Abstract

Faced with the challenges of academic pressure and independent living, university students often experience poor dietary quality and tend to consume dietary supplements as a strategy to compensate for nutritional deficiencies. This study aimed to explore the association between dietary quality and dietary supplement consumption among Chinese university students and to provide insights for strategies that support healthier dietary behaviors. A cross-sectional online survey was conducted among 459 Chinese university students aged 18 to 26 years. Dietary quality was assessed using five indicators derived from the Dietary Quality Questionnaire (DQQ): (1) the Food Group Diversity Score (FGDS), (2) the “All Five Recommended Food Groups” (ALL-5) score, (3) the Non-Communicable Disease (NCD)-Protect score, (4) the NCD-Risk score, and (5) the Global Dietary Recommendation (GDR) score. Multivariate regression models were employed to explore associations between these dietary quality indicators and dietary supplement consumption. Sociodemographic differences were analyzed using chi-square tests, independent t-tests, and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests. Subgroup analyses were additionally performed by sex and age group (18–22 vs. 23–26 years). The median scores observed were: FGDS 8 (interquartile range [IQR]: 7–9), All-5 5 (IQR: 4–5), NCD-Protect 6 (IQR: 4–7), NCD-Risk 3 (IQR: 2–5), and GDR 11 (IQR: 10–13). Lower scores on FGDS, ALL-5, and GDR were significantly associated with a higher prevalence of dietary supplement consumption, with odds ratios (ORs) of 5.67 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 2.29–14.07), 2.13 (95% CI: 1.37–3.33), and 3.96 (95% CI: 2.43–6.45), respectively. In conclusion, poorer dietary quality was associated with a higher prevalence of dietary supplement consumption among Chinese university students, but causality cannot be inferred given the study’s cross-sectional design. These findings highlight the urgent need for targeted nutritional services and culturally appropriate dietary education.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-11947-2.

Keywords: Dietary quality, Dietary quality questionnaire (DQQ), Dietary supplement, University students, Dietary assessment

Subject terms: Nutrition, Public health, Epidemiology

Dietary quality refers to the assessment of the quality and variety of food intake by comparing it to dietary guidelines, enabling the identification of associations between dietary intake and health status1. As public awareness of dietary nutrition continues to grow, numerous tools has been developed to assess dietary quality, such as the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) score2, the Mediterranean Diet Score3, the Healthy Eating Index(HEI)4, and the Dietary Quality Index (DQI)5. However, these instruments typically require detailed nutrient data and complex computations, constraining their practicality in resource-constrained environments6. In this context, the Dietary Quality Questionnaire (DQQ) has attracted attention for its low cost, efficiency, and strong cross-cultural applicability. Comprising 29 food groups, the DQQ has shown good reliability and validity across diverse populations6–8.

Despite advances in dietary assessment tools, global dietary quality remains suboptimal and continues to decline. A multinational study of children and adolescents using the NOVA classification reported that ultra-processed foods accounted for 18% and 25% of total energy intake in Brazil and Colombia, respectively9. In high-income countries such as Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States, these figures ranged from 47–68%9. According to the U.S. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), the proportion of adults with ideal dietary quality increased only slightly from 0.66% in 1999 to 1.58% in 2020. Although the proportion of adults with poor dietary quality decreased from 48.8 to 37.4%, the burden of diet-related diseases remains alarmingly high10. In China, rapid economic development and urbanization have driven a notable nutrition transition, characterized by increased intake of red meat, refined grains, fried foods, and sugar-sweetened beverages11,12. These changes highlight that improving dietary quality remains a critical public health goal. Against this backdrop, university students are undergoing rapid physical development, while also experiencing substantial changes in their lifestyle and environment13–15. Many of them exhibit unhealthy eating behaviors such as skipping breakfast and consuming inadequate amounts of fruits and vegetables15,16. These nutritional issues are of significant concern given their potential long-term impact on health.

Governments worldwide have implemented nutrition education programs, food policy reforms, and community-based interventions to improve population dietary quality17,18. However, these strategies have achieved limited success. Meanwhile, the consumption of dietary supplements has increased significantly, particularly following the COVID-19 pandemic19,20. The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) defines dietary supplements as products in pill, tablet, or liquid form that provide nutrients or bioactive compounds21. These products are commonly consumed to meet specific nutritional requirements or enhance physiological functions, particularly among pregnant women and elite athletes22,23. Studies have demonstrated that individuals with poor dietary quality frequently consume supplements to address perceived nutrient deficiencies24–26. According to the Health Belief Model (HBM), perceived nutritional risk and belief in the benefits of supplements can influence consumption behavior27. Recent surveys indicate that over 50% of university students in China, Italy, and South Korea consume dietary supplements28–30. Notably, high consumption rates have also been observed among students without diagnosed deficiencies in countries such as the United States and the United Arab Emirates13,14. These patterns may obscure underlying dietary issues, delay necessary improvements, and increase health risks31. Despite these findings, there remains a paucity of comprehensive research on dietary supplement consumption behaviors among university students. Most existing studies focus on prevalence, awareness, or potential side effects, whereas few have employed empirical approaches to explore the association between dietary quality and supplement consumption. Furthermore, much of the existing literature is grounded in Western dietary models. In contrast, traditional Chinese dietary patterns are cereal-based, involve relatively low consumption of dairy products, and are profoundly influenced by the concept of “medicine and food homology”32,33. These cultural and dietary distinctions may restrict the applicability of findings from Western contexts to Chinese populations.

To address these gaps, this study conducted a cross-sectional survey to explore the association between dietary quality and dietary supplement consumption among Chinese university students. The findings seek to inform targeted nutrition education strategies and promote healthier, evidence-based eating behaviors among this population.

Methods

Study design and populations

A convenience non-probability sampling method was employed. Given the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and the high digital engagement among Chinese university students34, online platforms such as WeChat and QQ were considered practical and effective for data collection. The survey link (Uniform Resource Locator) was distributed by students from multiple universities via individual messages and group chats. Upon accessing the link, participants were informed about the study’s purpose and procedures and were required to provide electronic informed consent. Only those who provided consent could proceed with the questionnaire. Eligible participants were undergraduate or graduate students aged 18–26 years, living on campus or within a 30-minute commute, capable of completing a 3-day dietary record (including all meals and snacks). Exclusion criteria included non-Chinese students (to ensure consistency with the Chinese dietary context), individuals taking physician-prescribed supplements (e.g., iron for anemia), those who had adhered to specific dietary interventions (e.g., low-carbohydrate or ketogenic diets) in the past month, individuals with chronic conditions affecting diet (e.g., diabetes or hyperthyroidism), and those unwilling to disclose dietary or supplement consumption.

A total of 608 responses were received, of which 149 students were excluded from the analysis due to their age related criteria (n = 49) or incomplete or missing responses to some questions (n = 100). Finally, a total of 459 students were included in the analysis.

The online survey consisted of a questionnaire on dietary quality and dietary supplement consumption, which was divided into the following sections: (1) sociodemographic characteristics, (2) dietary quality assessments, and (3) dietary supplement consumption.

Sociodemographic characteristics

Sociodemographic variables included sex, age, academic status, household income, monthly food expenses, and body mass index (BMI). Academic status was categorized as undergraduate or graduate. Students estimated their annual household income based on subjective perception, which was classified into three levels: poor (in debt), medium (some discretionary income), and good (comfortable with savings)35. Monthly food expenses were also self-reported. BMI was calculated from self-reported height and weight, and classified as underweight (BMI < 18.5 kg/m2), normal weight (18.5 ≤ BMI < 24.0 kg/m2), overweight (24.0 ≤ BMI < 28.0 kg/m2), or obese (BMI ≥ 28.0 kg/m2)36. Health-related variables included smoking status, alcohol consumption frequency, and physical activity levels37. Smoking status was categorized as never, former, or current smoker. Alcohol consumption frequency was grouped as ≤ 3 times per year, 3–4 times per month, or ≥ 3 times per week. Physical activity levels were categorized as ≤ 2 times per week, 3–4 times per week, and > 5 times per week.

Assessment of dietary quality

The DQQ is a validated tool for assessing dietary patterns based on foods consumed by over 95% of the population. It uses binary (yes/no) responses across 29 food groups based on intake within the previous 24 h. In this study, five indicators derived from the DQQ were used to evaluate dietary quality in terms of nutritional adequacy, chronic disease prevention, and adherence to dietary guidelines: the Food Group Diversity Score (FGDS), the “All Five Recommended Food Groups” (ALL-5) score, the Non-Communicable Disease (NCD)-Protect score, the NCD-Risk score, and the Global Dietary Recommendations (GDR) score. Each food group was coded as 1 (“yes”) or 0 (“no”). The FGDS reflects micronutrient adequacy based on the consumption of at least 5 out of 10 key food groups. The ALL-5 score indicates whether all five recommended food groups were consumed, with scores < 5 denoting incomplete intake. The NCD-Protect score (range: 0–9) measures intake of foods protective against non-communicable diseases, while the NCD-Risk score (range: 0–9) assesses intake of ultra-processed and high-risk foods. The GDR score is calculated as NCD-Protect - NCD-Risk + 9, providing an overall measure of adherence to global dietary recommendations. Higher GDR scores indicate better alignment with international dietary guidelines6,8.

Assessment of the dietary supplement consumption

Participants were asked whether they had consumed dietary supplements in the month prior to the questionnaire. Responses were coded as 1 (“yes”) or 0 (“no”). Those who reported consumption were asked to specify the types of supplements used. Reported supplements were reviewed and categorized into four groups: vitamins, minerals, bioactive substances, and herbal products38.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were summarized as frequencies and percentages, and continuous variables (e.g., age) were reported as medians (P50) with interquartile ranges (P25, P75). Sociodemographic differences between supplement consumers and non-consumers were assessed using chi-square tests, independent t-tests, or Wilcoxon rank-sum tests, as appropriate. Associations between dietary quality scores and supplement consumption were examined using multivariable logistic regression. Adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated after controlling for sex, age, academic status, household income, monthly food expenses, BMI, smoking status, alcohol consumption, and physical activity levels. Stratified analyses by sex (male vs. female) and age group (18–22 vs. 23–26 years) were conducted to assess effect modification. All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 27.0, with significance set at P < 0.05.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Chongqing Medical University (202312046 S). All the study procedures were conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments. All participants provided oral and written informed consent.

Results

Participant characteristics

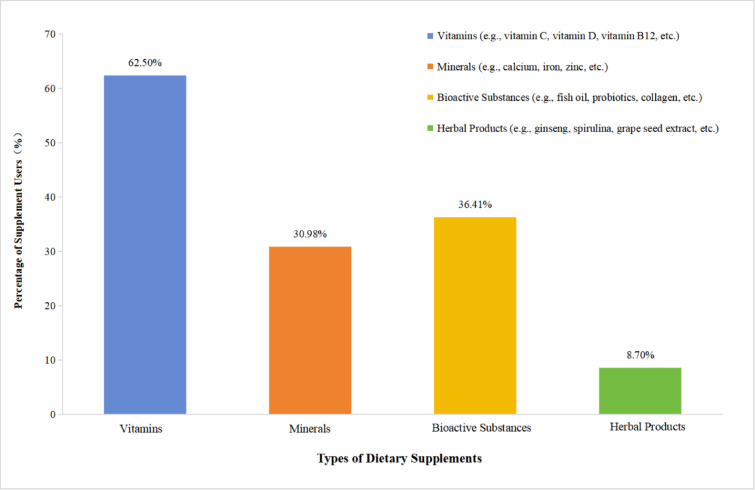

A total of 459 Chinese university students aged 18–26 years participated in the study, with 64.3% being female. The overall prevalence of dietary supplement consumption was 40.1% (n = 184), while 59.9% (n = 275) reported no use. Supplement consumption was significantly more common among students aged 18–22 than among those aged 23–26. Non-smokers were also more likely to consume supplements than smokers (P < 0.05) (Table 1). Among supplement consumers, the most frequently consumed types were vitamins (62.5%), followed by bioactive substances (36.4%), minerals (31.0%), and herbal products (8.7%) (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Distribution of characteristics of participants (n = 459). BMI, body mass index; Non-users, participants who did not use dietary supplements; users, participants who used dietary supplements.

| Characteristics | Group | Non-users (n = 275) |

Users (n = 184) |

Z/χ2 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 89(32.4%) | 75(40.8%) | 3.39 | 0.07 |

| Female | 186(67.6%) | 109(59.2%) | |||

| Age | 21(20,22) | 21.00(20,23) | -2.37 | P < 0.05 | |

| 18–22 | 213(77.5%) | 124(67.4%) | 5.721 | P < 0.05 | |

| 23–26 | 62(22.5%) | 60(32.6%) | |||

| Academic status | Undergraduate students | 236( 85.8%) | 148( 80.4%) | 2.34 | 0.13 |

| Graduate students | 39( 14.2%) | 36( 19.6%) | |||

| Household income | Poor | 28( 10.2%) | 16( 8.7%) | 0.31 | 0.86 |

| Medium | 191( 69.5%) | 131( 71.2%) | |||

| Good | 56( 20.4%) | 37( 20.1%) | |||

| Monthly food expenses | > 2500 | 164( 59.6%) | 89( 48.4%) | 5.69 | 0.13 |

| 2000–2500 | 60( 21.8%) | 52( 28.3%) | |||

| 1500–1999 | 36( 13.1%) | 31( 16.8%) | |||

| < 1500 | 15( 5.5%) | 12( 6.5%) | |||

| BMI | < 18.5 | 54( 19.6%) | 28( 15.2%) | 1.72 | 0.63 |

| 18.5–23.9 | 191( 69.5%) | 134( 72.8%) | |||

| 24-27.9 | 26( 9.5%) | 18( 9.8%) | |||

| ≥ 28 | 4( 1.5%) | 4( 2.2%) | |||

| Smoking status | Never smoked | 253( 92.0%) | 156( 84.8%) | 10.60 | P < 0.01 |

| Former smoked | 10( 3.6%) | 21( 11.4%) | |||

| Current smoke | 12( 4.4%) | 7( 3.8%) | |||

| Drinking frequency | ≤ 3 times/year | 256( 93.1%) | 173( 94.0%) | 0.96 | 0.62 |

| 3–4 times/month | 15( 5.5%) | 7( 3.8%) | |||

| ≥ 3 times/week | 4( 1.5%) | 4( 2.2%) | |||

| Physical activity levels | ≤ 2 times/week | 227( 82.5%) | 136( 73.9%) | 5.16 | 0.08 |

| 3–4 times/week | 30( 10.9%) | 32( 17.4%) | |||

| >5 times/week | 18( 6.5%) | 16( 8.7%) |

Fig. 1.

Distribution of dietary supplement types among Chinese University Students (n = 184). Values are presented as the percentage of students reporting consumption of various supplement types in the past month, including vitamins, minerals, bioactive substances, and herbal products.

Dietary quality scores of participants

The median dietary quality scores (interquartile range) among participants were: FGDS, 8 (7–9); ALL-5, 5 (4–5); GDR, 11 (10–13); NCD-Risk, 3 (2–5); and NCD-Protect, 6 (4–7). FGDS scores differed significantly by sex, monthly food expenses, and physical activity levels (P < 0.05). NCD-Risk scores varied significantly with monthly food expenses, smoking status, alcohol consumption frequency, and physical activity levels (P < 0.05). Similarly, NCD-Protect scores showed significant differences based on sex, monthly food expenses, and physical activity levels (P < 0.05) (Supplementary Table S1).

Associations of dietary quality scores with dietary supplement consumption

After adjusting for sex, age, academic status, household income, monthly food expenses, BMI, smoking status, drinking frequency, and physical activity levels, significant negative associations were observed between dietary supplement consumption and the FGDS, ALL-5, and GDR scores, analyzed both as continuous and categorical variables (P < 0.05). Participants with FGDS scores < 5 had significantly higher odds of supplement consumption compared to those with scores ≥ 5 (OR = 5.67, 95% CI: 2.29–14.07). Those with ALL-5 scores < 5 had higher odds than those scoring 5 (OR = 2.13, 95% CI: 1.37–3.33). For the GDR score, participants scoring < 10 had greater supplement consumption than those scoring ≥ 10 (OR = 3.96, 95% CI: 2.43–6.45). A negative association was also found between NCD-Protect scores and supplement consumption (OR = 0.71, 95% CI: 0.63–0.79), indicating that individuals with more protective dietary patterns were less likely to consume supplements (Table 2).

Table 2.

Association between dietary quality scores and dietary supplements use.

| Dietary status | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR(95%CI) | P | OR(95%CI) | P | OR(95%CI) | P | |

| FGDS | ||||||

| continuous | 0.80(0.72,0.88) | P < 0.001 | 0.78(0.70,0.87) | P < 0.001 | 0.75(0.67,0.84) | P < 0.001 |

| Categories | ||||||

| ≥ 5 | 1.00(Ref.) | 1.00(Ref.) | 1.00(Ref.) | |||

| < 5 | 4.41(1.81,10.71) | P < 0.01 | 4.78(1.95,11.73) | P < 0.01 | 5.67(2.29,14.07) | P < 0.001 |

| ALL-5 | ||||||

| continuous | 0.59(0.44,0.80) | P < 0.01 | 0.56(0.41,0.76) | P < 0.001 | 0.52(0.38,0.72) | P < 0.001 |

| Categories | ||||||

| 5 | 1.00(Ref.) | 1.00(Ref.) | 1.00(Ref.) | |||

| < 5 | 1.81(1.19,2.76) | P < 0.001 | 2.00(1.30,3.10) | P < 0.01 | 2.13(1.37,3.33) | P < 0.001 |

| GDR | ||||||

| continuous | 0.72(0.65,0.80) | P < 0.001 | 0.71(0.64,0.79) | P < 0.001 | 0.71(0.64,0.79) | P < 0.001 |

| Categories | ||||||

| ≥ 10 | 1.00(Ref.) | 1.00(Ref.) | 1.00(Ref.) | |||

| < 10 | 3.57(2.24,5.70) | P < 0.001 | 3.94(2.44,6.38) | P < 0.001 | 3.96(2.43,6.45) | P < 0.001 |

| NCD-Protect | 0.75(0.68,0.83) | P < 0.001 | 0.74(0.67,0.82) | P < 0.001 | 0.71(0.63,0.79) | P < 0.001 |

| NCD-Risk | 1.10(0.95,1.17) | 0.33 | 1.06(0.95,1.17) | 0.32 | 1.02(0.92,1.14) | 0.68 |

Model 1 made no modifications; Model 2 adjusted for sex and age; Model 3 adjusted for sex, age, study status, household income, monthly food expenses, BMI, smoking status, drinking frequency, and physical activity levels.

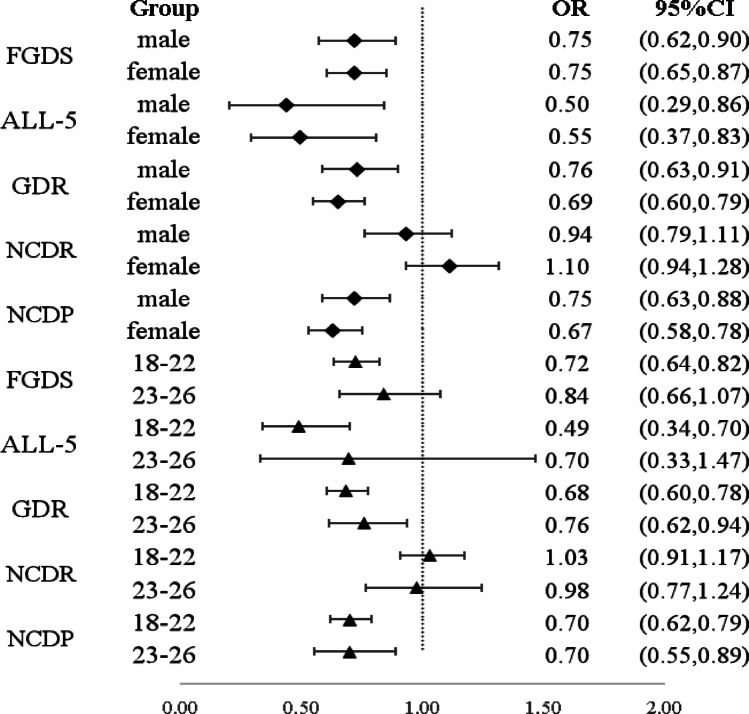

Sex-stratified analyses revealed significant inverse associations between dietary supplement consumption and FGDS, ALL-5, GDR, and NCD-Protect scores in both males and females. Among males, the odds ratios were 0.75 (95% CI: 0.62–0.90) for FGDS, 0.50 (0.29–0.86) for ALL-5, 0.76 (0.63–0.91) for GDR, and 0.75 (0.63–0.88) for NCD-Protect. Among females, the corresponding odds ratios were 0.75 (0.65–0.87), 0.55 (0.37–0.83), 0.69 (0.60–0.79), and 0.67 (0.58–0.78), respectively. Associations were stronger among males for FGDS, GDR, and NCD-Protect, and in females for ALL-5. Age-stratified analyses indicated that participants aged 18–22 years with higher FGDS (OR = 0.72, 95% CI: 0.64–0.82), ALL-5 (OR = 0.49, 95% CI: 0.34–0.70), GDR (OR = 0.68, 95% CI: 0.60–0.78), and NCD-Protect (OR = 0.70, 95% CI: 0.62–0.79) had lower odds of supplement consumption. Among those aged 23–26, higher GDR (OR = 0.76, 95% CI: 0.62–0.94) and NCD-Protect (OR = 0.70, 95% CI: 0.55–0.89) scores were significantly associated with lower consumption, with stronger effect sizes than among the younger group (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Association between Dietary Quality Scores and Consumption of Dietary Supplements (differentiated by sex and age). Results are from regression models adjusted for study status, household income, monthly food expenses, BMI, smoking status, drinking frequency, and physical activity levels.

Discussion

To comprehensively evaluate dietary quality, this study employed five indicators from the DQQ tool. The median FGDS was 8 (IQR: 7–9), indicating relatively adequate micronutrient intake6. The ALL-5 score was 5 (IQR: 4–5), suggesting that most students met the minimum recommended intake across food groups, though some may still lack essential food types6. The median NCD-Protect score was 6 (IQR: 4–7), comparable to findings among females in Vietnam and the Solomon Islands8, reflecting a generally adequate intake of protective foods6. However, variability across participants indicates the need for targeted interventions. The NCD-Risk score was 3 (IQR: 2–5), reflecting low intake of processed and high-fat foods6, although some students may still benefit from further dietary improvements. The GDR score was 11 (IQR: 10–13), higher than that reported among Chinese adolescents34, potentially attribute to greater nutrition awareness and autonomy in university students. Nevertheless, the score remains below the theoretical maximum of 18, highlighting a gap between current dietary patterns and global recommendations for chronic disease prevention39. Overall, while dietary quality among Chinese university students appears generally adequate, further improvements in dietary diversity, protective food intake, and the reduction of risky food consumption are needed.

China is currently undergoing a transition away from traditional dietary patterns, driven by industrialization and urbanization40. According to Popkin’s nutrition transition model, this transformation has led to increased intake of animal fats and energy-dense foods, decreased fiber intake, and greater reliance on fast food12,41,42. Among university students, factors such as academic stress, urban living, and insufficient sleep may contribute to poor dietary habits and low dietary diversity, leading some to consume supplements to compensate for perceived nutritional deficiencies8,35–38. In this study, 40.1% of Chinese university students reported consuming supplements, a rate comparable to that in Poland (41.0%)42 and Canada (43.4%)43, but lower than in the United States (51.2%)24, Serbia (55.7%)44, and Australia (69%)45. These cross-national differences may reflect cultural variations in health beliefs. In Western societies, supplements are often viewed as tools for health promotion and disease prevention14,26, whereas in China, the traditional concept of “food and medicine from the same source” emphasizes meeting nutritional needs through the regular diet32,33. This cultural perspective may reduce the perceived necessity of supplements among Chinese students. Consistent with global trends, vitamins were the most frequently consumed supplements, likely due to widespread awareness of their perceived benefits43–46. In contrast, the lower consumption of herbal products may reflect concerns about complex formulations and the limited availability of standardized evidence on their safety and efficacy47. Furthermore, our findings show that non-smokers were more likely to consume supplements, consistent with previous studies13,37. Research based on the Knowledge-Attitude-Practice (KAP) model also suggests that such individuals tend to be more health-conscious, possess greater nutritional knowledge, and engage more actively in healthy behaviors48.

Contrary to findings from the United States24, Croatia25, and France26 , which suggest that dietary supplement consumers typically have better dietary quality, our study observed an opposite trend among Chinese university students. Those with lower dietary quality, as indicated by FGDS ≥ 5, ALL-5 < 5, and GDR < 10, reported higher supplement consumption. These associations remained significant after adjusting for sex, age, monthly food expenses, and BMI. This pattern may reflect gaps in nutrition education and common misconceptions about supplement consumption. In Western countries, supplement consumers often have higher education levels and better socioeconomic status24 , which may contribute to more informed health behaviors. In contrast, Chinese universities generally lack adequate nutrition education programs30,32 , and many students have limited evidence-based knowledge about supplements7. According to the dietary compensation hypothesis, students with poor diets may consume supplements to compensate for perceived nutritional deficiencies49,50. These findings highlight the need for targeted nutrition education on Chinese university campuses to correct misconceptions and promote evidence-based dietary practices.

The NCD-Risk score reflects poor dietary habits, particularly those related to high intake of sugary, fatty, and processed foods6,8. In this study, we further explored its association with dietary supplement consumption, but no statistically significant association was found. One possible explanation is that individuals at higher risk for chronic diseases often engage in multiple health behaviors simultaneously, such as improving diet, exercising, or taking medications49 , making it difficult to isolate the effects of supplements. Longitudinal cohort studies are warranted to clarify these associations.

In our stratified analysis, male students exhibited stronger negative associations between FGDS, NCD-Protect, and GDR scores and supplement consumption, indicating that those with poorer dietary quality and lower dietary diversity were more likely to consume supplements. This is consistent with findings by Horyi and Kim48,51 , and may be explained by males’ higher metabolic demands for micronutrients and protein, along with greater concern about cardiovascular health and blood glucose regulation35. In contrast, among female students, a stronger negative association was observed between ALL-5 scores and supplement consumption, potentially influenced by psychosocial factors such as body image concerns, relationship stress, and restrictive eating behaviors52. Given that the ALL-5 score reflects minimal nutrient adequacy6, perceived dietary insufficiency may drive supplement consumption as a compensatory strategy. Additionally, students aged 23–26 exhibited stronger negative associations between NCD-Protect and GDR scores and supplement consumption compared to those aged 18–22. This may reflect shifting social roles, as older students entering graduate programs or the workforce may have greater self-regulation and financial independence, increasing both access to and reliance on supplements13,45. Future research should investigate the psychological and behavioral mechanisms underlying dietary choices across age groups to inform targeted nutrition interventions.

To address the dietary challenges among Chinese university students, a multi-level intervention based on the KAP model is recommended. At the micro level, nutrition education should be integrated into university curricula and supported by targeted lectures to raise awareness of dietary balance, supplement safety, and related health risks30. At the meso level, the campus food environment can be improved by diversifying meal options, optimizing cafeteria layouts, and introducing food labeling systems2,53, thereby fostering healthier dietary attitudes. Personalized nutrition counseling and psychological support should also be provided to reinforce positive beliefs. Students with healthy eating habits should be encouraged to sustain them and avoid unnecessary supplement consumption, while those with poor dietary quality should receive professional guidance. At the macro level, stronger government regulation is warranted to curb misleading supplement marketing, reduce exposure to misinformation, and promote student-centered policies that support healthier behaviors through environmental modifications.

Several limitations of the present study should be acknowledged. First, the cross-sectional design precludes causal inference between dietary quality and supplement consumption. Longitudinal studies are needed to examine behavioral changes over time. Second, convenience sampling and recruitment via social media may introduce selection bias; future research should consider stratified random sampling to enhance representativeness. Third, the 24-hour dietary recall may be prone to recall bias and may not reflect habitual intake. The use of food frequency questionnaires (FFQs) could enhance the accuracy of dietary assessment54. Fourth, supplement consumption was assessed using a binary (yes/no) response, which limits interpretability. Future studies should collect more detailed data on frequency, dosage, and duration of consumption. Lastly, the sample was limited to Chinese university students, which may restrict generalizability. Broader, more diverse samples are recommended.

Conclusions

This study assessed dietary quality among Chinese university students using five indicators from the DQQ tool. Although overall dietary quality was generally adequate, gaps persist in dietary diversity, intake of protective foods, and reduction of dietary risks. Students with poorer dietary quality were significantly more likely to consume dietary supplements (P < 0.05), and this association persisted after adjusting for sex, age, monthly food expenses, and BMI. These findings highlight the need for comprehensive nutrition education and targeted guidance for students with suboptimal diets. Interventions should also take into account cultural dietary norms. As the study is cross-sectional, causality cannot be inferred; longitudinal research is warranted to clarify underlying mechanisms.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors express gratitude to those who volunteered to participate in this study.

Author contributions

Xueqin Yan and Mei Zhao conceived the idea of the study. Mei Zhao developed the statistical analysis plan and conducted statistical analyses. Xueqin Yan and Sen Chen drafted the original manuscript. Tingting Wu and Jing Zhang revised the manuscript. Weiwei Liu supervised the study. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Data availability

The data analyzed in the study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Xueqin Yan and Mei Zhao contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Weiwei Liu, Email: lww102551@cqmu.edu.cn.

Tingting Wu, Email: wutingting@cqctcm.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Petersen, K. S. & Kris-Etherton, P. M. Diet quality assessment and the relationship between diet quality and cardiovascular disease risk. Nutrients13, 4305 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Appel, L. J. et al. Dietary approaches to prevent and treat hypertension: a scientific statement from the American heart association. Hypertension47, 296–308 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fung, T. T. et al. Diet-quality scores and plasma concentrations of markers of inflammation and endothelial dysfunction. Am. J. Clin. Nutr.82, 163–173 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krebs-Smith, S. M. et al. Update of the healthy eating index: HEI-2015. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet.118, 1591–1602 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dorrington, N., Fallaize, R., Hobbs, D., Weech, M. & Lovegrove, J. A. Diet quality index for older adults (DQI-65): development and use in predicting adherence to dietary recommendations and health markers in the UK National diet and nutrition survey. Br. J. Nutr.128, 2193–2207 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herforth, A. W., Wiesmann, D., Martínez-Steele, E., Andrade, G. & Monteiro, C. A. Introducing a suite of Low-Burden diet quality indicators that reflect healthy diet patterns at population level. Curr. Dev. Nutr.4, nzaa168 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang, H., Herforth, A. W., Xi, B. & Zou, Z. Validation of the diet quality questionnaire in Chinese children and adolescents and relationship with pediatric overweight and obesity. Nutrients14, 3551 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Uyar, B. T. M. et al. The DQQ is a valid tool to collect Population-Level food group consumption data: A study among women in ethiopia, vietnam, and Solomon Islands. J. Nutr.153, 340–351 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neri, D. et al. Ultraprocessed food consumption and dietary nutrient profiles associated with obesity: a multicountry study of children and adolescents. Obes. Rev. : Off J. Int. Assoc. Study Obes.23 (Suppl 1), e13387 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu, J. & Mozaffarian, D. Trends in diet quality among U.S. Adults from 1999 to 2020 by race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic disadvantage. Ann. Intern. Med.177, 841–850 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mente, A. et al. Diet, cardiovascular disease, and mortality in 80 countries. Eur. Heart J.44, 2560–2579 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang, J., Lin, X., Bloomgarden, Z. T. & Ning, G. The Jiangnan diet, a healthy diet pattern for Chinese. J. Diabetes. 12, 365–371 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Radwan, H. et al. Prevalence of dietary supplement use and associated factors among college students in the united Arab Emirates. J. Community Health. 44, 1135–1140 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lieberman, H. R. et al. Patterns of dietary supplement use among college students. Clin. Nutr.34, 976–985 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sprake, E. F. et al. Dietary patterns of university students in the UK: a cross-sectional study. Nutr. J.17, 90 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alhazmi, A., Kuriakose, B. B., Mushfiq, S., Muzammil, K. & Hawash, M. M. Prevalence, attitudes, and practices of dietary supplements among middle-aged and older adults in Asir region, Saudi arabia: A cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 18, e0292900 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sogari, G., Velez-Argumedo, C., Gómez, M. I. & Mora, C. College students and eating habits: A study using an ecological model for healthy behavior. Nutrients10, 1823 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Foo, W. L., Faghy, M. A., Sparks, A., Newbury, J. W. & Gough, L. A. The effects of a nutrition education intervention on sports nutrition knowledge during a competitive season in highly trained adolescent swimmers. Nutrients13, 2713 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chopra, A. S. et al. The current use and evolving landscape of nutraceuticals. Pharmacol. Res.175, 106001 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Djaoudene, O. et al. A global overview of dietary supplements: regulation, market trends, usage during the COVID-19 pandemic, and health effects. Nutrients15, 3320 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Food supplements | EFSA. (2024). https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/topics/topic/food-supplements

- 22.Liu, Y., Guo, N., Feng, H. & Jiang, H. The prevalence of trimester-specific dietary supplements and associated factors during pregnancy: an observational study. Front. Pharmacol.14, 1135736 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baltazar-Martins, G. et al. Prevalence and patterns of dietary supplement use in elite Spanish athletes. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr.16, 30 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen, F. et al. Association among dietary supplement use, nutrient intake, and mortality among U.S. Adults: A cohort study. Ann. Intern. Med.170, 604–613 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mudnić, Ž. et al. Assessment of nutrient intake and diet quality in adolescent dietary supplement users vs. Non-Users: the CRO-PALS longitudinal study. Nutrients15, 2783 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pouchieu, C. et al. Sociodemographic, lifestyle and dietary correlates of dietary supplement use in a large sample of French adults: results from the NutriNet-Santé cohort study. Br. J. Nutr.110, 1480–1491 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Albasheer, O. et al. Utilisation of the health belief model to study the behavioural intentions relating to obesity management among university students: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open.14, e079783 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu, H. et al. Investigation and comparison of nutritional supplement use, knowledge, and attitudes in medical and non-medical students in China. Nutrients10, 1810 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gallè, F. et al. Assessment of dietary supplement consumption among Italian university students: the multicenter disco study. Nutr. (burbank Angeles Cty. Calif). 107, 111902 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang, L., Yoo, H. J., Abe, S. & Yoon, J. Dietary supplement use and its related factors among Chinese international and Korean college students in South Korea. Nutr. Res. Pract.17, 341–355 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Owens, D. J. et al. Efficacy of High-Dose vitamin D supplements for elite athletes. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc.49, 349–356 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang-Chen, Y., Kellow, N. J. & Choi, T. S. T. Exploring the determinants of food choice in Chinese immigrants living in Australia and Chinese people living in Mainland china: a qualitative study. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. : Off J. Br. Diet. Assoc.36, 1576–1588 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hou, Y. & Jiang, J. G. Origin and concept of medicine food homology and its application in modern functional foods. Food Funct.4, 1727–1741 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xie, X. et al. Associations of diet quality and daily free sugar intake with depressive and anxiety symptoms among Chinese adolescents. J. Affect. Disord. 350, 550–558 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miskeen, E. et al. Factors influencing family planning decisions in Saudi Arabia. BMC Women’s Health. 25, 222 (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen, C., Lu, F. C. & Department of Disease Control Ministry of Health, PR China. The guidelines for prevention and control of overweight and obesity in Chinese adults. Biomed. Environ. Sci. : BES. 17 (Suppl), 1–36 (2004). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Iłowiecka, K. et al. Eating habits, and health behaviors among dietary supplement users in three European countries. Front. Public. Health. 10, 892233 (2022). Lifestyle. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dietary supplement fact sheets. https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/list-all/

- 39.Nguyen, P. H., Neupane, S., Pant, A., Avula, R. & Herforth, A. Diet quality among mothers and children in india: roles of social and behavior change communication and Nutrition-Sensitive social protection programs. J. Nutr.154, 2784–2794 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Healthy diet. https://www.who.int/china/health-topics/healthy-diet

- 41.Popkin, B. M. & Ng, S. W. The nutrition transition to a stage of high obesity and noncommunicable disease prevalence dominated by ultra-processed foods is not inevitable. Obes. Rev. : Off J. Int. Assoc. Study Obes.23, e13366 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhao, R. et al. Geographic variations in dietary patterns and their associations with overweight/obesity and hypertension in china: findings from China nutrition and health surveillance (2015–2017). Nutrients14, 3949 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sicinska, E., Madej, D., Szmidt, M. K., Januszko, O. & Kaluza, J. Dietary supplement use in relation to Socio-Demographic and lifestyle factors, including adherence to Mediterranean-Style diet in university students. Nutrients14, 2745 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.El Khoury, D., Hansen, J., Tabakos, M., Spriet, L. L. & Brauer, P. Dietary supplement use among Non-athlete students at a Canadian university: A Pilot-Survey. Nutrients12, 2284 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vidović, B., Đuričić, B., Odalović, M., Milošević Georgiev, A. & Tadić, I. Dietary supplements use among Serbian undergraduate students of different academic fields. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 19, 11036 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Barnes, K., Ball, L., Desbrow, B., Alsharairi, N. & Ahmed, F. Consumption and reasons for use of dietary supplements in an Australian university population. Nutrition32, 524–530 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nakhal, S. A., Domiati, S. A., Amin, M. E. K. & El-Lakany, A. M. Assessment of pharmacy students’ knowledge, attitude, and practice toward herbal dietary supplements. J. Am. Coll. Health: J. ACH. 70, 1826–1830 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Elsahoryi, N. A. et al. Prevalence of dietary supplement use and knowledge, attitudes, practice (KAP) and associated factors in student population: A cross-sectional study. Heliyon9, e14736 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wiltgren, A. R. et al. Micronutrient supplement use and diet quality in university students. Nutrients7, 1094–1107 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ishitsuka, K., Asakura, K. & Sasaki, S. Food and nutrient intake in dietary supplement users: a nationwide school-based study in Japan. J. Nutr. Sci.11, e29 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kim, H., Hu, E. A. & Rebholz, C. M. Ultra-processed food intake and mortality in the USA: results from the third National health and nutrition examination survey (NHANES III, 1988–1994). Public. Health Nutr.22, 1777–1785 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bangasser, D. A. & Cuarenta, A. Sex differences in anxiety and depression: circuits and mechanisms. Nat. Rev. Neurosci.22, 674–684 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wu, J. et al. Dietary knowledge, attitude, practice survey and nutritional knowledge-based intervention: a cross-sectional and randomized controlled trial study among college undergraduates in China. Nutrients16, 2365 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hartman, T. J. et al. Self-reported dietary supplement use is reproducible and relatively valid in the cancer prevention study-3 diet assessment substudy. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet.122, 1665–1676e2 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data analyzed in the study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.