Abstract

Sarcopenia, or age-related decline in muscle form and function, exerts high personal, societal, and economic burdens when untreated. Integrity and function of the neuromuscular junction (NMJ), as the nexus between the nervous and muscular systems, is critical for input and dependable neural control of muscle force generation. As such, the NMJ has long been a site of keen interest in the context of skeletal muscle function deficits during aging and in the context of sarcopenia. Historically, changes of NMJ morphology during aging have been investigated extensively but primarily in aged rodent models. Aged rodents have consistently shown features of NMJ endplate fragmentation and denervation. Yet, the presence of NMJ changes in older humans remains controversial, and conflicting findings have been reported. This review article describes the physiological processes involved in NMJ transmission, discusses the evidence that supports NMJ transmission failure as a possible contributor to sarcopenia, and speculates on the potential of targeting these defects for therapeutic development. The technical approaches that are available for assessment of NMJ transmission, whether each approach has been applied in the context of aging and sarcopenia, and the associated findings are summarized. Like morphological studies, age-related NMJ transmission deficits have primarily been studied in rodents. In preclinical studies, isolated synaptic electrophysiology recordings of endplate currents or potentials have been mostly used, and paradoxically, have shown enhancement, rather than failure, with aging. Yet, in vivo assessment of single muscle fiber action potential generation using single fiber electromyography and nerve-stimulated muscle force measurements show evidence of NMJ failure in aged mice and rats. Together these findings suggest that endplate response enhancement may be a compensatory response to post-synaptic mechanisms of NMJ transmission failure in aged rodents. Possible, but underexplored, mechanisms of this failure are discussed including the simplification of post-synaptic folding and altered voltage-gated sodium channel clustering or function. In humans, there is limited clinical data that has selectively investigated single synaptic function in the context of aging. If sarcopenic older adults turn out to exhibit notable impairments in NMJ transmission (this has yet to be examined but based on available evidence appears to be plausible) then these NMJ transmission defects present a well-defined biological mechanism and offer a well-defined pathway for clinical implementation. Investigation of small molecules that are currently available clinically or being testing clinically in other disorders may provide a rapid route for development of interventions for older adults impacted by sarcopenia.

Keywords: Dynapenia, Older adults, Muscle weakness, Physical function, Mobility, Skeletal muscle function deficits

1. Introduction

Sarcopenia, or age-related decline in muscle form and function, is classified as a specific disorder (Anker et al., 2016; Cao and Morley, 2016) that is associated with negative health effects and risk factors in older adults. The prevalence of sarcopenia varies tremendously depending on the operational definition used, but when a definition based on the presence of low muscle mass and low muscle strength or low physical performance is used the prevalence of sarcopenia is upwards of 30% in community-dwelling older adults (Cruz-Jentoft et al., 2010). Sarcopenia has been linked to increased risk of falls and fractures (Bischoff-Ferrari et al., 2015; Schaap et al., 2018), the inability to perform activities of daily living (Malmstrom et al., 2016; McGrath et al., 2019a), the development of impaired mobility (Morley et al., 2011; Manini et al., 2007), lowered quality of life (Beaudart et al., 2017), loss of independence or need for long-term care placement (Dos Santos et al., 2017; Akune et al., 2014; Steffl et al., 2017), and death (De Buyser et al., 2016; McGrath et al., 2019b). Thus, sarcopenia has high personal, societal, and economic burdens when untreated.

Although there is no consensus on the operational definition of sarcopenia, the most recent (2019) definition set forth by the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People describes sarcopenia as “muscle failure” (Cruz-Jentoft et al., 2019). This definition represents a shift in the conceptualization of sarcopenia away from low muscle mass towards low muscle function (e.g., weakness) being the principal determinant and fundamental crux of sarcopenia (note that age-related muscle weakness is also referred to as “dynapenia” in the literature (Manini and Clark, 2011); Clark and Manini, 2008). The shift in focus from low muscle mass to low muscle strength as the key characteristic of sarcopenia is based on findings that include the fact that low grip strength is independently associated with recurrent falls (Schaap et al., 2018), low grip strength is a stronger predictor of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality than systolic blood pressure (Leong et al., 2015), and both low grip and leg extensor strength is associated with mobility impairment (Manini et al., 2007; Alley et al., 2014).

It is well-accepted that muscle strength is determined by a combination of neurologic and skeletal muscle factors (Clark and Manini, 2008; Narici and Maffulli, 2010; Russ et al., 2012; Enoka et al., 2003; Tieland et al., 2018). Integrity and function of the neuromuscular junction (NMJ), as the nexus between these two systems, is critical for input and dependable neural control of muscle force generation. As such, the NMJ has long been a site of keen interest in the context of skeletal muscle function deficits during aging and in the context of sarcopenia (Taetzsch and Valdez, 2018; Li et al., 2018; Badawi and Nishimune, 2020; Bao et al., 2020; NCHS, 2018; Jones et al., 2017; Anagnostou and Hepple, 2020; Rudolf et al., 2016; Tintignac et al., 2015; Hepple and Rice, 2016; Iyer et al., 2021a; Pratt et al., 2021; Fahim and Robbins, 1982; Smith and Rosenheimer, 1982; Valdez et al., 2010; Courtney and Steinbach, 1981; Jang and Van, 2011). The NMJ is a highly specialized chemical synapse responsible for reliably converting minute nerve action potentials from the presynaptic motor neuron to trigger contraction of the postsynaptic muscle fiber. Thus, deficits in NMJ transmission directly result in reduced force output. In this article we will describe the physiological processes involved in NMJ transmission, discuss the evidence that supports NMJ transmission failure as a possible contributor to sarcopenia, and the potential of targeting these defects for therapeutic development.

2. Brief overview of NMJ structure and evidence for age-related instability

The NMJ is a simple synapse between the nerve terminal of the spinal motor neuron and the surface of a striated muscle fiber cell membrane (i.e., the sarcolemma). While it is a simple synapse, the NMJ is nonetheless complex in both its anatomical structure and physiological function. Mammalian NMJs are very small (~30 μm long) when compared to the length of the muscle fibers they innervate, which are commonly > 100 mm and can run upwards of 600 mm (e.g., the sartorius, the longest muscle in the body) (Slater, 2017; Rodriguez Cruz et al., 2020; Harris et al., 2005). In general, skeletal muscle fibers are innervated via a single innervating NMJ where the motor axon joins the muscle fiber. While there are different ways to classify the NMJ, in this article we will divide the NMJ into a presynaptic terminal, a postsynaptic muscle membrane, and the space that lies between (the synaptic cleft).

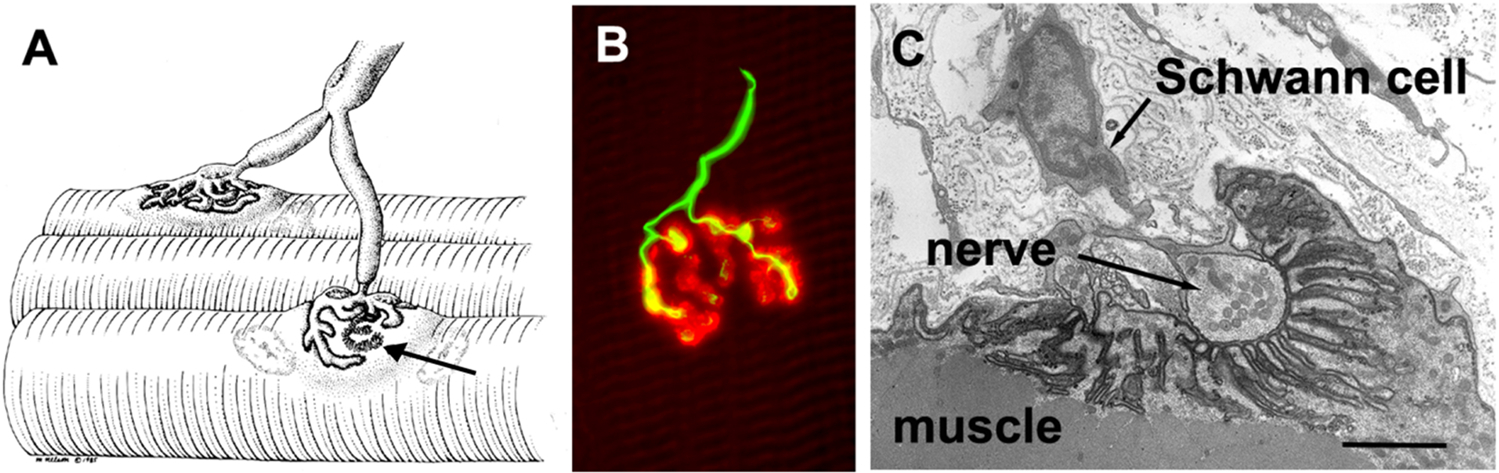

A general illustration of the mammalian NMJ structure is shown in Fig. 1. The small motor nerve terminal forms numerous varicosities (“boutons”) that release the neurotransmitter acetylcholine (ACh) (Slater, 2017; Rodriguez Cruz et al., 2020). The nerve terminals contain many mitochondria and arrays of endoplasmic reticulum as well as membrane-bound synaptic vesicles containing ACh (Slater, 2017). These synaptic vesicles are centered around the “active zones”, which are the electron-dense sites where the neurotransmitter is released. The boutons, which are capped by several non-neural Schwann cells (perisynaptic Schwann cells), adhere to the muscle cell surface with a very narrow (50–100 nm) extracellular matrix gap that is typically a discrete basal lamina (Slater, 2017; Rodriguez Cruz et al., 2020). At this synaptic cleft the enzyme acetylcholinesterase (AChE), which terminates synaptic transmission by breaking down acetylcholine, is attached to the basal lamina via NMJ-specific collagen-like tail (i.e., “Colq”; the collagen like tail subunit of asymmetric acetylcholinesterase) (Ohno et al., 1998). The postsynaptic surface of the muscle cell is densely packed with ACh receptors (AChRs) (~10,000 AChRs/μm2) (Heuser and Salpeter, 1979). These receptors are ligand-gated ion channels that are associated with a plethora of membrane and cytoskeletal proteins (Wu et al., 2010). The post-synaptic membrane is folded, with the folds extending up to ~ 1 μm into cytoplasm such that the total area of the postsynaptic membrane is effectively increased 8-fold (Slater, 2017; Rodriguez Cruz et al., 2020). At the bottoms of the folds, voltage-gated Na+ channels are concentrated to facilitate the excitability of the postsynaptic membrane (Rodriguez Cruz et al., 2020). Human NMJs are typically smaller and less complex than those seen in rodent studies (Jones et al., 2017). Yet, human NMJs exhibit a higher degree of postsynaptic membrane folding than other species increasing surface area 8-fold (Slater, 2017; Zanetti et al., 2018). Very importantly, junctional folds increase input resistance and thus excitability, and this combined with the densely located voltage-gated sodium channels at the troughs of the junctional folds together amplify transmission (Wood and Slater, 2001).

Fig. 1. Structure of the mammalian neuromuscular junction (NMJ).

A: Illustration of a motor axon extensively branching to innervate two muscle fibers at the respective NMJs. The arrow indicates a section where the nerve has been removed to allow better visualization of the postsynaptic folds. B: A human NMJ illustrating the nerve terminal in green and the post-synaptic acetylcholine receptors (AChRs) in red. The nerve terminals enlarged boutons, from which ACh is released, are readily seen. (The scale bar is 20 μm). C: An electron micrograph section through a single human bouton highlighting the extensive infoldings of the postsynaptic myofiber membrane. (The scale bar is 1 μm). Reprinted from Slater via an open access Creative Common CC BY license (Slater, 2017). See section II for further discussion.

Many original and review articles have described the age-related changes in NMJ morphology. Thus, we will not extensively review age-related morphological changes here and refer the reader to other reviews (see (Anagnostou and Hepple, 2020); Rudolf et al., 2016; Tintignac et al., 2015; Hepple and Rice, 2016; Iyer et al., 2021a; Pratt et al., 2021). In brief, data suggest that with advancing age the pre-synaptic structures undergo numerous degenerative changes, such as axonal denervation, reinnervation, and remodeling (Fahim and Robbins, 1982; Smith and Rosenheimer, 1982; Balice-Gordon, 1997). Additionally, aging results in increased fragmentation, loss of junctional folds, reduced numbers of pre-synaptic vesicles and nerve terminals, increased dispersion in the area of motor endplates, reduced number of AChRs as well as lowered binding affinity to AChRs (Fahim and Robbins, 1982; Valdez et al., 2010; Courtney and Steinbach, 1981; Kurokawa et al., 1999; Rosenheimer, 1990; Smith and Chapman, 1987). With regards to denervation, there is a preferential denervation of fast fibers with reinnervation via axonal sprouting from slow motor neurons results in a conversion from Type II (fast) fibers to Type I (slow) fibers (Jang and Van, 2011). The presynaptic terminal Schwann cells also display alterations with age, including a shallowing of junctional folds, retraction, and abnormal infiltration into the synaptic cleft (Wokke et al., 1990). A recent study reported findings that conflicted with these prior studies suggesting that human NMJs, in contrast to rodents, are remarkably stable throughout the lifespan showing minimal signs of age-related remodeling (Jones et al., 2017). A limitation of this more recent work, however, was the lack of healthy young controls as control tissues were obtained from young adults during limb amputation (Jones et al., 2017). Thus, there remains uncertainty about how aging impacts the structure of human NMJs, but a more critical knowledge gap is whether older adults with sarcopenia are more likely to demonstrate altered NMJ structure, a question that is entirely unaddressed.

3. Normal NMJ transmission and evidence for age-related failure

3.1. The “safety factor”

In contrast to age-related structural NMJ changes, much less attention has been given to NMJ transmission (i.e., the propagation of an AP from the nerve terminal to the muscle), both in preclinical and in clinical studies. Thus, whether the above-mentioned NMJ structural changes are a cause of muscle failure in aging is not clear (Iyer et al., 2021a); however, morphological alterations of the NMJ, theoretically, could result in reduced NMJ transmission efficacy (e.g., reduced junctional folding could decrease input resistance and thus reduce myofiber excitability (Wood and Slater, 2001)). The term “safety factor” is used to describe the redundant ability of NMJ transmissions in the healthy condition to reliably trigger muscle fiber action potential responses (i.e., to trigger a response in a 1:1 fashion between nerve and muscle), even during intense, sustained contractions (Wood and Slater, 2001). During NMJ transmission, the arrival of a nerve action potential at the pre-synaptic terminal opens voltage-gated Ca2+ channels resulting in the influx of Ca2+ at presynaptic active zones. Calcium influx interacts with SNARE proteins resulting in the fusion of synaptic vesicles with the presynaptic membrane and release of ACh molecules. The estimated number of ACh vesicles released with each nerve impulse (referred to as quantal content) varies by species, nerve impulse rate, and muscle, but compared with other species, humans have lower estimates of quantal content (Wood and Slater, 2001).

Following the release of ACh and diffusion across the synaptic cleft, ACh molecules bind nicotinic AChR receptors causing increased permeability and influx of Na+ ions which result in a localized change in the membrane potential (endplate potential). In the healthy condition, the endplate potential far exceeds threshold for opening of voltage-gated Na+channels in the muscle sarcolemma to trigger an action potential. As mentioned, this redundancy (known as the safety factor) is sometimes several fold the magnitude required for the all-or-none action potential generation (Wood and Slater, 2001). Estimates of the safety factor in humans have generally been in the range of two fold that required for action potential generation and are lower as compared with other species, including rodents (Wood and Slater, 2001). In addition to the events and channels described above, skeletal muscle specific ClC-1 chloride ion channels play an important role in stabilizing skeletal muscle excitability contributing up to 70–80% of resting membrane conductance, and during sustained intense muscle activity are inhibited helping to maintain the safety factor and ensure adequate NMJ transmission during repeated AP firing (i.e., it helps to maintain the safety factor) (Pedersen et al., 2016; Riisager et al., 2016; Pedersen et al., 2009). Despite redundancy of the safety factor in the healthy state, there are many well-described genetic, autoimmune, and neurodegenerative disorders that can result in NMJ transmission failure and subsequent muscle weakness (or paralysis in severe cases) (Slater, 2017; Rodriguez Cruz et al., 2020; Wood and Slater, 2001; Arnold et al., 2021; Campanari et al., 2016). These conditions result in varying presynaptic, synaptic, and postsynaptic alterations in NMJ transmission that result in loss of safety factor and muscular weakness. Accordingly, it seems plausible that age-related degeneration of the neuromuscular system could similarly result in loss of the safety factor at the NMJ and accordingly result in transmission failure and weakness.

3.2. Evidence for NMJ transmission failure during aging

Several approaches can be used to assess efficacy of NMJ transmission in clinical and preclinical studies, and one of the major goals of this review is to examine the evidence for NMJ transmission failure in the context of aging. Methods for NMJ transmission assessment exist that can be applied at the levels of muscle, motor unit, and single muscle fibers/synapse. Such approaches usually employ recordings of electrical signals, but measurements of mechanical force can also be used to look at sufficiency of NMJ transmission. A notable caveat of measuring mechanical force as a readout of NMJ function, as compared with excitation of the muscle sarcolemma, is that loss of force can also stem from decoupling of excitation from contraction.

3.2.1. Whole muscle measurements

The earliest clinical assessment of defective NMJ transmission was the “Jolly test” described in 1895 in the context of myasthenia gravis, an autoimmune disorder that disrupts postsynaptic AChR’s (von, 1895). The Jolly test measures electrically evoked muscle force, and in the case of myasthenia gravis showed a decline following repeated stimulations. Like the Jolly test (and in some cases referred to as such), repetitive nerve stimulation is a technique that includes stimulation of a peripheral nerve with a train of stimuli and recording the stability of the summated electromyogram (EMG) response, which is commonly referred to as a compound muscle action potential (CMAP) or M wave (Allman and Rice, 2002; Juel, 2019). For additional discussion about quantifying the CMAP to understand neuromuscular propagation function in the context of aging and fatigue please see (Allman and Rice, 2002). Clinically, repetitive nerve stimulation is usually assessed at low frequencies (usually 2–5 Hz) due to discomfort and difficulty with muscle movement associated with higher rates of stimulation (i.e., tetanic contraction due to short interpulse intervals that preclude full muscle relaxation). Testing of force loss, similar to the Jolly test, have been applied sparsely in the context of aging (Padilla et al., 2021; Fogarty et al., 2019; Cupido et al., 1992). In two preclinical studies, using in situ (diaphragm) and in vivo (gastrocnemius) preparations in aged rat models, electrically stimulated force showed significant decline during tetanic trains of stimuli indicative of age-related NMJ failure (Padilla et al., 2021; Fogarty et al., 2019). Similarly, CMAP measurements following high frequency repetitive nerve stimulation have been applied to the gastrocnemius in anesthetized rodents (mice and rats) and have shown deficits during aging (Padilla et al., 2021; Gao et al., 2020). In contrast, a single study in a small number of relatively “young” older adults (n = 9; mean age: 67 years) that assessed repetitive electrically stimulated muscle force and CMAP responses recorded from the tibialis anterior showed no significant differences between young versus older adults (Cupido et al., 1992). Thus, at the whole muscle force level, there are discrepant findings between preclinical and clinical studies. Limited utilization of the Jolly or repetitive nerve stimulation tests in clinical studies is likely due, at least in part, to the fact that rapid stimulation is uncomfortable and poorly tolerated (Juel, 2019).

3.2.2. Electromyographic motor unit measurements

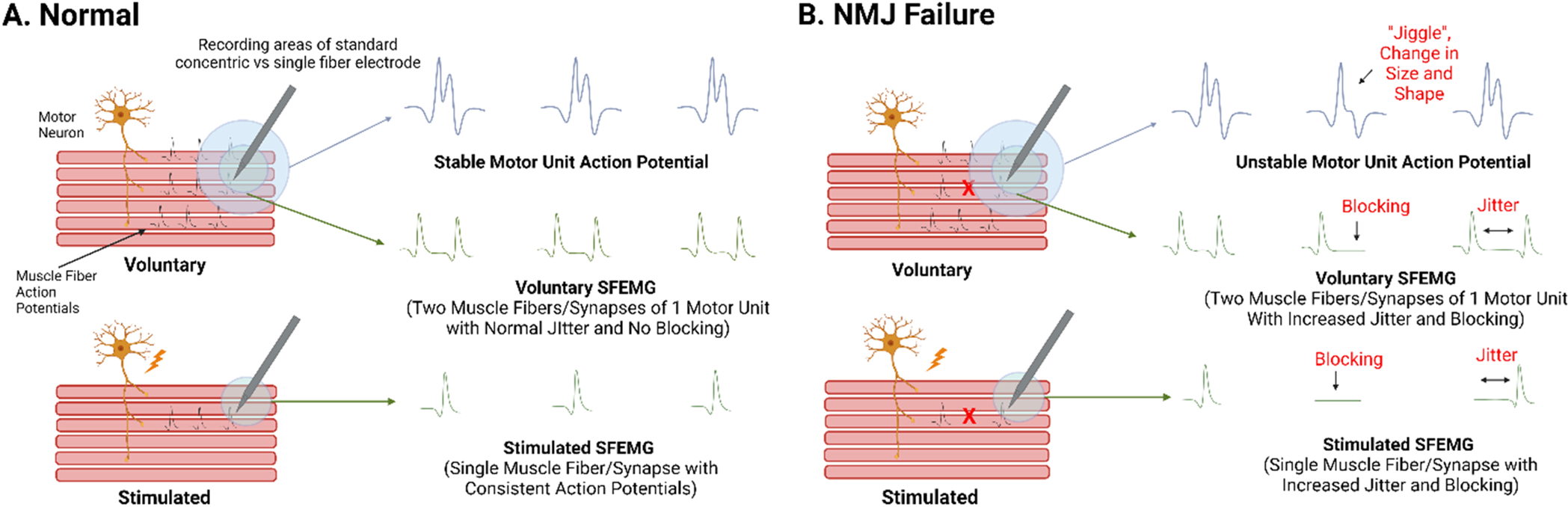

In the healthy state, the muscles fibers of a motor unit (all the muscle fibers innervated and controlled by a single motor neuron) depolarize in a time-locked, “all-or-none” fashion such that each muscle fiber is excited with each depolarization of the innervating motor. Similarly, motor unit action potentials (summated recorded responses recorded from a single motor unit in the region of the recording electrode) in healthy conditions, occur as “all-or-none” responses. In a healthy state, motor unit action potentials are relatively stable in their size and shape. However, even in healthy individuals, there is still some variation in the size and shape observed, which is referred to as “jiggle”. The factors that contribute to jiggle in the healthy state are not well defined, but could include both technical factors (e.g., variable positioning of the recording electrode) as well as physiological factors (e.g., variable nerve or muscle fiber conduction velocities within a motor unit) (Sanders et al., 2019). During disease states of NMJ transmission, the jiggle becomes notably more pronounced (i.e., the motor unit action potentials display increasingly variable size and shapes) (Fig. 2) (Stalberg and Sonoo, 1994). Increased jiggle of a motor unit action potential response is most often attributed to failure of a subset of its muscle fibers to depolarize (Fig. 2B), but variability of the time at which muscle fiber action potentials arrive at the recording electrode between motor unit discharges (variability of temporal summation of a motor unit discharge) could also possibly explain jiggle. In addition, movement is another potential source of jiggle (electrode movement within the muscle or movement of the muscle during a contraction). Jiggle is evident in disorders such as myasthenia gravis as well as disorders of immature reinnervation (Stalberg and Sonoo, 1994).

Fig. 2. Neuromuscular junction transmission (NMJ) at the motor unit and single muscle fiber levels in health and disease.

A. In the healthy state, a motor unit, the muscles fibers innervated by a single motor neuron, discharges as summated, all-or-none responses. NMJ transmission can be assessed on the motor unit level (motor unit action potentials) as indicated by relatively stable size and shape between discharges. Similarly, NMJ transmission can be assessed at the single fiber level (single fiber electromyography, SFEMG) as indicated by consistent timing and occurrence of action potentials relative between two synapses of the same motor unit (in voluntary SFEMG) or relative to axonal stimulus (in stimulated SFEMG) indicate integrity of NMJ transmission. B. In contrast, in conditions of NMJ failure, the size and shape of motor unit action potential responses vary between discharges, termed “jiggle” and SFEMG shows increased variability of action potential latency (jitter) and intermittent all-or-none action potential failure (blocking). Of note, voluntary SFEMG can only be performed with low intensity contractions as such only interrogates muscle fiber pairs of low threshold motor units. Conversely, stimulated SFEMG interrogates synapses independent of threshold. Conceptual figure not drawn to scale. Created with biorender.com.

During standard clinical needle electromyography, jiggle is only investigated qualitatively, but advances in automated triggering and decomposition techniques have allowed development of techniques that allow quantification of motor unit stability during trains of discharges (Allen et al., 2015; Stashuk, 1999). In 2015, Hourigan and colleagues reported that “near fiber” jiggle was increased the tibialis anterior and vastus lateralis in older men (n = 9, mean age: 77 years) compared with young controls (n = 9, mean age: 23 years) (tibialis anterior: 36.0 μs vs. 26.5 μs; vastus lateralis: 31.3 μs vs. 23.9 μs) suggesting failure of NMJ transmission (Hourigan et al., 2015). Near fiber analysis is performed by high pass filtering motor units to more selectively analyze fibers close to the recording needle, within ~350 μm (Allen et al., 2015). In contrast, Piasecki and colleagues reported no change in near fiber jiggle in the tibialis anterior of older men (n = 14, mean age: 71 years) versus young men (n = 18, mean: 26 years) (27.5 μs vs. 26.7 μs) and increased near fiber jiggle in men that were master athletes (n = 13, mean age: 69 years; 30.4 μs) versus the young men (Piasecki et al., 2016a). In another study, Piasecki and colleagues reported that near fiber jiggle was slightly increased in the vastus lateralis of older (n = 20;mean age: 71 years) versus younger (n = 22; mean age: 25 years) men (26.2 μs vs. 23.7 μs) (Piasecki et al., 2016b). Thus, while the automated approach has allowed quantification of near fiber jiggle, the results have been variable when reported in the context of aging. Additionally, there is wide variation across healthy young individuals in which the safety factor is expected to be consistently preserved raising the question if technical factors may impact the validity of near fiber jiggle as an index of NMJ transmission. As such, interpretation of these findings should be made with caution. Limitations of this technique include the fact that such motor unit recordings are limited to low to moderate voluntary contraction intensities and thus will not fully interrogate higher threshold motor units. Also, the need for voluntary contraction limits these approaches to clinical studies. Recent advances in electronics and indwelling electrodes that include high density recording electrodes or simultaneous multimodal recordings (such as electrophysiology and ultrafast ultrasound) may allow future investigation of motor unit discharge characteristics more readily (Carbonaro et al., 2022).

3.2.3. Individual synaptic measurements

Recording of individual synapses can be accomplished with extracellular and intracellular recordings. Intracellular recordings of NMJ transmission require an ex vivo preparation but allow the most precise and detailed analyses of synaptic function (Zanetti et al., 2018). Spontaneous and evoked responses are typically assessed and can be quantified using preparations that assess membrane voltage and current transients. For simplicity, we will primarily refer to potentials (voltage), but there are advantages and disadvantages to both approaches (Wood and Slater, 2001). The main parameters assessed include the amplitude of the endplate potential, frequency and amplitude of the miniature endplate potential, and quantal content. The single most important measure of the functional status of an NMJ is the measure of the endplate response (i.e., the endplate potential) following axonal stimulation. Miniature endplate potentials are measured during the spontaneous release of ACh and represent the endplate response to the binding of the ACh molecules released from a single vesicle. Quantal content is the term used to describe the number of vesicles following nerve stimulation and is calculated by dividing the endplate potential amplitude by the miniature endplate potential amplitude. Of all the parameters assessed, the endplate potential is what directly relates to and determines the safety factor, and counterintuitively, findings in limb and diaphragm muscles from aged rodents have consistently shown enhancement of the endplate potential (or current) compared with young controls (Banker et al., 1983; Fahim, 1997; Willadt et al., 2016). These findings would contribute to an improvement of the safety factor.

Intracellular NMJ recordings are challenging to apply to clinical studies as an intact muscle must be invasively removed and quickly analyzed using technical capabilities that are feasible for very few research groups. As such, these approaches have only been used in certain human muscles, such as intercostal or anconeus muscles, and usually in the context of genetic or autoimmune myasthenic disorders and not in aging or sarcopenia. Therefore, how the findings of endplate potential enlargement (enhancement) in aged rodent models are related to what occurs in humans is entirely unknown.

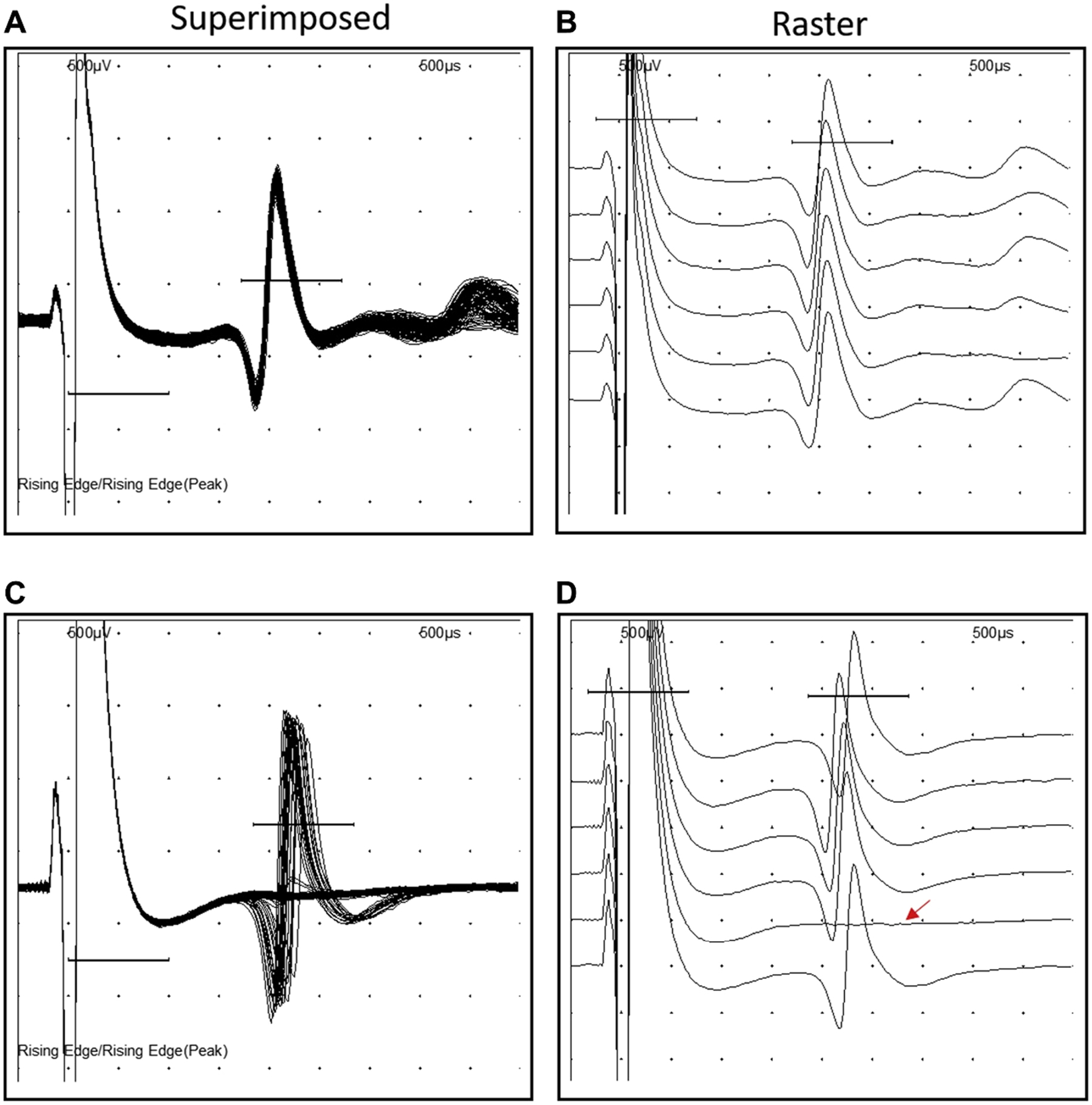

In contrast to intracellular approaches, extracellular recordings can be performed using minimally invasive approaches and are more clinically applicable. Single fiber EMG (SFEMG) is a well-established extracellular technique primarily used clinically for the diagnosis of neuromuscular disorders such as myasthenia gravis (Juel, 2019). SFEMG uses a highly specialized and selective electrode to record extracellular single muscle fiber action potentials either during voluntary activation (voluntary SFEMG) or nerve stimulation (stimulated SFEMG) (Fig. 2). For electrode comparison, motor unit analysis recording electrodes have recording surface area in the range of 0.019–0.07 mm2 versus ~0.00125 mm2 for SFEMG electrodes. During voluntary SFEMG, the constancy of response (i.e., normal, consistent response versus no response [blocking]) and variability of the latency (i.e., jitter) are quantified between two muscle fibers controlled by a single motor neuron within the recording area of the single fiber electrode. Of important note regarding similarities and differences between jitter and jiggle, jitter is associated with no change of single muscle fiber action potential shapes, only change in latency, whereas jiggle is associated with changes of motor unit action potential shape. During stimulated SFEMG, jitter and blocking are quantified from single synapses and relative to the stimulus (Fig. 3). SFEMG is considered the most sensitive test of NMJ transmission in vivo (Juel, 2019). Despite the routine use of SFEMG in clinical diagnosis and management of neuromuscular disorders, SFEMG has only sparsely been reported in the context of aging and never specifically in a cohort with sarcopenia (Lange, 1992; A.H.C.o.T. A.S.I.G.o.S.F. and Gilchrist, 1992). A few preclinical studies have applied stimulated SFEMG to aged rodents (mice and rats) and have consistently shown NMJ transmission deficits in the form of increased transmission variability (jitter) and overt NMJ transmission failure (blocking) (Padilla et al., 2021; Chugh et al., 2020; Chung et al., 2017, 2018; Iyer et al., 2021b; Chugh et al., 2021).

Fig. 3. Representative Single Fiber Electromyography recordings.

A-B. Normal jitter and no blocking at a normal synapse (right: superimposed, left: rastered). C-D. Increased jitter and blocking at a failing synapse (right: superimposed, left: rastered). SFEMG recorded at an axonal stimulation frequency of 10 Hz from the gastrocnemius muscle in a young (A-B) and aged (C-D) C57BL/6 mouse. Sweep speed of 500 μs and a sensitivity of 500 μV. Reprinted with permission from Chugh et al., 2020.

The findings on SFEMG suggest that NMJ transmission is, in fact, defective during aging, contrasting findings on intracellular NMJ recordings that suggest enhancement of the endplate response (Padilla et al., 2021; Chugh et al., 2020). This discrepancy suggests a post-synaptic mechanism for NMJ transmission failure that requires additional study. It is important to note that post-synaptic calcium signaling is involved in the feedback control of pre-synaptic ACh release such that loss of muscle fiber action potential generation triggers increased presynaptic release of ACH (Ouanounou et al., 2016). Thus, based on these findings, we postulate that the increased endplate response that has been noted on isolated synaptic recordings in aged rodents could represent a presynaptic compensation in response to NMJ failure to trigger action potentials (Ouanounou et al., 2016).

The safety factor also depends on effectiveness of the endplate potential to stimulate voltage-gated sodium channels, and therefore one untested possibility is that failed NMJ transmission is related to reduced density or function of voltage-gated sodium channels (Rodríguez Cruz et al., 2020). Importantly, such a defect would not be apparent on intracellular NMJ recordings as action potential generation is prevented during recordings, and thus these steps of NMJ transmission are not assessed (Chugh et al., 2020). Clinically, SFEMG has only been applied in two studies both of which were not specifically testing for age-related deficits (Lange, 1992; A.H.C.o.T.A.S.I.G.o.S.F. and Gilchrist, 1992). These studies demonstrated that jitter is increased with age, but failure of transmission was not specifically examined or reported (Lange, 1992; A.H.C.o.T.A.S.I.G.o.S.F. and Gilchrist, 1992). Another limitation of these studies was that voluntary SFEMG was applied. Voluntary SFEMG technique requires participants to maintain a very low level of contraction, and thus only investigates synapses from low threshold motor units. Thus, there is limited clinical data that has selectively investigated single synaptic function in the context of aging.

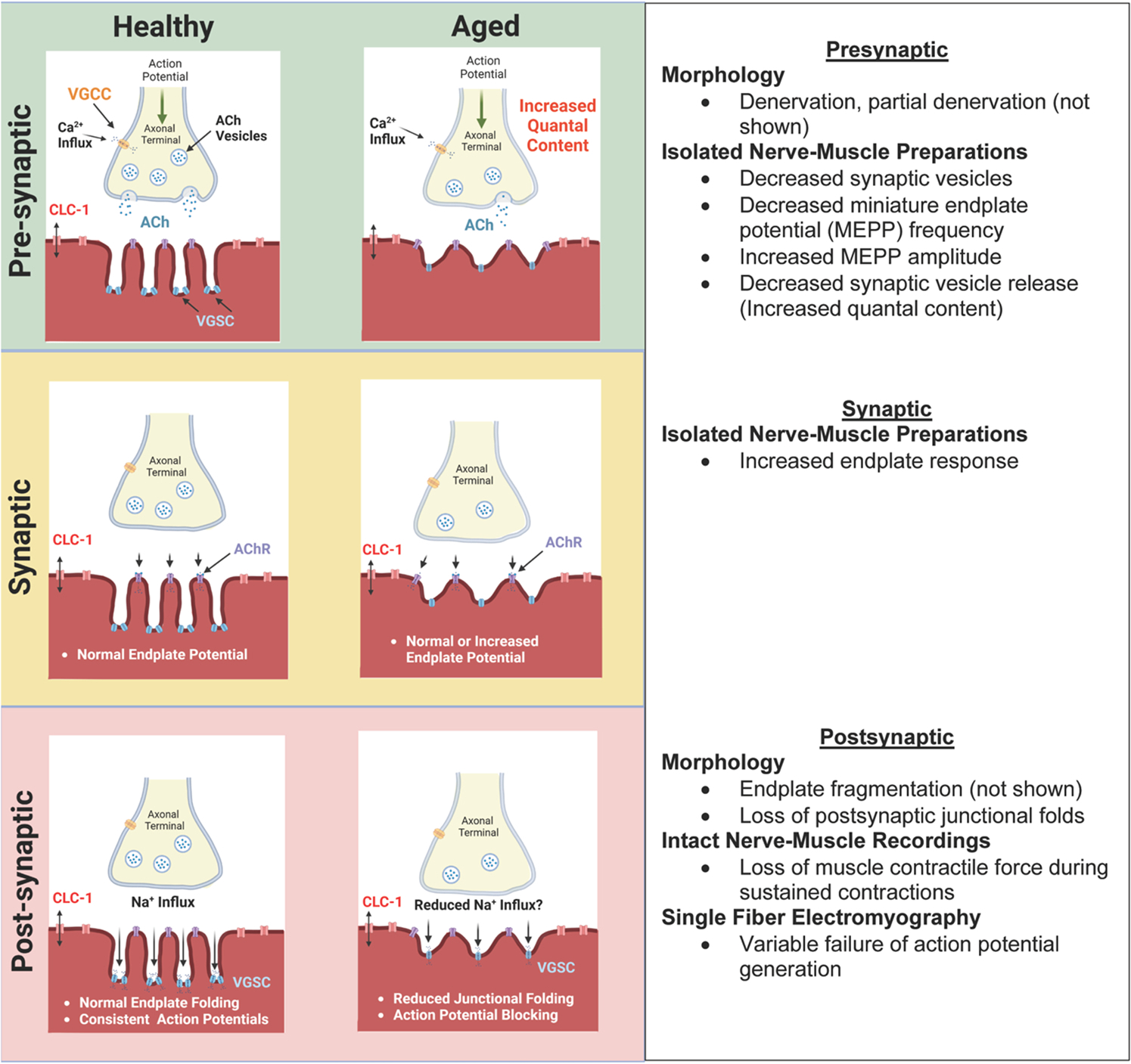

4. Mechanisms of NMJ transmission failure

The available preclinical physiological data support that there is a loss of the safety factor and failure of NMJ transmission during aging (Fig. 4). Yet, direct evidence from clinical populations, specifically those impacted by sarcopenia, are lacking. Based on the combined findings of single fiber EMG evidence of NMJ transmission failure and the findings of endplate response enhancement, age-related failure of transmission appears to occur related to downstream mechanisms at the postsynaptic membrane. Accordingly, the presynaptic and synaptic events that result in normal or enhanced endplate response are likely compensatory in nature (Presynaptic, Fig. 4). Yet, the mechanisms of NMJ transmission failure, despite preservation of the endplate response, are undefined.

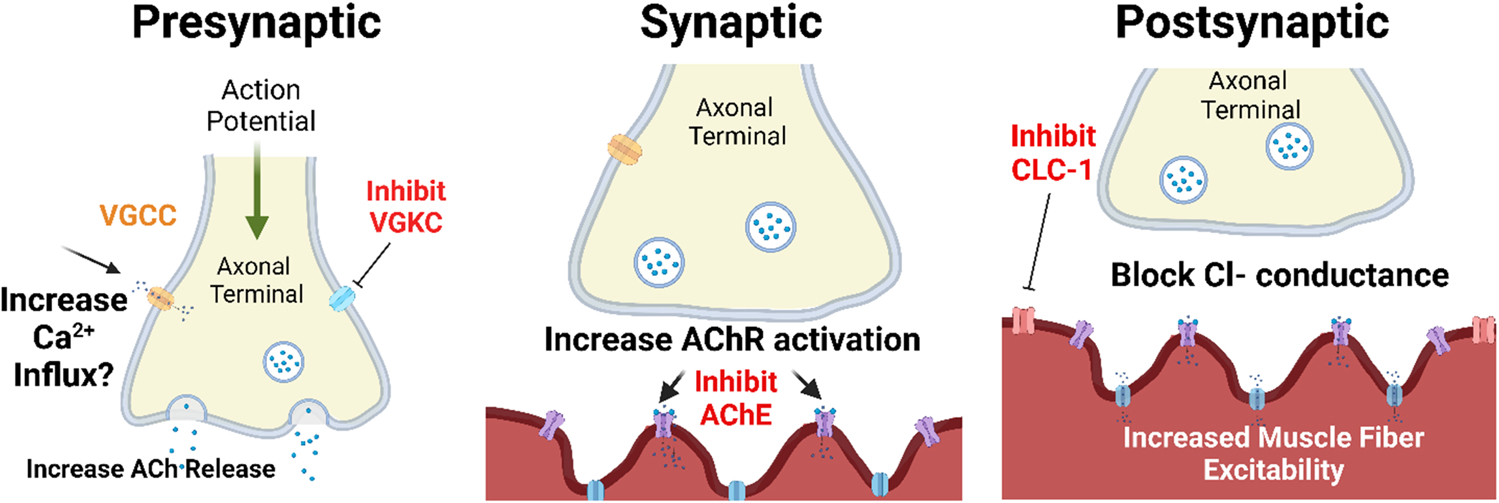

Fig. 4. Conceptual model of age-related changes in NMJ form and function.

The available preclinical physiological data support that there is a loss of the safety factor and failure of NMJ transmission during aging. Yet, direct evidence from clinical populations, specifically those impacted by sarcopenia, are lacking. Here we present a conceptual model of the age-related changes in presynaptic (upper panel), synaptic (middle panel), and post-synaptic (lower panel) form and function. See sections III and IV for further discussion. Created with biorender.com. ACh: Acetylcholine, AChR: Acetylcholine receptor, VGCC: voltage-gated calcium channel, CLC-1: ClC-1 chloride channel, VGSC: voltage-gated sodium channel.

Postsynaptic junctional folds and clustering of voltage-gated sodium channels in the troughs of these folds serve to amplify the endplate response to generate an action potential. Alterations such as simplification (reduced junctional folding) of the postsynaptic membrane structure, loss or reduced density of voltage-gated sodium channels, or channel dysfunction could contribute to loss of reliable action potential generation (Postsynaptic, Fig. 4). A recent article highlighted the importance of voltage gate sodium channel clustering in the troughs of junctional folds at the endplate, as mediated by ankyrin, for maintenance of action potentials during sustained activation (Zhang et al., 2021). Thus, it is plausible that distribution of voltage gated sodium channels on the postsynaptic membrane could be altered during aging but hasn’t been investigated. Although outside the scope of this review, it is worth mentioning that failure of action potential propagation along the length of a muscle fiber (outside the region of the NMJ) is another potential contributor to muscle failure that has not been investigated. As previously mentioned, there are striking differences between human and rodent NMJs, anatomically and physiologically. Accordingly, it is possible that mechanisms of NMJ transmission failure during aging may diverge between species.

A seemingly obvious, but still hypothetical, cause of NMJ dysfunction is that denervation and reinnervation during aging result in secondary disruption of the safety factor. Loss of spinal motor neurons and motor unit numbers and compensatory motor unit remodeling are well established features of aging though how these contribute to onset and progress of sarcopenia phenotype remains incompletely understood (Hepple and Rice, 2016; Doherty et al., 1993). Theoretically, the NMJs of failing motor units (e.g., motor neurons that are dying back) as well as newly formed compensatory NMJs of surviving motor units could have reduced safety factors. This is supported by findings of NMJ transmission insufficiency in other disorders of motor neuron and axon degeneration such as spinal muscular atrophy and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis as well as immature reinnervation (Arnold et al., 2021; Campanari et al., 2016; Stalberg and Sonoo, 1994; Kouyoumdjian et al., 2020). One possible link between denervation and NMJ failure during aging could be related to loss of junctional folds as this has been observed in aged rodents and humans and models of denervation (Taetzsch and Valdez, 2018; Wokke et al., 1990; Matsuda et al., 1988; Miledi and Slater, 1968). The molecular mechanisms that drive junctional folding (and losses during denervation) are not fully understood. Alternative to secondary changes related to motor unit losses and remodeling, primary NMJ alterations or muscle fiber dysfunction has also been proposed. In support of this, one study that repeatedly imaged the same NMJs longitudinally during aging in intact mice observed focal muscle fiber necrosis which resulted in subsequent fragmentation of involved NMJ structure, but functional impact was not investigated (Li et al., 2011).

5. Therapeutically targeting the NMJ for sarcopenia

Physical activity and therapeutic exercise are important interventions for age-related decline of neuromuscular function as well as overt sarcopenia (Law et al., 2016). There is growing evidence that older adults with healthy aging and older adults who remain physically active are more likely to show morphological and electrophysiological evidence of improved reinnervation, and the converse has been shown in individuals with evidence of frailty and sarcopenia (Mosole et al., 2014; Sonjak et al., 2019; Piasecki et al., 2018, 2019). Yet, these clinical studies have mostly not focused on NMJ transmission, and one study noted paradoxically worsened NMJ transmission in men master athletes compared with older control men based on decomposition-based analyses of trains of motor units (Piasecki et al., 2016a). Thus, clinically, the impact of exercise on NMJ transmission deserves additional attention. Findings of beneficial impact on both NMJ form and function have been noted in preclinical studies of naturally aged wildtype mice (Valdez et al., 2010; Chugh et al., 2021). For instance, we recently showed that aged mice, exposed to a voluntary running wheel between 22 and 27 months of age, demonstrated improved NMJ transmission as assessed with stimulated SFEMG (Chugh et al., 2021). Interestingly, in our work we showed that running wheel exercise improved NMJ transmission but not improved motor unit number possibly suggesting that separate mechanisms may drive age-related deficits at the NMJ and motor unit levels (Chugh et al., 2021). Temporally, we had previously demonstrated that onset and progression of motor unit loss and NMJ failure are not associated with each other (Chugh et al., 2020). Prior work has also investigated isolated NMJ recordings during exercise, and interestingly the endplate responses varied by age of mice whereas endplate potential increased in young mice following exercise as compared to a reduction in aged mice (Fahim, 1997) Thus, it seems plausible that the normalization of endplate response in aged mice following exercise could be related to reversed “compensatory” increase of endplate response.

One of the most straightforward interventional approaches to improving NMJ transmission could include the symptomatic use of NMJ modulating small molecule compounds (Fig. 5). Several agents, some of which are FDA approved, are routinely used clinically for NMJ transmission enhancement in genetic and autoimmune forms of NMJ disorders such as myasthenia gravis, Lambert Eaton Myasthenic syndrome (LEMS), as well as genetic congenital myasthenic disorders. Acting at the pre-synapse (Fig. 5, left panel), amifampridine (a salt of 3,4 diaminopyridine) is clinically approved for use in the presynaptic NMJ disorder of LEMS (Yoon et al., 2019). LEMS is related to autoimmune dysfunction of the voltage-gated calcium channel due to autoantibodies causing reduced Ca2+ ion influx into the presynaptic terminal upon arrival of a nerve action potential. Amifampridine is a voltage gated potassium channel antagonist that prolongs the presynaptic nerve action potential and increases Ca2+ ion influx. Preclinical studies have developed and investigated additional molecules to directly increase Ca2+ ion influx via voltage gated calcium channels and have been tested in models of LEMS and are being studied in aged rodents (Meriney et al., 2018). Recent work has shown that the NMJ is regulated by sympathetic input, and in these studies, salbutamol, β2-adrenergic agonist, has also been shown to increase presynaptic ACh release in mice (Rodrigues et al., 2019). Salbutamol has shown efficacy in some forms of congenital myasthenic syndrome (Tsao, 2016).

Fig. 5. Small molecule treatments that could, conceptually, be used to enhance neuromuscular junction transmission in sarcopenia.

These small molecules are already approved by the FDA or in the pipeline for approval for a variety of neuromuscular diseases that are characterized by muscle weakness. Presynaptic (left panel): 3,4 Diaminopyridine blocks presynaptic voltage gated potassium channels to prolong presynaptic nerve action potential to increase Ca2+ influx. Synaptic (center panel): The acetylcholinesterase inhibitor (AChE) pyridostigmine increases persistence of acetylcholine (ACh) at the synapse. Postsynaptic (right Panel): The CLC-1 channel inhibitor blocks Cl− ion conductance and increases sarcolemmal excitability. See section V for further discussion. Created with biorender.com. ACh: Acetylcholine, AChR: Acetylcholine receptor, VGCC: voltage-gated calcium channel, VGKC: voltage-gated potassium channel; AChE: Acetylcholinesterase; CLC-1: ClC-1 chloride channel.

Acting at the synapse (Fig. 5, middle panel), the acetylcholinesterase inhibitor, pyridostigmine, is routinely used for treatment of the autoimmune NMJ disorder myasthenia gravis which is related to autoimmune attack targeting the AChR. Pyridostigmine inhibits acetylcholinesterase and thus increases ACh at the synapse.

There are no small molecule treatments that are currently available for clinical use that are known to specifically target the postsynaptic aspects of NMJ transmission. However, acting at the post-synaptic membrane, there is preclinical evidence that inhibition of the postsynaptic CLC-1 channel improves muscle fiber excitability and thus NMJ transmission in models of NMJ transmission failure (Fig. 5, right panel) (Pedersen et al., 2021). A small molecule CLC-1 inhibitor has received Orphan Drug Designation from FDA for the treatment of patients with myasthenia gravis and is currently in clinical trials. Additionally, in preclinical studies in postsynaptic models of genetic NMJ dysfunction (congenital myasthenic syndrome), salbutamol has also been shown to increase AChR staining and NMJ functionality (Webster et al., 2020).

6. Conclusions

Modulation of muscle force production, from a single muscle twitch to maximal tetanic output is reliant on reliable and sustained NMJ transmission. In health, NMJ transmission is remarkably reliable. However, the available data suggests that aging results in the loss of NMJ transmission, but data from older clinical cohorts is indirect and evidence is specifically lacking about whether NMJ deficits contribute to the onset and progression of sarcopenia. Thus, there is need for future work that focuses on assessing NMJ transmission in human cohorts stratified by functional status including criteria for sarcopenia.

If indeed sarcopenic older adults turn out to exhibit notable impairments in NMJ transmission (this has yet to be examined but based on available evidence appears to be plausible) then these NMJ transmission defects present a well-defined biological mechanism and offer a well-defined pathway for clinical implementation. Measures of NMJ transmission as physiological biomarkers could provide information regarding sarcopenia diagnosis, classification, treatment stratification (i.e., identification of individuals who would be expected to respond to a NMJ targeted therapeutic), and target engagement. Therefore, exploration of NMJ transmission phenotypes in sarcopenia may help accelerate treatment development and implementation. Investigation of small molecules that are currently available clinically or being tested clinically in other disorders may provide a rapid route for development of interventions for older adults impacted by sarcopenia. The potential impact of a function promoting therapy is extremely large when one considers that sarcopenia is costly to healthcare systems and that it increases risk of falls and fractures, impairs ability to perform activities of daily living, leads to mobility disorders, and contributes to lowered quality of life, loss of independence or need for long-term care placement, and death (Cruz-Jentoft et al., 2019).

Acknowledgments

This work supported in part by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (National Institute on Aging R01AG067758 and R03AG067387). The authors would like to thank Dr. Steven Segal for his feedback on an initial version of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Declaration of Competing Interest

In the past 5 years, W. David Arnold has received research funding from NIH, NMD Pharma, and Avidity Biosciences. In the past 5 years, W. David Arnold has received consulting fees from Amplo Biosciences, NMD Pharma, Avidity Biosciences, Dyne Therapeutics, Novartis, La Hoffmann Roche, Genentech, Design Therapeutics, Cadent Therapeutics, and Catalyst Pharmaceuticals.

In the past 5 years, Brian Clark has received research funding from the NIH, NMD Pharma, Astellas Pharma Global Development, Inc., and RTI Health Solutions for contracted studies that involved aging and muscle related research. In the past 5-years, Brian Clark has received consulting fees from Regeneron Pharmaceuticals and the Gerson Lehrman Group for consultation specific to age-related muscle weakness. Brian Clark is a co-founder with equity of OsteoDx Inc.

Data availability

No data was used for the research described in the article.

References

- (NCHS), N.C.f.H.S., Health, United States, 2018, N.C.f.H. Statistics, Editor. 2018: Hyattsville, MD. [Google Scholar]

- A.H.C.o.T.A.S.I.G.o.S.F EMG, Gilchrist JM, 1992. Single fiber EMG reference values: a collaborative effort. Muscle Nerve 15 (2), 151–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akune T, et al. , 2014. Incidence of certified need of care in the long-term care insurance system and its risk factors in the elderly of Japanese population-based cohorts: the ROAD study. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int 14 (3), 695–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen MD, et al. , 2015. Increased neuromuscular transmission instability and motor unit remodelling with diabetic neuropathy as assessed using novel near fibre motor unit potential parameters. Clin. Neurophysiol. 126 (4), 794–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alley DE, et al. , 2014. Grip strength cutpoints for the identification of clinically relevant weakness. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 69 (5), 559–566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allman BL, Rice CL, 2002. Neuromuscular fatigue and aging: central and peripheral factors. Muscle Nerve 25 (6), 785–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anagnostou ME, Hepple RT, 2020. Mitochondrial mechanisms of neuromuscular junction degeneration with aging. Cells 9, 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anker SD, Morley JE, von Haehling S, 2016. Welcome to the ICD-10 code for sarcopenia. J. Cachex-.-. Sarcopenia Muscle 7 (5), 512–514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold WD, et al. , 2021. Persistent neuromuscular junction transmission defects in adults with spinal muscular atrophy treated with nusinersen. BMJ Neurol. Open 3 (2), e000164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badawi Y, Nishimune H, 2020. Impairment mechanisms and intervention approaches for aged human neuromuscular junctions. Front Mol. Neurosci. 13, 568426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balice-Gordon RJ, 1997. Age-related changes in neuromuscular innervation. Muscle Nerve Suppl. 5, S83–S87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banker BQ, Kelly SS, Robbins N, 1983. Neuromuscular transmission and correlative morphology in young and old mice. J. Physiol. 339, 355–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao Z, et al. , 2020. AChRs Degeneration at NMJ in Aging-Associated Sarcopenia-A Systematic Review. Front Aging Neurosci. 12, 597811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaudart C, et al. , 2017. Validation of the SarQoL(R), a specific health-related quality of life questionnaire for Sarcopenia. J. Cachex-.-. Sarcopenia Muscle 8 (2), 238–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bischoff-Ferrari HA, et al. , 2015. Comparative performance of current definitions of sarcopenia against the prospective incidence of falls among community-dwelling seniors age 65 and older. Osteoporos. Int 26 (12), 2793–2802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campanari M-L, et al. , 2016. Neuromuscular junction impairment in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: reassessing the role of acetylcholinesterase. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao L, Morley JE, 2016. Sarcopenia is recognized as an independent condition by an international classification of disease, tenth revision, clinical modification (ICD-10-CM) code. J. Am. Med Dir. Assoc. 17 (8), 675–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbonaro M, et al. , 2022. Physical and electrophysiological motor unit characteristics are revealed with simultaneous high-density electromyography and ultrafast ultrasound imaging. Sci. Rep. 12 (1), 8855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chugh D, et al. , 2020. Neuromuscular junction transmission failure is a late phenotype in aging mice. Neurobiol. Aging 86, 182–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chugh D, et al. , 2021. Voluntary wheel running with and without follistatin overexpression improves NMJ transmission but not motor unit loss in late life of C57BL/6J mice. Neurobiol. Aging 101, 285–296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung T, et al. , 2017. Evidence for dying-back axonal degeneration in age-associated skeletal muscle decline. Muscle Nerve 55 (6), 894–901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung T, et al. , 2018. Increased single-fiber jitter level is associated with reduction in motor function with aging. Am. J. Phys. Med Rehabil. 97 (8), 551–556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark BC, Manini TM, 2008. Sarcopenia =/= dynapenia. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med Sci. 63 (8), 829–834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtney J, Steinbach JH, 1981. Age changes in neuromuscular junction morphology and acetylcholine receptor distribution on rat skeletal muscle fibres. J. Physiol. 320, 435–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz-Jentoft AJ, et al. , 2010. Sarcopenia: European consensus on definition and diagnosis: Report of the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People. Age Ageing 39 (4), 412–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz-Jentoft AJ, et al. , 2019. Sarcopenia: revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing 48 (1), 16–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cupido CM, Hicks AL, Martin J, 1992. Neuromuscular fatigue during repetitive stimulation in elderly and young adults. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. Occup. Physiol. 65 (6), 567–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Buyser SL, et al. , 2016. Validation of the FNIH sarcopenia criteria and SOF frailty index as predictors of long-term mortality in ambulatory older men. Age Ageing 45 (5), 602–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty TJ, Vandervoort AA, Brown WF, 1993. Effects of ageing on the motor unit: a brief review. Can. J. Appl. Physiol. 18 (4), 331–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dos Santos L, et al. , 2017. Sarcopenia and physical independence in older adults: the independent and synergic role of muscle mass and muscle function. J. Cachex-.-. Sarcopenia Muscle 8 (2), 245–250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enoka RM, et al. , 2003. Mechanisms that contribute to differences in motor performance between young and old adults. J. Electro Kinesiol 13 (1), 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahim MA, 1997. Endurance exercise modulates neuromuscular junction of C57BL/6NNia aging mice. J. Appl. Physiol. 83 (1), 59–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahim MA, Robbins N, 1982. Ultrastructural studies of young and old mouse neuromuscular junctions. J. Neurocytol. 11 (4), 641–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fogarty MJ, et al. , 2019. Diaphragm neuromuscular transmission failure in aged rats. J. Neurophysiol. 122 (1), 93–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao N, et al. , 2020. A Role of Lamin A/C in Preventing Neuromuscular Junction Decline in Mice. J. Neurosci. 40 (38), 7203–7215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris AJ, et al. , 2005. Muscle fiber and motor unit behavior in the longest human skeletal muscle. J. Neurosci. 25 (37), 8528–8533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hepple RT, Rice CL, 2016. Innervation and neuromuscular control in ageing skeletal muscle. J. Physiol. 594 (8), 1965–1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heuser JE, Salpeter SR, 1979. Organization of acetylcholine receptors in quick-frozen, deep-etched, and rotary-replicated Torpedo postsynaptic membrane. J. Cell Biol. 82 (1), 150–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hourigan ML, et al. , 2015. Increased motor unit potential shape variability across consecutive motor unit discharges in the tibialis anterior and vastus medialis muscles of healthy older subjects. Clin. Neurophysiol. 126 (12), 2381–2389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer CC, et al. , 2021b. Follistatin-induced muscle hypertrophy in aged mice improves neuromuscular junction innervation and function. Neurobiol. Aging 104, 32–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer SR, Shah SB, Lovering RM, 2021a. The Neuromuscular Junction: Roles in Aging and Neuromuscular Disease. Int J. Mol. Sci. 22, 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang YC, Van H, 2011. Remmen, Age-associated alterations of the neuromuscular junction. Exp. Gerontol. 46 (2–3), 193–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones RA, et al. , 2017. Cellular and Molecular Anatomy of the Human Neuromuscular Junction. Cell Rep. 21 (9), 2348–2356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juel VC, 2019. Clinical neurophysiology of neuromuscular junction disease. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 161, 291–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouyoumdjian JA, Ronchi LG, de Faria FO, 2020. Jitter evaluation in denervation and reinnervation in 32 cases of chronic radiculopathy. Clin. Neurophysiol. Pr. 5, 165–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurokawa K, et al. , 1999. Age-related change in peripheral nerve conduction: compound muscle action potential duration and dispersion. Gerontology 45 (3), 168–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange DJ, 1992. Single fiber electromyography in normal subjects: reproducibility, variability, and technical considerations. Electro Clin. Neurophysiol. 32 (7–8), 397–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law TD, Clark LA, Clark BC, 2016. Resistance Exercise to Prevent and Manage Sarcopenia and Dynapenia. Annu Rev. Gerontol. Geriatr. 36 (1), 205–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leong DP, et al. , 2015. Prognostic value of grip strength: findings from the Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology (PURE) study. Lancet 386 (9990), 266–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Xiong WC, Mei L, 2018. Neuromuscular Junction Formation, Aging, and Disorders. Annu Rev. Physiol. 80, 159–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Lee Y, Thompson WJ, 2011. Changes in aging mouse neuromuscular junctions are explained by degeneration and regeneration of muscle fiber segments at the synapse. J. Neurosci. 31 (42), 14910–14919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malmstrom TK, et al. , 2016. SARC-F: a symptom score to predict persons with sarcopenia at risk for poor functional outcomes. J. Cachex-.-. Sarcopenia Muscle 7 (1), 28–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manini TM, et al. , 2007. Knee extension strength cutpoints for maintaining mobility. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 55 (3), 451–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manini TM, Clark BC, 2011. Dynapenia and Aging: An Update. The journals of gerontology. Ser. A, Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda Y, et al. , 1988. Scanning electron microscopic study of denervated and reinnervated neuromuscular junction. Muscle Nerve 11 (12), 1266–1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath R, et al. , 2019a. Decreased handgrip strength is associated with impairments in each autonomous living task for aging adults in the united states. J. Frailty Aging 8 (3), 141–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath R, et al. , 2019b. Weakness May Have a Causal Association With Early Mortality in Older Americans: A Matched Cohort Analysis. J. Am. Med Dir. Assoc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meriney SD, et al. , 2018. Lambert–Eaton myasthenic syndrome: mouse passive-transfer model illuminates disease pathology and facilitates testing therapeutic leads. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1412 (1), 73–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miledi R, Slater CR, 1968. Electrophysiology and Electron-Microscopy of Rat Neuromuscular Junctions After Nerve Degeneration. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B, Biol. Sci. 169 (1016), 289–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morley JE, et al. , 2011. Sarcopenia with limited mobility: an international consensus. J. Am. Med Dir. Assoc. 12 (6), 403–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosole S, et al. , 2014. Long-term high-level exercise promotes muscle reinnervation with age. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 73 (4), 284–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narici MV, Maffulli N, 2010. Sarcopenia: characteristics, mechanisms and functional significance. Br. Med Bull. 95, 139–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohno K, et al. , 1998. Human endplate acetylcholinesterase deficiency caused by mutations in the collagen-like tail subunit (ColQ) of the asymmetric enzyme. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95 (16), 9654–9659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouanounou G, Baux G, Bal T, 2016. A novel synaptic plasticity rule explains homeostasis of neuromuscular transmission. eLife 5, e12190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padilla CJ, et al. , 2021. Profiling age-related muscle weakness and wasting: neuromuscular junction transmission as a driver of age-related physical decline. Geroscience 43 (3), 1265–1281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen TH, et al. , 2009. Comparison of regulated passive membrane conductance in action potential-firing fast- and slow-twitch muscle. J. Gen. Physiol. 134 (4), 323–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen TH, et al. , 2016. Role of physiological ClC-1 Cl− ion channel regulation for the excitability and function of working skeletal muscle. J. Gen. Physiol. 147 (4), 291–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen TH, et al. , 2021. Chloride channel inhibition improves neuromuscular function under conditions mimicking neuromuscular disorders. Acta Physiol. (Oxf. ) 233 (2), e13690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piasecki M, et al. , 2016a. Motor unit number estimates and neuromuscular transmission in the tibialis anterior of master athletes: evidence that athletic older people are not spared from age-related motor unit remodeling. Physiol. Rep. 4, 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piasecki M, et al. , 2016b. Age-related neuromuscular changes affecting human vastus lateralis. J. Physiol. 594 (16), 4525–4536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piasecki M, et al. , 2018. Failure to expand the motor unit size to compensate for declining motor unit numbers distinguishes sarcopenic from non-sarcopenic older men. J. Physiol. 596 (9), 1627–1637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piasecki M, et al. , 2019. Long-Term Endurance and Power Training May Facilitate Motor Unit Size Expansion to Compensate for Declining Motor Unit Numbers in Older Age. Front. Physiol. 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt J, et al. , 2021. Neuromuscular Junction Aging: A Role for Biomarkers and Exercise. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med Sci. 76 (4), 576–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riisager A, et al. , 2016. Protein kinase C-dependent regulation of ClC-1 channels in active human muscle and its effect on fast and slow gating. J. Physiol. 594 (12), 3391–3406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues AZC, et al. , 2019. Sympathomimetics regulate neuromuscular junction transmission through TRPV1, P/Q- and N-type Ca(2+) channels. Mol. Cell Neurosci. 95, 59–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez Cruz PM, et al. , 2020. The Neuromuscular Junction in Health and Disease: Molecular Mechanisms Governing Synaptic Formation and Homeostasis. Front Mol. Neurosci. 13, 610964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez Cruz PM, et al. , 2020. , The Neuromuscular Junction in Health and Disease: Molecular Mechanisms Governing Synaptic Formation and Homeostasis. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenheimer JL, 1990. Factors affecting denervation-like changes at the neuromuscular junction during aging. Int J. Dev. Neurosci. 8 (6), 643–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolf R, Deschenes MR, Sandri M, 2016. Neuromuscular junction degeneration in muscle wasting. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 19 (3), 177–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russ DW, et al. , 2012. Evolving concepts on the age-related changes in “muscle quality”. J. Cachex-.-., Sarcopenia Muscle. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders DB, et al. , 2019. Guidelines for single fiber EMG. Clin. Neurophysiol. 130 (8), 1417–1439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaap LA, et al. , 2018. Associations of sarcopenia definitions, and their components, with the incidence of recurrent falling and fractures: the longitudinal aging study Amsterdam. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med Sci. 73 (9), 1199–1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slater CR, 2017. The structure of human neuromuscular junctions: some unanswered molecular questions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 18, 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DO, Chapman MR, 1987. Acetylcholine receptor binding properties at the rat neuromuscular junction during aging. J. Neurochem 48 (6), 1834–1841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DO, Rosenheimer JL, 1982. Decreased sprouting and degeneration of nerve terminals of active muscles in aged rats. J. Neurophysiol. 48 (1), 100–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonjak V, et al. , 2019. Fidelity of muscle fibre reinnervation modulates ageing muscle impact in elderly women. J. Physiol. 597 (19), 5009–5023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stalberg EV, Sonoo M, 1994. Assessment of variability in the shape of the motor unit action potential, the “jiggle,” at consecutive discharges. Muscle Nerve 17 (10), 1135–1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stashuk DW, 1999. Detecting single fiber contributions to motor unit action potentials. Muscle Nerve 22 (2), 218–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steffl M, et al. , 2017. Relationship between sarcopenia and physical activity in older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Inter. Aging 12, 835–845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taetzsch T, Valdez G, 2018. NMJ maintenance and repair in aging. Curr. Opin. Physiol. 4, 57–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tieland M, Trouwborst I, Clark BC, 2018. Skeletal muscle performance and ageing. J. Cachex-.-. Sarcopenia Muscle 9 (1), 3–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tintignac LA, Brenner HR, Ruegg MA, 2015. Mechanisms Regulating Neuromuscular Junction Development and Function and Causes of Muscle Wasting. Physiol. Rev. 95 (3), 809–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsao CY, 2016. Effective Treatment With Albuterol in DOK7 Congenital Myasthenic Syndrome in Children. Pedia Neurol. 54, 85–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdez G, et al. , 2010. Attenuation of age-related changes in mouse neuromuscular synapses by caloric restriction and exercise. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107 (33), 14863–14868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von JF, 1895. Ueber myasthenia gravis pseudoparalytica. Berl. Klin. Wochenschr. 32, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Webster RG, et al. , 2020. Effect of salbutamol on neuromuscular junction function and structure in a mouse model of DOK7 congenital myasthenia. Hum. Mol. Genet. 29 (14), 2325–2336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willadt S, Nash M, Slater CR, 2016. Age-related fragmentation of the motor endplate is not associated with impaired neuromuscular transmission in the mouse diaphragm. Sci. Rep. 6, 24849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wokke JH, et al. , 1990. Morphological changes in the human end plate with age. J. Neurol. Sci. 95 (3), 291–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood SJ, Slater CR, 2001. Safety factor at the neuromuscular junction. Prog. Neurobiol. 64 (4), 393–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H, Xiong WC, Mei L, 2010. To build a synapse: signaling pathways in neuromuscular junction assembly. Development 137 (7), 1017–1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon CH, et al. , 2019. Amifampridine for the management of lambert-eaton myasthenic syndrome: a new take on an old drug. Ann. Pharmacother. 54 (1), 56–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanetti G, et al. , 2018. Electrophysiological recordings of evoked end-plate potential on murine neuro-muscular synapse preparations. Bio Protoc. 8 (8), e2803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C, et al. , 2021. Ankyrin-dependent Na(+) channel clustering prevents neuromuscular synapse fatigue. Curr. Biol. 31 (17), 3810–3819 e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No data was used for the research described in the article.