SUMMARY

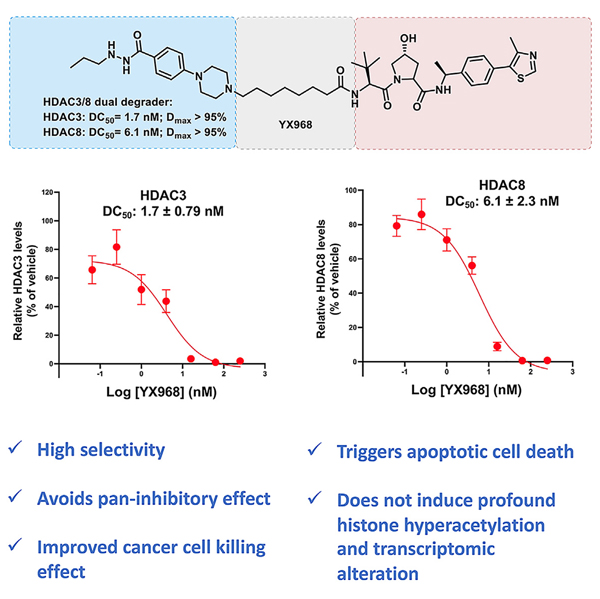

HDAC3 and HDAC8 have critical biological functions and represent highly sought-after therapeutic targets. Because histone deacetylases (HDACs) have a very conserved catalytic domain, developing isozyme-selective inhibitors remains challenging. HDAC3/8 also have deacetylase-independent activity, which cannot be blocked by conventional enzymatic inhibitors. Proteolysis-targeting chimeras (PROTACs) can selectively degrade a target enzyme, abolishing both enzymatic and scaffolding function. Here, we report a novel HDAC3/8 dual degrader YX968 that induces highly potent, rapid, and selective degradation of both HDAC3/8 without triggering pan-HDAC inhibitory effects. Unbiased quantitative proteomic experiments confirmed its high selectivity. HDAC3/8 degradation by YX968 does not induce histone hyperacetylation and broad transcriptomic perturbation. Thus, histone hyperacetylation may be a major factor for altering transcription. YX968 promotes apoptosis and kills cancer cells with a high potency in vitro. YX968 thus represents a new probe for dissecting the complex biological functions of HDAC3/8.

In brief

Xiao et al. discovered and characterized a potent and selective dual PROTAC degrader (YX968) of HDAC3 and HDAC8. Their degradation by YX968 neither triggers histone hyperacetylation nor significantly perturbs the transcriptome, suggesting that histone hyperacetylation is a main driver for altering gene expression.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Epigenetic regulation profoundly impacts cellular gene expression and phenotypes.1 Histone acetylation is a major epigenetic modification that activates or represses gene expression.2–4 Histone acetylases (HATs) and deacetylases (HDACs) attach or remove, respectively, an acetyl group in diverse substrates including histones and non-histone proteins.5,6 The human genome encodes 18 deacetylases that depend on zinc or nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) for their catalytic activity. The 11 zinc-dependent HDACs can be divided into four groups: class I (HDAC1–3 and 8), class IIa (HDAC4, 5, 7, and 9), class IIb (HDAC6 and 10), and class IV (HDAC11).5 These HDACs display substrate specificity and distinct cellular functions. In addition to the classical deacetylase activity on protein substrates, recent studies show that HDAC10 specifically deacetylates the key cellular metabolites polyamines.7 Further, HDACs could remove other types of acyl group from proteins. For example, HDAC1–3 were recently shown to act as histone lysine delactylases,8 while HDAC11 can remove a long-chain fatty acid moiety attached to a lysine residue in a protein substrate.9,10

Increased expression of HDACs is linked to the pathogenesis of various diseases, such as cancer, neurodegenerative and autoimmune diseases, and viral infection.11 Numerous HDAC inhibitors (HDACi) with distinct chemical scaffolds are developed over the last thirty years,11,12 and the therapeutic potential of inhibiting HDACs is validated in the clinic for cancer treatment. Four HDACi are approved for the treatment of lymphomas, including vorinostat (SAHA), romidepsin (FK-228), belinostat (PXD-101), and tucidinostat (chidamide) (previous conditional approvals for panobinostat [LBH-589] for multiple myeloma [in combination with bortezomib] and romidepsin for peripheral T-cell lymphoma [PTCL] were recently withdrawn by the FDA). However, these drugs are pan-HDACi, raising safety and tolerability concerns. Each HDAC isozyme has its distinct biological functions, intracellular localization, and tissue distribution profile. HDAC1–3 also form specific deacetylase complexes with distinct subunits and unique roles in epigenetic regulation.13 To unlock the full therapeutic potential of targeting HDAC and develop specific tool molecules to study HDAC biology, there are increased efforts in developing isozyme-selective HDACi.11 Whereas many isozyme-selective HDACi are reported, recent inhibitory kinetic and chemical proteomics studies questioned that some widely used isozyme-selective HDACi are not as selective as previously reported and may have unexpected off targets, highlighting the challenge of developing truly isozyme-selective HDACi.14–17 Moreover, with >300 Zn-dependent enzymes in cells, there is also a general off-target concern as most HDACi carry a strong zinc binding group (ZBG).18 These limitations, coupled with the lack of an efficient method to assess the global selectivity, call for alternative strategies to develop isozyme-selective modalities to probe the specific biological functions of different HDAC isozymes.

PROTAC has emerged as a revolutionary tool in drug discovery and chemical biology.19 In contrast to the conventional occupancy-driven pharmacology by small-molecule inhibitors, PROTACs catalytically degrade a protein of interest (POI) by hijacking the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) through recruiting E3 ligases. PROTACs offer possibilities to target traditionally undruggable or difficult-to-drug targets such as transcriptional factors, scaffolding proteins, and multi-functional proteins that may not be inhibited with one inhibitor. Further, because efficient degradation depends on the formation of stable E3:PROTAC: POI ternary complexes and the accessibility of lysine residues on the target protein,20–22 it is well established that a promiscuous inhibitor can be converted into a highly selective degrader.23–25 Importantly, the global protein degradation selectivity of PROTACs can be assessed by unbiased proteomics studies.25,26 The degradability of HDAC isozymes is explored27 and PROTACs targeting HDAC1/2/3,28,29 HDAC3,30,31 HDAC6,32–37 and HDAC838–40 are reported (Figure S1). However, except PROTACs degrading HDAC6, most of the reported HDAC degraders show moderate degradation potency yet retain a strong HDAC inhibitory effect, rendering them less versatile as tool molecules.

We reported an HDAC3-selective PROTAC XZ9002 (Figure S1), constructed by connecting a von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) E3 ligase ligand with an HDAC inhibitor of the hydrazide class.31,41 XZ9002 degrades HDAC3 with a DC50 (the PROTAC concentration that results in 50% protein degradation) of 42 nM after 14 h treatment. However, due to its warhead compound 13 (Table S1) is a pan-Class I HDACi, XZ9002 also inhibits HDAC1, 2, 3, and 8. With an IC50 for HDAC3 (350 nM) within 10-fold of its DC50 and a pan-class I inhibition activity, the utility of XZ9002 as a tool molecule may be limited. To overcome this potential limitation and improve the physicochemical properties of XZ9002, we carried out a structural optimization study with changes of the HDAC warhead and the linkage unit. Our goal is to identify a PROTAC that can degrade HDAC3 at a low concentration that has minimal enzymatic inhibition of HDACs and other potential off-target effects. We first optimized the HDACi part through a structure-activity relationship (SAR) study on replacing the terminal phenyl ring. The optimized warhead 15 was then conjugated with a VHL E3 ligase ligand through different linkers to yield various PROTACs. Here we report the discovery of YX968 with a DC50 of 1.7 nM, 8 h in degrading HDAC3, which is >two-order of magnitude lower than its HDAC1 and HDAC3 inhibition (IC50 = 591 nM and 284 nM, respectively). Unexpectedly, YX968 also potently degrades HDAC8 (DC50 = 6.1 nM, 8h), which was not observed with XZ9002. As a result, this highly potent HDAC3/8 dual degrader exhibits distinct effects on modulating cellular functions and is much more potent in inhibiting breast cancer cell proliferation than XZ9002.

RESULTS

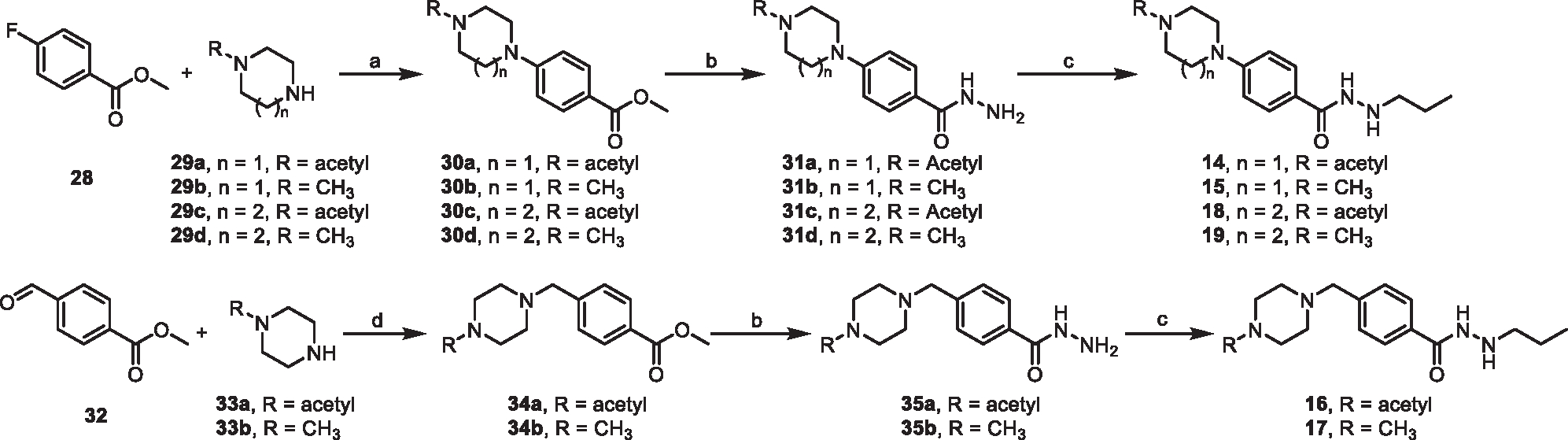

Design, synthesis, and evaluation of new PROTACs

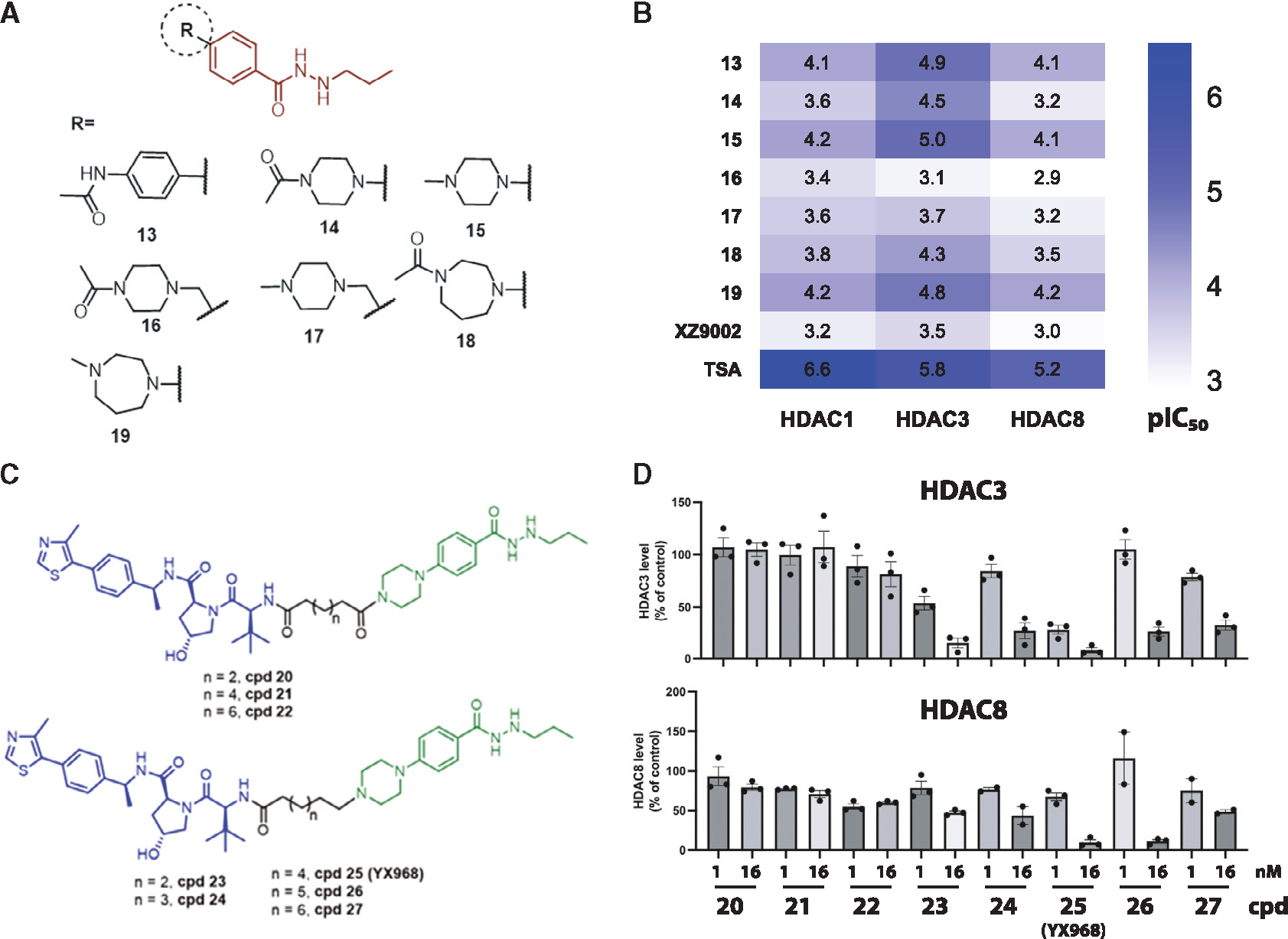

We sought to improve the HDAC3 inhibitory potency and selectivity, as well as the physicochemical properties of the warhead, so that the corresponding PROTACs may achieve more robust HDAC3 degradation. Our first generation HDAC3 PROTACs was based on the N′-propyl-4-phenylbenzohydrazide scaffold (compound 13, Figure 1A).31 Since the propylhydrazide moiety is a preferred ZBG for HDAC3 and the conjugated phenyl group can form a π-π interaction within the binding pocket,31,42 we retained the N′-propylbenzohydrazide moiety and focused on replacing the terminal phenyl group with a more hydrophilic moiety. We avoided big changes on the warhead because large alteration of shape, size, and orientation might disrupt the ternary complex formation thus diminishing the selectivity and potency for HDAC3. A focused mini-library of compounds (14–19) was synthesized with the phenyl ring replaced by a piperazine or a 1,4-diazepane ring (Figure 1A). HDAC1/3/8 inhibitory activity was determined in vitro (Figure 1B and Table S1) as an assessment for the binding affinity of the new compounds to the HDAC catalytic center. Compound 15, which bears an N-methylpiperazinyl group, exhibited the highest potency among all the new analogues, with almost identical IC50 values on HDAC1, HDAC3, and HDAC8 to those of 13 (Figure 1B). While also preferentially inhibited HDAC3, compound 14, in which the methyl group in 15 was replaced by an acetyl group, was ~3- to 7-fold less potent than 15 for the three HDAC isozymes. Inserting a methylene group between the piperazine and phenyl ring (compounds 16 and 17) caused a dramatic decline of selectivity and potency. 1,4-Diazepane ring containing compounds 18 and 19 exhibited similar HDAC3 inhibitory activity compared to their corresponding piperazine substituted compounds 14 and 15. Interestingly, among three pairs of compounds we synthesized, the N-methyl containing analogues consistently displayed higher potency against HDAC3 compared with their corresponding N-acetyl containing analogues, suggesting that alkylamine linkage could have more favorable outcome than amide linkage in PROTAC design.

Figure 1. Inhibitory activity of modified warheads and degradation activity of PROTACs.

(A) The structures of modified HDAC inhibitors.

(B) The HDAC1/3/8 inhibitory activities of modified warheads. pIC50 was plotted as a heatmap. Each value is the average of two independent assays.

(C) The structures of new PROTACs.

(D) MDA-MD-231 cells were treated with the PROTACs for 14 h. Shown are average values ±SEM (n = 2 or 3). See also Table S1 and Figures S1–S3.

We subsequently synthesized a small set of PROTACs based on 14 and 15 (Figure 1C). Our previous study indicated that VHL-recruiting PROTACs were more potent than CRBN-recruiting PROTACs in inducing HDAC3 degradation.27,31 Thus we focused on VHL-recruiting PROTAC and varying the length of the alkane linker. The piperazine ring of 14 and 15 is projected to be solvent exposed and presents a synthetically amenable handle for linker incorporation. As we have a long-standing interest in breast cancer (BC) biology, and Class I HDACs are well expressed in BC cell lines (Figure S2), the ability of these PROTACs in degrading HDAC3 was initially assessed in several BC cell lines including the triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) line MDA-MB-231 by Western blot in a broad range of concentrations. Some of these PROTACs effectively degraded HDAC3 at a low nM concentration after an overnight incubation. Cells were therefore treated with 1 nM or 16 nM PROTAC for 14 h, and the percentages of remaining protein relative to control were quantified (Figure 1D). Amide linkage containing PROTACs 20–22 did not effectively degrade HDAC3 (<20% reduction at 16 nM). Surprisingly, replacing the amide with a C-N bond led to a dramatic increase in HDAC3 degradation. Compound 25 (YX968), in which the alkane linker contains eight carbons, appeared to have the optimal potency with ~75% and >90% HDAC3 reduction, respectively, when treated at 1 and 16 nM (Figure 1D).

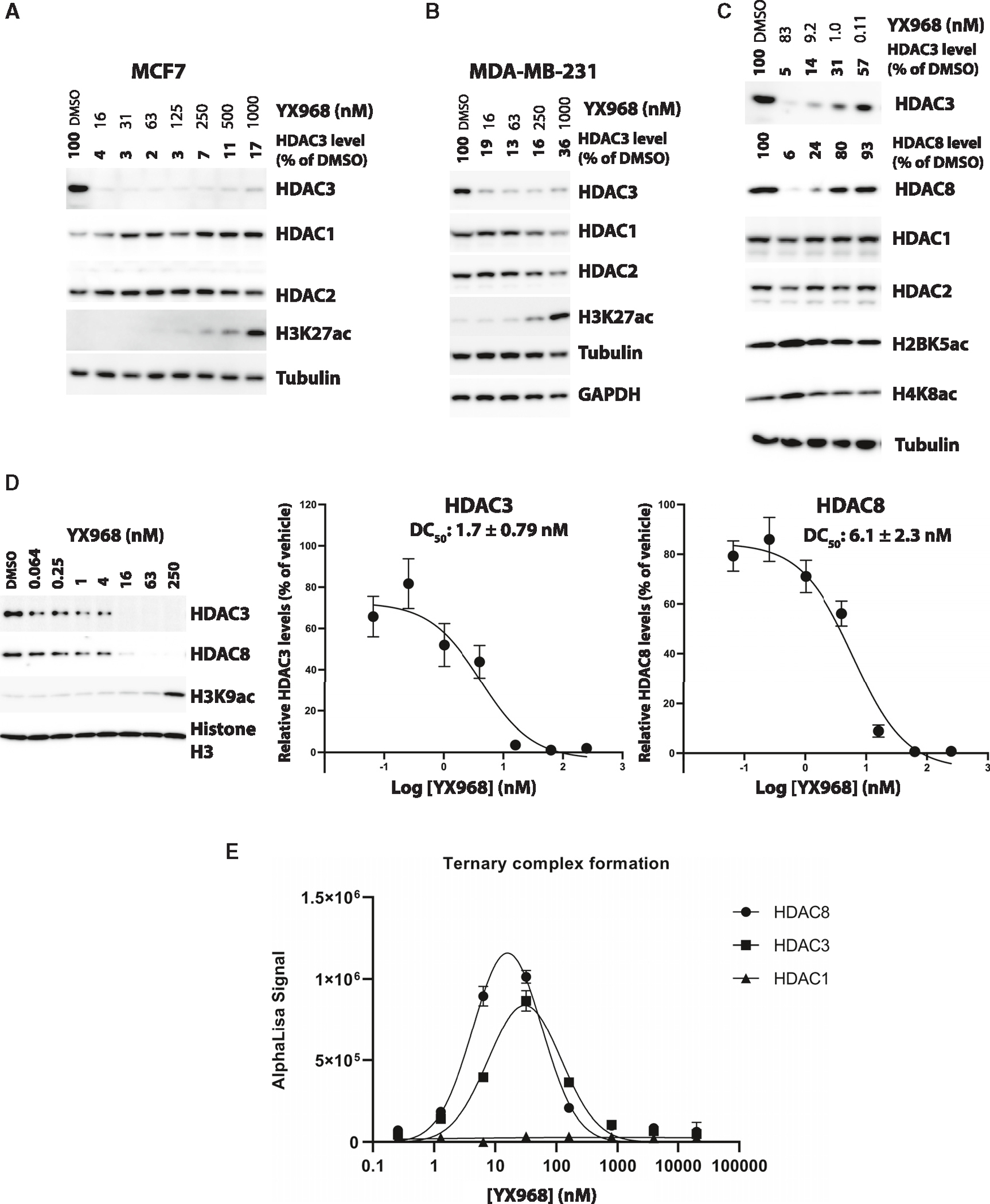

YX968 potently and selectively degrades HDAC3 and HDAC8

As the most potent HDAC3 degrader in the series, YX968 was selected for further characterization. While YX968 potently degraded HDAC3, it did not affect HDAC1 or HDAC2, in both MCF7 (an estrogen receptor [ER]-positive BC cell line) and MDA-MB-231 with a DC50 value of 1.7 nM in MDA-MB-231 cells treated for 8 h (Figures 2A, 2B, and 2D). We further tested HDAC8, another class I HDAC isozyme since the warhead we used can also bind to HDAC8. To our surprise, HDAC8 was also potently degraded by YX968 in MDA-MB-231 cells treated for 8 h with a DC50 value of 6.1 nM (Figures 2C and 2D). Thus, YX968 appeared to be a potent dual degrader of HDAC3/8. The ability of other PROTACs in the series to degrade HDAC8 was also evaluated in MDA-MB-231 cells (Figure 1D). A similar SAR trend was observed with HDAC8 degradation among the PROTACs, where PROTACs with a C-N bond linkage appeared to be more favorable than the amide linkage, and YX968 was also the most potent in degrading HDAC8 among its analogues. YX968 was 25-fold more potent than XZ9002 in degrading HDAC3, while the latter did not affect HDAC8 protein level (Figure S3). However, in vitro, the two had a comparable HDAC inhibitory profile (IC50 = 591, 283, and 740 nM against HDAC1, 3, and 8, respectively for YX968 and IC50 = 650, 350, and 1,093 nM against HDAC1, 3, and 8, respectively for XZ9002). The DC50 values of YX968 in degrading HDAC3 and HDAC8 are >100-fold lower than its IC50 values for the respective isozymes. With such a large concentration difference, we expect the new degrader will have minimal deacetylase inhibitory activity at effective degradation concentrations. One caveat is that HDAC inhibition assays were performed in vitro using purified proteins while degradation was based on cellular assays. Nonetheless, our previous report shows that cellular HDAC inhibitory potency of HDACi is generally reduced compared to in vitro assays.41 Notably, a hook effect was not observed for YX968 up to 1 μM (Figures 2A and 2B). Nonetheless, a notable hook effect was seen at a much higher YX968 concentration (64 μM) for both HDAC3 and HDAC8 (Figure S4B). We have performed in vitro ternary complex formation assay using purified HDAC1, 3, and 8 with a broad range of YX968 concentrations. A classic bellshape ternary complex formation was observed for HDAC3 and HDAC8. Strong HDAC3/8-YX968-VHL complex (consisting of VHL, and elongin B and C) ternary complex was evident at a low YX968 concentration (Figure 2E). YX968 was not able to induce a complex between HDAC1 and the VHL complex (Figure 2E). In vitro deacetylase activity assays indicated that YX968 was more potent to inhibit HDAC3 and HDAC8 in the presence of the VHL complex than in its absence, indicating a positive inhibitory cooperativity (Figure S4D). These data provide an explanation for the marked selectivity and potency of YX968 for degrading HDAC3/8.

Figure 2. YX968 selectively degrades HDAC3 and HDAC8.

(A–C) Western blots showing the levels of the indicated proteins in MCF7 (A), MDA-MD-231 (B and C) cells treated with YX968 for 14 h. HDAC3/8 band intensity was normalized against that of tubulin in each sample.

(D) The dose-response curves and DC50 values of HDAC3/8 degradation in MDA-MB-231 cells (treatment for 8 h). Representative Western blot images are shown.

(E) Ternary complex formation between the VHL complex consisting of VHL, elongin B and C, and HDAC1, 3, or 8, and YX968 based on in vitro AlphaLISA assay. Data are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 3). See also Figures S3 and S4.

We then evaluated the effects on the acetylation levels of several core histones (H3K27ac, H2BK5ac, and H4K8ac) after PROTAC treatment. YX968 dose-dependently increased the levels of acetylated core histones (Figures 2 and S4). However, the induction of histone acetylation occurred at much higher concentrations than the concentrations required for degrading HDAC3/8 in both MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells (Figures 2 and 3). Whereas it is well-documented that both HDAC3/8 can deacetylate histones,43–45 these observations suggest that the degradation of HDAC3/8 is insufficient to induce global histone hyperacetylation, although localized effects on histone acetylation cannot be excluded. At high YX968 concentrations, other HDACs (such as HDAC1/2) are inhibited although not degraded, resulting in global histone hyperacetylation. This result indicated that YX968 could be a useful tool to study mechanistic and functional effects of HDAC3/8 depletion.

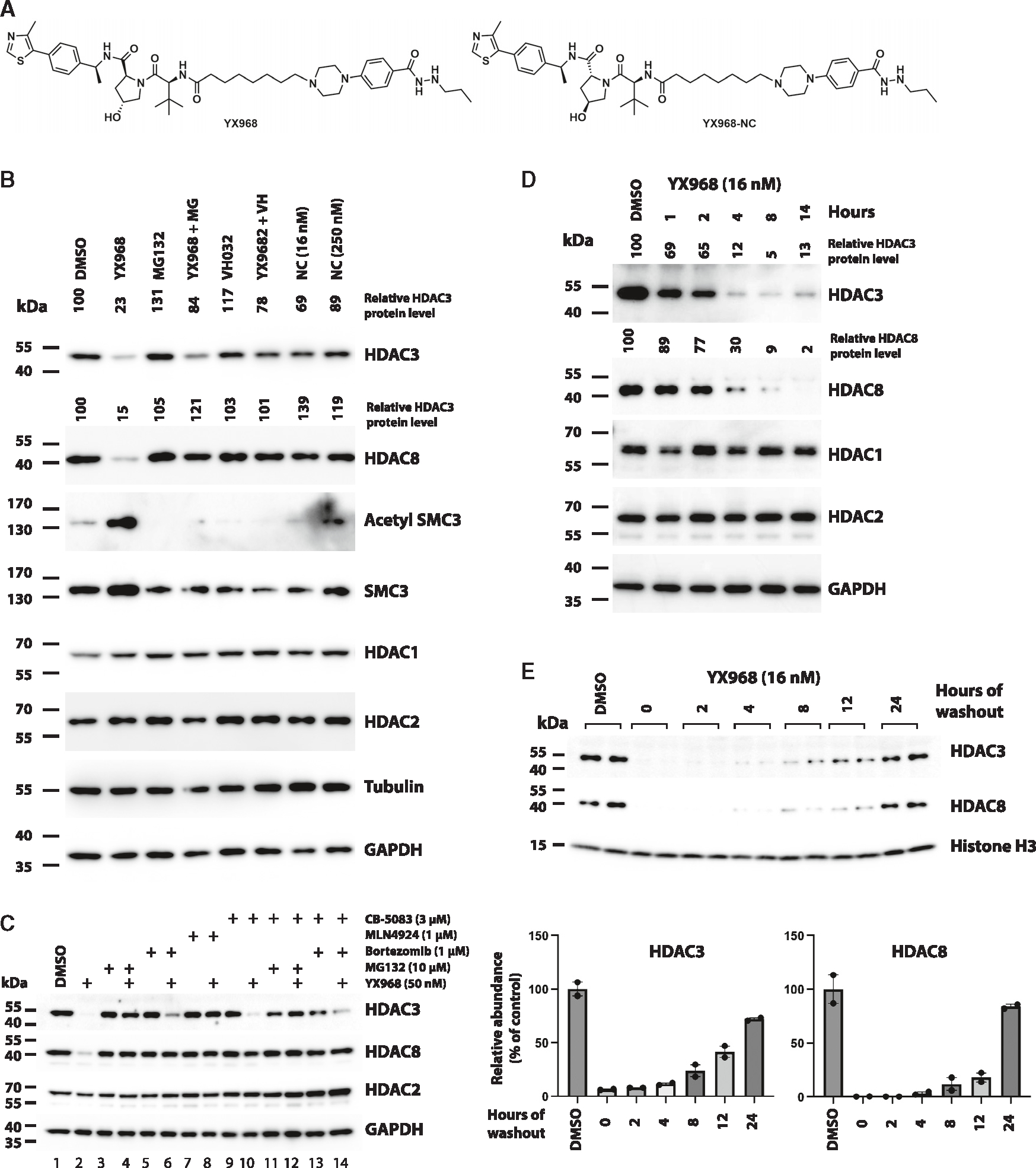

Figure 3. Mechanism underlying YX968-induced degradation of HDAC3 and HDAC8.

(A) Chemical structure of XY968 and YX968-NC (the negative control of YX968 that does not bind VHL).

(B) MDA-MB-231 cells were pretreated with 1 μM MG132 (MG), or 10 μM VHL ligand VH032 for 1 h followed by adding YX968 (16 nM) for 14 h. Cells were also similarly treated with YX968-NC (Shown as NC in Figure 3B). Western blot was done for detecting the indicated proteins.

(C) Additional probes for assessing the mechanism by which YX968 degrades HDAC3/8.

(D) Time-course assay in MDA-MB-231 cells after treatment with 16 nM YX968.

(E) MDA-MB-231 cells were incubated with 16 nM YX968 for 24 h followed by drug washout, and the treated cells were cultured in drug-free medium for the indicated time points. Samples from two independent assays are loaded. The normalized levels of HDAC3/8 protein are plotted. See also Figures S2 and S4.

YX968 rapidly degrades HDAC3 and HDAC8 via the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS)

To confirm that YX968 degrades HDAC3/8 through co-opting the UPS, we performed a mechanism of action (MOA) study. Pretreating cell with proteasome inhibitor MG132 blocked the degradation of both HDAC3 and HDAC8 (Figure 3B), confirming that the degradation is mediated by proteasome. Furthermore, VHL ligand VH032 effectively competed against YX968 for HDAC3/8 degradation, indicating that the degradation was through recruiting the VHL E3 ligase. Importantly, the corresponding negative control compound YX968-NC (Figure 3A), in which two chiral centers in the VHL binding motif of YX968 were reversed, abolishing binding to VHL, were unable to degrade HDAC3/8. SMC3 is a well-established deacetylation substrate of HDAC8.46 Notably, the levels of acetylated SMC3 were increased in cells treated with YX968, and this increase was reversed when HDAC8 degradation was blocked (Figure 3B). These data confirmed the molecular effects of YX968-mediated HDAC8 degradation. Of note, while HDAC8 degradation was effectively blocked with a pretreatment with MG132 at 3 μM, HDAC3 degradation was only moderately reversed (Figure 3B). However, MG132 pretreatment at 10 μM more effectively rescued HDAC3 from YX968-mediated degradation (Figure 3C, lane 4). Moreover, bortezomib, another proteasome inhibitor, could also reverse HDAC3 degradation (Figure 3C, lane 6). The neddylation inhibitor MLN4924 was highly effective in blocking HDAC3/8 degradation by YX968 (Figure 3C, lane 8). The AAA+-type ATPase p97/VCP unfolds ubiquitinated proteins to facilitate their proteasomal degradation.47 Interestingly, while VCP/p97 inhibitor CB-5803 at 3 μM effectively blocked HDAC8 degradation by YX968, this inhibitor only slightly rescued HDAC3 from degradation (Figure 3C, lane 10). A combination of CB-5803 with bortezomib also only partially blocked HDAC3 degradation by YX968 (Figure 3C, lane 14). Because HDAC3 degradation seems less sensitive to proteasomal inhibition, we explored whether selective autophagy is involved in YX968-mediated HDAC3 degradation. Neither 3-methyladenine, which inhibits autophagosome formation, nor bafilomycin A1, which blocks lysosomal acidification by specifically inhibiting vacuolar H+ ATPase (v-ATPase), rescued HDAC3/8, suggesting that selective autophagy is not involved in YX968-mediated degradation of HDAC3/8 (Figure S4C).

In a time-course experiment, YX968 rapidly degraded HDAC3/8 in 1 h and the maximum degradation was seen within 4 h. HDAC3/8 degradation was also reversible. After drug washout, the protein levels of both HDAC3/8 rebounded gradually. At 24 h after drug washout, HDAC3/8 reached to 72% and 84% of their steady levels, respectively (Figure 3E). Interestingly, the recovery rate of HDAC8 appeared slower than that of HDAC3 up to 12 h after YX968 washout. Our data collectively demonstrate that YX968 mediates ubiquitination of HDAC3/8 by recruiting VHL E3 ligase, resulting in their subsequent degradation by the proteasome.

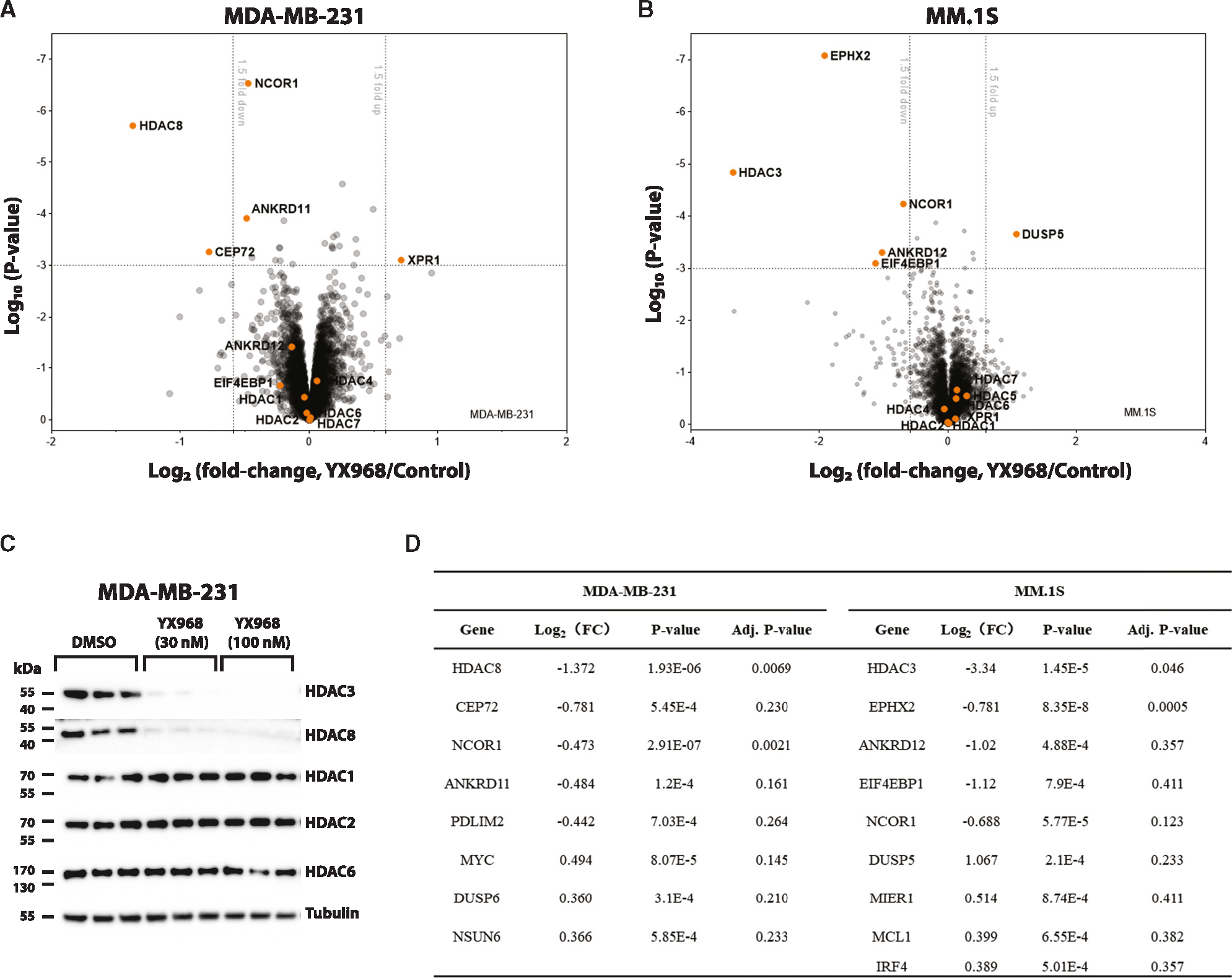

YX968 exhibits high selectivity for its targets

To assess the proteome-wide target specificity of YX968, we performed two independent quantitative proteomic studies in two different cancer cell lines. Since HDACs regulate histone acetylation and gene transcription, we chose a short-time treatment to alleviate the potential false positive results due to indirect transcriptional downregulation of HDAC-regulated genes. In a Tandem Mass Tag (TMT)-based quantitative proteomic profiling experiment (Figure 4A), the samples were prepared by treating MDA-MB-231 cells with either YX968 (100 nM) or DMSO for 2 h. We first confirmed the HDAC3/8 degradation by Western blot in the same cell lysates used for TMT profiling (Figure 4C). The TMT proteomic profiling enabled detection and quantification of >7,000 proteins, including HDAC isozymes HDAC8, HDAC1, HDAC2, HDAC4, HDAC6, and HDAC7 (Figure 4A). However, for an unknown reason, HDAC3 was not captured in all replicates including DMSO in this cell line. Data that enable the identification and quantification of >7,000 proteins in a TMT profiling experiment are generally considered to be of high quality. Many factors such as cell lines, protein abundance, TMT labeling, instruments, analytical methods, processing software, and protease digestion condition can affect the number of quantifiable proteins. The lack of HDAC3 detection did not affect the high reliability of the data since our primary goal was to globally evaluate the off-target effects. Notably, HDAC8 degradation was confirmed in this TMT proteomic profiling. Profound HDAC8 degradation was observed [(Fold change (FC) = 2.58] at 100 nM compared to DMSO group. Meantime, we did not detect any other significantly downregulated protein (log2FC < −1 and p < 0.01) except for HDAC8 and NCOR1 after degrader treatment. HDAC1/2 were not downregulated in the proteomic studies, in agreement with our Western blot analysis results (Figures 2 and 3). Western blot analysis of the same cell lysate used for the TMT profiling study confirmed that other HDACs including HDAC1, 2, and 6 were not degraded while the abundance of HDAC3/8 were significantly reduced (Figure 4C). In the second proteome-level analysis experiment, a diaPASEF-based label-free proteomic study in MM.1S myeloma cells for YX968 (50 nM, 3 h) was conducted. ~6,400 proteins were quantified in this study, including HDAC3, but not HDAC8. The result showed that HDAC3 is the topmost down-regulated protein (FC = 10.1) after YX968 treatment. Four other proteins EPHX2, NCOR1, ANKRD12, and EIF3EBP1 were also significantly downregulated but the fold changes were less than that for HDAC3. HDAC3 is the catalytic subunit of the N-Cor corepressor complex that contains several subunits including TBL1X, TBL1XR1, and GPS2 along with the NCOR1/NCOR2 (also known as SMRT) scaffold.48,49 NCOR1 downregulation was identified in both proteomic profiling experiments (Figures 4A, 4B, and Table S2). Interestingly, two related proteins ANKRD11 (also known as ANCO-1) and ANKRD12 (ANCO-2) were downregulated in YX968-treated MDA-MB-231 and MM.1S cells, respectively (Figures 4A, 4B, and 4D). ANKRD11 was shown to interact with HDACs including HDAC1 and HDAC3 and nuclear receptor coactivator p160 (NCOA1).50 These data suggest that targeting HDAC3 by YX968 might induce collateral degradation of NCOR1 and ANKRD11/12. Collateral degradation of subunits associated with a PROTAC target in a protein complex has been observed.27,51 While these proteomic profiling data show a small reduction of NCOR1 level, other subunits of the N-Cor complex such as TBL1X were not affected (also see Figure S4A and Table S2). Subunits of HDAC1/2-containing complexes were also not significantly perturbed (Figure S4A and Table S2). Overall, these data show that YX968 is highly specific in targeted HDAC3/8 degradation.

Figure 4. Proteomic profiling of YX968-mediaded degradation.

(A) A scatterplot depicting the log2(fold change) of relative protein abundance in MDA-MB-231 cells treated with YX968 (100 nM, 2 h) compared to those treated with DMSO in TMT proteomic profiling.

(B) A scatterplot depicting the log2(fold change) of relative protein abundance in MM.1S cells treated with YX968 (50 nM, 3 h) compared to those treated with DMSO in diaPASEF based label-free proteomic profiling.

(C) Western blot confirmation of HDAC3/8 degradation of the cell lysates used for TMT profiling in three replicates in MDA-MB-231 cells in (A).

(D) Top hits identified by TMT (A) and diaPASEF (B) proteomic profiling. See also Table S2.

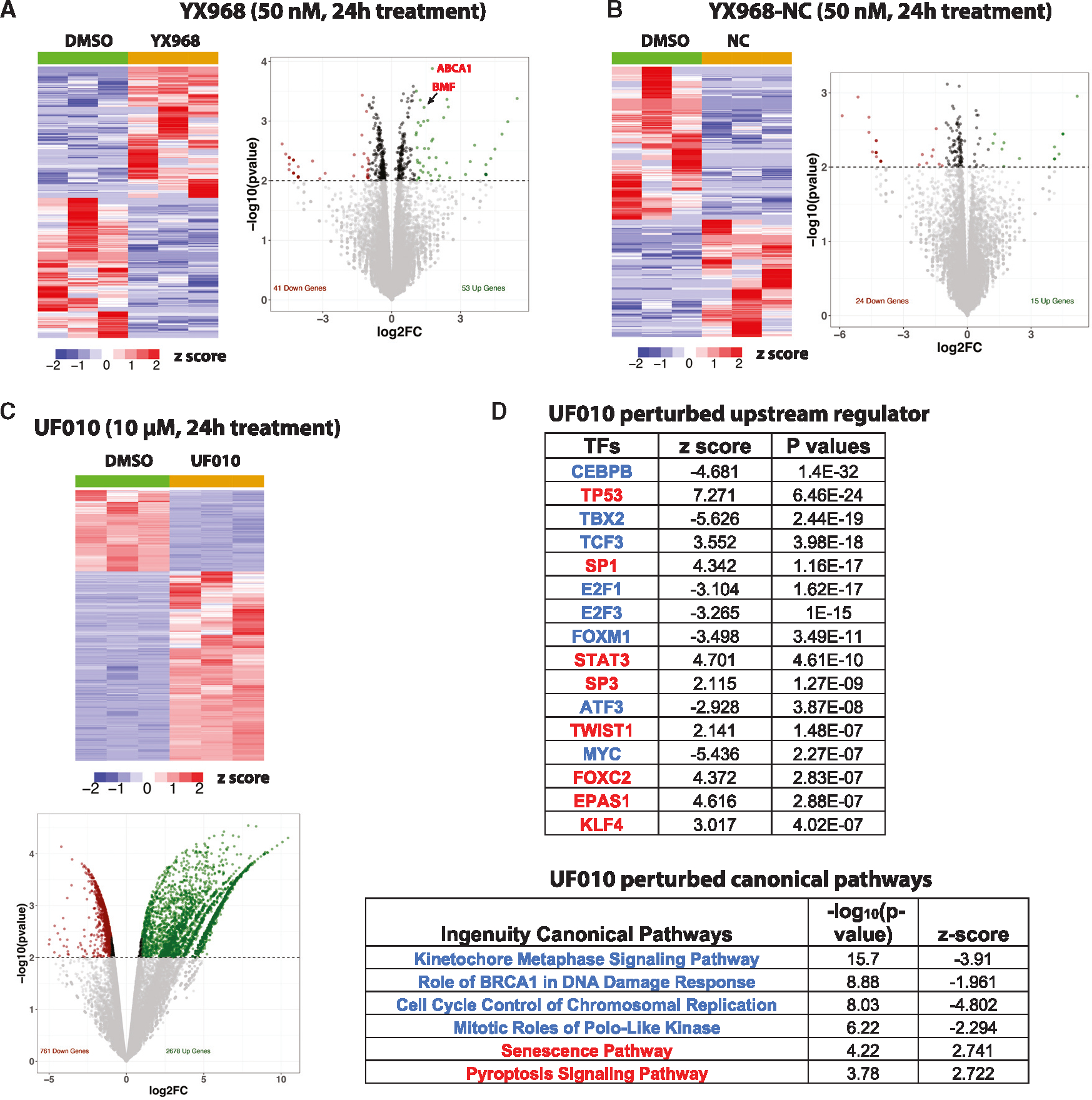

HDAC3/8 degradation does not significantly affect gene expression

As HDAC3 and HDAC8 are implicated in transcriptional regulation,44,45,52 we examined the global effect of the HDAC3/8 dual degrader YX968 on gene expression by performing RNA-seq in MDA-MB-231 cells (Figures 5 and S5). We chose to treat cells at low (3 nM) and moderate (30 and 50 nM) concentrations of the PROTAC for short (6 h) and longer (14 and 24 h) periods. Under these conditions, HDAC3/8 were moderately or significantly degraded, while the global H3K27ac level was not detectably altered (Figure 2). We reasoned that the genes commonly perturbed under these conditions are likely the direct effects of HDAC3/8 degradation rather than due to pan-class I HDAC inhibition or potential off-target effects. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs, fold-change≥|2|, p ≤ 0.01) were identified by comparing transcript levels in the RNA-seq data from cells treated with YX968 to those from cells exposed to DMSO. There was relatively low number of genes that were up- or downregulated across all conditions. For example, there were 53 and 41 up- and downregulated genes, respectively, in cells exposed to 50 nM YX968 for 24h (Figure 5A). Meanwhile, MDA-MB-231 cells were also treated with the negative-control compound (YX968-NC) at 50 nM for 6 and 24 h. Similarly, only a small number of genes were perturbed in cells treated with YX968-NC (Figures 5B and S5). However, these DEGs were mostly different from those in cells treated with YX968; there were only four shared DEGs between cells treated with YX968 and YX968-NC. Notably, ABCA1 and BMF were the only two perturbed (upregulated) genes in cells treated with YX968 under three different conditions (Figures 5B and S5), and both were not affected by YX968-NC. ABCA1, encoding a transporter of phospholipids and cholesterol, and BMF, encoding a pro-apoptotic BCL2 protein, were previously identified as genes induced by HDACi.53–56 Interestingly, ABCA1 seems to be repressed by HDAC3,57 while HDAC8 inhibits BMF expression.58,59 In contrast, in MDA-MB-231 cells treated with UF010 (a hydrazide-based pan inhibitor of class I HDACs, similar to the warheads used in PROTACs),41 2,678 and 761 genes were up- and downregulated (Figure 5C). Bioinformatic analyses revealed that UF010 profoundly inhibited cell cycle progression and DNA repair, while activating cellular senescence and cell death pathways (Figure 5C). Consistently, upstream regulator analysis indicated that UF010 activates p53, while inhibiting MYC and E2F transcription factors. These pathways are commonly perturbed by HDACi, signifying shared MOA between UF010 and other classes of HDACi. To control false discovery rate (FDR) in our DEG analysis, we applied q-value (adjusted p value with multiple hypothesis tests) of ≤0.05 and fold-change ≥|2.0|. With this more stringent statistical threshold, there are no significant DEGs in cells treated with YX968. However, in cells treated with UF010, there are 1,792 upregulated and 572 downregulated DEGs. Taken together, our data suggest that HDAC3/8 degradation does not significantly perturb gene expression in MDA-MB-231 cells.

Figure 5. YX968 does not significantly alter transcriptome.

(A–C) A heatmap of RNA-seq data and a volcano plot of DEGs in cells treated with YX968 (A), YX968-NC (B), or UF010 (C) for 24 h.

(D) IPA pathways (representative upstream regulators and canonical pathways) activated (red types) or inhibited (blue types) by UF010. See also Figure S5.

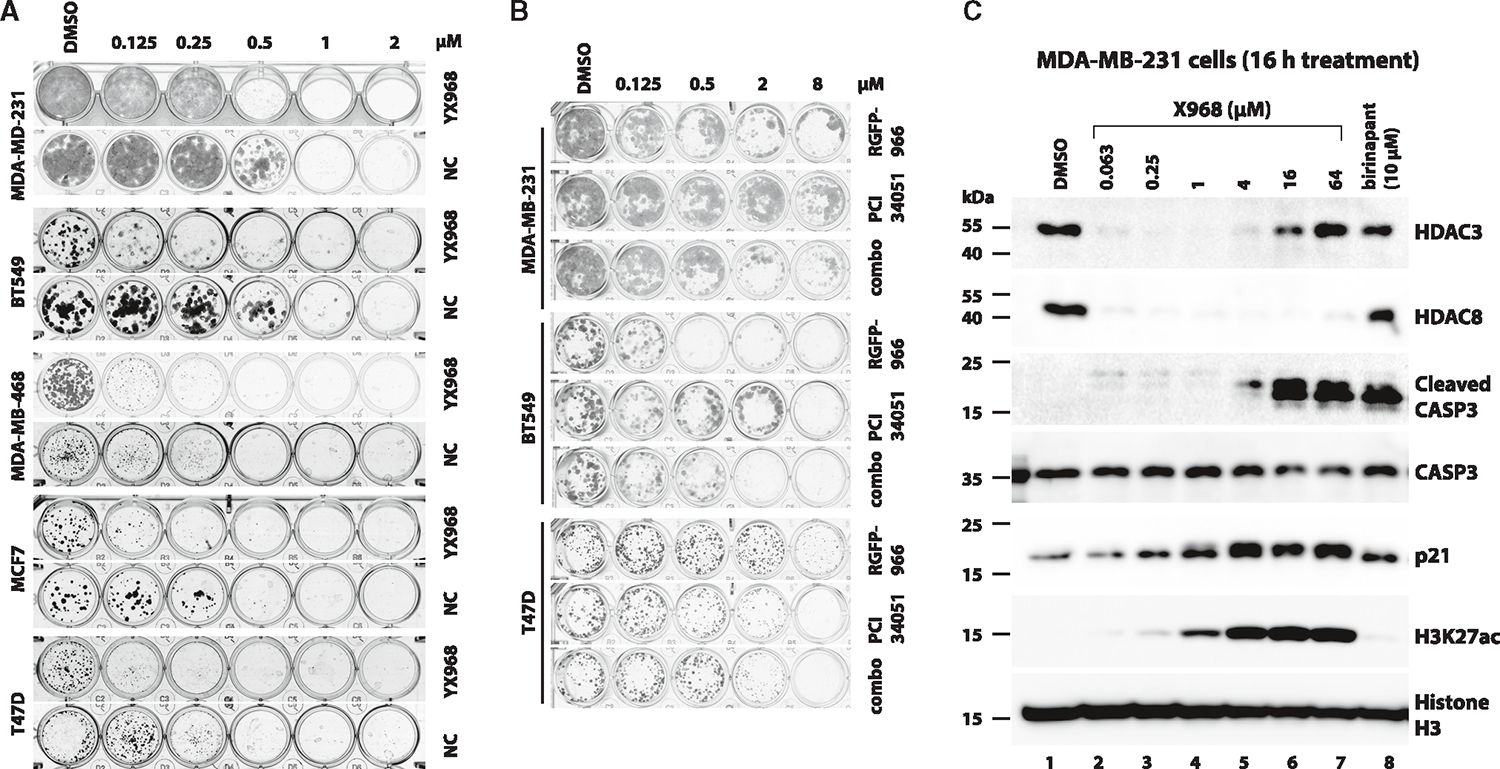

YX968 is highly potent on suppressing the growth of cancer cell lines

Both HDAC3 and HDAC8 have been suggested to play roles in tumorigenesis and cancer progression. To evaluate whether high potency in degrading HDAC3/8 would lead to increased anti-proliferation activity, we first assessed effects of YX968 on cell cycle progression. Treatment with YX968 for 24 h induced a strong G1 arrest at 1 μM but negligibly perturbed the cell cycle at 0.1 μM (Figure S6A). We then treated various breast and lung cancer cell lines at different concentrations of YX968 in clonogenic growth assays (Figures 6A and S6B). The estrogen receptor-positive BC cell lines MCF7 and T47D as well as the TNBC cell lines BT549, MDA-MB-468 and HCC1806 were highly sensitive to YX968, as their growth was effectively inhibited at 125 nM (Figures 6A and S6B). The MDA-MB-231, another TNBC cell line, was less sensitive to YX968, but its growth was effectively suppressed at a sub-μM concentration (Figure 6A). Notably, YX968-NC were 2- to 4-fold less potent to halt cancer cell growth than YX968, confirming that the degrader activity of YX968 is important to cell growth suppression (Figure 6A). We also assessed the cell growth inhibitory effects of YX968 on the non-small cell lung cancer cell lines A549 and H1299. A549 cells exhibited similar sensitivity as MDA-MB-231 cells, but H1299 was quite resistant to YX968 (Figure S6B). Our first-generation HDAC3 PROTAC XZ9002 was less potent in degrading HDAC3. It showed moderate inhibition of the clonogenic growth of MDA-MB-231 cells at a high concentration (3 μM, Figure S6C). These data indicate that our new PROTAC YX968 is much more potent than XZ9002 in suppressing tumor cell growth.

Figure 6. YX968 is highly potent to suppress cancer cell growth.

(A) Colony formation assays using the indicated cell lines that were exposed to DMSO, YX968, or YX968-NC at the indicated concentrations. Colonies were fixed and stained after treatment. Representative results of four replicates.

(B) Colony formation assays using the indicated cell lines that were exposed to DMSO, RGFP-966, PCI 34051, or a combination (combo) of RGFP-966 + PCI 34051. Representative results of four replicates.

(C) YX968 promotes CASP3 activation. MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with YX968 at the indicated concentrations for 16 h. The cells were also treated with the IAP inhibitor birinapant as a control. The lysates of the treated cells were analyzed by Western blot with antibodies against the indicated proteins. See also Figure S6.

To further assess the importance of degrader activity in inhibiting cell growth, we conducted colonogenic growth assays of several BC cell lines on treatment with DMSO, RGFP-966, an HDAC3-selective inhibitor, PCI 34051, an HDAC8-selective inhibitor, or their combination (combo). As shown in Figure 6B, whereas sensitivity of the cell lines to these inhibitors varied, RGFP-966 and PCI 34051 alone or in combination were less potent than YX968 to suppress cell growth. We conclude that degradation of HDAC3/8 is crucial to suppressing tumor cell growth. HDAC3 is a pan-essential gene in human cells based on CRISPR gene essentiality screens.60,61 Targeted knockout of HDAC3 also severely inhibits cell viability,62 suggesting that HDAC3 degradation is the major determinant of YX968-mediated cell killing. These data indicate that the HDAC3/8 dual degrader activity of YX968 renders it more potent to induce cancer cell death.

To probe if YX968 induces classical apoptotic cell death, MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with YX968 at increasing concentrations and the activation of the effector caspase 3 (CASP3) was assessed. CASP3 cleavage (activation) was induced by YX968 in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 6C). A weak CASP3 activation was already notable at 63 nM of YX968. Likewise, the IAP (inhibitor of apoptosis protein) inhibitor birinapant63 also activated CASP3. These data indicate that YX968 promotes apoptosis. The cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitor p21 (encoded by the CDKN1A gene) induces cell-cycle arrest and is an established marker of HDACi treatment.64 As shown in Figures 6A and 6C, weak p21 induction was seen in cells treated with 250 nM of YX968. p21 accumulation was intensified with increased YX968 concentrations. H3K27ac was weakly detectable at 63 nM of YX968 and steadily accumulated in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 6C). The p21 induction profile is consistent with our cell cycle profiling data (Figure S6A) as well as the notion that histone hyperacetylation rather than HDAC3/8 degradation underlies cell cycle perturbation.

DISCUSSION

The difficulty of developing isozyme-selective HDACi represents a major hurdle for realizing the considerable clinical potential of targeting HDACs. HDACs also have non-enzymatic functions that cannot be blocked by conventional inhibitors. Several recent studies highlighted important non-enzymatic functions of HDAC3 by using genetic strategies. A recent study show that HDAC3 knockout in macrophages exhibits anti-inflammatory effects, apparently through engaging HDAC3’s non-canonical deacetylase-independent function.65 Deacetylase-independent function of HDAC3 is also involved in regulating transcription,66 metabolism,67 and protein stability.68 These studies mainly rely on genetic tools because the deacetylase-independent functions of HDAC3 are potentially derived from its protein complex scaffolding role that cannot be targeted by conventional inhibitors. HDAC8 also appears to exhibit deacetylase-independent activity. For example, HDAC8 can stabilize SMG5 (also known as EST1B) independently of its deacetylase activity.69 Importantly, for genes like HDAC3 essential for cell survival or proliferation, constitutive genetic knockout is not feasible. In addition, due to possible gene compensatory effect, genetic knockout tools such as CRISPR/Cas9 have limitations to study protein functions. Compared to traditional genetic editing methods, a PROTAC can degrade its target in a rapid, transient, reversible, and controllable manner. Importantly, PROTACs generally have high target selectivity due to the added requirements, such as the formation of a productive POI:PROTAC:E3 ternary complex and the accessibility of lysine residues on the POI, for efficient degradation. Therefore, PROTAC is ideally suited to target HDAC’s deacetylase independent functions, especially for pan-essential genes like HDAC3. Here, through modifications of the exit vector on the HDAC binding moiety and linker unit of the HDAC3-selective PROTAC XZ9002, we discovered YX968, a VHL-recruiting PROTAC that degrades HDAC3 with a DC50 of 1.7 nM (8 h treatment), a 25-fold increase in degradation potency compared to XZ9002. Unexpectedly, YX968 also potently degrades HDAC8 with a DC50 of 6.1 nM (8 h treatment) while having no detectable degradation of other HDAC isozymes. The potency and specificity were further confirmed by unbiased global proteomic experiments. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first selective HDAC3/8 dual degrader and YX968 is the most potent HDAC3 or HDAC8 degrader among the reported selective degraders of HDAC330,31 and HDAC8.38–40

Since HDACs share a highly similar catalytic domain, it is remarkable that YX968 selectively degrades HDAC3/8. Although the hydrazide ZBG is a selective binder of class I HDACs,41,70 HDAC1/2 are not degraded by YX968. Based on the in vitro inhibition of HDAC1 (Table S1) and HDAC2 (data not shown), YX968 should bind HDAC1/2. The inability of YX968 to degrade HDAC1/2 could be due to that the PROTAC cannot effectively bridge the formation of a productive ternary complex containing HDAC1 or HDAC2, YX968, and VHL, which is consistent with our in vitro assay (Figure 2E). HDAC1/2 are a subunit of several complexes including the SIN3, NuRD, and CoREST complexes.71 These complexes may be incompatible for forming a ternary E3 ligase complex required for ubiquitination. Regardless, the molecular basis of the markedly increased degradation potency and dual selectivity for HDAC3/8 by YX968 will require further studies.

PROTAC-mediated degradation of HDACs is effective in achieving isoform selectivity even when the PROTACs are built from promiscuous warheads. For example, HDAC6-selective PROTACs were synthesized based on a pan-hydroxamic acid HDACi.34 However, when HDAC PROTACs are used to elucidate the function and downstream effects of a particular HDAC isoform, it is important to consider whether they have sufficient degradation potency to distinguish the degradation effects from the consequences of deacetylase enzymatic inhibition. With a >100-fold difference between the degradation DC50 and HDAC inhibitory IC50, YX968 is expected to have better utilities as a tool compound to study the biological effects of chemical knockdown of HDAC3/8 without interference from pan-class I HDAC inhibition.

YX968 does not appear to provoke a global histone hyperacetylation at a relatively low concentration when HDAC3/8 are effectively degraded (Figures 2 and 3), suggesting that HDAC3/8 depletion might not be sufficient to induce histone hyperacetylation. Consistent with this notion, genetic knockout of HDAC1/2 reduces HDAC activity by nearly 50% and markedly increases global histone acetylation, while HDAC3 knockout has virtually no such an effect,66,72 suggesting that HDAC1/2 are the major HDACs that deacetylate histones.62 PROTAC-mediated HDAC3 degradation also did not seem to induce histone hyperacetylation.73 Nonetheless, effects of HDAC3/8 on acetylation at specific genes are well-documented.45,74,75 Alternatively, at a high concentration, it can be envisioned that YX968 degrades HDAC3/8 at a higher kinetic rate, which could enable a gradual accumulation of histone acetylation for a longer period. Nonetheless, our data suggest that the combined effects of HDAC3/8 degradation and enzymatic inhibition of HDAC1/2 in cells treated with YX968 at high concentrations may account for marked histone hyperacetylation. Regardless, the ability of YX968 to deplete HDAC3/8 rapidly and potently makes it a useful tool to elucidate how they regulate gene-specific acetylation and transcription.

Interestingly, our RNA-seq data revealed that YX968 had a small effect on transcriptome when HDAC3/8 were effectively degraded (Figures 5 and S5). In contrast, UF010, a hydrazide analog of the warheads that we used to synthesize the HDAC PROTACs, had a profound effect on gene expression (Figure 5). In agreement with our results, Baker et al. reported that PROTACs degrading HDAC1, 2, and 3 exert a broad effect on transcriptome, while an HDAC3-selective PROTAC has only limited effects on gene expression.73 The HDAC1–3 degrading PROTACs also markedly induces histone hyperacetylation, but the HDAC3-selective degrader does not seem to increase histone acetylation. Along with our findings, these data collectively suggest that histone hyperacetylation is critical to significantly altering gene expression. Indeed, histone hyperacetylation was shown to underpin increased and reduced mRNA transcription.2,76–78 HDACi including UF010 perturb cell cycle progression by downregulating E2F and MYC target genes required for DNA replication and mitosis (Figure 5D). YX968 at 0.1 μM did not alter cell cycle but markedly induced G1 arrest at 1 μM (Figure S7A). As YX968 at 1 μM but not 0.1 μM increased histone acetylation (Figures 2 and S4), the observed effects of YX968 on cell cycle again suggest that cell cycle perturbation by HDAC inhibition stems from altered gene expression due to global histone hyperacetylation rather than HDAC3/8 degradation. HDAC3 is recruited to enhancers that are also bound by HDAC1/2.2,76,79,80 Enhancer regulations by these three members of class I HDACs seem redundant, as entinostat that inhibits all three HDACs is more potent to block enhancer function than HDAC1/2-specific inhibitor or HDAC3-selective inhibitor.76 Therefore, these observations provide a possible explanation for the limited effects of HDAC3 degradation by YX968 on gene expression.

Our data show that YX968 suppressed cancer cell growth at a sub-μM concentration (Figures 6 and S6). As stated above, HDAC3 is a pan-essential gene.60,61 According to data available in the DepMap portal, HDAC8 is apparently not essential to cell survival but an oncogenic function for HDAC8 is well documented.45,81,82 Notably, the HDAC3-selective PROTAC XZ9002 is less potent than YX968 to suppress cancer cell growth31 (Figure S6C), suggesting that simultaneous degradation of HDAC3/8 confers a high potency on growth suppression. Inhibitors specific to HDAC3/8 were much less potent to kill cancer cells than YX968 (Figure 6B), arguing that non-enzymatic activity plays an important role in conferring cell survival. YX968 activates the proapoptotic gene BMF (Figures 5 and S5), so do conventional enzymatic inhibitors.54,59 At concentrations that effectively degraded HDAC3/8, YX968 did not induce histone hyperacetylation, broad transcriptional perturbation, p21 induction, and cell-cycle arrest (Figures 2, 5, 6, S4, and S5). Notably, a higher concentration of YX968 is required for suppressing cell growth than for effective HDAC3/8 degradation. This suggests that effects in addition to HDAC3/8 degradation such as HDAC1/2 inhibition may also contribute to induced cell demise by YX968. Significantly, YX968 dose-dependently induced CASP3 activation (Figure 6C), suggesting a major role for apoptosis in YX968-mediated cell death.

HDAC3 is implicated in BC progression and metastasis.83 Interestingly, HDAC3-mediated gene expression appears to be critical to tumorigenesis in Kras mutant non-small cell lung cancer; this mechanism also seems to confer resistance to the MEK (mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase) inhibitor trametinib.84 Genetic depletion and pharmacological inhibition of HDAC3 enhances cancer immunotherapy in mouse cancer models.85 HDAC8 also has well-established roles in epigenetic regulation44 and is implicated in several diseases including cancer.44 For examples, similar to HDAC3, HDAC8 is highly upregulated in BC and promotes progression and metastasis.81,86,87 Thus, simultaneously targeting HDAC3/8 is a promising approach in cancer therapy. Our data show that YX968 is more potent than XZ9002 in inhibiting cancer cell proliferation (Figures 6 and S6), indicating a potential synergistic effect by targeting both HDAC3 and HDAC8.

Limitations of the study

Our gene expression study is based on the MDA-MB-231 cell line. HDAC3/8-mediated gene expression programs may vary in different cell types. Another caveat is that histone acetylation was assessed only by Western blot for a limited set of histone acetylation marks. Other methods such as mass spectrometry should enable the detection and quantification of a broad range of substrates whose posttranslational acetylation may be affected by YX968.

STAR★METHODS

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Lead contact

Requests for resources and reagents should be directed to the lead contact: Daiqing Liao (dliao@ufl.edu).

Materials availability

The reagents generated in this study will be made available subject to a completed Materials Transfer Agreement.

Data and code availability

Section 1: Data. All data is available in the main text or the supplementary materials. RNA sequencing data associated with this study have been deposited to Gene Expression Omnibus with accession number GEO: GSE211758 and GSE228026. The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the iProX partner repository with the dataset identifiers PXD040941 and PXD040980.

Section2: Code. This paper does not report original code.

Section 3: Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND STUDY PARTICIPANT DETAILS

Cell lines and cell line culture

Cell lines used in this study were obtained from ATCC (details are described in the key resources table). All cells were cultured in DMEM (Corning, Cat. # 10013CV) supplemented with 10% bovine calf serum (Cytiva, Cat. # SH30072.03), 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Corning, Cat. # 30002CI). MDA-MB-231, MDA-MB-468, BT-549, HCC1806, MCF7 and T47D cell lines were derived from female subjects, where A549 and NCI-H1299 cell lines were derived from male subjects. All cell lines used in this study were authenticated by STR profiling and tested negative of mycoplasma contamination.

KEY RESOURCES TABLE.

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Antibodies | ||

|

| ||

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-HDAC1 | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat.# 34589; RRID: AB_2756821 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-HDAC3 | Abcam | Cat.# Ab32369; RRID: AB_732780 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-HDAC3 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Cat# sc-11417, RRID: AB_2118706 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-HDAC8 | Proteintech | Cat# 17548–1-AP, RRID: AB_2116926 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-HDAC2 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Cat# sc-7899, RRID: AB_2118563 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-HDAC2 | Abcam | Abcam Cat# ab32117, RRID: AB_732777 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-HDAC6 | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 7558, RRID: AB_10891804 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-RCOR1 (CoREST1) | Proteintech | Cat# 27686–1-AP, RRID: AB_2880947 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-MTA2 | Proteintech | Cat# 66195–1-Ig, RRID: AB_2877118 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-MIER2 | Proteintech | Cat# 11452–1-AP, RRID: AB_10733247 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-TBL1X | Proteintech | Cat# 13540–1-AP; RRID: AB_2199783 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-LSD1 | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 2139; RRID: AB_2070135 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-H3K27ac | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 8173; RRID: AB_10949503 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-H3K9ac | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 9649; RRID: AB_823528 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-Histone H3 | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 3638; RRID: AB_1642229 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-H2BK5ac | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 12799; RRID: AB_2636805 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-H4K8ac | Abcam | Cat# ab45166; RRID: AB_732937 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-SMC3 | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 5696; RRID: AB_10705575 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-acetyl SMC3 (Lys 105/106) | Millipore | Cat# MABE1073; RRID: AB_2877126 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-alpha/beta Tubulin | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 2148; RRID: AB_2288042 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-Caspase 3 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Cat# SC-7148; AB_637828 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-Cleaved Caspase 3 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Cat# 9664; AB_2070042 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-p21 | BD Biosciences | Cat# 556431; RRID: AB_396415 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-GAPDH | Proteintech | Cat# 60004–1-Ig; RRID: AB_2107436 |

| Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 7074; RRID: AB_2099233 | |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-Anti-mouse IgG, HRP-linked antibody | Cell Signaling Technology | Rabbit polyclonal anti-Anti-rabbit IgG, HRP-linked antibody |

|

| ||

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

|

| ||

| Compounds 13 to 27 | This article | N/A |

| RGFP966 | APExBIO | Cat# A8803; CAS: 1357389–11-7 |

| PCI 34051 | Cayman Chemical Company | Cat# 10444; CAS: 950762–95-5 |

| CB-5083 | Cayman Chemical Company | Cat# 19311; CAS: 1542705–92-9 |

| Bafilomycin A1 | Cayman Chemical Company | Cat# 11038; CAS: 88899–55-2 |

| MG132 (MG-132) | Sigma | Cat# C2211; CAS: 133407–82-6 |

| Bortezomib, Free Base | LC Laboratories | Cat# B-1408; CAS: 179324–69-7 |

| MLN4924 | ChemieTek | Cat# CT-M4924; CAS: 905579–51 -3 |

| 3-Methyladenine | Provided by Dr. William Dunn, University of Florida | CAS: 5142–23-4 |

| Recombinant HDAC1 protein | Enzo | Cat# BML-SE456–0050 |

| Recombinant HDAC3/NcoR2 proteins | BPS Bioscience | Cat# 50003 |

| Recombinant HDAC8 protein | BPS Bioscience | Cat# 50008 |

| Recombinant VHL complex protein (VHL, Elogin B and C) | US Biological | Cat# 029641 |

|

| ||

| Critical commercial assays | ||

|

| ||

| CellTiter-Glo | Promega | G7570 |

| HDAC-Glo™ I/II Assays and Screening System | Promega | G6420 |

| glutathione-donor beads | PerkinElmer | Cat# 6765300 |

| 6x His-acceptor beads | PerkinElmer | Cat# AL178M |

|

| ||

| Deposited data | ||

|

| ||

| Raw and analyzed RNA-seq data | This paper | GEO: GSE211758 |

| Raw and analyzed RNA-seq data | This paper | GEO: GSE228026 |

| Raw proteomic data | This paper | PXD040941 |

| Raw proteomic data | This paper | PXD040980 or MSV000091511 |

|

| ||

| Experimental models: Cell lines | ||

|

| ||

| Human: MDA-MB-231 | ATCC | Cat# HTB-26 |

| Human: MDA-MB-468 | ATCC | Cat# HTB-132 |

| Human: BT-549 | ATCC | Cat# HTB-122 |

| Human: HCC1806 | ATCC | Cat# CRL-2335 |

| Human: MCF7 | ATCC | Cat# HTB-22 |

| Human: T47D | ATCC | Cat# HTB-133 |

| Human: A549 | ATCC | Cat# CCL-185 |

| Human: H1299 (NCI-H1299) | ATCC | Cat# CRL-5803 |

|

| ||

| Software and algorithms | ||

|

| ||

| ImageJ | Schneider et al.88 | https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/ |

| GraphPad Prism | GraphPad Software Inc | https://www.graphpad.com/scientificsoftware/prism/ |

| Scaffold Q + S | Proteome Software | https://www.proteomesoftware.com/products/scaffold-qs |

| MaxQuant | Max Planck Institute | https://maxquant.org/ |

| HISAT2 | Kim et al.89 | http://daehwankimlab.github.io/hisat2/ |

| Samtools | Li et al.90 | http://samtools.sourceforge.net/ |

| Picard | “Picard Toolkit.” 2018. Broad Institute, GitHub Repository. | https://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/ |

| HTseq | Putri et al.91 | https://htseq.readthedocs.io/en/master/ |

| Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) software | Qiagen, Krämer et al.92 | http://www.ingenuity.com |

METHOD DETAILS

HDAC activity assays

Purified HDAC1, HDAC2, HDAC3 (in complex with the deacetylase activation domain of the human NCOR2 (amino acids 395–498)) and HDAC8 were purchased from Enzo Life Sciences (HDAC1, catalog # BML-SE456– 0050) and BPS Bioscience (HDAC2, catalog # 50002; HDAC3, catalog # 50003; and HDAC8, catalog # 50008), respectively. For inhibitory cooperativity assay, 200 nM VHL complex consisting of VHL, Elogin B and C was pre-mixed with compounds before adding to the HDAC protein. The enzyme activities were assayed using the HDAC-Glo I/II reagents (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s protocol as described previously.41 Briefly, inhibitor compounds were diluted in 3- to 5-fold serial dilution with the HDAC-Glo I/II assay buffer and tested in 10-point dose-response assay in triplicate in a white 96-well assay plate (Corning product # 3912). A positive control compound (e.g., trichostatin A) was similarly diluted. An equal volume of diluted HDAC enzyme (~1 ng/μL) in the HDAC-Glo I/II assay buffer was then added to each well with a diluted compound. Wells without an inhibitor and without HDAC enzymes were included as controls. The enzyme/inhibitor solutions were incubated at room temperature for 30 mins. The developer reagent was diluted 1:2,000 with the reconstituted HDAC-Glo I/II substrate solution. This solution was then added to the enzyme/inhibitor mixture at an equal volume. The plate was rotated for 30–60 seconds using an orbital shaker at 500 rpm and set at room temperature for 15 mins. Luminescence was detected using a BMG POLARstar Omega microplate reader. IC50 values were obtained from dose-response assays using log(inhibitor) vs. response (three parameters) and least-square fit implemented in the Prism 9 software.

Colony formation assay

Cells were cultured with DMEM supplemented with 10% bovine calf serum, penicillin to 10 units/mL, and streptomycin to 10 μg/mL. Colony formation assays were conducted essentially as described.31 Briefly, cells (~1,000 cells/well) were seeded in a 24-well plate in quadruplicates. At 24 h after seeding, DMSO, a PROTAC compound, or an HDAC inhibitor was added at a specified concentration. Medium was replaced with freshly prepared medium containing DMSO, a PROTAC, or an HDAC inhibitor every five days until visible colonies appeared, typically in 15 to 20 days after initial cell seeding. Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min and stained with 2% methylene blue in 20% ethanol for 30 min to 1 h. The cells were washed twice with distilled water and dried in air.

Western blotting

Cell cultures were exposed to compounds as indicated in relevant figures. Medium was removed from culture plate, and 1x RIPA buffer [50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS, weight/volume), 0.5% sodium deoxycholate (weight/volume), 1% IGEPAL CA-630 (weight/volume)] was then added. The plates were frozen at −80°C overnight and thawed at room temperature. The total cell lysates were mixed with one filth volume of 6x SDS sample buffer [0.375 M Tris pH 6.8, 12% SDS (weight/volume), 60% glycerol (weight/volume), 0.6 M dithiothreitol (DTT), 0.06% bromophenol blue (weight/volume)], heated at 95°C for 5 min and cooled on ice. The lysates were cleared by centrifugation and then subjected to SDS-PAGE using a precast Novex™ WedgeWell™ Tris-Glycine 4 to 20% gradient gel (ThermoFisher, catalog # XP04205BOX), and Western blotting essentially as described.93 Antibodies used for Western blotting include anti-HDAC3 (Abcam, Ab32369, 1:5,000 dilution), anti-HDAC3 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, SC-11417, 1:5,000 dilution), anti-HDAC8 (ProteinTech, 17548–1-AP, 1:10,000 dilution), anti-HDAC1 (Cell Signaling Technology, 34589, 1:10,000 dilution), anti-HDAC2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, SC-7899, 1:10,000 dilution), anti-HDAC6 (Cell Signaling Technology, 7558, 1:1,000 dilution), anti-histone H3 (Cell Signaling Technology, 3638, 1:10,000 dilution), anti-histone H3 acetylated at lysine 27 (H3K27ac, Cell Signaling Technology, 8173, 1:10,000 dilution), anti-histone H3 acetylated at lysine 9 (H3K9ac, Cell Signaling Technology, 9649, 1:10,000 dilution), anti-histone H2B acetylated at lysine 5 (H2BK5ac, Cell Signaling Technology, 15799), anti-histone H4 acetylated at lysine 8 (H4K8ac, Epitomics, 1796–1, 1:10,000 dilution), anti-SMC3 (Cell Signaling Technology, 5696, 1:2,000 dilution), anti-SMC3 acetylated at lysines 105 and 106 (Millipore-Sigma, MABE1073, 1:2,000 dilution), anti-a-tubulin (Sigma-Aldrich, T5168, 1:20,000 dilution), anti-Caspase 3 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, SC-7148, 1:10,000 dilution), anti-Cleaved Caspase 3 (Cell Signaling Technology, 9664, 1:3,000 dilution), anti-p21 (BD Biosciences, 556431, 1:5,000 dilution), anti-GAPDH (ProteinTech, 60004–1-Ig, 1:10,000 dilution). Protein band intensities in Western blots were quantified using ImageJ. The band intensities of HDAC3 or HDAC8 were normalized against that of a loading control (Tubulin or GAPDH).

Protein quantification and DC50 determination

The levels of a protein band in a Western blot image were digitized using the NIH IamgeJ program. The levels of a POI were then normalized against that of a loading control. The relative protein abundance was calculated based on the ratio of the levels of a POI in cells treated with a PROTAC to that in cells treated with solvent (DMSO). For determining DC50 values, the quantified levels of a POI in a dose-response experiment were fitted into a dose-response curve using log(inhibitor) vs. response (three parameters) and least-square fit implemented in the Prism 9 software.

AlphaLISA assay for ternary complex formation

10 μL of 60 nM His-tagged recombinant HDAC1, 3, and 8 protein and 10 μL of 60 nM recombinant active glutathione-S-transferase (GST)-tagged VHL–Elongin B–Elongin C complex (Cat. No. 029641, US Biological) was incubated with varying concentrations of a test compounds (YX968) in fivefold serial dilutions. After 45 min of incubation at room temperature, 5 μl of alpha glutathione-donor beads (160 μg/mL, Cat. No. 6765300, PerkinElmer) were added to each well and incubated for 60 min. Thereafter, 5 μL of 6× His-acceptor beads (160 μg/mL, Cat. No. AL128M, PerkinElmer) were added to each well for an additional 60 min at room temperature. The resulting mixture was then scanned using the Alpha program on Biotek’s Synergy Neo2 multimode plate reader. The data were expressed as AlphaLISA signal and plotted against different concentrations of compounds. The data was plotted against different concentrations of compounds using GraphPad Prism 9 software.

RNA-seq experiment

MDA-MB-231 cells were cultured in 6-well plate and treated with DMSO, 3, 30 nM of YX968 for 14 h, 50 nM YX968, or YX968-NC for 6 or 24h. Total RNAs were isolated using the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen). Total RNAs were used for RNA-seq Poly A library constructions and sequencing was done with 50M raw reads/sample using the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 S4 2×150 platform at the Interdisciplinary Center for Biotechnology Research, University of Florida. For RNA-seq data analysis, we used the RNA-seq data analysis pipeline reported previously.94,95 In brief, we aligned fastq files to Genome Reference Consortium Human Build 38 (GRCh38) using HISAT2 (version 2.2.1–3n). We performed transcripts assembling using StringTie (version v1.3.4) with RefSeq as transcripts ID. We called the normalized counts (by FPKM) using Ballgown (version v2.12.0). We performed differential expression analysis using edgeR96; and the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) with fold-change of ≥|2| and p ≤0.01 were used for pathway enrichment analysis with the Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) software.92

Proteomics studies

TMT-based proteomics

Sample preparation and and LC-MS/MS analysis.

MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with DMSO or 100 nM YX968 for 2 h. Cells were harvested by centrifugation and washed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) before snap freezing in liquid nitrogen. Cells were lysed by addition of lysis buffer (8 M Urea, 50 mM NaCl, 50 mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (EPPS) pH 8.5, Protease and Phosphatase inhibitors) and homogenization by bead beating (BioSpec) for three repeats of 30 seconds at 2400. Bradford assay was used to determine the final protein concentration in the clarified cell lysate. Total protein from cell pellets was reduced, alkylated, and purified by chloroform/methanol extraction prior to digestion with sequencing grade modified porcine trypsin (Promega). Tryptic peptides were labeled using tandem mass tag isobaric labeling reagents (Thermo) following the manufacturer’s instructions and combined into one 11-plex sample group. The labeled peptide multiplex was separated into 46 fractions on a 100 × 1.0 mm Acquity BEH C18 column (Waters) using an UltiMate 3000 UHPLC system (Thermo) with a 50 min gradient from 99:1 to 60:40 buffer A:B ratio under basic pH conditions, and then consolidated into 18 super-fractions. Each super-fraction was then further separated by reverse phase XSelect CSH C18 2.5 um resin (Waters) on an in-line 150 × 0.075 mm column using an UltiMate 3000 RSLCnano system (Thermo). Peptides were eluted using a 75 min gradient from 98:2 to 60:40 buffer A:B ratio. Eluted peptides were ionized by electrospray (2.4 kV) followed by mass spectrometric analysis on an Orbitrap Eclipse Tribrid mass spectrometer (Thermo) using multi-notch MS3 parameters. MS data were acquired using the FTMS analyzer in top-speed profile mode at a resolution of 120,000 over a range of 375 to 1500 m/z. Following CID activation with normalized collision energy of 35.0, MS/MS data were acquired using the ion trap analyzer in centroid mode and normal mass range. Using synchronous precursor selection, up to 10 MS/MS precursors were selected for HCD activation with normalized collision energy of 65.0, followed by acquisition of MS3 reporter ion data using the FTMS analyzer in profile mode at a resolution of 50,000 over a range of 100–500 m/z. Buffer A = 0.1% formic acid, 0.5% acetonitrile; Buffer B = 0.1% formic acid, 99.9% acetonitrile; Both buffers adjusted to pH 10 with ammonium hydroxide for offline separation.

Data processing and analysis

Proteins were identified and MS3 reporter ions quantified using MaxQuant (version 2.0.3.0; Max Planck Institute) against the Homo sapiens UniprotKB database (March 2021) with a parent ion tolerance of 3 ppm, a fragment ion tolerance of 0.5 Da, and a reporter ion tolerance of 0.003 Da. Scaffold Q+S (Proteome Software) was used to verify MS/MS based peptide and protein identifications (protein identifications were accepted if they could be established with less than 1.0% false discovery and contained at least 2 identified peptides; protein probabilities were assigned by the Protein Prophet algorithm97 and to perform reporter ion-based statistical analysis. Protein TMT MS3 reporter ion intensity values were assessed for quality using ProteiNorm for a systematic evaluation of normalization methods.98 Cyclic loess normalization99 was utilized since it had the highest intragroup correlation and the lowest variance amongst the samples. Statistical analysis was performed using Linear Models for Microarray Data (limma) with empirical Bayes (eBayes) smoothing to the standard errors.99 All biochemical curves and associated statistical analyses were produced using Prism 8 (GraphPad Software).

DiaPASEF label-free proteomics

Sample preparation for label-free quantitative mass spectrometry

MM.1S cells were treated with DMSO or 50 nM YX968 for 3 h. Cells were harvested by centrifugation and washed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) before snap freezing in liquid nitrogen.

Cells were lysed by addition of lysis buffer (8 M Urea, 50 mM NaCl, 50 mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (EPPS) pH 8.5, Protease and Phosphatase inhibitors) and homogenization by bead beating (BioSpec) for three repeats of 30 seconds at 2400. Bradford assay was used to determine the final protein concentration in the clarified cell lysate. 50 μg of protein for each sample was reduced, alkylated and precipitated using methanol/chloroform as previously described100 and the resulting washed precipitated protein was allowed to air dry. Precipitated protein was resuspended in 4 M Urea, 50 mM HEPES pH 7.4, followed by dilution to 1 M urea with the addition of 200 mM EPPS, pH 8. Proteins were first digested with LysC (1:50; enzyme: protein) for 12 h at RT. The LysC digestion was diluted to 0.5 M Urea with 200 mM EPPS pH 8 followed by digestion with trypsin (1:50; enzyme: protein) for 6 h at 37°C. Sample digests were acidified with formic acid to a pH of 2–3 prior to desalting using C18 solid phase extraction plates (SOLA, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Desalted peptides were dried in a vacuum-centrifuged and reconstituted in 0.1% formic acid for LC-MS analysis.

Data were collected using a TimsTOF Pro2 (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany) coupled to a nanoElute LC pump (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany) via a CaptiveSpray nano-electrospray source. Peptides were separated on a reversed-phase C18 column (25 cm × 75 μm ID, 1.6 μM, IonOpticks, Australia) containing an integrated captive spray emitter. Peptides were separated using a 50 min gradient of 2–30% buffer B (acetonitrile in 0.1% formic acid) with a flow rate of 250 nL/min and column temperature maintained at 50°C.

DDA (data-dependent acquisition) was performed in parallel accumulation-serial fragmentation (PASEF) mode to determine effective ion mobility windows for downstream diaPASEF (data-independent acquisition PASEF) data collection.101 The ddaPASEF parameters included: 100% duty cycle using accumulation and ramp times of 50 ms each, 1 TIMS-MS scan and 10 PASEF ramps per acquisition cycle. The TIMS-MS survey scan was acquired between 100 – 1700 m/z and 1/k0 of 0.7 – 1.3 V.s/cm2. Precursors with 1 – 5 charges were selected and those that reached an intensity threshold of 20,000 arbitrary units were actively excluded for 0.4 min. The quadrupole isolation width was set to 2 m/z for m/z <700 and 3 m/z for m/z >800, with the m/z between 700–800 m/z being interpolated linearly. The TIMS elution voltages were calibrated linearly with three points (Agilent ESI-L Tuning Mix Ions; 622, 922, 1,222 m/z) to determine the reduced ion mobility coefficients (1/K0). To perform diaPASEF, the precursor distribution in the DDA m/z-ion mobility plane was used to design an acquisition scheme for DIA data collection which included two windows in each 50 ms diaPASEF scan. Data was acquired using sixteen of these 25 Da precursor double window scans (creating 32 windows) which covered the diagonal scan line for doubly and triply charged precursors, with singly charged precursors able to be excluded by their position in the m/z-ion mobility plane. These precursor isolation windows were defined between 400 – 1200 m/z and 1/k0 of 0.7 – 1.3 V.s/cm2.

LC-MS data analysis

The diaPASEF raw file processing and controlling peptide and protein level false discovery rates, assembling proteins from peptides, and protein quantification from peptides was performed using directDIA analysis in Spectronaut 14 (Version 15.5.211111.50606, Biognosys). DirectDIA mode includes first extracting the DIA data into a collection of MS2 spectra which are searched using Spectronaut’s Pulsar search engine. The search results are then used to generate a spectral library which is then employed for the targeted analysis of the DIA data. MS/MS spectra were searched against a Swissprot human database (January 2021). Database search criteria largely followed the default settings for directDIA including tryptic with two missed cleavages, fixed carbamidomethylation of cysteine, and variable oxidation of methionine and acetylation of protein N-termini and precursor Q-value (FDR) cut-off of 0.01. Precursor quantification was performed using the default of MS2 areas, cross run normalization was set to localized and imputation strategy was set to no imputation. Proteins with poor quality data were excluded from further analysis (summed abundance across channels of <100 and mean number of precursors used for quantification <2). Protein abundances were scaled using in-house scripts in the R framework and statistical analysis was carried out using the limma package within the R framework.99 All biochemical curves and associated statistical analyses were produced using Prism 8 (GraphPad Software).

Chemistry methods

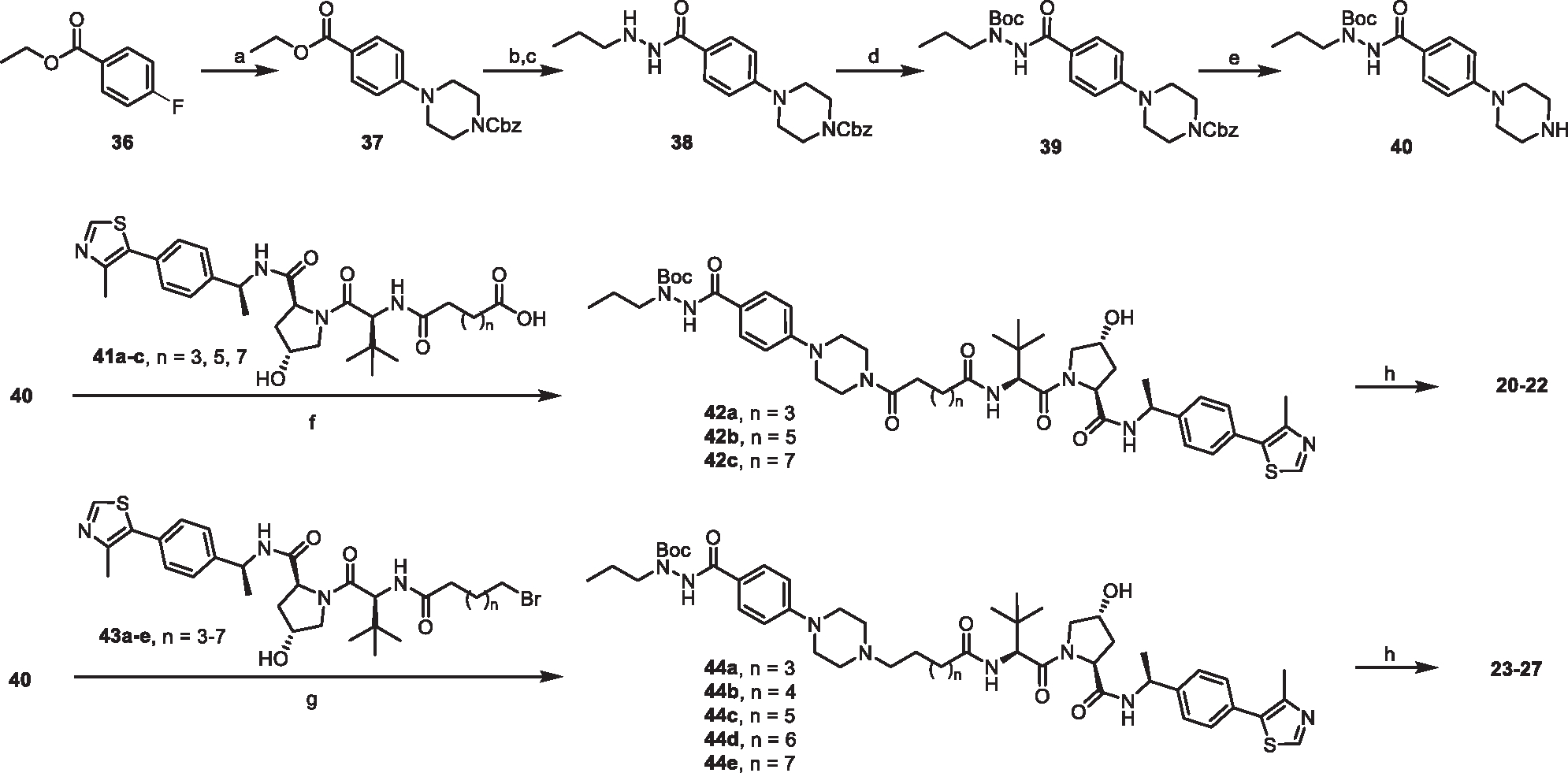

The synthesis of compounds 14–19 is depicted in Scheme 1 image below. Briefly, methyl 4-fluorobenzoate (28) was reacted with acetyl or methyl substituted piperazine or 1,4-diazepane (29a-d). The resulting intermediates 30a-d were converted to the corresponding hydrazides 31a-d by refluxing with hydrazine monohydrate in EtOH. Reductive amination of 31a-d with propionaldehyde yielded compounds 14, 15, 18, and 19. Compounds 16 and 17 were obtained through reacting methyl 4-formylbenzoate (32) with substituted piperazine followed by the same procedures as described above. The warhead precursor (40) for PROTAC synthesis was prepared by coupling 36 with mono-Cbz protected piperazine to yield 37, followed by conversion to hydrazide 38, Boc protection, and removal of Cbz (Scheme 2 image below). PROTACs 20–22 were prepared by coupling 40 with the corresponding VHL-linker-carboxylic acids 41a-c102,103 followed by de-Boc. PROTACs 23–27 were prepared by coupling 40 with the corresponding VHL-linker-bromides 43a-e followed by de-Boc (Scheme 2 image below).

Scheme 1. Synthesis of the compounds 14–19a.

aReagents and conditions: (a) K2CO3, DMF, 90°C, 12 h; (b) Hydrazine monohydrate, EtOH, reflux, overnight; (c) Propionaldehyde, THF/MeOH, rt, 30 min, then NaBH4, MeOH, rt, 2 h; (d) NaBH(OAc)3, DCM, rt, overnight.

Scheme 2. Synthesis of compounds 20–27a.

aReagents and conditions: (a) 1-Cbz-piperazine, K2CO3, DMF, 90°C, 12 h; (b) Hydrazine monohydrate, EtOH, reflux, overnight; (c) Propionaldehyde, THF/MeOH, rt, 30 min, then NaBH4, MeOH, rt, 2 h; (d) Boc2O, TEA, DCM, rt, overnight; (e) H2, Pd/C (10%), MeOH, 4 h; (f) HATU, DIPEA, DCM, rt, overnight; (g) K2CO3, KI, MeCN, 65°C, overnight; (h) TFA, DCM, rt, 2 h.

General chemistry methods

DMF and DCM were obtained via a solvent purification system by filtering through two columns packed with activated alumina and 4 Å molecular sieve, respectively. Water was purified with a Milli-Q Simplicity 185 Water Purification System (Merck Millipore). All other chemicals and solvents obtained from commercial supliers were used without further purification. Flash chromatography was performed using silica gel (230–400 mesh) as the stationary phase. Reaction progress was monitored by thin-layer chromatography (silica-coated glass plates) and visualized by 256 nm and 365 nm UV light, and/or by LC-MS. 1 H NMR spectra were recorded in CDCl3 or CD3OD at 600 MHz, and 13C NMR spectrum was recorded at 151 MHz using a Bruker (Billerica, MA) DRX Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectrometer. Chemical shifts δ are given in ppm using tetramethylsilane as an internal standard. Multiplicities of NMR signals are designated as singlet (s), doublet (d), doublet of doublets (dd), triplet (t), quartet (q), A triplet of doublets (td), A doublet of triplets (dt), and multiplet (m). All final compounds for biological testing were of ≥95.0% purity as analyzed by LC-MS, performed on an Advion AVANT LC system with the expression CMS using a Thermo Accucore™ Vanquish™ C18+ UHPLC Column (1.5 μm, 50 × 2.1 mm) at 40°C. Gradient elution was used for UHPLC with a mobile phase of acetonitrile and water containing 0.1% formic acid. High resolution mass spectra (HRMS) were recorded on an Agilent 6230 Time-of-Flight (TOF) mass spectrometer.

General procedure A for the synthesis of 30a-d: Methyl 4-fluorobenzoate (1.0 equiv) was dissolved in DMF, followed by the addition of K2CO3 (3.0 equiv) and substituted piperazine or 1,4-diazepane (2.0 equiv). The mixture was heated to 90°C and stirred overnight. The reaction was cooled to room temperature and water and EtOAc were added. The organic phase was washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4, filtered, concentrated. The residue was purified by Flash chromatography using to yield desired compounds.

Synthesis and characterization of specific compounds

methyl 4-(4-acetylpiperazin-1-yl)benzoate (30a):

By using general procedure A, 275 mg 30a (1.05 mmol, 72% yield) was obtained from methyl 4-fluorobenzoate (200 mg, 1.30 mmol) and 1-(piperazin-1-yl)ethan-1-one (332 mg, 2.60 mmol) as white solid. 1H NMR (600 MHz, Chloroform-d) δ 7.99 – 7.90 (m, 2H), 6.91 – 6.83 (m, 2H), 3.86 (s, 3H), 3.80 – 3.74 (m, 2H), 3.66 – 3.60 (m, 2H), 3.39 – 3.30 (m, 4H), 2.14 (s, 3H). ESI+, m/z 263.3 [M+H] +.

methyl 4-(4-methylpiperazin-1-yl)benzoate (30b).

By using general procedure A, 196 mg 30b (0.84 mmol, 65% yield) was obtained from methyl 4-fluorobenzoate (200 mg, 1.30 mmol) and 1-methylpiperazine (260 mg, 2.60 mmol) as white solid. 1H NMR (600 MHz, Chloroform-d) δ 7.94 – 7.90 (m, 2H), 6.88 – 6.85 (m, 2H), 3.86 (s, 3H), 3.38 – 3.33 (m, 4H), 2.58 – 2.54 (m, 4H), 2.35 (s, 3H). ESI+, m/z 235.3 [M+H] +.

methyl 4-(4-acetyl-1,4-diazepan-1-yl)benzoate (30c).

By using general procedure A, 193 mg 30c (0.70 mmol, 51% yield) was obtained from methyl 4-fluorobenzoate (200 mg, 1.30 mmol) and 1-(1,4-diazepan-1-yl)ethan-1-one (369 mg, 2.60 mmol) as light yellow solid.1H NMR (600 MHz, Chloroform-d) δ 7.88 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 2H), 6.68 – 6.62 (m, 2H), 3.85 (s, 3H), 3.65 – 3.61 (m, 2H), 3.54 (t, J = 6.3 Hz, 2H), 2.74 – 2.70 (m, 2H), 2.59 – 2.54 (m, 2H), 2.39 (s, 3H), 2.03 (p, J = 6.2 Hz, 2H). ESI+, m/z 277.3 [M+H] +.

methyl 4-(4-methyl-1,4-diazepan-1-yl)benzoate (30d).

By using general procedure A, 193 mg 28d (0.70 mmol, 58% yield) was obtained from methyl 4-fluorobenzoate (200 mg, 1.30 mmol) and 1-methyl-1,4-diazepane (296 mg, 2.60 mmol) as light yellow solid.1H NMR (600 MHz, Chloroform-d) δ 7.88 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 2H), 6.68 – 6.62 (m, 2H), 3.85 (s, 3H), 3.65 – 3.61 (m, 2H), 3.54 (t, J = 6.3 Hz, 2H), 2.74 – 2.70 (m, 2H), 2.59 – 2.54 (m, 2H), 2.39 (s, 3H), 2.03 (p, J = 6.2 Hz, 2H). ESI+, m/z 249.4 [M+H] +.

General procedure B for the synthesis of 34a and 34b: A mixture of corresponding amine (1.0 equiv) and aldehyde (1.0 equiv) in anhydrous DCM (0.06 M) was stirred for 10 min at rt, and then NaBH(OAc)3 (2.0 equiv) was added. The reaction mixture was stirred for 2h before being quenched by 10% aqueous K2CO3 solution, water and EtOAc were added. The organic phase was washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4, filtered, concentrated. The residue was purified by Flash chromatography using to yield desired compounds.

methyl 4-((4-acetylpiperazin-1-yl)methyl)benzoate (34a).

By using general procedure B, 311 mg 34a (1.12 mmol, 92% yield) was obtained from methyl 4-formylbenzoate (200 mg, 1.22 mmol) and 1-(piperazin-1-yl)ethan-1-one (234 mg, 1.83 mmol) as light yellow oil. 1H NMR (600 MHz, Chloroform-d) δ 7.91 – 7.86 (m, 2H), 7.33 – 7.27 (m, 2H), 3.80 (s, 3H), 3.54 – 3.48 (m, 2H), 3.48 – 3.43 (m, 2H), 3.40 – 3.33 (m, 2H), 2.37 – 2.26 (m, 4H), 1.97 (s, 3H). ESI+, m/z 277.4 [M+H] +.

(1f) methyl 4-((4-methylpiperazin-1-yl)methyl)benzoate (34b).

By using general procedure B, 650 mg 34b (2.62 mmol, 86% yield) was obtained from 4-formylbenzoate (500 mg, 3.05 mmol) and 1-methylpiperazine (457 mg, 4.57 mmol) as light yellow oil. 1H NMR (600 MHz, Chloroform-d) δ 8.00 – 7.96 (m, 2H), 7.40 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 2H), 3.91 (s, 3H), 3.55 (s, 2H), 2.73 – 2.32 (m, 8H), 2.29 (s, 3H). ESI+, m/z 249.2[M+H] +.

General procedure C for the synthesis of compound 14 to 19. To a solution of corresponding ester (1.0 equiv) and hydrazine monohydrate (10.0 equiv) in ethanol was refluxed for 24 h before cooling to the room temperature. Solvent was removed under vacuum. The resulting slurry 30a to d, 34a and 34b was dissolved in MeOH/THF (5:1). Propionyl anhydride (2.0 equiv) was added, and the reaction was stirred at room temperature for 1h. The solvent and excessive propionyl anhydride were removed under vacuum and the resulting crude was redissolved in methanol. NaBH4 was added portion wise under ice bath and the reaction was continued for 2h before it was quenched by water. EtOAc was added and the organic phase was separated and washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4, filtered and concentrated. The residue was purified by Flash chromatography to yield desired compounds.

4-(4-acetylpiperazin-1-yl)-N′-propylbenzohydrazide (14).

By using general procedure C, 68 mg 14 (0.22 mmol, 39% yield) was obtained from propionyl anhydride (66 mg, 1.15 mmol) and 30a (150 mg, 0.57 mmol) as white solid. 1H NMR (600 MHz, Chloroform-d) δ 7.68 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H), 7.52 (s, 1H), 6.90 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 3.84 – 3.75 (m, 2H), 3.68 – 3.58 (m, 2H), 3.30 (dt, J = 22.8, 5.1 Hz, 4H), 2.89 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H), 2.15 (s, 3H), 1.57 (q, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H), 0.97 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 3H). ESI+, m/z 305.2 [M+H] +.

4-(4-methylpiperazin-1-yl)-N′-propylbenzohydrazide (15).

By using general procedure C, 48 mg 14 (0.17 mmol, 37% yield) was obtained from propionyl anhydride (54 mg, 0.93 mmol) and 30b (100 mg, 0.47 mmol) as white solid. 1H NMR (600 MHz, Chloroform-d) δ 7.70 – 7.63 (m, 2H), 7.53 (s, 1H), 6.94 – 6.87 (m, 2H), 3.36 – 3.28 (m, 4H), 2.89 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H), 2.62 – 2.51 (m, 4H), 2.35 (s, 3H), 1.56 (q, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H), 0.97 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 3H). ESI+, m/z 277.3 [M+H] +.

4-((4-acetylpiperazin-1-yl)methyl)-N′-propylbenzohydrazide (16).

By using general procedure C, 60 mg 16 (0.19 mmol, 52% yield) was obtained from propionyl anhydride (42 mg, 0.72 mmol) and 34a (100 mg, 0.36 mmol) as white solid. 1H NMR (600 MHz, Chloroform-d) δ 7.73 – 7.69 (m, 2H), 7.60 (s, 1H), 7.41 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H), 3.62 (t, J = 5.1 Hz, 2H), 3.56 (s, 2H), 3.47 – 3.44 (m, 2H), 2.91 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 2.45 – 2.40 (m, 4H), 2.08 (s, 3H), 1.58 (q, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H), 0.98 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 3H). ESI+, m/z 319.2 [M+H] +.

4-((4-acetylpiperazin-1-yl)methyl)-N′-propylbenzohydrazide (17).

By using general procedure C, 41 mg 17 (0.14 mmol, 51% yield) was obtained from propionyl anhydride (32 mg, 0.56 mmol) and 34b (70 mg, 0.28 mmol) as white solid. 1H NMR (600 MHz, Chloroform-d) δ 7.73 – 7.69 (m, 2H), 7.60 (s, 1H), 7.41 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H), 3.62 (t, J = 5.1 Hz, 2H), 3.56 (s, 2H), 3.47 – 3.44 (m, 2H), 2.91 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 2.45 – 2.40 (m, 4H), 2.08 (s, 3H), 1.58 (q, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H), 0.98 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 3H). ESI+, m/z 291.4 [M+H] +.

4-(4-acetyl-1,4-diazepan-1-yl)-N′-propylbenzohydrazide (18).

By using general procedure C, 10 mg 18 (0.03 mmol, 22% yield) was obtained from propionyl anhydride (17 mg, 0.28mmol) and 30c (40 mg, 0.14 mmol) as colorless oil. 1H NMR (600 MHz, Chloroform-d) δ 7.68 – 7.63 (m, 2H), 7.52 (s, 1H), 6.72 – 6.67 (m, 2H), 3.79 – 3.58 (m, 6H), 3.47 – 3.35 (m, 2H), 2.89 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H), 2.13 – 1.98 (m, 5H), 1.60 – 1.54 (m, 2H), 0.97 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 3H). ESI+, m/z 319.3 [M+H] +.

4-(4-methyl-1,4-diazepan-1-yl)-N′-propylbenzohydrazide (19).

By using general procedure C, 4.5 mg 19 (0.015 mmol, 19% yield) was obtained from propionyl anhydride (9 mg, 0.16 mmol) and 30d (20 mg, 0.08 mmol) as white solid. 1H NMR (600 MHz, Chloroform-d) δ 7.66 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 2H), 7.44 (s, 1H), 6.69 – 6.65 (m, 2H), 3.92 – 3.86 (m, 1H), 3.69 – 3.62 (m, 1H), 3.56 – 3.52 (m, 2H), 3.24 – 3.19 (m, 1H), 3.11 – 3.06 (m, 1H), 2.95 – 2.88 (m, 3H), 2.85 – 2.80 (m, 1H), 2.66 (s, 3H), 2.55 – 2.51 (m, 1H), 2.08 – 1.99 (m, 1H), 1.59 – 1.54 (m, 2H), 0.97 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 3H). ESI+, m/z 291.3 [M+H]+.

benzyl 4-(4-(ethoxycarbonyl)phenyl)piperazine-1-carboxylate (37).

To a solution of Ethyl 4-fluorobenzoate (2.0 g, 11.89 mmol) in DMF (20 mL) was added K2CO3 (4.9 g, 35.68 mmol) and benzyl piperazine-1-carboxylate (5.24 g, 23.78 mmol). The mixture was heated to 90°C and stirred overnight. The reaction was cooled to room temperature and diluted with water (50 mL) and EtOAc (200 mL). The organic phase was washed with brine (50 mL), dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated. The residue was purified by silica gel column chromatography using DCM/MeOH (50:1) to yield 37 (2.74 g, 63%) as a white solid. 1H NMR (600 MHz, Chloroform-d) δ 7.97 – 7.92 (m, 2H), 7.40 – 7.31 (m, 5H), 6.89 – 6.84 (m, 2H), 5.17 (s, 2H), 4.33 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 3.71 – 3.62 (m, 4H), 3.31 (s, 4H), 1.37 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H). ESI+, m/z 369.2 [M+H] +.

benzyl 4-(4-(2-ethylhydrazine-1-carbonyl)phenyl)piperazine-1-carboxylate (38).