Abstract

Background

Gastrointestinal (GI) cancers are among the most prevalent and lethal malignancies worldwide. Early, non-invasive detection is essential for timely intervention and improved survival. To address this clinical need, we developed GutSeer, a blood-based assay combining DNA methylation and fragmentomics for multi-GI cancer detection.

Methods

Genome-wide methylome profiling identified 1,656 markers specific to five major GI cancers and their tissue origins. Based on these findings, we designed GutSeer, a targeted bisulfite sequencing panel, which was trained and validated using plasma samples from 1,057 cancer patients and 1,415 non-cancer controls. The locked model was blindly tested in an independent cohort of 846 participants, encompassing both inpatient and outpatient settings across five hospitals.

Results

In the validation cohort, GutSeer achieved an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.950 [95% Confidence Interval (CI): 0.937–0.962] for cancer detection, with 82.8% sensitivity (95% CI: 79.5–86.0) and 95.8% specificity (95% CI: 94.3–97.2). It detected 92.2% of colorectal, 75.5% of esophageal, 65.3% of gastric, 92.9% of liver, and 88.6% of pancreatic cancers. The independent test cohort included 198 early-stage cancers (stage I/II, 66.4%) and 63 advanced precancerous lesions. GutSeer maintained robust performance, with 81.5% sensitivity (95% CI: 77.1–85.9) for GI cancers and 94.4% specificity (95% CI: 92.4–96.5). It also demonstrated the ability to detect advanced precancerous lesions in the colorectum, esophagus, and stomach as a single, non-invasive blood test.

Conclusions

By integrating DNA methylation and fragmentomics into a compact panel, GutSeer outperformed genome-wide sequencing in both accuracy and clinical applicability. Its high sensitivity for early-stage GI cancers and practicality as a non-invasive assay highlights its potential to revolutionize early cancer detection and improve patient outcomes.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT05431621.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12943-025-02367-x.

Keywords: Gastrointestinal cancer, Multi-cancer early detection (MCED), Cell-free DNA (cfDNA), Methylation, Fragmentomics, Multi-dimensional features

Background

Gastrointestinal (GI) cancers, including colorectal, esophageal, gastric, liver, and pancreatic cancers, represent a significant global health challenge, accounting for approximately 4.8 million new cases (23.9% of all cancer cases) and 3.2 million cancer-related deaths (33.2% of all cancer deaths) annually [1, 2]. These malignancies are not only highly prevalent but are often diagnosed at advanced stages, when treatment options are less effective and prognosis is poor [3]. Despite the critical need for early detection, diagnosing GI cancers remains particularly challenging. Symptoms such as weight loss, abdominal pain, and changes in bowel habits are typically nonspecific and can overlap with benign conditions, often leading to delayed diagnosis. Furthermore, disparities in access to GI specialists and regional inequities in medical resources further hinder timely detection and intervention. Given these challenges, there is a pressing need for a multi-cancer early detection (MCED) test specifically designed for GI cancers, one that is both clinically practical and capable of improving early diagnosis before the need for invasive procedures.

MCED assays capable of detecting a broad spectrum of cancers often encounter challenges in follow-up diagnostics and logistical implementation in real-world settings. Therefore, a well-defined intended use, a clearly identified target population, and streamlined follow-up strategies are essential for the successful development, validation, and clinical adoption of an MCED test. GI cancers possess distinct genetic, epidemiological and clinical characteristics that justify a focused detection strategy. These malignancies originate within digestive system, leading to overlapping symptomology and referral pathways that align well with existing gastroenterology practices. Furthermore, GI cancers are known to shed circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) into the bloodstream, making them particularly well-suited for detection via liquid biopsy. By concentrating on GI cancers, an MCED assay can address a clear clinical need, target high-risk populations, and seamlessly integrate into GI workflows, ultimately enhancing detection efficiency and clinical impact [4–6].

Recent advancements in liquid biopsy have established cell-free DNA (cfDNA) methylation in blood as the most sensitive and widely accepted biomarker for early cancer detection [7–9]. However, current DNA methylation-based MCED approaches rely on large sequencing panels containing 67,832 to 161,984 markers [7, 10–13], making them resource-intensive and expensive for widespread clinical adoption [14–16]. Additionally, while low-pass whole-genome sequencing (WGS) of cfDNA fragment profile shows promise for cancer detection and tumor localization [17–20], its application has been tested only in limited samples sizes [18, 21, 22] or specific cancer types [19, 23, 24], highlighting the need for a more targeted and efficient approach.

Integrating cfDNA methylation and fragmentomics has been proposed as a strategy to enhance detection accuracy [25]. While some studies have utilized multiple assays separately [26, 27] others have integrated fragmentomics and methylation features through multi-step enzymatic methylation sequencing procedures [28–31], which significantly increases operational complexity and costs. Given that DNA methylation changes are often accompanied by alterations in chromatin status, such as changes in nucleosome occupancy [32] or copy number variations [33], cfDNA fragments carrying methylation markers could inherently enrich fragmentomics information as well [34]. Thus, a targeted methylation panel capable of extracting both methylation and fragmentomics features from cfDNA may offer a more efficient and effective approach for early detection and tissue-of-origin (TOO) prediction.

To advance this concept, we extensively modified and built upon PanSeer, a previously reported blood-based DNA methylation assay for detecting cancers in asymptomatic populations [35]. While PanSeer served as an important proof-of-principle, it was limited by sample size, cancer types coverage, and TOO prediction accuracy. To address these limitations and enhance both technical performance and clinical applicability, we conducted the GUIDE study (Gastrointestinal cancer cohort study for mUlti-cancer non-Invasive early DEtection) to develop GutSeer, a next generation targeted sequencing assay specifically designed for the early detection of five major GI cancers. GutSeer utilizes a highly optimized panel of 1,656 markers, integrating both methylation and fragmentomics features to improve detection accuracy. The assay was rigorously trained, validated, and independently tested on a cohort of 3,318 participants recruited from five medical centers. Notably, in a direct comparison, GutSeer’s integrated model outperformed WGS-based fragmentomics approach, underscoring its superior potential as a practical, non-invasive tool for early GI cancer detection and diagnostic support.

Methods

Participants enrollment

Participants in the GUIDE study were prospectively recruited from inpatient and outpatient care at five medical centers between November 15, 2020, and July 31, 2023. For every participant, demographics, general clinical information, medical history, as well as cancer diagnosis data were collected. Participants were stratified into three diagnostic categories – cancer, advanced precancerous lesion, and non-cancer – based on pathological or radiological assessments, following the standards of the latest cancer diagnosis and treatment guidelines (Supplementary Table 1). The clinical stages of cancers were defined according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer 8 th edition, except for liver cancer, which was staged with reference to the China Liver Cancer Staging System (CNLC). Informed consent was obtained from all participants before the study. More details and the inclusion/exclusion criteria for the participants are provided in the Supplementary Methods.

Sample collection and pre-processing

Genomic DNA of tissue samples was extracted from scrapings of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) specimens using the QIAGEN FFPE DNA Mini Kit (QIAGEN) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Blood samples were collected in cfDNA BCT tubes (Streck). The blood was first centrifuged at 1,600 g for 10 min at 4 °C to separate the plasma from the red blood cells and buffy coat, after which the plasma was subjected to a second centrifugation at 16,000 g for 10 min at 4 °C to remove residual cell debris. The clarified plasma was aliquoted into nuclease-free tubes and stored at −80 °C. Cell-free DNA was then extracted from plasma using the QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid kit (QIAGEN, 55114) according to the manufacturer’s protocol, with a modification in the lysis step that included a 1-h incubation at 60 °C. The extracted DNA was stored at −20 °C until further use. The details of the sample processing and QC metrics are provided in the Supplementary Table 2 and 3.

DNA library construction and sequencing

Reduced representation bisulfite sequencing (RRBS) was performed as previously described [35]. Briefly, a total of 50 ng genomic DNA or 20 ng cfDNA was digested with MspI and ligated to methylated adapters. The ligated products were bisulfite-converted, purified, and recovered using the MethylCode™ Bisulfite Conversion Kit (ThermoFisher, MECOV50) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Bisulfite-converted DNA was subsequently amplified to add Illumina sequencing indices. Libraries were quantified using the KAPA Library Quantification Kit (KAPA, KK4844) and sequenced on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 in pair-end 150-bp mode, requiring approximately 40 million reads per sample.

A targeted methylation sequencing library was constructed as previously described [35]. First, 10–20 ng of cfDNA was subjected to bisulfite conversion with the MethylCode™ Bisulfite Conversion Kit (ThermoFisher, MECOV50) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Next, the bisulfite-converted DNA was dephosphorylated and ligated to a randomized 6 N splint adapter with a unique molecular identifier (UMI). After the second strand synthesis and purification step, the DNA underwent semi-targeted amplification. This approach captures one fragment end within the targeted region while preserving the natural cfDNA end on the opposite side, enabling the analysis of fragmentomic features such as regional fragment densities and end motifs. Following purification, a second PCR was performed to add sample-specific barcodes and full-length sequencing adapters. The libraries were then quantified using the KAPA Library Quantification Kit for Illumina (KAPA, KK4844). Finally, the libraries were sequenced on the Illumina NextSeq 6000 platform in paired-end 150-bp sequencing mode with a requirement of a minimum of 40 million reads per sample.

Methylation sequencing data processing

Paired-end reads originating from the same DNA fragment were merged using PEAR software (Version 0.9.6). Adapters at the end of fragments were trimmed using trim_galore (Version 0.4.0), and UMIs were extracted from each read (for targeted methylation sequencing data). The preprocessed reads were aligned to the CT and GA-converted hg19 reference sequences using Bismark (Version 0.17.0) with Bowtie2 (Version 2.3.1). After the sequence alignment step, unique methylation haplotypes were obtained by deduplication based on alignment inference or UMI information.

For each genomic region in each sample, the methylation levels were quantified by measurements, including the average methylation fraction (AMF) and the methylation haplotype fraction (MHF). Additionally, for target sequencing samples, fragmentomics patterns, such as the tFPKM and the end motif, were also quantified for each marker and across all the target regions, respectively. The details of the measurements are provided in the Supplementary Methods.

Marker discovery for the GutSeer panel

Two primary datasets were used for marker discovery: (1) The TCGA (The Cancer Genome Atlas) database provided data on 1,552 tissue samples of the five cancers and 121 para-carcinoma samples along with plasma from healthy subjects and blood cell data from GSE35069, GSE40005, and GSE68777 serving as background control (N = 44). (2) RRBS data of 514 in-house samples, including 190 FFPE tumor tissue samples from the five cancers, 190 matched normal FFPE tissue samples, 114 plasma samples, and 20 whole blood cell samples from healthy subjects (Supplementary Table 4).

A sliding window-based approach was utilized for marker discovery. The AMF values of 200 bp sliding windows were calculated for each sample to generate their methylation profiles. In order to minimize interference from the blood cell background, windows with high methylation variation (standard deviation > 0.05) in blood cells were excluded before downstream selection. Cancer markers were identified by comparing methylation profiles of cancer tissues with those of normal tissues. Additionally, comparisons among different cancer types were conducted to identify TOO markers. For each comparison, methylation differences and Benjamini-Hochberg (BH)-corrected P-values from the Mann–Whitney U test were calculated. A window was classified as a cancer marker if it exhibited a methylation difference > 0.2 and a corrected P-value < 0.05 between the target cancer tissue and the matched normal tissue. Likewise, a window was identified as a TOO marker if it demonstrated a methylation difference > 0.2 and a corrected P-value < 0.05 across all the comparisons between the target cancer tissue and each of the other GI cancer tissues. The selected targets were finally compiled into the GutSeer panel.

GutSeer panel validation

Tissue samples with pathological diagnoses were sequenced to validate the ability of the customized GutSeer panel to detect and localize GI cancers by differential methylation analysis and uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP). Synthetic cfDNA samples were generated to evaluate the GutSeer panel in terms of the technical variation, the limit of detection (LoD), and tumor fraction estimation. DNA from the GM12878 and five commonly used GI cancer cell lines (liver cancer: PLC; pancreatic cancer: PANC1; gastric cancer: HGC27; esophageal cancer: KYSE150; colorectal cancer: SW480) were segmented into fragments with a length of ~ 160 bp to simulate cfDNA samples from healthy donors and each of the five GI cancer types. The details of synthetic samples and the evaluation of the GutSeer panel are provided in the Supplementary Methods.

GutSeer model building

The training cohort was randomly divided into 10 groups for ten-fold cross-validation. This grouping structure was consistently maintained across all phases of model development. The cancer model and TOO model were trained separately. Two independent models were developed: the cancer detection model and the TOO identification model. The cancer model was trained using the complete dataset comprising both cancer and non-cancer samples, while the TOO model was specifically trained on cancer samples only, implementing a hierarchical modeling approach (Supplementary Fig. 1).

In the first hierarchical layer, four specialized submodels were independently trained. Three of these models were trained using distinct molecular signatures: AMF/MHF, end motif, and tFPKM features. The fourth model was trained through deep learning architecture, utilizing methylation-encoded sequencing reads as input features. Comprehensive technical details regarding these submodels are described in the Supplementary Methods. The second hierarchical layer was established through logistic regression integration of the outputs from the first-layer submodels. The logistic regression model was chosen due to its superior performance and robustness compared to other classifiers, along with its high interpretability and computational efficiency. Model hyperparameters were optimized using GridSearchCV from the sklearn library (v0.22.2.post1, python v3.5.2). For the cancer model, the hyperparameters tuned included the regularization strength 'C' (with values 0.01, 0.1, 1, 10, and 100) and 'class_weight' (balanced or none). For the TOO model, an additional hyperparameter 'multi_class' (auto, ovr, and multinomial) was tuned alongside those previously mentioned. The final prediction integrated information from methylation (AMF/MHF and MES) and fragmentomics (end motif and tFPKM) features, yielding a probabilistic output concerning cancer presence or TOO localization. Predictions for samples outside the training cohort were obtained by averaging the scores generated by the ten cross-validated classifiers, while for samples within the training cohort, scores from each cross-validated fold were utilized.

WGS sample library, sequencing, and data processing

After the GutSeer assay was performed, the samples with sufficient plasma cfDNA underwent WGS. Twenty ng of cfDNA from each sample was used to construct a sequencing library using a KAPA Hyper Prep Kit (Roche) kit, following the manufacturer’s protocol. During the library preparation, a 10-bp UMI was liganded to the 3’ end of each fragment. The constructed libraries were subjected to paired-end sequencing with a read length of 150 bp on the Illumina NovaSeq (Illumina). The details of WGS data processing are provided in the Supplementary Methods.

Statistical analysis and metrics evaluation

The model construction and calculation of its performance metrics, including the sensitivity [TP/(TP + FN)], specificity [TN/(TN + FP)], accuracy [(TP + TN)/(TP + FP + TN + FN)], and AUC, were conducted using the scikit-learn library in Python. TP indicates true positive, TN indicates true negative, FP indicates false positive, and FN indicates false negative. For covariate analysis, the samples were categorized by sex, age, BMI, smoking status, drinking status, hospital, UMI count, and DNA amount groups. Cancer scores were compared pairwise using the U-test with Bonferroni correction. For sequencing depth analysis, mapped reads were down-sampled to 10 M, 5 M, 2 M, 1 M, 0.5 M, and 0.1 M. Sensitivity, TOO accuracy, and correlation between AMF values were evaluated to assess the impact of sequencing depth.

Confidence intervals were estimated based on bootstrap with 10,000 times for AUC, and binomial proportion for sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy, respectively. Hypothesis tests and the Delong test were performed in Python, and the BH correction was applied when necessary, for which a (corrected) P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. PCA, ANOVA, and correlation analyses were conducted in R. R packages, including UMAP (v0.2.5.0), pheatmap (v1.0.12) and ggplot2 (v3.4.4) were used for data visualization, and HOMER (v4.11.1) was used for enrichment analysis. Multivariate analysis was performed using the Python package statsmodels.api (v0.14.4).

Results

Study design and participants

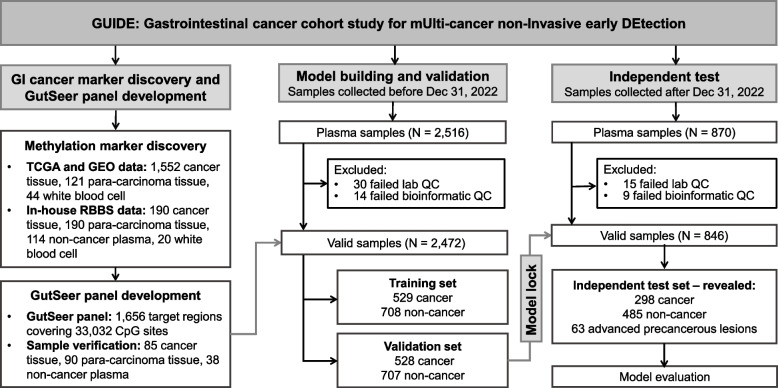

The GUIDE study was conducted in three key stages: (1) marker discovery for GI cancers, (2) model development of GutSeer for cancer detection and TOO localization, and (3) independent evaluation of GutSeer’s performance (Fig. 1). To identify the most effective methylation targets for GI cancers, we analyzed 1,717 publicly available TCGA and GEO datasets along with 514 in-house RRBS datasets. From this comprehensive analysis, we selected the 1,656 most informative markers for inclusion in the GutSeer panel, which were subsequently validated using an additional set of 213 tissue and plasma samples. The GUIDE study recruited participants from both inpatient and outpatient settings across five medical centers, ensuring a diverse representation of GI conditions. Samples collected before December 31, 2022, were used for model development, with an even split between training and validation cohorts. To ensure robust learning, cancer and non-cancer samples in the training set were age-matched. During model construction, we integrated methylation and fragmentomics features to enhance GutSeer’s performance (Supplementary Fig. 1) and compared it with WGS-based fragmentomics approach to evaluate its accuracy and reliability (Supplementary Fig. 2). For independent validation, the GutSeer model underwent blinded testing on a prospectively collected set of 870 samples, which were enrolled after the initial registration of the clinical trial.

Fig. 1.

Overall design of the GutSeer study

In total, 3,386 individuals participated in the GUIDE study, including 1,355 patients with GI cancers (249 colorectal, 263 esophageal, 305 gastric, 405 liver, and 133 pancreatic cancers), 63 patients with advanced precancerous lesions, and 1,900 non-cancer participants (Table 1). Notably, early-stage cancers were well represented, with 64.0% of cancer patients diagnosed at Stage I (534; 39.4%) and Stage II (334; 24.6%), providing a strong foundation for evaluating GutSeer’s effectiveness in the early detection of GI cancers (Supplementary Table 5).

Table 1.

Patient information

| Cohort and dataset | Training | Validation | Test | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-cancer | Cancer | Non-cancer | Cancer | Non-cancer | Advanced precancerous lesions | Cancer | ||

| (N = 708) | (N = 529) | (N = 707) | (N = 528) | (N = 485) | (N = 63) | (N = 298) | ||

|

Age (years) |

Mean ± SD | 61 ± 10 | 62 ± 11 | 56 ± 12 | 62 ± 11 | 55 ± 12 | 63 ± 7 | 62 ± 10 |

| ≤ 60, No (%) | 315 (44.5) | 219 (41.4) | 421 (59.5) | 220 (41.7) | 305 (62.9) | 19 (30.2) | 116 (38.9) | |

| > 60, No (%) | 393 (55.5) | 310 (58.6) | 286 (40.5) | 308 (58.3) | 180 (37.1) | 44 (69.8) | 182 (61.1) | |

| Gender | Male, No (%) | 321 (45.3) | 366 (69.2) | 322 (45.5) | 386 (73.1) | 240 (49.5) | 45 (71.4) | 190 (63.8) |

| Female, No (%) | 387 (54.7) | 163 (30.8) | 385 (54.5) | 142 (26.9) | 245 (50.5) | 18 (28.6) | 108 (36.2) | |

| Stagea | I, No (%) | 200 (37.8) | 199 (37.7) | 135 (45.3) | ||||

| II, No (%) | 135 (25.5) | 136 (25.8) | 63 (21.1) | |||||

| III, No (%) | 128 (24.2) | 127 (24.1) | 60 (20.1) | |||||

| IV, No (%) | 66 (12.5) | 66 (12.5) | 40 (13.4) | |||||

| Sample type | Colorectum, No (%) | 90 (17.0) | 90 (17.0) | 17 (27.0) | 69 (23.2) | |||

| Esophagus, No (%) | 103 (19.5) | 106 (20.1) | 18 (28.6) | 54 (18.1) | ||||

| Stomach, No (%) | 121 (22.9) | 118 (22.3) | 28 (44.4) | 66 (22.1) | ||||

| Liver, No (%) | 172 (32.5) | 170 (32.2) | 63 (21.1) | |||||

| Pancreas, No (%) | 43 (8.1) | 44 (8.3) | 46 (15.4) | |||||

| Benign, No (%) | 314 (44.4) | 314 (44.4) | 247 (50.9) | |||||

| Healthy, No (%) | 394 (55.6) | 393 (55.6) | 238 (49.1) | |||||

aThe clinical stages of cancers were defined according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer 8 th edition, except for liver cancer, which was staged with reference to the China liver cancer staging system (CNLC)

Development of the GutSeer panel

We profiled the genome-wide DNA methylome of 514 samples using the RRBS approach (Supplementary Table 4) and integrated publicly available microarray data from 1,773 samples in TCGA and GEO. Briefly, utilizing a sliding window approach (200 bp), we identified genomic regions exhibiting significant methylation differences (BH-corrected Mann–Whitney U-test P-values < 0.05 and methylation differences > 0.2) between cancerous and para-carcinoma tissues as potential cancer markers. Regions demonstrating the highest methylation tissue specificity were subsequently prioritized as TOO markers. Highly variable regions (standard deviation > 0.05) in plasma and white blood cell samples from healthy subjects were excluded to enhance specificity. Ultimately, we selected 1,656 methylation markers spanning 33,032 CpG sites for the customized GutSeer panel (Fig. 1, see Methods).

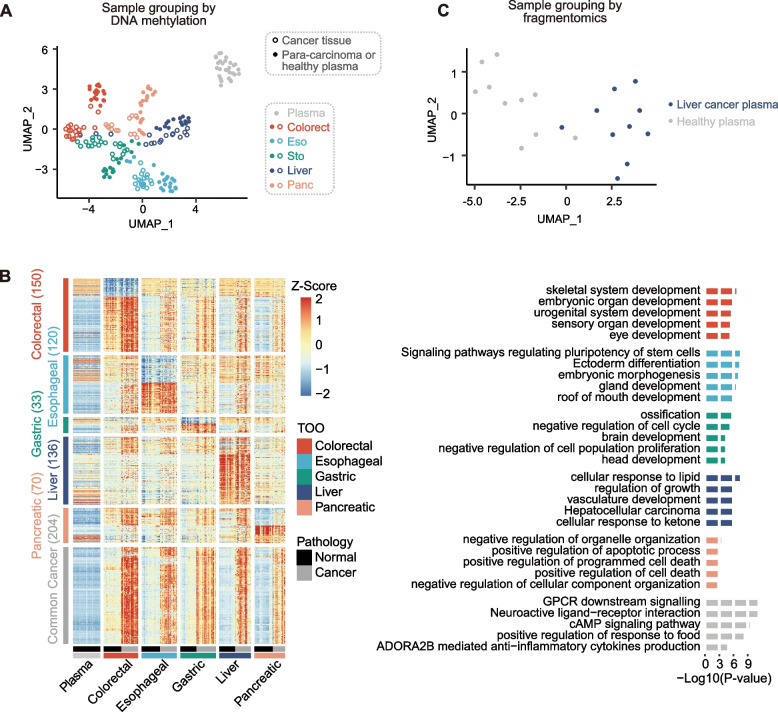

After the final design of the GutSeer panel, the effectiveness of the compiled markers was assessed by an independent set of 213 samples, including 85 cancer, 90 para-carcinoma, and 38 plasma samples from healthy subjects (Supplementary Table 6). We confirmed that 1,064 (of the total 1,656) markers exhibited significant signals in at least one cancer type from this independent assessment dataset (Mann–Whitney U-test, P-value < 0.05). The results demonstrate that, despite a limited number of independent validation samples, we were able to validate the majority of the screened biomarkers, establishing the feasibility of the biomarker screening strategy. Among these, 770 markers showed cancer-associated signals across all five GI cancer types, while 524 markers demonstrated strong tissue specificity, distributed as follows: 150 for colorectal, 89 for esophageal, 28 for gastric, 136 for liver, and 121 for pancreas cancer. Methylation patterns of these samples, analyzed via U-MAP clustering based on the AMF measurement of all markers, demonstrated a clear separation of cancer types from para-carcinoma and samples from healthy subjects, confirming the GutSeer panel’s ability to accurately detect GI cancers and their tissue origins (Fig. 2A). Functional enrichment analysis revealed that the selected markers were associated with key biological pathways related to cancer development (Fig. 2B). Furthermore, we derived the fragmentomics feature tFPKM from the GutSeer panel, which effectively distinguished liver cancer plasma from plasma from healthy subjects in U-MAP clustering (Fig. 2C). This finding supports the hypothesis that the GutSeer markers, initially selected based on differential methylation status, inherently encode cancer-associated fragmentomics features.

Fig. 2.

Validity of the GutSeer panel. A The validity of the GutSeer panel was verified by the methylation feature (i.e., average methylation fraction, AMF). Tissue samples of cancer and para-carcinoma, and plasma samples from healthy subjects are well-separated by U-MAP of the AMF data. B The heatmap based on AMF for different cancer types, with top associated biological processes enrichment listed. C The validity of the GutSeer panel was verified by the fragmentomics feature (i.e., tFPKM). Plasma samples from liver cancer patients and plasma from healthy subjects were separated by U-MAP using the tFPKM data

Technically, GutSeer was developed with excellent analytical performance, with high reproducibility, low false discovery rate at a relatively low input requirement (10 ng), and very low level of limit of detection (LoD) (Supplementary Fig. 3, see Supplementary Methods).

Building GutSeer model for GI cancer detection

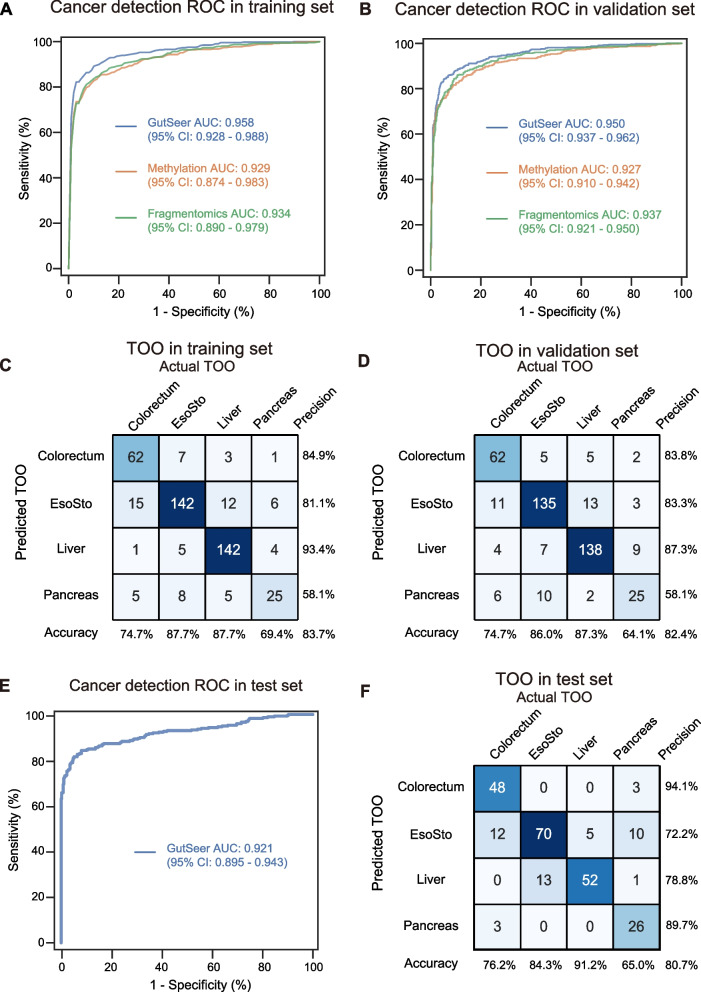

The GutSeer model was developed using data from 1,237 plasma samples, comprising 529 samples from cancer patients and 708 from age-matched non-cancer participants. Baseline characteristics were comparable between groups (Table 1). The training cohort had a mean age of 61.1 ± 10.4 years, with 44.5% female (550/1,237). Cancer patients showed a marginally higher mean age (61.5 vs 60.8 years) and were predominantly diagnosed at early stages (63.3% stage I/II; 335/529 cases). To ensure robustness and generalizability, we employed a ten-fold cross-validation approach. Specifically, four submodels were constructed, each capturing distinct methylation (AMF/MHF and MES) and fragmentomics features (end motif and tFPKM) (see Supplementary Methods). These submodels were trained using nine of the ten folds in the cross-validation process, and their predictions were integrated through logistic regression to generate the final GutSeer model score (Supplementary Figs. 1 and 4). Through ten-fold cross-validation on the training set, the GutSeer model achieved an average AUC of 0.958 (95% confidence interval: 0.928–0.988), with a sensitivity of 83.7% (80.6%−86.9%) and a specificity of 95.8% (94.3%−97.2%) (Fig. 3A, Supplementary Fig. 5 A and Supplementary Table 7). The model’s robustness was further validated in the validation set comprising 528 cancer patients and 707 non-cancer controls (Table 1), The validation cohort (mean age 58.3 ± 11.9 years, 42.7% female) demonstrated a significant age disparity between cancer (61.6 years) and non-cancer (55.9 years) subgroups (P-value < 0.001), with early-stage tumors predominating (63.4% stage I/II). In the validation set, GutSeer maintained a sensitivity of 82.8% (79.5%−86.0%) and a specificity of 95.8% (94.3%−97.2%) with an AUC of 0.950 (0.937–0.962) (Fig. 3B and Supplementary Table 7). Notably, when specificity was adjusted to exceed 99.0%, the sensitivity of cancer detection was 66.2% (62.1%−70.2%) in the training set and 64.0% (59.9%−68.1%) in the validation set (Supplementary Fig. 6 and Supplementary Table 8).

Fig. 3.

Evaluation of GutSeer in cancer/non-cancer identification and TOO localization. A,B ROC of cancer/non-cancer prediction, with comparisons among methylation, fragmentomics, and the integrated measurements. A The average ROC based on ten-fold cross-validation in the training set. B The ROC based on the validation set. Methylation: the commonly used methylation measurements, AMF and MHF; fragmentomics: tFPKM and end motif. C,D Confusion matrices of TOO prediction based on the training (C) and validation (D) datasets. Accuracy (column rates) represents the percentage of correct localization within each actual TOO; precision (row rates) represents the percentage of correct localization within each predicted TOO. EsoSto represents esophageal and/or gastric cancers

The GutSeer model demonstrated high sensitivity across various GI cancers, ranging from nearly 70% to over 90%. In the training cohort, it achieved sensitivities of 92.2% (86.7%−97.8%) for colorectal, 75.7% (67.4%−84.0%) for esophageal, 69.4% (61.2%−77.6%) for gastric, 94.2% (90.7%−97.7%) for liver, and 83.7% (72.7%−94.8%) for pancreatic cancer, while maintaining a specificity of 95.8% (94.3%−97.2%) among non-cancer participants. These performance metrics were consistent in the validation set, with sensitivities of 92.2% (86.7%−97.8%), 75.5% (67.3%−83.7%), 65.3% (56.7%−73.8%), 92.9% (89.1%−96.8%), and 88.6% (79.3%−98.0%) for the respective cancer types, with specificity remaining at 95.8% (94.3%−97.2%) (Supplementary Table 7).

Moreover, the model demonstrated robust performance across various cancer stages (Supplementary Table 9). For early-stage cancers (Stage I and I/II), GutSeer achieved an overall sensitivity of 76.0% (70.1%−81.9%) and 79.1% (74.8%−83.5%) in the training set, respectively and 70.4% (64.0%−76.7%) and 75.8% (71.2%−80.4%), respectively, in the validation set (Fig. 4A). Sensitivity for stage I/II cancers varied across cancer types, ranging from 54.4% (43.4%−65.4%) for gastric cancer to 90.4% (85.2%−95.6%) for liver cancer in the validation set (Fig. 4B-F). This high sensitivity in detecting early-stage cancers, when tumors are still amenable to complete surgical resection, underscores GutSeer’s potential to significantly enhance patient outcomes.

Fig. 4.

Assessment of GutSeer in differentiating non-cancer versus different stages of cancer. Sensitivity (y-axis) is reported by clinical stage (x-axis) in the all five GI cancers (A) and in each of the five cancers (B-F), at the specificity of 95.8% and 94.4% for training/validation and independent test cohorts, respectively. Sensitivities were plotted with 95% confidence interval. Numbers indicate samples in training, validation and independent test sets

Additionally, the GutSeer model demonstrated robust accuracy in TOO localization. Given the common diagnostic use of upper endoscopy for esophageal and gastric cancers, these two cancer types were grouped together for TOO prediction. The model achieved an overall TOO accuracy of 83.7% (80.3%−87.2%) in the training set (Fig. 3C and Supplementary Table 7) and 82.4% (78.8%−86.0%) in the validation set (Fig. 3D and Supplementary Table 7). Specifically, the TOO accuracies in the training cohort were 74.7% (65.3%−84.1%) for colorectal, 87.7% (82.6%−92.7%) for esophageal/gastric, 87.7% (82.6%−92.7%) for liver, and 69.4% (54.4%−84.5%) for pancreatic cancer. Comparable accuracy was observed in the validation set, with TOO accuracies of 74.7% (65.3%−84.1%), 86.0% (80.6%−91.4%), 87.3% (82.2%−92.5%), and 64.1% (49.0%−79.2%) for the respective cancers. This ability to accurately localize tumor origin enhances GutSeer’s clinical utility, providing valuable insights to guide downstream diagnostic confirmation and treatment planning.

Integration of methylation and fragmentomics data improved detection accuracy

To confirm the advantages of integrating methylation and fragmentomics features, GutSeer was evaluated against models utilizing single feature approaches, such as methylation (AMF/MHF) or fragmentomics (tFPKM and end motif), using the same sample cohort. In cancer detection, cross-validation on the training set yielded an average AUC of 0.929 (0.874–0.983) for the methylation-only model and 0.934 (0.890–0.979) for the fragmentomics-only model, both significantly lower than the integrated model’s AUC of 0.958 (0.928–0.988) (Fig. 3A and Supplementary Table 10). Statistical comparison using the Delong test confirmed the superiority of the integrated model, with P-value = 4.1 × 10–10 and 1.9 × 10 –6 when compared to the methylation-only and fragmentomics-only models, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 5B and C). We observed that the fragmentomics signal performed similarly to the methylation signal (P-value = 0.491, Delong test), likely due to the well-defined targeted regions of the GutSeer panel and the optimized library construction, which specifically enriched for cancer-related signals and minimized noise. Similar performance trends were observed in the validation set (Fig. 3B and Supplementary Table 10). A comprehensive sensitivity analysis for distinguishing cancer from non-cancer cases across all validation samples further underscored the enhanced accuracy of the integrated model in cancer detection (Supplementary Fig. 7, Supplementary Tables 11 and 12).

For TOO prediction, the integrated model achieved an accuracy of 83.7% (80.3%−87.2%) in the training set, significantly surpassing the performance of models using methylation alone (76.3%, 72.1%−80.5%) or fragmentomics alone (78.8%, 74.8%−82.7%) (Supplementary Fig. 8 A and C). Statistical analysis confirmed the superiority of the integrated approach, with χ2 test P-value of 0.003 and 0.03 when compared to the methylation-only and fragmentomic-only models, respectively (Supplementary Table 13). A similar accuracy improvement was observed in the validation set (Supplementary Fig. 8B, D and Supplementary Table 13), further reinforcing the benefits of combining methylation and fragmentomics for precise TOO identification.

Evaluation of the GutSeer in the independent test cohort with early-stage patients

The integration of dual-dimensional features in the GutSeer model demonstrated a clear advantage over models using methylation or fragmentomics alone (Supplementary Fig. 5B, 5 C, 7 and 8, Supplementary Table 10–13). To further validate its performance, we evaluated the locked model in an independent test cohort of 846 prospectively collected samples. This cohort included 298 patients diagnosed with GI cancers, comprising 69 colorectal, 54 esophageal, 66 gastric, 63 liver, and 46 pancreatic cancers (Table 1). Notably, 66.4% of cancer patients were diagnosed at stage I/II. Compared with non-cancer controls, cancer patients exhibited a significantly older mean age (62.2 vs. 55.0 years; P-value < 0.001) and higher male predominance (63.8% vs. 49.5%; P-value < 0.001).

As anticipated, GutSeer achieved an AUC of 0.921 (0.895–0.943), with a sensitivity of 81.5% (77.1%−85.9%) for cancer detection and a specificity of 94.4% (92.4%−96.5%) for non-cancer patients (Fig. 3E). Sensitivity by cancer type was 91.3% (84.7%−98.0%) for colorectal, 74.1% (62.4%−85.8%) for esophageal, 65.2% (53.7%−76.6%) for gastric, 90.5% (83.2%−97.7%) for liver, and 87.0% (77.2%−96.7%) for pancreatic cancer (Supplementary Table 7). The model also maintained robust performance in TOO prediction, achieving an overall accuracy of 80.7% (75.7%−85.6%). TOO accuracies for specific cancer types were 76.2% (65.7%−86.7%) for colorectal, 84.3% (76.5%−92.2%) for esophageal/gastric, 91.2% (83.9%−98.6%) for liver, and 65.0% (50.2%−79.8%) for pancreatic cancer (Fig. 3F, Supplementary Table 7). Additionally, a total of 63 patients were diagnosed with advanced precancerous lesions (Supplementary Table 14). Patients with colorectal precancerous lesions were primarily identified at 62.8 ± 6.4 years old, including 14 tubular or tubulovillous adenomas with high-grade intraepithelial neoplasms and 3 cases of sessile serrated adenomas with high-grade neoplasms. Patients with esophageal precancerous lesions were at 65.6 ± 5.8 years, as high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions. Gastric precancerous lesions developed at 62.4 ± 7.7 years, presenting as high-grade dysplasia or intraepithelial neoplasms. GutSeer identified cancer-associated signals in 8/17 colorectal (sensitivity: 47.1%, 95% confidence interval: 23.3%−70.8%), 7/18 esophageal (38.9%, 16.4%−61.4%), and 6/28 gastric (21.4%, 6.2%−36.6%) precancerous cases (Supplementary Fig. 9). While the sample size was limited, these findings highlight GutSeer’s potential for detecting early cancer signals, including advanced precancerous lesions, offering promise for earlier intervention and improved patient outcomes.

Although conventional serum-based cancer markers are not recommended for tumor testing, they remain widely used in clinics practice due to the absence of superior alternatives. In the validation and independent test sets of the GUIDE study, serum marker testing results were available for 146 cancer cases and 73 non-cancer controls, including carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), cancer antigen 19–9 (CA19-9), and alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) (Supplementary Table 15). As expected, GutSeer significantly outperformed these conventional markers in distinguishing cancer cases from non-cancer controls, with all comparisons yielding P-values < 0.05 (Supplementary Fig. 10). These findings underscore GutSeer’s superior diagnostic performance and its potential to serve as a more reliable and clinically actionable tool for cancer detection.

Comparison of GutSeer assay and WGS-based fragmentomics approaches

WGS-based fragmentomics approaches have recently demonstrated potential for multiple-cancer detection. To directly compare performance, we conducted a head-to-head evaluation of GutSeer against a representative method [18] (referred to as FragD) (Supplementary Fig. 2). In the training and validation sets, a total of 1,176 samples, comprising 769 cancer and 407 non-cancer controls, with sufficient plasma cfDNA underwent WGS sequencing at an average depth of 14.4 × (ranging from 7.5 × to 29.3 ×) (Supplementary Table 16). These datasets enabled the development and comparison of separate models for cancer detection and TOO prediction. GutSeer demonstrated superior performance over FragD in both cancer detection (AUC: 0.963 [0.952–0.973] vs. 0.887 [0.863–0.908], P-value < 0.001) (Fig. 5A) and TOO prediction (accuracy: 79.6% [75.6%−83.7%] vs. 59.0% [54.1%−63.9%], P-values < 0.001) (Fig. 5B, Supplementary Fig. 11 A and B). These finding highlight GutSeer’s ability to effectively capture genome-wide fragmentomics signatures while leveraging multi-dimensional features within a compact panel, achieving superior performance at a fraction of the cost.

Fig. 5.

Head-to-head comparison between GutSeer and the WGS-based approach. A ROC of cancer/non-cancer classification in the test dataset for GutSeer and FragD, which is a representative WGS-based approach. The P-value of Delong test between GutSeer and FragD was shown in the plot. B Accuracy of the tissue of origin (TOO) identification in the test dataset, for all cancers and each cancer type. Numbers indicate samples in each data set. Comparison was performed between GutSeer and FragD using χ.2 test. N.s., no significance; *, P-values < 0.05; **, P-values < 0.01

Impact of confounding factors and dependence on the sequencing depth

We assessed GutSeer’s robustness against potential confounding factors and variations sequencing depth. We first conduct multivariate and covariate analyses to evaluate the independence of GutSeer for cancer detection and assess the influence of potential confounding factors on GutSeer’s prediction probability (i.e., cancer score). The multivariate analysis demonstrated that GutSeer remained a strong predictor for cancer detection (P = 2.05 × 10–88) (Supplementary Table 17), confirming its ability to capture cancer-specific biological signals independent of other factors. As anticipated, two technical parameters – total DNA quantity (ng) and unique DNA molecules (N_unique_reads) – were statistically significant predictors, reflecting the frequent elevation of cfDNA in cancer patients [36]. Further analysis revealed that both metrics had significantly less predictive power for cancer than GutSeer (all P-values < 0.001, Delong test). Similarly, age and sex were also identified as independent predictors of cancer. The covariate analysis also indicated minimal differences in cancer prediction probabilities between sexes (Supplementary Fig. 12B and D). To further account for confounders, we conducted a propensity score matching analysis to balance age and sex between cancer and non-cancer groups in the validation and test sets. The resulting matched subset, comprising 147 colorectal, 145 esophageal, 169 gastric, 212 liver, and 85 pancreatic cancer cases, along with corresponding controls, maintained high performance, achieving an AUC of 0.938 (0.927–0.950) (Supplementary Fig. 12 C).

Additionally, no significant differences were observed for other potential confounders, including age, sample collection sites, BMI, smoking status, drinking status, DNA quantity, and the number of unique DNA molecules (Supplementary Fig. 12 A and E-J). To assess GutSeer’s dependence on sequencing depth, we conducted in silico down-sampling to simulate reduced sequencing coverage. Our findings demonstrate that reducing the sequencing depth to 5% resulted in an 8.6% decline in cancer detection sensitivity and a 7.1% reduction in TOO identification accuracy, with only minor shifts observed in AMF distributions (Supplementary Fig. 13, Supplementary Table 18). These findings underscore the robustness of the GutSeer model, demonstrating its resilience against confounding factors and its stability across varying sequencing depths, further reinforcing its reliability and effectiveness in cancer detection and tumor origin prediction.

Discussion

This study introduces GutSeer, a novel targeted sequencing assay that integrates multi-dimensional features for the early detection of GI cancers. By leveraging both methylation and fragmentomics data from a compact 1,656-marker panel, GutSeer demonstrates high sensitivity, specificity, and TOO accuracy, positioning it as a promising tool for clinical translation. Our findings underscore its potential to advance MCED strategies, with broad implications for improving patient outcomes, reducing mortality, and optimizing healthcare resource allocation. This study identified a batch of new methylation markers for early detection and tissue localization of digestive system tumors, providing precious resources for future research on tumor molecular mechanisms or tissue damage detection.

The development of GI-specific MCED tests is driven by several compelling factors. First, given the high aggregate prevalence of GI cancers, early detection can substantially lower mortality rates, particularly in developing regions [37, 38]. Second, the nonspecific nature of many GI symptoms in primary care settings underscores the urgent need for diagnostic tools that can efficiently triage patients and support clinical decision-marking. Third, MCED tests can enhance diagnostic efficiency by focusing resources on high-risk individuals, improving both accessibility and cost-effectiveness. Collectively, these advantages highlight the value of GI-targeted MCED tests as a complementary tool within existing diagnostic pathways [39]. GutSeer could be effectively implemented in clinical settings as a diagnostic aid for patients in primary care, prioritizing those with positive results for timely referrals and appropriate intervention [14].

Several MCED approaches have been developed to demonstrate effective performance in cancer detection. We benchmarked GutSeer against recently published MCED assays with respect to the detection of five GI cancer across different stages (Supplementary Table 19) [40, 41]. GutSeer shows high sensitivity for GI cancers, particularly in early-stages, which is likely attributed to the relatively large proportion of early-stage cancer participants in the GUIDE cohort (39.4% for stage I, compared to 24.4% and 30.1% in other cohorts). Moreover, GutSeer was optimized as a compact and cost-effective panel, making it potentially feasible for clinical implementation and use in healthcare settings.

Striking a balance between the benefits and risks of MCED tests for the intended population is crucial, and specificity thresholds play a key role in this determination. While an ultra-high specificity (e.g., 99%) may be ideal for broad population screening [13, 42], a slightly lower specificity (e.g., 95%) could be more practical for targeted cancer detection in outpatient settings. This approach reduces unnecessary deferrals of standard-of-care interventions while ensuring timely follow-up for positive cases using affordable, well-tolerated diagnostics methods such as ultrasonography or endoscopy [16, 43]. Furthermore, studies have shown that blood-based tests can detect cancer signals years before formal diagnostic confirmation [35], suggesting that even in cases where immediate diagnosis is inconclusive, continued monitoring is advisable for individuals with positive MCED results [44].

Harmonizing pre-analytical practices across institutions is essential for the successful implementation of liquid biopsy in clinical settings, as these practices can impact mutation detection, methylation profiling, end motif analysis, and copy number measurements [45]. To address this, we standardized sample collection, processing, and storage procedures as detailed in Supplementary Table 2, aiming to reduce batch effects and improve data comparability [46, 47]. To maintain the Streck tubes' ambient temperature within the safe range of 6–37 °C, heating pads and ice packs were used as needed during periods of extreme temperatures. Blood, plasma, and cfDNA samples were processed in a centralized lab to minimize experimental variability. Future efforts should focus on adopting validated protocols, ensuring consistent personnel training, utilizing digital tracking, enforcing internal quality controls, and establishing standardized biobanking practices across sites [48].

To our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate the efficacy of a small-panel, multi-omics approach for GI cancer detection. In contrast, previous fragmentomic-only methods struggled to provide accurate TOO predictions [18, 49], while sequencing technique integrated with protein detection also failed to deliver precise TOO localization [50, 51]. Although methylation-based approaches have achieved strong TOO prediction when using large sequencing panels (spanning megabases to tens of megabases) with deep sequencing or genome-wide methylation profiling, these methods come at a significantly higher sequencing cost [10, 11, 13, 40]. Additionally, multimodal cfDNA strategies that rely on whole genome or methylome sequencing for GI cancer detection are similarly cost-prohibitive [31, 50, 52]. GutSeer, by contrast, achieved high accuracy with a single assay using a small, targeted panel, offering a cost-effective solution that is scalable for population-level screening.

Despite these advancements, several limitations warrant further investigation. First, the use of bisulfite sequencing imposes stringent DNA input requirements and may introduce biases in fragmentomics analysis. While bisulfite-free methods such as enzymatic Methyl-seq mitigate these issues, their associated costs and batch variability require further optimization. Second, although the study analyzed over 3,000 samples, the cohort size for specific cancer types remains relatively limited, highlighting the need for larger and more diverse datasets. Third, the sparse and heterogeneous nature of cfDNA released into the bloodstream during early tumorigenesis, when tumor size is still limited, results in relatively low and varied sensitivities among early-stage cancers in current MCED assays [53, 54]. This variability presents a significant challenge to the effectiveness of cancer screening, highlighting early-stage detection as a critical goal. Recent advancements in artificial intelligence algorithms promise to overcome these limitations, enabling more effective marker selection, improved library conversion rates, and the development of sophisticated integrated models combining multi-dimensional features, including clinical inputs. Additionally, a large-scale prospective study is planned to further refine the GutSeer assay, with particular emphasis on improving early-stage cancer detection. Finally, a longitudinal follow-up of tested healthy controls is essential to reduce misclassification, enhancing the overall reliability of GutSeer.

In conclusion, GutSeer represents a major breakthrough in the early detection of GI cancer, offering a powerful combination of high accuracy and cost-effectiveness. Its potential for widespread clinical implementation could significantly reduce the burden of advanced GI cancers, improve survival rates, and minimize treatment-related complications. Future studies should focus on validating its real-world clinical utility while addressing the technical and logistical challenges identified in this study.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Yunzhi Zhang, Chengcheng Ma, Minjie Xu, Jin Sun, Kehui Xie, Hua Chen, Yiying Liu, Weizhong Chen, Ruiqing Fu, Wei Li, Mingyang Su, Qi Liu, and Hongming Wang for their help in experiment preparation, sample processing, and data analysis.

Abbreviations

- GI

Gastrointestinal

- TOO

Tissue of origin

- MCED

Multi-cancer early detection

- cfDNA

Cell-free DNA

- WGS

Whole-genome sequencing

- GUIDE

Gastrointestinal cancer cohort study for mUlti-cancer non-Invasive early DEtection

- CNLC

China liver cancer staging system

- UMI

Unique molecular identifier

- AMF

Average methylation fraction

- MHF

Methylation haplotype fraction

- tFPKM

Targeted FPKM

- MES

Methylation encoding score

- LoD

Limit of detection

- U-MAP

Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection

- BMI

Body mass index

- TP

True positive

- TN

True negative

- FP

False positive

- FN

False negative

- RRBS

Reduced representation bisulfite sequencing

- TCGA

The Cancer Genome Atlas

Authors’ contributions

A.H., D.G., Z.S., Y.Z., L.L., Z.X., and Q.H. performed the methodology and data analysis. D.H., B.Y., Qu.L., Z.F., W.W., P.L., M.H., Z.Q., Q.G., J.C., Z.S., S.Z., W.G., Qi.L., G.L., H.S., S.Q., and J.F. collected samples and clinical data. J.Z., X.Y., G.J., and R.L. conceptualized the study. A.H., D.G., R.L., Z.S., Y.Z., L.L., Z.X., A.G., G.J., X.Y., and J.Z. wrote the manuscript draft, and all authors reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Noncommunicable Chronic Diseases-National Science and Technology Major Project (2024ZD0525400, 2024ZD0525401, 2024ZD0525405, 2024ZD0525406); the National Key Research & Development Program of China (2019YFC1315800, 2019YFC1315802, 2021YFC2501900); the State Key Program of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81830102); the Original Discovery Program of National Natural Science Foundation of China (82150004); the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82473484, 82488101, 82341027, 82072715); Shanghai Municipal Science and Technology Major Project; Eastern Talent Program (Leading project); the project of Shanghai Municipal Health Commission (201940075, 2022LJ005); the projects from the Shanghai Science and Technology Commission (21140900300, 22S31901800); the project from Shanghai hospital development center (SHDC2023 CRD025); the projects from Science Foundation of Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan University (2021ZSCX28, 2020ZSLC31). The funding agencies had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Data availability

The datasets generated during the current study are available in the BioProject database of the China National Center for Bioinformation under the Project ID PRJCA021793 (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/bioproject/). Code and source data to reproduce figures have been deposited in a Zenodo repository with DOI 10.5281/zenodo.15023391.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was obtained from the institutional review boards and the ethical committee of all participating centers: Zhongshan Hospital of Fudan University (No. B2020-291R), Changhai Hospital (No. CHEC2020-113), Qingpu Branch of Zhongshan Hospital affiliated to Fudan University (No. 2020-35), Xuhui Central Hospital (No. 2020-178), and Hubei Cancer Hospital (No. LCKY2021021). Informed consent was obtained from all participants before the study. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and compliant with GCP guidelines.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Ao Huang, De-Zhen Guo, Zhi-Xi Su, Yun-Shi Zhong, Liang Liu and Zhi-Guo Xiong contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Rui Liu, Email: rliu@singleragenomics.com.

Gang Jin, Email: jingang@smmu.edu.cn.

Xin-Rong Yang, Email: yang.xinrong@zs-hospital.sh.cn.

Jian Zhou, Email: zhou.jian@zs-hospital.sh.cn.

References

- 1.Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74:229–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crosby D, Bhatia S, Brindle KM, Coussens LM, Dive C, Emberton M, Esener S, Fitzgerald RC, Gambhir SS, Kuhn P, et al. Early detection of cancer. Science. 2022;375:eaay9040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miller KD, Nogueira L, Devasia T, Mariotto AB, Yabroff KR, Jemal A, Kramer J, Siegel RL. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin. 2022;72:409–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Han CJ, Reding K, Cooper BA, Paul SM, Conley YP, Hammer M, Wright F, Cartwright F, Levine JD, Miaskowski C. Symptom clusters in patients with gastrointestinal cancers using different dimensions of the symptom experience. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2019;58:224–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lu L, Mullins CS, Schafmayer C, Zeissig S, Linnebacher M. A global assessment of recent trends in gastrointestinal cancer and lifestyle-associated risk factors. Cancer Commun (Lond). 2021;41:1137–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grady WM, Yu M, Markowitz SD. Epigenetic Alterations in the gastrointestinal tract: current and emerging use for biomarkers of cancer. Gastroenterology. 2021;160:690–709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jamshidi A, Liu MC, Klein EA, Venn O, Hubbell E, Beausang JF, Gross S, Melton C, Fields AP, Liu Q, et al. Evaluation of cell-free DNA approaches for multi-cancer early detection. Cancer Cell. 2022;40(1537–1549): e1512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Conway AM, Pearce SP, Clipson A, Hill SM, Chemi F, Slane-Tan D, Ferdous S, Hossain A, Kamieniecka K, White DJ, et al. A cfDNA methylation-based tissue-of-origin classifier for cancers of unknown primary. Nat Commun. 2024;15:3292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen S, Petricca J, Ye W, Guan J, Zeng Y, Cheng N, Gong L, Shen SY, Hua JT, Crumbaker M, et al. The cell-free DNA methylome captures distinctions between localized and metastatic prostate tumors. Nat Commun. 2022;13:6467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kandimalla R, Xu J, Link A, Matsuyama T, Yamamura K, Parker MI, Uetake H, Balaguer F, Borazanci E, Tsai S, et al. EpiPanGI Dx: a cell-free DNA methylation fingerprint for the early detection of gastrointestinal cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 2021;27:6135–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stackpole ML, Zeng W, Li S, Liu CC, Zhou Y, He S, Yeh A, Wang Z, Sun F, Li Q, et al. Cost-effective methylome sequencing of cell-free DNA for accurately detecting and locating cancer. Nat Commun. 2022;13:5566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liang N, Li B, Jia Z, Wang C, Wu P, Zheng T, Wang Y, Qiu F, Wu Y, Su J, et al. Ultrasensitive detection of circulating tumour DNA via deep methylation sequencing aided by machine learning. Nat Biomed Eng. 2021;5:586–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu MC, Oxnard GR, Klein EA, Swanton C, Seiden MV, Consortium C. Sensitive and specific multi-cancer detection and localization using methylation signatures in cell-free DNA. Ann Oncol. 2020;31:745–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang K, Fu R, Liu R, Su Z. Circulating cell-free DNA-based multi-cancer early detection. Trends Cancer. 2024;10:161–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schrag D, Beer TM, McDonnell CH 3rd, Nadauld L, Dilaveri CA, Reid R, Marinac CR, Chung KC, Lopatin M, Fung ET, Klein EA. Blood-based tests for multicancer early detection (PATHFINDER): a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2023;402:1251–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nicholson BD, Oke J, Virdee PS, Harris DA, O’Doherty C, Park JE, Hamady Z, Sehgal V, Millar A, Medley L, et al. Multi-cancer early detection test in symptomatic patients referred for cancer investigation in England and Wales (SYMPLIFY): a large-scale, observational cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2023;24:733–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ding SC, Lo YMD. Cell-Free DNA Fragmentomics in liquid biopsy. Diagnostics (Basel). 2022;12:978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cristiano S, Leal A, Phallen J, Fiksel J, Adleff V, Bruhm DC, Jensen SO, Medina JE, Hruban C, White JR, et al. Genome-wide cell-free DNA fragmentation in patients with cancer. Nature. 2019;570:385–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bao H, Wang Z, Ma X, Guo W, Zhang X, Tang W, Chen X, Wang X, Chen Y, Mo S, et al. Letter to the editor: an ultra-sensitive assay using cell-free DNA fragmentomics for multi-cancer early detection. Mol Cancer. 2022;21:129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herberts C, Annala M, Sipola J, Ng SWS, Chen XE, Nurminen A, Korhonen OV, Munzur AD, Beja K, Schonlau E, et al. Deep whole-genome ctDNA chronology of treatment-resistant prostate cancer. Nature. 2022;608:199–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guo W, Chen X, Liu R, Liang N, Ma Q, Bao H, Xu X, Wu X, Yang S, Shao Y, et al. Sensitive detection of stage I lung adenocarcinoma using plasma cell-free DNA breakpoint motif profiling. EBioMed. 2022;81: 104131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ma X, Chen Y, Tang W, Bao H, Mo S, Liu R, Wu S, Bao H, Li Y, Zhang L, et al. Multi-dimensional fragmentomic assay for ultrasensitive early detection of colorectal advanced adenoma and adenocarcinoma. J Hematol Oncol. 2021;14:175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Doebley AL, Ko M, Liao H, Cruikshank AE, Santos K, Kikawa C, Hiatt JB, Patton RD, De Sarkar N, Collier KA, et al. A framework for clinical cancer subtyping from nucleosome profiling of cell-free DNA. Nat Commun. 2022;13:7475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.De Sarkar N, Patton RD, Doebley AL, Hanratty B, Adil M, Kreitzman AJ, Sarthy JF, Ko M, Brahma S, Meers MP, et al. Nucleosome patterns in circulating tumor DNA reveal transcriptional regulation of advanced prostate cancer phenotypes. Cancer Discov. 2023;13:632–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Keup C, Kimmig R, Kasimir-Bauer S. Combinatorial power of cfDNA, CTCs and EVs in oncology. Diagnostics (Basel). 2022;12:870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen L, Abou-Alfa GK, Zheng B, Liu JF, Bai J, Du LT, Qian YS, Fan R, Liu XL, Wu L, et al. Genome-scale profiling of circulating cell-free DNA signatures for early detection of hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhotic patients. Cell Res. 2021;31:589–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nguyen VTC, Nguyen TH, Doan NNT, Pham TMQ, Nguyen GTH, Nguyen TD, Tran TTT, Vo DL, Phan TH, Jasmine TX, et al. Multimodal analysis of methylomics and fragmentomics in plasma cell-free DNA for multi-cancer early detection and localization. Elife. 2023;12:RP89083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Siejka-Zielinska P, Cheng J, Jackson F, Liu Y, Soonawalla Z, Reddy S, Silva M, Puta L, McCain MV, Culver EL, et al. Cell-free DNA TAPS provides multimodal information for early cancer detection. Sci Adv. 2021;7:eabh0534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Erger F, Norling D, Borchert D, Leenen E, Habbig S, Wiesener MS, Bartram MP, Wenzel A, Becker C, Toliat MR, et al. cfNOMe - a single assay for comprehensive epigenetic analyses of cell-free DNA. Genome Med. 2020;12:54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li Y, Xu J, Chen C, Lu Z, Wan D, Li D, Li JS, Sorg AJ, Roberts CC, Mahajan S, et al. Multimodal epigenetic sequencing analysis (MESA) of cell-free DNA for non-invasive colorectal cancer detection. Genome Med. 2024;16:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bie F, Wang Z, Li Y, Guo W, Hong Y, Han T, Lv F, Yang S, Li S, Li X, et al. Multimodal analysis of cell-free DNA whole-methylome sequencing for cancer detection and localization. Nat Commun. 2023;14:6042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Collings CK, Anderson JN. Links between DNA methylation and nucleosome occupancy in the human genome. Epigenetics Chromatin. 2017;10:18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shi X, Radhakrishnan S, Wen J, Chen JY, Chen J, Lam BA, Mills RE, Stranger BE, Lee C, Setlur SR. Association of CNVs with methylation variation. NPJ Genom Med. 2020;5:41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Noe M, Mathios D, Annapragada AV, Koul S, Foda ZH, Medina JE, Cristiano S, Cherry C, Bruhm DC, Niknafs N, et al. DNA methylation and gene expression as determinants of genome-wide cell-free DNA fragmentation. Nat Commun. 2024;15:6690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen X, Gole J, Gore A, He Q, Lu M, Min J, Yuan Z, Yang X, Jiang Y, Zhang T, et al. Non-invasive early detection of cancer four years before conventional diagnosis using a blood test. Nat Commun. 2020;11:3475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schwarzenbach H, Hoon DS, Pantel K. Cell-free nucleic acids as biomarkers in cancer patients. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:426–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu Y, Li Y, Giovannucci E. Potential impact of time trend of lifestyle risk factors on burden of major gastrointestinal cancers in China. Gastroenterology. 2021;161:1830-1841 e1838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Johnson SE, Jayasekar Zurn S, Anderson BO, Vetter BN, Katz ZB, Milner DA Jr. International perspectives on the development, application, and evaluation of a multicancer early detection strategy. Cancer. 2022;128(Suppl 4):875–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Theresa JH, Daniel JC, Daniel HP, Omar E, Philip JJ, Rashika F, Timothy JC. Ultrasonography in surveillance for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatoma Research. 2023;9:12. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gao Q, Lin YP, Li BS, Wang GQ, Dong LQ, Shen BY, Lou WH, Wu WC, Ge D, Zhu QL, et al. Unintrusive multi-cancer detection by circulating cell-free DNA methylation sequencing (THUNDER): development and independent validation studies. Ann Oncol. 2023;34:486–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Klein EA, Richards D, Cohn A, Tummala M, Lapham R, Cosgrove D, Chung G, Clement J, Gao J, Hunkapiller N, et al. Clinical validation of a targeted methylation-based multi-cancer early detection test using an independent validation set. Ann Oncol. 2021;32:1167–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gao Q, Zeng Q, Wang Z, Li C, Xu Y, Cui P, Zhu X, Lu H, Wang G, Cai S, et al. Circulating cell-free DNA for cancer early detection. Innovation (Camb). 2022;3: 100259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Loosen SH, Scholer D, Luedde M, Eschrich J, Luedde T, Kostev K, Roderburg C. Differential role of chronic liver diseases on the incidence of cancer: a longitudinal analysis among 248,224 outpatients in Germany. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2023;149:3081–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chubak J, Burnett-Hartman AN, Barlow WE, Corley DA, Croswell JM, Neslund-Dudas C, Vachani A, Silver MI, Tiro JA, Kamineni A. Estimating cancer screening sensitivity and specificity using healthcare utilization data: defining the accuracy assessment interval. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2022;31:1517–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Janssen FW, Lak NSM, Janda CY, Kester LA, Meister MT, Merks JHM, van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM, van Noesel MM, Zsiros J, Tytgat GAM, Looijenga LHJ. A comprehensive overview of liquid biopsy applications in pediatric solid tumors. NPJ Precis Oncol. 2024;8:172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Greytak SR, Engel KB, Parpart-Li S, Murtaza M, Bronkhorst AJ, Pertile MD, Moore HM. Harmonizing cell-free DNA collection and processing practices through evidence-based guidance. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26:3104–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moser T, Kuhberger S, Lazzeri I, Vlachos G, Heitzer E. Bridging biological cfDNA features and machine learning approaches. Trends Genet. 2023;39:285–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Coppola L, Cianflone A, Grimaldi AM, Incoronato M, Bevilacqua P, Messina F, Baselice S, Soricelli A, Mirabelli P, Salvatore M. Biobanking in health care: evolution and future directions. J Transl Med. 2019;17:172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhou X, Zheng H, Fu H, Dillehay McKillip KL, Pinney SM, Liu Y. CRAG: de novo characterization of cell-free DNA fragmentation hotspots in plasma whole-genome sequencing. Genome Med. 2022;14:138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cohen JD, Li L, Wang Y, Thoburn C, Afsari B, Danilova L, Douville C, Javed AA, Wong F, Mattox A, et al. Detection and localization of surgically resectable cancers with a multi-analyte blood test. Science. 2018;359:926–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lennon AM, Buchanan AH, Kinde I, Warren A, Honushefsky A, Cohain AT, Ledbetter DH, Sanfilippo F, Sheridan K, Rosica D, et al. Feasibility of blood testing combined with PET-CT to screen for cancer and guide intervention. Science. 2020;369:eabb9601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bae M, Kim G, Lee TR, Ahn JM, Park H, Park SR, Song KB, Jun E, Oh D, Lee JW, et al. Integrative modeling of tumor genomes and epigenomes for enhanced cancer diagnosis by cell-free DNA. Nat Commun. 2017;2023:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Thierry AR. Circulating DNA fragmentomics and cancer screening. Cell Genom. 2023;3: 100242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Phallen J, Sausen M, Adleff V, Leal A, Hruban C, White J, Anagnostou V, Fiksel J, Cristiano S, Papp E, et al. Direct detection of early-stage cancers using circulating tumor DNA. Sci Transl Med. 2017;9:eaan2415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during the current study are available in the BioProject database of the China National Center for Bioinformation under the Project ID PRJCA021793 (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/bioproject/). Code and source data to reproduce figures have been deposited in a Zenodo repository with DOI 10.5281/zenodo.15023391.