Abstract

Lipids are biological molecules that play vital roles in all living organisms. They perform many cellular functions, such as 1) forming cellular and subcellular membranes, 2) storing and using energy, and 3) serving as chemical messengers during intra‐ and inter‐cellular signal transduction. The large‐scale study of the pathways and networks of cellular lipids in biological systems is called “lipidomics” and is one of the fastest‐growing omics technologies of the last two decades. With state‐of‐the‐art mass spectrometry instrumentation and sophisticated data handling, clinical studies show how human lipid composition changes in health and disease, thereby making it a valuable medium to collect for clinical applications, such as disease diagnostics, therapeutic decision‐making, and drug development. This review gives a comprehensive overview of current workflows used in clinical research, from sample collection and preparation to data and clinical interpretations. This is followed by an appraisal of applications in 2022 and a perspective on the exciting future of clinical lipidomics.

Abbreviations

- ACSL4

Acyl‐CoA synthetase long‐chain family member 4

- AIDS

Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

- AIF

All‐ion fragmentation

- COVID‐19

Coronavirus disease 2019

- CVD

Cardiovascular disease

- DDA

Data‐dependent acquisition

- DI

Direct infusion

- DIA

Data‐independent acquisition

- ESI

Electrospray ionisation

- FA

Fatty acyls

- FAB

Fast atom bombardment

- FID

Flame ionisation detector

- FWHM

Full‐width at half maximum

- GC

Gas chromatography

- GC‐MS

Gas chromatography‐mass spectrometry

- GL

Glycerolipids

- GP

Glycerophospholipids

- HILIC

Hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography

- HIV

Human immunodeficiency virus

- HRMS

High‐resolution mass spectrometry

- ICPerMed

International Consortium for Personalised Medicine

- (IFN)γ

Interferon gamma

- IMS

Ion mobility spectrometry

- IRI

Irinotecan

- LC

Liquid chromatography

- LC‐MS

Liquid chromatography‐mass spectrometry

- LIPID MAPS

Lipid Metabolites and Pathways Strategy

- LMSD

LIPID MAPS Structure Database

- LRMS

Low‐resolution mass spectrometry

- LTEC

Long‐term elite controller

- MEPS

Micro‐extraction by packed sorbent

- MetS

Metabolic syndrome

- MRM

Multiple reaction monitoring

- MS

Mass spectrometry

- NAFLD

Non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease

- NMR

Nuclear magnetic resonance

- NPLC

Normal‐phase liquid chromatography

- OPLS‐DA

Orthogonal projection to latent structure discriminant analysis

- PBMC

Peripheral blood mononuclear cell

- PC

Lysophosphatidylcholines

- PCA

Principal component analysis

- PE

Lysophosphatidylethanolamines

- PI

Phosphatidylinositols

- PK

Polyketides

- PKCβII

Protein kinase C βII

- PLS‐DA

Partial least squares discriminant analysis

- PR

Prenol lipids

- PRM

Parallel reaction monitoring

- RPLC

Reversed‐phase liquid chromatography

- SARS‐CoV‐2

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

- SL

Saccharolipids

- SP

Sphingolipids

- SPE

Solid‐phase extraction

- SRM

Selected reaction monitoring

- ST

Sterol lipids

- SWATH

Sequential window of all theoretical fragment‐ion spectra

- T2D

Type 2 diabetes

- TB

Tuberculosis

- TSA

Tuberculostearic acid

- WHO

World Health Organisation

1. INTRODUCTION

Lipids are dynamic, ubiquitous molecules that play vital roles across all biological systems. They perform the following essential functions within cells: energy storage and metabolism, building blocks of cellular and subcellular membranes and intra‐ and inter‐cellular signalling. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 Mammalian cells express tens to hundreds of thousands of different lipid species. 5 , 6 Endogenous and exogenous factors, such as age, diet, disease, genetics, and environment can influence lipid composition or expression, which means as molecules, they present unique signatures of invaluable information regarding cellular status that is of high interest for the wider scientific community. 4

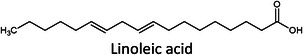

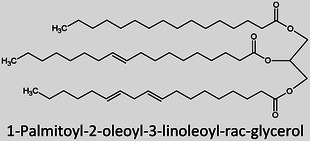

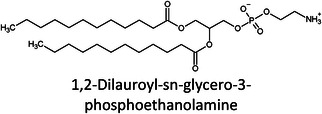

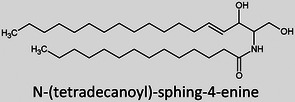

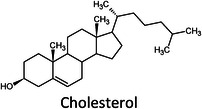

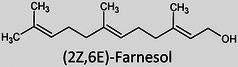

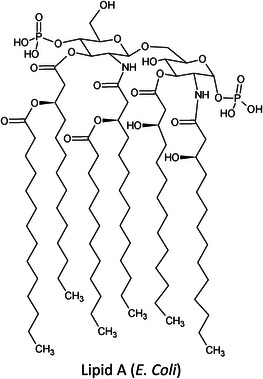

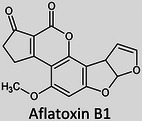

The term “lipids” covers a large chemical space of small molecules that are chemically and structurally diverse, varying in aspects such as the length of the hydrocarbon backbone, branching, degrees of unsaturation, and functional groups (Table 1). 7 These differences occur due to a number of different biochemical transformations during their biosynthesis. 8 Despite falling under the same umbrella term “lipids”, the variability between these molecules is greater than those of genomics and proteomics with an estimated number of structural variations exceeding > 105. 9 , 10 Formally, they are defined as “hydrophobic or amphipathic small molecules that may originate entirely or in part by carbanion‐based condensations of thioesters and/or by carbocation‐based condensations of isoprene units”. 11 Since 2005, the International Lipid Classification and Nomenclature Committee under the sponsorship of the Lipid Metabolites and Pathways Strategy (LIPID MAPS) consortium established the “Comprehensive Classification System for Lipids” that divided all lipids into eight lipid categories: fatty acyls, glycerolipids, glycerophospholipids, sphingolipids, sterol lipids, prenol lipids, saccharolipids, and polyketides (Table 1). As of 13th January 2023, the LIPID MAPS Structure Database (LMSD), which is the largest online lipid database, contains 47,800 unique lipid structures. 12 Researchers refer to the entire collection of lipid species in a cell, organ, or biological system as a “lipidome” and the large‐scale analytical study of this lipidome as well as the lipids’ interactions with other lipids, proteins, and metabolites as “lipidomics”. 2 , 3

TABLE 1.

Lipid categories as per LIPID MAPS classification system 12 with example structures. With the exception of various fatty acyls, the logP values taken 13 show the high hydrophobicity of lipids. The number of molecules in LMSD reported has been updated as of 13th January 2023.

| Lipid category | Example structure | LogP | No. of molecules in LMSD |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Fatty acyls (FA) |

|

–5–15 | 10,524 |

|

Glycerolipids (GL) |

|

5–35 | 7,731 |

|

Glycerophospholipids (GP) |

|

5–25 | 10,074 |

|

Sphingolipids (SP) |

|

5–25 | 4,967 |

|

Sterol lipids (ST) |

|

0–20 | 3,614 |

|

Prenol lipids (PR) |

|

0–20 | 2,396 |

|

Saccharolipids a (SL) |

|

0–30 | 1,345 |

|

Polyketides a (PK) |

|

0–15 | 7,149 |

These lipids are not synthesised in mammals and therefore within a clinical context should only represent a small portion of the lipidome.

It was only approximately 40 years ago that lipidomics experiments were made possible due to technological advancements in mass spectrometry (MS). Before this, traditional lipid analysis was performed using techniques such as gas chromatography (GC), high‐performance liquid chromatography, thin‐layer chromatography, nuclear magnetic resonance and other spectroscopic methods, or MS using electron ionisation, chemical ionisation, and field desorption. 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 The major limitations in the past involved addressing the chemical complexity of lipids in biological samples, i.e., the need for instrumentation that can first adequately volatilise and ionise the compounds, and then sensitively analyse and differentiate hundreds of molecules simultaneously. For example, using the molecules shown in Table 1, aflatoxin B1 and 1‐palmitoyl‐2‐oleoyl‐3‐linoleoyl‐rac‐glycerol with boiling points of 528°C 19 and 801°C, 20 respectively, are unlikely to readily volatilise in GC without derivatisation, and cholesterol and (2Z,6E)‐farnesol lack ionisable functional groups for efficient soft ionisation. Another notable limitation was the lack of soft ionisation that made intact lipid characterisations and quantification near impossible.

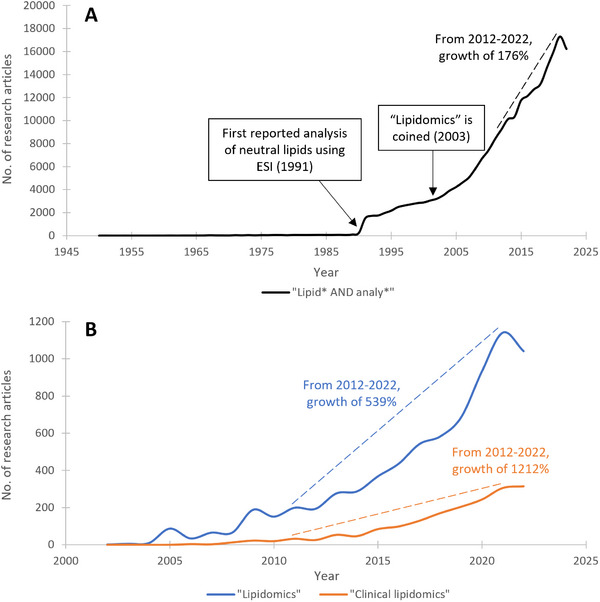

The first breakthrough for intact lipid analysis was the development of fast atom bombardment (FAB) by Michael Barber 21 that showed considerable success for the analysis of polar involatile lipids, such as phospholipids 22 , 23 and fatty acids, 24 , 25 where lipid class separation and detection with minimal fragmentation was made possible. 22 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 Unfortunately, this was not the case for nonpolar lipids, such as triglycerides, where extensive fragmentation limited its differentiation from other lipid species. 18 Further, a lack of sensitivity and reproducibility of FAB limited its use in large‐scale analyses. The next breakthrough came through the invention of electrospray ionisation (ESI) by John Fenn in 1989 31 that greatly accelerated lipid analysis (Figure 1) due to the softer ionisation mechanism, increased ionisation efficiency of nonpolar lipids through adduct formation, and ease of use for quantification. 18 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 Now, ESI is the most common ionisation technique used for LC‐MS lipidomics, accounting for nearly two‐thirds of all lipidomics articles since 2010. 41 Lipidomics is one of today's fastest‐growing research fields (Figure 1) 10 and it continues to grow through community‐driven advances in technology (MS, chromatography, bioinformatics), creation of shared online lipid databases, and commercial availability of lipid standards. 42 , 43

FIGURE 1.

Number of peer‐reviewed research articles published on Web of Science (as of 13th January 2023) using the search terms: (A) “lipid* AND analyte*” between 1950 and 2022, and (B) “lipidomics” and “clinical lipidomics” between 2002 and 2022. Annotated calculations regarding publication growth are calculated as the number of publications in 2022 divided by the number of publications in 2012, multiplied by 100.

Still in its infancy, the wealth of information offered by lipidomics analysis to understand physiological and pathological processes is currently underutilised in clinics. For the last 60 years, the main manifestation of clinical lipid analyses has consisted of total triglycerides, total cholesterol, low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol, and high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol measurements, which are well established for diagnostics but lack insight concerning the total lipidomic profile. 44 Clinical lipidomics is an emerging subfield focussed on clinical and consumer access to lipidomics data for disease diagnostics and health management. 44 , 45 The main goal of clinical lipidomics is to establish meaningful assays that can inform clinical outcomes. Here, a review of all clinical lipidomics literature published in 2022 found using the Scopus search terms “lipidomics” AND “clinic*” on 15th December 2022 was performed to give a snapshot of the current practices. This review is split into two main parts: 1) a discussion of the overall annual trends identified and how they relate to the conventional lipidomics workflow and 2) a more in‐depth discussion of select research articles on key topic areas.

2. 2022 IN REVIEW: MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Sample collection and experimental considerations

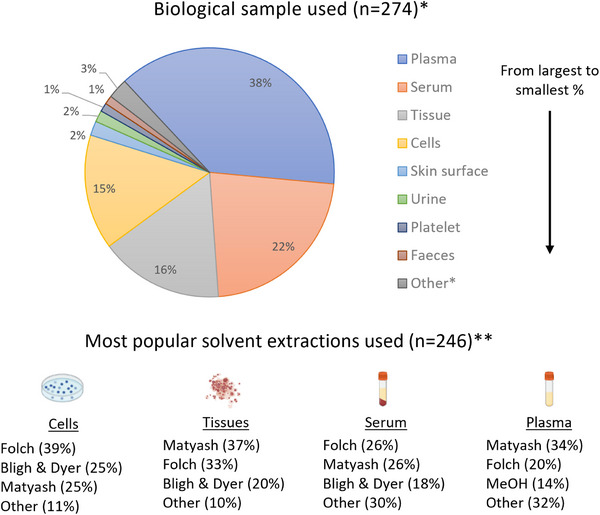

A wide variety of biological samples can be used for clinical lipidomics analysis. The samples chosen are often driven by the clinical question being investigated. Biofluids are commonly studied for biomarker discovery, whereas tissues or cells are commonly used to investigate physiological mechanisms. 46 In 2022, as shown in Figure 2, the most popular samples were plasma, serum, and tissue, accounting for 38%, 22%, and 16% of all publications, respectively. Blood samples contain rich signatures due to their sensitivity to the effects of disease, environment, nutrition, and genetic variation. They are also routinely obtained from patients and stored in biobanks, 47 making them readily available for scientific investigations.

FIGURE 2.

Bibliometric analyses of clinical lipidomics publications in 2022 using Scopus search terms “lipidomics” AND “clinic*” on 15th December 2022. 51 , 60 , 61 , 68 , 77 , 155 , 156 , 157 , 166 , 177 , 178 , 179 , 180 , 181 , 182 , 183 , 184 , 185 , 186 , 187 , 188 , 189 , 190 , 191 , 192 , 193 , 194 , 195 , 196 , 197 , 198 , 199 , 200 , 201 , 202 , 203 , 204 , 205 , 206 , 212 , 213 , 214 , 215 , 232 , 233 , 234 , 235 , 236 , 237 , 238 , 239 , 240 , 241 , 242 , 243 , 244 , 245 , 246 , 247 , 248 , 249 , 250 , 251 , 252 , 253 , 254 , 255 , 256 , 257 , 258 , 259 , 260 , 261 , 262 , 263 , 264 , 265 , 266 , 267 , 268 , 269 , 270 , 271 , 272 , 273 , 274 , 275 , 276 , 277 , 278 , 279 , 280 , 281 , 282 , 283 , 284 , 285 , 286 , 287 , 288 , 289 , 290 , 291 , 292 , 293 , 294 , 295 , 296 , 297 , 298 , 299 , 300 , 301 , 302 , 303 , 304 , 305 , 310 , 311 , 312 , 313 , 314 , 322 , 323 , 324 , 325 , 326 , 327 , 328 , 329 , 330 , 331 , 332 , 333 , 334 , 335 , 345 , 346 , 347 , 348 , 349 , 350 , 351 , 352 , 353 , 354 , 355 , 356 , 357 , 358 , 359 , 360 , 361 , 362 , 363 , 364 , 365 , 366 , 367 , 368 , 369 , 370 , 371 , 372 , 373 , 374 , 375 , 376 , 377 , 378 , 379 , 380 , 381 , 382 , 383 , 384 , 385 , 386 , 387 , 388 , 389 , 390 , 391 , 392 , 393 , 394 , 395 , 396 , 397 , 398 , 399 , 400 , 401 , 402 , 403 , 404 , 405 , 406 , 407 , 408 , 409 , 410 , 411 , 412 , 413 , 414 , 415 , 416 , 417 , 418 , 419 , 420 , 421 , 422 , 423 , 424 , 425 , 426 , 427 , 428 , 429 , 430 , 431 , 432 , 433 , 434 , 435 , 436 , 437 , 438 , 439 , 440 , 441 , 442 , 443 , 444 , 445 , 446 , 447 , 448 , 449 , 450 , 451 , 452 , 453 , 454 , 455 , 456 , 457 . *Note: All biological sample types with more than 1.0% of total publications have been reported individually with all remainder combined under “Other”. **Note: For trending purposes, the unmodified and modified versions of the classic methods (Folch, Bligh & Dyer and Matyash) were combined. The sample images have been created using BioRender.com.

The method and timing of sample collection can have a significant impact on the downstream lipid profile. Fasting status and circadian rhythms for blood samples, for example, have been shown to influence lipidomes. 48 , 49 , 50 To minimise the intra‐ and inter‐variation of cohorts, most studies sample blood at the fasting state to measure baseline levels; however, profiling in the postprandial state could also prove useful. For instance, Velenosi et al. analysed pre‐ and postprandial human plasma samples using standardised mixed meals of control and non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) patients by untargeted lipidomics. Here, insulin‐related increases in multiple diacylglycerol species at 4 h postprandially were found specifically in NAFLD patients and not in controls, which have been linked to the hepatic secretion of endogenous and not meal‐derived lipids. 51

Sample handling and storage will also cause variations in lipid profiles. For blood samples, the choice of anticoagulants and collection tubes has been demonstrated to have an impact on lipid extraction and MS ionisation. 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 , 56 , 57 , 58 , 59 Two studies performed by Beger et al. and Yadav et al. in 2022 investigated the effects of formalin fixations on the untargeted lipid profiles of brain and skin tissue samples, respectively. 60 , 61 Both studies highlight how preservation added bias to the lipid classes observed, resulting in reduced quality data; therefore, any preservation used should be considered by scientists prior to their study regardless of sample type. After sampling, tissues should be immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and any biofluids should either be processed immediately or stored at −80°C to limit enzymatic activity or chemical degradation. 41 The multitude of factors that can impact the sampled lipidomes stresses the importance of optimal sampling and storage.

Appropriate experimental design is crucial for clinical lipidomics due to the large intra‐ and inter‐individual biological variability of the human lipidome, resulting in further disease heterogeneity. 62 , 63 , 64 Small sample sizes or the lack of suitable study participants can lead to underpowered designs, resulting in inconclusive or misleading results. Power calculations for discovery experiments are necessary, but difficult with unknown effect sizes, to account for technical and biological variance. 65 , 66 This is especially true for small‐cohort studies where the variability could obscure trends or lead to high false discovery rates. Bias and confounding factors (e.g. differences in storage conditions, testing sites, sampling time) should be factored into the experimental design. Uncontrollable factors (e.g. ethnicity and diet) should also be accounted for in the study design through replication, randomization, and blocking schemes. 67 Further consideration of the clinical application of your study should influence your study design to answer questions such as: what patient population would benefit from these biomarkers, or in which clinical settings will these tests be used? 68 This would aid the translation of research to clinics, where aspects such as costs, facilities available, transportation, and patient demographics may be of relevance. 45

2.2. Sample preparation

After the sample has been collected, it typically undergoes pre‐treatment before analysis for multiple reasons: 1) extraction from biological material, 2) sample matrix clean‐up, 3) analyte preconcentration, and 4) compatibility with instrumentation. For untargeted analyses, where profiling the entire lipidome is of interest, it is important to consider the sampling bias introduced by the extraction method chosen. 69 , 70 , 71 , 72 , 73 , 74 , 75 , 76 , 77 This is a bottleneck in lipidomics workflows due to the large structural diversities of lipids present in biological matrices. The most suitable extraction method for the highest coverage should be investigated through research or literature review prior to experimentation. The amount of sample could also influence the extraction selected. 69 , 78 For targeted approaches, sample preparation is a key area to optimise to make substantial gains in method performance. Here, pre‐treatment approaches, such as solid‐phase extraction (SPE) or derivatisation, for example, esterification, silylation, or charge‐switch derivatisation, can drastically increase analyte sensitivity and/or decrease matrix effects. 41 , 79 , 80 , 81 , 82 , 83 Disadvantages associated with both SPE and derivatisation include their costs, time‐consuming, and cumbersome nature, as well as issues with repeatability due to either batch‐to‐batch variation in sorbents or reagents and/or analyst consistency. 78 , 84 , 85 , 86 , 87 , 88

Solvent extractions are the gold standard in lipidomics sample preparation. Historically, the most widely used solvent extraction systems are the biphasic chloroform/methanol/water mixtures, e.g. “Folch” 89 and “Bligh & Dyer” 90 protocols; however, these classical methods are becoming superseded by new liquid extraction methods, such as the biphasic “Matyash” 91 or “BUME” protocols, or alternatively monophasic alcoholic solutions using isopropanol or methanol, due to their reduced toxicity, automation potential, costs, and/or ease of use. 2 , 69 , 76 , 91 , 92 , 93 , 94 , 95 , 96 , 97 Due to the large sample sizes used, automation of sample preparation is highly advantageous for speed, throughput, and reproducibility. 92 , 96 , 97 With or without the automation of the sample preparation, it is crucial that solvent selection is not only driven by chemistry but also by eco‐friendliness. Analytical studies should aim to develop selective extraction methods to promote green chemistry. 98 , 99 , 100 This shift has been reflected in the trends observed for 2022, where the Folch and Matyash protocols competed to be the most popular extractions for cells, tissues, serum, and plasma (Figure 2). Interestingly, a new monophasic extraction protocol has been developed in 2022 by Fu et al. for untargeted human platelet extraction utilising methanol/methyl tert‐butyl ether/isopropanol (1.3:1:1 v/v/v), reporting almost 100% extraction recoveries of polar and nonpolar lipids. With large‐scale clinical lipidomics studies in mind, the advantages of their solvent system include practicality, eco‐friendliness (reduced solvent consumption and no halogenated solvents), speed, and adaptability to other biofluids. 77

Lastly, the use of internal standards is key to monitoring extraction efficiency (e.g. recovery and repeatability) and accounting for any analyte losses downstream. In 2022, ∼27% of research publications used internal standards.1 Ideally, there should be an internal standard representative of the analyte being quantified, such as an isotopically labelled lipid standard; however, this is not practically possible for untargeted methods involving thousands of compounds. Here, the standardisation of analyte responses is typically performed through the use of commercially available, synthetic lipid standards from AVANTI Polar Lipids through the LIPID MAPS initiative to aid lipid quantification and identification. 42 , 43 The final extract is typically evaporated and reconstituted prior to the introduction to the analytical platform.

2.3. Data acquisition

2.3.1. Separation sciences

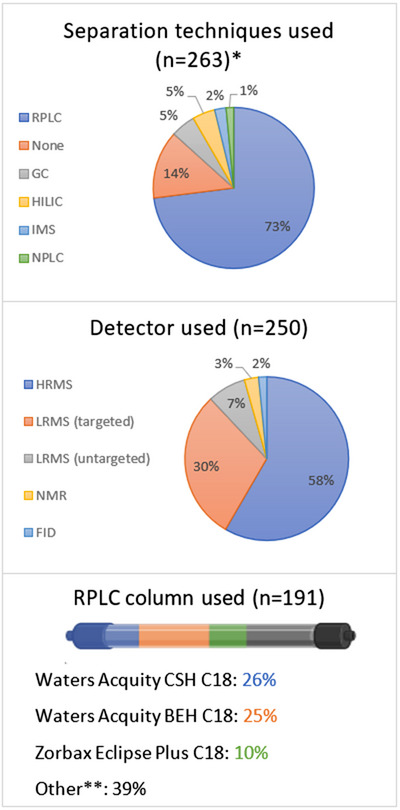

The complexity of biological matrices can be reduced through the implementation of separation prior to detection. For lipidomics, this is usually performed using either GC or liquid chromatography (LC) (Figure 3). These techniques can potentially separate isomers and isobars, reduce matrix effects, increase low abundance analyte sensitivities, and minimise the reliance on the detector for quantification and identification purposes. This, however, comes at the expense of lower sample throughput and complicated data processing in comparison to direct infusion approaches. 2 Unconventional approaches include two‐dimensional chromatography 101 , 102 , 103 , 104 , 105 or ion mobility spectrometry. 106 , 107 , 108 , 109

FIGURE 3.

Bibliometric analyses of clinical lipidomics publications in 2022 according to separation techniques, detectors, and RPLC columns used. 51 , 60 , 61 , 68 , 77 , 155 , 156 , 157 , 166 , 177 , 178 , 179 , 180 , 181 , 182 , 183 , 184 , 185 , 186 , 187 , 188 , 189 , 190 , 191 , 192 , 193 , 194 , 195 , 196 , 197 , 198 , 199 , 200 , 201 , 202 , 203 , 204 , 205 , 206 , 212 , 213 , 214 , 215 , 232 , 233 , 234 , 235 , 236 , 237 , 238 , 239 , 240 , 241 , 242 , 243 , 244 , 245 , 246 , 247 , 248 , 249 , 250 , 251 , 252 , 253 , 254 , 255 , 256 , 257 , 258 , 259 , 260 , 261 , 262 , 263 , 264 , 265 , 266 , 267 , 268 , 269 , 270 , 271 , 272 , 273 , 274 , 275 , 276 , 277 , 278 , 279 , 280 , 281 , 282 , 283 , 284 , 285 , 286 , 287 , 288 , 289 , 290 , 291 , 292 , 293 , 294 , 295 , 296 , 297 , 298 , 299 , 300 , 301 , 302 , 303 , 304 , 305 , 310 , 311 , 312 , 313 , 314 , 322 , 323 , 324 , 325 , 326 , 327 , 328 , 329 , 330 , 331 , 332 , 333 , 334 , 335 , 345 , 346 , 347 , 348 , 349 , 350 , 351 , 352 , 353 , 354 , 355 , 356 , 357 , 358 , 359 , 360 , 361 , 362 , 363 , 364 , 365 , 366 , 367 , 368 , 369 , 370 , 371 , 372 , 373 , 374 , 375 , 376 , 377 , 378 , 379 , 380 , 381 , 382 , 383 , 384 , 385 , 386 , 387 , 388 , 389 , 390 , 391 , 392 , 393 , 394 , 395 , 396 , 397 , 398 , 399 , 400 , 401 , 402 , 403 , 404 , 405 , 406 , 407 , 408 , 409 , 410 , 411 , 412 , 413 , 414 , 415 , 416 , 417 , 418 , 419 , 420 , 421 , 422 , 423 , 424 , 425 , 426 , 427 , 428 , 429 , 430 , 431 , 432 , 433 , 434 , 435 , 436 , 437 , 438 , 439 , 440 , 441 , 442 , 443 , 444 , 445 , 446 , 447 , 448 , 449 , 450 , 451 , 452 , 453 , 454 , 455 , 456 , 457 All legends are in order of largest to smallest percentage. *Note: All techniques that represent ≥1.0% of total publications have been reported. **Note: all "Other" named columns constituted ≤5% of publications. The column image has been created in BioRender.com. Key: NPLC = normal‐phase liquid chromatography, RPLC = reversed‐phase liquid chromatography, HILIC = hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography, GC = gas chromatography, IMS = ion mobility spectrometry, HRMS = high‐resolution mass spectrometry, LRMS = low‐resolution mass spectrometry, FID = flame ionisation detector, NMR = nuclear magnetic resonance.

GC separates compounds based primarily on differences in volatility combined with interactions with the stationary phase. 110 Lipids generally have low volatility and for any carboxylic acids, there can be interactions with stationary phase siloxane groups that result in undesirable late‐eluting broad peaks. To combat this, derivatisation approaches, such as transesterification to fatty acid methyl esters, silylation to trimethylsilyl esters and charge‐switch derivatisation, are performed. 41 , 79 , 80 , 81 , 82 Derivatisations are laborious and tend to complicate interpretation due to the presence of derivatisation artifacts 111 ; however, a key advantage of derivatisation is its selectivity. Derivatisation typically targets specific chemical functionalities, which means that for complex biological samples, this theoretically could limit the number of analytes in GC‐MS chromatograms, allowing easier interpretation and quantification.

Unlike GC, LC is not limited to volatile compounds. LC separates compounds based on interactions of the sample with a mobile and stationary phase. There are many different types of LC, but generally, reversed‐phase LC (RPLC) for nonpolar separations and hydrophilic interaction LC (HILIC) for polar separations are the most popular. As a rule of thumb, RPLC will retain analytes with a logP ≥ ‐1 and HILIC will retain analytes with a logP ≤ 1. 112 , 113 Based on the physicochemical properties of lipids (Table 1), it comes as no surprise that RPLC continues to be the most popular separation technique, accounting for 73% of the literature published in 2022 (Figure 4).

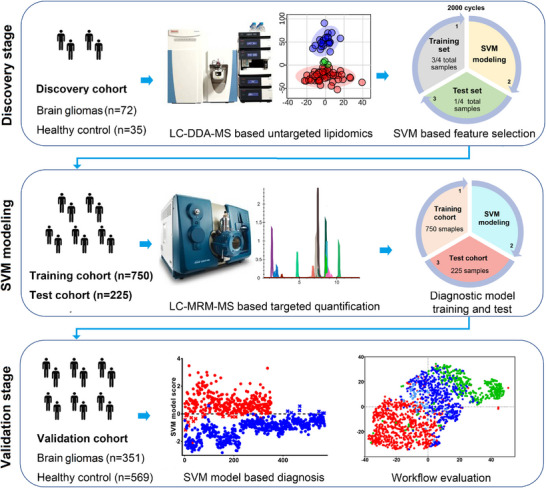

FIGURE 4.

The study design and development of a liquid chromatography‐mass spectrometry (LC‐MS) method from initial biomarker discovery to validation for the diagnosis of malignant brain gliomas. Towards the left of every panel, notice the increase in cohort size as the method enter validation to make it more meaningful for clinical implementation. In the middle of the first two panels, see how the discovery was performed using untargeted high‐resolution MS (HRMS) analysis for screening all lipids and showing clear discrimination between healthy versus disease through a principal component analysis (PCA) plot, whereas the clinical method uses a simpler, targeted method for quantification. Finally, towards the right of the first two panels, see how machine learning through support vector machine modelling is applied, where the model is trained and validated after each study. Reprinted with permission. 155

RPLC uses a nonpolar stationary phase and a polar aqueous mobile phase to generally elute analytes in order of decreasing polarity. Analytes are separated according to two phenomena, namely partitioning and/or adsorption via hydrophobic interactions to the bonded stationary phase. The degree to which each phenomenon contributes to an analyte's retention varies but has been shown through molecular simulations to be dependent on stationary phase alkyl chain length and functional group type. 114 For lipidomics, the retention order predominantly relies on the analyte alkyl chain length and degree of unsaturation. 115 The most popular RPLC columns in 2022 were the Acquity CSH column (26%), the Acquity BEH C18 column (25%), and the Zorbax Eclipse Plus C18 (10%) (Figure 3).

HILIC uses a polar stationary phase and a nonpolar organic‐rich mobile phase to generally elute analytes in order of increasing polarity. It is a variant of normal‐phase LC (NPLC) and complementary to RPLC. Due to a water‐enriched layer adsorbed onto the stationary phase, HILIC separates ions using a mixed‐mode retention mechanism. This mechanism will involve, to different degrees, the following phenomena: hydrophilic partitioning between the mobile phase and the water layer, adsorption to the stationary phase, and/or electrostatic interactions and hydrogen bonding with the stationary phase moieties. The retention order predominantly relies on the lipid headgroup polarity. 106 , 116 Example lipids analysed by HILIC include ceramides, glycerolipids, glycolipids, phospholipids, and sphingolipids. 102 , 106 , 116 , 117 , 118 , 119

2.3.2. Detection

Due to its high sensitivity and specificity, it comes as no surprise that MS was the most popular detector in 2022, accounting for an overall 95% of the literature published in 2022 with high‐resolution MS (HRMS) making up 58% and low‐resolution MS (LRMS) making up 37% (Figure 3). MS is an analytical technique that creates gas‐phase ions from atoms or molecules and measures their mass‐to‐charge ratios (m/z). 120 Mass spectrometers discriminate between ions of different m/z by subjecting them to constant, pulsed, or periodically time‐varying electric and/or magnetic fields. 121 For lipidomics, mass spectrometers are the detectors of choice, where they are capable of (but not limited to): 1) molecular mass, elemental, and isotopic composition determinations, 2) structural elucidation, and 3) quantification. HRMS is commonly defined as mass spectrometers that are capable of resolving powers ≥ 10,000 full‐width at half maximum (FWHM). Generally, HRMS, such as time‐of‐flight and orbitraps, would be used for untargeted analyses due to their higher resolving powers that allow accurate mass measurements, improvements in signal:background ratios, and wider mass ranges. For targeted applications and quantitative approaches, LRMS, such as triple quadrupoles in tandem, are commonly used for their high specificity, sensitivity, and wide linear dynamic ranges.

There are three main mass spectrometric approaches: direct‐infusion MS (termed “shotgun” lipidomics), chromatographically coupled MS (typically LC or GC), or MS imaging (MSI). Key aspects that could influence the approach chosen include matrix effects, confidence in identification, and ease of quantification. Matrix effects, in particular, ion suppression by more dominant and/or easily ionisable lipid species, such as phospholipids, 122 , 123 , 124 , 125 is a major challenge in lipidomics. This problem is more pronounced for shotgun lipidomics as all lipid species are analysed simultaneously, which consequently leads to detection problems concerning low‐level lipid species. Ion suppression can be overcome by either incorporating chromatography or derivatisation. 41 , 79 It is important to note that LC (RPLC or HILIC) can readily separate different lipid classes and therefore resolve their lipid‐lipid interactions and suppression (i.e., interclass interactions), but within‐class interactions (i.e., intraclass interactions) could be significantly increased and this could counterproductively result in greater ion suppression at large concentrations. 101 , 126 In terms of identifications, shotgun lipidomics and MSI offer less confidence due to the lack of molecular separation and retention time information; whereas, through chromatographic coupling, ions are separated from one another prior to detection adding confidence in identification at the expense of more chemical waste and low throughput due to longer analytical run times. Finally, for quantification, in shotgun lipidomics, the steady ionisation environment allows robust quantification using a lipid standard mix with one compound of each lipid class. This approach is dissimilar to chromatographically coupled MS or MSI because the ionisation environment is constantly changing. This means that more thorough calibration work is needed for quantification. 80 Further, MSI analyses lipids in situ with the key advantage of capturing spatial information about the analyte. 127

For untargeted screening methods, the HRMS acquisition modes typically used are full scan, data‐dependent acquisition (DDA), and data‐independent acquisition (DIA). Full scan is an MS1 approach that obtains all m/z measurements across a defined m/z window. In DDA mode, the HRMS performs a full scan on MS1 followed by an MS2 analysis of select precursor ions for structural information. This selection is intensity‐based, which means that the DDA data are biased and lower‐intensity lipids will therefore not have any associated MS2 data. In DIA mode, the HRMS performs a full scan on MS1 followed by an MS2 analysis of all precursor ions through instrument cycles. Commonly used DIA methods include all‐ion fragmentation (AIF) or sequential window of all theoretical fragment‐ion spectra (SWATH). 128 The main advantage of DIA is that it is less biased than DDA and there is no undersampling of peaks. Therefore, all precursor peaks are fragmented; however, this results in more complicated MS/MS spectra, often losing the connection between the product ions to their precursor due to ion overlap. 129 , 130 Several studies highlight the loss of 2‐5x sensitivity when using DIA versus DDA or full scan modes. 131 , 132 , 133 For more information, the following reviews are recommended. 129 , 131 , 134

Based on information from discovery experiments and/or literature, targeted lipidomics experiments can be performed, where a pre‐defined set of lipids with a known m/z of precursor and product ions are analysed in a quantitative manner across large sample sets. Here, selected or multiple reaction monitoring (SRM/MRM) on triple quadrupole instrumentation, and recently parallel reaction monitoring (PRM) on quadrupole time‐of‐flight and orbitraps are employed. 135 Specialised tools, such as LipidCreator 136 and METLIN‐MRM, 137 can aid experimental method development and processing steps. In comparison to untargeted data processing (discussed below), the post‐acquisition processing of targeted data is relatively straightforward using open‐access tools, such as Skyline 138 or XCMS‐MRM, 137 or vendor software, such as TargetLynx, 139 that can automate peak integration, relative and absolute quantification, and evaluate data quality. 140

2.4. Data processing

The high‐throughput nature of lipidomics and the ‘big data’ generated, in particular for untargeted experiments, results in high complexity analysis that has become heavily reliant on statistical testing, mathematical treatment, and computational algorithms. 141 , 142 First, raw data are typically converted to a data format that is compatible with downstream processing through either commercial software packages, such as Progenesis QI, 143 or freely available ones, such as MSConvert that allow a direct conversion of raw data that can be read by software programs, such as MetaboAnalyst, 144 after deconvolution using software such as MZmine, 145 or packages such as XCMS 146 or eRah 147 in R. These programs use algorithms for spectral filtering, baseline correction, peak alignments, normalisation, peak picking, and putative annotations. An example of these programs is the peak detection tool “NeatMS”, which was published by Gloaguen et al. in 2022, to combat the current challenges of irreproducibility and peak overpicking experienced in omics data post‐acquisition. It is an open‐source automated tool that uses machine learning to better differentiate between chemical signals and noise that can readily be added to existing workflows. 148

Then, advanced biostatistical tools are applied to analyse and interpret the data in the context of clinical information. After all, the assumption behind the collection of these lipidomics data is that the co‐variation of a small set of analyte abundances should inform the biological phenomenon being studied. The challenge here is to identify and isolate the lipids that are specific to the phenomenon from the ones that are not relevant. Supervised or unsupervised statistical methods are used. Briefly, these include (but are not limited to) approaches, such as partial least squares discriminant analysis (PLS‐DA), orthogonal projection to latent structure discriminant analysis (OPLS‐DA), and principal component analysis (PCA). 142 , 149 From this, analytes of interest observed to be specific to the biological phenomenon can be further identified through automated programmatic approaches to allow database searching 140 and/or subjected to pathway analysis. Through pathway analyses, the dysregulated lipids observed can be associated with specific metabolic pathways, potentially representing the body's response to a disease or drug treatment (Figure 6). 150 , 151

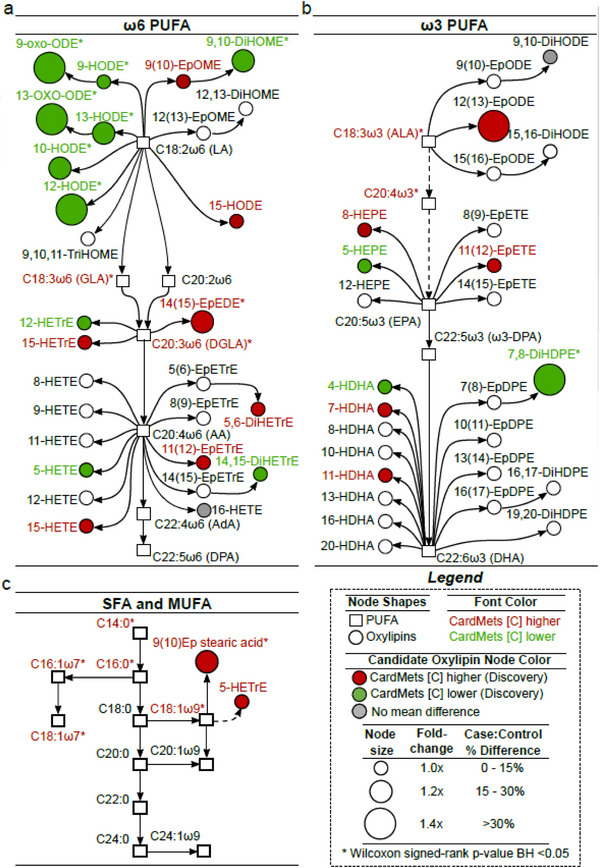

FIGURE 6.

Pathway analysis of oxylipins (n = 54; circles) and fatty acids (n = 25; squares) identified that can discriminate patients with MetS from controls. The metabolic pathways of oxylipin biosynthesis from omega‐6 PUFA (A), omega‐3 PUFA (B), and SFA/MUFAs (C). The oxylipins of interest from the analytical testing are highlighted in colour, where red = upregulated in metabolic syndrome patients, green = downregulated in metabolic syndrome patients, and grey = no difference. Dashed lines represent indirect pathways including intermediate metabolites. Size of nodes represents fold changes between the two cohorts. Reprinted with permission. 294

Finally, as part of the big data revolution, machine learning has gained popularity for building models, e.g. diagnostic tests, to help translate research into clinical practice. Machine learning is the study of computational algorithms that make predictions and decisions based on experience and data, without being explicitly programmed. 152 It is an approach to data analysis that involves building and adapting models to “learn” from experience to further improve their ability to make predictions. 153 , 154 A good example of machine learning applications as applied to biomarker discovery is shown in the articles by Zhou et al. (Figure 4) 155 and Wang et al. 156 Machine learning algorithms, such as lasso (or ridge) regressions, decision trees, support vector machines (ensembles or wrappers of these), and artificial neural networks, are powerful tools for pattern recognition or classification that have significantly accelerated the identification of biomarkers. Interestingly, in Luan et al.’s biomarker discovery work studying spontaneous miscarriage in IVF‐ET women, they approach machine learning in a systematic approach, whereby five classifiers and four feature selection methods were optimised to give the best classification model with the highest accuracy and stability. 157

3. 2022 IN REVIEW: RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

It is known that many diseases are characterised by lipid dysregulation. Lipidomics articles within clinical research generally have two main objectives: to understand molecular mechanisms of lipid metabolisms or establish diagnostic biomarkers. Biomarker studies aim to translate to routine clinical practice; whereas, physiological mechanism studies lend themselves to understanding disease manifestations, identifying therapeutic drug targets, and aiding drug development. To translate this to clinical lipidomics, these profiles need to be integrated with patient phenotypes to potentially identify disease severity‐, duration‐, stage‐, subtype‐ and prognosis‐specific lipidome changes. 45

A biomarker is defined as: “A defined characteristic that is measured as an indicator of normal biological processes, pathogenic processes, or biological responses to an exposure or intervention, including therapeutic interventions”. 158 An ideal biomarker should be: 1) binary or at least quantifiable, 2) the testing should have a turnaround speed appropriate to the clinical indication and be adoptable into routine clinical practice, 3) highly sensitive and/or specific and 4) readily detectable in a non‐invasive biofluid. There are essential method development steps (Figure 4) to establish biomarkers for a disease, namely biomarker discovery and validation. A panel of biomarkers may be used for better performance in terms of diagnostic accuracy. 159 , 160 , 161 , 162 , 163 In the following sections, selected research articles from the most popular subject areas of 2022 will be briefly discussed: oncology, metabolic diseases (e.g. cardiovascular disease (CVD), diabetes, liver disease, and obesity), and infectious diseases (Figure 5).

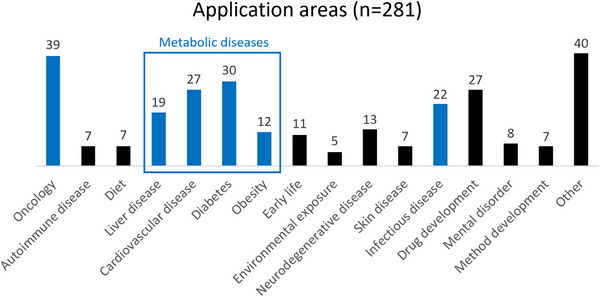

FIGURE 5.

Application areas with ≥ 5 publications have been represented. Application areas with < 5 publications have been sorted under “Other”. *Note: “Early life” combines pregnancy and infant lipidomics studies. Application areas in blue are discussed in this review.

3.1. Oncology

Cancer is the second largest cause of death worldwide with an overall incidence rate of 20.2% over a human lifetime. 164 It has been shown that lipid metabolism in cells is drastically elevated during the different stages of cancer development. 165 , 166 , 167 Increased lipids are needed for plasma membrane synthesis and energy production, but also influence cell membrane compositions to favour metastasis and trigger signalling events within cancer cells. Further, these increased lipids also facilitate metabolic crosstalk between the tumour and surrounding cells within the tumour microenvironment. 165 , 167 The upregulation of fatty acids and cholesterol are common in cancer as their synthetic pathways help facilitate cell proliferation 168 and tumour growth, 169 respectively. Further, lysophospholipid levels have been associated with cancer cell migration, invasion ability of cancer cells, and potentially tumour immunity. 170 , 171 , 172 , 173 Lipidomic analyses have revealed cancer‐specific lipid dysregulations that could potentially serve as promising biomarkers for screening purposes, 174 , 175 as demonstrated by Lee et al. in a plasma analysis of 140 human samples that could differentiate five cancers (liver, lung, gastric, colorectal, and thyroid). 176 It is therefore of no surprise with its known lipid dysregulation and urgency that oncology was the biggest application area in 2022, where the following cancers were studied: bladder, 177 brain, 155 breast, 178 , 179 , 180 , 181 , 182 colorectal, 183 , 184 , 185 , 186 , 187 , 188 endometrial, 189 gallbladder, 190 gastric, 191 kidney, 192 liver, 193 , 194 , 195 , 196 , 197 lungs, 156 , 198 , 199 , 200 nasopharyngeal, 201 ovarian, 202 paediatric, 203 prostate, 204 , 205 and skin. 206

To maximize the survival rates of cancer patients, it is important to identify cancer at its early stages, where tumours can be surgically removed or treated with milder drug regimens. 207 The average 5‐year survival rate in the early stages is 91%; whereas, the average 5‐year survival rate in the late stages is 26%. 208 The most common cancers for men are prostate (20%), lung and bronchus (13%), and colorectal (9%) cancers; whereas, for women, they are breast (30%), lung and bronchus (13%), and colorectal (8%) cancers. 208 The “harder to suspect” cancers due to non‐specific symptoms that typically require multiple consultations that delay diagnosis are multiple myeloma, pancreatic cancer, ovarian, stomach, and lung cancers. 209 Wang et al. discovered for early‐stage lung cancer that the lipid metabolism was dysregulated with the glycerophospholipid metabolism being the most altered. For biomarker discovery, untargeted RPLC‐HRMS analysis of plasma samples revealed nine key lipids for early‐stage cancer detection. Using these, a targeted RPLC‐MS/MS method with a run time of 19 min was developed to separate and quantify these lipids. This assay reached 100% specificity on the validation cohort, and subsequently, out of 1,145 participants from different medical centres, achieved more than 90% sensitivity and 92% specificity. 156

Tumour formation is characterised by the successful circumvention of cell death regulation to allow unlimited replication and immortality. 210 Ferroptosis is a newly identified iron‐dependent form of cell death driven by lipid peroxidation that has garnered interest in the scientific community for its potential as an alternative cancer therapy. 211 Traditional tumour treatments, such as chemotherapy and radiotherapy, are often not as effective due to the breadth of their targets and tumour cell tolerance. 210 , 211 Ferroptosis activation may be a potential strategy for treating cancers that are unsuccessfully targeted by conventional therapies. Zhang et al. used untargeted RPLC‐HRMS analyses of cells to study the molecular mechanisms of ferroptosis, namely the sensors and their link to the amplification process of lipid peroxidation. The enzyme protein kinase C βII (PKCβII) was found critical in ferroptosis in its role of phosphorylation and activating the enzyme Acyl‐CoA synthetase long‐chain family member 4 (ACSL4) required for the lipid peroxidation. The activation of the PKCβII‐ACSL4 pathway could be a potential therapeutic target. 212 Further, Liao et al. showed that T cell‐derived interferon (IFN)γ with arachidonic acid‐induced tumour ferroptosis through the activation of ACSL4 pathway by several methods, including a targeted phospholipid analysis using NPLC‐MS/MS. These data demonstrated how T cells can selectively reprogram tumour cells via the IFNγ signalling pathway. Potential supplementation of arachidonic acid could be an effective therapy for tumour regression. 213

To understand how lipidomics could be used to influence treatment decisions, three studies focusing on drug development will be discussed. Chen et al. demonstrated using untargeted ambient single‐cell HRMS that metformin, an oral antidiabetic drug, has a synergistic effect with the cancer drug irinotecan (IRI) to overcome the drug resistance of previously IRI‐resistant colorectal cancer cells. This was done by studying the metabolome changes in model systems of drug‐resistant cancer cells with both metformin monotherapy and metformin/IRI co‐therapy. Metformin monotherapy induced downregulation of lipids and fatty acids, potentially through the inhibition of fatty acid synthase, whereas co‐treatment resulted in reduced production of ceramide phosphoethanolamine. 214 Antona et al. explored drug repurposing to identify new potential therapies for colorectal cancer that are overall quicker and cheaper than de novo drug synthesis. Spiperone, an antipsychotic drug, was shown to have anticancer effects by inducing apoptosis in colorectal cancer cells. The drug action involved phospholipase C activation, intracellular calcium homeostasis dysregulation, and endoplasmic reticulum stress induction, which caused significant lipid metabolism alterations. This study used several techniques including untargeted RPLC‐HRMS to study drug‐induced changes to the overall cancer cell lipidome. 186 Hatfield et al. analysed the pretransplant serum of patients receiving allogeneic stem cell transplantation to treat haematological malignancies using untargeted DI‐MS/MS. These procedures have a high risk of treatment‐related morbidity and mortality. Through hierarchical clustering analyses, associations between pretransplant lipid profiles and posttransplant complications (including death due to disease relapse or treatment toxicity) were found, demonstrating that patients could be subclassified prior to transplants to direct therapies and inform treatment outcomes according to the individual. 215

3.2. Metabolic diseases

Metabolic diseases occur when abnormal chemical reactions disrupt the body's metabolism. Due to modern sedentary lifestyles and changed nutritional behaviours, they are becoming increasingly prevalent worldwide and currently pose a large burden on global healthcare systems. 216 , 217 The major metabolic diseases include type 2 diabetes (T2D), NAFLD and metabolic syndrome (MetS). Of these, T2D affects more than 200 million people 216 and NAFLD affects an estimated one‐third of the adult population worldwide. 218 There has been an alarming increase in MetS 219 , 220 with an estimated prevalence in 1/4th of the global population. 221 , 222 MetS, also known as syndrome X, 223 insulin resistance syndrome, 224 and the deadly quartet, 225 refers to the co‐occurrence of several cardiovascular risk factors, such as glucose intolerance, obesity, insulin resistance, hypertension and dyslipidaemia. 226 MetS is closely associated with the development of T2D, fatty liver, CVD, and cancer. 227 , 228 , 229 , 230 , 231 Due to the elevated risk of mortality with these diseases, there is a need for strategies in its identification, prevention, and treatment within healthcare. In 2022, as evidenced in Figure 5, the bulk of research articles focussed on related diseases: CVD, 232 , 233 , 234 , 235 , 236 , 237 , 238 , 239 , 240 , 241 , 242 , 243 , 244 , 245 , 246 , 247 , 248 , 249 , 250 , 251 , 252 , 253 , 254 , 255 diabetes, 166 , 233 , 249 , 250 , 256 , 257 , 258 , 259 , 260 , 261 , 262 , 263 , 264 , 265 , 266 , 267 , 268 , 269 , 270 , 271 , 272 , 273 , 274 , 275 , 276 , 277 , 278 liver disease, 51 , 279 , 280 , 281 , 282 , 283 , 284 , 285 , 286 , 287 , 288 , 289 , 290 , 291 , 292 , 293 MetS 277 , 294 , 295 and obesity. 277 , 295 , 296 , 297 , 298 , 299 , 300 , 301 , 302 , 303 , 304 , 305

Coleman et al. investigated the pathogenesis and involvement of the gastrointestinal tract with the syndrome through multiple experiments including an untargeted RPLC‐MS/MS analysis of faecal samples of people with MetS and healthy controls. No signs of intestinal inflammation or increased permeability were found in the MetS patients compared to the controls; however, significant increases in 417 lipid features, including various glycerolipids, glycerophospholipids, sphingolipids, fatty acyls, and polyketides, in the gut lipidome were observed, suggesting alterations of the intestinal host‐microbiota metabolism. 277 Further, Dalle et al. quantitatively analysed plasma for over 130 oxylipins of 476 participants using two orthogonal analytical platforms for added confidence: targeted RPLC‐MS/MS and GC‐MS using fatty acid methyl ester derivatisation. This work demonstrates how a comprehensive understanding of oxylipins as lipid mediators, regulating many cardiometabolic functions, can help elucidate MetS pathophysiology through effective pathway analysis (Figure 6). Some of these oxylipins are directly linked to key molecular pathways, including oxidative stress, inflammation, blood clotting, glucose homeostasis, and adipogenesis, providing additional information that is not provided by the current clinical diagnostic tests. A classification model of 23 oxylipins was developed to stratify patients with MetS at risk of cardiometabolic diseases. 294

Several groups performed large‐cohort longitudinal lipidomics experiments to develop models for disease prognosis. By studying the plasma samples of 4,067 participants over 23 years using DI‐HRMS, Lauber et al. applied machine learning models to develop a lipidomics‐based risk score using 184 lipid concentrations to assess a patient's future risk of developing T2D, CVD, and obesity. Individual lipidomes are stratified into different classifications (low‐high risk) such that interventions could be introduced years before disease incidence for prevention. 233 Al‐Sari et al. used a combination of clinical measurements and omics analyses of plasma samples of 537 participants with type 1 diabetes over 5 years to develop risk scores using machine learning approaches to predict a patient's progression to diabetes complications, such as diabetic kidney disease or diabetic retinopathy. Lipidomic analyses were performed using untargeted RPLC‐HRMS. Thus, the models, using a combination of clinical measurements, metabolites, and lipids, have the potential for the early detection and prevention of complications. 276

3.3. Infectious diseases

Infectious diseases are illnesses caused by microorganisms, such as bacteria, viruses, fungi, or parasites, that are transmitted from an infected person, animal, or object to a susceptible host. According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), they cause an estimated quarter of all deaths worldwide 306 and this number is only expected to grow with climate change, issues with global food supply chains, and international travel that allow these diseases to spread. Globally, it is the leading cause of childhood mortality. 307 As lipids combine with other metabolites and specific pathways to support the human lifecycle, these compounds are involved in the interplay between the infectious agent and its host. This includes how pathogens become internalised into the host's cells, interactions between the pathogen and the host's lipid metabolism and microbiota, and the immune system. 308 , 309 Malaria, tuberculosis, and Human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS) remain within the 10 top causes of death in low‐ to middle‐income countries. 306 These diseases have been subject to clinical lipidomics experiments to further disease understanding and manifestation. 310 , 311 , 312 , 313 , 314

Tuberculosis (TB) is a highly contagious airborne disease, dating back more than 9,000 years, 315 caused by the bacteria Mycobacterium tuberculosis. In 2020, the WHO reported an estimated 10 million new tuberculosis cases and 1.5 million TB‐related deaths globally with two‐thirds of the cases spread across eight countries: India, China, Indonesia, Philippines, Pakistan, Nigeria, Bangladesh, and South Africa. 316 Brandenburg et al. showed by using a targeted shotgun HRMS analysis that tuberculostearic acid (FA 19:0; TSA)‐containing phosphatidylinositols (PI) are molecular markers of infection with clinically relevant M. tuberculosis complex strains and signify bacterial burden. They developed an indirect, culture‐free targeted lipid assay for bacterial cultures that can be performed within a day (30x faster than conventional methods) to measure the pathogen loads of M. tuberculosis in infected murine microphages, human neutrophils, and murine lung tissue. These PIs were found to be enriched in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from active TB patients. The focus on PBMC analysis instead of blood analysis was chosen to avoid variation caused by the metabolic state of patients. 310

HIV is a virus that attacks the body's immune system with the most advanced infection stage being AIDS. 317 According to the WHO, there were 1.5 million new HIV cases and approximately 650,000 HIV‐related deaths in 2021. 318 Sub‐Saharan Africa contains a disproportionate amount of HIV cases, accounting for more than 70% of all global cases. 318 , 319 , 320 Masip et al. studied plasma samples using untargeted RPLC‐HRMS of long‐term elite controllers (LTECs), a small subset of HIV individuals that have long‐term viral and immunological HIV control that are used as models of a functional cure, using untargeted RPLC‐HRMS. Here, a panel of 45 lipids could differentiate the clinical outcome of LTEC individuals on whether they are losing viral and/or immunological control, which could inform therapeutic interventions. 311 Wang et al. analysed plasma samples using RPLC‐HRMS of women with or at high risk of HIV to study alterations in host gut microbiota upon infection. The data together with network analysis showed positive associations between enriched pathogenic gut bacteria Fusobacterium and Proteus to the host lipidomic and metabolomic profiles, particularly in lysophosphatidylcholines (PC), lysophosphatidylethanolamines (PE), and diglycerides, which are associated with the progression of atherosclerosis. 252

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) is a positive‐sense RNA virus responsible for the global coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic that started in 2019 with more than 660 million people infected and more than 6.7 million deaths (on 12th January 2023). 321 Since its outbreak in 2019, the world population has experienced a drastic change in lifestyle due to the unpredictable nature of the disease. Despite the explosive efforts by the scientific community, there remain many questions regarding its pathological mechanisms, treatment, and the clinical management of patients that research groups have attempted to address through lipidomics experiments. 322 , 323 , 324 , 325 , 326 , 327 , 328 , 329 , 330 , 331 , 332 , 333 , 334 , 335

Castañé et al. analysed serum using RPLC‐HRMS in a semi‐quantitative approach to compare the lipidomic signatures of hospitalised COVID‐19 patients against disease controls (other infectious/inflammatory diseases, e.g. CVD, diabetes, kidney diseases and cancer) and healthy controls. Clear differences in acylcarnitines, fatty acids, and oxylipins were observed between COVID‐19 and healthy patients, but more importantly, this study shows how many of these lipid alterations were not specific to COVID‐19 patients and was shared with other infectious/inflammatory diseases. Altered levels in oxylipins, bile acids, and glycerophospholipids were found to best distinguish between COVID‐19 and negative controls. 323

Biagini et al. quantified the plasma levels of 48 oxylipins and five cytokines using micro‐extraction by packed sorbent (MEPS)‐RPLC‐MS/MS of hospitalised COVID‐19 ward and ICU patients to study their inflammatory responses to COVID‐19, in particular the cytokine and oxylipin storms. 336 Here, ICU patients were found to have significantly lower levels of oxylipins, suggesting an impaired inflammatory response that would put them at higher risk of severe viral attacks. 328 Similarly, Karu et al. quantified the plasma levels of 63 signalling lipids (free fatty acids, oxylipins and their intermediates, and immune‐active endocannabinoids) by RPLC‐MS/MS to understand COVID‐19 severity and progression. Substantial differences between the signalling lipid profiles of COVID‐19 patients were found at varying disease stages. The metabolic picture of severe patients was correlated with persistent inflammation and a disruption in the balance of signalling lipids, which could potentially prevent an effective shift into the resolution of inflammation. 330

Finally, Saud et al. studied the molecular composition of the SARS‐CoV‐2 lipid envelope using virus particles by HILIC‐MS/MS. This knowledge is important to design anti‐viral agents as well as improve our understanding of viral‐host interactions, infectivity, pathogenicity, and immune system clearance. The SARS‐CoV‐2 lipid membrane was observed to be primarily composed of PC, PE, and PI with a high proportion of external aminophospholipids. The molecular fatty acyl species may vary depending on the host cell. Further, in vitro and randomised controlled clinical studies of COVID‐19 patients using surfactant‐containing mouthwashes were found to be a potential antiviral approach for wider prevention and societal control strategies. 322

3.4. Future perspectives

In this review, we have demonstrated the relevance of lipidomics data for the elucidation of potential biomarkers and disease mechanisms in clinical studies. With future development, these could improve the diagnosis and prognosis of various diseases and be used to predict and measure treatment efficacy. They are largely not yet ready to be used in a clinical setting, as reflected by the low number of omics‐based biomarkers that have been approved by regulatory agencies and used in clinical settings, 337 , 338 and consequently, omics technologies are often perceived as over‐promising and/or underdelivering in clinical applications. The main challenges here include the inappropriate design of clinical trials and lack of validation, 339 , 340 and the difficulty and lack of standardisation of analytical methods. 339 , 340 , 341 With the number of lipidomics research articles concerning biomarker discovery continually increasing, there is a growing demand to convert these complex multivariate signatures into reliable cost‐effective assays that can routinely be used in practice. Lipidomics plays a key role here in first discovering a biomarker in a small cohort, then trialling its suitability through larger, validation cohorts with diverse participants for representation and inclusion, before translating its detection to a cheaper reliable method that can be used by the wider community at a clinic or at home (exemplified in Figure 4). 342

An exciting opportunity for clinical lipidomics is precision medicine (also known as personalised medicine), which aims to provide individualised healthcare in terms of disease treatment and prevention. It involves assessing the genotype and/or phenotype of a patient before treatment to more accurately and comprehensively direct therapy, 340 , 343 acknowledging the importance of an individual's characteristics in response to treatment. It would rework the current healthcare practices, from the one‐size‐fits‐all approach typically after a patient reports symptoms to one that tests a patient with an ability to preventatively predict diseases and determine which medical treatments will be safest and most effective for the individual patient. 343 This approach is more likely to detect non‐communicable diseases. According to Leroy Hood, a pioneer in this area, precision medicine promises to 1) provide deep insights into disease mechanisms, 2) make blood a diagnostic window for both the health and disease of an individual, 3) stratify complex diseases into subtypes, 4) provide new ways to drug target discovery, and 5) generate metrics for evaluating wellness. 341 It aims to be preventative, predictive, personalised, and participatory (termed “P4 medicine”). 341 According to the International Consortium for Personalised Medicine (ICPerMed), the implementation of precision medicine is targeted to be before 2030. 344

4. CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the most popular clinical research areas of 2022 in lipidomics were oncology, metabolic diseases (e.g. CVD, diabetes, liver disease and obesity), drug development, and infectious diseases. This is likely due to both their urgency and their known lipid dysregulations. MS‐based lipid analyses and sophisticated bioinformatics approaches are growing in parallel and can revolutionise lipidomic research. Still in its infancy, lipidomics has a strong potential to change the face of current clinical practices for disease stratification and precision medicine approaches; however, clear hurdles, such as the difficulty to convert complex laboratory procedures to simple reliable tests, lack of clinical sizes and validation cohorts for regulatory approval, prevent its current translation.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Caroline Géhin: Conceptualisation, investigation, visualisation, and writing—original draft. Stephen J. Fowler: Reviewing and editing. Drupad K. Trivedi: Conceptualisation, reviewing, and editing.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Géhin C, Fowler SJ, Trivedi DK. Chewing the fat: How lipidomics is changing our understanding of human health and disease in 2022. Anal Sci Adv. 2023;4:104–131. 10.1002/ansa.202300009

Footnotes

The bibliometric analysis was performed on the Google Scholar search engine (10th April 2023) using two searches: 1) an in‐text search of the keywords “lipidomics clinic*” limited to research articles in 2022 and 2) an in‐text search of the keywords “lipidomics clinic*” AND “internal standard*” limited to research articles in 2022. A percentage was calculated by dividing the number of publications for search #2 by search #1, then multiplying by 100.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

REFERENCES

- 1. Han X. Lipidomics for studying metabolism. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2016;12:668‐679. 10.1038/nrendo.2016.98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Yang K, Han X. Lipidomics: techniques, applications, and outcomes related to biomedical sciences. Trends Biochem Sci. 2016;41:954‐969. 10.1016/j.tibs.2016.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Benedusi V. Lipidomics . Mater Methods. 2018;8:2665. 10.13070/mm.en.8.2665 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4. O'Donnell VB, Ekroos K, Liebisch G, Wakelam M. Lipidomics: current state of the art in a fast moving field. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Syst Biol Med. 2020;12:e1466. 10.1002/wsbm.1466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Muro E, Atilla‐Gokcumen GE, Eggert US. Lipids in cell biology: how can we understand them better? Mol Biol Cell. 2014;25:1819‐1823. 10.1091/mbc.e13-09-0516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gross RW. The evolution of lipidomics through space and time. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Biol Lipids. 2017;1862:731‐739. 10.1016/j.bbalip.2017.04.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hinterwirth H, Stegemann C, Lipidomics Mayr M.. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2014;7:941‐954. 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.114.000550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fahy E, Cotter D, Sud M, Subramaniam S. Lipid classification, structures and tools. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Biol Lipids. 2011;1811:637‐647. 10.1016/j.bbalip.2011.06.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dennis EA. Lipidomics joins the omics evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2009;106:2089‐2090. 10.1073/pnas.0812636106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Züllig T, Köfeler HC. High resolution mass spectrometry in lipidomics. Mass Spectrom Rev. 2021;40:162‐176. 10.1002/mas.21627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fahy E, Subramaniam S, Brown HA, et al. A comprehensive classification system for lipids. J Lipid Res. 2005;46:839‐861. 10.1194/jlr.E400004-JLR200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. LIPID MAPS Structure Database (LMSD) n.d. Accessed January 13, https://lipidmaps.org/databases/lmsd/overview 2023.

- 13. Aldana J, Romero‐Otero A, Cala MP. Exploring the lipidome: current lipid extraction techniques for mass spectrometry analysis. Metabolites. 2020;10:231. 10.3390/metabo10060231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Christie WW. Lipid Analysis. Pergamon Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Robins SJ, Patton GM. Separation of phospholipid molecular species by high performance liquid chromatography: potentials for use in metabolic studies. J Lipid Res. 1986;27:131‐139. 10.1016/S0022-2275(20)38844-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. McCluer RH, Ullman DM, Jungalwala FB. HPLC of glycosphingolipids and phospholipids. Adv Chromatogr. 1986;25:309‐353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wood R, Harlow RD. Structural analyses of rat liver phosphoglycerides. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1969;135:272‐281. 10.1016/0003-9861(69)90540-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Duffin KL, Henion JD, Shieh JJ. Electrospray and tandem mass spectrometric characterization of acylglycerol mixtures that are dissolved in nonpolar solvents. Anal Chem. 1991;63:1781‐1788. 10.1021/ac00017a023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. ChemSpider . (‐)‐Aflatoxin B1 2023. Accessed April 12, http://www.chemspider.com/Chemical‐Structure.162470.html 2023.

- 20. ChemSrc . 1‐Palmitoyl‐2‐oleoyl‐3‐linoleoyl‐rac‐glycerol 2023. Accessed April 12, https://www.chemsrc.com/en/cas/2680‐59‐3_1030794.html 2023.

- 21. Barber M, Bordoli RS, Sedgwick RD, Tyler AN. Fast atom bombardment of solids (F.A.B.): a new ion source for mass spectrometry. J Chem Soc, Chem Commun. 1981:325‐327. 10.1039/C39810000325 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fenwick GR, Eagles J, Self R. Fast atom bombardment mass spectrometry of intact phospholipids and related compounds. Biol Mass Spectrom. 1983;10:382‐386. 10.1002/bms.1200100608 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Münster H, Stein J, Budzikiewicz H. Structure analysis of underivatized phospholipids by negative ion fast atom bombardment mass spectrometry. Biomed Environ Mass Spectrom. 1986;13:423‐427. 10.1002/bms.1200130808 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tomer KB, Jensen NJ, Gross ML. Fast atom bombardment and tandem mass spectrometry for determining structural modification of fatty acids. Anal Chem. 1986;58:2429‐2433. 10.1021/ac00125a017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wheelan P, Zirrolli JA, Murphy RC. Low‐energy fast atom bombardment tandem mass spectrometry of monohydroxy substituted unsaturated fatty acids. Biol Mass Spectrom. 1993;22:465‐473. 10.1002/bms.1200220808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kayganich KA, Murphy RC. Fast atom bombardment tandem mass spectrometric identification of diacyl, alkylacyl, and alk‐1‐enylacyl molecular species of glycerophosphoethanolamine in human polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Anal Chem. 1992;64:2965‐2971. 10.1021/ac00047a015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Byrdwell WC, Emken EA, Neff WE, Adlof RO. Quantitative analysis of triglycerides using atmospheric pressure chemical ionization‐mass spectrometry. Lipids. 1996;31:919‐935. 10.1007/BF02522685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cole MJ, Enke CG. Direct determination of phospholipid structures in microorganisms by fast atom bombardment triple quadrupole mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 1991;63:1032‐1038. 10.1021/ac00010a020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gross RW. Identification of plasmalogen as the major phospholipid constituent of cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum. Biochemistry. 1985;24:1662‐1668. 10.1021/bi00328a014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gross RW. High plasmalogen and arachidonic acid content of canine myocardial sarcolemma: a fast atom bombardment mass spectroscopic and gas chromatography‐mass spectroscopic characterization. Biochemistry. 1984;23:158‐165. 10.1021/bi00296a026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Fenn JB, Mann M, Meng CK, Wong SF, Whitehouse CM. Electrospray ionization for mass spectrometry of large biomolecules. Science. 1989;246:64‐71. 10.1126/science.2675315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Han X, Gross RW. Electrospray ionization mass spectroscopic analysis of human erythrocyte plasma membrane phospholipids. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1994;91:10635‐10639. 10.1073/pnas.91.22.10635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Han X, Gross RW. Structural determination of picomole amounts of phospholipids via electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 1995;6:1202‐1210. 10.1016/1044-0305(95)00568-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Han X, Gross RW. Structural determination of lysophospholipid regioisomers by electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry †. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:451‐457. 10.1021/ja952326r [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ford DA, Han X, Horner CC, Gross RW. Accumulation of unsaturated acylcarnitine molecular species during acute myocardial ischemia: metabolic compartmentalization of products of fatty acyl chain elongation in the acylcarnitine pool. Biochemistry. 1996;35:7903‐7909. 10.1021/bi960552n [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Weintraub ST, Pinckard RN, Hail M, Gaskell SJ. Electrospray ionization for analysis of platelet‐activating factor. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 1991;5:309‐311. 10.1002/rcm.1290050702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Han X, Yang J, Cheng H, Ye H, Gross RW. Toward fingerprinting cellular lipidomes directly from biological samples by two‐dimensional electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. Anal Biochem. 2004;330:317‐331. 10.1016/j.ab.2004.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hoischen C, Ihn W, Gura K, Gumpert J. Structural characterization of molecular phospholipid species in cytoplasmic membranes of the cell wall‐less Streptomyces hygroscopicus L form by use of electrospray ionization coupled with collision‐induced dissociation mass spectrometry. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:3437‐3442. 10.1128/jb.179.11.3437-3442.1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kim H‐Y, Wang T‐CL, Ma Y‐C. Liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry of phospholipids using electrospray ionization. Anal Chem. 1994;66:3977‐3982. 10.1021/ac00094a020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Yang K, Cheng H, Gross RW, Han X. Automated lipid identification and quantification by multidimensional mass spectrometry‐based shotgun lipidomics. Anal Chem. 2009;81:4356‐4368. 10.1021/ac900241u [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Köfeler HC, Ahrends R, Baker ES, et al. Recommendations for good practice in MS‐based lipidomics. J Lipid Res. 2021;62:100138. 10.1016/j.jlr.2021.100138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Moore JD, Caufield W V., Shaw WA. Quantitation and standardization of lipid internal standards for mass spectroscopy. Methods Enzymol. 2007;432:351‐367. 10.1016/S0076-6879(07)32014-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wenk MR. Lipidomics: new tools and applications. Cell. 2010;143:888‐895. 10.1016/j.cell.2010.11.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Meikle TG, Huynh K, Giles C, Meikle PJ. Clinical lipidomics: realizing the potential of lipid profiling. J Lipid Res. 2021;62:100127. 10.1016/j.jlr.2021.100127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lv J, Zhang L, Yan F, Wang X. Clinical lipidomics: a new way to diagnose human diseases. Clin Transl Med. 2018;7:12. 10.1186/s40169-018-0190-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Chetwynd AJ, Dunn WB, Rodriguez‐Blanco G. Collection and preparation of clinical samples for metabolomics. In: Metabolomics: From Fundamentals to Clinical Applications. Springer International Publishing; 2017. pp. 19‐44. 10.1007/978-3-319-47656-8_2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Burla B, Arita M, Arita M, et al. MS‐based lipidomics of human blood plasma: a community‐initiated position paper to develop accepted guidelines. J Lipid Res. 2018;59:2001‐2017. 10.1194/jlr.S087163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Chua EC‐P, Shui G, Lee IT‐G, et al. Extensive diversity in circadian regulation of plasma lipids and evidence for different circadian metabolic phenotypes in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2013;110:14468‐14473. 10.1073/pnas.1222647110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ang JE, Revell V, Mann A, et al. Identification of human plasma metabolites exhibiting time‐of‐day variation using an untargeted liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry metabolomic approach. Chronobiol Int. 2012;29:868‐881. 10.3109/07420528.2012.699122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kasukawa T, Sugimoto M, Hida A, et al. Human blood metabolite timetable indicates internal body time. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2012;109:15036‐15041. 10.1073/pnas.1207768109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Velenosi TJ, Ben‐Yakov G, Podszun MC, et al. Postprandial plasma lipidomics reveal specific alteration of hepatic‐derived diacylglycerols in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2022;162:1990‐2003. 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.03.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Gonzalez‐Covarrubias V, Dane A, Hankemeier T, Vreeken RJ. The influence of citrate, EDTA, and heparin anticoagulants to human plasma LC–MS lipidomic profiling. Metabolomics. 2013;9:337‐348. 10.1007/s11306-012-0450-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Bowen RAR, Remaley AT. Interferences from blood collection tube components on clinical chemistry assays. Biochem Medica. 2014;24:31‐44. 10.11613/BM.2014.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Yin P, Peter A, Franken H, et al. Preanalytical aspects and sample quality assessment in metabolomics studies of human blood. Clin Chem. 2013;59:833‐845. 10.1373/clinchem.2012.199257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Yin P, Lehmann R, Xu G. Effects of pre‐analytical processes on blood samples used in metabolomics studies. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2015;407:4879‐4892. 10.1007/s00216-015-8565-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Dorow J, Becker S, Kortz L, Thiery J, Hauschildt S, Ceglarek U. Preanalytical investigation of polyunsaturated fatty acids and eicosanoids in human plasma by liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry. Biopreserv Biobank. 2016;14:107‐113. 10.1089/bio.2015.0005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Hammad SM, Pierce JS, Soodavar F, et al. Blood sphingolipidomics in healthy humans: impact of sample collection methodology. J Lipid Res. 2010;51:3074‐3087. 10.1194/jlr.D008532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Wolrab D, Chocholoušková M, Jirásko R, et al. Determination of one year stability of lipid plasma profile and comparison of blood collection tubes using UHPSFC/MS and HILIC‐UHPLC/MS. Anal Chim Acta. 2020;1137:74‐84. 10.1016/j.aca.2020.08.061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Kano K, Matsumoto H, Kono N, Kurano M, Yatomi Y, Aoki J. Suppressing postcollection lysophosphatidic acid metabolism improves the precision of plasma LPA quantification. J Lipid Res. 2021;62:100029. 10.1016/j.jlr.2021.100029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Beger AW, Hauther KA, Dudzik B, Woltjer RL, Wood PL. Human brain lipidomics: investigation of formalin fixed brains. Front Mol Neurosci. 2022;15:835628. 10.3389/fnmol.2022.835628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Yadav M, Chaudhary PP, D'Souza BN, Spathies J, Myles IA. Impact of skin tissue collection method on downstream MALDI‐imaging. Metabolites. 2022;12:497. 10.3390/metabo12060497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. McClellan J, King M‐C. Genetic heterogeneity in human disease. Cell. 2010;141:210‐207. 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Nair ATN, Wesolowska‐Andersen A, Brorsson C, et al. Heterogeneity in phenotype, disease progression and drug response in type 2 diabetes. Nat Med. 2022;28:982‐988. 10.1038/s41591-022-01790-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Young AL, Marinescu R V, Oxtoby NP, et al. Uncovering the heterogeneity and temporal complexity of neurodegenerative diseases with Subtype and Stage Inference. Nat Commun. 2018;9:4273. 10.1038/s41467-018-05892-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Zhao X, Niu L, Clerici C, Russo R, Byrd M, Setchell KDR. Data analysis of MS‐based clinical lipidomics studies with crossover design: a tutorial mini‐review of statistical methods. Clin Mass Spectrom. 2019;13:5‐17. 10.1016/j.clinms.2019.05.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Blaise BJ, Correia G, Tin A, et al. Power analysis and sample size determination in metabolic phenotyping. Anal Chem. 2016;88:5179‐5188. 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b00188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Burger B, Vaudel M, Barsnes H. Importance of block randomization when designing proteomics experiments. J Proteome Res. 2021;20:122‐128. 10.1021/acs.jproteome.0c00536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]