Abstract

Immunoglobulin G (IgG) is the main isotype of antibody in human blood. IgG consists of four subclasses (IgG1 to IgG4), encoded by separate constant region genes within the Ig heavy chain locus (IGH). Here, we report a genome-wide association study on blood IgG subclass levels. Across 4334 adults and 4571 individuals under 18 years, we discover ten new and identify four known variants at five loci influencing IgG subclass levels. These variants also affect the risk of asthma, autoimmune diseases, and blood traits. Seven variants map to the IGH locus, three to the Fcγ receptor (FCGR) locus, and two to the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) region, affecting the levels of all IgG subclasses. The most significant associations are observed between the G1m (f), G2m(n) and G3m(b*) allotypes, and IgG1, IgG2 and IgG3, respectively. Additionally, we describe selective associations with IgG4 at 16p11.2 (ITGAX) and 17q21.1 (IKZF3, ZPBP2, GSDMB, ORMDL3). Interestingly, the latter coincides with a highly pleiotropic signal where the allele associated with lower IgG4 levels protects against childhood asthma but predisposes to inflammatory bowel disease. Our results provide insight into the regulation of antibody-mediated immunity that can potentially be useful in the development of antibody based therapeutics.

Subject terms: Genome-wide association studies, Inflammatory diseases, Immunogenetics

Immunoglobulin G (IgG) is the main isotype of antibody in human blood. Here the authors describe 14 genetic variants that affect IgG levels in blood. The data provide new insight into the regulation of humoral immunity that could be useful in the development of antibody-based therapeutics.

Introduction

Immunoglobulin G (IgG) represents ~75% of all antibodies in human blood, and consists of four subclasses (IgG1, IgG2, IgG3 and IgG4), named in order of their abundance. Each subclass is defined by distinct constant regions encoded by highly repetitive and homologous genes (IGHG1-4) within the Ig heavy chain locus (IGH)1. Individual B cells are committed to the production of only one subclass following class switching recombination. As a result, IgG subclasses are distinguished by their Fc region, and differ from each other in half-life and effector functions, including complement activation, Fc receptor binding, and placental transfer2.

Previous work on the genetics of IgG subclasses has focused on the IGH locus. Missense variants in IGHG1-4 (traditionally called allotypes) have been associated with IgG subclass levels3–5, susceptibility to infections, and autoimmune diseases6. Rare mutations and deletions in IGHG1-4 have been found in immunodeficiencies7,8. However, no genome-wide association study (GWAS) on IgG subclass levels has been reported. Moreover, in GWASs on total IgG, IgA, IgM and IgE levels9,10, relatively few sequence variants were found to associate with total IgG, possibly because different sequence variants associate with different IgG subclasses, meaning that individual signals are diluted when studying combined IgG levels and/or due to limitations of the genotyping methods to represent the extensive diversity at the IGH locus. To search for sequence variants that influence blood IgG subclass levels, we carried out a GWAS in 2585 adult Icelanders and 1749 adult Swedes. Because IgG subclass levels increase with age, with adult levels reached around 18 years11, we also did a separate GWAS in 4571 Icelanders younger than 18 years. In this work we discover ten new and identify four known associations, 12 of which map to the IGH, FCGR and HLA loci and affect all IgG subclasses. In addition, we present selective associations with IgG4 levels at 16p11.2 (ITGAX) and 17q21.1 (IKZF3, ZPBP2, GSDMB, ORMDL3), where the latter coincides with the most replicated asthma locus that has also been reported to associate with several autoimmune diseases.

Results

The IgG subclass concentrations for the Icelanders were obtained from clinical laboratories for 2585 adults aged 18 to 92 years, as well as for 4371 children and adolescents under 18 years (Supplementary Data 1). To generate the Swedish dataset, we measured IgG subclass concentrations in 1749 adult blood donors. Participants were genotyped on single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) microarrays, and the genotypes were imputed with reference whole-genome sequence (WGS) data. For the Icelandic dataset, the reference panel consisted of 49,708 WGS Icelanders, while for the Swedish dataset the reference panel consisted of 17,408 WGS individuals of Northwest European origin, including 3704 Swedes. We used linear regression to test for association between standardized IgG-subclass levels, as measured with radial immunodiffusion (Iceland) and Optilite® analyser (Sweden), and genotypes (using Illumina technology), in each dataset separately, for about 22 million well-imputed variants with minor allele frequency (MAF) greater than 0.1%. The results from the two dataset were then meta-analysed using a fixed-effect inverse variance method. To correct for multiple testing, we partitioned variants into five classes on the basis of genomic annotation and applied weighted Bonferroni adjustment, taking into account the predicted functional impact of variants within each class (“Methods”)12.

Association testing in the combined Icelandic and Swedish adult datasets, followed by step-wise conditional analysis, yielded 14 variants at 5 loci that associated with levels of at least one IgG subclass (Table 1, Supplementary Data 2 and Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2). No difference was detected in effect estimates between the two datasets (Table 1). Functional annotation of the IgG subclass associated variants revealed that 11 were protein-altering variants (missense or splice region variants within 95% credible sets of plausible causal variants and highly correlated with the lead variant; “Methods”) whereof 4 also affected or were highly correlated with variants affecting mRNA expression (measured by RNA sequencing of whole blood and isolated immune cells) of genes at the same locus in blood (cis-expression quantitative trait loci; cis-eQTLs) (Supplementary Data 3 and 4). In Icelanders younger than 18 years, 8 out of the 14 variants associated below the P < 0.05/14 threshold with the respective IgG subclass levels with consistent direction of effect (Table 1) while 5 variants associated at genome-wide significance threshold, all of which were on loci also identified in the adults (Supplementary Fig. 3 and Supplementary Data 5).

Table 1.

Genomic variants associated with IgG subclass levels

| IgG subtype | Gene | Adults | Children | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iceland | Sweden | Combined | Iceland | |||||||||||||||

| Loci | Position Hg38 | Sequence variant | OA | EA | EAF | β | P | β | P | β | P | Pbonf | Phet | Ve (%) | β | P | ||

| IgG1 | 1q23.3a | 161625940 | rs143596860 | FCGR3B | C | A | 45.2 | 0.142 | 9.2E-06 | 0.160 | 3.9E-05 | 0.149 | 1.5E-09 | 0.066 | 0.72 | 1.10% | 0.074 | 0.035 |

| IgG1 | 1q23.3 | 161642443 | rs7554873 | FCGR2B | T | C | 5.31 | −0.264 | 0.00013 | −0.417 | 2.5E-07 | −0.329 | 4.0E-10 | 0.018 | 0.15 | 1.09% | −0.208 | 0.0058 |

| IgG1 | 6p21.32 | 32662128 | rs2647032 | HLA-DQB1 | T | C | 5.32 | −0.269 | 5.9E-05 | −0.346 | 1.5E-07 | −0.308 | 4.3E-11 | 2.9E-05 | 0.41 | 0.96% | −0.019 | 0.80 |

| 14q32.33 | 105769806 | rs74093865b | IGHG3 | G | A | 36.9 | 0.190 | 9.7E-10 | 0.245 | 1.30E-07 | 0.207 | 1.1E-15 | 7.3E-10 | 0.32 | 1.99% | 0.099 | 0.0049 | |

| IgG2 | 14q32.33a | 105641600 | rs4983498b | MIR8071-2 | G | A | 42.5 | 0.368 | 1.2E-39 | 0.385 | 6.40E-20 | 0.373 | 7.6E-58 | 1.1E-50 | 0.74 | 6.80% | 0.079 | 0.021 |

| 14q32.33 | 105644492 | rs191766497b | IGHG2 | T | C | 0.68 | −0.918 | 2.2E-13 | −0.535 | 1.30E-01 | −0.876 | 1.2E-13 | 8.0E-08 | 0.31 | 1.04% | −1.157 | 5.9E-11 | |

| IgG3 | 1q23.3 | 161656661 | rs199991552 | FCGR2B | TC | T | 13.0 | −0.230 | 1.1E-07 | −0.253 | 2.1E-05 | −0.238 | 1.1E-11 | 0.00045 | 0.76 | 1.28% | −0.233 | 1.6E-06 |

| IgG3 | 14q32.33a | 105673363 | rs587597004 | IGHG1 | G | A | 0.27 | 1.616 | 3.3E-12 | 0.740 | 0.27 | 1.522 | 3.9E-12 | 0.00049 | 0.3 | 1.22% | 1.889 | 1.5E-11 |

| IgG3 | 14q32.33 | 105769430 | rs77307099b | ELK2AP | C | T | 36.7 | −0.643 | 1.9E-103 | −0.517 | 1.1E-30 | −0.605 | 2.2E-131 | 4.2E-125 | 0.019 | 17.01% | −0.532 | 1.2E-50 |

| IgG3 | 14q32.33 | 105767701 | rs142065266 | . | G | A | 5.18 | 0.47 | 4.5E-15 | 0.337 | 0.0012 | 0.437 | 4.1E-17 | 5.2E-09 | 0.27 | 1.88% | 0.423 | 8.2E-09 |

| IgG4 | 6p21.32 | 32438927 | rs3763321 | HLA-DRA | G | T | 24.15 | 0.281 | 1.3E-15 | 0.236 | 8.6E-08 | 0.264 | 9E-22 | 6.6E-15 | 0.43 | 2.55% | 0.186 | 8.0E-07 |

| IgG4 | 14q32.33 | 105736956 | rs2753545 | . | C | T | 8.21 | −0.284 | 1.1E-06 | −0.423 | 9.3E-05 | −0.315 | 8.4E-10 | 0.037 | 0.26 | 1.50% | −0.225 | 0.00050 |

| IgG4 | 16p11.2 | 31363214 | rs2230429 | ITGAX | C | G | 32.5 | −0.236 | 1.4E-13 | −0.252 | 1.4E-11 | −0.243 | 1.3E-23 | 8.6E-18 | 0.75 | 2.59% | −0.125 | 0.00037 |

| IgG4 | 17q21.1 | 39867492 | rs4795397 | IKZF3 | G | A | 50.8 | 0.118 | 8.2E-05 | 0.211 | 4.1E-09 | 0.157 | 1.1E-11 | 8.0E-05 | 0.048 | 1.23% | 0.025 | 0.46 |

Association results for the 14 variants that associate with the levels IgG subclasses both for adults and children. The table shows for each variant, the loci, its position in NCBI Hg38 build, the rs-ID, the gene, other allele (OA), effect allele (EA), effect allele frequency (EAF) as average over frequencies in Iceland and Sweden, and the adjusted association results (adjusted for the effects of other associated variants at the same locus) as effect β and two-sided P values, logistic regression of adjusted and standardized IgG subclass levels on genotype count. For adults, the table include results from a meta-analysis of associations results in the Icelandic and the Swedish datasets. Pbonf is the Bonferroni adjusted P value, i.e. the P value adjusted for the significance threshold for the corresponding variant class the variant belongs to. Phet is a P value for a test of heterogeneitiy of difference in the effect estimates between the two datasets. Ve is the variance explained by the variant of the corresponding IgG subclass measurements.

aAssociation results from conditional analysis.

bVariants representing previously reported IgG subclass associations (same variant or highly correlated).

Seven of the 14 variants mapped to the IGH locus, three to FCGR and two to the HLA loci. Only two variants mapped to other loci, and these associated only with IgG4 (Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1). Ten of the variants have not previously been associated with IgG subclass levels, while three (rs74093865, rs4983498 and rs77307099) tagged IgG allotypes that are known to associate with subclass levels3,4 (Supplementary Data 6–9) and one is a rare splice region variant (rs191766497, MAF = 0.68%) in the IGHG2 gene, previously reported in a familial IgG2 deficency7. The combined variance explained by the 14 variants is between 5.14% and 21.4% of the variance in the IgG subclass levels in adults (Table 1).

We searched for associations of the variants in the credible sets described above, with diseases and other traits in the GWAS Catalog13. We observed associations with total IgG levels (3 variants), IgM (1 variant), blood and immune cell counts (2 variants), red blood cell traits (2 variants), blood protein levels (2 variants), as well as inflammatory diseases (1 variant; references to the previous publications are found in Supplementary Data 10). Various coding variants in the FCGR genes have been associated with auto- and alloimmune diseases14,15 and one of those variants in the promoter of FCGR2B correlates (r2 = 0.71) with the FCGR variant influencing IgG3 subclass levels (Supplementary Data 11). In the HLA region, two variants, rs2647032[T > C] and rs3763321[G > T] associated with IgG1 (P = 4.3×10−11, β = −0.31, effect allele frequency (EAF) = 5.3%) and IgG4 (P = 9.0×10−22, β = 0.26, EAF = 24.2%), respectively. The rs2647032 is a missense variant (p.Asp167Gly) in HLA-DQB1 representing the classical HLA-DQB1*02:02 allele (r2 = 1) that has been shown to predispose to celiac disease16 whereas rs3763321 is modestly correlated with several classical HLA alleles (Supplementary Data 12).

Associations with the IGH locus

Seven of the variants represent are found at the IGH locus (Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. 2). The genetic complexity of the IGH locus with highly homologous sets of genes17, plus the fact that there were fewer WGS individuals in the Swedish than the Icelandic reference dataset, resulted in lower imputation accuracy for variants at the IGH locus in the Swedish data than at other regions.

The most significant associations are represented by missense variants in IGHG1, IGHG2 and IGHG3. First, a missense variant in IGHG3 that decreases IgG3 (rs77307099 [C > T]; p.Ser314Asn, P = 1.4 × 10−132, β = −0.607, EAF = 36.7%) is associated with increased mRNA expression of IGHG1 and IGHV4-34 as measured with RNA sequencing of whole blood (Supplementary Data 4). rs77307099 is also highly correlated, r2 = 1, with a missense variant in IGHG1, rs74093865 [G > A] (p.Pro221Leu), that associated with increased mRNA expression af IGHG1 in blood (β = 0.229, P = 7.5 × 10−94) and measured IgG1 levels (β = 0.207, P = 1.1 × 10−15) indicating that the low IgG3 levels are accompanied by increased expression of IGHG1 (Supplementary Data 4 and Table 1). A lead intronic variant in IGHG2 associated with increased IgG2 levels (rs4983498 [G > A]; P = 7.6 × 10−58, β = 0.373, EAF = 42.5%) and is highly correlated with two missense variants in IGHG2 p.Val161Met (rs809156, r2 = 0.88) and Pro72Thr (rs11627594, r2 = 0.84). The increased levels of IgG2 in serum mediated by rs4983498:A was further supported by increased mRNA expression of IGHG2 in blood (Supplementary Data 4 and Table 1).

Structural polymorphisms in IGH genes were originally described as serologically discriminating IgG allotypes (referred to as Genetic marker (Gm) where G1m-G4m specify the IgG1-4 subclasses, respectively). The allotype polymorphisms consist of one or more missense variants, with the largest number observed in IgG32 (Supplementary Data 6). The lead signals for IgG1, IgG2 and IgG3 levels described above are all missense variants or highly correlated to missense variants that are used to define different G1m, G2m and G3m allotypes (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Data 7). We therefore used the phased haplotype data to define the known IgG allotypes in the Icelandic and Swedish datasets and compared the association of the IgG subclass levels with the allotypes to the associations observed with the SNPs. The IgG1 associating SNP rs74093865 and the IgG3 associating SNP rs77307099 were both highly correlated with imputed genotypes for allotypes G1m(f) and G3m(b*) with r2 = 0.88 and 0.82, respectively (Supplementary Data 8), while the IgG2 associating SNP rs4983498 correlates with both G2m(.) (r2 = 0.72) and G2m(n) (r2 = 0.74).

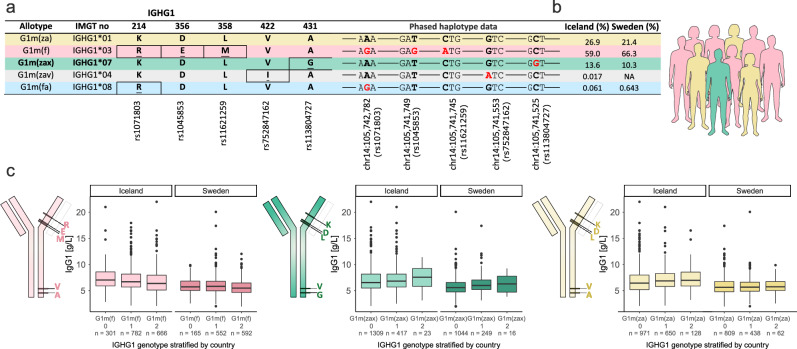

Fig. 1. Frequency of IgG1 allotypes in Iceland and Sweden and association with IgG1 levels.

IgG1 allotypes are defined by one or more missense variants. For each allotype, we include the conventional allotype name, the IMGT numbering, and allotype defining amino acids (AA) at given positions within the IgG1 protein (Eu numbering). Below the respective rsID for the single-nucleotide polymorphism is indicated. Underlined AAs indicate changes from the top allotype, G1m(za). We used phased haplotype data to define the IgG1 allotypes based on the unique presence/absence combination of the missense variants detected in IGHG1 in both Icelanders and Swedes. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) corresponding to the underlined AA changes are shown in red. Positions of the missense variants are given in the human reference genome build Hg38 (a). Frequency (%) of the different allotypes found in Icelanders and Swedes (b). Schematic representation of antibody molecules showing the approximate location of the allotype defining AAs. Box plots showing absolute IgG1 serum levels, stratified on allotypes. IgG1 serum levels are plotted for the three most frequent allotypes in Iceland and Sweden (c). Throughout the figure we keep the same color code for the different allotypes, yellow=G1m(za), pink=G1m(f), green=G1m(zax), grey=G1m(zav) and blue=G1m(fa). Single letter codes are used for the AAs, Lysine (K), Aspartic Acid (D), Leucine (L), Valine (V), Alanine (A), Arginine (R), Glutamic Acid (E), Methionine (M), Glycine (G) and Isoleucine (I). In the box plots, the bottom and top of the boxes correspond to the 25th (Q1) and 75th (Q3) percentiles, the line inside the box is the median, and the whiskers are located at Q1 – 1.5 IQR and Q3 + 1.5 IQR (where IQR is the interquartile range, Q1–Q3). c n represents number of carriers where a given IgG1 allotype 0 = non-carrier, 1 = heterozygous carriers and 2 = homozygous carriers.

The G1m(f) is the most common IgG1 allotype both in Iceland (59.0%) and Sweden (66.3%) and associated with reduced IgG1 levels (β = −0.178, P = 4.2 × 10−14) with similar effect as observed for the major allele of the lead SNP (rs74093865:G, β = −0.207, P = 1.1 × 10−15). The two other common IgG1 allotypes are G1m(za) (26.9% in Iceland and 21.4% in Sweden) and G1m(zax) (13.6% in Iceland and 10.3% in Sweden) that both associated with increased levels of IgG1 (Fig. 1b, c and Supplementary Data 9) but that association is fully explained by G1m(f) (Supplementary Data 8).

For IgG2 and IgGg3 the strongest associations were with the common allotypes G2m(n) (P = 6.8 × 10−53, β = 0.343) and G3m(b*) (P = 5.3 × 10−126, β = −0.543). Similar to what was observed for IgG1, these associations were comparable to what was observed with the lead IgG2 and IgG3 SNPs (Supplementary Data 8). Following conditional analyses we note that the association with IgG1, IgG2 and IgG3 levels is consistent with being driven by one of the allotypes, G1m(f), G2m(n) and G3m(b*), respectively (Supplementary Data 8). No allotype for IGHG4 associates with IgG4 levels, but the allotype nG4m(b) associates with both IgG2 and IgG3, although this association can be explained by correlation with allotypes in those genes. In general, allotype association with measurement of other IgG subclasses can be explained by correlations with allotypes in those genes (Supplementary Data 8).

Among the other associations at the IGH locus was a rare splice region variant rs191766497[T > C] that associated with lower IgG2 levels in plasma (P = 1.2 × 10−13, β = −0.876, EAF = 0.68%) and has been reported in a familial IgG2 deficency7. We observed that the rs191766497 rare allele induces an alternative donor splice site from exon one to exon two, that is 16 bp upstream of the canonical splice site. This leads to a frameshift mutation and introduces a pre-mature stop codon in exon 3 leading to 11.1% (P = 1.0 × 10−443) decrease in usage of the canonical isoform (Supplementary Fig. 4).

A novel rare variant confers a large increase in IgG3 (rs587597004 [C > T], P = 3.9 × 10−12, β = 1.552, EAF = 0.27%), with an even larger effect in Icelanders under 18 years (P = 5.1 × 10−11, β = 1.889) (Table 1). The association in adults is driven by the Icelandic dataset (P = 3.3 × 10−12, β = 1.616) while no association was seen in the Swedish data (P = 0.27) due to the fact that we did not have IgG subclass measurement for any of the Swedish carriers. Five WGS homozygous carriers of this variant were found in the Icelandic dataset, four of which were found to be homozygous for a ~28 kb (Hg38 chr14:105,734,756–105,762,914) deletion spanning the IGHG1 gene (Hg38 chr14:105,741,473–105,743,070) indicating that the variant was tagging the deletion (Fig. 2a). Further investigation identified 396 WGS heterozygous Icelandic carriers of the variant where 395 were heterozygous for the deletion, and in 8 WGS Swedes, 7 were also heterozygous for the deletion. We imputed the deletion into the Icelandic dataset and the imputed deletion correlates well with rs587597004 (r2 = 0.90) and its association with increased IgG3 levels is similar (P = 9.1 × 10−12, β = 1.53, EAF = 0.38%). Although the deletion primarily affects the IgG3 plasma levels, we note that the IGHG1 deletion associates with lower IgG1 levels (β = -0.672, P = 0.021) and higher IgG2 levels (β = 0.571, P = 0.035), but does not associate with IgG4 (Fig. 2b). None of the homozygotes had available IgG subclass data. The effects of the deletion on RNA expression of the IGHG1-4 genes in whole blood mirrored those on blood IgG subclass protein levels with significant effect observed for decreased IGHG1 (β = −0.677, P = 5.5 × 10−9) and increased IGHG3 (β = 0.951; P = 7.1 × 10−22) expression, and smaller effect observed for IGHG2 and IGHG4 transcription (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Data 13). The IGHG1 deletion causes a total absence of IGHG1 mRNA levels in a homozygote (Fig. 2d). The IGHG1 deletion does not seem to associate with the number of circulating B cells, estimated by RNA levels of B-cell marker genes CD19 and CD20 in blood and B cells (Supplementary Fig. 5 and Supplementary Data 13). Increased incidence of asthma, atopy, congenital cardiopathy and autoimmune diseases in selective IgG1 deficiency has previously been reported18,19 and all four IgG1-deficient homozygotes had at least one of those diagnosis (Supplementary Data 14).

Fig. 2. Deletion of the IGHG1 gene associates with increased IgG3 levels in serum.

a A coverage plot showing the rare deletion of the IGHG1 gene that is tagged by the lead variant, rs587597004. Six individuals with different status of the ~28 kb deletion at Hg38-chr14:105734756–105762914 are shown in the figure where each row represents the coverage for an individual. The two individuals on the top are homozygous for the deletion, next two are heterozygous and the bottom two are non-carriers of the deletion (b) Box plots showing absolute serum levels of each IgG subclass, stratified on IGHG1 deletion genotype. c Normalized expression of each IgG subclass gene mRNA in whole blood, stratified on IGHG1 deletion genotype, showing effects consistent with the serum protein levels. d A graph showing the median RNA-sequence coverage of the IGHG1 gene region in whole blood, stratified by the IGHG1 deletion alleles. RNA sequencing data was available for one homozygous deletion carrier, showing no IGHG1 mRNA. In the box plots, the bottom and top of the boxes correspond to the 25th (Q1) and 75th (Q3) percentiles, the line inside the box is the median, and the whiskers are located at Q1 – 1.5 IQR and Q3 + 1.5 IQR (where IQR is the interquartile range, Q1–Q3). b, c n represents number of carriers for the rare deletion where WT wild-type/non-carriers, Het heterozygous carriers and Hom homozygous carriers.

Finally, we identified additional two novel non-coding IGH variants, both of which are common. One is intronic in IGHG3 and associated with increased IgG3 levels (rs142065266 [G > A]), P = 3.5 × 10−17, β = 0.438, EAF = 5.2%) in line with increased IGHG3 mRNA expression detected for this variant in blood (Supplementary Data 4 and Table 1), and the other, located in 3’UTR of IGHG1, associated with decreased IgG4 levels (rs2753545[C > T], P = 8.4 × 10−10, β = −0.315, EAF = 8.2%).

Associations with the FCGR locus

Fc receptors for IgG (FcγR) can be broadly classified to mediate activating (FcγRI, FcγRIIA, FcγRIIC and FcγRIIIA) and inhibitory (FcγRIIB) signaling to generate a well-balanced immune response20. The genes encoding these receptors (FCGR1A, FCGR2A, FCGR2C, FCGR3A and FCGR2B) are in a gene cluster on chromosome 1q23 and are expressed in both lymphoid and myeloid cells. Most immune cells express a combination of activating and inhibitory FcγRs on their surface except for B cells that express the inhibitory FcγRIIB as their sole FcγR21.

We identified three independent associations with the FCGR locus. Two of these associate with IgG1 levels (rs7554873[T > C], P = 4.0 × 10−10, β = −0.329, EAF = 5.3% and rs143596860 [C > A], P = 1.5 × 10−9, β = 0.149, EAF = 45.2%, Table 1). Both of these signals have been reported to affect total IgG9 (Supplementary Data 10). The third association, a single base deletion at FCGR2B, associates with IgG3 (rs199991552 [TC > T], P = 1.1 × 10−11, β = −0.238, EAF = 13.0%) and correlates with a cis-eQTL for increased FCGR2B expression in blood (P = 4.0 × 10−1435, β = 1.279, Supplementary Data 4) implicating that increased FCGR2B expression results in lower IgG3 levels. Further, rs199991552 correlates (r2 = 0.71) with a previously reported variant rs3219018 in a FCGR2B promoter (a G-C substitution at position −343 relative to the start of transcription) that has been linked with reduced expression of FCGR2B and increased risk of autoimmune diseases22 (Supplementary Data 11).

In addition to those associations, we note that a rare Iceland-specific loss-of-function variant in FCGR2B, that we previously found to associate with increased IgG levels9, also associates with increased IgG1, (rs755222686 [CAAT > C], NP003992.3:p.Asn106del, P = 5.8 × 10−5, β = 1.33), further pointing to the importance of FCGR2B regulation for IgG subclass levels. Further, a missense variant in FCGR2A, a double nucleotide polymorphism Gln27Trp: rs9427397[C > T]/rs9427398[A > G], that we recently reported to associate with increased risk of rheumatoid arthritis23, is the variant at this locus that associates most strongly with IgG1 levels in children (P = 3.2 × 10−8, β = −0.270, EAF = 12.8%, Supplementary Data 5). In vitro analysis revealed that Gln27Trp did not affect the binding affinity of IgG1 to the FcγRIIA (Supplementary Fig. 6) but others have reported that this variant mediates defective downstream signaling24. This variant is weakly correlated with the two variants associated with IgG1 levels in adults, r2 = 0.25 with rs7554873 and r2 = 0.10 with rs143596860, but it fully explains the association of those variants with IgG1 levels in children while the reverse is not true (Supplementary Data 15). In contrast, Gln27Trp does not associate with IgG1 levels in adults after adjusting for rs7554873 and rs143596860. This may indicate that the activating FcγRs may be especially important for IgG1 production and persistence during maturation of the immune system in early life when the immune repertoire is expanding more than in adults25.

Associations with IgG4

Outside the IGH, FCGR and HLA loci, we detected two specific associations with IgG4 (Table 1 and Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2), the least abundant IgG subclass. IgG4 does not activate complement, has low to intermediate affinity for all FcγRs and is often induced by allergens2.

The first signal is a missense variant (rs2230429[C > G], p.Pro517Arg, P = 1.3 × 10−23, β = -0.243, EAF = 32.5%) in the ITGAX gene at 16p11.2 (Supplementary Fig. 3). ITGAX encodes the αX chain (CD11c) which together with integrin β2 (CD18) forms complement receptor 4 (CR4). CR4 binds the Factor I-cleaved complement factor 3b (iC3b), which acts as an opsonin. Pro517Arg introduces a positive charge at the contact surface of integrins αX and β2 (Supplementary Fig. 7), potentially affecting the stability of the CR4 heterodimer. The IgG4 decreasing allele (rs2230429[C > G]) is highly correlated with a previously reported IgA nephropathy risk allele (r2 = 0.96, Supplementary Data 10)26.

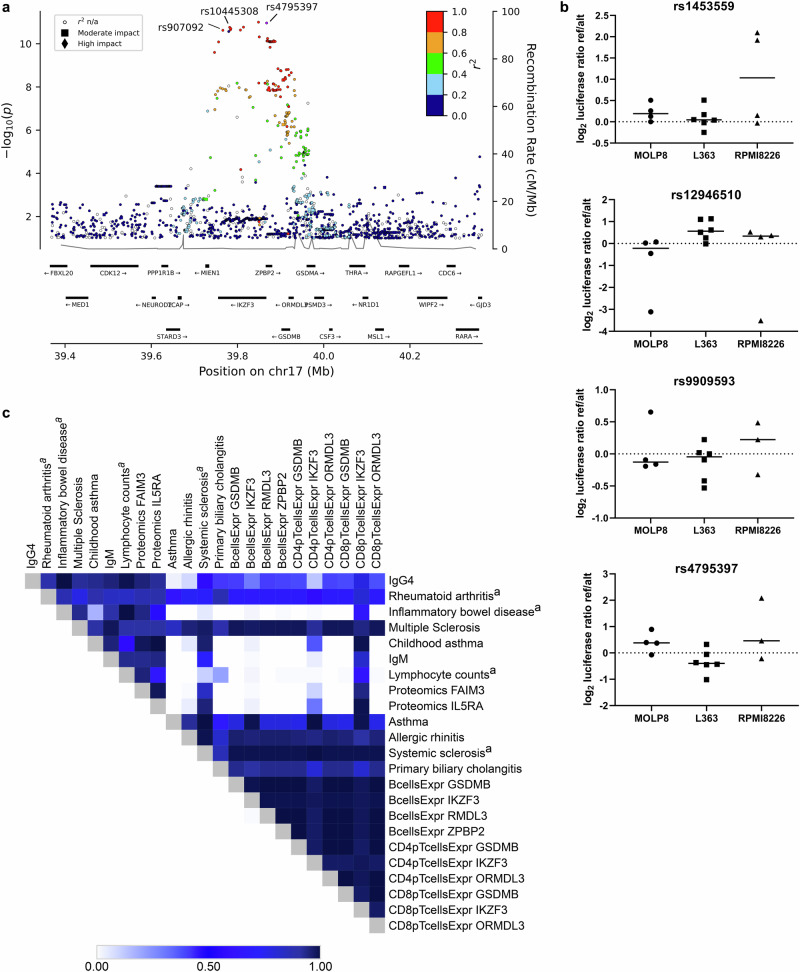

The second IgG4 signal maps to 17q21.1 (rs4795397[A > G], P = 1.1 × 10−11, β = −0.157, MAF = 49.2%) and is correlated with variants reported to associate with various inflammatory diseases and other traits, including IgM, asthma, allergy, autoimmune diseases as well as eosinophil and lymphocyte counts (Supplementary Data 10)9,27–30. The allele associated with reduced IgG4 levels also associates with decreased risk of asthma and allergic rhinitis but increased risk of various autoimmune diseases (Supplementary Data 10). However, although allergens often induce IgG431, neither rs4795397 nor any of the other IgG4 variants affected IgE levels (Supplementary Data 16).

The associated region of 17q21.1 spans 160 kb and includes four genes, IKZF3, ZPBP2, GSDMB and ORMDL3, all expressed in pre-B cells, B cells, plasma cells and T cells (Fig. 3a). We used various datasets to look for transcriptional effects of the IgG4-associated signal and thereby attempted to identify the causal gene. First, we performed eQTL analysis in pre-existing dataset of CD138+ immunomagnetic bead-enriched plasma cells isolated from 1445 multiple myeloma patients32. eQTL analysis in plasma cells showed that the allele that decreased IgG4 associated with increased expression of IKZF3 and ZPBP2 but not with the expression of GSDMB or ORMDL3 or other genes in the region (Supplementary Data 17). This was in contrast with eQTL analysis based on RNA sequencing of immunomagnetic bead enriched CD19+ B-cells (n = 758), CD4+ T-cells (n = 837), CD8+ T-cells (n = 807) as well as whole blood (n = 17,848) from Icelanders, where the IgG4 decreasing allele also associated with expression of GSDMB and ORMDL3 but in the opposite direction of IKZF3 and ZPBP2 (i.e., the IgG4 decreasing allele associated with increased expression of IKZF3 and ZPBP2 but decreased expression of GSDMB and ORMDL3; Supplementary Data 4). The IgG4-associated signal at 17q21.1 is represented by multiple highly correlated variants and we performed assay for transposase-accessible chromatin with sequencing (ATAC-seq) analysis to try to identify the putative causal variant. We identified four variants that map to genomic regions with chromatin accessible in multiple hematopoietic cell types, including B, T and plasma cells (Supplementary Fig. 8). One of the variants, rs1453559, maps to the IKZF3 promoter and a luciferase experiment in plasma cell lines showed increased transcriptional activity of the IgG4 decreasing allele, compared to the other allele, consistent with direction in the eQTL analysis (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Data 18). No transcriptional effects were observed for the other three variants tested.

Fig. 3. Pleiotropic signal at 17q21.1 associates with IgG4 and immune-related traits.

Locus plot showing –log10 P value (calculated using a generalized form of linear regression with two-sided P values) for the top IgG4-associated variant (rs4795397, shown in purple) and all other variants colored by degree of correlation (r2) with the lead variant. Two additional variants are labelled in the figure; rs10445308 is the top eQTL for IKZF3 in plasma cells and rs907092 is the top eQTL for ZPBP2 in plasma cells as well as the top early onset asthma associated variant at the locus (a). Luciferase assays performed for variants identified by ATAC-seq analysis. Graphs showing results for four variants (labelled above each graph) tested in three different plasma cell lines (MOLP8, L363 and RPMI8226). Each data point represents the luciferase activity ratio of ref/alt allele for one experiment with 4 independent experiments performed for MOLP8 and RPMI8226, and 6 experiments for L363. The raw data (renilla-normalized luminescence) was log2 transformed and median-centered. For statistical analysis, we used the Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test with two-sided P values. The test is done pooling all 12 data points (12 experiments) for the three cell lines together rs1453559: P = 0.0134, rs12946510: P = 0.0942, rs9909593: P = 0.51, rs4795397: P = 0.84 (b). Heatmap showing pair-wise co-localization analysis for correlated association signals for immunoglobulins (IgG4, IgM), various inflammatory diseases, proteomics pQTL’s (FAIM3, IL5RA), and eQTL’s in B, CD4pT and CD8pT cells at the 17q21.1 locus. The co-localization is done using the coloc R package (Methods) and the colors show the posterior probability for a one shared genetic signal (PPR4) between the different traits, where white color indicates the lowest probability and dark blue the highest probability (c). Further details on the co-localization analyses can be found in Supplementary Data 19.

Analysis of protein quantitative trait loci (pQTL) in plasma samples of 35,559 Icelanders, that had Somascan protein measurements33 also showed that the IgG4 reducing allele associated with reduced plasma levels of IL5RA, central to Type 2 immune responses34, and with reduced plasma levels of Fas apoptotic inhibitory molecule 3 (FAIM3) that has been shown to be Fc receptor for IgM35 (Supplementary Data 4).

In order to understand whether the correlated association signals at 17q21.1 for IgG4, IgM, the cis eQTLs and the trans pQTLs, and the various inflammatory diseases represented the same or distinct signals, we performed a co-localization analyses36. These analyses were not consistent with a one common association signal and rather the signals could be split into two groups (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Data 19). The IgG4 and IgM association signals, and the trans pQTLs for IL5RA and FAIM3, are consistent with being the same signal as observed for childhood asthma and inflammatory bowel disease, whereas they are distinct from the association signals for all asthma, allergic rhinitis and primary biliary cholangitis. The latter signal colocalizes with the eQTL’s for GSDMB, IKFZ3, ORMDL3 and ZPBP2 in whole blood, B and T cells, whereas the IgG4-associated signal is highly correlated (r2 = 0.98) with the plasma cell-specific eQTLs for IKZF3 and ZPBP2 (Supplementary Data 17) indicating that at least part of the pleiotropic associations observed at this locus could be explained by cell type-specific transcriptional regulation.

Discussion

We report the first GWAS on IgG subclass levels in human blood. We identified 14 significant associations, 10 of which are novel. Through additional genomic studies, we delineated candidate genes and mechanisms underlying the identified IgG subclass associations.

Imputation of the known IgG allotypes, based on missense variants at the IGH locus, confirmed that IgG subclass variation can partly be explained by serologically defined Gm allotypes. To our knowledge, this is the first attempt at evaluating the association between IgG subclass levels and Gm allotypes by GWAS. Although the functional consequences of the different allotypes remain largely unknown, our data are consistent with differences in function being partly explained by different half-lives of IgG allotypes. We observed that carriers of the G1m(za) allotype have greater IgG1 levels than those with G1m(f) consistent with previous reports showing that the G1m(za) binds with higher affinity to the neonatal FcR (FcRn), known to increase half-life of IgG37. Furthermore, different IgG3 allotypes have also been reported to have different half-lives due to different binding affinity to FcRn38.

We observed that G1m(f) is the most prevalent IgG1 allotype in our data in line with previous reports on allotype frequency in Europe39. Anti-drug antibodies (ADA) have been reported upon repeated administrations of many therapeutics based on monoclonal antibodies (mAbs). ADAs have been reported to associate with reduced response to treatment that is likely mediated by accelerated clearance of the drug from circulation or altered bioavailability40. Interestingly, some of the mAbs that induce ADA in more than 50% of patients such as the anti-TNFα infliximab and the anti-CD52 alemtuzumab are produced on the background of the G1m(za) allotype that is only found in 46.5% Icelanders and 38.2% Swedes. In contrast mAbs with reported ADA in less than 2% of patients, such as the anti-RSV palivizumab and anti-IL2R basiliximab bear the most common allotype G1m(f)40. Indeed, G1m allotype incompatibility has been associated with less response to treatment with infliximab in rheumatoid arthritis patients41 although other studies have indicated that allotype incompatibility does not increase ADA42. The repeated and highly homologous sets of genes at the IGH locus have restricted comprehensive characterization of polymorphisms within this region and thereby associations with diseases and other traits in GWAS including those studying response to mAbs treatment43–46. We propose that this should be revisited with datasets with higher resolution of this complex locus, such as the one we present here, to look for association with the major IGH allotypes and/or other polymorphisms at this locus. In addition, we found three unreported polymorphisms at the IGH locus, most notably a rare IGHG1 deletion that confers a large increase in IgG3 levels both in adults and children.

IgG4-related disease (IgG4-RD) is a chronic, inflammatory disorder that often manifests with tumor-like masses in various organs and often an increased IgG4 levels47. Sequence variants at HLA and FCGR2B have been reported to associate with IgG4-RD in a Japanese cohort48. Similar to this study we found a significant IgG4 association at the HLA locus although not the same as reported in Japan as expected by the different geographic patterns of HLA frequencies, whereas we found no IgG4 association at the FCGR locus. Interestingly, the only two variants, found outside of the IGH, HLA and FCGR loci, showed specific association with the least abundant Ig subclass, IgG4, typically accounting for less than 5% of total IgG in healthy human serum. First, a missense variant (Pro517Arg) in ITGAX at 16p11.2 associated with reduced IgG4 levels and coincides with a previously reported IgA nephropathy variant26. Secondly, we found an association between a non-coding variant at 17q21.1 and IgG4 levels that coincedes with a highly pleiotropic signal, previously reported to associate with asthma, autoimmunity and IgM levels9,30,49. Transcriptional analysis in plasma cells revealed that the allele associated with reduced IgG4 levels also associated with increased expression of IKZF3 and ZPBP2, implicating these two genes in the mechanisms underlying the immunoglobulin association. Interestingly, the IgG4 reducing signal co-localized with reported signals associating with lower risk for childhood asthma and increased risk of inflammatory bowel disease and other autoimmune diseases. However, we note that for some of the traits, in particular rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis and systemic sclerosis, the association signals at this locus are not strong, hence the co-localization analysis is not well powered to discriminate between the two signals. Co-localization analyses indicate that the IgG4 signal is separate from the top eQTL signals observed in B and T cells that was much stronger for the two other genes at the locus, ORMDL3 and GSDMB, that have been more commonly suggested as the causative genes in asthma and autoimmune diseases30,49,50. Recently, two studies have reported cell type-specific genetic control observed with single cell RNA sequencing51,52, that together with our results of different transcriptional control for this locus in plasma cells versus other lymphoid cells suggest that cell type-specificity could further explain the pleiotropic associations observed for the 17q21.1 locus.

Our study has some limitations. First, IgG subclass measurements are performed on limited number of individuals that are all Caucasian origin. Secondly, the highly homologous sets of genes at the IGH locus, results in lower imputation accuracy for variants at this locus than in other regions and recent publications have revealed that we are still lacking comprehensive characterization of polymorphisms within this locus39,53 Therefore, further sequencing and imputation of alternate haplotypes in the IGH locus in larger datasets, preferably in different ancestral populations, is needed to better understand polymorphisms at the IGH as well as other loci and their role in antibody-mediated immunity.

Our results provide new insight into the biological processes underlying the different IgG subclass levels that may improve the understanding of the humoral immune response and have implications for the rational design of therapeutic mAbs.

Methods

Ethics

We confirm that our research complies with all relevant ethical regulations. The Icelandic study was approved by the National Bioethics Committee in Iceland (Approval no. 15-023) following a review by the Icelandic Data Protection Authority. The personal identities of the participants and biological samples were encrypted using a third-party system approved and monitored by the Icelandic Data Protection Authority. Swedish samples were collected subject to ethical approval (Lund University Ethical Review Board, dnr 2013/54). All participating subjects, in Iceland and Sweden, who donated blood signed informed consent. Participants received no compensations.

Icelandic study population

All existing results of blood IgG subclass measurements performed by radial immunodiffusion at the Department of Immunology (1999–2015) were obtained from Landspitali, the National University Hospital of Iceland (LSH), a total of 9563 serum sample measurements of IgG1, IgG2, IgG3 and IgG4.

Individuals with known diagnoses of multiple myeloma, monoclonal gammopathy of unknown significance, Waldenström’s disease, lymphoid malignancies, liver cirrhosis or primary biliary cirrhosis in deCODE’s phenotype database were excluded as all of these diseases are known to heavily affect IgG levels and therefore it would likely mask the effect of genetic variant. The measured IgG subclass level values were log transformed and adjusted for sex and age at measurement. For individuals with multiple measurements, the most recent one was used in the analysis. Finally, the datasets were standardized by subtracting the mean from each value and dividing by the standard deviation. After this treatment, association analysis could be performed on measured serum levels in 2585 adults and 4571 children.

Swedish study population

We measured IgG subclass levels in a cohort of 2336 randomly ascertained Swedish blood donors from Skåne county, southern Sweden. Sample collection took place during summer and autumn of 2014. IgG1, IgG2, IgG3 and IgG4 levels were measured using Optilite® analyser (The Binding Site Group Ltd, Birmingham, United Kingdom) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. One or more IgG subclasses could not be measured in some samples due to insufficient material. The measured IgG subclass levels were corrected for age at sample collection, log transformed, adjusted for population substructure by adjusting for 20 genetic principle components (see below), and scaled to have mean zero and variance one. After exclusion of samples based on genotype yield and genetic ancestry analysis, 1749 individuals were included in the analysis.

Genotyping and imputation

Imputation of the Icelandic samples is based on whole-genome sequencing (WGS), using Illumina standard TruSeq methodology, of whole blood of 49,708 Icelanders individuals, and chip genotyping of 166,281 indivduals using various Illumina chips, that have participated in various disease projects at deCODE genetics54. Variants that did not pass quality control were excluded from the analysis and only samples with genome-wide average coverage of 20X in the WGS were included. The WGS genotypes were called using Graphtyper (https://github.com/DecodeGenetics/graphtyper)55 long-range phased56 and used as an reference-set to impute 88 million genetic variants into long-range phased genotypes for the chip genotyped individuals. Information about haplotype sharing was used to improve variant genotyping, taking advantage of the fact that all sequenced individuals had also been chip-typed and long-range phased. In addition familial imputation was used to imputed variants into non-chip-typed Icelanders that have genotyped close relatives in the dataset.

The Swedish samples were genotyped Illumina OmniExpress-24 and Global Screening single-nucleotide polymorphism microarrays and phased together with 570,100 samples of North-Western Europe origin using Eagle (https://alkesgroup.broadinstitute.org/Eagle/)57. Samples and variants with <98% yield were excluded. For imputation, we created a haplotype reference panel by phasing the WGS genotypes for 17,408 individuals of European origin, including 3704 Swedish samples, sequenced using HiSeqX and NovaSeq PCR-free Illumina technology to a mean depth of at least 30X54. Single-nucleotide polymorphisms and indels were called using joint calling with Graphtyper55. The 17,408 individuals were also genotyped using the Illumina OmniExpress and Global Screening microarrays and those genotypes were long-range phased using Eagle. The sequence genotypes were phased with chip genotypes and 170 million variants identified in the WGSwere imputed into the phased chip data56.

At the IGH locus at 14q32.33 we used the phased sequencing data to define an allotype for each unique presence/absence combination of the missense variants detected in the IGHG1, IGHG2, IGHG3 and IGHG4 genes, respectively, in both the Icelandic and Swedish datasets. These allotypes were then used as reference and imputed in the Icelandic and Swedish genotype dataset as any other genetic variants. The genetic complexity of the IGH loci is, however, challenging for phasing and imputing genotypes into the samples. For the Icelandic samples the imputation yield for the allotypes (fraction of chromosome with allotypes assigned) was between 93% to 97% depending on gene, and for the Swedish samples the yield was about 93.5%. This is similar imputation yield as for the associated variants at this locus listed in Table 1, but considerably lower than imputation yield for the other associated variants in Table 1 which is about 99%.

Genetic ancestry analysis for the Swedish samples

We ran ADMIXTURE v1.23 (http://www.genetics.ucla.edu/software)58 in supervised mode with 1000 Genomes populations CEU, CHB, and YRI59 as training samples and Swedish individuals as test samples. Long-range LD regions were removed60 and the data was LD-pruned with PLINK v.190b3a (http://pngu.mgh.harvard.edu/purcell/plink/)61. Samples with less than 0.9 CEU ancestry were excluded. To identify, and exclude, individuals of Finish/Saami origin, we included individuals with less than 0.3 CHB (Asian) and less than 0.05 YRI (African) ancestry. Remaining samples were projected onto a principal component analysis (PCA), calculated with an European reference panel to calculate the 20 first principal components for each population. UMAP (https://github.com/diazale/umap_review)62 was used to reduce the coordinates of test samples to two dimensions. Additional European samples not in the original reference set were also projected onto the PCA and UMAP components to identify ancestries, and samples with Swedish ancestry were identified. Including putatively Finnish/Saami individuals allowed us to confirm that we could identify a distinct, separable UMAP cluster of individuals with the following properties: (a) elevated CHB (Asian) ancestry according to ADMIXTURE; (b) enriched for individuals who we knew to have been born in Finland; (c) on principal component 1 and 2, were positioned in the region occupied by Finnish individuals. Those individuals were excluded from the analysis. After exclusion, the analysis included 68,944 unique individuals of Swedish ancestry of which 1748 have IgG-subclass measurements.

Calling and imputation of rare 28 kb deletion at IGH locus

The presence of the ~28 kb deletion at Hg38-chr14:105,734,756–105,762,914, was determined using sequence coverage in a total of 47k whole genome sequenced Icelanders and 3734 Swedes through our Gorpipe pileup command (https://github.com/gorpipe/gor)63, whereby non-primary alignments and reads that fail quality checks, were filtered out. To correct for difference in sequence depth between individuals, a 200 kb region at Hg38-chr14:39,100,000–39,300,000 was used for normalisation. The deletion was subsequently imputed into both the Icelandic and Swedish datasets.

Association testing and meta-analysis

A generalized form of linear regression was used to test for association, and estimating the effects, of adjusted and standardized IgG subclass levels with genotypes, assuming an additive model, in the Icelandic and Swedish data separately. We assume that the quantitative measurements follow a normal distribution with a mean that depends linearly on the expected allele at the variant and a variance–covariance matrix proportional to the kinship matrix64. As the distributions of IgG subclass levels were standardized to have variance one prior to association analysis, the effect estimates β are in units of standard deviations (SD) of the original distribution. We used linkage disequilibrium (LD) score regression to account for distribution inflation in the dataset due to cryptic relatedness and population stratification65.

We performed meta-analysis by combining results from the different study groups using an inverse-variance weighted fixed effect model in which the groups were allowed to have different population frequencies for alleles and genotypes but were assumed to have a common effect. We meta-analysed results for 22,121,872 variants with imputation info >0.8 and minor allele frequency >0.1% in either dataset. Heterogeneity was tested by comparing the null hypothesis of the effect being the same in all populations to the alternative hypothesis of each population having a different effect using a likelihood-ratio test. I2 lies between 0 and 100% and describes the proportion of total variation in study estimates that is due to heterogeneity.

We applied genome-wide significance thresholds corrected for multiple testing using an adjusted Bonferroni procedure weighted for variant classes and predicted functional impact. With 22,121,872 sequence variants being tested the weights given in Sveinbjornsson et al. were rescaled to control the family-wise error rate (FWER)12. The adjusted significance thresholds are 3.75 × 10−7 for high impact variants, 7.50 × 10−8 for variants with moderate impact, 6.81 × 10−9 for low-impact variants, 3.41 × 10−9 for other variants in DNAse I hypersensitivity sites and 1.14 × 10−9 for all other variants.

We used step-wise conditional analysis using genotype data to look for additional signals at each locus. The lead variant of each association signal was selected from meta-analysis as the variant with lowest Bonferroni adjusted P value. Then all other variants in a 2 Mb region at each locus were tested conditional on that variant for association with IgG subclass levels. This was done separately for the Icelandic and Swedish dataset and the results combined using a fixed effect meta-analysis. We applied the same genome-wide significance threshold to the secondary signals as the primary signal and if a secondary signal met that criteria, the procedure was repeated until no variant associated. Once a set of conditionally independent variants at each locus had been identified, we calculated adjusted effects βadj and adjusted P values Padj for each variant conditional on all other associated variants at the locus.

We calculated 95% credible sets of plausible causal variants for each independent association signal using a Bayesian refinement approach66 weighting the variants using the same weights as were used to define the class specific genome-wide significance thresholds. At loci were multiple independent variants associated, each credible set was created after adjusting all variants for the association with other variants at the locus.

The fraction of variance explained was calculated using the formula 2 f (1 – f) a2, where f is the frequency of the variant and a is its additive effect. As an estimate of the population frequency for adults, we used a simple average of the frequency in the Icelandic and the Swedish sample sets.

Expression analysis

We looked for cis-eQTL association in whole blood for the IgG-subclass signals in RNA sequencing data from 17.848 Icelandic blood samples. The generation of poly(A)+ cDNA sequencing libraries, RNA sequencing and data processing of the whole blood derived data were carried out as described before67,68. Association between sequence variants and gene expression (cis-eQTL) was estimated using a generalized linear regression, assuming additive genetic effect and quantile-normalized gene expression estimates, adjusting for measurements of sequencing artefacts, demography variables, and leave-one-chromosome-out principal components of the gene-expression matrix69.

Measurements of expression in isolated cell populations

Venous blood samples were collected into EDTA-coated collection tubes and used for cell isolation the same day. Untouched cell subsets (B-, CD4 + T-, and CD8 + T-cells) were isolated directly from whole blood using EasySep magnetic cell sorting (StemCell Technologies, cat. # 19674, 19662, and 19663, respectively) according to manufacturer’s instructions. RNA was isolated from each sample using RNeasy Micro kit (Qiagen, Cat. 74004) following manufacturer’s instructions and resuspended in EB buffer prior to sequencing. RNA sequencing and data processing was carried out as described for the whole blood on CD4 + T-cells (n = 837), CD8 + T-cells (n = 807) and B-cells (n = 758).

To identify effects on expression in plasma cells, we analyzed pre-existing eQTL data for immunomagnetic bead-enriched CD138+ plasma cells isolated from 1445 patients with multiple myeloma from the United Kingdom, Germany, and the USA70.

Cis-pQTLs

We looked for cis-pQTL association for the IgG-subclass signals in a dataset of 4907 proteins measured in plasma samples from 39,155 Icelanders with genetic information33. The protein levels were measured using the SomaScan® (SomaLogic Inc.). which is based on aptamers that have beem modified to recognize specific proteins that are then quantified on a DNA microarray. We performed a proteome-wide association study and evaluated whether the IgG subclass associating sequence variants associated with protein levels (pQTL). Statistical analysis of the findings was performed using linear regression of log-transformed protein levels against SNP allele count.

ATAC-sequencing data analysis

To identify regions of accessible chromatin, we used pre-existing, pre-processed ATAC-sequencing data for 17 sorted blood cell types71,72. The regional ATAC-sequencing signal intensities were visualized using UCSC Browser (https://genome.ucsc.edu/).

Luciferase assays

Luciferase constructs were generated by cloning genomic sequences (Integrated DNA Technologies; Supplementary Data 18) centered on variants-of-interest into the pGL3-basic vector. The constructs were co-transfected with Renilla plasmid by electroporation using a Neon system (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Luciferase and Renilla activity was measured at 24 h post-transfection using DualGlo Luciferase (cat no. E1960; Promega) on a GLOMAX 20/20 Luminometer. Luciferase luminescence was normalized to Renilla, and values were log2 transformed and median-centered for statistical analysis.

Recombinant Fc-receptor production

DNA encoding the extracellular domain of human CD32A (FcγRIIA) 131H and a C-terminal 10xHis tag and AVI tag, respectively, was synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies, USA. The gene fragment was generated with flanking HindIII and EcoRV restriction sites for cloning into pcDNA3.1 (+) expression vector (Invitrogen, USA) using Rapid Ligation Kit (Thermo Scientific, USA). Subsequently, ligation products were transformed into DH5α heat-shock competent cells (Thermo Scientific, USA). The Q27W mutation was introduced by site-directed mutagenesis using specific primers and Quickchange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent, USA). Insert sequences were verified by Sanger sequencing in a 3730 DNA Analyzer. Both constructs were transiently transfected into HEK293 Freestyle cells (Thermo Scientific, USA) and after 5 days the protein-containing cell supernatant was harvested as described by Dekkers et al.73. Isolation of the His-tagged recombinant receptors was performed by using an affinity chromatography His trap column (GE Healthcare, The Netherlands) on ÄKTA prime (GE Healthcare, The Netherlands) and site-specific biotinylation on the AVI tag was performed using BirA500 biotin-protein ligase standard reaction kit (Avidity, USA).

Cells

HEK293 Freestyle cells were transfected with linearized CD32A 27Q, CD32A 27 W or mock pcDNA3.1 expression vectors using 293fectin (Invitrogen, USA). These cell lines were cultured in suspension in serum-free FreeStyle 293 Expression Medium (Gibco Life Technologies, USA) with added G418 (PAA the cell culture company, Austria) as selection marker.

Flow cytometry

CD32A 27Q, CD32A 27W and mock-transfected HEK293 cells (1.5 × 105 cells per well) were incubated with FITC-conjugated mouse anti-human CD32 clone AT10 (Bio-Rad, Germany) or isotype control for 1 hour at 4 °C. For IgG binding, cells were incubated at 37 °C with monoclonal human IgG1 (anti-trinitrophenol) and subsequently with secondary PE-conjugated goat anti-human IgG1 F(ab’)2 (Southern Biotech, USA). Sample fluorescence was measured on a FacsCanto II cytometer (BD Biosciences, USA) and at least 10,000 events were recorded per sample. Flow cytometry data was analyzed using FlowJo software (FlowJo, USA). cSPRi data was analyzed using SprintX software (IBIS Technologies B.V., The Netherlands) and Rstudio software (RStudio, USA). GraphPad Prism 8.0.2 (GraphPad Software, Inc., USA) was used to generate sensorgrams.

Surface plasmon resonance imaging (SPRi)

Experiments and KD calculations were performed as described previously by Dekkers et al.73. Here, recombinant CD32A 27Q and CD32A 27 W were immobilized onto the streptavidin-coated sensor (Ssens, The Netherlands) in duplicate and in threefold dilutions ranging from 30 nM to 1 nM. Subsequently, human α-D IgG1 in PBS with 0.075%Tween-80 (pH 7.4) was injected at serial dilutions ranging from 1000 nM to 0.49 nM. Measurements have been performed three times.

Cellular SPRi

A pre-activated Easy2spot G-type sensor (Ssens, The Netherlands) was spotted using a Continuous Flow Microspotter (Wasatch Microfluids, USA). Monoclonal human IgG1 isotype (100, 30 10 nM) and mouse anti-CD32 IgG1 clone AT10 (Bio-Rad, Germany) (100, 30 nM) in 10 mM sodium acetate/acetic acid + 0.075% Tween-80 at pH 5.0, and human serum albumin (HSA; Sanquin, the Netherlands) (100 nM) for control purposes in 10 mM sodium acetate/acetic acid + 0.075% Tween-80 at pH 4.0. Deactivation of the sensor was performed with HSA. Cell binding was performed in an IBIS MX96 (IBIS Technologies B.V., The Netherlands). HEK CD32A 27Q, HEK CD32A 27 W and HEK mock were injected into the flow chamber at 1.25 × 106 cells/ml. System and analyte buffer was PBS, pH 7.4, supplemented 0.5% BSA and regeneration was done using Glycine HCl pH 2.2 + 0.075% Tween-80.

Functional assessment of FcγRII Gln27Trp

Binding of human IgG1 to immobilized wildtype human, the previously described FcγRIIA-131His-27Gln and the variant associating with IgG1 levels in children, Gln27Trp, was measured by SPR imaging. C-terminus biotinylated FcγRs were coupled at 30 nM, 10 nM, 3 nM and 1 nM on individual streptavidin spots on the SPR sensor. IgG1 binding affinities were determined by flowing different concentrations of IgG1 over the sensor, ranging from 1000 nM to 0.49 nM. Binding affinities were determined with KD values in molar (+/− SD).

HEK cells expressing FcγRIIa with either Gln or Trp in position 27 were analyzed with FACS and cellular SPRi (cSPRi). In the FACS analyses, cells were incubated with FITC-conjugated anti-CD32 or isotype control, with mock-transfected HEK cells as negative control. Results are given as geometric mean of fluorescence intensity.

In the cSPRi analyses IgG binding cells were incubated with human anti-TNP IgG1 and subsequently with secondary PE-conjugated F(ab’)2 fragments goat anti-human IgG1, for control purposes cells were also incubated with the secondary only. Cells were flowed over immobilized anti-FcγRIIa (CD32) and human IgG1 at different concentrations. Cells were injected into the flow chamber and allowed to sediment for 6 min. The next ten minutes, the flow speed was increased stepwise from 1 to 120 µl/s. HEK cells expressing FcγRIIa were flowed over the spots. Results are given as RU values that are relative to cell flow signals, to correct for possible fluctuations in flowed cell amounts.

Co-localization analyses

To test for co-localization of the IgG subclass signals with signals in other traits we used the COLOC software package implemented in R (https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/coloc/vignettes/a01_intro.html)36. Using summary statistics for the IgG subclass trait A and the trait B, i.e. effects and P values, we calculated Bayes factors for each of the variants in the associated region for the two traits and used COLOC to calculate the posterior probability for two hypotheses: (1) that the association with the pQTL A and the trait B are independent signals (PP3) and (2) that the association with the pQTL A and the trait B are due to a shared signal (PP4).

At the 17q21.1 locus, we tested for co-localization between correlated association signals for IgG4 and several disease and quantitative traits and expression and proteomic traits. In the co-localization, we used publicly available meta-analysis for rheumatoid arthritis (14,261 cases and 4023 controls from 18 European datasets74, inflammatory bowel disease (12,882 cases and 21,770 controls from 15 European datasets75, systemic sclerosis (9095 cases and 17,584 controls from 14 European datasets76, and lymphocyte counts (524,923 European individuals77. We tested variants in the 17q21.1 locus for association in previously unpublished datasets for multiple sclerosis (16,980 cases and 1,185,452 controls from Iceland, UK, Norway, Sweden and Finland), childhood asthma (22,561 cases and 1,066,331 controls from Iceland, UK and Finland), asthma (155,322 cases and 1,152,498 controls from Iceland, UK, USA, Finland and Japan), allergic rhinitis (75,268 cases and 1,467,559 controls from Iceland, UK, Denmark and Finland), primary biliary cholangitis (701 cases and 633,646 controls from Iceland and UK) and IgM (59,866 individuals from Iceland and Sweden). For pQTLs and eQTLs, we used the expression and proteomics data from Iceland described above. For look-ups of the IgG-subclass lead variants and credible set variants, we used the GWAS catalog (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/gwas/, downloaded November 17, 2022). R version 3.6.0 was used to analyze data and create plots for this manuscript.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Source data

Acknowledgements

We thank all study participants and the staff at the Icelandic Patient Recruitment Center and the deCODE genetics core facilities. We are indebted to the blood donors and staff at Lundatappen who participated in the project, as well as to Ellinor Johnsson for her assistance through the years. This work was supported by research grants from the Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research (KF10-0009, B.N.), the Marianne and Marcus Wallenberg Foundation (2010.0112, B.N.), the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation (2012.0193, B.N.), the Arne and Inga-Britt Lundberg Foundation (2017-0055, B.N), and the Swedish Research Council (2012-1753 and 2017-02023, B.N.).

Author contributions

T.A.O., S.J., D.F.G., G.T., U.T., I.J., B.N. and K.S. coordinated and designed the study. G.I.E., B.R.L., I.O., O.S., H.H. I.J. P.T.Ö., T.A.O., and U.S.B. coordinated and managed collection of samples and ascertainment of phenotype data in Iceland. A.L.d.L.P. collected samples and phenotype data in Sweden. T.A.O., S.J., A.N., A.L.d.L.P., F.W.A., H.P.E., B.V.H., G.H.H., P.M., A.J., S.S., G.E.T. A.S., L.S., P.S., D.F.G., and G.T. carried out statistical and bioinformatic analyses of genetic, transcriptomic and proteomic data. A.B., A.J., A.S., S.G., K.G., G.L.N., A.O.A., R.T., and G.V. carried out functional experiments and analysis. T.A.O., G.T., S.J., A.L.d.L.P., I.J., B.N. and K.S. drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to the final manuscript.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Chikashi Terao and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Data availability

The sequence variants passing GATK filters in our previously described Icelandic population whole-genome sequence data have been deposited at the European Variant Archive under accession code PRJEB15197. The GWAS summary statistics generated in this study are available at https://www.decode.com/summarydata/ upon registration. The Icelandic proteomics data have been described previously33 and GWAS summary statistics for all 4907 aptamers are available at https://www.decode.com/summarydata/ upon registration. The ATAC-seq data for CD138+ MM plasma cells used in this study have been described before71 and are available in the European Genome-phenome Archive (EGA), accession nos. EGAS00001005394 and EGAD00001007814https://ega-archive.org/. ATAC-seq data for 17 sorted blood cell types used in this study have been previously described72 and are available under Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) accession GSE74912. eQTL data for CD138+ immunomagnetic bead-enriched plasma cells isolated from 1445 multiple myeloma patients used in this study have been previously described70 and are available from the authors on a collaborative basis. Individual level phenotype and genotype data are protected and cannot be shared according to Icelandic law. The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article, in supplementary files or at https://www.decode.com/summarydata. Source data are provided with this paper.

Competing interests

T.A.O., G.T., L.S., A.J., H.P.E., G.H.H., G.E.T., A.O.A., S.G., K.G., B.V.H., H.H., P.M., G.L.N., S.S., A.S., U.T., P.S., D.F.G., I.J. and K.S. are employees of deCODE Genetics/Amgen, Inc. S.J. is an employee of Alvotech. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Thorunn A. Olafsdottir, Email: thorunno@decode.is

Björn Nilsson, Email: bjorn.nilsson@med.lu.se.

Kari Stefansson, Email: kstefans@decode.is.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-024-52470-8.

References

- 1.Watson, C. T. & Breden, F. The immunoglobulin heavy chain locus: genetic variation, missing data, and implications for human disease. Genes Immun.13, 363–373 (2012). 10.1038/gene.2012.12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vidarsson, G., Dekkers, G. & Rispens, T. IgG subclasses and allotypes: from structure to effector functions. Front. Immunol.5, 520 (2014). 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morell, A., Skvaril, F., Steinberg, A. G., Van Loghem, E. & Terry, W. D. Correlations between the concentrations of the four sub-classes of IgG and Gm allotypes in normal human sera. J. Immunol.108, 195–206 (1972). 10.4049/jimmunol.108.1.195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sarvas, H., Rautonen, N. & Makela, O. Allotype-associated differences in concentrations of human IgG subclasses. J. Clin. Immunol.11, 39–45 (1991). 10.1007/BF00918793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seppala, I. J., Sarvas, H. & Makela, O. Low concentrations of Gm allotypic subsets G3 mg and G1 mf in homozygotes and heterozygotes. J. Immunol.151, 2529–2537 (1993). 10.4049/jimmunol.151.5.2529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oxelius, V. A. & Pandey, J. P. Human immunoglobulin constant heavy G chain (IGHG) (Fcgamma) (GM) genes, defining innate variants of IgG molecules and B cells, have impact on disease and therapy. Clin. Immunol.149, 475–486 (2013). 10.1016/j.clim.2013.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhao, Y., Pan-Hammarstrom, Q., Zhao, Z., Wen, S. & Hammarstrom, L. Selective IgG2 deficiency due to a point mutation causing abnormal splicing of the Cgamma2 gene. Int. Immunol.17, 95–101 (2005). 10.1093/intimm/dxh192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pan, Q. & Hammarstrom, L. Molecular basis of IgG subclass deficiency. Immunol. Rev.178, 99–110 (2000). 10.1034/j.1600-065X.2000.17815.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jonsson, S. et al. Identification of sequence variants influencing immunoglobulin levels. Nat. Genet.49, 1182–1191 (2017). 10.1038/ng.3897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Granada, M. et al. A genome-wide association study of plasma total IgE concentrations in the Framingham Heart Study. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol.129, 840–845.e821 (2012). 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.09.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garcia-Prat, M. et al. Age-specific pediatric reference ranges for immunoglobulins and complement proteins on the Optilite() automated turbidimetric analyzer. J. Clin. Lab Anal.32, e22420 (2018). 10.1002/jcla.22420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sveinbjornsson, G. et al. Weighting sequence variants based on their annotation increases power of whole-genome association studies. Nat. Genet.48, 314–317 (2016). 10.1038/ng.3507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sollis, E. et al. The NHGRI-EBI GWAS catalog: knowledgebase and deposition resource. Nucleic Acids Res.51, D977–D985 (2023). 10.1093/nar/gkac1010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsang, A. S. M. W. et al. Fc-gamma receptor polymorphisms differentially influence susceptibility to systemic lupus erythematosus and lupus nephritis. Rheumatology55, 939–948 (2016). 10.1093/rheumatology/kev433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meinderts, S. M. et al. Nonclassical FCGR2C haplotype is associated with protection from red blood cell alloimmunization in sickle cell disease. Blood130, 2121–2130 (2017). 10.1182/blood-2017-05-784876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Poddighe, D., Rebuffi, C., De Silvestri, A. & Capittini, C. Carrier frequency of HLA-DQB1*02 allele in patients affected with celiac disease: a systematic review assessing the potential rationale of a targeted allelic genotyping as a first-line screening. World J. Gastroenterol.26, 1365–1381 (2020). 10.3748/wjg.v26.i12.1365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rodriguez, O. L. et al. A novel framework for characterizing genomic haplotype diversity in the human immunoglobulin heavy chain locus. Front. Immunol.11, 2136 (2020). 10.3389/fimmu.2020.02136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lacombe, C., Aucouturier, P. & Preud’homme, J. L. Selective IgG1 deficiency. Clin. Immunol. Immunopathol.84, 194–201 (1997). 10.1006/clin.1997.4386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith, C. I., Hammarstrom, L., Henter, J. I. & de Lange, G. G. Molecular and serologic analysis of IgG1 deficiency caused by new forms of the constant region of the Ig H chain gene deletions. J. Immunol.142, 4514–4519 (1989). 10.4049/jimmunol.142.12.4514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nimmerjahn, F., Gordan, S. & Lux, A. FcgammaR dependent mechanisms of cytotoxic, agonistic, and neutralizing antibody activities. Trends Immunol.36, 325–336 (2015). 10.1016/j.it.2015.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bournazos, S., Gupta, A. & Ravetch, J. V. The role of IgG Fc receptors in antibody-dependent enhancement. Nat. Rev. Immunol.20, 633–643 (2020). 10.1038/s41577-020-00410-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blank, M. C. et al. Decreased transcription of the human FCGR2B gene mediated by the -343 G/C promoter polymorphism and association with systemic lupus erythematosus. Hum. Genet.117, 220–227 (2005). 10.1007/s00439-005-1302-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saevarsdottir, S. et al. Multiomics analysis of rheumatoid arthritis yields sequence variants that have large effects on risk of the seropositive subset. Ann. Rheum. Dis.81, 1085–1095 (2022). 10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-221754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Flinsenberg, T. W. et al. A novel FcgammaRIIa Q27W gene variant is associated with common variable immune deficiency through defective FcgammaRIIa downstream signaling. Clin. Immunol.155, 108–117 (2014). 10.1016/j.clim.2014.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Simon, A. K., Hollander, G. A. & McMichael, A. Evolution of the immune system in humans from infancy to old age. Proc. Biol. Sci.282, 20143085 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kiryluk, K. et al. Discovery of new risk loci for IgA nephropathy implicates genes involved in immunity against intestinal pathogens. Nat. Genet.46, 1187–1196 (2014). 10.1038/ng.3118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Panganiban, R. A. et al. A functional splice variant associated with decreased asthma risk abolishes the ability of gasdermin B to induce epithelial cell pyroptosis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 142, 1469–1478 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Moffatt, M. F. et al. A large-scale, consortium-based genomewide association study of asthma. New Engl. J. Med.363, 1211–1221 (2010). 10.1056/NEJMoa0906312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moffatt, M. F. et al. Genetic variants regulating ORMDL3 expression contribute to the risk of childhood asthma. Nature448, 470–473 (2007). 10.1038/nature06014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Verlaan, D. J. et al. Allele-specific chromatin remodeling in the ZPBP2/GSDMB/ORMDL3 locus associated with the risk of asthma and autoimmune disease. Am. J. Hum. Genet85, 377–393 (2009). 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.08.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Michailidou, D., Schwartz, D. M., Mustelin, T. & Hughes, G. C. Allergic aspects of IgG4-related disease: implications for pathogenesis and therapy. Front. Immunol.12, 693192 (2021). 10.3389/fimmu.2021.693192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weinhold, N. et al. The 7p15.3 (rs4487645) association for multiple myeloma shows strong allele-specific regulation of the MYC-interacting gene CDCA7L in malignant plasma cells. Haematologica100, e110–e113 (2015). 10.3324/haematol.2014.118786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ferkingstad, E. et al. Large-scale integration of the plasma proteome with genetics and disease. Nat. Genet.53, 1712–1721 (2021). 10.1038/s41588-021-00978-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wilson, T. M. et al. IL-5 receptor alpha levels in patients with marked eosinophilia or mastocytosis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol.128, 1086–1092.e1081-1083 (2011). 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.05.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shima, H. et al. Identification of TOSO/FAIM3 as an Fc receptor for IgM. Int. Immunol.22, 149–156 (2010). 10.1093/intimm/dxp121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Giambartolomei, C. et al. Bayesian test for colocalisation between pairs of genetic association studies using summary statistics. PLoS Genet.10, e1004383 (2014). 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ternant, D. et al. IgG1 allotypes influence the pharmacokinetics of therapeutic monoclonal antibodies through FcRn binding. J. Immunol.196, 607–613 (2016). 10.4049/jimmunol.1501780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stapleton, N. M. et al. Competition for FcRn-mediated transport gives rise to short half-life of human IgG3 and offers therapeutic potential. Nat. Commun.2, 599 (2011). 10.1038/ncomms1608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bashirova, A. A. et al. Population-specific diversity of the immunoglobulin constant heavy G chain (IGHG) genes. Genes Immun.22, 327–334 (2021). 10.1038/s41435-021-00156-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vaisman-Mentesh, A., Gutierrez-Gonzalez, M., DeKosky, B. J. & Wine, Y. The molecular mechanisms that underlie the immune biology of anti-drug antibody formation following treatment with monoclonal antibodies. Front. Immunol.11, 1951 (2020). 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Montes, A. et al. Rheumatoid arthritis response to treatment across IgG1 allotype- anti-TNF incompatibility: a case-only study. Arthritis Res. Ther.17, 63 (2015). 10.1186/s13075-015-0571-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bartelds, G. M. et al. Surprising negative association between IgG1 allotype disparity and anti-adalimumab formation: a cohort study. Arthritis Res. Ther.12, R221 (2010). 10.1186/ar3208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cui, J. et al. Genome-wide association study and gene expression analysis identifies CD84 as a predictor of response to etanercept therapy in rheumatoid arthritis. PLoS Genet.9, e1003394 (2013). 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu, C. et al. Genome-wide association scan identifies candidate polymorphisms associated with differential response to anti-TNF treatment in rheumatoid arthritis. Mol. Med.14, 575–581 (2008). 10.2119/2008-00056.Liu [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Plant, D. et al. Genome-wide association study of genetic predictors of anti-tumor necrosis factor treatment efficacy in rheumatoid arthritis identifies associations with polymorphisms at seven loci. Arthritis Rheum.63, 645–653 (2011). 10.1002/art.30130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Umicevic Mirkov, M. et al. Genome-wide association analysis of anti-TNF drug response in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis.72, 1375–1381 (2013). 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wu, S. & Wang, H. IgG4-related digestive diseases: diagnosis and treatment. Front. Immunol.14, 1278332 (2023). 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1278332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Terao, C. et al. IgG4-related disease in the Japanese population: a genome-wide association study. Lancet Rheumatol.1, e14–e22 (2019). 10.1016/S2665-9913(19)30006-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stein, M. M. et al. A decade of research on the 17q12-21 asthma locus: piecing together the puzzle. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol.142, 749–764.e743 (2018). 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.12.974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]