Abstract

Objectives:

To determine if cigarette and e-cigarette tobacco retail outlet (TRO) marketing influenced past 30-day (P30D) cigarette and e-cigarette use trajectories across early adolescence through young adulthood.

Methods:

A prospective cohort design in the five major counties in Texas was conducted using twelve survey waves from 2014–2020 with 3,892 students in 6th, 8th, and 10th grade at baseline. Growth curve modeling was used to determine the association between self-reported exposure to TRO marketing and P30D use and whether this relationship varied by age.

Results:

Across ages 11–22, exposure to TRO cigarette marketing increased the odds of P30D cigarette use (OR=1.05, 95% CI=1.01–1.09) and TRO e-cigarette marketing increased the odds of P30D e-cigarette use (OR=1.06, 95% CI=1.03–1.09), on average. The effect of marketing on P30D cigarette use was stable across ages, while the effect on P30D e-cigarette use was stronger at younger ages.

Conclusions:

Exposure to TRO marketing increases the odds of tobacco product use for youth aging into young adulthood. E-cigarette marketing may be particularly influential in early adolescence. Tobacco retail outlet marketing restrictions are needed to reduce tobacco use among youth and young adults.

Keywords: marketing, youth, e-cigarettes, cigarettes, longitudinal, retail tobacco outlets, point-of-sale, young adults

INTRODUCTION

While the prevalence of cigarette use among youth is lower than in previous decades, with 4.0% of 12th graders in the United States (U.S.) using cigarettes in the past 30 days,1 prevalence continues to increase throughout early young adulthood.2 Data from the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study show that, in 2019, 2.3% of 12–17 year olds engaged in past 30-day (P30D) cigarette use and the prevalence increased almost nine-fold to 18.1% among young adults aged 18–24.3 As compared to cigarette use, e-cigarette use, also known as electronic nicotine delivery system use or vaping, has increased among youth. According to data from the 2022 Monitoring the Future Study, 7.1% of 8th graders and 20.7% 12th graders vaped nicotine in the past 30 days.1 Additionally, PATH data show that, in 2019, 8.6% of 12–17 year olds had engaged in P30D electronic nicotine product use and the prevalence more than triples into young adulthood (26.2% at ages 18–24).3 As such, understanding the factors associated with the growth in cigarette and e-cigarette use over adolescence into early young adulthood is still needed.

Marketing at tobacco retail outlets (TROs) is used by the tobacco industry to increase exposure to, and promote, their products, particularly to youth4 and young adults.5–7 TROs are a key location for youth exposure.8 In a national sample of U.S. tobacco retailers, 95% of stores displayed tobacco marketing and 75.1% had at least one visible tobacco product price promotion.9 Further, data on tobacco marketing exposure among middle school students from the 2012–2022 National Youth Tobacco Surveys, show that, while cigarette advertisement exposure at TROs did decline from a high of 80.6% in 2014, retail exposure was still very high in 2020, with 69.3% of participants reporting seeing cigarette advertising.10 In 2020, 59.2% of middle school youth reported exposure to TRO e-cigarette marketing, down from high of 68% in 2015.10 Among a sample of adolescents from the PATH study who had never used e-cigarettes in 2016 (Wave 4), TROs were the most common channel of exposure (50.3%) with exposure rates almost two times greater than the next most prevalent channel of exposure (i.e. television).11 Further, adolescents report TRO e-cigarette marketing is influential in both purchasing and use decisions, and they cite the large wall of tobacco, or tobacco power wall, found behind the counters at retail outlets as particularly influential.12

Exposure to TROs themselves, as measured by asking youth if they visit TROs, has been associated with increased likelihood of tobacco/nicotine product use. Among 7th and 8th graders in Cleveland, Ohio, stopping at retail outlets was strongly associated with P30D use of both cigarettes and e-cigarettes.13 Further, youth who visit convenience, liquor, or small grocery stores more frequently are more likely to initiate cigarette use.14 While these associations are not focused specifically on tobacco marketing, it may be that given the high levels of tobacco and nicotine product marketing in TROs, visiting these locations exposes youth to this large amount of marketing. Using data from the PATH study with a sample of tobacco naïve youth at Wave 1 and who remained e-cigarette naïve at Wave 2, those that visited convenience stores weekly, were 1.79 times more likely to initiate e-cigarette use by Wave 3.15 These studies suggest the powerful influence of the retail setting itself on tobacco use and initiation for youth.

Exposure to cigarette and e-cigarette marketing have also been linked with product use and initiation,8 however, most studies have used cross-sectional data or limited waves of data. No studies have examined developmental trends in tobacco use, given exposure to marketing at TROs. Using data from a cross-sectional study of 13–17-year-olds in 2019, exposure to tobacco promotions, as defined by an index of exposure to various channels over the past 30 days, was associated with a greater risk of ever and P30D smoking and vaping. Though this index included multiple channels of exposure, retail outlets were the most common, with 71% of the sample reporting exposure.16 Further, in a cross-sectional study of students in 41 schools in New Jersey, greater e-cigarette advertising volume, as defined by total number of e-cigarette advertisements around a school multiplied by the proportion of all tobacco advertisements that were for e-cigarettes, was found to increase the likelihood of P30D e-cigarette use.17 Among a sample of adolescents in Texas, recall of tobacco marketing at TROs was associated with ever and P30D use of e-cigarettes as well as susceptibility to e-cigarettes 6 months later.18 Finally, two studies used longitudinal data from PATH to examine e-cigarette marketing exposure and e-cigarette use. The first included tobacco naïve youth from Wave 4 and found that exposure to e-cigarette marketing predicted greater likelihood of e-cigarette initiation one year later.11. The second found that e-cigarette marketing exposure in TROs at Wave 4.5 was associated with lifetime use among adolescents aged 12–17 overall and among those who were e-cigarette naïve at Wave 4.5.19

While exposure to TRO tobacco marketing has been linked with youth tobacco/nicotine use, few studies have examined the association prospectively, particularly from early adolescence into early young adulthood. Further, much of the recent work has focused on e-cigarettes and has not examined the impact of cigarette marketing on cigarette use in the contemporary landscape of tobacco products which has changed the nature of the tobacco retail environment. Therefore, the purpose of the present study was to determine if self-reported recall of exposure to cigarette and e-cigarette TRO marketing influenced the trajectory of P30D use of cigarettes and e-cigarettes over the course of early adolescence through young adulthood (ages 11–22).

METHOD

Participants and Procedure

Participants in the present study were part of the Texas Adolescent Tobacco & Marketing Surveillance Study (TATAMS).20 21 On enrollment (Wave 1), students participated in a web-based survey in school about tobacco use, administered via tablet computers. Approximately every 6 months thereafter, participants took the same web-based survey outside of school on their own tablet, computer, or smartphone. At baseline (Wave 1; Fall, 2014), TATAMS participants (n=3,907) included three cohorts of adolescents living in major metropolitan areas of Texas (Houston, Dallas-Ft. Worth, San Antonio, Austin) who were in the 6th (n=1,122), 8th (n=1,322), and 10th (n=1,463) grades.

To be included in the present study, participants had to be 11–22 years old and have valid data on age, gender, race/ethnicity, and socioeconomic status (SES) at wave 1, as well as marketing exposures and tobacco use outcomes for at least one wave of data between Waves 1–12. Age was limited due to small sample sizes at both ends of the age range (e.g. 10 and 23, 24). This resulted in a total of 3,892 participants included in the present study (99.6% of the original sample). Fifty-six percent of the participants reported being female, 38.5% identified as Hispanic/Latinx, 31% identified as non-Hispanic White, 16% identified as non-Hispanic Black, and 14.5% identified as another race.

The present study uses longitudinal, repeated measures data from Wave 1 (Fall, 2014) through Wave 12 (Fall, 2020). Retention across Waves ranged from 63% to 85% and did not vary by cohort at any Wave. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Texas School of Public Health, Houston, Texas (HSCSPH-13–0377).

Measures

Outcome Variables

P30D Cigarette Use.

Participants self-reported P30D cigarette use with one item that asked: “During the past 30 days, on how many days did you smoke cigarettes?”. This item was coded to represent any P30D cigarette use (0 days=0, any use=1).

P30D E-Cigarette Use.

Participants self-reported P30D e-cigarette use, with one item that asked: “During the past 30 days, on how many days did you use an electronic cigarette, vape pen, or e-hookah?”. This item was coded to represent any P30D e-cigarette use (0 days=0, any use=1).

Independent Variables

Two variables, one for recall of cigarette TRO marketing and one for recall of e-cigarette TRO marketing, were used to calculate marketing exposure scores. Each of these variables was based on a composite of two additional variables: 1) frequency of visiting retail outlets and 2) recall of tobacco marketing at these outlets.

To assess frequency of visits to TROs at wave 1, store types were separated into two questions: “During the past 30 days, how often have you visited the following places near your school?” with one question assessing “Gas station, convenience/corner stores” and the other assessing “Grocery Stores.” In Waves 2–12, one question was used that combined all store types into one question: “During the past 30 days, how often have you visited gas station/corner/convenience stores and grocery stores near your school?” Response options were the same at all waves and were coded to reflect weekly exposure: “never”=0 visits/week; “once a month”=0.23 visits/week [(1/30)x7]; “two or three times a month”=0.58 visits/week [(2.5/30)x7]; “once a week”= 1 visit/week; “two or three times a week”=2.5 visits/week; and “almost every day”=6 visits/week. Recoded response options were on an ordinal scale from 0=“Never” to 6=“Almost Every Day”.14

Recall of tobacco marketing in these retail outlets was assessed with one item per product (i.e., cigarettes and e-cigarettes) that asked: “When you visited gas station/corner/convenience stores and grocery stores, how often did you see signs marketing [tobacco product type]?” Response options ranged from “never/not that I remember”=0 to “every time”=3.

Weekly exposure to TRO cigarette marketing was then calculated as the product of the weekly store visit variable (1) and recall of cigarette advertisements (2), with a possible range of 0–18. Weekly exposure to TRO e-cigarette marketing was calculated as the product of the weekly store visit variable (1) and recall of e-cigarette advertisements (2), with a possible range of 0–18.

Age.

Date of birth was collected at the initial study wave. Age was calculated at each wave by subtracting date of birth from the survey date, rounded to the nearest whole year. Age was used as the “time variable” in this study; the x-axis for the growth curves represents age-based developmental trends.

Covariates

Wave.

To control for secular trends in P30D cigarette and e-cigarette use and marketing, survey Wave (1–12) was used.

Gender.

Participants self-reported gender at Wave 1 by responding to the following question: “What is your gender?” with the response options of 0=“male” or 1=“female”.

Racial/Ethnic Identity.

Participants self-reported racial and ethnic identity at Wave 1 by responding to the following two questions. “Are you Hispanic or Latino/a?” with the response options of 0=“No”; 1=“Yes, I am Mexican, Mexican American, or Chicano/a”; 2=“Yes, I am some other Hispanic or Latino/a ethnicity not listed here.”, and “What race or races do you consider yourself to be?” with the multiple response options of “white,” “Black or African American,” “Asian,” “American Indian or Alaskan Native,” “Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander,” or “Other.” Responses were grouped into a nominal variable denoting racial/ethnic identity group membership among the following mutually exclusive categories non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, and Other, with non-Hispanic white as the referent group.

Socioeconomic Status (SES).

Participants self-reported SES at the initial study wave by responding to the following question: “In terms of income, what best describes your family’s standard of living in the home where you live most of the time? Would you say your family is:” with the response options of 1=“very well off,” 2=“living comfortable,” 3=“just getting by,” 4=“nearly poor,” or 5=“poor”.22 Response options were recoded to reflect three categories of SES: Low (including “just getting by”, “nearly poor”, and “poor”) indicated by 22.5% of the sample, Middle (“living comfortably”) indicated by 62% of the sample, and High (“very well off”) indicated by 15.4% of the sample.

Ever Cigarette Use at Wave 1.

To control for any previous cigarette use, one question was use which asked participants: “Have you ever smoked a cigarette, even one or two puffs?”. The question was coded to represent Ever Cigarette Use at Wave 1 (yes=ever user, no=never user).

Ever E-Cigarette Use Use at Wave 1.

To control for any previous e-cigarette use, one question was used which asked participants: “Have you EVER used an electronic cigarette, vape pen, or e-hookah, even one or two puffs?”. The question was coded to represent any Ever E-Cigarette Use at Wave 1 (yes=ever user, no=never user).

Analysis

Descriptive statistics using Stata 17.023 were calculated for (a) weekly exposure to TRO cigarette marketing and cigarette use, by age; and (b) weekly exposure to TRO e-cigarette marketing and e-cigarette use, by age (Table 1).

Table 1.

Prevalence of Product Use and Average Exposure to Product TRO Marketing (n=3,892)

| Age | Cigarette Use Prevalence (%) | Average Cigarette Weekly Marketing Exposure (0–18) | E-cigarette Use Prevalence (%) | Average E-cigarette Weekly Marketing Exposure (0–18) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11 | 0.25 | 2.05 | 0.99 | 1.26 |

| 12 | 0.39 | 1.98 | 0.51 | 1.14 |

| 13 | 0.89 | 2.01 | 2.05 | 1.23 |

| 14 | 1.15 | 2.10 | 3.61 | 1.41 |

| 15 | 2.30 | 2.06 | 6.81 | 1.47 |

| 16 | 2.94 | 2.05 | 8.42 | 1.48 |

| 17 | 3.62 | 1.86 | 8.90 | 1.46 |

| 18 | 4.56 | 1.92 | 11.36 | 1.62 |

| 19 | 6.91 | 1.94 | 14.81 | 1.75 |

| 20 | 6.85 | 1.89 | 14.93 | 1.72 |

| 21 | 6.96 | 1.98 | 12.49 | 1.75 |

| 22 | 9.64 | 2.32 | 13.50 | 2.22 |

First, to determine the growth curve of P30D cigarette use and P30D e-cigarette use across time for adolescents aged 11–22, we fit repeated measures generalized linear mixed models of P30D cigarette use and P30D e-cigarette use with a logit link function for a binary distribution with the Stata 17 melogit function23 using maximum likelihood estimation.24 Age was the primary independent variable in these models and we adjusted for wave, gender, race/ethnicity, SES, ever cigarette use at Wave 1, and ever e-cigarette use at Wave 1. All models were multilevel, nesting repeated measures within individuals, and individuals within the schools from which they were recruited.25 To determine the trajectories of cigarette and e-cigarette use, separate linear (age), quadratic (age-squared), and cubic (age-cubed) models were fit for each outcome. Linear, quadratic, and cubic models were compared using the Bayesian information criterion (BIC), accounting for both model complexity and sample size in determining the best-fit.26

Second, to examine the impact of recall of weekly exposure to TRO marketing on use, we fit two growth curve models, using the best fitting models as described above, adding in the exposure measure of weekly exposure to TRO marketing. Model 1 was specific to recall of exposure to cigarette TRO marketing and cigarette use and Model 2 was specific to recall of exposure to e-cigarette TRO marketing and e-cigarette use.

Third, to examine the time-varying impact of recall of weekly marketing to determine if the effect of marketing changed as participants aged, we added an interaction term for recall of weekly exposure to cigarette marketing multiplied by age to Model 1 and weekly exposure to e-cigarette marketing multiplied by age to Model 2.

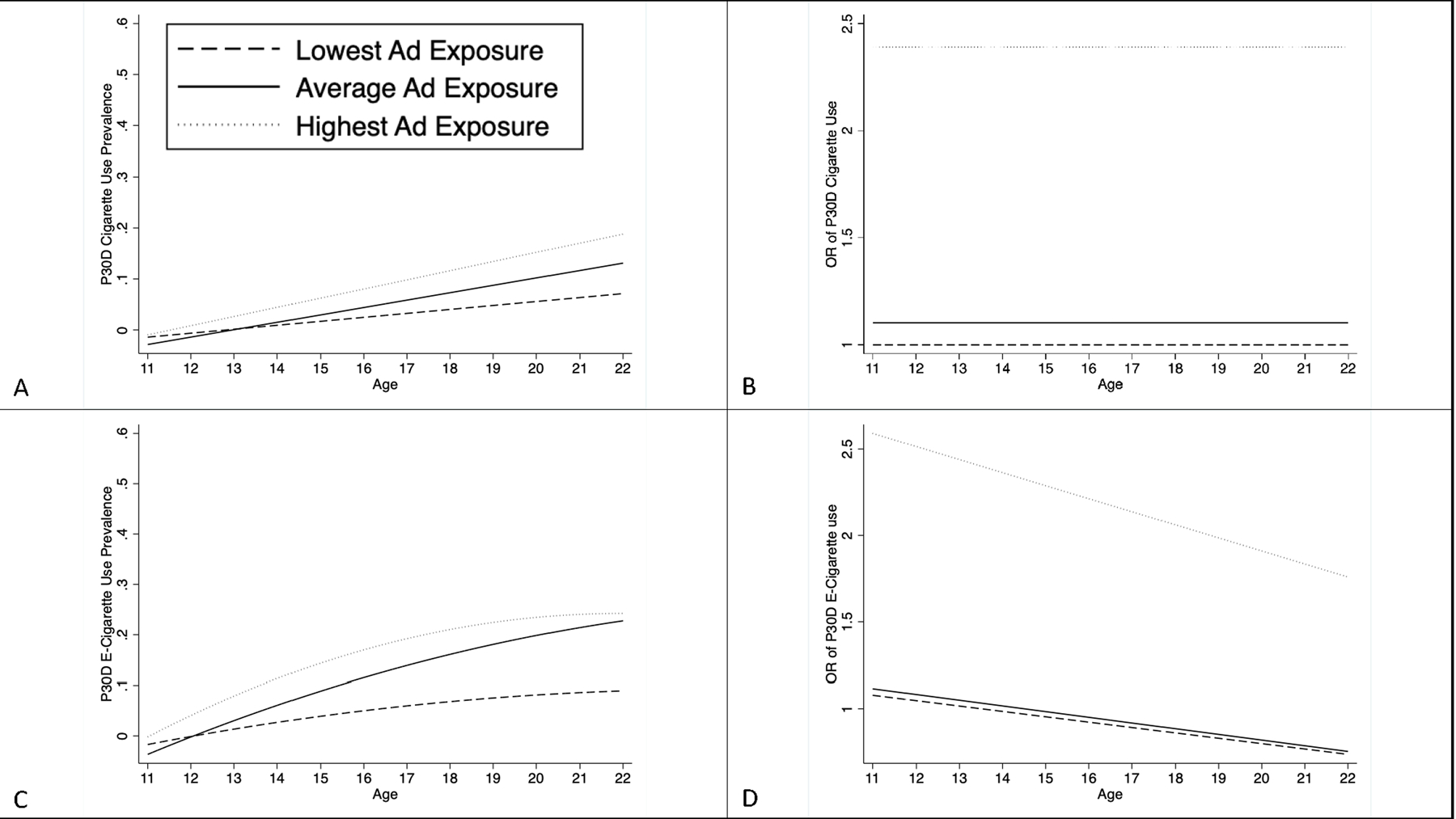

Finally, to visualize the overall effect of recall of weekly exposure to cigarette and e-cigarette marketing on P30D cigarette use and e-cigarette use, we plotted the average trajectories of cigarette use and e-cigarette use across ages 11–22, as well as predicted trajectories for individuals with the highest and lowest levels of cigarette and e-cigarette marketing exposure.27 To aid in interpreting the interaction of weekly exposure to product marketing by age, we also plotted the odds ratios for the association between weekly exposure to cigarette and e-cigarette marketing and product use across age at the lowest, average, and highest levels of exposure.

RESULTS

The prevalence of cigarette use consistently increased over time with 0.25% of 11-year-olds reporting P30D cigarette use and 6.91% of 19-year-olds reporting use (see Table 1). Use declined slightly at age 20 to 6.85% but then increased again to 9.64% at age 22. The prevalence of e-cigarette use increased consistently starting with 0.99% of 11-year-olds reporting P30D e-cigarette use to 14.93% reporting P30D use. Prevalence declined to 12.49% at age 21 but began to increase again at age 22 to 13.5%. Average weekly exposure to TRO cigarette and e-cigarette marketing increased from age 11 to age 22 (see Table 1).

Model 1–Cigarette Use

The linear (age) model had the best fit for cigarette use (linear model BIC= 3112.05; quadratic model BIC= 3121.78; cubic model BIC= 3131.71), indicating that P30D cigarette use increased monotonically by age, or that we observed a linear developmental trend in P30D use. After controlling for wave, gender, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, ever cigarette use at wave 1, ever e-cigarette use at wave 1, and random variation at the participant-level and school-level, the impact of weekly exposure to cigarette marketing on P30D cigarette use was statistically significant (OR=1.05, 95% CI=1.01–1.09), indicating that participants exposed to more cigarette advertisements had higher odds of P30D cigarette use, on average, from 11 to 22 years of age (See Table 2). Figure 1A presents trajectories of P30D cigarette use across ages 11 to 22, with separate lines showing the trajectories of cigarette use at the lowest, average, and highest levels of exposure to cigarette TRO marketing.

Table 2.

Cigarette Use Model Parameters (n=3,892)

| Variable | Odds Ratio | 95% C.I. |

|---|---|---|

| Time | ||

| Age | 1.55 | 1.32 – 1.84 |

| Wave | 1.04 | 0.95 – 1.15 |

| Gender | ||

| Male (reference) | - | - |

| Female | 0.86 | 0.57 – 1.30 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic White (reference) | - | - |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.31 | 0.14 – 0.68 |

| Hispanic | 0.77 | 0.46 – 1.30 |

| Other | 0.63 | 0.32 – 1.23 |

| Socioeconomic Status | ||

| Low (reference) | - | - |

| Middle | 1.89 | 1.05 – 3.37 |

| High | 2.58 | 1.29 – 5.14 |

| Ever Cigarette Use at Wave 1 | 33.29 | 18.38 – 60.30 |

| Ever E-Cigarette Use at Wave 1 | 5.66 | 3.38 – 9.52 |

| Cigarette Ad Exposure | 1.05 | 1.01 – 1.09 |

Variance Estimate for Level 2 (participant) = 5.80 (95% C.I.=4.37–7.70)

Variance Estimate for Level 3 (school) = 0.31 (95% C.I.=0.08–1.14)

Figure 1a.

Trajectories of P30D cigarette use prevalence across ages 11 to 22 (n=3,892).

Figure 1b. Odds ratio of P30D cigarette use given exposure to TRO cigarette marketing across ages 11 to 22 (n=3,892).

Figure 1c. Trajectories of P30D e-cigarette use prevalence across ages 11 to 22 (n=3,892).

Figure 1d. Odds ratio of P30D e-cigarette use given exposure to TRO e-cigarette marketing across ages 11 to 22 (n=3,892).

The interaction term for exposure to cigarette marketing*age was not statistically significant (OR=0.99, 95% CI=0.97–1.02), suggesting that the effect of exposure to cigarette marketing on P30D cigarette use was stable across ages. Figure 1B presents odds ratios for the association between exposure to cigarette marketing and P30D cigarette use across age at the lowest, average, and highest levels of TRO marketing exposure.

Model 2–E-Cigarette Use

The quadratic (age-squared) model had the best fit for e-cigarette use (linear model BIC= 6535.21; quadratic model BIC= 6523.43; cubic model BIC= 6530.57), indicating that e-cigarette use increased exponentially by age, or that e-cigarette use increased more rapidly as the sample aged. After controlling for wave, gender, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, ever cigarette use at wave 1, ever e-cigarette use at wave 1, and random variation at the participant-level and school-level, the impact of recall of weekly exposure to e-cigarette marketing on P30D e-cigarette use was statistically significant (OR=1.06, 95% CI=1.03–1.09), indicating that participants exposed to more e-cigarette advertisements had higher odds of P30D e-cigarette use (See Table 3), on average, from 11 to 22 years of age. Figure 1C presents trajectories of P30D e-cigarette use across ages 11 to 22, with separate lines showing the trajectories of e-cigarette use at the lowest, average, and highest levels of exposure to e-cigarette TRO marketing.

Table 3.

E-Cigarette Use Model Parameters (n=3,892)

| Variable | Odds Ratio | 95% C.I. |

|---|---|---|

| Time | ||

| Age | 19.39 | 5.77 – 65.08 |

| Age-squared | 0.91 | 0.88 – 0.95 |

| Wave | 1.09 | 1.02 – 1.15 |

| Gender | ||

| Male (reference) | - | - |

| Female | 0.68 | 0.53 – 0.87 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic White (reference) | - | - |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.28 | 0.18 – 0.44 |

| Hispanic | 0.49 | 0.36 – 0.68 |

| Other | 0.47 | 0.32 – 0.69 |

| Socioeconomic Status | ||

| Low (reference) | - | - |

| Middle | 0.80 | 0.59 – 1.07 |

| High | 0.99 | 0.67 – 1.47 |

| Ever Cigarette Use at Wave 1 | 2.51 | 1.76 – 3.57 |

| Ever E-Cigarette Use at Wave 1 | 28.02 | 19.99 – 39.28 |

| E-Cigarette Ad Exposure | 1.06 | 1.03 – 1.09 |

Variance Estimate for Level 2 (participant) = 3.13 (95% C.I.=2.54–3.86)

Variance Estimate for Level 3 (school) = 0.29 (95% C.I.=0.14–0.58)

The interaction term for exposure to e-cigarette marketing*age was significant (OR=0.97, 95% CI=0.96–0.99), suggesting that the effect of weekly exposure to e-cigarette marketing on e-cigarette use decreased as age increased. Said another way, e-cigarette marketing had a stronger effect on younger participants. Figure 1D presents odds ratios for the association between exposure to e-cigarette marketing and P30D e-cigarette use across age at the lowest, average, and highest levels of TRO marketing exposure.

DISCUSSION

Our study found that greater weekly exposure to cigarette and e-cigarette marketing at TROs was associated with increased odds of cigarette and e-cigarette use, respectively, over early adolescence through early young adulthood, or from the ages of 11–22. Further, the impact of exposure to cigarette marketing was consistent across this period, suggesting that exposure at any age has the same impact on the odds of P30D cigarette use. Alternatively, for e-cigarettes, exposure to e-cigarette marketing had a greater impact during early adolescence with the effect lessening over time through early young adulthood, suggesting exposure at younger ages is particularly important. The present study confirms previous work that has also found that exposure to TRO cigarette and e-cigarette marketing is associated with cigarette and e-cigarette use.8 11 15 28 However, the present study extends previous work by examining this relationship prospectively over a period of eleven years and covers the developmental periods of early adolescence through early young adulthood when most young people begin and sustain tobacco use. No studies have examined developmental trends like these.

Tobacco marketing in the retail environment has consistently been documented as a key factor related to tobacco use among youth and young adults. As such, policy strategies are needed to reduce the impact of tobacco marketing on tobacco use. Recent research using the Health Information National Trends Survey data, a nationally representative dataset from adults over the age of 18 in the US, shows there is strong support for restricting tobacco product marketing at the point-of-sale and keeping products out of view of the check-out counter.29 Further, regulatory strategies such as banning tobacco product sales within 1000ft of schools or limiting retailer density can reduce youth exposure to tobacco marketing at retail outlets.30 31 These strategies also are particularly important for reducing the disparate exposure of tobacco marketing in communities of color and lower income communities.31 32 As suggested by Kong & Henriksen (2022), in order to have comprehensive tobacco control and a focus on equity, governments need to create strategies to regulate the retail environment.33 In fact, recent work evaluating tobacco sales bans in two cities in California has shown retailers complied with the ban (almost 90% were compliant) and tobacco marketing was almost eliminated,34 suggesting these strategies are effective.

While this is one of the first studies to examine the association between exposure to cigarette and e-cigarette marketing and cigarette and e-cigarette use over eleven years across youth and early young adulthood, there are limitations to be noted. First, our study sample is drawn only from youth in Texas which may limit generalizability to the larger population. However, this study used a complex, multi-stage, probability sampling design, recruiting 6th, 8th, and 10th graders from the five largest metropolitan areas of in one of the largest states in the U.S. Further, Texas is home to one out of every 10 people under the age of 18 in the U.S.35 and has been the testing ground for several tobacco marketing campaigns. As such, Texas does serve as a prime location to determine how tobacco marketing influences tobacco use among youth. Future work which examines these associations in larger national samples is needed to continue to build the evidence base showing how tobacco marketing impacts tobacco use. Second, our measure of marketing‐exposure is limited by the use of self-reported recall of marketing in retail settings. However, our measure does capture both the frequency of store visits and recall of in-store marketing, both of which have been used previously and have shown impacts on tobacco use. Our measure does not capture the objective volume, placement, or creative content of advertisements encountered (e.g., power-wall size, price promotions). Future work should continue to examine how the themes and images in tobacco marketing impacts the trajectories of tobacco/nicotine use. Finally, the 2014–2020 period of the study spanned several major U.S. policy shifts, including the 2016 FDA Deeming Rule, local/national Tobacco-21 laws (2019), the 2020 federal flavour restrictions on cartridge-based e-cigarettes, and pandemic-related retail disruptions that may have altered both marketing and product use. We partially addressed these secular changes by adjusting for survey wave in all models. Nonetheless, residual policy effects could persist; replication in post-2020 cohorts and evaluations of specific policy interventions are warranted.

CONCLUSIONS

Through the use of longitudinal growth curve modeling, we were able to determine that exposure to cigarette marketing at retail outlets is associated with increased odds of P30D cigarette use over time and the influence is consistent across this time period. We also found that while exposure to e-cigarette marketing at retail outlets also is associated with increased odds of P30D e-cigarette use over this 11-year period, the influence is stronger in early adolescence. Interventions focused on youth and young adult tobacco prevention and cessation are needed throughout the life-course but messages about e-cigarette marketing may need to be especially emphasized in early adolescence. Policy strategies that limit retailer density and outdoor marketing, particularly around schools, are also needed to reduce the influence of TRO marketing on tobacco use among youth and young adults.

What is already known on this topic:

Marketing for tobacco products at tobacco retail outlets has been shown to influence youth and young adult tobacco use.

What this study adds:

This paper provides the first examination of the impact of cigarette and e-cigarette tobacco retail outlet marketing on the longitudinal trajectories of cigarette and e-cigarette use across ages 11 to 22.

Exposure to TRO cigarette marketing and e-cigarette marketing increased the odds of P30D cigarette and e-cigarette use, respectively, across adolescence and into young adulthood.

While the effect of marketing on P30D cigarette use was stable across ages, the effect on P30D e-cigarette use was stronger at younger ages.

How this study might affect research, policy or practice:

While both cigarette and e-cigarette TRO marketing are associated with increased odds of use throughout youth and young adulthood, e-cigarette marketing may be particularly influential in early adolescence, suggesting the need for early prevention messages as well as policy strategies which limit exposure to TRO marketing.

Funding:

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health from the National Cancer Institute (NCI) and the FDA Center for Tobacco Products (CTP) [1 P50 CA180906 and 1R01 CA239097]. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) or the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Neither NIH nor FDA had any role in the study design, data collection, analysis, or writing of this paper.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: Dr. Harrell was a consultant in litigation that involved the vaping industry.

REFERENCES

- 1.Johnston LD, Miech RA, Patrick ME, et al. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use 1975–2022: Overview, key findings on adolescent drug use. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perry CL, Pérez A, Bluestein M, et al. Youth or young adults: which group is at highest risk for tobacco use onset? Journal of Adolescent Health 2018;63(4):413–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.United States Department of Health and Human Services. PATH Study Data Tables and Figures: Waves 1–5 (2013–2019). In PATH Study Data Tables and Figures Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor]: National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Drug Abuse, and United States Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration, Center for Tobacco Products. , 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cummings KM, Morley CP, Horan JK, et al. Marketing to America's youth: evidence from corporate documents. Tob Control 2002;11 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):I5–17. doi: 10.1136/tc.11.suppl_1.i5 [published Online First: 2002/03/15] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ling PM, Glantz SA. Why and How the Tobacco Industry Sells Cigarettes to Young Adults: Evidence From Industry Documents. American Journal of Public Health 2002;92(6) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lavack AM, Toth G. Tobacco point-of-purchase promotion: examining tobacco industry documents. Tobacco Control 2006;15(5):377–84. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.014639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pollay RW. More than meets the eye: on the importance of retail cigarette merchandising. Tobacco Control 2007;16(4):270–4. doi: 10.1136/tc.2006.018978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robertson L, McGee R, Marsh L, et al. A systematic review on the impact of point-of-sale tobacco promotion on smoking. Nicotine Tob Res 2015;17(1):2–17. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu168 [published Online First: 2014/09/01] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ribisl KM, D'Angelo H, Feld AL, et al. Disparities in tobacco marketing and product availability at the point of sale: Results of a national study. Preventive Medicine 2017;105:381–88. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.04.010 [published Online First: 2017/04/11] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li X, Kaiser N, Borodovsky JT, et al. National Trends of Adolescent Exposure to Tobacco Advertisements: 2012–2020. Pediatrics 2021;148(6) doi: 10.1542/peds.2021-050495 [published Online First: 2021/12/02] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stanton CA, Pasch KE, Pericot-Valverde I, et al. Longitudinal associations between U.S. youth exposure to E-cigarette marketing and E-cigarette use harm perception and behavior change. Prev Med 2022;164:107266. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2022.107266 [published Online First: 2022/09/25] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gaiha SM, Lempert LK, Lung H, et al. Appealing characteristics of E-cigarette marketing in the retail environment among adolescents. Prev Med Rep 2024;43:102769. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2024.102769 [published Online First: 2024/06/17] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trapl E, Anesetti-Rothermel A, Pike Moore S, et al. Association between school-based tobacco retailer exposures and young adolescent cigarette, cigar and e-cigarette use. Tob Control 2021;30(e2):e104–e10. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2020-055764 [published Online First: 2020/08/21] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Henriksen L, Schleicher NC, Feighery EC, et al. A longitudinal study of exposure to retail cigarette advertising and smoking initiation. Pediatrics 2010;126(2):232–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.D'Angelo H, Patel M, Rose SW. Convenience Store Access and E-cigarette Advertising Exposure Is Associated With Future E-cigarette Initiation Among Tobacco-Naive Youth in the PATH Study (2013–2016). J Adolesc Health 2021;68(4):794–800. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.08.030 [published Online First: 2020/10/12] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fielding-Singh P, Epperson AE, Prochaska JJ. Tobacco Product Promotions Remain Ubiquitous and Are Associated with Use and Susceptibility to Use Among Adolescents. Nicotine Tob Res 2021;23(2):397–401. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntaa136 [published Online First: 2020/07/30] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Giovenco DP, Casseus M, Duncan DT, et al. Association Between Electronic Cigarette Marketing Near Schools and E-cigarette Use Among Youth. Journal of Adolescent Health 2016;59(6):627–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pasch KE, Nicksic NE, Opara SC, et al. Recall of Point-of-Sale Marketing Predicts Cigar and E-Cigarette Use among Texas Youth. Nicotine & Tobacco Research 2018. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntx237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sun T, Vu G, Lim CCW, et al. Longitudinal association between exposure to e-cigarette advertising and youth e-cigarette use in the United States. Addict Behav 2023;146:107810. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2023.107810 [published Online First: 2023/07/30] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pérez A, Harrell M, Malkani R, et al. Texas Adolescent Tobacco and Marketing Surveillance System’s Design. Tob Regul Sci 2017;3(2):151–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harrell MB, Chen B, Clendennen SL, et al. Longitudinal trajectories of E-cigarette use among adolescents: A 5-year, multiple cohort study of vaping with and without marijuana. Prev Med 2021;150:106670. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106670 [published Online First: 2021/06/05] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gore S, Aseltine RH Jr, Colten ME. Social structure, life stress, and depressive symptoms in a high school-age population. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 1992:97–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stata Statistical Software: Release 17 [program]: StataCorp LLC, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ng ES- W, Carpenter JR, Goldstein H, et al. Estimation in generalised linear mixed models with binary outcomes by simulated maximum likelihood. Statistical Modelling 2006;6:23–42. doi: 10.1191/1471082X06st106oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gelman A, Hill J. Data Analysis Using Regression and Multilevel/Hierarchical Models Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Raftery AE. Bayesian Model Selection in Social Research. Sociological Methodology 1995;25:111–63. doi: 10.2307/271063 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Singer JD, Willet JB. Applied Longitudinal Data Analys. Modeling Change and Event Occurence. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Robertson L, Cameron C, McGee R, et al. Point-of-sale tobacco promotion and youth smoking: a meta-analysis. Tobacco Control 2016;25(e2):e83–e89. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2015-052586 [published Online First: 2016/01/06] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blake KD, Gaysynsky A, Mayne RG, et al. U.S. public opinion toward policy restrictions to limit tobacco product placement and advertising at point-of-sale and on social media. Prev Med 2022;155:106930. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106930 [published Online First: 2021/12/27] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Obinwa U, Pasch KE, Jetelina KK, et al. A Simulation of the potential impact of restricting tobacco retail outlets around middle and high schools on tobacco advertisements. Tob Control 2022;31(1):81–87. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2020-055724 [published Online First: 2020/12/15] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Obinwa U, Pasch KE, Jetelina KK, et al. Restricting Tobacco Retail Outlets Around Middle and High Schools as a Way to Reduce Tobacco Marketing Disparities: A Simulation Study. Nicotine Tob Res 2022;24(12):1994–2002. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntac150 [published Online First: 2022/06/24] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ribisl KM, Luke DA, Bohannon DL, et al. Reducing Disparities in Tobacco Retailer Density by Banning Tobacco Product Sales Near Schools. Nicotine Tob Res 2017;19(2):239–44. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntw185 [published Online First: 2016/09/11] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kong AY, Henriksen L. Retail endgame strategies: reduce tobacco availability and visibility and promote health equity. Tob Control 2022;31(2):243–49. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2021-056555 [published Online First: 2022/03/05] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Henriksen L, Andersen-Rodgers E, Voelker DH, et al. Evaluations of Compliance With California’s First Tobacco Sales Bans and Tobacco Marketing in Restricted and Cross-Border Stores. Nicotine & Tobacco Research 2024;ntae043 doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntae043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Texas Comproller of Public Account. A Review of the Texas Economy Young Texans: Demographic Overview PART 1 OF A TWO-PART SERIES 2020 [Available from: https://comptroller.texas.gov/economy/fiscal-notes/archive/2020/feb/texans.php accessed July 19, 2024 2024. [Google Scholar]