Abstract

Mitosis is the stage of the cell cycle during which replicated chromosomes must be precisely divided to allow the formation of two daughter cells possessing equal genetic material. Much of the careful spatial and temporal organization of mitosis is maintained through post-translational modifications, such as phosphorylation and ubiquitination, of key cellular proteins. Here, we will review evidence that sumoylation, conjugation to the SUMO family of small ubiquitin-like modifiers, also serves essential regulatory roles during mitosis. We will discuss the basic biology of sumoylation, how the SUMO pathway has been implicated in particular mitotic functions, including chromosome condensation, centromere/kinetochore organization and cytokinesis, and what cellular proteins may be the targets underlying these phenomena.

Keywords: Mitosis, SUMO, Condensin, Topoisomerase, Kinetochore

10.1. Introduction

Mitosis is the most visually dramatic stage of the cell cycle, wherein the replicated genetic material is segregated into two daughter cells. Although there are morphological variations between different cells types and between species, mitosis invariably involves chromatin condensation, bipolar spindle assembly, separation of sister chromatids and ultimately cytokinesis (Matsumoto and Yanagida 2005). All these steps are stringently regulated because any mistake will lead to aneuploidy and its consequences. Post-translational modifications like phosphorylation and ubiquitination have been well-documented as mechanisms of temporal and spatial control of mitosis (Devoy et al. 2005). Many lines of evidence suggest that sumoylation is an additional post-translational modification that is essential to proper progression of mitosis (Dasso 2008). Here, we will discuss how the sumoylation pathway has been implicated in particular mitotic functions, including chromosome condensation, centromere/kinetochore organization and cytokinesis.

10.2. The SUMO Pathway

SUMO proteins are a family of small ubiqiutin-related modifiers that become covalently conjugated to cellular proteins in a reversible process called sumoylation. There is only one SUMO in fungi (called Smt3p in S. cerevisiae), while there are three widely expressed SUMOs in vertebrates (SUMO1–3). Mature SUMO2 and 3 are around 97% identical, while each is roughly 45% identical to SUMO1. It is clear that SUMO1 has different dynamics and a distinct profile of target proteins from SUMO2 and 3 (Ayaydin and Dasso 2004), and that some proteins with SUMO interacting motifs (SIMs) distinguish SUMO1 from the other paralogues (Hecker et al. 2006). No functional differences have yet been found between SUMO2 and SUMO3, and they will collectively be called SUMO2/3 in circumstances where they are indistinguishable.

The enzymes responsible for sumoylation and desumoylation have been the objects of intensive study during the past decade (Johnson 2004; Mukhopadhyay and Dasso 2007). All SUMOs are synthesized as pro-peptides that must undergo proteolytic maturation by SUMO-specific proteases, called SENPs (Sentrin-specific protease) in vertebrates and Ulps (Ubiquitin-like protein protease) in yeast; this cleavage exposes a C-terminal diglycine motif. The carboxyl terminus of mature SUMOs is activated by ATP-dependent thioester linkage with the Aos1/Uba2 hetero-dimer (E1 enzyme), then transferred to a conserved cysteine of Ubc9 (E2 enzyme) and ultimately to substrates with the help of SUMO ligases (E3 enzymes). SENP/Ulp proteases mediate deconjugation of SUMOs from their target proteins (Mukhopadhyay and Dasso 2007). There are two Ulp proteases in yeast, Ulp1 and Ulp2, and there are six SUMO-specific SENPs in humans, SENP1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7. These enzymes display a considerable degree of specialization with respect to their enzymatic specificity and their localization (Mukhopadhyay and Dasso 2007).

Proteins that possess a variant RING-finger motif (SP-RING domain) are a conserved family of SUMO E3 enzymes found in all eukaryotes. Budding yeast SP-RING family members are called Siz (SAP and miz-finger domain) proteins, while the major vertebrate family members are called PIAS (protein inhibitor of activated STAT) proteins (reviewed in Palvimo 2007). Siz1p and Siz2p are responsible for the bulk of Smt3p conjugation in budding yeast, although other E3 enzymes of this class (Zip3p and Mms21p) are important for meiotic synaptonemal complex assembly (Cheng et al. 2006) and DNA repair (Potts and Yu 2005), respectively. The five vertebrate PIAS proteins (PIAS1, PIAS3, PIASxα, PIASxβ and PIASy) are important for a broad variety processes, including gene expression, genome maintenance and signal transduction. Mammals also express an Mms21p homologue, as well as two other SP-RING proteins (hZIMP7 and hZIMP10) that have been implicated in androgen receptor-dependent gene expression (Beliakoff and Sun 2006). Other vertebrate E3 enzymes, including the polycomb group protein Pc2 (Kagey et al. 2003) and the nucleoporin RanBP2 (Pichler et al. 2002), lack obvious homologues in yeast.

10.3. Outcomes of SUMO Modification

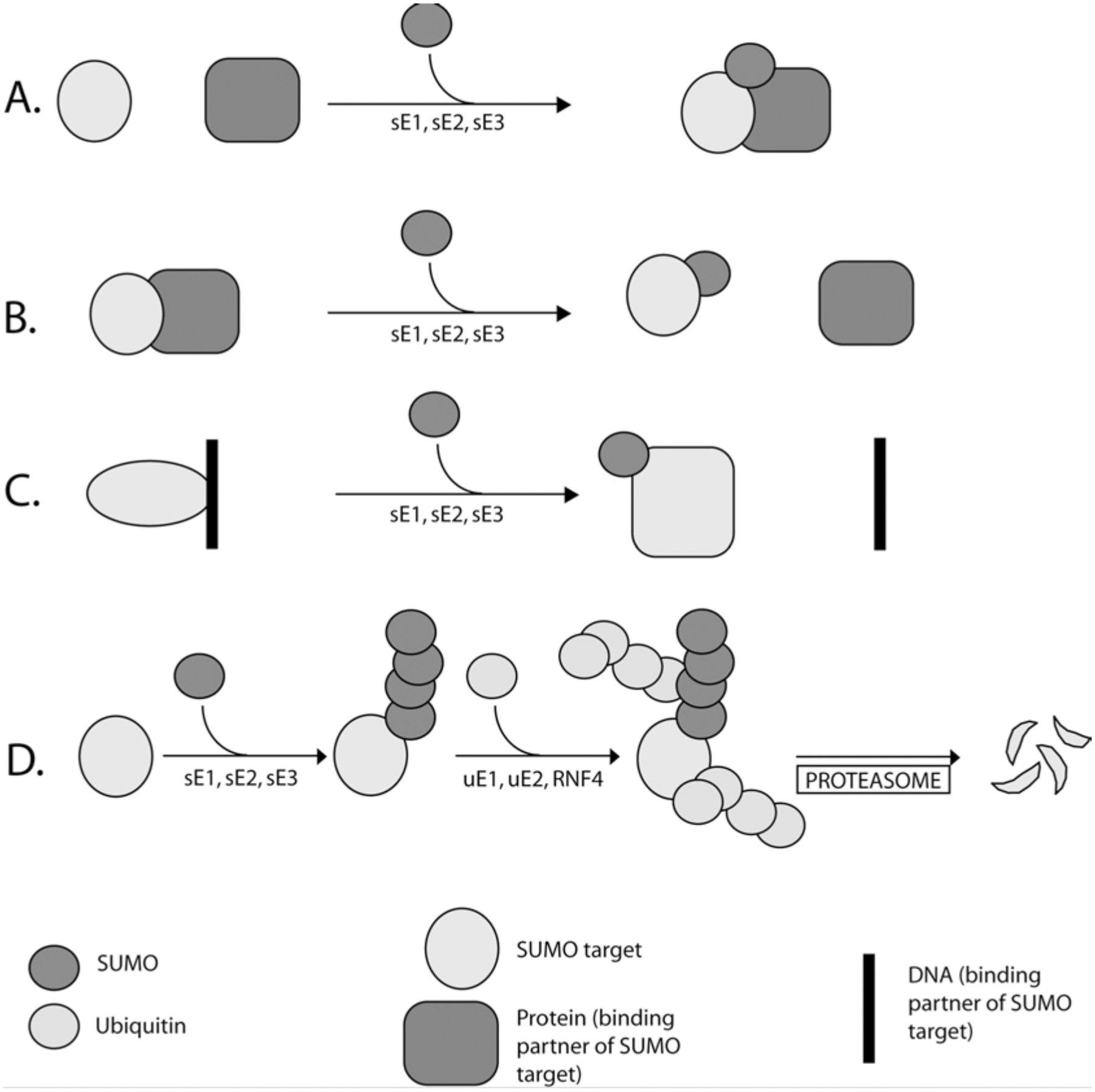

Sumoylation has been demonstrated to cause a variety of different outcomes, dependent upon the target protein, including changes in the target’s sub-cellular localization, activity, protein-protein interactions, and stability (Fig. 10.1). Mechanistically, these changes can reflect the loss or acquisition of interaction surfaces upon conjugation of the SUMO group. An exciting recent development in this field has been the description of SUMO-interacting motifs (SIMs) in many proteins (Minty et al. 2000; Song et al. 2005; Hannich et al. 2005; Hecker et al. 2006) SIMs are characterized by consensus sequence, V/I-V/I-X-V/I, with hydrophobic residues frequently punctuated at the third position (X) by an acidic amino acid. This core is frequently flanked by a stretch of acidic residues near its N- or C-terminus. SIMs allow low-affinity, non-covalent interactions between SIM-containing proteins and free or conjugated SUMOs. They may discriminate between different SUMOs, facilitating paralogue recognition and establishing functional distinctions between different SUMOs (Zhu et al. 2008; Hecker et al. 2006). SIMs are found in enzymes of the SUMO pathway as well as many SUMO target proteins. In some cases, SIM-based interactions allow targets to form higher-order protein complexes after sumoylation (Shen et al. 2006; Lin et al. 2006). For other SUMO target proteins, SIM motifs help to recruit SUMO-linked Ubc9, thereby promoting conjugation in an E3-independent manner (Meulmeester et al. 2008; Zhu et al. 2008). Finally, if a sumoylated protein possesses a SIM, intramolecular binding of the SIM to the conjugated SUMO can cause a change in the conformation of the target, thus influencing its activity or behavior (Geiss-Friedlander and Melchior 2007; Baba et al. 2005).

Fig. 10.1.

Alternative outcomes of sumoylation. (a) SUMO modification can lead to higher order complex formation. (b) Sumoylation can disrupt protein-protein interaction. (c) SUMO modification can induce conformational alteration, leading to decreased DNA binding affinity. (d) PolySUMO chains can act as a signal for RNF4-mediated ubiquitination and subsequent degradation by the proteasome. SUMO pathway enzymes and ubiquitin pathway enzymes are indicated with “s” and “u” prefix, respectively

Protein-protein interactions mediated by SIMs have recently been shown to contribute to target protein instability: A class of RING finger ubiquitin E3 ligases (RNF4 in vertebrates, Slx5p-Slx8p in budding yeast) possess multiple SIMs that they utilize to specifically recognize highly sumoylated proteins (Xie et al. 2007; Tatham et al. 2008; Lallemand-Breitenbach et al. 2008). These enzymes ubiquitinate the sumoylated proteins and target them for proteasomal degradation. Notably, specialized SUMO chain editing enzymes like Senp6 (Mukhopadhyay et al. 2006) and Ulp2p in yeast (Bylebyl et al. 2003) appear to antagonize this degradation pathway.

10.4. The Role of SUMO in Mitotic Chromosome Structure

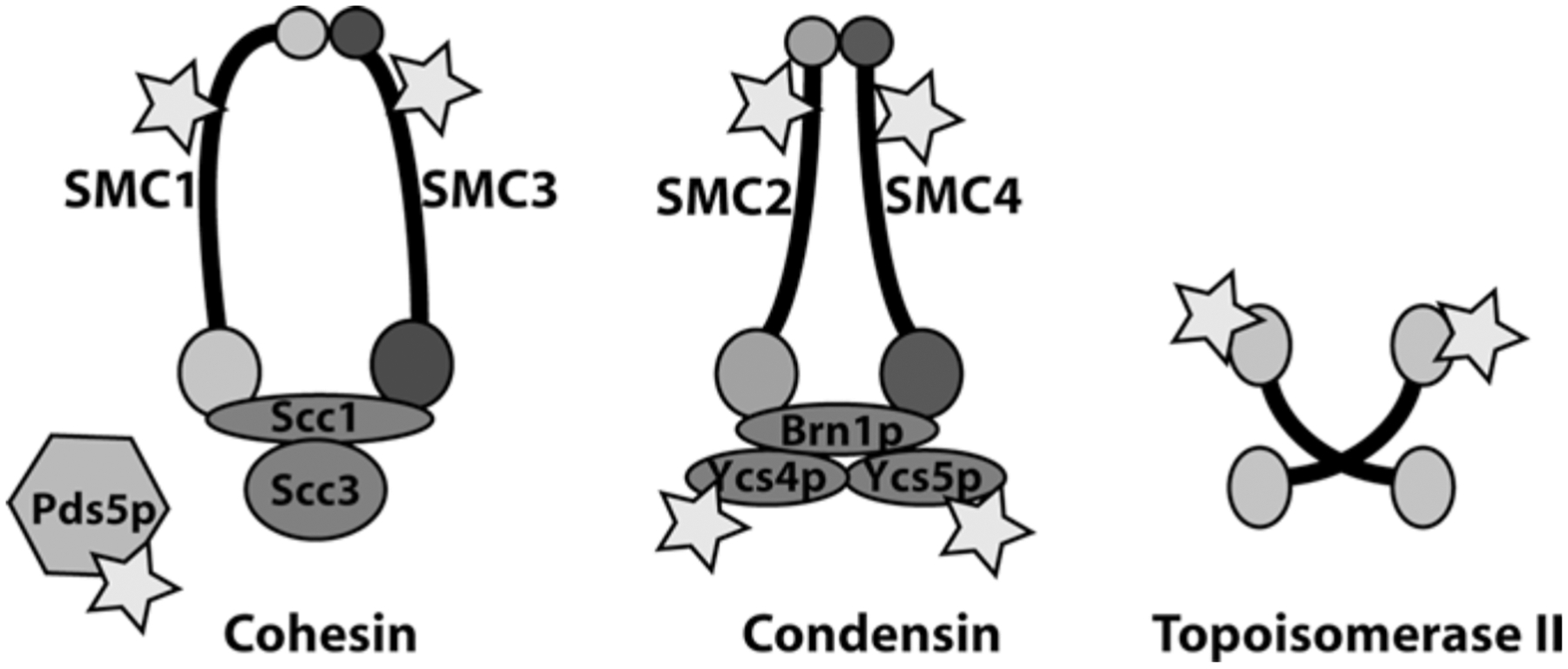

At the onset of mitosis, decondensed interphase chromatin undergoes condensation. In vertebrates, this results in well-defined structures wherein the replicated sister chromatids can be clearly observed microscopically. Condensation facilitates chromatid separation and segregation during anaphase, preventing damage to the chromosomes. The molecular events involved in mitotic chromosome condensation are poorly understood (Belmont 2006). However, it is well established that condensins, cohesins and topoisomerase II are major structural components of condensed chromosomes, which are required for their assembly and maintenance (Fig. 10.2).

Fig. 10.2.

Sumoylation targets involved in chromosome condensation and sister chromatid cohesion. Stars indicate subunits of each complex that have been experimentally confirmed as sumoylation targets

Condensins and Cohesin are large multi-protein complexes that play central roles in mitotic chromosome structure and in accurate chromosome segregation (Haering and Nasmyth 2003; Hirano 2005). Each of these complexes possesses two subunits that belong to the family of SMC (structural maintenance of chromosome) proteins. Common motifs within all SMC family members include an ATP binding domain and a DNA-binding globular domain, separated by a long anti-parallel coiled- coiled region. All SMCs exist as dimers: the Smc1p/Smc3p heterodimer is present in Cohesin, which maintains sister chromatid cohesion until the onset of anaphase. The Smc2p/Smc4p heterodimer are constituents of the Condensin I and II complexes, which are required for chromosome condensation and segregation. All SMC proteins have been demonstrated to be sumoylated (Takahashi et al. 2008).

In addition to Smc1p and Smc3p, yeast Cohesin complexes contain Scc3p and a “kleisin” subunit, called Scc1p (also known as Rad21p or Mcd1p) (Haering and Nasmyth 2003). Vertebrates possess two mitotic orthologs of Scc3p, called SA1 and SA2, which are incorporated into Cohesin complexes in a mutually exclusive manner. Cohesins may act as clip, holding the sister chromatids until anaphase and thereby preventing their premature separation (Michaelis et al. 1997). Cohesin release from chromatin during mitosis is bi-phasic: during prophase, Cohesin is released from the chromosome arms in a manner that is dependent on the Polo-like kinase 1 (Plk1) and Aurora B kinases (Hauf et al. 2005). During this initial phase of Cohesin release from the arms, the centromeric cohesion is protected by Shugoshins (Wang and Dai 2005). Shugoshins are released in metaphase when sister chromosomes bi-orient and tension is established, (Lee et al. 2008). This allows the second phase of Cohesin release from centromeric regions at anaphase by cleavage of the Scc1p subunit by separase. The sumoylation of Smc1p and Smc3p in nocodazole-arrested cells depends on Mms21p, and correlates with proper distribution of cohesin within the ribosomal DNA (rDNA) (Takahashi et al. 2008). The functional significance of this distribution is not entirely clear.

Another way that sumoylation may regulate Cohesin is through Pds5p, a Cohesin-associated protein important for cohesion maintenance (Denison et al. 1993). Budding yeast Pds5p is sumoylated in a cell cycle dependent manner, peaking just before anaphase onset (Stead et al. 2003). Ulp2p over expression causes desumoylation of Pds5p and ameliorates the temperature sensitivity and cohesion defects of pds5-ts alleles. Conversely, Siz1p over expression causes Pds5p hypersumoylation and exacerbates temperature sensitivity in these strains. These results are consistent with a model wherein the strength of sister chromatid cohesion is enhanced by Pds5p-Cohesin interaction, while sumoylation disrupts this interaction to facilitate cohesion release.

The yeast Condensin complex contains Smc2p and Smc4p, as well as the kleisin Brn1p and non-SMC subunits Ycs4p and Ycs5p (Hirano 2006). Smc2p, Smc4p, Ycs4p and Ycs5p are all subject to mitotic sumoylation (Takahashi et al. 2008), and Brn1p has been identified as a potential sumoylation target in yeast proteomic screens (Denison et al. 2005; Wohlschlegel et al. 2004). Mms21p has been implicated as the E3 enzyme responsible for Smc2p modification, as well as a contributor to the sumoylation of Smc4p and Ycs4p (Takahashi et al. 2008). Regulation of Condensin by sumoylation was initially indicated by the findings that Ulp2p over expression suppresses conditional lethality of yeast with a temperature sensitive smt2–6 allele (Strunnikov et al. 2001). Although yeast Condensin is constitutively associated with rDNA, GFP-tagged Condensin localizes to the inner kinetochore region during S phase, immediately after spindle pole body duplication (Bachellier-Bassi et al. 2008). This recruitment to kinetochores is disrupted in ulp2 mutants, indicating that it is controlled by sumoylation. Accurate segregation of the rDNA and telomeres requires the protein phosphatase Cdc14, which is also required for the efficient sumoylation of Ycs4p during anaphase (D’Amours et al. 2004). These findings might suggest that Cdc14p promotes sumoylation of Condensin at anaphase, which in turn promotes its recruitment to rDNA. This model would predict that inactivation of Ulp2p and increased Condensin sumoylation should enhance Condensin concentration at the rDNA. Although one study has validated this prediction (Bachellier-Bassi et al. 2008) others have found the opposite effect of Ulp2p inactivation (D’Amours et al. 2004; Strunnikov et al. 2001). The precise role of sumoylation in Condensin targeting to rDNA thus remains unclear, and the process might be more complex than it has been proposed.

Topoisomerase II is an important sumoylation substrate in both mitotic yeast and vertebrate cells. Siz1p and Siz2p appear to be the primary ligases for yeast Topoisomerase II (Top2p) (Takahashi et al. 2006). The closely similar chromosome segregation defects observed in siz1 siz2 double mutants and non-sumoylatable top2 mutants suggests that Top2p is among the most important substrates for these enzymes. In ulp2 strains, centromeric cohesion is disrupted, but this defect can be suppressed by over expression of Top2p or by physiological levels of a top2 mutant lacking sumoylation sites (Bachant et al. 2002). These observations particularly indicate that elevated sumoylation of Top2p promotes precocious centromeric separation. Notably, a tagged Top2p-Smt3p fusion protein is preferentially concentrated in pericentromeric chromatin, as measured through chromatin immunoprecipitation assays (Takahashi et al. 2006), suggesting that sumoylation may contribute toward the loss of cohesion through increased Top2p recruitment to centromeres. Sumoylation is also involved in nucleolar localization of Top2p: insertion of multiple Smt3p repeats within the Top2p polypeptide near the natural site of sumoylation targets a GFP-Top2p fusion protein to a sub-nucleolar compartment (Takahashi and Strunnikov 2008). Optimal nucleolar targeting was observed in fusion proteins possessing four or five tandem Smt3p polypeptides. It is attractive to speculate that such targeting may contribute significantly toward the requirement for sumoylation in rDNA segregation (Strunnikov et al. 2001; Takahashi et al. 2008).

Vertebrate Topoisomerase II (Topo II) is a major sumoylated species associated with mitotic chromosomes (Azuma et al. 2003). This modification has been most intensely studied in Xenopus egg extracts (XEEs), where Topo II is conjugated preferentially to SUMO-2/3. Inhibition of sumoylation also causes a striking failure of sister chromatid separation during anaphase that closely resembles defects observed after treatment of XEEs with Topo II inhibitors (Azuma et al. 2003; Shamu and Murray 1992). Sumoylation does not appear to affect Topo II decatenation activity (Azuma et al. 2003). One interesting alternative possibility is that different levels of sumoylation might direct Topo II to different chromosomal loci, analogous to observations in yeast. Perhaps consistent with this idea, a small proportion of Topo II is tightly associated with mitotic chromatin in XEEs; inhibition of sumoylation causes dramatic increase of this population (Azuma et al. 2003), indicating that sumoylation promotes dynamic remodeling of Topo II on mitotic chromosomes.

Analogous to the conjugation of Top2p by Siz1p and Siz2p in yeast, PIASy is responsible for SUMO modification of Topo II in XEEs (Azuma et al. 2005). PIASy modifies Topo II in a chromatin-dependent manner (Azuma et al. 2005). Consistent with the findings in Xenopus, PIASy-depleted HeLa cells fail to properly localize Topo II to mitotic chromosome axes and to centromeres (Díaz-Martínez et al. 2006). PIASy-depleted cells also show delayed anaphase, caused by activation of an Aurora B- and Mad2-dependent checkpoint. Anaphase can be induced in PIASy-depleted HeLa cells through chemical inhibition of Aurora B, but they show a strong defect in sister chromatid disjunction, indicating a defect in cohesion release (Díaz-Martínez et al. 2006). Interestingly, these defects do not appear to result from abnormal retention of Cohesin. It has been reported that unconventional SUMO ligase RanBP2 is responsible for mitotic sumoylation of Topo II in mice (Dawlaty et al. 2008). While this observation potentially explains why PIASy is not required during mouse development (Wong et al. 2004), it is surprising that a pathway conserved between yeast, frogs and humans is not apparently utilized in mice.

10.5. SUMO and Centromere/Kinetochore Organization

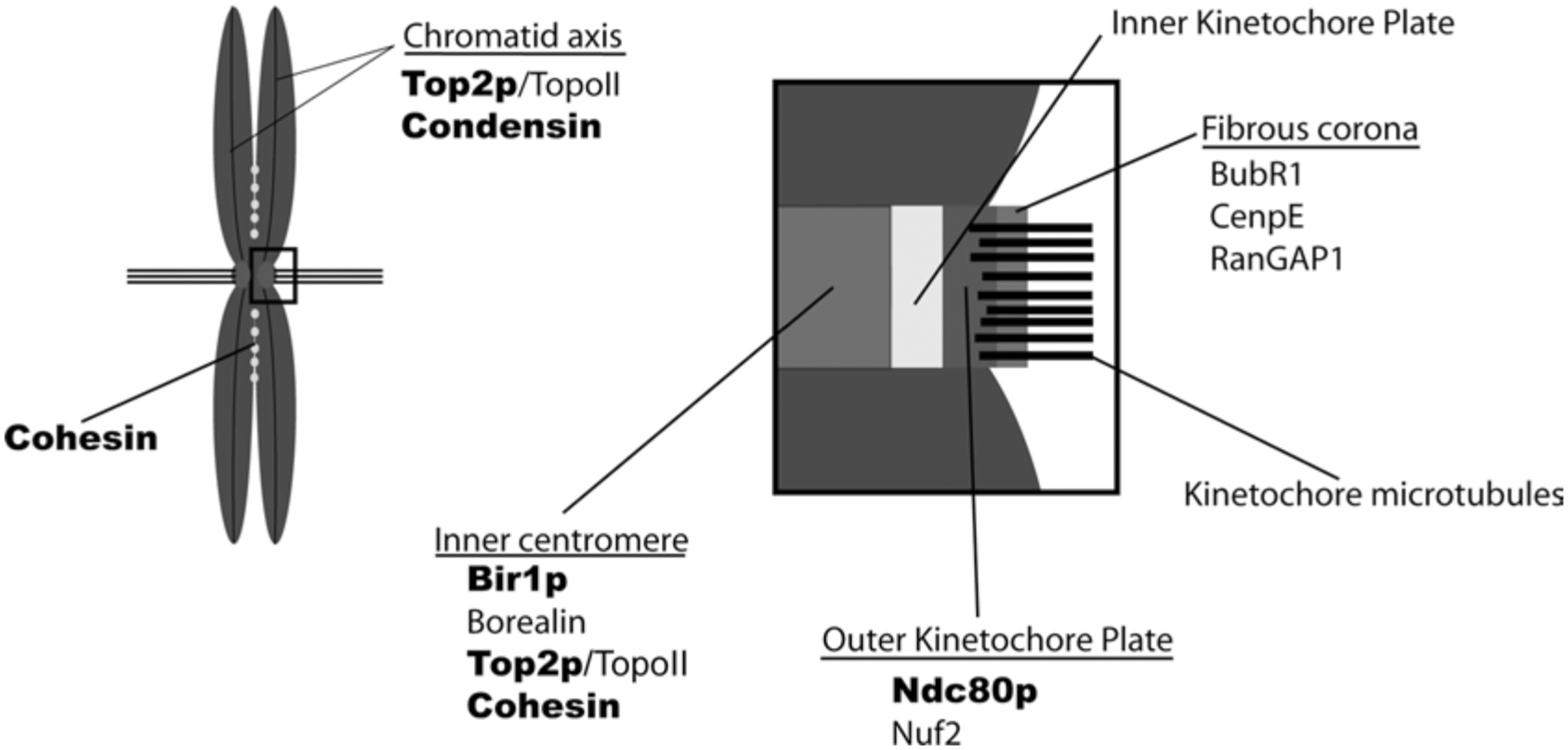

Centromeres are specialized chromatin domains on each sister chromatid. In budding yeast, the cen DNA constitutes the cis element where centromeres form. In higher eukaryotes, centromeres are maintained epigenetically by a set of centromeric proteins that associates with highly repetitive centromeric satellite DNA and are typically present at the primary constriction of mitotic chromosomes. Centromeric nucleosomes contain a histone variant, CenpA (Cse4p in S. cerevisiae), which plays a central role in the recruitment and maintenance of other centromeric proteins (Cenps) (Cleveland et al. 2003). During every mitosis, centromeres serve as sites for assembly of kinetochores, proteinaceous structures that provide the sites of attachment for microtubules (MTs)) of the kinetochore fibers (k-fibers) that connect sister chromatids to spindle poles (Musacchio and Salmon 2007; Cheeseman and Desai 2008). Correct attachment of k-fibers to opposite spindle poles is central to the accurate segregation of sister chromatids. Kinetochores also have a key role in the spindle assembly checkpoint (SAC), which prevents loss of sister chromatid cohesion and mitotic exit until all chromosomes are attached and aligned correctly on the metaphase plate. Proteins responsible for MT attachment and stability as well as for the SAC largely reside in the outer kinetochore and fibrous corona (FC), vertebrate kinetochore domains defined by electron microscopic imaging. The inner centromeric region (ICR) is the chromatin domain between the sister kinetochores that contains factors responsible for centromeric cohesion and chromosomal passenger proteins, which play essential roles in detecting and correcting mis-attachments of k-fibers (Andrews et al. 2004; Lan et al. 2004). Multiple functions of sumoylation have been proposed within mitotic centromeres and kinetochores, and recent reports have suggested that many proteins within these domains are sumoylation targets (Fig. 10.3).

Fig. 10.3.

Localization of chromosomal sumoylation targets. The distribution of confirmed targets is represented schematically, based upon previously reported localization of the vertebrate homologues. These reported localizations generally reflect the bulk of each vertebrate protein on mitotic chromosomes, not specifically the sumoylated forms. The names of yeast proteins are indicated in boldface type, while vertebrate proteins are in standard type.

There are over 60 proteins associated with the yeast centromere (McAinsh et al. 2003), many of which were found as sumoylation targets in proteomic screens (Denison et al. 2005; Wohlschlegel et al. 2004). Yeast centromeric components can be grouped into six major complexes (McAinsh et al. 2003), three of which contain confirmed sumoylation substrates:

The Cbf3 complex contains four subunits: Ndc10p/Cbf2p, Ctf13p, Cep3p and Skp1p. The sumoylation of Ndc10p and Cep3p have been demonstrated (Montpetit et al. 2006). This complex plays a critical role in kinetochore assembly because it is required for association of all other kinetochore components to the yeast centromere (McAinsh et al. 2003). Mutants that eliminate Ndc10p sumoylation cause mislocalization of Ndc10p from the mitotic spindle, abnormal anaphase spindles, and chromosome instability (Montpetit et al. 2006). In these mutants, Cep3p was mislocalized, indicating improper targeting of the Cbf3 complex in absence of Ndc10p sumoylation.

The Bir1 complex contains Bir1p, Sli15p and Ipl1. The sumoylation of Bir1p has been confirmed in vivo (Montpetit et al. 2006). This complex can link CBF3 to MTs in vitro, and may sense tension to activate the Ipl1p kinase in the vicinity of syntelic k-fiber attachments (Sandall et al. 2006). The vertebrate counterpart of Bir1 complex is the chromosomal passenger complex (CPC): Survivin (Bir1), INCENP (Sli15) and Aurora B (Ipl1) in combination with Borealin constitute the CPC (Ruchaud et al. 2007). The CPC is an important mitotic regulator which has key roles in controlling sister cohesion, kMT attachment, and cytokinesis. Interestingly, ndc10 sumoylation mutants altered Bir1p sumoylation, but did not affect its localization on the spindle (Montpetit et al. 2006). The absence of Cbf3p did not produce a comparable effect, suggesting that Ndc10p sumoylation has a Cbf3p-independent role in modulation of Bir1p sumoylation (Montpetit et al. 2006).

The Ndc80 complex contains Ndc80p, Nuf2p, Spc24p, and Spc25p. This complex plays a central role in kinetochore-MT attachment. It is also essential for SAC function and for the recruitment of many kinetochore proteins (McAinsh et al. 2003). The modification of Ndc80p has been confirmed in vivo (Montpetit et al. 2006). While the majority of Ndc80p sumoylation can be attributed to modification of a single lysine residue (K231), phenotypic consequences of mutations at this site have not been reported. Ndc80p sumoylation is distinguished from modification of Ndc10p, Bir1p, and Cep3p by the fact that it remains sumoylated after exposure of yeast cells to the microtubule poison nocodazole and activation of the SAC. Ndc10p, Bir1p, and Cep3p become desumoylated under these circumstances, suggesting that that they are regulated differently than Ndc80p.

In vertebrates, sumoylation has been demonstrated for ICR, outer kinetochore and fibrous corona proteins (Zhang et al. 2008; Klein et al. 2009). Chromatin assembled in XEEs shows pronounced accumulation of SUMO-2/3-conjugated species at the ICR in a PIASy-dependent manner (Azuma et al. 2005). Much of this signal may arise from Topo II sumoylation, but other ICR proteins are likely to be modified as well. Recently, Borealin was been demonstrated to be SUMO-2/3 conjugated in HeLa cells during early metaphase (Klein et al. 2009). Borealin interacts with RanBP2, which promotes its mitotic sumoylation. It can also interact with SENP3, and co-localizes with SENP3 in interphase nucleoli, leading to its desumoylation. The biological role of Borealin sumoylation is not clear as nonconjugatable Borealin mutants localize correctly to the ICR and causes no obvious mitotic defect.

CENP-C is an inner kinetochore protein that is the vertebrate homologue of budding yeast Mif2p (Meluh and Koshland 1995). It is important for outer kinetochore assembly, checkpoint signaling and proper chromosome segregation (Kwon et al. 2007). CENP-C is a substrate for sumoylation in vitro (Chung et al. 2004), and a number of genetic observations suggest that it may be regulated through this modification. DT40 chicken lymphoma cell lines were engineered to express mutant CENP-C cDNA constructs with changes in conserved amino acids (Fukagawa et al. 2001). One of these cell lines (ts4–11 cells) was temperature sensitive, displaying metaphase delay and chromosome missegregation under restrictive conditions, eventually arresting in the G(1) phase of the cell cycle. A HeLa cDNA library was screened for the capacity to rescue these defects, and SUMO-1 was identified as a suppressor. This relationship is reminiscent of the discovery of budding yeast SMT3 as a suppressor of the mif2 phenotype (Meluh and Koshland 1995). There is currently no evidence that CENP-C becomes sumoylated in vivo, so it remains possible that suppression of the ts4–11 phenotype results from of sumoylation of a CENP-C interacting (Zhang et al. 2008).

CENP-E is a plus end-directed microtubule motor of the kinesin superfamily that localizes to the outer plate of the kinetochore and FC (Yen et al. 1991; Cooke et al. 1997). It is important for congression of chromosomes with single unattached kinetochores to the metaphase plate (Kapoor et al. 2006), for the maintenance of bipolar attachment of microtubules to kinetochores (McEwen et al. 2001), for generation of tension across sister kinetochores (Kim et al. 2008), and for the SAC (Putkey et al. 2002). Suppression of mitotic sumoylation in HeLa cells by over expression of SENP2 leads to a chromosome segregation defect through disruption of CENP-E targeting to kinetochores (Zhang et al. 2008). Moreover, CENP-E itself is both a SUMO-2/3 target and poly-SUMO-2/3 binding protein. The latter activity is particularly critical, since mutation of SUMO-2/3 interacting motifs (SIM-2/3) blocked kinetochore recruitment of CENP-E. To identify conjugated species that may be recognized by the SIM-2/3 motifs of CENP-E, Zhang et al. (2008) examined the sumoylation of proteins that were previously implicated in targeting of CENP-E to kinetochores. Two of these proteins, Nuf2 and BubR1 displayed sumoylation when expressed as FLAG-tagged fusion proteins in HeLa cells. Nuf2 is the vertebrate homologue of Nuf2p in budding yeast (McAinsh et al. 2003), and it resides at the outer kinetochore in a conserved complex that also contains Hec1, the vertebrate homologue of Ndc80, as well as Spc24p and Spc25p homologues (Bharadwaj et al. 2004; Wei et al. 2005; Cheeseman and Desai 2008). As in yeast, this complex plays a pivotal role in the kinetochore-MT interface (Cheeseman and Desai 2008). BubR1 is an outer kinetochore kinase that has an essential role in the SAC (Musacchio and Salmon 2007). Notably, Nuf2 and BubR1 are both modified in a SUMO-2/3-specific fashion that is antagonized by SENP2 over expression. Together, these findings suggest that CENP-E binds kinetochore-associated species containing multiple SUMO-2/3 conjugates that may include BubR1 and Nuf2, and that this binding is essential for CENP-E localization and function.

RanGAP1 is the GTPase activating protein for the small GTPase Ran, which controls interphase nuclear transport and mitotic spindle assembly (Dasso 2006). RanGAP1 is an extremely efficient target for SUMO-1 conjugation (Mahajan et al. 1998; Matunis et al. 1998). Sumoylation promotes RanGAP1 assembly into a complex containing RanBP2 and Ubc9 (Saitoh et al. 1997, 1998), which is stable throughout the cell cycle (Joseph et al. 2004). During interphase, this complex is incorporated into nuclear pores, the primary conduits of nuclear-cytoplasmic trafficking (Mahajan et al. 1998; Matunis et al. 1998). During mitosis, it is targeted to the outer kinetochore or FC in a MT-dependent fashion (Joseph et al. 2002), where it performs an important role in k-fiber assembly (Arnaoutov et al. 2005). The binding of SUMO-1-conjugated RanGAP1 and Ubc9 occurs at the same domain of RanBP2 that has been shown to possess SUMO ligase activity, the IR domain (Pichler et al. 2002). Formation of this complex blocks IR activity in vitro (Reverter and Lima 2005), and it will be interesting to determine how its assembly may modulate RanBP2 ligase activity in vivo. While some species have developed sumoylation-independent mechanisms for targeting of RanGAP1 to spindles and kinetochores (Jeong et al. 2005), IR domain-containing proteins are only found in vertebrates (Dasso 2002), indicating that this mechanism of RanGAP1 localization is vertebrate specific.

10.6. SUMO and Cytokinesis

At the end of mitosis, daughter cells are physically separated by formation of a contractile ring composed of actin, myosin and septins (Glotzer 2005). Septins are the most prominent nonchromosomal mitotic sumoylation targets in budding yeast (Johnson and Blobel 1999). Septins exist as GTP binding hetero-oligomers, which forms polymeric filaments and are crucial for bridging microtubules to the contractile ring (Versele and Thorner 2005). There are five different types of yeast Septins: Cdc3, Cdc10, Cdc11, Cdc12 and Ssh1/Sep7. Among these, Cdc3, Cdc11 and Ssh1 become highly sumoylated during mitosis (Johnson and Blobel 1999). Septin modification is tightly controlled both temporally and spatially by the action of Siz1p and Ulp1p (Makhnevych et al. 2007). Septins form a collar at the bud neck of dividing yeast cells. At the onset of anaphase, sumoylation of Septins occurs abruptly and exclusively on the mother cell side septin collar (Johnson and Blobel 1999). At the beginning of cytokinesis, the septin collar splits laterally (Versele and Thorner 2005). Desumoylation of the Septin ring correlates with this splitting and the onset of cytokinesis (Johnson and Blobel 1999). The asymmetry of Septin sumoylation may be related to Septin ring separation or to the polarized distribution of kinases and other cell cycle regulators involved in the budding yeast morphogenesis checkpoint (Keaton and Lew 2006). While sumoylation of Septins has been demonstrated in other fungi (Martin and Konopka 2004), it has not been reported in metazoans. On the other hand, Drosophila Septins can interact with components of the SUMO conjugation machinery in vitro, and Drosophila SUMO localizes to the midbody, suggesting that sumoylation of septins or other midzone proteins may occur during cytokinesis in Drosophila (Shih et al. 2002).

Eliminating sumoylation sites of Cdc3p, Cdc11p and Shs1p drastically decreased sumoylation at the bud neck in S. cerevisiae, and markedly lowered the overall level of sumoylation within G2/M phase cells (Johnson and Blobel 1999). These triple mutants were defective in dismantling the septin ring of the mother cell bud neck, suggesting that sumoylation is important for Septin ring dynamics during the cell cycle. This conclusion is supported by the improper separation of Septin collars of cells arrested in mitosis in ts-ubc9 strains (Johnson and Blobel 1999). Notably, the triple mutants show synthetic lethality with the cdc12–1 temperature sensitive allele at normally permissive temperatures. Cdc10p and Cdc12p have been subsequently identified as sumoylation targets in proteomic screens (Panse et al. 2004; Denison et al. 2005), raising the possibility that low-level sumoylation of Cdc10p and Cdc12p may compensate for the absence of Cdc3p, Cdc11p and Shs1p sumoylation, and thus explain the absence of any overt cell cycle defects in the triple mutants cells.

10.7. Conclusions and Perspectives

It has been slightly more than a decade since the discovery of post-translational modification through the SUMO pathway (Mahajan et al. 1998; Matunis et al. 1998). During this time, there has been rapid progress in understanding both the enzymology of this pathway and its role in different cellular processes, including progression through mitosis. It is now clear that sumoylation is involved with many mitotic events, including remodeling of chromosome structure, kinetochore function, and cytokinesis. Much remains to be understood, however, regarding the mechanisms through which sumoylation facilitates these events.

Important aspects for future study will include:

Identification of new sumoylation substrates: while a growing number of substrates have been documented in both yeast and metazoans, it seems highly likely that many more remain to be discovered. This notion is supported by the large number of proteins identified through proteomic screens of sumoylated proteins in budding yeast (Panse et al. 2004; Wohlschlegel et al. 2004; Zhou et al. 2004; Denison et al. 2005; Hannich et al. 2005; Wykoff and O’Shea 2005) The identification and verification of individual sumoylation targets will be a major task for the foreseeable future, as will be the study of the physiological circumstances under which they are modified.

Determination of molecular consequences of sumoylation: the capacity of SIM-containing proteins to distinguish sumoylated species should allow discrimination based upon paralogues, as well as upon the extent of multi-sumoylation or SUMO chain assembly. We are only beginning to investigate how this capacity may be used. This topic will be particularly fascinating under circumstances where SIM-containing proteins may compete with each other to determine the fate of the conjugated target. For instance, the fact that CENP-E is targeted by multiple SUMO-2/3 conjugated proteins (Zhang et al. 2008), while these same proteins are substrates for both SENP6-mediated deconjugation (Mukhopadhyay et al. 2006) and for ubiquitin-mediate proteolysis (Tatham et al. 2008), may hit at extremely dynamic and sensitive mechanisms whereby sumoylation can control of kinetochore composition.

Coordination of different events through sumoylation: sumoylation is important for many aspects of mitotic function. In this sense, it may be well-suited to coordinate different cellular events with each other, in a manner similar to previously described regulatory pathways that feature mitotic kinases of regulated proteasomal protein degradation. It will be important both to establish how sumoylation is coordinated between targets, and to understand the interplay between sumoylation and previously described regulatory pathways.

References

- Andrews PD, Ovechkina Y, Morrice N, Wagenbach M, Duncan K, Wordeman L, Swedlow JR (2004) Aurora B regulates MCAK at the mitotic centromere. Dev Cell 6:253–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnaoutov A, Azuma Y, Ribbeck K, Joseph J, Boyarchuk Y, Karpova T, McNally J, Dasso M (2005) Crm1 is a mitotic effector of Ran-GTP in somatic cells. Nat Cell Biol 7:626–632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayaydin F, Dasso M (2004) Distinct in vivo dynamics of vertebrate SUMO paralogues. Mol Biol Cell 15:5208–5218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azuma Y, Arnaoutov A, Dasso M (2003) SUMO-2/3 regulates topoisomerase II in mitosis. J Cell Biol 163:477–487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azuma Y, Arnaoutov A, Anan T, Dasso M (2005) PIASy mediates SUMO-2 conjugation of Topoisomerase-II on mitotic chromosomes. EMBO J 24:2172–2782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baba D, Maita N, Jee J, Uchimura Y, Saitoh H, Sugasawa K, Hanaoka F, Tochio H, Hiroaki H, Shirakawa M (2005) Crystal structure of thymine DNA glycosylase conjugated to SUMO-1. Nature 435:979–982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachant J, Alcasabas A, Blat Y, Kleckner N, Elledge SJ (2002) The SUMO-1 isopeptidase Smt4 is linked to centromeric cohesion through SUMO-1 modification of DNA topoisomerase II. Mol Cell 9:1169–1182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachellier-Bassi S, Gadal O, Bourout G, Nehrbass U (2008) Cell cycle-dependent kinetochore localization of condensin complex in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Struct Biol 162:248–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beliakoff J, Sun Z (2006) Zimp7 and Zimp10, two novel PIAS-like proteins, function as androgen receptor coregulators. Nucl Recept Signal 4:e017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belmont AS (2006) Mitotic chromosome structure and condensation. Curr Opin Cell Biol 18:632–638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bharadwaj R, Qi W, Yu H (2004) Identification of two novel components of the human NDC80 kinetochore complex. J Biol Chem 279:13076–13085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bylebyl GR, Belichenko I, Johnson ES (2003) The SUMO isopeptidase Ulp2 prevents accumulation of SUMO chains in yeast. J Biol Chem 278:44113–44120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheeseman IM, Desai A (2008) Molecular architecture of the kinetochore-microtubule interface. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 9:33–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng C, Lo Y, Liang S, Ti S, Lin F, Yeh C, Huang H, Wang T (2006) SUMO modifications control assembly of synaptonemal complex and polycomplex in meiosis of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev 20:2067–2081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung TL, Hsiao HH, Yeh YY, Shia HL, Chen YL, Liang PH, Wang AH, Khoo KH, Shoei-Lung Li S (2004) In vitro modification of human centromere protein CENP-C fragments by small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO) protein: definitive identification of the modification sites by tandem mass spectrometry analysis of the isopeptides. J Biol Chem 279(38):39653–39662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleveland DW, Mao Y, Sullivan KF (2003) Centromeres and kinetochores: from epigenetics to mitotic checkpoint signaling. Cell 112:407–421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke CA, Schaar B, Yen TJ, Earnshaw WC (1997) Localization of CENP-E in the fibrous corona and outer plate of mammalian kinetochores from prometa-phase through anaphase. Chromosoma 106:446–455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Amours D, Stegmeier F, Amon A (2004) Cdc14 and condensin control the dissolution of cohesin-independent chromosome linkages at repeated DNA. Cell 117:455–469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dasso M (2002) The Ran GTPase: theme and variations. Curr Biol 12:R502–R508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dasso M (2006) Ran at kinetochores. Biochem Soc Trans 34:711–715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dasso M (2008) Emerging roles of the SUMO pathway in mitosis. Cell Div 3:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawlaty MM, Malureanu L, Jeganathan KB, Kao E, Sustmann C, Tahk S, Shuai K, Grosschedl R, van Deursen JM (2008) Resolution of sister centromeres requires RanBP2-mediated SUMOylation of topoisomerase IIalpha. Cell 133:103–115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denison SH, Käfer E, May GS (1993) Mutation in the bimD gene of Aspergillus nidulans confers a conditional mitotic block and sensitivity to DNA damaging agents. Genetics 134:1085–1096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denison C, Rudner AD, Gerber SA, Bakalarski CE, Moazed D, Gygi SP (2005) A proteomic strategy for gaining insights into protein sumoylation in yeast. Mol Cell Proteomics 4:246–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devoy A, Soane T, Welchman R, Mayer RJ (2005) The ubiquitin-proteasome system and cancer. Essays Biochem 41:187–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Martínez LA, Giménez-Abián JF, Azuma Y, Guacci V, Giménez-Martín G, Lanier LM, Clarke DJ (2006) PIASgamma is required for faithful chromosome segregation in human cells. PLoS ONE 1:e53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukagawa T, Regnier V, Ikemura T (2001) Creation and characterization of temperature-sensitive CENP-C mutants in vertebrate cells. Nucleic Acids Res 29:3796–3803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiss-Friedlander R, Melchior F (2007) Concepts in sumoylation: a decade on. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 8:947–956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glotzer M (2005) The molecular requirements for cytokinesis. Science 307:1735–1739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haering CH, Nasmyth K (2003) Building and breaking bridges between sister chromatids. Bioessays 25: 1178–1191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannich JT, Lewis A, Kroetz MB, Li S, Heide H, Emili A, Hochstrasser M (2005) Defining the SUMO-modified proteome by multiple approaches in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem 280:4102–4110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauf S, Roitinger E, Koch B, Dittrich CM, Mechtler K, Peters J (2005) Dissociation of cohesin from chromosome arms and loss of arm cohesion during early mitosis depends on phosphorylation of SA2. PLoS Biol 3:e69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hecker C, Rabiller M, Haglund K, Bayer P, Dikic I (2006) Specification of SUMO1- and SUMO2-interacting motifs. J Biol Chem 281:16117–16127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano T (2005) Condensins: organizing and segregating the genome. Curr Biol 15:R265–R275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano T (2006) At the heart of the chromosome: SMC proteins in action. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 7:311–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong SY, Rose A, Joseph J, Dasso M, Meier I (2005) Plant-specific mitotic targeting of RanGAP requires a functional WPP domain. Plant J 42:270–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson ES (2004) Protein modification by SUMO. Annu Rev Biochem 73:355–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson ES, Blobel G (1999) Cell cycle-regulated attachment of the ubiquitin-related protein SUMO to the yeast septins. J Cell Biol 147:981–994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph J, Tan S, Karpova TS, McNally JG, Dasso M (2002) SUMO-1 targets RanGAP1 to kinetochores and mitotic spindles. J Cell Biol 156:595–602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph J, Liu S, Jablonski SA, Yen TJ, Dasso M (2004) The RanGAP1-RanBP2 complex is essential for microtubule-kinetochore interactions in vivo. Curr Biol 14:611–617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagey MH, Melhuish TA, Wotton D (2003) The polycomb protein Pc2 is a SUMO E3. Cell 113:127–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapoor TM, Lampson MA, Hergert P, Cameron L, Cimini D, Salmon ED, McEwen BF, Khodjakov A (2006) Chromosomes can congress to the metaphase plate before biorientation. Science 311:388–391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keaton MA, Lew DJ (2006) Eavesdropping on the cyto-skeleton: progress and controversy in the yeast morphogenesis checkpoint. Curr Opin Microbiol 9:540–546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y, Heuser JE, Waterman CM, Cleveland DW (2008) CENP-E combines a slow, processive motor and a flexible coiled coil to produce an essential motile kinetochore tether. J Cell Biol 181:411–419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein UR, Haindl M, Nigg EA, Muller S (2009) RanBP2 and SENP3 function in a mitotic SUMO2/3 conjugation-deconjugation cycle on borealin. Mol Biol Cell 20:410–418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon M, Hori T, Okada M, Fukagawa T (2007) CENP-C is involved in chromosome segregation, mitotic checkpoint function, and kinetochore assembly. Mol Biol Cell 18:2155–2168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lallemand-Breitenbach V, Jeanne M, Benhenda S, Nasr R, Lei M, Peres L, Zhou J, Zhu J, Raught B, de Thé H (2008) Arsenic degrades PML or PML-RARalpha through a SUMO-triggered RNF4/ubiquitin-mediated pathway. Nat Cell Biol 10:547–555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan W, Zhang X, Kline-Smith SL, Rosasco SE, Barrett-Wilt GA, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF, Walczak CE, Stukenberg PT (2004) Aurora B phosphorylates centromeric MCAK and regulates its localization and microtubule depolymerization activity. Curr Biol 14:273–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Kitajima TS, Tanno Y, Yoshida K, Morita T, Miyano T, Miyake M, Watanabe Y (2008) Unified mode of centromeric protection by shugoshin in mammalian oocytes and somatic cells. Nat Cell Biol 10:42–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin D, Huang Y, Jeng J, Kuo H, Chang C, Chao T, Ho C, Chen Y, Lin T, Fang H, Hung C, Suen C, Hwang M, Chang K, Maul GG, Shih H (2006) Role of SUMO-interacting motif in Daxx SUMO modification, subnuclear localization, and repression of sumoylated transcription factors. Mol Cell 24:341–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahajan R, Gerace L, Melchior F (1998) Molecular characterization of the SUMO-1 modification of RanGAP1 and its role in nuclear envelope association. J Cell Biol 140:259–270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makhnevych T, Ptak C, Lusk CP, Aitchison JD, Wozniak RW (2007) The role of karyopherins in the regulated sumoylation of septins. J Cell Biol 177:39–49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin SW, Konopka JB (2004) SUMO modification of septin-interacting proteins in Candida albicans. J Biol Chem 279:40861–40867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto T, Yanagida M (2005) The dreaPm of every chromosome: equal segregation for a healthy life of the host. Adv Exp Med Biol 570:281–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matunis MJ, Wu J, Blobel G (1998) SUMO-1 modification and its role in targeting the Ran GTPase-activating protein, RanGAP1, to the nuclear pore complex. J Cell Biol 140:499–509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAinsh AD, Tytell JD, Sorger PK (2003) Structure, function, and regulation of budding yeast kinetochores. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 19:519–539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BF, Chan GK, Zubrowski B, Savoian MS, Sauer MT, Yen TJ (2001) CENP-E is essential for reliable bioriented spindle attachment, but chromosome alignment can be achieved via redundant mechanisms in mammalian cells. Mol Biol Cell 12:2776–2789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meluh PB, Koshland D (1995) Evidence that the MIF2 gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae encodes a centromere protein with homology to the mammalian centromere protein CENP-C. Mol Biol Cell 6:793–807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meulmeester E, Kunze M, Hsiao HH, Urlaub H, Melchior F (2008) Mechanism and consequences for paralog-specific sumoylation of ubiquitin-specific protease 25. Mol Cell 30:610–619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaelis C, Ciosk R, Nasmyth K (1997) Cohesins: chromosomal proteins that prevent premature separation of sister chromatids. Cell 91:35–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minty A, Dumont X, Kaghad M, Caput D (2000) Covalent modification of p73alpha by SUMO-1. Two-hybrid screening with p73 identifies novel SUMO-1-interacting proteins and a SUMO-1 interaction motif. J Biol Chem 275:36316–36323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montpetit B, Hazbun TR, Fields S, Hieter P (2006) Sumoylation of the budding yeast kinetochore protein Ndc10 is required for Ndc10 spindle localization and regulation of anaphase spindle elongation. J Cell Biol 174:653–663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhyay D, Dasso M (2007) Modification in reverse: the SUMO proteases. Trends Biochem Sci 32:286–295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhyay D, Ayaydin F, Kolli N, Tan S, Anan T, Kametaka A, Azuma Y, Wilkinson KD, Dasso M (2006) SUSP1 antagonizes formation of highly SUMO2/3-conjugated species. J Cell Biol 174: 939–949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musacchio A, Salmon ED (2007) The spindle-assembly checkpoint in space and time. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 8:379–393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palvimo JJ (2007) PIAS proteins as regulators of small ubiquitin-related modifier (SUMO) modifications and transcription. Biochem Soc Trans 35:1405–1408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panse VG, Hardeland U, Werner T, Kuster B, Hurt E (2004) A proteome-wide approach identifies sumoylated substrate proteins in yeast. J Biol Chem 279:41346–41351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pichler A, Gast A, Seeler JS, Dejean A, Melchior F (2002) The nucleoporin RanBP2 has SUMO1 E3 ligase activity. Cell 108:109–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potts PR, Yu H (2005) Human MMS21/NSE2 is a SUMO ligase required for DNA repair. Mol Cell Biol 25:7021–7032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putkey FR, Cramer T, Morphew MK, Silk AD, Johnson RS, McIntosh JR, Cleveland DW (2002) Unstable kinetochore-microtubule capture and chromosomal instability following deletion of CENP-E. Dev Cell 3:351–365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reverter D, Lima CD (2005) Insights into E3 ligase activity revealed by a SUMO-RanGAP1-Ubc9-Nup358 complex. Nature 435:687–692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruchaud S, Carmena M, Earnshaw WC (2007) Chromosomal passengers: conducting cell division. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 8:798–812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitoh H, Pu R, Cavenagh M, Dasso M (1997) RanBP2 associates with Ubc9p and a modified form of RanGAP1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 94:3736–3741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitoh H, Sparrow DB, Shiomi T, Pu RT, Nishimoto T, Mohun TJ, Dasso M (1998) Ubc9p and the conjugation of SUMO-1 to RanGAP1 and RanBP2. Curr Biol 8:121–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandall S, Severin F, McLeod IX, Yates JR, Oegema K, Hyman A, Desai A (2006) A Bir1-Sli15 complex connects centromeres to microtubules and is required to sense kinetochore tension. Cell 127:1179–1191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamu CE, Murray AW (1992) Sister chromatid separation in frog egg extracts requires DNA topoisomerase II activity during anaphase. J Cell Biol 117: 921–934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen TH, Lin H, Scaglioni PP, Yung TM, Pandolfi PP (2006) The mechanisms of PML-nuclear body formation. Mol Cell 24:331–339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih H, Hales KG, Pringle JR, Peifer M (2002) Identification of septin-interacting proteins and characterization of the Smt3/SUMO-conjugation system in Drosophila. J Cell Sci 115:1259–1271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song J, Zhang Z, Hu W, Chen Y (2005) Small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO) recognition of a SUMO binding motif: a reversal of the bound orientation. J Biol Chem 280:40122–40129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stead K, Aguilar C, Hartman T, Drexel M, Meluh P, Guacci V (2003) Pds5p regulates the maintenance of sister chromatid cohesion and is sumoylated to promote the dissolution of cohesion. J Cell Biol 163:729–741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strunnikov AV, Aravind L, Koonin EV (2001) Saccharomyces cerevisiae SMT4 encodes an evolutionarily conserved protease with a role in chromosome condensation regulation. Genetics 158:95–107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi Y, Strunnikov A (2008) In vivo modeling of polysumoylation uncovers targeting of Topoisomerase II to the nucleolus via optimal level of SUMO modification. Chromosoma 117:189–198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi Y, Yong-Gonzalez V, Kikuchi Y, Strunnikov A (2006) SIZ1/SIZ2 control of chromosome transmission fidelity is mediated by the sumoylation of topoisomerase II. Genetics 172:783–794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi Y, Dulev S, Liu X, Hiller NJ, Zhao X, Strunnikov A (2008) Cooperation of sumoylated chromosomal proteins in rDNA maintenance. PLoS Genet 4:e1000215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatham MH, Geoffroy M, Shen L, Plechanovova A, Hattersley N, Jaffray EG, Palvimo JJ, Hay RT (2008) RNF4 is a poly-SUMO-specific E3 ubiquitin ligase required for arsenic-induced PML degradation. Nat Cell Biol 10:538–546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Versele M, Thorner J (2005) Some assembly required: yeast septins provide the instruction manual. Trends Cell Biol 15:414–424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Dai W (2005) Shugoshin, a guardian for sister chromatid segregation. Exp Cell Res 310:1–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei RR, Sorger PK, Harrison SC (2005) Molecular organization of the Ndc80 complex, an essential kinetochore component. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102:5363–5367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wohlschlegel JA, Johnson ES, Reed SI, Yates JR (2004) Global analysis of protein sumoylation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem 279:45662–45668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong KA, Kim R, Christofk H, Gao J, Lawson G, Wu H (2004) Protein inhibitor of activated STAT Y (PIASy) and a splice variant lacking exon 6 enhance sumoylation but are not essential for embryogenesis and adult life. Mol Cell Biol 24:5577–5586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wykoff DD, O’Shea EK (2005) Identification of sumoylated proteins by systematic immunoprecipitation of the budding yeast proteome. Mol Cell Proteomics 4:73–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Y, Kerscher O, Kroetz MB, McConchie HF, Sung P, Hochstrasser M (2007) The yeast Hex3.Slx8 heterodimer is a ubiquitin ligase stimulated by substrate sumoylation. J Biol Chem 282:34176–34184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yen TJ, Compton DA, Wise D, Zinkowski RP, Brinkley BR, Earnshaw WC, Cleveland DW (1991) CENP-E, a novel human centromere-associated protein required for progression from metaphase to anaphase. EMBO J 10:1245–1254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Goeres J, Zhang H, Yen TJ, Porter ACG, Matunis MJ (2008) SUMO-2/3 modification and binding regulate the association of CENP-E with kinetochores and progression through mitosis. Mol Cell 29:729–741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou W, Ryan JJ, Zhou H (2004) Global analyses of sumoylated proteins in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Induction of protein sumoylation by cellular stresses. J Biol Chem 279:32262–32268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J, Zhu S, Guzzo CM, Ellis NA, Sung KS, Choi CY, Matunis MJ (2008) Small ubiquitin-related modifier (SUMO) binding determines substrate recognition and paralog-selective SUMO modification. J Biol Chem 283:29405–29415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]