Abstract

Plants grow within a complex web of species that interact with each other and with the plant1–10. These interactions are governed by a wide repertoire of chemical signals, and the resulting chemical landscape of the rhizosphere can strongly affect root health and development7–9,11–18. Here, to understand how interactions between microorganisms influence root growth in Arabidopsis, we established a model system for interactions between plants, microorganisms and the environment. We inoculated seedlings with a 185-member bacterial synthetic community, manipulated the abiotic environment and measured bacterial colonization of the plant. This enabled us to classify the synthetic community into four modules of co-occurring strains. We deconstructed the synthetic community on the basis of these modules, and identified interactions between microorganisms that determine root phenotype. These interactions primarily involve a single bacterial genus (Variovorax), which completely reverses the severe inhibition of root growth that is induced by a wide diversity of bacterial strains as well as by the entire 185-member community. We demonstrate that Variovorax manipulates plant hormone levels to balance the effects of our ecologically realistic synthetic root community on root growth. We identify an auxin-degradation operon that is conserved in all available genomes of Variovorax and is necessary and sufficient for the reversion of root growth inhibition. Therefore, metabolic signal interference shapes bacteria–plant communication networks and is essential for maintaining the stereotypic developmental programme of the root. Optimizing the feedbacks that shape chemical interaction networks in the rhizosphere provides a promising ecological strategy for developing more resilient and productive crops.

Plant phenotypes, and ultimately fitness, are influenced by the microorganisms that live in close association with them1–3. These microorganisms—collectively termed the plant microbiota—assemble on the basis of plant and environmentally derived cues1,4–6, resulting in myriad interactions between plants and microorganisms. Beneficial and detrimental microbial effects on plants can be either direct3,7–9, or an indirect consequence of microorganism–microorganism interactions2,10. Although antagonistic interactions between microorganisms are known to have an important role in shaping plant microbiota and protecting plants from pathogens2, another potentially important class of interactions is metabolic signal interference11,12: rather than direct antagonism, microorganisms interfere with the delivery of chemical signals produced by other microorganisms, which alters plant-microorganism signalling12–14.

Plant hormones—in particular, auxins—are both produced and degraded by an abundance of plant-associated microorganisms15–18. Microbially derived auxins can have effects on plants that range from growth promotion to the induction of disease, depending on context and concentration9. The intrinsic root developmental patterns of the plant are dependent on finely calibrated auxin and ethylene concentration gradients with fine differences across tissues and cell types19; it is not known how the plant integrates exogenous, microbially derived auxin fluxes into its developmental plan.

Here we apply a synthetic community to axenic plants as a proxy for root-associated microbiomes in natural soils to investigate how interactions between microorganisms shape plant growth. We establish plant colonization patterns across 16 abiotic conditions to guide stepwise deconstruction of the synthetic community, which led to the identification of multiple levels of microorganism–microorganism interaction that interfere with the additivity of bacterial effects on root growth. We demonstrate that a single bacterial genus (Variovorax) is required for maintaining the intrinsically controlled developmental programme of the root, by tuning its chemical landscape. We establish Variovorax as a core taxon in the root microbiota of diverse plants grown in diverse soils. Finally, we identify a locus conserved across Variovorax strains that is responsible for this phenotype.

Microbial interactions control root growth

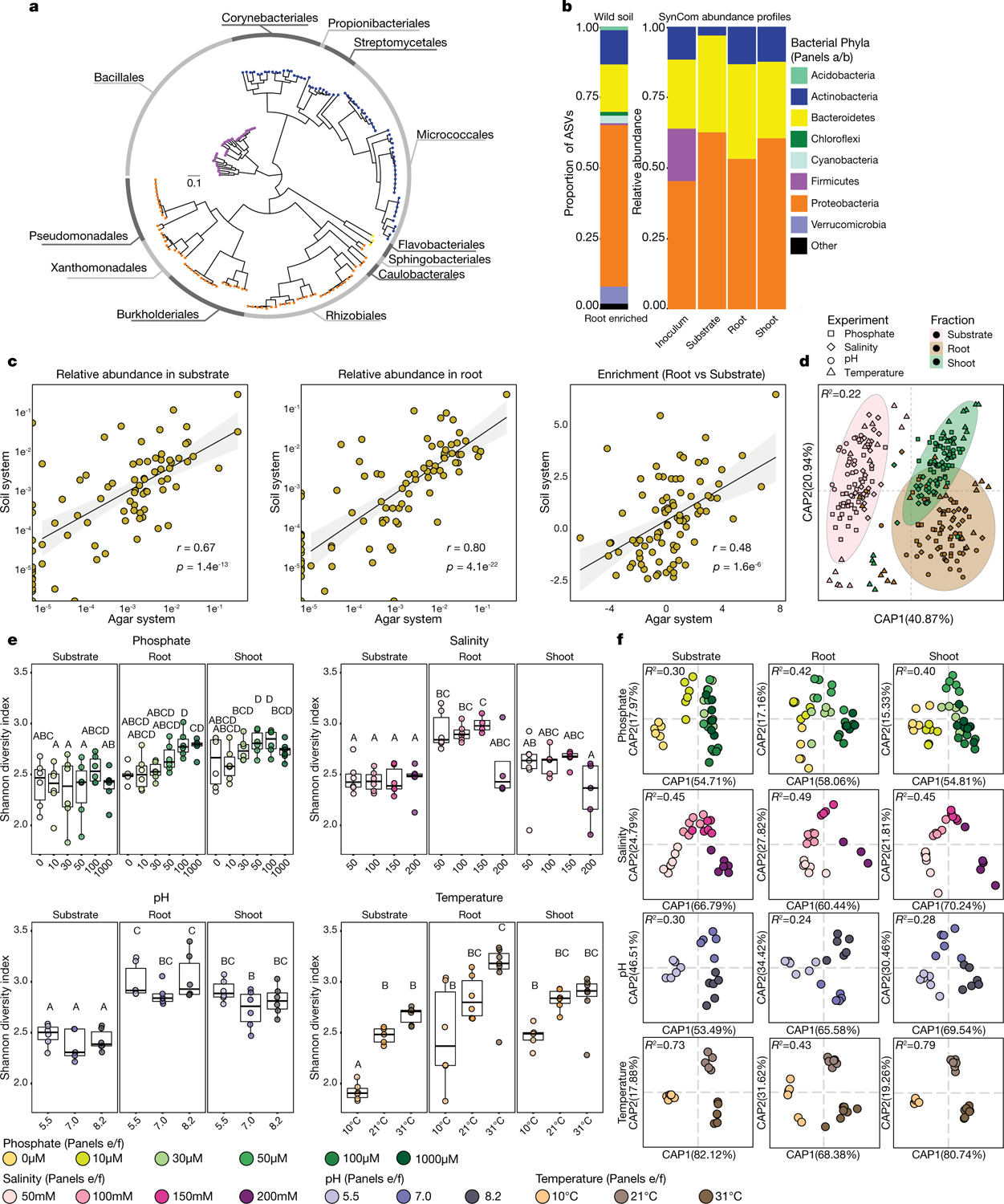

To model plant–microbiota interactions in a fully controlled setting, we established a plant–microbiota microcosm that represents the native bacterial root-derived microbiota on agar plates. We inoculated 7-day-old seedlings with a defined 185-member bacterial synthetic community5 composed of the major root-associated phyla1,4–6,20 (Extended Data Fig. 1a, Supplementary Table 1). We exposed this microcosm to each of 16 abiotic contexts by manipulating one of four variables (salinity, temperature, a previously reported phosphate concentration gradient5 and pH). We measured the composition of the synthetic community in root, shoot and agar fractions 12 days after inoculation using 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing.

The composition of the resulting root and shoot microbiota recapitulated phylum-level plant-enrichment patterns seen in soil-planted Arabidopsis1 (Extended Data Fig. 1b). We validated the patterns observed in the agar-based system using seedlings grown in sterilized potting soil21 that were inoculated with the same synthetic community. Both relative abundance and plant-enrichment patterns at the unique sequence level were significantly correlated between the agar- and soil-based systems, which confirms the applicability of our relatively high-throughput agar-based system as a model for the assembly of plant microbiota (Extended Data Fig. 1c). Within the agar system, both fraction (substrate, root or shoot) and abiotic conditions significantly affected α- and β-diversity (Extended Data Fig. 1d–f).

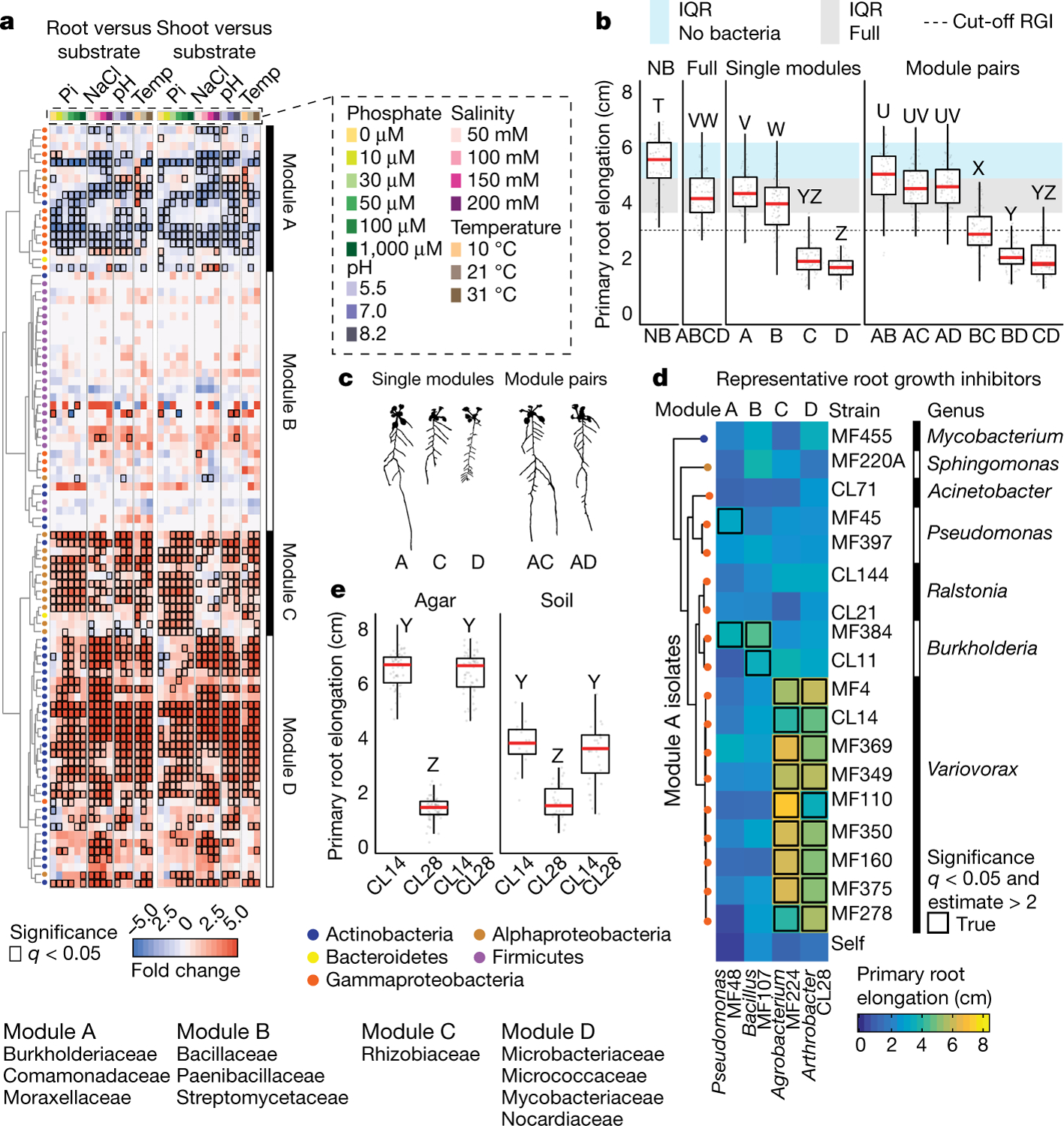

To guide the deconstruction of the synthetic community into modules, we calculated pairwise correlations in relative abundance across all samples, and identified four well-defined modules of co-occurring strains that we termed modules A, B, C and D (Fig. 1a, Supplementary Table 2). These modules formed distinct phylogenetically structured guilds in association with the plant. Module A contained mainly Gammaproteobacteria and was predominantly more abundant in the substrate than in the seedling; module B contained mainly low-abundance Firmicutes, with no significant enrichment trend; and modules C and D were composed mainly of Alphaproteobacteria and Actinobacteria, respectively, and showed plant enrichment across all abiotic conditions. Both Alphaproteobacteria (module C) and Actinobacteria (module D) are consistently plant enriched across plant species4, which suggests that these clades contain plant-association traits that are deeply rooted in their evolutionary histories.

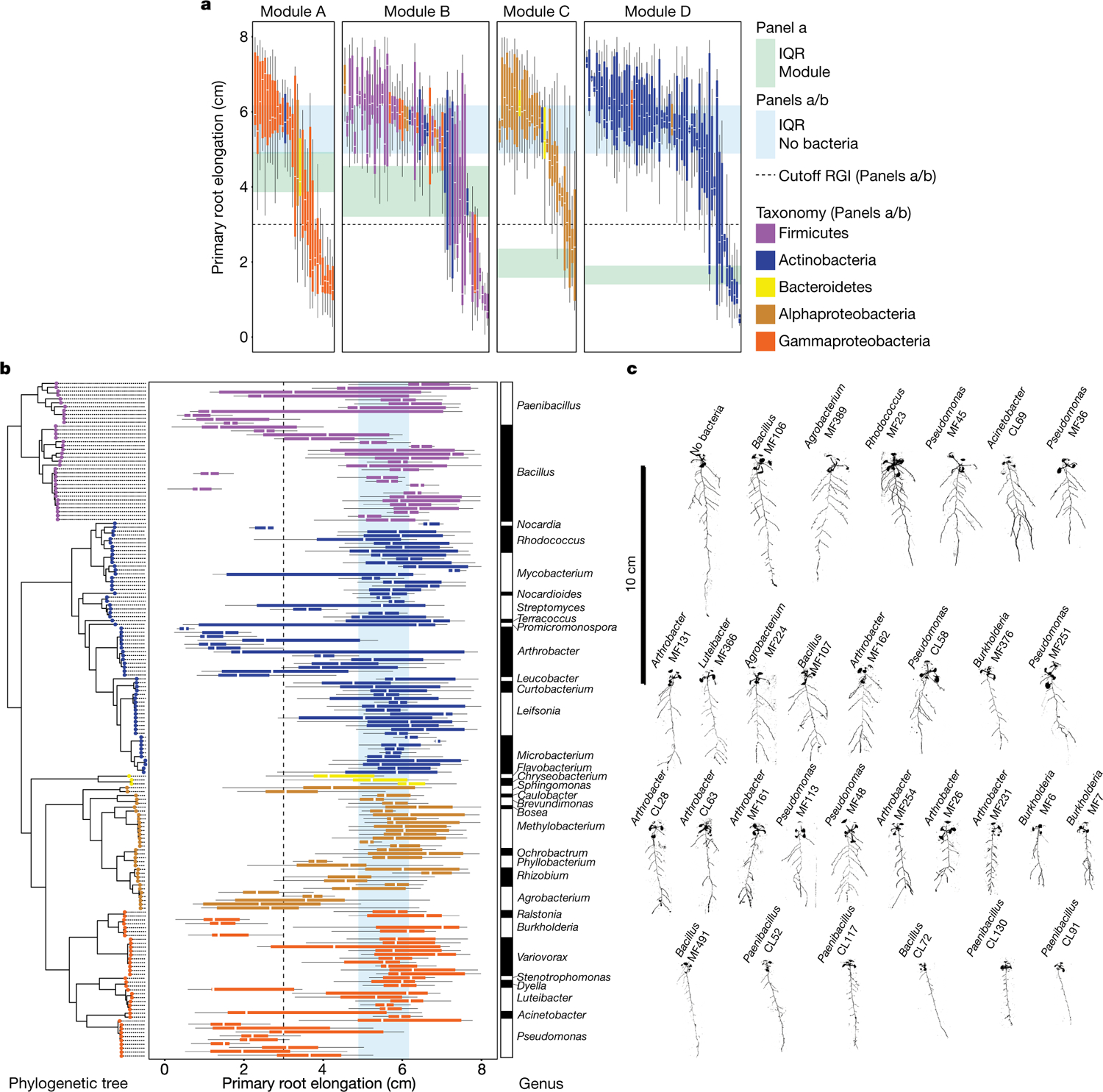

Fig. 1 |. Arabidopsis root length is governed by bacteria–bacteria interactions within a community.

a, Fraction enrichment patterns of the synthetic community across abiotic gradients. Each row represents a unique sequence. The four modules of co-occurring strains (A, B, C and D) are represented. Dendrogram tips are coloured by taxonomy. Heat maps are coloured by log2-transformed fold changes derived from a fitted generalized linear model and represent enrichments in plant tissue (root or shoot) compared with substrate. Comparisons with false-discovery-rate (FDR)-corrected q-value < 0.05 are contoured in black. Enriched families within each module are listed below the heat map. n = 6 biological replicates across 2 independent experiments. Pi, inorganic phosphate; temp, temperature. b, Primary root elongation of seedlings grown axenically (no bacteria, NB), with the full synthetic community (ABCD) or its subsets: modules A, B, C and D alone (single modules), and all pairwise combination of modules (module pairs). Significance was determined via analysis of variance (ANOVA); letters correspond to a Tukey post hoc test. n = 75, 89, 68, 94, 87, 77, 76, 96, 82, 84, 89 and 77 (from left to right) biological replicates across 2 independent experiments. c, Binarized image of representative seedlings inoculated with modules A, C and D, and with module combinations A–C and A–D. d, Heat map coloured by average primary root elongation of seedlings inoculated with four representative RGI-inducing strains from each module (columns A–D) in combination with isolates from module A (rows) or alone (self). Significance was determined via ANOVA. e, Primary root elongation of seedlings inoculated with Arthrobacter CL28 and Variovorax CL14 individually or jointly across two substrates. Significance was determined via ANOVA, letters are the results of a Tukey post hoc test. n = 64, 64, 63, 17, 36 and 33 (from left to right) biological replicates across 2 independent experiments. In all box plots, the centre line represents the median, box edges show the 25th and 75th percentiles, and whiskers extend to 1.5× the interquartile range (IQR).

We next asked whether the different modules of co-occurring strains have different roles in determining plant phenotype. We inoculated seedlings with synthetic communities composed of modules A, B, C and D singly or in all six possible pairwise combinations, and imaged the seedlings 12 days after inoculation. We observed strong primary root growth inhibition (RGI) in seedlings inoculated with plant-enriched module C or D (Fig. 1b, c). RGI did not occur in seedlings inoculated with module A or B, which do not contain plant-enriched strains (Fig. 1b). To test whether the root phenotype derived from each module is an additive outcome of its individual constituents, we inoculated seedlings in mono-association with each of the 185 members of the synthetic community. We observed that 34 taxonomically diverse strains, distributed across all 4 modules, induced RGI (Extended Data Fig. 2a–c). However, neither the full synthetic community nor derived synthetic communities that consisted of module A or B exhibited RGI (Fig. 1b). Thus, binary plant–microorganism interactions were not predictive of interactions in this complex-community context.

In seedlings inoculated with module pairs, we observed epistatic interactions: in the presence of module A, the RGI caused by modules C and D was reverted (Fig. 1b, c). Thus, by deconstructing the synthetic community into four modules, we found that bacterial effects on root growth are governed by multiple levels of microorganism–microorganism interaction. This is exemplified by at least four instances: within module A or B and between module A and module C or D. Because three of these interactions involve module A, we predicted that this module contains strains that strongly attenuate RGI and preserve stereotypic root development.

Variovorax maintain stereotypic root growth

To identify strains within module A that are responsible for intra- and intermodule attenuation of RGI, we reduced our system to a tripartite plant–microorganism–microorganism system. We individually screened the 18 non-RGI strains from module A for their ability to attenuate RGI caused by representative strains from all 4 modules. We found that all the tested strains from the genus Variovorax (family Comamonadaceae) suppressed the RGI caused by representative RGI-inducing strains from module C (Agrobacterium MF224) and module D (Arthrobacter CL28) (Fig. 1d). The strains from modules A (Pseudomonas MF48) and B (Bacillus MF107) were not suppressed by Variovorax, but rather by two closely related Burkholderia strains (CL11 and MF384) (Fig. 1d). A similar pattern was observed when we screened two selected RGI-suppressing Variovorax strains (CL14 and MF160) and Burkholderia CL11 against a diverse set of RGI-inducing strains. Variovorax attenuated 13 of the 18 RGI-inducing strains that we tested (Extended Data Fig. 3a).

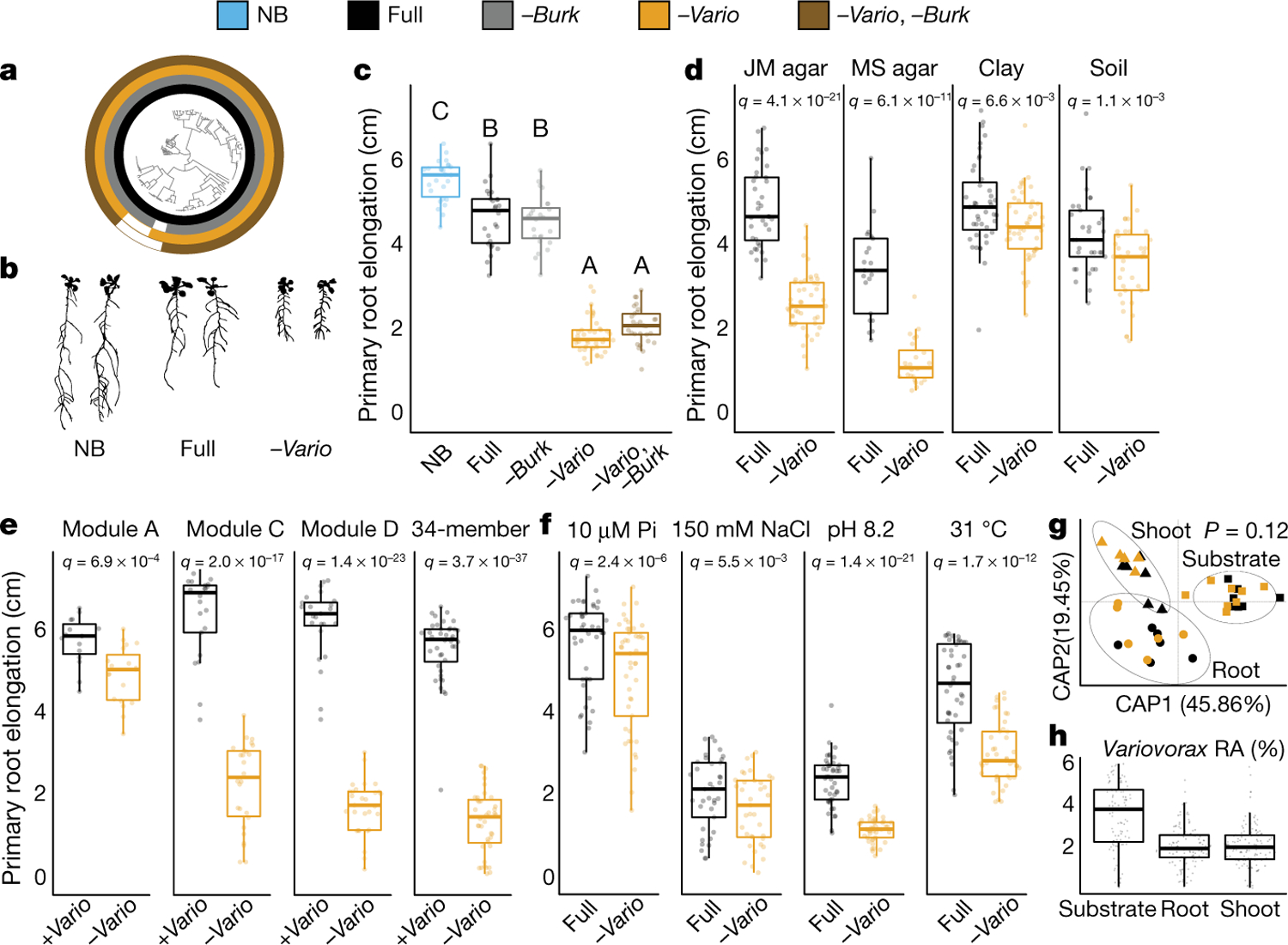

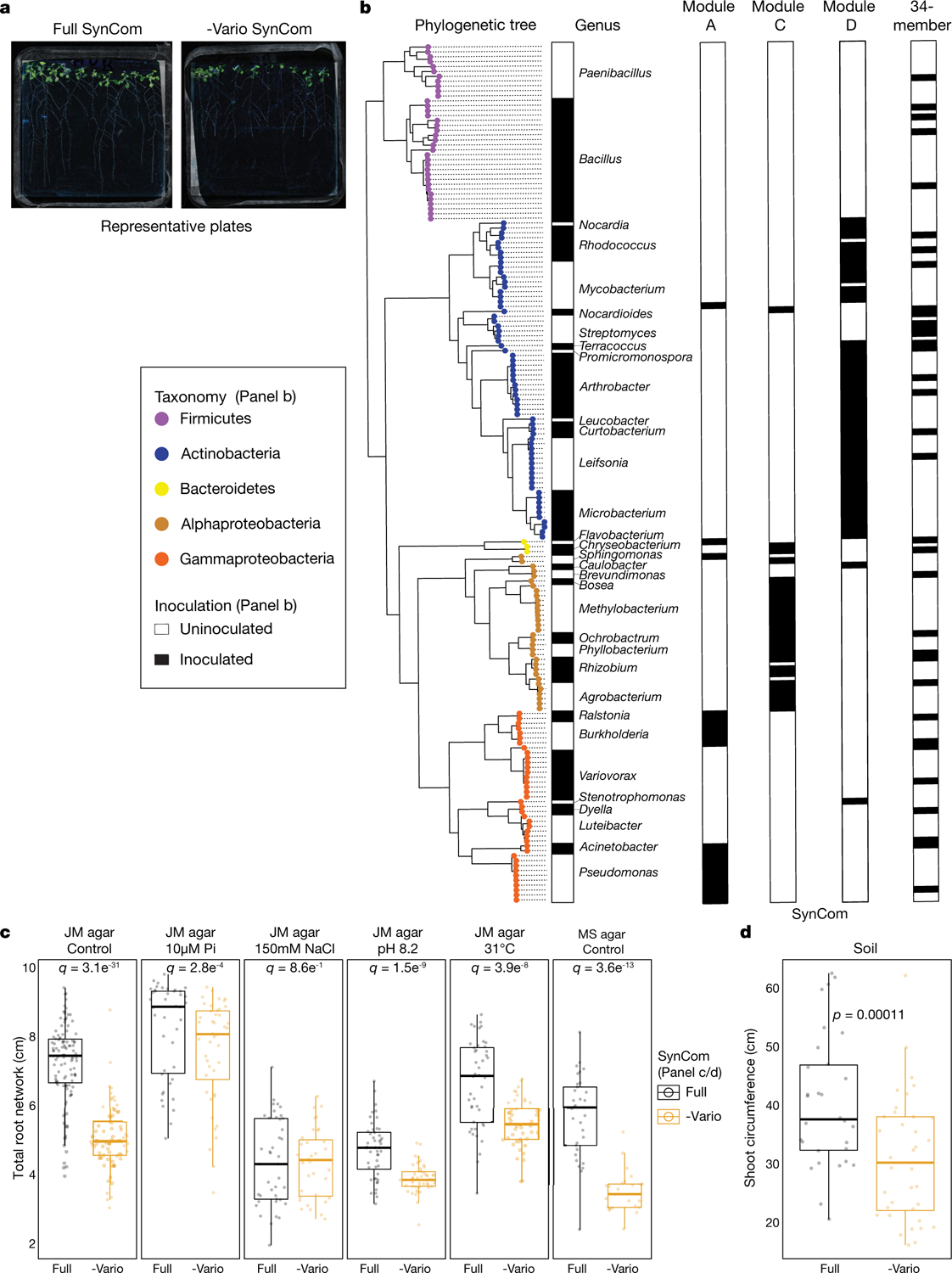

To test whether the RGI induction and suppression we observed on agar occur in soil as well, we germinated Arabidopsis on sterile soil inoculated with an RGI-suppressing and -inducing pair of strains: the RGI-inducing Arthrobacter CL28 and the RGI-suppressing Variovorax CL14. As expected, Arthrobacter CL28 induced RGI, which was reverted by Variovorax CL14 in soil (Fig. 1e). We generalized this observation by showing that Variovorax-mediated attenuation of RGI extended to tomato seedlings, in which Variovorax CL14 reverted Arthrobacter CL28-mediated RGI (Extended Data Fig. 3b). Finally, we tested whether the RGI-suppressing strains maintain their capacity to attenuate RGI in the context of the full 185-member community. We compared the root phenotype of seedlings exposed to either the full synthetic community or to the same community after dropping out all ten Variovorax strains and/or all six Burkholderia strains present in the synthetic community (Fig. 2a). We found that Variovorax is necessary and sufficient to revert RGI within the full community (Fig. 2b, c, Extended Data Fig. 4a). This result was robust across a range of substrates (including soil), and under various biotic and abiotic contexts (Fig. 2d–f, Extended Data Fig. 4b). Further, the presence of Variovorax in the synthetic community increases both the total length of root network of the plant and its shoot size (Extended Data Fig. 4c, d). Importantly, the latter is considered a reliable proxy for relative plant fitness22,23, which suggests that Variovorax-mediated suppression of RGI is adaptive.

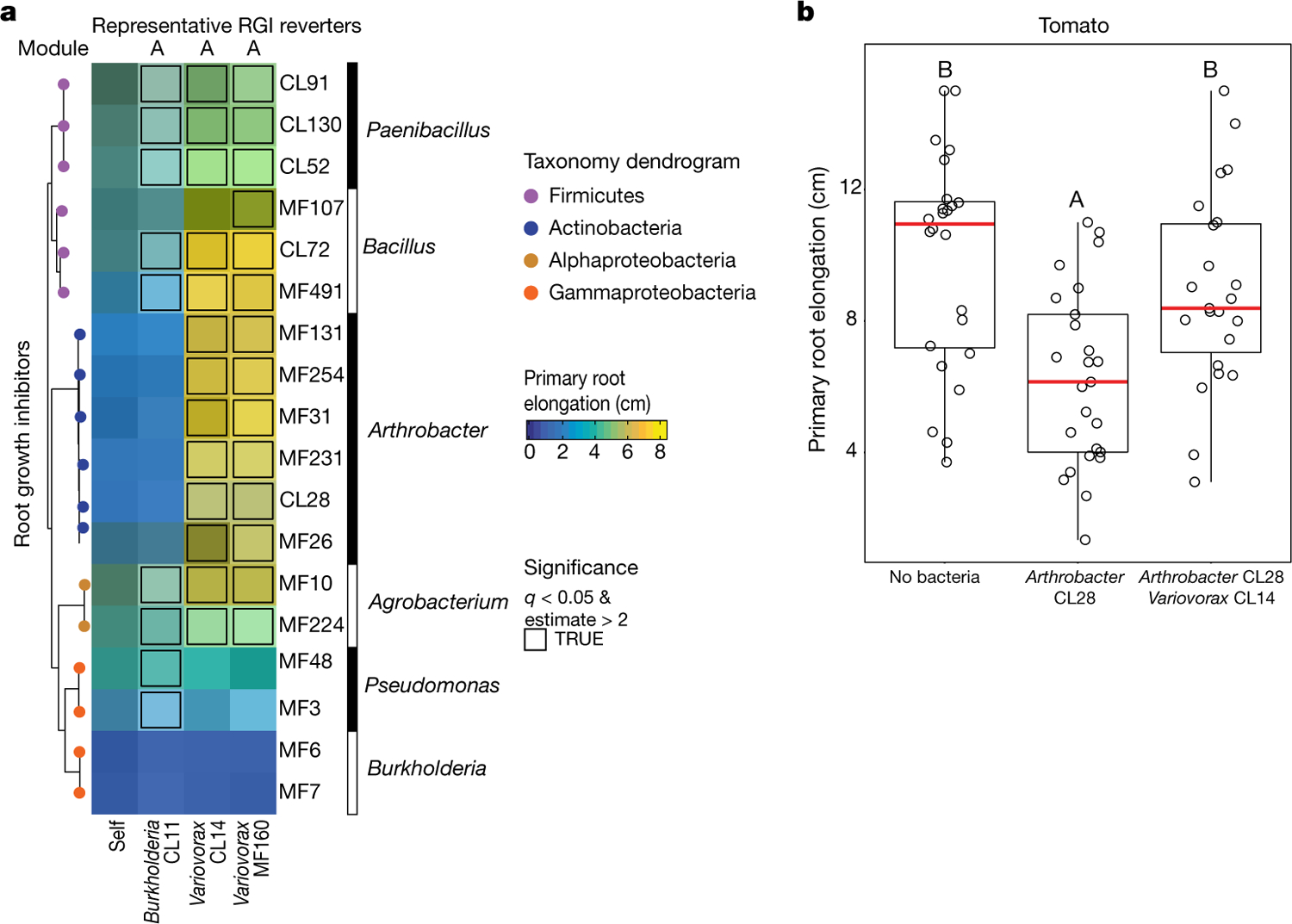

Fig. 2 |. Variovorax maintains stereotypic root development.

a, Phylogenetic tree of 185 bacterial isolates. Concentric rings represent isolate composition of each synthetic community treatment. NB, uninoculated (no bacteria); full, full synthetic community; −Burk, Burkholderia drop-out; −Vario, Variovorax drop-out; −Vario, −Burk, Burkholderia and Variovorax drop-out. b, Binarized image of representative seedlings inoculated or not with the full synthetic community or the Variovorax drop-out synthetic community. c, Primary root elongation of seedlings grown axenically (NB) or inoculated with the different synthetic community treatments outlined in a. Significance was determined via ANOVA, letters correspond to a Tukey post hoc test. n = 26, 26, 24, 37 and 29 (from left to right) biological replicates. d, Primary root elongation of seedlings inoculated with the full synthetic community or with the Variovorax drop-out synthetic community across different substrates: Johnson medium (JM) agar, Murashige and Skoog (MS) agar, sterilized clay or potting soil. n = 36, 47, 21, 24, 43, 48, 33 and 36 (from left to right) biological replicates across 2 independent experiments. e, Primary root elongation of seedlings inoculated with four subsets of the full synthetic community (module A, C, D or a previously described 35-member synthetic community with its single Variovorax strain removed (34-member)1), with (+Vario) or without (−Vario) Variovorax isolates. n = 40, 40, 15, 19, 22, 26, 25 and 29 (from left to right) biological replicates across 2 independent experiments. f, Primary root elongation of seedlings inoculated with the full synthetic community or with the Variovorax drop-out synthetic community across different abiotic stresses: low phosphate, high salt, high pH and high temperature. n = 43, 45, 37, 37, 43, 44, 44 and 43 (from left to right) biological replicates across 2 independent experiments. Significance was determined within each condition via ANOVA in d, f, and with a two-sided t-test in e. FDR-adjusted P values are displayed. g, Canonical analysis of principal coordinates (CAP) scatter plots comparing the compositions of the full synthetic community and Variovorax drop-out synthetic community (colour code as in a) across fractions (substrate (squares), root (circles) and shoot (triangles)). Permutational multivariate ANOVA (PERMANOVA) P value is shown. n = 7 (substrate + full), 8 (substrate + −Vario), 6 (root + full), 6 (root + −Vario), 5 (shoot + full) or 5 (shoot + −Vario). h, Relative abundance (RA) of the Variovorax genus within the full synthetic community across the agar, root and shoot fractions. n = 127, 119 and 127 biological replicates for agar, root and shoot, respectively, across 16 independent experiments.

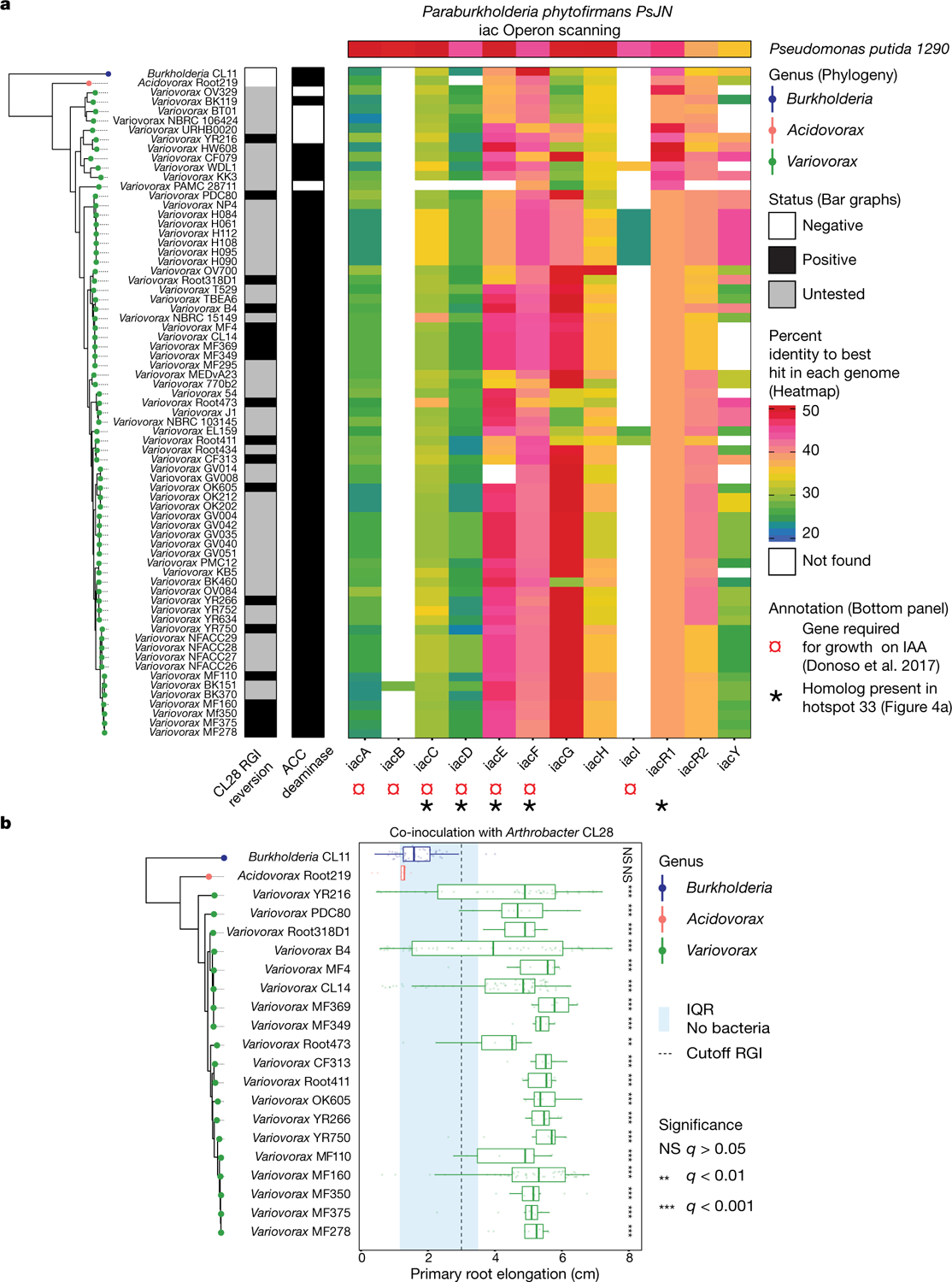

To ascertain the breadth of the ability of Variovorax to attenuate RGI, we tested additional Variovorax strains from across the phylogeny of this genus (Extended Data Fig. 5a, Supplementary Table 1). All 19 of the Variovorax strains we tested reverted the RGI induced by Arthrobacter CL28. A strain from the nearest plant-associated outgroup to this genus (Acidovorax root21924) did not revert RGI (Extended Data Fig. 5a, b). Thus, all tested strains—representing the broad phylogeny of Variovorax—interact with a wide diversity of bacteria to enforce stereotypic root development within complex communities, independent of biotic or abiotic contexts. Importantly, we found no evidence that this phenotype is achieved by outcompeting or antagonizing RGI-inducing strains (Fig. 2g, h, Extended Data Fig. 6).

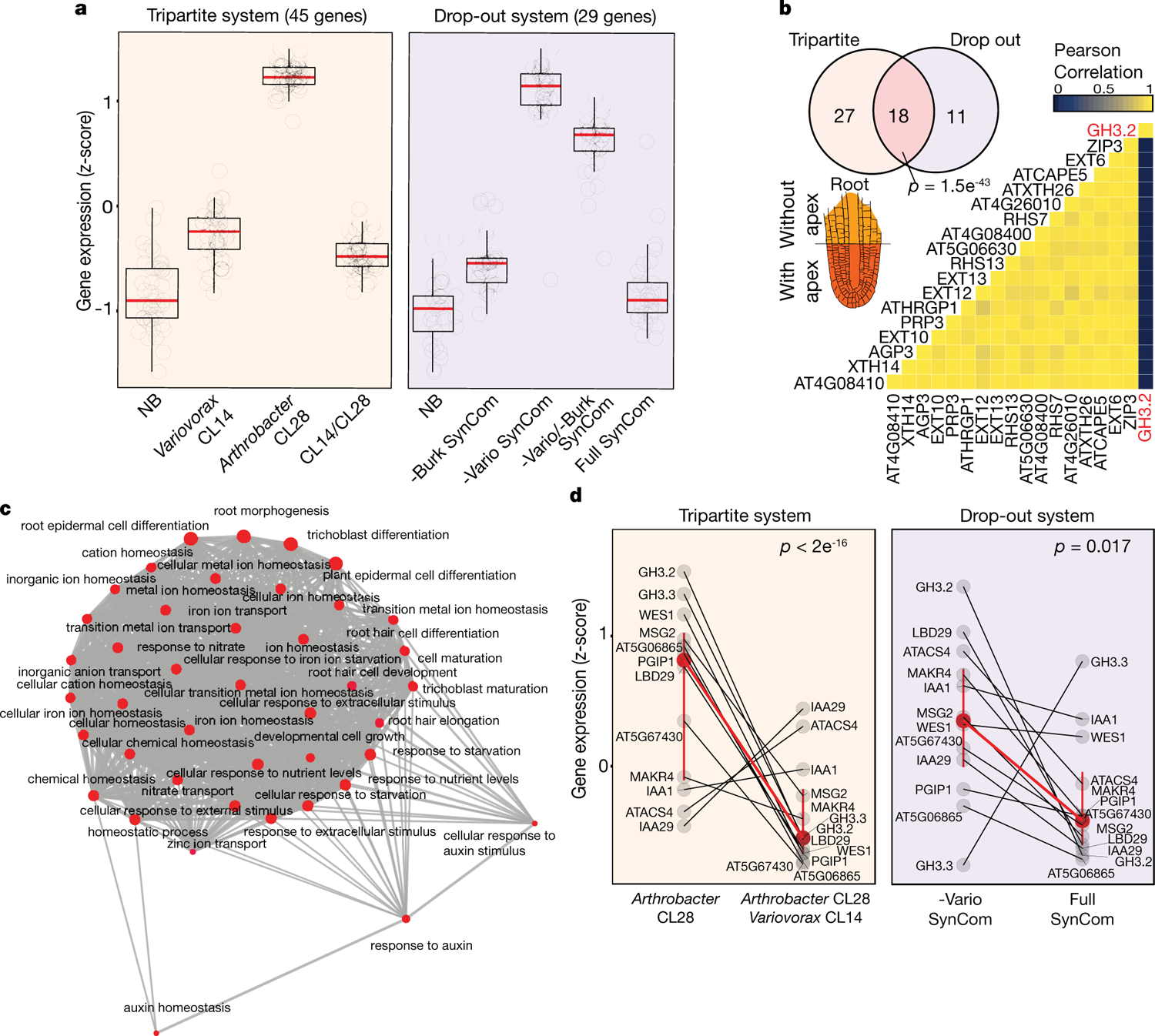

Variovorax manipulates auxin and ethylene

To study the mechanisms that underlie bacterial effects on root growth, we analysed the transcriptomes of seedlings colonized for 12 days with the RGI-inducing strain Arthrobacter CL28 and the RGI-suppressing strain Variovorax CL14, either in mono-association with the seedling or in a tripartite combination (Fig. 1e). We also performed RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) on seedlings colonized with the full synthetic community (no RGI) or the Variovorax drop-out synthetic community (RGI) (Extended Data Fig. 7a). Eighteen genes were significantly induced only under RGI conditions (RGI-induced) across both experiments (Extended Data Fig. 7a, b). Seventeen of these genes are co-expressed with genes that have proposed functions related to the root apex25 (Extended Data Fig. 7b, c). The remaining gene, GH3.2, encodes indole-3-acetic acid-amido synthetase, which conjugates excess amounts of the plant hormone auxin and is a robust marker for late auxin responses26,27 (Extended Data Fig. 7b). The production of auxins is a well-documented mechanism by which bacteria modulate plant root development13. Indeed, the top 12 auxin-responsive genes from a previous RNA-seq study examining acute auxin response in Arabidopsis26 exhibited an average transcript increase in seedlings exposed to our RGI-inducing conditions (Extended Data Fig. 7d). We hypothesized that the suppression of RGI by Variovorax is probably mediated by interference with bacterially produced auxin signalling.

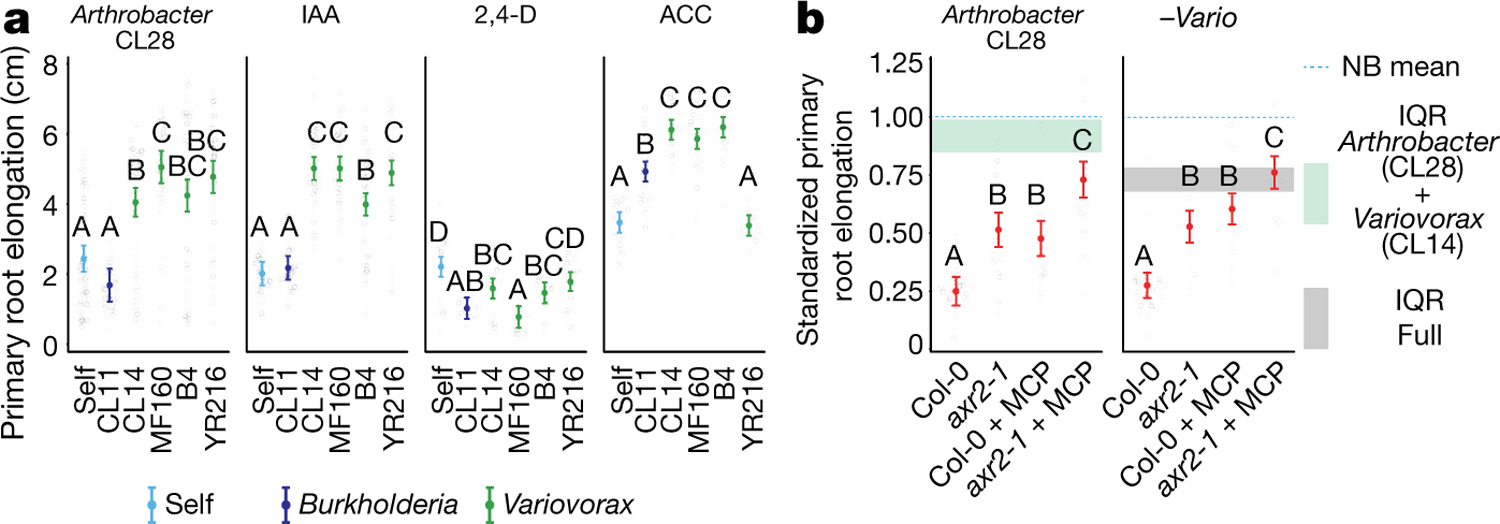

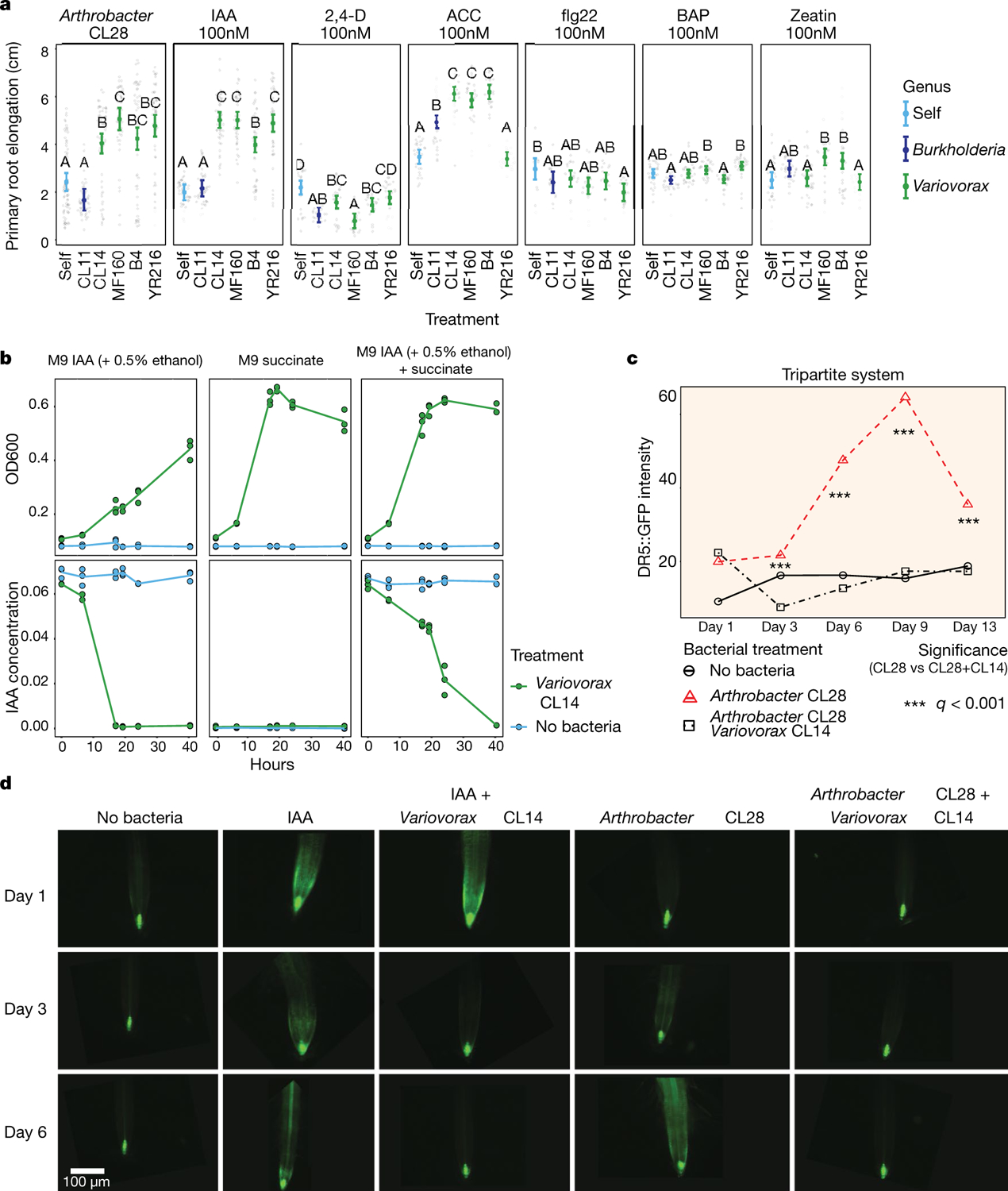

We asked whether the suppression of RGI by Variovorax is directly and exclusively related to auxin signalling. Besides auxin, other small molecules cause RGI. These include the plant hormones ethylene28 and cytokinin29, as well as microbial-associated molecular patterns such as the flagellin-derived peptide flg2230. We tested the ability of diverse Variovorax strains and of the Burkholderia strain CL11 to revert the RGI induced by auxins (indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) and the auxin analogue 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid), ethylene (the ethylene precursor 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid (ACC)), cytokinins (zeatin and 6-benzylaminopurine) and the flg22 peptide. All of the Variovorax strains we tested suppressed the RGI induced by IAA or ACC (Fig. 3a)—with the exception of Variovorax YR216, which did not suppress ACC-induced RGI and does not contain an ACC deaminase gene, a plant-growth-promoting feature that is associated with this genus28 (Extended Data Fig. 5a). Burkholderia CL11 only partially reverted ACC-induced RGI (Fig. 3a). None of the Variovorax strains attenuated the RGI induced by 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid, flg22 or cytokinins (Fig. 3a, Extended Data Fig. 8a). Importantly, this function is mediated by recognition of auxin by Variovorax and not by the plant auxin response per se, as the auxin response (RGI) induced by 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid is not reverted. Indeed, we found that Variovorax CL14 degrades IAA in culture (Extended Data Fig. 8b) and quenches fluorescence of the Arabidopsis auxin reporter line DR5::GFP caused by the RGI-inducing Arthrobacter CL28 (Extended Data Fig. 8c, d).

Fig. 3 |. Variovorax suppression of RGI is related to auxin and ethylene signalling.

a, Primary root elongation of seedlings grown with RGI-inducing Arthrobacter CL28 or three hormonal treatments (100 nM IAA, 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D) or ACC), individually (self) or with Burkholderia CL11 or one of four Variovorax isolates (CL14, MF160, B4 or YR216). Significance was determined within each treatment via ANOVA; letters correspond to a Tukey post hoc test. n = 74, 46, 61, 48, 49, 49, 45, 44, 46, 43, 49, 40, 22, 19, 22, 19, 20, 25, 28, 30, 29, 29, 29 and 29 (from left to right) biological replicates across 2 independent experiments. b, Primary root elongation, standardized to axenic conditions, of wild-type (Col-0), auxin-unresponsive (axr2-1), ethylene-unresponsive (Col-0 + MCP) or auxin- and ethylene-unresponsive (axr2-1 + MCP) seedlings inoculated with RGI-inducing Arthrobacter CL28 or the Variovorax drop-out synthetic community (−Vario). The blue dotted line marks the relative mean length of uninoculated seedlings. Horizontal shading is the IQR of seedlings grown with Arthrobacter CL28 +Variovorax CL14 (aqua) or the full synthetic community (grey). Significance was determined via ANOVA; letters correspond to a Tukey post hoc test. n = 37, 25, 24, 23, 35, 21, 22 and 20 (from left to right) biological replicates across 2 independent experiments. In a, b, data represent the mean ± 95% confidence interval.

Auxin and ethylene are known to act synergistically to inhibit root growth31. To ascertain the roles of both auxin and ethylene perception by the plant in responding to RGI-inducing strains, we used the auxin-insensitive axr2-1 mutant32 combined with a competitive inhibitor of ethylene receptors, 1-methylcyclopropene (1-MCP)33. We inoculated wild-type seedlings and axr2-1 mutants, treated or not with 1-MCP, with the RGI-inducing Arthrobacter CL28 strain or the Variovorax drop-out synthetic community. We observed in both cases that bacterial RGI is reduced in axr2-1 and 1-MCP-treated wild-type seedlings, and is further reduced in doubly insensitive 1-MCP-treated axr2-1 seedlings; this demonstrates that both auxin and ethylene perception in the plant contribute additively to bacterially induced RGI (Fig. 3b). Thus, in the absence of Variovorax, a complex synthetic community can induce severe morphological changes in root phenotypes via both auxin- and ethylene-dependent pathways, but both are reverted when Variovorax is present.

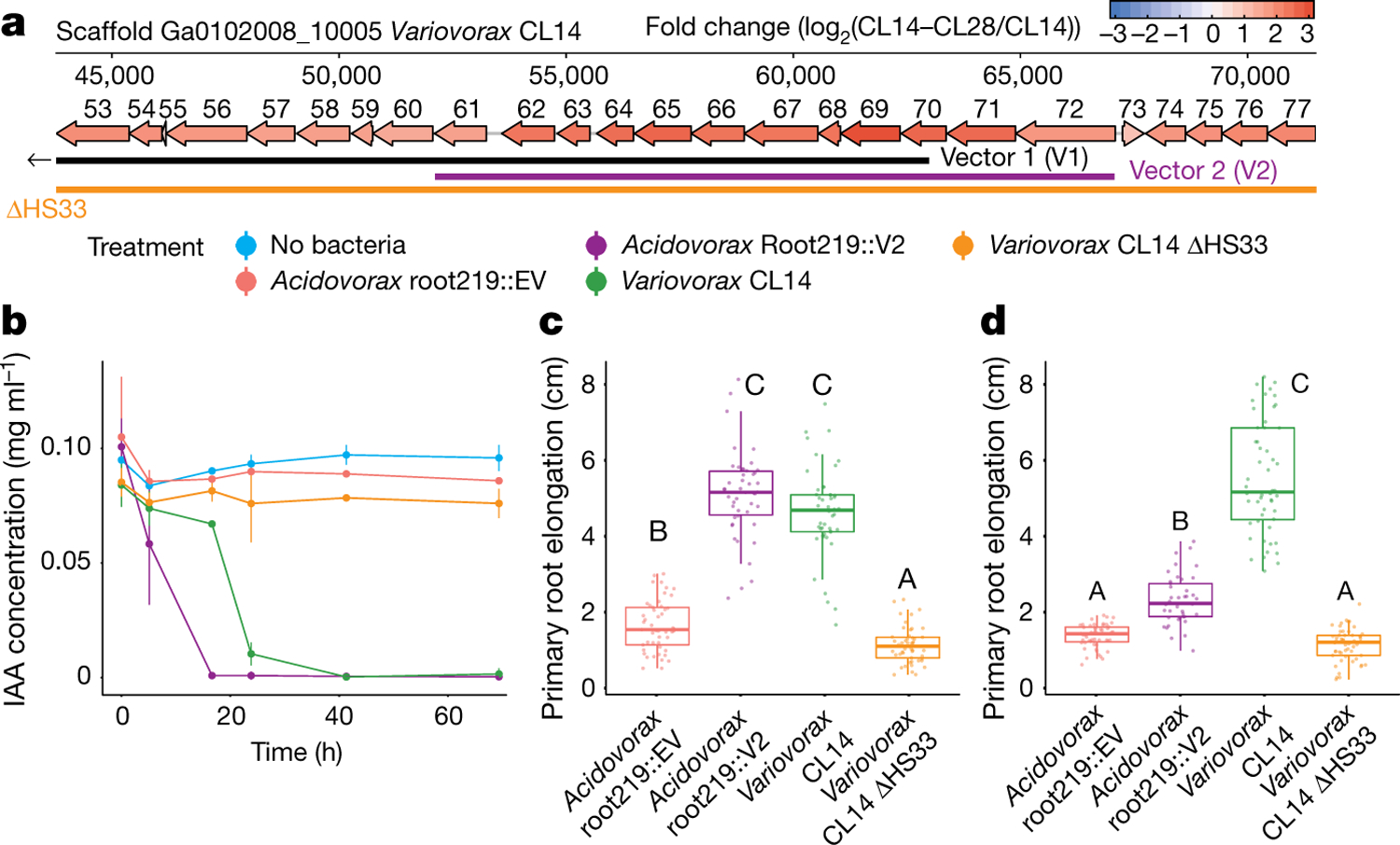

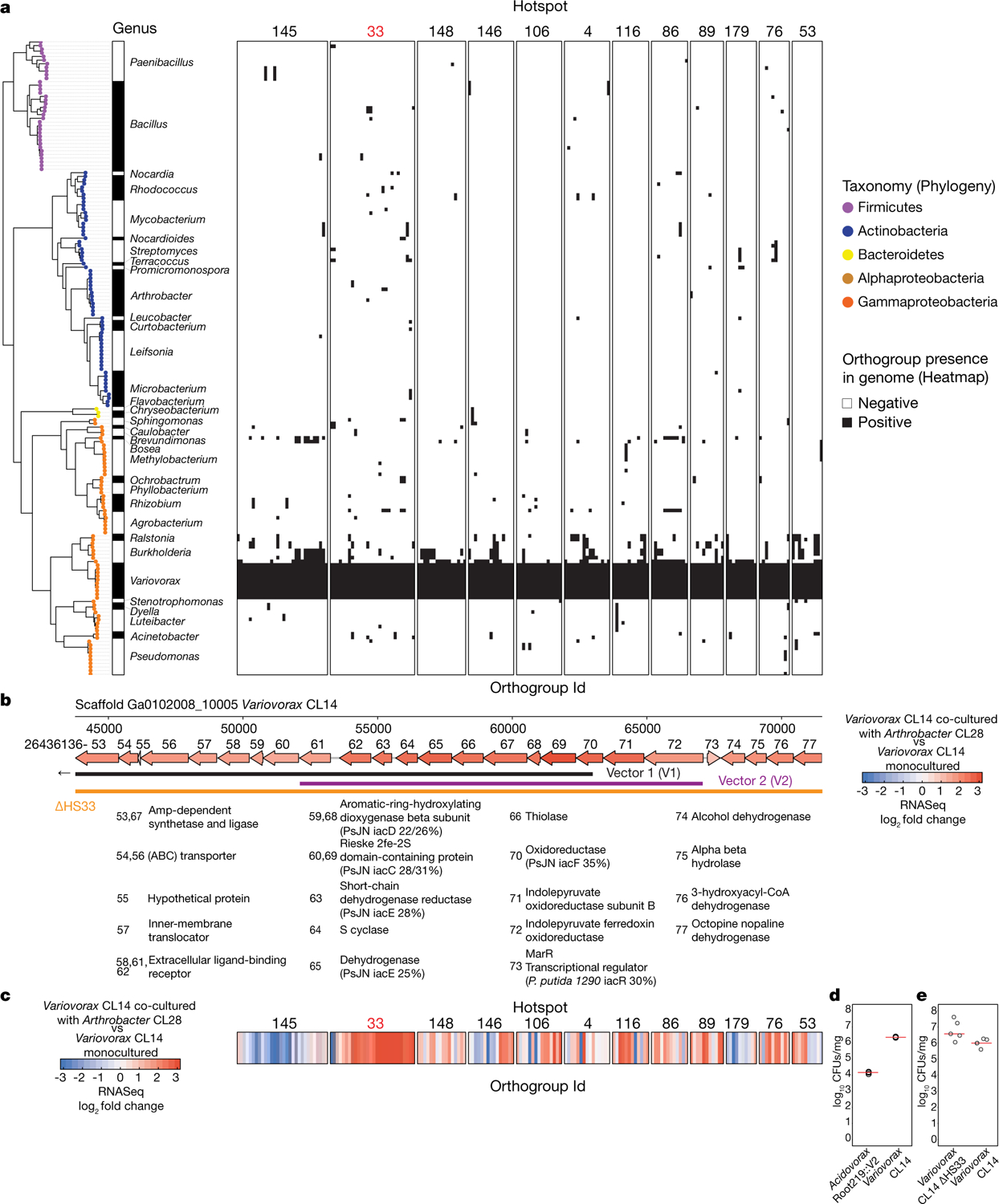

To identify the bacterial mechanism or mechanisms that are involved in the attenuation of RGI, we compared the genomes of the 10 Variovorax strains in the synthetic community to the genomes of the other 175 members of the synthetic community. Using de novo orthologue clustering across all 185 genomes, we identified 947 genes unique to Variovorax, with <5% prevalence across the 175 non-Variovorax members of the synthetic community and 100% prevalence among all 10 Variovorax strains. We grouped these genes into regions of physically contiguous genes (genomic hotspots) and focused on the 12 hotspots that contained at least 10 genes unique to Variovorax (Extended Data Fig. 9a, Supplementary Table 3). One of these hotspots (designated hotspot 33) contains weak homologues (average of about 30% identity) to the genes iacC, iacD, iacE, iacF and iacR of the IAA-degrading iac operon of Paraburkholderia phytofirmans strain PsJN18, but lacks iacA, iacB and iacI—which are known to be necessary for Paraburkholderia growth on IAA17 (Fig. 4a, Extended Data Fig. 9b). To test whether the hotspots we identified are responsive to RGI-inducing bacteria, we analysed the transcriptome of Variovorax CL14 in monoculture and in coculture with the RGI-inducing Arthrobacter CL28. We observed extensive transcriptional reprogramming of Variovorax CL14 when cocultured with Arthrobacter CL28 (Supplementary Table 4). Among the 12 hotspots we identified, the genes in hotspot 33 were the most highly upregulated (Fig. 4a, Extended Data Fig. 9b, c). We thus hypothesized that hotspot 33 contains an uncharacterized auxin-degradation operon.

Fig. 4 |. An auxin-degrading operon in Variovorax is required for root development.

a, A map of the auxin-degrading hotspot 33. Genes are annotated with the last two digits of their IMG gene identifier (26436136XX) (Extended Data Fig. 9b), and are coloured by the log2-transformed fold change in their transcript abundance in Variovorax CL14 cocultured with Arthrobacter CL28 (CL14–CL28) relative to Variovorax CL14 (CL14) in monoculture (measured by RNA-seq). Genes contained in vector 1 (V1) and vector 2 (V2), and the region knocked-out in Variovorax CL14 ΔHS33, are shown below the map. b, In vitro degradation of IAA by Acidovorax root219::EV, Acidovorax Root219::V2, Variovorax CL14 and Variovorax CL14 ΔHS33. n = 3 biological replicates. c, d, Primary root elongation of seedlings treated with IAA (c) or co-inoculated with Arthrobacter CL28 combined with Acidovorax root219::EV, Acidovorax root219::V2, Variovorax CL14 and Variovorax CL14 ΔHS33 (d). Significance was determined via ANOVA; letters correspond to a Tukey post hoc test. c, n = 49, 46, 46 and 49 (from left to right); d, n = 51, 41, 52 and 53 (from left to right) biological replicates across 2 independent experiments.

In parallel, we constructed a Variovorax CL14 genomic library in Escherichia coli with >12.5-kb inserts in a broad host-range vector, and screened the resulting E. coli clones for auxin degradation. Two clones from the approximately 3,500 that we screened degraded IAA (denoted V1 and V2) (Supplementary Table 5). The Variovorax CL14 genomic inserts in both of these clones contained portions of hotspot 33 (Fig. 4a, Extended Data Fig. 9b). The overlap common to both of these clones contained nine genes, among them the weak homologues to Paraburkholedria iacC, iacD and iacE. To test whether this genomic region is sufficient to revert RGI in plants, we transformed Acidovorax root219, a relative of Variovorax that does not cause or revert RGI (Extended Data Fig. 5a, b), with the shorter functional insert (V2) (Fig. 4a, Extended Data Fig. 9b) or with an empty vector (EV). The resulting gain-of-function strain Acidovorax root219::V2 gained the ability to degrade IAA in culture (Fig. 4b). We inoculated Acidovorax root219::V2 or the control Acidovorax root219::EV onto plants treated with IAA or inoculated with the RGI-inducing Arthrobacter CL28. Acidovorax root219::V2 fully reverted IAA-induced RGI (Fig. 4c) and partially reverted Arthrobacter CL28-induced RGI, despite colonizing roots at significantly lower levels than Variovorax CL14 (Fig. 4d, Extended Data Fig. 9d). In addition, we deleted hotspot 33 from Variovorax CL14 (Fig. 4a) to test whether this putative operon is necessary for the reversion of RGI. The resulting strain Variovorax CL14 ΔHS33—which is not impaired in plant colonization (Extended Data Fig. 9e)—did not degrade IAA in culture (Fig. 4b), and did not revert IAA-induced (Fig. 4c) or Arthrobacter CL28-induced RGI (Fig. 4d). Thus, this Variovorax-specific gene cluster is necessary for the suppression of RGI and for auxin degradation. It is thus the critical genetic locus required by Variovorax to maintain stereotypic root development in the context of a phylogenetically diverse microbiome.

Conclusions

Signalling molecules and other secondary metabolites are products of adaptations that allow microorganisms to survive competition for primary metabolites. Our results illuminate the importance of a trophic layer of microorganisms that use these secondary metabolites for their own benefit, while potentially providing the unselected exaptation34 of interfering with signalling between the bacterial microbiota and the plant host. Such metabolic signal interference has previously been demonstrated in the case of quorum quenching12, the degradation of microbial-associated molecular patterns35 and the degradation of bacterially produced auxin, including among Variovorax13–15. Plant development relies on tightly regulated auxin concentration gradients19, which can be distorted by auxin fluxes emanating from the microbiota. Some Variovorax strains have the capacity to both produce and degrade auxin, which suggests a capacity to fine-tune auxin concentrations in the rhizosphere15,28.

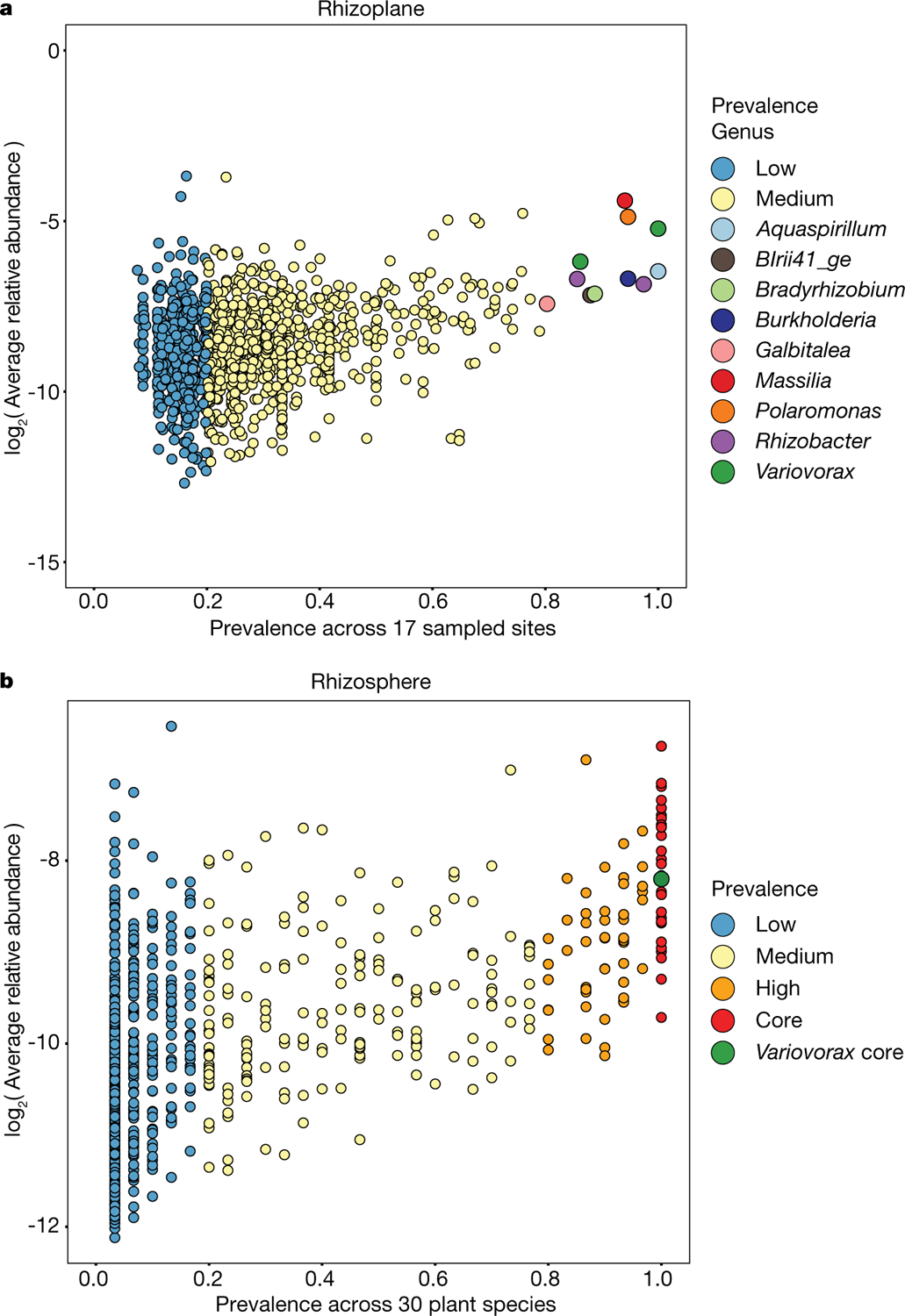

We have shown here that the chemical homeostasis enforced by the presence of Variovorax in a phylogenetically diverse, realistic synthetic community allows the plant to maintain its developmental programme within a chemically complex matrix. Variovorax was recently found to have the rare property of improved plant colonization upon late arrival to an established community10, which suggests that they use bacterially produced or induced—rather than plant-derived—substrates. Furthermore, after re-analysing a recent large-scale time and spatially resolved survey of the Arabidopsis root microbiome6 and a common garden experiment including 30 plant species4, we noted that Variovorax is among a limited group of core bacterial genera found in 100% of the sampled sites and plant species (Extended Data Fig. 10a, b). These ecological observations, together with our results using a reductionist microcosm, reinforce the importance of Variovorax as a key player in the bacteria–bacteria–plant communication networks that are required to maintain root growth within a complex biochemical ecosystem.

Methods

No statistical methods were used to predetermine sample size. The experiments were randomized, and investigators were not blinded to allocation during experiments and outcome assessment.

Arabidopsis with bacterial synthetic community microcosm across four stress gradients

This section relates to Fig. 1a, Extended Data Fig. 1.

Bacterial culture and plant inoculation.

The 185-member bacterial synthetic community used here contains genome-sequenced isolates obtained from surface-sterilized Brassicaceae roots, nearly all Arabidopsis thaliana, planted in two soils from North Carolina (USA). A detailed description of this collection and isolation procedures can be found in ref.20. One week before each experiment, bacteria were inoculated from glycerol stocks into 600 μl KB medium in a 96-deep-well plate. Bacterial cultures were grown at 28 °C, shaking at 250 rpm. After 5 days of growth, cultures were inoculated into fresh medium and returned to the incubator for an additional 48 h, resulting in 2 copies of each culture (7 days old and 48 h old). We adopted this procedure to account for variable growth rates of different members of the synthetic community and to ensure that nonstationary cells from each strain were included in the inoculum. After growth, 48-h and 7-day plates were combined and optical density of cultures was measured at 600 nm (OD600) using an Infinite M200 Pro plate reader (TECAN). All cultures were then pooled while normalizing the volume of each culture to OD600 = 1. The mixed culture was washed twice with 10 mM MgCl2 to remove spent medium and cell debris, and vortexed vigorously with sterile glass beads to break up aggregates. OD600 of the mixed, washed culture was then measured and normalized to OD600 = 0.2. The synthetic community inoculum (100 μl) was spread on 12 × 12-cm vertical square agar plates with amended Johnson medium (JM)1 without sucrose before transferring seedlings.

In vitro plant growth conditions.

All seeds were surface-sterilized with 70% bleach, 0.2% Tween-20 for 8 min, and rinsed 3 times with sterile distilled water to eliminate any seed-borne microorganisms on the seed surface. Seeds were stratified at 4 °C in the dark for 2 days. Plants were germinated on vertical square 12 × 12-cm agar plates with JM containing 0.5% sucrose, for 7 days. Then, 10 plants were transferred to each of the agar plates inoculated with the synthetic community. The composition of JM in the agar plates was amended to produce environmental variation. We added to the previously reported phosphate concentration gradient (0, 10, 30, 50, 100 and 1,000 μM Pi)5 three additional environmental gradients: salinity (50, 100, 150 and 200 mM NaCl), pH (5.5, 7.0 and 8.2) and incubation temperature (10, 21 and 31 °C). Each gradient was tested separately, in two independent replicas. Each condition included three synthetic community + plant samples, two no-plant controls and one no-bacteria control. Thus, the total sample size for each condition was n = 6. Previous publications1,3,5 have shown that an n ≥ 5 is provides sufficient power for synthetic community profiling. Plates were placed in randomized order in growth chambers and grown under a 16-h dark/8-h light regime at 21-°C day/18-°C night for 12 days. Upon collection, DNA was extracted from roots, shoots and the agar substrate. Here and hereafter, all measurements were taken from distinct samples.

DNA extraction.

Roots, shoots and agar were collected separately, pooling 6–8 plants for each sample. Roots and shoots were placed in 2-ml Eppendorf tubes with 3 sterile glass beads. These samples were washed three times with sterile distilled water to remove agar particles and weakly associated microorganisms. Tubes containing the samples were stored at −80 °C until processing. Root and shoot samples were lyophilized for 48 h using a Labconco freeze-dry system and pulverized using a tissue homogenizer (MPBio). Agar from each plate was collected in 30-ml syringes with a square of sterilized Miracloth (Millipore) at the bottom and kept at −20 °C for 1 week. Syringes were then thawed at room temperature and samples were squeezed gently through the Miracloth into 50-ml falcon tubes. Samples were centrifuged at maximum speed for 20 min and most of the supernatant was discarded. The remaining 1–2 ml of supernatant, containing the pellet, was transferred into clean 1.5-ml Eppendorf tubes. Samples were centrifuged again, supernatant was removed and pellets were stored at −80 °C until DNA extraction. DNA extractions were carried out on ground root and shoot tissue and agar pellets using 96-well-format MoBio PowerSoil Kit (MOBIO Laboratories; Qiagen) following the manufacturer’s instruction. Sample position in the DNA extraction plates was randomized, and this randomized distribution was maintained throughout library preparation and sequencing.

Bacterial 16S rRNA sequencing.

We amplified the V3–V4 regions of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene using the primers 338F (5′-ACTCCTACGGGA GGCAGCA-3′) and 806R (5′-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3′). Two barcodes and six frameshifts were added to the 5′ end of 338F and six frameshifts were added to the 806R primers, on the basis of a previously published protocol36. Each PCR reaction was performed in triplicate, and included a unique mixture of three frameshifted primer combinations for each plate. PCR conditions were as follows: 5 μl Kapa Enhancer, 5 μl Kapa Buffer A, 1.25 μl 5 μM 338F, 1.25 μl 5 μM 806R, 0.375 μl mixed plant rRNA gene-blocking peptide nucleic acids (PNAs) (1:1 mix of 100 μM plastid PNA and 100 μM mitochondrial PNA36), 0.5 μl Kapa dNTPs, 0.2 μl Kapa Robust Taq, 8 μl dH2O, 5 μl DNA; temperature cycling: 95 °C for 60 s; 24 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s; 78 °C (PNA) for 10 s; 50 °C for 30 s; 72 °C for 30 s; 4 °C until use. Following PCR clean up, using AMPure beads (Beckman Coulter), the PCR product was indexed using 96 indexed 806R primers with the Kapa HiFi Hotstart readymix with the same primers as above; temperature cycling: 95 °C for 60 s; 9 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s; 78 °C (PNA) for 10 s; 60 °C for 30 s; 72 °C for 35 s; 4 °C until use. PCR products were purified using AMPure XP magnetic beads (Beckman Coulter) and quantified with a Qubit 2.0 fluorometer (Invitrogen). Amplicons were pooled in equal amounts and then diluted to 10 pM for sequencing. Sequencing was performed on an Illumina MiSeq instrument using a 600-cycle V3 chemistry kit. DNA sequence data for this experiment are available at the NCBI Bioproject repository (accession PRJNA543313). The abundance matrix, metadata and taxonomy are available at https://github.com/isaisg/variovoraxRGI.

16S rRNA amplicon sequence data processing.

Synthetic community sequencing data were processed with MT-Toolbox37. Usable read output from MT-Toolbox (that is, reads with 100% correct primer and primer sequences that successfully merged with their pair) were quality-filtered using Sickle38 by not allowing any window with Q score under 20. The resulting sequences were globally aligned to a reference set of 16S rDNA sequences extracted from genome assemblies of members of the synthetic community. For strains that did not have an intact 16S rDNA sequence in their assembly, we sequenced the 16S rRNA gene using Sanger sequencing. The reference database also included sequences from known bacterial contaminants and Arabidopsis organellar sequences. Sequence alignment was performed with USEARCH v.7.109039 with the option usearch_global at a 98% identity threshold. On average, 85% of sequences matched an expected isolate. Our 185 isolates could not all be distinguished from each other based on the V3–V4 sequence and were thus classified into 97 unique sequences. A unique sequence encompasses a set of identical (clustered at 100%) V3–V4 sequences coming from a single or multiple isolates.

Sequence mapping results were used to produce an isolate abundance table. The remaining unmapped sequences were clustered into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) using UPARSE40 implemented with USEARCH v.7.1090, at 97% identity. Representative OTU sequences were taxonomically annotated with the RDP classifier41 trained on the Greengenes database42 (4 February 2011). Matches to Arabidopsis organelles were discarded. The vast majority of the remaining unassigned OTUs belonged to the same families as isolates in the synthetic community. We combined the assigned unique sequence and unassigned OTU count tables into a single count table. In addition to the raw count table, we created rarefied (1,000 reads per sample) and relative abundance versions of the abundance matrix for further analyses.

The resulting abundance tables were processed and analysed with functions from the ohchibi package (https://github.com/isaisg/ohchibi). An α-diversity metric (Shannon diversity) was calculated using the diversity function from the vegan package v.2.5–343. We used ANOVA to test for differences in α-diversity between groups. β-Diversity analyses (principal coordinate analysis and canonical analysis of principal coordinates (CAP)) were based on Bray–Curtis dissimilarity calculated from the relative abundance matrices. We used the capscale function from the vegan R package v.2.5–343 to compute the CAP. To analyse the full dataset (all fractions and all abiotic treatments), we constrained by fraction and abiotic treatment while conditioning for the replica and experiment effect. We explored the abiotic conditions effect inside each of the four abiotic gradients tested (phosphate, salinity, pH and temperature). We performed the fraction–abiotic interaction analysis within each fraction independently, constraining for the abiotic conditions while conditioning for the replica effect. In addition to CAP, we performed PERMANOVA using the adonis function from the vegan package v.2.5–343. We used the package DESeq2 v.1.22.144 to compute the enrichment profiles for unique sequences present in the count table.

We estimated the fraction effect across all the abiotic conditions tested by creating a group variable that merged the fraction variable and the abiotic condition variable together (for example, Root_10Pi, Substrate_10Pi). We fitted the following model specification using this group variable: abundance ~ rep + experiment + group.

From the fitted model, we extracted—for all levels within the group variables—the following comparisons: substrate versus root and substrate versus shoot. A unique sequence was considered statistically significant if it had a FDR-adjusted P value < 0.05.

All scripts and dataset objects necessary to reproduce the synthetic community analyses are deposited in the following GitHub repository: https://github.com/isaisg/variovoraxRGI.

Co-occurrence analysis.

The relative abundance matrix (unique sequences × samples) was standardized across the unique sequences by dividing the abundance of each unique sequence in its sample over the mean abundance of that unique sequence across all samples. Subsequently, we created a dissimilarity matrix based on the Pearson correlation coefficient between all the pairs of strains in the transformed abundance matrix, using the cor function in the stats base package in R. Finally, hierarchichal clustering (method ward.D2, function hclust) was applied over the dissimilarity matrix constructed above.

Heat map and family enrichment analysis.

We visualized the results of the generalized linear model (GLM) testing the fraction effects across each specific abiotic condition tested using a heat map. The rows in the heat map were ordered according to the dendrogram order obtained from the unique sequences co-occurrence analysis. The heat map was coloured on the basis of the log2-transformed fold change output by the GLM model. We highlighted in a black shade the comparisons that were significant (q value < 0.05). Finally, for each of the four modules, we computed for each family present in that module a hypergeometric test testing if that family was overrepresented (enriched) in that particular module. Families with an FDR-adjusted P value < 0.1 are visualized in the figure.

Deconstructing the synthetic community to four modules of co-occurring strains

This section relates to Fig. 1a–c.

Bacterial culture and plant-inoculation.

Strains belonging to each module A, B, C and D (‘Co-occurrence analysis’ in ‘Arabidopsis with bacterial synthetic community microcosm across four stress gradients’) were grown in separate deep 96-well plates and mixed as described in ‘Bacterial culture and plant-inoculation’ in ‘Arabidopsis with bacterial synthetic community microcosm across four stress gradients’. The concentration of each module was adjusted to OD600 = 0.05 (1/4 of the concentration of the full synthetic community). Each module was spread on the plates either separately, or in combination with another module at a total volume of 100 μl. In addition, we included a full synthetic community control and an uninoculated control, bringing the number of synthetic community combinations to 12. We performed the experiment in two independent replicates and each replicate included five plates per synthetic community combination.

In vitro plant growth conditions.

Seed sterilization and germination conditions were the same as in ‘In vitro plant growth conditions’ in ‘Arabidopsis with bacterial synthetic community microcosm across four stress gradients’. Plants were transferred to each of the synthetic-community-inoculated agar plates containing JM without sucrose. Plates were placed in randomized order in growth chambers and grown under a 16-h dark/8-h light regime at 21-°C day/18-°C night for 12 days. Upon collection, root morphology was measured.

Root and shoot image analysis.

Plates were imaged 12 days after transfer, using a document scanner. Primary root length elongation was measured using ImageJ45 and shoot area and total root network were measured with WinRhizo software (Regent Instruments).

Primary root elongation analyses.

Primary root elongation was compared across the no bacteria, full synthetic community, single modules and pairs of modules treatments jointly using a two-sided ANOVA model controlling for the replicate effect. We inspected the normality assumptions (here and elsewhere) using qqplots and Shapiro tests. Differences between treatments were indicated using the confidence letter display derived from the Tukey’s post hoc test implemented in the package emmeans46.

Inoculating plants with all synthetic community isolates separately

This section relates to Extended Data Fig. 2a–c.

Bacterial culture and plant inoculation.

Cultures from each strain in the synthetic community were grown in KB medium and washed separately (‘Bacterial culture and plant inoculation’ in ‘Arabidopsis with bacterial synthetic community microcosm across four stress gradients’), and OD600 was adjusted to 0.01 before spreading 100 μl on plates. We performed the experiment in two independent replicates and each replicate included one plate per each of the 185 strains. In vitro growth conditions were the same as described in ‘In vitro plant growth conditions’ in ‘Deconstructing the synthetic community to four modules of co-occurring strains’. Upon collection, root morphology was measured (‘Root and shoot image analysis’ in ‘Deconstructing the synthetic community to four modules of co-occurring strains’). Isolates generating an average main root elongation of <3 cm were classified as RGI-inducing strains.

Tripartite plant–microorganism–microorganism experiments

This section relates to Fig. 1d, e, Extended Data Fig. 3a.

Experimental design.

To identify strains that revert RGI (Fig. 1d), we selected all 18 non-RGI-inducing strains in module A and co-inoculated them with each of four RGI-inducing strains, one from each module. The experiment also included uninoculated controls and controls consisting of each of the 22 strains inoculated alone, amounting to 95 separate bacterial combinations.

To confirm the ability of Variovorax and Burkholderia to attenuate RGI induced by diverse bacteria (Extended Data Fig. 3a), three RGI-suppressing strains were co-inoculated with a selection of 18 RGI-inducing strains. The experiment also included uninoculated controls and controls consisting of each of the 21 strains inoculated alone. Thus, the experiment consisted of 76 separate bacterial combinations. We performed each of these two experiments in two independent replicates and each replicate included one plate per each of the strain combinations.

Bacterial culture and plant-inoculation.

All strains were streaked on agar plates, then transferred to 4 ml liquid KB medium for over-night growth. Cultures were then washed, and OD600 was adjusted to 0.02 before mixing and spreading 100 μl on each plate. Upon collection, root morphology was measured (‘Root and shoot image analysis’ in ‘Deconstructing the synthetic community to four modules of co-occurring strains’) and plant RNA was collected and processed from uninoculated samples, and from samples with Variovorax CL14, the RGI-inducing strain Arthrobacter CL28 and the combination of both (‘Experimental design’ in ‘Tripartite plant–microorganism–microorganism experiments’).

Primary root elongation analysis.

We fitted ANOVA models for each RGI-inducing strain we tested. Each model compared the primary root elongation with the RGI-inducing strains alone against root elongation when the RGI-inducing strain was co-inoculated with other isolates. The P values for all the comparisons were corrected for multiple testing using FDR.

RNA extraction.

RNA was extracted from A. thaliana seedlings following previously published methods47. Four seedlings were pooled from each plate and 3–5 samples per treatment were flash frozen and stored at −80 °C until processing. Frozen seedlings were ground using a TissueLyzer II (Qiagen), then homogenized in a buffer containing 400 μl of Z6-buffer; 8 M guanidine HCl, 20 mM MES, 20 mM EDTA at pH 7.0. Four hundred μl phenol:chloroform:isoamylalcohol, 25:24:1 was added, and samples were vortexed and centrifuged (20,000g, 10 min) for phase separation. The aqueous phase was transferred to a new 1.5-ml Eppendorf tube and 0.05 volumes of 1 N acetic acid and 0.7 volumes 96% ethanol were added. The RNA was precipitated at −20 °C overnight. Following centrifugation (20,000g, 10 min, 4 °C), the pellet was washed with 200 μl sodium acetate (pH 5.2) and 70% ethanol. The RNA was dried and dissolved in 30 μl of ultrapure water and stored at −80 °C until use.

Plant RNA sequencing.

Illumina-based mRNA-seq libraries were prepared from 1 μg RNA following previously published methods3. mRNA was purified from total RNA using Sera-mag oligo(dT) magnetic beads (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) and then fragmented in the presence of divalent cations (Mg2+) at 94 °C for 6 min. The resulting fragmented mRNA was used for first-strand cDNA synthesis using random hexamers and reverse transcriptase, followed by second-strand cDNA synthesis using DNA polymerase I and RNaseH. Double-stranded cDNA was end-repaired using T4 DNA polymerase, T4 polynucleotide kinase and Klenow polymerase. The DNA fragments were then adenylated using Klenow exo-polymerase to allow the ligation of Illumina Truseq HT adapters (D501–D508 and D701–D712). All enzymes were purchased from Enzymatics. Following library preparation, quality control and quantification were performed using a 2100 Bioanalyzer instrument (Agilent) and the Quant-iT PicoGreen dsDNA Reagent (Invitrogen), respectively. Libraries were sequenced using Illumina HiSeq4000 sequencers to generate 50-bp single-end reads.

RNA-seq read processing.

Initial quality assessment of the Illumina RNA-seq reads was performed using FastQC v.0.11.7 (Babraham Bioinformatics). Trimmomatic v.0.3648 was used to identify and discard reads containing the Illumina adaptor sequence. The resulting high-quality reads were then mapped against the TAIR10 Arabidopsis reference genome using HISAT2 v.2.1.049 with default parameters. The featureCounts function from the Subread package50 was then used to count reads that mapped to each one of the 27,206 nuclear protein-coding genes. Evaluation of the results of each step of the analysis was performed using MultiQC v.1.151. Raw sequencing data and read counts are available at the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus accession number GSE131158.

Variovorax drop-out experiment

This section relates to Fig. 2a–c, g, h, Extended Data Fig. 4a.

Bacterial culture and plant-inoculation.

The entire synthetic community, excluding all 10 Variovorax isolates and all 5 Burkholderia isolates, was grown and prepared as described in ‘Bacterial culture and plant inoculation’ in ‘Arabidopsis with bacterial synthetic community microcosm across four stress gradients’. The Variovorax and Burkholderia isolates were grown in separate tubes, washed and added to the rest of the synthetic community to a final OD600 of 0.001 (the calculated OD600 of each individual strain in a 185-member synthetic community at a total of OD600 of 0.2), to form the following five mixtures: (i) full community: all Variovorax and Burkholderia isolates added to the synthetic community; (ii) Burkholderia drop-out: only Variovorax isolates added to the synthetic community; (iii) Variovorax drop-out: only Burkholderia isolates added to the synthetic community; (iv) Variovorax and Burkholderia drop-out: no isolates added to the synthetic community; (v) uninoculated plants: no synthetic community. The experiment consisted of six plates per synthetic community mixture, amounting to 30 plates. Upon collection, root morphology was measured and analysed (‘Root and shoot image analysis’ in ‘Deconstructing the synthetic community to four modules of co-occurring strains’, and in ‘Primary root elongation analysis’ in ‘Tripartite plant–microorganism–microorganism experiments’); and bacterial DNA (‘DNA extraction’ and ‘Bacterial 16S rRNA sequencing’ in ‘Arabidopsis with bacterial synthetic community microcosm across four stress gradients’) and plant RNA (‘RNA extraction’ and ‘Plant RNA sequencing’ in ‘Tripartite plant–microorganism–microorganism experiments’) were collected and processed.

Variovorax drop-out under varying abiotic contexts

This section relates to Fig. 2d, f, Extended Data Fig. 4c, d.

Bacterial culture and plant-inoculation.

The composition of JM in the agar plates was amended to produce abiotic environmental variation. These amendments included salt stress (150 mM NaCl), low phosphate (10 μM phosphate), high pH (pH 8.2) and high temperature (plates incubated at 31 °C), as well as an unamended JM control. Additionally, we tested a different medium (1/2-strength Murashige and Skoog (MS)) and a soil-like substrate. As a soil-like substrate, we used calcined clay (Diamond Pro), prepared as follows: 100 ml of clay was placed in Magenta GA7 jars. The jars were then autoclaved twice. Forty ml of liquid JM was added to the Magenta jars, with the corresponding bacterial mixture spiked into the media at a final OD600 of 5 × 10−4. Four 1-week old seedlings were transferred to each vessel, and vessels were covered with Breath-Easy gas permeable sealing membrane (Research Products International) to maintain sterility and gas exchange.

The entire synthetic community, excluding all 10 Variovorax isolates, was grown and prepared as described in ‘Bacterial culture and plant inoculation’ in ‘Arabidopsis with bacterial synthetic community microcosm across four stress gradients’. The Variovorax isolates were grown in separate tubes, washed and added to the rest of the synthetic community to a final OD600 of 0.001 (the calculated OD600 of each individual strain in a 185-member synthetic community at an OD600 of 0.2), to form the following five mixtures: (i) full community: all Variovorax isolates added to the synthetic community; (ii) Variovorax drop-out: no isolates added to the synthetic community; (iii) uninoculated plants: no synthetic community.

We inoculated all 3 synthetic community combinations in all 7 abiotic treatments, amounting to 21 experimental conditions. We performed the experiment in 2 independent replicates and each replicate included 3 plates per experimental conditions, amounting to 63 plates per replicate. Upon collection, root morphology was measured (‘Root and shoot image analysis’ in ‘Deconstructing the synthetic community to four modules of co-occurring strains’); and Bacterial DNA (‘DNA extraction, ‘Bacterial 16S rRNA sequencing’ and ‘16S rRNA amplicon sequence data processing’ in ‘Arabidopsis with bacterial synthetic community microcosm across four stress gradients’) and plant RNA (‘RNA extraction’, ‘Plant RNA sequencing’ and ‘RNA-seq read processing’ in ‘Tripartite plant–microorganism–microorganism experiments’) were collected and processed.

Root image analysis.

For agar plates, roots were imaged as described in ‘Root and shoot image analysis’ in ‘Deconstructing the synthetic community to four modules of co-occurring strains’. For calcined clay pots, four weeks after transferring, pots were inverted, and whole root systems were gently separated from the clay by washing with water. Root systems were spread over an empty Petri dish and scanned using a document scanner.

Primary root elongation and total root network analysis.

Primary root elongation was compared between synthetic-community treatments within each of the different abiotic contexts tested independently. Differences between treatments were indicated using the confidence letter display derived from the Tukey’s post hoc test implemented in the package emmeans.

Bacterial 16S rRNA data analysis.

To be able to compare shifts in the community composition of samples treated with and without the Variovorax genus, we in silico-removed the 10 Variovorax isolates from the count table of samples inoculated with the full community treatment. We then merged this count table with the count table constructed from samples inoculated without the Variovorax genus (Variovorax drop-out treatment). Then, we calculated a relative abundance of each unique sequence across all the samples using the merged count matrix. Finally, we applied CAP over the merged relative abundance matrix to control for the replica effect. In addition, we used the function adonis from the vegan R package to compute a PERMANOVA test over the merged relative abundance matrix and we fitted a model evaluating the fraction and synthetic community (presence of Variovorax) effects over the assembly of the community.

Variovorax drop-out under varying biotic contexts

This section relates to Fig. 2e, Extended Data Fig. 4b.

Bacterial culture and plant inoculation.

Strains belonging to modules A (excluding Variovorax), C and D were grown in separate wells in deep 96-well plates and mixed as described in ‘Bacterial culture and plant inoculation’ in ‘Arabidopsis with bacterial synthetic community microcosm across four stress gradients’. The concentration of each module was adjusted to OD600 = 0.05 (1/4 of the concentration of the full synthetic community). The Variovorax isolates were grown in separate tubes, washed and added to the rest of the synthetic community to a final OD600 of 0.001.

In a separate experiment, the 35-member synthetic community used in ref.1 was grown, excluding Variovorax CL14, to create a taxonomically diverse, Variovorax-free subset of the full 185-member community. The concentration of this synthetic community was adjusted to OD600 = 0.05. The Variovorax isolates were grown in separate tubes, washed and added to the rest of the synthetic community to a final OD600 of 0.001.

These two experiments included the following mixtures (Extended Data Fig. 4b): (i) module A excluding Variovorax; (ii) module C; (iii) module D; (iv) module A including Variovorax; (v) module C + all 10 Variovorax; (vi) module D + all 10 Variovorax; (vii) 35-member synthetic community excluding the one Variovorax found therein; (viii) 34-member synthetic community + all 10 Variovorax; (ix) uninoculated control. The experiment with modules A, C and D was performed in two independent experiments, with two plates per treatment in each. The experiment with the 34-member synthetic community was performed once, with 5 plates per treatment. Upon collection, root morphology was measured (‘Root and shoot image analysis’ in ‘Deconstructing the synthetic community to four modules of co-occurring strains’).

Primary root elongation analysis.

We directly compared differences between the full synthetic community and Variovorax drop-out treatment using a t-test and adjusting the P values for multiple testing using FDR.

Phylogenetic inference of the synthetic community and Variovorax isolates

This section relates to Figs. 1d, 2a, Extended Data Figs. 1a, 2b, 3a, 4b, 5a, b, 9a.

To build the phylogenetic tree of the synthetic community isolates, we used the previously described super matrix approach20. We scanned 120 previously defined marker genes across the 185 isolate genomes from the synthetic community using the hmmsearch tool from the hmmer v.3.1b252. Then, we selected 47 markers that were present as single-copy genes in 100% of our isolates. Next, we aligned each individual marker using MAFFT53 and filtered low-quality columns in the alignment using trimAl54. Then, we concatenated all filtered alignments into a super alignment. Finally, FastTree v.2.155 was used to infer the phylogeny using the WAG model of evolution. For the tree of the relative of Variovorax, we chose 56 markers present as single copy across 124 Burkholderiales isolates and implemented the same methodology described above.

Measuring how prevalent the RGI suppression trait is across the Variovorax phylogeny

This section relates to Fig. 3a, Extended Data Fig. 5a, b.

Bacterial culture and plant inoculation.

Fifteen Variovorax strains from across the phylogeny of the genus were each co-inoculated with the RGI-inducing Arthrobacter CL28. All 16 strains were grown in separate tubes, then washed and OD600 was adjusted to 0.01 before mixing. Pairs of strains were mixed in 1:1 ratios and spread at a total volume of 100 μl onto agar before seedling transfer. The experiment also included uninoculated controls and controls consisting of each of the 16 strains inoculated alone. Thus, the experiment consisted of 32 separate bacterial combinations. We performed the experiment one time, which included three plates per bacterial combination. Upon collection, primary root elongation was analysed as described in “Root and shoot image analysis’ in ‘Deconstructing the synthetic community to four modules of co-occurring strains’.

Measuring RGI in tomato seedlings

This section relates to Extended Data Fig. 3b.

Experimental design.

This experiment included the following treatments: (i) no bacteria, (ii) Arthrobacter CL28, (iii) Variovorax CL14 and (iv) Arthrobacter CL28 + Variovorax CL14. Each treatment was repeated in three separate agar plates with five tomato seedlings per plate. The experiment was repeated in two independent replicates.

Bacterial culture and plant inoculation.

All strains were grown in separate tubes, then washed and OD600 was adjusted to 0.01 before mixing and spreading (‘Bacterial culture and plant inoculation’ in ‘Tripartite plant–microorganism–microorganism experiments’). Four hundred μl of each bacterial treatment was spread on 20 × 20 agar plates containing JM agar with no sucrose.

In vitro plant growth conditions.

We used tomato cultivar Heinz 1706 seeds. All seeds were soaked in sterile distilled water for 15 min, then surface-sterilized with 70% bleach, 0.2% Tween-20 for 15 min, and rinsed 5 times with sterile distilled water to eliminate any seed-borne microorganisms on the seed surface. Seeds were stratified at 4 °C in the dark for 2 days. Plants were germinated on vertical square 10 × 10 cm agar plates with JM containing 0.5% sucrose, for 7 days. Then, 5 plants were transferred to each of the synthetic-community-inoculated agar plates. Upon collection, root morphology was measured (‘Root and shoot image analysis’ in ‘Deconstructing the synthetic community to four modules of co-occurring strains’).

Primary root elongation analysis.

Differences between treatments were indicated using the confidence letter display derived from the Tukey’s post hoc test from an ANOVA model.

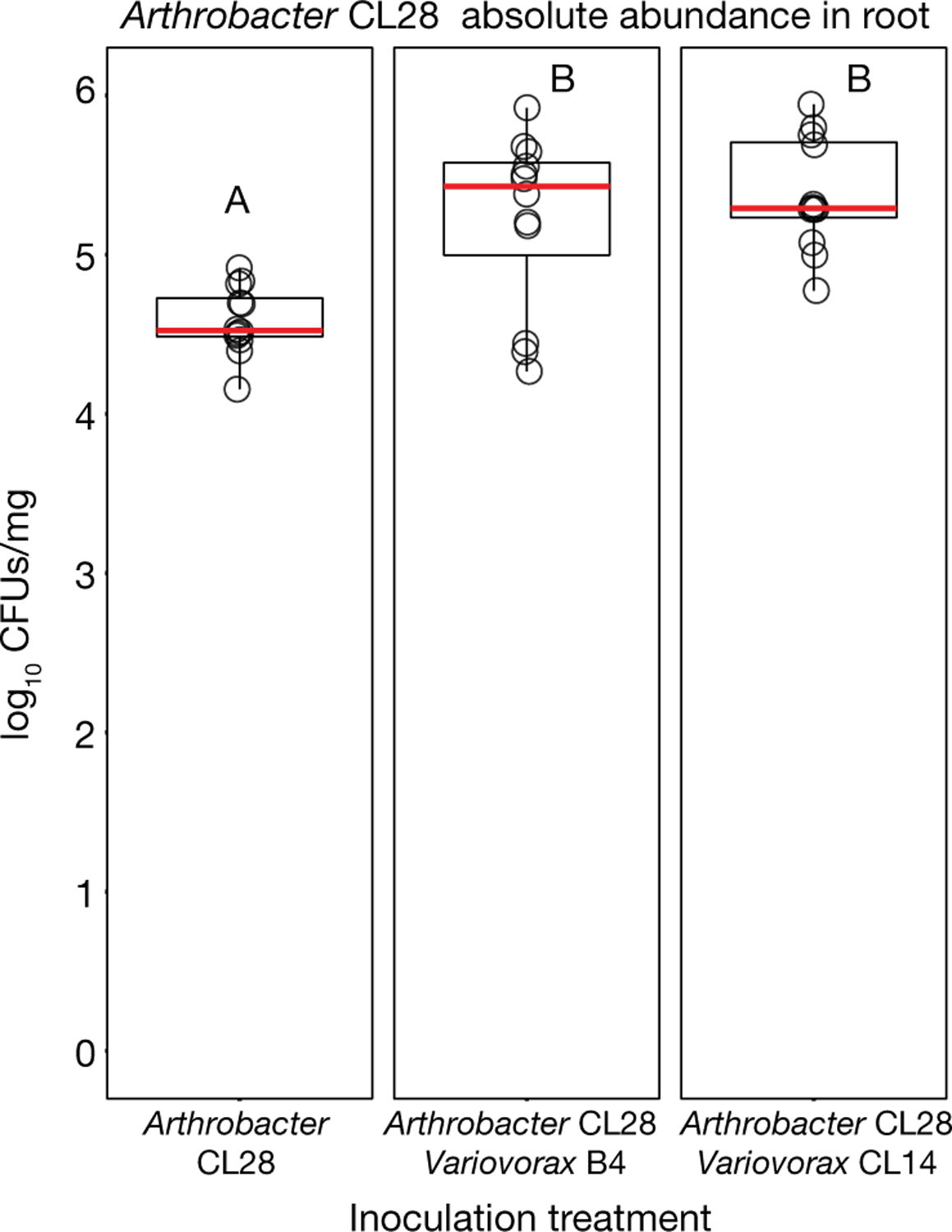

Determination of Arthrobacter CL28 colony forming units from roots

This section relates to Extended Data Fig. 6.

Arabidopsis seedlings were inoculated with (i) Arthrobacter CL28 alone, (ii) Arthrobacter CL28 + Variovorax CL14 or (iii) Arthrobacter CL28 + Variovorax B4, as described in ‘Bacterial culture and plant inoculation’ in ‘Tripartite plant–microorganism–microorganism experiments’. Each bacterial treatment included four separate plates, with nine seedlings in each plate. Upon collection, all seedlings were placed in pre-weighed 2-ml Eppendorf tubes containing 3 glass beads, 3 seedlings per tube (producing 12 data points per treatment). Roots were weighed, and then homogenized using a bead beater (MP Biomedicals). The resulting suspension was serially diluted, then plated on LB agar plates containing 50 μg/ml of apramycin to select for Arthrobacter CL28 colonies and colonies were counting after incubation of 48 h at 28 °C.

Arabidopsis RNA-seq analysis

This section relates to Extended Data Fig. 7.

Detection of RGI-induced genes.

To measure the transcriptional response of the plant to the different synthetic community combinations, we used the R package DESeq2 v.1.22.144. The raw count genes matrixes for the drop-out and tripartite experiments were used independently to define differentially expressed genes (DEGs). For the analysis of both experiments we fitted the following model specification: abundance gene ~ synthetic community.

From the fitted models, we derived the following contrasts to obtain DEGs. A gene was considered differentially expressed if it had a q-value < 0.1. For the tripartite system (‘Tripartite plant–microorganism–microorganism experiments’), we performed the following contrasts: Arthrobacter CL28 versus no bacteria (NB) and Arthrobacter CL28 versus Arthrobacter CL28 co-inoculated with Variovorax CL14. The logic behind these two contrasts was to identify genes that were induced in RGI plants (Arthrobacter CL28 versus NB) and repressed by Variovorax CL14. For the drop-out system (‘Variovorax drop-out experiment’), we performed the following contrasts, Variovorax drop-out versus NB, and Variovorax drop-out versus full synthetic community. The logic behind these two contrasts was identical to the tripartite system: to identify genes that are associated with the RGI phenotype (Variovorax drop-out versus NB contrast) and repressed when Variovorax are present (Variovorax drop-out versus full synthetic community contrast).

For visualization purposes, we applied a variance stabilizing transformation (DESeq2) to the raw count gene matrix. We then standardized each gene expression (z-score) along the samples. We subset DEGs from this standardized matrix and calculated the mean z-score expression value for each synthetic community treatment.

To identify the tissue-specific expression profile of the 18 intersecting genes between the tripartite and drop-out systems, we downloaded the spatial expression profile of each gene from the Klepikova atlas25 using the bio-analytic resource of plant biology platform. Then, we constructed a spatial expression matrix of the 18 genes and computed pairwise Pearson correlation between all pairs of genes. Finally, we applied hierarchical clustering to this correlation matrix.

Comparison with acute auxin response dataset.

This section relates to Extended Data Fig. 7d. We applied the variance stabilizing transformation (DESeq2) to the raw count gene matrix. We then standardized each gene expression (z-score) along the samples. From this matrix, we subset 12 genes that in a previous study26 exhibited the highest fold change between auxin-treated and untreated samples. Finally, we calculated the mean z-score expression value of each of these 12 genes across the synthetic community treatments. We estimated the statistical significance of the trend of these 12 genes between a pair of synthetic community treatments (full synthetic community versus Variovorax drop-out, Arthrobacter CL28 versus Arthrobacter CL28 plus Variovorax CL14) using a permutation approach: we estimated a P value by randomly selecting 12 genes 10,000 times from the expression matrix and comparing the mean expression between the two synthetic community treatments (for example, full synthetic community versus Variovorax drop-out) with the actual mean expression value from the 12 genes reported as robust auxin markers.

Measuring the ability of Variovorax to attenuate RGI induced by small molecules IAA, 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid, ethylene (ACC), cytokinins (zeatin and 6-benzylaminopurine) and flagellin 22 peptide (flg22)

This section relates to Fig. 3a, Extended Data Fig. 8a.

Bacterial culture and plant inoculation.

We embedded each of the following compounds in JM plates: 100 nM IAA (Sigma), 100 nM 1- ACC) (Sigma), 100 nM 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (Sigma), 100 nM flg22 (PhytoTech labs), 100 nM 6-benzylaminopurine (BAP) (Sigma) and 100 nM zeatin (Sigma). As some of these compound stocks were initially solubilized in ethanol, we included comparable amounts of ethanol in the control treatments. Plates with each compound were inoculated with one of the Variovorax strains CL14, MF160, B4 or YR216 or with Burkholderia CL11. These strains were grown in separate tubes, then washed and OD600 was adjusted to 0.01 before spreading 100 μl on plates. In addition, we included uninoculated controls for each compound. We also included unamended JM plates inoculated with the RGI-inducing Arthrobacter CL28 co-inoculated with each of the Variovorax or Burkholderia strains, or alone. Thus, the experiment included 42 individual treatments. The experiment was repeated twice, with three independent replicates per experiment. Upon collection, root morphology was measured (‘Root and shoot image analysis’ in ‘Deconstructing the synthetic community to four modules of co-occurring strains’).

Primary root elongation analysis.

Primary root elongation was compared between bacterial treatments within each of RGI treatments tested. Differences between treatments were estimated as described in ‘Primary root elongation analysis’ in ‘Tripartite plant–microorganism–microorganism experiments’. We plotted the estimated means with 95% confidence interval of each bacterial treatment across the different RGI treatments.

In vitro growth of Variovorax

This section relates to Fig. 4b, Extended Data Figs. 8b, 9d, e.

Variovorax CL14 was grown in 5-ml cultures for 40 h at 28 °C in 1 × M9 minimal salts medium (Sigma M6030) supplemented with 2 mM MgSO4, 0.1 mM CaCl2, 10 μM FeSO4, and a carbon source: either 15 mM succinate alone, 0.4 mM IAA with 0.5% ethanol for IAA solubilization, or both. Optical density at 600 nm and IAA concentrations were measured at six time points. IAA concentrations were measured using the Salkowski method modified from ref.56. One hundred μl of Salkowski reagent (10 mM FeCl3 in 35% perchloric acid) was mixed with 50 μl culture supernatant or IAA standards and colour was allowed to develop for 30 min before measuring the absorbance at 530 nm.

Measuring plant auxin response in vivo using a bioreporter line

This section relates to Extended Data Fig. 8c, d.

Bacterial culture and plant-inoculation.

Seven-day-old transgenic Arabidopsis seedlings expressing the DR5::GFP reporter construct57 were transferred onto plates containing: (i) 100 nM IAA, (ii) Arthrobacter CL28, (iii) 100 nM IAA + Variovorax CL14, (iv) Arthrobacter CL28 + Variovorax CL14, (v) uninoculated plates. For treatments (ii) and (iii), Bacterial strains were grown in separate tubes, then washed and OD600 was adjusted to 0.01. For treatment (iv), OD-adjusted cultures were mixed in 1:1 ratios and spread onto agar before seedling transfer.

Fluorescence microscopy.

GFP fluorescence in the root elongation zone of 8–10 plants per treatment were visualized using a Nikon Eclipse 80i fluorescence microscope at days 1, 3, 6, 9 and 13 after inoculation. The experiment was performed in two independent replicates.

From each root imaged, 10 random 30 × 30 pixel squares were sampled and average GFP intensity was measured using imageJ45. Treatments were compared within each time point using ANOVA tests with Tukey’s post hoc in the R base package emmeans. For visualization purposes, we plotted the estimated means of each bacterial across the different time points.

Measuring the dual role of auxin and ethylene perception in synthetic-community-induced RGI

This section relates to Fig. 3b.

Bacterial culture and plant inoculation.

We transferred four 7-day-old wild-type seedling and four axr2-1seedlings to each plate in this experiment. The plates contained one of five bacterial treatments: (i) Arthrobacter CL28, (ii) Arthrobacter CL28 + Variovorax CL14, (iii) Variovorax drop-out synthetic community, (iv) full synthetic community, (v) uninoculated, prepared as described in ‘Bacterial culture and plant inoculation’ in ‘Variovorax drop-out under varying abiotic contexts’, and in ‘Bacterial culture and plant inoculation’ in ‘Measuring plant auxin response in vivo using a bioreporter line’. Plates were placed vertically inside sealed 86 × 68 cm Ziploc bags. In one of the bags, we placed an open water container with 80 2.5 g sachets containing 0.014% 1-MCP (Ethylene Buster, Chrystal International BV). In the second bag we added, as a control, an open water container. Both bags were placed in the growth chamber for 12 days. After 6 days of growth, we added 32 additional sachets to the 1-MCP-treated bag to maintain 1-MCP concentrations in the air. Upon collection, root morphology was measured (‘Root and shoot image analysis’ in ‘Deconstructing the synthetic community to four modules of co-occurring strains’).

Primary root elongation analysis.

Primary root elongation was standardized to the no-bacteria control of each genotype, and compared between genotype and 1-MCP treatments within the Arthrobacter CL28 treatment and within the Variovorax drop-out synthetic community treatment, independently. Differences between treatments were estimated as described in ‘Primary root elongation analysis’ in ‘Tripartite plant–microorganism–microorganism experiments’. We plotted the estimated means with 95% confidence interval of each bacterial treatment across the four genotypes. We calculated the IQR for the full and Arthrobacter CL28 with Variovorax CL14 treatments, pooling the four genotypes and MCP treatments.

Preparation of binarized plant images

This section relates to Figs. 1c, 2b, Extended Data Fig. 2c.

To present representative root images, we increased contrast and subtracted background in ImageJ, then cropped the image to select representative roots. Neighbouring roots were manually erased from the cropped image.

Mining Variovorax genomes for auxin degradation operons and ACC-deaminase genes and comparative genomics of Variovorax genomes against the other synthetic community members

This section relates to Extended Data Fig. 5a, Supplementary Table 4.

We used local alignment (BLASTp)58 to search for the presence of the 10 genes (iacA, iacB, iacC, iacD, iacE, iacF, iacG, iacH, iacI and iacY) from a previously characterized auxin degradation operon in a different genus17 across the 10 Variovorax isolates in our synthetic community. A minimal set of seven of these genes (iacA, iacB, iacC, iacD, iacE, iacF and iacI) was shown to be necessary and sufficient for auxin degradation17. We identified homologues for these genes across the Variovorax phylogeny (Extended Data Fig. 5a) at relatively low sequence identity (27–48%). Two genes of the minimal set of seven genes did not have any homologues in most Variovorax genomes (iacB and iacI). In addition to the iac operon, we scanned the genomes for the auxin degradation operon described in ref.59 and could not identify it in any of the Variovorax isolates.

We also searched for the ACC deaminase gene by looking for the KEGG orthology identifier K01505 (1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate deaminase) across the IMG annotations available for all our genomes.

We used orthofinder v.2.2.160 to construct orthogroups (group of homologue sequences) using all the coding sequences of the 10 Variovorax isolates included in the full 185-member synthetic community. We aligned each orthogroup using MAFFT v.70753 and proceeded to build hidden Markov model (HMM) profiles from the alignments using hmmbuild v.3.1b252. We then used the HMM profiles that consist of core genes (present in the 10 isolates) in the Variovorax genus and scanned the 175 remaining genomes in the synthetic community for these HMM profiles using hmmsearch v.31.b252. We then selected orthogroups that were less than 5% prevalent in the 175 remaining isolates scanned. Finally, taking the Variovorax CL14 genome as a reference, we built hotspots of physically adjacent selected orthogroups. We used an iterative approach that extended adjacent orthogroups if they were less than 10 kb from each other. As a final filtering step, we selected hotspots that contained more than 10 selected orthogroups.

Variovorax CL14 RNA-seq in monoculture and in coculture with Arthrobacter CL28

This section relates to Fig. 4a, Extended Data Fig. 9b, c.

Bacterial culture.

Variovorax CL14 was grown either alone or in coculture with Arthrobacter CL28 in 5 ml of 1/10 2× YT medium (1.6 g/l tryptone, 1 g/l yeast extract, 0.5 g/l NaCl) in triplicate. The monoculture was inoculated at OD600 of 0.02 and the coculture was inoculated with OD600 of 0.01 of each strain. Cultures were grown at 28 °C to early stationary phase (approximately 22 h) and cells were collected by centrifugation at 4,100g for 15 min and frozen at −80 °C before RNA extraction.

RNA extraction and RNA-seq.

Cells were lysed for RNA extraction using TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer instructions. Following cell lysis and phase separation, RNA was purified using the RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen) including the optional on column DNase Digestion with the RNase-Free DNase Set (Qiagen). Total RNA quality was confirmed on the 2100 Bioanalyzer instrument (Agilent) and quantified using a Qubit 2.0 fluorometer (Invitrogen). RNA-seq libraries were prepared using the Universal Prokaryotic RNA-Seq, Prokaryotic AnyDeplete kit (Tecan, formerly NuGEN). Libraries were pooled and sequenced on the Illumina HiSeq4000 platform to generate 50-bp single-end reads.

RNA-seq analysis.

We mapped the generated raw reads to the Variovorax CL14 genome (fasta file available on https://github.com/isaisg/variovoraxRGI/blob/master/rawdata/2643221508.fna) using bowtie261 with the ‘very sensitive’ flag. We then counted hits to each individual coding sequence annotated for the Variovorax CL14 genome using the function featureCounts from the R package Rsubread, inputting the Variovorax CL14 gff file (available on https://github.com/isaisg/variovoraxRGI/blob/master/rawdata/2643221508.gff) and using the default parameters with the flag allowMultiOverlap = FALSE. Finally, we used DESeq2 to estimate DEGs between treatments with the corresponding fold change estimates and FDR-adjusted P values.

Variovorax CL14 genomic library construction and screening

This section relates to Fig. 4a, Extended Data Fig. 9b, Supplementary Table 5.

Library construction.

High-molecular -eight Variovorax CL14 genomic DNA was isolated by phenol–chloroform extraction. This genomic DNA was partially digested with Sau3A1 (New England Biolabs), and separated on the BluePippin (Sage Science) to isolate DNA fragments >12.5 kb. Vector backbone was prepared by amplifying pBBR-1MCS262 using Phusion polymerase (New England Biolabs) with primers JMC277–JMC278 (Supplementary Table 6), digesting the PCR product with BamHI-HF (New England Biolabs), dephosphorylating with Quick CIP (New England Biolabs), and gel extracting using the QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen). The prepared Variovorax CL14 genomic DNA fragments were ligated to the prepared pBBR1-MCS2 vector backbone using ElectroLigase (New England Biolabs) and transformed by electroporation into NEB 10-beta Electrocompetent E. coli (New England Biolabs). Clones were selected by blue–white screening on LB plates containing 1.5% agar, 50 μg/ml kanamycin, 40 μg/ml X-gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside), and 1 mM isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) at 37 °C. White colonies were screened by colony PCR using Taq polymerase and JMC247–JMC270 primers (Supplementary Table 6) to eliminate clones with small inserts. The screened library clones were picked into LB medium + 50 μg/ml kanamycin, grown at 37 °C, and stored at −80 °C in 20% glycerol. The Variovorax CL14 genomic library comprises approximately 3,500 clones with inserts >12.5 kb in vector pBBR1-MCS2 in NEB 10-beta E. coli.

Library screening for IAA degradation.