ABSTRACT

Aim

Breast cancer imposes a serious disease and economic burden on patients. This guideline aims to develop a living evidence‐based clinical practice recommendations to guide the use of integrative therapies for the improvement of patient‐reported outcomes (PROs) in breast cancer survivors.

Methods

We searched systematic reviews and meta‐analyses or conducted de nova systematic reviews and meta‐analyses to support the recommendations. The grading of recommendations, assessment, development, and evaluation approach was used to rate the certainty of evidence and the strength of recommendations.

Results

The guideline panel issued 17 recommendations: for alleviating anxiety, strong recommendations in favor of muscle relaxation training, yoga, acceptance and commitment therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, psychological education, and Tai Chi in general breast cancer survivors; for alleviating depression, strong recommendations in favor of mindfulness therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, group psychotherapy, muscle relaxation training, acceptanceand commitment therapy in general breast cancer survivors, and exercise intervention for patients received radiotherapy; for sleep quality, conditional recommendations for all therapies; for pain, strong recommendations in favor of exercise intervention for postoperative breast cancer survivors; for alleviating fatigue, strong recommendations in favor of mindfulness therapy and group psychotherapy in general breast cancer survivors; for improving the quality of life, strong recommendations in favor of mindfulness therapy in general breast cancer survivors, Baduanjin and exercise intervention for patients undergoing anticancer treatment.

Conclusion

This proposed guideline provides recommendations for improving the PROs of breast cancer survivors. We hope these recommendations can help support practicing physicians and other healthcare providers for breast cancer survivors.

Keywords: breast cancer survivors, clinical practice guideline, integrative therapies, patient‐reported outcomes

1. Background

Breast cancer has exceeded lung cancer as the most diagnosed cancer, with an estimated 2.3 million new cases, accounting for 11.7% of all cancer cases, according to 2020 statistics [1]. The prevalence of breast cancer risk factors includes postponing childbearing and fewer children, hormonal risk factors (e.g., early age at menarche, late age at menopause, menopausal hormone therapy, oral contraceptives, etc.), lifestyle risk factors (e.g., alcohol intake, excess weight, physical inactivity, etc.), as well as screening mammography [2]. Breast cancer ranks as the fifth leading cause of cancer death, accounting for nearly 690,000 of all cancer deaths [1], whereas more than 7.8 million women have been breast cancer survivors diagnosed in the past five years [3].

Integrative oncology coordinates evidence‐based complementary therapies with conventional cancer care [4]. Complementary and alternative therapies are generally considered to be any medical system, practice, or product that is not part of conventional medical care [5, 6]. As cancer patients believe that conventional medical care does not completely meet their needs and are afraid of the side effects of medication or prefer a holistic approach [7]. These patients often seek integrative medicine therapies to promote health, improve quality of life, and alleviate disease symptoms and side effects of conventional medical care [7, 8]. Complementary and integrative therapies are also frequently used by breast cancer patients and breast cancer survivors as supportive care during treatment [8]. Integrative therapies including acupuncture, exercise, yoga, cognitive behavioral therapy and mindfulness have shown improvement in anxiety, depression, insomnia, fatigue, quality of life, physical function, etc. [9]. Although several guidelines have suggested the use of integrative therapies in breast cancer survivors [4, 8, 10], there were several limitations to restricting the implementation of these guidelines. For example, the evidence supporting recommendations was not updated or was not systematically reviewed; the grading of recommendation evaluation, development, and evaluation (GRADE) approach was not used to assess the certainty of evidence; the recommendations were not actionable due to no information on practice points of interventions, moreover; the recommendations across these guidelines were inconsistent.

There is growing recognition that the use of patient‐reported outcomes (PROs) to quantify the impact of disease and treatment on health, function, and quality of life, among other things, from the patient's perspective provides important information for clinical practice and research [11]. A core set of PROs on cancer survivors’ long‐term health, functioning, and quality of life incorporates 12 outcomes, including depression, anxiety, pain, fatigue, overall quality of life, etc. [12]. Therefore, we aim to develop a living evidence‐based recommendations with detailed practice points to guide the use of integrative therapies for the improvement of PROs in breast cancer survivors. Considering the burden on breast cancer survivors, we focused on the six outcomes first, including anxiety, depression, sleep quality, pain, fatigue, and quality of life. We plan to develop recommendations for other PROs in the next version of this guideline.

2. Methods

This guideline was developed adhering to the Institution of Medicine (IOM) [13], and the “World Health Organization Handbook for Guideline Development” [14]. The guideline was reported followed the Reporting Items for Practice Guidelines in Healthcare (RIGHT) statement [15]. Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation (AGREE II) was applied for quality assessment of the guideline [16]. The certainty of evidence and strength of the recommendations were rated according to GRADE approach [17].

2.1. Registration

This guideline has been registered on the International Practice Guidelines Registry Platform with the registration number of PREPARE‐2023CN201.

2.2. Guideline Panel

The working group consisted of four subgroups: a steering committee, expert consensus groups, an evidence review group, and an academic secretariat group. The expert consensus groups comprised three subpanels focusing on traditional Chinese medicine, exercise therapies, psychological, and art interventions, respectively. Each subpanel primarily reviewed relevant interventions within their respective fields and reached consensus first; then, all panel members reached consensus on all recommendations. All guideline members completed a disclosure form detailing financial and other interests, including relationships with commercial entities, and no member reported conflicts of interest.

2.3. Evidence Collection

We searched three English databases (PubMed, the Cochrane Library, and Embase) and four Chinese databases (China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), Wanfang data, VIP, and Chinese Biomedicine Literature Database (CBM)) to include randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and systematic reviews with meta‐analyses (SRMAs) that assessed the efficacy of integrative therapies for PROs in breast cancer survivors. There were no restrictions on the publication dates, publication language, and type of integrative therapies. Detailed search strategies are provided in Appendix Text S1.

For the six clinical questions, we directly used the published SRMAs to inform the recommendations where the best SRMAs were available; otherwise, we conducted de nova SRMAs via searching RCTs. We defined the best SRMAs to be published within five years (after 2020) and moderate or high quality based on AMSTAR‐2 assessment. We estimated risk ratios (RRs) and corresponding 95% confidence interval (95% CI) for dichotomous outcomes and estimated mean differences (MDs) for continuous outcomes. To facilitate comparisons and understanding, we converted standardized mean differences (SMDs) to MDs using the method described by Thorlund et al. [18]. The certainty of evidence for each outcome was rated using GRADE approach, which classifies evidence as high, moderate, low, or very low certainty [19, 20]. We used minimally important differences (MIDs) to assess the imprecision of summary effect estimates and categorized effects as either important or trivial to no effect. For each outcome, we estimated the MID as 0.5 times the standard deviation (SD) of the MD in the control group of the RCTs included in the SRMAs (Table 1) [21].

TABLE 1.

Measurement tools and minimally important differences for each outcome.

| Outcome | Measurement tool | MID |

|---|---|---|

| Anxiety | Self‐Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) | 2.55 |

| Depression | Self‐Rating Depression Scale (SDS) | 2.56 |

| Pain | Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) | 2.00 |

| Fatigue | Brief Fatigue Inventory (BFI) | 1.28 |

| Sleep quality | Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) | 1.81 |

| Quality of life | Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy‐Breast (FACT‐B) | 10.99 |

A total of 16,161 records were identified through the literature search. After applying the eligibility criteria, 224 SRMAs published after 2020 were initially included. After applying AMSTAR‐2 assessment [22], the recommended criteria, and updating the available evidence (1 SRMA was included), 27 SRMAs were finally included to support the guideline recommendations. The details assessment results are provided in Appendix Text S2.

2.4. Patient Preferences and Values

We searched for quantitative (e.g., cross‐sectional surveys), qualitative (e.g., interviews, focus groups), and mixed‐methods studies on breast cancer survivors' preferences and values. Quantitative studies used an adapted version of the GRADE approach to assess the risk of bias of studies, and qualitative studies used the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme qualitative research checklist. Details on the methods and basic characteristics of the included studies are provided in Appendix Text S3.

2.5. Formulation of Recommendations

After systematical reviewing, we selected the interventions reached the following criteria for further expert consensus: (1) the differences between intervention and standard care should be statistically significant; (2) the effect size of point estimate reached at or above MID. For interventions that met the above recommendation criteria, 31 multidisciplinary consensus experts used GRADE grid method to formulate the recommendations and rated the strength of recommendations as “strong” and “conditional” (sometime guidelines may use terms such as “conditional” or “discretionary” instead of weak) by comprehensively considering the balance of benefits and harms, the certainty of evidence, the patient preferences and values, resources, and other factors [19, 20]. (1) A consensus was reached, except for “no clear recommendation,” if the number of votes in any box exceeds 50%, the direction and strength of the recommendation would be deemed directly determined; (2) if the total number of votes for the two squares on one side of “no clear recommendation” exceeded 70%, the recommendation strength was directly defined as “weak.” In the first round of Delphi survey, all recommendations reached a consensus. The 31 multidisciplinary experts addressed six clinical questions and formulated 17 recommendations across 20 therapies. The panel strongly recommended six therapies for anxiety management (muscle relaxation training, yoga, acceptance and commitment therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, psychological education, and Tai Chi), while conditionally recommending five others. The experts also strongly recommended six therapies for depression management, with an additional strong recommendation for exercise intervention specifically for patients undergoing radiotherapy. For sleep quality, the panel made conditional recommendations for all therapies. For pain management, they strongly recommended exercise intervention for postoperative breast cancer survivors, with conditional recommendations for additional specific interventions. The panel strongly recommended mindfulness therapy and group psychotherapy for fatigue alleviation, while conditionally recommending four other therapies. For quality of life improvement, they strongly recommended mindfulness therapy for general breast cancer survivors, and both Baduanjin and exercise intervention for patients undergoing anticancer treatment. The details are shown in Appendix Text S4.

2.6. Drafting, Critical Review, and Dissemination

The guideline was drafted by the academic secretariat. After an internal review, a document was prepared for open discussion. After receiving feedback from experts, the guideline was finalized by another round of peer review facilitated by the journal editor. When the guideline is published, we will disseminate and promote the guideline primarily through the following three ways: (1) academic forums and conferences in relevant fields; (2) organizing physicians in traditional Chinese medicine, integrating Chinese and Western, and other related medical workers to learn about the guideline; (3) interpreting the guideline through social media platforms such as WeChat and Facebook.

2.7. Updates

We plan to launch the next iteration of this guideline within two years and will update the current recommendations when new evidence is available; meanwhile, we will incorporate more outcomes based on the feedback received for this edition. Updated guideline will follow the Checklist for the Reporting of Updated Guidelines (CheckUp) [23].

3. Recommendations

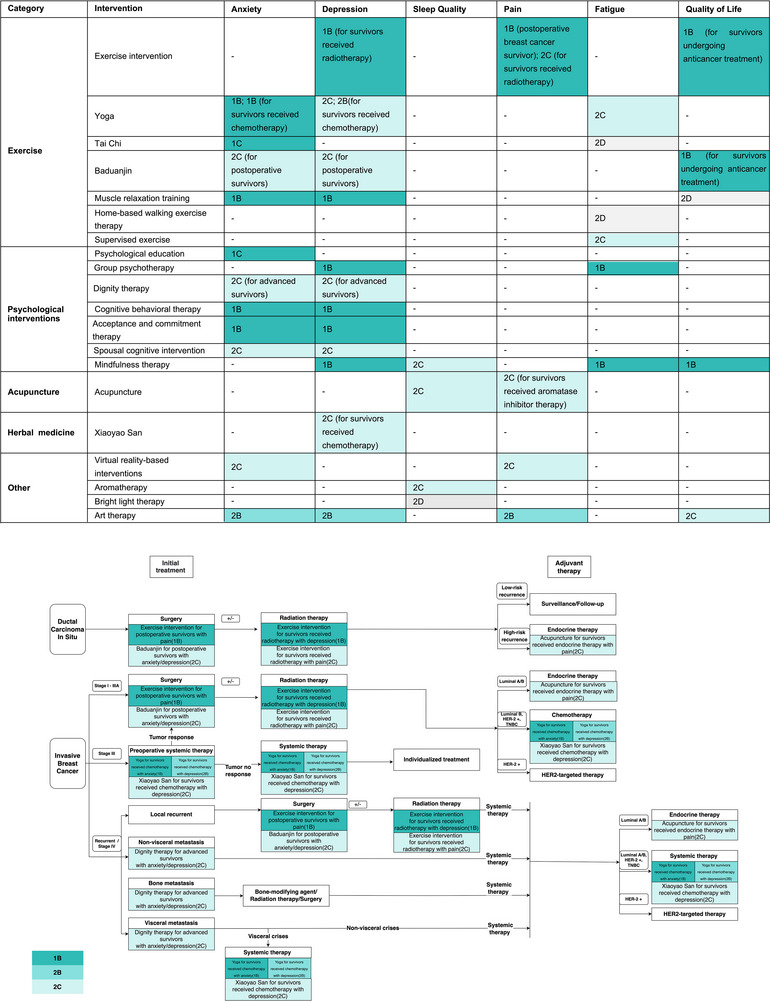

Figure 1 maps the recommendations, which show the patient‐reported outcomes improvement with various integrative therapies.

FIGURE 1.

Recommendations summary.

Clinical question 1: Which integrative therapies can be used to improve anxiety in breast cancer survivors?

Recommendation 1.1 Strong recommendations in favor of muscle relaxation training (moderate certainty), yoga (moderate certainty), acceptance and commitment therapy (moderate certainty), cognitive behavioral therapy (moderate certainty), psychological education (low certainty), and Tai Chi (low certainty); conditional recommendations in favor of art therapy (moderate certainty), spousal cognitive intervention (low certainty), and virtual reality‐based interventions (low certainty); to alleviate anxiety in general breast cancer survivors.

Recommendation 1.2 Conditional recommendations in favor of Baduanjin to alleviate anxiety in postoperative breast cancer survivors (low certainty).

Recommendation 1.3 Conditional recommendations in favor of dignity therapy to alleviate anxiety in advanced breast cancer survivors (low certainty).

Recommendation 1.4 Strong recommendations in favor of yoga to alleviate anxiety in breast cancer survivors received chemotherapy (moderate certainty).

The evidence

Forty‐six SRMAs were included, assessing 36 integrative therapies covering four categories: exercise, psychological, Traditional Chinese Medicine, and other interventions. Eight different anxiety measure scales were used, and we converted them into SAS, which is commonly used (the details see Appendix Text S5). Among 36 assessed integrative therapies (GRADE summary of findings for all therapies can be found in Appendix Text S6), compared to standard care, 12 presented statistical significance and the effect size reached at or above MID (see the effect size and certainty of evidence in Table 2), including muscle relaxation training, yoga (general breast cancer survivors), yoga (breast cancer survivors received chemotherapy), acceptance and commitment therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, art therapy, psychological education, Tai Chi, spousal cognitive intervention, virtual reality‐based interventions, Baduanjin (postoperative breast cancer survivors), and dignity therapy (advanced breast cancer survivors) [24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35].

TABLE 2.

GRADE summary of findings for anxiety (integrative therapies vs. standard care).

| Certainty of evidence | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Integrative therapies | No. of studies | Effect size MD, 95% CI | I 2, % | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Publication bias | Overall |

| Muscle relaxation training (Fang, 2022) a | 6 | −8.96 (–10.06to –7.86) | 5.6% | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Moderate |

| Yoga (Hsueh, 2021) a | 8 | −6.87 (–10.64 to –3.05) | 93% | Serious & | Serious & | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Moderate & |

| Acceptance and commitment therapy (Sun, 2022) a | 7 | −6.52 (–7.79 to –5.29) | 45% | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Moderate |

| Cognitive behavioral therapy (Getu, 2021) a | 5 | −2.80 (–3.77 to –1.83) | 0% | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Moderate |

| Yoga (Yi, 2021) b | 5 | −2.55 (–3.56 to –1.58) | 46% | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Moderate |

| Art therapy (Cheng, 2021) a | 8 | −5.60 (–10.59 to –1.63) | 94% | Serious & | Serious & | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Moderate & |

| Psychological education (Setyowibowo,2022) a | 15 | −3.61 (–7.13 to –0.15) | 89.2% | Serious & | Serious & | Not serious | Not serious | Serious | Low & |

| Tai Chi (Luo, 2020) a | 2 | −4.25 (–5.87 to –2.63) | 0% | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Serious | Not serious | Low |

| Spousal cognitive intervention (Zhao, 2021) a | 12 | −5.14 (–7.89 to –2.39) | 95% | Serious & | Serious & | Not serious | Not serious | Serious | Low & |

| Virtual reality‐based interventions (Zhang, 2022) a | 3 | −10.54 (–19.39 to –1.73) | 95% | Serious & | Serious & | Not serious | Serious | Not serious | Low & |

| Baduanjin (Ye, 2022) c | 3 | −8.02 (–9.26 to –6.78) | 10% | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Serious | Not serious | Low |

| Dignity therapy (Li, 2020) d | 9 | −5.45 (–7.99 to –2.95) | 91% | Serious & | Serious & | Not serious | Serious | Not serious | Low & |

The certainty of evidence was downgraded by one level due to risk of bias and inconsistency, as the risk of bias was suspected to be the cause of the inconsistency.

General breast cancer survivors.

Breast cancer survivors received chemotherapy.

Postoperative breast cancer survivors.

Advanced breast cancer survivors.

Clinical question 2: Which integrative therapies can be used to improve depression in breast cancer survivors?

Recommendation 2.1 Strong recommendations in favor of mindfulness therapy (moderate certainty), cognitive behavioral therapy (moderate certainty), group psychotherapy (moderate certainty), muscle relaxation training (moderate certainty), acceptance and commitment therapy (moderate certainty); conditional recommendations in favor of art therapy (moderate certainty), yoga (low certainty), and spousal cognitive intervention (low certainty); to alleviate depression in general breast cancer survivors.

Recommendation 2.2 Conditional recommendations in favor of Baduanjin to alleviate depression in postoperative breast cancer survivors (low certainty).

Recommendation 2.3 Conditional recommendations in favor of yoga (moderate certainty), and Xiaoyao San (low certainty) to alleviate depression in breast cancer survivors received chemotherapy.

Recommendation 2.4 Strong recommendations in favor of exercise intervention to alleviate depression in breast cancer survivors received radiotherapy (moderate certainty).

Recommendation 2.5 Conditional recommendations in favor of dignity therapy to alleviate depression in advanced breast cancer survivors (low certainty).

The evidence

Forty‐seven SRMAs were included, assessing 37 integrative therapies covering four categories: exercise, psychological, Traditional Chinese Medicine, and other interventions. Five different depression measure scales were used, and we converted them into SDS, which is commonly used (the details see Appendix Text S5). Among 37 assessed integrative therapies (GRADE summary of findings for all therapies can be found in Appendix Text S6), compared to standard care, 13 presented statistical significance and the effect size reached at or above MID (see the effect size and certainty of evidence in Table 3), including mindfulness therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, group psychotherapy, muscle relaxation training, acceptance and commitment therapy, art therapy, yoga (general breast cancer survivors), yoga (breast cancer survivors received chemotherapy), spousal cognitive intervention, Baduanjin (postoperative breast cancer survivors), Xiaoyao San (breast cancer survivors received chemotherapy), exercise intervention (breast cancer survivors received radiotherapy), and dignity therapy (advanced breast cancer survivors) [24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 31, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39].

TABLE 3.

GRADE summary of findings for depression (integrative therapies vs. standard care).

| Certainty of evidence | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Integrative therapies | No. of studies | Effect size MD, 95% CI | I 2, % | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Publication bias | Overall |

| Mindfulness therapy (Chang, 2021) a | 6 | −6.76 (–11.16 to –2.36) | 97% | Serious & | Serious & | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Moderate & |

| Cognitive behavioral therapy (Getu, 2021) a | 5 | −4.10 (–6.91 to –1.28) | 87% | Serious & | Serious & | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Moderate & |

| Group psychotherapy (Zhou,2020) a | 11 | −3.53 (–5.58 to –1.54) | 85% | Serious & | Serious & | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Moderate & |

| Muscle relaxation training (Fang, 2022) a | 6 | −9.31(–11.96 to –6.65) | 84.6% | Serious & | Serious & | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Moderate & |

| Acceptance and commitment therapy (Sun, 2022) a | 9 | −5.89 (–7.58 to –4.20) | 66% | Serious & | Serious & | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Moderate & |

| Art therapy (Cheng, 2021) a | 10 | −3.64 (–6.09 to –1.18) | 87% | Serious & | Serious & | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Moderate & |

| Yoga (Hsueh, 2021) a | 12 | −5.02 (–8.40 to –1.64) | 94% | Serious & | Serious & | Not serious | Not serious | Serious | Low & |

| Yoga (Yi, 2021) b | 6 | −2.87 (–5.38 to –0.36) | 84% | Serious & | Serious & | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Moderate & |

| Spousal cognitive intervention (Zhao, 2021) a | 11 | −5.07 (–7.58 to –2.61) | 94% | Serious & | Serious & | Not serious | Not serious | Serious | Low & |

| Baduanjin (Ye, 2022) c | 2 | −4.45 (–5.62 to –3.28) | 32% | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Serious | Not serious | Low |

| Xiaoyao San (Xie, 2021) b | 2 | −11.30 (–15.66 to –6.94) | 0% | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Serious | Not serious | Low |

| Exercise intervention (Shen, 2020) e | 8 | −2.61 (–4.97 to –0.20) | 91.6% | Not serious | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Moderate |

| Dignity therapy (Li, 2020) d | 10 | −6.71 (–9.83 to –3.58) | 94% | Serious & | Serious & | Not serious | Serious | Not serious | Low & |

The certainty of evidence was downgraded by one level due to risk of bias and inconsistency, as the risk of bias was suspected to be the cause of the inconsistency.

General breast cancer survivors.

Breast cancer survivors received chemotherapy.

Postoperative breast cancer survivors.

Advanced breast cancer survivors.

Breast cancer survivors received radiotherapy.

Clinical question 3: Which integrative therapies can be used to improve sleep quality in breast cancer survivors?

Recommendation 3.1 Conditional recommendations in favor of mindfulness therapy (low certainty), aromatherapy (low certainty), acupuncture (low certainty), and bright light therapy (very low certainty) to improve sleep quality in general breast cancer survivors.

The evidence

Twenty‐nine SRMAs were included, assessing 17 integrative therapies covering four categories. Four different sleep measure scales were used, and we converted them into PSQI, which is commonly used (the details see Appendix Text S5). Among 17 assessed integrative therapies (GRADE summary of findings for all therapies can be found in Appendix Text S6), compared to standard care, 4 presented statistical significance and the effect size reached at or above MID, including mindfulness therapy (5 RCTs; MD = –2.42, 95% CI –5.16 to 0.29; low CoE due to very serious risk of bias), aromatherapy (2 RCTs; MD = –3.54, 95% CI –5.67 to –1.44; low CoE due to very serious risk of bias), acupuncture (4 RCTs; MD = –1.81, 95% CI –2.56 to –1.01; low CoE due to very serious risk of bias), and bright light therapy (5 RCTs; MD = –12.53, 95% CI –16.53 to –8.52; very low CoE due to very serious risk of bias and serious imprecision) for general breast cancer survivors [36, 40, 41, 42].

Clinical question 4: Which integrative therapies can be used to improve pain in breast cancer survivors?

Recommendation 4.1 Conditional recommendations in favor of art therapy (moderate certainty) and virtual reality‐based interventions (low certainty) to improve pain in general breast cancer survivors.

Recommendation 4.2 Conditional recommendations in favor of acupuncture to improve skeletal muscle pain with aromatase inhibitor‑induced arthralgia in breast cancer survivors (low certainty).

Recommendation 4.3 Conditional recommendations in favor of exercise intervention to improve pain in breast cancer survivors received radiotherapy (low certainty).

Recommendation 4.4 Strong recommendations in favor of exercise intervention (moderate certainty) to improve pain in postoperative breast cancer survivors.

The evidence

Thirty‐seven SRMAs were included, assessing 25 integrative therapies covering four categories. Six different pain measure scales were used, and we converted them into BPI, which is commonly used (the details see Appendix Text S5). Among 25 assessed integrative therapies (GRADE summary of findings for all therapies can be found in Appendix Text S6), compared to standard care, 5 presented statistical significance and the effect size reached at or above MID, including art therapy (5 RCTs; MD = –2.34, 95% CI –4.53 to –0.18; moderate CoE due to serious inconsistency) and virtual reality‐based interventions (4 RCTs; MD = –2.92, 95% CI –4.27 to –1.15; low CoE due to serious risk of bias and inconsistency) for general breast cancer survivors; exercise intervention for breast cancer survivors received radiotherapy (7 RCTs; MD = –3.66, 95% CI –6.21 to –1.10; low CoE due to serious risk of bias and inconsistency); and acupuncture (2 RCTs; MD = –3.03, 95% CI –3.9 to –2.16; low CoE due to serious inconsistency and imprecision) for breast cancer survivors received aromatase inhibitor‑induced arthralgia; exercise intervention (6 RCTs; MD = –2.30, 95% CI –3.40 to –1.19; moderate CoE due to serious risk of bias) for postoperative breast cancer survivors [28, 39, 43, 44, 45].

Clinical question 5: Which integrative therapies can be used to improve fatigue in breast cancer survivors?

Recommendation 5.1 Strong recommendations in favor of mindfulness therapy (moderate certainty) and group psychotherapy (moderate certainty); conditional recommendations in favor of Tai Chi (very low certainty), yoga (low certainty), supervised exercise (low certainty), and home‐based walking exercise therapy (very low certainty) to alleviate fatigue in general breast cancer survivors.

The evidence

Fifty‐seven SRMAs were included, assessing 22 integrative therapies covering four categories. Seven different fatigue measure scales were used, and we converted them into BFI, which is commonly used (the details see Appendix Text S5). Among 22 assessed integrative therapies (GRADE summary of findings for all therapies can be found in Appendix Text S6), compared to standard care, 6 presented statistical significance and the effect size reached at or above MID, including mindfulness therapy (8 RCTs; MD = –1.43, 95% CI –2.14 to –0.71; moderate CoE due to serious risk of bias), group psychotherapy (3 RCTs; MD = –2.19, 95% CI –3.64 to –0.74; moderate CoE due to serious risk of bias), Tai Chi (3 RCTs; MD = –2.83, 95% CI –3.90 to –1.76; very low CoE due to serious risk of bias, serious inconsistency, serious imprecision and publication bias), yoga (14 RCTs; MD = –2.52, 95% CI –3.98 to –1.10; low CoE due to serious risk of bias, serious inconsistency, and serious imprecision), supervised exercise (20 RCTs; MD = –1.89, 95% CI –2.52 to –1.22; low CoE due to serious risk of bias, serious inconsistency, and publication bias), and home‐based walking exercise therapy (8 RCTs; MD = –1.81, 95% CI –2.88 to –0.74; very low CoE due to serious risk of bias, serious inconsistency, serious imprecision and publication bias) for general breast cancer survivors [25, 30, 37, 46, 47, 48].

Clinical question 6: Which integrative therapies can be used to improve the quality of life of breast cancer survivors?

Recommendation 6.1 Strong recommendations in favor of mindfulness therapy (moderate certainty); conditional recommendations in favor of muscle relaxation training (very low certainty), and art therapy (low certainty) to improve the quality of life in general breast cancer survivors.

Recommendation 6.2 Strong recommendations in favor of exercise intervention (moderate certainty) and Baduanjin (moderate certainty) to improve the quality of life in breast cancer patients undergoing anticancer treatment.

The evidence

Seventy‐two SRMAs were included, assessing 15 integrative therapies covering four categories. Five different quality of life measure scales were used, and we converted them into FACT‐B, which is commonly used (the details see Appendix Text S5). Among 15 assessed integrative therapies (GRADE summary of findings for all therapies can be found in Appendix Text S6), compared to standard care, 5 presented statistical significance and the effect size reached at or above MID, including mindfulness therapy (10 RCTs; MD = 17.58, 95% CI 6.15 to 29.01; moderate CoE due to serious inconsistency), muscle relaxation training (8 RCTs; MD = 13.13, 95% CI 7.24 to 19.02; very low CoE due to serious risk of bias and very serious inconsistency), and art therapy (8 RCTs; MD = 12.75, 95% CI 0.44 to 24.84; low CoE due to serious risk of bias and serious inconsistency) for general breast cancer survivors; exercise intervention (59 RCTs; MD = 11.43, 95% CI 8.35 to 14.29; moderate CoE due to serious inconsistency), and Baduanjin (4 RCTs; MD = 18.24, 95% CI 12.75 to 23.74; moderate CoE due to serious risk of bias) breast cancer patients undergoing anticancer treatment [24, 28, 46, 49, 50].

3.1. Safety

The evidence from SRMAs supporting the recommendations suggests that mild adverse events were mainly associated with exercise interventions (i.e., muscle discomfort, hip pain, weakness, shortness of breath), acupuncture (i.e., bruising, pain or bleeding, fatigue, syncope), and aromatherapy (i.e., headache, sneezing). There were no withdrawals reported due to adverse effects related to integrative therapies.

3.2. Practice Issues

Exercise interventions (e.g., home‐based walking exercise therapy, supervised exercise) include aerobic, resistance, and strength exercises if no specific in the recommendations. Patients should formulate individualized exercise prescriptions according to the frequency, intensity, duration, type, volume, and progression of exercise, and are dynamically monitored and adjusted. Baduanjin originated in China, which consists of eight types of body movements, including body movement and breath conditioning. Tai Chi is a form of traditional Chinese martial arts that can help individuals to strengthen body and adjust breath. Baduanjin and Tai Chi are used for a variety of conditions, and available at videos and booklets. Muscle relaxation training focuses on the contraction and relaxation of specific, sequential muscle groups and is usually combined with breathing and imagery exercises [51]. Yoga is a mind‐body practice that encompasses a multitude of forms and styles. Yoga is most beneficial for breast cancer patients and survivors under the guidance of a certified yoga instructor. Psychological education, group psychotherapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, acceptance and commitment therapy, dignity therapy, and spouse's cognitive intervention are usually provided by trained mental health professionals. Mindfulness therapy is a form of psychotherapy that focuses on acceptance and awareness of the present experience, treating oneself and one's surroundings without judgment. Aromatherapy is a therapeutic practice that employs essential oils, hydrosols, and carrier oils extracted from aromatic plants. It absorbed into the body through the respiratory tract or skin by means of massages, baths, or incense to relieve mental stress and promote physical health. Low‐level laser therapy has been approved by the FDA for the treatment of lymphedema following breast cancer surgery and should be administered by trained users [52]. Acupuncture is a form of traditional and complementary medicine that originated 3000 years ago in China, that inserts needles into specific acupoints on the human meridians (paths through which the vital energy known as “qi” flows) to correct disruptions in harmony [53]. Licensed acupuncturists generally have attended formal schools of Asian medicine and have passed national certification examinations. The detailed practice points for each recommended integrative therapy can be found in Appendix Text S7.

3.3. Preferences and Values

Seven studies involving 4507 patients investigated breast cancer survivors’ preferences, attitudes, and barriers to complementary, alternative and integrative medicine [54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60]. The majority of breast cancer survivors use complementary, alternative and integrative medicine (ranging from 46% to 69%) as their cancer progresses as well as during treatment. The reasons for using complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) among breast cancer survivors were boosting their autoimmunity, improving sleep disturbances, fatigue, and especially pain, and increasing hope for healing. The most commonly used complementary and alternative therapies include physical exercise, physical therapy, herbs, supplements, meditation, acupuncture, and massage. The average cost of CAM therapies for young breast cancer survivors is around €50 per month, and about 50% of patients would support the inclusion of acupuncture in insurance coverage for cancer pain management. The cost of treatment, accessibility of therapies, and cost of treatment time may be barriers to the use of complementary alternative medicine in breast cancer survivors.

3.4. Costs

A systematic review included 43 studies on the financial burden of CAM in cancer treatment [61]. The review recommended a comprehensive approach that encompasses both direct and indirect costs for assessing costs. In the United States, cancer survivors accounted for 6.9% of the total population, a higher proportion of cancer survivors report using CAM than the cancer‐free adults [62]. The spent for vitamins, minerals, and CAM accrued over 11.4% of adults' annual out‐of‐pocket costs.

As for assessing cost, muscle relaxation training is low‐cost, safe, and portable [8]. Yoga is relatively inexpensive and can be practiced at home with instructional videos [8]. Tai Chi and Baduanjin are access to information from radio, videos, and booklets at low or no cost from trained clinical staff at cancer centers. Mindfulness therapy does not require a specific place, has no time constraints, helps patients take an active role in stress reduction and symptom improvement through the self‐regulatory process of meditation [63]. Psychotherapies (e.g., psychological education, group psychotherapy, cognitive behavioral therapy) are entirely or partly paid for out‐of‐pocket by patients. In oncology populations, CAM has the possibility of reducing healthcare use, particularly drug use [64]. Despite the increasing acceptance of numerous non‐pharmacological integrative therapies and evidence for their utility, most of them are not or only partially covered by health insurance [65]. In the United States, the 2012 National Health Interview Survey revealed that most adults receiving acupuncture or massage were not covered by health insurance, and those with insurance coverage were more likely to pay only part of the cost [66]. As the patient is required to pay for the CAM out‐of‐pocket, the average cost ranges from $435 to $590 [65]. Additional out‐of‐pocket costs are a significant barrier to using or recommending these integrative therapies.

3.5. Accessibility

Breast cancer survivors usually experience psychosocial distress, insomnia, fatigue, and cognitive impairment lasting months to years after treatment [67]. CAM has been currently incorporated into symptom management strategies, and effective management of symptoms can improve the patient with breast cancer experience and outcomes [67]. The majority of integrative therapies that we recommended are accessible for outcome improvement in breast cancer patients or survivors. However, integrative therapies are generally not covered by health insurance and many countries with universal health care do not provide routine integrated health care, its use is generally limited to those who can afford out‐of‐pocket costs [7]. Several countries have taken measures to improve the accessibility of integrative therapies. For instance, the World Federation of Acupuncture‐Moxibustion Societies (WFAS) found that 39 countries included acupuncture in their medical insurance, and 31 encouraged or permitted its use [68]. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) has reported that physicians provide acupuncture therapy for 3 to 6 million patients in the United States annually [69]. Acupuncture therapy has been incorporated into the United States health insurance plans and made easily accessible. A study identified that increased resources are a common predictor of the use of CAM, both at the individual level (in terms of education and financial pressures) and at the country‐level (in terms of per capita health expenditures) [70].

3.6. Patients and Clinicians Communication

Breast cancer survivors should find their level of comfort with integrative therapies based on their belief systems, personal coping mechanisms, and individual preferences [71]. Clinicians should monitor people at each stage of diagnosis, treatment, and survivorship, providing emotional, social, and physical support as needed [71]. When selecting therapies, strongly recommended therapies are encouraged based on the patient's specific symptoms (e.g., anxiety, depression, pain, fatigue, etc.). Additionally, conditionally recommended therapies can be considered based on patient‐specific stages, preferences and values, and financial conditions. In individualized care, patient's preferences and values should be fully considered, allowing them to choose therapies of interest and affordability according to their treatment stages.

4. Discussion

A large amount of evidence has documented the benefits of traditional, complementary, and integrative medicine (TCIM) in the symptom management of breast cancer survivors. Compared the guidelines existed, this guideline shows several advantages. First, we systematically searched all available SRs and MAs and used GRADE approach to rate the certainty of evidence. After a systematical evaluation, we finally included 27 SRMAs involving 487 RCTs to support our recommendations. Second, to compare the differences among TCIMs, we converted various effect sizes of dichotomous outcomes as well as continuous outcomes. Third, we used umbrella review to compare effect sizes of different TCIMs based on common comparisons. In addition, because of the wide range of therapies involved in the guidelines, multiple subpanels were formed, each consisting of 31 experts, and after Delphi expert consensus was reached within the subpanel, all experts formed a consensus on the final recommendation in a transparent process, considering the magnitude of the effect indicators, certainty of evidence, patient preferences and values, cost, policy, and accessibility.

For the 6 clinical questions, we used the published SRMAs comprising 152 therapies, of which 20 integrative therapies were strongly or conditionally recommended, constituting 13% (20/152) of all therapies. Muscle relaxation training, yoga, acceptance and commitment therapy, and cognitive behavioral therapy should be strongly recommended, and art therapy should be conditionally recommended to improve anxiety in general breast cancer survivors. Mindfulness therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, group psychotherapy, muscle relaxation training, and acceptance and commitment therapy should be strongly recommended in general breast cancer survivors, and exercise intervention in breast cancer survivors received radiotherapy. Art therapy should be conditionally recommended to improve depression in general breast cancer survivors and yoga in breast cancer survivors received chemotherapy. Art therapy should be conditionally recommended for general breast cancer survivors, and exercise intervention should be strongly recommended for postoperative breast cancer survivors undergoing pain. Mindfulness therapy and group psychotherapy should be strongly recommended to improve fatigue in general breast cancer survivors. Mindfulness therapy should be strongly recommended for general breast cancer survivors, and exercise intervention and Baduanjin should be strongly recommended for breast cancer patients undergoing anticancer treatment to improve patients' quality of life. These recommendations are strong or conditional, based on at least moderate evidence certainty and an overall assessment that the benefits outweigh the harms. When considering interventions, clinicians, and patients should first consider strong recommendation in favor, then conditional in favor. Patient preferences and values, availability, and cost of interventions should be considered in decision making with breast cancer survivors.

However, there were some limitations in this guideline. First, several integrative therapies, such as Qigong, Huaier Granules, and Chaihu Shugan San, failed to meet the recommended criteria due to unavailability of pooled data and low or very low certainty of evidence. Further research should prioritize exploring the efficacy of these integrative therapies for improving PROs among breast cancer survivors. Second, several recommendations are based on low or very low evidence certainty. For these evidence, future research should conduct high‐quality, large‐sample RCTs of these interventions to improve the certainty of evidence.

In conclusion, we have proposed the evidence‐based guideline recommendations for the improvement of PROs among breast cancer survivors using integrative medicine approaches. The dissemination and implementation of this guideline is an essential component of our goals to address the management of breast cancer survivors. The lack of high‐quality evidence limits the strength of the recommendations and highlights the need for further research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supporting information

Supporting Information

Acknowledgments

We thank all members of the Guideline Panel for their contribution. Details on the guideline development panel are provided in Appendix Text S8.

Tingting Lu and Honghao Lai contributed equally to this work.

Funding: This study was supported by the Research on the Construction of an Ecological Chain of Evidence for the Integration of Advantageous Diseases in Chinese and Western Medicine (No. CI2021A05502), and the National Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine International Cooperation Special Traditional Chinese Medicine Overseas Development and Promotion Base (No. XDZYJZC‐002).

Contributor Information

Long Ge, Email: gelong2009@163.com.

Jie Liu, Email: dr.liujie@163.com.

Luqi Huang, Email: huangluqi01@126.com.

References

- 1. Sung H., Ferlay J., Siegel R. L., et al., “Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries,” CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 71, no. 3 (2021): 209–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Thun M. J., Linet M. S., Cerhan J. R., Haiman C. A., and Schottenfeld D., Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention (Oxford University Press, 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lei S., Zheng R., Zhang S., et al., “Global Patterns of Breast Cancer Incidence and Mortality: A Population‐Based Cancer Registry Data Analysis From 2000 to 2020,” Cancer Communications 41, no. 11 (2021): 1183–1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lyman G. H., Greenlee H., Bohlke K., et al., “Integrative Therapies During and After Breast Cancer Treatment: ASCO Endorsement of the SIO Clinical Practice Guideline,” Journal of Clinical Oncology 36, no. 25 (2018): 2647–2655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. CAM Definitions | About CAM | Health Information | OCCAM, https://cam.cancer.gov/health_information/cam_definitions.htm.

- 6. NCCIH . Complementary, Alternative, or Integrative Health: What's In a Name?, https://www.nccih.nih.gov/health/complementary‐alternative‐or‐integrative‐health‐whats‐in‐a‐name.

- 7. Mao J. J., Ismaila N., Bao T., et al., “Integrative Medicine for Pain Management in Oncology: Society for Integrative Oncology‐ASCO Guideline,” Journal of Clinical Oncology 40, no. 34 (2022): 3998–4024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Greenlee H., Dupont‐Reyes M. J., Balneaves L. G., et al., “Clinical Practice Guidelines on the Evidence‐Based Use of Integrative Therapies During and After Breast Cancer Treatment,” CA Cancer Journal for Clinicians 67, no. 3 (2017): 194–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cathcart‐Rake E. J., Tevaarwerk A. J., Haddad T. C., D'andre S. D., and Ruddy K. J., “Advances in the Care of Breast Cancer Survivors,” Bmj 382 (2023): e071565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chinese Association of Integrated Traditional and Western Medicine , Chinese Association of Traditional Chinese Medicine , Chinese Medical Association , “Diagnosis and Treatment Guide of Integrated Chinese and Western Medicine for Breast Cancer,” Beijing Traditional Chinese Medicine 43, no. 1 (2024): 7–16. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Greenhalgh J., Dalkin S., Gooding K., et al., Functionality and Feedback: A Realist Synthesis of the Collation, Interpretation and Utilisation of Patient‐Reported Outcome Measures Data to Improve Patient Care (NIHR Journals Library, 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ramsey I., Corsini N., Hutchinson A. D., Marker J., and Eckert M., “A Core Set of Patient‐Reported Outcomes for Population‐Based Cancer Survivorship Research: A Consensus Study,” Journal of Cancer Survivorship 15, no. 2 (2021): 201–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Standards for Developing Trustworthy Clinical Practice Guidelines. Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust (National Academies Press (US), 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 14. World Health Organization . WHO Handbook for Guideline Development. 2nd ed 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chen Y., Yang K., Marušić A., et al., “A Reporting Tool for Practice Guidelines in Health Care: The RIGHT Statement,” Annals of Internal Medicine 166, no. 2 (2017): 128–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Brouwers M. C., Kho M. E., Browman G. P., et al., “AGREE II: Advancing Guideline Development, Reporting and Evaluation in Health Care,” Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 63, no. 12 (2010): 1308–1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Schünemann H. J., Mustafa R., Brozek J., et al., “GRADE Guidelines: 16. GRADE Evidence to Decision Frameworks for Tests in Clinical Practice and Public Health,” Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 76 (2016): 89–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Thorlund K., Walter S. D., Johnston B. C., Furukawa T. A., and Guyatt G. H., “Pooling Health‐related Quality of Life Outcomes in Meta‐analysis—A Tutorial and Review of Methods for Enhancing Interpretability,” Research Synthesis Methods 2, no. 3 (2011): 188–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Guyatt G. H., Oxman A. D., Vist G. E., et al., “GRADE: An Emerging Consensus on Rating Quality of Evidence and Strength of Recommendations,” Bmj 336, no. 7650 (2008): 924–926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. GRADE Handbook , https://training.cochrane.org/resource/grade‐handbook.

- 21. Wang Y., Devji T., Carrasco‐Labra A., et al., “A Step‐by‐Step Approach for Selecting an Optimal Minimal Important Difference,” Bmj 381 (2023): e073822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Shea B. J., Reeves B. C., Wells G., et al., “AMSTAR 2: A Critical Appraisal Tool for Systematic Reviews That Include Randomised or Non‐Randomised Studies of Healthcare Interventions, or Both,” Bmj 358 (2017): j4008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Vernooij R. W. M., Alonso‐Coello P., Brouwers M., and Martínez García L., “Reporting Items for Updated Clinical Guidelines: Checklist for the Reporting of Updated Guidelines (CheckUp),” PLoS Medicine 14, no. 1 (2017): e1002207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fang J., Yu C., Liu J., et al., “A Systematic Review and Meta‐Analysis of the Effects of Muscle Relaxation Training vs. Conventional Nursing on the Depression, Anxiety and Life Quality of Patients With Breast Cancer,” Translational Cancer Research 11, no. 3 (2022): 548–558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hsueh E.‐J., Loh E. W., Lin J. J. A., and Tam K.‐W., “Effects of Yoga on Improving Quality of Life in Patients With Breast Cancer: A Meta‐Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials,” Breast Cancer (Tokyo, Japan) 28, no. 2 (2021): 264–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yi L.‐J., Tian X., Jin Y.‐F., Luo M.‐J., and Jiménez‐Herrera M. F., “Effects of Yoga on Health‐Related Quality, Physical Health and Psychological Health in Women With Breast Cancer Receiving Chemotherapy: A Systematic Review and Meta‐Analysis,” Annals of Palliative Medicine 10, no. 2 (2021): 1961–1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sun Q., Ye H., and Yang L., “Meta‐Analysis of the Intervention Effect of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy on Breast Cancer Patients,” Chinese Journal of Nursing 57, no. 9 (2022): 1070–1079. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cheng P., Xu L., Zhang J., Liu W., and Zhu J., “Role of Arts Therapy in Patients With Breast and Gynecological Cancers: A Systematic Review and Meta‐Analysis,” Journal of Palliative Medicine 24, no. 3 (2021): 443–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Getu M. A., Chen C., Panpan W., Mboineki J. F., Dhakal K., and Du R., “The Effect of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy on the Quality of Life of Breast Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta‐Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials,” Quality of Life Research 30, no. 2 (2021): 367–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Luo X.‐C., Liu J., Fu J., et al., “Effect of Tai Chi Chuan in Breast Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta‐Analysis,” Frontiers in Oncology 10 (2020): 607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zhao F.‐Y., Wang M., Liu J.‐E., and Sun Y.‐H., “Meta‐Analysis of the Impact of Spousal Cognitive Intervention on Psychological Status and Quality of Life of Breast Cancer Patients,” Chinese Nursing Management 21, no. 9 (2021): 1351–1357. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Setyowibowo H., Yudiana W., Hunfeld J. A. M., et al., “Psychoeducation for Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta‐Analysis,” Breast (Edinburgh, Scotland) 62 (2022): 36–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zhang H., Xu H., Zhang Z. X., and Zhang Q., “Efficacy of Virtual Reality‐based Interventions for Patients With Breast Cancer Symptom and Rehabilitation Management: A Systematic Review and Meta‐Analysis,” BMJ Open 12, no. 3 (2022): e051808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ye X.‐X., Ren Z.‐Y., Vafaei S., et al., “Effectiveness of Baduanjin Exercise on Quality of Life and Psychological Health in Postoperative Patients With Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta‐Analysis,” Integrative Cancer Therapies 21 (2022): 15347354221104092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Li Y., Li X., Hou L., Cao L., Liu G., and Yang K., “Effectiveness of Dignity Therapy for Patients With Advanced Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta‐Analysis of 10 Randomized Controlled Trials,” Depression and Anxiety 37, no. 3 (2020): 234–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Chang Y. C., Yeh T. L., Chang Y. M., and Hu W. Y., “Short‐Term Effects of Randomized Mindfulness‐Based Intervention in Female Breast Cancer Survivors: A Systematic Review and Meta‐Analysis,” Cancer Nursing 44, no. 6 (2021): E703–E714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zhou X.‐L., Guang L., Chen C.‐R., et al., “Meta‐Analysis of the Effect of Group Psychotherapy on Intervention of Breast Cancer Patients,” Modern Preventive Medicine 47, no. 10 (2020): 1914–1920. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Xie Z. M., Luo L., Yang Z., and Long F. X., “Tang DX. Meta‐Analysis of Modified Xiaoyao San Combined With Chemotherapy in the Treatment of Breast Cancer,” Lishizhen Medicine and Materia Medica Research 32, no. 7 (2021): 1779–1785. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Shen Q. and Yang H., “Impact of Post‐radiotherapy Exercise on Women With Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta‐Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials,” Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine 52, no. 10 (2020): jrm00112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Cheng H., Lin L., Wang S., et al., “Aromatherapy With Single Essential Oils Can Significantly Improve the Sleep Quality of Cancer Patients: A Meta‐analysis,” BMC Complementary Medicine and Therapies 22, no. 1 (2022): 187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Zhang Y., Sun Y., Li D., et al., “Acupuncture for Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta‐Analysis of Patient‐Reported Outcomes,” Frontiers in Oncology 11 (2021): 646315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Xiao P., Ding S., Duan Y., et al., “Effect of Light Therapy on Cancer‐Related Fatigue: A Systematic Review and Meta‐Analysis,” Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 63, no. 2 (2022): e188–e202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kannan P., Lam H. Y., Ma T. K., Lo C. N., Mui T. Y., and Tang W. Y., “Efficacy of Physical Therapy Interventions on Quality of Life and Upper Quadrant Pain Severity in Women With Post‐mastectomy Pain Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta‐Analysis,” Quality of Life Research 31, no. 4 (2022): 951–973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Tian Q., Xu M., Yu L., Yang S., and Zhang W., “The Efficacy of Virtual Reality‐Based Interventions in Breast Cancer‐Related Symptom Management: A Systematic Review and Meta‐Analysis,” Cancer Nursing 46, no. 5 (2023): E276–E287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Qi Q.‐L., Han X., and Tang C, “Effects of Acupuncture on Breast Cancer Patients Taking Aromatase Inhibitors,” BioMed Research International 2022 (2022): 1164355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lin L.‐Y., Lin L.‐H., Tzeng G.‐L., et al., “Effects of Mindfulness‐Based Therapy for Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta‐Analysis,” Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings 29, no. 2 (2022): 432–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Reverte‐Pagola G., Sánchez‐Trigo H., Saxton J., and Sañudo B., “Supervised and Non‐Supervised Exercise Programs for the Management of Cancer‐Related Fatigue in Women With Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta‐Analysis,” Cancers 14, no. 14 (2022): 3428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Yuan Y., Lin L., Zhang N., et al., “Effects of Home‐Based Walking on Cancer‐Related Fatigue in Patients With Breast Cancer: A Meta‐Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials,” Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 103, no. 2 (2022): 342–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Gong X., Rong G., Wang Z., Zhang A., Li X., and Wang L., “Baduanjin Exercise for Patients With Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta‐Analysis,” Complementary Therapies in Medicine 71 (2022): 102886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Andersen H. H., Vinther A., Lund C. M., et al., “Effectiveness of Different Types, Delivery Modes and Extensiveness of Exercise in Patients With Breast Cancer Receiving Systemic Treatment—A Systematic Review and Meta‐Analysis,” Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology 178 (2022): 103802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. NCCIH . Relaxation Techniques for Health, https://www.nccih.nih.gov/health/relaxation‐techniques‐what‐you‐need‐to‐know.

- 52. FDA . Product Classification, https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfPCD/classification.cfm.

- 53. Kaptchuk T. J., “Acupuncture: Theory, Efficacy, and Practice,” Annals of Internal Medicine 136, no. 5 (2002): 374–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Boon H., Stewart M., Kennard M. A., et al., “Use of Complementary/Alternative Medicine by Breast Cancer Survivors in Ontario: Prevalence and Perceptions,” Journal of Clinical Oncology 18, no. 13 (2000): 2515–2521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Buettner C., Kroenke C. H., Phillips R. S., Davis R. B., Eisenberg D. M., and Holmes M. D., “Correlates of Use of Different Types of Complementary and Alternative Medicine by Breast Cancer Survivors in the Nurses' Health Study,” Breast Cancer Research and Treatment 100, no. 2 (2006): 219–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Hammersen F., Pursche T., Fischer D., Katalinic A., and Waldmann A., “Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine Among Young Patients With Breast Cancer,” Breast Care 15, no. 2 (2020): 163–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Hann D., Baker F., Denniston M., and Entrekin N., “Long‐term Breast Cancer Survivors' use of Complementary Therapies: Perceived Impact on Recovery and Prevention of Recurrence,” Integrative Cancer Therapies 4, no. 1 (2005): 14–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Boon H., Brown J. B., Gavin A., Kennard M. A., and Stewart M., “Breast Cancer Survivors' perceptions of Complementary/Alternative Medicine (CAM): Making the Decision to Use or Not to Use,” Qualitative Health Research 9, no. 5 (1999): 639–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Templeton A. J., Thürlimann B., Baumann M., et al., “Cross‐Sectional Study of Self‐Reported Physical Activity, Eating Habits and Use of Complementary Medicine in Breast Cancer Survivors,” BMC Cancer 13 (2013): 153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Matthews A. K., Sellergren S. A., Huo D., List M., and Fleming G., “Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use Among Breast Cancer Survivors,” Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine 13, no. 5 (2007): 555–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Huebner J., Prott F. J., Muecke R., et al., “Economic Evaluation of Complementary and Alternative Medicine in Oncology: Is There a Difference Compared to Conventional Medicine?,” Medical Principles and Practice 26, no. 1 (2017): 41–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. John G. M., Hershman D. L., Falci L., Shi Z., Tsai W.‐Y., and Greenlee H., “Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use Among US Cancer Survivors,” Journal of Cancer Survivorship 10, no. 5 (2016): 850–864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Reich R. R., Lengacher C. A., Alinat C. B., et al., “Mindfulness‐Based Stress Reduction in Post‐Treatment Breast Cancer Patients: Immediate and Sustained Effects Across Multiple Symptom Clusters,” Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 53, no. 1 (2017): 85–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Tillery R. and McGrady M. E, “Do Complementary and Integrative Medicine Therapies Reduce Healthcare Utilization Among Oncology Patients? A Systematic Review of the Literature and Recommendations,” European Journal of Oncology Nursing 36 (2018): 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Behzadmehr R., Dastyar N., Moghadam M. P., Abavisani M., and Moradi M., “Effect of Complementary and Alternative Medicine Interventions on Cancer Related Pain Among Breast Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review,” Complementary Therapies in Medicine 49 (2020): 102318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Nahin R. L., Barnes P. M., and Stussman B. J., “Insurance Coverage for Complementary Health Approaches among Adult Users: United States, 2002 and 2012,” NCHS Data Brief no. 235 (2016): 1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Henneghan A. M. and Harrison T., “Complementary and Alternative Medicine Therapies as Symptom Management Strategies for the Late Effects of Breast Cancer Treatment,” Journal of Holistic Nursing 33, no. 1 (2015): 84–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. World Acupuncture Policy and Legislation Overview Search Platform, http://rx.yunlib.cn:800/Opac/Index/bookview?book_id=1315550.

- 69. NCCIH . Acupuncture: In Depth, https://www.nccih.nih.gov/.

- 70. Fjær E. L., Landet E. R., McNamara C. L., and Eikemo T. A., “The Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) in Europe,” BMC Complementary Medicine and Therapies 20, no. 1 (2020): 108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Carlson L. E., Ismaila N., Addington E. L., et al., “Integrative Oncology Care of Symptoms of Anxiety and Depression in Adults With Cancer: Society for Integrative Oncology‐ASCO Guideline,” Journal of Clinical Oncology 41, no. 28 (2023): 4562–4591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information