Abstract

The Social Readjustment Rating Scale, originally devised in 1967 by Holmes and Rahe, measures the impact of life events stress. At the time, the SRRS advanced its field of research by standardising the impact of stress with a set of independently derived weights called ‘life change units’ (LCUs) for 43 life events found to predict illness onset. The scale has been criticised for being outdated, e.g. “Mortgage over $10,000” and biased, e.g. “Wife begin or stop work”. The aim of this cross-sectional survey study is to update and improve the SRRS whilst allowing backwards compatibility. We successfully updated the SRRS norms/LCUs using the ratings of 540 predominantly UK adults aged 18 to 84. Moreover, we also updated wording of 12 SRRS items and evaluated the impact of demographics, personal experience and loneliness. Using non-parametric frequentist and Bayesian statistics we found that the updated weights were higher but broadly consistent with those of the original study. Furthermore, changes to item wording did not affect raters’ evaluations relative to the original thereby ensuring cross-comparability with the original SRRS. The raters were not unduly influenced by their personal experiences of events nor loneliness. The target sample was UK rather than US-based and was proportionately representative regarding age, sex and ethnicity. Moreover, the age range was broader than the original SRRS. In addition, we modernised item wording, added one optional extra item to the end of the scale to evaluate the readjustment to living alone and identified 3 potential new items proposed by raters. Backwards-compatibility is maintained.

Introduction

The Social Readjustment Rating Scale (SRRS) is a 43-item list of typically experienced life change events commonly used by researchers interested in the impact of stress on health and well-being. It was designed to predict the allostatic load (physiological cost) of the transient social adjustment required when certain life events occur (e.g. marriage, traffic ticket or a loan). It is well-validated and is cited in over 6000, widely varied, scientific publications. For example, it has been used to measure the association between experienced stress and accelerated cognitive ageing [1–4], to measure suicide risk [5] and to evaluate the impact of stress severity on dermatitis [6]. The life events were chosen based on sound empirical evidence [see references 1–12 cited in 7] that is arguably still relevant today [e.g. 8–11]. Numerous updates to the rating norms and modifications to the scale items have been undertaken [10,12–15] to address validity and reliability concerns [e.g. 16–18], yet many researchers still use the original version [e.g. 1,19,20]. A brief history of the SRRS’ development is provided, highlighting reasons for updates and modifications and why these may have failed to persuade researchers to deviate from the original. The proposed updates are then outlined.

The SRRS evolved from the Schedule of Recent Life Events (SRE) [21,22] which captures a broad spectrum of 42 positively and negatively valenced items which require some level of social readjustment, desirable or undesirable, life-changing or minor [23]. Social readjustment refers to the amount and duration of change in one’s usual routine resulting from various life events. Holmes and Rahe’s SRRS comprises the 42 SRE items plus “Christmas”. Holmes and Rahe’s [7] SRRS study revealed marked similarity between sub-groups in terms of the relative significance of the life events (e.g. ‘marriage’ vs. ‘death of a spouse’), indicating some level of universal agreement for certain experiences. The primary aim of the SRRS was to improve the precision with which the impact of life events on illness onset was measured. Each item has an averaged weighting based on the estimated magnitude of change assigned by a convenience sample (n = 394) of males (n = 179) and females (n = 215) who varied in age, class, education, marital status, religion and race. The raters were asked to rate the magnitude of social readjustment required for each life event irrespective of the desirability of the event, using all their experience as well as what they had learned to be the case for others, relative to the social readjustment needed after marriage. Marriage served as the anchor item with an arbitrary value of 500. The weight for each item was then derived by taking the raters’ average weight and dividing by 10. These weights represent ‘Life Change Units’ (LCU). This set of 43 LCUs provides a set of norms that accompany the SRRS. Social Readjustment Rating Scale respondents would indicate which of the 43 items they have experienced over a certain time-frame (e.g. the previous 12 months). All the LCUs corresponding to the respective items are then summed to produce a total LCU value, which may be used to predict physiological and/or psychological impact for each respondent. For example, a respondent might tick “Death of Spouse” which is 100 LCUs, “Troubles with the boss” (30 LCUs) and “Change in residence” (32 LCUs) giving a total of 162 LCUs. Based on empirical work, Rahe [24] found that a score of about 150 suggested that the respondent would remain healthy over the next 12 months while those falling ill over the same period were typically found to score > 300.

The SRRS and SRE were applauded for adding an objective element to the study of life stress and its impact on health. However it was also argued that the scale was inherently flawed because the event items were not equally well-comprehended by less educated samples [e.g. 25] and the accuracy of event-reporting varied [17]. Furthermore, operationalising “illness” and “life events” are difficult [26]. One review indicated life events likely explained no more than 9% of illness variance [27] and Rahe and colleagues themselves stated that precipitating stressful life events were a necessary but not sufficient antecedent to illness onset [28]. Researchers have sought to address some of these and other concerns as described below.

Muhlenkamp and colleagues [12] noted that the SRRS normative sample did not include those over age 70. They published an extension, providing independent ratings from a sample (n = 41) of 65 to 84 year-olds and modified the instructions by assigning a value of 50 for marriage, rather than 500, to provide a more meaningful and familiar anchor for participants. The study found that raters gave higher ratings for most items relative to the original but there was significant agreement regarding the rank ordering of items. However, these weights were never used in conjunction with any subsequent application of the SRRS by researchers including Miller and Rahe’s [13] update, which replicated the characteristics of the original sample. Moreover, no further validation was undertaken of Miller and Rahe’s [13] update, which may have hindered its adoption in future studies. To our knowledge, researchers have sought only to apply the original weights though modifications to the scale items were undertaken on an ad hoc basis. For example Komaroff and colleagues [25] substituted “marital reconciliation with spouse” with “getting back together” as it was more meaningful to the target population.

Hobson and colleagues [14,15] addressed sample and content criticisms of the original SRRS with an extended, modified “Social Readjustment Rating Scale Revised” (SRRS-R). To address the SRRS’ outdated and insufficiently representative sample the SRRS-R was based on norms derived from a larger sample (n = 3122), representative of a cross-section of Americans regarding age, race, gender, ethnicity, income and geographical location. To address criticisms around content, Hobson and colleagues asked a 30-member expert panel to add, amend or remove existing items, which produced a 51-item scale. Other criticisms of the original version were that some items can be interpreted as symptoms/outcomes rather than precipitating events—the ‘contamination hypothesis’, e.g. “Change in sleeping habits”, could indicate that a new job, like shift work (precipitating event), has occurred or it could indicate the symptom/outcome of a stressful experience. Some items lack representativeness in modern, multi-cultural societies (e.g. “Christmas”) and some items’ wording is ambiguous, biased or out-dated (e.g. “Mortgage or loan greater than $10,000”). Using their extended, modified scale, Hobson et al. [14] found that there were significant differences in the way individuals evaluated the stressfulness of different events. On this basis they concluded that using simple unitary weights (occurred vs. not occurred) risked masking these differences and that further work needs to assess the impact of using group-based weights vs. individually derived weights vs. unit weights. Whilst they found that results were statistically significant, effect sizes were very small and ratings were remarkably similar across age, gender and income categories. Their approach validly addressed concerns however the SRRS-R departed notably from the original SRRS negating any opportunity for cross-comparability and, consequently, the SRRS-R has not been incorporated into any subsequent publications to the best of our knowledge.

Around the same time, Scully and colleagues [10] published updated SRRS ratings and addressed 3 content-related criticisms of the SRRS. They assessed the validity of the contamination hypothesis, mentioned previously. In addition, some evidence suggest that undesirable life events would have a stronger stress response than desirable ones [29,30] though not all findings agree [31]. Similarly, uncontrollable life events would have a more potent stress impact than controllable ones (ibid). In phase 1 of Scully and colleagues’ study [10], the original SRRS instructions were administered to a random sample of Florida residents (n = 200) whose ratings were used to derive updated weights (LCUs) for all items. In phase 2, another sample completed the SRRS, reporting experienced events a) within the last 12 months and b) ever. They also completed a modified version of the Symptom Checklist-90 which measures stress-related symptoms. A group of university staff and student raters (n = 7) categorised all the SRRS items as desirable, undesirable or neutral. A separate group of student raters (n = 7) categorised the items as either controllable or uncontrollable. Comparisons of symptom reporting were conducted based on these categorisations. Regression analyses revealed that the SRRS in its original form was predictive of stress symptoms. In addition, consistently more variance was explained when regression models included all items than when only respective undesirable/uncontrollable items were included. Thus, including only negative items was found to limit the utility of the SRRS. They also found that symptoms associated with events reported over the last 12 months had greater predictive power, suggesting that the stress impact of life events diminished with passing time. They [10] concluded that “the SRRS is a robust instrument for identifying the potential for stress-related outcomes” (p.875).

Twenty years on from the last attempts to modernise the SRRS, the primary aim of the current study was to update and improve the SRRS without fundamentally changing the scale to allow for cross-comparison of studies, which may have played a role in previous updates not being incorporated into subsequent versions. Six areas of focus were identified: First, the original weightings are 5 decades old and required updating. Second, biases in item wording were removed. Third, the complete and accurate wording from the raters’ version was re-instated. As Holmes and David [32] pointed out: “We regret the decision to save space on the Social Readjustment Rating Scale, because the complete wording is the accurate and more helpful form.” (p.30). The SRRS ‘rating’ questionnaire comprised detailed statements, along with examples in some cases. The actual scale’s wording is much simplified. For example:

Raters assessed: “Major change in usual type and/or amount of recreation”. The final SRRS used to evaluate illness onset was simplified to: “Change in recreation”.

Raters assessed: “Minor violations of the law e.g. traffic tickets, jay walking, disturbing the peace”. The final version was simplified to: “Minor violations of the law”.

Thus, the final version leaves the reader to make assumptions about what ‘counts’ and what does not, resulting in increased inter-individual differences in responding. This portion of inter-individual variability was reduced by reinstating the ‘rater’ version of items.

Fourth, information was collected regarding the potential for systematic bias that may have affected the magnitude of weight that raters assigned to each item. Raters were asked to indicate the extent to which their rating was based on their own personal experiences of events. They were also asked how lonely they were and how frequently they felt lonely. Loneliness was chosen for two reasons, firstly as part of the evaluation of a new item, “Single person, living alone”, that was added to the end of the scale and secondly, as a proxy for depression which is associated with loneliness and stress [33–36]. Thus, loneliness allowed the evaluation of whether ratings varied based on emotional state at the time of rating.

Fifth, the rater sample was made more representative, proportionately reflecting the demographics within the UK regarding age, gender and ethnicity.

Sixth, the need for new items was considered. A rating was added to the norms set for being single and living alone, with its inclusion as optional at the end of the SRRS. In addition, an opportunity was provided for raters to add an item and its weight, which they believed could improve future work regarding what people find difficult to adjust to at the current time.

In this cross-sectional survey study, an assessment was made of the extent to which the sample’s ratings deviated from those of the original, replicating earlier similar analyses. Previous work indicates that this is likely. For example, Miller and Rahe [13] in their update found ratings differed when comparing males and females and married with unmarried individuals. Women’s ratings were, on average, 17% higher than those of men. Muhlenkamp et al. [12] measured differences between their elderly sample and the original raters with items categorised into ‘family’, ‘personal’, ‘work’ and ‘finance’. A replication of this analysis was undertaken. The extent to which the rank order of items from the updated SRRS agreed with that of the original was also evaluated.

Materials and method

Study design

A survey method was used comprising a series of questionnaires administered via Qualtrics in a single, online-only session. The present study broadly replicates that of Holmes and Rahe [7] who recruited a convenience sample of adults aged ≥ 18 years to rate a list of 42 life events, using a proportional scaling method.

Participants

Six hundred and thirty adults aged 18 to 85 accepted the invitation to participate. The sample selection criteria were based on the UK’s current age distribution and gender breakdown and England and Wales’ ethnicity breakdown published by the ONS [37]. Based on ONS estimates for England and Wales, 84.8% of the population is white. Roughly that proportion of Caucasians was recruited with the remaining proportion comprising non-Caucasian ethnic groups. Regarding sex, a 50/50 split was targeted, reflecting a similar split within the UK population. Ethnic and sex breakdowns were nested within age bands proportioned as per ONS statistics.

Participants were recruited via social media, word-of-mouth, SONA (local university student recruiting platform) and Prolific, an online participant recruitment platform. Participants had to be ≥ 18 years to be included in this study. Within the Prolific platform participants currently located in the UK were selected and anyone who had taken part in any of our previous studies were excluded. No other exclusion criteria were applied. Participants were recruited and data collected from February 2021 to May 2021. Respondents were anonymous; no personally identifiable information was collected. Thus, participants could not be identified during or after data collection. Participants volunteered either without payment, received a small payment or course credits. The study was approved by the University of Essex Faculty of Science and Engineering Ethics Committee (ETH2021-0829). All participants gave written informed consent using an online form, which had to be read and agreed to before they could gain access to the study.

Measures

Social Readjustment Rating Questionnaire (SRRQ)

The updated SRRQ with instructions administered to the rater sample is provided in Appendix 1 (S1 Appendix). For comparison, the original SRRQ instructions are provided in Appendix 2 (S2 Appendix). To reduce potential variations in interpretation, the SRRQ was administered with modified instructions based on those of Muhlenkamp et al. [12] who changed the weight for marriage from 500 to 50 and simplified the instructions themselves. Using marriage (50) as the anchor point, participants were instructed to rate each item from 0 to 100. Some wording was simplified but kept as close to the original as possible, asking participants to draw on their experience and those of others when giving their ratings, as in the original version. Note that in the original SRRQ participants rated 42 items (relative to marriage). The updated SRRQ includes a 43rd item to be rated: ‘Single person, living alone’. The outcome variables for the SRRQ were the mean weights assigned to each of 43 items (range: 0–100). The mean ratings were derived by averaging the ratings given across participants for each respective item.

Social Readjustment Rating Scale 2022 updated

The updated SRRS, used in conjunction with the SRRQ ratings, is provided in Appendix 3 (S3 Appendix). In accordance with the SRRQ, the updated SRRS also contains the new item at the end of the scale, ‘Single person, living alone’. Consequently, the total number of life change units for a given participant is based on 44 items rather than the original 43. Participants were asked to respond ‘yes’ or ‘no’ with the instruction: “Please indicate which of the following events have occurred in your whole life”. The order of items were randomised and then presented in the same order across participants. Some subtle updates or clarifications to wording were applied e.g. ‘spouse’ became ‘spouse/life partner’. Due to inflation the monetary value used for loans was removed, as recommended by Holmes and David [32]. The outcome variable was the binary value for each of the items multiplied by the corresponding item ‘weight’ (life change units). The products were then summed to provide a total life change units score which represents one’s life change intensity [38]. A higher value indicates greater intensity (i.e. a greater level of adaptation to change was needed).

Invitation to add own item

In this single-item questionnaire respondents were asked: “If you could add one more item to the list, what would it be?”. Participants used the free text box to provide a response or they could leave it blank and continue. In the follow-up question, participants were asked to provide a rating for this item relative to marriage. Valid responses therefore required 2 components: a life event (given in their own words) and a corresponding rating.

Experiential basis for SRRS ratings

An instruction was given to measure the extent to which the participants’ ratings were based on their own experience: “At the start of this survey you were asked to rate a range of life events by comparing them to marriage. To what extent was your chosen rating based on your own personal experience? Please slide the scale to indicate as best you can how much your rating was based on your own experience from ’not at all based on my own experience’ (0) to ’completely based on my own experience’ (100).” Appendix 4 (S4 Appendix) provides a copy of this questionnaire. The outcome variable was the value given for each item (range: 0 to 100).

Loneliness questionnaire

The ONS recommends the following 4 questions to measure loneliness: “How often do you feel that you lack companionship?”, “How often do you feel left out?” and “How often do you feel isolated from others?” with response options of ‘hardly ever or never = 1’, ‘some of the time = 2’ and ‘often = 3’. Scores for these 3 items are summed (range: 3 to 9). A higher score indicates a greater degree of loneliness. The 4th question asked: “How often do you feel lonely?” with 6 response options ranging from ‘often/always’ = 1 to ‘never’ = 5 and ‘prefer not to say’ = 6 [37]. A lower score indicates a greater level of loneliness. The first 3 questions were taken from the University of California, Los Angeles loneliness scale (UCLA v3) [39] which was adapted to a 3-item scale: R-UCLA [40] as used in English Longitudinal Study of Ageing [33]. The UCLA scale has good reliability (coefficient α range: 0.89 to 0.94) and test re-test reliability (r = 0.73). The scale’s reliability and validity was tested on students, teachers, nurses and elderly participants (> 65 years). The R-UCLA has an alpha coefficient of 0.72 with good internal consistency [40]. The final question forms part of the Community Life Survey [41]. Appendix 5 (S5 Appendix) provides a copy of these survey items. Thus, loneliness was measured with two outcome measures: loneliness level as a summed value (range: 3 to 9); loneliness frequency as a single-item value (range: 1 to 5).

Procedure

Participants read the information sheet, accepted the invitation to take part, gave online informed consent by completing a check-list then provided biographical details, namely age, ethnicity, gender, religion, relationship status and employment status (see Results). They were presented with the following in sequential order: the updated SRRQ (rating questionnaire), updated SRRS, new item with corresponding rating, personal experience questionnaire, 4-item loneliness questionnaire.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics are provided for all items. Data were analysed using parametric and/or non-parametric analyses alongside equivalent Bayesian comparisons, depending on whether distributions were normal or skewed. Where any disparity existed between frequentist and Bayesian results, conclusions were based on the Bayes factors (BF), which is not subject to the stopping rule as with the frequentist method. Bayesian analyses were conducted in JASP 0.16.2.0 [42]. Sensitivity analyses for BFs for between-groups comparisons were also conducted to ensure that expected effect sizes were robust.

Numerous previous SRRS studies used geometric means. However, the original SRRS weights were derived using arithmetic weights therefore these were used (see the Results section). For frequentist analyses, alpha levels at < .05 were applied to control for type 1 error. To be comparable to Miller and Rahe (1997), 99% confidence intervals were used.

Gpower 3.1.9.7 [43] indicated that for correlational analyses a sample size of 319 would be required to achieve a power of .80 assuming a small effect size (0.2); for chi square analyses with 1 degree of freedom it was 197. However, an independent samples t-test comparison would require a sample size of 788 and a Mann-Whitney U test would require 824 participants. Due to budget and time constraints, we set the N value at the top end of these constraints. For the Bayesian analyses sensitivity analyses were also performed to evaluate the robustness of BFs. In JASP, the default prior effect size is modelled on a Cauchy distribution scaled to which captures small effects efficiently but has fatter tales than the normal distribution to also capture larger effects. JASP performs sensitivity analyses automatically for parametric tests (i.e. independent t-tests) by varying the scale. Thus, is substituted with a wide (Chaucy prior scale = 1.00) and then an ultra-wide (Chaucy prior scale = ) scale. Bayes factors are robust when they remain stable under these varied conditions. When non-parametric between-groups tests are performed, a similar approach will be taken by manually performing these additional BF calculations using the different scaling parameters. The latter mitigates the limitation posed by the smaller-than-needed sample size for between-groups comparisons.

The open-ended item (‘Invitation to add own item’ outlined earlier) was analysed by a simple frequency method where the number of times a particular event was given was counted as ‘1’. Only events with an accompanying rating were counted.

Results

Six hundred and thirty respondents were recruited and consented to take part in the study. Ninety of 630 respondents logged off from the study part-way and their data could not be used. Of the remaining 540 respondents, all completed the study in full apart from 5 who completed most of the study (≥ 90%). As part of the informed consent, all participants had agreed that any data collected up to the point of withdrawal may be used. These 5 respondents’ data were therefore retained. None provided data for the loneliness questionnaire, which was the last item of the study. Four of the 5 respondents rated the SRRQ and gave responses to the SRRS but logged off without completing the remaining items (personal experience, selecting own item, loneliness). Two further participants did not answer the question regarding loneliness frequency. Thus for loneliness frequency, 7 respondents’ data are missing. Two participants identified as ‘gender fluid’. For clarity, participants were therefore grouped by biological sex (male vs. female) and the gender-fluid participants’ data were excluded from all gender/sex-based analyses. Analyses were conducted with all available data using list-wise or pair-wise deletion, as appropriate. Sample sizes are given for each table.

Descriptive statistics for demographic details are given in Table 1. There were 453 Prolific participants (84%), SONA (8%) and social media/word-of-mouth (8%). Eighty-seven percent of the sample were British, 4% were EU nationals, 2% were USA nationals and 7% were from other countries. Most (95%) reported English as their first language.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics for biodemographic details of the total sample.

| mean (min-max) | median (IQR) | n* (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | < 30 years | 23.08 (18–29) | 22 (20–27) | 116 (21.5) |

| 30 to 60 years | 45.18 (30–60) | 45 (37–53) | 291 (53.9) | |

| > 60 years | 69.81 (61–84) | 70 (65–75) | 133 (24.6) | |

| Gender | female | 308 (57) | ||

| male | 230 (42.6) | |||

| gender-fluid | 2 (0.4) | |||

| Education | years | 15.31 (12–21) | 15 (14–17) | 540 (100) |

| Relationship status | married | 236 (43.7) | ||

| long-term relationship | 107 (19.8) | |||

| in a relationship | 30 (5.6) | |||

| separated | 5 (0.9) | |||

| divorced | 21 (3.9) | |||

| widowed | 11 (2) | |||

| life partner died | 5 (0.9) | |||

| single | 125 (23.2) | |||

| Ethnicity | white | 455 (84.3) | ||

| mixed race (all) | 23 (4.3) | |||

| Asian (southern/southeastern Asia) | 24 (4.4) | |||

| Chinese (east Asian) | 7 (1.3) | |||

| black (any region) | 31 (5.7) | |||

| Religion | no religion | 266 (49.3) | ||

| Christian | 234 (43.3) | |||

| Buddhist | 4 (0.7) | |||

| Hindu | 5 (0.9) | |||

| Jewish | 6 (1.1) | |||

| Muslim | 17 (3.2) | |||

| Sikh | 5 (0.9) | |||

| any other religion | 3 (0.6) | |||

| Employment status | full-time or part-time employed | 348 (64.4) | ||

| currently unemployed, looking for work | 14 (2.6) | |||

| long-term sick or disabled | 11 (2) | |||

| looking after home or family | 28 (5.2) | |||

| retired | 97 (18) | |||

| have never worked | 2 (0.4) | |||

| student (p/t or f/t) and currently unemployed | 39 (7.2) | |||

| other | 1 (0.2) |

*N = 540.

Wording was adjusted/modernised on 12 items of the rating questionnaire, as shown in Table 2. To assess whether this may have caused those weights to change by more than the unchanged items a Mann-Whitney U test was conducted on the difference scores (new minus original weight) by wording-changed vs. wording-unchanged items. The difference was not statistically significant (p > .685) (Mdnchanged 10.2 vs. Mdnunchanged 8.8) though the equivalent BF of 0.35 was within the anecdotal range, approaching the null, suggesting that participants’ ratings were unlikely to vary with the wording changes.

Table 2. Changed items.

| Original item wording | New item wording | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Death of spouse | Death of a spouse or life partner |

| 2. | Minor violations of the law (e.g. traffic ticket, jay walking, disturbing the peace) | Minor violations of the law (e.g. traffic ticket, disturbing the peace) |

| 3. | Pregnancy | Pregnancy (either yourself or being the father) |

| 4. | Gaining a new family member (e.g. through birth, adoption, oldster moving in, etc.) | Gaining a new family member (e.g. through birth, adoption, grandparent moving in, etc.) |

| 5. | Marital separation from mate | Marital separation |

| 6. | Major change in church activities (e.g. a lot more or a lot less than usual) | Major change in religious activities (e.g. a lot more or a lot less than usual) |

| 7. | Marital reconciliation with mate | Marital reconciliation |

| 8. | Being fired from work | Losing your job (redundancy, dismissal, etc.) |

| 9. | Major change in the number of arguments with spouse (e.g. either a lot more or a lot less than usual regarding child-rearing, personal habits, etc.) | Major change in the number of arguments with spouse or life partner (e.g. either a lot more or a lot less than usual regarding child-rearing, personal habits, etc.) |

| 10. | Spouse begins or stops working outside the home | Spouse or life partner begins or stops working |

| 11. | Taking on a mortgage greater than $10,000 (e.g. purchasing a home, business, etc.) | Taking on a mortgage or loan for a major purchase (e.g. purchasing a home, business, etc.) |

| 12. | Taking on a mortgage or loan less than $10,000 (e.g. purchasing a car or furniture, paying for college fees, etc.) | Taking on a loan for a lesser purchase (e.g. purchasing a car or furniture, paying for college fees, etc.) |

SRRS ratings then and now: A comparison with Holmes & Rahe (1967)

The original scale had a score-range of 0 to 1466, while the newly weighted version’s range extended to 1871, increasing the total by 405 life change units (LCUs). Of the original 42 event items rated, 39 increased and 4 decreased. Of the items that increased, 3 items increased by ≥ 25 LCUs relative to the original scale: ‘Foreclosure/repossession on mortgage or loan’ (62new vs. 30original), ‘Death of a close friend’ (64new vs. 37original) and ‘Pregnancy’ (65new vs. 40original). When including the new 43rd rater item, ‘Single person, living alone’, the range increases to 1909 (1871+38). A Mann-Whitney U test found that total LCUs were, on average, higher in the current (Mdn 40.1, n = 43) relative to the original scale (Mdn 29, n = 43) (z = -2.807, p = .005, r = .3). The Bayesian Mann-Whitney U test supported this finding with substantial evidence (BF = 6.22). Bayesian sensitivity analyses are provided in Appendix 6 (S6 Appendix) and indicate that applying different Bayesian priors did not affect the outcome, therefore the reported BFs are reliable. A Kendall’s tau correlation coefficient was conducted to evaluate the level of agreement between the two scales. This revealed that the original weights were strongly, positively associated with the new weights (r = .751, p < .001). The corresponding Bayesian Kendall’s tau provided decisive evidence for this finding (BF > 100), suggesting that the respondents in the new scale and the original rating sample were comparable in the hierarchy of change for their evaluations. Table 3 presents the descriptive statistics and rank order of the SRRS items for the original and new scale weights. The table provides the arithmetic means with their standard errors and 99% confidence intervals, plus the geometric means and median values. The events are ordered by the rank of absolute change in number of LCUs, from highest to lowest (1 to 43) to provide a visual comparison of change between original and new weights. Regarding how consistent participants’ ratings were for each item, it was observed that the range of ratings spanned the full range of 0 to 100 on most items (38/43). The magnitude of interquartile ranges (IQR) and 99% bias-corrected and accelerated (BCa) confidence intervals for each of the 43 items were therefore inspected to better ascertain consensus of ratings. Table 3 shows that the largest IQR magnitude was 40, which was for ‘Outstanding personal achievement’ and ‘Retirement from work’. Next largest were ‘Gaining a new family member’ (39), ‘Death of a close family member’ (35), ‘Son or daughter leaving home’ (35), ‘Losing your job’ (35), ‘Taking on a mortgage or loan for a major purchase’ (35), ‘Major business readjustment’ (35) and ‘Single person, living alone’ (35). The smallest IQR was for ‘Major change in social activities’ (20). Table 3 shows that the largest BCa confidence interval was for ‘Detention in jail or other institution’ (73.79–79.66) and the smallest was for ‘Revision of personal habits’ (20.95–24.85). Of the largest BCa confidence intervals, 3 coincided with some of the largest IQR items: ‘gaining a new family member’ (49.05–54.65), ‘Retirement from work’ (46.73–52.45) and ‘Single person, living alone’ (35.41–41.16). These results suggest that for 79% of items (34/43) participants were consistent in their ratings across items but for the remaining 21% (9/43) respondents were relatively less consistent.

Table 3. Present study vs. original weights and rank order of SRRS events*.

| Holmes & Rahe | Present Study | Difference Score | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Event | original rank | weight | present rank | Mean (SE)a | 99% CIb | Geometric Meanc | Median (IQR) | present—original weight | rank: absolute changed |

| Foreclosure/repossession on mortgage or loan | 21 | 30 | 9 | 62.39 (1.07) | 59.65, 65.09 | 32.71 | 40 (25–60) | 32.4 | 1 |

| Death of a close friend | 17 | 37 | 8 | 64.05 (1.12) | 61.08, 66.8 | 44.90 | 50 (40–70) | 27.1 | 2 |

| Pregnancy | 12 | 40 | 6 | 64.66 (1.06) | 62.03, 67.27 | 47.63 | 60 (40–70) | 24.7 | 3 |

| Change in residence | 32 | 20 | 19 | 42.69 (0.95) | 40.33, 44.99 | 34.54 | 40 (30–59.8) | 22.7 | 4 |

| Major change in work hours or conditions | 31 | 20 | 27 | 37.09 (0.84) | 34.76, 39.32 | 20.44 | 25 (10–40) | 17.1 | 5 |

| Major change in sleeping habits | 38 | 16 | 30 | 31.92 (0.84) | 29.83, 34.3 | 24.85 | 30 (20–40) | 15.9 | 6 |

| Changing to a new school | 33 | 20 | 28 | 34.6 (0.93) | 32.29, 36.95 | 29.50 | 35 (20–50) | 14.6 | 7 |

| Major change in living conditions | 28 | 25 | 24 | 39.36 (0.9) | 37.01, 41.75 | 23.76 | 30 (20–50) | 14.4 | 8 |

| Spouse/life partner begins or stops working | 26 | 26 | 22 | 40.06 (0.9) | 37.72, 42.36 | 21.22 | 30 (10–50) | 14.1 | 9 |

| Major change in financial state | 16 | 38 | 12 | 52.02 (0.94) | 49.68, 54.68 | 35.47 | 50 (30–65) | 14.0 | 10 |

| Losing your job | 8 | 47 | 10 | 60.97 (1.03) | 58.2, 63.5 | 24.33 | 30 (20–50) | 14.0 | 11 |

| Detention in jail or other institution | 4 | 63 | 2 | 76.88 (1.14) | 73.79, 79.66 | 61.65 | 80 (70–99) | 13.9 | 12 |

| Death of a spouse or life partner | 1 | 100 | 1 | 86.83 (0.98) | 84.16, 89.21 | 73.78 | 95 (80–100) | -13.2 | 13 |

| Death of a close family member | 5 | 63 | 3 | 75.84 (1.02) | 73.13, 78.46 | 67.57 | 80 (60.5–95) | 12.8 | 14 |

| Gaining a new family member | 14 | 39 | 13 | 51.81 (1.11) | 49.05, 54.65 | 29.09 | 40 (20–50) | 12.8 | 15 |

| Son or daughter leaving home | 23 | 29 | 21 | 41.66 (0.99) | 39.2, 44.19 | 21.75 | 30 (15–40) | 12.7 | 16 |

| Major change in eating habits | 40 | 15 | 35 | 27.39 (0.77) | 25.2, 29.47 | 15.72 | 20 (10–30) | 12.4 | 17 |

| Major change in the health or behaviour of a family member | 11 | 44 | 11 | 55.73 (0.98) | 53.06, 58.24 | 38.01 | 50 (30–70) | 11.7 | 18 |

| Major personal injury or illness | 6 | 53 | 7 | 64.36 (0.98) | 61.9, 66.91 | 55.98 | 70 (50–80) | 11.4 | 19 |

| Taking on a mortgage or loan for a major purchase | 20 | 31 | 20 | 42.22 (0.99) | 39.78, 44.79 | 34.98 | 45 (30–60) | 11.2 | 20 |

| Minor violations of the law | 43 | 11 | 40 | 22.14 (0.76) | 20.12, 24.19 | 14.99 | 20 (10–30) | 11.1 | 21 |

| Major change in usual type and/or amount of recreation | 34 | 19 | 34 | 29.08 (0.78) | 27.01, 31.04 | 11.43 | 15 (5–30) | 10.1 | 22 |

| Major change in the number of arguments with spouse-life partner | 19 | 35 | 18 | 44.21 (0.92) | 41.75, 46.56 | 31.10 | 40 (25.5–50) | 9.2 | 23 |

| Major change in responsibilities at work | 22 | 29 | 26 | 37.8 (0.83) | 35.54, 39.94 | 50.24 | 70 (50–80) | 8.8 | 24 |

| Taking on a loan for a lesser purchase | 37 | 17 | 36 | 25.12 (0.84) | 22.97, 27.6 | 17.36 | 20 (10–35) | 8.1 | 25 |

| Beginning or ceasing formal schooling | 27 | 26 | 29 | 33.88 (0.91) | 31.57, 36.14 | 31.07 | 40 (25–55) | 7.9 | 26 |

| Major change in number of family get-togethers | 39 | 15 | 38 | 22.88 (0.76) | 20.9, 24.92 | 20.74 | 25 (10–40) | 7.9 | 27 |

| Christmas | 42 | 12 | 43 | 19.78 (0.84) | 17.79, 21.93 | 11.80 | 10 (5–30) | 7.8 | 28 |

| Major business readjustment | 15 | 39 | 16 | 46.73 (1.06) | 43.96, 49.49 | 40.18 | 50 (30.8–70) | 7.7 | 29 |

| Vacation | 41 | 13 | 42 | 20.09 (0.81) | 18.03, 22.25 | 12.64 | 10 (6–30) | 7.1 | 30 |

| Major change in social activities | 36 | 18 | 37 | 24.39 (0.8) | 22.31, 26.45 | 17.35 | 20 (10–30) | 6.4 | 31 |

| Troubles with the boss | 30 | 23 | 33 | 29.15 (0.9) | 26.72, 31.74 | 15.66 | 20 (10–30) | 6.2 | 32 |

| Divorce | 2 | 73 | 4 | 67.86 (1.03) | 65.2, 70.41 | 56.03 | 70 (52.8–85) | -5.1 | 33 |

| Retirement from work | 10 | 45 | 15 | 49.64 (1.08) | 46.73, 52.45 | 35.58 | 50 (30–60) | 4.6 | 34 |

| Changing to a different line of work | 18 | 36 | 23 | 39.48 (0.85) | 37.3, 41.68 | 52.64 | 70 (45.8–80) | 3.5 | 35 |

| Outstanding personal achievement | 25 | 28 | 32 | 30.94 (0.96) | 28.49, 33.55 | 30.56 | 38.5 (21.3–50) | 2.9 | 36 |

| In-law troubles | 24 | 29 | 31 | 30.94 (0.91) | 28.62, 33.26 | 31.31 | 40 (25–60) | 1.9 | 37 |

| Marital separation | 3 | 65 | 5 | 66.9 (1.01) | 64.28, 69.33 | 55.98 | 70 (50–80) | 1.9 | 38 |

| Marital reconciliation | 9 | 45 | 17 | 46.24 (0.97) | 43.77, 48.59 | 51.32 | 65 (45–80) | 1.2 | 39 |

| Revision of personal habits | 29 | 24 | 39 | 22.8 (0.77) | 20.95, 24.85 | 30.96 | 40 (25–53.8) | -1.2 | 40 |

| Major change in religious activities | 35 | 19 | 41 | 20.09 (0.8) | 18.01, 22.2 | 22.07 | 30 (15–40) | 1.1 | 41 |

| Sexual difficulties | 13 | 39 | 25 | 38.07 (0.92) | 35.74, 40.61 | 53.44 | 70 (50–80) | -0.9 | 42 |

| Marriage (pre-set weight) | 7 | 50 | 14 | 50.00 | 0.0 | 43 | |||

| Single person, living alone | 38.16 (1.13) | 35.41, 41.16 | 24.14 | 40 (15–50) | |||||

* Table’s values are ordered by absolute change in weights.

a Mean (SE). Standard error obtained via BCa Bootstrap with 1000 samples.

b 99% confidence intervals obtained via BCa Bootstrap with 1000 samples.

c Where participants responded with a zero value, these were replaced with ’1’ to allow this value to be calculated.

d Rank is based on absolute change (difference score: 2022 weight—original weight). Negative signs were ignored in creating the rank order. Rank values in red indicate that the weight upon which it is based was higher in the original version.

The SRRS categorised as ‘family’, ‘personal’, ‘financial’ or ‘work’ life events

Rahe and colleagues delineated their 43 SRRS items in terms of ‘family’, ‘personal’, ‘work’ and ‘financial’ life events [24,38]. A copy is provided in Appendix 7 (S7 Appendix). The correlations between the original and new weightings were evaluated by these categories, using Kendall’s tau. The result revealed strong, positive associations between original and new weights for family (r = 0.818, p < .001), personal (0.638, p < .001) and work (0.905, p = .004) events. However, original and new weights showed no statistically significant association for financial items (p > .4). Bayesian Kendall’s tau correlations confirmed these findings with decisive evidence for family and personal categories (BF > 100) and strong evidence for work-related events (BF = 12.24). For financial items, the Bayesian Kendall’s tau revealed anecdotal evidence (BF = 0.68). Thus, original and new samples co-varied on all categories except financial events for which evidence was inconclusive.

Demographic differences were examined within each of the 4 categories. Table 4 provides medians with interquartile ranges for all variables analysed. Appendix 8 (S8 Appendix) provides medians and interquartile ranges for all broad categories for demographical variables.

Table 4. Descriptive statistics for SRRS events categorised by family, financial, personal and work.

| Mean SRRS weights | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sub-groups | overall weight | family items | financial items | personal items | work items | |

| Age | Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | ||

| < 30 years (n = 116) | 40.3 (30.3–54.3) | 53.6 (44.8–61) | 50 (33.8–55.8) | 35.5 (28.6–45.3) | 42.1 (31.6–54.3) | |

| 30 to 60 years (n = 291) | 39.7 (29.7–57.8) | 54.6 (45.7–64.3) | 45 (35–52.5) | 34.7 (28.9–43.3) | 43.6 (32.1–52.9) | |

| > 60 years (n = 133) | 39.4 (28.7–57.1) | 53.9 (46.1–61.1) | 46.5 (35.6–58.8) | 33.4 (26.4–46.6) | 42.9 (33.2–54.7) | |

| Sex | ||||||

| female (n = 308) | 43.9 (32.4–58.9) | 57.1 (48.9–64.9) | 47.5 (37.5–56.2) | 36.9 (30.6–46.5) | 45.7 (35.7–55.7) | |

| male(n = 230) | 35.4 (25.3–50.8) | 50.4 (42.4–58.8) | 42.5 (30–55) | 32.3 (24.7–40.5) | 40 (29.3–50) | |

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| white (n = 455) | 39.3 (28.7–56.3) | 54.3 (46.4–61.8) | 46.3 (35–55) | 34.2 (27.9–43.7) | 42.9 (32.9–52.9) | |

| non-whitea (n = 85) | 40.7 (32.5–53) | 55.4 (44.8–63.8) | 50 (37.4–59.4) | 37.9 (27.4–47.9) | 45.7 (31.8–55.7) | |

| Religion | ||||||

| no religion (n = 274) | 39 (28.1–55.4) | 55.5 (46.4–64.3) | 47.5 (35–57.5) | 35.7 (27.7–46.6) | 44.3 (33.4–54.4) | |

| religionb (n = 266) | 40.9 (30.1–56) | 53.6 (45.6–60.7) | 45 (35–54.1) | 33.9 (28–41.1) | 42.1 (32.1–52.1) | |

| Relationship status | ||||||

| marriedc (n = 343) | 40.7 (30.6–57.6) | 55 (46.8–64.5) | 46.5 (35–55) | 34.7 (28.4–45.3) | 42.9 (32.9–54.3) | |

| unmarried (n = 197) | 37.7 (29.8–53.2) | 53.6 (44.6–60.7) | 45.8 (34.8–55.6) | 34.7 (27.1–44.2) | 43.6 (32.5–52.9) | |

| Employment status | ||||||

| employed (n = 348) | 39.8 (28.3–55.9) | 54.3 (46.1–63) | 46 (35–55) | 34.7 (28.2–44.5) | 42.9 (32.9–55) | |

| unemployede (n = 192) | 39.2 (30.7–55.4) | 54.3 (45.8–61.1) | 47 (35–57.5) | 34.7 (27.3–44.7) | 43.2 (31.6–52.6) | |

a ’Non-white’ included all ethnicities: mixed race, Asian (southern/southeastern Asia), Chinese (east Asian), black (any region).

b ’Religious’ includes all religions: Christian, Buddhist, Hindu, Jewish, Muslim, Sikh, any other religion.

c ’married’ includes married and long-term partners.

d ’unmarried’ includes those who don’t qualify as ’c’: divorced, in a relationship, life partner died, separated, single, widowed.

e currently unemployed and looking for work, have never worked, long-term sick/disabled, looking after home or family, retired, student (p/t or f/t) and currently unemployed, other.

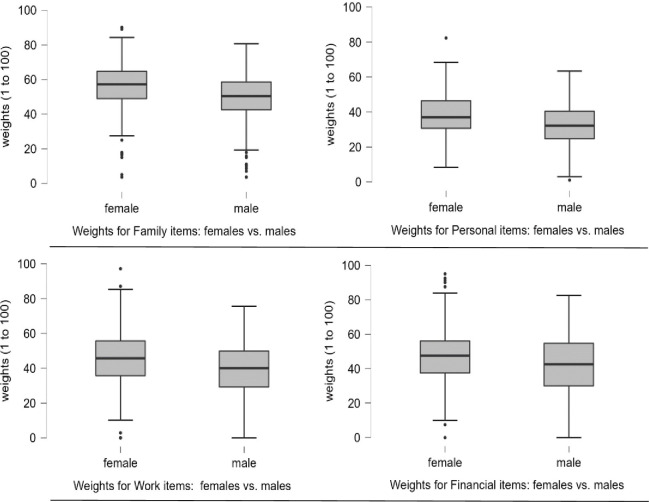

For age, ratings of young, middle-aged and older-aged groups were compared for each of the 4 categories with Kruskal-Wallis tests, which revealed no statistically significant differences between groups (p’s > .2). Bayesian Mann-Whitney U tests were used to compare the respective groups as there is no corresponding Bayesian non-parametric one-way ANOVA equivalent. The outcomes were congruent with the frequentist findings and consistently supported the null (BFs ≤ 0.26). Sensitivity analyses are provided in Appendix 6 (S6 Appendix) and support these BF results. Comparing female and male average ratings, in contrast, revealed a statistically significant difference using Mann-Whitney U tests for family events (Mdn 57.1 vs. 50.4), personal events (Mdn 36.9 vs. 32.3), financial events (Mdn 47.5 vs. 42.5) and work events (Mdn 45.7 vs. 40) (p’s < .001) with females’ ratings being consistently higher than males’, respectively. Bayesian Mann-Whitney U tests revealed strong evidence for financial items (BF = 27.22) and decisive evidence for all other categories (BF > 100). Sensitivity analyses are provided in Appendix 6 (S6 Appendix) and support these BFs. These results are shown in Fig 1. Ethnicity, religion, relationship status and employment variables were collapsed into dichotomised variables to simplify comparison. Details are given in Table 4. Appendix 8 (S8 Appendix) provides comparisons for full variables. For ethnicity, a Mann-Whitney U test of white vs. (combined) non-white sub-sets indicated no statistically significant between-groups differences for any of the 4 categories (p’s > .1). Likewise, the Bayesian analyses revealed evidence for the null for all comparisons (BFs ≤ 0.20). For religion, a Mann-Whitney U test comparing no-religion vs. (combined) religion groups revealed a statistically significant difference for personal events (Z = -2.006, p = .047) with the no-religion group assigning a higher average weight to this category of events than the religion group (Mdn 35.7 vs. 33.9, respectively). However, the Bayesian Mann-Whitney U test revealed anecdotal evidence (BF = 0.59). Comparisons for family, work and financial categories were not statistically significant (p’s > .1) which was confirmed by the Bayesian results which supported the null (BFs ≤ 0.28). For relationship status, a Mann-Whitney U test comparing (combined) married vs. (combined) unmarried groups showed a statistically significant difference for family events (Z = -2.144, p = .032) only with the married group giving higher ratings than the unmarried group (Mdn 55 vs. 53.6, respectively). However, the Bayesian Mann-Whitney U test revealed anecdotal evidence (BF = 1.74). The comparisons for personal, financial and work were not statistically significant (p’s > .3), confirmed by Bayesian evidence for the null (BFs ≤ 0.16). For employment status, a Mann-Whitney U test comparing employed vs. (combined) unemployed groups revealed no statistically significant differences (p’s > .2) for any of the categories. Congruent with this outcome, Bayesian Mann-Whitney U tests revealed evidence for the null for all comparisons (BFs ≤ 0.20). Sensitivity analyses are provided in Appendix 6 (S6 Appendix) for all the above-mentioned Bayesian Mann-Whitney U comparisons and support the reported BFs.

Fig 1. Box plots showing differences between males and females based on event categories.

From top-left to bottom-right the box plots shown are: ‘family’, ‘personal’, ‘work’ and ‘financial’.

SRRS weights: Comparing normative and 70+ sub-samples

Muhlenkamp and colleagues [12] who extended the original SRRS by adding weights to represent those aged ≥ 65 to 84 years compared the original 1967 normative sample’s ratings (<30 years to > 60 years, n = 394) with those from their new, older group (65 to 84 yrs, n = 41). A similar approach was followed here, however the present study’s older group was 70 to 84 years to minimise overlap with previously represented older age groups (e.g. 65 to 69 year-olds). The original study stated that there were 51 raters > 60 years (i.e. no maximum age was reported) while Muhlenkamp and colleagues [12] stated in their report that the original SRRS did not include adults over 70 years. Thus, in the present study, the sample was grouped as those aged 18 to 69 years (‘normative sample’, n = 473) vs. 70+ years (‘70+ sample’, n = 67). Between-groups differences were evaluated overall as well as within the previously mentioned 4 life events categories: ‘family’, ‘personal’, ‘work’ and ‘financial’.

In the overall assessment the normative sample’s summed total LCUs were higher (LCUtotal 1829) than that of the 70+ group (LCUtotal 1759), however a Mann-Whitney U test found no statistically significant difference between the two groups, on average (p > .7). Likewise, the Bayesian equivalent supported the null (BF = 0.24). Sensitivity analyses (S6 Appendix) were congruent with this outcome. Further, the Kendall’s tau indicated that the lists were strongly, positively correlated (r = .884, p < .001). The corresponding Bayesian Kendall’s tau provided decisive evidence for this finding (BF > 100). Of the 42 original items rated, only 12 were higher for the 70+ group. Thus, the normative and older samples co-varied strongly regarding the ratings, though the normative sample’s ratings were consistently higher for most items. To assess whether there were any systematic differences in ratings between the normative group and 70+ group based on the 4 categories, a chi-square was conducted with event category (family, personal, financial, work) and proportion of change (> adjustment required in 70+ participants vs. > adjustment required in normative participants). The association was not statistically significant (p = .648). Likewise, the Bayesian contingency tables test supported the null (BF = 0.17). These findings suggest that there were no significant age-based differences in ratings across the different categories of events.

SRRS weights: Comparing young, middle-aged and older adults

A set of SRRS weights and ranks for each age group were created and are provided in Table 5. Summing the weights by age group, it was found that YAs’ summed weights value or total life change units (LCUtotal) was 1866, for MAs the LCUtotal was 1875 and for OAs it was 1867. A Kruskal-Wallis test revealed no statistically significant differences (p > .997). Bayesian non-parametric Mann-Whitney U comparisons agreed with these findings, showing evidence for the null (BFs = 0.23). Bayes factor sensitivity analyses (S6 Appendix) were comparable. These results indicated comparable overall weights across the life span. In assessing the strength of association across all items between the pairs of age groups (YA vs. MA; MA vs. OA; YA vs. OA), Kendall’s tau correlation coefficients indicated very strong, positive correlations (r’s ≥ .835, p’s < .001). Bayesian Kendall’s tau coefficients agreed with these findings (BFs > 100).

Table 5. SRRS events by young, middle-aged and older adults’ weights and ranks.

| Holmes & Rahe | Present study | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Young adults | Middle-aged adults | Older adults | ||||||||

| Event | original rank | rank | Mean (SE)a | 99% CIb | rank | Mean (SE)a | 99% CIb | rank | Mean (SE)a | 99% CIb |

| Death of a spouse or life partner | 1 | 1 | 85.65 (2.1) | 79.53, 90.65 | 1 | 87.72 (1.24) | 84.24, 90.8 | 1 | 85.92 (2.07) | 80.27, 91.08 |

| Divorce | 2 | 6 | 65.13 (2.15) | 59.34, 70.87 | 4 | 68.28 (1.39) | 64.66, 71.64 | 4 | 69.34 (2.05) | 63.45, 74.43 |

| Marital separation | 3 | 7 | 62.17 (2.15) | 56.95, 67.54 | 5 | 68.09 (1.33) | 64.49, 71.59 | 5 | 68.44 (1.92) | 63.1, 73.18 |

| Detention in jail or other institution | 4 | 3 | 70.65 (2.53) | 63.62, 76.69 | 2 | 79.74 (1.38) | 76.4, 83.08 | 2 | 76.08 (2.4) | 69.22, 81.99 |

| Death of a close family member | 5 | 2 | 75.26 (2.44) | 68, 80.98 | 3 | 76.92 (1.38) | 73.26, 80.32 | 3 | 74 (2.02) | 68.54, 79.04 |

| Major personal injury or illness | 6 | 8 | 59.84 (2.14) | 53.53, 65.63 | 6 | 65.72 (1.31) | 62.46, 68.98 | 7 | 65.33 (1.89) | 60.53, 70.24 |

| Marriage (pre-set weight) | 7 | 14 | 50 | 14 | 50 | 13 | 50 | |||

| Losing your job | 8 | 9 | 59.05 (2.22) | 52.93, 64.54 | 10 | 61.7 (1.37) | 57.99, 65.51 | 9 | 61.06 (2.2) | 55.08, 67.03 |

| Marital reconciliation | 9 | 18 | 44.11 (1.95) | 38.77, 49.37 | 16 | 47.01 (1.36) | 43.26, 50.26 | 17 | 46.41 (1.9) | 41.07, 51.2 |

| Retirement from work | 10 | 13 | 50.16 (2.38) | 44.24, 56.17 | 15 | 49.9 (1.47) | 46.34, 53.55 | 16 | 48.63 (2.18) | 42.8, 53.99 |

| Major change in the health or behaviour of a family member | 11 | 15 | 49.13 (2.08) | 43.87, 54.63 | 11 | 57.75 (1.31) | 54.44, 61.2 | 11 | 57.06 (1.9) | 51.71, 62.19 |

| Pregnancy | 12 | 5 | 66.61 (2.45) | 60.49, 72.75 | 8 | 64.19 (1.36) | 60.74, 67.54 | 8 | 63.97 (1.99) | 58.47, 68.63 |

| Sexual difficulties | 13 | 30 | 34.47 (1.9) | 29.8, 39.8 | 25 | 38.94 (1.28) | 35.54, 42.3 | 24 | 39.29 (1.91) | 33.98, 44.56 |

| Gaining a new family member | 14 | 12 | 52.8 (2.38) | 47.02, 59.34 | 12 | 52.52 (1.55) | 48.36, 56.6 | 15 | 49.41 (2.02) | 44.34, 54.25 |

| Major business readjustment | 15 | 17 | 44.69 (2.27) | 37.94, 50.73 | 17 | 46.19 (1.43) | 42.65, 49.8 | 14 | 49.68 (2.24) | 44.15, 55.21 |

| Major change in financial state | 16 | 11 | 54.3 (2.04) | 49.06, 59.65 | 13 | 51.59 (1.24) | 48.35, 54.94 | 12 | 50.96 (1.95) | 45.2, 56.64 |

| Death of a close friend | 17 | 4 | 69.68 (2.37) | 63.06, 75.74 | 7 | 64.99 (1.54) | 60.83, 68.64 | 10 | 57.09 (2.17) | 51.23, 62.53 |

| Changing to a different line of work | 18 | 22 | 40.88 (2) | 35.67, 45.97 | 23 | 39.66 (1.14) | 36.82, 42.83 | 26 | 37.86 (1.83) | 33.26, 42.16 |

| Major change in the number of arguments with spouse/life partner | 19 | 19 | 42.55 (1.91) | 37.52, 47.67 | 18 | 44.42 (1.27) | 41.01, 47.6 | 19 | 45.22 (2.01) | 39.13, 50.98 |

| Taking on a mortgage or loan for a major purchase | 20 | 16 | 46.09 (2.25) | 40.23, 52.17 | 22 | 40 (1.28) | 37.09, 44.12 | 20 | 43.71 (2) | 38.3, 48.95 |

| Foreclosure/repossession on mortgage or loan | 21 | 10 | 55.22 (2.23) | 49.49, 61.59 | 9 | 63.09 (1.41) | 59.57, 66.72 | 6 | 67.11 (2.27) | 60.81, 72.56 |

| Major change in responsibilities at work | 22 | 26 | 38.16 (1.79) | 33.27, 42.88 | 28 | 37.09 (1.1) | 34.21, 40.3 | 25 | 39.02 (1.73) | 34.25, 43.78 |

| Son or daughter leaving home | 23 | 21 | 40.92 (1.97) | 35.67, 45.87 | 19 | 41.98 (1.38) | 38.62, 45.75 | 22 | 41.61 (1.99) | 36.39, 46.26 |

| In-law troubles | 24 | 34 | 30.3 (1.99) | 25.21, 35.09 | 32 | 30.25 (1.18) | 27.05, 33.34 | 31 | 33.02 (1.85) | 28.48, 38.37 |

| Outstanding personal achievement | 25 | 36 | 29.21 (2.07) | 24.57, 34.16 | 34 | 29.66 (1.23) | 26.45, 33.05 | 28 | 35.26 (1.98) | 30.36, 40.52 |

| Spouse/life partner begins or stops working | 26 | 23 | 40.34 (1.89) | 35.55, 45.12 | 20 | 41.88 (1.25) | 38.85, 45.73 | 27 | 35.84 (1.85) | 31.21, 40.86 |

| Beginning or ceasing formal schooling | 27 | 28 | 36.34 (2) | 30.93, 41.56 | 31 | 33.07 (1.18) | 30.26, 36.41 | 30 | 33.51 (2.02) | 28.31, 39.14 |

| Major change in living conditions | 28 | 24 | 39.28 (2.03) | 34.28, 45.03 | 24 | 39.38 (1.24) | 36.05, 42.25 | 23 | 39.38 (1.87) | 34.36, 44.22 |

| Revision of personal habits | 29 | 38 | 27.25 (1.93) | 22.7, 32.39 | 41 | 21.56 (1) | 19.19, 24.34 | 42 | 21.65 (1.39) | 17.89, 25.55 |

| Troubles with the boss | 30 | 40 | 24.69 (1.84) | 20.51, 29.09 | 33 | 30.03 (1.25) | 26.94, 33.46 | 33 | 31.12 (2.01) | 25.7, 36.14 |

| Major change in work hours or conditions | 31 | 25 | 38.64 (1.8) | 33.95, 43.11 | 26 | 38.41 (1.15) | 35.22, 42.12 | 32 | 32.85 (1.69) | 28.43, 37.43 |

| Change in residence | 32 | 20 | 41.01 (2.04) | 36.02, 46.2 | 21 | 41.75 (1.29) | 38.69, 44.92 | 18 | 46.23 (1.81) | 41.48, 50.53 |

| Changing to a new school | 33 | 27 | 37.5 (2.02) | 32.94, 42.68 | 29 | 33.51 (1.25) | 30.37, 36.51 | 29 | 34.44 (2.12) | 28.5, 40.14 |

| Major change in usual type and/or amount of recreation | 34 | 31 | 33.24 (1.86) | 28.83, 38.04 | 35 | 28.65 (1.02) | 26.2, 31.28 | 35 | 26.38 (1.5) | 22.8, 30.77 |

| Major change in religious activities | 35 | 39 | 26.08 (1.7) | 22.08, 30.2 | 44 | 18.05 (1.02) | 15.55, 20.85 | 44 | 19.33 (1.7) | 14.88, 24.21 |

| Major change in social activities | 36 | 37 | 28.78 (1.9) | 24.2, 33.82 | 38 | 23.3 (1.06) | 20.31, 26.5 | 39 | 22.95 (1.4) | 19.4, 26.91 |

| Taking on a loan for a lesser purchase | 37 | 35 | 29.83 (1.95) | 25.3, 35.2 | 37 | 23.51 (1.1) | 20.85, 26.6 | 36 | 24.55 (1.66) | 20.33, 28.88 |

| Major change in sleeping habits | 38 | 32 | 32.26 (2.13) | 27.13, 37.73 | 30 | 33.25 (1.12) | 30.21, 36.13 | 34 | 28.74 (1.49) | 25.24, 32.57 |

| Major change in number of family get-togethers | 39 | 41 | 24.53 (1.88) | 20.13, 29.1 | 40 | 21.73 (0.94) | 19.44, 24.4 | 38 | 23.97 (1.56) | 20.28, 28.06 |

| Major change in eating habits | 40 | 33 | 30.68 (1.94) | 26.24, 36.11 | 36 | 27.63 (1.06) | 24.81, 30.71 | 37 | 24 (1.36) | 20.63, 28.16 |

| Vacation | 41 | 42 | 21.45 (2.05) | 16.28, 26.5 | 43 | 19.13 (1.07) | 16.33, 22.04 | 43 | 21 (1.51) | 17.29, 25.52 |

| Christmas | 42 | 44 | 16.95 (1.7) | 12.65, 21.35 | 42 | 19.79 (1.09) | 16.76, 22.86 | 41 | 22.23 (1.93) | 17.62, 27.65 |

| Minor violations of the law | 43 | 43 | 19.85 (1.47) | 16.66, 24.09 | 39 | 22.72 (1.04) | 20, 25.45 | 40 | 22.87 (1.64) | 18.4, 27.3 |

| Single person, living alone | 29 | 34.96 (2.59) | 28.55, 41.39 | 27 | 37.84 (1.49) | 33.92, 41.51 | 21 | 41.66 (2.28) | 35.82, 48.26 | |

a SE = Standard Error.

b CI = Confidence Intervals.

SRRS weights: Comparing males and females

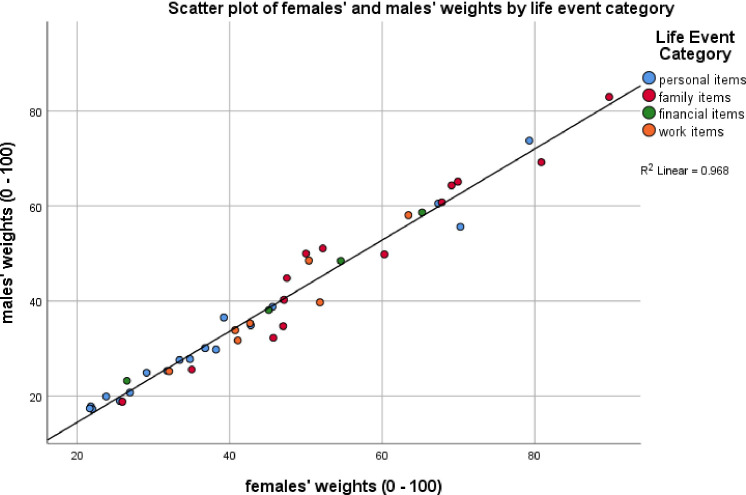

Miller and Rahe (1997) found that females’ ratings were 17% higher on average than that of males. Table 6 provides the descriptive statistics for the present samples’ weights and ranking by sex. Females’ summed weights (LCUtotal 1992) were found to be 14% higher than those for males (LCUtotal 1708). The corresponding Mann-Whitney U test revealed a trend (z = -1.840, p = .066, r = .2), suggesting that the average difference between males’ (Mdn 35.3, n = 43) and females’ (Mdn 45.1, n = 43) LCUtotal was statistically comparable. The corresponding Bayesian test revealed anecdotal evidence for this finding (BF = 1.42). Bayes factor sensitivity analyses (S6 Appendix) were comparable. A Kendall’s tau correlation coefficient indicated a very strong, positive correlation between males’ and females’ ratings (r = .892, p < .001), as indicated by Fig 2. The corresponding Bayesian Kendall’s tau correlation revealed decisive evidence for this finding (BF > 100). These results suggest that whilst females’ ratings were higher than males’ on all items, there was strong covariance between them. The 3 items with the greatest difference in ratings, with males’ ratings being lower in each case, were ‘Death of a close friend’ (-15 LCU), ‘Spouse/life partner begins or stops working’ (-13 LCU) and ‘Son or daughter leaving home’ (-12 LCU). A likewise comparison regarding the 3 items with the smallest difference were ‘Gaining a new family member’ (-1 LCU), ‘Retirement from work’ (-2 LCU) and ‘Marital reconciliation’ (-3 LCU).

Table 6. SRRS events by females’ and males’ weights and ranks.

| Female | Male | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Event | rank | M (SE) | 99% CI | rank | M (SE) | 99% CI |

| Death of a spouse or life partner | 1 | 89.73 (1.03) | 86.48, 92.62 | 1 | 82.96 (1.75) | 78.09, 87.37 |

| Divorce | 5 | 69.91 (1.31) | 66.38, 73.15 | 4 | 65.1 (1.68) | 61.02, 69.41 |

| Marital separation | 6 | 69.09 (1.23) | 65.79, 72.11 | 5 | 64.34 (1.68) | 59.93, 68.35 |

| Detention in jail or other institution | 3 | 79.28 (1.38) | 75.21, 83.25 | 2 | 73.78 (1.77) | 69.04, 78.63 |

| Death of a close family member | 2 | 80.85 (1.22) | 77.52, 84.07 | 3 | 69.23 (1.76) | 64.72, 74.2 |

| Major personal injury or illness | 8 | 67.33 (1.21) | 64.07, 70.62 | 7 | 60.52 (1.57) | 56.38, 64.28 |

| Marriage (arbitrary weight) | 16 | 50 | 15 | 50 | ||

| Losing your job | 10 | 63.43 (1.3) | 60.34, 66.66 | 9 | 58.09 (1.66) | 53.8, 61.99 |

| Marital reconciliation | 17 | 47.5 (1.16) | 44.07, 51.14 | 16 | 44.83 (1.52) | 41.11, 48.59 |

| Retirement from work | 15 | 50.39 (1.37) | 46.91, 54.32 | 14 | 48.51 (1.7) | 44.07, 52.58 |

| Major change in the health or behaviour of a family member | 11 | 60.28 (1.15) | 56.98, 63.32 | 10 | 49.82 (1.64) | 45.73, 53.98 |

| Pregnancy | 7 | 67.81 (1.35) | 64.44, 71.52 | 6 | 60.78 (1.73) | 56.34, 65.43 |

| Sexual difficulties | 27 | 39.24 (1.17) | 35.88, 42.18 | 26 | 36.52 (1.47) | 32.68, 40 |

| Gaining a new family member | 13 | 52.21 (1.44) | 48.95, 55.73 | 12 | 51.09 (1.8) | 45.9, 55.72 |

| Major business readjustment | 14 | 51.84 (1.33) | 48.6, 55.11 | 13 | 39.73 (1.61) | 35.45, 44.14 |

| Major change in financial state | 12 | 54.58 (1.21) | 51.52, 57.64 | 11 | 48.44 (1.49) | 44.56, 52.34 |

| Death of a close friend | 4 | 70.24 (1.36) | 66.8, 73.76 | 10 | 55.62 (1.88) | 51.5, 60.37 |

| Changing to a different line of work | 24 | 42.67 (1.16) | 39.52, 45.87 | 23 | 35.33 (1.26) | 32.05, 38.56 |

| Major change in the number of arguments with spouse-life partner | 18 | 47.12 (1.23) | 43.79, 50.4 | 17 | 40.27 (1.42) | 36.54, 43.59 |

| Taking on a mortgage or loan for a major purchase | 22 | 45.12 (1.25) | 42.06, 48.23 | 21 | 38.09 (1.49) | 33.95, 41.64 |

| Foreclosure/repossession on mortgage or loan | 9 | 65.23 (1.44) | 61.56, 68.54 | 8 | 58.65 (1.75) | 54.29, 63.21 |

| Major change in responsibilities at work | 26 | 40.72 (1.13) | 37.81, 43.77 | 25 | 33.86 (1.23) | 30.51, 37.15 |

| Son or daughter leaving home | 19 | 47.02 (1.27) | 44.07, 50.45 | 18 | 34.71 (1.45) | 30.96, 38.58 |

| In-law troubles | 30 | 35.04 (1.18) | 32.08, 38.33 | 29 | 25.56 (1.27) | 22.25, 28.63 |

| Outstanding personal achievement | 32 | 33.43 (1.35) | 30.1, 36.98 | 31 | 27.58 (1.31) | 23.73, 31.23 |

| Spouse/life partner begins or stops working | 20 | 45.73 (1.17) | 42.81, 48.54 | 19 | 32.25 (1.24) | 29.04, 35.63 |

| Beginning or ceasing formal schooling | 29 | 36.79 (1.2) | 33.98, 40.25 | 28 | 30.07 (1.38) | 26.45, 33.54 |

| Major change in living conditions | 23 | 42.76 (1.2) | 39.5, 46.39 | 22 | 34.89 (1.4) | 31, 38.96 |

| Revision of personal habits | 39 | 25.59 (1.11) | 22.56, 28.84 | 38 | 18.97 (1.03) | 16.52, 21.82 |

| Troubles with the boss | 33 | 32.07 (1.26) | 28.61, 35.55 | 32 | 25.19 (1.3) | 21.83, 28.38 |

| Major change in work hours or conditions | 25 | 41.06 (1.11) | 37.97, 44.21 | 24 | 31.7 (1.23) | 28.6, 34.82 |

| Change in residence | 21 | 45.63 (1.22) | 42.38, 48.8 | 20 | 38.79 (1.5) | 34.66, 42.62 |

| Changing to a new school | 28 | 38.2 (1.29) | 34.82, 41.54 | 27 | 29.76 (1.34) | 26.23, 33.14 |

| Major change in usual type and/or amount of recreation | 34 | 31.81 (1.03) | 29.2, 34.92 | 33 | 25.28 (1.11) | 22.33, 28.14 |

| Major change in religious activities | 42 | 21.8 (1.08) | 19.25, 24.56 | 41 | 17.77 (1.2) | 14.86, 21.02 |

| Major change in social activities | 36 | 26.93 (1.03) | 24.45, 29.45 | 35 | 20.73 (1.12) | 17.94, 23.51 |

| Taking on a loan for a lesser purchase | 37 | 26.53 (1.12) | 23.56, 29.65 | 36 | 23.19 (1.24) | 19.64, 26.52 |

| Major change in sleeping habits | 31 | 34.81 (1.15) | 31.64, 37.69 | 30 | 27.77 (1.22) | 24.9, 31.18 |

| Major change in number of family get-togethers | 38 | 25.93 (1.08) | 23.17, 28.91 | 37 | 18.78 (1) | 16.27, 21.23 |

| Major change in eating habits | 35 | 29.11 (1.03) | 26.46, 31.62 | 34 | 24.89 (1.15) | 22.09, 27.91 |

| Vacation | 41 | 22.01 (1.12) | 19.34, 24.97 | 40 | 17.21 (1.1) | 14.33, 20.1 |

| Christmas | 43 | 21.66 (1.16) | 18.87, 24.53 | 42 | 17.38 (1.18) | 14.5, 20.74 |

| Minor violations of the law | 40 | 23.82 (1.06) | 21.32, 26.44 | 39 | 19.87 (1.14) | 17.18, 22.73 |

| Single person, living alone* | 40.10 (1.55) | 35.91, 44.52 | 35.37 (1.76) | 30.48, 39.73 | ||

*’Single person, living alone’ was not included in the ranking as it was not included in the original rating of the SRRS.

Fig 2. Scatter plot showing the covariance of females’ and males’ weights by items.

Scatter plot shows the covariance of females’ and males’ weights by items with weights (life change units) ranging from 0 to 100, grouped by category: ‘family’, ‘financial’, ‘personal’ and ‘work’.

Impact of personal experience on SRRS ratings

To ascertain whether there was a link between ratings for each life event and personal experience of that item a series of correlations using Kendall’s tau were conducted. Table 7 provides the descriptive statistics for personal experience. Of 42 items, 18 showed a statistically significant correlation (p’s ≤ .042). However, all coefficients were very small (r ≤ .146). The Bayesian Kendall’s tau similarly found evidence ranging from substantial to decisive (BFs ≥ 3.0) for 15 items. Of these, 6 items were supported by ≥ very strong evidence but correlation coefficients remained small with magnitudes ranging from 0.108 to 0.146 as shown in Appendix 9 (S9 Appendix). These results suggest that there may have been some events for which personal experience were weakly, positively associated with event ratings. Overall, however, participants’ personal experiences did not appear to systematically bias their ratings.

Table 7. Descriptive statistics showing the extent to which ratings were based on personal experience.

| Life event | Mean % (SE)* | Median % (IQR) |

|---|---|---|

| Christmas | 83.39 (1.14) | 99 (76–100) |

| Vacation | 81.35 (1.1) | 93 (68–100) |

| Death of a close family member | 73.11 (1.55) | 90.5 (60–100) |

| Change in residence | 72.96 (1.42) | 85 (59–100) |

| Beginning or ceasing formal schooling | 68.05 (1.56) | 80 (45.5–100) |

| Pregnancy | 56.17 (1.95) | 77.5 (0–100) |

| Major change in the health or behaviour of a family member | 65.4 (1.53) | 75 (41–100) |

| Taking on a mortgage or loan for a major purchase | 58.39 (1.81) | 74 (2–100) |

| Gaining a new family member | 58.74 (1.78) | 70.5 (7.5–100) |

| Major change in sleeping habits | 62.54 (1.53) | 70 (29–100) |

| Changing to a new school | 58.56 (1.7) | 70 (13–100) |

| Troubles with the boss | 58.63 (1.63) | 70 (19.5–99) |

| Major change in financial state | 62.59 (1.43) | 70 (39–94.5) |

| Taking on a loan for a lesser purchase | 54.91 (1.8) | 68 (1.5–100) |

| Changing to a different line of work | 56.08 (1.6) | 66 (17–89.5) |

| Major change in number of family get-togethers | 57.12 (1.49) | 63.5 (26–86) |

| Major change in eating habits | 56.3 (1.55) | 63 (20.5–90) |

| Single person, living alone | 51.99 (1.89) | 61.5 (0–100) |

| Major change in responsibilities at work | 53.77 (1.55) | 61 (18–86) |

| Major change in work hours or conditions | 54.15 (1.5) | 61 (21–81) |

| Outstanding personal achievement | 51.31 (1.62) | 56 (13–85) |

| Major change in usual type and/or amount of recreation | 49.05 (1.51) | 55 (12–77) |

| Major personal injury or illness | 49.93 (1.73) | 54.5 (4–95.5) |

| Major change in social activities | 48.51 (1.5) | 53 (13.5–76) |

| Major change in living conditions | 47.19 (1.66) | 51 (1–82) |

| Losing your job | 46.81 (1.81) | 50.5 (0–93) |

| Major change in the number of arguments with spouse/life partner | 43.12 (1.58) | 44 (1–74) |

| Revision of personal habits | 42.1 (1.56) | 41.5 (3–72) |

| Minor violations of the law | 43.8 (1.8) | 35 (0–89) |

| Spouse/life partner begins or stops working | 42.17 (1.81) | 26.5 (0–90) |

| Death of a close friend | 40.33 (1.84) | 17 (0–90) |

| Sexual difficulties | 33.85 (1.64) | 15 (0–69) |

| In-law troubles | 32.57 (1.67) | 11 (0–66) |

| Major change in religious activities | 25.72 (1.51) | 2.5 (0–51) |

| Son or daughter leaving home | 34.66 (1.86) | 1 (0–87) |

| Marital separation | 26.48 (1.7) | 0 (0–55.5) |

| Death of a spouse or life partner | 17.71 (1.48) | 0 (0–11) |

| Divorce | 25.52 (1.71) | 0 (0–53) |

| Marital reconciliation | 15.4 (1.33) | 0 (0–10) |

| Major business readjustment | 20.75 (1.37) | 0 (0–31) |

| Retirement from work | 28.6 (1.75) | 0 (0–61) |

| Foreclosure/repossession on mortgage or loan | 11.04 (1.11) | 0 (0–3) |

| Detention in jail or other institution | 10.58 (1.18) | 0 (0–0) |

*Ordered from highest to lowest mean % personal experience.

A value of 100 indicates that the rating for an item was completely based on personal experience.

A value of 0 indicates that the rating for an item was not at all based on personal experience.

N = 536.

Impact of loneliness on SRRS ratings

Overall, participants’ average loneliness score (loneliness level), as measured by the R-UCLA (higher value = higher level of loneliness), was M 5.1 (SE .08), ranging from 3 to 9. In response to how often respondents felt lonely (loneliness frequency), with a lower value indicating feeling lonely more often, 9.8% (n = 53) were lonely ‘often/always’, 24.1% (n = 130) ‘some of the time, 24.3% (n = 131) ‘occasionally’, 27.6% (n = 149) ‘hardly ever’ while 13% (n = 70) indicated ‘never’.

To explore whether loneliness affected SRRS ratings, Kendall’s tau correlational analyses were conducted to test the association between the R-UCLA and loneliness frequency measures and each of the 43 SRRS rating items. The frequentist analyses for both level and frequency of loneliness revealed statistically significant correlations for 7 items (p’s ≤ .039), however the correlation coefficients were very small (r ≤ .128). For both level and frequency, 6 items were ‘Revision of personal habits’; ‘Foreclosure/repossession on mortgage or loan’; ‘Detention in jail or other institution’; ‘Major change in usual type and/or amount of recreation’; ‘Major change in work hours or conditions’ and ‘Major change in religious activities’. For loneliness level only, ‘Major change in sleeping habits’ was. For loneliness frequency only ‘Major change in social activities’ was significant. Bayesian analysis was only conducted for loneliness level as there was no equivalent non-parametric Bayesian analysis for loneliness frequency in JASP. The Bayesian Kendall’s tau conducted between R-UCLA scores and ratings revealed only two noteworthy results: decisive evidence for a small positive correlation (r = 0.128, BF > 100) between ‘Revision of personal habits’ and R-UCLA scores and substantial evidence for ’Single person, living alone’ and R-UCLA scores (r = 0.082, BF = 3.18). These outcomes indicated that an increase in level of loneliness experienced was associated with an increase in the respective ratings. All other associations either supported the null (nratings = 32; BF ≤ 0.30) or evidence was anecdotal (nratings = 9; ≤ 0.35 BF ≤ 2.42).

Extending the SRRS: New items

Proposed new item: ‘Single person, living alone’

Table 8 provides descriptive statistics and rank for this new item relative to the existing 43 life events. As the table shows, the overall averaged weight based on the arithmetic mean was 38 (SE 1.13), which places its rank as lower than marriage. Non-parametric frequentist and Bayesian statistics were used to evaluate whether ratings for this event differed depending on age, sex, ethnicity, relationship status, employment status or religion. Table 9 presents their descriptive statistics. A Kruskal Wallis test revealed no statistically significant differences between age groups (p > .07). Bayesian Mann-Whitney U tests compared all 2-way age group combinations and similarly found evidence supporting the null regarding YA vs. MA and MA vs. OA (BFs ≤ 0.17). Evidence comparing YA and OA was anecdotal (BF = 0.43). Comparing males and females, a Mann-Whitney U test revealed a statistically significant difference (z = -2.086, p = .034) with females (Mdn 40) rating this item higher than males (Mdn 30). The Bayesian Mann-Whitney U revealed anecdotal evidence (BF = 0.52), however. For ethnicity (white vs. non-white) and employment (employed vs. unemployed) ratings between groups were comparable for both frequentist (p > .3) and Bayesian (BF ≤ 0.14) tests. In contrast, both relationship status (married vs. unmarried) and religion (religion vs. no-religion) frequentist Mann Whitney tests revealed statistically significant outcomes. The married group (Mdn 40) assigned a higher rating than the unmarried group (Mdn 35) (z = -2.578, p = .01) and for the religion comparison, the religion group (Mdn 40) (z = -2.615, p = .009) rated this item higher than the no-religion group (Mdn 30). However, the corresponding Bayesian Mann-Whitney U results revealed anecdotal evidence for both relationship status (BF = 1.77) and religion (BF = 1.68). Thus, it remains unclear if participants from these respective sub-groups differ systematically regarding these items.

Table 8. New vs. original weights and rank order of SRRS events, including new item: ’Single person, living alone’.

| Holmes & Rahe | Present Study | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Event | rank | weight | rank | Mean (SE)a | 99% CIb | Geometric Meanc | Mdn (IQR)d |

| Death of a spouse or life partner | 1 | 100 | 1 | 86.83 (0.98) | 84.16, 89.21 | 73.78 | 95 (80–100) |

| Detention in jail or other institution | 4 | 63 | 2 | 76.88 (1.14) | 73.79, 79.66 | 61.65 | 80 (70–99) |

| Death of a close family member | 5 | 63 | 3 | 75.84 (1.02) | 73.13, 78.46 | 67.57 | 80 (60.5–95) |

| Divorce | 2 | 73 | 4 | 67.86 (1.03) | 65.2, 70.41 | 56.03 | 70 (52.8–85) |

| Marital separation | 3 | 65 | 5 | 66.9 (1.01) | 64.28, 69.33 | 55.98 | 70 (50–80) |

| Pregnancy | 12 | 40 | 6 | 64.66 (1.06) | 62.03, 67.27 | 47.63 | 60 (40–70) |

| Major personal injury or illness | 6 | 53 | 7 | 64.36 (0.98) | 61.9, 66.91 | 55.98 | 70 (50–80) |

| Death of a close friend | 17 | 37 | 8 | 64.05 (1.12) | 61.08, 66.8 | 44.9 | 50 (40–70) |

| Foreclosure/repossession on mortgage or loan | 21 | 30 | 9 | 62.39 (1.07) | 59.65, 65.09 | 32.71 | 40 (25–60) |

| Losing your job | 8 | 47 | 10 | 60.97 (1.03) | 58.2, 63.5 | 24.33 | 30 (20–50) |

| Major change in the health or behaviour of a family member | 11 | 44 | 11 | 55.73 (0.98) | 53.06, 58.24 | 38.01 | 50 (30–70) |

| Major change in financial state | 16 | 38 | 12 | 52.02 (0.94) | 49.68, 54.68 | 35.47 | 50 (30–65) |

| Gaining a new family member | 14 | 39 | 13 | 51.81 (1.11) | 49.05, 54.65 | 29.09 | 40 (20–50) |

| Marriage (pre-set weight) | 7 | 50 | 14 | 50 | |||

| Retirement from work | 10 | 45 | 15 | 49.64 (1.08) | 46.73, 52.45 | 35.58 | 50 (30–60) |

| Major business readjustment | 15 | 39 | 16 | 46.73 (1.06) | 43.96, 49.49 | 40.18 | 50 (30.8–70) |

| Marital reconciliation | 9 | 45 | 17 | 46.24 (0.97) | 43.77, 48.59 | 51.32 | 65 (45–80) |

| Major change in the number of arguments with spouse-life partner | 19 | 35 | 18 | 44.21 (0.92) | 41.75, 46.56 | 31.1 | 40 (25.5–50) |

| Change in residence | 32 | 20 | 19 | 42.69 (0.95) | 40.33, 44.99 | 34.54 | 40 (30–59.8) |

| Taking on a mortgage or loan for a major purchase | 20 | 31 | 20 | 42.22 (0.99) | 39.78, 44.79 | 34.98 | 45 (30–60) |

| Son or daughter leaving home | 23 | 29 | 21 | 41.66 (0.99) | 39.2, 44.19 | 21.75 | 30 (15–40) |

| Spouse/life partner begins or stops working | 26 | 26 | 22 | 40.06 (0.9) | 37.72, 42.36 | 21.22 | 30 (10–50) |

| Changing to a different line of work | 18 | 36 | 23 | 39.48 (0.85) | 37.3, 41.68 | 52.64 | 70 (45.8–80) |

| Major change in living conditions | 28 | 25 | 24 | 39.36 (0.9) | 37.01, 41.75 | 23.76 | 30 (20–50) |

| Single person, living alone | 25 | 38.16 (1.13) | 35.41, 41.16 | 24.14 | 40 (15–50) | ||

| Sexual difficulties | 13 | 39 | 26 | 38.07 (0.92) | 35.74, 40.61 | 53.44 | 70 (50–80) |

| Major change in responsibilities at work | 22 | 29 | 27 | 37.8 (0.83) | 35.54, 39.94 | 50.24 | 70 (50–80) |

| Major change in work hours or conditions | 31 | 20 | 28 | 37.09 (0.84) | 34.76, 39.32 | 20.44 | 25 (10–40) |

| Changing to a new school | 33 | 20 | 29 | 34.6 (0.93) | 32.29, 36.95 | 29.5 | 35 (20–50) |

| Beginning or ceasing formal schooling | 27 | 26 | 30 | 33.88 (0.91) | 31.57, 36.14 | 31.07 | 40 (25–55) |

| Major change in sleeping habits | 38 | 16 | 31 | 31.92 (0.84) | 29.83, 34.3 | 24.85 | 30 (20–40) |

| Outstanding personal achievement | 25 | 28 | 32 | 30.94 (0.96) | 28.49, 33.55 | 30.56 | 38.5 (21.3–50) |

| In-law troubles | 24 | 29 | 33 | 30.94 (0.91) | 28.62, 33.26 | 31.31 | 40 (25–60) |

| Troubles with the boss | 30 | 23 | 34 | 29.15 (0.9) | 26.72, 31.74 | 15.66 | 20 (10–30) |

| Major change in usual type and/or amount of recreation | 34 | 19 | 35 | 29.08 (0.78) | 27.01, 31.04 | 11.43 | 15 (5–30) |

| Major change in eating habits | 40 | 15 | 36 | 27.39 (0.77) | 25.2, 29.47 | 15.72 | 20 (10–30) |

| Taking on a loan for a lesser purchase | 37 | 17 | 37 | 25.12 (0.84) | 22.97, 27.6 | 17.36 | 20 (10–35) |

| Major change in social activities | 36 | 18 | 38 | 24.39 (0.8) | 22.31, 26.45 | 17.35 | 20 (10–30) |

| Major change in number of family get-togethers | 39 | 15 | 39 | 22.88 (0.76) | 20.9, 24.92 | 20.74 | 25 (10–40) |

| Revision of personal habits | 29 | 24 | 40 | 22.8 (0.77) | 20.95, 24.85 | 30.96 | 40 (25–53.8) |

| Minor violations of the law | 43 | 11 | 41 | 22.14 (0.76) | 20.12, 24.19 | 14.99 | 20 (10–30) |

| Major change in religious activities | 35 | 19 | 42 | 20.09 (0.8) | 18.01, 22.2 | 22.07 | 30 (15–40) |

| Vacation | 41 | 13 | 43 | 20.09 (0.81) | 18.03, 22.25 | 12.64 | 10 (6–30) |

| Christmas | 42 | 12 | 44 | 19.78 (0.84) | 17.79, 21.93 | 11.8 | 10 (5–30) |

Table ordered by Present Study’s ranks, including ’Single person, living alone’.

a Mean (SE). Standard error obtained via BCa Bootstrap with 1000 samples.

b 99% confidence intervals obtained via BCa Bootstrap with 1000 samples.

c Where participants responded with a zero value, these were replaced with ’1’ to allow this value to be calculated.

d Mdn (IQR) = Median and inter-quartile range in brackets.

Table 9. Descriptive statistics for ’Single person, living alone’.

| sub-groups | Mean (SE) | Median (IQR) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| < 30 years | 34.96 (2.61) | 30 (10–50) | |

| 30 to 60 years | 37.84 (1.52) | 35 (18–50) | |

| > 60 years | 41.66 (2.31) | 45 (20–65) | |

| Sex | |||

| female | 40.1 (1.51) | 40 (20–60) | |