Abstract

Introduction

Improving physical activity (PA) and healthy eating is critical for primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD). Behaviour change programmes delivered in sporting clubs can engage men in health behaviour change, but are rarely sustained or scaled-up post trial. Following the success of pilot studies of the Australian Fans in Training (Aussie-FIT) programme, a hybrid effectiveness–implementation trial protocol was developed. This protocol outlines methods to: (1) establish if Aussie-FIT is effective at supporting men with or at risk of CVD to sustain improvements in moderate-to-vigorous PA (primary outcome), diet and physical and psychological health and (2) examine the feasibility and utility of implementation strategies to support programme adoption, implementation and sustainment.

Methods and analysis

A pragmatic multistate/territory hybrid type 2 effectiveness–implementation parallel group randomised controlled trial with a 6-month wait list control arm in Australia. 320 men aged 35–75 years with or at risk of CVD will be recruited. Aussie-FIT involves 12 weekly face-to-face sessions including coach-led interactive education workshops and PA delivered in Australian Football League (Western Australia, Northern Territory) and rugby (Queensland) sports club settings. Follow-up measures will be at 3 and 6 months (both groups) and at 12 months to assess maintenance (intervention group only). Implementation outcomes will be reported using the Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, Maintenance framework.

Ethics and dissemination

This multisite study has been approved by the lead ethics committees in the lead site’s jurisdiction, the South Metropolitan Health Service Human Research Ethics Committee (Reference RGS4254) and the West Australian Aboriginal Health Ethics Committee (HREC1221). Findings will be disseminated at academic conferences, peer-reviewed journals and via presentations and reports to stakeholders, including consumers. Findings will inform a blueprint to support the sustainment and scale-up of Aussie-FIT across diverse Australian settings and populations to benefit men’s health.

Trial registration number

This trial is registered with the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ACTRN12623000437662).

Keywords: Obesity, Primary Prevention, Public Health, Randomized Controlled Trial, Cardiology

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

This is the first multistate/territory trial of a ‘fans in training’ style intervention.

Consumers and other stakeholders contributed to the development of the protocol, in particular recruitment and data collection methods.

Using a hybrid design will facilitate the concurrent assessment of intervention effectiveness and implementation outcomes, promoting efficient implementation and long-term impact of this evidence-based programme.

Due to the nature of the intervention, participants will not be blinded to treatment allocation.

Introduction

The cardiovascular benefits of physical activity (PA) and eating a healthy diet are well established; however, 55% of people who live in Australia do not meet PA guidelines, most eat an unhealthy diet and 67% are living with overweight or obesity.1 Among those with a cardiovascular disease (CVD) diagnosis, exercise adherence remains low. Most men with CVD fail to initiate or sustain health behaviour changes, decreasing quality of life and increasing risk of future CVD and premature death.2 For instance, only 30% of patients complete outpatient cardiac rehabilitation, and of those, less than 50% are sufficiently active 12 months after their cardiac event.2

A patient survey showed many patients lack self-management skills and are too dependent on exercise rehabilitation staff to sustain behaviour changes on completion of hospital-based exercise programmes.3 Recent estimates suggest that increasing participation in cardiac rehabilitation in Australia from 30% to 65% would result in $A36 million in healthcare savings, $A58 million in social and economic benefits and significantly reduce annual heart attack admissions.4 To reap these health and economic benefits, new strategies are required to increase PA adherence and healthy eating in people with or at risk of CVD. Gender-tailored programmes are important, because men and women experience differences in CVDs risks and occurrences.5 Gender-tailored health behaviour change programmes for men have been shown to be appealing and effective.6

The internationally recognised ‘Football Fans in Training’ (FFIT) programme and our Australian adaptation (Australian Fans in Training (Aussie-FIT)) are effective in engaging men to improve their health behaviours. FFIT7 and Aussie-FIT8 capitalise on men’s interest in sport to promote weight loss via sustained improvements in diet and PA. These structured 12-week programmes include 90 min of interactive education and group-based PA that aims to develop the skills and confidence of participants to self-regulate and maintain long-term behaviour change. Programmes are delivered to groups of men by trained coaches in professional sports facilities. The effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of FFIT was established in a randomised control trial (RCT).7 Mean between group weight lost at 12 months was 5 kg, and average weight loss maintenance of 2.9 kg was observed in the intervention group 3.5 years post baseline.9 FFIT was adapted for the European Fans in Training (EuroFIT) RCT in five European countries, where similar findings were revealed.10

Kwasnicka et al demonstrated feasibility of recruitment, engagement and retention of men living with overweight and obesity, as well as acceptability of the Aussie-FIT intervention and research procedures when delivered at top-tier Australian Football League (AFL) clubs in Western Australia (WA). Promising physical and mental health outcomes were observed.11 In a single-arm prefeasibility trial in Queensland (QLD), a version of Aussie-FIT adapted for rugby league (League-FIT) has engaged men living with overweight and obesity and demonstrated promise in supporting positive physical and mental health outcomes.12 In a feasibility study of the Aussie-FIT programme undertaken at second-tier AFL clubs for men with CVD, Smith et al,13 (manuscript in preparation) demonstrated feasibility of participant engagement and retention, and acceptability of the intervention and research procedures. However, recruiting men with CVD was challenging (Smith et al, manuscript in progress). Recruitment challenges were likely due to the smaller population of men with CVD (6.5% of men in Australia)14 compared with 75% of men with overweight and obesity in Australia,15 and the smaller fanbases of second-tier AFL clubs compared with top-tier clubs. The effectiveness of Aussie-FIT remains to be tested, as do implementation strategies designed to improve the adoption, implementation, sustainment and scale-up of the programme to reach diverse populations of at-risk men. This multistate/multiterritory trial aims to establish the effectiveness of the Aussie-FIT intervention for men with or at risk of CVD, while allowing for flexibility with club size (eg, top tier or second tier) across diverse Australian contexts.

A recent systematic review of five unique interventions concluded that, while FFIT has been successfully scaled up, not all health promotion interventions delivered through professional sport have been successfully scaled up, and thus a greater focus on the potential for scalability of these interventions is required.16 Scalability is the process of increasing the number of implementers (eg, sports clubs) that are willing to initiate delivery of effective interventions to reach a greater proportion of the target population.17 The potential for intervention scalability is increasingly considered across the research spectrum, rather than solely positioned at the end of a linear research pipeline after effectiveness testing.18 One increasingly common approach to considering implementation and scalability earlier in the research process is the use of hybrid effectiveness–implementation study designs, which allow for the assessment of intervention effectiveness alongside implementation outcomes.19 Implementation outcomes that are important for scalability include programme costs, fidelity, adaptability, delivery settings, infrastructure, workforce, reach and acceptability in diverse populations (Milat et al,20 2020).

This trial adopts a hybrid effectiveness–implementation design21 to examine the effectiveness of Aussie-FIT, and in parallel assess the feasibility and utility of implementation strategies to support programme adoption, implementation, sustainment and scalability, using the Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance (RE-AIM) framework. We pose two research questions to simultaneously address both the intervention and the implementation process aims22: (1) is the Aussie-FIT programme effective in increasing time spent in moderate-to-vigorous PA (MVPA) and improving other secondary outcomes among men with or at risk of CVD at 6-month follow-up; and (2) what are the facilitators and barriers to implementation, sustainment and scalability of the Aussie-FIT programme?

Method

This protocol follows the Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials (SPIRIT) approved reporting standards for standard protocol items (online supplemental file 1) and meets the requirements of the Standards for Reporting Implementation Studies22 (online supplemental file 2).

bmjopen-2023-078302supp001.pdf (88.4KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2023-078302supp002.pdf (720KB, pdf)

Study design

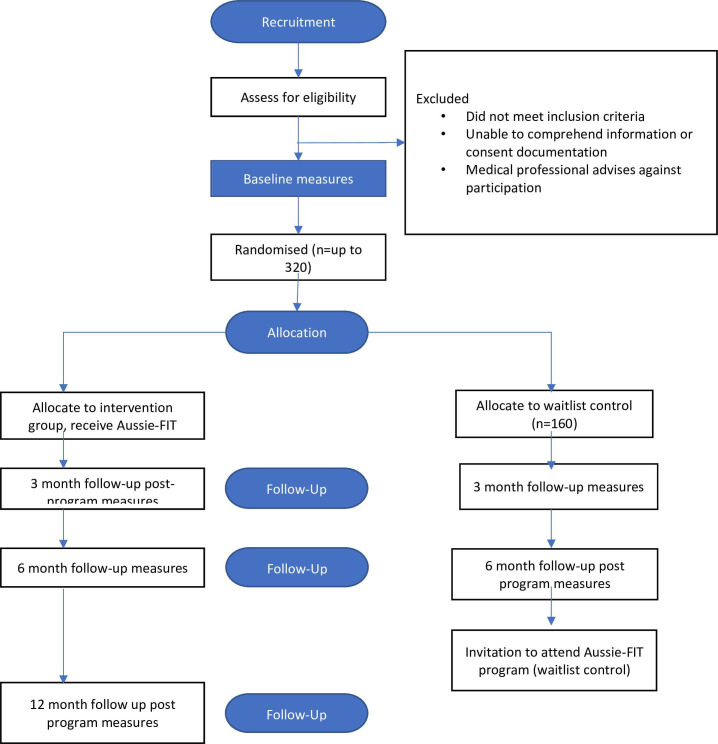

This study is a pragmatic multistate/multiterritory hybrid type 2 effectiveness–implementation parallel group RCT with a 6-month wait list control. Follow-up measures are at 3 and 6 months (primary outcome) post baseline for both the intervention and control groups and at 12 months for the intervention group to assess maintenance (see figure 1, Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials diagram). Observational implementation outcomes will be reported using the RE-AIM framework.23 This trial is registered with the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ACTRN12623000437662).

Figure 1.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials diagram of participant flow through the trial. Aussie-FIT, Australian Fans in Training.

Context

The study is set in and around the capital cities of Darwin (Northern Territory (NT)), Perth (WA) and Brisbane (QLD). These urban centres have distinct contextual characteristics. QLD and WA make up 20% and 10% of the national population, respectively, and are far more populated than the NT which makes up less than 1% of the national population.24 There is significant cultural diversity across each state/territory; for example, the proportion of males that identify as Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander in the NT (26.3%) is considerably higher than in QLD (4.6%) and WA (3.3%).25 Australian Football is the most popular sport in WA and the NT, whereas in QLD, Rugby League is most popular.26

Patient and public involvement

Patient and public engagement has been central to the development of the Aussie-FIT programme since its inception and in previous pilot studies in which the intervention was developed based on patient priorities. In preparation for and in the design of this trial, community advisory groups consisting of consumers (ie, men with or at risk of CVD, and former Aussie-FIT participants) and stakeholders (eg, Aussie-FIT coaches, sporting club or community representatives) have been formed in each state/territory. These groups include representation of Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander men. The first of these groups met in December 2022. Community advisory groups have helped identify potential barriers and enablers of project success and have codesigned responsive implementation strategies. These groups will continue to work in partnership with the research team throughout the lifespan of this project. This will include providing input on culturally appropriate recruitment strategies, retention strategies, involvement in dissemination planning and if the effectiveness of the intervention is established, providing advice on the sustainment and scalability of Aussie-FIT. The outcomes of our cross-site consumer and stakeholder involvement activities during the trial set-up period, and at later stages in the trial, will be reported in future publications. Presentations and reports for consumers and stakeholders will be codesigned with consumers and stakeholders and disseminated to participants and other consumer and community audiences.

Participants

Inclusion criteria

Men aged 35–75 years in WA (n=128), NT (n=96) and QLD (n=96) who self-report meeting one or more of the following criteria will be recruited:

CVD diagnosis more than 3 months prior to commencing the study, with no upper limit on length of time since diagnosis.

≥10% risk of CVD, according to the online calculator created by the Australian Chronic Disease Prevention Alliance, that assesses CVD 5-year risk (www.cvdcheck.org.au/calculator).

Body mass index (BMI)>28 kg/m2.

To determine whether they are eligible, potential participants will complete an online form, codesigned with consumers to ensure accessibility for men.

Participants from non-English speaking backgrounds will be offered interpreters if they wish to participate in the study. Men at risk of harm from PA will be excluded from vigorous PA and will instead undertake light or moderate PA as tolerated (if appropriate based on general practitioner (GP)/cardiologist’s advice). Where possible, men who have not participated in previous Aussie-FIT or League-FIT programmes will be prioritised.

Exclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria are: unable to comprehend information or consent documentation; unable to attend most of the weekly sessions, diagnosed with CVD less than 3 months prior to the baseline assessments date; experienced a cardiac event less than 3 months prior to the baseline assessments date; or a medical professional advises against participation (eg, due to having a cardiac condition not suitable for an exercise trial in the community such as severe aortic stenosis or ongoing angina).

Recruitment

Participants will be selected on a ‘first come, first served’ basis. Men with CVD will be identified from medical records at hospitals (WA only), cardiac rehabilitation programmes delivered in hospitals, or in the community, and GP or other primary healthcare services. Men with or at risk of CVD will be recruited from community sources including club members’ newsletters, traditional/social media, match-day publicity (eg, announcements, face-to-face recruitment), snowball sampling,27 sport publications and local health councils. Interested individuals who see the programme advertised will be directed to complete a web-based expression of interest (EOI) form. Men who prefer not to use the online EOI form will have the opportunity to express their interest, ask questions, check their eligibility and enrol (if eligible) by contacting the research team directly via phone or email. The online EOI form includes a series of questions to confirm eligibility.

This trial will host a nested ‘study within a trial’ (SWAT)28 to examine the utility of a self-directed online enrolment in comparison to a phone call enrolment process.29 Eligible men who complete the online EOI will be randomised via the online form to either immediately book their enrolment appointment online or to receive a call from a researcher to progress their enrolment. The SWAT will evaluate the effectiveness (including cost-effectiveness) of the online approach compared with the standard phone call on enrolment rates.29

Intervention (Aussie-FIT programme)

The intervention is described following the Template for Intervention Description and Replication guidance,30 see table 1. In brief, the 12, weekly, 90 min sessions will be delivered to groups of 16 men. One coach and one accredited exercise physiologist (AEP) or equivalent suitable health professional facilitate each group. Coaches and AEPs will be trained by the research team in the core content (PA and diet education), safe exercise for men with or at risk of CVD and in the use of principles of motivation and behaviour change. Coaches will lead on the programme content delivery and AEPs will be primarily responsible for exercise safety. Practical activities and discussions are designed to help men understand why and how to improve PA (eg, understanding exercise intensities, safe strength training, decreasing sedentary time) and dietary behaviours (eg, interpreting food labels, portion sizes, meal planning, eating out) and incorporate behaviour change techniques to support participants to adopt positive health behaviours in their daily lives. A range of PA intensities are promoted, and ball skills and circuit training like those undertaken by professional players but modified to be safe for each man’s limitations (eg, ball skill drills restricted to walking) undertaken. Men are encouraged to self-monitor walking, gradually increasing steps/day throughout the 12 weeks. Table 3 provides a week-by-week overview of session content. The AEP will codeliver the sessions and support the coach by monitoring participants (eg, blood pressure checks), providing advice on safe exercise and providing first aid, if required. The wait list control group (another 16 men from each club) will receive the programme 6 months later.

Table 1.

Intervention description aligned with the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) guidance

| TIDieR Checklist Item | |

| Why | Undertaking sufficient physical activity and healthy eating is critical to prevent people with lived experience of or at risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) from experiencing future heart problems. However, most people with or at risk of CVD fail to initiate or sustain these long-term health behaviours. This increases risks of future heart conditions and premature death. CVD is more common in men, but they are less likely than women to access interventions to help them manage their weight or improve their health behaviours. |

| What (materials) | Men participating will receive: a wrist worn physical activity monitor, a sports club team shirt and a participant workbook with educational content about nutrition, physical activity and health behaviour change (which is also covered in the face-to-face sessions). Coaches will receive a detailed intervention delivery guide and educational resources (eg, wallet cards to assess food labels) to support delivery of the weekly sessions. Coaches will use sports equipment (eg, Australian Football League and rugby league balls) from their respective clubs. The participant workbook and coach session delivery guides have previously been used in the Australian Fans in Training (Aussie-FIT) pilot studies. The participant workbook and coach session delivery guide were developed (and educational materials sourced), adapted from resources available from: Football Fans in Training programme, www.ffit.org.uk; Heart Foundation Australia, www.heartfoundation.org.au; Australian Government Department of Health, National Health and Medical Research Council, www.eatforhealth.gov.au; Alcohol Think Again, www.alcoholthinkagain.com.au; and Cancer Council Western Australia (WA), www.cancerwa.asn.au. Minor adaptations have been made to these resources to reflect the target population (men with or at risk of CVD) and the primary outcome (physical activity) in this trial, and to incorporate consumer and stakeholder feedback in WA, Queensland (QLD) and the Northern Territory (NT). |

| What (procedures) | Participants will attend 12 group sessions at their club that incorporates physical activity and workshop style education. The education involves practical activities and discussions to help men understand why and how to improve their diet (eg, interpreting food labels, portion sizes, meal planning, eating out) and physical activity habits (eg, understanding exercise intensities, safe strength training, decreasing sedentary time). Men will be encouraged to use behaviour change techniques (eg, self-monitoring, goal setting and problem-solving) to help put the recommendations into practice. Participants take part in physical activity within the sessions that starts off slowly in the initial weeks and gradually builds up over the course of the programme. Activities men participate in include ball skills and circuit training similar to that undertaken by Australian football and rugby league players but modified to be safe for each man’s abilities (eg, ball skill drills restricted to walking). Men are encouraged to self-monitor walking, gradually increasing steps/day throughout the 12 weeks. |

| Who provides | Coaches will be recruited from 10 sports clubs in Perth, Darwin and Brisbane. Aussie-FIT coaches will be already embedded in their respective clubs, knowledgeable about Australian Football or Rugby League, and have experience of leading physical activity or sports coaching sessions. Coaches should have good communication skills and the ability to help foster a supportive atmosphere with camaraderie between participants. Accredited exercise physiologists (AEPs), or other suitably qualified/accredited health professionals, will act as an assistant coach and cofacilitate programme delivery. They will support the coach by undertaking any required health monitoring of participants (eg, blood pressure checks), provide advice on safe exercise and provide first aid, if required. Club coaches and AEPs will be trained by the research team in the core programme content (physical activity, nutrition, motivation, behaviour change). The training is delivered face to face and comprises approximately 15 hours of interactive learning content and opportunities to practice session deliveries and receive feedback from the research team and peers. |

| How | The intervention will be delivered face to face to groups of approximately 16 men. Coaches are encouraged to use a communication style that supports psychological need satisfaction for autonomy, competence and relatedness in relation to physical activity and eating behaviours. |

| Where | The programme will be delivered in Australian Football (WA and NT) and rugby league (QLD) settings. This will include a suitable space for the educational programme component (eg, indoor clubroom) and access to the pitch/oval for physical activity. In some circumstances, outdoor spaces may be utilised to deliver the educational content and indoor spaces may be used for physical activity (eg, if there is gym access or in adverse weather conditions). |

| When and how much | Participants will attend 12, weekly, 90 min sessions. Aussie-FIT encourages gradual increases in moderate to vigorous physical activity levels outside of the weekly sessions in daily life. |

| Tailoring | The Aussie-FIT sessions and resources are informed by the best available evidence and population recommendations for age and CVD risk management (eg, Australian guide to healthy eating, physical activity guidelines and National Heart Foundation recommendations). The programme is not prescriptive in terms of physical activity and dietary changes the men make outside of the weekly sessions. Men are supported to self-monitor their diet and physical activity behaviours, then make their own education-informed decisions on setting goals that are relevant to them. Health behaviour change goals that are self-determined are more likely to be sustainable. Personalised feedback on goals men set is provided by coaches and peers in weekly sessions throughout the programme. Targeted behaviours for goal setting include portion size control, reduction of sugary drinks and energy dense foods, reduction in alcohol consumption, gradual increases in physical activity and reduced sedentary time. Men participating in Aussie-FIT will have varying physical fitness levels and health conditions. Throughout the programme AEPs and coaches will modify the physical activity within the sessions to suit men with differing physical capabilities. AEPs and coaches will be aware of pre-existing conditions and will interact with and observe participants during the programme sessions and tailor activities as required. |

Table 2.

Intervention content in each of the 12 sessions

| Week number and session title | Motivation and behaviour change | Nutrition component | Physical activity education component | Practical physical activity |

| Session 1. Motivation and monitoring progress | Motivation (identifying and developing higher quality motives); monitoring progress, ‘your activity’ and ‘your weight’ progress records. Action point: track daily step count and complete food diary | Energy balance (intake vs output) | Handing out activity monitors and explaining how to use them Walking for well-being Exercising safely for men with cardiovascular disease |

Short tour of the oval wearing activity monitors |

| Session 2. Steps towards better heart health and setting goals | Food diaries compared with healthy eating recommendations and changes going forward; changing unhealthy environmental triggers; education on setting; SMART goals | Heart Foundation five key nutrition messages, food groups and eating healthier; balanced plate (vegetables, wholegrains and protein) | PA for heart health; baseline step counts determined; understanding how to increase step count gradually; setting step count goals | Walking around the oval |

| Session 3. Planning, food labels and physical activity recommendations | SMART goals review; action planning and coping planning | How to read food labels | PA recommendations, benefits, types and intensities; pros and cons of PA; overcoming barriers to being physical inactive; reviewing steps and thinking about alternative activities | Introduction of warming up, cooling down and aerobic exercise |

| Session 4. Reviewing SMART goals, healthy swaps and small changes | Reviewing goals SMART goal to reduce junk food Motivation and staying on track Importance of support from others |

Junk foods impact on heart health; allowing yourself to be flexible; healthy snacks and heart healthy food swaps; reducing junk food intake | Being active every day and sitting less | Aerobic exercise with warm-up and cool down |

| Session 5. Reviewing plans and cutting down on booze | Reviewing goals | Pros and cons of drinking alcohol; facts about alcohol; alcohol standard drinks, recommendations | Reviewing steps and alternative activities | Aerobic exercise with warm-up and cool down |

| Session 6. Key factors to maintain health behaviour | Five key factors to maintain health behaviour; sharing experiences on setbacks; introduction to setbacks and tactics for dealing with them | Learning principles of body weight strength training; reviewing steps and alternative activities; introducing mobile applications for exercise | Strength exercises for major muscle groups with warm-up and cool down | |

| Session 7. Progress and staying on track | Representation of step increases achieved; SMART goals reviewed; reviewing how things are going so far and problem-solving; compensatory behaviours; staying on track | Reviewing steps and alternative activities Tips to increase PA, being active every day and decrease sitting time; principles of stretching and flexibility training |

Warming up and flexibility training Strength exercises for major muscle groups with warm-up and cool down |

|

| Session 8. Facts about fat, salt and sugar | Importance of developing eating routines and habits; how to choose healthier packet foods | Facts about fat, salt and sugar for heart health; healthier fat alternatives; added sugar in drinks | Reviewing steps and alternative activities | Aerobic, strength and flexibility activities including sport drills |

| Session 9. Physical activity habits and healthier ways to eat out | Developing PA habits | Choosing healthier food choices when having takeaway or eating out | Reviewing steps and activity review | Aerobic, strength and flexibility activities including sport drills |

| Session 10. Healthy cooking at home | Reviewing goals; triggers for setbacks and how to avoid them Action point: complete food diary to bring next week |

Healthy living and busting myths; healthy cooking and food preparation at home | Step count and activity review | Aerobic, strength and flexibility activities including sport drills |

| Session 11. Reviewing progress and acknowledging achievements | Revision of food diaries; revision of eating plans; behaviour control and staying on track; revision of SMART goals | PA levels, types, positives and challenges Reviewing steps and alternative activities |

Aerobic, strength and flexibility activities including sport drills | |

| Session 12. Looking ahead towards maintaining a healthy lifestyle | Reviewing progress throughout the programme; celebrating achievements; determining steps after the programme | Tips to maintaining nutrition habits for heart health | Tips to maintaining PA habits | AFL or rugby game |

Session one also includes general introductory content including aim and overview of the Australian Fans in Training programme, getting to know each other activities, creating group ground rules and Facebook group sign ups. Rapport building activities are also incorporated into each weekly session.

AFL, Australian Football League; PA, physical activity; SMART, Specific, Measurable, Attaninable, Relevant, Time-bound.

Description of the implementation strategy

Our consumer advisory groups have supported the development of our implementation strategies in the study set-up phase of this project, full details of which will be reported elsewhere. The implementation study is structured by the RE-AIM framework.12

Reach: programme recruitment strategies have been codesigned with men with or at risk of CVD. These strategies will be tailored for each state/territory in consultation with community advisory groups.

Effectiveness: individual effectiveness outcomes will be tested via the RCT. Negative or unintended consequences will also be documented.

Adoption: clubs will be invited to offer formal commitments to continue deliveries pending further funding opportunities in each state/territory. An infrastructure and costing model will be developed to support clubs in sustaining the programme, and preferences for models of sustained programme deliveries will be codesigned with stakeholders.

Implementation: a comprehensive coach delivery package will support fidelity of programme delivery. this package includes 15 hours of training for the coaches, detailed programme delivery speaking notes, a timing guide and rationales. Reusable teaching resources will also be provided to support high-quality delivery. Implementation costs, such as coaches’ time for delivering and preparing for sessions, have been included in the programme costing model.

Maintenance: our nested SWAT will evaluate an automated enrolment strategy, designed to improve programme sustainability when fewer resources are available compared with the trial phase. Resource sharing agreements will be developed, if required, to ensure the intervention materials can continue to be used post trial. Sustainability action plans will be developed with stakeholders, including identifying suitable charities as delivery partners for ongoing programme deliveries. Indications of individual participant-level behaviour change maintenance will be assessed at 12-month follow-up in the intervention group.

Throughout the implementation process, barriers and facilitators to implementation will be identified (by stakeholders, including consumers and researchers) and targeted in future modifications to the programme. Interviews with stakeholders will be conducted to identify these barriers and facilitators. Contextual adaptations required for the different States and Territories will be documented and evaluated. These adaptations will be codesigned with our consumer advisory groups to ensure contextual fit while preserving fidelity.

Blinding and randomisation

Blinding participants to the condition is not possible due to the nature of the intervention. Data collectors will be blinded as far as possible. Questionnaire data will be completed online, PA data will be device measured, and participants will be asked not to reveal whether they are in the intervention or wait list control arm, when objective measures of weight and blood pressure are taken.

Aligned with the EuroFIT trial, we propose an individual randomisation for each club, given the FFIT study confirmed that the minimal between-group contamination effects did not warrant higher sample size and costs of a cluster trial.10 Participants from each club (10 clubs, 32 participants per club) will be individually randomised (1:1 randomisation, in blocks of 8 to reduce prediction of group allocation). A statistician generated the randomisation list using the RANDOMBETWEEN1 2 function using Excel. The statistician, who is not involved in data collection, will not be told if group 1 or group 2 is the intervention arm to assure blindness during the analyses. Following completion of baseline measures, trained research assistants will use opaque, sealed envelopes to assign participants to intervention or control arms.

Primary outcome: physical activity

Participants will also be asked to wear an Actigraph GTX9 (ActiGraph LLC, Pensacola, Florida, USA) monitor continuously for 7 days on their non-dominant wrist at each data collection timepoint to provide a valid and reliable assessment of MVPA.31 The GT9X is a small (3.5×3.5×1 cm), lightweight (14 g) and waterproof triaxial accelerometer. The monitors will be initialised to collect data at a 30 Hz sampling rate. Men will be provided with written instructions for wearing the Actigraph.

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes include dietary intake, weight, blood pressure, cholesterol, self-esteem, affective states, quality of life, motivation for PA and use of behaviour change strategies targeted in the programme. A full list of variables assessed and measurement tools is included in table 3.

Table 3.

Summary of measures used in the Aussie-FIT trial and programme evaluation and time points

| Measurement instrument | Baseline | 3 months | 6 months* | |

| Objective measures (collected at the measurement sessions at football clubs by members of the research team or trained research assistants) | ||||

| PA and sedentary time | Participants will also be asked to wear an Actigraph GTX9 (ActiGraph LLC, Pensacola, Florida, USA) monitor continuously for 7 days on their non-dominant wrist at each data collection timepoint to provide a valid and reliable assessment of PA.32 The GT9X is a small (3.5×3.5×1 cm), lightweight (14 g) and waterproof triaxial accelerometer. The monitors will be initialised to collect data at a 30 Hz sampling rate. Men will be provided with written instructions for wearing the Actigraph. | X | X | X |

| Weight | Weight in kilograms measured with valid and reliable body scale (eg, Tanita); light clothing, no shoes and empty pockets; assessor blinded to condition. | X | X | X |

| Height | Height measured in centimetres using a stadiometer (eg, Seca); without shoes. | X | ||

| BMI | Calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in metres (kg/m2). | X | X | X |

| Waist circumference | Waist circumference is measured two times using a tape measure (three times, if the first two measurements differ by 5 mm or more) and the mean of all recorded measurements calculated. The participant is asked to locate the last rib and iliac crest, and the measure is performed at the midpoint between these to locate the waist. If the man cannot locate his last rib and iliac crest the researcher can ask the man to identify where his belly button is and the measurement can occur one inch/3 cm or width of two fingers above where man has indicated. If the first two measurements differ by 5 mm or more, measure third time. | X | X | X |

| Resting systolic and diastolic blood pressure | Resting blood pressure measured with a digital blood pressure monitor (Omron HBP-1320, Milton Keynes, UK) monitor after 5 min sitting still. If measured systolic blood pressure is over 150 mm Hg and/or measured diastolic blood pressure is over 95 mm Hg, two further measures will be taken and recorded. If blood pressure remains high, the man will be provided with a letter explaining the circumstances in which they had their blood pressure measured and recorded and they will be encouraged to consult their general practitioner. A mean will be calculated from the second and third measures. Feet flat on the floor, arm free of clothing or wearing loose/thin clothing, cuff at the level of heart and arm resting, same arm used (non-dominant arm), no talking. | X | X | X |

| Cholesterol | Cholesterol will be checked using handheld point of care device (Accutrend Plus) that measures cholesterol immediately. | X | X | X |

| Self-reported measures (completed at the measurement sessions at football clubs or online in the participant’s own time, depending on preference) | ||||

| Food intake | Intake24 is an open-source self-completed computerised dietary recall system based on multiple pass 24-hour recall. A trained interviewer will assist participants who may request assistance to complete the recall.15 16 | X | X | X |

| Positive and negative affect | The short form of the Positive and Negative Affect Scale.48 | X | X | X |

| Self-esteem | The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale.49 | X | X | X |

| Quality of life | The health-related quality of life measured using the EQ-5D-5L.41 | X | X | X |

| Demographics | Age, ethnicity, education, marital status, current employment status, income, housing status. | X | ||

| Motivation | Motivation to be physically active.50 | X | X | X |

| Automaticity | The ‘Self-Report Behavioural Automaticity Index’.51 | X | X | X |

| Goal conflict, facilitation | Goal conflict and goal facilitation scale.52 | X | X | X |

| Action and coping planning | Action planning and copying planning scale.53 | X | X | X |

| Self-reported programme evaluation measures | ||||

| Recruitment | How participants found out about the programme; programme uptake (number of people who expressed interest; number of people who fit inclusion criteria). | X | ||

| Programme evaluation: via questionnaires and interviews | Attendance to programme sessions and to measurement sessions; fidelity of programme delivery; perceptions of effectiveness and acceptability, assessed using the programme evaluation questionnaire, which is adapted from the original Aussie-FIT programme. Interviews with participants, coaches and accredited exercise physiologists will also provide further data on these points. | |||

| Training evaluation: via questionnaires and interviews | Coaches will evaluate the training provided to them by completing the coach training evaluation questionnaire on completing their training. The interviews will also ask the coaches about their training. | |||

* and 12 months, for intervention group only.

Aussie-FIT, Australian Fans in Training; BMI, body mass index; PA, physical activity.

Implementation outcomes

Implementation outcomes will be reported using the RE-AIM framework.23

Reach: we will report on the number of participants interested and recruited; descriptive statistics of their representativeness, using demographics (eg, comorbidities, weight, socioeconomic status, ethnicity) of those recruited in each locality.

Effectiveness: as per description of intervention outcomes and for effectiveness of implementation outcomes, with qualitative interview findings.

Adoption: records of adaptation to the intervention and implementation strategies (between clubs, locations, etc).

Implementation: fidelity to key content (eg, educational messages) and functions (eg, appropriate use of behaviour change techniques) via coding of a subsample of deliveries; adaptations to delivery in each location, ascertained from coach/participant interviews; barriers and facilitators to programme implementation from perspectives of coaches, administrators and participants via interviews.

Maintenance: intentions to continue delivering the programme (for clubs in this trial) and intentions to initiate programme delivery when further funding secured (new clubs).

Procedure

Participants will book an appointment to attend baseline measures (detailed in table 3) at the football or rugby club. Measurement sessions will be led by a team of trained research assistants. Participants will be asked to complete a survey, which will be presented to them on an iPad using Qualtrics software. The self-administered survey will ask men demographic questions including their age, ethnicity, education, marital status, current employment status, income and housing status. Weight, height and waist measurements will be taken by a trained researcher. Cholesterol will be checked using a finger-prick test that measures non-fasting cholesterol immediately. Participants will undertake a 24-hour dietary recall using the Intake24, an open-source self-completed computerised dietary recall system based on multiple pass 24-hour recall. A trained interviewer will assist participants to complete the recall. The self-administered survey will also include items assessing alcohol content, and participants will also be asked to respond to questions assessing their emotions (ie, positive and negative affect), quality of life, self-esteem, motivation to for PA and use of behaviour change strategies taught in Aussie-FIT (automaticity, goal conflict, goal facilitation, coping planning, action planning). Participants are asked to respond on Likert scales of 1–5 or 1–7. Participants can skip questions if they prefer not to answer them. All questions have established psychometric properties and have been used by the research team in studies with similar populations. The questionnaire pack should take less than 30 min to complete. A trained research assistant will be available to explain to participants how to complete the survey and to answer any questions they may have during completion of the questionnaire. All participants will be required to complete the Exercise and Sport Science Australia (ESSA): Adult Pre-Exercise Screening System (APSS)32 at the baseline measures session. ESSA stipulates that all participants who answer ‘yes’ to a screening question should see an allied health professional or their GP. To reduce the burden on participants of the need to attend a GP appointment, an AEP (or other equivalent allied health professional) will review every participant’s APSS form and discuss medical history with every participant, to determine whether they are at risk from PA. Wait list control group participants will be rescreened at the assessment they attend prior to starting the programme in case of any change in health status from baseline.

The full assessment process will usually take about 90 min. Following randomisation, participants will be informed as to whether they will receive the 12-week intervention immediately (ie, the intervention arm) or ~6 months later (ie, the wait list control group). Once the intervention arm participants have completed the programme, the assessment package will be repeated for both the control and intervention groups (3 months post baseline) and then at 6 months post baseline. After the 6 months measures, the wait list control arm will complete the 12-week programme. Finally, the intervention arm will be asked to attend one final assessment, 12 months post baseline.

Where applicable, information regarding the participants’ CVD diagnosis will be self-reported or obtained from medical records. Participant attendance at the programme will also be recorded. At baseline, participants will be asked to tick yes or no to the question ‘in the future we may wish to contact you to join a group or individual interview to talk about your experiences in the programme. Do you consent for us to contact you? Yes/No’. Approximately 20 of those who tick ‘yes’, will be contacted by telephone or email at 6 months and/or 12 months, and invited to take part in an interview, which will be conducted on Microsoft Teams videoconference or in person at the football/rugby club (depending on the person’s preference). Interview questions will be developed in collaboration with PhD candidates and an ethics amendment will be submitted for approval prior to undertaking any interviews. Any changes to the protocol will be reported on the study Open Science Framework page (https://osf.io/ev8px/).

Treatment of wait list control arm

All men will be directed to review evidence-based resources (ie, Heart Foundation online material) regarding PA and healthy eating after completion of the baseline assessments and men in the wait list control arm will be invited to participate in Aussie-FIT after the 6 months post baseline assessment.

Data analyses

PA data will be downloaded via the ActiLife software (V.6.13.4), where the raw accelerometer data will be processed in R using the GGIR V.1.5-21 package (cran.r-project.org/web/packages/GGIR/index.html).33 34 PA will be estimated from 5 s epochs, with the average daily activity calculated. To be classified as MVPA mean acceleration needs to be ≥100 mg.35 Time in activities lasting at least 1 min, for which 80% of the activity satisfied the 100 mg threshold criteria, will be calculated. Average acceleration (calculated as the mean acceleration across the 24-hour day as a proxy for the daily volume of PA) and intensity gradient (as a reflection of the distribution of intensity across the 24-hour day) will be calculated.36 37 We will only include in the analysis those participants with four or more valid days of accelerometry data, and at least 10 hours of wear time each day.

Deidentified objective measurements, questionnaire data and calculated PA data will be exported to Stata software for analyses by an independent biostatistician blinded to the group allocation. The characteristics of the participants will be summarised in mean (and SD) or median (and IQR) or frequency (and percentage), by treatment groups. Programme efficacy will be analysed following the intention-to-treat principle and per-protocol approaches outlined below. Changes in the postintervention outcomes will be analysed using linear mixed-effect regression models while controlling for the baseline measures. Sensitivity analyses will also be performed to include covariates such as age, BMI, types of comorbidities in the model to compare the beta coefficient of the models with and without the covariates. If group sizes permit, subgroup analyses will be performed to examine differences in intervention effects on primary and secondary outcomes between (1) states/territories, (2) men diagnosed with and without a CVD diagnosis, (3) men with BMI>25 and men with BMI<25 kg/m2 and (4) men who identify as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and men who do not. Further details are available regarding data management and statistical analysis plans on the project page of the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/ev8px/).

Sample size calculations

A total of 320 men will be recruited: in WA (n=128), NT (n=96) and QLD (n=96), 160 per arm. This estimate is based on observed changes in MVPA in the Aussie-FIT pilot11 and provides 90% power to detect a mean difference of 11 min/day (SD:27 min/day) of MVPA at 6 months (primary endpoint). The sample size powered on MVPA because PA reduces CVD risk independently, and mitigates other risk factors, such as high blood pressure.38 Change in MVPA of 5 min per day is considered the minimum clinically important difference.39 We allow for a trial attrition rate of 20%.

Economic evaluation

We will use an economic model of the type developed in the Aussie-FIT pilot.11 The cost-effectiveness analysis will be performed from a health system perspective. Costs will include direct costs associated with the programme (including setting up and promotion) as well as self-reported healthcare resource use. In terms of outcome measurement, we will include short-term outcomes that will allow us to look at the cost per clinically relevant change in MVPA (5 min per day39) and cost per quality-adjusted life years (QALYs). The QALY is the most widely used approach in economic evaluations for quantifying quality of life gains.40 The EQ-5D-5L questionnaire will be used to assess quality of life,41 which is a standardised measure of health status widely adopted in economic evaluations.42 The EQ-5D-5L responses will be converted into a utility score using the most recent preference weights generated from an Australian general population sample.43 Self-reported data relating to the number and type of health resources used will be collected at each measurement point. Unit costs for visits to health professionals (GP, practice nurses, physiotherapists, etc) will be sourced from the Medical Benefits Schedule.44 Unit costs for any inpatient stays and outpatient visits will be sourced from standard Australian public sector hospital costs.45 Unit costs for prescriptions will be sourced from the Pharmaceutical Benefits Schedule.46 Given uncertainty around parameters such as unit costs and utility values for calculating QALYs, we will undertake sensitivity analysis to check the robustness of the estimates.

Data management

Locked cabinets in the participating universities will be used to store hard copy data and no identifying information will be included. A file aligning ID codes with participants’ identifying information will be stored on the university server in a password-protected computer file. Only members of the research team will be able to access the physical and electronic data files.

Adverse events

Coaches will be instructed to report any adverse events during the programme sessions to the local trial co-ordinator, using a standardised form. Serious adverse events will be defined as a medical event believed by the investigators to be attributable to participation in the Aussie-FIT programme, based on the participant’s previous medical conditions and clinical presentation. Participants will also be asked to report any adverse events to the coach.

Ethics and dissemination

This multisite study has been approved by the lead ethics committees in the lead site’s jurisdiction, the South Metropolitan Health Service Human Research Ethics Committee (Reference RGS4254) and the West Australian Aboriginal Health Ethics Committee (HREC1221). Reciprocal approvals have been sought from the relevant ethics bodies in the partner site’s jurisdictions. All participants will read an electronic participant information sheet and offered a hard or electronic copy to keep. They will be asked to electronically indicate consent before the programme enrolment and will be offered a digital or paper copy of their consent form. The study will be disseminated to the academic community, via publication in peer-review journals, presentations at conferences and reports.

Discussion

In 2022, CVD was the leading cause of burden of disease in Australia, and this burden is higher in males than females.47 Insufficient PA and poor diet are key modifiable behavioural CVD risk factors. Pilot and feasibility studies of Aussie-FIT have illustrated that the programme is acceptable to men in WA, and feasible to deliver in AFL and West AFL clubs and rugby league clubs in QLD. Scale-up of Aussie-FIT in WA, and out to other states and territories creates an opportunity to reduce primary and secondary CVD risk among men with or at risk of CVD via modification of PA and dietary behaviours. Via this hybrid effectiveness–implementation trial, we will determine whether the programme is effective in improving health and health behaviours in men who take part, and test strategies to sustain longer term implementation of this programme.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The research on which this article is based was conducted as part of the Aussie-FIT: Kicking Goals for Men’s Heart Health Project. This work was supported by a 2021 Behaviour Change Strategic Grant (Award ID number 106534) from the National Heart Foundation of Australia (contact email Page 3: research@heartfoundation.org.au). Aussie-FIT builds on the FFIT programme, the development and evaluation of which was undertaken by a research team led by the University of Glasgow with funding from various grants including a Medical Research Council (MRC) grant (reference number MC_UU_12017/3), a Chief Scientist Office (CSO) grant (reference number CZG/2/504), and a National Institute for Health Research grant (NIHR) (reference number 09/3010/06). The development and evaluation of FFIT was facilitated through partnership working with the Scottish Professional Football League Trust (SPFLT). We thank the stakeholder and consumer advisory group members for their contributions to the development of this protocol.

Footnotes

Contributors: EQ, AM, GH, JAS, TP, TM, DAK, DK, JM, KH, LW and HG conceived the project and obtained the project funding. EQ, MDM, AM, KH, JCM, DAK, DK, HC, TP, LW, JAS, BB, BJS, SH and MM have made conceptual contributions to project design with opportunities for input from all authors. Specifically, JCM, MDM, EQ and KH designed the implementation strategies. EQ, MDM, KH and AM designed trial recruitment strategies and screening and assessment protocols. TP, JM and EQ designed the physical activity data analysis plan. SH, MDM, EQ, DK and DAK updated the intervention materials, with input from BB, JB, NW, TP, and AM. EQ, BJS, AM and MDM prepared the main ethics submission. EQ, BB, JAS and JB prepared the trial procedures and ethics submission for involvement of men who identify as Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islanders. MDM, BB, EQ, JAS and JB designed the project consumer involvement strategies. HC conducted the power analysis and designed the statistical analysis plan. MM designed the economic evaluation. TP, LW, JAS and BB prepared ethics submissions for reciprocal ethics from local state/territory committees. EQ and MDM drafted the manuscript and all authors read, edited and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by a 2021 Behaviour Change Strategic Grant (Award ID number 106534) from the National Heart Foundation of Australia.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Method section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; peer reviewed for ethical and funding approval prior to submission.

Preregistration: The trial has been registered with Australian and New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ACTRN12623000437662), prior to recruitment of the first participant (trail registration date 28 March 2023).

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- 1.Australian Bureau of Statistics . National Health Survey: first results 2017-18. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rippe JM. Lifestyle strategies for risk factor reduction, prevention, and treatment of cardiovascular disease. Am J Lifestyle Med 2019;13:204–12. 10.1177/1559827618812395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Flora PK, McMahon CJ, Locke SR, et al. Perceiving cardiac rehabilitation staff as mainly responsible for exercise: a dilemma for future self-management. Appl Psychol Health Well Being 2018;10:108–26. 10.1111/aphw.12106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Gruyter E, Ford G, Stavreski B. Economic and social impact of increasing uptake of cardiac rehabilitation services--A cost benefit analysis. Heart Lung Circ 2016;25:175–83. 10.1016/j.hlc.2015.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walli-Attaei M, Joseph P, Rosengren A, et al. Variations between women and men in risk factors, treatments, cardiovascular disease incidence, and death in 27 high-income, middle-income, and low-income countries (PURE): a prospective cohort study. The Lancet 2020;396:97–109. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30543-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sharp P, Spence JC, Bottorff JL, et al. One small step for man, one giant leap for men’s health: a meta-analysis of behaviour change interventions to increase men’s physical activity. Br J Sports Med 2021;55:816–7. 10.1136/bjsports-2020-102976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hunt K, Wyke S, Gray CM, et al. A gender-sensitised weight loss and healthy living programme for overweight and obese men delivered by Scottish Premier League football clubs (FFIT): a pragmatic randomised controlled trial. The Lancet 2014;383:1211–21. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62420-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quested E, Kwasnicka D, Thøgersen-Ntoumani C, et al. Protocol for a gender-sensitised weight loss and healthy living programme for overweight and obese men delivered in Australian football League settings (Aussie-FIT): a feasibility and pilot randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 2018;8:e022663. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-022663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gray CM, Wyke S, Zhang R, et al. Long-term weight loss trajectories following participation in a randomised controlled trial of a weight management programme for men delivered through professional football clubs: a longitudinal cohort study and economic evaluation. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2018;15:60. 10.1186/s12966-018-0683-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wyke S, Bunn C, Andersen E, et al. The effect of a programme to improve men’s sedentary time and physical activity. PLOS Med 2019;16:e1002736. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kwasnicka D, Ntoumanis N, Hunt K, et al. A gender-Sensitised weight-loss and healthy living program for men with overweight and obesity in Australian football League settings (Aussie-FIT): a pilot randomised controlled trial. PLOS Med 2020;17:e1003136. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pavey T, Wharton L, Polman R, et al. A Rugby League weight loss program for men–League-FIT: preliminary results from a pilot study. J Sci Med Sport 2022;25:S78–9. 10.1016/j.jsams.2022.09.101 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith BJ, Maiorana A, Ntoumanis N, et al. n.d. An Australian football theme can engage men with cardiovascular disease in a health behaviour change intervention: results from a feasibility randomized trial [Under review]. Heart [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare . Heart, stroke and vascular disease —Australian facts. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; 2023. Available: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/heart-stroke-vascular-diseases/hsvd-facts/contents/about [Google Scholar]

- 15.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare . Overweight and obesity; 2023. Available: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/overweight-obesity/overweight-and-obesity/contents/summary

- 16.George ES, El Masri A, Kwasnicka D, et al. Effectiveness of adult health promotion interventions delivered through professional sport. Sports Med 2022;52:2637–55. 10.1007/s40279-022-01705-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Milat AJ, King L, Bauman AE, et al. The concept of Scalability: increasing the scale and potential adoption of health promotion interventions into policy and practice. Health Promot Int 2013;28:285–98. 10.1093/heapro/dar097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moullin JC, Dickson KS, Stadnick NA, et al. Ten recommendations for using implementation frameworks in research and practice. Implement Sci Commun 2020;1:42. 10.1186/s43058-020-00023-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Curran GM, Landes SJ, McBain SA, et al. Reflections on 10 years of effectiveness-implementation hybrid studies. Front Health Serv 2022;2:1053496. 10.3389/frhs.2022.1053496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Milat AJ, King L, Bauman AE, et al. The concept of scalability: increasing the scale and potential adoption of health promotion interventions into policy and practice. Health Promot Int 2013;28:285–98. 10.1093/heapro/dar097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Curran GM, Bauer M, Mittman B, et al. Effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs. Med Care 2012;50:217–26. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182408812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pinnock H, Barwick M, Carpenter CR, et al. Standards for reporting implementation studies (Stari) statement. BMJ 2017;356:i6795. 10.1136/bmj.i6795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, Boles SM. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. Am J Public Health 1999;89:1322–7. 10.2105/ajph.89.9.1322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.National, state and territory population. Australian Bureau of Statistics; 2023. Available: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/population/national-state-and-territory-population/latest-release [Accessed 26 May 2023]. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Australian Bureau of Statistics . Australia: aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population summary. 2022. Available: https://www.abs.gov.au/articles/australia-aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-population-summary [Accessed 26 May 2023].

- 26.Ausplay results. Clearinghouse for Sport. Available: https://www.clearinghouseforsport.gov.au/research/ausplay/results#sportreport [Accessed 26 May 2023]. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Parker C, Scott S, Geddes A. Snowball sampling. Scientific Research Publishing; 2019. Available: https://www.scirp.org/(S(czeh2tfqw2orz553k1w0r45))/reference/referencespapers.aspx?referenceid=3131783 [Accessed 26 May 2023]. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Trial forge guidance 1: what is a Study Within A Trial (SWAT)?. Trials | Full Text. Available: https://trialsjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13063-018-2535-5 [Accessed 26 May 2023]. [Google Scholar]

- 29.McDonald MD, Moullin JC, Quested E. MRC hubs for trials methodology: the northern Ireland hub for trials methodology research, SWAT store, SWAT 208: comparative effectiveness of a self-directed online versus a phone call enrolment process. Available: https://www.qub.ac.uk/sites/TheNorthernIrelandNetworkforTrialsMethodologyResearch/FileStore/Filetoupload,1862717,en.pdf [Accessed 20 Jun 2023].

- 30.Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ 2014;348:bmj.g1687. 10.1136/bmj.g1687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dowd KP, Szeklicki R, Minetto MA, et al. A systematic literature review of reviews on techniques for physical activity measurement in adults: a DEDIPAC study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2018;15:15. 10.1186/s12966-017-0636-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pre-exercise screening systems. 2023. Available: https://www.essa.org.au/Public/Public/ABOUT_ESSA/Pre-Exercise_Screening_Systems.aspx [Accessed 11 Sep 2023].

- 33.Sabia S, van Hees VT, Shipley MJ, et al. Association between questionnaire- and accelerometer-assessed physical activity: the role of sociodemographic factors. Am J Epidemiol 2014;179:781–90. 10.1093/aje/kwt330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van Hees VT, Gorzelniak L, Dean León EC, et al. Separating movement and gravity components in an acceleration signal and implications for the assessment of human daily physical activity. PLoS ONE 2013;8:e61691. 10.1371/journal.pone.0061691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hildebrand M, VAN Hees VT, Hansen BH, et al. Age group comparability of raw accelerometer output from wrist- and hip-worn monitors. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2014;46:1816–24. 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Migueles JH, Rowlands AV, Huber F, et al. GGIR: A research community–driven open source R package for generating physical activity and sleep outcomes from multi-day raw accelerometer data. J Meas Phys Behav 2019;2:188–96. 10.1123/jmpb.2018-0063 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rowlands AV, Fairclough SJ, Yates T, et al. Activity intensity, volume, and norms: utility and interpretation of accelerometer metrics. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2019;51:2410–22. 10.1249/MSS.0000000000002047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mora S, Cook N, Buring JE, et al. Physical activity and reduced risk of cardiovascular events. Circulation 2007;116:2110–8. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.729939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rowlands A, Davies M, Dempsey P, et al. Wrist-worn accelerometers: recommending ~1.0 mg as the minimum clinically important difference (MCID) in daily average acceleration for inactive adults. Br J Sports Med 2021;55:814–5. 10.1136/bjsports-2020-102293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Drummond MF, Sculpher MJ, Claxton K, et al. Methods for the Economic Evaluation of Health Care Programmes. Oxford University Press, 2015: 461. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Herdman M, Gudex C, Lloyd A, et al. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Qual Life Res 2011;20:1727–36. 10.1007/s11136-011-9903-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brazier J, Ratcliffe J, Saloman J, et al. Measuring and Valuing Health Benefits for Economic Evaluation. Oxford University Press, 2017: 373. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Norman R, Cronin P, Viney R. A pilot discrete choice experiment to explore preferences for EQ-5D-5L health States. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 2013;11:287–98. 10.1007/s40258-013-0035-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care . [2023a]. MBS Online: Medical Benefits Schedule. Available: http://www.mbsonline.gov.au/internet/mbsonline/publishing.nsf/Content/Home [Accessed 26 Jul 2023]. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Independent Hospital Pricing Authority . Costing. 2023. Available: https://www.ihacpa.gov.au/health-care/costing

- 46.Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care . Pharmaceutical benefits scheme (PBS). 2023. Available: https://www.pbs.gov.au/pbs/home

- 47.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare . Australian burden of disease study 2022, summary. 2022. Available: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/burden-of-disease/australian-burden-of-disease-study-2022/contents/summary#CHD [Accessed 6 Jun 2023].

- 48.Thompson ER. Development and validation of an internationally reliable short-form of the positive and negative affect schedule (PANAS). J Cross Cult Psychol 2007;38:227–42. 10.1177/0022022106297301 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rosenberg M. Rosenberg self-esteem scale (RSE). In: Acceptance and Commitment Therapy Measures Package 61. 1965: 52. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rocchi MA, Wilson PM, Sylvester BD, et al. Toward brief tools assessing motivation for exercise: rationale and development of a Six- and 12-item version of the behavioral regulation in exercise 3 (BREQ3) questionnaire. Sport Exerc Perform Psychol 2023;12:205–27. 10.1037/spy0000321 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gardner B, Abraham C, Lally P, et al. Towards parsimony in habit measurement: testing the convergent and predictive validity of an Automaticity Subscale of the self-report habit index. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2012;9:102. 10.1186/1479-5868-9-102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Presseau J, Tait RI, Johnston DW, et al. Goal conflict and goal facilitation as predictors of daily accelerometer-assessed physical activity. Health Psychol 2013;32:1179–87. 10.1037/a0029430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sniehotta FF, Schwarzer R, Scholz U, et al. Action planning and coping planning for long-term lifestyle change: theory and assessment. Eur J Soc Psychol 2005;35:565–76. 10.1002/ejsp.258 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2023-078302supp001.pdf (88.4KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2023-078302supp002.pdf (720KB, pdf)