Abstract

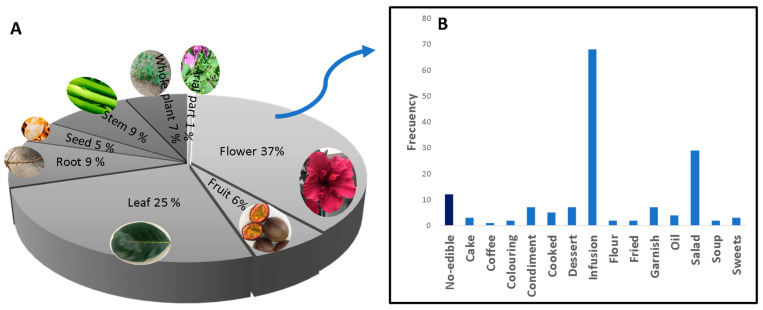

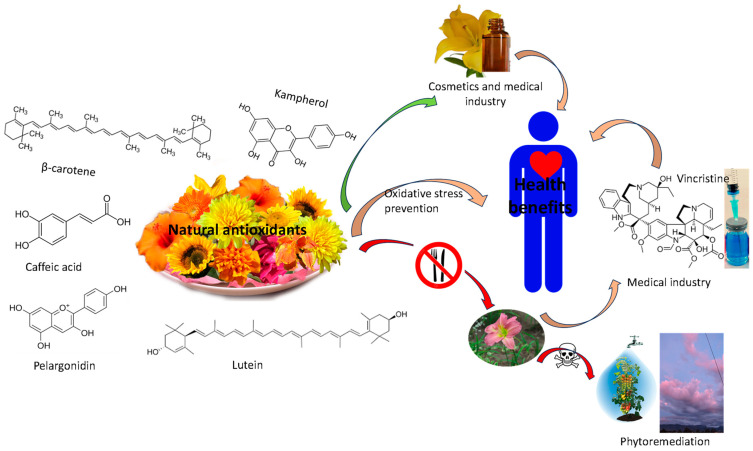

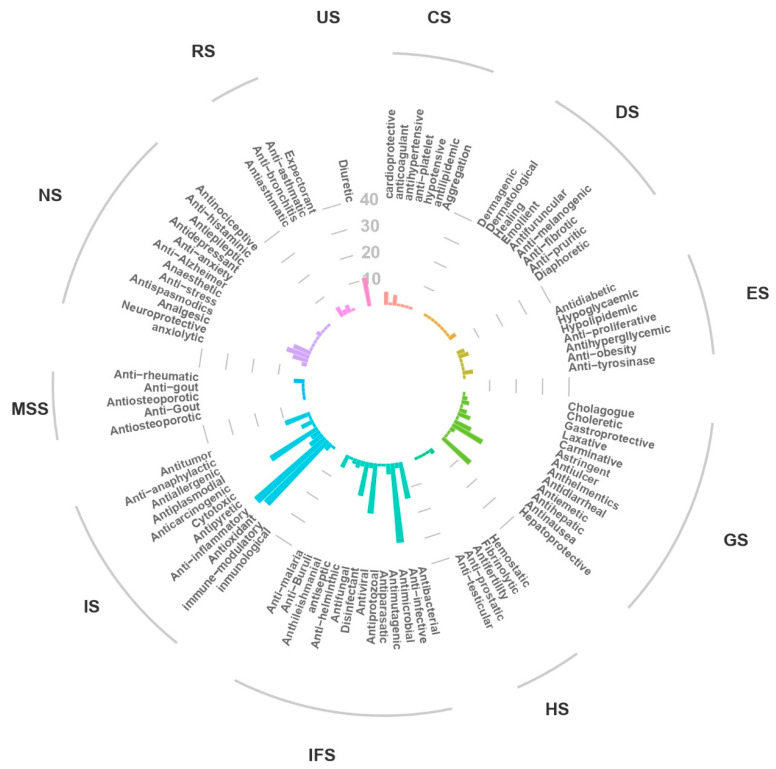

Flowers have played a significant role in society, focusing on their aesthetic value rather than their food potential. This study’s goal was to look into flowering plants for everything from health benefits to other possible applications. This review presents detailed information on 119 species of flowers with agri-food and health relevance. Data were collected on their family, species, common name, commonly used plant part, bioremediation applications, main chemical compounds, medicinal and gastronomic uses, and concentration of bioactive compounds such as carotenoids and phenolic compounds. In this respect, 87% of the floral species studied contain some toxic compounds, sometimes making them inedible, but specific molecules from these species have been used in medicine. Seventy-six percent can be consumed in low doses by infusion. In addition, 97% of the species studied are reported to have medicinal uses (32% immune system), and 63% could be used in the bioremediation of contaminated environments. Significantly, more than 50% of the species were only analysed for total concentrations of carotenoids and phenolic compounds, indicating a significant gap in identifying specific molecules of these bioactive compounds. These potential sources of bioactive compounds could transform the health and nutraceutical industries, offering innovative approaches to combat oxidative stress and promote optimal well-being.

Keywords: carotenoids, edible flowers, flavonoids, functional foods, nutraceuticals, phenolic compounds, natural dyes

1. Introduction

Since time immemorial, flowers have played a fundamental role in society. They are appreciated for their beauty and used for ornamental purposes in various spaces, whether in pots, gardens, landscaping, or as cut flower arrangements in containers. Grown specifically for their striking appearance, distinctive foliage, and delicate fragrance, ornamental plants add charm and distinction to any environment. Their presence goes beyond mere aesthetics, as throughout history, flowers have been symbols of emotion, used in celebrations, expressions of love, condolences, and religious rituals, and providing benefits for emotional well-being and mental health [1].

In recent years, the market for edible flowers has experienced remarkable growth. This phenomenon can be attributed to several reasons, including the increasing availability of information on their nutritional value and bioactive potential [2,3]. In addition, there has been a growing interest in the potential health benefits of specific secondary metabolites and other compounds commonly found in flowers, such as carotenoids, phenolic compounds, vitamins C and E, saponins, or phytosterols [4]. Carotenoids and phenolic compounds are responsible for the different colours of flowers [5,6] stand out for their health properties and versatility in agri-food and health applications [7,8,9,10].

Flowers are used in gastronomy for their pigments (such as carotenoids, flavonoids, and betalains), which improve the appearance of dishes [11], and for their characteristic flavours and odours, which make them an alternative food source [12]. Some societies, such as Asian, Greek, Ancient Roman, French, and Italian, have a long-standing tradition of eating flowers [3]. However, for a flower to be edible, it must not contain dangerous levels of toxic compounds that could affect the health of those who consume it [13,14]. On the other hand, the consumption of parts of plants is typical in traditional medicine, mainly in medicinal infusions or decoctions [15,16]. Flowers are recognised as alternative food sources to improve health and contribute to food security [4]. As sustainability is a global priority, especially in food production, which is considered the most significant human pressure on the Earth [17], using cultivated flowers for gastronomic purposes can be aligned with a responsible approach towards the environment and general well-being.

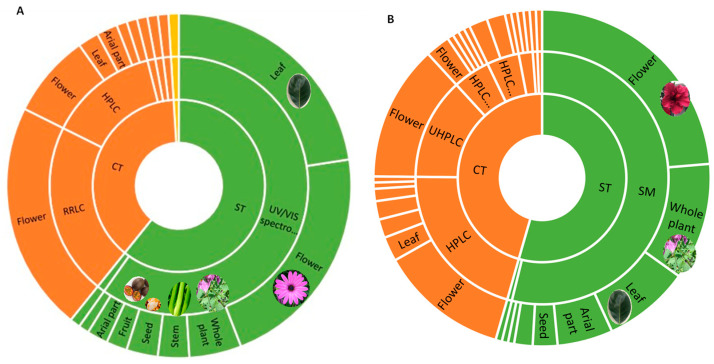

This review aimed to collect relevant information on ornamental plant flowers with potential health promotion as botanicals, foods, or other uses, following sustainability principles and the circular economy. Plants from fifty families are covered, including Asteraceae, Lamiaceae, Fabaceae, and Malvaceae, as well as plants with edible flowers from the families Asteraceae, Apiaceae, Brassicaceae, Oleacaceae, Malvaceae, and Ranunculaceae. Therefore, Table 1 contains a compilation of common plants characterised by their flowers, with detailed information on the family, common name, place of origin, part of the commonly used plant, uses in bioremediation, main chemical compounds, medicinal uses, gastronomic uses, and concentration of carotenoids and phenolic compounds, together with the technique used for each flower species. In addition, data on carotenoids and phenolic compounds in different flower species are presented in Table 2 and Table 3, respectively. This review aims to provide a comprehensive overview of flower possibilities and benefits in other areas, highlighting their potential in harmony with nature and general well-being.

Table 1.

Description, relevant synonymous, phytoremediation uses, toxic compounds, medicinal, and gastronomic uses of flowers.

| Family [18] | Species [18] | Common Name | Place of Origin | Most Used Part/Flower Image | Phytoremediation Uses | Main Chemical Groups | Medicinal Use | Gastronomic Uses | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acanthaceae | Aphelandra squarrosa Nees | Aphelandra, Kuda Belang, zebra plant, saffron spike [19,20] | Central and South America [19,20] | Root, leaf [21] |

|

na | Alkaloids (aphelandrine, spermin), phytoanticipins (2-benzoxazolinone (BOA), 2-hydroxy-1,4-benzoxazine-3-one (HBOA)), glucosides (cyclic hydroxamic acids and their corresponding glucosides) [21,22,23,24] Note: It presents allelopathic activity [25] |

Activity: antibacterial and antifungal [20,21] | Non-edible |

| Acanthaceae | Justicia aurea Schltdl. | Justicia, Yellow Jacobinia, Brazilian plume [26,27] | Central America [26] | Leaf [27,28] |

|

na | na | Treatment: coughs, epilepsy, anxiety, and malaria [26,27,28] | Leaf: juice [27] |

| Alstroemeriaceae | Alstroemeria aurea Graham | Amancay, Peruvian Lily, Lily of the Incas, Parrot Lily, and jingle bell [29,30] | Andean forests [30,31] | Flower, leaf, stem [29,30] |

|

na | Glucosides (tuliposide A), tulipalin A, phenols (6-hydroxy pelargonidin glycoside)s [32] | Treatment: gynaecological and obstetric [31] Toxicity: All parts can cause skin allergies [29,32] |

Non-edible [29] |

| Amaranthaceae | Celosia argentea L. | Lion hand, velvet, cockscomb, plumón, pluma, plumero rosa, cresta de gallo, celosia [33,34,35] | Asia [34], unknown origin [35] | Flower, seed, leaf [36,37] |

|

Soil decontamination [38] | Alkaloids, saponins, tannins, phenols (anthocyanin), glycoproteins [33,35,36,37,39] | Treatment: stop bleeding, liver heat, diseases of the blood, therapeutic eye diseases, and infections of the urinary tract [33,35,37]. Activity: antitumor, antiviral, hepatoprotective, immune-modulatory, antidiarrheal, anti-diabetic, anti-infective, anti-helminthic, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antinociceptive [33,35,36,37] |

Leaf: vegetables [36] Flower: vegetables, additive food [36,39] Seed: flour [33] |

| Amaryllidaceae | Allium schoenoprasum L. | Wild chives, scallions, garlic chives, brown garlic, leaf onions, kucai [40] | Central Asia [41] | Leaf, root, flower [40,42] |

|

Soil decontamination (Pb, Cd, Zn, and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons) [43] | Phenols, terpenes (volatile and essential oils), sulphur-compounds [41,42,44,45] Low toxicity (Daily doses: 60 g FW and 120 mg essential oil [41] |

Treatment: stop bleeding, lower blood pressure, and prevent infections of the urinary tract [40,44] Activity: antithrombotic, antitumor, hepatoprotective, immune-modulatory, antidiarrheal, anti-diabetic, anti-infective, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial (antifungal, antibacterial, antiviral, antiprotozoal, anthelmintic) [40,41,44] |

Leaf: vegetables, condiment [41,44]. All parts are edible [40] |

| Amaryllidaceae | Agapanthus africanus (L.) Hoffmanns | African Lily, Nile Lily, African agapanthus, love flower [46] | South Africa [46] | Leaf, root, flower [47] |

|

Water decontamination (TSS, COD, BOD, TP) [48] | Alkaloids (galantamine, tazatine), terpene (essential oil), tannins, phenolics (flavonoid)s, lipids (lecithin), proteins (polypeptides), saponins [46,49,50] | Treatment: heart diseases, hypertension, pregnancy and labour, cancer, and haemorrhoids [47,49,50,51] | Whole plant: infusion [50,51] |

| Amaryllidaceae |

Clivia miniata (Lindl.) Bosse Clivia miniata var. citrina S. Watson |

Bush lily, orange lily, umayime [52,53] | South Africa [54]. | Whole plant [52,53,55] |

|

Soil decontamination (Pb and carbon). | Alkaloids (galantamine), esters (3a-4-dihydro-lactone), benzopyran ((3,4-g) indole ring system), triazines (atrazine) [52,54,55,56] | Treatment: fever, relieve pain, facilitate childbirth, and as a snake bite remedy [52,54] Activity: antimicrobial, antiviral, uterotonic, antitumor, cytotoxic activities [52,54,56] Toxicity: All plants present high toxicity (alkaloids) [55]. |

Non-edible [56] |

| Apiaceae | Coriandrum sativum L. | Cilantro, Chinese parsley, European coriander, cilantrillo [57] | Mediterranean regions [57] | Whole plant [58,59] |

|

Soil decontamination (Pb, Cr and As). Water decontamination (Zn (II) ions from aqueous medium) [60,61] | Sugars, alkaloids, phenolics, resins, tannins, anthraquinones, sterols, and terpenes (essential oils) [42,57,58,59] | Activity: antimicrobial, antioxidant, anti-diabetic, anxiolytic, cardioprotective, antiepileptic, anthelmintic, antiulcer, anti-carcinogenic, diuretic, antidepressant, antimutagenic, anti-inflammatory, antilipidemic, antihypertensive, neuroprotective, diuretic [57,58,59,62] This presents cytoprotective effects in gastric epithelial cells. LD50 oil = 4.1 g/Kg [57] |

Arial part: several culinary uses [57,58] |

| Apocynaceae | Catharanthus roseus (L.) G. Don | Cape vinca, chavelita, teresita, vinca rosea, Isabelita, nayon-tara [27,63] | Madagascar [53] | Leaf, root [27] |

|

Soil decontamination (Cr, Pb, Ni and oil-contaminated soil) [64,65] | Hallucinogen (Ibogaine), alkaloids(ascartharathine, lochnenine, vindoline, vindolinenine, vincristine, vinblastine, reserpine, tetrahydroal-stronine, yohimbine, serpentine) [53,63,66] Note: the leaves have cytotoxicity [66] |

Treatment: leukaemia, a popular remedy for diabetes, headache, wasp stings, sore throat, eye irritation, low blood pressure, insomnia, Hodgkin’s disease, hypertension, neuroblastoma, malaria, rhabdomyosarcoma, Wilms tumour, vascular dementia, Alzheimer’s, dermatitis, acne [27,53,63,67] Activity: antifungal [68] |

Leaf: juice [27] |

| Apocynaceae | Nerium oleander L. | Adelfa, flower laurel, laurel rose, trinitaria [69] | Mediterranean regions [69] | Leaf, flower, root, stem [69] |

|

Soil decontamination (Ni and Cr) [70] | Alkaloids, tannins, steroids, terpenoids, flavonoids, saponins, and cardiac glycosides (nerifolin, peruvosid, vetoxin, thevethin A, thevethin B, ruvosid oleandrin, folinerin, adynerin, and digitoxigenin) [69,71,72] Note: Hazardous compounds (cardioactive steroids or cardiac glycosides) [55] |

Treatment: cardiac affections, diabetes, rheumatic pain, epilepsy, asthma, leprosy, nervous regulation, painful menstrual periods, malaria, indigestion, ringworm, venous diseases, skin problems, warts, and chemotherapeutic agents [69,71,73] Activity: antifungal, cytotoxic, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, analgesic, cardioprotective, neuroprotective, hepatoprotective [73] Toxicity: All plant causes abortions and skin irritant [29,55] |

Non-edible [29] |

| Apocynaceae | Trachelospermum jasminoides (Lind.) Len. | Star jazmín, fake jasmíne, milk jasmine, Chinese jasmine | Asia | Leaf, flower, stem [74,75] |

|

na | Lignans, alkaloids, triterpenoids, and phenolics [75,76] | Treatment: relieving rheumatic, arthritic pain, fever, gonarthritis, backache, and pharyngitis [76]. Activity: anti-inflammatory, analgesic, antitumor, antioxidant, and antimicrobial [76] |

Arial part: infusion [76] |

| Araceae | Aglaonema commutatum Schott | Aglaonema, cafeto ornamental [34] | Southeast Asia [34] | Leaf, fruit [77] |

|

Used as a vertical greenery system (VGS) to contribute to improving air quality [78] | Alkaloids (calcium oxalate crystals, polyhydroxy alkaloids), proteins (latex), terpenes (carotenoids) [77] | Treatment: Buruli ulcer (chronic and debilitating infection of the skin) and reduced swellings [79] | Non-edible. Toxic if consumed [34]. Leaf: infusion [79] |

| Araceae | Anthurium andraeanum Linden ex André | Anthurium, capotillo, flower of love, flamenco flower | America [80] | Leaf, flower |

|

Water decontamination (COD, P, coliforms) [48] | Alkaloids (calcium oxalate crystals), glycosides (cyanogenic glycosides), and phenolics [80,81] | na | na |

| Araceae | Spathiphyllum montanum (R. A. Baker) Grayum | Spath, peace liliescuina de moisés, guisnay [20,82,83] | Tropical America [20,82,83] | Leaf [84] |

|

Air decontamination with toxins [83] | Phenols (flavonoids) [84] | Activity: antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, anti-carcinogenic [20,84] | na |

| Asparagaceae | Chlorophytum comosum (Thunb.) Jacques | Tape, malamadre, clorofito, lasso of love, spider plant, ribbon plant [85] | Africa [86] | Leaf, flower, stem [85] |

|

Soil decontamination (Al, Pb, Cd salt, trichloroethylene, toluene, formaldehyde, particulate matter, and benzene) [86,87,88] Air decontamination (PM) [89] |

Saponin (gitogenin, ecogenin, tigogenin), glycosides and alkaloids [85,86] | Treatment: bronchitis, cough, fracture, and burns [85] Activity: antimicrobial, anti-carcinogenic, hepatoprotective, antitumour properties, and cytotoxicity against cancerous cell lines [85,86] |

Arial part: infusion [90] |

| Asteraceae | Bidens andicola Kunth | Ñachac, mìshico, quello-ttica, quico, chiri chiri, zumila [20,91,92,93] | South America [20,94] | Whole plant [93,94] |

|

na | Alkaloids, phenolics (flavonoids), saponins, tannins, cardiotonics, steroids, terpenoids (sesquiterpene lactones), and chalcones (chalcone ester glycosides) [91,94,95,96] | Treatment: excessive vaginal fluid, postpartum, diarrhoea, cholera, stomachache, nervous afflictions, skin problems, asthma, eye inflammation, and renal affections [92,94,96] Activity: uterine antihaemorrhagic, antirheumatic, anti-inflammatory, anti-allergenic, antibacterial, antidiabetic, antimalarial, antiviral, antihypertensive, antioxidant, antimicrobial activity, and antispasmodic properties [20,94] Toxicity: It presents a moderate toxic effect [91] |

Leaf: salad Whole plant: infusion [93] |

| Asteraceae | Calendula officinalis L. | Calendula, African marigold, Common marigold, Zergul, Garden Marigold, Marigold, Pot Marigold [97,98] | Southern Europe [99] | Flower [99] |

|

Soil decontamination (Cd, Pb) [100] | Saponins, sterols, terpenes (carotenoids, volatiles oils), tannins, resins, triterpenoids, phenols, coumarins, and quinones [42,72,97,101,102] | Treatment: used as emollient, vulnerary, moisturising, analgesic, cramps, ulcers, jaundice, and haemorrhoids [99,101] Activity: antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, antifungal, antiviral, antipyretic, antiseptic, antispasmodic, astringent, bitter, candidacies, cardiotonic, carminative, cholagogue, dermagenic, diaphoretic, diuretic, haemostatic, immunostimulant, lymphatic, uterotonic, and as a vasodilator [97,98,99,102,103] Toxicity: The leaves can cause phytodermatitis and cytotoxicity activity [55] |

It has a slightly bitter and spicy flavour. Flower: infusion [99] |

| Asteraceae | Centaurea seridis L. | Bracera marine, thorny broom | Mediterranean region [104] | na |

|

na | Glucosides, sesquiterpenoids [104,105] | Activity: anti-diabetic [104] | na |

| Asteraceae | Cichorium intybus L. | Brussels chicory, coffee chicory, root chicory, cikoria, nigana, cicoria, juju, radicheta [106,107,108] | Western Asia, Europe, and North Africa [106,107] | Whole plant [107] |

|

Soil decontamination with DDT (Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane) [88] | Sesquiterpenes lactones (lactucin, lactopicrin), aesculetin, Cichorium), coumarin (scopoletin, 6-7-dihydro coumarin, umbelliferone glycosides, terpenes (oils essential), phenolics [106,107,109] | Treatment: cardiovascular, digestive, and skin protection [107] Activity: antioxidant, hypolipidemic, anti-carcinogenic, anti-allergenic, anti-testicular, antidiabetic, diuretic, anti-inflammatory, analgesic, sedative, immunological, antimicrobial, antiprotozoal, hepatoprotective, neuroprotective, and gastroprotective [106,107] |

Leaf: salad, infusion Roots: flour [107] |

| Asteraceae | Chrysanthemum morifolium Ramat | Chrysanthema | Asia [3] | Flower [3] |

|

Soil decontamination with Pb | Pyrethroids (pyrethrins, deltamethrin), terpenes (sesquiterpene lactones), and phenolics (chrysanthemin) [3,110] | Treatment: used in the detoxification of blood, regulation of pressure, calming nerves, hypertension, angina, digestive system, muscular-skeletal system, respiratory system, arteriosclerosis, hypertension [3,111,112] Activity: antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-carcinogenic [111] Toxicity: the flowers present phytodermatitis [55] |

Flower: infusion, food supplement [3,111,113] |

| Asteraceae | Coreopsis grandiflora Hogg ex Sweet | Coreopsis | America [114] | Flower [115] |

|

Soil disturbance [116] | Phenolics [117] | Activity: antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, antimalarial, antileishmanial, and anti-Alzheimer [117] | Flower: food additive |

| Asteraceae | Cota tinctoria (L.) J. Gay | Golden marguerite, yellow chamomile [118] | Mediterranean region | Whole plant [118] |

|

Soil decontamination with B [119] | Terpenes (volatile oils), triterpenes, tannins, and phenolics [118,120,121] | Treatment: gastrointestinal disorders, stomach, haemorrhoids, antispasmodics, stimulating menstrual flow, hepatic insufficiency, and jaundice [118] Activity: antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, antispasmodic, and sedative [118,120] |

Flower: meat and dairy colouring [118] |

| Asteraceae | Dahlia coccinea Cav. | Dahlia, mirasol, mountain dahlia, wild dahlia, sunflower [122] | Mexico [122,123] | Flower, root [122] |

|

Soil decontamination with oil [64] | Terpenes (essential oils), polysaccharides (inulin), and acetylene compounds [122] | Activity: antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-carcinogenic, anti-obesity, and gastroprotective [122,124] | Flower: salad, dessert, garnish Root: soup [122] |

| Asteraceae | Dahlia pinnata Cav. | Dahlia, heron flower [20] | Mexico It was declared the national flower of Mexico [20,125] |

Flower, root [122] |

|

Soil decontamination oil [64] | Terpenes (essential oils), proteins (insulin), monosaccharides (fructose), acids (phytin, polyacetylenes, benzoic acid) [126] Note: Root exudates are nematode toxic |

Activity: antimicrobial [20] | Flower: salad dessert, garnish Root: soup [122] |

| Asteraceae | Gaillardia × grandiflora Hort. Ex Van Houtte | Gallant, flower blanket, gold button, bloodsucker, topasa dre | na | Flower |

|

na | Alkaloids (oxalates) Note: It presents an inhibitory effect on the pathogenic fungi [127] |

na | Non-edible [127] |

| Asteraceae | Tagetes erecta L. | Carnation of the moor, flower of the dead, carnation Chinese, damask, flower crest, French marigold [125,126] | Mexico The traditional day of the Dead flower in Mexico [127] |

Flower [127] |

|

Water decontamination (textile dye blue 160), HgCl, SnCl2 [128]. Soil decontamination with Cd (hyperaccumulator) and oil [64,129] |

Organic acids, terpenes (essential oil), alkaloids, and phenolics [125,130,131] Note: Essential oil is cytogenotoxic. It can be harmful in large amounts [132] |

Treatment: therapies and aromatherapies, digestive ailments (colic, parasites, discomfort, and diarrhoea), liver diseases, antiseptic, diuretic, depurative [125,127,133] Activity: antioxidant, anti-carcinogenic, anti-inflammatory, disinfectant, healing, and antifungal [125,127,131] Toxicity: the leaves present phytodermatitis [55,127] |

Flower: infusion, salad, fried. It is a natural colouring and has a bitter taste [12,113] |

| Asteraceae | Taraxacum campylodes G. E. Haglund | Dandelion, bitter chicory, diente de león [31,91,92] | Europe and Asia [120] | Whole plant [113,134] |

|

Soil decontamination (Cu, Zn, Mn, Ni, Cr, Fe, and Pb) [135,136] | Alkaloids (phytosterol, taraxacin, oxalates), phenolic (taraxastero, stigmasterol, chicoric acid, caffeic acid, acopoletin) [137,138,139,140] | Treatment: depuratives help the liver, kidney, stomachache, gall bladder, diuretic effect, constipation, clean skin impurities, acne, and hives [92,134,137,139] Activity: hepatoprotective, antirheumatic, spasmolytic, diuretic, anti-inflammatory, anti-carcinogenic, antirheumatic, anti-allergenic, anticoagulant, and anti-carcinogenic [31,137]. Toxicity: the leaves present phytodermatitis [55] |

Leaf: salad, cooked Root: coffee Flower: with olive oil, cakes, fries, and wine Whole plant: infusion [113,137] |

| Asteraceae | Zinnia elegans L. | Guadalajara, mystical rose, paper flower, field chinita | Mexico and Central America [141] | Leaf, flower |

|

Soil decontamination (Pb and Cr) [65] | Phenols (flavonoids), glycosides, tannins, and saponins [141] | Treatment: malaria and stomach pain Activity: hepatoprotective, antiparasitic, antifungal, antibacterial, and antioxidant [141] |

Flower: salad, infusion |

| Balsaminaceae | Impatiens walleriana Hook. f. | House joy, bear ears, balsam, miramelindo | Africa and Asia | Leaf, stem, flower |

|

Soil decontamination with Cd (hyperaccumulator) [129] | Naphthoquinones, phenols (flavonoids), saponins (triterpenoid saponins), alkaloids (phytosterols, proteins, and terpenes (essential oils) [129,142] | Treatment: abdominal pain, ulcers, amenorrhea [129] | Flower: infusion, salad, garrison It has a sweet flavour. |

| Begoniaceae | Begonia cucullata Willd. | Begonia, sugar flower [126] | Brazil [126] | Flower [143] |

|

Soil decontamination with oil [64] | Phenolics, terpenes [144] | Activity: antispasmodic, astringent, ophthalmic, poultice, and stomachic activity [143] | na |

| Begoniaceae | Begonia × tuberhybrida Voss | Begonia [12,126] | Andes [126] | Flower [12] |

|

na | Alkaloids (oxalic acid, tetracyclic triterpene), phenolics [113,144] | Activity: antispasmodic, astringent, ophthalmic, poultice, and stomachic [12,143] | Petals are edible. This flower has a lemon flavour [12,113,143] |

| Bignoniaceae | Tecoma capensis (Thunb.) Lindl. | Cape Honeysuckle, tecoma [145,146] | South Africa [147] | Leaf, flower, root [148] |

|

na | na It is an invasive species [147] |

Treatment: pneumonia, enteritis, diarrhoea, fragrance, tonic, eliminating placenta retained in childbirth, snakebite, sleeplessness, induced sleep [148,149,150] Activity: antimicrobial, antifungal, antipyretic, antioxidant [149] |

Arial part: infusion [148] |

| Bignoniaceae | Tecoma stans (L.) Juss. ex Kunth | Yellow bell, tronadora, huiztontli, huiztonxochitl [151] | Mexico [147,151] | Leaf, flower [152] |

|

Soil and water decontamination (FeCl3, CaCO3) [128] | Alkaloids (tecomine, tecostamine), phenolics, steroids, and tannins [151,153] | Treatment: arterial hypotension, hypoglycaemia, and urinary disorder [151,152] Activity: antidiabetic, antimicrobial, and antioxidant [149,152] |

Non-edible |

| Boraginaceae | Heliotropium arborescens L. | Vanilla of garden, heliotrope, grass of the mule, violoncello, cherry pie, heliotrope [154,155] | Peru | Leaf, stem, flower [155] |

|

na | Esters (heliotropin, benzyl acetate), alkaloids (heliotrine, oxalates), phenols (vanillin, cynoglossin, caffeic acid), benzaldehydes (benzaldehyde, p-anisaldehyde), lithospermic acid [139,154,155] |

Treatment: headache, sun stoke, sinus cancer, mucus relief, diuretic, uterine displacement, fever, migraine, high blood pressure, diarrhoea, breast cancer, kidney infection, pressure in the stomach and sternum, uterine displacement, and dysmenorrhea [139,155] | Arial part: infusion |

| Brassicaceae | Alyssum montanum L. | Spanish, garlic herb, rabies herb, rage herb | Europe [156] | Flower |

|

Soil decontamination (Cd, Ni, Pb, and Cu) [157,158] | Glucosinolates (goitrogenic glycosides) | na | Non-edible |

| Brassicaceae | Diplotaxis tenuifolia (L.) DC. | Rucola, yellow flower, rustic [159,160] | Mediterranean region [160] | Leaf |

|

Soil decontamination with Pb [161]. | Glucosinolates Note: It presents allelopathic properties (S-glucopyranosyl thiohydroximate) [162,163,164] |

Treatment: digestive, diabetes, cardiovascular disorders, and cancer [159] Activity: antitumor [159] |

Leaf: salad It is used in the food industry (IV gamma) [159,160] |

| Brassicaceae | Matthiola incana (L.) R. Br. | Alehí, Jasmine ashtray, White viola [134] | South Europe | Flower [134] |

|

na | Isoprenoids (tocopherols), proteins (hormones), and anti-pathogens [165] | Treatment: traditional medicine, stomachache, colic, and diarrhoea for frighten [134,165] | Arial part: infusion, garnish, salad, desserts [134] |

| Cannabaceae | Cannabis sativa L. | Marijuana, marihuana, hashish, hachís, hemp [53] | Asia [53] | Whole plant [47,166] |

|

Soil decontamination (Cu, Cd, As, Ti, Cr, and Ni) [167]. | Phenols (tannins), cannabinoids, terpenophenols (tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), cannabidiol (CDB)), and alkaloids [168,169] | Treatment: developmental disorder, hypertension, asthma, diabetes, heart conditions, blood pressure, epilepsy, and glaucoma [47,53,170] Activity: analgesic, antiemetic, anti-carcinogenic, antispasmodics [53] Note: the leaves are mutagenic without metabolic activation [66] |

Arial part: infusion. It is a source of fibre, food, oil, and medicine [169,171] |

| Cannaceae | Canna indica L. | Achira, achira roja, achera, sago, spark, Indian cane, papantla [20,34,172] | South America [20,34,173] | Root, flowers |

|

Water decontamination (Cu, Zn, fertilisers, carbamazepine, and insecticides) [48] | Alkaloids, phenols (tannins) [42,173,174] | Treatment: peptic ulcer, diarrhoea, and ulcerative colitis Activity: antibacterial, anthelmintic, antiviral, anti-inflammatory, hepatoprotective, antidiarrheal, anti-carcinogenic, analgesic, and antioxidant [20,62,173,175] |

Root: starch Leaf: food cover [174] |

| Caryophyllaceae | Dianthus caryophyllus L. | Carnation, claveles [176] | Europe and Asia [176] | Flower [134] |

|

na | Triterpenes, saponins, terpenoids (carotenoids), and phenolics [42,176,177] | Treatment: HIV, simple herpes, hepatitis, vomiting, and gastric disorders [134,176,178] Activity: antibacterial, anti-fungal, antiviral, cardiotonic, diaphoretic, vermifuge, gastroprotective, anti-carcinogenic [176,179] |

It has a slightly bitter flavour. Flower: salad, butter, garnish [180] |

| Caryophyllaceae | Dianthus chinensis L. | Dianthus, carnation, Chinese carnation, pae-raeng-ee-kot [181] | China [182] | Leaf, stem, flower |

|

na | Phenols (eugenol), alcohols (phenyl ethyl alcohol), glycosides (melosides A and L, dianchinenosides A, B, C, and D), saponins [181,183] | Treatment: menostasis, gonorrhoea, diuretics, emmenagogue, and cough [181,182,183] Activity: anti-inflammatory, diuretic, analgesic, anti-hepatotoxic, hypotensive, anthelmintic, intestinal peristaltic, antitumor, antioxidant, antitumor, antibacterial, antifungal [181,183] |

It is slightly bitter. Flower: infusion, salad, desserts, garnish [113] |

| Caryophyllaceae | Gypsophila paniculata L. | Cloud, bridal veil, paniculata, baby’s breath, sabunotu, Tibbi sabunotu [184] | Turkey, Caucasia, and Iran [185] | Leaf, stem, flower |

|

Soil decontamination (B) [185] | Allelochemical phenolic acids and saponins (triterpenoid saponins) Note: It presents insecticidal activity. It is an invasive perennial plant [184,186] |

Treatment: cough, respiration system, bronchitis, stomach disorders, bone deformations, pimples, bile disorders, liver problems, rheumatism, and skin diseases [185]. Activity: antimicrobial [184] |

Arial part: infusion |

| Caryophyllaceae | Saponaria officinalis L. | Soap dish, soap flower, sabunotu, tibbi sabunotu, karga sabunu, soapwort [185,187] | Turkey, Caucasia, and Iran | Root, leaf [185] |

|

Soil and water decontamination (hydrocarbon, Cd(II), Zn(II), Cu (II) [187] | Triterpenoid, saponins (saponarioside A/B) [185,187,188] | Treatment: influenza, stomach disorders, simple herpes, bone deformations, cough, bronchitis, rheumatism, pimples, skin diseases, bile disorders and hepatic eruptions, venereal ulcers, diuretic, diaphoretic, cholagogue, and hepatic eruptions [185,187,188] Activity: anti-microbial, antipyretic, antiseptic, anthelmintic, tonic, diuretic, anti-diabetic [185,187,189] |

Arial part: infusion [189] |

| Celastraceae | Euonymus japonicus Thunb. | Evonimo, bonetero | Japan [190] | Fruit, leaf, seed [190] |

|

Air decontamination [191] | Alkaloids, terpenes, phenolics [190,191,192] | na | Fruit: the powder is a natural colouring for butter [190] |

| Convolvulaceae | Convolvulus althaeoides L. | Bells of the virgin, carriguela, correhuela, bindweed, leblab elhokul [193] | Mediterranean region [193,194] | Leaf, root, flowers [194,195] |

|

na | Alkaloids, saponins, phenolics, chlorophylls, and terpenes (carotenoids) [193] Note: Essential oil presents cytotoxic activities and is considered “weed” [194] |

Treatment: wound healing, asthma Activity: laxative, purgative, antimalarial, antimicrobial, antioxidant [193,194,195] |

Arial part: infusion |

| Convolvulaceae | Convolvulus pseudoscammonia C. Koch | Meadow bell, scammony Syrian bidweed, Purgin bindweed. | Asia [196] | Leaf, stem, flower [196] |

|

na | Alkaloids, saponins, terpenes (resin), phenols (dihydroxy cinnamic acid, flavonols), and coumarins (beta-methyl-aesculetin) [62,196,197] | Treatment: uterotonic, abortifacient, treatment of oedema, ascites, simple obesity, lung fever, ardent fever, purgative, vasorelaxant [196] Activity: antimalarial, anti-platelet aggregation, anti-carcinogenic, cell protector effect, anti-carcinogenic [194,196] |

Arial part: infusion [196] |

| Crassulaceae | Kalanchoe blossfeldiana Poelln. | Kalanchoe [126] | Madagascar and East and South Africa [126,198] | Flower [198] |

|

Soil decontamination with benzene [88]. | Phenolics, coumarins, bufadienolides, triterpenoids, phenanthrenes, sterols, fatty acids, and kalanchosine dimalate salt [199,200] Note: All plants present high toxicity (cardioactive steroids or cardiac glycosides) [55] |

Treatment: skin problems, periodontal disease, cheilitis, cracking lips in children, wounds, insect bites, ear infections, dysentery, fever, abscesses, cholera, urinary disorders, arthritis, gastric ulcers, rheumatism, pulmonary disease, rheumatoid arthritis, coughs, gastric ulcers Activity: antimicrobial [199] |

Arial part: infusion |

| Cucurbitaceae | Citrullus lanatus (Thunb.) Matsum. and Nakai | Watermelon, Sandia, side, patilla [34,201,202] | Southern Africa [201,203] | Fruit, seed [53,201] |

|

Water decontamination with Cd [204] | Saponin, alkaloids, phenols (anthocyanins, tannins, phenolic acids, flavonoids), terpenes (carotenoids, monoterpenes) [201,203] | Activity: antimicrobial, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antispasmodic, anti-prostatic, analgesic, antidiabetic, laxative, antiulcer, and hepatoprotective [201,202,203] | Fruit: widely used in the food industry [34] |

| Cucurbitaceae | Cucurbita maxima Duchesne | Squash, pumpkin, flor de calabacín, auyama, calabaza, sapayo, zapallo [34,92] | South Africa [34] | Fruit, leaf [202] |

|

na | Saponins, alkaloids (cardenolides), and phenols (flavonoids) [202,205] | Treatment: Seed oil is used for the treatment of benign prostatic hypertrophy, laxative Activity: laxative, antimicrobial [92] Toxicity: LC50 = 4311 µg/mL |

Fruit: widely used in the food industry [34] |

| Ericaceae | Rhododendron simsii Planch. | Azalea indica, azalea [206] | China [207] | Leaf, flower [207] |

|

na | Alkaloids (grayanotoxane (pollen, nectar, and leaves)), phenols (flavonoids), and benzoic acid derivatives [207] | Treatment: gastrointestinal disorders, asthma, arthritis, skin diseases, cough, resolving sore toxin, amenorrhea, expectorant, and bronchitis [207] Activity: anti-inflammatory, anti-herpes, antioxidant, antiviral, hepatoprotective, and sedative [207,208] |

Arial part: infusion |

| Euphorbiaceae | Euphorbia milii Des Moul. | Crown of Christ, corona de espinas, espinas de cristo [34,209] | Madagascar [34] | Whole plant |

|

Air decontamination [210] | Terpenes (triterpenoids, diterpenoids), phenols (flavonoid, tannins s), proteins (latex) [210,211] | Treatment: respiratory tract inflammation, diarrhoea, skin ailments, gonorrhoea, tumours, cough, dysentery, asthma, hepatitis, abdominal oedema Activity: sedative and analgesic [211] |

Arial part: infusion |

| Fabaceae | Brownea macrophylla Linden | Brownea, Mountain rose, Cross stick, Male cross stick [212] | Colombia, Panama, and Venezuela [213] | Flower [212] |

|

na | na | Treatment: haemostatic, for haemorrhages, birth control, and against snake bites [212] | Non-edible |

| Fabaceae | Lathyrus aphaca L. | Yellow pea, aphaca, wild pea, Indian flower [214] | Europe, Asia, Africa [214] | Flower [214] |

|

na | Seeds contain toxic amino acids [133] | na | Seed: widely used in the food industry |

| Fabaceae | Senna alexandrina Mill. | Senna, cassia, sen, cassia angustifolia [53,214] | Egypt [214,215] | Leaf, fruit, flower [53,214,216] |

|

Soil decontamination (Al, Ba, Mn, and Zn) | Glycosides (anthraquinone derivatives, senna glycosides) [214,215] | Activity: laxative, antipyretic, purgative, diuretic, stomach [53,215,216] | Arial part: infusion |

| Fabaceae | Senna corymbosa (Lam.) H. S. Irwin & Barneby | Buttercup bush, Argentine Senna, sena del campo, rama negra, mata negra [20,217,218] | South America [20,217] | Flower |

|

na | Glycosides (anthraquinone glycosides, naphthoquinone), phenols (flavonoids) [217] | Activity: laxative, purgative, antidiabetic, hepatoprotective, antimalarial, antipyretic, antiasthmatic, antiviral, and antibacterial [20,217,218] | Arial part: infusion |

| Fabaceae | Senna didymobotrya (Fresen.) H. S. Irwin & Barneby | Senna, popcorn cassia [219] | na | Whole plant [220,221] |

|

na | Alkaloids, anthraquinones, phenols (condensed tannins, hydrolysable tannins), saponins, sterols, and steroids [221] | Treatment: madness, ringworm infections, leprosy, syphilis, diabetes, convulsions, stomach complaints, wound healing, an antidote for snakebites, haemorrhoids, sickle cell anaemia. Activity: purgative, anti-inflammatory, antimalarial, hepatoprotective, antimicrobial [219,220] |

Arial part: infusion |

| Fabaceae | Senna papillosa (Britton & Rose) H.S. Irwin & Barneby | Sena, candelillo | na | Flower |

|

na | Phenols (flavonoids), coumarins, mellilotic acid, and iridoids | Activity: antimalarial [222] | Non-edible |

| Fabaceae | Styphnolobium japonicum (L.) Schott | Acacia from Japan, sófora, Japanase pagoda tree, Huai, Chinese scholar tree [223] | China [223] | Leaf, root, flower, seed [224] |

|

Soil decontamination (Cu, Cr, Cd, Hg, Ni, Zn and Pb) [225,226] | Alkaloids, phenols (isoflavonoids), triterpenoids [223,224] | Treatment: haemorrhoids, uterus problems, intestinal bleeding, arteriosclerosis, hypertension, cooling blood, and haemostasis [223,224] Activity: anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, antiosteoporotic, antihyperglycemic, anti-obesity, and antitumor [223,224] |

Arial part: infusion [224] Flower: tea, cake [227] |

| Fabaceae | Trifolium alexandrinum L. | Clover, berseem clover [228] | Mediterranean | Whole plant [229] |

|

na | Cyanogenic glycosides [229] | Treatment: bronchitis, asthma, burns, cough, ulcers, sedation, polycystic ovary, heart disorders, colic Activity: anti-diabetic and laxative [229] |

na |

| Geraniaceae | Pelargonium domesticum L. H. Bailey | Geranium thinking, ral geranium, malvon thinking [230] | Africa [126] | Whole plant [230] |

|

Soil decontamination with benzene [88] | na | Treatment: respiratory infection, sleep disturbance, fatigue, loss of appetite, wound healing [230] Toxicity: the leaves and stems present phytodermatitis [55] |

Flower: dessert, cake, drink, salad, flower water, garnish. |

| Geraniaceae | Pelargonium peltatum (L.) L’Hér. | Gitanilla, geranium of ivy, geranio [230] | Africa [126] | Whole plant [230] |

|

na | Phenols, terpenes (essential oil) [231] | Treatment: heal wounds Activity: antioxidant and antimicrobial [230,231,232] Toxicity: the leaves and stems present phytodermatitis [55] |

Leaf has an astringent and bitter taste. The leaves and stems present gastrointestinal toxins. |

| Geraniaceae | Pelargonium × hortorum L. H. Bailey | Common geranium, malvon, garden geranium, geranio común | Africa [233] | Whole plant |

|

Soil decontamination (Cd and Pb) [234] | Triterpenoids, sterols, and phenols (flavonoids, anacardic acids) [235] | Treatment: respiratory infection, sleep disturbance, fatigue, loss of appetite, wound healing Activity: antioxidant and insecticidal [230,236] Toxicity: the flowers induce paralysis [237] |

Flower: dessert, cake, drink, salad, flower water, garnish. |

| Goodeniaceae | Scaevola aemula R. Bronw | Fan flower | Australian [238] | Flower |

|

na | na | na | Arial part: infusion |

| Hydrangeacea | Hydrangea petiolaris Siebold Zuc | Hydrangea | Himalaya | Flower |

|

na | na | Activity: anti-inflammatory, antibacterial [239] | Arial part: infusion |

| Iridaceae | Gladiolus communis L. | Gladiolo [240] | Africa [240] | na |

|

Water decontamination (Zn, Pb, Cu) [241] | na | Treatment: obesity, asthma, diabetes, and fertility | It tastes like lettuce. Flower: salad, garnish |

| Juglandaceae | Pterocarya stenoptera C. DC. | Chinese ash, Chinese wingnut, ghost maple, willow, gold trees [242,243] | China | Leaf, bark |

|

na | Phenols (tannins) [242] | Treatment: insecticide, remove scabies, eczema, abscesses, rheumatism, cold-damp bone ache, odontia, head pain, haemorrhoids, itch, pyrosis, ulcer [242,243,244] Activity: carminative, anthelmintic, anti-herpes [244] |

Arial part: infusion [244] |

| Lamiaceae | Agastache foeniculum (Pursh) Kuntze | Aniseed swab, hyssop [108,245] | North America [245] | Aerial parts, seed, root [245] |

|

na | Note: Essential oil presents toxicity with LC50 between 18.8 to 21.6 µL/L [245,246] | Activity: antimicrobial, antiviral, antimutagenic, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant [245] | The flower has an anise flavour. |

| Lamiaceae | Lavandula angustifolia Mill. | Alucema, lavender [126] | Mediterranean region [126,247] | Leaf, stem, flower |

|

na | Terpenes (essential oils, triterpenoids, sesquiterpene, linalool, linalyl acetate), phenols (flavonoids (apigenin, luteolin)), coumarins [247,248] | Treatment: respiratory, muscular-skeletal, and cardiovascular [249] Toxicity: the leaves can produce phytodermatitis [55] |

It is an aromatic herb. Arial part: infusion |

| Lamiaceae | Mentha suaveolens Ehrh. | Mastranzo, mint suaveolens [250] | Occidental Mediterranean | Leaf, stem, flower |

|

na | Terpenoids (essential oils), phenols (flavonoids) Note: It is toxic in high doses (peppermint oil) [251,252] |

Activity: antimicrobial, antiviral, antioxidant, tonic, stimulating, stomachic, carminative, analgesic, choleretic, antispasmodic, sedative, hypotensive, insecticidal, analgesic, anti-inflammatory [251] Toxicity: the leaves can cause phytodermatitis [55] |

It is used in the food industry. Arial part: infusion |

| Lamiaceae | Mentha × piperita L. | Peppermint, menta, hierbabuena [126] | Natural hybrid of Mentha aquatica and Mentha spicata [253] | Leaf, stem, flower |

|

Fatty acids, terpenes, and phenolics [253] | Treatment: disorders of the mental-nervous, respiratory, digestive, metabolic, and nutritional Activity: antifungal, antiviral, antioxidant, anti-allergenic [253] Toxicity: essential oils and the leaves can cause phytodermatitis [55] |

It is used in the food industry. Arial part: seasoning, cold drinks, salads [253] |

|

| Lamiaceae | Rosmarinus officinalis L. | Romero, Rosemary [31,108,126] | Mediterranean region [126] | Leaf, stem, flower |

|

Soil decontamination (Ni, Cu, Zn, Cr, Co, Pb, and Cd) [254] | Terpenoids (essential oil: pinene, camphene, cineol, borneol, camphor) [255] | Treatment: cardiovascular, skin, muscular-skeletal diseases, sensory, nutritional, reproductive, mental-nervous, digestive, and respiratory systems [31,178,249,250,255] | Arial part: dessert, sorbet, season meet, infusion [227] |

| Lamiaceae | Salvia leucantha Cav. | Mexican bush sage or sage [256] | East Mexican and Tropical America [20] | Flower |

|

na | Diterpenoids(salvigenane and isosalvipuberulan) [257] | Treatment: mental, nervous, gastrointestinal, menstrual, digestive disorder, blood circulatory regulator [256] Activity: antibacterial, antiviral, antitumor, spasmolytic, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory [20,256] |

Flower: flavouring, condiment |

| Lamiaceae | Salvia microphylla Kunth | Asia | Flower |

|

na | Terpenoids (essential oils, diterpenoids, sesquiterpenoids, triterpenoids), phenols (flavonoids) [258] | Treatment: digestive and respiratory problems | Arial part: infusion [257] | |

| Lamiaceae | Salvia splendens Sellow ex Schult. | Red salvia, banderilla, salvia scarlata | Brazil [259] | Flower |

|

na | Terpenoids (monoterpenes, diterpenoids, sesquiterpenes, and tanshinones) and phenols (flavonoids, savianin, monardacin, and their demalonyl derivatives). Note: It presents cytotoxic activity [257,260] |

Activity: antioxidant, neuroprotective, antimicrobial, antibacterial, anti-carcinogenic, anti-inflammatory, analgesic, anaesthetic, anti-stress, antiulcer, antimutagenic, antidiabetic, diuretic, haemostatic, hypoglycaemic, diaphoretic, and antidepressant [257,260,261] | It Is flavouring. Arial part: infusion, sweet-salty dishes [257] |

| Lamiaceae | Vitex agnus-castus L. | Pepper of the mountains, willow trigger | Mediterranean region | Flower |

|

Water decontamination [262] | Phenolics, terpenes (essential oils), alkaloids [263] | Treatment: premenstrual, digestive, respiratory system, premenstrual dysphoric disorder, lactation difficulties, low fertility, menopause [249,263,264,265,266] | It is used in the food industry. Arial part: infusion [266] |

| Lythraceae | Cuphea hyssopifolia Kunth | False brecina, cufea, false Mexican heather, false erica | Central and South America [267] | Flower |

|

na | Phenols (tannins, flavonoids, and phenolic acids), sterols, and terpenes (triterpenes) [267] Note: It presents cytotoxic activity [268] |

Treatment: stomach pain, syphilis, and cancer Activity: antiviral, antimicrobial, antioxidant, hepatoprotective, antitumor [267,268] |

Arial part: infusion |

| Lythraceae | Lagerstroemia indica L. | Jupiter tree, mousse, lilac of the Indies, southern lilac, crepe | China [269] | Flower |

|

Water decontamination with fluoride [270] | Alkaloids, glycosides (anthraquinone glycosides), phenols (flavonoids), saponins [271] Note: It presents cytotoxic activity. LC50 = 60 µg/mL and LC90 = 100 60 µg/mL [272] |

Treatment: stomach pain, weight loss, lower blood sugar Activity: antioxidant, antibacterial, antiviral, anti-inflammatory, anti-gout, anti-diarrheal, anti-obesity, and anti-fibrotic [271] |

Arial part: infusion |

| Lythraceae | Punica granatum L. | Pomegranate, Granada, Dalim gach [27] | Asia and Mediterranean Europe [273] | Fruit, leaf [27] |

|

Soil decontamination [274] | Phenols (catechins), alkaloids, [273,275] | Treatment: bronchitis, tuberculosis, diarrhoea, and protecting the kidney [27,249,276] Activity: anti-carcinogenic, antimicrobial, antihypertensive, anti-diabetic, anti-HSV-1, diuretic, antioxidant [67,273,276] |

Fruit: widely used in the food industry [276] Flower: infusion Leaf: fried [27] |

| Magnoliaceae | Magnolia grandiflora L. | Magnolia [126,277] | South-eastern United States [126,277] | Flower |

|

Soil decontamination (Cu, Cr, Zn, Ni, Cd, Hg) [226] | Phenols (flavonoids), terpenes (sesquiterpenes, essential oils) [277] | Treatment: flatulent dyspepsia, cough, asthma, digestive problems, and emotional distress [277] Activity: antifungal, anti-melanogenic, antioxidant and antimicrobial [277] |

Flower: infusion |

| Malvaceae | Ceiba speciosa (A.St.-Hil.) Ravenna | Chorisia, Bottle tree; Drunken tree | South America | Flower |

|

na | Phenols (flavonoids), alkaloids, coumarins, terpenes (sesquiterpenes, sesquiterpene lactones, triterpenes), steroids, lignans, cyclopropenium fatty acids, and oxidised naphthalenes [278,279] | Treatment: fever, diabetes, headache, diarrhoea, parasitic infections, rheumatism, and peptic ulcer Activity: anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, hepatoprotective, cytotoxic, antioxidant, hypoglycaemic, and antipyretic [279] |

It is used for a variety of ailments. Seed: culinary and industrial |

| Malvaceae | Gossypium arboreum L. | Cotton, cotonera, coto, algodón | Asia | Leaf, root, seed, flower |

|

Soil decontamination with oil [64] | Phenols (gossypetin 8-o-rhamnoside, gossypetin 8-o-glucoside) and terpenes (gossypol). | Treatment: healing of wounds, ulcers, bruises, respiratory, and skin diseases | Non-edible |

| Malvaceae | Hibiscus rosa-sinensis L. | Chinese rose, cayenne, pop, hibiscus, papo, San Joaquín, carnation, Laal joba [27] | Eastern Asia National flower of Malaysia, Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, Hawaii, Barranquilla, and Barrancabermeja (Colombia) |

Flower, root, leaf [27] |

|

Water decontamination with zinc ions [280] | Ketones (chloroacetophenone), phenolics (tannins), steroids, proteins (mucilage) [42,72,281] | Treatment: hypertension, inflammations, dysentery, and respiratory tract [27] Activity: antispasmodic, analgesic, astringent, laxative, antioxidant, antimicrobial, anti-diabetic, cardioprotective, and anti-anxiety [281,282,283] Toxicity: the leaves can cause phytodermatitis [55] |

Flower: salad, cooked, infusion Root: salad Leaf: juice [27] |

| Malvaceae | Hibiscus sabdariffa L. | Rose of Jamaica, rose of Abyssinia, hibiscus red sorrel, rosella, tart of guinea, alleluia, susur, flor de Jamaica [53,284] | West Africa [285] | Leaf, flower [285] |

|

Soil decontamination (Mn and As) [286] | Phenols (protocatechuic acid) [42,284,285] | Treatment: folk remedy for abscesses, bilious conditions, cancer, cough, dysuria, cardiovascular problems, and scurvy [249,284,287] Activity: antioxidant, antiseptic, astringent, diuretic, emollient, purgative, and sedative [53,285,287] |

It is a resource for food and medicine. Flower: food colouring, beverages, jams [285,287,288] |

| Malvaceae | Hibiscus syriacus L. | Altea, Syria rose, wasp, hibiscus [34] | Asia It is the national flower of Korea. Origin unknown [34,289] |

Leaf, flower, root |

|

na | Terpenes (essential oils, pentacyclic triterpene esters), lignans, coumarins, and phenolics [289] | Activity: antioxidant, dermatological, anti-proliferative, anti-carcinogenic, antimicrobial, antiviral, anti-inflammatory, anti-tyrosinase [289,290] | Flower and leaf: salad, cooked, infusion |

| Malvaceae | Malvaviscus arboreus Cav | Marshmallow, false hibiscus, azocopacle, manzanita [291] | South and Central America, Southeastern United States [292] | Flower [292] |

|

na | Phenolics, sterols, fatty acids [292] | Treatment: dysentery, stomach pain, ulcers, and coughs [292,293] Activity: antioxidant, antimicrobial, thrombolytic, anti-inflammatory, cytotoxic, hepatoprotective [292] |

Arial part: infusion, salads [292] |

| Nyctaginaceae | Bougainvillea spectabilis Willd. | Bougainvillea, bogambilya, bongabilya, great bougainvillea [294] | South America [20,294] | Leaf, stem [294] |

|

Soil decontamination (Cu, Zn) [295] | Phenols (flavonoids, tannins), saponins, sterols, triterpenes, and alkaloids [294,296] | Treatment: stomach, hepatitis, cough [294] Activity: analgesic, anti-diabetic, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, astringents, diuretics, antifertility [20,283,294,297] |

Flower: infusion, salad, fried [294] |

| Nyctaginaceae | Mirabilis jalapa L. | Don Diego at night, dompedros, parakeet, wonder of Peru, carnation [20] | South America [20,126] | Leaf, root, flower [298,299] |

|

Soil decontamination (total petroleum hydrocarbons) [64] | Triterpenes, proteins, phenolics, alkaloids, and steroids [298,299] |

Treatment: anthrax Activity: antitumor, virus inhibitor, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, antioxidant, and antidiarrheal [20,299,300] |

Flower: food colouring Leaf: cooked, infusion Root: infusion Seed: infusion |

| Oleaceae | Jasminum sambac (L.) Aiton | Diamela, Arabian Jasmine, Jasmine diamela, Jasmine paper, mostia, Lily jasmine [301] | India National flower of the Philippines. It is one of the three important flowers in Indonesia [301] |

Leaf, flower, root [227,301] |

|

Soil decontamination with Pb [302] | Alkaloids, phenols (flavonoids, tannins), terpenoids (essential oils), coumarins, glycosides (cardiac glycosides), steroids, saponins, and phytosterols [303] | Treatment: cough, reducing sputum, cancer, uterine bleeding, ulceration, leprosy, skin diseases, and wound healing [227,301] Activity: antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-carcinogenic, anti-obesity, and neuroprotective [301] |

Flower: infusion, salad [227] |

| Onagraceae | Fuchsia magellanica Lam. | Fuchsia magellanica [20] | Peru, Chile, and Argentina [20] | Leaf, stem, fruit, flower |

|

na | Phenolics [304] | Treatment: scarce menstruation and increased flow of urine [20] | It has a slightly acidic flavour. Fruit and flower: infusion |

| Orchidaceae | Phalaenopsis aphrodite Rchb. f. | Orchid | It is considered an Indonesian national flower. |

|

na | Alkaloids (phanaelopsin T), phenolics | Activity: antioxidant | na | |

| Passifloraceae | Passiflora × belotii Pépin | Passionflower | North, Central and South America [305] | Leaf, flower, fruit |

|

na | Phenols (flavonoids) [306] | Treatment: sedative, hypnotic, antispasmodic, and hypotensive | Flower: infusion |

| Plantaginaceae | Antirrhinum majus L. | Scrofularia, dragon mouth, bunnies, dragoncitos, gallitos [126,307] | Mediterranean region [126] | Flower |

|

Soil decontamination (Pb and petroleum) [308,309] |

Saponins, phenols [42] | Treatment: scurvy, liver disorders, tumours, haemorrhages Activity: diuretics [307] |

Flower: salad [58] |

| Plantaginaceae | Plantago major L. | Llantén [38] | Europe | Leaf, seed |

|

Soil decontamination (Cu, Mn, Zn, Pb and Cr) [214] | Proteins (mucilage), phenols (tannins), chromogenic glycosides (catapol), and alkaloids (noscapid) [309] | Treatment: digestive, stomach upset, intestine inflammation, abscesses, cold pimples, metabolic, muscular-skeletal, respiratory, mental-nervous, liver, kidney, rheumatism, wounds, dysentery, burns, angina, asthma, fever, tuberculosis, whooping cough, chronic renal inflammation, dermal diseases, bronchitis, purgative, arthrosis, skin problems, haemorrhoids, blood pressure, and heart afflictions [134,195,249,310,311] | Arial part: infusion [309] |

| Plantaginaceae | Russelia equisetiformis Schltdl. & Cham. | Ruselia, tears of love, firecracker, coral, fountain plant [312] | Tropical America [313] | Leaf, flower [313] |

|

na | Sterols, triterpenes, saponins [314] | Treatment: malaria, cancer, and inflammatory diseases [313] Activity: antimicrobial [314] Toxicity: Its present cytotoxic activity [312] |

Arial part: infusion [314] |

| Plumbaginaceae | Limonium sinuatum (L.) Mill. | Blue inmortelle, capitana, Straw flower, limoniun, paper flower [214] | Mediterranean region [315] | Flower [28] |

|

Soil decontamination with Pb [28] | na | Treatment: helps prevent the increase in glucose levels [28] Activity: antioxidant [316] |

Flower: food additive, infusion [316] |

| Plumbaginaceae | Plumbago auriculata Lam. | Plumbago, Blue Jasmine, azulina, cape leadwort [34] | South Africa [34] | Flower, root [150] |

|

Soil decontamination (metalliferous mines and phytoremediation) [317] | Phenolics (tannins) [318] | Treatment: headache, warts, fractures, oedema, malaria, and skin lesions Activity: sedative and antimicrobial [150,319] |

Arial part: infusion |

| Polygonaceae | Fallopia aubertii (L. Henry) Holub | Gabriele Falloppio, Fallopius [320] |

Turkestan [320] | Flower |

|

na | Phenols (flavonoids, tannins), terpenes (carotenoids, triterpenes), sterols, [320] | Activity: antioxidant, anti-carcinogenic, and antimutagenic Toxicity: It presents cytotoxic activity [320] |

na |

| Polygonaceae | Polygala vulgaris L. | Common polygala | Europe | Flower |

|

na | na | na | na |

| Portulacaceae | Portulaca oleracea L. | Verdolaga, ghotika, pinyin, krokot, little hogweed, purslane [40,126] | India | Leaf, stem, flower [40] |

|

Soil decontamination with Cr (VI) [321] | Alkaloids (oxalic acid), coumarins, phenols (flavonoids, tannins), glycosides (cardiac glycosides), anthraquinones, linoleic acid, saponins [322,323] | Treatment: used in musculoskeletal, nutritional, mental-nerve, cardiovascular, haemorrhoids, and gastrointestinal disorders [40,323] Activity: anti-diarrheal, anti-inflammatory, anthelmintic, diuretic, antiasthmatic, anti-bronchitis, anti-Buruli ulcer, antioxidant, and hypoglycaemic [40,79,324] |

Arial part: raw or cooked [40,323] |

| Ranunculaceae | Ranunculus asiaticus L. | Mediterranean region [325] | Flower |

|

na | Alkaloids | Activity: antibacterial [326] | na | |

| Rosaceae | Fragaria × ananassa (Duchesne ex Weston) Duchesne | Strawberry, fruit billa [250] | Europe | Fruit |

|

na | Phenolics, vitamin C [327] | Activity: antimicrobial, anti-allergenic, antihypertensive [327] | Fruit: widely used in the food industry |

| Rosaceae | Rosa hybrid Vill. | Rosa | na | Flower |

|

Soil decontamination (As, Co, Mo, and Ni) [328] | Phenols (glycosylated cyanidin’, pelargonidin) [329,330] | Treatment: used in respiratory and dermatological diseases and arthritis. Activity: antioxidant, anti-inflammatory laxative, and astringent [330] |

It is sweet and aromatic. Flower: dessert, sweet, savoury dishes |

| Rubiaceae | Gardenia jasminoides J. Ellis | Gardenia, Cape Jasmine | Asia | Fruit [331] |

|

Soil decontamination (alumina and aluminium salts) [332] | Phenols (flavonoids), terpenoids, and organic acids [333] | Activity: antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and fibrinolytic [331,333] Toxicity: the fruit can cause phytodermatitis. It presents a cytotoxic effect [55]. |

Fruit: food colouring [333] Flower: tea [331] |

| Rubiaceae | Ixora coccinea L. | Ixora, iosca, Santa Rita, geranium of the jungle, llama of the forests, corralito [334] | Asia [334] | Leaf, stem [334,335] |

|

Soil decontamination [336] | Alkaloids, glycosides, phenols (flavonoids, tannins), steroids, triterpenoids, saponins, and proteins (resins) Note: It has cytotoxic activity [334] |

Treatment: reduce cholesterol, control blood pressure, regeneration of tissues, reduce obesity Activity: antibacterial, antiviral, antimutagenic, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, anthelmintic, antileishmanial, anti-asthmatic, hepatoprotective [334] |

Arial part: infusion |

| Rubiaceae | Palicourea marcgravii A. St.-Hil. | Crying or golden | Brazil | Flower |

|

na | Alkaloids glucosides (croceaine A), triterpenes, coumarins, and phenols (phenolic acids) | Treatment: inflammation of the urinary tract Activity: antimicrobial Toxicity: It presents ictiotoxic and cytotoxic activity |

Arial part: infusion |

| Rubiaceae | Warszewiczia coccinea (Vahl) Klotszch | na | Central and South America [337] | Flower |

|

na | Triterpenes | Treatment: inhibitors of acetylcholinesterase [337] | na |

| Solanaceae | Capsicum annuum L. | Pepper, chilli, morron | Mediterranean region [338] | Fruit [79] |

|

Soil and water decontamination (carbofuran residue and Pb) [339,340] | Carotenoids (capsaicin, capsorubin), alkaloids [338,341] | Treatment: Buruli ulcer and gastrointestinal benefits [79] Activity: anti-haemorrhoidal, antirheumatic, anti-inflammatory, and analgesic [341] |

Fruit: macerated fruit tea, sweet and savoury dishes, salad, cooked seasoning [341] |

| Solanaceae | Lycianthes rantonnetii (Carrière) Bitter | Solano of blue flower, perennial dulcamara | Argentina and Paraguay [342] | Flower |

|

na | Alkaloids [342] | Treatment: seborrheic dermatitis, bronchitis, cough Activity: antioxidant and anti-hepatic Toxicity: It has high toxicity [342] |

Arial part: infusion |

| Solanaceae | Petunia × hybrida Vilm. | Petunia [126] | The hybrid of P. axillaris × P. integrifolia [126] | Flower [214] |

|

Soil decontamination (Pb, Cu, and Zn) [343] | Phenols (phenylpropanoids, anthocyanins) [344,345,346] | Activity: antimicrobial and antifungall [214,346] | Flower: garrison [214] |

| Solanaceae | Solanum lycopersicum L. | Tomato, jitomato, gold-apple [34] | Colombia, Peru, Ecuador [214] | Fruit [347,348] |

|

Soil decontamination (Cr, As, Zn, Cd, Pb, Cu, and Ni) [340,349] | Solanine (leaves and stems contain high concentrations) [214] | Treatment: cardiovascular diseases and macular degeneration [347,348] Activity: anti-carcinogenic, anti-furuncular [347,350] Toxicity: The leaves present phytodermatitis [55] |

Fruit: widely used in the food industry [34] |

| Verbenaceae | Aloysia citriodora Palau | Kidron, lemon verbena, verbena de Indias, María Luisa, Verbena olorosa, Verbena grass Louise, Arabic tea [194,214] | America [214] | Leaf, stem, flower [92,214,351] |

|

Soil decontamination (Cd and Ni) [352] | Terpenes (essential oil (neral, geranial, limonene, 1,8-cineole)), verbascosides and derivatives, and phenolics (flavonoids) Note: It has cytotoxic activity and allelopathic properties [351,353] |

Treatment: digestive and nervous systems Activity: antioxidant, antifungal, antiasthmatic, antimicrobial, anaesthetic, neuroprotective, spasmolytic, anxiolytic, anti-colitis, antibacterial activity, antispasmodic, stomach, sedative, antipyretic [92,214,351,353,354] |

Arial part: infusion [351] Dried leaf: marinated, seasoning, sauces [351,354] |

| Verbenaceae | Lantana camara L. | Lantana, Spanish flag, frutillo, supirrosa, cariaquito [214,355] | America [355] | Leaf, seed, flower [355] |

|

Soil decontamination (Pb, Cr, As, Zn, Cd, Cu, Hg, Ni) [356]. | Alkaloids (lanthamine), terpenoids, phytosterols, saponins, phenols (tannins, phycobatannins), and steroids [42,72] | Treatment: fever, flu, stomach problems, asthma, and rheumatism [214,355,357] Activity: antispasmodic, anti-carcinogenic, antitumor, and antimicrobial [214,355,358] Toxicity: the leaves and fruits present gastrointestinal toxins [55] |

Flower: infusion [355,358] |

| Verbenaceae | Verbena × hybrid Groenland & Rümpler | Verbena [143] | na | Flower [143] |

|

na | Phenols (flavones, flavonols) | na | Flower: raw, cooked, garnished [143] |

| Viola | Viola × wittrockiana Gams | Pansy, Wesel Ice [180] | na | Flower [180] |

|

Soil decontamination (As, Cd, Pb, and Se) [307] | na | Treatment: respiratory ailments, relaxation of blood vessels, and reduction of fevers and colds [12,113] Activity: anti-inflammatory [12,359] |

It has a sweet flavour [12]. |

| Zingiberaceae | Renealmia alpinia (Rottb.) Maas | x’kijit, Kumpia [360,361] | Mexico [362] | Fruit [361] |

|

na | na | Treatment: antiemetic, antinausea, and snake venom neutraliser [360,361,363,364] | Seed: oil food [361,365] |

Note: na, not available; COD, Chemical oxygen demand; PM, particulate matter; HIV, Human immunodeficiency virus; LC50, Lethal concentration; TSS, total suspended solids; BOD, Biochemical oxygen demand; TP, material contamination; PM, particulate matter; LD50, Dosage lethal media.

Table 2.

Methods for quantifying and concentrating carotenoids and phenolics in studied plants.

| Family [18] | Species [18] | Carotenoids Concentration/Quantification Technique | Phenolics Concentration/Quantification Technique |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acanthaceae | Aphelandra squarrosa Nees | Flower: 381.3 µg/g DW, individual carotenoids (RRLC) [366] | Root: 3.5 µmol Benzoxazinoid/g FW)/(HPLC) [22] |

| Acanthaceae | Justicia aurea Schltdl. | Flower: 47.9 µg violaxanthin/g DW (RRLC) [366] | na |

| Alstroemeriaceae | Alstroemeria aurea Graham | Flower: 4.5 to 4.9 µg total carotenoids/g DW (SM) [30]; 30 µg/g DW, individual carotenoids (RRLC) [366]; 536.6 µg/g β-carotene total carotenoids (SM) [214] | Flower: 3 mg GAE/g total phenolics (SM) [214] |

| Amaranthaceae | Celosia argentea L. | Flower: 22.1 and 116.3 µg total carotenoids/g DW, individual carotenoids (RRLC) [366] Leaf: 0.12 to 0.36 mg total carotenoids/g FW (SM) [36] |

Flower: 5.01 and 6.06 g total anthocyanin/100 g FW (SM) [36], 58.4 mg GAE/g water extract, 67.6 mg GAE/g ethanol extract (SM) [39]; 13.8 and 7.7 mg total phenolics/g DW, individual phenolics (RRLC) [366] Arial part: 2.2 and 9.4 mg GAE/g DW (SM) [367], 45.2 mg GAE/g extract, and 66.7 mg QE/g extract (SM) [37] |

| Amaryllidaceae | Allium schoenoprasum L. | Flower:58.2 mg total carotenoids/kg FW (SM) [368]; 70.1 µg total carotenoids/g DW, individual carotenoids (RRLC) [366]; 423.2 µg total carotenoids/g DW [214] Root: 0.08 mg β-carotene/100 g FW, 0.65 mg total carotenoids/100 g FW (review) [40] |

Flowers: 201.8 µg gallic acid/g DW, 207.3 µg coumaric acid/g DW, 887.4 µg ferulic acid/g DW, 20.3 µg rutin/g DW (HPLC) [369]; 375.8 mg total polyphenols/100 FW (SM) [368]; 9.3 mg total phenolics/g DW, individual phenolics (RRLC) [366]; 28.9 mg GAE/g DW (SM) [214] Leaf: 16.7 mg total flavonoids/g FW [42], 68.5 GAE/g (SM) [44] Root: 2.7 mg myricetin/100 g FW, 4.5 mg quercetin/100 g FW, 7.7 mg kaempferol/100 g FW, 21.0 mg GAE/100 g FW, 0.5 mg anthocyanin/100 g FW (review) [40] |

| Amaryllidaceae | Agapanthus africanus (L.) Hoffmanns | Flower: 8.1 µg total carotenoids/g DW, individual carotenoids (RRLC) [366]; 67.0 and 90.0 µg total carotenoids/g DW (SM) [214] | Flower: Identification of delphinidin, p-coumaroyl, kaempferol, and others (HPLC-MS) [370] 13.7 mg total phenolics/g DW, individual phenolics (RRLC) [366]; 23.6 and 25.7 mg GAE/g DW (SM) [214] |

| Amaryllidaceae |

Clivia miniata (Lindl.) Bosse Clivia miniata var. citrina S. Watson |

na | Flower: 1.8 total anthocyanin/100 mg FW (SM) [371] |

| Apiaceae | Coriandrum sativum L. | Flower: 267.6 µg total carotenoids/g DW, individual carotenoids (RRLC) [366]; 189.1 µg total carotenoids/g DW (SM) [214] Leaf: 152.8 to 169.2 mg total carotenoids/100 g DW, 38.3 to 58.6 mg β-carotene/100 g DW (before saponification), 27.1 to 47.5 mg β-carotene/100 g DW (after saponification) (SM) [372] Arial part: 2.0 g total carotenoids/kg DW, 0.6 g β-carotene/DW, 1.0 g lutein/kg DW (HPLC) [373] Seed: 1.8 to 2.2 mg total carotenoids/100 g DW, 0.3 to 0.6 mg β-carotene/100 g DW (SM) [372] |

Flower: 2.4 mg total phenolics/g DW, individual phenolics (RRLC) [366]; 16.5 mg GAE/g DW (SM) [214] Seed: 12.2 GAE/g, 12.6 total flavonoids (quercetin equivalents)/g, 133.74 µg GAE/mg hydro-alcohol extract, 44.5 µg total flavonoids/mg 70% ethanol extract (SM) [42]; individual phenolics, 2.2 mg/g (HPLC-MS) [374]; individual phenolics, 129.9 mg total phenolics acids/kg DW (HPLC-MS) [58]; Arial part: individual phenolics, 6273.5 mg total phenolics/kg DW (HPLC-MS) [58]; 10.0 g total phenolics/kg DW; 0.5 g chlorogenic acid/kg DW (SM and HPLC) [373] |

| Apocynaceae | Catharanthus roseus (L.) G. Don | Flower: 3.7 µg lutein/g DW (RRLC) [366]; 163.7 and 185.1 µg total carotenoids/g DW (SM) [214] Leaf: 0.5 to 0.7 mg carotenoids/g DW (SM) [375]; 9 to 1.3 mg carotenoid/g FW, 11.9 to 32.1 mg xanthophyll/g FW (SM) [376] |

Flower: 26.5 and 29.1 mg total phenolics/g DW, individual phenolics (RRLC) [366]; 67.1 and 55.5 mg GAE/g DW (SM) [214] Leaf: 05.0 to 19.0 mg phenolics/g DW (SM) [375]; 55.3 to 88.0 mg anthocyanin/g FW (SM) [376] |

| Apocynaceae | Nerium oleander L. | Flower: 1.0 to 3.4 µg lutein/g DW (RRLC) [366]; 51.2 to 67.6 µg total carotenoids/g DW (SM) [214] Leaf: 2.3 µmol carotenoids/g DW, 40.7 µmol β-carotene/g DW, 42.4 µmol lutein/g DW (SM) [377] |

Flower: 53.8 µg GAE/mg ethanol extract, 34.3 µg quercetin/mg ethanol extract (SM) [73]; 14.0 to 22.0 mg total phenolics/g DW, individual phenolics (RRLC) [366]; 58.0 to 67.1 mg GAE/g DW (SM) [214] |

| Apocynaceae | Trachelospermum jasminoides (Lind.) Len. | Flower: 3.6 µg lutein/g DW (RRLC) [366]; 14.7 µg total carotenoids/g DW (SM) [214] | Flower: 13.2 mg taxifolin/g, 9.5 mg isoquercitrin/g, 7.6 mg chlorogenic acid/g, and 0.2 mg gallic acid/g (HPLC) [75] Aerial part: five compounds were isolated [74]; 4.1 mg total phenolics/g DW, individual phenolics (RRLC) [366]; 110.3 mg GAE/g DW (SM) [214] |

| Araceae | Aglaonema commutatum Schott | Flower: 78.7 µg total carotenoids/g DW, individual carotenoids (RRLC) [366]; 191.6 µg total carotenoids/g DW (SM) [214] Leaf: α and β-carotene [77] Fruit: lycopene, lycoxanthin, violaxanthin,α, β, γ, δ-carotene [77]; 100.0 µg β-carotene/g DW, 110.0 µg cryptoxanthin/g DW, 1100.0 µg lycopene/g DW (polarization microscopy) [378] Seed: lutein [77] |

Flower: 12.5 mg GAE/g DW (SM) [367]; 0.6 mg total phenolics/g DW, individual phenolics (RRLC) [366]; 57.9 mg GAE/g DW (SM) [214] |

| Araceae | Anthurium andraeanum Linden ex André | Flower: 14.1 µg total carotenoids/g DW, individual carotenoids (RRLC) [366]; 61.9 µg total carotenoids/g DW (SM) [214] | Flower: Individual flavonoids (HPLC-MS) [80], individual flavonoids, 0.3 to 8.7 mg total anthocyanin/g FW (HPLC-ESI-MS) [81]; 12.0 to 26.0 mg flavonoids/g FW [379]; 7.7 mg total phenolics/g DW, individual phenolics (RRLC) [366]; 117.4 mg GAE/g DW (SM) [214] |

| Araceae | Spathiphyllum montanum (R. A. Baker) Grayum | Flower: 326.6 µg total carotenoids/g DW (SM) [214] | Flower: Phenols and flavonoids [84]; 87.3 mg GAE/g DW (SM) [214] |

| Asparagaceae | Chlorophytum comosum (Thunb.) Jacques | Flower: 93.9 µg total carotenoids/g DW, individual carotenoids (RRLC) [366]; 245.3 µg total carotenoids/g DW (SM) [214] Leaf: 0.5 to 3.0 mg total carotenoid/g FW (SM) [380] |

Flower: 21.1 mg total phenolics/g DW, individual phenolics (RRLC) [366]; 42.7 mg GAE/g DW (SM) [214] Arial part: 1.4 mg total phenolic/g [90] |

| Asteraceae | Bidens andicola Kunth | na | Arial part: Phytochemical screening (SM) [96] |

| Asteraceae | Calendula officinalis L. | Flower: 48.0 to 276 mg carotenoids/100 g FW, 270.0 to 3510.0 mg carotenoids/100 g DW [99]; 57.2 µg total carotenoids/g FW (SM) [296]; 50.0 to 350.0 µg carotenoid/g DW [100]; 1.0 to 1.3 mg β-carotene/g DW [102] | Flower: 313.4 mg total polyphenol/g 2% flowers extract, 19.4 mg flavonoid and quercetin/g 2% flowers extract, 28.6 mg total polyphenols/g, 18.8 mg total flavonoids/g, 12.2 mg rutin and narcissin/g [42]; 0.7 to 5.1 mg GAE/g FW, 0.7 to 3.30 mg total flavonoids/g FW [296]; individual phenolics (HPLC-MS), 0.03 to 5.5 mg GAE/g DW [101]; 15.0 to 20.0 mg caffeic acid/g DW [100] |

| Asteraceae | Centaurea seridis L. | na | na |

| Asteraceae | Cichorium intybus L. | Flower: 8.0 to 30.2 µg lutein/g FW, 0.1 to 0.4 µg β-cryptoxanthin/g FW, 3.3 to 14.1 µg β-carotene/g FW [109]; 64.5 µg total carotenoids/g DW (SM) [214] Root: 1.1 to 2.4 mg lutein/kg, 0.2 to 0.5 mg β-carotene/kg (HPLC) [106] |

Root: 12.8 to 101.5 mg quercetin/kg, 8.1 to 26.2 mg kaempferol/kg (HPLC-ESI-MS) [106] Flower: 20.0 to 130.0 mg GAE/100 g FW (SM) [109], 10.6 mg GAE/g FW (SM) [108]; 9.9 mg total phenolics/g DW, individual phenolics (RRLC) [366]; 46.0 mg GAE/g DW (SM) [214] Seed: 0.05 to 0.1 g total flavonoids/100 g DW; 0.5 to 2.5 g phenolic acids/100 g DW; 50.8 to 285.0 mg GAE/100 g DW; 43.3 to 150.0 mg total flavonoid/100 DW; sixty-four phenolic acids and flavonoids were extracted (SM, HPLC [42] |

| Asteraceae | Chrysanthemum morifolium Ramat | Flower: 0.1 to 0.2 mg carotenoid/g FW (SM) [381]; 11.8 to 165.5 µg lutein/g DW, 0.1 to 4.4 µg zeaxanthin/g DW, 0.1 to 1.9 µg β-cryptoxanthin/g DW, 0.1 to 2.9 µg 13-cis-β-carotene/g DW, 0.0 to 3.5 µg α-carotene/g DW, 1.4 to 21.9 g trans- β-carotene/g DW, 0.3 to 5.2 µg 9-cis- β-carotene/g DW (HPLC) [110] | Flower: 12.0 mg GAE/g DW (SM) [367]; individual phenols, 3732 to 12,562 mg total phenolics/g (HPLC-ESI) [111]; 0.5 to 5.5 mg total flavonoid/g FW, 0.2 to 2.5 total phenolic/g FW (SM) [381]; individual anthocyanin, 004 to 11.3 mg anthocyanin/g DW (HPLC-ESI-MS) [381] |

| Asteraceae | Coreopsis grandiflora Hogg ex Sweet | Flower: 1060 mg β-carotene/g (SM) [115]; 1060 µg total carotenoids/g DW (SM) [214] | Flower: 6.2 mg GAE/g DW (SM) [214] |

| Asteraceae | Cota tinctoria (L.) J. Gay | Flower: 0.7 mg α-carotene/g FW, 5.1 mg β-carotene/g FW (TLC) [115]; individual carotenoids, 46.9 mg carotenoid/100 g FW, 6.3 mg carotenoids/100 g DW (HPLC) [121] | Flower: 0.9 mg gallic acid/100 g DW, 26.8 mg chlorogenic acid/100 g DW, and other [118] Stem: 3.30 mg 4droxybenzoic acid/100 g DW, 1.3 mg caffeic acid/100 g DW, and other [118] Root: 0.01 mg quercetin/100 g DW and other (HPLC) [118] |

| Asteraceae | Dahlia coccinea Cav. | Flower: 2.5 to 24.0 g carotenoid/g DW (SM) [122] | Flower: 6.4 to 13.7 µg gallic acid/g DW, 0.9 to 4.7 µg caffeic acid/g DW, 2.7 to 16.4 µg chlorogenic acid/g DW, 3.7 to 5.8 µg hydroxybenzoic acid/g DW, 7.2 to 26.3 µg quercetin/g DW (HPLC), 2.0 to 125 mg gallic acid/g DW (SM) [122]; 86.6 mg GAE/g DW (SM) [214]; 15.7 mg total phenolics/g DW, individual phenolics (RRLC) [366] |

| Asteraceae | Dahlia pinnata Cav. | Flowers: 2.5 to 24.0 g total carotenoids/g DW (SM) [122] | Flower: 6.4 to 13.7 µg gallic acid/g DW, 0.9 to 4.7 µg caffeic acid/g DW, 2.7 to 16.4 µg chlorogenic acid/g DW, 3.7 to 5.8 µg hydroxybenzoic acid/g DW, 7.2 to 26.3 µg quercetin/g DW (HPLC), 2.0 to 125.0 mg gallic acid/g DW (SM) [122] |

| Asteraceae | Gaillardia × grandiflora Hort. Ex Van Houtte | na | na |

| Asteraceae | Tagetes erecta L. | Flower: 2.0 to 52.0 µg violaxanthin/g DW, 10.0 to 305.0 µg zeaxanthin/g DW, 0.2 to 8.2 µg luteolin/g DW, 1.0 to 36.0 µg α-carotene/g DW, 2.0 to 53.0 µg β-carotene/g DW, 1.0 to 3.8 µg 13-cis- β-carotene/g DW (HPLC) [130]; 1.9 to 11.6 mg lutein ester/g DW (HPLC) [382] | Flower: total phenolics and flavonoids, 62.3 mg GAE/g, 97.0 mg rutin equivalent/g (HPLC-MS) [131]; 27.1 to 42.2 mg GAE/g, 20.1 to 41.9 mg quercetin equivalent/g (SM) [127]; 4.6 g gallic acid/kg FW (SM) [180] |

| Asteraceae | Taraxacum campylodes G. E. Haglund | Flower: 41.9 mg total carotenoids/kg [138]; 259.0 µg carotenoids/g DW [383] Leaf: 206.4 mg total carotenoid/kg [138] Stem: 20.5 mg total carotenoid/kg [138] |

Flower: 441.4 µg gallic acid/g DW, 18.7 µg rutin/g DW, 274.9 µg resveratrol/g DW, 82.9 µg vanillic acid/g DW, 593.0 µg sinapic acid/g DW (HPLC) [369]; 11.1 mg quercetin/g DW [383]; 441.1 mg gallica acid/kg DW, 274.9 mg resveratrol/kg DW, 593.0 mg sinapic acid/kg DW [384]; 22.3 GAE/g DW [140] |

| Asteraceae | Zinnia elegans L. | Flower: 223.7 to 995.9 µg total carotenoids/g DW (SM) [214] | Flower: 87.5 to 985.0 µg total anthocyanin/g FW (SM) [385]; 22.7 to 25.7 mg GAE/g DW (SM) [214] Leaf: 2.6 mg total phenolics/g DW, 0.6 mg total flavonoids/g DW (SM) [141] |

| Balsaminaceae | Impatiens walleriana Hook. f. | Flower: 148.3 µg total carotenoids/g DW (SM) [214]; 2.9 µg total carotenoids/g DW, individual carotenoids (RRLC) [366] | Flower: 6.8 mg GAE/g (SM), 96.1 mg epicatechin/100 g, 183.5 mg gallic acid/100 g, 83.9 mg protocatechuic acid/100 g [235]; 4.9 g gallic acid/kg FW (SM) [180]; 111.8 mg GAE/g DW (SM) [214]; 8.4 mg total phenolics/g DW, individual phenolics (RRLC) [366] Leaf: 3.4 µg gallic acid/g DW, 71.9 µg protocatechuic acid/g DW, 12.8 µg 4-hydroxy benzoic/g DW, 8.2 µg vanillic acid/g DW, 7.6 µg cis-p-coumaric/g DW, and other (HPLC) [386] Aerial part: individual compounds (UHPLC-MS), 12.2 mg total phenolic/g DW, 2.7 mg total phenolic acids/g DW, 3.9 mg quercetin equivalent/g DW (SM) [142] |

| Begoniaceae | Begonia cucullata Willd. | Flower: 0.03 µg total carotenoids/g FW (SM) [143] | Flower: 448.8 mg total phenolics/100 g FW (SM) [143]; 1.8 to 9.8 µg quercetin/g FW [123] |

| Begoniaceae | Begonia × tuberhybrida Voss | Flower: 0.02 µg total carotenoids/g FW (SM) [143]; 187.6 µg total carotenoids/g DW (SM) [214]; 8.7 µg total carotenoids/g DW, individual carotenoids (RRLC) [366] | Flower: 100.9 mg total phenolics/100 g FW (SM) [143]; 107.2 mg GAE/g DW (SM) [214]; 8.7 mg total phenolics/g DW, individual phenolics (RRLC) [366] |

| Bignoniaceae | Tecoma capensis (Thunb.) Lindl. | Flower: 238.6 µg total carotenoids/g DW (SM) [214]; 37.6 µg total carotenoids/g DW, individual carotenoids (RRLC) [366] Leaf: 0.3 to 0.6 mg carotenoids/g FW [145] |

Flower: 19.2 mg GAE/g DW (SM) [214]; 1.3 mg total phenolics/g DW, individual phenolics (RRLC) [366] Leaf: Phytochemical screening [149] |

| Bignoniaceae | Tecoma stans (L.) Juss. ex Kunth | na | Leaf: 177.0 to 216.0 mg GAE/g DW [153] Whole plant: Phytochemical screening [387] |

| Boraginaceae | Heliotropium arborescens L. | Flower: 30.7 µg total carotenoids/g DW, individual carotenoids (RRLC) [366] | Flower: 1.2 mg total phenolics/g DW, individual phenolics (RRLC) [366] |

| Brassicaceae | Alyssum montanum L. | Flower: 238.6 µg total carotenoids/g DW (SM) [214]; 81.3 µg total carotenoids/g DW, individual carotenoids (RRLC) [366] Leaf: 0.14 to 0.16 mg total carotenoids/100 g FW (SM) [388] |

Flower: 45.8 mg GAE/g DW (SM) [214]; 1.7 mg total phenolics/g DW, individual phenolics (RRLC) [366] |

| Brassicaceae | Diplotaxis tenuifolia (L.) DC. | Flower: 257.2 µg total carotenoids/g DW (SM) [214]; 105.4 µg total carotenoids/g DW, individual carotenoids (RRLC) [366] Leaf: individual carotenoids, 3520 and 2970 µg total carotenoid/g DW (HPLC-MS) [159]; 5.3 mg lutein/100 g, 0.7 mg violaxanthin/100 g, 0.5 mg/100 g, 0.4 neoxanthin/g (HPLC) [389] |

Flower: 60.6 mg GAE/g DW (SM) [214]; 7.7 mg total phenolics/g DW, individual phenolics (RRLC) [366] Leaf: individual phenolics, 68,600 and 139,000 µg phenolics/g DW (UHPLC-Orbitrap-MS) [159]; 4.7 to 19.8 g/kg DW (HPLC-MS) [163] |

| Brassicaceae | Matthiola incana (L.) R. Br. | Flower: 200 to 1500 µg carotenoid/cm2 (SM) [390]; carotenoids identification by TLC and HPLC [168]; 64.6 µg total carotenoids/g DW (SM) [214]; 2.5 µg total carotenoids/g DW, individual carotenoids (RRLC) [366] | Flower: 0.1 mg GAE/g (SM), 11.1 mg protocatechuic acid (HPLC) [235]; 0.3 to 1.9 mg GAE/g [165]; anthocyanin and other flavonoids identification by TLC and HPLC [168]; 27.0 mg GAE/g DW (SM) [214]; 5.7 mg total phenolics/g DW, individual phenolics (RRLC) [366] |

| Cannabaceae | Cannabis sativa L. | Flower: 2.0 to 2.6 µg carotenoids/g FW [171]; 248.8 µg total carotenoids/g DW (SM) [214]; 19.8 µg total carotenoids/g DW, individual carotenoids (RRLC) [366] | Flower: 33.8 mg GAE/g DW (SM) [214]; 2.2 mg total phenolics/g DW, individual phenolics (RRLC) [366] Seed: 0.4 to 13.9 mg GAE/100 mg [391] |

| Cannaceae | Canna indica L. | Flower: 310.0 mg total carotenoids/kg FW, 189.0 mg total xanthophylls/kg FW, 628.0 mg xanthophylls/kg DW, 1054.0 mg total carotenoids/kg DW (HPLC) [392]; 451.5 and 2453.9 µg total carotenoids/g DW (SM) [214] | Flower: 0.06 to 1.0 mg GAE/100 g, 1.8 to 19.9 mg total flavonoid/100 g [393]; 11.0 and 12.2 mg GAE/g DW (SM) [214] Seeds: 4.8 µg flavonoids/g, 13.8 µg total polyphenols/g, anthocyanin identification [42] |

| Caryophyllaceae | Dianthus caryophyllus L. | Flowers: 1.0 to 10.0 µg total carotenoids/g FW [177]; 83.1 and 75.5 µg total carotenoids/g DW (SM) [214]; 1.6 and 15.8 µg total carotenoids/g DW, individual carotenoids (RRLC) [366] Leaf: 2.0 to 120.0 µg total carotenoid/g FW, individual carotenoids (HPLC) [177] |

Flowers: 0.4 mg GAE/g (SM), 52.4 mg cyanidin-3-glucoside/100 g and 150.7 mg protocatechuic acid/100 g (HPLC) [235]; 5.3 g gallic acid/kg FW (SM) [180]; 27.4 and 48.1 mg GAE/g DW (SM) [214]; 10.9 and 15.4 mg total phenolics/g DW, individual phenolics (RRLC) [366] |

| Caryophyllaceae | Dianthus chinensis L. | Flower: 261.6 µg total carotenoids/g FW (SM) [394]; 84.2 µg total carotenoids/g DW (SM) [214] Leaf: 95.0 µg total carotenoids/g DW [395]; 0.3 to 0.5 mg carotenoid/g DW [182] |

Flower: 5.3 mg GAE/g (SM), 73.2 mg catechin/100 g, 110.9 mg epicatechin/100 g (HPLC) [235]; 12.3 mg GAE/g FW, 443.5 mg total anthocyanins/100 g FW [394]; 32.6 mg GAE/g DW (SM) [214]; 9.5 mg total phenolics/g DW, individual phenolics (RRLC) [366] Leaf: 19.0 mg GAE/g DW, 65.7 total flavonoids/g DW [395] |

| Caryophyllaceae | Gypsophila paniculata L. | Flower: 80.0 to 450.0 µg β-carotene/g FW, and other carotenoids [396]; 71.8 µg total carotenoids/g DW (SM) [214]; 33.8 µg total carotenoids/g DW, individual carotenoids (RRLC) [366] | Flower: 44.6 mg GAE/g DW (SM) [214]; 22.2 mg total phenolics/g DW, individual phenolics (RRLC) [366] |

| Caryophyllaceae | Saponaria officinalis L. | Flower: 84.0 µg total carotenoids/g DW (SM) [214]; 9.5 µg total carotenoids/g DW, individual carotenoids (RRLC) [366] Leaf: 61.5 µg β-carotene/L [188] | Flower: 17.6 mg GAE/g DW (SM) [214]; 10.5 mg total phenolics/g DW, individual phenolics (RRLC) [366] Arial part: 6.5 µg GAE/mg [189] |