Abstract

The TATA box-binding protein (TBP) plays an essential role in transcription by all three eukaryotic nuclear RNA polymerases, polymerases (Pol) I, II, and III. In each case, TBP interacts with class-specific TBP-associated factors (TAFs) to form class-specific transcription initiation factors. For yeast Pol III transcription, TBP associates with Brf (from TFIIB-related factor) and B", two Pol III TAFs, to form Pol III transcription factor TFIIIB. Here, we identify TBP surface residues that are required for interaction with yeast Pol III TAFs. Ninety-one human TBP surface residue mutants with radical substitutions were analyzed for the ability to form stable gel shift complexes with purified Brf and B" and for their activities for in vitro synthesis of yeast U6 snRNA. Mutations in a large positively charged epitope extending from the top (that is, on the surface opposite the DNA-facing “saddle” of TBP) and onto the side of the first TBP repeat inhibited binding to Brf (residues K181, L185, R186, E206, R231, L232, R235, K236, R239, Q242, K243, K249, and F250). A triple-mutant TBP (R231E + R235E + R239S) had greatly reduced activity for yeast U6 snRNA gene transcription while remaining active for Pol II basal transcription. Similar results were observed when selected mutations were introduced into yeast TBP at equivalent positions. A C-terminal fragment of Brf lacking the region of homology with TFIIB retains the ability to bind TBP-DNA complexes (G. Kassavetis, C. Bardeleben, A. Kumar, E. Ramirez, and E. P. Geiduschek, Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:5299–5306, 1997); the same TBP mutations reduced binding by this fragment. Mutations in TBP residues that interact with TFIIB did not affect Brf binding or U6 gene transcription. These results indicate that Brf and TFIIB interact differently with TBP. An extensively overlapping epitope on the top surface of TBP was found previously to be required for activated Pol II transcription and has been hypothesized to interact with Pol II TAFs. Our results map the surface of TBP that interacts with Brf and suggest that Pol II and Pol III TAFs interact with the same surface of TBP.

The TATA box-binding protein (TBP) plays an essential role in transcription by each of the three eukaryotic nuclear RNA polymerases, polymerases (Pol) I, II, and III. In each case, TBP associates with class-specific TBP-associated factors (TAFs) to form class-specific multisubunit transcription initiation factors that determine with which polymerase TBP functions (9, 10, 30). TBP also interacts with Pol II general transcription factors TFIIA and TFIIB (reviewed in references 2 and 27). Here, we sought to map the TBP surface that makes molecular contacts with the well-characterized yeast Pol III TAFs. We did this to better understand the architecture of the Pol III initiation complex, its relation to the Pol II initiation complex, and competing interactions between TBP and alternative TAFs and general transcription factors.

In the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, TBP associates with two Pol III TAFs, Brf (for TFIIB-related factor) and B", to form the central Pol III initiation factor TFIIIB (7, 14, 40, 42). Pol III transcribes small untranslated RNAs whose genes can be divided into three subclasses based on their promoter elements and their dependence on TFIIIA and TFIIIC (14, 40, 42). TFIIIB assembled from recombinant TBP, Brf, and B" is required for transcription of all three classes of Pol III genes where it is bound centered over a region about 30 bp upstream of the transcription start site (11). While the human homolog of B" has not been identified, TBP and Brf are conserved between yeast and human proteins (25, 39), and the activity of a probable human homolog of B" has recently been described (37), suggesting that the entire TFIIIB assembly is conserved through evolution. Of the two yeast Pol III TAFs, TBP interacts more strongly with Brf to form a B′ complex separable from the B" factor by ion-exchange chromatography (15, 16). Incorporation of B" into a TBP-Brf-DNA complex stabilizes the DNA-protein complex to treatment with the polyanion heparin and to high salt concentrations, indicating great stabilization of DNA binding by B" (16).

The genes encoding yeast and human Brf have been identified (3, 4, 24, 25, 39). They show high homology to each other (∼30% identity and 53% similarity), and both have an N-terminal region of ∼310 residues that is homologous to the full length of TFIIB (human Brf shows ∼21% identity and 45% similarity with human TFIIB). The C-terminal half of Brf is less conserved, with the strongest homology (29% identity) located in a stretch of 54 amino acid residues. Both the N- and C-terminal domains of Brf are required for Brf function in yeast (4). In vitro, each domain has been reported to interact with TBP independently (18, 39). The yeast B" TFIIIB subunit gene also has been cloned (17, 31, 32), and B" was reported to interact weakly with TBP and the yeast U6 snRNA gene TATA box in the absence of Brf (31).

Earlier work has suggested that Brf interacts with a region on the top of the conserved TBP core domain. The Brf gene was isolated as a high-copy-number suppressor of a TBP mutant with two lysine-to-leucine substitutions in the H2 helix which forms the top (convex) surface of the first repeat in the saddle-shaped TBP conserved core domain (K133L and K138L in yeast TBP [3]). An extensive genetic analysis of yeast TBP mutants that cause temperature-sensitive growth revealed 16 surface residues on the top of the yeast TBP core domain where mutations reduced Pol III transcription in vivo while increasing Pol II transcription and having little effect on Pol I transcription (5). Overexpression of Brf partially suppressed temperature-sensitive TBP mutations in this region, leading to the suggestion that this surface interacts directly with Brf (5). However, overexpression of Brf also suppresses a mutation in a tRNA gene A box promoter element which interacts with TFIIIC subunits and is not thought to interact directly with TFIIIB (24).

We took advantage of the observation that human TBP will interact with yeast Brf and B" to form functional TFIIIB (13a) to analyze the interaction of these yeast Pol III TAFs with a set of 91 human TBP surface residue mutants with radical substitutions within the highly conserved (80% identity between human and yeast TBPs) 180-residue carboxy-terminal core domain (2), plus two additional mutants not constructed earlier (Q242E and K243E). Each of these mutants contains a single amino acid residue substitution within the core domain at a site where the side chain of the wild-type residue is exposed to solvent in the crystal structure of the TBP-TATA box-DNA complex (27). This set of mutants was useful in identifying TBP surface residues that interact with TFIIA and TFIIB and two additional regions required for activated Pol II transcription in vivo (2). Here, we analyzed the interactions of these TBP mutants with recombinant yeast Brf and B" by electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) and tested their abilities to support yeast U6 snRNA gene transcription in vitro. Our studies identified a large Brf binding epitope on TBP that is well removed from the TFIIB binding surface and interacts with the C-terminal domain of Brf, which lacks homology with TFIIB. Mutations in the TFIIB binding residues of TBP affected neither Brf binding nor U6 transcription, suggesting that if the TFIIB-homologous region of Brf interacts with TBP in a manner homologous to TFIIB, its role in TFIIIB-DNA complex stability and transcriptional activity is minor. The Brf binding surface on TBP overlaps a TBP surface required for activated, but not basal, Pol II transcription, which has been postulated to interact with Pol II TAFs (2).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

EMSA.

Two probes, named U6TATA and NruI, respectively, were used in EMSA. The U6TATA probe was used to detect complexes of TBP-DNA and TBP-Brf-DNA. The NruI probe was used to detect TFIIIB complex formation. To make the U6TATA probe, two synthetic oligonucleotides from the S. cerevisiae U6 snRNA gene TATA box region (1) were synthesized separately and annealed, and the double-stranded oligonucleotide was gel purified and labeled with [α-32P]dATP by Klenow reaction. The top strand was 5′ AAGTATTTCGTCCACTATTTTCGGCTACTATAAATAAATGTTTTTTTCGCAACTATGTGTTC 3′ (the U6 start site is underlined). The NruI probe was prepared by labeling the 3′ end of the 145-bp EcoRI-NruI fragment of plasmid pCS6 (1) with [32P]dATP by Klenow reaction. This fragment extends from −142 to +3 relative to the U6 start site.

DNA binding was analyzed in a solution of 40 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM potassium HEPES (pH 7.9), 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 20 μg of poly(dG-dC) · poly(dG-dC) per ml, 0.5 mg of bovine serum albumin per ml, 10% glycerol (vol/vol), and 0.1 mM EDTA, with 2 ng of TBP and the indicated amount of Brf or B". Reaction mixtures were incubated at 25°C for 45 min. In the experiment represented by Fig. 5, 50 mM KCl was used in the binding reaction. The reactions were then treated with poly(dA-dT) · poly(dA-dT) (final concentration, 0.1 mg/ml) for ∼5 min and then resolved on a 15-cm 4% native polyacrylamide gel in 0.5× TBE (45 mM Tris, 45 mM boric acid, 1 mM EDTA [pH 7.9]) at room temperature for 2 h at 150 V.

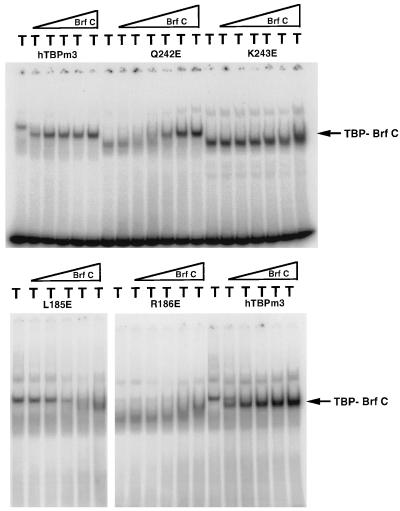

FIG. 5.

EMSAs with a C-terminal fragment of Brf. Two nanograms of hTBPm3, Q242E, K243E, L185E, and R186E were incubated with U6 TATA box probe and 0, 6.7, 20, 60, 180, and 540 fmol of a C-terminal fragment of Brf extending from amino acid residue 317 to the C terminus, at residue 596.

DNase I footprinting assays.

The footprinting probe was generated by 3′ end labeling of plasmid pG5E4TCAT (22) at the Asp718 site by Klenow reaction and then by cutting with HindIII. DNase I protection assays were conducted as described previously (22) in the same binding buffer as for EMSA.

In vitro transcription.

In vitro U6 transcription assays were performed as described previously (41) with some modifications. Briefly, TBP (30 ng), B" (44 fmol), Pol III (5 fmol), and Brf as indicated in the legend to Fig. 7 were preincubated with supercoiled pCS6 (100 ng) for 1 h at room temperature in a solution of 20 mM potassium HEPES (pH 7.9), 7 mM MgCl2, 3 mM dithiothreitol, 25 mM potassium acetate, 42 mM KCl, and 0.5 mg of bovine serum albumin per ml. The KCl concentration was then increased to 70 mM, and transcription was initiated by adding nucleotides to final concentrations of 200 μM GTP, 100 μM CTP, 100 μM UTP, and 25 μM ATP and 3 μCi of [α-32P]ATP in a final volume of 20 μl. Transcription was allowed to proceed for 30 min and was stopped by adding 180 μl of stop solution (1.75 M urea, 2.5 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 87.5 mM NaCl, 0.25% sodium dodecyl sulfate (wt/vol), 2.5 mM EDTA). Samples were phenol-chloroform extracted, ethanol precipitated, and analyzed by electrophoresis on denaturing 8% polyacrylamide gels. Gels were dried and subjected to autoradiography.

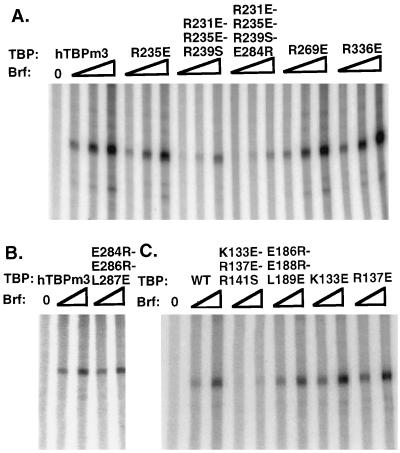

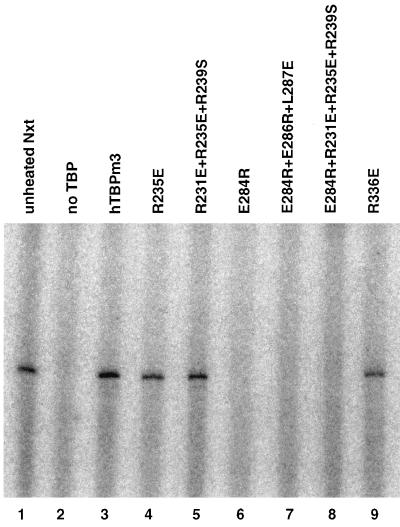

FIG. 7.

U6 snRNA gene transcription in vitro. (A) Reactions with human TBPs. All reaction mixtures contained constant amounts of hTBPm3 or the indicated TBP mutant and constant amounts of B" and yeast RNA Pol III. Either 0 (first lane) or 2.4, 7.3, or 22 fmol (from left to right) of Brf were added. Transcription products were analyzed by electrophoresis in a polyacrylamide gel followed by autoradiography. The band near the middle of the gel is in vitro-synthesized U6 snRNA. (B) Reactions with human TBP hTBPm3 or triple mutant E284R + E286R + L287E. Reaction mixtures were as described for panel A except that they contained 0, 2.4, or 7.3 fmol of Brf. (C) Reactions with yeast TBPs. For the wild type (WT) and each mutant TBP, transcription reactions were performed as described for panel A with 2.4 and 7.3 fmol of Brf.

In vitro Pol II basal transcription was performed as described previously (6) except that 2.5 mM unlabeled UTP was used in the reaction. For each reaction, 30 ng of hTBPm3 or another mutant TBP and 100 ng of G-less plasmid pΔMLP(C2AT) (29) were used.

Mutagenesis of TBP.

To generate the human TBP mutants Q242E, K243E, and triple mutants R231E + R235E + R239S and E284R + E286R + L287E, a BamHI-HindIII fragment containing hTBPm3 in pQE30 (2) was cloned into pBluescript (Stratagene). To generate the yeast TBP mutants, the wild-type yeast TBP gene from plasmid pAB24 (33) was cloned into pBluescript by introducing a BamHI site at the 5′ end and a SalI site at the 3′ end through PCR amplification. Mutations were generated by oligonucleotide-directed mutagenesis with Amersham Sculptor (for the triple mutants, three amino acid mutations were introduced simultaneously). Mutated TBP was cloned into pQE30 between the BamHI and HindIII sites (for human TBP) or the BamHI and SalI sites (for yeast TBP) and sequenced. To generate the quadruple human TBP mutant R231E + R235E + R239S + E284R, a StuI-HindIII fragment from the triple mutant R231E + R235E + R239S was excised and replaced with the StuI-HindIII fragment from the clone encoding the E284R mutant, and the construct was confirmed by sequencing.

Protein preparations.

For the initial screening of the TBP mutants, mutant TBPs were purified as described previously (2). Mutant proteins showing reduced activity in gel shift assays were purified again by the same procedure with the following modifications: cells from 500 ml of induced bacterial culture were pelleted and resuspended in 14 ml of cold 10 mM Tris–1 mM EDTA (pH 7.8) and frozen in liquid nitrogen. When processed for purification, 18 ml of buffer D300 (300 mM KCl, 20 mM potassium HEPES [pH 7.9], 20% [vol/vol] glycerol, 0.2 mM EDTA, 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol, and 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) and lysozyme (final concentration, 1 mg/ml) were added. Cells were then disrupted with an Ultrasonics, Inc., sonicator, model W-375, using eight 30-s pulses at setting 5, 50% input. Normally, 4 to 5 ml of heparin-Sepharose and 0.5 ml of Ni+-nitrilotriacetic acid-agarose were used for purification of TBP from each culture. Final TBP concentrations were determined by Bradford assay; purity (∼60 to 95%) was determined by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis followed by Coomassie blue staining.

Pol III, TFIIIC, recombinant B", and the C-terminal domain of Brf (residues 317 to 596) were purified and assayed as described or cited by Kassavetis et al. (13). Full-length Brf was purified as described previously (17).

RESULTS

Binding of Brf and B" to human TBP mutants.

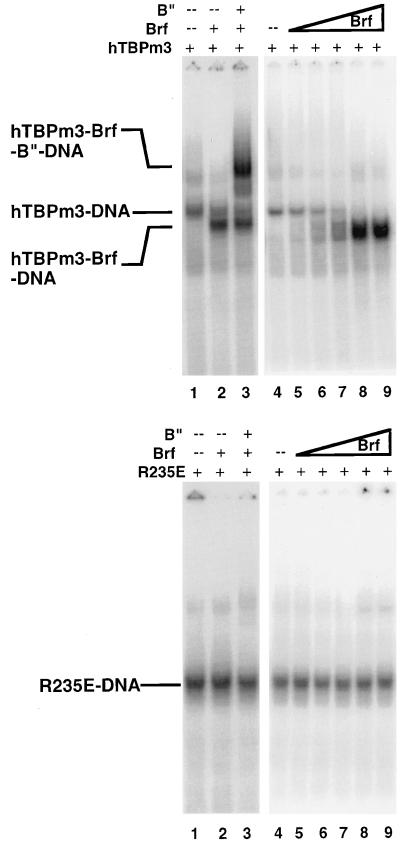

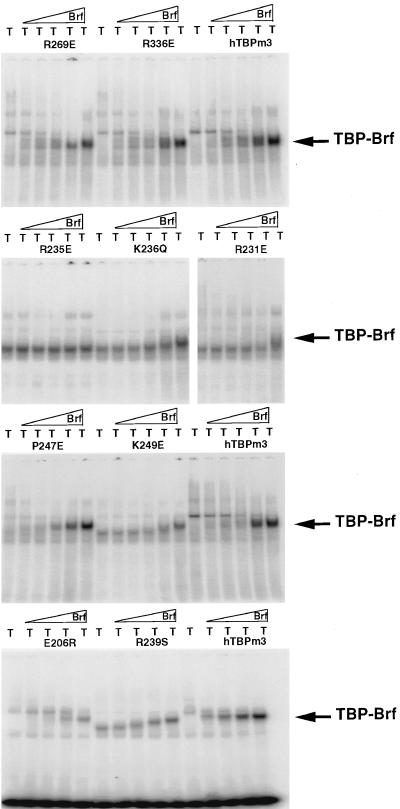

To analyze interactions between TBP mutants and Pol III TAFs, the stepwise assembly of TBP, TBP-Brf, and TBP-Brf-B" onto yeast SNR6 U6 promoter DNA was assayed by EMSA (11, 17). We chose the yeast U6 gene promoter because it has a TATA box at ∼−30, which allows detection of these intermediates in the assembly of TFIIIB, and because TFIIIB is the only factor in addition to Pol III required for in vitro U6 transcription (11, 26). The human TBP mutants were all built in the background of a three-residue substitution in the DNA binding surface of TBP that allows the molecule to bind to a TGTAAA box, simplifying the analysis of Pol II functions in vivo (2). This mutant of TBP with otherwise wild-type surface residues is called hTBPm3. hTBPm3 formed specific EMSA complexes with yeast Brf and Brf-B" (Fig. 1). Under our assay conditions, no binding of B" to a TBP-DNA complex was detected in the absence of Brf, as was observed previously for yeast TBP (11, 17). For hTBPm3 (and for wild-type human TBP [data not shown]), the TBP-Brf-DNA complex has greater mobility than does the TBP-DNA complex. The concentrations of TBP, Brf and B" used were determined empirically so that a twofold decrease in the amount of each generated an easily observed decrease in complex formation. Table 1 summarizes the results of EMSAs of mutant TBP-Brf complex formation for the 91 TBP mutants analyzed. Sixteen of the mutations had been previously suggested to cause the TBP to fold improperly and consequently to lose DNA binding activity (2). As expected, these mutants did not form detectable gel mobility shift complexes with Brf or Brf and B". Mutants E206R, R231E, L232E, R235E, K236Q, R239S, Q242E, K243E, K249E, and F250E all showed reduced binding of Brf in our initial screen of the human TBP mutants. R231E, R235E, and K236Q were also reduced in formation of TBP-Brf-B" complexes. Mutations in yeast TBP residues K83, L87, and H88 inhibit Brf binding (4a). Consequently, we carefully examined mutations in the equivalent human TBP residues (K181E, L185E, and R186E) and found that they also inhibit Brf binding to human TBP. All mutants that bound Brf similarly to the wild type were competent for binding B" to form the TBP-Brf-B" complex.

FIG. 1.

EMSAs of hTBPm3 and mutant R235E plus Brf and B" with a yeast U6 snRNA TATA box region probe. Results for hTBPm3 and R235E are shown at top and bottom, respectively. In each panel, the first three lanes show DNA-protein complexes formed with 2 ng of TBP, 6 fmol of Brf, and 88 fmol of B", as indicated at the top of the autoradiogram. The six lanes on the right, analyzed on a separate gel, show binding with hTBPm3 or R235E alone (2 ng) and with 1.1, 3.3, 9.8, 29, and 88 fmol (from left to right) of recombinant Brf. The positions of DNA-protein complexes are indicated.

TABLE 1.

Brf binding to mutants of human TBPa

| Mutant | TBP-Brf complexb | Relative affinity for Brfc |

|---|---|---|

| hTBPm3 | + | 1 |

| S156E | + | |

| E157R | + | |

| S158E | + | |

| S159E | + | |

| I161R | ? | |

| V162R | + | |

| L165E | No DNA binding | |

| N173E | + | |

| G175R | + | |

| C176R | + | |

| K177E | + | |

| D179R | + | |

| K181E | +/− | ∼0.1 |

| A184E | + | |

| L185E | − | ∼0.04 |

| R186E | − | ∼0.04 |

| R188E | No DNA binding | |

| N189E | + | |

| A190E | No DNA binding | |

| E191R | + | |

| Y192E | No DNA binding | |

| N193R | + | |

| P194E | + | |

| K195E | + | ∼0.3 |

| I201D | No DNA binding | |

| R203E | ? | |

| R205E | + | |

| E206R | +/− | ∼0.1 |

| R208E | + | |

| S215E | + | |

| S216R | ? | |

| G223R | No DNA binding | |

| E227R | No DNA binding | |

| E228A | + | |

| R231E | − | ∼0.04 |

| L232E | +/− | ∼0.1 |

| R235E | − | <0.04 |

| K236Q | − | ∼0.04 |

| R239S | +/− | ∼0.1 |

| V240Q | + | ∼0.3 |

| Q242E | +/− | ∼0.1 |

| K243E | − | ∼0.04 |

| L244E | ? | |

| G245E | + | |

| F246E | + | |

| P247E | + | ∼1 |

| K249E | +/− | ∼0.1 |

| F250E | +/− | ∼0.1 |

| L251E | + | |

| D252R | + | |

| F253E | No DNA binding | |

| K254E | + | |

| S261E | + | |

| D263R | + | |

| R265E | + | |

| F266E | No DNA binding | |

| P267E | + | |

| R269E | + | ∼1 |

| E271R | + | |

| L275R | + | |

| H277E | + | |

| Q278E | + | |

| A279E | + | |

| F280E | + | |

| S282E | + | |

| Y283E | No DNA binding | |

| E284R | + | |

| P285E | No DNA binding | |

| E286R | + | |

| L287E | + | |

| K297E | + | |

| R299E | + | |

| F305A | No DNA binding | |

| V306E | + | |

| S307F | No DNA binding | |

| K316E | No DNA binding | |

| V317E | + | |

| R318E | + | |

| A319R | + | |

| E320R | No DNA binding | |

| Y322E | + | |

| E323R | + | |

| E326A | + | |

| N327E | + | |

| Y329E | No DNA binding | |

| P330R | + | |

| K333E | + | |

| G334R | + | |

| R336E | + | ∼1 |

| K337E | + | |

| T338R | + |

All mutants were analyzed at least three times by EMSA with 2 ng of mutant TBP and 6 fmol of Brf, and the mutants which showed reduced binding to Brf were analyzed at least once with 6 fmol of the C-terminal domain of Brf (residues 317 to 596).

+, a complex with the mobility of the hTBPm3-Brf-DNA complex was observed; −, a complex was not observed at this position; +/−, a small fraction of the specific complex was at the position of the hTBPm3-Brf-DNA complex with most of the specific complex remaining at the position of the mutant TBP-DNA complex without the addition of Brf; ?, the mutant TBP showed reduced DNA binding activity but the mutant TBP-Brf-DNA complex was observed at the position of the hTBPm3-Brf-DNA complex.

Numbers are the concentration of Brf required to generate the hTBPm3-Brf-DNA complex divided by the concentration required to generate the mutant TBP-Brf-DNA complex, as determined by EMSAs with increasing concentrations of Brf (as in Fig. 1, 2, and 5). Where no value is given, such Brf titrations were not performed.

The mutants that were reduced in Brf binding in the initial assay were assayed in greater detail by incubation with Brf at increasing concentrations, followed by EMSA. Representative results for hTBPm3 and the most defective mutant in this assay, R235E, are shown in Fig. 1. No R235E-Brf-U6 DNA complex was formed, even at the highest Brf concentration used. For other mutants, the TBP-Brf-DNA complex formed only at higher Brf concentrations than that required to form a complex with hTBPm3 (data for representative mutants are shown in Fig. 2). Note that mutations on the top surface of the first repeat in human TBP that decrease the net charge of this highly basic region by one or two (R231E, K236Q, R239S, and K249E [also Q242E and K243E {see Fig. 3} and L232E and F250E {not shown}]) caused an increase in the mobility of the TBP-DNA complex, but the mobility of the TBP-Brf-DNA complex observed at high Brf concentrations with mutants R239S and K249E (Fig. 2), and with L232E, Q242E, and F250E (not shown), was similar to that observed with hTBPm3. The increase in Brf concentration required to generate a Brf-TBP-U6 DNA complex with hTBPm3 versus mutant TBPs was used as a rough measure of the decrease in affinity of the mutant TBPs for Brf (Table 1). Mutants K181E, L185E, R186E, E206R, R231E, L232E, R235E, K236Q, R239S, Q242E, K243E, K249E, and F250E were each reduced in affinity for Brf by a factor of 10 or more. R231E, R235E, and K236Q were also reduced in formation of TBP-Brf-B" complexes.

FIG. 2.

Brf binding to representative human TBP mutants. For the top three panels of EMSAs, 2 ng of hTBPm3 or the indicated mutant protein (whose presence is indicated by T above each lane) was incubated with U6 probe alone (left lanes) or with 1.1, 3.3, 9.8, 29, or 88 fmol of recombinant Brf (in the successive five lanes). For the bottom panel of EMSAs, 2 ng of hTBPm3 or mutant TBP was incubated with U6 probe alone (left lanes) or with 3.7, 11, 33, or 100 fmol of recombinant Brf (in the successive four lanes).

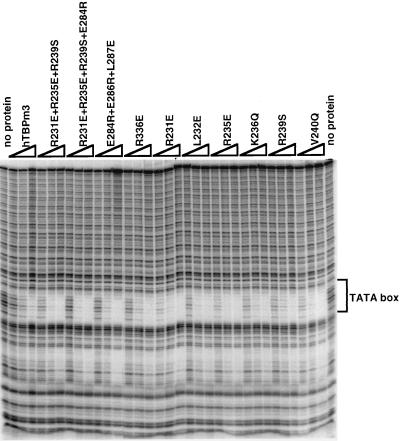

FIG. 3.

DNase I footprinting activity of TBP mutants on the adenovirus 2 E4 promoter. For each mutant, three titrations (2, 4, and 8 ng, from left to right) of TBP were assayed for DNase I footprinting activity. The protected TATA box is indicated at the right.

To test whether mutations that cause a defect in Brf binding affect the proper folding of the TBP core domain, we analyzed the DNA binding activity of the mutants by DNase I footprinting on a high-affinity TATA box (Fig. 3). We reasoned on the basis of the crystal structure of the TBP core domain-TATA box complex (27) that mutations disrupting the folding of the core domain would most likely impair TBP DNA binding activity. Our assay conditions were roughly quantitative, in the sense that increasing amounts of hTBPm3 yielded increased protection of the TATA box. All the mutants that showed reduced binding to Brf showed similar, or in some cases (for example, R235E) increased, TATA box-binding activity, indicating that the radical mutations did not cause the TBP molecule to fold improperly.

The mutations that reduced Brf binding without unfolding TBP are in residues that form an approximately continuous surface on the top and side of the N-terminal repeat of the TBP core domain (Fig. 4). We interpret these results to indicate that these residues form the surface of TBP that interacts directly with Brf in TFIIIB.

FIG. 4.

Locations of human TBP residues where mutations decrease the binding of Brf. At the top, the TBP molecule is viewed from its upstream-facing surface (relative to Pol II transcription on the adenovirus 2 major late promoter), with the N-terminal repeat to the right. DNA is shown as a wire diagram. At the bottom, TBP is shown rotated 90° so that the top of the molecule is viewed with the N-terminal repeat to the right. Residues where mutations reduce Brf binding in EMSA are darkened and designated.

Like full-length TBP, a C-terminal fragment of Brf completely lacking the region of homology with TFIIB (Brf residues 317 to 596) forms a stable complex with TBP and U6 TATA-box DNA (13). To determine if the C-terminal domain of Brf binds to a portion of the surface shown in Fig. 4, each of the TBP mutants defective for binding full-length Brf (Table 1), and several control mutants that bind full-length Brf like wild-type TBP, were assayed for interaction with Brf (residues 317 to 596). Representative results are shown in Fig. 5. Results with this C-terminal fragment of Brf were precisely the same as for full-length Brf. The same TBP mutations that decreased the affinity of TBP for full-length Brf had similar effects on the affinity of TBP for the C-terminal fragment of Brf. We conclude that the surface of TBP highlighted in Fig. 4 contacts the C-terminal domain of Brf and that the C-terminal domain of Brf makes the principal contacts with TBP that stabilize the Brf-TBP complex.

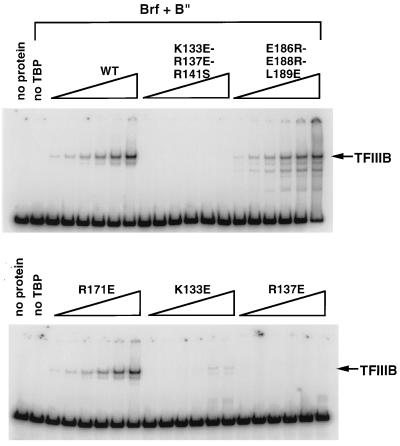

Homologous mutants of yeast TBP behave similarly.

The preceding experiments analyzed the effects of mutations in human TBP on its association with yeast Pol III TAFs. To confirm that these effects also pertain to the homologous yeast TBP, we introduced mutations into yeast TBP residues K133, R137, Q144, and K145, equivalent to human TBP residues R231, R235, Q242, and K243, respectively, where mutations were found to have significant effects on Brf binding to human TBP. As a control, a mutation which did not affect human TBP binding to Brf was also constructed in yeast TBP (yeast R171E, equivalent to human R269E). These yeast TBP mutants were analyzed for the ability to form the TBP-Brf-B"-DNA (i.e., TFIIIB-DNA) complex on U6 promoter DNA by incubating increasing amounts of wild-type or mutant yeast TBPs with a constant amount of labeled U6 promoter DNA, Brf, and B" (Fig. 6). Excess amounts of Brf and B" were added so that the TBP concentration was limiting in the assays. Under the conditions used, yeast TBP alone did not form a stable complex with the probe. Yeast mutants K133E and R137E were severely defective in this assay (as were Q144E and K145E [data not shown]), but R171E behaved like wild-type yeast TBP. The defect in the formation of the TFIIIB complex was due to a defect in TBP-Brf interaction (as assayed by EMSA [data not shown]), as for the human TBP mutants. Thus, the interactions of these yeast TBP mutants with Brf were consistent with the properties of their human TBP homologs.

FIG. 6.

EMSAs with mutant yeast TBPs. The wild type or the indicated mutant yeast TBPs were incubated with U6 TATA box probe, 100 fmol of Brf, 150 fmol of B", and increasing amounts (0.125, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, and 4 ng) of recombinant wild-type and mutant TBPs, as indicated.

U6 snRNA transcription.

To test the functional significance of the interaction between TBP and Brf through the TBP surface identified above, the effects of the TBP mutations on in vitro Pol III transcription of the yeast U6 gene were analyzed. Transcription reaction mixtures included recombinant yeast Brf, recombinant yeast B", purified yeast Pol III, and recombinant wild-type or mutant human or yeast TBP (Fig. 7). Surprisingly, even though human TBP mutant R235E and yeast TBP mutants K133E and R137E were extremely defective in forming complexes with Brf (Fig. 1 and 6), they showed relatively minor defects in in vitro transcription. Consequently, to test whether the TBP interaction with Brf through the TBP surface defined by the mutant study is significant for Pol III transcription, we constructed triple mutants of human and yeast TBP in which three of the critical residues in the proposed TBP interaction surfaces were mutated. As expected, the triple mutants (human TBP R231E + R235E + R239S and yeast TBP K133E + R137E + R141S) were severely defective in formation of the TBP-Brf-B" complex (Fig. 6 and data not shown for the human TBP mutant). To test if the triple mutations interfered with the folding of TBP, the human TBP (R231E + R235E + R239S) was tested for DNA binding activity by DNase I footprinting (Fig. 3). Both mutants were also tested for their TFIIB and TFIIA binding activities. While they bound to TFIIB similarly to the wild type, these mutant TBPs showed reduced activity for binding to TFIIA (data not shown). This was not surprising, since these mutations are located close to the surface on TBP that is required for TFIIA binding (2, 8, 34). The human triple mutant was also tested for function in a basal Pol II transcription assay. Individual mutations in these residues do not interfere with TBP function in the basal transcription assay (2) (also, see Fig. 8). Similarly, human TBP (R231E + R235E + R239S) was also active in this assay (Fig. 8). These results indicate that the R231E + R235E + R239S triple mutant is folded correctly. Nonetheless, these human and yeast TBP triple mutants were severely defective in in vitro Pol III transcription (Fig. 7A and C).

FIG. 8.

Basal in vitro Pol II transcription with human TBPs. Basal in vitro Pol II transcription from the adenovirus 2 major late promoter with a G-less cassette template was performed as described in Materials and Methods by using nuclear extract (Nxt) (lane 1), heat-treated nuclear extract (lane 2), or hTBPm3 or the indicated TBP mutant added to the heat-treated nuclear extract (lanes 3 to 9).

Since Brf was first identified as a TFIIB-related factor, it was surprising to us that we did not observe an effect by mutations in the surface of TBP that interacts with TFIIB (2, 27, 35) on Brf binding or on in vitro Pol III transcription. To explore this point further, we constructed triple mutants of the human and yeast TBP proteins in which three residues critical to TFIIB binding were simultaneously mutated (human E284R + E286R + L287E and yeast E186R + E188R + L189E). Human TBP (E284R + E286R + L287E) bound DNA (Fig. 3) and TFIIA (assayed by EMSA [data not shown]) similarly to wild-type human TBP, indicating that it folds normally. As expected, it was defective in basal Pol II transcription (Fig. 8). The yeast triple mutant formed an EMSA gel shift complex with Brf and B" of similar mobility to the complex formed with wild-type TBP, although minor, more rapidly migrating complexes were also observed (Fig. 6). In addition, both the human and yeast TBP triple mutants supported in vitro U6 transcription to a level similar to the wild-type proteins (Fig. 7B and C). These results indicate that these residues are not significantly involved in Brf binding. Moreover, we also constructed a quadruple mutant which combines the E284R mutation with the triple mutations of human TBP (R231E + R235E + R239S). The E284R mutation had only a minor additional effect on U6 transcription compared with the triple mutation (Fig. 7A).

To test the possible significance of a potential interaction between Brf and residues at the tip of the N-terminal stirrup of TBP, we reexamined human TBP mutations in that region (E191R, N193R, P194E, and K195E). These mutants did not show significant defects in Brf binding or in in vitro U6 transcription (data not shown). Furthermore, the C-terminal fragment of Brf (residues 317 to 596), which lacks the entire TFIIB homology region, retains the ability to bind TBP (13), and its affinity for TBP is affected similarly by TBP mutations that reduce the binding of full-length Brf (Fig. 5 and data not shown). Based on the combined data, we conclude that if there are any Brf-TBP interactions similar to those of TBP with the core of TFIIB (28), they are not required for the assembly of TFIIIB or for TFIIIB-dependent transcription.

DISCUSSION

Our study has identified a surface of the TBP molecule (Fig. 4) within which radical mutations impair the ability of TBP to bind the Pol III TAF Brf. We propose that this surface forms the principal interface between TBP and Brf in the TFIIIB complex. A C-terminal fragment of Brf completely lacking the region of homology with TFIIB also forms a stable complex with TBP and U6 promoter DNA (13). The same TBP mutations that inhibited binding to full-length Brf had comparable effects on the binding of this C-terminal domain of Brf. Also, neither point mutations of TBP that impair TFIIB binding nor mutation of all three of these TBP residues interfered with Brf binding or Pol III transcription of the U6 gene in vitro. We conclude that the principal contacts between Brf and TBP are through the C-terminal domain of Brf and that the TFIIB-homologous domain of Brf does not make functionally significant contacts with TBP homologous to the contacts made between TBP and the core of TFIIB (28).

We performed our initial screening with human TBP mutants and recombinant yeast Brf and B". Although a heterologous combination of proteins was used, we believe that the results are broadly relevant to TBP-Brf and TBP-Brf-B" interactions of TFIIIB in eukaryotes for the following reasons. First, the core domain of TBP is highly conserved between yeast and human proteins; 80% of the residues in the essential carboxy-terminal 180-residue core domain are identical between yeast and human, and most of the nonidentities are highly conservative substitutions. Moreover, the crystal structures of Arabidopsis, yeast, and human TBPs bound to TATA box DNA are extremely similar (12, 19, 21). Second, human TBP interacts with yeast Brf, yeast B", and yeast U6 snRNA promoter DNA to form complexes that are stable to native gel electrophoresis and active for in vitro transcription. Third, several yeast TBP mutants were constructed and analyzed and found to interact with Brf like the equivalent mutant human TBPs (Fig. 6 and 7). For the most defective human and yeast TBP mutants (human R235E and the yeast equivalent R137E), the TBP-Brf complex was not observed in EMSA, even at a 27-fold-higher Brf concentration than required to form a TBP-Brf complex with wild-type TBP.

The TBP residues where mutations interfere with Brf binding form a nearly continuous surface on the first TBP repeat, extending from the top to the side of the molecule (Fig. 4). Residues R188, A190, Y192, E227, and F253 lie close to this surface; however, the mutations we constructed in these residues interfered with DNA binding by the mutant TBPs. Consequently, we cannot conclude whether or not these residues contribute to the TBP interface with Brf. We used specific DNA binding to TATA box DNA as the assay to test proper folding of our TBP mutants. The residues in question lie far from the DNA binding surface of TBP, and consequently our mutants in these residues are probably defective in DNA binding because they fold improperly. Consequently, the interpretation of any protein-protein interaction assay results with these mutants would be complicated. Even if these mutants proved to be defective in binding to Brf by an assay other than EMSA, the defect could be due to an alteration in the overall structure of TBP rather than to the loss of specific contacts with the wild-type residue at that position.

Surprisingly, substitutions L185E, R186E, R231E, R235E, and K236Q in human TBP, and K133E and R137E in yeast TBP, caused significantly reduced Brf binding in vitro as assayed by EMSA (Fig. 3 and 6) but had relatively minor effects on in vitro U6 transcription (Fig. 7 and data not shown). A significant defect in U6 transcription was observed consistently only when the Brf interaction surface was extensively mutated, as in human TBP R231E + R235E + R239S and the equivalent yeast TBP (K133E + R137E + R141S) (Fig. 7). Remarkably, a low level of U6 transcription remained in reactions with the triple mutants, in spite of the extensive modification of the proposed TBP-Brf interacting surface. The different behaviors of these mutants in the gel shift and transcription assays probably result from significant differences in the details of these assays. EMSA requires that DNA-protein complexes be stable to electrophoresis and postbinding competition with the specific competitor poly(dA-dT). In contrast, Brf mutants which do not form stable EMSA complexes with TBP and a U6 promoter probe but nonetheless are active for in vitro U6 gene transcription have been characterized (13, 22b). It is likely that a much greater number of protein-protein and protein-DNA interactions occur in the transcription initiation complex than in the Brf-TBP-DNA complex, since the initiation complex also includes B" and the 16-subunit Pol III. Apparently, the additional contacts largely compensate for the loss of contacts between TBP single point mutants and Brf. In fact, we observed that at high B" concentrations, mutant R235E bound both Brf and B" to form TFIIIB (data not shown), indicating that B" binding alone can greatly compensate for a mutant’s defect in Brf binding.

The human TBP mutants were also assayed for the ability to form complete TFIIIB complexes (i.e., TBP-Brf-B") on the U6 promoter. None of the mutations outside of the Brf binding surface shown in Fig. 4 significantly affected formation of the TFIIIB complex. Thus, we did not observe evidence for specific contacts between TBP and B". Under our assay conditions, direct binding of B" to a TBP-DNA complex was not observed, Brf being strictly required (11, 17). These results suggest the following model for TBP interactions in the TFIIIB complex. The principal protein-protein contacts between TBP and Pol III TAFs are proposed to be with Brf. B" in the TFIIIB-DNA complex is proposed to make specific contacts principally with Brf and DNA and to associate with TBP indirectly through these. However, in opposition to this model, Roberts et al. (31) reported that at high concentrations, B" can form a specific complex with TBP on the U6 promoter that is detectable by EMSA, suggesting that specific B"-TBP interactions do occur. If that is the case, our failure to find a mutation in a TBP surface residue that affects the incorporation of B" into TFIIIB suggests that such specific TBP-B" contacts do not add greatly to the stability of the TFIIIB complex.

We also analyzed the human TBP mutants for tRNA gene transcription and for the ability to form a TFIIIC-TFIIIB complex on a tRNA gene, as assayed by EMSA (hTBPm3 and yeast TBP generated comparable levels of transcription and heparin-resistant TFIIIB-DNA complexes on the SUP4 tRNA gene [data not shown]). There was no clear indication of single, radical substitution mutants which were specifically defective for tRNA transcription but not U6 transcription (or vice versa). However, the human TBP triple mutant (E284R + E286R + L287E) was impaired for SUP4 tRNA gene transcription but nevertheless was as active as hTBPm3 for the formation of TFIIIB-TFIIIC-SUP4 DNA complexes (data not shown). The cause of this transcriptional defect has not yet been determined but may reflect a failure of this TFIIIB complex to fully displace the τ120 subunit of TFIIIC from start site-proximal DNA as has been observed with certain B" deletions (22a). Even with this one exception, our data suggest that TBP and Brf interact similarly in TFIIIB-DNA complexes formed on both the U6 snRNA and SUP4 tRNA genes. This is consistent with the finding that properties of TFIIIB binding to U6, tRNA, and 5S rRNA gene promoters are fundamentally similar in important features such as location relative to the transcription start site and stability to heparin and high salt concentrations (11). TFIIIC loads TFIIIB onto tRNA genes and, together with TFIIIA, loads TFIIIB onto 5S rRNA genes. Both forms of the TFIIIC-loaded TFIIIB-DNA complex are functionally equivalent to the TFIIIB complex formed around the TATA-box of the yeast U6 snRNA promoter, allowing specific Pol III subunits to interact with Brf, leading to initiation of transcription at a nearly fixed distance from the TFIIIB-DNA binding site (11, 14, 40).

The Brf binding surface of human TBP that is defined by our analysis of direct interactions between purified proteins and U6 promoter DNA (Fig. 4) agrees well with earlier studies of TBP mutants. Overexpression of Brf suppresses the temperature-sensitive growth of a yeast TBP double mutant, K133L + K138L (3), equivalent to mutations of human R231 and K236. Yeast TBP mutants F155S, K138L, and R137W (equivalent to mutations of human TBP residues F253, K236, and R235) were reported to be defective in binding the C-terminal region of Brf (18). An extract prepared from a temperature-sensitive yeast strain which contains mutation K138L showed decreased Pol III transcription but normal Pol I and II transcription (20).

In an extensive genetic analysis of yeast TBP, Cormack and Struhl (5) identified 16 residues on the surface of yeast TBP where mutations decreased tRNA gene transcription in vivo and increased Pol II transcription, while having little effect on rRNA gene transcription by Pol I. Overexpression of Brf partially suppressed the temperature-sensitive growth of yeast cells carrying these “Pol III-specific” TBP mutations, leading Cormack and Struhl to suggest that the 16-residue surface might be the interaction surface between Brf and TBP (5). However, a mutation in a tRNA A box promoter element, which interacts with subunits of TFIIIC, can also be suppressed by overexpression of Brf, probably because high concentrations of Brf drive assembly of the complete tRNA gene initiation complex by mass action (24). Consequently, it is not possible to interpret suppression by Brf overexpression as being due to a direct interaction between Brf and the mutant molecule whose phenotype is suppressed. Four of the 16 surface residues where mutations give the Pol III-specific phenotype (5) are in the TBP-Brf interface proposed in this study (yeast residues K133, R137, Q144, and F152, equivalent to human R231, R235, Q242, and F250 [Fig. 4]). The remaining Pol III-specific surface residues lie immediately next to our proposed Brf interface (Fig. 4) or extend onto the top of the second TBP repeat. As discussed below, the proposed Brf interaction surface overlaps a surface of TBP that is proposed to interact with Pol II TAFs. Consistent with this, Cormack and Struhl found that mutations of yeast residues R141 and Q144 (equivalent to human R239 and Q242) affect both Pol II and Pol III transcription in vivo. If Pol II and Pol III TAFs compete for binding to TBP molecules in yeast cells, mutations in the Cormack and Struhl Pol III-specific TBP surface residues may generate their effects in vivo by tipping the balance of competing binding reactions in favor of Pol II over Pol III TAFs. Alternatively, some of the Pol III-specific mutations may influence the assembly of B" into TFIIIB in a manner that is not detected by our in vitro EMSA and transcription assays.

Much of the TBP surface that interacts with Brf was also found to be required for TBP to support activated Pol II transcription in vivo by two unrelated activation domains (2). Human TBP mutants R231E, R235E, R239S, and F250E were found to interact normally with DNA, TFIIA, and TFIIB, as expected from the crystal structures of the TBP-TFIIA-DNA (8, 34) and TBP-TFIIB-DNA (28) complexes, and all except for F250E were found to support basal in vitro Pol II transcription normally. Since Pol II TAFs are required for activated transcription in vitro in mammalian systems, but not for basal transcription (9, 10), this is precisely the phenotype expected for a mutation that interferes with Pol II TAF interactions. Moreover, human TBP with the triple alanine substitution of R231A + R235A + R239A showed reduced in vitro binding to Pol II TAF 250 (36). Consequently, we postulated that the Pol II activation epitope that nearly coincides with our proposed Brf interaction surface is an interaction surface for a Pol II TAF (2), as did Tansey et al. (36).

From an evolutionary point of view, it seems reasonable that Pol I- , II- , and III-specific TAFs would interact with similar surfaces of TBP. The three nuclear RNA polymerase systems probably evolved from a common ancestor with a single nuclear RNA polymerase perhaps resembling modern day Archaea with their single, related RNA polymerase and general transcription factors (23, 38). As the three modern nuclear RNA polymerases evolved in eukaryotes, constraints on the evolution of protein-protein interaction surfaces may have maintained common surfaces of interaction between TBP and the TAFs associated with the three nuclear RNA polymerases. This appears to be the case, as we now report, for the interactions between TBP and Brf and between TBP and one or more factors, probably Pol II TAF(s), required for activated Pol II transcription.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The work at UCLA was supported by a grant from the NCI (CA25235); that at UCSD was supported by a grant from the NIGMS.

We thank Carol Eng, Cynthia Brent, and Enrique Ramirez for expert technical assistance, Steven Hahn and Ashok Kumar for communication of results prior to publication, and E. Peter Geiduschek for comments on the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brow D A, Guthrie C. Transcription of a yeast U6 snRNA gene requires a polymerase III promoter element in a novel position. Genes Dev. 1990;4:1345–1356. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.8.1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bryant G O, Martel L S, Burley S K, Berk A J. Radical mutations reveal TATA-box binding protein surfaces required for activated transcription in vivo. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2491–2504. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.19.2491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buratowski S, Zhou H. A suppressor of TBP mutations encodes an RNA polymerase III transcription factor with homology to TFIIB. Cell. 1992;71:221–230. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90351-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Colbert T, Hahn S. A yeast TFIIB-related factor involved in RNA polymerase III transcription. Genes Dev. 1992;6:1940–1949. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.10.1940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4a.Colbert, T., S. Lee, G. Schimmack, and S. Hahn. Personal communication.

- 5.Cormack B P, Struhl K. Regional codon randomization: defining a TATA-binding protein surface required for RNA polymerase III transcription. Science. 1993;262:244–248. doi: 10.1126/science.8211143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flores O, Lu H, Reinberg D. Factors involved in specific transcription by mammalian RNA polymerase II. Identification and characterization of factor IIH. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:2786–2793. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Geiduschek E P, Kassavetis G A. RNA polymerase III transcription complexes. In: McKnight S L, Yamamoto K R, editors. Transcriptional regulation. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1992. pp. 247–280. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Geiger J H, Hahn S, Lee S, Sigler P B. Crystal structure of the yeast TFIIA/TBP/DNA complex. Science. 1996;272:830–836. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5263.830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goodrich J A, Tjian R. TBP-TAF complexes: selectivity factors for eukaryotic transcription. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1994;6:403–409. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(94)90033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hernandez N. TBP, a universal eukaryotic transcription factor? Genes Dev. 1993;7:1291–1308. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.7b.1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Joazeiro C A, Kassavetis G A, Geiduschek E P. Identical components of yeast transcription factor IIIB are required and sufficient for transcription of TATA box-containing and TATA-less genes. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:2798–2808. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.4.2798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Juo Z S, Chiu T K, Leiberman P M, Baikalov I, Berk A J, Dickerson R E. How proteins recognize the TATA box. J Mol Biol. 1996;261:239–254. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kassavetis G, Bardeleben C, Kumar A, Ramirez E, Geiduschek E P. Domains of the Brf component of RNA polymerase III transcription factor IIIB (TFIIIB): functions in assembly of TFIIIB-DNA complexes and recruitment of RNA polymerase to the promoter. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:5299–5306. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.9.5299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13a.Kassavetis, G. A. Unpublished data.

- 14.Kassavetis G A, Bardeleben C, Braun B, Joazeiro C, Pisano M, Geiduschek E P. Transcription by RNA polymerase III. In: Conaway R C, Conaway J W, editors. Transcription mechanisms and regulation. Vol. 3. New York, N.Y: Raven Press; 1994. pp. 107–126. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kassavetis G A, Bartholomew B, Blanco J A, Johnson T E, Geiduschek E P. Two essential components of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae transcription factor TFIIIB: transcription and DNA-binding properties. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:7308–7312. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.16.7308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kassavetis G A, Joazeiro C A, Pisano M, Geiduschek E P, Colbert T, Hahn S, Blanco J A. The role of the TATA-binding protein in the assembly and function of the multisubunit yeast RNA polymerase III transcription factor, TFIIIB. Cell. 1992;71:1055–1064. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90399-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kassavetis G A, Nguyen S T, Kobayashi R, Kumar A, Geiduschek E P, Pisano M. Cloning, expression, and function of TFC5, the gene encoding the B" component of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae RNA polymerase III transcription factor TFIIIB. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:9786–9790. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.21.9786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khoo B, Brophy B, Jackson S P. Conserved functional domains of the RNA polymerase III general transcription factor BRF. Genes Dev. 1994;8:2879–2890. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.23.2879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim J L, Nikolov D B, Burley S K. Co-crystal structure of TBP recognizing the minor groove of a TATA element. Nature. 1993;365:520–527. doi: 10.1038/365520a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim T K, Roeder R G. Involvement of the basic repeat domain of TATA-binding protein (TBP) in transcription by RNA polymerases I, II, and III. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:4891–4894. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim Y, Geiger J H, Hahn S, Sigler P B. Crystal structure of a yeast TBP/TATA-box complex. Nature. 1993;365:512–520. doi: 10.1038/365512a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kobayashi N, Boyer T G, Berk A J. A class of activation domains interacts directly with TFIIA and stimulates TFIIA-TFIID-promoter complex assembly. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:6465–6473. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.11.6465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22a.Kumar, A., G. A. Kassavetis, E. P. Geiduschek, M. Hambalko, and C. J. Brent. Functional dissection of the B" component of RNA polymerase III transcription factor IIIB: a scaffolding protein with multiple roles in assembly and initiation of transcription. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:1868–1880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22b.Kumar, A., et al. Unpublished data.

- 23.Langer D, Hain J, Thuriaux P, Zillig W. Transcription in archaea: similarity to that in eucarya. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:5768–5772. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.13.5768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lopez-De-Leon A, Librizzi M, Puglia K, Willis I M. PCF4 encodes an RNA polymerase III transcription factor with homology to TFIIB. Cell. 1992;71:211–220. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90350-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mital R, Kobayashi R, Hernandez N. RNA polymerase III transcription from the human U6 and adenovirus type 2 VAI promoters has different requirements for human BRF, a subunit of human TFIIIB. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:7031–7042. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.12.7031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moenne A, Camier S, Anderson G, Margottin F, Beggs J, Sentenac A. The U6 gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae is transcribed by RNA polymerase C (III) in vivo and in vitro. EMBO J. 1990;9:271–277. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08105.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nikolov D B, Burley S K. RNA polymerase II transcription initiation: a structural view. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:15–22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.1.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nikolov D B, Chen H, Halay E D, Usheva A A, Hisatake K, Lee D K, Roeder R G, Burley S K. Crystal structure of a TFIIB-TBP-TATA-element ternary complex. Nature. 1995;377:119–128. doi: 10.1038/377119a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parvin J D, Shykind B M, Meyers R E, Kim J, Sharp P A. Multiple sets of basal factors initiate transcription by RNA polymerase II. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:18414–18421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rigby P W. Three in one and one in three: it all depends on TBP. Cell. 1993;72:7–10. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90042-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roberts S, Miller S J, Lane W S, Lee S, Hahn S. Cloning and functional characterization of the gene encoding the TFIIIB90 subunit of RNA polymerase III transcription factor TFIIIB. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:14903–14909. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.25.14903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ruth J, Conesa C, Dieci G, Lefebvre O, Dusterhoft A, Ottonello S, Sentenac A. A suppressor of mutations in the class III transcription system encodes a component of yeast TFIIIB. EMBO J. 1996;15:1941–1949. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schmidt M C, Kao C C, Pei R, Berk A J. Yeast TATA-box transcription factor gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:7785–7789. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.20.7785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tan S, Hunziker Y, Sargent D F, Richmond T J. Crystal structure of a yeast TFIIA/TBP/DNA complex. Nature. 1996;381:127–151. doi: 10.1038/381127a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tang H, Sun X, Reinberg D, Ebright R H. Protein-protein interactions in eukaryotic transcription initiation: structure of the preinitiation complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:1119–1124. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.3.1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tansey W P, Ruppert S, Tjian R, Herr W. Multiple regions of TBP participate in the response to transcriptional activators in vivo. Genes Dev. 1994;8:2756–2769. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.22.2756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Teichmann M, Dieci G, Huet J, Ruth J, Sentenac A, Seifart K. Functional interchangeability of TFIIIB components from yeast and human cells in vitro. EMBO J. 1997;16:4708–4716. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.15.4708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thomm M. Archaeal transcription factors and their role in transcription initiation. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1996;18:159–171. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1996.tb00234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang Z, Roeder R G. Structure and function of a human transcription factor TFIIIB subunit that is evolutionarily conserved and contains both TFIIB- and high-mobility-group protein 2-related domains. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:7026–7030. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.15.7026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.White R J. RNA polymerase III transcription. R. G. Austin, Tex: Landes Co.; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Whitehall S K, Kassavetis G A, Geiduschek E P. The symmetry of the yeast U6 RNA gene’s TATA box and the orientation of the TATA-binding protein in yeast TFIIIB. Genes Dev. 1995;9:2974–2985. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.23.2974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Willis I M. RNA polymerase III. Genes, factors and transcriptional specificity. Eur J Biochem. 1993;212:1–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb17626.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]