Abstract

Hypomagnesemia is 10-fold more common in individuals with type 2 diabetes (T2D) than in the healthy population. Factors that are involved in this high prevalence are low Mg2+ intake, gut microbiome composition, medication use, and presumably genetics. Hypomagnesemia is associated with insulin resistance, which subsequently increases the risk to develop T2D or deteriorates glycemic control in existing diabetes. Mg2+ supplementation decreases T2D-associated features like dyslipidemia and inflammation, which are important risk factors for cardiovascular disease (CVD). Epidemiological studies have shown an inverse association between serum Mg2+ and the risk of developing heart failure (HF), atrial fibrillation (AF), and microvascular disease in T2D. The potential protective effect of Mg2+ on HF and AF may be explained by reduced oxidative stress, fibrosis, and electrical remodeling in the heart. In microvascular disease, Mg2+ reduces the detrimental effects of hyperglycemia and improves endothelial dysfunction; however, clinical studies assessing the effect of long-term Mg2+ supplementation on CVD incidents are lacking, and gaps remain on how Mg2+ may reduce CVD risk in T2D. Despite the high prevalence of hypomagnesemia in people with T2D, routine screening of Mg2+ deficiency to provide Mg2+ supplementation when needed is not implemented in clinical care as sufficient clinical evidence is lacking. In conclusion, hypomagnesemia is common in people with T2D and is involved both as cause, probably through molecular mechanisms leading to insulin resistance, and as consequence and is prospectively associated with development of HF, AF, and microvascular complications. Whether long-term supplementation of Mg2+ is beneficial, however, remains to be determined.

Keywords: cardiovascular disease, heart failure, atrial fibrillation, macrovascular disease, microvascular disease, type 2 diabetes

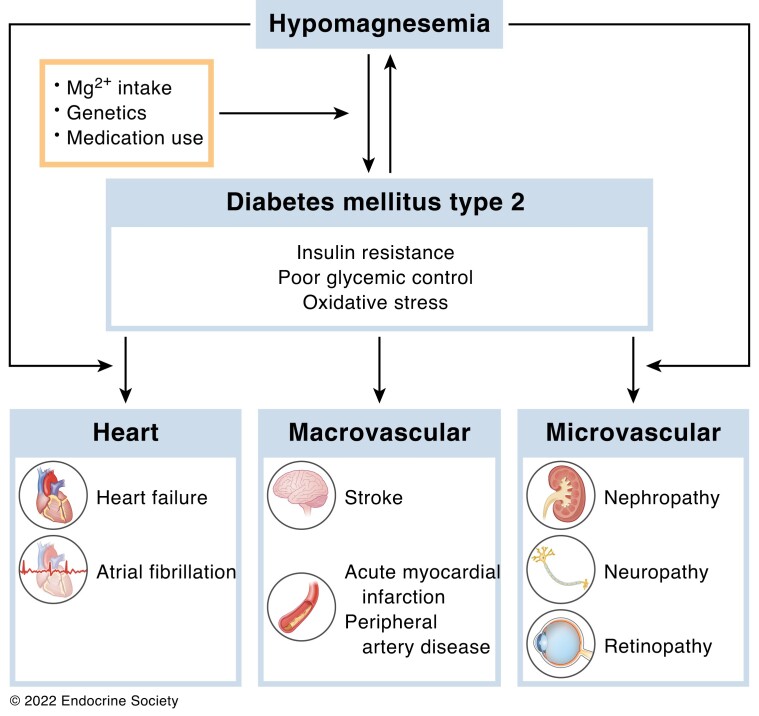

Graphical Abstract

Essential Points.

Hypomagnesemia independently contributes to the development of atrial fibrillation, heart failure, and microvascular disease in people with type 2 diabetes

Magnesium in involved in several molecular mechanisms that may explain the relationship with heart disease, including mitochondrial oxidative stress

The potential protective effect of magnesium on development of microvascular complications is largely explained by biochemical pathways that are activated upon hyperglycemia

Magnesium supplementation in people with type 2 diabetes has favorable effects on blood pressure, lipid levels, and endothelial dysfunction

Long-term magnesium supplementation studies are needed to determine whether increasing serum/plasma magnesium levels can improve cardiovascular outcomes

Hypomagnesemia (serum Mg2+ concentration <0.7 mmol/L) is common in type 2 diabetes (T2D) (1-3). In people with T2D, hypomagnesemia is reported approximately 10-fold more than in the general population and is associated with insulin resistance, hyperglycemia, and rapid diabetes disease progression (2, 4, 5). In type 1 diabetes (T1D) hypomagnesemia is rare (6, 7), suggesting that insulin resistance is the key factor related to disturbed Mg2+ homeostasis.

Hypomagnesemia may increase the risk of cardiovascular events and mortality in T2D. Epidemiological studies have shown that low serum or dietary Mg2+ concentration, or low dietary intake of Mg2+, is inversely associated with the occurrence of heart failure (HF), atrial fibrillation) (AF), coronary heart disease (CHD), stroke, and microvascular complications in T2D (8-12). However, whether Mg2+ supplementation is beneficial in T2D is unclear. Clinical trials with Mg2+ supplements demonstrate conflicting results and are limited by poor study design, absence of clinically relevant endpoints, and the low number of study participants. In addition, Mg2+ supplementation is quantitatively limited because of side effects. Consequently, Mg2+ supplements are still not recommended as a treatment in people with T2D.

This review describes the potential mechanisms and theoretical protective effects of Mg2+ with respect to CVD in T2D. First, we provide a comprehensive overview of clinical studies that have investigated the association between serum and dietary Mg2+ with CVD risk factors and incidents in T2D. Then we explain mechanistically the role of Mg2+ in the cardiovascular pathophysiology of people with T2D. We end by summarizing and describing the efficiency and challenges of Mg2+ treatment in people with T2D.

Hypomagnesemia in Type 2 Diabetes

Mg2+ is essential for many biological processes in the human body, such as DNA synthesis, energy production, and vascular homeostasis (13). The human body maintains serum Mg2+ concentration between 0.70 and 1.05 mmol/L, which is therefore the main indicator of Mg2+ status in clinical practice (14). Although measurements of the intracellular Mg2+ concentration have been proposed as an alternative, total serum/plasma Mg2+ concentration is preferred in people who are at risk for adverse clinical outcomes (15). Insulin resistance is suggested to contribute to hypomagnesemia in people with diabetes, explaining why it is more prevalent in T2D than in T1D (7). Here, we will describe the main determinants of hypomagnesemia in T2D. Moreover, we will discuss the potential mechanisms that contribute to hypomagnesemia.

Prevalence of hypomagnesemia

The prevalence of hypomagnesemia is approximately 2% in the healthy population (5), and is higher in people using diuretics and proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) (16). Low serum Mg2+ is more common in hospitalized patients and may rise as high as 60% in patients in the intensive care unit (17, 18). In T2D, cohort studies report a prevalence of hypomagnesemia between 9.1% and 47.7% (4, 5, 8, 19-23).

Glycemic control and insulin resistance are considered to be the most important determinants of hypomagnesemia in T2D (4, 20, 24-26). In a case–control study with a high prevalence of hypomagnesemia (50%), age, poor glycemic control, and low estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) were significant predictors of low serum Mg2+ levels (24). In a cross-sectional study including 929 individuals with T2D, serum Mg2+ was inversely associated with age, diabetes duration, body mass index, glycemic control (as HbA1c), and medication use (metformin, sulfonylurea derivatives, and DPP4 inhibitors) (20).

Causes of hypomagnesemia in type 2 diabetes

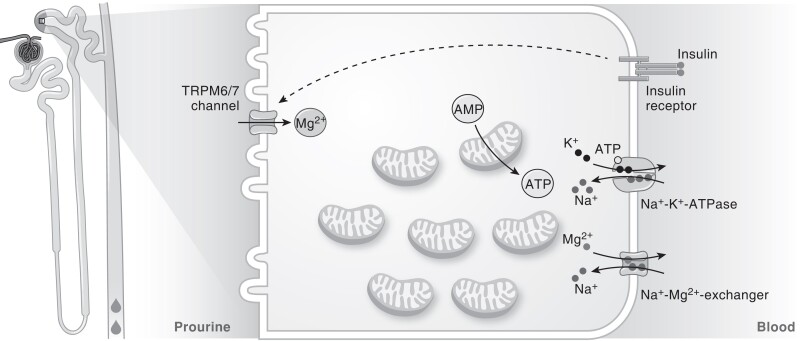

Hypomagnesemia is associated with increased risk of developing prediabetes and T2D (2). The incidence rate of T2D is inversely associated with serum Mg2+ concentration. In the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study, prospective analysis showed a 2-fold increase in incidence rate from the highest to the lowest serum Mg2+ concentration (from 11.1 in the highest serum Mg2+ group to 22.8 in the lowest serum Mg2+ group per 1000 person-years) in 12 128 people after 6 years of follow-up (27). These clinical studies demonstrate that hypomagnesemia may contribute to the development of T2D. In existing T2D, the pathophysiology of T2D may enhance Mg2+ loss, suggesting that Mg2+ homeostasis and T2D are part of a vicious circle (28). Mg2+ handling in T2D is visualized in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Mg2+ handling in people with T2D. In T2D, insulin resistance reduces Mg2+ reabsorption from the prourine in the DCT. Mg2+ is an important cofactor for ATP generation, and ATP is subsequently used by NA+-K+-ATPase to create a Na+ gradient that drives Mg2+ extrusion. Abbreviations: ATP, adenosine triphosphate; AMP, adenosine monophosphate; DCT, distal convoluted tubule; IR, insulin receptor; K+, potassium; Mg2+, magnesium; Na+, sodium; TRPM6/7, transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily M member 6/7; T2D, type 2 diabetes.

Mg2+ homeostasis is a tight balance between intestinal Mg2+ absorption, storage of Mg2+ in bone and soft tissues, and renal Mg2+ reabsorption (extensively reviewed by De Baaij et al (13)). In short, Mg2+ is absorbed paracellularly in the small intestine via tight junctions. Although the exact molecular pathway is unknown, claudins 2, 7, and 12 are selective for cations and may contribute to Mg2+ permeability (29,30). Fine-tuning of Mg2+ absorption is achieved in the distal segments of the ileum and colon in a transcellular fashion (31). In colonocytes, Mg2+ uptake is mediated via transient receptor potential melastatin (TRPM) type 6 and TRPM7 heterotetramers, and Mg2+ extrusion is facilitated by cyclin M4 (CNNM4) (13). Indeed, knockout models of these Mg2+-transporting proteins display impaired intestinal Mg2+ absorption and hypomagnesemia (32-35).

Approximately 70% of the blood Mg2+ content is ionized, as 30% is bound to albumin (36). The most common clinical pathology methods employed for measuring serum Mg2+ are dye binding and enzymatic assays (37, 38). Both methods determine the total Mg2+ content containing ionized as well as albumin-bound forms (37). Total serum Mg2+, rather than ionized Mg2+, is generally used clinically to assess blood Mg2+ status (38). In the kidney, the ionized Mg2+ is freely filtered, and subsequently 98% is reabsorbed along the nephron. Paracellular transport in the proximal tubule (PT) and thick ascending limb of Henle's loop (TAL) accounts for 90% of the tubular reabsorption (13). In particular, tight junction complexes in the TAL consisting of claudin 14/16/19 allow reabsorption of Mg2+ using the negative transepithelial voltage potential (39-41). In the distal convoluted tubule, the remaining 10% of filtered Mg2+ is reabsorbed by TRPM6/TRPM7 complexes (42). The activity of TRPM6 is highly regulated by estrogen, epidermal growth factor (EGF), insulin, ATP, pH, and [Mg2+]intracellular (43-48). The mechanisms of basolateral extrusion of Mg2+ in the distal convoluted tubule are under debate, but may include Na+–Mg2+ exchange via CNNM2, SLC41A1, and/or SLC41A3 proteins (49-52).

Several mechanism have been proposed that have an effect on intestinal absorption and renal excretion of Mg2+, including poor Mg2+ intake, alcoholism, medication use, microbiota, and genetic factors (23, 53). In the following paragraphs, we will specifically focus on factors that are relevant in individuals with T2D.

Dietary intake

The daily recommend intake for Mg2+ is 400 to 420 mg for males and 310 to 320 mg for females (54). As foods like vegetables and nuts are generally Mg2+ rich, people who consume refined and processed foods are at risk for hypomagnesemia (55, 56). Some studies in people with T2D report daily Mg2+ intake well below the daily recommend intake (57), while other studies report sufficient dietary intake of Mg2+ by people with T2D, which may reflect differences in dietary habits between individuals or populations (58). Moreover, a potential bias of the use of food questionnaires to determine Mg2+ intake is the presence of hidden confounders or well-known incomplete recordings of dietary intake. Nevertheless, a low dietary Mg2+ intake is inversely associated with the risk of developing T2D (59).

In recent years, the microbiome has emerged as a novel intestinal ecosystem important for human health. Indeed, changes in the composition and function of the microbiome have been described in individuals with T2D (60, 61), and dysbiosis is associated with low-grade inflammation and insulin resistance (62-64). Dietary Mg2+ intake has been demonstrated to affect the microbiome diversity both in people with T2D and in a diabetic mouse model (65, 66). Interestingly, studies in nondiabetic animal models showed that the effect of Mg2+ intake on microbiome composition may depend on Mg2+ status and on the use of PPIs (67, 68). To date, the relationship between the microbiome and T2D-induced hypomagnesemia is mainly based on association studies. Studies further investigating causality are urgently needed to understand the complex interplay between microbiota and host.

Medication

Polypharmacy is common in T2D (69). Hypomagnesemia-causing medication like thiazide diuretics and PPIs are commonly prescribed to individuals with T2D (70). Indeed, in the general population diuretics have been associated with renal Mg2+ loss (71, 72), and several groups have hypothesized that hypomagnesemia is more common in individuals with T2D using these drugs. Nevertheless, this association could not be confirmed in several cross-sectional cohorts consisting of T2D individuals who used diuretics and/or PPIs (4, 73). We found in a cohort of 395 T2D carefully phenotyped individuals that medication explained <10% of the variation in serum Mg2+ concentration (4). In this study, the use of metformin correlated significantly with a reduced serum Mg2+ level and the use of insulin correlated with a higher serum Mg2+ concentration. Metformin was demonstrated to downregulate TRPM6 expression and Mg2+ uptake in colon and kidney cells (74). Data from human cohort studies are scarce; in an intervention study metformin caused a minor but significant reduction in plasma Mg2+ of individuals with T2D (75). In contrast, metformin treatment in animal models of diabetes did not result in a reduced blood Mg2+ concentration (76, 77). Consequently, metformin-associated weight loss or adaptations in dietary patterns may contribute to the effects of metformin on blood Mg2+ concentration.

Hypermagnesiuria

Hypermagnesiuria, defined as a fractional excretion of Mg2+ above 4%, is generally considered to be the main cause of hypomagnesemia in T2D, affecting >40% of the individuals (4). Experiments in the 1970s and 1980s initially attributed Mg2+ loss to glucosuria (78, 79). However, this notion has recently been questioned due to the introduction of sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors. SGLT2 inhibitors inhibit glucose reabsorption in the PT, resulting in overt glucosuria, without renal Mg2+ loss (80, 81). In contrast, use of SGLT2 inhibitors even increased serum Mg2+ concentration in T2D (82).

An alternative explanation for increased magnesiuria is the presence of hyperfiltration and increased urinary flow (83). Mg2+ reabsorption in the PT and TAL is dependent on concentration gradient of Mg2+. Micropuncture studies have demonstrated that a 1.9 ratio between the concentration of Mg2+ in the tubular fluid and the interstitial fluid is required for passive Mg2+ reabsorption in the PT (84). Consequently, dilution of the Mg2+ concentration of the prourine by hyperfiltration may inhibit Mg2+ reabsorption.

Several studies suggest that TRPM6 plays a key role in T2D-associated hypermagnesiuria (76, 85, 86). Insulin regulates TRPM6 plasma membrane expression via a phosphoinositide 3 kinase–Akt–Rac1-dependent pathway (48). Decreased biological action of insulin (ie, insulin resistance) may therefore result in reduced TRPM6 activity. This is supported by the observation that common polymorphisms (single-nucleotide polymorphisms) that render the channel insensitive to insulin stimulation are associated with hypomagnesemia and increase the susceptibility to develop gestational diabetes (p.Val1393Ile [rs3750425] and p.Lys1584Glus [rs2274924]) (48, 85). In diabetic animal models, Trpm6 expression is upregulated in kidney and colon tissue (76, 86), which is explained as a compensatory effect in response to hypomagnesemia, but could not be demonstrated in all animal studies (87, 88). These studies highlight the complex regulatory pathways toward TRPM6 expression. Indeed, in addition to insulin, oxidative stress, lipid metabolism and bile acids have been demonstrated to regulate TRPM6 expression and activity (89-91).

Dyslipidemia

Dyslipidemia is a common characteristic of T2D. Nonesterified fatty acids (NEFAs) directly bind Mg2+ and thereby contribute to low Mg2+ levels with elevated free fatty acids levels in animals and humans (92). NEFAs are released by lipolysis of triglycerides (TGs) stored in white adipose tissue or consumed in a high-fat meal (93). Of note, TGs are not negatively charged and are therefore unlikely to bind Mg2+. Although NEFAs are suggested to be responsible for reduced Mg2+ levels in T2D, TGs are often associated with hypomagnesemia since TGs and NEFAs are strongly correlated and often elevated simultaneously (94). Kurstjens et al showed that plasma Mg2+ was associated with TGs and glucose levels in 395 people with T2D (4). Two separate cohorts, consisting of 285 overweight individuals and 395 people with T2D, respectively, reported an inverse relationship between TGs and serum Mg2+ levels (4, 92). Novel findings of recent studies do question the overall clinical relevance of the effect of TGs on Mg2+ concentration (95). In a large population of 680 people with T2D, the inverse association of serum Mg2+ with TGs disappeared after correcting for a large set of confounders, including glucose levels and dietary factors (96). There may be insufficient adjustment for confounders in previous studies or correcting for lipid consumption may attenuate the association of Mg2+ with TG levels.

Consequences of hypomagnesemia in type 2 diabetes

The mechanisms that explain the role of hypomagnesemia in the development of T2D include insulin resistance, oxidative stress, and low-grade systemic inflammation. As these mechanisms are also risk factors for CVD, we will briefly discuss them in the following paragraphs.

Insulin resistance

Hypomagnesemia is associated with poor glycemic control (reflected by HbA1c or fasting glucose levels) and insulin resistance in people with and without T2D (4, 97-102), and both are associated with increased CVD risk. Hypomagnesemia may contribute to the development of CVD in T2D directly or indirectly by enhancing poor glycemic control and insulin resistance (103-105). In transplant patients, the use of the calcineurin inhibitors is associated with new-onset diabetes. Interestingly, hypomagnesemia may partially explain this calcineurin inhibitor–induced diabetes after transplantation (106). However, a clinical trial with a Mg2+ supplement only showed a limited effect on glucose homeostasis (107).

Mg2+ is an essential cofactor for ATP and as such an important regulator of kinase activity in a multitude of intracellular signaling pathways (13). Several studies have therefore examined the role of Mg2+ in insulin signaling. In cell and animal experiments, Mg2+ was demonstrated to regulate the phosphorylation of the insulin receptor (IR) and downstream enzymes such as phosphoinositide 3 kinase and Akt (108-110). Consequently, hypomagnesemia leads to reduced glucose-transporter 4 (GLUT4) expression and trafficking to the membrane in myocytes (110-112). Crystal structures of the IR demonstrated that Mg2+ ions bind the tyrosine kinase domain and are essential for autophosphorylation of the IR (108, 109, 113). Hypomagnesemic rats have reduced levels of IR phosphorylation and insulin resistance (114, 115). Improving insulin signaling by Mg2+ supplementation shows generally positive results; IR and GLUT4 expression levels are increased in T2D rats (112, 116). Oral Mg2+ supplementation increased muscle GLUT4 expression in STZ-induced rats and thereby lowered serum glucose levels to normal range (117).

Oxidative stress

Oxidative stress is suggested to play a role in the pathogenesis of CVD in individuals with T2D (118-121). Hyperglycemia and dyslipidemia may contribute to mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) overproduction in endothelial cells and the myocardium (122-126). The primary ROS is the superoxide anion, which can be converted to hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) by superoxide dismutase (127, 128). The superoxide dismutase activity was dramatically decreased in mice upon a hypomagnesemia diet, consequently reducing the antioxidant defense (129). In T2D, mitochondrial ROS leads to endothelial dysfunction through multiple signaling pathways by the advanced glycosylation end products (AGEs), the protein kinase C (PKC) pathway, and the polyol and hexosamine pathways (119). In particular, nitric oxide (NO) is directly inactivated by excessive vascular ROS (130). Indeed, low Mg2+ levels resulted in decreased NO release in endothelial cells (131). Altogether, these studies demonstrate the role of Mg2+ in oxidative stress and reduced NO production.

Low-grade systemic inflammation

Insulin resistance contribute to development of CVD by increasing low-grade systemic inflammation (132-134), but Mg2+ may also directly cause inflammation. Many studies have described the association of serum Mg2+, dietary Mg2+ and Mg2+ supplements with inflammatory marker C-reactive protein (CRP) (135-137). Although, the mechanisms explaining the role of Mg2+ in endothelial inflammation are poorly described, low Mg2+ concentrations were reported to activate nuclear factor kappa light chain enhancer of activated B cells (NF-kB) in endothelial cells and induce the synthesis of proinflammatory cytokines (138, 139). In rodents, hypomagnesemia leads to an acute systemic inflammatory response, and is associated with increased levels of interleukin (IL)-1, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α (140). A proinflammatory cytokine profile induced by hypomagnesemia is often accompanied by ROS production, showing that oxidative stress and inflammation are closely linked (139, 141). Other mechanisms may include the increased production of substance P and Ca2+-induced degranulation of mast cells (140, 142, 143).

Hypomagnesemia and Cardiovascular Risk

T2D is well established as a risk factor for CVD (144). Here, we summarize and compare clinical studies that have assessed the association of serum Mg2+ level with macro and microvascular incidents (Table 1) or and the relationship with CVD risk factors (Table 2) with macrovascular and microvascular incidents and the relationship with CVD risk factors; hypertension, dyslipidemia, inflammation, and endothelial dysfunction in cohorts of people with T2D.

Table 1.

Epidemiology of serum Mg2+ with clinically relevant cardiovascular endpoints in people with T2D

| Authors, year | Population | Mg2+ level | Study type | CVD outcome | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adiwinoto et al, 2021 (154) | 3227 T2D of 17 studies, among 13 studies performed in India | Hypomagnesemia prevalence between 11 and 33% | Meta-analysis, cross-sectional and case–control | DR | 14/17 studies showed that hypomagnesemia increased the risk of developing DR in T2D |

| Oost et al, 2021 (8) | 4348 T2D | Mean baseline serum Mg2+ 0.80 ± 0.08 mmol/L (1.94 ± 0.19 mg/dL). The prevalence of hypomagnesemia (serum Mg2+ < 0.7 mmol/L) was 9.1% | Prospective cohort (follow-up 5.1-6.1 years) | AMI, CHD, HF, stroke, PAD, AF, DKD, DR, diabetic foot | Serum Mg2+ concentration is inversely associated with the risk of developing HF and AF and with the occurrence of CKD, diabetic retinopathy, and foot complications in T2D |

| Xing et al, 2021 (155) | 2222 T2D | Analyzed categorically in quartiles | Retrospective study | DR | Lower Mg2+ levels are associated with increased risk of DR |

| Muhurdaroglu et al, 2021 (299) | 116 T2D | Mean serum Mg2+ 1.82 ± 0.50 mg/dL (0.75 ± 0.21 mmol/L) | Cross-sectional | DN | Serum Mg2+ were significantly different in T2D with polyneuropathy |

| Salhi et al, 2021 (149) | 170 T2D | Analyzed categorically in 2 groups (low and normal Mg2+) | Case–control | DR, DN, DKD (as diabetic nephropathy), macroangiopathy and microangiopathy, hypertension | Low Mg2+ level is correlated with high blood pressure and nephropathy |

| Ferrè et al, 2019 (157) | 2056 and 187 (9.1%) with diabetes, type not defined | Serum Mg2+ mean ± SD value of 2.10 ± 0.20 mg/dL (0.86 ± 0.08 mmol/L). Analyzed categorically in quantiles and continuous | Case–control | DKD (eGFR decline) | Lower serum Mg2+ was associated with eGFR decline and more pronounced in participants with prevalent diabetes compared with patients without diabetes |

| Alswat, 2018 (145) | 285 T2D | Prevalence of hypomagnesemia (serum Mg2+ < 0.7 mmol/L) 28.4%. Serum Mg2+ mean 0.75 ± 0.1 mmol/L (1.82 ± 0.24 mg/dL) | Cross-sectional | DR, DN (including diabetic foot), DKD (as nephropathy), cardiac disease, pulse rate | T2D with hypomagnesemia have a higher pulse rate |

| Zhang et al, 2018 (156) | 256 T2D | Serum Mg2+ mean ± SD value of 0.83 ± 0.09 mmol/L (2.02 ± 0.22 mg/dL). Analyzed categorically in tertiles | Cross-sectional | DN | Lower serum Mg2+ was correlated with parameters of nerve conduction in T2D |

| Zhang et al, 2018 (10) | 1217 T1D and T2D | Analyzed categorically in 6 groups of serum Mg2+, range and mean not known | Cross-sectional | DR, DN, DKD, diabetic ketoacidosis, diabetic macroangiopathy, diabetic foot, hypertension, lipid levels | Serum Mg2+ is associated with DR, DN, DKD in males with diabetes. In females, DR, DKD, and diabetic macroangiopathy are stronger associated with serum Mg2+ |

| Gant et al, 2018 (12) | 450 T2D | Analyzed categorically in quartiles or continuously | Cross-sectional | CHD | Higher plasma Mg2+ is associated with a lower prevalence of CHD |

| Arpaci et al, 2015 (1) | 673 T2D | Mean serum Mg2+ level 1.97 ± 0.25 mg/dL (0.81 ± 0.1 mmol/L). Analyzed categorically in 2 groups (low and normal Mg2+) | Cross-sectional | DR, DN, urinary proteinuria, TG, LDL, and HDL cholesterol | Microalbuminuria was more common in the hypomagnesemia group. Negative correlation between serum Mg2+ and urine protein levels. No differences of DR, DN, and lipid levels between low and normal Mg2+ group |

| Lu et al, 2016 (153) | 3100 diabetes, type not defined | Analyzed categorically in tertiles and continuously | Cross-sectional | Albuminuria, DR, CRP | Albuminuria and DR decreased by approximately 20% for every 0.1 mmol/L increase in serum Mg2+. Serum Mg2+ negatively correlated with CRP |

| Peters et al, 2013 (11) | 940 T2D | Hypomagnesemia prevalence 19%. Analyzed continuously | Prospective cohort (follow-up 12.3 years) | CHD and cerebrovascular disease (stroke and transient attacks) | Incident cerebrovascular disease, but not CHD, was independently and inversely associated with serum Mg2+ |

| Pham et al, 2009 (158) | 550 T2D | Analyzed categorically in quartiles | Prospective cohort (follow-up between 93.8 and 99.4 months) | Serum creatinine | Long-term follow-up shows an association between low serum Mg2+ and worse renal outcomes in T2D |

| Pham et al, 2005 (159) | 550 T2D | Analyzed categorically in quartiles | Prospective cohort (follow-up 62.6 months) | Serum creatinine | A trend for worse proteinuria belonging to the lowest serum Mg2+ group |

Abbreviations: AF, atrial fibrillation; AMI, acute myocardial infarction; CHD, coronary heart disease; CVD, cerebrovascular disease; DKD, diabetic kidney disease; DN, diabetic neuropathy; DR, diabetic retinopathy; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; HF, heart failure; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; Mg2+, magnesium; PAD, peripheral artery disease; T2D, type 2 diabetes; TG, triglycerides.

Table 2.

Serum/plasma Mg2+studies with CVD-risk factors in people with T2D

| Authors, year | Population | Mg2+ level | Study type | CVD outcome | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| van Vuuren et al, 2019 (300) | 495 T2D | Mean serum Mg2+ 0.78 ± 0.12 mmol/L (1.9 ± 0.29 mg/dL) | Cross-sectional | Lipid levels | Positive, linear relationship between serum Mg2+ with total cholesterol and LDL, no association between HDL and TG |

| Alswat, 2018 (145) | 285 T2D | Prevalence of hypomagnesemia (serum Mg2+ < 0.7 mmol/L) 28.4%. Serum Mg2+ mean 0.75 ± 0.1 mmol/L (1.82 ± 0.24 mg/dL) | Cross-sectional | Lipid profile | Serum Mg2+ is positively correlated with total cholesterol and TG |

| Nizami et al, 2018 (152) | 75 T2D | Mean serum Mg2+ 1.68 ± 0.22 mg/dL (0.69 ± 0.09 mmol/L), in T2D | Case–control | hs-CRP | Negative correlation between hs-CRP and serum Mg2+ |

| Zhang et al, 2018 (96) | 8163 people with 680 (8.3%) T2D | Prevalence of hypomagnesemia (serum Mg2+ ≤ 0.65 mmol/L) 4.8% in the T2D group | Cross-sectional | Lipid profile | No significant change of HDL and LDL cholesterol between Mg2+ groups, in T2D |

| Kurstjens et al, 2017 (4) | 395 people with T2D | Prevalence of hypomagnesemia (plasma Mg2+ < 0.7 mmol/L) 30.6%. Mean plasma Mg2+ was 0.74 ± 0.10 mmol/L (1.8 ± 0.24 mg/dL) | Cross-sectional | Lipid profile, blood pressure, heart rate | Plasma Mg2+ was negatively correlated with TG, DBP, heart and positively with HDL. No association with SBP |

| Rasheed et al, 2012 (146) | 219 T2D and 100 controls | Prevalence of hypomagnesemia (serum Mg2+ < 0.70 mmol/L) 65.3%. Mean serum Mg2+ 1.6 ± 0.23 mg/dL (0.66 ± 0.09), in T2D | Case–control | Lipid profile | Serum Mg2+ was positively correlated with HDL and negatively with total cholesterol and LDL |

| Nasri, 2006 (147) | 112 people with diabetes, type not defined | Mean serum Mg2+ 2 ± 0.4 mg/dL (0.82 ± 0.16 mmol/L) | Cross-sectional | Lipid profile | Inverse correlation of serum Mg2+ with total cholesterol and serum LDL |

| Anetor et al, 2002 (148) | 40 T2D and 20 controls | Mean serum Mg2+ 0.75 ± 0.05 mmol/L (1.82 ± 0.12 mg/dL), in T2D | Case–control | Lipid profile | Serum Mg2+ showed a positive correlation with total cholesterol |

Abbreviations: eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, hs-CRP; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; Mg2+, magnesium; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; T2D, type 2 diabetes; TG, triglycerides.

Serum/plasma magnesium level and cardiovascular risk

Clinical endpoints

Systematic analyses of prospective cohort studies (Table 1) demonstrate that serum Mg2+ is inversely and independently associated with an increased risk of developing HF, AF, and possibly stroke in T2D. In a large cohort of 4348 T2D individuals (DCS [diabetes care system] cohort), serum Mg2+ was inversely associated with the future risk to develop HF and AF (8). After correcting for confounders, serum Mg2+ did not affect the risk to develop acute myocardial infarction (AMI), CHD, stroke, and peripheral arterial disease (PAD) (8). This is in contrast with other cross-sectional T2D studies that did find an association of serum Mg2+ with PAD and CHD incidences, but these studies were not corrected for confounders (12, 145). In the Fremantle Diabetes Study, serum Mg2+ was associated with incident cerebrovascular disease (stroke), but not CHD (11). Although stroke was significantly associated with serum Mg2+ concentration (P = .022) in the DCS cohort in an uncorrected statistical model, significance was lost after correcting for CVD-related confounders (8). As DCS and the Fremantle Diabetes Study imply a different method of Cox regression analysis, it is difficult to compare these studies and it is uncertain whether serum Mg2+ is really associated with the occurrence of stroke in T2D. Altogether, these results suggest that hypomagnesemia increases the risk of HF, AF, and potentially stroke. The association of low Mg2+ with CHD and PAD is mediated through other CVD risk factors.

CVD markers

Several studies have examined the effect of serum/plasma Mg2+ on surrogate endpoints for CVD risk in T2D. Lipid profile is the CVD risk factor that has been studied most in association with serum/plasma Mg2+ (Table 2). The majority of studies show that serum/plasma Mg2+ is inversely associated with TG levels, total cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, and positively with high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol (145-148).

Studies with hypertension as an outcome in the association of serum Mg2+ are scarce and conflicting in people with and without T2D (4, 10, 145, 149-151). Kurstjens et al showed using a multivariable regression model that the association of plasma Mg2+ with blood pressure is not significant in 395 individuals with T2D, although many subjects were on antihypertensives (4). The use of antihypertensives and the possibility that individuals with hypomagnesemia may not be hypertensive (151) may contribute to these conflicting data.

A number of studies has reported negative correlation of serum Mg2+ with the inflammatory marker high-sensitivity CRP (hs-CRP) (152, 153). There are currently no studies of serum/plasma Mg2+ with endothelial dysfunction markers, such as endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) and vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1). We conclude, that serum/plasma Mg2+ is presumably associated with dyslipidemia and CRP. Further studies are needed to unravel how Mg2+ is mediating CVD risk factors, like hypertension, inflammatory markers (such as ILs) and endothelial function.

Microvascular complications

Prospective cohort studies, retrospective cohort studies, case–control studies, and 1 meta-analysis, have shown that serum Mg2+ is inversely associated with the risk to develop diabetic retinopathy (DR), diabetic nephropathy, diabetic neuropathy (DN), and diabetic foot complications (8, 154-156) (Table 1). Only a few cross-sectional and case–control studies result in nonsignificant outcomes, regarding DR, DN, and macroangiopathy (1, 149), suggesting the need for prospective study designs for future research. Besides the risk to develop diabetic nephropathy, serum Mg2+ is inversely associated with diabetic kidney disease, declining eGFR rates, serum creatinine, and proteinuria (8, 157-159). These results suggest a direct prospective association between low serum/plasma Mg2+ and microvascular complications.

It should be noted that diabetic nephropathy is associated with increased cardiovascular mortality, independent of known CVD risk factors (160). In general, this effect has been attributed to the development of vascular calcification, as a consequence of high serum phosphate levels (161). Vascular calcification results in vascular stiffness, which results in a high peripheral resistance. Interestingly, high Mg2+ levels are associated with reduced vascular calcification in vitro, in animal models and in CKD patients. The mechanisms of reduced calcification by having an optimal Mg2+ concentration have been extensively reviewed by Ter Braake et al (162, 163).

Dietary magnesium intake and cardiovascular risk

Clinical endpoints

While it has been repeatedly demonstrated that a lower T2D risk is associated with a higher dietary Mg2+ intake (164-166), there are almost no studies that assess the association of dietary Mg2+ intake with macrovascular and microvascular incidents. In the DIALECT-1 study, plasma Mg2+ as well as a higher Mg2+ intake and 24-hour urinary Mg2+ excretion were associated with a lower prevalence of CHD. To our knowledge the DIALECT-1 study is the only dietary Mg2+ study that investigated the association with macrovascular risk (12). Additional follow-up research assessing dietary Mg2+ and the relation of hard clinical CVD endpoints are needed.

CVD markers

Regarding CVD risk markers, a large prospective study with 4497 people of whom 330 had diabetes found that Mg2+ intake was inversely associated with hs-CRP, IL-6, and blood clotting factor fibrogen (167). Additionally, a study with 1999 people with 417 T2D incidents showed that a higher Mg2+ intake lowers T2D risk, with significant interactions of hs-CRP (168). In a cross-sectional study with 210 T2D individuals, Mg2+ intake was inversely associated with TG levels and positively associated with HDL cholesterol (169).

Potential Molecular Mechanisms of Magnesium Involvement in Cardiovascular Disease

The mechanism on how hypomagnesemia contributes to the development of a specific macrovascular or microvascular disease incident is complex, since various metabolic signaling factors are involved which may be interrelated. Here, we explain and discuss how Mg2+ may lead to the CVD in T2D (see Graphical Abstract).

Molecular mechanisms of magnesium in macrovascular disease

Acute myocardial infarction, coronary heart disease, stroke and peripheral arterial disease

Epidemiological studies demonstrated that serum Mg2+ is associated with CHD, stroke, and PAD in uncorrected models (8, 12, 145). However, the DCS and Fremantle Diabetes Study demonstrate that classic CVD risk factors, such as blood pressure, lipid disturbances, and oxidative stress, explain effect of Mg2+ levels on AMI, CHD, stroke, and PAD incidents (8, 11). Indeed, Mg2+ supplementation studies have shown to reduce blood pressure, reduce ROS and inflammation, and dyslipidemia (170-179).

Hypomagnesemia enhances insulin resistance (101, 102, 108-110). Insulin resistance, does at least partly, contribute to CVD risk by increased blood pressure and ROS (11, 180-182). Hypertension and ROS are important factors that increase the risk for stroke incidences (183). CHD incidences are as well increased by high blood pressure (184). Therefore, effects of Mg2+ on blood pressure and oxidative stress may translate in increased risk for stroke. Hypomagnesemia increases blood pressure by stimulating the production of aldosterone and local vasodilators (185-189). Aldosterone is known to cause vascular damage in endothelial cells (190). An important key mechanism here is that aldosterone strongly increases ROS levels, by nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase, xanthine oxidase, or from mitochondrial sources (190-193). Increased ROS leads to decreased NO bioavailability and vasoconstriction (194). For example, in stroke-prone hypertensive rats, upon a low Mg2+ diet, blood pressure increased, including superoxide concentrations, leading to decreased endothelium-dependent relaxation (195). In animal models, hypomagnesemia is shown to be associated with increased ROS levels (195, 196). ROS is also known to play a role in the pathophysiology of many other cardiovascular complications; including HF, AF, and microvascular disease (197, 198). It is well known that the reduction of NO, by elevated ROS, causes atherosclerosis (194, 197). Atherosclerotic plaques can grow and decrease blood flow and may rupture, resulting in acute vascular occlusion leading to AMI or stroke (199). In conclusion, in people with T2D, hypomagnesemia causes hypertension and oxidative stress, which is in part mediated by insulin resistance, which are in particular risk factors for CHD, stroke and AMI.

Insulin resistance may also lead to increased assembly and secretion of VLDL. The resulting hypertriglyceridemia lowers HDL cholesterol levels and causes smaller depleted LDL cholesterol particles (200). Animal studies have confirmed that Mg2+ may directly alter lipogenesis and lipolysis. In yellow catfish, Mg2+ reduced hepatic lipid accumulation, which may be attributed to inhibited lipogenesis and increased lipolysis (201). In rats on a high carbohydrate diet, hypomagnesemia increased TG and free cholesterol and decreased esterified cholesterol levels. Moreover, the lipoprotein composition was altered upon hypomagnesemia; TG and total cholesterol were increased in the VLDL and LDL fractions, while total cholesterol was lower in the HDL fractions (202). More cholesterol in (V)LDL particles and less cholesterol removed by HDL particles leads to cholesterol accumulation in the arterial wall (203). Altogether these findings suggest that hypomagnesemia increases serum free fatty acids by enhanced lipolysis, resulting in plaque formation and at a later stage atherosclerosis. This suggest that Mg2+ deficiency contributes to dyslipidemia which may indirectly lead to increased risk of AMI and stroke incidences (199).

In people with T2D, hypomagnesemia is suggested to have no direct association with AMI, CHD, stroke, and PAD. There is a possibility that hypomagnesemia may indirectly contribute to macrovascular incidences by affecting hypertension, ROS and inflammation, and dyslipidemia that are in part worsened by insulin resistance.

Heart failure and atrial fibrillation

HF and AF often coexist and have interrelated mechanisms that exacerbate each other (204, 205). HF is a syndrome characterized by loss of pump capacity of the heart that may be associated with systolic or diastolic dysfunction. Increased left ventricular (LV) filling pressure is the hallmark of HF and stimulates LV remodeling and stress in the atrial wall. AF is characterized by an abnormal heart rate that is caused by disturbances of electrical impulse origination and/or propagation. An irregular heart rate may contribute to HF incidents, by shortening the LV filling time (206).

Serum Mg2+ is inversely associated with the risk of developing HF and AF in T2D (8). The association of low serum or dietary Mg2+ with HF and AF also occurs in the general population (207,208). This suggests that the molecular mechanism of hypomagnesemia to HF and AF incidences occurs in people with and without T2D. However, the 10-fold higher hypomagnesemia prevalence and the presence of additional T2D hallmarks, such as poor glycemic control and insulin resistance, renders the importance of hypomagnesemia in people with T2D.

Mitochondrial dysfunction and ROS formation are characteristics of HF in T2D (120, 209). Insulin resistance results in a shift in energy production and low ATP levels (210). Hypomagnesemia causes diastolic dysfunction which is associated with mitochondrial dysfunction and membrane depolarization in rodents (211, 212). In T2D mice with hypomagnesemia and cardiac diastolic dysfunction, mitochondrial ATP production was decreased with increased ROS levels, while the mitochondrial membrane potential was depolarized, all of which was reversed by Mg2+ supplementation (213). Hypomagnesemia, therefore, results in cardiac fibrosis and hypertrophy, which are associated with hypertension and oxidative stress in rodent models of T2D (214–216).

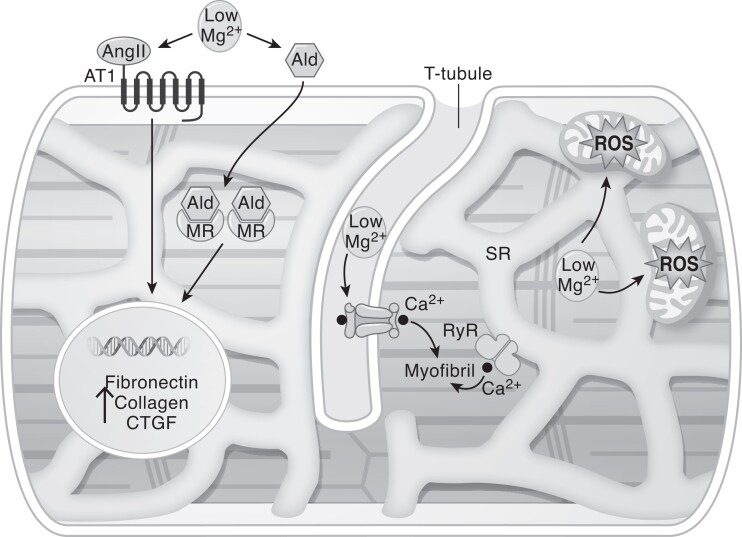

Mg2+ has a protective role on the heart by reducing oxidative stress, profibrotic signaling, but also electrical remodeling (Fig. 2). Because ROS production is a consequence of impaired glucose signaling, the role of hypomagnesemia is suggested to be more detrimental for HF incidents, in people with T2D. The occurrence of AF is in part triggered by ROS formation, but many effects of Mg2+ on electrical remodeling are suggested to be direct and not dependent on T2D pathophysiology.

Figure 2.

Potential pathways of explaining the interaction of hypomagnesemia and HF. Hypomagnesemia results in mitochondrial dysfunction, consequently decreasing ATP and increasing oxidative stress, which contribute to cardiac fibrosis. Activation of the RAAS system (increased Ang II and aldosterone levels) upon hypomagnesemia increases profibrotic transcription, including enhanced CTGF expression. Intracellular Ca2+ levels are increased upon hypomagnesemia due to activation of the L-type Ca2+ channels and Ca2+ is released from the SR. The combination of these factors result in disturbed myocardial contractility, fibrosis, and cardiac hypertrophy. Abbreviations: Ald, aldosterone; Ang II, angiotensin II; AT1, angiotensin II type 1 receptor, Ca2+, calcium; CTGF, connective tissue growth factor production; HF, heart failure; MR, mineralocorticoid receptor; RyR, ryanodine receptors; SR, sarcoplasmic reticulum; T2D, type 2 diabetes.

Hypomagnesemia further contributes to the development of HF by alterations of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS). Reduced cardiac output results in activation of RAAS to maintain blood pressure (217). However, if these systems are chronically activated hemodynamic stress causes further progression of HF (217, 218). Activation of the RAAS has been proposed as a major contributor to cardiovascular fibrosis in hypomagnesemic cardiomyocytes (219, 220). The regulation of Mg2+ was further demonstrated in studies with Mg2+ supplementation showing reduced angiotensin II-mediated connective tissue growth factor production in cardiac tissue (220). Hence, hypomagnesemia in people with and without T2D increases cardiac fibrosis triggered by RAAS activation.

In addition to RAAS, TRPM7-dependent changes in intracellular Mg2+ may influence cardiovascular health at various levels. In the heart, TRPM7+/Δkinase mice suffer from fibrosis, inflammation and cardiac hypertrophy (221, 222). In the vasculature, TRPM7 deficiency caused downregulation of the eNOS, vasoconstriction, and proinflammatory vascular responses (221). Indeed, intra-vital microscopy demonstrated impaired neutrophil rolling, increased neutrophil–endothelial attachment, and transmigration of leukocytes in TRPM7+/Δkinase mice (222). Interestingly, TRPM7 may regulate vascular smooth muscle cell function by directly binding to the EGF receptor and regulating its downstream signaling (223). Furthermore, TRPM7 was demonstrated to regulate phospholipase C signaling and store-operated Ca2+ entry in platelets (224). Consequently, mice without TRPM7 kinase activity were protected from stroke incidents. Interestingly, patients with a heterozygous p.C721G variant in TRPM7 suffer from macrothrombocytopenia and AF, further underlining the importance of the TRPM7 in the cardiovascular system (225). However, how these mechanisms contribute to CVD in people with T2D has never been investigated.

Whether the relationship between hypomagnesemia and future risk of developing HF in people with T2D relates to diastolic or systolic dysfunction has never been investigated. Hypomagnesemia has been shown to increase inflammation, ROS, and fibrosis in cardiomyocytes (211-216), which are metabolically related to both types of HF. However, diastolic dysfunction is the more common HF type in people with T2D (226), and mouse models using Mg2+ supplementation have only improved diastolic dysfunction (211, 213). Importantly, diastolic HF is mainly associated with the risk of developing microvascular disease and AF (226, 227).

HF-induced fibrosis can contribute to AF incidences, as increased collagen deposition in the atria impairs atrial conduction and causes fragmentation of propagating wavefronts, resulting in re-entry (228). This electrical remodeling is mainly caused by elevated ROS levels (228, 229). Mitochondria are the main source of ROS and, as already briefly discussed, Mg2+ decreases mitochondrial ROS in T2D cardiomyocytes (213).

Atrial action potentials are characterized by rapid Na+ influx, activation of Ca2+ channels to sustain the signal and inactivation by K+ efflux. All three phases are regulated by Mg2+. Hypomagnesemia is often accompanied by hypokalemia (230), which may also cause arrhythmias by suppression of K+ conductance and inhibition of Na+-K+-ATPase activity (231). The Rotterdam study showed that the association between hypokalemia and the risk of developing AF (including any type of rhythm disorder) was independent of serum Mg2+ levels (232), suggesting that these mechanisms do act independently of each other.

The sodium–potassium (Na+-K+-ATPase) pump is essential for the maintenance of Na+ and K+ concentrations across the membrane, allowing atrial action potentials. Hypomagnesemia diminishes Na+-K+-ATPase activity which may lead to an increase in intracellular Na+. Inhibition of the Na+-K+-ATPase pump causes cellular depolarization which contributes to AF incidence (233).

After depolarization of the cell membrane, voltage-gated Ca2+ channels open, which contribute to the long action potential plateau that is characteristic in human myocytes (234). Cardiomyocyte Ca2+ signaling is highly regulated by Mg2+ (235). Mg2+ limits intracellular Ca2+ overload by stimulating ischemic-induced lysophosphatidyl choline, which is an amphipathic phospholipid that is released from cardiac cell membranes (236). Hypomagnesemia is therefore associated with Ca2+ overload in cardiomyocytes, which increases the action potential and results in QT prolongation (237).

Subsequently, the K+ outward current opens and induces repolarization of the membrane potential that is required for relaxation (234, 238). In mice, hypomagnesemia has shown to downregulate the inward-rectifying K+ current and transient-outward K+ current, respectively, as Kir2.1 and Kv4.2. Intracellular Mg2+ deficiency directly upregulates the transcription factor NFAT and downregulates CREB, which reduces Kir2.1 and Kv4.2 channel activity and results in QT interval prolongation (239), directly reflecting a greater propensity to AF (240). Thus, hypomagnesemia completely disturbs the cardiac action potential in people with and without T2D mainly by disturbances of ion channels.

Molecular mechanisms of magnesium in microvascular disease

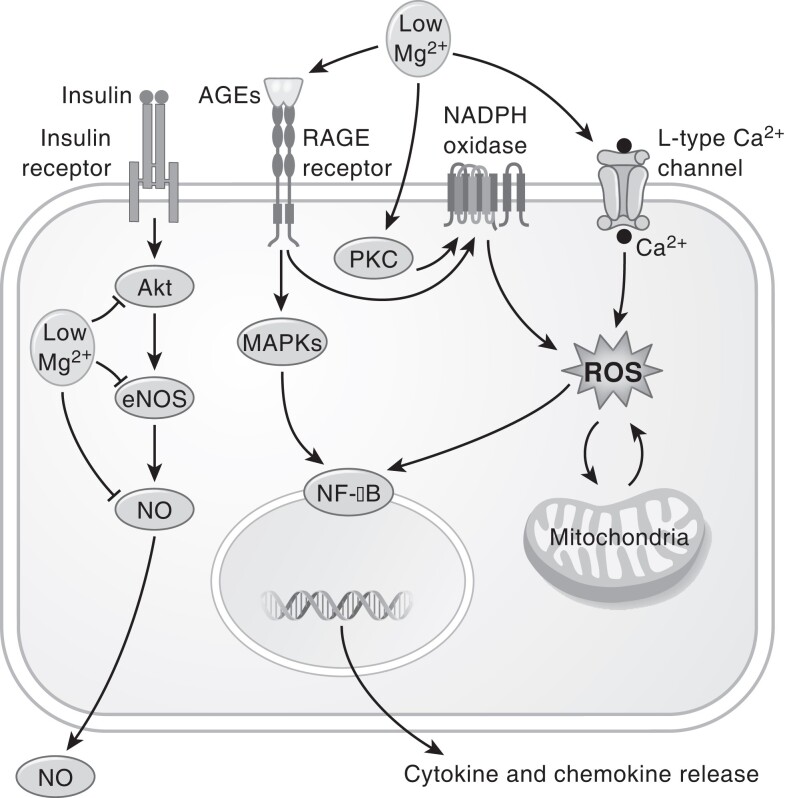

Endothelial dysfunction is probably involved in the development of microvascular complications in T2D. Reduced NO synthesis and changes in the AGE, PKC, polyol, and hexosamine pathways are the main biochemical pathways involved in the pathogenesis of microvascular disease (119). In a healthy physiological condition, Mg2+ leads to a tightened endothelial barrier (241). Silencing Mg2+ channel TRPM7 results in reduced Mg2+ cell entry, suggesting that this is the most important transporter for Mg2+ uptake in endothelial cells (242-244). In the following paragraphs, we will discuss the role of Mg2+ in the main pathways involved in endothelial dysfunction.

Endothelial cells maintain vascular permeability, mediate acute, and chronic immune responses and control of vascular tone (245). NO is a central mediator of endothelial function and, therefore, dysfunction of eNOS is associated with microvascular complications (246-248). Hypomagnesemia has been demonstrated to result in reduced eNOS mRNA expression and NO production (249). This reduced NO production may be mediated by decreased Akt activity (250). Indeed, Mg2+-incubated endothelial cells showed enhanced Akt phosphorylation and increased eNOS mRNA and protein levels compared with Mg2+-deficient endothelial cells (241).

In endothelial cells, it is shown that AGEs increase NADPH oxidase activity, but also promote phosphorylation of mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) p38 and ERK1/2 (251, 252). Serum Mg2+ is inversely associated with the potent dicarbonyl plasma methylglyoxal, leading to the formation of AGEs (253). AGE-increased NADPH oxidase activity upregulates intracellular ROS (252). Consequently, ROS may activate the NF-kB pathway and MAPK recruitment, resulting in the release of cytokines and chemokines (254, 255). Mg2+ is suggested to reduce apoptosis by diminishing MAPK and NF-kB signaling (255). Thus, hypomagnesemia may lead to increased AGE levels, as well as downstream signaling of MAPKs and NF-kB (251). Indeed, hypomagnesemia-induced changes in ROS are shown to directly activate NF-kB (139). Altogether, these studies suggest that hypomagnesemia can induce endothelial dysfunction by MAPK recruitment and/or increasing NF-kB signaling, subsequently leading to cytokine and chemokine release.

PKC is an additional factor that contributes to inflammation and reduced NO via ROS signaling in endothelial cells (256). Increased PKC activity has been demonstrated to result from Mg2+ deficiency, which is associated with activated NADPH oxidase activity and NF-kB signaling (256, 257). Endothelial ROS formation and inflammation may be further accelerated by activation of the RAAS system, uncontrolled hypertension, and dyslipidemia (258-260). Together, these pathways lead to oxidative stress and inflammation, which contributes to endothelial dysfunction and the development of microvascular incidents. The effects of Mg2+ deficiency on increasing AGE and PKC signaling may therefore both contribute to microvascular complications in people with T2D.

Hypomagnesemia-enhanced ROS production can also be caused by a high intracellular Ca2+ concentration (261). Mg2+ deficiency diminishes the inhibition of L-type calcium channels, leading to increased intracellular Ca2+ levels (262). Hypomagnesemia may also elevate intracellular Ca2+ through enhanced activation of the of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor, expressed specifically in the inner retina and neuronal cells (263, 264). In animal and in vitro models, hypomagnesemia caused increased intracellular Ca2+ levels, which were dependent on the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor, resulting in oxidative stress and toxicity (265-269). Prolonged oxidative stress is known to exacerbate neurodegenerative processes and renal fibrosis (263).

To conclude, AGEs and PKC activity are both elevated under hyperglycemic conditions and potentially increased by hypomagnesemia, resulting in oxidative stress. Hypomagnesemia directly affects signaling pathways that are associated with oxidative stress, by decreasing Akt phosphorylation, increasing MAPKs, NF-kB signaling, and intracellular Ca2+. These pathways result in endothelial dysfunction and diminished vasorelaxation by hampering NO release, while increasing inflammation and cytokine formation in endothelial cells (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Potential pathways of hypomagnesemia with microvascular disease in T2D. Hypomagnesemia exerts downstream of the insulin pathway by decreasing Akt phosphorylation, eNOS expression, and NO-mediated vasorelaxation. Hypomagnesemia increases oxidative stress by stimulating hyperglycemia-induced pathways as AGE formation and PKC activation, mitochondrial dysfunction, and increased intracellular Ca2+. Oxidative stress as well as MAPK signaling leads to increased NF-kB expression causing cytokine and chemokine release from endothelial cells. Abbreviations: AGE, advanced glycosylation end products; Ca2+, calcium; eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinases; NF-kB, nuclear factor kappa light chain enhancer of activated B cells; NO, nitric oxide; PKC, protein kinase C; T2D, type 2 diabetes.

Magnesium treatment in type 2 diabetes

The strong epidemiological evidence associating hypomagnesemia with CVD disease in T2D, suggests a direct role of Mg2+ in cardiovascular (dys)function. Mg2+ supplementation may therefore provide a promising approach to treat people with hypomagnesemia. In the following paragraphs the evidence and the challenges of Mg2+ supplementation will be discussed.

Efficacy of magnesium supplementation

Randomized clinical trials that assess the effect of Mg2+ supplementation on hard clinical endpoints in individuals with T2D are lacking. Prospective study designs for CVD incidents require a follow-up time of several years and large numbers of people. Consequently, most studies have investigated the effects of by Mg2+ supplementation on intermediate endpoints such as blood pressure, dyslipidemia and endothelial function (Table 3).

Table 3.

Mg2+ supplementation studies with CVD-risk factors in people with T2D

| Authors, year | Population | Mg2+ supplementa | Study type | CVD outcome | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asbaghi et al, 2020 (174) | 673 T2D, among 358 in the Mg2+ supplementation group, 315 in control group | 36.49-500 mg/day elemental Mg2+ (1.5-20.0 mmol/day elemental Mg2+) (various supplement forms) for 1-6 months | Meta-analysis of 11 randomized controlled trials | Blood pressure, body weight, BMI, waist circumference | More than 12 weeks of Mg2+ supplementation improves blood pressure. No effects on body weight, BMI, waist circumference |

| Asbaghi et al, 2020 (170) | 667 T2D among 345 in the Mg2+ supplementation group, 332 in control group | 36.49-500 mg/day elemental Mg2+ (1.5-20.0 mmol/day elemental Mg2+) (various supplement forms) for 1-6 months | Meta-analysis of 12 randomized controlled trials | Lipid profile | Mg2+ lowers LDL levels |

| Rashvand et al, 2019 (175) | 96 T2D, divided in 4 groups for co-supplementation using choline, 18 were analyzed in the Mg2+-only group | ∼305 mg/day elemental Mg2+ (∼12.5 mmol/day elemental Mg2+) (as magnesium oxide) for 2 months | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel, clinical trial | Inflammation and endothelial function | IL-6 levels and VCAM-1 (borderline significant) decreased in the Mg2+ supplementation group |

| Talari et al, 2019 (176) | 54 T2D hemodialysis patients, 27 in the Mg2+ supplementation group, 27 in control group | 250 mg/day elemental Mg2+ (10.3 mmol/day elemental Mg2+) (as magnesium oxide) for 6 months | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial | Carotid intima-media thickness, lipid profile, hs-CRP, NO, total antioxidant capacity, total GSH, MDA, eGFR | Mg2+ supplementation improved carotid intima–media thickness, total cholesterol, LDL, hs-CRP, total antioxidant capacity, and MDA levels |

| Zghoul et al, 2018 (177) | 47 T2D with hypomagnesemia (serum levels <0.74 mmol/L). | 336 mg/day elemental Mg2+ (13.8 mmol/day elemental Mg2+) (as magnesium-L-lactate) for 3 months | Open-label clinical trial | Inflammation | Mg2+ supplementation increased Mg2+ levels, while improvement in CRP levels was not observed, TNF-α and 8-isoprostane were decreased |

| Dibaba et al, 2017 (178) | 543 people, among 278 in the Mg2+ supplementation group, 265 in control group. 5/11 studies with T2D, other prediabetes or insulin resistant. | 365-450 mg/day elemental Mg2+ (15.0-18.5 mmol/day elemental Mg2+) (various supplement forms) for 1-6 months | Meta-analysis, of 11 randomized controlled trials | Blood pressure | Mg2+ supplementation lowers blood pressure |

| Verma et al, 2017 (171) | 1694 T2D among 834 in the Mg2+ supplementation group, 860 in control group | 300-1006 mg/day elemental Mg2+ (12.3-41.4 mmol/day elemental Mg2+) (various supplement forms) for 1-6 months | Meta-analysis, of 28 randomized controlled trials | Blood pressure, Lipid profile | Mg2+ supplementation has a favorable effect on SBP and lipid profile (total cholesterol, HDL, LDL, TG) |

| Simental-Mendía et al, 2017 (272) | 400 T2D, subgroup analysis | 300-730 mg/day elemental Mg2+ (12.3-30.0 mmol/day elemental Mg2+) (various supplement forms) for 3-4 months | Meta-analysis, of 5 randomized controlled trials. | Lipid profile | Mg2+ supplementation showed no effect on lipid profile |

| Solati et al, 2014 (179) | 54 T2D | 300 mg/day elemental Mg2+ (12.3 mmol/day elemental Mg2+) (as magnesium sulphate) for 3 months | Randomized double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial | Lipid profile, blood pressure, hepatic enzymes | Mg2+ supplementation improved all outcomes |

| Cosaro et al, 2014 (270) | 14 males with history of metabolic syndrome and/or T2D | 368 mg/day elemental Mg2+ (16.2 mmol/day elemental Mg2+) (as magnesium pidolate) for 2 months | Clinical trial | Blood pressure, endothelial function using FMD, arterial stiffness using the digital volume pulse method, and inflammation | No increase of plasma Mg2+ and no differences for other metabolic parameters |

| Barbagallo et al, 2010 (275) | 60 elderly diabetes, type not defined | 368 mg/day elemental Mg2+ (16.2 mmol/day elemental Mg2+) (as magnesium pidolate) for 1 month | Clinical trial | Endothelial function using FMD | Mg2+ supplementation improved post-ischemic endothelial-dependent flow-mediated dilation |

| Guerrero-Romero et al, 2009 (172) | 82 diabetes, type not defined, with hypomagnesemia (serum Mg2+ ≤ 0.74 mmol/L). | 450 mg/day elemental Mg2+ (18.5 mmol/day elemental Mg2+) (as magnesium chloride) for 4 months | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial | Blood pressure, lipid profile | Mg2+ supplementation decreased blood pressure and increased HDL |

| Lal et al, 2003 (173) | 40 T2D and 54 non-diabetic controls | 336 mg/day elemental Mg2+ (13.8 mmol/day elemental Mg2+) (as magnesium oxide) for 3 months | Case–control clinical trial | Lipid profile | Mg2+ supplementation decreased total cholesterol, LDL, TG, and raised HDL |

| De Valk et al, 1998 (271) | 50 T2D | ∼365 mg/day elemental Mg2+ (15 mmol/day elemental Mg2+) (as magnesium-aspartate-HCL) for 3 months | Randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial | Blood pressure, lipid profile | No differences |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; C-reactive protein, CRP; FMD, flow-mediated dilation; GSH, glutathione; IL-6, interleukin-6; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; MDA, malondialdehyde; Mg2+, magnesium; T2D, type 2 diabetes; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor alfa; TG, triglycerides; VCAM-1, vascular cell adhesion protein 1.

The elemental dose of Mg2+ is if missing calculated using the most common percentage of elemental Mg2+ (301).

Meta-analyses including T2D cohorts present a favorable effect of Mg2+ on blood pressure, and suggest that this is dependent on treatment duration and Mg2+ dose (174). A meta-analysis of 11 randomized controlled trials reported that Mg2+ supplementation lowered systolic blood pressure by −5.78 mmHg (95% CI −11.37; −0.19) and diastolic blood pressure by −2.50 mmHg (95% CI −4.58; −0.41) compared with the control group (174). In a subgroup analyses a more beneficial effect was observed in people with T2D who had hypomagnesemia (171). However, outcomes in T2D populations are variable: some clinical trials show no differences in blood pressure after Mg2+ supplementation (270, 271), others supplementing Mg2+ more than 3 months and a dose above 300 mg/day elemental Mg2+ show decreased blood pressure (172, 179).

Several studies have demonstrated that Mg2+ supplementation can reduce total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol levels and increase HDL cholesterol. In a meta-analysis of 12 randomized controlled trials, Mg2+ supplementation lowered serum LDL cholesterol levels by −6.8 mg/dL (95% CI −11.72; −1.96) in people with T2D compared with controls, but there was no effect on TG, total cholesterol, and HDL cholesterol (170). In a T2D subgroup analysis of a meta-analysis study, there was no effect of Mg2+ supplementation on cholesterol levels. This study consisted of only 5 T2D clinical trials with a rather short duration of 4 months (272). Shorter clinical trials with significantly altered lipid levels do use relatively high Mg2+ doses that are above 450 mg/day elemental Mg2+ (172, 173). This suggests that a higher Mg2+ supplementation dose might be required when the clinical trial has a relative short duration.

Endothelial dysfunction disrupts the permeability of the endothelial barrier and is part of an inflammatory response in the development of CVD (273). Noninvasive methods to assess endothelial dysfunction in individuals are flow-mediated dilation (FMD) involving ultrasound of the brachial artery, pulse wave velocity analysis, and finger plethysmography during postischemic hyperemia (274). In a clinical trial with 60 elderly people with diabetes, Mg2+ supplementation improved in only 1 month the postischemic endothelial-dependent FMD of the brachial artery using FMD (275). A smaller and shorter clinical trial containing only 16 males using 368 mg/day elemental Mg2+ with a study duration of 2 months did not show an effect on blood pressure, endothelial function using the FMD method, arterial stiffness using plethysmography, and inflammation levels (270). A long clinical trial of 6 months that supplemented 250 mg/day elemental Mg2+ showed improved carotid intima–media thickness, a surrogate marker of atherosclerosis. Besides, Mg2+ supplementation improved insulin sensitivity and decreased levels of inflammation and oxidative stress, indicating an amelioration of endothelial dysfunction (176).

Other markers that are involved in endothelial function are adhesion molecules, NO, and oxidative stress and inflammation (276). In a clinical trial that used just above 300 mg/day elemental Mg2+ for 2 months the inflammation marker IL-6 and adhesion marker VCAM-1 were decreased by Mg2+ supplementation (175). Furthermore, the inflammatory marker hs-CRP, the total antioxidant capacity, and malondialdehyde levels, which are involved in fatty acid peroxidation, were decreased by Mg2+ supplementation (176). In an open-label clinical trial using 336 mg/day elemental Mg2+ for 3 months there was no improvement of hs-CRP, but inflammation and oxidative stress markers such as TNF-α and 8-isoprostane were both decreased by Mg2+ supplementation (177).

In most studies, these findings show that Mg2+ supplementation has favorable effects on blood pressure, lipid levels, and endothelial dysfunction in T2D. Reducing blood pressure and inflammation by Mg2+ supplementation requires a Mg2+ dose of above 300 mg of elemental Mg2+ per day and a minimum duration of 3 months (172, 179). Regarding the lipid profile, both shorter studies (<3 months) with a Mg2+ dose above 450 mg elemental Mg2+ per day and longer studies (>3 months) show a favorable effect on lipid levels (171-173). Most of these studies were not selected for low Mg2+ levels. Screening for hypomagnesemia and the severity of T2D might be important prerequisites to obtain favorable effects of Mg2+ supplementation.

Challenges of magnesium supplementation

To obtain beneficial CVD effects of Mg2+ supplementation, serum Mg2+ needs to increase in people who have hypomagnesemia and stay within the physiological range between 0.7 and 1.05 mmol/L (14). In people with diabetes who were screened for hypomagnesemia (serum Mg2+ ≤ 0.74 mmol/L), Mg2+ increased by 0.18 mmol/L (from baseline 0.62 to 0.81 mmol/L), whereas controls increased 0.08 mmol/L (from baseline 0.61 to 0.68 mmol/L) after 4 months of magnesium chloride (equivalent to 40 mg/day elemental Mg2+) supplementation (172). In another clinical trial, consisting of 47 T2D with hypomagnesemia (serum levels <0.74 mmol/L) Mg2+ increased only by 0.02 mmol/L (from baseline 0.71 to 0.73 mmol/L) (177). In studies that were not selected for hypomagnesemia, serum/plasma Mg2+ levels were not affected or increased with a maximum of 0.08 mmol/L (0.2 mg/dL) by Mg2+ supplementation (175, 176, 179, 270, 271). The clinical studies that show a small but significant increase in serum/plasma Mg2+ did result in a beneficial effect on CVD markers (175, 176, 179). This suggests that even Mg2+ supplementation that causes a small increase in serum/plasma Mg2+ may result in favorable outcomes. In theory, Mg2+ supplementation in people with hypomagnesemia could result in more pronounced changes, but studies that specifically target people with low Mg2+ levels are lacking.

Mg2+ supplements are available in various preparations, which all have a different bioavailability, sometimes resulting in side effects (277). There are a few animal and human studies that show a higher bioavailability of organic Mg2+ salts (eg, magnesium citrate) compared with inorganic compounds (eg, magnesium oxide) (278-280), although most studies did not find any differences in bioavailability (281-284). Specifically for organic salts, Mg2+ bioavailability has shown to be the most efficient for magnesium gluconate compared with other forms such as magnesium chloride (278). Even with increased bioavailability, there is still a need to monitor individuals for potential gastrointestinal side effects. To prevent these side effects, providing Mg2+ supplements as a liquid rather than as tablets may help to reduce dose when needed. It is suggested that the type of salt is less important but that taking multiple low doses throughout the day improves bioavailability compared with a single higher dose (285), although more often dosing can also decrease compliance.

Altogether, oral Mg2+ supplements have very limited risk but may cause adverse events when taken in large doses (286). Diarrhea is the most prevalent and first sign of Mg2+ over supplementation (287). Prolonged hypermagnesemia may cause neuromuscular toxicity, respiratory failure, HF, and arrythmias (288) but is very rare, and most Mg2+ supplements have a minimal risk for developing hypermagnesemia (289). Certain health conditions like renal failure may increase risk of developing hypermagnesemia (290, 291).

Alternative approaches to increase the serum Mg2+ concentration, such as dietary fiber and SGLT2 inhibitors, are in experimental phases of development. Although promising results were obtained using dietary fiber, which increases intestinal absorption of Mg2+, this approach has not been examined in people with T2D to date (292). SGLT2 inhibitors were introduced as a novel glucose-lowering treatment for T2D. Cardiovascular outcome studies have shown that SGLT2 inhibitors reduce the risk of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality (293). These cardioprotective effects are probably not explained by the glucose-lowering effects, as similar effects have been demonstrated in patients without diabetes patients but with HF and chronic kidney disease (294, 295). Hence, additional mechanisms have been considered, including volume status, oxidative stress, and myocardial energetics (296). SGLT2 inhibitors also increase serum Mg2+ levels, particularly in people with T2D (82, 297). Since serum Mg2+ concentration is inversely associated with CVD risk, one may hypothesize that an increased serum Mg2+ concentration contributes to the cardioprotective effects of SGLT2 inhibitors. It should be noted that the increase in serum Mg2+ is modest (0.07 mmol/L Mg2+) (82, 297). Moreover, an analysis of the CANVAS trial suggests that serum Mg2+ levels do not mediate the cardioprotective effects of SGLT2 inhibition (298).

Conclusions and Research Perspectives

The high prevalence of hypomagnesemia in people with T2D can be explained by urinary Mg2+ loss, dyslipidemia, low Mg2+ intake, diversities in microbiome composition use, and genetic factors. While some medication use such as diuretics, PPIs, and metformin seem to affect the Mg2+ concentration, data are rather conflicting. So far, we can conclude that these medications explain <10% of the variance of the Mg2+ concentration. Insulin resistance and genetics (single-nucleotide polymorphisms in the genome) are presumably more fundamental for the Mg2+ concentration, because these regulate the activity of the Mg2+ transporter TRPM6.

Based on the literature discussed in this review, we can conclude that serum Mg2+ is, inversely, prospectively associated with HF and AF incidents in people with T2D. The occurrence of other macrovascular incidents such as AMI, CHD, stroke, and PAD seem indirectly associated with serum Mg2+. In contrast, many, but not all studies have established the association of serum/plasma Mg2+ with microvascular incidents (including renal failure, DR, and DN) in people with T2D. Only a few cross-sectional and case–control studies have resulted in conflicting results, suggesting the need for prospective study designs in the future.

Interestingly, the effect of hypomagnesemia on HF incidence seems to be related to insulin resistance, impaired glucose signaling, and mitochondrial oxidative stress. The inverse association of Mg2+ with AF incidence is more dependent on impaired Ca2+ and K+ ion activities that are involved in regulating the cardiac action potential. Because chronic hyperglycemia is the driving force of microvascular complications, the metabolic pathways of Mg2+ likely overlap with those of glucose. Hypomagnesemia is suggested to increase AGE and PKC signaling, leading to oxidative stress. Oxidative stress in turn causes downstream signaling resulting in diminished NO-mediated vasorelaxation and increased cytokine and chemokine release from endothelial cells. These combined fundamental and epidemiological findings suggest that Mg2+ independently contributes to HF and the endothelial pathophysiology in T2D.

Many gaps in research remain that require T2D cell and animal models to elucidate how hypomagnesemia causes HF, AF, and microvascular disease. The transcriptional regulation of Mg2+ transporter genes in relation to hypomagnesemia has never been assessed in T2D models. Additionally, the role of TRPM7-dependent changes in intracellular Mg2+ on heart and vasculature health has never been studied in T2D models. TRPM7-deficient mice with deletion of the kinase domain (TRPM7+/Δkinase) demonstrated infiltration of inflammatory cells (CD4+ T lymphocytes, and F4/80+ CD206+ cardiac macrophages) (222). Further in vitro experiments suggested that this infiltration may be (partially) Mg2+ dependent. The infiltration of inflammatory cells suggests that hypomagnesemia may be involved in leukocyte adhesion of the vasculature wall, although the relevance of this mechanism for TD2-associated CVD remains unclear. Furthermore, studies that assess the effect of Mg2+ on PKC activity, complete activation of the IR-Akt-NO pathway, and sources of stress signaling in endothelial cells are lacking in T2D models. In vitro and in vivo T2D studies using, for instance, noninvasive methods such as skin fluorescence are needed to determine whether hypomagnesemia increases AGE levels. Mg2+ supplementation trials using FMD and pulse wave velocity are needed to determine improvements in endothelial function in people with T2D.

We suggest that there is a therapeutic potential to prevent these CVD defects using Mg2+ supplements. In the DCS cohort study, the lowest quartile of serum Mg2+ level (Mg2+ < 0.75 mmol/L) was associated with HF and microvascular complications (8). Above this concentration, no additional reduction of the hazard ratio was observed. Consequently, it could be proposed that Mg2+ supplementation should aim for a serum Mg2+ concentration above 0.75 mmol/L. To date, clinical intervention trials demonstrating the effect of Mg2+ supplementation on hard clinical CVD endpoints are lacking. Mg2+ supplementation studies that assessed endothelial dysfunction by noninvasive methods such as FMD, pulse wave velocity, or digital volume pulse methods in people with T2D, while scare, do suggest beneficial effects (270, 275). Hence, there is an urgent need for large randomized clinical trials with long-term Mg2+ supplementation studies to establish whether increasing serum/plasma Mg2+ concentration reduces CVD mortality in people with T2D. Alternatively, dietary approaches using fiber- and Mg2+-rich nutrients may be examined to reduce CVD risk in T2D. While the inverse relation between T2D and its complications of Mg2+, a crucial ion in human physiology, already has a long history, details about this relationship and the long-term effects of Mg2+ supplementation are still lacking and need further study.

Abbreviations

- AF

atrial fibrillation

- AGE

advanced glycosylation end product

- AMI

acute myocardial infarction

- CHD

coronary heart disease

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- CVD

cardiovascular disease

- DN

diabetic neuropathy

- DR

diabetic retinopathy

- eGFR

estimated glomerular filtration rate

- eNOS

endothelial nitric oxide synthase

- FMD

flow-mediated dilation

- HDL

high-density lipoprotein

- HF

heart failure

- IL

interleukin

- IR

insulin receptor

- LDL

low-density lipoprotein

- LV

left ventricular

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- NEFA

nonesterified fatty acid

- NF-kB

nuclear factor kappa light chain enhancer of activated B cells

- PAD

peripheral arterial disease

- PKC

protein kinase C

- PPI

proton pump inhibitor

- PT

proximal tubule

- RAAS

renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SGLT2

sodium–glucose cotransporter 2

- TAL

thick ascending limb of Henle's loop

- T2D

type 2 diabetes

- TG

triglyceride

- TNF

tumor necrosis factor

- TRPM

transient receptor potential melastatin

- VCAM-1

vascular cell adhesion protein 1

Contributor Information

Lynette J Oost, Department of Physiology, Radboud Institute for Molecular Life Sciences, Radboud University Medical Center, 6500 HB, Nijmegen, The Netherlands.

Cees J Tack, Department of Internal Medicine, Radboud Institute for Molecular Life Sciences, Radboud University Medical Center, 6500 HB, Nijmegen, The Netherlands.

Jeroen H F de Baaij, Department of Physiology, Radboud Institute for Molecular Life Sciences, Radboud University Medical Center, 6500 HB, Nijmegen, The Netherlands.

Funding

Diabetes Fonds (2017-81-014).

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

References

- 1. Arpaci D, Tocoglu AG, Ergenc H, Korkmaz S, Ucar A, Tamer A. Associations of serum magnesium levels with diabetes mellitus and diabetic complications. Hippokratia. 2015;19(2):153‐157. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chen S, Jin X, Liu J, et al. Association of plasma magnesium with prediabetes and type 2 diabetes mellitus in adults. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):1‐8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Elderawi WA, Naser IA, Taleb MH, Abutair AS. The effects of oral magnesium supplementation on glycemic response among type 2 diabetes patients. Nutrients. 2019;11(1):12‐14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kurstjens S, de Baaij JHF, Bouras H, Bindels RJM, Tack CJJ, Hoenderop JGJ. Determinants of hypomagnesemia in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Eur J Endocrinol. 2017;176(1):11‐19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Simmons D, Joshi S, Shaw J. Hypomagnesaemia is associated with diabetes: not pre-diabetes, obesity or the metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2010;87(2):261‐266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. van Dijk PR, Waanders F, Qiu J, de Boer HHR, van Goor H, Bilo HJG. Hypomagnesemia in persons with type 1 diabetes: associations with clinical parameters and oxidative stress. Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab. 2020;11:2042018820980240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Oost LJ, Van Heck JIP, Tack CJ, De Baaij JHF. The association between hypomagnesemia and poor glycaemic control in type 1 diabetes is limited to insulin resistant individuals. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):6433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Oost LJ, van der Heijden AAWA, Vermeulen EA, et al. Serum magnesium is inversely associated with heart failure, atrial fibrillation, and microvascular complications in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(8):1757‐1765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fang X, Wang K, Han D, et al. Dietary magnesium intake and the risk of cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, and all-cause mortality: a dose–response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. BMC Med. 2016;14(1):1‐13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zhang Y, Li Q, Xin Y, Lv W, Ge C. Association between serum magnesium and common complications of diabetes mellitus. Technol Heal Care. 2018;26(1):379‐387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Peters KE, Chubb SAP, Davis WA, Davis TME. The relationship between hypomagnesemia, metformin therapy and cardiovascular disease complicating type 2 diabetes: the Fremantle Diabetes Study. PLoS One. 2013;8(9):2‐9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]