Abstract

The administration of opioid receptor antagonists is believed to overcome ventilatory depressant effects of opioids. Here we show that many ventilatory depressant effects of morphine are converted to excitatory responses after (mu1) μ1-opioid receptor blockade and that these responses are accompanied by ventilatory instability. We report in this study (1) the ventilatory responses elicited by morphine (10 mg/kg, IV) and (2) ventilatory responses elicited by a subsequent hypoxic-hypercapnic (H-H) challenge and return to room-air in male Sprague Dawley rats pre-treated with (i) vehicle, (ii) the centrally-acting selective μ1-opioid receptor antagonist, naloxonazine (1.5 mg/kg, IV), or (iii) the centrally-acting (delta1,2) δ1,2-opioid receptor antagonist, naltrindole (1.5 mg/kg, IV). The morphine-induced decreases in frequency of breathing, peak inspiratory flow, peak expiratory flow, EF50, inspiratory drive and expiratory drive, in vehicle-treated rats were converted to profound increases in naloxonazine pre-treated rats. The adverse effects of morphine on expiratory delay and apneic pause were augmented in naloxonazine-treated rats, and morphine increased ventilatory instability (i.e., non-eupneic breathing index) in naloxonazine-treated rats that was not due to increases in ventilatory drive. Subsequent exposure to a H-H challenge elicited qualitatively similar responses in both groups, whereas the responses upon return to room-air (e.g., frequency of breathing, inspiratory and expiratory times, end expiratory pause, relaxation time, expiratory delay, and non-eupneic breathing index) were substantially different in naloxonazine-treated versus vehicle-treated rats. The above effects of morphine were only marginally affected by naltrindole. These novel data highlight the complicated effects that μ1-opioid receptor antagonism exerts on the ventilatory effects of morphine.

Keywords: naloxonazine, morphine, ventilatory depression, ventilatory instability, male Sprague Dawley rats

SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT

This study shows that the systemic injection of morphine elicits a pronounced overshoot in ventilation in freely-moving rats pre-treated with the centrally-acting selective μ1-opioid receptor antagonist, naloxonazine, but not with the centrally-acting δ1,2-opioid receptor antagonist, naltrindole. This suggests that morphine can recruit a non-μ1-opioid receptor system that promotes breathing.

INTRODUCTION

The administration of μ1-opioid receptor (μ1-OR) antagonists such as naloxone (Narcan®) appear to simply overcome (often only partially) the ventilatory depressant effects of opioids such as morphine and fentanyl in humans in that there is no reported overshoot of ventilatory parameters above pre-opioid administration levels (1–4). However, we have evidence in unanesthetized rats that fentanyl-induced depression of minute ventilation is converted to excitation (i.e., an overshoot above baseline values) in the presence of systemically-injected naloxone, noting that it is often difficult to separate the effects of opioid drugs on ventilation versus behaviors (5). Moreover, systemic administration of a centrally acting dose of naloxone methiodide but not a peripherally acting dose caused a marked overshoot of numerous ventilatory parameters when given to rats at a time when baseline frequency of breathing, tidal volume and minute ventilation had fully recovered from a prior high dose of fentanyl (6). As such, systemically injected fentanyl may activate opposing opioid receptor (depressant) and non-opioid receptor (excitatory) systems that control breathing in rats (5, 6). The pharmacological, cellular, and molecular mechanisms by which opioids depress ventilation have been studied intensively (7–11) whereas systems by which opioids excite breathing has received little attention (6). However, the finding that systemic injections of low-doses of morphine elicit excitatory ventilatory responses in conscious rats (12) suggests that morphine and fentanyl can recruit these excitatory systems that likely exist in the central nervous system although the possibility that these excitatory responses involve activation of peripheral structures such as the carotid body-chemoafferent complex (13) or skeletal muscle-neural systems (14) cannot be discounted. Whether these counterbalancing opioid-stimulated ventilatory control systems in rats exist (can be recruited) in humans remains to be determined.

We are developing paradigms that elicit ventilatory excitatory effects of opioids to uncover the molecular, cellular, and pharmacological mechanisms responsible for these excitatory effects. This is being done with the intention of uncovering a novel therapeutic that can be used to help overcome opioid-induced respiratory depression (OIRD) in humans and especially as an adjunct to opioid receptor antagonists that struggle to overcome OIRD elicited by fentanyl and other powerful synthetic opioids that are driving the current ever-growing opioid crisis in the US (15–17). Direct binding/displacement and pharmacological studies have provided compelling evidence that naloxonazine (NLZ) (Bis-[5-α-4,5-Epoxy-3,14-dihydroxy-17-(2-propenyl)-morphinan-6-ylidene] hydrazine, see Supplemental Figure 1), is a selective, high-affinity μ1-OR antagonist with minimal activity at μ2-ORs (18–23). NLZ is centrally active upon peripheral administration and has been used in studies examining the roles of μ1-ORs in the actions of opioids (24–31). It should be noted that NLZ produces prolonged antagonism of central δ-OR activity in vivo (32).

The major objective of the present study was to determine whether blockade of μ1-ORs with NLZ reverses the ventilatory depressant effects of morphine and uncovers possible ventilatory excitant responses. The second objective was to determine whether NLZ modulates the ability of morphine to depress the ventilatory responses to a hypoxic-hypercapnic (H-H) gas challenge via the rebreathing method (33–36). These specific objectives were evaluated by looking at the ventilatory responses elicited via (a) an intravenous injection of vehicle or NLZ (1.5 mg/kg, IV) in freely-moving adult male Sprague Dawley rats, (b) subsequent injection of morphine (10 mg/kg, IV), and (c) subsequent exposure to a hypoxic-hypercapnic (H-H) gas challenge and return to room-air. To determine the role of δ1,2-ORs compared to μ1-ORs in the ventilatory responses of morphine-treated rats, we performed similar studies as described above in rats injected with the centrally-acting selective δ1,2-OR antagonist, naltrindole (NLT, see Supplemental Figure 1) (36–38). The present findings demonstrate that pretreatment with NLZ, and to a much lesser degree, NLT, uncovers pronounced and long-lasting ventilatory excitatory effects of morphine, and that these desirable effects on breathing elicited by morphine in NLZ-treated rats are accompanied by adverse effects on ventilatory stability.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Permissions, rats, and surgical procedures

All studies were done in compliance with the ARRIVE (Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments) guidelines (https://arriveguidelines.org/) and in strict accordance with the NIH Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publication No. 80–23) revised in 2011, and. The protocols received prior approval from the Animal Care and Use Committees of Galleon Pharmaceuticals, Inc., the University of Virginia, and Case Western Reserve University. Adult male Sprague Dawley rats (approximately 290–310 grams, 77–83 days of age) were purchased from Inotiv (Indianapolis, IN, USA). After 7 days of recovery from transport, the rats were anesthetized (2–3% isoflurane) and implanted with jugular vein catheters (5, 39) The rats were given 6 days to recover from jugular vein catheter surgery before use. Each catheter was flushed with 300 μL of 0.1 M (pH 7.4) phosphate-buffered saline 2–3h before starting a study in order to clear any potential blood clots that may have formed in the catheter during the recovery period. (+)-Morphine sulfate was purchased from Baxter Healthcare (Deerfield, IL). NLZ (naloxonazine dihydrochloride hydrate) powder was provided by Galleon Pharmaceuticals, Inc (Horsham, PA, USA). NLT (naltrindole hydrochloride) powder was from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). All protocols were done in a quiet room with a relative humidity of 49 ± 1% and ambient temperature of 21.2 ± 0.2°C. The syringes with vehicle (saline), or NLZ or NLT were prepared by one investigator whereas the plethysmography experiments were done by another investigator who did not know the identities of the drugs to be injected. Data files collected from the recording sessions were analyzed initially by other investigators in the team.

Whole body plethysmography studies

Ventilatory parameters in unrestrained freely-moving rats were continuously recorded via whole-body plethysmography (PLY3223; Data Sciences International, St. Paul, MN) as described in detail previously (39–42) and as defined in Supplemental Table 1 and Supplemental Figure 2 (43). The parameters and their abbreviations are: tidal volume (TV), frequency of breathing (Freq), minute ventilation (MV), inspiratory time (Ti), expiratory time (Te), Te/Ti, end inspiratory pause (EIP), end expiratory pause (EEP), peak inspiratory flow (PIF), peak expiratory flow (PEF), PEF/PIF, expiratory flow at 50% expired TV (EF50), relaxation time (RT), inspiratory drive (TV/Ti), expiratory drive (TV/Te), apneic pause [(Te/RT)-1], inspiratory delay (Te-RT), non-eupneic breathing index (NEBI) and NEBI corrected for Freq (NEBI/Freq). The numbers of rats in each group, ages, body weights and resting (Pre, baseline) parameters are shown in Table 1. On the day of study, the rats were put into individual plethysmography chambers and given 60 min to acclimatize so that resting (baseline) ventilatory values could be determined. Each rat was used only once for either Study 1 or Study 2. No rat received multiple treatments.

Table 1.

Resting (Baseline, Pre) values prior to the intravenous injection of vehicle, naloxonazine or naltrindole

| Treatment Groups |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study 1 | Study 2 | |||

|

| ||||

| Parameter | Vehicle | Naloxonazine | Vehicle | Naltrindole |

|

| ||||

| Number | 5 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| Age | 78.2 ± 0.5 | 77.7 ± 0.4 | 82.0 ± 0.4 | 82.5 ± 0.3 |

| Body Weight, grams | 291 ± 4 | 287 ± 3 | 307 ± 3 | 308 ± 3 |

| Frequency (Freq), breaths/min | 86 ± 5 | 80 ± 4 | 93 ± 6 | 92 ± 3 |

| Tidal Volume (TV), ml | 2.03 ± 0.19 | 2.11 ± 0.08 | 2.62 ± 0.12 | 2.53 ± 0.08 |

| Minute Ventilation, ml/min | 170 ± 7 | 166 ± 6 | 241 ± 16 | 232 ± 13 |

| Inspiratory Time (Ti), sec | 0.24 ± 0.01 | 0.26 ± 0.02 | 0.24 ± 0.01 | 0.23 ± 0.01 |

| Expiratory Time (Te), sec | 0.42 ± 0.07 | 0.45 ± 0.04 | 0.43 ± 0.04 | 0.43 ± 0.02 |

| Te/Ti | 1.76 ± 0.24 | 1.88 ± 0.10 | 1.79 ± 0.11 | 1.55 ± 0.19 |

| End Inspiratory Pause, sec | 7.6 ± 0.3 | 8.3 ± 0.2 | 7.7 ± 0.3 | 7.5 ± 0.3 |

| End Expiratory Pause, sec | 44.6 ± 5.4 | 37.8 ± 4.8 | 22.6 ± 1.7 | 23.4 ± 1.1 |

| Peak Inspiratory Flow (PIF), ml/sec | 15.0 ± 0.7 | 14.9 ± 0.4 | 17.1 ± 1.4 | 16.3 ± 1.2 |

| Peak Expiratory Flow (PEF), ml/sec | 11.5 ± 0.5 | 11.4 ± 0.2 | 12.3 ± 0.9 | 12.6 ± 0.7 |

| PEF/PIF | 0.78 ± 0.07 | 0.77 ± 0.02 | 0.76 ± 0.02 | 0.74 ± 0.02 |

| EF50, ml/sec | 0.49 ± 0.05 | 0.48 ± 0.03 | 0.48 ± 0.04 | 0.49 ± 0.02 |

| Rpef, ml/sec | 0.18 ± 0.02 | 0.18 ± 0.01 | 0.19 ± 0.02 | 0.18 ± 0.01 |

| Relaxation Time, sec | 0.25 ± 0.04 | 0.26 ± 0.02 | 0.24 ± 0.02 | 0.25 ± 0.02 |

| Apneic Pause, (TV/Te)-1 | 0.75 ± 0.14 | 0.81 ± 0.09 | 0.80 ± 0.05 | 0.73 ± 0.13 |

| Expiratory Delay, (Te-RT) | 0.18 ± 0.04 | 0.20 ± 0.02 | 0.19 ± 0.01 | 0.15 ± 0.03 |

| Inspiratory Drive (TV/Ti), ml/sec | 8.5 ± 0.5 | 8.4 ± 0.4 | 6.3 ± 0.4 | 5.4 ± 0.9 |

| Expiratory Drive (TV/Te), ml/sec | 5.0 ± 0.3 | 4.8 ± 0.4 | 6.3 ± 0.4 | 5.5 ± 0.8 |

| Non-eupneic breathing Index (NEBI), % | 1.77 ± 0.57 | 2.95 ± 0.62 | 3.10 ± 0.53 | 2.48 ± 0.30 |

| NEBI/Freq, (%/(breaths/min) x 100 | 2.12 ± 0.55 | 3.64 ± 0.86 | 3.22 ± 0.42 | 2.70 ± 0.41 |

The data are presented as mean ± SEM. There were 6 rats in each group. There were no between group differences for any parameter in Study 1 or Study 2 (P > 0.05, for all comparisons.

Study 1:

One group of rats received an injection of vehicle, and another was injected with NLZ (1.5 mg/kg, IV). After 15 min, both groups received an injection of morphine (10 mg/kg, IV) and after 75 min, the rats were subjected to a hypoxic-hypercapnic (H-H) challenge for 60 min. This consisted of the rebreathing method in which the airflow to the chambers was turned off and thus the rats rebreathed their own air which became increasing poor in oxygen and increasingly rich in CO2 (33–36). This method better represents physiologically what the animal is experiencing compared to an individual hypoxic or hypercapnic challenge. Airflow was then returned to the chambers and ventilatory parameters were recorded for another 30 min.

Study 2:

One group of rats received an injection of vehicle and another was injected with NLT (1.5 mg/kg, IV). After 15 min, both groups of rats received a bolus injection of morphine (10 mg/kg, IV) and after 75 min, the rats were subjected to H-H challenge for 60 min. Airflow was returned to the chambers and ventilatory parameters were recorded for another 30 min.

Since the two groups in Study 1 and two groups in Study 2 had similar body weights (P > 0.05, for all between-group parameter comparisons), volume parameters (e.g., TV, PIF, PEF and EF50) are shown without correction for body weight. Resident software (FinePointe) constantly adjusted digitized ventilatory values emanating from respiratory waveforms for changes in chamber humidity and temperature. Pressure values emanating from the waveforms were converted to volumetric values (e.g., TV, EF50, PIF, PEF) with the aid of algorithms provided by Epstein and colleagues (44, 45). Factoring in chamber humidity and temperature, the in-built cycle analyzers filtered the acquired signals, and FinePointe algorithms computed box flow data that identified a waveform segment as a breath and determined minimum and maximum values. These box-flow signals were adjusted by compensation factors from the algorithms to produce values for TV, EF50, PIF and PEF used to identify non-eupneic breathing events (e.g., apneas, type 1 and type 2 sighs, disordered breath) expressed as non-eupneic breathing index (NEBI, % of non-eupneic breaths per epoch) (40). Expiratory delay (expiratory time - relaxation time) and apneic pause [(expiratory time/relaxation time)-1] were also calculated (39).

Righting reflex as an index of morphine-induced sedation

Four groups of adult male Sprague–Dawley rats were used to evaluate the effects of NLZ on the duration of the loss of the righting reflex (inability to stand on all 4 legs) elicited by morphine (46). The rats were put into individual open plastic chambers to determine the length of time taken to recover from the morphine-induced loss of the righting reflex. The external end of the jugular vein catheter was connected to tubing connected to a syringe to allow for the injection drugs. The rats were given 60 min to acclimatize to their environment. The time when the rat stood reliably on all four paws for at least 10 sec after the injection of morphine was taken as the point of recovery of the righting reflex (47–49). Study 1: One group of rats (n=9, 289 ± 2 g; 77.6 ± 0.5 days of age) received an injection of vehicle, and a second group (n=9, 289 ± 2 g; 78.4 ± 0.5 days of age) received an injection of NLZ (1.5 mg/kg, IV). After 15 min, both groups of rats received an injection of morphine (10 mg/kg, IV). Study 2: One group of rats (n=9, 302 ± 3 g; 82.1 ± 0.5 days of age) received an injection of vehicle, and a second group (n=9, 303 ± 2 g; 82.4 ± 0.2 days of age) received an injection of NLT (1.5 mg/kg, IV and after 15 min, both groups of rats received an injection of morphine (10 mg/kg, IV). The duration of the loss of the righting reflex was determined by two investigators blinded to the protocols.

Data Analyses

All data are shown as mean ± SD in Figures 1 – 9 and mean ± SEM in Table 1. Data were analyzed by one-way or two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni corrections for multiple comparisons between the mean values using the error mean square terms from each ANOVA analysis (50, 51). A P < 0.05 value was taken as the initial level of significance and was modified by the number of between-mean comparisons. The modified t-statistic for 2 groups is t = (mean group 1 - mean group 2)/[s x (1/n1 + 1/n2)1/2] where s2 = mean square within groups term from the ANOVA and n1 and n2 are the number of rats in each group being compared. The statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA). A more detailed description of the statistical approach is provided in the Supplemental File (see Detailed Approach to Statistical Analyses. The ANOVA tables describing the F- and P-values for the summary figures in Figures 1–9 and Supplemental Figures 3–9 are presented in Supplemental Tables 2 and 3 (NLZ data) and Supplemental Tables 4 and 5 (NLT data), noting the values of the error mean square terms. The multiple comparisons testing sets the P value for the number of comparisons (e.g., P < 0.05 becomes P < 0.05/5 comparisons, when 5 comparisons between means are made), and the error mean square term is used in the formula to establish the actual value for which means are different from one another (50,51).

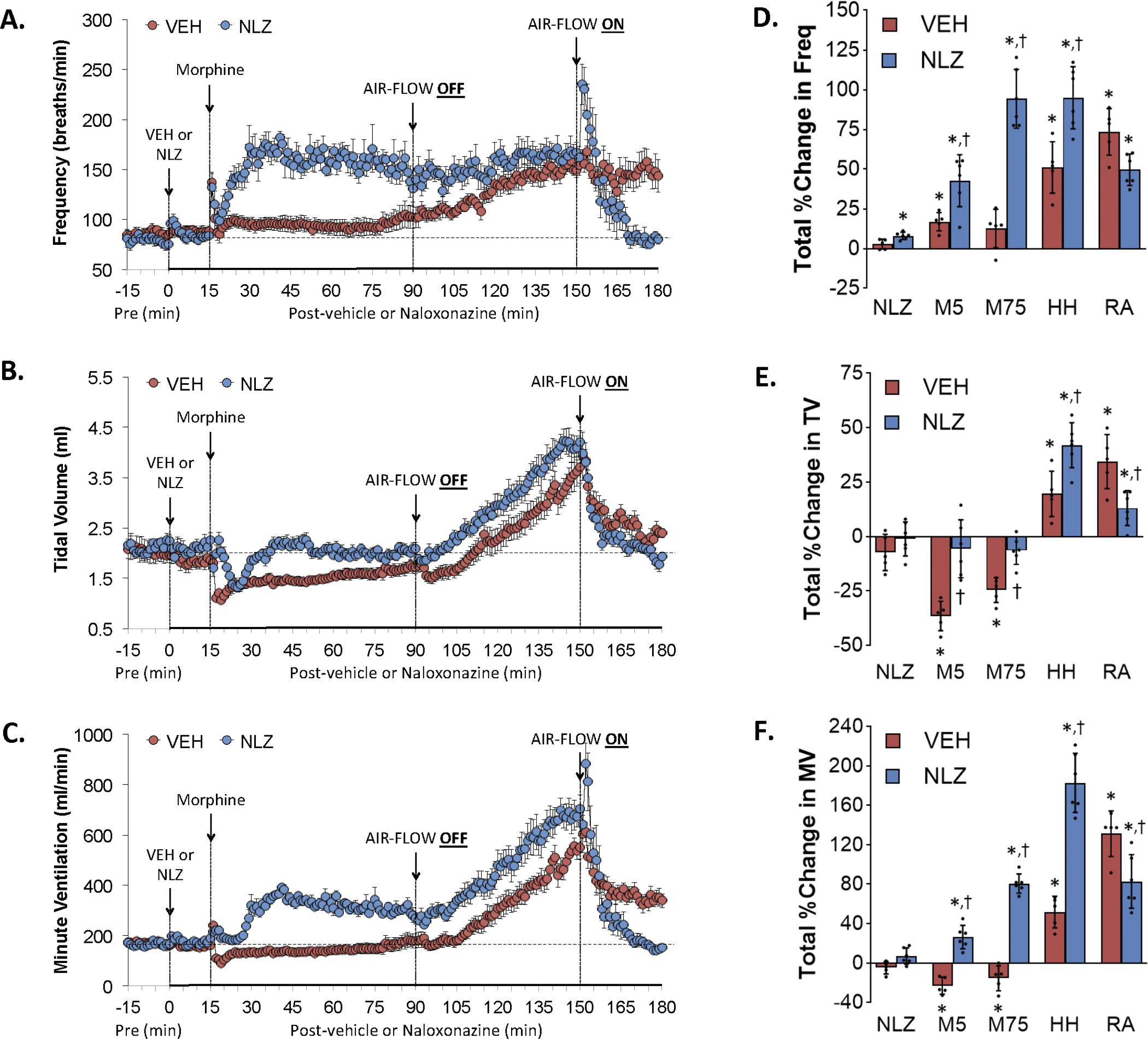

Figure 1.

Changes in frequency of breathing (Panel A), tidal volume (Panel B), and minute ventilation (Panel C) elicited by the injection of vehicle (VEH) or naloxonazine (NLZ, 1.5 mg/kg, IV), followed by the injection of morphine (10 mg/kg, IV), and a subsequent hypoxic-hypercapnic challenge (air-flow OFF) and return to room-air (air-flow ON). Summaries of the total changes in these parameters elicited by VEH or NLZ, by morphine over the first 5 min (M5) and over the 75 min (M75) post-injection period, and by the hypoxic-hypercapnic (HH) challenge and return to room-air (RA), are shown in Panels D, E and F, respectively. The data are presented as mean ± SD. There were 6 rats in each group. The summary data were analyzed by repeated measures ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni test for multiple comparisons. *P < 0.05, significant response from Pre-values. †P < 0.05/5 comparisons, responses in NLZ-treated rats versus vehicle-treated rats.

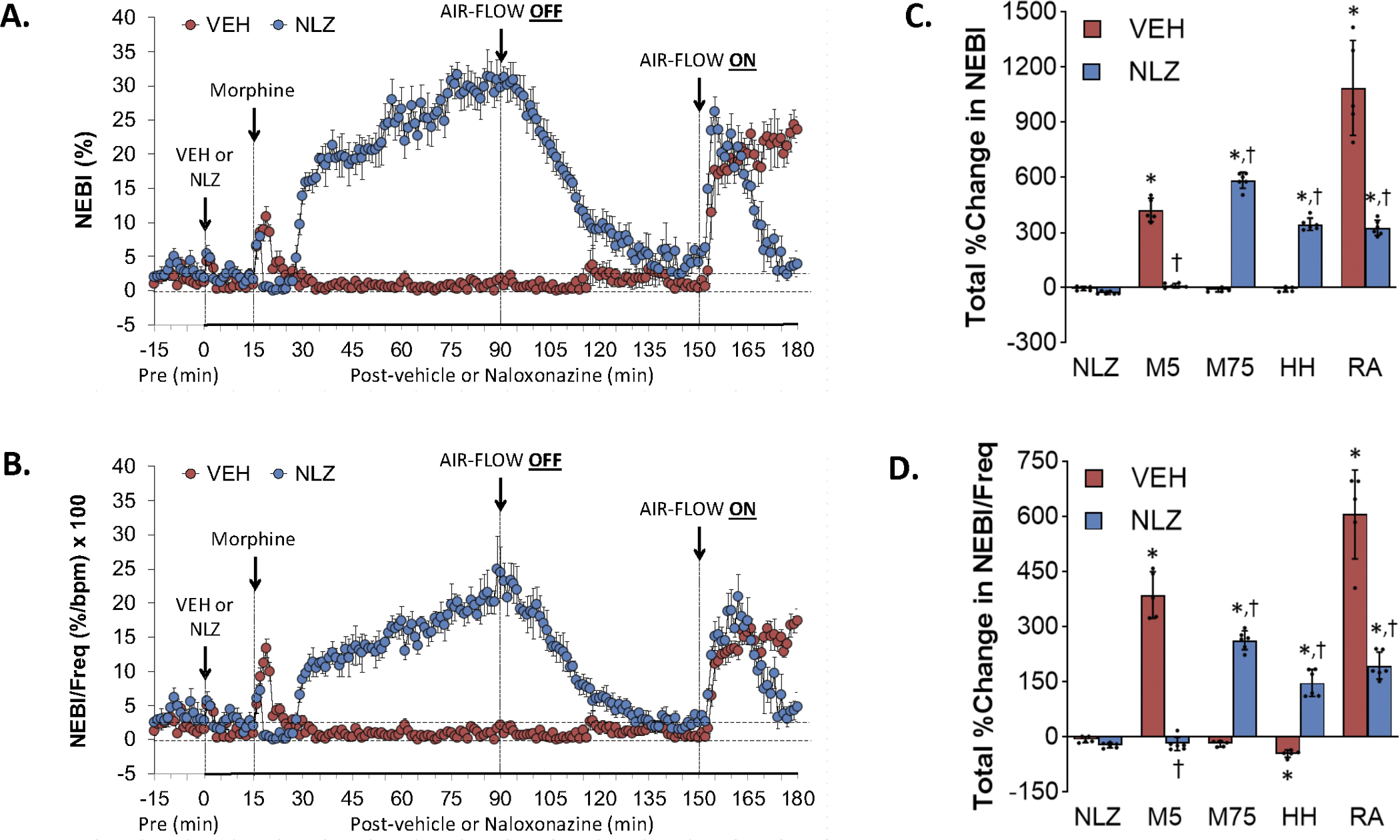

Figure 9.

Changes in non-eupneic breathing index (NEBI) (Panel A) and NEBI corrected for frequency of breathing (NEBI/Freq) (Panel B) elicited by injection of vehicle (VEH) or naloxonazine (NLZ, 1.5 mg/kg, IV), followed by the injection of morphine (10 mg/kg, IV), and a subsequent hypoxic-hypercapnic challenge (air-flow OFF) and return to room-air (air-flow ON). Summaries of the total changes in these parameters elicited by VEH or NLZ, by morphine over the first 5 min (M5) and over the 75 min (M75) post-injection period, and by the hypoxic-hypercapnic (HH) challenge and return to room-air (RA), are shown in Panels C and D, respectively. The data are presented as mean ± SD. There were 6 rats in each group. The summary data were analyzed by repeated measures ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni test for multiple comparisons. *P < 0.05, significant response from Pre-values. †P < 0.05/5 comparisons, responses in NLZ-treated rats versus vehicle-treated rats.

RESULTS

Resting parameters

The body weights and baseline (resting) ventilatory parameters of the groups of rats used for Study 1 (vehicle, NLZ) and Study 2 (vehicle, NLT) are summarized in Table 1. There were no between group differences in body weights and in any ventilatory parameter for Study 1 or Study 2 (P > 0.05 for all comparisons). The body weights, tidal volume and minute ventilation values in the two groups of rats in the NLZ study (Study 1) were somewhat less than those of the two groups in the NLT study (Study 2) (P < 0.05 for all comparisons).

Effects of NLZ or NLT on morphine-induced changes in frequency of breathing (Freq), tidal volume (TV) and minute ventilation (MV)

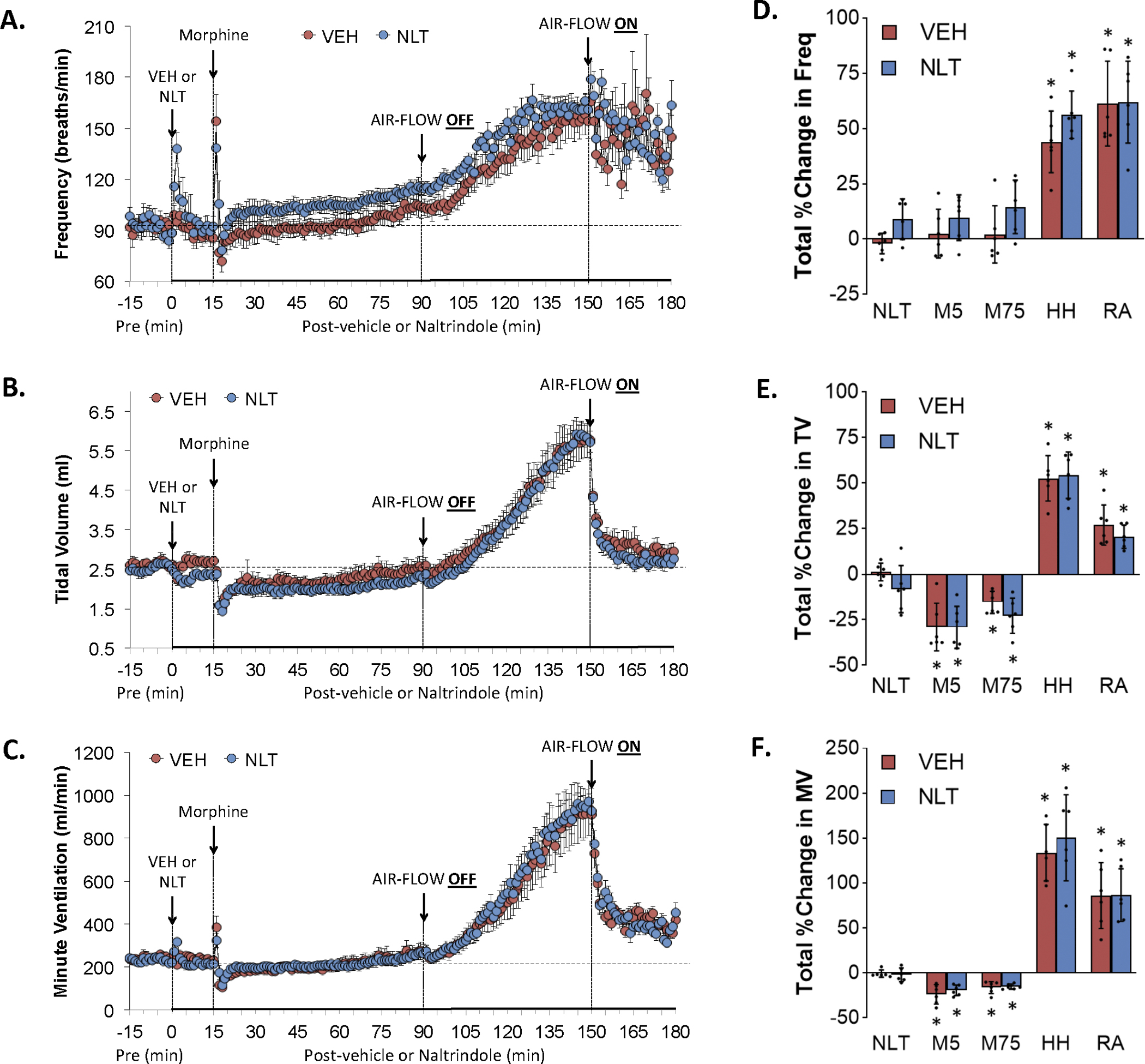

Figure 1 summarizes the changes in Freq (Panel A), TV (Panel C) and MV (Panel E) elicited by the injection of vehicle (VEH) or NLZ (1.5 mg/kg, IV), the injection of morphine (10 mg/kg, IV), a hypoxic-hypercapnic (HH) challenge (air-flow OFF), and return to room-air (air-flow ON). Summaries of the total changes in Freq, TV and MV elicited by vehicle or NLZ, by morphine over the first 5 min (M5) and 75 min (M75) post-injection period, and by the HH challenge and upon return to room-air (RA) are shown in Panels B, D and F, respectively. The injection of morphine in vehicle-treated rats elicited an initial transient increase in Freq that was followed by a relatively minor but sustained increase (Panel A). Subsequent exposure to the HH challenge caused a gradual and sustained increase in Freq that was sustained upon return to room-air. The injection of NLZ elicited minor transient increases in Freq. Subsequent injection of morphine elicited a similar initial spike in Freq as seen in vehicle-treated rats whereas the subsequent increase in Freq was much larger than in vehicle-treated rats (note that the righting reflex of NLZ-treated rats were fully recovered in about 5 min whereas vehicle-treated rats remained sedated, see below). The HH challenge did not further increase Freq so that the levels reached at the end of the challenge were similar in both groups. Freq rose initially upon return to room-air in NLZ-treated rats but fell to baseline levels within 10 min and remained there. The injection of morphine in vehicle-treated rats elicited substantial decrease in TV (Panel C) that resolved by 75 min post-injection. The HH challenge caused a gradual and sustained increase in TV returned toward but stayed above baseline upon return to room-air. The injection of NLZ did not affect resting TV values. The subsequent injection of morphine elicited a transient but substantial decrease in TV. TV values remained at baseline values thereafter and the HH challenge caused increases in TV that paralleled those in vehicle-treated rats. TV fell immediately upon return to room air and reached baseline levels. These effects on Freq and TV resulted in morphine causing a pronounced overshoot in MV in NLZ-treated rats (Panel E) whereas it did not affect the time-course of HH-induced-increase in MV (the temporal increases in MV were parallel in vehicle- and NLZ-treats rats) whereas the return to room-air increase in MV was less in NLZ-treated rats. Figure 2 summarizes the findings in NLT-treated rats and key findings were that NLT had minimal effects on resting Freq, TV and MV values and that NLT did not alter the changes in these parameters elicited by morphine, HH challenge or the return to room-air.

Figure 2.

Changes in frequency of breathing (Panel A), tidal volume (Panel B), and minute ventilation (Panel C) elicited by the injection of vehicle (VEH) or naltrindole (NLT, 1.5 mg/kg, IV), followed by the injection of morphine (10 mg/kg, IV), and a subsequent hypoxic-hypercapnic challenge (air-flow OFF) and return to room-air (air-flow ON). Summaries of total changes in these parameters elicited by VEH or NLT, by morphine over the first 5 min (M5) and over the 75 min (M75) post-injection period, and by the hypoxic-hypercapnic (HH) challenge and return to room-air (RA), are shown in Panels D, E and F, respectively. Data are shown as mean ± SD. There were 6 rats in each group. The summary data were analyzed by repeated measures ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni test for multiple comparisons. *P < 0.05, significant response from Pre-values. There were no between-group differences in the responses (P > 0.05, for all comparisons).

Effects of NLZ or NLT on morphine-induced changes in inspiratory time (Ti), expiratory time (Te) and Te/Ti

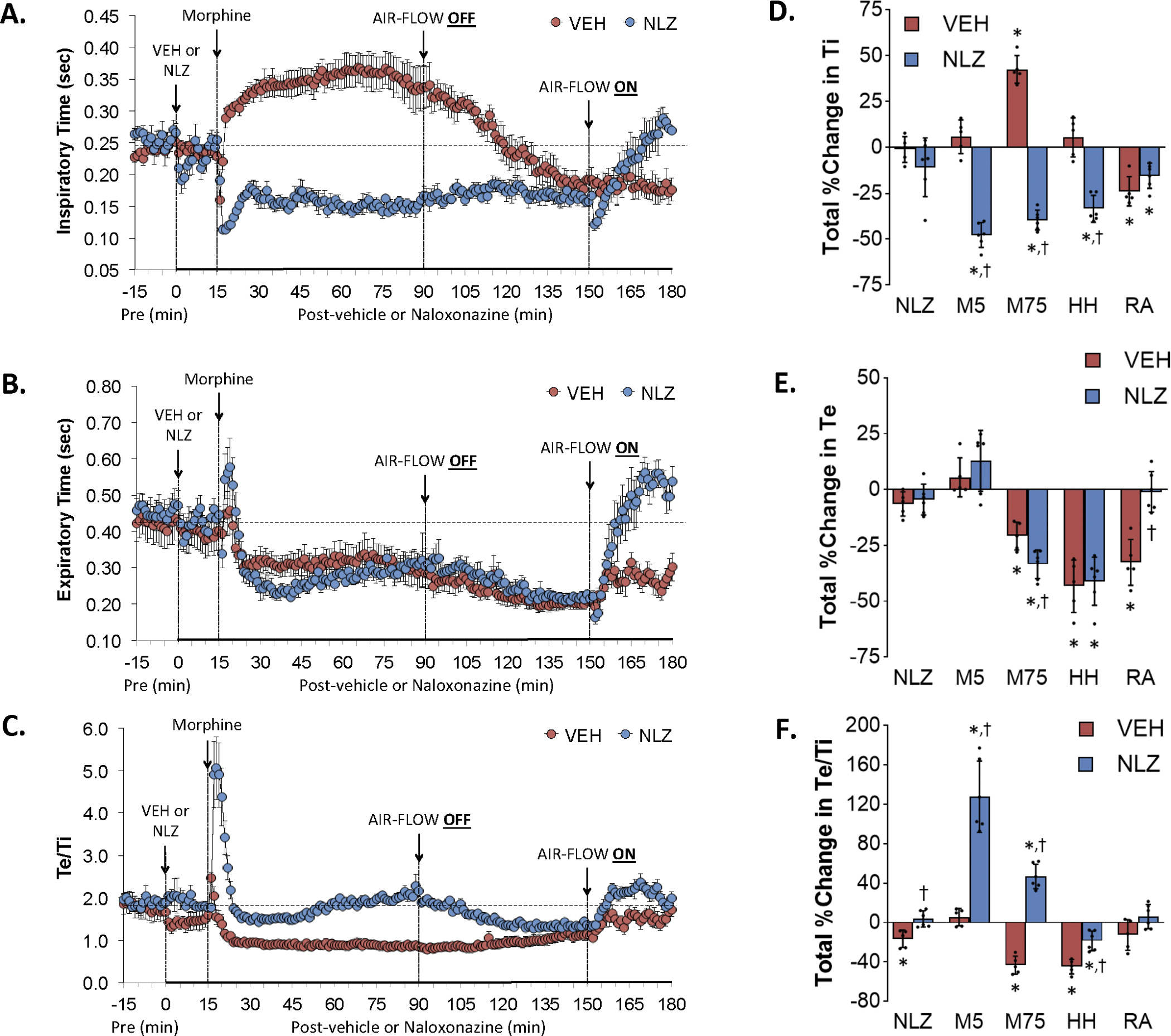

Figure 3 summarizes the changes in Ti (Panel A), Te (Panel C) and Te/Ti (Panel E) elicited by the injection of vehicle (VEH) or NLZ (1.5 mg/kg, IV), injection of morphine (10 mg/kg, IV), a HH challenge (air-flow OFF), and return to room-air (air-flow ON). Summaries of the total changes in Ti, Te and Te/Ti elicited by vehicle or NLZ, by morphine over the first 5 min (M5) and over the 75 min (M75) post-injection period, and by HH challenge and return to room-air (RA) are shown in Panels B, D and F, respectively. The injection of morphine in vehicle-treated rats elicited an initial transient decrease in Ti followed by a sustained increase (Panel A). The HH challenge caused a gradual and sustained decrease in Ti to below baseline levels that was sustained at these levels upon return to room-air. The injection of NLZ elicited minor changes in Ti. Morphine elicited a sustained decrease in Ti that stayed below baseline levels to the end of the HH challenge. Ti values fell briefly and then rose to baseline values upon return to room air. The injection of morphine in vehicle-treated rats elicited an initial increase followed by a sustained decrease in Te (Panel C) that remained suppressed during HH challenge and subsequent return to room air. NLZ did not affect resting Te values but augmented morphine-induced decreases in Te. The HH-induced decreases in Te were not modified by NLZ whereas Te rose quickly to values above baseline upon return to room air. These effects on Ti and Te resulted in morphine causing a pronounced and sustained decrease in Te/Ti in vehicle-treated rats (Panel E) but a pronounced transient increase in Te/Ti in NLZ-treated rats that was sustained during HH challenge. No between group differences were seen upon return to room-air. Supplemental Figure 3 summarizes the findings in NLT-treated rats and key findings were that NLT had minimal effects on resting Ti, Te and Te/Ti values and that NLT did not affect the changes in these parameters elicited by morphine, HH challenge or return to room-air except it diminished the initial increase in Te elicited by morphine (column designated M5 in panel D).

Figure 3.

Changes in inspiratory time (Ti) (Panel A), expiratory time (Panel B) and Te/Ti (Panel C) elicited by the injection of vehicle (VEH) or naloxonazine (NLZ, 1.5 mg/kg, IV), followed by the injection of morphine (10 mg/kg, IV), and a subsequent hypoxic-hypercapnic challenge (air-flow OFF) and return to room-air (air-flow ON). Summaries of the total changes in these parameters elicited by VEH or NLZ, by morphine over the first 5 min (M5) and over the 75 min (M75) post-injection period, and by the hypoxic-hypercapnic (HH) challenge and return to room-air (RA), are shown in Panels D, E and F, respectively. The data are presented as mean ± SD. There were 6 rats in each group. The summary data were analyzed by repeated measures ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni test for multiple comparisons. *P < 0.05, significant response from Pre-values. †P < 0.05/5 comparisons, responses in NLZ-treated rats versus vehicle-treated rats.

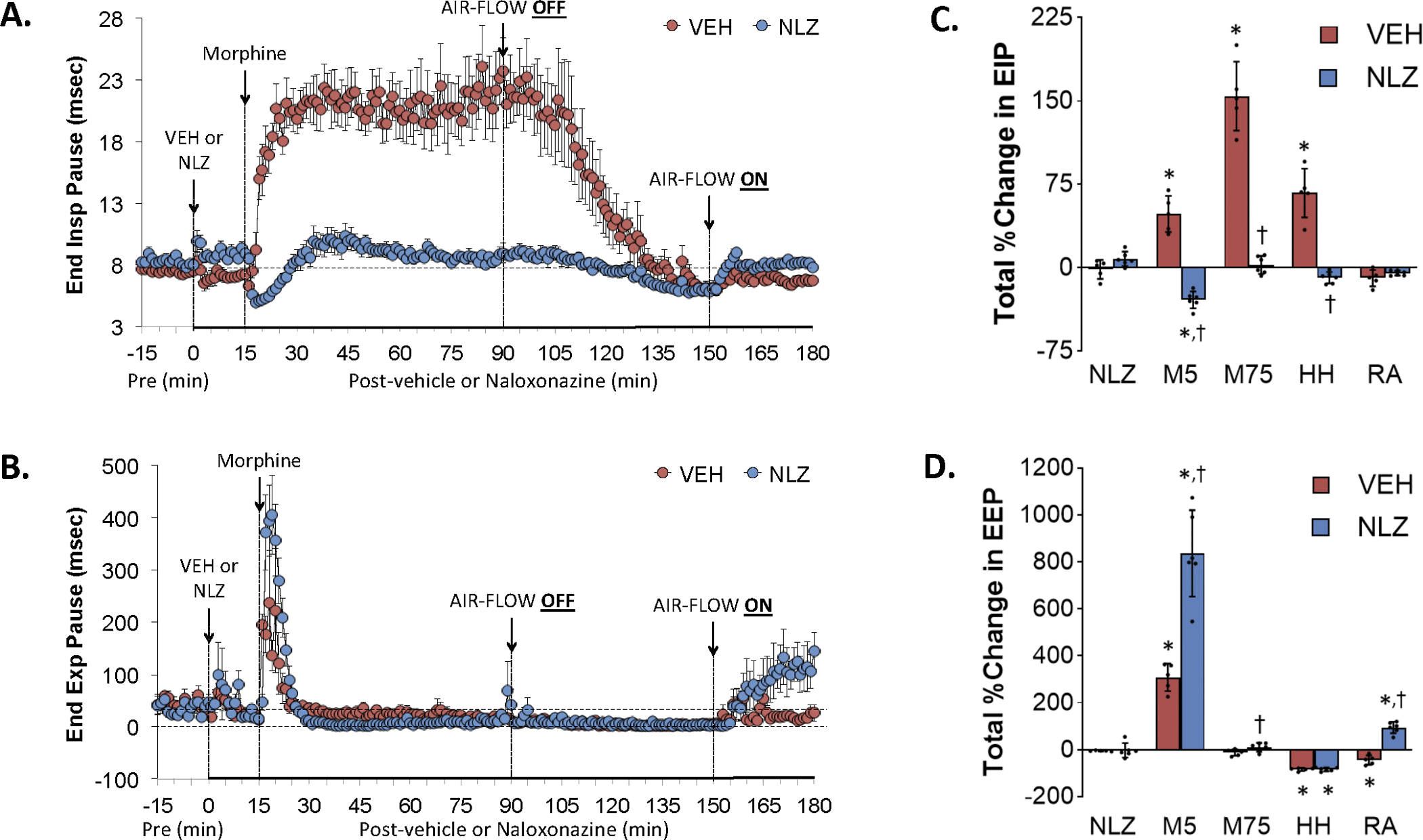

Effects of NLZ or NLT on morphine-induced changes in end inspiratory pause (EIP) and end expiratory pause (EEP)

Figure 4 summarizes the changes in EIP (Panel A) and EEP (Panel C) elicited by the injection of vehicle (VEH) or NLZ (1.5 mg/kg, IV), the injection of morphine (10 mg/kg, IV), a HH challenge (air-flow OFF), and return to room-air (air-flow ON). Summaries of the total changes in these parameters elicited by VEH or NLZ, by morphine over the first 5 min (M5) and 75 min (M75) post-injection period, and by HH challenge and upon return to room-air (RA) are shown in Panels B and D, respectively. Morphine elicited a prompt and sustained increase in EIP (Panel A) that subsided to baseline levels toward the end of the HH challenge and which remained at baseline upon return to room air. NLZ did not affect resting EIP values but converted the morphine responses to a transient decrease with minimal changes in EIP during HH challenge and upon return to room air. Morphine elicited a transient increase in EEP in vehicle-treated rats (Panel C). The HH challenge elicited a relatively minor decrease in EEP which returned to baseline values upon return to room air. The initial increase in EEP elicited by morphine was greater in NLZ-treated rats and EEP rose upon return to room air in these rats. As can be seen in Supplemental Figure 4, NLT did not affect resting EIP but diminished the increases in EIP elicited by morphine and those during the HH challenge. NLT elicited a minor but sustained decrease in EEP but did not alter the effects of morphine, HH challenge or return to room air on EEP.

Figure 4.

Changes in end inspiratory pause (End Insp Pause, EIP) (Panel A) and end expiratory pause (End Exp Pause, EEP) (Panel B) elicited by the injection of vehicle (VEH) or naloxonazine (NLZ, 1.5 mg/kg, IV), followed by the injection of morphine (10 mg/kg, IV), and a subsequent hypoxic-hypercapnic challenge (air-flow OFF) and return to room-air (air-flow ON). Summaries of the total changes in these parameters elicited by VEH or NLZ, by morphine over the first 5 min (M5) and over the 75 min (M75) post-injection period, and by the hypoxic-hypercapnic (HH) challenge and return to room-air (RA), are shown in Panels C and D, respectively. The data are presented as mean ± SD. There were 6 rats in each group. The summary data were analyzed by repeated measures ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni test for multiple comparisons. *P < 0.05, significant response from Pre-values. †P < 0.05/5 comparisons, responses in NLZ-treated rats versus vehicle-treated rats.

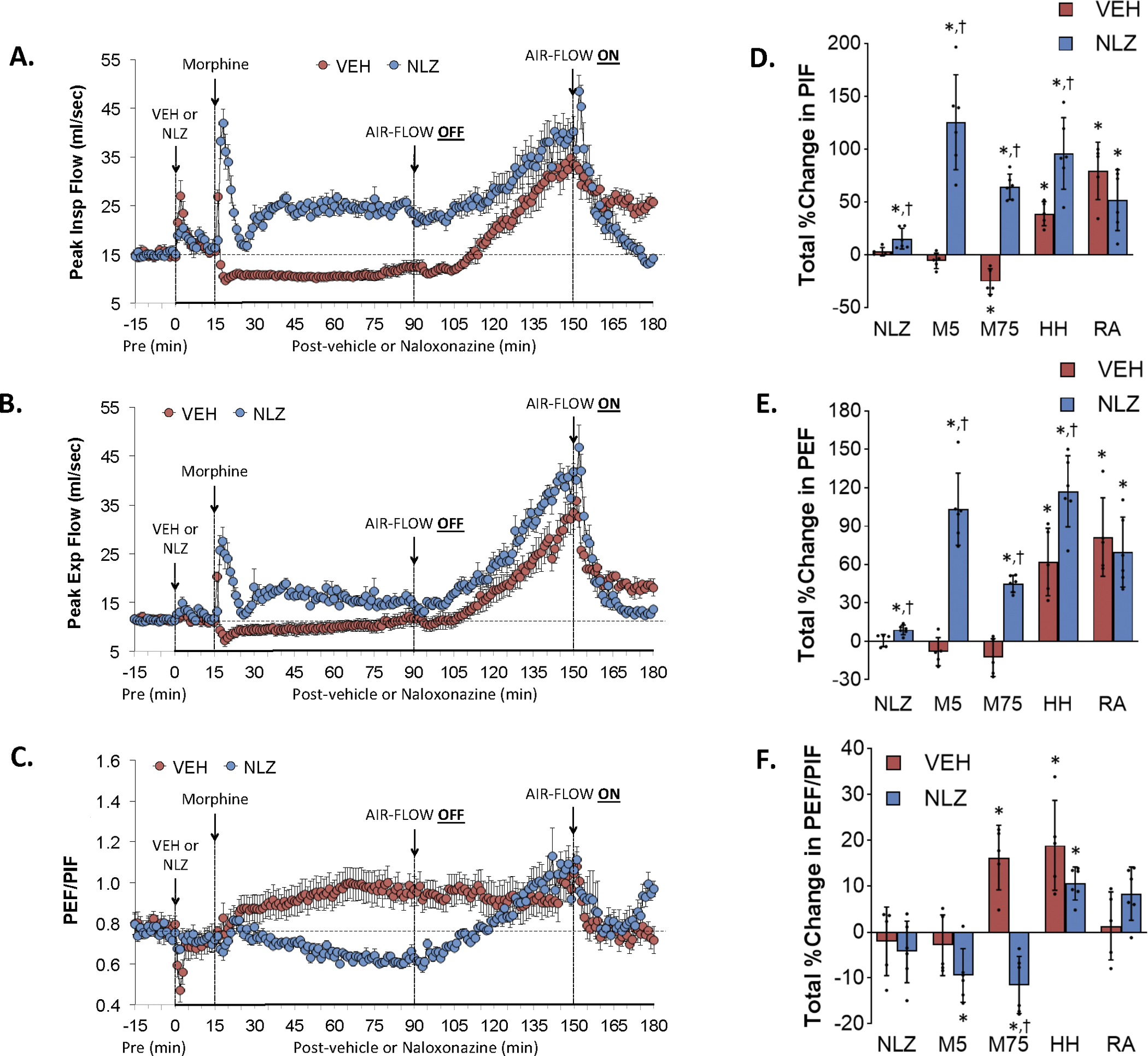

Effects of NLZ or NLT on morphine-induced changes in peak inspiratory flow (PIF), peak expiratory flow (PEF) and PEF/PIF

Figure 5 summarizes the changes in PIF (Panel A), PEF (Panel C) and PEF/PIF (Panel E) elicited by injection of vehicle (VEH) or NLZ (1.5 mg/kg, IV), injection of morphine (10 mg/kg, IV), a HH challenge (air-flow OFF), and return to room-air (air-flow ON). Summaries of the total changes in PIF, PEF and PEF/PIF elicited by vehicle or NLZ, by morphine over the first 5 min (M5) and 75 min (M75) post-injection period, and by HH challenge and upon return to room-air (RA) are shown in Panels B, D and F, respectively. The injection of morphine in vehicle-treated rats elicited an initial transient increase followed by a sustained decrease in PIF (Panel A). HH challenge caused a gradual and sustained increase in PIF that was maintained upon return to room-air. The injection of NLZ elicited minor increases in PIF and the subsequent injection of morphine elicited an initial spike in PIF followed by a sustained increase that evident at the time the HH challenge was given. HH challenge caused an increase in PIF to levels above those in vehicle-treated rats. PIF spiked initially upon return to room air and then subsided to baseline. The injection of morphine in vehicle-treated rats elicited minor decreases in PEF (Panel C) and the HH challenge caused a gradual and sustained increase in PEF that returned toward but stayed above baseline upon return to room-air. NLZ elicited minor increases in PEF and morphine elicited an initial spike in PEF that was followed by a sustained increase. The HH challenge increased PEF to levels above those in vehicle-treated rats. PEF subsided to baseline values upon return to room air. These effects on PIF and PEF resulted in a morphine-induced increase in PEF/PIF in vehicle-treated rats (Panel E) but a sustained decrease in NLZ-treated rats. PEF/PIF values reached similar maximums during HH challenge in both groups and the responses were similar upon return to room air. Supplemental Figure 5 summarizes the findings in NLT-treated rats and the key finding was that NLT elicited an increase in PIF without a change in PEF so that PEF/PIF fell significantly. NLT reduced the morphine-induced increase in PEF/PIF and increases in PEF/PIF during the HH challenge.

Figure 5.

Changes in peak inspiratory flow (Peak Insp Flow, PIF) (Panel A), peak expiratory flow (Peak Exp Flow, PEF) (Panel B) and PEF/PIF (Panel C) elicited by the injection of vehicle (VEH) or naloxonazine (NLZ, 1.5 mg/kg, IV), followed by the injection of morphine (10 mg/kg, IV), and a subsequent hypoxic-hypercapnic challenge (air-flow OFF) and return to room-air (air-flow ON). Summaries of the total changes in these parameters elicited by VEH or NLZ, by morphine over the first 5 min (M5) and over the 75 min (M75) post-injection period, and by the hypoxic-hypercapnic (HH) challenge and return to room-air (RA), are shown in Panels D, E and F, respectively. The data are presented as mean ± SD. There were 6 rats in each group. The summary data were analyzed by repeated measures ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni test for multiple comparisons. *P < 0.05, significant response from Pre-values. †P < 0.05/5 comparisons, responses in NLZ-treated rats versus vehicle-treated rats.

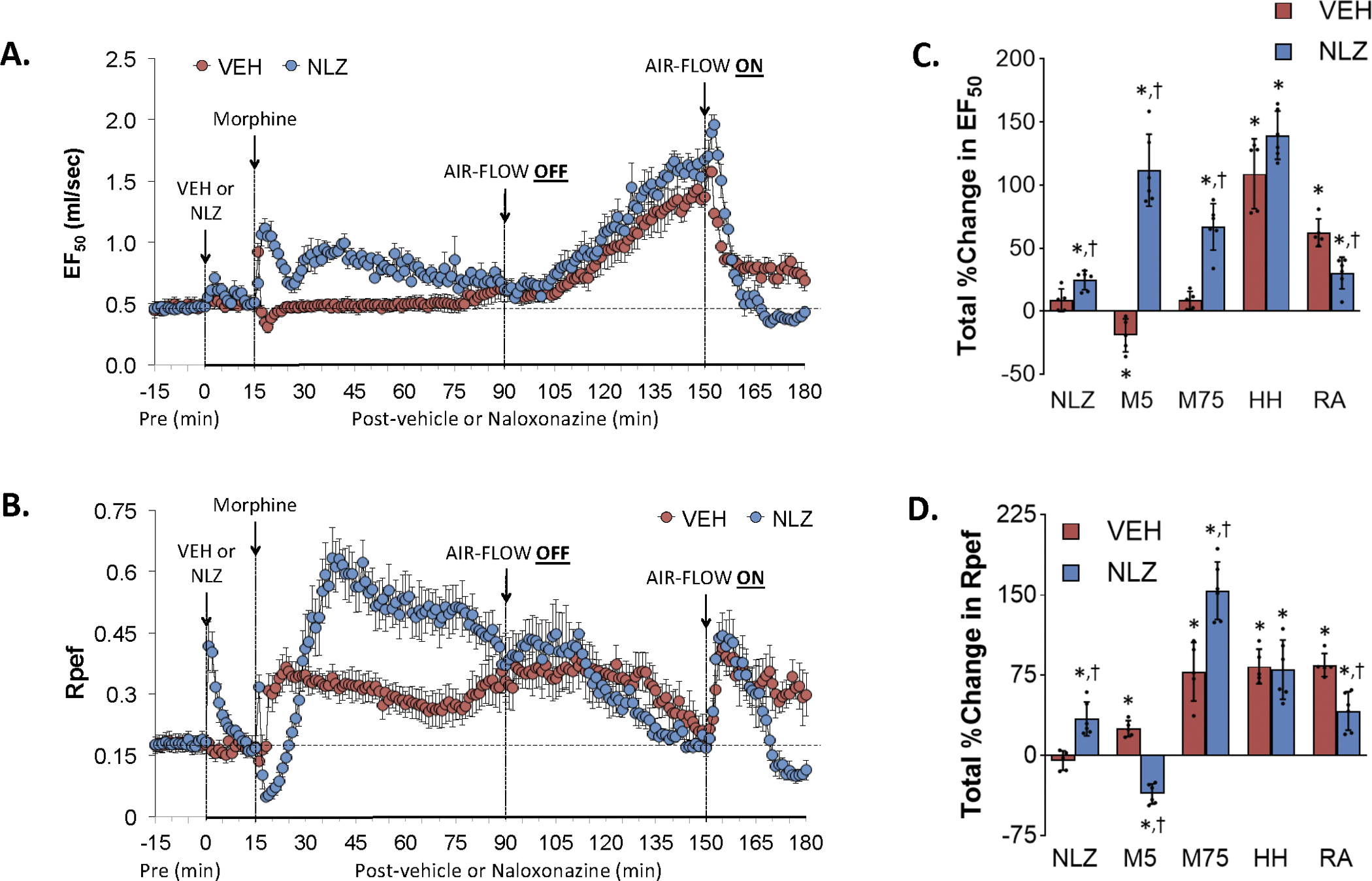

Effects of NLZ or NLT on morphine-induced changes in expiratory flow at 50% expired tidal volume (EF50) and rate of achieving peak expiratory flow (Rpef)

Figure 6 summarizes the changes in EF50 (Panel A) and Rpef (Panel C) elicited by the injection of vehicle (VEH) or NLZ (1.5 mg/kg, IV), the injection of morphine (10 mg/kg, IV), a HH challenge (air-flow OFF), and return to room-air (air-flow ON). Summaries of the total changes in these parameters elicited by VEH or NLZ, by morphine over the first 5 min (M5) and 75 min (M75) post-injection period, and by the HH challenge and upon return to room-air (RA) are shown in Panels B and D, respectively. Morphine elicited a minor transient decrease in EF50 in vehicle-treated rats (Panel A). The HH challenge increased EF50 substantially and EF50 fell toward (but remained above) baseline levels upon return to room air. NLZ elicited a relatively small increase in EF50. Morphine caused a substantial increase in EF50 in these rats that subsided during the HH challenge. The HH challenge elevated EF50 similarly to that in vehicle-treated rats whereas EF50 fell to baseline levels upon return to room air. NLZ elicited a pronounced but transient increase in Rpef (Panel C). Morphine caused an initial fall followed by augmented increases in Rpef in these NLZ-treated rats. The changes in Rpef during HH challenge were similar to those in vehicle-treated rats whereas Rpef showed similar initial increases in Rpef upon return to room air in both groups whereas Rpef fell to below baseline levels in NLZ-treated rats. As seen in Supplemental Figure 6, NLT produced transient increases in EF50 and Rpef but minimally affected the changes in these parameters elicited by morphine, HH challenge or return to room air with the exception that Rpef rose substantially for several minutes upon return to room air in NLT-treated rats.

Figure 6.

Changes in expiratory flow at 50% expired tidal volume (EF50) (Panel A) and rate of achieving peak inspiratory flow (Rpef) (Panel B) elicited by the injection of vehicle (VEH) or naloxonazine (NLZ, 1.5 mg/kg, IV), followed by the injection of morphine (10 mg/kg, IV), and a subsequent hypoxic-hypercapnic challenge (air-flow OFF) and return to room-air (air-flow ON). Summaries of the total changes in these parameters elicited by VEH or NLZ, by morphine over the first 5 min (M5) and over the 75 min (M75) post-injection period, and by the hypoxic-hypercapnic (HH) challenge and return to room-air (RA), are shown in Panels C and D, respectively. The data are presented as mean ± SD. There were 6 rats in each group. The summary data were analyzed by repeated measures ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni test for multiple comparisons. *P < 0.05, significant response from Pre-values. †P < 0.05/5 comparisons, responses in NLZ-treated rats versus vehicle-treated rats.

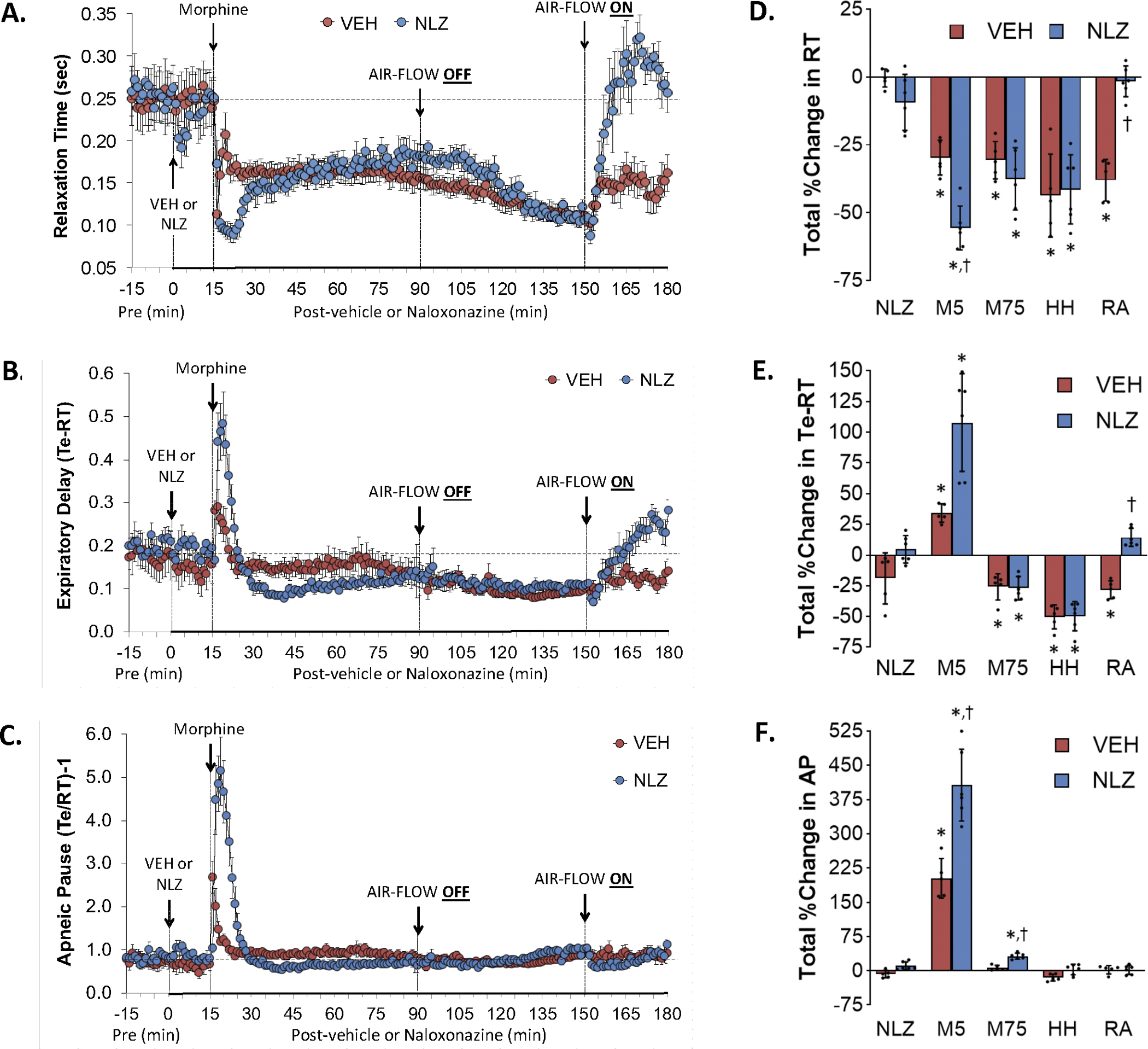

Effects of NLZ or NLT on morphine-induced changes in relaxation time (RT), expiratory delay (Te-RT) and apneic pause [Te/RT)-1]

Figure 7 summarizes the changes in relaxation time (Panel A), expiratory delay (Panel C) and apneic pause (Panel E) elicited by injection of vehicle (VEH) or NLZ (1.5 mg/kg, IV), the injection of morphine (10 mg/kg, IV), a HH challenge (air-flow OFF), and return to room-air (air-flow ON). Summaries of the total changes elicited by vehicle or NLZ, by morphine over the first 5 min (M5) and 75 min (M75) post-injection period, and HH challenge and upon return to room-air (RA) are shown in Panels B, D and F, respectively. The injection of morphine in vehicle-treated rats elicited sustained decrease in relaxation time (Panel A) that was sustained during HH challenge and upon return to room air. NLZ elicited minor decreases in relaxation time and facilitated the initial decreases elicited by morphine. Subsequent changes in relaxation time after morphine administration and exposure to HH challenge were similar to vehicle-treated rats. In contrast to vehicle-treated rats, relaxation time returned immediately to baseline levels upon return to room air in NLZ-treated rats. The injection of morphine elicited an initial short-lived increase in expiratory delay (Panel C) and apneic pause (M5 columns) (Panel E) that were followed by relatively minor falls in expiratory delay but not apneic pause. The HH challenge caused a sustained decrease in expiratory delay (but not apneic pause) that was sustained upon return to room-air. The initial increases in expiratory delay and apneic pause elicited by morphine were augmented in NLZ-treated rats. The remaining responses were similar in vehicle- and NLZ-treated rats except for the reversal of the depressed expiratory delay in NLZ-treated rats. Supplemental Figure 7summarizes the findings in NLT-treated rats and the key findings were that NLT elicited decrease in relaxation time that were accompanied by increases in expiratory delay and apneic pause. NLT had minimal effects on the changes in these parameters induced by morphine, HH challenge and return to room air.

Figure 7.

Changes in relaxation time (RT) (Panel A), expiratory delay (Te-RT) (Panel B) and apneic pause ((Te-RT) – 1, AP) (Panel C) elicited by the injection of vehicle (VEH) or naloxonazine (NLZ, 1.5 mg/kg, IV), followed by the injection of morphine (10 mg/kg, IV), and a subsequent hypoxic-hypercapnic challenge (air-flow OFF) and return to room-air (air-flow ON). Summaries of the total changes in these parameters elicited by VEH or NLZ, by morphine over the first 5 min (M5) and over the 75 min (M75) post-injection period, and by the hypoxic-hypercapnic (HH) challenge and return to room-air (RA), are shown in Panels D, E and F, respectively. The data are shown as mean ± SD. There were 6 rats in each group. The summary data were analyzed by repeated measures ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni test for multiple comparisons. *P < 0.05, significant response from Pre-values. †P < 0.05/5 comparisons, responses in NLZ-treated rats versus vehicle-treated rats.

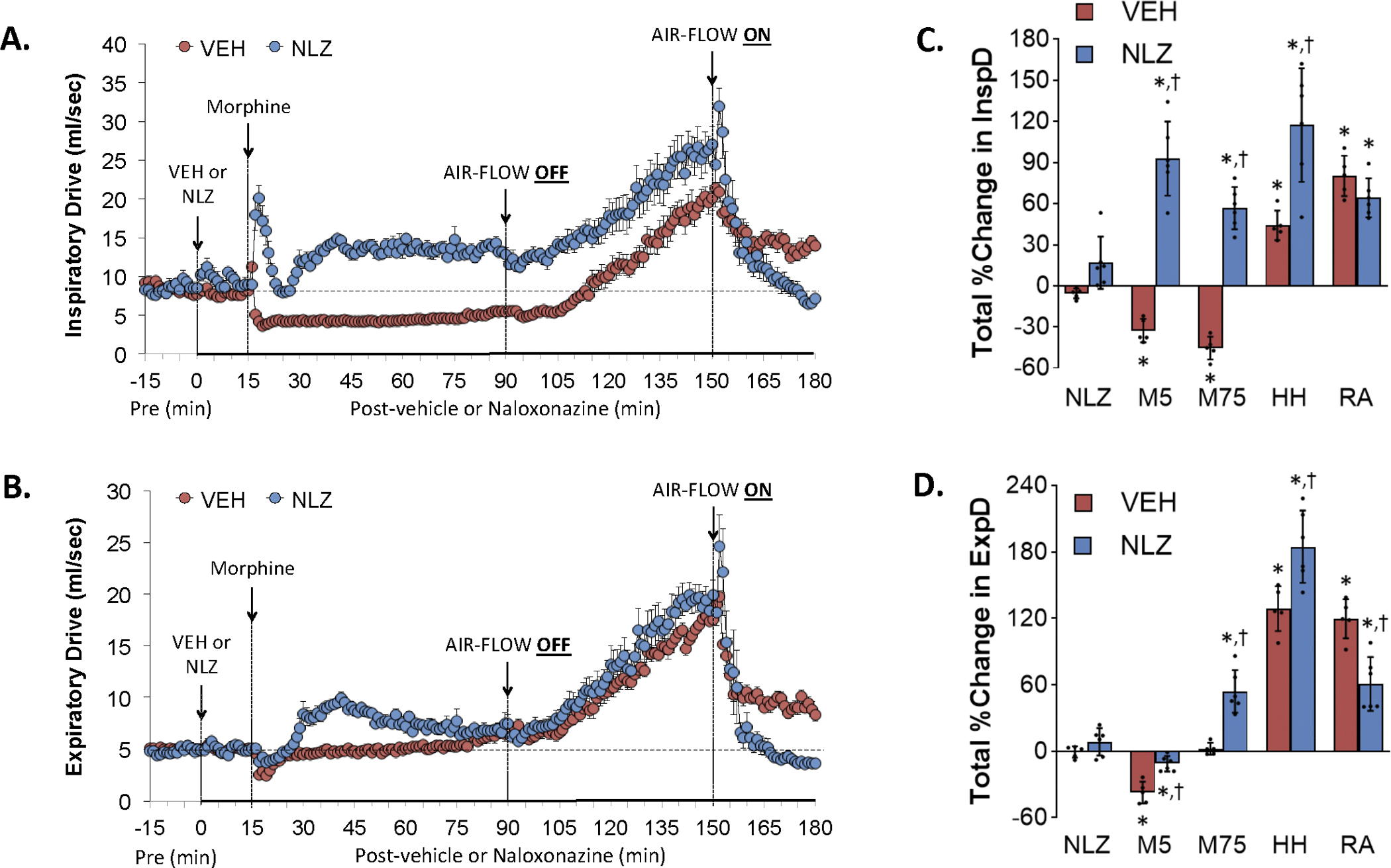

Effects of NLZ or NLT on morphine-induced changes in inspiratory drive and expiratory drive

Figure 8 summarizes the changes in inspiratory drive (Panel A) and expiratory drive (Panel C) elicited by the injection of vehicle (VEH) or NLZ (1.5 mg/kg, IV), the injection of morphine (10 mg/kg, IV), a HH challenge (air-flow OFF), and return to room-air (air-flow ON). Summaries of the total changes elicited by vehicle or NLZ, by morphine over the first 5 min (M5) and 75 min (M75) post-injection period, and by the HH challenge and upon return to room-air (RA) are shown in Panels B and D, respectively. The injection of morphine in vehicle-treated rats elicited a sustained decrease in inspiratory drive (Panel A) and the HH challenge elevated these levels to well above baseline levels that subsided somewhat upon return to room air. Injection of morphine in NLZ-treated rats caused a transient increase in inspiratory drive followed by a sustained increase with the HH challenge further elevating inspiratory drive to levels above those in vehicle-treated rats. Inspiratory drive fell back to baseline levels upon return to room air in NLZ-treated rats. The injection of morphine elicited minor transient decreases in expiratory drive (Panel C) in the vehicle-treated rats. HH challenge caused a gradual and sustained increase in expiratory drive that returned toward but stayed above baseline upon return to room-air. Morphine elicited rise in expiratory drive in NLZ-treated rats that had largely resolved when the HH challenge was given. The increases in expiratory drive elicited by the HH challenge were similar to those in the vehicle-treated rats whereas expiratory time fell back to baseline levels upon return to room-air. Supplemental Figure 8 summarizes the findings in NLT-treated rats and in essence NLT had minimal effects on the changes in these parameters elicited by morphine, HH challenge and return to room air.

Figure 8.

Changes in inspiratory drive (InspD) (Panel A) and expiratory drive (ExpD) (Panel B) elicited by the injection of vehicle (VEH) or naloxonazine (NLZ, 1.5 mg/kg, IV), followed by the injection of morphine (10 mg/kg, IV), and a subsequent hypoxic-hypercapnic challenge (air-flow OFF) and return to room-air (air-flow ON). Summaries of the total changes in these parameters elicited by VEH or NLZ, by morphine over the first 5 min (M5) and over the 75 min (M75) post-injection period, and by the hypoxic-hypercapnic (HH) challenge and return to room-air (RA), are shown in Panels C and D, respectively. The data are presented as mean ± SD. There were 6 rats in each group. The summary data were analyzed by repeated measures ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni test for multiple comparisons. *P < 0.05, significant response from Pre-values. †P < 0.05/5 comparisons, responses in NLZ-treated rats versus vehicle-treated rats.

Effects of NLZ or NLT on morphine-induced changes in non-eupneic breathing index (NEBI) and NEBI corrected for frequency (NEBI/Freq)

Figure 9 summarizes the changes in NEBI (Panel A) and NEBI/Freq (Panel C) elicited by the injection of vehicle (VEH) or NLZ (1.5 mg/kg, IV), the injection of morphine (10 mg/kg, IV), a HH challenge (air-flow OFF), and return to room-air (air-flow ON). Summaries of the total changes elicited by vehicle or NLZ, by morphine over the first 5 min (M5) and 75 min (M75) post-injection period, and by the HH challenge and upon return to room-air (RA) are shown in Panels B and D, respectively. Morphine elicited transient increases in NEBI (Panel A) and NEBI/Freq (Panel C) in the vehicle-rats (M5) that returned to near-zero values throughout the post-morphine and HH challenge periods. There was a sustained increase in NEBI and NEBI/Freq upon return to room air. The injection of morphine in NLZ-treated rats elicited a smaller initial increase in NEBI and NEBI/Freq (M5) but then a substantial and sustained increase in NEBI and NEBI/Freq. These parameters gradually returned to baseline values during the HH challenge. Both NEBI and NEBI/Freq increased upon return to room air but unlike the vehicle-treated rats, these parameters returned to baseline values. Supplemental Figure 9 summarizes the findings in NLT-treated rats and in essence NLT had minimal effects on the changes in NEBI or NEBI/Freq elicited by morphine and HH challenge whereas it potentiated the return to room air responses of both parameters.

Effects of NLZ or NLT on morphine-induced changes in righting reflex

The administration of morphine (10 mg/kg, IV) elicited immediate sedation and loss of movement in vehicle-treated rats. The rats usually were on their side or on their stomachs with the underside of their heads laying against the wall of the chamber. In Study 1, the righting reflex (ability to stand on all four legs) recovered within 76.3 ± 6.3 min in vehicle-pretreated rats and within the much shorter time of 5.5 ± 0.9 min in the NLZ-treated rats (P < 0.05, NLZ versus vehicle). After a brief (5–15 sec) of activity (movement, rearing, grooming) the NLZ-treated rats usually stood quietly, occasionally grooming and moving around the chamber. In Study 2, the righting reflex recovered within 73.2 ± 7.7 min in vehicle-pretreated rats and within a similar time of 80.8 ± 7.4 min in the NLT-treated rats (P > 0.05, NLT versus vehicle). These two groups of rats (and the other vehicle-injected group) were obviously sedated although they had recovered full motor activity.

DISCUSSION

Realizing the importance and involvement of both μ1- and δ1,2- receptors in the actions of opioids (24–32), we studied the effects of NLZ and NLT respectively on morphine-induced changes in ventilation knowing that morphine and these opioid receptor antagonists (NLZ and NLT) will act both peripherally and centrally. This study shows that intravenous injection of the selective μ1-OR antagonist, NLZ (18–23), elicits relatively minor and transient effects on some ventilatory parameters including (a) an increase in Freq associated with a decrease in Ti and relaxation time, and (b) increases in PIF, PEF, EF50 and Rpef. As such, it appears that on-going endogenous opioid signaling in ventilatory control pathways (52–55) using μ1-ORs have a relatively minor role in the regulation of breathing in rats. Morphine (10 mg/kg, IV) caused a minor increase in Freq in vehicle-treated rats. This evidence is consistent with evidence that lower doses of morphine increase Freq (12). The sustained effects of morphine in the NLZ-treated rats were probably due to the pharmacological interactions of the two drugs, since Freq remains unchanged for at least 90 min after the injection of a 1.5 mg/kg dose of NLZ (Getsy et al., unpublished observations). The lack of effect of the 10 mg/kg dose of morphine on frequency of breathing may argue that it does not elicit respiratory depression. However, the evidence that morphine elicited a pronounced increase in inspiratory time certainly proves “respiratory depression,” noting that the accompanying decrease in expiratory time resulted in minor increases in frequency. Moreover, the sustained effects of morphine on tidal volume and other parameters, such as PIF and inspiratory drive, certainly demonstrate ventilatory depression. These morphine-induced increases in Freq were augmented substantially in rats pre-treated with NLZ. However, this NLZ-induced augmentation of morphine-induced increase in Freq was accompanied by substantial increases in NEBI. This was probably a true increase in ventilatory instability including disordered breaths, apneas, and type 1 and 2 sighs (40) since correcting the increases in NEBI for the increases in Freq (NEBI/Freq) still translated into an increase in non-eupneic breathing. Although the NLZ-treated rats recovered rapidly from the sedative effects of morphine (in about 5 min) they did not display behavioral signs suggesting they were in stress. As such, NLZ uncovers potent stimulant effects of morphine on central/peripheral pathways that drive Freq. The sustained nature of morphine-induced increase in Freq in NLZ-treated rats may involve progressively greater levels of morphine metabolites, morphine-3-glucuronide and morphine-6-glucuronide (56, 57) that affect ventilatory control systems by non-opioid receptor mechanisms as in other physiological systems (58, 59). It should be noted that Peat et al (60) reported that whereas morphine-6-glucuronide did not affect resting Freq, MV and end-tidal CO2 in humans it blunted the ventilatory stimulatory effects of a 5.5% CO2 challenge. Whether morphine-6-glucuronide can drive rather than inhibit Freq in the presence of NLZ is to be determined. Neurochemical systems underlying this facilitated breathing are likely to be multi-factorial but may involve direct interactions between μ1-OR signaling pathways with N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor signaling events as seen pain control systems (61, 62). This possibility is supported by evidence that the synthetic opioid, fentanyl, shifts discharge threshold of respiratory neurons in the brainstem to more negative membrane potentials by opioid receptor-mediated postsynaptic increases in NMDA receptor current (63).

The findings with tidal volume contrast markedly to those for Freq. More specifically, morphine elicited substantial reductions in tidal volume of about 55–60 min in duration in vehicle-treated rats. Morphine elicited markedly smaller reductions in TV in NLZ-treated rats but unlike Freq, there was no rise above baseline levels. Accordingly, blockade of μ-ORs does not uncover an excitatory pathway driving tidal volume as it does in fentanyl-injected rats (35). This disparity between Freq and tidal volume is consistent with evidence that signaling pathways controlling these two physiological systems diverge with respect to their spatial organization in the brain and spinal cord and in their neurochemical (e.g., neurotransmitters, neuromodulators) and molecular (e.g., expression of receptors, ion channels and enzymes) components (64–72). These data show that fentanyl and morphine have distinct activity profiles due to their differences in receptor pharmacology (73–75), effects on ventilatory systems (76–79) and analgesic profiles and propensity to cause tolerance and algesia/hyperalgesia (80, 81).

The changes in Ti, Te, EIP and EEP that drive morphine-induced changes in Freq in vehicle-treated rats displayed wide disparity. Morphine elicited substantial and sustained increases in Ti and EIP that were associated with substantial and sustained decreases in Te but a transient increase in EEP. The ability of morphine to increase Ti is consistent with it inhibiting processes driving inspiration (8, 82–85). In contrast, the morphine-induced decrease in Te (more rapid expiration) explains why morphine appeared to have minimal effects on Freq (increase in Ti and EIP balanced by a decrease in Te) highlights why monitoring Ti and Te provide an essential understanding of the effects of opioids on respiratory timing. The mechanisms by which morphine decreases Te have not been addressed. The findings that morphine caused pronounced and sustained decreases in PIF and inspiratory drive, transient decreases in PEF, EF50 and expiratory drive and sustained increases in Rpef (achieving PEF occurred faster) further shows the disparate effects of morphine on inspiratory and expiratory timing events. NLZ exerted pronounced and disparate effects on these latter parameters. More specifically, the morphine-induced decreases in PIF, PEF, EF50, inspiratory and expiratory drives were reversed to increases (overshoot above baselines) whereas the decreases in relaxation time were enhanced. These beneficial effects were counter-balanced by NLZ promoting adverse effects of morphine on expiratory delay (Te-RT), apneic pause [(Te/RT)-1], NEBI and NEBI/Freq. The opposing effects of NLZ on ventilatory responses elicited by morphine would need to be considered in therapeutic efforts designed to bring NLZ to the clinic.

The administration of the centrally-acting δ1,2-OR antagonist, NLT (36–38) produced transient changes in several parameters including (a) increases in Freq with accompanying decreases in Ti and Te and EEP, (b) a transient increase in PIF, EF50, and Rpef, (c) a decrease in relaxation time that coupled to minimal changes in expiratory time resulted in increases in expiratory delay (Te-RT) and apneic pause [(Te/RT)-1], and (d) minor increases in NEBI and NEBI/Freq. It is apparent that δ1,2-ORs play subtle but diverse tonically active roles in these ventilatory control processes. Although no direct comparisons were made, it appeared to us that the effects of NLT were larger and more diverse than those elicited by NLZ. In comparison to NLZ, NLT exerted relatively minor effects on the sedative and ventilatory actions of morphine. More specifically, NLT (a) slightly facilitated the morphine-induced increase in Freq and accompanying decrease in Te, (b) decreased morphine-induced increase in EIP (pause before inspiration), EF50 and apneic pause. Nonetheless, these results do suggest that δ1,2-ORs do play a role in the pharmacological processes by which morphine affects expiratory timing and flows in male Sprague-Dawley rats.

In general, neither NLZ nor NLT had substantial effects on the ventilatory responses elicited by HH challenge in morphine-treated rats. More specifically, despite disparate effects of morphine in vehicle- and NLZ-/NLT-treated rats, these ventilatory parameters reached similar values by the end of the HH challenge. In particular, these findings suggest that the deleterious effects of morphine on these ventilatory parameters could be largely overcome by the continuous HH challenge. Whether this is because hypercapnia and/or hypoxia elicit signaling cascades that impair opioid-receptor signaling events or trigger signaling events that indirectly overcome the opioid-induced cascades remains to be determined (33, 36). In contrast, the ventilatory responses that occurred upon return to room air were markedly affected by NLZ and to a lesser extent by NLT. The ability of NLZ to reverse the effects of morphine on the responses in response to the return to room air were targeted to (a) the increases in Freq, (b) decreases in Ti, Te and EEP, (c) increases in EF50 and Rpef, (d) decreases in relaxation time and expiratory delay, (e) increases in inspiratory and expiratory delays and (f) the increase in NEBI and NEBI/Freq. In contrast, the effects of NLZ were targeted to changes in Rpef and apneic pause, and as opposed to NLZ, which diminished the increases in NEBI and NEBI/Freq, NLT enhanced these increases. This suggests that μ1-ORs and δ1,2-ORs play diametrically opposite roles in the ventilatory instability associated with the return to room air in morphine-treated rats. It remains possible that the effects of NLZ are due to itself or its metabolites that affect other receptor systems. The findings that the injections of vehicle, NLZ, or NLT elicited minimal responses that had subsided before the injection of morphine was given, suggests that the subsequent effects of morphine are related to the pharmacological blockade of opioid receptors rather than effects of the antagonists on baseline values. It should be noted that the morphine-treated rats that were given NLZ did not behave in an obviously different manner from naïve rats (i.e., rats given no morphine) except for the first few minutes following NLZ injection when they were finding their feet while losing the sedative effects of the opioid. As such the peak ventilatory responses were recorded when the rats were often lying still or on occasion, gently grooming. The finding that many of the ventilatory depressant effects of morphine were diminished in the presence of NLZ suggests that μ1-ORs play a key role in the effects of morphine. The relative lack of efficacy of NLT suggests that morphine can exert its effects by mechanisms other than activation of δ1,2-ORs. As mentioned, although the 10 mg/kg dose of morphine did not affect Freq, it did have pronounced counterbalancing effects on Ti and Te, thus affecting respiratory timing events. It should be noted that a 10 mg/kg dose of morphine caused relatively minor and transient effects on Freq in one study (41) and, in contrast, substantial and sustained decreases in Freq in another study (42). We cannot explain the differences in effects of morphine on Freq (all injections were given at similar times of day, namely, between 10 am and noon), but presume that factors, such as circannual rhythm changes in opioid receptor expression and/or associate cell-signaling partners may be involved.

In summary, morphine can activate excitatory effects on ventilatory parameters after the blockade of μ1-ORs in male Sprague Dawley rats. It should be noted that in the NLZ study, morphine caused a minor initial increase in Freq, whereas in the NLT study it did not. This minor discrepancy may be due to numerous reasons, including that the NLZ and NLT studies were done 40 days apart, but at the same time of day. Although the ventilatory increases caused by morphine may be beneficial, the increases are not observed during the first minutes of respiratory depression and may be due to the effects of morphine metabolites (e.g., morphine-3-glucuronide and morphine-6-glucuronide) or other unrelated effects. The ventilatory increase may also be a rebound from the long-lasting hypoxia and/or hypercapnia, or due to changes in sedation over time, with sedation subsiding before respiratory depression. We chose to study male rats separately from female rats because previous data has shown that the ventilatory effects of opioids in human females are often qualitatively and quantitatively different than in males (86), and sex-differences in ventilatory responses to opioids in rats also exist (87). Whether NLZ can uncover excitatory ventilatory responses in female Sprague Dawley rats will be determined in future studies. Identifying the neuroanatomical and neurochemical identities of this excitatory system would boost the search for therapeutics that could overcome opioid-induced respiratory depression in male and female subjects. While the 1.5 mg/kg dose of NLZ had substantial effects on the pharmacological actions of morphine, further studies with higher doses may more clearly determine the efficacy profile of this selective μ1-OR antagonist. Similarly, a higher dose of NLT may exert effects implicating δ1,2-ORs.

Supplementary Material

SUPPLEMENTAL DATA

Supplemental file located at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28811099.v1.

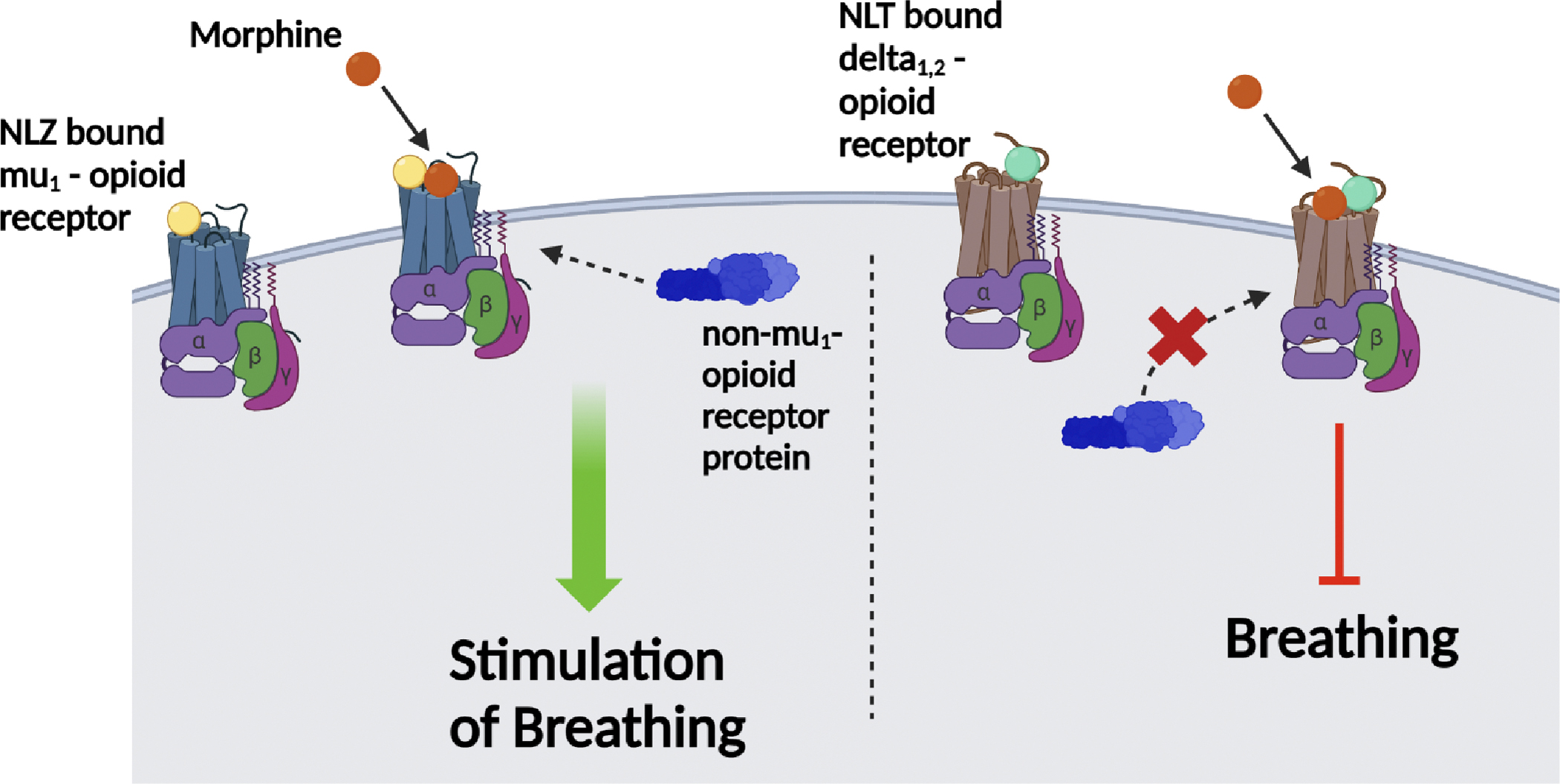

Figure 10.

Naloxonazine (NLZ), the centrally-acting selective mu1 (μ1)-opioid receptor antagonist, binds to the mu1-opioid receptor. However, NLZ alone does not alter ventilatory responses in Sprague Dawley male rats. Addition of morphine to the μ1-opioid receptor bound with NLZ recruits a possible non-μ1-opioid receptor protein signaling complex, which trigger downstream signaling events that promote breathing. Contrarily, when naltrindole (NLT), the centrally-acting delta1,2 (δ1,2)-opioid receptor antagonist, is bound to the δ1,2-opioid receptor, the ventilatory depressant responses on breathing following the addition of morphine are observed and there is no recruitment of a non-μ1-opioid receptor protein signaling complex that promotes breathing. Therefore, centrally-acting μ1-opioid receptor antagonism with NLZ recruits a complicated protein signaling complex that exerts alterations on the ventilatory effects of morphine which are not seen with other selective opioid receptor antagonists, such as NLT.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors wish to sincerely thank the staff at the Animal Care Facilities at Case Western Reserve University, the University of Virginia, and Galleon Pharmaceuticals, Inc., for their expert assistance with the care of the rats. The authors also wish to acknowledge Dr. James N. Bates (CMO, Atelerix Life Sciences) for his assistance in detailing the clinical significance of our findings.

GRANTS

These studies were supported in part by grants from Galleon Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (to SL) and from NIH/NIDA U01DA051373 (to SL). The authors declare that this study received funding from Galleon Pharmaceuticals, Inc. but that this funder was not involved in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of this article, or the decision to submit it for publication.

ABBREVIATIONS:

- Apneic pause

(expiratory time/relaxation time)-1

- EEP

end expiratory pause

- EF50

expiratory flow at 50% expired tidal volume

- EIP

end inspiratory pause

- Freq

frequency of breathing

- inspiratory drive

(tidal volume/inspiratory time)

- MV

minute ventilation

- NEBI

non-eupneic breathing index

- NEBI/Freq

NEBI corrected for Frequency of breathing

- NLT

naltrindole

- NLZ

naloxonazine

- OIRD

opioid-induced respiratory depression

- PEF

peak expiratory flow

- PIF

peak inspiratory flow

- RT

relaxation time

- Te

expiratory time

- Te-RT

inspiratory delay

- TF

tail-flick latencies

- Ti

inspiratory time

- TV

tidal volume

- TV/Te

expiratory drive

- TV/Ti

inspiratory drive

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

The co-author, Santhosh M. Baby, was employed by Galleon Pharmaceuticals, Inc. The leadership of Galleon Pharmaceuticals were not directly involved in this study as a commercial entity. Only the principal scientists of Galleon Pharmaceuticals were involved in study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, writing of the article and decision to submit. The remaining authors declare that the research was performed in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. All authors declare no competing interests.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1.Evans JM, Hogg MI, Lunn JN, Rosen M. Degree and duration of reversal by naloxone of effects of morphine in conscious subjects. Br Med J 2: 589–591, 1974. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5919.589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rawal N, Schött U, Dahlström B, Inturrisi CE, Tandon B, Sjöstrand U, Wennhager M. Influence of naloxone infusion on analgesia and respiratory depression following epidural morphine. Anesthesiology 64: 194–201, 1986. doi: 10.1097/00000542-198602000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Olofsen E, van Dorp E, Teppema L, Aarts L, Smith TW, Dahan A, Sarton E. Naloxone reversal of morphine- and morphine-6-glucuronide-induced respiratory depression in healthy volunteers: a mechanism-based pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic modeling study. Anesthesiology 112: 1417–1427, 2010. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181d5e29d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boom M, Niesters M, Sarton E, Aarts L, Smith TW, Dahan A. Non-analgesic effects of opioids: opioid-induced respiratory depression. Curr Pharm Des 18: 5994–6004, 2012. doi: 10.2174/138161212803582469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Henderson F, May WJ, Gruber RB, Discala JF, Puskovic V, Young AP, Baby SM, Lewis SJ. Role of central and peripheral opiate receptors in the effects of fentanyl on analgesia, ventilation and arterial blood-gas chemistry in conscious rats. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 191: 95–105, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2013.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baby SM, May WJ, Getsy PM, Coffee GA, Nakashe T, Bates JN, Levine A, Lewis SJ. Fentanyl activates opposing opioid and non-opioid receptor systems that control breathing. Front Pharmacol 15: 1381073, 2024. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2024.1381073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ling GS, Spiegel K, Lockhart SH, Pasternak GW. Separation of opioid analgesia from respiratory depression: evidence for different receptor mechanisms. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 232:149–155, 1985. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lalley PM. Mu-opioid receptor agonist effects on medullary respiratory neurons in the cat: evidence for involvement in certain types of ventilatory disturbances. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 285: R1287–R1304, 2003. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00199.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lalley PM. Opioidergic and dopaminergic modulation of respiration. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 164: 160–167, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2008.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baldo BA, Rose MA. Mechanisms of opioid-induced respiratory depression. Arch Toxicol 96: 2247–2260, 2022. doi: 10.1007/s00204-022-03300-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bateman JT, Levitt ES. Opioid suppression of an excitatory pontomedullary respiratory circuit by convergent mechanisms. Elife 12: e81119, 2023. doi: 10.7554/eLife.81119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Henderson F, May WJ, Gruber RB, Young AP, Palmer LA, Gaston B, Lewis SJ. Low-dose morphine elicits ventilatory excitant and depressant responses in conscious rats: Role of peripheral μ-opioid receptors. Open J Mol Integr Physiol 3: 111–124, 2013. doi: 10.4236/ojmip.2013.33017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baby SM, Gruber RB, Young AP, MacFarlane PM, Teppema LJ, Lewis SJ. Bilateral carotid sinus nerve transection exacerbates morphine-induced respiratory depression. Eur J Pharmacol 834: 17–29, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2018.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Torralva R, Janowsky A. Noradrenergic Mechanisms in Fentanyl-Mediated Rapid Death Explain Failure of Naloxone in the Opioid Crisis. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 371:453–475, 2019. doi: 10.1124/jpet.119.258566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Armenian P, Vo KT, Barr-Walker J, Lynch KL. Fentanyl, fentanyl analogs and novel synthetic opioids: A comprehensive review. Neuropharmacology 134: 121–132, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2017.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Comer SD, Cahill CM. Fentanyl: Receptor pharmacology, abuse potential, and implications for treatment. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 106: 49–57, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Han Y, Yan W, Zheng Y, Khan MZ, Yuan K, Lu L. The rising crisis of illicit fentanyl use, overdose, and potential therapeutic strategies. Transl Psychiatry 9: 282, 2019. doi: 10.1038/s41398-019-0625-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hahn EF, Pasternak GW. Naloxonazine, a potent, long-lasting inhibitor of opiate binding sites. Life Sci 31: 1385–1388, 1982. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(82)90387-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson N, Pasternak GW. Binding of [3H]naloxonazine to rat brain membranes. Mol Pharmacol 26: 477–483, 1984. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cruciani RA, Lutz RA, Munson PJ, Rodbard D. Naloxonazine effects on the interaction of enkephalin analogs with mu-1, mu and delta opioid binding sites in rat brain membranes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 242: 15–20, 1987. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pick CG, Paul D, Pasternak GW. Comparison of naloxonazine and beta-funaltrexamine antagonism of mu 1 and mu 2 opioid actions. Life Sci 48: 2005–2011, 1991. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(91)90155-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Verborgh C, Meert TF. Antagonistic effects of naloxone and naloxonazine on sufentanil-induced antinociception and respiratory depression in rats. Pain 83: 17–24, 1999. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(99)00068-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chaijale NN, Aloyo VJ, Simansky KJ. A naloxonazine sensitive (mu1 receptor) mechanism in the parabrachial nucleus modulates eating. Brain Res 1240: 111–118, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.08.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ling GS, Simantov R, Clark JA, Pasternak GW. Naloxonazine actions in vivo. Eur J Pharmacol 129: 33–38, 1986. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(86)90333-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Simone DA, Bodnar RJ, Portzline T, Pasternak GW. Antagonism of morphine analgesia by intracerebroventricular naloxonazine. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 24: 1721–1727, 1986. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(86)90511-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heyman JS, Williams CL, Burks TF, Mosberg HI, Porreca F. Dissociation of opioid antinociception and central gastrointestinal propulsion in the mouse: studies with naloxonazine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 245: 238–243, 1988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paul D, Pasternak GW. Differential blockade by naloxonazine of two mu opiate actions: analgesia and inhibition of gastrointestinal transit. Eur J Pharmacol 149: 403–404, 1988. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(88)90680-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Negus SS, Pasternak GW, Koob GF, Weinger MB. Antagonist effects of beta-funaltrexamine and naloxonazine on alfentanil-induced antinociception and muscle rigidity in the rat. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 264: 739–745, 1993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rossi GC, Pasternak GW, Bodnar RJ. Synergistic brainstem interactions for morphine analgesia. Brain Res 624: 171–180, 1993. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)90075-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mhatre M, Holloway F. Mu1-opioid antagonist naloxonazine alters ethanol discrimination and consumption. Alcohol 29: 109–116, 2003. doi: 10.1016/s0741-8329(03)00021-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mori T, Komiya S, Uzawa N, Inoue K, Itoh T, Aoki S, Shibasaki M, Suzuki T Involvement of supraspinal and peripheral naloxonazine-insensitive opioid receptor sites in the expression of mu-opioid receptor agonist-induced physical dependence. Eur J Pharmacol 715: 238–245, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2013.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dray A, Nunan L. Evidence that naloxonazine produces prolonged antagonism of central delta opioid receptor activity in vivo. Brain Res 323: 123–127, 1984. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(84)90273-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.May WJ, Henderson F, Gruber RB, Discala JF, Young AP, Bates JN, Palmer LA, Lewis SJ. Morphine has latent deleterious effects on the ventilatory responses to a hypoxic-hypercapnic challenge. Open J Mol Integr Physiol 3: 134–145, 2013. doi: 10.4236/ojmip.2013.33019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Palmer LA, May WJ, deRonde K, Brown-Steinke K, Gaston B, Lewis SJ. Hypoxia-induced ventilatory responses in conscious mice: gender differences in ventilatory roll-off and facilitation. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 185: 497–505, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2012.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Getsy PM, Coffee GA, May WJ, Baby SM, Bates JN, Lewis SJ. The Reducing Agent Dithiothreitol Modulates the Ventilatory Responses That Occur in Freely Moving Rats during and following a Hypoxic-Hypercapnic Challenge. Antioxidants (Basel) 13: 498, 2024. doi: 10.3390/antiox13040498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Young AP, Gruber RB, Discala JF, May WJ, McLaughlin D, Palmer LA Lewis SJ. Co-activation of μ- and δ-opioid receptors elicits tolerance to morphine-induced ventilatory depression via generation of peroxynitrite. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 186: 255–264, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2013.02.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Portoghese PS, Sultana M, Takemori AE. Naltrindole, a highly selective and potent non-peptide delta opioid receptor antagonist. Eur J Pharmacol 146: 185–186, 1988. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(88)90502-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rogers H, Hayes AG, Birch PJ, Traynor JR, Lawrence AJ. The selectivity of the opioid antagonist, naltrindole, for delta-opioid receptors. J Pharm Pharmacol 42: 358–359, 1990. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1990.tb05428.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gaston B, Baby SM, May WJ, Young AP, Grossfield A, Bates JN, Seckler JM, Wilson CG, Lewis SJ. D-Cystine di(m)ethyl ester reverses the deleterious effects of morphine on ventilation and arterial blood gas chemistry while promoting antinociception. Sci Rep 11: 10038, 2021. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-89455-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Getsy PM, Davis J, Coffee GA, May WJ, Palmer LA, Strohl KP, Lewis SJ. Enhanced non-eupneic breathing following hypoxic, hypercapnic or hypoxic-hypercapnic gas challenges in conscious mice. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 204: 147–159, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2014.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Getsy PM, Baby SM, May WJ, Bates JN, Ellis CR, Feasel MG, Wilson CG, Lewis THJ, Gaston B, Hsieh Y-H, Lewis SJ. L-cysteine methyl ester reverses the deleterious effects of morphine on ventilatory parameters and arterial blood-gas chemistry in unanesthetized rats. Front Pharmacol 13: 968378, 2022. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.968378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Getsy PM, Baby SM, May WJ, Young AP, Gaston B, Hodges MR, Forster HV, Bates JN, Wilson CG, Lewis THJ, Hsieh YH, Lewis SJ. D-Cysteine Ethyl Ester Reverses the Deleterious Effects of Morphine on Breathing and Arterial Blood-Gas Chemistry in Freely-Moving Rats. Front Pharmacol 13: 883329, 2022. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.883329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lomask M Further exploration of the Penh parameter. Exp Toxicol Pathol 57 Suppl 2:13–20, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.etp.2006.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Epstein MA, Epstein RA. A theoretical analysis of the barometric method for measurement of tidal volume. Respir Physiol 32: 105–120, 1978. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(78)90103-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Epstein RA, Epstein MA, Haddad GG, Mellins RB. Practical implementation of the barometric method for measurement of tidal volume. J Appl Physiol 49: 1107–1115, 1980. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1980.49.6.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jenkins MW, Khalid F, Baby SM, May WJ, Young AP, Bates JN, Cheng F, Seckler JM, Lewis SJ. Glutathione ethyl ester reverses the deleterious effects of fentanyl on ventilation and arterial blood-gas chemistry while prolonging fentanyl-induced analgesia. Sci Rep 11: 6985, 2021. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-86458-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ren J, Ding X, Greer JJ. 5-HT1A receptor agonist Befiradol reduces fentanyl-induced respiratory depression, analgesia, and sedation in rats. Anesthesiology 122: 424–434, 2015. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ren J, Ding X, Greer JJ. Countering Opioid-induced Respiratory Depression in Male Rats with Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor Partial Agonists Varenicline and ABT 594. Anesthesiology 132: 1197–1211, 2020. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000003128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yu C, Yuan M, Yang H, and Zhuang X, Li H. P-Glycoprotein on Blood-Brain Barrier Plays a Vital Role in Fentanyl Brain Exposure and Respiratory Toxicity in Rats. Toxicol Sci 164: 353–362, 2018. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfy093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Getsy PM, Davis J, Coffee GA, Lewis THJ, Lewis SJ. Hypercapnic signaling influences hypoxic signaling in the control of breathing in C57BL6 mice. J Appl Physiol (1985) 134: 1188–1206, 2023. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00548.2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Getsy PM, Coffee GA, Lewis SJ. Loss of ganglioglomerular nerve input to the carotid body impacts the hypoxic ventilatory response in freely-moving rats. Front Physiol 14: 1007043, 2023. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2023.1007043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Santiago TV, Edelman NH. Opioids and breathing. J Appl Physiol (1985) 59: 1675–1685, 1985. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1985.59.6.1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shook JE, Watkins WD, Camporesi EM. Differential roles of opioid receptors in respiration, respiratory disease, and opiate-induced respiratory depression. Am Rev Respir Dis 142: 895–909, 1990. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/142.4.895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang D, and Teichtahl H. Opioids, sleep architecture and sleep-disordered breathing. Sleep Med Rev 11: 35–46, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2006.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bodnar RJ. Endogenous opiates and behavior: 2023. Peptides 179: 171268, 2024. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2024.171268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Christrup LL. Morphine metabolites. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 41: 116–122, 1997. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.1997.tb04625.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Doyle HH, Murphy AZ. Sex-dependent influences of morphine and its metabolites on pain sensitivity in the rat. Physiol Behav 187: 32–41, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2017.11.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Grung M, Skurtveit S, Aasmundstad TA, Handal M, Alkana RL, Mørland J. Morphine-6-glucuronide-induced locomotor stimulation in mice: role of opioid receptors. Pharmacol Toxicol 82:3–10, 1988. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1998.tb01390.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gabel F, Hovhannisyan V, Berkati AK, Goumon Y. Morphine-3-Glucuronide, Physiology and Behavior. Front Mol Neurosci 15: 882443, 2022. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2022.882443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Peat SJ, Hanna MH, Woodham M, Knibb AA, Ponte J. Morphine-6-glucuronide: effects on ventilation in normal volunteers. Pain 45: 101–104, 1991. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(91)90170-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yamazaki H, Ohi Y, Haji A. Mu-opioid and N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors are localized at laryngeal motoneurons of guinea pigs. Biol Pharm Bull 32: 293–296, 2009. doi: 10.1248/bpb.32.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tandon OP, Mehta AK, Halder S, Khanna N, Sharma KK. Peripheral interaction of opioid and NMDA receptors in inflammatory pain in rats. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol 54: 21–31, 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lalley PM, Mifflin SW. Oscillation patterns are enhanced and firing threshold is lowered in medullary respiratory neuron discharges by threshold doses of a μ-opioid receptor agonist. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 312: R727–R738, 2017. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00120.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Clark FJ, von Euler C. On the regulation of depth and rate of breathing. J Physiol 222: 267–295, 1972. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1972.sp009797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Adams JM, Attinger FM, Attinger EO. Medullary and carotid chemoreceptor interaction for mild stimuli. Pflugers Arch 374: 39–45, 1978. doi: 10.1007/BF00585695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mizusawa A, Ogawa H, Kikuchi Y, Hida W, Kurosawa H, Okabe S, Takishima T, Shirato K. In vivo release of glutamate in nucleus tractus solitarii of the rat during hypoxia. J Physiol 478: 55–66, 1994. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bonham AC. Neurotransmitters in the CNS control of breathing. Respir Physiol 101: 219–230, 1995. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(95)00045-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Powell FL, Milsom WK, Mitchell GS. Time domains of the hypoxic ventilatory response. Respir Physiol 112: 123–134, 1998. doi: 10.1016/s0034-5687(98)00026-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tipton MJ, Harper A, Paton JFR, Costello JT. The human ventilatory response to stress: rate or depth? J Physiol 595: 5729–5752, 2017. doi: 10.1113/JP274596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nicolò A, Girardi M, Bazzucchi I, Felici F, Sacchetti M. Respiratory frequency and tidal volume during exercise: differential control and unbalanced interdependence. Physiol Rep 6: e13908, 2018. doi: 10.14814/phy2.13908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]