Abstract

Objective

Nausea and vomiting remain life-threatening obstacles to successful treatment of chronic diseases, despite a cadre of available antiemetic medications. Our inability to effectively control chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) highlights the need to anatomically, molecularly, and functionally characterize novel neural substrates that block CINV.

Methods

Behavioral pharmacology assays of nausea and emesis in 3 different mammalian species were combined with histological and unbiased transcriptomic analyses to investigate the beneficial effects of glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide receptor (GIPR) agonism on CINV.

Results

Single-nuclei transcriptomics and histological approaches in rats revealed a topographical, molecularly distinct, GABA-ergic neuronal population in the dorsal vagal complex (DVC) that is modulated by chemotherapy but rescued by GIPR agonism. Activation of DVCGIPR neurons substantially decreased behaviors indicative of malaise in cisplatin-treated rats. Strikingly, GIPR agonism blocks cisplatin-induced emesis in both ferrets and shrews.

Conclusion

Our multispecies study defines a peptidergic system that represents a novel therapeutic target for the management of CINV, and potentially other drivers of nausea/emesis.

Keywords: Incretin, Chemotherapy, Vomiting, Obesity, Diabetes, Antiemetic

Highlights

-

•

GIPR agonism attenuates cisplatin-induced emesis in ferrets and shrews.

-

•

Activation of hindbrain GIPR + neurons decreases malaise in cisplatin-treated rats.

-

•

Cisplatin induces profound transcriptomic alternations in hindbrain GABAergic neurons.

-

•

GIPR agonism may exert its anti-emetic actions by restoring GABA-ergic activity.

-

•

The GIPR system represents a novel therapeutic target for the management of CINV.

1. Introduction

Nausea and vomiting protect mammalian survival [1]. Unfortunately, emetic “side effects” are ubiquitously reported for FDA-approved pharmacotherapeutics and are nearly always associated with detrimental outcomes related to survival, such as poor nutrition, quality of life, and patient prognosis in many clinical fields [2,3]. In fact, despite antiemetic treatments, virtually all patients undergoing chemotherapy still exhibit emesis and nausea [[4], [5], [6], [7]]. Thus, a reassessment of the neural substrates that mediate nausea and emesis using modern behavioral and neurogenetic approaches is required to achieve the ultimate goal of effective, long-term control of nausea and vomiting in modern health care.

Two interconnected hindbrain nuclei in the dorsal vagal complex (DVC): the nucleus tractus solitarii (NTS) and the area postrema (AP), play a critical role in ingestive behavior, emesis, and nausea [3,8]. Widely used emetogenic chemotherapeutics (e.g. cisplatin) and other emetic stimuli activate neurons in the AP/NTS, also known as the chemoreceptive trigger zone [[9], [10], [11]]. Here, we suggest that among the ancestral heterogeneity of the AP/NTS neuronal populations [[12], [13], [14]], there exists a novel antiemetic system characterized by inhibitory (i.e. GABA-ergic) neurons that express the glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) receptor (GIPR) [13].

GIP is a hormone released from the proximal intestine shortly after a meal begins [15], and has been historically characterized as an incretin for its role in regulating post-prandial plasma glucose concentrations by augmenting insulin secretion [[16], [17], [18]]. While GIP-based therapeutics were initially cast aside due to their overall weak biological effects compared to its sister incretin, glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), recent studies employing GIPR/GLP-1R dual agonism to treat type 2 diabetes and obesity are yielding promising results in pre-clinical models and clinical trials by providing greater body weight loss and superior glycemic control compared to GLP-1R agonism alone [[19], [20], [21], [22], [23]]. Importantly, when doses were corrected and matched for efficacy, GIPR/GLP-1R dual agonism shows a reduction in the incidence of gastric-related adverse events compared to GLP-1R mono-agonist treatments [20,[22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27]]. These results are mechanistically supported by our pre-clinical studies demonstrating that GIPR activation was capable of attenuating emesis and illness-like behaviors elicited by GLP-1R activation [13]. As the DVC expresses the GIPR and is known to control food intake, as well as nausea/emesis, the central GIPR system was hypothesized to have an uninvestigated role as an antiemetic target with the potential to counteract CINV.

Here we report that GIPR agonism is capable of blocking emesis and nausea induced by chemotherapy treatment in three different mammalian species. We also provided mechanistical insights supporting the hypothesis that GIP acts by counteracting the cisplatin-induced shift toward an excitatory glutamatergic signaling in areas of the brainstem critical for the mediation of emesis and nausea. Altogether, these results support the clinical use of GIP analogs for the treatment of nausea and emesis in oncology patients with the goal to increase the efficacy of current therapeutic regimes and patient compliance.

2. Methods

2.1. Experimental models

Adult male ferrets (n = 20, 0.9–1.8 kg, at least 16 weeks old) were obtained from Marshall Farms. During the test period, ferrets were individually housed in stainless steel cages and fed twice a day with approximately 30 g of Ferret Diet #2072C (Envigo RMS, Inc.). Animals were maintained under a 12-hour:12-hour light/dark cycle in a temperature- and humidity-controlled environment.

Adult male shrews (Suncus murinus) weighing ∼50–70 g (n = 32 total), were bred and maintained at the University of Pennsylvania. These animals were offspring from a colony previously maintained at the University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute (courtesy of Dr. Charles Horn); a Taiwanese strain derived from stock originally supplied by the Chinese University of Hong Kong. Shrews were single housed in plastic cages (37.3 × 23.4 × 14 cm, Innovive) under a 12-hour:12-hour light/dark cycle in a temperature- and humidity-controlled environment. Animals were fed ad libitum with a mixture of feline (75%, Laboratory Feline Diet 5003, Lab Diet) and mink food (25%, High Density Ferret Diet 5LI4, Lab Diet) and had ad libitum access to tap water except where noted.

Adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles River) weighing ∼250–270 g (n = 87) at arrival were housed under a 12-hour:12-hour light/dark cycle in a temperature- and humidity-controlled vivarium. Rats were individually housed in hanging wire-bottomed cages with ad libitum access to chow diet (Purina Lab Diet 5001), tap water and also had ad libitum access to kaolin pellets (Research Diets, K50001). Rats were exposed to kaolin for at least 5 days prior to measuring kaolin consumption in pica testing.

All animals were habituated to single housing in their home cage and injections at least 1 wk prior to experimentation. All animals were naïve to experimental drugs and tests prior to the beginning of the experiment. For all in vivo experiments involving cisplatin, injections were administered using a between-subject design. Injections were performed shortly before dark-onset, except when noted. Power analyses were performed ahead according to a model of 20% minimum effect size (α = 0.05, β = 0.10) for kaolin/food intake, with estimated standard deviation based on our published work. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Care and Use Committee of the University of Pennsylvania and Eli Lilly and Company.

2.2. Method details

2.2.1. Drugs and route of administration, and related study design

The short-acting GIPR agonist GIP-532 (aka, GIPRA) and the long-acting GIPR agonist GIP-085 (aka, LAGIPRA) were synthesized at Eli Lilly and Company [13,28]. GIP-085 and GIP-532 were dissolved in 40 mM Tris HCl buffer (pH 8) 0.02% Tween-80. Cisplatin (Sigma Aldrich) was dissolved in saline. For the study in rats, all drugs were injected intraperitoneally (IP) at a volume of 1 ml/kg of body weight, except cisplatin, which was injected at 6 ml/kg. In shrews, GIP-085 was injected IP at a volume of 10 ml/kg and cisplatin was injected IP at a volume of 30 ml/kg. In ferrets GIP-532 was injected subcutaneously (SC) at a volume of 1 ml/kg, while cisplatin was injected IP at a volume of 1 ml/kg.

2.2.2. Effects of GIP-532, cisplatin and GIP-532/cisplatin co-treatments on emesis in ferrets

Ferrets (n = 5/group) were habituated to the experimental conditions as described above. The animals were pre-treated with GIP-532 (3 nmol/kg, SC) or vehicle 1 h prior to cisplatin (10 mg/kg, IP) or saline injection. Emetic episodes were analyzed by an observer blinded to treatment groups. Emetic episodes were characterized by strong rhythmic abdominal contractions associated with either oral expulsion from the gastrointestinal tract (i.e. vomiting) or without the passage of materials (i.e. retching). Latency to the first emetic episode and total number of emetic episodes (with and without oral expulsion) were quantified.

2.2.3. Effects of GIP-085, cisplatin and GIP-085/cisplatin co-treatments on emesis in shrews

Shrews (n = 48) were habituated to the experimental conditions as described above. The animals were pre-treated with GIP-085 (300 nmol/kg, IP) or vehicle 1 h prior to cisplatin (30 mg/kg, IP) or saline injection. Animals were video-recorded (Vixia HF-R62, Canon) for 180 min. After 180 min, the animals were returned to their cages. Emetic episodes were analyzed by an observer blinded to treatment groups. Emetic episodes were characterized by strong rhythmic abdominal contractions associated with either oral expulsion from the gastrointestinal tract (i.e. vomiting) or without the passage of materials (i.e. retching). Latency to the first emetic episode, total number of emetic episodes, number of emetic episodes per minute and per 20-minute intervals were quantified.

2.2.4. Effects of GIP-085, cisplatin and GIP-085/cisplatin on energy balance in shrews

Using a similar paradigm to the effects on food intake and body weight of GIP-085, cisplatin and GIP-085/cisplatin dual treatment were assessed. Food was removed 2 h prior to dark onset and body-weight matched shrews (n = 56) received IP injection of GIP-085 (300 nmol/kg), or vehicle, followed by an IP injection of cisplatin (30 mg/kg IP) or saline 1 h later. At dark onset food was given back to the animals. Shrews had ad libitum access to powdered food through a circular (3 cm diameter) hole in the cage. Food intake was evaluated using our custom-made feedometers, consisting of a standard plexiglass rodent housing cage (29 × 19 × 12.7 cm) with mounted food hoppers resting on a plexiglass cup (to account for spillage). Food intake was manually measured at 6, 24, 48 and 72 h post GIP-085 (or vehicle) injection. Body weight was taken at 0, 24, 48 and 72 h.

2.2.5. Effects of GIP-085, cisplatin and GIP-085/cisplatin dual treatment on food and kaolin consumption and body weight in rats

Kaolin intake (i.e., pica, a well-established as a model of nausea in rats [29]) was measured in addition to food intake. Rats (n = 56, 300–350 g) received an IP administration of GIP-085 (300 nmol/kg) or vehicle, followed 30 min later by an IP injection of cisplatin (6 mg/kg) or saline. Food and kaolin intake were measured at 3, 6, 24, 48 and 72 h post-injection and body weight was measured at 0, 24, 48 and 72 h. Rats were stratified into injection treatment groups by body weight.

2.2.6. Assessment of neuronal activation following GIP-085, cisplatin and GIP-085/cisplatin treatments in rats

Body weight-matched rats (n = 5/group) received IP injection of GIP-085 (300 nmol/kg) or saline followed 1 h after (i.e. shortly prior to dark onset) by a cisplatin (6 mg/kg) or saline injection. Food was removed to avoid feeding-related changes in c-Fos expression between groups. Three hours later, rats were deeply anesthetized with IP triple cocktail of ketamine, xylazine and acepromazine (180 mg/kg, 5.4 mg/kg and 1.28 mg/kg, respectively) and transcardially perfused with 0.1 M PBS (Boston Bioproducts), followed by 4% PFA (in 0.1 M PBS, pH 7.4, Boston Bioproducts). Brains were removed and post fixed in 4% PFA for 48 h and then stored in 25% sucrose for two days. Brains were subsequently frozen in cold hexane and stored at −20 °C until further processing. Thirty micrometer-thick frozen coronal sections containing the DVC were cut in a cryomicrotome (CM3050S, Leica Microsystem), collected and stored in cryoprotectant (30% sucrose, 30% ethylene glycol, 1% polyvinyl-pyrrolidone-40, in 0.1 M PBS) at −20 °C until further processing. IHC was conducted according to previously described procedure [30,31]. Briefly, free-floating sections were washed with 0.1 M PBS (3 × 8min), incubated in 0.1 M PBS containing 0.3% Triton X-100 (PBST) and 5% normal donkey serum (NDS) for 1 h, followed by an overnight incubation with rabbit anti-Fos antibody (1:1000 in PBST; s2250; Cell Signaling). After washing (3 × 8min) with 0.1 M PBS sections were incubated with the secondary antibody donkey anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 (1:500 in 5% NDS PBST; Jackson Immuno Research Laboratories) for 2 h at room temperature. After final washing (3 × 8min in 0.1 M PBS) the sections were mounted onto glass slides (Superfrost Plus, VWR) and coverslipped with Fluorogel (Electron Microscopy Sciences). c-Fos-positive neurons spanning the medio-caudal DVC (i.e. 14.0–13.5 mm caudal to Bregma) were visualized (20×; Nikon 80i, NIS Elements AR 3.0) and quantified (FIJI software) using fluorescence microscopy. For each animal a total of 3 sections per region were used to quantify the number of c-Fos-labeled cells in the region of interest were quantified similarly as previously described [30,31] by an experimenter blinded to the treatment.

2.2.7. AP/NTS transcriptome profile of single nuclei in rats

2.2.7.1. Tissue collection

Rats (n = 11, ∼400 g) were injected with GDF15 (100 μg/kg, n = 3), cisplatin (6 mg/kg, n = 4) or saline (n = 4) at dark onset. Food was removed to avoid feeding-related changes in gene expression between groups. Six hours later, rats were deeply anesthetized with IP triple cocktail of ketamine, xylazine and acepromazine. Brains were removed and snap-frozen in dry ice-cold hexane. Three adjacent micro-punch samples (each 1 cubic mm) containing the AP and left and right NTS were collected from coronally-prepared brains on a cryostat, pooled together and stored at −80 °C until further processing.

2.2.7.2. Isolation of nuclei

Nuclei were isolated from frozen AP and NTS punches, as we previously described [13,32,33]. Briefly, AP and NTS tissue punches from a single animal were homogenized together in lysis buffer using 20 strokes of the loose pestle and 10 strokes of the tight pestle. The homogenate was diluted with lysis buffer and left to lyse on ice for an additional 5 min, followed by addition of an equal volume of wash buffer. Samples were then passed through a 30 μm cell strainer and centrifuged at 500×g for 7 min at 4 °C. Supernatants were decanted and pellets were resuspended in 3 ml wash buffer. Samples were passed through a 30 μm cell strainer for a second time and centrifuged at 500×g for 10 min at 4 °C. Supernatants were decanted and pellets were resuspended in 1.5 ml wash buffer and centrifuged at 500×g for 10 min at 4 °C. Supernatants were decanted and pellets were resuspended.

2.2.7.3. 10x ibrary preparation and sequencing

Microfluidic capture and sequencing library preparation were performed with the 10× Genomics 3′ gene expression assay per manufacturer's instructions. Target capture was ∼10,000 nuclei per sample. Unique dual-indexed sequencing libraries were prepared per manufacturer protocols, and all libraries were sequenced on a single Illumina NovaSeq 6000 S4 flow cell.

2.2.7.4. QC and clustering

10x Genomics Cell Ranger v3.1 was used to align reads to the rat pre-mRNA transcriptome (Rattus_norvegicus.Rnor_6.0.101). Filtered read count matrices for all animals were merged using Seurat v3.1. The distributions of the numbers of genes and unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) were assessed to identify potential outliers. Nuclei in the bottom 0.5% for number of genes (<550) were removed due to likely being uninformative, similar to prior reports [[34], [35], [36], [37]]. Nuclei in the top 0.5% of gene count (>4,769) and/or top 1% of UMI count (>10,937) were removed as putative multiplets, also similar to previous reports [[34], [35], [36], [37]]. Finally, as previously described, nuclei in which >5% of transcripts were of mitochondrial origin were removed and all mitochondrial transcripts were removed from the data set [38].

Counts were normalized to 10,000 counts per subject and scaled in Seurat. Variably expressed genes were identified with the FindVariableFeatures function in Seurat using the mean. var.plot selection method and analyzing only genes with mean scaled expression between 0.003 and 2. These parameters identified 1,286 highly variable genes, which were used to generate principal components (PCs). Clustering was performed in Seurat using the first 50 PCs, generating 34 clusters at a resolution of 0.5. Six clusters were represented in only 2 of the 4 samples, with three of these clusters expressing Slc17a7 (VGLUT1), a gene that is not present in the AP or NTS. These six clusters likely represent capture of adjacent brain stem regions and were removed.

2.2.7.5. Annotation of cell clusters

Major cell types were identified using known markers of major cell types [35]: Microglia: Cx3cr1, Mrc1; Endothelial – Cldn5; Astrocytes – Cldn10, Glul, Aqp4; Oligodendrocyte Precursor Cells – Pcdh15, Pdgfra, Olig1, Olig2; Oligodendrocytes – Mag, Mog, Plp1, Mobp, Mbp; Excitatory Neurons – Slc17a6; Inhibitory Neurons – Gad1, Gad2, Slc32a1; Neurons – Snap25, Stmn2; Tanycytes – Vim [12]; Ependymocytes – Cfap52, Vim [12]; Radial Glia – Notch2 [39], Slc1a3 [40]. Seven clusters with mixed major cell type markers were removed and the remaining nuclei were reclustered at a resolution of 0.25 for a final total of 20 clusters.

2.2.7.6. Differential gene expression

Differential expression analysis was performed using a pseudobulking strategy. Comparisons were made between the cisplatin or GDF15 experimental groups and saline controls for each cluster using the EdgeR method with likelihood ratio test (LRT) within the Libra R package [41].

2.3. Quantification and statistical analysis

Body weight changes were calculated by subtracting body weight on any given post-treatment day from the rat's weight on the day of injection. In all behavioral studies, food intake, kaolin intake, emesis and body weight changes data were analyzed using ordinary one-way or two-way ANOVAs followed by Tukey's post hoc tests. For the analysis of c-Fos expression an ordinary one-way ANOVA was used, followed by Tukey's post hoc tests. All data were expressed as mean ± SEM. For all statistical tests, a p-value less than 0.05 was considered significant. Information on replicates and significance is reported in the figure legends. All data were analyzed using Prism 9 GraphPad Software (San Diego, California).

2.4. Data and materials availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents. Further information should be directed to and will be fulfilled by Bart C. De Jonghe (bartd@nursing.upenn.edu) and Matthew R. Hayes (hayesmr@pennmedicine.upenn.edu). Single-nuclei RNA sequencing data are available at the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) under accession numbers GSE167981, GSE167991, and GSE216247.

3. Results

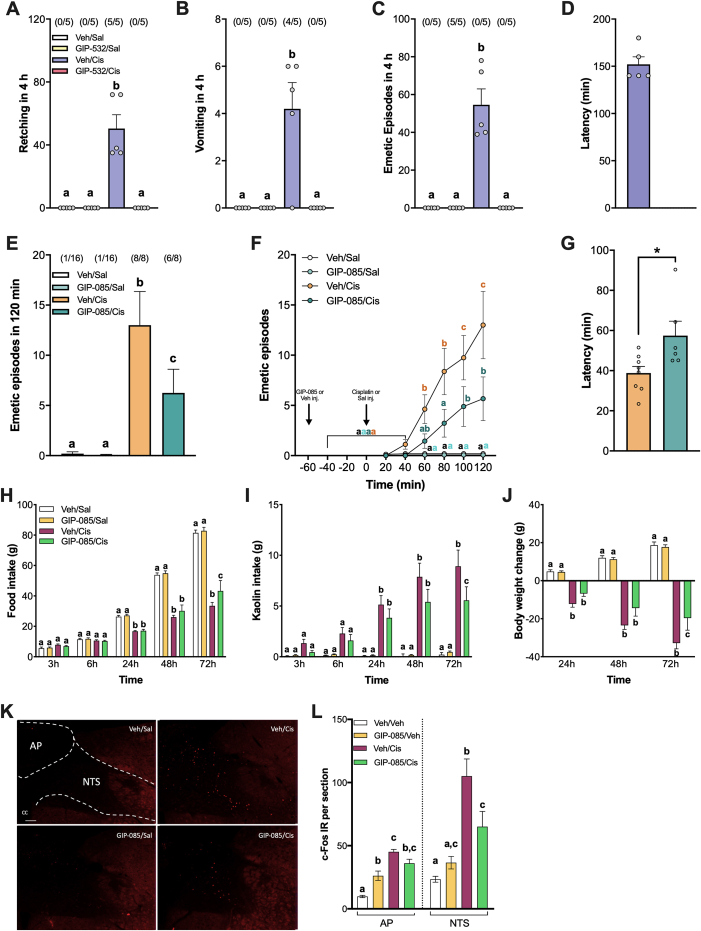

Using the ferret model, the gold standard pre-clinical model of CINV, we first determined the effect of a systemically administered short-acting GIPR agonist (GIPRA [28]) on cisplatin-induced emesis. GIPR activation alone did not cause emesis, but pre-treatment with the GIPRA 1 h before cisplatin administration prevented emesis and retching that occurred within the first 4 h of all cisplatin-treated ferrets (Figure 1A–D). In the subsequent 4–8 h, only one ferret, experienced emesis after GIPR agonism (suppl. Figure. S1).

Figure 1.

GIPR agonism attenuates nausea and emesis in 3 different mammalian species. A) GIPR agonism (GIP-532, 3 nmol/kg, SC) blocks retching induced by the chemotherapeutic agent cisplatin (10 mg/kg, IP) in ferrets (n = 5/group). B) While cisplatin (10 mg/kg, IP) produces severe emesis in 4 out of 5 ferrets, pre-treatment with GIPR agonist GIP-523 (3 nmol/kg, SC) completely prevents cisplatin-induced vomiting (n = 5/group). C) GIPR agonism blocks the insurgence of cisplatin-induced emetic episodes (i.e. retching and vomiting) in ferrets (n = 5/group). D) Latency to the first emetic episode following each treatment condition in ferrets. E) In shrews, the profound emesis induced by cisplatin (30 mg/kg, IP) is significantly attenuated by GIP-085 (300 nmol/kg) pre-treatment (n = 8–16/group). F) Cumulative emetic episodes across time in shrews (n = 8–16/group). G) Latency to the first emetic episode following cisplatin treatment with or without GIPR agonist pre-treatment in shrews (n = 6–8/group). H) Cisplatin (6 mg/kg, IP) -induced anorexia is attenuated by GIPR agonism (GIP-085, 300 nmol/kg, IP) in rats (n = 12–15/group). I) Cisplatin leads to increased kaolin consumption (a proxy for nausea in rodents). GIPR agonism significantly attenuated cisplatin-induced kaolin consumption in rats (n = 12–15/group). J) Cisplatin-induced body weight loss is attenuated in rats pre-treated with GIP-085 (n = 12–15/group). K) Representative immunofluorescent images showing c-Fos-positive cells in the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS) and area postrema (AP) (∼250 μm rostral to the obex) after GIP-085 (300 nmol/kg IP), cisplatin (6 mg/kg IP) or dual treatments. H) Quantification of c-Fos-positive neurons in the medial NTS and in the AP (n = 5/group). All data expressed as mean ± SEM. In the emetic studies, the number of animals vomiting and/or exhibiting retching, expressed as a fraction of the total number of animals tested are indicated above each treatment group. Data in (A, B, C, D, E, L) were analyzed with one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test. Data in (F, H, I, J) were analyzed with two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test. Means with different letters are significantly different from each other (P < 0.05). Data in (G) were analyzed with a two-tailed Student's t-test (∗P < 0.05).

In parallel experiments using the musk shrew (S. murinus), a small, phylogenetically ancestral non-rodent mammalian model capable of emetic and anorectic profiles similar to humans [[42], [43], [44], [45]], we utilized a long-acting GIPR agonist (LAGIPRA [13]) to examine whether GIPR agonism prevents CINV in the shrew similar to ferrets. Indeed, in shrews GIPR agonism by itself was also well tolerated, corroborating findings in the ferret. In line with previous reports [45,46], cisplatin treatment induced the expected emetic response in shrews (Figure 1E–F) along with significant anorexia and body weight loss (suppl. Figure. S2). By contrast, pre-treatment with the LAGIPRA in the shrew strongly reduced the incidence and severity of emetic episodes caused by cisplatin, as well as delaying its insurgence (Figure 1E–G and Suppl. Figure. S3), consistent with our data collected in ferrets. Specifically, GIPR agonism in the shrew reduced the number of emetic episodes by >50% compared to cisplatin-treated controls. Overall, these studies collectively demonstrate robust antiemetic properties of GIPR agonism in two mammalian species with emetic physiology recapitulating that of humans. Additionally, since our studies were conducted using two different GIPR agonists, both with high specificity for the GIPR receptor, one can exclude, beyond reasonable doubt, that the observed effects were due to non-GIPR off-target effects specific to the agonist used. Lastly, the inclusion of a multi-day active GIPR agonist [13] enhances the clinical relevance and the translational potential in humans.

While shrews and ferrets represent gold-standard models to study emesis, the broad application of the GIP system as a therapeutic approach to block illness behaviors will be enhanced by demonstration of the ability of GIPR agonism to attenuate behaviors indicative of nausea and malaise in rodent models. To this end, pica behavior (i.e. ingestion of non-nutritive substances such as kaolin) can be quantified in non-emetic models, such as rats [47], to examine malaise from agents known to cause nausea in humans [[48], [49], [50]]. A single dose of cisplatin in rats induces significant kaolin consumption, anorexia (Figure 1H–I) and weight loss relative to vehicle injections (Figure. 1J). Consistent with our previous studies in rats, there was no effect of LAGIPRA treatment alone, however GIPR activation reduced pica behavior and partially rescued anorexia and body weight loss induced by cisplatin administration. Furthermore, a significant attenuation of neural activation, as read out by c-Fos expression in the NTS, occurred following pre-treatment with the LAGIPRA compared to the robust c-Fos activation induced by cisplatin treatment alone in the DVC of rats (Figure. 1K-L). These results suggest that a single GIPR agonist injection may not only be an antiemetic therapeutic target, but also importantly an anti-nausea pharmacotherapeutic target as well. These findings separate GIPR agonists with critical distinction from existing antiemetics, given the relatively greater lack of clinical control and basic understanding of drug-induced nausea compared to vomiting [51,52]. Since nausea requires the transmission of information from the hindbrain to more rostral sites in the brain where a more conscious sensation is generated [53], the data presented here highlight the potential for GIPR agonism to counteract not just the stimulus of vomiting, but also to reduce illness behaviors associated with nausea.

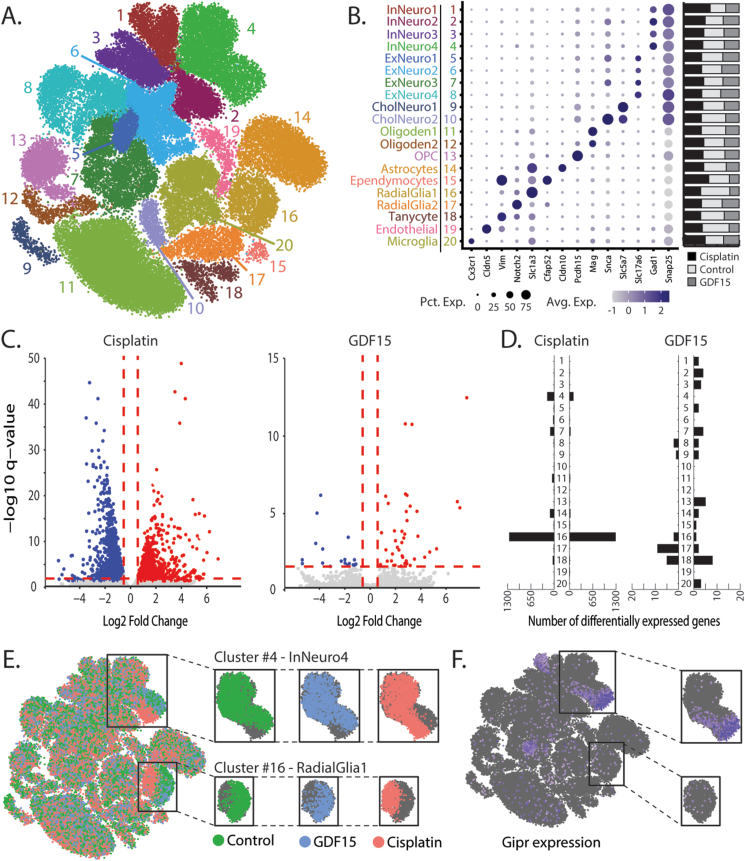

To provide deeper mechanistic and molecular insights underlying the behavioral and neuronal effects of GIPR signaling in the context of CINV, we performed an unbiased systematic characterization of the AP/NTS cells using single-nuclei RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq). We investigated the distinct molecular characteristics of AP/NTS cell types that are affected by cisplatin treatment and to the emetic cytokine growth differentiation factor 15 (GDF15), as a portion of cisplatin-induced illness behaviors has recently been shown to be mediated, in part, by GDF15 signaling [11,54,55]. The inclusion of the GDF15 treatment analysis allows us the opportunity to look at cisplatin-induced differential gene expression changes in the AP/NTS independent of GDF15 signaling directly [56]. In line with our previous reports [13,32], the snRNA-seq data identified several transcriptomically distinct populations of excitatory, inhibitory, and cholinergic neurons (clusters 1–10; Figure 2A–B), as well as non-neuronal populations (clusters 11–20; Figure 2A–B). The analysis of the differential gene expression revealed 3,370 differentially expressed genes (DEG) induced by cisplatin and 60 DEGs induced by GDF15 (Figure. 2C) 6 h after treatment. DEGs induced by cisplatin and GDF15 were detected in both neuronal and glial clusters, with 54.7% of DEGs being upregulated and 45.3% downregulated by cisplatin (Figure 2D and Suppl. Tables S1-2) and 31.7% upregulated and 68.3% downregulated by GDF15 (Figure 2D and Suppl. Tables S3-4). In particular, cisplatin treatment induced a dramatic alteration in the transcriptomic profile in two distinct nuclei clusters, i.e. inhibitory GABA-ergic neurons (cluster 4) and radial glia progenitor cells (cluster 16), that was not observed after GDF15 treatment (Figure. 2E). Notably, the cisplatin-induced transcriptomic break in the inhibitory neuron cluster overlaps with a subpopulation of Gipr-expressing cells (Figure 2F). Taken together, these data suggest that this inhibitory neuron population, which underwent pronounced transcriptome alterations after cisplatin treatment, would also be the primary site of action for the GIPR agonist that were shown to reduce emetic and anorexic effects on a multispecies basis. Importantly, while cisplatin is known to increase GDF15 production [11,54], the marked increase in DEGs in the cisplatin group, compared to GDF15-treated animals, suggests that the cisplatin-induced alterations in gene expression are induced in a GDF15-independent mechanism. Further supporting this conclusion is a considerable increase in DEGs in the radial glial progenitor AP/NTS cell population, accounting for ∼75% of all cisplatin-induced differential gene expression, which was almost entirely GDF15-independent.

Figure 2.

Cisplatin primarily alters the transcriptome of GABA-ergic neurons and radial glia progenitor cells. A) A uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) of AP/NTS identifying 20 cell types. B) Cellular subtypes were annotated with known markers of AP/NTS cellular subtypes. The size and color of dots are proportional to the percentage of cells expressing the gene (Pct. Exp.) and the average expression level of the gene (Avg. Exp.), respectively. The cluster numbers and colors are matched to that of the UMAP. Bar graphs represent the proportion of nuclei originating from each phenotype and were similar in all clusters. C) Volcano plots depicting the number of significant differential expression events induced by cisplatin and GDF15 treatment. D) The number of genes with cisplatin- or GDF15-altered expression per cluster. E) A highlighted UMAP showing the distribution of nuclei from the three phenotypes throughout all clusters. Cisplatin treatment induced a large enough alteration of the transcriptome in a population of GABA-ergic inhibitory neurons and radial glia progenitor cells to induce phenotype-specific partitioning of their UMAP, which coincided with these clusters having the largest number of differentially expressed genes. F) A highlighted UMAP identifying nuclei containing transcripts for Gipr.

Downstream analysis of the gene expression alterations of the inhibitory neuron and radial glial progenitor cell populations in response to cisplatin identified several shared and cell-type-specific alterations. To understand how cisplatin affected direct and secondary neurobiological mechanisms, we first compared cluster-specific DEGs to Gene ontology (GO) terms (Suppl. Table S5) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways (Suppl. Table S6) to identify cell-type-specific shared and unique neurobiological mechanisms in the AP/NTS using FUMA [57]. GO and KEGG analysis identified multiple dysregulated biological process associated with regulation of synapse and synaptic signaling in the GABA-ergic neuronal population, while radial glial progenitor cells had considerable dysregulation of the biological processes related to cellular regulation and differentiation. To identify metabolic and cell signaling pathways that are likely to be altered in response to cisplatin treatment, we performed canonical pathway analyses with Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) using cluster-specific DEGs. IPA revealed significant downregulation of CREB signaling, calcium signaling, and synaptic long-term depression pathways in the inhibitory GABA-ergic neuronal cluster 4 (Suppl. Figure S4 and Suppl. Table S7). These results give potential mechanistic insight regarding the context of GIPR signaling given the high abundance of Gipr expression in this inhibitory neuronal cluster. Indeed, the data suggest that GIPR activation may exert its anti-emetic action by restoring a missing basal excitatory neural input to the inhibitory neurons thus counteracting the effects of cisplatin in downregulating glutamatergic inputs to these inhibitory neurons. Further experiments, including the transcriptomic profiling after GIPR alone and in combination with cisplatin, are needed to provide additional and conclusive mechanistic explanations behind the anti-emetic effects of GIPR signaling.

4. Conclusions

Overall, the collective complementary results in these three mammalian preclinical models stress the beneficial effects of GIPR agonism in counteracting CINV, fostering the discovery of a novel first-in-class therapeutic target to treat CINV. The discoveries presented here also highlight the presence of a poorly characterized central peptidergic system with potent anti-emetic actions that could be exploited for the treatment of not only CINV, but also other diseases and pharmacological treatments that drive unwanted illness-inducing anorexia, nausea, and emesis that compromise metabolic health and patient's quality of life.

Despite current anti-emetic regimes, CINV still remains a major challenge in the oncology field. Our inability to control CINV in patients undergoing chemotherapy stresses the need to look beyond classical pathways and to seek alternative approaches to reduce the occurrence and severity of emesis and nausea in patients. In 2006, neurokinin receptor 1 antagonists (i.e. aprepitant), were the last new class of drugs to receive FDA approval for the treatment of CINV [1]. Since then, no major advances have been made and no new class of anti-emetics has been discovered and successfully employed in the clinic. In spite of some compelling historic evidence of anti-emetic efficacy of GABA analogs (e.g. gabapentin), their broad clinical use is severely limited by their side effects [58,59]. We reasoned that a treatment that could selectively target a subpopulation of inhibitory neurons within the AP/NTS, thus increasing the local GABA-ergic tone, could provide an efficacious and better tolerated strategy to counteract the increased in AP/NTS neuronal activity caused by chemotherapy that is the underlying reason for emesis and nausea. GIP-based analogs may also have the additional benefit of counteracting, due to their glucoregulatory property, the insurgence of cancer-induced insulin resistance, a very common phenomenon in oncology patients that contributes to the cancer-anorexia-cachexia syndrome, which ultimately decreases quality of life, hinders treatment success, and negatively affects prognosis [[60], [61], [62]].

The road that led to the characterization of current anti-emetics was paved with several serendipitous discoveries that resulted in the repurposing of existing medications [1]. Such is perhaps also the case with GIP, a key incretin hormone with modest hypophagic actions compared to other gut hormones, that was initially overlooked in favor of more effective agents that regulate glucose homeostasis and control feeding behavior [63,64]. Interestingly, however, our newly generated data in three different mammalian species, uncovers a new role for the GIPR system by demonstrating that GIPR signaling is capable of antagonizing emesis and nausea induced by chemotherapy treatment by counteracting the shift toward an excitatory glutamatergic signaling in areas of the brain critical for the mediation of emesis and nausea. These results highlight a potential new clinical use for GIP analogs to increase the efficacy of current therapeutic regimes for the treatment of nausea and emesis in oncology patients.

Author contributions

TB, MA, RJS, BCDJ, and MRH conceived and designed the experimental approach. TB, BCR, CDF, SAD, JA, RCC performed experiments and analyzed data. TB, BCR, MA, RJS, BCDJ and MRH prepared the manuscript. All authors edited the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH)-National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) 021397 (MRH), National Institutes of Health (NIH)-National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) 130239 (MRH, BCDJ), National Institutes of Health (NIH)-National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) 112812 (BCDJ), by the Swiss National Science Foundation (Grant SNF P400PB_186728) (TB) and an investigator-initiated sponsored agreement from Eli Lilly & Company. (MRH, BCDJ).

Declaration of Competing Interest

MRH and BCR receive research funding from Boehringer Ingelheim and Novo Nordisk that were not used in support of these studies. MRH and BCDJ are CEO and CSO of Cantius Therapeutics, LLC that pursues biological work unrelated to the current study. RC, MA, and RJS are employees of Eli Lilly & Co. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Samantha Fortin, Lauren Stein and Marcos Sanchez for technical assistance.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molmet.2023.101743.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.Sanger G.J., Andrews P.L.R. A history of drug discovery for treatment of nausea and vomiting and the implications for future research. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:913. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.00913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lacy B.E., Parkman H.P., Camilleri M. Chronic nausea and vomiting: evaluation and treatment. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113:647–659. doi: 10.1038/s41395-018-0039-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hesketh P.J. Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2482–2494. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0706547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Basch E., Prestrud A.A., Hesketh P.J., Kris M.G., Feyer P.C., Somerfield M.R., et al. Antiemetics: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:4189–4198. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.34.4614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grunberg S.M., Deuson R.R., Mavros P., Geling O., Hansen M., Cruciani G., et al. Incidence of chemotherapy-induced nausea and emesis after modern antiemetics. Cancer. 2004;100:2261–2268. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keeley P.W. Nausea and vomiting in people with cancer and other chronic diseases. Clin Evid. 2009;2009 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hattori T., Yakabi K., Takeda H. Cisplatin-induced anorexia and ghrelin. Vitam Horm. 2013;92:301–317. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-410473-0.00012-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grill H.J., Hayes M.R. Hindbrain neurons as an essential hub in the neuroanatomically distributed control of energy balance. Cell Metabol. 2012;16:296–309. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller A.D., Leslie R.A. The area postrema and vomiting. Front Neuroendocrinol. 1994;15:301–320. doi: 10.1006/frne.1994.1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Babic T., Browning K.N. The role of vagal neurocircuits in the regulation of nausea and vomiting. Eur J Pharmacol. 2014;722:38–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2013.08.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Borner T., Shaulson E.D., Ghidewon M.Y., Barnett A.B., Horn C.C., Doyle R.P., et al. GDF15 induces anorexia through nausea and emesis. Cell Metabol. 2020;31:351–362 e355. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2019.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang C., Kaye J.A., Cai Z., Wang Y., Prescott S.L., Liberles S.D. Area postrema cell types that mediate nausea-associated behaviors. Neuron. 2021;109:461–472 e465. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2020.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Borner T., Geisler C.E., Fortin S.M., Cosgrove R., Alsina-Fernandez J., Dogra M., et al. GIP receptor agonism attenuates GLP-1 receptor agonist-induced nausea and emesis in preclinical models. Diabetes. 2021;70:2545–2553. doi: 10.2337/db21-0459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ludwig M.Q., Cheng W., Gordian D., Lee J., Paulsen S.J., Hansen S.N., et al. A genetic map of the mouse dorsal vagal complex and its role in obesity. Nat Metab. 2021;3:530–545. doi: 10.1038/s42255-021-00363-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baggio L.L., Drucker D.J. Biology of incretins: GLP-1 and GIP. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:2131–2157. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dupre J., Ross S.A., Watson D., Brown J.C. Stimulation of insulin secretion by gastric inhibitory polypeptide in man. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1973;37:826–828. doi: 10.1210/jcem-37-5-826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fehmann H.C., Goke R., Goke B. Cell and molecular biology of the incretin hormones glucagon-like peptide-I and glucose-dependent insulin releasing polypeptide. Endocr Rev. 1995;16:390–410. doi: 10.1210/edrv-16-3-390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Muller T.D., Finan B., Bloom S.R., D’Alessio D., Drucker D.J., Flatt P.R., et al. Glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) Mol Metabol. 2019;30:72–130. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2019.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Killion E.A., Wang J., Yie J., Shi S.D., Bates D., Min X., et al. Anti-obesity effects of GIPR antagonists alone and in combination with GLP-1R agonists in preclinical models. Sci Transl Med. 2018;10 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aat3392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coskun T., Sloop K.W., Loghin C., Alsina-Fernandez J., Urva S., Bokvist K.B., et al. LY3298176, a novel dual GIP and GLP-1 receptor agonist for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus: from discovery to clinical proof of concept. Mol Metabol. 2018;18:3–14. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2018.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Norregaard P.K., Deryabina M.A., Tofteng Shelton P., Fog J.U., Daugaard J.R., Eriksson P.O., et al. A novel GIP analogue, ZP4165, enhances glucagon-like peptide-1-induced body weight loss and improves glycaemic control in rodents. Diabetes Obes Metabol. 2018;20:60–68. doi: 10.1111/dom.13034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frias J.P., Bastyr E.J., Vignati L., Tschöp M.H., Schmitt C., Owen K., et al. The sustained effects of a dual GIP/GLP-1 receptor agonist, NNC0090-2746, in patients with type 2 diabetes. Cell Metabol. 2017;26:343–352. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2017.07.011. e342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frias J.P., Nauck M.A., Van J., Kutner M.E., Cui X., Benson C., et al. Efficacy and safety of LY3298176, a novel dual GIP and GLP-1 receptor agonist, in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomised, placebo-controlled and active comparator-controlled phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2018;392:2180–2193. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32260-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Finan B., Ma T., Ottaway N., Müller T.D., Habegger K.M., Heppner K.M., et al. Unimolecular dual incretins maximize metabolic benefits in rodents, monkeys, and humans. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5:209ra151. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3007218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Min T., Bain S.C. The role of tirzepatide, dual GIP and GLP-1 receptor agonist, in the management of type 2 diabetes: the SURPASS clinical trials. Diabetes Ther. 2021;12:143–157. doi: 10.1007/s13300-020-00981-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Frias, Tirzepatide J.P. A glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) and glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) dual agonist in development for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Expet Rev Endocrinol Metabol. 2020;15:379–394. doi: 10.1080/17446651.2020.1830759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Frias J.P., Nauck M.A., Van J., Benson C., Bray R., Cui X., et al. Efficacy and tolerability of tirzepatide, a dual glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide and glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist in patients with type 2 diabetes: a 12-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study to evaluate different dose-escalation regimens. Diabetes Obes Metabol. 2020;22:938–946. doi: 10.1111/dom.13979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Samms R.J., Cosgrove R., Snider B.M., Furber E.C., Droz B.A., Briere D.A., et al. GIPR agonism inhibits PYY-induced nausea-like behavior. Diabetes. 2022;71:1410–1423. doi: 10.2337/db21-0848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Andrews P.L., Horn C.C. Signals for nausea and emesis: implications for models of upper gastrointestinal diseases. Auton Neurosci. 2006;125:100–115. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2006.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Borner T., Shaulson E.D., Tinsley I.C., Stein L.M., Horn C.C., Hayes M.R., et al. A second-generation glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist mitigates vomiting and anorexia while retaining glucoregulatory potency in lean diabetic and emetic mammalian models. Diabetes Obes Metabol. 2020;22:1729–1741. doi: 10.1111/dom.14089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Borner T., Workinger J.L., Tinsley I.C., Fortin S.M., Stein L.M., Chepurny O.G., et al. Corrination of a GLP-1 receptor agonist for glycemic control without emesis. Cell Rep. 2020;31:107768. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.107768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reiner B.C., Workinger J.L., Tinsley I.C., Fortin S.M., Stein L.M., Chepurny O.G. Single nuclei RNA sequencing of the rat AP and NTS following GDF15 treatment. Mol Metabol. 2022;56:101422. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2021.101422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reiner B.C., Zhang Y., Stein L.M., Perea E.D., Arauco-Shapiro G., Ben Nathan J., et al. Single nucleus transcriptomic analysis of rat nucleus accumbens reveals cell type-specific patterns of gene expression associated with volitional morphine intake. Transl Psychiatry. 2022;12:374. doi: 10.1038/s41398-022-02135-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mathys H., Davila-Velderrain J., Peng Z., Gao F., Mohammadi S., Young J.Z., et al. Single-cell transcriptomic analysis of Alzheimer’s disease. Nature. 2019;570:332–337. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1195-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nagy C., Maitra M., Tanti A., Suderman M., Theroux J.F., Davoli M.A., et al. Single-nucleus transcriptomics of the prefrontal cortex in major depressive disorder implicates oligodendrocyte precursor cells and excitatory neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41593-020-0621-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schirmer L., Velmeshev D., Holmqvist S., Kaufmann M., Werneburg S., Jung D., et al. Neuronal vulnerability and multilineage diversity in multiple sclerosis. Nature. 2019;573:75–82. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1404-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Velmeshev D., Schirmer L., Jung D., Haeussler M., Perez Y., Mayer S., et al. Single-cell genomics identifies cell type-specific molecular changes in autism. Science. 2019;364:685–689. doi: 10.1126/science.aav8130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Osorio D., Cai J.J. Systematic determination of the mitochondrial proportion in human and mice tissues for single-cell RNA-sequencing data quality control. Bioinformatics. 2021;37:963–967. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btaa751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mase S., Shitamukai A., Wu Q., Morimoto M., Gridley T., Matsuzaki F. Notch1 and Notch2 collaboratively maintain radial glial cells in mouse neurogenesis. Neurosci Res. 2021;170:122–132. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2020.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pollen A.A., Nowakowski T.J., Chen J., Retallack H., Sandoval-Espinosa C., Nicholas C.R., et al. Molecular identity of human outer radial glia during cortical development. Cell. 2015;163:55–67. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Squair J.W., Gautier M., Kathe C., Anderson M.A., James N.D., Hutson T.H., et al. Confronting false discoveries in single-cell differential expression. Nat Commun. 2021;12:5692. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-25960-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.De Jonghe B.C., Horn C.C. Chemotherapy agent cisplatin induces 48-h Fos expression in the brain of a vomiting species, the house musk shrew (Suncus murinus) Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2009;296:R902–R911. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.90952.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Horn C.C., Henry S., Meyers K., Magnusson M.S. Behavioral patterns associated with chemotherapy-induced emesis: a potential signature for nausea in musk shrews. Front Neurosci. 2011;5:88. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2011.00088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ueno S., Matsuki N., Saito H. Suncus murinus: a new experimental model in emesis research. Life Sci. 1987;41:513–518. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(87)90229-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Matsuki N., Ueno S., Kaji T., Ishihara A., Wang C.H., Saito H. Emesis induced by cancer chemotherapeutic agents in the Suncus murinus: a new experimental model. Jpn J Pharmacol. 1988;48:303–306. doi: 10.1254/jjp.48.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sam T.S., Cheng J.T., Johnston K.D., Kan K.K., Ngan M.P., Rudd J.A., et al. Action of 5-HT3 receptor antagonists and dexamethasone to modify cisplatin-induced emesis in Suncus murinus (house musk shrew) Eur J Pharmacol. 2003;472:135–145. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(03)01863-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Horn C.C., Kimball B.A., Wang H., Kaus J., Dienel S., Nagy A., et al. Why can’t rodents vomit? A comparative behavioral, anatomical, and physiological study. PLoS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Takeda N., Hasegawa S., Morita M., Matsunaga T. Pica in rats is analogous to emesis: an animal model in emesis research. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1993;45:817–821. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(93)90126-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mitchell D., Wells C., Hoch N., Lind K., Woods S.C., Mitchell L.K. Poison induced pica in rats. Physiol Behav. 1976;17:691–697. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(76)90171-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yamamoto K., Matsunaga S., Matsui M., Takeda N., Yamatodani A. Pica in mice as a new model for the study of emesis. Methods Find Exp Clin Pharmacol. 2002;24:135–138. doi: 10.1358/mf.2002.24.3.802297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Feyer P., Jordan K. Update and new trends in antiemetic therapy: the continuing need for novel therapies. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:30–38. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Olver I.N., Eliott J.A., Koczwara B. A qualitative study investigating chemotherapy-induced nausea as a symptom cluster. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22:2749–2756. doi: 10.1007/s00520-014-2276-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sanger G.J., Andrews P.L. Treatment of nausea and vomiting: gaps in our knowledge. Auton Neurosci. 2006;129:3–16. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2006.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hsu J.Y., Crawley S., Chen M., Ayupova D.A., Lindhout D.A., Higbee J., et al. Non-homeostatic body weight regulation through a brainstem-restricted receptor for GDF15. Nature. 2017;550:255–259. doi: 10.1038/nature24042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Breen D.M., Kim H., Bennett D., Calle R.A., Collins S., Esquejo R.M., et al. GDF-15 neutralization alleviates platinum-based chemotherapy-induced emesis, anorexia, and weight loss in mice and nonhuman primates. Cell Metabol. 2020;32:938–950 e936. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2020.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang C., Vincelette L.K., Reimann F., Liberles S.D. A brainstem circuit for nausea suppression. Cell Rep. 2022;39:110953. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2022.110953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Watanabe K., Taskesen E., van Bochoven A., Posthuma D. Functional mapping and annotation of genetic associations with FUMA. Nat Commun. 2017;8:1826. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01261-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Guttuso T., Jr. Gabapentin's anti-nausea and anti-emetic effects: a review. Exp Brain Res. 2014;232:2535–2539. doi: 10.1007/s00221-014-3905-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Quintero G.C. Review about gabapentin misuse, interactions, contraindications and side effects. J Exp Pharmacol. 2017;9:13–21. doi: 10.2147/JEP.S124391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Porporato P.E. Understanding cachexia as a cancer metabolism syndrome. Oncogenesis. 2016;5 doi: 10.1038/oncsis.2016.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chevalier S., Farsijani S. Cancer cachexia and diabetes: similarities in metabolic alterations and possible treatment. Appl Physiol Nutr Metabol. 2014;39:643–653. doi: 10.1139/apnm-2013-0369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Petruzzelli M., Wagner E.F. Mechanisms of metabolic dysfunction in cancer-associated cachexia. Genes Dev. 2016;30:489–501. doi: 10.1101/gad.276733.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Finan B., Muller T.D., Clemmensen C., Perez-Tilve D., DiMarchi R.D., Tschop M.H. Reappraisal of GIP pharmacology for metabolic diseases. Trends Mol Med. 2016;22:359–376. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2016.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Samms R.J., Coghlan M.P., Sloop K.W. How may GIP enhance the therapeutic efficacy of GLP-1? Trends Endocrinol Metabol. 2020;31:410–421. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2020.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.