Abstract

Purpose

The United States Supreme Court’s Dobbs decision in June 2022 may have worsened mental health among reproductive-aged women nationally. We examined whether the Dobbs decision preceded an increase in suicides among reproductive-aged women using national, monthly data, from January 2018-December 2023.

Methods

We retrieved national monthly suicide counts from January 2018 to December 2023 for women and men 15–49 years of age (overall and stratified by two age groups- 15–24 years, 25–49 years) from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Wide-ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research Multiple Cause of Death database. We used time series analyses to examine whether residuals of nationally aggregated counts of monthly suicides among women 15–49, 15–24- and 25–49-years of age (outcomes) exhibited higher-than-expected values following the Dobbs decision, controlling for autocorrelation and concomitant monthly series of suicides among men.

Results

We observed higher-than-expected residuals of suicides in July and September 2022 among 15–49-year-old women, and in September, October, December 2022 and March 2023 among 15–24-year-old women. No residual outliers were observed among 25–49-year-old women post-Dobbs. Results from time-series analyses indicate an average of 52.5 additional suicides in outlier months among 15–49-year-old women post-Dobbs (95% confidence interval [CI]: 14.85, 90.15). The increase appeared pronounced among younger age (15–24 years) women (coefficient = 19.6, 95% CI: 11.17, 28.03). Results suggest 104 additional suicides among 15–49-year-old women, and 78 excess suicides among 15–24-year-old women, nationally, post-Dobbs.

Conclusions

Findings highlight the adverse impact of the Dobbs ruling on mental health among reproductive-aged women.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00127-025-02902-7.

Keywords: Dobbs, Suicides, Abortion restriction, Time-series analysis

Introduction

The U.S. Supreme Court’s Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization decision in June 2022 overturned the federal right to abortion previously established by Roe v. Wade (1973). The Dobbs ruling returned regulatory authority over abortion to states. Subsequently, as of August 2024, 22 states have banned or heavily restricted abortion, whereas others have maintained or improved access [1]. The ruling has raised grave concerns regarding the physical, psychological, and social implications of restricted access to abortion care [2–6]. Unsurprisingly, the immediate post-Dobbs period has been marked by higher mental distress, anxiety and depression symptoms among reproductive-aged women [7–9].

Restricting access to abortion care may harm mental health among people with the capacity for pregnancy, regardless of their pregnancy status [2, 3, 7–13]. Abortion restrictions may induce a cascade of stressors such as loss of autonomy, stigma, interpersonal conflict, and socio-economic challenges that may worsen mental health in this population [2, 3, 7–13]. Importantly, abortion itself does not cause adverse mental health; rather, the denial of choice may lead to significant distress, which is an important distinction for understanding the mental health effects of restrictive abortion laws [14–16].

Pregnancy intention forms a key predictor of mental health among pregnant people [12]. People with unintended pregnancies exhibit nearly twice the risk of depression relative to their counterparts with intended pregnancies, with symptoms often persisting beyond pregnancy [17, 18]. Individuals with pre-existing mental health conditions or those who experience traumatic events, such as intimate partner violence, may face more severe outcomes if denied abortion care [10, 11]. Anxiety, depression, trauma, and exposure to violence and abuse may increase the risk of suicide mortality. An ecological study examining the association between abortion restrictions and suicides in the US found a 6% increase in state-level suicides among reproductive-aged women following enforcement of restrictive abortion policies, from 1974 to 2016[12]. Denial of abortion services and associated stigma are linked to lasting mental distress, extending well beyond pregnancy. This mental distress may negatively affect self-esteem and life satisfaction, potentially eroding optimism about the future or positive future orientation [19–21].

Positive future orientation, or an individual’s optimistic outlook on their potential future, is closely linked to lower suicide risk [22–27]. When people envision a hopeful future, they are more likely to feel motivated to overcome present challenges and view their lives as meaningful. This sense of purpose and hope serves as a protective factor against suicidal thoughts and behaviors [28, 29]. Research consistently shows that individuals with a strong belief in their ability to achieve future goals and aspirations experience lower levels of depression and hopelessness, which are two key predictors of suicide [22–27]. Conversely, a lack of positive future orientation, characterized by pessimism or a sense of hopelessness about what lies ahead, increases the risk of suicidal ideation, self-harm and suicide mortality [22–27]. This relation is also observed at the population level, with decline in collective optimism about the future corresponding with higher-than-expected suicide mortality [30, 31]. Abortion restrictions can exacerbate this dynamic, particularly for reproductive-aged women, as they may face significant life disruptions, including financial instability, loss of autonomy, and social stigma [19–21]. These stressors can diminish a person’s sense of control over their future and foster a pessimistic outlook, increasing mental distress. Policies limiting reproductive autonomy, such as the Dobbs decision, may thus elevate suicide risk by undermining hope and optimism for the future across the population.

In this study, we examine whether and to what extent, the timing of the Dobbs decision (June 2022) precedes an increase in suicides among reproductive-aged women (15–49 years) nationally in the US. We hypothesize that the Dobbs ruling (June 2022) would precede an immediate increase in suicides among reproductive-age women (15–49 years) nationally in the U.S. Young women exhibit the highest risk of unintended pregnancy and pregnancy-related adverse mental health symptoms in the US [32, 33]. As such, we also hypothesize that the post-Dobbs increase in suicides would be higher among young (15–24 years) reproductive-age women relative to their older counterparts (25–49 years).

Methods

Data

We retrieved national monthly data on suicide deaths for reproductive-aged (15–49 years) women and similarly-aged men from January 2018 to December 2023 (72 months), from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) Wide-ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research (WONDER) Multiple Cause of Death database[34]. We further stratified suicide data for women and men by two age groups: 15–24 years and 25–49 years. CDC WONDER is a publicly accessible system that provides cause of death-specific mortality data for the US, with provisional aggregate data available for recent months and years. We identified suicide deaths using International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes (X60-X84), by month, gender (male/female) and age groups (15–24 vs. 25–49 y) across underlying causes and contributing factors (i.e., multiple causes) compiled by the CDC using death certificate databases. We opted for these two broad age groups based on (i) age-group-specific risk of unintended pregnancy [32, 33], and (ii) changes in abortion rates immediately preceding 2022 in the US wherein abortion rates from 2020 to 2021 increased among women aged 15–24 years, but declined/did not change among women aged 25 years and above [35].

Variables

We defined, as our outcomes, the monthly count of suicides nationally in the US (2018–2023) for reproductive-aged women overall and for the two age subgroups: 15–24 years and 25–49 years. We utilized the concomitant series of monthly suicides among men (per age group) as a control variable. We defined our exposure as the timing of the Dobbs decision (June 2022).

Analysis

The monthly patterning of population-level suicides may exhibit seasonality, trends and temporal patterns, collectively referred to as autocorrelation [36]. Autocorrelation violates fundamental requirements of correlational tests as the observed values of any monthly series of suicides in a stable population are not independent of prior values and may exhibit non-constant variance. AutoRegressive Integrated Moving Average (ARIMA) time-series analysis offers an efficient way to address these violations and is suitable for examining the association of exogenous exposures (e.g., the Dobbs decision) with suicides due to its ability to model complex temporal data and account for trends, seasonality, and random fluctuations [37, 38]. ARIMA’s autoregressive (AR) component captures the relationship between current suicide counts and past observations, allowing us to control for and remove the effect of past levels of suicides on future patterns [37, 38]. The moving average (MA) component models the residuals or “shocks” from previous time points, accounting for irregular fluctuations in suicides following the Dobbs decision [37, 38]. Suicide data may exhibit non-stationarity, where patterns like trends or seasonality change over time. ARIMA models are designed to address non-stationarity through differencing (the “integrated” component), which removes secular trends and stabilizes the mean [37, 38]. Taken together, ARIMA analysis helps in identifying the core signal of a series using the AR, I, MA parameters (referred to as the ARIMA “signature” of a series) that collectively yield the unobserved counterfactual (i.e. fitted or predicted values) and residual values (observed less fitted values) [37–40]. ARIMA-derived residuals offer analytic benefits of zero mean and constant variance, and permit examination of the association between an exogenous exposure and consequent perturbations in the outcome, net of autocorrelation [37–40]. For this longitudinal, observational, ecologic study, we used ARIMA analysis to examine the association between the timing of the Dobbs decision and ARIMA-derived residuals of observed series of monthly suicides among reproductive-aged women in the US through the following 4 steps using Scientific Computing Associates software designed for time series analyses [41].

We used Box-Jenkins iterative pattern recognition routines to identify the ARIMA signature of our outcome series in the pre-Dobbs period (i.e., January 2018-May 2022), controlling for the concomitant series of suicides among men of the same age group. This control series (also referred to as a covariate transfer function) helped account for shared temporal patterning of suicides across women and men over our study period, including any shared influence of other macrosocial stressors (e.g., the COVID-19 pandemic).

We used the pre-Dobbs ARIMA signature identified in step 1 to forecast (predict) values of the outcome for the 18-month period after the Dobbs decision (i.e. June 2022 to December 2023). These predicted or fitted values served as statistical counterfactuals and reflected the expected monthly count of female suicides if, counter to fact, the Dobbs decision had not occurred [39, 40].

We used the ARIMA signature identified in step 1 and expected values from step 2 to obtain residual values (observed less fitted) of our outcome series.

We used the pre-Dobbs standard error of residuals to develop pre-Dobbs 95% confidence intervals (CI; prediction interval of monthly series of suicides among reproductive women overall and for the two age groups from January 2018 to May 2022). We extended the pre-Dobbs prediction interval to the full residual series (January 2018-December 2023) for each outcome. Next, we noted whether any residuals deviated from this prediction interval post-Dobbs (i.e., June 2022 onward) [42–48].

If the outcome series exhibited outliers in the post-Dobbs period following step 4, we created a binary indicator of the month-specific timing of any identified outliers in residuals of suicides among reproductive-aged women post-Dobbs (1 for months with outliers, 0 otherwise) to quantify the average change in suicides post-Dobbs. This data-driven approach also helps avoid multiple testing that could increase chances of false rejection of the null.

We applied the binary indicator of month-specific outliers (from step 5) to the ARIMA-derived residuals of outcomes to determine the magnitude of outcome deviation from expected levels in the months with residual outliers. This sequential approach (steps 1–6) has also been utilized in prior research examining changes in reproductive health outcomes following unprecedented exogenous macrosocial shocks, particularly in circumstances where exposure lags are difficult to hypothesize a priori [42–48].

Owing to our use of publicly available, aggregate, de-identified data, this study was deemed exempt from review by The Ohio State University’s Institutional Review Board. We followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines for reporting observational studies. We specified 2-tailed tests using statistical significance level of p < 0.05.

Results

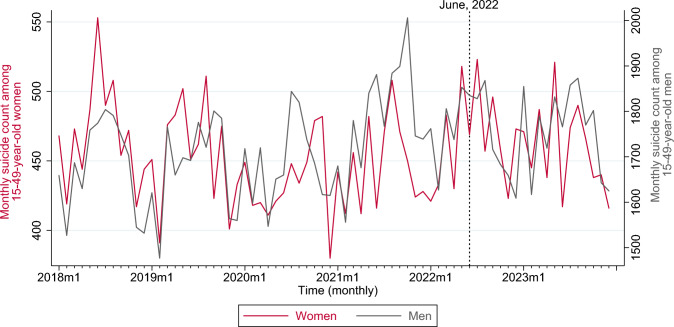

Our analytic dataset (2018–2023, 72 months) comprised 156,847 suicides among women and men 15–49 years of age, of which about 20.9% occurred among women (Table 1). Over our study period, suicide counts averaged 455.1 per month among reproductive-aged women, and were markedly lower compared to the mean count among men (1723.4), in congruence with other reports (Table 1) [49]. Nationally, monthly suicides averaged 101.5 among younger reproductive-aged (15–24 years) women, and 353.6 among older, reproductive-aged (25–49 years) women. Figure 1 graphs the trend in monthly suicides among reproductive-aged women and men over our study period. Supplement Figure S1 shows national monthly suicide trends among women in the younger and older age groups.

Table 1.

Suicides among women and men by age groups, United States, 2018–2023

| Total count | Monthly mean | Monthly Standard Deviation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Women 15–49 years | 32,765 | 455.1 | 34.4 |

| 15–24 years | 7307 | 101.5 | 12.9 |

| 25–49 years | 25,458 | 353.6 | 31.4 |

| Men 15–49 years | 124,082 | 1723.4 | 105.9 |

| 15–24 years | 29,440 | 408.9 | 32.3 |

| 25–49 years | 94,642 | 1314.5 | 90.7 |

SD standard deviation

Fig. 1.

Monthly trends in suicides (count) among women (red) and men (gray) 15–49 years of age, United States, 2018–2023

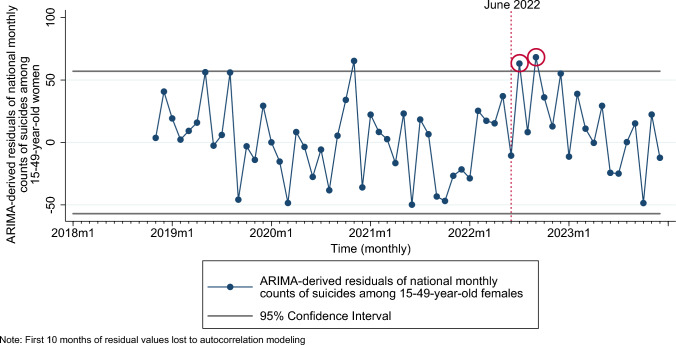

Over the pre-Dobbs period (January 2018- May 2022), Box-Jenkins routines identified AR(10) parameter as the ARIMA signature of the national monthly series of suicides among reproductive-aged women, controlling for the concomitant series of male suicides (Table 2). The residuals over the pre-Dobbs period exhibited a standard deviation of 29.1 (Table 2), which was used to develop a 95% Confidence Interval (i.e. pre-Dobbs prediction interval) of outcome residuals. Predicted or expected values of the national monthly series of suicides (obtained from the pre-Dobbs ARIMA signature) for the full study period (January 2018 to December 2023) among reproductive-aged women are shown in Fig. 2. The difference between observed and expected values (observed less expected) yields the outcome residuals.

Table 2.

Time-series parameters and Residuals statistics for pre-Dobbs identification of ARIMA signature for the series of national monthly suicides among women 15–49 years of age, United States, January 2018 to May 2022

| Parameters | Coefficient | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lower bound | Upper bound | ||

| Suicides among 15–49-year-old males | 0.25**** | 0.24 | 0.26 |

| Autoregression (AR) lag | |||

| 10 | 0.44*** | 0.17 | 0.71 |

| Residuals statistics | |||

| T-value of residual mean (against zero) | 0.29 | ||

| Standard deviation of residuals | 29.1 | ||

*p < 0.1; **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01, ****p < 0.001; two-tailed test

AR autoregression; CI confidence interval

Fig. 2.

Time-series graph of ARIMA-derived expected (predicted) values of suicides among women 15–49 years of age, United States, January 2018 to December 2023

Application of pre-Dobbs prediction interval to ARIMA-derived residuals of suicides among reproductive-aged women for the full outcome series (January 2018 to December 2023) revealed higher-than-expected suicides in July and September 2022 (Fig. 3). Results from ARIMA time-series analyses showed an average of 52.5 additional suicides (95% CI: 14.85, 90.15) in these outlier months (coded as a composite binary variable indicating months with residual outliers post-Dobbs) among reproductive-aged women (Table 3). This increase corresponds with 104 additional suicides nationally, among reproductive-aged women immediately following the Dobbs decision (coefficient of binary outlier indicator × number of outlier months = 52 × 2 = 104).

Fig. 3.

Time-series graph of ARIMA-derived residuals of suicides among women 15–49 years of age and pre-Dobbs 95% confidence (prediction) interval of residuals (applied to full series), United States, January 2018 to December 2023. Residual outliers post-Dobbs (June 2022) are circled in red

Table 3.

Results from ARIMA time-series analysis of monthly suicides among women 15–49 years of age, as a function of binary indicator of months with residual outliers post-Dobbs, concomitant series of age group-specific male suicides and autocorrelation, United States, 2018–2023

| Variables | Coefficient | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lower bound | Upper bound | ||

| Binary indicator of months with residual outliers post-Dobbs | 52.5*** | 14.85 | 90.15 |

| Suicides among men 14–49 years of age | 0.26**** | 0.25 | 0.27 |

| Autocorrelation parameters | |||

| AR 10 | 0.33** | 0.11 | 0.55 |

*p < 0.1; **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01, ****p < 0.001; two-tailed test

AR autoregression, CI confidence interval

The pre-Dobbs ARIMA parameters for suicides among 15–24-year and 25–49-year-old reproductive-aged women are presented in Supplement Table S1 and corresponding expected values are presented in Supplement Figure S2. Examination of the patterning of ARIMA-derived residuals indicates positive outliers in September, October, December 2022 and March 2023 among 15–24-year-old women (Fig. 4), but not among the 25–49-year-old group (Supplement Figure S3). Results from time-series analyses, with outlier months coded as a binary variable, suggest an average of 19.6 additional suicides (95% CI: 11.17, 28.03) among 15–24-year-old women over 4 outlier months that corresponds with 78.4 excess suicide deaths in this age group post-Dobbs (Table 4). We did not test this relation among 25–49-year-old women owing to no residual outliers observed post-Dobbs for this group (Supplement Figure S3).

Fig. 4.

Time-series graph of ARIMA-derived residuals of suicides among women 15–24 years of age and pre-Dobbs 95% confidence (prediction) intervals of residuals (applied to full series), United States, January 2018 to December 2023. Residual outliers post-Dobbs (June 2022) are circled in red

Table 4.

Results from ARIMA time-series analysis of monthly suicides among women 15–24 years of age, as a function of binary indicator of months with residual outliers post-Dobbs, concomitant series of age group-specific male suicides and autocorrelation, United States, 2018–2023

| Variables | Coefficient | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lower bound | Upper bound | ||

| Binary indicator of months with residual outliers post-Dobbs | 19.6**** | 11.17 | 28.03 |

| Suicides among men (per age group, respectively) | 0.25**** | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| Autocorrelation parameters | |||

| AR 3 | − 0.39*** | − 0.64 | − 0.14 |

| AR 6 | − 0.30** | − 0.56 | − 0.04 |

*p < 0.1; **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01, ****p < 0.001; two-tailed test

AR autoregression, CI confidence interval, NA not applicable

Across all our analyses, we do not observe any negative residual outliers in suicides among reproductive-aged women post-Dobbs. The autocorrelation function values and Ljung-Box Q test statistics for ARIMA models (pre-Dobbs identification of ARIMA signature) are presented in Supplement Table S2, which indicate absence of residual autocorrelation over first 12 lags for all specified models [50].

Discussion

We found an increase in suicides among reproductive-aged women in the U.S. following the Dobbs decision, controlling for autocorrelation, secular trends, seasonality, and the possible effect of other contemporaneous macrosocial shocks. The increase was more pronounced among younger (15–24-year-old) women post-Dobbs. Our findings extend recent research documenting that reproductive-aged women experienced higher mental distress, anxiety and depression symptoms immediately post-Dobbs [7, 8]. Our focus on suicide deaths calls attention to the most serious of mental health conditions. Furthermore, by using mortality outcomes from vital records, which have the benefits of universal coverage and standardization in their documentation of data [51], our findings are less susceptible to misclassification or selection bias, which could have been present in earlier studies of mental conditions post-Dobbs that relied on self-reported survey data [7, 8]. It is also important to note that the effect of the Dobbs decision could extend beyond pregnant persons; its psychiatric impact could ripple across all persons with the capacity for pregnancy, regardless of current pregnancy status [7, 8].

Strengths of our analysis include the use of publicly available national data that permit independent verification and replication of our results. Our use of time-series analysis reduces confounding from secular trends, seasonality, and autocorrelation [37]. Our analytic approach establishes temporal order in that the Dobbs decision precedes changes in the outcome and our use of concomitant series of male suicides as covariate transfer functions reduces potential confounding from shared antecedents of changes in the population-level patterning of suicides. For our results to arise from an external national shock other than the timing of the Dobbs decision, such a factor would have to: (1) be unrelated with the Dobbs decision but occur in the period of June 2022, (2) correspond with an increase in suicides among 15–49 and 15–24-year-old women but not among men of the same age group, and (3) be uncorrelated with any downstream consequences of the Dobbs decision pertaining to mental health of women. We know of no such factor and contend that the timing of the Dobbs decision offers the most parsimonious explanation for our observed pattern of results.

As with any ecological analysis, limitations include that our results are not indicative of the individual-level risk of suicide following abortion restrictions [52]. We also cannot comment on whether the higher-than-expected count of suicide decedents identified in our results sought abortion care, had pre-existing psychiatric conditions, or were victimized through intimate partner violence following the Dobbs ruling. Our results, rather, pertain to a national psychiatric response indicated by the most extreme outcome of adverse mental health- suicide- following a large shock represented by the Dobbs decision. We encourage future research to examine the role of precipitating circumstances in suicidal ideation/self-harm and suicide mortality following restrictive abortion legislations using detailed healthcare and social services utilization data.

For this study, we relied on the CDC WONDER database, which categorizes suicide data into two gender categories: males and females. However, this binary classification fails to account for the mental health challenges experienced by minoritized sexual and gender groups, who may face disproportionately adverse health consequences following abortion restrictions [53]. These groups often encounter heightened stress, stigma, and barriers to reproductive [54, 55] and mental health care [56, 57], which may exacerbate the risk of suicide post-Dobbs. By only considering male and female data, we likely missed key nuances regarding the broader impact of abortion restrictions on diverse sexual and gender identities. We acknowledge this limitation and encourage future research to collect and analyze more inclusive identity data. This will be crucial to understanding the mental health outcomes of abortion restrictions, particularly among vulnerable and marginalized populations, and may help develop more inclusive health policies.

Our findings suggest that the Dobbs decision may have served as a national-level policy shock that preceded a surge in suicides among reproductive-aged women. We encourage future research to build upon the present study and extend our national-level analysis to detailed state-specific changes in suicides among reproductive-aged females following enactment of abortion restrictions. Owing to data restrictions within CDC WONDER (suppression of mortality data for cell sizes < 10), we were unable to examine monthly state-level changes in suicides post-Dobbs. Future research may utilize detailed restricted-use mortality vital statistics data to examine state-level changes in suicides among reproductive-aged women in relation to month-specific changes in abortion laws pre- and post-Dobbs [58]. Extant research uses broad state-group categorizations to examine differential impact of the Dobbs ruling on mental health symptoms among women in restrictive versus protective states. For instance, Thornburg et al. (2024) leverage trigger bans and report differentially higher adverse mental health symptoms among reproductive-aged women in states that enacted trigger bans post-Dobbs, relative to others [7]. Similarly, Dave et al. (2023) group states by trigger and/or anticipatory abortion bans and find higher mental distress among 18–44-year-old women in restrictive states within 3 months following the Dobbs decision [8]. However, anticipatory restrictions or trigger ban-based categorizations may not fully capture the complexities in state-based abortion laws that preceded and continued after Dobbs. Several states increased abortion restrictiveness after June 2022 by enacting new (non-trigger) laws (e.g., 6-week gestational bans) while others increased protections concomitantly (e.g., shield laws) [59]. On the other hand, some states enacted severe abortions restrictions several months prior to Dobbs. For instance, Texas enacted a near-total abortion ban almost one year before Dobbs, and it remains unclear if the state’s trigger ban following Dobbs substantially changed abortion access as the existing laws (pre-Dobbs) were already heavily restrictive [60, 61]. In other states, abortion restrictions increased over time post-Dobbs, despite the absence of trigger bans. The state of Florida, for instance, did not have a trigger ban in place but instituted increasingly harsher abortion restrictions between June 2022 and June 2024 [59]. Anderson et al. (2024) use the state-level timing of total or 6-week gestational bans to examine proximate changes in anxiety symptoms among women post-Dobbs [9]. However, this categorization does not account for states like Ohio which imposed a 6-week ban immediately after Dobbs [62] but later rescinded the ban following judicial directives [63]. More recently, several states voted to expand abortion access in November 2024, with some formerly restrictive states overturning restrictive abortion laws [64]. Owing to the rapidly evolving landscape of abortions laws, detailed analyses at the state-month level may aid our understanding of how abortion restrictions correspond with suicides. We encourage researchers to develop state-month-level abortion restrictiveness scales that would account for the spatial and temporal patterning of abortion laws in the present context. This type of spatio-temporal index is needed to examine changes in suicides among reproductive-aged women at sub-national levels.

Given prior research indicating that emergency department (ED) visits and inpatient admissions for self-harm and suicidal ideation closely track suicide mortality [65, 66], we encourage future research to examine whether these visits increased in response to abortion restrictions following the Dobbs decision. National and state level electronic health records or insurance claims-based datasets that provide high temporal and spatial resolution may be used to assess whether observed increases in suicide mortality among reproductive-aged women align with trends in suicide-related healthcare utilization. This approach may (i) independently verify the consistency of our findings with respect to the timing of population-level increase in suicide-related outcomes post-Dobbs and (ii) assess whether heightened suicide risk is reflected not only in mortality data but also in patterns of healthcare-seeking behavior for suicidal ideation/self-harm.

The provision of mental health care to those with the capacity for pregnancy, particularly younger people, is critical given that psychiatric comorbidities are one of the leading risk factors for maternal mortality [67–69]. Our observed national increase in suicides among women following the loss of the federal constitutional right to abortion may foreshadow a broader rise in maternal mortality, as untreated mental health issues are likely to escalate with increasing abortion restrictions. Anecdotal reports align with this concern, underscoring the urgent need for mental health services [70]. Additionally, Dobbs may portend grave implications for postpartum depression. People who were unable to access needed abortion services could face increased emotional and psychological distress, elevating their risk of postpartum depression and, consequently, suicide [71]. This highlights the need for integrating mental health care into reproductive health services, especially in contexts where reproductive options are restricted, to mitigate the potential for adverse outcomes.

Conclusion

The Dobbs decision has fundamentally altered the reproductive rights landscape in the US. The denial of reproductive choice not only violates a human right to autonomy but may exert grave health, social, and economic consequences. While evidence is accumulating on the health harms from abortion restrictions, limited studies have examined the potential effects on mental health[2, 3, 7–13]. Our finding that suicide deaths increased among reproductive-age women following Dobbs indicates that more research is urgently needed in this area.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank Benjamin M. Son for their feedback on the analyses for this manuscript.

Author contributions

PS designed the study, collected the data, performed data analysis, prepared the first draft of the manuscript and directed quality assurance and control. MG helped supervise the study’s analytic strategy and contributed to manuscript development (writing, editing and reviewing). AC helped conduct the literature review and wrote sections of the manuscript. SC, JA contributed to manuscript development and wrote sections of the manuscript. All authors certify that they have participated sufficiently in the work and believe in its overall validity and take public responsibility for appropriate portions of its content.

Funding

This study was not funded by any external sources.

Data availability

Data availability statement: Data used in this study are publicly available at https://wonder.cdc.gov/.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study used de-identified, aggregated, publicly available data and was deemed exempt from IRB review.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.The Guttmacher Institute Interactive Map: US abortion policies and access after roe. https://states.guttmacher.org/policies/

- 2.Coverdale J, Gordon MR, Beresin EV et al (2023) Access to abortion after Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization: advocacy and a call to action for the profession of psychiatry. Acad Psychiatry 47:1–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rajkumar RP (2022) The relationship between access to abortion and mental health in women of childbearing age: analyses of data from the global burden of disease studies. Cureus, 14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Gemmill A, Franks AM, Anjur-Dietrich S, et al (2024) US abortion bans and infant mortality. JAMA [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Bell SO, Franks AM, Arbour D, et al (2025) US abortion bans and fertility. JAMA [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Singh P, Gallo MF (2024) National trends in infant mortality in the US after dobbs: a time series analysis. JAMA Pediatr In Press [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Thornburg B, Kennedy-Hendricks A, Rosen JD, Eisenberg MD (2024) Anxiety and depression symptoms after the Dobbs abortion decision. JAMA 331:294–301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dave D, Fu W, Yang M (2023) Mental distress among female individuals of reproductive age and reported barriers to legal abortion following the US Supreme Court decision to overturn Roe v Wade. JAMA Netw Open 6:e234509–e234509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anderson MR, Burtch G, Greenwood BN (2024) The impact of abortion restrictions on American mental health. Sci Adv 10:eadl5743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Biggs MA, Upadhyay UD, McCulloch CE, Foster DG (2017) Women’s mental health and well-being 5 years after receiving or being denied an abortion: a prospective, longitudinal cohort study. JAMA Psychiat 74:169–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Horvath S, Schreiber CA (2017) Unintended pregnancy, induced abortion, and mental health. Curr Psychiatry Rep 19:1–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zandberg J, Waller R, Visoki E, Barzilay R (2023) Association between state-level access to reproductive care and suicide rates among women of reproductive age in the United States. JAMA Psychiat 80:127–134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McKetta S, Chakraborty P, Gimbrone C et al (2024) Restrictive abortion legislation and adverse mental health during pregnancy and postpartum. Ann Epidemiol 92:47–54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steinberg JR, Jordan B, Wells ES (2009) Science prevails: abortion and mental health. Contraception 79:81–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cohen SA (2013) Still True: Abortion does not increase women’s risk of mental health problems. In: Guttmacher Policy Rev. https://www.guttmacher.org/gpr/2013/06/still-true-abortion-does-not-increase-womens-risk-mental-health-problems

- 16.Steinberg JR, McCulloch CE, Adler NE (2014) Abortion and mental health: findings from the national comorbidity survey-replication. Obstet Gynecol 123:263–270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abajobir AA, Maravilla JC, Alati R, Najman JM (2016) A systematic review and meta-analysis of the association between unintended pregnancy and perinatal depression. J Affect Disord 192:56–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mercier RJ, Garrett J, Thorp J, Siega-Riz AM (2013) Pregnancy intention and postpartum depression: secondary data analysis from a prospective cohort. BJOG An Int J Obstet Gynaecol 120:1116–1122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu SY, Benny C, Grinshteyn E et al (2023) The association between reproductive rights and access to abortion services and mental health among US women. SSM-Population Heal 23:101428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Foster DG, Biggs MA, Ralph L et al (2022) Socioeconomic outcomes of women who receive and women who are denied wanted abortions in the United States. Am J Public Health 112:1290–1296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Treder KM, Amutah-Onukagha N, White KO (2023) Abortion bans will exacerbate already severe racial inequities in maternal mortality. Women’s Heal Issues 33:328–332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stewart SM, Kennard BD, Lee PWH et al (2005) Hopelessness and suicidal ideation among adolescents in two cultures. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 46:364–372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chang EC, Yu EA, Lee JY et al (2013) An examination of optimism/pessimism and suicide risk in primary care patients: does belief in a changeable future make a difference? Cognit Ther Res 37:796–804 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chang EC, Wan L, Li P et al (2017) Loneliness and suicidal risk in young adults: does believing in a changeable future help minimize suicidal risk among the lonely? J Psychol 151:453–463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kirtley OJ, Melson AJ, O’Connor RC (2018) Future-oriented constructs and their role in suicidal ideation and enactment. A posit psychol approach to suicide theory, Res Prev 17–36

- 26.Sun RCF, Shek DTL (2012) Beliefs in the future as a positive youth development construct: a conceptual review. Sci world J 2012:527038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kirtley OJ, Lafit G, Vaessen T et al (2022) The relationship between daily positive future thinking and past-week suicidal ideation in youth: an experience sampling study. Front Psychiatry/Frontiers Res Found (Lausanne, Switzerland)-Lausanne, 2010, currens 13:1–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Testa A, Turney K, Jackson DB, Jaynes CM (2022) Police contact and future orientation from adolescence to young adulthood: findings from the pathways to desistance study. Criminology 60:263–290 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Turney K, Testa A, Jackson DB (2022) Police stops and the erosion of positive future orientation among urban adolescents. J Adolesc Heal 71:180–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Catalano RA, Goldman-Mellor S, Karasek DA et al (2020) Collective optimism and selection against male twins in utero. Twin Res Hum Genet 23:45–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Singh P, Gailey S, Das A, Bruckner TA (2023) National trends in suicides and male twin live births in the US, 2003 to 2019: an updated test of collective optimism and selection in utero. Twin Res Hum Genet 26:353–360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Finer LB, Zolna MR (2016) Declines in unintended pregnancy in the United States, 2008–2011. N Engl J Med 374:843–852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hall KS, Richards JL, Harris KM (2017) Social disparities in the relationship between depression and unintended pregnancy during adolescence and young adulthood. J Adolesc Heal 60:688–697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2021) Mortality 2007–2020 on CDC WONDER Online Database. In: Natl. Vital Stat. Syst. Mult. Cause Death Files. http://wonder.cdc.gov/mcd-icd10

- 35.Kortsmit K, Nguyen AT, Mandel MG et al (2023) Abortion surveillance—United States, 2021. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 72:1–29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ajdacic-Gross V, Bopp M, Ring M et al (2010) Seasonality in suicide—a review and search of new concepts for explaining the heterogeneous phenomena. Soc Sci Med 71:657–666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shumway RH, Stoffer DS, Stoffer DS (2000) Time series analysis and its applications. Springer [Google Scholar]

- 38.Box GEP, Jenkins GM, Reinsel GC, Ljung GM (2015) Time series analysis: forecasting and control. John Wiley & Sons [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schaffer AL, Dobbins TA, Pearson S-A (2021) Interrupted time series analysis using autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) models: a guide for evaluating large-scale health interventions. BMC Med Res Methodol 21:1–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bernal JL, Cummins S, Gasparrini A (2017) Interrupted time series regression for the evaluation of public health interventions: a tutorial. Int J Epidemiol 46:348–355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu L-M, Hudak GB, Box GEP, et al (1992) Forecasting and time series analysis using the SCA statistical system. Scientific Computing Associates DeKalb, IL

- 42.Bruckner TA, Huo S, Fresson J, Zeitlin J (2024) Preterm births among male and female conception cohorts in France during initial COVID-19 societal restrictions. Ann Epidemiol 91:58–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Margerison CE, Zamani-Hank Y, Catalano R et al (2023) Association of the 2021 child tax credit advance payments with low birth weight in the US. JAMA Netw Open 6:e2327493–e2327493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bruckner TA, Bustos B, Margerison C et al (2023) Selection in utero against male twins in the U nited S tates early in the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Hum Biol 35:e23830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Margerison CE, Bruckner TA, MacCallum-Bridges C et al (2023) Exposure to the early COVID-19 pandemic and early, moderate and overall preterm births in the United States: a conception cohort approach. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 37:104–112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Catalano R, Casey JA, Gemmill A, Bruckner T (2023) Expectations of non-COVID-19 deaths during the pre-vaccine pandemic: a process-control approach. BMC Public Health 23:155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gemmill A, Casey JA, Margerison CE et al (2022) Patterned outcomes, unpatterned counterfactuals, and spurious results: perinatal health outcomes following COVID-19. Am J Epidemiol 191:1837–1841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gemmill A, Casey JA, Catalano R et al (2021) Changes in preterm birth and caesarean deliveries in the United States during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 10.1111/ppe.12811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Garnett MF, Curtin SC (2023) Suicide Mortality in the United States, 2001–2021 [PubMed]

- 50.Ljung GM, Box GEP (1978) On a measure of lack of fit in time series models. Biometrika 65:297–303 [Google Scholar]

- 51.CDC C for DC (1989) Mortality data from the national vital statistics system. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 38:118–123 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Van Poppel F, Day LH (1996) A test of Durkheim’s theory of suicide--without committing the" Ecological fallacy". Am Sociol Rev, 500–507

- 53.Moseson H, Fix L, Gerdts C et al (2022) Abortion attempts without clinical supervision among transgender, nonbinary and gender-expansive people in the United States. BMJ Sex Reprod Heal 48:e22–e30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Baptiste-Roberts K, Oranuba E, Werts N, Edwards LV (2017) Addressing health care disparities among sexual minorities. Obstet Gynecol Clin 44:71–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Everett BG, Higgins JA, Haider S, Carpenter E (2019) Do sexual minorities receive appropriate sexual and reproductive health care and counseling? J Women’s Heal 28:53–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dahlhamer JM, Galinsky AM, Joestl SS, Ward BW (2016) Barriers to health care among adults identifying as sexual minorities: a US national study. Am J Public Health 106:1116–1122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lund EM, Burgess CM (2021) Sexual and gender minority health care disparities: barriers to care and strategies to bridge the gap. Prim Care Clin Off Pract 48:179–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.National Center for Health Statistics (2022) Restricted-use vital statistics data. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/nvss-restricted-data.htm

- 59.LawAtlas post-dobbs state abortion restrictions and protections. https://lawatlas.org/datasets/post-dobbs-state-abortion-restrictions-and-protections

- 60.Bell SO, Stuart EA, Gemmill A (2023) Texas’ 2021 ban on abortion in early pregnancy and changes in live births. JAMA 330:281–282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gemmill A, Margerison CE, Stuart EA, Bell SO (2024) Infant deaths after Texas’ 2021 ban on abortion in early pregnancy. JAMA Pediatr [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 62.Ohio Policy Evaluation Network (OPEN) (2022) Ohio after Dobbs: FAQ. https://open.osu.edu/ohio-after-dobbs-faq/

- 63.American Health Law Association (2022) Ohio court temporarily blocks state’s six-week abortion Ban. https://www.americanhealthlaw.org/content-library/health-law-weekly/article/41ad4ef1-571a-4ef0-8a1d-4762e10248aa/ohio-court-temporarily-blocks-state-s-six-week-abo

- 64.Kaiser Family Foundation (2024) Ballot tracker: outcome of abortion-related state constitutional amendment measures in the 2024 election. https://www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/dashboard/ballot-tracker-status-of-abortion-related-state-constitutional-amendment-measures/

- 65.Goldman-Mellor SJ, Bhat HS, Allen MH, Schoenbaum M (2022) Suicide risk among hospitalized versus discharged deliberate self-harm patients: generalized random forest analysis using a large claims data set. Am J Prev Med 62:558–566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Goldman-Mellor S, Olfson M, Lidon-Moyano C, Schoenbaum M (2019) Association of suicide and other mortality with emergency department presentation. JAMA Netw open 2:e1917571–e1917571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Oates M (2003) Perinatal psychiatric disorders: a leading cause of maternal morbidity and mortality. Br Med Bull 67:219–229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Oates M (2003) Suicide: the leading cause of maternal death. Br J Psychiatry 183:279–281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Trost SL, Beauregard JL, Smoots AN et al (2021) Preventing pregnancy-related mental health deaths: insights from 14 us maternal mortality review committees, 2008–17: study examines maternal mortality and mental health. Health Aff 40:1551–1559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Goldberg M (2024) It was only a metter of time before abortion bans killed someone. New York Times, Cham [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shi P, Ren H, Li H, Dai Q (2018) Maternal depression and suicide at immediate prenatal and early postpartum periods and psychosocial risk factors. Psychiatry Res 261:298–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data availability statement: Data used in this study are publicly available at https://wonder.cdc.gov/.