Abstract

Biomarkers remain the highest value proposition in cancer medicine today—especially protein biomarkers. Despite decades of evolving regulatory frameworks to facilitate the review of emerging technologies, biomarkers have been mostly about promise with very little to show for improvements in human health. Cancer is an emergent property of a complex system, and deconvoluting the integrative and dynamic nature of the overall system through biomarkers is a daunting proposition. The last 2 decades have seen an explosion of multiomics profiling and a range of advanced technologies for precision medicine, including the emergence of liquid biopsy, exciting advances in single-cell analysis, artificial intelligence (machine and deep learning) for data analysis, and many other advanced technologies that promise to transform biomarker discovery. Combining multiple omics modalities to acquire a more comprehensive landscape of the disease state, we are increasingly developing biomarkers to support therapy selection and patient monitoring. Furthering precision medicine, especially in oncology, necessitates moving away from the lens of reductionist thinking toward viewing and understanding that complex diseases are, in fact, complex adaptive systems. As such, we believe it is necessary to redefine biomarkers as representations of biological system states at different hierarchical levels of biological order. This definition could include traditional molecular, histologic, radiographic, or physiological characteristics, as well as emerging classes of digital markers and complex algorithms. To succeed in the future, we must move past purely observational individual studies and instead start building a mechanistic framework to enable integrative analysis of new studies within the context of prior studies. Identifying information in complex systems and applying theoretical constructs, such as information theory, to study cancer as a disease of dysregulated communication could prove to be “game changing” for the clinical outcome of cancer patients.

Keywords: proteomics, cancer biomarkers, protein biomarkers, complex adaptive systems, clinical proteomics

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

Protein biomarkers will be key to deconvoluting the complexity of cancer.

-

•

Redefine biomarkers as representations of hierarchical biological system states.

-

•

Big data and AI could be transformative for biomarker discovery in the future.

-

•

Biomarkers discovery will require theoretical constructs to separate signal from noise.

-

•

Build mechanistic frameworks to enable new data analytics in context of prior studies.

In Brief

Biomarkers are the highest value proposition in cancer medicine today. Despite progress in molecular sciences and evolving regulatory frameworks for biomarkers, the field has been more about promise than improving human health. Achieving precision medicine necessitates moving away from reductionist thinking to studying complex diseases as complex adaptive systems and defining biomarkers as representations of biological system states. This approach will enable redefining cancer as a disease of dysregulated communication, which could ultimately prove to be game changing for the field of biomarkers and the patients who will benefit.

Much has been written over the last two-plus decades about the inadequacies of both biomarker discovery and the distressing lack of the successful development and clinical adoption of cancer biomarkers (1, 2, 3, 4, 5). Literally, thousands of biomarkers are in the published literature, and if reports of biomarker discoveries mattered in terms of patient benefit, we should have countless biomarkers employed clinically today (3, 5). However, despite this “wealth” of reported discoveries, the number of Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved cancer biomarkers has changed little for several decades (6). Moreover, the problems leading to the dismal success of protein biomarkers has been reviewed, discussed, and rereviewed to the point that many of the sources of failure are well known for the biomarkers that do enter development (1, 2, 4, 5, 7, 8, 9). The authors that have studied, reported, and opined on why biomarkers (proteins and beyond) fail in end-to-end development (discovery to FDA approval and clinical application) cite various reasons for these dismal results ranging from the obvious example of poor quality samples to underpowering studies and bias to more complex regulatory questions of context of use and the fit for purpose of biomarker development that aims to become FDA-approved, clinically relevant assays (8, 9, 10).

However, nowhere in this dizzying array of studies, research reports, perspectives, or commentaries on biomarker failure is denial of their critical role in fundamentally understanding and ultimately controlling cancer. Biomarkers are crucial to achieving precision oncology.

Biomarkers are key to predicting cancer risk (screening), diagnosing the presence or absence of cancer, supporting disease prognosis, predicting therapy selection, subtyping patients for clinical trials, and monitoring both the safety and therapeutic signals in patients. In addition, biomarkers are key to developing pharmacodynamic biomarkers that can serve as endpoints for clinical trials and potentially become surrogate endpoints. All of these biomarker “classes” require assays that employ specific R&D strategies for establishing the metrics to determine the sensitivity (measure of positives) and specificity (measure of negatives) for specific context of uses (11). Positive and negative predictive values represent true positives and true negatives (12). These performance measures require careful consideration in the development of all biomarker assays and are especially relevant in cancer screening where even a seemingly small decrement in sensitivity or specificity can have a major impact on test outcomes and their ultimate value.

Interestingly, protein biomarkers remain the main target for biomarker discovery and development. In fact, most investigators agree that protein cancer biomarkers are key to realizing the promise of the decades of research that is currently driving the emerging concept of precision medicine. The Human Genome Project and subsequent large-scale projects such as The Cancer Genome Atlas, International Cancer Genome Consortium, Clinical Proteomics Tumor Analysis Consortium (CPTAC), and normal and tumor “atlases” at nearly all biologic scales now makes it possible to create a molecular profile of an individual patient’s cancer to predict therapy selection in the context of precision oncology (13, 14, 15). The combination of these “omics” profiles with clinical and real-world data is creating an unprecedented “big data” revolution that offers opportunities to apply machine and deep learning and other artificial intelligence (AI) approaches to potentially transform the discovery and development of new generations of cancer biomarkers. It is important to note that the initial generation, quality assessment, and interpretation of molecular data sets from these large-scale initiatives required iterative inputs from teams of disease experts, pathologists, technology platform specialists, and data scientists to separate true biological insights from misleading batch effects and other artifacts.

Given the history of biomarker discovery, it is possible that the impact of AI and other advanced technologies may not all be positive in improving the science of biomarkers but may further exacerbate problems that have historically plagued the field. Technologies such as liquid biopsy, digital pathology, advanced imaging, and broader availability of affordable genome sequencing may create unmanageable amounts of data of questionable quality that will add significant additional complexity to biomarker discovery and development (16, 17, 18, 19). For example, liquid biopsy has evolved in a short period of time to gain the confidence of the clinical oncology world, setting the stage for collecting unprecedented quantities of patient data at unprecedented speeds. Further complicating this picture, liquid biopsy will also drive the emerging field of multicancer early detection (MCED) assays, which will provide complex data sets with limited existing knowledge to support meaningful analysis (https://prevention.cancer.gov/news-and-events/blog/blood-samples-could-help) (20, 21, 22).

Despite the dismal success rate of protein biomarkers, given their effector roles in nearly every aspect of biology, they remain the primary choice for the discovery and development of biomarkers of outcome and theragnosis in oncology. To achieve success in the discovery and development of protein biomarkers, the field must engage the interrogation of dysregulated cancer biology with new thinking that views and studies cancer as a complex adaptive system (CAS) (23, 24). The convergence of AI, “multiomics” profiling, liquid biopsies, MCED assays, imaging, and advanced technologies that capture complex spatial information from patients portend different paths for the discovery and development of protein biomarkers (alone or in combination with other interrogative technologies). For example, how will information-driven systems of proteins versus an expressed protein from a relatively simple alteration in a gene, or even a few genes, change what we know about the disease to inform and improve both biomarkers and prediction for therapeutic interventions.

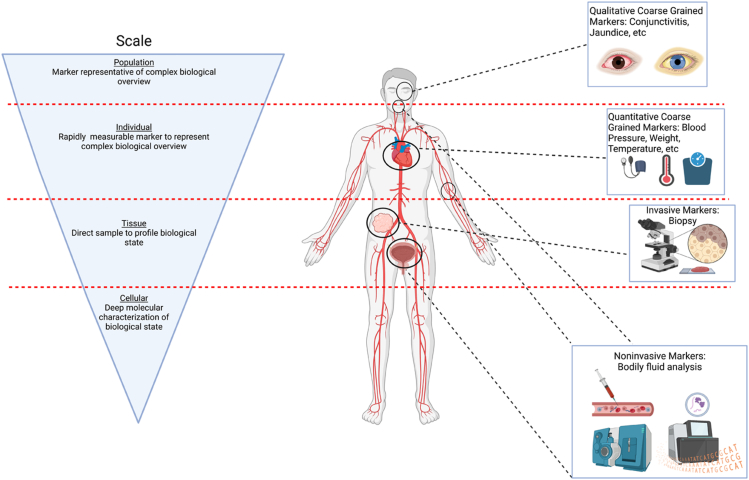

In the following paragraphs, we will briefly trace some of the history of biomarker discovery and development as a backdrop for what we may expect in the future. It has taken decades to reach a point where we can reasonably expect to collect and integrate high quality data from multiple biological scales to identify and develop biomarkers that could be transformative. We are at an inflection point. It now requires rethinking what biomarkers are—and are not—and recognizing that biomarkers as a technology class are tools that must capture the complexity of the biology of cancer to achieve their promise. In that regard, we must move beyond single genomic alterations and/or small sets of altered genes in cancer to embrace systems proteomics, which may in the final analysis produce “coarse-grained” biomarkers that more accurately represent measurable changes reflected in disease phenotypes using a combination of invasive, minimally invasive, and noninvasive platforms (25, 26, 27, 28) (Fig. 1). Future progress in the field will depend in large measure on understanding the origin, multiscale dynamics, and management of information (29, 30, 31, 32). Given the need for application of mathematical constructs and information theories to make sense of “big data,” this may well represent the biggest challenge we have faced to date in cancer research.

Figure 1.

An overview of biomarkers. Cancer is an emergent property of a complex adaptive system (CAS) that requires we move beyond the single analyte–disease correlation model and instead look at biomarkers as multiscaled. Complex (sometimes termed “Coarse grain”) biomarkers will be required to capture sufficient mutiscale information that represents an overall system state and allow us to build the mechanistic framework to describe the “diagnostic window” transitionary state between healthy and diseased. This new generation of biomarkers can be simple representations of vastly more complex biological systems, that is, jaundice and the diagnosis of liver failure. (Created with BioRender.com).

The Dismal History of Protein Biomarkers and Some Hopeful Signs

The field of biomarker science and the development paths for biomarkers discovery and development have struggled for years to determine what biomarkers are (and are not) and if protein biomarkers even existed at all. Some of this confusion comes from attempts to define what the term biomarker means, especially in terms of regulatory review. Currently most studies employ the definition of a biomarker as defined “officially” in 2001 by a task force of the National Institutes of Health and the FDA. This often-referenced definition, “A characteristic that is objectively measured and evaluated as an indicator of normal biological processes, pathogenic processes, or pharmacologic responses to a therapeutic intervention” (33) provides a reasonable construct for identifying a biomarker. Related, and as important, is the definition of a surrogate endpoint (33). Perhaps the best and most accepted definition of a surrogate endpoint was proposed in 1995 by Dr Robert Temple of the FDA, “a surrogate endpoint in a clinical trial is ‘a laboratory measurement’ or a physical sign used as substitute for a clinically meaningful endpoint that measures directly how a patient feels, functions, or survives.” (34) Interestingly, as biomarker discovery and development continue to advance, it is likely that these definitions will also need to evolve (35).

Biomarkers are likely the highest value proposition in biomedicine today, especially protein biomarkers for cancer, but frankly even with the rise of multiomics and wider use of companion diagnostics for therapeutics and significant improvements in mass spectrometry and the protein technologies, the discovery and development of biomarkers remains somewhat daunting. This should not be a surprise as the bar for clinically useful biomarkers is extremely high, especially for cancer biomarkers. Depending on the use envisioned for a cancer biomarker to be used in patients, some or all the following may apply. The authors propose that a biomarker must be (1) integrative to reflect the complexity of cancer; (2) represent the dynamics of cancer; (3) deconvolute mixed subtypes of cancer; (4) ubiquitous; (5) simple to interpret; (6) sample friendly in terms of patients; (7) be derived from high quality fit for purpose samples; (8) amenable to develop using simple technologies; (9) able to seamlessly integrate into clinical practice, hospitals, and clinical care workflows; and (10) be cost effective. The bar is even higher for a biomarker surrogate endpoint that purports to be a direct measure of how a patient feels, functions, or survives (34). These criteria point to the fact that the discovery and development of a clinically useful (successful) cancer biomarker is a formidable challenge that cost in excess of 100 million dollars end-to-end (36).

A number of authors have reviewed in detail the difficulties that have plagued the field of protein biomarkers (3, 4, 5, 27, 36), and virtually all of these explorations make clear that the failure of protein biomarker begins in biomarker discovery and cascades through the entire biomarker development cycle. As shown in Table 1, biomarkers (particularly protein cancer biomarkers) have proven especially hard to discover, and false discovery has resulted in less than a single protein biomarker being approved by the FDA since the early 1990s (27). Clearly, the failure of protein biomarkers in discovery is inexorably linked to our lack of understanding of the biology of expressed proteins that derive from dysregulated genes that exist in cells which are themselves highly complex-regulated environments.

Table 1.

Why protein biomarker fail in discovery and what has changed

| Failure source | What goes wrong | Changes that mitigate the problem |

|---|---|---|

| An interesting but irrelevant clinical question | Biomarker does not address the clinical question or is not sufficiently different from an existing clinical biomarker (5). | “Multiomics,” MRM mass spectrometry, new generation proteomic technologies imaging, AI, and engagement of multidisciplinary teams are vastly improving opportunities to understand root causes of disrupted molecular pathways; and with the addition of real-world patient data, biomarker discovery will become more successful (27, 47, 48, 67, 70, 125, 126, 127). |

| Experimental design | Design is underpowered, does not recognize or control for bias anticipated analytics needs, or specifically address the question (10, 39, 128, 129). | Improved statistical models, Bayesian designs, and AI are proving new approaches to design robust proteomics biomarkers that minimize bias and other confounders (130). |

| Samples | Poor quality (often convenience) samples of insufficient numbers to power the study (8, 131). | The last decade has steadily improved the sources and quality of human samples—including approaches that maintain the fidelity of the biology of the sample, including preanalytics (https://biospecimens.cancer.gov/bestpractices/index.asp) (132, 133). |

| Technology standards | Technology standards in areas such as mass spectrometry, sequencing technologies, etc. are not used to ensure quality and reproducibility (131). | Increased sophistication of protein measurement technologies, especially mass spectrometry, increasingly requires wider spread of use of standards at all levels of sample interrogation (27, 45). |

| Data quality and metadata | Poor samples equal to data that does not assess the biology targeted in the hypothesis; lack of metadata (especially clinical data) renders the biomarker useless (134, 135). | Data quality remains a major challenge, but the eras of “big data” is requiring investigators to consider data relative to sample quality and ensure appropriately consented metadata (27, 45, 66). |

| Flawed analytics | Biomarker studies require increasingly sophisticated analytics—well beyond “p values” and many researchers are not trained in ML and AI overall (136, 137). | The analytics space remains a work in progress. Data quantity, quality, and velocity from proteomics technologies require new thinking and approaches in the design phase of biomarker discovery inclusive of analytics that are AI based (138). |

| Reproducibility | All of the above and more render many biomarker studies irreproducible—significant source of overall failure (4, 131, 139). | Reproducibility of results across all of oncology, especially biomarker, research was (and remains) a major source of biomarker failure. FDA has emphasized the critical nature of sensitivity, specificity, and reproducibility of biomarkers in all of their guidance documents and reviews—which is helping (45, 128) (https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/BILLS-114hr34enr/pdf/BILLS-114hr34enr.pdf). |

Deconvoluting the underlying complexity of cancer through biomarkers is a mandate for all aspects of discovery studies that aim to identify any type of cancer biomarkers, especially proteins. Unfortunately, as pointed out in numerous studies, just the opposite is true, with a plethora of reports of false discovery. Table 1 summarizes many of the reasons for the failure of biomarkers including beginning with an irrelevant clinical question; flawed experimental design; convenience samples of poor quality and insufficient numbers; lack of technology standards (even if they exist); poor data quality, especially lack of metadata; inadequate or just wrong analytics; and lack of attention to the reproducibility of results.

Table 1 also illustrates that some of the root causes for biomarker failure are being addressed, but the creation of robust protein cancer biomarker pipelines will require solutions for these barriers and some that are less obvious. For example, addressing preanalytical variability of patient samples is a critical, but often overlooked, source of failure for protein biomarkers, and fortunately, standards are in various stages of development (4, 37, 38, 39). For example, application of the National Cancer Institute’s (NCI) best practices is designed to minimize preanalytical variability (https://biospecimens.cancer.gov/bestpractices/index.asp), and the goals of consortia such as BloodPAC aim to improve the reproducibility and value of blood-based cancer assays through the development of standards and frameworks (40). All of these efforts are reenforced by the need for biomarker studies to be clinically relevant in response to the FDA’s requirements that workflows warrant standard operating procedures ensure “fit for purpose” (41) with NCI’s biospecimen evidence-based practices serving as a potential guide. Despite these efforts there are, as of this writing, no national standards to control the impact of preanalytics on biomarker discovery and derivative development pipelines. The reason for this lack of uniform standards is in the spirit of siloed science, as there is an abundance of standards. Unfortunately, to date, the focus has been more on standards development than harmonization—and the result is limited progress in the lack of reproducibility of biomarker research.

The “big data” revolution is proving to be both an asset and a liability for biomarker discovery and development. Siloed science drives data protectionism and sequestered data sets that are of insufficient power to drive quality biomarker studies. In addition, to establish predictive clinical cancer biomarkers will require agreement on common data elements, data harmonization standards and significant increase in open access to longitudinal and paired clinical outcomes data (5, 42, 43). Recent federal initiatives purport to address some of the problems associated with data availability, harmonization, and longitudinal data access through mandate that data from federally funded grants (e.g., NCI) be publicly available (https://www.whitehouse.gov/ostp/news-updates/2022/08/31/what-they-are-saying-white-house-federally-funded-research-guidance-hailed-as-a-win-for-innovation-and-equity/) (44, 45).

Looking into the future where cancer is viewed as a complex adaptive (and evolving) system versus a collection of “parts,” it will be necessary to develop systems level biomarkers. It could be argued that the best systems level biomarkers we have for cancer today are stage and grade, which offer “snapshots” and something of a surrogate for the extent of tumor development over time inclusive of evolution and the resulting heterogeneity that defines most cancers. Although these may be systems level representations of cancer, they tell you almost nothing about the cancer that is actionable. Cancer is an emergent property of a complex system, and deconvoluting the integrative and dynamic nature of the overall system through biomarkers is a daunting proposition. That said, perhaps these biomarkers will be more reflective of measures of system states at hierarchical levels more reflective of the phenotype. Such biomarkers will require multidisciplinary teams (cancer biologists and clinicians, mathematicians, physicists, and engineers) to iteratively optimize and monitor multiscale systems dynamics (46, 47, 48). Perhaps in the future, there will be more integrative, coarse-grained biomarkers such as a patient’s performance score, which may well offer a measure of the integrative and dynamics aspects of the overall system.

Technology Advances Promise Biomarker Success—but to Date a “Slow Slog”

As noted in the prior section, biomarker discovery and subsequent development has maintained an uncertain and often detached, relationship with advances in technologies—often delaying and sometimes slowing progress. For example, the success of imatinib for chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) is the best example of how advances in technology informed the development of a highly clinically important biomarker discovery. The Philadelphia chromosome discovery was first reported by David Hungerford and Peter Nowell, based on application of new cytogenetics techniques that revealed the alterations in chromosome numbers in seven CML patients (49). A decade later, Janet Rowley’s use of quinacrine fluorescence karyotyping nine CML patients revealed the origin of the Philadelphia chromosome and paved the way for a new methodology to characterize chromosomal alterations across cancers (50). Both discoveries, at the time, were dismissed and mired by problems that continue to plague biomarker studies today: insufficient patient samples to determine whether the results were artifacts of new technologies or potential new clinical insights. Now we know these initial discoveries paved the way to the identification of the BCR-ABL fusion gene as the principal pathogenetic driver of CML and approval of the first successful tyrosine kinase inhibitor targeting the function of a fusion gene, imatinib, by the FDA in 2001 based on the dramatic results of pivotal clinical trials (51).

Imatinib initiated an era of biomarker discovery focused on finding “more” BCR-ABL–like targets and spurred 2 decades of evolution of molecular profiling technologies. We are now in an era of multiomics, with advances in genomics, transcriptomics, and epigenomics; are protein biomarkers still considered the “holy grail of biomarkers?” Although genomics and transcriptomics are often touted as comprehensive for creating patient molecular profiles, the fact is that these modifications do not necessarily manifest in the proteome (36). The proteome remains perhaps the most impacted biological measure of disease on a broadscale that reflects the state of the underlying biology (3). Protein posttranslational modifications alter signaling networks which create opportunities for discovery of new therapeutic targets (52). Although all aspects of the digital information that derives from the genomic alterations play some role in cancer, it is the systems of proteins (systems proteomics) that affect functional changes that provide a path to fundamentally understand and control cancer.

PSA—A Learning Experience and Cautionary Tale

The imatinib experience taught us that achieving an increased understanding of a disease at the molecular level does not necessarily lead to the discovery of clinically important protein biomarkers. Although protein cancer biomarkers (and cancer biomarkers overall) have historically suffered from significant failure, we have gained valuable lessons that cancer is not a singular event but rather a dynamic state change that evolves across space and time. Clearly, the early and somewhat naïve assumption that single protein biomarkers would capture cancer’s complexity led to the unfortunate reality that approximately 1% of published biomarkers achieved clinical utilization (4). For example, first approved by FDA in 1986, prostate-specific antigen (PSA), a single protein, was one of the few early biomarkers that advanced to clinical use, and it has taught us a great deal about the challenges associated with its use in both the screening and diagnostics settings for a heterogenous disease like prostate cancer.

The expansive deployment of PSA tests in the United States in the early 1990s led to significant overdiagnosis and unnecessary invasive and often harmful therapeutic interventions (53, 54). It was estimated during this time that only 25 to 30% of “positive” cases would ultimately develop cancer, and by 2009, PSA screening represented over $750 million a year in unnecessary follow-up testing (36). Another learning experience from PSA testing was the realization that signals from other biological processes, such as inflammation and trauma (55), could produce positive PSA results and an abundance of false positives. It also became clear that a PSA test offered little, if any, guidance on the optimal point for disease intervention, and it became clear that deployment of a screening test like PSA in the population at large requires exquisitely validated sensitivity and specificity (56, 57, 58). Validation across all affected populations and the addition of familial history, multiomics profiles, and clinical data have continued to improve the value of PSA (59).

Ironically, although PSA does not capture the complexity of prostate cancer, it has recently demonstrated the value of an imperfect screening test for early detection of this disease. As early as 2014, and again in 2018, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommended that men of 55 to 69 years should decide if they wanted to have PSA screening, or not, and further recommended that men of 70 years of age or older should not receive PSA screening (https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/index.php/recommendation/prostate-cancer-screening). In subsequent years, prostate cancer increased 3% per year from 2014, and the proportion of advanced prostate cancer has more than doubled over the past 10 years (https://www.cancer.org/research/cancer-facts-statistics/all-cancer-facts-figures/2023-cancer-facts-figures.html). This alarming increase in late stage prostate cancer prompted the American Cancer Society to make evidence-based recommendations in 2023 for screening that combines age, risk, and PSA results (https://www.cancer.org/research/cancer-facts-statistics/all-cancer-facts-figures/2023-cancer-facts-figures.html). Although PSA is not a perfect test and research is required to determine if PSA screening has differential effects in affected populations, it is a cautionary tale. PSA tests apparently measure an important disease signal, and its deployment as a screening assay plays a significant role in identifying disease at a point where intervention is warranted. The tradeoffs in terms of slowing or preventing advanced disease speak to the value of identifying early disease signals, even in the setting of accepting a percentage of false positive results. In addition to the potential role of PSA in identifying key disease signals, one of the major outcomes from the PSA experience is the extent to which efforts to improve the assay have enabled significant advances in understanding the complex biology of prostate cancer. Imperfect tests, especially PSA, have made clear that cancer biomarkers will require a high degree of dimensionality to reflect the heterogeneity and complexity of most cancers and the need to understand how biomarkers can be leveraged to understand state changes in cancer. These findings and improvements in protein biomarker discovery, development, plus the availability of new FDA regulatory pathways have benefitted the field of biomarker science, especially the promise of protein biomarkers.

In recent years, multiple advances in technologies, like the BCR-ABL story, are supporting and accelerating the successful discovery and development of the protein biomarkers of the future. Sequencing technologies and multiomics approaches are evolving rapidly to enable sequencing workflows, reduce costs, and enable progress in precision medicine, especially oncology. Fortunately, the story of protein biomarker discovery and development is not all doom and gloom. There are several examples that demonstrate the power of multiomics technologies and protein-based biomarkers to support more effective discovery, development, and utilization of clinically important cancer biomarkers.

Launched in 2010, the I-SPY 2 consortium is an excellent example of a learning system that utilizes a suite of biomarkers to pair patients with the most rational therapeutic intervention for their disease. The I-SPY 2 consortium has continuously enrolled patients on a multiarmed, master protocol to evaluate new neoadjuvant therapies in combination with standard-of-care chemotherapy for breast cancer (60). Utilizing Bayesian adaptive randomization and clinical biomarkers to assign patients to specific breast cancer biomarker–based subtypes, a number of therapies have successfully “graduated” to move on to small phase 3 trials (61). Moreover, the multiple arms of the trial and biomarker-based subtype treatments support advancing successful therapies to patients and in parallel provide the power needed for biomarker regulatory approval. This innovative approach to trial design is reducing the costs of clinical trials, and as an enduring “platform” trial, it is streamlining the organization and set-up of further clinical trials (62). Master protocols have been employed to perform adaptive platform trials beyond breast cancer including the Beat AML trial (63) and the GBM AGILE Trial (64) for glioblastoma, and the model continues to be adopted across other diseases (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04488081). As observed in I-SPY 2, these trials offer exciting opportunities to identify protein biomarkers that can serve to assign treatment based on molecular biomarkers, subtype disease, and advance precision oncology.

Whole exome sequencing of specimens in lung cancer cohorts have identified numerous genomic alterations, with somatic mutations as high as 8 to 10 mutation per mega base, reflecting the vast genetic heterogeneity in lung cancer (43). Next generation sequencing (NGS) mutations can be traced to single base-pair resolution levels, without sacrificing accuracy or precision, and multiple cancer types are beginning to leverage these technologies for better multiomics resolution and associated biomarker development. In fact, genomics screening has quickly become a standard of care in non–small cell lung cancer as the National Comprehensive Cancer Network’s 2023 principle of molecular and biomarker analysis guidelines have recommended nine genomic screening biomarkers along with PD-L1 expression for therapeutic decision making in non–small cell lung cancer (65). Multiomics changes also differentiate tumors from normal tissues, paving the way for improved targeted therapeutic intervention to extend patient survival (66). The NCI lung-MAP trial and the UK national lung matrix trial are just two examples of trials that are leveraging NGS to identify multiple gene panels as biomarkers for lung cancer.

As sequencing methods continue to advance in depth of coverage, so does the ability to potentially develop high sensitivity and specificity protein biomarkers to detect early-stage tumors. While multiomics markers are providing much needed support for targeted therapies, especially in precision oncology, markers for immunotherapy remain a major challenge. Complex (black box) biomarkers such as tumor mutational burden (43) are of limited use in predicting patient response and monitoring patients that do respond. Patient molecular profiles based on classic genomics without consideration of epigenomics are insufficient to support optimal decision making by physicians. Epigenetic changes are common across all human cancers, as posttranslational and histone modifications play significant roles in altering the expression of various oncogenes and tumor suppressors (67). It has been shown that mRNA levels tend to correlate poorly with protein abundance, but by leveraging genomic level data, prediction of protein expression will improve (67, 68, 69). Although transcriptomics has allowed us to have a better understanding of the genetically driven RNA transcript alterations, genomic, epigenetic, and transcriptomic alterations will manifest in ways that will impact protein expression, making proteomics the strongest candidate for clinically relevant biomarkers. In recognition of these findings, proteogenomics as an emerging field has increased significantly in recent years as the science has evolved. By combining multiple omics modalities to acquire a more comprehensive landscape of the disease state, we are increasingly developing biomarkers to support therapy selection and patient monitoring.

Proteogenomics

Proteogenomics represents an application of multiomics to biomarker discovery and development. Proteogenomics, the combination of genomics and proteomics, has emerged rapidly over the past decade to define genomics-driven proteomic workflows. The NCI CPTAC flagship programs have been largely successful in developing assays and potential markers across multiple cancers, leveraging the proteogenomic approach (38, 70, 71, 72). As of 2022, over 3500 assays for 3224 unique peptides and 1742 unique proteins have been validated by the CPTAC initiative to develop reproducible targeted mass spectrometry–based assays for biomarkers in cancer (73, 74, 75). Advances in NGS will allow for ever-better identification of proteins to create pipelines of interest to both CPTAC and the industry. Selected companies maintain that next generation biomarker research should encompass genomic sequencing, transcriptomics, neoantigen prediction, immune profiling, and single-cell sequencing (https://www.science.org/content/resource/genomic-biomarkers-multiomics-next-generation-sequencing-cancer-research). Proteogenomics continues to advance, with recent CPTAC reports demonstrating the ability of these pipelines to generate biomarkers of patient responses to chemotherapy and therapeutics (71). Progress in proteogenomic-based approaches are powerful and promising technologies that look to improve and advance the discovery and development of protein biomarkers to support precision oncology in the future (76).

The emergence of proteogenomics highlights the need for integration across the research discovery, development, and delivery continuum. The focus on individual investigator studies has historically focused on single genes and/or proteins and resulted in what has become “siloed science.” Nowhere is that truer than in oncology where thousands of “biomarkers” are reported in the literature (77) and few ever even make it into development. To achieve progress in proteogenomics, and deconvolute the complexity of cancer, it will require that silos come down and the “omics” research communities unite through seamless partnerships that will result in high value biomarkers that will move the field forward (https://www.cancer.gov/news-events/cancer-currents-blog/2021/cancer-moonshot-midpoint-progress-update). As discussed later in this perspective, these partnerships are essential to fundamentally understand that cancer is an emergent multiscale complex system driven by dysregulated communication where each scale has its own integrative structure and emergent properties.

Liquid Biopsy

Proteogenomics is not alone in what portends an improved future for protein biomarkers, and one of these advances, liquid biopsy, may prove to be transformative for all aspects of cancer diagnosis, treatment, and even prevention. Liquid biopsy for cancer generally refers to the analysis of circulating tumor DNA but may also include isolation and analysis of other tumor-derived material from bodily fluid matrices. Isolating these fractions is challenging, as the abundance of circulating tumor DNA to cell-free DNA in circulation can range from 0.1% to 90%, and although imperfect, it is generally reflective of the tumor burden in a given patient (20). Despite several challenges, the method has expanded exponentially recently as a popular orthogonal technique to analyze patients that is less invasive compared to traditional needle biopsy.

Early Multiple Cancer Detection Assays

The rapid evolution and expansion of liquid biopsy methodologies is best personified in what is a new class of MCEDs. As of 2022, there are more than 27 companies developing MCED assays. Many MCED assays claim to detect over 50 cancers using CpG methylation analysis of cell-free DNA coupled to NGS or other methods. This assay is in a trial to evaluate results in 140,000 patients to validate its predictive value. Whether or not these assays will make a difference in cancer survival is yet to be determined, but the field of MCED is without question a highly promising development for biomarker research (78).

Although overall liquid biopsy continues to develop, and similar to biomarkers, reproducibility in this setting illustrates the critical need for larger data to power these technologies. For example, it has been posited that liquid biopsy–based MCEDs may be the next PSA, leaving little doubt that a great deal of more research is required for these assays to ever become screening tools for early detection of cancer in the population (https://prevention.cancer.gov/news-and-events/blog/blood-samples-could-help). Liquid biopsy in general, and MCEDs, in particular, offer hope that achieving scale and application of stringent quality control metrics in sampling will significantly improve biomarkers for all phases of the patient’s journey—well beyond detecting early cancer “signals” (21, 22). Reflecting the promise of the MCEDs as diagnostics, federal agencies are attempting to develop infrastructure to determine if identifying potential cancers very early also increases survival (https://prevention.cancer.gov/news-and-events/blog/blood-samples-could-help). In hopes of answering this question, the NCI has expanded trials to evaluate 24,000 patients over a span of 4 years (https://prevention.cancer.gov/major-programs/multi-cancer-detection-mcd-research). One thing is clear, for these assays to be effective as screening tools in the general population will require near perfect sensitivity and specificity.

Single-Cell Analysis

The science of biomarkers is also benefiting from single-cell analysis. For example, the NCI Cancer Moonshot is establishing a clinical, experimental, computational, and organizational framework to create publicly available tumor atlases that includes single-cell analysis (44, 45). In addition, single-cell analysis is enabling deeper profiling of the microenvironment, an increasingly important source of potential cancer biomarkers, as is mass spectrometry imaging that profiles single-cell populations within the tumor immune microenvironment. This approach allows investigators to identify cellular subtypes by combining both tandem mass tags with antibodies for a targeted proteomic approach that can be further multiplexed to provide biomarkers that characterize the overall cancer immune profile (79, 80, 81). Targeting single-cell interactions promises to transform therapeutic intervention as cellular subtypes associated with resistance to hormone ablation therapy in prostate cancer and in melanoma patients have been identified using these technologies (82, 83). Although there are myriad challenges (e.g., reproducibility and scaling) in single-cell proteomic analysis, these technologies offer much needed opportunities to molecularly characterize the tumor immune microenvironment and increase the effectiveness of these therapies in cancer patients (84). Single-cell analysis continues to grow, and new guidelines have also been established by the community at large to help continue its maturity (85).

As briefly reviewed here, the last 2 decades have seen an explosion of multiomics profiling and a range of advanced technologies designed to support precision medicine. This review does not include advanced imaging technologies, nanotechnology devices, synthetic biomarkers, and several other advances that enable probing the proteome. The emergence of liquid biopsy, continued development of single-cell analysis, and these other technologies could have the potential to transform biomarker discovery. However, in all of these domains, it will ultimately be critical to understand how information is encoded into defined pathways and networks, and to map the perturbations in those networks in the context of a given disease, and importantly around a clinical decision. Clearly translating multiomics profiling into an understanding of biological signaling networks as they relate to disease highlights the challenge of understanding the overlap of these networks in complex systems. Diseases are often more than the sum of their parts, and while a singular focus on omics domains may yield a lot of data, it will not be sufficient to capture the information needed to define a disease phenotype or drive improved clinical decision making. Advancing precision medicine necessitates moving away from the lens of reductionist thinking toward the understanding that complex diseases are in fact CASs. In addition, the field needs to adopt communication models that maximizes information and reduces noise at all levels in a CAS (Fig. 2). Theoretical constructs such as Shannon information theory is one approach that may be able to decode the information needed for biomarkers at various biologic scales.

Figure 2.

Information transfer. Understanding where and how biological information is encoded and transferred is essential to collect the right data to support accurate measurements. Uni-dimensional collection of a singular parameter is susceptible to bias and can lead to misrepresentation of the biological state in question (Created with BioRender.com).

Discussion: Embracing Complexity, Realizing the Diagnostic Promise of Protein Biomarkers

Embracing Complexity

Clearly, for the biomarkers of the future, especially protein biomarkers, to be more predictive requires that they increasingly capture the complexity of cancer information and associated signals. In that regard, it will become necessary to redefine biomarkers as representations of a biological system state at different hierarchical levels of biological order (Fig. 1). This definition would include traditional molecular, histologic, radiographic, or physiological characteristics, as well as emerging classes of digital markers and complex algorithms. In the case of protein biomarkers, it will be necessary to move away from single or small numbers of proteins to effectively capture the information in protein networks and systems. Over 90% of the human proteome has now been validated at high stringency to better enable the understanding of the proteome networks, thanks in large part to efforts from the Human Proteome Organization (86, 87). Systems proteomics will support the discovery and development of biomarkers that can capture complex systems information throughout the health-to-disease continuum of patients and thus enable the development of efficacious treatments and high value diagnostics and theragnostics. In this regard, using biomarkers to understand information architectures and information processing in complex biological systems will be of key importance for making precision oncology a reality.

Reframing Cancer Diagnostics as an Information Transfer and Systems Management Problem

As we look forward the next decade of cancer biomarker–related studies, one of our greatest opportunities to succeed will come from reframing the challenge of biomarker discovery and accordingly the approaches taken for data analysis and interpretation. To date, much of the focus of biomarker studies has been through the lens of univariate binary classification. This framing essentially states the biomarker challenge as, “find a protein whose abundance differentiates state X (i.e., healthy) from state Y (i.e., diseased).” In the case of diagnostics for infectious disease, such a phrasing is reasonable. There is a clear mechanistic link, and appropriate reductionism, between the presence of a pathogen in the body and the presence of a pathogen’s shed material in locations that can be easily sampled. Furthermore, the wide molecular gulf between a pathogen and its host makes the differentiation of signals from the pathogen and background signals straightforward to interpret. Because there is such a significant difference between host and pathogen, it can often be straightforward to look at one or a few pathogen-derived biomarkers as differentiators in a relatively time-invariant manner. In therapeutics, the distinction between disease and healthy state is often referred to as the “therapeutic window” and enables thinking about how straightforward it is to therapeutically target a given disease. We adopt the term “diagnostic window” to describe the magnitude of difference between disease states and healthy states.

Unfortunately, when finding diagnostics for diseases like cancer, the binary classification framing of biomarker studies is unlikely to succeed. The simplest diagnostic windows, such as those in many infectious diseases, are ones in which a marker or set of markers are absent in one state and present in another. More complex diagnostic windows might operate with different effective set points, such as low in one state and high in another (such as with serum troponin before and after cardiac arrest (88)). However, as tumors are extremely like their host, particularly in their earliest stages, the signals from those cancers are less differentiated and thus the diagnostic window is likely incredibly small as within person, and across person, biological variance can be large and state-to-state difference can be small. Furthermore, cancers are multiscale, complex adaptive, and dynamic systems, so the signals they are producing are constantly changing, further exacerbating the challenge of finding a marker whose single-timepoint measurement is radically different between states (Fig. 2). Given these two factors, it becomes necessary to reframe the biomarker-based diagnostics challenge away from univariate binary classification and toward a more descriptive information-rich framework. These innovative approaches are already influencing the field of proteomics, with the Human Proteome Grand Project representing an excellent example of an increased understanding that proteomics functions as a network of networks (https://hupo.org/page-1757429).

We cast the challenge of describing the state and trajectory of a tumor as an information transfer and management problem as illustrated by the following example. Remote sensing dates back to mid-19th century when aerial photographs were taken from hot air balloons or by camera-bearing carrier pigeons. The term “remote sensing” was first used in the United States in the 1950s by the Office of Naval Research (89) and is now commonly used to describe the science of identifying, observing, and measuring an object without coming into direct contact with it. One can deconstruct such problems as containing two pieces: the first is the signal(s) coming from the monitored object(s) and the second is the communication of that signal from the source through a communication channel to a receiving device (Fig. 2). A communications framework (90) gives us both a language and set of techniques for interrogating our biological problem of biomarker discovery. It is quite natural to recast the early detection and therapeutic response prediction/monitoring problems as information transfer and management problems. Essentially, for cancer early detection and therapeutic response characterization, we would like to discern the presence and trajectory of a tumor without requiring direct measurement of that tumor. The “source” in our model would be the tumor or the host response to that tumor. The “signal” would be the protein(s) from that tumor, and the “channel” would be the poorly characterized and extremely noisy process of shedding by which proteins travel from the tumor into the circulation and persist therein (Fig. 2). Through this lens, proteins are “transmitted” from the tumor to the circulation as governed by a series of information transfer functions. Alternately, signals influenced by the tumor, but not generated by the tumor, such as the immune response or changes in the microbiome could be considered in this framework. The sensor at the receiver may be one of a wide variety of techniques ranging from ELISA to broadscale proteomic profiling.

An additional benefit of a communications framework is that it enables the use of time-dependent, multiscale models describing signal origins and signal transfer. Despite thousands of case-control profiling studies attempting to discover biomarkers, the number of studies asking simple, fundamental questions about biomarker origins is extremely small (91, 92, 93, 94, 95, 96, 97). The existence of biomarkers is predicated on the assumption that processes occurring at the tumor are reflected at a distance, such as in the circulation, urine, or in breath exudate. Proteomics-based biomarker discovery approaches have asserted that many potential markers are tumor-derived proteins that may be detected in the circulation, via shedding (secreted, cleaved from the cell surface, or released from the cell by either lysis or exocytosis) from the tumor, and then transited into blood (77, 98). Consequently, the composition and dynamics of the tumor proteome may be reflected in the circulating proteome (99, 100, 101, 102, 103). Based upon the assumption of a relationship between the tumor proteome and the circulating proteome, logical arguments are presented regarding the need to give higher priority to abundant tumor proteins (94, 104, 105, 106). As shown in Figure 2, it is possible to examine these assumptions. In particular, we must examine how molecular changes propagate to the cell scale and are impacted by tissue and host scale effects. For example, what if the proteins produced by the tumor change over the course of its progression, such as through evolution of the cellular heterogeneity or changes in the microenvironment? Likewise, what if there is a nonmonotonic relationship between the abundance of a protein in the tumor and in the blood. Though attractive, the monotonicity assumption may not be universally true; there may be a wide range of functions relating a protein’s tumor levels to its circulating levels. This is especially true given the likely wide range of degradation and clearance rates (107, 108, 109, 110); for reference, decades of research shows that intracellular protein turnover rates (111) vary from minutes, weeks, or even months (112, 113, 114, 115). Consequently, it is possible that proteins with large case versus control differences in abundance at the tumor site may be either unobservable or uninformative when interrogated in the circulation. Furthermore, as both the patient and the cancer are constantly changing, it is highly likely that we will need diagnostics that anticipate time-dependent variation, such as those that arise through circadian rhythm or from changes in weight or as induced by hormonal therapy (116, 117, 118). To succeed going forward, we must get past purely observational studies and instead start building a communications framework in which to better interpret the vast array of observational data. The biomarkers must also look for the dynamic changes of the tumor, as many studies have shown static cells with tumor-associated molecular changes that do not cause harm to the host (119, 120).

Building the communication frameworks needed to drive progress in the discovery of biomarkers that represent complex systems states will benefit from several current opportunities including the integrative analysis of new studies within the context of prior studies. For example, there are nearly 2000 publications citing TIMP1 as a putative biomarker in diseases as wide range as pancreatic cancer and rheumatoid arthritis. Unfortunately, with new studies being done in isolation, it is hard to contextualize any potential biomarker. Resources like MarkerDB and the GVK 13,000 biomarker database could potentially help in the future (121, 122). There is also an opportunity to use multidata-type analysis, such as the integration of transcriptome and proteome data, especially given that at the cell scale, there are key linkages between molecular scales (e.g., transcriptome to proteome) that can give a synergistic boost to data interpretation. To recognize this boost, it is necessary to treat the data, not simply as additional dimensions but instead as linked multivariate entities. Learning these relationships within any singular dataset is currently an intractable problem. However, appropriate use of prior information and prior mechanistic models can enable more grounded, integrative analysis. Finally, the field will benefit greatly from the development of controlled vocabularies and repositories for both biomarker-associated data and experimental metadata and results of these studies.

Looking Forward: A Portentous Future

Dating to the mid 1990s, viewing cancer as a CAS is not a new concept (23). Albeit biologic CAS is increasingly defined in greater detail; simply stated, they consist of large numbers of interacting components with simple rules of operation that exhibit selforganization and information processing. CAS is also characterized by internal information flows and dynamic input from external information flows. These properties lead to subsystems (complex interacting networks) that exhibit properties that cannot be predicted based on understanding the individual components. Complex systems adapt and evolve giving rise to collective emergent properties, which cannot be predicted from studying the parts of the system. In fact, cancer is perhaps best described as an emergent property of a CAS.

The future of cancer biomarker discovery, especially protein biomarkers, will depend in large measure on identifying and understanding the dysregulated information architecture, transfer, and management processes of cancer in a CAS context. Information in biological systems is stored everywhere and flows everywhere in time scales that are difficult for most current technologies to capture, but coarse-grained elements of these systems can be measured and used as surrogates. Most of the problems encountered in biomarker discovery to date reflect this lack of understanding of what information is, where it is, and how information is related to data. Some of the current AI approaches in development today promise to reduce the dimensionality of the data from a dysregulated system like cancer, but the translation to information will require identifying the signal based on a defined biological context. However, capturing the complexity and trajectory of the cancer CAS through systems of protein biomarkers will require the application of novel communication frameworks including theoretical constructs such as information theory (24, 123) that provide a basis for understanding how information is encoded and transmitted, which offers an opportunity to reduce uncertainty in the predictions based on converting data to information (90, 124). One such theoretical construct, mathematically based Shannon information theory (90), is especially promising for its applicability to biological information. The theory enables defining information based on context (including temporal and spatial information) and distinguishing signal (information) from noise (entropy) at escalating levels of complexity in cancer. Evolution suggests that signaling networks in biology are optimized to match information sources, which will open new areas of investigation based on dysregulated signaling in cancer (24).

Achieving this transition will not be easy. However, it is increasingly a scientific imperative that the identification of clinically relevant biomarkers (especially proteins) be developed for a cancer patient’s journey from diagnosis to survivorship. Ideally, the future will embrace the discovery, development, and delivery of complex information-based biomarkers gleaned through theoretical constructs that capture cancer as a disease of multiscalar communication in the context of a CAS.

Conflict of interest

A. D. B. declares the following financial relationships: Ellison Institute for Transformative Medicine, Caris Life Sciences, Pancreatic Cancer Action Network, and Sage Bionetworks. A. D. B. declares the following noncompensated relationships: NCI National Cancer Advisory Board, American Association for Cancer Research, Arizona State University, Milken Institute, Quantum Leap Healthcare Collaborative, and Friends of Cancer Research. P. M. is a paid faculty member of Stanford University, Paid Founder and Chief Scientist of Nautilus Biotechnology, a compensated member of the Scientific Advisory Boards of ChromaCode, OncImmune, and January AI, and an uncompensated President of The Dream Finder Foundation. J. S. H. L. is the paid Chief Science and Innovation Officer of EITM, paid faculty member of USC, advisory board member of AtlasXomics, Inc, and paid consultant of the Henry M. Jackson Foundation outside the submitted work. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions

A. D. B. conceptualization; A. D. B., M. M. A., P. M., and J. S. H. L. writing–original draft; A. D. B., M. M. A., P. M., D. B. A., and J. S. H. L. writing–review and editing; D. B. A. supervision.

References

- 1.Pepe M.S., Etzioni R., Feng Z.D., Potter J.D., Thompson M.L., Thornquist M., et al. Phases of biomarker development for early detection of cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2001;93:1054–1061. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.14.1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Diamandis E.P. Cancer biomarkers: can we turn recent failures into success? J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2010;102:1462–1467. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rifai N., Gillette M.A., Carr S.A. Protein biomarker discovery and validation: the long and uncertain path to clinical utility. Nat. Biotechnol. 2006;24:971–983. doi: 10.1038/nbt1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kern S.E. Why your new cancer biomarker may never work: recurrent patterns and remarkable diversity in biomarker failures. Cancer Res. 2012;72:6097–6101. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-3232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Poste G., Compton C.C., Barker A.D. The national biomarker development alliance: confronting the poor productivity of biomarker research and development. Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn. 2015;15:211–218. doi: 10.1586/14737159.2015.974561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Selleck M.J., Senthil M., Wall N.R. Making meaningful clinical use of biomarkers. Biomark Insights. 2017 doi: 10.1177/1177271917715236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diamandis E.P. Analysis of serum proteomic patterns for early cancer diagnosis: drawing attention to potential problems. J. Natl. Cancer. 2004;96:353–356. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mischak H., Ioannidis J.P., Argiles A., Attwood T.K., Bongcam-Rudloff E., Broenstrup M., et al. Implementation of proteomic biomarkers: making it work. Eur. J. Clin. Invest. 2012;42:1027–1036. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2012.02674.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Committee on the Review of Omics-Based Tests for Predicting Patient Outcomes in Clinical Trials, Board on Health Care Services, Board on Health Sciences Policy, Institute of Medicine, Micheel C.M., Nass S.J., Omenn G.S. Evolution of Translational Omics: Lessons Learned and the Path Forward. National Academies Press (US); Washington, DC: 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ransohoff D.F. Opinion - bias as a threat to the validity of cancer molecular-marker research. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2005;5:142–149. doi: 10.1038/nrc1550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trevethan R. Sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values: foundations, pliabilities, and pitfalls in research and practice. Front. Public Health. 2017;5:307. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2017.00307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Safari S., Baratloo A., Elfil M., Negida A. Evidence based emergency medicine part 2: positive and negative predictive values of diagnostic tests. Emerg. (Tehran) 2015;3:87–88. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Edwards N.J., Oberti M., Thangudu R.R., Cai S., McGarvey P.B., Jacob S., et al. The CPTAC data portal: a resource for cancer proteomics research. J. Proteome Res. 2015;14:2707–2713. doi: 10.1021/pr501254j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jensen M.A., Ferretti V., Grossman R.L., Staudt L.M. The NCI genomic data commons as an engine for precision medicine. Blood. 2017;130:453–459. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-03-735654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Milella M., Lawlor R.T., Luchini C., Johns A.L., Casolino R., Yoshino T., et al. ICGC-ARGO precision medicine: an update on familial matters in pancreatic cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2022;23:991–992. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(22)00448-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gentry-Maharaj A., Blyuss O., Ryan A., Burnell M., Karpinskyj C., Gunu R., et al. Multi-marker longitudinal algorithms incorporating HE4 and CA125 in ovarian cancer screening of postmenopausal women. Cancers(Basel) 2020;12:1931. doi: 10.3390/cancers12071931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuk C., Kulasingam V., Gunawardana C.G., Smith C.R., Batruch I., Diamandis E.P. Mining the ovarian cancer ascites proteome for potential ovarian cancer biomarkers. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2009;8:661–669. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M800313-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Theil G., Fornara P. [Innovations in personalized medicine: molecular characterization of liquid biopsy-fake or fact?] Urologe A. 2018;57:1069–1074. doi: 10.1007/s00120-018-0692-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goldstein N.S., Hewitt S.M., Taylor C.R., Yaziji H., Hicks D.G., Comm A.-H. Recommendations for improved standardization of immunohistochemistry. Appl. Immunohistochem. Mol. Morphol. 2007;15:124–133. doi: 10.1097/PAI.0b013e31804c7283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Corcoran R.B., Chabner B.A. Application of cell-free DNA analysis to cancer treatment. New Engl. J. Med. 2018;379:1754–1765. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1706174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Walker N.J., Rashid M., Yu S.R., Bignell H., Lumby C.K., Livi C.M., et al. Hydroxymethylation profile of cell-free DNA is a biomarker for early colorectal cancer. Sci. Rep. 2022;12:16566. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-20975-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khoo B.L., Grenci G., Jing T.Y., Lim Y.B., Lee S.C., Thiery J.P., et al. Liquid biopsy and therapeutic response: circulating tumor cell cultures for evaluation of anticancer treatment. Sci. Adv. 2016;2 doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1600274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schwab E.D., Pienta K.J. Cancer as a complex adaptive system. Med. Hypotheses. 1996;47:235–241. doi: 10.1016/s0306-9877(96)90086-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brennan M.D., Cheong R., Levchenko A. Systems biology. How information theory handles cell signaling and uncertainty. Science. 2012;338:334–335. doi: 10.1126/science.1227946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Olivier M., Asmis R., Hawkins G.A., Howard T.D., Cox L.A. The need for multi-omics biomarker signatures in precision medicine. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20:4781. doi: 10.3390/ijms20194781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yasui Y., Pepe M., Thompson M.L., Adam B.L., Wright G.L., Qu Y.S., et al. A data-analytic strategy for protein biomarker discovery: profiling of high-dimensional proteomic data for cancer detection. Biostatistics. 2003;4:449–463. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/4.3.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boys E.L., Liu J., Robinson P.J., Reddel R.R. Clinical applications of mass spectrometry-based proteomics in cancer: where are we? Proteomics. 2022;23 doi: 10.1002/pmic.202200238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim J., Schoeberl B. Beyond static biomarkers-the dynamic response potential of signaling networks as an alternate biomarker? Sci. Signal. 2015;8:fs21. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aad4989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alber M., Buganza Tepole A., Cannon W.R., De S., Dura-Bernal S., Garikipati K., et al. Integrating machine learning and multiscale modeling-perspectives, challenges, and opportunities in the biological, biomedical, and behavioral sciences. NPJ Digit. Med. 2019;2:115. doi: 10.1038/s41746-019-0193-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Deisboeck T.S., Wang Z., Macklin P., Cristini V. Multiscale cancer modeling. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2011;13:127–155. doi: 10.1146/annurev-bioeng-071910-124729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gentles A.J., Gallahan D. Systems biology: confronting the complexity of cancer. Cancer Res. 2011;71:5961–5964. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boehm K.M., Khosravi P., Vanguri R., Gao J., Shah S.P. Harnessing multimodal data integration to advance precision oncology. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2022;22:114–126. doi: 10.1038/s41568-021-00408-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.FDA-NIH Biomarker Working Group . BEST (Biomarkers, EndpointS, and Other Tools) Resource [Internet] Food and Drug Administration (US); Silver Spring, MD: 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Temple R.J. In: Clinical Measurement in Drug Evaluation. Nimmo W.S., Tucker G.T., editors. John Wiley & Sons; New York: 1995. A regulatory authority’s opinion about surrogate endpoints; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Delgado A., Guddati A.K. Clinical endpoints in oncology - a primer. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2021;11:1121–1131. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Paulovich A.G., Whiteaker J.R., Hoofnagle A.N., Wang P. The interface between biomarker discovery and clinical validation: the tar pit of the protein biomarker pipeline. Proteomics Clin. Appl. 2008;2:1386–1402. doi: 10.1002/prca.200780174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Godsey J.H., Silvestro A., Barrett J.C., Bramlett K., Chudova D., Deras I., et al. Generic protocols for the analytical validation of next-generation sequencing-based ctDNA assays: a joint consensus recommendation of the BloodPAC's analytical variables working group. Clin. Chem. 2020;66:1156–1166. doi: 10.1093/clinchem/hvaa164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Addona T.A., Abbatiello S.E., Schilling B., Skates S.J., Mani D.R., Bunk D.M., et al. Multi-site assessment of the precision and reproducibility of multiple reaction monitoring-based measurements of proteins in plasma. Nat. Biotechnol. 2009;27:633–641. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Klont F., Horvatovich P., Govorukhina N., Bischoff R. Pre- and post-analytical factors in biomarker discovery. Methods Mol. Biol. 2019;1959:1–22. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-9164-8_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Clarke C.A., Lang K., Putcha G., Beer J.P., Champagne M., Ferris A., et al. BLOODPAC: collaborating to chart a path towards blood-based screening for early cancer detection. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2022;16:5–9. doi: 10.1111/cts.13427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moore H.M. Moving toward biospecimen harmonization with evidence-based practices. Biopreserv. Biobank. 2014;12:79–80. doi: 10.1089/bio.2014.1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lawler M., Haussler D., Siu L.L., Haendel M.A., McMurry J.A., Knoppers B.M., et al. Sharing clinical and genomic data on cancer - the need for global solutions. New Engl. J. Med. 2017;376:2006–2009. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1612254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Swanton C., Govindan R. Clinical implications of genomic discoveries in lung cancer. New Engl. J. Med. 2016;374:1864–1873. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1504688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Page D.B. The human tumor atlas network's beginning steps toward the future of collaborative multi-omic discovery. Cell Rep. Med. 2022;3 doi: 10.1016/j.xcrm.2022.100532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rozenblatt-Rosen O., Regev A., Oberdoerffer P., Nawy T., Hupalowska A., Rood J.E., et al. The human tumor atlas network: charting tumor transitions across space and time at single-cell resolution. Cell. 2020;181:236–249. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.03.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kwong G.A., Ghosh S., Gamboa L., Patriotis C., Srivastava S., Bhatia S.N. Synthetic biomarkers: a twenty-first century path to early cancer detection. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2021;21:655–668. doi: 10.1038/s41568-021-00389-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nakayasu E.S., Gritsenko M., Piehowski P.D., Gao Y., Orton D.J., Schepmoes A.A., et al. Tutorial: best practices and considerations for mass-spectrometry-based protein biomarker discovery and validation. Nat. Protoc. 2021;16:3737–3760. doi: 10.1038/s41596-021-00566-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mateo J., Steuten L., Aftimos P., Andre F., Davies M., Garralda E., et al. Delivering precision oncology to patients with cancer. Nat. Med. 2022;28:658–665. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-01717-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nowell P.C., Hungerford D.A. A minute chromosome in human chronic granulocytic-leukemia. Science. 1960;142:1497. doi: 10.1126/science.144.3623.1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rowley J.D. Letter: a new consistent chromosomal abnormality in chronic myelogenous leukemia identified by quinacrine fluorescence and giemsa staining. Nature. 1973;243:290–293. doi: 10.1038/243290a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Druker B.J., Talpaz M., Resta D.J., Peng B., Buchdunger E., Ford J.M., et al. Efficacy and safety of a specific inhibitor of the BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase in chronic myeloid leukemia. New Engl. J. Med. 2001;344:1031–1037. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200104053441401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jimenez C.R., Verheul H.M. Mass spectrometry-based proteomics: from cancer biology to protein biomarkers, drug targets, and clinical applications. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book. 2014:e504–e510. doi: 10.14694/EdBook_AM.2014.34.e504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Brawley O.W., Thompson I.M., Jr., Gronberg H. Evolving recommendations on prostate cancer screening. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book. 2016;35:e80–e87. doi: 10.1200/EDBK_157413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lu-Yao G.L., McLerran D., Wasson J., Wennberg J.E. An assessment of radical prostatectomy. Time trends, geographic variation, and outcomes. The prostate patient outcomes research team. JAMA. 1993;269:2633–2636. doi: 10.1001/jama.269.20.2633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Prensner J.R., Rubin M.A., Wei J.T., Chinnaiyan A.M. Beyond PSA: the next generation of prostate cancer biomarkers. Sci. Transl. Med. 2012;4:127rv3. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Baron J.A. Screening for cancer with molecular markers: progress comes with potential problems. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2012;12:368–371. doi: 10.1038/nrc3260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Maxim L.D., Niebo R., Utell M.J. Screening tests: a review with examples. Inhal. Toxicol. 2014;26:811–828. doi: 10.3109/08958378.2014.955932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tikkinen K.A.O., Dahm P., Lytvyn L., Heen A.F., Vernooij R.W.M., Siemieniuk R.A.C., et al. Prostate cancer screening with prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test: a clinical practice guideline. BMJ. 2018;362:k3581. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k3581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Crosby D., Bhatia S., Brindle K.M., Coussens L.M., Dive C., Emberton M., et al. Early detection of cancer. Science. 2022;375 doi: 10.1126/science.aay9040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Barker A.D., Sigman C.C., Kelloff G.J., Hylton N.M., Berry D.A., Esserman L.J. I-SPY 2: an adaptive breast cancer trial design in the setting of neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2009;86:97–100. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2009.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang H.Y., Yee D. I-SPY 2: a neoadjuvant adaptive clinical trial designed to improve outcomes in high-risk breast cancer. Curr. Breast Cancer Rep. 2019;11:303–310. doi: 10.1007/s12609-019-00334-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.DiMasi J.A., Hansen R.W., Grabowski H.G. The price of innovation: new estimates of drug development costs. J. Health Econ. 2003;22:151–185. doi: 10.1016/S0167-6296(02)00126-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Burd A., Levine R.L., Ruppert A.S., Mims A.S., Borate U., Stein E.M., et al. Precision medicine treatment in acute myeloid leukemia using prospective genomic profiling: feasibility and preliminary efficacy of the beat AML master trial. Nat. Med. 2020;26:1852–1858. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-1089-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Alexander B.M., Ba S., Berger M.S., Berry D.A., Cavenee W.K., Chang S.M., et al. Adaptive global innovative learning environment for glioblastoma: Gbm AGILE. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018;24:737–743. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-0764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ettinger D.S., Wood D.E., Aisner D.L., Akerley W., Bauman J.R., Bharat A., et al. NCCN Guidelines® insights: non–small cell lung cancer, version 2.2023. J. Natl. Compr. Canc. Netw. 2023;21:340–350. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2023.0020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tannock I.F., Hickman J.A. Limits to personalized cancer medicine. New Engl. J. Med. 2016;375:1289–1294. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb1607705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhang B., Whiteaker J.R., Hoofnagle A.N., Baird G.S., Rodland K.D., Paulovich A.G. Clinical potential of mass spectrometry-based proteogenomics. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2019;16:256–268. doi: 10.1038/s41571-018-0135-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Meissner F., Scheltema R.A., Mollenkopf H.J., Mann M. Direct proteomic quantification of the secretome of activated immune cells. Science. 2013;340:475–478. doi: 10.1126/science.1232578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Koussounadis A., Langdon S.P., Um I.H., Harrison D.J., Smith V.A. Relationship between differentially expressed mRNA and mRNA-protein correlations in a xenograft model system. Sci. Rep. 2015;5 doi: 10.1038/srep10775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kennedy J.J., Abbatiello S.E., Kim K., Yan P., Whiteaker J.R., Lin C.W., et al. Demonstrating the feasibility of large-scale development of standardized assays to quantify human proteins. Nat. Methods. 2014;11:149–155. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Anurag M., Jaehnig E.J., Krug K., Lei J.T., Bergstrom E.J., Kim B.J., et al. Proteogenomic markers of chemotherapy resistance and response in triple-negative breast cancer. Cancer Discov. 2022;12:2586–2605. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-22-0200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hoofnagle A.N., Becker J.O., Wener M.H., Heinecke J.W. Quantification of thyroglobulin, a low-abundance serum protein, by immunoaffinity peptide enrichment and tandem mass spectrometry. Clin. Chem. 2008;54:1796–1804. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2008.109652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Whiteaker J.R., Halusa G.N., Hoofnagle A.N., Sharma V., MacLean B., Yan P., et al. CPTAC assay portal: a repository of targeted proteomic assays. Nat. Methods. 2014;11:703–704. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Son M., Kim H., Yeo I., Kim Y., Sohn A., Kim Y. Method validation by CPTAC guidelines for multi-protein marker assays using multiple reaction monitoring-mass spectrometry. Biotechnol. Bioprocess Eng. 2019;24:343–358. [Google Scholar]