Abstract

Introduction

Traditional, complementary and alternative medicine (TCAM) are popular healthcare choices among consumers globally. The latest national data on the use of TCAM practitioners in New Zealand (NZ) were collected over a decade ago. Robust data on the use of natural health products (NHPs) and TCAM practices alongside conventional medicines are not yet available in NZ.

Objectives

This study aimed to develop and test a bespoke questionnaire (All-MedsNZ) that included comprehensive data collection elements exploring NHPs’ and conventional medicines’ use.

Methods

This was a questionnaire design study involving expert panel feedback, and engagement with TCAM users, in the development process. This work comprised questionnaire development (stage 1) followed by a questionnaire-testing study (stage 2). The questionnaire was developed on the basis of literature review findings and the research team’s expertise. The questionnaire content was then validated by an expert panel comprising practitioners in TCAM and conventional medicine. Then, a two-phase study was utilised to test the questionnaire. Phase 1 involved participants (NHP users) completing the web-based questionnaire and providing feedback by answering probing questions added throughout the questionnaire to evaluate users’ comprehension of the questions and to identify issues with the questionnaire. In phase 2, selected participants were interviewed online to gain in-depth insights into issues identified in phase one. Based on these findings, the questionnaire was revised.

Results

The expert panel (n = 9) confirmed the questionnaire had high face and content validity; most original questions were retained. In the questionnaire-testing study, 95 and 27 participants completed the phase 1 and 2 studies, respectively. Most questions achieved a high response rate of ≥ 90%, and participants had no major issues understanding and answering the questionnaire. Problematic questions were those relating to providing product barcodes and photographs, and information on product costs. Most of the NHPs data entered by participants included the brand/generic name, manufacturer/company name, main ingredient(s) and dose form. Generally, these NHP-related data were of acceptable quality. However, information on the main ingredient(s) of products entered by participants was less satisfactory: approximately one-third of the 143 NHPs recorded in the study had the main ingredient(s) missing or incorrectly stated. Interviews with participants reiterated the issues identified in the phase 1 study. The low response rates for some of the questions were partly due to participants’ unpreparedness (i.e. not having NHPs/medicines on hand) to complete the questionnaire. In addition, a lack of clarity for the term ‘natural health practitioner’ led to confusion among some participants.

Conclusion

Overall, no major design-, method- or questionnaire-related issues were identified in this development and testing work. The questionnaire demonstrated adequate face and content validity and acceptability among participants. The data collected were reasonably complete and of sufficient quality for analysis. Future studies should pilot the revised All-MedsNZ questionnaire with a larger, nationally representative sample to ascertain its feasibility and utility.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40801-023-00389-9.

Key Points

| A new bespoke questionnaire (All-MedsNZ) comprising comprehensive data collection elements on natural health products’ (NHPs) and conventional medicines’ use was developed and pretested. |

| Overall, the questionnaire had good acceptability among a sample of NHP users, and the data collected were of adequate quality to undertake preliminary analyses of prevalence and patterns of NHPs’ use. |

| Following minor revisions to the questionnaire, future studies should pilot the All-MedsNZ to confirm its feasibility and utility. |

Introduction

Traditional, complementary and alternative medicine (TCAM), including TCAM products [also described as traditional medicines (TMs)/natural health products (NHPs)/complementary medicines (CMs)], and TCAM practices/therapies (e.g. acupuncture, chiropractic or osteopathic manipulation, reiki) are popular healthcare choices among consumers globally [1, 2]. Many Western countries, including the USA [2, 3], United Kingdom [4] and Australia [5], have nationally representative data on the prevalence of use of TCAM, but only limited data are available for New Zealand (NZ). Several NZ health surveys report data on prevalence of use of TCAM; however, these studies explored selected TCAM approaches and were conducted over a decade ago [6, 7]. These limited data indicate that the use of TCAM in NZ is likely to be substantial, but robust, recent data are not yet available.

At present, TMs/NHPs/CMs [collectively ‘natural health products’ (NHPs)] remain without specific regulations in NZ. Consumers can access NHPs through numerous routes (e.g. pharmacies, grocery/health-food and online stores, natural-health/traditional-medicine practitioners, and others) [8]. Given the easy access to NHPs and their likely substantial (yet largely unrecorded) use, the lack of current information on the prevalence, trends and patterns of use of NHPs, and users’ access to and expenditure on these products, is of concern. Further, if comprehensive data on NHPs’ use can be collected, coded and linked with existing national health datasets, such as medicines dispensing and hospital admissions data, this could (ultimately) provide opportunities to explore associations between NHPs’ use (exposure) and health outcomes. Evidence from data-linked population-based studies (mainly involving conventional medicines) has been shown to influence health policies and enhance the quality of clinical care and patient outcomes [9]. If robust TCAMs exposure data were available in large electronic health datasets through routine collection, it would be possible to explore whether similar impacts can be achieved with respect to TCAMs exposure and health outcomes.

Existing questionnaires that collect data on the use of (exposure to) NHPs [10, 11] have limitations. For example, these tools typically capture use of NHPs by product categories (e.g. ‘herbal supplements’) rather than by seeking detailed information on individual products/preparations used (e.g. HealthBest Ashwagandha dried root ethanolic extract). Also, standardised measurement of TCAM use and definitions for individual terms (e.g. NHPs, TCAM practitioners and practices/therapies) are challenging to apply across countries/regions and may not be universally relevant [12]. Boundaries between TCAM practices/therapies/products and conventional medicines/practices are not static or defined, and differ across countries/regions. Hence, each country needs a measurement tool tailored to its specific context.

Many countries design and utilise national surveys to collect data on the use of NHPs [12], but these are unlikely to translate well across settings, including in NZ. For example, in the USA, an adult and child complementary medicines’ use questionnaire was developed and field-tested in a National Health Interview Survey (NHIS). Throughout different waves of the NHIS, the questionnaire’s content was modified on the basis of an iterative questionnaire development process that included literature reviews, expert panel feedback and cognitive interviewing [13]. Other countries, such as Switzerland, Korea and Taiwan, have also administered their national surveys to explore NHP usage trends [12]. Questionnaires are typically customised to suit the local context. For example, differences in terminology between countries are considered, such as NHPs being known as 'dietary supplements' in the USA [14] and as 'complementary medicines' in Australia [15]. Moreover, regulatory disparities have an impact on questionnaire design, with product registration numbers being incorporated as questionnaire items where regulations exist for NHPs. NZ has a unique indigenous traditional medicine system—rongoā Māori [16]—that is not explored elsewhere. Also, NZ is a bi-cultural country founded on Te Tiriti o Waitangi (the treaty partnership between Māori and non-Māori), but exists as a multicultural society with special recognition of Māori as indigenous people. As such, people from different ethnic and cultural groups living in NZ may use healthcare approaches from traditional medicine systems different to those used in other countries. For these reasons, a bespoke questionnaire is required to collect detailed information on NHPs’ use designed to suit the NZ context and setting. As a result, the questionnaire encompassed response choices such as ‘rongoā Māori’, ‘traditional Māori healer’ and ‘Pacific traditional healer’, in line with the NZ Health Survey [6]. Furthermore, an ‘other’ option was included to account for TCAM products and practices not explicitly listed in the questionnaire.

An international questionnaire - the I-CAM-Q - was developed and published by researchers in 2009 to standardise measurement of broader TCAM use and to allow comparisons across populations [11]. The tool has been translated and adapted across multiple languages and cultures [17–21] with mixed success. The I-CAM-Q was found to have low face validity and acceptability across five European Union (EU) countries: many terms, including types of practitioners, practices/therapies and product categories, were unknown to, or misunderstood by, participants as definitions were not provided in the tool [18]. Several countries adapted the I-CAM-Q by modifying the list of practitioners, practices/therapies and product categories [19, 22, 23], and question response options (e.g. perceived ‘helpfulness’ was changed to ‘benefit’ [24]) to suit their local context; in some countries, changes to the questionnaire were so substantial [17, 25] that the original intention for a standardised tool may have been compromised. In addition, the I-CAM-Q only allowed participants to list up to three TCAM products in four pre-specified categories (‘herbs/herbal medicine’, ‘vitamins/minerals’, ‘homeopathic remedies’ and ‘other supplements’); this approach may miscategorise and/or underestimate the prevalence of use of NHPs, including types of traditional medicines.

The I-CAM-Q also captures the use of TCAMs in isolation: use of conventional medicines is not collected. To understand patterns of use of TCAM, including whether TCAMs are used in addition to, or instead of, conventional medicines, it is essential that both TCAM and conventional medicine use are recorded collectively. Drug interactions between conventional medicines and TCAMs can occur, and some drug–herb interactions have been associated with adverse reactions [26, 27]. Therefore, to answer questions on the prevalence of the use of NHPs, and to fully understand the context of use of NHPs, it is necessary to conduct a nationally representative study and also to explore respondents’ use of TCAM practices/therapies (e.g. acupuncture, chiropractic, etc.) and conventional medicines.

Pretesting is necessary before fielding a questionnaire to assess a tool’s validity and reliability. Cognitive interviewing is a method used to refine questionnaire items and assess validity by exploring item clarity, relevance and participants’ response processes. Typically, cognitive interviews are conducted face-to-face, but this approach has limitations due to small sample sizes, possibly leading to missing or overestimating questionnaire issues or response patterns [28].

Applying cognitive interviewing techniques using web-based questionnaires enables the recruitment of larger and more diverse samples with comprehensive geographic coverage [28, 29]. However, employing web-based administration may result in lower quality data, especially for complex tasks that require participants to explain their responses [29]. To compensate for this, web-based administration can be used to identify obvious problems with questionnaires and then supplemented with in-depth, exploratory, cognitive interviews to provide insight into the more complex aspects of the question evaluation [29].

Thus, this project aimed to develop and test a bespoke questionnaire (All-MedsNZ) comprising comprehensive data collection elements on NHPs’, TCAM practices/therapies’ and conventional medicines’ use. Specifically, the project sought to:

Assess the completeness and quality of data provided by NHP users using the bespoke questionnaire

Explore the understanding, views and perceptions of users of NHPs in New Zealand on a bespoke questionnaire designed to collect data on the use of NHPs, TCAM practices/therapies and conventional medicines

Explore views of NHP users on the design and methods (e.g. web-based mode) of the bespoke questionnaire.

Methods

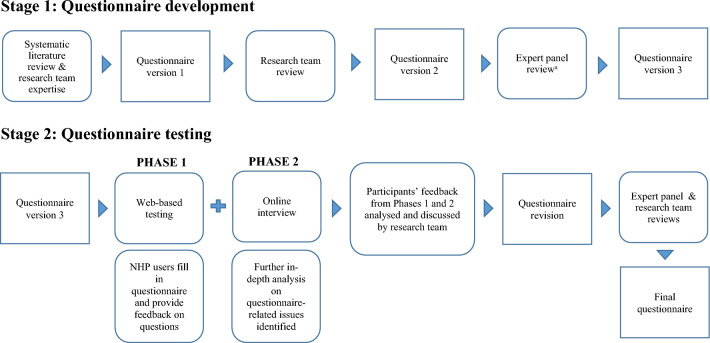

This study utilised two questionnaire pre-testing methods to establish face and content validity: researcher and expert reviews, and cognitive interviewing [30]. Broadly, this project comprised two stages: stage 1 questionnaire development and stage 2 questionnaire testing (Fig. 1). In stage 2, the phase 1 web-based study aimed to identify any questionnaire-related issues across a range of participant demographics. The phase 2 follow-up online interviews aimed to gain further insights into any issues identified in phase 1.

Fig. 1.

Questionnaire development and testing process. a The expert panel comprised the following practitioners in TCAM and/or conventional medicine: traditional Māori healer, traditional Chinese medicine practitioner, Pacific medicine researcher, homeopath, naturopath and herbalist, general practitioner with interest and practice in integrative medicine, practising pharmacist, Pacific pharmacist, Māori pharmacist

Stage 1: Questionnaire development

Guided by a systematic review of the literature [12] and research team expertise, E.L. drafted and developed a self-administered web-based questionnaire (version 1). The research team conducted a systematic review [12] that focussed on the methods and tools employed in national studies investigating the prevalence of TCAM use in the general population. Based on the findings from this systematic review and the tools used in the NZ Health Survey [6] and NZ Nutrition Survey [7], the All-MedsNZ questionnaire was developed.

Research team and expert panel reviews

Version 1 of the questionnaire underwent two rounds of reviews. First, the research team members (authors), comprising three academic pharmacists, reviewed the questionnaire to ensure it was designed to collect the information needed to meet the research objectives. In addition, the research team checked the questionnaire design and questions, focussing on the terms and wording, structure, response alternatives, order of questions, navigational rules, layout and on identifying typographical errors. The revised questionnaire (version 2) was then reviewed by an expert panel comprising one of each of the following practitioners in TCAM and/or conventional medicine: traditional Māori healer; traditional Chinese medicine practitioner; Pacific medicine researcher; homeopath; naturopath and herbalist; general practitioner with interest and practice in integrative medicine; community/hospital pharmacist; Pacific pharmacist; Māori pharmacist.

The expert panel focussed on the terms and wording of questions and response categories to ensure clarity and applicability to capture participants’ use of NHPs, TCAM therapies and conventional medicines. Based on the feedback from the expert panel, the questionnaire was revised (version 3) and then tested.

Questionnaire content

The questionnaire (version 3) comprised four sections that collected information about participants’:

Use of, access to and expenditure on NHPs (42 questions)

Visits to and expenditure on natural-health and traditional-medicine practitioners (11 questions)

Use of prescription and non-prescription (over-the-counter) medicines, expenditure on non-prescription medicines (10 questions)

Demographics (8 questions).

On the instruction page of the questionnaire, participants were informed of the questionnaire’s structure, and that questions were not mandatory to answer. Also, participants were advised to have on hand all the NHPs and conventional medicines they currently take/use to facilitate capture of information and uploading of photograph(s) of each NHP.

Operational definitions

At the beginning of the questionnaire, an operational definition for NHPs, including a list of examples, was displayed to participants (Online Resource 1). The operational definition was developed with reference to definitions/descriptions from the World Health Organization (WHO) [31], Cochrane Collaboration [32] and the US National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH). Throughout the questionnaire, the term ‘current use’ of NHPs/medicines was defined as ‘products/preparations/medicines that you are taking daily, or at regular intervals over time (e.g. you take the product once a week), as well as products that you only take when needed (e.g. products for seasonal allergies)’.

In section 3 of the questionnaire participants were asked about conventional medicines they take/use that are prescribed by a health practitioner; health practitioner was described as ‘an authorised prescriber (e.g. general practitioner/family doctor, specialist medical doctor, or other medical/health professional who is legally able to prescribe medicines)’. In the same section, ‘non-prescription medicines’ were defined as ‘also known as “over-the-counter” (OTC) medicines, are medicines that can be obtained from pharmacies and retail outlets, such as supermarkets, without a prescription’.

Section 1: Use of, access to and expenditure on NHPs

Participants were asked if they have ever used any NHPs and, if so, to indicate how many different NHPs they currently take/use and had taken/used in the last 12 months. Then, participants were asked if they are currently taking any NHPs that were ‘obtained from a natural health or traditional medicine practitioner/healer’ and any NHPs ‘not obtained from a natural health or traditional medicine practitioner/healer’ and to list the names of the products/preparations, respectively.

For each product ‘obtained from a natural health or traditional medicine practitioner/healer’, participants were asked to indicate the term(s) they would use to describe the type of product, dose form, route of administration, type of TCAM practitioner who recommended the product, cost of the product (or consultation, if the cost of the product itself is not known) the last time they bought the product/saw the practitioner, and how they paid the cost; participants were asked to upload a photograph of the front label of the product (or contents if there is no label) and enter the product’s barcode number (if available).

For each product that was ‘not obtained from a natural health or traditional medicine practitioner/healer practitioner’, participants were asked to indicate the term(s) they would use to describe the product, state the manufacturer/company name, the main ingredient(s) in the product, dosage form, route of administration, where they obtained the product, type of practitioner (TCAM and/or conventional medicine) who recommended the product, cost of the product the last time it was purchased, and how they paid the cost; participants were asked to provide the product’s barcode number (if available) and upload photographs of the product’s front label and ingredient list.

Then, participants were asked if they are currently taking any ‘other’ products/preparations for their health that they had not listed previously and to list the names of these products/preparations; kale powder, pea protein powder and medicinal cannabis were provided as examples. For each ‘other’ product/preparation listed, participants were asked to answer the same set of questions for products ‘not obtained through a practitioner’. In addition, participants were asked why they did not (at least initially) consider this product/preparation to be an NHP.

Section 2: Visits to and expenditure on natural health and traditional medicine practitioners

Participants answered questions on the type of TCAM practitioners they had ever met/consulted/had an appointment with, those they had met/consulted/had an appointment with in the last 12 months, and those they are currently meeting/consulting. For each TCAM practitioner that participants had met/consulted/had an appointment with in the last 12 months, participants were asked to indicate the number of times they met/consulted/had an appointment with the specified practitioner in the previous 12 months, the types of treatments/therapies they received, specify if the practitioner is also a conventional medicine practitioner (and, if so, the type of conventional medicine practitioner), the cost of consultation and treatment at their last visit, and how they paid the cost.

Section 3: Use of prescription and non-prescription (over-the-counter) medicines, expenditure on non-prescription medicines

In this section, participants were asked if they are currently using any prescribed or non-prescribed/‘over-the-counter’ conventional medicines and, if so, to list the names of these medicines, respectively. For each prescribed conventional medicine, participants were asked to state the proprietary (‘brand’) and/or manufacturer name of the medicine and the dose form. For non-prescribed conventional medicines, participants were asked to indicate the brand and/or manufacturer name, dose form, cost of the medicine the last time they bought it, and how they paid the cost.

Section 4: Demographics

Participants were asked questions on their age, sex, ethnicity, location (region of New Zealand and urban/rural area), birth country, father’s birth country and mother’s birth country.

Stage 2: Questionnaire testing

Questionnaire testing involved two phases:

Phase 1: Self-administered web-based questionnaire

Phase 2: Follow-up online/telephone interviews.

Based on cognitive interviewing techniques, probes (follow-up questions) were added to the questionnaire (after each question or set of questions) to understand participants’ comprehension of the question(s), recall process of relevant information to answer a question, interpretation of and response to the questions in the questionnaire (Online Resource 2). Participants were asked to rate the clarity of questions on a three-point scale (clear, a bit unclear, very unclear). For questions considered to be ‘a bit unclear’ or ‘very unclear’, participants were asked to describe the difficulties in responding to the particular question or set of questions. Besides clarity, probing questions on the difficulty in answering questions, remembering the costs of the product(s)/preparation(s)/medicine(s)/consultation(s) and types of TCAM practitioners participants have consulted were included (Online Resource 2). These probing questions were displayed only when relevant; for instance, the probing question on difficulties in answering questions about visits to TCAM practitioners was displayed only when participants indicated that they have met/consulted/had an appointment with such a practitioner.

The main focus of the questionnaire was to collect data related to NHPs; because these products are not authorised/specifically regulated in NZ, and because consumers could be taking products purchased overseas, there are inherent difficulties in establishing precisely which products are being described. For these reasons, participants were asked to capture and upload photographs of the product(s)/preparation(s) that they were currently taking. These photographs were used to check the accuracy of the information (e.g. manufacturer/company name, the main ingredient(s), dose form of products/preparations) participants entered/indicated in the questionnaire.

At the end of the questionnaire, other questions sought participants’ feedback on the survey process. Participants rated the survey length, number of questions, the complexity of questions and relative intrusiveness of questions on a scale (from 1—absolutely not acceptable—to 5—highly acceptable). Participants were also asked if they would take part in this survey again and, if not, why. A few open-ended questions were included for participants to comment on taking part in the survey and their thoughts about the questionnaire. Finally, participants were asked if they would prefer to complete the questionnaire in a different language and method (e.g. paper-based/interview instead of web-based).

Participant recruitment and study procedure

Ultimately, the purpose of the All-MedsNZ is to gather data on the prevalence and patterns of TCAM use, including in the context of conventional medicines’ use, in the general population. However, the primary focus of this study was on testing the questionnaire, particularly the items related to NHPs’ use at the granular (i.e. product) level, as they are novel elements. Consequently, the study specifically recruited NHP users to participate in testing the questionnaire.

Participants were self-reported current users of NHPs, aged 18 years and older, living in New Zealand, able to provide consent and complete a questionnaire in English. In addition, participants who volunteered for the phase 2 study were required to have access to the internet/telephone and to be able to be interviewed in English. Data were collected from 1 April 2021 to 9 June 2021.

Phase 1: Web-based questionnaire

The phase 1 study aimed to recruit approximately 100 participants. In particular, we aimed to conduct interviews with approximately 30 participants. Anticipating a 30% agreement to participate in the interview (phase 2), we estimated that around 100 individuals would be needed to complete the web-based survey (phase 1) to have around 30 individuals consent to participate in an interview. The study was advertised on the 1 April 2021 through the University of Auckland’s School of Pharmacy and Faculty of Medical and Health Sciences (FMHS) research study recruitment webpages, the FMHS ‘junk mail’ list, which includes academic and general staff and postgraduate students, the study expert panel network, and approximately 1 month of paid Facebook advertising in May 2021.

Potential participants clicking on the web-based questionnaire link in the email invitations and study advertisement were directed to a webpage with a downloadable Participant Information Sheet, and then asked to complete a consent form. The consent form sought participants’ contact details (name, email address and telephone number) if they also volunteered for the phase 2 interview study. After accepting the terms in the consent form, participants were directed to the questionnaire. For completing the questionnaire, participants were offered a NZ$20 shopping voucher that would be posted to them after the end of the study. To receive this, participants were asked to provide a name and address in a separate voucher survey form.

Participants could request a paper-based copy of the questionnaire from the research team. For participants who requested a paper-based copy, a study pack containing the participant information sheet, consent form, study questionnaire, voucher survey form and three pre-paid addressed envelopes for returning the questionnaire, signed consent form and completed voucher survey form were mailed to these participants.

Phase 2: Online interview

A list of participants interested in being interviewed was obtained from responses on the consent forms. The study aimed to contact up to 30 people via telephone or email from this list. During the phase 1 recruitment period, at the end of each week, the demographics of participants who had consented to a phase 2 interview were tracked. Interview participants were selected across several demographic variables: age groups (18–25 years, 26–64 years, 65+ years), sex (male, female), ethnicity (NZ European, Māori, Pacific, Chinese, Indian, Other) and location (urban/rural), and users of various types of NHPs where possible.

E.L. contacted selected participants to arrange a mutually acceptable date and time for an interview. Interviews took place online through Zoom, a video communication platform, and were audio recorded. Before the interview, participants were emailed a copy of their responses to the web-based questionnaire. Those responses, with an interview schedule, were used to guide the interview discussion. Interviewed participants were offered a NZ$50 store voucher.

E.L. transcribed the interviews; J.B. checked 10% of the transcripts for accuracy. On the consent form, participants indicated their choice to review their interview transcripts. Where participants accepted this offer, they were emailed a password-protected copy of their transcript and invited to make/highlight their changes and return the transcript to the study team within 2 weeks of receipt. If transcripts were not returned, it was assumed that the participant did not wish to make changes.

Data analysis

Data from the web-based questionnaire were exported from Qualtrics to Microsoft Excel in Office 365 v16.75.2 (Seattle, USA) for conducting descriptive analysis. Focussing on the NHPs-related questions, question response rates were reviewed to indicate those that were unanswered by a proportion of participants. Then, the completeness and quality of information provided by participants were assessed by analysing a subset of data (data on NHPs ‘not obtained from a natural health or traditional medicine practitioner/healer practitioner’).

To assess completeness of information provided by participants, the types of responses given (whether they were what the question intended to collect) were assessed. For each NHP recorded in the data subset, participants’ answers to questions on product name, manufacturer/company name, the main ingredient(s), dosage form and barcode number were checked for correctness of the type of information entered.

To assess data quality, the product information entered was checked against the product photographs uploaded by participants. Each product was scored from 0 to 4, where 1 mark was given for each correctly entered product brand/generic name (e.g. multivitamin and mineral boost), manufacturer name (e.g. HealthyWay), the main ingredient(s) (e.g. multivitamin and multimineral), and dose form (e.g. capsules). For the main ingredient(s) criteria, the research team developed and applied the following rules:

All main ingredient(s) or categories of ingredient(s) must be stated; for example, ‘probiotics’ (category) and ‘Lactobacillus acidophilus M23’ (individual ingredient) are accepted as correct

No marks were given if one or more wrong ingredient(s) was entered

For multivitamin products, ‘multivitamin(s)’ was accepted as correct.

Barcodes were searched in two databases [33, 34] to verify if the barcode matched the product name.

Participants answered a question on the ‘terms’ they would use to describe each product (Box 1). For products where only ‘vitamin(s) and/or mineral(s)’ was selected, the ingredients in the products were checked using photographs uploaded by participants to determine whether or not any non-vitamin and/or non-mineral ingredients were listed on the label.

The chi-squared test of independence was used to determine whether significant differences exist between correctly stated main ingredient(s) and product type (single or multi-ingredient). Fisher’s exact test was used to determine if there were statistically significant differences between ‘products correctly described as a vitamin(s) and/or mineral(s) only’ and type of product (single or multi-ingredient). Inferential statistics were conducted using R 4.0.3, and the significance level was set at p < 0.05.

Box 1.

Question about terms used to describe types of natural health products/preparations

|

Which term(s) would you use to describe this product/preparation? Select all that apply |

|

□ Dietary supplement(s) or nutraceutical(s) □ Herbal medicine(s)/ herbal remedy/ies □ Homeopathic remedy/ies or biochemic tissue salt(s) □ Flower remedy/ies or essences □ Probiotic(s) □ Traditional Māori medicine(s) □ Traditional Pacific medicine(s) □ Traditional Chinese medicine(s) □ Traditional Ayurvedic medicine(s) □ Vitamin(s) and/or mineral(s) □ Sports supplement(s) □ Essential oil(s) □ Specially compounded formulation(s) □ Other; please state: __________ |

Responses to the probing (follow-up) questions were analysed to identify issues with comprehension, recall and judgement. In addition, participants’ views regarding the study methods (preference for language, questionnaire delivery method) were summarised. Open-ended questions were collated and selected participants’ responses were reported verbatim.

As the intent of the interviews was to elicit information on the relevance and clarity of the questionnaire items (questions), the individual item (as opposed to the individual participant) was regarded as the unit of analysis.

Findings from phases 1 and 2 were collated and used to guide the research team’s decisions about keeping, deleting, or modifying the questions in the questionnaire. The proposed changes to the questionnaire were shared with the expert panel for feedback.

Ethics approval

The questionnaire testing study was approved by the University of Auckland Human Participants Ethics Committee on 08/03/2021 for three years, with reference number UAHPEC2550.

Results

Expert panel review

Feedback was obtained from all members of the expert panel. Overall, the questionnaire had high content validity and most of the original questions were retained. Some parts of the questionnaire were modified on the basis of suggestions from the expert panel. This included modifying the definition of several terms; for instance, the term ‘traditional Māori medicines’ was revised from ‘native plant-based preparations (rongoā rakau)’ to ‘preparations usually made from certain plants, minerals, animal products and/or other substances’. Under the NHP definition, product categories were added (e.g. specially compounded formulations) and revised (e.g. separating definitions for homeopathic and flower remedies), and examples were added for the different product categories to help improve participants’ understanding of the terminologies used. Where participants were asked to indicate the number of different NHPs they take, photographs were included to help participants determine what is considered to be one product (e.g. a preparation containing a mixture of crude herbs is one product).

Initially, participants were asked to list the names of all products/preparations they currently take as a single question; subsequently, this question was split to ask participants to list the names of products they obtained from natural health and/or traditional medicine practitioners and those obtained elsewhere. This change was suggested as some of the subsequent questions [e.g. manufacturer name and main ingredient(s)] may not be relevant for products/preparations obtained from natural-health and/or traditional medicine practitioners.

For visits to TCAM practitioners, a question on the types of treatment/therapies received by participants was added, because multiple treatments/therapies may be provided by TCAM practitioners (e.g. naturopaths may provide lifestyle/dietary advice and/or prescribe herbal medicines and/or homeopathic remedies).

Other minor changes were incorporated into the questionnaire, such as rewording some questions to improve clarity. For example, ‘Have you ever consulted any of the following practitioners for your own health?’ was revised to ‘Have you ever met/consulted/had an appointment with any of the following practitioners for your own health?’. For several close-ended questions, additional response choices were included; for instance, ‘Work and Income New Zealand (WINZ)’ and ‘koha’ (a New Zealand Māori term for gift, present, offering, donation, contribution—especially one maintaining social relationships—and has connotations of reciprocity) were added as choices for the question ‘How did you pay the cost?’.

Several questions were removed from the questionnaire. For example, questions regarding health reason(s) for taking individual NHPs and conventional medicines and the dose, frequency and duration of use for each NHP and conventional medicine named were removed. These questions are relevant and provide useful information about exposures to NHPs/conventional medicines but increased the length of the questionnaire and respondent burden. The removal of these questions did not affect the primary purpose of the questionnaire, which is to collect comprehensive data on the prevalence of use of TCAM in New Zealand.

Modifications to study methods comprised inclusion of a paper-based option for completing the questionnaire to facilitate response and minimise under coverage, particularly among the older, rural population with limited internet access and digital literacy. Participant remuneration was revised from offering a prize draw to offering a NZ$20 shopping voucher for each participant in the phase 1 study as this was deemed more appropriate considering the length of the questionnaire and to encourage response.

Questionnaire testing

In total, 95 and 27 participants completed the phase 1 and phase 2 studies, respectively. All participants completed the web-based version of the questionnaire. The median time taken to complete the questionnaire was 25 minutes [interquartile range (IQR) 16–39 min]. Interviews ranged from 20 to 48 min in duration. Participants were mostly 20–39 years old, female, NZ European and living in Auckland (Table 1).

Table 1.

Participants’ characteristics for the phase 1 (n = 95) and phase 2 (n = 27) studies

| Phase 1 study (N = 95), n |

Phase 2 study (N = 27), n | |

|---|---|---|

| Age group | ||

| 16–19 years | 8 | 1 |

| 20–39 years | 49 | 14 |

| 40–59 years | 20 | 4 |

| 60–69 years | 15 | 7 |

| 70+ years | 3 | 1 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 20 | 2 |

| Female | 73 | 24 |

| Not stated | 2 | 1 |

| Ethnicity (prioritised)a | ||

| New Zealand European | 51 | 14 |

| Māori | 3 | 3 |

| Samoan | 0 | 0 |

| Cook Islands Māori | 1 | 0 |

| Tongan | 0 | 0 |

| Niuean | 0 | 0 |

| Chinese | 12 | 3 |

| Indian | 7 | 2 |

| Other | 20 | 5 |

| Not stated | 1 | 0 |

| Location | ||

| Northland | 2 | 1 |

| Auckland | 50 | 14 |

| Waikato | 4 | 1 |

| Bay of Plenty | 1 | 1 |

| Gisborne | 0 | 0 |

| Hawke’s Bay | 1 | 0 |

| Manawatu-Wanganui | 8 | 1 |

| Taranaki | 3 | 0 |

| Wellington | 5 | 3 |

| Tasman | 3 | 1 |

| Nelson | 2 | 1 |

| Marlborough | 0 | 0 |

| Canterbury | 7 | 0 |

| West Coast | 1 | 1 |

| Otago | 7 | 2 |

| Southland | 1 | 1 |

| Location | ||

| Urban | 81 | 20 |

| Rural | 14 | 7 |

| Birth country | ||

| New Zealand | 58 | 13 |

| Overseas | 37 | 14 |

| Father’s birth country | ||

| New Zealand | 40 | 12 |

| Overseas | 53 | 15 |

| Do not know | 1 | 0 |

| Mother’s birth country | ||

| New Zealand | 42 | 11 |

| Overseas | 51 | 16 |

| Do not know | 1 | 0 |

aEach person is allocated to a single ethnic group based on the ethnic groups they have identified with, which are, in order of priority: Māori, Pacific, Asian and European/other

Most participants (n = 80) obtained their NHPs through self-selection (i.e. not through a natural health/traditional medicine practitioner). More than half of the participants (n = 53) were currently taking prescribed conventional medicines, and approximately one-third (n = 37) were currently using non-prescription/‘over-the-counter’ conventional medicines. Over two-thirds (n = 72) of NHP users also used conventional medicines. About 40% of the participants met/consulted/had an appointment with one or more natural health and/or traditional medicine practitioners in the previous 12 months (Table 2).

Table 2.

Participants’ use of natural health products and conventional medicines, and visits to natural health and/or traditional medicine practitioners

| Phase 1 study (N = 95), n (range) | Phase 2 study (N = 27), n (range) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Current use of NHPs ‘obtained from a natural health and/or traditional medicine practitioner’ | ||

| Yes | 27 | 9 |

| No | 68 | 18 |

| If yes, number of products/preparations | (1–12) | (1–12) |

| 1–5 | 18 | 6 |

| 6–10 | 4 | 2 |

| > 10 | 2 | 1 |

| Not stated | 3 | 0 |

| Current use of NHPs ‘not obtained from a natural health and/or traditional medicine practitioner’ (self-selected) | ||

| Yes | 80 | 24 |

| No | 14 | 3 |

| Not stated | 1 | 0 |

| If yes, number of products/preparations | (1–14) | (1–8) |

| 1–5 | 69 | 19 |

| 6–10 | 9 | 5 |

| > 10 | 2 | 0 |

| Current use of ‘other’ NHPs | ||

| Yes | 22 | 9 |

| No | 73 | 18 |

| If yes, number of products/preparations | (1–8) | (1–4) |

| 1–5 | 21 | 9 |

| 6–10 | 1 | 0 |

| > 10 | 0 | 0 |

| Current use of prescribed conventional medicines | ||

| Yes | 53 | 16 |

| No | 42 | 11 |

| If yes, number of products/preparations | (1–8) | (1-8) |

| 1–5 | 48 | 14 |

| 6–10 | 4 | 2 |

| > 10 | 0 | 0 |

| Not stated | 1 | 0 |

| Current use of non-prescribed/‘over-the-counter’ conventional medicines | ||

| Yes | 37 | 9 |

| No | 57 | 18 |

| Not stated | 1 | 0 |

| Number of products/preparations | (1–5) | (1–2) |

| 1–5 | 36 | 8 |

| 6–10 | 0 | 0 |

| > 10 | 0 | 0 |

| Not stated | 1 | 1 |

| Met/consulted/had an appointment with one or more natural health and/or traditional medicine practitioners in the last 12 months | ||

| Yes | 39 | 14 |

| No | 56 | 13 |

| If yes, number of practitioners | (1–9) | (1–5) |

| 1–5 | 37 | 14 |

| 6–10 | 2 | 0 |

| > 10 | 0 | 0 |

| Current use of NHPs and conventional medicines | ||

| Yes | 72 | 20 |

| No | 23 | 7 |

| Total number of NHPs currently used—from all sources | (1–18) | (1–18) |

| 1–5 | 68 | 16 |

| 6–10 | 20 | 10 |

| >10 | 5 | 1 |

| Unable to compute | 2a | 0 |

NHPs Natural health products

aParticipants indicated that they were using NHPs, but did not list the names of the products/preparations used

Overall, 97 and 265 entries for NHPs that were obtained from a natural health or traditional medicine practitioner/healer or through self-selection were recorded, respectively. Additionally, 40 ‘other’ products/preparations were recorded. In total, 141 entries for prescribed conventional medicines and 64 for non-prescribed medicines were listed by participants. For consultations with TCAM practitioners, 86 entries were recorded.

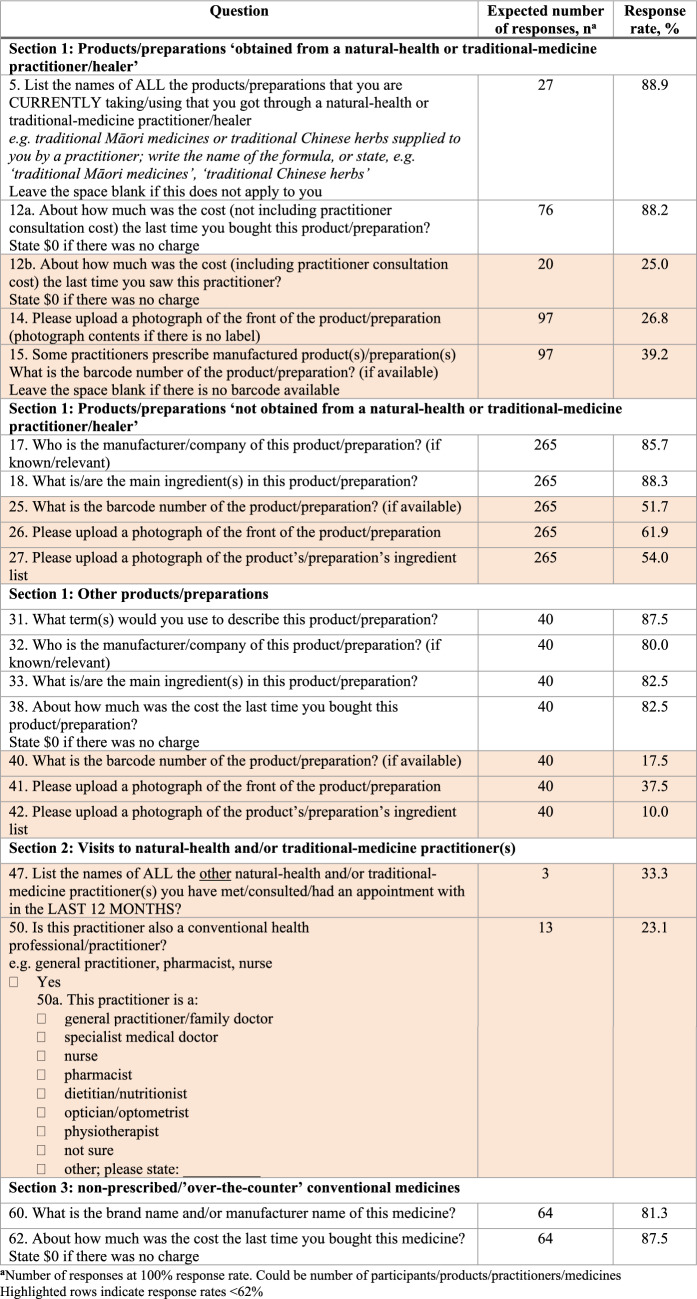

Phase 1 study: Response rates

Most questions had a response rate ≥ 90%, except for several questions in sections 1 to 3 of the questionnaire (Table 3). Almost all questions with low response rates were open-ended (rather than multiple-choice). Few participants did not provide information about manufacturer name and main ingredient(s) of product(s)/preparation(s)/medicine(s). Question response rates < 62% were mainly related to cost, and providing barcodes and photographs of products/preparations (highlighted rows in Table 3).

Table 3.

Questions with a response rate below 90%

Phase 1 study: Data completeness

Of the 265 NHPs that were ‘not obtained from a natural health or traditional medicine practitioner/healer’, > 80% had the correct type of product information entered (Table 4). The relatively high percentage (10–15%) of blank responses in the manufacturer/company name and main ingredient(s) questions was because some participants had included this information (60% and 87% of blank responses, respectively) in other columns (e.g. product brand/generic name) instead.

Table 4.

Review of the type of product information entered by participants (n = 265)

| Correct type of information entered, n (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Did not answer/blank | Unsure/do not knowa | Other/not applicableb | |

| Product brand/generic name | 265 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Manufacturer/company name | 213 (80.4) | 1 (0.4) | 40 (15.1) | 4 (1.5) | 7 (2.6) |

| Main ingredient(s) | 229 (86.4) | 2 (0.8) | 31 (11.7) | 2 (0.8) | 1 (0.4) |

| Dosage form | 250 (94.3) | 1 (0.4) | 14 (5.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

aParticipant indicated that they do not know or were unsure

bExamples where manufacturer name is not available (e.g. prescription item that was pre-packed and dispensed with generic pharmacy labelling) or not applicable (e.g. products were home grown)

From the total NHPs recorded (n = 265), only 137 (51.7%) had a barcode entered and 113 (82.5%) of these were valid (e.g. correct length).

Phase 1 study: Data quality

Overall, 143 (55.9%) NHP entries had photographs of both the front label and ingredient list uploaded; of these, 58 (40.6%) and 85 (59.4%) were single- and multi-ingredient products, respectively. Since participants answered specific product information (e.g. manufacturer name) in other columns (e.g. product name), data quality was assessed and scored on the basis of the product information entered in totality, regardless of whether the information was recorded in the correct column (Box 2). Overall, most products had a score ≥ 3 (Table 5); of the products with a score of 3, 53 (89.8%) were not given a full score due to the main ingredient(s) information being missing or incorrect. Multi-ingredient products were more likely to have the main ingredient(s) information missing or incorrectly stated (χ2 = 53.4; df = 1, p < 0.01) compared with single-ingredient products.

Table 5.

Data quality assessment (n = 143)

| Score | Count (%) |

|---|---|

| 0 | 0 (0.0) |

| 1 | 0 (0.0) |

| 2 | 5 (3.5) |

| 3 | 59 (41.3) |

| 4 | 68 (47.6) |

| Unable to computea | 11 (7.7) |

Each product was scored from 0 to 4, where 1 mark was given for each correctly entered product name, manufacturer/brand name, main ingredient(s) and dosage form

aScores not calculated due to errors with photographs (e.g. unclear photo, unable to open file)

Approximately half (45.5%) of 33 products were incorrectly described by participants as being ‘vitamin(s) and/or mineral(s)’ only. These products included other ingredients, such as herbs (e.g. echinacea, rose hip, ashwagandha), amino acids, collagen and coenzyme Q10. When compared with single-ingredient products, multi-ingredient products were more likely to be incorrectly described as ‘vitamin(s) and mineral(s) only’ (Fisher’s exact test; p < 0.01).

Of the 113 valid barcodes, 70 (61.9%) matched the product entered; the remaining barcodes did not match the product, or were not found in the barcode database search.

Box 2.

Example of scores given on the basis of the product information entered

| Product brand/generic name | Manufacturer/brand name | Main ingredient(s) | Dosage form | Total score given |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthylife Immune | Healthylife | Echinacea, propolis | Capsule | 4 |

| Healthylife Immune capsules, Echinacea, propolis | – | – | – | 4 |

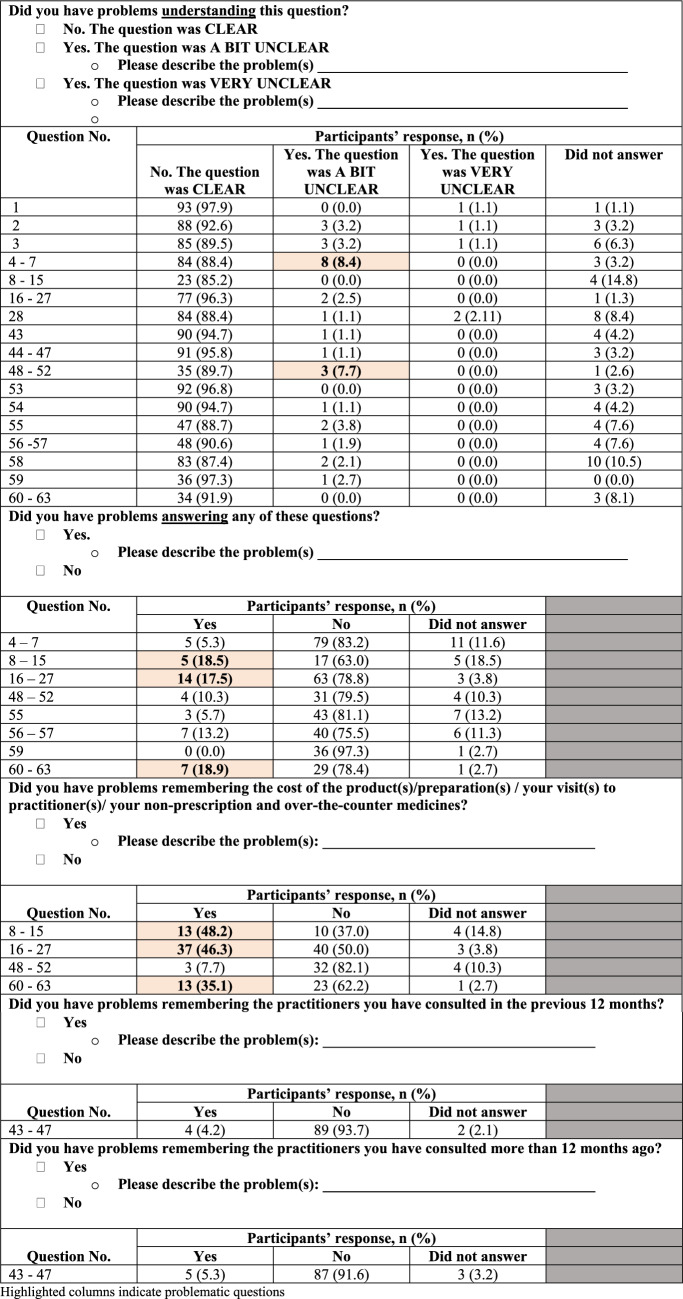

Phase 1 study: Responses to probing questions

Overall, participants had no major problems understanding and answering questions in the questionnaire; some minor issues were identified (highlighted items in Table 6).

Table 6.

Participants’ responses to probing questions in the web-based questionnaire

Over 85% of participants rated the questions as ‘clear’ and had no problems understanding the questions. Questions that were rated ‘a bit unclear’ and ‘very unclear’ (by ~ 8% of participants) were related to listing the names of NHPs the participants were currently taking (questions 4–7) and answering a set of questions about participants’ visits to TCAM practitioners over the past 12 months (questions 48–52). From open-ended text responses, few participants stated difficulties in differentiating products they obtained and did not obtain from a natural health or traditional medicine practitioner/healer. Some participants were unsure of the definition of the term ‘natural health practitioner’ used in this study.

Generally, most participants did not have problems answering questions in the questionnaire. Questions that were rated problematic to answer (by ~ 20% of participants) were the set on participants’ use of NHPs ‘obtained from a natural health or traditional medicine practitioner/healer’ (questions 8–15), ‘not obtained from a natural-health or traditional-medicine practitioner/healer’ (questions 16–27) and use of non-prescribed/‘over-the-counter’ conventional medicines (questions 60–63). A few participants described their problems with answering these questions; the reasons included difficulties in remembering the cost of products/medicines and not being able to upload photographs as they did not have the products/medicines during completion of the questionnaire.

Approximately half and one-third of the participants had difficulty remembering the costs of their NHPs and non-prescribed/‘over-the-counter’ conventional medicines, respectively. Some participants were unable to remember the cost of each product/medicine because these products/medicines are not kept in their original packaging with the price tag, were purchased some time ago, or paid for together with other products/medicines.

For participants taking ‘other’ products/preparations (besides the NHPs obtained and not obtained from a natural health or traditional medicine practitioner/healer), some explained that they considered the particular product/preparation (e.g. chia seeds, protein powders, collagen powders) a ‘food’ rather than an NHP or were not sure if the product/preparation is an NHP. Many other participants actually considered these ‘other’ product(s)/preparation(s) an NHP, but had forgotten/overlooked the product(s)/preparation(s) when completing the previous questions in the questionnaire.

Phase 1 study: Feedback on the questionnaire

Most participants rated the survey length, number, complexity and relative intrusiveness of questions acceptable (Table 7). Two (2.11%) participants indicated that they would not take part in this survey again; the reason given was ‘survey was too repetitive’ and ‘took too long’. Three participants would prefer to complete the questionnaire in a different language: two stated Chinese/mandarin, one stated Spanish. Four participants would prefer to complete the questionnaire using a different method: two preferred an interview, one preferred using a computer rather than a mobile telephone and one did not state the method desired.

Table 7.

Participants’ rating of the web-based questionnaire

| Participants’ responses, n (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Survey length | 0 (0.0) | 4 (4.2) | 17 (17.9) | 39 (41.1) | 35 (36.8) |

| The number of questions | 0 (0.0) | 8 (8.4) | 13 (13.7) | 34 (35.8) | 40 (42.1) |

| Complexity of questions | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.1) | 8 (8.4) | 41 (43.2) | 45 (47.4) |

| Relative intrusiveness of questions | 2 (2.1) | 1 (1.1) | 12 (12.8) | 31 (33.0) | 48 (51.1) |

Participants rated on a scale of 1–5, where 1 is Absolutely NOT Acceptable, and 5 is Highly Acceptable

In open-ended questions, 59 and 25 participants provided their thoughts about the questionnaire and comments about participating in the study, respectively. In general, participants had positive experiences with the questionnaire and study and did not face major issues with completing the questionnaire. A few participants raised some minor problems related to the length of the questionnaire, difficulties with cost-related questions, uploading photographs of NHPs and clarity regarding how some terminologies used in the questionnaire relate to different contexts of access (e.g. are vitamins prescribed by a general practitioner considered natural health products?).

Phase 2: Qualitative interview data

Data from the interviews reiterated the main issues found from the phase 1 study and further explained the problems with the questionnaire. Selected quotes from participants are included in Online Resource 3.

One issue was that participants did not have all the NHPs and conventional medicines on hand during completion of the questionnaire; this partly contributed to the low response rates for some questions (e.g. the main ingredient(s) and uploading photographs). Some participants were unaware that a statement recommending participants to record all their NHPs and conventional medicines they currently take was displayed at the beginning of the questionnaire.

The term ‘natural health practitioner’ was unclear for some participants where they were unable to distinguish if a practitioner (e.g. a nutritionist) is a TCAM or conventional medicine practitioner. Some participants did not remember the type(s) of practitioners they had consulted, hence, they were unsure if they had visited a ‘natural health practitioner’.

Differentiating the NHPs obtained (question 5) and not obtained (question 7) from natural health or traditional medicine practitioners/healers was challenging for some participants. Some NHPs, like vitamins and minerals, may be prescribed by conventional medicine practitioners and participants were unsure if these NHPs should be included in their response to question 7. For some participants who were natural health or traditional medicine practitioners themselves, these questions become confusing when the NHPs they take are self-prescribed.

Interpretation of question 28 (‘Are you currently taking/using any other natural health-type product(s)/preparation(s) for your health that you have not listed previously?’) differed between participants. Some participants understood the question as asking for products/preparations considered ‘food’ rather than NHPs. In contrast, others felt the question was a reminder to include NHPs they may have forgotten to list earlier. For some participants, going through prior questions allowed them to gauge the scope and context of the questionnaire, and the ‘other’ products/preparation question provided them with an avenue to include NHPs they had not mentioned.

Listing the main ingredient(s) of products/preparations was also a challenge for some participants. Some participants were unaware of the ingredient(s) in the products/preparations they took, or the list of ingredients on the product label was too long to include in the questionnaire. For some participants, the product ingredients information entered was incomplete. One participant who entered one ingredient only for a multi-ingredient product explained that the product was used for the purpose of one of its ingredients only (e.g. biotin), although it is a multi-ingredient product containing other ingredients (e.g. marine collagen, horsetail).

There were two main reasons for the low response rates for questions related to manufacturer/proprietary (brand) name and providing barcodes: participants had removed the product from its original packaging, or the information was not available on the product label. Similarly, some participants could not provide photographs of NHPs as the original packaging was no longer available to them. Other participants were unaware of the questionnaire instructions stating that photographs of NHPs would be required; hence, they were unprepared to submit photographs (e.g. did not have products available and/or completed the survey away from their home). A few participants did not provide photographs because of the inconvenience and, for some, technical complexity of doing so.

Interviews with participants revealed that questions on costs (‘About how much was the cost the last time you bought this product/preparation/medicine?’) were particularly difficult to answer for various reasons. For product(s)/preparation(s)/treatment(s) obtained from a practitioner, the cost may not be known to participants, as payments are typically made together with consultation fees. Some participants could not remember the costs of products/medicines because they purchased them some time ago and/or products did not have a price tag. Participants also said that cost would differ based on the product pack size (e.g. 30 versus 60 capsules) they had chosen to purchase (participants were asked to state the cost the last time they bought the product); this has implications for the interpretation of the data collected on costs of NHPs. One way to mitigate this is to ask participants additional questions regarding the cost of a product/preparation/medicine, which was explored during the interviews. Participants were asked if they could estimate how long the product/preparation would last them; most were able to answer without much difficulty (Online Resource 4). It was more difficult for participants to answer this where products are not taken regularly; however, they were still able to provide an estimated duration of use. Alternatively, participants were also asked if they were able to estimate their average total spending per month on NHPs; most participants found this challenging because, usually, not all products they are taking were purchased at the same time.

Expert panel and research team reviews

A summary of results, including the revisions made to the questionnaire, was sent to the expert panel; no further comments were received. Following input from a Māori research team member, several questions exploring barriers to TCAM access were also included on the basis that the data collected from these questions would provide some understanding of the demand for TCAM and, to some extent, explain (the low) prevalence of use for some categories of TCAM (e.g. types of traditional medicine).

Summary of changes to the questionnaire

Overall, no major study methods or questionnaire-related issues were identified. Based on the minor issues found in the questionnaire testing study and reviews from the expert panel and research team members, parts of the questionnaire were revised (final version) (Online Resource 5). Changes made to the questionnaire are available in Online Resource 6. The main changes are described below.

Due to the uncertainty about separating and listing the names of NHPs obtained and not obtained from a ‘natural health or traditional medicine practitioner/healer’ [i.e. where to include products (e.g. iron tablets) prescribed by a conventional health practitioner, such as a general practitioner?], the questions were changed to ‘formulated or specially compounded products/preparations’ and ‘manufactured/commercial natural health or traditional medicine products/preparations’. This change would allow participants to list all types of products, including those prescribed by conventional medicine practitioners.

The cost question was revised to asking participants to estimate the cost to the nearest NZ$5, specifying ‘for one unit/bottle/box/packet of the product/medicine’. In addition to asking about the cost of a particular product/preparation/medicine, we added questions on the date of last purchase and the length of time that one unit/bottle/box/packet of purchased product/medicine would last the respondent.

Despite the problems (low response rates, inaccuracies with information entered) with the questions on the barcodes, main ingredient(s) and uploading photographs, these questions were retained in the questionnaire. This is because barcodes and photographs, where provided by participants, are useful to check the accuracy of information [including main ingredient(s)] entered by participants.

Several questions exploring barriers to TCAM access were added; these questions were adapted from the New Zealand Health Survey [35]. Questions asking participants if they had a medical problem or TCAM prescription/recommendation in the last 12 months, but did not visit a TCAM practitioner or purchase recommended TCAM products/preparations, respectively, because of cost or other reasons, were added.

Discussion

This project developed and tested a bespoke questionnaire (All-MedsNZ) that included comprehensive data collection elements relating to NHPs’, TCAM practices/therapies’ and conventional medicines’ use. Findings from this project were used to guide refinement of the questionnaire and methods for a future, nationally representative study on NHPs’, TCAM therapies and conventional medicines’ use in NZ. To our knowledge, this is the first study in NZ that explored self-reported TCAM data at a granular (e.g. specific TCAM product) level. We argue that it is essential to obtain comprehensive TCAM use data at this level rather than merely a category level (e.g. ‘herbal medicines’) directly from participants. However, we acknowledge the inherent trade-off between data quality and completeness, as the collection of information at such a detailed level can impose a higher burden on respondents. Nevertheless, the findings from this testing study provide valuable insights into the complexities in collecting TCAM data in NZ and serve as a basis for future research in this field.

The development, testing and refinement of All-MedsNZ were based on systematic literature reviews, expert panel input and cognitive interviewing methods, which are widely-used questionnaire pretesting methods, including by the US NHIS [13]. The contents of this study’s questionnaire were validated by an expert panel encompassing TCAM and conventional medicine health practitioners. During the testing phase, the questionnaire had good acceptability among participants (NHP users). Most participants completed the questionnaire and indicated they had no problems understanding and answering the questions.

Involving consumers/patients in designing a new questionnaire has been shown to improve questionnaire comprehensiveness and relevance while reducing item ambiguities [36, 37]. Some participants found questions related to cost challenging to answer: 8–48% indicated problems remembering the costs of products/preparations/medicines/visits to practitioners. Participants had difficulties answering the original cost question because prices of products/preparations/medicines are dependent on the purchased pack size (e.g. 30 versus 60 capsules/bottle). The two-phase testing adopted in this study permits further examination of the issue during the phase 2 online interviews, elucidating the various reasons why the cost questions were difficult to answer, which is difficult to explore within the questionnaire. In addition, the qualitative nature of the interviews allowed exploration of participants’ thoughts about potential revisions to the cost questions. In previous studies, the cost of TCAM was explored using various methods. The US NHIS asked respondents to provide the cost the last time they (respondent) purchased NHPs (e.g. vitamins and minerals) and how often these NHPs were bought. For TCAM practitioner visits, the ‘average’ amount spent per visit, or total cost over 12 months, was collected [38]. In Australia, respondents were asked to estimate, to the nearest dollar, the monthly cost of NHPs purchased and the approximate total yearly cost of visits to TCAM practitioners [39]. In the phase 2 interviews in the present study, participants were asked about the ease of estimating the cost of each NHP and their average monthly spending on NHPs. Subsequently, the questionnaire was revised, and several other cost-related questions (date of last purchase and the length of time that a purchased product would last the participant) were added to the questionnaire.

Another issue concerned asking participants to list the main ingredient(s) of NHPs, particularly for multi-ingredient products. About one-third of the 143 NHPs for which photographs of the product’s front label and ingredient list were provided had one or more of the main ingredient(s) missing or incorrectly stated in the self-reported data. Some participants were unaware of the ingredient(s); for some NHPs, the ingredients list was too long to list in the questionnaire. Also, some participants listed particular ingredient(s) of interest while disregarding other (potentially active) NHP ingredient(s). Hence, consumers may not reliably self-report the ingredient(s) of the NHPs they take, especially for multi-ingredient products. While this may not affect broad-level analyses (e.g. the prevalence of use of NHPs in a population), there are implications for more defined analyses at the NHP category/product level (e.g. the prevalence of use of herbal medicines or products containing ‘echinacea’). To achieve data accuracy for such defined analyses, product barcodes and photographs uploaded by participants can be used to cross-check lists of ingredient(s) entered by participants. However, this approach is resource intensive for researchers and (ultimately) for curators of real-world health datasets that include data on TCAM exposures. From participants’ perspectives, entering barcode numbers and uploading photographs is burdensome; low response rates for these items were observed in this study (Table 3). In some countries, such as Australia [40] and the UK [41], where (many) TCAMs are regulated, product registration numbers can be collected; this would alleviate the need for participants to transfer information provided on product labels to a questionnaire. Currently, there are no regulations or legislation specific to NHPs in NZ. In July 2023, the proposed Therapeutic Products Bill received Royal Assent, becoming the Therapeutic Products Act (2023) [42]. This Act will include regulations for NHPs. The regulations will aim to ensure acceptable safety and quality of NHPs, although full details of how these will be assured are not yet known [42]. The All-MedsNZ questionnaire may require revision following implementation of regulations proposed by the Bill. It is also important to consider that the proposed bill may not capture all NHPs; for instance, individuals could continue to import products from overseas for personal use.

Approximately half of the 33 NHPs described as ‘vitamin(s) and mineral(s) only’ actually were labelled as containing non-vitamin and/or non-mineral ingredients (e.g. herbs, amino acids) when the individual product’s ingredient list was checked using photographs uploaded by participants. Despite the small sample size, this finding indicates that relying on consumers to self-report the use of NHPs in pre-specified categories is not feasible. This issue also arose in the implementation of the I-CAM-Q, where respondents declared their use of NHPs in four pre-specified categories (‘herbs/herbal medicine’, ‘vitamins/minerals’, ‘homeopathic remedies’ and ‘other supplements’): considerable data cleaning was required in one study to recode NHPs reported by participants to the correct category [43]. Another concern, particularly with multi-ingredient NHPs, is that these products (e.g. vitamin C plus echinacea) may fall into more than one category (e.g. vitamins and herbals). Although using pre-specified categories may cue respondents to remember the products they take, collecting data in such a manner is error-prone and may underestimate the use of NHPs.

This study has several limitations. More broadly, a universal definition for TCAM and what constitutes a TCAM approach does not exist. Hence, as with all TCAM studies, findings depend on respondents’ understanding of terminologies (e.g. ‘NHPs’), which may vary considerably across individuals. To ensure consistent interpretation of terms among participants, comprehensive operational definitions/descriptions of terminologies are needed and were used in this study. Still, participants’ awareness, understanding and use of these definitions in providing their responses is not guaranteed. We acknowledge the potential for subjectivity in the participants’ responses, as well as the influence of recall bias in their reporting. These factors should be taken into consideration when interpreting the findings of this research.

Beyond TCAM, this work also raises methodological issues. Web-based studies are challenging, especially among the older, rural population who have limited access to the internet and low(er) digital literacy. The focus of this study was to test a questionnaire that is self-administered through the web, which is known to be a convenient and cost-efficient delivery method. However, this mode of data collection must be weighed against the risk of population under coverage. Hence, paper-based copies of the questionnaire were also offered to participants in this study. No request for a paper-based questionnaire was received. Therefore, findings from this study are limited to individuals with internet access and who are technology literate.

In this project, the sample of study participants was not intended to represent the general population in NZ, rather to provide depth and breadth in shared perspectives. Although care was taken to select individuals for the online interviews who differed in demographic characteristics, the choice of sample was limited by the demographics of those who had completed the questionnaire and was clearly not nationally representative. Therefore, the findings from this study cannot be generalised. A larger, nationally representative pilot study should be conducted to explore the feasibility and utility of the revised All-MedsNZ (Online Resource 1). Also, it is expected that future quantitative analyses on the validity and reliability of the questionnaire will supplement the work described in this pre-testing study to inform further refinements of the questionnaire.

Conclusion

Overall, no major design-, method- or questionnaire-related problems were identified in the testing study of the All-MedsNZ. This bespoke questionnaire collects comprehensive data relating to NHPs’ and conventional medicines’ use. The questionnaire had adequate face and content validity and acceptability among participants, and most of the data collected on NHPs’ use is complete and of sufficient quality for analysis. The questionnaire was revised to enhance the clarity of several questions and to mitigate some of the minor issues with the questions on costs. The final questionnaire should be piloted in a larger, nationally representative study to confirm its feasibility and utility.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Declarations

Funding

This study was funded by the University of Auckland Postgraduate Research Student Support (PReSS) account, which provides funds for doctoral students to help cover direct research costs.

Conflict of Interest

E.L. has received a bursary from the University of Maryland School of Medicine/Cochrane Complementary Medicine Field for working on a Cochrane Systematic Review and is currently a doctoral candidate studying the prevalence of use of TCAM and conventional medicines in New Zealand; part of this work is funded by a Health Research Council grant (2020-2022) for which J. Barnes is the principal investigator. J.H. was a co-investigator for a Health Research Council grant that explored prevalence of use of TCAM and conventional medicines in New Zealand. J.B. has: received fees, honoraria and travel expenses from the Pharmaceutical Society of New Zealand (PSNZ) for preparation and delivery of continuing education material on complementary medicines (CMs) for pharmacists (2013, 2015); provided consultancy to the Pharmacy Council of New Zealand on Code of Ethics statements on complementary medicines (unpaid) and competence standards (paid); was a member of the New Zealand Ministry of Health Natural Health Products (NHPs) Regulations Subcommittee on the Permitted Substances List (2016-2017), and led the Herbal and Traditional Medicines Special Interest Group (2017-2022) of the International Society of Pharmacovigilance. J.B. is a registered pharmacist (academic) in NZ and has a personal viewpoint that supports regulation for NHPs/complementary medicines. J.B. was the principal investigator for a Health Research Council grant that explored prevalence of use of TCAM and conventional medicines in New Zealand. J.B. has undertaken other research exploring pharmacists’ views on and experiences with complementary medicines, supported by: the Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain (RPSGB), New Zealand Pharmacy Education and Research Fund; University of Auckland. J.B. was the principal author of a reference textbook on complementary medicines and received royalties from Pharmaceutical Press, the publishing arm of the RPSGB. J.B. is a co-author/co-editor of other books relevant to complementary medicines and receives royalties from Elsevier and SpringerNature/MacMillan Education. As a member of the School of Pharmacy staff, University of Auckland, J.B. has interactions with individuals in senior positions in the pharmacy profession. The School of Pharmacy has strategic relationships with several pharmacy organisations and receives support in various forms, such as sponsorship of student prizes/events and guest lectures given by individuals from those organisations.

Availability of data and material

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available as the researchers do not have the permissions from the participants or from a research ethics committee to share the data.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

The questionnaire testing study was approved by the University of Auckland Human Participants Ethics Committee on 08/03/2021 for three years with reference number UAHPEC2550.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the idea for the article. E.L. drafted the article, and J.B. and J.H. critically revised the work. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Harris PE, Cooper KL, Relton C, Thomas KJ. Prevalence of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) use by the general population: a systematic review and update. Int J Clin Pract. 2012;66(10):924–939. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2012.02945.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clarke TC, Black LI, Stussman BJ, Barnes PM, Nahin RL. Trends in the use of complementary health approaches among adults: United States, 2002–2012. Natl Health Stat Report. 2015;79:1–16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Center for Health Statistics. National Health Interview Survey—2017 Data Release: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/nhis_2017_data_release.htm. Accessed 15 Jan 2023.

- 4.Posadzki P, Watson LK, Alotaibi A, Ernst E. Prevalence of use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) by patients/consumers in the UK: systematic review of surveys. Clin Med (Lond) 2013;13(2):126–131. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.13-2-126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steel A, McIntyre E, Harnett J, Foley H, Adams J, Sibbritt D, et al. Complementary medicine use in the Australian population: results of a nationally-representative cross-sectional survey. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):17325. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-35508-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ministry of Health. A portrait of health. Key results of the 2006/07 New Zealand Health Survey. Wellington: Ministry of Health; 2008.

- 7.University of Otago, Ministry of Health. A Focus on Nutrition: Key findings of the 2008/09 New Zealand Adult Nutrition Survey. Wellington: Ministry of Health; 2011.

- 8.Awad A, Al-Shaye D. Public awareness, patterns of use and attitudes toward natural health products in Kuwait: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Altern Med. 2014;14:105. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-14-105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mitchell R, Braithwaite J. Evidence-informed health care policy and practice: using record linkage to uncover new knowledge. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2021;26(1):62–67. doi: 10.1177/1355819620919793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patterson C, Arthur H. A complementary alternative medicine questionnaire for young adults. Integr Med Insights. 2009;4:1–11. doi: 10.4137/IMI.S2281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Quandt SA, Verhoef MJ, Arcury TA, Lewith GT, Steinsbekk A, Kristoffersen AE, et al. Development of an international questionnaire to measure use of complementary and alternative medicine (I-CAM-Q) J Altern Complement Med. 2009;15(4):331–339. doi: 10.1089/acm.2008.0521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee EL, Richards N, Harrison J, Barnes J. Prevalence of use of traditional, complementary and alternative medicine by the general population: a systematic review of national studies published from 2010 to 2019. Drug Saf. 2022;45(7):713–735. doi: 10.1007/s40264-022-01189-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stussman BJ, Bethell CD, Gray C, Nahin RL. Development of the adult and child complementary medicine questionnaires fielded on the National Health Interview Survey. BMC Altern Med. 2013;13:328. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-13-328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.US Food and Drug Administration. Dietary supplements. https://www.fda.gov/food/dietary-supplementsAccessed 10 Nov 2022.

- 15.Australian regulatory guidelines for complementary medicines: Therapeutic Goods Administration; 2018. https://www.tga.gov.au/sites/default/files/australian-regulatory-guidelines-complementary-medicines-argcm.pdf. Accessed 7 Nov 2022.

- 16.Ministry of Health. Rongoā Māori: traditional Māori healing [cited 2022 Feb 15]. https://www.health.govt.nz/our-work/populations/maori-health/rongoa-maori-traditional-maori-healing. Accessed 15 Feb 2022.