Abstract

Diabetic cardiomyopathy (DCM) is characterized by structural and functional abnormalities in the myocardium affecting people with diabetes. Treatment of DCM focuses on glucose control, blood pressure management, lipid-lowering, and lifestyle changes. Due to limited therapeutic options, DCM remains a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in patients with diabetes, thus emphasizing the need to develop new therapeutic strategies. Ongoing research is aimed at understanding the underlying molecular mechanism(s) involved in the development and progression of DCM, including oxidative stress, inflammation, and metabolic dysregulation. The goal is to develope innovative pharmaceutical therapeutics, offering significant improvements in the clinical management of DCM. Some of these approaches include the effective targeting of impaired insulin signaling, cardiac stiffness, glucotoxicity, lipotoxicity, inflammation, oxidative stress, cardiac hypertrophy, and fibrosis. This review focuses on the latest developments in understanding the underlying causes of DCM and the therapeutic landscape of DCM treatment.

Keywords: cardiovascular diseases, diabetic cardiomyopathy, fibrosis, glucotoxicity, inflammation, insulin signaling, lipotoxicity, oxidative stress, type 2 diabetes

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a medical condition characterized by fasting blood glucose levels of ⩾126 mg/dL than those within the normal fasting range of 72–99 mg/dL. If left untreated, diabetes can lead to life-threatening complications resulting in adverse effects on vital organs, such as brain, liver, heart, and kidneys. Diabetes is one of the leading causes of cardiovascular disease (CVD), with diabetic cardiomyopathy (DCM) regarded as a leading cause of diabetes-associated morbidity and mortality. Patients suffering from diabetes have a two- to fourfold increased risk of developing heart failure (HF) and other CVDs.1,2 Although ischemic events are predominant among the cardiac consequences of diabetes, the risk of developing HF is elevated in diabetic patients even in the absence of an overt myocardial ischemia and hypertension. 3 Moreover, in patients without a clinical diagnosis of DM, a correlation between fasting blood glucose levels of >200 mg/dL and long-term mortality due to HF has been observed.1,4 Diabetic patients are more likely to experience severe outcomes after ischemia or hypoxic damage due to reduced glycolytic activity in the heart muscles, which may potentially be a significant contributing factor. 5

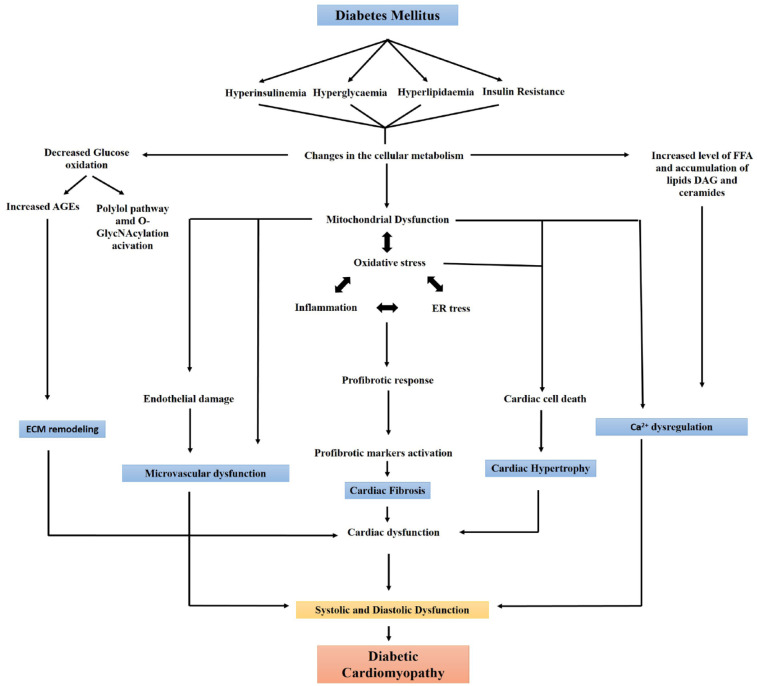

DCM is a serious pathological condition of the heart and is clinically associated with systolic or diastolic cardiac dysfunctions that are independent of any other CVD risk factor(s), such as hypertension, coronary artery disease, or valvular diseases. The condition usually remains asymptomatic during initial stages, with functional and structural changes caused of the heart including hypertrophy, stiffness, diastolic and systolic dysfunction, and interstitial fibrosis of the tissue, culminating in clinical HF syndrome.6,7 Cardiac energy impairment is significant and likely responsible for many of the deficits seen in experimental models of HF. 8 Reduced cardiac phosphocreatine/adenosine triphosphate (ATP) ratios have been reported using 31P magnetic resonance spectroscopy in patients with systolic HF, regardless of pathophysiology, with disruption of energy generation and increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) production.8–11 Also, structural and functional modifications of coronary pre-arterioles and arterioles due to hypertension, increased free fatty acids (FFAs), and aging contribute to coronary microvascular dysfunction (CMD). These alterations markedly increase the risk of severe cardiovascular events like exertional angina or myocardial ischemia. 12 Additionally, DM also increases the risk of HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), a condition in which heart filling deficits are noted. 13 Meta-analysis has shown that 50% of diabetic patients are at heightened risk of developing HFpEF compared to non-diabetic patients. 14 Systemic metabolic problems, abnormalities in subcellular components, inappropriate activation of the renin-angiotensin system, inflammation, and improper immunological regulation are some of the pathophysiological aspects of diabetes that contribute to the development of DCM (Figure 1). There is also growing evidence supporting that DCM results from factors other than the typical diabetes-associated coronary atherosclerosis and that the cause of heart muscle damage must be due to some other aspects of diabetes.1,2,15 In this article, we have reviewed the latest advances made to unravel the underlying mechanism of DCM and the various potential targets that are being or could be investigated to treat DCM.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram showing different causes of diabetes-associated cardiomyopathy.

AGEs, advanced glycation end products; NO, nitric oxide; RAAS, renin angiotensin aldosterone system; RAGE, receptor for advanced glycation end product; TGF-β, transforming growth factor-β.

Impaired insulin signaling

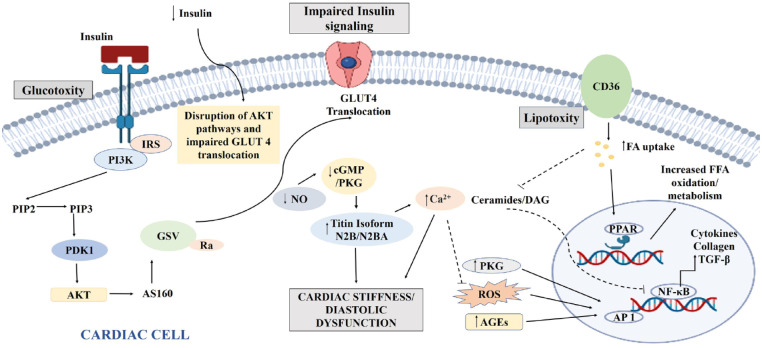

Insulin signaling in cardiac cells is essential for cellular homeostasis, controlling protein synthesis, substrate use, and cell survival. Under normal physiological conditions, insulin binds to the corresponding receptor on the cardiac cells, leading to the activation of insulin receptor substrate (IRS-1/2) and the downstream phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/protein kinase B (PI3K/Akt) pathway (Figure 2). This activation induces the translocation of glucose transporter type 4 (GLUT4) from the cytoplasm to the cell membrane to facilitate glucose uptake. 16 The crucial element of the insulin signaling pathway necessary for the activation of Akt/PKB is 3-phosphoinositide-dependent kinase-1. 17 Impaired insulin signaling in DCM has been reported in various animal models, mainly due to reduced GLUT4 translocation to the plasma membrane.18,19 Moreover, insulin resistance leads to ROS generation. ROS-mediated PI3K/Akt impairment deteriorates PI3K/Akt signaling, affecting GLUT4 expression and myocardial function.20,21 Besides, the signaling also influences endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), triggering the bioavailable nitric oxide (NO) for proper microvascular flow and myocardial function.20,22 Several epidemiological studies have reported a connection between abnormal insulin signaling and HF.23,24 Insulin resistance has also been correlated with increased serum concentrations of pro-inflammatory cytokines, catecholamines, and growth hormones in HF.25–27 Impaired insulin signaling can activate pathways such as AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), protein kinase C (PKC), mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), and mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), which can alleviate DCM.17,28–31 Oxidative stress is a well-accepted cause of cardiac dysfunction in the insulin resistant state, which can be partially reversed with antioxidant therapy. 32 Overexpression of G-protein receptor kinase 2 (GRK2) has been shown to inhibit myocardial insulin signaling 33 ; therefore, GRK2 represents an attractive target that would directly modulate insulin signaling pathways in cardiomyocytes. Insulin signaling and anomalies in cardiac excitation–contraction coupling are emerging as useful targets for the treatment of HF. The rapidly evolving gene therapy technology offers another powerful tool to rectify genetic anomalies by using vector-based gene transfer methods. Currently, such approaches, primarily designed to stop the underlying remodeling mechanisms that cause pathological alterations in the myocardium during HF, 34 are under development. Other potential alterations useful in the treatment of DCM can be generated through the expression of sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase 2a (SERCA2a) and Na+–Ca2+ exchanger (NCX), inhibition of calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII), stabilization of ryanodine receptors (RyRs), all mainly focusing on the regulation of calcium handling and prevention of abnormalities in the activation of PI3K and glucose oxidation.34–38 Inhibition of CaMKII has a protective role in the maladaptive remodeling of imprudent expression of beta-arrestin and myocardial infarction and a cardioprotective action as well (Table 1). 35 In addition, calcium plays a vital role in the contraction–relaxation of cardiac muscle, receptor activation, glucose transport, and glycogen metabolism. 39 Calcium signaling dysregulation may thus hinder insulin action and lead to insulin resistance. RyRs in the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) of cardiac cells cause cardiac muscles to contract by releasing Ca2+ ions from SR into the cytoplasm. 40 Conversely, SERCA pumps Ca2+ ions back from the cytoplasm into SR, allowing the heart muscle to relax. 41 Therefore, any diabetes-mediated impairment in the RyR or SERCA activity can lead to calcium dysregulation and inappropriate heart function. 41 The activity of SERCA is regulated by the phospholamban (PLN) protein 42 such that phosphorylation of PLN relieves SERCA inhibition and promotes calcium reuptake by the SR. Mutation(s) in the PLN gene or change in the phosphorylation/dephosphorylation pattern of PLN can disrupt Ca2+ reuptake during the relaxation cycle of cardiac muscle.43,44 Another calcium influx system of cardiac muscle cells involves the voltage-gated L-type calcium channels (LTCCs) are voltage-gated calcium channels 45 which allow the intake of Ca2+ ions during the cardiac action potential, resulting in muscle contraction. This calcium influx if dysregulated through aberrant expression of LTCCs, results in excess calcium influx and potentially in DCM. 46

Figure 2.

Mechanism contributing to impaired insulin signaling, glucotoxicity, and lipotoxicity in DCM.

AGE, advanced glycation end product; Akt, protein kinase B; AP-1, activator protein 1; AS160, Akt substrate of 160 kDa; cGMP, cyclic guanosine monophosphate; DAG, diacylglycerol; DCM, diabetic cardiomyopathy; FA, fatty acid; FFA, free fatty acids; GLUT4, glucose transporter 4; GSV, GLUT4 storage vesicle; IRS, insulin receptor substrate; NF-κB, nuclear factor-κB; NO, nitric oxide; PDK1, 3-phosphoinositide-dependent kinase 1; PI3K, phosphoinositide-3-kinase; PIP2, phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate; PIP3, phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate; PKG, protein kinase G; PPAR, peroxisome proliferators activated receptors; ROS, reactive oxygen species; TGF-β, transforming growth factor-β.

Table 1.

Mechanisms contributing to various pathophysiological roles in DCM.

| S. no | Cause | Mechanism of action | Effect on the development and progression of DCM | Available drugs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Impaired insulin signaling | - GRK2 overexpression - CaMKII activation |

Inhibits myocardial insulin signaling Remodels imprudent expression of beta-AR and myocardial infarction |

Thiazolidinediones have been reported to increase insulin sensitivity which also influenced the cardioprotective effect positively. |

| 2. | Oxidative stress | - JNK activation - NF-κB stimulation in the presence of ROS and AGEs |

Inflammation and apoptosis ROS and AGEs influence NF-κB to express pro-inflammatory cytokines and profibrotic genes |

- C66 – potent antioxidant JNK inhibitor - Pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate – potent NF-κB inhibitor reducing oxidative stress, mitochondrial structure integrity improvement, ATP synthesis, improve the bioavailability of NO |

| 3. | Glucotoxicity | SGLT2 | Reabsorption of glucose from glomerular filtrate causing hyperglycemia | Dapagliflozin, canagliflozin, empagliflozin – SGLT2 inhibitor with cardioprotective effects |

| 4. | Lipotoxicity | Protein Kinase R | Induces cardiomyopathy via lipotoxicity | Imoxin – PKR inhibitor |

| 6. | Inflammatory Responses | TNF-α and related cytokines and increased proteasome activity Inflammation in general ERK and NF-κB |

Pro-inflammatory activities due to hyperglycemic effects Diabetes induces proteasomal activities NF-κB and JNK/p38MAPK phosphorylation are important players of inflammation in hyperglycemic cardiomyocytes Causes inflammation, cardiac fibrosis, and hypertrophy |

Ursolic acid – Anti-inflammatory activities and cardioprotective MG132 – Proteasome inhibitor causing proteasomal degradation of Nrf-2 and IkB-a LCZ696 – Angiotensin receptor–neprilysin inhibitor, reduced inflammation, and death by inhibiting the transfer of NF-κB and JNK/p38MAPK phosphorylation Isosteviol sodium – Inhibits ERK and NF-κB |

| 7. | Cardiac hypertrophy and cardiac fibrosis | TNF-α Angiotensin Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 |

Fibrosis, inflammation Hypertension, myocardial interstitial fibrosis Induces hyperglycemia by damaging GLP-1 |

Anti-TNF-α monoclonal antibody – Reduced cardiac fibrosis in DCM rat model Losartan – Angiotensin receptor blocker, blocks JAK/STAT pathway and TGF-β expression reduces fibrosis DPP-4 inhibitors – Prevent heart hypertrophy and cardiac diastolic dysfunction by inhibiting oxidative stress and fibrosis |

| 8. | Cardiac cell death | GLP-1 | Positively affects cardiomyopathy by enforcing cardioprotective effect via antiapoptotic and antioxidant | Dulaglutide GLP-1 analog – Cardioprotective and anti-diabetic in nature |

AGE, advanced glycation end product; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; GRK2, G-protein receptor kinase 2; GLP-1, Glucagon like protein-1; CaMKII, calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II; JNK, c-Jun N-terminal Kinase; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; NF-κB, nuclear factor-κB; NO, nitric oxide; PKR, protein kinase R; ROS, reactive oxygen species; SGLT2, sodium-glucose cotransporter-2; STAT, signal transducer of activation pathway; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor alpha; TGF-β, transforming growth factor-β.

Targeting oxidative stress in the cardiac cells

Oxidative stress is one of the major contributing factors to DCM pathogenesis. 47 Upregulation of ROS in cardiomyocytes creates a highly oxidized intracellular environment that triggers the cardioprotection membrane repair protein mitsugumin-53 (MG-53) to undergo oxidation-induced oligomerization to eventually forms a complex with phosphatidylserine domains in intracellular vesicles.48,49 ROS upregulation occurs due to cardiac mitochondrial dysfunction, calcium mishandling, and activation of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase, and xanthine oxidase (XO). 50 Under normal physiological conditions, cardiac mitochondrial phosphorylation and citric acid cycle use FFA, glucose, lactate, ketone bodies, and amino acids for ATP production.1,51 However, in the case of DCM, diversion of mitochondrial glucose oxidation to FFA oxidation leads to increased free electron formation due to less ATP generation causing mitochondrial proton leak and ROS upregulation. The higher levels of ROS in the cardiac cells significantly decrease the eNOS expression and eNOS uncoupling, leading to a significant decrease of NO in endothelial cells, contributing to endothelial dysfunction. 52 DM also decreases endothelial prostacyclin secretion, impairs fibrinolytic ability, alters endothelium-dependent hyperpolarizing factor-mediated responses, increases procoagulant activity, increases production of growth factors and extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins, and increases endothelial permeability, all contributing factor for CMD.12,52–55 Simultaneously, due to altered calcium transport and accumulation, the mitochondrial transition pores open, causing cardiomyocyte apoptosis. 56 The elevated level of Ca2+ plays a role in the activation of NADPH oxidase and ROS overproduction. Therefore, NADPH oxidase regulation can help in the treatment of DCM. 47 Molecular proteins such as peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPAR), MAPK, c-Jun N-terminal Kinase (JNK), nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB), necrosis-related factor-2 (Nrf-2) also have a major role to play in inducing oxidative stress in the cardiomyocytes (Table 1).1,16,57 Moreover, overexpression of PPAR-α switches mitochondrial oxidation from glucose to FFA and decreases Ca2+ uptake. PPAR-β/δ mostly regulates FFA metabolism and gene expression (Figure 2). PPAR-γ acts as an agonist and improves insulin sensitivity and glucose uptake. Other important targets that need exploration are the micro RNAs (miRNAs). miRNAs are small, single-stranded, non-coding RNAs. The exact mechanism through which miRNAs plays a role in DCM is not fully understood, but available evidence suggests that a correlation exists. 58 For instance, expression of miRNA-22 may ameliorate oxidative damage by upregulating Sirtuin-1 (Sirt-1). Additionally, miR-200c reduces endothelium-dependent relaxation by decreasing zinc finger E-box-binding homeobox 1 (ZEB-1) expression and increases prostaglandin E2 synthesis, which in turn increases cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2) expression in endothelial cells. 59 These changes are reported to have an anti-hypertrophic, anti-inflammatory effect. 1 MAPK, including extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) 1/2, p38 MAPK, and JNK activation are key players in pathological cardiac remodeling.16,60,61 JNK signaling is mainly activated due to oxidative stress and inflammation. This pathway equally contributes to the development of DCM and its inhibition prevents inflammation and apoptosis. The novel curcumin analog C66 [(2E,6E)−2,6-bis(2-(trifluoromethyl)benzylidene) cyclohexanone] is a potent antioxidant JNK inhibitor. C66 may dysregulate JNK levels and prevent cardiac fibrosis, oxidative stress, and apoptosis. 62 NF-κB is a transcription factor that remains unstimulated under normal conditions. However, in the presence of ROS and advanced glycation end products (AGEs), is activated and affects the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokine, profibrotic genes, and cell survival. Pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate is a potent NF-κB inhibitor reported to reduce oxidative stress, restore mitochondrial structural integrity, improve ATP synthesis, and the bioavailability of NO to restore cardiac function. 63 In endothelial cells, sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P), which binds to S1P receptors (S1PRs), also controls a variety of physiologic processes. Recent research has shown that the increased ROS and decreased NO seen in endothelial cells exposed to high glucose (HG) levels can be reversed either by inducing S1PR1 or decreasing S1PR2. 64 Another important player of oxidative stress is Nrf-2, a leucine zipper protein that helps to neutralize oxidative stress by regulating the production of antioxidant proteins, such as heme oxygenase. 65 Thus, MG-53, PPAR, MAPK, NF-κB, and Nrf-2 are good targets for the treatment of DCM which merit further investigation.

Abnormal metabolite associated toxicity

Glucotoxicity

Hyperglycemia is a potential cause for increased mortality in HF patients, as shown both in clinical trials and population-based studies.66–70 Hyperglycemia damages in cardiomyocytes by oxidative stress, apoptosis, and by reducing autophagy. It also negatively impacts cardiomyocyte contractility by perturbation of calcium signaling leading to impairment of action potential and apoptosis. 71 Moreover, hyperglycemia increases the expression of profibrotic genes and inflammatory cytokines, which in turn may contribute to cardiac fibrosis in DCM. 72 Several mechanisms, such as flux of glucose in the polyol pathway, increased formation of AGEs, PKC activation and increased flux of hexosamine pathway have been proposed as possible molecular mechanism of glucotoxicity in DCM.6,30 The acceleration of the polyol pathway reduces NADPH availability, a cofactor required for the glutathione-dependent antioxidant system. The reduction of this system contributes to oxidative stress, which in turn leads to tissue damage. AGE formation irreversibly alters the structure and function of proteins. Moreover, the interaction of AGE with its corresponding receptor for advanced glycation end product (RAGE) increases NADPH oxidase-mediated ROS production.73,74

Traditional therapies focused on reducing blood glucose levels have shown very limited efficacy in reducing CVD. The new class of drugs recently approved for diabetes treatment target sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2), the main isoform expressed in the kidneys. SGLT2 facilitates the reabsorption of glucose from the glomerular filtrate and its inhibition increases urinary glucose excretion, thereby reducing hyperglycemia with considerably reduced risk of hypoglycemia. 75 Dapagliflozin, canagliflozin, and empagliflozin are the recently approved SGLT2 inhibitors for the treatment of type 2 DM. These pharmacologic agents have shown cardioprotective effects in diabetic patients. 76 Canagliflozin in CANVAS Program, 77 empagliflozin in EMPA-REG Outcome trial, 78 and dapagliflozin in DECLARE-TIMI 58 trial 79 have been shown to reduce mortality caused by cardiac complications. 78 Although the underlying mechanism through which SGLT2 inhibitors reduce cardiac-associated mortality is not fully understood, these inhibitors change cardiac energy metabolism by decreasing myocardial glucose absorption, which may enhance heart function and minimize myocardial damage. 80 Additionally, SGLT2 inhibitors reduce pro-inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), and interleukin 6 (IL-6),80–82 oxidative stress markers such as ROS, thereby, protecting the heart from the negative impact.82,83 Several studies have reported that anti-hyperglycemic medications provide cardioprotection via the activation of the AMPK pathway. The activation of AMPK in cardiomyocytes and diabetic heart has a beneficial effect on cardiomyocytes via autophagy repair and helps in the preservation of cardiac structure and function. 84 Currently, several AMPK activators are under evaluation for their cardioprotective efficacy. 85 We have recently shown that oxidative stress and apoptosis induced by glucolipotoxicity in cardiomyocytes can be reversed with canagliflozin and dapagliflozin, the SGLT1 inhibitors. 86

Lipotoxicity

Under diabetic conditions, levels of circulating free FFA increase due to increased hepatic lipid synthesis and increased lipid breakdown by adipocytes, which then induces lipotoxicity in the cardiomyocytes.87–89 High levels of oxidized FFA increase mitochondrial membrane potential and lead to increased ROS production. The increased production of ceramide, a long-chain fatty acid amide derivative of sphingoid bases inhibits the mitochondrial respiratory chain and induces apoptosis in cardiomyocytes. 90 Moreover, increased levels of FFA alter the membrane action potential, which in turn affects myocardial contraction. Excessive accumulation of triacylglycerol contributes to left ventricular dysfunction and increased diacylglycerol causes impaired insulin-stimulated glucose uptake in the heart. 91 CD36, a N-linked glycosylated transmembrane protein, plays an important role in the uptake of long-chain fatty acids and gets upregulated in response to HG in beta-cell, resulting in an increased uptake of fatty acids in beta-cells (Figure 2) and increased pro-inflammatory cytokines. Elevated levels of AGEs, oxidative stress, altered insulin signaling cascade, problems with calcium handling, and microvascular deficits are all connected with CD36 signaling. 92 Together, these findings suggest that CD36 is closely associated with the progression of CVD and can be a new therapeutic target for lipotoxicity-induced CVD. The role of miRNAs such as miRNA-320, and miR-344g-5p in cardiac lipotoxicity has been highlighted93,94; therefore, advancing our understanding of their underlying mechanism will help manage lipotoxicity in the cardiomyocytes. Targeting cardiac lipotoxicity has been challenging due to a lack of understanding of the type of FFAs being elevated under lipotoxic conditions. Nevertheless, recent advances in the treatment of cardiac lipotoxicity have raised hopes for treatment. Increasing fatty acid oxidation leads to decreased ceramide, diacylglycerol, and triacylglycerol which can reduce lipotoxicity. However, lowering the rate of fatty acid oxidation may improve carbohydrate metabolism in myocardial cells and improve the contractile efficiency of the heart.90,91 Evidence shows that several synthetic and natural compounds have a reverse effect on lipotoxicity-induced cardiomyopathy. We have recently shown that glucolipotoxicity-induced DCM is mediated via the upregulation of protein kinase R (PKR) and that the inhibition of PKR reverses DCM phenotypes significantly.89,95 Likewise, other groups have demonstrated beneficial outcomes of canagliflozin 96 ; exendin-4, a GLP-1 analog; saxagliptin, a dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor 97 ; metreleptin, a recombinant leptin 98 ; and extracts from plants such as Turbina oblongata 99 in the treatment of lipotoxicity-induced cardiomyopathy.

Autophagy eliminates dysfunctional cell organelles, protein aggregates, and pathogens via lysosomal mechanisms. In rat insulinoma cells, it was reported that palmitate treatment increases autophagosome numbers and causes their activation, indicating a protective role against palmitate-induced death. Given that the activation of autophagy by fatty acids in beta-cells has been reported to be an apoptotic signal, 100 these contradictory findings suggest that induction of autophagy can either exert harmful or protective roles. Hence, the role of autophagy in lipotoxicity-associated DCM requires further investigation.

Cardiac stiffness and impaired contractility

Cardiac stiffness and impaired contractility are seen during the initial stages of DCM and once present have only finite chances to repair. Pathophysiological changes, for instance, inappropriate Renin-Angiotensin sytem (RAS) activation despite water and salt excess, oxidative stress, increased cardiomyocyte death, impaired cardiomyocyte autophagy, and maladaptive immune responses, all contribute to cardiac stiffness/diastolic dysfunction.101,102 The phosphorylation of eNOS at Ser1177 mediated by activated protein kinase B (PKB/Akt) is critical for NO generation. 103 Increased bioavailable NO mediates myocardial energy balance and coronary vasodilation. Diabetic patients have decreased NO-mediated vascular relaxation and increased cardiac stiffness, both caused by dysregulated cardiac insulin signaling, which also affects diastolic relaxation. 1 Arachidonic acid metabolism pathway, microsomal P-450 enzymes, NADPH oxidases, XO, and NO synthase activity increases upon activation of PKC following increased electron donor and mitochondrial proton gradient by glucose. 104 Furthermore, eNOS releases NO, which may combine with the NADPH oxidase generated superoxide to form peroxynitrite. 105 Inhibition of guanylyl cyclase and lowering of cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) levels accompanied by a decrease in protein kinase G (PKG) activity are determined by decreased bioavailability of NO in cardiac cells. The large cytoskeletal protein titin, which regulates diastolic cardiac distensibility is hypophosphorylated in cardiomyocytes when PKG activity is reduced. 106 Diastolic dysfunction is caused by delayed relaxation, increased diastolic stiffness, and a decrease in cardiomyocyte elastance. HFpEF diastolic stiffness is influenced by the activities of the NO, cGMP, and PKG pathway, regardless of ejection fraction.107,108 The NO–cGMP–PKG–titin pathway is anticipated to be a primary predictor of left ventricle (LV) diastolic stiffness in diabetic HFpEF patients given the findings of severe oxidative stress, vascular inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, and lower bioavailability of NO in cardiomyocytes of DCM patients.109,110 Calcium–calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II, a Ca2+activated enzyme promotes cardiac adaptation by increasing energy generation, glucose absorption, SR Ca2+ release/reuptake, sarcolemmal ion fluxes, and myocyte contraction/relaxation. 111 CaMKII activation occurs downstream of the neurohormonal stimulation, involving a variety of posttranslational modifications such as autophosphorylation, oxidation, S-nitrosylation, O-GlcNAcylation. This enzyme also modulates excitation–contraction and excitation–transcription coupling, mechanics, and energetics in cardiac cells causing arrhythmogenic changes in Ca2+ handling, ion channels, cell-to-cell communication, and metabolism.111,112 The molecular knowledge of cardiac remodeling, arrhythmia, and CaMKII signaling may lead to the discovery of novel therapeutic targets and, eventually, more effective treatments for diabetes and heart diseases in particular. 111

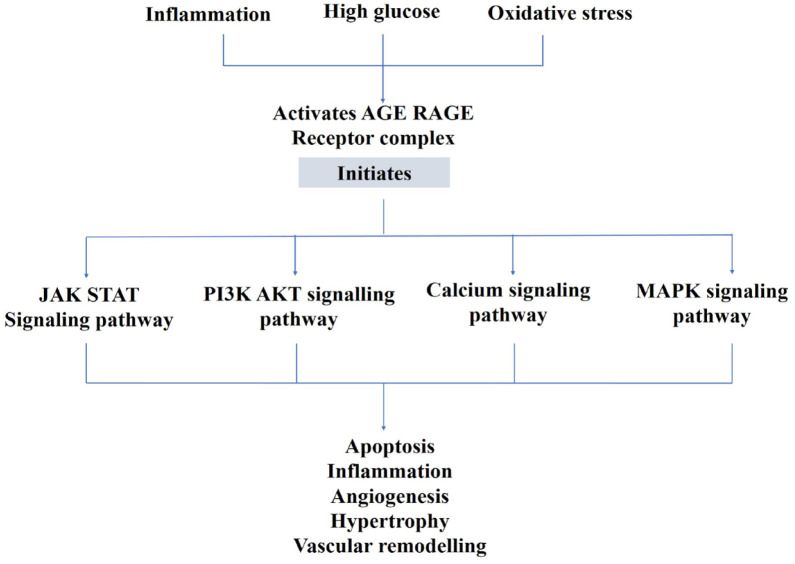

AGEs accretion triggered by HG, oxidative stress, and inflammation results in the activation of various signaling pathways initiated by AGE–RAGE interaction (Figure 3), remodeling of the ECM with collagen–elastin cross-linkage, production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, TGF-β, and NF-κB signaling, increased ROS production and cardiac oxidative stress decreased SR function with reduced Ca2+ reuptake into SR, and the switch from the alpha-myosin heavy chain (MHC) to beta-MHC which causes myocardial stiffness and myocyte enlargement.113–115 In patients with type 1 diabetes, correlations have been documented between AGEs serum levels, isovolumetric relaxation time, and LV diameter during diastole. 116

Figure 3.

Schematic illustration of the role of AGEs in DCM.

AGE, advanced glycation end product; Akt, protein kinase B; DCM, diabetic cardiomyopathy; JAK-STAT, Janus kinase–signal transducer and activator of transcription; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; PI3K, phosphoinositide-3-kinase; RAGE, receptor for advanced glycation end product.

Inflammatory mediators

Multiple pro-inflammatory pathways are upregulated in the heart due to hyperglycemia, hyperinsulinemia, and elevated angiotensin II levels. The PI3K–Akt pathway, which leads to GLUT4-regulated cellular glucose uptake, is suppressed under diabetic hyperinsulinemic conditions. Hyperinsulinemia in turn induces phosphorylation of MAPK, a hypertrophy regulating pathway that causes endothelin mediated vasoconstriction and releases pro-inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α, IL-6. 117 Additionally, damaged endothelial cells or endothelial dysfunction can cause the production of inflammatory mediators such as TNF-α and IL-1, which further lead to the expression of adhesion molecules intercellular adhesion molecule (ICAM-1), vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1), E-selectin, and P-selectin on the surface of the endothelial cells.118–120 Hyperglycemia leads to the formation of AGEs, inducing secretion of transcription factor NF-κB, which in turn releases pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α, and IL-6 and ICAMs, together causing damage to the cardiac muscle. 117 Multiple other accessory pathways are involved in the pro-inflammatory response fueled by the hyperglycemic effects, such as the JNK/NF-κB pathway (Table 1).121,122 Additionally, hyperglycemia also suppresses the activity of Sirt-1, a protein involved in blocking NF-κB transcription and inflammation. 123 Increased levels of lipids and fatty acids in circulation also lead to toll-like receptor (TLR4) production, a potent NF-κB activator, and PKC production, a MAPK pathway activator. TLR4 deactivation by siRNA-mediated silencing causes a significant decrease in triglyceride accumulation and a reduction in inflammatory responses.88,117,124 Naturally occurring ursolic acid (UA) is a pentacyclic triterpenoid compound with a wide range of beneficial effects derived from its anti-tumor to anti-inflammatory and vasoprotective properties. 125 UA has shown promising preliminary cardioprotective effects in CVD. 126 Prolonged treatment with UA in diabetic rats significantly reduces TNF-α and related cytokines. 57 UA has also been shown to significantly improve diastolic dysfunction and restore normal cardiac function in DCM rats. 57 The therapeutic significance of MG-132, a proteasome inhibitor in DCM was recently reported in a study showing that MG-132 treatment increases the cardiac expression of antioxidant genes via the upregulation of Nrf-2, besides decreasing the levels of IκB-α and nuclear accumulation of NF-κB in the heart. 127 LCZ696, neprilysin, an angiotensin receptor inhibitor, can reduce inflammation and death by inhibiting the nuclear transfer of NF-B and JNK/p38MAPK phosphorylation in diabetic mice and H9C2 cardiomyocytes under HG condition. 128 Isosteviol sodium inhibited ERK and NF-κB reduces cardiac fibrosis, inflammation, and hypertrophy, equivalent heart-to-body weight ratio, and antioxidant capabilities nearly identical to the normal controls. 129

Cardiac hypertrophy and cardiac fibrosis

Cardiac fibrosis is a strong contributing factor in the pathogenesis of DCM. Increased expression of TGF-β in association with cardiac fibrosis has been reported in DCM. 130 Factors responsible for TGF-β upregulation in DCM include hyperinsulinemia, hyperglycemia, renin angiotensin aldosterone system activation, and AGE-mediated signaling pathway. 21 Moreover, increased activity of β1/Suppressor of mothers against Decapentaplegic (SMAD) signaling pathway in association with reduced NO availability, compromised insulin metabolism, and increased oxidative stress leads to increased deposition of fibronectin and collagen in the myocardium, which in turn causes fibrosis. 21 Reduced GRK2 signaling is reported to contribute to cardiac hypertrophy in aged animals. 33 Insulin induces ventricular hypertrophy through several mechanisms, most notably the activation of Akt and ERK. 23 This potentially contributes to ventricular hypertrophy in diabetics. 23 Enhanced 1-adrenergic production and signaling brought on by sympathetic nervous system activation, can lead to myocyte hypertrophy, interstitial fibrosis, and decreased contractile performance, along with an increase in myocyte death. 16 Myocardial hypertrophy, cardiac fibrosis, poor myocardial-endothelial signaling, and the death of myocardial and endothelial cells can be due to impaired signal transduction through MAPK, Other molecular pathways may also contribute to the above conditions. 131

Patients with diabetes have lower levels of miR-15a/b in their myocardium, causing transforming growth factor receptor-1 and connective tissue growth factor to signal fibrosis. 59 It has been reported that the accumulation of fibroblasts caused by elevated endothelin 1 (ET-1) levels in the heart of diabetic patients is linked to cardiac fibrosis through endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition. 132 Targeted suppression of the ET-1 gene can prevent this shift from occurring and delay the onset of cardiac fibrosis. 132 Additionally, ET-1 receptor inhibition normalizes the excessive contractile response of mesenteric arteries to ET-1 and dramatically improves LV developed pressure, peak rate of LV pressure, and LV rate of contraction. 133 The use of stem cells in therapeutics has raised new hopes in the treatment of diseases, including DCM and studies have shown that cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis can be reversed through stem cell therapy. By injecting stem cells into the heart, damaged cardiomyocytes can be replaced or regenerated, thus, restoring cardiac tissue and function.134,135 Besides, the paracrine effects of stem cells, such as the production of growth factors, cytokines, and anti-inflammatory substances stimulate tissue repair, decreased inflammation, promotion of angiogenesis, decreased fibrosis, and improved microenvironment within of injured heart tissue, can all thus enhance heart function.136,137 Various drugs with promising effects on fibrosis and collagen deposition, attenuation activity in DCM models is summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Drugs with a protective action on cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis.

| S. no. | Drug name | DCM prevention mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Ursolic acid 57 | Fibrosis ↓ Oxidative stress ↓ Hyperglycemic stress ↓ |

| 2. | Cannabidiol 138 | Fibrosis and collagen deposition ↓ Inflammation ↓ Apoptosis ↓ |

| 3. | TNF-α monoclonal antibody 139 | Fibrosis ↓ by downregulating MAPK and pro-inflammatory cytokines |

| 4. | Relaxin38,140 | Mesenchymal differentiation ↓ Collagen deposition ↓ Metalloproteinase-1 ↓ ECM degrading matrix metalloproteinase-13 ↑ |

| 5. | Losartan 141 | Angiotensin 1 recptor (AT1R) blocker JAK/STAT pathway ↓ TGF-β ↓ Collagen deposition ↓ |

| 6. | Free-radical scavenger Szeto-Schiller peptide SS31 142 | Diastolic dysfunction ↓ Cardiac fibrosis and hypertrophy ↓ |

| 7. | Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitors143,144 | Fibrosis ↓ Oxidative stress ↓ Hypertrophy ↓ |

| 8. | Coenzyme Q (10) 145 | Akt phosphorylation and signaling ↑ Fibrosis ↓ Cardiomyocyte hypertrophy ↓ |

| 9. | Co-administration of hydrogen and metformin 146 | AMPK/mTOR/Nod-like receptor protein 3NLRP3 pathway ↓ TGF-β1/SMAD pathway ↓ Pyroptosis and fibrosis ↓ |

| 10. | Mesenchymal stem cell therapy 134 | Endogenous regeneration of cardiomyocytes ↑ Cardiac fibroblast activity ↓ Collagen deposition ↓ |

Akt, protein kinase B; AMPK, AMP-activated protein kinase; ECM, extracellular matrix; JAK-STAT, Janus kinase–signal transducer and activator of transcription; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; TGF-β, transforming growth factor-β; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor alpha.

Preventing cardiac cell death

Generally, it is believed that cell death during DCM is the ultimate step. Cell death may be divided morphologically into four categories: apoptosis, autophagy, necrosis, and entosis. 147 Unfolded protein response, also known as endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress is a cell stress response that has been retained throughout evolution when ER-associated processes are disrupted. ER stress is originally intended to repair damage; however, if the stress is too much or lasts too long, it might eventually cause cell death. 148

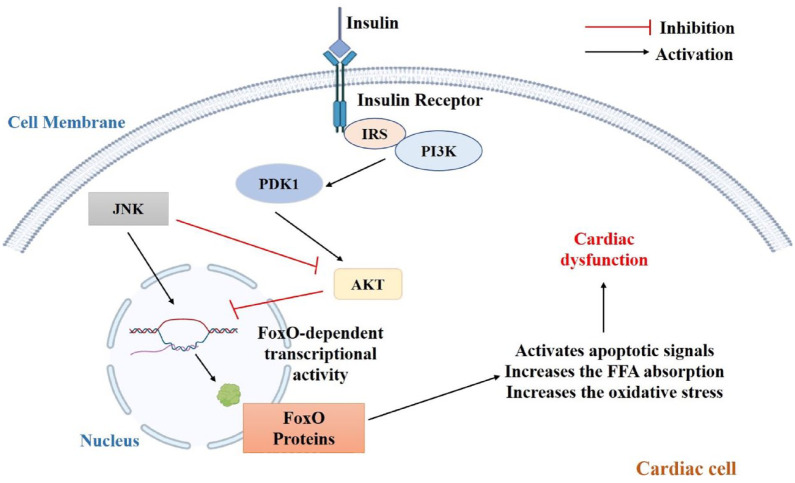

Through the AMPK-mTOR-p70S6K signal-mediated autophagy, activation of the cannabinoid receptor 2 with HU308 may impart a cardioprotective effect in DCM, as well as in cardiomyocytes after HG stress. 149 Inhibition of (poly[ADP-ribose] polymerase-1 (PARP-1) decreased the inflammatory response brought on by HG, including the release of TNF-α, IL-1, and IL-6 as well as the expression of ICAM-1 and inducible nitric oxide synthase. Additionally, insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-1R/Akt pathway activation and downregulation of cleaved caspase-3 and caspase-9 together with PARP-1 suppression reduces HG-induced cardiomyocyte death.150,151 In mice, the inflammatory response and cardiomyocyte apoptosis caused by hyperglycemia were attenuated by PARP-1 deletion. 150 A major cardiac phosphatase called protein phosphatase 2A controls the activity of various myocytes by binding to its target molecules. 147 Forkhead box protein O (FoxO), a transcription factor is abundantly present in the cardiac cells and is described as an important regulator of several cellular processes in the myocardium and as a potential therapeutic target.152,153 FoxO-dependent transcriptional activity is reduced by PI3K-Akt signaling. 154 FoxO factors are involved in cell cycle regulation, autophagy, apoptosis, oxidative stress responses, cellular remodeling, besides facilitating response to environmental changes.155,156 During insulin resistance in cardiomyocytes, downregulation of Akt phosphorylation increases the expression of FoxO protein, which in turn activates apoptotic signaling in the cardiomyocytes (Figure 4). 156 Studies have also shown that the inhibition of FoxO-dependent transcriptional activity by PI3K-Akt signaling has an even more complex regulatory feedback mechanism, as FoxO protein is a key element of insulin signaling pathway. 156 However, future studies using both in vitro and in vivo approaches are needed to explore its value as a therapeutic target. Tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 (TNFR1) and Fas receptors are ligands to death receptors that drive the process of necroptosis upon HG stimulation. Necroptosis is also induced by PKR complexes, damage-associated molecular patterns, and nucleotide-binding and oligomerization domain-like receptors. The route that activates necroptosis and which has received the highest attention is the TNFR1-mediated necroptosis. There are three distinct activities that TNF-α may perform after binding to TNFR1; cell survival, apoptosis, or necroptosis via the formation of different complexes. Complex I being prosurvival, Complex IIa proapoptotic, and Complex IIb pronecroptotic.157,158 By enabling the fusion of autophagosome and lysosome, Mfn2 is essential for the cardiac autophagic process. Mfn2 loss hinders this fusion, which eventually increases cardiac susceptibility and dysfunction. 159 Nicorandil boosts B-cell lymphoma-2 (bcl-2) expression in the heart of diabetic rats while decreasing the expression of bcl-2-associated X (Bax), TdT-mediated dUTP nick end labeling-positive cells, and cleaved caspase 3. 160 Furthermore, when H9C2 cardiomyocytes were stimulated with HG levels, the competitive antagonist of nicorandil, 5-HD, increased apoptosis but decreased the phosphorylation of P13K, Akt, eNOS, and mTOR. 160 One of the recently studied targets is GLP-1, an incretin that is synthesized by intestinal L cells following nutrient ingestion. GLP-1 analogs are reported to have a cardioprotective effect via antiapoptotic and antioxidant activity (Table 1). 161 Clinical trials have further demonstrated the cardiovascular benefits of several GLP-1 analogs in diabetic patients, with liraglutide showing appreciable benefits in mitigating CVD risk.161,162 A recently approved GLP-1 analog, dulaglutide is useful for primary and secondary cardiovascular prevention. 163 Although GLP-1 analogs have shown cardioprotective benefits in preclinical and early clinical trials, 164 studies need to be conducted to identify the underlying molecular mechanism(s) through which GLP-1 analogs exert their therapeutic benefits in DCM.

Figure 4.

Role of FoxO proteins in DCM.

Akt, protein kinase B; DCM, diabetic cardiomyopathy; FoxO, Forkhead box protein O; JAK, Janus kinase; PDK1, 3-phosphoinositide-dependent kinase; PI3K, phosphoinositide-3-kinase.

Conclusion

Preclinical as well as clinical studies have reported multiple mechanisms involved in the pathogenesis of DCM. Currently, there are no specific treatments for the management of DCM and most of the currently available anti-hyperglycemic medications are not effective in preventing CVD in diabetic patients. The molecular foundation of DCM targeted therapy comprises several interrelated pathways and processes. Myocardial hypertrophy, fibrosis, poor myocardial-endothelial signaling, and cellular dysfunction are all symptoms of DCM. Several important molecular mechanisms contribute to the formation and progression of DCM. Regardless of ejection fraction, impaired signaling via the NO, cGMP, and PKG pathways might contribute to diastolic stiffness in DCM. Such dysfunctional signaling can cause endothelial dysfunction, decreased vasodilation, and increased fibrosis, all of which contribute to diastolic dysfunction. Ongoing research and well-designed clinical trials are required to understand the molecular basis of DCM better and to develop targeted therapeutics that can successfully prevent, delay, or reverse the progression of this cardiac problem. In addition to the treatments discussed above, which are predominantly tailored toward a specific pathway, stem cell therapy has proven effective in treating a variety of CVDs. Although stem cell therapy has not yet been tested in the treatment of DCM, data from in vivo and in vitro studies are showing promising results. Future studies in line with target-specific drug development like targeting FoxO protein, ET-1, CaMKII, and others, can potentially offer effective therapeutic options.

Acknowledgments

Authors acknowledge the language proofreading support provided by Dr. Raj Thakur, Department of English, Central University of Jammu.

Footnotes

ORCID iD: Audesh Bhat  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2892-3910

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2892-3910

Contributor Information

Arti Dhar, Department of Pharmacy, Birla Institute of Technology and Science Pilani, Hyderabad, Telangana, India.

Jegadheeswari Venkadakrishnan, Department of Pharmacy, Birla Institute of Technology and Science Pilani, Hyderabad, Telangana, India.

Utsa Roy, Department of Pharmacy, Birla Institute of Technology and Science Pilani, Hyderabad, Telangana, India.

Sahithi Vedam, Department of Pharmacy, Birla Institute of Technology and Science Pilani, Hyderabad, Telangana, India.

Nikita Lalwani, Department of Pharmacy, Birla Institute of Technology and Science Pilani, Hyderabad, Telangana, India.

Kenneth S. Ramos, Center for Genomics and Precision Medicine, Texas A&M College of Medicine, Houston, TX 77030, USA.

Tej K. Pandita, Center for Genomics and Precision Medicine, Texas A&M College of Medicine, Houston, TX 77030, USA.

Audesh Bhat, Centre for Molecular Biology, Central University of Jammu, Samba, Jammu and Kashmir (UT) 184311, India.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate: Not applicable.

Consent for publication: All authors have read and approved the manuscript for publication.

Author contributions: Arti Dhar: Methodology; Supervision; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Jegadheeswari Venkadakrishnan: Data curation; Methodology; Visualization; Writing – original draft.

Utsa Roy: Methodology; Writing – original draft.

Sahithi Vedam: Methodology; Writing – original draft.

Nikita Lalwani: Writing – original draft.

Kenneth S. Ramos: Writing – review & editing.

Tej K. Pandita: Supervision; Writing – review & editing.

Audesh Bhat: Conceptualization; Project administration; Supervision; Writing – review & editing.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: AB acknowledges the financial support from the Indian Council of Medical Research (Grant nos. 5/10/15/CAR-SMVDU/2018-RBMCH and 6719/2020-DDl/BMS) and AD acknowledges the financial support from the Indian Council of Medical Research (Grant no. 6719/2020-DDl/BMS). KSR acknowledges the financial support from the Governors University Research Initiative of Texas.

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Availability of data and materials: Not applicable.

References

- 1. Jia G, Hill MA, Sowers JR. Diabetic cardiomyopathy: an update of mechanisms contributing to this clinical entity. Circ Res 2018; 122: 624–638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wang J, Song Y, Wang Q, et al. Causes and characteristics of diabetic cardiomyopathy. Rev Diabet Stud 2006; 3: 108–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bugger H, Abel ED. Molecular mechanisms of diabetic cardiomyopathy. Diabetologia 2014; 57: 660–671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Stranders I, Diamant M, van Gelder RE, et al. Admission blood glucose level as risk indicator of death after myocardial infarction in patients with and without diabetes mellitus. Arch Intern Med 2004; 164: 982–988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lopaschuk GD, Stanley WC. Glucose metabolism in the ischemic heart. Circulation 1997; 95: 313–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Marsh SA, Dellitalia LJ, Chatham JC. Interaction of diet and diabetes on cardiovascular function in rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2009; 296: H282–H292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Duckworth W, Abraira C, Moritz T, et al. Glucose control and vascular complications in veterans with type 2 diabetes. New Engl J Med 2009; 360: 129–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Singh S, Schwarz K, Horowitz J, et al. Cardiac energetic impairment in heart disease and the potential role of metabolic modulators a review for clinicians. Circ Cardiovasc Genet 2014; 7: 720–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Crilley JG, Boehm EA, Blair E, et al. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy due to sarcomeric gene mutations is characterized by impaired energy metabolism irrespective of the degree of hypertrophy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003; 41: 1776–1782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Neubauer S, Horn M, Cramer M, et al. Myocardial phosphocreatine-to-ATP ratio is a predictor of mortality in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation 1997; 96: 2190–2196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Shen W, Asai K, Uechi M, et al. Progressive loss of myocardial ATP due to a loss of total purines during the development of heart failure in dogs: a compensatory role for the parallel loss of creatine. Circulation 1999; 100: 2113–2118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Deng J. Research progress on the molecular mechanism of coronary microvascular endothelial cell dysfunction. IJC Heart Vasc 2021; 34: 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cheng YJ, Kanaya AM, Araneta MRG, et al. Prevalence of diabetes by race and ethnicity in the United States, 2011–2016. JAMA 2019; 322: 2389–2398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lam CS, Lyass A, Kraigher-Krainer E, et al. Cardiac dysfunction and noncardiac dysfunction as precursors of heart failure with reduced and preserved ejection fraction in the community. Circulation 2011; 124: 24–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kalra J, Mangali SB, Dasari D, et al. SGLT1 inhibition boon or bane for diabetes-associated cardiomyopathy. Fundam Clin Pharmacol 2020; 34: 173–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jia G, DeMarco VG, Sowers JR. Insulin resistance and hyperinsulinaemia in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2016; 12: 144–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zamora M, Villena JA. Contribution of impaired insulin signaling to the pathogenesis of diabetic cardiomyopathy. Int J Mol Sci 2019; 20: 2833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Velez M, Kohli S, Sabbah HN. Animal models of insulin resistance and heart failure. Heart Fail Rev 2014; 19: 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Anker SD, Ponikowski P, Varney S, et al. Wasting as independent risk factor for mortality in chronic heart failure. J Lancet 1997; 349: 1050–1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cook SA, Varela-Carver A, Mongillo M, et al. Abnormal myocardial insulin signalling in type 2 diabetes and left-ventricular dysfunction. Eur Heart J 2010; 31: 100–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jia G, Habibi J, DeMarco VG, et al. Endothelial mineralocorticoid receptor deletion prevents diet-induced cardiac diastolic dysfunction in females. Hypertension 2015; 66: 1159–1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Patten D, Harper M-E, Boardman N. Harnessing the protective role of OPA1 in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Acta Physiol 2020; 229: 1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Riehle C, Abel ED. Insulin signaling and heart failure. Circ Res 2016; 118: 1151–1169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Miettinen H, Lehto S, Salomaa V, et al. Impact of diabetes on mortality after the first myocardial infarction. Diabetes Care 1998; 21: 69–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Anker SD, Chua TP, Ponikowski P, et al. Hormonal changes and catabolic/anabolic imbalance in chronic heart failure and their importance for cardiac cachexia. Circulation 1997; 96: 526–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Schulze PC, Kratzsch J, Linke A, et al. Elevated serum levels of leptin and soluble leptin receptor in patients with advanced chronic heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail 2003; 5: 33–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hambrecht R, Schulze PC, Gielen S, et al. Reduction of insulin-like growth factor-I expression in the skeletal muscle of noncachectic patients with chronic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002; 39: 1175–1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Qi H, Liu Y, Li S, et al. Activation of AMPK attenuated cardiac fibrosis by inhibiting CDK2 via p21/p27 and miR-29 family pathways in rats. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids 2017; 8: 277–290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Du XJ, Fang L, Gao XM, et al. Genetic enhancement of ventricular contractility protects against pressure-overload-induced cardiac dysfunction. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2004; 37: 979–987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Liu Q, Chen Y, Auger-Messier M, et al. Interaction between NFκB and NFAT coordinates cardiac hypertrophy and pathological remodeling. Circ Res 2012; 110: 1077–1086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yan Z, Wu H, Yao H, et al. Rotundic acid protects against metabolic disturbance and improves gut microbiota in type 2 diabetes rats. Nutrients 2019; 12: 1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Boudina S, Bugger H, Sena S, et al. Contribution of impaired myocardial insulin signaling to mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in the heart. Circulation 2009; 119: 1272–1283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Vila-Bedmar R, Cruces-Sande M, Lucas E, et al. Reversal of diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance by inducible genetic ablation of GRK2. Sci Signal 2015; 8: ra73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Dobrin JS, Lebeche D. Diabetic cardiomyopathy: signaling defects and therapeutic approaches. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther 2010; 8: 373–391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zhang R, Khoo MS, Wu Y, et al. Calmodulin kinase II inhibition protects against structural heart disease. Nat Med 2005; 11: 409–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hoshijima M. Gene therapy targeted at calcium handling as an approach to the treatment of heart failure. Pharmacol Ther 2005; 105: 211–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kaye DM, Krum H. Drug discovery for heart failure: a new era or the end of the pipeline? Nat Rev Drug Discov 2007; 6: 127–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Samuel CS. Relaxin: antifibrotic properties and effects in models of disease. Clin Med Res 2005; 3: 241–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Klec C, Ziomek G, Pichler M, et al. Calcium signaling in ß-cell physiology and pathology: a revisit. Int J Mol Sci 2019; 20: 6110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lanner JT, Georgiou DK, Joshi AD, et al. Ryanodine receptors: structure, expression, molecular details, and function in calcium release. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2010; 2: 1–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Xu H, Van Remmen H. The SarcoEndoplasmic Reticulum Calcium ATPase (SERCA) pump: a potential target for intervention in aging and skeletal muscle pathologies. Skelet Muscle 2021; 11: 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Glaves JP, Primeau JO, Espinoza-Fonseca LM, et al. The phospholamban pentamer alters function of the sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium pump SERCA. Biophys J 2019; 116: 633–647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Weber DK, Reddy UV, Wang S, et al. Structural basis for allosteric control of the SERCA-phospholamban membrane complex by Ca2+ and phosphorylation. eLife 2021; 10: 1–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Vasanji Z, Dhalla NS, Netticadan T. Increased inhibition of SERCA2 by phospholamban in the type I diabetic heart. Mol Cell Biochem 2004; 261: 245–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Cooper D, Dimri M. Biochemistry, calcium channels. StatPearls, 2022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Sanchez-Alonso JL, Loucks A, Schobesberger S, et al. Nanoscale regulation of L-type calcium channels differentiates between ischemic and dilated cardiomyopathies. EBioMedicine 2020; 57: 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Teshima Y, Takahashi N, Nishio S, et al. Production of reactive oxygen species in the diabetic heart. Roles of mitochondria and NADPH oxidase. Circ J 2014; 78: 300–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Jiang W, Liu M, Gu C, et al. The pivotal role of mitsugumin 53 in cardiovascular diseases. Cardiovasc Toxicol 2021; 21: 2–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Zhong W, Benissan-Messan DZ, Ma J, et al. Cardiac effects and clinical applications of MG53. Cell Biosci 2021; 11: 115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Matsushima S, Sadoshima J. Yin and Yang of NADPH oxidases in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion. Antioxidants 2022; 11: 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Vega RB, Horton JL, Kelly DP. Maintaining ancient organelles: mitochondrial biogenesis and maturation. Circ Res 2015; 116: 1820–1834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Sena CM, Pereira AM, Seiça R. Endothelial dysfunction – a major mediator of diabetic vascular disease. Biochim Biophys Acta 2013; 1832: 2216–2231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Endemann DH, Schiffrin EL. Endothelial dysfunction. J Am Soc Nephrol 2004; 15: 1983–1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Cooke CL, Davidge ST. Peroxynitrite increases iNOS through NF-kappaB and decreases prostacyclin synthase in endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2002; 282: C395–C402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. De Caterina R. Endothelial dysfunctions: common denominators in vascular disease. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2000; 3: 453–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Weiss JN, Korge P, Honda HM, et al. Role of the mitochondrial permeability transition in myocardial disease. Circ Res 2003; 93: 292–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Wang XT, Gong Y, Zhou B, et al. Ursolic acid ameliorates oxidative stress, inflammation and fibrosis in diabetic cardiomyopathy rats. Biomed Pharmacother 2018; 97: 1461–1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Asrih M, Steffens S. Emerging role of epigenetics and miRNA in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Cardiovasc Pathol 2013; 22: 117–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Zhang W, Xu W, Feng Y, et al. Non-coding RNA involvement in the pathogenesis of diabetic cardiomyopathy. J Cell Mol Med 2019; 23: 5859–5867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Bueno OF, Molkentin JD. Involvement of extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1/2 in cardiac hypertrophy and cell death. Circ Res 2002; 91: 776–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Mutlak M, Kehat I. Extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1/2 as regulators of cardiac hypertrophy. Front Pharmacol 2015; 6: 149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Wang Y, Zhou S, Sun W, et al. Inhibition of JNK by novel curcumin analog C66 prevents diabetic cardiomyopathy with a preservation of cardiac metallothionein expression. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2014; 306: E1239–E1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Mariappan N, Elks CM, Sriramula S, et al. NF-kappaB-induced oxidative stress contributes to mitochondrial and cardiac dysfunction in type II diabetes. Cardiovasc Res 2010; 85: 473–483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Knapp M, Tu X, Wu R. Vascular endothelial dysfunction, a major mediator in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2018; 40: 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Niture SK, Khatri R, Jaiswal AK. Regulation of Nrf2-an update. Free Radic Biol Med 2014; 66: 36–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. MacDonald MR, Petrie MC, Varyani F, et al. Impact of diabetes on outcomes in patients with low and preserved ejection fraction heart failure: an analysis of the Candesartan in Heart Failure: Assessment of Reduction in Mortality and Morbidity (CHARM) programme. Eur Heart J 2008; 29: 1377–1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Pocock SJ, Wang D, Pfeffer MA, et al. Predictors of mortality and morbidity in patients with chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J 2006; 27: 65–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Aguilar D, Solomon SD, Køber L, et al. Newly diagnosed and previously known diabetes mellitus and 1-year outcomes of acute myocardial infarction: the VALsartan In Acute myocardial iNfarcTion (VALIANT) trial. Circulation 2004; 110: 1572–1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Mosterd A. The prognosis of heart failure in the general population. The Rotterdam Study. Eur Heart J 2001; 22: 1318–1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. From AM, Leibson CL, Bursi F, et al. Diabetes in heart failure: prevalence and impact on outcome in the population. Am J Med 2006; 119: 591–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Sorrentino A, Borghetti G, Zhou Y, et al. Hyperglycemia induces defective Ca2+ homeostasis in cardiomyocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2017; 312: H150–H161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Chang W-T, Cheng J-T, Chen Z-C. Telmisartan improves cardiac fibrosis in diabetes through peroxisome proliferator activated receptor δ (PPARδ): from bedside to bench. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2016; 15: 113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Kaiser N, Sasson S, Feener EP, et al. Differential regulation of glucose transport and transporters by glucose in vascular endothelial and smooth muscle cells. Diabetes 1993; 42: 80–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Battault S, Renguet E, Van Steenbergen A, et al. Myocardial glucotoxicity: mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets. Arch Cardiovasc Dis 2020; 113: 736–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Wright EM, Loo DFD, Hirayama BA. Biology of human sodium glucose transporters. Physiol Rev 2011; 91: 733–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Steiner S. Empagliflozin, cardiovascular outcomes, and mortality in type 2 diabetes. Zeitschrift fur Gefassmedizin 2016; 13: 17–18. [Google Scholar]

- 77. Carbone S, Dixon DL. The CANVAS Program: implications of canagliflozin on reducing cardiovascular risk in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2019; 18: 64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Sattar N, McLaren J, Kristensen SL, et al. SGLT2 inhibition and cardiovascular events: why did EMPA-REG Outcomes surprise and what were the likely mechanisms? Diabetologia 2016; 59: 1573–1574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Mosenzon O, Wiviott SD, Heerspink HJL, et al. The effect of dapagliflozin on albuminuria in DECLARE-TIMI 58. Diabetes Care 2021; 44: 1805–1815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Vallon V, Verma S. Effects of SGLT2 inhibitors on kidney and cardiovascular function. Annu Rev Physiol 2021; 83: 503–528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Scisciola L, Cataldo V, Taktaz F, et al. Anti-inflammatory role of SGLT2 inhibitors as part of their anti-atherosclerotic activity: data from basic science and clinical trials. Front Cardiovasc Med 2022; 9: 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Llorens-Cebrià C, Molina-Van den Bosch M, Vergara A, et al. Antioxidant roles of SGLT2 inhibitors in the kidney. Biomolecules 2022; 12: 1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. La Grotta R, de Candia P, Olivieri F, et al. Anti-inflammatory effect of SGLT-2 inhibitors via uric acid and insulin. Cell Mol Life Sci 2022; 79: 273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Xie Z, He C, Zou MH. AMP-activated protein kinase modulates cardiac autophagy in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Autophagy 2011; 7: 1254–1255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Olivier S, Foretz M, Viollet B. Promise and challenges for direct small molecule AMPK activators. Biochem Pharmacol 2018; 153: 147–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Dasari D, Bhat A, Mangali S, et al. Canagliflozin and dapagliflozin attenuate glucolipotoxicity-induced oxidative stress and apoptosis in cardiomyocytes via inhibition of sodium-glucose cotransporter-1. ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci 2022; 5: 216–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Sun L, Yu M, Zhou T, et al. Current advances in the study of diabetic cardiomyopathy: from clinicopathological features to molecular therapeutics (Review). Mol Med Rep 2019; 20: 2051–2062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Tan Y, Zhang Z, Zheng C, et al. Mechanisms of diabetic cardiomyopathy and potential therapeutic strategies: preclinical and clinical evidence. Nat Rev Cardiol 2020; 17: 585–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Mangali S, Bhat A, Jadhav K, et al. Upregulation of PKR pathway mediates glucolipotoxicity induced diabetic cardiomyopathy in vivo in wistar rats and in vitro in cultured cardiomyocytes. Biochem Pharmacol 2020; 177: 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Ussher JR. The role of cardiac lipotoxicity in the pathogenesis of diabetic cardiomyopathy. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther 2014; 12: 345–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Liu L, Shi X, Bharadwaj KG, et al. DGAT1 expression increases heart triglyceride content but ameliorates lipotoxicity. J Biol Chem 2009; 284: 36312–36323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Shu H, Peng Y, Hang W, et al. The role of CD36 in cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc Res 2022; 118: 115–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Li H, Fan J, Zhao Y, et al. Nuclear miR-320 mediates diabetes-induced cardiac dysfunction by activating transcription of fatty acid metabolic genes to cause lipotoxicity in the heart. Circ Res 2019; 125: 1106–1120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Li S, Qian X, Gong J, et al. Exercise training reverses lipotoxicity-induced cardiomyopathy by inhibiting HMGCS2. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2021; 53: 47–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Mangali S, Bhat A, Udumula MP, et al. Inhibition of protein kinase R protects against palmitic acid-induced inflammation, oxidative stress, and apoptosis through the JNK/NF-κB/NLRP3 pathway in cultured H9C2 cardiomyocytes. J Cell Biochem 2019; 120: 3651–3663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Sun P, Wang Y, Ding Y, et al. Canagliflozin attenuates lipotoxicity in cardiomyocytes and protects diabetic mouse hearts by inhibiting the mTOR/HIF-1α pathway. iŞçience 2021; 24: 1–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Wu L, Wang K, Wang W, et al. Glucagon-like peptide-1 ameliorates cardiac lipotoxicity in diabetic cardiomyopathy via the PPARα pathway. Aging Cell 2018; 17: 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Nguyen M-L, Sachdev V, Burklow TR, et al. Leptin attenuates cardiac hypertrophy in patients with generalized lipodystrophy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2021; 106: e4327–e4339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Erukainure OL, Chukwuma CI, Matsabisa MG, et al. Turbina oblongata protects against oxidative cardiotoxicity by suppressing lipid dysmetabolism and modulating cardiometabolic activities linked to cardiac dysfunctions. Front Pharmacol 2021; 12: 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Oh YS, Bae GD, Baek DJ, et al. Fatty acid-induced lipotoxicity in pancreatic beta-cells during development of type 2 diabetes. Front Endocrinol 2018; 9: 384: 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Jia G, Whaley-Connell A, Sowers JR. Diabetic cardiomyopathy: a hyperglycaemia- and insulin-resistance-induced heart disease. Diabetologia 2018; 61: 21–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Teupe C, Rosak C. Diabetic cardiomyopathy and diastolic heart failure. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2012; 97: 185–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Liang XX, Wang RY, Guo YZ, et al. Phosphorylation of Akt at Thr308 regulates p-eNOS Ser1177 during physiological conditions. FEBS Open Bio 2021; 11: 1953–1964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Kassab A, Piwowar A. Cell oxidant stress delivery and cell dysfunction onset in type 2 diabetes. Biochimie 2012; 94: 1837–1848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Münzel T, Daiber A, Ullrich V, et al. Vascular consequences of endothelial nitric oxide synthase uncoupling for the activity and expression of the soluble guanylyl cyclase and the cGMP-dependent protein kinase. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2005; 25: 1551–1557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. van Heerebeek L, Hamdani N, Falcão-Pires I, et al. Low myocardial protein kinase G activity in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circulation 2012; 126: 830–839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Cai Z, Wu C, Xu Y, et al. The NO-cGMP-PKG axis in HFpEF: from pathological mechanisms to potential therapies. Aging Dis 2023; 14: 46–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Pfeffer MA, Shah AM, Borlaug BA. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction in perspective. Circ Res 2019; 124: 1598–1617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Lam CS. Diabetic cardiomyopathy: an expression of stage B heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Diabetes Vasc Dis Res 2015; 12: 234–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Evangelista I, Nuti R, Picchioni T, et al. Molecular dysfunction and phenotypic derangement in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Int J Mol Sci 2019; 20: 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Hegyi B, Bers DM, Bossuyt J. CaMKII signaling in heart diseases: emerging role in diabetic cardiomyopathy. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2019; 127: 246–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Schulman H, Anderson ME. Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II in heart failure. Drug Discov Today Dis Mech 2010; 7: e117–e122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Prandi FR, Evangelista I, Sergi D, et al. Mechanisms of cardiac dysfunction in diabetic cardiomyopathy: molecular abnormalities and phenotypical variants. Heart Fail Rev 2023; 28: 597–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. El Hayek MS, Ernande L, Benitah JP, et al. The role of hyperglycaemia in the development of diabetic cardiomyopathy. Arch Cardiovasc Dis 2021; 114: 748–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Wang M, Li Y, Li S, et al. Endothelial dysfunction and diabetic cardiomyopathy. Front Endocrinol 2022; 13: 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Falcão-Pires I, Leite-Moreira AF. Diabetic cardiomyopathy: understanding the molecular and cellular basis to progress in diagnosis and treatment. Heart Fail Rev 2012; 17: 325–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Nunes S, Soares E, Pereira F, et al. The role of inflammation in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Int J Interferon Cytokine Mediat Res 2012; 4: 59–73. [Google Scholar]

- 118. Matsumoto K, Sera Y, Ueki Y, et al. Comparison of serum concentrations of soluble adhesion molecules in diabetic microangiopathy and macroangiopathy. Diabet Med 2002; 19: 822–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Rask-Madsen C, King GL. Mechanisms of disease: endothelial dysfunction in insulin resistance and diabetes. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab 2007; 3: 46–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Kado S, Nagata N. Circulating intercellular adhesion molecule-1, vascular cell adhesion molecule-1, and E-selectin in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 1999; 46: 143–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Olefsky JM, Glass CK. Macrophages, inflammation, and insulin resistance. Annu Rev Physiol 2010; 72: 219–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Solinas G, Karin M. JNK1 and IKKβ: molecular links between obesity and metabolic dysfunction. FASEB J 2010; 24: 2596–2611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Yeung F, Hoberg JE, Ramsey CS, et al. Modulation of NF-kappaB-dependent transcription and cell survival by the SIRT1 deacetylase. EMBO J 2004; 23: 2369–2380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Frati G, Schirone L, Chimenti I, et al. An overview of the inflammatory signalling mechanisms in the myocardium underlying the development of diabetic cardiomyopathy. Cardiovasc Res 2017; 113: 378–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Woźniak L, Skąpska S, Marszałek K. Ursolic acid: a pentacyclic triterpenoid with a wide spectrum of pharmacological activities. Molecules 2015; 20: 20614–20641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Yang J, Gong Y, Shi J. Study on the effect of ursolic acid (UA) on the myocardial fibrosis of experimental diabetic mice. 2013; 29: 353–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Wang Y, Sun W, Du B, et al. Therapeutic effect of MG-132 on diabetic cardiomyopathy is associated with its suppression of proteasomal activities: roles of Nrf-2 and NF-κB. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2013; 304: H567–H578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Ge Q, Zhao L, Ren XM, et al. Feature article: LCZ696, an angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitor, ameliorates diabetic cardiomyopathy by inhibiting inflammation, oxidative stress and apoptosis. Exp Biol Med 2019; 244: 1028–1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Tang SG, Liu XY, Ye JM, et al. Isosteviol ameliorates diabetic cardiomyopathy in rats by inhibiting ERK and NF-κB signaling pathways. J Endocrinol 2018; 238: 47–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Yue Y, Meng K, Pu Y, et al. Transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) mediates cardiac fibrosis and induces diabetic cardiomyopathy. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2017; 133: 124–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Lebeche D, Davidoff AJ, Hajjar RJ. Interplay between impaired calcium regulation and insulin signaling abnormalities in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med 2008; 5: 715–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. Widyantoro B, Emoto N, Nakayama K, et al. Endothelial cell-derived endothelin-1 promotes cardiac fibrosis in diabetic hearts through stimulation of endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Circulation 2010; 121: 2407–2418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Verma S, Arikawa E, McNeill JH. Long-term endothelin receptor blockade improves cardiovascular function in diabetes. Am J Hypertens 2001; 14: 679–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. da Silva JS, Gonçalves RGJ, Vasques JF, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell therapy in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Cells 2022; 11: 1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135. Nasser MI, Qi X, Zhu S, et al. Current situation and future of stem cells in cardiovascular medicine. Biomed Pharmacother 2020; 132: 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136. Rheault-Henry M, White I, Grover D, et al. Stem cell therapy for heart failure: medical breakthrough, or dead end? World J Stem Cells 2021; 13: 236–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137. Bilgimol JC, Ragupathi S, Vengadassalapathy L, et al. Stem cells: an eventual treatment option for heart diseases. World J Stem Cells 2015; 7: 1118–1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138. Rajesh M, Mukhopadhyay P, Bátkai S, et al. Cannabidiol attenuates cardiac dysfunction, oxidative stress, fibrosis, and inflammatory and cell death signaling pathways in diabetic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010; 56: 2115–2125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139. Westermann D, Van Linthout S, Dhayat S, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha antagonism protects from myocardial inflammation and fibrosis in experimental diabetic cardiomyopathy. Basic Res Cardiol 2007; 102: 500–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140. Samuel CS, Hewitson TD, Zhang Y, et al. Relaxin ameliorates fibrosis in experimental diabetic cardiomyopathy. Endocrinology 2008; 149: 3286–3293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141. Wang L, Li J, Li D. Losartan reduces myocardial interstitial fibrosis in diabetic cardiomyopathy rats by inhibiting JAK/STAT signaling pathway. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 2015; 8: 466–473. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142. Doehner W, Frenneaux M, Anker SD, et al. Metabolic impairment in heart failure: the myocardial and systemic perspective. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014; 64: 1388–1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143. Bostick B, Habibi J, Ma L, et al. Dipeptidyl peptidase inhibition prevents diastolic dysfunction and reduces myocardial fibrosis in a mouse model of Western diet induced obesity. Metabolism 2014; 63: 1000–1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144. Huynh K, Bernardo BC, McMullen JR, et al. Diabetic cardiomyopathy: mechanisms and new treatment strategies targeting antioxidant signaling pathways. Pharmacol Ther 2014; 142: 375–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145. Huynh K, Kiriazis H, Du XJ, et al. Coenzyme Q10 attenuates diastolic dysfunction, cardiomyocyte hypertrophy and cardiac fibrosis in the db/db mouse model of type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia 2012; 55: 1544–1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146. Zou R, Nie C, Pan S, et al. Co-administration of hydrogen and metformin exerts cardioprotective effects by inhibiting pyroptosis and fibrosis in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Free Radic Biol Med 2022; 183: 35–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147. Chen Y, Hua Y, Li X, et al. Distinct types of cell death and the implication in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Front Pharmacol 2020; 11: 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148. Xu J, Zhou Q, Xu W, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and diabetic cardiomyopathy. Exp Diabetes Res 2012; 2012: 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149. Wu A, Hu P, Lin J, et al. Activating cannabinoid receptor 2 protects against diabetic cardiomyopathy through autophagy induction. Front Pharmacol 2018; 9: 1292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150. Qin WD, Liu GL, Wang J, et al. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 inhibition protects cardiomyocytes from inflammation and apoptosis in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Oncotarget 2016; 7: 35618–35631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151. Kajstura J, Fiordaliso F, Andreoli AM, et al. IGF-1 overexpression inhibits the development of diabetic cardiomyopathy and angiotensin II-mediated oxidative stress. Diabetes 2001; 50: 1414–1424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152. Ronnebaum SM, Patterson C. The FoxO family in cardiac function and dysfunction. Annu Rev Physiol 2010; 72: 81–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153. Ferdous A, Battiprolu PK, Ni YG, et al. FoxO, autophagy, and cardiac remodeling. J Cardiovasc Transl Res 2010; 3: 355–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]