Abstract

Ethnomedicinal plants are important sources of drug candidates, and many of these plants, especially in the Western Ghats, are underexplored. Humboldtia, a genus within the Fabaceae family, thrives in the biodiversity of the Western Ghats, Kerala, India, and holds significant ethnobotanical importance. However, many Humboldtia species remain understudied in terms of their biological efficacy, while some lack scientific validation for their traditional uses. However, Humboldtia sanjappae, an underexplored plant, was investigated for the phytochemical composition of the plant, and its antioxidant, enzyme-inhibitory, anti-inflammatory, and antibacterial activities were assessed. The LC-MS analysis indicated the presence of several bioactive substances, such as Naringenin, Luteolin, and Pomiferin. The results revealed that the ethanol extract of H. sanjappae exhibited significant in vitro DPPH scavenging activity (6.53 ± 1.49 µg/mL). Additionally, it demonstrated noteworthy FRAP (Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power) activity (8.46 ± 1.38 µg/mL). Moreover, the ethanol extract of H. sanjappae exhibited notable efficacy in inhibiting the activities of α-amylase (47.60 ± 0.19µg/mL) and β-glucosidase (32.09 ± 0.54 µg/mL). The pre-treatment with the extract decreased the LPS-stimulated release of cytokines in the Raw 264.7 macrophages, demonstrating the anti-inflammatory potential. Further, the antibacterial properties were also evident in both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. The observed high zone of inhibition in the disc diffusion assay and MIC values were also promising. H. sanjappae displays significant anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antidiabetic, and antibacterial properties, likely attributable to its rich composition of various biological compounds such as Naringenin, Luteolin, Epicatechin, Maritemin, and Pomiferin. Serving as a promising reservoir of these beneficial molecules, the potential of H. sanjappae as a valuable source for bioactive ingredients within the realms of nutraceutical and pharmaceutical industries is underscored, showcasing its potential for diverse applications.

Keywords: Humboldtia sanjappae, LC-MS analysis, radical scavenging, anti-inflammatory activity, cytokine release

1. Introduction

Humans have always battled with various infections. In addition to these, recent decades have witnessed a significant increase in the occurrence of various non-communicable diseases. These diseases have been associated with increased mortality globally. The changes in lifestyle comprising dietary changes and reduced physical activity have resulted in a sudden increase in the number of patients. The role of oxidative stress and inflammation is impeccable in the onset of these diseases. Oxidative stress, the imbalance between the generation of reactive molecules and its scavenging, plays significant roles in non-communicable diseases [1]. Together with this, numerous studies have established that inflammation has a role in the progression of different diseases. The link between inflammatory response and the onset of different cancers such as ovarian cancer and pancreatic cancer has been studied well [2,3]. Recent studies suggest that neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s will escalate the disease progression Recently, studies on Gynostemma pentaphyllum (Thunb.) Makino demonstrated a protective effect against the inflammation [4,5]. New therapies indicate that the anti-inflammatory treatments associated with cardiovascular disease are a promising strategy to bring down the succession of the disease [6]. Inflammatory processes in the host defense system should be highly regulated, and the loss of control is problematic. So, the inflammatory molecules have become the primary target for the prevention of various diseases, in which the main signaling pathways such as the nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) signaling pathway, Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription (JAK/STAT) signaling pathway, and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathway might be brought under control to prevent the diseases [7,8,9]; the JAK/STAT is focused on more because this pathway is associated with the pathogenesis of different inflammatory diseases such as Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) and Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) [10,11]. Even though inflammation is an evolutionarily conserved mechanism for the organism’s survival [12], it is essential to control the prolonged release of anti-inflammatory mediators to prevent the development of various diseases [13]. Different natural products have recently been investigated and have given satisfactory results in this respect [14,15]. Excess inflammation in the body will lead to the development of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS); if the concentration of the same exceeds a limit, the body will not be able to neutralize the same [16]. Due to this reason, pharmaceutical and food industries have considerably used natural products with antioxidant capabilities, and herbal products that promote health have also become highly popular in recent years [17,18].

It has been discovered that several plant medicines have a variety of pharmacological properties, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anticancer, neuroprotective, and hypolipidemic properties [8,19,20]. These activities are attributed to the non-nutritive chemicals present in the plants [10]. Findings from studies conducted in mice suggest that the leaves of Hemigraphis alternata exhibit anti-inflammatory, anti-nociceptive, and anti-diarrheal activities [21]. These kinds of phytochemicals are reported in several plant families such as Lamiaceae, Zingiberaceae, Malvaceae, Acanthaceae, and Apocyanacea [22,23]. Fabaceae is one such family with an abundance of different phytochemicals which are good in curing various diseases [24].

The genus Humboldtia belongs to the family Fabaceae. The plants of the particular genus are well known for their traditional uses and pharmacological properties [25]. Research has been conducted on certain species of Humboldtia, revealing their rich phytochemical composition. These plants have been found to contain valuable phytochemicals, including phenols, flavonoids, saponins, tannins, terpenoids, cardiac glycosides, apigenin, steroids, phlobatannins, and more [26,27,28]. In the realm of traditional medicine, the bark of Humboldtia species held curative significance, being employed to address conditions such as biliousness, leprosy, ulcers, and epilepsy and acting as an anticonvulsant [29]. The remediation of biliousness, impurities in the blood, ulcers, and epilepsy all involved the preparation of a decoction from the bark powder [30].

Humboldtia brunonis Wall, Humboldtia unijuga Bedd., and Humboldtia vahliana Wight are well known for their pharmacological efficiency and their antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anticancer, antimicrobial, and anti-depressant effects [28,29,31,32,33]. H. brunonis fulfilled roles as a styptic, demulcent, anthelmintic, ulcer remedy, stomachic, astringent, and treatment for menstrual and urinary issues [34]. Furthermore, the local populations residing in Karnataka’s Shiradi and Bisle Ghats harnessed the leaves and bark of H. brunonis for arthritis and diabetes treatments, a practice detailed by Prasad and Kumar [26]. It was documented that the H. brunonis bark and leaves were utilized for addressing wounds, menstruation disorders, and overgrowth issues [35]. Humboldtia unijuga, referred to as ‘palakan’ by the Kani tribes in Agasthyamala, was employed to treat ailments such as headaches, chickenpox, and snake bites [36]. It has been discovered that the plant possesses Erythrodiol-3-acetate and 2,4-di-tert-butylphenol, which have been demonstrated to exhibit anti-inflammatory and anticancer properties [25].

The plant species Humboldtia sanjappae, belonging to the Fabaceae family, and its related species exhibit a diverse range of pharmacological properties [28,29,31,32,33]. However, the phytochemical constituents and pharmacological effects of this plant remain largely unexplored. Currently, there are no existing reports on the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities of this plant, and data regarding its phytochemical composition are also lacking. Consequently, this study represents a pioneering effort to investigate the phytochemical profile of the plant and evaluate its potential antioxidant, enzyme-inhibitory, anti-inflammatory, and antibacterial properties. To identify the bioactive phytochemicals, LC-MS analysis is employed as a key analytical technique.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Quantitative and Qualitative Estimation of Phytochemicals in H. sanjappae

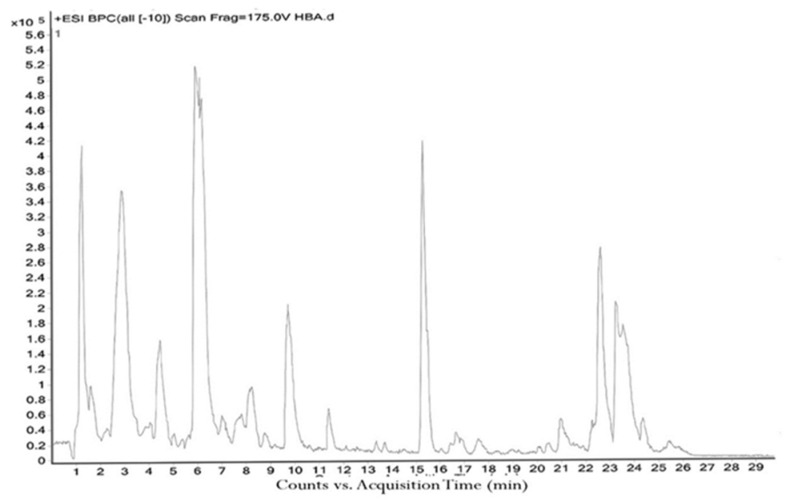

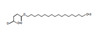

The H. sanjappae extract was analyzed using LC-MS, which indicated the presence of flavonoids, including Naringenin, Luteolin, and Pomiferin, as well as phenols such as Epicatechin and Maritemin (Figure 1, Table 1). Flavonoids and phenolic substances not only have antioxidant properties, but they also work well as anti-inflammatory agents [37]. Various studies provide support for the immune-modulating effects of polyphenols and flavonoids. Seed polyphenols extracted from Nigella sativa L. were evaluated for their analgesic and anti-inflammatory properties. The study findings demonstrated that these polyphenols effectively reduced paw edema induced by carrageenan [38]. Concentrated extract derived from Dendrobium loddigesii Rolfe, rich in polyphenols, was administered to treat diabetic mice. The outcomes indicated that this extract exhibited the capability to lower blood glucose levels, reduce body weight, decrease levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and elevate insulin levels within the mice [39]. Flavonoids are part of the category of polyphenolic natural compounds, encompassing over 4000 identified variations. The advantageous biological effects of flavonoids are unquestionably intertwined with their structural composition and properties, rendering them prime contenders for pharmaceutical development. Numerous inflammatory molecules such as TNF-α, IL-1, IL-6, IL-17, and IFN-γ, released via the activation of various signaling pathways, primarily the NF-κB pathway, have been demonstrated to be inhibited upon administration of flavonoid [40]. Scientists detected that supplementation of Epicatechin potentially contributed to reducing inflammation and enhancing insulin sensitivity in visceral adipose tissue of high-fat fed mice [41]. The presence of phytochemicals such as Epicatechin in the plant may be responsible for its observed antidiabetic activity. However, additional experiments and studies are necessary to validate this hypothesis and confirm the specific compounds and mechanisms involved in the plant’s potential benefits for diabetes management. Certainly, the antioxidant properties of the extract can play a crucial role in managing oxidative stress in individuals with diabetes. As diabetes can cause substantial cellular damage, including in the brain, combating oxidative stress with antioxidant compounds becomes important [42]. By reducing oxidative stress, the extract’s antioxidant properties may help protect cells, mitigate damage, and contribute to improved overall health in diabetic patients.

Figure 1.

The LC−MS total ion chromatogram of H. sanjappae ethanol extract.

Table 1.

LC−MS analysis and chemical composition of H. sanjappae.

| Sl. No. | RT | m/z a | m/z b | Name of the Compound | Fragments | Mol. Wt. | Chemical Formula | Structure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3.575 | 577.14 | 577.14 | Richotomine | 483.13, 315.11, 197.80 | 532.14 | C30H20N4O6 |

|

| 2 | 3.773 | 579.15 | 579.15 | Procyanidin B7 | 579.14, 443.15, 383.12, 227.17 | 578.14 | C30H26O12 |

|

| 3 | 4.166 | 289.07 | 289.07 | (−)−Epicatechin | 289.07, 226.07 | 290.08 | C15H14O6 |

|

| 4 | 4.633 | 513.14 | 513.14 | 2″,6″−Di-O-acetylononin | 513.14, 289.07 | 514.15 | C26H26O11 |

|

| 5 | 5.908 | 494.24 | 494.24 | Ryanodine | 494.23, 189.07 | 493.23 | C25H35NO9 |

|

| 6 | 5.919 | 465.16 | 465.16 | Pomiferin | 421.16, 213.07 | 420.16 | C25H24O6 |

|

| 7 | 6.312 | 549.22 | 549.22 | Cymorcin diglucoside | 431.10, 253.03 | 490.21 | C22H34O12 |

|

| 8 | 8.763 | 287.05 | 287.06 | Maritimetin | 287.05, 283.15, 267.15 | 286.05 | C15H10O6 |

|

| 9 | 9.101 | 285.04 | 285.04 | Luteolin | 285.04, 215.09 | 286.05 | C15H10O6 |

|

| 10 | 9.475 | 271.06 | 271.06 | Naringenin | 271.06, 259.12, 248.97 | 272.07 | C15H12O5 |

|

| 11 | 9.681 | 271.06 | 271.06 | Coriandrone E | 251.16, 179.10 |

248.07 | C13H12O5 |

|

| 12 | 10.067 | 271.06 | 271.06 | Morindone | 271.05, 267.15, 253.14 | 270.05 | C15H10O5 |

|

| 13 | 10.197 | 301.07 | 301.07 | (+)-Sophorol | 271.05, 301.06, 295.18, 277.17 | 300.06 | C16H12O6 |

|

| 14 | 10.485 | 269.08 | 269.08 | Formononetin | 258.04, 179.10, 139.15 | 268.07 | C16H12O4 |

|

| 15 | 11.846 | 283.19 | 283.19 | Lactapiperanol C | 279.09, 265.17 | 282.18 | C16H26O4 |

|

| 16 | 15.229 | 507.23 | 507.22 | Limonoate | 507.22, 351.25, 238.12 | 506.22 | C26H34O10 |

|

| 17 | 16.573 | 295.23 | 295.23 | 17−Hydroxylinolenic acid | 295.22, 284.32, 277.21 | 294.22 | C18H30O3 |

|

| 18 | 19.676 | 645.42 | 645.42 | Capsanthin 5,6−epoxide | 529.30, 403.26, 238.89 | 600.42 | C40H56O4 |

|

| 19 | 21.644 | 593.27 | 593.27 | Ganoderic acid F | 415.35, 227.17, 570.41 | 570.28 | C32H42O9 |

|

| 20 | 22.179 | 471.35 | 471.35 | delta−Maslinic acid | 471.85, 311.17, 248.97 | 472.36 | C30H48O4 |

|

| 21 | 23.291 | 413.26 | 413.27 | D8’−Merulinic acid A | 391.28, 279.15, 149.02 | 390.28 | C24H38O4 |

|

a: calculated m/Z ratio, b: Reference m/Z ratio.

Several investigators have noted natural substances’ anti-inflammatory properties, including multiple preclinical experiments [43,44,45,46]. As a result, we infer that the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties exhibited by the ethanol extract of H. sanjappae must be due to the presence of various phytochemical components such as polyphenols, flavonoids, isocoumarins, etc., and also that these many different phytochemicals in plants offer a valuable source of antimicrobial compounds with immense therapeutic potential [47]. Antibiotic-resistant bacteria have emerged as a significant global health concern [48,49]. Plants have long been renowned for their antibacterial powers as nature’s medicine [50]. Polyphenols and essential oils, among other bioactive substances, have powerful antibacterial properties [30,51,52,53]. Adopting plant phenomena might open the way for innovative and long-lasting antibacterial treatments because traditional antibiotics are becoming less effective, leading to a pressing need for the development of new and effective antimicrobial agents. In this context, the rich diversity of plant species provides a vast array of bioactive compounds that can be explored for their antimicrobial properties. Polyphenols and flavonoids possess well-documented antimicrobial properties [54,55], exhibiting inhibitory effects against a broad spectrum of bacteria [55,56].

Our research has supplied substantiating proof of the elevated levels of these compounds in the ethanol extract of H. sanjappae. Specifically, the total phenolic content measured at 378.77 ± 6.62 µg equivalent per milligram and the total flavonoid content recorded at 204.76 ± 6.10 µg equivalent per milligram both emphasize the concentration within the extract (Table 2). Given its rich content of polyphenols and flavonoids, the extract from H. sanjappae shows promise as a potential source for the development of novel antibiotics. Considering its antimicrobial potential, the polyphenol- and flavonoid-rich extract of H. sanjappae warrants further exploration in the search for new antibiotic compounds.

Table 2.

The total polyphenol and flavonoid contents of H. sanjappae ethanol extract.

| Assay | µg Equivalent/mg of Extract |

|---|---|

| Total phenolic content | 378.77 ± 6.62 |

| Total flavonoid content | 204.76 ± 6.10 |

2.2. In Vitro Antioxidant Activities of H. sanjappae Extract

Species of the Fabaceae family consist of phytochemicals responsible for the plant’s antioxidant potential [57]. The different genera of the family are established as having antioxidant potential [58]. In vivo studies of Tamarindus, a related genus of Humbodtia, showed that it exhibits potent antioxidant activity [59], and the antioxidant potential of species within the genus Humboldtia has been previously explored, and their effectiveness has been reported [27,31]. The IC50 value of H. sanjappae bark extract in the anti-DPPH radical scavenging assay was shown to be 6.53 ± 1.49 µg/mL. Likewise, Table 3 shows other antioxidant activity in Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power, represented by its value of 8.46 ± 1.38 µg/mL. The antioxidant properties of the plant must be assigned to the different phytochemicals present in the extract; those bioactive compounds identified from LC-MS analysis are listed in the Table 1. For example, previous studies demonstrated that anticancer properties of Epicatechin are linked to its antioxidative potential [60]. Another component present in the extract is Luteolin, which is found in glycosylated forms in a variety of vegetables and fruits and is classified within the flavone subclass of flavonoids. Its documented effects include in vivo anti-inflammatory [61], antioxidative [62,63,64], antidiabetic [61], antimicrobial [65], and anticancer [66,67] activities. The antioxidant properties of Naringenin [68,69], Morindone [70,71], Capsanthin 5,6-epoxide [72,73], and Ganoderic acid F [74] have been previously established. Therefore, these compounds could potentially account for the robust antioxidant activity observed in the extract. Oxidative stress plays a critical role as an independent factor in the development of numerous chronic diseases, including cancer, diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases [75,76,77,78]. Therefore, the antioxidant properties found in the plant extract can be beneficial in the management of diseases that are linked to oxidative stress.

Table 3.

In vitro antioxidant and antidiabetic activities of H. sanjappae expressed as IC50 values (µg/mL).

| Activity | IC50 Value(µg/mL) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| HSE | Ascorbic Acid | Acarbose | |

| DPPH scavenging | 6.53 ± 1.49 | 2.11 ± 0.25 | >200 |

| FRAP value | 8.46 ± 1.38 | 4.15 ± 0.47 | >200 |

| α-amylase | 47.60 ± 0.19 | 33.92 ± 2.54 | 122.18 ± 3.08 |

| α-glucosidase | 32.09 ± 0.54 | 29.85 ± 2.01 | 103.45 ± 2.68 |

2.3. Enzyme Inhibitory Properties of H. sanjappae Ethanol Extract

The extract was examined for its enzyme-inhibitory properties against key enzymes associated with type 2 diabetes mellitus, namely α-amylase and α-glucosidase. The IC50 value for the inhibition of α-amylase and α-glucosidase by the extract was determined to be 47.60 ± 0.19 µg/mL and for the inhibition of β-glucosidase, 32.09 ± 0.54 µg/mL (Table 3). The standard antidiabetic drug acarbox exibited an IC50 value of 122.18 ± 3.08 and 103.45 ± 2.68 µg/mL against α-amylase and α-glucosidase enzymes, respectively. Hence, the plant extract contains stronger antidiabetic compounds compared to the acarbose. The α-amylase and α-glucosidase are enzymes that play crucial roles in carbohydrate metabolism and are frequently targeted by antidiabetic medications [79]. Indeed, the inhibition of α-amylase and α-glucosidase by the H. sanjappae extract may contribute to its potent antidiabetic activity. By inhibiting these enzymes involved in carbohydrate metabolism, the extract can potentially help regulate blood glucose levels and manage diabetes effectively. The enzyme-inhibitory properties are well corroborated by the major bioactive substances observed in the plant using LC-MS analysis. Epicatechin, Luteolin, and Naringenin were reported to inhibit the α-amylase and α-glucosidase in in vitro and animal model studies [80,81]. In addition, the reports clearly indicated the antidiabetic properties of these bioactive compounds in independent studies.

2.4. Anti-Inflammatory Activity of H. sanjappae

The anti-inflammatory activity of the extract was evaluated using Raw 264.7 macrophages as the model. Raw 264.7 cells stimulated with lipopolysacchride (LPS) are a widely utilized cellular model of inflammation [82]. The lipopolysaccharide is the cell wall component of most of the Gram-negative bacteria; the LPS stimulates the macrophage in a toll-like-receptor-dependent manner [83]. In the present study, the normal macrophage was estimated for the level of IL-1β, and it was estimated to be 64.6 ± 1.9 pg/mg protein. However, there was observed a significant elevation in the IL-1β levels upon stimulation with the lipopolysaccharide to 573.4 ± 4.5 pg/mg protein. The increased level of IL-1β is an indicator of inflammation in the cellular conditions [84,85,86]. However, the pre-treatment of macrophages with the different doses of HSE resulted in a significant reduction in IL-1β levels (Table 4). The pre-treatment of Raw 264.7 cells with 5 µg/mL of HSE resulted in cellular IL-1β levels of 403.7 ± 6.2 pg/mg protein (p < 0.01). Similarly, the pre-treatment with 10 µg/mL (298.5 ± 8.4 pg/mg protein) and 20 µg/mL of HSE (156.2 ± 3.4 pg/mg protein) resulted in lower IL-1β levels (p < 0.001). The reduction in IL-1β levels is indicative of the anti-inflammatory potential of the HSE at the respective treatment doses.

Table 4.

Anti-inflammatory activity of H. sanjappae extract against lipopolysaccharide-induced activation of Raw 264.7 cells and comparison with standard aspirin (1 mM).

| IL-1β (pg/mg Protein) |

IL-6 (pg/mg Protein) |

TNF-α (pg/mg Protein) |

NO (µM/mg Protein) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Untreated | 64.6 ± 1.9 | 133.4 ± 5.8 | 115.2 ± 3.1 | 10.7 ± 0.64 |

| LPS Control | 573.4 ± 4.5 | 628.5 ± 8.2 | 856.0 ± 11.2 | 75.2 ± 2.1 |

| Aspirin (1 mM) | 147.5 ± 5.1 *** | 209.5 ± 9.1 *** | 247.5 ± 6.3 *** | 22.7 ± 1.7 *** |

| HSE 5 µg/mL | 403.7 ± 6.2 ** | 507.1 ± 8.1 * | 715.2 ± 8.8 * | 58.8 ± 3.4 * |

| HSE 10 µg/mL | 298.5 ± 8.4 *** | 388.4 ± 2.8 *** | 602.8 ± 5.2 *** | 42.3 ± 1.9 *** |

| HSE 20 µg/mL | 156.2 ± 3.4 *** | 291.3 ± 6.6 *** | 493.7 ± 6.4 *** | 30.7 ± 2.5 *** |

* indicates significant variation with respect to LPS control (p < 0.05); ** indicates higher significant variation with respect to that of LPS control (p < 0.01), and *** indicates highest significant variation with respect to that of LPS control (p < 0.001). All the results are indicated as mean ± standard deviation of six independent experiments.

Together with IL-1β, IL-6 was also found to significantly influence the inflammation in macrophages [87,88]. IL-6 has a major role in the innate immune defense systems [89]; however, the same molecule is associated with the progression of various diseases [90,91]. The level of IL-6 in the untreated macrophages without LPS stimulation was estimated to be 133.4 ± 5.8 pg/mg protein; however, the exposure of LPS elevated the cellular IL-6 levels to 628.5 ± 8.2 pg/mg protein. On the contrary, the level was brought down by the treatment with 5 and 10 µg/mL of H. sanjappae extract, which reduced the cellular IL-6 levels to 507.1 ± 8.1 (p < 0.05) and 388.4 ± 2.8 pg/mg protein (p < 0.001). In the highest concentration of H. sanjappae extract treatment, the IL-6 was estimated to be 291.3 ± 6.6 pg/mg protein (p < 0.001).

The TNF-α levels are crucial for the survival and proliferation of various cancer cells [92]. The cytokine is also important in the progression events of cancers including metastasis and stemness [93]. The level of TNF-α in the untreated and unstimulated Raw 264.7 macrophages was estimated to be 115.2 ± 3.1 pg/mg protein. However, the level was elevated to 856.0 ± 11.2 pg/mg protein upon stimulation by the LPS. This clearly indicated the induction of acute inflammation in the experimental condition. In 5 µg/mL H. sanjappae treated macrophages, the level of TNF-α was reduced to 715.2 ± 8.8 pg/mg protein. A similar decrease in the TNF-α level was also noted in the 10 and 20 µg/mL H. sanjappae treatment, which brought down the TNF-α level to 602.8 ± 5.2 and 493.7 ± 6.4 pg/mg protein.

The nitric oxide level is also an important inflammatory indicator in cells; the inducible nitric oxide synthase is an enzyme responsible for the overwhelming load of nitric oxide in the body [94]. Despite its physiological and immunological importance, nitric oxide is often associated with chronic inflammation and is thereby involved in many of the degenerative diseases [95]. The level of nitric oxide in the untreated macrophage cells was estimated to be 10.7 ± 0.64 µM/mg protein. The level was increased to 75.2 ± 2.1 µM/mg protein in the macrophages exposed to LPS. Interestingly, the level was brought down by the pre-treatment with the 5 µg/mL of HSE (58.8 ± 3.4 µM/mg protein). In the 10 µg/mL of H. sanjappae extract treatment, the NO level was estimated to be 42.3 ± 1.9 µM/mg protein, and, in the 20 µg/mL HSE treatment, it was further reduced to 30.7 ± 2.5 µM/mg protein. Hence, it is clearly indicated that the pre-treatment with different doses of HSE dose-dependently reduced the inflammatory insults in cultured macrophages.

Pathogen-associated molecular pattern molecules (PAMPs) or damage-associated molecular pattern molecules (DAMPs) are the two types of molecules that trigger the production and release of IL-1β. LPS is the main outer surface membrane component and is a highly potent PAMP which stimulates innate or natural immunity in various eukaryotic cells [96]. LPS-induced inflammatory responses are linked to the production of ROS in cells [97]. H. sanjappae extract was found to possess anti-inflammatory potential in a dose-dependent manner (Table 4). In vitro analysis revealed that it inhibits nitric oxide (NO) radicals. The inflammatory insults caused by LPS are prevented in cells pre-treated with H. sanjappae extract, and cytokine level is also reduced as a result. Interleukin-1β (IL- 1β) is a potent proinflammatory cytokine vital in the host cell defense reaction to infection [98]. After LPS stimulation, macrophages were shown to have a considerably higher level of IL-1β; however, pre-treatment with H. sanjappae extract at various dosages dramatically reduced the IL-1β levels in the macrophages. Like IL-β, interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) are significant mediators of innate immunity [99]. LPS also elevated the level of these cytokines. Application of the H. sanjappae extract reduced the elevated levels of TNF-α and IL-6.

The bioactive flavonoids present in the H. sanjappae extract such as Epicatechin, Luteolin, and Naringenin might play an important role in the anti-inflammatory potential of the plant. Independent studies have reported the anti-inflammatory potential of these bioactive flavonoid molecules in cultured macrophages and animals [37].

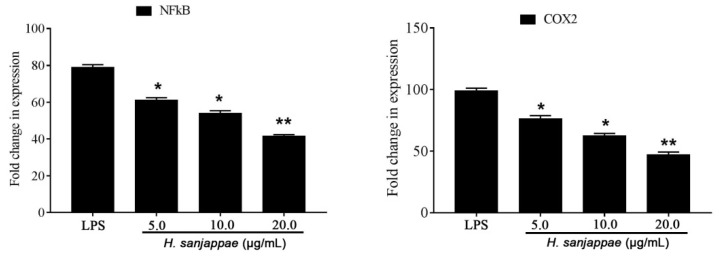

To further explain the mechanism of anti-inflammatory activity, the expression of genes NF-KB and COX2 was assessed. Compared to the untreated LPS control, the H. sanjappae extract treatment significantly brought down the expression of NF-KB and COX2. The expression of NF-KB is a crucial event in inflammation, and it is associated with various diseases including cancers. Likewise, the COX2 is a well-known inflammatory enzyme associated with the production of prostaglandins. The expression of COX2 is also evident in different forms of cancers (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The expression of NF-KB and COX2 genes in the Raw 264.7 macrophages treated with LPS and different doses of H. sanjappae leaf methanol extract. * indicates significant variation with respect to LPS control (p < 0.05); ** indicates higher significant variation with respect to that of LPS control (p < 0.01).

2.5. Antibacterial Activity of H. sanjappae

The antibacterial activity of H. sanjappae is being documented for the first time, while antimicrobial properties of H. brunonis have previously been reported [100]. Previous studies have investigated the antimicrobial potential of different extracts from H. brunonis, where the methanolic extract of the leaves [101] and aqueous extract of stem and leaf [33] exhibited significant antibacterial activity. It is worth noting that many species within the genus have not been extensively studied in this regard. Therefore, there remains a considerable knowledge gap regarding the antimicrobial potential of the majority of species within the genus. The present study observed a significant antibacterial activity of the plant against different pathogenic microbes (Table 5). The highest activity was observed against Pseudomonas aeruginosa (24.1 ± 0.3 mm) followed by Salmonella enterica (22.1 ± 0.1 mm). The lowest activity was observed against E. coli (18.5 ± 0.2 mm). The standard antibiotic gentamicin (20 µg) had growth inhibition zones of 21.7 ± 0.5, 22.1 ± 0.1, 19.7 ± 0.2, and 20.5 ± 0.2 mm against E. coli, P. aeuginosa, S. aureus, and S. enterica, respectively. Likewise, the minimum inhibitory concentration was found to be highly effective against P. aeruginosa (0.625 ± 0.02 mg/mL) followed by Salmonella enterica (1.00 ± 0.01 mg/mL). The lowest activity was observed against E. coli (1.50 ± 0.01 mg/mL). The MIC values of gentamicin were found to range between 0.325 and 0.625 mg/mL (Table 5).

Table 5.

Efficacy of H. sanjappae (HSE) as an antimicrobial agent estimated using disc diffusion method and minimum inhibitory concentrations and comparison with gentamicin (GM).

| Bacteria | Zone of Inhibition (mm) | MIC Concentration (mg/mL) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HSE | GM (20 µg) |

HSE | GM | |

| Escherichia coli | 18.5 ± 0.2 | 21.7 ± 0.5 | 1.50 ± 0.01 | 0.325 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 24.1 ± 0.3 | 22.1 ± 0.1 | 0.625 ± 0.02 | 0.325 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 20.6 ± 0.3 | 19.7 ± 0.2 | 1.25 ± 0.04 | 0.625 |

| Salmonella enterica | 22.1 ± 0.1 | 20.5 ± 0.2 | 1.00 ± 0.01 | 0.625 |

All the results are indicated as mean ± standard deviation of six independent experiments.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Humboldtia sanjappae Collection and Extraction

The Humboldtia sanjappae plant samples were collected on 12 December 2022 from Ernakulam District, Western Ghats of Kerala (10.04829° N, 76.8399° E). The mature leaves and the bark of the plants collected were carefully cleaned of all kinds of dust via washing. These materials were dried under shade for 21 days and powdered using a mixer grinder; the powder was extracted with 100% ethanol. About 5 g of each material was subjected to 6 h of extraction. All the extracts were evaporated to dryness using a rotary evaporator, and extract yield was calculated for the same.

3.2. Phytochemical Analysis of Humboldtia sanjappae

A preliminary phytochemical analysis of all samples was performed to determine the presence of biologically important secondary metabolites such as alkaloids, flavonoids, terpenoids, steroids, carbohydrates, saponins, etc. All tests were conducted following the conventional procedures described by Yadav, Agarwala, and Harborne [102,103]. The total phenolic content (TPC) and the total flavonoid content (TFC) were determined spectrophotometrically. TPC was found using the Folin–Ciocalteu reagent assay [104]. A standard curve was constructed using Gallic Acid standards. TPC was measured in Gallic Acid Equivalents (GAE). TFC was determined using an aluminium chloride colorimetric assay [105]. The flavonoid content was estimated using the standard quercetin calibration curve. TFC was measured in terms of quercetin equivalents.

The LC-MS analysis was carried out according to the previous methods of House et al. [106]. Briefly, the HR-LCMS-Q-TOF analysis was carried out using Agilent 1290 UHPLC system (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Accurately, 10 µL of the extract was injected into the system, and the run was carried out using water (0.1% formic acid v/v) (A) and methanol (B) as solvents. The gradient elution mode was used as follows: 1–10 min 95% A, 10–20 min 75% A, 20–25 min 50% A, 25–30 min 30% A, 30–40 min 95% B. The flow rate was set at 0.3 mL/min, and pressure was 1200 bar.

3.3. Analysis of the Antioxidant Activity of H. sanjappae Ethanol Extract

The antioxidant activities were assessed by evaluating the scavenging potentials of various radicals, such as diphenyl picryl hydrazyl (DPPH) and FRAP (Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power). These methods allow for the measurement of the ability of the tested samples to neutralize or reduce these radicals, providing insights into their antioxidant properties [96,97]. A solution of DPPH was prepared by dissolving it in methanol at a concentration of 0.1 mM. Varying concentrations of the extract were mixed with the DPPH solution. The resulting mixture was then incubated in a dark environment at a temperature of 30 degrees Celsius for 20 min. The change in absorbance of the solution was measured and used to estimate the percentage inhibition [96]. The stock solutions consisted of a 300 mM acetate buffer (prepared by dissolving 3.1 g of sodium acetate and 16 mL of acetic acid) with a pH of 3.6, a 10 mM TPTZ (2, 4, 6-tripyridyl-s-triazine) solution (3.12 mg/mL) in 40 mM HCl, and a 20 mM FeCl3 solution (3.25 mg/mL). To prepare the fresh working solution, 25 mL of acetate buffer, 2.5 mL of TPTZ solution, and 2.5 mL of FeCl3 solution were mixed together. The resulting solution was warmed at 37 °C before use. For the FRAP assay, a test sample of varying concentrations was mixed with 2.80 mL of the prepared FRAP solution. The mixture was allowed to react for 30 min under dark conditions. After the incubation period, the absorbance of the colored product, known as the ferrous tripyridyltriazine complex, was measured at a wavelength of 593 nm [98]. The control in the experiment refers to the reaction mixture in which the test sample was not added.

3.4. Analysis of the H. sanjappae Ethanol Extract on Activities of Enzymes

To assess the enzyme-inhibitory properties of the test samples, specific enzymes related to diabetes and secondary diabetic complications were targeted. The inhibitory effects on α-amylase [45] and α-glucosidase [46] were examined using standard procedures.

3.5. Effect of H. sanjappae Ethanol Extract on Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Anti-Inflammatory Activity in Macrophages

The murine Raw 264.7 cells were seeded at 1 × 107 cells/mL in a 24-well plate containing complete growth media. The H. sanjappae extract was diluted in RPMI-1640 media at different concentrations (5, 10, and 20 µg/mL). A standard anti-inflammatory compound, aspirin, was also used as positive control at a concentration of 1 mM. The cells were then treated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) at a concentration of 1 μg/mL for 24 h. The levels of inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-1β, interleukin-6, and tumor necrosis factor-α were measured using PeproTech ELISA kits. The production of nitric oxide in the media by the macrophages was quantified biochemically using the Griess method [106]. The gene expression of NF-KB and Cyclooxygenase 2 was determined by real-time PCR according to the ΔΔCT method. Briefly, the total RNA was isolated, and cDNA was synthesized using standard kits from Takara (Banglore, India). The real-time PCR analysis was carried out using the temperature cycle of 95 °C (melting temperature) for 15 s, 60 °C (annealing temperature) for 45 s, and 73 °C (extension temperature) for 30 s. The cycle was repeated 40 times, and CT values were calculated using the Applied Biosystems 7300 software. The primer sequences used in the study are listed in Supplementary Table S5.

3.6. Antibacterial Activity of H. sanjappae Ethanol Extract

The antibacterial activity of H. sanjappae was estimated in terms of the disc diffusion method according to the methods of Webber et al. [107]. The extracts were placed in circular discs and kept in the bacterial culture plate at 80 mm distance to one another. The growth inhibition zone in each of the bacterial cultures was determined and expressed as zone of inhibition in mm. The MIC value was determined according to the previous methods of Morgan et al. [108]. The gentamicin was used as a standard antibacterial agent at a concentration of 20 µg.

3.7. Statistical Analysis

The data were represented as mean of three independent experiments with triplicate analysis. The statistical operations were carried out using GraphPad Prism 7.0.

4. Conclusions

Most of the species in the genus Humboldtia have not been evaluated for their pharmacological potential despite their relevance in ethnomedicine. The present study for the first time reports the phytochemical composition and antioxidant, antimicrobial, and anti-inflammatory activities of H. sanjappae, a native of the Western Ghats of India. The study concludes that the plant has strong antioxidant properties in terms of radical scavenging and reducing potentials, and it is also effective as an antibacterial agent. Further, the extract inhibited the cytokine levels in Raw 264.7 macrophages, which is indicative of its anti-inflammatory properties. Enzymes such as α-amylase and α-glucosidase are important in controlling how our bodies absorb carbs and are frequently targeted by diabetic drugs [79]. Indeed, the potent antidiabetic actions of HSE may be connected to its capacity to inhibit α-amylase and α-glucosidase. The extract may help regulate blood sugar levels and successfully manage diabetes by inhibiting certain carbohydrate-processing enzymes.

By carefully studying and testing, we have clearly shown that bark extract of H. sanjappae made with ethanol is really good at reducing inflammation, controlling diabetes, fighting bacteria, and acting as an antioxidant. These different benefits not only highlight how valuable H. sanjappae is, but also remind us that using plants for medicine has always been a great way to create a variety of medicines. There are many examples from history where medicinal plants have led to big changes in medicine. For example, aspirin, which comes from the bark of the willow tree (Salix alba L.), changed how we manage pain and helped develop other drugs such as NSAIDs (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) [109]. Additionally, the Madagascar periwinkle plant (Catharanthus roseus L.) gave us vinblastine and vincristine, powerful compounds that have really changed how we treat cancer [110].

Significantly, more than half of the drugs utilized worldwide in modern pharmaceuticals have their origins in natural sources [111,112]. The worldwide commercial success of established and effective pharmaceuticals taken from many plant kinds demonstrates the importance of medicinal plants as potential drug reservoirs. Quinine, an anti-malarial alkaloid derived from the bark of Cinchona officinalis L., is one example. Furthermore, chloroquine, derived from quinine, not only modulates inflammatory autoimmune responses but has recently shown promise in anticancer therapy [112,113].

The polypharmacological potential of H. sanjappae, as evidenced by its diverse array of beneficial properties, aligns perfectly with this lineage of discovery. Its capacity to simultaneously tackle a range of health factors—spanning from inflammation and diabetes to bacterial infections and oxidative stress—resonates with the holistic approach of medicinal plants. These qualities offer the potential for more complete and refined therapeutic treatments, acknowledging the complexities of human health.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the funding support from Researchers Supporting Project Number (RSP2023R11), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. The DBT-STAR (project number: BT/HRD/11/09/2020) scheme supported infrastructural development in St. Joseph’s College (Autonomous), Devagiri, Calicut.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/molecules28196875/s1. Table S1: Qualitative analysis of phytochemicals present in different extracts of Humboldtia sanjappae; Table S2: Percentage yield of different extracts of H. sanjappae; Table S3: Antioxidant activity of different extracts of H. sanjappae; Table S4: Total phenol and total flavonoid contents of different extracts of H. sanjappae; Table S5: The forward and reverse primer sequences of different genes used for real-time PCR analysis.

Author Contributions

J.S.: analysis, manuscript preparation, experimentation. S.G.: study design, methodology, experimentation, analysis, funding acquisition, manuscript editing. R.R.: analysis, manuscript preparation, experimentation. A.A.: study design, methodology, experimentation, analysis, funding acquisition, manuscript editing. O.J.O.: study design, methodology, experimentation, analysis, funding acquisition, manuscript editing. A.N.: study design, methodology, experimentation, analysis, funding acquisition, manuscript editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data may be shared upon valid request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Sample Availability

Samples of the compounds are available from the authors.

Funding Statement

The authors acknowledge the funding support from Researchers Supporting Project Number (RSP2023R11), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Authors acknowledge the financial support from Mohammed VI Polytechnic University, Morocco.

Footnotes

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

References

- 1.Kumar V., Bishayee K., Park S., Lee U., Kim J. Oxidative stress in cerebrovascular disease and associated diseases. Front. Endocrinol. 2023;14:1124419. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2023.1124419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jia D., Nagaoka Y., Katsumata M., Orsulic S. Inflammation is a key contributor to ovarian cancer cell seeding. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:12394. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-30261-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hausmann S., Kong B., Michalski C., Erkan M., Friess H. The role of inflammation in pancreatic cancer. Inflamm. Cancer. 2014;816:129–151. doi: 10.1007/978-3-0348-0837-8_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mastinu A., Bonini S.A., Premoli M., Maccarinelli G., Mac Sweeney E., Zhang L., Lucini L., Memo M. Protective Effects of Gynostemma pentaphyllum (var. Ginpent) against Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Inflammation and Motor Alteration in Mice. Molecules. 2021;26:570. doi: 10.3390/molecules26030570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rahman S., Atikullah M., Islam M.N., Mohaimenul M., Ahammad F., Islam M.S., Saha B., Rahman H. Anti-inflammatory, antinociceptive and antidiarrhoeal activities of methanol and ethyl acetate extract of Hemigraphis alternata leaves in mice. Clin. Phytoscience. 2019;5:16. doi: 10.1186/s40816-019-0110-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Golia E., Limongelli G., Natale F., Fimiani F., Maddaloni V., Pariggiano I., Bianchi R., Crisci M., D’Acierno L., Giordano R. Inflammation and cardiovascular disease: From pathogenesis to therapeutic target. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 2014;16:435. doi: 10.1007/s11883-014-0435-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iqbal J., Abbasi B.A., Mahmood T., Kanwal S., Ali B., Shah S.A., Khalil A.T. Plant-derived anticancer agents: A green anticancer approach. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2017;7:1129–1150. doi: 10.1016/j.apjtb.2017.10.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kasote D.M., Katyare S.S., Hegde M.V., Bae H. Significance of antioxidant potential of plants and its relevance to therapeutic applications. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2015;11:982. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.12096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oguntibeju O.O. Medicinal plants with anti-inflammatory activities from selected countries and regions of Africa. J. Inflamm. Res. 2018;11:307. doi: 10.2147/JIR.S167789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coulibaly A.Y., Hashim R., Sulaiman S.F., Sulaiman O., Ang L.Z.P., Ooi K.L. Bioprospecting medicinal plants for antioxidant components. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 2014;7:S553–S559. doi: 10.1016/S1995-7645(14)60289-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Okach D., Nyunja A., Opande G. Phytochemical screening of some wild plants from Lamiaceae and their role in traditional medicine in Uriri District-Kenya. Int. J. Herb. Med. 2013;1:135–143. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu C.H., Abrams N.D., Carrick D.M., Chander P., Dwyer J., Hamlet M.R., Macchiarini F., PrabhuDas M., Shen G.L., Tandon P. Biomarkers of chronic inflammation in disease development and prevention: Challenges and opportunities. Nat. Immunol. 2017;18:1175–1180. doi: 10.1038/ni.3828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nunes C.d.R., Barreto Arantes M., Menezes de Faria Pereira S., Leandro da Cruz L., de Souza Passos M., Pereira de Moraes L., Vieira I.J.C., Barros de Oliveira D. Plants as sources of anti-inflammatory agents. Molecules. 2020;25:3726. doi: 10.3390/molecules25163726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zammel N., Saeed M., Bouali N., Elkahoui S., Alam J.M., Rebai T., Kausar M.A., Adnan M., Siddiqui A.J., Badraoui R. Antioxidant and anti-Inflammatory effects of Zingiber officinale roscoe and Allium subhirsutum: In silico, biochemical and histological Study. Foods. 2021;10:1383. doi: 10.3390/foods10061383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Apaza Ticona L., Pérez-Uz B., García Esteban M.T., Aguilar Rico F., Slowing K. Anti-melanogenic and Anti-inflammatory Activities of Hibiscus sabdariffa. Rev. Bras. De Farmacogn. 2022;32:127–132. doi: 10.1007/s43450-022-00236-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ďuračková Z. Some current insights into oxidative stress. Physiol. Res. 2010;59:459–469. doi: 10.33549/physiolres.931844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rodriguez-Garcia I., Silva-Espinoza B.A., Ortega-Ramirez L.A., Leyva J.M., Siddiqui M.W., Cruz-Valenzuela M.R., Gonzalez-Aguilar G.A., Ayala-Zavala J.F. Oregano Essential Oil as an Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Additive in Food Products. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2016;56:1717–1727. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2013.800832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mhatre S., Srivastava T., Naik S., Patravale V. Antiviral activity of green tea and black tea polyphenols in prophylaxis and treatment of COVID-19: A review. Phytomedicine. 2021;85:153286. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2020.153286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alagumanivasagam G., Veeramani P. A review on medicinal plants with hypolipidemic activity. Int. J. Pharm. Anal. Res. 2015;4:129–134. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fu W., Zhuang W., Zhou S., Wang X. Plant-derived neuroprotective agents in Parkinson’s disease. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2015;7:1189. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shamsudin N.F., Ahmed Q.U., Mahmood S., Shah S.A.A., Sarian M.N., Khattak M.M.A.K., Khatib A., Sabere A.S.M., Yusoff Y.M., Latip J. Flavonoids as Antidiabetic and Anti-Inflammatory Agents: A Review on Structural Activity Relationship-Based Studies and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022;23:12605. doi: 10.3390/ijms232012605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gangaram S., Naidoo Y., Dewir Y.H., El-Hendawy S. Phytochemicals and Biological Activities of Barleria (Acanthaceae) Plants. 2021;11:82. doi: 10.3390/plants11010082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Olivia N.U., Goodness U.C., Obinna O.M. Phytochemical profiling and GC-MS analysis of aqueous methanol fraction of Hibiscus asper leaves. Future J. Pharm. Sci. 2021;7:59. doi: 10.1186/s43094-021-00208-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Njamen D., Djiogue S., Zingue S., Mvondo M.A., Nkeh-Chungag B.N. In vivo and in vitro estrogenic activity of extracts from Erythrina poeppigiana (Fabaceae) J. Complement. Integr. Med. 2013;10:63–73. doi: 10.1515/jcim-2013-0018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nair R.V., Jayasree D.V., Biju P.G., Baby S. Anti-inflammatory and anticancer activities of erythrodiol-3-acetate and 2, 4-di-tert-butylphenol isolated from Humboldtia unijuga. Nat. Prod. Res. 2018;34:2319–2322. doi: 10.1080/14786419.2018.1531406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kumar J.K., Prasad A.D., Chaturvedi V. Phytochemical screening of five medicinal legumes and their evaluation for in vitro anti-tubercular activity. Ayu. 2014;35:98. doi: 10.4103/0974-8520.141952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pavithra G., Naik A.S., Siddiqua S., Vinayaka K., TR P.K., Mukunda S. Antioxidant and antibacterial activity of flowers of Calycopteris floribunda (Roxb.) Poiret, Humboldtia brunonis Wall and Kydia calycina Roxb. Int. J. Drug Dev. Res. 2013;5:301–310. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sindhu S., Manorama S., Sumathi P., Adira S. Antimicrobial studies on the endemic medicinal plant Humboldtia brunonis wall. (Caesalpiniaceae) Int. J. Pharmaceut. Sci. Health Care. 2014:4. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Asirvatham R., Yesudanam S. Neuropharmacological study of Humboldtia vahliana Wight. Sch. Acad. J. Pharm. 2018;7:171–183. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sanjappa M. A revision of the genus Humboldtia Vahl (Leguminosae-Caesalpinioideae) Blumea Biodivers. Evol. Biogeogr. Plants. 1986;31:329–339. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Asirvatham R., Yesudanam S. Evaluation of antioxidant potential of Humboldtia Vahliana Wight in Neuropharmacological screening on mice. J. Int. Res. Med. Pharm. Sci. 2017;11:41–53. [Google Scholar]

- 32.John B., Sulaiman C., George S., Reddy V. Total phenolics and flavonoids in selected medicinal plants from Kerala. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2014;6:406–408. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sheik S., Chandrashekar K. Antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of Kingiodendron pinnatum (DC.) Harms and Humboldtia brunonis Wallich: Endemic plants of the Western Ghats of India. J. Natl. Sci. Found. Sri Lanka. 2014;42:307. doi: 10.4038/jnsfsr.v42i4.7729. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nisbet L.J., Moore M. Will natural products remain an important source of drug research for the future? Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 1997;8:708–712. doi: 10.1016/S0958-1669(97)80124-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nagabhushan R.K., Raveesha A. Ethnobotanical survey and scientific validation of medicinal plants used in the treatment of fungal infections in Agumbe region of Western Ghats, India. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2015;7:273–277. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vijayan A., Liju V.B., John R.J.V., Parthipan B., Renuka C. Traditional Remedies of Kani Tribes of Kottoor Reserve Forest, Agasthyavanam, Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala. CSIR; New Delhi, India: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Al-Khayri J.M., Sahana G.R., Nagella P., Joseph B.V., Alessa F.M., Al-Mssallem M.Q. Flavonoids as potential anti-inflammatory molecules: A review. Molecules. 2022;27:2901. doi: 10.3390/molecules27092901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ghannadi A., Hajhashemi V., Jafarabadi H. An investigation of the analgesic and anti-inflammatory effects of Nigella sativa seed polyphenols. J. Med. Food. 2005;8:488–493. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2005.8.488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li X.-W., Chen H.-P., He Y.-Y., Chen W.-L., Chen J.-W., Gao L., Hu H.-Y., Wang J. Effects of Rich-Polyphenols Extract of Dendrobium loddigesii on Anti-Diabetic, Anti-Inflammatory, Anti-Oxidant, and Gut Microbiota Modulation in db/db Mice. Molecules. 2018;23:3245. doi: 10.3390/molecules23123245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ginwala R., Bhavsar R., Chigbu D.G.I., Jain P., Khan Z.K. Potential Role of Flavonoids in Treating Chronic Inflammatory Diseases with a Special Focus on the Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Apigenin. Antioxidants. 2019;8:35. doi: 10.3390/antiox8020035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bettaieb A., Cremonini E., Kang H., Kang J., Haj F.G., Oteiza P.I. Anti-inflammatory actions of (−)-epicatechin in the adipose tissue of obese mice. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2016;81:383–392. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2016.08.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reagan L.P., Magarinos A.M., McEWEN B.S. Neurological changes induced by stress in streptozotocin diabetic rats. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1999;893:126–137. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb07822.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Freitas L.M., Antunes F.T.T., Obach E.S., Correa A.P., Wiiland E., de Mello Feliciano L., Reinicke A., Amado G.J.V., Grivicich I., Fialho M.F.P. Anti-inflammatory effects of a topical emulsion containing Helianthus annuus oil, glycerin, and vitamin B3 in mice. J. Pharm. Investig. 2021;51:223–232. doi: 10.1007/s40005-020-00508-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ou Z., Zhao J., Zhu L., Huang L., Ma Y., Ma C., Luo C., Zhu Z., Yuan Z., Wu J. Anti-inflammatory effect and potential mechanism of betulinic acid on λ-carrageenan-induced paw edema in mice. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019;118:109347. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2019.109347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kwon Y.-I.I., Vattem D.A., Shetty K. Evaluation of clonal herbs of Lamiaceae species for management of diabetes and hypertension. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006;15:107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shai L., Magano S., Lebelo S., Mogale A. Inhibitory effects of five medicinal plants on rat alpha-glucosidase: Comparison with their effects on yeast alpha-glucosidase. J. Med. Plants Res. 2011;5:2863–2867. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Matu E.N., Van Staden J. Antibacterial and anti-inflammatory activities of some plants used for medicinal purposes in Kenya. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2003;87:35–41. doi: 10.1016/S0378-8741(03)00107-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Frieri M., Kumar K., Boutin A. Antibiotic resistance. J. Infect. Public Health. 2017;10:369–378. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2016.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.MacGowan A., Macnaughton E. Antibiotic resistance. Medicine. 2017;45:622–628. doi: 10.1016/j.mpmed.2017.07.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Alibi S., Crespo D., Navas J. Plant-derivatives small molecules with antibacterial activity. Antibiotics. 2021;10:231. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics10030231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Guimarães A.C., Meireles L.M., Lemos M.F., Guimarães M.C.C., Endringer D.C., Fronza M., Scherer R. Antibacterial activity of terpenes and terpenoids present in essential oils. Molecules. 2019;24:2471. doi: 10.3390/molecules24132471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Simirgiotis M.J., Burton D., Parra F., López J., Muñoz P., Escobar H., Parra C. Antioxidant and antibacterial capacities of Origanum vulgare L. essential oil from the arid Andean Region of Chile and its chemical characterization by GC-MS. Metabolites. 2020;10:414. doi: 10.3390/metabo10100414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.El Moussaoui A., Jawhari F.Z., Almehdi A.M., Elmsellem H., Benbrahim K.F., Bousta D., Bari A. Antibacterial, antifungal and antioxidant activity of total polyphenols of Withania frutescens L. Bioorganic Chem. 2019;93:103337. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2019.103337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Reglodi D., Renaud J., Tamas A., Tizabi Y., Socías S.B., Del-Bel E., Raisman-Vozari R. Novel tactics for neuroprotection in Parkinson’s disease: Role of antibiotics, polyphenols and neuropeptides. Prog. Neurobiol. 2017;155:120–148. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2015.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ramata-Stunda A., Petriņa Z., Valkovska V., Borodušķis M., Gibnere L., Gurkovska E., Nikolajeva V. Synergistic effect of polyphenol-rich complex of plant and green propolis extracts with antibiotics against respiratory infections causing bacteria. Antibiotics. 2022;11:160. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics11020160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Haghjoo B., Lee L.H., Habiba U., Tahir H., Olabi M., Chu T.-C. The synergistic effects of green tea polyphenols and antibiotics against potential pathogens. Adv. Biosci. Biotechnol. 2013;4:959. doi: 10.4236/abb.2013.411127. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Usman M., Khan W.R., Yousaf N., Akram S., Murtaza G., Kudus K.A., Ditta A., Rosli Z., Rajpar M.N., Nazre M. Exploring the phytochemicals and anti-cancer potential of the members of Fabaceae family: A comprehensive review. Molecules. 2022;27:3863. doi: 10.3390/molecules27123863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zonyane S., Fawole O.A., La Grange C., Stander M.A., Opara U.L., Makunga N.P. The implication of chemotypic variation on the anti-oxidant and anti-cancer activities of Sutherlandia frutescens (L.) R.Br.(Fabaceae) from different geographic locations. Antioxidants. 2020;9:152. doi: 10.3390/antiox9020152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Borquaye L.S., Doetse M.S., Baah S.O., Mensah J.A. Anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidant activities of ethanolic extracts of Tamarindus indica L. (Fabaceae) Cogent Chem. 2020;6:1743403. doi: 10.1080/23312009.2020.1743403. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Abdulkhaleq L.A., Assi M.A., Noor M.H.M., Abdullah R., Saad M.Z., Taufiq-Yap Y.H. Therapeutic uses of epicatechin in diabetes and cancer. Vet. World. 2017;10:869–872. doi: 10.14202/vetworld.2017.869-872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dong H., Yang X., He J., Cai S., Xiao K., Zhu L. Enhanced antioxidant activity, antibacterial activity and hypoglycemic effect of luteolin by complexation with manganese (II) and its inhibition kinetics on xanthine oxidase. RSC Adv. 2017;7:53385–53395. doi: 10.1039/C7RA11036G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Alshehri S., Imam S.S., Altamimi M.A., Hussain A., Shakeel F., Elzayat E., Mohsin K., Ibrahim M., Alanazi F. Enhanced dissolution of luteolin by solid dispersion prepared by different methods: Physicochemical characterization and antioxidant activity. ACS Omega. 2020;5:6461–6471. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.9b04075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kim N.M., Kim J., Chung H.Y., Choi J.S. Isolation of luteolin 7-O-rutinoside and esculetin with potential antioxidant activity from the aerial parts of Artemisia montana. Arch. Pharmacal Res. 2000;23:237–239. doi: 10.1007/BF02976451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Xu H., Linn B.S., Zhang Y., Ren J. A review on the antioxidative and prooxidative properties of luteolin. React. Oxyg. Species. 2019;7:136–147. doi: 10.20455/ros.2019.833. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Guo Y., Liu Y., Zhang Z., Chen M., Zhang D., Tian C., Liu M., Jiang G. The antibacterial activity and mechanism of action of luteolin against Trueperella pyogenes. Infect. Drug Resist. 2020;13:1697–1711. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S253363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Çetinkaya M., Baran Y. Therapeutic Potential of Luteolin on Cancer. Vaccines. 2023;11:554. doi: 10.3390/vaccines11030554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Potočnjak I., Šimić L., Gobin I., Vukelić I., Domitrović R. Antitumor activity of luteolin in human colon cancer SW620 cells is mediated by the ERK/FOXO3a signaling pathway. Toxicol. Vitr. 2020;66:104852. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2020.104852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cavia-Saiz M., Busto M.D., Pilar-Izquierdo M.C., Ortega N., Perez-Mateos M., Muñiz P. Antioxidant properties, radical scavenging activity and biomolecule protection capacity of flavonoid naringenin and its glycoside naringin: A comparative study. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2010;90:1238–1244. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.3959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Patel K., Singh G.K., Patel D.K. A review on pharmacological and analytical aspects of naringenin. Chin. J. Integr. Med. 2018;24:551–560. doi: 10.1007/s11655-014-1960-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ismail N.H., Mohamad H., Mohidin A., Lajis N.H. Antioxidant activity of anthraquinones from Morinda elliptica. Nat. Prod. Sci. 2002;8:48–51. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chee C.W., Zamakshshari N.H., Lee V.S., Abdullah I., Othman R., Lee Y.K., Hashim N.M., Rashid N.N. Morindone from Morinda citrifolia as a potential antiproliferative agent against colorectal cancer cell lines. PLoS ONE. 2022;17:e0270970. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0270970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Guil-Guerrero J., Martínez-Guirado C., del Mar Rebolloso-Fuentes M., Carrique-Pérez A. Nutrient composition and antioxidant activity of 10 pepper (Capsicum annuun) varieties. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2006;224:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s00217-006-0281-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sun T., Xu Z., Wu C.T., Janes M., Prinyawiwatkul W., No H. Antioxidant activities of different colored sweet bell peppers (Capsicum annuum L.) J. Food Sci. 2007;72:S98–S102. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2006.00245.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ahmad M.F., Wahab S., Ahmad F.A., Ashraf S.A., Abullais S.S., Saad H.H. Ganoderma lucidum: A potential pleiotropic approach of ganoderic acids in health reinforcement and factors influencing their production. Fungal Biol. Rev. 2022;39:100–125. doi: 10.1016/j.fbr.2021.12.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Dubois-Deruy E., Peugnet V., Turkieh A., Pinet F. Oxidative stress in cardiovascular diseases. Antioxidants. 2020;9:864. doi: 10.3390/antiox9090864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ndrepepa G. Myeloperoxidase–A bridge linking inflammation and oxidative stress with cardiovascular disease. Clin. Chim. Acta. 2019;493:36–51. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2019.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hayes J.D., Dinkova-Kostova A.T., Tew K.D. Oxidative stress in cancer. Cancer Cell. 2020;38:167–197. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2020.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yaribeygi H., Sathyapalan T., Atkin S.L., Sahebkar A. Molecular mechanisms linking oxidative stress and diabetes mellitus. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2020;2020:8609213. doi: 10.1155/2020/8609213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Alqahtani A.S., Hidayathulla S., Rehman M.T., ElGamal A.A., Al-Massarani S., Razmovski-Naumovski V., Alqahtani M.S., El Dib R.A., AlAjmi M.F. Alpha-Amylase and Alpha-Glucosidase Enzyme Inhibition and Antioxidant Potential of 3-Oxolupenal and Katononic Acid Isolated from Nuxia oppositifolia. Biomolecules. 2019;10:61. doi: 10.3390/biom10010061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Semaan D.G., Igoli J.O., Young L., Marrero E., Gray A.I., Rowan E.G. In vitro anti-diabetic activity of flavonoids and pheophytins from Allophylus cominia Sw. on PTP1B, DPPIV, alpha-glucosidase and alpha-amylase enzymes. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2017;203:39–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2017.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Feunaing R.T., Tamfu A.N., Gbaweng A.J.Y., Mekontso Magnibou L., Ntchapda F., Henoumont C., Laurent S., Talla E., Dinica R.M. In vitro Evaluation of α-amylase and α-glucosidase Inhibition of 2,3-Epoxyprocyanidin C1 and Other Constituents from Pterocarpus erinaceus Poir. Molecules. 2022;28:126. doi: 10.3390/molecules28010126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Facchin B.M., dos Reis G.O., Vieira G.N., Mohr E.T.B., da Rosa J.S., Kretzer I.F., Demarchi I.G., Dalmarco E.M. Inflammatory biomarkers on an LPS-induced RAW 264.7 cell model: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Inflamm. Res. 2022;71:741–758. doi: 10.1007/s00011-022-01584-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hoppstädter J., Dembek A., Linnenberger R., Dahlem C., Barghash A., Fecher-Trost C., Fuhrmann G., Koch M., Kraegeloh A., Huwer H., et al. Toll-Like Receptor 2 Release by Macrophages: An Anti-inflammatory Program Induced by Glucocorticoids and Lipopolysaccharide. Front. Immunol. 2019;10:1634. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kaneko N., Kurata M., Yamamoto T., Morikawa S., Masumoto J. The role of interleukin-1 in general pathology. Inflamm. Regen. 2019;39:12. doi: 10.1186/s41232-019-0101-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Pyrillou K., Burzynski L.C., Clarke M.C.H. Alternative Pathways of IL-1 Activation, and Its Role in Health and Disease. Front. Immunol. 2020;11:613170. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.613170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bent R., Moll L., Grabbe S., Bros M. Interleukin-1 Beta—A Friend or Foe in Malignancies? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018;19:2155. doi: 10.3390/ijms19082155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Chen J., Wang W., Ni Q., Zhang L., Guo X. Interleukin 6-regulated macrophage polarization controls atherosclerosis-associated vascular intimal hyperplasia. Front. Immunol. 2022;13:952164. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.952164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hirani D., Alvira C.M., Danopoulos S., Milla C., Donato M., Tian L., Mohr J., Dinger K., Vohlen C., Selle J., et al. Macrophage-derived IL-6 trans-signalling as a novel target in the pathogenesis of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Eur. Respir. J. 2022;59:2002248. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02248-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Rose-John S., Jenkins B.J., Garbers C., Moll J.M., Scheller J. Targeting IL-6 trans-signalling: Past, present and future prospects. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2023;23:666–681. doi: 10.1038/s41577-023-00856-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Chen J., Wei Y., Yang W., Huang Q., Chen Y., Zeng K., Chen J. IL-6: The Link Between Inflammation, Immunity and Breast Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2022;12:903800. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.903800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Rašková M., Lacina L., Kejík Z., Venhauerová A., Skaličková M., Kolář M., Jakubek M., Rosel D., Smetana K., Jr., Brábek J. The Role of IL-6 in Cancer Cell Invasiveness and Metastasis-Overview and Therapeutic Opportunities. Cells. 2022;11:3698. doi: 10.3390/cells11223698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Al Obeed O.A., Alkhayal K.A., Al Sheikh A., Zubaidi A.M., Vaali-Mohammed M.A., Boushey R., McKerrow J.H., Abdulla M.H. Increased expression of tumor necrosis factor-α is associated with advanced colorectal cancer stages. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014;20:18390–18396. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i48.18390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Zhao P., Zhang Z. TNF-α promotes colon cancer cell migration and invasion by upregulating TROP-2. Oncol. Lett. 2018;15:3820–3827. doi: 10.3892/ol.2018.7735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Król M., Kepinska M. Human Nitric Oxide Synthase—Its Functions, Polymorphisms, and Inhibitors in the Context of Inflammation, Diabetes and Cardiovascular Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021;22:56. doi: 10.3390/ijms22010056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Iwata M., Inoue T., Asai Y., Hori K., Fujiwara M., Matsuo S., Tsuchida W., Suzuki S. The protective role of localized nitric oxide production during inflammation may be mediated by the heme oxygenase-1/carbon monoxide pathway. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 2020;23:100790. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrep.2020.100790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Liu D., Guo Y., Wu P., Wang Y., Golly M.K., Ma H. The necessity of walnut proteolysis based on evaluation after in vitro simulated digestion: ACE inhibition and DPPH radical-scavenging activities. Food Chem. 2020;311:125960. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.125960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Lai S.-C., Ho Y.-L., Huang S.-C., Huang T.-H., Lai Z.-R., Wu C.-R., Lian K.-Y., Chang Y.-S. Antioxidant and antiproliferative activities of Desmodium triflorum (L.) DC. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2010;38:329–342. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X10007889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Konaté K., Souza A., Coulibaly A., Meda N., Kiendrebeogo M., Lamien-Meda A., Millogo-Rasolodimby J., Lamidi M., Nacoulma O. In vitro antioxidant, lipoxygenase and xanthine oxidase inhibitory activities of fractions from Cienfuegosia digitata Cav. Sida alba L. and Sida acuta Burn f.(Malvaceae). Pak. J. Biol. Sci. PJBS. 2010;13:1092–1098. doi: 10.3923/pjbs.2010.1092.1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Tanaka T., Narazaki M., Kishimoto T. IL-6 in inflammation, immunity, and disease. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2014;6:a016295. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a016295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Samaraweera U., Sotheeswaran S., Uvais M., Sultanbawa S. 3,5,7,3′, 5′-Pentahydroxyflavan and 3α-methoxyfriedelan from Humboldtia laurifolia. Phytochemistry. 1983;22:565–567. doi: 10.1016/0031-9422(83)83047-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Dyamavvanahalli S.L., Raveesha K.A., Nagabhushan S. Bioprospecting of selected medicinal plants for antibacterial activity against some pathogenic bacteria. J. Med. Plants Res. 2011;5:4087–4093. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Yadav R., Agarwala M. Phytochemical analysis of some medicinal plants. J. Phytol. 2011;3:10–14. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Harborne A. Phytochemical Methods a Guide to Modern Techniques of Plant Analysis. Springer Science & Business Media; London, UK: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Singleton V.L., Rossi J.A. Colorimetry of total phenolics with phosphomolybdic-phosphotungstic acid reagents. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1965;16:144–158. doi: 10.5344/ajev.1965.16.3.144. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Zhishen J., Mengcheng T., Jianming W. The determination of flavonoid contents in mulberry and their scavenging effects on superoxide radicals. Food Chem. 1999;64:555–559. doi: 10.1016/S0308-8146(98)00102-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 106.House N.C., Puthenparampil D., Malayil D., Narayanankutty A. Variation in the polyphenol composition, antioxidant, and anticancer activity among different Amaranthus species. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2020;135:408–412. doi: 10.1016/j.sajb.2020.09.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Webber D.M., Wallace M.A., Burnham C.D. Stop Waiting for Tomorrow: Disk Diffusion Performed on Early Growth Is an Accurate Method for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing with Reduced Turnaround Time. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2022;60:e0300720. doi: 10.1128/jcm.03007-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Morgan B.L., Depenbrock S., Martínez-López B. Identifying Associations in Minimum Inhibitory Concentration Values of Escherichia coli Samples Obtained From Weaned Dairy Heifers in California Using Bayesian Network Analysis. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022;9:771841. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2022.771841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Di Simone S.C., Acquaviva A., Libero M.L., Chiavaroli A., Recinella L., Leone S., Brunetti L., Politi M., Giannone C., Campana C., et al. The association of Tanacetum parthenium and Salix alba extracts reduces cortex serotonin turnover, in an ex vivo experimental model of migraine. Processes. 2022;10:280. doi: 10.3390/pr10020280. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Iskandar N.N., Iriawati I. Vinblastine and Vincristine production on Madagascar Periwinkle (Catharanthus roseus (L.) G. Don) callus culture treated with polethylene glycol. Makara J. Sci. 2016;20:7–16. doi: 10.7454/mss.v20i1.5656. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Rao P., Knaus E.E. Evolution of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs): Cyclooxygenase (COX) inhibition and beyond. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2008;11:81s–110s. doi: 10.18433/J3T886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Khumalo G.P., Van Wyk B.E., Feng Y., Cock I.E. A review of the traditional use of southern African medicinal plants for the treatment of inflammation and inflammatory pain. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2022;283:114436. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2021.114436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Bharadwaj K.C., Gupta T., Singh R.M. Synthesis of Medicinal Agents from Plants. Elsevier; Amsterdam, The Netherlands: 2018. Alkaloid group of Cinchona officinalis: Structural, synthetic, and medicinal aspects; pp. 205–227. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data may be shared upon valid request.