Abstract

Background

Males with eating disorders (EDs) are an underrepresented population whose symptomatology and treatment needs are poorly understood, having been overlooked in clinical research to date. The role of gastrointestinal disorders, such as gastroparesis, in the context of restrictive EDs is similarly under-explored. Making use of emerging evidence regarding conditions that co-occur with severe EDs to consider potential differential diagnoses in cases of complex and uncertain symptomatology can assist in providing more individualised and empathetic care, preventing avoidable outcomes, including death.

Case presentation

The case of a male patient with a longstanding history of restrictive eating and diagnosis of anorexia nervosa is presented. After hospital admission, they developed severe complications, including aspiration pneumonia. Despite medical interventions, the patient’s complex presentation and the lack of individualised treatment options contributed to the tragic outcome of death. A postmortem diagnosis revealed gastroparesis, a condition that had gone undetected during his life. Prior to his death, the patient had presented with symptoms overlapping with Avoidant Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID) and neurodivergence, which are worth considering for how they may have played a role in complicating the clinical picture and making diagnosis and treatment more challenging.

Conclusions

The case illustrates the value of exploring differential diagnoses when providing individualised and comprehensive treatment for ED patients with diverse symptomatology and identities. Even where diagnoses of co-occurring conditions do not apply, traditional research and knowledge from lived experience show how adopting an integrative stance is valuable for all patients. Specifically, there is an urgent need for improved treatment protocols for males with restrictive EDs, which accommodate co-occurring conditions like gastroparesis and possible differential diagnoses such as ARFID and neurodivergent conditions. Recommendations are given for how providers can implement gender-specific treatment, comprehensive assessments, and a multidisciplinary approach. Co-creating knowledge with patients themselves is central to achieving more empathetic, well-fitting, and effective treatment that appreciates the complexities of overlapping physical and psychological conditions, and ultimately reduces the risk of preventable deaths.

Keywords: Eating disorders, Anorexia, Males, Gastroparesis, Neurodivergence, ARFID, Diagnosis, Ethics, Individualised treatment, Medical management

Introduction

Male eating disorders are overlooked

Traditionally seen as conditions that primarily affect females, eating disorders (EDs) are under-recognised and under-treated in males, despite their significant prevalence and high morbidity [1–3]. Much of the clinical research underpinning conceptualisations and treatments for EDs has failed to adequately report demographic characteristics [4], with a limited diversity of participants, often omitting males [5, 6]. However, evidence suggests that approximately one-third of individuals with eating disorders are male [7]; the rate of male EDs is increasing faster than in females [8]; and men may experience more severe illness with worse outcomes, as reflected in the eightfold greater risk of mortality in males with anorexia nervosa (AN) compared with females [9].

Males with EDs may present differently from females across cognitive, behavioural, and physiological domains [10], leading to delays in diagnosis and treatment that poorly accommodates their needs [11–13]. Societal and clinical biases, combined with gendered stereotypes, contribute to the persistent misconception that EDs primarily affect women [14, 15], reinforcing the barriers males face when seeking and accessing treatment [16, 17]. Qualitative studies report that, of the males who do access support, many experience specialist services as overly feminised and stigmatising [18, 19].

Co-occurring conditions are underexplored leading to worse outcomes

An additional layer of complexity arises from the potential underdiagnosis of Avoidant Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID) and Autistic Spectrum Conditions (ASC) in male ED patients. ARFID was introduced as a diagnosis in the DSM-5 (in 2013) [20], and is characterised by restrictive eating patterns that are not driven by body image concerns, but rather by sensory sensitivities, a lack of interest in eating, or a fear of negative consequences [21, 22]. Meanwhile, ASC and other neurodevelopmental differences are increasingly recognised as being more prevalent among those with EDs in general [23, 24], with studies indicating that up to 30% of individuals with AN may meet the diagnostic criteria for ASC [23, 25] and a strong association with ARFID in particular [26, 27]. This may be explained by the common occurrence of heightened sensory sensitivities, differences in interoception (such as hunger and satiety cues), and co-occurring medical conditions amongst neurodivergent people [28–31], making them particularly prone to developing restrictive eating patterns. A wide range of gastrointestinal abnormalities have been described in ASC, too [32], and research has explored the role of genetics and other neurobiological factors in the aetiology of ARFID [33, 34].

In relation to psychosocial dimensions of illness, similarities in cognitive profiles between those with restrictive EDs (such as AN) and ASC are well documented, particularly in the presence of obsessive–compulsive tendencies common to both conditions [35, 36]. Many autistic individuals experience social isolation as a result of communication differences [37–39], as well as discrimination and stigmatisation that can contribute to worsened mental health [40, 41], including ED symptoms [42]. It is important to remember that these adversities may be magnified amongst those who hold multiple marginalised identities [43, 44]. The low self esteem that may result from such experiences can elevate the risk of developing an ED or exacerbate a pre-existing diagnosis [45–47].

These factors considered, it is no surprise that autistic patients with AN have a worse prognosis than their neurotypical counterparts [48], with conventional treatments that are not accommodating of neurodivergence failing to produce positive, durable outcomes [49, 50]. Despite male sex being a predictor for both ARFID and ASC [51], men who display restrictive eating behaviours often remain undiagnosed, or are misdiagnosed with AN/another ED due to a lack of understanding regarding nuanced differences in overlapping clinical presentations and the distinct mechanisms underpinning their symptomatology [52–54].

Methods: Co-producing knowledge for better outcomes

This case study offers a complex portrait of a young man struggling with restrictive eating behaviours, obsessive tendencies, and increasing social isolation, resulting in tragic consequences. We have written this paper in order to assess the knowledge and treatment gaps that may have been present, conducting our analysis in relation to evidence from research and a synthesis of our personal and professional experience and expertise. This collaboration between perspectives is an example of co-production in action, where research led by people with lived experience of EDs can create depth of understanding and drive change in the field [55–57].

With this in mind, selective examples from author JD’s personal experience have been included in a sensitive manner when discussing the case, where this adds relevant insights that enhance understanding. Respecting the many unknowns that will never be resolved for this particular patient and their family, we draw out a range of practical considerations for those providing care for other, similarly-presenting patients. Thus, the latter half of this paper aims to serve as an educational resource for effectively approaching medical complexity, comorbidity, and diversity in clinical practice.

Part 1: A Case Study of a male with restrictive eating behaviours

| A caucasian cis-gendered male, 193 cm tall, began showing restrictive eating patterns while working as a lifeguard in his early 20 s. His food intake had always been selective, but over time, his eating became more restricted. He increasingly focused on exercise and protein supplements to build muscle strength, but this obsession with physical fitness gradually became more extreme. His social circle contracted, and he became defensive when questioned about his eating habits and weight loss, which his parents and siblings grew concerned about. Despite these concerns, he often denied having any problems |

| At home, he stopped eating with his family and began purging in secret after meals. His weight dropped from 86 to 54 kg, and his physical weakness forced him to leave his job. Aged 25, he was admitted to a specialist Eating Disorders Unit, many miles from home, where his body mass index (BMI) was recorded as 16. During a six-month inpatient stay, he received treatment for both his physical and psychological issues. He was provided with oral nutritional and micronutrient supplements and his weight gradually increased to 80 kg. He received cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), but a formal diagnosis of a neurodivergent condition was not made at this time. Despite his physical improvement, his mental health problems persisted |

| Upon returning home, he resumed restrictive eating behaviours and purging, and his social isolation deepened. Despite re-entering the workforce as a window cleaner’s assistant, his physical stamina declined, and he left the job within six months. Over time, he preferred to walk alone at night, minimising social interactions. His weight dropped to 48 kg, but he concealed this from his family by wearing baggy clothes and minimising contact. The presence of a neurodevelopmental condition such as autism was strongly suspected by the family but he declined multiple offers from community mental health services for assessment and potential confirmation of this. As a result, a wider range of tailored community support was never accessed and the potential for closer monitoring of his condition was effectively reduced. His family pleaded with him to accept the proffered help but he persistently declined this, refusing to engage with any of the services offered |

| In March 2024, he was found collapsed several miles from home, suffering from severe hypothermia, hypoglycemia, and unrecordable blood pressure. Despite initial medical interventions, his condition worsened, and he died at the age of 34, with aspiration pneumonia and gastroparesis identified as causative and contributing factors. At post-mortem two litres of gastric contents were found in situ, with a further litre in the lungs |

The details of this case summarise a complex range of experiences over a long duration of illness. Despite being abridged, the information shared is sufficient to bring to light the range of difficulties that males with EDs may experience, and the need for more effective strategies to improve the acceptability and efficacy of treatment in order to prevent adverse outcomes including death. The following areas are pertinent to this specific case, and to the creation of more inclusive and effective treatment in general:

The role of being male

The diverse symptoms and experiences of men with EDs, some of which are clearly present here, need to be incorporated into assessment and treatment planning in order to offer appropriately targeted and effective intervention. In addition to the range of differencesthat have already been outlined, males with EDs may face unique psychological challenges related to societal expectations of masculinity. For example, the role of hegemonic masculine ideals in reducing male help-seeking for physical and mental health-related concerns is well known [58, 59], and has been identified as a particular problem for minority groups such as Black men [60].

Additionally, males may experience a drive towards muscularity as the masculine bodily ideal [61, 62]. In aiming to achieve this, they may develop symptoms including excessive exercise, which carries a range of negative health outcomes [63, 64]. Steroid abuse amongst men with EDs is a particularly worrying concern as it can pose substantial physiological risks [65, 66], and is poorly understood and often stigmatised amongst healthcare professionals [67].

In this case, the role of the patient’s experience as a male may have warranted further exploration. For example, wider discourses of masculinity may have shaped how he approached both seeking and accepting help, which were central barriers to his treatment. Muscularity-oriented ideals of masculinity may also have contributed to the patient’s focus on exercise and body image. The focus on muscle building, combined with his eventual physical frailty, may have given rise to feelings of emasculation that have been noted in qualitative research of males with EDs [68–70], compounding the unique stigmas they already face.

Considering neurodivergence, ARFID, and co-occurring psychiatric needs

ARFID represents a plausible but overlooked diagnosis in this case. The patient’s long-standing selective eating, which became progressively more restrictive, aligns with features of ARFID, and could be driven by sensory sensitivities and food aversions. However, unlike AN, ARFID is not usually driven by body image concerns, so discriminating between these diagnoses in this case may have involved closer attention being given to the motivations underpinning obsessive exercise behaviours. The fact that “his food intake had always been selective” points towards ARFID in that its onset is more commonly associated with childhood, though it can present at different stages of life [71].

Clinically, discussing the origins of selective eating with the patient and his family would have been helpful in gathering more information about the aetiology of symptoms such as food selectivity and over-exercise. Social withdrawal, defensiveness around eating, and the resulting significant weight loss and malnutrition further point to ARFID, where food-related anxiety and avoidance can severely impact daily functioning and quality of life. These impacts could also be attributed to co-occurring psychiatric diagnoses such as anxiety and/or depression, another undiagnosed neurodivergent condition, or any combination of these which may or may not be in addition to a diagnosis of ARFID.

Indeed, the patient’s longstanding selective eating, difficulty adapting to social situations, and eventual withdrawal from family and friends suggests a possible neurodivergent profile. His worsening symptoms and physical decline were associated with marked social isolation and withdrawal from his family and social network. Social isolation and loneliness are hallmark features of autism and may in part be a product of social and communication differences that make understanding and responding to neurotypical social cues challenging (which usually worsens with malnutrition) [72]. A restricted range of interests and obsessive behaviours may also indicate autism, and other neurodivergent conditions such as Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) are also worth considering, as ADHD can contribute to excessive exercise both as a symptom of hyperactivity and/or as a strategy for self-regulation [73].

Similarly, increased incidence of anxiety, depression and childhood trauma are associated with exercise addiction [74, 75], making careful and comprehensive psychiatric assessment and formulation essential in providing an appropriate and effective treatment plan for this patient. Again, including the family in assessing the possible role of neurodivergence is an important aspect of neurodevelopmental assessment which would shed light on which of the patient’s difficulties predated the diagnosis of an ED [76, 77].

The presence of delayed gastric emptying

In the case study, gastroparesis emerged as a critical medical complication, playing a significant role in the patient’s eventual decline. Gastroparesis is a chronic condition characterised by delayed gastric emptying in the absence of mechanical obstruction [78, 79]. Often associated with diabetes, post-surgical complications, or of idiopathic origin [80], gastroparesis is frequently accompanied by severe malnutrition [81] and restrictive eating behaviours, such as those seen in AN, ARFID, and within this case study [82, 83]. Despite this, management of co-occurring gastroparesis is not addressed in depth in ED clinical guidelines [84].

Author JD has published an account of his delayed stomach emptying contributing to a diagnosis of AN as a result of avoiding eating on the basis of the physical discomfort it involved. Subsequently, binge eating and purging arose as a result of mechanical (rather than solely psychological) restriction of food intake [53]. A later diagnosis of gastroparesis, managed via prokinetic medications and a liquid diet, helped in achieving medical stabilisation after a lengthy illness that was often life-threatening in severity, involving multiple distressing hospital admissions. Similarly, late diagnosis with autism contributed to a more tailored response to his ED symptoms.

Gastroparesis can be understood as implicated in EDs both as an aetiological factor, and/or as a product of ED symptoms. For instance, prolonged periods of undernourishment and restrictive eating can impair the functioning of the stomach muscles, as in gastroparesis, leading to shared symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, bloating, and early satiety [85, 86]. These symptoms can, in turn, exacerbate food avoidance. In this case, unrecognised gastroparesis may have contributed to further weight loss and malnutrition, ultimately culminating in fatal aspiration pneumonia - a condition linked to gastroparesis, where delayed gastric emptying leads to the inhalation of stomach contents [87].

The overlap in symptoms between gastroparesis and purging can also lead to a serious misdiagnosis, as treatment of each is diametrically different. A nasogastric feeding tube may be appropriate in some cases of severe malnutrition, but in gastroparesis it is necessary to avoid excessive gastric distension because of the risk of fatal aspiration. In the case we describe, a nasogastric drainage tube to reduce the volume of gastric contents might have proved life-saving. Although an assessment of gastric emptying rates is the gold-standard investigation for gastroparesis, a simple ultrasonographic estimation of the volume of gastric contents can assist clinicians in deciding the most appropriate intervention in an acute clinical setting.

The apparent absence of recognition and management of gastroparesis in this patient’s care underscores the overall importance of addressing gastrointestinal complications as part of a comprehensive treatment plan for AN, ARFID, and related disorders [88–90].

Part 2: An integrated approach to treatment

| As this case study shows, multidisciplinary approaches to treating EDs and possible co-occurring conditions are essential to ensuring good outcomes. Despite the patient’s initial weight restoration, their persistent ED symptoms, psychosocial impairment, and physiological decline were not adequately addressed, leading to relapse and eventual death. As such, effective treatment requires a comprehensive and sustained strategy that addresses the medical, psychological, and social aspects of illness in an appropriately integrated and sustained fashion, as outlined in the remainder of this paper. |

A) Medical considerations

Whilst EDs can have life-threatening impacts,it is important to remember that the majority of physical sequelae in EDs are reversible and ensuring medical stability is essential to avoid preventable deaths [91, 92]. Similarly, many of the psychological aspects of illness can improve and/or resolve with adequate nutritional rehabilitation and social support [93, 94]. It is particularly vital to remember that patients may not have the capacity to consent to lifesaving treatment despite often being highly informed about their condition and its risks [95, 96]. Thus, careful assessment of capacity by suitably trained staff is required [97]. The ethical imperative to preserve life must take priority, even where patients resist treatment [98, 99].

Providing adaptations where possible to make treatment more acceptable and less distressing for patients is a vital facilitator of treatment, as is tending to the therapeutic alliance through which all healthcare is given. For example, providing acute medical care for autistic patients may involve making adjustments such as reducing sensory stimuli in the clinical environment and offering clear, structured plans that detail the sequence of treatment.

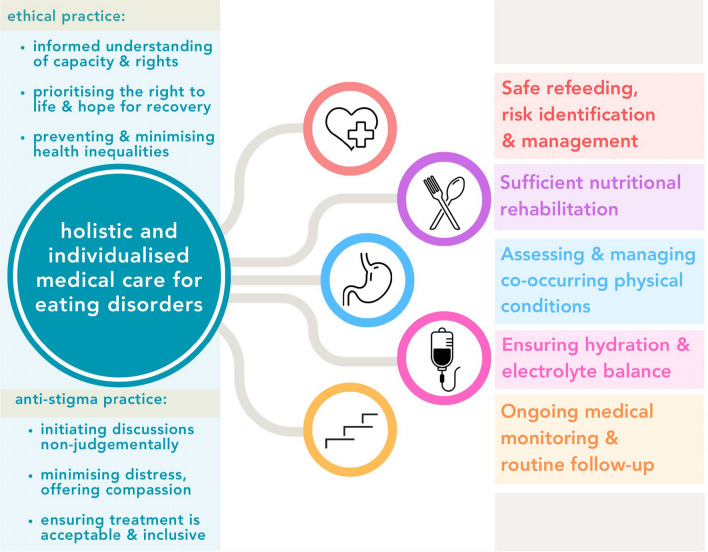

The following sections provide an overview of areas to be considered in the medical management of EDs, summarised in Fig. 1, below. The Medical Emergencies in Eating Disorders (MEED) guidelines, developed by the Royal College of Psychiatrists, are an essential reference point for the recognition and management of risks to life [84].

Fig. 1.

Components of holistic and individualised medical care for eating disorders

Safe refeeding

Refeeding syndrome is a potentially fatal condition that occurs when nutrition is reintroduced too quickly after a period of severe malnutrition or starvation [100]. It is characterised by severe electrolyte imbalances, particularly hypophosphatemia, which can lead to heart failure, respiratory distress, and neurological problems [101, 102]. Careful monitoring of electrolyte levels and the gradual reintroduction of calories are essential components of the refeeding process [103, 104]. Caloric intake should be increased with great care, with close observation of phosphate, magnesium, and potassium levels to avoid triggering refeeding syndrome [105].

Ensuring hydration and electrolyte balance

As highlighted, maintaining proper hydration and electrolyte balance is vital during acute stages of the refeeding process, and the same is true throughout treatment, especially as ED patients frequently suffer dehydration and electrolyte disturbances across diagnoses. Purging via vomiting, excessive exercise, and the misuse of laxatives and diuretics poses further risks, with males being more likely to self-induce vomiting than females [106]. Severe complications associated with inadequate nutrition include hypokalaemia and/or hypomagnesaemia, which can precipitate life-threatening symptoms such as cardiac arrhythmias, hypotension, cardiac arrest, and even sudden death [101, 107]. Intravenous fluids and electrolyte supplementation may be required where oral supplementation is intolerable or insufficient [84].

Recognition and management of hypoglycemia

In the case study, concerns were raised regarding hypoglycemia - a serious but often overlooked complication in EDs - which can present with dizziness, confusion, tremors, and, in severe cases, seizures or loss of consciousness [92, 101]. Hypoglycemia can result from inadequate glycogen stores due to prolonged malnutrition, or from excessive insulin secretion if carbohydrate intake increases too rapidly during refeeding [105]. Males with restrictive EDs face specific risks relating to hypoglycemia. Their lower fat reserves provide less of an energy buffer during periods of restriction, making males more susceptible to rapid glycogen depletion and fasting-induced hypoglycemia. Similarly, higher lean muscle mass in males also increases baseline energy expenditure, which can accelerate glucose and glycogen depletion, further heightening risk [13].

As such, regular monitoring of blood glucose levels is essential, especially during the early stages of refeeding, as fluctuations can be unpredictable [105]. If symptomatic hypoglycemia occurs, prompt intervention with fast-acting glucose, such as oral dextrose or intravenous glucose, or subcutaneous or intramuscular glucagon may be required [84]. A balanced refeeding plan that includes complex carbohydrates, adequate protein, and healthy fats can help stabilise blood sugar levels and reduce the risk of recurrent hypoglycemic episodes. Ongoing assessment is particularly crucial for individuals with comorbid conditions such as diabetes to ensure safe insulin and glucose management [108].

Nutritional rehabilitation

Alongside refeeding protocols, nutritional rehabilitation focuses on meeting the patient’s caloric and nutritional needs in a safe and sustainable manner. For patients with ARFID, this often involves working with a dietitian to create meal plans that introduce variety without overwhelming the patient, who may have significant aversions to certain foods based on texture, colour, or smell [109]. Ensuring an adequate intake of essential vitamins, minerals, and macronutrients is key to reversing the effects of malnutrition and supporting the psychosocial components of recovery. Too often, underweight patients are discharged from specialist treatment with extremely low BMIs despite better long term outcomes being achieved with higher discharge weights [110]. With males, lower fat reserves may contribute to more severe symptoms at higher BMIs (as in the case study, where a BMI of ~ 16 represents moderate malnutrition but presented with significant impairment and suffering) [13]. It is therefore essential not to normalise the acceptance of sustained periods of malnutrition to any degree, and to take this especially seriously in males.

Recognition and management of gastroparesis

Careful medical assessment can shed light on the presence of gastroparesis, with care needing to be taken not to attribute all gastrointestinal symptoms to the presence of an ED. Initial assessments may uncover symptoms of nausea, vomiting, bloating, and early satiety [85], and curiosity about whether these preceded the onset of ED symptoms could be insightful. The gold standard test for gastroparesis is gastric emptying scintigraphy (GES), which measures the rate of gastric emptying using a radioactive meal [111]. A non-digestible capsule which tracks pH, pressure, and temperature as it moves through the GI tract has been developed as a nonradioactive, standardised, ambulatory alternative to scintigraphy [112], while upper endoscopy helps rule out underlying structural abnormalities [85]. A breath test measuring exhaled carbon dioxide after ingestion of a labelled meal provides a non-invasive option [113].

Management of gastroparesis is often complex and varies depending on the severity of symptoms, requiring a tailored approach to address both the gastrointestinal and nutritional challenges involved. With dietetic support, patients are encouraged to eat smaller, more frequent meals that are low in fat and fibre, or to opt for liquid foods to help ease digestion and reduce delays in gastric emptying [114]. Prokinetic medications may be prescribed to enhance motility, alongside symptomatic management of the nausea with antiemetics [115]. For refractory cases that do not respond to pharmacological interventions, gastric electrical stimulation (GES) or botulinum toxin (botox) injections into the pyloric sphincter may be considered [116, 117]. However, more research into these novel treatment options is required to establish their effectiveness and long term outcomes [118, 119], and evidence for the role and management of gastroparesis in EDs remains sparse.

Ongoing monitoring and follow-up

Thiscase study shows the vital importance of ongoing monitoring and taking an active approach to follow-up with patients after medical stabilisation, especially when they may belong to a group that is more likely to be marginalised from specialist services. Monitoring needs to include regular weight checks, blood tests to monitor electrolytes, full blood count, and liver function, and assessment of cardiac and renal health, which can be compromised due to prolonged malnutrition [120, 121]. Regular assessment of bone density can help monitor risk of osteoporosis,which increases with prolonged malnutrition [122], and fractures, which are noted as more common amongst males than females with AN [13]. As part of rehabilitation, a physiotherapy-led approach to rebuilding strength and fitness can support patients with EDs byproviding oversight and opportunities for risk assessment where compulsive exercise may previously have been a problem [123, 124]. This may have been a fitting approach for the symptoms and individual interests of the patient in this case.

Whilst potentially life-saving, initial treatment (such as stabilisation in acute settings or time-limited therapies) may be insufficient for creating long-term change. As such, a stepped care approach is essential, allowing for transitions between different levels of care to match clinical needs [125, 126]. For example, greater integration with other health services, such as primary care [127, 128], can provide a more collaborative approach to treatment and contingency planning that can act as a safeguard. In addition to medical stabilisation, addressing the psychological components of illness alongside increasing social support may help prevent decline, and taking a non-stigmatising approach to males with EDs may make it easier for them to access care again if needed in future. An integrated biopsychosocial approach takes care to avoid false binaries between physical and mental health concerns: each component of treatment can support the other [53, 94, 129].

B) Psychosocial components of treatment

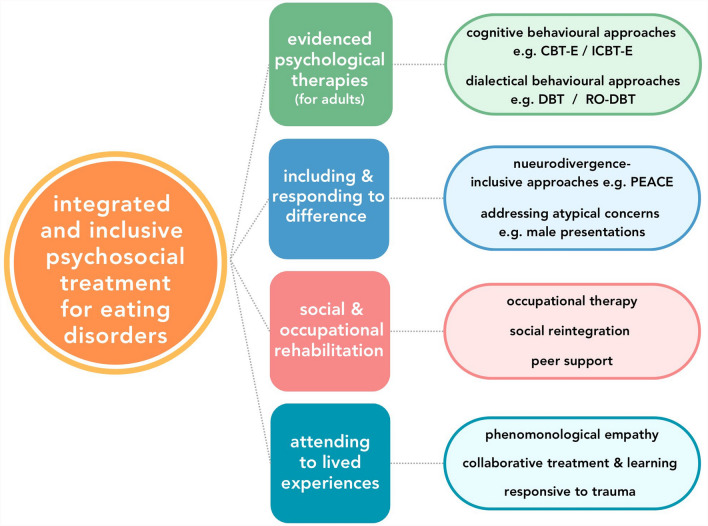

Illustrated in Fig. 2 below, the following aspects of care are important to consider within a comprehensive treatment approach to treatment that accommodates the individually unique needs of ASC, ARFID, and males:

Fig. 2.

A multi-dimensional approach to integrated and inclusive psychosocial treatment

Psychological therapies

A major factor to consider in this case is the effectiveness of any psychological interventions that were given, particularly during an inpatient stay in a specialist ED unit. Irrespective of any psychological treatment that may have been provided, the fact that restrictive eating behaviours and compulsive over-exercise resumed shortly after discharge is illustrative of the challenges that exist in sustaining progress following treatment. This may arise as a result of treatment being inappropriately targeted, not intense enough, lacking a therapeutic relationship characterised by alliance, excluding co-occurring conditions and differences, and/or a lack of effective and planned transitioning into community care following discharge. Ensuring appropriate intensity and integration of treatment within a comprehensive treatment pathway is therefore vital, and has been shown to substantially improve recovery rates compared to treatment as usual amongst patients with longstanding, severe AN in a real-life clinical sample using Integrated and Enhanced Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (I-CBTE) [109].

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) is a common first-line treatment for EDs for adults in its enhanced form (known as CBT-E) [130], and focuses on identifying and restructuring unhelpful thoughts and behaviours related to food, body image, and anxiety [131–133]. For ARFID, specific adaptations of CBT may be necessary to target sensory sensitivities and fears around eating [134]. For example, an exposure and response-prevention approach to therapy has been used to helppatients gradually become desensitised to sensory components of avoided foods perceived as aversive [135, 136]. This targeted CBT approach could have been beneficial in this case if it were found that the cognitive patterns driving selective eating were in fact rooted in sensory differences or gastrointestinal symptoms.

Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) is a skills-based, structured, and intensive psychotherapeutic approach that has also been used in the treatment of EDs [137, 138]. DBT can be particularly useful for individuals who struggle with emotional regulation, distress tolerance and interpersonal difficulties [139, 140], which may well have been the case here. An adapted version, Radically Open DBT (RO-DBT), has shown promise in treating individuals with EDs who exhibit low receptivity to new experiences and change, traits often associated with AN, ARFID, and ASC [141]. By introducing novel experiences, often with the aim of creating greater social connectedness, RO-DBT helps patients become more flexible in their thinking, behaviour and relationships [142]. This could have been beneficial in this patient’s case for the many reasons already outlined.

Neurodivergence-inclusive and trauma-responsive care

There is a growing recognition of the need to adjust treatment for neurodivergent patients [143]. Specific approaches, such as the ‘Pathway for Education and Autism Clinical Excellence’ (PEACE), have been developed to make treatment more acceptable and beneficial for autistic patients [144]. By incorporating strategies to reduce sensory overload during meals, and introducing gradual and structured changes to eating habits, PEACE offers specialist providers effective tools to balance the central requirement of nutritional rehabilitation with patients’ sensory and communication differences, and their need for routine and predictability [145].

EDs are also commonly associated with experiences of trauma [146, 147] which can shape manifestations of illness [148] and requires interventions that integrate the treatment of co-occurring post-traumatic conditions and ED symptoms [149, 150]. The role of iatrogenic trauma (i.e. trauma arising within treatment) has received attention in EDs, with qualitative accounts describing how patients may find inpatient treatment settings particularly coercive and distressing [151–153]. The medical neglect of ED patients [154], who endure significant suffering with limited or no contact with healthcare, cannot be underestimated in this case either. Specific assessment and targeted treatment for trauma could have been beneficial. The wider movement towards trauma-informed and trauma-responsive psychiatric care [155, 156] could help prevent and minimise the impacts of trauma sustained during treatment for patients with EDs, especially where compulsory treatment is necessary and has to be provided in as compassionate a manner as possible [157, 158].

Social and occupational rehabilitation

For neurodivergent individuals, structured learning to improve communication and interpersonal effectiveness skills can help in more effectively navigating social situations that they may find overwhelming or confusing, leading to reduced stress and loneliness [159–161]. It is important to note that, as with other psychological therapies, patients have raised concerns about approaches to treatment that impose deficit-based conceptualisations of their neurodivergence [162, 163]. Failing to appreciate the role of wider systemic factors that drive the exclusion and harm of those who are somehow different can be harmful, as can seeking to erase difference in favour of more normative standards of behaviour.

In more general terms, reintegrating patients with EDs into social and occupational environments can be a central aspect of achieving and maintaining long-term recovery [164–166]. These factors are often identified by patients themselves as particularly valuable and motivating goals [167, 168]. In this case, the patient became progressively more isolated after his initial recovery, eventually losing his job and avoiding social contact. Occupational Therapy can play a crucial role in helping patients rebuild their daily routines, engage in meaningful activities, and regain their independence [169, 170]. For this patient, Occupational Therapy might have focused on helping him re-engage with work and social activities in a structured and more supportive way. Similarly, peer support is yet another missing component of his care that could have been beneficial, especially in finding connection with others with similar identities and experiences [171, 172]. Research has highlighted the important role that both carers and peers can play in offering empathy and instilling hope for recovery [173].

Attending to difference with curiosity and compassion

As demonstrated here, attending to individual patients' specific lived experiences can help create more accurate understandings of EDs. The phenomenology of a person’s subjective experience of their health can offer invaluable insights into the aetiology, symptomatology, and maintenance of their illness, as well as any other diagnoses that may be involved [53, 94]. This in turn increases the likelihood of an accurate diagnosis, a more collaborative therapeutic alliance, and more targeted treatment planning that leads to recovery. Phenomenological empathy is not a luxury, or somehow unscientific in this regard [174].

Therefore, holding a willing curiosity about the nuances of a patient’s condition from their perspective is an essential clinical skill which depends on humanistic qualities such as active listening, therapeutic warmth, and taking a non-judgemental stance [175, 176]. Tailoring assessment methods to the communication style of patients is also important,especially for autistic individuals whose communication differences may have resulted in experiences of feeling misunderstood or blamed in the context of healthcare settings [177, 178]. Similarly, maintaining an explicitly non-judgemental stance can help facilitate information gathering, remembering that patients may feel embarrassment or stigmatised in relation to their illness -a common experience amongst males with EDs [179, 180] and those from minority backgrounds in general [181, 182].

Conclusion

A key theme of this paper is the critical importance of recognising EDs in men and adapting treatment to account for the distinct ways in which they may present. As shown in the case study, this can require a more nuanced approach that goes beyond standard treatment protocols, which are often not tailored to male patients. The tragic consequences of insufficient care and limited understanding are clear.

Creating a more inclusive and integrated approach to treatment for all ED patients, including males, requires a multifaceted and system-wide effort. Significant investment is needed in under-resourced specialist services [185], alongside enhanced levels of training in EDs across healthcare professions [186]. Further research is needed to identify the most helpful assessment tools, treatment targets, and adaptations to existing ED treatment that will make care more acceptable and effective for underserved groups of patients such as males [4–6, 187]. Considering how co-occurring physical and psychiatric conditions are the norm in EDs [183, 184], it is imperative that treatment providers consider alternative diagnoses and have clinical curiosity beyond normative presentations of illness and narrowly-defined symptomatology.

Many papers on the subject of EDs begin by stating how AN specifically has the highest mortality rate of all psychiatric diagnoses. We end this paper saying that this is not a given. EDs pose significant threats to life when untreated, under-treated, or poorly treated. Yet, even in the most severe and longstanding cases, tragic outcomes for patients with EDs are not inevitable [188, 189]. Where they have occurred, it is imperative to learn from deaths in order to improve care provision and uphold the duty to protect life. Improving treatment for males with EDs will not be achieved overnight. However, in the here and now, adopting a more curious, holistic, and compassionate stance can help providers individualise treatment for males in ways that mitigate risk and maintain the prospect of recovery.

Acknowledgements

The authors express their gratitude to the family who have so generously shared their experiences for this publication. We hope that this pertinent example will help to address critical gaps in knowledge and clinical practice, creating better outcomes for males with eating disorders.

Author Contributions

J.D. wrote the main text and created the figures and structure of the paper. C.K. wrote the case study and oversaw medical content. Both authors conceptualised and reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

The authors received no funding for this work.

Availability of data and materials

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Written permission to use the case study material has been provided by the family.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Trompeter N, Bussey K, Mitchison D. Epidemiology of eating disorders in boys and men. In: Nagata JM, Brown TA, Murray SB, Lavender JM, editors. eating disorders in boys and men. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2021. p. 37–52. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Halbeisen G, Laskowski N, Brandt G, Waschescio U, Paslakis G. Eating disorders in men: an underestimated problem, an unseen need. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2024;121(3):86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keski-Rahkonen A, Mustelin L. Epidemiology of eating disorders in Europe: prevalence, incidence, comorbidity, course, consequences, and risk factors. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2016;29(6):340–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burnette CB, Luzier JL, Weisenmuller CM, Boutté RL. A systematic review of sociodemographic reporting and representation in eating disorder psychotherapy treatment trials in the United States. Int J Eat Disord. 2022;55(4):423–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pike KM, Dunne PE, Addai E. Expanding the boundaries: reconfiguring the demographics of the “typical” eating disordered patient. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2013;15:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Halbeisen G, Brandt G, Paslakis G. A plea for diversity in eating disorders research. Front Psych. 2022;13:820043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mitchison D, Mond J, Bussey K, Griffiths S, Trompeter N, Lonergan A, et al. DSM-5 full syndrome, other specified, and unspecified eating disorders in Australian adolescents: prevalence and clinical significance. Psychol Med. 2020;50(6):981–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gorrell S, Murray SB. Eating disorders in males. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clinics. 2019;28(4):641–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quadflieg N, Strobel C, Naab S, Voderholzer U, Fichter MM. Mortality in males treated for an eating disorder—a large prospective study. Int J Eat Disord. 2019;52(12):1365–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murray SB, Griffiths S, Lavender JM. Introduction to a special issue on eating disorders and related symptomatology in male populations. Int J Eat Disord. 2019;52(12):1339–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olivardia R, Pope HG Jr, Borowiecki JJ III, Cohane GH. Biceps and body image: the relationship between muscularity and self-esteem, depression, and eating disorder symptoms. Psychol Men Masc. 2004;5(2):112. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ricciardelli LA, McCabe MP. A biopsychosocial model of disordered eating and the pursuit of muscularity in adolescent boys. Psychol Bull. 2004;130:179–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ganson KT, Golden NH, Nagata JM. Medical management of eating disorders in boys and men: current clinical guidance and evidence gaps. InEating disorders in boys and men. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Springmann ML, Svaldi J, Kiegelmann M. A qualitative study of gendered psychosocial processes in eating disorder development. Int J Eat Disord. 2022;55(7):947–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Drummond M. Understanding masculinities within the context of men, body image and eating disorders. Men, Masculinities and Health: Critical Perspectives. Palgrave Macmillan; 2009:198–215.

- 16.Bomben R, Robertson N, Allan S. Barriers to help-seeking for eating disorders in men: a mixed-methods systematic review. Psychol Men Masc. 2022;23(2):183. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Räisänen U, Hunt K. The role of gendered constructions of eating disorders in delayed help-seeking in men: a qualitative interview study. BMJ Open. 2014;4(4):e004342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Downs J, Mycock G. Eating disorders in men: limited models of diagnosis and treatment are failing patients. BMJ. 2022. 10.1136/bmj.o537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bartel H, Downs J. Opening a New Space for Health Communication: Twitter and the Discourse of Eating Disorders in Men. InMasculinities and Discourses of Men’s Health. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 20.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fisher MM, Rosen DS, Ornstein RM, Mammel KA, Katzman DK, Rome ES, et al. Characteristics of avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder in children and adolescents: a “new disorder” in DSM-5. J Adolesc Health. 2014;55(1):49–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zimmerman J, Fisher M. Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID). Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2017;47(4):95–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kerr-Gaffney J, Halls D, Harrison A, Tchanturia K. Exploring relationships between autism spectrum disorder symptoms and eating disorder symptoms in adults with anorexia nervosa: a network approach. Front Psych. 2020;11:401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boltri M, Sapuppo W. Anorexia nervosa and autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review. Psychiatry Res. 2021;306:114271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Westwood H, Tchanturia K. Autism spectrum disorder in anorexia nervosa: an updated literature review. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2017;19:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bourne L, Mandy W, Bryant-Waugh R. Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder and severe food selectivity in children and young people with autism: a scoping review. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2022;64(6):691–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koomar T, Thomas TR, Pottschmidt NR, Lutter M, Michaelson JJ. Estimating the prevalence and genetic risk mechanisms of ARFID in a large autism cohort. Front Psych. 2021;12:668297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yule S, Wanik J, Holm EM, Bruder MB, Shanley E, Sherman CQ, et al. Nutritional deficiency disease secondary to ARFID symptoms associated with autism and the broad autism phenotype: a qualitative systematic review of case reports and case series. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2021;121(3):467–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adams KL, Mandy W, Catmur C, Bird G. Potential mechanisms underlying the association between feeding and eating disorders and autism. Neurosc Biobeh Rev. 2024. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2024.105717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rastam M. Eating disturbances in autism spectrum disorders with focus on adolescent and adult years. Clin Neuropsychiatry. 2008;5(1):31–42. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zickgraf HF, Richard E, Zucker NL, Wallace GL. Rigidity and sensory sensitivity: independent contributions to selective eating in children, adolescents, and young adults. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2022;51(5):675–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Madra M, Ringel R, Margolis KG. Gastrointestinal issues and autism spectrum disorder. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2020;29(3):501–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kennedy HL, Dinkler L, Kennedy MA, Bulik CM, Jordan J. How genetic analysis may contribute to the understanding of avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID). J Eat Disord. 2022;10(1):53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thomas JJ, Lawson EA, Micali N, Misra M, Deckersbach T, Eddy KT. Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder: a three-dimensional model of neurobiology with implications for etiology and treatment. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2017;19:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cooper K, Smith LG, Russell A. Social identity, self-esteem, and mental health in autism. Eur J Soc Psychol. 2017;47(7):844–54. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oldershaw A, Treasure J, Hambrook D, Tchanturia K, Schmidt U. Is anorexia nervosa a version of autism spectrum disorders? Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2011;19(6):462–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wood-Downie H, Wong B, Kovshoff H, Cortese S, Hadwin JA. Research review: A systematic review and meta-analysis of sex/gender differences in social interaction and communication in autistic and nonautistic children and adolescents. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2021;62(8):922–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ee D, Hwang YI, Reppermund S, Srasuebkul P, Trollor JN, Foley KR, Arnold SR. Loneliness in adults on the autism spectrum. Autism in Adulthood. 2019;1(3):182–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grace K, Remington A, Lloyd-Evans B, Davies J, Crane L. Loneliness in autistic adults: a systematic review. Autism. 2022;26(8):2117–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Turnock A, Langley K, Jones CR. Understanding stigma in autism: a narrative review and theoretical model. Autism Adulthood. 2022;4(1):76–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Perry E, Mandy W, Hull L, Cage E. Understanding camouflaging as a response to autism-related stigma: a social identity theory approach. J Autism Dev Disord. 2022;52(2):800–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mason TB, Mozdzierz P, Wang S, Smith KE. Discrimination and eating disorder psychopathology: a meta-analysis. Behav Ther. 2021;52(2):406–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lawrence SE, Watson RJ, Eadeh HM, Brown C, Puhl RM, Eisenberg ME. Bias-based bullying, self-esteem, queer identity pride, and disordered eating behaviors among sexually and gender diverse adolescents. Int J Eat Disord. 2024;57(2):303–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Goel NJ, Thomas B, Boutté RL, Kaur B, Mazzeo SE. “What will people say?”: mental health stigmatization as a barrier to eating disorder treatment-seeking for South Asian American women. Asian Am J Psychol. 2023;14(1):96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mora F, Rojo SF, Banzo C, Quintero J. The impact of self-esteem on eating disorders. Eur Psychiatry. 2017;41(S1):S558–S558. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Krauss S, Dapp LC, Orth U. The link between low self-esteem and eating disorders: a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Clinical Psychol Sci. 2023;11(6):1141–58. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Colmsee ISO, Hank P, Bošnjak M. Low self-esteem as a risk factor for eating disorders. Zeitschrift für Psychol. 2021. 10.1027/2151-2604/a000433. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Saure E, Laasonen M, Lepistö-Paisley T, Mikkola K, Ålgars M, Raevuori A. Characteristics of autism spectrum disorders are associated with longer duration of anorexia nervosa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Eat Disord. 2020;53(7):1056–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kelly C, Kelly C. What is different about eating disorders for those with autistic spectrum condition. Int J Psychiatry Res. 2021;4(2):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Babb C, Brede J, Jones CR, Elliott M, Zanker C, Tchanturia K, et al. ‘It’s not that they don’t want to access the support… it’s the impact of the autism’: The experience of eating disorder services from the perspective of autistic women, parents and healthcare professionals. Autism. 2021;25(5):1409–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Farag F, Sims A, Strudwick K, Carrasco J, Waters A, Ford V, et al. Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder and autism spectrum disorder: clinical implications for assessment and management. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2022;64(2):176–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Soffritti EM, Passos BCL, Rodrigues DG, Freitas SRD, Nazar BP. Adult avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder: a case report. J Bras Psiquiatr. 2019;68(4):252–7. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Downs J. The body is not just impacted by eating disorders–biology drives them. Trends Mol Med. 2024;30:301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Brown TA, Griffiths S, Murray SB. Eating disorders in males. In: Clinical Handbook of Complex and Atypical Eating Disorders. 2018:309–326.

- 55.Lubieniecki G, Fernando AN, Randhawa A, Cowlishaw S, Sharp G. Perceived clinician stigma and its impact on eating disorder treatment experiences: a systematic review of the lived experience literature. J Eat Disord. 2024;12(1):161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cobbaert L, Millichamp AR, Elwyn R, Silverstein S, Schweizer K, Thomas E, et al. Neurodivergence, intersectionality, and eating disorders: a lived experience-led narrative review. J Eat Disord. 2024;12(1):187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nimbley E, Maloney E, Buchan K, Sader M, Gillespie-Smith K, Duffy F. Barriers and facilitators to ethical co-production with Autistic people with an eating disorder. J Eat Disord. 2024;12(1):113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Galdas PM, Cheater F, Marshall P. Men and health help-seeking behaviour: literature review. J Adv Nurs. 2005;49(6):616–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Möller-Leimkühler AM. Barriers to help-seeking by men: a review of sociocultural and clinical literature with particular reference to depression. J Affect Disord. 2002;71(1–3):1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lateef H. Adherence to African-centered norms and help seeking for emotional distress among black men. Fam Soc. 2023;104(4):570–82. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wienke C. Negotiating the male body: men, masculinity, and cultural ideals. J Men’s Stud. 1998;6(3):255–82. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lennon SJ, Johnson KK. Men and muscularity research: a review. Fash Text. 2021;8(1):20. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lavender JM, Brown TA, Murray SB. Men, muscles, and eating disorders: an overview of traditional and muscularity-oriented disordered eating. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2017;19:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Murray SB, Accurso EC, Griffiths S, Nagata JM. Boys, biceps, and bradycardia: the hidden dangers of muscularity-oriented disordered eating. J Adolesc Health. 2018;62(3):352–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kanayama G, Hudson JI, Pope HG Jr. Anabolic-androgenic steroid use and body image in men: a growing concern for clinicians. Psychother Psychosom. 2020;89(2):65–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Björk T, Skårberg K, Engström I. Eating disorders and anabolic androgenic steroids in males-similarities and differences in self-image and psychiatric symptoms. Subst Abuse Treatm, Prevent, Policy. 2013;8:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yu J, Hildebrandt T, Lanzieri N. Healthcare professionals’ stigmatization of men with anabolic androgenic steroid use and eating disorders. Body Image. 2015;15:49–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lyons G, McAndrew S, Warne T. Disappearing in a female world: men’s experiences of having an eating disorder (ED) and how it impacts their lives. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2019;40(7):557–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.de Beer Z, Wren B. Eating disorders in males. In: Fox JRE, Goss KP, editors. Eating and its Disorders. Wiley; 2012. p. 427–41. 10.1002/9781118328910.ch27. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Foye U, Mycock G, Bartel H. “It’s a Touchy Subject”: service providers’ perspectives of eating disorders in men and boys. J Men’s Stud. 2024;32(1):65–87. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zucker N, Copeland W, Franz L, Carpenter K, Keeling L, Angold A, Egger H. Psychological and psychosocial impairment in preschoolers with selective eating. Pediatrics. 2015;136(3):e582–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mitchell P, Sheppard E, Cassidy S. Autism and the double empathy problem: implications for development and mental health. Br J Dev Psychol. 2021;39(1):1–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Berger NA, Müller A, Brähler E, Philipsen A, de Zwaan M. Association of symptoms of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder with symptoms of excessive exercising in an adult general population sample. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Peñas-Lledó E, Vaz Leal FJ, Waller G. Excessive exercise in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: relation to eating characteristics and general psychopathology. Int J Eat Disord. 2002;31(4):370–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Colledge F, Buchner U, Schmidt A, Wiesbeck G, Lang U, Pühse U, et al. Individuals at risk of exercise addiction have higher scores for depression, ADHD, and childhood trauma. Front Sports Active Liv. 2022;3:761844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.de Clercq H, Peeters T. A partnership between parents and professionals. In: Pérez JM, González M, Comí ML, Nieto C, editors. New Developments in Autism: The Future is Today. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers; 2007. p. 310–40. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mandy W, Clarke K, McKenner M, Strydom A, Crabtree J, Lai MC, et al. Assessing autism in adults: an evaluation of the developmental, dimensional and diagnostic interview—Adult version (3Di-adult). J Autism Dev Disord. 2018;48:549–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hasler WL. Gastroparesis: symptoms, evaluation, and treatment. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2007;36(3):619–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Parkman HP, Hasler WL, Fisher RS. American gastroenterological association medical position statement: diagnosis and treatment of gastroparesis. Gastroenterology. 2004;127(5):1589–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Parkman HP, Yates KP, Hasler WL, Nguyen L, Pasricha PJ, Snape WJ, et al. Dietary intake and nutritional deficiencies in patients with diabetic or idiopathic gastroparesis. Gastroenterology. 2011;141(2):486–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bharadwaj S, Meka K, Tandon P, Rathur A, Rivas JM, Vallabh H, et al. Management of gastroparesis-associated malnutrition. J Dig Dis. 2016;17(5):285–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Norris ML, Harrison ME, Isserlin L, Robinson A, Feder S, Sampson M. Gastrointestinal complications associated with anorexia nervosa: a systematic review. Int J Eat Disord. 2016;49(3):216–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hollis E, Murray HB, Parkman HP. Relationships among symptoms of gastroparesis to those of avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder in patients with gastroparesis. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2024;36(2):e14725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Royal College of Psychiatrists. College report CR233: Medical emergencies in eating disorders: Guidance on recognition and management. 2023. Available at: https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/docs/default-source/improving-care/better-mh-policy/college-reports/college-report-cr233-medical-emergencies-in-eating-disorders-(meed)-guidance.pdf?sfvrsn=2d327483_63

- 85.Camilleri M, Chedid V, Ford AC, Haruma K, Horowitz M, Jones KL, et al. Gastroparesis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4(1):41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rao SS. Gastroparesis: pathophysiology, presentation, and treatment. Gastroenterology. 2013;144(5):1146. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Schwisow S, Falyar C, Silva S, Muckler VC. A protocol implementation to determine aspiration risk in patients with multiple risk factors for gastroparesis. J Perioper Pract. 2022;32(7–8):172–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sato Y, Fukudo S. Gastrointestinal symptoms and disorders in patients with eating disorders. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2015;8:255–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Staller K, Abber SR, Murray HB. The intersection between eating disorders and gastrointestinal disorders: a narrative review and practical guide. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;8(6):565–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Santonicola A, Gagliardi MP, Guarino MPL, Siniscalchi M, Ciacci C, Iovino P. Eating disorders and gastrointestinal diseases. Nutrients. 2019;11(12):3038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ayton A, Ibrahim A, Downs J, et al. From awareness to action: an urgent call to reduce mortality and improve outcomes in eating disorders. Br J Psychiatry. 2024;224:3–5. 10.1192/bjp.2023.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Mehler PS, Andersen AE. Eating disorders: a comprehensive guide to medical care and complications. 4th ed. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Birch E, Downs J, Ayton A. Harm reduction in severe and long-standing anorexia nervosa: part of the journey but not the destination—a narrative review with lived experience. J Eat Disord. 2024;12:140. 10.1186/s40337-024-01063-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Downs J. Please see the whole picture of my eating disorder. BMJ. 2021. 10.1136/bmj.m4569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.van Elburg A, Danner UN, Sternheim LC, Lammers M, Elzakkers I. Mental capacity, decision-making and emotion dysregulation in severe enduring anorexia nervosa. Front Psych. 2021;12:545317. 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.545317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Tan DJ, Hope PT, Stewart DA, Fitzpatrick PR. Competence to make treatment decisions in anorexia nervosa: thinking processes and values. Philos Psychiatry Psychol. 2006;13(4):267–82. 10.1353/ppp.2007.0032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Elzakkers IFFM, Danner UN, Grisso T, Hoek HW, van Elburg AA. Assessment of mental capacity to consent to treatment in anorexia nervosa: a comparison of clinical judgment and MacCAT-T and consequences for clinical practice. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2018;58:27–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Tan J, Jamieson SK, Anderson S. Ethical Issues in the Treatment of Eating Disorders. InEating Disorders: An International Comprehensive View. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland; 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Downs J, Ayton A, Collins L, Baker S, Missen H, Ibrahim A. Untreatable or unable to treat? Creating more effective and accessible treatment for long-standing and severe eating disorders. Lancet Psychiatry. 2023;10(2):146–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Vignaud M, Constantin JM, Ruivard M, Villemeyre-Plane M, Futier E, Bazin JE, Annane D. Refeeding syndrome influences outcome of anorexia nervosa patients in intensive care unit: an observational study. Crit Care. 2010;14(5):R172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Mehler PS, Brown C. Anorexia nervosa–medical complications. J Eat Disord. 2015;3:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Sachs KV, Harnke B, Mehler PS, Krantz MJ. Cardiovascular complications of anorexia nervosa: a systematic review. Int J Eat Disord. 2016;49(3):238–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Schlapfer L, Fujimoto A, Gettis M. Impact of caloric prescriptions and degree of malnutrition on incidence of refeeding syndrome and clinical outcomes in patients with eating disorders: a retrospective review. Nutr Clin Pract. 2022;37(2):459–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Brodie E, van Veenendaal N, Platz E, Fleming J, Gunn H, Johnson D, et al. The incidence of refeeding syndrome and the nutrition management of severely malnourished inpatients with eating disorders: an observational study. Int J Eat Disord. 2024;57(3):661–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Brown CA, Sabel AL, Gaudiani JL, Mehler PS. Predictors of hypophosphatemia during refeeding of patients with severe anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2015;48(7):898–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Van Eeden AE, Van Hoeken D, Hoek HW. Incidence, prevalence and mortality of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2021;34(6):515–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Westmoreland P, Krantz MJ, Mehler PS. Medical complications of anorexia nervosa and bulimia. Am J Med. 2016;129(1):30–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Partridge H, Figueiredo C, Chapman S. The complex interplay of type 1 diabetes and eating disorders. In: Eating Disorders: An International Comprehensive View. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2024

- 109.Białek-Dratwa A, Szymańska D, Grajek M, Krupa-Kotara K, Szczepańska E, Kowalski O. ARFID—strategies for dietary management in children. Nutrients. 2022;14(9):1739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Ibrahim A, Ryan S, Viljoen D, Tutisani E, Gardner L, Collins L, Ayton A. Integrated enhanced cognitive behavioural (I-CBTE) therapy significantly improves effectiveness of inpatient treatment of anorexia nervosa in real life settings. J Eat Disord. 2022;10(1):98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Abell TL, Camilleri M, Donohoe K, Hasler WL, Lin HC, Maurer AH, et al. Consensus recommendations for gastric emptying scintigraphy: a joint report of the American Neurogastroenterology and Motility Society and the Society of Nuclear Medicine. J Nucl Med Technol. 2008;36(1):44–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Kuo B, McCallum RW, Koch KL, Sitrin MD, Wo JM, Chey WD, et al. Comparison of gastric emptying of a nondigestible capsule to a radio-labelled meal in healthy and gastroparetic subjects. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27(2):186–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Szarka LA, Camilleri M, Vella A, Burton D, Baxter K, Simonson J, Zinsmeister AR. A stable isotope breath test with a standard meal for abnormal gastric emptying of solids in the clinic and in research. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6(6):635–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Limketkai BN, LeBrett W, Lin L, Shah ND. Nutritional approaches for gastroparesis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5(11):1017–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Stevens JE, Jones KL, Rayner CK, Horowitz M. Pathophysiology and pharmacotherapy of gastroparesis: current and future perspectives. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2013;14(9):1171–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Shine A, Abell TL. Role of gastric electrical stimulation in the treatment of gastroparesis. Gastrointest Disord. 2020;2(1):3. [Google Scholar]

- 117.Thomas A, de Souza RB, Malespin M, de Melo SW. Botulinum toxin as a treatment for refractory gastroparesis: a literature review. Curr Treat Opt Gastroenterol. 2018;16:479–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Sharma A, Coles M, Parkman HP. Gastroparesis in the 2020s: new treatments, new paradigms. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2020;22:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Samaan JS, Toubat O, Alicuben ET, Dewberry S, Dobrowolski A, Sandhu K, et al. Gastric electric stimulator versus gastrectomy for the treatment of medically refractory gastroparesis. Surg Endosc. 2022;36(10):7561–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Voderholzer U, Haas V, Correll CU, Körner T. Medical management of eating disorders: an update. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2020;33(6):542–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Wonderlich S, Mitchell JE, Crosby RD, Myers TC, Kadlec K, LaHaise K, et al. Minimizing and treating chronicity in the eating disorders: a clinical overview. Int J Eat Disord. 2012;45(4):467–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Solmi M, Veronese N, Correll CU, Favaro A, Santonastaso P, Caregaro L, et al. Bone mineral density, osteoporosis, and fractures among people with eating disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2016;133(5):341–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Bergmeier HJ, Morris H, Mundell N, Skouteris H. What role can accredited exercise physiologists play in the treatment of eating disorders? A descriptive study. Eat Disord. 2021;29(6):561–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Miñano-Garrido E, Catalan-Matamoros D, Gómez-Conesa A. Physical therapy interventions in patients with anorexia nervosa: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(21):13921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.de Jong M, Spinhoven P, Korrelboom K, Deen M, van der Meer I, Danner UN, et al. Effectiveness of enhanced cognitive behavior therapy for eating disorders: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Eat Disord. 2020;53(5):717–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Pehlivan MJ, Miskovic-Wheatley J, Le A, Maloney D, Research Consortium NE, Touyz S, Maguire S. Models of care for eating disorders: findings from a rapid review. J Eat Disord. 2022;10(1):166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Sangha S, Oliffe JL, Kelly MT, McCuaig F. Eating disorders in males: how primary care providers can improve recognition, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Mens Health. 2019;13(3):1557988319857424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Sim LA, McAlpine DE, Grothe KB, Himes SM, Cockerill RG, Clark MM. Identification and treatment of eating disorders in the primary care setting. Mayo Clinic Proc. 2010;85(8):746–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Aftab A. The false binary between biology and behavior. Philos Psychiatry Psychol. 2020;27(3):317–9. [Google Scholar]

- 130.National Institute of Clinical Excellence. Eating disorders: recognition and treatment. 2020. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng69 [PubMed]

- 131.Hay P. Current approach to eating disorders: a clinical update. Intern Med J. 2020;50(1):24–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Fairburn CG, Bailey-Straebler S, Basden S, Doll HA, Jones R, Murphy R, et al. A transdiagnostic comparison of enhanced cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT-E) and interpersonal psychotherapy in the treatment of eating disorders. Behav Res Ther. 2015;70:64–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Dalle Grave R, Sartirana M, Calugi S. Enhanced cognitive behavioral therapy for adolescents with anorexia nervosa: outcomes and predictors of change in a real-world setting. Int J Eat Disord. 2019;52(9):1042–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Willmott E, Dickinson R, Hall C, Sadikovic K, Wadhera E, Micali N, et al. A scoping review of psychological interventions and outcomes for avoidant and restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID). Int J Eat Disord. 2024;57(1):27–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Thomas JJ, Becker KR, Kuhnle MC, Jo JH, Harshman SG, Wons OB, et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder: feasibility, acceptability, and proof-of-concept for children and adolescents. Int J Eat Disord. 2020;53(10):1636–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Thomas JJ, Becker KR, Breithaupt L, Murray HB, Jo JH, Kuhnle MC, et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for adults with avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder. J Behav Cognit Therapy. 2021;31(1):47–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Federici A, Wisniewski L. An intensive DBT program for patients with multidiagnostic eating disorder presentations: a case series analysis. Int J Eat Disord. 2013;46(4):322–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Federici A, Wisniewski L. Dialectical behavior therapy for clients with complex and multidiagnostic eating disorder presentations. In: Choate LH, editor. Eating Disorders and Obesity: A Counselor’s Guide to Prevention and Treatment. Wiley; 2015. p. 375–97. [Google Scholar]

- 139.Linehan MM. Dialectical behavior therapy in clinical practice. Guilford Publications; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 140.Panos PT, Jackson JW, Hasan O, Panos A. Meta-analysis and systematic review assessing the efficacy of dialectical behavior therapy (DBT). Res Soc Work Pract. 2014;24(2):213–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Lynch TR, Gray KL, Hempel RJ, Titley M, Chen EY, O’Mahen HA. Radically open-dialectical behavior therapy for adult anorexia nervosa: feasibility and outcomes from an inpatient program. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Cornwall PL, Simpson S, Gibbs C, Morfee V. Evaluation of radically open dialectical behaviour therapy in an adult community mental health team: effectiveness in people with autism spectrum disorders. BJPsych Bulletin. 2021;45(3):146–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Li Z, Halls D, Byford S, Tchanturia K. Autistic characteristics in eating disorders: treatment adaptations and impact on clinical outcomes. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2022;30(5):671–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Tchanturia K, Smith K, Glennon D, Burhouse A. Towards an improved understanding of the anorexia nervosa and autism spectrum comorbidity: peace pathway implementation. Front Psych. 2020;11:640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Li Z, Hutchings-Hay C, Byford S, Tchanturia K. A qualitative evaluation of the pathway for eating disorders and autism developed from clinical experience (PEACE): clinicians’ perspective. Front Psych. 2024;15:1332441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Brewerton TD. Eating disorders, trauma, and comorbidity: focus on PTSD. Eat Disord. 2007;15(4):285–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Nelson JD, Cuellar AE, Cheskin LJ, Fischer S. Eating disorders and posttraumatic stress disorder: a network analysis of the comorbidity. Behav Ther. 2022;53(2):310–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Scharff A, Ortiz SN, Forrest LN, Smith AR. Comparing the clinical presentation of eating disorder patients with and without trauma history and/or comorbid PTSD. Eat Disord. 2021;29(1):88–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Brewerton TD. An overview of trauma-informed care and practice for eating disorders. J Aggr, Maltreat Trauma. 2019;28(4):445–62. [Google Scholar]

- 150.Brewerton TD. The integrated treatment of eating disorders, posttraumatic stress disorder, and psychiatric comorbidity: a commentary on the evolution of principles and guidelines. Front Psych. 2023;14:1149433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Guarda AS, Pinto AM, Coughlin JW, Hussain S, Haug NA, Heinberg LJ. Perceived coercion and change in perceived need for admission in patients hospitalized for eating disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(1):108–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Elwyn R. A lived experience response to the proposed diagnosis of terminal anorexia nervosa: learning from iatrogenic harm, ambivalence and enduring hope. J Eat Disord. 2023;11(1):2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.MacDonald B, Gustafsson SA, Bulik CM, Clausen L. Living and leaving a life of coercion: a qualitative interview study of patients with anorexia nervosa and multiple involuntary treatment events. J Eat Disord. 2023;11(1):40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Hart LM, Granillo MT, Jorm AF, Paxton SJ. Unmet need for treatment in the eating disorders: a systematic review of eating disorder specific treatment seeking among community cases. Clin Psychol Rev. 2011;31(5):727–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Butler LD, Critelli FM, Rinfrette ES. Trauma-informed care and mental health. Direct Psychiatry. 2011;31(3):197–212. [Google Scholar]

- 156.Reeves E. A synthesis of the literature on trauma-informed care. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2015;36(9):698–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Watson TL, Bowers WA, Andersen AE. Involuntary treatment of eating disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(11):1806–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Elzakkers IF, Danner UN, Hoek HW, Schmidt U, van Elburg AA. Compulsory treatment in anorexia nervosa: a review. Int J Eat Disord. 2014;47(8):845–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Gantman A, Kapp SK, Orenski K, Laugeson EA. Social skills training for young adults with high-functioning autism spectrum disorders: a randomized controlled pilot study. J Autism Dev Disord. 2012;42:1094–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Hotton M, Coles S. The effectiveness of social skills training groups for individuals with autism spectrum disorder. Rev J Autism Dev Disord. 2016;3:68–81. [Google Scholar]

- 161.Dubreucq J, Haesebaert F, Plasse J, Dubreucq M, Franck N. A systematic review and meta-analysis of social skills training for adults with autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2022;52(4):1598–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Kapp S. How social deficit models exacerbate the medical model: autism as case in point. Autism Policy Practice. 2019;2(1):3–28. [Google Scholar]

- 163.Chapple M, Davis P, Billington J, Williams S, Corcoran R. Challenging empathic deficit models of autism through responses to serious literature. Front Psychol. 2022;13:828603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Harrison A, Mountford VA, Tchanturia K. Social anhedonia and work and social functioning in the acute and recovered phases of eating disorders. Psychiatry Res. 2014;218(1–2):187–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Patel K, Tchanturia K, Harrison A. An exploration of social functioning in young people with eating disorders: a qualitative study. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(7):e0159910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Linville D, Brown T, Sturm K, McDougal T. Eating disorders and social support: perspectives of recovered individuals. Eat Disord. 2012;20(3):216–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Siegel JA, Sawyer KB. “We don’t talk about feelings or struggles like that”: white men’s experiences of eating disorders in the workplace. Psychol Men Mascul. 2020;21(4):533. [Google Scholar]

- 168.Safi F, Aniserowicz AM, Colquhoun H, Stier J, Nowrouzi-Kia B. Impact of eating disorders on paid or unpaid work participation and performance: a systematic review and meta-analysis protocol. J Eat Disord. 2022;10(1):7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]