Summary

Approximately 15% of US adults have circulating levels of uric acid above its solubility limit, which is causally linked to the disease gout. In most mammals, uric acid elimination is facilitated by the enzyme uricase. However, human uricase is a pseudogene, having been inactivated early in hominid evolution. Though it has long been known that uric acid is eliminated in the gut, the role of the gut microbiota in hyperuricemia has not been studied. Here we identify a widely distributed bacterial gene cluster that encodes a pathway for uric acid degradation. Stable isotope tracing demonstrates that gut bacteria metabolize uric acid to xanthine or short chain fatty acids. Ablation of the microbiota in uricase-deficient mice causes severe hyperuricemia, and anaerobe-targeted antibiotics increase the risk of gout in humans. These data reveal a role for the gut microbiota in uric acid excretion and highlight the potential for microbiome-targeted therapeutics in hyperuricemia.

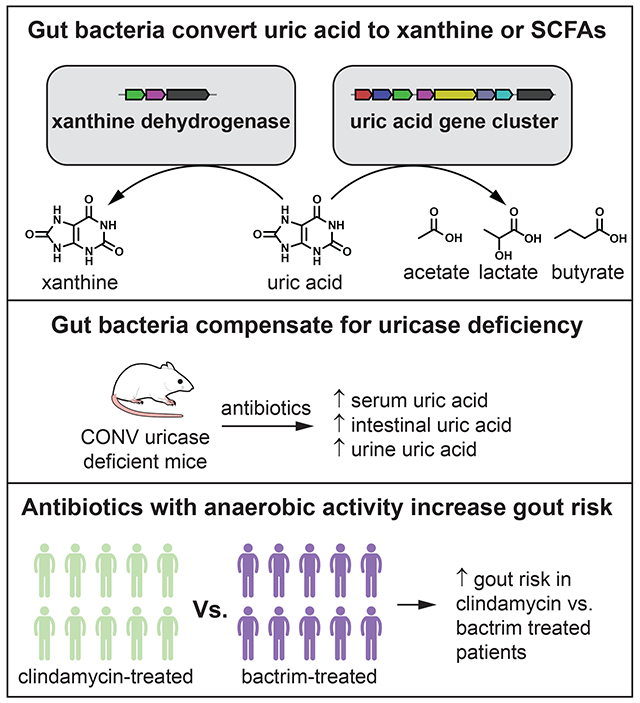

Graphical Abstract

In Brief:

Anaerobic bacteria of the gut microbiome are able to metabolize uric acid, compensating for the uricase deficiency of their host. This conversion of uric acid to xanthine or SCFAs is important for maintaining low levels of uric acid in serum, lowering gout risk.

Introduction

Uric acid is an intermediate in purine degradation in mammals. In most mammals, uric acid is converted to freely soluble allantoin via urate oxidase (uricase) which is then excreted via the kidney. However, early in hominid evolution progressive mutations occurred in the uricase gene decreasing its activity until uricase function was completely lost1. Although uricase pseudogenization may have been beneficial for our ancestors1–3, in modern times it has become a liability. Approximately 14.6% of the US population has hyperuricemia (defined by plasma levels of uric acid > 6.8 mg/dL (> 0.4 mM)) and 3.9% have clinical features of gout, a painful inflammatory arthritis caused by precipitation of uric acid crystals4. Therapies for gout include inhibitors of xanthine oxidase – upstream of uric acid in the purine metabolism pathway – or drugs that block reabsorption of uric acid in the proximal renal tubule. Most of these medications suffer either from poor efficacy, poor compliance, or intolerable side effects, thus new therapies for gout are needed.

Three independent lines of evidence suggest that the gut is an important site for uric acid elimination in humans: First, radioisotope studies in healthy individuals revealed that ~1/3 of uric acid is disposed from the gut; in patients with kidney disease, this proportion rises to ~2/3 (Figure 1A)5. Second, variants in the intestinal/renal transporter ABCG2 diminish intestinal uric acid elimination6 and ABCG2 mutations are risk factors for hyperuricemia and gout7,8. Third, extensive literature exists for a parallel process involving the excretion of oxalate via bacterial metabolism in the gut9. Certain strains of bacteria, such as Oxalobacter formigenes, consume oxalate in the gut and limit kidney stone formation10. While it is presumed that bacteria in the gut break down uric acid to products that are absorbed and excreted by the host5, uric acid metabolism by commensal gut bacteria has not been studied.

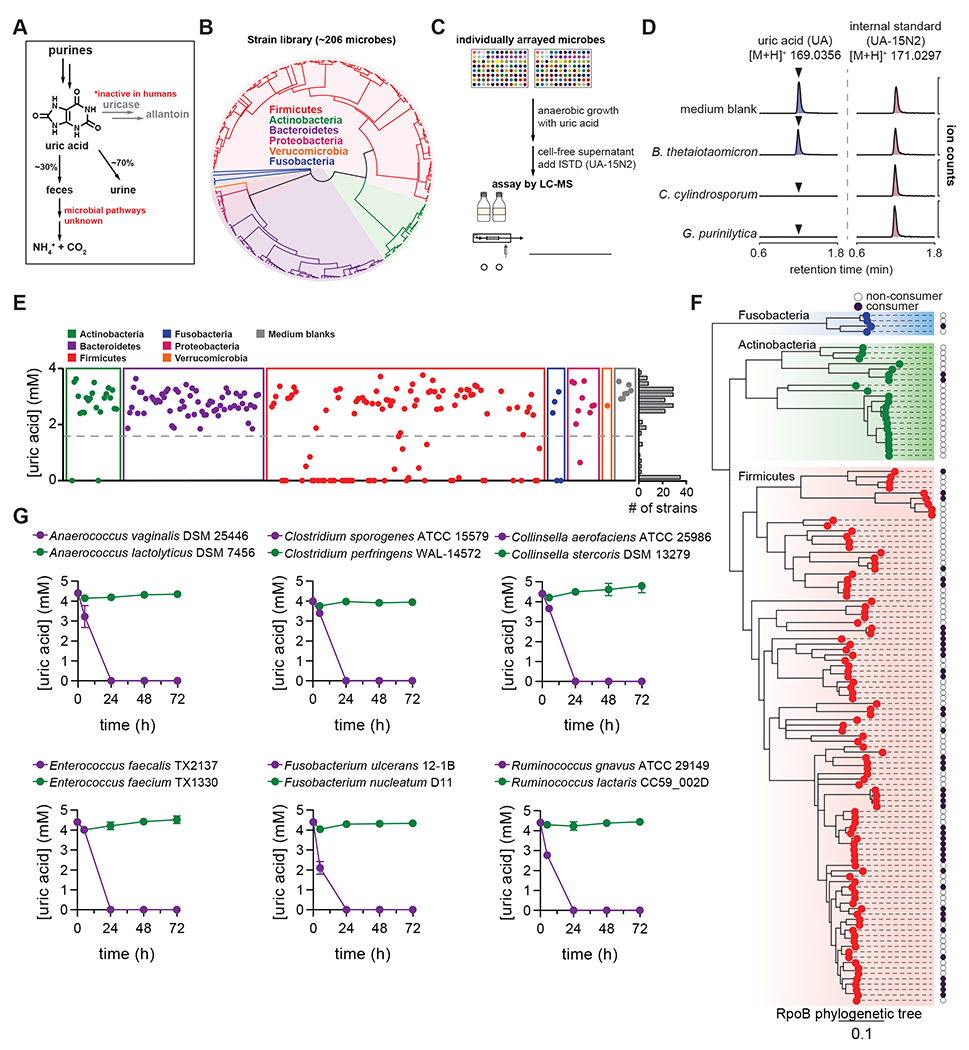

Figure 1. Anaerobic uric acid metabolism is widespread among human gut bacteria.

A) Overview of purine metabolism in humans. B) Phylogenetic distribution of human gut bacteria in the strain library used for this study. C) Overview of experimental approach to screen for uric acid metabolism. D) Extracted ion chromatograms for uric acid and the uric acid internal standard (ISTD; [15N2]-uric acid) in medium blank and after incubation with a non-consumer (B. thetaiotaomicron) and two known purine-consuming bacteria (C. cylindrosporum and G. purinilytica). E) Results from uric acid screen in rich medium, grouped by phylum. Each dot represents a single bacterial strain. The frequency of strains is shown on the right of the plot. F) Phylogenetic distribution of uric acid consuming bacteria within the Actinobacteria, Fusobacteria, and Firmicutes phyla. Dark purple dots represent strains that consume >50% of the uric acid. Only those strains for which assembled genomes are available were included. G) Uric acid consumption in closely related bacteria during growth in rich media. For D and E, data represent the results from a single experiment. For G, data represent the means ± standard deviations of n = 3 biological replicates.

Here, we report that a large number of gut bacteria consume uric acid anaerobically, converting it to either xanthine or lactate and the short chain fatty acids (SCFAs), acetate and butyrate. Transcriptional profiling and genetics reveal a gene cluster that is required for conversion of uric acid to SCFAs and is widely distributed across phylogenetically distant bacterial taxa. We find that human gut bacteria compensate for the loss of uricase in genetic and chemically-induced mouse models, and that antibiotics targeting anaerobic bacteria, which would ablate gut bacteria, increase the risk for developing gout in humans. Together, our findings uncover a previously unknown mechanism by which gut bacteria contribute to uric acid homeostasis in the host.

Results

Anaerobic uric acid metabolism is widespread among gut bacteria

While uric acid metabolism is well known to occur among aerobic bacteria, anaerobic uric acid metabolism has been described in only a few purine-degrading bacteria isolated from soil. Early biochemical studies with Clostridium cylindrosporum established the enzymatic activities involved in anaerobic purine metabolism11–15; however, the identity of genes supporting this purinolytic pathway is not known16–18. Thus, no marker genes are available to query gut bacterial genomes for uric acid metabolism.

To identify uric acid consuming gut bacteria, we cultured our phylogenetically diverse human gut bacterial strain library (Figure 1B) with uric acid and quantified remaining uric acid by isotope dilution LC-MS (Figure 1C). We first validated the assay, showing that known purine degrading bacteria (C. cylindrosporum and Gottschalkia purinilytica)19 consume uric acid whereas Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron does not (Figure 1D). Next, we found that uric acid consumption was remarkably widespread among gut bacteria, with over 1/5 (46/206) of strains in our library consuming >50% of uric acid after 48 h of anaerobic growth (Figure 1E). Uric acid consumption was distributed across 4 phyla (Actinobacteria, Firmicutes, Fusobacteria, and Proteobacteria), but notably absent in the Bacteroidetes. We repeated this screen with an expanded library of strains under carbohydrate limiting conditions (Figure S1A). Results from the second screen: i) confirmed findings for most of the organisms in the first screen, ii) identified additional uric acid consuming strains, bringing the total to 59/240 strains tested, and iii) revealed that some strains consume more uric acid in the absence of carbohydrates (Figure S1B).

By combining results from the two screens, we found that uric acid consumption varies widely, even among closely related bacteria (Figure 1F). We cultured a subset of related species with uric acid, and confirmed that uric acid metabolism is not strictly conserved even within closely related bacterial lineages (Figure 1G). While we cannot rule out that laboratory adaptation may have selected for loss of uric acid metabolism, we note that several type strains - more likely to be highly passaged - retain uric acid metabolism activity. These findings suggest that the capacity to consume uric acid may have been gained or lost multiple times during bacterial evolution.

Gut bacteria convert uric acid into xanthine and short chain fatty acids

Having identified numerous uric acid consuming gut bacteria, we next asked what is the metabolic fate of uric acid in these bacteria? We found that some strains accumulated xanthine in supernatants when consuming uric acid (Figure S1C). However, these xanthine producing strains represented just a subset of uric acid consumers, indicating that many bacteria produce other yet unidentified metabolites.

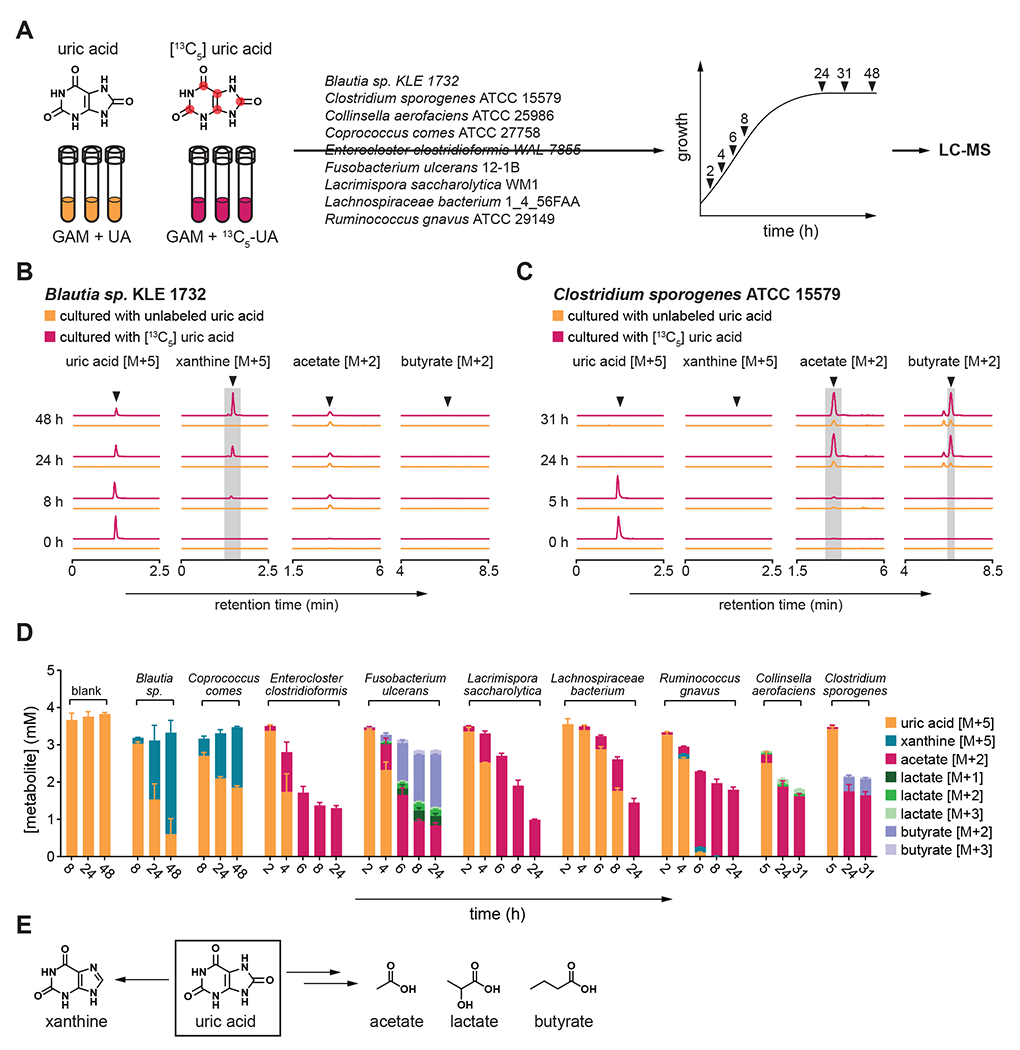

Next, we performed stable isotope tracing in xanthine-producing and non-producing strains using uniformly labeled [13C5]-uric acid (Figure 2A). Over time, the xanthine-producing strain Blautia sp. KLE 1732 consumed [13C5]-uric acid and the M+5 isotopologue of xanthine accumulated in culture supernatants (Figure 2B). In contrast, while the xanthine non-producing strain C. sporogenes ATCC 15579 consumed [13C5]-uric acid, M+5 xanthine did not accumulate (Figure 2C). Rather, we detected an increase in the M+2 isotopologues of acetate and butyrate, suggesting that C. sporogenes converts uric acid to SCFAs (Figure 2C). M+2 acetate also appeared in the Blautia sp. KLE 1732 cultures, but the levels were equivalent in both unlabeled and labeled uric acid supplemented cultures (Figure 2B), thus reflecting natural isotope abundances within acetate produced during growth (Figure S2A). Therefore, for all strains tested, we subtracted isotopologues during growth with unlabeled uric acid from isotopologues during growth with labeled uric acid. Our results identify two routes for uric acid metabolism among gut bacteria, i) conversion of uric acid to xanthine, and ii) more complete breakdown of uric acid where carbons are diverted to lactate and the SCFAs, acetate and butyrate (Figure 2D–E). By comparing uric acid metabolism in rich and more limited media, we found that nutrient availability influences uric acid consumption to different extents among phylogenetically diverse bacteria (Figure S2B).

Figure 2. Gut bacteria convert uric acid into xanthine or lactate and short chain fatty acids.

A) Overview of stable isotope tracing. Bacteria were cultured in rich media containing either unlabeled or uniformly labeled [13C5] uric acid and metabolites were quantified at indicated times by LC-MS. B-C) Extracted ion chromatograms for labeled substrates or products when (B) Blautia sp. KLE 1732 or (C) Clostridium sporogenes ATCC 15579 was cultured with labeled or unlabeled uric acid. D) Labeled substrates and products detected in cell-free culture supernatants of all nine bacteria studied. E) Uric acid is converted either to xanthine or lactate and the SCFAs acetate and butyrate. For B and C, arrows indicate expected retention times for indicated compounds. For C, the peak eluting 0.3 min before butyrate [M+2] was identified as isobutyrate [M+2]. For B and C, experiments were performed in triplicate and representative data are shown. For D, data represent the means ± standard deviations of n = 3 biological replicates. Strains include: Blautia sp. KLE 1732, Coprococcus comes ATCC 27758, Enterocloster clostridioformis WAL-7855, Fusobacterium ulcerans 12-1B, Lacrimispora saccharolytica WM1, Lachnospiraceae bacterium 1_4_56FAA, Ruminococcus gnavus ATCC 29149, Collinsella aerofaciens ATCC 25986, and Clostridium sporogenes ATCC 15579. GAM, Gifu anaerobic medium.

Identification of a uric acid-inducible gene cluster required for anaerobic uric acid metabolism

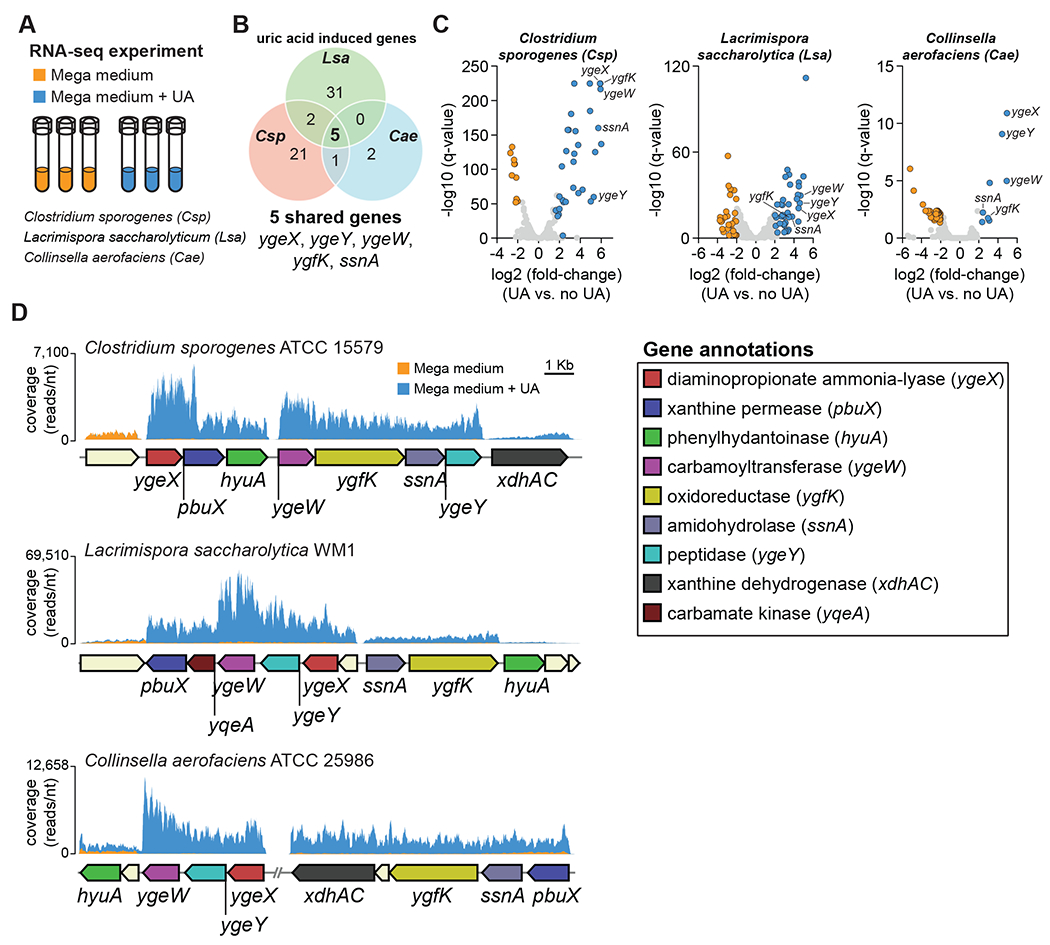

To identify genes involved in uric acid conversion to SCFAs, we cultured three phylogenetically distinct organisms (C. sporogenes, L. saccharolytica, and C. aerofaciens) in rich medium with or without uric acid and performed RNAseq analysis (Figure 3A). We found 5 uric acid inducible genes (ygeX, ygeY, ygeW, ygfK, and ssnA) shared across the three bacteria (Figure 3B) that were among the most highly induced genes (Figure 3C and Table S1) and mapped to discrete gene clusters shared across the three bacteria (Figure 3D). Notably, annotations for these genes derive from Escherichia coli where they code for enzymes whose activities are predicted at the family level, but for which substrate specificities and cellular roles are unknown. Putative annotations for these gene products include ammonia lyase (YgeX), peptidase (YgeY), carbamoyl transferase (YgeW), oxidoreductase (YgfK), and amidohydrolase (SsnA) which are enzymes that may reduce and cleave bonds present in uric acid. These findings reveal a conserved set of uric acid-inducible genes that are shared across diverse gut bacterial taxa.

Figure 3. RNA-seq reveals a uric acid-inducible gene cluster in gut bacteria.

A) Overview of experimental design. Three organisms (C. sporogenes, L. saccharolytica, and C. aerofaciens) were cultured in rich medium with and without supplemental uric acid and transcriptomes were analyzed by RNA-seq. B) Venn diagram showing significantly induced genes for all three organisms (FDR corrected P-value (q-value) < 0.05, fold-change > 4). C) Volcano plots showing differentially regulated genes in the three organisms. Cut-offs include FDR corrected P-value (q-value) < 0.05 and |fold-change| > 4. Each dot represents a single gene. Blue dots represent genes that are induced and orange dots represent genes that are repressed when uric acid is present. D) Genomic context and RNA-seq coverage for conserved uric acid-inducible genes. For RNA-seq experiments, three biological replicates were performed for each condition. For D, representative data are shown.

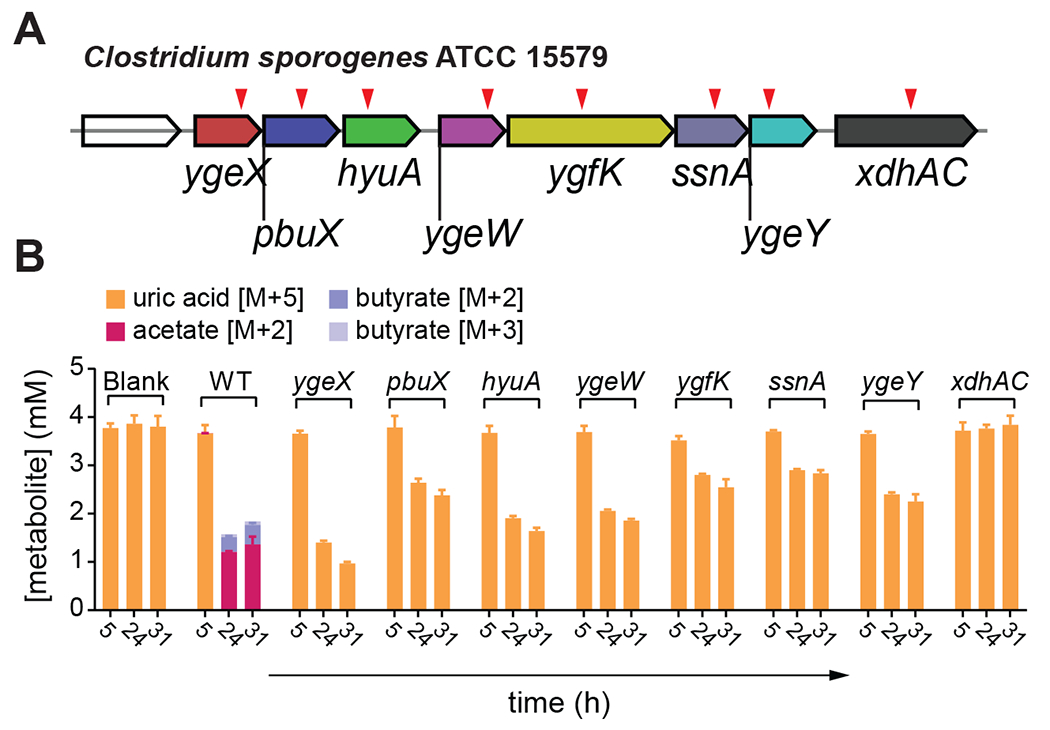

Genetics and stable isotope tracing in C. sporogenes revealed that mutations either partially (ygeX, pbuX, hyuA, ygeW, ygfK, ssnA, ygeY) or completely (xdhAC) blocked uric acid metabolism (Figure 4A–B). Neither labeled acetate nor labeled butyrate were detected in culture supernatants of any of the mutant strains (Figure 4B). These findings provide evidence that the uric acid-inducible genes in C. sporogenes are required for conversion of uric acid to SCFAs including acetate and butyrate.

Figure 4. Uric acid-inducible genes are required for conversion of uric acid to short chain fatty acids.

A) Individual mutants (indicated by red triangles) were generated in C. sporogenes using the ClosTron system. B) Stable isotope tracing in wild-type and mutant C. sporogenes strains. For B, data represent the means ± standard deviations of n = 3 biological replicates.

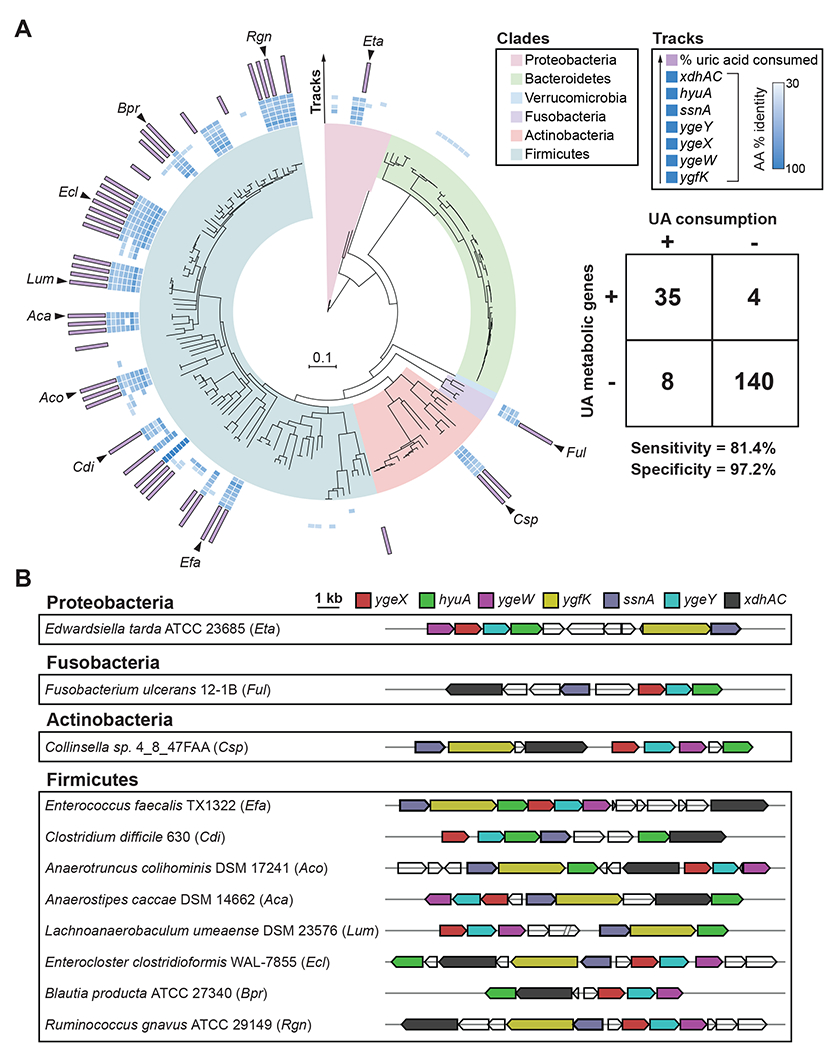

Uric acid-inducible genes are widely distributed across human gut bacteria

Phylogenetic analyses revealed that the uric acid metabolic genes are broadly distributed across gut bacteria, occurring within 4 phyla, 19 families, and 21 genera (Figure 5A and Table S2). The presence of uric acid metabolic genes showed strong concordance with the capacity for uric acid metabolism and explained differences in uric acid consumption between phylogenetically related bacteria in Figure 1G (Table S2). We also found that these uric acid metabolic genes mapped to conserved gene clusters across broad taxonomic lineages (Figure 5B). Those bacteria that did not carry the genes, but consumed uric acid included: i) previously studied purine degrading bacteria (Clostridium cylindrosporum and Gottschalkia purinilytica) known to convert uric acid to acetate, but likely involving a different set of genes, and ii) bacteria that we found convert uric acid to xanthine (Figure S3A). These xanthine-producing bacteria harbor putative xanthine dehydrogenase genes (Figure S3B), and we conclude that these strains likely convert uric acid to xanthine in a single step involving xanthine dehydrogenase.

Figure 5. Uric acid gene cluster is conserved across uric acid consuming gut bacteria.

A) RpoB phylogenetic tree for strains screened for uric acid metabolism in this study. Only those strains with assembled genomes are included (n = 187). Clades are colored by phylum. Inner blue shaded tracks represent the % amino acid identity of protein homologs identified from BLASTp searches using C. sporogenes proteins as queries. The outer most track represents the % uric acid consumed by each strain. Uric acid consumption values are only shown for strains with ≥ 50% uric acid consumption. Table shows number of bacteria positive or negative for genes (cut-off ≥ 5 of 7 genes) vs. positive or negative for uric acid consumption (cut-off ≥ 50% uric acid consumption). The cut-off of ≥ 5 of 7 genes was determined by analyzing sensitivity and specificity at different gene cut-off values (Table S2). B) Genomic context of uric acid metabolic genes from representative uric acid consuming strains corresponding to black arrows in Figure 5A.

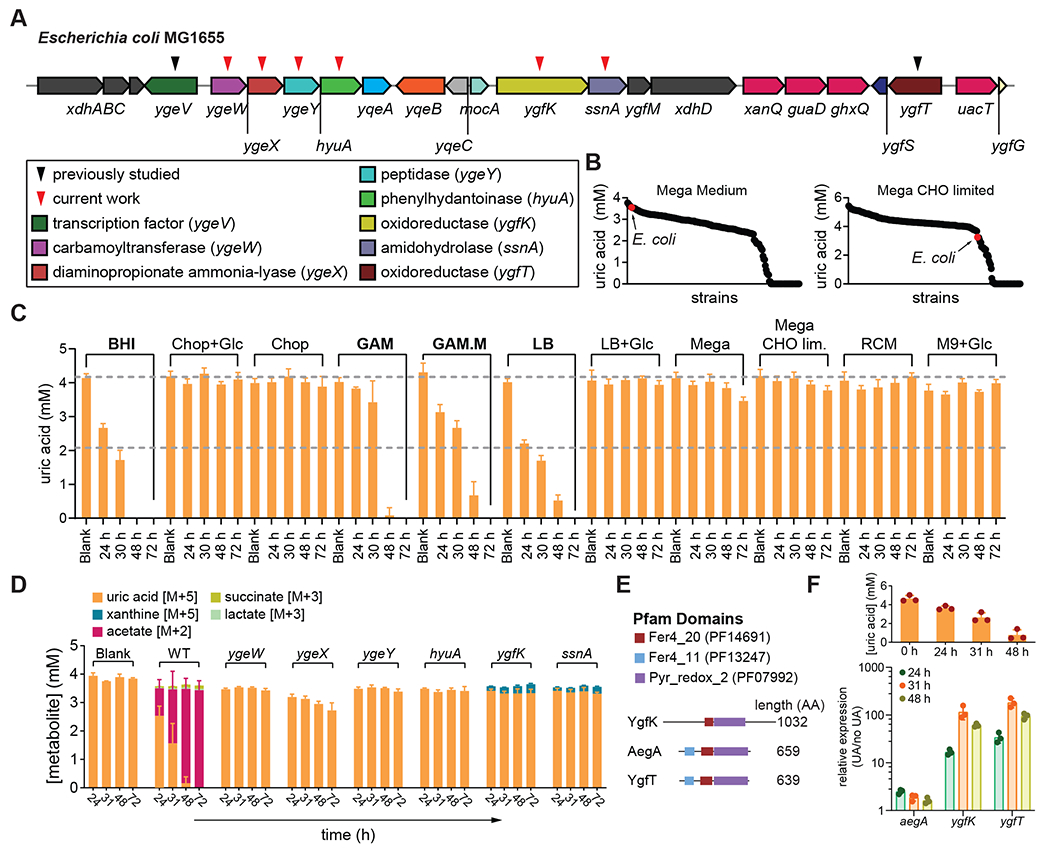

Escherichia coli converts uric acid to acetate anaerobically

The E. coli genome harbors a gene cluster containing most of the uric acid-inducible genes identified in our study. E. coli has previously been demonstrated to consume uric acid under anaerobic conditions in a mechanism requiring formate and involving several genes including aegA, ygfT, and ygeV 20 Of note, the ygfT and ygeV genes map to the same gene locus as the ygeW, ygeX, ygeY, hyuA, ygfK, ssnA genes identified in our study (Figure 6A). However, the role of these latter genes in uric acid metabolism by E. coli has not been studied.

Figure 6. Nutrient dependence of E. coli uric acid metabolism and role of genes in conversion of uric acid to acetate.

A) Genomic context for uric acid metabolic genes in E. coli. Black triangles indicated previously studied genes, and red triangles indicate genes targeted in the current study. B) Results from uric acid metabolism screens under carbohydrate (CHO) replete (left) or CHO limited (right) conditions. Strains are ordered by amount of uric acid remaining and E. coli is indicated by a red dot. C) Uric acid metabolism by E. coli under different nutrient conditions. D) Stable isotope tracing in wild-type and mutant E. coli strains. Strains were cultured in modified Gifu anaerobic medium containing either labeled or unlabeled uric acid. Labeled substrates and products were quantified by LC-MS. E) Pfam domains for YgfK and two gene products (AegA and YgfT) previously shown to be involved in uric acid metabolism by E. coli. F) Relative expression of ygfK, aegA, and ygfT in uric acid supplemented vs. non-supplemented conditions. Uric acid remaining in the medium is shown in the upper panel. For B, data in the two panels represent the results from a single experiment per condition. For C, D, and F, data represent the means ± standard deviations of n = 3 biological replicates.

Despite containing the genes for uric acid metabolism, under the conditions of our initial screen, Escherichia coli was not identified as a uric acid consuming bacterium (Figure 6B). To test whether E. coli consumes uric acid under anaerobic conditions, we cultured the MG1655 strain in 11 different anaerobic media supplemented with uric acid and monitored uric acid over time by LC-MS. Consistent with results from our initial screen, uric acid was not substantially consumed in mega media (Figure 6C). However, we identified four different media which supported complete consumption of uric acid (Figure 6C). Our findings suggest that E. coli consumes uric acid and that nutrient availability dramatically influences this phenotype.

Next, we created markerless deletion mutants in E. coli MG1655 and used stable isotope tracing to quantify uric acid metabolism during growth in modified Gifu anaerobic medium (GAM.M). Under these conditions, the wild-type E. coli strain consumed all the uric acid within 48 hours, and culture supernatants accumulated M+2 acetate (Figure 6D). By comparison, the mutant strains were partially blocked in uric acid metabolism and none of the cultures accumulated M+2 acetate (Figure 6D). These findings provide evidence that under certain nutrient conditions, E. coli degrades uric acid to acetate, in a pathway that involves ygeW, ygeX, ygeY, hyuA, ygfK, and ssnA.

A previous study identified aegA and ygfT as genes involved in formate-dependent uric acid metabolism in E. coli 20. These two genes encode putative oxidoreductases that harbor iron sulfur cluster binding domains and a pyridine-dependent oxidoreductase domain (Figure 6E). AegA and YgfT have been proposed to accept electrons from formate dehydrogenase and transfer them to NADP+ or directly to uric acid20. We found that YgfK also shares two of the three domains present in AegA and YgfT (Fer4_20 and Pyr_redox_2), suggesting that these three enzymes might perform analogous reactions under different nutrient conditions. We found that during growth in GAM.M, uric acid highly induced the expression of ygfK and ygfT, but had only a modest influence on aegA expression (Figure 6F). These results suggest that both ygfT and ygfK are likely involved in uric acid metabolism under these conditions, whereas aegA is not.

Comparison of two facultative anaerobes (E. coli and Enterococcus faecalis) showed that uric acid was consumed only under anaerobic conditions (Figure S4). These findings, coupled with the observation that most of the strains harboring uric acid genes are facultative or obligate anaerobes, lead us to reason that the genes identified in our study are likely to be specific to anaerobic uric acid metabolism.

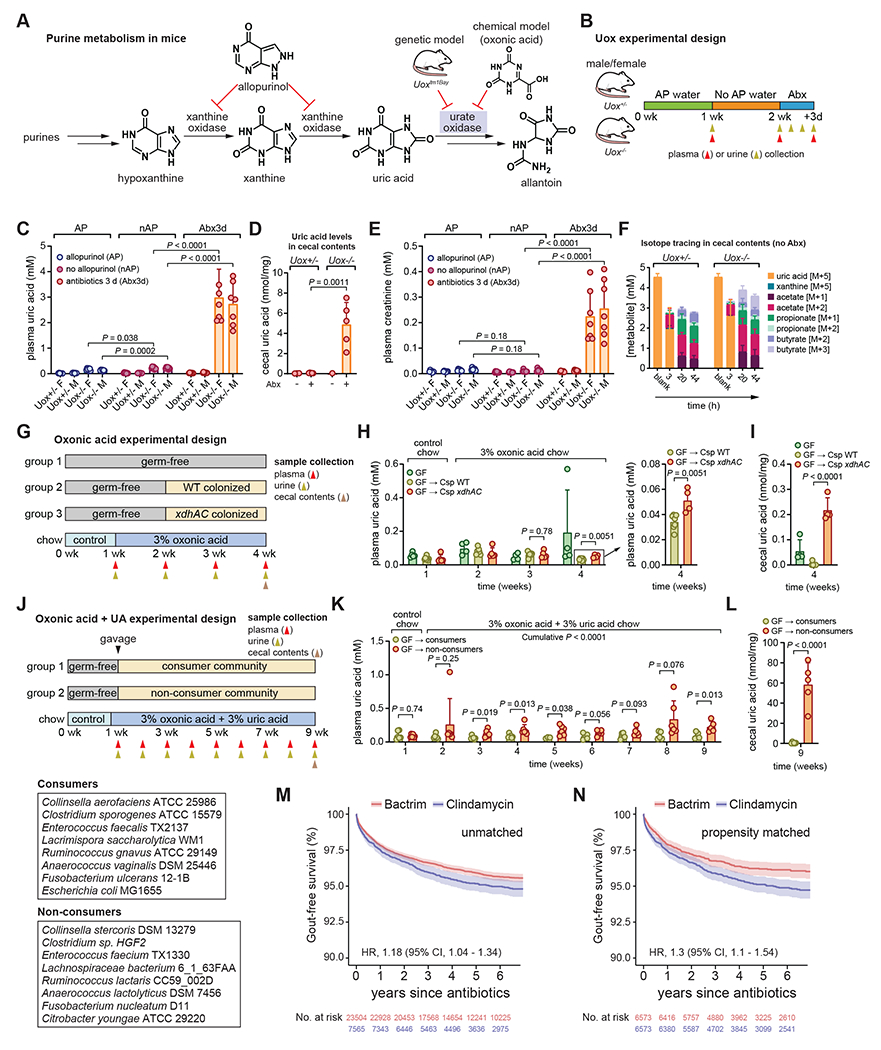

Gut bacteria compensate for uricase deficiency in mice.

Unlike humans, mice have a functional uricase enzyme (also known as urate oxidase (Uox)) and wild-type mice have lower levels of plasma uric acid compared to humans21. To investigate the role of the microbiome in hyperuricemia, we used two mouse models: 1) mice carrying a targeted mutation in the Uox gene22 and 2) chemical inhibition of uricase with oxonic acid (Figure 7A). Uox knockout (Uox−/−) mice are hyperuricemic, accumulate uric acid crystals in the kidney, and suffer from early lethality22. To overcome perinatal lethality, we provided allopurinol (a xanthine oxidase inhibitor) in the drinking water during breeding and after weaning (Figure 7A) 22. We also confirmed results from prior studies23, showing that addition of the xanthine oxidase inhibitor (allopurinol) in the blood collection tube limits false in vitro elevation of uric acid (Figure S5A). Thus, we used this sampling method in all our mouse experiments.

Figure 7. Gut bacteria compensate for loss of uricase.

A) Overview of purine metabolism in mice. B) Overview of Uox mouse experimental design. C) Plasma uric acid levels in male and female Uox+/− or Uox−/− mice. D) Cecal uric acid levels in Uox+/− or Uox−/− mice with or without antibiotic treatment. E) Plasma creatinine levels in male and female Uox+/− or Uox−/− mice. F) Isotope tracing in cecal contents of non-antibiotic treated Uox+/− or Uox−/− mice. G) Overview of oxonic acid only experiment with gnotobiotic C57Bl/6 mice. WT, wild-type C. sporogenes; xdhAC, xanthine dehydrogenase mutant C. sporogenes. H) Plasma uric acid levels in GF, WT, or xdhAC colonized mice. Panel at right represents a zoomed in view of the final timepoint. I) Cecal uric acid levels in GF, WT, or xdhAC colonized mice. J) Overview of oxonic acid + uric acid experiment with gnotobiotic C57Bl/6 mice. Community members are indicated in the boxes. K) Plasma uric acid levels in non-consumer or consumer colonized mice. L) Cecal uric acid levels in non-consumer or consumer colonized mice. M) Kaplan-Meier survival curves for unmatched patients treated with oral Bactrim or Clindamycin (≥ 5 day course) with a diagnosis of gout as the end-point. N) Kaplan-Meier survival curves for propensity score matched patients treated with Bactrim or Clindamycin (≥ 5 day course) with a diagnosis of gout as the end-point. For B, G, J, timing of sample collection is indicated with gold (urine), red (plasma), or brown (cecal contents) arrows. For C and E, data represent means ± standard deviations from n = 7-8 mice per group. For D, data represent means ± standard deviations from n = 5 mice (antibiotic treated Uox+/− or Uox−/− mice) or pools for non-antibiotic treated mice (6 mice into 3 pools for Uox+/− and 3 mice into 1 pool for Uox−/−). For F, data represent means ± standard deviations from n = 4 mice (Uox+/−) or n = 8 mice (Uox−/−). For H-I, data represent means ± standard deviations from n = 5-7 mice per group. For K-L, data represent means ± standard deviations from n = 6 mice per group. P-values are from two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-tests. AP, allopurinol; nAP, no allopurinol; Abx, antibiotics.

To test whether the gut microbiota can compensate for uricase deficiency, we treated male and female Uox−/− mice and their heterozygous (Uox+/−) littermate controls with an antibiotic cocktail and measured serum and urine uric acid concentrations (Figure 7B). Allopurinol treatment had a modest influence on serum and urine uric acid in Uox−/− mice (Figure 7C and Figure S5B), however antibiotic treated Uox−/− mice became ill and developed severe hyperuricemia (Figure 7C). Intestinal levels of uric acid in the cecal contents were increased in antibiotic treated Uox−/− mice indicating that bacterial depletion diminished intestinal uric acid metabolism (Figure 7D). In the three days after antibiotic administration, urine uric acid excretion progressively decreased, suggesting that kidney function was impaired (Figure S5B). Indeed, antibiotic treated Uox−/− mice showed evidence of acute kidney injury with markedly elevated concentrations of plasma creatinine (Figure 7E) and urea (Figure S5C). This rise in plasma creatinine and urea reflects acute kidney injury, and the combination of acute kidney injury with acute hyperuricemia is reminiscent of acute uric acid nephropathy seen in tumor lysis syndrome in humans22.

Cecal contents from both Uox+/− and Uox−/− mice consumed uric acid in vitro, converting it to a mixture short chain fatty acids (Figure 7F). These findings show that the microbiota of these mice have the capacity to consume uric acid and convert it to short chain fatty acids similar to those we detected for bacteria grown in vitro (Figure 2D). Assembly of shotgun metagenomics reads from cecal contents of Uox+/− and Uox−/− mice identified eight contigs belonging to three separate bacterial families each containing the uric acid gene cluster (Figure S5D–E). This indicates that bacteria harboring the uric acid gene cluster are present within the microbiota of these mice. However, gene cluster abundances or expression was not significantly different between Uox−/− and. Uox+/− mice (Figure S5F–G). Thus, our metagenomics analysis establishes that bacteria encoding the uric acid genes are present in microbiota colonizing the cecum of Uox mice, although the gene abundance and expression do not differ between Uox+/− and Uox−/− mice.

Next, we adopted a widely used model for chemically induced hyperuricemia24 to more concretely connect bacterial uric acid metabolism to uric acid levels in the host. In germ-free mice, oxonic acid chow induced modest elevations in plasma and urine uric acid and plasma creatinine (Figure S6A–B). By contrast, the oxonic acid and uric acid chow induced severe hyperuricemia, hyperuricosuria, and elevated plasma creatinine (Figure S6C–D). This latter model phenocopies microbiota-depletion in uricase deficient mice.

We then compared germ-free mice and mice mono-colonized with either wild-type C. sporogenes or its xanthine dehydrogenase (xdhAC) mutant, which does not consume uric acid in vitro (Figure 4B). Mice were fed a control diet for one week, then switched to oxonic acid chow for one week prior to colonization (Figure 7G). Despite the mild hyperuricemia induced by this diet, we detected a significant decrease in uric acid levels in both the plasma and in the cecal contents for wild-type compared with xdhAC colonized mice after two weeks (Figure 7H–I). Urine uric acid levels were not significantly different between groups of mice (Figure S6E). Next, we compared gnotobiotic mice colonized with bacterial communities consisting of uric acid consuming bacteria or phylogenetically matched non-uric acid consuming bacteria (Figure 7J). These mice were fed a control diet for six days and then switched to a diet containing both oxonic acid and uric acid. Mice colonized with a consumer community had lower uric acid levels in the plasma and cecal contents (Figure 7K–L) and in the urine (Figure S6F) compared to non-consumer colonized mice. Together, these experiments establish that bacterial uric acid metabolism in the gut reduces uric acid levels in the host.

Antibiotics targeting anaerobic gut microbes increase risk for Gout in humans.

Given our findings that antibiotic treatment induced severe hyperuricemia in Uox−/− mice, we next asked whether antibiotic treatment might be a risk factor for gout in humans. To address this, we compared two commonly prescribed oral antibiotics: i) Clindamycin, which is known to target both aerobic and anaerobic microbes, and ii) trimethorprim/sulfamethoxazole (Bactrim) which targets aerobic microbes. We hypothesized that clindamycin might uniquely disrupt uric acid degrading gut bacteria because they are anaerobic microbes. We conducted a retrospective cohort study using electronic health records collected from the Stanford Health Care system between 2015 and 2019. We examined all adult patients (regardless of gout history) and compared rates of incident gout diagnosis in the years following treatment with ≥ 5 days of oral Clindamycin (N = 7,565) vs. ≥ 5 days of oral Bactrim (N = 23,504). The two groups were similar in age (53.1 vs. 53.4 years), sex distribution (59.6% vs. 59.1% female), and comorbid illness (average comorbidity score 3.2 vs. 3.5) (Table S3). In the unmatched cohort, patients treated with Clindamycin had a higher risk for developing a diagnosis of gout compared to patients treated with Bactrim (Hazard Ratio, 1.18, 95% CI, 1.04-1.34, P = 0.0091) (Figure 7M). After propensity score matching (N = 6,573 for Clindamycin or Bactrim), the risk for a gout diagnosis increased for patients treated with Clindamycin compared with those treated with Bactrim (Hazard Ratio, 1.3, 95% CI, 1.1-1.54, P = 0.0026) (Figure 7N). These findings suggest that disruption of the anaerobic gut microbiota by broad-spectrum antibiotics with anaerobic activity increases the risk of developing gout in humans.

To address whether microbiota depletion influences fecal uric acid levels, we re-analyzed metabolomics data from the Food and Resulting Microbial Metabolites (FARMM) study exploring the role of diet in microbiome metabolite recovery after disruption with antibiotics and polyethylene glycol25. We found that microbiota depletion resulted in dramatically elevated fecal levels of uric acid (Figure S7A). Fecal uric acid levels rapidly returned to baseline in subjects fed a vegan or omnivore diet, but those fed a fiber-free synthetic diet (EEN) showed a protracted recovery with persistent elevations of fecal uric acid throughout the recovery phase (Figure S7A). To explore whether the uric acid gene cluster varied in abundance across FARMM study subjects, we used gutSMASH26,27 to identify 782 gene clusters from human gut bacterial reference genomes and mapped metagenomic reads from study subjects to 107 representative gene clusters using BiG-MAP28. The abundance of uric acid genes was significantly reduced post-antibiotic treatment in study subjects fed an EEN diet compared with study subjects fed an omnivore or a vegan diet (Figure S7B). The authors of the FARMM study found that bacteria from the Firmicutes phylum showed delayed recovery in the EEN group. Our findings are consistent with this observation, showing that differences in uric acid gene cluster abundance between EEN and omnivore/vegan groups are largely driven by members of the Firmicutes phylum, notably the Oscillospiraceae, Lachnospiraceae, Peptostreptococcaceae, and Clostridiaceae families (Figure S7C, yellow boxes). These results suggest that a lack of dietary fiber following microbiome perturbation imparts a sustained dysregulation of uric acid metabolism in the gut.

Discussion

Uric acid is one of the most abundant nitrogenous compounds on the planet, being a key intermediate in purine metabolism29. While evidence of aerobic uric acid metabolism can be found across all domains of life, anaerobic uric acid metabolism has been studied in only a handful of bacteria isolated from soil or marine sediments30. Here we find that anaerobic uric acid metabolism is widespread among members of the human gut microbiome, occurring in ~1/5 of bacteria from 4 of 6 major phyla. In contrast to aerobic pathways that rely on oxygen-dependent uricase to initiate uric acid metabolism, we find that anaerobic pathways break down uric acid through action of uncharacterized ammonia lyase, peptidase, carbamoyl transferase, and oxidoreductase enzymes. The genes encoding these enzymatic functions map to a conserved gene cluster that is broadly distributed across distantly related bacterial taxa and are required for anaerobic uric acid metabolism to lactate and SCFAs. Intriguingly, previously characterized purine degrading Clostridia (e.g., G. purinilytica, G. acidiurici, and C. cylindrosporum) do not encode these genes16–18, suggesting that distinct pathways for anaerobic uric acid metabolism evolved independently among bacteria. However, the uric acid genes identified in our study are highly predictive of uric acid metabolism activity in gut bacteria, indicating this gene cluster encodes a predominant pathway for anaerobic uric acid metabolism in the gut. A recent study also identified uric acid degrading gut bacteria, the same set of genes, and demonstrated that gut bacteria influence uric acid levels in the host, thus reinforcing our conclusions31.

In most mammals, purines are degraded via uricase to freely soluble allantoin, which is excreted in the urine, however uricase was inactivated early in hominid evolution. One prominent hypothesis for why uricase was inactivated suggests uricase may be a thrifty (pseudo)gene. Uricase inactivation occurred gradually over nearly 50 million years with full inactivation occurring in the early Miocene1. Notably, this coincided with global climatic cooling with rainforests receding towards the equator. Consequently, frugivorous apes underwent periods of starvation, especially during cooler winter months. Studies in mice and rats have shown that loss or inhibition of uricase i) increases fat storage from fructose, ii) limits beta-oxidation of fats, iii) stimulates gluconeogenesis, and iv) increases blood pressure. These studies provide evidence of uricase as a “thrifty gene”, the inactivation of which promoted survival of our ancestors during times of starvation32. Our results suggest that the gut microbiota play a compensatory role for uricase loss, enabling homeostatic control over uric acid levels. The implications of this are that loss of uric acid consuming bacteria may explain the high prevalence of hyperuricemia and gout in industrialized nations.

Our study provides insights into the role of the gut microbiota in hyperuricemia and gout, two common disorders affecting the US population. There are two important implications of these results: First, antibiotic therapies that might disrupt the gut microbiota should be carefully considered in patients predisposed to gout. If antibiotics are administered to these patients, a low fiber diet may cause a protracted return to normal uric acid metabolism in the gut. Second, approaches to promote uric acid metabolism in the gut represent potentially important therapies for treating patients with hyperuricemia. Along these lines, recent studies have shown that oral (non-absorbable) enzyme therapy with recombinant uricase reduces plasma uric acid concentration in uricase-deficient mice33, and decreases plasma concentration in healthy volunteers34. The uric acid pool is distributed across different body compartments which include the plasma, joints, kidney, and intestines, the latter two being primary excretion routes mediated by bi-directional transporters35. It is thought that enzymatic degradation of intestinal uric acid affects equilibrium of the uric acid pool, diminishing overall hyperuricemia33. We envision that live biotherapeutic products consisting of uric acid consuming bacteria could also be an important therapeutic modality to treat hyperuricemia and gout.

Limitations of the study

Uricase-deficient mice develop severe hyperuricemia, akin to tumor lysis syndrome in humans. Given the gradual loss of uricase during hominid evolution, it is likely that adaptive mechanisms appeared to regulate uric acid levels. Selection for uric acid consuming gut bacteria may have been one such adaptive mechanism, however further studies are needed to test whether uric acid consuming bacteria are enriched in uricase-deficient mammals and how microbial dysbiosis may contribute to hyperuricemia and gout. Our finding that patients given antibiotics with anaerobic activity have an increase in gout diagnosis provides support to the idea that bacteria play a protective role in uric acid homeostasis. However, our inclusion criteria were very broad with patients differing by age, sex, diagnosis, drug doses and durations. Despite these broad inclusion criteria, patients who received clindamycin carried higher risk for gout, which became more significant after propensity score matching. In this sense, this finding is robust because it is generalizable to a broad population of patients. Nevertheless, it will be important to independently test and validate these findings in different populations and with more strictly defined inclusion criteria.

STAR METHODS

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Lead Contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Dylan Dodd (ddodd2@stanford.edu).

Materials availability

All unique/stable reagents generated in this study are available from the lead contact without restriction.

Data and code availability

Data: All metabolite measurements by LC-MS are provided in Table S4. The RNA-seq data has been uploaded to the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus under accession number GSE206419. Bacterial genome assemblies analyzed in this study (e.g., for phylogenetic trees and BLASTp searches) are from publicly available sources and relevant accession numbers are provided in Table S4. Metagenomic sequence reads from Uox mice are deposited at NCBI under BioProject PRJNA947216. Metagenome assembled contigs containing uric acid genes from Uox mice are provided in Supplemental Data File S1. Metabolomics and metagenomics data re-analyzed from a study investigating microbiota recovery after depletion25 was obtained from the Metabolomics Workbench (Study ID ST001519) and NCBI (BioProject PRJNA675301), respectively. Reference genomes of the HMP dataset were obtained from NCBI BioProject PRJNA43021.

Code: The custom R script for the metagenomic data processing and figure generation can be found at https://github.com/HAugustijn/uric_acid_project/.

Additional information: Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND STUDY PARTICIPANT DETAILS

Bacterial strain construction

Gene disruption in Clostridium sporogenes ATCC 15579 using ClosTron.

For Clostridium sporogenes, gene disruptions were constructed using the Intron targeting and design tool on the ClosTron website (http://www.clostron.com/clostron2.php) with the Perutka algorithm36. The intron within the pMTL007C-E2 plasmid was re-targeted to the sites listed in the key resource table and the targeting sequences were synthesized as gBlocks by IDT. Re-targeted plasmids were made by digesting the pMTL007C-E2-CLOSPO_00316-736s37 plasmid with BsrGI and HindIII, followed by gel-purification of the plasmid backbone and Gibson assembly with re-targeted intron gBlock fragments using the Gibson Assembly Master Mix (NEB). Gibson assemblies were transformed into E. coli by electroporation, selected on LB-chloramphenicol (25 μg/mL) plates and sequenced to confirm the correct retargeted sequence. Intron re-targeted plasmids were transformed into E. coli s17-1 λpir and subsequently conjugated into C. sporogenes as described previously38. Mutants were verified by PCR and Sanger sequencing using the sequencing primers listed the key resource table.

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial and virus strains | ||

| Wild-type gut bacterial strains used in this study | See Table S4 | See Table S4 |

| E. coli Stbl4 ElectroMax | Invitrogen | 11635018 |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| 3-nitrophenylhydrazine hydrochloride | Sigma Aldrich | N21804 |

| acetic acid | Sigma Aldrich | 6283 |

| acetic acid-d4, ≥99.9 atom % D | Sigma Aldrich | 233315 |

| acetonitrile | Fisher Scientific | A955-4 |

| allopurinol | Sigma Aldrich | A8003 |

| ammonium acetate | Fisher Scientific | A11450 |

| ammonium hydroxide solution | Honeywell Fluka | 4427310X1ML |

| butyric acid | Sigma Aldrich | B103500 |

| calcium chloride | Alfa Aesar | 89866 |

| chloramphenicol | Sigma Aldrich | C1919 |

| chopped meat medium | Anaerobe Systems | AS-811 |

| creatinine | Sigma Aldrich | C4255 |

| creatinine (N-methyl-D3, 98%) | Cambridge Isotope Laboratories | DLM-3653 |

| D(−)-fructose | Sigma Aldrich | F0127 |

| D(+)-cellobiose | Fluka Chemie GMBH | 22150 |

| D(+)-maltose, monohydrate | Acros | 329915000 |

| dansyl chloride | Sigma Aldrich | D2625 |

| D-cycloserine | Sigma Aldrich | C6880 |

| dextrose (D-glucose), anhydrous | Fisher Scientific | D16-500 |

| Difco Brain Heart Infusion Broth | BD | 237500 |

| Difco Brain Heart Infusion Agar | BD | 241810 |

| Difco LB Broth, Miller (Luria-Bertani) | BD | 244610 |

| Difco Reinforced Clostridial Medium (RCM) | BD | 218081 |

| dimethyl sulfoxide | MP Biomedicals | 219605590 |

| erythromycin | Sigma Aldrich | E5389 |

| ethanol | Fisher Scientific | BP2818 |

| ferrous sulfate heptahydrate | Fisher Scientific | I146 |

| formic acid | Fisher Scientific | A117-50 |

| GAM Agar | Nissui | 05420 |

| GAM Broth | Nissui | 05422 |

| GAM Broth, Modified | Nissui | 05433 |

| glycerol | Fisher Scientific | BP229-1 |

| glycine | Sigma Aldrich | G7126 |

| hematin, porcine | Sigma Aldrich | H3281 |

| hydrochloric acid | Fisher Scientific | SA49 |

| hydrocinnamic acid-d9 (phenylpropionic acid-d9) | C/D/N Isotopes | D-5666 |

| isobutyric acid | Sigma Aldrich | 58360 |

| isovaleric acid | Sigma Aldrich | 129542 |

| lactic acid | Fisher Chemical | A159-500 |

| L-cysteine hydrochloride monohydrate | Sigma Aldrich | C7880 |

| L-histidine | Sigma Aldrich | H8000 |

| M9 Minimal Salts, 5x | BD | 248510 |

| magnesium sulfate heptahydrate | Fisher Scientific | M63-500 |

| meat extract | Sigma Aldrich | 70164 |

| menadione | Sigma Aldrich | M5625 |

| methanol | Fisher Scientific | A456-4 |

| mucin type III | Sigma Aldrich | M1778 |

| N-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-N′-ethylcarbodiimide | Sigma Aldrich | 3449 |

| n-butyric acid | Sigma Aldrich | B103500 |

| potassium oxonate | Ambeed | A157215 |

| potassium phosphate dibasic | Fisher Scientific | BP363 |

| potassium phosphate monobasic | Fisher Scientific | BP362 |

| propionic acid | Sigma Aldrich | 402907 |

| pyridine | Sigma Aldrich | 270970 |

| resazurin, sodium salt | Acros | 418900050 |

| sodium acetate | Sigma Aldrich | S2889 |

| sodium bicarbonate | Fisher Scientific | S233-500 |

| sodium butyrate | Sigma Aldrich | 303410 |

| sodium carbonate | Fisher Scientific | S263-500 |

| sodium chloride | Fisher Scientific | S271-500 |

| sodium fumarate dibasic | Sigma Aldrich | F1506 |

| sodium hydroxide | Fisher Scientific | S318-500 |

| sodium phosphate, dibasic, anhydrous | Caisson Labs | S018-500GM |

| sodium propionate | Sigma Aldrich | P1880 |

| sodium thioglycolate | BD | B12081 |

| sterilized rumen fluid | Bar Diamond Inc. | SRF |

| succinic acid | Tokyo Chemical Industry (TCI) | S0100 |

| thiamphenicol | Sigma Aldrich | T0261 |

| trace mineral supplement | ATCC | MD-TMS |

| tryptone | BD | 211705 |

| tryticase peptone, pancreatic digest of casein | BD | 221921 |

| tween 80 | Fisher Scientific | T164-500 |

| uric acid | Sigma Aldrich | U2625 |

| uric acid (1,3-15N2, 98%+) | Cambridge Isotope Laboratories | NLM-1697-PK |

| uric acid (13C5, 99.3%) | Acanthus Research | U-10826-01 |

| valeric acid | Sigma Aldrich | 240370 |

| vitamin K1 | Sigma Aldrich | V3501 |

| vitamin supplement | ATCC | MD-VS |

| water | Fisher Scientific | W6-4 |

| xanthine | Tokyo Chemical Industry (TCI) | X0004 |

| xanthine (1,3-15N2, 98%+) 90% PURE | Cambridge Isotope Laboratories | NLM-1698-PK |

| yeast extract | BD | 288620 |

| Medium formulations | See Table S4 | See Table S4 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| AcroPrep Advance Filter Plates for Ultrafiltration with Omega Membrane, MWCO 3K | Pall Corporation | 8033 |

| DNA Clean & Concentrator-5, Capped Columns | Zymo Research | D4013 |

| RNAprotect Bacteria Reagent | Qiagen | 76506 |

| PowerUp SYBR Green Master Mix | ThermoFisher | A25778 |

| PrimeSTAR Max DNA Polymerase | Takara | R045A |

| Qubit RNA BR assay kit | ThermoFisher | Q10210 |

| SuperScript IV VILO Master Mix with ezDNase Enzyme | ThermoFisher | 11766050 |

| Terra PCR Direct Genotyping Kit | Takara | 639285 |

| Urea Assay Kit | Sigma Aldrich | MAK006 |

| Deposited data | ||

| RNA-seq data | NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus | GSE206419 |

| Metagenomic reads from Uox mice | NCBI BioProject | PRJNA947216 |

| Metagenomic data re-analyzed from the FARMM study | NCBI BioProject | PRJNA675301 |

| Metabolomics data re-analyzed from the FARMM study | Metabolomics Workbench | Study ID ST001519 |

| Reference genomes analyzed from the Human Microbiome Project | NCBI BioProject | PRJNA43021 |

| Custom R script for the metagenomic data processing and figure generation | Github | https://github.com/HAugustijn/uric_acid_project/ |

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

| Uricase deficient mice (B6; 129S7-Uoxtm1Bay/J) | The Jackson Laboratory | 002223;RRID:IMSR_JAX:002223 |

| Germ-free C57BL/6 mice (C57BL/6NTac) | Taconic Biosciences | http://www.taconic.com |

| C. sporogenes ATCC 15579; wild-type | ATCC | http://www.atcc.org |

| C. sporogenes ATCC 15579; ygeX(1026a)::CT | This study | N/A |

| C. sporogenes ATCC 15579; pbuX(952a)::CT | This study | N/A |

| C. sporogenes ATCC 15579; hyuA(524a)::CT | This study | N/A |

| C. sporogenes ATCC 15579; ygeW(1034a)::CT | This study | N/A |

| C. sporogenes ATCC 15579; ygfK(1440a)::CT | This study | N/A |

| C. sporogenes ATCC 15579; ssnA(784s)::CT | This study | N/A |

| C. sporogenes ATCC 15579; ygeY(358s)::CT | This study | N/A |

| C. sporogenes ATCC 15579; xdhAC(1084s)::CT | This study | N/A |

| E. coli MG 1655; wild-type | E. coli Genetic Stock Center | http://www.cgsc.biology.yale.edu |

| E. coli MG 1655; Δ(ygeW::cat)1 | This study | N/A |

| E. coli MG 1655; Δ(ygeX::cat)1 | This study | N/A |

| E. coli MG 1655; Δ(ygeY::cat)1 | This study | N/A |

| E. coli MG 1655; Δ(hyuA::cat)1 | This study | N/A |

| E. coli MG 1655; Δ(ygfK::cat)1 | This study | N/A |

| E. coli MG 1655; Δ(ssnA::cat)1 | This study | N/A |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| ygeX (CLOSPO_02124, 1026a) gBlock: ATAAAGTTGTGTAATTTTTAAGCTTTATAATTATCCTT AGACTCCCCTGATGTGCGCCCAGATAGGGTGTTAA GTCAAGTAGTTTAAGGTACTACTCTGTAAGATAACA CAGAAAACAGCCAACCTAACCGAAAAGCGAAAGCT GATACGGGAACAGAGCACGGTTGGAAAGCGATGAG TTACCTAAAGACAATCGGGTACGACTGAGTCGCAAT GTTAATCAGATATAAGGTATAAGTTGTGTTTACTGAA CGCAAGTTTCTAATTTCGATTGAGTCTCGATAGAGG AAAGTGTCTGAAACCTCTAGTACAAAGAAAGGTAAG TTAATATCAGGGACTTATCTGTTATCACCACATTTGT ACAATCTGTAGGAGAACCTATGG |

Integrated DNA technologies | N/A |

| pbuX (CLOSPO_02125, 952s) gBlock: ATAAAGTTGTGTAATTTTTAAGCTTTATAATTATCCTT ACAAAACGTAGGGGTGCGCCCAGATAGGGTGTTAA GTCAAGTAGTTTAAGGTACTACTCTGTAAGATAACA CAGAAAACAGCCAACCTAACCGAAAAGCGAAAGCT GATACGGGAACAGAGCACGGTTGGAAAGCGATGAG TTACCTAAAGACAATCGGGTACGACTGAGTCGCAAT GTTAATCAGATATAAGGTATAAGTTGTGTTTACTGAA CGCAAGTTTCTAATTTCGGTTTTTTGTCGATAGAGGA AAGTGTCTGAAACCTCTAGTACAAAGAAAGGTAAGT TAAGCCCTACGACTTATCTGTTATCACCACATTTGTA CAATCTGTAGGAGAACCTATGG |

Integrated DNA technologies | N/A |

| hyuA (CLOSPO_02126, 524a) gBlock: ATAAAGTTGTGTAATTTTTAAGCTTTATAATTATCCTT ACTGTACGTATACGTGCGCCCAGATAGGGTGTTAA GTCAAGTAGTTTAAGGTACTACTCTGTAAGATAACA CAGAAAACAGCCAACCTAACCGAAAAGCGAAAGCT GATACGGGAACAGAGCACGGTTGGAAAGCGATGAG TTACCTAAAGACAATCGGGTACGACTGAGTCGCAAT GTTAATCAGATATAAGGTATAAGTTGTGTTTACTGAA CGCAAGTTTCTAATTTCGGTTTACAGTCGATAGAGG AAAGTGTCTGAAACCTCTAGTACAAAGAAAGGTAAG TTATGGTATACGACTTATCTGTTATCACCACATTTGT ACAATCTGTAGGAGAACCTATGG |

Integrated DNA technologies | N/A |

| ygeW (CLOSPO_02127, 1034a) gBlock: ATAAAGTTGTGTAATTTTTAAGCTTTATAATTATCCTT ACTGATCCAGCTAGTGCGCCCAGATAGGGTGTTAA GTCAAGTAGTTTAAGGTACTACTCTGTAAGATAACA CAGAAAACAGCCAACCTAACCGAAAAGCGAAAGCT GATACGGGAACAGAGCACGGTTGGAAAGCGATGAG TTACCTAAAGACAATCGGGTACGACTGAGTCGCAAT GTTAATCAGATATAAGGTATAAGTTGTGTTTACTGAA CGCAAGTTTCTAATTTCGGTTATCAGTCGATAGAGG AAAGTGTCTGAAACCTCTAGTACAAAGAAAGGTAAG TTAGGTAGCTGGACTTATCTGTTATCACCACATTTGT ACAATCTGTAGGAGAACCTATGG |

Integrated DNA technologies | N/A |

| ygfK (CLOSPO_02128, 1440a) gBlock: ATAAAGTTGTGTAATTTTTAAGCTTTATAATTATCCTT AGTATTCTCCTTAGTGCGCCCAGATAGGGTGTTAAG TCAAGTAGTTTAAGGTACTACTCTGTAAGATAACACA GAAAACAGCCAACCTAACCGAAAAGCGAAAGCTGA TACGGGAACAGAGCACGGTTGGAAAGCGATGAGTT ACCTAAAGACAATCGGGTACGACTGAGTCGCAATGT TAATCAGATATAAGGTATAAGTTGTGTTTACTGAACG CAAGTTTCTAATTTCGATTAATACTCGATAGAGGAAA GTGTCTGAAACCTCTAGTACAAAGAAAGGTAAGTTA GCTAAGGAGACTTATCTGTTATCACCACATTTGTAC AATCTGTAGGAGAACCTATGG |

Integrated DNA technologies | N/A |

| ssnA (CLOSPO_02129, 784s) gBlock: ATAAAGTTGTGTAATTTTTAAGCTTTATAATTATCCTT AATAGCCGTACATGTGCGCCCAGATAGGGTGTTAA GTCAAGTAGTTTAAGGTACTACTCTGTAAGATAACA CAGAAAACAGCCAACCTAACCGAAAAGCGAAAGCT GATACGGGAACAGAGCACGGTTGGAAAGCGATGAG TTACCTAAAGACAATCGGGTACGACTGAGTCGCAAT GTTAATCAGATATAAGGTATAAGTTGTGTTTACTGAA CGCAAGTTTCTAATTTCGGTTGCTATCCGATAGAGG AAAGTGTCTGAAACCTCTAGTACAAAGAAAGGTAAG TTACAATGTACGACTTATCTGTTATCACCACATTTGT ACAATCTGTAGGAGAACCTATGG |

Integrated DNA technologies | N/A |

| ygeY (CLOSPO_02130, 358s) gBlock: ATAAAGTTGTGTAATTTTTAAGCTTTATAATTATCCTT AGGCGGCATGGCCGTGCGCCCAGATAGGGTGTTAA GTCAAGTAGTTTAAGGTACTACTCTGTAAGATAACA CAGAAAACAGCCAACCTAACCGAAAAGCGAAAGCT GATACGGGAACAGAGCACGGTTGGAAAGCGATGAG TTACCTAAAGACAATCGGGTACGACTGAGTCGCAAT GTTAATCAGATATAAGGTATAAGTTGTGTTTACTGAA CGCAAGTTTCTAATTTCGATTCCGCCTCGATAGAGG AAAGTGTCTGAAACCTCTAGTACAAAGAAAGGTAAG TTAGAGGCCATGACTTATCTGTTATCACCACATTTGT ACAATCTGTAGGAGAACCTATGG |

Integrated DNA technologies | N/A |

| xdhAC (CLOSPO_02131, 1084s) gBlock: ATAAAGTTGTGTAATTTTTAAGCTTTATAATTATCCTT AGATGGCGATGGAGTGCGCCCAGATAGGGTGTTAA GTCAAGTAGTTTAAGGTACTACTCTGTAAGATAACA CAGAAAACAGCCAACCTAACCGAAAAGCGAAAGCT GATACGGGAACAGAGCACGGTTGGAAAGCGATGAG TTACCTAAAGACAATCGGGTACGACTGAGTCGCAAT GTTAATCAGATATAAGGTATAAGTTGTGTTTACTGAA CGCAAGTTTCTAATTTCGATTCCATCTCGATAGAGG AAAGTGTCTGAAACCTCTAGTACAAAGAAAGGTAAG TTAACTCCATCGACTTATCTGTTATCACCACATTTGT ACAATCTGTAGGAGAACCTATGG |

Integrated DNA technologies | N/A |

| ygeX (CLOSPO_02124) sequencing Csp.ygeX-F: AGTAACTGGAGATATGCCTA Csp.ygeX-R: TACTAAAGTTGCTATGCCT |

Integrated DNA technologies | N/A |

| pbuX (CLOSPO_02125) sequencing Csp.pbuX-F: TTTTGTTTTATTATGGCACCT Csp.pbuX-R: TGCCAAACATAGCTATACCA |

Integrated DNA technologies | N/A |

| hyuA (CLOSPO_02126) sequencing Csp.hyuA-F: AAATCATTGATGCTCATGG Csp.hyuA-R: TAATCTAACCCTAACTTACAGG |

Integrated DNA technologies | N/A |

| ygeW (CLOSPO_02127) sequencing Csp.ygeW-F: CATCTTATGGTAAGCCACT Csp.ygeW-R: GTTCTTCAAACTTTAGGGCTG |

Integrated DNA technologies | N/A |

| ygfK (CLOSPO_02128) sequencing Csp.ygfK-F: CTTCTAAAGGCAAACAAGC Csp.ygfK-R: TAACCTTTCCATTTCCGAT |

Integrated DNA technologies | N/A |

| ssnA (CLOSPO_02129) sequencing Csp.ssnA-F: AAGGAAAACTTATAATGCCAG Csp.ssnA-R: CATTTCAGGAATTTCGGTC |

Integrated DNA technologies | N/A |

| ygeY (CLOSPO_02130) sequencing Csp.ygeY-F: TTTTAAAAGAAGGTGCTCT Csp.ygeY-R: TTCATACACATTTATTACCCC |

Integrated DNA technologies | N/A |

| xdhAC (CLOSPO_02131) sequencing Csp.xdhAC-F: ATTATTACAGCACAAGATGTCC Csp.xdhAC-R: CGCATGATGTTGTACACTCA |

Integrated DNA technologies | N/A |

| ygeW (b2870) λ-red recombination knockout F: TTTGCCTGTCATTCCACTACCGGGACTTTATGATGG TGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTC R: ATCGGCCCGAGGGGTTATTTCACGCGTTCTTGCGC CCATATGAATATCCTCCTTAGT |

Integrated DNA technologies | N/A |

| ygeX (b2871) λ-red recombination knockout F: CCCTCTATTTCCAGAGGCCAAAAGGATAGGATATGG TGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTC R: TTCCAATAGGGTGATTAAGGTGCTACAGCGTGTTTC CATATGAATATCCTCCTTAGT |

Integrated DNA technologies | N/A |

| ygeY (b2872) λ-red recombination knockout F: AAAACGGGGAGTAAAAAATCTGGAGAAAAATAATGG TGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTC R: GCCCATGATAGATACGCCGTTAGTTGAGAAGGTCC CCATATGAATATCCTCCTTAGT |

Integrated DNA technologies | N/A |

| hyuA (b2873) λ-red recombination knockout F: TCCGGTTCGCCGGAGGGTTTTTGGAGTTTGCTATG GTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTC R: ATCCCTGGCAGTGGTTAGAGCACGGGAGGGACAAA CCATATGAATATCCTCCTTAGT |

Integrated DNA technologies | N/A |

| ygfK (b2878) λ-red recombination knockout F: CAATGATATCTGTATAAGCTAAGGAGAGGGTTATGG TGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTC R: CGCCAGGCTGAAGACGGTGATTTTGTCTTTGTACGC CATATGAATATCCTCCTTAGT |

Integrated DNA technologies | N/A |

| ssnA (b2879) λ-red recombination knockout F: CATTATCTGCTGGGCCGCGTGGAGGTGTAATCATG GTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTC R: AGGGCATCTGTCATTTATGCCAGCGCATCCATCCGC CATATGAATATCCTCCTTAGT |

Integrated DNA technologies | N/A |

| ygeW (b2870) sequencing Ec.ygeW-CHF: GAATTTGCATCAATACTGACTG Ec.ygeW-CHR: TAACCTTCCCATGCCGTGTC |

Integrated DNA technologies | N/A |

| ygeX (b2871) sequencing Ec.ygeX-CHF: GAGCGTACTGAATTGCTGCG Ec.ygeX-CHR: CGTACGGATCGAAGTCCCAG |

Integrated DNA technologies | N/A |

| ygeY (b2872) sequencing Ec.ygeY-CHF: TGAAGCACTACCGCGAAGTT Ec.ygeY-CHR: TCGTAACTGCGTTCGTCCAA |

Integrated DNA technologies | N/A |

| hyuA (b2873) sequencing Ec.hyuA-CHF: CTGAAGCGCATGCACCTAAC Ec.hyuA-CHR: TCAGTTTTTGCGGCAGCTTC |

Integrated DNA technologies | N/A |

| ygfK (b2878) sequencing Ec.ygfK-CHF: AGGCAATCCAACGACCCAAT Ec.ygfK-CHR: ATCGCGCTGATTGAGTAGGG |

Integrated DNA technologies | N/A |

| ssnA (b2879) sequencing Ec.ssnA-CHF: TCCAGAACCGTTTCCAGACG Ec.ssnA-CHR: AGGCCAGGTAGTCCTCGATT |

Integrated DNA technologies | N/A |

| aegA (b2468) RT-qPCR (Amplification factor 2.07) Ec.aegA-F: AGGTCACTGCACTACGTTGCT Ec.aegA-R: ATGATGAGCAACATGTCCTGAGCC |

Integrated DNA technologies | N/A |

| ygfK (b2878) RT-qPCR (Amplification factor 2.03) Ec.ygfK-F: TTGACGCGCATATTTGATGAATACC Ec.ygfK-R: AGGTTTCACCGAAGACGCTAACA |

Integrated DNA technologies | N/A |

| ygfT (b2887) RT-qPCR (Amplification factor 2.04) Ec.ygfT-F: TCGCATCATCCCGTAAGTCCC Ec.ygfT-R: ATCTTAACTGTGAAATTGGCCGCG |

Integrated DNA technologies | N/A |

| rpoH (b3461) RT-qPCR (Amplification factor 1.98) Ec.rpoH-F: CACTGCTTTCATCAGGCCGA Ec.rpoH-R: AAACGCTGATCCTGTCTCACC |

Integrated DNA technologies | N/A |

| K127_2399939 ygeX RT-qPCR (Amplification factor 1.97) YgeX-F: TATTTAGGGCTTGGTGAGGTTTACA YgeX-R: TTTGCTATGTAACGTGCCATGG |

Integrated DNA technologies | N/A |

| K127_2399939 ygeY RT-qPCR (Amplification factor 1.96) YgeY-F: TCTGCCGAGTGTTAAGAAATATGGG YgeY-R: TAGCACTCGATAGGATATACCAGGT |

Integrated DNA technologies | N/A |

| K127_2399939 ssnA RT-qPCR (Amplification factor 1.94) SsnA-F: TTATGTACTACGCAGGTATCGGT SsnA-R: GGATATTCTGGGACCAAAGACGA |

Integrated DNA technologies | N/A |

| K127_1837117 ygeX RT-qPCR (Amplification factor 2.00) YgeX-F: TCTGTTGAGAACATGAGCACA YgeX-R: TCCTTTCCGCCATTATGGAG |

Integrated DNA technologies | N/A |

| K127_1837117 ygeY RT-qPCR (Amplification factor 1.95) YgeY-F: AGTGGGTTCAGTGGAGATGAC YgeY-R: ACTGCGACGGTATGTGCTG |

Integrated DNA technologies | N/A |

| K127_1837117 ssnA RT-qPCR (Amplification factor 1.91) SsnA-F: CCGTTGATAATAGTAGTGCGGCA SsnA-R: TGATTGTCATGGATTACAAGCCCT |

Integrated DNA technologies | N/A |

| K127_2793018 ygeX RT-qPCR (Amplification factor 2.00) YgeX-F: AGAAGTCGGTTGTACATATGCCG YgeX-R: CGCCATACGGACACATTCATCA |

Integrated DNA technologies | N/A |

| K127_2793018 ygeY RT-qPCR (Amplification factor 1.97) YgeY-F: GTTCGGTGCAGGAGGAAGAC YgeY-R: CGGTCGGTTCGGTCGAAATA |

Integrated DNA technologies | N/A |

| K127_2793018 ssnA RT-qPCR (Amplification factor 1.87) SsnA-F: TTCGGCATGATGGGCAAGAA SsnA-R: TGACTGCTCCATCGTCCATG |

Integrated DNA technologies | N/A |

| UOx genotyping oIMR1621: CGAGACCTTTGCAATGAACA oIMR1622: CTCATCTGCTCCACCTCACA oIMR6218: CCTTCTATCGCCTTCTTGACG |

The Jackson Laboratory | Protocol 31298 |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| Plasmid pMTL007C-E2-ygeX (CLOSPO_02124); 1026a | This paper | N/A |

| Plasmid pMTL007C-E2-pbuX (CLOSPO_02125); 952s | This paper | N/A |

| Plasmid pMTL007C-E2-hyuA (CLOSPO_02126); 524a | This paper | N/A |

| Plasmid pMTL007C-E2-ygeW (CLOSPO_02127); 1034a | This paper | N/A |

| Plasmid pMTL007C-E2-ygfK (CLOSPO_02128); 1440a | This paper | N/A |

| Plasmid pMTL007C-E2-ssnA (CLOSPO_02129); 784s | This paper | N/A |

| Plasmid pMTL007C-E2-ygeY (CLOSPO_02130); 358s | This paper | N/A |

| Plasmid pMTL007C-E2-xdhAC (CLOSPO_02131); 1084s | This paper | N/A |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| MassHunter Workstation LC/MS Data Acquisition | Agilent Technologies | v.10.1 |

| MassHunter Workstation Quantitative Analysis | Agilent Technologies | v.10.0 |

| CLC Genomics Workbench | QIAGEN | v.21.0.4 |

| GraphPad Prism | GraphPad Software, LLC | v.9.3.1 |

| QuantStudio 5 qPCR Data Analysis Software | ThermoFisher Scientific | v.1.5.1 |

Gene disruption in Escherichia coli MG1655 using λ-red recombination.

Gene disruption in Escherichia coli was first constructed by the λ-red recombination deletion method39 in BW25113 strain and then was transferred to MG1655 by P1 transduction40. The antibiotic resistance cassettes were removed by FLP-mediated excision39 before being used in experiments. Mutants were verified by PCR using primers listed in the key resource table. All strains generated in this study are listed in the key resource table.

Mouse studies

Uricase deficient mice.

Uox (B6; 129S7-Uoxtm1Bay/J) mice were resuscitated from frozen embryos by The Jackson Laboratory (strain # 002223). Animal experiments were performed following a protocol approved by the Stanford University Administrative Panel on Laboratory Animal Care. The mouse strain was maintained by heterozygous female (+/−) x homozygous male (−/−) mating. Mice were kept on standard chow (LabDiet Cat. # 5K67) and allopurinol water (100 mg/L) with access to food and water ad libitum in a facility on a 12-hour light/dark cycle with temperature controlled between 20-22°C and humidity between 40-60%. Genotyping was performed using Terra PCR Direct Genotyping Kit (Takara, 639285) following protocol modified from The Jackson Laboratory. For antibiotic treatment, water was supplemented with 0.5 mg/mL vancomycin, 1 mg/mL neomycin, 1 mg/mL metronidazole and 1 mg/mL colistin. Blood sampling was performed from live mice via the facial vein, collecting ~100 μL of blood into tubes containing concentrated sodium EDTA (final ~12 mM) as an anticoagulant and allopurinol (final ~12 μM) to inhibit xanthine oxidase23. After centrifugation at 1,500 g for 10 min at 10 °C, plasma was transferred to new tubes. Urine was collected by manually expressing urine from individual mice into sterile tubes. Cecal contents were surgically collected from humanely euthanized animals into sterile tubes. All samples were stored at −80 °C. Uric acid and creatinine were measured by LC-MS, and urea was measured by Urea Assay Kit.

Gnotobiotic mouse experiments.

Mouse experiments were performed on male or female gnotobiotic C57BL/6 germ-free mice (8-12 weeks of age) originally obtained from Taconic Biosciences (Mus musculus, Tac:B6) maintained in aseptic flexible film isolators (CBC, Madison, WI). Animal experiments were performed following a protocol approved by the Stanford University Administrative Panel on Laboratory Animal Care. Mice were maintained on standard chow (LabDiet Cat. # 5K67) and sterile water with access to food and water ad libitum in a facility on a 12-hour light/dark cycle with temperature controlled between 20-22 °C and humidity between 40-60%. Sterility of germ-free mice was confirmed before each experiment by culturing fecal pellets from each mouse anaerobically in GAM medium for 48 h. For chemically induced hyperuricemia experiments, mice were fed either a casein-fiber refined control chow (TD.210629), a casein-fiber plus 3% oxonic acid chow (TD.210630), or a casein-fiber plus 3% oxonic acid and 3% uric acid chow (TD.210631). Timing of chow administration, colonization, and sampling is outlined in the experimental summaries of the corresponding figures. Bacteria used in mouse experiments were cultured overnight anaerobically at 37 °C in rich medium, mixed in equal volumes as necessary, and administered to individual mice via intragastric gavage. Diets were formulated by Invito (formerly Envigo) and diet compositions are provided in Supplementary Data File S2.

METHOD DETAILS

Reagents used in this study.

All chemicals and reagents used in this study were of the highest possible purity and are listed in the key resource table. Uniformly labeled [13C5] uric acid was synthesized by Acanthus Research Inc. (Mississauga, Ontario, Canada). This chemical is available for purchase from Acanthus Research Inc. as catalog # U-10826-01. Due to solubility issues, uric acid or its 13C5 isotopologue was made fresh as follows: stock solutions of uric acid were prepared at 125 mM in 1 N NaOH (for screening) or 120 mM in 0.4 N NaOH (for all other experiments), sterile filtered and then diluted appropriately in anaerobic media for uric acid consumption assays.

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

Bacterial strains used in this study were obtained from culture collections as listed in Table S4 and medium formulations are provided in Table S4. All bacteria were cultured at 37 °C in a Coy type B anaerobic chamber using a gas mix containing 5% hydrogen, 10% carbon dioxide, and 85% nitrogen. An anaerobic gas infuser was used to maintain hydrogen levels of 3.3%. All media and plasticware were pre-reduced in the anaerobic chamber for at least 24 hours before use. E. coli for genetic manipulation was cultured under aerobic conditions using LB broth and LB plates, with temperature and antibiotic selection varying depending on the manipulation being done. E. coli uric acid consumption was performed under anaerobic conditions using pre-reduced media. For analysis of uric acid consumption under aerobic conditions, E. coli or Enterococcus faecalis TX2137 were cultured in 1.5 mL volumes in 14 mL round bottom culture tubes at 37 °C with vigorous aeration (300 rpm on an orbital shaker).

Culture conditions for uric acid consumption assays.

Bacterial strains used in the library screening, along with their culture media, are listed in Table S4. All strains were stored at −80 °C as anaerobically prepared 20% glycerol stocks, sealed to ensure anoxic conditions for long term storage. All bacteria were cultured in 96-deep well plates anaerobically unless otherwise indicated.

For bacteria library screening, glycerol stocks were first inoculated in rich media without uric acid at 37 °C for 24 h. Cultures were then diluted (10-fold) into medium containing uric acid (5 mM) and continued to incubate for 48 h. The cells were sedimented by centrifugation at 5,000 g for 25 min, 4 °C. Aliquots of supernatants were transferred to 96-well microtiter plates, tightly sealed, and stored at −80 °C prior to sample preparation for LC-MS analysis. Uric acid precipitation may influence our results in our screening assays; therefore we chose a relatively strict threshold of 50% uric acid consumption to identify uric acid consuming bacteria.

For other in vitro culture assays, bacteria were first streaked on GAM or RCM plates, and individual well-isolated colonies were picked to inoculate in liquid medium. E. coli was cultured in modified GAM broth unless otherwise indicated. Other strains were cultured in GAM broth. Individual colonies were picked and inoculated in rich media with 2 mM uric acid for 16-18 h and then diluted 50-fold in media with 4 mM uric acid. At designated time points, aliquots of cultures were harvested by centrifugation (5,000 g, room temperature, 5 min). Supernatants were collected and aliquoted into two plates, one that was used for SCFA measurement, and the other that was mixed with NH4OH (final 10 mM) and used for uric acid measurement. Both plates were stored at −80 °C until analysis by LC-MS.

Stable isotope tracing with 13C5 labeled uric acid.

For stable isotope tracing, strains were first cultured in rich medium with unlabeled uric acid (2 mM) for 16-18 h before being diluted into medium supplemented with either unlabeled uric acid (4 mM) or uniformly 13C5 labeled uric acid (4 mM). At designated times, aliquots were harvested as described above. When cultured without labeled uric acid, isotopologues (e.g., M+2 acetate and M+2 butyrate) were detectable in some of the cultures. We found that this reflected isotope natural abundances resulting from the large amount of short chain fatty acids produced from nutrients (amino acids and carbohydrates) present in the rich medium. Therefore, to correct for natural isotope abundance, we cultured organisms with labeled and unlabeled uric acid. After quantifying SCFA isotopologues, we subtracted concentrations of isotopologues in cultures with unlabeled uric acid from those cultured with labeled uric acid.

Sample preparation for analysis of uric acid, xanthine, and creatinine by liquid chromatography – mass spectrometry (LC-MS).

Uric acid or xanthine was made fresh at 120 mM in 0.4 N NaOH each time. Creatinine was dissolved at 500 mM in LC-MS grade water and stored at −20 °C. The stock solutions were diluted in 10 mM aqueous NH4OH to serve as a calibration standard for LC-MS assays. To account for matrix effects, the same portion of medium or double charcoal treated human plasma was added to the standard curves for in vitro samples or mouse plasma samples, respectively. Because charcoal treated human serum still has ~100 μM uric acid and ~70 μM creatinine, freshly made 13C5-uric acid and creatinine-d5 were used as calibrants for plasma measurements. Calibrants were treated the same as samples during LC-MS preparation.

Culture supernatants, mouse plasma, mouse urine or calibrants were first mixed with internal standard (ISTD) and 10 mM NH4OH, and then filtered by AcroPrep Omega 3K MWCO filter plates (Pall Corporation, 8033) at 3,000 g for 30 min at room temperature. The flow through was collected and diluted in NH4OH (final 3 to 5 mM) before subjecting to LC-MS analysis.

For mouse cecal samples containing low amount of uric acid (≤ 5 nmol/mg), 100 ± 10 mg samples were weighed in 2 mL impact resistant screw cap tubes (USA Scientific, 1420-9600) containing ~100 mg glass beads (Sigma, catalog no. G1145) and 150 μL ISTD. Then 750 μL extraction solution (75% acetonitrile/25% methanol) was added and samples were homogenized with a mixer mill (RETSCH MM400) at room temperature, 25/s, for 30 min. The supernatant was collected after centrifugation at 13,000 g for 5 min at room temperature. Supernatants were then diluted 5-fold in LC-MS water and submitted for LC-MS analysis.

For mouse cecal contents containing high amount of uric acid, 50 ± 5 mg cecal contents were weighed in 2 mL impact resistant screw cap tubes (USA Scientific, 1420-9600) containing glass beads (Sigma, catalog no. G1145) and 950 μL 20 mM ammonium hydroxide. Samples were homogenized with a mixer mill (RETSCH MM400) at room temperature, 25/s, for 30 min, and then centrifuged at 13,000 g for 5 min at room temperature. 100 μL of ammonium hydroxide extracted supernatants were mixed with 150 μL ISTD and 750 μL extraction solution (75% acetonitrile/25% methanol), and vortexed for 5 seconds. Then the samples were centrifuged at 13,000 g for 5 min at room temperature. Supernatants were collected and diluted 5-fold in LC-MS water and submitted for LC-MS analysis.

Mouse cecal calibrants were freshly made and serial diluted in 10 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.5. 100 μL cecal calibrant was mixed with 150 μL ISTD and 750 μL extraction solution (75% acetonitrile/25% methanol), and vortexed for 5 seconds. Samples were then centrifuged at 13,000 g for 5 min at room temperature. Supernatants were collected and diluted 5-fold in LC-MS water and submitted for LC-MS analysis.

Sample preparation for analysis of short chain fatty acids by LC-MS.

Culture supernatants were first mixed with internal standard (ISTD) in a V-bottom, polypropylene 96-well plate, and then extracted by mixing with extraction solution (75% acetonitrile/25% methanol) at 1:3 ratio. The plate was covered with a lid and centrifuged at 5,000 g for 15 min at 4 °C. Supernatant was collected for 3-nitrophenylhydrazine derivatization before subjecting to LC-MS analysis.

3-Nitrophenylhydrazine (NPH) derivatization protocol.

This derivatization method targets compounds containing a free carboxylic acid. Extracted samples were diluted in 50% acetonitrile and then mixed with 3-nitrophenylhydrazine (200 mM in 80% acetonitrile) and N-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-N’-ethylcarbodiimide (120 mM in 6% pyridine) at 2:1:1 ratio. The plate was sealed with a plastic sealing mat (Thermo Fisher Scientific cat. # AB-0566) and incubated at 40 °C, 600 rpm in a thermomixer for 60 min to derivatize the carboxylate containing compounds. The reaction mixture was quenched with 0.02% formic acid in 20% acetonitrile/water before LC-MS analysis.

Quantification of metabolites by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS).

During this study, two different LC-MS conditions were used (C18 positive underivatized and 3-nitrophenylhydrazine derivatized C18 negative). An overview of the general method is provided here and the specific instrument parameters for the different analytical methods are provided in Table S5. Samples were injected via refrigerated autosampler into mobile phase and chromatographically separated by an Agilent 1290 Infinity II UPLC and detected using an Agilent 6545XT Q-TOF equipped with a dual jet stream electrospray ionization source operating under extended dynamic range (EDR 1700 m/z). MS1 spectra were collected in centroid mode, and peak assignments in samples were made based on comparisons of retention times and accurate masses from authentic standards using MassHunter Quantitative Analysis v.10.0 software from Agilent Technologies. Compounds were quantified from calibration curves constructed with authentic standards using isotope-dilution mass spectrometry with appropriate internal standards (Table S5).

RNA purification for RNA-seq experiment.

All cultures were grown at 37 °C under anaerobic conditions. Clostridium sporogenes ATCC 15579, Collinsella aerofaciens ATCC 25986, and Lacrimispora saccharolytica WM1 were streaked from frozen stocks onto blood agar plates. Three individual colonies were selected for each bacterium and were inoculated into separate overnight cultures in Mega medium. The following day, each culture was precultured in Mega medium, and after three hours diluted to an OD of 0.1 into two experimental cultures, one containing standard Mega medium and one with Mega medium containing 5 mM uric acid. Bacteria were allowed to grow until reaching an OD that was commensurate with approximately 50% uric acid degradation as determined by previous experiments. Cell cultures were then combined with two volumes of RNAprotect (Qiagen) in an anaerobic chamber, mixed thoroughly and then allowed to sit for five minutes. Cells were then centrifuged (5,000 g, 4 °C, 10 min) and the supernatant was decanted. Cells were then subjected to lysozyme digestion, Proteinase K digestion and mechanical disruption with a mixer mill (RETSCH MM400) at 4 °C, 25/s, for 30 min. RNA was then purified using RNeasy kit (Qiagen), followed by DNase digestion and second RNA purification step using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen). RNA integrity was determined using a bioanalyzer (Agilent) and RNA-seq was performed by the Roy J. Carver Biotechnology Center at the University of Illinois.

RNA-seq library preparation and data collection.

Ribosomal RNA was removed with the Ribo-Zero Bacteria kit (Illumina). The RNA-seq libraries were prepared using a TruSeq Stranded mRNAseq Sample Prep kit with each sample individually ligated with unique adapters (Illumina). The libraries were quantitated by qPCR, pooled, and sequenced on one lane for 101 cycles from one end of the fragments on a NovaSeq 6000 using a NovaSeq SP reagent kit. Fastq files were generated and demultiplexed with the bcl2fastq v2.20 Conversion Software (Illumina) and adaptors were removed from the 3′ end of the reads. Read 1 aligns to the antisense strand and read 2 aligns to the sense strand.

RNA-seq data analysis.

RNA-seq processing was performed using CLC Genomics Workbench (v.21.0.4). Reads were trimmed using a quality score limit of 0.05 and ambiguous nucleotides (n = 2), and automatic read-through adapter trimming was performed. Next, genomes were downloaded from NCBI in GenBank file format (.gbff) for each of the three bacteria (NCBI assembly accession numbers: GCF_010509075.1, Collinsella aerofaciens ATCC 25986; GCF_000144625.1, Lacrimispora saccharolytica WM1; GCF_000155085.1, Clostridium sporogenes ATCC 15579). Genomes were uploaded into CLC Genomics Workbench and converted to tracks. RNAseq was performed using the genome track as the reference sequence and genes for the gene track. Mapping settings included: Mismatch cost, 2; Insertion cost, 3; Deletion cost, 3; Length fraction, 0.8; Similarity fraction, 0.8; maximum number of hits for a read, 10. Expression settings included: Strand setting, both; Library type setting, bulk; Expression value, TPM. Statistical comparisons were made between organisms cultured with or without uric acid using multi-factorial statistics based on a negative binomial GLM as implemented in CLC Genomics Workbench (v.21.0.4). The expression and CDS tracks were then exported as Excel files and expression and annotation tracks were merged in Excel using the VLOOKUP function based on the chromosome coordinates. For volcano plots, the −Log10 False Discovery Rate (FDR) corrected P-value was plotted against the Log2 fold-change for cultures grown with vs. without uric acid.

RNA purification for RT-qPCR.

All cultures were grown at 37 °C under anaerobic conditions. Escherichia coli MG1655 was streaked out from frozen stocks onto GAM plates. Individual colonies were selected and were inoculated into separate cultures in GAM modified medium with or without 2 mM uric acid. Three individual cultures were used for each condition. After 16 hours, the overnight cultures were diluted 50-fold in GAM modified medium with or without 4 mM uric acid and continued to incubate at 37 °C. At 24 h, 31 h and 48 h, one aliquot of culture was saved for uric acid LC-MS measurement, and another aliquot of culture was mixed with two volumes of RNAprotect Bacteria Reagent anaerobically to stabilize the RNA. RNA was extracted as described above. The total RNA concentration was measured by Qubit RNA BR Assay Kit. Two micrograms of total RNA were used for ezDNase digestion and then was reverse transcribed to cDNA by SuperScript IV VILO in a 20 μL reaction following manufacturer’s guidelines. Q-PCR was performed using PowerUp SYBR Green Master Mix with 4 replicates and an Applied Biosystems QuantStudio™ 5 real-time PCR instrument (ThermoFisher). E. coli gDNA concentration was measured using Qubit dsDNA BR Assay Kit. Primer validation was performed using six serial 10-fold dilutions of E. coli gDNA, spanning 2 ng/μL to 0.002 pg/μL per reaction. Primer amplification factor (Ep) and efficiency were calculated by ThermoFisher qPCR Efficiency Calculator. Three housekeeping genes (dnaK, fliA and rpoH) were tested and rpoH was selected as the reference gene because its Ct was consistent regardless of uric acid addition and was most similar to the Ct of target genes. Relative fold change of the target gene was calculated as follows:

| eq (1) |

Stable isotope tracing in Uox mouse cecal contents.

Fresh cecal contents (~20 mg) were resuspended in 200 μL 1X M9 salts with uniformly 13C5 labeled uric acid (final 4 mM) and Cysteine-Na2S (final 0.025%, each) in 1.5 mL tubes. The samples were incubated in an anaerobic chamber at 37 °C. At designated times, the sample tubes were centrifuged at 20,000 g at room temperature for 2 min anaerobically. Supernatant aliquots were harvested and saved one set directly for short chain fatty acids measurement and another set in ammonium hydroxide (final 10 mM) for uric acid measurement. The rest of the sample were resuspended again and continued to incubate at 37 °C until next time point. Supernatant samples were stored at −80 °C until sample processing and LC-MS analysis for uric acid and short chain fatty acids as described above.

Metagenomic analysis of uric acid genes in cecal contents of Uox mice.

Freshly collected cecal contents (~100 mg) were used for RNA purification by RNeasy PowerFecal Pro Kit (QIAGEN, 78404) and ~100 mg samples were saved at −80 °C until DNA extraction using QIAamp PowerFecal Pro DNA Kit (QIAGEN, 51804). Following extraction, purified genomic DNA was quantified using a Qubit fluorometer (ThermoFisher). Between 100-500 ng of each sample were taken forward to construct metagenomics sequencing libraries using the Illumina DNA Prep kit, with half-volumes being utilized at each step to minimize cost. Post PCR, libraries were purified using a 0.8x bead clean and were quantified again using the Qubit. Equal masses of each metagenomics library were pooled, and a dual-sided AMPure XP (Beckman Coulter) bead clean was performed on the pooled material to ensure proper size-selection for sequencer loading. Sequencing was performed on the NovaSeq6000 (Illumina) using a PE155 read configuration.