Abstract

Prenylation is an irreversible post-translational modification that supports membrane interactions of proteins involved in various cellular processes, including migration, proliferation, and survival. Dysregulation of prenylation contributes to multiple disorders, including cancers and vascular and neurodegenerative diseases. Prenyltransferases tether isoprenoid lipids to proteins via a thioether linkage during prenylation. Pharmacological inhibition of the lipid synthesis pathway by statins is a therapeutic approach to control hyperlipidemia. Building on our previous finding that statins inhibit membrane association of G protein γ (Gγ) in a subtype-dependent manner, we investigated the molecular reasoning for this differential inhibition. We examined the prenylation of carboxy-terminus (Ct) mutated Gγ in cells exposed to Fluvastatin and prenyl transferase inhibitors and monitored the subcellular localization of fluorescently tagged Gγ subunits and their mutants using live-cell confocal imaging. Reversible optogenetic unmasking-masking of Ct residues was used to probe their contribution to prenylation and membrane interactions of the prenylated proteins. Our findings suggest that specific Ct residues regulate membrane interactions of the Gγ polypeptide, statin sensitivity, and extent of prenylation. Our results also show a few hydrophobic and charged residues at the Ct are crucial determinants of a protein’s prenylation ability, especially under suboptimal conditions. Given the cell and tissue-specific expression of different Gγ subtypes, our findings indicate a plausible mechanism allowing for statins to differentially perturb heterotrimeric G protein signaling in cells depending on their Gγ-subtype composition. Our results may also provide molecular reasoning for repurposing statins as Ras oncogene inhibitors and the failure of using prenyltransferase inhibitors in cancer treatment.

Keywords: GPCR, G proteins, prenylation, prenyltransferases, statin, cholesterol, mevalonate pathway, HMG-CoA reductase, optogenetics

Post-translational lipid modifications, including N-myristoylation, palmitoylation, prenylation, glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchor addition, and cholesterol attachment, expand the functional and structural diversity of the eukaryotic proteome (1, 2). The chemical and physical properties, activities, and cellular distribution of proteins are significantly modified by the covalent attachment of a non-peptidic hydrophobic moiety to a protein. These post-translational modifications of proteins, including prenylation, allow their interactions with cellular membranes, a crucial requirement for proper cell signaling and functions (2). Prenylation includes both farnesylation and geranylgeranylation and is an irreversible covalent modification found in all eukaryotic cells. These modifications are catalyzed by three prenyltransferase enzymes. Farnesyltransferase or geranylgeranyltransferase type 1 (GGTase-I) catalyzes the covalent attachment of a single farnesyl (15 carbon) or geranylgeranyl (20 carbon) isoprenoid group, respectively, to a cysteine residue located in a C-terminal (Ct) consensus sequence commonly known as the "CaaX box," in which "C" is cysteine, "a" generally represents an aliphatic amino acid, and the "X" residue determines which isoprenoid is attached to the protein target (3). Geranylgeranyltransferase type 2 (GGTase-II or Rab geranylgeranyltransferase) catalyzes the addition of two geranylgeranyl groups to two cysteine residues in sequences such as CXC or CCXX close to the Ct of Rab proteins (4, 5).

Inhibition of hepatic cholesterol biosynthesis is widely accepted to mitigate cardiovascular diseases such as coronary heart disease (6). This is achieved by inhibiting the rate-limiting enzyme, HMG-CoA reductase, of the cholesterol biosynthesis (mevalonate) pathway (7). Commonly called statins, these HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors interfere with the synthesis of intermediate products of the cholesterol biosynthesis pathway, such as isoprenoids (8, 9). Isoprenoids are precursor lipids for synthesizing cholesterol and other lipid derivatives, including farnesyl, geranyl, and geranylgeranyl pyrophosphates, squalene, dolichol, and ubiquinone. The above-mentioned pyrophosphates are required for the prenylation of small and heterotrimeric G proteins (10, 11). Our previous work revealed the influence of statin usage on Gβγ and, consequently heterotrimeric G-protein signaling due to the inhibition of Gγ prenylation (12). We showed that not only do statins disrupt Gγ prenylation, but Gγ farnesylation is more susceptible to this inhibition than geranylgeranylation (12).

The essential role of farnesylation in modulating the oncogenic activity of Ras function led to the discovery of farnesyltransferase inhibitors (FTIs) such as Tipifarnib and Lonafarnib (13, 14, 15). The combined anti-tumor activity and low toxicity of these FTIs observed in animal models directed clinical trials to use FTIs as anti-tumor drugs (16). However, discouraging results have been observed due to the alternative prenylation exhibited in KRas and NRas (to a lesser extent), where the effect of FTIs is evaded by the activity of GGTase-I (16). Therefore, a thorough understanding of the molecular mechanism of prenylation and post-prenylation processing is crucial to develop more efficient drugs for tumor progression prevention. Given the antiproliferative effects of statins, repurposing them as anticancer drugs can also be considered (17). Observations from in vitro and in vivo preclinical studies and clinical studies report the anticancer effects of statins (18). Statins have shown antiproliferative effects in various cancers by primarily inhibiting the synthesis of cholesterol and its metabolites (19, 20, 21), which result in tumor growth suppression, induction of apoptosis and autophagy, inhibition of cell migration and invasion, and inhibition of angiogenesis (22, 23, 24). Therefore, statins are believed to influence patient survival and cancer recurrence (25). Several pleiotropic effects, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and immune-modulatory properties, are also associated with statin usage, which can be causing their antiproliferative properties (26). In vitro studies conducted in a broad range of cancer cell lines present evidence for the anticancer properties of statins (18). For instance, Simvastatin exhibited anticancer potential in several cancer types, such as hepatoma, breast cancer, endometrial cancer, osteosarcoma, and lung adenocarcinoma (22, 27, 28, 29). Additionally, Atorvastatin exhibited anticancer effects on ovarian cancer in a study conducted using Hey and SKOV3 cells (23). The anticancer efficacy of statins has also been demonstrated during in vivo pre-clinical studies using xenograft animal models. For example, a xenograft mouse study showed the anti-tumor effect of Pitavastatin on glioblastoma (30). This evidence suggests the potential use of statins and prenyltransferase inhibitors as anticancer drugs in a combinatorial therapy approach. Gβγ interacts with many effectors, regulates a wide range of physiological functions, and thus has been established as a major signaling regulator (31). Although prenylation is crucial for not only Gβγ function but also GPCR-G protein signaling, molecular details are lacking on how statins influence Gγ prenylation.

Our data suggest that the residues adjacent to the prenyl-Cys (pre-CaaX) region differentially regulate G protein γ sensitivity to prenylation disruptors; statins that reduce prenyl pyrophosphate substrate availability, and prenyltransferase inhibitors that inhibit the catalyst enzymes. We believe our findings will help utilize these new molecular details to open new therapeutic windows to target G proteins-associated diseases.

Results

Gγ subtypes show differential sensitivities to statin-mediated perturbation of the plasma membrane localization

Prenylated Gγs primarily stay bound to the plasma membrane when they are in the Gαβγ heterotrimer (Fig. 1A-Control) (32). Gγs also show a minor presence at endomembranes, likely due to heterotrimer shuttling (33, 34), activities of Guanine nucleotide Exchange Factors (GEFs) that activate minor amounts of heterotrimers (35), or interactions with endomembrane-residing GPCRs (36). In this study, we examined Gγ or Gγ mutant localization in HeLa cells by transfecting only fluorescently tagged Gγ subunits and relied on endogenous Gα and Gβ subunits to govern the subcellular distributions. When Gγs are not prenylated, they show a cytosolic distribution due to the failure of the membrane anchoring (12, 37). We have previously demonstrated that while statin treatment significantly reduces the membrane anchoring of several Gγ types, indicated by their presence in the cytosol (Fig. 1- Gγ1 in control versus Flu), other Gγ types showed a disruption of membrane binding only partially. We observed that the partial inhibition is indicated by the absence of Gγ localization at endomembranes and reduced plasma membrane localization. Further, these Gγs show minor to significant cytosolic distribution, and the extent depended on the Gγ subtype (e.g., Fig. 1- Gγ2 in control versus Flu) (12). Gγs with more cytosolic presence upon statin exposure also exhibit a nuclear localization, as indicated by homogenous cell interior fluorescence. However, the molecular underpinnings of these Gγ subtype-dependent differential de-localizations upon satin exposure were unclear. Although it is generally accepted that the CaaX motif determines the type of prenylation (farnesylation or geranylgeranylation) of a G protein, it has also been suggested that amino acids beyond this motif, up to 25 Ct residues, are also involved (38). To understand whether the observed statin-induced protein localization signatures of different Gγ types are exclusively dependent on their type of prenylation, we examined Fluvastatin (20 μM)-induced prenylation perturbation of the entire Gγ family (Fig. 1A-Flu). In our previous study, we tested several statins, that is, Fluvastatin, Lovastatin, and Atorvastatin, for their ability to disrupt membrane localization of Gγ and, thereby, Gβγ-mediated downstream signaling. Of these three statins, Fluvastatin exhibited the highest efficiency in perturbing Gγ localization and Gβγ signaling (12). Considering all the optimized conditions, we used Fluvastatin to examine statin-induced Gγ de-localization in this study. Three Gγ types reported to be exclusively farnesylated (Gγ1, 9, and 11) showed near-complete sensitivity to Fluvastatin, indicated by the cytosolic and nuclear distribution of YFP-Gγ while they also lacked plasma membrane distribution (Fig. 1A-Flu). We have previously shown that partial sensitivity to statins is characterized by the (i) absence of distinguishable Gγ fluorescence at the endomembrane and (ii) demarcated fluorescence appearance in the nucleus due to prenylation-lacking Gγ entering, while some plasma membrane-bound Gγs are detected (12). Interestingly, the supposedly geranylgeranylated Gγ types (Gγ2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 8, 10, 12, and 13) showed two distinct phenotypes. Gγ2, 3, 4, 7, 8, and 12 showed partial sensitivity, while unexpectedly, the rest (Gγ5, 10, and 13) showed a near-complete sensitivity to statins (Fig. 1A-Flu). Are these Gγs (5, 10, 13) geranylgeranylated as predicted? To answer this question, we examined the exact type of Gγ prenylation by exposing cells expressing each Gγ subtype to FTI, Tipifarnib - 1 μM or geranylgeranyl transferase inhibitor (GGTI), GGTI286 - 10 μM. As expected, Gγ1, 9, and 11 showed a completely inhibited phenotype upon FTI exposure (Fig. 1A- FTI). This also indicated that the remaining Gγ members are geranylgeranylated. Interestingly these FTI insensitive Gγs showed varying sensitivities to GGTI, from moderate to high. Particularly Gγ5, 10, and 13 showed near-complete cytosolic-nuclear distribution, while Gγ2, 3, 4, 7, 8, and 12 showed only a partial perturbation, interestingly recapitulating their phenotypes in response to statin (Fig. 1A-GGTI).

Figure 1.

Gγ subtypes show differential sensitivities to statin-induced inhibition of membrane binding.A, images of HeLa cells expressing YFP tagged Gγ members under the vehicle (control), Fluvastatin (20 μM), FTI (1 μM), or GGTI (10 μM) treated conditions. Images represent the prominent phenotype observed in each population at the given experimental condition (scale: 5 μm; n ≥ 15 for each Gγ type). Whisker box plots generated using fluorescence recovery after half-cell photobleaching (half-cell FRAP) represented as mobility half-time (t1/2) of Gγ subtypes in (B) control, (C) Fluvastatin-treated, (D) FTI-treated, and (E) GGTI-treated cells (Average whisker box plots were plotted using mean ± SD; Error bars: control: n ≥ 12 cells for each Gγ from 154 cells, Fluvastatin-treated: n ≥ 10 cells for each Gγ from 200 cells, FTI-treated: n ≥ 11 cells for each Gγ from 132 cells, GGTI-treated: n ≥ 11 cells for each Gγ three from 135 cells (each treatment was performed in 3≤ independent experiments; Statistical comparisons were performed using One-way-ANOVA; p < 0.05. Flu, Fluvastatin; FTI, Farnesyl transferase inhibitor; GGTI, Geranylgeranyl transferase inhibitor; SD, Standard deviation).

Since the visual inspection of Gγ membrane localization inhibition provides only a qualitative estimate of membrane anchorage inhibition, we employed mobilities of Gγ, or lack thereof, as a measure of prenylation. Compared to prenylated Gγ, Gγ with impaired prenylation is expected to have faster mobilities due to reduced membrane interactions (33). To evaluate the mobilities of YFP-tagged Gγ, we examined recovery after photobleaching of half-cell fluorescence (half-cell FRAP) and calculated the time to half maximum fluorescence recovery, which we termed mobility half-time (t1/2) (Table 1) (34). When proteins are not membrane-bound, they move faster since they are cytosolic. However, when only a fraction of the protein population is membrane-anchored, the mobility represents an ensemble movement of both the membrane-bound and cytosolic species. Regardless of the Gγ subtype and their type of prenylation, mobility t1/2 values of all the control (untreated) Gγs in the heterotrimer were nearly similar, with the average t1/2 of 97 ± 4 s (one-way ANOVA: F11,174 = 1.763, p = 0.064) (Fig. 1B). This indicates that Gγs in control cells are in the heterotrimeric form, making their mobility rates Gγ subtype independent (33). When examined, the mobility t1/2 of Fluvastatin exposed Gγ1, 9, and 11 were nearly similar and 11 ± 5 s, 9 ± 5 s, and 9 ± 5 s, respectively (one-way ANOVA: F2,33 = 0.615, p = 0.547) (Fig. 1C- Gγ1, 9 and 11). These mobility t1/2 values are comparable with the mobility t1/2 of the prenylation-deficient Gγ3C72A mutant (10 ± 5 s) that showed a complete cytosolic distribution (one-way ANOVA: F3,84 = 0.406, p = 0.749) (Fig. 1C-Gγ3C72A). When Gγ3 expressing cells were exposed to Fluvastatin, the observed mobility t1/2 (55 ± 13 s) falls between that of prenylated Gγ3 in control (101 ± 14 s) and the completely cytosolic mutant (10 ± 5 s) (Fig. 1C- Gγ3). Other C→A CaaX motif mutants of Gγs also exhibited distributions and mobilities similar to Gγ3C72A (Figs. S2 and S3). This mobility of Fluvastatin-exposed Gγ3 suggests the presence of both cytosolic and membrane-bound Gγs, indicating partial disruption of membrane anchorage. Compared to untreated conditions, the ∼2-fold reduction in Gγ3 mobility t1/2 upon Fluvastatin treatment also signifies the increased cytosolic fraction of Gγ3. Similarly, GGTI exposed Gγ3 also showed an intermediate mobility t1/2 (43 ± 9 s) (Fig. 1E- Gγ3), indicating partial geranylgeranylation inhibition. FTI exposed Gγ3 showed a mobility t1/2 (98 ± 15 s) that is not significantly different from control Gγ3 (101 ± 14 s) (one-way ANOVA: F1,24 = 0.250, p = 0.621), suggesting that FTI cannot inhibit the activity of geranylgeranyl transferase-I (Fig. 1D- Gγ3). Upon FTI treatment, the mobility t1/2 of farnesylation-sensitive Gγs (Gγ1, 9, and 11) are significantly reduced (∼9–10 s) while that of geranylgeranylation-sensitive Gγs remained nearly unchanged, confirming the exclusive farnesylation-sensitivities of these Gγs (Fig. 1D). As expected, upon exposing cells to GGTI, only geranylgeranylation-sensitive Gγs showed a significant reduction in mobility t1/2 (Fig. 1E), while their mobility was unaffected upon FTI exposure (Fig. 1D). However, GGTI-induced prenylation perturbation of geranylgeranylation-sensitive Gγs also showed a wide range, from near complete (as in Gγ5, 10, and 13) to partial (as in Gγ2, 3, 4, 7, 8, and 12).

Table 1.

Mobility properties of Gγ types

| Gγ type | Ct sequence | Mobility t1/2 (s) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Flua | FTIa | GGTIa | ||

| Gγ1-WT | N P F K E L K G G C V I S | 101 ± 9 | 11 ± 5 | 10 ± 4 | 100 ± 10 |

| Gγ2-WT | N P F R E K K F F C A I L | 90 ± 11 | 49 ± 10 | 97 ± 12 | 41 ± 9 |

| Gγ3-WT | N P F R E K K F F C A I L | 102 ± 14 | 55 ± 12 | 98 ± 15 | 43 ± 9 |

| Gγ4-WT | N P F R E K K F F C T I L | 97 ± 11 | 58 ± 17 | 92 ± 10 | 47 ± 12 |

| Gγ5-WT | N P F R P Q K V - C S F L | 101 ± 9 | 17 ± 8 | 97 ± 12 | 14 ± 4 |

| Gγ7-WT | N P F K D K K P - C I I L | 94 ± 12 | 22 ± 8 | 98 ± 9 | 13 ± 4 |

| Gγ8-WT | N P F R D K R L F C V I L | 105 ± 9 | 55 ± 11 | 100 ± 10 | 42 ± 8 |

| Gγ9-WT | N P F K E - K G G C I I S | 96 ± 13 | 9 ± 5 | 9 ± 3 | 95 ± 10 |

| Gγ10-WT | N P F R E P R S - C A I L | 97 ± 9 | 9 ± 5 | 95 ± 8 | 16 ± 5 |

| Gγ11-WT | N P F K E − K G S C V I S | 97 ± 7 | 9 ± 5 | 10 ± 4 | 96 ± 10 |

| Gγ12-WT | N P F K D K K T - C I I L | 96 ± 7 | 49 ± 8 | 102 ± 12 | 27 ± 5 |

| Gγ13-WT | N P W V E K G K - C T I L | 95 ± 12 | 8 ± 5 | 95 ± 18 | 9 ± 4 |

Mobility t1/2 of major phenotype.

Statin-induced Gγ delocalization to the cytosol is prenylation-type independent

Our previous work has established that Gγ subunits such as γ9, γ1, and γ11 show faster translocation with t1/2 of a few seconds and greater magnitudes. They were identified as low membrane affinity Gγs. Conversely, Gγ with higher translocation t1/2 values and lower magnitudes, including Gγ2, γ3, and γ4, are considered to be high membrane affinity Gγs (39). Differential translocation abilities of Gβγ complexes to the cell interior have been identified a regulatory mechanisms for transmitting cell surface signals to various organelles (40, 41, 42). Interestingly, when examined, the fastest translocating Gγ9 and the slowest translocating Gγ3 also exhibited two distinct sensitivities to Fluvastatin-induced membrane-anchorage-inhibition; Gγ9 with near-complete cytosolic distribution and Gγ3 with partial cytosolic distribution (Fig. 1, A and C) (12). To quantitatively define these two classifications (complete cytosolic versus partial cytosolic), we assigned Gγs with 0 to 24 s mobility t1/2 values as complete cytosolic and Gγ with 25 to 60 s mobility t1/2 as partial cytosolic. According to this classification, upon Fluvastatin exposure, ∼100% of the Gγ9 cells showed a prominently increased cytosolic fluorescence due to cytosolic Gγ, while the fraction of cells with partial cytosolic distribution was nearly zero and insignificant (Fig. 2, A and B and Table 2, Gγ9-WT). Interestingly, ∼99% of Gγ3 cells showed partial inhibition of membrane binding, while near-complete inhibition was inconsequential with Fluvastatin treatment (Fig. 2, A and B and Table 2, Gγ3-WT). To examine the contribution of the CaaX sequence in determining the degree of statin-induced retardation of membrane binding, we compared CaaX motif mutants of Gγ9 and Gγ3 with their corresponding wild types. Similar to Gγ9-WT, when exposed to Fluvastatin, ∼99% of cells expressing a Gγ9 mutant with the CaaX sequence of Gγ3 (Gγ9CALL) exhibited near-complete cytosolic distribution, indicating complete disruption of membrane binding (Fig. 2, A and B and Table 2, Gγ9CALL). However, the FTI and GGTI sensitivities of the Gγ9CALL mutant showed that it is geranylgeranylated as predicted from its CaaX (CALL) sequence (Fig. 2A, Gγ9CALL). Similarly, the Gγ3 mutant containing the CaaX sequence of Gγ9 (Gγ3CIIS) showed a partial disruption of membrane anchoring when cells were exposed to Fluvastatin even though it is farnesylation sensitive (Fig. 2A, Gγ3CIIS). This response was prominent in ∼97% of the mutant-expressing cells, while only ∼3% of the total population exhibited near-complete inhibition of membrane binding (Fig. 2B and Table 2- Gγ3CIIS). We also calculated mobility rates of the wild type and 2 Gγ mutants (Fig. 2C and Table 3). Even though switching the CaaX motif switched the FTI and GGTI sensitivities of Gγ9 and Gγ3, the Fluvastatin sensitivity remained unchanged between the WT controls and the corresponding mutants, implying distinct molecular determinants governing the statin sensitivity of Gγ.

Figure 2.

Statin sensitivity and prenylation efficacy of Gγ are prenylation type independent.A, subcellular distribution of GFP tagged wild type Gγ9, Gγ3, and mutants Gγ9CALL, and Gγ3CIIS, with vehicle (control), Fluvastatin (20 μM), FTI (1 μM), or GGTI (10 μM) treated conditions. Images represent the prominent phenotype observed in each population under the given experimental condition (scale: 5 μm; n ≥ 15 for each Gγ type). B, grouped box chart shows the percentages of categorized cells in each Gγ type into two phenotypes: near-complete (black) and partial (red) cytosolic distribution upon Fluvastatin treatment. C, the whisker box plots show mobility half-time (t1/2) of proteins in (A) determined using half-cell FRAP. (Average box plots were plotted using mean±SD; Error bars: Gγ9 WT: n = 571 total number of cells from seven independent experiments, Gγ3 WT: n = 597 total number of cells from seven independent experiments, Gγ9CALL: n = 624 total number of cells from seven independent experiments, Gγ3CIIS: n = 408 total number of cells from five independent experiments; Statistical comparisons were performed using One-way-ANOVA; p < 0.05; Flu, Fluvastatin; FTI, Farnesyl transferase inhibitor; GGTI, Geranylgeranyl transferase inhibitor; SD, Standard deviation; WT, wild type).

Table 2.

Fluvastatin-induced prenylation inhibition (or partial inhibition) of Gγ3, Gγ9 and their Ct mutants

| Gγ mutant | Ct sequence | Percent cells (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Complete | Partial | ||

| Gγ9-WT | N P F K E − K G G C I I S | 99.7 ± 0.5 | 0 |

| Gγ3-WT | N P F R E K K F F C A I L | 0 | 98.7 ± 1.2 |

| Gγ9CALL | N P F K E − K G G C A L L | 98.6 ± 1.2 | 0 |

| Gγ3CIIS | N P F R E K K F F C I I S | 2.9 ± 0.7 | 97.1 ± 0.7 |

| Gγ9Gγ3PC | N P F R E K K F F C I I S | 23.8 ± 12.9 | 74.5 ± 13.4 |

| Gγ3Gγ9PC | N P F K E - K G G C A I L | 99.3 ± 0.9 | 0 |

| Gγ9GG→FF | N P F K E − K F F C I I S | 87.4 ± 2.7 | 12.5 ± 2.7 |

| Gγ3FF→GG | N P F R E K K G G C A I L | 94.5 ± 1.3 | 5.5 ± 1.3 |

| Gγ3FF→LL | N P F R E K K L L C A I L | 4.1 ± 3.1 | 95.9 ± 3.1 |

| Gγ3FF→VV | N P F R E K K V V C A I L | 88.2 ± 4.5 | 11.8 ± 4.5 |

| Gγ3FF→YY | N P F R E K K Y Y C A I L | 87.9 ± 2.3 | 12.1 ± 2.3 |

| Gγ3FF→AA | N P F R E K K A A C A I L | 92.8 ± 3.0 | 7.2 ± 3.0 |

| Gγ9KEK-GG→ REK-GG | N P F R E − K G G C I I S | 83.6 ± 1.6 | 15.7 ± 0.7 |

| Gγ9KEK-GG→REKKGG | N P F R E K K G G C I I S | 65.2 ± 3.8 | 35.7 ± 5.9 |

| Gγ9KEK-GG→KEKKFF | N P F K E K K F F C I I S | 51.3 ±6.3 | 48.5 ± 6.4 |

| Gγ3F70G | N P F R E K K G F C A I L | 28.9 ± 1.1 | 72.6 ± 0.9 |

| Gγ3F71G | N P F R E K K F G C A I L | 20.0 ± 0.4 | 77.7 ± 5.6 |

Table 3.

Mobility properties of Gγ mutants

| Gγ mutant | Ct sequence | Mobility t1/2 (s) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Flu-Complete | Flu-Partial | FTIa | GGTIa | ||

| Gγ9CALL | N P F K E − K G G C A L L | 95 ± 7 | 7 ± 4 | - | 94 ± 8 | 7 ± 5 |

| Gγ3CIIS | N P F R E K K F F C I I S | 102 ± 10 | - | 53 ± 10 | 15 ± 4 | 95 ± 10 |

| Gγ9Gγ3PC | N P F R E K K F F C I I S | 101 ± 10 | 10 ± 5 | 31 ± 10 | 11 ± 4 | 99 ± 15 |

| Gγ3Gγ9PC | N P F K E - K G G C A I L | 101 ± 11 | 5 ± 3 | 55 ± 11 | 101 ± 14 | 5 ± 3 |

| Gγ9GG→FF | N P F K E − K F F C I I S | 101 ± 11 | 6 ± 3 | 26 ± 5 | 12 ± 5 | 105 ± 11 |

| Gγ3FF→GG | N P F R E K K G G C A I L | 98 ± 12 | 5 ± 2 | 31 ± 9 | 94 ± 10 | 10 ± 4 |

| Gγ3FF→LL | N P F R E K K L L C A I L | 97 ± 10 | 9 ± 3 | 45 ± 10 | 99 ± 13 | 52 ± 11 |

| Gγ3FF→VV | N P F R E K K V V C A I L | 103 ± 13 | 7 ± 6 | 28 ± 8 | 93 ± 11 | 9 ± 7 |

| Gγ3FF→YY | N P F R E K K Y Y C A I L | 95 ± 13 | 9 ± 5 | 31 ± 7 | 96 ± 8 | 12 ± 4 |

| Gγ3FF→AA | N P F R E K K A A C A I L | 98 ± 9 | 5 ± 2 | 31 ± 6 | 96 ± 11 | 6 ± 3 |

| Gγ9KEK-GG→ REK-GG | N P F R E − K G G C I I S | 101 ± 17 | 12 ± 6 | 45 ± 8 | 7 ± 4 | 95 ± 10 |

| Gγ9KEK-GG→REKKGG | N P F R E K K G G C I I S | 98 ± 11 | 6 ± 5 | 47 ± 14 | 11 ± 4 | 99 ± 9 |

| Gγ9KEK-GG→KEKKFF | N P F K E K K F F C I I S | 94 ± 11 | 4 ± 1 | 25 ± 4 | 10 ± 5 | 100 ± 8 |

| Gγ3F70G | N P F R E K K G F C A I L | 104 ± 12 | 12 ± 3 | 38 ± 6 | 103 ± 11 | 17 ± 4 |

| Gγ3F71G | N P F R E K K F G C A I L | 100 ± 10 | 13 ± 3 | 40 ± 8 | 100 ± 9 | 18 ± 5 |

Mobility t1/2 of major phenotype.

Pre-CaaX sequences of Gγs control their statin sensitivity

Since Fluvastatin-induced membrane binding inhibition profiles of Gγ family members were Gγ-type dependent, we examined the molecular reasoning for this behavior, especially considering that Fluvastatin sensitivity of Gγ is independent of their prenylation type. We have extensively documented that, in addition to prenyl and carboxymethyl modifications on the Ct Cys of Gγ, its adjacent pre-CaaX region also controls Gβγ-membrane interactions (39, 43, 44). Our previous work showed the crucial involvement of pre-CaaX residues in specific Gγs regulating their membrane affinity (43). Therefore, we examined whether the chemistry of pre-CaaX amino acids also controls the protein's statin sensitivity (Fig. 3A). For this, we computationally determined the hydrophobicity of the Ct polypeptide of Gγ only comprising pre-CaaX and CaaX regions (before prenylation), using octanol-water partition coefficient (KOW)-based Log Cavity Energy (Log CE) calculation (please see Log cavity energy (Log CE) calculation Gγ Ct peptides (pre-CaaX+CaaX)) (Fig. 3B, Table S1). It has been shown that the difference between the free energy of cavity formation in the organic and water solvents indicates a peptide's relative affinity between the two phases and its hydrophobicity (45). All the Gγ-derived peptides showed higher positive ΔG values for water (ΔGW). Interestingly, Gγ2, 3, 4, 5, and eight exhibited lower but positive ΔG values for octanol (ΔGO), indicating that they have a higher affinity to the lipid phase (Table S1).

Figure 3.

The pre-CaaX sequence determines statin sensitivity and prenylation efficacy of Gγ.A, comparison of Ct domain amino acid sequences of Gγ. The Ct domain of Gγ consists of the starting conserved NPF sequence, followed by the pre-CaaX region and the CaaX motif. Gγ subtypes with a C-terminal Ser (Black) at the 'X' position are farnesylated, and Leu (light blue) are geranylgeranylated. During prenylation, the prenyl moiety is attached to the prenylated Cys (maroon), and this Cys is further modified during post-prenylation processing (proteolysis at the C-terminal three -aaX residues by the Ras converting CaaX endopeptidase 1 (RCE1), and then carboxymethylation of the new isoprenylcysteine C-terminus by isoprenylcysteine carboxyl methyltransferase (ICMT)). In the pre-CaaX region, hydrophobic Phe residues are shown in red, and positively charged residues are in blue. B, the scatter plot shows the log CE values to measure the hydrophobicity of pre-CaaX+CaaX Ct polypeptide regions of Gγ. C, images of HeLa cells expressing GFP tagged Gγ9-WT, Gγ3-WT, Gγ9Gγ3PC, and Gγ3Gγ9PC, exposed to vehicle (Control), Fluvastatin (20 μM), FTI (1 μM), or GGTI (10 μM). Images represent the prominent phenotype observed in each population under given experimental conditions (scale: 5 μm; n ≥ 15 for each Gγ type). As reference images, we reused Gγ3 WT and Gγ9 WT cell images, both control and treated, from Figure 2A. D, grouped box chart shows the percentages categorized cells in each Gγ type into two phenotypes; near-complete (black) and partial (red) cytosolic distribution upon Fluvastatin treatment. The circles indicate the % cells showed near-complete (black) and partial cytosolic (red) distribution in each corresponding wild type Gγ (γ9-closed circles, γ3-open circles) expressing cells as reference points. E, the whisker box plots show mobility half-time (t1/2) determined using half-cell FRAP (Average box plots were plotted using mean±SD; Error bars: Gγ9 WT: n = 571 total number of cells from seven independent experiments, Gγ3 WT: n = 597 total number of cells from seven independent experiments, Gγ9Gγ3PC: n = 686 total number of cells from eight independent experiments, Gγ3Gγ9PC: n = 754 total number of cells from eight independent experiments. As references to compare, we reused Gγ3 WT and Gγ9 WT plots from Figure 2C. Statistical comparisons were performed using One-way-ANOVA; p < 0.05; Flu, Fluvastatin; FTI, Farnesyl transferase inhibitor; GGTI, Geranylgeranyl transferase inhibitor; PC, pre-CaaX; SD, Standard deviation).

The cavity energy of pre-CaaX+CaaX peptides of Gγ indicates that Gγ4, 3, 2, and 8 possess significantly higher stability in lipids compared to Gγ1, 9, and 11. Interestingly, log CE of pre-CaaX+CaaX of Gγ10 and 13 also showed less favorable values for lipids in the same range as Gγ1, 9, and 11 (Fig. 3B, Table S1). These log CE values agree with our unexpected observation that similar to Gγ1, 9, 11, geranylgeranylated Gγ10, 13 also possess similar sensitivity to Fluvastatin (Figs. 1 and 3B). This aligns with our hypothesis that unprenylated polypeptide regulates prenylation by interacting differentially with membranes where prenylation occurs. Further, the pre-CaaX+CaaX peptides from Gγ5, 7, and 12 that showed log CE values between the above two groups (Gγ2, 3, 4, 8 versus Gγ1, 9, 11) also exhibited partial, however, more significant prenylation perturbation than Gγ2, 3, 4, 8 upon Fluvastatin, supporting our hypothesis (Fig. 3B and Table S1).

Since these findings suggest the involvement of the pre-CaaX region in regulating Gγ-membrane interactions, and different Gγ types show distinct sensitivities to statin, regardless of the type of prenylation, we tested the hypothesis that the pre-CaaX region hydrophobicity of Gγ polypeptide govern their statin sensitivity. We first examined the influence of exchanging pre-CaaX sequences between Gγ3 and Gγ9, representative Gγs of the two extremes of Gγ membrane affinities (39). We comparatively determined the statin sensitivity of the Gγ9 mutant containing the pre-CaaX (PC) of Gγ3 (Gγ9Gγ3PC or -NPFREKKFFCLIS) that we reported previously (43) and a new Gγ3 mutant containing the pre-CaaX of Gγ9 (Gγ3Gγ9PC or -NPFKEKGGCALL). Interestingly, in the presence of Fluvastatin, cells expressing Gγ9Gγ3PC exhibited a prominent partial inhibition of membrane binding (note the near-complete cytosolic distribution in WT Gγ9-black filled circle in Fig. 3D), while Gγ3Gγ9PC showed a near-complete inhibition of membrane anchorage (compare the partial cytosolic distribution in WT Gγ3- Red open circle in Fig. 3D) (Fig. 3, C and D and Table 2- Gγ9Gγ3PC and Gγ3Gγ9PC). Although the images here represent the most abundant phenotype, the grouped box chart shows the percent abundance of each phenotype of the respective Gγ mutant (Fig. 3, C and D). Interestingly, compared to Gγ9-WT, Gγ9Gγ3PC also shows a significant reduction in the near-complete inhibition phenotype (from ∼100% in WT to ∼24% in the mutant) (Fig. 3, C and D and Table 2- Gγ9Gγ3PC, black). This phenotype additionally showed a significantly faster mobility compared to that of the partial cytosolic phenotype (complete cytosolic: 5 ± 3 s, partial cytosolic: 55 ± 11 s, one-way ANOVA: F1,36 = 477.158, p = 0.0001) (Fig. 3E and Table 3- Gγ9Gγ3PC), which is the most abundant Gγ9Gγ3PC phenotype (∼75%) of Fluvastatin-exposed cells (Fig. 3D - Gγ9Gγ3PC, red). However, Fluvastatin exposed Gγ3Gγ9PC cells only exhibited near-complete cytosolic phenotype (from 0% in WT to ∼99% in the mutant) (Fig. 3D and Table 2- Gγ3Gγ9PC, black), eliminating the partial cytosolic phenotype (Fig. 3D and Table 2- Gγ3Gγ9PC, red). Mobility data confirmed the complete inhibition of membrane association (Fig. 3E and Table 3- Gγ3Gγ9PC). This is distinctly different from the response of WT Gγ3 cells to Fluvastatin treatment (Figs. 2B and 3D- Red open circle). Further, by exposing these pre-CaaX mutants to prenyltransferase inhibitors, we show that pre-CaaX switching did not change their type of prenylation (Fig. 3C-FTI and GGTI-bottom two panels). For instance, similar to Gγ9-WT, the Gγ9Gγ3PC mutant showed sensitivity to FTI but not to GGTI. We have confirmed this membrane binding inhibition phenotype data by examining their mobility t1/2 (Fig. 3E and Table 3- Gγ9Gγ3PC and Gγ3Gγ9PC).

Hydrophobicity character of near prenyl-cys residues indicates statin sensitivity of Gγ

Next, we focused on the pre-CaaX region hydrophobicity in determining the statin sensitivity of Gγ. We employed a Gγ3 mutant, in which the Phe-duo adjacent to prenyl-Cys is replaced with two Gly residues (Gγ3FF→GG: NPFREKKGGCALL), and a Gγ9 mutant carrying two Phe residues in place of Gly (Gγ9GG→FF: NPFKEK-FFCLIS) (43). Unlike in Gγ9-WT, which showed ∼100% near-complete cytosolic phenotype, the Gγ9GG→FF mutant showed a significant reduction in membrane anchorage inhibition down to ∼69% while its partial inhibition cytosolic population increased to ∼31% (Fig. 4, B and C and Table 2- Gγ9GG→FF). These full and partial phenotypes were further confirmed using mobility rates (Fig. 4D and Table 3- Gγ9GG→FF). However, the anchorage inhibitory effect upon FTI, but not due to GGTI, showed that the prenylation type of this Gγ9GG→FF mutant remained unchanged (farnesylated). Similarly, compared to Gγ3-WT, however, more substantially, the Fluvastatin exposed Gγ3FF→GG mutant cells exhibited a higher susceptibility to membrane anchorage inhibition, in which the near-complete cytosolic distribution became the prominent phenotype (∼83%) (Fig. 4, B and C and Table 2- Gγ3FF→GG, black and 4D and Table 3-Gγ3FF→GG), while the partial inhibition was reduced (∼17%) (Fig. 4, B–D and Table 2- Gγ3FF→GG, red). The sensitivity to GGTIs and lack thereof to FTIs indicated that the type of prenylation of this Gγ3FF→GG mutant remained unchanged (geranylgeranylated) (Fig. 4, B and D- Gγ3FF→GG). Building on these observations, we propose that Gγ9GG→FF is a gain-of-function mutant in which the gain is the resistance to statin sensitivity. However, the gain here is smaller than the significant loss observed in Gγ3FF→GG that we identified as the loss of function mutant. We then examined the individual contribution of each Phe residue in the Phe-duo towards the prenylation extent. We generated 2 Gγ3 mutants, Gγ3F70G and Gγ3F71G, and examined their statin sensitivity (Fig. S1). Based on their sensitivity to GGTI, we confirmed that both mutants are geranylgeranylation sensitive (Fig. S1). Compared to Gγ3-WT (Fig. 1, B and C), a significantly higher fraction of both mutant cell populations showed near-complete inhibition of membrane localization (Gγ3F70G: ∼29%, Gγ3F71G: ∼20%) (Fig. S1 and Table 2-Gγ3F70G and Gγ3F71G-black). Considering that the near-complete inhibition is absent in Gγ3-WT, these data indicate a crucial role of each Phe for Gγ3 to gain its efficient prenylation. Further, compared to the 55 ± 13 s mobility t1/2 observed in Fluvastatin exposed Gγ3-WT, both the mutants showed enhanced mobilities (Gγ3F70G: 38 ± 6 s, Gγ3F71G: 40 ± 8 s) in their partial inhibition populations (Table 3). This suggests that the extent of statin sensitivity increases upon substitution of each Phe with Gly. These data collectively demonstrate that the hydrophobic character of the residues adjacent to prenyl-Cys is a crucial determinant of G proteins' statin sensitivity.

Figure 4.

Hydrophobic residues adjacent to prenylating Cys contribute to the enhanced prenylation and statin sensitivity of Gγ.A, comparison of Ct domain amino acid sequences of Gγ3-WT and Gγ9-WT. B, images of HeLa cells expressing GFP tagged Gγ9GG→FF, Gγ3FF→GG, Gγ3FF→LL, Gγ3FF→VV, Gγ3FF→YY, and Gγ3FF→AA mutants exposed to vehicle (Control), Fluvastatin (20 μM), FTI (1 μM), or GGTI (10 μM). Images represent the prominent phenotype observed in each population under the given experimental conditions (scale: 5 μm; n ≥ 15 for each Gγ type). C, grouped box chart shows the percentages of categorized cells in each Gγ mutant into two phenotypes; near-complete (black) and partial (red) cytosolic distribution upon Fluvastatin treatment. The circles indicate the % cells showed near-complete (black) and partial cytosolic (red) distribution in each corresponding wild type Gγ (γ9-closed circles, γ3-open circles) expressing cells as reference points. D, the whisker box plots show mobility half-time (t1/2) of proteins in (B) determined using half-cell FRAP. (Average box plots were plotted using mean ± SD; Error bars: Gγ9GG→FF: n = 884 total number of cells from nine independent experiments, Gγ3FF→GG: n = 225 total number of cells from three independent experiments, Gγ3FF→LL: n = 428 total number of cells, Gγ3FF→VV: n = 364 total number of cells, Gγ3FF→YY: n = 407 total number of cells, Gγ3FF→AA: n = 358 total number of cells; Each Gγ mutant was examined in three independent experiments; Statistical comparisons were performed using One-way-ANOVA; p < 0.05; Flu, Fluvastatin; FTI, Farnesyl transferase inhibitor; GGTI, Geranylgeranyl transferase inhibitor; SD, standard deviation; WT, wild type).

To further confirm the influence of prenyl-Cys-adjacent hydrophobic residues on the protein's statin sensitivity, we altered the Gγ pre-CaaX hydrophobicity by mutating the Phe-duo in Gγ3. When the Phe-duo is mutated to two Leu residues, which has a similar hydrophobicity as Phe (46, 47), similar to the wild type (Gγ3 WT), the majority of the Gγ3FF→LL (NPFREKKLLCALL) mutant cells still showed partial inhibition of membrane anchorage (∼96%) primarily (Fig. 4, B and C and Table 2- Gγ3FF→LL, red), while a minor percentage (∼4%) showed a near-complete inhibition (Fig. 4C and Table 2- Gγ3FF→LL, black). Interestingly mutants generated by replacing the Phe-duo either with Val, Ala, or Tyr (Gγ3FF→VV, Gγ3FF→AA, or Gγ3FF→YY), which possess significantly lower hydrophobicity indices than Phe (46, 47), showed a prominent (∼95–100%) near-complete membrane localization inhibition upon Fluvastatin exposure (Fig. 4, B and C and Table 2). To obtain quantitative data corroborating the imaging observations, we next examined the mobilities of mutant Gγ subunits under pharmacological perturbation. While the mobility of partially inhibited Gγ3FF→LL was similar to that of Gγ3-WT (Fig. 1C-Gγ3 WT), completely inhibited populations of the rest of the mutants containing less hydrophobic residues adjacent to their prenyl-Cys (Gγ3FF→VV, Gγ3FF→YY, Gγ3FF→AA) exhibited significantly faster mobilities upon Fluvastatin treatment (Fig. 4D and Table 3). The similar and substantially slower mobility of Fluvastatin-treated Gγ3-WT and Gγ3FF→LL indicates the considerable presence of a prenylated Gγ population bound to membranes, suggesting their significant resistance to membrane localization inhibition by statins. Contrastingly, significantly faster mobility of Gγ3FF→VV, Gγ3FF→YY, and Gγ3FF→AA (Fig. 4D and Table 3) were also closer to the mobility of cytosolic Gγ9-WT observed in Fluvastatin-treated cells (Fig. 1C- Gγ9 WT), indicating that even for G proteins undergoing geranylgeranylation, the hydrophobic character of the pre-CaaX is a crucial regulator of their prenylation process. We also observed that the above Gγ3 mutations did not alter the prenylation type (Fig. 4, B, and D and Table 3, FTI and GGTI).

Interestingly, our data show that GGTI-mediated geranylgeranylation inhibition is partial in highly hydrophobic pre-CaaX residues carrying Gγ3 WT and Gγ3FF→LL mutant cells. On the contrary, GGTI induced a highly effective near-complete inhibition of geranylgeranylation in Gγ3FF→VV, Gγ3FF→AA, or Gγ3FF→YY mutants (Fig. 4, B and D). Here, we hypothesize that compared to the above three mutants, the observed partial prenylation in GGTI-exposed Gγ3-WT and Gγ3FF→LL mutant cells results from the enhanced hydrophobicity of their pre-CaaX region. This may allow these Gγs to undergo geranylgeranylation to a significant extent, likely using the residual geranylgeranyl transferase activity remaining in the cell. Further supporting the significance of pre-CaaX residues in regulating the prenylation process, mutant cells exposed to GGTI also showed mobility half times similar to those observed in cells exposed to Fluvastatin (Fig. 4D and Table 3). Therefore, these data suggest that the hydrophobicity of the pre-CaaX region is a primary regulator of a G protein's resistivity to prenyltransferase inhibitors.

Optogenetically controlled reversible unmasking-masking confirms the significance of Ct hydrophobic residues on prenylation and the membrane affinity of prenylating proteins

To examine how the Cys-adjacent hydrophobic residues first influence the prenylation process and then regulate membrane binding of the prenylated protein, we engineered an improved light-induced dimer (iLID)-based, blue-light-gated, monomeric photo-switch to expose and mask the Phe-duo of a protein with a geranylgeranylating CaaX (CALL) at the Ct (iLIDFCALL) (Fig. 5A-top panel, Fig. 5B). Since iLID is ending with a Phe (F449), the Ct sequence of this protein is —FFCALL (48). Upon prenylation, this protein should become iLIDF ending with geranylgeranylated and carboxymethylated Cys. With the incorporated second Phe (F550), we therefore created a Phe-duo in this protein, Venus-iLIDFCALL (Fig. 5B). Upon blue light exposure, regardless of the prenylation state of the protein, we expected the Phe-duo to be exposed (Fig. 5A-bottom panel, and B-right).

Figure 5.

Optogenetic masking-unmasking of amino acids shows pre-CaaX hydrophobicity-dependent prenylation and membrane interaction ability of prenylated proteins.A, the modeled structures of the two model proteins iLIDFCALL and iLIDGGGGFFCALL (based on PDB ID-4WF0) before prenylation. To create a masked Phe-duo utilizing iLID’s Phe549, Phe550 (orange) followed by the Gγ3 CaaX motif, CALL was inserted into iLID (iLIDFCALL-Top). As a control, an iLID variant with a potentially exposed Phe-duo (Phe554 and Phe555-light orange) was generated by placing a linker sequence (GGGG-light orange loop region) between iLID and Phe-duo (FF) (iLIDGGGGFFCALL- Bottom). The introduced F550 in iLIDFCALL fits into a hydrophobic pocket on the surface of the per-arnt-sim (PAS) domain made up of I417, I428, F429, and Y508 (green), while in iLIDGGGGFFCALL F549 fits into this hydrophobic pocket allowing the Phe-duo to be exposed. B, optogenetic regulation of prenylated . Blue light-induced Jα helix relaxation results in iLID’s SsrA peptide unmasking, likely exposing the Phe-duo, promoting membrane interaction of iLIDF through membrane insertion of the Phe-duo (F549 and F550) and the geranylgeranyl moiety into the hydrophobic tail region of the lipid bilayer. The magnified view shows hydrophobic interactions of F549 in with the hydrophobic pocket in the PAS domain before blue light irradiation. C, images of HeLa cells expressing Venus-iLIDFCALL (top), overnight blue light-exposed Venus-iLIDFCALL (middle), and Venus-iLIDGGGGFFCALL (control, bottom) show the initial subcellular distribution of proteins and their blue light-induced changes (Scale bar: 5 μm). Yellow arrows indicate Venus-iLIDFCALL and Venus-iLIDGGGGFFCALL proteins showing elevated localization in the endomembrane regions. The whisker box plots show the Golgi:Nucleus Venus fluorescence ratio under each condition before blue light (No BL) and after blue light (BL) (Average box plots were plotted using mean ± SD; Error bars: Statistical comparisons were performed using One-way-ANOVA; p < 0.05). D, the plot shows the reversible recruitment of iLIDFCALL (5C-top panel) to the Golgi upon blue light (error bars: SD, 10< n). E, images of HeLa cells expressing Venus-iLIDFCALL or Venus-iLIDGGGGFFCALL show completely cytosolic distributions when the cells are exposed to GGTI (10 μM), before and after blue light irradiation. F, 3D images of blue light irradiated HeLa cells expressing Venus-iLIDFCALL, GalT-dsRed, and CFP-KDEL. Blue light-induced Golgi recruitment of Venus-iLIDFCALL is confirmed by its co-localization with the Golgi marker GalT-dsRed and non-overlapping distribution with the ER marker CFP-KDEL (Scale bar: 5 μm). We have incorporated this figure (Fig. 5) with a color scheme compatible with color vision impaired JBC readers. BL, Blue light; GGTI, Geranylgeranyl transferase inhibitor; SD, Standard deviation.

When Venus-iLIDFCALL was expressed in HeLa cells, it showed primarily a cytosolic distribution with a minor Golgi localization (Fig. 5C-top, Before, and After 5 min in Dark). To quantify the subcellular distribution of this protein, we calculated the normalized Venus fluorescence ratio of the Golgi and nucleus. Indicating that Venus-iLIDFCALL is not prenylating efficiently, it showed a uniform cytosolic and nuclear distribution (Fig. 5C-top images). The minor Golgi distribution before blue light was indicated by the Golgi: Nucleus fluorescence ratio of 1.3 ± 0.1 (Fig. 5C-top box plot). It has been demonstrated that prenylation of CaaX sequence at the Ct of a protein alone is insufficient for proteins to interact with the plasma membrane (49, 50, 51, 52). Therefore, at this point, it was unclear whether the observed primarily cytosolic localization of the protein is due to the masked Phe-duo in the Jα helical conformation of the prenylated protein (Fig. 5B-left) or limited prenylation of the protein polypeptide, again due to the masked Phe-duo (38). When we exposed cells to blue light (445 nm) to activate the photoswitch while imaging Venus at 515 nm excitation and 542 ± 30 nm emission at 1 Hz frequency, a robust Golgi recruitment of Venus was observed with a t1/2 = 2 ± 1 s. Blue light significantly increased Golgi:Nucleus fluorescence ratio to 1.7 ± 0.2 (one-way ANOVA: F1,23 = 44.393, p < 0.001) (Fig. 5C-Top, 5D-plot, and Movie S1). The Golgi recruitment of Venus was accompanied by a complementary reduction in cytosolic Venus fluorescence. The recruitment to the Golgi was confirmed using the co-localization of Venus with the trans-Golgi marker, GalT-dsRed (Fig. 5F and Movie S2). We further confirmed that this recruitment was primarily to Golgi, by showing that the ER marker CFP-KDEL does not overlap with the Venus-recruited regions upon blue light exposure (Fig. 5F). After the Venus fluorescence in Golgi reaches the steady state, termination of blue light resulted in the dislodging of Golgi-bound iLID to near pre-blue light level (Fig. 5C- top-After 5 min in Dark, 5D plot, and Movie S1). These observations suggested that a fraction of the prenylated proteins remains cytosolic before blue light exposure. Unmasking the Phe-duo promotes their interaction with the Golgi membrane. Blue light termination associated Phe-duo masking disrupts this interaction. These observations validate our hypothesis that the prenyl anchor adjoining Phe-duo is crucial in promoting protein-membrane interactions. Next, to examine whether the masked Phe-duo in Venus-iLIDFCALL determines its prenylation potential during protein expression, we exposed cells to 450 nm blue LED light after the transfection (5-s ON-OFF cycles for 12 h in a CO2 incubator) (Fig. 5C-middle). The resultant cells showed a significant Golgi localization of Venus with Golgi: Nucleus of 1.6 ± 0.1, which increased to 1.8 ± 0.1, upon blue light exposure (one-way ANOVA: F1,18 = 4.893, p = 0.040). As a control experiment, we generated a Venus-iLID variant with an exposed Phe-duo by placing a linker sequence (GGGG) at iLID Ct and a Phe-duo (FF) before CALL (Venus-iLIDGGGGFFCALL) (Fig. 5C-bottom). Compared to the cytosolic distribution observed upon expression of Venus-iLIDFCALL, Venus-iLIDGGGGFFCALL, showed an enhanced Golgi and a detectable ER distribution (Fig. 5C-bottom). The Golgi: Nucleus Venus ratio (1.8 ± 0.2) was the highest here, with very low Venus fluorescence in the nucleus. This is expected since in Venus-iLIDGGGGFFCALL expressing cells, prenyl-Cys-adjacent Phe-duo is exposed and free to interact with the endomembrane, improving prenylation. It was also not surprising that the blue light irradiation did not significantly change the distribution of Venus (Golgi: Nucleus 1.9 ± 0.1) (one-way ANOVA: F1,22 = 1.759, p = 0.198) (Fig. 5C-bottom). These data indicated that, in addition to the prenyl group, membrane-accessible hydrophobic residues significantly enhance the membrane interaction of the engineered protein. Further, the decreasing presence of nuclear fluorescence, starting from Figure 5C top to bottom panels suggested that prenylated proteins do not enter the nucleus.

When cells are exposed to GGTI286 during protein expression, Venus in both Venus-iLIDFCALL and Venus-iLIDGGGGFFCALL showed completely cytosolic distributions, indicating these proteins are geranylgeranylation sensitive (Fig. 5E). Furthermore, the blue light irradiation did not recruit Venus to the Golgi in Venus-iLIDFCALL under GGTI286-treated conditions (Fig. 5E, Movies S3 and S4). To further confirm that geranylgeranylation is required for Golgi recruitment of this protein, we examined Venus-iLIDFCALL expressing cells under FTI or Fluvastatin-treated conditions. Similar to GGTI-treated cells (Fig. 5E), Fluvastatin-treated cells showed uniform Venus distribution throughout the cytosol and the nucleus and failed to show blue light-induced Venus recruitment to Golgi (Fig. S4). However, cells upon FTI treatment (only inhibits farnesylation) behaved similar to control cells and exhibited blue light-induced Venus recruitment to Golgi (Fig. S4-A). To emphasize that blue light-induced Golgi recruitment of these two proteins depends on their prenylation state, we used C→A mutant variants of iLIDFCALL and iLIDGGGGFFCALL (Venus-iLIDFAALL and Venus-iLIDGGGGFFAALL). They showed complete cytosolic distribution before and no sensitivity to blue light irradiation (Fig. S4-B).

Overall, the data suggest that overnight blue light exposure during protein expression enhances the prenylation of Venus-iLIDFCALL since the Phe-duo in the photoswitch is continuously being exposed, improving polypeptide-membrane interactions. The significant nuclear localization of Venus in Venus-iLIDFCALL, cells (due to reduced prenylation) and the reduced presence of nuclear-Venus in Venus-iLIDGGGGFFCALL cells and overnight blue light exposed Venus-iLIDFCALL cells (due to enhanced prenylation) also collectively suggest that the unmasked Phe-duo enhances the prenylation. Therefore, Venus-iLIDFCALL cells exposed to overnight blue light must have enhanced prenylation and thus a significantly higher concentration of proteins compared to the control cells, as reflected by the significantly elevated Venus localization in the Golgi. Collectively, these experiments demonstrate a previously unknown mechanism of prenylation regulation. To our knowledge, this is the first presentation for dynamic control of molecular interactions using reversible optogenetic control to regulate membrane interactions of proteins before and after their lipidation.

Contribution of pre-CaaX positively charged residues on Gγ prenylation and statin sensitivity is moderate, however significant

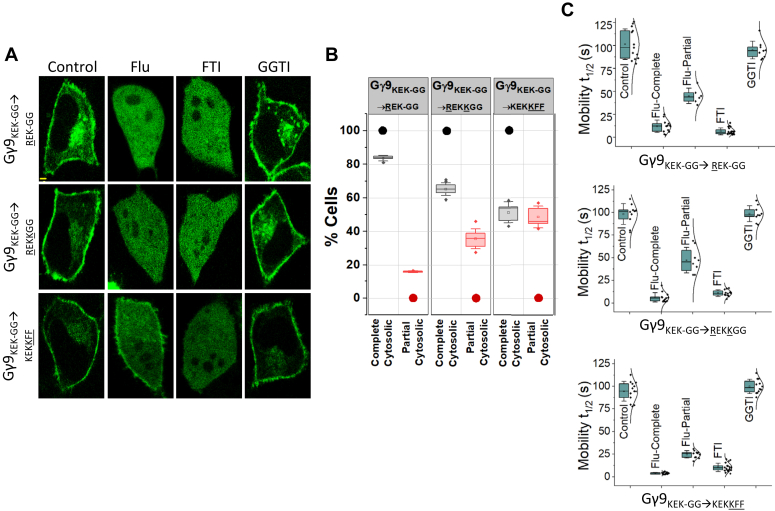

Both Gγ3-WT and Gγ9-WT contain homologous sequences consisting of positively charged Lys, Arg residues, or both at the beginning of their pre-CaaX regions (Fig. 3A). Our previous work indicated that the positively charged side chains of these residues help Gγ to maintain transient interactions with the phospholipid head groups of the membrane (43). To understand the collective role of hydrophobic and positively charged residues on enhanced membrane interactions of Gγ3-WT, we systematically mutated the pre-CaaX of Gγ9 to gradually achieve Gγ3-like characteristics without changing the prenylation type. Although both Lys and Arg are positively charged, to examine whether Gγ3 achieved its improved membrane interactions and thereby resistance to Fluvastatin-induced inhibition of its membrane anchoring due to the higher geometric stability provided by Arg (53), we mutated the 61st Lys in Gγ9 to Arg (Gγ9KEK-GG→REK-GG) (Fig. 6A). It has been reported that compared to Lys, the guanidinium group of Arg allows the formation of stable and a larger number of electrostatic interactions in three different directions (53). The higher pKa of Arg may also contribute to forming more stable ionic interactions than Lys (53). Only ∼84% of the Gγ9KEK-GG→REK-GG mutant cells exhibited near-complete cytosolic distribution compared to ∼100% in Gγ9-WT (Fig. 6, A and B and Table 2- Gγ9KEK-GG→REK-GG). The appearance of a ∼16% cell population with partial cytosolic phenotype is also indicated by 45 ± 9 s mobility t1/2, as opposed to the 9 ± 5 s t1/2 of Gγ9 (Fig. 6C and Table 3- Gγ9KEK-GG→REK-GG). These data showed that the pre-CaaX Arg grants Gγ3 a higher membrane affinity, thereby increasing prenylation and reducing statin sensitivity. Next, to understand the role of the additional Lys residue at the 69th position of Gγ3-WT, we introduced an additional Lys to this mutant, creating the Gγ9KEK-GG→REKKGG mutant. Compared to both the wild type and Gγ9KEK-GG→REK-GG cells expressing Gγ9KEK-GG→REKKGG showed further reduced sensitivity to Fluvastatin (∼65% near-complete membrane anchorage inhibition) (Fig. 6, A and B and Table 2- Gγ9KEK-GG→REKKGG). This mutant also showed increased partial inhibition (∼36% cell) (Fig. 6B and Table 2- Gγ9KEK-GG→REKKGG). These data indicate that basic pre-CaaX residues significantly enhance the prenylation while reducing the statin sensitivity of Gγ3. Building on this, we next generated a Gγ9 mutant (Gγ9KEK-GG→KEKKFF) to understand the cumulative effect of the additional Lys69 and the Phe-duo in Gγ3 pre-CaaX. Compared to Gγ9-WT, Gγ9KEK-GG→KEKKFF mutant cells exhibited elevated prenylation and reduced statin sensitivity, indicated by the significantly reduced near-complete membrane anchorage inhibition to ∼51%, and the increased partial inhibition to ∼48% (Fig. 6, A and B and Table 2). This mutant only differs from the Gγ9KEKGG→KEKFF mutant by having an additional Lys, which increases the partial inhibition from ∼16% to ∼51%. The sensitivity of these mutants to FTI, but not to GGTI, confirmed that their prenylation type is unchanged and remains farnesylated.

Figure 6.

Positively charged pre-CaaX residues also contribute to Gγ prenylation and statin sensitivity.A, images of HeLa cells expressing GFP tagged Gγ9KEK-GG→ REK-GG, Gγ9KEK-GG→REKKGG, and Gγ9KEK-GG→KEKKFF mutants treated with vehicle (control), Fluvastatin (20 μM), FTI (1 μM), or GGTI (10 μM). Images represent the prominent phenotype observed in each population under the given experimental conditions (scale: 5 μm; n ≥ 15 for each Gγ type). B, grouped box chart shows the percentages of cells in each Gγ mutant (Gγ9KEK-GG→REK-GG, Gγ9KEK-GG→REKKGG, and Gγ9KEK-GG→KEKKFF mutants) showing near-complete (black) and partial (red) cytosolic distribution with Fluvastatin treatment. Circles indicate the % cells showed near-complete (black) and partial cytosolic (red) distribution as reference points. C, the whisker box plots show mobility half-time (t1/2) of proteins in (A) determined using half-cell FRAP. (Average box plots were plotted using mean ± SD; Error bars: Gγ9KEK-GG→REK-GG: n = 397 total number of cells from five independent experiments, Gγ9KEK-GG→REKKGG: n = 764 total number of cells from seven independent experiments, Gγ9KEK-GG→KEKKFF: n = 546 total number of cells from five independent experiments; Statistical comparisons were performed using One-way-ANOVA; p < 0.05; Flu, Fluvastatin; FT, Farnesyl transferase inhibitor; GGTI, Geranylgeranyl transferase inhibitor; SD, Standard deviation).

To rule out bias in imaging data analysis, in addition to quantification of Gγ mobility with different treatment conditions, we carried out a blind control experiment with an experimenter who was blind to the type of mutation and the treatment condition in experiments discussed in 3.1 to 3.4 and 3.6. When comparing the results obtained by the blind control experimenter and the experimenter using one-way ANOVA, we did not observe a significant difference (Fig. S5). We further support our data by providing multi-cell images representing different phenotypes of each population of Gγ, WTs, or their mutants in response to different treatments (Figs. S6 and S7).

Discussion

Post-translational modifications play central roles in the membrane association of the G proteins, such as Ras superfamily and heterotrimeric G proteins (32). Since G protein signaling pathways mediate a vast array of physiological responses, their dysregulation contributes to many diseases, including cancer, heart disease, hypertension, endocrine disorders, and blindness (54). In an early study, we showed that Gγ membrane interactions and associated signaling are inhibited in the presence of statins, likely due to the inhibition of prenylation (12). However, we also observed differential extents of membrane binding inhibitions of Gγ, indicating diverse statin sensitivities (12). The present study shows potential molecular reasoning for this differential statin sensitivity of the Gγ family while indicating a novel mechanism that may govern its prenylation under suboptimal conditions.

Although prenylation is essential, it alone is insufficient for the plasma membrane interaction of prenylated G proteins (49, 50, 51, 52). Studies show that in addition to the prenyl anchor, the amino acids antecedent to the CaaX motif further support membrane anchorage of proteins (39, 43, 44, 50, 51, 55, 56). However, in the absence of prenylation, the contributions of membrane-interacting Ct residues alone are insufficient to support the recruitment of a protein to a membrane (12, 37). We validated this by generating prenylation deficient Gγ mutants with the CaaX motif Cys mutated to Ala (C→A) (Figs. S2 and S3). Despite their prenylated versions provided distinct translocation abilities to Gβγ, also indicating different membrane affinities (39, 56), these C→A mutants exhibited complete cytosolic distributions and faster and similar mobilities, indicating that without the prenyl anchor, the pre-CaaX region alone cannot support the membrane binding. The positively charged poly Lys region on KRas-4b is a classic example showing the participation of prenyl-Cys-adjacent amino acids in targeting prenylated proteins to the plasma membranes (50, 51, 55). Here, KRas-4b membrane interaction is maintained by the thermodynamically favored insertion of the farnesyl lipid anchor into the membrane lipid bilayer. This is in concert supported by the electrostatic interactions of the 10 Lys residues (positively charged) in the pre-CaaX region with the negatively charged polar headgroups of the plasma membrane phospholipids (55). It has also been shown that the polybasic residues in the pre-CaaX region of a protein can function as a sorting signal to prevent proteins from entering the Golgi (57). In HRas, a Cys residue adjacent to CaaX motif undergoes palmitoylation and serves as a second signal to traffic the protein to different cell membranes (57). Two prenylation types and variable second signals encoded by the pre-CaaX region have been suggested to target a protein to different microdomains within the plasma membrane (57). Along with the above evidence, we have recently established that the Phe-duo adjacent to prenylated Cys (in several Gγ subtypes) strongly promotes membrane anchorage (43).

Although each Gγ is prenylated with either a 15-C farnesyl or a 20-C geranylgeranyl anchor, the 12 members of the family exhibit a broad range of membrane affinities, spanning from the lowest observed in farnesylated Gγ9 to the highest in geranylgeranylated Gγ3 (39, 43, 44). When Gγs are prenylated, they reside at the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane as GαGDPβγ heterotrimer, bound to or near GPCRs (58, 59). When GPCRs are activated, Gα exchanges the bound GDP to GTP, dissociating the heterotrimer into GαGTP and Gβγ. Upon GPCR activation, all Gγ members translocate from the plasma membrane to endomembranes as Gβγ, in a Gγ type-specific manner, in which Gγ9 shows fastest translocation and with a higher magnitude, while Gγ3 response is many folds slower and smaller (39, 56). These Gγ type-dependent translocation rates and extents have been used as a measure of the membrane affinity of a specific Gγ (39, 42, 43, 44, 56, 60, 61). According to this classification, the 3 Gγs with the highest membrane affinities (Gγ2, γ3, and γ4) contain two conserved Phe residues (Phe-duo) next to the prenylated and carboxymethylated Cys (43). An early study suggested that aromatic residues such as Phe in the membrane-interacting domain of a protein enhance membrane-protein interactions via hydrophobic binding (62). This enhanced interaction is achieved by inserting the hydrophobic side chains into the fatty acid tail region of the lipid bilayer (62). Our recent work also indicated that the aromatic side chain of Phe residues is crucial for the enhanced membrane affinity of Gγ2, 3, and 4 (43). In contrast, the Gγ with the lowest membrane affinity, Gγ9, possesses two Gly residues (less hydrophobic) at the corresponding position. This lowest observed membrane affinity of Gγ9 can easily be understood by considering its prenylation type (farnesylation) and its less hydrophobic pre-CaaX region.

When the statin sensitivities of the 12 Gγ subtypes were examined by measuring the inhibition of membrane anchoring, as opposed to the complete disruption observed for Gγ9, 1, and 11, we observed a partial perturbation of membrane anchorage in Gγ2, 3, 4, 7, 8, and 12. Interestingly, the same Gγ group also exhibited a partial membrane anchorage disruption upon exposure to the GGTI. We propose that Gγ group's highly effective prenylation allows them to achieve a considerable prenylation by utilizing the residual geranylgeranyl transferase activity remaining under GGTI. Our data with prenyltransferase inhibitors indicated that, as generally accepted, CaaX motif sequence determines the type of prenylation, and mobility t1/2 is a reliable measure of the G protein prenylation extent (63, 64). However, the complete to partial Fluvastatin sensitivity of Gγs carrying geranylgeranylating CaaX questioned whether these membrane anchorage inhibitions are prenylation type dependent. Experiments with CaaX and pre-CaaX mutants of Gγ3 and Gγ9 have been helpful to examine the mechanism. The results from Gγ9CALL and Gγ3CIIS ruled out the idea that Gγ sensitivity to statin is prenylation-type dependent since both Gγ9CALL and Gγ3CIIS mutants retained their wild-type statin sensitivity despite the switched prenylation type. The significant membrane anchorage changes observed in statin-exposed cells upon switching the pre-CaaX regions between Gγ9 and Gγ3 demonstrated that the pre-CaaX region likely controls the statin sensitivity of Gγ. Our data from Gγ9GG→FF and Gγ3FF→GG mutants further indicated that the pre-CaaX hydrophobic residues reduce the statin sensitivity of Gγ.

Our optogenetic approach allowed reversible unmasking-masking of pre-CaaX Phe-duo and helped further establish the significance of hydrophobic residues, first on protein prenylation and, subsequently, the membrane anchorage of the prenylated protein. When the Phe-duo is masked, our data indicate that the protein has a low prenylation extent. The behavior of the iLID model protein suggests that not only the masked Phe-duo suppressed the prenylation process but also limited the Golgi recruitment of the prenylated population only to a small fraction in the absence of blue light. Therefore, Blue light-induced robust Golgi recruitment clearly indicates that the pre-CaaX hydrophobicity plays a crucial role in controlling membrane interactions of prenylated proteins. Although the exact reason is unclear, it has been shown that when other proteins do not support them, prenylated G proteins accumulate primarily at the Golgi, not in ER or the plasma membrane (65). Optical activation-induced Golgi recruitment of iLID model protein agrees with this. When the prenylated protein population increases, we propose that the Golgi is saturated and excess iLID protein binds the ER. This is evident from the major Golgi and minor ER distribution of the iLID model protein in cells exposed to blue light pulses overnight. In the iLID protein with GGGGFF pre-CaaX motif, the Phe-duo should be constitutively unmasked, increasing prenylation. This protein also showed both Golgi and ER localization. Consistent with the expected positive contribution of basic residues to membrane interactions of proteins (66, 67, 68), our data further show that positively charged pre-CaaX residues, Lys and Arg, allow Gγs to combat statin as well as the prenyltransferase inhibitor influence. Data also indicate that the influence of Arg is stronger than Lys, and their relative location on the pre-CaaX matters.

Our findings that hydrophobic and positively charged residues in the Gγ pre-CaaX region determine the extent of a G protein’s sensitivity to satin and prenyltransferase inhibitors may shed light on the prenylation mechanism. We, therefore, propose that pre-CaaX controls transient interactions of Gγ polypeptide with membranes or prenyltransferases or both during prenylation and post-prenylation processing. While our study focuses on Gγ prenylation regulation, the findings could extend to areas of greater physiological significance. For instance, RAS protein prenylation serves as a potential biomarker in cancer diagnosis and prognosis (69, 70, 71, 72, 73). Specific RAS mutations have been shown to increase affinity for prenyltransferases (3, 14, 74, 75, 76), and if this results in enhanced prenylation, increased RAS activity-associated uncontrolled cell proliferation, apoptosis resistance, and angiogenesis, leading to poor patient outcomes in RAS-related cancers, such as colorectal, lung, and pancreatic cancer. Thus, examining molecular links between mutations in RAS proteins, their influence on prenylation, and the resultant tumor association could inform therapy development. Additionally, due to the involvement of Ras family G proteins and some Gγ subtypes in the oncogenesis (77, 78, 79, 80), prenyltransferase inhibitors have been explored for chemotherapy (81). Tipifarnib, Lonafarnib, BMS-214662, L-778, and L-123 are a few farnesyltransferase inhibitors tested in phase-II clinical trials. Nevertheless, they failed, and the mutations acquired in the oncogene or cancer reaching the metastatic state were considered culprits (14, 82). Examining the pre-CaaX composition of oncogenic G proteins in specific tumors may allow revisiting these inhibitors for treating certain cancers. Given the cell and tissue-specific distribution of 12 Gγ types with distinct pre-CaaX motifs (83, 84, 85, 86), our data may also provide a likely rationale for statins to differentially perturb G protein signaling depending on the Gγ composition of a cell.

In summary, though the CaaX motif determines the type of prenylation, and Gγ types that undergo farnesylation possess higher sensitivity to statin-induced prenylation disruption, out data here suggest that neither the CaaX motif nor the prenylation-type controls the statin sensitivity or the prenylation of Gγ. Instead, the data collectively indicate that pre-CaaX amino acids provide varying and sequence-specific gain or loss of sensitivity to statins and prenyltransferase inhibitors depending on their R group hydrophobicity, charge, location, and abundance. Under suboptimal prenylation conditions, either due to limited substrate prenyl lipid availability or prenyl transferase enzyme activity, this pre-CaaX-dependent regulation becomes prominent. Given that Gγ shows cell-type specific expression profiles, our results suggest that statins and prenyltransferase inhibitors likely impose cell-tissue-specific GPCR and G protein signaling perturbations. Overall, we believe our findings are pharmacologically significant, considering that prenyltransferase inhibitors have advanced only up to phase II clinical trials for cancer, and statins are already used in combination chemotherapy.

Experimental procedures

Reagents

The reagents used were as follows: Fluvastatin, Tipifarnib, and GGTI286 (Cayman Chemical) were dissolved in appropriate solvents according to the manufacturer’s instructions and diluted in 1% Hanks' Balanced Salt solution supplemented with NaHCO3 or regular cell culture medium before being added to cells.

DNA constructs and cell lines

For the engineering of DNA constructs used, GFP-Gγ9Gγ3PC, GFP-Gγ9GG→FF, Gγ3FF→GG, mCh-Gγ3C72A YFP-tagged Gγ1–Gγ13, GFP-Gγ9, GFP-Gγ3, GFP-Gγ9CALL, GFP-Gγ3CIIS, CFP-KDEL, and GalT-dsRed have been described previously (12, 40, 43, 56). Dr Brian Kuhlman from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, North Carolina kindly provided permission to use the iLID construct. Gγ3, Gγ9 mutants, and iLID constructs were generated by PCR amplifying the parent constructs in pcDNA3.1 (GFP-Gγ3, GFP-Gγ9, and Venus-iLID) with overhangs containing expected nucleotide mutations and DpnI (NEB) digestion (to remove the parent construct) followed by Gibson assembly (NEB) (87). Cloned cDNA constructs were confirmed by sequencing (Genewiz). The HeLa cell line was originally purchased from the American Type Culture Collection and authenticated using a commercial kit to amplify nine unique STR loci.

Cell culture and transfections

HeLa cells were cultured in minimum essential medium (MEM-Cellgro) with 10% heat-inactivated dialyzed fetal bovine serum (DFBS; from Atlanta Biologicals) and 1% penicillin−streptomycin (PS) in 60 mm tissue culture dishes and maintained in a 37 °C, 5% CO2 incubator. When the cells reached ∼80% confluency, they were lifted from the dish using versene-EDTA (Cell-Gro) and resuspended in their growth medium at a cell density of 1 × 106/ml. For imaging experiments (Gγ subcellular distribution analysis, fluorescence recovery after half-cell photobleaching for Gγ mobility analysis, subcellular distribution analysis, and blue light-induced membrane interaction analysis of Ct-modified iLID), cells were seeded on 35 mm cell culture–grade glass-bottomed dishes (Cellvis) at a density of 8 × 104 cells. The day following cell seeding, cells were transfected with appropriate DNA combinations (YFP-tagged Gγ1–Gγ13: 0.8 μg, GFP tagged Gγ or Gγ mutants: 0.2 μg, Venus-iLIDFCALL and Venus-iLIDGGGGFFCALL: 0.8 μg per each dish) using Lipofectamine 2000 transfection reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol and stored in a 37 °C, 5% CO2 incubator. After 3.5/5 h of transfection, cells were replenished with the growth medium containing either dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) or the respective inhibitor (Fluvastatin-20 μM, FTI-1 μM, or GGTI-10 μM). Live-cell imaging was performed ∼16 h post-transfection.

Live cell imaging, half-cell photobleaching, iLID photoactivation, image analysis, and data processing

Live-cell imaging experiments were performed using a spinning disk (Dragonfly 505) XD confocal TIRF imaging system composed of a Nikon Ti-R/B inverted microscope with a 60×, 1.4 NA oil objective and iXon ULTRA 897BV back-illuminated deep-cooled EMCCD camera. Photobleaching and photoactivation of spatially confined regions of interest (ROIs) of cells were performed using a laser combiner with 40 to 100 mW solid-state lasers (445, 488, 515, and 594 nm) equipped with Andor FRAP-PA unit (fluorescence recovery after photobleaching and photoactivation), controlled by Andor iQ 3.1 software (Andor Technologies). For selective photobleaching of YFP or GFP, 488 nm (3.1 mW) and 515 nm (1.5 mW) lasers at the focal plane (60× oil 1.49 NA objective) were used. Photobleaching speed: ∼100 μs per half cell (∼a 100 μm2 area). The photobleaching covers the entire depth of the cell along the Z axis. For photoactivation of iLID 445 nm laser at 6.3 μW was used. Proteins tagged with Venus/YFP were imaged using 515 nm excitation and 542 nm emission; GFP using 488 nm excitation−515 nm emission; CFP imaging or blue light activation of optogenetically active iLID constructs were performed using 445 nm excitation and 478 nm emission. For global and confined optical activation of iLID-expressing cells, the power of 445 nm solid-state laser was adjusted to 5 mW. Additional adjustments of laser power with 0.1% to 1% transmittance were achieved using the Integrated Lase Engine (ILE). Data acquisition, time-lapse image analysis, processing, and statistical analysis were performed as explained previously (12). Briefly, time-lapse images were analyzed using Andor iQ 3.1 software by acquiring the mean pixel fluorescence intensity changes of the entire cell or the selected ROIs. The majority of data was acquired by an experimenter who was not blinded to the expression level of fluorescently tagged proteins. However, the treatment condition and Gγ-type blinded experimenter performed the blind control experiments.

Log cavity energy (log CE) calculation Gγ Ct peptides (pre-CaaX+CaaX)

The hydrophobicity of a molecule can be quantified using octanol-water partition coefficient (KOW)-based Log Cavity energy (Log CE) value. The methodology to computationally determine Log CE using density functional theory (DFT) and the Solvent Model based on Density (SMD) was previously shown to have excellent agreement with experimental Log CE values for various molecules, including peptides (88, 89). We employed the M11 meta-functional (90) with SMD (91) and computed the Log CE using the equation, for the unprenylated Gγ polypetide (consisting pre-CaaX and CaaX regions) and prenylated and carboxymethylated Ct peptides representing the Gγ family members at 37 ⁰C (310 K). The peptide structures were optimized with a split-valance basis (3–21G∗), and the solvation energies (Table S1) were computed with a polarized triple-zeta basis set (6–311 + G∗∗). All computations were performed using Gaussian16 (Revision C.01) software (92).

Computationally modeled structure generation of the iLID-based photoswitch

We used the amino acid sequence of iLID (48) to generate the modeled protein structures in Figure 5, A and B using AlphaFold2. First, we added the respective additional amino acids “FCALL” and “GGGGFFCALL” at the C terminus of the iLID to generate iLIDFCALL and iLIDGGGGFFCALL. We then fed these sequences to AlphaFold2 and built homology models. Structures that best fit the experimental iLID structure (PDB ID: 4WF0) were selected for protein folding validation. Finally, the protein preparation tool in Schrodinger Maestro13.3.121 was used to optimize the selected protein model. When generating the modeled (before blue light irradiation), we used the 3D builder tool of Schrodinger and generated the carboxymethylated geranylgeranylated cys in 2D format. Then the structure was optimized using the protein preparation tool in Schrodinger Maestro for a low-energy 3D structure with corrected chirality. We followed a similar approach to generate the carboxymethylated geranylgeranylated Ct peptide () of light-activated in 2D format, however used the Schrodinger Maestro LigPrep tool for optimizing the 3D structure. We then depicted AANDE residues of iLID as an unstructured peptide that connects AsLOV2 of iLID with the above-prepared . This structure is shown as the blue light-activated protein in Figure 5B.

Statistical data analysis

All experiments were repeated multiple times to test the reproducibility of the results. Statistical analysis and data plot generation were done using OriginPro software (OriginLab). Results were analyzed from multiple cells and represented as mean ± SD. The number of cells used in the analysis is given in respective figure legends. For Gαβγ heterotrimer mobility analysis using fluorescence recovery after half-cell photobleaching, after obtaining all the baseline-subtracted data employing the Nonlinear Curve Fitting (NLFit) tool in OriginPro, Gαβγ mobility dynamics plots were fitted to the ExpAssoc1 function under the Pharmacology category. For each fitting half time was calculated using [half-time = ln (2)/K = ln (2)∗Tau] equation where K is the rate constant and Tau is the time constant (Tau = 1/K). The mean values of half-time obtained from nonlinear curve fitting for all cells are given as mean mobility t1/2. One-way ANOVA statistical tests were performed using OriginPro to determine the statistical significance between two or more populations of signaling responses. Tukey's mean comparison test was performed at the p < 0.05 significance level for the one-way ANOVA statistical test.

Blind control experiment

For each mutant with different treatment conditions, the blind control experimenter was given multiple images from experiments conducted on different days and instructed to categorize each cell image for its Gγ distribution, whether cytosolic or partially cytosolic. The mean values for each category of the blind control were compared with the values observed by the experimenter. The compared mean values were not significantly different between the blind control experimenter and the experimenter (one-way ANOVA).

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Supporting information

This article contains supporting information.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest concerning the contents of this article.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Department of Biology, Saint Louis University, for providing instrumentation and other support. Ohio Supercomputer Center for providing access to high-performance computing clusters and Gaussian software for DFT calculations. We also thank the Saint Louis University Institute for Drug and Biotherapeutic Innovation for providing computational resources and access to Schrödinger software, with funding from the Saint Louis University Research Institute. We also thank Ajith lab members Sithurandi Ubeysinghe, Dhanushan Wijayaratna, Senuri Piyawardana, Chathuri Rajarathna, and Aditya Chandu for various experimental support, comments, and discussions.

Author contributions