ABSTRACT

Fusobacterium nucleatum (F. nucleatum) is an oral commensal bacterium that can become pathogenic and is associated with periodontitis, adverse pregnancy outcomes, and colorectal cancer (CRC). MicroRNAs are conserved, non-coding RNA molecules that regulate gene expression and are detected in microbial infections. This study aims to characterize the microRNA expression kinetics in the mandibles of C57BL/6J mice infected with F. nucleatum for 8 and 16 weeks and to identify miRNAs as potential biomarkers using NanoString nCounter miRNA panels. Mice were divided into four groups: 8 weeks of infection, 16 weeks of infection, and their respective sham infection. F. nucleatum-infected mice showed 100% bacterial colonization on the gingival surface, along with a significant increase in alveolar bone resorption (P < 0.0001) and intravascular dissemination to the heart, indicating its invasive potential. Out of 577 miRNAs analyzed, seven miRNAs were upregulated, and two miRNAs were downregulated in the 8 weeks of infection group. In the 16 weeks of infection group, seven miRNAs were upregulated while 13 miRNAs were downregulated. Notably, miR-205, miR-210, and miR-199a-3p were differentially expressed at 8 weeks as well as miR-28 at 16 weeks and have been previously reported in human periodontitis. The 13 miRNAs induced by F. nucleatum (e.g., miR-361-5p) are linked to 13 multiple malignancies. In addition, miR-126-5p has been identified as a potential biomarker for patients with PD and cardiovascular disease. These results indicate that F. nucleatum induces several PD-related miRNAs and links them to systemic comorbidities. Furthermore, this study revealed F. nucleatum induction of 14 oncogenic miRNAs, and specifically, 12 miRNAs were linked with CRC.

IMPORTANCE

Our study investigated oral commensal Fusobacterium nucleatum, a critical bacterium associated with gum disease, adverse pregnancy outcomes, and enriched several tumors, including colorectal cancer (CRC). Recently, microRNAs have emerged as critical players in the interactions between host and microbes, and many host functions have been reported to be regulated by miRNAs during infection. F. nucleatum oral infection in mice induced gum disease, disseminated to the heart, lungs, and several miRNAs. Elevated miR-361 expression was linked to multiple cancers. In addition, miR-126-5p expression has been reported as a potential biomarker in patients with periodontitis and coronary artery disease, indicating F. nucleatum’s virulence potential. The 13 miRNAs induced by F. nucleatum are linked to 13 multiple malignancies, including CRC. These results indicate that F. nucleatum acts as a potent cancer-causing bacterium. This study opens new avenues for exploring F. nucleatum’s role in gum disease and its link with cancer.

KEYWORDS: F. nucleatum, periodontal disease, miRNAs, CRC miRNAs, machine learning models

INTRODUCTION

The ubiquitous oral symbiont F. nucleatum is a heterogeneous species with five known subspecies. It is the most predominant and abundant species in the oral cavity, present in both diseased and healthy individuals (1). As a dominant microbe in the periodontium, it is a periodontal bacterium, a non-spore-forming obligate anaerobe, that does not possess fimbriae, pili, or flagella, and is detected at higher levels in the oral cavity of periodontitis patients (2). It is known to coaggregate/bridge/synergize with various microbial species and is a prominent intermediate oral pathobiont in the physical interaction and microbial complexes between Gram-positive and Gram-negative late colonizing bacteria, such as Porphyromonas gingivalis, Treponema denticola, and Tannerella forsythia (3, 4). It is an intermediate colonizer that colonizes the tooth and epithelial surface (5, 6), often implicated in various extra-oral diseases (4). Previous in vivo subcutaneous co-infection (7) and oral co-infection studies (8) have demonstrated that the inclusion of F. nucleatum synergistically enhances bacterial virulence and disease severity. Prior chronic oral infection established F. nucleatum colonization in the oral cavity, induced significant humoral IgG and IgM antibody response, and resulted in significant ABR and detection of genomic DNA in systemic organs (heart, aorta, liver, kidney, lung), indicating bacteremia (9). In addition, vascular inflammation was detected by enhanced systemic cytokines (CD30L, IL-4, IL-12), oxidized LDL, and serum amyloid A, as well as an altered serum lipid profile (cholesterol, triglycerides, chylomicrons, VLDL, LDL, HDL) in infected mice. An altered aortic gene expression in infected ApoEnull hyperlipidemic mice further supports its virulence (9).

Several studies have also reported the association of F. nucleatum with pregnancy complications, including chorioamnionitis, spontaneous abortion, preterm birth, stillbirth, neonatal sepsis, and preeclampsia (10). Emerging reports in the last two decades indicate a significant link between F. nucleatum and the progression of multiple digestive tract cancers, including esophageal (11), gastric (12), pancreatic (13), CRC (14, 15), lung cancers (16), and oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) (17). F. nucleatum interacts with the molecular hallmarks of gastrointestinal cancers, inducing genomic mutations and promoting a permissive immune microenvironment by impairing anti-tumor checkpoints (18). F. nucleatum binds to the stressed epithelial cells using the Gal-GalNAc moiety and spreads to the extraoral site by the hematogenous route (19–21).

microRNAs (miRNAs) are small (21–25 nucleotides) noncoding, regulatory RNAs that regulate gene expression by directly binding to the 3′ untranslated regions of their target miRNAs (22). Approximately 60% of all genes in each mammalian genome are estimated to be regulated by 2,000 miRNAs (23, 24). Several studies on miRNAs have implicated them in many human systemic diseases. They regulate the immune response of hosts infected with exogenous pathogenic bacteria such as Helicobacter pylori (25), Treponema pallidum (26), M. tuberculosis (27), Salmonella (28), Listeria monocytogenes (29), Mycobacterium avium (30), and endogenous periodontal microbiome (31–34). Hence, understanding miRNA expression patterns could lead to the development of novel diagnostic and therapeutic biomarkers for microbial infection-mediated inflammatory diseases, including periodontal disease (PD). Gingival tissue from chronic inflammatory PD has revealed a panel of microRNAs (hsa-miR-223-3p, hsa-miR-203b-5p, hsa-miR-146a-5p, hsa-miR-146b-5p, and hsa-miR-155-5p) (35) and miR-146a expression in a rodent model (36). Hence, understanding the expression pattern of miRNAs could potentially lead to the development of novel diagnostic biomarkers for PD. Recently, we reported sex-specific differential miRNA expression (miR-9, miR-148a, miR-669a, miR-199a-3p, miR-1274a, miR-377, and miR-690) in mice infected with partial human mouth microbes (PAHMM) using a novel ecological time-sequential polybacterial periodontal infection (ETSPPI) mouse model (34). In addition, we have also reported individual monobacterial periodontal infections with P. gingivalis, T. denticola, T. forsythia, and S. gordonii in the mouse model and identified several miRNAs linked with PD, various systemic diseases, and malignancies (31–33). To date, the role of miRNAs in response to oral infection by the periodontal microbe F. nucleatum in a mouse model of PD has not been examined. Accordingly, this study aimed to enhance our understanding of whether intraoral infection of mice with F. nucleatum could lead to unique alterations in miRNA expression patterns. The present study was designed to analyze miRNA differential expression (DE) kinetics at two time points (8 weeks and 16 weeks) in F. nucleatum-infected male and female C67BL/6J mice using high-throughput NanoString analysis with nCounter miRNA expression profiling. In addition to analyzing the complicated interactions between F. nucleatum infection, PD, and oncogenic miRNAs, we utilized machine-learning (ML) algorithms such as XG Boost (XGB), Random Forest classifier (RFC), Logistic Regression (LR), Support Vector Classifier (SVC), and Multilayer Perceptron (MLP). In recent studies, we analyzed miRNAs in response to oral monobacterial infection in the mouse model using several ML algorithms (33, 37), which clarifies the understanding of miRNAs’ association with PD, its systemic comorbidities, and multiple tumors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal models, ethical statement, and grouping

Male and female wild-type C57BL/J mice aged 8 weeks were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory. All the animal procedures were performed according to the guidelines of the University of Florida Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee protocol # 202200000223. Mice were divided into four groups (in each group, n = 10; five males and five females): Group I was infected with F. nucleatum for 8 weeks, Group II was sham infected for 8 weeks, Group III was infected with F. nucleatum for 16 weeks, and Group IV was sham-infected mice for 16 weeks (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Gingival plaque samples tested positive for F. nucleatum gDNA using PCRa

| Group/bacteria (weeks) | Positive gingival plaque samples (n = 10) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8-week time point | 16-week time point | |||

| 2 weeks | 4 weeks | 6 weeks | 12 weeks | |

| Group I/F. nucleatum ATCC 49256 (8 weeks) | 5/10 | 3/10 | 10/10 | NC |

| Group II/sham infection (8 weeks) | 0/10 | NC | NC | NC |

| Group III/F. nucleatum ATCC 49256 (16 weeks) | 6/10 | 9/10 | 10/10 | NC |

| Group IV/sham infection (16 weeks) | 0/10 | NC | NC | 0/10 |

Total numbers of gingival plaque samples collected after infections (2, 4, 6, and 12 weeks), and positive infections were determined by PCR analysis. NC, not collected to allow bacterial biofilm to adhere to the gingival surface, invade epithelial cells, and multiply. The first value corresponds to the number of mice that assessed positive for the respective genomic DNA, and the second value corresponds to the total number of mice in the group.

Bacterial strain, culture, and mice-oral administration

F. nucleatum ATCC 49256 subspecies vincentii was isolated from periodontal pocket (38) grown on blood agar plates in a Coy anaerobic chamber at 37°C for 2–3 days, harvested, and prepared for intra-oral infections in mice as described previously (9, 34, 39–42). Mice in Group I were intraorally infected with 108 F. nucleatum cells/mouse, suspended in reduced transport fluid (RTF) and equal volumes of carboxymethyl cellulose (6% CMC) for four times a week every other week for a total of 8 weeks. In Group III, the infection scheme was for a total of 16 weeks. Group II and IV mice were treated with a 1:1 ratio of RTF and 6% CMC as sham infections for 8 and 16 weeks, respectively. After the designated infection period, mice were euthanized (CO2 inhalation), and blood and organ samples (mandibles, maxilla, brain, heart, liver, lungs, spleen, and kidney) were collected. RNAlater solution was used to preserve the left maxilla and mandibles for miRNA analysis, whereas the right maxilla and mandibles were used for horizontal alveolar bone resorption (ABR) morphometry measurements (34).

DNA isolation and molecular detection of the bacteria genome

Gingival plaque samples from the mice that received oral F. nucleatum infection were collected in Tris EDTA (TE) buffer (34, 43). F. nucleatum genomic DNA (gDNA) present in the oral plaque samples and the distal organs of the heart, lungs, brain, liver, kidney, and spleen were detected using 16S rRNA gene-specific primers 5′-TAAAGCGCGTCTAGGTGGTT-3′ and reverse primer 5′-ACAGCTTTGCGACTCTCTGT-3′ (34). Colony PCR was adopted to detect F. nucleatum gDNA in the gingival plaque samples. Qiagen Dneasy Blood and Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD, USA) was used to extract the gDNA from the distal organs and stored at –20°C (34). F. nucleatum culture DNA was used as a positive control, and sterile milli Q water was considered a negative control in the PCR. The amplified F. nucleatum-specific DNA was run through agarose electrophoresis and visualized in the UVP GelStudio touch Imaging System (Analytik Jena US LLC, CA, USA).

Measurement of ABR

After euthanasia, the mandibles and maxilla were dissected and placed in a beaker, autoclaved to remove the soft flesh over the jawbone. Two-dimensional alveolar bone imaging was performed using a stereo dissecting microscope (Stereo Discovery V8, Carl Zeiss Microimaging, Inc., Thornwood, NY, USA). The pattern of the horizontal ABR area was measured by histomorphometry, as described previously (34, 43). Two examiners were blinded to measure ABR, and the data acquired were used for quantitative analysis.

Total RNA isolation and quality assessment

Total RNA was isolated from left mandibles using the mirVana miRNA Isolation Kit (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA). The final RNA yield, quality assessments, and purity were determined as follows (31, 32, 34): RNA with an OD 260/230 ratio of >2 and an OD 260/280 ratio of >2 was quantified using an Epoch Microplate Spectrophotometer (BioTek, USA, Winooski, VT, USA) and taken for NanoString analysis.

miRNA-transcriptome expression profiling

We used high-throughput nCounter expression panels (NanoString Technologies, Seattle, WA, USA) for miRNA-transcriptome analysis in the mandibles of the mice. Panels can identify 577 miRNAs in the sample using molecular barcodes and can detect even a low number of miRNAs without the need for reverse transcription (RT) or amplification. The probability of introducing artifacts is limited as it does not involve cDNA conversion as in Real-Time PCR. The NanoString nCounter Mouse miRNA Assay kit v1.5 is a highly sensitive multiplexed method that detects miRNA using nCounter reporter probes. This step does not require reverse transcription. The details of the NanoString experimental procedure were explained in detail from our previous publications (31–34, 37). Briefly, NanoString’s nCounter utilizes a chemistry that distinguishes miRNAs with single-nucleotide differences and has a 6-log dynamic range for direct digital counts. Accordingly, the process of reverse transcription is not required. nCounter miRNA expression assay is highly reproducible with R² >0.99 in replicate counts. To verify the sensitivity and specificity, we have performed the q-PCR validation of the inflammatory miRNA 146a and found that both the q-PCR and NanoString data were similar (41). Two independent studies also support the idea that there is no need to validate the NanoString data using stem-loop Real-Time PCR. The study from Prokopec et al. compared two key medium-throughput platforms—NanoString’s nCounter Analysis System and ABI’s OpenArray System—to gold-standard quantitative real-time RT-PCR for the specific factors signal:noise ratios, correlations, dynamic range, and detection accuracy comparison across the three platforms and found that all three measurement technologies showed good concordance but with divergent price/time/sensitivity trade-offs (44). In another independent study, Veldman-Jones et al. reported that NanoString nCounter shows excellent technical reproducibility (45).

The nCounter Mouse miRNA Assay kit v1.5 provided six positive hybridization controls and eight negative control probes to monitor hybridization efficiency. Twelve samples per cartridge were processed in a single run, which took 3 h. This was followed by digital analysis, which involved the transfer of the cartridge to the multichannel epifluorescence digital analyzer. A cartridge definition file with a maximum field of view (FOV) count of 555 per flow cell was taken for digital analysis. The number of images taken per scan corresponded to the number of immobilized reporter probes on the cartridge. A separate Reporter Code Count (RCC) file for each sample containing the count for each probe was downloaded and used for data analysis. The final Reporter Code Count (RCC) data files were evaluated using nSolver 4.0 software as described (31–34, 37). The data that support the findings of this study are openly available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSM7915885 (accessed on 4 December 2023).

Bioinformatics analysis

The normalized miRNA data were analyzed using the HyperScale architecture developed by ROSALIND, Inc. (San Diego, CA) (https://rosalind.bio/ (accessed on 16 September 2023) (46). Fold changes in the miRNA were calculated following the standard formula (33) and limma R library (47). The DE miRNAs were validated for miRNA-target gene interactions using the MiRTarBase database (48). A Venn diagram for the DE miRNAs was drawn using Venny 2.1 (34).

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) is an integrated database (49), and its pathways were plotted using the DIANA-miRPath v.3.0 database (50), taking the MIMAT accession number, calculating the false discovery rate (FDR) using the Benjamini and Hochberg method (34).

Multiple ML model analysis

The ML models used in our study were created and executed using version 3.11.4 of the Python programming language. We used XGBoost version 1.7.6 and the Scikit-learn version 1.3.0 implementations of LR, SVC, MLP, and RFC. A full list of the hyperparameters used for each ML model is available in Appendix S1 in the Supplemental material. SHAP version 0.42.1 was used to obtain feature importance results (37). The code for executing the ML models on the NanoString copy data is available on GitHub at (https://github.com/uflcod/miRNA-periodontal-disease (accessed on 1 February 2024) in the “notebooks” directory. The notebooks for analyzing the F. nucleatum NanoString data begin with the prefix “Fn_” (e.g., Fn_randomforest_miRNA.ipynb, Fn_xgboost_miRNA.ipynb).

Statistical analysis

All the data in the graphs were presented as mean ± SEM. Data for alveolar bone resorption were analyzed using ordinary two-way ANOVA, with Tukey’s multiple comparison test with a single pooled variance in Prism 9.4.1 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) (34, 37, 51). P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The DE miRNAs with FC of ±1 were considered significant. The identification of significant DE-miRNA was done based on two-tailed t-tests. The Welch–Satterthwaite equation was used to calculate the distribution of the t-statistics. The volcano plot was drawn using GraphPad Software (34).

RESULTS

Chronic infection of F. nucleatum, colonized in the mice gingival tissue

Intraoral infection of F. nucleatum induced a time-dependent colonization on the gingiva and aided periodontal miRNA expression in periodontitis. Time-dependent gingival colonization for P. gingivalis, T. denticola, T. forsythia, and S. gordonii was observed in our earlier studies (31–33, 37). F. nucleatum bacterial colonization initiated PD on chronic intraoral infection in a time-dependent manner. Testing of oral swabs collected from the gingival plaque for 16S rRNA gene-specific PCR confirmed that gingival plaque samples in Group I mice had 50% F. nucleatum-specific DNA at the 2 weeks of intraoral infection time point and tested positive for all the mice after 6 weeks of F. nucleatum infection. Group III mice were 60%, 90%, and 100% positive for F. nucleatum after 2, 4, and 6 weeks of infections, respectively (Table 1).

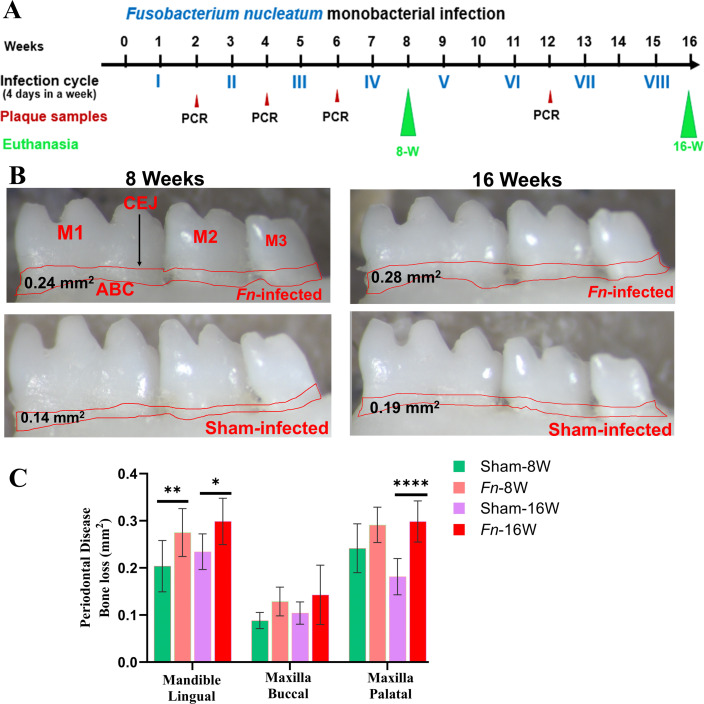

Alveolar bone resorption and bacterial genomic DNA (gDNA) in the distal organs

The pathogenic factors of periodontal bacteria, along with inflammatory cytokines mediated activation of osteoclasts, collectively contribute to ABR (52). Microscopic images of the mandibles in F. nucleatum-infected and sham-infected groups are shown in Fig. 1B. Mice infected with F. nucleatum at both 8 week and 16 week time points showed significantly higher ABR in the mandible (lingual) P < 0.05 (adjusted P-value = 0.001) (Fig. 1B and C). ABR measured in the maxilla did not show a significant difference between sham- versus F. nucleatum-infected groups. In the 8 weeks infection group, bacteria-specific gDNA was identified from the heart (Table S1) (3/10), lungs (2/10), and the liver (1/10). Similarly, in 16 weeks of infected mice, F. nucleatum gDNA was detected in the heart (5/10), the lungs (6/10), and the kidney (1/10) samples (Table S1). This finding suggests the physiological colonization/infection of the gingival epithelium and the intravascular dissemination of bacteria to the distal organs, representing the invasive potential of F. nucleatum.

Fig 1.

Intraoral infection with F. nucleatum significantly induced ABR. (A) Schematic diagram of the experimental design depicting the monobacterial infection with F. nucleatum (4 days per week on every alternate week), plaque sampling for PCR, and euthanasia. (B) Representative images showing horizontal ABR in the mandible (lingual view) of F. nucleatum-infected and sham-infected mice, with the ABR area outlined from the alveolar bone crest (ABC) to the cementoenamel junction (CEJ). (C) Morphometric analysis of the mandible and maxillary ABR at 8 and 16 weeks post-infection. A significant increase in ABR was seen in F. nucleatum-infected mice compared to sham-infected mice (****P < 0.0001; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05; ordinary two-way ANOVA). Data points and error bars are represented as mean ± SEM (n = 10).

NanoString analysis of miRNA in F. nucleatum-infected mandibles

The NanoString platform is an amplification-free technology that uses molecular barcodes. It directly quantifies the RNA molecules without the events of reverse transcription and is strongly reliable in working with multiple sample types. The total RNA extracted from purified mandibles was further analyzed for global miRNA profiling in the 8 weeks and 16 weeks of F. nucleatum-infected mice (Table 2). nCounter miRNA expression profiling showed seven upregulated miRNAs, including most significantly miR-361-5p, miR-26a-5p, miR193a-3p, miR-126-5p, miR-324-5p, miR-24-3p, and miR-99b-5p and two downregulated miRNAs of miR-362-3p and miR-720 in 8 weeks of F. nucleatum-infected mandibles compared to sham-infected mandibles (Table 2). Similarly, a total of seven upregulated DE miRNAs (miR-361-5p, miR-99b-5p) and thirteen downregulated miRNAs (miR-323-3p, miR-488) were shown in 16 weeks of F. nucleatum-infected mandibles compared to the sham-infected mandibles. The analysis between F. nucleatum-infected female vs male mice showed 12 upregulated (miR-206, miR-210) and 12 downregulated miRNAs (miR-376a, miR-350) in the 8 weeks of infection group and 5 upregulated (miR-152, miR-125b-5p) and 14 downregulated miRNAs (miR-375, miR-376a) in the 16 weeks of infection group. The upregulated miR-210 in the 8 weeks of F. nucleatum-infected female mice was found to be downregulated in the 16 weeks of infected female mice (Table 2). A P-value of <0.05 and a fold change of 1.1 and above were considered for analysis and to be significant. DE upregulated miRNAs between 8 and 16 weeks of analysis target function and target genes are shown in Tables 3 and 4, and downregulated miRNAs are shown in Table S2. The list of DE miRNAs (upregulated and downregulated) for 8 and 16 weeks of analysis is shown in Table S3. The upregulated and downregulated miRNAs in the female vs male comparison study for the 8 weeks of infection are shown in Table S4 and for 16 weeks shown in Table S5.

TABLE 2.

Differentially expressed miRs during 8 and 16 weeks of F. nucleatum infection in micea

| Weeks, infection, and sex | Upregulated miRNAs (P < 0.05) | Downregulated miRNAs (P < 0.05) |

|---|---|---|

| 8 weeks—F. nucleatum-infected vs 8 weeks—sham infection (n = 10) | 7 (e.g., miR-361-5p, miR-99b-5p) | 2 (miR-362-3p, miR-720) |

| 8 weeks—F. nucleatum-infected female vs male (n = 5) | 12 (e.g., miR-206, miR-210) | 12 (e.g., miR-376a, miR-350) |

| 16 weeks—F. nucleatum-infected vs 16 weeks—sham infection (n = 10) | 7 (e.g., miR-361-5p, miR-99b-5p) | 13 (e.g., miR-323-3p, miR-488, miR-350) |

| 16 weeks—F. nucleatum-infected female vs male (n = 5) | 5 (e.g., miR-152, miR-125b-5p) | 14 (e.g., miR-375, miR-210, miR-376a, miR-362-3p) |

| 8 weeks—F. nucleatum-infected vs 16 weeks—F. nucleatum-infected (n = 10) | 14 (e.g., miR-133a, miR-22) | 47 (e.g., miR-323-3p, miR-1902) |

The number of DE miRNAs was shown for F. nucleatum-infected mice after 8 and 16 weeks of infections. The commonly expressed miRNAs between 8 and 16 weeks of bacterial-infected groups are shown in brackets. Two miRNAs expressed in bacterial-infected groups were unique and specific to the 8 and 16 weeks of infections.

TABLE 3.

F. nucleatum-infection-induced upregulated miRNAs (8 weeks), reported functions, and target genesa

| miR (FC) | P-value | Reported functions | Target genes |

|---|---|---|---|

| miR-361-5p (1.3) | 0.0311 | Downregulated in the 13 types of cancer, including CRC (53). Upregulated in stable coronary heart disease, acute coronary heart syndrome (54). | 16 (e.g., Ctbp2, Tfam, Nol7) |

| miR-26a-5p (1.23) | 0.0008 | Downregulated in the gingiva of periodontitis patients (55). Associated with cardiovascular diseases (56). Associated with CRC (57). | 426 (e.g., Kpna2, Nus1, Rgs17) |

| miR193a -3p (1.21) | 0.0150 | Downregulated in plasma and salivary exosomes of Chronic periodontitis patients (58). Downregulated in the P. gingivalis-LPS-treated human periodontal ligament cells (59). Dysregulated in pancreatic cancer (60), colorectal cancer (61), and endometrial cancer (62). A novel biomarker for Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis (63). Downregulated in the microbiota-mediated ulcerative colitis (64). | 8 (e.g., Gla, Ifngr2, Metap2) |

| miR-126-5p (1.2) | 0.0308 | Upregulated in T. denticola-induced periodontitis (32). Preventing alveolar bone resorption in diabetic periodontitis (65). Upregulated miR in the gingiva of PD patients (66). Associated with colorectal cancer (67), promoting chemoresistance of ovarian cancer cells (68). Upregulated in coronary artery ectasia patients (69). Upregulated in thoracic aorta aneurysm patients (70). Reported as a molecular target for myocardial infarction treatment (71). Reported as a poultry meat quality and food safety marker miRNA (72). | 55 (e.g., Gfpt1, H2-D1, Il10rb, Kras) |

| miR-324-5p (1.18) | 0.0164 | Downregulated in the gingival tissue of periodontitis patients (73). Reported as a therapeutic miR in cervical cancer, colorectal cancer, gastric cancer, brain tumors, and hepatocellular carcinoma (74). Diagnostic miRNA in the human cases with heart failure (75). Downregulated in osteoporosis patients (76). | 12 (E.g., Zfp295, Zscan12, Kcnk6) |

| miR-24-3p (1.17) | 0.0160 | Downregulated in the unstimulated saliva of chronic periodontitis patients (58). Reported as a defensive miR against periodontal inflammation (77). A diagnostic marker for multiple cancers (78). | 375 (e.g., Oxt, Chrna1, Birc5) |

| miR-99b-5p (1.14) | 0.0120 | Downregulated in the gingiva of periodontitis patients (73). Upregulated in the P. gingivalis-induced periodontitis (31). Downregulated in the saliva of chronic periodontitis patients (58). Upregulated in M. tuberculosis-infected murine dendritic cells (79). Novel chemosensitizing miRNAs in high-risk neuroblastoma (80, 81). Associated with the cancer conditions to ovaries (82), prostate (83), colorectal (84), gastric (85), liver (86), and lungs (87). | 4 (e.g., Comp, Grik3, Slc35d2) |

The upregulated miRNAs for 8 weeks of F. nucleatum infection were associated with aggressive periodontitis in human subjects’ saliva and gingival tissue (e.g., miR-26a-5p; miR-193a-3p). Bold indicates miRNAs associated with multiple cancers, and italics indicate miRNAs associated with periodontitis details of the biological.

TABLE 4.

F. nucleatum infection induced upregulated miRNAs (16 weeks), reported functions, and target genesa

| miR (FC) | P-value | Reported functions | Target genes |

|---|---|---|---|

| let-7a-5p (1.28) | 0.0011 | Downregulated in T. denticola-induced periodontitis (32). Downregulated in the saliva of patients with aggressive periodontitis (88). Upregulated in gingival tissue of chronic periodontitis patients (89). IL-13, a cytokine essential for allergic lung diseases, is regulated by mmu-let-7a-5p (90). Downregulated in bronchial biopsy of severe asthma patients (91). Associated with CRC (92). | 28 (e.g., Lin28a, IL6, Hoxa9) |

| miR-127-3p (1.28) | 0.0217 | Upregulated in T. forsythia-induced rodent periodontitis models (33). Upregulated in the inflamed primary human gingival fibroblasts (93). Upregulated in the human advanced carotid atheroma (94). May play an important role in acute myocardial injury (95). Tumor suppressor miRNA in triple-negative breast cancer cells (96). Associated with CRC (97). | 10 (e.g., Rtl1, Gpi1, Ghdc) |

| miR-3615p (1.19) | 0.0357 | Reported in 8 weeks of analysis study | |

| miR-345-5p (1.16) | 0.0034 | Reliable biomarker in patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma (98). Acting as an anti-inflammatory miRNA in mice with allergic rhinitis (99). Reported as a protective miRNA during gestational diabetes mellitus subjects (100). Associated with CRC (101). | 10 (e.g., Ccdc127, Eaf1, Atic) |

| let-7f-5p (1.16) | 0.0298 | Upregulated in human periodontitis gingival tissue (66). Potential biomarker for abdominal aortic aneurysm (102). Involvement in the pathogenesis of SLE-lupus nephritis (103). Associated in CRC (92). | 16 (e.g., Atp2b2, Ifnar1, Nf2). |

| miR-99b-5p (1.15) | 0.0299 | Reported in 8 weeks of analysis study | |

| miR-218-5p (1.15) | 0.0333 | Upregulated in the T. forsythia-induced rodent periodontitis models (33). Downregulated in the gingival fibroblasts and is essential for myofibroblast differentiation (104). Upregulated in the inflamed gingiva (105). Reduced expression was observed in the atherosclerosis cohort and considered a clinical marker for atherosclerosis (106). Downregulated in smokers without airflow limitation and in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (107). Associated with CRC (108). | 20 (e.g., Epg5, Prdm1, Bsn, Eno2) |

Details of the biological function and target genes were given for the top 10 significantly expressed miRNAs in 16 weeks of infected mice mandibles. The upregulated miRNAs for 16 weeks of F. nucleatum infection were associated with aggressive periodontitis in the saliva and gingival tissue of human subjects (mmu-let-7a-5p; mmu-let-7f-5p), acute myocardial injury (miR-127-3p), and a clinical marker for atherosclerosis (miR-218-5p). Bold indicates miRNAs associated with multiple cancers, and italics indicate miRNAs associated with periodontitis.

Identification of differentially expressed miRNAs

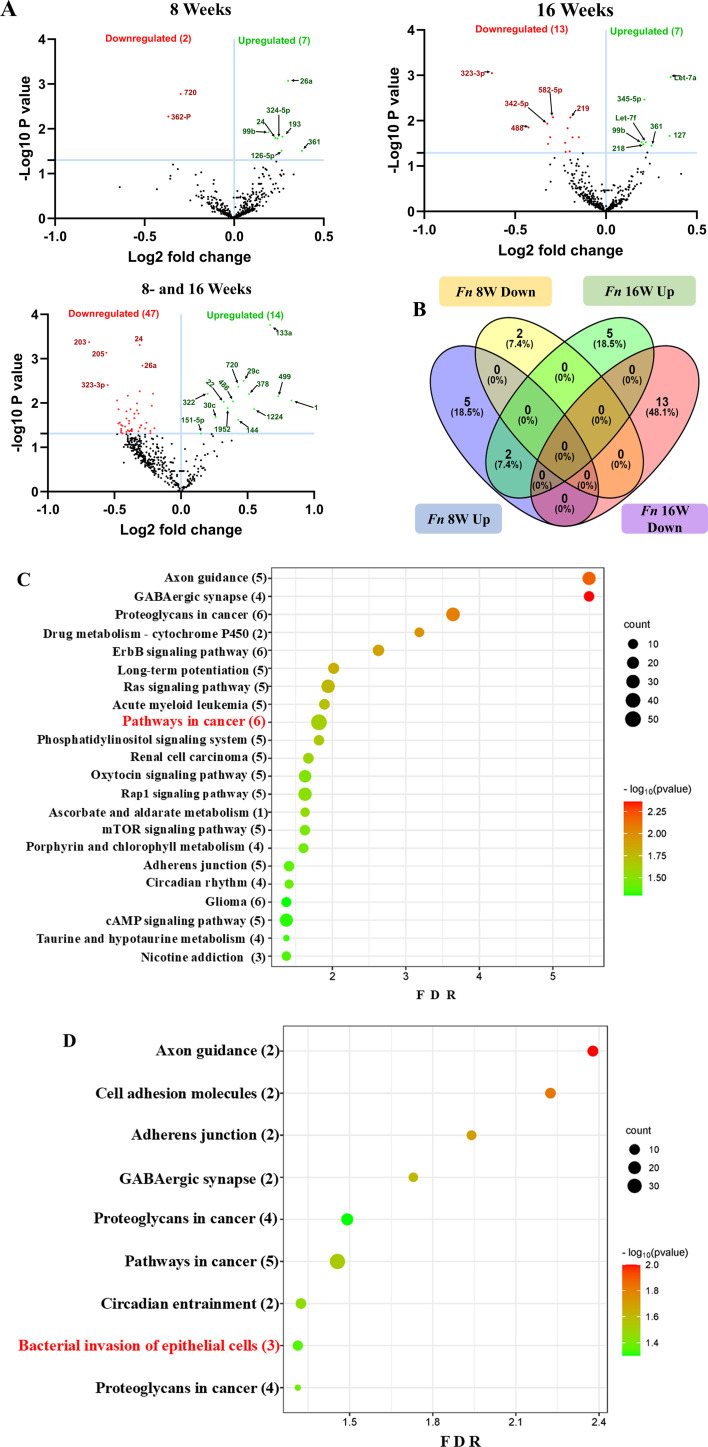

Two F. nucleatum-infected and two sham-infected groups were analyzed using high-throughput nCounter miRNA Expression Panels. To find the statistical significance in differentially expressed (DE)-miRNA, we performed volcano plot analysis. It was plotted against log2 fold change on the x-axis and the negative log of P-value on the y-axis. The identified downregulated miRNAs indicated in red and 14 upregulated miRNAs (green) showed a fold difference of +1.1 with a P-value of <0.05 in the 8 weeks of F. nucleatum-infected mice compared to the 16 weeks of infected group (Fig. 2A). All the black dots represent miRNAs that do not pass the filter parameters. In the 8 weeks of the infection study, seven miRNAs showed higher expression (e.g., miR-361-5p, miR-99b-5p) (Table 3). Similarly, seven miRNAs (e.g., miR-361-5p, miR-99b-5p) showed higher expression in 16 weeks of F. nucleatum-infected mandibles (Fig. 2B; Table 4).

Fig 2.

DE miRNAs in F. nucleatum-infected mandibles (8 and 16 weeks). (A) The volcano plot depicts the upregulated (green) and downregulated (red) miRNAs that showed a fold difference of ±1.1 with a P-value of <0.05. The log2 fold change is on the x-axis, and the negative log of the P-value is on the y-axis. The black dots stand for the miRNAs that do not pass the filter parameters. Seven significant upregulated miRNAs and two downregulated miRNAs were found in 8 weeks of F. nucleatum-infected mice compared to 8 weeks of sham-infected mice (n = 10). Seven significant upregulated miRs and 13 downregulated miRs were found in 16 weeks of F. nucleatum-infected mice compared to 16 weeks of sham-infected mice (n = 10). (B) Venn diagram analysis illustrates the distribution of DE miRNAs in 8 weeks and 16 weeks of infections with F. nucleatum. (C and D) Predicted functional pathway analysis of DE miRNAs from F. nucleatum-infected mandibles. Bubble plot of KEGG analysis on predicted target genes of DE miRNAs in F. nucleatum-infected mice at 16 weeks of infection compared to sham-infected mice. The KEGG pathways are displayed on the y-axis, and the x-axis represents the false discovery rate (FDR), which means the probability of false positives in all tests. The size and color of the dots represent the number of predicted genes and the corresponding P-value, respectively.

Upregulated miRNAs reported in the 8 weeks have been associated as diagnostic miRNAs in humans (miR-361-5p), identified in the gingiva of PD patients (miR-26a-5p), attenuating the sepsis-induced myocardial injury in the mice (miR-193a-3p), associated with heart failure diagnosis in human subjects (miR-324-5p), regulating the cell survival in periodontal ligament cells (miR-24-3p), associated with mice PD infections induced by T. denticola (miR-126-5p) and P. gingivalis (miR-99b-5p). The 16 weeks of upregulated miRNAs were associated with PD diagnostic miRNA in humans (miR-361-5p), gingival tissue in chronic periodontitis patients (let-7a-5p), in the human periodontitis gingival tissue (let-7f-5p), reliable biomarker in patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma (miR-345-5p), clinical marker for atherosclerosis (miR-218-5p), and associated in mice PD infections induced by P. gingivalis (miR-99b-5p).

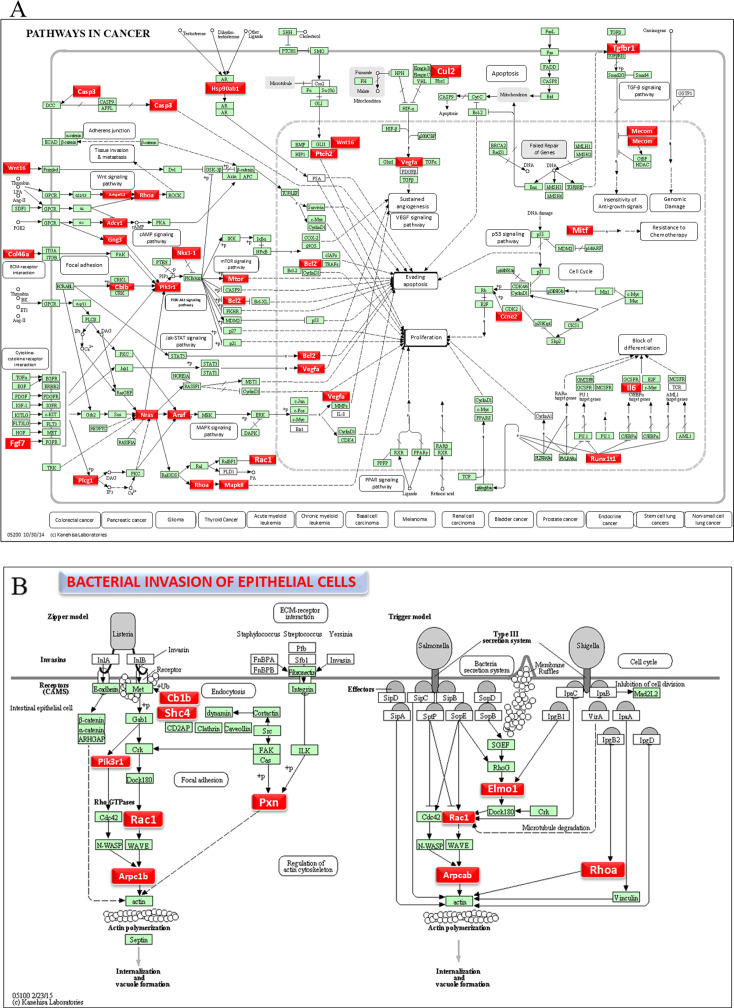

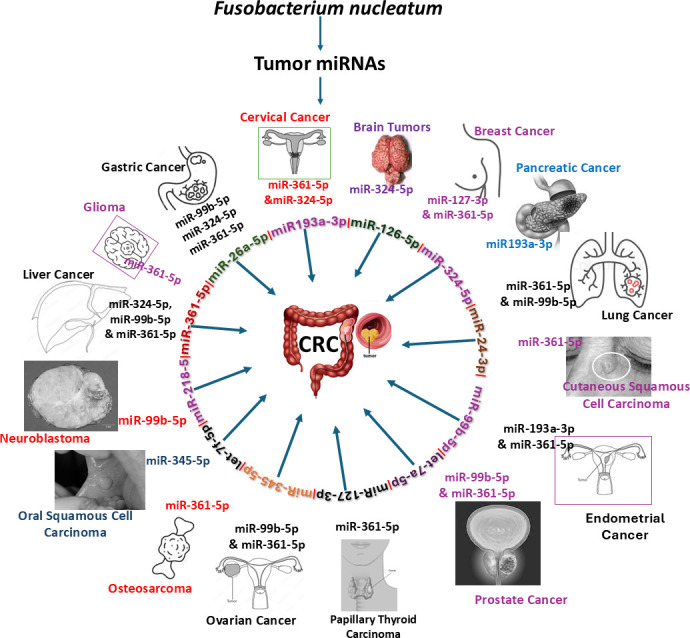

DE miRNAs and functional pathway analysis

Functional enrichment analysis for the upregulated and downregulated miRNAs was performed using DIANA-miRPath software to predict the biological function. The resulting KEGG pathway analysis revealed that the upregulated miRs in the 8-week analysis were associated with the pathways in cancer, axon guidance pathway, ErbR signaling pathway, renal cell carcinoma, mTOR signaling pathway, porphyrin metabolism, adherens junction, glioma, cAMP signaling pathway, etc. (Fig. 2C). The upregulated miRNAs in the 16-week analysis (miR-99b-5p, miR-361-5p, miR-345-5p, miR-218-5p, and miR-127-3p) associated with the proteoglycans in cancer, pathways in cancer, axon guidance pathway, cell adhesion molecules pathway, adherens junction pathway, GABAergic synapse pathway, circadian entrainment, bacterial invasion of epithelial cells, and proteoglycans in cancer (Fig. 2D). The miRs of miR-361-5p (Cblb, Rhoa, Rac1), miR-218-5p (Pik3r1, Arpc1b, Elmo1, Shc4), and miR-345-5p (Pxn) were associated with bacterial invasion of epithelial cells pathways having the target genes in the brackets (Fig. 3; Table S6). Pathways in cancer in both 8- and 16-week upregulated miRNAs have a single miRNA (miR-361-5p) that has the potential to interact with all of the genes in the pathway. The upregulated miRNAs associated with multiple malignancies including CRC are depicted in Fig. 4. The DE miRNAs upregulated in the 8 and 16 weeks of F. nucleatum infection have a regulatory role on 50 and 37 genes (Fig. 4), respectively, in the cancer pathways. The miR-361-5p, which is associated with pathways in cancer, has a regulatory target on 11 genes, including the Crebbp gene, which has the unusual largest interactions in the pathways of cancer. The reviewed information revealed that genetic aberrations of CREBBP/EP300 were observed in various types of solid tumors and hematologic malignancies and considered promising therapeutic targets (109). Detailed reported functions of the upregulated miRNAs during 8 and 16 weeks of F. nucleatum infection are shown in Tables 3 and 4, respectively. The list of upregulated miRNAs associated with the bacterial invasion of epithelial cells (Table S6), as well as pathways in cancers, is shown in Tables S7 and S8. The number of target genes for each upregulated miRNA in the 8- and 16-week- infection group was analyzed using miRTarBase. We used mmu-miR-361-5p as the example for an upregulated DE miRNA during 8 weeks of infection in identifying the target genes using miRTarBase (Table S9). Each miRNA has different target genes and a specific miRTarBase ID. F. nucleatum-infection-induced DE-upregulated mmu-miR-361-5p has 15 different target genes with 15 different miRTarBase IDs as stated in Table S9. The list of target genes for 16 weeks of upregulated miRNAs and the miRTarBase IDs are shown in Table S10.

Fig 3.

DE miRNAs and mirPath V.3—KEGG predicted functional pathways (KEGG pathway # mmu05200 and mmu05100). (A) A total of 37 genes (identified by KEGG) were involved in the pathways in cancer and (B) 10 genes were involved in the bacterial invasion of epithelial cells signaling pathway during 16 weeks of F. nucleatum infection. Red boxes indicate genes with significantly increased expression during pathways in cancer and bacterial invasion of epithelial cells. Green boxes indicate no change in gene expression. Many pathogenic bacteria can invade phagocytic and non-phagocytic cells and colonize them intracellularly, then become disseminated to other cells. Invasive bacteria induce their uptake by non-phagocytic host cells (e.g., epithelial cells) using two mechanisms referred to as the zipper model and trigger model. Listeria, Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, and Yersinia are examples of bacteria that can enter using the zipper model. These bacteria express proteins on their surfaces that interact with cellular receptors, starting signaling cascades that result in close apposition of the cellular membrane around the entering bacteria. Shigella and Salmonella are examples of bacteria entering cells using the trigger model. An arrow indicates a molecular interaction and a line without an arrowhead indicates a molecular interaction that results in inhibition.

Fig 4.

F. nucleatum upregulated miRNAs are linked with 13 multiple malignancies, including CRC. F. nucleatum-induced miR-361-5p alone is associated with 13 types of tumor, and 12 out of 14 miRNAs are associated with CRC.

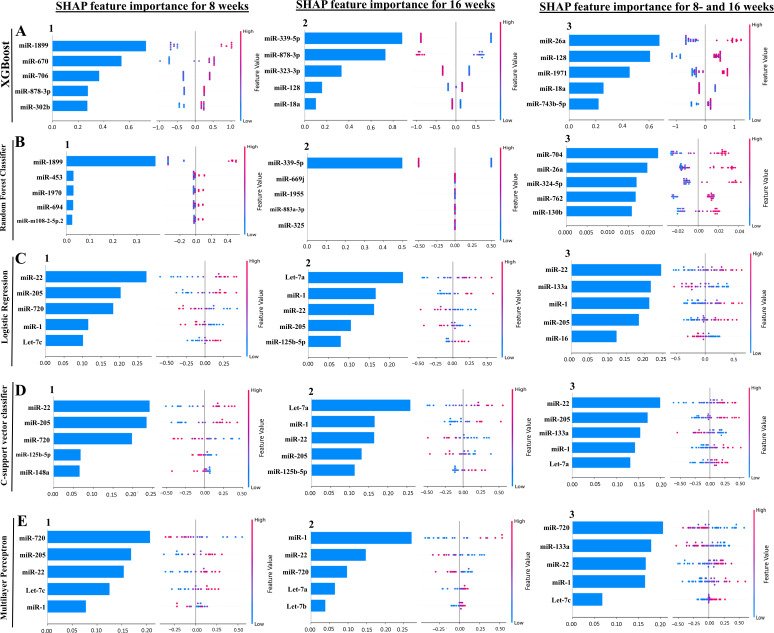

Machine learning analysis of NanoString miRNA copies

Our ML analysis results are divided into two groups: tree-based methods, consisting of XGB and RFC, and non-tree-based methods, consisting of LR, SVC, and MLP. In the 8-week data set, mmu-miR-1899 had the highest impact on the tree-based models (Fig. 5A1, XGB; Fig. 5B1, RFC), LR and SCV were most impacted by mmu-miR-22, and miR-720 in MLP had the highest impact (Fig. 5C1, LR; Fig. 5D1, SVC; Fig. 5E1, MLP). For the 16-week data set, mmu-miR-339-5p had the highest impact on the tree-based models (XGB, RFC; Fig. 5A2 and B2), while mmu-miR-7a had the highest impact on LR and SVC, and miR-1 in MLP was most impacted by miR-1 (LR, SVC, Fig. 5C2 and D2 and MLP; Fig. 5E2). Finally, in the combined 8- and 16-week data set, the most impactful miRNAs were mmu-miR-26a-5p in XGB, miR-704 in RFC was again the most impactful for the tree-based models (XGB, RFC; Fig. 5A3 and B3), mmu-miR-22 in LR and SVC, and mmu-miR-720 in MLP (LR, SVC, Fig. 5C3 and D3 and MLP, Fig. 5E3). The results of the SHAP value analysis are summarized in Fig. S1 to S5; Table 5 summarizes the most impactful miRNAs for each ML model and descriptions of the miRNA functions, and Table 6 summarizes the top five important miRNAs.

Fig 5.

A summary of the most prominent features in the five machine learning models using SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) values. In panels A–E, feature importance is ranked from the top (the most important) to the bottom (the least important). The x-axis shows the impact that a feature has on the model. The bar charts show the overall impact of a feature, whereas the swarm plot shows both the positive and negative impacts. In the swarm plots, each dot represents an instance of a miRNA variable, and the color bar shows the variable’s value (high to low). The three study groups are (1) mice assessed at 8 weeks, (2) mice assessed at 16 weeks, and (3) 8 and 16 weeks together.

TABLE 5.

Summary of the miRNA and its importance for each machine learning modela

| miRNA (feature rank) | ML model | MIMAT# | Target functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| 8-week analysis | |||

| mirR-22 (1) | LR, SVC | MIMAT0000531 | Upregulated in periodontal disease and obesity (110). |

| miR-205 (2) | LR, SVC, MLP | MIMAT0000238 | Downregulated in chronic periodontitis patients (111, 112). |

| miR-720 (3) | LR, SVC | MIMAT0003484 | Novel miRNA regulating the differentiation of dental pulp cells (113). |

| miR-1899 (1) | XGB, RFC | MIMAT0007869 | –b |

| 16-week analysis | |||

| let-7a-5p (1) | LR, SVC | MIMAT0000521 | Downregulated in aggressive periodontitis patients (88). Promotes the osteogenesis of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (114). |

| miR-1(2) | LR, SVC | MIMAT0000123 | Noninvasive biomarker for breast cancer (115). Upregulated in patients with myocardial infarction (116). |

| miR-22 (3) | LR, SVC | MIMAT0000531 | Shown in the 8-week analysis |

| miR-205 (4) | LR, SVC | MIMAT0000238 | Shown in the 8-week analysis |

| miR-125b-5p (5) | LR, SVC | MIMAT0000135 | Associated with osteogenic differentiation (117). Overlapping miRNA between periodontitis and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (118). |

| miR-339-5p (1) | XGB, RFC | MIMAT0000584 | Most predictive periodontal miRNA in the T. forsythia-induced mice periodontitis (33). |

| 8- and16-week analysis | |||

| miR-22 (1) | LR, SVC | MIMAT0000531 | Shown in the 8-week analysis |

| miR-133a (2) | LR, MLP | MIMAT0000145 | Upregulated in the T. denticola-induced mice periodontitis (32). |

| miR-1 (4) | SVC, MLP | MIMAT0000123 | Shown in the 16-week analysis |

The rank (or importance) of miRNA in predicting whether the mouse was infected is in parentheses. The higher the rank, the more important the miRNA was for making the prediction. For the 8- and 16-week cohort, XGB and RFC did not agree on the importance of miRNA. Models: logistic regression (LR), C-support vector classifier (SVC), multilayer perceptron (MLP), random forest classifier (RFC), and extreme gradient boosting (XGB).

“–” indicates that no research articles were found related to that microRNA.

TABLE 6.

Summary of the importance and miRNA for each machine learning modela

| Cohort | miRNA | miRNA feature rank | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| 8 weeks | miR-22 | LR, SVC | –b | MLP | – | – |

| miR-205 | – | LR, SVC, MLP | – | – | – | |

| miR-720 | MLP | – | LR, SVC | – | – | |

| miR-1 | – | – | – | LR | MLP | |

| let-7c | – | – | – | MLP | LR | |

| miR-125b-5p | – | – | – | SVC | – | |

| miR-148a | – | – | – | – | SVC | |

| miR-1899 | XGB, RFC | – | – | – | – | |

| miR-670 | – | XGB | – | – | – | |

| miR-706 | – | – | XGB | – | – | |

| miR-878-3p | – | – | – | XGB | – | |

| miR-302b | – | – | – | – | XGB | |

| miR-453 | – | RFC | – | – | – | |

| miR-1970 | – | – | RFC | – | – | |

| miR-694 | – | – | – | RFC | – | |

| miR-m108-2-5p.2 | – | – | – | – | RFC | |

| 16 weeks | let-7a-5p | LR, SVC | – | – | MLP | – |

| miR-1 | MLP | LR, SVC | – | – | – | |

| miR-22 | – | MLP | LR, SVC | – | – | |

| miR-205 | – | – | – | LR, SVC | – | |

| miR-125b-5p | – | – | – | – | LR, SVC | |

| miR-720 | – | – | MLP | – | – | |

| let-7b | – | – | – | – | MLP | |

| miR-339-5p | XGB, RFC | – | – | – | – | |

| miR-878-3p | – | XGB | – | – | – | |

| miR-323-3p | – | – | XGB | – | – | |

| miR-128 | – | – | – | XGB | – | |

| miR-18a | – | – | – | – | XGB | |

| 8 and 16 weeks | miR-22 | LR, SVC | – | MLP | – | – |

| miR-133a | – | LR, MLP | SVC | – | – | |

| miR-1 | – | – | LR | SVC, MLP | – | |

| miR-205 | – | SVC | – | LR | – | |

| miR-16 | – | – | – | – | LR | |

| miR-720 | MLP | – | – | – | – | |

| let-7a-5p | – | – | – | – | SVC | |

| let-7c | – | – | – | – | MLP | |

| miR-26a-5p | XGB | RFC | – | – | – | |

| miR-128 | – | XGB | – | – | – | |

| miR-1971 | – | – | XGB | – | – | |

| miR-18a | – | – | – | XGB | – | |

| miR-743b-5p | – | – | – | – | XGB | |

| miR-704 | RFC | – | – | – | – | |

| miR-324-5p | – | – | RFC | – | – | |

| miR-762 | – | – | – | RFC | – | |

| miR-130b | – | – | – | – | RFC | |

The higher the rank, the more important the model found the miRNA to be for predicting if the mouse was infected. Models: logistic regression (LR), C-support vector classifier (SVC), multilayer perceptron (MLP), random forest classifier (RFC), and extreme gradient boosting (XGB). LR—logistic regression, SVC-C—support vector classifier, MLP—multilayer perceptron, RFC—random forest classifier, and XGB—extreme gradient boosting.

“–” indicates that no machine language model ranked the miRNA at the that specific rank.

In addition to determining which miRNAs were most impactful on the ML models (Table 5), we also found high levels of agreement in the miRNAs ranked 2 to 5 (Table 6). Interestingly, the tree-based models did not agree on the importance of miRNAs for ranks between 2 and 5 in the 8 weeks, 16 weeks, and the combined 8 and 16 weeks of data sets. In the 8 weeks of data set, the non-tree-based models ranked miR-205 as the second most important feature, and LR and SVC ranked miR-720 third. In the 16 weeks of data set, LR and SVC ranked miR-1 as second, miR-22 as third, miR-205 as fourth, and miR-125b-5p as the fifth most important feature. Lastly, in the combined 8 and 16 weeks of data set, LR and MLP ranked miR-133a as the second most important feature, and SVC and MLP ranked miR-1 as fourth.

DISCUSSION

The frequent involvement of F. nucleatum in extra-oral systemic infections and comorbidities (2), including adverse pregnancy outcomes, and various malignancies such as CRC (14, 15) supports this species’s role in multiple disease pathogeneses. Since F. nucleatum can survive, spread hematogenously, and replicate at sites distant from the oral cavity, it uses its FadA adhesion to bind and invade both endothelial and epithelial cells (119), which plays a significant role in the development of periodontitis and its systemic comorbidities. Although the etiologic role of F. nucleatum as an important bacterium in the progression of PD is known, the underlying molecular genetic mechanisms are not completely understood. Recently, several studies have suggested that aberrant expression of miRNAs is involved in both infectious and non-infectious diseases, influencing the initiation and progression of pathology and the development of miRNAs as diagnostic biomarkers in CRC. To the best of our knowledge, this study will be the first investigation to examine F. nucleatum oral infection, global miRNA induction, and genes involved in periodontitis.

In this report, we focused on how F. nucleatum selectively modulates host gingival epithelial cell responses with robust and specific miRNA expression during the progression of PD. We demonstrate that chronic oral infection with F. nucleatum in male and female mice results in physiological colonization/infection of the gingival surfaces after four infection cycles, invades gingival epithelium, and induces PD outcome measures such as ABR, which are significantly higher in mice at both 8 and 16 weeks of infection time points. In addition, F. nucleatum can spread via intravascular dissemination to distal organs, including the heart, suggesting its invasive potential and ability to modulate the host immune response. This invasive potential to the heart and other tissues was robust when F. nucleatum was administered with late colonizers such as P. gingivalis, T. denticola, and T. forsythia and the early colonizer S. gordonii (34), suggesting their physiological, nutritional, and metabolic synergistic interactions in the gingiva. This co-dependence enhances microbial multiplication and invasion of the gingival epithelium, leading to systemic intravascular dissemination. The partial human mouth microbes (PHAMM) ecological time sequential polybacterial periodontal infection (ETSPPI) model involves an array of five bacteria-mediated intraoral infections, which colonize bacteria on the gingiva, induce periodontitis, and lead to induced sex-specific miRNA expression. These miRNAs are linked to numerous systemic diseases and comorbidities (34). Monobacterial intraoral infections with P. gingivalis, T. denticola, T. forsythia, and S. gordonii also induced periodontitis with robust alterations in miRNAs in mice models (31–33, 37).

This study analyzed 577 mouse miRNAs in mandibles from F. nucleatum-infected and sham-infected mice using the high-throughput NanoString nCounter miRNA profiling. Most of the DE miRNAs were unique, except for two miRNAs (361, 99b), and specific to the time point, indicating that miRNA induction is transient and time-dependent. A total of 29 miRNAs were DE in mandible tissue during 8 and 16 weeks of F. nucleatum infection compared with sham infection. Of these, 14 miRNAs were upregulated, and 15 miRNAs were downregulated. Among all the 14 upregulated miRNAs at 8 and 16 weeks, four miRNAs were reported in human periodontitis studies, indicating that these upregulated miRNAs are associated with the induction of PD. Specifically, miR-26a-5p was downregulated in the gingiva of periodontitis patients (55), mmu-let-7a-5p was found in the saliva of patients with aggressive periodontitis (88), and in the gingival tissue of chronic periodontitis patients (89), and mmu-let-7f-5p was found in human periodontitis gingival tissue (66), indicating that preclinical in vivo miRNA data corroborate with clinical PD miRNA data. Three of the upregulated miRNAs have been associated with preclinical mouse studies: miR-99b-5p in P. gingivalis-induced PD (31), miR-126-5p in T. denticola-induced PD (32), and miR-127-3p in T. forsythia-induced PD (33), and were also expressed during F. nucleatum infection. Furthermore, the two miRNAs, miR-361-5p and miR-99b-5p, were commonly expressed and upregulated at both time points.

In addition, the miRNAs miR-361-5p, miR-193a-3p, miR-324-5p, miR-99, miR-127-3p, miR-345-5p, miR-218-5p, and let-7f-5p are associated with cardiovascular diseases (54, 75, 95, 106, 120–122). miR-324-5p and miR-345-5p are linked to adipocyte differentiation (123, 124), while miR-127-3p, miR-345-5p, and miR-99 are associated with tumor malignancies (96, 98, 125–127). Interestingly, a single miRNA can be associated with different disease conditions. For example, miR-324-5p is linked to osteoporosis (76) and multiple myeloma (128), let-7a-5p is associated with various inflammatory conditions (90, 129), chemotherapy-exposed mouse ovaries (130), an antifibrotic role under hypoxic stress (131), and asthma (91). miR-24-3p is involved in phagocytosis (77), periodontal ligament cells (132), and gingival fibroblasts (104), let-7f-5p is linked to abdominal aortic aneurysm (102) and lupus nephritis (103). Different miRNAs are also associated with microbial infection-exposed immune cells. For example, miR-99 is linked to M. tuberculosis-infected murine dendritic cells (79), miR-127-3p is involved in macrophage anti-microbial responses (133), and miR-24-3p is associated with S. aureus-caused osteomyelitis (134).

Recent reports demonstrate microbiological, molecular, and genetic links between F. nucleatum and multiple digestive tract cancers, including esophageal, gastric, pancreatic, and CRC. Interestingly, our study showed 37 significantly increased gene expressions in multiple cancers and several miRNAs associated with both multiple cancers, including CRC and PD in humans (135), some of which also link PD with inflammatory systemic comorbidities. Several studies identified oncogenic marker miRNAs (oncomiRs) in CRC tumors (miR-126-5p, miR-99b-5p, miR-26a-5p, miR-24-3p, miR-361-5p, miR-193a-3p, miR-218-5p, let-7a-5p, and let-7f-5p), which were also expressed in mouse mandibles during F. nucleatum infection. This indicates a link between invasive F. nucleatum and multiple tumors, including CRC, further strengthening the association between periodontitis and CRC. By contrast, P. gingivalis oral infection in mice showed DE miR-185, miR-22, miR-152, miR-423, miR-151, miR-28, and miR-145, which were also found to be upregulated in various malignancies such as prostate, breast, glioma, gastric, and hepatocellular carcinoma (31). The data indicate that periodontal bacteria-expressed miRNA in gingival tissues and other systemic diseases have common mRNA targets mediating disease progression.

KEGG pathway analysis revealed that the most target genes of upregulated miRNAs during the 8 week period were linked with several pathways, including those involved in cancer, axon guidance, GABAergic synapse, proteoglycans in cancer, drug metabolism-cytochrome P450, ErbR signaling pathway, acute myeloid leukemia, phosphatidylinositol signaling system, renal cell carcinoma, adherens junction, glioma, and cAMP signaling pathway.

Periodontal disease-causing infectious oral microbes are commonly detected in atherosclerotic plaques and are associated with many systemic diseases. F. nucleatum is linked with more systemic diseases than other known periodontal microbes and has been isolated from more than 10 sites of systemic infection (2). Periodontal infection is associated with atherosclerosis, where atherosclerotic arteries of patients tested positive for F. nucleatum genomic DNA (84%) (136). There is evidence that F. nucleatum sub-species have fine-tuning capabilities to drive disease progression and niche colonization in the disease habitat. Zepeda-Rivera et al. revealed that the F. nucleatum strains causing colorectal cancer (Fna C2 strains) have a close genome sequence with F. nucleatum present in the oral cavity of patients with colorectal cancer (135). Polymicrobial oral infection in the mice, including F. nucleatum as a member, caused the hematogenous dissemination of F. nucleatum organisms into the heart and aorta (137). In rodent models, the predicted hypothesis of transient bacteremia caused by F. nucleatum facilitated its transmission from the oral cavity to the uterus, resulting in premature delivery, stillbirths, and no sustained live births (138). The abundance/enrichment of F. nucleatum in colorectal tumor specimens confirmed its correlation with colorectal cancer (139). One of the limitations of the current study is the inability to utilize saliva in this microRNA analysis.

The machine learning model analysis for F. nucleatum showed some similarities with the ML algorithm in the S. gordonii (Sg) monoinfection. In our present study, tree-based models identified miR-339-5p and miR-323-3p as significant features, which were also observed in S. gordonii-induced PD mice. The miRNA features miR-22, miR-205, miR-720, miR-1, mmu-let-7c, and mmu-miR-7a were identified in non-tree-based models in both the S. gordonii study and our present study. The miR-125b-5p feature was uniquely observed in the MLP model of S. gordonii infection and the LR and SVC models of our present study. Similarly, miR-133a was an observed feature in the SVC model of the S. gordonii PD studies and was reported in the non-tree-based models of our present study (37). In addition, tree-based models in our present study and in T. forsythia-induced PD mice identified common features including miR-18a, miR-339-5p, miR-130b, and miR-704 (33). We acknowledge that further research is necessary to elucidate how F. nucleatum influences the development of PD versus cancer. Furthermore, we recognize that key factors may still be unidentified that direct the progression toward PD rather than cancer, despite the robust induction of the many oncogenic miRNAs. This area requires more investigation to fully understand the underlying mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets.

In conclusion, this is the first in vivo study using rodent models of F. nucleatum intraoral infection-induced periodontitis with emphasis on global miRNA profiling. Elevated miR-361 expression during 8 and 16 weeks of infection was linked to multiple malignancies. miR-127 and miR-26a might be involved in the initial immune response against F. nucleatum infection. miR-361 and miR-99b were unique in both 8 and 16 weeks of F. nucleatum infection. It is interesting that miR-126-5p has been reported as a potential biomarker in patients with periodontitis and coronary artery disease. These findings highlight F. nucleatum’s multi-pathogenic role in periodontitis and systemic comorbidities, and specifically, 13 oncogenic miRNAs (oncomiRs) are linked with CRC. Further studies should focus on the role of miR-361 in periodontitis and as therapeutic miRNA in periodontitis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge Dr. Andreas Gonzalez, M.D., Parvathi Gurusamy for editing the manuscript, and Dr. Yiping Han, Ph.D., for previewing the introduction section. Copyright permission of KEGG is granted (KEGG permission # 251435) for the reproduced KEGG database.

This study was supported by the NIH National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR) (R01 DE028536) to L. Kesavalu and E. K. L. Chan. The funders had no role in study design, data collection, analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

A.C. performed mouse experiments and analyzed the data. V.M.K. and S.J. did the molecular analysis of distal organ dissemination. S.J. performed bioinformatic and statistical analyses, initial drafting, and submission of data at NCBI. W.D. performed multiple ML models; L.K. was responsible for the conception, experimental design, analysis, initial drafting, editing, supervision, project administration, interpretation, and funding acquisition. L.K. and S.J. were involved in the final revision and editing of the manuscript. L.K. and E.K.L.C. are the Principal Investigators of the NIH (NIDCR) study. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Contributor Information

L. Kesavalu, Email: kesavalu@dental.ufl.edu.

Nicholas Chia, Argonne National Laboratory, Lemont, Illinois, USA.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSM7915885 (accessed on 4 December 2023).

ETHICS APPROVAL

All animal procedures were approved by the University of Florida Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) under protocol number 202200000223.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

The following material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1128/msystems.01732-24.

Supplemental figures and tables.

ASM does not own the copyrights to Supplemental Material that may be linked to, or accessed through, an article. The authors have granted ASM a non-exclusive, world-wide license to publish the Supplemental Material files. Please contact the corresponding author directly for reuse.

REFERENCES

- 1. Krieger M, AbdelRahman YM, Choi D, Palmer EA, Yoo A, McGuire S, Kreth J, Merritt J. 2024. Stratification of Fusobacterium nucleatum by local health status in the oral cavity defines its subspecies disease association. Cell Host Microbe 32:479–488. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2024.02.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bolstad AI, Jensen HB, Bakken V. 1996. Taxonomy, biology, and periodontal aspects of Fusobacterium nucleatum. Clin Microbiol Rev 9:55–71. doi: 10.1128/CMR.9.1.55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Socransky SS, Haffajee AD, Cugini MA, Smith C, Kent RL Jr. 1998. Microbial complexes in subgingival plaque. J Clin Periodontol 25:134–144. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1998.tb02419.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Han YW. 2015. Fusobacterium nucleatum: a commensal-turned pathogen. Curr Opin Microbiol 23:141–147. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2014.11.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kolenbrander PE, London J. 1993. Adhere today, here tomorrow: oral bacterial adherence. J Bacteriol 175:3247–3252. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.11.3247-3252.1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kolenbrander PE. 2000. Oral microbial communities: biofilms, interactions, and genetic systems. Annu Rev Microbiol 54:413–437. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.54.1.413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ebersole JL, Feuille F, Kesavalu L, Holt SC. 1997. Host modulation of tissue destruction caused by periodontopathogens: effects on a mixed microbial infection composed of Porphyromonas gingivalis and Fusobacterium nucleatum. Microb Pathog 23:23–32. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1996.0129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Settem RP, El-Hassan AT, Honma K, Stafford GP, Sharma A. 2012. Fusobacterium nucleatum and Tannerella forsythia induce synergistic alveolar bone loss in a mouse periodontitis model. Infect Immun 80:2436–2443. doi: 10.1128/IAI.06276-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Velsko IM, Chukkapalli SS, Rivera-Kweh MF, Chen H, Zheng D, Bhattacharyya I, Gangula PR, Lucas AR, Kesavalu L. 2015. Fusobacterium nucleatum alters atherosclerosis risk factors and enhances inflammatory markers with an atheroprotective immune response in ApoE(null) mice. PLoS One 10:e0129795. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ghosh A, Jaaback K, Boulton A, Wong-Brown M, Raymond S, Dutta P, Bowden NA, Ghosh A. 2024. Fusobacterium nucleatum: an overview of evidence, demi-decadal trends, and its role in adverse pregnancy outcomes and various gynecological diseases, including cancers. Cells 13:717. doi: 10.3390/cells13080717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yin H, Zhang J, Zhang H, Li Q, Qiu H, Hong K, Wang W, Xiao Y, Yu B. 2023. Fusobacterium nucleatum promotes proliferation in oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma via AHR/CYP1A1 signalling. FEBS J 290:837–854. doi: 10.1111/febs.16619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lehr K, Nikitina D, Vilchez-Vargas R, Steponaitiene R, Thon C, Skieceviciene J, Schanze D, Zenker M, Malfertheiner P, Kupcinskas J, Link A. 2023. Microbial composition of tumorous and adjacent gastric tissue is associated with prognosis of gastric cancer. Sci Rep 13:4640. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-31740-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hayashi M, Ikenaga N, Nakata K, Luo H, Zhong P, Date S, Oyama K, Higashijima N, Kubo A, Iwamoto C, Torata N, Abe T, Yamada Y, Ohuchida K, Oda Y, Nakamura M. 2023. Intratumor Fusobacterium nucleatum promotes the progression of pancreatic cancer via the CXCL1-CXCR2 axis. Cancer Sci 114:3666–3678. doi: 10.1111/cas.15901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rubinstein MR, Wang X, Liu W, Hao Y, Cai G, Han YW. 2013. Fusobacterium nucleatum promotes colorectal carcinogenesis by modulating E-cadherin/β-catenin signaling via its FadA adhesin. Cell Host Microbe 14:195–206. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.07.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kostic AD, Chun E, Robertson L, Glickman JN, Gallini CA, Michaud M, Clancy TE, Chung DC, Lochhead P, Hold GL, El-Omar EM, Brenner D, Fuchs CS, Meyerson M, Garrett WS. 2013. Fusobacterium nucleatum potentiates intestinal tumorigenesis and modulates the tumor-immune microenvironment. Cell Host Microbe 14:207–215. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.07.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chu S, Cheng Z, Yin Z, Xu J, Wu F, Jin Y, Yang G. 2022. Airway Fusobacterium is associated with poor response to immunotherapy in lung cancer. Onco Targets Ther 15:201–213. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S348382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. McIlvanna E, Linden GJ, Craig SG, Lundy FT, James JA. 2021. Fusobacterium nucleatum and oral cancer: a critical review. BMC Cancer 21:1212. doi: 10.1186/s12885-021-08903-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Baima G, Ribaldone DG, Romano F, Aimetti M, Romandini M. 2023. The gum-gut axis: periodontitis and the risk of gastrointestinal cancers. Cancers (Basel) 15:4594. doi: 10.3390/cancers15184594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Abed J, Emgård JEM, Zamir G, Faroja M, Almogy G, Grenov A, Sol A, Naor R, Pikarsky E, Atlan KA, Mellul A, Chaushu S, Manson AL, Earl AM, Ou N, Brennan CA, Garrett WS, Bachrach G. 2016. Fap2 mediates Fusobacterium nucleatum colorectal adenocarcinoma enrichment by binding to tumor-expressed gal-GalNAc. Cell Host Microbe 20:215–225. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2016.07.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tuttle RS, Strubel NA, Mourad J, Mangan DF. 1992. A non-lectin-like mechanism by which Fusobacterium nucleatum 10953 adheres to and activates human lymphocytes. Oral Microbiol Immunol 7:78–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1992.tb00513.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Abed J, Maalouf N, Manson AL, Earl AM, Parhi L, Emgård JEM, Klutstein M, Tayeb S, Almogy G, Atlan KA, Chaushu S, Israeli E, Mandelboim O, Garrett WS, Bachrach G. 2020. Colon cancer-associated Fusobacterium nucleatum may originate from the oral cavity and reach colon tumors via the circulatory system. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 10:400. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2020.00400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bartel DP. 2004. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell 116:281–297. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00045-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Faulkner JL, Sullivan JC. 2022. Circulating cell-free micro-RNA as biomarkers: from myocardial infarction to hypertension. Clin Sci (Lond) 136:1341–1346. doi: 10.1042/CS20220056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Friedman RC, Farh KK-H, Burge CB, Bartel DP. 2009. Most mammalian mRNAs are conserved targets of microRNAs. Genome Res 19:92–105. doi: 10.1101/gr.082701.108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Li X, Zhu M, Zhao G, Zhou A, Min L, Liu S, Zhang N, Zhu S, Guo Q, Zhang S, Li P. 2022. MiR-1298-5p level downregulation induced by Helicobacter pylori infection inhibits autophagy and promotes gastric cancer development by targeting MAP2K6. Cell Signal 93:110286. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2022.110286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Huang T, Zhang J, Ke W, Zhang X, Chen W, Yang J, Liao Y, Liang F, Mei S, Li M, Luo Z, Zhang Q, Yang B, Zheng H. 2020. MicroRNA expression profiling of peripheral blood mononuclear cells associated with syphilis. BMC Infect Dis 20:165. doi: 10.1186/s12879-020-4846-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Davuluri KS, Chauhan DS. 2022. microRNAs associated with the pathogenesis and their role in regulating various signaling pathways during Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 12:1009901. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2022.1009901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Aguilar C, Cruz AR, Rodrigues Lopes I, Maudet C, Sunkavalli U, Silva RJ, Sharan M, Lisowski C, Zaldívar-López S, Garrido JJ, Giacca M, Mano M, Eulalio A. 2020. Functional screenings reveal different requirements for host microRNAs in Salmonella and Shigella infection. Nat Microbiol 5:192–205. doi: 10.1038/s41564-019-0614-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cassidy BR, Zhang M, Sonntag WE, Drevets DA. 2020. Neuroinvasive Listeria monocytogenes infection triggers accumulation of brain CD8+ tissue-resident memory T cells in a miR-155-dependent fashion. J Neuroinflammation 17:259. doi: 10.1186/s12974-020-01929-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nishimura T, Tamizu E, Uno S, Uwamino Y, Fujiwara H, Nishio K, Nakano Y, Shiono H, Namkoong H, Hoshino Y, Iwata S, Hasegawa N. 2017. Hsa-miR-346 is a potential serum biomarker of Mycobacterium avium complex pulmonary disease activity. J Infect Chemother 23:703–708. doi: 10.1016/j.jiac.2017.07.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Aravindraja C, Vekariya KM, Botello-Escalante R, Rahaman SO, Chan EKL, Kesavalu L. 2023. Specific microRNA signature kinetics in Porphyromonas gingivalis-induced periodontitis. Int J Mol Sci 24:2327. doi: 10.3390/ijms24032327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Aravindraja C, Jeepipalli S, Vekariya KM, Botello-Escalante R, Chan EKL, Kesavalu L. 2023. Oral spirochete Treponema denticola intraoral infection reveals unique miR-133a, miR-486, miR-126-3p, miR-126-5p miRNA expression kinetics during periodontitis. Int J Mol Sci 24:12105. doi: 10.3390/ijms241512105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Aravindraja C, Jeepipalli S, Duncan W, Vekariya KM, Bahadekar S, Chan EKL, Kesavalu L. 2023. Unique miRomics expression profiles in Tannerella forsythia-infected mandibles during periodontitis using machine learning. Int J Mol Sci 24:16393. doi: 10.3390/ijms242216393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Aravindraja C, Kashef MR, Vekariya KM, Ghanta RK, Karanth S, Chan EKL, Kesavalu L. 2022. Global noncoding microRNA profiling in mice infected with partial human mouth microbes (PAHMM) using an ecological time-sequential polybacterial periodontal infection (etsppi) model reveals sex-specific differential microRNA expression. Int J Mol Sci 23:5107. doi: 10.3390/ijms23095107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Guzeldemir-Akcakanat E, Sunnetci-Akkoyunlu D, Balta-Uysal VM, Özer T, Işik EB, Cine N. 2023. Differentially expressed miRNAs associated with generalized aggressive periodontitis. Clin Oral Investig 28:7. doi: 10.1007/s00784-023-05404-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Nahid MA, Rivera M, Lucas A, Chan EKL, Kesavalu L. 2011. Polymicrobial infection with periodontal pathogens specifically enhances microRNA miR-146a in ApoE-/- mice during experimental periodontal disease. Infect Immun 79:1597–1605. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01062-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Aravindraja C, Jeepipalli S, Duncan WD, Vekariya KM, Rahaman SO, Chan EKL, Kesavalu L. 2024. Streptococcus gordonii supragingival bacterium oral infection-induced periodontitis and robust miRNA expression kinetics. Int J Mol Sci 25:25. doi: 10.3390/ijms25116217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Dzink JL, Sheenan MT, Socransky SS. 1990. Proposal of three subspecies of Fusobacterium nucleatum Knorr 1922: Fusobacterium nucleatum subsp. nucleatum subsp. nov., comb. nov.; Fusobacterium nucleatum subsp. polymorphum subsp. nov., nom. rev., comb. nov.; and Fusobacterium nucleatum subsp. vincentii subsp. nov., nom. rev., comb. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol 40:74–78. doi: 10.1099/00207713-40-1-74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kesavalu L, Sathishkumar S, Bakthavatchalu V, Matthews C, Dawson D, Steffen M, Ebersole JL. 2007. Rat model of polymicrobial infection, immunity, and alveolar bone resorption in periodontal disease. Infect Immun 75:1704–1712. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00733-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Chukkapalli SS, Ambadapadi S, Varkoly K, Jiron J, Aguirre JI, Bhattacharyya I, Morel LM, Lucas AR, Kesavalu L. 2018. Impaired innate immune signaling due to combined Toll-like receptor 2 and 4 deficiency affects both periodontitis and atherosclerosis in response to polybacterial infection. Pathog Dis 76:fty076. doi: 10.1093/femspd/fty076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Chukkapalli SS, Easwaran M, Rivera-Kweh MF, Velsko IM, Ambadapadi S, Dai J, Larjava H, Lucas AR, Kesavalu L. 2017. Sequential colonization of periodontal pathogens in induction of periodontal disease and atherosclerosis in LDLRnull mice. Pathog Dis 75:ftx003. doi: 10.1093/femspd/ftx003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Velsko IM, Chukkapalli SS, Rivera-Kweh MF, Zheng D, Aukhil I, Lucas AR, Larjava H, Kesavalu L. 2015. Periodontal pathogens invade gingiva and aortic adventitia and elicit inflammasome activation in αvβ6 integrin-deficient mice. Infect Immun 83:4582–4593. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01077-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Aravindraja C, Sakthivel R, Liu X, Goodwin M, Veena P, Godovikova V, Fenno JC, Levites Y, Golde TE, Kesavalu L. 2022. Intracerebral but not peripheral infection of live Porphyromonas gingivalis exacerbates Alzheimer’s disease like amyloid pathology in APP-TgCRND8 mice. Int J Mol Sci 23:3328. doi: 10.3390/ijms23063328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Prokopec SD, Watson JD, Waggott DM, Smith AB, Wu AH, Okey AB, Pohjanvirta R, Boutros PC. 2013. Systematic evaluation of medium-throughput mRNA abundance platforms. RNA 19:51–62. doi: 10.1261/rna.034710.112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Veldman-Jones MH, Brant R, Rooney C, Geh C, Emery H, Harbron CG, Wappett M, Sharpe A, Dymond M, Barrett JC, Harrington EA, Marshall G. 2015. Evaluating robustness and sensitivity of the nanostring technologies ncounter platform to enable multiplexed gene expression analysis of clinical samples. Cancer Res 75:2587–2593. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-0262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Cioce M, Rutigliano D, Puglielli A, Fazio VM. 2022. Butein-instigated miR-186-5p-dependent modulation of TWIST1 affects resistance to cisplatin and bioenergetics of malignant pleural mesothelioma cells. Cancer Drug Resist 5:814–828. doi: 10.20517/cdr.2022.56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ritchie ME, Phipson B, Wu D, Hu Y, Law CW, Shi W, Smyth GK. 2015. Limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res 43:e47. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Huang H-Y, Lin Y-C-D, Cui S, Huang Y, Tang Y, Xu J, Bao J, Li Y, Wen J, Zuo H, et al. 2022. miRTarBase update 2022: an informative resource for experimentally validated miRNA-target interactions. Nucleic Acids Res 50:D222–D230. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkab1079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kanehisa M, Furumichi M, Sato Y, Kawashima M, Ishiguro-Watanabe M. 2023. KEGG for taxonomy-based analysis of pathways and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res 51:D587–D592. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkac963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Vlachos IS, Zagganas K, Paraskevopoulou MD, Georgakilas G, Karagkouni D, Vergoulis T, Dalamagas T, Hatzigeorgiou AG. 2015. DIANA-miRPath v3.0: deciphering microRNA function with experimental support. Nucleic Acids Res 43:W460–W466. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Chukkapalli SS, Velsko IM, Rivera-Kweh MF, Larjava H, Lucas AR, Kesavalu L. 2017. Global TLR2 and 4 deficiency in mice impacts bone resorption, inflammatory markers and atherosclerosis to polymicrobial infection. Mol Oral Microbiol 32:211–225. doi: 10.1111/omi.12165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Usui M, Onizuka S, Sato T, Kokabu S, Ariyoshi W, Nakashima K. 2021. Mechanism of alveolar bone destruction in periodontitis - Periodontal bacteria and inflammation. Jpn Dent Sci Rev 57:201–208. doi: 10.1016/j.jdsr.2021.09.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Xu D, Dong P, Xiong Y, Yue J, Ihira K, Konno Y, Kobayashi N, Todo Y, Watari H. 2019.. MicroRNA-361: a multifaceted player regulating tumor aggressiveness and tumor microenvironment formation. Cancers (Basel) 11:1130. doi: 10.3390/cancers11081130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Zhang W, Chang G, Cao L, Ding G. 2021. Dysregulation of serum miR-361-5p serves as a biomarker to predict disease onset and short-term prognosis in acute coronary syndrome patients. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 21. doi: 10.1186/s12872-021-01891-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Uttamani JR, Naqvi AR, Estepa AMV, Kulkarni V, Brambila MF, Martínez G, Chapa G, Wu CD, Li W, Rivas-Tumanyan S, Nares S. 2023. Downregulation of miRNA-26 in chronic periodontitis interferes with innate immune responses and cell migration by targeting phospholipase C beta 1. J Clin Periodontol 50:102–113. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.13715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Mildeberger L, Bueto J, Wilmes V, Scheiper-Welling S, Niess C, Gradhand E, Verhoff MA, Kauferstein S. 2023. Suitable biomarkers for post-mortem differentiation of cardiac death causes: quantitative analysis of miR-1, miR-133a and miR-26a in heart tissue and whole blood. Forensic Sci Int Genet 65:102867. doi: 10.1016/j.fsigen.2023.102867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Carbajal-López B, Martínez-Gutierrez AD, Madrigal-Santillán EO, Calderillo-Ruiz G, Morales-González JA, Coronel-Hernández J, Lockhart J, Millan-Catalan O, Mendoza-Rodriguez MG, Lino-Silva LS, Calderillo-Trejo G, Sumagin R, Pérez-Plasencia C, Pérez-Yépez EA. 2024. miR-3065-5p and miR-26a-5p as clinical biomarkers in colorectal cancer: a translational study. Cancers (Basel) 16:3649. doi: 10.3390/cancers16213649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Nik Mohamed Kamal NNS, Awang RAR, Mohamad S, Shahidan WNS. 2020. Plasma- and saliva exosome profile reveals a distinct microRNA signature in chronic periodontitis. Front Physiol 11:587381. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2020.587381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Du A, Zhao S, Wan L, Liu T, Peng Z, Zhou Z, Liao Z, Fang H. 2016. MicroRNA expression profile of human periodontal ligament cells under the influence of Porphyromonas gingivalis LPS. J Cell Mol Med 20:1329–1338. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Girolimetti G, Pelisenco IA, Eusebi LH, Ricci C, Cavina B, Kurelac I, Verri T, Calcagnile M, Alifano P, Salvi A, Bucci C, Guerra F. 2024. Dysregulation of a subset of circulating and vesicle-associated miRNA in pancreatic cancer. Noncoding RNA 10:29. doi: 10.3390/ncrna10030029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Wanram S, Klaewkla N, Pinyosri P. 2024. Downregulation of serum miR-133b and miR-206 associate with clinical outcomes of progression as monitoring biomarkers for metastasis colorectal cancer patients. Microrna 13:56–62. doi: 10.2174/0122115366266024240101075745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]