Abstract

Purpose.

Urologic chronic pelvic pain syndrome (UCPPS), which encompasses interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome in women and men, and chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome in men, is a common, often disabling, urological disorder that is neither well understood nor satisfactorily treated with medical treatments. The past 25 years have seen the development and validation of a number of behavioral pain treatments of which cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is arguably the most effective. CBT combines strategies of behavior therapy, which teaches patients more effective ways of behaving, and cognitive therapy, which focuses on correcting faulty thinking patterns. As a skills-based treatment, CBT emphasizes “unlearning” maladaptive behaviors and thoughts and replacing them with more adaptive ones that support symptom self-management.

Materials and methods.

This review describes the rationale, technical procedures, and empirical basis of CBT.

Results.

While evidence supports CBT for treatment-refractory chronic pain disorders, there is limited understanding of why or how CBT might work, for whom it is most beneficial, or the specific UCPPS symptoms (e.g., pain, urinary symptoms) it effectively targets. This is the focus of the Easing Pelvic Pain Interventions Clinical Research Program (EPPIC), a landmark NIH trial examining the efficacy of low-intensity CBT for UCPPS. relative to a nonspecific comparator featuring self-care recommendations of AUA guidelines.

Conclusions.

Systematic efforts to increase both the efficiency of CBT and the way it is delivered (e.g., home-based treatments) are critical to scaling up CBT, optimizing its therapeutic potential and reducing the public health burden of UCPPS.

Introduction

Urologic chronic pelvic pain syndrome (UCPPS), encompassing interstitial cystitis/ bladder pain syndrome (IC/BPS) in women and men, and chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CP/CPPS) in men, is estimated to affect nearly 5 million Americans1, 2 3. The hallmark symptom of UCPPS is chronic pain in the pelvic region and/or genitalia. Additional urinary symptoms include urgency and/or frequency. UCPPS lacks a diagnostic biomarker and is neither well understood nor satisfactorily treated with conventional medical, dietary or rehabilitative treatments4. Economically, UCPPS exacts steep annual costs estimated at $881.5 million for outpatient care for females alone5–7. This figure does not include the cost of medications8. The associated disease burden 7, 9 leaves UCPPS patients10 11, providers 12, employers, and payers largely dissatisfied, seeking more effective treatment options.

Beyond the pelvis

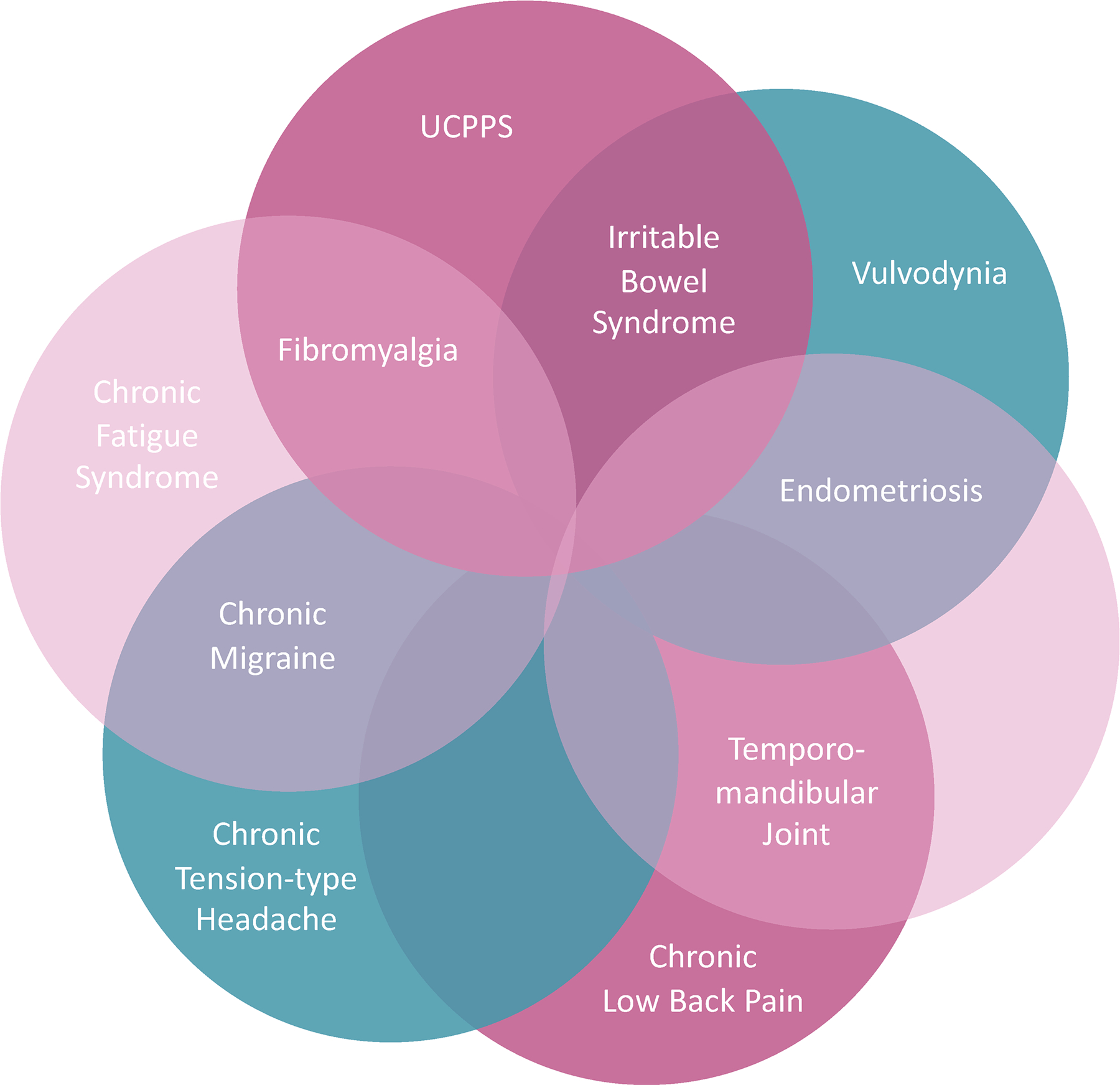

Treatment is further complicated by the frequency of a specific subset of co-occurring pain conditions (e.g., irritable bowel syndrome, fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome). This clinical phenomenon, collectively referred to as Chronic Overlapping Pain Conditions13 (COPC; Figure 1), are also poorly understood and share common underlying disease mechanisms (e.g., altered nociceptive processing resulting in hypersensitivity to noxious stimuli) that result in symptoms in multiple distinct organ systems (e.g., bladder, abdomen, head, musculoskeletal) without corresponding evidence of physical pathology or somatosensory change 14. COPCs interact with UCPPS to potentiate its onset15 and complicate symptom presentation, quality of life, and treatment response16. UCPPS patients suffer considerable lifetime morbidity resulting in significant loss of work productivity and quality of life 17 18, 19.

Figure 1.

Urologic chronic pelvic pain and co-occuring chronic overlapping pain conditions (COPCs)

The illness burden of UCPPS involves significant medical and psychiatric comorbidity associated with a wide range of psychosocial complications. For example, depression and anxiety diagnoses have been found to be 2.4–6.6 higher, respectively, in IC/BPS compared to healthy controls 20 21. Although less well studied, similar elevated rates of anxiety and depression are reported for CP/CPPS 22. Findings from the Multidisciplinary Approach to the Study of Chronic Pelvic Pain (MAPP) Research Network demonstrate increased negative affect, higher levels of current and lifetime stress, maladaptive coping, cognitive problems and quality of life impairment across mental and physical health domains. The severity of psychosocial problems increases among UCPPS patients with more severe urogenital symptoms as well as those with co-existing non-urogenital pain symptoms23. Seventy five percent of UCPPS patients report pain beyond the pelvis -- 38% of which is widespread -- suggesting that pelvic pain represents a local manifestation of a more widespread, centralized phenotype representative of COPCs 24.

The science of pelvic pain “chronification”

Notwithstanding their symptom and nosological distinctions, UCPPS and other regional COPCs involve a dysfunction in pain modulatory mechanisms that amplify processing or decrease inhibition of pain stimuli within the nervous system, particularly at the CNS level25. As pain persists beyond 3 months (i.e. chronic), it becomes, mechanistically, more strongly tied to cortical circuits (e.g., corticolimbic system26) that control pain’s affective-motivational system governing avoidance or escape responses to expectation of harm through associative learning and memory processes and the emotional unpleasantness of pain 27 (e.g., its suffering component or bothersomeness) than sensory-perceptual circuitry that encodes the intensity and spatiotemporal qualities of nociceptive signals from the periphery (pain sensations) 28. This neural processing shift in cortical and emotional circuitry is activated by higher-order cognitive factors (e.g., thoughts, attention, expectancies, memory, etc.) and negative emotional states (e.g., anxiety, depressed mood) 29, potentiating a “chronified” pain experience 30 that locks patients into persistent pain and suffering that (1) broadens the scope and depth of illness burden (distress, functionable disability, etc.), (2) undermines responsiveness to conventional therapies with antinociceptive properties by interfering with endogenous pain control29, and (3) challenges patients’ ability to self-regulate the very thoughts and emotions that influence symptom perception (e.g., pain) 29 31. The significant prevalence of other centralized pain states co-aggregating with UCPPS, across genders and diagnoses, strongly suggest a centralized pain phenotype whose shared maintaining factors define the symptom burden in a substantial subset of patients refractory to conventional medical therapies. Because complaints are widespread and their apparent mechanisms extend beyond organ-based, peripheral mechanisms (e.g., pain sensitization 32), UCPPS and frequently co-morbid COPCs are regarded as nociplastic pain states 33 14 mechanistically dissimilar from pain conditions with well-defined nociceptive or neuropathic involvement and clearer etiologies.i

Beyond descriptive similarities UCPPS shares with other widespread chronic pain conditions, the presence of psychosocial and widespread pain comorbidities has a clear and negative impact on health outcomes. In a 12-month prospective longitudinal MAPP study of usual care patients both presence of non-pelvic symptoms and decreased physical wellbeing at baseline predicted poorer outcomes after controlling for initial symptom severity 34. Another study found reciprocal relationships between pelvic pain and negative mood, such that negative mood changes directly corresponded with increased symptoms two weeks later and vice versa 35. Interacting emotional and cognitive processes36 are critical components of the pathophysiology of chronic pain as demonstrated by both clinical studies and a growing neuroimaging literature37 37 38 that implicates cognitive control brain networks governing emotional and pain responses underlying UCPPS. For example, a recent prospective study demonstrated that increased connectivity in frontal parietal cognitive control networks predicted UCPPS pain reduction over three-months, supporting the important role of cognitive factors modulating symptoms 39.

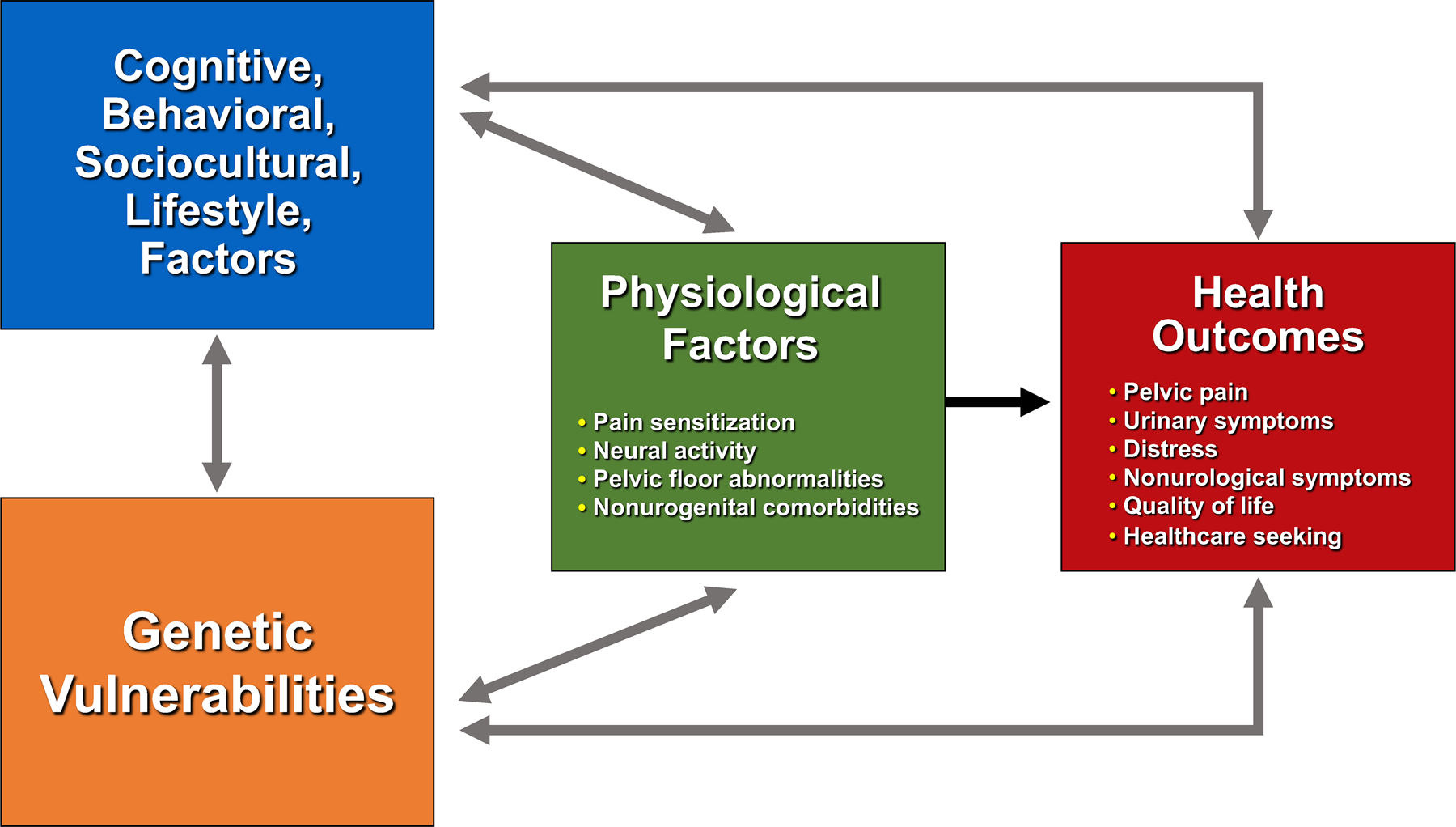

Last, pain -- the cardinal symptom of UCPPS -- is definitionally an emotional (unpleasantness) and sensory (intensity) experience 40 best understood from a biopsychosocial perspective (Figure 2) defined by physiological (e.g., underlying disease processes, genetic vulnerabilities) and psychological (e.g., cognitive-affective processes such as attention, emotions, expectations, memory, beliefs as well as learned behaviors) factors that are dynamically related and played out in a social context. The social context -- typically involving family, friends, coworkers, providers, caretakers et al -- is where persistent pain problems are expressed and maintained.

Figure 2.

Urologic chronic pelvic pain and co-occurring chronic overlapping pain conditions (COPCs)

The clinical advantage of maintenance vs vulnerability factors

A biobehavioral model emphasizes actionable factors (e.g., correctable skills deficits) that maintain symptoms as opposed to vulnerability processes that play a causal role in the emergence of UCPPS. To illustrate, there is evidence of a genetic predisposition to UCPPS in certain individuals. First-degree relatives are at increased risk 41 and twin studies have shown high concordance in monozygotic twins 42 43 44 with heritability approximately 40% 45, These figures do not explain whether family aggregation is due to genetic contributions and/or to shared experiences such as social learning, or “learning from others”, and modeling46. A child may develop similar pelvic pain symptoms as his/her parent(s) because of a genetic carryover and/or partly because of early observation of parental sick role behavior (e.g., overreliance on maladaptive coping strategies), parental reinforcement of offspring sick role behaviors (e.g., overprotective parenting style), or transmission of verbal threat information (e.g. children may become fearful when they hear or read that a pain stimulus is dangerous or has catastrophic consequences). Nonetheless, genetic contributions represent an important generalized biological vulnerability to develop UCPPS rather than a specific clinical syndrome itself. Clinically, biological vulnerabilities do not explicitly inform our understanding of how best to deliver treatments or identify proactively the subgroups of patients for whom they are most (or least) effective.

The same limitation applies to psychological vulnerability factors that arise, for example, from exposure to adverse childhood experiences (e.g. sexual trauma, neglect, family conflict) which is not uncommon among UCPPS patients 47. Psychological vulnerability may increase likelihood of developing UCPPS as well as mental health (e.g., anxiety) and medical comorbidities (e.g., COPCs) but are stable, resistant to change, and provide little practical guidance for clinical decision making. In fact, attributing symptoms to a distal vulnerability factor like genetics or abuse may make it more difficult for patients and providers to understand what actionable factors currently drive symptoms long after symptom onset, what evidence-based behavioral treatments have analgesic properties, and how behavioral self-management treatments overcome the influence of vulnerability mechanisms or other external forces beyond one’s personal control to provide symptom relief.

What is CBT?

Because the influence of psychosocial factors increase as pain persists beyond 3 months 48, behavioral interventions that reverse the core components that drive symptom experience have potential therapeutic value. The psychosocial treatment for which there is most empirical support for chronic pain disorders is cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT). Current American Urological Association guidelines49 provide a general recommendation of “behavioral modification” strategies drawn from cognitive behavioral model of chronic disease management 50 as a first line approach “to improve symptoms and ….manage…flares” 51.

CBT combines strategies of two skills-based treatments: (1) behavior therapy teaches patients more effective ways of behaving through skill- and reinforcement-based strategies (2) cognitive therapy focuses on correcting faulty thinking patterns (such as catastrophizing pain beliefs which is the tendency to focus on and magnify pain sensation and to feel helpless in the face of pain52). CBT rests on an empirically validated model of behavior change that assumes that the way individuals think about an event influences their reactions and thereby maintains a problem. CBT also assumes that because individuals’ response to pain – their behaviors (overt actions as well as covert ones like thoughts), emotions, physiology -- is shaped by their learning history53, these responses can be changed -- or unlearned -- which, leads to symptom relief and improvement in functioning. The way patients interpret themselves, their future and the world around them (i.e. cognitions) has a particularly strong impact on health outcomes (e.g., painful symptoms, compliance with medical regimen, physical activity) 54.

This “cognitive appraisal” model has had a major impact on our understanding of how people perceive pain 29 55, who transitions from acute to chronic states 56, and who suffers more from their impacts 57. This review focuses on CBT as it applies to UCPPS because it is the most studied and empirically validated psychological treatments for chronic pain. 58.ii

What does CBT involve?

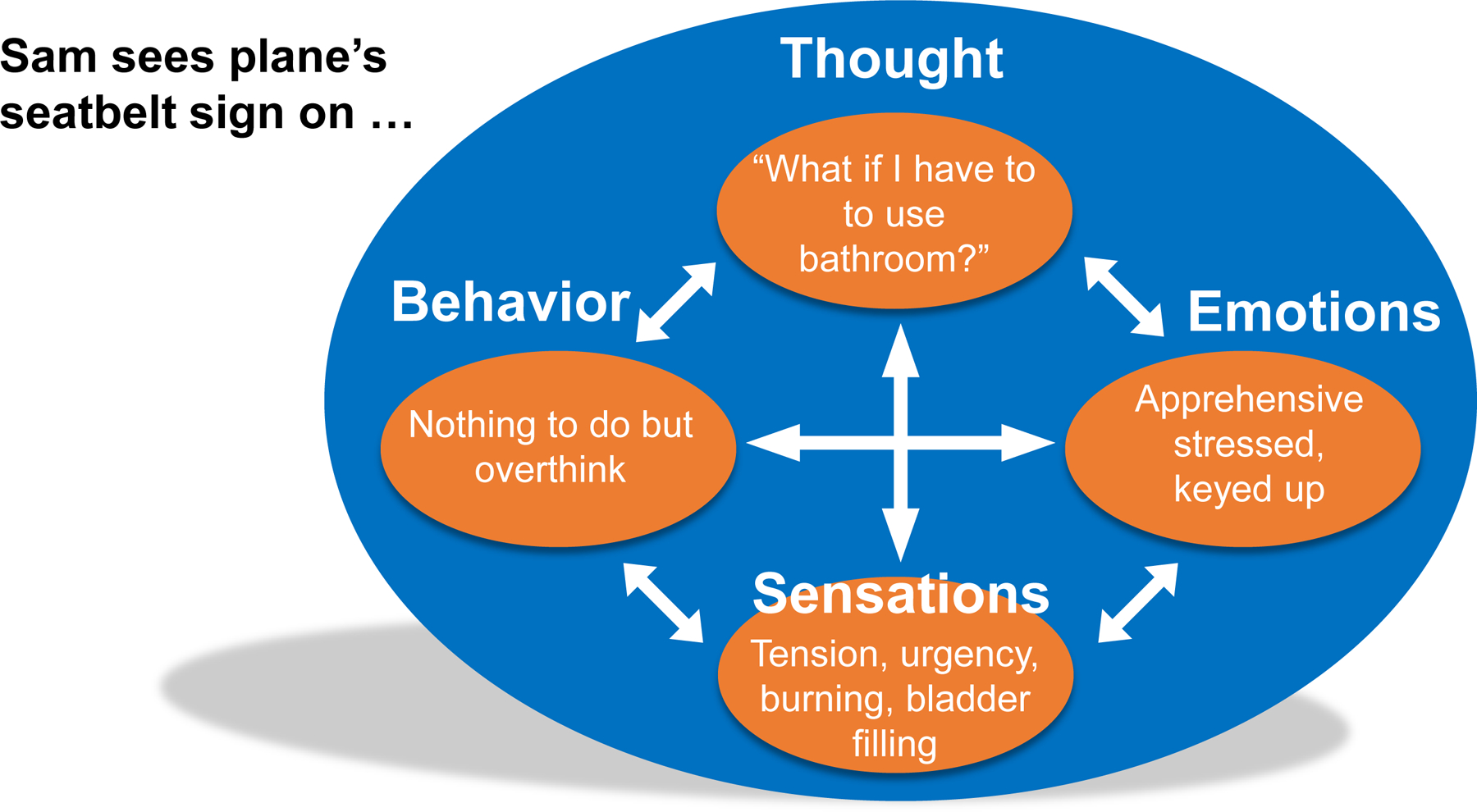

CBT aims to teach patients like Sam practical skills to break this chain of thoughts and feelings (emotions, bodily symptoms), and replace them with more useful patterns of thinking. CBT’s goal is not “positive thinking” or “mind over matter” but learning how to become more constructive in sizing up and responding to triggers with symptom-aggravating potential. CBT differs from traditional “talk therapy” in several ways. Rather than focusing on the root causes of a problem, CBT focuses on the cognitive and behavioral patterns that maintain symptoms. A focus on changing their maintaining mechanisms lends itself to UCPPS symptoms because their root cause is often unknown or when it is known (e.g., UTI, trauma) differs from actionable factors that perpetuate their severity. Another difference is that CBT is a learning-based treatment that teaches skills for controlling UCPPS symptoms much as a hypertensive patient learns behavioral strategies for lowering blood pressure (e.g., lowering salt intake, increasing physical activity).

CBT typically follows a standardized treatment manual and has structured or semi structured session content that is delivered like a course with a series of planned “lessons” for each session. Sessions are regularly scheduled (e.g., weekly, monthly) “classes” during which time a specific skill is introduced, practiced in session, and reinforced through regularly scheduled home practice to facilitate generalization to everyday situations much like an athlete learns and practices skills before game-time performance. Rather than a definitive set of techniques, CBT is an “umbrella” term that includes a set of strategies that share a common focus on “unlearning” the behaviors and thoughts that underlie symptom fluctuations. When combined into a cohesive treatment protocol, strategies typically proceed in three phases.

The first phase introduces the rationale for treatment, engages patient in treatment, and provides information and education about UCPPS with an introduction of the biopsychosocial model as an alternative to biomedical model for understanding long-term pelvic pain. Particular focus is on cognitive and behavioral factors that maintain symptoms long after pain progresses beyond an acute (0–6 month) phase when peripheral factors dominate.

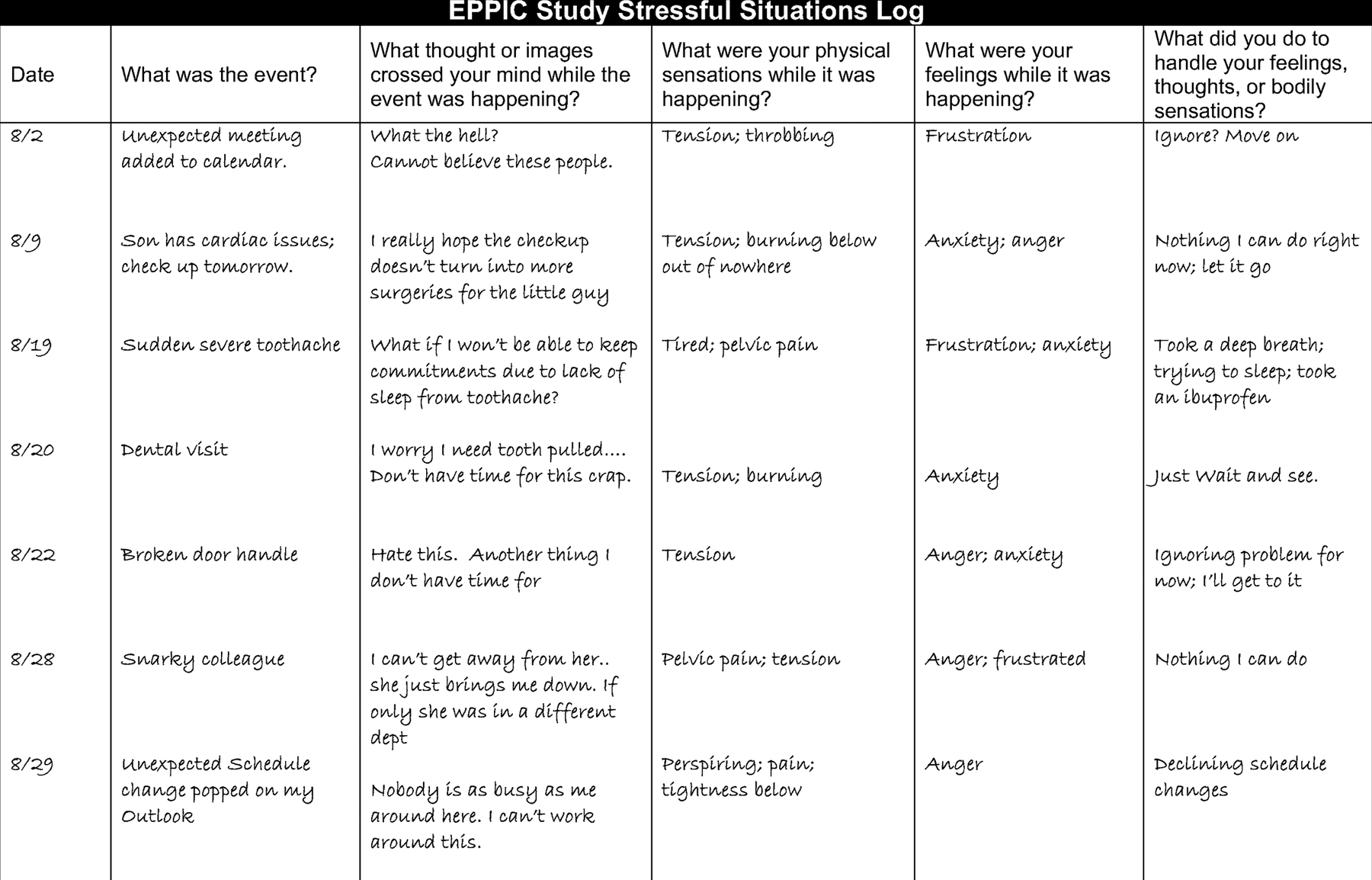

This approach is reinforced through real-time self-monitoring. Self-monitoring involves the ongoing, “in the moment” record keeping of important triggers and reactions to symptoms. Self-monitoring is a hallmark feature of CBT and essential to its success. CBT focuses on what a person is doing, feeling, and thinking in a specific situation that triggers symptoms. This focus reflects research showing that patients exhibit different behaviors in different situations and that problems do not always just “happen” or “come out of the blue” but are subject to situational factors. This means that if the goal is to change behavior, patients benefit from systematically assessing the environment where – and when and how -- the problem behavior occurs. In CBT for UCPPS, self-monitoring involves briefly tracking “chains” of externals triggers like work or family strain that cue symptoms as well as responses such as somatic sensations such as muscle tension, urinary symptoms, negative emotions, and associated thoughts). Patients are taught to complete monitoring forms as soon as possible as a problem event occurs. Real time monitoring is important to obtain accurate symptom data readings rather than relying on retrospective recall (e.g., end of day or week) data that are vulnerable to inaccuracy or distortion that comes with passage of time. An example of a self-monitoring sheet shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

A monitoring record showing the relationship between symptoms, triggers, and responses

With practice, patients learn how to become more objective observers of the often-predictable chain of internal (e.g., thoughts, emotions) and external (foods, stressors) cues that drive symptom flares. Self-monitoring promotes a critical understanding of patients’ automatic reactions and response habits which sets the stage for more advanced symptom self-management skills training in CBT’s second phase. Because the very act of self-monitoring increases awareness of the how symptoms unfold and the specific situational variables that influence them (reactivity)61, reactivity effects are particularly useful for UCPPS patients who describe “flare unpredictability” as a significant source of distress and life interference 62. This increased awareness can be self-reinforcing which offsets initial inconvenience of monitoring. This is reflected in the comments of one of our non-research patients after she completed her first week of monitoring.

“I definitely think tracking is very helpful! I found that I’m worrying a little bit less day-to-day than I was before I started tracking. Also stepping back and writing out my thoughts, triggers and reactions to things shows how one little worry quickly spirals out of control into big picture things, so I’m trying to stop the little worries sooner before things get out of control.”

For relaxation training, respiratory retraining is emphasized because it is an intuitive way of counteracting tension, easy to learn, and transferable to everyday life. Breathing retraining is based on the assumption that patients with stress-sensitive somatic complaints develop inefficient respiratory patterns (e.g., shallow chest breathing) which, if chronic, can intensify physiological arousal that aggravates physical sensations. Learning how to slow down respiration through diaphragmatic breathing dampens tension and elicits a sense of physical calm associated with increased parasympathetic tone. With home practice, an individual develops an extremely quick and portable tension-reduction strategy that they apply during their daily routine. A goal is for the person to use physical discomfort (pain, urgency) as a retrieval cue for activating a more effective coping response before tension escalates and aggravates UCPPS symptoms.

CBT’s second phase focuses on cognitive techniques designed to challenge and dispute biased thinking patterns that fuel symptoms. For many chronic pain patients, their thinking is characterized by a rigid “mindset” or cognitive style in the way they process information from their environment. They focus narrowly on potential threats (e.g., bodily harm) and interpret ambiguous (neutral) situations in a threatening way that overinflates the estimate of danger or harm of future events (thinking the worst: What if….?). When negative events occur, they focus on their costs or consequences without factoring in mitigating factors that reduce their impact (catastrophizing the meaning of a negative event and expressed as If only….) and help them bounce back quicker from setbacks. Because self-defeating thinking styles are learned (albeit incorrectly), CBT teaches patients to identify and treat biased thoughts as hypotheses to be tested and coaches them to generate more constructive ways of thinking by, for example, questioning the evidence to support or disconfirm thoughts. Patients learn to defuse worries about past events by learning distress tolerance skills that “reboots” uncomfortable internal reactions (e.g., separating the distress/discomfort a negative event (e.g., flare) elicits from its tolerability, gauging the usefulness of worries that do not generate a solution to an existing problem, “letting go” of reactions to situations over which s/he has no control. When individuals apply these thinking skills more objectively and systematically, stressors presumably evoke less intense reactions, and they can more effectively self-manage even more severe symptoms and optimize symptom-free periods.

Another skill CBT, flexible problem solving 63, aims to expand the range of coping skills for managing problems regardless of their controllability. Steps involved in flexible problem solving include appraising the controllability of a stressor then deploying a situationally appropriate coping response. For controllable stressors (e.g., a flat tire), the ideal response is active problem solving that aims to resolve a problem. For uncontrollable stressors (e.g., a loved one battling terminal cancer), the solution is emotion-focused coping responses that are geared toward managing the emotional unpleasantness of a stressor through cognitive reappraisal, enlisting support, muscle relaxation, etc. By deploying a situationally appropriate coping response based on an objective appraisal of stressor controllability (vs preference or habit), individuals learn to proactively dampen severity of stress-sensitive symptoms.

CBT’s second phase concludes by examining core beliefs that can aggravate symptoms. Core beliefs are firmly held rules or assumptions -- shaped by culture, childhood experiences, innate dispositions -- that inform how people see themselves and the world. Examples include perfectionism (e.g.: “I hate being less than the best at things”), need for approval (e.g.: “I must do well and get others’ approval or else am disappointed”), and illusion of control (e.g., “There is a solution for everything”). Whereas worries (“What if X ….?”, “If only Y …”) function as snapshots of how a patient sees the world at a given moment of time, core beliefs are the lens through which those snapshots are framed. When beliefs process incoming information in a biased, rigid way, they can aggravate stress-sensitive symptoms like pain. CBT teaches tools to identify and refute these beliefs, replacing them with more constructive strategies.

CBT’s third phase emphasizes relapse prevention skills for maintaining gains after treatment ends. This skill involves reviewing progress since starting treatment, with a focus on identifying the specific tools that the patient found most helpful. Patients are taught to identify warning signs (e.g., lack of control, work overload, conflict) and how they will deal with setbacks without returning to square one by treating them as learning opportunities for reestablishing progress made in treatment. Developing a personalized relapse management plan for “getting back on track” (self-monitoring, thought tracking, etc.) helps explain CBT’s track record of sustained treatment effects long after treatment ends 64. Specific CBT strategies for each phase are outlined in Table 1.

Table 1:

Components of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for UCPPS

|

Phase One: Psychoeducation and Behavioral Strategies 1. Psychoeducation (nature of UCPPS and its maintaining factors with focus on physiology, cognitions, behavior, treatment rationale, establish treatment goals, etc.) 2. Establish real-time self-monitoring. 3. Muscle relaxation (e.g., breathing retraining) 4. Home practice assignment Phase Two: Cognitive Strategies 1. Worry Control 2. Flexible problem solving 3. Challenging underlying core beliefs (e.g., perfectionism) 4. Home practice assignment Phase Three: Relapse Prevention 1. Review of progress tackling maintaining factors and planning for future. 2. Educating about risk of relapse, highlighting patient’s specific triggers for relapse (e.g., stress, diet), and importance of detecting problems early on 3. Specific plan for lapse and relapse scenarios 4. Home practice assignments |

Engaging the patient

While all UCPPS patients can benefit from support and encouragement to take an active role in their own care, providers may find the following patient characteristics a useful guide for identifying those patients that may benefit from targeted behavioral pain treatments.

Persistent UCPPS symptom without adequate symptom relief beyond 3 months of onset

Preference for a non-drug option

Moderate to severe symptoms that persist beyond 3 months, are distressing and interfere with function or well-being.

Illness behaviors (e.g., reassurance-seeking, request for additional diagnostic testing)

Symptom onset corresponds with major life stressors (e.g., a loss, transition from high school to college, relationship breakup, etc.).

Patients who recognize that managing the day-to-day UCPPS symptom burden is beyond the scope of treatment regimen.

Symptoms is a source of distress (anxiety, depressed mood, frustration, helplessness, worry) but the provider should not wait for distress to escalate to triage patient for behavioral support at which point they become more challenging and intractable.

Presence of non-urogenital symptoms including widespread pain (e.g., IBS, chronic fatigue, low back pain) suggestive of a centralized phenotype (even when urogenital pain is the focus of a clinical examination).

The following professional organizations have directories or locators on their websites for professionals (psychologist, clinical social workers, etc.) with experience delivering behavioral pain treatments:

American Psychological Association

Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies

Society for Behavioral Medicine

International Association for the Study of Pain

Psychology Today

Society of Clinical Psychology

Patients with major cognitive deficits due to brain trauma or organic pathophysiology are unlikely to be good candidates because they may struggle with the cognitive demands of a learning-based treatment like CBT at least without significant remediation. Patients with severe mental health symptoms may have difficulty with adherence and attendance until they are sufficiently stabilized and should be referred for such treatment before beginning a course of pain-focused CBT. CBT has a strong “intrapersonal” focus in that it targets patients’ thoughts and behaviors that aggravate symptoms in relative isolation of others in their social network (e.g. family members). Patients whose symptoms fluctuate with interpersonal stressors (e.g., marital discord, parental conflict) may require a more interpersonal focus that involves family member to optimize treatment gains. This is an unexplored empirical question.

Of course, one challenge is communicating a persuasive rationale that prompts patients to act on a referral for behavioral treatment without making them feel dismissed or frustrated. In our clinical and research work, we have developed a script to help physicians make a compelling case for why a medical doctor makes a referral to a behavioral medicine provider for a physical problem like chronic pelvic pain. An important part of the message is to validate the legitimacy of the patient’s symptoms without conveying a sense that they are imagined or a psychiatric problem or that the provider does not care. Framing the referral as a normative part of managing any chronic disease is intuitive to many patients and critical to “taking the referral baton” that empowers them to take control over symptoms where medical treatments fall short. It is also helpful for patients to know that they are referred to learn skills not to “have their head shrunk.” By describing symptoms as part of a chronic pain problem, the provider is giving a specific positive diagnosis (e.g., chronic pelvic pain) that is far more useful than telling patients what they don’t have (e.g., evidence of physical pathology that explains severity of symptoms). This recommendation echoes research showing that patients understand the difficulty and ambiguity in treating chronic pain but want an explanation for their symptoms65. This can be the basis for more fully engaging patient in a self-management approach.

Clinical Practice Considerations

A practical consideration concerns insurance reimbursement. As empirical support for behavioral treatments for pain has increased 66, barriers to fiscal authorization among carriers has decreased and health care insurance routinely covers CBT. Further, the Affordable Care Act mandates that health care companies cover mental health conditions on par with coverage for medical or surgical procedures, removing another barrier to coverage. The parity law also covers non-financial treatment limits. For instance, limits on the number of mental health visits allowed in a year were once common. The law has essentially eliminated such annual limits. However, it does not prohibit the insurance company from implementing limits related to “medical necessity” and this is something that the referring physician may need to add to referral letter. Individual plans and coverage vary depending on carriers and the patient may need to contact their provider for more detailed information. As an evidence-based treatment, CBT is covered by Medicare and Medicaid. Information on providers who accept Medicaid and Medicare can be obtained through the U. S Department of Health and Human Services webpage that provides links to various resources and information regarding providers who accept these types of insurance.

Billing Codes for CBT and ICD-11 for chronic pelvic pain

Pertinent CPT codes for CBT include 90832: Psychotherapy, 30 minutes; 90834: Psychotherapy, 45 minutes; 90837, Psychotherapy, 60 minutes. Relevant ICD-10 diagnostic codes include Pain disorder associated with both psychological factors and a general medical condition (F45.42) and appropriate secondary code (e.g., N30.10 for interstitial cystitis (chronic) without hematuria).

The new ICD classification system (ICD-1167) was developed to standardize the collection and reporting of health data 65 in better harmonization with what is known about pain conditions like UCPPS than ICD-10. Details regarding ICD-11 are beyond the scope of this review but can be found elsewhere including an informative webinar developed by the World Health Organization and the International Association for the Study of Pain68. ICD-11 features a multiaxial classification system that bifurcates chronic pain into chronic primary pain69 (i.e. disorders for which pain is a problem in its own right as, for example, fibromyalgia, chronic headaches, chronic pelvic pain) as well as chronic secondary pain for pain that is secondary to an underlying disease (e.g., inflammatory bowel disease, arthritis) but whose severity is discordant with disease severity and therefore requires multimodal treatments that targets biobehavioral drivers of pain 70. ICD-11 emphasizes a cut off time of longer than three months to define chronic primary pain. Because etiology is unknown for many chronic pain disorders (e.g., UCPPS and co-morbid COPCs), ICD-11 adopts an “agnostic” 71 approach to the underlying physical pathology of persistent pain not better explained by another painful medical condition. For the medical provider, this means that the defining issue for establishing chronic primary pain is the duration of pain and its impact on the patient in terms of distress (e.g., anxiety, depression, frustration) and functional disability (interference in ADLs, role limitations).

The designation of primary and secondary pain is not mutually exclusive (i.e., they can coexist in the same patient). ICD-11 also includes optional descriptors that capture pain intensity, pain-related distress and interference, as well as factors that contribute to pain (e.g., psychosocial factors 72). The rationale for the new classification system is that by promoting the notion that chronic pain is a problem in its own right with pathological changes and its set of clinical and behavioral characteristics, patients and their providers will disband (and unhelpful) anachronistic notions that pain is either “real”, medically explained and physical or “not real”, inexplicable and mental in nature and move away from the search for an elusive biomedical explanation/”fix” towards multimodal treatments 73and clinical practices that are more patient-centered, efficient, and firmly grounded in contemporary (i.e. biopsychosocial) understanding of chronic pain conditions like UCPPS and their “most helpful” 72 treatments (e.g., self-management therapies).

Future Directions

Empirical support for CBT as a self-management treatment for chronic pain is based on well over 20 systematic reviews58. Meta-analyses generally conclude that CBT improves pain, wellbeing, and ability to perform daily activities when compared to usual care. Evidence supporting CBT vs an active control is strongest for COPCs (IBS74, headache75) that frequently co-occur with UCPPS. The efficacy profile of CBT is less fully developed for UCPPS in part because RCTs have focused on specific disorders within the syndrome. 76, 77 To the extent that CBT relieves UCPPS symptoms, it is important to know which symptoms are most responsive. Pelvic pain/discomfort? Urinary frequency? Urgency? Nonurogenital symptoms? How do symptom changes compare to improvement in other clinically relevant outcomes (e.g., distress, disability, quality of life) used to gauge the efficacy profile of pelvic pain treatments? One may expect that psychological treatments have a stronger impact on psychological outcomes but in our research with other centralized pain disorders behavioral treatments are consistently more effective at reducing target pain complaint than comorbid depression or anxiety 78. It is unclear whether this pattern extends to behaviorally treated chronic pelvic pain patients. RCTs with UCPPS patients have not included all genders and have tended to focus on specific diagnoses within UCPPS complex (IC/BPS or CP/CPPS). There is a need for studying a “transdiagnostic” (across disorder) version of CBT that effectively treats all diagnoses within UCPPS complex as well as those that co-aggregate and influence UCPPS severity (e.g., IBS, headache, anxiety etc.). Because transdiagnostic interventions target shared processes underlying mechanistically related disorders, they emphasize symptom-driving commonalties across different disorders rather than their relatively superficial symptomatic or diagnostic differences (pain location in patients with IC/BPS vs CP/CPPS). Emphasizing a common set of therapeutic procedures effective for a class of mechanistically similar (e.g., nociplastic) disorders (UCPPS and others COPCs) could improve real-world applicability of treatment protocols by reducing their complexity, cost, and training demands of community-based practitioners and create opportunities for integrated care in clinical settings where UCPPS patients are seen (primary care, urology clinics).

This is the focus of the Easing Pelvic Pain Interventions Clinical Research Program (EPPIC). EPPIC, a landmark NIH trial led by the University at Buffalo in partnership with the University of Michigan and UCLA, examines the efficacy of a very brief regimen of CBT for UCPPS and its durability 3- and 6-months post treatment79 relative to a credible nonspecific comparator that emphasizes AUA self-care guidelines 51 (e.g., stress, diet modification) and accounts for the generic effects of simply entering treatment. Additional aims include characterizing the operative processes, so called mediators, that drive CBT-induced UCPPS symptom relief and pre-treatment patient variables that moderate or predict differential treatment response. In an era of personalized medicine80 that recognizes that individuals respond differently to treatments (many of which are, on average, equally effective), and that these differences can be studied and characterized81, research on treatment “moderators” is needed to inform providers, payers, and policy makers about treatments tailored to the specific needs and characteristics of UCPPS patients to optimize their efficacy profile. In this respect, lessons learned from EPPIC have implications for strengthening the quality of clinical trials for urological disorders beyond UCPPS and reducing their public health impact.

Supplementary Material

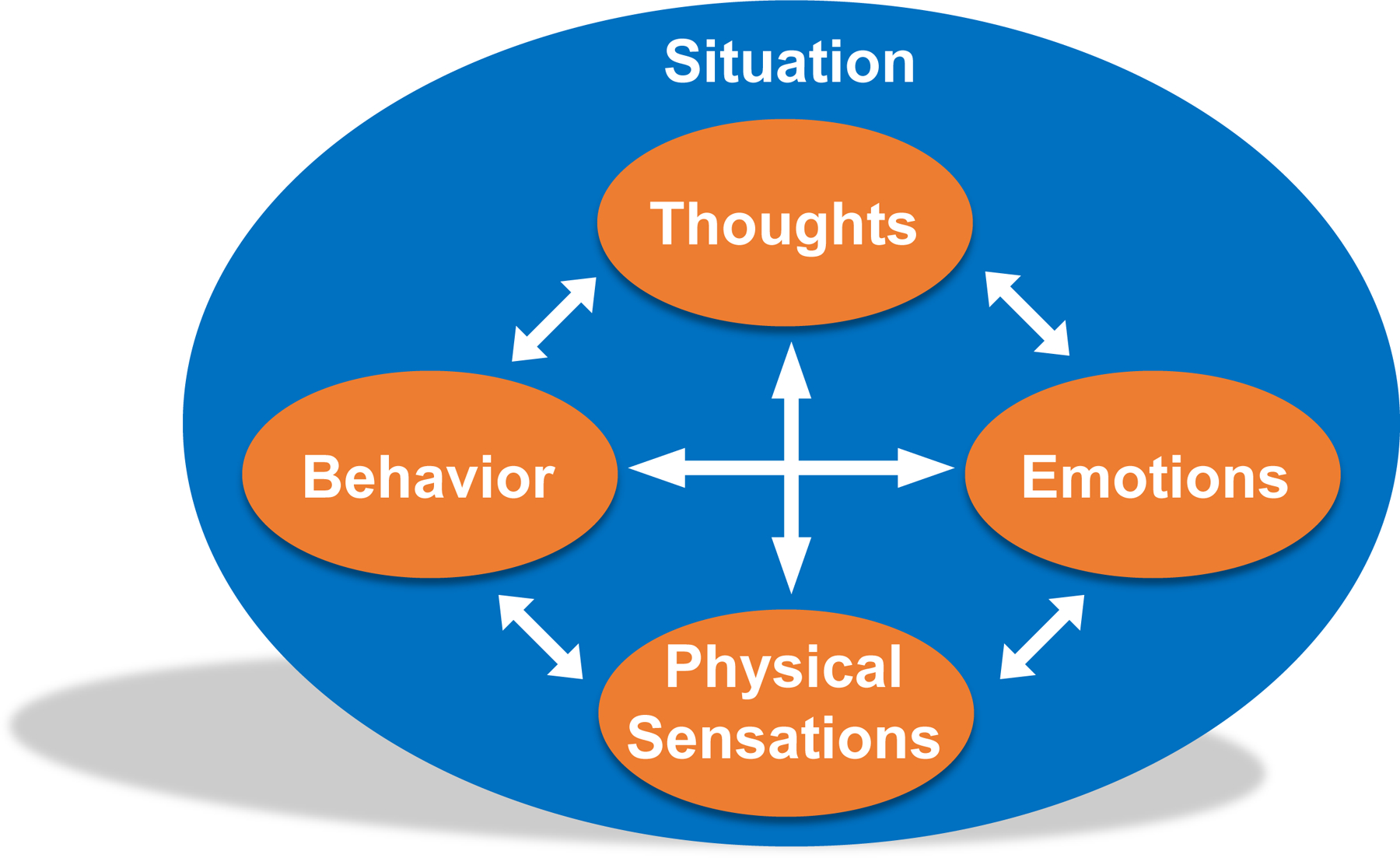

Figure 3.

Biobehavioral Factors are Interconnected in CBT

Figure 4.

Biobehavioral Factors are Interconnected in CBT for UCPPS

The reciprocal relationship among pelvic pain, thought, and emotion: A case example.

CBT does not regard cognitions (thoughts) and emotions as background noise to presenting symptoms but interconnected (Figure 3) in a way that that fuels their severity. Consider Sam, a 42-year-old IC female, who is buckled in the middle seat on a cross-country flight waiting for takeoff (Figure 4). As she raises her head from her iPad, Sam notices the lit seatbelt sign (situation) and immediately thinks that she will need to use the bathroom before the sign turns off. This thought triggers a cascade of anxious – and unhelpful -- worries (thought) each more catastrophic than the previous: waiting will trigger an unbearable flare, if not an accident, the embarrassment (emotion) that will ensue inf front of two strangers sitting next to her, uncertainty (thought) about whether she packed extra pair of underwear in her carry-on, and if not, the tortuous walk to baggage claim. As her mind races, anxiety (emotion) heightens as do feelings of urgency, bladder fullness, burning, and muscle tension (bodily symptoms). Gripping the arm rests, all she can think about is a desire to use the bathroom-- but she can’t and it’s eating away at her.

Optimizing the goals of managing persistent pelvic pain and other chronic urological diseases depends on patients’ ability to self-manage treatment refractory symptoms by learning specific skills. For guidance on practical strategies to motivate patients to facilitate behavior changes chronic disease management requires, please see supplemental file.

As you know, we are dealing with a challenging chronic pain problem. Unlike acute pain that is short lived, chronic pelvic pain lasts long after the body has had a chance to heal from physical injury caused by infection, trauma, etc. There is no simple cure or fix for chronic pelvic pain. This is hard to accept but I owe it to you to be straightforward and help map out a plan for getting better. Like other chronic conditions like high blood pressure or diabetes, multiple factors influence pelvic pain. Some factors I can help you with through medications or procedures. As effective as they are for some patients, they oftentimes aren’t enough for others. This is where you come in. I will need you to learn how to play a more active role in taking control of some aspects of pain beyond the reach of what I can offer. I would like you to work with specialists at the Behavioral Medicine Clinic who will teach you practical skills for learning how to work around pain to improve the quality of life, function at your best, and live more comfortably. I am not asking you to consult with these specialists because I think pelvic pain is “in your head” or that it is “not real”. I want you to follow up with them because I care for my patients. I want to see that you get the best care possible based on what science tells us works best for patients with pain problems like yours. You know yourself better than anyone. If you feel that you are managing things just fine, there is no reason for us to consult with these pain specialists. But if you find that that pelvic pain is taking a toll, please make an appointment to get the help you deserve.

Acknowledgement.

This manuscript was supported by the NIH/NIDDK DK096606. Clinical examples were generously provided by EPPIC study volunteers whose identities are protected to preserve their privacy. We thank the Chronic Pain Research Alliance for granting permission to use the image in Figure 1. We thank Stephanie Cummings of WNY Urology Associates and Kate Gard of UBMD Behavioral Medicine for their support.

Abbreviations:

- CBT

cognitive behavioral therapy

- UCPPS

urologic chronic pelvic pain syndrome

- COPC

chronic overlapping pain conditions

- AUA

American Urological Association

- ITT

intent to treat

- IC

interstitial cystitis

- BPS

bladder pain syndrome

- CP

chronic prostatitis

- CPP

chronic pelvic pain syndrome

- RCT

randomized clinical trial

- UTI

urinary tract infection

- MAPP

Multidisciplinary Approach to the Study of Chronic Pelvic Pain

- ICD

International Classification of Diseases

- ADL

activities of daily living

Footnotes

The nociplastic pain term is the pain phenotype previously known as centralized pain or central sensitization.

This reviews focus on CBT is not to dismiss the clinical utility of alternative approaches (e.g., acceptance and commitment, mindfulness, exposure-based therapies) but the literature supporting their efficacy is not sufficiently developed to make evidence-based conclusions for clinical urologists, urogynecologists and other providers 58. Williams, A. C. C., Fisher, E., Hearn, L., Eccleston, C.: Psychological therapies for the management of chronic pain (excluding headache) in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 8: Cd007407, 2020. We have chosen not to include behavioral treatments based on operant conditioning principles by which patients receive rewards for pain-incompatible behaviors such as physical activity as opposed to pain behaviors (moaning, medication, limping) 59. Gatzounis, R., Schrooten, M., Crombez, G., Vlaeyen, J.: Operant Learning Theory in Pain and Chronic Pain Rehabilitation. Curr Pain Headache Report, 16, 2012. These treatments have no empirical advantage over cognitive behavioral approaches and little, if any, analgesic properties60. Eccleston, C., Morley, S. J., Williams, A. C.: Psychological approaches to chronic pain management: evidence and challenges. Br J Anaesth, 111: 59, 2013.

References

- 1.Berry SH, Elliott MN, Suttorp M et al. : Prevalence of symptoms of bladder pain syndrome/interstitial cystitis among adult females in the United States. J Urol, 186: 540, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Link CL, Pulliam SJ, Hanno PM et al. : Prevalence and psychosocial correlates of symptoms suggestive of painful bladder syndrome: results from the Boston area community health survey. J Urol, 180: 599, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Suskind AM, Berry SH, Ewing BA et al. : The prevalence and overlap of interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome and chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome in men: results of the RAND Interstitial Cystitis Epidemiology male study. J Urol, 189: 141, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mullins C, Bavendam T, Kirkali Z, Kusek JW: Novel research approaches for interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome: thinking beyond the bladder. Translational Andrology and Urology, 4: 524, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Latthe P, Latthe M, Say L et al. : WHO systematic review of prevalence of chronic pelvic pain: a neglected reproductive health morbidity. BMC public health, 6: 177, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matheis A, Martens U, Kruse J, Enck P: Irritable bowel syndrome and chronic pelvic pain: a singular or two different clinical syndrome? World J Gastroenterol, 13: 3446, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mathias SD, Kuppermann M, Liberman RF et al. : Chronic pelvic pain: prevalence, health-related quality of life, and economic correlates. Obstet Gynecol, 87: 321, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clemens JQ, Mullins C, Kusek JW et al. : The MAPP research network: a novel study of urologic chronic pelvic pain syndromes. BMC Urol, 14: 57, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hutton D, Mustafa A, Patil S et al. : The burden of Chronic Pelvic Pain (CPP): Costs and quality of life of women and men with CPP treated in outpatient referral centers. PLOS ONE, 18: e0269828, 2023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Savidge CJ, Slade P, Stewart P, Li TC: Women’s Perspectives on their Experiences of Chronic Pelvic Pain and Medical Care. J Health Psychol, 3: 103, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McGowan L, Luker K, Creed F, Chew-Graham CA: How do you explain a pain that can’t be seen?: the narratives of women with chronic pelvic pain and their disengagement with the diagnostic cycle. Br J Health Psychol, 12: 261, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Turner JA, Ciol MA, Von Korff M, Berger R: Health Concerns of Patients With Nonbacterial Prostatitis/Pelvic Pain. JAMA Internal Medicine, 165: 1054, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maixner W, Fillingim RB, Williams DA et al. : Overlapping Chronic Pain Conditions: Implications for Diagnosis and Classification. The Journal of Pain, 17: T93, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fitzcharles MA, Cohen SP, Clauw DJ et al. : Nociplastic pain: towards an understanding of prevalent pain conditions. Lancet, 397: 2098, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Warren JW, Wesselmann U, Morozov V, Langenberg PW: Numbers and types of nonbladder syndromes as risk factors for interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome. Urology, 77: 313, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leue C, Kruimel J, Vrijens D et al. : Functional urological disorders: a sensitized defence response in the bladder–gut–brain axis. Nature Reviews Urology, 14: 153, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Till SR, As-Sanie S, Schrepf A: Psychology of Chronic Pelvic Pain: Prevalence, Neurobiological Vulnerabilities, and Treatment. Clin Obstet Gynecol, 62: 22, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Temml C, Brossner C, Schatzl G et al. : The natural history of lower urinary tract symptoms over five years. Eur Urol, 43: 374, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nickel JC, Teichman JM, Gregoire M et al. : Prevalence, diagnosis, characterization, and treatment of prostatitis, interstitial cystitis, and epididymitis in outpatient urological practice: the Canadian PIE Study. Urology, 66: 935, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clemens JQ, Brown SO, Calhoun EA: Mental health diagnoses in patients with interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome and chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome: a case/control study. J Urol, 180: 1378, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McKernan LC, Walsh CG, Reynolds WS et al. : Psychosocial co-morbidities in Interstitial Cystitis/Bladder Pain syndrome (IC/BPS): A systematic review. Neurourol Urodyn, 37: 926, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Egan KJ, Krieger JN: Psychological problems in chronic prostatitis patients with pain. Clin J Pain, 10: 218, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Naliboff BD, Stephens AJ, Afari N et al. : Widespread Psychosocial Difficulties in Men and Women With Urologic Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndromes: Case-control Findings From the Multidisciplinary Approach to the Study of Chronic Pelvic Pain Research Network. Urology, 85: 1319, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lai HH, Jemielita T, Sutcliffe S et al. : Characterization of Whole Body Pain in Urological Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome at Baseline: A MAPP Research Network Study. J Urol, 198: 622, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Müller H: Neuroplasticity and chronic pain. Anasthesiologie, Intensivmedizin, Notfallmedizin, Schmerztherapie: AINS, 35: 274, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vachon-Presseau E, Tétreault P, Petre B et al. : Corticolimbic anatomical characteristics predetermine risk for chronic pain. Brain, 139: 1958, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mercer Lindsay N, Chen C, Gilam G et al. : Brain circuits for pain and its treatment. Sci Transl Med, 13: eabj7360, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kuner R, Flor H: Structural plasticity and reorganisation in chronic pain. Nat Rev Neurosci, 18: 20, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bushnell MC, Ceko M, Low LA: Cognitive and emotional control of pain and its disruption in chronic pain. Nature reviews. Neuroscience, 14: 502, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Borsook D, Youssef AM, Simons L et al. : When pain gets stuck: the evolution of pain chronification and treatment resistance. Pain, 159: 2421, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Solberg L, Roach AR, Carlson CR et al. : Self-Regulation, Executive Functions, and Chronic Pain. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 39: S45, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Woolf CJ: Central sensitization: implications for the diagnosis and treatment of pain. Pain, 152: S2, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.International Association for the Study of Pain: IASP terminology. Pain Terms, 19: 2019, 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Naliboff BD, Stephens AJ, Lai HH et al. : Clinical and Psychosocial Predictors of Urological Chronic Pelvic Pain Symptom Change in 1 Year: A Prospective Study from the MAPP Research Network. J Urol, 198: 848, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Naliboff BD, Schrepf AD, Stephens-Shields AJ et al. : Temporal Relationships between Pain, Mood and Urinary Symptoms in Urological Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome: A MAPP Network Study. J Urol, 205: 1698, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Villemure C, Bushnell MC: Cognitive modulation of pain: how do attention and emotion influence pain processing? Pain, 95: 195, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhao Y, Lin J, Dong Y et al. : Neuroimaging Studies of Chronic Prostatitis/Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome. Pain Res Manag, 2022: 9448620, 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gupta A, Mayer EA, Acosta JR et al. : Early adverse life events are associated with altered brain network architecture in a sex- dependent manner. Neurobiol Stress, 7: 16, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kutch JJ, Labus JS, Harris RE et al. : Resting-state functional connectivity predicts longitudinal pain symptom change in urologic chronic pelvic pain syndrome: a MAPP network study. Pain, 158: 1069, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Raja SN, Carr DB, Cohen M et al. : The revised International Association for the Study of Pain definition of pain: concepts, challenges, and compromises. PAIN, 161: 1976, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dimitrakov J, Guthrie D: Genetics and phenotyping of urological chronic pelvic pain syndrome. J Urol, 181: 1550, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tunitsky E, Barber MD, Jeppson PC et al. : Bladder pain syndrome/interstitial cystitis in twin sisters. J Urol, 187: 148, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Warren JW, Keay SK, Meyers D, Xu J: Concordance of interstitial cystitis in monozygotic and dizygotic twin pairs. Urology, 57: 22, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Altman D, Lundholm C, Milsom I et al. : The genetic and environmental contribution to the occurrence of bladder pain syndrome: an empirical approach in a nationwide population sample. Eur Urol, 59: 280, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gasperi M, Krieger JN, Panizzon MS et al. : Genetic and Environmental Influences on Urinary Conditions in Men: A Classical Twin Study. Urology, 129: 54, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Goubert L, Vlaeyen JWS, Crombez G, Craig KD: Learning About Pain From Others: An Observational Learning Account. The Journal of Pain, 12: 167, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schrepf A, Naliboff B, Williams DA et al. : Adverse Childhood Experiences and Symptoms of Urologic Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome: A Multidisciplinary Approach to the Study of Chronic Pelvic Pain Research Network Study. Ann Behav Med, 52: 865, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chapman CR, Stillman M: Pathological Pain. In: Handbook of Perception: Pain and Touch Edited by Krueger L. New York: Academic Press, pp. 315 – 340, 1996 [Google Scholar]

- 49.Allegrante JP, Wells MT, Peterson JC: Interventions to Support Behavioral Self-Management of Chronic Diseases. Annu Rev Public Health, 40: 127, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fisher EB, Fitzgibbon ML, Glasgow RE et al. : Behavior Matters. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 40: e15, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Clemens JQ, Erickson DR, Varela NP, Lai HH: Diagnosis and Treatment of Interstitial Cystitis/Bladder Pain Syndrome. J Urol, 208: 34, 2022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sullivan M, Thorn B, Haythornthwaite JA et al. : Theoretical perspectives on the relation between catastrophizing and pain. Clin J Pain, 17: 52, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Edwards RR, Dworkin RH, Sullivan MD et al. : The Role of Psychosocial Processes in the Development and Maintenance of Chronic Pain. J Pain, 17: T70, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Turk DC: Understanding pain sufferers: the role of cognitive processes. Spine J, 4: 1, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wiech K: Deconstructing the sensation of pain: The influence of cognitive processes on pain perception. Science, 354: 584, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Young Casey C, Greenberg MA, Nicassio PM et al. : Transition from acute to chronic pain and disability: A model including cognitive, affective, and trauma factors. Pain, 134: 69, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Petrini L, Arendt-Nielsen L: Understanding Pain Catastrophizing: Putting Pieces Together. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Williams ACC, Fisher E, Hearn L, Eccleston C: Psychological therapies for the management of chronic pain (excluding headache) in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 8: Cd007407, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gatzounis R, Schrooten M, Crombez G, Vlaeyen J: Operant Learning Theory in Pain and Chronic Pain Rehabilitation. Curr Pain Headache Report, 16, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Eccleston C, Morley SJ, Williams AC: Psychological approaches to chronic pain management: evidence and challenges. Br J Anaesth, 111: 59, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Korotitsch WJ, Nelson-Gray RO: An overview of self-monitoring research in assessment and treatment. Psychological Assessment, 11: 415, 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 62.Clemens JQ, Mullins C, Ackerman AL et al. : Urologic chronic pelvic pain syndrome: insights from the MAPP Research Network. Nat Rev Urol, 16: 187, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Radziwon C, Lackner JM: Coping Flexibility, GI Symptoms, and Functional GI Disorders: How Translational Behavioral Medicine Research Can Inform GI Practice. Clin Transl Gastroenterol, 6: e117, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lackner JM, Jaccard J, Radziwon CD et al. : Durability and Decay of Treatment Benefit of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Irritable Bowel Syndrome: 12-Month Follow-Up. Am J Gastroenterol, 114: 330, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kang Y, Trewern L, Jackman J et al. : Chronic pain: definitions and diagnosis. BMJ: e076036, 2023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Integration of behavioral and relaxation approaches into the treatment of chronic pain and insomnia. NIH Technology Assessment Panel on Integration of Behavioral and Relaxation Approaches into the Treatment of Chronic Pain and Insomnia. Jama, 276: 313, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.World Health Organization: International Classification of Diseases (ICD) n.d, [Google Scholar]

- 68.Korwiski B, International Association for the Study of Pain: Introduction to ICD-11’s chronic pain classification. In: Unlocking the potential of ICD-11 for chronic pain: World Health Organization, 2023 [Google Scholar]

- 69.Treede RD, Rief W, Barke A et al. : Chronic pain as a symptom or a disease: the IASP Classification of Chronic Pain for the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11). Pain, 160: 19, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Aziz Q, Giamberardino MA, Barke A et al. : The IASP classification of chronic pain for ICD-11: chronic secondary visceral pain. Pain, 160: 69, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ballantyne JC, Sullivan MD: Is Chronic Pain a Disease? The Journal of Pain, 23: 1651, 2022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Nicholas M, Vlaeyen JWS, Rief W et al. : The IASP classification of chronic pain for ICD-11: chronic primary pain. Pain, 160: 28, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Toye F, Seers K, Allcock N et al. : Patients’ experiences of chronic non-malignant musculoskeletal pain: a qualitative systematic review. Br J Gen Pract, 63: e829, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lackner JM, Jaccard J, Keefer L: Improvement in gastrointestinal symptoms after cognitive behavior therapy for refractory irritable bowel syndrome (vol 155, pg 47, 2018). Gastroenterology, 155: 1281, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Holroyd KA, O’Donnell FJ, Stensland M et al. : Management of chronic tension-type headache with tricyclic antidepressant medication, stress management therapy, and their combination: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA, 285: 2208, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Nickel JC, Mullins C, Tripp DA: Development of an evidence-based cognitive behavioral treatment program for men with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. World J Urol, 26: 167, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Urits I, Callan J, Moore WC et al. : Cognitive behavioral therapy for the treatment of chronic pelvic pain. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol, 34: 409, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lackner JM, Morley S, Mesmer C et al. : Psychological treatments for irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Consult Clin Psychol, 72: 1100, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lackner JM, Jaccard J, Quigley BM et al. : Study protocol and methods for Easing Pelvic Pain Interventions Clinical Research Program (EPPIC): a randomized clinical trial of brief, low-intensity, transdiagnostic cognitive behavioral therapy vs education/support for urologic chronic pelvic pain syndrome (UCPPS). Trials, 23: 651, 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hamburg MA, Collins FS: The path to personalized medicine. N Engl J Med, 363: 301, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lackner JM, Jaccard J, IBS Outcome Study Research Group: Factors Associated With Efficacy of Cognitive Behavior Therapy vs Education for Patients With Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol, 17: 1500, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.