Abstract

Objective

The gain of function (GOF) CTNNB1 mutations (CTNNB1 GOF ) in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) cause significant immune escape and resistance to anti-PD-1. Here, we aimed to investigate the mechanism of CTNNB1 GOF HCC-mediated immune escape and raise a new therapeutic strategy to enhance anti-PD-1 efficacy in HCC.

Design

RNA sequencing was performed to identify the key downstream genes of CTNNB1 GOF associated with immune escape. An in vitro coculture system, murine subcutaneous or orthotopic models, spontaneously tumourigenic models in conditional gene-knock-out mice and flow cytometry were used to explore the biological function of matrix metallopeptidase 9 (MMP9) in tumour progression and immune escape. Single-cell RNA sequencing and proteomics were used to gain insight into the underlying mechanisms of MMP9.

Results

MMP9 was significantly upregulated in CTNNB1 GOF HCC. MMP9 suppressed infiltration and cytotoxicity of CD8+ T cells, which was critical for CTNNB1 GOF to drive the suppressive tumour immune microenvironment (TIME) and anti-PD-1 resistance. Mechanistically, CTNNB1 GOF downregulated sirtuin 2 (SIRT2), resulting in promotion of β-catenin/lysine demethylase 4D (KDM4D) complex formation that fostered the transcriptional activation of MMP9. The secretion of MMP9 from HCC mediated slingshot protein phosphatase 1 (SSH1) shedding from CD8+ T cells, leading to the inhibition of C-X-C motif chemokine receptor 3 (CXCR3)-mediated intracellular of G protein-coupled receptors signalling. Additionally, MMP9 blockade remodelled the TIME and potentiated the sensitivity of anti-PD-1 therapy in HCC.

Conclusions

CTNNB1 GOF induces a suppressive TIME by activating secretion of MMP9. Targeting MMP9 reshapes TIME and potentiates anti-PD-1 efficacy in CTNNB1 GOF HCC.

Keywords: HEPATOCELLULAR CARCINOMA, MUTATIONS, CANCER IMMUNOBIOLOGY, IMMUNOTHERAPY

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

CTNNB1 GOF in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) has been proved to be associated with immune exclusion, leading to primary resistance to anti-PD-1 therapy in HCC patients. The suppressive tumour immune microenvironment (TIME) in these cases is characterised with exclusion of T cells, deficiency of dendritic cells recruitment, and alteration of cytokine profile.

Matrix metallopeptidase 9 (MMP9), which is significantly upregulated in HCC, plays a crucial role in the degradation of extracellular matrices such as gelatin and collagens, thereby promoting tumour progression. Moreover, MMP9 is able to proteolyze extracellular signal proteins from various cells.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

MMP9, as a key effector of CTNNB1 GOF , induced suppression of CD8+ T cells infiltration and cytotoxicity, which was critical to driving the suppressive TIME and anti-PD-1 resistance in HCC.

CTNNB1 GOF downregulated sirtuin 2 (SIRT2), resulting in disinhibition of β-catenin/lysine demethylase 4D (KDM4D) complex formation that fostered the transcriptional activation of MMP9.

MMP9 mediated SSH1 shedding from CD8+ T cells, leading to the inhibition of CXCR3-mediated intracellular G protein-coupled receptors signalling and suppression of CD8+ T cells infiltration and cytotoxicity.

Targeting MMP9 with an inhibitor or specific antibody remodels the suppressive TIME and enhances the efficacy of anti-PD-1 therapy.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

MMP9 presents itself as a promising target for CTNNB1 GOF to improve immune activation and anti-PD-1 efficacy, raising an effective combination strategy for immunotherapy.

Introduction

Antitumour immunotherapy has ushered in a new era in cancer treatment.1–3 Nonetheless, patients with HCC exhibited an objective response rate of only 15% to immune checkpoint blockade (ICB).4 5 Evasion of ICB in HCC is mainly attributed to the intricate tumour immune microenvironment (TIME) arising from diverse somatic mutations,6 which highlights the pressing need to investigate the intrinsic correlation between HCC somatic mutations and TIME to improve the efficacy of immunotherapy.

CTNNB1 mutations have been observed in 20%–39% of HCC.7–9 Most of mutations occur in CTNNB1 exon3 (93.38%) at serine/threonine sites or neighbouring amino acids,8 leading to the activation of Wnt/β-catenin (Wnt-on). Once in the Wnt-on state, the cytoplasmic protein β-catenin translocates into the nucleus, promoting target genes expression via binding to T cell factor (TCF) family members.10–12 Such gain of function (GOF) mutations of CTNNB1 (CTNNB1 GOF ) lead to a suppressive TIME characterised with T cell exclusion, defective recruitment of dendritic cells (DCs) and re-expression of chemokines.13–15 CTNNB1 GOF HCC is described as the‘cold’tumour, which diminishes the efficacy of immunotherapy. Therefore, resetting the ‘cold’ tumour to ‘hot’ tumour is of great concern to provide a new therapeutic option for patients with CTNNB1 GOF HCC.15

Matrix metallopeptidase 9 (MMP9) is a zinc-dependent endopeptidase,16 and tumours with high level of MMP9 were reported to be associated with worse prognosis in multiple cancer types.17–20 MMP9 enables the degradation of gelatin and collagens to function tissue remodelling, facilitating tumour invasion, metastasis and angiogenesis.21 Moreover, MMP9 is able to proteolyze extracellular signal proteins including interleukin 8 (IL-8), IFN-inducible T cell α chemoattractant (I-TAC) and CD100.22–24 Furthermore, SB-3CT, an inhibitor of MMP2/9, was developed to reduce the tumour burden and prolong survival by stimulating anti-tumour immunity in melanoma and lung cancer.25 However, the mechanism of MMP9 in regulating TIME in HCC needs to be further deciphered.

C-X-C motif chemokine receptor 3 (CXCR3) is a seven-transmembrane domain G-protein coupled receptor (GPCRs), which is mainly expressed on cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs), natural killer cells (NK cells) and natural killer T cells (NKT cells).26 27 The CXCR3 chemokine system, which is critical for promoting T cell migration, differentiation and activation,28 29 has been verified to be a biomarker for sensitivity to anti-PD-1 therapy, indicating that stimulating the CXCR3 chemokine system might enhance immunotherapeutic efficacy.30

In this study, we revealed the crucial role of MMP9 as the downstream of CTNNB1 GOF to induce suppressive TIME in CTNNB1 GOF HCC. MMP9 regulated the infiltration and cytotoxicity of CD8+ T cells through proteolysis SSH1 on the surface of CD8+ T cells. Furthermore, targeting MMP9 was feasible to sensitise anti-PD-1 therapy in CTNNB1 GOF HCC. The present study provides a promising combination strategy for the immunotherapy in HCC.

Materials and methods

Additional materials and methods are included in online supplemental material.

gutjnl-2023-331342supp001.pdf (3MB, pdf)

Results

MMP9 is upregulated in CTNNB1 GOF HCC

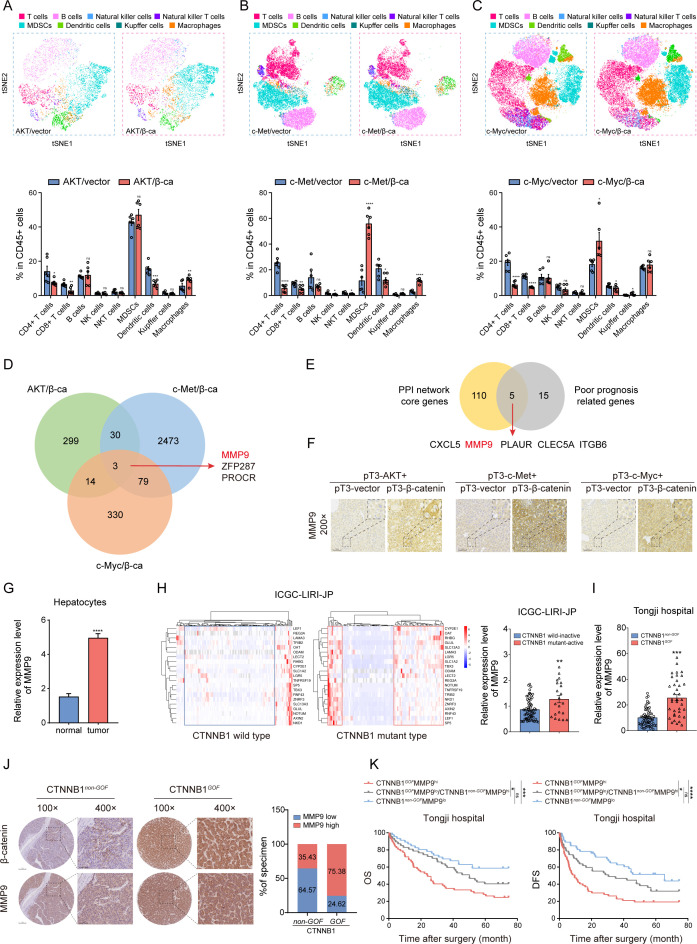

To identify activated genes driven by CTNNB1 GOF , we constructed three types of HCC models with CTNNB1 GOF background via hydrodynamic tail vein injection (HTVi) of activated AKT/β-catenin, c-Met/β-catenin, and c-Myc/β-catenin plasmids (online supplemental figure S1A). The ΔN90-β-catenin plasmid combined with another oncogenic plasmid through HTVi contributed to spontaneous tumourigenesis in liver.15 31–33 Mice receiving two oncogene plasmids formed observed lesions, while the control groups did not display noticeable pathologic changes (online supplemental figure S1B,C). Accumulation of β‐catenin in nucleus indicated the activation of Wnt/β‐catenin pathway (online supplemental figure S1B). Then, the liver immune microenvironment was analysed using flow cytometry (FCM) and t-distributed stochastic neighbour embedding (t-SNE) analysis. Consistent with previous reports,15 the infiltration of macrophages and myeloid-derived suppressor cells was increased, while DCs, CD8+ and CD4+ T cells were decreased in the CTNNB1 GOF HCC (figure 1A–C, online supplemental figure S2A,B). Meanwhile, CD8+Granzyme B+ T cells were decreased, indicating impaired cytotoxicity of CTLs (online supplemental figure S1D). The overall survival (OS) was shortened in the experimental groups due to the higher tumour burden (online supplemental figure S1E). Subsequently, RNA-seq was conducted for three pairs of models. The Venn diagram displayed the overlaps of 3 up-regulated genes (MMP9, PROCR, ZFP287) (Fold change (FC)>1.0, p<0.05) (figure 1D, online supplemental table S1). To identify core genes associated with immune regulation and poor prognosis, we analysed differentially expressed genes (DEGs) screened by ImmuneScore and StromalScore using the PPI network and univariate COX regression in The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) dataset (online supplemental figure S3A,B; online supplemental tables S2-4). As a result, five genes (CXCL5, MMP9, PLAUR, CLEC5A, ITGB6) were identified (figure 1E). The intersection of these two gene sets determined that MMP9 was the potential CTNNB1 GOF -driven gene that might reshape TIME in HCC. Then, MMP9 was verified to be highly expressed in CTNNB1 GOF tumours (figure 1F, online supplemental figure S1F).

Figure 1.

MMP9 is upregulated in CTNNB1 GOF HCC (A–C) The t-SNE plot and composition of key immune cells in the three groups of CTNNB1 GOF HCC models via HTVi of activated AKT (myr-AKT)/β-catenin (ΔN90-β-catenin), c-Met/β-catenin and c-Myc (MYC-IRES-Luc)/β-catenin plasmids (n=6). (D) Venn diagram illustrating the overlap of upregulated genes in the three groups of CTNNB1 GOF HCC models. (E) Venn diagram of core genes positively correlated with immune regulation and poor prognosis in TCGA dataset. (F) Representative images of IHC staining for MMP9 in the three groups of CTNNB1 GOF HCC models. (G) The mRNA expression level of MMP9 between normal hepatocytes and tumour cells in 10 HCC patients (normal, n=1788; tumour, n=14 202). (H) HCCs were categorised into four clusters using a 21-gene-signature in ICGC-LIRI-JP dataset (left panel). The mRNA expression level of MMP9 in the CTNNB1 wild inactive type and CTNNB1 mutant active type HCC tissue (right panel) (n=86). (I) The mRNA expression level of MMP9 in the CTNNB1 non-GOF and CTNNB1 GOF HCC tissue from Tongji cohort (n=99). (J) Representative images of IHC staining for β-catenin and MMP9 in the CTNNB1 non-GOF and CTNNB1 GOF HCC tissue from Tongji cohort. The statistical results are shown on the right (n=196). (K) Kaplan-Meier analysis of the OS and DFS of patients with HCC from Tongji cohort based on the CTNNB1 GOF and MMP9 IHC staining score (n=104). ns, no significance, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001. Mean±SEM. Unpaired Student’s t-test (A–C, G, H, I), Log-rank test (K). CTNNB1 GOF , gain of function mutations in CTNNB1; DFS, disease-free survival; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HTVi, hydrodynamic tail vein injection; ICGC, International Cancer Genome Consortium; IHC, immunohistochemistry; OS, overall survival; t-SNE, t-distributed stochastic neighbour embedding; TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas.

MMP9 was verified to be upregulated in several Gene Expression Omnibus datasets in HCC (online supplemental figure S3C). Furthermore, MMP9 in hepatocytes exhibited the most pronounced elevation during the progression of HCC according to Lu’s single-cell sequencing data (figure 1G, online supplemental figure S3D).34 Additionally, we investigated the activation status of CTNNB1 using a 21-gene signature in the International Cancer Genome Consortium dataset.35 Results showed MMP9 was upregulated on the CTNNB1 mutant active status (figure 1H). The upregulation of MMP9 in CTNNB1 GOF HCC was also observed in Tongji cohort (figure 1I and J, online supplemental figure S4A). Meanwhile, tumours with CTNNB1 GOF MMP9high correlated to worse survival and lower disease-free survival rates (figure 1K). These results suggested MMP9 was upregulated in CTNNB1 GOF HCC and correlated with poor prognosis.

To further verify the regulation of MMP9 by CTNNB1, Hepa1-6 cells were treated with various concentration of XAV939 (Wnt/β-catenin inhibitor), and MMP9 was inhibited in a dose-dependent manner (online supplemental figure S5A–C). Meanwhile, MMP9 was upregulated on the laduviglusib (Wnt/β-catenin activator) in a time-dependent manner (online supplemental figure S5D,E). Co-treatment with XAV939 or actinomycin D abolished the upregulation of MMP9 by β-catenin at the transcriptional level (online supplemental figure S5F). To further investigate the cisregulatory elements within the MMP9 promoter that mediate β-catenin-dependent MMP9 expression, a series of luciferase reporter constructs were generated with truncated or mutated MMP9 promoters (online supplemental figure S5G). The deletion of the region spanning from −950bp to −250 bp within the MMP9 promoter resulted in a significant reduction in β-catenin-dependent MMP9 promoter activity (online supplemental figure S5G), indicating that this particular region plays a crucial role in inducing MMP9 transcription by β-catenin. Additionally, the mutation of both putative TCF7 and TCF12 binding sites within this region dramatically reduced β-catenin-dependent activation of MMP9 promoter (online supplemental figure S5G). These results indicate that TCF7 and TCF12 are indispensable for β-catenin-dependent MMP9 promoter activation.

MMP9 promotes progression of HCC through inducing suppressive TIME

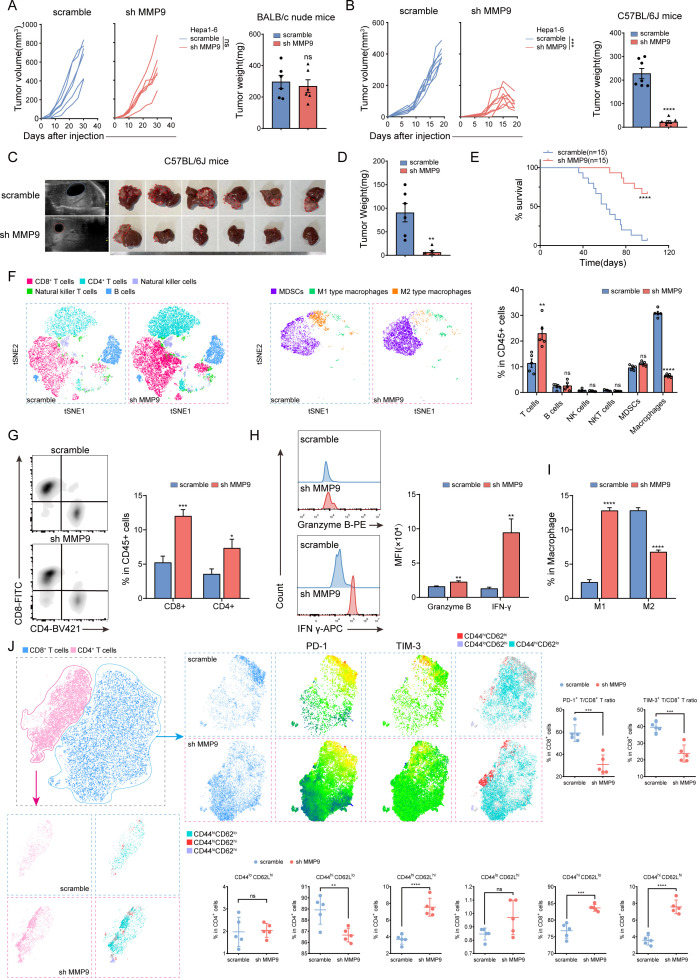

Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) showed MMP9 expression was correlated with suppressive TIME in TCGA-LIHC dataset (online supplemental figure S6A). MMP9 had little impact on tumour proliferation in vitro and BALB/c nude mice (figure 2A, online supplemental figure S6B–E,S7A). However, knockdown of MMP9 significantly diminished tumour volume and weight in C57BL/6 J mice (figure 2B, online supplemental figure S7B). FCM analysis of spleens from both groups of mice confirmed the absence of mature CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in BALB/c nude mice, despite the comparable proportion of T lymphocytes (online supplemental figure S7C).

Figure 2.

MMP9 promotes progression of HCC through inducing suppressive TIME (A, B) Growth curves and tumour weight of Hepa1-6 (scramble/sh MMP9) subcutaneous tumours in BALB/c nude mice and C57BL/6 J mice (n=6/7). (C) Representative B-US and general images of orthotopic tumours derived from Hepa1-6 (scramble/sh MMP9) C57BL/6 J mouse models. (D) The tumour weight of C57BL/6 J mouse models (n=6). (E) Survival curves of mice in each group of C57BL/6 J mouse models (n=15). (F) The t-SNE plot and composition of key immune cells in tumour tissue from C57BL/6 J mouse models (n=5). (G–I) Representative flow cytometry data showing the proportion of T cells and macrophages in tumour tissue from C57BL/6 J mouse models. The statistics results are shown on the right. (J) The t-SNE plots and composition of PD-1 and TIM-3 positive T cells and immune memory (CD44lo CD62Lhi, CD44hi CD62Llo and CD44hi CD62Lhi) T cells in tumour tissue from C57BL/6 J mouse models (n=5). The statistics results were shown as below. ns, no significance, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001. Mean±SEM. Unpaired Student’s t-test (A, B, D, F–J), log-rank test (E). B-US, B-ultrasound; ICB, immune checkpoint blockade; PD-1, programmed death-1; sh MMP9, MMP9-knockdown; t-SNE, t-distributed stochastic neighbour embedding; TIM-3, t cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain-3.

Then, the orthotopic HCC model was constructed using Hepa1-6 cells treated with MMP9 downregulation, demonstrating a significant suppression of tumour formation and improvement of survival (figure 2C–E). FCM analysis revealed an increase in total T lymphocytes, CD8+ and CD4+ T cells, while macrophages were reduced in the MMP9-knockdown group (figure 2F and G, online supplemental figure S8A). Meanwhile, the increased presence of granzyme B and interferon γ (IFN-γ) in CD8+ T cells indicated an enhanced cytotoxicity of CTLs (figure 2H). IHC and multiplex immunofluorescence (mIF) assays further confirmed the results (online supplemental figure S9A,B). Although there was a reduction in the overall number of macrophages, a shift from M2-phenotype to M1-phenotype was observed (figure 2I). Subsequent analysis revealed that PD-1 and T cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain-3 (TIM-3) were decreased in CD8+ T cells (figure 2J, online supplemental figure S8B). Additionally, the labelling of CD8+ and CD4+ T cells with CD44 and CD62L demonstrated an elevation in the level of immune memory response following MMP9 knockdown (figure 2J, online supplemental figure S8C). Collectively, these findings suggest that MMP9 promotes the progression of HCC through inducing a suppressive TIME.

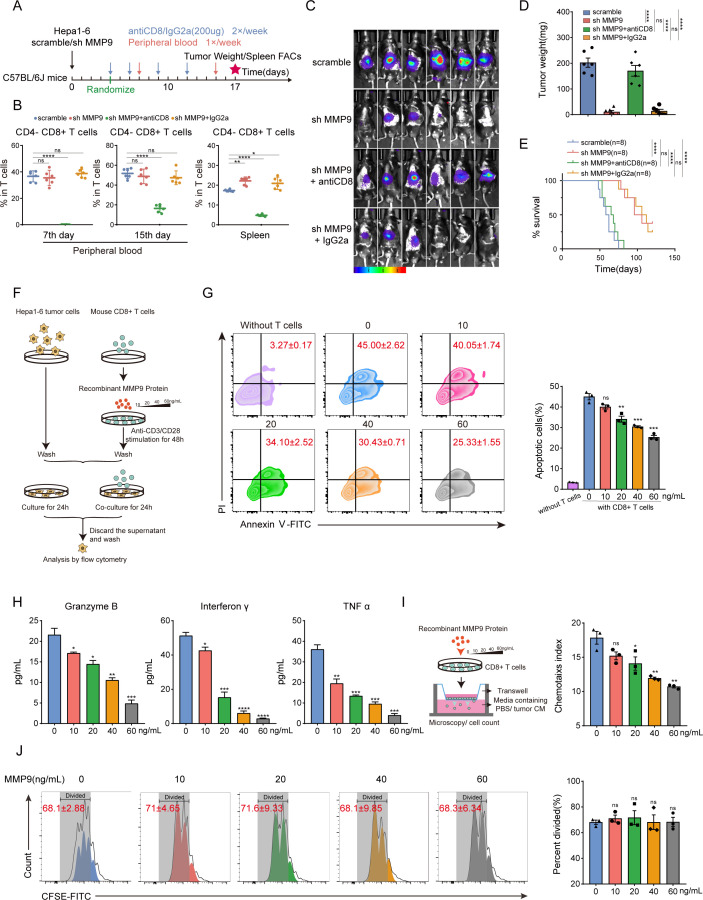

MMP9 inhibits activation and migration of CD8+ T cells

Given that both T lymphocytes and macrophage polarisation were changed after downregulation of MMP9, we further identified specific subset of immune cells regulated by MMP9 through eliminating CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells or macrophages. Orthotopic HCC models were treated with anti-CD4-neutralising antibody, anti-CD8-neutralising antibody or clophosome, respectively (figure 3A, online supplemental figure S10C,I). The effect of scavengers was monitored by FCM (figure 3B, online supplemental figure S10A,D,E and J). Depletion of CD8+ T cells deprived the tumour-inhibitory effect of MMP9 downregulation, leading to a heavier tumour burden and shortened survival (figure 3C–E, online supplemental figure S10B). On the contrary, the depletion of CD4+ T cells and macrophages was unable to restore tumour growth (online supplemental figure S10F–H and K–M). These results confirmed that suppressing CD8+ T cells was indispensable for MMP9 to promote tumour progression.

Figure 3.

MMP9 inhibits activation and migration of CD8+ T cells (A) Schematic representation of the treatment schedule for CD8-neutralising antibodies or IgG2a. (B) Flow cytometry analysis of depletion efficiency of CD8+ T cells from peripheral blood and spleen tissue. (C) The bioluminescent images of Hepa1-6 tumours from the orthotopic allograft tumour model of C57BL/6 J mice obtained at the endpoint. (D) The tumour weight of C57BL/6 J mouse models (CD8-neutralising antibodies, 200 µg/mice; IgG2a, 200 µg/mice, n=6). (E) Survival curves of mice in each group of C57BL/6 J mouse models (n=8). (F) CD8+ T cells were stimulated with MMP9 (10/20/40/60 ng/mL) and cocultured with Hepa1-6 cells for 24 hours. (G) Apoptosis of Hepa1-6 cells caused by CD8+ T cells stimulated with MMP9 was measured using Annexin V—PI staining. (H) CD8+ T cells were stimulated with MMP9 (10/20/40/60 ng/mL) followed by Elisa to detect the granzyme B, IFN-γ and TNFα secretion level from culture medium supernatant. (I) CD8+ T cells with the indicated treatments were determined by the transwell assay, and the chemotaxis index was shown. (J) The CFSE proliferation analyses of CD8+ T cells stimulated with MMP9 (10/20/40/60 ng/mL). ns, no significance, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001. Mean±SEM. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (B,D), unpaired Student’s t-test (G–J), log-rank test (E). ANOVA, analysis of variance; CM, conditioned medium; FACs, Fluorescence-activated cell staining; PI, propidium iodide; TNF α, tumour necrosis factor α.

In vitro coculture studies were conducted to unveil the impact of MMP9 on the activation of CD8+ T cells. Mouse splenic CD8+ T cells were stimulated by recombinant MMP9 protein and cocultured with Hepa1-6 cells for 24 hours (figure 3F). Tumour cytotoxicity of CD8+ T cells was weakened on MMP9 stimulation in a dose-dependent manner (figure 3G). Elisa assays of cell culture supernatants from CD8+ T on MMP9 stimulation showed MMP9 suppressed the secretion of granzyme B, IFN-γ, and tumour necrosis factor α (TNF α) (figure 3H). To delineate the role of MMP9 in CD8+ T cell migration, tumour-conditioned medium (CM) was added into the lower chambers and the migration of CD8+ T cells to the lower chambers was assessed. (figure 3I). Results indicated that MMP9 suppressed chemotaxis of CD8+ T cells (figure 3I). In addition, MMP9 did not influence the proliferation of CD8+ T cells (figure 3J). Collectively, these observations suggest that MMP9 hinders the activation and migration of CD8+ T cells to cause the suppressive TIME.

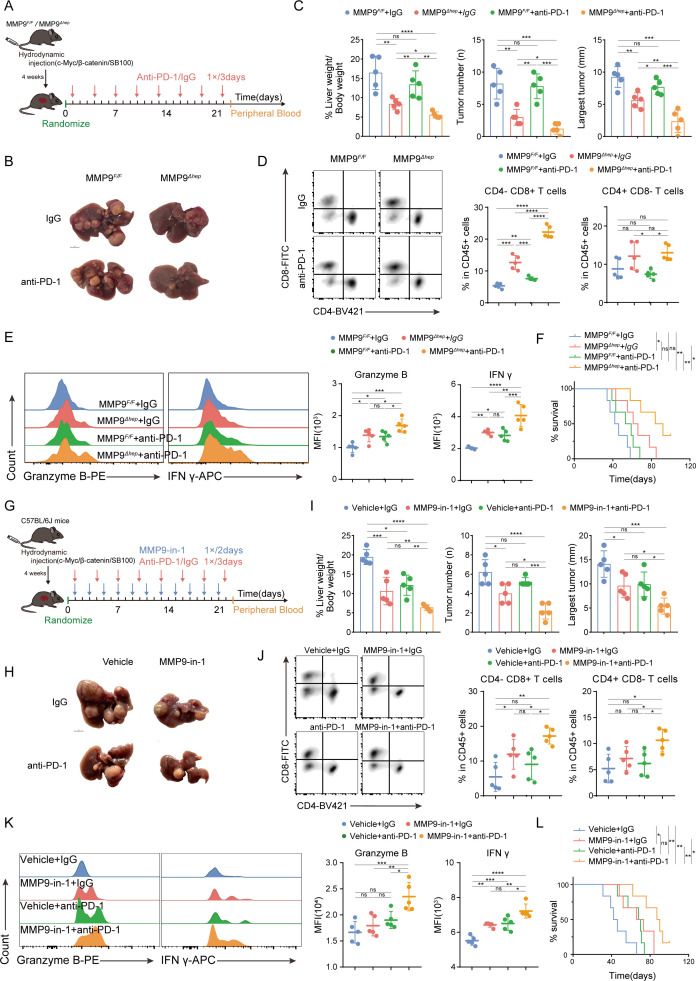

MMP9 blockade improves the TIME and potentiates anti-PD-1 efficacy in CTNNB1 GOF HCC

Anti-PD-1-based immunotherapy has been widely used in HCC treatment, and tumour-infiltrated CD8+ T cells have been reported as a biomarker for anti-PD-1 therapy.36 37 Given the impact of MMP9 on the CD8+ T cells, we speculated that MMP9 blockade might enhance the efficacy of anti-PD-1 therapy.

To assess the impact of MMP9 blockade on the anti-PD-1 efficacy in CTNNB1 GOF HCC, we constructed spontaneous tumourigenic models with CTNNB1 GOF in MMP9 hepatocyte conditional knockout mice (MMP9 F/F ; MMP9-Alb-cre, MMP9 Δhep for simplicity hereinafter). Following tumour formation, a subset of mice was administered with anti-PD-1 antibody (figure 4A). All mice were determined as CTNNB1 GOF bearing HCC model, verified by liver morphology, H&E staining and IHC (figure 4B; online supplemental figure S11A). Notably, MMP9 Δhep mice treated with anti-PD-1 antibody showed significant tumour suppression and survival prolongation in comparison with other groups (figure 4C, F). FCM analysis demonstrated a significant increase of CD8+ cells in MMP9 Δhep mice receiving anti-PD-1 compared with other groups (figure 4D). The heightened presence of granzyme B and IFN-γ in CD8+ T cells indicated enhanced cytotoxicity of CTLs (figure 4E). In addition, no lesions were observed in multiple organs in the combination group, indicating the overall safety of combination treatment of MMP9-blocking and anti-PD1 (online supplemental figure S11A). The blood routine and blood biochemistry analyses showed the combination treatment effectively alleviated the liver and kidney damage caused by tumour burden (online supplemental figure S11B).

Figure 4.

MMP9 blockade improves the TIME and potentiates anti-PD-1 efficacy in CTNNB1 GOF HCC (A) Schematic representation of the therapy schedule for MMP9 CKO, anti-PD-1 or combination therapy. (B, C) Representative images and the statistical results from spontaneous HCC models that received the indicated treatments (anti-PD-1, 200 µg/mice; IgG, 200 µg/mice, n=5). (D, E) Representative flow cytometry data showing the proportion of T cells and MFI of granzyme B and IFN-γ on CD8+ T cells in tumour tissue from spontaneous HCC models. The statistics results were shown on the right. (F) Survival curves of mice in each group of spontaneous HCC models (n=6). (G) Schematic representation of the therapy schedule for MMP9-in-1, anti-PD-1 or combination therapy. (H, I) Representative images and the statistical results from spontaneous HCC models that received the indicated treatments (MMP9-in-1, 20 mg/kg; anti-PD-1, 200 µg/mice; IgG, 200 µg/mice, n=5). (J, K) Representative flow cytometry data showing the proportion of T cells and MFI of granzyme B and IFN-γ on CD8+ T cells in tumour tissue from spontaneous HCC models. The statistics results were shown on the right. (L) Survival curves of mice in each group of spontaneous HCC models (n=6). ns, no significance, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001. Mean±SEM. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (C–E, I–K), Log-rank test (F, L). ANOVA, analysis of variance; CKO, conditional knockout; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; MFI, mean fluorescence intensity; TIME, tumour immune microenvironment.

We further introduced MMP-9-in-1, a specific MMP9 inhibitor that selectively targets the haemopexin (PEX). Similarly, MMP-9-in-1 was combined with anti-PD-1 to treat CTNNB1 GOF HCC models (figure 4G, online supplemental figure S12A). Consistently, the combination therapy yielded more substantial tumour regression and survival prolongation compared with MMP-9-in-1 or anti-PD-1 monotherapy (figure 4H1 and L, online supplemental figure S12B,E). FCM analysis demonstrated that the combination treatment enhanced the infiltration and cytotoxicity of CD8+ T cells (figure 4J and K, online supplemental figure S12C,D). The safety of combination therapy was validated in the same way (online supplemental figure S11C,D).

These results suggest that the MMP9 blockade has potential to reshape the TIME of CTNNB1 GOF HCC and sensitises the anti-PD-1 therapy.

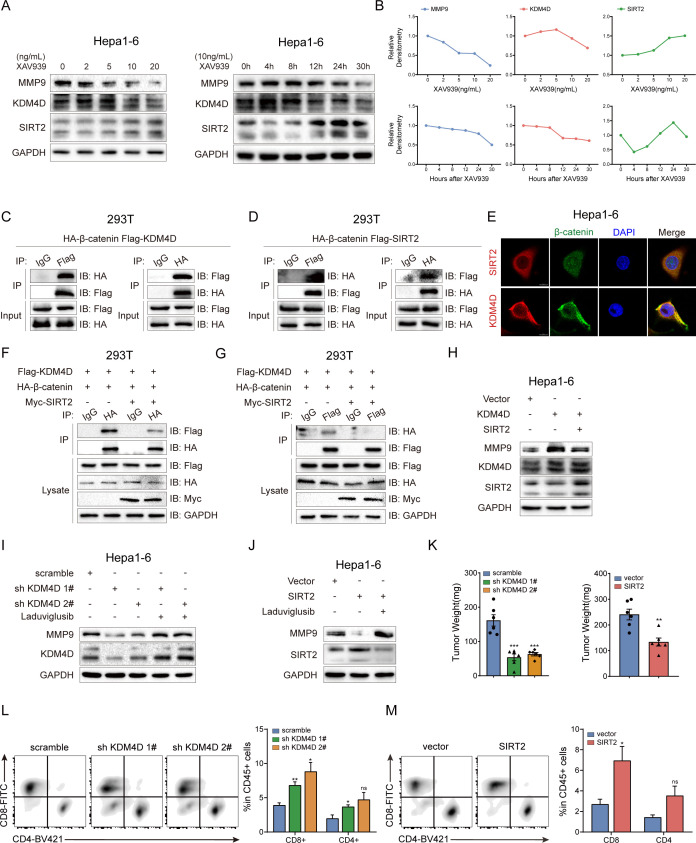

β-catenin-mediated inhibition of SIRT2 upregulates MMP9 by promoting the formation of β-catenin/KDM4D complex

We further investigated the precise mechanism of β-catenin in regulating MMP9. Before assembling the transcription complex, β-catenin interacts with various proteins to form different protein complexes, carrying out distinct functions.38 KDM4D was reported to interact with β-catenin, resulting in demethylation of H3K9me3 at MMP9 promoters.39 SIRT2 could directly interact with β-catenin to suppress Wnt signalling output, and inhibition of Wnt/β-catenin signalling enhances SIRT2 promoter activity.40 41 We found activation of Wnt/β-catenin signalling by XAV939 promoted the KDM4D expression and suppressed the SIRT2 expression in a dose-dependent and time-dependent manner (figure 5A, B). Coimmunoprecipitation (CoIP) results validated the binding of β-catenin with KDM4D or SIRT2, respectively (figure 5C, D). Immunofluorescence confirmed the colocalisation of β-catenin with KDM4D or SIRT2 in the cytoplasm and nucleus of Hepa1-6 cells (figure 5E).

Figure 5.

β-catenin-mediated inhibition of SIRT2 upregulates MMP9 by promoting the formation of β-catenin/KDM4D complex (A) Hepa1-6 cells were treated with XAV939 (2/5/10/20 ng/mL for 48 hours or 20 ng/mL for 4/8/12/24/30 hours,) followed by western blotting to detect the expression of MMP9, KDM4D and SIRT2. (B) Densitometry graphs of MMP9, KDM4D and SIRT2 of each treatment group. (C, D) CoIP assays were performed in HEK293 (5×106) cells cotransfected with HA-β-catenin (5 µg) and indicated plasmids (3 µg) for 30 hours. (E) Immunofluorescence assays for β-catenin (green) with SIRT2 (red) or KDM4D (red) in Hepa1-6 cells. (F, G) CoIP assays were performed in HEK293 (5×106) cells cotransfected with HA-β-catenin (5 µg), and Flag-KDM4D (3 µg) together with or without Myc-SIRT2 (3 µg) for 30 hours. (H) Western blotting was performed in Hepa1-6 cells cotransfected with pcDNA3.1-Vector (5 µg) and pcDNA3.1-KDM4D (5 µg) together with or without pcDNA3.1-SIRT2 (5 µg). (I, J) Stable Hepa1-6 cell lines of KDM4D knockdown (sh KDM4D) and SIRT2 overexpression were treated with laduviglusib (10 ng/mL) followed by western blotting to detect the expression of MMP9, KDM4D and SIRT2. (K) The tumour weight of Hepa1-6 (scramble/sh KDM4D or vector/SIRT2) orthotopic tumours in C57BL/6 J mice (n=6/6). (L, M) Representative flow cytometry data showing the proportion of T cells in tumour tissue from orthotopic tumours. The statistics results were shown on the right (n=6/6). ns, no significance, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001. Mean±SEM. Unpaired Student’s t-test (K–M).

Based on the above observations, we hypothesised that SIRT2 and KDM4D might be competitively combined with β-catenin. Results of CoIP indicated the overexpression of SIRT2 significantly suppressed the binding of β-catenin and KDM4D (figure 5F, G). Moreover, the overexpression of SIRT2 in KDM4D-overexpressing Hepa1-6 cells limited the upregulation of MMP9 (figure 5H). Subsequently, the downregulation of MMP9 protein induced by KDM4D knockdown or SIRT2 overexpression was reversed on the stimulation of laduviglusib (figure 5I, J). Furthermore, KDM4D knockdown or SIRT2 overexpression inhibited the expression of MMP9 and conferred activation of TIME, resulting in suppression of tumour formation (figure 5K–M, online supplemental figure S13A-C). These results indicate that inhibition of SIRT2 by β-catenin promotes the formation of β-catenin/KDM4D complex, which contributes to a suppressive TIME through upregulating MMP9.

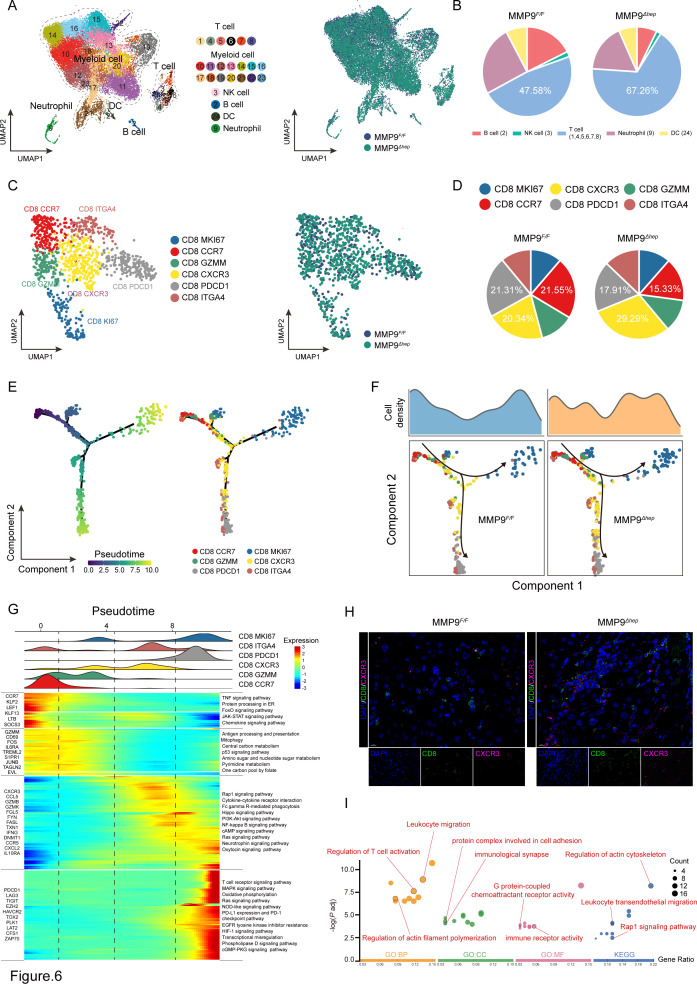

MMP9 suppresses the infiltration of CD8+CXCR3+ T cells in CTNNB1 GOF HCC

We next performed scRNA-seq to explore the mechanism of MMP9 in reshaping TIME. Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) was used to isolate tumour CD45+ cells from CTNNB1 GOF HCC tissue of MMP9 F/F and MMP9 Δhep mice (online supplemental figure S14A,B). Unsupervised uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) analysis of the total CD45+ cell populations identified 23 subclusters (figure 6A). The identified immune cell populations encompassed T cells, myeloid cells, NK cells, B cells, DCs and neutrophils (online supplemental figure S15A). All cells expressed high levels of housekeeping gene ACTB, whereas immune cells were PTPRC+, AFP-, indicating the accuracy of our data (online supplemental figure S15B). These cell subtypes were shared among MMP9 F/F and MMP9 Δhep mice (figure 6A). Given the substantial proportion of myeloid cells, we conducted a separate analysis to determine the proportions of myeloid and non-myeloid cells (figure 6B, online supplemental figure S15C). Notably, the infiltration levels of T cells were significantly augmented following MMP9 knockout.

Figure 6.

MMP9 suppresses the infiltration of CD8+CXCR3+ T cells in CTNNB1 GOF HCC (A) The UMAP plot, showing the annotation and colour codes for immune cell types in the HCC ecosystem (left panel), and MMP9 F/F and MMP9 Δhep origins (right panel). (B) Tortadiagram indicating the proportion of non-myeloid immune cells. (C) The UMAP plot, showing the annotation and colour codes for CD8+ T cell types (left panel), and MMP9 F/F and MMP9 Δhep origins (right panel). (D) Tortadiagram indicating the proportion of CD8+ T cells from MMP9 F/F and MMP9 Δhep samples. (E) Pseudotime-ordered analysis of CD8+ T cells from MMP9 F/F and MMP9 Δhep samples. T cell subtypes are labelled by colours. (F) Two-dimensional graph of the pseudotime-ordered CD8+ T cells, from MMP9 F/F and MMP9 Δhep samples. The cell density distribution, by state, is shown at the top of the figure. (G) Heatmap showing the dynamic changes in gene expression along the pseudotime (lower panel). The distribution of CD8 subtypes during the transition (divided into 4 phases), along with the pseudo-time. Subtypes are labelled by colours (upper panel). (H) Representative images of immunofluorescence costaining for CD8 (green) with CXCR3 (pink) in the MMP9 F/F and MMP9 Δhep samples. (I) GO and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of CD8+CXCR3+ T cells. GO, Gene Ontology; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopaedia of Genes and Genomes; UMAP, Unsupervised uniform manifold approximation and projection.

Having previously established the role of MMP9 in promoting HCC in a CD8+ T cell-dependent manner, we conducted unsupervised clustering analysis of CD8+ T cells. The results unveiled six distinct subtypes of CD8+ T cells, namely CD8 MKI67, CD8 CCR7, CD8 GZMM, CD8 CXCR3, CD8 PDCD1 and CD8 ITGA4 (figure 6C, online supplemental figure S15D,E). In particular, the MMP9 Δhep samples demonstrated the most significant increase of CD8 CXCR3 cells (figure 6D). We observed that the transcriptional profile of CD8 CXCR3 cells was consistent with reported CD8 CX3CR1 cells associated with functions of effector T cells (online supplemental figure S15D,E).42

We subsequently investigated the dynamic immune state of CD8+ T cells. Pseudotime analysis revealed that the transition process commenced with CD8 CCR7 cells, progressing through an intermediate cytotoxic state characterised by CD8 GZMM and CD8 CXCR3 cells, and ultimately resulting in either proliferation (CD8 MKI67 cells) or exhaustion, characterised by CD8 PDCD1 and CD8 ITGA4 cells (figure 6E). To further delineate the transition states, we analysed the trajectories of CD8+ T cells from MMP9 F/F and MMP9 Δhep samples separately. Surprisingly, CD8 CXCR3 cells were predominantly distributed in MMP9 Δhep samples (figure 6F, G). Consequently, we concluded that the MMP9 knockout primarily impacts the infiltration and function of CD8+ CXCR3+ T cells. This result was further supported by the mIF staining assay, confirming the enrichment of CD8+CXCR3+ T cells in MMP9 Δhep samples (figure 6H). Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopaedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analysis demonstrated that CD8+CXCR3+ T cells specifically exhibit enrichment in G protein-coupled chemoattractant receptor activity, regulation of T cell activation, leucocyte migration and cell adhesion (figure 6I).

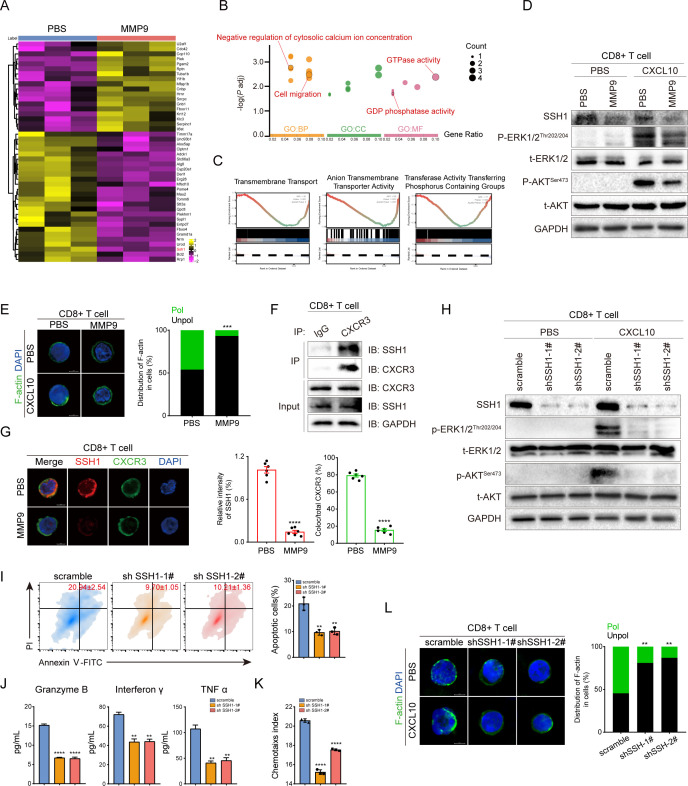

MMP9 inhibits the CXCR3-mediated intracellular signalling of GPCRs by proteolysis SSH1 shedding from CD8+ T cells

We further aimed to elucidate the mechanism of MMP9 in regulating CD8+CXCR3+ T cells. MMP9 was involved in the proteolysis of extracellular membrane proteins from various types of immune cells.23 24 Thus, we hypothesised that MMP9 mediated the cleavage of proteins on the surface of CD8+ T cells, which inhibited CXCR3-mediated intracellular signalling of GPCRs. Proteomics identified 26 downregulated proteins in CD8+ T cells following MMP9 stimulation (figure 7A, online supplemental figure S16A), and these proteins were enriched in GTPase activity, GDP phosphatase activity, regulation of cytosolic calcium ion concentration and cell migration (figure 7B). GSEA further demonstrated that MMP9 stimulation was associated with a variety of membrane transport processes (figure 7C, online supplemental figure S16B). Similarly, MMP9 inhibited CXCR3-mediated phosphorylation of ERK and AKT in CD8+ T cells (figure 7D). F-actin was scattered over the periphery of CD8+ T cells stimulated with MMP9, while accumulated in the leading edge of T cells without simulation of MMP9 (figure 7E). These data suggested that MMP9 inhibited CXCR3-mediated intracellular signalling of GPCRs. Furthermore, SSH1 which promotes directional cell migration and T cell response to antigenic stimulation was significantly reduced in CD8+ T cells on MMP9 stimulation (figure 7A, D).43 44 The observed negative correlation between MMP9 and SSH1 implicated a potential role of MMP9 in SSH1 cleavage.

Figure 7.

MMP9 inhibits the CXCR3-mediated intracellular signalling of GPCRs by proteolysis SSH1 shedding from CD8+ T cells. (A) Heatmap showing the differential expression of proteins in MMP9-stimulated CD8+ T cells versus control CD8+ T cells. (B) GO pathway enrichment analysis of proteins cleaved by MMP9. (C) GSEA of proteomics data revealed that the protein transmembrane transporter activity, anion transmembrane transporter activity and transferase activity transferring phosphorus-containing groups were significantly decreased in the MMP9-stimulated CD8+ T cells group. (D) Phosphorylation and total levels of ERK and AKT in CD8+ T cells with the indicated treatments were determined by immunoblotting (MMP9, 60 ng/mL; CXCL10 100 ng/mL). (E) CD8+ T cells with the indicated treatments were stained for F-actin. Shown are representative images of polarised F-actin distribution and the frequency of cells with either polarised or unpolarised F-actin distribution. (F) Endogenous CoIP was performed in CD8+ T cells. (G) Representative immunofluorescence microscopy images of SSH1 binding to CXCR3 in CD8+ T cells. Shown are relative intensity of SSH1 (red bar) and quantifications of colocalisation signals in percentages of CXCR3 (green bar) (n=6). (H) Phosphorylation and total levels of ERK and AKT in CD8+ T cells (scramble/sh SSH1) were determined by immunoblotting (CXCL10 100 ng/mL). (I) Apoptosis of Hepa1-6 cells caused by CD8+ T cells (scramble/sh SSH1) was measured using Annexin V—PI staining. (J) CD8+ T cells (scramble/sh SSH1) followed by Elisa to detect the granzyme B, IFN-γ and TNFα secretion level from culture medium supernatant. (K) CD8+ T cells (scramble/sh SSH1) were determined by the transwell assay, and the chemotaxis index was shown. (L) CD8+ T cells (scramble/sh SSH1) were stained for F-actin. Shown are representative images of polarised F-actin distribution and the frequency of cells with either polarised or unpolarised F-actin distribution. **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001. Mean±SD. Unpaired Student’s t-test (G, I, J, K), two-tailed χ2 test (L).

The role of SSH1 in CD8+ T cells was further investigated. CoIP and immunofluorescent staining demonstrated SSH1 could be bound with CXCR3, but disassociated on MMP9-mediated cleavage of SSH1 (figure 7F,G). Knockdown of SSH1 in CD8+ T cells inhibited the stimulation of ERK and AKT phosphorylation on CXCL10 (figure 7H), and hindered the activation, migration and polarisation of CD8+ T cells (figure 7I–L). Moreover, SSH1 upregulation abrogated the suppression of migration and activation of CD8+ T cells induced by MMP9 (online supplemental figure S17A–C). Collectively, these findings indicated that MMP9 impedes the CXCR3-mediated intracellular signalling of GPCRs by cleaving SSH1 shedding from the surface of CD8+ T cells.

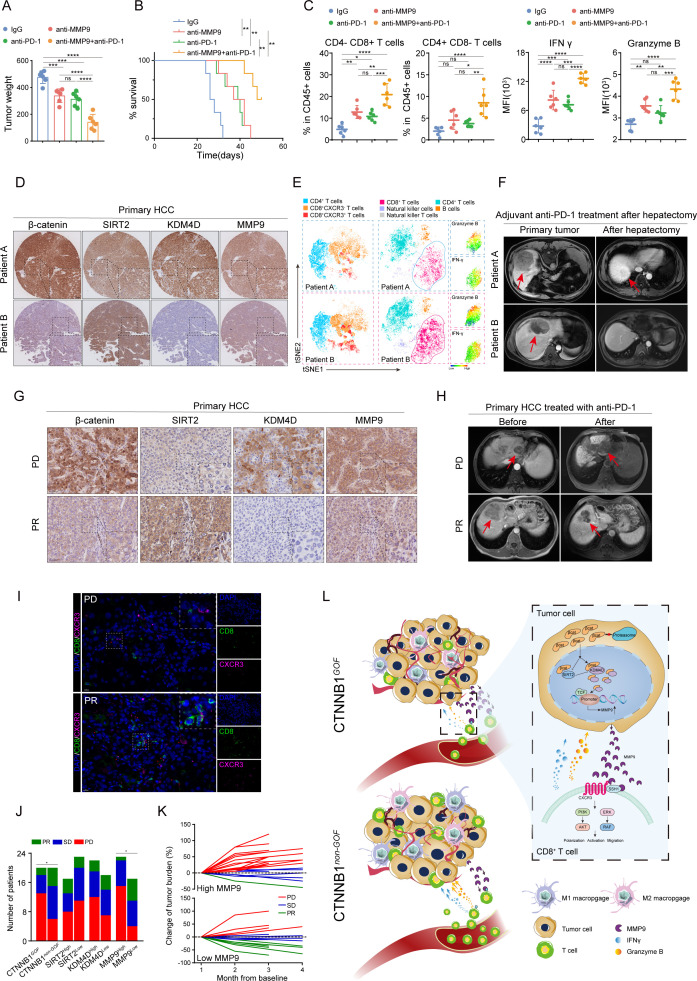

MMP9 confers a valuable therapeutic target and biomarker for immunotherapy in HCC

These investigations inspired us to raise a new therapeutic by targeting MMP9. A new anti-MMP9 rabbit monoclonal antibody (mAb) was developed and assessed the potential therapeutic value for immunotherapy in clinical practice (online supplemental figure S18A). Either anti-PD-1 or anti-MMP9 monotherapy inhibited tumour growth to some extent (figure 8A; online supplemental figure S18B,C), while the combination treatment yielded a more pronounced suppression of tumour growth and extended survival (figure 8A and B, online supplemental figure S18C). FCM analysis revealed the combination treatment augmented the infiltration and cytotoxicity of CD8+ T cells (figure 8C). In addition, no significant toxicity was observed in the treatment groups, ensuring the safety of anti-MMP9 mAb (online supplemental figure S18D,E). Collectively, these results showed the therapeutic value of anti-MMP9 mAb, and the combination of anti-MMP9 and anti-PD-1 might be a promising strategy for immunotherapy in HCC.

Figure 8.

MMP9 confers a valuable therapeutic target and biomarker for immunotherapy in HCC (A) the tumour weight of Hepa1-6 orthotopic models that received the indicated treatments (anti-MMP9, 200 µg/mice; anti-PD-1, 200 µg/mice; IgG, 200 µg/mice, n=6). (B) Survival curves of mice in each group of orthotopic HCC models (n=6). (C) The flow cytometry data results of the proportion of T cells and MFI of granzyme B and IFN-γ on CD8+ T cells in tumour tissue. (D) Representative images of IHC staining for β-catenin, SIRT2, KDM4D and MMP9 in tumour tissue from patients A and B (patient A, a CTNNB1 GOF patient; patient B, a CTNNB1 non-GOF patient). (E) The t-SNE plot in tumour tissue from patients A and B. (F) MRI images of lesions for HCC patients A, B. (G) Representative images of IHC staining for β-catenin, SIRT2, KDM4D and MMP9 in tumour tissue from the PD or PR patients. (H) MRI images of lesions for HCC patients (PD and PR). (I) Representative images of immunofluorescence co-staining for CD8 (green) with CXCR3 (pink) in tumour tissue from the PD or PR patients. (J) Patients were categorised into high and low groups according to β-catenin, SIRT2, KDM4D and MMP9 levels; a correlation analysis of their levels and the efficacy of anti-PD-1 treatment was performed. (K) Patients were categorised into high and low groups according to the MMP9 level in tumour tissue; a fold line diagram was used to detect the changes in the tumour size of HCC patients after anti-PD-1 treatment. (L) Schematic diagram depicting the TIME induced by MMP9 in patients with CTNNB1 GOF HCC. ns, no significance, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001. Mean±SEM. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (A, C), log-rank test (B), two-tailed χ2 test (J). ANOVA, analysis of variance; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; t-SNE, t-distributed stochastic neighbour embedding.

Clinically, we collected primary HCC specimens by hepatectomy or biopsy from Tongji Hospital for further analysis. In the cohort receiving postoperative anti-PD-1 adjuvant therapy (n=38), the IHC staining results showed that MMP9 expression positively correlated with β-catenin and KDM4D, while negatively correlated with SIRT2 (figure 8D). The tSNE analysis demonstrated that patients with high level of MMP9 experienced decreased infiltration of CD8+CXCR3+T cells and weakened cytotoxicity of CD8+T cells within tumours (figure 8E, online supplemental figure S19A,B). Furthermore, patients with high MMP9 expression were more likely to recur after surgery compared with patients with lower MMP9 (figure 8F, online supplemental figure S20). Similarly, for patients receiving anti-PD-1 neoadjuvant therapy (n=40), high level of MMP9 caused a suppressive TIME and lower response rate to anti-PD-1 therapy (figure 8G–K).

Discussion

Anti-PD-1-based immunotherapy has emerged as a promising strategy with durable clinical benefits in multiple cancers.45 However, the exploration of precision medicine in cancer has shed light on the fact that patients with somatic mutations in CTNNB1 generally do not respond to anti-PD-1 monotherapy.46 The unresponsiveness could be attributed to the ‘cold tumour’ nature of CTNNB1 GOF HCC.47 This correlation between CTNNB1 GOF and T cell exclusion has been confirmed in several cancers,14 highlighting the pressing need to explore novel strategies to transform CTNNB1 GOF HCC into‘hot tumour’. The present study reveals MMP9 is upregulated in CTNNB1 GOF HCC, which inhibits the activation and migration of CD8+ T cells (figure 8L). In vivo inhibition of MMP9 or anti-MMP9 mAb treatment effectively restrains tumour growth and synergistically enhances the anti-PD-1 immunotherapy efficacy.

Currently, multiple treatment options are available for reshaping the TIME of CTNNB1 GOF HCC, including supplementation of cytokine, adoptive therapy of DC or T cell and targeting the downstream of CTNNB1 mutations.15 48–50 Nonetheless, the inherent limitation of supplementing antitumour immune cells or cytokine is the tendency to induce serious adverse effects. For instance, overexpressing CCL5 in CTNNB1 GOF HCC enables the higher recruitment of CD103+ DCs, antigen-specific CD8+ T cells, and the restoration of immune surveillance.15 However, CCL5 has been observed to confine liver regeneration by inhibiting the secretion of hepatocyte growth factor from reparative macrophages.51 Besides, the present study revealed the significant increase of macrophages in CTNNB1 GOF HCC, suggesting that increasing CCL5 might result in more harm than benefit. Therefore, exploring and intervening the critical downstream targets of CTNNB1 GOF might be more efficient and safer for CTNNB1 GOF HCC to reset TIME and sensitise anti-PD-1 therapy. In this study, MMP9 was identified as the crucial downstream of CTNNB1 GOF , leading to a suppressive TIME by suppressing the migration and activation of CD8+ T cells. Mechanistically, CTNNB1 GOF inhibited SIRT2 and promoted formation of β-catenin/KDM4D complex, ultimately enhancing MMP9 promoter activity. The proteolytic property of MMP9 enables the degradation of structural proteins and remodelling of extracellular matrix, facilitating tumour cells penetrating the basement membrane and invading into adjacent normal tissues. In addition, MMP9 involved in the release and activation of various bioactive molecules which were responsible for the tumour progression.52 In this study, we demonstrated that MMP9 proteolyzed SSH1 from the surface of tumour-infiltrating CD8+ T cells, resulting in the blocking of CXCR3-mediated intracellular signalling of GPCRs (figure 8L). Since CXCR3 chemokine system regulates the early-stage migration of T cells to tumours, of which the infiltration determines anti-PD-1 efficacy, the CXCR3-mediated regulation of T cell infiltration is required to respond to the anti-PD-1 therapy in HCC.30 53 Therefore, our results supported that CTNNB1 GOF induced suppressive TIME through MMP9-mediated dysfunction of CD8+ T cells, suggesting a potential combination strategy for CTNNB1 GOF HCC.

Here, we demonstrated that MMP9 blockade potentially reshapes the CTNNB1 GOF HCC TIME characterised with elevated infiltration and cytotoxicity of CD8+ T cells. The combination of MMP9 blockade and anti-PD-1 significantly suppressed tumour progression and extended survival of tumour-bearing mice. These evidences supported that targeting MMP9 reversed CTNNB1 GOF -induced suppressive TIME and MMP9-blocking potentiate the response to anti-PD-1 therapy in CTNNB1 GOF HCC. Antibodies targeting MMP9 have demonstrated favourable safety and clinical efficacy in several clinical trials,54 55 while the effect of anti-MMP9 mAb in HCC has not yet been reported. Our findings inspired us to apply the anti-MMP9 mAb to increase the efficacy of anti-PD-1 in HCC in clinical practice. The anti-MMP9 mAb sensitised the anti-PD-1 therapy with more pronounced tumour suppression and improved OS in HCC in a preclinical model. Furthermore, anti-MMP9 exhibited a favourable safety profile. These results indicated that TIME-reshaping-strategy with anti-MMP9 mAb might have potential application in immunotherapy for HCC.

The present study provides a new insight into the combination strategy for immunotherapy in CTNNB1 GOF HCC. The efficacy of anti-MMP9 mAb in HCC needs to be further validated in additional animal models, and provide sufficient evidence for clinical trials in the future. Previous studies showed that MMP9 secreted by neutrophils and macrophages might alleviate liver fibrosis,56 57 however, recent studies found that targeting MMP9+ cells might also be a promising antifibrotic strategy.58 Given that MMP9 itself exhibits no activity against collagen type I, and the initial cleavage of collagen type I is crucial for the overall regression of liver fibrosis,59 the exact role of MMP9 on liver fibrosis requires further investigation in detail. In addition, the progression of liver fibrosis caused by anti-MMP9 agents used in clinical has not yet been reported. Collectively, the effect on liver fibrosis should be paid attention to in the preclinical and clinical application of anti-MMP9 mAb.

In summary, the present study reveals the critical role of MMP9 in regulating tumour immune evasion in CTNNB1 GOF HCC. Targeting MMP9 reversed CTNNB1 GOF -induced suppressive TIME and MMP9 blockade potentiate the response to anti-PD-1 therapy in CTNNB1 GOF HCC. In addition, TIME-reshaping with anti-MMP9 mAb might be a promising strategy in anti-tumour immunotherapies.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Guangxin Wang, Yan Wang and Yuan Sun (Institute of Hydrobiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences) for technical assistance in laser confocal imaging and in vivo imaging system. The authors thank Libo Luo and Wenjing Xiong (Universal Biotech Company, Shanghai) for technical assistance in flow cytometry data analysis. The authors thank Wuhan Mabnus Biotech Co.,Ltd for technical assistance in the development of the anti-MMP9 monoclonal antibody.

Footnotes

Contributors: NC, KC, YM and SL are joint first authors. NC developed the study design and was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. NC, KC, YM and SL performed the experiments and statistical analysis. YM and WJ contributed to the bioinformatics analysis. NC, YM and DL contributed to the in vitro experiments. NC, KC, YM, SL and DL contributed to the in vivo experiments. RT, YL, BG and JZ contributed to the collection of clinical specimens and provided clinical pathology evaluations. NC, HL and LX analysed and interpreted the results of the study. WZ, JC and ZD conceived, designed and supervised the study and provided a critical review of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript. NC and WZ are responsible for the overall content as the guarantor.

Funding: This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82173319, 82373054, 82272836, and 82273441), Knowledge Innovation Program of Wuhan-Shuguang Project (2022020801020456), and the first level of the public health youth top talent project of Hubei province (2022SCZ051).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as online supplemental information.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study involves human participants and this study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tongji Hospital (TJ-IRB20220935). Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

References

- 1. Llovet JM, Kelley RK, Villanueva A, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2021;7:6. 10.1038/s41572-020-00240-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sangro B, Sarobe P, Hervás-Stubbs S, et al. Advances in Immunotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021;18:525–43. 10.1038/s41575-021-00438-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Vogel A, Meyer T, Sapisochin G, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet 2022;400:1345–62. 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01200-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Qin S, Ren Z, Meng Z, et al. Camrelizumab in patients with previously treated advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a Multicentre, open-label, parallel-group, randomised, phase 2 trial. The Lancet Oncology 2020;21:571–80. 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30011-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. El-Khoueiry AB, Sangro B, Yau T, et al. Nivolumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (Checkmate 040): an open-label, non-comparative, phase 1/2 dose escalation and expansion trial. Lancet 2017;389:2492–502. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31046-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yuen V-H, Chiu D-C, Law C-T, et al. Using mouse liver cancer models based on somatic genome editing to predict immune Checkpoint inhibitor responses. J Hepatol 2023;78:376–89. 10.1016/j.jhep.2022.10.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Guichard C, Amaddeo G, Imbeaud S, et al. Integrated analysis of somatic mutations and focal copy-number changes identifies key genes and pathways in hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Genet 2012;44:694–8. 10.1038/ng.2256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rebouissou S, Franconi A, Calderaro J, et al. Genotype-phenotype correlation of Ctnnb1 mutations reveals different SS-Catenin activity associated with liver tumor progression. Hepatology 2016;64:2047–61. 10.1002/hep.28638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network . Comprehensive and integrative Genomic characterization of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell 2017;169:1327–41. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.05.046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gao C, Chen Y-G. Dishevelled: the Hub of WNT signaling. Cell Signal 2010;22:717–27. 10.1016/j.cellsig.2009.11.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Schwarz-Romond T, Fiedler M, Shibata N, et al. The DIX domain of Dishevelled confers WNT signaling by dynamic polymerization. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2007;14:484–92. 10.1038/nsmb1247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Vlad A, Röhrs S, Klein-Hitpass L, et al. The first five years of the WNT Targetome. Cell Signal 2008;20:795–802. 10.1016/j.cellsig.2007.10.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Xiao X, Mo H, Tu K. Ctnnb1 Mutation suppresses infiltration of immune cells in hepatocellular carcinoma through miRNA-mediated regulation of Chemokine expression. Int Immunopharmacol 2020;89. 10.1016/j.intimp.2020.107043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Luke JJ, Bao R, Sweis RF, et al. WNT/Β-Catenin pathway activation correlates with immune exclusion across human cancers. Clin Cancer Res 2019;25:3074–83. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-1942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ruiz de Galarreta M, Bresnahan E, Molina-Sánchez P, et al. Β-Catenin activation promotes immune escape and resistance to anti-PD-1 therapy in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Discov 2019;9:1124–41. 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-19-0074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mondal S, Adhikari N, Banerjee S, et al. Matrix Metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) and its inhibitors in cancer: a Minireview. Eur J Med Chem 2020;194. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.112260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dong H, Diao H, Zhao Y, et al. Overexpression of matrix Metalloproteinase-9 in breast cancer cell lines remarkably increases the cell malignancy largely via activation of transforming growth factor beta/SMAD signalling. Cell Prolif 2019;52:e12633. 10.1111/cpr.12633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jiang K, Chen H, Fang Y, et al. Exosomal Angptl1 attenuates colorectal cancer liver metastasis by regulating Kupffer cell secretion pattern and impeding Mmp9 induced vascular Leakiness. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2021;40:21. 10.1186/s13046-020-01816-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Reggiani F, Labanca V, Mancuso P, et al. Adipose progenitor cell secretion of GM-CSF and Mmp9 promotes a Stromal and immunological Microenvironment that supports breast cancer progression. Cancer Res 2017;77:5169–82. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-0914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Scheau C, Badarau IA, Costache R, et al. The role of matrix Metalloproteinases in the epithelial-Mesenchymal transition of hepatocellular carcinoma. Anal Cell Pathol (Amst) 2019. 10.1155/2019/9423907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Winer A, Adams S, Mignatti P. Matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors in cancer therapy: turning past failures into future successes. Mol Cancer Ther 2018;17:1147–55. 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-17-0646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Van den Steen PE, Proost P, Wuyts A, et al. Neutrophil Gelatinase B potentiates Interleukin-8 tenfold by Aminoterminal processing, whereas it degrades CTAP-III, PF-4, and GRO-alpha and leaves RANTES and MCP-2 intact. Blood 2000;96:2673–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cox JH, Dean RA, Roberts CR, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase processing of Cxcl11/I-TAC results in loss of Chemoattractant activity and altered Glycosaminoglycan binding. J Biol Chem 2008;283:19389–99. 10.1074/jbc.M800266200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yang S, Wang L, Pan W, et al. Mmp2/Mmp9-mediated Cd100 shedding is crucial for inducing Intrahepatic anti-HBV Cd8 T cell responses and HBV clearance. J Hepatol 2019;71:685–98. 10.1016/j.jhep.2019.05.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ye Y, Kuang X, Xie Z, et al. Small-molecule Mmp2/Mmp9 inhibitor SB-3Ct modulates tumor immune surveillance by regulating PD-L1. Genome Med 2020;12:83. 10.1186/s13073-020-00780-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Karin N. Cxcr3 ligands in cancer and Autoimmunity, Chemoattraction of Effector T cells, and beyond. Front Immunol 2020;11:976. 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tokunaga R, Zhang W, Naseem M, et al. Cxcl9, Cxcl10, Cxcl11/Cxcr3 axis for immune activation - A target for novel cancer therapy. Cancer Treat Rev 2018;63:40–7. 10.1016/j.ctrv.2017.11.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Groom JR, Richmond J, Murooka TT, et al. Cxcr3 Chemokine receptor-ligand interactions in the lymph node optimize Cd4+ T helper 1 cell differentiation. Immunity 2012;37:1091–103. 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.08.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hickman HD, Reynoso GV, Ngudiankama BF, et al. Cxcr3 Chemokine receptor enables local Cd8(+) T cell migration for the destruction of virus-infected cells. Immunity 2015;42:524–37. 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.02.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chow MT, Ozga AJ, Servis RL, et al. Intratumoral activity of the Cxcr3 Chemokine system is required for the efficacy of anti-PD-1 therapy. Immunity 2019;50:1498–512. 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.04.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tao J, Calvisi DF, Ranganathan S, et al. Activation of Β-Catenin and Yap1 in human Hepatoblastoma and induction of Hepatocarcinogenesis in mice. Gastroenterology 2014;147:690–701. 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Liang B, Zhou Y, Qian M, et al. Tbx3 functions as a tumor Suppressor downstream of activated Ctnnb1 Mutants during Hepatocarcinogenesis. J Hepatol 2021;75:120–31. 10.1016/j.jhep.2021.01.044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Stauffer JK, Scarzello AJ, Andersen JB, et al. Coactivation of AKT and Β-Catenin in mice rapidly induces formation of Lipogenic liver tumors. Cancer Res 2011;71:2718–27. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lu Y, Yang A, Quan C, et al. A single-cell Atlas of the Multicellular Ecosystem of primary and metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Commun 2022;13. 10.1038/s41467-022-32283-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Abitbol S, Dahmani R, Coulouarn C, et al. AXIN deficiency in human and Mouse hepatocytes induces hepatocellular carcinoma in the absence of Β-Catenin activation. J Hepatol 2018;68:1203–13. 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.12.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Topalian SL, Taube JM, Anders RA, et al. Mechanism-driven biomarkers to guide immune Checkpoint blockade in cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer 2016;16:275–87. 10.1038/nrc.2016.36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kim TK, Vandsemb EN, Herbst RS, et al. Adaptive immune resistance at the tumour site: mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2022;21:529–40. 10.1038/s41573-022-00493-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Liu J, Xiao Q, Xiao J, et al. Wnt/Β-Catenin signalling: function, biological mechanisms, and therapeutic opportunities. Sig Transduct Target Ther 2022;7. 10.1038/s41392-021-00762-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Peng K, Kou L, Yu L, et al. Histone demethylase Jmjd2D interacts with Β-Catenin to induce transcription and activate colorectal cancer cell proliferation and tumor growth in mice. Gastroenterology 2019;156:1112–26. 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.11.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Nguyen P, Lee S, Lorang-Leins D, et al. Sirt2 interacts with Β-Catenin to inhibit WNT signaling output in response to radiation-induced stress. Mol Cancer Res 2014;12:1244–53. 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-14-0223-T [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Li C, Zhou Y, Kim JT, et al. Regulation of Sirt2 by WNT/Β-Catenin signaling pathway in colorectal cancer cells. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res 2021. 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2021.118966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zheng C, Zheng L, Yoo J-K, et al. Landscape of infiltrating T cells in liver cancer revealed by single-cell sequencing. Cell 2017;169:1342–56. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.05.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Nishita M, Tomizawa C, Yamamoto M, et al. Spatial and temporal regulation of Cofilin activity by LIM kinase and slingshot is critical for directional cell migration. J Cell Biol 2005;171:349–59. 10.1083/jcb.200504029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ramirez-Munoz R, Castro-Sánchez P, Roda-Navarro P. Ultrasensitivity in the Cofilin signaling Module: a mechanism for tuning T cell responses. Front Immunol 2016;7:59. 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Gong J, Chehrazi-Raffle A, Reddi S, et al. Development of PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors as a form of cancer Immunotherapy: a comprehensive review of registration trials and future considerations. J Immunother Cancer 2018;6:8. 10.1186/s40425-018-0316-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hong JY, Cho HJ, Sa JK, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma patients with high circulating cytotoxic T cells and intra-Tumoral immune signature benefit from Pembrolizumab: results from a single-arm phase 2 trial. Genome Med 2022;14:1. 10.1186/s13073-021-00995-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kang HJ, Oh J-H, Chun S-M, et al. Immunogenomic landscape of hepatocellular carcinoma with immune cell Stroma and EBV-positive tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes. J Hepatol 2019;71:91–103. 10.1016/j.jhep.2019.03.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Zhang L, Ding J, Li H-Y, et al. Immunotherapy for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma, where are we? Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer 2020;1874. 10.1016/j.bbcan.2020.188441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Santos PM, Butterfield LH. Dendritic cell-based cancer vaccines. J Immunol 2018;200:443–9. 10.4049/jimmunol.1701024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Perugorria MJ, Olaizola P, Labiano I, et al. Wnt-Β-Catenin signalling in liver development, health and disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019;16:121–36. 10.1038/s41575-018-0075-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Huang M, Jiao J, Cai H, et al. C-C motif Chemokine ligand 5 confines liver regeneration by down-regulating Reparative macrophage-derived hepatocyte growth factor in a Forkhead box O 3A-dependent manner. Hepatology 2022;76:1706–22. 10.1002/hep.32458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Augoff K, Hryniewicz-Jankowska A, Tabola R, et al. Mmp9: a tough target for targeted therapy for cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2022;14. 10.3390/cancers14071847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Chuah S, Lee J, Song Y, et al. Uncoupling immune Trajectories of response and adverse events from anti-PD-1 Immunotherapy in hepatocellular carcinoma. Journal of Hepatology 2022;77:683–94. 10.1016/j.jhep.2022.03.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Bendell J, Sharma S, Patel MR, et al. Safety and efficacy of Andecaliximab (GS-5745) plus Gemcitabine and NAB-paclitaxel in patients with advanced Pancreatic adenocarcinoma: results from a phase I study. Oncologist 2020;25:954–62. 10.1634/theoncologist.2020-0474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Yoshikawa AK, Yamaguchi K, Muro K, et al. Safety and tolerability of Andecaliximab as monotherapy and in combination with an anti-PD-1 antibody in Japanese patients with gastric or gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma: a phase 1B study. J Immunother Cancer 2022;10. 10.1136/jitc-2021-003518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Wu Y, Lu S, Huang X, et al. Targeting cIAPs attenuates CCL4-Induced liver fibrosis by increasing Mmp9 expression derived from neutrophils. Life Sci 2022;289. 10.1016/j.lfs.2021.120235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Roderfeld M, Rath T, Pasupuleti S, et al. Bone marrow transplantation improves hepatic fibrosis in Abcb4-/- mice via Th1 response and matrix metalloproteinase activity. Gut 2012;61:907–16. 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Fabre T, Barron AMS, Christensen SM, et al. Identification of a broadly Fibrogenic macrophage subset induced by type 3 inflammation. Sci Immunol 2023;8. 10.1126/sciimmunol.add8945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Hemmann S, Graf J, Roderfeld M, et al. Expression of Mmps and Timps in liver fibrosis - a systematic review with special emphasis on anti-Fibrotic strategies. J Hepatol 2007;46:955–75. 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

gutjnl-2023-331342supp001.pdf (3MB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as online supplemental information.