Abstract

BACKGROUND:

The impact of work-related asthma (WRA) on quality of life (QoL) and work productivity remains largely neglected/uncertain despite its high prevalence.

OBJECTIVE:

To investigate the association of WRA with QoL and work productivity as compared with subjects with non-WRA and those without asthma and rhinitis.

METHODS:

A cross-sectional survey was carried out among workers during their periodic occupational health visit in Belgium. The Mini Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire, the 8-item Medical Outcome Study Short Form instrument, and the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment—General Health questionnaire were administered. Survey participants were divided into 3 groups: (1) WRA (current asthma with ≥2 respiratory symptoms at work; n = 89); (2) non-WRA (current asthma without work-related respiratory symptoms; n = 119); and (3) the reference group (no asthma and no lower respiratory, nasal, or eye symptoms; n = 815). Associations of QoL and work productivity with WRA were evaluated by multivariable regression analyses.

RESULTS:

WRA and having poor asthma control were significantly associated with lower global Mini Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire scores compared with non-WRA. Asthmatic subjects had significantly lower physical and mental health component scores of the 8-item Medical Outcome Study Short Form instrument and overall work productivity compared with the reference group, with greater impairment in workers with WRA than in those without WRA. Moreover, workers with WRA had higher percentages of doctor visits and income reduction because of respiratory symptoms than those with non-WRA. Work-related rhinitis and depression were associated with reduced QoL, independent of the effect of WRA.

CONCLUSIONS:

WRA should be managed comprehensively to reduce the worsening of QoL and work productivity of those affected.

Keywords: Quality of life, Socioeconomic burden, Work productivity, Work-related asthma

The Global Burden of Disease Study reported that asthma was deemed accountable for 21.6 million (95% uncertainty interval, 17.1–27.0) disability-adjusted life-years in 2019, which was one-fifth of the total disability-adjusted life-years from chronic respiratory disease.1

Occupational exposure accounts for approximately 16% of all cases of adult-onset asthma.2 The term “work-related asthma” (WRA) encompasses both occupational asthma (OA) and work-exacerbated asthma (WEA).3,4 OA is defined as asthma caused by a specific exposure at work, whereas WEA is defined as “pre-existing or concurrent asthma that is worsened by workplace conditions.”3

Asthmagen exposure in the workplace has been associated with poor asthma control.5,6 WRA may have a considerable impact on the socioeconomic conditions of the affected subjects because it most often implies job changes to avoid or reduce exposure.4,7 In addition, WRA may be associated with increased use of health care resources and/or an impaired health-related quality of life (QoL).8–13 Unfortunately, studies assessing the impact of WRA on QoL or work productivity had a small sample size,12 lacked a nonasthmatic control group,11 and/or showed conflicting results.8 In fact, despite being potentially preventable and associated with improved QoL if addressed properly, WRA has been relatively neglected from a clinical and scientific point of view.1

Our study aimed to simultaneously compare WRA with both non-WRA cases and a nonasthmatic reference group from a general workforce survey, which evaluated the association of WRA not only with health-related QoL but also with work productivity.

METHODS

Study design and population

A cross-sectional questionnaire-based survey was conducted on a sample of workers employed in various industrial sectors in the French-speaking part of Belgium. The design of this survey has been previously described.14 The participants were recruited at the time of their periodic visit to medical examination centers of an occupational health service (Service de Prévention et Protection au Travail—Centre de Service Interentreprises) from 2008 to 2011. Periodic examination of salaried workers by internal or external occupational health services is mandatory in Belgium. All workers who attended a medical examination on a selected day were asked to participate. The study days were randomly allocated after weighting for the annual activity of each examination center. For all assessments, when preexistent questionnaires were applied, we used their validated versions in French. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Centre Hospitalier Universitaire UCL Namur (approval no. B0392006772), and written informed consent was obtained from each participant.

Procedures

Screening questionnaire.

A 2-step integrated questionnaire was administered under the supervision of clinical research assistants. In the first step, the participants were asked to complete a “screening questionnaire,” aimed at identifying those with asthma as well as those with rhinitis.14 The screening questionnaire gathered information on (1) demographic, medical, and occupational characteristics; (2) asthma and rhinitis symptoms as well as their relationship with work exposure and medications; (3) general health—related QoL using the 8-item Medical Outcome Study Short Form (SF-8) (4-week recall French version 1.0 for Belgium provided by QualityMetric, Inc, Lincoln, Rhode Island); and (4) impairment in work productivity because of general health assessed through the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment—General Health (WPAI-GH) generic instrument.15 Participants with a self-reported or physician-based diagnosis of asthma who had wheezing or whistling sounds in the chest (apart from colds) in the last 12 months or were currently taking any medication for asthma were considered as having current asthma.

In the second step, all subjects who screened positive for current asthma were invited to complete an “asthma-specific questionnaire” during the same visit.

Asthma-specific questionnaire.

Participants screened for asthma were administered an “asthma-specific questionnaire” that aimed to collect information pertaining to the level of asthma control (Asthma Control Test [ACT])16,17 and asthma-related QoL (Mini Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire [mAQLQ]).18 Participants with current asthma who merely have respiratory symptoms at work were excluded from the study.

Rhinitis-related questionnaire.

Rhinitis-related questionnaires, including rhinitis-specific QoL, work disability, and health care utilization due to rhinitis, were administered to participants with a symptom-based diagnosis of rhinitis or with a self-reported or physician-based diagnosis of allergic rhinitis.19

Identification of diseases

The screening questionnaire included items on respiratory symptoms extracted from the European Community Respiratory Health Survey questionnaire.20 The list of definitions of symptoms/diseases and outcomes is presented in Table E1 (in the Online Repository available at www.jaci-inpractice.org).

“Ever asthma” was defined by an affirmative answer to 1 of the following 2 questions: (1) “Did you ever suffer from asthma or ‘asthmatic bronchitis’?” (ie, self-reported asthma) or (2) “Has a doctor ever told you that you have asthma or ‘asthmatic bronchitis’?” (ie, physician-based asthma). Those participants with self-reported or physician-based asthma (ever asthma) were categorized as having current asthma if they also provided a positive answer to any of the following questions: (1) “Have you had wheezing or whistling sounds in your chest apart from colds in the last 12 months?” or (2) “Are you currently taking any medicine for asthma?” Poor asthma control was defined as having an ACT score of less than or equal to 19.17

WRA was considered when participants reported current asthma20 and experienced at least 2 asthma symptoms related to work exposure identified using the following question: “When you are at work or during the hours following your work shift, do you notice the onset of any of the following symptoms: wheezing, chest tightness, shortness of breath, or cough?”21 Asthma unrelated to work (non-WRA) was considered present when the worker reported current asthma without asthma symptoms related to work exposure.

A diagnosis of current rhinitis was assigned to participants reporting that they regularly experienced at least 2 nasal symptoms (ie, runny nose, stuffy nose, or sneezing), apart from a cold or flu, during the last 12 months.14,22 Subjects were regarded as having allergic rhinitis in the presence of either self-reported or physician-based allergic rhinitis.23 Work-related rhinitis (WRR) was defined by the presence of current rhinitis and at least 2 nasal symptoms at work.14 Work-related conjunctivitis was identified by reporting itchy and red eyes at work.

Comorbidity

Information on comorbidities was collected through a questionnaire. Participants were asked if they had ever been diagnosed with diabetes, cancer, headaches, cardiovascular diseases, arterial hyper-tension, gastrointestinal diseases, musculoskeletal disorders, arthritis, and chronic dermatitis. Questions on respiratory-based comorbidities including chronic bronchitis and emphysema were also asked among workers who reported asthma. The term “chronic phlegm” is used most frequently in Belgium to designate chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Outcome measures

Quality of life.

Health-related QoL was assessed using 2 validated instruments: (1) the generic SF-8 questionnaire administered to all participants and (2) the mAQLQ,18 which was completed by participants who reported current asthma.

The SF-8 questionnaire is a shortened generic instrument assessing 8 health concepts (general health, physical functioning, physical role, bodily pain, vitality, mental health, role emotional, and social functioning) that are summarized into 2 aggregate scores: the physical component summary (PCS) and the mental component summary (MCS) measures. The SF-8 raw scales are transformed into 0 to 100 scales, with higher scores indicating better health status. The summary measures are standardized using scoring algorithms to have a mean value of 50 and an SD of 10.

The mAQLQ is a 15-item self-administered questionnaire designed to evaluate asthma-specific QoL by addressing 4 domains: symptoms (5 items), limitations in daily activities (4 items), emotional function (3 items), and exposure to environmental stimuli (3 items). The degree of impairment during the preceding 2 weeks is scored on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (severe impairment) to 7 (no impairment) for each item. The answers are summarized into 4 domain scores and a mean global score.

Work productivity.

The impact of general health on work productivity was assessed in all participants using the French version of the WPAI-GH self-administered instrument.15,24 This questionnaire is designed to produce 4 outcome measures evaluated over the last 7 days: (1) the work time missed because of general health (ie, absenteeism); (2) the productivity impairment while working because of health (ie, impaired presenteeism); (3) the overall work impairment as the sum of absenteeism and impaired presenteeism, and (4) the impairment in usual off-work activities. These metrics are expressed as percentages from 0% to 100%, with higher percentages indicating greater impairment. The generic “general health” version of the WPAI was used because this instrument is generalizable across diseases and allowed for comparing impairment in work productivity between participants with and without asthma. The existence of “any overall work impairment” was defined as having a WPAI-GH score of more than 0.

Socioeconomic and health care utilization related to respiratory symptoms.

The participants also completed a questionnaire that inquired whether they ever had to change or leave their job or reduce working time because of their respiratory symptoms. This questionnaire also collected information about work days missed, visits to physicians (general practitioners and specialists), and hospitalizations because of respiratory symptoms over the last 12 months. Respiratory sickness absence was defined as 1 or more days of work loss because of respiratory symptoms in the previous year.25

Data analysis

Survey participants were divided into 3 groups: WRA, non-WRA, and the reference population (defined as participants who did not report either asthma or any lower respiratory, nasal, or eye symptoms). Continuous variables were presented as medians and interquartile ranges and categorical variables as percentages. The χ2 or the Fisher exact test was used for comparing categorical variables, and the Mann-Whitney test or the Kruskal-Wallis test was used for comparing continuous variables. Multivariable linear regression analysis was used to evaluate factors associated with the mAQLQ overall score and SF-8 PCS/MCS scores. Multivariable logistic regression analysis was used to evaluate the determinants of any work productivity impairment. For each outcome modeled, we fit a base model composed of the main determinant (the presence of WRA or non-WRA) and the potential confounders (age, sex, smoking habits, body mass index, education level, and current job duration). Other clinical factors (comorbidities) for the modeled outcome with a univariable P value less than .10 were added to the base model. Multivariable regression analysis with backward stepwise selection, using an exclusion criterion of P value greater than .10, was carried out to obtain the final models. Statistical analysis was performed using the IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows version 25 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY). Statistical significance was defined by a P value less than or equal to .05. We did not impute missing values. Post hoc power calculation using G*Power version 3.1.9.626 revealed that with 56 WRA and 74 non-WRA participants, we could detect a mean difference of 0.9 in the mAQLQ global score with 5% alpha and 99% power.

RESULTS

Participants

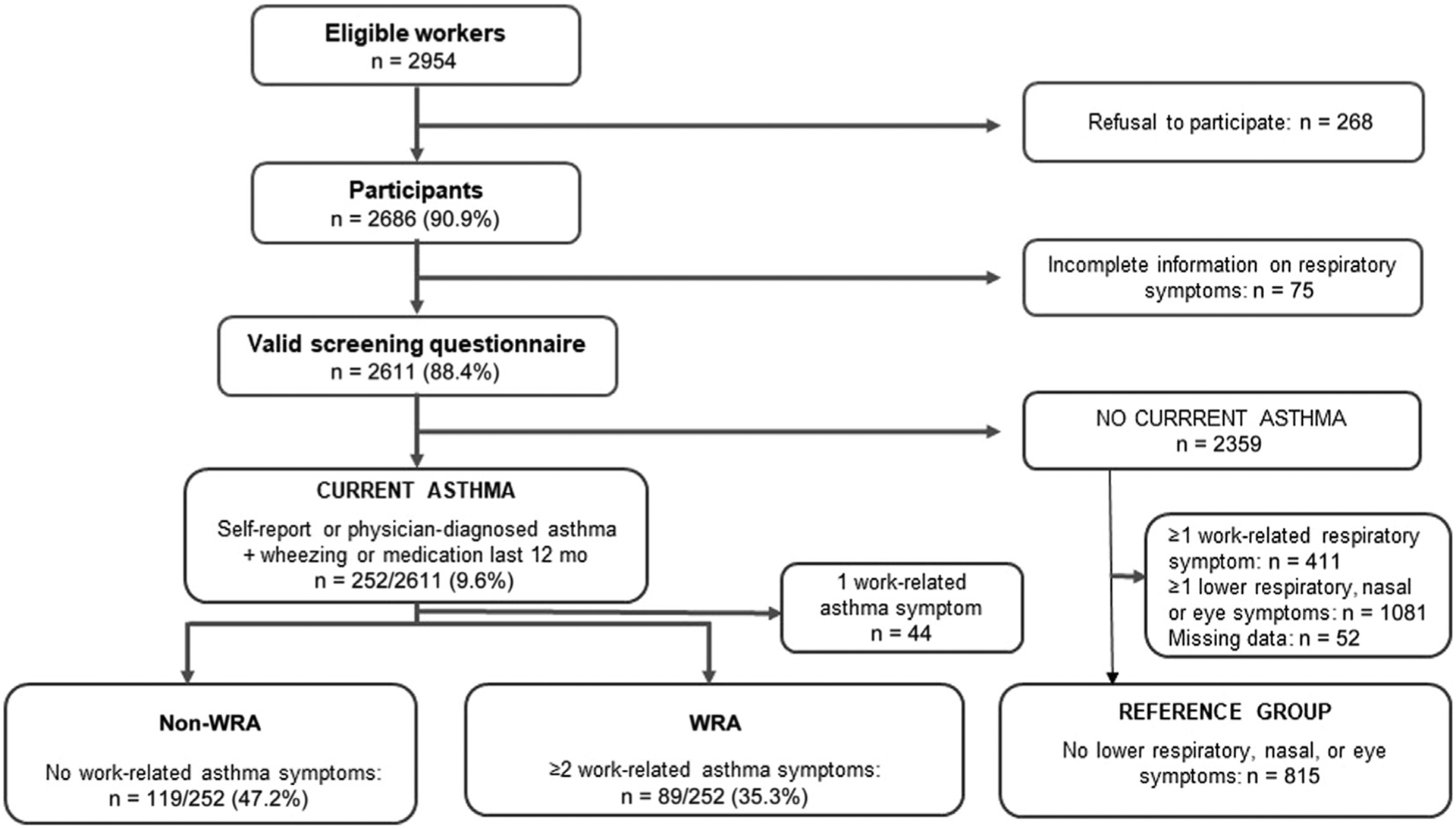

Of 2954 eligible workers invited to participate in the survey, 2686 (90.9%) agreed to complete the questionnaires (Figure 1). Valid information on respiratory symptoms was obtained from 2611 (88.4%) workers. Among the 252 (9.6%) subjects with current asthma, 89 (35.3%) were categorized as having WRA and 119 (47.2%) as non-WRA. Forty-four (17.5%) participants with current asthma who experienced only 1 respiratory symptom at work were excluded from both the WRA and non-WRA groups and were not included in the data analyses. Nonasthmatic workers who did not report any lower respiratory, nasal, or eye symptoms were regarded as the reference group (n = 815).

FIGURE 1.

Flowchart of the study recruitment.

Workers’ characteristics

Workers with WRA and non-WRA were younger and had a higher prevalence of physician-based diagnosis of depression compared with workers in the reference group (Table I). Two-thirds of the WRA group were female participants, whereas the proportion of female participants in the non-WRA and reference groups was close to 50%. Workers with WRA showed lower ACT scores (ie, poorer asthma control) and had a higher prevalence of WRR, work-related conjunctivitis, chronic phlegm, and physician-based diagnosis of depression when compared with workers with non-WRA (P value range, <0.001–0.006). The use of asthma treatments, including short-acting and long-acting β2-agonists, and inhaled corticosteroids, was similar between workers with WRA and non-WRA.

TABLE I.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of participants with WRA, non-WRA, and the reference population

| Characteristics | Missing values* | WRA (n = 89) | Non-WRA (n = 119) | Reference group (n = 815) | P value† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex: female | 0/0/3 | 59 (66.3) | 54 (45.4) | 383 (47.2) | .002 |

| Age (y) | 2/1/19 | 38.1 (30.5–47.4) | 37.5 (30.4–45.9) | 40.7 (32.5–48.5) | .023 |

| Smoking status | 0/0/12 | .050 | |||

| Current smoker | 37 (41.6) | 39 (32.8) | 216 (26.9) | ||

| Ex-smoker | 13 (14.6) | 21 (17.6) | 147 (18.3) | ||

| Never smoked | 39 (43.8) | 59 (49.6) | 441 (54.9) | ||

| Body mass index | 4/6/61 | 25.3 (23.01–27.9) | 24.1 (21.9–27.1) | 24.8 (22.5–27.8) | .174 |

| Normal weight | 39 (45.9) | 66 (58.4) | 369 (48.9) | .193 | |

| Overweight (≥25 kg/m2) | 46 (54.1) | 47 (41.6) | 385 (51.1) | ||

| Education level | .127 | ||||

| >12 y | 1/0/26 | 28 (31.8) | 54 (45.4) | 300 (38) | |

| ≤12 y | 60 (68.2) | 65 (54.6) | 490 (62) | ||

| Current job duration | 8/7/70 | 6.3 (2.02–11.1) | 5.5 (1.8–11.6) | 7.0 (2.1–16.0) | .164 |

| Asthma preexisting to current job | 16/17/– | 57 (78.1) | 84 (82.4) | NA | .240 |

| Use of asthma treatment | 0/0/– | 67 (75.3) | 85 (71.4) | NA | .535 |

| SABA | 33/47/– | 35 (62.5) | 39 (54.2) | NA | .344 |

| LABA | 33/47/– | 17 (30.4) | 18 (25.0) | NA | .500 |

| ICS | 33/47/– | 18 (32.1) | 21 (29.2) | NA | .717 |

| Oral corticosteroid | 33/47/– | 3 (5.4) | 1 (1.4) | NA | .318 |

| Asthma control | |||||

| ACT score | 21.0 (17.0–23.0) | 23.0 (21.0–24.0) | NA | <.001 | |

| ACT score ≤ 19 | 30/46/- | 27 (45.8) | 13 (17.8) | NA | .001 |

| Associated conditions | |||||

| Allergic rhinitis‡ | 1/0/– | 67 (76.1) | 89 (74.8) | NA | .824 |

| WRR§ | 1/0/– | 31 (34.8) | 7 (5.9) | NA | <.001 |

| Work-related conjunctivitis|| | 0/0/– | 22 (24.7) | 6 (5.0) | NA | <.001 |

| Chronic phlegm | 1/3/– | 25 (28.4) | 15 (12.9) | NA | .006 |

| Depression, physician-based | 0/0/1 | 24 (27.0) | 17 (14.3) | 69 (8.5) | <.001 |

| Nonrespiratory, nondepression comorbidity | 0/0/0 | 30 (33.7) | 42 (35.3) | 324 (39.8) | .387 |

ICS, Inhaled corticosteroid; LABA; long-acting β2-agonist; NA, not applicable; SABA; short-acting β2-agonist.

Data are presented as number (% of available data) of subjects or medians (interquartile ranges).

Missing data for WRA, non-WRA, and the reference groups, respectively.

Between WRA, non-WRA, and the reference group.

Allergic rhinitis is defined as either self-reported or physician-based allergic rhinitis.

Work-related is rhinitis defined by current rhinitis (the presence of at least 2 nasal symptoms on a regular basis during the last 12 mo) associated with at least 2 nasal symptoms at work.

Work-related conjunctivitis is defined as itchy and red eyes at work.

QoL impairment

Asthma-specific QoL.

Subjects with WRA showed significantly lower overall and subdomain mAQLQ scores than those with non-WRA, indicating a higher level of QoL impairment (Table II). Univariable and multivariable associations with overall mAQLQ score are provided in Table III. The multivariable linear regression analysis conducted among subjects with current asthma revealed that a greater impairment in asthma-specific QoL was independently associated with poor asthma control (ie, ACT score ≤ 19), WRA, and WRR.

TABLE II.

Asthma-specific QoL (mAQLQ) and socioeconomic outcomes in WRA and non-WRA

| Outcomes | Missing values | WRA (n = 89) | Non-WRA (n = 119) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mAQLQ domains | ||||

| Global | 45/33 | 5.3 (4.2–6.3) | 6.3 (5.7–6.7) | <.001 |

| Symptoms | 44/30 | 5.0 (3.4–5.8) | 6.2 (5.2–6.6) | <.001 |

| Activities | 43/33 | 6.0 (4.6–6.5) | 6.8 (6.0–7.0) | <.001 |

| Emotions | 42/30 | 5.7 (4.3–7.0) | 6.7 (6.0–7.0) | .001 |

| Environment | 42/31 | 5.0 (4.0–6.1) | 6.0 (5.3–7.0) | <.001 |

| Respiratory-related work disability* | 36/22 | 7 (10.4) | 0 (0) | .003 |

| Respiratory sickness absence, last 12 mo† | 37/27 | 13 (21.0) | 12 (14.6) | .320 |

| Any income reduction due to respiratory symptoms‡ | 36/24 | 9 (13.8) | 3 (3.6) | .024 |

| Hospitalization due to respiratory symptoms | 22/36 | 4 (6.0) | 3 (3.5) | .701 |

| Visit to a general practitioner due to respiratory symptoms | 22/37 | 45 (67.2) | 38 (46.3) | .011 |

| Visit to a specialist due to respiratory symptoms | 22/36 | 19 (28.4) | 20 (24.1) | .554 |

Data are presented as number (percentages) of subjects or medians (interquartile ranges), and P values are for comparing WRA with non-WRA.

Defined as ever having had to change or leave the job or reduce working time because of respiratory symptoms.

Defined as at least 1 work day lost because of respiratory symptoms.

Slight or substantial income reduction (self-reported).

TABLE III.

Univariable analysis and multivariable model for the mAQLQ global score among asthmatic subjects

| Characteristics | Univariable associations | Final multivariable model | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (IQR) | P value | Unstandardized β coefficient (95% CI) | P value | |

| Sex* | .007 | |||

| Female | 5.7 (4.9–6.4) | |||

| Male | 6.2 (5.4–6.7) | |||

| Age (y)* | .590 | |||

| <35 | 5.7 (4.9–6.5) | |||

| 35–45 | 6.2 (5.1–6.5) | |||

| ≥45 | 6.2 (5.1–6.5) | |||

| Smoking habit* | .702 | |||

| Never smoked | 6.0 (5.2–6.4) | |||

| Ex-smoker | 5.7 (4.8–6.7) | |||

| Current smoker | 6.1 (5.1–6.5) | |||

| Body mass index (kg/m2)* | .03 | |||

| <25 | 6.3 (5.4–6.6) | |||

| ≥25 | 5.7 (4.9–6.4) | |||

| Education level* | .729 | |||

| >12 y | 6.1 (5.3–6.5) | |||

| ≤12 y | 6.1 (4.9–6.5) | |||

| Current job duration* | .064 | |||

| <5 y | 5.7 (4.3–6.4) | |||

| ≥5 y | 6.0 (5.4–6.5) | |||

| Asthma preexisting to current job | ||||

| Yes | 5.7 (4.9–6.4) | .006 | ||

| No | 6.4 (5.7–6.7) | |||

| Asthma control* | <.001 | |||

| ACT score > 19 | 6.3 (5.7–6.7) | Reference | ||

| ACT score ≤ 19 | 4.8 (3.7–5.4) | −1.4 (−1.8 to −1.1) | <.001 | |

| Asthma* | ||||

| Non-WRA | 6.3 (5.7–6.7) | <.001 | Reference | |

| WRA† | 5.3 (4.2–6.3) | −0.4 (−0.7 to −0.01) | .044 | |

| Asthma medication | .001 | |||

| No | 6.2 (5.5–6.7) | |||

| Yes | 5.4 (4.1–6.3) | |||

| Allergic rhinitis‡ | .282 | |||

| Absent | 6.2 (5.4–6.6) | |||

| Present | 6.0 (5.0–6.5) | |||

| WRR§ | .017 | |||

| Absent | 6.3 (6.1–7.0) | Reference | ||

| Present | 5.6 (5.0–6.4) | −0.4 (−0.8 to −0.02) | .061 | |

| Work-related conjunctivitis|| | .637 | |||

| Absent | 6.0 (5.1–6.5) | |||

| Present | 6.1 (5.1–6.4) | |||

| Chronic phlegm* | .004 | |||

| Absent | 6.1 (5.4–6.5) | |||

| Present | 5.0 (3.9–6.3) | |||

| Depression, physician-based | .677 | |||

| Absent | 6.0 (5.1–6.5) | |||

| Present | 5.9 (4.8–6.5) | |||

| Nonrespiratory, nondepression comorbidity | .393 | |||

| Absent | 6.0 (5.0–6.5) | |||

| Present | 6.1 (5.2–6.6) | |||

IQR, Interquartile range.

Analysis was done in the WRA and non-WRA groups because AQLQ is an asthma-specific questionnaire. Multivariable analysis was done on 106 subjects and incorporated well-known confounders such as age, sex, smoking habits, body mass index, academic level, and current job duration (marked with asterisks) and other covariates with a P value of <.1 in univariable analyses.

Well-known confounders included in the multivariable analysis.

WRA is defined as current asthma associated with ≥2 WRA symptoms.

Allergic rhinitis is defined as either self-reported or physician-based allergic rhinitis.

WRR is defined as current rhinitis with ≥2 WRR symptoms.

Work-related conjunctivitis is defined as red and itchy eyes at work.

General health—related QoL.

Analysis of the SF-8 questionnaire (Table IV) revealed that the median PCS score was worse in participants with WRA (46.4) and non-WRA (51.8) as compared with that in the reference group (54.4; P < .01). Subjects with WRA and non-WRA also showed lower MCS scores (45.7 and 50.7, respectively) than the reference group (52.4; P < .01). The PCS and MCS scores were significantly lower in subjects with WRA than in those with non-WRA or the reference group (Table IV). Univariable and multivariable analyses of the factors that determined physical health impairments are summarized in Table V. In the final multivariable model, being female, having non-WRA, having WRA, and having depression and other comorbidities were significantly and independently associated with lower PCS scores. Compared with the reference group, the PCS scores were lower by averages of 6.9 points (95% CI, −8.8 to −5.3; P < .001) for the WRA group and 2.2 points (95% CI, −3.7 to −0.9; P = .002) for the non-WRA group.

TABLE IV.

General health—related QoL (SF-8) and work productivity impairments in participants with WRA and non-WRA compared with the reference population*†

| Outcomes | Missing values | WRA (n = 89) | Non-WRA (n = 119) | Reference group (n = 815) | P value (non-WRA group vs reference group) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SF8-PCS score | 1/5/42 | 46.4 (38.6–51.5) | 51.8 (46.4–56.2) | 54.4 (50.0–56.9) | .001 |

| SF8-MCS score | 1/5/42 | 45.7 (36.6–52.4) | 50.7 (43.9–56.3) | 52.4 (48.2–57.5) | .016 |

| Any work time missed (absenteeism) | 11/8/90 | 14 (17.9) | 5 (4.5) | 19 (2.6) | .469 |

| Any impairment at work (presenteeism) | 19/11/132 | 33 (47.1) | 25 (23.1) | 58 (8.5) | <.01 |

| Any overall work impairment | 21/11/139 | 31 (45.6) | 27 (25.0) | 58 (8.6) | <.01 |

| Any activity impairment | 7/6/56 | 45 (54.9) | 32 (28.3) | 77 (10.1) | <.01 |

Data are presented as number (% of available data) of subjects or medians (interquartile ranges).

Comparisons between the 3 groups were all significant (P < .001).

Comparison between the WRA group vs the non-WRA group, as well as the WRA group vs the reference group were all significant (P < .01).

TABLE V.

Univariable analysis and multivariable model for physical components of general health—related QoL (SF-8 PC) in all subjects

| Characteristics | Univariable associations | Final multivariable model | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (IQR) | P value | Unstandardized β coefficient (95% CI) | P value | |

| Sex* | <.001 | |||

| Female | 52.9 (46.4–56.4) | −1.6 (−2.6 to −0.6) | .001 | |

| Male | 54.5 (49.4–57.1) | Reference | ||

| Age (y)* | <.001 | −0.1 (−0.1 to −0.05) | <.001 | |

| <35 | 55.4 (50.8–57.7) | |||

| 35–45 | 54.2 (48.8–56.7) | |||

| ≥45 | 52.9 (50.8–57.8) | |||

| Smoking habit* | .064 | |||

| Never smoked | 54.2 (48.5–56.7) | |||

| Ex-smoker | 52.7 (46.4–56.5) | |||

| Current smoker | 54.3 (48.7–56.9) | |||

| Body mass index (kg/m2)* | <.001 | |||

| <25 | 54.8 (49.9–57.3) | Reference | ||

| ≥25 | 52.9 (46.3–56.3) | −1.7 (−2.7 to −0.7) | .001 | |

| Education level* | .573 | |||

| >12 y | 54.2 (48.4–56.7) | |||

| ≤12 y | 54.1 (48.1–56.7) | |||

| Current job duration* | <.001 | |||

| <5 y | 54.9 (50.1–57.5) | |||

| ≥5 y | 53.6 (46.8–56.4) | |||

| Asthma preexisting to current job | ||||

| Yes | 49.8 (43.5–55.6) | .978 | ||

| No | 51.7 (44.4–54.2) | |||

| Asthma control | <.001 | |||

| ACT score > 19 | 51.7 (45.8–56.2) | |||

| ACT score ≤ 19 | 41.2 (37.0–48.4) | |||

| Asthma* | <.001 | |||

| Absent | 54.4 (49.9–56.7) | Reference | ||

| Non-WRA | 51.8 (46.4–56.2) | −2.3 (−3.7 to −0.9) | .002 | |

| WRA† | 46.4 (38.6–51.5) | −6.9 (−8.7 to −5.3) | <.001 | |

| Depression, physician-based | .001 | |||

| Absent | 54.3 (48.7–56.7) | |||

| Present | 51.3 (44.1–55.7) | |||

| Nonrespiratory, nondepression comorbidity | <.001 | |||

| Absent | 54.7 (49.9–57.2) | Reference | ||

| Present | 52.8 (44.6–56.2) | −2.3 (−3.4 to −1.3) | <.001 | |

IQR, Interquartile range.

Multivariable analysis was done on 822 subjects and incorporated well-known confounders such as age, sex, smoking habits, body mass index, academic level, and current job duration (marked with asterisks) and other covariates with a P value of <.1 in univariable analyses. Asthma control was not included because the information was available only among asthmatic subjects.

Well-known confounders included in the multivariable analysis.

WRA is defined as current asthma associated with ≥2 WRA symptoms.

Univariable and multivariable regression models with mental health impairment as the dependent variable are summarized in Table VI. Similarly, being a female, having non-WRA, having WRA, and having depression and other comorbidities were significantly and independently associated with lower MCS scores. Having WRA lowered the MCS scores by 4.6 points (95% CI, −6.5 to −2.7; P < .001), whereas having non-WRA lowered the MCS scores by 2.1 points (95% CI, −3.7 to −0.5; P = .011).

TABLE VI.

Univariable analysis and multivariable model for mental components of general health—related QoL (SF-8 MC) in all subjects

| Characteristics | Univariable associations | Final multivariable model | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (IQR) | P value | Unstandardized β coefficient (95% CI) | P value | |

| Sex* | <.001 | |||

| Female | 50.0 (43.5–56.0) | −2.4 (−3.5 to −1.3) | <.001 | |

| Male | 53.9 (49.3–57.4) | Reference | ||

| Age (y)* | .447 | |||

| <35 | 52.1 (46.8–57.3) | |||

| 35–45 | 52.1 (47.1–57.5) | |||

| ≥45 | 51.0 (43.0–57.5) | |||

| Smoking habit* | .248 | |||

| Never smoked | 52.1 (47.0–57.5) | |||

| Ex-smoker | 52.4 (46.1–57.5) | |||

| Current smoker | 51.3 (44.8–57.3) | |||

| Body mass index (kg/m2)* | .279 | |||

| <25 | 52.3 (46.9–57.5) | |||

| ≥25 | 51.3 (45.0–57.4) | |||

| Education level* | .458 | |||

| >12 y | 51.5 (46.7–57.3) | |||

| ≤12 y | 52.0 (46.3–57.5) | |||

| Current job duration* | .047 | |||

| <5 y | 52.3 (48.1–57.5) | |||

| ≥5 y | 51.4 (45.2–57.4) | |||

| Asthma preexisting to current job | ||||

| Yes | 49.4 (42.1–54.8) | .505 | ||

| No | 49.6 (39.0–54.6) | |||

| Asthma control | .016 | |||

| ACT score > 19 | 49.9 (42.9–55.0) | |||

| ACT score ≤ 19 | 46.1 (40.3–51.6) | |||

| Asthma* | <.001 | |||

| Absent | 52.4 (48.2–57.5) | Reference | ||

| Non-WRA | 50.7 (43.9–56.3) | −2.1 (−3.7 to −0.5) | .009 | |

| WRA† | 45.7 (36.6–52.4) | −4.6 (−6.5 to −2.7) | <.001 | |

| Depression, physician-based | <.001 | |||

| Absent | 52.3 (48.1–57.5) | Reference | ||

| Present | 43.7 (37.1–52.3) | −7.6 (−9.3 to −5.8) | <.001 | |

| Nonrespiratory, nondepression comorbidity | .006 | |||

| Absent | 52.5 (46.8–57.5) | Reference | ||

| Present | 50.8 (45.6–56.6) | −2.1 (−3.3 to −0.9) | <.001 | |

IQR, Interquartile range.

Multivariable analysis was done on 822 subjects and incorporated well-known confounders such as age, sex, smoking habits, body mass index, academic level, and current job duration (marked with asterisks) and other covariates with a P value of <.1 in univariable analyses. Asthma control was not included because the information was available only among asthmatic subjects.

Well-known confounders included in the multivariable analysis.

WRA is defined as current asthma associated with ≥2 WRA symptoms.

Work productivity impairment

Asthma-related work disability and health care utilization.

Respiratory-related work disability was reported by 10.4% of workers with WRA and none in the non-WRA group (P = .003) (Table II). Thirteen percent of the WRA group and 12% of the non-WRA group reported missed work days or had respiratory absences in the past 12 months (P = .320). However, workers with WRA had higher percentages of at least 1 visit to their general practitioner (67.2%) as well as income reduction because of respiratory symptoms (13.8%) than those with non-WRA (46.3%, P = .011 and 3.6%, P= .024, respectively).

General health—related work productivity.

Data in Table IV show that the WRA group had the highest proportion (17.9%) of workers with any work time missed because of general health (absenteeism) in the last 7 days compared with both the non-WRA group (4.5%) and the reference group (2.6%) (P = .001). Workers with WRA also had the highest proportions of any impairment at work (presenteeism), any overall work impairment, and any activity impairment compared with the non-WRA and reference groups (all P < .001). Table VII presents the univariable and multivariable associations between sociodemographic and clinical characteristics and any overall work impairment on the basis of the WPAI-GH. In the final multivariable regression model (Table VII), having WRA increased the risk of having any overall work impairment more than 4-fold (odds ratio, 4.5; 95% CI, 2.5–8.1; P < .001), whereas having non-WRA increased the risk by more than 2-fold (odds ratio, 2.0; 95% CI, 1.2–3.5; P = .008). An additional analysis among asthmatic workers shows that asthma control was not associated with work productivity (see Table E2 in this article’s Online Repository at www.jaci-inpractice.org).

TABLE VII.

Univariable analysis and multivariable model for any overall work impairment based on WPAI-GH

| Characteristics | Univariable associations | Final multivariable model | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any overall work impairment, n (%) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Sex* | .034 | |||

| Female | 86 (55.8) | 1.4 (0.9–2.1) | .093 | |

| Male | 68 (44.2) | Reference | ||

| Age (y)* | .747 | |||

| <35 | 46 (31.1) | |||

| 35–45 | 46 (31.1) | |||

| ≥45 | 56 (37.8) | |||

| Smoking habit* | .035 | |||

| Never smoked | 82 (53.6) | |||

| Ex-smoker | 38 (24.8) | |||

| Current smoker | 33 (21.6) | |||

| Body mass index (kg/m2)* | .035 | |||

| <25 | 65 (45.5) | Reference | ||

| ≥25 | 78 (54.5) | 1.5 (0.9–2.2) | .055 | |

| Education level* | .051 | |||

| >12 y | 72 (47.4) | Reference | ||

| ≤12 y | 80 (52.6) | 0.7 (0.5–1.0) | .070 | |

| Current job duration* | .986 | |||

| <5 y | 61 (43.0) | |||

| ≥5 y | 81 (57.0) | |||

| Asthma preexisting to current job | ||||

| Yes | 42 (87.5) | .229 | ||

| No | 6 (12.5) | |||

| Asthma control | .004 | |||

| ACT score > 19 | 17 (53.1) | |||

| ACT score ≤ 19 | 15 (46.9) | |||

| Asthma* | <.001 | |||

| Absent | 96 (62.3) | Reference | ||

| Non-WRA | 27 (17.5) | 2.0 (1.2–3.5) | .008 | |

| WRA† | 31 (20.1) | 4.5 (2.5–8.1) | <.001 | |

| Depression, physician-based | .037 | |||

| Absent | 131 (85.1) | Reference | ||

| Present | 23 (14.9) | 1.8 (0.9–3.3) | .085 | |

| Nonrespiratory, nondepression comorbidity | .003 | |||

| Absent | 77 (50.0) | Reference | ||

| Present | 77 (50.0) | 1.9 (1.2–2.9) | .004 | |

Multivariable analysis was done on 713 subjects and incorporated well-known confounders such as age, sex, smoking habits, body mass index, academic level, and current job duration (marked with asterisks) and other covariates with a P value of <.1 in univariable analyses. Asthma control was not included because the information was available only among asthmatic subjects.

Well-known confounders included in the multivariable analysis.

WRA is defined as current asthma associated with ≥2 WRA symptoms.

DISCUSSION

This study shows that workers with WRA had significantly lower asthma QoL in all domains compared with those with non-WRA. Workers with WRA and non-WRA had significantly lower physical and mental health status and overall work productivity compared with the reference group, with greater impairment in workers with WRA than in those with non-WRA. Consistent with published literature,4,7,10 workers with WRA had a higher percentage of doctor visits and income reduction because of respiratory symptoms than those with non-WRA.

These main findings were consistent with our evaluation of the impact of rhinitis that workers with WRR and non-WRR had significantly lower physical and mental health status and overall work productivity compared with workers without nasal symptoms, with greater impairment in workers with WRR than in those with non-WRR.14 Our present study suggests that WRR was associated with a reduced asthma-related QoL, independently from having WRA.

Other previous studies also suggest that workers with WRA, either OA or WEA, tend to have impaired QoL and/or work productivity. A cross-sectional study in Tunisia showed that most patients with OA had a poor QoL, but there was no control group.11 In another study of 43 German bakers with allergic OA, a third of the participants reported “moderate” problems in the “anxiety/depression” dimension. Although the overall QoL was high, asthma symptoms triggered by exposure to dust showed the greatest impairment.12 A large survey of workers with asthma related to workplace dampness and mold exposure was conducted in Finland. It used the SF-12 questionnaire and found that patients with WRA had significantly lower QoL in physical but not mental components compared with patients with asthma-like symptoms and those with upper respiratory tract symptoms.9 On the contrary, Moullec et al8 compared workers with WRA and nonasthmatic workers and did not find significant differences in SF-36 scores except for the emotional dimension. Nevertheless, they found that workers with OA were more likely to change jobs than those with WEA and nonasthmatic workers. They also found that the QoL of workers with WRA remained impaired long after the diagnosis, which indicated the sustained impairment even after being removed from the workplace exposure. Workers with WRA also had more clinical visits compared with nonasthmatic workers. Knoeller et al13 used the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System health-related QoL indicators to evaluate the ever-employed adults with current asthma in the United States. WRA was defined as adults with current asthma who reported that they were ever told by a doctor or other health professional that their asthma was related to any job they ever had,19 or their asthma was caused or made worse by exposure in the workplace. They showed that workers with WRA were significantly more prone to have poor self-rated health, impaired physical and mental health, as well as activity limitations than those with non-WRA.13

We would like to highlight our findings that female sex and depression were associated with both worse physical and mental domains of QoL and impaired work productivity, independent of the effect of WRA. These findings were consistent with our previous study of WRR, in which female sex and depression were associated with impaired QoL and overall work productivity, independent of the effect of WRR.14 A previous study among Canadian workers also found a high prevalence of mental health problems among those with WRA.8 Screening for mental health problems such as anxiety and depression should be considered in guidelines for occupational physicians treating patients with WRA to avoid poorer results of QoL in all domains.

Strength and limitations

To our knowledge, this study is one of the largest to evaluate the impact of WRA on health-related QoL and work productivity compared with non-WRA and nonasthmatic subjects in the general workforce population using validated instruments for assessing QoL and work productivity. The survey instruments used in the study, such as the mAQLQ, had been validated.27 SF-8 demonstrated a good reflection of physical, mental, and overall health28 and has been validated in numerous populations.29 Nevertheless, given the cross-sectional design of our study, one should interpret our findings with caution. Ideally, a longitudinal study (eg, a cohort of workers exposed to occupational sensitizers) could be more suitable to demonstrate the impact of the development of WRA on the decline in QoL. The WPAI-GH is a commonly used tool to evaluate work and activity impairment, but it evaluates impairment only in the past 7 days.24

There were 186 (17.6%) subjects with at least 1 missing sociodemographic and/or clinical characteristic, with most missing information being on body mass index and/or job duration. Therefore, the multivariable analyses were conducted with 80% to 90% of those who completed the QoL or work productivity questionnaires. Despite the high number of missing values, the proportions of missing characteristics were not significantly different across the WRA, non-WRA, and reference groups. Moreover, the distributions of the mAQLQ overall score, SF-8 PCS/MCS scores, and any work productivity impairment were comparable (ie, no statistically significant difference) between the group with and without missing values.

Because of the questionnaire design, we could not distinguish between the 2 major types of WRA cases (OA vs WEA) or the types of agents responsible for these cases. Therefore, this study was unable to investigate differences stratified by these characteristics. Information on whether asthma onset was preexisting to the current job was available in only 83% of subjects with current asthma. Sixteen of 73 (21.9%) subjects in the WRA group with asthmaonset information had asthma that existed before the current job. This number was too low to compare OA and WEA cases. In addition, periodic examination of workers by an occupational health service is obligatory in Belgium, but only for salaried workers. Therefore, some categories of self-employed workers with a high risk of WRA (ie, bakers, farmers, wood workers, and hairdressers) might have been underrepresented in our study population. Nevertheless, the prevalence of asthma in our population (9.6%) was similar to that reported in a previous survey of the Belgian population (7.2%)30 and in the European Union (8.2% in adults).31

CONCLUSIONS

Both WRA and non-WRA workers were associated with lower general healthe–related QoL as well as overall work productivity compared with the nonasthmatic workers, with an incrementally greater impairment in workers with WRA compared with those with non-WRA. WRR and depression appeared to be associated with reduced QoL, independent of the effect of WRA. These findings suggest that work-related airway disease should be comprehensively managed to reduce the worsening of QoL and the work productivity of those affected, thus contributing to reducing the global burden of asthma. Moreover, we suggest thorough mental health screenings for patients with WRA.

Supplementary Material

What is already known about this topic?

There is scarce and often discordant information on the impact of work-related asthma (WRA) on quality of life and work productivity compared with non-WRA.

What does this article add to our knowledge?

Asthmatic subjects have a lower general health-related quality of life and overall work productivity compared with nonasthmatic subjects, with greater impairment in subjects with WRA than in those with non-WRA.

How does this study impact current management guidelines?

A more holistic approach to identifying and managing work-related airway disease in clinical practice is needed to reduce the global burden of asthma.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by a grant from the Fonds Scientifique CESI. The funding source had no role in the analysis and interpretation of the data or in the preparation of the article. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Abbreviations used

- ACT

Asthma Control Test

- mAQLQ

Mini Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire

- MCS

mental component summary

- OA

occupational asthma

- PCS

physical component summary

- QoL

quality of life

- SF-8

8-item Medical Outcome Study Short Form

- WEA

work-exacerbated asthma

- WPAI-GH

Work Productivity and Activity Impairment—General Health

- WRA

work-related asthma

- WRR

work-related rhinitis

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare that they have no relevant conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2020;396:1204–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blanc PD, Annesi-Maesano I, Balmes JR, Cummings KJ, Fishwick D, Miedinger D, et al. The occupational burden of nonmalignant respiratory diseases. An official American Thoracic Society and European Respiratory Society statement. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2019;199:1312–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tarlo SM, Lemiere C. Occupational asthma. N Engl J Med 2014;370:640–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Henneberger PK, Redlich CA, Callahan DB, Harber P, Lemiere C, Martin J, et al. An official American Thoracic Society statement: work-exacerbated asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011;184:368–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dumas O, Varraso R, Boggs KM, Descatha A, Henneberger PK, Quinot C, et al. Association of hand and arm disinfection with asthma control in US nurses. Occup Environ Med 2018;75:378–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Le Moual N, Carsin AE, Siroux V, Radon K, Norback D, Toren K, et al. Occupational exposures and uncontrolled adult-onset asthma in the European Community Respiratory Health Survey II. Eur Respir J 2014;43:374–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vandenplas O Socioeconomic impact of work-related asthma. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 2008;8:395–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moullec G, Lavoie KL, Malo JL, Gautrin D, L’Archeveque J, Labrecque M. Long-term socioprofessional and psychological status in workers investigated for occupational asthma in Quebec. J Occup Environ Med 2013;55:1052–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karvala K, Uitti J, Luukkonen R, Nordman H. Quality of life of patients with asthma related to damp and moldy work environments. Scand J Work Environ Health 2013;39:96–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lemiere C, Forget A, Dufour MH, Boulet LP, Blais L. Characteristics and medical resource use of asthmatic subjects with and without work-related asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2007;120:1354–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Henchi MA, Omrane A, Amri C, Bouzgarrou L, Rassas I, Mahfoudhi A, et al. The quality of life and professional future among Tunisian workers suffering from occupational asthma. Recent Pat Inflamm Allergy Drug Discov 2017;11:64–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bittner C, Garrido MV, Harth V, Preisser AM. IgE reactivity, work related allergic symptoms, asthma severity, and quality of life in bakers with occupational asthma. Adv Exp Med Biol 2016;921:51–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Knoeller GE, Mazurek JM, Moorman JE. Health-related quality of life among adults with work-related asthma in the United States. Qual Life Res 2013;22:771–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vandenplas O, Suarthana E, Rifflart C, Lemiere C, Le Moual N, Bousquet J. The impact of work-related rhinitis on quality of life and work productivity: a general workforce-based survey. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2020;8:1583–1591.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reilly Associates. Health outcomes research. Accessed January 7, 2008. http://www.reillyassociates.net/

- 16.Nathan RA, Sorkness CA, Kosinski M, Schatz M, Li JT, Marcus P, et al. Development of the asthma control test: a survey for assessing asthma control. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2004;113:59–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schatz M, Sorkness CA, Li JT, Marcus P, Murray JJ, Nathan RA, et al. Asthma Control Test: reliability, validity, and responsiveness in patients not previously followed by asthma specialists. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2006;117:549–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Juniper EF, Guyatt GH, Cox FM, Ferrie PJ, King DR. Development and validation of the Mini Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire. Eur Respir J 1999;14:32–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoy R, Burdon J, Chen L, Miles S, Perret JL, Prasad S, et al. Work-related asthma: a position paper from the Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand and the National Asthma Council Australia. Respirology 2020;25:1183–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burney PG, Laitinen LA, Perdrizet S, Huckauf H, Tattersfield AE, Chinn S, et al. Validity and repeatability of the IUATLD (1984) Bronchial Symptoms Questionnaire: an international comparison. Eur Respir J 1989;2:940–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vandenplas O, Delwiche JP, Evrard G, Aimont P, van der Brempt X, Jamart J, et al. Prevalence of occupational asthma due to latex among hospital personnel. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1995;151:54–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Asher MI, Keil U, Anderson HR, Beasley R, Crane J, Martinez F, et al. International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC): rationale and methods. Eur Respir J 1995;8:483–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shaaban R, Zureik M, Soussan D, Neukirch C, Heinrich J, Sunyer J, et al. Rhinitis and onset of asthma: a longitudinal population-based study. Lancet 2008;372:1049–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reilly MC, Tanner A, Meltzer EO. Work, classroom and activity impairment instruments. Validation studies in allergic rhinitis. Clin Drug Invest 1996;11:278–88. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim JL, Blanc PD, Villani S, Olivieri M, Urrutia I, van Sprundel M, et al. Predictors of respiratory sickness absence: an international population-based study. Am J Ind Med 2013;56:541–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang A-G, Buchner A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods 2007;39:175–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adams RJ, Ruffin RE, Smith BJ. Validity of a modified version of the Marks Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire. J Asthma 2000;37:131–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wirtz MA, Schulz A, Brahler E. Confirmatory and bi-factor analysis of the Short Form Health Survey 8 (SF-8) scale structure in a German general population sample. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2021;19:73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lang L, Zhang L, Zhang P, Li Q, Bian J, Guo Y. Evaluating the reliability and validity of SF-8 with a large representative sample of urban Chinese. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2018;16:55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wijnant SRA, Lahousse L, De Buyzere ML, Brusselle GG, Rietzschel ER. Prevalence of asthma and COPD and blood eosinophil count in a middle-aged Belgian population. J Clin Med 2019;8:1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Selroos O, Kupczyk M, Kuna P, Lacwik P, Bousquet J, Brennan D, et al. National and regional asthma programmes in Europe. Eur Respir Rev 2015;24: 474–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.