Abstract

Biologic function of the majority of microRNAs (miRNAs) is still unknown. Uncovering the function of miRNAs is hurdled by redundancy among different miRNAs. The deletion of Dgcr8 leads to the deficiency in producing all canonical miRNAs, therefore, overcoming the redundancy issue. Dgcr8 knockout strategy has been instrumental in understanding the function of miRNAs in a variety of cells in vitro and in vivo. In this review, we will first give a brief introduction about miRNAs, miRNA biogenesis pathway and the role of Dgcr8 in miRNA biogenesis. We will then summarize studies performed with Dgcr8 knockout cell models with a focus on embryonic stem cells. After that, we will summarize results from various in vivo Dgcr8 knockout models. Given significant phenotypic differences in various tissues between Dgcr8 and Dicer knockout, we will also briefly review current progresses on understanding miRNA-independent functions of miRNA biogenesis factors. Finally, we will discuss the potential use of a new strategy to stably express miRNAs in Dgcr8 knockout cells. In future, Dgcr8 knockout approaches coupled with innovations in miRNA rescue strategy may provide further insights into miRNA functions in vitro and in vivo.

Keywords: Drosha, Cell cycle, Glycolysis, Alternative splicing, Glial progenitor cells, Reproductive system, Neural system, Immune system

Introduction

Around 2% of human genome codes for protein genes, while the majority of it codes for various noncoding RNAs including ribosome RNAs (rRNAs), transfer RNAs (tRNAs), long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) and miRNAs. The first miRNA, lin-4, was discovered in C. elegans around 25 years ago [1]; since then the number of miRNA genes has been significantly expanded and the function of miRNAs has been extensively investigated in numerous biologic processes including animal development and diseases. As a result, many miRNA-based therapeutic interventions are currently under development for curing diseases including virus infection and cancer [2, 3].

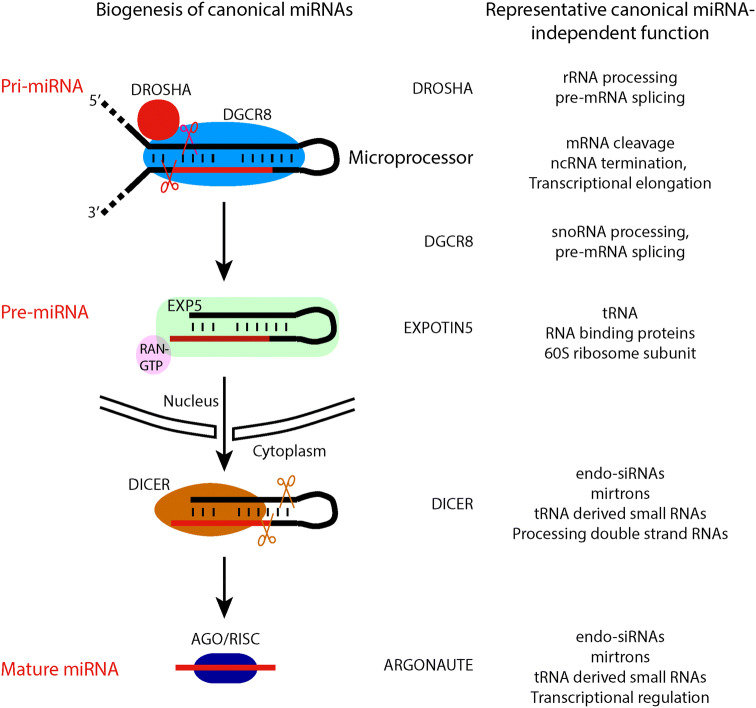

The size of miRNAs is around 22 nucleotides. They are typically transcribed as a part of longer RNA transcripts known as pri-miRNAs that range from hundreds to thousands of nucleotides in length [4, 5]. Pri-miRNAs are first processed into around 70 nucleotides long and stem–loop structured pre-miRNAs in nucleus by the Microprocessor complex (MC) consisting of DROSHA and DGCR8 [6–10] (Fig. 1). The pre-miRNAs are specifically bound and exported into cytoplasm by exportin-5 and further processed into short double-stranded RNAs by RNase III enzyme DICER [11–15]. For some pre-miRNAs, the DICER-mediated cleavage process is facilitated and tuned by partner proteins including TRBP and PACT [16]. The mature miRNA strand is then loaded into the guide-strand channel of an Argonaute protein (AGO) to form a RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) [17, 18]. Guided by a seed sequence which is a small stretch of nucleotides at the 5′ end of mature miRNAs (2nd–8th), miRNA RISC binds and regulates the expression of its mRNA targets post-transcriptionally and negatively through an imperfect paring between miRNAs and their mRNA targets [19]. In most scenarios, miRNAs regulate gene expression through the inhibition of protein translation and/or mRNA destabilization [20]. However, there are also many examples that miRNAs mediate the cleavage of mRNA targets when extensive base pairing between them exists [21–23].

Fig. 1.

Biogenesis pathway of canonical miRNAs. Canonical miRNA-independent functions of key factors are indicated on the right

To date, as recorded in miRBase (http://www.mirbase.org), approximately 2500 and 1900 miRNA genes have been identified in human and mouse genome [24, 25]. Most human mRNAs are predicted to be miRNA targets [26], suggesting that miRNAs are probably involved in all biological processes at some degree [27]. However, until today, functions for the majority of miRNAs are still unknown. The study of miRNA function is made difficult at least partially by the redundancy among miRNA genes. For example, the let-7 family has 14 and 13 different members encoded at multiple loci in mouse and human genome [28]. In addition, miRNAs from different families can repress the same mRNA targets or different mRNA targets along the same pathway, leading to additional layers of functional redundancy [29, 30]. Therefore, to understand the function of miRNAs, approaches to overcome the redundancy issue of miRNAs are required.

Microprocessor and DGCR8

Using immunoaffinity chromatography and gel filtration assay, Gregory and Kim et al. have determined the components of MC [6–10]. The core MC contains two proteins: double-stranded RNA binding protein DGCR8 and RNase III enzyme DROSHA which carries out the cleavage reaction during the processing of pri-miRNAs. Results from single-molecule photo-bleaching experiments suggest a heterotrimeric model of human MC with one molecule of DROSHA and two molecules of DGCR8 [31, 32]. The specific recognition of pri-miRNAs depends on both DROSHA and DGCR8 [32–34]. Pri-miRNAs have an imperfect stem–loop structure flanked by single-strand RNA segments (basal segments). DROSHA recognizes the basal segments and serves as a ruler to measure and then cut ~ 11 bp from the basal junction into the stem. DGCR8 binds the apical loop to enhance the accuracy and efficiency of DROSHA-mediated cleavage. Interestingly, DGCR8 is reported as a heme-binding protein [35]. In vitro experiments show that the binding of heme to DGCR8 is required for proper processing of at least a subset of pri-miRNAs, which have stronger binding affinity for DROSHA at apical than basal junctions [33, 34]. In addition, DGCR8 also promotes the stability and activates the cleavage activity of DROSHA. In vitro reconstitution assay has shown that both DGCR8 and DROSHA are required for the biogenesis of miRNAs [8, 9]. Depletion of either DROSHA or DGCR8 in cultured cells leads to deficiency in producing most miRNAs, indicating that the biogenesis of the majority of miRNAs depends on the MC. Moreover, multiple auxiliary factors may assist or fine-tune pri-miRNA processing in a tissue-specific manner. TAR DNA-binding protein 43 (TDP43) is reported to directly interact with both DROSHA and DICER complex to regulate the sequential processing of a subset of miRNAs, which are important for neuronal differentiation [36, 37]. RNA helicases DDX5 and DDX17 are also shown to facilitate the DROSHA-mediated processing of a subset of miRNAs [38, 39]. When the association between DROSHA and DDX5 is disturbed by Cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2), miR-183, miR-23b and miR-146b are downregulated in liver to help protection against insulin resistance [40]. Interestingly, nuclear YAP can bind and sequester DDX17 to disrupt its association with DROSHA, which could explain the widespread suppression of miRNAs in cancer cells [38]. In neural stem cells (NSCs), nuclear receptor TLX interacts with MC and DDX5 to repress the processing of miR-219, which inhibits NSC proliferation and is upregulated in NSCs derived from schizophrenia patient [41].

DGCR8 is a gene located in the DiGeorge Syndrome chromosomal (or critical) region (DGCR). The monoallelic deletion of DGCR in human leads to the development of DiGeorge Syndrome, which is characterized by a variety of defects including psychiatric disorders, congenital heart defects, abnormal facial features and immune system defects [42–46]. These defects are at least partially attributed to the loss of DGCR8 and miRNAs. However, how heterozygous deletion of DGCR8 leads to the downregulation of miRNAs in various tissues is not clear, since DGCR8 and miRNA levels are not significantly changed in mouse ESCs deleting one allele of Dgcr8, due to a feedback control of Dgcr8 mRNA levels by MC [47–49]. Interestingly, Dgcr8 mRNA is ubiquitously expressed in human and mouse tissues from adult and fetus, suggesting the general importance of miRNAs for the development and homeostasis of human and mouse [50]. Consistently, Dgcr8 knockout mouse dies at early post-implantation stage around E6.5 [49]. Nevertheless, Dgcr8 knockout mouse ESCs are obtained through a conditional knockout strategy by inserting two flox segments flanking exon 3 and then treated with Cre recombinase [49]. The deletion of exon3 leads to a frame shift to form multiple premature stop codons in Dgcr8 mRNA, which is likely destabilized by nonsense-mediated decay. Microarray analysis and small RNA sequencing experiments demonstrate that the biogenesis of most miRNAs is dependent on Dgcr8 [49, 51]. However, miRNA profiling in Dgcr8 knockout ESCs also finds dozens of miRNAs including miR-320 and miR-484 that are not dependent on Dgcr8 for their biogenesis [51]. It is notable that most of these non-canonical miRNAs are expressed at relatively low levels. Therefore, Dgcr8 knockout model provides an efficient means to uncover phenotypes associated with comprehensive loss of canonical miRNAs and underlying molecular mechanisms.

miRNA-independent functions of DGCR8, DROSHA and DICER

Recently, an increasing body of evidence showed that the core miRNA-processing factors have miRNA-independent functions. These functions are related to a variety of biological processes, including RNA processing, transcriptional regulation and the control of RNA stability. Moreover, recent studies demonstrate the direct involvement of all three proteins in antiviral processes [52–57] and DNA damage responses [58–63]. Since these results are important for the interpretation of mechanisms behind phenotypes associated with the knockout of Dgcr8, Drosha and Dicer, we briefly summarize these findings below. More thorough summary of these topics can be found in Pong’s, Yang’s and Burger’s reviews [64–66].

miRNA-independent functions of DROSHA and DGCR8

Control of RNA abundance by DROSHA and DGCR8 Theoretically, the Microprocessor could bind non-miRNA substrates to negatively impact their abundance. It is first demonstrated by Han et al. that DROSHA/DGCR8 can bind and cleave the mRNA of Dgcr8, which contributes to homeostatic control of miRNA biogenesis [47]. Microarray analysis proposes that many other mRNAs may be regulated by DROSHA/DGCR8 [47]. This hypothesis is later further supported by HITS-CLIP study of DGCR8 [67]. Macias et al. shows DGCR8 binding thousands of mRNAs and lncRNAs. At least some of these binding events may lead to the downregulation of corresponding RNAs. In addition, DROSHA/DGCR8 modulates the abundance of alternative splicing isoforms through binding to specific exons of different isoforms [67]. DROSHA/DGCR8 also binds RNAs derived from human long interspersed element 1 (LINE-1), Alu and SVA retro-transposons and negatively regulates their retrotransposition activity [68]. Consistent with DGCR8 HITS-CLIP study, a study using an improved CLIP strategy (fCLIP-Seq) has also identified dozens of non-miRNA substrates of DROSHA [69]. The importance of DROSHA/DGCR8-mediated cleavage of mRNA substrates has been beautifully demonstrated in neural and immune systems. The destabilization of Ngn2 and NeuroD1 by Microprocessor facilitates the maintenance of forebrain neural progenitors [70, 71]. DROSHA inhibits oligodendrocytic differentiation of hippocampal stem cells by directly cleaving NFIB [72]. In addition, DROSHA and DGCR8 are proposed to inhibit Tbr1 expression through directly cleaving evolutionarily conserved hairpins during corticogenesis [73]. In immune system, DROSHA promotes the differentiation of dendritic cells by cleaving mRNAs of myelopoiesis inhibitors including Myl9 and Todr1 [74]. These studies suggest that cleavage of mRNA substrates by Microprocessor may have widespread biological significance in many tissues.

Control of transcriptional events by DROSHA/DGCR8 The Microprocessor is reported to be important for the transcriptional regulation and chromatin remodeling of HIV promoter [75]. Mechanistically, the nascent TAR RNA recruits DROSHA/DGCR8 which then cleaves this stem–loop-bearing RNA. The cleaved RNA products further recruit termination factors SETX and XRN2, and the 3′–5′ exo-ribonuclease, RRP6, to initiate RNA polymerase II pausing and premature termination [75]. At least a subset of cellular genes may be regulated by the similar mechanism since ChIP-Seq data shows the association of DROSHA with a significant number of cellular genes [69]. On the other hand, the association of DROSHA/DGCR8 with cellular genes may also positively regulate transcription. ChIP-on-Chip analysis reveals that DROSHA and DGCR8 are enriched at the transcriptional start site of many human genes in a transcription-dependent way [76]. In this study, knocking down DROSHA causes the down-regulation of nascent gene transcription, suggesting a positive role of DROSHA/DGCR8 in transcriptional initiation. Interestingly, the Microprocessor also contributes to the termination of pol II transcripts, although this activity is only restricted to most lncRNAs serving as miRNA precursors (lnc-pri-miRNAs) but not for protein-coding genes [77].

Other miRNA-independent functions of DROSHA and DGCR8 The Microprocessor has recently been shown to regulate splicing of a small subset of genes. It promotes exon skipping for DROSHA transcript [78] and exon inclusion for eIF4H gene [79]. In both cases, the cleavage activity is likely not involved. In addition, Wu et al. show that DROSHA is important for the processing of 12S pre-rRNA and may also be involved in the processing of 32S pre-rRNA [80]. This activity is likely independent of DGCR8 since we have shown that rRNA processing is not defective in Dgcr8 knockout ESCs [49]. Interestingly, DGCR8 modulates the stability of snoRNAs (small nucleolar RNAs) and telomerase RNA by acting as an adaptor to recruit exosome complex in a DROSHA-independent fashion [67, 81]. These studies suggest that DROSHA and DGCR8 may form their own complex with other proteins to regulate different biological processes.

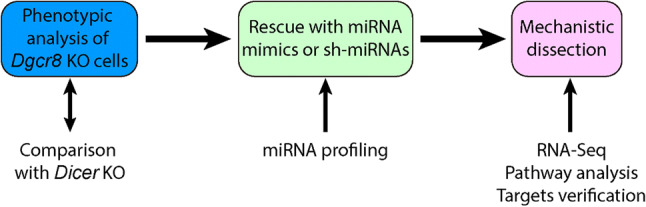

The Dgcr8 knockout strategy to study miRNA functions

Due to the redundancy issue discussed above, it often requires knocking out multiple miRNA genes before a strong phenotype is observed. Knocking out multiple genes is clearly a laborious process and sometimes impractical especially when lacking information on which miRNAs and phenotypes to go after. For this reason, characterization of cells knocking out Drosha, Dgcr8 or Dicer could provide an initial glimpse on what biological processes are significantly affected by the loss of miRNAs, which forms the basis for the further identification of candidate miRNAs. Nevertheless, various miRNA-independent functions have been shown for the core components of miRNA biogenesis pathway (Fig. 1) as we discussed above. Therefore, the defects associated with knocking out these genes are not necessarily due to the loss of miRNAs. To assign miRNA functions, we suggest identifying common defects in models knocking out two different genes, favorably Dgcr8 and Dicer, since these two genes regulate two different steps of miRNA biogenesis. More importantly, rescue of defects by the reintroduction of miRNAs can help determine whether identified defects are indeed caused by miRNAs (Fig. 2). Many researchers including ourselves have used Dgcr8 knockout strategy followed by miRNA rescue to identify functional miRNAs. Dgcr8 knockout strategy has an advantage over Dicer knockout strategy since the long-term stable expression of miRNAs may be achieved by a short hairpin RNA (shRNA) vector in Dgcr8 but not Dicer knockout cells.

Fig. 2.

Dgcr8 knockout strategy to identify miRNA functions. This strategy has been successfully applied in ESCs and GPCs. However, due to the lack of robust approaches to express miRNAs in Dgcr8 knockout cells in vivo, it has not been widely used in identifying functional miRNAs in vivo

miRNA functions in ESCs

The first Dgcr8 knockout mammalian cell model is made in mouse ESCs. Since then it has provided immense insights into both stem cell biology and miRNA regulation. Characterization of phenotypes in Dgcr8 knockout ESCs followed by miRNA mimic rescue has allowed the identification of key miRNAs in regulating important biologic processes including cell cycle [93, 94], pluripotency [95], epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) [96], glycolysis metabolism [97] and pre-mRNA alternative splicing [98].

miRNAs regulating ESC cell cycle

ESCs are highly proliferating cells with an extremely short G1 phase. However, Dgcr8 knockout mouse ESCs proliferate slowly with more cells accumulated in G1 phase, suggesting a function of miRNAs in shaping the ESC-specific cell cycle structure [93]. Through screening more than 250 miRNA mimics, miRNAs from the miR-290 and miR-302 clusters are found to rescue both proliferation and G1 accumulation defects [93]. These miRNAs share similar seed sequence “AAGUGCU” and are named ESC-specific cell cycle-regulating (ESCC) miRNAs. Consistent with their important roles, ESCC miRNAs are highly enriched in mouse ESCs [93]. Despite the initial study is done in ESCs cultured in serum media, the function of ESCC miRNAs is conserved in ESCs cultured in chemically defined medium (2i media) supplemented with inhibitors to MEK and GSK3 [99, 100]. In addition to its role at normal growth condition, ESCC miRNAs are later found to suppress the G1 arrest under cytostatic conditions including serum starvation and contact inhibition [94]. Mechanistically, ESCC miRNAs target many G1/S transition inhibitors including Cdkn1a (also called p21), Lats2, Rb1, and Rbl2. Additionally, ESCC miRNAs also indirectly increase the expression of proliferation-promoting genes such as Lin28 and Myc [101], which may partially contribute to their proliferation and cell cycle promoting function.

miRNAs regulating glycolysis metabolism

The rapid proliferation of ESCs requires sufficient energy supply and abundant building blocks for the production of cellular components. Interestingly, like cancer cells, ESCs prefer glycolysis rather than more efficient aerobic respiration for energy supply [102–104]. Dgcr8 knockout ESCs display decreased glycolysis and increased oxidative/phosphorylation, suggesting miRNAs playing a role in controlling metabolism of ESCs [97]. Through a small-scale screen, highly ESC-enriched miR-290 cluster of miRNAs are identified to stimulate glycolysis. A transcriptional repressor, Mbd2, is found to be the direct target of miR-290s [97]. The suppression of Mbd2 by miR-290s leads to the upregulation of a transcriptional activator Myc, which in turn increases the expression of glycolytic enzymes such as Pkm2 and Ldha [97]. Interestingly, miRNA–Mbd2–Myc–Pkm2/Ldha circuit is conserved in human cells and can be manipulated to promote the reprogramming of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) in both mouse and human [97].

miRNAs regulating ESC-specific alternative splicing

Alternative pre-mRNA splicing is an essential mechanism to increase the complexity of gene expression, which is important for cellular differentiation and animal development. High-throughput sequencing and bioinformatics analysis has identified 578 alternative splicing events differentially regulated between Dgcr8 knockout and wild-type ESCs [98]. More than two-thirds of these events are at least partially rescued by miR-294, a representative member of ESCC miRNAs. Canonical splicing factors, Mbnl1 and Mbnl2, are the direct targets of ESCC miRNAs and contribute to 60% of these differentially regulated alternative splicing events [98]. As demonstrated by this study, the interplay between miRNAs and splicing factors plays important roles in shaping specific splicing pattern to regulate pluripotency in ESCs [98].

miRNAs regulating the transcriptional heterogeneity of ESCs

Single cell sequencing study reveals significant transcriptional heterogeneity between individual ESCs [105]. Knockout of Dgcr8 increases the overall heterogeneity of gene expression in ESCs [105]. Introducing miR-294 into Dgcr8 knockout ESCs reduces, while introducing let-7c miRNAs further increases the transcriptional heterogeneity. In these experiments, 2i are included in the culture media to prevent cell differentiation. Therefore, the effects of miR-294 and let-7 are not secondary to cell differentiation. More interestingly, miR-294 suppresses and let-7 increases the correlation of cell cycle gene expression within each cell cycle phase [105]. However, the exact mechanism for the opposing function of miR-294 and let-7 on the phasing of cell cycle genes is not clear. In another single cell sequencing study, Dgcr8 or Dicer knockout ESCs cultured in serum media are found to be more similar to wild-type ESC cultured in 2i/Lif media [106]. This state transition is partially driven by the down-regulation of Myc and Lin28 upon the loss of ESCC miRNAs [106]. These studies reveal that miRNAs are important regulators of transcriptional heterogeneity in ESCs. Whether similar roles are played by miRNAs in other cell types warrants further investigation.

miRNAs regulating the maintenance and silencing of pluripotency

Dgcr8 knockout ESCs cannot silence their self-renewal even under differentiation conditions, a defect also observed in Dicer knockout ESCs [49, 107, 108]. Dozens of miRNAs are later identified to silence the self-renewal of Dgcr8 knockout ESCs [94, 101, 109]. These miRNAs have largely different seed sequences and are enriched in different tissues and cell lineages [110], suggesting that different miRNAs may promote differentiation of ESCs into different lineages, while all of them have the ability to silence the self-renewal. Interestingly, some miRNAs including miR-134 and miR-145 are able to silence the self-renewal of ESCs in wild-type background [111, 112]. However, other miRNAs including miR-26a, miR-99b, miR-193, miR-199a-5p, miR-218, miR-24 and miR-27a can only silence the self-renewal of ESCs in Dgcr8 knockout background [94, 109]. In wild-type ESCs, their ability to promote differentiation is blocked by the highly expressed ESCC miRNAs. ESCC miRNAs suppress EMT and apoptotic pathways [96]. Surprisingly, combined but not separate suppression of the two pathways mimics the effect of ESCC miRNAs in preventing the silencing of self-renewal by differentiation-inducing miRNAs [96]. The synergy between different miRNA families has been reported in various studies in neural stem cells [113–115]. However, the synergy between pathways targeted by the same miRNA has not been carefully analyzed. These results indicate that multiple pathways targeted by miRNAs may function synergistically to regulate complicated cellular processes [96], although more studies are required to support the generality of this type of synergistic regulation in other contexts.

Exit of naive state during early differentiation

Pluripotent stem cells exist in distinct states that can be captured by different growth conditions [116]. Mouse ESCs are in naive pluripotency state that can be maintained in serum/Lif or 2i/Lif conditions. In addition, serum/Lif ESCs are sometimes called as transition state, and 2i/Lif ESCs are called as ground state. Being developmentally not as potent as ESCs, mouse epiblast stem cells (EpiSCs) are known as primed state of pluripotent stem cells which are derived from post-implantation embryos [117, 118]. Unlike ESCs that can be maintained upon the inhibition of MEK pathway, EpiSCs require MEK pathway to self-renew, therefore, are normally maintained in FGF containing media. Studying naive to primed pluripotency transition such as ESC to epiblast-like cell (EpiLC) differentiation provides significant insights into the mechanism controlling early mammalian embryo development [119]. Interestingly, Dgcr8 knockout ESCs fail to silence the naive pluripotency program efficiently during differentiation to EpiLCs [95]. By focusing on miRNAs highly expressed in ESCs and during ESC to EpiLC transition, a targeted miRNA screen has identified numerous miRNAs promoting naive to primed pluripotency transition. Surprisingly, miR-290 and miR-302 clusters, previously reported as pluripotency promoting miRNAs, show the strongest effects in silencing naive pluripotency [95]. Knockout of both miR-290 and miR-302 clusters only partially mimics the phenotypes observed in Dgcr8 knockout ESCs, consistent with other miRNAs such as miR-17–20 clusters playing similar roles in silencing naive pluripotency. Mechanistically, miR-290/302 facilitates the exit of naive pluripotency by increasing MEK activity and repressing AKT activity [95]. However, the direct targets that are responsible for the regulation of naive to primed pluripotency transition are still not clear. This study suggests that the same miRNAs may play different and even opposing roles at different contexts.

miRNA functions in glia progenitor cells (GPCs)

Using an ESC line in which Dgcr8 can be deleted upon the addition of tamoxifen (Dgcr8-inducible knockout, Dgcr8 iKO), the function of miRNAs is studied in ESC-derived GPCs [120]. Loss of Dgcr8 does not affect the survival and proliferation of GPCs. However, the differentiation of GPCs into astrocytes is significantly blocked by the deletion of Dgcr8. Screen of 570 miRNA mimics leads to the identification of miR-125 and let-7 that can rescue the differentiation defects in Dgcr8 iKO GPCs [120]. Interestingly, although Jak–Stat signaling is important for the astrocyte differentiation of wild-type GPCs and is abnormally downregulated in Dgcr8 iKO GPCs, miR-125 or let-7 enables the astrocyte differentiation through apparently Jak–Stat-independent pathways [120]. These results suggest that other miRNAs or miRNA-independent function of Dgcr8 may be important for the induction of Jak–Stat signaling during astrocyte differentiation. This study demonstrates a successful example that function of miRNAs can be investigated in progenitor cells or other cells through in vitro differentiation of ESCs followed by iKO of Dgcr8.

miRNA functions in vivo

To date, miRNAs have been proved to play essential roles in diverse developmental, cellular, and physiological processes using in vivo Dgcr8 knockout strategy (Table 1). Zygotic knockout of Dgcr8 or other miRNA-processing genes leads to early embryonic death with severe development defects [49, 121, 122]. Nevertheless, the functional dissection of miRNAs in vivo is made possible by knocking out Dgcr8 using tissue-specific Cre recombinase. In the following section, we will elaborate the findings from Dgcr8 knockout models in representative systems including reproductive, immune and neural systems. In instances where Dicer knockout models are available to compare, we will also present the findings from Dicer knockout studies and discuss the potential regulation by miRNA and miRNA-independent factors. Findings from Dgcr8 conditional knockout (cKO) in various other systems are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of Dgcr8 knockout studies in vivo

| Tissue | Cell type | Cre line | Defect | Dicer model | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reproductive system | Male germ cells | Ddx4::Cre | Infertile, reduced testis size and near-complete absence of mature spermatozoa | More severe defects | [123] |

| Oocytes | Zp3::Cre | Develop normally and produce normal offspring when fertilized by wild-type sperm | Severely abnormal spindle resulting in the failure of meiotic maturation | [124–126] | |

| Uterine epithelium and stroma | PR::Cre | Infertile due to shorter uterine horns, a reduced number of glands, and severe stromal atrophy with aberrant hormone responsiveness | Similar defects, without decrease in myometrial thickness | [130, 131] | |

| Immune system | Helper T cells | Cd4::Cre | Abnormal IFN-γ production; decreased proliferation rate | Similar defects | [132] |

| Natural killer cells | Ubc::Cre-ERT2 | Increased apoptosis and decreased turnover rate; ITAM-containing receptors is impaired | Similar defects | [134] | |

| Thymic epithelial cells | FoxN1::Cre | Grossly abnormal thymic architecture with a significantly reduced number of TECs | Similar defects | [136–138] | |

| Splenic B cells | Mb1::Cre | Complete block of pro-B to pre-B cell transition | Similar defects, lower level of mHC expression observed in Dgcr8 cKO mice but not Dicer cKO mice | [139, 140] | |

| Adipose system | Mature adipocytes | Adiponectin::Cre | Enlarged but pale interscapular brown fat with impaired function of brown adipose; impaired insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia | NA | [153] |

| Visual system | Cone | D4::Cre | Loss of outer segment; dysfunction of cones; significantly reduced light responses | NA | [154] |

| Retinal pigmented epithelium | Dct::Cre/pVMAD2::rtTA–TRE-Cre/Best1::Cre | Defects in phagocytosis of photoreceptor outer segment discs and regeneration of visual chromophore | Similar defects; promotes the survival of RPE | [86, 155, 156] | |

| Vascular smooth muscle | Vascular smooth muscle cells | SM22::Cre | Died at E12.5–E13.5; extensive liver hemorrhage, dilated blood vessels and disarrayed vascular architecture | Similar defects but died at E17.5 | [157, 158] |

| Vascular smooth muscle cells | SMA::Cre-ERT2 | Inhibited cell proliferation, migration, neointima formation, blood pressure, and vascular reactivity | Similar defects | [159, 160] | |

| Bone | Osteoprogenitor cells | Col1a::Cre | Increased osteoblast activity, which further leads to the increase of bone volume, trabecular number, and trabecular thickness in femur | Much more severe phenotypes including compromised fetal survival | [161, 162] |

| Osteoclasts | Ctsk::Cre | Impaired osteoclastic development and bone resorption; increased trabecular bone mass, trabecular thickness, and trabecular numbers and significantly decreased trabecular space in femur | Similar defects | [163, 164] | |

| Skin | Skin epithelial stem cells | Keratin14::Cre | Survived up to 5–6 days after birth with rough skin, defects in hair follicle and epidermal differentiation | Similar defects | [165, 166] |

| Neural system | Schwann cells | P0::Cre | Reduced peripheral nerve myelination, SC degeneration and increased macrophage infiltration | Less severe defects in differentiation, no SC degeneration | [142, 144, 145] |

| Cortex | Nex::Cre | Pleiotropic defects in brain including microcephaly due to cortical thinning, decreased soma size, and loss of dendritic complexity; severe behavior phenotypes including clasping, tremors and ataxia | Similar defects | [147, 148] | |

| Heart | Cardiomyocytes | MCK::Cre | Median survival at 31 days; fibrosis in ventricular walls; dilated cardiomyopathy and heart failure | Die within 4 days after birth; heart failure but no fibrosis and no increases in MYH7 expression | [167, 168] |

| Cardiac neural crest cells | Wnt1::cre | Persistent truncus arteriosus (PTA) and ventricular septal defect (VSD); elevated apoptosis in migratory cardiac neural crest cells (cNCCs) | Similar defects in OFT morphogenesis; subtle differences as to apoptosis in different pharyngeal arches | [169, 170] | |

| Kidney | Pax8::Cre | Died prematurely within the first 2 months after birth, developed massive hypothyroidism and end-stage renal disease | Similar defects | [171–173] | |

| Ksp::Cre | Severe hydronephrosis, kidney cysts, progressive renal failure and premature death within the first 2 months after birth | Similar defects but with lower penetrance | [171–173] |

Reproductive system

In male germ cells, Ddx4::Cre-mediated knockout of Dgcr8 cKO leads to disrupted spermatogenesis. As a result, Dgcr8 cKO males are infertile and have reduced size of testis and sperm counts. Many defects are accumulated during spermatogenesis which causes oligospermia, terato-zoospermia or azoospermia. In addition, apoptosis is significantly increased in Dgcr8 cKO testis [123]. Interestingly, similar defects are observed in Dicer cKO testis in the same study. However, defects in Dgcr8 cKO are generally less severe than Dicer cKO [123]. Therefore, both miRNAs and endo-siRNAs play important roles during the development of male germ cells. Contrast to severe defects in Dgcr8 cKO male germ cells, oocytes deficient in Dgcr8 develop normally and are capable of producing normal offspring when fertilized with wild-type sperms [124]. However, Dicer cKO oocytes have a severely abnormal spindle leading to the failure of meiotic maturation [125, 126]. Therefore, endo-siRNAs but not miRNAs are important for the maturation of oocytes [127–129].

PR::Cre is expressed in all compartments of the uterus. Dgcr8 cKO female mice generated by PR::Cre are infertile due to multiple abnormalities in immune modulation, reproductive cycle, and steroid hormone responsiveness during uterine development [130]. Dicer cKO female mice show similar defects [131]. However, some defects including decrease of myometrial thickness are only observed in Dgcr8 cKO female mice [130, 131]. These results indicate miRNA-dependent and -independent functions of Dgcr8 in uterine development.

Immune system

Dgcr8 cKO mediated by Cd4::Cre causes various defects in helper T cells (Th cells) including decreased proliferation rate and abnormal IFN-γ production [132]. These defects are predicted to be regulated mainly by canonical miRNAs since side by side comparison shows similar defects in Dicer cKO Th cells [132]. Based on small RNA profiling in activated wild-type Th cells, the authors choose 110 miRNAs for a functional screen in Dgcr8 cKO Th cells [132]. Eight miRNAs from miR-17 –92 cluster are found to promote the proliferation of Th cells. These include five miRNAs from miR-17 seed family and three miRNAs from miR-25 seed family [132]. These results are consistent with widely reported proliferation-promoting function of miR-17–92 cluster in numerous cell types. In addition, miR-29a and miR-29b are found to repress abnormal IFN-γ production [132]. In this study, miR-29a/b is hypothesized to regulate IFN-γ production through directly repressing transcription factors T-bet and Eomes [132]. Interestingly, another study [133] published around the same time as this study finds that miR-29 directly represses IFN-γ mRNA. These results suggest that miR-29 may repress IFN-γ production through multiple layers of regulation.

In natural killer (NK) cells, conditional deletion of Dgcr8 or Dicer by tamoxifen-induced Cre-ER activity leads to increased apoptosis and decreased turnover rate [134]. In addition, the function of ITAM-containing receptors but not cytokine receptors is significantly impaired by Dgcr8 or Dicer cKO. Upon MCMV infection, the expansion of Ly49H+ NK cells is significantly reduced in Dgcr8 or Dicer cKO mice primarily due to increased apoptosis [134]. This study demonstrates important roles of miRNAs in the homeostasis and effector function of NK cells, consistent with functions of individual miRNAs reported in NK cells [135].

Thymic epithelial cells (TECs), including cortical thymic epithelial cells (cTECs) and medullary thymic epithelial cells (mTECs), are essential to T cell development in vivo. Conditional deletion of Dgcr8 by FoxN1::Cre leads to grossly abnormal thymic architecture with a significantly reduced number of TECs [136]. Dgcr8 is essential for the maturation of mTECs, especially the Aire+ cells that are important for the negative selection of T cells. As a result, more pathogenic autoreactive T cell clones can be expanded from Dgcr8 cKO mice [136]. Similar defects are also reported for mice with Dicer cKO TECs [137, 138]. These studies support the important function of miRNAs for controlling TEC differentiation, proliferation and central tolerance.

Deletion of Dgcr8 at the early stage of B cell development by Mb1::Cre leads to a nearly complete block of pro-B to pre-B cell transition [139]. As a result, very few IgM-positive B cells are detected in the peripheral systems including spleens and lymph nodes of Dgcr8 cKO mice. Supporting miRNA roles in pro-B to pre-B cell transition, conditional knockout of Dicer [140] or miR-17–92 cluster [141] causes the similar maturation defects. Interestingly, the lower level of mHC expression observed in Dgcr8 cKO mice is not reported in Dicer cKO mice [140], raising a question whether non-canonical function of Dgcr8 plays a role in controlling the expression of mHC.

Neural system

By crossing Dgcr8flox/flox mice with P0::Cre mice which display Cre activity starting at around E14 in most Schwann cells (SCs) in peripheral nervous system, Lin et al. [142] show that miRNAs are required for SC differentiation and myelin formation. Dgcr8 cKO SCs express high levels of genes such as Sox2 that are normally expressed in immature SCs and fail to turn on the expression of genes related to myelin formation (e.g., Egr2) [142]. Overall, the defects in Dgcr8 cKO SCs are very similar to those observed in mouse models of congenital hypomyelination [143]. In addition, sonic hedgehog (Shh) and injury-induced genes are upregulated upon Dgcr8 cKO in SCs. Expression of Sox2, Egr2 and Shh are also upregulated in Dgcr8 cKO SCs at adult stage [142]. Dicer deletion during development (P0::Cre) shows mostly similar defects to Dgcr8 deletion [142, 144]. However, Dgcr8 cKO SCs have more severe sorting defects. Furthermore, deletion of Dgcr8 but not Dicer at adult stage leads to severe defects in myelin maintenance [142, 145]. These studies demonstrate both miRNA-dependent and -independent functions of Dgcr8 in the formation and maintenance of myelin as well as the suppression of injury-related genes. However, the exact miRNAs or other related factors responsible for the corresponding defects have not been identified.

NEX::Cre is expressed majorly in pyramidal neurons from neocortex and hippocampus starting around E11.5 [146]. NEX::Cre-mediated deletion of Dgcr8 leads to pleiotropic defects in brain including microcephaly due to cortical thinning, decreased soma size, and loss of dendritic complexity [147]. These mice display severe behavior phenotypes including clasping, tremors and ataxia. Moreover, they are predisposed to spontaneous seizure and chemoconvulsant-induced seizure [147]. Consistent with behavioral defects, a strong decrease in the frequency of inhibitory postsynaptic currents is observed, as well as reductions of parvalbumin interneurons and perisomatic inhibitory synapses [147]. Dicer knockout in cortex shows largely similar defects to Dgcr8 knockout [147, 148]. Future studies need to dissect the exact miRNAs and their targets underlying these defects.

Differences between Dgcr8 and Dicer knockout models

As demonstrated in Table 1, in most scenarios, knocking out Dgcr8 and Dicer shares key similarities. However, significant differences between the two knockout models in various tissues or cells are also observed. The molecular mechanism behind phenotypic difference is often explained by miRNA-independent functions of DGCR8 or DICER, which we have discussed above. Exact mechanisms are still unclear for most cases; therefore, extensive investigations into these issues are warranted in future. These studies may lead to the discovery of new layers of gene regulation by DGCR8 and DICER.

In mouse ESCs, both Dicer and Dgcr8 knockout cells show strong defects in proliferation and differentiation. However, the defects for Dicer knockout ESCs are reportedly more severe, demonstrating slower growth rate and higher resistance to differentiation [49, 107, 108]. Babiarz et al. try to understand the mechanisms underlying the differences between Dicer and Dgcr8 knockout ESCs by performing small RNA profiles in these cells. Interestingly, they have identified several non-canonical miRNAs that are Dgcr8-independent but Dicer-dependent [51]. These miRNAs appear to be derived from endogenous shRNAs, mirtrons and long hairpin RNAs that can serve as substrates of DICER. This study also discovers a small number of Dicer-independent and Dgcr8-dependent small RNAs [51]. The exact biogenesis pathways for these small RNAs are not clear. They could be generated by MC cleavage followed by 5′–3′ degradation. Alternatively, their precursors may be directly loaded and processed by AGO2, exemplified by miR-451 [149]. Systematic bioinformatics analysis followed by genetics experiments will give us more insights into the function of small RNAs other than miRNAs. In addition, other miRNA-independent functions of DICER, especially newly identified nuclear functions, should also be considered.

Dicer and Dgcr8 knockout in oocytes also show profound differences. As we discussed above, oocytes deficient in Dgcr8 develop and function normally when fertilized [124]. However, the failure of meiotic maturation is observed in Dicer cKO oocytes due to abnormal spindle and chromosome condensation [125, 126]. It is proposed that endo-siRNAs generated by DICER are essential for repressing genes involved in microtubule dynamics [127–129], although direct evidence showing the association and targeting of endo-siRNAs to these genes is still lacking.

In post-mitotic neurons, deletion of Dicer results in earlier lethality and more severe morphological abnormalities than Dgcr8 [150]. Babiarz et al. have compared small RNA profiles in conditional Dgcr8 or Dicer knockout hippocampus and cortex [150]. They find that non-canonical miRNAs from mirtron and snoRNA precursors but not endogenous siRNAs are highly expressed in mouse brains. Again, as in ESCs, these molecular differences have not been directly linked to the phenotypic difference between Dgcr8 and Dicer knockout.

Other than the above-mentioned examples, Dicer knockout also displays more severe phenotypes than Dgcr8 knockout in other systems including osteoprogenitor cells, male germ cells, retinal pigmented epithelium (RPE) and cardiomyocytes (Table 1). Similarly, there are also many cases where Dgcr8 knockout displays more severe defects than Dicer knockout, including splenic B cells, Schwann cells and kidney. Whether these differences are due to small RNAs or other RNA substrates is not clear. Systematic approaches such as small RNA sequencing and CLIP-Seq coupled with low-throughput validation experiments are required to solve these mysteries. Answering these questions will not only improve our understanding on the molecular regulation of relevant systems, but also contribute to our knowledge about crosstalk between miRNAs and these various other pathways.

Dgcr8-independent stable miRNA expression strategy (DISME)

Identification of functional miRNAs is usually conducted by transfection of chemically synthesized miRNA mimics in Dgcr8 knockout cells in vitro. Because transfected miRNA mimics can only exist for a short period of time, this strategy has many disadvantages including high cost and not suitable for genetic selection and long-term functional study. Theoretically, miRNAs can be expressed through a shRNA strategy in Dgcr8 knockout cells. However, due to imprecise cutting of shRNAs by Dicer [151], small RNAs with seed sequences different from intended miRNAs may be produced to confound the interpretation of rescue results. To overcome these disadvantages, we have recently developed a DISME strategy to stably express miRNAs in Dgcr8 knockout background [152], which is based on an RNA polymerase III-driven shRNA strategy that allows relatively accurate processing by DICER [151]. DISME expresses miRNAs with precise 5′ ends, therefore, can be designed to produce miRNAs with exact seed sequences as intended. MiR-294 is one of the most highly expressed miRNAs in ESCs. We show that DISME is capable of expressing miR-294 in Dgcr8 knockout ESCs at its equivalent level in wild-type ESCs [152]. Overexpression of miR-294 by DISME has successfully rescued previously reported defects in Dgcr8 knockout ESCs [152]. Moreover, we are able to study the long-term impact of miR-294 in the differentiation of Dgcr8 knockout ESCs and find that miR-294 (or miRNAs in the same seed family as miR-294) has regulatory roles in the formation of meso-endoderm lineages during embryoid body differentiation [152]. Furthermore, DISME allows for pooled screen of miRNA function. Using DISME pool of 20 miRNAs, we have successfully identified miR-183–182 cluster of miRNAs with a function in promoting self-renewal of ESCs [152]. These miRNAs are redundant to the miR-290 cluster in the regulation of ESC self-renewal as knockout of both clusters but not individual ones makes ESC prone to let-7 induced differentiation [152]. This study demonstrates the power of DISME in identifying functional miRNAs in Dgcr8 knockout ESCs. As discussed above, Dgcr8 knockout strategy has helped to reveal essential functions of miRNAs in a variety of tissues. However, identification of exact miRNAs responsible for the defects associated with Dgcr8 knockout mice has been hampered by the lack of means to stably express miRNAs in Dgcr8 knockout tissues. Using appropriate virus-based vectors, DISME may facilitate the identification of miRNAs with important physiologic functions in Dgcr8 knockout models in vivo.

Summary and future work

Dgcr8 knockout strategy has provided initial insights into miRNA functions in a variety of biological processes. Combined with Dicer knockout model, it has also helped to dissect biogenesis pathways of various small RNAs in cells and tissues. Coupled with miRNA rescue experiments, Dgcr8 knockout strategy has enabled identification of exact miRNAs responsible for key processes in ESCs and GPCs. In future, sophisticated methods should be designed to rescue miRNA expression in Dgcr8 knockout models in vivo. These studies may contribute to complete understanding of miRNA functions in physiological and pathological processes in vivo, and eventually lead to the development of miRNA-based approaches to cure human diseases. Finally, given key differences existing between various Dgcr8 and Dicer knockout models, non-canonical functions of miRNA biogenesis factors should be investigated more extensively in future.

Acknowledgements

The research in Wang laboratory is supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2016YFA0100701 and 2018YFA0107601) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31471222, 31622033, 31821091 and 91640116). WTG is supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (3332018008). Due to the breadth of this review, we apologize for the unavoidable exclusion of references to research done by many outstanding investigators working in relevant areas.

Abbreviations

- APA

Alternative polyadenylation

- AGO

Argonaute

- cKO

Conditional knockout

- cNCCs

Cardiac neural crest cells

- COX-2

Cyclooxygenase 2

- cTECs

Cortical thymic epithelial cells

- DGCR

DiGeorge syndrome chromosomal (or critical) region

- DISME

DGCR8-independent stable miRNA expression strategy

- EMT

Epithelial–mesenchymal transition

- EpiLC

Epiblast-like cells

- EpiSCs

Epiblast stem cells

- ESC

Embryonic stem cell

- ESCC

ESC-specific cell cycle regulating

- GPCs

Glia progenitor cells

- iKO

Inducible knockout

- iPSCs

Induced pluripotent stem cells

- LINE-1

Long interspersed element 1

- lncRNA

Long noncoding RNA

- MC

Microprocessor complex

- miRNA

microRNA

- mTECs

Medullary thymic epithelial cells

- NK

Natural killer

- NSCs

Neural stem cells

- PACT

Protein activator of PKR

- PTA

Persistent truncus arteriosus

- RISC

RNA-induced silencing complex

- RPE

Retinal pigmented epithelium

- rRNA

Ribosomal RNA

- SCs

Schwann cells

- Shh

Sonic hedgehog

- shRNA

Short hairpin RNA

- snoRNA

Small nucleolar RNA

- TDP43

TAR DNA-binding protein 43

- TECs

Thymic epithelial cells

- TRBP

HIV trans-activating response RNA-binding protein

- Th cells

Helper T cells

- tRNA

Transfer RNA

- VSD

Ventricular septal defect

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

4/29/2019

The section: “miRNA‑independent functions of DICER” was missed between the section “miRNA‑independent functions of DROSHA and DGCR8” and the section “The Dgcr8 knockout strategy to study miRNA functions” in the original publications.

References

- 1.Lee RC, Feinbaum RL, Ambros V. The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14. Cell. 1993;75(5):843–854. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90529-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chakraborty C, et al. Therapeutic miRNA and siRNA: moving from bench to clinic as next generation medicine. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2017;8:132–143. doi: 10.1016/j.omtn.2017.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Christopher AF, et al. MicroRNA therapeutics: discovering novel targets and developing specific therapy. Perspect Clin Res. 2016;7(2):68–74. doi: 10.4103/2229-3485.179431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ha M, Kim VN. Regulation of microRNA biogenesis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15(8):509–524. doi: 10.1038/nrm3838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lin S, Gregory RI. MicroRNA biogenesis pathways in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2015;15(6):321–333. doi: 10.1038/nrc3932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee Y, et al. The nuclear RNase III Drosha initiates microRNA processing. Nature. 2003;425(6956):415–419. doi: 10.1038/nature01957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Denli AM, et al. Processing of primary microRNAs by the Microprocessor complex. Nature. 2004;432(7014):231–235. doi: 10.1038/nature03049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gregory RI, et al. The Microprocessor complex mediates the genesis of microRNAs. Nature. 2004;432(7014):235–240. doi: 10.1038/nature03120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Han J, et al. The Drosha-DGCR8 complex in primary microRNA processing. Genes Dev. 2004;18(24):3016–3027. doi: 10.1101/gad.1262504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Landthaler M, Yalcin A, Tuschl T. The human DiGeorge syndrome critical region gene 8 and its D. melanogaster homolog are required for miRNA biogenesis. Curr Biol. 2004;14(23):2162–2167. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bohnsack MT, Czaplinski K, Gorlich D. Exportin 5 is a RanGTP-dependent dsRNA-binding protein that mediates nuclear export of pre-miRNAs. RNA. 2004;10(2):185–191. doi: 10.1261/rna.5167604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lund E, et al. Nuclear export of microRNA precursors. Science. 2004;303(5654):95–98. doi: 10.1126/science.1090599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yi R, et al. Exportin-5 mediates the nuclear export of pre-microRNAs and short hairpin RNAs. Genes Dev. 2003;17(24):3011–3016. doi: 10.1101/gad.1158803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang H, et al. Single processing center models for human Dicer and bacterial RNase III. Cell. 2004;118(1):57–68. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Park JE, et al. Dicer recognizes the 5′ end of RNA for efficient and accurate processing. Nature. 2011;475(7355):201–205. doi: 10.1038/nature10198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fukunaga R, et al. Dicer partner proteins tune the length of mature miRNAs in flies and mammals. Cell. 2012;151(3):533–546. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.09.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mourelatos Z, et al. miRNPs: a novel class of ribonucleoproteins containing numerous microRNAs. Genes Dev. 2002;16(6):720–728. doi: 10.1101/gad.974702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kawamata T, Tomari Y. Making RISC. Trends Biochem Sci. 2010;35(7):368–376. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2010.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bartel DP. Metazoan MicroRNAs. Cell. 2018;173(1):20–51. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huntzinger E, Izaurralde E. Gene silencing by microRNAs: contributions of translational repression and mRNA decay. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12(2):99–110. doi: 10.1038/nrg2936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yekta S, Shih IH, Bartel DP. MicroRNA-directed cleavage of HOXB8 mRNA. Science. 2004;304(5670):594–596. doi: 10.1126/science.1097434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shin C, et al. Expanding the microRNA targeting code: functional sites with centered pairing. Mol Cell. 2010;38(6):789–802. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karginov FV, et al. Diverse endonucleolytic cleavage sites in the mammalian transcriptome depend upon microRNAs, Drosha, and additional nucleases. Mol Cell. 2010;38(6):781–788. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chiang HR, et al. Mammalian microRNAs: experimental evaluation of novel and previously annotated genes. Genes Dev. 2010;24(10):992–1009. doi: 10.1101/gad.1884710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kozomara A, Griffiths-Jones S. miRBase: annotating high confidence microRNAs using deep sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(Database issue):D68–D73. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lewis BP, Burge CB, Bartel DP. Conserved seed pairing, often flanked by adenosines, indicates that thousands of human genes are microRNA targets. Cell. 2005;120(1):15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Friedman RC, et al. Most mammalian mRNAs are conserved targets of microRNAs. Genome Res. 2009;19(1):92–105. doi: 10.1101/gr.082701.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roush S, Slack FJ. The let-7 family of microRNAs. Trends Cell Biol. 2008;18(10):505–516. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fischer S, et al. Unveiling the principle of microRNA-mediated redundancy in cellular pathway regulation. RNA Biol. 2015;12(3):238–247. doi: 10.1080/15476286.2015.1017238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Olive V, Minella AC, He L. Outside the coding genome, mammalian microRNAs confer structural and functional complexity. Sci Signal. 2015;8(368):re2. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2005813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Herbert KM, et al. A heterotrimer model of the complete Microprocessor complex revealed by single-molecule subunit counting. RNA. 2016;22(2):175–183. doi: 10.1261/rna.054684.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nguyen TA, et al. Functional anatomy of the human microprocessor. Cell. 2015;161(6):1374–1387. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nguyen TA, et al. Microprocessor depends on hemin to recognize the apical loop of primary microRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46(11):5726–5736. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Partin AC, et al. Heme enables proper positioning of Drosha and DGCR8 on primary microRNAs. Nat Commun. 2017;8(1):1737. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01713-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Faller M, et al. Heme is involved in microRNA processing. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14(1):23–29. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Di Carlo V, et al. TDP-43 regulates the microprocessor complex activity during in vitro neuronal differentiation. Mol Neurobiol. 2013;48(3):952–963. doi: 10.1007/s12035-013-8564-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kawahara Y, Mieda-Sato A. TDP-43 promotes microRNA biogenesis as a component of the Drosha and Dicer complexes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(9):3347–3352. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1112427109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mori M, et al. Hippo signaling regulates microprocessor and links cell-density-dependent miRNA biogenesis to cancer. Cell. 2014;156(5):893–906. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.12.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hong S, et al. Signaling by p38 MAPK stimulates nuclear localization of the microprocessor component p68 for processing of selected primary microRNAs. Sci Signal. 2013;6(266):ra16. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2003706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Motino O, et al. Regulation of MicroRNA 183 by cyclooxygenase 2 in liver is DEAD-box helicase p68 (DDX5) dependent: role in insulin signaling. Mol Cell Biol. 2015;35(14):2554–2567. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00198-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Murai K, et al. The TLX-miR-219 cascade regulates neural stem cell proliferation in neurodevelopment and schizophrenia iPSC model. Nat Commun. 2016;7:10965. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stark KL, et al. Altered brain microRNA biogenesis contributes to phenotypic deficits in a 22q11-deletion mouse model. Nat Genet. 2008;40(6):751–760. doi: 10.1038/ng.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hornstein E, Shomron N. Canalization of development by microRNAs. Nat Genet. 2006;38(Suppl):S20–S24. doi: 10.1038/ng1803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fenelon K, et al. Deficiency of Dgcr8, a gene disrupted by the 22q11.2 microdeletion, results in altered short-term plasticity in the prefrontal cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(11):4447–4452. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1101219108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Merico D, et al. MicroRNA dysregulation, gene networks, and risk for schizophrenia in 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Front Neurol. 2014;5:238. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2014.00238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Amin H, et al. Developmental excitatory-to-inhibitory GABA-polarity switch is disrupted in 22q11.2 deletion syndrome: a potential target for clinical therapeutics. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):15752. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-15793-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Han J, et al. Posttranscriptional crossregulation between Drosha and DGCR8. Cell. 2009;136(1):75–84. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.10.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Triboulet R, et al. Post-transcriptional control of DGCR8 expression by the microprocessor. RNA. 2009;15(6):1005–1011. doi: 10.1261/rna.1591709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang Y, et al. DGCR8 is essential for microRNA biogenesis and silencing of embryonic stem cell self-renewal. Nat Genet. 2007;39(3):380–385. doi: 10.1038/ng1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shiohama A, et al. Molecular cloning and expression analysis of a novel gene DGCR8 located in the DiGeorge syndrome chromosomal region. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;304(1):184–190. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(03)00554-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Babiarz JE, et al. Mouse ES cells express endogenous shRNAs, siRNAs, and other microprocessor-independent, dicer-dependent small RNAs. Genes Dev. 2008;22(20):2773–2785. doi: 10.1101/gad.1705308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Aguado LC, et al. RNase III nucleases from diverse kingdoms serve as antiviral effectors. Nature. 2017;547(7661):114–117. doi: 10.1038/nature22990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shapiro JS, et al. Drosha as an interferon-independent antiviral factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(19):7108–7113. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1319635111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Maillard PV, et al. Antiviral RNA interference in mammalian cells. Science. 2013;342(6155):235–238. doi: 10.1126/science.1241930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Li Y, et al. RNA interference functions as an antiviral immunity mechanism in mammals. Science. 2013;342(6155):231–234. doi: 10.1126/science.1241911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li Y, et al. Induction and suppression of antiviral RNA interference by influenza A virus in mammalian cells. Nat Microbiol. 2016;2:16250. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Qiu Y, et al. Human virus-derived small RNAs can confer antiviral immunity in mammals. Immunity. 2017;46(6):992–1004. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Calses PC, et al. DGCR8 mediates repair of UV-induced DNA damage independently of RNA processing. Cell Rep. 2017;19(1):162–174. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tang KF, et al. Decreased Dicer expression elicits DNA damage and up-regulation of MICA and MICB. J Cell Biol. 2008;182(2):233–239. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200801169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wei W, et al. A role for small RNAs in DNA double-strand break repair. Cell. 2012;149(1):101–112. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Francia S, et al. Site-specific DICER and DROSHA RNA products control the DNA-damage response. Nature. 2012;488(7410):231–235. doi: 10.1038/nature11179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang Q, Goldstein M. Small RNAs recruit chromatin-modifying enzymes MMSET and Tip60 to reconfigure damaged DNA upon double-strand break and facilitate repair. Cancer Res. 2016;76(7):1904–1915. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-2334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chen X, et al. Dicer regulates non-homologous end joining and is associated with chemosensitivity in colon cancer patients. Carcinogenesis. 2017;38(9):873–882. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgx059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pong SK, Gullerova M. Noncanonical functions of microRNA pathway enzymes—drosha, DGCR8, dicer and ago proteins. FEBS Lett. 2018;592(17):2973–2986. doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.13196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yang JS, Lai EC. Alternative miRNA biogenesis pathways and the interpretation of core miRNA pathway mutants. Mol Cell. 2011;43(6):892–903. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Burger K, Gullerova M. Swiss army knives: non-canonical functions of nuclear Drosha and Dicer. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2015;16(7):417–430. doi: 10.1038/nrm3994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Macias S, et al. DGCR8 HITS-CLIP reveals novel functions for the microprocessor. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2012;19(8):760–766. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Heras SR, et al. The Microprocessor controls the activity of mammalian retrotransposons. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2013;20(10):1173–1181. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kim B, Jeong K, Kim VN. Genome-wide mapping of DROSHA cleavage sites on primary MicroRNAs and noncanonical substrates. Mol Cell. 2017;66(2):258–269. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Knuckles P, et al. Drosha regulates neurogenesis by controlling neurogenin 2 expression independent of microRNAs. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15(7):962–969. doi: 10.1038/nn.3139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hoffmann N, et al. DGCR8 promotes neural progenitor expansion and represses neurogenesis in the mouse embryonic neocortex. Front Neurosci. 2018;12:281. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2018.00281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rolando C, et al. Multipotency of adult hippocampal NSCs in vivo is restricted by drosha/NFIB. Cell Stem Cell. 2016;19(5):653–662. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Marinaro F, et al. MicroRNA-independent functions of DGCR8 are essential for neocortical development and TBR1 expression. EMBO Rep. 2017;18(4):603–618. doi: 10.15252/embr.201642800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Johanson TM, et al. Drosha controls dendritic cell development by cleaving messenger RNAs encoding inhibitors of myelopoiesis. Nat Immunol. 2015;16(11):1134–1141. doi: 10.1038/ni.3293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wagschal A, et al. Microprocessor, Setx, Xrn2, and Rrp6 co-operate to induce premature termination of transcription by RNAPII. Cell. 2012;150(6):1147–1157. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gromak N, et al. Drosha regulates gene expression independently of RNA cleavage function. Cell Rep. 2013;5(6):1499–1510. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.11.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Dhir A, et al. Microprocessor mediates transcriptional termination of long noncoding RNA transcripts hosting microRNAs. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2015;22(4):319–327. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lee D, Nam JW, Shin C. DROSHA targets its own transcript to modulate alternative splicing. RNA. 2017;23(7):1035–1047. doi: 10.1261/rna.059808.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Havens MA, Reich AA, Hastings ML. Drosha promotes splicing of a pre-microRNA-like alternative exon. PLoS Genet. 2014;10(5):e1004312. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wu H, et al. Human RNase III is a 160-kDa protein involved in preribosomal RNA processing. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(47):36957–36965. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005494200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Macias S, et al. DGCR8 acts as an adaptor for the exosome complex to degrade double-stranded structured RNAs. Mol Cell. 2015;60(6):873–885. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bernstein E, et al. Role for a bidentate ribonuclease in the initiation step of RNA interference. Nature. 2001;409(6818):363–366. doi: 10.1038/35053110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Doi N, et al. Short-interfering-RNA-mediated gene silencing in mammalian cells requires Dicer and eIF2C translation initiation factors. Curr Biol. 2003;13(1):41–46. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(02)01394-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Okamura K, Lai EC. Endogenous small interfering RNAs in animals. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9(9):673–678. doi: 10.1038/nrm2479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Yang N, Kazazian HH., Jr L1 retrotransposition is suppressed by endogenously encoded small interfering RNAs in human cultured cells. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13(9):763–771. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kaneko H, et al. DICER1 deficit induces Alu RNA toxicity in age-related macular degeneration. Nature. 2011;471(7338):325–330. doi: 10.1038/nature09830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hu Q, et al. DICER- and AGO3-dependent generation of retinoic acid-induced DR2 Alu RNAs regulates human stem cell proliferation. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2012;19(11):1168–1175. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Rybak-Wolf A, et al. A variety of dicer substrates in human and C. elegans. Cell. 2014;159(5):1153–1167. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Krol J, et al. Ribonuclease dicer cleaves triplet repeat hairpins into shorter repeats that silence specific targets. Mol Cell. 2007;25(4):575–586. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Much C, et al. Endogenous mouse dicer is an exclusively cytoplasmic protein. PLoS Genet. 2016;12(6):e1006095. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.White E, et al. Human nuclear Dicer restricts the deleterious accumulation of endogenous double-stranded RNA. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2014;21(6):552–559. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Neve J, et al. Subcellular RNA profiling links splicing and nuclear DICER1 to alternative cleavage and polyadenylation. Genome Res. 2016;26(1):24–35. doi: 10.1101/gr.193995.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wang Y, et al. Embryonic stem cell-specific microRNAs regulate the G1-S transition and promote rapid proliferation. Nat Genet. 2008;40(12):1478–1483. doi: 10.1038/ng.250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Wang Y, et al. miR-294/miR-302 promotes proliferation, suppresses G1-S restriction point, and inhibits ESC differentiation through separable mechanisms. Cell Rep. 2013;4(1):99–109. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.05.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Gu KL, et al. Pluripotency-associated miR-290/302 family of microRNAs promote the dismantling of naive pluripotency. Cell Res. 2016;26(3):350–366. doi: 10.1038/cr.2016.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Guo WT, et al. Suppression of epithelial-mesenchymal transition and apoptotic pathways by miR-294/302 family synergistically blocks let-7-induced silencing of self-renewal in embryonic stem cells. Cell Death Differ. 2015;22(7):1158–1169. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2014.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Cao Y, et al. miR-290/371-Mbd2-Myc circuit regulates glycolytic metabolism to promote pluripotency. EMBO J. 2015;34(5):609–623. doi: 10.15252/embj.201490441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Wu DR, et al. Opposing roles of miR-294 and MBNL1/2 in shaping the gene regulatory network of embryonic stem cells. EMBO Rep. 2018;19(6):e45667. doi: 10.15252/embr.201745657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Wray J, Kalkan T, Smith AG. The ground state of pluripotency. Biochem Soc Trans. 2010;38(4):1027–1032. doi: 10.1042/BST0381027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Yan Y, et al. Significant differences of function and expression of microRNAs between ground state and serum-cultured pluripotent stem cells. J Genet Genomics. 2017;44(4):179–189. doi: 10.1016/j.jgg.2017.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Melton C, Judson RL, Blelloch R. Opposing microRNA families regulate self-renewal in mouse embryonic stem cells. Nature. 2010;463(7281):621–626. doi: 10.1038/nature08725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kondoh H, et al. A high glycolytic flux supports the proliferative potential of murine embryonic stem cells. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2007;9(3):293–299. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Prigione A, et al. The senescence-related mitochondrial/oxidative stress pathway is repressed in human induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cells. 2010;28(4):721–733. doi: 10.1002/stem.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Varum S, et al. Energy metabolism in human pluripotent stem cells and their differentiated counterparts. PLoS One. 2011;6(6):e20914. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Gambardella G, et al. The impact of microRNAs on transcriptional heterogeneity and gene co-expression across single embryonic stem cells. Nat Commun. 2017;8:14126. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kumar RM, et al. Deconstructing transcriptional heterogeneity in pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2014;516(7529):56–61. doi: 10.1038/nature13920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Murchison EP, et al. Characterization of Dicer-deficient murine embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(34):12135–12140. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505479102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Kanellopoulou C, et al. Dicer-deficient mouse embryonic stem cells are defective in differentiation and centromeric silencing. Genes Dev. 2005;19(4):489–501. doi: 10.1101/gad.1248505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Ma Y, et al. Functional screen reveals essential roles of miR-27a/24 in differentiation of embryonic stem cells. EMBO J. 2015;34(3):361–378. doi: 10.15252/embj.201489957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Landgraf P, et al. A mammalian microRNA expression atlas based on small RNA library sequencing. Cell. 2007;129(7):1401–1414. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.04.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Xu N, et al. MicroRNA-145 regulates OCT4, SOX2, and KLF4 and represses pluripotency in human embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2009;137(4):647–658. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Tay Y, et al. MicroRNAs to Nanog, Oct4 and Sox2 coding regions modulate embryonic stem cell differentiation. Nature. 2008;455(7216):1124–1128. doi: 10.1038/nature07299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Schouten M, et al. MicroRNA-124 and -137 cooperativity controls caspase-3 activity through BCL2L13 in hippocampal neural stem cells. Sci Rep. 2015;5:12448. doi: 10.1038/srep12448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Santos MC, et al. miR-124, -128, and -137 orchestrate neural differentiation by acting on overlapping gene sets containing a highly connected transcription factor network. Stem Cells. 2016;34(1):220–232. doi: 10.1002/stem.2204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Pons-Espinal M, et al. Synergic functions of miRNAs determine neuronal fate of adult neural stem cells. Stem Cell Reports. 2017;8(4):1046–1061. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2017.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Weinberger L, et al. Dynamic stem cell states: naive to primed pluripotency in rodents and humans. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2016;17(3):155–169. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2015.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Tesar PJ, et al. New cell lines from mouse epiblast share defining features with human embryonic stem cells. Nature. 2007;448(7150):196–199. doi: 10.1038/nature05972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Brons IG, et al. Derivation of pluripotent epiblast stem cells from mammalian embryos. Nature. 2007;448(7150):191–195. doi: 10.1038/nature05950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Kalkan T, Smith A. Mapping the route from naive pluripotency to lineage specification. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2014;369(1657):20130540. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2013.0540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Shenoy A, Danial M, Blelloch RH. Let-7 and miR-125 cooperate to prime progenitors for astrogliogenesis. EMBO J. 2015;34(9):1180–1194. doi: 10.15252/embj.201489504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Morita S, et al. One Argonaute family member, Eif2c2 (Ago2), is essential for development and appears not to be involved in DNA methylation. Genomics. 2007;89(6):687–696. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Bernstein E, et al. Dicer is essential for mouse development. Nat Genet. 2003;35(3):215–217. doi: 10.1038/ng1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Zimmermann C, et al. Germ cell-specific targeting of DICER or DGCR8 reveals a novel role for endo-siRNAs in the progression of mammalian spermatogenesis and male fertility. PLoS One. 2014;9(9):e107023. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0107023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Suh N, et al. MicroRNA function is globally suppressed in mouse oocytes and early embryos. Curr Biol. 2010;20(3):271–277. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.12.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Tang F, et al. Maternal microRNAs are essential for mouse zygotic development. Genes Dev. 2007;21(6):644–648. doi: 10.1101/gad.418707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Murchison EP, et al. Critical roles for Dicer in the female germline. Genes Dev. 2007;21(6):682–693. doi: 10.1101/gad.1521307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Tam OH, et al. Pseudogene-derived small interfering RNAs regulate gene expression in mouse oocytes. Nature. 2008;453(7194):534–538. doi: 10.1038/nature06904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Watanabe T, et al. Endogenous siRNAs from naturally formed dsRNAs regulate transcripts in mouse oocytes. Nature. 2008;453(7194):539–543. doi: 10.1038/nature06908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Stein P, et al. Essential Role for endogenous siRNAs during meiosis in mouse oocytes. PLoS Genet. 2015;11(2):e1005013. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Kim YS, et al. Deficiency in DGCR8-dependent canonical microRNAs causes infertility due to multiple abnormalities during uterine development in mice. Sci Rep. 2016;6:20242. doi: 10.1038/srep20242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Hawkins SM, et al. Dysregulation of uterine signaling pathways in progesterone receptor-Cre knockout of dicer. Mol Endocrinol. 2012;26(9):1552–1566. doi: 10.1210/me.2012-1042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Steiner DF, et al. MicroRNA-29 regulates T-box transcription factors and interferon-gamma production in helper T cells. Immunity. 2011;35(2):169–181. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Ma F, et al. The microRNA miR-29 controls innate and adaptive immune responses to intracellular bacterial infection by targeting interferon-gamma. Nat Immunol. 2011;12(9):861–869. doi: 10.1038/ni.2073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Bezman NA, et al. Distinct requirements of microRNAs in NK cell activation, survival, and function. J Immunol. 2010;185(7):3835–3846. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Leong JW, Sullivan RP, Fehniger TA. Natural killer cell regulation by microRNAs in health and disease. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2012;2012:632329. doi: 10.1155/2012/632329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Khan IS, et al. Canonical microRNAs in thymic epithelial cells promote central tolerance. Eur J Immunol. 2014;44(5):1313–1319. doi: 10.1002/eji.201344079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Zuklys S, et al. MicroRNAs control the maintenance of thymic epithelia and their competence for T lineage commitment and thymocyte selection. J Immunol. 2012;189(8):3894–3904. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]