86611) | 3002.56 (1999.75,4424.09) | 126,907 (84413–181242) | 3186.71 (2021.86,4852.96) | -0.14 (-0.22–0.06) |

| South Asia | 9,604,922 (7145543–13003646) | 2966.61 (2118.11,4162.09) | 18,281,089 (13436020–24475212) | 3430.96 (2397.54,4800.12) | -0.43 (-0.71–0.14) |

| Southeast Asia | 3,270,260 (2396535–4331212) | 2232.24 (1524.94,3160.67) | 5,015,565 (3584888–6866744) | 2905.77 (1919.85,4165.21) | 0.17 (-0.1-0.44) |

| Southern Latin America | 591,413 (444295–752580) | 4504.18 (3241.76,6070.73) | 919,891 (659060–1227120) | 5894.86 (4020,8228.99) | 0.13 (-0.17-0.43) |

| Southern Sub-Saharan Africa | 533,142 (398426–709916) | 3192.08 (2255.7,4404.77) | 1,009,599 (735760–1343803) | 4667.53 (3227.25,6504.31) | 0.61 (0.31–0.9) |

| Tropical Latin America | 1,681,640 (1260047–2235887) | 3597.68 (2565.3,4961.22) | 2,307,653 (1729764–3097352) | 4376.25 (3115.61,6043.84) | -0.43 (-0.97-0.11) |

| Western Europe | 4,212,258 (3334047–5270388) | 4935.23 (3658.08,6525.02) | 4,527,472 (3250728–6038278) | 6197.39 (4123.58,8796.22) | 0.07 (-0.21-0.35) |

| Western Sub-Saharan Africa | 1,738,051 (1249712–2375163) | 3022.46 (2047.4,4332.44) | 4,813,917 (3444264–6600077) | 3094.37 (2076,4521.45) | -0.11 (-0.25-0.03) |

| DALYs | |||||

| Global | 7,025,089 (4512560–10171661) | 451.46 (285.3,673.54) | 10,718,195 (6792136–15633301) | 567.77 (353.32,857.9) | 0.14 (-0.06-0.35) |

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 4,367,171 (2813054–6296235) | 568.67 (359.85,847.62) | 6,469,752 (4113643–9396058) | 701.21 (437.59,1055.8) | 0.07 (-0.19-0.33) |

| Male | 2,657,918 (1699507–3883716) | 337.29 (211.64,505.9) | 4,248,443 (2704223–6258555) | 440.32 (272.16,667.62) | 0.14 (-0.08-0.37) |

| Sociodemographic index | |||||

| Low SDI | 759,817 (472159–1116982) | 517.51 (314.63,784.83) | 2,094,964 (1268940–3087420) | 588.07 (356.72,902.58) | -0.07 (-0.22-0.08) |

| Low-middle SDI | 1,634,993 (1038201–2408604) | 470.57 (294.63,712.32) | 3,084,347 (1946037–4492344) | 556.77 (344.43,843.58) | -0.13 (-0.35-0.09) |

| Middle SDI | 2,157,055 (1383168–3136955) | 385.91 (243.54,577.43) | 2,574,805 (1643530–3783562) | 463.75 (287.54,700.09) | -0.04 (-0.26-0.18) |

| High-middle SDI | 1,266,357 (824677–1827131) | 430.42 (274.32,638.36) | 1,170,484 (734971–1738150) | 513.94 (313.26,779.55) | 0.03 (-0.17-0.24) |

| High SDI | 1,200,974 (783360–1723403) | 590.49 (381.79,871.18) | 1,785,617 (1165099–2617760) | 940.07 (605.52,1402.29) | 0.92 (0.69–1.15) |

| Region | |||||

| Andean Latin America | 41,530 (25975–60896) | 348.55 (209.47,533.33) | 87,264 (53200–132552) | 495.17 (290.89,778.96) | 0.19 (-0.22-0.61) |

| Australasia | 46,192 (29725–67373) | 929.47 (588.86,1378.82) | 60,893 (38457–92590) | 1044.29 (638.15,1620.56) | 0.31 (0.21–0.42) |

| Caribbean | 56,923 (35793–84202) | 523.95 (320,805.91) | 66,837 (40575–100480) | 576.69 (341.61,901.83) | -0.36 (-0.63–0.09) |

| Central Asia | 81,623 (51221–121701) | 417.58 (257.89,633.25) | 114,009 (71936–169649) | 523.23 (317.29,811.16) | 0.17 (-0.04-0.38) |

| Central Europe | 94,145 (60194–136808) | 325.96 (204.09,488.67) | 77,220 (49111–112479) | 421.29 (253.25,644.83) | -0.13 (-0.45-0.18) |

| Central Latin America | 183,906 (117587–270293) | 349.02 (216.97,528.87) | 350,939 (223149–518516) | 529.31 (327.64,807.11) | 0.71 (0.45–0.97) |

| Central Sub-Saharan Africa | 134,054 (81237–201919) | 815.55 (484.03,1280.94) | 376,502 (222278–571808) | 885.76 (510.54,1403.15) | -0.01 (-0.14-0.13) |

| East Asia | 1,303,974 (831087–1892288) | 324.64 (207.62,482.62) | 535,009 (345137–776864) | 222.19 (139.03,330.72) | -1.34 (-1.46–1.23) |

| Eastern Europe | 191,172 (123695–278442) | 403.6 (250,608.24) | 179,232 (115357–263048) | 558.34 (345.21,851.27) | -0.01 (-0.3-0.28) |

| Eastern Sub-Saharan Africa | 332,560 (208539–490411) | 570.52 (350.12,861.81) | 926,424 (568457–1357235) | 658.7 (395.14,1010.81) | -0.16 (-0.33-0.02) |

| High-income Asia Pacific | 167,392 (107711–240653) | 382.72 (244.63,566.61) | 142,956 (90977–214074) | 520.01 (326.63,777.86) | 0.64 (0.49–0.78) |

| High-income North America | 467,202 (307931–674946) | 739.83 (475.13,1100.3) | 988,790 (667742–1435479) | 1361.79 (890.37,2009.98) | 1.19 (0.89–1.5) |

| North Africa and Middle East | 750,117 (463752–1119163) | 709.53 (429.9,1089.7) | 1,409,383 (837694–2147155) | 875.45 (507.63,1380.27) | 0.31 (0.12–0.49) |

| Oceania | 8852 (5529–13314) | 436.82 (265.02,679.63) | 18,385 (10699–28632) | 462.3 (262.27,741.17) | -0.12 (-0.19–0.05) |

| South Asia | 1,390,864 (884030–2043039) | 431.15 (272,648.32) | 2,668,685 (1677332–3868540) | 499.86 (312.59,755.61) | -0.29 (-0.53–0.04) |

| Southeast Asia | 492,271 (315220–718391) | 337.33 (207.68,512.5) | 744,160 (468701–1091144) | 429.79 (260,655.68) | 0.18 (-0.06-0.42) |

| Southern Latin America | 84,884 (54632–122901) | 648.04 (410.33,975.97) | 130,746 (83256–190564) | 833.56 (511.12,1264.02) | 0.12 (-0.16-0.4) |

| Southern Sub-Saharan Africa | 79,169 (50389–114472) | 476.24 (299.55,708.92) | 144,888 (90671–211209) | 670.83 (416.16,1003.73) | 0.55 (0.29–0.82) |

| Tropical Latin America | 236,248 (151562–343527) | 506.91 (323.13,756.73) | 321,988 (206527–477624) | 606.75 (384.08,915.22) | -0.41 (-0.92-0.1) |

| Western Europe | 623,828 (415298–893628) | 724.39 (467.33,1063.72) | 654,187 (418715–971956) | 891.96 (540.69,1371.31) | 0.07 (-0.19-0.33) |

| Western Sub-Saharan Africa | 258,183 (161470–376842) | 452.9 (276.69,685.74) | 719,696 (447969–1054866) | 467.05 (284.33,716.42) | -0.05 (-0.17-0.07) |

EAPC estimated annual percentage change; ASR age-standardised rate; SDI Sociodemographic Index.

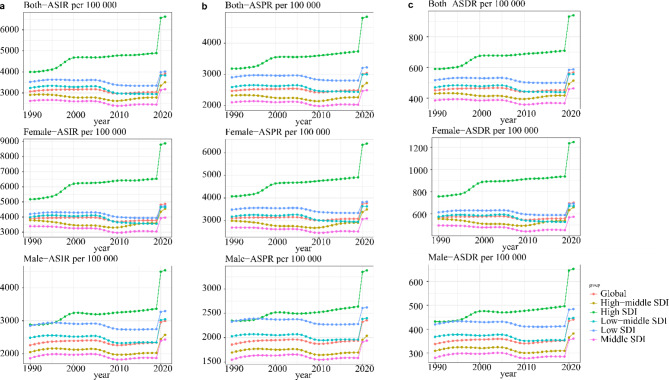

Fig. 1.

Burden of depression trends in global and five SDI regions for adolescents aged 10–24 years, from 1990 to 2019.

Trends in depression burden by socio-demographic index (SDI)

From 1990 to 2021, the ASPR, ASIR and ASDR significantly increased in high SDI regions, while no significant changes were observed in the other four SDI regions (Table 1; Fig. 1). Additionally, we found that in all five SDI regions, the prevalence (Supplementary Fig. 1), incidence (Supplementary Fig. 2), and DALYs (Supplementary Fig. 3) for all age groups showed a gradual increase with age, with a consistent male-to-female ratio of less than 1. Similarly, among the five SDI regions, the 20–24 age group accounted for the highest proportion of prevalence (Supplementary Fig. 4), incidence (Supplementary Fig. 5), and DALYs (Supplementary Fig. 6), while the 10–14 age group accounted for the lowest.

Trends in depression burden by regional

The GBD study divides the world into 21 regions, showing significant differences in the ASPR, ASIR, and ASDR of adolescent depression, as illustrated in Table 1. Most regions showed stable trends in ASPR, ASIR, and ASDR from 1990 to 2021. However, high-income regions such as High-income North America, Central Latin America, and High-income Asia Pacific exhibited increasing trends in these metrics. In contrast, middle- and low-income regions like East Asia, South Asia, and the Caribbean showed decreasing trends. Specifically, the High-income North America region had the fastest growth in ASPR (EAPC = 1.04, 95% CI 0.77–1.31), ASIR (EAPC = 1.30, 95% CI 0.96–1.64), and ASDR (EAPC = 1.19, 95% CI 0.89–1.50) from 1990 to 2021. Conversely, the East Asia region saw the most significant decreases in ASPR (EAPC = -1.14, 95% CI -1.25 - -1.04), ASIR (EAPC = -1.56, 95% CI -1.70 - -1.43), and ASDR (EAPC = -1.34, 95% CI -1.46 - -1.23) over the same period.

Trends in depression burden by national

In 2021, India, the United States, and China had the highest number of adolescent depression cases, incidence, and DALYs among all countries. India led with 10,939,519 prevalent cases (95% UI 8,600,946 − 14,044,761), 13,633,078 incident cases (95% UI 10,084,023 − 18,360,052), and 1,995,395 DALYs (95% UI 1,255,760–2,917,188), as shown in Supplementary Table 1. The distribution of age-standardized rates across 204 countries is depicted in Fig. 2. Greenland reported the highest ASPR of 10,252.85 per 100,000 (95% UI 6,790.05–14,704.25), ASIR of 15,032.63 per 100,000 (95% UI 9,725.34–22,117.91), and ASDR of 2,071.79 per 100,000 (95% UI 1,196.95–3,299.58) (Supplementary Table 1). Malaysia showed the most significant increases in ASPR (EAPC = 1.79, 95% CI 1.31–2.27), ASIR (EAPC = 2.07, 95% CI 1.52–2.62), and ASDR (EAPC = 2.01, 95% CI 1.48–2.55) (Supplementary Table 1, Supplementary Fig. 7). Changes in the number and rate of prevalent cases, incident cases, and DALYs from 1990 to 2021 across 204 countries are detailed in the Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. 8.

Fig. 2.

Maps showing (a) age-standardised incidence rate, (b) age-standardised prevalence rate and (c) age-standardised disability-adjusted life-years rate of depression among adolescents aged 10–24 years, in 204 countries and territories, between 1990 and 2021 (Image generated in R software version 4.3.1(https://www.r-project.org/)).

Fig. 3.

Change in rates of depression among adolescents aged 10–24 years for both genders, in 204 countries and territories. (a). Change in incidence rates (b) Change in prevalence rates. (c) Change in disability-adjusted life-years rates(Image generated in R software version 4.3.1(https://www.r-project.org/)).

Age-period-cohort effects on global trends

From 1990 to 2021, the risk of incident depression increased with age for both females (net drift 0.189, 95% CI 0.1002 to 0.2779) and males (net drift 0.3022, 95% CI 0.2429 to 0.3616) (Supplementary Table 2). The annual change rates increased in the 10–14 and 15–19 age groups, while they decreased in the 20–24 age group (Supplementary Fig. 9 and Table 3). The highest incidence rates of depression were observed in the 20–24 age group (Supplementary Fig. 10 and Table 4). Period effects indicated that the risk of depression incidence, prevalence, and DALYs first increased and then decreased over time for both males and females (Supplementary Fig. 11). Compared to the reference period of 2002–2006, the risk was lowest during 1992–1996 for incidence, prevalence, and DALYs, regardless of gender (Supplementary Table 5). Across the eight consecutive 5-year birth cohorts from 1970 to 2009, the cohort risks of depression incidence, prevalence, and DALYs initially decreased and then increased. Since the 1985–1989 birth cohort, the risks in successive cohorts have been rising (Supplementary Fig. 12). Compared to the 1985–1989 birth cohort, the later cohorts (post-1989) exhibited higher risks of incidence, prevalence, and DALYs (Supplementary Table 6).

Decomposition analysis

In the five regions with epidemiological changes adjusted for demographic factors-East Asia, Western Europe, Eastern Europe, High-Income Asia Pacific, and Central Europe-the overall prevalence of depression decreased from 1990 to 2021, regardless of gender (Supplementary Fig. 13). In contrast, the global prevalence of depression increased, primarily driven by epidemiological changes (Supplementary Fig. 13). Similar trends were observed in the incidence rates and DALYs across the 21 GBD regions (Supplementary Figs. 14–15).

The impact of COVID-19

The study employed the BAPC model to forecast the years 2020–2035 based on data from 1990 to 2019. The BAPC model predicted the prevalence, incidence, and DALYs for females in 2020 to be 3,065.07 per 100,000, 3,765.4 per 100,000, and 556.49 per 100,000, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 16, Table 2). However, the actual reported values for females in 2020 were 3,748.40 per 100,000 for prevalence, 4,830.71 per 100,000 for incidence, and 697.81 per 100,000 for DALYs. For males, the model predicted a prevalence of 1,933.41 per 100,000, an incidence of 2,334.03 per 100,000, and DALYs of 351.37 per 100,000 for 2020. The actual reported values for males in 2020 were 2,321.78 per 100,000 for prevalence, 2,947.81 per 100,000 for incidence, and 433.32 per 100,000 for DALYs. For 2021, the BAPC model predicted a prevalence of 3,064.4 per 100,000, an incidence of 3,765.12 per 100,000, and DALYs of 556.45 per 100,000 for females (Supplementary Fig. 16, Table 2). The actual reported values for females in 2021 were 3,776.27 per 100,000 for prevalence, 4,875.11 per 100,000 for incidence, and 702.98 per 100,000 for DALYs. For males, the model predicted a prevalence of 1,937.25 per 100,000, an incidence of 2,339.35 per 100,000, and DALYs of 352.19 per 100,000 for 2021 (Supplementary Fig. 16, Table 2). The actual reported values for males in 2021 were 2,349.97 per 100,000 for prevalence, 2,991.66 per 100,000 for incidence, and 439.14 per 100,000 for DALYs. Table 2 provides a detailed comparison between the predicted values and actual reported values for the five different SDI regions. The results indicate that, both globally and across all SDI regions, the predicted data for 2020 and 2021 were significantly lower than the actual reported values. To understand the trend of the depression burden beyond 2021, we used a Bayesian Age-Period-Cohort model to project prevalence, incidence, and DALYs by gender for the period 2022–2037. As shown in the Supplementary Fig. 17, the prevalence, incidence, and DALYs for both females and males globally are expected to continue increasing through 2037.

Table 2.

Predicted values from the BAPC Model based on 1990–2019 data compared to actual reported values.

| location | Sex | Prevalence | Incidence | DALYs | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 2021 | 2020 | 2021 | 2020 | 2021 | ||||||||

| predicted | actual | predicted | actual | predicted | actual | predicted | actual | predicted | actual | predicted | actual | ||

| Global | Female | 3064.40 | 3748.40 | 3062.99 | 3776.27 | 3765.4 | 4830.71 | 3765.12 | 4875.11 | 556.49 | 697.81 | 556.45 | 702.98 |

| Male | 1933.41 | 2321.78 | 1937.25 | 2349.97 | 2334.03 | 2947.81 | 2339.35 | 2991.66 | 351.37 | 433.32 | 352.19 | 439.14 | |

| High SDI | Female | 4914.21 | 6492.18 | 4931.31 | 6543.74 | 6541.94 | 8913.31 | 6567.11 | 8986.67 | 938.61 | 1262.10 | 941.98 | 1271.90 |

| Male | 2643.2 | 3461.85 | 2654.61 | 3490.00 | 3372.69 | 4595.48 | 3389.81 | 4637.84 | 496.91 | 666.27 | 499.18 | 671.92 | |

| High-middle SDI | Female | 2894.61 | 3413.88 | 2884.69 | 3522.73 | 3596.14 | 4383.99 | 3583.27 | 4568.49 | 535.19 | 641.06 | 533.18 | 664.50 |

| Male | 1683.53 | 1985.43 | 1679.98 | 2060.26 | 2016.73 | 2467.07 | 2012.61 | 2591.60 | 307.05 | 369.66 | 306.32 | 385.52 | |

| Middle SDI | Female | 2495.08 | 3096.92 | 2486.3 | 3115.31 | 3029.05 | 3955.81 | 3017.72 | 3989.48 | 450.57 | 574.49 | 448.96 | 578.20 |

| Male | 1574.41 | 1916.41 | 1572.73 | 1941.73 | 1861.67 | 2396.83 | 1858.77 | 2436.56 | 283.33 | 355.43 | 283.06 | 360.67 | |

| Low-middle SDI | Female | 2926.12 | 3656.83 | 2926.2 | 3655.23 | 3543.72 | 4682.08 | 3546.8 | 4679.94 | 524.48 | 675.65 | 524.84 | 674.34 |

| Male | 1954.6 | 2377.20 | 1958.24 | 2393.68 | 2342.17 | 3014.02 | 2348 | 3039.05 | 353.05 | 442.27 | 353.98 | 445.84 | |

| Low SDI | Female | 3322.22 | 3677.32 | 3326.41 | 3712.34 | 3933.22 | 4572.48 | 3940.87 | 4621.58 | 587.34 | 665.13 | 588.51 | 671.28 |

| Male | 2273.98 | 2488.53 | 2280.11 | 2508.49 | 2747.52 | 3151.95 | 2756.85 | 3179.75 | 411.58 | 460.01 | 412.97 | 463.80 | |

Moreover, in 1990, the difference in DALY rates between the highest and lowest was − 7.80 per 100,000 people, increasing to 19.97 per 100,000 in 2019, and further rising to 112.06 per 100,000 in 2021 (Fig. 4). This significant growth indicates that the inequality in age-standardized burden of adolescent depression between high-income and low-income countries has widened between 2019 and 2021. The analysis of relative inequality shows that the concentration index for DALYs increased by 0.007 from 1990 to 2019, and by 0.029 in 2021 (Fig. 4). This suggests that economic disparities in certain regions have widened, particularly following the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, highlighting that the global inequality in adolescent depression remains an ongoing issue.

Fig. 4.

Absolute (a) and relative (b) income-related health inequalities in adolescent depression for 1990, 2019, and 2021. Absolute Health Inequalities (a) is represented by the regression line, which illustrates disparities in adolescent depression burden based on income levels. Relative Health Inequalities (b) is depicted using the concentration curve (Lorenz curve) and the concentration index (CI). These metrics assess the distribution of adolescent depression cases relative to income levels across countries or regions. Points represent countries or regions, with different sizes indicating population scale (yellow for 1990, blue for 2019/2021).

Discussion

This study, based on data from the GBD 2021, presents the latest findings on the burden and trends of adolescent depression among individuals aged 10–24 years across 204 countries and regions from 1990 to 2021. Over the past 32 years, even though the EAPC results indicate that the incidence, prevalence, and DALYs of adolescent depression have remained stable, the overall increase in prevalence, incidence, and DALYs underscores the persistence of the global burden of adolescent depression. The number of adolescent depression cases has risen significantly, with prevalence cases increasing by 49.41%, incidence cases by 54.61%, and DALYs by 52.57% from 1990 to 2021. This trend can be attributed to a range of risk factors, including economic recessions, substance use, violence, sleep disorders, excessive use of electronic devices, and home isolation due to the COVID-19 pandemic22–24.

The results of the GBD 2021 analysis indicate that the burden of depression is higher among females and older adolescents. In terms of gender, the burden of adolescent depression among females remained higher than that among males in 2021. The gender differences in the burden of adolescent depression can be attributed to hormonal changes associated with puberty, such as fluctuations in estradiol levels25. Furthermore, females are more susceptible to risk factors such as gender discrimination, violence, sexual abuse, and internalizing psychological disorders compared to males26–28. Additionally, the study found that the burden of depression is significantly higher in late adolescence (20–24 years) compared to other stages of adolescence. APC analysis revealed that, for both males and females, the burden ocf adolescent depression increases with age. This may be due to significant biological and social changes experienced by older adolescents, such as changes in the developmental trajectories of the limbic and striatal regions, and the various pressures related to economic conditions and interpersonal relationships29–31.

The study reveals that while global trends in adolescent depression appear relatively stable, significant regional disparities emerge upon closer examination. Analysis based on the five Sociodemographic Index (SDI) regions indicates a notable increase in prevalence, incidence, and Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) in high-SDI regions. Similarly, data from the 21 regions defined by the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study show marked growth in these metrics in high-income areas, such as High-income North America, Central Latin America, and High-income Asia Pacific. In contrast, certain low- and middle-income regions, including East Asia, South Asia, and the Caribbean, exhibit stable or even declining trends. At the national level, India, the United States, and China were identified as having the highest prevalence, incidence, and DALYs for adolescent depression in 2021. These patterns suggest that global stability may obscure critical regional differences, emphasizing the importance of tailoring public health interventions to specific regional contexts. It is worth noting, however, that these trends may partially reflect increased reporting rather than an actual rise in cases. As illustrated in Figs. 1 and 4, while high-SDI regions experienced a disproportionate rise in DALYs during the pandemic, health inequities between high-income and low-income countries have significantly widened. The burden of adolescent depression has notably increased in low-income countries, highlighting the profound impact of socioeconomic conditions and the distribution of healthcare resources on mental health outcomes.

In the early stages of the pandemic, many high-income countries rapidly enhanced the diagnosis and reporting of adolescent depression, contributing to improved identification and higher reporting rates, which partly explains the substantial increase in DALYs32. These countries typically have more robust healthcare systems capable of effectively identifying and documenting cases of depression. This capability was further bolstered during the pandemic by heightened societal awareness of mental health issues and advancements in diagnostic techniques and mental health services7. Despite relatively well-developed healthcare infrastructures and mental health service systems, adolescents in high-income countries faced significant social, academic, and familial stressors during the pandemic. These included challenges in adapting to online education, social isolation, and increased financial strain within families, all of which exacerbated mental health issues33. Consequently, while high-income countries were better equipped to deliver effective mental health interventions, the burden of adolescent depression still increased, reflecting the multifaceted pressures brought about by the pandemic. In contrast, healthcare systems in low- and middle-income countries are generally less developed, and during the pandemic, many resources and public health services were severely strained. In these regions, COVID-19 worsened existing health inequities, significantly reducing the availability and quality of mental health services. School closures, social isolation, and heightened economic pressures created additional barriers for adolescents seeking help for mental health issues32–34. Moreover, cultural stigma surrounding mental health problems in many low-income countries often discourages adolescents from seeking support, further hindering progress in diagnosis and treatment8. The lack of adequate mental health resources, compounded by pandemic-induced social and economic stressors, has led to a heavier burden of adolescent depression in low-income countries, often exceeding historical expectations. The pandemic has starkly highlighted global disparities in healthcare resource distribution, particularly in low- and middle-income countries where COVID-19 intensified pre-existing health inequalities. While high-income countries faced significant challenges, they possess greater capacity for implementing mental health interventions, education, and resource allocation34. In contrast, low-income countries face substantial deficits in these areas, leaving their adolescent populations more vulnerable to the pandemic’s adverse effects. Additionally, family and community networks in low-income regions often lack sufficient support structures, depriving adolescents of effective psychological support in coping with the socioeconomic shocks of the pandemic. This absence of social support, combined with scarce healthcare resources, has created formidable challenges for adolescents in low-income areas in managing depression. Our analysis highlights the widening gap in the burden of adolescent depression between low-income and high-income countries, a disparity exacerbated by the pandemic. Low-SDI regions have faced disproportionate challenges, including reduced access to mental health services, heightened economic pressures, and intensified social disruptions, all of which have disproportionately affected their adolescent populations. While high-income countries have also faced challenges, they are generally better positioned to mitigate these effects through more accessible mental health resources and digital health interventions.

Decomposition analysis from 1990 to 2021 indicates that changes in epidemiological trends, rather than demographics, have primarily driven the overall increase in adolescent depression prevalence over time. This pattern holds true globally and in most regions. However, a previous decomposition analysis based on 1990–2019 GBD data suggested that demographic factors were the main drivers of the increase in adolescent depression prevalence, highlighting an inconsistency in findings8.This discrepancy is largely attributed to the outbreak and pandemic of COVID-19 at the end of 2019, underscoring the severe impact of the pandemic on mental health.

The analysis of GBD 2021 data reveals a significant discrepancy between the predicted values from the BAPC model, based on 1990–2019 data, and the actual reported values for adolescent depression in 2020 and 2021, both globally and across the five SDI regions. The actual reported values were considerably higher than the predicted estimates, which is likely attributable to the profound impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic has introduced unprecedented levels of stress, social isolation, and disruption, particularly among adolescents, exacerbating mental health issues and leading to a surge in depression cases that exceeded historical trends32–34. Additionally, the BAPC model, using data from 1990 to 2021, projects a continued increase in the burden of adolescent depression from 2022 to 2037. This sustained increase can be largely attributed to the lingering effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. The ongoing challenges related to social and economic recovery, continued uncertainty, and the long-term psychological impacts of the pandemic are expected to contribute to this upward trend35,36. The pandemic has not only intensified existing risk factors for depression but has also created new ones, such as prolonged periods of social isolation, disruptions in education and routine, and increased exposure to family stress and economic hardship. For example, a cross-sectional study found that individuals who underwent COVID-19 isolation were at a higher risk of developing depression37. Adolescents, in particular, as a vulnerable group, are more susceptible to depression due to lifestyle changes and the constant threat of infection23. A global survey indicated that COVID-19 impact indicators, especially the daily SARS-CoV-2 infection rate and reduced human activity, were associated with an increase in the prevalence of major depressive disorder. Younger age groups were more affected than older ones. The report estimated that, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, there were 52.3 million additional cases of major depressive disorder globally (range: 44.8 to 62.9 million), representing a 27.6% increase (range: 25.1–30.3%), with a total prevalence of 3,152.9 cases per 100,000 people (range: 2,722.5 to 3,654.5)38. In conclusion, the COVID-19 pandemic has significantly amplified the global burden of adolescent depression, pushing actual rates far beyond previous projections. As we move forward, it is crucial to recognize and address the lasting effects of the pandemic on adolescent mental health.

The strength of this study lies in its use of the most recent epidemiological analysis of global trends in adolescent depression based on GBD 2021 data. This study not only examines the three key indicators - incidence, prevalence, and DALYs - at global, regional, and national levels from 1990 to 2021, but also provides an in-depth exploration of how the burden of adolescent depression has evolved in the context of the pandemic. It comprehensively analyzes the impact of COVID-19 on adolescent depression, with particular attention to changes in health inequalities over time.

However, there are several limitations to this study. First, the quality of data is constrained by the diagnostic systems and reporting standards of different countries and regions, potentially leading to an underestimation of the actual burden in low-income countries. Second, the impact of healthcare resource reallocation on mental health services during the pandemic has not been fully quantified. Finally, long-term trends predicted by the models rely on certain assumptions, and future data may necessitate revisions to these projections.

In summary, this study presents the latest global situation regarding the burden of depression among adolescents aged 10 to 24 years. From 1990 to 2021, there were notable regional, gender, and age differences in the burden of adolescent depression, with particular attention needed for adolescents in high SDI regions, females, and those aged 20 to 24 years. Notably, the outbreak of COVID-19 had a significant impact on the burden of depression among adolescents. More seriously, the pandemic exacerbated health inequalities between regions of differing economic development levels, with adolescents in low-income and middle-income countries being particularly affected.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

FYZ, with contributions from FG , conceptualized and drafted this manuscript. FG contributed to the review and finalization. YY, MSP, TLY, JMX, RCC and WJZ provided data, participated in the analysis, or reviewed the findings (or a combination of these), and contributed to the interpretation. All authors approved the final version of the paper.

Data availability

These data are available through the Global Health Data Exchange GBD Results Tool (http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool).

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Walker, E. R., McGee, R. E. & Druss, B. G. Mortality in mental disorders and global disease burden implications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 72, 334–341. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.2502 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mackner, L. M. et al. Depression Screening in Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease clinics: recommendations and a toolkit for implementation. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr.70, 42–47. 10.1097/mpg.0000000000002499 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang, J., Liu, D., Ding, L. & Du, G. Prevalence of depression in junior and senior adolescents. Front. Psychiatry. 14, 1182024. 10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1182024 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greenfield, B. L., Venner, K. L., Kelly, J. F., Slaymaker, V. & Bryan, A. D. The impact of depression on abstinence self-efficacy and substance use outcomes among emerging adults in residential treatment. Psychol. Addict. Behaviors: J. Soc. Psychologists Addict. Behav.26, 246–254. 10.1037/a0026917 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim, J. & Lee, J. Prospective study on the reciprocal relationship between intimate partner violence and depression among women in Korea. Soc. Sci. Med.99, 42–48. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.10.014 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fergusson, D. M., Goodwin, R. D. & Horwood, L. J. Major depression and cigarette smoking: results of a 21-year longitudinal study. Psychol. Med.33, 1357–1367. 10.1017/s0033291703008596 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim, S. et al. Psychosocial alterations during the COVID-19 pandemic and the global burden of anxiety and major depressive disorders in adolescents, 1990–2021: challenges in mental health amid socioeconomic disparities. World J. Pediatrics: WJP. 20, 1003–1016. 10.1007/s12519-024-00837-8 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang, C. H. et al. Global, regional and national burdens of depression in adolescents and young adults aged 10–24 years, from 1990 to 2019: findings from the 2019 global burden of Disease study. Br. J. Psychiatry: J. Mental Sci. 1–10. 10.1192/bjp.2024.69 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Li, Z. B. et al. Burden of depression in adolescents in the Western Pacific Region from 1990 to 2019: an age-period-cohort analysis of the Global Burden of Disease study. Psychiatry Res.336, 115889. 10.1016/j.psychres.2024.115889 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hua, Z., Wang, S. & Yuan, X. Trends in age-standardized incidence rates of depression in adolescents aged 10–24 in 204 countries and regions from 1990 to 2019. J. Affect. Disord.350, 831–837. 10.1016/j.jad.2024.01.009 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burden and risk factors of mental and substance use disorders among adolescents and young adults in Kenya: results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. EClinicalMedicine 67, 102328, (2024). 10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.102328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Global incidence. Prevalence, years lived with disability (YLDs), disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs), and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 371 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations, 1990–2021: a systematic analysis for the global burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet (London England). 403, 2133–2161. 10.1016/s0140-6736(24)00757-8 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Global burden of 369. diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet (London, England) 396, 1204–1222, (2020). 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30925-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Sawyer, S. M. et al. Adolescence: a foundation for future health. Lancet379, 1630–1640. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60072-5 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sawyer, S. M., Azzopardi, P. S., Wickremarathne, D. & Patton, G. C. The age of adolescence. Lancet Child. Adolesc. Health. 2, 223–228. 10.1016/S2352-4642(18)30022-1 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu, J., Liu, Y., Ma, W., Tong, Y. & Zheng, J. Temporal and spatial trend analysis of all-cause depression burden based on global burden of Disease (GBD) 2019 study. Sci. Rep.14, 12346. 10.1038/s41598-024-62381-9 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stevens, G. A. et al. Guidelines for Accurate and Transparent Health estimates reporting: the GATHER statement. Lancet (London England). 388, e19–e23. 10.1016/s0140-6736(16)30388-9 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang, K. et al. Global burden of type 1 diabetes in adults aged 65 years and older, 1990–2019: population based study. BMJ (Clinical Res. ed). 385, e078432. 10.1136/bmj-2023-078432 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bell, A. Age period cohort analysis: a review of what we should and shouldn’t do. Ann. Hum. Biol.47, 208–217. 10.1080/03014460.2019.1707872 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang, K. et al. Global, Regional, and National Epidemiology of Diabetes in Children from 1990 to 2019. JAMA Pediatr.177, 837–846. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2023.2029 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang, J. et al. Global burden and epidemiological prediction of polycystic ovary syndrome from 1990 to 2019: a systematic analysis from the global burden of Disease Study 2019. PloS One. 19, e0306991. 10.1371/journal.pone.0306991 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thapar, A., Collishaw, S., Pine, D. S. & Thapar, A. K. Depression in adolescence. Lancet (London England). 379, 1056–1067. 10.1016/s0140-6736(11)60871-4 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen, F. et al. Depression and anxiety among adolescents during COVID-19: a cross-sectional study. Brain. Behav. Immun.88, 36–38. 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.061 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blake, M. J., Trinder, J. A. & Allen, N. B. Mechanisms underlying the association between insomnia, anxiety, and depression in adolescence: implications for behavioral sleep interventions. Clin. Psychol. Rev.63, 25–40. 10.1016/j.cpr.2018.05.006 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Balzer, B. W., Duke, S. A., Hawke, C. I. & Steinbeck, K. S. The effects of estradiol on mood and behavior in human female adolescents: a systematic review. Eur. J. Pediatrics. 174, 289–298. 10.1007/s00431-014-2475-3 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abate, K. H. Gender disparity in prevalence of depression among patient population: a systematic review. Ethiop. J. Health Sci.23, 283–288. 10.4314/ejhs.v23i3.11 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Parker, G. & Brotchie, H. Gender differences in depression. Int. Rev. Psychiatry (Abingdon). 22, 429–436. 10.3109/09540261.2010.492391 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Salk, R. H., Hyde, J. S. & Abramson, L. Y. Gender differences in depression in representative national samples: Meta-analyses of diagnoses and symptoms. Psychol. Bull.143, 783–822. 10.1037/bul0000102 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Whittle, S. et al. Structural brain development and depression onset during adolescence: a prospective longitudinal study. Am. J. Psychiatry. 171, 564–571. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13070920 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Braet, C., Van Vlierberghe, L., Vandevivere, E., Theuwis, L. & Bosmans, G. Depression in early, middle and late adolescence: differential evidence for the cognitive diathesis-stress model. Clin. Psychol. Psychother.20, 369–383. 10.1002/cpp.1789 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Crone, E. A. & Dahl, R. E. Understanding adolescence as a period of social-affective engagement and goal flexibility. Nat. Rev. Neurosci.13, 636–650. 10.1038/nrn3313 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O’Connor, D. B. et al. Effects of COVID-19-related worry and rumination on mental health and loneliness during the pandemic: longitudinal analyses of adults in the UK COVID-19 mental health & wellbeing study. J. Ment. Health. 32, 1122–1133. 10.1080/09638237.2022.2069716 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Magklara, K. & Kyriakopoulos, M. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on children and young people. Psychiatrike = Psychiatriki. 34, 265–268. 10.22365/jpsych.2023.024 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Selak, Š. et al. Depression, anxiety, and help-seeking among Slovenian postsecondary students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Psychol.15, 1461595. 10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1461595 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mahdavinoor, S. M. M., Rafiei, M. H. & Mahdavinoor, S. H. Mental health status of students during coronavirus pandemic outbreak: A cross-sectional study. Annals of medicine and surgery 78, 103739, (2012). 10.1016/j.amsu.2022.103739 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Barendse, M. E. A. et al. Longitudinal change in adolescent depression and anxiety symptoms from before to during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Res. Adolescence: Official J. Soc. Res. Adolescence. 33, 74–91. 10.1111/jora.12781 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim, Y., Kwon, H. Y., Lee, S. & Kim, C. B. Depression during COVID-19 Quarantine in South Korea: a propensity score-matched analysis. Front. Public. Health. 9, 743625. 10.3389/fpubh.2021.743625 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Global prevalence and burden of depressive. and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet (London, England) 398, 1700–1712, (2021). 10.1016/s0140-6736(21)02143-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

These data are available through the Global Health Data Exchange GBD Results Tool (http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool).