Abstract

X-chromosome inactivation (XCI) is a crucial mechanism of dosage compensation in female mammals ensuring that genes from only one X chromosome are expressed, initiated through expression of the long noncoding RNA Xist. Recent evidence underscores the significance of molecular crowding—most likely via liquid–liquid phase separation (LLPS)—in forming Xist RNA-driven condensates critical for establishing and sustaining the silenced state. By integrating existing knowledge and emerging ideas, we provide a comprehensive perspective on the molecular underpinnings of XCI and outline how manipulation of LLPS-based mechanisms offers new avenues for novel therapeutic approaches.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13059-025-03666-8.

Keywords: Xist, X-chromosome inactivation, Liquid-liquid phase separation, X-reactivation, X-linked disorders, RNA-binding proteins, Condensates, Condensate-modifying therapeutics

Introduction

In female mammals, one of the two X chromosomes is epigenetically silenced in all somatic cells through a process known as X-chromosome inactivation (XCI) [1–6]. This process plays a crucial role in maintaining gene dosage parity between the sexes and contributing to regulating X-linked gene expression in female cells [1]. In mouse embryos, XCI occurs during early female development, in the epiblast cells of implanting blastocysts, and is initiated by the expression of the key orchestrator Xist. Xist is a 15–17-kb long noncoding RNA (lncRNA) transcribed from the X-Inactivation Centre (XIC), a complex locus that determines the number and identity of X chromosomes to be inactivated [2, 7] via an interconnected interplay of lncRNAs [8–15], transcription factors [16–19], and chromatin remodelers [20, 21]. During the initiation phase of XCI, Xist is expressed and coats the future inactive X chromosome (Xi, Barr body) in cis, recruiting various repressive protein complexes through direct and indirect binding mostly to six repetitive elements, within Xist RNA Repeats A to F [1] (Fig. 1). The recruitment of these proteins coordinates a series of epigenetic modifications that result in the formation of a compact heterochromatin structure and spatial 3D structural rearrangement of the X chromosome, effectively silencing most genes on the Xi, with the exception of certain escapee genes that remain expressed [22]. Each of these repeats serves a unique function by recruiting specific RNA-binding proteins (RBPs). For instance, the A-repeat plays a crucial role in initiating XCI by recruiting the transcriptional repressor SPEN and RBM15, which facilitate gene silencing through mechanisms like histone deacetylation and N6-methyladenosine (m6A) RNA modification, respectively [23]. In contrast, the B/C repeats are indispensable for stabilizing and maintaining the silent state of the X chromosome, as they recruit repressive proteins, through the interaction with HNRNPK, and promote chromatin modifications such as H2AK119ub and H3K27me3, thereby ensuring long-term silencing [24]. The A/E repeats are essential for the accumulation of intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs)-containing proteins on the Xi, establishing functional gradients of silencing factors by means of phase separation [25, 26]. In vitro studies using mouse cells have shown that dimeric Xist foci initiate the formation of large protein complexes resembling phase-separated condensates such as paraspeckles in size, shape, and composition, ensuring effective and sustained X-chromosome inactivation [27]. This process is driven by transient homotypic and heterotypic interactions between nucleic acids and IDR-containing proteins, which are key in facilitating liquid–liquid phase separation (LLPS) [27]. Although LLPS was predicted to be the main mechanism for condensate formation and supported by four independent papers [26, 28–30], other mechanisms are possible. Indeed, different types of phase separation can occur—for instance, polymerization-induced microphase separation, gelation, or percolation [31–33].

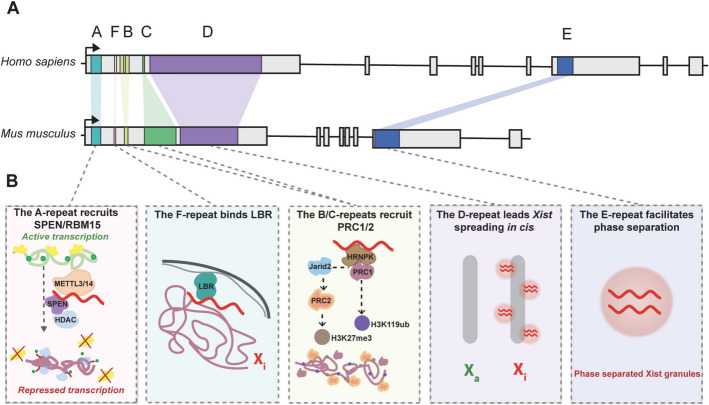

Fig. 1.

Comparative overview of Xist RNA repeat regions in humans and mice. A The Xist repeats exhibit evolutionary conservation between humans and mice, although most repeat regions vary considerably in copy number. B Xist (shown in red) comprises five functionally distinct repeat regions whose coordinated activities drive X‑chromosome inactivation (XCI): the A‑repeat at the 5′ end is highly conserved in both sequence and copy number and nucleates XCI initiation by recruiting SPEN to block RNA polymerase II (yellow) and promote removal of histone acetylation marks (green dots); the F‑repeat anchors the inactive X (Xi) to the nuclear lamina via the Lamin B Receptor (LBR), preserving higher‑order chromatin organization and sustained silencing; the B/C‑repeats engage Polycomb repressive complexes PRC1 and PRC2 to deposit H2AK119ub and H3K27me3, reinforcing chromatin compaction and maintenance of gene repression; the D‑repeat directs Xist RNA in cis along the Xi chromosome to ensure thorough coating of its target; and the E‑repeat drives phase separation to form Xist granules that concentrate silencing factors essential for stable gene silencing

In both humans and mice, the maintenance of the inactive state of the X chromosome is achieved through a combination of chromatin factors, chromosome conformation, and nuclear compartmentalization [34]. In the context of developing therapies for human X-linked disorders, detailed knowledge of the inactive X chromosome maintenance mechanisms is essential, as they stabilize silencing and present barriers to reactivation strategies. XCI is particularly significant for the expression of X-linked dominant disorders, as X chromosomes can carry mutated alleles. In males, mutations on the single X chromosome are often lethal [35]. In contrast, in females, the same mutation can result in variable phenotypes due to their somatic mosaicism [34]. Some cells express the wild-type (WT) X chromosome, while others express the mutated one [36]. Once XCI occurs, the inactive X chromosome retains an epigenetic memory of silencing, which is typically stable across cell divisions [37, 38]. However, this epigenetic memory is fully reversible at the initial stages of XCI [37, 39]. Reactivation of the inactive X chromosome (XCR) naturally occurs in mice during early development, when many of the repressive chromatin mechanisms on the Xi are either partially or completely erased. In humans, XCR takes place in primordial germ cells (PGCs) and the inner cell mass (ICM), where both X chromosomes are active in female cells, although, whether a true XCR happens after early dampening is still debated [36]. Studies on XCR have provided valuable insights into the mechanisms of repressive chromatin erasure, epigenetic reprogramming, gene silencing stability, and chromatin organization [40]. Understanding X chromosome inactivation can enhance our knowledge of gene regulation and offers potential therapeutic avenues for selectively or semi-selectively reactivating WT alleles on the Xi [36].

The aim of this review is to provide an overview of XCI and its reactivation by describing its fundamental mechanisms and key molecular players, which are crucial for forming and maintaining stable silencing in the Barr body. While we will examine current and emerging strategies for reactivating the Xi, including pharmacological approaches, genetic and epigenetic editing techniques, our review will focus on the modulation of LLPS as a promising new avenue for future therapeutic intervention.

Key regulatory regions of Xist RNA in X chromosome inactivation: mechanisms of gene silencing by Xist tandem repeats

Several tandem repeats of the lncRNA Xist play a fundamental role in regulating the silencing process. Most mechanistic insights derive from studies in differentiating female mESCs, with growing evidence in human cells indicating a high degree of conservation but also some species-specific nuances. The A-repeat region of Xist, located near the 5' end, is essential for recruiting the transcriptional repressor SPEN (SHARP) and RBM15, an auxiliary subunit of the multiprotein complex that catalyzes RNA m6A (Fig. 1). Live imaging using mouse neuronal progenitor cells demonstrates that SPEN, a ~ 400 kDa RBP, binds to Xist RNA immediately after Xist activation, implying that SPEN-driven repression begins in tandem with Xist coating [23]. Consistently, in human ESCs, it has also been shown to interact with XIST RNA by RIP/CLIP experiments, confirming that this mechanism of binding is conserved between mouse and human systems [41]. SPEN localizes to transcriptionally active promoters and enhancers on the X chromosome and initiates silencing by associating the histone deacetylase complexes (NURD, NCOR/SMRT), which also includes HDAC3, through its SPOC domain [23, 42]. The action of these repressive complexes strongly reduces the accessibility of RNA polymerase II to the chromatin, thereby preventing gene transcription [42–45] (Fig. 1). Counterintuitively, at the early stages of XCI, before gene silencing occurs, nucleosomes at promoters become less compact, a process that relies on the BAF complex [21, 23]. In mouse ESCs, depletion of key BAF components such as SMARCC1 or SMARCA4 prevents Xist spreading, polycomb-associated repressive marks are not established, and gene silencing is impaired [21, 23]. Once gene silencing is established, nucleosomes condense again, and SPEN dissociates from chromatin and it is no longer required for silencing maintenance, indicating that its role is primarily in the establishment of XCI [21, 23], including proper Xist RNA upregulation at the onset of XCI [46].

RBM15 through direct interaction with Xist RNA [47] recruits the m6A RNA methylation machinery, particularly the METTL3/14 complex, which is responsible for modifying Xist RNA [48] (Fig. 1). These events are critical for Xist functionality in silencing, reinforcing the importance of the A-repeat for successful XCI initiation. Wutz et al. further highlights this by demonstrating in mouse that a 0.9 kb deletion at the 5' end of the lncRNA, encompassing the A-repeat region, completely abolishes its silencing activity [39] (Fig. 1).

The Repeats B/C are essential for preserving the silent state of the X chromosome through the recruitment of repressive proteins such as HNRNPK (Heterogeneous Nuclear RiboNucleoProtein K) (Fig. 1). In mouse, HNRNPK directly binds this cytosine-rich region mediating the recruitment of the non-canonical Polycomb repressive complex 1 (PRC1) [24] adorning the Xi chromosome with a single ubiquitin molecule to histone H2A at Lys119 (H2AK119ub1) [39, 48–50]. In human fibroblasts, HNRNPK associates with the equivalent B/C-proximal region of XIST [51]. The accumulation of H2AK119ub mirrors the pattern of Xist spreading, starting near the Xist locus and extending to gene-dense areas that are in topological contact with Xist entry sites and eventually reaching nearby intergenic regions [52–57]. This chromatin modification is fundamental for the recruitment of Jarid2, the cofactor of the Polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2), which catalyzes mono-, di-, and tri-methylation of histone H3 at Lys27 (H3K27me1, H3K27me2, and H3K27me3, respectively) [58, 59]. PRC1 and PRC2 localize to the same genomic regions in most instances, creating Polycomb chromatin domains [60, 61] (Fig. 1). Bowness et al. recently compared the roles of SPEN and PRC1, which are both involved in the initial XCI stages and recruited by different Xist repeats. These proteins work cooperatively in gene silencing and disruption of either pathway led altered XCI [62]. SMCHD1, a protein that accumulates on the Xi about 3–4 days after Xist induction in mouse, relies on H2AK119ub but not H3K27me3 for its recruitment [62–65] (Fig. 1). Although its role seems crucial during XCI establishment, it is not essential for maintaining gene silencing once established, as its removal does not reactivate many genes. Indeed, SMCHD1 primarily silences genes repressed later in XCI and requires differentiation for its function [62, 66, 67]. Interestingly, while the A-repeat plays a crucial role in the initiation of XCI, the B/C repeats seem to be fundamental for the stabilization and maintenance of the heterochromatinization of the Barr body, and the lack of these regions leads to changes in the chromatin organization of the Xi in the nucleus heading defects in the silencing of most of its genes [68, 69].

The E-repeat region of Xist is critical for directing Xist to the future Xi [28]. In mouse, the absence of this region leads to gene reactivation and decrease of PcG marks during the maintenance phase of X chromosome inactivation [28]. Several proteins, including the nuclear matrix protein CIZ1 (CDKN1A-Interacting Zinc Finger Protein 1), bind to the E-repeat, playing a key role in confining Xist RNA molecules to the X chromosome [28, 70, 71]. Additionally, proteins such as PTBP1, MATR3, CELF1, and TDP-43 organize into specific functional clusters that appear to contribute to efficient Xist-mediated gene silencing forming phase-separated nuclear compartments [27, 28] (see “Phase-separated Xist condensates” paragraph) (Fig. 1).

The F-repeat region contains multiple binding sites for YY1 (Yin and Yang 1), a transcription factor crucial for regulating Xist expression [20, 72]. Xist interaction with LBR (Lamin B receptor) is also important [52–54, 73, 74] (Fig. 1). It has been demonstrated, using an inducible Xist in male ESCs, that deleting this region significantly disrupts transcriptional silencing by preventing the efficient tethering of the Xi to the LBR at the periphery of the nucleus [72, 75–77]. Although an interaction between Xist RNA and LBR was proposed to be sufficient for its spreading during X-chromosome inactivation [77], other studies show only minor silencing defects upon its depletion, suggesting that it may not strictly required for XCI [78, 79]. Thus, while LBR may help to establish and stabilize gene repression, its precise role in XCI remains uncertain, due LBR multiple cellular functions.

The D‑repeat of Xist, comprising multiple copies of a 290‑nucleotide motif, serves as the primary binding site for scaffold attachment factor A (SAF‑A/Hnrnpu), which is essential for broad localization of Xist RNA to the Xi [80, 81]. However, Repeat D may not act alone in ensuring Xist localization [82]. Evidence indicates that multiple regions of Xist likely contribute synergistically or redundantly to its targeting, leaving open the question of whether Repeat D is sufficient or additional elements are required [83]. Deletion studies using CRISPR/Cas9 have highlighted the importance of Repeat D in regulating Xist expression and silencing X-linked genes. The absence of Repeat D results in reduced Xist levels and upregulation of X-linked genes, underscoring its crucial role in Xist functionality and the maintenance of X chromosome inactivation [84] (Fig. 1).

To summarize, XCI is a complex process that involves multiple regions of the Xist RNA, each responsible for different aspects of gene silencing and chromatin organization. The A-repeat initiates gene silencing, while the B/C repeats, although also involved in the initiation, mostly maintain the silent chromatin state. The E-repeat ensures proper recruitment of repressive proteins to Xist RNA, and the F-repeat anchors the Xi to the nuclear periphery through interactions with LBR, maintaining the long-term stability of the inactivation process.

3D chromosome architecture and gene silencing during X chromosome inactivation

The inactive X chromosome is only approximately 1.2 times more compressed than the active X chromosome in both mice and humans [85, 86]. Originally, the Barr body was identified near the peri-nucleolar region of the nucleus [87–89]. In addition, more recent studies, both in mouse and human, have shown that the Xi is typically located at the periphery of the nucleus [90–93]. Although peripheral localization seems not to be strictly required for XCI initiation, it might play a role in maintenance of gene silencing [79, 94, 95]. It exhibits a distinct heterochromatic landscape and undergoes significant 3D reorganization during XCI, highlighting the close relationship between 3D chromosome structure and gene expression regulation [96]. These structural differences between the Xa and Xi territories have been long observed. Hi-C analysis shows that the Xi is structured into two large megadomains, separated by the Dxz4 region, which is abundant in CTCF-binding sites unique to the Xi due to its lower DNA methylation (Fig. 2).

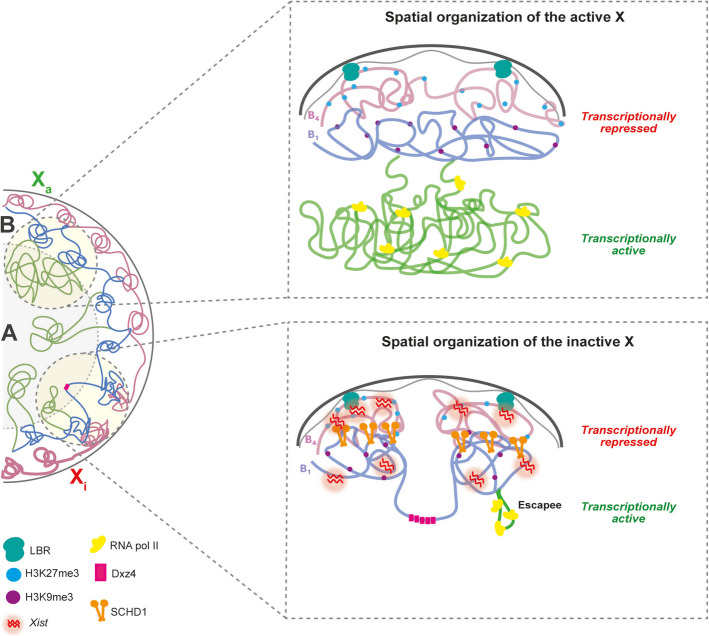

Fig. 2.

Spatial organization of the active and inactive X chromosome in the nucleus. Chromosomes are organized into distinct territories within the nucleus and are further divided into compartments (right), A compartment (green), which contains highly transcribed regions and B compartment which comprises heterochromatin and is divided into B1 (in blue, characterized by an abundance of Polycomb mark H3K27me3) and B4 subcompartment (in pink, tethered to the nuclear lamina). Top. The active X chromosome exhibits a chromatin arrangement dominated by A compartments (euchromatin, green), which allow RNA polymerase II to transcribe genes efficiently. Additionally, B compartments (heterochromatin, pink and blue) are present, although less prominent. Bottom. The spatial configuration of the inactive X chromosome (Xi) differs significantly. During differentiation, certain domains from the active X shift from the A compartment into the B compartment. The newly formed Xi predominantly adopts a repressed, B-like structure. In the early stages of X chromosome inactivation (XCI), Xist RNA selectively coats active regions, recruiting them into a B1-like subcompartment via Polycomb-associated chromatin modifications. Subsequently, SMCHD1 is recruited to the Xi, facilitating the partial merging of B subcompartments. This allows Xist RNA to further spread into the B4-like subcompartment, resulting in nearly complete silencing of the X chromosome. Escape regions, however, remain in the A-like compartment, preserving euchromatin and forming large chromatin loops

This region, along with other elements like Xist and Firre, forms long-range chromatin interactions known as superloops [75, 96–99]. Unlike the Xa, which is organized into over 100 topologically associated domains (TADs) throughout its length, similarly to the escapee genes [97], the Xi lacks these large-scale structures and instead features frequent intrachromosomal contacts [100]. The boundary between the two megadomains on the Xi, located near the microsatellite repeat DXZ4 in humans or Dxz4 in mice, is conserved across species. While mega-domains rely on Cohesin for their structural organization, super loops function independently of it [75, 96–99]. Though these mega-domains are conserved in mice and humans, they are not crucial for XCI or gene escapee [63, 98, 101]. Deletion or inversion of Dxz4 disrupts the bipartite structure but does not significantly affect gene silencing [98]. Despite its highly condensed, heterochromatic state, the Xi retains a compartment-like organization similar to the A/B compartments (A, transcriptionally active and B, transcriptionally repressed) of the Xa, albeit in a larger and less sharply defined form, both mice and humans. The Xi B compartment is divided into B1- and B4-like subcompartments marked by distinct histone modifications—B1 with H3K27me3 and Xist coating, and B4 with H3K9me3 and nuclear lamina association [102, 103] (Fig. 2). The SMCHD1 protein merges these subcompartments, assisting Xist in spreading and stabilizing the silenced state of genes [63]. During XCI, Xist RNA first coats the X chromosome, triggering gene silencing and leading to the formation of distinct B subcompartments, characterized by the loss of RNA polymerase activity [63, 67, 86]. At this early stage, YY1 binds the nucleation site in exon 1 of the Xist gene—anchoring the RNA to the DNA of the inactive X chromosome—and its displacement from Xi has been shown to delay the onset of silencing [104]. This binding is crucial for the lncRNA to remain attached and spread along the chromosome in cis [75]. As gene silencing progresses, SMCHD1 spreads across these compartments, ensuring the stable silencing of genes (Fig. 2). Without SMCHD1, some genes fail get silenced properly, and the silencing defect results in female-specific embryonic lethality of SmcHD1 mutant mice [63, 67, 69]. Additionally, the Xi undergoes reorganization at the sub-megabase level, with attenuated TADs, which are maintained only in expressed regions like Xist and escape genes. SMCHD1 plays a crucial role in this process by reducing CTCF and cohesin occupancy, maintaining the compact chromatin structure of the Xi. The Xi forms a heterochromatic Barr body, largely composed of B subcompartments and reliant on SMCHD1 for full gene silencing and chromatin condensation [63, 67, 97].

Mechanisms of XCI stability

The maintenance of XCI is a multifaceted process involving a range of factors working in concert to ensure the stable and heritable silencing of one X chromosome [39]. Understanding the interplay of these factors (e.g., Xist RNA, repressing factors and RBPs) is essential for unraveling the intricacies of XCI maintenance and stability. Among these components, histone modifications are particularly central to the process.

Polycomb repressive complexes, PRC1 and PRC2 are important for XCI maintenance. PRC1 contributes to chromatin compaction and transcriptional repression, while PRC2 contributes by modifying histones to further stabilize the silent state. These complexes ensure that the Xi remains repressed by modifying chromatin and preventing gene expression [39]. In particular, H2AK119ub and H3K27me3 play essential roles in altering the chromatin structure, rendering it less accessible for transcription and reinforcing the silent state of the Xi [105–107].

Another significant factor is the histone variant macroH2A, which replaces the standard histone H2A during XCI [108–110]. While its role in maintaining XCI is somewhat debated, mouse studies indicate that its deletion in late differentiation does not severely disrupt XCI, as female mice lacking this variant are viable and fertile [108–110]. MacroH2A can also be monoubiquitinated, but the relevance of this modification in XCI remains unclear [105]. Nonetheless, the presence of this variant suggests it may play a role in both establishing and stabilizing XCI [105, 108]. DNA methylation is another crucial layer in XCI maintenance. During the inactivation process, CpG islands associated with promoters on the Xi become hypermethylated [64, 111–113]. This hypermethylation correlates with gene silencing and is regulated by the DNA methyltransferase enzyme DNMT3B. In contrast, gene bodies and gene-poor intergenic regions on the Xi are hypomethylated, with DNA methylation at CpG islands being essential for maintaining the inactive state [21, 114–118]. Xist RNA is fundamental in initiating XCI, but its role diminishes over time. Xist is primarily involved in the establishment of XCI and it also contributes to the transition from Xist-dependent to Xist-independent silencing [39]. However, conditional Xist-knockout studies in mice revealed that the effect of Xist deletion on gene reactivation is tissue-dependent, with most tissues showing only limited re-expression from the Xi, whereas blood and gut exhibited severe oncogenic outcomes upon Xist loss [73, 119–121].It is unclear whether SPEN remains in the Xi compartment after XCI initiation; however, its presence may explain the maintenance of silencing in the absence of Xist before DNA methylation is established [122].

Phase-separated Xist condensates

LLPS is a process that occurs when the concentration of specific molecular components increases to the point of creating a supersaturated solution, which separates into distinct phases [32, 123, 124] (Fig. 3A). LLPS is widely used in cells to form condensates, i.e., membrane-less organelles with specialized functions. This compartmentalization creates a microenvironment that enhances the efficiency of biochemical reactions occurring within the condensates and while their fluid nature allows for the exchange of molecules with the surrounding environment [125, 126] (Fig. 3A). To date, several membrane-less organelles have been characterized, including stress granules (SGs) that store translationally arrested mRNA and RBPs in response to stress signals; P-bodies, specialized in RNA metabolism and storage; and paraspeckles, nuclear structures involved in gene expression regulation and transcription machinery assembly [126–128]. The formation of phase-separated condensates relies on numerous weak, noncovalent homotypic and heterotypic interactions between nucleic acids and proteins, resulting in the exclusion of solvent molecules (Fig. 3A). The interactions governing partitioning into condensates typically include hydrophobic, electrostatic, π–π stacking, and π–cation forces [32]. Proteins with IDRs, modular protein repeats, and nucleic acids characterized by multivalent binding domains are commonly found in these assemblies [32]. Studies of membrane-less organelles indicate that intrinsic disorder underpins a wide array of molecular interaction networks [129]. Molecules within these condensates can often be categorized into “scaffolds,” which nucleate and maintain the phase-separated state, and “clients,” which are recruited or excluded based on their specific interactions with scaffold components [126, 130, 131].

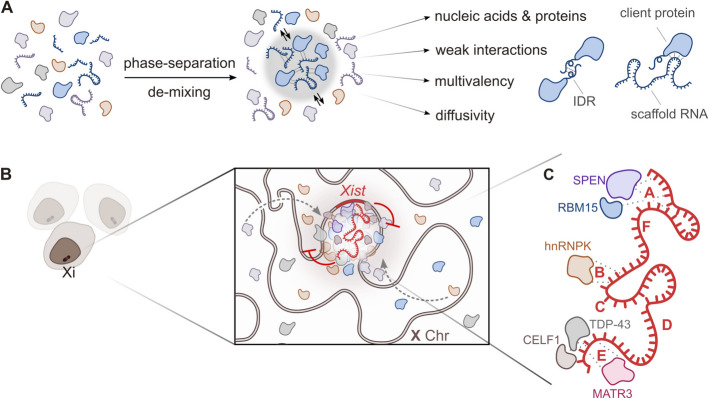

Fig. 3.

Xist-mediated phase separation and protein recruitment on the inactive X chromosome (Xi). A Mechanism of phase separation driven by weak, multivalent interactions between nucleic acids and proteins. These interactions facilitate the formation of membrane-less condensates through phase separation. Condensate-promoting features are illustrated. Scaffold RNAs, such as Xist, initiate condensate assembly by recruiting proteins containing intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs), resulting in dynamic, reversible molecular environments. B Illustration of Xist RNA localization to the Xi in a population of cells, emphasizing its role in molecular crowding and the formation of Xist condensates. C Detailed view of Xist RNA with its characteristic repeats (A–F) interacting with various proteins known to harbor iIDRs. Key protein interactors include SPEN, RBM15, HNRNPK, TDP-43, CELF1, and MATR3. Dashed lines represent specific RNA–protein interactions mediated by the Xist transcript

A key question in the XCI field is how a relatively small number of Xist foci [132, 133] can regulate a vast number of X-linked genes across the entire chromosome through the establishment of large macromolecular complexes [32] (Fig. 3B and C). Xist recruits a high number of proteins that was predicted to undergo LLPS [27, 134] (Fig. 3B and C). Each repeat element in Xist comprises small tandem repeats that confer specific functional properties by attracting distinct RBPs [135]. The defined secondary structures of Repeats A, B, and E, along with the partially structured Repeat D and the predominantly single-stranded 3′ region of Xist [27, 136], are involved in the selective recruitment of RBPs. These structural features create binding sites and conformations that enhance the recruiting of RBPs, facilitating the assembly of large multiprotein complexes through extensive protein–protein and protein-RNA interactions [32]. Furthermore, many proteins that interact with Xist not only contain disordered regions, which contribute to the dynamic nature of these interactions, but have been reported to undergo phase separation in SGs and paraspeckles (e.g., TDP-43, HNRNPK, CELF1, HnRNPR and RBM14) [27] (Fig. 3B and C). Xist repeat regions attract RBPs (Fig. 3B), resembling the NEAT1 lncRNA, which sequesters proteins and drives paraspeckle formation through LLPS [137].

Based on these observations, it was proposed that the recruitment of proteins by Xist drives the formation of condensates with increased molecular crowding, facilitating efficient and stable X-chromosome inactivation [27, 134] (Fig. 3B). This hypothesis was successively validated by experimental studies [26, 29, 30]. Standard fluorescence microscopy revealed that Xist and its interacting proteins form large complexes, observed as foci distributed across the X chromosome [52, 138]. Remarkably, only 50 to 150 foci were detected on the Xi, raising questions about how a relatively small number of complexes could control the expression of numerous X-linked genes [70, 133, 139]. With the development of quantitative super-resolution microscopy methodologies, researchers were able to demonstrate that Xist foci drive the formation of membrane-less compartments that extend across the X chromosome [26, 133]. These nuclear compartments, also called supramolecular complexes (SMACs), are highly dynamic structures that depend on transient, multivalent interactions between Xist-binding proteins. Three-dimensional structured illumination microscopy measurements of distances among various Xist interactors—SPEN, PCGF5, CELF1, and CIZ1—revealed significantly shorter distances when these proteins are associated with Xist compared to the rest of the nucleus [26]. The recruitment of proteins by Xist results in a local increase in protein concentration relative to the surrounding nuclear environment. Protein accumulation within the SMAC during the Xi transition varies depending on their specific roles. For instance, SPEN shows an increase in concentration, while CELF1 decreases, and others, such as PTBP1 and HNRNPK, remain stable. This observation suggests that an increase in concentration of certain proteins (i.e., SPEN) is critical for function (i.e., gene silencing), whereas for other proteins, their recruitment at basal levels is sufficient to fulfil their roles. The SPEN IDR domain is essential not only for SPEN recruitment to SMACs but also for the formation of dynamic condensates. Another study also demonstrated that SPEN can form concentration-driven clusters in the nucleus through homotypic multivalent interactions mediated by its IDR domain [29]. SPEN binding to Xist via its RNA-binding protein domains appears necessary for its accumulation through the IDR, suggesting that RNA–protein interactions are also crucial in driving this molecular crowding [26]. Experiments utilizing single-cell RNA sequencing and RNA FISH demonstrated that, in the absence of the SPEN IDR domain, silencing of X-linked genes is lost. This finding indicates that this domain is crucial for the regulation of gene expression mediated by SPEN across the entire chromosome [26, 29]. Similarly, the direct binding of SPEN to Xist A-repeat through its RRM domains is essential for the proper functioning of SPEN in gene silencing [29]. On the one hand, SPEN spatial amplification explains how Xist achieves gene silencing across the entire X chromosome. On the other hand, the low levels of Xist expression ensure that this silencing remains specific to the X chromosome and does not extend to autosomes. It has been proposed that a feedback regulatory loop, governed by Xist-SPEN, maintains Xist levels low, thereby preserving the specificity of its function [29]. However, other mechanisms beyond the Xist-SPEN regulatory feedback loop were described to maintain the Xist expression at the appropriate levels [20, 46, 140].

It should be stressed that molecular crowding on Xi likely involves more than just the A-repeat and SPEN. For example, the B-repeat region appears to play a significant role in the accumulation of SMACs by recruiting key factors like PRC1 and SMCHD1. Yet, the E-repeat recruits several proteins that are capable of undergoing phase separation (e.g., PTBP1, CELF1 and TDP-43). The proteins assemble on the E-repeat and, through homotypic and heterotypic protein–protein and RNA–protein interactions, form large higher-order assemblies. E-repeat are loosely characterized by structured regions interspaced by linear RNA portions [141]. Interestingly, linear RNAs within condensates are disordered, allowing them to form multiple interactions with RNAs and to recruit disordered proteins [129]. Xist harbors regions that are expected to be linear [27, 142], and they might contribute to build the network of interactions required for the condensate formation.

Moreover, it was recently revealed that Xist’s B-repeat and the RGG domain of HNRNPK cooperatively drive LLPS, forming condensates that engage with Xist RNA and may facilitate its internalization and spreading along the Xi territory [30]. Repeat B enables HNRNPK to phase separate at lower physiological concentrations and induces a further phase transition that makes the droplets more dynamic, by changing its material properties. These changes enhance condensates ability to entrap silencing factors such as SPEN, YY1, SMCHD1, and RING1B, all of which contain IDRs. In addition, these alterations promote the entrapment of silencing factors and facilitate the spreading of Xist within HNRNPK-organized chromosomes, enabling efficient cis-limited inactivation across the X chromosome [30]. Importantly, the study from the Lee lab, demonstrated that a mutant version of HNRNPK defective in LLPS but still able to bind RNA, fails to support proper Xist spreading, providing strong evidence for the functional importance of phase separation in vivo. These findings indicate that LLPS plays a crucial role not only in the initiation and maintenance of silencing but also in facilitating its effective spreading across chromosome [143].

In the nuclear environment—where RNA concentration is higher than in the cytoplasm—various condensates, such as paraspeckles, speckles, Cajal bodies, and nucleoli, form through RNA–RBP interactions [144]. Xist granules may represent an additional nuclear compartment that helps compartmentalize specific biochemical processes, thereby enhancing their efficiency.

The formation of Xist-containing condensates and their role in gene silencing have been primarily studied in mouse systems, with limited functional evidence available from human cells (Table 1). However, we envision that similar molecular organizations exist in the human context. For example, the A-repeat, which contributes to the formation of SMACs, is highly conserved between human and mouse in both copy number and sequence consensus [145], suggesting a conserved structural role in XCI. Furthermore, recent work has shown that SPEN, a key effector in mouse XCI, also associates with XIST in naïve human embryonic stem cells and is required for dampening gene expression [41]. Interestingly, proteins known to bind the E-repeat of Xist in mouse ESCs—namely PTBP1 and MATR3—have also been implicated in the maintenance of XCI in human cells. In adult human B cells, these factors were found to be important for the repression of the X-linked immune gene TLR7, suggesting a possible role in repression maintenance in adult human cells [146]. Given the described roles for E-repeat in the maintenance of gene silencing and Xist localization [28], these observations raise the possibility that similar mechanisms may operate in human cells, with potential species-specific differences yet to uncover. Notably, MATR3 harbors an IDR, further supporting the idea that E-repeat–binding proteins may contribute to XCI maintenance through phase separation–related mechanisms.

Table 1.

Summary of key studies on Xist-mediated condensates and their associated cellular models. This table summarizes key studies investigating the formation and function of Xist-mediated condensates, detailing the cell types used, species of origin, main findings, and whether human cell systems were included. Abbreviations: ESCs, embryonic stem cells; MEFs, mouse embryonic fibroblasts; 3D-SIM, three-dimensional structured illumination microscopy; U2OS, human osteosarcoma cell line; HEK293T, human embryonic kidney cell line; SMACs, supramolecular complexes; LLPS, liquid–liquid phase separation; Xi, inactive X chromosome

| Study | Cell type(s) | Species | Main finding | Human cell system contribution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Pandya-Jones et al., Nature 2020 [28] |

- ESCs, - Female MEFs, - Male tet-inducible XistΔTsix V6.5 ES cells |

Mouse | E-repeat–binding proteins form a condensate on the Xi that is essential for Xist anchoring, gene silencing, and its maintenance (mouse) | Human PTBP1 and CELF1 used in droplet assay |

|

Markaki et al., Cell 2021 [26] |

- Female ESCs, - Epiblast-like cells - Fibroblasts |

Mouse (ESCs) Human (Fibroblasts) |

Xist seeds local protein gradients to form SMACs, enabling chromosome-wide silencing through spatial concentration of repressive complexes (mouse) | Human fibroblasts used in 3D-SIM to study the variability of Xist foci number |

|

Jachowicz et al., Nat Struct Mol Biol 2022 [29] |

- Female ESCs, - HEK293T |

Mouse (ESCs) Human (HEK293T) |

Xist amplifies SHARP recruitment via concentration-dependent assemblies to achieve chromosome-wide silencing while maintaining specificity (mouse) | SHARP biochemical and biophysical properties studied in human HEK293T cells |

| Ding et al., Cell 2025 [30] |

- ESCs, - MEFs, - U2OS cells |

Mouse (ESCs MEFs) Human (U2OS) |

B-repeat and HNRNPK co-drive LLPS to encapsulate the X chromosome, enabling local concentration and cis-limited spreading of silencing factors (mouse) | HNRNPK phase separation studied in human U2OS cells |

The Xi and X-linked genetic disorders

XCI is not always perfectly random. Skewing has been reported in several X-linked disorders [147, 148]. The direction and extent of XCI skewing (i.e., imbalance in maternal and paternal X silencing) significantly shape the severity of diseases influenced by X chromosome inactivation [147, 148]. In female carriers of X-linked mutations, the X chromosome bearing the mutation can be selectively inactivated, thereby preserving the function of the normal X chromosome and ensuring proper autosomal dosage [149, 150]. However, this skewing is not always consistent; in cases where it is limited or absent, an additional pathogenic variant on the second X chromosome can result in the expression of one of the detrimental mutations, leading to variable disease severity [151].

XCI also plays a critical role in the clinical presentation of both recessive and dominant X-linked disorders (Additional file 1: Table S1) [152–162]. In females, mosaic XCI allows for partial compensation, as cells in which the X chromosome carrying the mutant allele is inactivated can mitigate the phenotypic impact, often resulting in milder symptoms or even asymptomatic presentations. By contrast, males, who are hemizygous for X-linked genes, generally exhibit more severe symptoms due to the complete expression of mutations on their single X chromosome. This discrepancy underscores the role of XCI in modulating disease severity [163, 164]. For neurodevelopmental disorders, where nearly 20% of X-linked genes are implicated, whether a gene is silenced or escapes XCI has a profound impact on the clinical phenotype [151]. Genes that escape inactivation in female cells can lead to overexpression, further influencing the disease course. Such mechanisms hold therapeutic potential, particularly in neural cells, where reactivating or silencing specific X-linked genes and manipulating XCI skewing may prove beneficial [147, 150, 165]. However, protein transfer (when possible) and cell selection interplay further influence the clinical manifestations in female heterozygotes [166]. Functional proteins produced by WT cells can compensate for deficits in mutant cells, while cell selection dynamics in early development —favoring either WT or mutant cells—can amplify the impact of the disease. When mutant cells gain a growth advantage, they may outcompete WT cells, worsening disease severity [166].

X-linked dominant disorders primarily affect females, as males carrying pathogenic mutations often experience embryonic lethality [32, 164, 167] (Additional file 1: Table S1). The genes implicated in several X-linked dominant disorders have been identified and can be categorized based on their phenotype in relation to the XCI pattern (see selected examples below). This classification highlights the diverse regulatory mechanisms of X-linked genes and their influence on disease pathology [35]. In some instances, the disease phenotype aligns closely with the known function of the associated gene, as seen with OFD1 (Oral–facial-digital type I syndrome). OFD syndrome type I is marked by early male lethality and central nervous defects in 40% of cases, leading to intellectual disability, hydrocephalus, and other brain abnormalities) [168]. The OFD1 gene encodes a protein expressed in affected tissues, with most mutations causing protein truncation and loss of function [169, 170]. However, in other cases, the connection between gene function and the observed phenotype is unclear [35]. For example, certain genes are generally expressed and play vital roles for cellular function, yet their associated disorders display highly tissue-specific symptoms. This discrepancy may arise from differences in each tissue’s capacity to handle cell damage or dysfunction when the X chromosome with the WT allele is inactivated [35].

Rett syndrome (OMIM 312750) serves as an example of a disease linked to a gene that undergoes random XCI, resulting from mutations in the gene encoding methyl-CpG-binding protein 2 (MECP2) [171, 172] (Additional file 1: Table S1). The loss of this essential protein predominantly affects females (1 in 10,000 female births). Nearly 900 pathogenic mutations have been identified, with half clustering in eight hotspots [172, 173] and affected females develop normally for the first 6–18 months but then regress, losing verbal and motor skills and exhibiting gait abnormalities and stereotypic hand movements [174]. While regression stabilizes over time patients require lifelong palliative care [175]. Other dominant X-linked disorders associated with genes subject to inactivation include microphthalmia with linear skin defects (MLS, OMIM 309801) [176–178]. MLS is a rare condition characterized by microphthalmia, linear skin defects, intellectual disability, seizures, and occasionally cardiac anomalies. It results from deletions or unbalanced translocations involving the Xp22.3 region, causing monosomy. Despite some phenotypic overlap with Aicardi and Goltz syndromes, MLS is now recognized as a distinct disorder [178] (Additional file 1: Table S1).

Different approaches for treating X-linked dominant disorders

Most dominant X-linked syndromes currently lack a cure, but promising advancements are paving the way for potential therapeutic interventions. These approaches can be broadly categorized into four main groups: (i) functional gene restoration, (ii) gene-editing technologies, (iii) nonsense read-through therapies, and (iv) reactivation of the Xi (Fig. 4).

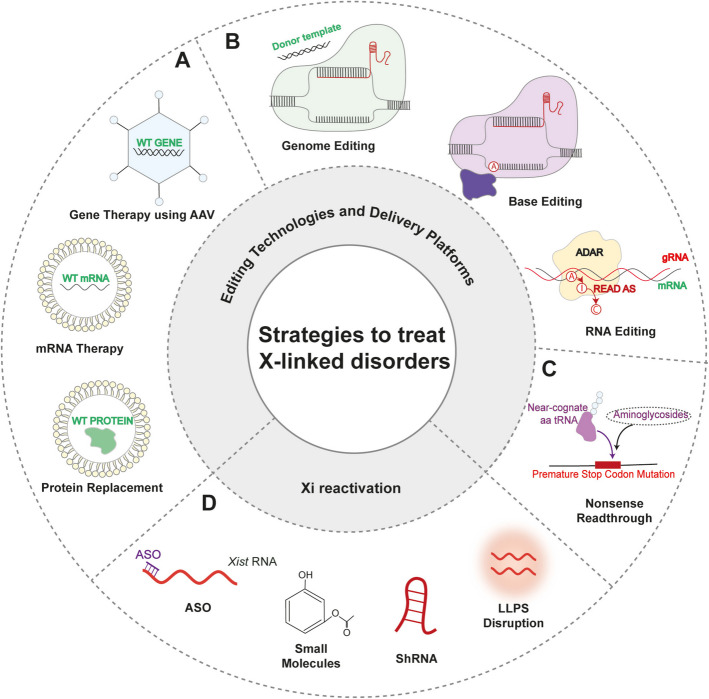

Fig. 4.

Therapeutic strategies for X-linked disorders. These methodologies include both gene function restoration and targeted editing, as well as reactivation of the inactive X chromosome. A Functional restoration via AAV (adeno‑associated viral)‑mediated gene therapy, mRNA‑based treatments, and protein replacement. B DNA and RNA editing approaches, including CRISPR‑Cas9 genome editing, base editing, and RNA editing. C Nonsense read‑through therapies to bypass premature stop codons. D Xi reactivation strategies employing antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs), small‑molecule modulators, short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs), and disruption of liquid–liquid phase separation (LLPS)

Functional restoration

Gene transfer, mRNA therapeutics (MRT), and protein replacement all aim to reintroduce a working gene product. In gene transfer, adeno‑associated virus (AAV) vectors deliver a synthetic copy of the defective gene [179], achieving long‑term expression but risking immune reactions (especially at high doses), inflammation, and limited brain distribution [180] (Fig. 4A). MRT encapsulates codon‑optimized, UTR‑modified mRNA (e.g., MECP2) into lipid nanoparticles to restore protein function without DNA alteration [181–184], yet is limited by innate immune sensing and blood–brain barrier penetration [185]. Protein replacement therapy directly supplies recombinant protein to bypass the genetic defect, but depends on correct post‑translational modification, precise cellular targeting, frequent dosing, and carries overexpression toxicity risks [186].

DNA and RNA-editing technologies

Direct correction of genetic mutations is exemplified by CRISPR–Cas9, which employs guide RNAs to introduce site‑specific DNA breaks and relies on homology‑directed repair (HDR) with an exogenous template to restore the wild‑type sequence [187] (Fig. 4B). Because HDR is inefficient in post‑mitotic neurons [188] base editors were developed to catalyze precise C → T or A → G conversions without creating double‑strand breaks [189]. These tools have reached editing efficiencies of up to 60% in murine cortex, although effective delivery and off‑target editing remain hurdles. To avoid genomic alterations entirely, RNA editing uses ADAR2 guided by programmable RNAs to deaminate adenosine into inosine—interpreted as guanosine during translation [190]—making it especially attractive for correcting G > A transitions that give rise to early stop codons [191, 192] (Fig. 4B). While this approach is inherently cell cycle–independent and effective in vitro and in certain in vivo models, current limitations include narrow mutation scope, gRNA design challenges, immunogenicity, and delivery constraints [193, 194].

Nonsense read-through therapies

An additional strategy is nonsense mutation read-through which aims to bypass premature stop codons in the mutated gene by promoting the insertion of near-cognate tRNA [195–197] (Fig. 4C). Approaches like the use of aminoglycosides have been tested to promote this read-through effect, but results have been inconsistent [198, 199]. Difficulties such as limited drug delivery across the blood–brain barrier (BBB), the risk of toxicity at therapeutic doses, and the lack of target specificity, which could impact other proteins, remain significant obstacles [200].

Reactivation of the Xi

Reactivating the Xi offers a promising strategy for heterozygous females by restoring expression from the silent, healthy gene copy (Fig. 4D). This can be achieved through small molecules, shRNA knockdown of Xist-interacting proteins, or ASOs targeting Xist lncRNA [201–203]. However, concerns remain regarding brain delivery, toxicity, broad gene reactivation, and vector-related immune-reaction risk (Fig. 4D) [116]. Targeting signaling pathways has also proven effective: inhibition of MAPK and Gsk3, along with Akt activation, promotes Xi destabilization, mimicking double-X dosage [204]. Pathways beyond MAPK and Gsk3, as for instance BMP/TGFß and Aurora kinases, which are required for proper XCI maintenance, have emerged as potential therapeutic targets [205]. Other strategies involve modulating trans-acting XCI factors (e.g., DNMT1, STC1) to alter Xist expression and localization [206] or using JAK/STAT inhibitors like AG490 and Jaki to restore MeCP2 in Rett models [207].

Combinatorial approaches, such as using 5-azadC with Aurora kinase inhibitors, or SGK1 and ACVR1 inhibitors, have shown efficacy in enhancing reactivation and rescuing disease phenotypes [115, 208]. Despite progress, challenges like poor brain delivery, limited efficacy in neurons, and off-target effects persist [115, 205]. Leveraging gene-specific features—such as promoter type, gene length, and X-chromosome evolutionary strata—may aid in developing targeted reactivation strategies [201, 209]. Small molecules with BBB permeability and favorable pharmacokinetics are one of the most promising avenues to treat X-linked female biased disorders [201, 210].

Exploring LLPS modulation as a therapeutic avenue in XCI maintenance

The following section discusses emerging ideas and hypothetical strategies, with a focus on how LLPS modulation might be harnessed in future therapeutic approaches to XCI-related disorders. Recent progress in understanding the dynamics of RNA and RBP condensates has underscored their role in maintaining cellular balance and highlighted the potential for therapeutic intervention in diseases linked to their dysfunction [211–213]. Ligands can influence condensates through thermodynamic control, a concept known as polyphasic linkage. This principle explains how compounds can modulate the balance of interactions—either enhancing or suppressing phase separation—by targeting scaffold macromolecules [214, 215]. Targeting condensates with small molecules offers a new strategy to precisely alter their molecular composition, structural organization, and behavior [216, 217]

Disrupting the internal network or promoting the dissolution of these assemblies could help restore cellular equilibrium in pathological conditions. Emerging evidence links altered condensate behavior to diseases like neurodegeneration [218]. In amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and frontotemporal dementia, the primarily nuclear RBP TDP-43 forms pathological cytoplasmic inclusions [219]. ALS-associated mutations in the disordered regions of TDP-43 alter its LLPS properties, promoting protein aggregation [220]. Efforts to restore normal condensate behavior or eliminate aberrant TDP-43 assemblies have included strategies such as using RNA molecules, also known as aptamers [221], to prevent its inclusion formation by blocking self-interaction [222], as well as testing small molecules for their ability to modulate TDP-43 phase separation [223]. Biomolecular condensates play a significant role also in cancer by influencing gene expression through mechanisms such as super-enhancer formation and transcriptional condensate assembly, which support the overexpression of oncogenes [224, 225]. Compounds like JQ1 have shown effectiveness in disrupting condensates by dissolving super-enhancer-driven transcriptional condensates, inhibiting oncogene expression and impeding cancer cell proliferation [226]. Alternatively small molecules targeting the RBP NONO have been developed to relocate and trap this RBP in nuclear foci by stabilizing protein-RNA interaction, effectively reducing the expression of the androgen receptor in prostate cancer cells [227].

In the context of XCI maintenance, LLPS is likely to facilitate the recruitment and exchange of proteins with the surrounding nuclear environment, enabling the accumulation of silencing factors and thereby creating an Xist compartment. Manipulating phase separation represents a possible avenue to modulate Xist condensate function in X-linked dominant diseases, by inhibiting specific interactions or by adjusting regulatory mechanisms within these compartments. Although Xi silencing is robust and is initially believed to be permanent, partial Xi reactivation can be achieved for instance by Xist ablation, confirming that it is not only required for initiation of gene silencing but also for the long-term maintenance of a subset of X-linked genes [93, 120]. The possibility to selectively reactivate genes on the Xi has started to be exploited as a putative therapeutic strategy to restore the expression of missing proteins for instance in Rett syndrome [115, 119, 205, 206, 228] (see paragraph “The Xi and X-linked genetic disorders”).

In the context of targeting X-condensate formation for therapeutic purposes, several strategies are feasible. Depending on the desired outcome, LLPS can be modulated to either promote the partial dissolution or formation of the Xist condensate. Since the formation of the Xist condensate is essential for its silencing function, dissolving the condensate would facilitate expression reactivation, especially of genes mostly dependent on Xist RNA functionality, while stabilizing the condensate would maintain silencing (Fig. 5). Notably, the Xist compartment exhibits the characteristics of a phase-separated condensate, unlike the rest of the inactive Xi compartments [229]. This distinct property makes the Xist-mediated phase separation an intriguing target for therapeutic intervention. By specifically modulating the phase separation dynamics of the Xist condensate, it may be possible to develop highly selective therapeutic strategies aimed at reactivating silenced genes or reinforcing silencing where needed (Fig. 5). Potential approaches include (i) designing drugs that target the scaffold molecule responsible for condensate formation, i.e., Xist; (ii) modulating condensate composition by disrupting the recruitment or partitioning of specific client proteins; or (iii) altering the activity of specific components within the condensate itself. These possibilities are discussed in the following paragraphs (Figs. 5 and 6) and although largely hypothetical at this stage, these insights provide a conceptual framework for future studies aimed at therapeutic intervention.

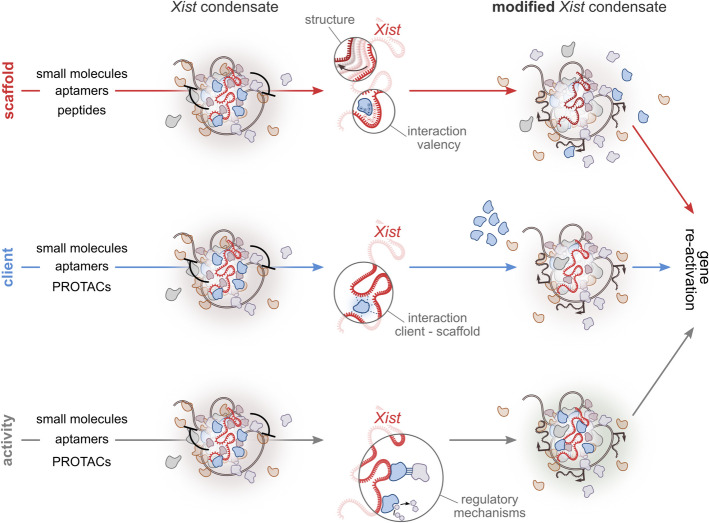

Fig. 5.

Modulation of Xist condensate for therapeutic intervention. Schematic representation of possible strategies to target the Xist condensate formation to reactivate gene expression from the inactive X chromosome (Xi). Top, Targeting the scaffold (Xist): Modifying the structure or interaction valency of the Xist RNA scaffold using small molecules, aptamers, or peptides. These changes can alter Xist structural properties or weaken specific molecular interactions (e.g., electrostatic interactions), leading to reduced condensate stability. Middle, Targeting a condensate client: Disrupting the interactions between the client molecule and the scaffold (e.g., via small molecules, aptamers, or PROTACs) can result in the exclusion or mispartitioning of specific condensate components, thereby weakening the condensate. Bottom, Targeting condensate activity: Modulating protein–protein interactions or enzymatic activity within the condensate can interfere with its regulatory mechanisms. This approach alters condensate function and may promote reactivation of X-linked gene expression. All strategies aim to destabilize the Xist condensate, enabling the reactivation of previously silenced X-linked genes

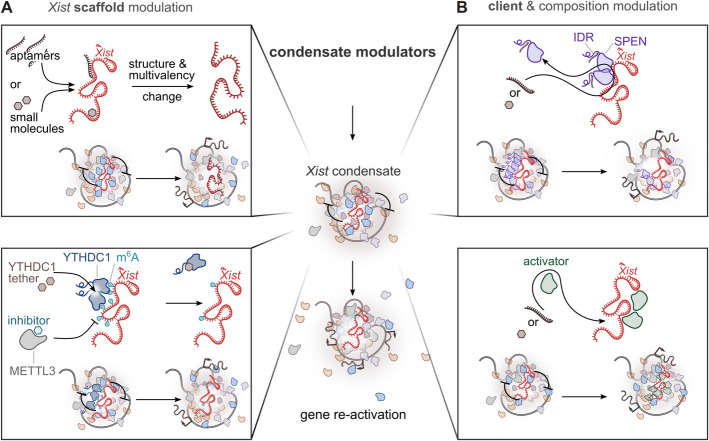

Fig. 6.

Strategies for the development of therapeutics targeting Xist condensates. Potential therapeutic approaches for targeting Xist condensates to achieve gene reactivation on the Xi. This figure represents just some of the possibilities for leveraging condensate biology as a therapeutic strategy. At the center, the general concept is depicted: targeting the Xist condensate to promote Xi reactivation. A Top square: Xist scaffold modulation through structural modification. Small molecules or RNA aptamers can directly bind the Xist RNA scaffold, altering its structure and multivalency. These modifications can disrupt RNA–protein interactions, destabilize the condensate, and promote gene reactivation. Bottom square: Xist scaffold modulation through m6A-dependent regulation. Inhibitors of the m6A writer METTL3 can reduce Xist methylation, impairing its ability to recruit m6A readers such as YTHDC1. Alternatively, tethering YTHDC1 directly to Xist can bypass the need for m6A, restoring condensate function and enabling precise control of gene silencing. B Top square: Client exclusion. Targeting client proteins recruited by Xist, such as SPEN (harboring an intrinsically disordered region, IDR), can disrupt essential protein interactions within the condensate, destabilizing it and enabling gene reactivation. Bottom square: De novo partitioning. Activators of gene expression can be selectively recruited to the condensate, promoting transcription and gene reactivation

Modulate the Xist scaffold activity: blocking Xist-proteins interaction

In the formation of dynamic SMACs, Xist acts as a scaffold recruiting repressing proteins. Condensates form through LLPS of essential scaffold molecules, with various client molecules incorporated into the condensate via selective partitioning [230, 231] (Fig. 3C). The architectural role of Xist could be therapeutically targeted by modulating its multivalency, potentially inhibiting condensate formation or enhancing complex assembly, depending on the desired outcome (Figs. 5 and 6A). Modulation of the interactions facilitated by Xist could be achieved by influencing the folding of its repeat elements. Indeed, RNA structures can modulate the binding affinity of RNA molecules for RBPs, thereby affecting the stoichiometry of condensate components [7, 144, 232]. The A-repeat secondary structure, consisting of a single stem-loop structure repeated several times [233–235] and serves as a multimerization platform, crucial for the formation of SMACs [26, 27].

A-repeat has already been exploited in drug development through an affinity-selection mass spectrometry screen aimed at identifying small molecules that bind to Xist [236]. This approach identified the compound “X1,” which binds the A-repeat, disrupting Xist interactions with PRC2 and SPEN, inhibiting histone methylation and preventing X chromosome gene silencing [236]. The impact of X1-induced A-repeat conformational changes on Xist condensate formation is unknown (Fig. 6A). Targeting Xist requires identifying structurally complex RNA motifs for high-affinity and specific binding by drug-like molecules [237, 238]. Examples such as Branaplam [239, 240] and SMA-C5 highlight the success of small molecules targeting specific RNA structural motifs, often stabilized by protein interactions. Integrated screening strategies should be applied for the identification of small molecules targeting Xist RNA, including for instance (systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment) SELEX or InfoRNA [241, 242]. Small-molecule ligands for Xist RNA must be tailored to the physicochemical features of the transcript. A positive charge is desirable to engage the negatively charged phosphate backbone, while strategically placed functional groups (e.g., hydrogen-bond donors/acceptors, π-stacking, or hydrophobic moieties) enable sequence- and structure-specific contacts within folded RNA motifs [243, 244]. Conjugating aminoglycosides with nucleobases improves RNA target specificity, as does modifying ligands to recognize stem-loop structures in oncogenic miRNA precursors [245, 246]. The rational design of small molecules or high-throughput screening for the identification of compounds binding Xist have to rely on the information about the RNA structure [243, 247]. Specific interactions depend on the three-dimensional structure of the target and should form specific pockets. Although several studies gave insights into the structural properties of Xist [39, 141, 233–235], a consensus is still lacking. Achieving a deeper understanding of Xist structural elements is crucial for the development of highly specific small molecules targeting its scaffolding functions.

RNA can be druggable also through the usage of oligonucleotide-based therapies, such as ASOs [248–250] or DNA/RNA aptamers. However, delivering these compounds remains highly challenging [251]. RNA aptamers, i.e., single-stranded DNA or RNA molecule that folds into distinct three-dimensional structure, binding to specific target molecules, could be engineered to bind selectively to the A-repeat region of Xist. By competing with or displacing Xist protein partners, aptamers can alter the kinetic of interacting proteins and thereby hinder the formation and maintenance of interactions required for proper macromolecular crowding. Similarly, short peptides or small molecules that mimic key Xist partners could be developed. By introducing peptides that competitively inhibit the binding of Xist interactors, it is possible to prevent the assembly of the protein complexes that Xist scaffolds to form condensates. Lastly, Xist levels—and thus its scaffolding function—could be reduced using ribonuclease-targeting chimeras (RIBOTACs), which couple an RNA-binding ligand to a moiety that recruits and activates RNase L, triggering selective degradation of the target RNA [252].

Post-transcriptional modifications of RNA are critical regulators of its function and can influence the capacity of RNA molecules to undergo phase separation [144, 253]. Xist RNA is modified with m6A and it has been implicated in the regulation of Xist turnover and therefore RNA levels [254]. These sites downstream of the A-repeat have a minor effect on RNA structure, but it mediates the recruitment of YTHDC1. Importantly, YTHDC1 harbors IDRs and can drive phase separation and formation of nuclear condensate that partially overlap with other nuclear speckles [255]. The recruitment of YTHDC1 is possible to play an important role in the formation of Xist condensates. In this context, inhibiting m6A deposition could potentially diminish the phase-separation propensity of Xist, thereby weakening its silencing effect. Modulation of Xist methylation, for instance by blocking m6A writer METTL3/14 [256], may represent another route for condensate tuning (Fig. 6A). Notably, it has been shown that when anchored to Xist, YTHDC1 can rescue gene silencing following m6A removal [47]. Building on this, engineering YTHDC1 interactors to specifically target Xist condensates—such as by conjugating them to nucleic acid recognition elements designed to bind Xist [257]—or developing METTL3/14 inhibitors with enhanced specificity for Xist-associated methylation sites, could provide innovative strategies to modulate condensate dynamics and X-linked gene silencing (Fig. 6A). However, recent findings suggest that disrupting METTL3 can enhance Xist-mediated silencing [254], a result that contrasts with previous studies reporting an impairment of silencing upon interference with the m6A pathway [47, 258]. The precise role of m6A modification in Xist-mediated silencing should be clarified in the context of Xist condensates and for pursuing therapeutic strategies targeting this pathway. In addition, given the broad role of METTL3/14 in regulating m6A modification across numerous transcripts, global inhibition may lead to unintended effects on other cellular RNAs.

Regions of Xist beyond the A-repeat also exhibit scaffold activity, promoting the recruitment and local enrichment of various proteins to form Xist compartments. The E-repeat, in particular, attracts proteins such as PTBP1, MATR3, TDP-43, and CELF1, which are known to undergo phase separation and form assemblies (Fig. 4B) [28, 259, 260]. These multivalent interactions between RBPs and RNA likely play a crucial role in triggering condensate formation, resulting in the formation of the Xi compartment, which contributes to Xi [261]. In the absence of the E-repeat, silencing begins correctly but fails to be sustained over time [28]. Given the interest in gene-specific XCR, targeting the E-repeat, in addition to the A-repeat, could represent an effective strategy to disrupt Xist condensates and subsequently reverse X-linked gene silencing. However, it remains unclear whether the A- and E-repeats act in concert to form a unified condensate structure or if they contribute to separate yet interconnected assemblies. Similarly, the B-repeat has now been shown to influence HNRNPK condensates, playing a key role in silencing spreading [30]. Therefore also this region may hold potential for therapeutic modulation of Xist condensates.

Modulating client partitioning in condensates: approaches for altering the composition of Xist condensates

Another strategy for Xist reactivation involves modulating the composition of Xist condensates by disrupting the interaction of factors (i.e., Xist clients) essential for Xist-mediated silencing (Fig. 5). For example, molecules that bind to the IDRs of a protein can influence its intermolecular interactions within the condensate (Fig. 6B). Different RBPs undergoing LLPS, as for instance CELF1, remain enriched in the Xi compartment—through its protein interactome—suggesting that these proteins may also play a role in shaping the Xist compartment even after differentiation [28]. It is unclear whether SPEN spatially remains associated within these compartments. However, homotypic multivalent interactions mediated by SPEN IDRs are essential for the formation of Xist-mediated assemblies, targeting these regions could significantly alter SPEN crowding and, consequently, reduce gene silencing. RNA aptamers could be engineered to target the SPEN IDR, thereby inhibiting its phase separation and neutralizing its silencing activity (Fig. 6B). RNA aptamers could be engineered—using computational tools as demonstrated in the case of aptamers targeting TDP-43 aggregation [221]—to bind Xist-associated proteins and control their localization within the Xist compartment. Saturation concentration can be adjusted by small molecules binding directly to proteins, altering their chemical properties and influencing condensate dynamics [223, 262, 263]. Small molecules have also been identified that bind to protein IDRs, enhancing the therapeutic potential of these regions [264]. For instance planar aromatic compounds, such as mitoxantrone, disrupt ALS-associated RBPs in stress granules [265], while karyopherin-β2 inhibits FUS phase separation by stabilizing interactions and preventing LLPS [266].

While disrupting client protein partitioning within Xist condensates may not be sufficient to remove repressive marks or induce gene reactivation on its own, it could act synergistically with chromatin-targeting strategies to enhance their efficacy (see “Different approaches for treating X-linked dominant disorders” section for more details).

SPEN and other client molecules within Xist-mediated assemblies could be targeted and redirected into “non-functional” condensates. For example, small molecules targeting NONO have been shown to induce its assembly into nuclear puncta, effectively reducing androgen receptor expression in prostate cancer cells [227].

On the one hand, removing repressive factors from Xist assemblies may promote the reactivation of X-linked genes; on the other hand, recruiting an activator presents an alternative approach that could be implemented concurrently (Fig. 6B). Avrainvillamide can restore the nuclear localization of NPM1 protein [267], this is a proof of principle that small molecules can selectively interact with a protein and modify its localization in a targeted manner. The loss of Xist RNA in somatic cells has been shown to facilitate the reappearance of certain activating factors. Indeed, Xist not only recruits repressive complexes but also actively repels BRG1–SWI/SNF [268] and cohesins [203]. Importantly, BRG1 potentiates XCR after treatment with a DNA methylation inhibitor (5’-azacytidine) and a topoisomerase 2b inhibitor [268]; therefore, recruiting BRG1 and promoting the BRG1–Xist interaction could enhance the selectivity of Xi reactivation (Fig. 6B).

In the context of therapies targeting phase-separated condensates, valuable insights can be drawn from the development of antivirals [212]. Strategies have been developed to promote the dissolution of viral condensates to disrupt their biological functions. The phase separation of the SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid (NC) is linked to the inactivation of innate antiviral immunity [269]. A peptide targeting the dimerization domain was screened to disrupt the LLPS of SARS-CoV-2 NC, demonstrating [270] its ability to inhibit viral replication and restore innate antiviral immunity.

Targeting components of the Xist condensate for degradation represents a promising strategy to interfere with gene silencing and promote X-linked gene reactivation. One potential approach involves the use of PROteolysis-Targeting Chimeras (PROTACs), heterobifunctional small molecules designed to induce for instance targeted protein degradation by recruiting E3 ubiquitin ligases to specific proteins of interest [271, 272]. PROTACs have not only progressed to late-stage clinical trials for cancer therapy but have also shown promise in treating neurodegenerative diseases [273] by targeting proteins with critical roles in neurological conditions, such as TDP-43, alpha-synuclein, and Tau [274–276]. To target Xist condensate components, the choice of a nuclear-localized E3 ligase, such as DCAF16, could be crucial for ensuring effective degradation within the nuclear environment [277]. Furthermore, the properties of phase-separated environments may enhance the effectiveness of PROTACs. The addition of a nuclear IDR to a PROTAC has been shown to significantly improve its ability to degrade nuclear targets [277, 278]. These findings highlight the potential of leveraging PROTAC technology to disrupt Xist condensates and achieve XCR.

Affecting the activity of Xist-condensate components

A strategy to modulate the Xist condensate is by tuning the behavior of individual proteins that reside within the Xist-driven compartments (or SMACs) (Fig. 5). Current research on condensate-modifying therapeutics has revealed several avenues for manipulating dynamic interaction networks in biomolecular assemblies [279] without necessarily disrupting the entire condensate [211]. For instance, the silencing factor SPEN is recruited by Xist to initiate repression, but if SPEN activity can be dampened post-development—i.e., by blocking its interaction partners—it might partially release silenced genes. In this context, bifunctional small molecules, also known as “molecular glues,” could be particularly useful. These molecules engage multiple targets to modulate protein proximity, alter interaction networks, and inhibit specific protein–protein interactions [280].

Alter post-translational modifications (PTMs) on key condensate proteins could be used as a strategy to modify function. Studies of phase separation have shown that PTMs such as phosphorylation or ubiquitination can dramatically influence condensates formation and stability [281–284]. Hyperphosphorylation of RNA polymerase II large subunit alters its affinity from transcription condensate to those specialized in RNA splicing [284]. Translating these insights to Xist compartments means strategically modifying proteins essential for Xist-based silencing—thereby switching the local environment toward reactivation.

One promising approach to modifying condensate function is to target enzymes that reside within them [285]. Molecules can be designed to target enzymes partitioned within the Xist condensate. Xist orchestrates the inactivation of one of the two X chromosomes by recruiting multiple enzymes responsible for DNA hypermethylation and histone deacetylation. Small molecules could be designed to preferentially partition within the Xist compartment. This approach could enhance the efficiency of therapeutic agents and minimize off-target effects by concentrating activity within the condensate microenvironment.

Compounds that modulate phase separation represent a tool for modifying condensate behavior, material properties, and therefore function. For instance, lipoamide was recently shown to alter SG assembly via a redox regulatory pathway [286]. 4,4’-dianilino-1,1’-binaphthyl-5,5’-disulfonic acid (bis-ANS) have been shown to modulate the LLPS of TDP43 IDR. At elevated concentrations, these molecules disassemble liquid droplets via a reversible phase transition driven by electrostatic forces [223]. Alternatively, the DisCo (Disassembly of Condensates) technique demonstrates a proof of principle for disrupting biomolecular condensates. By using chemical-induced dimerization to recruit a ligand near the condensate-forming region of a scaffold protein, this method induces condensate dissociation. While the precise mechanism remains unclear, DisCo highlights the potential for targeted disruption of condensates as a therapeutic strategy [287]. However, in the context of Xist condensates, a complete dissolution or change in material of the compartments is unlikely to be the desired outcome of a therapeutic strategy, as excessive reactivation of X-linked genes could lead to negative effects that outweigh the intended upregulation of the target gene.

By applying these principles to the Xist condensate, it may be possible to dismantle or remodel the silencing environment (Figs. 5 and 6). Critically, the Xist-induced protein gradients that expand silencing across the chromosome rely on proper condensate assembly and maintenance. Small molecules capable of altering local protein concentration or compartment coalescence could promote selected genes reawakening.

Challenges and perspectives for LLPS-based Xi reactivation strategies

Intervening in LLPS dynamics underlying Xist-mediated silencing offers a compelling opportunity to semi-selectively reactivate genes on Xi. However, several critical considerations must be addressed to transform this concept into therapies.

First, although SMACs on the Xi have been hypothesized to form via LLPS—supported by the finding that SPEN accumulation in SMACs depends on IDRs—it remains uncertain whether these assemblies fully exhibit hallmarks of LLPS [26, 29]. While some concentration-dependent assemblies indeed arise from LLPS, this is not the only mechanism by which they can form [31, 128, 288]. As such, in-depth characterization of the biophysical and chemical properties of Xist-induced compartments is essential, including refined assays to determine their composition and to probe the three-dimensional structure of Xist within these condensates. A robust understanding of how Xist drives molecular crowding in these domains is pivotal for targeted interventions. From a therapeutic perspective, reactivation of the Xi would likely need to occur in somatic cells, as proper XCI is essential for early embryonic development [289]. Therefore, as postulated for other Xi reactivation strategies [290], targeting Xist condensates would ideally be applied in a post-XCI context. Supporting this view, experimental studies in mice have demonstrated that post-natal Xi reactivation in somatic cells can be well tolerated without significant morbidity [121, 291]. Apparently distinct Xist-protein condensates have been described, each associated with specific Xist repeats (A-repeat, B-repeat, or E-repeat) and protein factors. However, it remains unclear whether these condensates represent parallel structures or reflect functionally distinct stages of XCI progression. If these condensates indeed mediate different phases of XCI, selectively targeting specific structures could help identify the optimal therapeutic window. For instance, E-repeat–dependent protein assemblies have been shown to maintain gene silencing independently of Xist in mouse cells [28], suggesting that targeting proteins recruited via the E-repeat might specifically influence the maintenance of established XCI in somatic cells. Several of these proteins have also been implicated in sustaining gene repression on the Xi in adult human cells [146]. Thus, it is plausible that Xist condensate components remain functionally relevant beyond the initiation phase, potentially making the Xi amenable to targeted interventions even in post-XCI somatic contexts. We hypothesize that targeting Xist condensates during the initiation of XCI could disrupt the early recruitment of repressive complexes and hinder the proper establishment of gene silencing. In contrast, targeting condensates during the maintenance phase of XCI might interfere with the continued interactions required to sustain silencing, potentially facilitating expression of previously silent genes but not achieving whole Xi reactivation. It is crucial to investigate whether condensates involved in XCI initiation differ structurally or functionally from those maintaining the silent state, and highlight the importance of studying condensate dynamics at both stages to inform therapeutic strategies.

Second, appropriate screening platforms are needed to evaluate chemical libraries or rationally designed molecules that could disrupt or modulate Xist condensates, thereby reactivating specific X-linked genes. Such strategies might include high-throughput screening, phenotypic assays, and computational methods, but one must keep in mind the species-specific differences in Xist activity [238]. Indeed, molecules effective in mouse models may not always translate directly to human XIST. Additionally, identifying cellular and mouse models that faithfully recapitulate Xi silencing will be critical for demonstrating both efficacy and safety [290]. While the involvement of Xist condensates in XCI has been primarily characterized in mouse models, it remains to be determined whether similar condensate-based mechanisms operate in human cells. Future studies will be essential to determine whether condensate formation is a conserved hallmark of XIST activity in the human system. Nevertheless, insights from mouse models may help define whether targeting such assemblies could be effective in X-linked disorders.

Third, even if effective Xi reactivation is achieved for a target locus (e.g., MECP2 in Rett syndrome), there is a risk of unwanted re-expression of other X-linked genes. For example, depletion of Xist in mouse models triggers reactivation of over ten additional genes [291], underscoring the need for careful titration of reactivation levels. Nonetheless, in certain disease contexts—particularly Rett syndrome—therapeutic benefit of restoring MECP2 likely outweighs potential side effects from partial reactivation of additional loci.

Lastly, the challenge of drug delivery remains a major hurdle. Therapeutic approaches relying on Xi reactivation will necessarily depend on the specific organs or tissues affected by the disorder. In this regard, strategies aimed at reactivating Xi should ideally include selective targeting to minimize unnecessary exposure of unaffected tissues and organs. Because Rett syndrome manifests as a neurodevelopmental disorder, therapeutic agents must effectively cross the BBB and achieve sufficient intracellular concentrations in the relevant neural tissues. Moreover, any therapeutic intervention would likely require repeated administration to sustain its beneficial effects, posing challenges related to treatment frequency and long-term feasibility.

These requirements add another layer of design complexity, as carriers or formulations that enable brain-specific targeting may be necessary for clinical success.

Conclusions

XCI plays a critical role in gene dosage parity and regulating X-linked gene expression in female mammals [4–6, 292]. During early development, XCI silences one of the two X chromosomes in somatic cells, orchestrated by the Xist RNA, which recruits repressive proteins to form a compact heterochromatin structure [2, 7]. The stability of XCI is maintained through chromatin modifications and nuclear compartmentalization, ensuring that the silenced state is kept [37].