Abstract

Objectives

Hemorrhoids, a common anorectal condition, can be managed through surgical or conservative treatments. The aim of this meta-analysis is to compare the efficacy and safety of surgical and conservative treatments for hemorrhoids.

Methods

A systematic search was conducted from of PubMed, Embase, the Cochrane Library, and Web of Science from their inception to September 25, 2024. Eligible studies compared surgical treatments with non-invasive conservative treatments in hemorrhoids. Statistical analyses included pooled odds ratios (ORs) and mean differences (MDs)/standard mean differences (SMDs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Results

Seven studies, including 760 patients, were analyzed. Surgery achieved higher rates of complete symptom resolution than conservative therapy (OR = 2.96, 95% CI: 1.66–5.28, p < 0.001). Overall pain scores favored surgery (SMD = -0.93, 95% CI: 1.73 to -0.13, p = 0.02). Subgroup analysis showed clear superiority within four days (SMD = -1.26, 95% CI -1.84 to -0.68) but parity beyond ten days (SMD = 0.00, 95% CI -0.44 to 0.44; p = 0.99). Comparable patterns were observed in pregnant women with thrombosed external hemorrhoids. Rates of postoperative bleeding (OR: 1.09; 95% CI: 0.42 to 2.82, p = 0.86; I2 = 41%, p = 0.15) and urinary retention (OR: 1.75; 95% CI: 0.30 to 10.31, p = 0.54; I2 = 45%, p = 0.18) did not differ significantly between groups. Surgical-specific adverse events were infrequent (incontinence 3%, persistent pain 5%, watery discharge 6%). Surgery shortened recovery in pregnant thrombosed cases by approximately seven days (MD: -6.80; 95% CI: -7.64 to -5.96, p < 0.001; I2 = 55%, p = 0.14) and reduced overall recurrence (95% CI: 0.10 to 0.37, p < 0.001; I2 = 0%, p = 0.97).

Conclusion

Surgical treatments provide superior symptom relief, faster recovery, and lower recurrence but with some specific post-treatment complications, while conservative treatments are safer and less invasive but with provides slower symptom relief and higher recurrence rates. Individualized treatment should consider symptom severity, patient preferences, and risk tolerance.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12876-025-04089-2.

Keywords: Hemorrhoids, Surgical treatment, Conservative treatment, Meta-Analysis

Introduction

Hemorrhoids is one of the most prevalent anorectal conditions globally, significantly affecting the quality of life of millions of patients due to symptoms such as pain, bleeding, and prolapse [1, 2]. the prevalence of hemorrhoids varies significantly, with factors such as obesity, abdominal obesity, depression, and prior pregnancy identified as significant risk factors These physical symptoms can lead to discomfort during daily activities and reduced quality of life, emphasizing the importance of effective management strategies [3, 4].

Management strategies for hemorrhoidal disease primarily include surgical and conservative treatments. Surgical interventions, such as hemorrhoidectomy, are highly effective for alleviating severe symptoms in the short term [5, 6]. Hemorrhoidectomy remains the gold standard for advanced disease due to its definitive symptom relief; however, it is associated with considerable postoperative pain, urinary retention, and complications such as anal stenosis [5, 6]. On the other hand, conservative management encompasses pharmacological interventions, dietary modifications, and completely non-invasive therapies, offering a less invasive alternative for mild to moderate cases. Dietary and lifestyle modifications, including increased fiber intake, are often the first therapeutic steps for improving symptoms such as bleeding and prolapse [7, 8]. Although some reviews and meta-analyses have classified office-based procedures like rubber band ligation, sclerotherapy, and infrared coagulation as part of conservative management, the 2024 guidelines from the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons exclude these modalities from the definition of conservative treatment [1]. Consequently, our study did not included the office-based procedures to ensure a clearer evaluation of conservative management options.

Despite the widespread use of these surgical and conservative interventions, there remains a lack of comprehensive, comparative evidence synthesizing their relative efficacy and safety. This study aims to address these gaps by conducting a rigorous meta-analysis to evaluate and compare the outcomes of surgical versus conservative treatments for hemorrhoids. By systematically analyzing data on key outcomes such as symptom relief, recurrence rates, and complication occurence, this research would provide evidence-based insights to guide clinical decision-making and optimize individualized treatment strategies.

Methods

Search strategy

This meta-analysis was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [9]. A comprehensive literature search was performed using PubMed, Embase, the Cochrane Library, and Web of Science databases from their inception to September 25, 2024. The search strategy combined Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and free-text terms related to hemorrhoids, surgical interventions, and completely non-invasive conservative treatments. Keywords included “hemorrhoids”, “surgery”, “hemorrhoidectomy”, “Doppler-guided hemorrhoidal artery ligation”, “conservative treatment”, “non-surgical”, “medical therapy”, “diet”, and “fiber”. The full search strategy for each database was presented in Table S1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The literature screening process was conducted independently by two authors (L.Q. and X.B.), any discrepancies resolved through consultation with a third author (F.C.). Studies were included if they met the following criteria: (1) Studies with patients with a confirmed diagnosis of hemorrhoids; (2) Studies with comparison between surgical treatments (e.g., hemorrhoidectomy, Doppler-guided hemorrhoidal artery ligation) and completely non-invasive conservative treatments (e.g., pharmacological interventions, dietary modifications); (3) Studies are randomized controlled trials (RCTs) or observational cohort studies; (4) Studies published in English. Exclusion criteria were: (1) duplicate publications; (2) non-clinical studies, including reviews, expert opinions, case reports, conference abstracts, and animal studies; (3) Studies without a control group or single-arm studies; (4) Studies with inaccessible full texts or incomplete/unextractable data; (5) Studies employing minimally invasive procedures such as rubber band ligation, sclerotherapy, or infrared coagulation.

Data extraction

Data was extracted independently by two reviewers (L.Q. and X.B.). The following information was collected: First author, publication year, study design, sample size, age, type of surgical procedure, specifics of conservative treatment, symptom resolution, pain reduction, types and rates of complication, recovery, and recurrence. Any discrepancies in data extraction were resolved through consensus. The methods and time points of measuring pain scores were presented in Table S2.

Quality assessment

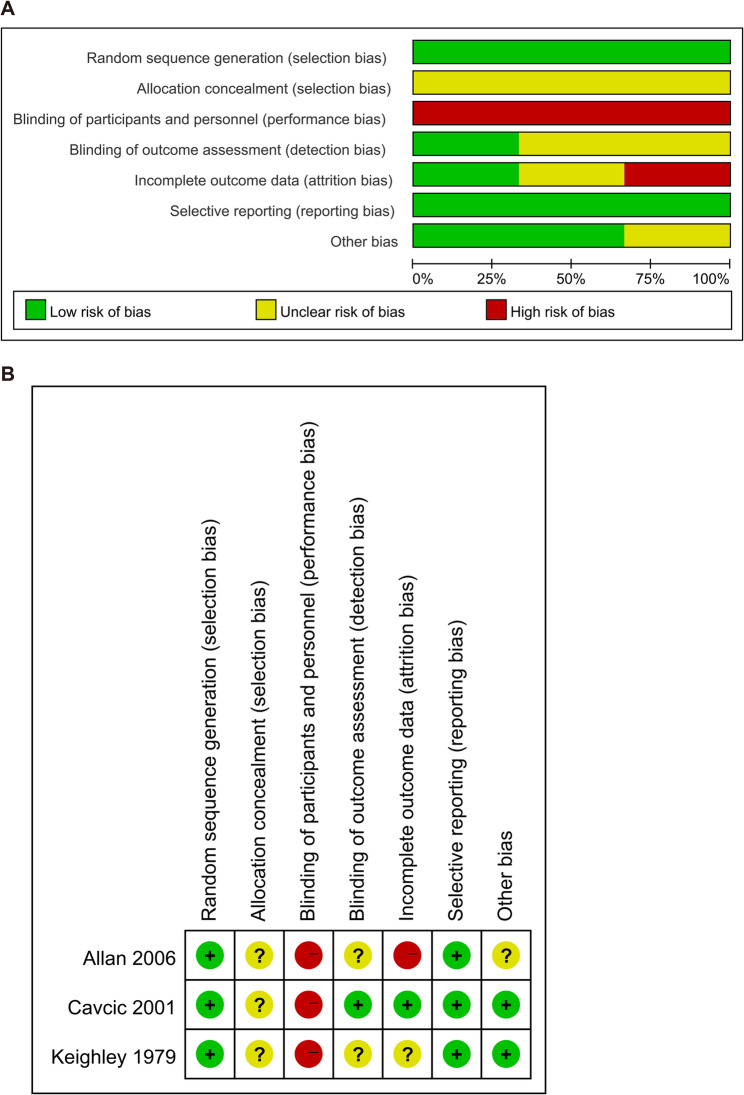

Quality assessment was performed independently by two reviewers (L.Q. and X.B.). The Cochrane Collaboration’s bias assessment tool was utilized for evaluating the quality of the included RCTs. This tool evaluates several domains of bias, including random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting, and other biases. Each domain was classified as ‘low risk,’ ‘high risk,’ or ‘unclear risk’ of bias. The methodological quality of non-RCT studies was assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS). This tool evaluates studies based on three domains: selection, comparability, and outcome. Each study can receive a maximum of nine stars, with higher scores indicating better methodological quality.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Review Manager (RevMan) version 5.4 and Stata 18. Dichotomous outcomes were expressed as odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and continuous outcomes were presented as mean differences (MDs) or standard mean differences (SMDs) with 95% CIs. Heterogeneity among studies was assessed using the Cochrane’s Q test (Chi2), and the degree of heterogeneity was described using the I2 and Tau2 statistics. Substantial heterogeneity was considered present if the Q test p-value was < 0.05 and the I2 value was greater than 50%, prompting the use of a random-effects model; otherwise, a fixed-effects model was applied. Single-arm meta-analyses (i.e., pooled occurrence of complications) were conducted using Stata 18. Subgroup analysis was performed based on the detection time of pain intensity. Publication bias was not formally assessed due to the small number of included studies (< 10), since funnel plot asymmetry tests have limited power and may be misleading in such cases [10].

Results

General characteristics

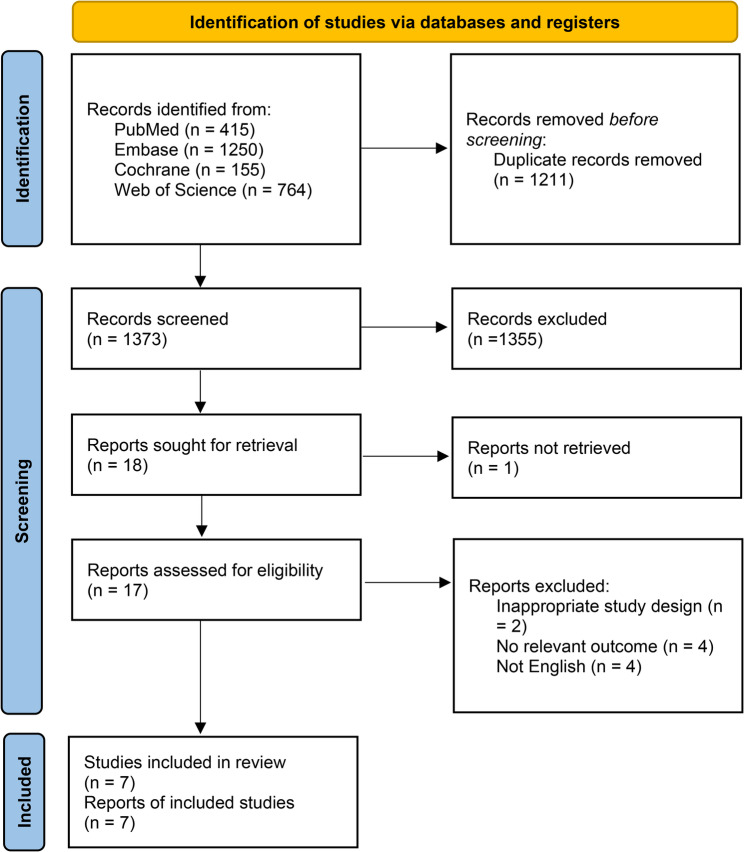

The systematic search identified 2,584 studies, of which 1,373 remained after duplicates were removed. Following title and abstract screening, 1,355 studies were excluded for not meeting inclusion criteria. Among the 18 articles assessed, one article could not be obtained in full text, and 10 were excluded due to inappropriate study design, irrelevant outcomes, or non-English language. Finally, 7 studies were included in the meta-analysis (Fig. 1) [11–17]. These studies, comprising 3 RCTs, 3 retrospective cohort study and a prospective observational cohort study, involved a total of 760 patients. The general characteristics of these studies were presented in Table 1. Risk of bias of non-RCT studies was assessed using the NOS (Table 2). NOS scores ranged from 5 to 8, indicating moderate to high quality for most studies. Risk of bias of RCT studies was assessed using the Cochrane Collaboration’s bias assessment tool (Fig. 2A and B). All three RCTs were assessed as having low risk in random sequence generation and selective reporting. However, due to the nature of the interventions, all were judged to be at high risk for performance bias resulting from lack of blinding. Other domains were generally rated as low or unclear risk.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flowchat for the selected studies

Table 1.

General characteristics of included studies

| Study | Study design | Types of hemorrhoids | Group (n) | Age, year |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Keighley et al., 1979 [11] | RCT | Symptomatic hemorrhoids |

Surgical treatment-high-pressure group (n = 34) Diet group (n = 37) |

Mean ± SD 41 ± 10.5 42 ± 10.7 |

|

Surgical treatment-low-pressure group (n = 36) Diet group (n = 37) |

Mean ± SD 48 ± 7.3 47 ± 11.9 |

|||

| Cavcic et al., 2001 [12] | RCT | Symptomatic hemorrhoids |

Incision surgical treatment group (n = 50) Excision surgical treatment group (n = 50) Conservative treatment group (n = 50) |

/ |

| Greenspon et al., 2004 [13] | Retrospective cohort study | Thrombosed external hemorrhoids |

Surgical treatment group (n = 112) Conservative treatment group (n = 119) |

Mean 41.9 43.2 |

| Allan et al., 2006 [14] | RCT | Prolapsed thrombosed internal hemorrhoids |

Surgical treatment group (n = 25) Conservative treatment group (n = 25) |

Median (range) 47 (29–86) 52 (25–74) |

| Eberspacher et al., 2020 [15] | Retrospective cohort study | External hemorrhoidal |

Surgical treatment group (n = 20) Conservative treatment group (n = 36) |

Mean 80.9 |

| Luo et al., 2023 [16] | Retrospective cohort study | Thrombosed external hemorrhoids |

Surgical treatment group (n = 35) Conservative treatment group (n = 46) |

Mean ± SD 30.20 ± 3.44 29.00 ± 2.98 |

| Medkova et al., 2024 [17] | Prospective observational cohort study | Thrombosed external hemorrhoids |

Surgical treatment group (n = 22) Conservative treatment group (n = 26) |

Median (IQR) 32.5 (30.2–37.0) 32.5 (29.2–35.0) |

RCT Randomized controlled trials, SD Standard Deviation, IQR Interquartile range. /: Indicates that the data was not mentioned in the study

Table 2.

Quality assessment of included non-RCT studies (NOS)

| Study | Selection | Comparability | Outcome | Quality score | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Representativeness of the exposed cohort | Selection of the non-exposed cohort | Ascertainment of exposure | Demonstration that outcome of interest was not present at start of study | Comparability of cohorts on the basis of the design or analysis | Assessment of outcome | Was follow-up long enough for outcomes to occur | Adequacy of follow up of cohorts | ||

| Greenspon et al., 2004 [13] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | 8 |

| Eberspacher et al., 2020 [15] | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 7 |

| Luo et al., 2023 [16] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | 8 |

| Medkova et al., 2024 [17] | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | No | Yes | 5 |

Fig. 2.

Risk of bias assessment. A Risk of bias graph; B risk of bias summary

Symptom resolution and pain reduction

Surgical treatments demonstrated superior efficacy in achieving symptom resolution and reducing pain compared to conservative treatments. Surgical treatments were significantly more effective in achieving asymptomatic status compared to conservative treatments, with a pooled OR of 2.96 (95% CI: 1.66 to 5.28, p < 0.001; I2 = 50%, p = 0.11) (Fig. 3A). In the overall analysis of pain reduction, surgical treatments had significantly lower pain scores compared to conservative treatments, with a pooled SMD of −0.93 (95% CI: −1.73 to −0.13, p = 0.02; I2 = 91%, p < 0.001). Among the included studies, two specifically evaluated pregnant women with thrombosed external hemorrhoids (TEH). The pooled analysis of these two studies showed no significant difference in pain relief between conservative and surgical treatments (MD: −1.26, 95% CI: −2.98 to 0.47, p = 0.15). Then, subgroup analysis based on the timing of assessment showed that surgical treatments significantly outperformed conservative treatments in short-term relief (< 4 days), with a SMD of −1.26 (95% CI: −1.84 to −0.68, p < 0.001; I2 = 74%, p = 0.02). However, when pain was assessed more than 10 days after treatment, the advantage of surgery had disappeared (SMD = 0.00, 95% CI −0.44 to 0.44; p = 0.99). Thus, surgery offers faster pain relief, whereas conservative management reaches a comparable level only after a longer interval (Fig. 3B). Similarly, in the subgroup of pregnant women with TEH, surgical treatments provided significantly greater short-term pain relief (< 4 days) compared to conservative treatments (MD: −1.97, 95% CI: −3.35 to −0.58, p = 0.005), yet no difference persisted beyond 10 days (MD = 0.00, 95% CI: −0.34 to 0.34; p = 0.99). In other words, surgery offers a faster reduction in pain, whereas conservative treatment delivers comparable relief once sufficient time has elapsed.

Fig. 3.

Comparative efficacy of surgical and conservative treatments in achieving asymptomatic status and pain reduction (A) number of patients asymptomatic; (B) pain scores

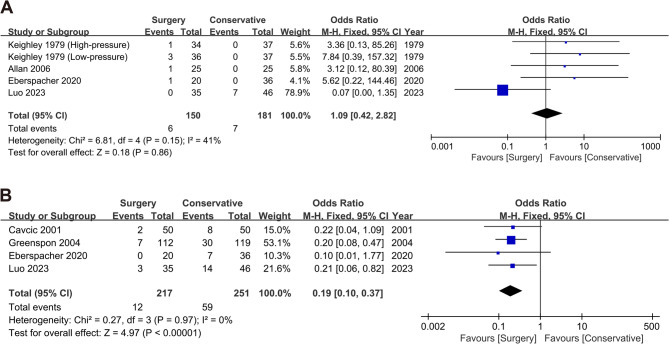

Post-treatment complications

Both surgical and conservative treatments exhibited relatively low rates of post-treatment complications. The comparison revealed no significant differences in the occurrence of bleeding (OR: 1.09; 95% CI: 0.42 to 2.82, p = 0.86; I2 = 41%, p = 0.15; Figs. 4A) or urinary retention (OR: 1.75; 95% CI: 0.30 to 10.31, p = 0.54; I2 = 45%, p = 0.18). In addition, patients undergoing surgical treatment may experience specific complications. The pooled occurrence of incontinence was 0.03 (95% CI: −0.03 to 0.09), post-treatment pain was 0.05 (95% CI: −0.00 to 0.10), and profuse watery discharge was 0.06 (95% CI: −0.02 to 0.13). Although these events were relatively infrequent, their presence should be considered in clinical decision-making.

Fig. 4.

Comparison of post-treatment bleeding and recurrence rate between surgical and conservative treatments (A) Bleeding; (B) Recurrence rates

Recovery and recurrence

Surgical treatments demonstrated advantages in recovery and recurrence outcomes compared to conservative treatments. Notably, only two studies specifically assessed the recovery time in pregnant women with TEH. In these studies, patients undergoing surgical treatments exhibited a significantly shorter time to full recovery compared to conservative treatments (MD: −6.80; 95% CI: −7.64 to −5.96, p < 0.001; I2 = 55%, p = 0.14). Surgical treatments also significantly reduced the recurrence rates compared to conservative treatments, with an OR of 0.19 (95% CI: 0.10 to 0.37, p < 0.001; I2 = 0%, p = 0.97) (Fig. 4B).

Discussion

Hemorrhoids represent a common yet challenging condition to manage, with treatment options ranging from conservative approaches to surgical interventions [18]. This meta-analysis comparing the clinical outcomes of different treatments found that surgery resulted in significantly higher rates of achieving asymptomatic status and better short-term pain relief than conservative treatment. Patients who underwent surgery also had shorter recovery times and lower recurrence rates. Furthermore, considering the limited evidence on the management of hemorrhoids in pregnant women, we analyzed the results of existing studies to provide additional observations that may inform future research.

Our analysis confirmed that surgical treatment was more effective than conservative treatment in achieving a symptom-free state. This superiority may stem from the limited and often transient efficacy of conservative measures, particularly in patients with more advanced disease. A long-term retrospective study pointed out that more than 50% of patients who received conservative treatment required surgical treatment in the following years [19]. Another study showed that up to 30–40% of patients who received conservative treatment may experience symptom recurrence or worsening of the disease, especially when diet and lifestyle habits are not changed [20]. However, substantial heterogeneity was observed in the analysis of symptom-free outcomes, likely due to differences in hemorrhoid grade distribution, treatment protocols, and outcome definitions across the included studies. It is worth noting that the main indications for conservative treatment are patients with grade I and II hemorrhoids [21]. These early stages of hemorrhoids can usually be effectively controlled by increasing dietary fiber intake [22], improving bowel habits [23], and local drug treatment [24]. Once hemorrhoids reach the most advanced stage, patients still need surgery [25]. The results of Stratta et al. showed that the success rate of symptom control in patients with grade I-II hemorrhoids treated conservatively can reach 70–80%, but for grade III-IV hemorrhoids, the probability of conservative treatment failure is higher [26]. However, not all included studies reported the hemorrhoid grade of the included patients, which limited our ability to perform subgroup analyses according to disease stage. Lack of information may lead to differences in treatment effects across studies, thus affecting the stability of the overall effect estimate. In addition, the high recurrence rate in conservatively treated patients may be related to the limitations of conservative treatment itself in achieving a symptom-free state. In our results, the recurrence rate after surgical treatment was indeed significantly lower than that in patients treated conservatively, including pregnant women. This shows that surgical treatment fundamentally solves the core cause of symptoms by directly removing the diseased tissue, thereby significantly reducing the possibility of recurrence.

In terms of pain management, the study found that the pain relief effect of the surgical group was significantly better than that of conservative treatment within the first 4 days after treatment, but after more than 7 days, the difference in pain relief between the two groups was no longer significant. This finding suggests that while surgical treatment may provide more immediate pain relief, conservative treatment has the potential to achieve similar comparable level of pain relief over time given enough time [27]. However, it is important to note that substantial heterogeneity was observed in the pooled analysis of pain outcomes, especially in short-term pain relief. This heterogeneity likely reflects variability in surgical techniques, differences in analgesic protocols, and inconsistent timing or tools used for pain assessment. Long-term pain after surgical treatment is affected by postoperative tissue healing, scar formation, or local nerve irritation, and some modified hemorrhoidectomy may reduce pain, such as laser hemorrhoidoplasty and stapled hemorrhoidopexy [28, 29]. But conservative treatment may be a viable option for patients with mild to moderate symptoms who may wish to avoid the risks of surgery. Unlike some previous studies [30], our study found that surgically treated patients had a significantly faster rate of complete recovery than conservatively treated patients. This may since the concept of “time to recovery” was not uniformly defined across studies in the literature included in this study, with some referring to the time to complete symptom resolution and others to the return to baseline activity. This lack of standardization highlights the need for future studies to adopt consistent, clearly defined recovery endpoints to improve comparability and strengthen the evidence base.

In terms of complications, our analysis showed comparable complication rates between surgical and conservative treatment, including postoperative bleeding and urinary retention. These complications were relatively uncommon in both groups. Among them, postoperative urinary retention is a recognized but relatively uncommon complication following hemorrhoidectomy. Although its overall occurrence is low, urinary retention can significantly affect postoperative recovery by prolonging hospital stay and increasing the need for urinary catheterization, which in turn may raise the risk of urinary tract infections. In contrast, conservative treatments are non-invasive and thus less likely to induce urinary retention. This aligns with our findings, which showed no significant difference in the occurrence of urinary retention between the two treatment approaches. Urinary incontinence, post-treatment pain, and heavy watery discharge were complications specific to surgery and may be related to the tissue dissection or sphincter manipulation during surgery. This finding reflects the advancement of surgical techniques in recent years and the safety of conservative treatment and provides more basis for clinical selection of treatment options.

Pregnant women are a high-risk group for hemorrhoids. In this study, pregnant patients with TEH who underwent surgical intervention showed a short-term advantage in pain relief, which may be attributed to the immediate removal of hemorrhoidal thrombosis and prolapse. This short-term benefit, however, diminished over time. This is consistent with the findings of Al-Sawat et al. [31]. In addition, surgery takes less time to fully recover than conservative treatment. Previous studies have shown that surgery can be performed successfully without risk to the fetus, but most pregnant women with TEH seek conservative treatment due to concerns about the risks of surgery or anesthesia to the fetus. Currently, only one study has reported on urinary retention after surgery in pregnant women with TEH. Further research is needed on complications after surgery in pregnant women and whether surgery poses risks to the fetus [32].

Conclusion

This meta-analysis highlights the trade-offs between surgery and conservative treatment. Although surgical intervention provides better symptom relief, faster recovery, and less recurrence, it also carries some specific post-treatment complications. On the other hand, conservative treatment is a safer and less invasive approach, but it provides slower symptom relief and higher recurrence rates. For special populations such as pregnant women with hemorrhoids, the decision to undergo surgical treatment remains a clinical challenge. Due to concerns about fetal safety and limited evidence, further research is needed to guide optimal treatment strategies in this group.

Limitation

Although this study provides valuable evidence regarding the efficacy and safety of surgical and conservative treatments in hemorrhoid management, it has certain limitations. First, the hemorrhoid grading of included patients was not uniformly and explicitly reported, the duration and definition of follow-up also varied across studies. This heterogeneity might introduce confounding effects on the study results, limiting the generalizability of the conclusions. Second, although our initial goal was to include more RCTs to enhance methodological rigor, only seven studies met the inclusion criteria, and among them, only three were strictly randomized controlled trials. The scarcity of RCTs directly comparing surgical and completely non-invasive conservative treatments likely reflects ethical and practical challenges in randomizing patients to treatment options. As a result, we included high-quality observational studies to ensure sufficient sample size and comprehensive outcome assessment. While this approach broadens the evidence base, it may also introduce inherent biases associated with non-randomized study designs, despite our efforts to rigorously assess study quality. Moreover, because the overall number of included studies was limited (< 10), formal assessment of publication bias was not conducted. However, we qualitatively reviewed study characteristics and found no obvious indications of selective reporting, though the possibility of publication bias cannot be ruled out. Besides, among the included studies, only one article investigated TEH in an acute setting. Other studies focused on symptomatic hemorrhoids without specifying whether treatment was elective or emergent. Therefore, the majority of our analysis pertains to mixed clinical settings, and findings may not be directly extrapolated to acute thrombosed cases. Lastly, there was considerable variation in the follow-up periods of the studies included, which could lead to bias in interpreting conclusions across different timeframes. These issues highlight directions for future research.

Supplementary Information

Authors’ contributions

Longfang Quan: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing - Original Draft Preparation and Project Administration. Xuelian Bai: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing - Original Draft Preparation and Project Administration. Fang Cheng: Data Curation. Jin Chen: Formal Analysis. Hangkun Ma: Visualization. Pengfei Wang: Formal Analysis. Ling Yao: Visualization. Shaosheng Bei: Supervision and Writing - Review & Editing. Xiaoqiang Jia: Supervision and Writing - Review & Editing.

Funding

This article was funded by the Hospital capability enhancement project of Xiyuan Hospital, CACMS. (NO. XYZX0203-03).

Data availability

The data that support the results of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Longfang Quan and Xuelian Bai contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Shaosheng Bei, Email: xyyybss@163.com.

Xiaoqiang Jia, Email: jxq391@sina.com.

References

- 1.Hawkins AT, et al. The American society of Colon and rectal surgeons clinical practice guidelines for the management of hemorrhoids. Dis Colon Rectum. 2024;67(5):614–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kibret AA, Oumer M, Moges AM. Prevalence and associated factors of hemorrhoids among adult patients visiting the surgical outpatient department in the university of Gondar comprehensive specialized hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(4):e0249736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pata F, et al. Anatomy, physiology and pathophysiology of haemorrhoids. Rev Recent Clin Trials. 2021;16(1):75–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Devi V, et al. Hemorrhoid disease: A review on treatment, clinical research and patent data. Infect Disord Drug Targets. 2023;23(6):e270423216271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moldovan C, et al. Ten-year multicentric retrospective analysis regarding postoperative complications and impact of comorbidities in hemorrhoidal surgery with literature review. World J Clin Cases. 2023;11(2):366–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yu Q, et al. Efficacy of Ruiyun procedure for hemorrhoids combined simplified Milligan-Morgan hemorrhoidectomy with dentate line-sparing in treating grade III/IV hemorrhoids: a retrospective study. BMC Surg. 2021;21(1):251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lohsiriwat V. Hemorrhoids: from basic pathophysiology to clinical management. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18(17):2009–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Godeberge P, et al. Micronized purified flavonoid fraction in the treatment of hemorrhoidal disease. J Comp Eff Res. 2021;10(10):801–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Page MJ, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lau J, et al. The case of the misleading funnel plot. BMJ. 2006;333(7568):597–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keighley MRB, Buchmann P, Minervini S. Prospective trials of minor surgical procedures and high-fibre diet for haemorrhoids. BMJ. 1979;2(6196):967–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cavcić J, et al. Comparison of topically applied 0.2% Glyceryl trinitrate ointment, incision and excision in the treatment of perianal thrombosis. Dig Liver Disease. 2001;33(4):335–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greenspon J, et al. Thrombosed external hemorrhoids: outcome after Conservative or surgical management. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47(9):1493–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Allan A, et al. Prospective randomised study of urgent haemorrhoidectomy compared with non-operative treatment in the management of prolapsed thrombosed internal haemorrhoids. Colorectal Dis. 2006;8(1):41–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eberspacher C, et al. External hemorrhoidal thrombosis in the elderly patients: Conservative and surgical management. Minerva Chirurgica. 2020;75(2):117–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Luo H, et al. Comparision of Ligasure hemorrhoidectomy and Conservative treatment for thrombosed external hemorrhoids (TEH) in pregnancy. BMC Surg. 2023;23(1):15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Medkova Y, et al. Thrombosed external hemorrhoids during pregnancy: surgery versus conservative treatment. Updates Surg. 2024;76(2):539–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ray-Offor E, Amadi S. Hemorrhoidal disease: predilection sites, pattern of presentation, and treatment. Ann Afr Med. 2019;18(1):12–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vasyliuk S, et al. Surgical treatment of chronic hemorrhoids (Literature review). Kharkiv Surgical School. 2022.

- 20.Kreisler E, Biondo S. Selection of patients to the surgical treatment of hemorrhoids. Hemorrhoids. 2017;2:91–101.

- 21.Susmallian S, et al. Analysis of two treatment modalities for Post-surgical pain after hemorrhoidectomy. Chirurgia (Bucur). 2024;119(3):247–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perez-Miranda M, et al. Effect of fiber supplements on internal bleeding hemorrhoids. Hepatogastroenterology. 1996;43(12):1504–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hosseini SV. Lifestyle modifications and dietary factors versus surgery in benign anorectal conditions; hemorrhoids, fissures, and fistulas. Iran J Med Sci. 2023;48(4):355–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perivoliotis K, et al. Comparison of ointment-based agents after excisional procedures for hemorrhoidal disease: a network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2023;408(1):401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Altomare DF, Giuratrabocchetta S. Conservative and surgical treatment of haemorrhoids. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;10(9):513–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stratta E, Gallo G, Trompetto M. Conservative treatment of hemorrhoidal disease. Rev Recent Clin Trials. 2021;16(1):87–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garg P. Hemorrhoid treatment needs a relook: more room for Conservative management even in advanced grades of hemorrhoids. Indian J Surg. 2017;79(6):578–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wee IJY, et al. Laser hemorrhoidoplasty versus conventional hemorrhoidectomy for grade II/III hemorrhoids: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Coloproctol. 2023;39(1):3–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ruan QZ, et al. A systematic review of the literature assessing the outcomes of stapled haemorrhoidopexy versus open haemorrhoidectomy. Tech Coloproctol. 2021;25(1):19–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mott T, Latimer K, Edwards C. Hemorrhoids: diagnosis and treatment options. Am Fam Physician. 2018;97(3):172–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Al-Sawat A, et al. The effect of high altitude on Short-Term outcomes of Post-hemorrhoidectomy. Cureus. 2023;15(1):e33873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luo H, et al. Comparision of Ligasure hemorrhoidectomy and Conservative treatment for thrombosed external hemorrhoids (TEH) in pregnancy. BMC Surg. 2023;23(1):15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the results of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.