Abstract

Background

Migraine is a debilitating neurological disorder. Emerging evidence suggests that metabolic dysregulation and immune dysfunction contribute to migraine pathogenesis while the molecular mechanisms linking these processes remain unclear. Lactylation may serve as a crucial integrator of metabolic and immune signals in migraine.

Methods

We performed a comprehensive multi-omics Mendelian randomization study integrating DNA methylation, gene expression, and protein abundance data with genome-wide association studies on migraine. Summary-data-based Mendelian randomization, Bayesian colocalization, and two-sample MR analyses were conducted to identify lactylation-related genes causally associated with migraine. We further explored immune cell mediation using genetic data from 731 immune phenotypes and validated findings through single-cell RNA sequencing of peripheral blood mononuclear cells from migraine patients and controls.

Results

EP300, SIRT1, and SLC16A1 were identified as key regulators of migraine susceptibility across methylation, expression, and protein levels. EP300 and SLC16A1 were associated with increased migraine risk, while SIRT1 conferred a protective effect. Mediation analyses revealed that genetic effects of these genes were partially transmitted through specific immune cell subsets, particularly B cells and natural killer T cells. Single-cell transcriptomic profiling further demonstrated EP300 upregulation in B cells and T cells of migraine patients. These findings support a novel “lactylation–immune mediation–migraine axis” linking metabolic and immune dysregulation to migraine pathogenesis.

Conclusion

This integrative multi-omics analysis uncovers lactylation-related genes as causal drivers of migraine through immunometabolic pathways. Targeting lactylation-regulated metabolic and immune mechanisms may offer novel precision therapeutic strategies for migraine, particularly in patients with inflammatory or metabolic endophenotypes.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s10194-025-02075-3.

Keywords: Migraine, Lactylation, Mendelian randomization, Immune mediation, Multi-omics, Single-cell RNA sequencing

Introduction

Migraine is a debilitating neurological disorder with a significant burden in terms of disability for individuals and costs for society, characterized by recurrent episodes of intense headaches, often accompanied by symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, photophobia, and phonophobia [1, 2]. It is a major public health burden, consistently ranking among the top causes of disability globally and severely impairing the quality of life for sufferers [3]. Migraine is also a highly heterogeneous disorder with substantial individual variability in attack frequency, aura, comorbidities, and treatment response. Moreover, it involves complex interplay across neurological, vascular, metabolic, and immune dimensions, which underscores the need for integrated pathophysiological frameworks beyond single-disease paradigms [4]. Despite significant advances in understanding the genetic, environmental, and pathophysiological factors contributing to its onset, the precise mechanisms underlying migraine remain incompletely understood.

Recent evidence highlights the critical roles of metabolic dysregulation and immune system alterations in the pathogenesis of migraine [5–8]. However, the molecular mechanisms through which these factors interact remain poorly defined.

Lactylation, a recently identified post-translational modification, serves as a marker of cellular metabolic status and plays a crucial role in regulating both energy metabolism and gene transcription [9]. This modification influences several cellular processes, including metabolic adaptation, immune response modulation, inflammation resolution, and cellular stress responses [10]. Dysregulated lactylation has been implicated in numerous diseases, such as cancer, autoimmune disorders, metabolic diseases, and neurodegenerative conditions [11, 12].

Although no prior studies have directly investigated lactylation in the context of migraine, accumulating evidence suggests that altered lactate metabolism may play a role in migraine pathophysiology. For instance, MRS studies have observed elevated lactate in the occipital cortex of migraine patients in several reports—particularly in cases involving aura [13, 14]. Migraine is also commonly reported in mitochondrial disorders such as MELAS, where energy dysregulation and lactate accumulation are central features [15, 16]. Moreover, physical exertion—which transiently elevates lactate—has been linked to both the triggering and possible prevention of migraine attacks, potentially by modulating the migraine threshold, though the underlying mechanisms are not fully understood [17]. A clinical connection between metabolic disturbances—such as lactate accumulation during physical exertion—and migraine attacks is well established [17–19]. Furthermore, emerging evidence suggests that immune dysregulation contribute to migraine pathogenesis [7, 20]. These findings support the hypothesis that lactate-linked metabolic stress plays a contributory role in migraine development. However, the precise pathways linking metabolic changes, immune dysfunction, and migraine remain unclear. Given lactylation’s capacity to integrate metabolic signals with epigenetic regulation, it presents a promising mechanism for bridging these gaps.

In this study, we propose a novel framework for migraine pathogenesis, which we term the “lactylation–immune mediation–migraine axis.” We hypothesize that lactylation-related genes contribute to migraine susceptibility by regulating metabolic pathways and immune cell functions. Specifically, we aim to investigate the causal relationship between lactylation modifications and migraine, with an emphasis on identifying how immune cells mediate these genetic effects.

Given the multifactorial nature of migraine and the complexity of its underlying biological processes, omics technologies—including genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics—have emerged as powerful tools for unraveling disease mechanisms and identifying therapeutic targets [21]. In this study, we applied an integrative multi-omics framework combining Mendelian randomization (MR), summary-data-based MR (SMR), and Bayesian colocalization analyses to evaluate the causal relevance of lactylation-related genes in migraine. MR uses genetic variants to assess whether a risk factor truly causes a disease, helping to avoid common biases found in traditional observational studies, such as confounding and reverse causation [22]. SMR leverages genetic variants from large-scale genome-wide association studies (GWAS) and molecular quantitative trait loci (QTLs), including DNA methylation (mQTL), expression (eQTL), and protein abundance (pQTL), to systematically assess how lactylation-associated molecular features influence migraine risk [23, 24]. Furthermore, we employed MR-based mediation analyses using immune cell QTL data to explore whether specific immune cell subsets mediate the effects of lactylation-related genes on migraine susceptibility.

To complement these genetic findings with cell-type–specific resolution, we analyzed publicly available single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) data (GSE269117) from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) of migraine patients and healthy controls [25]. This analysis enabled the identification of immune cell subpopulations differentially expressing key lactylation-related genes, offering direct insight into the cellular contexts in which lactylation may influence migraine pathogenesis.

Together, this study represents one of the first comprehensive efforts to delineate a “lactylation–immune mediation–migraine axis,” integrating genetic, epigenetic, and transcriptomic data. By uncovering causal molecular drivers and their immune cell intermediaries, we provide novel insights into migraine biology and highlight potential targets for precision therapies aimed at restoring metabolic and immune balance in migraine patients.

Methods

Research purpose and design

This study aimed to elucidate the potential role of lactylation modification in the pathogenesis of migraine and to further investigate whether immune cells mediate this association. Genetic variants associated with lactylation-related genes at DNA methylation, gene expression, and protein abundance levels were extracted and used as instrumental variables (genetic proxies for exposure). Two-sample MR and SMR analyses were conducted using these instrumental variables to evaluate the causal relationships between lactylation-related genes and migraine. To enhance the robustness and accuracy of causal inference, we additionally performed colocalization analyses. Subsequently, we integrated the findings from methylation, expression, and protein abundance data to perform mediation analyses involving immune cells. Candidate genes with consistent evidence across multiple omics layers were selected for downstream analyses, and complementary single-cell RNA-seq analysis was performed to validate their potential causal roles, thereby elucidating the role of lactylation-related genes in migraine pathogenesis through immune cell-mediated mechanisms. Importantly, there was no sample overlap between exposure and outcome datasets, effectively minimizing the influence of confounding factors and bias (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Schematic overview of the analytical workflow. Genetic instruments (P < 5×10⁻⁸) for lactylation-related genes were identified from publicly available methylation (mQTL), expression (eQTL), and protein (pQTL) quantitative trait loci datasets following functional normalization and quality control. Two-sample Mendelian randomization (MR) analyses were conducted using inverse-variance weighted (IVW), MR-Egger regression, weighted median, and MR-PRESSO methods. Sensitivity analyses were performed to assess the robustness and consistency of causal estimates. Summary-data-based Mendelian randomization (SMR) results were evaluated using the HEIDI test and colocalization analysis, with PPH4 > 0.60 indicating evidence for a shared causal variant. Genes with consistent associations across at least two omics layers were prioritized for immune cell mediation analysis using GWAS summary statistics of 731 immune phenotypes. Finally, single-cell RNA sequencing was conducted to examine cell-type–specific expression of candidate genes in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from migraine patients and healthy controls. Abbreviations: mQTL, methylation quantitative trait loci; eQTL, expression quantitative trait loci; pQTL, protein quantitative trait loci; GWAS, genome-wide association study; MR, Mendelian randomization; SMR, summary-data-based Mendelian randomization; HEIDI, heterogeneity in dependent instruments; PPH4, posterior probability for a shared causal variant; PBMCs, peripheral blood mononuclear cells

Causal inference

Data sources for lactylation-related genes and QTLs for DNA methylation, gene expression, and protein abundance

Lactylation-related genes analyzed in this study were initially identified through comprehensive literature review and database mining. These candidate genes were subsequently matched with existing genetic datasets of methylation quantitative trait loci, expression quantitative trait loci, and protein quantitative trait loci. Only genes overlapping with mQTL, eQTL, or pQTL datasets were selected for subsequent analyses [26–28].

QTLs provide essential insights into the associations between single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and molecular phenotypes, including DNA methylation, gene expression, and protein abundance. In this study, mQTL data were obtained from the comprehensive meta-analysis conducted by Min et al., which analyzed DNA methylation in a total of 32,851 participants across 36 diverse populations and disease cohorts. To standardize methylation probe data, functional normalization was performed, adjusting for technical and biological covariates, including array type, sex, age, smoking status, cell counts, genetic principal components, and non-genetic principal components of DNA methylation [29].

eQTL data were acquired from the eQTLGen Consortium, encompassing cis-eQTL analyses based on transcriptomic data from peripheral blood samples of 31,684 individuals. Cis-eQTLs were defined as SNP-gene pairs within a distance of less than 1000 kb from the transcription start site, and associations were required to be tested in at least two independent cohorts. In total, this dataset includes cis-eQTL associations for 19,250 genes expressed in blood [30].

Summary-level genetic association data for circulating protein levels were retrieved from the UK Biobank Pharma Proteomics Project (UKB-PPP). This large-scale collaboration between the UK Biobank and 13 biopharmaceutical companies systematically characterized the plasma proteome of 54,219 UK Biobank participants. pQTL analyses were performed for 2,923 plasma proteins, resulting in the identification of 14,287 significant genetic associations [31].

Source of outcome data

Outcome data for migraine were obtained from publicly available GWAS from the FinnGen consortium and GWAS Catalog, with all participants being of European ancestry. The FinnGen dataset was used as the discovery dataset, comprising 55,116 migraine cases and 445,232 controls. Migraine cases were defined based on hospital discharge or cause-of-death diagnoses coded under ICD-10 G43 and/or prescriptions for triptans [32]. The GWAS Catalog dataset (study accession: GCST90000016) served as the replication dataset, including 26,052 migraine cases and 487,214 controls. Migraine cases in this dataset were identified based on migraine-specific prescriptions and diagnostic codes according to the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9: 346.XX) and Tenth Revision (ICD-10: G43). Cases were further classified as individuals with a Migraine Probability Algorithm (MPA) score greater than 10, indicating a high probability of migraine diagnosis. Controls included individuals without evidence of any headache disorder, those without migraine diagnoses, and those with an MPA score of exactly 10 [33].

Source of immune cell data

Immune cell-related phenotype data comprised a total of 731 distinct phenotypes categorized into four groups: median fluorescence intensity (MFI; n = 389), absolute cell counts (AC; n = 118), relative cell counts (RC; n = 192), and morphological parameters (MP; n = 32). The MFI, AC, and RC categories encompassed phenotypes associated with various immune cell populations, including bone marrow cells, B cells, mature T cells, monocytes, TBNK cells (T cells, B cells, and natural killer cells), and regulatory T (Treg) cell subsets. Morphological parameters pertained specifically to cell types within the CDC and TBNK groups. Initial GWAS analyzing these immune traits were performed in 3,757 individuals of European ancestry, ensuring no overlap between cohorts [34]. To enhance the accuracy and coverage of genotype data, approximately 22 million SNPs were imputed using a Sardinian-based sequencing reference panel [35]. Associations were further adjusted for potential confounding factors, including sex, age, and age squared.

Summary-data-based Mendelian randomization analysis

To identify potential upstream regulatory pathways involving lactylation-related genes in migraine pathogenesis, we conducted SMR analyses by integrating mQTL and eQTL data with migraine GWAS outcomes. SMR leverages summary-level statistics from both exposure and outcome GWAS datasets to assess the putative causal relationships between molecular traits (gene expression or DNA methylation) and disease risk. Compared to conventional two-sample Mendelian randomization approaches, SMR provides significant advantages by utilizing publicly available large-scale GWAS and QTL summary statistics without requiring individual-level data. This approach substantially enhances data accessibility and statistical efficiency. Moreover, SMR, when combined with the heterogeneity in dependent instruments (HEIDI) test, can effectively differentiate causal relationships from pleiotropic associations, thus yielding more reliable causal inference results, especially for complex diseases [23, 24].

The core procedure in the SMR analysis involved selecting the strongest cis-acting QTL (cis-QTL) for each target gene to ensure robustness of the findings. Specifically, cis-QTL variants were identified within a ± 1000 kb window surrounding the target gene. Only variants exhibiting genome-wide significant associations (P < 5.0 × 10^-8) were retained for subsequent analysis. To avoid biases arising from allele frequency discrepancies across datasets, we excluded SNPs exhibiting allele frequency differences greater than 0.2 between reference datasets. This stringent criterion was uniformly applied to linkage disequilibrium (LD) reference panels, eQTL summary statistics, and GWAS summary statistics datasets [23].

Furthermore, to discriminate between causal relationships and pleiotropy driven by linkage disequilibrium, we employed the HEIDI test. Associations were considered influenced by pleiotropy and excluded from further analyses if the HEIDI test produced a P-value (P_HEIDI) less than 0.01. SMR and HEIDI analyses were conducted using SMR software (version 1.3.1). Ultimately, only those associations that reached SMR significance (P < 0.05) and passed the HEIDI test (P_HEIDI > 0.01) were retained for subsequent colocalization analyses [23, 24].

Colocalization analysis

We conducted colocalization analyses to evaluate whether lactylation-related mQTLs or eQTLs share causal genetic variants with migraine susceptibility [36]. The analysis was performed using the R package coloc, which assesses five distinct hypotheses using posterior probabilities (PPH): 1) PPH0: No association with either trait. 2)PPH1: Association with gene expression only. 3) PPH2: Association with disease risk (migraine) only. 4) PPH3: Association with both traits but driven by distinct causal variants. 5) PPH4: Association with both traits driven by a shared causal variant. A posterior probability (PPH4) greater than 60% indicates robust evidence that the observed associations for gene expression (or methylation) and disease susceptibility are likely driven by the same causal variant within the tested genomic region [37]. The analysis was restricted to SNPs located within a ± 1000 kb window around the transcription start and end positions of each target gene to maintain precision and biological relevance. The primary objective of this approach was to determine whether shared genetic variants underlie both molecular traits and migraine susceptibility, thereby clarifying their potential causal relationships [38].

Two-sample Mendelian randomization results

To identify potential downstream regulatory pathways involving lactylation-related genes in migraine pathogenesis and to validate the findings from the SMR analyses, we performed two-sample MR analyses using eQTL, pQTL and migraine GWAS data. Genetic variants significantly associated with the exposure phenotype (P-value < 5.0 × 10⁻⁸) were selected from GWAS as IVs. These SNPs were clumped based on LD, applying an LD threshold of r² < 0.001 within a genomic window of 10,000 kb, using the European reference panel from the 1000 Genomes Project [39]. Proxy SNPs were used when direct exposure SNPs were not available in the outcome dataset. To ensure clarity and accuracy, palindromic and ambiguous SNPs were excluded. The strength and validity of instrumental variables were evaluated using the F-statistic, calculated as the squared ratio of SNP effect estimate to its standard error; SNPs with an F-statistic < 10, indicating weak instruments, were removed from further analyses.

All statistical analyses were conducted using R software (version 4.3.2) and the packages TwoSampleMR, MendelianRandomization, and MR-PRESSO [40–42]. The primary MR analyses employed the inverse-variance weighted (IVW) method, combining Wald ratios weighted by the inverse of the variance of the SNP-outcome associations. Specifically, IVW estimates are derived using the regression coefficients of SNPs associated with exposure (β_XZ) and outcome (β_YZ) [43]. To complement IVW results and strengthen causal inference, several sensitivity analyses were conducted using alternative MR methods, including MR-Egger regression, weighted median, simple mode, weighted mode, and MR-PRESSO.

MR-Egger analysis adds an intercept term to the regression, allowing for the assessment of horizontal pleiotropy [44]. The weighted median method provides reliable causal estimates even when up to 50% of instruments are invalid due to pleiotropy. MR-PRESSO incorporates three critical functions: detection of horizontal pleiotropy, correction of pleiotropic bias through removal of outliers, and comparison of causal estimates before and after correction [42]. The MR-PRESSO outlier test depends on the Instrument Strength Independent of Direct Effect (InSIDE) assumption, requiring that pleiotropic effects be independent of SNP-exposure effects, and that at least 50% of genetic instruments are valid [42, 45–47].

To further ensure robustness of the results, additional sensitivity analyses were performed. Cochran’s Q test was applied to evaluate heterogeneity in both IVW and MR-Egger analyses; a P-value < 0.05 was considered indicative of significant heterogeneity (30). Additionally, leave-one-out (LOO) analysis was conducted to detect influential SNPs, assessing the stability of causal estimates by sequentially excluding individual instruments [41, 43, 48].

Assessment of immune-mediated mechanisms

To investigate whether immune cells mediate the causal pathways linking lactylation-related genes to migraine susceptibility, we integrated genetic data from 731 immune cell-related phenotypes and implemented a MR framework for mediation analysis. Specifically, we employed an advanced analytical approach capable of decomposing the total causal effect into indirect (mediated via immune cells) and direct (immune cell-independent) components [49]. Lactylation-associated genes identified through the MR analyses and significantly associated immune cell traits were structured into explicit “exposure–mediator–outcome” causal paths. We then applied a two-step MR approach to quantify these mediation effects and calculated mediation proportions to assess the relative contribution of immune cells to the total causal effect.

More explicitly, the causal effect of lactylation-related genes on migraine risk was partitioned into: (1) a direct effect independent of immune cells (pathway C in Fig. 2A), and (2) an indirect effect mediated through immune cells (pathway A×B in Fig. 2B). By comparing the magnitude of indirect effects relative to total effects, we calculated mediation effects as a percentage of the total causal association. Furthermore, 95% CI for the mediation effects were precisely estimated using the delta method, enhancing the statistical rigor and robustness of our findings [50].

Fig. 2.

Conceptual framework for evaluating immune-mediated pathways linking lactylation-related genes to migraine risk. A The total causal effect of lactylation-related genes on migraine (path c) was estimated using Mendelian randomization (MR). Reverse causality (path d) was assessed in sensitivity analyses. B A two-step MR-based mediation model was implemented to partition the total effect into an indirect effect through immune cell traits (paths a and b) and a direct effect independent of immune mediation (path c). Note: Path c in panel (A) represents the total effect, while in panel (B) it denotes the direct effect independent of immune mediation. Abbreviations: MR, Mendelian randomization

Single-cell RNA sequencing analysis

Single-cell RNA-sequencing data were obtained from the GEO database (accession GSE269117), comprising peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) samples from five migraine patients and six healthy controls [25]. Raw 10× Genomics sequencing data were processed with Cell Ranger to generate gene-by-cell count matrices. Downstream analyses were performed in R (v4.3.2) using the Seurat package (v4.3.0) [51, 52].

First, we applied quality-control filters to remove low-quality cells, retaining only those with ≥ 200 detected genes and ≤ 5% mitochondrial gene content. Filtered counts were log-normalized, and the top 1,500 highly variable genes were selected for further analysis. To correct for batch effects across samples, we identified integration anchors using FindIntegrationAnchors and integrated the datasets with IntegrateData. The integrated dataset was scaled and subjected to principal component analysis (PCA); the number of significant PCs was determined by the JackStraw test and elbow plot, from which the top 30 PCs were retained [53]. Graph-based clustering was performed using the shared nearest neighbor (SNN) algorithm and the Louvain method at a resolution of 0.5. Two-dimensional visualization was achieved via t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE). Cell type annotation was automated with SingleR, using the MonacoImmuneData reference from the Celldex package, and annotations were manually curated at the cluster level [54]. For differential expression analysis between migraine and control groups, cells were grouped by combined cell-type and disease-status labels. We identified marker genes with|log₂ fold change| > 1 and a false discovery rate–adjusted P-value < 0.05. Finally, expression patterns of candidate lactylation-related genes were compared and visualized across annotated cell types and disease conditions.

Results

Summary-based Mendelian randomization results

Using the Finnish cohort as the outcome dataset, we performed SMR on lactylation-related gene methylation and migraine. After excluding associations with evidence of heterogeneity (P_HEIDI < 0.01), 13 CpG sites near 8 unique genes reached nominal significance (P < 0.05), all supported by strong colocalization (PPH4 > 0.60). Notably, effect directions varied among CpG sites within the same gene. For example, in AARS2, methylation at cg05917988 increased migraine risk (OR = 1.15; 95% CI: 1.06–1.25), whereas cg00910127 decreased risk (OR = 0.91; 95% CI: 0.85–0.97). Similarly, in SIRT1, cg00972288 was positively associated with migraine (OR = 1.04; 95% CI: 1.01–1.06), while cg23988827 and cg03211233 were inversely associated (OR = 0.91; 95% CI: 0.85–0.97; OR = 0.92; 95% CI: 0.87–0.98). In the replication cohort, six CpG sites near four genes reached nominal significance (P < 0.05) after P_HEIDI filtering and exhibited robust colocalization (PPH4 > 0.60). Notably, EP300 (cg20730595) and SIRT1 (cg00972288, cg23988827, cg03211233) methylation signals were successfully replicated (Fig. 3, Supplementary Tables S2 and S3).

Fig. 3.

SMR and colocalization results for CpG methylation sites associated with migraine. Summary-data-based Mendelian randomization (SMR) and colocalization analysis of DNA methylation (CpG sites) in relation to migraine risk. A Results from the primary analysis using the FinnGen cohort as the outcome dataset. B Replication results from the GWAS Catalog dataset (GCST90000016). Each dot represents an SMR association between a CpG probe and migraine risk. Horizontal lines denote 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Only associations passing the HEIDI test (P_HEIDI > 0.01) and showing strong colocalization (PPH4 > 0.60) are shown. Abbreviations: SMR, summary-data-based Mendelian randomization; PPH4, posterior probability for a shared causal variant; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval

In SMR analyses of gene expression and migraine within the Finnish cohort, six genes—EP300, HDAC3, SIRT1, AARS2, SLC16A1, and SMARCA4—showed nominally significant associations (P < 0.05). Among these, EP300 and HDAC3 also demonstrated strong colocalization support (PPH4 > 0.60). In the replication dataset, only EP300 and SIRT1 remained positive, each with significant colocalization evidence (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Tables S4-1 and S4-2).

Fig. 4.

SMR colocalisation of lactylation-related gene expression with migraine. Forest plots display odds ratios (OR) and 95 % confidence intervals (CI) from summary-data-based Mendelian randomisation (SMR) using cis-eQTL instruments. A Primary analysis using gene expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) and migraine GWAS data from the FinnGen cohort. B Replication results using the GWAS Catalog dataset (GCST90000016). Only genes with nominal significance (P < 0.05) are shown. Horizontal bars represent 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for odds ratios (ORs). Genes with strong colocalization support (PPH4 > 0.60) are considered to have evidence of shared causal variants. Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; eQTL, expression quantitative-trait locus; OR, odds ratio; PPH4, posterior probability of shared causal variant; SMR, summary-data-based Mendelian randomisation

Two sample Mendelian randomisation results

In the Finnish cohort, two-sample MR of eQTL-derived lactylation gene expression identified EP300, SIRT1, and SLC16A1 as significantly associated with migraine risk. A one–standard-deviation (1-SD) increase in EP300 expression corresponded to an 11.6% higher migraine risk (OR = 1.116; 95% CI: 1.070–1.165; P = 3.46 × 10⁻⁷). In contrast, a 1-SD increase in SIRT1 expression was protective, reducing risk by 3.4% (OR = 0.966; 95% CI: 0.948–0.983; P = 1.52 × 10⁻⁴). SLC16A1 showed a borderline positive association (OR = 1.077; 95% CI: 1.000–1.160; P = 0.049), consistent in direction with SMR eQTL findings. All three associations replicated in the independent validation cohort with consistent effect estimates. Heterogeneity was detected for EP300 and SIRT1 in the primary cohort (Cochran’s Q P = 0.01 and 0.02, respectively), though MR-PRESSO found no evidence of horizontal pleiotropy. In the validation cohort, SIRT1 exhibited both heterogeneity (P = 0.006) and horizontal pleiotropy (MR-PRESSO Global Test P = 0.004; MR-Egger intercept P = 0.01), whereas EP300 and SLC16A1 remained free of heterogeneity and pleiotropy (Fig. 5 and Supplementary Tables S5-1 and S5-2).

Fig. 5.

Two-sample MR analysis of lactylation-related gene expression and migraine risk. Forest plots displaying inverse-variance weighted Mendelian randomization (IVW-MR) estimates for the association between genetically predicted expression of EP300, SIRT1, and SLC16A1 and migraine risk. A Primary analysis using eQTL exposure data and migraine GWAS summary statistics from the FinnGen cohort. B Replication analysis using an independent GWAS dataset (GCST90000016). The inverse-variance weighted (IVW) method was used to estimate causal effects. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) represent the effect of a one–standard-deviation increase in gene expression on migraine risk. All shown associations reached nominal significance (P < 0.05). Abbreviations: MR, Mendelian randomization; IVW, inverse-variance weighted; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; eQTL, expression quantitative trait loci; GWAS, genome-wide association study

Protein-MR analysis in the Finnish cohort revealed only SIRT1 protein abundance as significantly protective. Each 1-SD increase in SIRT1 plasma level was associated with a 46.2% reduction in migraine risk (OR = 0.538; 95% CI: 0.512–0.565; P = 5.13 × 10⁻¹³⁸). This protective effect was similarly observed in the replication dataset. In the sensitivity analysis, the FinnGen cohort showed significant evidence of horizontal pleiotropy for SIRT1 (MR-Egger intercept p = 0.00049), whereas no heterogeneity was detected. However, no significant findings were observed in the replication dataset (Supplementary Tables S6-1 and S6-2).

Mediation analysis

Using the Finnish cohort as the outcome dataset, our MR analysis identified 39 immune cell traits positively associated with increased migraine risk, including Treg cells (n = 14), B cells (n = 9), myeloid cells (n = 7), maturation-stage T cells (n = 5), TBNK cells (n = 2), and monocytes and cDCs (n = 1 each). Conversely, 9 traits were inversely associated with migraine risk, involving maturation-stage T cells (n = 4), TBNK cells (n = 3), and B cells and myeloid cells (n = 1 each). In the replication dataset, 8 immune traits were linked to increased migraine risk, mainly involving TBNK cells (n = 6) and B cells (n = 2). Nine traits were associated with reduced risk, including B cells (n = 6), cDCs (n = 3), and monocytes, TBNK cells, and maturation-stage T cells (n = 1 each) (Fig. 6; Table 1 and Supplementary Tables S7 and S8).

Fig. 6.

Forest plot of Mendelian randomization associations between immune cell traits and migraine risk. Forest plot displaying representative 21 immune cell traits with significant associations with migraine risk (P < 0.05) based on inverse-variance weighted (IVW) Mendelian randomization analysis. Traits were selected from a panel of 731 immune phenotypes and include markers from B cells, TBNK cells, conventional dendritic cells (cDCs), monocytes, and maturation-stage T cells. Each point estimate represents the odds ratio (OR) per genetically predicted increase in the immune trait, with 95% confidence intervals shown. Abbreviations: MR, Mendelian randomization; IVW, inverse-variance weighted; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; AC, absolute count; cDC, conventional dendritic cell; TBNK, T, B, and NK cells; EM, effector memory; TD, terminally differentiated

Table 1.

The results of forward MR analysis between immune cells and migraine (FinnGen)

| Exposure | method | nsnp | b | se | pval | or | or_lci95 | or_uci95 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD45RA + CD8br %CD8br | Inverse variance weighted | 12 | -0.009 | 0.004 | 0.0309 | 0.991 | 0.982 | 0.999 |

| CD4 + CD8dim AC | Inverse variance weighted | 9 | -0.039 | 0.013 | 0.0037 | 0.962 | 0.937 | 0.987 |

| CD8br NKT AC | Inverse variance weighted | 3 | -0.086 | 0.033 | 0.0096 | 0.917 | 0.859 | 0.979 |

| CD28- DN (CD4-CD8-) AC | Inverse variance weighted | 3 | 0.066 | 0.025 | 0.0086 | 1.068 | 1.017 | 1.122 |

| CD20 on IgD + CD38- | Inverse variance weighted | 5 | 0.061 | 0.022 | 0.0055 | 1.063 | 1.018 | 1.110 |

| CD24 on transitional | Inverse variance weighted | 4 | -0.057 | 0.022 | 0.0101 | 0.944 | 0.904 | 0.986 |

| CD27 on CD24 + CD27+ | Inverse variance weighted | 34 | 0.020 | 0.006 | 0.0024 | 1.020 | 1.007 | 1.033 |

| CD27 on IgD + CD24+ | Inverse variance weighted | 20 | 0.023 | 0.008 | 0.0034 | 1.024 | 1.008 | 1.040 |

| CD27 on IgD + CD38- unsw mem | Inverse variance weighted | 16 | 0.024 | 0.007 | 0.0006 | 1.024 | 1.010 | 1.038 |

| CD27 on IgD- CD38- | Inverse variance weighted | 24 | 0.022 | 0.008 | 0.0067 | 1.022 | 1.006 | 1.038 |

| CD27 on IgD- CD38dim | Inverse variance weighted | 31 | 0.016 | 0.007 | 0.0153 | 1.016 | 1.003 | 1.029 |

| CD27 on memory B cell | Inverse variance weighted | 24 | 0.030 | 0.008 | 0.0001 | 1.030 | 1.015 | 1.046 |

| CD27 on unsw mem | Inverse variance weighted | 26 | 0.025 | 0.008 | 0.0010 | 1.025 | 1.010 | 1.041 |

| CD27 on sw mem | Inverse variance weighted | 33 | 0.019 | 0.006 | 0.0024 | 1.019 | 1.007 | 1.032 |

| CD3 on EM CD8br | Inverse variance weighted | 9 | 0.047 | 0.014 | 0.0010 | 1.049 | 1.019 | 1.079 |

| CD3 on EM CD4+ | Inverse variance weighted | 15 | 0.030 | 0.010 | 0.0014 | 1.031 | 1.012 | 1.050 |

| CD3 on TD CD4+ | Inverse variance weighted | 3 | 0.072 | 0.028 | 0.0098 | 1.074 | 1.017 | 1.135 |

| CD3 on CD45RA- CD4+ | Inverse variance weighted | 21 | 0.020 | 0.010 | 0.0424 | 1.020 | 1.001 | 1.039 |

| CD3 on CM CD8br | Inverse variance weighted | 17 | 0.026 | 0.012 | 0.0326 | 1.027 | 1.002 | 1.052 |

| CD3 on HLA DR + CD4+ | Inverse variance weighted | 10 | 0.044 | 0.012 | 0.0002 | 1.045 | 1.021 | 1.070 |

| CD3 on HLA DR + CD8br | Inverse variance weighted | 4 | 0.044 | 0.022 | 0.0401 | 1.045 | 1.002 | 1.090 |

| CD3 on CD39 + resting Treg | Inverse variance weighted | 4 | 0.054 | 0.020 | 0.0066 | 1.055 | 1.015 | 1.097 |

| CD3 on activated Treg | Inverse variance weighted | 31 | 0.015 | 0.006 | 0.0212 | 1.015 | 1.002 | 1.028 |

| CD3 on CD39 + activated Treg | Inverse variance weighted | 22 | 0.017 | 0.007 | 0.0099 | 1.018 | 1.004 | 1.031 |

| CD3 on CD39 + secreting Treg | Inverse variance weighted | 19 | 0.018 | 0.009 | 0.0430 | 1.018 | 1.001 | 1.036 |

| CD3 on activated & secreting Treg | Inverse variance weighted | 31 | 0.014 | 0.006 | 0.0227 | 1.014 | 1.002 | 1.027 |

| CD3 on CD8br | Inverse variance weighted | 18 | 0.023 | 0.010 | 0.0247 | 1.023 | 1.003 | 1.044 |

| CD3 on CD39 + CD4+ | Inverse variance weighted | 29 | 0.015 | 0.006 | 0.0130 | 1.016 | 1.003 | 1.028 |

| CD3 on CD28 + CD4+ | Inverse variance weighted | 17 | 0.023 | 0.010 | 0.0283 | 1.023 | 1.002 | 1.044 |

| CD3 on CD28 + CD45RA- CD8br | Inverse variance weighted | 21 | 0.024 | 0.010 | 0.0191 | 1.024 | 1.004 | 1.044 |

| CD3 on CD28 + CD45RA + CD8br | Inverse variance weighted | 28 | 0.018 | 0.007 | 0.0155 | 1.018 | 1.003 | 1.033 |

| CD3 on CD39 + CD8br | Inverse variance weighted | 9 | 0.046 | 0.014 | 0.0015 | 1.047 | 1.018 | 1.077 |

| CD3 on CD4 Treg | Inverse variance weighted | 34 | 0.015 | 0.006 | 0.0137 | 1.015 | 1.003 | 1.027 |

| CD3 on resting Treg | Inverse variance weighted | 36 | 0.014 | 0.006 | 0.0249 | 1.014 | 1.002 | 1.026 |

| HVEM on naive CD8br | Inverse variance weighted | 4 | -0.040 | 0.020 | 0.0490 | 0.961 | 0.924 | 1.000 |

| CCR7 on naive CD8br | Inverse variance weighted | 3 | -0.051 | 0.024 | 0.0354 | 0.950 | 0.906 | 0.997 |

| CD33 on CD33br HLA DR + CD14dim | Inverse variance weighted | 37 | 0.008 | 0.004 | 0.0374 | 1.008 | 1.000 | 1.016 |

| CD33 on CD33dim HLA DR + CD11b+ | Inverse variance weighted | 44 | 0.009 | 0.003 | 0.0098 | 1.009 | 1.002 | 1.016 |

| CD33 on CD33dim HLA DR + CD11b- | Inverse variance weighted | 46 | 0.010 | 0.004 | 0.0090 | 1.010 | 1.002 | 1.017 |

| CD33 on CD66b + + myeloid cell | Inverse variance weighted | 21 | 0.011 | 0.005 | 0.0181 | 1.012 | 1.002 | 1.021 |

| CD33 on Mo MDSC | Inverse variance weighted | 31 | 0.010 | 0.004 | 0.0104 | 1.010 | 1.002 | 1.018 |

| CD33 on CD33br HLA DR+ | Inverse variance weighted | 38 | 0.010 | 0.004 | 0.0073 | 1.010 | 1.003 | 1.017 |

| CD33 on CD33br HLA DR + CD14- | Inverse variance weighted | 38 | 0.010 | 0.004 | 0.0085 | 1.010 | 1.002 | 1.017 |

| CD4 on HLA DR + CD4+ | Inverse variance weighted | 4 | -0.042 | 0.020 | 0.0417 | 0.959 | 0.921 | 0.998 |

| FSC-A on plasmacytoid DC | Inverse variance weighted | 7 | 0.056 | 0.018 | 0.0016 | 1.058 | 1.021 | 1.095 |

| CX3CR1 on CD14- CD16- | Inverse variance weighted | 14 | 0.030 | 0.012 | 0.0164 | 1.030 | 1.005 | 1.055 |

| CD4 on naive CD4+ | Inverse variance weighted | 9 | -0.032 | 0.014 | 0.0208 | 0.969 | 0.943 | 0.995 |

| CD11b on CD14 + monocyte | Inverse variance weighted | 4 | -0.017 | 0.008 | 0.0412 | 0.983 | 0.967 | 0.999 |

To ensure analytical rigor and consistency, we carefully selected candidate genes for mediation analysis. Only genes that demonstrated statistical significance across multiple omics layers (i.e., DNA methylation, gene expression, and protein abundance) and showed consistent associations in both SMR and MR analyses were included. Notably, SLC16A1 exhibited significant associations with migraine across all three molecular levels in the Finnish dataset. In addition, EP300 and SIRT1 showed consistent associations with migraine at the DNA methylation and gene expression levels in both the primary and replication cohorts. Based on these criteria, and in conjunction with MR results linking immune cells to migraine risk, we evaluated the potential mediating role of immune cells.

Using SMR results as input, we observed that EP300 exerted indirect effects on migraine risk through multiple immune cell subsets in the Finnish cohort, with similar patterns replicated in the validation cohort. Among these, CD8br NKT AC (TBNK, TB_Trait548) emerged as the dominant mediator, accounting for 14.4% of the total effect. Other notable mediators included CD24 on transitional B cells (Bcells.trait451, 5.4%), CD27 on IgD⁺ CD38⁻ unswitched memory B cells (Bcells.trait563, 4.0%), and CX3CR1 on CD14⁻ CD16⁻ monocytes (mono. trait3, 2.8%). Beyond EP300, SIRT1 also showed partial immune-mediated effects, with CD27 on IgD⁺ CD24⁺ B cells (Bcells.trait561) mediating 6.8% of the total effect. SLC16A1 contributed to migraine risk via CD27 on IgD⁻ CD38^dim B cells (Bcells.trait567, 3.7%) and CD27 on switched memory B cells (Bcells.trait574, 4.4%). In the replication dataset, EP300 also mediated migraine risk via CD20 on transitional B cells (Bcells.trait401), with an indirect effect accounting for 7.9% of the total effect, further supporting the findings in the primary cohort (Table 2).

Table 2.

Mediation analysis of lactylation-related genes on migraine risk via immune cell traits using SMR and MR approaches

| lactylation-related gene | Analysis method | Source of outcome | Mediated immune cells | Total effect beta | Direct effect a | Direct effect b | Mediation effect | Mediated Proportion (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EP300 | SMR | Finngen | CD8br NKT AC | 0.147 | -0.244 | -0.086 | 0.021 | 0.144 |

| EP300 | SMR | Finngen | CD24 on transitional | 0.147 | -0.138 | -0.057 | 0.008 | 0.054 |

| EP300 | SMR | Finngen | CD27 on IgD + CD38- unsw mem | 0.147 | 0.248 | 0.024 | 0.006 | 0.040 |

| EP300 | SMR | Finngen | CX3CR1 on CD14- CD16- | 0.147 | 0.140 | 0.030 | 0.004 | 0.028 |

| EP300 | SMR | GCST90000016 | CD20 on transitional | 0.133 | -0.154 | -0.068 | 0.011 | 0.079 |

| SIRT1 | SMR | Finngen | CD27 on IgD + CD24+ | -0.025 | -0.072 | 0.023 | -0.002 | 0.068 |

| SLC16A1 | SMR | Finngen | CD27 on IgD- CD38dim | 0.114 | 0.268 | 0.016 | 0.004 | 0.037 |

| SLC16A1 | SMR | Finngen | CD27 on sw mem | 0.114 | 0.264 | 0.019 | 0.005 | 0.044 |

| EP300 | MR | Finngen | CD8br NKT AC | 0.110 | -0.244 | -0.086 | 0.021 | 0.191 |

| EP300 | MR | Finngen | CD24 on transitional | 0.110 | -0.138 | -0.057 | 0.008 | 0.072 |

| EP300 | MR | Finngen | CD27 on IgD + CD38- unsw mem | 0.110 | 0.248 | 0.024 | 0.006 | 0.054 |

| EP300 | MR | Finngen | CX3CR1 on CD14- CD16- | 0.110 | 0.140 | 0.030 | 0.004 | 0.038 |

| EP300 | MR | GCST90000016 | CD20 on transitional | 0.086 | -0.154 | -0.068 | 0.011 | 0.123 |

| SLC16A1 | MR | Finngen | CD27 on IgD- CD38dim | 0.074 | 0.268 | 0.016 | 0.004 | 0.057 |

| SLC16A1 | MR | Finngen | CD27 on sw mem | 0.074 | 0.264 | 0.019 | 0.005 | 0.067 |

| SLC16A1 | MR | GCST90000016 | BAFF-R on CD20- CD38- | 0.110 | -0.294 | -0.052 | 0.015 | 0.140 |

| SLC16A1 | MR | GCST90000016 | CD16-CD56 on HLA DR + NK | 0.110 | 0.297 | 0.092 | 0.027 | 0.248 |

| SIRT1 | MR | Finngen | CD27 on IgD + CD24+ | 0.110 | -0.072 | 0.023 | -0.002 | -0.015 |

Consistent mediation patterns were observed when MR-derived associations were used. In the Finnish cohort, EP300 primarily exerted its genetic effect through CD8br NKT AC (TB_Trait548), which mediated 19.1% of the total effect. B cell subsets also contributed, including CD24 on transitional B cells (Bcells.trait451, 7.2%) and CD27 on IgD⁺ CD38⁻ unswitched memory B cells (Bcells.trait563, 5.4%). CX3CR1 on CD14⁻ CD16⁻ monocytes (mono. trait3) showed a mediation effect of 3.8%. In the replication dataset, CD20 on transitional B cells (Bcells.trait401) mediated 12.3% of EP300’s effect on migraine risk, confirming the consistency of this pathway. SLC16A1 also demonstrated reproducible mediation through B cell subsets. In the Finnish cohort, CD27 on IgD⁻ CD38^dim B cells (Bcells.trait567) and CD27 on switched memory B cells (Bcells.trait574) mediated 5.7% and 6.7% of the total effect, respectively. In contrast, the replication cohort revealed a distinct mediation profile, with BAFF-R on CD20⁻ CD38⁻ B cells (Bcells.trait111) mediating 14.0%, and CD16⁻CD56⁺ on HLA-DR⁺ NK cells (TBNK, Blue.585.42. TBNK.trait3) mediating a more substantial 24.8% of the total effect (Table 2).

All mediation analyses were free of horizontal pleiotropy and heterogeneity, with the exception of the MR-based association between SIRT1 and CD27 on IgD⁺ CD24⁺ B cells (Bcells.trait561), which showed evidence of horizontal pleiotropy (P = 0.011).

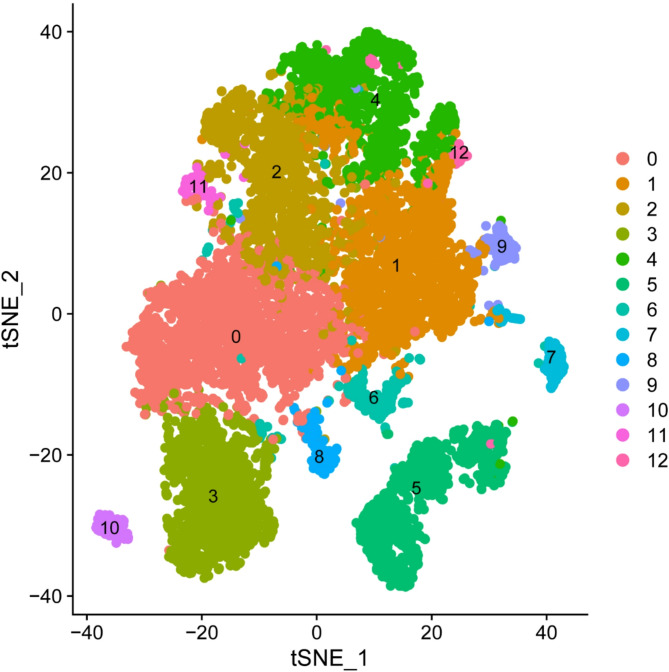

Single cell analysis

After stringent quality control, we retained PBMC profiles from three migraine patients (GSM8306600, GSM8306606, GSM8306608) and two healthy controls (GSM8306597, GSM8306613). t-SNE visualization of 13 consensus clusters revealed five major immune populations: T cells, CD4⁺ T cells, natural killer (NK) cells, B cells, and monocytes (Figs. 7 and 8).

Fig. 7.

t-SNE projection of unsupervised PBMC clusters. Single-cell transcriptomes from three migraine patients and two healthy controls were integrated and clustered with the Seurat shared-nearest-neighbor algorithm, yielding 13 transcriptionally distinct groups (labelled 0– 12). Each dot denotes one peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) and is coloured by its cluster identity. These clusters were subsequently used for cell-type annotation and differential expression analysis. The x- and y-axes correspond to the first and second t-SNE dimensions. Abbreviations: t-SNE, t-distributed stochastic neighbour embedding; PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cell

Fig. 8.

t-SNE projection of annotated immune cell types in peripheral blood mononuclear cells. t-SNE plot visualizes immune cell clusters derived from single-cell RNA sequencing of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) pooled from migraine patients and healthy controls. Cells are grouped by transcriptional similarity and annotated as T cells, CD4⁺ T cells, natural killer (NK) cells, B cells, and monocytes based on reference-based classification. Each dot represents one cell, colored according to its assigned identity. Cells lacking confident annotation are labeled as “NA.” The two axes correspond to the first and second t-SNE dimensions. Abbreviations: t-SNE, t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding; PBMCs, peripheral blood mononuclear cells; NK, natural killer; NA, not annotated

We then compared expression of the three candidate genes—EP300, SIRT1, and SLC16A1—between migraine and control samples at single-cell resolution. EP300 was significantly upregulated in B cells from migraine patients and also showed increased expression in the total T-cell compartment; CD4⁺ T cells exhibited a modest, non-significant upregulation. Conversely, EP300 expression was downregulated in monocytes and unchanged in NK cells. By contrast, SIRT1 and SLC16A1 displayed uniformly low expression across all five cell types, and no statistically significant differences were detected between migraine and control groups—particularly in CD4⁺ T cells, T cells, and NK cells, where transcript counts approached the detection limit (Figs. 9 and 10).

Fig. 9.

Single-cell t-SNE maps of EP300, SIRT1 and SLC16A1 expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cells. t-SNE plots depict log-normalised transcript counts for EP300, SIRT1 and SLC16A1 in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) pooled from migraine patients and healthy controls. Each dot represents one cell; colour denotes expression intensity from low (blue, 0) to high (red, ≥ 3). EP300 is detected in multiple clusters, whereas SIRT1 and SLC16A1 show uniformly low expression levels. Abbreviations: t-SNE, t-distributed stochastic neighbour embedding; PBMCs, peripheral blood mononuclear cells

Fig. 10.

Single-cell expression of EP300 in major peripheral immune cell subsets from migraine patients and healthy controls. Violin plots display log-normalized expression levels of EP300 in five immune cell types: A B cells, B T cells, C CD4+ T cells, D natural killer (NK) cells, and E monocytes. Expression data are shown separately for cells from migraine patients and healthy controls. Higher EP300 expression is observed in B cells and T cells from migraine samples, while expression in monocytes appears lower in migraine patients compared to controls. CD4+ T cells show comparable levels across groups. EP300 expression is minimal or absent in NK cells in both conditions. Abbreviations: NK, natural killer; MI, migraine

Discussion

In this study, we conducted a comprehensive, multi-omics Mendelian randomization and single-cell RNA sequencing analysis to systematically identify and functionally characterize lactylation-related genes that may contribute causally to migraine pathogenesis. Through SMR and two-sample MR analyses, we integrated methylation QTLs, expression QTLs, and protein QTLs with large-scale GWAS data on migraine. This multi-omics approach identified EP300, SIRT1, and SLC16A1 as key molecular regulators that link lactate metabolism to migraine susceptibility. These associations were replicated in independent cohorts, and were supported by consistent directionality and strong colocalization evidence. Furthermore, mediation analyses revealed that specific immune cell subsets—particularly B cells and natural killer T (NKT) cells—substantially mediated these genetic effects, pointing to a dynamic immunometabolic axis in migraine development. Single-cell transcriptomic profiling further validated these findings by confirming cell type–specific expression differences of the candidate genes across major immune populations. Building upon these findings, we propose the novel conceptual framework of a “lactylation–immune mediation–migraine axis,” in which lactate signaling and immune cell regulation jointly shape migraine risk.

EP300, SIRT1, and SLC16A1 as central molecular hubs in migraine susceptibility

Our multi-omics analysis consistently highlighted EP300, SIRT1, and SLC16A1 as genes with strong evidence of causality in migraine. In MR analyses, expression levels of all three genes were significantly associated with migraine in both the Finnish cohort and replication datasets. Notably, SIRT1 also demonstrated a protective association at the protein level. In SMR analyses, SLC16A1 showed significant associations across methylation, gene expression, and protein abundance. EP300 and SIRT1 similarly exhibited consistent effects across multiple omics layers and datasets.

The expression of EP300 showed a positive association with migraine risk. This relationship was validated through both SMR and two-sample MR approaches and reinforced by strong colocalization support.

EP300 expression was positively associated with migraine risk and this relationship was validated using both SMR and two-sample MR approaches, with strong support from colocalization analyses. Our data, supported by both Finnish GWAS and the GWAS Catalog, suggest that EP300—a histone acetyltransferase involved in lactylation—plays a key role in transcriptional regulation, mitochondrial function, inflammation, and energy metabolism [55, 56]. It has also been identified as a druggable gene with strong relevance to migraine pathogenesis [57]. Elevated EP300 expression may increase pro-inflammatory cytokine production, partly via p65 acetylation and activation of NF-κB signaling, promoting iNOS and TNF-α expression and contributing to neuroinflammation [58, 59], a core element in migraine development. Our MR findings support the involvement of EP300 in inflammatory pathways; however, the specific molecular mechanisms linking lactylation-driven epigenetic regulation to cytokine production require further experimental validation. In the context of migraine, neurovascular coupling dysfunction and blood-brain barrier permeability are well-documented physiological mechanisms [60–62], which may be exacerbated by EP300-mediated vascular dysregulation, thereby contributing to migraine pathogenesis. Furthermore, EP300 regulates pain-related genes (e.g., COX-2, P2 × 3) via acetylation of CREB and NF-κB, influences neuronal differentiation via NGF, and contributes to chronic pain sensitization [63–65]. Suppressing EP300 in dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons has been shown to mitigate stress-induced hyperalgesia [66], and its upregulation increases neuronal BDNF levels, promoting neuropathic pain [67]. The strong association between EP300 and increased migraine risk underscores its therapeutic potential, especially for patients with genetically driven inflammation.

Previous studies have shown that EP300 can promote lactylation modification. In contrast, SIRT1 negatively regulates lactylation modification, thereby antagonizing the function of EP300 [68]. Our study showed that, contrary to EP300, higher expression and protein abundance of SIRT1 were associated with a reduced risk of migraine. Transcript-level analyzes showed that each standard deviation increases in SIRT1 expression conferred a modest protective effect, while at the protein level, the protective effect was far more pronounced. Genetically predicted higher SIRT1 protein abundance was associated with an approximately 46.2% reduction in migraine risk. SIRT1 encodes an NAD⁺-dependent deacetylase critical for mitochondrial biogenesis, redox balance, and anti-inflammatory signaling [69–71]. It modulates brain lactate homeostasis and regulates oxidative stress and neuroinflammation [72–74]. Sensitization of central pain pathways—a well-established mechanism in migraine [75]—may be modulated by SIRT1 through ROS regulation, NMDA receptor signaling, and mitochondrial dynamics [76–80]. The consistency of these protective effects across omics layers and datasets reinforces the functional relevance of SIRT1 in migraine. Prior studies also indicate its ability to alleviate diverse chronic pain states, including neuropathic and cancer-related pain [79, 81–83]. Clinically, activation of SIRT1—through NAD⁺ precursors or small-molecule agonists—may serve as a promising preventive strategy, particularly for patients with mitochondrial dysfunction or chronic migraine.

SLC16A1, also known as monocarboxylate transporter 1 (MCT1), is a crucial component in the transport of lactate across cell membranes, which is vital for maintaining cellular metabolism and homeostasis [84, 85]. Lactate is an alternative fuel for the brain. SLC16A1 participates in the astrocyte-neuron-lactate shuttle in the central nervous system, promotes the uptake of lactate by neurons, and participates in the regulation of energy metabolism [86–88]. Brain energy imbalance is implicated in the chronic progression of migraine via neurovascular and neuroinflammatory changes [88, 89]. Upregulation of SLC16A1 may indicate underlying energetic deficits and lactate accumulation. Lactate not only fuels neuronal metabolism but also modulates immune function, and aberrant lactate transport may amplify neuroinflammation, particularly through promotion of glycolysis and proinflammatory microglial polarization [90–92]. In our study, higher expression of SLC16A1 was associated with increased migraine risk, suggesting that targeting lactate transport and neural energy metabolism may represent a novel therapeutic avenue for metabolically driven migraine subtypes.

Complex epigenetic regulation within lactylation-related genes

The summary-based Mendelian randomization analysis of DNA methylation revealed a complex and context-dependent pattern of epigenetic regulation among lactylation-related genes. Within individual genes such as SIRT1and AARS2, multiple CpG sites exhibited divergent effects on migraine risk, suggesting that methylation may exert its functional consequences in a site-specific manner rather than uniformly across the gene body. For example, in the SIRT1 gene, increased methylation at cg00972288 was associated with higher migraine risk, whereas cg23988827 and cg03211233 showed protective associations. A similar phenomenon was observed in the AARS2 gene, where different CpG sites exerted opposing influences on disease susceptibility.

This heterogeneity in methylation effects implies the presence of finely tuned epigenetic mechanisms that may regulate isoform-specific transcription, chromatin conformation, or cell-type specific gene expression [93, 94]. Recent evidence shows that SIRT1 mRNA stability and translation are enhanced via m6A modifications [95], and that specific methylation patterns can modulate SIRT1–p53 interactions, providing stress response protection. Our data support the concept that DNA methylation functions as a nuanced regulatory system that links cellular metabolism—including lactate flux—with migraine risk. Clinically, these methylation signatures may serve as predictive biomarkers or targets for personalized epigenetic therapies.

Immune cell subsets mediate genetic effects of lactylation-related genes

A key innovation of this study lies in its integration of immune cell mediation analysis. Using both SMR- and MR-based mediation approaches, we showed that the genetic effects of EP300, SIRT1, and SLC16A1 on migraine are significantly mediated by distinct immune cell subsets, especially B cells and NK cells.

EP300 was found to exert indirect effects through multiple immune subsets, including CD8⁺ NKT cells, unswitched memory B cells, and transitional B cells. Mechanistically, EP300 might promote H3K18 lactylation and co-activates B7-H3 transcription via CREB1, affecting T cells, γδ T cells, and NKT cells, ultimately altering the immune microenvironment [96–98]. For SIRT1, the mediation effects were primarily driven by CD27-positive unswitched memory B cells and CD24-positive transitional B cells. B cell subsets play a crucial role in the immune system, particularly in antigen presentation and cytokine regulation [99, 100]. SIRT1 is a key regulator of energy metabolism and cell survival. It can reduce autoinflammatory responses by regulating B cells, which is crucial for maintaining the balance of immune responses [101, 102]. While one analysis pathway showed horizontal pleiotropy (P = 0.011), the majority were robust and consistent across cohorts.

SLC16A1, on the other hand, demonstrated a broader spectrum of immune involvement, with its effects mediated by switched memory B cells, BAFF-R-expressing B cells, and CD56-positive NK cells. This suggests a potential interaction between metabolic signaling and adaptive immunity, where altered lactate transport influences immune cell function and ultimately contributes to the development of migraine.

The interaction between metabolic signals and adaptive immunity is a complex and challenging area of research. Lactate, as a metabolite, is not merely the end product of glycolysis but also plays a critical role in immune cell function. Studies have shown that lactate can regulate the function of immune cells by affecting their metabolic reprogramming, affecting the proliferation and function of immune cells [103]. In addition, lactate accumulation leads to acidification of the tissue microenvironment, which inhibits the function of immune effector cells, such as macrophages and natural killer cells [104].

Altered metabolic signaling may play a role in the development of migraines by affecting the function of immune cells [105]. Lactic acid, as a signaling molecule, can affect the role of immune cells in inflammation by regulating their metabolic pathways [106]. For example, lactate can induce metabolic reprogramming of immune cells, reducing glycolysis and increasing oxidative metabolism, thereby affecting the production of cytokines [107].

Taken together, these results indicate that the immune system plays an active and mechanistic role in translating lactylation-related genetic variation into disease risk. The identification of these immune mediators opens new avenues for targeted therapies, particularly in individuals with inflammatory or autoimmune components contributing to their migraine phenotype. Immunomodulatory interventions, including monoclonal antibodies or cell-based therapies targeting specific immune subsets, may offer effective treatments for patients with immune-mediated migraine pathogenesis [108].

Single-cell transcriptomic analysis highlights immune cell–specific expression of lactylation-related genes

In the scRNA-seq analysis of PBMCs from migraine patients and healthy controls, we observed distinct cell type–specific expression patterns of key candidate genes, providing further mechanistic insights into the lactylation–immune axis. Among the three primary genes identified through multi-omics Mendelian randomization, EP300 demonstrated consistent upregulation in B cells and T cells of migraine patients compared to controls. This expression pattern is consistent with our mediation analysis, in which EP300 exerted significant indirect effects via multiple B cell and T cell subsets. Functionally, elevated EP300 expression in B cells and T cells might enhance their activation and pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion through histone lactylation–mediated transcriptional regulation, thereby might contributing to the amplification of neuroinflammatory signaling within the nervous system [66, 67, 96–98].

In contrast, SIRT1 and SLC16A1 exhibited overall low transcript abundance across all PBMC-derived immune populations, and no significant differential expression was detected between migraine and control samples. This may reflect both a lower degree of immune mediation relative to EP300 and technical limitations of scRNA-seq, including small sample size (3 migraine vs. 2 control samples) and lack of multimodal data such as single-cell ATAC-seq or surface protein profiling [109]. It is also possible that the functional effects of SIRT1 and SLC16A1 occur primarily in metabolically active or low-abundance immune subsets (e.g., CD56⁺ HLA-DR⁺ NK cells) that were underrepresented in our single-cell PBMC dataset, due to their rarity or low transcriptomic signal [109–111].

Despite these limitations, the single-cell transcriptomic results provide important cellular resolution to our multi-omics findings, particularly reinforcing the immunological role of EP300 in migraine through its effects in B and T cell–mediated pathways. By anchoring genetic associations within defined immune cell contexts, these results further substantiate the proposed lactylation–immune–migraine axis, and offer a conceptual framework for cell-targeted immunomodulatory therapies in genetically susceptible migraine populations.

Strengths and limitations of the study

This study is strengthened by its integrative multi-omics design, which combines MR, SMR, colocalization, and mediation analyses, with validation across independent datasets. By incorporating DNA methylation QTLs, gene expression QTLs, and protein QTLs, our approach offers robust causal inference across multiple regulatory layers. The inclusion of protein-level QTL data adds functional relevance to transcriptomic findings, supporting the biological plausibility of EP300, SIRT1, and SLC16A1 as key regulators of migraine susceptibility. Furthermore, scRNA-seq provided complementary resolution at the cellular level, confirming EP300 upregulation in specific immune cell subsets—particularly B and T cells—of migraine patients. Together, these findings highlight a novel immunometabolic mechanism linking lactate-related epigenetic regulation to neuroinflammation in migraine.

Nonetheless, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, most of the QTL and GWAS datasets used were derived from individuals of European ancestry, which may limit the generalizability of our findings to other populations. Second, although horizontal pleiotropy was addressed through HEIDI filtering and multiple MR sensitivity analyses, residual confounding cannot be completely excluded. Third, the mediation analysis relied on summary-level data and lacked direct cellular resolution. While the scRNA-seq analysis offered transcript-level insight, it was limited by sample size and depth, and did not include complementary modalities such as single-cell ATAC-seq or multiome sequencing. As a result, we were unable to directly assess chromatin accessibility, transcription factor binding, or upstream regulatory mechanisms of the candidate genes.

In particular, although our single-cell transcriptomic analysis revealed EP300 expression differences across immune subsets between migraine patients and controls, the findings for SIRT1 and SLC16A1 were less conclusive. Additionally, the lack of multi-omic single-cell data limited our ability to explore gene regulation beyond the transcriptome. Future studies incorporating single-cell ATAC-seq, multiome profiling, or spatial transcriptomics could help elucidate the upstream chromatin-level and transcriptional regulatory mechanisms involved in lactylation-mediated migraine risk. While our findings were derived from GWAS datasets encompassing general migraine cases, we acknowledge the potential for heterogeneity across migraine subtypes and demographic strata. Future investigations leveraging sex-specific, age-specific, or subtype-defined genetic datasets may further elucidate the context-specific relevance of lactylation-related genes in migraine pathogenesis.

Finally, functional validation of these key genes and pathways in cellular or animal models will be essential to confirm causal mechanisms and support therapeutic translation.

Clinical implications and future perspectives

Our findings highlight EP300, SIRT1, and SLC16A1 as promising molecular targets linking lactate metabolism, immune regulation, and migraine susceptibility. Pharmacological inhibition of EP300 may benefit patients with inflammatory migraine subtypes, while activation of SIRT1—via NAD⁺ precursors or small-molecule agonists—could restore mitochondrial and immune homeostasis. Moreover, modulation of lactate transport through SLC16A1 represents a novel therapeutic strategy for metabolically driven migraine.

Site-specific DNA methylation patterns within these genes may serve as epigenetic biomarkers for risk stratification or therapeutic response prediction. Future research should explore the interplay between lactylation and other post-translational modifications, and validate these findings in diverse populations and experimental models. This integrative framework offers a new direction for precision medicine in migraine.

Conclusion

This study identifies EP300, SIRT1, and SLC16A1 as lactylation-related genes with causal roles in migraine pathogenesis, acting through metabolic and immune pathways. By integrating multi-omics MR and mediation analyses, we propose a novel “lactylation–immune mediation–migraine axis,” highlighting the interplay between lactate metabolism, immune cell function, and neuroinflammation. These findings offer potential molecular targets and open avenues for precision therapies tailored to immunometabolic migraine subtypes.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the participants and investigators of the FinnGen Consortium, the GWAS Catalog, the eQTLGen Consortium, the UK Biobank Pharma Proteomics Project, and the immune cell QTL study for making their data publicly available, without which this study would not have been possible. We also thank the authors of the GSE269117 dataset for providing access to the single-cell RNA-seq data from migraine patients and healthy controls. Their contributions to open science were critical in enabling the integrative multi-omics analyses performed in this work. We further acknowledge the authors of the mQTL meta-analysis by Min et al. for providing large-scale DNA methylation data, which was essential for our methylation-based causal inference analyses. Finally, we sincerely thank the developers of the SMR software and the R packages TwoSampleMR, MendelianRandomization, MR-PRESSO, and coloc for providing essential tools that supported our Mendelian randomization, summary-data-based MR, and colocalization analyses.

Abbreviations

- AARS2

Alanyl-tRNA synthetase 2, mitochondrial

- AC

Absolute cell counts

- B cells

B lymphocytes

- BAFF-R

B-cell activating factor receptor

- BDNF

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor

- CDCs

Conventional dendritic cells

- COX-2

Cyclo-oxygenase-2

- DRG

Dorsal root ganglion

- EP300

E1A binding protein p300

- eQTL

Expression quantitative trait locus

- GWAS

Genome-wide association study

- GWAS Catalog

Genome-Wide Association Studies Catalog

- H3K18

Histone 3 lysine 18

- HEIDI

Heterogeneity in Dependent Instruments

- InSIDE

Instrument Strength Independent of Direct Effect

- IVW

Inverse-variance weighted

- LD

Linkage disequilibrium

- LOO

Leave-one-out

- MCT1

Monocarboxylate transporter 1

- MFI

Median fluorescence intensity

- MP

Morphological parameters

- MPA

Migraine Probability Algorithm

- mQTL

Methylation quantitative trait locus

- MR

Mendelian randomization

- MR-Egger

Mendelian randomization Egger regression

- MR-PRESSO

Mendelian randomization Pleiotropy RESidual Sum and Outlier

- NAD⁺

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide

- NF-κB

Nuclear factor κB

- NK cells

Natural killer cells

- NKT cells

Natural killer T cells

- PBMCs

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- PCA

Principal component analysis

- PPH

Posterior probability

- PPH4

Posterior probability that both traits share one causal variant

- pQTL

Protein quantitative trait locus

- QTL

Quantitative trait locus

- RC

Relative cell counts

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- scRNA-seq

Single-cell RNA sequencing

- SD

Standard deviation

- SIRT1

Sirtuin 1

- SLC16A1

Solute carrier family 16 member 1

- SMR

Summary-data-based Mendelian randomization

- SNN

Shared nearest-neighbor

- SNP

Single-nucleotide polymorphism

- T cells

T lymphocytes

- TBNK cells

T cells, B cells, and natural killer cells

- Treg cells

Regulatory T cells

- t-SNE

t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding

Authors’ contributions

L.W., Z.L., Y.H., and Y.C. jointly conceptualized the study and developed the research hypothesis. L.W. drafted the initial version of the manuscript. Z.L. performed data acquisition, statistical analysis, and prepared all figures. Y.H. and Y.C. developed the statistical analysis plan, conducted data processing, and assisted with interpretation of results. L.W., Z.L., Y.H., and Y.C. also contributed to statistical analyses, ensured data accuracy, and supported the critical revision of the manuscript. They contributed equally to this work and are considered co-first authors. R.H. and Z.J. supervised the overall project, provided critical revisions, and ensured methodological rigor. R.H. and Z.J. are corresponding authors and jointly directed the study. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Guangxi Key R&D Program (Guike AB21220047) and Guangxi Key Clinical Specialty Construction Project.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are publicly available from established repositories. Summary-level genome-wide association study (GWAS) data for migraine were obtained from the FinnGen consortium and from the GWAS Catalog. Methylation quantitative trait loci (mQTL) data were derived from a large-scale meta-analysis by Min et al. (2021). Expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) data were retrieved from the eQTLGen Consortium, and protein quantitative trait loci (pQTL) data were obtained from the UK Biobank Pharma Proteomics Project (UKB-PPP) through the UK Biobank. Immune cell QTL data were obtained from the study by Orrù et al. Single-cell RNA sequencing data were retrieved from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) under accession number GSE269117. All processed data and analysis scripts generated during this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Liu Wang, Zhixuan Lan, Ying He and Yue Cheng contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Ruilin He, Email: 420334@sr.gxmu.edu.cn.

Zongbin Jiang, Email: jiangzongbin@sr.gxmu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Sutherland HG, Jenkins B, Griffiths LR (2024) Genetics of migraine: complexity, implications, and potential clinical applications. Lancet Neurol 23(4):429–446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khan J, Asoom LIA, Sunni AA, Rafique N, Latif R, Saif SA, Almandil NB, Almohazey D, AbdulAzeez S, Borgio JF (2021) Genetics, pathophysiology, diagnosis, treatment, management, and prevention of migraine. Biomed pharmacotherapy = Biomedecine Pharmacotherapie 139:111557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Safiri S, Pourfathi H, Eagan A, Mansournia MA, Khodayari MT, Sullman MJM, Kaufman J, Collins G, Dai H, Bragazzi NL et al (2022) Global, regional, and National burden of migraine in 204 countries and territories, 1990 to 2019. Pain 163(2):e293–e309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raggi A, Leonardi M, Arruda M, Caponnetto V, Castaldo M, Coppola G, Della Pietra A, Fan X, Garcia-Azorin D, Gazerani P et al (2024) Hallmarks of primary headache: part 1 - migraine. J Headache Pain 25(1):189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.He J, Zhou M, Zhao F, Cheng H, Huang H, Xu X, Han J, Hong W, Wang F, Xiao Y et al (2023) FGF-21 and GDF-15 are increased in migraine and associated with the severity of migraine-related disability. J Headache Pain 24(1):28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Halloum W, Dughem YA, Beier D, Pellesi L (2024) Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists for headache and pain disorders: a systematic review. J Headache Pain 25(1):112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang J, Simoes R, Guo T, Cao YQ (2024) Neuroimmune interactions in the development and chronification of migraine headache. Trends Neurosci 47(10):819–833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu CH, Chang FC, Wang YF, Lirng JF, Wu HM, Pan LH, Wang SJ, Chen SP (2024) Impaired glymphatic and meningeal lymphatic functions in patients with chronic migraine. Ann Neurol 95(3):583–595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li X, Yang Y, Zhang B, Lin X, Fu X, An Y, Zou Y, Wang JX, Wang Z, Yu T (2022) Lactate metabolism in human health and disease. Signal Transduct Target Therapy 7(1):305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu H, Huang H, Zhao Y (2023) Interplay between metabolic reprogramming and post-translational modifications: from Glycolysis to lactylation. Front Immunol 14:1211221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang J, Wang Z, Wang Q, Li X, Guo Y (2024) Ubiquitous protein lactylation in health and diseases. Cell Mol Biol Lett 29(1):23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jing F, Zhang J, Zhang H, Li T (2025) Unlocking the multifaceted molecular functions and diverse disease implications of lactylation. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc 100(1):172–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Watanabe H, Kuwabara T, Ohkubo M, Tsuji S, Yuasa T (1996) Elevation of cerebral lactate detected by localized 1H-magnetic resonance spectroscopy in migraine during the interictal period. Neurology 47(4):1093–1095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reyngoudt H, Achten E, Paemeleire K (2012) Magnetic resonance spectroscopy in migraine: what have we learned so far? Cephalalgia: Int J Headache 32(11):845–859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yorns WR Jr., Hardison HH (2013) Mitochondrial dysfunction in migraine. Semin Pediatr Neurol 20(3):188–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu K, Zhao H, Ji K, Yan C (2014) MERRF/MELAS overlap syndrome due to the m.3291T > C mutation. Metab Brain Dis 29(1):139–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Amin FM, Aristeidou S, Baraldi C, Czapinska-Ciepiela EK, Ariadni DD, Di Lenola D, Fenech C, Kampouris K, Karagiorgis G, Braschinsky M et al (2018) The association between migraine and physical exercise. J Headache Pain 19(1):83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sahin S, Cinar N, Benli Aksungar F, Ayalp S, Karsidag S (2010) Attenuated lactate response to ischemic exercise in migraine. Med Sci Monitor: Int Med J Experimental Clin Res 16(8):Cr378–382 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koppen H, van Veldhoven PL (2013) Migraineurs with exercise-triggered attacks have a distinct migraine. J Headache Pain 14(1):99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Subalakshmi S, Rushendran R, Vellapandian C (2025) Revisiting migraine pathophysiology: from neurons to immune cells through Lens of immune regulatory pathways. J Neuroimmune Pharmacology: Official J Soc NeuroImmune Pharmacol 20(1):30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lionetto L, Gentile G, Bellei E, Capi M, Sabato D, Marsibilio F, Simmaco M, Pini LA, Martelletti P (2013) The omics in migraine. J Headache Pain 14(1):55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burgess S, Labrecque JA (2018) Mendelian randomization with a binary exposure variable: interpretation and presentation of causal estimates. Eur J Epidemiol 33(10):947–952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhu Z, Zhang F, Hu H, Bakshi A, Robinson MR, Powell JE, Montgomery GW, Goddard ME, Wray NR, Visscher PM et al (2016) Integration of summary data from GWAS and eQTL studies predicts complex trait gene targets. Nat Genet 48(5):481–487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu Y, Zeng J, Zhang F, Zhu Z, Qi T, Zheng Z, Lloyd-Jones LR, Marioni RE, Martin NG, Montgomery GW et al (2018) Integrative analysis of omics summary data reveals putative mechanisms underlying complex traits. Nat Commun 9(1):918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cruz-Granados P, Frejo L, Perez-Carpena P, Amor-Dorado JC, Dominguez-Duran E, Fernandez-Nava MJ, Batuecas-Caletrio A, Haro-Hernandez E, Martinez-Martinez M, Lopez-Escamez JA (2024) Multiomic-based immune response profiling in migraine, vestibular migraine and Meniere’s disease. Immunology 173(4):768–779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]