Abstract

Background

There is mounting interest in the potential efficacy of low carbohydrate and very low carbohydrate ketogenic diets in various neurological and psychiatric disorders.

Aims

To conduct a systematic review and narrative synthesis of low carbohydrate and ketogenic diets (LC/KD) in adults with mood and anxiety disorders.

Method

MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO and Cochrane databases were systematically searched for articles from inception to 6 September 2022. Studies that included adults with any mood or anxiety disorder treated with a low carbohydrate or ketogenic intervention, reporting effects on mood or anxiety symptoms were eligible for inclusion. PROSPERO registration CRD42019116367.

Results

The search yielded 1377 articles, of which 48 were assessed for full-text eligibility. Twelve heterogeneous studies (stated as ketogenic interventions, albeit with incomplete carbohydrate reporting and measurements of ketosis; diet duration: 2 weeks to 3 years; n = 389; age range 19 to 75 years) were included in the final analysis. This included nine case reports, two cohort studies and one observational study. Data quality was variable, with no high-quality evidence identified. Efficacy, adverse effects and discontinuation rates were not systematically reported. There was some evidence for efficacy of ketogenic diets in those with bipolar disorder, schizoaffective disorder and possibly unipolar depression/anxiety. Relapse after discontinuation of the diet was reported in some individuals.

Conclusions

Although there is no high-quality evidence of LC/KD efficacy in mood or anxiety disorders, several uncontrolled studies suggest possible beneficial effects. Robust studies are now needed to demonstrate efficacy, to identify clinical groups who may benefit and whether a ketogenic diet (beyond low carbohydrate) is required and to characterise adverse effects and the risk of relapse after diet discontinuation.

Keywords: Ketogenic diet, nutritional psychiatry, mood disorders, low carbohydrate diet, anxiety disorders

Mood and anxiety disorders are a major global health burden with a significant unmet need.1 There is an urgent requirement for more effective treatments.2 Current treatments include antidepressants, which have variable response rates3 and increasing concerns regarding severe withdrawal experiences,4 and psychological therapies, whose apparent efficacy might be affected by positive publication bias.5 In recent years, both preclinical and clinical evidence has emerged that supports the role of diet as an adjunctive therapeutic approach for mood disorders.6 Therapeutic options include versions of the Mediterranean diet used in the PREDIMED,7 SMILES8 and HELFIMED trials9 and two other Australian trials in young adults.10,11 Dietary approaches (whether alone or as augmentation) may be especially appealing to people with mood disorders who have mild to moderate symptoms and physical comorbidities, and therefore the potential impact on the wider population and economic factors may be significant.

One proposed dietary approach is carbohydrate reduction (typically with moderate increases in fat and protein), in the form of low carbohydrate (<130 g carbohydrate/day) and very low carbohydrate (<25–50 g/day) ketogenic diets. These have been defined and operationalised (Table 1). Low carbohydrate and ketogenic diets (LC/KD) dating back to the 1860s12 and the 1970s Atkins diet13 have shown efficacy in type 2 diabetes, obesity and metabolic syndrome. There is increasing interest, albeit with debate, especially regarding longer-term efficacy and potential adverse effects (such as hypercholesterolaemia, nutritional deficiencies and renal stones14,15). Interestingly, improvements in mood, energy, sleep, mental clarity and affect stability have been reported with use of LC/KD in type 2 diabetes and obesity.16

Table 1.

Operational definitions: low carbohydrate and ketogenic diets (LC/KD)

| Term | Abbreviation | Carbohydrate content, g/day and/or % daily intake of a nominal 2000 kcal diet | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Moderate carbohydrate diet | 300–400 g or 26–45% | Western-pattern diets typically contain over 300 g carbohydrate/day | |

| Low carbohydrate diet | LC, LCD | <130 g or <26% | |

| Very low carbohydrate diet | VLCD | <30 g (some define 25–50 g) or <10% | Leads to nutritional ketosis if maintained beyond 4–7 days |

| Ketogenic diet | KD | Fat:carbohydrate:protein ratio calculated on an individual basis for children with epilepsy | High fat and very low carbohydrate: a ketogenic diet usually refers to the strict nutritional intervention for medication-resistant paediatric epilepsy17,18 (although the term is used more widely now). First described in 1921.19 Paediatric application requires specialist neurological and dietetic monitoring. Protein restricted: gluconeogenesis reduces ketosis. Diet modified according to child's weight and growth. Response rates are significant: at 3 months 55% are seizure-free and 85% have reduced seizures.17 Two types of ketogenic diet:20

|

| Keto-adaptation | After Phinney:23 metabolic switch from carbohydrate to ketones as primary fuel source, stabilising over several weeks | ||

| Ketones | β-hydroxybutyrate (β-HB), acetoacetate, acetone | ||

| Ketosis | Presence of circulating ketones β-HB 0.5–3.0 mmol/l; physiological response to starvation or carbohydrate reduction (‘nutritional ketosis’) | ||

| Ketoacidosis | Distinct from nutritional ketosis: ketoacidosis defined as β-HB >20 mmol/l in the context of acutely destabilised type 1 diabetes, with severe hyperglycaemia and acidosis | ||

| Low carbohydrate high fat diet | LCHF | May be ketogenic (carbohydrates <25–50 g/day) or non-ketogenic (130–50 g/day); similar to the modified Atkins diet (MAD)21 | |

| Low carbohydrate ketogenic diet | LCKD, KLCHF | The terms LCHF, KLCHF, LC/KD and ketogenic diet have some overlap and may appear interchangeably in the literature |

Source: modified from Accurso et al.32

The ketogenic diet has shown some efficacy for medication-resistant paediatric epilepsy, first suggested in 1921.19 An updated Cochrane review17 reported promising results for this intervention, with greater seizure reduction in those on a ketogenic diet compared with usual care: seizure freedom in up to 55% of children and seizure reduction in up to 85% after 3 months. However, conclusions were limited by the small number of studies and sample sizes and low to very low overall quality of evidence. Nevertheless, ketogenic diets are increasingly used for medication-resistant epilepsy, and there has been an increase in specialist ketogenic diet services.24 Together, research from epilepsy as well as studies describing improvements in mood and cognition in type 2 diabetes and obesity has stimulated interest in ketogenic diets for various psychiatric and neurological disorders, including cerebral glioma, Parkinson's disease, multiple sclerosis, chronic fatigue25,26 and mood disorders.26–28

Poor nutrition is a substantial driver of the global increase in non-communicable disorders.1,29–31 The pro-inflammatory and high carbohydrate content (typically >300 g/day32) of Western-pattern diets, especially high refined carbohydrates and ultra-processed foods, may be key factors.31

Importantly, it should be noted that the term ‘carbohydrates’ is now colloquially used to refer to highly refined carbohydrates, which make up a substantial part of Western diets. However, foods that are known to impart substantial health benefits due to their fibre content33 as well as dietary components used by gut bacteria to form molecules essential to health, such as polyphenols and resistant starch, including starchy vegetables, different whole-grain cereals and legumes, are also high in carbohydrates. These foods form a substantial part of Mediterranean diets, which have been linked to positive health outcomes.34 References to ‘carbohydrates’ throughout this review should be read with this important distinction in mind.

LC/KD are plausible therapies for mood disorders for several reasons. The relationship between mood disorders and carbohydrate intake is complex, with both acute and habitual effects at play. At a population level, sugar intake correlates with depression rates.35 High glycaemic index (GI) diets appear to negatively affect mood.36–45 Furthermore, ‘comfort eating’ is common in mood disorders and carbohydrate cravings are often present in seasonal affective disorder46 and atypical depression, which is common in bipolar disorder.47 Reducing carbohydrate intake might therefore alleviate mood disorder symptoms in some individuals. Indeed, animal models of depression suggest that a ketogenic diet might exert an antidepressant or anxiolytic effect.48 Case studies have also reported amelioration of psychotic symptoms following initiation of a ketogenic diet.49 However, randomised controlled trials (RCTs) are required to establish efficacy in reducing depression, anxiety and psychotic symptoms in psychiatric populations.

Although the efficacy of LC/KD for mood and anxiety disorders has not yet been established, public interest is increasing and clinicians may already encounter individuals utilising such approaches.50 A self-report uncontrolled survey of low carbohydrate diets in 1580 patients with a variety of conditions, including obesity and type 2 diabetes, reported significant improvements in mood, anxiety and energy and a reduction in antidepressant use (although psychiatric diagnoses were not provided).16 In contrast, a systematic review of LC/KD RCTs in obese and overweight adults without epilepsy or mood disorders (eight studies, n = 532, duration 8 weeks to 1 year) reported no overall psychological benefits.51 Two RCTs have also examined mood and behavioural effects of a ketogenic diet in paediatric epilepsy: Ijff et al reported reductions in anxious and mood-disturbed behaviour in those on a ketogenic diet,52 whereas Lambrechts et al found a tendency towards an increase in mood problems.53

Given this background, the aim of the current study was to systematically review low carbohydrate and ketogenic interventions in adults with mood and anxiety disorders to direct further avenues for research and to highlight uncertainties for clinical practice.

Method

This review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines54 and registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO: CRD42019116367). The following adjustments to the methods set out in the protocol were made during the review: (a) English language articles only were considered; (b) studies did not need to include a non-exposed comparison group to be eligible for inclusion, to widen the scope and generalisability of the review; (c) an adapted version of the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale was used for the risk of bias assessment,55 as it was more appropriate for the included study designs; and (d) grey literature was excluded in order to improve the quality of included studies.

Eligibility criteria

Eligibility criteria: (a) primary research article; (b) published between database inception to 6 September 2022; (c) published in a peer-reviewed journal; (d) human adult participants (>18 years of age); (e) published in the English language; (f) individuals with mood or anxiety disorders, defined here as depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder and schizoaffective disorder; (g) low carbohydrate diet or ketogenic diet as the intervention. Exclusion criteria were papers in which the population had a primary neurodevelopmental disorder diagnosis (such as autism spectrum disorder or attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder) and animal studies.

Information sources and search strategy

The search strategy was developed based on the research question ‘Do low carbohydrate or ketogenic diets confer mood benefits in mood and anxiety disorders?’ and the following PICOS (participants, interventions, comparisons, outcomes, study design) criteria:

participants: adults with depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder or schizoaffective disorder

interventions: low carbohydrate or ketogenic diets

comparisons: if reported, ‘normal’ or ‘moderate’ carbohydrate diet, or Western-pattern diet, or placebo, or usual care, or befriending, or psychological support

outcomes: reports of response, remission, relapse of symptoms (where reported, as defined by validated measures); adverse events; attrition

study design: RCTs; if RCTs were not available, cohort studies, case series, case reports.

A systematic search of MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO and Cochrane was performed on 6 September 2022. No lower date search limit was set. The search strategy is detailed in Supplementary file 1, available at https://dx.doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2023.36.

Study selection

Two reviewers (D.M.D. and M.H. and subsequently D.M.D. and J.K.-G.) independently assessed all retrieved records for inclusion using Covidence systematic review software (Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia; www.covidence.org). First, reviewers screened titles and abstracts for eligibility. Any potentially eligible or ambiguous records were retained for the second round of screening, in which full texts were examined. Any discrepancies in the final articles to be included were discussed in a consensus meeting.

Data extraction

Two authors (of D.M.D., J.K.-G., M.H. and W.M.) extracted the following information from included studies using Covidence software: author/date, study design, sample size, population characteristics (age, gender, comorbidities), type and duration of dietary intervention, adverse events and mental health-related outcomes, including measures of depression, anxiety and mood, and psychosis rating scales. The primary outcome was a clinically significant change in symptoms and/or change from baseline to last observation for relevant rating scales.

Study risk of bias assessment

An adapted version of the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale was used for the risk of bias assessment,55 using items appropriate for cross-sectional, observational, cohort and non-randomised interventional study designs.

Results

Characteristics of included studies

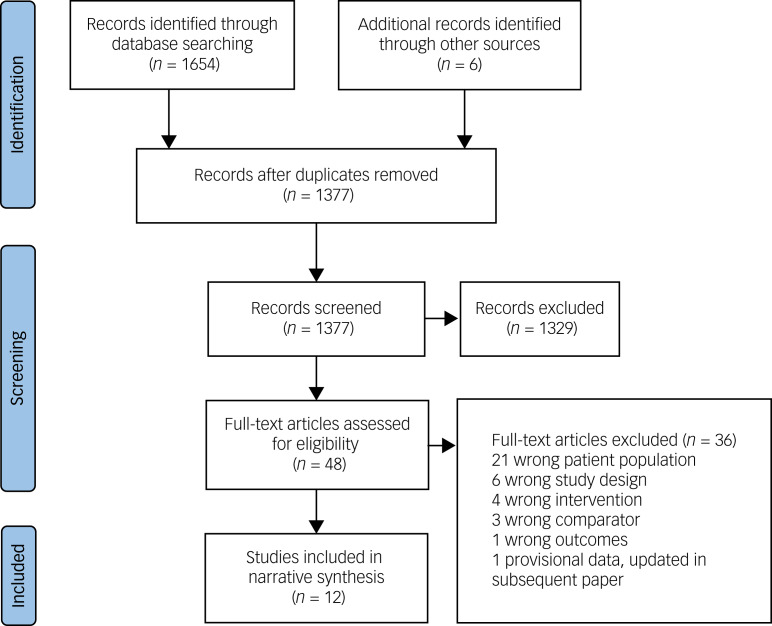

The results of the search strategy are summarised in Fig. 1. The search yielded 1377 articles, of which 48 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility. Of these studies, 36 were excluded. The 12 eligible studies are summarised in Table 2, stratified by study design. There were no RCTs. The studies comprised nine case reports, two cohort studies and one observational study. Bipolar disorder was the most studied mood disorder (n = 6 studies). All studies stated that the intervention was a ketogenic diet. However, there is no widely accepted definition of a ketogenic diet, carbohydrate intake was not reported in five studies and confirmation of ketosis was incomplete (blood ketone testing in two studies, urinary ketone testing in five, no confirmation in five). It is therefore possible that some of the interventions may have been a low carbohydrate rather than a ketogenic diet.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

Table 2.

Summary of included studies, stratified by study design

| Study | Design | Participants | Dietary intervention and duration | Adherence and, where available, confirmation by measurement and presence of ketosis | Main mood and psychiatric symptom outcomes | Adverse effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observational studies | ||||||

| Campbell & Campbell (2019)50 | Online observational analytic study | n = 274; bipolar disorder (age and gender n.r.) | Ketogenic diet (85 participants, 165 online posts) compared with omega-3 or vegetarian diet (94 posts) Carbohydrate intake n.r. Duration not consistently reported, but where available (or derived) varied: 1–5 months, >6 months and >12 months |

92.9% of participants ‘very likely’ to have achieved a state of ketosis | Remission or significant mood stabilisation reported in 56.4% of posts on ketogenic diet and 14.9% of posts on vegetarian diet or omega-3 supplementation In ketogenic diet, many detailed reports of the improvements experienced and several lasting for extended periods (months to years) In ketogenic diet, fewer episodes of depression (41.2%), improved clarity of thought and speech (28.2%), increased energy (25.9%) and weight loss in 25.9% Any mood destabilisation reported in 4.8% of posts on ketogenic diet and 10.6% of posts on vegetarian diet or omega-3 supplementation |

No instances of hospital admission or care-seeking reported in posts for either diet group Difficulties in keto-adaptation reported in 10.6% of posts |

| Cohort studies | ||||||

| Danan et al (2022)59 | Retrospective cohort study | n = 31; psychiatric in-patients: 13 bipolar II disorder, 12 schizoaffective disorder, 7 MDD (mean age: 50 years; 71% female) | Ketogenic diet (carbohydrate <20 g/day) Duration: at least 14 days, mean 59.1 days |

3 participants discontinued before 14 days. Ketosis (measured via urinary ketones) achieved by 64% of remaining participants. Dietary adherence characterised as excellent (39%), good (43%) or fair (18%) | Symptoms of depression and psychosis and overall clinical severity significantly reduced All patients who completed the HRSD achieved a reduction of ≥4 points and 95% achieved a reduction of ≥6 points. All patients who were assessed with the MADRS achieved a reduction of ≥6 points Number or dose of psychotropic medications was reduced in 64% of participants |

Most patients reported initial symptoms of keto-adaptation (headache, insomnia, irritability, excitation, dizziness, carbohydrate cravings), which resolved within 2 weeks; beyond this, 13% reported adverse effects (fat intolerance, diarrhoea, vomiting) |

| Kunin (1976)68 | Cohort study | n = 73; psychiatric out-patients with symptoms of anxiety, depression and ‘dysperception’ (age and gender n.r.) | Ketogenic diet (carbohydrate 0 g/day) until ketosis reached (or maximum 5 days); then ‘optimal carbohydrate level’/low carbohydrate (<120 g/day, mean 52 g/day), duration n.r.; then higher carbohydrate diet (>120 g/day), duration n.r. | 2 participants discontinued within 5 days. Ketosis measured via urinary ketones | Symptoms of anxiety, depression and dysperception improved with ketogenic and ‘optimal carbohydrate level’ diets in 82% of participants | 60% of participants reported transient adverse effects, including fatigue, nausea, weakness, headache and palpitations; improved after administration of potassium salts |

| Case reports | ||||||

| Chmiel (2021)64 | Case report | n = 1; ultra-rapid cycling bipolar disorder (not further specified but suggestive of bipolar II disorder) (27-year-old male) | Low carbohydrate high fat diet for 1 year; then ketogenic diet (carbohydrate <30 g/day, 2500 kcal, 15% protein, 80% fat, 5% carbohydrate) for 1 year; then ketogenic diet with 1 day fast every 7–10 days for 1 year | Average reported blood ketones: year 1 β-HB = 0.3–0.5 mmol/L; year 2 β-HB = 1.5–3 mmol/L; year 3 β-HB = 5 mmol/L on fasting days | Depression reduced, mood stabilised, increased energy, improved sleep, cognitive function and concentration, and elimination of anxiety; no hypomania Remission of depression in year 3. Discontinuation of quetiapine (previously up to 300 mg/day) and reduction of lamotrigine to 100 mg/day (previously up to 300 mg/day) |

n.r. |

| Cox et al (2019)65 | Case report | n = 1; type 2 diabetes and comorbid MDD (65-year-old female) | Ketogenic diet (65% fat, 25% protein, 10% carbohydrate) for 3 months | Blood ketones averaged 1.5 mmol/L by week 12 | PHQ-9 score decreased from 17 (baseline) to 0 (week 12); reported increased self-efficacy and self-confidence, increased energy, improved sleep, stability in mood and clearer cognition | n.r. |

| Ehrenreich (2006)60 | Case report | n = 1; panic disorder (47-year-old female) | Atkins diet (carbohydrate intake n.r.) for 4 weeks | Not assessed, but 17 lb (7.7 kg) weight loss reported | Increase in baseline anxiety level over the course of the diet | Internal sensation of ‘shakiness’, frequent panic attacks; resolved on cessation of diet |

| Kraft & Westman (2009)66 | Case report | n = 1; schizophrenia and comorbid depression (70-year-old female) | Ketogenic diet (carbohydrate <20 g/day) for 12 months | Reported 2–3 isolated episodes of non-adherence lasting several days; 10 kg weight loss reported | Reported increased energy and no longer experienced auditory or visual hallucinations | n.r. |

| Palmer (2017)58 | Case report | n = 2; schizoaffective disorder (33-year-old male, 31-year-old female), both with comorbid MDD | Ketogenic diet (carbohydrate intake n.r.); male for 12 months; female for 4 months | Male discontinued diet on 5 occasions and experienced relapse of positive and negative symptoms within 1–2 days; female discontinued diet once and developed paranoia and delusions | Reductions in hallucinations and delusions, improved mood, energy and concentration. PANSS scores reduced from 98 to 49 in the male and from 107 to 70 in the female |

n.r. |

| Phelps et al (2012)63 | Case report | n = 2; bipolar II disorder (69-year-old female, 30-year-old female) | Ketogenic diet (70% fat, 22% protein, 8% carbohydrate for 30-year-old; details n.r. for 69-year-old); 69-year-old for 2 years; 30-year-old for 3 years | Ketosis measured via urinary ketones: ranged between 0 and 80 mg/dL (over course of 7 months in 69-year-old; ketosis measurement n.r. for 30-year-old) | Sustained mood stability; diet enabled both to discontinue lamotrigine; no increase in anxiety. | None |

| Pieklik et al (2021)67 | Case report | n = 1; ‘mood disorder’ (not specified) with comorbid emotion dysregulation, body dysmorphic disorder and an eating disorder (21-year-old female) | Very low calorie ketogenic diet (details n.r.) (carbohydrate intake n.r.) for 4 weeks | Did not fully comply with diet (details n.r.); no measures of ketosis; weight reduced from 113.5 kg to 102 kg, some metabolic parameters improved | Partial improvement in well-being, mood stabilised, decreased anxiety, no suicidal thoughts. BDI score improved from 40 (severe depression) to 23 (moderate) Other interventions included sertraline, trazodone, metformin (timing, doses and duration n.r.), psychotherapy and psychoeducation |

Did not experience adverse effects but did not want to continue nutritional intervention; overall ‘therapeutic cooperation’ reported as ‘difficult’ |

| Saraga et al (2020)62 | Case report | n = 1; bipolar I disorder (60-year-old female) | ‘Mildly ketogenic’ diet (ratio of grams of fat to grams carbohydrate + protein of 2–3:1); duration n.r. | Ketosis measured via urinary ketones: 0.05–0.4 g/L | Decreased anxiety, maintenance of euthymia; enabled discontinuation of Sertindole; patient describesd clear improvement on both depressive and manic symptoms | n.r. |

| Yaroslavsky et al (2002)61 | Case report | n = 1; in-patient with bipolar I disorder (49-year-old female), treatment-resistant, rapid cycling | Ketogenic diet (carbohydrate intake n.r.) for 4 weeks | Urinary ketosis was not confirmed, nor was there any weight loss. Patient adherence reported as very good | No clinical improvement | n.r. |

β-HB, beta-hydroxybutyrate; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; GAD-7, seven-item Generalised Anxiety Disorder questionnaire; HRSD, Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; MADRS, Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale; MDD, major depressive disorder; n.r., not reported; PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; PHQ-9, nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire (depression module).

Risk of bias assessment

Cohort and observational studies were assessed for risk of bias (Supplementary file 2). Owing to the heterogeneity in study designs, we did not provide a quality score for each study and instead provided a qualitative assessment.56 None of the studies employed representative sampling techniques and confounders were not controlled for. Changes in anxiety, depression and/or psychotic symptoms were measured via validated questionnaires in four studies.57–59 One study additionally measured depression symptoms and illness severity via clinical interview.59

Synthesis of results

Considering the methodological heterogeneity between studies, a quantitative appraisal was not possible. Findings were therefore synthesised narratively, clustered by study type and then stratified as either ‘no efficacy’ or ‘possible efficacy’ of the intervention. Discontinuation effects and adverse events were described where reported (for clarity, these have been grouped together, given the limited data).

Case reports

No efficacy of LC/KD intervention

Two case reports reported no apparent benefits of the intervention (duration 4 weeks each). One report described a participant with panic disorder (n = 1)60 on a ketogenic diet who experienced negative effects (internal ‘shakiness’, increase in anxiety and recurrence of panic attacks, despite increasing sertraline dose). These symptoms resolved on discontinuation of the ketogenic diet. The other case report described an unsuccessful attempt at a ketogenic diet in a hospital in-patient with rapid cycling bipolar disorder (mania predominant) (n = 1).61 Ketosis was not achieved despite reported adherence to the diet, so this may have been a low carbohydrate diet rather than a ketogenic one.

Possible efficacy of LC/KD intervention

Seven case reports reported possible efficacy (duration of diet between 1 month and 3 years). Three described substantial improvements in symptoms in individuals with bipolar disorder (n = 4), including greater mood stability, reductions in frequency of mood episodes and decreased anxiety.62–64 Four patients discontinued or reduced their antipsychotic or mood stabiliser medication. Ketosis was measured by blood β-hydroxybutyrate in one report64 and by urinary ketones in two62,63 reports. The other four case reports described a female with type 2 diabetes and comorbid major depressive disorder,65 a female with schizophrenia and comorbid depression,66 a female with a mood disorder and comorbid emotion dysregulation, body dysmorphic disorder and an eating disorder,67 and two people (one male, one female) with schizoaffective disorder and comorbid major depressive disorder.58 Reported benefits included improved mood, energy, concentration and cognition, as well as reduced psychotic symptoms in those with schizoaffective disorder.

Cohort studies

No efficacy of LC/KD intervention

No studies.

Possible efficacy of LC/KD intervention

Possible efficacy was reported in a cohort study of ketogenic and low carbohydrate diets in out-patients with anxiety, depression and ‘dysperception’ (n = 73; duration not reported)68 and in a study of a ketogenic diet in in-patients with bipolar II disorder, major depressive disorder or schizoaffective disorder (n = 31, mean duration 59.1 days).59 The first study reported improvements in anxiety, depression and ‘dysperception’ in 82% of participants. Similarly, the second study reported improvements in self- and clinician-rated depression, as well as overall severity of illness in participants with mood disorders; further, around two-thirds of participants reduced the number or dose of psychotropic medications by the end of the intervention.

Observational studies

No efficacy of LC/KD intervention

No studies.

Possible efficacy of LC/KD intervention

In the only observational study in the review, Campbell & Campbell50 reported an analytic study of posts on online forums about a ketogenic diet versus omega-3 supplementation or a vegetarian diet from people with bipolar disorder (n = 274; reporting of diet duration incomplete but where available it was between 1 month and >12 months). Remission or significant mood stabilisation was reported in 56.4% of posts discussing a ketogenic diet, compared with 14.9% of posts on a vegetarian diet or omega-3 supplementation. Posts discussing mood destabilisation were few overall, but more commonly associated with a vegetarian diet or omega-3 supplementation than a ketogenic diet.

Effects of discontinuation of LC/KD intervention

Of the ten studies that reported symptom improvement with LC/KD, only four reported information on symptom changes on stopping LC/KD. Campbell & Campbell50 reported recurrence of bipolar disorder symptoms in 7.1% of participants on stopping a ketogenic diet and Kunin68 reported recurrence of symptoms in 82% of participants with depression, anxiety and ‘dysperception’ on cessation of a low carbohydrate diet. Two case reports reported mixed results. Kraft & Westman66 reported no recurrence of psychotic symptoms during dietary relapses in a person with schizophrenia and comorbid depression; however, Palmer58 reported recurrence of psychotic symptoms during dietary relapse in two individuals with schizoaffective disorder, despite continuing antipsychotic medication in one of them. Symptoms resolved when ketosis was induced; however. an increase in the individual's antipsychotic medication dosage may also explain this improvement.

Adverse events

Adverse events were not reported systematically (Table 2). Six studies did not report on adverse events.58,61,62,64–66 Two studies reported no adverse events (n = 3).63,67 Four studies reported adverse events, including: transient symptoms associated with keto-adaptation (e.g. fatigue, nausea, headache, palpitations) (n not recorded),50,59,68 ‘shakiness’, increase in anxiety and recurrence of panic attacks (n = 1),60 fat intolerance (n = 2) and gastrointestinal symptoms (n = 2).59

Discussion

This systematic review examined the efficacy of low carbohydrate and ketogenic diets (LC/KD) in individuals with mood and anxiety disorders. Despite anecdotal reports and biological plausibility, little research has been conducted to date and no high-grade evidence was found. Heterogeneity and data quality limit interpretation of the included studies, and statistical analysis including meta-analysis was not possible, leading to a narrative review.

It should be noted that nutritional intake and measurements of ketosis were variable and incomplete, and although the interventions were stated to be ketogenic diets, there was no consistent threshold for ketone levels to define ketosis and it is possible that some individuals were on low carbohydrate rather than ketogenic diets, either throughout the duration of the study or periodically, and did not reach the required threshold for ketosis.

Although two studies suggested no benefits of LC/KD, several case reports, cohort studies and the observational study suggest possible efficacy of a ketogenic diet in bipolar disorder, schizoaffective disorder, anxiety disorders and unipolar depression. Reported therapeutic effects of a ketogenic diet include mood stability, increased energy and concentration, and reductions in symptoms of anxiety, depression and psychosis. Relapse occurred in several individuals on discontinuation of the diet. Adverse effects were not systematically reported but included fatigue, nausea and headaches on induction of ketosis, although this was not universal.

Potential benefits of a ketogenic diet reported here concur with previous research exploring self-reported benefits of low carbohydrate diets in other populations.16,69 The present paper expands on reviews by Bostock et al26 and Brietzke et al28 by incorporating low carbohydrate interventions (not just a ketogenic diet) and a wider clinical context: this may increase generalisability to community samples of individuals with mood disorders. In contrast, in individuals without mood disorders, El Ghoch et al51 found no overall evidence of psychological benefits of LC/KD (eight studies, n = 532; duration 8 weeks to 1 year). However, in El Ghoch et al's review: (a) two studies did not meet criteria for a low carbohydrate diet,70,71 (b) ketosis was measured in only five studies72–76 and (c) several included studies utilised the 24 h Food Frequency Questionnaire, the validity of which has been questioned.77 Alternatively, it might be that LC/KD are efficacious only in individuals with clinical mood disorders and thus more severe psychopathology, but not in non-clinical samples with milder symptoms. It is also possible that LC/KD are more useful in those with greater metabolic burden, such as threshold metabolic syndrome.78

Context and mechanisms

Any response to LC/KD may be modulated via multiple mechanistic pathways. For example, LC/KD have been suggested to reduce inflammation, which is increasingly acknowledged to be involved in the development of depression and, in particular, treatment-resistant depression.79–82 A systematic review83 showed that low glycaemic index and low glycaemic load diets were associated with reduced inflammatory markers in 5 out of 9 observational studies; 3 of 13 interventional trials showed significant anti-inflammatory effects and 4 suggested beneficial trends. Reduced inflammation correlates with reduced depression in obesity and overweight,84,85 which may be related to reduced inflammatory adipokines.86,87

Mitochondrial energy generation – which can be affected by ketosis – is also important, because mood disorders, especially bipolar disorder, are associated with abnormal mitochondrial energy generation.88,89 Depression is characterised by reduced energy generation, and mania is characterised by increased mitochondrial biogenesis.90 A ketogenic diet has the potential to increase the efficiency of mitochondrial biogenesis and may target this core pathway.88,91,92

Furthermore, improvements in insulin signalling conferred by LC/KD (as evident in treatment of obesity and type 2 diabetes) may be associated with mood benefits. Calkin et al showed that individuals with bipolar disorder and comorbid type 2 diabetes or insulin resistance had three times higher odds of chronicity and rapid cycling and more than eight times the odds of lithium resistance, even after controlling for antipsychotic use and body mass index (BMI).93 Subsequently, in a first RCT, Calkin et al showed that reversing insulin resistance by adding metformin in treatment-resistant bipolar depression had a large effect size on clinician-rated depressive symptoms – but only in participants whose insulin resistance was reversed.94 Reversing insulin resistance is clearly a plausible outcome of a low carbohydrate diet, not requiring ketogenic diet levels of carbohydrate reduction. In patients at risk, low carbohydrate diets can be advocated for prevention of obesity, metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes, with the possible additional benefit of an antidepressant effect in bipolar disorders. Thus, the role of insulin resistance in mood disorders may justify the application of LC/KD interventions in this population.

Ketosis has neuroprotective mechanisms in epilepsy,95 so it is possible that ketosis may also confer positive mood outcomes in non-epileptic disorders. As proof of concept, short-term fasting (generating ketosis) may improve mood and induce mild euphoria in individuals with mood disorders.96 Longer-term ketosis-related mood stabilisation in bipolar disorder is reflected in the self-reports analysed by Campbell & Campbell.50 Putative mechanisms of ketosis on mood may involve several factors, including increased fatty acid synthesis and oxidation, neurotransmitters, ion channels, mitochondrial genesis, cell signalling, second messengers and reduced oxidative stress.97,98 Notably, the seizure-reducing effects of ketosis in epilepsy have not been clarified. Ketosis also induces brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) gene expression;99 this is important as a low BDNF level adversely affects neuroplasticity100 and BDNF increases with effective treatment.101 Weight loss associated with a ketogenic diet might also be a relevant mechanism, although reports of significant mood improvement as early as 4 days into a ketogenic diet, which precedes any significant weight loss, is consistent with ketosis-mediated effects on mood rather than weight loss per se. A further factor potentially playing a role in mediating effects of a ketogenic diet on mood is reduced appetite,102 as discussed in more detail below.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this review, partly related to the low number of studies on this topic and their general poor quality (for example, lack of non-exposed control groups and consideration of confounding factors). The broad inclusion criteria, including lower levels of evidence, may have resulted in heterogeneity between studies and variable data quality.

We pragmatically grouped depression, anxiety, bipolar disorders and schizoaffective disorders together, given some overlapping symptomatology, because of the paucity of LC/KD evidence for individual disorders. A case could also be made against the inclusion of studies with limited information on psychiatric diagnoses,57,68 as the results of these studies may not be generalisable to individuals with mood disorders without such comorbidities.103

The effects of LC/KD on mood disorders might also involve confounding factors, which were rarely assessed in the studies included in this review. These include concurrent pharmacotherapy, reduced alcohol intake (high carbohydrate content), reduced hunger (ketosis effect on appetite hormones),103 weight loss, improved sleep and (in those on a well-formulated low carbohydrate diet) presumed increased intake of folate, micronutrients, vitamin D and omega-3 fatty acids (LC/KD typically increase intake of leafy green vegetables and fish).

The exclusion of certain foods may also be an important confounder. For example, reduced gluten intake in LC/KD has been suggested to be a confounder in a limited number of studies, as there are reports of anti-gluten antibodies in psychosis104 and bipolar disorder.105 Furthermore, an unnecessary gluten-free diet (which LC/KD might entail) might increase the risk of nutritional deficiencies106 and gastrointestinal and cardiovascular side-effects.107,108

Another potential confounder is the potentially low content of fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides and polyols (FODMAPs) in LC/KD (depending on the dietary formulation). FODMAPs, poorly absorbed short-chain carbohydrates (for example in bread), may cause bloating and fatigue in some individuals and are implicated in the symptomatology of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS): FODMAP reduction or exclusion improves IBS.109 The relevance here is that IBS and various psychiatric disorders (notably, anxiety disorders and, possibly, current major depression) are often comorbid.110 Interestingly, the omission of FODMAPs confounds gluten-free diet trials in IBS109 and although there is uncertainty regarding the psychiatric effects of FODMAPs,111 it could be argued that omitting FODMAPs might confound any apparent psychiatric effects of LC/KD.

Three of the included studies58,61,64 also report intake of exogenous ketogenic food supplements: medium-chain triglycerides. The role of exogenous ketogenic food supplements is unclear112 and it must be noted that these compounds are high in saturated fatty acids, which may increase the risk of cardiovascular disease.113

Finally, no studies assessed gut microbiota, which may affect mood and/or anxiety.113 A ketogenic diet may be associated with changes in alpha diversity and beneficial microbial metabolites such as short-chain fatty acids,114 although the data are limited and clinical implications uncertain. Further discussion is beyond the scope of this review.

Implications for clinical practice

Clinicians in primary care, mental health services and dietetics/nutrition may increasingly encounter patients who wish to follow LC/KD for depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder or schizoaffective disorder. Shared decision-making and good communication of the current absence of data able to clearly support or refute the efficacy of a ketogenic diet is important. Some of these issues are discussed below and in Table 3.

Table 3.

Uncertainties regarding the use of LC/KD for mood and anxiety disorders in clinical practice

| Efficacy |

|

| Adherence |

|

| Adverse effects |

|

| Potential effects on pharmacotherapy |

|

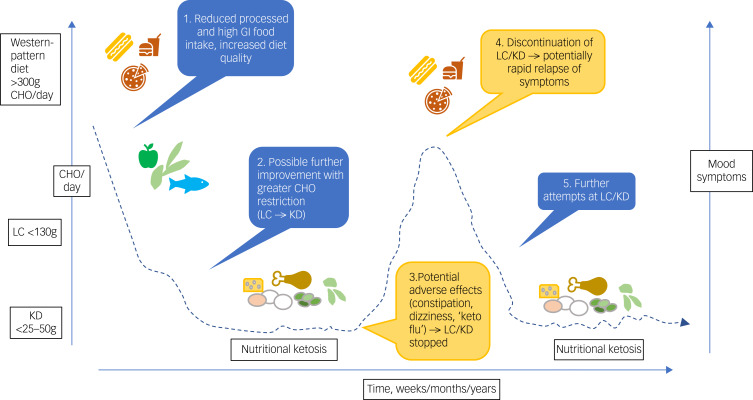

Low carbohydrate diets – and especially ketogenic diets – are by nature highly restricted diets, whereas ‘whole of diet’ approaches are preferable and more likely to be sustainable in people with mood disorders.115 As illustrated in Fig. 2, adherence to these diets, especially ketogenic diets, may be challenging, leading to either premature cessation (before potential benefits) or after therapeutic nutritional ketosis has been reached (which could equally apply to other treatment modalities).

Fig. 2.

Schematic illustration of potential impact of low carbohydrate and ketogenic diets (LC/KD) on mood symptoms.

Symptoms may improve as carbohydrate (CHO) intake drops, for example when intake is <25–50 g/day for >4 days, inducing nutritional ketosis, although further evidence is required. Adverse effects may be challenging for some, causing discontinuation of the diet and relapse of mood symptoms. Some individuals may make further attempts at a low carbohydrate (LC) or ketogenic diet (KD). Clinical supervision is required to manage potential adverse effects and adherence problems across all phases of ketogenic dietary interventions.

Adverse effects include (a) early ‘flu-like’ symptoms during induction of ketosis,112,116 predominantly due to early electrolyte changes (especially sodium diuresis), contributing to fatigue, constipation, cramps, palpitations and postural hypotension, and (b) perhaps renal stones, gout, osteoporosis and cardiovascular and gastrointestinal disease (see below) in the longer term.

The data on longer-term LC/KD adherence in various clinical populations remain uncertain. In epilepsy, a Cochrane review (n = 932 children and adults) found that adults following a ketogenic diet may be up to five times more likely to drop out of studies compared with those receiving usual care.17 In contrast, an online nutritional ketosis programme for adults with type 2 diabetes (n = 349) reported 74% adherence at 2 years (n = 194/262), compared with 78% adherence for those in usual care (n = 68/87).117 The level of support provided to help participants follow the dietary intervention is likely to affect attrition rates, but this factor has not been systematically studied in relation to ketogenic diets. Further, these data have uncertain generalisability to patients with mood disorders, as it is possible that LC/KD adherence may be more challenging for individuals with such disorders. Pertinently, carbohydrate cravings and impulsivity present in many psychiatric disorders118 would presumably increase the chance of consumption of high carbohydrate foods, with resultant dietary relapse (as shown in Fig. 2). Furthermore, repeated attempts at LC/KD with initial efficacy but relapse after challenges might exacerbate feelings of guilt and failure. It would therefore be crucial to develop strategies to overcome these challenges in clinical populations.

Several practical aspects, especially of ketogenic diets, warrant consideration. First, daily carbohydrate counting (which may be required to help maintain ketosis) might exacerbate disordered eating and/or obsessive traits. Second, although confirmation of ketosis might be preferable, especially for individuals new to ketogenic diets, this might unnecessarily ‘medicalise’ normal eating patterns.

In addition, measurements of ketosis are temporally variable, may be imprecise (especially in mild nutritional ketosis, in contrast to diabetic ketoacidosis) and may pose logistical challenges. Methods for confirming ketosis include urine (acetoacetate), blood (β-hydroxybutyrate) and breath (acetone) analyses. Urinary ketone testing strips, although popular (they are low cost, non-invasive and easy to use), are unreliable: in mild dietary ketosis sensitivity is 35–76% and specificity 78–100%.119 Blood ketone monitoring (venous, capillary) is more reliable: depending on the magnitude of ketosis, sensitivity is 98–100% and specificity 85–93.3%;120 however, it may be impractical in the real world because of the cost and discomfort of blood tests or finger-prick testing (for related reasons, in diabetes, regular finger-prick glucose testing is being replaced by indwelling interstitial glucose devices,121 but interstitial ketone monitoring devices are not currently available). Breath ketone analysis is a relatively recent technology with uncertain accuracy and some devices are not registered with the Food and Drug Administration.122

The involvement of dietitians was an important part of clinical trials of dietary interventions in participants with depression such as the SMILES and HELFIMED trials.8,9 This is also supported by a recent meta-analysis that reported that dietitian-led intervention trials showed a greater improvement in depressive symptoms.79 This may be resource-intensive in naturalistic settings, but group sessions or internet-based delivery may be acceptable alternatives.123

Importantly, a paucity of longitudinal studies has led to uncertainty and debate regarding aspects of long-term LC/KD safety, especially potential cardiovascular disease (CVD) and gastrointestinal risks from increased saturated fatty acid intake and reduced dietary fibre. Increased saturated fatty acid intake has an unpredictable effect on lipids (a surrogate marker for CVD).124–128 Reduced dietary fibre has potentially negative effects on gut metabolites and microbiota, which may increase the risk of CVD, gastrointestinal and other diseases.129–131

Finally, the potential effect of LC/KD on medications is important. Careful monitoring is essential and medication amendments may be warranted. For example, a ketogenic diet may affect pharmacokinetics and valproate levels.132,133 Ketogenic diet-related diuresis (especially during keto-adaptation) may cause electrolyte changes that could affect lithium levels. These factors might pose additional challenges if individuals have intermittent adherence to LC/KD.

Recommendations for further research

Robust RCTs are required to investigate the effects of low carbohydrate and ketogenic dietary interventions (with cross-over) on short- and longer-term outcomes in dysthymia, generalised anxiety disorder, major depressive disorder, atypical depression, bipolar disorder and schizoaffective disorder. Rating scale subgroup analysis might identify specific LC/KD effects on mood, anxiety, energy and sleep. The comparison of low carbohydrate diets with ketogenic diets is especially pertinent because, if efficacious, the less restrictive nature of low carbohydrate diets could increase generalisability. It would also be important to determine whether comorbid obesity/metabolic syndrome affects efficacy, adherence and relapse rates. Continuous interstitial glucose monitoring, such as in the large (n = 1100) multinational PREDICT I nutrition study,134 combined with daily self-rated mood measures (for example, the True Colours app135) might enable a fine degree of personalisation. This might, for example, show that individuals with impaired carbohydrate metabolism (a larger post-prandial glucose incremental area under the curve136) are more likely to respond to LC/KD, but (perhaps) not those with normal response.

These studies may be informed by the first RCT of a ketogenic diet in psychosis (NCT03873922), an open label trial of a ketogenic diet in euthymic bipolar disorder and schizophrenia (NCT03935854) and a feasibility study of a ketogenic diet in bipolar disorder (ISRCTN61613198). LC/KD effects on pharmacotherapy also require further study.

Neuroimaging may be informative. In people with epilepsy treated with a ketogenic diet, magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) shows an increase in cerebral energy,137,138 which is thought to be a potential mediator of ketogenic diet efficacy. MRS might therefore also be relevant to ketogenic diets in populations with mood disorders, especially bipolar disorder, given the anomalies of mitochondrial biogenesis.88,91,92 Positron emission tomography or functional magnetic resonance imaging might also inform any ketosis-mediated neuroplasticity and neuroprotection, including changes in higher cortical function and cognition.139 Imaging research could also target the putative anti-inflammatory actions of LC/KD, focusing on changes in microglial activation85,140,141 with translocator protein density142 in the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex and prefrontal cortex (PFC). Functional BDNF imaging (amygdala, hippocampus, PFC) would add further information on potential mechanisms of LC/KD.143,144 Measurement of lactate might be the simplest biomarker of bioenergetics.145

Further research on LC/KD in mood disorders should include appetite hormones (including insulin, leptin and ghrelin), because of the interplay between LC/KD, appetite, insulin sensitivity and mood disorders.87,146,147 These factors might also link with inflammation noted above. Briefly, the role of appetite hormones and mood disorders is complex and may differ between disorders.147 For example, Cordas et al showed that reduced leptin is present in depression, especially atypical and bipolar depression; additionally, leptin is associated with current depression.148 Conversely, Pasco et al showed that leptin is elevated in women with a history of unipolar major depression and elevated leptin predicts future depressive disorder.149

Notwithstanding this, leptin has multiple roles in glucose homeostasis, including improving insulin sensitivity,146 which, as noted above, has been shown to be important in treating bipolar depression.93,94 LC/KD reduces leptin while also improving sensitivity to leptin.150 The role of ghrelin in mood disorders is unclear,147 but ketosis rapidly suppresses ghrelin, reducing appetite within a few days.102

Thus, the degree and rate of change of appetite hormones and mood disorder symptoms in various disorders during LC/KD interventions would be instructive. These findings may have important translation potential (Table 3) and might lead to formulation of dietary recommendations for mood disorders (as suggested for those with chronic pain).151

Finally, the effect of LC/KD on overall healthcare costs in mood disorders would also be of interest, as these costs have been shown to be reduced by LC/KD in people with type 2 diabetes.152

This review was conducted in the context of debate around many aspects of nutrition, especially ‘low carb’ diets, and mounting scientific and public interest. There is a very limited and low-quality evidence base on the efficacy of KD in mood disorders. Efficacy and adherence are unclear, and there are concerns about potential adverse effects. Nevertheless, some individuals already employ these strategies, and definitive and rigorous trials are needed to clarify safety and efficacy to guide clinical practice.

Acknowledgements

D.M.D. is grateful to Helen Elwell, British Medical Association Library, London, for expert help with literature searches and to Emmanuelle Bostock, University of Tasmania, for substantial input during the initial stages of this project..

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit http://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2023.36.

click here to view supplementary material

Data availability

Data availability is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Author contributions

D.M.D., A.H.Y., A.R. and V.M. conceived the study. D.M.D., J.K.-G., M.H. and W.M. conducted the study selection and data extraction. D.M.D. led all stages of the manuscript preparation and wrote the original draft. All authors read and provided comments on the final manuscript.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of interest

D.M.D. is a GP Partner in the National Health Service (NHS); he has received fees for presentations, including Royal College of Psychiatrists International Congress Edinburgh 2013 (travel and accommodation only), webinars for general practitioners, PRIMHE (Primary care Mental Health & Education), Network Locums and BMJ Masterclasses; he received an honorarium from Lundbeck for a symposium presentation at the British Association of Psychopharmacology 2019 Summer Meeting on ‘The primary/secondary care interface for treating depression: challenges and future perspectives’, which covered practical ways to improve to help patient care and there was no endorsement of any pharmaceutical treatment or product. J.K.-G. owns shares in AstraZeneca and GSK plc. M.H. is supported by an Australian Rotary Health PhD Scholarship. W.M. is currently funded by an NHMRC (National Health and Medical Research Council) Investigator Grant (#2008971) and a Multiple Sclerosis Research Australia early-career fellowship and has previously received funding from the Cancer Council Queensland and university grants/fellowships from La Trobe University, Deakin University, University of Queensland, and Bond University; he has received industry funding and has attended events funded by Cobram Estate Pty. Ltd., has received travel funding from Nutrition Society of Australia, and consultancy funding from Nutrition Research Australia and ParachuteBH; he has received speakers honoraria from The Cancer Council Queensland and the Princess Alexandra Research Foundation. A.H.Y. is Deputy Editor of BJPsych Open and did not take part in the review or decision-making process of this paper; he is employed by King's College London, is an Honorary Consultant at SLaM (South London and Maudsley) (NHS UK); his independent research is funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Maudsley Biomedical Research Centre at SLaM NHS Foundation Trust and King's College London; he has given paid lectures and advisory boards for the following companies with drugs used in affective and related disorders: Astrazenaca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, LivaNova, Lundbeck, Sunovion, Servier, Livanova, Janssen, Allegan, Bionomics, Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma, COMPASS, Sage, Novartis, Neurocentrx; he is Principal Investigator in the Restore-Life VNS (vagus nerve stimulation) registry study funded by LivaNova, Principal Investigator on ESKETINTRD3004: ‘An Open-label, Long-term, Safety and Efficacy Study of Intranasal Esketamine in Treatment-resistant Depression’, Principal Investigator on ‘The Effects of Psilocybin on Cognitive Function in Healthy Participants’, Principal Investigator on ‘The Safety and Efficacy of Psilocybin in Participants with Treatment-Resistant Depression (P-TRD)’, UK Chief Investigator for Compass; COMP006 & COMP007 studies, UK Chief Investigator for Novartis MDD (Major Depressive Disorder) study MIJ821A12201; grant funding (past and present): NIMH (National Institute of Mental Health) (USA); CIHR (Canadian Institutes of Health Research) (Canada); NARSAD (National Alliance for Research in Schizophrenia and Affective Disorders) (USA); Stanley Medical Research Institute (USA); MRC (Medical Research Council) (UK); Wellcome Trust (UK); Royal College of Physicians (Edin); BMA (British Medical Association) (UK); UBC-VGH (University of British Colombia - Vancouver General Hospital) Foundation (Canada); WEDC (Western Economic Diversification Canada) (Canada); MSFHR (Michael Smith Health Research) (Canada); NIHR (National Institute for Health Research) (UK); Janssen (UK) EU Horizon 2020. M.B. is supported by a NHMRC Senior Principal Research Fellowship and Leadership 3 Investigator grant (1156072 and 2017131); he has received grant/research support from National Health and Medical Research Council, Wellcome Trust, Medical Research Future Fund, Victorian Medical Research Acceleration Fund, Centre for Research Excellence CRE, Victorian Government Department of Jobs, Precincts and Regions and Victorian COVID-19 Research Fund; he received honoraria from Springer, Oxford University Press, Cambridge University Press, Allen and Unwin, Lundbeck, Controversias Barcelona, Servier, Medisquire, HealthEd, ANZJP, EPA, Janssen, Medplan, Milken Institute, RANZCP, Abbott India, ASCP, Headspace and Sandoz (past 3 years). V.M. has received research funding from Johnson & Johnson, a pharmaceutical company interested in the development of anti-inflammatory strategies for depression, but the research described in this paper is unrelated to this funding. V.M. is supported by MQ Brighter Futures grants (MQBF/1 IDEA) and (MQBF/4), by the Medical Research Foundation (Grant: MRF-160-0005-ELP-MONDE) and by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and King's College London. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the funders, the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

References

- 1.Forouzanfar MH, Alexander L, Anderson HR, Bachman VF, Biryukov S, Brauer M, et al. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks in 188 countries, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2013. Lancet 2015; 386: 2287–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leichsenring F, Steinert C, Rabung S, Ioannidis JPA. The efficacy of psychotherapies and pharmacotherapies for mental disorders in adults: an umbrella review and meta-analytic evaluation of recent meta-analyses. World Psychiatry 2022; 21: 133–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cleare A, Pariante CM, Young AH, Anderson IM, Christmas D, Cowen PJ, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for treating depressive disorders with antidepressants: a revision of the 2008 British Association for Psychopharmacology guidelines. J Psychopharmacol 2015; 29: 459–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hengartner MP, Schulthess L, Sorensen A, Framer A. Protracted withdrawal syndrome after stopping antidepressants: a descriptive quantitative analysis of consumer narratives from a large internet forum. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol 2020; 10: 2045125320980573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Driessen E, Hollon SD, Bockting CLH, Cuijpers P, Turner EH, Lu L. Does publication bias inflate the apparent efficacy of psychological treatment for major depressive disorder? A systematic review and meta-analysis of US National Institutes of health-funded trials. Lu L, editor. PLoS One 2015; 10(9): e0137864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marx W, Moseley G, Berk M, Jacka F. Nutritional psychiatry: the present state of the evidence. Proc Nutr Soc 2017; 76: 427–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sánchez-Villegas A, Martínez-González MA, Estruch R, Salas-Salvadó J, Corella D, Covas MI, et al. Mediterranean dietary pattern and depression: the PREDIMED randomized trial. BMC Med 2013; 11(1): 208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jacka FN, O'Neil A, Opie R, Itsiopoulos C, Cotton S, Mohebbi M, et al. A randomised controlled trial of dietary improvement for adults with major depression (the ‘SMILES’ trial). BMC Med 2017; 15(1): 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parletta N, Zarnowiecki D, Cho J, Wilson A, Bogomolova S, Villani A, et al. A Mediterranean-style dietary intervention supplemented with fish oil improves diet quality and mental health in people with depression: a randomized controlled trial (HELFIMED). Nutr Neurosci 2019; 22: 474–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bayes J, Schloss J, Sibbritt D. The effect of a Mediterranean diet on the symptoms of depression in young males (the “AMMEND” study): a randomized control trial. Am J Clin Nutr 2022; 116: 572–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Francis HM, Stevenson RJ, Chambers JR, Gupta D, Newey B, Lim CK. A brief diet intervention can reduce symptoms of depression in young adults – a randomised controlled trial. PLoS One 2019; 14(10): e0222768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Banting W. Letter on corpulence, addressed to the public. Obes Res 1993; 1: 153–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Atkins RC. Dr. Atkins’ Diet Revolution: The High Calorie Way to Stay Thin Forever. David McKay, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Andrewski E, Cheng K, Vanderpool C. Nutritional deficiencies in vegetarian, gluten-free, and ketogenic diets. Pediatr Rev 2022; 43: 61–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kang HC, Chung DE, Kim DW, Kim HD. Early- and late-onset complications of the ketogenic diet for intractable epilepsy. Epilepsia 2004; 45: 1116–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cucuzzella MT, Tondt J, Dockter NE, Saslow L, Wood TR. A low-carbohydrate survey: evidence for sustainable metabolic syndrome reversal. J Insulin Resist 2017; 2(1): 25. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martin-McGill KJ, Bresnahan R, Levy RG, Cooper PN. Ketogenic diets for drug-resistant epilepsy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2020; 6: CD001903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neal EG, Chaffe H, Schwartz RH, Lawson MS, Edwards N, Fitzsimmons G, et al. The ketogenic diet for the treatment of childhood epilepsy: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Neurol 2008; 7: 500–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wilder R. The effects of ketonemia on the course of epilepsy. Mayo Clin Proc 1921; 2: 307–8. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matthew's Friends. Matthew's Friends - Ketogenic Diet. Matthew's Friends, 2023 (http://www.matthewsfriends.org/). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kossoff EH, Dorward JL. The modified Atkins diet. Epilepsia 2008; 49(suppl 8): 37–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pfeifer HH, Thiele EA. Low-glycemic-index treatment: a liberalized ketogenic diet for treatment of intractable epilepsy. Neurology 2005; 65: 1810–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Phinney SD. Ketogenic diets and physical performance. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2004; 1(1): 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Whiteley VJ, Martin-McGill KJ, Carroll JH, Taylor H, Schoeler NE. Nice to know: impact of NICE guidelines on ketogenic diet services nationwide. J Hum Nutr Diet 2020; 33: 98–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paoli A, Rubini A, Volek JS, Grimaldi KA. Beyond weight loss: a review of the therapeutic uses of very-low-carbohydrate (ketogenic) diets. Eur J Clin Nutr 2013; 67: 789–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bostock ECS, Kirkby KC, Taylor BVM. The current status of the ketogenic diet in psychiatry. Front Psychiatry 2017; 8: 43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.El-Mallakh RS, Paskitti ME. The ketogenic diet may have mood-stabilizing properties. Med Hypotheses 2001; 57: 724–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brietzke E, Mansur RB, Subramaniapillai M, Banlanzá-Martínez V, Vinberg M, González-Pinto A, et al. Ketogenic diet as a metabolic therapy for mood disorders: evidence and developments. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2018; 94: 11–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Molendijk M, Molero P, Ortuño Sánchez-Pedreño F, Van der Does W, Angel Martínez-González M. Diet quality and depression risk: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. J Affect Disord 2017; 226: 346–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marx W, Veronese N, Kelly JT, Smith L, Hockey M, Collins S, et al. The dietary inflammatory index and human health: an umbrella review of meta-analyses of observational studies. Adv Nutr Res 2021; 12: 1681–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lane MM, Davis JA, Beattie S, Gómez-Donoso C, Loughman A, O'Neil A, et al. Ultraprocessed food and chronic noncommunicable diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 43 observational studies. Obes Rev 2021; 22(3): e13146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Accurso A, Bernstein RK, Dahlqvist A, Draznin B, Feinman RD, Fine EJ, et al. Dietary carbohydrate restriction in type 2 diabetes mellitus and metabolic syndrome: time for a critical appraisal. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2008; 5: 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reynolds A, Mann J, Cummings J, Winter N, Mete E, te Morenga L. Carbohydrate quality and human health: a series of systematic reviews and meta analyses. Lancet 2018; 393: 434–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martinez-Lacoba R, Pardo-Garcia I, Amo-Saus E, Escribano-Sotos F. Mediterranean diet and health outcomes: a systematic meta-review. Eur J Public Health 2018; 28: 955–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Westover AN, Marangell LB. A cross-national relationship between sugar consumption and major depression? Depress Anxiety 2002; 16: 118–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Christensen L. The effect of carbohydrates on affect. Nutrition 1997; 13: 503–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Benton D. Carbohydrate consumption, mood and anti-social behaviour. In Lifetime Nutritional Influences on Cognition, Behaviour and Psychiatric Illness (ed Benton D): 160–79. Woodhead Publishing, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Benton D, Nabb S. Carbohydrate, memory, and mood. Nutr Rev 2003; 61: S61–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Breymeyer KL, Lampe JW, McGregor BA, Neuhouser ML. Subjective mood and energy levels of healthy weight and overweight/obese healthy adults on high-and low-glycemic load experimental diets. Appetite 2016; 107: 253–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gangwisch JE, Hale L, Garcia L, Malaspina D, Opler MG, Payne ME, et al. High glycemic index diet as a risk factor for depression: analyses from the women's health initiative. Am J Clin Nutr 2015; 102: 454–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu C, Xie B, Chou CP, Koprowski C, Zhou D, Palmer P, et al. Perceived stress, depression and food consumption frequency in the college students of China seven cities. Physiol Behav 2007; 92: 748–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Akbaraly TN, Brunner EJ, Ferrie JE, Marmot MG, Kivimaki M, Singh-Manoux A. Dietary pattern and depressive symptoms in middle age. Br J Psychiatry 2009; 195: 408–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sánchez-Villegas A, Toledo E, de Irala J, Ruiz-Canela M, Pla-Vidal J, Martínez-González MA. Fast-food and commercial baked goods consumption and the risk of depression. Public Health Nutr 2012; 15: 424–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Haghighatdoost F, Azadbakht L, Keshteli AH, Feinle-Bisset C, Daghaghzadeh H, Afshar H, et al. Glycemic index, glycemic load, and common psychological disorders. Am J Clin Nutr 2016; 103: 201–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Knüppel A, Shipley MJ, Llewellyn CH, Brunner EJ. Sugar intake from sweet food and beverages, common mental disorder and depression: prospective findings from the Whitehall II study. Sci Rep 2017; 7(1): 6287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jacobsen FM, Wehr TA, Sack DA, James SP, Rosenthal NE. Seasonal affective disorder: a review of the syndrome and its public health implications. Am J Public Health 1987; 77: 57–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rahe C, Baune BT, Unrath M, Arolt V, Wellmann J, Wersching H, et al. Associations between depression subtypes, depression severity and diet quality: cross-sectional findings from the BiDirect Study. BMC Psychiatry 2015; 15(1): 426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Murphy P, Likhodii S, Nylen K, Burnham WM. The antidepressant properties of the ketogenic diet. Biol Psychiatry 2004; 56: 981–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sarnyai Z, Palmer CM. Ketogenic therapy in serious mental illness: emerging evidence. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2021; 23: 434–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Campbell IH, Campbell H. Ketosis and bipolar disorder: controlled analytic study of online reports. BJPsych Open 2019; 5(4): e58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.El Ghoch M, Calugi S, Dalle Grave R. The effects of low-carbohydrate diets on psychosocial outcomes in obesity/overweight: a systematic review of randomized, controlled studies. Nutrients 2016; 8(7): 402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.IJff DM, Postulart D, Lambrechts DAJE, Majoie MHJM, de Kinderen RJA, Hendriksen JGM, et al. Cognitive and behavioral impact of the ketogenic diet in children and adolescents with refractory epilepsy: a randomized controlled trial. Epilepsy Behav 2016; 60: 153–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lambrechts DAJE, Bovens MJM, De la Parra NM, Hendriksen JGM, Aldenkamp AP, Majoie MJM. Ketogenic diet effects on cognition, mood, and psychosocial adjustment in children. Acta Neurol Scand 2013; 127: 103–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Altman D, Antes G, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med 2009; 151: 264–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wells G, Shea B, O'Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomized Studies in Meta-Analyses. Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, 2012. (http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp).

- 56.Page MJ, Mckenzie JE, Higgins JPT. Tools for assessing risk of reporting biases in studies and syntheses of studies: a systematic review. BMJ Open 2018; 8: e019703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shegelman A, Carson KA, McDonald TJW, Henry-Barron BJ, Diaz-Arias LA, Cervenka MC. The psychiatric effects of ketogenic diet therapy on adults with chronic epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav 2021; 117: 107807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Palmer CM. Ketogenic diet in the treatment of schizoaffective disorder: two case studies. Schizophr Res 2017; 189: 208–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Danan A, Westman EC, Saslow LR, Ede G. The ketogenic diet for refractory mental illness: a retrospective analysis of 31 inpatients. Front Psychiatry 2022; 13: 951376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ehrenreich MJ. A case of the re-emergence of panic and anxiety symptoms after initiation of a high-protein, very low carbohydrate diet. Psychosomatics 2006; 47: 178–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yaroslavsky Y, Stahl Z, Belmaker RH. Ketogenic diet in bipolar illness. Bipolar Disord 2002; 4(1): 75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Saraga M, Misson N, Cattani E. Ketogenic diet in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord 2020; 22(7): 765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Phelps JR, Siemers Sv, El-Mallakh RS. The ketogenic diet for type II bipolar disorder. Neurocase 2013; 19: 423–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chmiel I. Ketogenic diet in therapy of bipolar affective disorder - case report and literature review. Psychiatria Polska 2021; 56: 1–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cox N, Gibas S, Salisbury M, Gomer J, Gibas K. Ketogenic diets potentially reverse Type II diabetes and ameliorate clinical depression: a case study. Diabetes Metab Syndr 2019; 13: 1475–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kraft BD, Westman EC. Schizophrenia, gluten, and low-carbohydrate, ketogenic diets: a case report and review of the literature. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2009; 6: 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pieklik A, Pawlaczyk M, Rog J, Karakuła-Juchnowicz H. The ketogenic diet: a co-therapy in the treatment of mood disorders and obesity - a case report. Curr Probl Psychiatry 2021; 22: 17–25. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kunin RA. Ketosis and the optimal carbohydrate diet: a basic factor in orthomolecular psychiatry. Orthomolecular Psychiatry 1976; 5: 203–11. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ernst A, Shelley-Tremblay J. Non-ketogenic, low carbohydrate diet predicts lower affective distress, higher energy levels and decreased fibromyalgia symptoms in middle-aged females with fibromyalgia syndrome as compared to the Western pattern diet. J Musculoskelet Pain 2013; 21: 365–70. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dalle Grave R, Calugi S, Gavasso I, El Ghoch M, Marchesini G. A randomized trial of energy-restricted high-protein versus high-carbohydrate, low-fat diet in morbid obesity. Obesity 2013; 21: 1774–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Galletly C, Moran L, Noakes M, Clifton P, Tomlinson L, Norman R. Psychological benefits of a high-protein, low-carbohydrate diet in obese women with polycystic ovary syndrome-A pilot study. Appetite 2007; 49: 590–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rosen JC, Hunt DA, Sims EA, Bogardus C. Comparison of carbohydrate-containing and carbohydrate-restricted hypocaloric diets in the treatment of obesity: effects of appetite and mood. Am J Clin Nutr 1982; 36: 463–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rosen JC, Gross J, Loew D, Sims EA. Mood and appetite during minimal-carbohydrate and carbohydrate-supplemented hypocaloric diets. Am J Clin Nutr 1985; 42: 371–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Halyburton AK, Brinkworth GD, Wilson CJ, Noakes M, Buckley JD, Keogh JB, et al. Low- and high-carbohydrate weight-loss diets have similar effects on mood but not cognitive performance. Am J Clin Nutr 2007; 86: 580–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Brinkworth GD, Noakes M, Buckley JD, Keogh JB, Clifton PM. Long-term effects of a very-low-carbohydrate weight loss diet compared with an isocaloric low-fat diet after 12 mo. Am J Clin Nutr 2009; 90: 23–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Saslow LR, Kim S, Daubenmier JJ, Moskowitz JT, Phinney SD, Goldman V, et al. A randomized pilot trial of a moderate carbohydrate diet compared to a very low carbohydrate diet in overweight or obese individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus or prediabetes. PLoS One 2014; 9: e91027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Archer E, Pavela G, Lavie CJ. The inadmissibility of what we eat in America and NHANES dietary data in nutrition and obesity research and the scientific formulation of national dietary guidelines. Mayo Clin Proc 2015; 90: 911–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Volek JS, Feinman RD. Carbohydrate restriction improves the features of metabolic syndrome. metabolic syndrome may be defined by the response to carbohydrate restriction. Nutr Metab 2005; 2: 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Firth J, Marx W, Dash S, Carney R, Teasdale SB, Solmi M, et al. The effects of dietary improvement on symptoms of depression and anxiety: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Psychosom Med 2019; 81: 265–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Firth J, Veronese N, Cotter J, Shivappa N, Hebert JR, Ee C, et al. What is the role of dietary inflammation in severe mental illness? A review of observational and experimental findings. Front Psychiatry 2019; 10: 350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Baumeister D, Russell A, Pariante CM, Mondelli V. Inflammatory biomarker profiles of mental disorders and their relation to clinical, social and lifestyle factors. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2014; 49: 841–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Nettis MA, Lombardo G, Hastings C, Zajkowska Z, Mariani N, Nikkheslat N, et al. Augmentation therapy with minocycline in treatment-resistant depression patients with low-grade peripheral inflammation: results from a double-blind randomised clinical trial. Neuropsychopharmacology 2021; 46: 939–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Buyken AE, Goletzke J, Joslowski G, Felbick A, Cheng G, Herder C, et al. Association between carbohydrate quality and inflammatory markers: systematic review of observational and interventional studies. Am J Clin Nutr 2014; 99: 813–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Perez-Cornago A, de la Iglesia R, Lopez-Legarrea P, Abete I, Navas-Carretero S, Lacunza CI, et al. A decline in inflammation is associated with less depressive symptoms after a dietary intervention in metabolic syndrome patients: a longitudinal study. Nutr J 2014; 13: 36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Baumeister D, Russell A, Pariante CM, Mondelli V. Inflammatory biomarker profiles of mental disorders and their relation to clinical, social and lifestyle factors. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2014; 49: 841–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Mancuso P. The role of adipokines in chronic inflammation. Immunotargets Ther 2016; 5: 47–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Forsythe CE, Phinney SD, Fernandez ML, Quann EE, Wood RJ, Bibus DM, et al. Comparison of low fat and low carbohydrate diets on circulating fatty acid composition and markers of inflammation. Lipids 2008; 43: 65–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Morris G, Puri BK, Carvalho A, Maes M, Berk M, Ruusunen A, et al. Induced ketosis as a treatment for neuroprogressive disorders: food for thought? Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2020; 23: 366–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Campbell I, Campbell H. A pyruvate dehydrogenase complex disorder hypothesis for bipolar disorder. Med Hypotheses 2019; 130: 109263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Morris G, Walder K, McGee SL, Dean OM, Tye SJ, Maes M, et al. A model of the mitochondrial basis of bipolar disorder. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2017; 74(Pt A): 1–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Morris G, Maes M, Berk M, Carvalho AF, Puri BK. Nutritional ketosis as an intervention to relieve astrogliosis: possible therapeutic applications in the treatment of neurodegenerative and neuroprogressive disorders. Eur Psychiatry 2020; 63(1): e38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Morris G, Walder KR, Berk M, Marx W, Walker AJ, Maes M, et al. The interplay between oxidative stress and bioenergetic failure in neuropsychiatric illnesses: can we explain it and can we treat it? Mol Biol Rep 2020; 47: 5587–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Calkin CV, Ruzickova M, Uher R, Hajek T, Slaney CM, Garnham JS, et al. Insulin resistance and outcome in bipolar disorder. Br J Psychiatry 2015; 206: 52–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]