Abstract

Post-separation abuse is a pervasive societal and public health problem. This literature review aims to critically synthesize the evidence on tactics and consequences of post-separation abuse. We examined 48 published articles in the US and Canada from 2011 through May 2022. Post-separation abuse encompasses a broad range of tactics perpetrated by a former intimate partner including patterns of psychological, legal, economic, and mesosystem abuse as well as weaponizing children. Functional consequences include risk of lethality and deprivation of fundamental human needs. Connecting tactics of post-separation abuse to harms experienced by survivors and their children is crucial for future research, policy, and intervention work to promote long-term safety, health, and well-being of children and adult survivors.

Keywords: Child custody, family court, intimate partner, violence, post-separation abuse

Violence in families is widespread. One in three US women experiences intimate partner violence (IPV) during their lifetime, and intimate partner homicide is a leading cause of mortality for women of reproductive age (Campbell et al., 2003; Wilson et al., 2022). Separation is commonly assumed to be the solution to ending IPV. Yet, a robust body of research has identified that separation is a risk factor for lethality, continued or worsened IPV, and the occasional initiation of IPV (Rezey, 2020). Post-separation abuse encompasses a broad range of tactics perpetrated by a former intimate partner that includes patterns of legal, economic, psychological, and mesosystem abuse, as well as weaponizing children (Spearman et al., 2022; Stark & Hester, 2019).

Post-separation abuse tactics target the fundamental human needs of survivors and cause generalized fear, entrapment, and loss of agency and autonomy (Spearman et al., 2022; Stark & Hester, 2019). Post-separation abuse is often a continuation or escalation of patterns of “intimate terrorism” that occurred in the relationship (Johnson et al., 2014). These forms of abuse should be differentiated from “situational violence”, where for example, individuals resort to physical violence during conflict, but not with the intent or motive to dominate and control their partner (Johnson et al., 2014). The purpose of this literature review is to critically synthesize the broad range of tactics of post-separation abuse as they relate to harms experienced by survivors.

Understanding the post-separation context

What distinguishes the post-separation context is the increased risk for lethality in intimate partner homicides (Campbell et al., 2003), and the increased prevalence of other forms of victimization (Rezey, 2020). The other distinguishing factor is the role of family court and legal systems that regulate the post-separation context, particularly when children are shared. How abuse is framed has significant implications for how abuse is addressed. The divorce and custody literature—which focuses primarily on conflict—has largely developed apart from the domestic violence literature (Hardesty et al., 2012). But when conflict is conflated with abuse, the wrong interventions may be applied. The assaults on the autonomy, liberty, and fundamental needs of a human being give violence its power and meaning, and family violence must be understood within this context.

Separation, gender, and IPV

Post-separation abuse is a gendered phenomenon. IPV patterns differ by gender, marital status, and motherhood status (Catalano, 2012), with the most persistent forms of coercive control (Stark & Hester, 2019), intimate terrorism (Johnson et al., 2014), severe physical violence (Smith et al., 2018), and lethality (Wilson et al., 2022) perpetrated by men against their female partners. When examining IPV by household composition, Catalano (2012) found that rates of IPV are highest for households that are comprised of one adult female and children—more than 10 times higher than married women with children, and six times higher than households with one female only. This data is limited in that it is cross-sectional and does not provide temporal ordering of separation and victimization. The sociolegal context of gendered expectations, patriarchal norms, and childcare burdens place mothers at increased risks of exposure to post-separation abuse and its consequences. Following separation, survivors and their children must continue to negotiate family court and coparenting arrangements, a legal context that enables new patterns of abusive behavior.

The existing literature on post-separation abuse focuses almost entirely on male perpetrated abuse against their (former) female partners and mothers of their children. Men commit the majority of intimate partner homicides of women and children following separation. Because of the gendered nature of post-separation abuse and the increased risk of lethality for women and their children in the post-separation context, this literature review focuses on male perpetrated post-separation abuse against former female partners and children.

Separation and intimate partner homicide

Based on data from 42 reporting states in the NVDRS in 2019, half (50.8%) of women murdered are killed by a current or former intimate partner compared with 7.2% of men (Wilson et al., 2022). The number of women killed by men increased 24% in 2020 from 2019 during the Covid-19 pandemic, with 60% of known perpetrators being current or former intimate partners based on data from the FBI’s Supplemental Homicide Report (VPC, 2022). Separation is well-established with an increased risk for lethality for women and children (Adhia et al., 2019; Campbell et al., 2003). Separation, divorce, and child custody disputes, i.e. family court involvement, were identified as pre-cursors to nearly half (46%) of family homicides involving multiple victims in a study of mass shootings compiled (Fridel, 2021).

In the Campbell et al. (2003) landmark case-control study, 44% of women murdered by an intimate partner had separated or were in the process of leaving. The combination of a highly controlling perpetrator and separation was especially lethal: the risk of femicide increased ninefold (adjusted OR = 8.98; 95% CI = 3.25, 24.83) (Campbell et al., 2003). In a study of homicide-suicides from 2003–2011, 61.1% of cases involving child homicides had intimate partner problems (IPV, separation/divorce, child custody) identified as an antecedent (Holland et al., 2018).

Separation, courts, and abuse allegations

Social constructs of power provide the crucial context between intimate partners when IPV occurs as well as within the legal system. The family court system in the US and elsewhere is a civil legal system that requires resources to access. Victim-survivors are nearly always under-resourced compared to their perpetrators. Research based on qualitative studies with survivors indicate that there is a culture of mother-blaming, punishment, and humiliation for maternal survivors of IPV who report abuse in family court (Gutowski & Goodman, 2022). When mothers are perceived as “alienators”, unprotective, hypervigilant, or histrionic (Haselschwerdt et al., 2011), these perceptions hinder help-seeking.

As noted above, robust epidemiological data in the US and elsewhere supports increased rates of physical and sexual violence, and increased risk of lethality for individuals who are separated from intimate partners. Yet, allegations of violence following separation are often not believed, especially in family court cases and among family court professionals. A qualitative study by Haselschwerdt et al. (2011) found that among custody evaluators who have not had training in domestic violence, these custody evaluators believed that 40–80% of their case load involves false allegations. However, the US Department of Health and Human Services (2022) reported that out of a total of 3.3 million reports, only 1,223 reports (0.04%) of child abuse were intentionally false. In a study of child welfare investigations in Canada, Trocmé and Bala (2005) found that only 4% of all reports of child maltreatment (n = 135,574) were intentionally false, and just 12% of deliberately false reports of child maltreatment were made during a custody or access dispute (n = 903), with 43% of these false reports made by non-custodial parents (mostly fathers). In this study, custodial caregivers (usually mothers) (14%) and children (2%) made the least intentionally false allegations of abuse (Trocmé & Bala, 2005).

Current systematic literature review

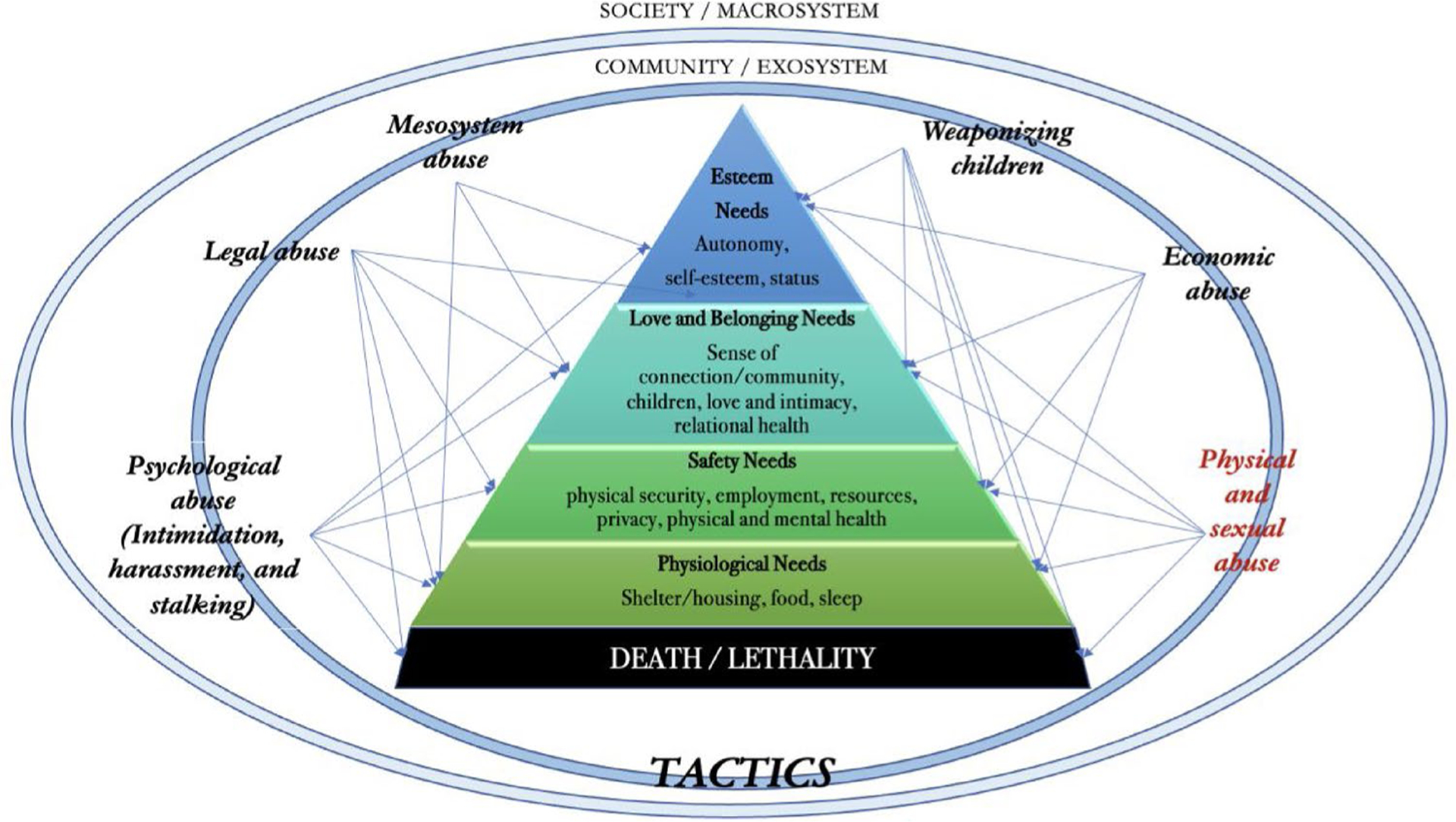

The aim of this literature review was to synthesize the evidence on post-separation abuse, with a focus on elucidating the broad range of tactics of post-separation abuse and consequences. Maslow’s Theory of Motivation (1943) and Bronfenbrenner (1994) Ecological Systems Theory served as guiding theories and were integrated to inform a new conceptual framework.

Conceptual framework

Maslow (1943) originally described fundamental human needs as the basic human needs that motivate behavior, including physiological, safety, love, esteem, and self-actualization needs. Disruptions in meeting these basic human needs are social determinants of health, and root causes of morbidity and mortality. Despite being decades old, Maslow’s Theory of Motivation (1943) continues to be widely cited. The hierarchy of needs proposed by Maslow (1943) provides an organizing framework to understand how the consequences of post-separation tactics are harmful, and was specifically chosen to illustrate the importance of moving beyond a physical incident model of IPV. Post-separation abuse involves a range of tactics to terrorize and exploit a former partner’s critical vulnerabilities, in other words their fundamental human needs. Actual or imminent thwarting of these fundamental needs is a psychological threat, associated with a range of harmful outcomes given the body’s stress response.

The range of tactics employed by an abusive partner are not just at an individual level, but also exploit other relationships, community, and system level elements that provide the context in which the victim-survivor lives. Therefore, this literature review was also informed by Bronfenbrenner (1994) ecological systems theory of human development. Bronfenbrenner (1994) identified four levels of systems that interact and influence each other to shape human behavior as the macrosystem (societal), exosystem (community), mesosystem (relationships), and microsystem (individual). The macrosystem describes the overarching societal culture and norms (e.g., patriarchal gender norms). The exosystem includes community level factors that influence individuals and relationships (e.g., neighborhood context or family court decisions). The mesosystem includes relationships from an individual to their community and how they interconnect. The microsystem describes factors at the individual level—where most IPV research has focused. This literature review incorporates these two theories to propose a new conceptual framework of the tactics and consequences of post-separation abuse (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Assaults on fundamental needs: connecting tactics of post-separation abuse to consequences.

Method

In order to synthesize the evidence on tactics and consequences of post-separation abuse, the authors conducted a literature search of PubMed, CINAHL PLUS, and Embase using keywords including: “post-separation abuse”, “post-separation violence”, “post-separation assault”, “estrangement violence”, “separation violence”, “intimate partner violence” AND “separation”, “intimate partner violence” AND “coparenting”, “intimate partner violence” AND “custody”, “separation” AND “victimization”. The first author conducted the literature search which was run in October 2021 and again in May 2022. The search returned all articles on post-separation abuse published since 1987. Because of differences in legal jurisdictions, this literature review focused on the US and Canada; however, we wish to acknowledge much important scholarly work is being done on this topic outside of the US. Final inclusion criteria comprised of 1) qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods studies; literature reviews; or theoretical research, 2) published over the last decade from 2011 through May 2022, and 3) focused on the US or Canada. This literature review critically examined the 48 manuscripts that met these inclusion criteria. Exclusion criteria included non-peer reviewed manuscripts and commentary returned from the search. Descriptions of studies, sampling designs, tactics and consequences, and a PRISMA diagram are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Results

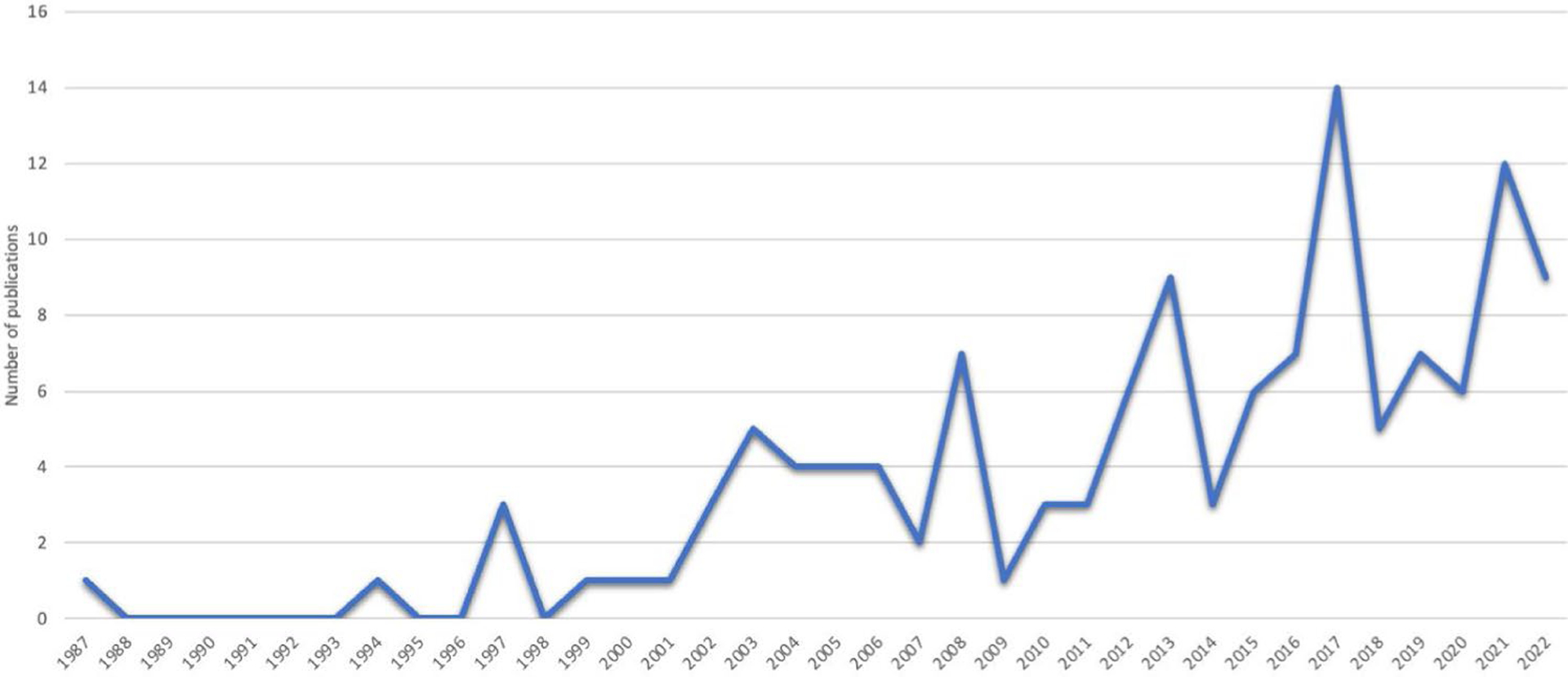

The literature review indicated that the body of scholarship addressing post-separation abuse is growing since the first publication in 1987 that addressed this phenomenon (Figure 2). We examined all published articles on post-separation abuse (n = 127), but this review concentrated on the evidence published in the last decade focused on the US and Canada.

Figure 2.

Published articles on post-separation abuse from 1987–2022.

Tactics

Because IPV is about a pattern of behavior, it is important to understand the context in which tactics are used. Tactics often overlap and cannot be neatly compartmentalized into separate categories. For example, legal abuse may become a vehicle for economic abuse by using litigation to deplete a survivor’s resources. And “weaponizing children” may involve both legal abuse and psychological abuse. Intimate terrorists use a wide range of shifting tactics based on their intimate knowledge of survivor’s personal histories, vulnerabilities, values, and priorities.

Weaponizing children

A common tactic reported by survivors in qualitative studies is how perpetrators use children to coerce or control, and use tactics that harm survivors’ identities as mothers (Gutowski & Goodman, 2022; Hayes, 2017; Toews & Bermea, 2017). Weaponizing children encompasses neglecting children’s needs to cause the other parent distress, perpetrating physical or sexual abuse against children, using children to keep track of the mother’s whereabouts or force contact, threatening to harm children, and threatening to kidnap children or “custody stalking” (Clements et al., 2021; Crossman et al., 2016; Elizabeth, 2017; Hayes, 2017; Khaw & Hardesty, 2015). Custody stalking is a post-separation abuse tactic whereby an abuser uses the courts to obtain parenting time not intended to create more meaningful involvement with their children, but to retaliate against the other parent (Clements et al., 2021). Hayes (2017) found that separation increased the odds of experiencing indirect abuse through threats to harm children in a hospital-based sample of abused women. Research findings from this review in qualitative studies and small sample size quantitative studies indicate that abusers may use legal custody to deny children access to medications or prevent them from obtaining needed health care (Silberg & Dallam, 2019; Toews & Bermea, 2017). Technological abuse has emerged as a way that abusers use children to surveil and harass the survivor (Markwick et al., 2019).

Legal abuse

Legal abuse is a form of abuse that arises specific to the post-separation context (Gutowski & Goodman, 2022). It provides another avenue for perpetrators to force contact through repeated court proceedings (Watson & Ancis, 2013). Perpetrators frequently manipulate the legal environment by distorting information, blame-shifting, gaslighting, obscuring evidence of abuse, or claiming “parental alienation” (Meier, 2020; Saunders, 2015; Toews & Bermea, 2017). For example, abusers manipulate the environment in response to a survivor’s help-seeking behaviors. To accomplish this, perpetrators may file for restraining orders against their victims, make false allegations of child abuse, make allegations of ‘parental alienation’, and file for custody. The legal system is often used by perpetrators to psychologically abuse survivors through threatening their custody and contact with their children, and publicly humiliating them (Rivera et al., 2018). Additionally, perpetrators may engage third parties and court professionals in the harassment and denigration of the survivor (Hans et al., 2014; Watson & Ancis, 2013). Court professionals (e.g., attorneys, guardians ad litem, custody evaluators, judges, magistrates) who are not aware of the patterns of the perpetrator’s tactics may unwittingly be used to further harm or abuse survivors. Family court is the primary legal venue to perpetrate post-separation abuse, yet other legal systems may be weaponized against survivors, including defamation lawsuits, financial lawsuits, and bankruptcy.

Legal abuse can take the form of economic abuse if perpetrators use legal tactics to hide assets, avoid child support, or refuse to share resources that could benefit children. Because of the costs involved to obtain private legal counsel, many survivors find themselves unable to obtain adequate representation (Miller & Smolter, 2011; Watson & Ancis, 2013). Additionally, judges have the authority and power to render financial judgments against survivors, which can result in bankruptcy; loss of homes, retirement savings, and children’s educational funds; and garnishment of wages that can continue for years. Even when judges order perpetrators to share financial resources, perpetrators may use tactics to delay or avoid payment, forcing survivors to use limited resources to enforce their rights. Legal abuse and economic abuse are compounded by structural inequities resulting from gendered notions of caregiving and patterns of control that are characteristic of IPV. Maternal survivors with young children are often underemployed or not employed outside the home as stay-at-home caregivers, and may experience employment instability for years after experiencing IPV. This employment instability leads to maternal survivors often being under-resourced compared to perpetrators, increasing their vulnerability to these tactics of legal and economic abuse.

Economic abuse

Economic abuse can be considered an invisible form of IPV. Economic abuse involves tactics designed to control or exploit an individual’s access to finances, assets, and employment. All forms of economic abuse contribute to difficulties in meeting fundamental needs and results in consequences for survivors such housing and food insecurity, and difficulty in maintaining employment. Survivors who become impoverished as a result of perpetrators’ tactics lack choice or resources to fulfill basic needs (Lin et al., 2022). Prior studies have found a high prevalence of economic abuse in the post-separation context, with 94–99% of IPV survivors in one study reporting experiences of economic abuse (Lin et al., 2022). In the post-separation context, economic abuse can include hiding assets, failing to pay child support, withholding medical expenses, failing to pay for children’s health care/insurance, coercing survivors to agree to unfair financial settlements, sabotaging employment, and creating childcare hardships (Clements et al., 2021; Crossman et al., 2016; Watson & Ancis, 2013).

Psychological abuse

Psychological abuse includes intimidation, harassment, and stalking and can manifest through gaslighting, damaging property, and coercive threats. Intimidation may include threats that capitalize on perpetrators’ relative social power, such as their access to greater financial resources or relationships to people in positions of authority that can be used to gain advantage. Stalking is generally considered to include a constellation of intrusive and unwanted behaviors such as loitering near a victim, repeated unwanted phone, mail, or technological contact, and vandalizing property (Fleming et al., 2012). Established risk factors for stalking include having shared children and separation from an intimate partner (Fleming et al., 2012). Stalking is associated with fatal intimate partner violence and contributes to the fear that characterizes experiences of post-separation abuse. Harassment can also take the form described by Broughton and Ford-Gilboe (2017) as ‘intrusion’ that diverts time and resources away from survivors’ priorities in the post-separation context. Few studies have examined the way that abusers target the critical vulnerabilities of children. For survivors, knowing that their children may be experiencing intimidation tactics that target a beloved pet, favorite hobby, toy, or fear of injury to siblings or their mother, also contributes to psychological distress. While little research has examined coercive control on parenting, perpetrators who are highly controlling of their former partners often interact in similar ways that constrain and engender fear in their children (Lapierre et al., 2022; Stark & Hester, 2019)

Mesosystem abuse

The qualitative literature is replete with examples of survivors describing ways that abusers targeted their support system. “Mesosystem” (Bronfenbrenner, 1994) refers to the interlinked connections of a person’s community, such as relationships with school, employment, neighbors, friends, and other social support systems. Abusers target these connections to isolate, discredit, and harm a survivor’s support system and also to continue to force contact with the survivor (Hayes, 2017). As one tactic to harm survivors’ support systems, perpetrators may frighten people in the survivors’ social network (Nielsen et al., 2016). This form of abuse may also involve enlisting third parties in abuse toward a partner. Technology allows abusers to overcome geographical boundaries. For example, qualitative studies in the US and elsewhere have discussed how survivors described abusers enlisting strangers in networked abuse, through social media, and through revenge porn (Markwick et al., 2019). Perpetrators may spread rumors about survivors’ mental health or character, portraying them as “unfit mothers” or “alienators” in order to discredit them (Gutowski & Goodman, 2022; Miller & Manzer, 2021).

Functional consequences

Post-separation abuse tactics include repeated attacks on a woman’s autonomy and agency, resources, and connections to other people. Coercive control during the relationship may place women at risk of future violence following separation, including post-separation sexual assault, escalating physical violence, or threats to their lives or lives of their children (Stark & Hester, 2019). The resulting functional consequences of post-separation abuse tactics harm survivors’ physiological, safety, love, belonging, and esteem needs (Figure 1).

Lethality

As previously detailed, separation, divorce, and child custody disputes are well-established risk factors for homicides of women and children (Adhia et al., 2019; Campbell et al., 2003; Spearman et al., 2022). An examination of data from the NVDRS for 16 states has identified that about 20% of child homicides (n = 1,386) in 2005–2014 are related to parental IPV (Adhia et al., 2019), with parental separation a precipitating factor where the child was killed in retaliation for the adult female leaving the relationship. Even the fear of lethality can be a way of weaponizing children and make it difficult for survivors to have their stories of abuse heard or believed. As one participant in a qualitative study recounted her child saying, “If I talk, daddy will kill mommy” (Gutowski & Goodman, 2020).

Physiological needs

Basic physiological needs include shelter, food, and sleep. Housing instability is a well-established consequence for survivors leaving abusive relationships (Abdulmohsen Alhalal et al., 2012). Perpetrators who withhold child support and other resources can cause housing instability and food insecurity for survivors and their children. Housing instability can also occur as a result of legal abuse and subsequent forced bankruptcy due to litigation related fees and expenses to maintain custody of children. Relocation and loss of housing can also occur due to safety concerns, where a survivor must leave her home and seek shelter somewhere that is not known to the abuser (Abdulmohsen Alhalal et al., 2012). Sleep is another physiological need that abusers may target. In the post-separation context this can be through stalking or technological harassment (e.g., calling repeatedly in the middle of the night, breaking into the home during the night), or as a by-product of chronic fear (Abdulmohsen Alhalal et al., 2012; Miller & Manzer, 2021; Shepard & Hagemeister, 2013).

Safety needs

In addition to fundamental physiological needs, one of the most intuitive concerns of IPV is the threat to physical safety, including children’s safety. One of the consequences of post-separation abuse was that mothers—nearly all in the qualitative study by Gutowski and Goodman (2020)—felt powerless to protect their children. While the human brain is wired for connection, when repeatedly under threat, the brain reorganizes for protection to meet safety needs. Institutional betrayal, a consequence of post-separation abuse (Spearman et al., 2022), can contribute to a loss of safety when the institutions (e.g., civil and criminal legal systems) do not adequately respond. As abusers violate orders with impunity, a lack of institutional response and recourse to perpetrators’ actions adds to survivors’ fear, anger, shame, and sense of injustice (Gutowski & Goodman, 2020).

Safety needs also include the need for privacy, employment, resources, and healthcare. Privacy can become impossible when survivors are surveilled and harassed, and family court processes require survivors to comply with excessive discovery requests, waivers of their health privilege to disclose their medical and mental health records, and disclosing other sensitive personal information to their former partner and the court system. Economic abuse and attempts to sabotage survivors’ employment create an acute sense of distress and fear of being unable to cover basic needs (Toews & Bermea, 2017). Physical and mental health consequences of post-separation abuse include increased mortality (i.e., lethality following separation) and morbidity. Long-term health consequences for survivors of post-separation abuse include PTSD, depression, and anxiety (Ford-Gilboe et al., 2023). The repeated forced contact through on-going legal abuse interferes with survivors ability to heal from trauma (Gutowski & Goodman, 2020; Zeoli et al., 2013). Extraordinary fees and costs borne by survivors in order to protect themselves and their children also impact safety needs.

Perpetrators’ use of children as an abuse tactic significantly predicts depression and PTSD, and increased anxiety among mothers in the post-separation context (Rivera et al., 2018). Maternal loss of custody as a result of custody stalking is not well recognized and creates a profound, distressing loss that is “culturally invisible”; loss of custody is associated with high levels of distress and intense grief for mothers (Elizabeth, 2017). No research to our knowledge examined the health consequences for children removed from the care and custody of their protective mothers. However, a study on overturned cases (n = 27) indicated high rates of suicidality among children removed from their protective parent and placed by the courts in the care of an abusive parent (Silberg & Dallam, 2019). Maternal survivors who retain custody of children report an inability to obtain needed health care for their children because their abusive former partner refused to consent to needed services or because they feared engaging court processes in order to obtain needed care (Silberg & Dallam, 2019; Zeoli et al., 2013).

Love and belonging needs

Relational health is fundamental to human well-being, and IPV tactics destroy that sense of safety and connection. Through mesosystem abuse tactics, abusers target their victim’s relationships with their children and isolate them from family, friends, and community (Crossman et al., 2016; Zeoli et al., 2013). Ongoing social conflict has been identified as a significant “cost” of post-separation intrusion (Abdulmohsen Alhalal et al., 2012).

Esteem needs

Esteem needs include the need for autonomy, liberty, and self-esteem. Many survivors are constrained by court orders and acts of perpetrators to exercise autonomy in their lives and the lives of their children. Lack of agency, autonomy, and “felt constraint” (Crossman et al., 2016) is a central feature of coercive control (Stark & Hester, 2019). Entrapment has been identified as an essential attribute of post-separation abuse (Spearman et al., 2022; Stark & Hester, 2019). Tactics of psychological abuse and weaponizing children impact mothers’ self-esteem, with self-blame a common theme (Khaw & Hardesty, 2015). Mothers experiencing post-separation abuse report feeling powerless, blamed, and like failures as mothers (Gutowski & Goodman, 2020).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic literature review on post-separation abuse. It expands on work done by Walker et al. (2004) nearly 20 years ago on separation in the context of victimization and integrates much of the newer knowledge developed in the last decade around legal abuse, custody stalking, and technological abuse. Many tactics identified in this review may not reach statutory or criminal levels of abuse. Although nonphysical forms of abuse have rarely been viewed as violence by policymakers, law enforcement, or court officials, post-separation abuse tactics directly target a survivor’s fundamental human rights and needs, and thus warrant greater attention.

Recommendations for court professionals

It is imperative that family court professionals learn to distinguish between “high conflict” and post-separation abuse by examining the systematic pattern of tactics that deprive a former partner of fundamental human needs. Training provided by experts in domestic violence should be mandatory for court professionals (e.g., lawyers, mediators, custody evaluators, guardian ad litem, judges, magistrates) so they can differentiate between situational couple violence and intimate terrorism (Haselschwerdt et al., 2011). Attorneys and court professionals should assess for stalking, harassment, generalized fear, and help individuals understand their risk of lethality through the use of tools such as the Danger Assessment (Campbell et al., 2009). When intimate terrorism is present, a separate physical space for survivors should be provided to increase their sense of safety (Gutowski & Goodman, 2020). Without nuanced understanding of abusive tactics, consequences, and lethality risk in the post-separation period, family court decision-makers may place children in unsafe—and potentially lethal—situations.

There is an urgent need to address litigation strategies used by abusive former partners to prevent victims of violence from help-seeking and asserting their constitutionally protected rights to parent their children. The literature suggests that perpetrators may file for custody in response to survivors’ help seeking behaviors. A survivor’s ability to mobilize the law to enforce her rights and protect her children must be understood through an intersectional context. For example, structural racism, sexism, classism, and legacies of institutional violence and oppression create inequalities in the ability to access the legal system. Professionals should not limit their evaluations of the impact of violence on children to specific physical incidents, but should consider the more subtle abuse strategies that impact children’s daily life and functioning. Given the increased risk of lethality in the post-separation period, all parenting plans should provide provisions that require universal safe storage of firearms around children at a minimum, and relinquishment of firearms when lethality risk is identified.

Recommendations for future research

While researchers have paid more attention in the last decade to the overarching context in which abuse occurs (Hardesty & Ogolsky, 2020), this literature review suggests that measures of IPV that are time-bound and incident-specific may miss the chronicity and severity of post-separation abuse. The development of reliable and valid screening instruments on post-separation abuse is an important direction for research and practice. Longitudinal research that examines family court outcomes and longer-term health and developmental outcomes for children following custody cases involving child abuse and domestic violence allegations is needed. This longitudinal research should differentiate between situational couple violence and intimate terrorism, and could inform domestic violence training, better equip custody evaluators and other court professionals (Haselschwerdt et al., 2011), as well as inform policy. The impact of post-separation abuse on children is underexplored and is a crucial area for further exploration.

In child custody cases when allegations of IPV were substantiated by other sources such as police and criminal records, this evidence is often not included in family court case files (Ogolsky et al., 2022). Further research is needed to understand the role of court gatekeepers to understanding the ways in which documented histories of abuse can be obfuscated and excluded from child custody trial records, and the larger problem of how IPV may not be adequately or appropriately handled in custody cases (Zeoli et al., 2013). More attention and accountability (Gutowski & Goodman, 2020) is needed on both judicial decision making and the roles of gatekeepers such as best interest attorneys, guardians ad litem, and custody evaluators (Haselschwerdt et al., 2011). More research is needed on post-separation abuse perpetrated amongst same-sex couples, diverse family structures, and female perpetrated post-separation abuse, which were outside the scope of this review.

Recommendations for policy

Enhanced systems coordination across civil and criminal legal systems as well as child welfare/CPS is a necessity (Saunders & Oglesby, 2016). State legislatures must prioritize domestic violence and child maltreatment training for judges, as well as for custody evaluators, children’s attorneys, and CPS. Providing specialized training for judges and court professionals is an important first step to improving system responses. Yet, training may be insufficient without enhanced accountability and transparency for courts.

Friendly parent provisions, which require that parents support and promote the other parent, present a challenge when one parent is abusive. Few guidelines exist for nonoffending parents on how to navigate the complicated situation of needing to protect the child from abuse, and also simultaneously being required by the court to promote the relationship with an abusive parent. There is a need to differentiate between protective custodial interference versus abusive custodial interference intended to sabotage a parent-child relationship. This suggests the need for legislative efforts to address friendly parent and shared parenting policies. A focus on functional consequences—identified in the conceptual framework in Figure 1—can help policymakers identify where to intervene based on different contexts of violence. For example, policies that bolster economic security for women may provide a powerful protective effect that reduces exposure to post-separation abuse.

Limitations

A significant limitation of this review is the lack of attention to diversity and overlapping forms of oppression throughout the literature on post-separation abuse. Post-separation abuse and systems responses are intricately linked to issues of power and oppression. Thus, an intersectional lens in future research on post-separation abuse is crucial to understanding how intersecting identities and locations impact survivors’ experiences of post-separation abuse, how well survivors can mobilize the law to obtain safety post-separation, and how the legal system responds to their efforts. Furthermore, understanding the scope and impact of post-separation abuse is limited by persistent measurement dilemmas, and a lack of epidemiological data on the incidence, prevalence, and severity of post-separation abuse.

Despite these limitations, this systematic review is a significant contribution to the literature by connecting post-separation abuse tactics with the harms and consequences experienced by survivors. As other researchers have noted, there is a need to limit intrusion in the post-separation context and build health promotion capacity for mothers and children (Ford-Gilboe et al., 2023; Hardesty et al., 2012). Many of the existing studies on post-separation abuse have focused narrowly on a few types of IPV post-separation, and this literature review provides a synthesis of the broad range of post-separation abuse tactics. In addition, this review proposes a new conceptual framework to guide future research, practice, and policy.

Conclusion

Post-separation abuse presents many challenges to survivors and their children. More attention is needed on the systems that enable perpetrators to abuse with impunity and to reduce the barriers to safety and health for survivors. The body of literature on post-separation abuse demonstrates the need for differential systems responses to respond to the range of abuse tactics and consequences following separation. The results of this literature review underscore the importance of a dyadic approach and breaking down the siloed professional responses toward domestic violence and child mal-treatment. The tactics of abuse toward mothers cannot be seen in isolation from those tactics toward children. Systems need integrated, coordinated, and dyadic responses that hold perpetrators accountable and support survivors’ fundamental human needs for safety, shelter, employment, health promotion, and ongoing protection for themselves and their children.

Supplementary Material

Funding

This work was supported by Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Grant/Award Number: T32-HD 094687.

Biographies

Kathryn J. Spearman, MSN, RN is a PhD candidate at the Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing in Baltimore, MD. Her research training has been supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Insititue of Child Health and Devleopment T32 in trauma and violence (T32-HD 094687) and F31 (F31 HD111297-01).

Viola Vaughan-Eden, PhD, MSW, MJ is a Professor and the PhD Program Director with the Ethelyn R. Strong School of Social Work at Norfolk State University. She is also the President and CEO of UP For Champions, a nonprofit in partnership with The UP Institute, a think tank for upstream child abuse solutions.

Jennifer L. Hardesty, PhD is a Professor in the Department of Human Development and Family Studies at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign in Urbana, IL.

Jacquelyn Campbell, PhD, RN, FAAN is a Professor at the Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing in Baltimore, MD. She is known for her research on Intimate Partner Violence and health outcomes and created and validated the Danger Assessment, which helps abused women accurately assess their risk of homicide.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Abdulmohsen Alhalal E, Ford-Gilboe M, Kerr M, & Davies L (2012). Identifying factors that predict women’s inability to maintain separation from an abusive partner. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 33(12), 838–850. 10.3109/01612840.2012.714054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adhia A, Austin S, Fitzmaurice G, & Hemenway D (2019). The role of intimate partner violence in homicides of children aged 2–14 years. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 56(1), 38–46. 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.08.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U (1994). Ecological models of human development. In Husen T & Postlethwaite T (Eds.), International encyclopedia of education (2nd ed., Vol. 3, pp. 1643–1647). Pergamon Press/Elsevier Science. [Google Scholar]

- Broughton S, & Ford-Gilboe M (2017). Predicting family health and well-being after separation from an abusive partner: Role of coercive control, mother’s depression and social support. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 26(15–16), 2468–2481. 10.1111/jocn.13458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JC, Webster D, Koziol-McLain J, Block C, Campbell D, Curry MA, Gary F, Glass N, McFarlane J, Sachs C, Sharps P, Ulrich Y, Wilt SA, Manganello J, Xu X, Schollenberger J, Frye V, & Laughon K (2003). Risk factors for femicide in abusive relationships: Results from a multisite case control study. American Journal of Public Health, 93(7), 1089–1097. 10.2105/ajph.93.7.1089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JC, Webster DW, & Glass N (2009). The danger assessment: Validation of a lethality risk assessment instrument for intimate partner femicide. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 24(4), 653–674. 10.1177/0886260508317180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalano S (2012). Intimate partner violence, 1993–2010 (NCJ Publication No. 239203). U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/ipv9310.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Clements KAV, Sprecher M, Modica S, Terrones M, Gregory K, & Sullivan CM (2021). The use of children as a tactic of intimate partner violence and its relationship to survivors’ mental health. Journal of Family Violence, 37, 1049–1055. 10.1007/s10896-021-00330-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crossman KA, Hardesty JL, & Raffaelli M (2016). “He could scare me without laying a hand on me”: Mothers’ experiences of nonviolent coercive control during marriage and after separation. Violence against Women, 22(4), 454–473. 10.1177/1077801215604744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elizabeth V (2017). Custody stalking: A mechanism of coercively controlling mothers following separation. Feminist Legal Studies, 25(2), 185–201. 10.1007/s10691-017-9349-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming KN, Newton TL, Fernandez-Botran R, Miller JJ, & Ellison Burns V (2012). Intimate partner stalking victimization and posttraumatic stress symptoms in post-abuse women. Violence against Women, 18(12), 1368–1389. 10.1177/1077801212474447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford-Gilboe M, Varcoe C, Wuest J, Campbell J, Pajot M, Heslop L, & Perrin N (2023). Trajectories of depression, post-traumatic stress, and chronic pain among women who have separated from an abusive partner: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 38(1–2), 1540–1568. 10.1177/08862605221090595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fridel EE (2021). A multivariate comparison of family, felony, and public mass murders in the United States. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(3–4), 1092–1118. 10.1177/0886260517739286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutowski E, & Goodman LA (2020). “Like I’m Invisible”: IPV survivor-mothers’ perceptions of seeking child custody through the family court system. Journal of Family Violence, 35(5), 441–457. 10.1007/s10896-019-00063-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gutowski ER, & Goodman LA (2022). Coercive control in the courtroom: The legal abuse scale (LAS). Journal of Family Violence, 10.1007/s10896-022-00408-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hans JD, Hardesty JL, Haselschwerdt ML, & Frey LM (2014). The effects of domestic violence allegations on custody evaluators’ recommendations. Journal of Family Psychology JFP: Journal of the Division of Family Psychology of the American Psychological Association (Division 43), 28(6), 957–966. 10.1037/fam0000025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardesty JL, Raffaelli M, Khaw L, Thomann Mitchell E, Haselschwerdt ML, & Crossman KA (2012). An integrative theoretical model of intimate partner violence, coparenting after separation, and maternal and child well-being. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 4(4), 318–331. 10.1111/j.1756-2589.2012.00139.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hardesty JL, & Ogolsky BG (2020). A socioecological perspective on intimate partner violence research: A decade in review. Journal of Marriage and Family, 82(1), 454–477. 10.1111/jomf.12652 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haselschwerdt ML, Hardesty JL, & Hans JD (2011). Custody evaluators’ beliefs about domestic violence allegations during divorce: Feminist and family violence perspectives. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 26(8), 1694–1719. 10.1177/0886260510370599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes BE (2017). Indirect abuse involving children during the separation process. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 32(19), 2975–2997. 10.1177/0886260515596533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland KM, Brown SV, Hall JE, & Logan JE (2018). Circumstances preceeding homicide-suicides involving child victims: A qualitative analysis. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 33(3), 379–401. 10.1177/0886260515605124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MP, Leone JM, & Xu Y (2014). Intimate terrorism and situational couple violence in general surveys: Ex-spouses required. Violence against Women, 20(2), 186–207. 10.1177/1077801214521324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khaw L, & Hardesty JL (2015). Perceptions of boundary ambiguity in the process of leaving an abusive partner. Family Process, 54(2), 327–343. 10.1111/famp.12104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapierre S, Côté I, & Lessard G (2022). “He was the king of the house” children’s perspectives on the men who abused their mothers. Journal of Family Trauma, Child Custody & Child Development, 19(3–4), 244–260. 10.1080/26904586.2022.2036284 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lin H-F, Postmus JL, Hu H, & Stylianou AM (2022). IPV experiences and financial strain over time: Insights from the blinder-oaxaca decomposition analysis. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 10.1007/s10834-022-09847-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markwick K, Bickerdike A, Wilson-Evered E, & Zeleznikow J (2019). Technology and family violence in the context of post-separated parenting. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy, 40(1), 143–162. 10.1002/anzf.1350 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maslow AH (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50(4), 370–396. 10.1037/h0054346 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meier J (2020). U.S. child custody outcomes in cases involving parental alienation and abuse allegations: what do the data show? Journal of Social Welfare and Family Law, 42(1), 92–105. 10.1080/09649069.2020.1701941 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miller SL, & Manzer JL (2021). Safeguarding children’s well-being: Voices from abused mothers navigating their relationships and the civil courts. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(9–10), 4545–4569. 10.1177/0886260518791599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller SL, & Smolter N (2011). “Paper abuse”: When all else fails, batterers use procedural stalking. Violence against Women, 17(5), 637–650. 10.1177/1077801211407290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen SK, Hardesty JL, & Raffaelli M (2016). Exploring variations within situational couple violence and comparisons with coercive controlling violence and no violence/no control. Violence against Women, 22(2), 206–224. 10.1177/1077801215599842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogolsky BG, Hardesty JL, Theisen JC, Park SY, Maniotes CR, Whittaker AM, Chong J, & Akinbode TD (2022). Parsing through public records: When and how is self-reported violence documented and when does it influence custody outcomes? Journal of Family Violence, 10.1007/s10896-022-00401-w [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rezey ML (2020). Separated women’s risk for intimate partner violence: A multiyear analysis using the national crime victimization survey. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 35(5–6), 1055–1080. 10.1177/0886260517692334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera EA, Sullivan CM, Zeoli AM, & Bybee D (2018). A longitudinal examination of mothers’ depression and PTSD symptoms as impacted by partner-abusive men’s harm to their children. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 33(18), 2779–2801. 10.1177/0886260516629391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders DG (2015). Research based recommendations for child custody evaluation practices and policies in cases of intimate partner violence. Journal of Child Custody, 12(1), 71–92. 10.1080/15379418.2015.1037052 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders DG, & Oglesby KH (2016). No way to turn: Traps encountered by many battered women with negative child custody experiences. Journal of Child Custody, 13(2–3), 154–177. 10.1080/15379418.2016.1213114 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shepard MF, & Hagemeister AK (2013). Perspectives of rural women: custody and visitation with abusive ex-partners. Affilia, 28(2), 165–176. 10.1177/0886109913490469 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Silberg J, & Dallam S (2019). Abusers gaining custody in family courts: A case series of over turned decisions. Journal of Child Custody, 16(2), 140–169. 10.1080/15379418.2019.1613204 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SG, Zhang X, Basile KC, Merrick MT, Wang J, Kresnow M, & Chen J (2018). The national intimate partner and sexual violence survey (NISVS): 2015 data brief—updated release. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- Spearman KJ, Hardesty JL, & Campbell J (2022). Post-separation abuse: A concept analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 00(n/a) 10.1111/jan.15310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark E, & Hester M (2019). Coercive control: Update and review. Violence against Women, 25(1), 81–104. 10.1177/1077801218816191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toews ML, & Bermea AM (2017). I was naive in thinking, ‘I divorced this man, he is out of my life’: A qualitative exploration of post-separation power and control tactics experienced by women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 32(14), 2166–2189. 10.1177/0886260515591278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trocmé N, & Bala N (2005). False allegations of abuse and neglect when parents separate. Child Abuse & Neglect, 29(12), 1333–1345. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.06.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Administration on Children, Youth and Families, Children’s Bureau. (2022). Child Maltreatment 2020. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/cb/data-research/child-maltreatment

- VPC. (2022). When men murder women: An analysis of 2020 homicide data. https://vpc.org/when-men-murder-women-section-one/

- Walker R, Logan TK, Jordan C, & Campbell J (2004). An integrative review of separation in the context of victimization: Consequences and implications for women. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 5(2), 143–193. 10.1177/1524838003262333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson L, & Ancis J (2013). Power and control in the legal system: From marriage/relationship to divorce and custody. Violence against Women, 19(2), 166–186. 10.1177/1077801213478027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RF, Liu G, Lyons BH, Petrosky E, Harrison DD, Betz CJ, & Blair JM (2022). Surveillance for violent deaths – National violent death reporting system, 42 States, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico, 2019. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Surveillance Summaries (Washington, D.C. : 2002), 71(6), 1–40. 10.15585/mmwr.ss7106a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeoli AM, Rivera EA, Sullivan CM, & Kubiak S (2013). Post-separation abuse of women and their children: Boundary-setting and family court utilization among victimized mothers. Journal of Family Violence, 28(6), 547–560. 10.1007/s10896-013-9528-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.