Abstract

Background

Systemic Immune-inflammation Index (SII) and body composition parameters are easily assessed, and can predict overall survival (OS) in various cancers, allowing early intervention. This study aimed to assess the correlation between CT-derived body composition parameters and SII and OS in patients with advanced gastric cancer receiving dual programmed death-1 (PD-1) and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) blockade.

Materials and methods

This retrospective study enrolled patients with advanced gastric cancer treated with dual PD-1 and HER2 blockade from March 2019 to June 2022. We developed a deep learning model based on nnU-Net to automatically segment skeletal muscle, subcutaneous fat and visceral fat at the third lumbar level, and calculated the corresponding Skeletal Muscle Index, skeletal muscle density, subcutaneous fat area (SFA) and visceral fat area. SII was computed using the formula that total peripheral platelet count×neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio. Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analysis were used to determine the associations between SII, body composition parameters and OS.

Results

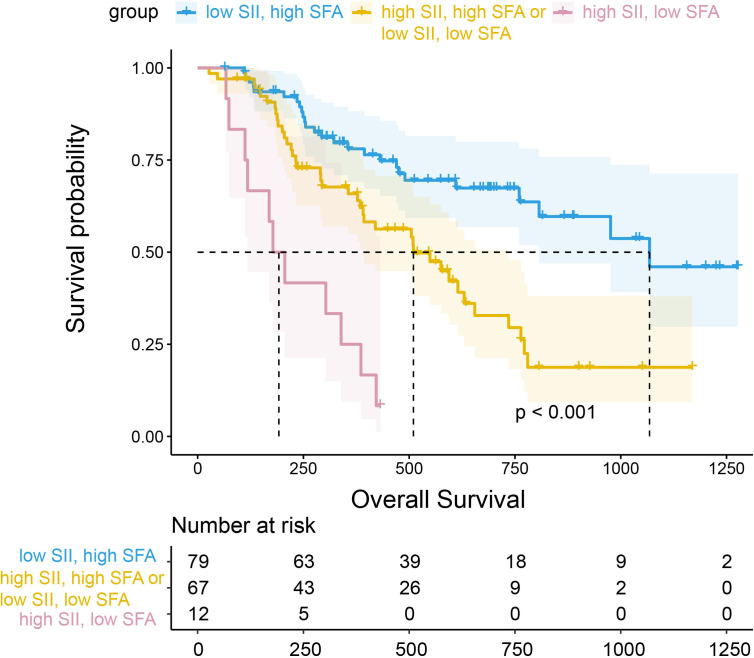

The automatic segmentation deep learning model was developed to efficiently segment body composition in 158 patients (0.23 s/image). Multivariate Cox analysis revealed that high SII (HR=2.49 (95% CI 1.54 to 4.01), p<0.001) and high SFA (HR=0.42 (95% CI 0.24 to 0.73), p=0.002) were independently associated with OS, whereas sarcopenia was not an independent prognostic factor for OS (HR=1.41 (95% CI 0.86 to 2.31), p=0.173). In further analysis, patients with high SII and low SFA had worse long-term prognosis compared with those with low SII and high SFA (HR=8.19 (95% CI 3.91 to 17.16), p<0.001).

Conclusion

Pretreatment SFA and SII were significantly associated with OS in patients with advanced gastric cancer. A comprehensive analysis of SII and SFA may improve the prognostic stratification of patients with gastric cancer receiving dual PD-1 and HER2 blockade.

Keywords: gastrointestinal neoplasms, immunotherapy, inflammation, tumor biomarkers

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

In several cancers, muscle and adipose tissue play an important role in shaping the immune response; however, the prognostic impact of body composition parameters in patients with advanced gastric cancer treated with targeted therapy combined with immunotherapy remains to be investigated.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

Our results demonstrate that subcutaneous fat, but not visceral fat, and the systemic immune-inflammatory index had significant prognostic value in patients with advanced gastric cancer receiving dual programmed death-1 and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 blockade.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

Further study will be needed to investigate the mechanisms by which subcutaneous fat and systemic immune-inflammation affect survival in patients with advanced gastric cancer. Clinical interventions specially targeting the loss of subcutaneous adiposity may improve the quality of life and prognosis of patients with advanced gastric cancer.

Introduction

Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-positive gastric cancer (GC) is a special type that accounts for approximately 17–30.5% of all GC.1 2 The randomized controlled Trastuzumab for Gastric Cancer (ToGA) study, a landmark in targeted therapy for GC, showed that patients with HER2-positive advanced GC who received trastuzumab combined with chemotherapy as first-line treatment had an overall survival (OS) of more than 1 year.3 The emergence of immunotherapy as a treatment option has provided new hope for patients with HER2-positive GC. The prospective international multicenter KEYNOTE 811 research indicated that dual programmed death-1 (PD-1) and HER2 blockade significantly prolonged survival for HER-2-positive patients.4 It also showed that microsatellite instability-high (MSI-H) GC responded better to immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs). However, the fraction of MSI-H in advanced GC is only 3.5%,5 necessitating the need for exploring additional and accurate biomarkers in patients with advanced GC to optimize the strategy of combination therapy.

Skeletal muscle depletion has long been recognized as a significant prognostic factor for cancer that is independent of body mass index (BMI).6 Sarcopenia is characterized by decreased muscle strength and low muscle quantity or quality, and is prevalent in patients with GC.7 Sarcopenia has previously been found to be associated with poorer prognosis in patients treated with targeted therapy and ICIs for several types of malignancies, such as non-small cell lung cancer,8 melanoma9 and gastrointestinal tumors.10–12 The tumor-induced systemic immunological inflammatory response produces substantial metabolic alterations and muscle catabolism, further contributing to a vicious cycle of cachexia. The systemic inflammatory state presented by sarcopenia combined with elevated serum inflammatory markers is considered a potential predictive biomarker for ICIs, according to previous research.13 14 However, a phase III capecitabine and cisplatin with or without cetuximab for patients with previously untreated advanced gastric cancer (EXPAND) trial found that systemic inflammatory response was strongly associated with sarcopenia, while sarcopenia was revealed to be merely a symptom, lacking the direct causative mechanism connected to survival.15

In contrast to sarcopenia, the prognostic impact of obesity (subcutaneous and visceral fat tissue) is uncertain, with studies showing a protective, detrimental, or no effect. Recent studies have shown that overweight/obesity is a protective factor for survival in patients with advanced cancer, defined as ‘obesity paradox’, particularly in those treated with ICIs.16 On the other hand, the relationship between obesity and systemic inflammation, which was manifested as a low-grade chronic inflammation with dysregulated immune response, was termed ‘metaflammation’. Metaflammation may be related to the infiltration of macrophages and CD8 T cells into adipose tissue, which undergoes a marked pro-inflammatory transformation.17

So far, there is growing evidence that muscle and adipose tissue play an important role in shaping the immune response. Studies have highlighted the clinical significance of assessing body composition in patients with advanced GC. However, the potential impact of body composition parameters (muscle and fat) and inflammation markers on prognosis in patients with advanced GC treated with dual PD-1 and HER2 blockade remains unknown. CT cross-sectional imaging of the third lumbar spine (L3) is a valid and reliable method for diagnosing sarcopenia and obesity, which has been recommended by guidelines.18 In this study, we developed a deep learning model that automatically localized the L3 level and segmented and calculated body composition parameters to investigate the relationship between muscle, adiposity, and systemic immune inflammation with survival in patients with advanced GC receiving dual PD-1 and HER2 blockade.

Methods

Patients

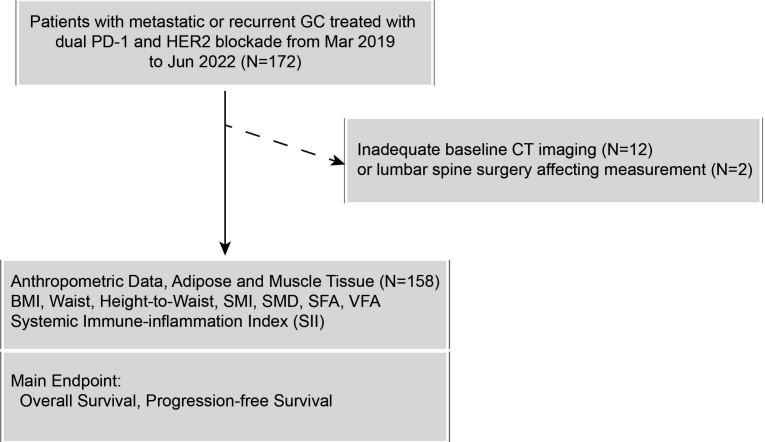

We retrospectively collected 172 patients with advanced GC treated with dual PD-1 and HER2 blockade at Peking University Cancer Hospital between March 2019 and June 2022 (figure 1). Inclusion criteria: (1) pathologically confirmed GC; (2) CT-confirmed presence of unequivocal distant metastases and clarified as stage IV disease; (3) concurrent administration of at least one dose of anti-PD-1 and anti-HER2-targeted combination regimen. Exclusion criteria: (1) lack of baseline CT imaging (within 1 month before treatment) (n=12); (2) lumbar spine surgery affecting muscle or fat measurement (n=2).

Figure 1.

The flow diagram of patient selection. BMI, body mass index; GC, gastric cancer; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; PD-1, programmed death-1; SFA, subcutaneous fat area; SII, Systemic Immune-inflammation Index; SMD, skeletal muscle density; SMI, Skeletal Muscle Index; VFA, visceral fat area.

Clinical information including age, gender, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS), BMI, tumor location, number of lines treated, HER2 status, Lauren classification, degree of differentiation, Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV), mismatch repair (MMR) status, and serum absolute blood counts (neutrophils, lymphocytes, and platelets) were collected from the medical records. The Systemic Immune-inflammation Index (SII) was computed using the formula total peripheral platelet count×neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio. To determine OS, the date of treatment initiation was noted and patients were observed until mortality. Progression-free survival (PFS) was defined as the time from treatment initiation to disease progression or death. Response to treatment was assessed using the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors V.1.1 (RECIST V.1.1). Objective response rate (ORR) was defined as the proportion of patients experiencing complete response (CR) or partial response (PR) as the best response rate (BOR), whereas disease control rate (DCR) was defined as the proportion of patients experiencing CR, PR, or stable disease (SD) as the BOR. Patients who achieved CR or PR were defined as responders, whereas patients who achieved SD or progression disease (PD) were defined as non-responders.

Molecular type classification

Four proteins were immunohistochemically stained to routinely check the status of MMR (MLH1, PMS2, MSH2, and MSH6). The defective MMR phenotype tumors were indicative of the loss of one or more MMR proteins expression. Tumors with proficient MMR (pMMR) protein expression were considered to have a pMMR phenotype.

In situ hybridization of EBV-encoded small RNA was conducted by using a fluorescein-labeled oligonucleotide probe (INFORM EBER Probe, Ventana). A negative signal in normal tissue and strong EBER signals in tumor cells was considered a positive result.

Segmentation of regions of interest and calculation of body composition parameters

We retrieved CT scans of 262 patients diagnosed with GC from the picture archiving and communication system (PACS). A radiologist (MH) was trained to annotate regions at the L3 level using a threshold method by establishing density thresholds of −29 to +150 hounsfield units (HU) for muscle tissue (including ventral abdominal muscle, spinal muscle, and psoas muscle), −190 to −30 HU for subcutaneous fat tissue and −150 to −50 HU for visceral fat tissue. The fat regions included the visceral fat area (VFA) and subcutaneous fat area (SFA).

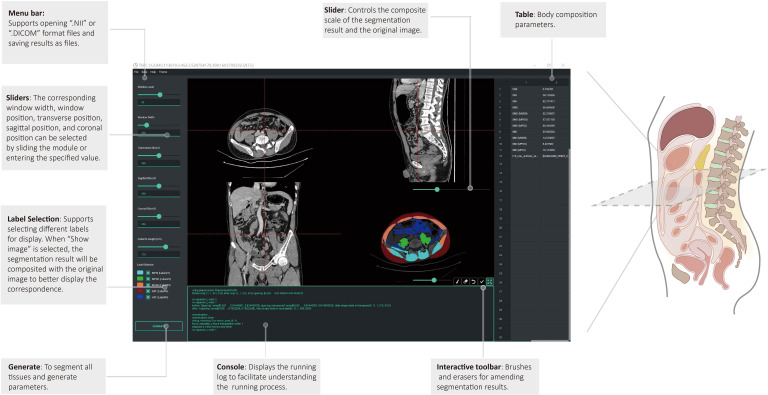

We trained the 2D-UNet model based on the nnU-Net framework to segment the above three tissues and randomly selected 153 CT images for training, 53 CT images for internal validation, and the remaining 56 CT images for external validation. Before training, the images were preprocessed using an abdominal window with the window level of 50 HU and the window width of 350 HU. Using the training model, we developed a tool for automatic tissue segmentation and parameter calculation and incorporated manual interactions for fine-tuned adjustments (figure 2). The final tool was constructed to automatically localize at the L3 level, segment regions of interest of muscle and fat, and calculate the corresponding body composition parameters. The Skeletal Muscle Index (SMI) was normalized by dividing the area of skeletal muscle by the square of the corresponding height (m2). Another radiologist with 18 years of experience (TL) confirmed the appropriateness of lumbar spine selection and segmentation, with all segmentations being reviewed and revised by the two radiologists. According to the criteria typically employed in Asian patients with cancer based on CT, sarcopenia was defined as SMI ≤40.8 cm2/m2 in men and ≤34.9 cm2/m2 in women,19–21 and myosteatosis was defined as skeletal muscle density (SMD) <41 HU in patients with BMI <25 kg/m2, and <33 HU in patients with BMI ≥25 kg/m2. A detailed illustration of this technique is shown in online supplemental video, and the software is available on GitHub at https://github.com/czifan/TSPC.PyQt5.

Figure 2.

Pretreatment CT images were used to measure subcutaneous fat area (SFA), and visceral fat area (VFA) deposits, as well as the skeletal muscle (SM) area and density. SFA, VFA and SM segmentation analyses were conducted at the lumbar spine third level. Hounsfield units reflecting the radiodensity of the respective tissue types are indicated. The anthropometric data included body mass index, waist circumference (waist), and height-to-waist ratio (height/waist).

jitc-2023-007054supp001.pdf (699.5KB, pdf)

jitc-2023-007054supp002.mp4 (12.2MB, mp4)

Statistical analysis

All continuous variables were tested by Shapiro-Wilk test to check their normality and were compared using t-test or Mann-Whitney U test. Categorical variables were compared using Fisher’s exact test or χ2 test. Pearson correlation coefficient was used to determine relationship between body composition parameters and clinical variables. Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses were used to identify potential risk factors for OS and PFS. Thereafter, additional adjustments were made for sarcopenia, SFA, and SII to investigate the interdependence. The Dice similarity coefficient was used to measure the level of agreement between the model and manual segmentation. The C-index was used to evaluate the predictive capability of the Cox regression model with 95% CIs derived from 2000 bootstrapping samples. Kaplan-Meier analysis and log-rank test were used to compare the differences in survival curves between groups. Cut-off values were determined to best separate the two groups based on time to death. Deep learning was performed using Python V.3.7, and statistical analysis was performed using R software V.4.2.2. Two-tailed p values<0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics

A total of 158 patients were included in the analysis, with a median interval of 11.5 days (IQR 6.0–19.0) between baseline CT and initiation of dual PD-1 and HER2 therapy. The median age was 63 (56.0–69.3), 129 men and 29 women, and the clinical and pathological information of the patients is shown in table 1. The majority of patients were non-esophagogastric cancer (102, 64.6%) and 60.1% were treated for the first line. The median PFS was 264.3 days, and disease progression occurred in 122 patients; the median OS was 677.6 days, and 76 patients were deceased.

Table 1.

Patients’ information

| Variables | Patients, N=158 (%) | Responders (CR/PR), N=89 (%) |

Non-responders (SD/PD), N=64 (%) | P value |

| Clinical information (median (IQR)) | ||||

| Age | 63.0 (56.0–69.3) | 64.0 (57.0–70.0) | 63.0 (55.3–69.0) | 0.566 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 129 (81.6) | 73 (82.0) | 52 (81.3) | 0.903 |

| Female | 29 (18.4) | 16 (18.0) | 12 (18.8) | |

| BMI | 22.03 (19.72–24.07) | 22.48 (19.97–24.34) | 20.89 (19.07–22.76) | 0.016 |

| Primary tumor | 0.613 | |||

| EGJ | 56 (35.4) | 31 (34.8) | 25 (39.1) | |

| Non-EGJ | 102 (64.6) | 58 (65.2) | 39 (60.9) | |

| ECOG PS | 0.443 | |||

| 0 | 67 (42.4) | 41 (46.1) | 24 (37.5) | |

| 1 | 85 (53.8) | 46 (51.7) | 37 (57.8) | |

| 2–3 | 6 (3.8) | 2 (2.2) | 3 (4.7) | |

| Line of therapy | <0.001 | |||

| 1 | 95 (60.1) | 67 (75.3) | 25 (39.1) | |

| 2 | 33 (20.9) | 13 (14.6) | 20 (31.3) | |

| 3 or more | 30 (19.0) | 9 (10.1) | 19 (29.7) | |

| HER2 status | 0.003 | |||

| 2+&FISH+ or 3+ | 143 (90.5) | 87 (97.8) | 53 (82.8) | |

| 2+&FISH− | 11 (7.0) | 2 (2.2) | 8 (12.5) | |

| 2+FISH undetermined | 4 (2.5) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (4.7) | |

| Lauren | 0.639 | |||

| Intestinal type | 112 (46.9) | 65 (73.0) | 45 (70.3) | |

| Diffuse type | 19 (7.9) | 8 (9.0) | 10 (15.6) | |

| Mixed type | 20 (8.4) | 12 (13.5) | 7 (10.9) | |

| NA | 7 (2.9) | 4 (4.5) | 2 (3.1) | |

| Differentiation grade | 0.111 | |||

| Low | 57 (36.1) | 29 (32.6) | 26 (40.6) | |

| Median/median-low | 99 (62.7) | 60 (67.4) | 36 (56.3) | |

| High | 2 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (3.1) | |

| EBV | 0.903 | |||

| Negative | 127 (80.4) | 71 (79.8) | 53 (82.8) | |

| Positive | 1 (0.6) | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

| NA | 30 (19.0) | 17 (19.1) | 11 (17.2) | |

| MSI | 0.660 | |||

| dMMR | 2 (1.3) | 2 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) | |

| pMMR | 146 (92.4) | 82 (92.1) | 60 (93.8) | |

| NA | 10 (6.3) | 6 (6.7) | 4 (6.3) | |

| PD-L1 | 0.101 | |||

| Negative | 52 (32.9) | 25 (28.1) | 25 (39.1) | |

| Positive (TC/TIC) | 58 (36.7) | 40 (44.9) | 18 (28.1) | |

| NA | 48 (30.4) | 24 (27.0) | 21 (32.8) | |

| No. of metastatic organs | 0.226 | |||

| 1–2 | 107 (67.7) | 63 (70.8) | 39 (60.9) | |

| 3 or more | 51 (32.3) | 26 (29.2) | 25 (39.1) | |

| SII | 600.71 (392.64–1041.37) | 570 (408.36–1033.41) | 622.46 (382.29–1219.37) | 0.428 |

| Body composition parameters (median (IQR)) | ||||

| Waist | 0.81 (0.76–0.86) | 0.82 (0.76–0.87) | 0.80 (0.74–0.86) | 0.204 |

| Height to waist | 2.07 (1.93–2.20) | 2.03 (1.90–2.18) | 2.11 (1.98–2.23) | 0.087 |

| SMI | 41.05 (37.01–46.91) | 43.56 (37.48–48.49) | 39.79 (34.81–42.76) | <0.001 |

| CT-determined sarcopenia | 69 (43.7) | 29 (32.6) | 38 (59.4) | 0.001 |

| SMD | 42.10 (36.60–48.50) | 42.36 (36.60–47.37) | 41.69 (36.45–50.21) | 0.540 |

| CT-determined myosteatosis | 55 (34.8) | 30 (33.7) | 25 (39.1) | 0.496 |

| SFA | 85.38 (49.23–121.74) | 95.05 (60.09–126.98) | 73.52 (30.26–111.72) | 0.035 |

| VFA | 54.64 (17.72–114.81) | 67.89 (18.81–117.26) | 42.87 (11.83–113.16) | 0.473 |

Among the 158 patients, the treatment response of 153 patients was evaluable based on the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors V.1.1. Patients who achieved complete response or partial response were defined as responders, while those who achieved stable disease or progression disease were defined as non-responders.

BMI, body mass index; dMMR, deficient mismatch repair; EBV, Epstein-Barr virus; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; EGJ, esophagogastric junction; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; MSI, microsatellite instability; PD-L1, programmed death ligand 1; pMMR, proficient mismatch repair; SFA, subcutaneous fat area; SII, Systemic Immune-inflammation Index; SMD, skeletal muscle density; SMI, Skeletal Muscle Index; TC, tumor cells; TIC, tumor-infiltrating immune cells; VFA, visceral fat area.

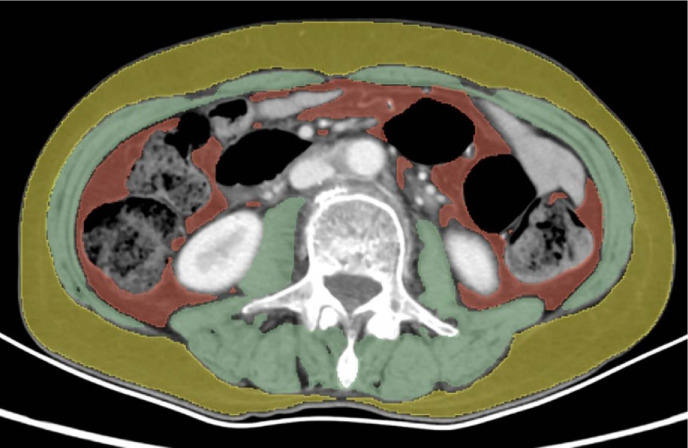

We developed a deep learning model based on the nnU-Net architecture for automatically segmenting muscle tissue, subcutaneous fat, and visceral fat tissue at the L3 level. The performance of the model in the internal and external validation sets is presented in table 2. The model allowed for rapid and accurate automatic segmentation of the above body composition and simultaneous calculation of SMI, SMD, SFA and VFA. The time required to complete the automatic outline and calculation for a single case could be accelerated to 0.23 s. Moreover, we built the automatic segmentation software, providing flexibility for interactive manual corrections. Importantly, the model can effectively and accurately eliminate intestinal luminal fat outside the visceral fat region (figure 3).

Table 2.

Dice similarity coefficient and 95% CI of the automatic segmentation model

| Interval validation (n=53) | External validation (n=56) | |||

| DSC | 95% CI | DSC | 95% CI | |

| MPSI | 0.985 | 0.983 to 0.986 | 0.982 | 0.982 to 0.984 |

| MPSO | 0.971 | 0.967 to 0.974 | 0.970 | 0.970 to 0.973 |

| MVEN | 0.972 | 0.968 to 0.976 | 0.972 | 0.972 to 0.975 |

| SFT | 0.958 | 0.918 to 0.980 | 0.967 | 0.943 to 0.980 |

| VFT | 0.954 | 0.941 to 0.964 | 0.947 | 0.928 to 0.963 |

| Average | 0.968 | 0.958 to 0.975 | 0.968 | 0.959 to 0.974 |

DSC, Dice similarity coefficient; MPSI, spinal muscle; MPSO, psoas muscle; MVEN, ventral abdominal muscle; SFT, subcutaneous fat tissue; VFT, visceral fat tissue.

Figure 3.

Measurement of skeletal muscle, subcutaneous fat, and visceral fat using CT images. The muscle was measured on the cross-sectional image of spinal level L3 with a threshold set as −29 to +150 HU (green), including psoas, erector spinae, quadratus lumborum, transversus abdominus, external and internal obliques, and rectus abdominus. Fat segmentation was measured with a threshold set as −190 to +30 HU for subcutaneous fat tissue and −150 to −50 HU for visceral fat tissue, indicated by yellow and red, respectively. HU, hounsfield units.

We finally identified 69 patients with sarcopenia and 55 patients with myosteatosis. The optimal cut-off value for SII was 823×109/L, patients were stratified into high (≥823×109/L, n=56) and low SII (<823×109/L, n=102) groups. The optimal threshold values for SFA and VFA were divided according to gender. Based on this method, SFA <33 cm2 for men, and <76 cm2 for women were defined as low SFA, and patients with VFA <156 cm2 for men and <74 cm2 for women were defined as low VFA.

Assessment of treatment response

We evaluated the efficacy of RECIST V.1.1 in the 153 evaluable patients, of whom 3 patients achieved CR, 86 PR, 40 SD, and 24 PD, with an overall ORR rate of 56.33% and a DCR rate of 81.65% (table 3). The ORR rate was significantly higher in the high SFA group compared with the low SFA group (62.6% vs 34.3%, p=0.004), while there was no difference in DCR between the two groups (83.7% vs 74.3%, p=0.324). The ORR (43.3% vs 69.8%, p=0.001) and DCR (76.7% vs 84.2%, p=0.044) were significantly lower in the sarcopenia group compared with the non-sarcopenia group. However, there was no significant difference in ORR and DCR between patients with low and high SII (p=0.998 and 0.535).

Table 3.

Efficacy outcomes stratified by SFA, sarcopenia, and SII

| Variables | Low SFA (n=35) | High SFA (n=123) | P value | Non-sarcopenia (n=86) | Sarcopenia (n=67) | P value | Low SII (<823×109/L) (n=102) | High SII (≥823×109/L) (n=56) | P value | Total (n=158) |

| ORR, n (%) | 12 (34.3) | 77 (62.6) | 0.004 | 60 (69.8) | 29 (43.3) | 0.001 | 57 (55.8) | 32 (57.1) | 0.998 | 89 (56.3) |

| DCR, n (%) | 26 (74.3) | 103 (83.7) | 0.324 | 77 (89.5) | 52 (77.6) | 0.044 | 86 (84.2) | 43 (76.7) | 0.183 | 129 (81.6) |

| Best overall response | ||||||||||

| CR, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (2.4) | – | 2 (2.2) | 1 (1.4) | – | 3 (2.9) | 0 (0.0) | – | 3 (1.9) |

| PR, n (%) | 12 (34.3) | 74 (60.2) | – | 58 (65.2) | 28 (40.6) | – | 54 (52.9) | 32 (57.1) | – | 86 (54.4) |

| SD, n (%) | 14 (40.0) | 26 (21.1) | – | 17 (19.1) | 23 (33.3) | – | 29 (28.4) | 11 (19.6) | – | 40 (25.3) |

| PD, n (%) | 7 (20.0) | 17 (13.8) | – | 9 (10.1) | 15 (21.7) | – | 12 (11.8) | 12 (21.4) | – | 24 (15.2) |

| Not assessed, n (%) | 2 (5.7) | 3 (2.4) | – | 3 (3.4) | 2 (2.9) | – | 4 (3.9) | 1 (1.8) | – | 5 (3.2) |

CR, complete response; DCR, disease control rate; ORR, objective response rate; PD, progression disease; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; SFA, subcutaneous fat area; SII, Systemic Immune-inflammation Index.

Progression-free survival

We used the same threshold settings for PFS as we did for OS. Univariate analysis showed that ECOG PS 2–3, two or more lines of therapy, high SII and high SFA were significant prognostic factors for poor PFS (table 4). Multivariate Cox regression analysis revealed that a larger line of therapy was associated with shorter PFS, and high SFA (HR=0.628, 95% CI (0.410 to 0.962), p=0.032) was the sole independent body composition parameter associated with PFS (table 4).

Table 4.

Univariable and multivariable Cox regression for PFS

| Variable (reference) | Univariable | Multivariable | ||

| HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Age | 0.989 (0.974 to 1.004) | 0.145 | ||

| Sex (female) | 0.85 (0.539 to 1.341) | 0.485 | ||

| EGJ (non-EGJ) | 0.869 (0.598 to 1.263) | 0.462 | ||

| BMI | 0.991 (0.941 to 1.044) | 0.733 | ||

| ECOG PS 2–3 (0–1) | 1.468 (1.015 to 2.123) | 0.041 | 1.379 (0.937 to 2.029) | 0.103 |

| Lauren (intestinal type) | Reference | |||

| Diffuse type | 0.924 (0.548 to 1.558) | 0.768 | ||

| Mixed type | 0.746 (0.408 to 1.363) | 0.341 | ||

| NA | 0.468 (0.171 to 1.278) | 0.139 | ||

| Differentiation (low) | ||||

| Median | 0.953 (0.656 to 1.386) | 0.803 | ||

| High | 0.667 (0.151 to 2.946) | 0.593 | ||

| Line of therapy (1) | Reference | |||

| 2 | 1.979 (1.253 to 3.125) | 0.003 | 1.886 (1.190 to 2.988) | 0.007 |

| 3 or more | 2.379 (1.535 to 3.686) | < 0.001 | 2.050 (1.275 to 3.297) | 0.003 |

| HER2 status (2+&FISH−) | ||||

| 2+&FISH+/3+ | 0.786 (0.398 to 1.555) | 0.49 | ||

| 2+&FISH undetermined | 2.252 (0.604 to 8.393) | 0.227 | ||

| No. of metastatic organs, 3 or more (1–2) | 1.491 (1.028 to 2.161) | 0.035 | 1.278 (0.858 to 1.908) | 0.228 |

| SII ≥823×109/L (<823×109/L) | 1.524 (1.057 to 2.198) | 0.024 | 1.286 (0.870 to 1.900) | 0.207 |

| Waist | 0.533 (0.059 to 4.783) | 0.574 | ||

| Height to waist | 1.245 (0.59 to 2.628) | 0.566 | ||

| CT-determined sarcopenia | 1.197 (0.838 to 1.71) | 0.322 | ||

| CT-determined myosteatosis | 0.911 (0.626 to 1.324) | 0.624 | ||

| SFA high (low) | 0.637 (0.419 to 0.969) | 0.035 | 0.628 (0.410 to 0.962) | 0.032 |

| VFA high (low) | 0.984 (0.602 to 1.610) | 0.949 | ||

BMI, body mass index; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; EGJ, esophagogastric junction; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; SFA, subcutaneous fat area; SII, Systemic Immune-inflammation Index; VFA, visceral fat area.

Overall survival

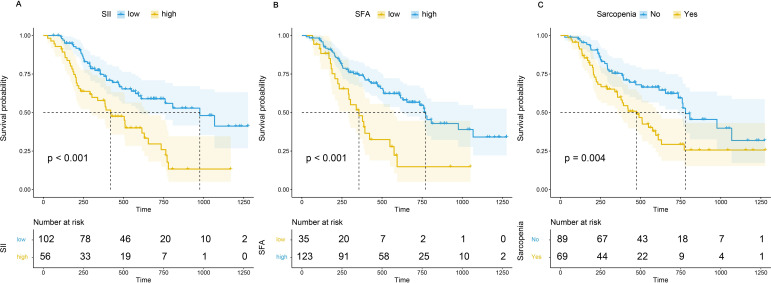

Univariate Cox regression analysis showed that the first line of therapy, HER2 positive (immunohistochemistry (IHC) 2+&FISH+ or IHC 3+), low SII, non-sarcopenia, and high SFA were protective factors for OS. Kaplan-Meier analysis revealed that patients with high SII had a significantly worse prognosis than those with low SII (HR=2.392 (95% CI 1.518 to 3.797), p<0.001) and patients with sarcopenia had a significantly worse prognosis than those without sarcopenia (HR=1.930 (95% CI 1.227 to 3.038), p=0.004), whereas patients with high SFA had a significantly better prognosis than those with low SFA (HR=0.398 (95% CI 0.241 to 0.655), p<0.001) (figure 4A–C). However, BMI, SMD/CT-determined myosteatosis, and VFA were not significantly associated with OS.

Figure 4.

Comparison of overall survival between patients with high Systemic Immune-inflammation Index (SII), subcutaneous fat area (SFA) or sarcopenia and those with low SII, SFA or non-sarcopenia.

In multifactorial Cox regression analysis, before adjustment for body composition parameters or SII, HER2 positive (HR=0.465 (95% CI 0.225 to 0.961), p=0.039), high SII (HR=2.488 (95% CI 1.543 to 4.014), p<0.001) and SFA high (HR=0.422 (95% CI 0.244 to 0.731), p=0.002) were independently associated with OS (table 5 and online supplemental table S1). When adjusting for sarcopenia or SFA alone, both sarcopenia and SFA were independent prognostic factors (table 6, Model 2 and Model 3, both p<0.05). However, when adjusting for SII alone and simultaneously including sarcopenia and SFA, only SFA was an independent factor for prognosis, indicating that the prognostic effect of skeletal muscle could be obscured by subcutaneous fat (table 6, Model 1, p=0.167 and p=0.007).

Table 5.

Univariable and multivariable Cox regression for overall survival

| Variable (reference) | Univariable | Multivariable | VIF | ||

| HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | ||

| Age | 0.984 (0.965 to 1.003) | 0.089 | |||

| Sex male (female) | 0.641 (0.377 to 1.088) | 0.099 | |||

| EGJ (non-EGJ) | 1.151 (0.723 to 1.831) | 0.554 | |||

| BMI | 0.967 (0.901 to 1.038) | 0.355 | |||

| ECOG PS 1–2 (0) | 1.393 (0.87 to 2.231) | 0.168 | |||

| Lauren (intestinal type) | Reference | ||||

| Diffuse type | 1.159 (0.587 to 2.290) | 0.671 | |||

| Mixed type | 1.342 (0.699 to 2.576) | 0.377 | |||

| NA | 0.460 (0.112 to 1.894) | 0.282 | |||

| Differentiation (low) | Reference | ||||

| Median | 0.754 (0.472 to 1.205) | 0.239 | |||

| High | 0.629 (0.084 to 4.708) | 0.652 | |||

| Line of therapy (1) | Reference | Reference | 1.029 | ||

| 2 | 1.933 (1.083 to 3.448) | 0.026 | 1.528 (0.845 to 2.765) | 0.161 | |

| 3 or more | 2.133 (1.231 to 3.695) | 0.007 | 1.640 (0.922 to 2.917) | 0.092 | |

| HER2 status (2+&FISH−) | Reference | Reference | 1.010 | ||

| 2+&FISH+/3+ | 0.406 (0.2 to 0.823) | 0.012 | 0.465 (0.225 to 0.961) | 0.039 | |

| 2+&FISH undetermined | 0.682 (0.146 to 3.175) | 0.626 | 0.600 (0.122 to 2.944) | 0.635 | |

| No. of metastatic organs, 3 or more (1–2) | 1.405 (0.888 to 2.221) | 0.146 | |||

| SII ≥823×109/L (<823×109/L) | 2.392 (1.518 to 3.797) | <0.001 | 2.488 (1.543 to 4.014) | <0.001 | 1.035 |

| Waist | 1.282 (0.065 to 25.386) | 0.87 | |||

| Height to waist | 0.865 (0.303 to 2.472) | 0.786 | |||

| CT-determined sarcopenia | 1.93 (1.227 to 3.038) | 0.004 | 1.410 (0.860 to 2.311) | 0.173 | 1.177 |

| CT-determined myosteatosis | 0.914 (0.566 to 1.476) | 0.713 | |||

| SFA | |||||

| SFA high (low) | 0.398 (0.241 to 0.655) | <0.001 | 0.422 (0.244 to 0.731) | 0.002 | 1.156 |

| VFA | 1.058 (0.570 to 1.965) | 0.858 | |||

BMI, body mass index; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; EGJ, esophagogastric junction; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; SFA, subcutaneous fat area; SII, Systemic Immune-inflammation Index; VIF, variance inflation factor.

Table 6.

Association between sarcopenia, SFA, SII and overall survival

| Variable (reference) | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||

| HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | |

| No. of previous therapy (1) | Reference | |||||

| 2 | 1.704 (0.952 to 3.052) | 0.073 | 1.543 (0.851 to 2.796) | 0.153 | 1.584 (0.867 to 2.895) | 0.135 |

| 3 or more | 2.013 (1.143 to 3.547) | 0.015 | 1.782 (1.014 to 3.134) | 0.045 | 1.569 (0.889 to 2.769) | 0.121 |

| HER2 status (2+&FISH−) | Reference | |||||

| 2+&FISH+/3+ | 0.487 (0.239 to 0.993) | 0.048 | 0.446 (0.217 to 0.920) | 0.029 | 0.463 (0.221 to 0.971) | 0.041 |

| 2+&FISH undetermined | 0.425 (0.089 to 2.023) | 0.284 | 0.595 (0.121 to 2.928) | 0.523 | 0.862 (0.178 to 4.172) | 0.854 |

| SII ≥823×109/L (<823×109/L) | – | 2.483 (1.543 to 3.996) | <0.001 | 2.302 (1.436 to 3.690) | 0.001 | |

| CT-determined sarcopenia | 1.420 (0.863 to 2.335) | 0.167 | – | 1.718 (1.076 to 2.741) | 0.023 | |

| SFA high (low) | 0.469 (0.270 to 0.815) | 0.007 | 0.373 (0.221 to 0.630) | <0.001 | – | |

HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; SFA, subcutaneous fat area; SII, Systemic Immune-inflammation Index.

In addition, we performed survival analysis for the combination of SII and SFA (figure 5). In comparison to patients with low SII and high SFA, patients with high SII and low SFA had the worst OS (HR=8.19 (95% CI 3.91 to 17.16), p<0.001), followed by patients with high SII and high SFA, or low SII and low SFA (HR=2.40 (95% CI 1.45 to 3.97), p=0.001). Kaplan-Meier survival curves with log-rank tests were performed according to sex, age, SII, and programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression between low and high groups to further examine the prognostic impact of SFA or SII on OS under different conditions (online supplemental figure S1 and S2). A high SFA was associated with a significantly more favorable OS in both men and women, patients with high and low SII, and patients with PD-L1 positive and negative.

Figure 5.

Survival analysis for the combination of SII and SFA. SFA, subcutaneous fat area; SII, Systemic Immune-inflammation Index.

All variables were examined for their multicollinearity before inclusion in the multivariate Cox analyses by calculating the variance inflation factor.

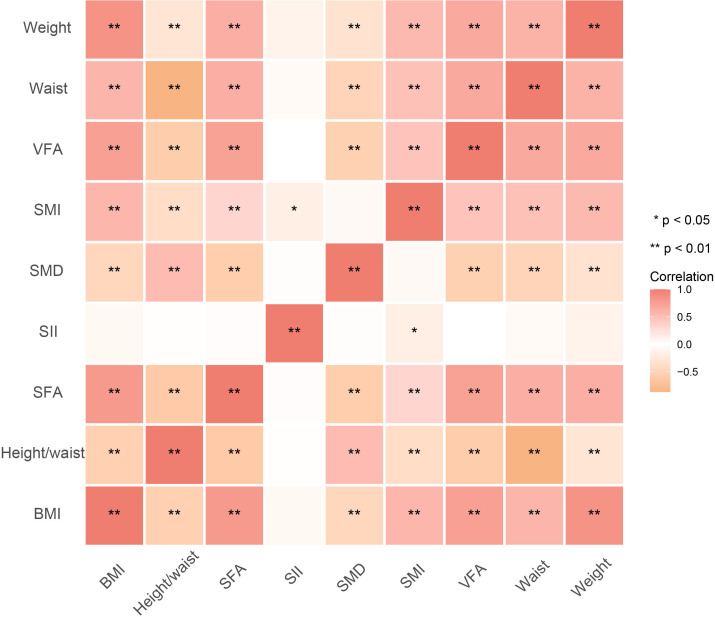

Association between body composition parameters and SII

Among the SII and body composition parameters, SFA and SII were significantly associated with SMI (ρ=0.329, p=0.001 and ρ=−0.179, p=0.025), while there was no significant correlation between SFA and SII (ρ=0.018, p=0.824) (figure 6 and online supplemental figure S3).

Figure 6.

The heatmap showing the correlation between body composition parameters and SII. BMI, body mass index; SFA, subcutaneous fat area; SII, Systemic Immune-inflammation Index; SMD, skeletal muscle density; SMI, Skeletal Muscle Index; VFA, visceral fat area.

Discussion

In this study, we developed an automatic segmentation deep learning model based on nnU-Net that can automatically localize the L3 level and segment body compositions. We examined the influence of baseline body composition parameters and SII on PFS and OS for patients with advanced GC receiving dual PD-1 and HER2 blockade. We discovered that low SFA was an independent predictor of PFS and OS. Furthermore, the combination of low SFA and high SII were significant prognostic biomarkers for OS in patients receiving targeted therapy combined with immunotherapy.

Previous studies8–12 reported that sarcopenia was an independent prognostic factor for OS in patients with various solid tumors receiving immunotherapy. Kim et al demonstrated that, although CT-determined sarcopenia was associated with a poorer prognosis for patients with GC receiving ICIs, it did not serve as an independent determinant for OS.11 SMI reflects the nutritional reserve of patients against the depletion of body mass by advanced malignancies. This nutrient depletion is often influenced by tumor-induced immunity/inflammation, with low nutrient levels resulting in impaired immune function and reduced immunotherapeutic efficacy. Several studies have shown that body composition parameters must be used in conjunction with other inflammatory markers to achieve precise stratification of GC by evaluating overall nutritional quality of patients.22–24

Therefore, we incorporated body composition parameters and SII to perform multivariate regression analysis and found that only SFA and SII were independent prognostic factors for OS. We further performed an adjusted analysis. After adjusting for SFA, sarcopenia and SII were independent factors of prognosis (Model 3), but after adjusting for SII, sarcopenia lost its independent effect on prognosis (Model 1). Moreover, SII exhibited a significant negative correlation with SMI, indicating that skeletal muscle reflects a certain degree of erosion of the body’s nutritional reserve caused by the tumor-induced inflammatory immune response. Additionally, the findings suggested that the influence of adipose tissue and the accompanying systemic inflammatory state may outweigh the effect of skeletal muscle on the prognosis of immunotherapy. Neutrophils, lymphocytes, and platelets are the components of the SII calculation formula that may reveal the balance between inflammation and immune response in the tumor microenvironment. Neutrophils secrete immunosuppressive mediators and vascular growth factors that promote tumor cell proliferation, invasion and metastasis.25 26 Platelets can shield tumor cells from cytotoxicity by immune cells, induce epithelial-mesenchymal transition and promote tumor extravasation and migration.27 28 On the other hand, lymphocytes are crucial in immunotherapy by inhibiting tumor cell proliferation and triggering cytotoxic cell death. ICIs work to modulate the tumor microenvironment and enhance the antitumor effects of T lymphocytes. Therefore, high SII indicating lymphopenia, neutrophilia, and thrombocytosis, was associated with poor prognosis in patients treated with ICIs.29–31

Subcutaneous and visceral adiposity have different characteristics and functional roles in immune and metabolic regulation. In obese individuals, increased visceral adiposity is associated with metabolic disturbances and pro-inflammatory properties. The expression of insulin-like growth factor receptor (IGF-IR) was found to be significantly higher in tumor samples from patients with visceral obesity than in non-obese patients.32 The activation of the IGF-IR signaling pathway promotes tumor cell proliferation and metastasis. Moreover, IGF-IR forms heterodimers with HER2, increasing HER2 phosphorylation and resistance to anti-HER2-targeted therapy.33 However, subcutaneous adiposity has beneficial effects on metabolism and anti-inflammatory, preclinical experiments have demonstrated that transplanting subcutaneous adiposity into the peritoneal cavity of obese mice can produce metabolically beneficial outcome.34 Our results suggest a relative survival advantage for patients with high subcutaneous but not visceral adiposity. This is consistent with findings from the preoperative body composition analysis of resectable GC.35 The observed phenomenon could potentially be attributed to the proximity of GC to visceral adiposity, which may result in the propagation of intra-abdominal metastases, subsequently impacting the measurement of visceral fat.

Preclinical modeling studies showed that obesity-induced elevated leptin level was associated with elevated PD-1 expression and T-cell depletion, thus ICIs exerted more significant effects in obese mouse models.36 A retrospective study by McQuade et al suggested that the beneficial prognostic effects of obesity appear to be most prevalent among patients undergoing targeted therapy and immunotherapy as opposed to chemotherapy.37 This suggestion is crucial for patients receiving dual PD-1 and HER2 blockade therapy. In cases of body composition loss caused by consumptive diseases like GC, patients have a significantly lower BMI than those with other tumor types, which probably leads to misclassify the body composition (fat and muscle) of patients. Conversely, obesity reflected by SFA is more indicative of prognostic value.

CT scans are part of the standardized clinical management in GC. The assessment of muscle and fat based on regular follow-up CT examinations is stable and reliable. Several manual or semiautomatic software have been previously developed for muscle or fat segmentation. Cruz et al reported that it took approximately 8 min to measure skeletal muscle, visceral and subcutaneous fat by semiautomatic method in liver transplant patients.38 Therefore, manual and semiautomatic methods are not user-friendly and have limited applicability in clinical work. In contrast, the automated segmentation model we developed based on deep learning reduced time to milliseconds and was highly reproducible, making it easy to apply in clinical practice of GC.

This study has several limitations. First, it is a retrospective single-center study with a limited sample size, and further validation in an external cohort is required. Second, diverse dual PD-1 and HER2 blockade regimens were administered to our patients, resulting in the heterogeneity of the research population. Third, no treatment-related adverse events were reported, including ICIs-related adverse effects. Further studies involving larger and multicenter samples are necessary, as previous studies reported obesity had a higher frequency of immune-related toxicity.39

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that SII and subcutaneous fat obesity measured by baseline CT are important prognostic factors for patients with advanced GC receiving dual PD-1 and HER2 blockade regimens. Our findings suggest that multimodal clinical management strategies to address the loss of subcutaneous adiposity may improve quality of life and prognosis of patients with advanced GC, and this need to be further investigated.

Footnotes

MH and Z-FC contributed equally.

Contributors: Conception and design: XZ, BD, Z-YL, TL. Administrative support: LS, JJ. Provision of study materials or patients: XG, XZ, TL. Collection and assembly of data: MH, XC. Data analysis and interpretation: Z-FC, MH, LZ, H-SL. Manuscript writing: All authors. Final approval of manuscript: All authors. Guarantor: TL.

Funding: This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 91959205 (LS), 12090022 (BD), 11831002 (BD), 81801778 (LZ)); Beijing Natural Science Foundation under Grants Z200015 (XZ); Science Foundation of Peking University Cancer Hospital JC202301 (TL).

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. The CT imaging data and clinical information, analyzed during the current study are not publicly available for patient privacy purposes. Please contact author TL for data requests. Associated codes to process and analyze data are available on GitHub (https://github.com/czifan/TSPC.PyQt5).

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study was exempted by the institutional review board at the Peking University Cancer Hospital and was performed according to the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was given by each individual before the treatment.

References

- 1. Baretton G, Kreipe HH, Schirmacher P, et al. Her2 testing in gastric cancer diagnosis: insights on variables influencing Her2-positivity from a large, multicenter, observational study in Germany. Virchows Arch 2019;474:551–60. 10.1007/s00428-019-02541-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Janjigian YY, Werner D, Pauligk C, et al. Prognosis of metastatic gastric and gastroesophageal junction cancer by Her2 status: a European and USA International collaborative analysis. Ann Oncol 2012;23:2656–62. 10.1093/annonc/mds104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bang Y-J, Van Cutsem E, Feyereislova A, et al. Trastuzumab in combination with chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for treatment of Her2-positive advanced gastric or Gastro-Oesophageal junction cancer (Toga): a phase 3, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2010;376:687–97. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61121-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Janjigian YY, Kawazoe A, Yañez P, et al. The KEYNOTE-811 trial of dual PD-1 and Her2 blockade in Her2-positive gastric cancer. Nature 2021;600:727–30. 10.1038/s41586-021-04161-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lee J, Kim ST, Kim K, et al. Tumor Genomic profiling guides patients with metastatic gastric cancer to targeted treatment: the VIKTORY umbrella trial. Cancer Discov 2019;9:1388–405. 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-19-0442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Martin L, Birdsell L, Macdonald N, et al. Cancer Cachexia in the age of obesity: Skeletal muscle depletion is a powerful Prognostic factor, independent of body mass index. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:1539–47. 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.2722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kamarajah SK, Bundred J, Tan BHL. Body composition assessment and Sarcopenia in patients with gastric cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastric Cancer 2019;22:645–50. 10.1007/s10120-019-00939-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wang J, Cao L, Xu S. Sarcopenia affects clinical efficacy of immune Checkpoint inhibitors in non-small cell lung cancer patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Immunopharmacology 2020;88:106907. 10.1016/j.intimp.2020.106907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Daly LE, Power DG, O’Reilly Á, et al. The impact of body composition parameters on Ipilimumab toxicity and survival in patients with metastatic Melanoma. Br J Cancer 2017;116:310–7. 10.1038/bjc.2016.431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dercle L, Ammari S, Champiat S, et al. Rapid and objective CT Scan Prognostic scoring identifies metastatic patients with long-term clinical benefit on anti-PD-1/-L1 therapy. European Journal of Cancer 2016;65:33–42. 10.1016/j.ejca.2016.05.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kim Y-Y, Lee J, Jeong WK, et al. Prognostic significance of Sarcopenia in Microsatellite-stable gastric cancer patients treated with programmed Death-1 inhibitors. Gastric Cancer 2021;24:457–66. 10.1007/s10120-020-01124-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chen B-B, Liang P-C, Shih TT-F, et al. Sarcopenia and Myosteatosis are associated with survival in patients receiving Immunotherapy for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur Radiol 2023;33:512–22. 10.1007/s00330-022-08980-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kim N, Yu JI, Park HC, et al. Incorporating Sarcopenia and inflammation with radiation therapy in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma treated with Nivolumab. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2021;70:1593–603. 10.1007/s00262-020-02794-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bilen MA, Martini DJ, Liu Y, et al. Combined effect of Sarcopenia and systemic inflammation on survival in patients with advanced stage cancer treated with Immunotherapy. Oncologist 2020;25:e528–35. 10.1634/theoncologist.2019-0751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hacker UT, Hasenclever D, Baber R, et al. Modified Glasgow Prognostic score (mGPS) is correlated with Sarcopenia and dominates the Prognostic role of baseline body composition parameters in advanced gastric and Esophagogastric junction cancer patients undergoing first-line treatment from the phase III EXPAND trial. Ann Oncol 2022;33:685–92. 10.1016/j.annonc.2022.03.274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Xu H, Cao D, He A, et al. The Prognostic role of obesity is independent of sex in cancer patients treated with immune Checkpoint inhibitors: A pooled analysis of 4090 cancer patients. Int Immunopharmacol 2019;74:S1567-5769(19)31160-9. 10.1016/j.intimp.2019.105745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Han J, Wang Y, Qiu Y, et al. Single-cell sequencing UNVEILS key contributions of immune cell populations in cancer-associated Adipose wasting. Cell Discov 2022;8:122. 10.1038/s41421-022-00466-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Bahat G, Bauer J, et al. Sarcopenia: revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing 2019;48:601. 10.1093/ageing/afz046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Su H, Ruan J, Chen T, et al. CT-assessed Sarcopenia is a predictive factor for both long-term and short-term outcomes in gastrointestinal oncology patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Imaging 2019;19:82. 10.1186/s40644-019-0270-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Huang D-D, Zhou C-J, Wang S-L, et al. Impact of different Sarcopenia stages on the postoperative outcomes after radical Gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Surgery 2017;161:680–93. 10.1016/j.surg.2016.08.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zhuang C-L, Huang D-D, Pang W-Y, et al. Sarcopenia is an independent Predictor of severe postoperative complications and long-term survival after radical Gastrectomy for gastric cancer: analysis from a large-scale cohort. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e3164. 10.1097/MD.0000000000003164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Skipworth RJE. A tale of two CT studies: the combined impact of multiple human body composition projects in cancer. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2019;10:6–8. 10.1002/jcsm.12406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dolan RD, Almasaudi AS, Dieu LB, et al. The relationship between computed tomography-derived body composition, systemic inflammatory response, and survival in patients undergoing surgery for colorectal cancer. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2019;10:111–22. 10.1002/jcsm.12357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Feliciano EMC, Kroenke CH, Meyerhardt JA, et al. Association of systemic inflammation and Sarcopenia with survival in Nonmetastatic colorectal cancer: results from the C SCANS study. JAMA Oncol 2017;3:e172319. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.2319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Felix K, Gaida MM. Neutrophil-derived proteases in the Microenvironment of Pancreatic cancer -Active players in tumor progression. Int J Biol Sci 2016;12:302–13. 10.7150/ijbs.14996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cools-Lartigue J, Spicer J, McDonald B, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps Sequester circulating tumor cells and promote metastasis. J Clin Invest 2013;123:3446–58. 10.1172/JCI67484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Orellana R, Kato S, Erices R, et al. Platelets enhance tissue factor protein and metastasis initiating cell markers, and act as Chemoattractants increasing the migration of ovarian cancer cells. BMC Cancer 2015;15:290. 10.1186/s12885-015-1304-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Labelle M, Begum S, Hynes RO. Direct signaling between platelets and cancer cells induces an epithelial-Mesenchymal-like transition and promotes metastasis. Cancer Cell 2011;20:576–90. 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.09.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chen J-H, Zhai E-T, Yuan Y-J, et al. Systemic immune-inflammation index for predicting prognosis of colorectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2017;23:6261–72. 10.3748/wjg.v23.i34.6261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cursano MC, Kopf B, Scarpi E, et al. Prognostic role of systemic inflammatory indexes in germ cell tumors treated with high-dose chemotherapy. Front Oncol 2020;10:1325. 10.3389/fonc.2020.01325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tian B-W, Yang Y-F, Yang C-C, et al. Systemic immune-inflammation index predicts prognosis of cancer Immunotherapy: systemic review and meta-analysis. Immunotherapy 2022;14:1481–96. 10.2217/imt-2022-0133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Alemán JO, Eusebi LH, Ricciardiello L, et al. Mechanisms of obesity-induced gastrointestinal Neoplasia. Gastroenterology 2014;146:357–73. 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.11.051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Nahta R, Yuan LXH, Zhang B, et al. Insulin-like growth factor-I receptor/human Epidermal growth factor receptor 2 Heterodimerization contributes to Trastuzumab resistance of breast cancer cells. Cancer Res 2005;65:11118–28. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hwang I, Jo K, Shin KC, et al. GABA-stimulated Adipose-derived stem cells suppress subcutaneous Adipose inflammation in obesity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2019;116:11936–45. 10.1073/pnas.1822067116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Han J, Tang M, Lu C, et al. Subcutaneous, but not visceral, Adipose tissue as a marker for prognosis in gastric cancer patients with Cachexia. Clinical Nutrition 2021;40:5156–61. 10.1016/j.clnu.2021.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wang Z, Aguilar EG, Luna JI, et al. Paradoxical effects of obesity on T cell function during tumor progression and PD-1 Checkpoint blockade. Nat Med 2019;25:141–51. 10.1038/s41591-018-0221-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. McQuade JL, Daniel CR, Hess KR, et al. Association of body-mass index and outcomes in patients with metastatic Melanoma treated with targeted therapy, Immunotherapy, or chemotherapy: a retrospective, Multicohort analysis. The Lancet Oncology 2018;19:310–22. 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30078-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Cruz RJ, Dew MA, Myaskovsky L, et al. Objective Radiologic assessment of body composition in patients with end-stage liver disease: going beyond the BMI. Transplantation 2013;95:617–22. 10.1097/TP.0b013e31827a0f27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Dos Santos DMC, Rejeski K, Winkelmann M, et al. Increased visceral fat distribution and body composition impact cytokine release syndrome Onset and severity after Cd19 Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy in advanced B-cell malignancies. Haematologica 2022;107:2096–107. 10.3324/haematol.2021.280189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

jitc-2023-007054supp001.pdf (699.5KB, pdf)

jitc-2023-007054supp002.mp4 (12.2MB, mp4)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. The CT imaging data and clinical information, analyzed during the current study are not publicly available for patient privacy purposes. Please contact author TL for data requests. Associated codes to process and analyze data are available on GitHub (https://github.com/czifan/TSPC.PyQt5).