Abstract

Objective

Patients experiencing unexplained chronic throat symptoms (UCTS) are frequently referred to gastroenterology and otolaryngology outpatient departments for investigation. Often despite extensive investigations, an identifiable structural abnormality to account for the symptoms is not found. The objective of this article is to provide a concise appraisal of the evidence-base for current approaches to the assessment and management of UCTS, their clinical outcomes, and related healthcare utilisation.

Design

This multidisciplinary review critically examines the current understanding of aetiological theories and pathophysiological drivers in UCTS and summarises the evidence base underpinning various diagnostic and management approaches.

Results

The evidence gathered from the review suggests that single-specialty approaches to UCTS inadequately capture the substantial heterogeneity and pervasive overlaps among clinical features and biopsychosocial factors and suggests a more unified approach is needed.

Conclusion

Drawing on contemporary insights from the gastrointestinal literature for disorders of gut–brain interaction, this article proposes a refreshed interdisciplinary approach characterised by a positive diagnosis framework and patient-centred therapeutic model. The overarching aim of this approach is to improve patient outcomes and foster collaborative research efforts.

Keywords: MOTILITY DISORDERS, DYSPHAGIA, NEUROGASTROENTEROLOGY

Summary box.

Unexplained chronic throat symptoms (UCTS) are a common presentation to gastroenterology and otolaryngology departments and cause considerable burden in both primary and specialist care.

The yield of diagnostic tests is low and the assessment and management of UCTS differs widely across specialty settings, involving contradictory aetiological concepts, nomenclature and terminology, fragmenting patient care, consequently leading to variable outcomes.

Clinical characteristics are non-specific and occur in heterogeneous fashion between diagnostic divides. Their correlation to postulated diagnoses remains unresolved, presenting a diagnostic and management dilemma for clinicians.

Key multifactorial pathophysiological concepts include chronic laryngopharyngeal inflammation, sensory and motor dysfunctions, symptom hypervigilance, intersected by diverse biopsychosocial factors, with significant overlaps with disorders of gut–brain interaction.

Evidence suggests a more unified symptom construct and interdisciplinary approach may offer advantages both for patient outcomes and collaborative research endeavours.

Introduction

Chronic throat symptoms, including cough, dysphonia, dysphagia, globus sensation and throat clearing, are frequently encountered in outpatient clinics.1–3 Differential diagnoses for these bothersome symptoms intersect multiple specialties, including otolaryngology, gastroenterology and respiratory medicine.4 5 However, identifying a definitive organic cause is often challenging for these symptoms, even with extensive evaluations.1 5 6

Scenarios involving unexplained chronic throat symptoms (UCTS) present a dilemma for clinicians, as they contend with clinical ambiguity and unclear management directions. Their aetiology and pathophysiology though widely postulated continue to have unresolved clinical correlations. Current research frequently polarises rather than unites, with conclusions confounded by diverse clinical taxonomies and specialty concepts.7 8 Consequently, cohesive, evidence-driven guidelines for UCTS remain absent.

There is no common terminology adopted for clinical presentations involving UCTS,9 which hinders precise prevalence estimates. Notwithstanding, UCTS is estimated to constitute a significant burden in primary care4 5 and often necessitate additional specialist evaluations.10–12 While often overlooked in the absence of clinical red flags,13 these symptoms are associated with significant morbidity, indicating a potentially under-recognised public health issue.14–17

In response to this area of need, we assembled a collaborative team of otolaryngology and gastroenterology specialists with the goal of providing a concise appraisal of aetiological and pathophysiological concepts in this field, including existing terminologies and their clinical implications. A key objective was to review the evidence and outcomes of existing single specialty-led approaches to UCTS diagnosis and management.

Next, based on the findings of our review, we aimed to provide readers with a practical evidence-based framework for the assessment and management of UCTS presentations.

Methodology

A multidisciplinary team with diverse clinical backgrounds collaborated to define the objectives of this narrative review and synthesise the pivotal findings.

A comprehensive literature search was conducted using PubMed, Scopus and MEDLINE until June 2023. Keywords and MeSH terms pertinent to chronic aerodigestive symptoms were used. Manual citation analysis revealed additional pertinent studies. We evaluated original research, review articles, clinical trials and impactful editorials. Data concerning the clinical manifestations, patient characteristics, aetiological concepts, diagnosis and management approaches, and terminology related to UCTS were extracted and assessed. Authors independently assessed articles, collaboratively synthesised key findings and reached consensus. Findings are presented thematically, grouping related concepts and key insights to underscore complex interactions and challenges. Based on the review findings, a suggested evidence-based multidisciplinary biopsychosocial framework for UCTS was developed incorporating aetiological perspectives and encompassing multifaceted symptom influences.

UCTS: epidemiology and public health importance

Chronic throat symptoms listed in table 1 encompass persistent complaints (>8 weeks) related to the throat, upper airway, voice or swallowing. Given the complex interactions between the aerodigestive structures and the symptom heterogeneity, multidisciplinary engagement is often necessitated.1–3 Differential diagnoses span various aerodigestive lesions and other structural pathologies (table 2). Typically, distinctive symptom insights within organic disease frameworks facilitate a targeted assessment strategy for the undifferentiated patient, which is influenced by presenting symptoms and pertinent patient factors such as medical history and smoking status. These relationships expedite the exclusion of malignant diseases, steering investigations towards the most relevant aetiologic considerations, which permits efficient care across diverse specialty realms.

Table 1.

Chronic throat symptoms encountered in primary care and specialist outpatient centres

| Symptoms | Clinical red flags | Patient red flags |

| Cough Dysphonia Globus sensation Oropharyngeal dysphagia Repetitive throat clearing Catarrh/sensation of mucus in the throat Abnormal throat sensations |

Progressive symptoms Regurgitation of undigested foods Odynophagia Haemoptysis New dysphagia Airway limitation symptoms Weight loss Constitutional symptoms Bone pain or generalised aches Palpable or radiological thyroid mass or nodule Palpable or radiological lymphadenopathy |

Smoker or ex-smoker Immunosuppression Prior head and neck cancer Prior head and neck radiation History of skin cancer Prior haematological malignancy History of respiratory cancer History of oesophageal cancer History of Barrett’s oesophagus |

Table 2.

Structural and pathological causes of chronic throat symptoms

|

Structural disease Malignant lesions of the aerodigestive tract Benign lesions of the aerodigestive tract Tonsillar hypertrophy Pharyngeal diverticulum Reinkes oedema Vocal cord palsy Fixed larynx Laryngeal trauma Pharyngeal web Candidiasis Regional disease Thyroid nodules or goitre Neck masses (benign and malignant) Neck cysts (benign and malignant) Cervical lymphadenopathy |

Oesophageal pouch/diverticulum Oesophageal web Mediastinal tumours Lymphoma Eagles’ syndrome Cricopharyngeal spasm Intrusive cervical osteophytes Neurological disease Stroke (including brainstem infarcts with bulbar involvement) Parkinson’s disease CNS tumour Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis Multiple sclerosis Polymyositis Myotonic dystrophy Bulbar palsy |

Laryngeal dystonia Guillain Barre syndrome Myasthenia gravis Spasmodic tremor Motor neuron disease Muscular dystrophy Cerebral palsy Respiratory disease Asthma (and variants) Allergic rhinitis Rhinosinusitis Restrictive lung disease Bronchiectasis Chronic bronchitis Eosinophilic bronchitis Bronchogenic cancer Tuberculosis Cystic fibrosis Primary ciliary dyskinesia |

Systemic disease Sjogren syndrome Systemic lupus erythematosus Mixed connective tissue disease Rheumatoid arthritis Systemic sclerosis Wagner’s Hypothyroidism Amyloidosis Relapsing polychondritis Sarcoidosis Epidermolysis bullosa Pemphigoid Angioneurotic oedema Medications Tricyclic antidepressants Potassium supplements NSAIDs |

Nitrates Calcium channel blockers Opioids ACE inhibitors Bisphosphonates Anticholinergics Iatrogenic Head and neck surgery Head and neck radiation Intubation trauma Non-invasive ventilation |

ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; CNS, central nervous system.

UCTS describe the scenario when no clear organic or structural pathology is identified despite thorough evaluations of the presenting complaints. The lack of standardised terminology for UCTS complicates accurate prevalence estimates.9 Table 3 summarises prevalence data reported for individual symptoms, alongside the proportion of cases labelled ‘idiopathic’ or ‘functional’ after investigation. These data suggest that no discernible structural pathology is evident in 31–93% of UCTS presentations, depending on the symptom and assessment method. Given the high prevalence of chronic throat symptoms in general populations, this supports estimates that UCTS may collectively account for 5–10% of total primary care visits5 and precipitates significant numbers of referrals to otolaryngology, gastroenterology, respiratory and other specialty departments.4 5 However, inconsistent terminology for ‘non-organic’ throat symptoms and limited examinations may understate their true prevalence. While UCTS are generally considered benign, growing evidence of their impact on quality-of-life14–17 indicates a public health significance that may be under appreciated.

Table 3.

Epidemiology of chronic throat symptoms

| Chronic throat symptom | Prevalence (general populations) | Per cent of cases without organic disease cause |

| Cough | 2–18%113 | 42%113 |

| 10%155 | 37%155 | |

| 12.5%156 | ||

| 8.2%157 | ||

| 2.5%135 | ||

| Dysphonia | 7.6%158 | 42.5%47 |

| 3–15%47 | 43.7%6 | |

| 6.6–7.5%6 | 60%159 | |

| 10%48 | 31%48 | |

| Globus sensation | 45%110 | 86–90% |

| 12.5%114 | 92.6%160 | |

| 22%161 | ||

| 26.48%129 | ||

| Oropharyngeal dysphagia | 40%162 | 51–21%163 |

| 16.4%164 | 58%165 | |

| 22%166 | 3.2%167 (incidence of functional dysphagia in general population) | |

| 13%168 | ||

| 43.8%169 | ||

| 20%170 | ||

| Catarrh/mucus sensation | ND | ND |

| Repetitive throat clearing | ND | ND |

ND, no data.

Diagnostic and clinical classifications of UCTS

Several aetiological theories have emerged over decades of scientific enquiry to account for UCTS and inform divergent diagnoses and treatment approaches employed for these complaints. These may be broadly divided into chronic inflammatory and functional symptom concepts, the prominent theories and diagnoses of which are summarised below.

Chronic inflammatory concepts

Occult irritation of the aerodigestive tract causing chronic inflammation of the larynx or laryngopharynx is promoted as a cause of non-specific UCTS. Potential contributors include refluxed gastroduodenal content, inhaled irritants, respiratory allergens and voice behaviours. However, inflammatory indicators from nasoendoscopy18 are non-specific to both symptoms and postulated inflammatory aetiology in most literature investigating this relationship,3 5 8 19 are often identified in asymptomatic individuals20 and are subject to variable interpretations, highlighting diagnostic complexities.

Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease

Laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR) is theorised to result from the back flow of gastroduodenal contents into the laryngopharynx, leading to chronic inflammation.21–23 Central to its pathophysiology is the inflammatory reaction to these contents, with pepsin being a primary culprit.24–27 Although gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) is more prevalent among those with chronic throat issues,3 attributing aerodigestive symptoms to LPR is contentious.1 22 28–30 Unlike GORD, reflux-associated throat symptoms are non-specific,1 often seen in upright individuals during the day, regardless of BMI, and typically without heartburn.4

Diagnostic approach

Diagnosing LPR is complex. Nasoendoscopic findings reflect secondary mucosal inflammation and are open to interpretation.5 7 19 21 The gold standard for GORD diagnosis, intraluminal oesophageal pH-impedance (pH-II), has poor sensitivity and specificity for LPR, offering little therapeutic guidance.28 31–34 The search for a definitive diagnostic tool for LPR continues, making the current diagnosis largely clinical.

Treatment approach

Treatment often mirrors those used in treatment of GORD, emphasising lifestyle changes although their effectiveness has yet to be validated. Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) were once the go-to for LPR, but recent studies question their efficacy for reflux-induced laryngeal symptoms,35–38 possibly due to the role of pepsin. Liquid alginates consumed after meals may have modest benefits based on early research.39 40 Anti-reflux surgery appears to be more effective than acid suppression therapies,22 41–46 but its symptomatic relief does not always correlate with acid and impedance metrics,33 43 leading to varied interpretations in the literature and challenges in patient selection.

Vocal demand and voice behaviour

Dysphonia and other irritating throat symptoms are more prevalent among professional voice users6 due to prolonged or exaggerated vocal fold vibration, which cause mechanical epithelial injury and inflammation, termed phonotrauma.47–53 Laryngeal muscle tension and fatigue related to excess vocal strain may play a role7 10 54–56 and contributions from psychosomatic factors are common themes in the literature.10 48 57–60

Diagnostic approach

A history of increased voice demand is sought although chronic phonatory symptoms (cough and throat clearing) are also considered potential precipitants.61 Nasoendoscopic findings involving laryngeal inflammation, motor tension or disrupted vocal cord movement may be contributory although such features are non-specific.7 62

Treatment approach

Treatments include strategies to improve vocal hygiene and minimise excess voice demands, as well as targeted therapies to normalise aberrant motor patterns or tension63–65 and address sensory components which may drive phonotraumatic symptoms.66–68 Patients may also be provided with reflux therapies in a ‘cover all’ approach.

Aerosolised irritants

Numerous airborne aerosols are irritative or noxious to the respiratory tract, including the laryngopharynx.47 52 69–74 Irritants are classified by occupational, domestic and environmental source. Impacts on the aerodigestive tract are specific to irritating agents and are associated with several throat symptoms.

Diagnostic and treatment approach

Comprehensive analysis of environmental aerodigestive irritants and proposed aerodigestive symptom implications are available, including diagnostic and therapeutic strategies.52 70 73

Respiratory allergy

Allergic rhinitis (AR) and asthma are among the most common allergic manifestations in the general population.75 76 Despite a continuous respiratory epithelium extending between the nasal and lower airways,75 the larynx and pharynx are excluded among defined airway allergy phenotypes.75 77 Chronic throat symptoms are more prevalent in allergic populations78–80 and vice versa.81 Historically, throat symptoms when present are regarded as secondary manifestations, caused by irritative secretions travelling up from the lower airway or falling from the nasal cavity or via unified airway pathophysiology.82–86 However, emerging evidence advances IgE-mediated eosinophilic inflammation within the laryngopharynx as a previously under-recognised consequence of allergen sensitisation in some.77 83 87 88 This concept of an ‘allergic laryngitis’ (AL) is supported by a developing literature that points to epidemiological evidence and results from direct allergy provocation studies in both animal and human studies.80 87 89 Further research is needed to clarify its biological basis and clinical implications.

Diagnostic and treatment approach

AL is yet to be accepted as a valid diagnosis of airway allergy and has no established diagnostic or treatment directions beyond chronic cough under the ‘upper airway cough syndrome’ framework.

Functional throat disorders (FTD)

Throat symptoms appear to, in some cases, reflect patterns of abnormal aerodigestive sensation, motility and/or reflex function.11 90 These physiological disruptions to usual function are proposed to account for varied symptom presentations in patients without structural disease.

Sensory disruptions

Hypersensitisation of aerodigestive structures is a common theme among symptom theories related to UCTS.11 15 51 66 91–98 Cough hypersensitivity syndrome (CHS) and laryngeal hypersensitivity and diagnoses which typify this pathophysiological pattern, reinforced by emerging research.10 15 22 51 66 71 91 92 97–103 The core understanding implicates sensory dysregulation of aerodigestive tract or related reflexes in symptom emergence, most notably cough and globus sensation.92 104–108 Postulated mechanisms encompass epithelial sensory receptor adaptations in response to chronic inflammation or other stimuli,90 somatosensory adaptations involving the vagus nerve or higher centres involved in neuromotor regulation of the aerodigestive tract.95 109

Motor disruptions

Beyond sensory dysfunction, dysregulated motor patterns impacting the laryngeal or supraglottic musculature are detected during laryngoscopic evaluations in patients with UCTS.10 54–56 Two predominant phenotypes emerge: vocal cord dysfunction syndromes that, barring inducible laryngeal obstructions, do not compromise respiratory function; and muscle tension syndromes, particularly concerning the supraglottic musculature. Manifestations include a spectrum of chronic throat symptoms, with dysphonia, globus, throat clearing and cough often highlighted.11 Oropharyngeal dysphagia and globus sensation are likewise proposed to show association with motor tone or coordination dysfunctions affecting the upper oesophageal sphincter or proximal oesophagus.41 110–112

Aetiology of FTDs

The aetiology of sensory and motor dysfunctions in FTD remains elusive. Associations encompass psychosomatic factors, central adaptations, personality, gender, trauma, chronic pain, overlapping functional gastrointestinal disorders now considered as disorders of gut–brain interaction (DGBI), viral infections, microbiome and prolonged inflammatory stimuli of various sorts.11 89 97 109 113–115 CL is identified as a key risk factor for physiological changes proposed to underlie functional symptoms, and sensory and/or motor changes may themselves predispose patients to chronic laryngitis through various mechanisms. Differentiating inflammatory from functional causes is therefore challenging among intertwined pathophysiological relationships.13 51

Diagnostic approach

Diagnoses that identify sensory or motor changes as the cause of symptoms in UCTS are numerous. They may relate to specific symptoms (eg, CHS), refer to postulated symptom mechanisms (eg, laryngeal dysfunction), or a combination thereof (eg, muscle tension dysphonia). Diagnostic approaches vary but typically couple symptom and patient factors with functional disruptions on a clinical basis after organic disease exclusion, occasionally incorporating nasoendoscopic findings.

Treatment approach

Treatments for FTD restore normal sensory and motor aerodigestive functions and may directly target potential precipitants or symptoms. Non-pharmacological interventions include sensory and motor rehabilitation programmes63 and other behavioural interventions.116 117 On the pharmacological front, neuromodulators and antidepressants may mitigate sensory and motor irregularities15 64 67 85 91 118 and bolster normal functions by addressing central adaptations and psychosomatic factors.10 11 59 119

Biopsychosocial interactions in UCTS

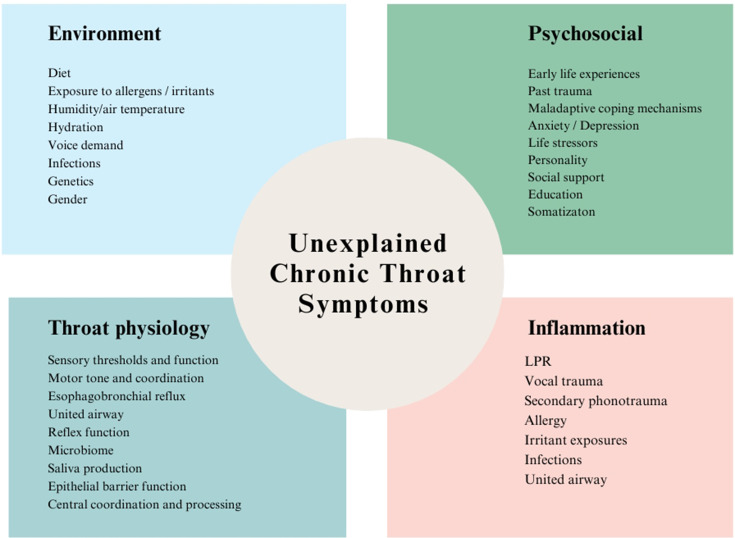

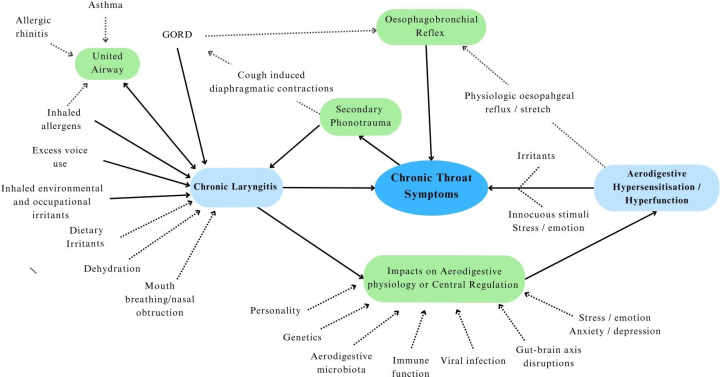

The aerodigestive tract is an intricate physiological structure. Its optimal function hinges on the sophisticated interplay of somatosensory feedback, central processing and coordinated motor responses.28 58 104 108 120–124 This interplay is mediated through dense vagal networks linking the aerodigestive structures with regulatory centres in the brain stem and cortex, which are enhanced by voluntary somatic inputs.57 101 125 126 In addition, locoregional organ feedback and disease states influence function through unified airway and oesophagobronchial mechanisms.108 127 128 The aerodigestive mucosa is unique in its exposure to inhaled air with variable temperature, humidity and particulate content; endogenous secretions; and diverse ingested materials. Various biopsychosocial factors (figure 1) further modulate its function and are yet to be fully explored (figure 1).91 113 129–133 The complex potential for interaction among these factors in the generation of UCTS is outlined in figure 2 and is reminiscent of those that characterise DGBI.

Figure 1.

Biopsychosocial influences in unexplained chronic throat symptoms. LPR, laryngopharyngeal reflux.

Figure 2.

Biopsychosocial model of unexplained chronic throat symptoms. GORD, gastroesophageal reflux disease.

Taxonomy and terminology of UCTS and related diagnoses

UCTS involves diverse symptom presentations, in the absence of structural causes, and encompasses divergent aetiological theories and specialty approaches. This clinical dilemma is the subject of highly divided terminology and taxonomy, involving specialty and regional divides and presents a challenge in developing consistent clinical guidelines. Divisions reflect varying interpretations of symptom mechanisms, origins and significance, as detailed above.

In table 4, diagnoses and other labels relevant to UCTS in the literature are presented and categorically divided according to inflammatory and functional concepts. Terms with a shared clinical or pathophysiological focus are further grouped. Current understanding of clinical features, symptom mechanisms, disease associations and other identified biopsychosocial factors for each were synthesised from the literature and are summarised in the table. Similarly, biopsychosocial associations associated with each UCTS reported in the literature are summarised in table 5.

Table 4.

Clinical features reported in association with unexplained chronic throat symptoms

| Chronic inflammation—chronic laryngitis (CL) | Functional throat disorders (FTD) | |||||

| Common pathophysiology | Chronic non-eosinophilic inflammation of the ADT | Chronic eosinophilic inflammation of the ADT | Abnormal sensory or motor function within the ADT or components, without clear organic disease correlates | |||

| Aetiology | GORD | Aeorsolised irritants | Voice behaviours | Aerosolised allergens | Aerodigestive sensory/reflex dysfunction | Aerodigestive motor dysfunction |

| Diagnoses | LPR, EER, RL | OL, WAL, WUACS, WAILS, OCS | VA, VTL, SD, MTD | LA, AL | ILS, LH, SLN, LD, CHS, ICC, RCC, GP | LD, MTD, FD, LHS, UESD, CPS, VCD, PVFM, STD |

| Reported symptoms | ||||||

| Cough | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| Dysphonia | ++ | ++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| Dysphagia | + | + | + | + | ++ | +++ |

| Globus | ++ | + | + | + | +++ | ++ |

| Paraesthesia | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | + |

| Throat clearing | ++ | ++ | ++ | +++ | ++ | ++ |

| Reported nasoendoscopic findings | ||||||

| Features of mucosal inflammation | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| Vocal cord dysfunction | + | + | ++ | + | ++ | ++ |

| Abnormal muscle tone or coordination | ++ | ++ | +++ | ++ | +++ | +++ |

| Sensitive and specific clinical findings or biochemical markers | No | No | No | No | No | No |

AL, allergic laryngitis; CHS, cough hypersensitivity syndromes; CPS, cricopharyngeal spasm; EER, extraesophageal reflux; FD, functional dysphonia; GORD, gastro-oesophageal reflux disease; GP, Globus pharyngeus; ICC, idiopathic chronic cough; ILS, irritable larynx syndrome; LA, laryngeal allergy; LD, laryngeal dysfunction; LH, laryngeal hypersensitivity; LHS, laryngeal hyperfunction syndromes; LPR, laryngopharyngeal reflux; MTD, muscle tension dysphonia; OCS, occupational cough syndrome; OL, occupational laryngitis; PVFM, Paradoxical vocal fold movement (excluding inducible laryngeal obstruction); RCC, refractory chronic cough; RL, reflux laryngitis; SD, Singers dysphonia; SLN, superior laryngeal nerve neuropathy; STD, supraglottic tension dysphonia ; UESD, upper oesophageal sphincter dysfunction; VA, vocal abuse; VCD, vocal cord dysfunction; VTL, vocal tension laryngitis; WAILS, Workplace associated irritable larynx syndrome OCS ; WAL, workplace-associated laryngitis; WUACS, Workplace upper airway cough syndrome .

Table 5.

Symptom associations in unexplained chronic throat symptoms

| Associations | Cough | Dysphonia | Globus | Dysphagia |

| Female gender | ++ | ++ | +++ | + |

| Anxiety/depression | ++ | ++ | +++ | +++ |

| Professional voice use | ++ | +++ | ++ | + |

| Environmental irritants | +++ | ++ | ++ | – |

| GORD | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ |

| Allergy | ++ | ++ | ++ | + |

| Vocal cord dysfunction | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| Supraglottic tension | ++ | ++ | +++ | + |

| Chronic laryngitis | +++ | +++ | ++ | ++ |

GORD, gastro-oesophageal reflux disease.

On review of the literature, three broad themes emerged in terms of diagnostic taxonomy and nomenclature:

Symptom-centric terms

Various diagnoses in the UCTS landscape identify a predominant symptom profile following the exclusion of structural pathologies (eg, idiopathic cough, functional dysphonia). This extends the symptom-directed approach that guides the assessment of organic and structural disease concepts in patients with undifferentiated throat symptoms.

Mechanism-centric terms

Diagnoses may identify a central mechanism for UCTS and likewise imply the absence of identifiable organic disease. They may relate to single symptoms (eg, CHS, muscle tension dysphonia) or encompass multiple symptom manifestations (eg, Laryngeal dysfunction).

Disease-centric terms

UCTS may be empirically attributed to consequences of underlying disease states, such as reflux or allergy (LPR, AL). These diagnoses are distinguished from those in table 2 by the inherent challenge in both identifying the proposed disease and establishing the symptom–disease correlation.

Are existing clinical classifications and divisions of UCTS substantiated?

We assessed whether the diagnostic and descriptive divisions outlined table 4 correspond to substantiable clinical phenotypes or populations, separable by defined clinical criteria, investigation findings or biopsychosocial factors. Our literature review summarised in tables 4 and 5 revealed poor performance and specificity of current symptom-centric, mechanism-centric and disease-centric labels, with considerable overlapping symptom profiles and clinical features across the common diagnostic categories for UCTS. Furthermore, symptoms were found to rarely occur in isolation, despite their division through varying diagnostic concepts.99 134 Present taxonomic approaches and related terminology were therefore found to reflect a dualistic, ‘all-or-nothing’ diagnostic paradigms, which appeared not to recognise the extensive clinical heterogeneity and shared multifactorial biopsychosocial influences. The absence of clear structural pathology diminishes the predictive power of symptom indicators, which, in tandem with variations in clinician approach, specialty perspectives and symptom interpretations, complicates the establishment of uniform assessment and management protocols. Our review has highlighted a consequent divergence in diagnostic and therapeutic approaches across specialties.5 7 8 This may contribute to fragmented care, patient dissatisfaction and anxiety,135 and increased healthcare resource use as clinicians’ resort to repeated and often overlapping investigations in pursuit of diagnostic or treatment direction.

The case for a more unified approach to UCTS

In a study involving 344 prospective patients with UCTS, no association was found between symptoms and nasoendoscopic features.5 In addition, attempts to define distinct patient subgroups through assessment of clinical, demographic and biopsychosocial factors have been unsuccessful.5 This notable finding aligns with the qualitative assessment presented here, highlighting the indistinct boundaries among UCTS presentations and strongly suggests the need for a more holistic and unified perspective. Recurrent themes involving inflammatory stimuli, psychosomatic influences, aerodigestive sensitisation and motor disruptions and overlap with other functional disease syndromes are consistent in the literature surveyed. A syndrome-based perspective offers the potential for a comprehensive framework that captures the diverse manifestations of UCTS and is substantiated by increasing support in the literature.4 5 59 134 This shift may pave the way for holistic, patient-centric research and therapeutics that encompass multifactorial influences on symptoms.

This collaborative review has highlighted several important themes and challenges related to UCTS, drawn from the relevant specialty literature. Our review has highlighted that UCTS profoundly affects patients’ well-being. The widespread division among varied terminologies and specialty perspectives may underestimate its prevalence and public health impact. Such symptoms, when persistent, commonly drive primary care visits and negatively impact patient quality of life.

Moreover, the non-specificity of UCTS has proven to be clinically challenging. Although clinical phenotypes may be present and offer potentially valuable therapeutic directions, the present reliance on symptom characteristics for diagnosis may mislead clinicians who extrapolate symptom meanings applicable within structural and organic symptom frameworks. While definitions for non-structural throat complaints continue to develop and evolve across specialty literature, this review highlights the limitations of these often unilateral, single specialty approaches. The absence of a unified symptom language and minimal interdisciplinary collaboration in both clinical and scientific contexts have hampered progress.

Our review highlighted that the diagnostic approach often varies based on specialty perspectives, leading to inconsistent treatment plans. The inability to link UCTS to objective disease markers makes establishing causality difficult. Because of the non-distinct nature of these symptom presentations, responses to varied therapeutic interventions are inconsistent and differ significantly among patients. This indicates an intricate pathophysiology not completely represented by current diagnostic approaches. Finally, our review highlighted the significant overlap between DGBI and UCTS involving complex aerodigestive sensorimotor dysfunction, symptom hypervigilance and complex biopsychosocial interactions.

Are UCTS part of a spectrum of DGBI?

It is clear from the findings of our review that the profile of UCTS closely mirrors functional gastrointestinal disorders, now classified as DGBI, with symptoms not explained by structural abnormalities, redundant tests, multifactorial pathophysiology and stigmatisation, resulting in patient dissatisfaction and inflated healthcare costs.136

Current approaches to the diagnosis and management of UCTS are rooted in dualistic aetiological theories, resulting in fragmented diagnoses and inconsistent treatments. However, within gastroenterology, the introduction of the Rome IV DGBI criteria has marked an important shift. Modern evidence from DGBI literature has evolved to refute simplistic mind–body dualistic notions,137 instead uncovering characteristic and complex physiologic disruptions in these patients, even if a biochemical marker or structural aberrations cannot be readily represented.114 138 139

The Rome IV criteria unify previously disparate diagnoses by focussing on symptom clusters and multidimensional clinical profiles, as opposed to speculative aetiological theories, streamlining the diagnostic process and promoting efficient delivery of effective therapy for patients.139 They underscore the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration in DGBI management, integrating the expertise of gastroenterologists, dietitians, psychologists and primary care physicians. This holistic approach recognises the intricate interplay of biological, psychological and social factors, promotes enhanced patient outcomes and empowerment and fosters healthcare efficiency by reducing superfluous tests and expediting interventions.140–144

The structured DGBI framework has also spurred significant research advances through the adoption of a common language for ‘non-organic’ gastrointestinal symptoms, deepening the understanding of epidemiology, pathophysiology and evidence-based treatments in this field, ultimately optimising patient care.

Transferring insights from gastroenterology towards a comprehensive approach to UCTS

Inspired by these transformative strides within DGBI and gastroenterology, there is a compelling case for adopting a similar paradigm in UCTS. The potential benefits of translating this approach to UCTS include:

Diagnostic clarity

A structured, symptom-focused diagnostic criteria may unite divided practice, validating and authenticating patient experience through adoption of a positive diagnostic strategy. A cohesive system would demystify diagnoses for both patients and clinicians reduce ambiguities and enhance patient trust in the diagnostic journey.

Multidisciplinary collaboration

An integrated collaborative stance incorporating multidisciplinary specialist and allied health expertise can offer a comprehensive perspective, ensuring that all aspects—physical, physiological, psychological, and social—are considered.

Comprehensive care strategies

Adopting a biopsychosocial care model promotes holistic, patient-focused treatments, which may improve outcomes and enhance patient satisfaction.

Efficient care delivery

Streamlined approach may minimise redundant tests, reduce hospital visits, expedite symptomatic treatments, and reduce healthcare costs.

Research impetus

Stimulate collaborative research endeavours, deepening understanding of its aetiology, treatments, and potential prevention strategies.

‘Irritable throat syndrome’ as a unifying concept

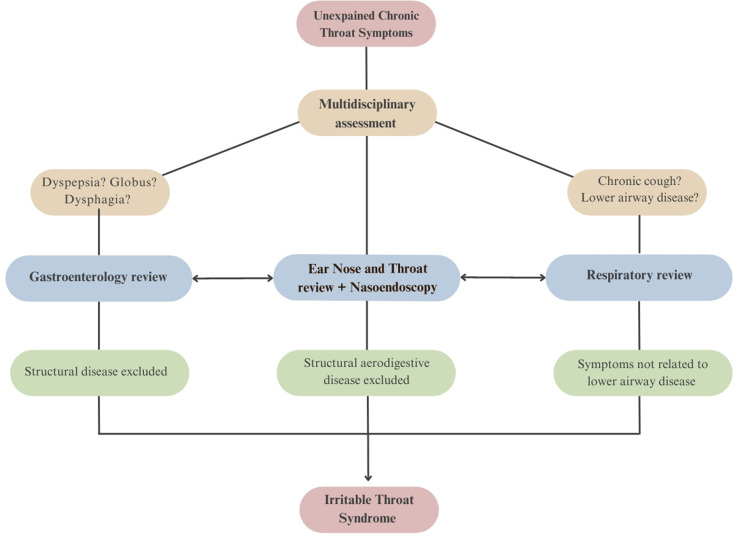

Our findings suggest that there is a pressing need for an updated multidisciplinary strategy for patients presenting with UCTS. While current Rome IV diagnostic criteria for oesophageal DGBI do incorporate some patients with UCTS under globus and functional dysphagia criteria,145 this review article has highlighted the need to broaden the spectrum given the breadth and heterogeneity of symptom presentations of patients with UCTS. A model for such an approach, under a proposed ‘irritable throat’ framework, is outlined here (figure 3), drawing on the key findings of this collaborative review of literature while incorporating existing Rome IV diagnostic criteria for globus and functional dysphagia.145

Figure 3.

Suggested approach for a positive diagnosis of irritable throat syndrome.

The term ‘irritable throat syndrome’ (ITS) appears variably in the literature, with inconsistent definitions.52 57 59 68 71 146 The term is advantageous because of its simplicity, clear anatomical correlations and parallels to the well-accepted Rome criteria for irritable bowel syndrome. Our findings suggest that this term could be repurposed through a broadened and interdisciplinary construct for patients with chronic throat symptoms that are inadequately explained by structural abnormalities, believed to result from complex interactions between biopsychosocial factors.

Establishing a positive diagnosis: suggested criteria for ‘irritable throat syndrome’

The pursuit of a positive diagnostic paradigm has standardised the approach to DGBI and permitted clinicians to proactively pursue a diagnosis based on defined symptom clusters, after excluding mimics. Based on our findings, we propose that a similar evidence-based model might be adopted for a positive diagnosis in patients with irritable throat-like symptoms following evaluation of chronic throat symptoms to rule out discernible structural causes and mimics (box 1). This positive diagnosis framework offers a structured approach, eliminating the need for repetitive and usually unremarkable tests. Further, it supports the adoption of a common medical language to validate patient symptoms, standardise interdisciplinary approaches, strengthen patient–clinician rapport, promote prompt delivery of therapy and encourages judicious use of resources.

Box 1. Proposed diagnostic criteria for irritable throat syndrome.

Presence of one or more of the following unexplained chronic throat symptoms; cough, dysphonia, globus

sensation, oropharyngeal dysphagia, repetitive throat clearing, catarrh/sensation of mucus in the throat, abnormal throat sensations, for at least 1 day each week, over the last 12 weeks, with:

No explanation from comorbid diagnoses.

No explanation from routine physical examinations and investigations.

Exclusion of structural or other organic pathology of the aerodigestive tract via nasoendoscopy.

Additional criteria

Patients with PPI refractory reflux symptoms: Throat (extra-oesophageal) symptoms persist despite standard GORD therapies. In patients with PPI-resistant reflux/dyspeptic symptoms (in addition to throat symptoms), gastroenterology evaluation excludes structural gastrointestinal abnormalities and objective evidence of pathological gastro-oesophageal reflux.

Patients with globus sensation: Exclusion of a structural lesion identified on physical examination, laryngoscopy or endoscopy, absence of a gastric inlet patch in the proximal oesophagus, exclusion of a major oesophageal motor disorder and exclusion of eosinophilic oesophagitis. If overlapping PPI refractory oesophageal reflux symptoms consider oesophageal pH studies to exclude pathological gastro-oesophageal reflux.

Patients with overlapping oesophageal dysphagia: Gastroenterology evaluation excludes structural oesophageal causes, eosinophilic oesophagitis and major oesophageal motor disorders.

Patients with lower airway disease: A respiratory physician confirms that refractory throat symptoms cannot be adequately explained by comorbid lower airway pathology.

Patients with chronic cough: A respiratory physician excludes organic lower airway causes of cough.

GORD, gastro-oesophageal reflux disease; PPI, proton pump inhibitor.

Rationale for an updated treatment approach for patients with irritable throat-like symptoms

In DGBI, a holistic approach addressing biopsychosocial factors has been shown to be superior to single specialist-led care.141 This multidisciplinary model centres on the patient, enabling tailored treatment pathways through collaboration. We propose extending this model to include irritable throat symptoms. Depending on the patient’s symptom profile, optimal care for refractory irritable throat-like symptoms may require collaboration between otolaryngologists, gastroenterologists, respiratory specialists, speech therapists, psychologists and others, addressing the full range of biopsychosocial factors implicated in UCTS.

The key goals of this treatment approach include:

Validating the impact of symptoms on patient well-being and providing education and reassurance.

Promoting education and strategies to enhance aerodigestive tract health and overall patient well-being, which encourages patient participation in symptom management.

Thorough assessments to individualise treatment goals and strategies according to patient needs.

The regular evaluation of symptom progression to refine treatment strategy.

Open communication within a multidisciplinary team, especially for complex cases.

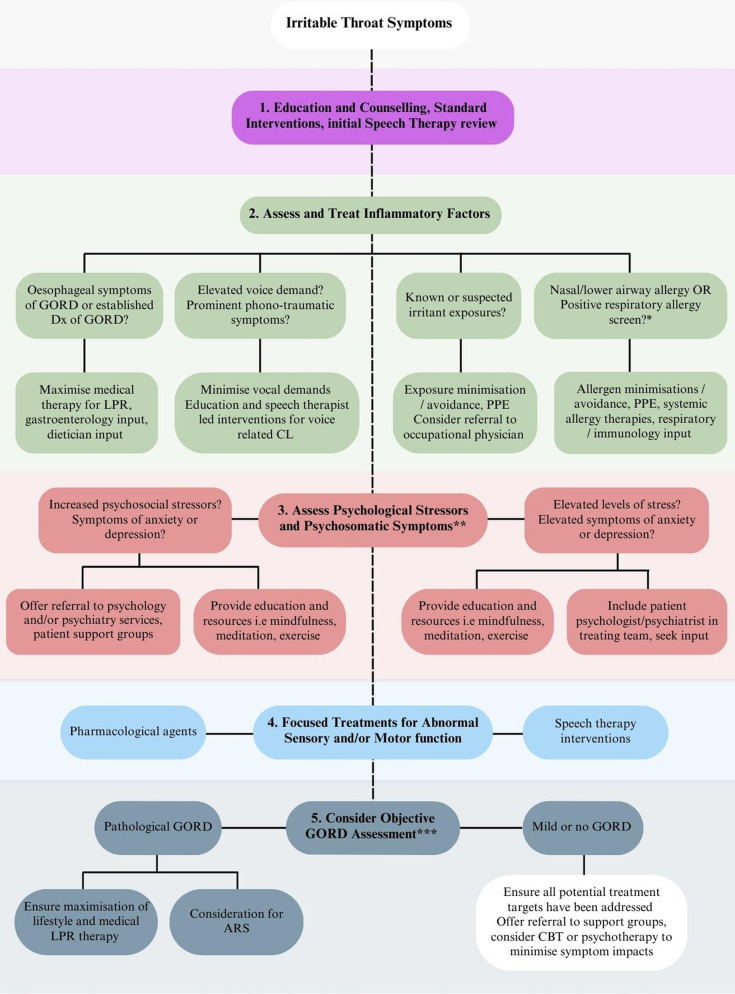

The evidence base for current therapeutic targets for irritable throat-like symptoms synthesised from our literature review to inform a suggested evidence-based treatment framework (figure 4) is summarised in the online supplemental table.

Figure 4.

Therapeutic strategies for irritable throat syndrome.* Respiratory allergy screening may invoice skin prick testing (with specific attention to aerosolised allergens) or radioallergosorbent test which identifies allergen-specific IgE in blood serum. ** A history of co-morbid psychiatric diagonoses should be taken. Screening tools which detect elevated levels of psychosomic ditress or identify elevated levels of anxiety or depressive symptoms may be useful adjuncts. *** 24-hour impedance pH manometry is the preferred assessment and aims to identify patients with high reflux burdens who may warrant consideration of ARS. ARS, anti-reflux surgery; GORD, gastro-oesophageal reflux disease; LPR, laryngopharyngeal reflux; CBT, cognitive behavioural therapy.

bmjgast-2022-000883supp001.pdf (146.6KB, pdf)

This evidence-based framework involves a stepwise progression of the therapeutic strategies below.

Standard therapies and education: Patient education to optimise habits for aerodigestive health, reassurance surrounding long-term symptom implications and preliminary speech therapies for primary symptom concerns.

Psychosocial interventions: Patients with comorbid anxiety and depression or who report elevated psychological stress are offered interventions to support mental well-being, relaxation and decreased symptom hypervigilance.

Assessment and treatment of potential inflammatory causes: Considers targeted interventions for reflux, allergy, voice behaviour and environmental/occupational exposures.

Empirical trial of neuromodulators and other sensory targeted therapies: Offered for persistent symptoms in suitable candidates.

Objective reflux quantification: Indicated for patients with refractory symptoms despite maximal non-invasive therapies, where a defined high reflux burden might initiate considerations for surgical intervention.

Specific treatment recommendations

Speech therapy as a core treatment: Speech therapists are pivotal in addressing diverse throat symptoms.10 50 67 95 110 147 Their treatment strategies may address sensory vigilance or hypersensitisation, motor tension and aberrant coordination and assist in disrupting self-sustaining phonotraumatic symptom cycles. All patients are recommended speech therapist-led treatment programmes to complement other therapeutic avenues.

Psychometric screening and behavioural interventions: The brain–gut connection in DGBI has highlighted the value of behavioural interventions for persistent non-structural symptoms, including throat symptoms.63 110 117 142 148–151 Psychological and behavioural interventions in the management of irritable throat symptoms therefore warrants further consideration.

Empirical PPI therapy: Sufficient data now establishes the limited efficacy of this option for isolated throat symptoms.35 38 152 153 We suggest that PPI is used principally when oesophageal symptoms of GORD are present.

Invasive reflux assessments: The value of invasive reflux assessments for guiding treatment and predicting response to reflux therapies for throat symptoms appears limited.28 33 34 154 Therefore, we recommend invasive reflux assessments only in patients with refractory symptoms, where surgical intervention might be warranted should a high reflux burden be detected.

Allergy screening and treatment The concept of AL is emerging and complements the proposed links between lower and nasal airway allergy and chronic throat symptoms. We suggest straightforward respiratory allergen sensitisation screening (ie, RAST panel) where allergy status is uncertain. A positive result may warrant trial of low-risk allergy therapies until evidence-based recommendations can be made.

Neuromodulators: Growing literature suggests moderate symptom benefits in patients with cough, dysphonia, globus and throat clearing when treated with neuromodulating agents. Given potential side effects, we suggest their empirical trial should be reserved for patients for whom first-line treatments have failed, and inflammatory contributions have been addressed or excluded, where applicable.

Limitations and future of therapeutic strategies

At present, the therapeutic landscape for irritable throat symptoms is inadequately explored, particularly with respect to biopsychosocial models. An interdisciplinary approach for irritable throat seeks to promote common perspectives and terminologies that enhance research data. We anticipate that these strategies, presented here as a starting point, will evolve considerably, benefiting from expanded options and evidence-based refinements.

Footnotes

Contributors: NQ performed literature review and drafted the paper; SM, DHV and SV helped write the paper and critically reviewed and revised the article; SV is the guarantor.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

No data are available.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

References

- 1.Powell J, O’Hara J, Wilson JA. Are persistent throat symptoms atypical features of gastric reflux and should they be treated with proton pump inhibitors? BMJ 2014;349:g5813. 10.1136/bmj.g5813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ates F, Vaezi MF. Approach to the patient with presumed extraoesophageal GERD. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2013;27:415–31. 10.1016/j.bpg.2013.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lechien JR, Akst LM, Hamdan AL, et al. Evaluation and management of Laryngopharyngeal reflux disease: state of the art review. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2019;160:762–82. 10.1177/0194599819827488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vaezi MF. Editorial: reflux and laryngeal symptoms: a sea of confusion. Am J Gastroenterol 2016;111:1525–7. 10.1038/ajg.2016.315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’Hara J, Fisher H, Hayes L, et al. Persistent throat symptoms' versus 'Laryngopharyngeal reflux': a cross-sectional study refining the clinical condition. BMJ Open Gastroenterol 2022;9:e000850. 10.1136/bmjgast-2021-000850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen SM, Kim J, Roy N, et al. Prevalence and causes of dysphonia in a large treatment-seeking population. The Laryngoscope 2012;122:343–8. 10.1002/lary.22426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohen SM, Garrett CG. Hoarseness: is it really laryngopharyngeal reflux Laryngoscope 2008;118:363–6. 10.1097/MLG.0b013e318158f72d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patel DA, Blanco M, Vaezi MF. Laryngopharyngeal reflux and functional laryngeal disorder: perspective and common practice of the general gastroenterologist. Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018;14:512–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schneider GT, Vaezi MF, Francis DO. Reflux and voice disorders: have we established causality Curr Otorhinolaryngol Rep 2016;4:157–67. 10.1007/s40136-016-0121-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vertigan AE, Bone SL, Gibson PG. The impact of functional Laryngoscopy on the diagnosis of Laryngeal hypersensitivity syndromes. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2022;10:597–601. 10.1016/j.jaip.2021.10.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hull JH, Backer V, Gibson PG, et al. Laryngeal dysfunction: assessment and management for the clinician. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2016;194:1062–72. 10.1164/rccm.201606-1249CI [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koufman JA, Amin MR, Panetti M. Prevalence of reflux in 113 consecutive patients with laryngeal and voice disorders. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2000;123:385–8. 10.1067/mhn.2000.109935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Francis DO, Vaezi MF. Should the reflex be reflux? Throat symptoms and alternative explanations. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;13:1560–6. 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.08.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cohen SM, Kim J, Roy N, et al. The impact of laryngeal disorders on work-related dysfunction. Laryngoscope 2012;122:1589–94. 10.1002/lary.23197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ryan NM, Vertigan AE, Birring SS. An update and systematic review on drug therapies for the treatment of refractory chronic cough. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2018;19:687–711. 10.1080/14656566.2018.1462795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Young EC, Smith JA. Quality of life in patients with chronic cough. Ther Adv Respir Dis 2010;4:49–55. 10.1177/1753465809358249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Siupsinskiene N, Adamonis K, Toohill RJ. Quality of life in laryngopharyngeal reflux patients. Laryngoscope 2007;117:480–4. 10.1097/MLG.0b013e31802d83cf [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Belafsky PC, Postma GN, Koufman JA. The validity and reliability of the reflux finding score (RFS). Laryngoscope 2001;111:1313–7. 10.1097/00005537-200108000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eren E, Arslanoğlu S, Aktaş A, et al. Factors confusing the diagnosis of laryngopharyngeal reflux: the role of allergic rhinitis and inter-rater variability of laryngeal findings. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2014;271:743–7. 10.1007/s00405-013-2682-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen M, Hou C, Chen T, et al. Reflux symptom index and reflux finding score in 91 asymptomatic volunteers. Acta Otolaryngol 2018;138:659–63. 10.1080/00016489.2018.1436768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Belafsky PC, Postma GN, Amin MR, et al. Symptoms and findings of laryngopharyngeal reflux. Ear Nose Throat J 2002;81:10–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krause AJ, Walsh EH, Weissbrod PA, et al. An update on current treatment strategies for Laryngopharyngeal reflux symptoms. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2022;1510:5–17. 10.1111/nyas.14728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cohen JT, Bach KK, Postma GN, et al. Clinical manifestations of laryngopharyngeal reflux. Ear Nose Throat J 2002;81(9 Suppl 2):19–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wood JM, Hussey DJ, Woods CM, et al. Biomarkers and laryngopharyngeal reflux. J Laryngol Otol 2011;125:1218–24. 10.1017/S0022215111002234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnston N, Dettmar PW, Lively MO, et al. Effect of Pepsin on laryngeal stress protein (Sep70, Sep53, and Hsp70) response: role in laryngopharyngeal reflux disease. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 2006;115:47–58. 10.1177/000348940611500108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gill GA, Johnston N, Buda A, et al. Laryngeal epithelial defenses against Laryngopharyngeal reflux: investigations of E-Cadherin, carbonic Anhydrase isoenzyme III, and Pepsin. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 2005;114:913–21. 10.1177/000348940511401204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bardhan KD, Strugala V, Dettmar PW. Reflux revisited: advancing the role of Pepsin. Int J Otolaryngol 2012:646901. 10.1155/2012/646901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Duricek M, Banovcin P, Halickova T, et al. Acidic pharyngeal reflux does not correlate with symptoms and Laryngeal injury attributed to Laryngopharyngeal reflux. Dig Dis Sci 2019;64:1270–80. 10.1007/s10620-018-5372-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jamal N, Wang MB. Laryngopharyngeal reflux disease. In: Laryngopharyngeal Reflux Disease. Cham: Springer International Publishing 2019:33-45, 2019. 10.1007/978-3-030-12318-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kendall KA. Controversies in the diagnosis and management of Laryngopharyngeal reflux disease. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2006;14:113–5. 10.1097/01.moo.0000193195.47720.c3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carroll TL, Fedore LW, Aldahlawi MM. PH impedance and high-resolution manometry in Laryngopharyngeal reflux disease high-dose proton pump inhibitor failures. Laryngoscope 2012;122:2473–81. 10.1002/lary.23518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ribolsi M, Savarino E, De Bortoli N, et al. Reflux pattern and role of impedance-pH variables in predicting PPI response in patients with suspected GERD-related chronic cough. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2014;40:966–73. 10.1111/apt.12919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Francis DO, Goutte M, Slaughter JC, et al. Traditional reflux parameters and not impedance monitoring predict outcome after fundoplication in extraesophageal reflux. Laryngoscope 2011;121:1902–9. 10.1002/lary.21897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dulery C, Lechot A, Roman S, et al. A study with pharyngeal and esophageal 24-hour pH-impedance monitoring in patients with Laryngopharyngeal symptoms refractory to proton pump inhibitors. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2017;29. 10.1111/nmo.12909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kahrilas PJ, Altman KW, Chang AB, et al. Chronic cough due to gastroesophageal reflux in adults: CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest 2016;150:1341–60. 10.1016/j.chest.2016.08.1458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Takeda N, Takemura M, Kanemitsu Y, et al. Effect of anti-reflux treatment on gastroesophageal reflux-associated chronic cough: implications of Neurogenic and Neutrophilic inflammation. J Asthma 2020;57:1202–10. 10.1080/02770903.2019.1641204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.O’Hara J, Stocken DD, Watson GC, et al. Use of proton pump inhibitors to treat persistent throat symptoms: Multicentre, double blind, randomised, placebo controlled trial. BMJ 2021;372:m4903. 10.1136/bmj.m4903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spantideas N, Drosou E, Bougea A, et al. Proton pump inhibitors for the treatment of Laryngopharyngeal reflux. J Voice 2020;34:918–29.:S0892-1997(19)30102-X. 10.1016/j.jvoice.2019.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McGlashan JA, Johnstone LM, Sykes J, et al. The value of a liquid Alginate suspension (Gaviscon advance) in the management of Laryngopharyngeal reflux. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2009;266:243–51. 10.1007/s00405-008-0708-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bor S, Kalkan İH, Çelebi A, et al. Alginates: from the ocean to gastroesophageal reflux disease treatment. Turk J Gastroenterol 2019;30:109–36. 10.5152/tjg.2019.19677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stewart SJ, Wee JO. Antireflux surgery and Laryngopharyngeal reflux. Curr Otorhinolaryngol Rep 2016;4:63–6. 10.1007/s40136-016-0104-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hessler LK, Xu Y, Shada AL, et al. Antireflux surgery leads to durable improvement in Laryngopharyngeal reflux symptoms. Surg Endosc 2022;36:778–86. 10.1007/s00464-020-08279-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Krill JT, Naik RD, Higginbotham T, et al. Association between response to acid-suppression therapy and efficacy of Antireflux surgery in patients with Extraesophageal reflux. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017;15:675–81. 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.10.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sahin M, Vardar R, Ersin S, et al. The effect of Antireflux surgery on Laryngeal symptoms, findings and voice parameters. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2015;272:3375–83. 10.1007/s00405-015-3657-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Aiolfi A, Cavalli M, Saino G, et al. Laparoscopic Toupet Fundoplication for the treatment of Laryngopharyngeal reflux: results at medium-term follow-up. World J Surg 2020;44:3821–8. 10.1007/s00268-020-05653-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Carroll TL, Nahikian K, Asban A, et al. Nissen Fundoplication for Laryngopharyngeal reflux after patient selection using dual pH, full column impedance testing: a pilot study. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 2016;125:722–8. 10.1177/0003489416649974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.González-Gamboa M, Segura-Pujol H, Oyarzún PD, et al. Are occupational voice disorders accurately measured? a systematic review of prevalence and Methodologies in Schoolteachers to report voice disorders. J Voice 2022. 10.1016/j.jvoice.2022.10.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Martins RHG, do Amaral HA, Tavares ELM, et al. Voice disorders: etiology and diagnosis. J Voice 2016;30:761. 10.1016/j.jvoice.2015.09.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dikkers FG, Nikkels PG. Benign lesions of the vocal folds: Histopathology and Phonotrauma. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1995;104(9 Pt 1):698–703. 10.1177/000348949510400905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Behrman A, Rutledge J, Hembree A, et al. Vocal hygiene education, voice production therapy, and the role of patient adherence: a treatment effectiveness study in women with Phonotrauma. J Speech Lang Hear Res 2008;51:350–66. 10.1044/1092-4388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Francis DO, Slaughter JC, Ates F, et al. Airway hypersensitivity, reflux, and Phonation contribute to chronic cough. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;14:378–84. 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.10.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Denton E, Hoy R. Occupational aspects of irritable Larynx syndrome. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 2020;20:90–5. 10.1097/ACI.0000000000000619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Roy N, Merrill RM, Thibeault S, et al. Prevalence of voice disorders in teachers and the general population. J Speech Lang Hear Res 2004;47:281–93. 10.1044/1092-4388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Angsuwarangsee T, Morrison M. Extrinsic Laryngeal muscular tension in patients with voice disorders. J Voice 2002;16:333–43. 10.1016/s0892-1997(02)00105-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ogawa M, Hosokawa K, Yoshida M, et al. Immediate effectiveness of humming on the supraglottic compression in subjects with muscle tension Dysphonia. Folia Phoniatr Logop 2013;65:123–8. 10.1159/000353539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Morrison MD, Rammage LA. Muscle misuse voice disorders: description and classification. Acta Otolaryngol 1993;113:428–34. 10.3109/00016489309135839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Morrison M, Rammage L, Emami AJ. The irritable Larynx syndrome. J Voice 1999;13:447–55. 10.1016/s0892-1997(99)80049-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Meyer TK. The Larynx for Neurologists. Neurologist 2009;15:313–8. 10.1097/NRL.0b013e3181b1cde5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Andrianopoulos MV, Gallivan GJ, Gallivan KH. EPL, and irritable Larynx syndrome: what are we talking about and how do we treat it. J Voice 2000;14:607–18. 10.1016/s0892-1997(00)80016-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ruotsalainen J, Sellman J, Lehto L, et al. Systematic review of the treatment of functional Dysphonia and prevention of voice disorders. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2008;138:557–65. 10.1016/j.otohns.2008.01.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Santana ÉR, Masson MLV, Araújo TM. The effect of surface hydration on teachers' voice quality: an intervention study. J Voice 2017;31:383. 10.1016/j.jvoice.2016.08.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Barry DW, Vaezi MF. Laryngopharyngeal reflux: more questions than answers. Cleve Clin J Med 2010;77:327–34. 10.3949/ccjm.77a.09121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Poovipirom N, Ratta-Apha W, Maneerattanaporn M, et al. Treatment outcomes in patients with globus: a randomized control trial of Psychoeducation, Neuromodulators, and proton pump inhibitors. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2023;35:e14500. 10.1111/nmo.14500 Available: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/toc/13652982/35/3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kirch S, Gegg R, Johns MM, et al. Globus Pharyngeus: effectiveness of treatment with proton pump inhibitors and Gabapentin. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 2013;122:492–5. 10.1177/000348941312200803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Manabe N, Tsutsui H, Kusunoki H, et al. Pathophysiology and treatment of patients with globus sensation--from the viewpoint of Esophageal motility dysfunction. J Smooth Muscle Res 2014;50:66–77. 10.1540/jsmr.50.66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ryan NM, Gibson PG. Characterization of Laryngeal dysfunction in chronic persistent cough. Laryngoscope 2009;119:640–5. 10.1002/lary.20114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gibson PG, Vertigan AE. Management of chronic refractory cough. BMJ 2015;351:h5590. 10.1136/bmj.h5590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bonnet U, Ossowski A, Schubert M, et al. On the differential diagnosis of intractable psychogenic chronic cough: neuropathic Larynx irritable - Gabapentin’s Antitussive action. Fortschr Neurol Psychiatr 2015;83:568–77. 10.1055/s-0035-1553860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Moscato G, Pala G, Cullinan P, et al. EAACI position paper on assessment of cough in the workplace. Allergy 2014;69:292–304. 10.1111/all.12352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tarlo SM, Altman KW, Oppenheimer J, et al. Occupational and environmental contributions to chronic cough in adults: chest expert panel report. Chest 2016;150:894–907. 10.1016/j.chest.2016.07.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Anderson JA. Work-associated irritable Larynx syndrome. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 2015;15:150–5. 10.1097/ACI.0000000000000144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pankova VB. Occupational diseases of upper respiratory tract caused by Ecologic factors. Vestn Otorinolaringol 1995:38–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Raju S, Siddharthan T, McCormack MC. Indoor air pollution and respiratory health. Clin Chest Med 2020;41:825–43. 10.1016/j.ccm.2020.08.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chung KFP, Pavord IDP. Prevalence, pathogenesis, and causes of chronic cough. Lancet 2008;371:1364–74. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60595-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Stachler RJ, Dworkin-Valenti JP. Allergic Laryngitis: unraveling the myths. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2017;25:242–6. 10.1097/MOO.0000000000000354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Braunstahl G-J, Hellings PW. Allergic rhinitis and asthma: the link further unraveled. Curr Opin Pulm Med 2003;9:46–51. 10.1097/00063198-200301000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Krouse JH. Allergy and Laryngeal disorders. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2016;24:221–5. 10.1097/MOO.0000000000000244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Roth DF, Ferguson BJ. Vocal allergy: recent advances in understanding the role of allergy in Dysphonia. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2010;18:176–81. 10.1097/MOO.0b013e32833952af [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Simberg S, Sala E, Tuomainen J, et al. Vocal symptoms and allergy--a pilot study. J Voice 2009;23:136–9. 10.1016/j.jvoice.2007.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Campagnolo A, Benninger MS. Allergic Laryngitis: chronic Laryngitis and allergic sensitization. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol 2019;85:263–6. 10.1016/j.bjorl.2019.02.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Brook CD, Platt MP, Reese S, et al. Utility of allergy testing in patients with chronic Laryngopharyngeal symptoms: is it allergic Laryngitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2016;154:41–5. 10.1177/0194599815607850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Turley R, Cohen SM, Becker A, et al. Role of rhinitis in Laryngitis: another dimension of the unified airway. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 2011;120:505–10. 10.1177/000348941112000803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wang Y-T, Chang G-H, Yang Y-H, et al. Allergic rhinitis and Laryngeal pathology: real-world evidence. Healthcare 2021;9:36. 10.3390/healthcare9010036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Grossman J. One airway, one disease. Chest 1997;111(2 Suppl):11S–16S. 10.1378/chest.111.2_supplement.11s [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sanu A, Eccles R. Postnasal drip syndrome. two hundred years of controversy between UK and USA. Rhinology 2008;46:86–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Pratter MR. Chronic upper airway cough syndrome secondary to Rhinosinus diseases (previously referred to as Postnasal drip syndrome): ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest 2006;129:63S–71S. 10.1378/chest.129.1_suppl.63S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Campbell BA, Teng SE. The Laryngeal manifestations of allergic sensitization: a current literature review. Curr Otorhinolaryngol Rep 2022;10:195–201. 10.1007/s40136-022-00392-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Randhawa PS, Nouraei S, Mansuri S, et al. Allergic Laryngitis as a cause of Dysphonia: a preliminary report. Logoped Phoniatr Vocol 2010;35:169–74. 10.3109/14015431003599012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Spantideas N, Bougea A, Drosou E, et al. The role of allergy in Phonation. J Voice 2019;33:811. 10.1016/j.jvoice.2018.02.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lacourt TE, Vichaya EG, Chiu GS, et al. The high costs of low-grade inflammation: persistent fatigue as a consequence of reduced cellular-energy availability and non-adaptive energy expenditure. Front Behav Neurosci 2018;12:78. 10.3389/fnbeh.2018.00078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Chung KF. 'Chronic 'cough hypersensitivity syndrome': a more precise label for chronic cough'. Pulm Pharmacol Ther 2011;24:267–71. 10.1016/j.pupt.2011.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Benninger MS, Campagnolo A. Chronic Laryngopharyngeal vagal neuropathy. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol 2018;84:401–3. 10.1016/j.bjorl.2018.04.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ryan NM. A review on the efficacy and safety of Gabapentin in the treatment of chronic cough. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2015;16:135–45. 10.1517/14656566.2015.981524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Vertigan AE, Gibson PG. Chronic refractory cough as a sensory neuropathy: evidence from a Reinterpretation of cough triggers. J Voice 2011;25:596–601. 10.1016/j.jvoice.2010.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Mahoney J, Hew M, Vertigan A, et al. Treatment effectiveness for vocal cord dysfunction in adults and adolescents: A systematic review. Clin Exp Allergy 2022;52:387–404. 10.1111/cea.14036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Vertigan AE, Gibson PG, Theodoros DG, et al. The role of sensory dysfunction in the development of voice disorders, chronic cough and paradoxical vocal fold movement. Int J Speech Lang Pathol 2008;10:231–44. 10.1080/17549500801932089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Vertigan AE, Kapela SM, Kearney EK, et al. Laryngeal dysfunction in cough hypersensitivity syndrome: A cross-sectional observational study. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2018;6:2087–95. 10.1016/j.jaip.2018.04.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Chung KF, McGarvey L, Song W-J, et al. Cough hypersensitivity and chronic cough. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2022;8:45.:45. 10.1038/s41572-022-00370-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Pacheco A. Chronic cough: from a complex dysfunction of the neurological circuit to the production of persistent cough. Thorax 2014;69:881–3. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2014-205661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Ogawa H, Fujimura M, Takeuchi Y, et al. Dealing with cough-related Laryngeal sensations for a substantial reduction in chronic cough. Pulm Pharmacol Ther 2014;27:127–8. 10.1016/j.pupt.2013.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Niimi A, Chung KF. Evidence for neuropathic processes in chronic cough. Pulm Pharmacol Ther 2015;35:100–4. 10.1016/j.pupt.2015.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Sundar KM, Stark AC, Hu N, et al. Is Laryngeal hypersensitivity the basis of unexplained or refractory chronic cough ERJ Open Res 2021;7:00793–2020. 10.1183/23120541.00793-2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Yu JL, Becker SS. Postnasal drip and Postnasal drip-related cough. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2016;24:15–9. 10.1097/MOO.0000000000000226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Canning BJ. Afferent nerves regulating the cough reflex: mechanisms and mediators of cough in disease. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 2010;43:15–25. 10.1016/j.otc.2009.11.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Hilton E, Marsden P, Thurston A, et al. Clinical features of the urge-to-cough in patients with chronic cough. Respir Med 2015;109:701–7. 10.1016/j.rmed.2015.03.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Jeyakumar A, Brickman TM, Haben M. Effectiveness of amitriptyline versus cough Suppressants in the treatment of chronic cough resulting from Postviral vagal neuropathy. Laryngoscope 2006;116:2108–12. 10.1097/01.mlg.0000244377.60334.e3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Canning BJ. Functional implications of the multiple afferent pathways regulating cough. Pulm Pharmacol Ther 2011;24:295–9. 10.1016/j.pupt.2011.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Amarasiri DL, Pathmeswaran A, de Silva HJ, et al. Response of the Airways and autonomic nervous system to acid perfusion of the esophagus in patients with asthma: a laboratory study. BMC Pulm Med 2013;13:33. 10.1186/1471-2466-13-33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Gale CR, Wilson JA, Deary IJ. Globus sensation and psychopathology in men: the Vietnam experience study. Psychosom Med 2009;71:1026–31. 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181bc7739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Lee BE, Kim GH. Globus Pharyngeus: a review of its etiology, diagnosis and treatment. World J Gastroenterol 2012;18:2462–71. 10.3748/wjg.v18.i20.2462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Schindler A, Mozzanica F, Alfonsi E, et al. Upper Esophageal sphincter dysfunction: Diverticula-globus Pharyngeus. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2013;1300:250–60. 10.1111/nyas.12251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Moser G, Vacariu-Granser GV, Schneider C, et al. High incidence of Esophageal motor disorders in consecutive patients with globus sensation. Gastroenterology 1991;101:1512–21. 10.1016/0016-5085(91)90386-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Morice A, Dicpinigaitis P, McGarvey L, et al. Chronic cough: new insights and future prospects. Eur Respir Rev 2021;30:162.:210127. 10.1183/16000617.0127-2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Drossman DA. Functional gastrointestinal disorders: history, pathophysiology, clinical features and Rome IV. Gastroenterology 2016;150:1262. 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Brown SR, Schwartz JM, Summergrad P, et al. Globus Hystericus syndrome responsive to antidepressants. Am J Psychiatry 1986;143:917–8. 10.1176/ajp.143.7.917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Vasant DH, Whorwell PJ. Gut-focused Hypnotherapy for functional gastrointestinal disorders: evidence-base, practical aspects, and the Manchester protocol. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2019;31:e13573. 10.1111/nmo.13573 Available: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/toc/13652982/31/8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Kiebles JL, Kwiatek MA, Pandolfino JE, et al. Do patients with globus sensation respond to hypnotically assisted relaxation therapy? A case series report. Dis Esophagus 2010;23:545–53. 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2010.01064.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Shi G, Shen Q, Zhang C, et al. Efficacy and safety of Gabapentin in the treatment of chronic cough: A systematic review. Tuberc Respir Dis 2018;81:167. 10.4046/trd.2017.0089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Low K, Ruane L, Uddin N, et al. Abnormal vocal cord movement in patients with and without airway obstruction and asthma symptoms. Clin Exp Allergy 2017;47:200–7. 10.1111/cea.12828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.McCarty EB, Chao TN. Dysphagia and swallowing disorders. Med Clin North Am 2021;105:939–54. 10.1016/j.mcna.2021.05.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Altman KW, Lane AP, Irwin RS. Otolaryngology aspects of chronic cough. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2019;7:1750–5. 10.1016/j.jaip.2019.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Widdicombe JG. Sensory Neurophysiology of the cough reflex. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1996;98(5 Pt 2):S84–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Mazzone SB, Mori N, Canning BJ. Synergistic interactions between airway afferent nerve subtypes regulating the cough reflex in guinea-pigs. J Physiol 2005;569(Pt 2):559–73. 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.093153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Robbins J. Upper Aerodigestive tract Neurofunctional mechanisms: lifelong evolution and exercise. Head Neck 2011;33 Suppl 1:S30–6. 10.1002/hed.21902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Bourke JH, Langford RM, White PD. The common link between functional somatic syndromes may be central Sensitisation. J Psychosom Res 2015;78:228–36. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2015.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Ward PH, Hanson DG, Berci G. Observations on central neurologic etiology for Laryngeal dysfunction. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1981;90(5 Pt 1):430–41. 10.1177/000348948109000504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Rosztóczy A, Makk L, Izbéki F, et al. Asthma and gastroesophageal reflux: clinical evaluation of Esophago-bronchial reflex and proximal reflux. Digestion 2008;77:218–24. 10.1159/000146083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Ekström T, Tibbling L. Esophageal acid perfusion, airway function, and symptoms in asthmatic patients with marked bronchial Hyperreactivity. Chest 1989;96:995–8. 10.1378/chest.96.5.995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Tang B, Wang X, Chen C, et al. The differences in Epidemiological and psychological features of globus symptoms between urban and rural Guangzhou, China: a cross-sectional study. Medicine 2018;97:e12986. 10.1097/MD.0000000000012986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Xiao S, Li J, Zheng H, et al. An Epidemiological survey of Laryngopharyngeal reflux disease at the Otorhinolaryngology-head and neck surgery clinics in China. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2020;277:2829–38. 10.1007/s00405-020-06045-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Martinucci I, Albano E, Marchi S, et al. Extra-Esophageal presentation of gastroesophageal reflux disease: new understanding in a new era. Minerva Gastroenterol 2017;63:221–34. 10.23736/S1121-421X.17.02393-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Vaezi MF, Katzka D, Zerbib F. Extraesophageal symptoms and diseases attributed to GERD: where is the pendulum swinging now? Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018;16:1018–29. 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Galmiche JP, Clouse RE, Bálint A, et al. Functional Esophageal disorders. Gastroenterology 2006;130:1459–65. 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.08.060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Pacheco A, Cobeta I. Refractory chronic cough, or the need to focus on the relationship between the Larynx and the esophagus. Cough 2013;9:10. 10.1186/1745-9974-9-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Kang S-Y, Won H-K, Lee SM, et al. Impact of cough and unmet needs in chronic cough: a survey of patients in Korea. Lung 2019;197:635–9. 10.1007/s00408-019-00258-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Hearn M, Whorwell PJ, Vasant DH. Stigma and irritable bowel syndrome: a taboo subject? Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020;5:607–15. 10.1016/S2468-1253(19)30348-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Swift BMC, Meade N, Barron ES, et al. The development and use of Actiphage® to detect viable mycobacteria from bovine tuberculosis and Johne’s disease-infected animals. Microb Biotechnol 2020;13:738–46. 10.1111/1751-7915.13518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.on behalf of the EURONET-SOMA Group, Burton C, Fink P, et al. Functional somatic disorders: discussion paper for a new common classification for research and clinical use. BMC Med 2020;18. 10.1186/s12916-020-1505-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Vasant DH, Paine PA, Black CJ, et al. British society of Gastroenterology guidelines on the management of irritable bowel syndrome. Gut 2021;70:1214–40. 10.1136/gutjnl-2021-324598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Chang FY. Irritable bowel syndrome: the evolution of multi-dimensional looking and Multidisciplinary treatments. WJG 2014;20:2499. 10.3748/wjg.v20.i10.2499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Saito YA, Prather CM, Van Dyke CT, et al. Effects of Multidisciplinary education on outcomes in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2004;2:576–84. 10.1016/s1542-3565(04)00241-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]