Abstract

Background:

Mutual-help organizations (MHOs) play a crucial role for many individuals with alcohol use disorder (AUD) or other drug disorders in achieving stable remission. While there is now substantial research characterizing who uses 12-step MHOs, very little is known about who becomes affiliated with newer and rapidly growing MHOs, such as Self-Management and Recovery Training (“SMART” Recovery). More research could inform knowledge regarding who may be best engaged by these differing pathways.

Methods:

Cross-sectional analysis of participants (N=361) with AUD recruited mostly from the community starting a new recovery attempt self-selecting into one of four different recovery paths: 1. SMART Recovery (“SMART-only”; n=75); 2. Alcoholics Anonymous (“AA-only”; n=73); 3. Both SMART and AA (“Both”; n=53); and 4. Neither SMART nor AA (“Neither”; n=160) assessed on demographic, clinical history, treatment and recovery support service use, and indices of functioning and well-being. Descriptives were computed and inferential analyses conducted according to data structure.

Results:

Compared to study participants choosing AA-only or Both, SMART-only participants were more likely to be White, married, have higher income and more education, be full-time employed, and evince a pattern of lower clinical severity characterized by less lifetime and recent treatment and recovery support services usage, lower alcohol use intensity and fewer consequences, and lower legal involvement. AUD symptom levels, lifetime psychiatric diagnoses, psychiatric distress, and functioning were similar across MHO-engaged groups.

Conclusion:

SMART appears to attract individuals who show a pattern of greater psychosocial stability and economic advantage and less severe histories of alcohol-related impairment and legal involvement. Findings suggest that certain aspects specific to the SMART Recovery group approach, format, and/or contents, may be appealing to individuals exhibiting this type of profile. As such, SMART appears to provide an additional resource that expands the repertoire of options for those seeking AUD recovery.

Keywords: SMART Recovery, Alcoholics Anonymous, mutual-help, self-help, recovery

Introduction

Alcohol and other drug use disorders confer a prodigious burden of disease, disability and premature mortality in most middle- and high-income countries globally. To help alleviate this burden, most countries provide an array of professionally-delivered addiction treatment services (Degenhardt et al., 2018). Yet, despite these efforts, such services are often unable to meet both acute care and long-term relapse prevention needs of the millions or tens of millions affected annually. In response, most countries also possess an array of informal peer recovery support services which can provide ongoing assistance as well as some unique things that treatment is not designed to provide, such as community and recovery-supportive friendships (Kelly et al., 2017b). The oldest and largest of these are the 12-step mutual-help organizations (MHOs), such as Alcoholics Anonymous (AA). Rigorous research evidence has now demonstrated that when AA is subjected to the same scientific standards as other addiction focused interventions, it does as well on most outcomes measures, is better at sustaining abstinence and remission over time, and is highly cost effective (Humphreys and Moos, 2001; 2007; Kelly, 2022; Kelly et al., 2020). That said, not everyone chooses AA as a pathway to recovery and alternative MHO options, although much newer and smaller, are growing and may contain many of the same positive therapeutic elements and dynamics possessed by AA (Kelly, 2017a; Kelly et al., 2009) and may confer similar benefits for those who choose them (Zemore et al., 2017).

Beginning in the 1970s in the USA, a number of additional MHOs began to emerge, starting with Rational Recovery – a cognitive-behaviorally based AA alternative. From Rational Recovery, a similar group - Self-Management and Recovery Training or “SMART” Recovery - emerged. Other MHOs emerged later too, that were either secular (e.g., LifeRing), more religious (e.g., Refuge Recovery, Celebrate Recovery), focused on specific populations (e.g., Women for Sobriety), or focused purely on moderation goals for non-addicted alcohol/drug users (e.g., Moderation Management). In more recent years others have begun to emerge including many purely online MHO resources (e.g., the Luckiest Club; the Tempest, In the Rooms). Among these comparatively newer, non-12 step, MHOs, however, the longest running and arguably most well-known, is SMART Recovery.

SMART Recovery incorporates motivational, and cognitive and behavioral, treatment (CBT) strategies derived from formal treatment paradigms, but provides them in a community-based mutual-help format. Typically, meetings last for 60 to 90 minutes. SMART encourages abstinence but allows for additional personalized goals including non-harmful use. SMART also welcomes anyone with any kind of substance or behavioral addiction problem, addressing them with the same CBT-grounded principles and practices. AA and other 12-step MHOs, in contrast, nearly always focus on individual drugs or behaviors within each MHO type (e.g., alcohol in AA, cocaine in CA, marijuana in MA, overeating in OA, etc.), presumably to maximize similarities and therapeutic cohesion among group members as alluded to in its operations policies (AA, 1952). SMART Recovery meetings appear also to possess similar elements of cohesion which may help with CBT skills practice outside of meetings (Kelly et al., 2015). SMART meetings are facilitated by a trained facilitator who may or may not be in recovery themselves. This is different from most MHOs, which typically rely exclusively on peers with lived experience to run groups (Humphreys, 2004). SMART Recovery has grown in recent years (Horvath & Yeterian, 2012) and now has approximately two thousand meetings across the United States. International growth has also been evident, stimulated in part by COVID-19 (Kelly et al., 2021).

SMART Recovery has always differentiated its approach from 12-step MHOs through its foundation in, and focus on, science-based cognitive-behavioral and motivational psychological behavior change principles. A main assumption is that, just like professionally-delivered CBTs, individuals suffering from addiction problems can be taught the necessary skills to prevent relapse. The partially didactic, lecture-style format is liked by many adult participants but may be a turnoff for younger members (Lum et al., 2022). SMART Recovery also distinguishes itself from 12-step approaches by the explicit formal absence of any spiritual/quasi-religious elements or emphasis on beliefs in external “higher powers”; focusing, instead, on what it terms “self-empowerment” facilitated through individually-focused skills training taught during meetings (SMART members may share about anything, however, including religious/spiritual matters if they wish). Similar to suppositions underlying professional CBT (Marlatt and Gordon, 1985), relapse prevention skills are presumed to be learnable and absorbed fairly quickly (within a few months) by attendees. Consequently, SMART typically downplays, but does not actively discourage, long-term attendance, despite the fact that shorter duration attendance appears to be associated with less benefit (e.g., O’Sullivan et al., 2016). Also, unlike 12-step MHOs which explicitly emphasize helping other addicted individuals within a “fellowship” in order to help oneself (e.g., through “12th step work”; sponsorship; AA, 1952), SMART does not emphasize this principle; and, in general, places less explicit importance on social network change factors to help initiate and sustain change.

These differences in catering to non-abstinence goals, self-empowerment, cognitive-behavioral relapse prevention skills acquisition, and lack of explicit therapeutic emphasis on social networks, distinguish it from 12-step approaches. AA, for example, caters typically to people wishing to abstain completely, and focuses intentionally on belief and reliance on a “higher power”, long-term (even life-long) attendance, and recovery-focused social network change through 12-step fellowship engagement (AA, 1952; Kelly and Yeterian, 2012).

In contrast to many criticisms leveled at AA - based mostly on its quasi-religious/spiritual origins and emphasis (Peele, 1999; Bufe, 1998) - SMART Recovery has largely avoided, but not completely escaped, criticisms. Being based on CBT principles, for example, SMART Recovery is susceptible to the same types of criticisms facing its professional counterpart; that it may be overly didactic, intellectual, and too “academic”, containing concepts and ideas that are beyond many individuals’ conceptual grasp; and may be overly complex for the many individuals with cognitive-affective post-acute withdrawal challenges that so often manifest during the critical early stages of recovery from addiction (Gorski and Miller, 1982; 1986). A lack of explicit spiritual emphasis may also be less attractive to certain addicted population sub-groups for whom recovery focused spiritual/religious approaches may be important (e.g., those identifying as Black race; Kelly and Eddie, 2020).

As more research has begun to emerge on this important MHO (Beck et al., 2017; Campbell et al., 2016; Hester et al., 2013; Zemore et al., 2018), and in light of SMART Recovery’s philosophical and practical orientation and criticisms noted above, one important lingering question for those seeking recovery has been who in particular appears to be attracted to and engaged by SMART Recovery. Additionally, whether, and how, such individuals may differ from other individuals who choose to engage with AA, or indeed, those who do not attend any MHOs at all. Zemore and colleagues (2018) conducted one of the very few naturalistic studies of individuals engaged in a variety of MHOs, and found that SMART participants tended to be White, more educated and with less severe addiction histories (Zemore et al., 2017). Of interest too, are those who may attend SMART in addition to 12-step MHOs like AA. While this combined use of AA and SMART has been observed in preliminary work (O’Sullivan et al., 2015) and in our clinical practice observations, little is known from a more systematic empirical standpoint regarding the characteristics of individuals who may affiliate with both organizations. It could be that some individuals capitalize on strengths of each organization (e.g., the cognitive and behavioral skills building approaches of SMART and the easy accessibility and strong social network support available in AA).

To provide more empirical information in this expanding MHO arena, the current study compares the 1. demographic, 2. clinical and service use; 3. resources and barriers; and, 4. functioning and quality of life, of four groups of individuals beginning a new alcohol use disorder recovery attempt who chose to affiliate with: 1. SMART Recovery (“SMART-only”); 2. AA (“AA-only”); 3. Both SMART and AA (“Both”); or 4. Neither SMART nor AA (“Neither”). Greater knowledge about who may affiliate with these MHOs (or not) may help inform future MHO matching and clinical referrals and provide insights into which types of organizations are likely to be attractive and engaging to which types of individuals.

Methods

Participants

Adults (18+) who reported a primary alcohol use problem, who met DSM 5 AUD criteria, and had consumed alcohol in the past 90 days were eligible for the study. Participants could be using other drugs, besides alcohol. They also were required to live in New England or San Diego and to report currently making a new recovery attempt, defined as attending the SMART Recovery, AA, or Both MHOs for at least some part of the past 90 days (or intending to participate within the next 14 days) and that this was their chosen current pathway. The Neither group had to have not attended an MHO within the past 90 days and report no intention of attending any in the next 14 days. Participants also needed to provide locator contact information for two close friends/family members in case of inability to locate participant, their social security number for reimbursement or be willing to not receive reimbursement, and have a stable home address. San Diego was chosen to recruit more SMART participants as we were struggling to get sufficient flow from Boston based San Diego had the largest number of SMART meetings in one region and we were able to include it due to COVID-related transition to remote assessments (beginning March 2020).

Procedure

Participants were recruited through SMART Recovery meetings, outpatient treatment(n=6) , and a variety of commercial recruitment sources during the recruitment period (January 2019 to January 2022) including ResearchMatch, PeRC, TrialFacts, Rally for Recruitment, Facebook, Craigslist, and Reddit as well as newspaper, radio, and Boston commuter transport networks to take part in a two-year prospective study of AUD recovery pathways. AA participants were not recruited directly from AA meetings due to AA policies surrounding anonymity at meetings. Interested individuals called or emailed study contact persons directly or filled out an online screening form and subsequently participated in a brief 10–15-minute phone screen, during which eligibility criteria were confirmed.

Enrollment visits were conducted from February 6, 2019 to February 2, 2022. Prior to COVID-19 restrictions, all assessments were conducted with a study research coordinator in person and consisted of staff-administered and self-administered surveys completed via REDCap. For in person visits, baseline assessments lasted approximately 3 hours and participants were compensated $45. During COVID-19 restrictions, all assessments transitioned to remote assessment beginning March 2020.

Human Subjects Protection (Internal Review Board [IRB] Review and Approval IRB Statement:

All study procedures were approved by the Partners HealthCare Institutional Review Board. This is a naturalistic study and research protocol and thus was not pre-registered online. Consequently, findings herein should be considered exploratory and preliminary. A detailed published protocol summary, however, can be obtained here: https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/13/2/e066898

Measures

For a full detailed description of all measures used, see https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/13/2/e066898

Demographics Background:

Gender, race, ethnicity, current living situation, current marital status, sexual orientation, highest level of schooling, employment status, total annual household income, type of health insurance, and financial well-being of their family all were assessed using the GAIN and Form 90 (Dennis et al., 2002; Miller and Delboca, 1994).

Substance Use History:

participants answered a series of questions about their use of alcohol and other drugs throughout their lifetime including age of first/regular use of each substance, frequency and intensity of use (standard drinks per day), primary substance, using items from the Global Appraisal of Individual Needs (GAIN-I; Dennis et al., 2002) and the Form-90 which incorporated the Timeline Follow Back (TLFB) calendar method (Miller and Delboca, 1994). Alcohol and other substance use disorder diagnoses were captured using the semi-structured DART interview (McCabe et al., 2017).

Anti-Craving/Anti-Relapse Medications and Psychotropic Medications:

Participants reported whether they had ever been prescribed a medication to prevent them from drinking alcohol or using opioids, or to help them with a mental health condition using the Form 90 (Miller and Delboca, 1994).

Mental and Emotional Health: Diagnoses:

Participants reported whether they had ever been told that they had a mental health condition by a doctor, nurse, or counselor and if so, which disorder(s) they had ever been diagnosed with (e.g., bipolar disorder, major depression etc.). using the GAIN-I (Dennis et al., 2002).

12-step/MHO Attendance History:

assessed lifetime and past 90 day MHO attendance at 12 different MHOs, with an “other” option specified by participant (Kelly et al., 2011): 1) Alcoholics Anonymous (AA); 2) Narcotics Anonymous (NA); 3) Marijuana Anonymous (MA); 4) Cocaine Anonymous (CA); 5) Crystal Methamphetamine Anonymous (CMA); 6) SMART Recovery; 7) LifeRing Secular Recovery; 8) Moderation Management; 9) Celebrate Recovery; 10) Women for Sobriety; and 11) Refuge Recovery

Recovery Support Services and Formal Treatment Programs (RSSTX):

The questionnaire assessed history of participation in nine psychosocial treatment and recovery support services: 1) Sober living environment; 2) Recovery high school; 3) College recovery program/community 4) Recovery community center (RCC); 5) Faith-based recovery services (e.g., a recovery group provided by a church, synagogue, mosque, etc.); 6) State or local recovery community organization (RCO); 7) Outpatient addiction treatment; 8) Alcohol/drug detoxification services; 9) Inpatient or residential treatment. If they responded yes to any treatment service (7, 8 or 9), they reported the number of times they used the service (i.e., number of treatment episodes) in their lifetime and the past 3 months. (Dennis et al., 2002; Miller and Delboca, 1994).

Criminal Justice Involvement:

Form-90 (Miller and Delboca, 1994) assessed lifetime arrest (yes/no).

Psychiatric Distress and Perceived Stress:

The Kessler-6 (K6) is a six-item scale assessing frequency of psychiatric symptoms on a scale from all of the time (1) to none of the time (5), with regard to: feeling nervous, hopeless, restless or fidgety, so depressed that nothing could cheer you up, that everything was an effort, and feeling worthless (Kessler et al., 2003). Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-4) assessed frequency of stress in the past month using four items (never (1) to very often (5)) (Warttig et al., 2013).

Alcohol and Drug Abstinence Self Efficacy (A-DSES-20):

assessed confidence to not use alcohol or other drugs in various situations in past week rated on a scale of not at all confident (1) to extremely (5) (Diclemente et al., 1994).

Penn Alcohol and Drug Craving (PADCS-5):

Assessed frequency and strength of cravings to use alcohol/ other drugs during past week including how often and how much time spent thinking about drinking/using drugs, how strong cravings were when most severe, how difficult it would have been to resist, and overall craving. Options ranged from never thought about drinking/using drugs and never had the urge to drink/use drugs to Thought about drinking/using drugs nearly all of the time and had the urge to drink/use drugs nearly all of the time (Flannery et al., 1999).

Drinking Goal:

assessed the one alcohol use goal that currently was most true to them from 5 options: 1) Total abstinence - never use again; 2) Total abstinence - but realize a slip is possible; 3) Occasional use when urges strongly felt; 4) Temporary abstinence; or 5) Controlled use.

Commitment to Sobriety Scale (CSS-5):

In this questionnaire, participants were asked 5 questions about their commitment to not using alcohol/drugs. Participants rated the extent to which they agreed with these statements on a scale from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (6) (Kelly and Greene, 2014).

Alcohol/Drug Use Consequences (Short Inventory of Problems: SIP-2R)

assessed how often participants experienced various drinking/drug problems during the past 3 months ranging from never to daily or almost daily (Miller et al., 1995).

Brief Assessment of Recovery Capital (BARC-10)

consists of 10-items (Vilsaint et al., 2017) measuring personal (e.g., “I take full responsibility for my actions”), social (e.g., “I get lots of support from friends”), physical (e.g., “I have enough energy to complete the tasks I set for myself”), and environmental resources (e.g., “My living space has helped to drive my recovery journey”) used to initiate and sustain recovery rated on a scale from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (6).

Impulsivity (SUPPS-S):

This questionnaire assessed impulsivity. Participants rated their agreement with 20 items describing situations or feelings related to impulsivity on a scale of agree strongly (1) to disagree strongly (4) (Coskunpinar et al., 2013).

Quality of Life

was measured using three scales assessing current status and satisfaction related to physical health, mood, relationships, activities, and finances: the Q-LES-Q (Endicott et al., 1993); the EQ5D3L (Devlin and Brooks, 2017); and the EUROHIS-QOL (da Rocha et al., 2012).

Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI)

assessed average hours of sleep experienced per night in the past month and self-rated quality of sleep on a scale from very good (1) to very bad (4) (Buysse et al., 1989).

Pain Visual Analogue Scale (VAS):

Participants rated current severity of pain using a visual analogue scale from 0 (no pain) to 100 (very severe pain) (Wewers and Lowe, 1990).

International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ):

Assessed level of physical activity over the past seven days including vigorous and moderate physical activity and walking; how much time a day usually spent on each activity; and how many hours usually spent sitting (Hagstromer et al., 2006).

Meals:

Participants reported how many meals on average they had eaten per day during the past 3 months.

Self-Esteem, Happiness, and Satisfaction with Life:

Three single-item measures assessed self-esteem (Robins et al., 2001), happiness (Kelly et al, 2018), and satisfaction with life (Diener et al., 1985). For self-esteem, participants indicated their agreement with the statement “I have high self-esteem” on a scale from 1 (not very true of me) to 10 (very true of me). For happiness, participants rated how happy they were with their life in general on a scale of 1 (completely unhappy) to 10 (completely happy). For satisfaction with life, participants indicated agreement with the statement “I am satisfied with my life” on a scale of strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (7).

Daily Spiritual Experiences Scale (DSES):

assessed spiritual and/or religious experiences; 16 items describe spiritual and/or religious experiences and participants rated how often they experienced each ranging from many times a day (1) to never or almost never (6) (Underwood and Teresi, 2002)

Analytic Strategy

The focus of this study is the comparison of the four groups identified naturalistically at baseline based on their choice of mutual help organization selection (i.e., SMART only, AA only, both SMART and AA, neither SMART nor AA). To describe these four groups, we calculated means with standard deviations for continuous variables, and percentages with noted sample sizes for categorical variables. To test if these groups differed significantly from each other, we performed analysis of variance for continuous variables, and chi-square tests for categorical variables. For categorical variables with rare cell counts (i.e., fewer than 5 observations in a given category), we used Fisher’s exact test. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4. In these exploratory analyses, we deemed tests statistically significant at p < 0.05 without correction for multiple testing. Significant 4-group comparisons were followed up with pair-wise comparisons to identify the nature of the differences. In the summary tables and figures, we used superscripts to denote statistically significant pairwise comparisons, where groups sharing a superscript did not differ from each other.

Results

Demographics

As shown in Table 1, of the total number of study participants (N=361) at the baseline assessment, n = 75 were attending SMART only, n = 73 were attending AA only, n = 53 were attending both SMART and AA, and n = 160 were attending neither SMART nor AA; 52.1 % of participants were female; 74.2% identified as White, 13.9% as Black/African American, 2.8% as Asian, 4.7% as another race, and 4.2% as more than one race; 9.1% identified as Hispanic/Latino ethnicity. Mean age was 46.2 (SD = 12.9); 35.5% were married, engaged, or living with a partner as if married, 47.4% were not married nor living together, and 15.8% were separated, divorced, or widowed; 38.2% were unemployed, 18.8% were employed part time (including irregular work) and 42.1% were employed fulltime (more than 35 hours/week); 13% had a high school diploma or less, 36% had completed some college or other degree, and 50.1% had completed a BA or higher; 12% had a household income of less than $10,000, 41% between $10,000 and $49,999, and 44.9% $50,000 or more.

Table 1a -.

Demographic Characteristics

| Total n=361 |

SMART n=75 |

AA n=73 |

Both n=53 |

Neither n=160 |

Group Difference |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M / % | (SD/n) | M / % | (SD/n) | M / % | (SD/n) | M / % | (SD/n) | M / % | (SD/n) | p | |

| Age (in mean, SD) | 46.2 | (12.9) | 49.1 | (13.1) | 46.2 | (11.5) | 45.8 | (13.4) | 45.1 | (13.1) | 0.17 |

| Gender (% female) | 52.1 | (188) | 40.0a | (30) | 49.3ab | (36) | 50.9ab | (27) | 59.4b | (95) | 0.05 |

| Sexual orientation (% non-heterosexual) | 21.6 | (78) | 20.0 | (15) | 26.0 | (19) | 20.8 | (11) | 20.6 | (33) | 0.77 |

| Hispanic (% yes) | 9.1 | (33) | 16.0b | (12) | 1.4a | (1) | 9.4ab | (5) | 9.4b | (15) | 0.02 |

| Race | 0.01 | ||||||||||

| White | 74.2 | (268) | 88.0 b | (66) | 76.7a | (56) | 66.0a | (35) | 69.4a | (111) | |

| Black or African American | 13.9 | (50) | 1.3 | (1) | 17.8 | (13) | 18.9 | (10) | 16.3 | (26) | |

| Asian | 2.8 | (10) | 0.0 | (0) | 1.4 | (1) | 1.9 | (1) | 5.0 | (8) | |

| American Indian or Alaskan Native | 0.8 | (3) | 0.0 | (0) | 1.4 | (1) | 0.0 | (0) | 1.3 | (2) | |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 0.3 | (1) | 1.3 | (1) | 0.0 | (0) | 0.0 | (0) | 0.0 | (0) | |

| Multi-racial | 4.2 | (15) | 5.3 | (4) | 2.7 | (2) | 5.7 | (3) | 3.8 | (6) | |

| Other | 3.6 | (13) | 4.0 | (3) | 0.0 | (0) | 7.5 | (4) | 3.8 | (6) | |

| Education | < 0.001 | ||||||||||

| High school or less | 13.0 | (47) | 5.3b | (4) | 15.1a | (11) | 18.9a | (10) | 13.8a | (22) | |

| Some college or other degree | 36.0 | (130) | 22.7 | (17) | 46.6 | (34) | 28.3 | (15) | 40.0 | (64) | |

| BA or higher | 50.1 | (181) | 72.0 | (54) | 37.0 | (27) | 52.8 | (28) | 45.0 | (72) | |

| Income (i.e., total household past year) | < 0.0001 | ||||||||||

| Less than $10,000 | 13.0 | (47) | 4.0c | (3) | 16.4a | (12) | 18.9ab | (10) | 13.8b | (22) | |

| $10,000 to $49,999 | 41.0 | (148) | 22.7 | (17) | 57.5 | (42) | 47.2 | (25) | 40.0 | (64) | |

| $50,000 or more | 44.9 | (162) | 73.3 | (55) | 26.0 | (19) | 30.2 | (16) | 45.0 | (72) | |

| Employment (90 days prior to baseline) | 0.07 | ||||||||||

| Unemployed | 38.2 | (138) | 28.0 | (21) | 42.5 | (31) | 47.2 | (25) | 38.1 | (61) | |

| Part-time (including irregular work) | 18.8 | (68) | 16.0 | (12) | 24.7 | (18) | 17.0 | (9) | 18.1 | (29) | |

| Full-time (35+ hrs/week) | 42.1 | (152) | 56.0 | (42) | 31.5 | (23) | 34.0 | (18) | 43.1 | (69) | |

| Marital status | < 0.01 | ||||||||||

| In a relationship (married, living as married, engaged) | 35.5 | (128) | 53.3b | (40) | 26.0a | (19) | 28.3a | (15) | 33.8a | (54) | |

| No longer together (divorced, widowed, separated) | 15.8 | (57) | 18.7 | (14) | 16.4 | (12) | 17.0 | (9) | 13.8 | (22) | |

| Not married nor living together (single, in a relationship) | 47.4 | (171) | 28.0 | (21) | 56.2 | (41) | 52.8 | (28) | 50.6 | (81) | |

| Location (% from San Diego) | 17.5 | (63) | 37.3a | (28) | 5.5b | (4) | 37.7a | (20) | 6.9b | (11) | < 0.0001 |

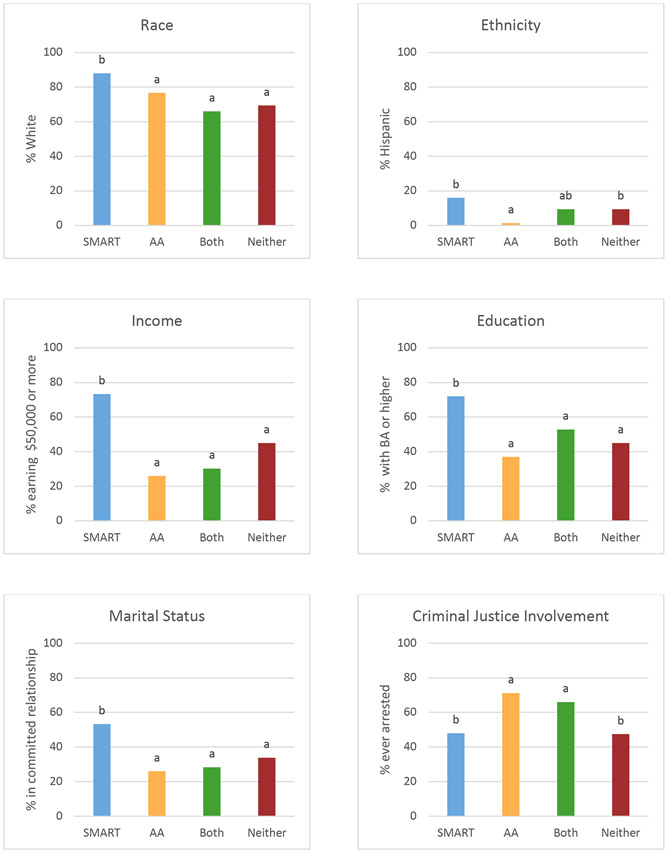

The four groups differed substantially in their demographic indices (Table 1). Compared to the other three groups, participants in the SMART-only group were more likely to be White (88% vs. 77% or less in the other groups), have a higher education (72% with BA or higher vs. 52% or less in the other groups), have a higher income (73% with an annual income of $50,000 or more vs. 45% or less in the other groups), and more likely to be in a committed relationship (53% vs. 36% or less in the other groups). Other significant differences also emerged, but were more nuanced. SMART-only participants were less likely to be female (40%) than participants in the Neither group (60%), but not the AA or Both groups. Participants in the SMART-only group were more likely to be Hispanic (16%) than participants in the AA group (1%), but it should be noted that more SMART participants were recruited in the San Diego area than the Boston area, so that these differences likely reflect demographics of that recruitment area rather than differences between chosen mutual help path.

Alcohol Use Disorder Severity, Psychiatric Histories, and Prior Legal System Involvement

In terms of indices of AUD severity and treatment goals, the SMART groups did not stand out as systematically different. Instead, the Neither group stood out as having lower AUD severity (68% with severe AUD vs. 85% or more in the other groups) and endorsing non-abstinence focused drinking goals more frequently than the other groups (36% endorsing ‘controlled use’ vs. 19% or less in the other groups). The Neither group also had more drinking days (50 drinking days out of the past 90 days vs. 42 or less in the other groups). Drinking intensity was highest among the AA groups, where participants in the AA and Both groups reported drinking, on average, 10 drinks per drinking day, while participants in the SMART and Neither group reported, on average, 7 drinks per drinking day. The groups did not differ on the frequency of other substance use. Groups also were found to not differ on the proportion who reported receiving a prior psychiatric diagnosis (other than SUD) or on the number of prior psychiatric diagnoses received. Criminal justice involvement was lower in the SMART-only (48%) and Neither (47%) groups than the AA-only (71%) or Both (66%) group.

Frequency of attendance of MHOs

At the time participants enrolled into the study (Table 2), most participants had experience with the path they chose for this recovery attempt (i.e., 98% of those choosing an AA path had AA experience; ≥91% of those choosing a SMART path had SMART experience). The frequency with which they attended meetings was higher for AA than SMART meetings. Participants in the AA-only and Both groups attended AA meetings on 31 and 22 days, respectively, during the past 90 days. Participants in the SMART-only and Both groups attended SMART meetings on 11 and 12 days, respectively.

Table 2 -.

Utilization of addiction and recovery services

| Total n=361 |

SMART n=75 |

AA n=73 |

Both n=53 |

Neither n=160 |

Sig Difference |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M / % | (SD/n) | M / % | (SD/n) | M / % | (SD/n) | M / % | (SD/n) | M / % | (SD/n) | p | |

| Mutual Help Groups | |||||||||||

| Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) (% ever) | 67.0 | (242) | 69.3b | (52) | 98.6a | (72) | 98.1a | (52) | 41.3c | (66) | < 0.0001 |

| % in past 3 months | 33.2 | (120) | 9.3b | (7) | 89.0a | (65) | 86.8a | (46) | 1.3c | (2) | < 0.0001 |

| # of meetings in past 3 months | 9.4 | (24) | 0.1b | (1) | 30.5a | (39) | 21.5a | (24) | 0.2b | (2) | < 0.0001 |

| Narcotics Anonymous (NA) | 28.8 | (104) | 16.0b | (12) | 49.3a | (36) | 54.7a | (29) | 16.9b | (27) | < 0.0001 |

| % in past 3 months | 10.8 | (39) | 1.3b | (1) | 26.0a | (19) | 32.1a | (17) | 1.3b | (2) | < 0.0001 |

| Other 12-Step Group (MA, CA, CMA, DDA) | 6.1 | (22) | 1.3a | (1) | 8.2a | (6) | 20.8b | (11) | 2.5a | (4) | < 0.0001 |

| % in past 3 months | 1.4 | (5) | 0.0b | (0) | 1.4ab | (1) | 7.5a | (4) | 0.0b | (0) | < 0.0001 |

| SMART Recovery | 39.1 | (141) | 96.0a | (72) | 9.6b | (7) | 90.6a | (48) | 8.8b | (14) | < 0.0001 |

| % in past 3 months | 30.7 | (111) | 88.0a | (66) | 0.0b | (0) | 83.0a | (44) | 0.6b | (1) | < 0.0001 |

| # of meetings in past 3 months | 4.1 | (12) | 11.0a | (17) | 0.0b | (0) | 12.1a | (18) | 0.0b | (0) | < 0.0001 |

| LifeRing Secular Recovery | 0.8 | (3) | 0.0 | (0) | 0.0 | (0) | 3.8 | (2) | 0.6 | (1) | 0.16 |

| Moderation Management | 1.7 | (6) | 2.7 | (2) | 1.4 | (1) | 1.9 | (1) | 1.3 | (2) | 0.89 |

| Celebrate Recovery | 1.9 | (7) | 1.3 | (1) | 2.7 | (2) | 5.7 | (3) | 0.6 | (1) | 0.08 |

| Women for Sobriety | 2.8 | (10) | 4.0 | (3) | 1.4 | (1) | 7.5 | (4) | 1.3 | (2) | 0.07 |

| Refuge Recovery | 5.0 | (18) | 6.7a | (5) | 2.7ab | (2) | 18.9c | (10) | 0.6b | (1) | < 0.0001 |

| Other % in the past 3 months | 10.2 | (37) | 10.7 | (8) | 12.3 | (9) | 11.3 | (6) | 8.8 | (14) | 0.85 |

| % in past 3 months (any mutual-help attendance other than 12-step or SMART) | 10.2 | (37) | 12.0ab | (9) | 9.6b | (7) | 24.5a | (13) | 5.0b | (8) | < 0.001 |

| Use of medication | |||||||||||

| Medication for AUD (% ever) | 42.7 | (154) | 52.0a | (39) | 63.0a | (46) | 60.4a | (32) | 23.1b | (37) | < 0.0001 |

| Naltrexone (Revia, Vivitrol) | 34.9 | (126) | 46.7a | (35) | 53.4a | (39) | 52.8a | (28) | 15.0b | (24) | < 0.0001 |

| Campral (Acamprosate) | 11.6 | (42) | 14.7a | (11) | 19.2a | (14) | 17.0a | (9) | 5.0b | (8) | < 0.01 |

| Antabuse (Disulfiram) | 10.8 | (39) | 8.0 | (6) | 15.1 | (11) | 18.9 | (10) | 7.5 | (12) | 0.06 |

| Medication for AUD (% in past 3 months) | 20.5 | (74) | 28.0a | (21) | 26.0a | (19) | 35.8a | (19) | 9.4b | (15) | < 0.0001 |

| Medication for OUD (% ever) | 8.9 | (32) | 6.7ab | (5) | 16.4a | (12) | 13.2a | (7) | 5.0b | (8) | 0.02 |

| Medication for mental health (excluding SUDs; % ever) | 74.0 | (267) | 72.0 | (54) | 79.5 | (58) | 83.0 | (44) | 69.4 | (111) | 0.12 |

| Formal treatment | |||||||||||

| Hospitalizations (for alcohol or drug use; % ever) | 36.0 | (130) | 30.7b | (23) | 50.7a | (37) | 56.6a | (30) | 25.0b | (40) | < 0.0001 |

| Outpatient addiction treatment | |||||||||||

| % ever | 44.3 | (160) | 45.3b | (34) | 65.8a | (48) | 75.5a | (40) | 23.8c | (38) | < 0.0001 |

| if ever, # of times past 3 months (M, SD) | 1.5 | (5.1) | 1.1 | (3.1) | 2.2 | (7.6) | 0.8 | (1.9) | 1.5 | (5.1) | 0.64 |

| Detoxification | |||||||||||

| % ever | 39.1 | (141) | 36.0b | (27) | 69.9a | (51) | 58.5a | (31) | 20.0c | (32) | < 0.0001 |

| if ever, # of times past 3 months | 0.5 | (0.7) | 0.6ab | (0.6) | 0.5a | (0.7) | 0.9b | (1.0) | 0.1c | (0.3) | < 0.001 |

| Residential Treatment | |||||||||||

| % ever | 41.3 | (149) | 38.7b | (29) | 67.1a | (49) | 67.9a | (36) | 21.9c | (35) | < 0.0001 |

| if ever, # of times past 3 months | 0.4 | (0.6) | 0.4a | (0.5) | 0.4a | (0.6) | 0.6a | (0.9) | 0.1b | (0.3) | < 0.01 |

| Use of recovery support services | |||||||||||

| Sober living environment | 27.4 | (99) | 17.3b | (13) | 47.9a | (35) | 49.1a | (26) | 15.6b | (25) | < 0.0001 |

| Recovery high schools | 0.6 | (2) | 0.0 | (0) | 1.4 | (1) | 0.0 | (0) | 0.6 | (1) | 0.62 |

| College recovery programs | 1.9 | (7) | 2.7 | (2) | 2.7 | (2) | 3.8 | (2) | 0.6 | (1) | 0.23 |

| Recovery community centers (RCC) | 9.1 | (33) | 6.7ac | (5) | 15.1ab | (11) | 24.5b | (13) | 2.5c | (4) | < 0.0001 |

| Faith-based recovery services | 8.3 | (30) | 10.7 | (8) | 12.3 | (9) | 9.4 | (5) | 5.0 | (8) | 0.21 |

| State or local recovery community organization (RCO) | 7.8 | (28) | 4.0ac | (3) | 12.3ab | (9) | 22.6b | (12) | 2.5c | (4) | < 0.0001 |

A substantial number of participants (29%) reported having attended NA meetings in their lifetime. NA attendance was higher among those choosing the AA paths for this recovery attempt (i.e., 55% and 49% for Both and AA-only participants). Utilization of other mutual help groups was rare and did not differ between groups except for greater participation in the Buddhism-influenced Refuge Recovery where substantially more of the Both group reported having attended more frequently.

Use of medication

The use of medications for AUD was high among mutual help group participation pathways (SMART only, AA only, and Both), with ≥52% of participants having tried these medications in their lifetime, with no differences between these groups. It was lower for participants in the Neither group (23%). The use of medications for OUD was low in all groups (9%); participants in the SMART groups did not differ from the other two groups. Lifetime use of medications for mental health problems was very high across all groups (74%) and did not differ across groups.

Utilization of formal treatment

Lifetime utilization of formal treatment (Table 2) was relatively high among study participants in general, with 44% having participated in outpatient treatment for a substance use problem, 41% having participated in residential treatment, 39% having undergone detoxification, and 36% having been hospitalized for a substance use problem. Formal treatment options differed across the four groups. It was highest among the AA groups. Fewer participants in the SMART-only group used these formal treatment modalities, though more so than the participants in the Neither group (except for hospitalizations, where the SMART-only and Neither group did not differ).

Use of recovery support services

The most commonly used recovery support service among participants in this study was recovery housing, with 27% of participants having used this service in their lifetime. Using recovery housing was more common among the AA groups (i.e., AA-only and Both), ≥47% of whom used this recovery support service compared to ≤17% among participants in the other two groups. The use of other recovery support services was low. Notably, 9% had utilized a recovery community center or participated in recovery community organizations (7%). Participants in the Both group more commonly reported participating in these services.

Recovery resources and barriers

The four groups differed on measurements of recovery capital (BARC-10), abstinence self-efficacy (A-DSES-20), and commitment to sobriety (CSS-5). These differences, however, largely were observed for the Neither group, which indicated lower recovery capital, lower self-efficacy, and a lower commitment to sobriety than most of the other groups. The SMART-only and AA-only groups did not differ on these indices.

In terms of barriers to recovery, no differences between the four groups were observed regarding craving or impulsivity. A difference was noted on alcohol-related problems. Here, the AA groups (AA-only, Both) reported experiencing more alcohol-related problems than either the SMART-only or the Neither group; the SMART-only group did not differ on alcohol-related problems from the Neither group.

Well-being and quality of life

No differences were observed between the four groups on indices of stressors and quality of life. Two differences were observed in indices of well-being, neither of which set the SMART-only group apart from the other groups. The Neither group reported lower quality of sleep than the mutual-help engaged groups (i.e., SMART-only, AA-only, Both). The AA groups (AA-only, Both) reported a greater frequency of daily spiritual experiences than the other two groups; the SMART-only group did not differ from the Neither group.

Discussion

Increased empirical validation of the value of community based continuing care resources (e.g., AA) to confer ongoing recovery-related benefits for patients suffering from alcohol and other drug use disorders has led to the expansion and growth of a variety of mutual-help organizations, including SMART Recovery (Kelly and White, 2012). The continuation and expansion of SMART since the 1980s (Horvarth and Yeterian, 2012) has garnered scientific attention to understand more formally its clinical and public health utility and also who, in particular, is most likely to affiliate and engage with it. The pattern of findings observed here suggest that, compared to individuals with AUD initiating a recovery attempt who engage in other recovery pathways, those who engage with SMART appear to be those who are of White race, and who are more psychosocially stable and economically advantaged, with lower alcohol use intensity and related consequences, lower levels of formal treatment and recovery support services usage, fewer prior legal problems, and who are less spiritual. Findings suggest that certain aspects specific to the SMART Recovery group approach, format, and/or contents may be appealing to individuals exhibiting this type of profile in particular. As such, SMART appears to provide an additional resource that expands the repertoire of valuable options for those seeking AUD recovery. In addition, despite the fact that SMART was started as a philosophically and practically distinct alternative to AA, the observation that many individuals seeking recovery are choosing to attend both SMART and AA reflects sufferers’ ability to psychologically accommodate distinct theoretical perspectives and potentially capitalize on each organization's strengths – observations that have been found in other mutual help research on women attending both AA and Women for Sobriety (e.g., Kaskutas, 1994).

There were some notable differences observed among individuals choosing to engage with SMART Recovery compared to other pathways. Specifically, the SMART group was comprised of mostly White race individuals with only one Black individual, whereas the AA, Both, and Neither groups, all had between 16% and 19%. The comparative almost complete absence of Black SMART participants was a surprise given the generally all-inclusive ethos of the SMART organization as a whole (e.g., welcoming of anyone with any type of addictive problem and supportive of personal, self-identified, recovery goals including non-abstinence, and use of opioid agonist medications). It could be that, given the strong religious and spiritual orientation of Black individuals and how they have been found to attest to the central importance of religious/spiritual beliefs and practices in the addiction recovery process (Kelly and Eddie, 2020), they tend to gravitate toward approaches that include and support those (e.g., 12-step). The substantially lower observed Black participation may also be related to the higher socio-economic status of SMART participants (along with the White majority composition) which may highlight perceived society-wide disadvantage and discrimination leading to a diminished feeling of belonging and lower engagement among Black individuals (Stepanikova and Oates, 2017). Qualitative investigation with former and existing Black SMART attendees may help inform, more specifically, the exact reasons for the very low participation among Black individuals. Notably, Hispanic individuals were overrepresented among the SMART group compared to other groups, which is potentially explained by the greater proportion of recruited SMART participants that stemmed from the San Diego, California, area where there is a much higher Hispanic population prevalence. Nevertheless, it suggests that Hispanic individuals are attracted by, and may be able to engage with, SMART successfully.

Some other noteworthy differences among demographic variables were the magnitude of those pertaining to economic advantage and psychosocial stability. Specifically, education, income, and being in committed relationship were all substantially higher among SMART group participants. There was also a similar trend (although not quite reaching the cutoff for statistical significance; p=.07; table 1) for employment, whereby SMART participants were less likely to be unemployed, and more likely to be employed full time. This overall pattern of findings suggests SMART Recovery may possess specific elements in aspects of its operations, group format, social dynamics, and/or content, that individuals starting a new AUD recovery attempt with this type of profile find attractive and engaging. This is also similar to prior findings from Zemore et al. (2018) that found SMART group participants were more likely to be White and have greater psychosocial stability.

Regarding indices of alcohol-related involvement and impairment, psychiatric histories, and legal system involvement, there were also some similarities and some differences detected across the four groups. Specifically, DSM 5 AUD symptom severity was similar among the three mutual-help organization-engaged groups, but with the Neither group having lower severity. The SMART-only and Neither groups, however, were drinking substantially less intensively than the AA-only and Both groups, that reached a moderate to large standardized effect size difference (Cohens d = −0.60). The SMART-only and Neither groups also reported significantly fewer alcohol-related consequences and much lower legal system involvement than the AA-only and Both groups. Of note, however, none of the groups differed in other drug use days, nor in the proportion who reported receiving a prior psychiatric diagnosis (other than SUD) or in the total average number of prior psychiatric diagnoses received; psychiatric distress and general perceived stress also did not differ among any of the groups. Consequently, in addition to attracting individuals with greater psychosocial stability and economic resources, SMART Recovery appears also to be more likely to attract individuals with less heavy and less consequential alcohol use patterns and legal histories, despite having similar degrees of AUD symptomatology and psychiatric histories as other mutual-help-engaged individuals. SMART’s ability to engage generally less severe and more psychosocially stable individuals is similar to findings from research on the mutual-help organization, Moderation Management, which found a similar profile among its attendees (Humphreys and Klaw, 2001).

Participation in mutual-help organizations in the past 90 days prior to entering the study showed roughly double or triple the rates of participation for the AA-only and Both groups compared to the SMART only group. This may be indicative of the much greater availability and accessibility of AA than SMART meetings, but also could be related to the greater clinical severity of alcohol involvement, impairment, and consequences, associated with the AA-only and Both group participants that is predictive of more need for support and more intensive help-seeking (Finney and Moos, 1999; Kelly and Dow, 2013). Of note, also was that the Both group were much more likely also to have attended the Buddhist-influenced, Refuge Recovery. This pattern of greater use of mutual-help organizations may reflect a higher level of motivation and perceived need for help, possibly underwritten by greater susceptibility to relapse. The comparatively greater use of Refuge Recovery, is also noteworthy. This Buddhist-oriented addiction recovery organization is becoming increasingly well-known and utilized and fits with broader recent cultural trends toward mindfulness in addiction treatment (e.g., Bowen et al, 2019) and warrants further study.

Regarding lifetime and recent use of formal AUD inpatient, outpatient, and detoxification treatment services as well as use of recovery residences and recovery community centers, a robust pattern was observed reflecting much greater use of these among the AA-only and Both groups. The observed pattern of greater use of formal treatment and recovery support services is consistent with the more consequential and impactful patterns of heavier alcohol use noted above that often produces greater neurotoxicity and neurophysiological deterioration over time that in turn frequently require more intensive medically managed and medically monitored interventions; such deterioration also can impair AUD sufferers’ ability to gain or maintain hold of other recovery beneficial assets noted above (e.g., income, employment, education) that were observed among the SMART group members. Of note, lifetime prevalence of use of AUD-specific treatment medications was quite high and was similar across the mutual-help engaged groups, but significantly lower in the Neither group.

When starting this new AUD recovery attempt, there was no difference observed between our mutual-help organization engaged groups across the formal measures of current recovery resources and barriers (e.g., abstinence self-efficacy, recovery capital, commitment to sobriety etc), or indices measuring current quality of life, functioning, and well-being, with the exception of spiritual experiences which, as expected, were more commonly reported among the AA-only and Both groups. Thus, interestingly and somewhat surprisingly, whereas the AA and Both groups reported greater AUD consequences and treatment/recovery support services usage and legal histories than other groups, this was not reflected in these other measures of quality of life, functioning, and well-being. It is unclear whether these measures are the correct types of measures to capture functional difference across groups or whether they lack the psychometric sensitivity to detect the kinds of actual differences that may be present and relevant. More investigation is needed in this regard.

Limitations

Findings here should be considered in light of some important limitations inherent in the study design. The study is cross-sectional and focuses on differences in characteristics of individuals with AUD who are starting a new AUD recovery attempt organically self-selecting into one of four different recovery pathways. As such, while discussion here pertains to attraction to and engagement with SMART or other mutual-help and neither pathways (AA-only, Both, Neither), nothing can be inferred directly from findings here regarding relative efficacy about SMART’s specific ability to confer, or not confer, recovery benefits in helping sufferers achieve and maintain AUD remission. Nevertheless, attraction and engagement with an organization is one very important metric in examining its utility. Also, recruitment was regional, occurring in the metro Boston and San Diego areas of the USA and, thus, it is not possible to know how representative such regions are of all SMART Recovery group participant characteristics nationally or internationally. A lot of the recruitment also occurred during COVID-19 and this may have affected estimates in unknown ways that may not be generalizable to other timeframes. Thus, inferences and extrapolations should be made with caution. Also, recruitment differed substantially across the SMART vs. non-SMART group participants with 37% of the SMART group participants recruited in the metro San Diego region vs. only 6% of the non-SMART. Finally, given the exploratory and hypothesis generating nature of this investigation along with relatively small sub-group sample sizes affecting statistical power, we were more concerned with type II, than type I, statistical errors; thus, we did not control for potential type I error inflation. Consequently, whereas we hope that figures reported herein provide useful benchmarks for future investigations, more confirmatory research is needed to substantiate both the magnitude and statistical significance of the findings observed here.

Conclusions

In sum, the overall pattern of findings suggest that SMART Recovery may attract individuals evincing a general pattern of similar levels of AUD symptomatology, psychiatric histories, and current distress, as well as similar levels of current functioning and well-being as groups such as AA, but who also report much less intense recent alcohol involvement and impairment and lower lifetime and recent levels of prior formal AUD treatment and recovery support services usage, as well as less prior legal system involvement. SMART may also attract and engage individuals with characteristics consistent with patterns of greater psychosocial stability and economic advantage in the domains of education, income, relationships and employment. Although SMART appears to be able to attract and engage Hispanic individuals within a densely populated Hispanic region (San Diego, CA), compared to AA, it does not appear to attract or engage AUD individuals identifying as Black race. The observed high proportion of White individuals in SMART is similar to prior racial group composition estimates in other SMART samples (O’Sullivan, 2015; Zemore, 2017; SMART Membership Survey, 2017). More qualitative investigation may be helpful to discover why it is that fewer Black individuals in particular are attending SMART.

Although much more is to be learned regarding the actual recovery benefits derived from SMART Recovery participation over time following initiation of a new AUD recovery attempt, SMART Recovery appears to be providing another valuable, accessible, and much needed recovery support pathway that is attracting and engaging individuals with particular AUD and psychosocial profiles characterized broadly by lower clinical severity and more resources and greater stability. As such, SMART may be another welcome and helpful resource in the growing array of recovery support services (White et al., 2012) that may facilitate both greater numbers of individuals embarking on a journey of recovery as well as providing an option that may engage people sooner in the process.

Figure 1.

Demographics Differences Across Four Different Recovery Pathway Groups

Figure 2.

Clinical Characteristics Across Four Different Recovery Pathway Groups

Table 1b -.

Clinical and Legal System Characteristics

| Total n=361 |

SMART n=75 |

AA n=73 |

Both n=53 |

Neither n=160 |

Group Difference |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M / % | (SD/n) | M / % | (SD/n) | M / % | (SD/n) | M / % | (SD/n) | M / % | (SD/n) | p | |

| AUD severity past 90 days | < 0.001 | ||||||||||

| Mild | 5.8 | (21) | 2.7a | (2) | 5.5a | (4) | 3.8a | (2) | 8.1b | (13) | |

| Moderate | 13.3 | (48) | 12.0 | (9) | 4.1 | (3) | 1.9 | (1) | 21.9 | (35) | |

| Severe | 79.8 | (288) | 85.3 | (64) | 90.4 | (66) | 94.3 | (50) | 67.5 | (108) | |

| Drinking goal | < 0.0001 | ||||||||||

| Total abstinence; never use again | 19.1 | (69) | 17.3a | (13) | 27.4a | (20) | 34.0a | (18) | 11.3b | (18) | |

| Total abstinence; but realize a slip is possible | 39.1 | (141) | 44.0 | (33) | 52.1 | (38) | 47.2 | (25) | 28.1 | (45) | |

| Occasional use when urges strongly felt | 11.4 | (41) | 9.3 | (7) | 6.8 | (5) | 9.4 | (5) | 15.0 | (24) | |

| Temporary abstinence | 5.3 | (19) | 8.0 | (6) | 2.7 | (2) | 3.8 | (2) | 5.6 | (9) | |

| Controlled use | 22.4 | (81) | 18.7 | (14) | 9.6 | (7) | 5.7 | (3) | 35.6 | (57) | |

| Alcohol/drug use past 90 days | |||||||||||

| # of drinking days (out of 90) | 42.0 | (29.4) | 41.9a | (30.0) | 34.7ab | (27.7) | 26.5b | (21.9) | 50.3c | (29.3) | < 0.0001 |

| # of heavy drinking days (out of 90) | 29.8 | (28.5) | 27.6 | (25.4) | 29.9 | (26.3) | 22.5 | (21.2) | 33.3 | (32.5) | 0.11 |

| Average # of drinks/drinking day | 8.0 | (5.7) | 6.8b | (4.9) | 10.2a | (6.5) | 10.2a | (6.9) | 6.8b | (4.6) | < 0.0001 |

| # of other substance use days (out of 90) | 17.0 | (28.7) | 14.9 | (26.8) | 18.9 | (28.9) | 15.4 | (24.7) | 17.5 | (30.7) | 0.82 |

| Psychiatric Diagnoses | |||||||||||

| % any diagnosis (not including SUD) | 71.5 | (258) | 72.0 | (54) | 76.7 | (56) | 77.4 | (41) | 66.9 | (107) | 0.31 |

| if yes, # of diagnoses | 2.9 | (1.9) | 2.5 | (1.6) | 3.3 | (2.2) | 3.0 | (1.9) | 2.8 | (1.8) | 0.11 |

| Criminal justice involvement (% ever arrested) | 55.1 | (199) | 48.0b | (36) | 71.2a | (52) | 66.0a | (35) | 47.5b | (76) | < 0.01 |

Table 3 -.

Recovery indices

| Cronbach Coefficient Alpha |

Total n=361 |

SMART n=75 |

AA n=73 |

Both n=53 |

Neither n=160 |

Group Difference |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | M | (SD) | M / % | (SD/n) | M / % | (SD/n) | M / % | (SD/n) | M / % | (SD/n) | p | ||

| Resources | |||||||||||||

| Recovery capital (BARC) | 0.84 | 350 | 4.47 | 0.80 | 4.55ab | 0.84 | 4.58a | 0.78 | 4.63a | 0.70 | 4.33b | 0.80 | 0.04 |

| Self Efficacy (A-DSES-20) | 0.96 | 352 | 3.11 | 0.95 | 3.27a | 0.90 | 3.19ab | 0.94 | 3.30a | 1.01 | 2.93b | 0.93 | 0.02 |

| Commitment to sobriety (CSS-5) | 0.93 | 352 | 4.40 | 1.27 | 4.48a | 1.12 | 4.87ab | 1.21 | 4.96b | 1.11 | 3.95c | 1.26 | < 0.0001 |

| Barriers | |||||||||||||

| Craving (PADCS-5) | 0.89 | 355 | 2.59 | 1.39 | 2.64 | 1.35 | 2.43 | 1.39 | 2.29 | 1.38 | 2.75 | 1.41 | 0.14 |

| Drinking Problems (SIP-2R) | 0.93 | 352 | 1.55 | 0.75 | 1.49b | 0.67 | 1.86a | 0.73 | 1.85a | 0.65 | 1.34b | 0.75 | < 0.0001 |

| Impulsivity (SUPPSP) | 0.84 | 348 | 2.22 | 0.45 | 2.17 | 0.51 | 2.24 | 0.45 | 2.34 | 0.44 | 2.19 | 0.43 | 0.13 |

Table 4 -.

Well-being and Quality of Life

| Cronbach Coefficient Alpha |

Total n=361 |

SMART n=75 |

AA n=73 |

Both n=53 |

Neither n=160 |

Group Difference |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | M | (SD) | M / % | (SD/n) | M / % | (SD/n) | M / % | (SD/n) | M / % | (SD/n) | p | ||

| Well-being | |||||||||||||

| Quality of Sleep (PSQI) | n/a | 344 | 1.30 | 0.76 | 1.17a | 0.75 | 1.24a | 0.75 | 1.11a | 0.78 | 1.46b | 0.74 | < 0.01 |

| Pain (rated on 0-100 scale) | n/a | 331 | 27.4 | 26.8 | 21.4 | 21.5 | 29.8 | 28.3 | 32.2 | 28.7 | 27.6 | 27.6 | 0.12 |

| Physical activity (IPAQ) | n/a | 339 | 498 | 499 | 464 | 420 | 508 | 465 | 645 | 575 | 459 | 517 | 0.13 |

| Number of meals per day | n/a | 344 | 2.49 | 0.84 | 2.48 | 0.65 | 2.49 | 0.92 | 2.54 | 0.91 | 2.48 | 0.87 | 0.97 |

| Spiritual experiences (DSES) | 0.96 | 345 | 4.05 | 1.26 | 4.40b | 1.22 | 3.67a | 1.27 | 3.72a | 1.23 | 4.16b | 1.22 | < 0.001 |

| Self-esteem | n/a | 345 | 5.60 | 2.38 | 5.90 | 2.19 | 5.39 | 2.37 | 5.76 | 2.39 | 5.49 | 2.47 | 0.51 |

| Stressors | |||||||||||||

| Stress (PSS-4) | 0.70 | 355 | 2.84 | 0.70 | 2.76 | 0.69 | 2.91 | 0.69 | 2.86 | 0.64 | 2.83 | 0.73 | 0.61 |

| Distress (K6) | 0.88 | 356 | 3.45 | 0.86 | 3.51 | 0.82 | 3.35 | 0.75 | 3.49 | 0.81 | 3.46 | 0.94 | 0.69 |

| Quality of Life | |||||||||||||

| QLESQ | 0.91 | 348 | 3.44 | 0.67 | 3.58 | 0.67 | 3.38 | 0.64 | 3.44 | 0.59 | 3.40 | 0.70 | 0.25 |

| EQ5D3L Descriptive | 0.68 | 347 | 0.41 | 0.33 | 0.34 | 0.29 | 0.46 | 0.34 | 0.46 | 0.34 | 0.40 | 0.34 | 0.11 |

| Physical Health (rated on 0-100 scale) | n/a | 332 | 71.2 | 18.2 | 74.9 | 14.5 | 72.4 | 16.3 | 71.3 | 18.5 | 68.6 | 20.5 | 0.11 |

| Mental Health (rated on 0-100 scale) | n/a | 324 | 65.9 | 21.3 | 68.3 | 18.7 | 65.0 | 20.6 | 68.5 | 18.4 | 64.1 | 23.8 | 0.44 |

| EUROHIS-QOL | 0.82 | 349 | 3.37 | 0.70 | 3.56 | 0.69 | 3.31 | 0.66 | 3.28 | 0.67 | 3.35 | 0.73 | 0.08 |

| Satisfaction with Life | n/a | 346 | 4.21 | 1.67 | 4.45 | 1.73 | 3.97 | 1.68 | 4.10 | 1.58 | 4.23 | 1.66 | 0.36 |

Funding:

This work was supported by NIAAA (R01AA026288; Kelly, JF PI), Massachusetts General Hospital Recovery Research Institute and NIAAA (K24AA022136; Kelly, JF PI).

Footnotes

Declarations of interests: None.

References

- Alcoholics Anonymous (1952) Twelve Steps and Twelve Traditions. Alcoholics Anonymous World Services, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AK, Forbes E., Baker AL, Kelly PJ, Deane FP, Shakeshaft A, Hunt D, Kelly JF (2017) Systematic review of SMART Recovery: Outcomes, process variables, and implications for research. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors 31(1):1–20. 10.1037/adb0000237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bufe C (1998) Alcoholics Anonymous: Cult or cure? See Sharp Press, Arizona. [Google Scholar]

- Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF 3rd, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ (1989) The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res 28(2):193–213. 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell W, Hester RK, Lenberg KL, Delaney HD (2016) Overcoming Addictions, a Web-Based Application, and SMART Recovery, an Online and In-Person Mutual Help Group for Problem Drinkers, Part 2: Six-Month Outcomes of a Randomized Controlled Trial and Qualitative Feedback From Participants. Journal of Medical Internet Research 18(10):e262. 10.2196/jmir.5508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coskunpinar A, Dir AL, Cyders MA (2013) Multidimensionality in impulsivity and alcohol use: a meta-analysis using the UPPS model of impulsivity. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 37(9):1441–1450. 10.1111/acer.12131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Rocha NS, Power MJ, Bushnell DM, Fleck MP (2012) The EUROHIS-QOL 8-item index: comparative psychometric properties to its parent WHOQOL-BREF. Value Health 15(3):449–457. 10.1016/j.jval.2011.11.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degenhardt L, Charlson F, Ferrari A, Santomauro D, Erskine H, Mantilla-Herrara A,Whiteford H, Leung J, Naghavi M, Griswold M, Rehm J, Hall W, Sartorius B, Scott J, Vollset SE, Knudsen AK, Haro JM, Patton G, Kopec J, Malta DC, Topor-Madry R, McGrath J, Haagsma J, Allebeck P, Hay S, Foreman K, Lim S, Mokdad A, Smith M, Gakidou E, Murray C, Vos T (2018) The global burden of disease attributable to alcohol and drug use in 195 countries and territories, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. The Lancet Psychiatry 5(12):987–1012. 10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30337-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis ML, Titus J, White M, Unsicker J, Hodkgins D (2002) Global Appraisal of Individual Needs (GAIN): Administration Guide for the GAIN and Related Measures. Chestnut Health Systems, Illinois. [Google Scholar]

- Devlin NJ and Brooks R (2017) EQ-5D and the EuroQol Group: Past, Present and Future. Applied Health Economics and Health Policy 15(2):127–137. 10.1007/s40258-017-0310-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diclemente CC, Carbonari JP, Montgomery RPG., Hughes SO (1994) The Alcohol Abstinence Self-Efficacy Scale. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 55(2):141–148. 10.15288/jsa.1994.55.141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E., Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S (1985) The Satisfaction With Life Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment 49(1):71–75. 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dow SJ and Kelly JF (2013) Listening to youth: Adolescents' reasons for substance use as a unique predictor of treatment response and outcome. Psychology of addictive behaviors: journal of the Society of Psychologists in Addictive Behaviors 27(4):1122–1131. 10.1037/a0031065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endicott J, Nee J, Harrison W, Blumenthal R (1993) Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire - A New Measure. Psychopharmacology Bulletin 29(2):321–326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finney JW, Moos RH, Humphreys K (1999) A Comparative Evaluation of Substance Abuse Treatment: II. Linking Proximal Outcomes of 12-Step and Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment to Substance Use Outcomes. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 23:537–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flannery BA, Volpicelli JR, Pettinati HM (1999) Psychometric properties of the Penn Alcohol Craving Scale. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 23(8):1289–1295. 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1999.tb04349.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorski TT and Miller M (1982) Counseling for relapse prevention. Independence Press, Missouri. [Google Scholar]

- Gorski TT and Miller M (1986) Staying Sober: A Guide for Relapse Prevention. Independence Press, Missouri. [Google Scholar]

- Hagstromer M, Oja P, Sjostrom M (2006) The International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ): a study of concurrent and construct validity. Public Health Nutrition 9(6):755–762. 10.1079/phn2005898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hester RK, Lenberg KL, Campbell W, Delaney HD (2013) Overcoming Addictions, a web-based application, and SMART Recovery, an online and in-person mutual help group for problem drinkers, part 1:Three-month outcomes of a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research 15(7):e134. 10.2196/jmir.2565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath AT and Yeterian J (2012) Smart recovery: Self-empowering, science-based addiction recovery support. Journal of Groups in Addiction & Recovery 7(2-4):102–117. 10.1080/1556035X.2012.705651 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys K (2004) Circles of recovery: Self-help organizations for addictions. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys K, Klaw E. (2001) Can targeting nondependent problem drinkers and providing internet-based services expand access to assistance for alcohol problems? A study of the moderation management self-help/mutual aid organization. J Stud Alcohol. 2001 Jul;62(4):528–32. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys K and Moos R (2001) Can Encouraging Substance Abuse Patients to Participate in Self-Help Groups Reduce Demand for Health Care? A Quasi-Experimental Study. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 25:711–716. 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2001.tb02271.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys K and Moos RH (2007) Encouraging Posttreatment Self-Help Group Involvement to Reduce Demand for Continuing Care Services: Two-Year Clinical and Utilization Outcomes. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 31:64–68. 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00273.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaskutas LA. (1994) What do women get out of self-help? Their reasons for attending Women for Sobriety and Alcoholics Anonymous. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1994 May-Jun;11(3):185–95. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(94)90075-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JF (2017a) Is Alcoholics Anonymous religious, spiritual, neither? Findings from 25 years of mechanisms of behavior change research. Addiction 12(6):929–936. 10.1111/add.13590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JF (2022) The Protective Wall of Human Community: The New Evidence on the Clinical and Public Health Utility of Twelve-Step Mutual-Help Organizations and Related Treatments. The Psychiatric clinics of North America 45(3):557–575. 10.1016/j.psc.2022.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JF, Bergman B, Hoeppner BB, Vilsaint C, White WL (2017b) Prevalence and pathways of recovery from drug and alcohol problems in the United States population: Implications for practice, research, and policy. Drug and alcohol dependence 181:162–169. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.09.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JF and Eddie D. (2020) The Role of Spirituality and Religiousness in Aiding Recovery From Alcohol and Other Drug Problems: An Investigation in a National U.S. Sample. Psychology of religion and spirituality 12(1):116–123. 10.1037/rel0000295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JF and Greene MC (2013) The Twelve Promises of Alcoholics Anonymous: Psychometric measure validation and mediational testing as a 12-step specific mechanism of behavior change. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 133(2):633–640. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.08.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JF and Greene MC (2014) Beyond motivation: Initial validation of the commitment to sobriety scale. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 46(2):257–263. 10.1016/j.jsat.2013.06.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JF, Greene MC, Bergman BG (2018) Beyond Abstinence: Changes in Indices of Quality of Life with Time in Recovery in a Nationally Representative Sample of U.S. Adults. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 42:770–780. 10.1111/acer.13604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JF, Humphreys K, Ferri M (2020) Alcoholics Anonymous and other 12-step programs for alcohol use disorder. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 3:CD012880. 10.1002/14651858.CD012880.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JF, Magill M, Stout RL (2009) How do people recover from alcohol dependence? A systematic review of the research on mechanisms of behavior change in Alcoholics Anonymous. Addict Res Theory 17(3):236–259. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JF, Urbanoski KA, Hoeppner BB, Slaymaker V (2011) Facilitating comprehensive assessment of 12-step experiences: A Multidimensional Measure of Mutual-Help Activity. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly 29(3):181–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JF and William WL (2012) Broadening the Base of Addiction Mutual-Help Organizations, Journal of Groups in Addiction & Recovery 7:2-4, 82–101. 10.1080/1556035X.2012.705646 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JF and Yeterian JD (2012) Empirical awakening: the new science on mutual help and implications for cost containment under health care reform. Substance abuse 33(2):85–91. 10.1080/08897077.2011.634965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly PJ, Deane FP, Baker AL (2015) Group cohesion and between session homework activities predict self-reported cognitive–behavioral skill use amongst participants of SMART recovery groups. Journal of substance abuse treatment 51:53–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly PJ, McCreanor K, Beck AK, Ingram I, O'Brien D, King A, McGlaughlin R, Argent A, Ruth M, Hansen BS, Andersen D, Manning V, Shakeshaft A, Hides L, Larance B (2021) SMART Recovery International and COVID-19: Expanding the reach of mutual support through online groups. Journal of substance abuse treatment 131:108568. 10.1016/j.jsat.2021.108568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Barker PR, Colpe LJ, Epstein JF, Gfroerer JC, Hiripi E, Howes MJ, Normand SLT, Manderscheid RW, Walters EE, Zaslavsky AM (2003) Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Archives of General Psychiatry 60(2):184–189. 10.1001/archpsyc.60.2.184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lum A, Damianidou D, Bailey K, Cassel S, Unwin K, Beck A, Kelly P, Argent A, Deane F, Langford S, Baker AL, McCarter K (2022) SMART Recovery for Youth: A Qualitative Study Exploring the Potential of a Mutual-Aid, Peer Support Health Behaviour Change Program for Young People. SSRN preprint. 10.2139/ssrn.4121575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlatt GA and Gordon JR (1985) Relapse prevention. Guilford Press, New York. [Google Scholar]

- McCabe RE, Milosevic I, Rowa K, Shnaider P, Pawluk EJ, Antony MM, the DART Working Group (2017) Diagnostic Assessment Research Tool (DART). St. Joseph's Healthcare Hamilton/McMaster University. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR and Delboca FK (1994) Measurement of Drinking Behavior Using the Form-90 Family of Instruments. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 12:112–118. 10.15288/jsas.1994.s12.112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Tonigan JS, Longabaugh R (1995) The Drinker Inventory of Consequences (DrInC): An instrument for assessing adverse consequences of alcohol abuse. Test manual. In Mattson ME & Marshall LA (Eds.), Project MATCH Monograph Series (Vol. 4). National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. [Google Scholar]

- O’Sullivan D, Blum JB, Watts J, Bates JK (2015) SMART Recovery: Continuing Care Considerings for Rehabilitation Counselors. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin 58(4):203–216. 10.1177/0034355214544971 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O'Sullivan D, Watts JR, Xiao Y, Bates-Maves J (2016) Refusal Self-Efficacy Among SMART Recovery Members by Affiliation Length and Meeting Frequency. Journal of Addictions & Offender Counseling 37(2):87–101. [Google Scholar]

- Peele S (1990) Research issues in assessing addiction treatment efficacy: how cost effective are Alcoholics Anonymous and private treatment centers? Drug Alcohol Depend 25(2):179–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins RW, Hendin HM, Trzesniewski KH (2001) Measuring global self-esteem: Construct validation of a single-item measure and the Rosenberg self-esteem scale. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27(2):151–161. 10.1177/0146167201272002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt S, Muhlan H, Power M (2006) The EUROHIS-QOL 8-item index: psychometric results of a cross-cultural field study. European Journal of Public Health 16(4):420–428. 10.1093/eurpub/cki155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SMART Recovery (2017) Annual Report. SMART Recovery. https://www.smartrecovery.org/about-us/annual-surveys/ [Google Scholar]

- Stepanikova I, Oates GR. (2017). Perceived Discrimination and Privilege in Health Care: The Role of Socioeconomic Status and Race. Am J Prev Med. 52(1S1):S86–S94. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Underwood LG and Teresi JA (2002) The daily spiritual experience scale: Development, theoretical description, reliability, exploratory factor analysis, and preliminary construct validity using health-related data. Annals of Behavioral Medicine 24(1):22–33. 10.1207/s15324796abm2401_04 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilsaint CL, Kelly JF, Bergman BG, Groshkova T, Best D, White W (2017) Development and validation of a Brief Assessment of Recovery Capital (BARC-10) for alcohol and drug use disorder. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 177:71–76. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.03.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warttig SL, Forshaw MJ, South J, White AK (2013) New, normative, English-sample data for the Short Form Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-4). Journal of Health Psychology 18(12):1617–1628. 10.1177/1359105313508346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wewers ME and Lowe NK (1990) A Critical Review of Visual Analog Scales in the Measurement of Clinical Phenomena. Research in Nursing & Health 13(4):227–236. 10.1002/nur.4770130405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White WL, Kelly JF, Roth JD (2012) New addiction-recovery support institutions: Mobilizing support beyond professional addiction treatment and recovery mutual aid. Journal of Groups in Addiction & Recovery 7(2-4):297–317. 10.1080/1556035X.2012.705719 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zemore SE, Kaskutas LA, Mericle A, Hemberg J (2017) Comparison of 12-step groups to mutual help alternatives for AUD in a large, national study: Differences in membership characteristics and group participation, cohesion, and satisfaction. Journal of substance abuse treatment 73:16–26. 10.1016/j.jsat.2016.10.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zemore SE, Lui C, Mericle A, Hemberg J, Kaskutas LA (2018) A longitudinal study of the comparative efficacy of Women for Sobriety, LifeRing, SMART Recovery, and 12-step groups for those with AUD. Journal of substance abuse treatment 88:18–26. 10.1016/j.jsat.2018.02.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]