Abstract

The house mouse (Mus musculus) is an exceptional model system, combining genetic tractability with close evolutionary affinity to humans1,2. Mouse gestation lasts only 3 weeks, during which the genome orchestrates the astonishing transformation of a single-cell zygote into a free-living pup composed of more than 500 million cells. Here, to establish a global framework for exploring mammalian development, we applied optimized single-cell combinatorial indexing3 to profile the transcriptional states of 12.4 million nuclei from 83 embryos, precisely staged at 2- to 6-hour intervals spanning late gastrulation (embryonic day 8) to birth (postnatal day 0). From these data, we annotate hundreds of cell types and explore the ontogenesis of the posterior embryo during somitogenesis and of kidney, mesenchyme, retina and early neurons. We leverage the temporal resolution and sampling depth of these whole-embryo snapshots, together with published data4–8 from earlier timepoints, to construct a rooted tree of cell-type relationships that spans the entirety of prenatal development, from zygote to birth. Throughout this tree, we systematically nominate genes encoding transcription factors and other proteins as candidate drivers of the in vivo differentiation of hundreds of cell types. Remarkably, the most marked temporal shifts in cell states are observed within one hour of birth and presumably underlie the massive physiological adaptations that must accompany the successful transition of a mammalian fetus to life outside the womb.

Subject terms: Embryogenesis, Organogenesis, Gene expression

Single-cell transcriptome profiling of mouse embryos and newborn pups is combined with previously published data to construct a tree of cell-type relationships tracing development from zygote to birth.

Main

Since 2017, many studies have applied single-cell methods to characterize biological development at the scale of the whole organism7–17. Most such studies are time series, in which each embryo is analysed at one developmental stage—by profiling of transcription via single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) or chromatin accessibility via single-cell sequencing assay for transposase-accessible chromatin (scATAC-seq)—resulting in a series of snapshots that can be pieced together, analogous to the single frames that are put together to create a film. Inevitably, there are trade-offs between the developmental span studied, the temporal resolution and the sampling depth of the snapshots taken. For example, 2 studies intensely profiled mouse gastrulation, together quantifying gene expression in 150,000 cells from more than 500 embryos spanning embryonic day (E)6.5 to E8.57,17, and another study profiled 2 million nuclei from 61 embryos spanning E9.5–E13.514. We recently integrated such scRNA-seq datasets to produce an initial tree of mouse developmental cell states spanning E3.5–E13.58. However, early organogenesis was coarsely sampled (with 24-h intervals), and the remainder of prenatal development remained unsampled at the whole-organism scale, limited in part by the sheer number of cells.

Ontogenetic staging

To progress towards a more comprehensive, continuous view of transcriptional dynamics throughout prenatal development, we sought to deeply sample single nuclei from mouse embryos precisely staged at 2- to 6-h intervals spanning late gastrulation (E8) to birth (postnatal day (P)0). In staging embryos, we distinguish between gestational age and developmental progression. Mouse gestational age, based on the observation of a vaginal plug for which noon on that day is declared E0.5, only loosely approximates the time elapsed since conception. Stochastic differences in the timing of mating or fertilization, together with genetic factors and litter size, can result in significant variation among embryos of identical gestational age18. Conversely, embryonic morphogenesis is highly ordered, reproducible, and inherently reflective of an embryo’s developmental age with respect to absolute position within a morphogenetic trajectory and the dynamic progression of underlying cell states9,19. Therefore, we staged embryos by well-defined morphological criteria—for example, somite number and limb bud geometry—initially to 45 temporal bins at 6-h increments from E8 to P0 (Fig. 1a and Extended Data Fig. 1). From a total of 523 embryos staged at the Jackson Laboratory, we selected 75 for whole-embryo scRNA-seq, targeting 1 embryo for every somite count from 0 to 34 (2-h increments) and one embryo for every 6-h bin from E10 to P0 (Supplementary Table 1).

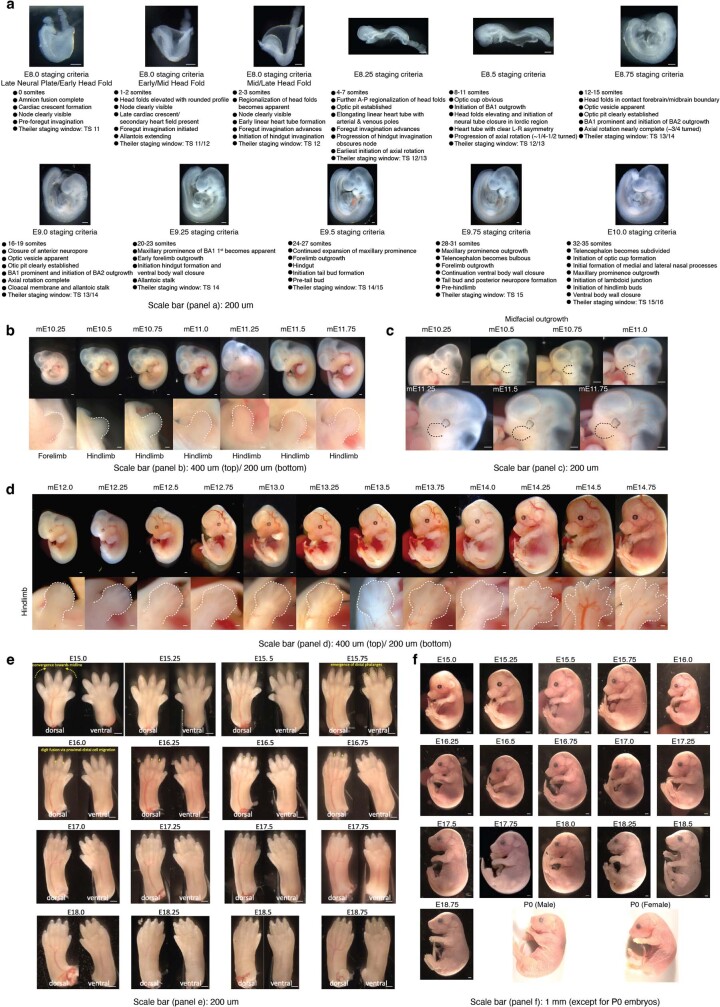

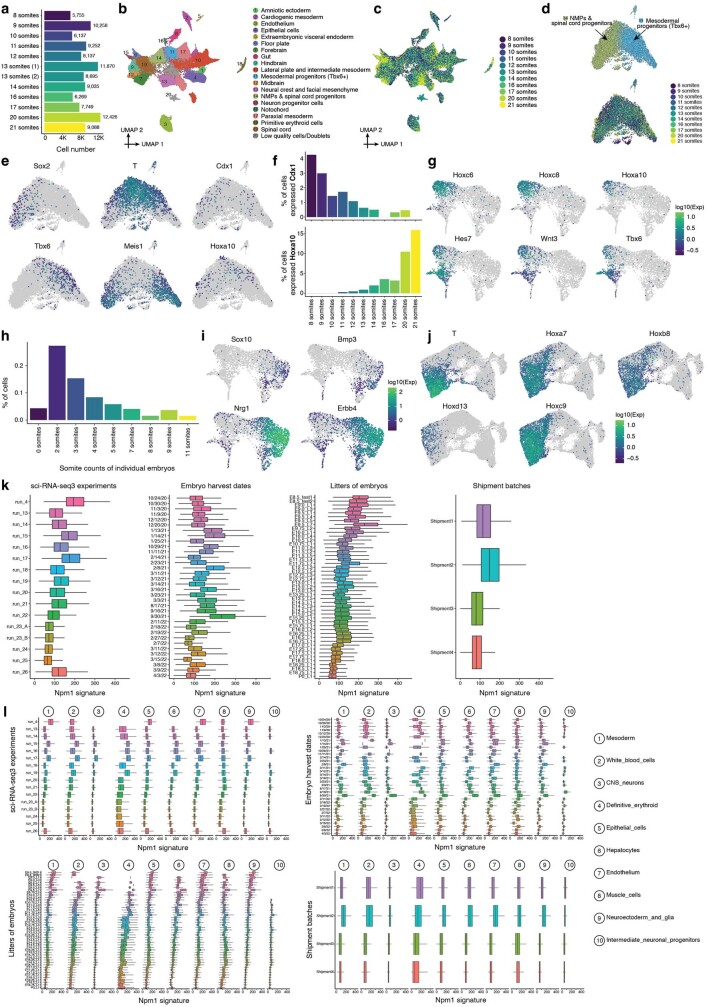

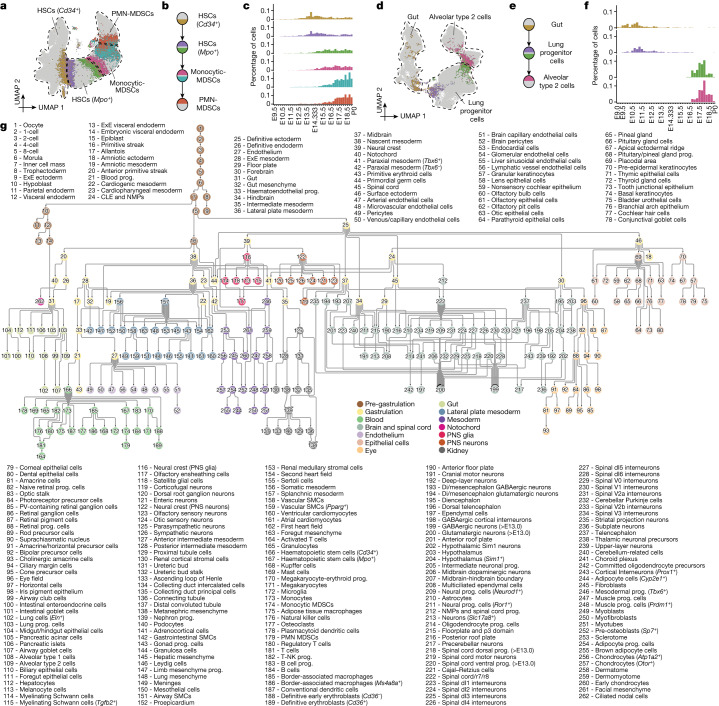

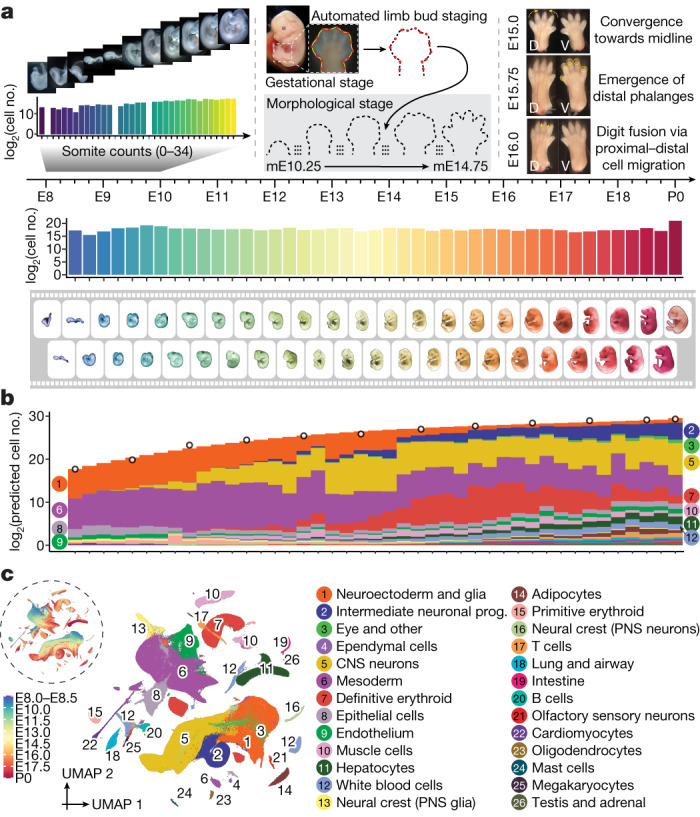

Fig. 1. A single-cell transcriptional time-lapse of mouse development, from gastrula to pup.

a, Embryos were collected and precisely staged based on morphological features, including by counting somite numbers (up to E10) and an automated process that leverages limb bud geometry (E10–E15) (Methods). Each embryo was assigned to one of 45 temporal bins at 6-h increments from E8 to P0, and to more highly resolved 2-h bins at earlier timepoints based on somite counts (0–34 somites). The first three bins (E8.0, E8.25 and E8.5) are combined. Embryos with somite counts 1, 13 and 19 are missing from the series (blue ticks in sub-axis). The number (log2 scale) of nuclei profiled at each timepoint, is shown adjacent to the horizontal timeline, for 2-h bins (0–34 somites) for E8–E10 and for 6-h bins for E8–P0. b, Composition of embryos from each 6-h bin by major cell cluster. The y axis is scaled to the estimated cell number (log2 scale) at each timepoint. In brief, we isolated and quantified total genomic DNA from whole embryos to estimate cell number at 12 stages (1-day bins, highlighted by black circles), and then predicted cell number at 43 timepoints using polynomial regression (Methods). c, Two-dimensional uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) visualization of the whole dataset. The inset dashed circle shows the same UMAP coloured by developmental stage (plotting a uniform number of cells per timepoint). Colours and numbers in b,c correspond to the 26 listed major cell cluster annotations. Prog., progenitor.

Extended Data Fig. 1. Embryos were collected and staged based on morphological features, including somite number and limb bud geometry.

a, Embryos harvested between E8 and E10 were precisely staged based upon somite counting. Harvested embryos were grouped into bins based on somite counting and further characterized based upon morphological features. Stage-representative images are shown with details of the main staging criteria for each coarse temporal bin listed. The approximately overlapping Theiler Stage (TS) is also noted for reference. Scale bar: 200 um. b, After E10, embryos were precisely staged based on morphological features. This was mainly done using the embryonic mouse ontogenetic staging system (eMOSS), an automated process that leverages limb bud geometry to infer developmental stage71,72. Staging results derived from eMOSS are designated with “mE” for morphometric embryonic day. Specifically, for each temporal bin at 6-hr increments from E10.25-E11.75, an image of a stage-representative embryo is shown in the top row. Images of each embryo’s limb bud (white dashed outline) used for staging are shown in the bottom row. Scale bar: 400 um (top)/200 um (bottom). c, View of the craniofacial region of embryos shown in panel b demonstrates that limb bud staging also recreates the ordered ontogenetic progression of craniofacial morphogenesis, including development of the brain, eye, and outgrowth of facial prominences (black dashed line highlights maxillary process). Scale bar: 200 um. d, For each temporal bin at 6-hr increments from E12.0-E14.25, an image of a randomly selected embryo is shown in the top row. The subview of its hindlimb is shown in the bottom row. Scale bar: 400 um (top)/200 um (bottom). e, eMOSS is able to stage E10.25-E14.75, after which limb morphology becomes too complex. We defined additional dynamics related to digit formation to stage E15.0-E16.75 embryos. However, the remaining timepoints (E17.0-E18.75) were staged based upon gestational age. For each temporal bin at 6-hr increments from E15.0-E18.75, an image of the hindlimbs of a randomly selected embryo is shown. Scale bar: 200 um. f, For each temporal bin at 6-hr increments from E15.0-P0, an image of a stage-representative embryo is shown. Scale bar: 1 mm (except for P0 embryos).

Whole-embryo scRNA-seq

Flash-frozen embryos were shipped to the University of Washington, where they were pulverized and subjected to an optimized protocol for single-nucleus transcriptional profiling by combinatorial indexing3 (sci-RNA-seq3). Sequencing data were generated across 15 sci-RNA-seq3 experiments and 21 Illumina Novaseq runs (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). In total, 160 billion reads were demultiplexed, trimmed, mapped, deduplicated and grouped on the basis of constituent cellular indices. Following aggressive filtering of low-quality nuclei and potential doublets, the resulting cell-by-gene count matrix includes transcriptional profiles for 11,441,407 nuclei from 74 embryos spanning E8 to P0 (Fig. 1a and Extended Data Fig. 2a–f), 1% of which (somite counts 0–12) were previously reported8. On average, 154,614 nuclei were profiled per embryo (range 1,700 to 1.6 million; Fig. 1a and Supplementary Table 1).

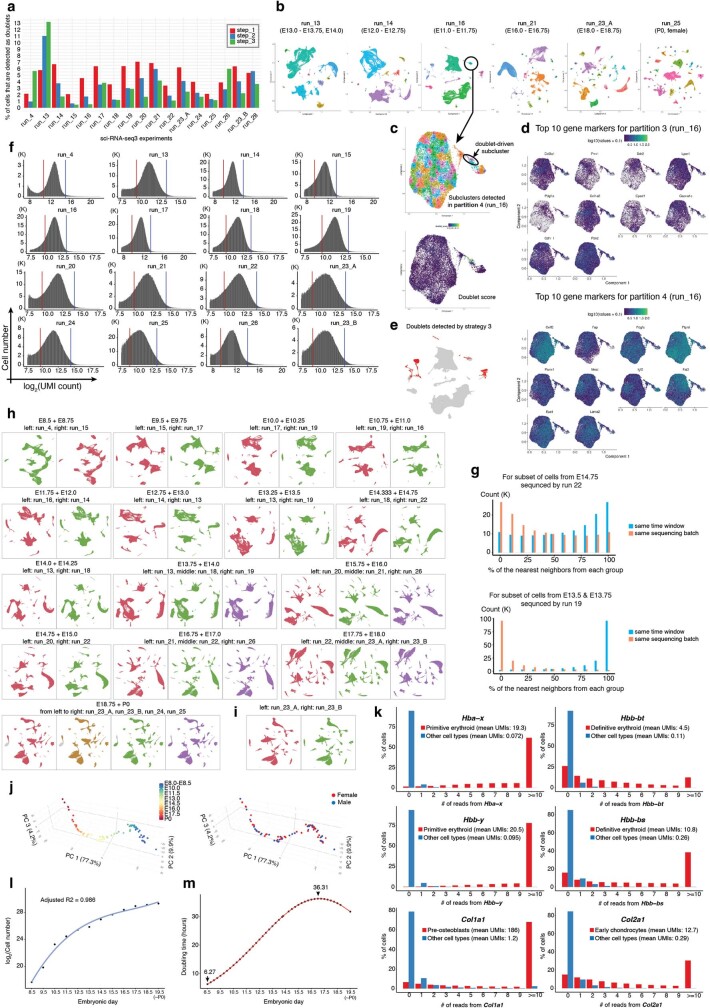

Extended Data Fig. 2. Quality control on sci-RNA-seq3 experiments.

a, We performed three steps to detect and remove potential doublets from each single sci-RNA-seq3 experiment. First, we used Scrublet to calculate a doublet score for each cell. Cells with a doublet score over 0.2 were annotated as detected doublets. Second, we clustered and subclustered the entire dataset. Subclusters with a detected doublet ratio over 15% were annotated as doublet-derived subclusters. Third, after removing doublets detected by the first two steps, we performed clustering again to identify the major cell partitions (i.e. disjoint trajectories). Three experiments (runs 4, 15, and 17) that profiled embryos before E10 used cell clusters instead of cell partitions. We then generated a union gene list by combining the top 10 differentially expressed genes from each cell partition. This gene list was used to perform subclustering on each cell partition. Subclusters that showed low expression of target cell partition-specific markers and enriched expression of non-target cell cluster-partition markers were identified as doublet-driven clusters. More details are provided in the Methods. The percentage of cells detected and removed as doublets by each of the three steps in individual sci-RNA-seq3 experiments is shown. b, The labeled cell partitions for each of six selected experiments are shown, after removing doublets from the first two steps. c, Example of detection of doublet-driven subclusters via step 3. Re-embedded 2D UMAP of cells from partition 4 of experiment run_16, with cells colored by subclusters. The same UMAP is shown below, with cells colored by doublet score calculated by Scublet. d, The same UMAP as in panel c, colored by the normalized gene expression of the top 10 differentially expressed genes in either partition 3 (top) or partition 4 (bottom). e, The same UMAP as experiment run_16 in panel b, highlighted by doublets detected in step 3 (red). f, Histograms of log2(UMI count) per single nucleus for each of 15 sci-RNA-seq3 experiments. For the 14 newly performed experiments (run_13 to run_26), upper (blue line) and lower (red line) thresholds used for quality filtering correspond to the mean plus 2 standard deviations and mean minus 1 standard deviation of log2-scaled values, respectively, after excluding cells with >85% of reads mapping to exonic regions (except for the lower bound of 500, which was manually assigned for run_25), are shown with vertical lines. The data of run_4, which was reported previously8, was subjected to the same thresholds used in the original study, i.e. the mean +/− 2 standard deviations of log2-scaled values (blue and red vertical lines, respectively), after excluding cells with >85% of reads mapping to exonic regions. Run_23_A & B were from the same sci-RNA-seq3 experiment, but with nuclei which were sequenced separately. g, Although most of the embryos from the same approximate stage (e.g. E14.0-E14.75) were included in the same sci-RNA-seq3 experiment (Supplementary Table 1), we profiled extra nuclei in some experiments for a handful of timepoints to ensure sufficient coverage. Here we sought to leverage those instances to check for potential batch effects across experiments. For this, on the embedding learned from all of the data, we asked whether these cells’ profiles are more similar to cells from the same experiment or, alternatively, cells from the same time window. Top: for a random subset of cells from E14.75 which were profiled in experiment run_22 (primarily E17.0-E17.75), we performed a k-nearest neighbors (kNN, k = 10) approach in the global 3D UMAP to find the nearest neighboring cells either from the same experiment (red) or the same time window (E14.0-E14.75) but different experiment (blue). The percentages of the nearest neighboring cells from the two groups for individual cells are presented in the histogram. Bottom: a similar analysis was performed for a random subset of cells from E13.5 & E13.75 which were profiled in experiment run_19 (primarily E10.5-E11). In both examples, we observe that nearest neighbors are overwhelmingly cells from a different experiment (but the same time window), rather than cells from the same experiment (but a different time window). h, Cells processed in different experiments are well-integrated without batch correction. To further check for potential batch effects, we generated co-embeddings of samples processed from adjacent timepoints in different experiments, without batch correction. i, We also generated a co-embedding of cells from run_23_A (red) and run_23_B (green), which derived from the same sci-RNA-seq3 experiment but were sequenced on different NovaSeq runs. j, Embeddings of pseudo-bulk RNA-seq profiles of 74 mouse embryos in PCA space with visualization of top three PCs. Embryos are colored by either developmental stage (left) or data-inferred sex (right). k, Ambient noise (e.g. as might be due to transcript leakage) was assessed by examining hemoglobin and collagen transcripts. The distribution of the number of reads mapping to each selected hemoglobin or collagen gene across cells, for the cell type that is expected to express that gene at high levels (red) vs. all other cell types (blue). The mean UMI counts of cells in each group are also reported. The overall levels of ambient noise as assessed by these transcripts was low, e.g. the mean number of UMIs for Hbb-bs was 10.8 in definitive erythroid cells and 0.26 in all other cells, and for Col1a1 was 186 in pre-osteoblasts vs. 1.23 in all other cells. l, Quantitatively estimating cell number for individual mouse embryos as a function of developmental stage. Based on the experimentally estimated cell numbers of the 12 embryos (ranging from E8.5 to P0), we applied polynomial regression (degree = 3) to fix a curve across embryos between the embryonic day and log2-scaled cell number. P0 was treated as E19.5 in the model. m, The estimated “doubling time” of the total cell number in a whole mouse embryo are plotted as a function of timepoints. The timepoints with the longest (E17.0) and shortest (E8.5) estimated “doubling times” are highlighted.

This dataset greatly improves upon our previous single-cell atlas of mouse organogenesis14 with respect to sampling depth (from 2 million to 11.4 million nuclei), profiling depth (median 671 to 2,545 unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) per nucleus), temporal resolution (24-h to 2- to 6-h intervals) and developmental span (E9.5–E13.5 to E8–P0). In performing quality control, we found that cells from the same or adjacent stages but profiled in different experiments were well integrated (Extended Data Fig. 2g–i). Furthermore, principal component analysis (PCA) of pseudobulked RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) profiles resulted in a major first component that strongly correlated with developmental time (PC1 = 77%; Extended Data Fig. 2j). Ambient noise due to RNA leakage or barcode swapping was present at low levels (Extended Data Fig. 2k).

What kind of ‘shotgun cellular coverage’ of the mouse embryo are we achieving? Leveraging total DNA quantification of staged embryos, we estimate that the embryo grows 3,000-fold from E8.5 to P0 (210,000 to 670 million cells), with its cellular doubling time slowing from around 6 h to 1.5 days (Fig. 1b, Extended Data Fig. 2l,m and Supplementary Table 3). Thus, even with the many nuclei profiled here, our cellular coverage remains modest, ranging from 0.5-fold for early stages (summing 6 embryos, somite counts 7–12) to 0.002-fold immediately before birth (summing 6 embryos, E17.5–E18.75).

Cell-type annotation

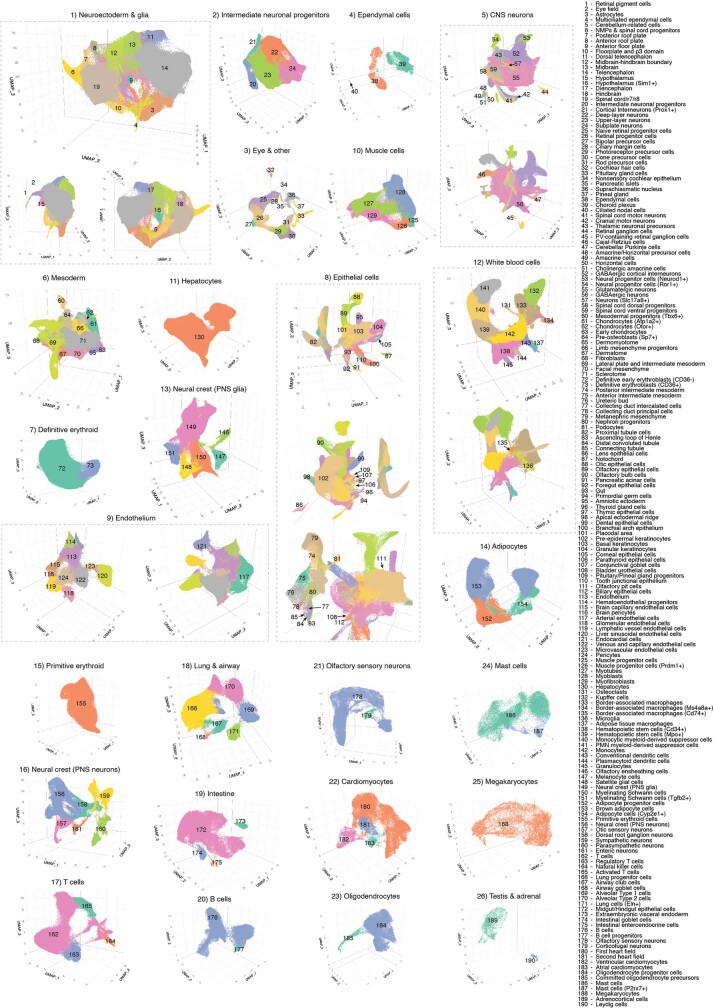

To get our bearings, we used Scanpy20 to generate a global embedding of the 11.4 million cell × 24,552 gene count matrix, and annotated 26 major clusters on the basis of marker genes (Fig. 1b,c and Supplementary Table 4). As expected, cell clusters whose proportions decline over developmental time either stream towards derivatives (for example, neuroectoderm and glia to central nervous system (CNS) neurons and intermediate neuronal progenitors) or are displaced by functionally analogous but developmentally distinct lineages (for example, primitive erythroid to definitive erythroid). However, the resolution of these major clusters was somewhat arbitrary and affected by abundance. To balance the resolution, we performed another iteration of clustering and annotation, resulting in 190 labelled cell types (Extended Data Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 5). These annotations are preliminary, and we welcome their refinement by the community.

Extended Data Fig. 3. Cell type annotations.

For each of the 26 major cell clusters, we performed subclustering and then annotated each of 190 subclusters using at least two literature-nominated marker genes per cell type label (Supplementary Table 5).

We also performed deeper dives into the ontogenesis of the posterior embryo during somitogenesis, kidney, mesenchyme, retina and early neurons. These analyses, summarized below, illustrate the richness of this dataset and highlight opportunities for its further exploration.

Posterior embryo during somitogenesis

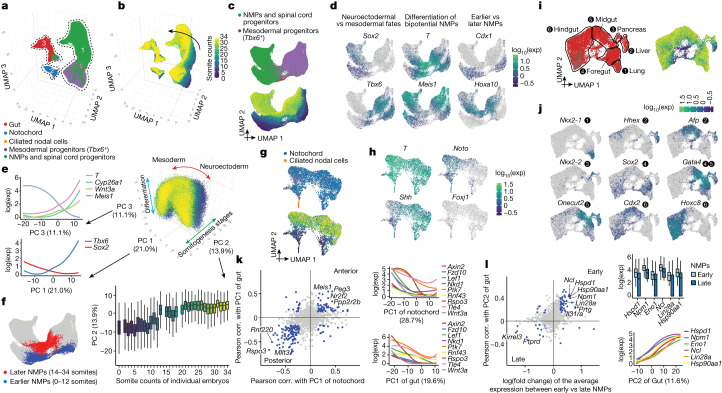

Neuromesodermal progenitors (NMPs) are a population of bipotent cells with both neural (spinal cord) and mesodermal (trunk and tail somites) derivatives21. Towards extending our previous investigations of NMP heterogeneity8, we re-embedded 121,118 cells from all somite-staged embryos (0–34 somites) initially annotated as NMPs and spinal cord progenitors, mesodermal progenitors (Tbx6+), notochord or gut (Fig. 2a–c).

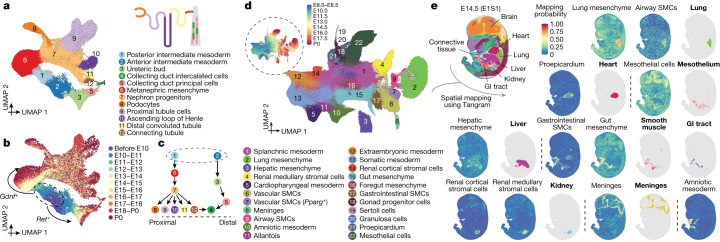

Fig. 2. Transcriptional heterogeneity in the posterior embryo during early somitogenesis.

a, Re-embedded 3D UMAP of 121,118 cells from selected posterior embryonic cell types at early somitogenesis (somite counts 0–34; E8–E10). Three clusters are identified. b, The same UMAP as in a, coloured by somite counts. c, Re-embedded 2D UMAP of cells from cluster 1. d, The same UMAP as in c, coloured by marker gene expression for NMP subpopulations (Supplementary Table 12). Exp, expression. e, 3D visualization of the top three principal components of gene expression variation in cluster 1. Correlations between top three principal components and the normalized expression of selected genes (left) or somite counts (bottom). f, The same UMAP as in c, with earlier (n = 4,949 cells) and later (n = 3,910 cells) NMPs highlighted. NMPs: T+, (raw count ≥ 5) and Meis1− (raw count = 0). g, Re-embedded 2D UMAP of cells from cluster 2. h, The same UMAP as in g, coloured by marker gene expression for notochord or ciliated nodal cells (Foxj1+). i, Re-embedded 2D UMAP of cells from cluster 3. Black circles highlight gut cell subpopulations. j, The same UMAP as in i, coloured by marker gene expression for gut cell subpopulations (Supplementary Table 12). k, Left, Pearson correlation (corr.) with PC1 of notochord or gut for highly variable genes. Right, gene expression of selected Wnt signalling genes versus PC1 of notochord or gut. l, Left, fold changes between early and late NMPs and Pearson correlation with PC2 of gut are plotted for highly variable genes. Right, gene expression of selected genes (several MYC targets, Lin28a and Hsp90aa1) versus early and late NMPs or PC2 of gut. In c,g,i, cells are coloured by either initial annotations or somite counts. Box plots in e (n = 98,545 cells) and l (n = 8,859 cells) represent inter-quartile range (IQR) (25th, 50th and 75th percentile) and whiskers represent 1.5× IQR.

First focusing on NMPs and their immediate derivatives (cluster 1 in Fig. 2a), we performed PCA on highly variable genes. The top three principal components, which explain nearly half of transcriptional variation, appear to correspond to neural versus mesodermal fate (PC1), developmental stage (PC2) and bipotentiality versus differentiation towards either fate (PC3) (Fig. 2d,e and Supplementary Table 6). Assuming that PC3 tracks differentiation consistently between neural versus mesodermal fates, our data suggest that being brachyury-positive (T+) and Meis1− may better indicate bipotency than being T+ and Sox2+, consistent with recent studies of NMPs’ genetic dependencies22–24 (Fig. 2e,f). Cyp26a1 (whose gene product inactivates retinoids) and Wnt3a (involved in canonical Wnt signalling) were also strongly correlated with bipotency.

We observe marked contrasts between earlier (0–12 somites) and later (14–34 somites) NMPs, which may correspond to the ‘trunk-to-tail’ transition25 (Fig. 2c–f). This observation is consistent with differences between NMPs from microdissected E8.5 versus E9.5 embryos26, implicating many of the same genes (for example, Cdx1 (early) and Hoxa10 (late); Fig. 2d and Supplementary Table 7). However, given concern about batch effects, we profiled an additional 12 embryos (8–21 somites). This new experiment validated and refined the estimated timing of this transition (Extended Data Fig. 4a–f).

Extended Data Fig. 4. Transcriptional heterogeneity in the posterior embryo during early somitogenesis.

a, A validation sci-RNA-seq3 dataset of mouse embryos from somites 8 to 21. To validate findings related to differences between embryos staged with early vs. late somite counts, particularly in NMPs, we profiled another 12 precisely staged mouse embryos, ranging from 8 to 21 somites, in an independent sci-RNA-seq3 experiment. The resulting library was sequenced on an Illumina NextSeq 2000, resulting in 104,671 cells in total, with a median UMI count of 513 and a median gene count of 446 per cell. The number of cells profiled from each embryo. b, 2D UMAP visualization of the validation dataset (all cell types). c, The same UMAP as in panel b, with cells colored by somite count of the originating embryo. d, Re-embedded 2D UMAP of 9,686 cells from NMPs & spinal cord progenitors (cluster 11) and mesodermal progenitors (Tbx6 + ) (cluster 14) in panel b. Cells are colored by either the original annotation (top) or somite count (bottom). e, The same UMAP as in panel d, colored by gene expression of marker genes which appear specific to different subpopulations of NMPs: column 1: differences between neuroectodermal (Sox2 + ) vs. mesodermal (Tbx6 + ) fates; column 2: the differentiation of bipotential NMPs (T +, Meis1-) towards either fate; column 3: earlier (Cdx1 + ) vs. later (Hoxa10 + ) NMPs. References for marker genes are provided in Supplementary Table 12. f, Within the cells shown in panel d, the proportion of cells (y-axis) which express either Cdx1 (top) or Hoxa10 (bottom) are plotted as a function of somite count of the originating embryo. g, Transcriptional heterogeneity in the posterior embryo during the early somitogenesis. The same UMAP as in Fig. 2g, colored by gene expression of marker genes which appear specific to the subpopulation of notochord cluster that is Noto +, including posterior Hox genes (Hoxc6, Hoxc8, Hoxa10), and genes involved in Notch signaling (Hes7), Wnt signaling (Wnt3) and mesodermal differentiation (Tbx6). h, Cell proportions falling into the ciliated nodal cell cluster for embryos with different somite counts. i, The same UMAP as in Fig. 2g, colored by gene expression of marker genes which appear specific to the subpopulation of the notochord Noto- and more strongly Shh +, including Sox10, Bmp3, Nrg1, and Erbb4. j, The same UMAP as in Fig. 2i, colored by gene expression of marker genes which appear specific to the posterior gut endoderm, including T, Hoxa7, Hoxb8, Hoxd13, and Hoxc9. k, Checking the consistency of Npm1 signatures across different batches. First, we downsampled the dataset to ~1 M cells using geosketch79 and performed k-means clustering to ensure that each cluster contained roughly 500 cells. Second, we aggregated UMI counts for cells within each cluster to generate 2,289 meta-cells, and normalized the UMI counts for each meta-cell followed by log2-transformation. Third, we performed Pearson correlation between each protein-coding gene and Npm1, and selected genes with correlation coefficients > 0.6 (738 genes, ~3% of the total protein coding genes). A gene set enrichment analysis suggests that the module is associated with RNP complexes (corrected p-value = 1.4e-105), cytoplasmic translation (corrected p-value = 2.8e-90), and ribosomal proteins (corrected p-value = 7.4e-71). Finally, we summed the normalized UMI counts of these genes to calculate a Npm1 signature for individual cells. The resulting Npm1 signatures are subsetted in four plots, from left to right: by sci-RNA-seq3 experiment, embryo harvest date, litter of embryos, or shipment batch. l, Same as panel k, but further stratified by the top 10 abundant major cell clusters. Boxplots, in panel k (n = 1,144,141 cells) and l (n = 299,725 cells in Mesoderm, n = 127,150 cells in White blood cells, n = 104,205 cells in CNS neurons, n = 73,005 cells in Definitive erythroid, n = 66,772 cells in Epithelial cells, n = 64,845 cells in Hepatocytes, n = 62,951 cells in Endothelium, n = 61,249 cells in Muscle cells, n = 52,748 cells in Neuroectoderm and glia, n = 45,940 cells in Intermediate neuronal progenitors), represent IQR (25th, 50th, 75th percentile) with whiskers representing 1.5× IQR.

Another cell type marked by the master transcriptional regulator T is the notochord (cluster 2 in Fig. 2a). In 0–12 somite embryos, we observe distinct notochordal subsets, one expressing Noto (notochord homeobox) and another Shh (sonic hedgehog) (Fig. 2g,h). As somitogenesis progresses, the inferred derivatives of these subsets remain distinguishable. The Noto+ subset is marked by posterior Hox genes, Notch and Wnt signalling, and mesodermal differentiation modules (Extended Data Fig. 4g). Within this subset, we identify a few cells that strongly express Foxj1 and motile ciliogenesis genes. These ciliated nodal cells, which set the left-right axis27, are both extremely rare and transient, peaking at the 2-somite stage (Fig. 2g,h and Extended Data Fig. 4h).

By contrast, the inferred derivatives of the Shh+ subset express genes involved in neurogenesis and synaptogenesis—for example, Sox10, Bmp3, Nrg1 and Erbb4 (Extended Data Fig. 4i). We speculate that the Noto+ subset corresponds to posterior notochord, arising from the node, whereas the Shh+ subset corresponds to anterior mesendoderm (that is, anterior head process and possibly prechordal plate), arising by condensation of dispersed mesenchyme and possibly contributing to forebrain patterning28–31. These presumably anterior–posterior differences are a major source of notochordal heterogeneity (PC1 = 29%; Supplementary Table 8).

Turning to gut (cluster 3 in Fig. 2a), we again observe distinct progenitor subsets that transition to a continuum as somitogenesis progresses (Fig. 2i). A major aspect of this continuum also reflects anterior–posterior patterning, with subsets corresponding to lung, liver, pancreas, foregut, midgut and hindgut progenitors (PC1 = 20%; Fig. 2j and Supplementary Table 9). As T is classically associated with notochord and posterior mesoderm, we were initially surprised by strong T expression in the putative posterior hindgut, coincident with posterior Hox genes (Extended Data Fig. 4j). However, this pattern has been documented32, and is consistent with the ancestral role of T in closing the blastopore33 as well as hindgut defects in Drosophila brachyenteron and Caenorhabditis elegans mab-9 mutants34,35.

Of note, there is strong overlap between genes underlying the inferred anterior–posterior axis of axial mesoderm (notochord; PC1; n = 591) and endoderm (gut; PC1; n = 502) (198 overlapping genes, 86% directionally concordant; P < 10−28, χ2-test; Fig. 2k and Supplementary Table 10). Concordantly posterior-associated genes are highly enriched for Wnt signalling and posterior Hox genes. One model to explain these overlaps between germ layers is that they are residual to the common origin of anterior mesendodermal derivatives from early and mid-gastrula organizers (anterior head process, prechordal plate and anterior endoderm) versus posterior mesendodermal derivatives from the node28 (notochord and posterior endoderm). Alternatively, they could be explained by physically coincident progenitors of these germ layers being exposed to similar patterns of Wnt signalling.

A second overlap between germ layers involves genes correlated with early versus late somite counts in NMPs (n = 257) versus gut (PC2; n = 502) (82 overlapping genes, 70 (85%) directionally concordant; P < 10−15, χ2-test) (Fig. 2l and Supplementary Table 11). Given concern about batch effects, we re-examined the aforementioned replication series (8–21 somite embryos). Seventy-seven per cent of the overlapping, concordant genes replicated in terms of directionality-of-change between early versus late NMPs and gut (54 out of 70; expected value 25%; Extended Data Fig. 4a–f). Genes reproducibly associated with early stages in both germ layers were strongly enriched for MYC targets, and included Lin28a, a deeply conserved regulator of developmental timing36. Other genes, such as Npm1 and Hsp90 isoforms are plausibly associated with batch effects. However, analysis of a module of genes correlated with Npm1 revealed that this module declined with developmental time across the entire time series, rather than being correlated with batch variables (Extended Data Fig. 4k,l).

Intermediate and lateral plate mesoderm

Above, we investigated aspects of axial and paraxial mesoderm, which give rise to notochord and somites, respectively. Next, we focus on the transition from intermediate mesoderm to nephrons, and lateral plate mesoderm (LPM) to organ-specific mesenchyme.

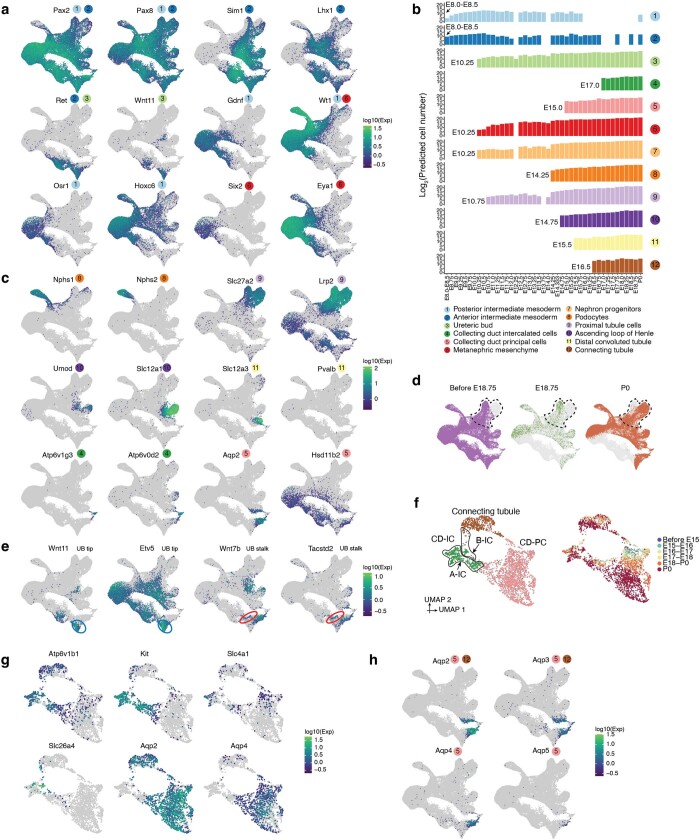

Our aim was to explore the continuum of transcriptional states that span the transition from intermediate mesoderm to functional nephrons. Re-embedding 95,226 relevant cells, we observe two major trajectories, one corresponding to posterior intermediate mesoderm→renal tubules, and another corresponding to anterior intermediate mesoderm→collecting ducts (Fig. 3a–c). In late gastrulation, posterior (Gdnf+) and anterior (Ret+) intermediate mesoderm37,38 initially progress to metanephric mesenchyme and ureteric bud states, respectively, then onwards to functional components of the nephron (Extended Data Fig. 5a–c). Cells annotated as podocytes and proximal tubule cells but unexpectedly appearing as early as E10.5 may correspond to mesonephric tubules37. Metanephric mesenchyme and ureteric bud states persist through P0, presumably reflecting ongoing nephrogenesis, which continues for a few days after birth39. The apparent bifurcation of proximal tubule cell states at later stages corresponds to major differences in cells obtained before versus after birth (Extended Data Fig. 5d). We return to this observation further below.

Fig. 3. Diversification of the intermediate mesoderm and LPM.

a, Re-embedded 2D UMAP of 95,226 cells corresponding to renal development. A schematic of a nephron is shown at the top right. b, The same UMAP as in a, coloured by developmental stage (plotting a uniform number of cells per time window). The inset dashed circle highlights posterior and anterior intermediate mesoderm, with arrows highlighting derivative trajectories expressing Gdnf and Ret, respectively. c, Manually inferred relationships between annotated renal cell types. Label annotations in a. d, Re-embedded 2D UMAP of 745,494 cells from lateral plate and intermediate mesoderm derivatives. The inset dashed circle highlights the same UMAP with cells coloured by developmental stage. SMC, smooth muscle cell. e, The spatial origin of each lateral plate and intermediate mesoderm derivative was inferred based on a public dataset, Mosta46, together with our data and the Tangram algorithm47 (Methods). An image of one selected section (E1S1) from E14.5 of the Mosta data is shown at the top left with major regions labelled. The spatial mapping probabilities across voxels on this section for selected subtypes are shown (non-bold label), with the regional annotation appearing to best correspond to the inferred spatial pattern shown alongside (labelled in bold). GI, gastrointestinal.

Extended Data Fig. 5. Transcriptional heterogeneity in renal development.

a, The same UMAP as in Fig. 3a, colored by expression of marker genes which appear specific to anterior intermediate mesoderm (Pax2 +, Pax8 +, Sim1 +, Lhx1 +, Ret +), posterior intermediate mesoderm (Pax2 +, Pax8 +, Gdnf1 +, Wt1 +, Osr1 +, Hoxc6 +), ureteric bud (Ret +, Wnt11 +) or metanephric mesenchyme (Wt1 +, Six2 +, Eya1 +). References for marker genes are provided in Supplementary Table 5. b, The predicted absolute number (log2 scale) of cells of each renal cell type at each timepoint. The predicted absolute number was calculated by the product of its sampling fraction in the overall embryo and the predicted total number of cells in the whole embryo at the corresponding timepoint (Fig. 1b). For each row, the first timepoint with at least 10 cells assigned that cell type annotation is labeled, and all observations prior to that timepoint are discarded. c, The same UMAP as in Fig. 3a, colored by expression of marker genes which appear specific to podocytes (Nphs1 +, Nphs2 +), proximal tubule cells (Slc27a2 +, Lrp2 +), ascending loop of Henle (Umod +, Slc12a1 +), distal convoluted tubule (Slc12a3 +, Pvalb +), collecting duct intercalated cells (Atp6v1g3 +, Atp6v0d2 +) or collecting duct principal cells (Aqp2 +, Hsd11b2 +). References for marker genes are provided in Supplementary Table 5. d, The same UMAP as Fig. 3a is shown three times, with colors highlighting cells from before E18.75 (left), E18.75 (middle), or P0 (right). Dotted cycles highlight cells which appear to correspond to the proximal tubule. e, The same UMAP as in Fig. 3a, colored by expression of marker genes which appear specific to the ureteric bud tip (Wnt11 +, Ret +, Etv5 +) or stalk (Wnt7b +, Tacstd2 +)40. Ureteric bud tip and stalk are highlighted by blue and red circles, respectively. f, Re-embedded 2D UMAP of 2,894 cells from connecting tubule cells, collecting duct principal cells (CD-PC), and collecting duct intercalated cells (CD-IC). Cells are colored by either their initial annotations (top) or timepoint (bottom). Black circles highlight the cells which appear to be either type A (A-IC) or type B (B-IC) intercalated cells. g, The same UMAP as in panel f, colored by expression of marker genes specific to CD-IC (Atp6v1b1 + ), A-IC (Kit +, Slc4a1 +), B-IC (Slc26a4 +), CD-PC (Aqp2 +, Aqp4 +), and connecting tubule (Aqp2 +, Aqp4-) (Supplementary Table 12). h, The same UMAP as in Fig. 3a, colored by expression of marker genes which appear specific to connecting tubule cells (Aqp2 +, Aqp3 +, Aqp4-) or collecting duct cells (Aqp2 +, Aqp3 +, Aqp4 +, Aqp5 +)80.

Both tip and stalk cells are identified within the ureteric bud—the tip cells giving rise to the collecting duct, and the stalk cells giving to the ureter40,41 (Extended Data Fig. 5e). Notably, we observe transcriptional ‘convergence’ of the posterior and anterior trajectories in collecting duct intercalated cells (cluster 4 in Fig. 3a,b). More detailed investigation supports a contribution of the posterior trajectory to the collecting duct, consistent with recent lineage tracing experiments demonstrating a dual origin for intercalated cell types from distal nephron and ureteric lineages42 (Fig. 3c and Extended Data Fig. 5f–h).

The LPM is considerably more complex than the axial, paraxial and intermediate mesoderms43. Although some LPM derivatives have been intensely studied (for example, limb and heart), others remain poorly understood, in particular the mesoderm lining the body wall and internal organs. This aspect of LPM gives rise to a remarkable diversity of cell types and structures (including fibroblasts, smooth muscle, mesothelium, pericardium, adrenal cortex and others) and its reciprocal interactions with other germ layers has a key role in organ patterning44,45.

To annotate understudied LPM derivatives, we leveraged spatial transcriptomic data to impute coordinates for our cells46,47, which enabled us to annotate 22 subtypes of the LPM and intermediate mesoderm major cluster, including cardiac (proepicardium), brain (meninges), lung, liver, foregut and gut mesenchyme, and airway versus gastrointestinal versus vascular smooth muscle (Fig. 3d,e, Extended Data Fig. 6 and Supplementary Table 12). Two subtypes spatially mapped to the kidney, one to the cortex and the other heterogeneously, which we term renal cortical stromal cells and renal medullary stromal cells, respectively48 (Fig. 3d,e and Extended Data Fig. 7a–c). Although both express Foxd1+, focused analyses suggest distinct origins, with renal cortical stromal cells appearing to derive from the intermediate mesoderm and metanephric mesenchyme, and renal medullary stromal cells appearing to derive from LPM (Extended Data Fig. 7d,e). However, lineage tracing experiments would be necessary to provide conclusive evidence for this. Of note, renal medullary stromal cells exhibited heterogeneity along what may be a cortical–medullary spatial axis (Extended Data Fig. 7f).

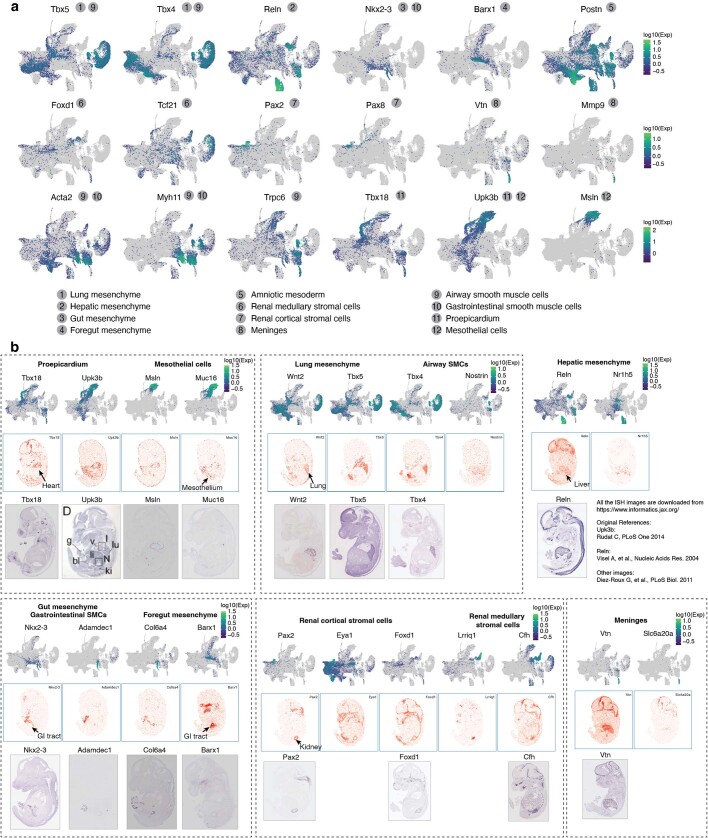

Extended Data Fig. 6. Transcriptional heterogeneity in mesenchyme.

a, The same UMAP as in Fig. 3d, colored by expression of marker genes which appear specific to lung mesenchyme (Tbx5 +, Tbx4 + ), hepatic mesenchyme (Reln + ), gut mesenchyme (Nkx2-3 + ), foregut mesenchyme (Barx1 + ), amniotic mesoderm (Postn + ), renal medullary stromal cells (Foxd1 +, Tcf21 + ), renal cortical stromal cells (Pax2 +, Pax8 + ), meninges (Vtn + ), airway smooth muscle cells (Trpc6 +, Tbx5 + ), gastrointestinal smooth muscle cells (Nkx2-3 + ), proepicardium or mesothelium (Msln + ). References for marker genes are provided in Supplementary Table 12. b, Published in situ hybridization (ISH) images support our annotations of lateral plate and intermediate mesoderm derivatives. In each subpanel (defined by dotted rectangles), three rows are shown for one or two lateral plate and intermediate mesoderm derivative cell types. Notably, each of these cell types was annotated based on spatial mapping analysis, as shown in Fig. 3e. Top: The same UMAP as in Fig. 3d, colored by gene expression of marker genes which appear specific to the given cell type. Middle: Virtual in situ hybridization (ISH) images of individual genes from one selected section (E1S1) from E14.5 of the Mosta data (https://db.cngb.org/stomics/mosta/). Bottom: In situ hybridization (ISH) images of individual genes were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory Mouse Genome Informatics (MGI) website (https://www.informatics.jax.org/). The original reference for these ISH images are81–83.

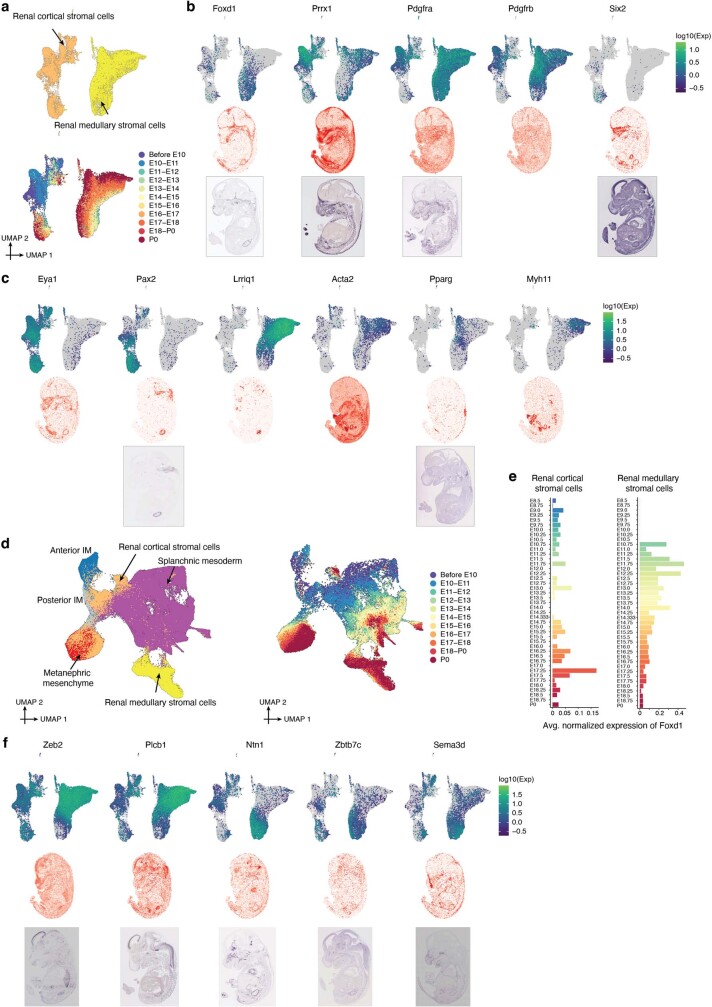

Extended Data Fig. 7. Assessing the potential origins of LPM subsets annotated as renal cortical & medullary stromal cells.

a, Re-embedded 2D UMAP of 39,468 cells from renal cortical & medullary stromal cells. Cells are colored by either annotation (top) or timepoint (bottom, after downsampling to a uniform number of cells per time window). b, Top: The same UMAP as in panel a, colored by gene expression of marker genes which appear specific to renal cortical & medullary stromal cells. Both cell types express Foxd1, Prrx1, Pdgfra, and Pdgfrb, but only renal cortical stromal cells express Six2. Middle: Virtual in situ hybridization (ISH) images of individual genes. Bottom: ISH images of individual genes. c, Top: The same UMAP as in panel a, colored by gene expression of marker genes which appear specific to renal cortical stromal cells (Eya1 +, Pax2 + ), and renal medullary stromal cells (Lrriq1 +, Acta2 +, Pparg +, Myh11 + ). Middle: Virtual ISH images of individual genes. Bottom: ISH images of individual genes. d, Re-embedded 2D UMAP of 206,908 cells from renal cortical & medullary cells, anterior intermediate mesoderm, posterior intermediate mesoderm, metanephric mesenchyme, and splanchnic mesoderm. Cells are colored by either their initial annotations (left) or timepoint (right, after downsampling to a uniform number of cells per time window). e, The average normalized expression of Foxd1 over time is shown for renal cortical stromal cells (left) and renal medullary stromal cells (right). Gene expression was normalized by the size factor estimated by Monocle/3. f, Top: The same UMAP as in panel a, colored by gene expression of marker genes which appear specific to two subsets of renal stromal cells: medullary renal stromal cells (Zeb2 +, Plcb1 + ) and cortical renal stromal cells (Ntn1 +, Zbtb7c +, Sema3d + ), respectively. Middle: Virtual ISH images of individual genes. Bottom: ISH images of individual genes. In panel b, c, and f, virtual ISH images of individual genes were obtained from one selected section (E1S1) from E14.5 of the Mosta data (https://db.cngb.org/stomics/mosta/). ISH images were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory Mouse Genome Informatics (MGI) website (https://www.informatics.jax.org/). The original reference for these ISH images are81,82,84.

The temporal resolution of our studies enables us to narrow the window during which various organ-specific mesenchymes are specified (Extended Data Fig. 8a). We also applied a mutual nearest neighbours (MNN) heuristic to identify putative precursors of each subtype (Extended Data Fig. 8b–g)—for example, subsets of splanchnic mesoderm most highly related to foregut mesenchyme, hepatic mesenchyme or proepicardium—which may correspond to the ‘territories’ in which these organ-specific mesenchymes are induced (Extended Data Fig. 8b–d). For example, hepatic and foregut mesenchyme are distinguished both from one another as well as from their inferred progenitors by Gata4 and Barx1 expression, respectively49,50. However, their inferred progenitors are also distinct from one another, with inferred hepatic mesenchymal progenitors expressing a programme of epithelial–mesenchymal transition and inferred foregut mesenchymal progenitors expressing multiple guidance cue programmes (for example, semaphorins, ephrins, SLIT family proteins and netrins) (Extended Data Fig. 8c and Supplementary Table 13).

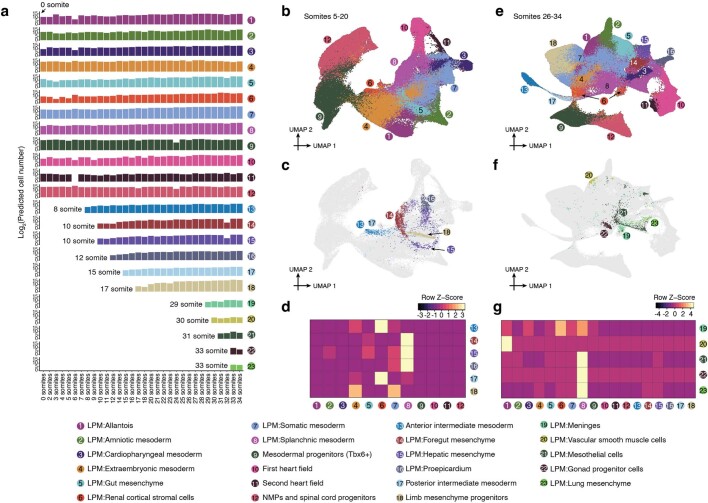

Extended Data Fig. 8. The emergence of mesenchymal subtypes from the patterned mesoderm.

a, The predicted absolute number (log2 scale) of cells of each mesoderm cell type at each somite count. The predicted absolute number was calculated by the product of its sampling fraction in the overall embryo and the predicted total number of cells in the whole embryo at the corresponding timepoint. Because cell numbers were only predicted for the broader bins (Fig. 1b), rather than individual somite counts, these were used for roughly corresponding sets (0-12 somite stage: E8.5; 14-15 somite stage: E8.75; 16-18 somite stage: E9.0; 20-23 somite stage: E9.25; 24-26 somite stage: E9.5; 27-31 somite stage: E9.75; 32-34 somite stage: E10.0). For each row, the first somite count with at least 10 cells assigned that cell type annotation is labeled, and all observations prior to that somite count are discarded. b, Re-embedded 2D UMAP of 110,753 cells from the selected cell types of mesoderm (clusters 1-12 as listed in panel a) from 5-20 somite stage embryos. c, The same UMAP as in panel b, but with inferred progenitor cells colored by derivative cell type with the highest mutual nearest neighbors (MNN) pairing score. d, Normalized MNN pairing score between mesodermal territories (column) and their inferred derivative cell types (row) from 5-20 somite stage embryos. The selected cell populations are first embedded into 30 dimensional PCA space, and then for individual derivative cell types, MNN pairs (k = 10 used for k-NN) between their earliest 500 cells (in absolute time) and cells from mesodermal territories are identified. e, Re-embedded 2D UMAP of 275,000 cells from the selected cell types of mesoderm (clusters 1-18 as listed in panel a) from 26-34 somite stage embryos. f, The same UMAP as in panel e, but with inferred progenitor cells colored by derivative cell type with the highest MNN pairing score. g, Normalized MNN pairing score between mesodermal territories (column) and their inferred derivative cell types (row) from 26-34 somite stage embryos. The selected cell populations are first embedded into 30 dimensional PCA space, and then for individual derivative cell types, MNN pairs (k = 10 used for k-NN) between their earliest 500 cells (in absolute time) and cells from mesodermal territories are identified.

From patterned neuroectoderm to neurons

We now turn from mesoderm to neuroectoderm. Relative to our previous studies14, optimizations of sci-RNA-seq3 have markedly improved our ability to distinguish neuronal subtypes. For example, in Supplementary Note 1, we describe the timing and trajectories of prenatal diversification of the retina. In that context, we can distinguish 15 retinal ganglion subtypes by P0, on par with expectation51, each well defined by specific transcription factor combinations (Extended Data Fig. 9a–l and Supplementary Table 14).

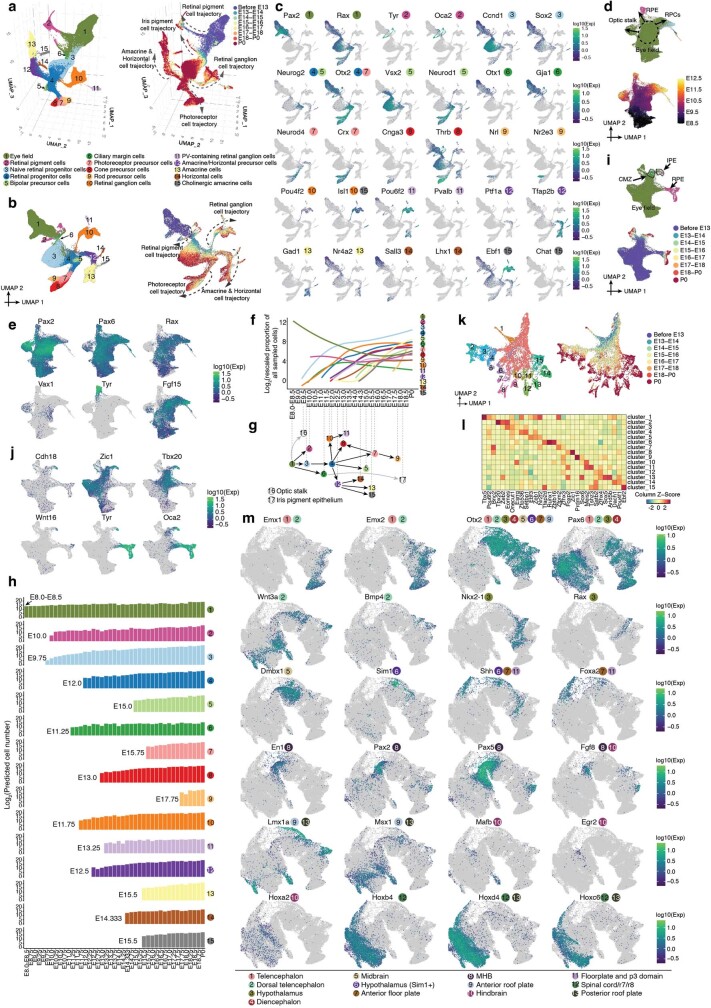

Extended Data Fig. 9. The timing and trajectories of retinal development, and marker gene expression for different neuroectodermal territories.

a, Re-embedded 3D UMAP of 160,834 cells corresponding to the retinal development from E8 to P0. Cells are colored by either their initial annotations (left) or timepoint (right, after downsampling to a uniform number of cells per time window). Arrows highlight five of the main trajectories observed. b, Re-embedded 2D UMAP of 160,834 cells corresponding to the retinal development from E8 to P0. The same UMAP as in panel a, except 2D instead of 3D projection. c, The same UMAP as in panel b, colored by gene expression of marker genes for each annotated retinal cell type. References for marker genes are provided in Supplementary Table 5. d, Re-embedded 2D UMAP of the subset of cells in panel a from stages <= E12.5. Cells are colored by either their initial annotations (top) or timepoint (bottom). e, The same UMAP as in panel d, colored by gene expression of markers of retinal progenitor cells RPCs (Pax2 +, Pax6 +, Rax +, Fgf15 +), RPE (Tyr +), and the optic stalk (Pax2 +, Vax1 +, Rax−). References for marker genes are provided in Supplementary Table 12. f, Rescaled proportion of profiled cells (log2; y-axis) for each cell type shown in panel a, as a function of developmental time (x-axis). For rescaling, the % of profiled cells in the entire embryo assigned a given annotation was multiplied by 100,000, prior to taking the log2. Line plotted with geom_smooth function in ggplot2. g, Schematic of retinal cell types emphasizing the timing at which they first appear and their inferred developmental relationships from E8-P0, based on manual review of the trajectories. The gray lines indicate subsets of the eye field and RPE subsequently annotated as the optic stalk (label 16) and iris pigment epithelium (label 17), respectively. Cell types are positioned along the x-axis at the timepoint at which they are first observed (as shown in panel h). h, The predicted absolute number (log2 scale) of cells of each retinal cell type at each timepoint. The predicted absolute number was calculated by the product of its sampling fraction in the overall embryo and the predicted total number of cells in the whole embryo at the corresponding timepoint (Fig. 1b). For each row, the first timepoint with at least 10 cells assigned that cell type annotation is labeled, and all observations prior to that timepoint are discarded. i, Re-embedded 2D UMAP of a subset of cells in panel a corresponding to eye field, RPE and CMZ. Cells are colored by either their initial annotations (top) or timepoint (bottom). j, The same UMAP as in panel i, colored by gene expression of marker genes for IPE or pigment epithelium more generally (Tyr & Oca2). RPE: retinal pigment epithelium. CMZ: ciliary marginal zone. RPCs: retinal progenitor cells. IPE: iris pigment epithelium. References for marker genes are provided in Supplementary Table 12. k, Re-embedded 2D UMAP of retinal ganglion cells. Cells are colored by either clusters (left; Leiden clustering followed by downselection to late-appearing clusters) or timepoint (right). l, The top 3 TF markers of the 15 clusters shown in panel k. Marker TFs were identified using the FindAllMarkers function of Seurat/v363. Their mean gene expression values in each cluster are represented in the heatmap, calculated from original UMI counts normalized to total UMIs per cell, followed by natural-log transformation. The full list of significant TFs is provided in Supplementary Table 14. m, Marker gene expression for different neuroectodermal territories. The same UMAP as in Fig. 4a, colored by gene expression of marker genes for each neuroectodermal territory. References for marker genes are provided in Supplementary Table 5.

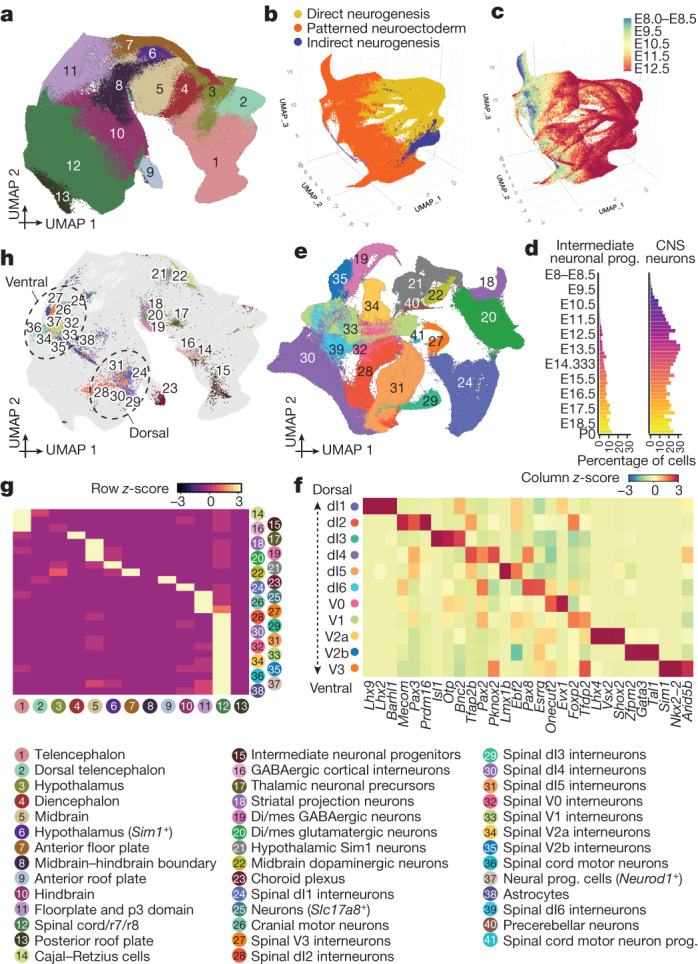

In our earliest embryos (0–12 somites), we previously defined a continuum of cell states that correlated with anatomical patterning of the ‘pre-neurogenesis’ neuroectoderm8. Extending this analysis through early organogenesis (E8–E13), we observe clusters corresponding to territories that will give rise to the major regions of the mammalian brain (Fig. 4a and Extended Data Fig. 9m). As development unfolds further, we observe many trajectories of neurogenesis arising from these inferred territories (Fig. 4b,c).

Fig. 4. The emergence of neuronal subtypes from the patterned neuroectoderm.

a, Re-embedded 2D UMAP of 1,185,052 cells, corresponding to different neuroectodermal territories from neuroectoderm and glia; major cell clusters, from stages before E13. b, Re-embedded 3D UMAP of 1,772,567 cells from neuroectodermal territories together with derived cell types, from stages before E13. Patterned neuroectoderm comprises neuroectoderm and glia and choroid plexus; direct neurogenesis comprises CNS neurons; indirect neurogenesis comprises intermediate neuronal progenitors. c, The same UMAP as in b, coloured by timepoint. d, Composition of embryos from each 6-h bin by intermediate neuronal progenitor (left) and CNS neuron (right) major cell clusters. e, Re-embedded 2D UMAP of 296,020 cells (glutamatergic neurons, GABAergic neurons, and spinal cord dorsal and ventral progenitors) from stages before E13. f, The top 3 transcription factor markers of the 11 spinal interneurons. Marker transcription factors were identified using the FindAllMarkers function of Seurat v363. The heat map shows mean gene expression values per cluster, calculated from normalized UMI counts. g, The row-scaled number of MNN pairs identified for each derivative cell type between its earliest 500 cells and cells from neuroectodermal territories. Some derivative cell types are excluded owing to low cell number or MNN pairs. h, The same UMAP as in a, but with inferred progenitor cells coloured by derivative cell type with the most frequent MNN pairs. Dotted circles highlight the dorsal and ventral spinal interneuron neurogenesis domains of the hindbrain and spinal cord. Di/mes, diencephalon and mesencephalon.

Beginning as early as the 16-somite stage, most neuronal diversity derives from direct neurogenesis (Fig. 4d), including motor neurons, cerebellar Purkinje cells, Cajal–Retzius cells and many other subtypes (CNS neurons sub-panel of Extended Data Fig. 3). Indirect neurogenesis52 has a later start, with intermediate neuronal progenitors first detected at E10.25, later giving rise to deep-layer neurons, upper-layer neurons, subplate neurons, and cortical interneurons (Fig. 4d and Extended Data Fig. 10a,b). Although many subtypes deriving from direct neurogenesis are easily distinguished, the majority (55%) of these 2.1 million cells could initially only be coarsely annotated as glutamatergic or GABAergic (γ-aminobutyric acid-producing) neurons or dorsal or ventral spinal cord progenitors. To leverage the greater heterogeneity evident at early stages as these trajectories ‘launch’ from the patterned neuroectoderm, we re-analysed the pre-E13 subset. This facilitated much more granular annotation, while also highlighting sources of heterogeneity—for example, anterior versus posterior or inhibitory versus excitatory (Fig. 4e, Extended Data Fig. 10c,d and Supplementary Table 12).

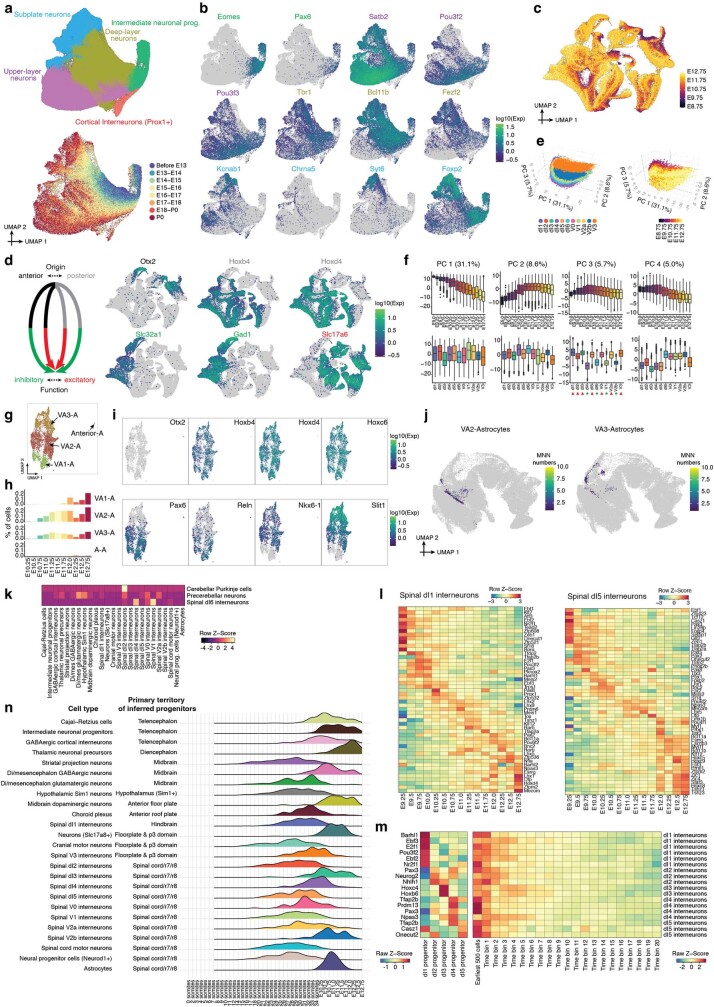

Extended Data Fig. 10. Subtypes of intermediate neuronal progenitors, glutamatergic & GABAergic neurons, and early astrocytes, and the timing of neuronal subtype differentiation from the patterned neuroectoderm.

a, Re-embedded 2D UMAP of 628,251 cells within the intermediate neuronal progenitors major cell cluster, colored by either cell type (top) or developmental stage (bottom, after downsampling to a uniform number of cells per time window). b, The same UMAP as in panel a, colored by gene expression of marker genes which appear specific to intermediate neuronal progenitors (Eomes +, Pax6 + ), upper-layer neurons (Satb2 +, Pou3f2 +, Pou3f3 + ), deep-layer neurons (Tbr1 +, Bcl11b +, Fezf2 + ), or subplate neurons (Kcnab1 +, Chrna5 +, Syt6 +, Foxp2 + ). References for marker genes are provided in Supplementary Table 5. c, The same UMAP as in Fig. 4e, with cells colored by timepoints. d, Left: Neuronal subtypes shown in Fig. 4e originate from anterior vs. posterior of neuroectoderm, and then subsequently display inhibitory vs. excitatory functions after differentiation. Right: The same UMAP as in Fig. 4e, colored by gene expression of marker genes which appear specific to anterior (Otx2 + ) vs. posterior (Hoxb4 +, Hoxd4 + ) origins, or inhibitory (Slc32a1 +, Gad1 + ) vs. excitatory (Slc17a6 + ) functions. References for marker genes are provided in Supplementary Table 12. e, 3D visualization of gene expression variation in 11 spinal interneurons, colored by cell type (left) or timepoint (right). f, Correlations between top four PCs and timepoints (top row) or cell types (bottom row). Boxplots (n = 97,842 cells) represent IQR (25th, 50th, 75th percentile) with whiskers representing 1.5× IQR. Red triangles and green stars highlight glutamatergic and GABAergic spinal cord interneurons, respectively. g, Subtypes of early astrocytes and their inferred progenitors. Re-embedded 2D UMAP of 5,928 cells within the astrocytes from stages <E13. h, Composition of embryos from each 6-hr bin by different subpopulations of astrocytes. i, The same UMAP as in panel g, colored by gene expression of marker genes which appear specific to anterior (Otx2 + ) or posterior (Hoxb4 +, Hoxd4 +, Hoxc6 + ) astrocytes, VA1-astrocytes (Pax6 +, Reln + ), VA2-astrocytes (Pax6 +, Reln +, Nkx6-1 +, Slit1 + ), and VA3-astrocytes (Nkx6-1 +, Slit1 + ). References for marker genes are provided in Supplementary Table 12. j, The same UMAP of the patterned neuroectoderm as in Fig. 4a, with inferred progenitor cells of astrocytes colored by the frequency that has been identified as a MNN with either VA2-astrocytes (left) or VA3-astrocytes (right). k, For those three cell types (cerebellar Purkinje cells, precerebellar neurons, spinal dI6 interneurons) which were excluded from the analyses represented in Fig. 4g, h due to having fewer than 50 MNN pairs, we performed a recursive mapping to identify whether they might share progenitors with another derived cell type, essentially repeating the analysis but attempting to map the earliest cells of these cell types to other derivative cell types rather than the patterned neuroectoderm. The heatmap shows the number of MNN pairs between pairwise cell types. In brief, this analysis suggests that spinal dl2 interneurons and cerebellar astrocytes share progenitors, while the progenitors of the other two re-analyzed cell types remain ambiguous. l, Gene expression across timepoints, for the specific TF markers of spinal dI1 (left) or spinal dI5 (right) interneurons. m, Left: gene expression for 18 selected TFs, across progenitor cells of dI1-5 from the neuroectodermal territories. Right: gene expression for 18 selected TFs across 21 time bins for dl1-5 spinal interneurons in which the TF has been nominated as marker TF. For individual spinal interneurons (each row), the first time bin involves the earliest 500 cells, then the left cells break into 20 bins ordered by their timepoints and with the same number of cells in each bin. Only cells from stages <E13 are included. n, For each neuronal subtype in Fig. 4g, h, we selected the annotation in the patterned neuroectoderm to which the most inferred progenitors had been assigned, and plotted the distribution of timepoints for that subset of inferred progenitors.

Among these more refined annotations of direct neurogenesis derivatives were 11 spinal interneuron subtypes; similar to retinal ganglion subtypes, these were well defined by transcription factor combinations53 (Fig. 4f and Supplementary Table 15). The top principal components of transcriptional heterogeneity among spinal interneurons appear to correspond to neuronal differentiation (PC1 and PC2), glutamatergic versus GABAergic identity (PC3), and dorsal versus ventral identity (PC4) (PC1–4 (50%); Extended Data Fig. 10e,f and Supplementary Table 16).

We next sought to infer the progenitors from which various neuronal and non-neuronal cell types derive. First, we took pre-E13 cells annotated as astrocytes, choroid plexus or any direct or indirect neurogenesis derivative, and co-embedded them with cells of the patterned neuroectoderm. Next, for each derivative cell type in the co-embedding, we selected the 500 ‘youngest’ cells, identified their patterned neuroectoderm MNNs and then mapped these back to our original embedding of patterned neuroectoderm (Fig. 4g,h). The resulting distribution of inferred progenitors is considerably more granular than our annotations of anatomical territories (compare Fig. 4h with Fig. 4a).

For non-neuronal subtypes, the inferred progenitors of the choroid plexus overwhelmingly map to the anterior roof plate (91%), with a minor subset in the dorsal diencephalon (5%), although this balance is likely impacted by the time window of this analysis54 (E8–E13). Inferred astrocyte progenitors exhibit a more complex distribution, with VA2 progenitors primarily assigned to the spinal cord, r7 and r8 (83%) and hindbrain (16%), and VA3 progenitors to the spinal cord, r7 and r8 (57%) and floorplate and p3 domain55 (32%) (Extended Data Fig. 10g–j). VA1 astrocytes arise later than VA2 and VA3 astrocytes, and were not present in sufficient numbers for their progenitors to be inferred.

For neuronal subtypes, inferred progenitors largely fall within the expected territories, but with considerable granularity (Fig. 4h). For example, inferred progenitors of dorsal and ventral spinal interneurons cluster distinctly. Although the progenitors of three neuronal subtypes (cerebellar Purkinje neurons, precerebellar neurons and spinal dI6 interneurons) were not clearly defined by the method described above, an iterative variant of the MNN heuristic suggested that cerebellar Purkinje neurons and dl2 spinal interneurons have common or at least transcriptionally similar progenitors, which may have confounded the original analysis (Extended Data Fig. 10k).

We next examined how the identities of neuronal subtypes are established and maintained56. We identified transcription factors specific to each of the 11 spinal interneuron subtypes (median 53 per subtype; Fig. 4f and Supplementary Table 15). However, within each subtype, these transcription factors exhibit complex temporal dynamics, with most only expressed transiently (Extended Data Fig. 10l). Focusing on spinal interneurons dl1–dl5, we could also identify transcription factors specific to the inferred progenitors of each subtype, relative to the inferred progenitors of other dorsal spinal interneurons (Extended Data Fig. 10m, left). Most of these were basic helix–loop–helix or homeodomain transcription factors57. However, consistent with the transitional expression of other subtype-specific transcription factors, their expression was generally not maintained for very long after neuronal specification (Extended Data Fig. 10m, right).

Finally, we sought to systematically delineate the timing of differentiation (Extended Data Fig. 10n). This analysis suggests that the emergence of each derivative cell type from the patterned neuroectoderm is both cell-type-specific and modestly asynchronous. For example, about 95% of inferred progenitors of dl2 spinal interneurons are from 20-somite to E11 stage embryos, whereas 95% of dl4 spinal interneurons inferred progenitors are from 27-somite to E11.75 stage embryos.

Together, these analyses are consistent with a model articulated by Sagner and Briscoe56 in which both spatial and temporal factors heavily contribute to the specification of neuronal subtypes as they emerge from the patterned neuroectoderm. Furthermore, they highlight the complexity of this process not only at the initiation of each neuronal subtype, but also over the course of their early maturation—for example, at 6-h resolution, we can observe each spinal interneuron subtype expressing a dynamic succession of developmentally potent transcription factors (Extended Data Fig. 10l).

A cell-type tree from zygote to birth

A primary objective of developmental biology is to delineate the lineage relationships among cell types. Transcriptional profiles of single cells do not explicitly contain lineage information. However, assuming that a continuity of transcriptional states spans all cell-type transitions, we can envision a tree accurately relating cell types based solely on scRNA-seq data58. Indeed, we and others have constructed such trees for portions of worm, fly, fish, frog and mouse development7,9–14,17.

On the basis of these learnings, we constructed a rooted tree of cell types that spans mouse development from zygote to birth, based on four published datasets4–7 (110,000 cells; E0–E8.5) and the dataset reported here (11.4 million cells; E8–P0) (Supplementary Table 17). Challenges included the heterogeneity of technologies used to generate the data, that cells’ transcriptional states are only loosely synchronized with developmental time, the multiple scenarios by which cell state manifolds may be misleading58, and finally, the sheer complexity of this organism. To overcome these challenges, we took a heuristic approach.

First, we split cells into 14 subsystems to be separately analysed and subsequently integrated (pre-gastrulation, gastrulation, and 12 organogenesis and fetal subsystems; Supplementary Tables 17 and 18).

Second, dimensionality reduction was performed on each subsystem and 283 cell-type nodes were defined, largely but not entirely corresponding to our original cell-type annotations (Supplementary Table 19 and 20). The cells comprising each node derived from a single data source, but usually from multiple timepoints within that data source.

Third, we sought to draw edges between nodes (Fig. 5a–f). Within each subsystem, we identified pairs of cells that were MNNs in 30-dimensional PCA space. Although the overwhelming majority of MNNs occurred within nodes, some MNNs spanned nodes, presumably enriched for bona fide cell-type transitions. Each possible edge (that is, node pair) was ranked based on a normalized count of inter-node MNNs (Supplementary Table 21). The MNN approach is robust to technical factors or parameter choices (Extended Data Fig. 11a–c and Supplementary Note 2).

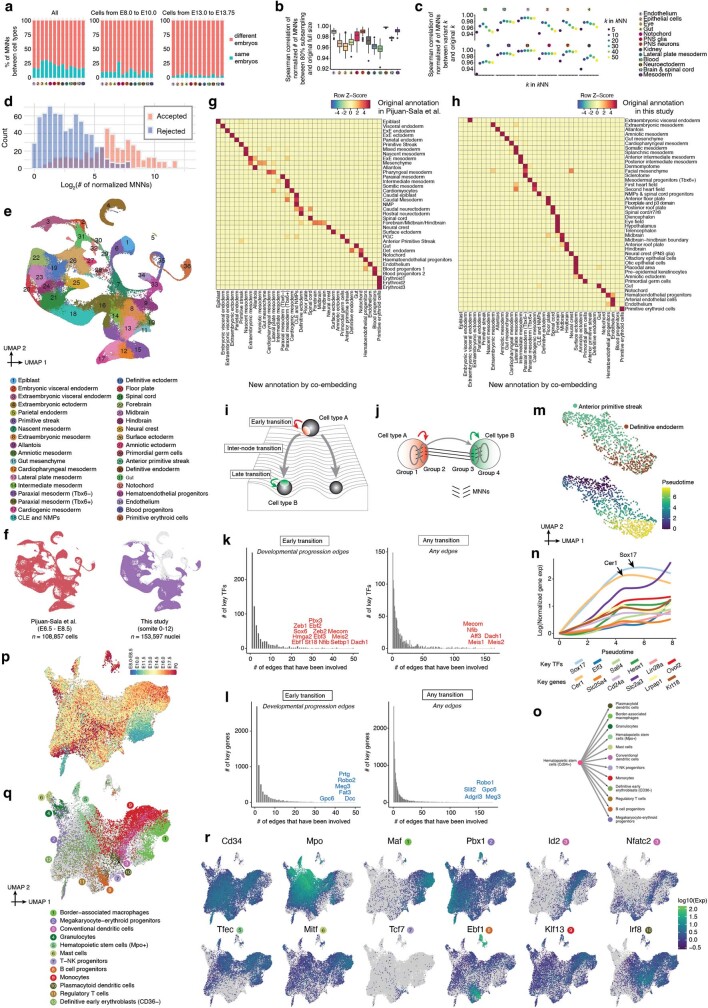

Fig. 5. A data-driven tree relating cell types throughout mouse development, from zygote to pup.

a, Illustration of the basis for the edge inference heuristic. Re-embedded 2D UMAP of 101,001 cells from Cd34+ HSCs, Mpo+ HSCs, monocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) and PMN MDSCs within the ‘blood’ subsystem. Cells involved in MNN pairs that bridge cell types are coloured. b, Inferred lineage relationships between annotated cell types in a, with corresponding colour scheme. c, The percentage of inter-cell-type MNN cells (y axis) versus the total number of cells profiled from embryos from the corresponding time bin, with colour scheme as in a,b. d, Additional illustration of the basis for the edge inference heuristic. Re-embedded 2D UMAP of 71,718 cells from gut, lung progenitor cells and alveolar type 2 cells within the ‘gut’ subsystem. Cells involved in MNN pairs that bridge cell types are coloured. e, Inferred lineage relationships between annotated cell types in d, with corresponding colour scheme. f, The percentage of inter-cell-type MNN cells (y axis) versus the total number of cells profiled from embryos from the corresponding time bin, with colour scheme as in d,e. g, A rooted, directed graph corresponding to development of a mouse, spanning E0 to P0 (Methods). For presentation purposes, we removed most ‘spatial continuity’ edges and merged nodes with redundant labels derived from different datasets, resulting in a rooted graph comprising 262 cell-type nodes and 338 edges. Nodes are coloured and labelled by each of the 14 subsystems. CLE, caudal lateral epiblast; ExE, extra-embryonic; NK-T cell, natural killer T cell; PV, parvalbumin.

Extended Data Fig. 11. Identifying equivalent cell type nodes across datasets, and systematically nominating TFs and other genes for cell type specification.

a, The MNN approach used for graph construction is robust to subsampling and choice of the k parameter. The percentage of MNNs between different cell types, from the same embryo (blue) or from different embryos (red), is shown for each developmental system during organogenesis & fetal development, for all cells (left), cells from E8.0 to E10.0 (middle), or cells from E13.0 to E13.75 (right). b, The Spearman correlation coefficients of the normalized number of MNNs between cell types, comparing random subsampling of 80% of the cells to the full set of cells. The subsampling was repeated 100 times. The number of MNNs between cell types were normalized by the total number of possible MNNs between them. Boxplot (n = 1,200 correlation coefficients) represents IQR (25th, 50th, 75th percentile) with whiskers representing 1.5× IQR. Outliers are shown as the dots outside the whiskers. c, The Spearman correlation coefficients of the normalized number of MNNs between cell types, comparing various choices for k parameter (k = 5, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50) and the choice of k parameter (k = 15) when applying kNN to the developmental systems during organogenesis & fetal development. The number of MNNs between cell types were normalized by the total number of possible MNNs between them. Colors and numbers in panels a-c correspond to each developmental system annotations listed at the top right. d, 1,155 edges with the number of normalized MNNs > 1 were manually reviewed for biological plausibility. Histogram of edges that were accepted or rejected as a function of normalized MNN score. e, Integration of scRNA-seq profiles from gastrulation and early somitogenesis to identify equivalent cell type nodes across datasets generated by distinct technologies. 2D UMAP visualization of co-embedded cells, derived both from a gastrulation dataset based on cells from E6.5 to E8.5 generated on the 10x Genomics platform7 (n = 108,857 cells) and the earliest ~1% of this dataset (0-12 somite stage embryos) generated by sci-RNA-seq3 (n = 153,597 nuclei), after batch correction63. This is essentially an updated version of an analysis that we have done previously8. We performed clustering and cell type annotation on the integrated co-embedding, as shown. f, The same UMAP as in panel e is shown twice, with colors highlighting cells/nuclei from Pijuan-Sala’s dataset7 (left) or early somitogenesis8 (right). g, For cells from the original Pijuan-Sala’s dataset7, we quantify and display the overlap between the original annotations and the new annotations shown in panel e. For each row, the proportions of cells that are distributed across each column are transformed to z-score. h, For nuclei from the early somitogenesis embryos8, we quantify and display the overlap between the original annotations and the new annotations shown in panel e. These mappings were the basis for dataset equivalence edges between the “gastrulation” and 12 “organogenesis & fetal development” subsystems. For each row, the proportions of cells that are distributed across each column are transformed to z-score. CLE: Caudal lateral epiblast. NMPs: Neuromesodermal progenitors. i, A Waddington landscape cartoon illustrating how a cell type transition might be broken into three phases. j, Given a directional edge between two nodes, A → B, we identified the subset of cells within each node that were either MNNs of the other cell type (inter-node; groups 2 & 3) or MNNs of those cells (intra-node; groups 1 & 4). If A → B, this effectively models the transition as group 1 → 2 → 3 → 4. k, Histograms of the number of edges in which TFs are differentially expressed. The left histogram counts only genes when they are differentially expressed across the early phase of an developmental progression edge, while the right histogram counts genes when they are differentially expressed in any phase of all edges. l, Same as panel k, but for all genes rather than only TFs. m, Re-embedded 2D UMAP of 988 cells participating in groups 1-4 of the transition from anterior primitive streak → definitive endoderm. Cells are colored by either cell type annotations (top) or estimated pseudotime (bottom) using Monocle314. n, For cells in panel m, normalized gene expression of selected genes are plotted as a function of estimated pseudotime. Gene expression values were calculated from original UMI counts normalized to total UMIs per cell, followed by natural-log transformation. The line of gene expression was plotted by the geom_smooth function in ggplot2. We manually added an offset based on their expression at pseudotime = 0 to the y-axis for individual genes. o, A sub-graph of Fig. 5g, including hematopoietic stem cells (Cd34 + ) and 12 cell type nodes which appear derived from it. p, Re-embedded 2D UMAP of 37,750 cells from hematopoietic stem cells (Cd34 + ), colored by developmental stage (after downsampling to a uniform number of cells per stage). q, The same UMAP as in panel p, but with inferred progenitor cells (the cells participating in the MNNs that support the edges) colored by derivative cell type with the most frequent MNN pairs. r, The same UMAP as in panel p, colored by gene expression of selected top key TFs which were upregulated during the “early transition” for each derivative.

Fourth, we manually curated the top 1,155 candidate edges for biological plausibility (Extended Data Fig. 11d), leaving 452 edges, which we further categorized as likely reflecting ‘developmental progression’ or ‘spatial continuity’ (Supplementary Table 22). Notably, where nodes were connected to multiple other nodes, distinct subsets of cells were generally involved in each edge, and inter-node MNN pairs exhibited temporal coincidence (Fig. 5a–f). As only a handful of cells were profiled in the pre-gastrulation subsystem, its edges were added manually.

Finally, to bridge subsystems, we performed batch correction and co-embedding of selected timepoints from different data sources, resulting in a third category of ‘dataset equivalence’ edges (Extended Data Fig. 11e–h). Ten of the organogenesis and fetal development subsystems could be linked to equivalent cell-type nodes in the gastrulation subsystem in a data-driven manner, and two required edges to be manually added based on biological plausibility. Altogether, we added 55 inter-subsystem edges.

The resulting developmental cell-type tree, spanning E0 to P0, can be represented as a rooted, directed graph (Fig. 5g).

Key drivers of cell-type transitions

We next sought to test which transcription factors or other genes sharply change in expression with the emergence of each cell type. First, for each directional cell-type transition edge between two nodes in the graph (A→B), we identified both ‘inter-node’ MNNs, as well as ‘intra-node’ MNNs of the inter-node MNNs. Rather than considering the entirety of A versus B, this heuristic focuses our attention on the cells most proximate to each cell-type transition (groups 1→2→3→4 in Extended Data Fig. 11i,j). Next, we identified differentially expressed transcription factors (DETFs) and differentially expressed genes (DEGs) across each phase of the modelled transition—that is, early (1→2), inter-node (2→3) and late (3→4). Notably, the early phase is within node A, which may facilitate identification of changes that precede the A→B transition itself.

We applied this heuristic to 436 edges of the rooted tree shown in Fig. 5g, nominating ranked lists of median 28 (IQR 12–51) DETFs and 171 (IQR 76–389) DEGs per edge (Supplementary Tables 23 and 24). Most genes were nominated for only one or a few edges, with outliers that may have more general roles in cell-type specification (Extended Data Fig. 11k,l). Many of the top-ranked upregulated DETFs for the early phase of a transition correspond to an established driver of the derivative cell type (for example, Mitf for melanocytes, Ebf1 and Pax5 for B cell progenitors, Lef1 for B cells and Zfpm1 for megakaryocyte–erythroid progenitors). We also nominated potentially novel drivers that warrant further investigation (including Tcf7l2 for Kupffer cells, Ltf for monocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells, Esrrg for dorsal telencephalon-derived choroid plexus, Zfp536 for myelinating Schwann cells and Rreb1 for adipocyte progenitors) (Supplementary Table 23).

Digging into a well-studied transition, Sox17 is the sole upregulated DETF during the early phase of the anterior primitive streak→definitive endoderm transition, whereas other transcription factors (Elf3, Sall4, Hesx1, Lin28a, Hmga1 and Ovol2, but not Sox17) are upregulated during the transition itself (Supplementary Table 23). Non-transcription factor DEGs specific to the early phase of this transition include Cer1, ADP/ATP translocase 1 (Slc25a4) and Slc2a3 (also known as Glut3) (Supplementary Table 24). To examine this further, we subjected all cells participating in groups 1–4 of this transition to conventional pseudotime analysis14. This analysis supported the upregulation of Sox17 as preceding other nominated transcription factors, and further highlighted Cer1 as the only non-transcription factor DEG with Sox17-like kinetics (Extended Data Fig. 11m,n).

A more complex example involves Cd34+ haemopoietic stem cells (HSCs), which in the graph are the origin of a dozen cell types (Extended Data Fig. 11o). Notably, although Cd34+ HSCs constitute a single node, the cells composing this node are very heterogeneous, with distinct subsets participating in the MNN pairs that support edges to various lymphoid, myeloid and erythroid derivatives (Extended Data Fig. 11p,q). Correspondingly, the heuristic nominates different transcription factors as early regulators of each transition—for example, Ebf1 for B cells and Id2 and Nfatc2 for conventional dendritic cells (Extended Data Fig. 11r).

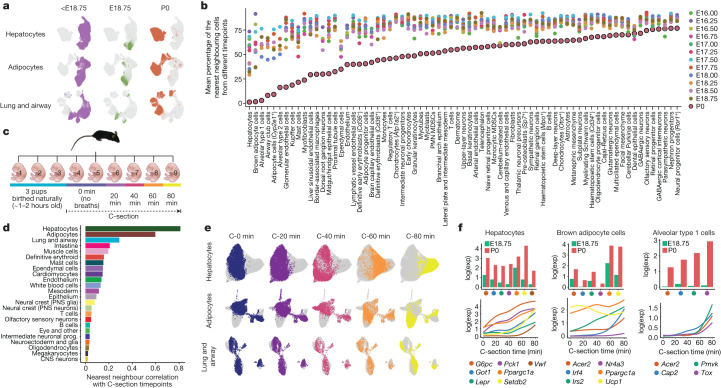

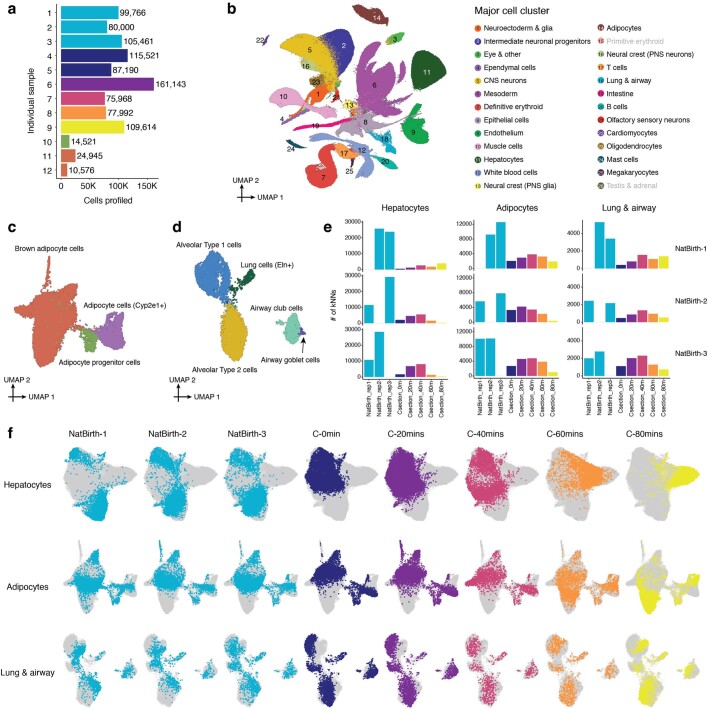

Marked changes immediately after birth

As touched on above, we anecdotally noticed that proximal tubule cells deriving from P0 pups were unusually well-separated from those deriving from late-stage fetuses (Extended Data Fig. 5d). A similar phenomenon was noted for hepatocytes, adipocytes, and various lungs and airway cell types (Fig. 6a). This contrasts sharply with the bulk of the time-lapse, in which cells of a given type were overwhelmingly well mixed across adjacent timepoints. Concerned this was due to batch effects or the pitfalls of over-interpreting UMAPs59, we conducted a timepoint correlation analysis, testing for each cell type whether the k-nearest neighbours of cells of a given timepoint were derived from the same or different timepoints. In this framing, a low proportion of neighbours from different timepoints suggests a temporally abrupt change in transcriptional state. For nearly all cell types, P0 cells exhibited a lower proportion for this metric than all other timepoints (Fig. 6b). Although a trivial explanation would be a longer interval between E18.75 and P0 than 6 h, the pattern was highly non-uniform across cell types, with extreme examples including the aforementioned cell types as well as various endothelial and blood lineages. In sharp contrast, P0 cells from most neuronal cell types were relatively well mixed with cells deriving from earlier timepoints.

Fig. 6. Rapid shifts in transcriptional state occur in a restricted subset of cell types upon birth.