Abstract

Background

Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales are among the most serious antimicrobial resistance (AMR) threats. Emerging resistance to polymyxins raises the specter of untreatable infections. These resistant organisms have spread globally but, as indicated in WHO reports, the surveillance needed to identify and track them is insufficient, particularly in less resourced countries. This study employs comprehensive search strategies with data extraction, meta-analysis and mapping to help address gaps in the understanding of the risks of carbapenem and polymyxin resistance in the nations of Africa.

Methods

Three comprehensive Boolean searches were constructed and utilized to query scientific and medical databases as well as grey literature sources through the end of 2019. Search results were screened to exclude irrelevant results and remaining studies were examined for relevant information regarding carbapenem and/or polymyxin(s) susceptibility and/or resistance amongst E. coli and Klebsiella isolates from humans. Such data and study characteristics were extracted and coded, and the resulting data was analyzed and geographically mapped.

Results

Our analysis yielded 1341 reports documenting carbapenem resistance in 40 of 54 nations. Resistance among E. coli was estimated as high (> 5%) in 3, moderate (1–5%) in 8 and low (< 1%) in 14 nations with at least 100 representative isolates from 2010 to 2019, while present in 9 others with insufficient isolates to support estimates. Carbapenem resistance was generally higher among Klebsiella: high in 10 nations, moderate in 6, low in 6, and present in 11 with insufficient isolates for estimates. While much less information was available concerning polymyxins, we found 341 reports from 33 of 54 nations, documenting resistance in 23. Resistance among E. coli was high in 2 nations, moderate in 1 and low in 6, while present in 10 with insufficient isolates for estimates. Among Klebsiella, resistance was low in 8 nations and present in 8 with insufficient isolates for estimates. The most widespread associated genotypes were, for carbapenems, blaOXA-48, blaNDM-1 and blaOXA-181 and, for polymyxins, mcr-1, mgrB, and phoPQ/pmrAB. Overlapping carbapenem and polymyxin resistance was documented in 23 nations.

Conclusions

While numerous data gaps remain, these data show that significant carbapenem resistance is widespread in Africa and polymyxin resistance is also widely distributed, indicating the need to support robust AMR surveillance, antimicrobial stewardship and infection control in a manner that also addresses broader animal and environmental health dimensions.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13756-023-01220-4.

Introduction

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is of growing concern as multidrug resistant organisms (MDRO) become more prevalent globally, undermining the efficacy of medicines needed for the treatment of infections and threatening patient safety and economic wellbeing [1]. Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales (CRE) infections are of particular concern as treatment options are highly limited [2] with carbapenems considered critical drugs for treatment of infections with documented or suspected resistance to alternative antimicrobials. Healthcare environments are the dominant source of human exposure to MDRO such as CRE [3] but exposure may also occur in the community, where organisms spread not only after transfer from patients exposed in healthcare settings, but also through contact with food, animals, and the environment [4–8].

Resistance to carbapenems arises through intrinsic or acquired mechanisms [3]. Acquired resistance [9–14] typically occurs due to carbapenemase enzymes encoded on plasmids or other genetic elements that are readily transferred among organisms [2, 15]. Major resistance determinants present worldwide include expression of Class A Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemases (KPC), Class B metallo-β-lactamases such as New Delhi metallo-β-lactamases (NDM), Verona integron-encoded metallo-β-lactamases (VIM), Imipenemase metallo-β-lactamases (IMP), and Class D oxacillinase β-lactamases (OXA), and alterations in outer membrane proteins (OMP) [15]. The polymyxin antibiotics, including polymyxin E (colistin) and polymyxin B, hereon in referred to as polymyxin(s), are polycationic peptides widely used until the 1970s, when largely abandoned as less toxic antibiotics became available [16, 17]. Currently, as one of few antimicrobial classes effective against CRE, polymyxins have regained importance. Determinants of acquired polymyxin resistance include transferable plasmid encoded mobile colistin resistance (mcr) genes as well as chromosomally encoded genes such as mgrB, phoP/phoQ, and pmrA/pmrB [16, 18]. The risk of organisms acquiring both carbapenem and polymyxin resistance is alarming as it severely limits treatment options. While rare to date, such dual resistance has been increasingly documented [19–22].

Despite the association of MDRO with excess morbidity, mortality and costs, major gaps exist in surveillance, particularly in under-resourced areas [23]. The WHO Global Action Plan to Tackle AMR (GAP-AMR) provides a roadmap for the treatment and prevention of resistant infections [24]. Since 2014, WHO has encouraged collection of data on carbapenem susceptibility and has published the limited available data in reports of the Global Antimicrobial Resistance Use and Surveillance System (GLASS) [1, 25–27]. In 2018, noting that only 7 of 47 WHO Africa nations had reported data on CRE to WHO [12, 28–30], we developed search and metanalytic approaches to utilize data from diverse sources to estimate and map carbapenem resistance and related genotypes in the WHO Africa region. We were able to identify and analyze data from 31 of 47 nations [2] documenting carbapenem-resistant Escherichia coli or Klebsiella spp. in 22, typically at low to moderate levels [2]. We subsequently refined these approaches to characterize carbapenem and polymyxin resistance and their concerning overlaps in Southeast Asia [31].

Since our initial study, reporting on carbapenem resistance in Africa has increased [32–34] but comprehensive analyses are not available. Information on polymyxin resistance is more limited but recent reviews document mcr plasmids as causes of resistance in several African nations [35, 36]. The 2020 WHO GLASS report included only 10 of 54 nations reporting data on carbapenems and just 4 on polymyxins. Given these persistent data gaps there is a major unmet need for information to inform medical and public health investments, strategies and practices. We applied our previously-developed approaches to locate available useful data on polymyxin/colistin resistance and related genes, as well as to broadly update analyses of carbapenem resistance to reflect emerging data and extend the scope of study to all continental Africa. The results provide a comprehensive database and maps of carbapenem and polymyxin resistance in Africa, documenting the significant ongoing spread of both throughout the continent.

Methods

Literature review and other data sources

Three comprehensive Boolean searches were constructed and utilized to query scientific and medical databases (Embase, Global Health, PubMed and Web of Science). Grey literature sources including ProMED-mail [37], ResistanceMap [38] and HealthMap [39] were also examined for data from African nations, as described [2, 31]. Data were further supplemented by review and, where meeting criteria, extraction of relevant primary data located based on citations identified through included studies or from other referenced reviews and meta-analyses, as well as directly utilizing data from World Health Organization GLASS reports [1, 25–27] and author correspondence. As detailed previously, for nations with fewer than 4 reports from these sources, manual Google Scholar searches were conducted and additional sources such as African Journals Online, Bioline International and Global Index Medicus were hand-searched for relevant documents [2].

Search strategy

As described [2, 31], search strategies were designed and executed to capture data describing susceptibility or resistance, and/or related genotypic findings, of Escherichia coli and Klebsiella isolates from humans. The searches (search operators capitalized) generally followed the structure of place (e.g. terms for Africa OR country names) AND terms for AMR (including general OR specific AMR terms OR synonym drug terms) AND species/mechanisms (including resistance enzymes and plasmid-mediated genotypes). As detailed (Additional file 1) the search strings also contained MeSH terms to optimize sensitivity while enhancing specificity. The first database search updated data from the WHO Africa Region nations (United Nations geoscheme) through 31 December 2019 [2]. The second search identified data published from 1 January 1996 to 31 December 2019 on carbapenem susceptibility or resistance for seven African countries not included in our original report (Djibouti, Egypt, Libya, Morocco, Tunisia, Somalia, and Sudan) [2]. The final search for 1 January 1996 to 31 December 2019 identified data for polymyxin susceptibility or resistance for all African nations.

Exclusion and inclusion criteria and data collection

Two authors (DMV and AYB) screened search result titles and excluded irrelevant materials. Remaining studies were examined for relevant information regarding carbapenem and/or polymyxin(s) susceptibility and/or resistance amongst E. coli and Klebsiella isolates from humans. Minimum criteria for inclusion in the study database were description of study design and sampling process, characteristics of participants, places and dates of data collection and use of recognized, standardized testing methods at the time of performance. Studies not including these data elements were excluded. Data were extracted and coded from studies meeting criteria and any coding questions resolved through mutual agreement amongst researchers.

Underlying data from 313 reports in our previous dataset [2] on carbapenem resistance in WHO Africa nations (from searches through 31 June 2017) were also incorporated into the current dataset. If a newly found study reported data duplicative of or overlapping with that included in earlier analyses, only the original report was included. We also examined the results of database searches for similar reports (e.g. in terms of country, dates and species) to detect potentially duplicative or overlapping reporting of the same data. In circumstances where searches yielded duplicative or overlapping data, the most complete study was utilized unless both included unique data, in which case any additional details from the second report were included on a separate line of the database without duplicate reporting. When a study provided potentially important findings, but substantive uncertainties were present, authors were contacted, when possible, for clarification. Outreach to authors was made for 167 studies and responses obtained for 85, of which 55 were included in the manuscript (see acknowledgements).

Database construction, definitions and data entry

A structured Microsoft Excel Version 1808 (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, USA) template with predefined attributes was developed and utilized, as described [2, 31]. Data extracted included study characteristics, patient populations, and phenotypic and genotypic carbapenem and polymyxin resistance. Study type was classified as clinical laboratory-based, case series, outbreak, or surveillance, and populations were classified as from acute or chronic healthcare facilities, community-based, travelers or unknown [31]. Selected subpopulations, if studied, were defined by clinical attributes (e.g. pregnant, intensive care unit, clinical syndrome), travel status (e.g. immigrants, refugees) and/or occupation (e.g. farmers, students, healthcare workers). WHO age classification was utilized where applicable, unless age was otherwise classified by authors [31, 40].

Reports on subsets of laboratory isolates selected based on their resistance properties were coded noting the selection criteria utilized (e.g. ESBL or CRE). If results of susceptibility testing to multiple carbapenems were reported, all data were entered in the database with the value for the drug with the highest percentage resistance then used to represent overall carbapenem resistance, so long as the numbers of isolates tested for each drug were similar. On occasions where the differences in total numbers of isolates tested against different carbapenems were large (e.g. an order of magnitude), we used results from the drug with the most isolates tested to represent resistance. Isolates reported as having intermediate susceptibility were classified as resistant. For studies presenting disaggregated susceptibility results (e.g. by ESBL status), data were reaggregated to reflect resistance in the entire original set of isolates. Documentation of specific carbapenem or polymyxin resistance-associated genotypes was recorded whenever available. For quality control, all database entries were checked and confirmed by an additional reviewer.

Data analyses

Defining the presence of resistance and/or specific resistance genotypes

Any report of at least one carbapenem and/or polymyxin-resistant E. coli or Klebsiella isolate, or an isolate with a resistance-associated genotype, signified the presence of resistance in that nation. This included findings of phenotypic resistance or resistance inducing genotypes in any isolate, whether from population-based studies or narrower studies of outbreaks, case series, highly selected subpopulations, or from studies of isolates themselves selected for known resistance to any antibiotic(s) including carbapenem and polymyxin.

Crude national resistance proportion estimates

Analysis was conducted using R version 3.5.2 (R Core Team, 2014). To estimate crude national resistance proportions, data from studies with a minimum number of isolates tested (20 for carbapenems and 10 for polymyxin, given the paucity of available data) that were deemed to originate from reasonably ‘generalizable’ populations (i.e. representative of individuals in overall healthcare populations), were aggregated and analyzed across studies. These estimates excluded any data from outbreaks or from studies reporting resistance in certain highly selected subpopulations (burn injury, oncology or transplantation) that typically have levels of resistance significantly greater than general acute-care populations. Similarly, data reporting resistance among organisms selected based on their known resistance to any antibiotic were not considered generalizable and therefore not included in resistance estimates.

To better reflect recent resistance, crude resistance proportions were calculated using data available on isolates collected from 2010 onward. If the total of generalizable E. coli or Klebsiella isolates tested for susceptibility to carbapenems or polymyxin(s) from 2010 onward was at least 100, we calculated that nation’s mean and, across qualifying studies, median resistance proportions using R v.3.5.2. For nations with at least 100 generalizable isolates of E. coli or Klebsiella, a crude estimated median resistance category was assigned consistent with prior studies [2, 31] as follows: not detected, low (< 1%), moderate (1–5%) or high (> 5%). If the total of generalizable isolates for a nation was less than 100, a category of either ‘Insufficient isolates – Resistance detected’ or ‘Insufficient isolates – Resistance not detected’ was assigned.

Geocoding and mapping

ArcGIS Desktop 10.6 (ESRI, Redlands, CA, USA) was used to map median resistance proportions and genotypes at the national level. Sample origin was geocoded at facility level, or to the closest local administrative unit such as City or State/Province using Google Maps.

Data sharing

The supplementary material, including search strings (Additional file 1) and outputs (Additional file 2), explanation of data elements extracted for analyses (Additional file 3), and all study data (Additional file 4) are available through Mendeley.

Results

Data characteristics

The searches yielded 8631 studies of which 1191 passed initial screening and 749 then met inclusion criteria. Three were in French, all others were in English. Because a given study may contain data on more than one organism, sets of isolates, or populations, the 749 study documents yielded a total of 1479 unique data reports together providing data on carbapenem and/or polymyxin resistance from 48 of 54 African countries. Three nations (Egypt, Nigeria and South Africa) accounted for 647 (43.7%) of all reports in the database. In contrast, no relevant reports were identified from 6 nations and nearly 30 nations each accounted for less than 1% of reports.

Selected general attributes of the data reports are displayed in Table 1. Six hundred and ninety-two (46.8%) reported on E. coli, while 787 (53.2%) were on Klebsiella spp. More than half of the data reports (67.5%) were from clinical laboratory-based studies, while 22.6% were from case series, 8.2% from surveillance and 2% from outbreaks. Aside from 34.6% of reports of multiple sample sources, most reports were of isolates from urine (23.3%) or blood (20.6%). Subject ages were reported as all (30%), adults (20.2%) and children (13.1%) or as unknown (34.2%). The majority (83.4%) of reports included isolates collected in acute healthcare settings, others included community-based settings (29.0%), chronic health-care facilities (0.5%), unknown healthcare settings (4.2%), travelers (1.0%) and unknown sources (1.7%).

Table 1.

Key data attributes

| Age group | Number (%) | Population type | Number (%) | Study type | Number (%) | Specimen type | Number (%) | Specimen type | Number (%) | Species | Number (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adolescent | 37 (2.5%) | Community | 429 (29.0%) | Case series | 334 (22.6%) | Ascitic fluid | 3 (0.2%) | Pus | 17 (1.2%) | E. coli a | 692 (46.8%) |

| Adult | 299 (20.2%) | HC-acute | 1234 (83.4%) | Clinical lab | 998 (67.5%) | Aspirate | 1 (0.1%) | Rectal | 1 (0.1%) | K. spp. b | 787 (53.2%) |

| All | 444 (30.0%) | HC-long | 8 (0.5%) | Outbreak | 29 (2.0%) | BAL | 1 (0.1%) | Respiratory | 6 (0.4%) | ||

| Child | 194 (13.1%) | HC-unknown | 62 (4.2%) | Surveillance | 121 (8.2%) | Bedsore | 1 (0.1%) | Sperm | 1 (0.1%) | ||

| Elderly | 16 (1.1%) | Travelers | 15 (1.0%) | Blood | 304 (20.6%) | Sputum | 9 (0.6%) | ||||

| Infant | 56 (3.8%) | Unknown | 25 (1.7%) | Catheter | 2 (0.1%) | Stool | 184 (12.4%) | ||||

| Neonate | 61 (4.1%) | Cervicovaginal | 2 (0.1%) | Tissue | 7 (0.5%) | ||||||

| Unknown | 506 (34.2%) | CSF | 8 (0.5%) | Umbilical | 1 (0.1%) | ||||||

| Ear | 6 (0.4%) | Unknown | 62 (4.2%) | ||||||||

| Endocervical | 2 (0.1%) | Urine | 345 (23.3%) | ||||||||

| Endotracheal | 3 (0.2%) | Vaginal | 7 (0.5%) | ||||||||

| ETA | 4 (0.3%) | Wound | 69 (4.7%) | ||||||||

| Gastric fluid | 2 (0.1%) | ||||||||||

| Hand | 3 (0.2%) | ||||||||||

| IV fluid | 1 (0.1%) | ||||||||||

| Multiple | 512 (34.6%) | ||||||||||

| Nasal | 7 (0.5%) | ||||||||||

| Otitis media | 2 (0.1%) | ||||||||||

| Peritoneal fluid | 11 (0.7%) | ||||||||||

| Peritoneum | 1 (0.1%) |

Numbers and % of 1479 unique data reports including the indicated subgroups. In some categories total is > 1479 as reports may contain multiple subgroups

aEscherichia coli

bKlebsiella spp.

Carbapenem resistance: overview of data from all years

There were a total of 1341 data reports, derived from 708 studies, providing data on carbapenem susceptibility from 48 of 54 nations (Table 2). These included 622 (46.4%) on E. coli isolates and 719 (53.6%) on Klebsiella from 48 and 42 nations, respectively. Of the total 1341 reports, 879 (65.5%) were from nations in WHO Africa (including 313 incorporated from the earlier analysis [2]) while 462 (34.5%) were from the other African nations. Phenotypic and or genotypic carbapenem resistance was reported among either species in 40 of 48 nations (83.3%) from which data were available. Specifically, resistance was detected among E. coli in 36 of 48 nations (75%) with available data and among Klebsiella in 35 of 42 (83.3%). There were no data available on E. coli or Klebsiella from 6 nations (Burundi, Comoros, Lesotho, Liberia, Seychelles and Swaziland) while data were available on E. coli but not Klebsiella from an additional 6 (Cape Verde, Djibouti, Eritrea, Guinea, Lesotho, Somalia and South Sudan). Tables 3 and 4 present national-level carbapenem resistance data for all years studied, including whether resistance was reported, specific genotypes detected and, for samples from generalizable studies, percent mean resistance.

Table 2.

Available reports on E. coli and Klebsiella carbapenem and polymyxin susceptibility, resistance, and related genes

| Nation | All reports on named species (reports identifying resistance or determinants related to resistance) | References | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbapenem | Polymyxin (colistin and polymyxin B) | ||||

| E. coli | Klebsiella | E. coli | Klebsiella | ||

| Algeria | 33 (12) | 37(18) | 17(4) | 22(3) | [48–97] |

| Angola | 2(2) | 2(2) | 1(0) | 1(0) | [98, 99] |

| Benin | 6(4) | 2(1) | 2(0) | 2(0) | [100–105] |

| Botswana | 1(0) | 1(0) | 0 | 0 | [106] |

| Burkina Faso | 12(4) | 13(0) | 3(2) | 1(0) | [25, 107–121] |

| Cameroon | 11(3) | 7(3) | 3(2) | 1(0) | [116, 122–133] |

| Cape Verde | 1(0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | [116] |

| Central African Republic | 2(0) | 3(0) | 0 | 0 | [25, 134, 135] |

| Chad | 8(4) | 4(1) | 1(0) | 0 | [57, 116, 136–141] |

| Congo | 2 (0) | 1 (1) | 1(0) | 0 | [142, 143] |

| Cote d'lvoire | 4(1) | 5(1) | 1 (1) | 0 | [144–150] |

| Democratic Republic of the Congo | 3(0) | 2(1) | 0 | 0 | [151–153] |

| Djibouti | 2(1) | 0 | 1(0) | 0 | [57, 154] |

| Egypt | 106(66) | 125 (98) | 28 (14) | 34(15) | [1, 25–27, 57, 78, 116, 155–293] |

| Equatorial Guinea | 1(0) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | [294] |

| Eritrea | 1(0) | 0 | 1(0) | 0 | [295] |

| Ethiopia | 19(10) | 27(17) | 4(4) | 6(4) | [1, 112, 296–316] |

| Gabon | 4(0) | 5(1) | 0 | 0 | [317–321] |

| Gambia | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | [322] |

| Ghana | 15(5) | 15(8) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | [116, 323–337] |

| Guinea | 1(0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | [116] |

| Guinea-Bissau | 1(0) | 1(0) | 0 | 0 | [338] |

| Kenva | 26(11) | 25 (21) | 2(1) | 2(0) | [116, 168, 268, 282, 339–362] |

| Libya | 17(10) | 22(20) | 3(0) | 8(4) | [57, 78, 363–385] |

| Madagascar | 14(3) | 12(6) | 0 | 0 | [1, 26, 27, 112, 116, 168, 386–395] |

| Malawi | 4(3) | 7(5) | 1(0) | 2(0) | [26, 27, 396–398] |

| Mali | 4(3) | 2(1) | 1(0) | 0 | [1, 57, 399, 400] |

| Mauritania | 1 (1) | 1(0) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | [401] |

| Mauritius | 4(2) | 6(5) | 1(0) | 2(1) | [25, 57, 168, 183, 402–404] |

| Morocco | 24(13) | 39(24) | 6(2) | 10(2) | [25, 57, 78, 116, 183, 268, 282, 405–433] |

| Mozambique | 6(1) | 4(0) | 1(0) | 0 | [1, 116, 427, 434–438] |

| Namibia | 1(0) | 5(1) | 0 | 0 | [25, 183, 439] |

| Niger | 5(2) | 2(0) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | [57, 440–443] |

| Nigeria | 82(53) | 80(46) | 3203) | 28(15) | [1, 27, 116, 444–561] |

| Rwanda | 7(3) | 6(2) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | [562–568] |

| Sao Tome and Principe | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 | [569] |

| Senegal | 10(2) | 11(6) | 1 (1) | 3(1) | [56, 78, 112, 116, 145, 570–581] |

| Sierra Leone | 5(3) | 4(3) | 0 | 0 | [116, 582, 583] |

| Somalia | 1(0) | 0 | 1(0) | 0 | [295] |

| South Africa | 69(25) | 109(82) | 18(8) | 20(10) | [1, 25, 78, 168, 183, 268, 282, 519, 584–663] |

| South Sudan | 1(0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | [664] |

| Sudan | 12(7) | 10(5) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | [1, 27, 112, 116, 665–673] |

| Tanzania | 29(6) | 26(7) | 2(1) | 2(1) | [56, 112, 116, 168, 674–700] |

| Togo | 6(4) | 4(3) | 3(1) | 3(1) | [116, 701–706] |

| Tunisia | 34(14) | 70(43) | 15(4) | 29(13) | [1, 26, 27, 78, 168, 183, 268, 282, 707–774] |

| Uganda | 17(10) | 16(11) | 2(1) | 2(1) | [1, 26, 27, 168, 775–788] |

| Zambia | 3(1) | 4(4) | 0 | 0 | [26, 27, 789, 790] |

| Zimbabwe | 3 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | [116, 791, 792] |

| All reporting nations | 942(622) | 451 (19) | 75(158) | 76(183) | |

Reports on carbapenem or polymyxin susceptibility were not identified from the following searched nations: Burundi, Comoros, Lesotho, Liberia, Seychelles and Swaziland

Table 3.

Carbapenem resistance (R) and resistance determinants in Escherichia coli isolates: data from all years

| Findings in reports from all study years meeting criteria for generalizability | Identified resistance determinants | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nations | Number of reports | Specimens in all reports | Any R | Reports meeting criteria | Total specimens meeting criteria | Range of specimens among studies | Resistant specimens (#) | Resistant specimens (%) | |

| Algeria | 33 | 4304 | Y | 15 | 4201 | 30—1184 | 13 | 0.3 | NDM-5, OXA-48, OXA-181, VIM-19 |

| Angola | 2 | 52 | Y | 0 | 0 | – | – | – | NDM-1, NDM-5, OXA-181 |

| Benin | 6 | 692 | Y | 5 | 687 | 84–221 | 18 | 2.6 | |

| Botswana | 1 | 27 | N | 0 | 0 | – | – | – | |

| Burkina Faso | 12 | 787 | Y | 6 | 743 | 26–296 | 5 | 0.7 | GES, OXA, OXA-181 |

| Cameroon | 11 | 330 | Y | 6 | 313 | 21–163 | 7 | 2.2 | NDM-4 |

| Cape Verde | 1 | 1 | N | 0 | 0 | – | – | – | |

| CAR | 2 | 84 | N | 2 | 84 | 33–51 | 0 | 0 | |

| Chad | 8 | 402 | Y | 5 | 382 | 31–128 | 6 | 1.6 | NDM-5, OXA, OXA-181 |

| Congo | 2 | 112 | Y | 2 | 112 | 23–89 | 4 | 3.6 | OXA-48 |

| Côte d'Ivoire | 4 | 145 | Y | 2 | 121 | 57–64 | 0 | 0 | |

| DRC | 3 | 451 | N | 3 | 451 | 21–376 | 0 | 0 | |

| Djibouti | 2 | 32 | Y | 1 | 31 | – | 0 | 0 | OXA-48 |

| Egypt | 106 | 8657 | Y | 56 | 7549 | 20–3177 | 425 | 5.6 | KPC, GES, IMP, NDM, NDM-1, NDM-5, OXA-48, OXA-181, VIM, VIM-1, VIM-2 |

| Equatorial Guinea | 1 | 39 | N | 1 | 39 | – | 0 | 0 | |

| Eritrea | 1 | 14 | N | 0 | 0 | – | – | – | |

| Ethiopia | 19 | 1794 | Y | 12 | 1729 | 31–235 | 54 | 3.1 | KPC |

| Gabon | 4 | 142 | N | 3 | 133 | 30–57 | 0 | 0 | |

| Gambia | 1 | 8 | Y | 0 | 0 | – | – | – | |

| Ghana | 15 | 621 | Y | 9 | 568 | 25–124 | 27 | 4.8 | NDM-1, OXA-48 |

| Guinea | 1 | 1 | N | 0 | 0 | – | – | – | |

| Guinea-Bissau | 1 | 83 | N | 1 | 83 | – | 0 | 0 | |

| Kenya | 26 | 10,654 | Y | 18 | 10,554 | 25–5165 | 57 | 0.5 | |

| Libya | 17 | 1387 | Y | 8 | 1154 | 75–346 | 62 | 5.4 | OXA-48 |

| Madagascar | 14 | 1381 | Y | 8 | 1355 | 31–672 | 7 | 0.5 | |

| Malawi | 4 | 2601 | Y | 2 | 2592 | 657–1935 | 54 | 2.1 | NDM-5, OXA-48 |

| Mali | 4 | 211 | Y | 3 | 210 | 31–132 | 25 | 11.9 | NDM-4, OXA-181 |

| Mauritania | 1 | 366 | Y | 1 | 366 | – | 4 | 1.1 | |

| Mauritius | 4 | 202 | Y | 1 | 183 | – | 5 | 2.7 | OXA-181 |

| Morocco | 24 | 3585 | Y | 10 | 3459 | 49–1174 | 41 | 1.2 | IMP-1, OXA-48 |

| Mozambique | 6 | 188 | Y | 3 | 161 | 35–75 | 0 | 0 | |

| Namibia | 1 | 23 | N | 1 | 23 | – | 0 | 0 | |

| Niger | 5 | 720 | Y | 3 | 502 | 27–434 | 0 | 0 | OXA-181 |

| Nigeria | 82 | 5072 | Y | 43 | 4161 | 21–400 | 319 | 7.7 | GES, NDM, OXA, OXA-48, OXA-181, VIM |

| Rwanda | 7 | 3009 | Y | 6 | 3002 | 55–2473 | 201 | 6.7 | |

| Sao Tome and Principe | 1 | 30 | Y | 0 | 0 | – | – | – | OXA-181 |

| Senegal | 10 | 581 | Y | 4 | 554 | 33–398 | 1 | 0.2 | OXA-48 |

| Sierra Leone | 5 | 14 | Y | 0 | 0 | – | – | – | DIM-1, OXA-58, VIM |

| Somalia | 1 | 27 | N | 1 | 27 | – | 0 | 0 | |

| South Africa | 69 | 36,224 | Y | 41 | 35,930 | 20–14,348 | 333 | 0.9 | NDM, NDM-1, NDM-5, OXA-48, VIM, VIM-1 |

| South Sudan | 1 | 65 | N | 0 | 0 | – | – | – | |

| Sudan | 12 | 1085 | Y | 4 | 978 | 71–458 | 72 | 7.4 | IMP, NDM |

| Tanzania | 29 | 1977 | Y | 16 | 1793 | 20–837 | 18 | 1 | KPC, IMP, NDM, OXA-48, VIM |

| Togo | 6 | 238 | Y | 2 | 109 | 35–74 | 1 | 0.9 | |

| Tunisia | 34 | 23,696 | Y | 17 | 23,619 | 31–9485 | 214 | 0.9 | KPC-2, NDM-1, OXA-48 |

| Uganda | 17 | 1532 | Y | 6 | 1302 | 22–930 | 167 | 12.8 | KPC, IMP, OXA-48, VIM |

| Zambia | 3 | 477 | Y | 3 | 477 | 56–343 | 341 | 71.5 | |

| Zimbabwe | 3 | 204 | Y | 2 | 203 | 23–180 | 27 | 13.3 | |

| All reporting countries | 622 | 114,327 | Y | 332 | 109,940 | 20–14,348 | 2508 | 2.3** | |

Y One or more resistant isolates identified phenotypically or genotypically

N No resistant isolates identified phenotypically or genotypically

**Calculation should not be considered an estimate of overall resistance due to varying totals of specimens meeting criteria across nations

–Data not available

Table 4.

Carbapenem resistance (R) and resistance determinants in Klebsiella spp. isolates: data from all years

| Findings in reports from all study years meeting criteria for generalizability | Identified resistance determinants | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nations | Number of reports | Specimens in all reports | Any R | Reports meeting criteria | Total specimens meeting criteria | Range of specimens among studies | Resistant specimens (#) | Resistant specimens (%) | |

| Algeria | 37 | 2174 | Y | 12 | 1968 | 24–608 | 25 | 1.3 | KPC-3, NDM, NDM-1, OXA-48, VIM-19 |

| Angola | 2 | 49 | Y | 0 | 0 | – | – | – | NDM-1, NDM-5, OXA-181 |

| Benin | 2 | 51 | Y | 1 | 41 | – | 1 | 2.4 | |

| Botswana | 1 | 40 | N | 0 | 0 | – | – | – | |

| Burkina Faso | 13 | 297 | N | 4 | 242 | 20–109 | 0 | 0 | |

| Cameroon | 7 | 299 | Y | 4 | 276 | 28–99 | 5 | 1.8 | |

| CAR | 3 | 77 | N | 2 | 67 | 24–43 | 0 | 0 | |

| Chad | 4 | 87 | Y | 3 | 86 | 23–35 | 1 | 1.2 | OXA |

| Congo | 1 | 12 | Y | 0 | 0 | – | – | – | |

| Côte d'Ivoire | 5 | 237 | Y | 4 | 229 | 22–107 | 0 | 0 | |

| DRC | 2 | 167 | Y | 2 | 167 | 21–146 | 1 | 0.6 | |

| Egypt | 125 | 7320 | Y | 59 | 5501 | 20–594 | 1545 | 28.1 | KPC, KPC-2, IMP, IMP-1, NDM, NDM-1, OXA-48, VIM, VIM-1, VIM-2 |

| Equatorial Guinea | 1 | 30 | Y | 1 | 30 | – | 1 | 3.3 | |

| Ethiopia | 27 | 808 | Y | 9 | 675 | 30–154 | 78 | 11.6 | KPC, NDM-1 |

| Gabon | 5 | 161 | Y | 2 | 146 | 67–79 | 0 | 0 | NDM-7 |

| Gambia | 1 | 9 | Y | 0 | 0 | – | – | – | |

| Ghana | 15 | 537 | Y | 10 | 505 | 20–107 | 85 | 16.8 | NDM, OXA-48 |

| Guinea-Bissau | 1 | 91 | N | 1 | 91 | – | 0 | 0 | |

| Kenya | 25 | 1471 | Y | 15 | 1419 | 25–272 | 131 | 9.2 | KPC, NDM, NDM-1, NDM-5, OXA-48, OXA-58, VIM |

| Libya | 22 | 709 | Y | 8 | 514 | 24–158 | 202 | 39.3 | KPC, NDM, NDM-1, OXA-48 |

| Madagascar | 12 | 472 | Y | 6 | 418 | 22–122 | 13 | 3.1 | NDM-1 |

| Malawi | 7 | 1315 | Y | 2 | 1276 | 173–1103 | 60 | 4.7 | KPC-2, OXA-48 |

| Mali | 2 | 67 | Y | 2 | 67 | 26–41 | 7 | 10.4 | |

| Mauritania | 1 | 137 | N | 1 | 137 | – | 0 | 0 | |

| Mauritius | 6 | 235 | Y | 2 | 222 | 104–118 | 13 | 5.9 | NDM-1, OXA-181 |

| Morocco | 39 | 1784 | Y | 10 | 1380 | 24–389 | 69 | 5 | IMP-1, NDM-1, OXA-48, VIM-1 |

| Mozambique | 4 | 63 | N | 1 | 21 | – | 0 | 0 | |

| Namibia | 5 | 313 | Y | 2 | 303 | 23–280 | 1 | 0.3 | |

| Niger | 2 | 21 | N | 0 | 0 | – | – | – | |

| Nigeria | 80 | 4111 | Y | 42 | 3524 | 21–600 | 318 | 9 | GES, NDM, NDM-1, NDM-5, OXA, OXA-48, OXA-181, VIM |

| Rwanda | 6 | 1222 | Y | 5 | 1214 | 22–975 | 108 | 8.9 | |

| Sao Tome and Principe | 1 | 4 | Y | 0 | 0 | – | – | – | OXA-181 |

| Senegal | 11 | 249 | Y | 5 | 173 | 21–40 | 2 | 1.2 | OXA-48 |

| Sierra Leone | 4 | 15 | Y | 0 | 0 | – | – | – | DIM-1, OXA-58, VIM |

| South Africa | 109 | 45,588 | Y | 53 | 42,915 | 20–15,589 | 4214 | 9.8 | KPC, KPC-2, GES, IMP, NDM, NDM-1, OMP, OXA, OXA-48, OXA-181, OXA-232, VIM, VIM-1 |

| Sudan | 10 | 988 | Y | 5 | 940 | 21–404 | 98 | 10.4 | IMP, NDM |

| Tanzania | 26 | 947 | Y | 14 | 790 | 20–139 | 16 | 2 | KPC, IMP, NDM, OXA-48, VIM |

| Togo | 4 | 165 | Y | 1 | 86 | – | 3 | 3.5 | OXA-181 |

| Tunisia | 70 | 12,842 | Y | 26 | 12,117 | 21–2826 | 1417 | 11.7 | KPC, NDM, NDM-1, OMP, OXA-48, OXA-58, OXA-232, VIM, VIM-4 |

| Uganda | 16 | 319 | Y | 3 | 116 | 22–55 | 14 | 12.1 | KPC, IMP, NDM-1, OXA-48, VIM |

| Zambia | 4 | 683 | Y | 4 | 683 | 58–432 | 435 | 63.7 | |

| Zimbabwe | 1 | 130 | Y | 1 | 130 | – | 10 | 7.7 | |

| All reporting countries | 719 | 86,296 | Y | 322 | 78,469 | 20–15,589 | 8873 | 11.3** | |

Y One or more resistant isolates identified phenotypically or genotypically

N No resistant isolates identified phenotypically or genotypically

**Calculation should not be considered an estimate of overall resistance due to varying totals of specimens meeting criteria across nations

–Data not available

Carbapenem resistance among more recent E. coli isolates

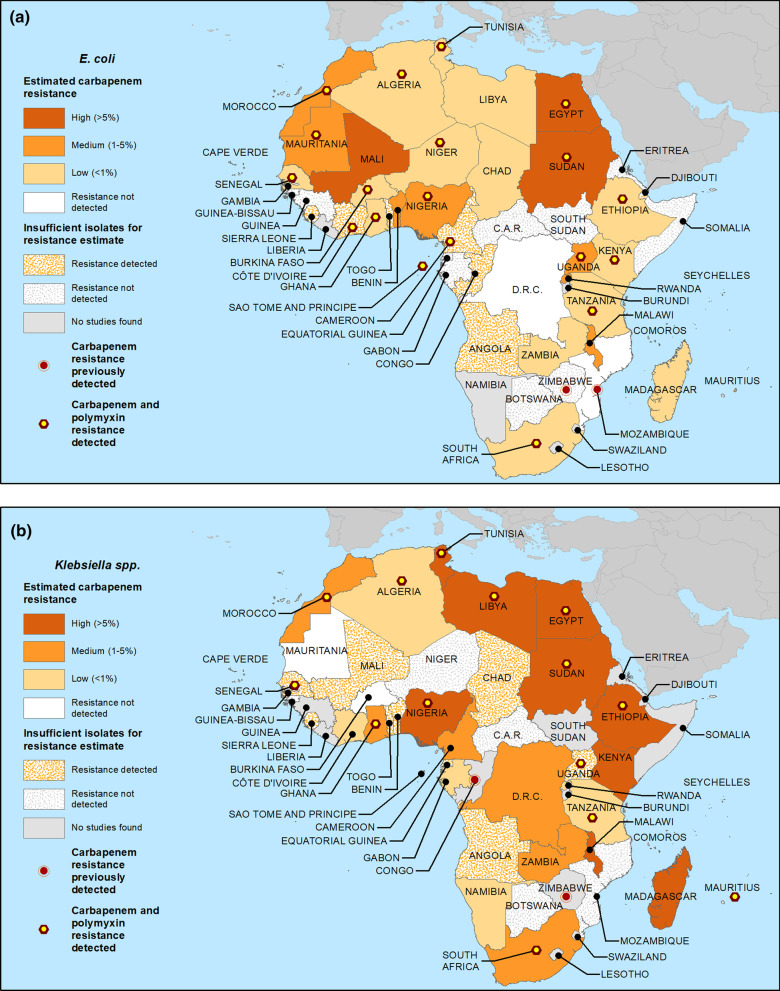

Table 5 displays carbapenem resistance data for E. coli based on samples collected in 2010 and later, including the mean and range of resistance percentages across studies, and, for nations with at least 100 generalizable isolates since 2010, crude estimated national resistance proportions (median across qualifying reports). Three nations (Egypt, Mali and Sudan) had high estimated resistance. Eight (Benin, Malawi, Mauritania, Mauritius, Morocco, Nigeria, Rwanda and Uganda) had moderate estimated resistance, and resistance in 14 nations (Algeria, Burkina Faso, Chad, Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Libya, Madagascar, Niger, Senegal, South Africa, Tanzania, Tunisia and Zambia) was estimated as low. Resistance was not detected among ≥ 100 E. coli isolates from either the Democratic Republic of the Congo or Mozambique. Among nations with insufficient E. coli isolates to allow estimates, resistance was detected in nine (Angola, Cameroon, Congo, Côte d’Ivoire, Djibouti, Gambia, Sao Tome and Principe, Sierra Leone and Togo) and not detected in 11 (Botswana, Cape Verde, Central African Republic, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Gabon, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Somalia, South Sudan and Zimbabwe). No relevant data were identified from Namibia. Resistance data for E. coli are mapped in Fig. 1a.

Table 5.

Carbapenem resistance (R) estimates and data for Escherichia coli isolates from studies including samples from 2010 and later

| Findings in reports from all study years meeting criteria for generalizability | Resistance estimate category | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nations | Number of reports | Specimens in all reports | Any R | Reports meeting criteria | Total specimens meeting criteria | Range of specimens among studies | Resistant specimens (#) | Resistant specimens (%) | Resistant range (%) | Median R | |

| Algeria | 21 | 2434 | Y | 10 | 2371 | 30–1184 | 13 | 0.5 | 0–12.7 | 0 | Low |

| Angola | 2 | 52 | Y | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | Insufficient isolates—resistance detected |

| Benin | 5 | 503 | Y | 4 | 498 | 84–221 | 11 | 2.2 | 0–8 | 2.3 | Moderate |

| Botswana | 1 | 27 | N | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | Insufficient isolates—resistance not detected |

| Burkina Faso | 10 | 651 | Y | 5 | 611 | 26–296 | 5 | 0.8 | 0–16.1 | 0 | Low |

| Cameroon | 6 | 69 | Y | 2 | 54 | 24–30 | 5 | 9.3 | 0–16.7 | N/A* | Insufficient isolates—resistance detected |

| Cape Verde | 1 | 1 | N | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | Insufficient isolates—resistance not detected |

| CAR | 2 | 84 | N | 2 | 84 | 33–51 | 0 | 0 | 0–0 | N/A* | Insufficient isolates—resistance not detected |

| Chad | 8 | 402 | Y | 5 | 382 | 31–128 | 6 | 1.6 | 0–4.7 | 0 | Low |

| Congo | 1 | 89 | Y | 1 | 89 | - | 3 | 3.4 | - | N/A* | Insufficient isolates—resistance detected |

| Côte d'Ivoire | 2 | 71 | Y | 1 | 57 | - | 0 | 0 | - | N/A* | Insufficient isolates—resistance detected |

| DRC | 3 | 451 | N | 3 | 451 | 21–376 | 0 | 0 | 0–0 | 0 | Resistance not detected |

| Djibouti | 2 | 32 | Y | 1 | 31 | - | 0 | 0 | - | N/A* | Insufficient isolates—resistance detected ^ |

| Egypt | 71 | 4094 | Y | 36 | 3274 | 21–486 | 377 | 11.5 | 0–83.3 | 7.9 | High |

| Equatorial Guinea | 1 | 39 | N | 1 | 39 | - | 0 | 0 | - | N/A* | Insufficient isolates—resistance not detected |

| Eritrea | 1 | 14 | N | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | Insufficient isolates—Resistance not detected |

| Ethiopia | 19 | 1794 | Y | 12 | 1729 | 31–235 | 54 | 3.1 | 0–41.8 | 0.9 | Low |

| Gabon | 3 | 85 | N | 2 | 76 | 30–46 | 0 | 0 | 0–0 | N/A* | Insufficient isolates—RESISTANCE not detected |

| Gambia | 1 | 8 | Y | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | Insufficient isolates—resistance detected |

| Ghana | 12 | 394 | Y | 6 | 341 | 25–118 | 27 | 7.9 | 0–40.6 | 0 | Low |

| Guinea | 1 | 1 | N | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | Insufficient isolates—resistance not detected |

| Guinea-Bissau | 1 | 83 | N | 1 | 83 | - | 0 | 0 | - | N/A* | Insufficient isolates—resistance not detected |

| Kenya | 13 | 8603 | Y | 11 | 8595 | 25–5165 | 37 | 0.4 | 0–13 | 0 | Low |

| Libya | 14 | 1133 | Y | 7 | 1035 | 75–346 | 62 | 6 | 0–52 | 0.6 | Low |

| Madagascar | 9 | 1190 | Y | 5 | 1171 | 46–672 | 7 | 0.6 | 0–2 | 0.6 | Low |

| Malawi | 3 | 2600 | Y | 2 | 2592 | 657–1935 | 54 | 2.1 | 1.4–4.1 | 2.7 | Moderate |

| Mali | 3 | 164 | Y | 2 | 163 | 31–132 | 25 | 15.3 | 3.3–18.2 | 10.7 | High |

| Mauritania | 1 | 366 | Y | 1 | 366 | - | 4 | 1.1 | - | 1 | Moderate |

| Mauritius | 2 | 184 | Y | 1 | 183 | - | 5 | 2.7 | - | 3 | Moderate |

| Morocco | 15 | 3292 | Y | 7 | 3197 | 83–1174 | 41 | 1.3 | 0–5.7 | 1.1 | Moderate |

| Mozambique | 5 | 176 | N | 3 | 161 | 35–75 | 0 | 0 | 0–0 | 0 | Resistance not detected |

| Niger | 4 | 679 | Y | 2 | 461 | 27–434 | 0 | 0 | 0–0 | 0 | Low |

| Nigeria | 62 | 3095 | Y | 30 | 2567 | 21–278 | 265 | 10.3 | 0–63 | 2.7 | Moderate |

| Rwanda | 5 | 417 | Y | 4 | 410 | 55–139 | 8 | 2 | 0–8 | 1.7 | Moderate |

| Sao Tome and Principe | 1 | 30 | Y | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | Insufficient isolates—resistance detected |

| Senegal | 6 | 174 | Y | 3 | 156 | 33–74 | 1 | 0.6 | 0–3 | 0 | Low |

| Sierra Leone | 5 | 14 | Y | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | Insufficient isolates—resistance detected ^ |

| Somalia | 1 | 27 | N | 1 | 27 | - | 0 | 0 | - | N/A* | Insufficient isolates—resistance not detected |

| South Africa | 36 | 24,270 | Y | 22 | 24,135 | 20–14,348 | 264 | 1.1 | 0–82.6 | 0 | Low |

| South Sudan | 1 | 65 | N | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | Insufficient isolates—Resistance NOT detected |

| Sudan | 10 | 614 | Y | 3 | 520 | 71–326 | 72 | 13.8 | 9–36.6 | 10.7 | High |

| Tanzania | 22 | 912 | Y | 13 | 819 | 20–164 | 18 | 2.2 | 0–19.2 | 0 | Low |

| Togo | 5 | 164 | Y | 1 | 35 | - | 0 | 0 | - | N/A* | Insufficient isolates—resistance detected |

| Tunisia | 17 | 21,324 | Y | 10 | 21,299 | 48–9485 | 207 | 1 | 0–3.7 | 0.6 | Low |

| Uganda | 13 | 598 | Y | 5 | 372 | 22–181 | 18 | 4.8 | 0–19 | 4.5 | Moderate |

| Zambia | 3 | 477 | Y | 3 | 477 | 56–343 | 341 | 71.5 | 0–99.3 | 0 | Low |

| Zimbabwe | 2 | 24 | N | 1 | 23 | - | 0 | 0 | - | N/A* | Insufficient isolates—resistance not detected |

| All reporting countries | 432 | 81,970 | Y | 229 | 78,934 | 20–14,348 | 1930 | 2.4** | – | – | – |

Y one or more resistant isolates identified phenotypically or genotypically

N no resistant isolates identified phenotypically or genotypically

^Only genotypic resistance reported

*Insufficient isolates (< 100) for carbapenem resistance estimate

**Calculation should not be considered an estimate of overall resistance due to varying totals of specimens meeting criteria across nations

-Data not available

–Not calculated

Fig. 1.

Estimated crude median national carbapenem resistance proportions for a E. coli and b Klebsiella spp. for studies including samples from 2010 and later. For those nations with ≥ 100 isolates from qualifying studies (see Methods), median proportions across studies were calculated. Where < 100 isolates, data were deemed insufficient to estimate proportions and resistance is represented as either detected or not

Carbapenem resistance among more recent Klebsiella isolates

Median carbapenem resistance among recent Klebsiella isolates (Table 6) was estimated as high in 10 nations (Egypt, Ethiopia, Kenya, Libya, Madagascar, Malawi, Mauritius, Nigeria, Sudan and Tunisia). Six nations had moderate estimated resistance (Cameroon, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ghana, Morocco, South Africa and Zambia), while resistance in 6 others (Algeria, Côte d’Ivoire, Gabon, Namibia, Rwanda and Tanzania) was estimated as low. Burkina and Mauritania had no resistance detected in ≥ 100 isolates. Among nations with insufficient Klebsiella isolates to allow estimates, resistance was detected in 11 (Angola, Benin, Chad, Equatorial Guinea, Gambia, Mali, Sao Tome and Principe, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Togo and Uganda) and not detected in 5 (Botswana, Central African Republic, Guinea-Bissau, Mozambique and Niger). No relevant data were identified from 8 nations (Cape Verde, Congo, Djibouti, Eritrea, Guinea, Somalia, South Sudan and Zimbabwe). Resistance data for Klebsiella are mapped in Fig. 1b.

Table 6.

Carbapenem resistance (R) estimates and data for Klebsiella spp. isolates from studies including samples from 2010 and later

| Findings in reports from all study years meeting criteria for generalizability | Resistance estimate category | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nations | Number of reports | Specimens in all reports | Any R | Reports meeting criteria | Total specimens meeting criteria | Range of specimens among studies | Resistant specimens (#) | Resistant specimens (%) | Resistant range (%) | Median R | |

| Algeria | 24 | 1205 | Y | 6 | 1029 | 24–608 | 25 | 2.4 | 0–20 | 0 | Low |

| Angola | 2 | 49 | Y | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | Insufficient isolates—resistance detected |

| Benin | 2 | 51 | Y | 1 | 41 | - | 1 | 2.4 | - | N/A* | Insufficient isolates—Resistance detected |

| Botswana | 1 | 40 | N | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | Insufficient isolates—resistance not detected |

| Burkina Faso | 11 | 234 | N | 2 | 179 | 70–109 | 0 | 0 | 0–0 | 0 | Resistance not detected |

| Cameroon | 3 | 154 | Y | 2 | 151 | 52–99 | 4 | 2.6 | 0–4 | 2 | Moderate |

| CAR | 2 | 34 | N | 1 | 24 | - | 0 | 0 | - | N/A* | Insufficient isolates—Resistance not detected |

| Chad | 4 | 87 | Y | 3 | 86 | 23–35 | 1 | 1.2 | 0–2.9 | N/A* | Insufficient isolates—resistance detected |

| Côte d'Ivoire | 2 | 115 | Y | 1 | 107 | - | 0 | 0 | - | 0 | Low |

| DRC | 2 | 167 | Y | 2 | 167 | 21–146 | 1 | 0.6 | 0–4.8 | 2.4 | Moderate |

| Egypt | 94 | 4925 | Y | 45 | 3617 | 20–425 | 1321 | 36.5 | 0–86.4 | 26 | High |

| Equatorial Guinea | 1 | 30 | Y | 1 | 30 | - | 1 | 3.3 | - | N/A* | Insufficient isolates—resistance detected |

| Ethiopia | 27 | 808 | Y | 9 | 675 | 30–154 | 78 | 11.6 | 0–30 | 10.7 | High |

| Gabon | 5 | 161 | Y | 2 | 146 | 67–79 | 0 | 0 | 0–0 | 0 | Low |

| Gambia | 1 | 9 | Y | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | Insufficient isolates—Resistance detected |

| Ghana | 12 | 366 | Y | 7 | 334 | 20–91 | 84 | 25.1 | 0–57.1 | 1.6 | Moderate |

| Guinea-Bissau | 1 | 91 | N | 1 | 91 | - | 0 | 0 | - | N/A* | Insufficient isolates—resistance not detected |

| Kenya | 17 | 964 | Y | 10 | 929 | 25–272 | 117 | 12.6 | 0–30 | 5.5 | High |

| Libya | 20 | 655 | Y | 7 | 464 | 24–158 | 202 | 43.5 | 0–92 | 26.9 | High |

| Madagascar | 8 | 306 | Y | 4 | 261 | 22–122 | 13 | 5 | 0–17 | 8.6 | High |

| Malawi | 5 | 1310 | Y | 2 | 1276 | 173–1103 | 60 | 4.7 | 2.7–17.3 | 10 | High |

| Mali | 2 | 67 | Y | 2 | 67 | 26–41 | 7 | 10.4 | 0–17.1 | N/A* | Insufficient isolates—resistance detected |

| Mauritania | 1 | 137 | N | 1 | 137 | - | 0 | 0 | - | 0 | Resistance not detected |

| Mauritius | 3 | 223 | Y | 2 | 222 | 104–118 | 13 | 5.9 | 1.9–9 | 5.4 | High |

| Morocco | 27 | 1671 | Y | 9 | 1348 | 24–389 | 69 | 5.1 | 0–22.5 | 3.1 | Moderate |

| Mozambique | 3 | 44 | N | 1 | 21 | - | 0 | 0 | - | N/A* | Insufficient isolates—resistance not detected |

| Namibia | 1 | 280 | Y | 1 | 280 | - | 1 | 0.4 | - | 0.4 | Low |

| Niger | 1 | 9 | N | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | Insufficient isolates—resistance not detected |

| Nigeria | 58 | 2642 | Y | 28 | 2343 | 21–600 | 287 | 12.2 | 0–81 | 8.9 | High |

| Rwanda | 5 | 247 | Y | 4 | 239 | 22–91 | 4 | 1.7 | 0–4.6 | 0 | Low |

| Sao Tome and Principe | 1 | 4 | Y | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | Insufficient isolates—resistance detected |

| Senegal | 5 | 116 | Y | 2 | 55 | 21–34 | 2 | 3.6 | 2.9–5 | N/A* | Insufficient isolates—resistance detected |

| Sierra Leone | 4 | 15 | Y | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | Insufficient isolates—resistance detected ^ |

| South Africa | 62 | 37,049 | Y | 27 | 34,593 | 21–15,589 | 4051 | 11.7 | 0–90.1 | 3.5 | Moderate |

| Sudan | 8 | 576 | Y | 4 | 536 | 21–249 | 98 | 18.3 | 0–58 | 14.3 | High |

| Tanzania | 19 | 689 | Y | 11 | 618 | 20–139 | 16 | 2.6 | 0–13.6 | 0 | Low |

| Togo | 3 | 79 | Y | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | Insufficient isolates—resistance detected |

| Tunisia | 38 | 10,256 | Y | 12 | 9766 | 24–2826 | 1414 | 14.5 | 0–41.2 | 12.9 | High |

| Uganda | 14 | 262 | Y | 2 | 61 | 22–39 | 1 | 1.6 | 0–4.3 | N/A* | Insufficient isolates—resistance detected |

| Zambia | 4 | 683 | Y | 4 | 683 | 58–432 | 435 | 63.7 | 1–99.2 | 4.3 | Moderate |

| All reporting countries | 503 | 66,810 | Y | 216 | 60,576 | 20–15,589 | 8306 | 13.7** | – | – | – |

Y one or more resistant isolates identified phenotypically or genotypically

N no resistant isolates identified phenotypically or genotypically

^Only genotypic resistance reported

*Insufficient isolates (< 100) for carbapenem resistance estimate

**Calculation should not be considered an estimate of overall resistance due to varying totals of specimens meeting criteria across nations

-Data not available

–Not calculated

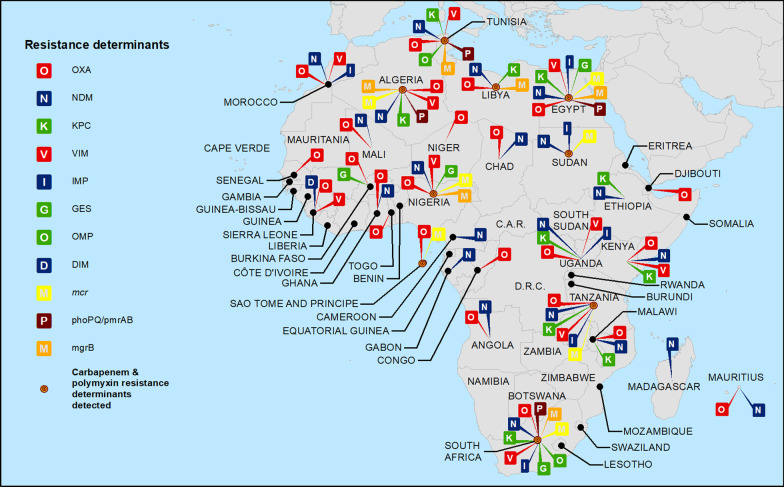

Carbapenem resistance genotypes

There were 94 data reports from 25 nations identifying at least one carbapenem resistance associated genotype among E. coli isolates (Table 3 and Fig. 2). The most common were blaOXA-48 and blaOXA-181, detected in 14 and 10 nations respectively. blaVIM was identified in 6 nations and blaNDM, blaNDM-1 and blaNDM-5 each reported in 5. blaGES was identified in 3 nations and blaNDM-4, blaOXA, and blaVIM-1 each identified in 2. blaDIM-1, blaIMP, blaIMP-1, blaKPC, blaKPC-2, blaOXA-58, blaVIM-2 and blaVIM-19 were each noted in one nation.

Fig. 2.

Carbapenem and polymyxin(s) resistance determinants reported from African nations

For Klebsiella spp., there were 187 reports from 24 nations identifying at least one carbapenem resistance genotype (Table 4 and Fig. 2). As also noted for E. coli, blaOXA-48 and blaOXA-181 were most common, detected in 14 and 10 nations, respectively. blaKPC was identified in 8 nations, blaNDM-5 and blaVIM in 6, with blaIMP, blaNDM and blaNDM-1 each found in 5. blaKPC-2 was identified in 3 nations and blaIMP-1, blaNDM-4, blaOXA and blaVIM-1 were each identified in 2. blaDIM-1, blaGES, blaKPC-3, blaVIM-2 and blaVIM-19 were each identified in 1 nation.

Polymyxin resistance: overview of data from all years

We found 341 unique data reports, derived from 208 studies, reporting data on polymyxin susceptibility from 33 of 54 African nations (Table 2). These reports included 158 (46.3%) on E. coli and 183 (53.7%) on Klebsiella, originating from 33 and 24 nations, respectively. Resistance was phenotypically or genotypically identified in 23 of the 33 nations (69.6%) from which any data were available. Tables 7 and 8 present national-level polymyxin resistance data for all years studied, including whether resistance was reported, specific genotypes detected and, for samples from generalizable studies, percent mean resistance.

Table 7.

Polymyxin (colistin and polymyxin B) resistance (R) and resistance determinants in Escherichia coli isolates: data from all years

| Findings in reports from all study years meeting criteria for generalizability | Identified resistance determinants | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nations | Number of reports | Specimens in all reports | Any R | Reports meeting criteria | Total specimens meeting criteria | Range of specimens among studies | Resistant specimens (#) | Resistant specimens (%) | |

| Algeria | 17 | 2249 | Y | 11 | 2235 | 13–1184 | 1 | < 0.1 | mcr-1 |

| Angola | 1 | 23 | N | 0 | 0 | – | – | – | |

| Benin | 2 | 97 | N | 1 | 92 | – | 0 | 0 | |

| Burkina Faso | 3 | 262 | Y | 3 | 262 | 26–205 | 40 | 15.3 | |

| Cameroon | 3 | 41 | Y | 1 | 30 | – | 30 | 100 | |

| Chad | 1 | 18 | N | 1 | 18 | – | 0 | 0 | |

| Congo | 1 | 89 | N | 1 | 89 | – | 0 | 0 | |

| Côte d'Ivoire | 1 | 177 | Y | 1 | 177 | – | 14 | 7.9 | |

| Djibouti | 1 | 31 | N | 1 | 31 | – | 0 | 0 | |

| Egypt | 28 | 1276 | Y | 14 | 678 | 11–212 | 32 | 4.7 | mcr-1, mgrB, phoPQ/pmrAB |

| Eritrea | 1 | 14 | N | 0 | 0 | – | – | – | |

| Ethiopia | 4 | 163 | Y | 3 | 150 | 17–78 | 76 | 50.7 | |

| Ghana | 1 | 49 | Y | 1 | 49 | – | 3 | 6.1 | |

| Kenya | 2 | 7 | Y | 0 | 0 | – | – | – | |

| Libya | 3 | 127 | N | 2 | 126 | 51–75 | 0 | 0 | |

| Malawi | 1 | 8 | N | 0 | 0 | – | – | – | |

| Mali | 1 | 47 | N | 1 | 47 | – | 0 | 0 | |

| Mauritania | 1 | 366 | Y | 1 | 366 | – | 6 | 1.6 | |

| Mauritius | 1 | 183 | N | 1 | 183 | – | 0 | 0 | |

| Morocco | 6 | 896 | Y | 4 | 890 | 51–398 | 47 | 5.3 | |

| Mozambique | 1 | 33 | N | 1 | 33 | – | 0 | 0 | |

| Niger | 1 | 21 | Y | 1 | 21 | – | 4 | 19 | |

| Nigeria | 32 | 1757 | Y | 21 | 1607 | 12–568 | 674 | 41.9 | mcr-1 |

| Rwanda | 1 | 2473 | Y | 1 | 2473 | – | 35 | 1.4 | |

| Sao Tome and Principe | 1 | 1 | Y | 0 | 0 | – | – | – | mcr-1 |

| Senegal | 1 | 33 | Y | 1 | 33 | – | 1 | 3 | |

| Somalia | 1 | 27 | N | 0 | 0 | – | – | – | |

| South Africa | 18 | 2665 | Y | 10 | 2605 | 16–683 | 98 | 3.8 | mcr-1, mgrB, phoPQ/pmrAB |

| Sudan | 1 | 71 | Y | 0 | 0 | – | – | – | mcr-1 |

| Tanzania | 2 | 99 | Y | 1 | 30 | – | 0 | 0 | mcr-1 |

| Togo | 3 | 80 | Y | 1 | 74 | – | 1 | 1.4 | |

| Tunisia | 15 | 15,852 | Y | 10 | 15,839 | 26–12,574 | 24 | 0.2 | |

| Uganda | 2 | 66 | Y | 1 | 61 | – | 10 | 16.4 | |

| All reporting countries | 158 | 29,301 | Y | 95 | 28,199 | 11–12,574 | 1096 | 3.9** | |

Y one or more resistant isolates identified phenotypically or genotypically

N No resistant isolates identified phenotypically or genotypically

**Calculation should not be considered an estimate of overall resistance due to varying totals of specimens meeting criteria across nations

–Data not available

Table 8.

Polymyxin (colistin and polymyxin B) resistance (R) and resistance determinants in Klebsiella spp. isolates: data from all years

| Findings in reports from all study years meeting criteria for generalizability | Identified resistance determinants | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nations | Number of reports | Specimens in all reports | Any R | Reports meeting criteria | Total specimens meeting criteria | Range of specimens among studies | Resistant specimens (#) | Resistant specimens (%) | |

| Algeria | 17 | 2249 | Y | 11 | 2235 | 13–1184 | 1 | < 0.1 | mcr-1 |

| Angola | 1 | 23 | N | 0 | 0 | – | – | – | |

| Benin | 2 | 97 | N | 1 | 92 | – | 0 | 0 | |

| Burkina Faso | 3 | 262 | Y | 3 | 262 | 26–205 | 40 | 15.3 | |

| Cameroon | 3 | 41 | Y | 1 | 30 | – | 30 | 100 | |

| Chad | 1 | 18 | N | 1 | 18 | – | 0 | 0 | |

| Congo | 1 | 89 | N | 1 | 89 | – | 0 | 0 | |

| Côte d'Ivoire | 1 | 177 | Y | 1 | 177 | – | 14 | 7.9 | |

| Djibouti | 1 | 31 | N | 1 | 31 | – | 0 | 0 | |

| Egypt | 28 | 1276 | Y | 14 | 678 | 11–212 | 32 | 4.7 | mcr-1, mgrB, phoPQ/pmrAB |

| Eritrea | 1 | 14 | N | 0 | 0 | – | – | – | |

| Ethiopia | 4 | 163 | Y | 3 | 150 | 17–78 | 76 | 50.7 | |

| Ghana | 1 | 49 | Y | 1 | 49 | – | 3 | 6.1 | |

| Kenya | 2 | 7 | Y | 0 | 0 | – | – | – | |

| Libya | 3 | 127 | N | 2 | 126 | 51–75 | 0 | 0 | |

| Malawi | 1 | 8 | N | 0 | 0 | – | – | – | |

| Mali | 1 | 47 | N | 1 | 47 | – | 0 | 0 | |

| Mauritania | 1 | 366 | Y | 1 | 366 | – | 6 | 1.6 | |

| Mauritius | 1 | 183 | N | 1 | 183 | – | 0 | 0 | |

| Morocco | 6 | 896 | Y | 4 | 890 | 51–398 | 47 | 5.3 | |

| Mozambique | 1 | 33 | N | 1 | 33 | – | 0 | 0 | |

| Niger | 1 | 21 | Y | 1 | 21 | – | 4 | 19 | |

| Nigeria | 32 | 1757 | Y | 21 | 1607 | 12–568 | 674 | 41.9 | mcr-1 |

| Rwanda | 1 | 2473 | Y | 1 | 2473 | – | 35 | 1.4 | |

| Sao Tome and Principe | 1 | 1 | Y | 0 | 0 | – | – | – | mcr-1 |

| Senegal | 1 | 33 | Y | 1 | 33 | – | 1 | 3 | |

| Somalia | 1 | 27 | N | 0 | 0 | – | – | – | |

| South Africa | 18 | 2665 | Y | 10 | 2605 | 16–683 | 98 | 3.8 | mcr-1, mgrB, phoPQ/pmrAB |

| Sudan | 1 | 71 | Y | 0 | 0 | – | – | – | mcr-1 |

| Tanzania | 2 | 99 | Y | 1 | 30 | – | 0 | 0 | mcr-1 |

| Togo | 3 | 80 | Y | 1 | 74 | – | 1 | 1.4 | |

| Tunisia | 15 | 15,852 | Y | 10 | 15,839 | 26–12,574 | 24 | 0.2 | |

| Uganda | 2 | 66 | Y | 1 | 61 | – | 10 | 16.4 | |

| All reporting countries | 158 | 29,301 | Y | 95 | 28,199 | 11–12,574 | 1096 | 3.9** | |

Y one or more resistant isolates identified phenotypically or genotypically

N No resistant isolates identified phenotypically or genotypically

**Calculation should not be considered an estimate of overall resistance due to varying totals of specimens meeting criteria across nations

–Data not available

Polymyxin resistance among more recent E. coli isolates

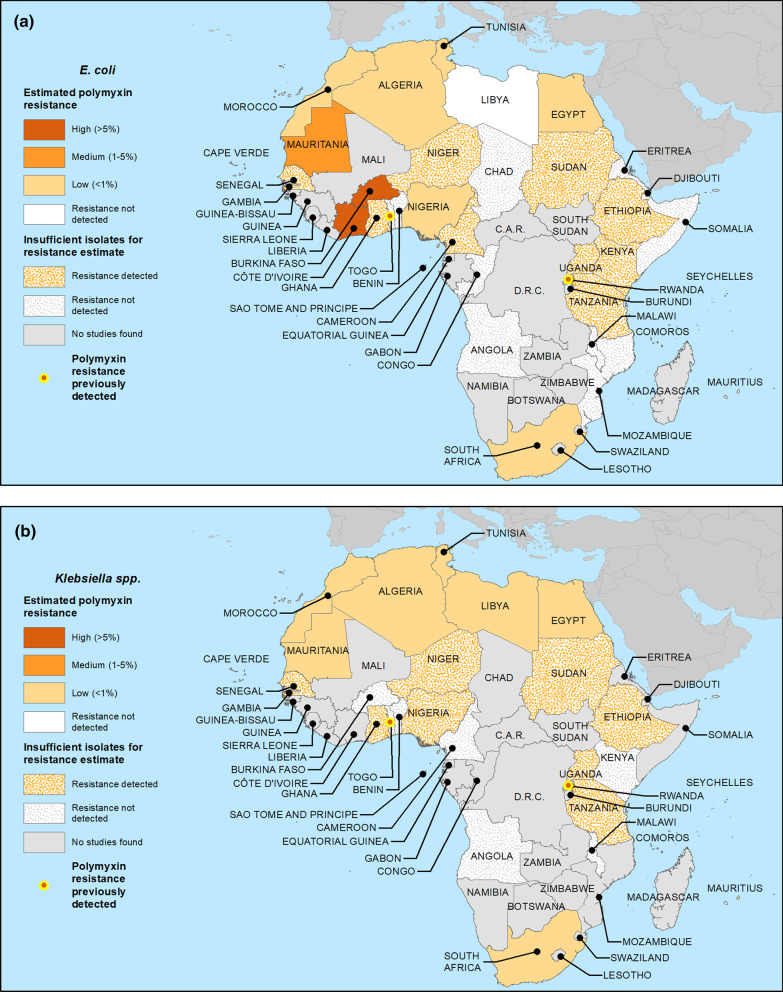

Polymyxin resistance was identified among more recent E. coli isolates from 21 of 33 nations where either phenotypic or genotypic testing was performed (Table 9). Among 11 nations where at least 100 relevant E. coli isolates from 2010 onwards were tested, median polymyxin resistance was estimated as high in Burkina Faso and Côte d’Ivoire, moderate in Mauritania, low in Algeria, Egypt, Morocco, Nigeria, South Africa and Tunisia, and was not detected in Libya and Mauritius. Although resistance was detected, there were insufficient isolates to support estimates for 10 nations (Cameroon, Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Niger, Sao Tome and Principe, Senegal, Sudan, Tanzania and Uganda). Similarly, there were 10 nations with insufficient E. coli isolates to support estimates where resistance was not detected (Angola, Benin, Chad, Congo, Djibouti, Eritrea, Malawi, Mozambique, Somalia and Togo). No relevant data were found from 18 nations (Botswana, Cape Verde, Central African Republic, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Gambia, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Madagascar, Mali, Namibia, Rwanda, Sierra Leone, South Sudan, Zambia and Zimbabwe). Resistance data for E. coli are mapped in Fig. 3a.

Table 9.

Polymyxin (colistin and polymyxin B) resistance (R) estimates and data for Escherichia coli isolates from studies including samples from 2010 and later

| Findings in reports from all study years meeting criteria for generalizability | Resistance estimate category | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nations | Number of reports | Specimens in all reports | Any R | Reports meeting criteria | Total specimens meeting criteria | Range of specimens among studies | Resistant specimens (#) | Resistant specimens (%) | Resistant range (%) | Median R | |

| Algeria | 14 | 2168 | Y | 9 | 2155 | 13–1184 | 1 | < 0.1 | 0–0.4 | 0 | Low |

| Angola | 1 | 23 | N | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | Insufficient isolates—resistance not detected |

| Benin | 2 | 97 | N | 1 | 92 | - | 0 | 0 | - | N/A* | Insufficient isolates—resistance not detected |

| Burkina Faso | 3 | 262 | Y | 3 | 262 | 26–205 | 40 | 15.3 | 0–61.3 | 10 | High |

| Cameroon | 3 | 41 | Y | 1 | 30 | - | 30 | 100 | - | N/A* | Insufficient isolates—resistance detected |

| Chad | 1 | 18 | N | 1 | 18 | - | 0 | 0 | - | N/A* | Insufficient isolates—resistance not detected |

| Congo | 1 | 89 | N | 1 | 89 | - | 0 | 0 | - | N/A* | Insufficient isolates—resistance not detected |

| Côte d'Ivoire | 1 | 177 | Y | 1 | 177 | - | 14 | 7.9 | - | 7.9 | High |

| Djibouti | 1 | 31 | N | 1 | 31 | - | 0 | 0 | - | N/A* | Insufficient isolates—resistance not detected |

| Egypt | 20 | 1015 | Y | 9 | 431 | 11–212 | 17 | 3.9 | 0–17.4 | 0.9 | Low |

| Eritrea | 1 | 14 | N | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | Insufficient isolates—resistance not detected |

| Ethiopia | 2 | 68 | Y | 1 | 55 | - | 50 | 90.9 | - | N/A* | Insufficient isolates—resistance detected |

| Ghana | 1 | 49 | Y | 1 | 49 | - | 3 | 6.1 | - | N/A* | Insufficient isolates—resistance detected |

| Kenya | 2 | 7 | Y | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | Insufficient isolates—resistance detected |

| Libya | 3 | 127 | N | 2 | 126 | 51–75 | 0 | 0 | 0–0 | 0 | Resistance not detected |

| Malawi | 1 | 8 | N | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | Insufficient isolates—resistance not detected |

| Mauritania | 1 | 366 | Y | 1 | 366 | - | 6 | 1.6 | - | 1.7 | Moderate |

| Mauritius | 1 | 183 | N | 1 | 183 | - | 0 | 0 | - | 0 | Resistance not detected |

| Morocco | 5 | 893 | Y | 4 | 890 | 51–398 | 47 | 5.3 | 0–11.3 | 0.3 | Low |

| Mozambique | 1 | 33 | N | 1 | 33 | - | 0 | 0 | - | N/A* | Insufficient isolates—resistance not detected |

| Niger | 1 | 21 | Y | 1 | 21 | - | 4 | 19 | - | N/A* | Insufficient isolates—Resistance detected |

| Nigeria | 8 | 125 | Y | 3 | 111 | 18–50 | 1 | 0.9 | 0–2.3 | 0 | Low |

| Sao Tome and Principe | 1 | 1 | Y | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | Insufficient isolates—resistance detected |

| Senegal | 1 | 33 | Y | 1 | 33 | - | 1 | 3 | - | N/A* | Insufficient isolates—Resistance detected |

| Somalia | 1 | 27 | N | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | Insufficient isolates—resistance not detected |

| South Africa | 14 | 2005 | Y | 6 | 1945 | 16–683 | 12 | 0.6 | 0–0.9 | 0.15 | Low |

| Sudan | 1 | 71 | Y | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | Insufficient isolates—resistance detected ^ |

| Tanzania | 2 | 99 | Y | 1 | 30 | - | 0 | 0 | - | N/A* | Insufficient isolates—resistance detected |

| Togo | 2 | 6 | N | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | Insufficient isolates—Resistance not detected |

| Tunisia | 11 | 3014 | Y | 7 | 3002 | 26–1075 | 13 | 0.4 | 0–1.3 | 0 | Low |

| Uganda | 2 | 66 | Y | 1 | 61 | - | 10 | 16.4 | - | N/A* | Insufficient isolates—resistance detected |

| All reporting countries | 109 | 11,137 | Y | 58 | 10,190 | 11–1184 | 249 | 2.4** | – | – | – |

Y one or more resistant isolates identified phenotypically or genotypically

N no resistant isolates identified phenotypically or genotypically

^Only genotypic resistance reported

*Insufficient isolates (< 100) for polymyxin resistance estimate

**Calculation should not be considered an estimate of overall resistance due to varying totals of specimens meeting criteria across nations

-Data not available

–Not calculated

Fig. 3.

Estimated crude median national polymyxin(s) resistance proportions for a E. coli and b Klebsiella spp. for studies including samples from 2010 and later. For those nations with ≥ 100 isolates from qualifying studies (see Methods), median proportions across studies were calculated. Where < 100 isolates, data were deemed insufficient to estimate proportions and resistance is represented as either detected or not

Polymyxin resistance among more recent Klebsiella isolates

Polymyxin resistance was identified among more recent Klebsiella isolates from 18 of 24 nations where either phenotypic or genotypic testing was performed (Table 10). Resistance was detected in all 8 nations with at least 100 generalizable Klebsiella isolates studied (Algeria, Egypt, Libya, Mauritania, Mauritius, Morocco, South Africa and Tunisia), and was estimated as low in each. Among nations with insufficient isolates to support a resistance estimate, resistance was detected in 8 (Ethiopia, Ghana, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, Sudan, Tanzania and Uganda) and not detected in 7 (Angola, Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Kenya, Malawi and Togo). No studies were identified from 25 nations (Botswana, Cape Verde, Central African Republic, Chad, Congo, Côte d’Ivoire, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Djibouti, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Gabon, Gambia, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Madagascar, Mali, Mozambique, Namibia, Rwanda, Sao Tome and Principe, Sierra Leone, Somalia, South Sudan, Zambia and Zimbabwe). Resistance data for Klebsiella are mapped in Fig. 3b.

Table 10.

Polymyxin (colistin and polymyxin B) resistance (R) estimates and data for Klebsiella spp. isolates from studies including samples from 2010 and later

| Findings in reports from all study years meeting criteria for generalizability | Resistance estimate category | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nations | Number of reports | Specimens in all reports | Any R | Reports meeting criteria | Total specimens meeting criteria | Range of specimens among studies | Resistant specimens (#) | Resistant specimens (%) | Resistant range (%) | Median R | |

| Algeria | 17 | 1056 | Y | 6 | 1015 | 13–608 | 2 | 0.2 | 0–4.3 | 0 | Low |

| Angola | 1 | 24 | N | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | Insufficient isolates—resistance not detected |

| Benin | 2 | 51 | N | 2 | 51 | 10–41 | 0 | 0 | 0–0 | N/A* | Insufficient isolates—resistance not detected |

| Burkina Faso | 1 | 5 | N | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | Insufficient isolates—resistance not detected |

| Cameroon | 1 | 3 | N | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | Insufficient isolates—resistance not detected |

| Egypt | 27 | 1084 | Y | 10 | 605 | 14–183 | 11 | 1.8 | 0–50 | 0 | Low |

| Ethiopia | 4 | 53 | Y | 3 | 51 | 10–30 | 17 | 33.3 | 0–90 | N/A* | Insufficient isolates—resistance detected |

| Ghana | 1 | 38 | Y | 1 | 38 | - | 5 | 13.2 | - | N/A* | Insufficient isolates—Resistance detected |

| Kenya | 1 | 5 | N | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | Insufficient isolates—Resistance not detected |

| Libya | 8 | 179 | Y | 3 | 136 | 24–76 | 6 | 4.4 | 0–25 | 0 | Low |

| Malawi | 2 | 8 | N | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | Insufficient isolates—resistance not detected |

| Mauritania | 1 | 137 | Y | 1 | 137 | - | 1 | 0.7 | - | 0.8 | Low |

| Mauritius | 2 | 119 | Y | 1 | 118 | - | 0 | 0 | - | 0 | Low |

| Morocco | 7 | 245 | Y | 4 | 232 | 10–118 | 28 | 12.1 | 0–22.9 | 0.6 | Low |

| Niger | 1 | 4 | Y | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | Insufficient isolates—resistance detected |

| Nigeria | 9 | 95 | Y | 4 | 80 | 10–32 | 0 | 0 | 0–0 | N/A * | Insufficient isolates—Resistance detected |

| Senegal | 1 | 34 | Y | 1 | 34 | - | 3 | 8.8 | - | N/A* | Insufficient isolates—resistance detected |

| South Africa | 15 | 2286 | Y | 7 | 1682 | 10–839 | 18 | 1.1 | 0–2.9 | 0 | Low |

| Sudan | 1 | 50 | Y | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | Insufficient isolates—resistance detected^ |

| Tanzania | 2 | 59 | Y | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | Insufficient isolates—resistance detected |

| Togo | 2 | 31 | N | 1 | 30 | - | 0 | 0 | - | N/A* | Insufficient isolates—resistance not detected |

| Tunisia | 20 | 4250 | Y | 11 | 4148 | 11–2826 | 60 | 1.4 | 0–6.2 | 0.5 | Low |

| Uganda | 2 | 20 | Y | 1 | 12 | - | 3 | 25 | - | N/A* | Insufficient isolates—resistance detected |

| All reporting countries | 128 | 9836 | Y | 56 | 8369 | 10–2826 | 154 | 1.8** | – | – | – |

Y one or more resistant isolates identified phenotypically or genotypically

N no resistant isolates identified phenotypically or genotypically

^Only genotypic resistance reported

*Insufficient isolates (< 100) for polymyxin resistance estimate

**Calculation should not be considered an estimate of overall resistance due to varying totals of specimens meeting criteria across nations

-Data not available

–Not calculated

Polymyxin resistance genotypes

Genotypic determinants of polymyxin resistance in E. coli were characterized in 15 data reports on isolates from 7 nations (Table 7 and Fig. 2), with mcr-1 found in all (Algeria, Egypt, Nigeria, Sao Tome and Principe, South Africa, Sudan and Tanzania). phoPQ/pmrAB and mgrB were identified in E. coli from Egypt and South Africa. Among Klebsiella, genotypic polymyxin resistance determinants were identified in 12 reports on isolates from 7 nations (Table 8 and Fig. 2). mcr-1 was identified in Egypt, South Africa and Sudan, and mcr-8 in Algeria. mgrb was reported from six nations (Algeria, Egypt, Libya, Nigeria, South Africa and Tunisia), and phoPQ/pmrAB identified from 4 (Algeria, Egypt, South Africa and Tunisia).

Documented geographic overlaps of carbapenem and polymyxin resistance

Overlapping resistance to carbapenems and polymyxin(s) among E. coli or Klebsiella, whether phenotypic and/or genotypic, was documented in 23 nations with overlapping genotypic resistance present in 9 (Fig. 2). Specific geographic overlaps between NDM carbapenemases and mcr genetic determinants were identified in 6 nations (Algeria, Egypt, Nigeria, South Africa, Sudan and Tanzania).

Discussion

We searched for and conducted meta-analyses and mapping of available data on carbapenem and polymyxin resistance in E. coli and Klebsiella isolates from humans in Africa. These analyses, which included 1479 unique data reports through the end of 2019, show that resistance to each of these important antibiotic classes has become increasingly widespread on the continent.

The availability of a large amount of additional data since our prior report on WHO Africa nations [2] provided substantive new insights into the distribution of carbapenem resistance and its genotypic determinants, with resistance documented in approximately ¾ of African nations (compared to less than half previously for WHO Africa [2]). Carbapenem resistance among Klebsiella was significant in most countries with sufficient isolates to support a resistance estimate and categorized as high in 10, and moderate and low in 6 nations respectively. Among E. coli, estimated resistance was generally somewhat lower: high in 3, moderate in 7, and low in 14 nations with sufficient isolates. Levels of carbapenem resistance appeared high in contiguous areas of Northern and Eastern Africa (e.g. for Klebsiella in Libya, Egypt, Sudan, Ethiopia and Kenya, Fig. 1b). The most widespread genes conferring carbapenem resistance in both species, including in that area, were blaOXA-48, blaNDM-1 and blaOXA-181. Taken together, the analyses document continuing continent-wide spread of carbapenem resistance and of a broad variety of transferrable resistance plasmids, raising concerns about the future reliability of carbapenems.

Given their importance in treating resistant infections, and the paucity of available data, we also searched for and analyzed available information on polymyxin susceptibility. We located data on polymyxin susceptibility for E. coli and/or Klebsiella spp. isolates from 33 of 54 African nations, with resistance identified in 23 of those 33 nations (69.7%) from which any data were available. For the small minority of nations with ≥ 100 isolates studied from 2010 and later, estimated resistance among E. coli to polymyxins was high in 2, moderate in 1 and low in 6. Although resistance was estimated as high in two nations, estimates were based on relatively limited isolate and study numbers, and, in many cases, older methods of susceptibility testing, and should be interpreted with caution. Estimated resistance to polymyxins was low among Klebsiella in all 8 nations with sufficient isolates to support an estimate. Polymyxin resistance genetic determinants were evaluated among E. coli and Klebsiella in 7 nations each, with the mobile mcr-1 determinant shown to be predominant, consistent with recent reviews of the genetics of colistin resistance in E. coli both globally [35] and in Africa [36].

Our analyses also show, even based on limited information available from many areas (particularly with respect to polymyxins), that geographic overlapping of carbapenem and polymyxin resistance has become common and widespread, with 23 nations having documented phenotypic and/or genotypic resistance for both. Furthermore, overlapping plasmid mediated resistance to the two drug classes was documented in 9 nations, including the presence of both NDM carbapenemases and mcr genetic determinants in 6. These findings document highly concerning ongoing risks from transferrable resistance, including, were blaNDM and mcr to be acquired by the same organism(s), the risk of infections not susceptible to currently available antibiotics.

Despite efforts to enhance surveillance, major information gaps remain. For example, searches yielded no data on polymyxin resistance from 21 nations, and 6 nations with no available data on carbapenem resistance. Furthermore, even from countries where data were available, there were often less than 100 recent isolates studied, not meeting minimal pre-specified criteria to support crude estimation of resistance proportions.

It is important to note a number of limitations of these analyses, discussed in detail previously [2, 31]. Despite use of predefined study inclusion criteria and employment of common data elements, the inherently diverse data sources, time periods and locations, as well as study designs and methods, mean that inferences must be made with caution and the data should be interpreted in the context of the timing, location and populations studied. Interested readers can access further details, including the primary data from individual reports on specific nations, in the supplemental material (Additional file 4). In addition, susceptibility testing methods and standards for breakpoints to interpret their results have evolved considerably over time and often differ among laboratories. Therefore, comparability of results across laboratories, nations and time periods may be affected by such differences. For carbapenems, minimum inhibitory concentrations considered susceptible have decreased over time, meaning that some decrease in the proportion of isolates susceptible may be expected due to changing standards. There are also major caveats with respect to the interpretation of reported polymyxin susceptibility testing results. Rather than utilizing currently recommended broth microdilution methods, most studies were performed using previously employed disk diffusion methods which may be inconsistent and may overestimate susceptibility. Therefore, while the presence and spread of resistance to polymyxins is well documented, often at both phenotypic and genotypic levels, rate estimates must be interpreted with caution.

Looking at the totality of the data, despite well over a thousand data reports from hundreds of studies, the available information from many countries was limited or, in some cases, absent. Additionally, lag periods between data acquisition and reporting, along with the analysis time since the searches included in the current study, which utilized data available through December 31, 2019, mean that the continued documentation and spread of resistance to new areas is fully expected. Thus, the non-detection of resistance in a nation should not be considered as evidence that resistance was or is absent. Ensuring a more complete picture of resistance distribution and rates will require both ongoing surveillance and continued updating of data and analyses. As also noted, where resistance proportions have been estimated, these should generally be considered to be crude approximations based on non-random reporting and samples, although in our prior study of Southeast Asia [31] the results from similarly performed meta-analyses generally tracked with national surveillance where available. Similarly, available genotypic data are even more limited, with laboratories often assaying for a limited number of specific genotype(s) rather than broadly characterizing isolates with multiplex or sequence-based methods, likely leading to under-detection of less recognized or uncommon genotypes. Other potential factors may also affect the representativeness of the data, including the tendency toward publication of positive results and the likelihood that laboratories performing susceptibility testing may be located in more urban and regional centers, typically associated with more complex care and drug resistance. We attempted to address such issues by searching not only for positive but also for negative results such as in publications where susceptibility testing was reported but not as the focus of the studies.

Despite such limitations, the findings show the widespread and overlapping presence of carbapenem and polymyxin resistance among E. coli and Klebsiella isolates from humans in Africa and highlight the urgent need to better address remaining gaps in surveillance, including to systematically determine and track rates of carbapenem and polymyxin resistance, and to monitor for the emergence of dually resistant organisms. To do so will require adequate support for sustainable laboratory and epidemiologic capacity, as stressed by both WHO [41] and the African Union and Africa CDC [42]. Robust ongoing longitudinal AMR surveillance is also critical to inform antibiotic stewardship initiatives [41, 43]. Furthermore, the widespread nature of the CRE and polymyxin resistance threats reinforces the importance of strong infection prevention and control in healthcare facilities [41, 44]. Beyond enhanced stewardship of antimicrobials and measures to contain the spread of MDRO in healthcare, the continuing use of important antimicrobials, including colistin, in animal production remains a problem that must be fully addressed [45]. Resistant organisms may also be present in and spread through waste water, including from healthcare facilities [46], agriculture, and aquaculture [46].

Conclusions

Carbapenem resistance among E. coli and Klebsiella is widely distributed in Africa, and documented in 40 of 54 nations. Although resistance rates for nations with sufficient isolates to support estimates were typically low to moderate, high rates (> 5%) were found in several nations, including 10 nations with high rates among Klebsiella. Although far less data are available concerning polymyxins, resistance was documented in 23 of 33 nations with available data. The most widespread resistance associated genotypes were, for carbapenems, blaOXA-48, blaNDM-1 and blaOXA-181 and, for polymyxins, mcr-1, mgrB, and phoPQ/pmrAB. Overlapping phenotypic and/or genotypic resistance to both carbapenems and polymyxins was documented in 23 nations, including the presence of both transferrable NDM carbapenemases and mcr determinants of polymyxin resistance in 6. These findings point to ongoing and significant risks to patient safety and public health from carbapenem and polymyxin resistance. Despite progress in recent years, resistance appears to be spreading and numerous data gaps remain, indicating the need to fully support robust AMR surveillance, antimicrobial stewardship and infection control in a manner that also addresses animal and environmental health dimensions. A One Health approach that enhances surveillance and reduces both the inappropriate use of critical antibiotics and the spread of resistant organisms in all relevant settings is essential [47].

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Boolean search strings constructed for searches of scientific databases.

Additional file 3: Annotation on data entry columns and abbreviations.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the following individuals who kindly discussed their study findings with us: Dr. Nadjat Aggoune [81], Dr. Carolyn S. Reid [109], Dr. Landry Beyala Bita’a [121], Dr. M. Y. Dehayem [126], Dr. Eugene Vernyuy Yeika [124], Dr. Oumar Ouchar Mahamat [137], Dr. Hisham A. Abbas [271], Dr. Mohamed A. El-Mokhtar [237], Dr. Rasha H. Hassan and Dr. Elham A. Hassan [265], Dr. Noha G. Khalaf [275], Dr. Reham Osama [164], Dr. Dina E. Rizk [173], Dr. Howayda E. Gomaa [184], Dr. Noha A. Hassuna [197], Dr. Anita Hallgren [167], Dr. Stephen Hawser [267], Dr. Harald Seifert [182], Dr. Philipp Zanger [294], Dr. Beza Eshetu [315], Dr. Alex Owusu-Ofori [329], Dr. Jibril Mohammed [324], Dr. Adelaide Ogutu Ayoyi [358], Dr. Tarig M.S. Alnour [371], Dr. Zoly Nantenaina Ranosiarisoa [388], Dr. Anthony G. Charles [395], Dr. Touria Essayagh [416], Dr. Adil Maleb [420], Dr. Anthony Ayodeji Adegoke [506, 517], Dr. Paul Akinniyi Akinduti [468], Dr. Charles J. Elikwu [490], Dr.Yusuf Ibrahim [497], Dr. Gbolahan O Babalola [498], Dr. Christiana Jesumirhewe [514], Dr. Ikechukwu Benjamin Moses [460], Dr. Mamadou Saidou Barry [576], Dr. Lo Seynabou [572], Dr. A. Dramowski [597], Dr. Brian Godman [602], Dr. Chetna Govind [603], Dr. Laurent Poirel [613], Dr. Johann D. D. Pitout [621], Dr. Jesús Rodríguez-Baño [643], Dr. Amidou Samie [654], Dr. John Osei Sekyere [656], Dr. A. Singh-Moodley [658], Dr. Sandeep Vasaikar [661], Dr. Jason S. Biswas [663], Dr. Malik I. A. [671], Dr. Mokline Amel [707], Dr. Carmen Torres [713], Dr. C. Chouchani [727], Dr. Ramzi Jeddi [748], Dr. Elaa Maamar [756], and Dr. Josephine Tumuhamye [781]. The authors also thank C. Scott Dorris of the Dahlgren Memorial Library at Georgetown University School of Medicine for advice on search strategies.

Author contributions