Highlights

-

•

We identified public health guidelines on postpartum physical activity from 22 countries and on postpartum sedentary behavior from 11 countries.

-

•

Physical activity guidance focused on type, frequency, duration, and intensity, as well as progression for each of these from pregnancy to postpartum.

-

•

Half the guidelines supported physical activity while breastfeeding, while the other half did not address the topic.

-

•

Eight guidelines remarked on the impact of delivery (i.e., vaginal, caesarean section) on physical activity.

-

•

Sedentary behavior guidance included limiting long-term sitting and interrupting sitting with physical activity.

Keywords: Breastfeeding, Caesarean section, Guidelines, Postnatal, Recommendations

Abstract

Background

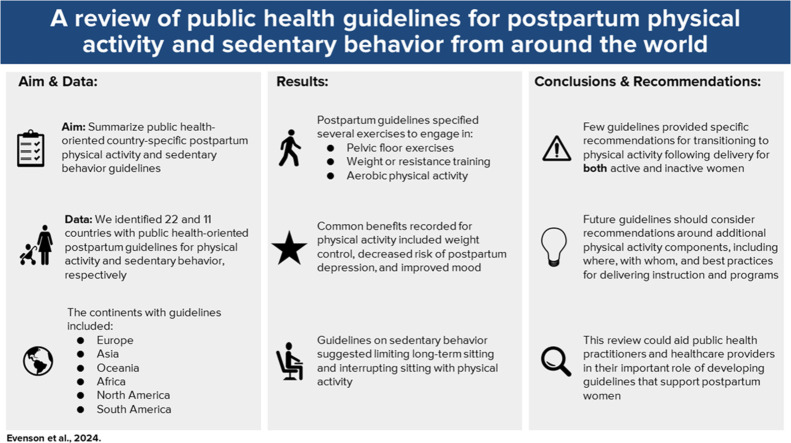

The period following pregnancy is a critical time window when future habits with respect to physical activity (PA) and sedentary behavior (SB) are established; therefore, it warrants guidance. The purpose of this scoping review was to summarize public health-oriented country-specific postpartum PA and SB guidelines worldwide.

Methods

To identify guidelines published since 2010, we performed a (a) systematic search of 4 databases (CINAHL, Global Health, PubMed, and SPORTDiscus), (b) structured repeatable web-based search separately for 194 countries, and (c) separate web-based search. Only the most recent guideline was included for each country.

Results

We identified 22 countries with public health-oriented postpartum guidelines for PA and 11 countries with SB guidelines. The continents with guidelines included Europe (n = 12), Asia (n = 5), Oceania (n = 2), Africa (n = 1), North America (n = 1), and South America (n = 1). The most common benefits recorded for PA included weight control/management (n = 10), reducing the risk of postpartum depression or depressive symptoms (n = 9), and improving mood/well-being (n = 8). Postpartum guidelines specified exercises to engage in, including pelvic floor exercises (n = 17); muscle strengthening, weight training, or resistance exercises (n = 13); aerobics/general aerobic activity (n = 13); walking (n = 11); cycling (n = 9); and swimming (n = 9). Eleven guidelines remarked on the interaction between PA and breastfeeding; several guidelines stated that PA did not impact breast milk quantity (n = 7), breast milk quality (n = 6), or infant growth (n = 3). For SB, suggestions included limiting long-term sitting and interrupting sitting with PA.

Conclusion

Country-specific postpartum guidelines for PA and SB can help promote healthy behaviors using a culturally appropriate context while providing specific guidance to public health practitioners.

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

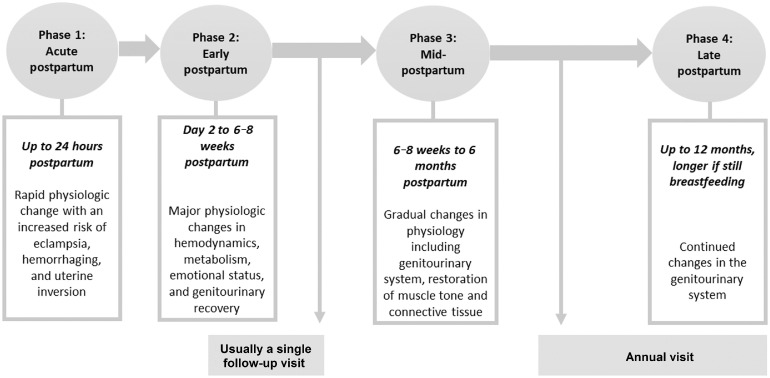

According to the life course perspective, postpartum is a critical time for setting in place sustained healthy physical behaviors, including increased physical activity (PA) and decreased sedentary behavior (SB).1 There is consensus that the postpartum period begins at birth of the newborn.2 There is less consensus on when postpartum ends. We identified 4 phases of the postpartum period, extending the 3-phase model proposed by others3 to include acute postpartum, early postpartum, mid-postpartum, and late postpartum. Fig. 1 illustrates some of the physiological changes that occur during postpartum along with common points of contact with health care providers. The time course for physiological changes during postpartum should be considered when creating recommendations for PA.

Fig.1.

Phases of the postpartum period based on time course and physiologic changes.

Evidence supports moderate intensity PA during postpartum for reducing symptoms of depression and improving cardiovascular disease risk factors.4, 5, 6, 7, 8 Returning to PA after pregnancy may be associated with other positive health benefits, including promotion of healthy weight,5,6 better sleep quality and duration,9 improved psychosocial well-being,10 improved cardiovascular fitness,11,12 and less urinary stress incontinence.13,14 The benefits of reducing postpartum SB, a distinct behavior separate from PA,15 are less clear and merit further study.5,6

Due to the benefits of PA, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends regular PA during postpartum among those without contraindications.16,17 They recommend at least 150 min/week of moderate intensity aerobic PA throughout the week, a variety of muscle strengthening exercises, and gentle stretching. Moreover, postpartum women should limit their time in SB, replacing it with PA of any intensity including light intensity.16 Guidance for those returning to sport postpartum is available,18, 19, 20 but it is based on limited evidence.21 Despite these recommendations, observational studies indicate that the prevalence of PA during postpartum is low.22,23 Some pregnant women do not return to their pre-pregnancy PA levels.23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28 While SB may remain stable during the pregnancy period,29 there is conflicting evidence on typical SB patterns during the postpartum period.26,27

National recommendations are a way to provide evidence-based, stakeholder-supported guidance to the public and practitioners using appropriate cultural contexts. While countries may draw upon the WHO guidance, country-specific recommendations could provide more detail, which may improve the ability to interpret information in a culturally appropriate way. A prior review summarized postpartum PA guidelines up to 2009.30 The purpose of this scoping review was to summarize the country-specific public health-oriented postpartum PA and SB guidelines published since 2010.

2. Methods

The protocol was developed following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) statement31 and followed the 5-stage approach outlined elsewhere.32 The completed PRISMA-ScR checklist can be found in Supplementary Table 1.

2.1. Data sources and search strategy

The research team used multiple methods for identifying public health-oriented postpartum PA guidelines from both academic and grey literature. First, guidelines were identified by reviewing the relevant academic literature, which included previous reviews and comparisons of guidelines for PA during pregnancy and postpartum. We searched 4 databases (CINAHL (EBSCO), Global Health (EBSCO), PubMed, and SPORTDiscus (EBSCO)) on April 7, 2023, for articles published since January 1, 2010 using the search strategies described in Supplementary Table 2.

Second, a structured and repeatable web-based search was conducted separately for each country using the Google search engine. Specifically, an advanced search was conducted separately for each of the 194 countries recognized as part of the WHO with relevant search terms using Boolean operators. This ensured a sensitive search to retrieve as many guidelines as possible from all domains (i.e., *.gov, *.edu, *.com). The search terms can be found in Supplementary Table 2. The web-based searches were completed in March 2023. Third, the authors contacted international experts to identify additional guidelines not identified in the search.

2.2. Study selection

Guidelines were screened and included if they were (a) inclusive of recommendations regarding PA or SB during postpartum; (b) country wide in focus; (c) authored by a public health source; and (d) published in 2010 or later. Only the most recent country-specific public health guidelines were included. Inclusion was determined by a first author (KRE) and then checked by a second (MH). Disagreements were resolved by consensus.

Guidelines were excluded if they (a) did not include keywords such as “exercise” or “physical activity” or “sedentary behavior” AND “postpartum” AND “guideline/s” or “statement” or “consensus” or “expert opinion”; (b) were developed by a non-governmental organization or a national public health institute but were not officially endorsed by a government body; (c) were not public health-oriented, such as those that were clinically focused (obstetrics, gynecology, midwifery) or sports focused (exercise science); (d) primarily focused on a particular condition (such as gestational diabetes mellitus) where PA was recommended as a treatment; or (e) provided tips but not specific guidelines.

2.3. Data extraction

Guidelines in languages other than English were translated and cross-referenced by native speakers from the relevant countries. Data were extracted using a tool developed and piloted by a similar review focused on pregnancy.33 The data were independently entered into Covidence systematic review software (www.covidence.org; Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, VIC, Australia) by 1 author and checked by 1 of 3 second authors (KRE, AKB, or EBS), with discrepancies resolved by consensus. We report frequencies and quotations when applicable.

3. Results

Of the 194 countries recognized by the WHO, we identified 22 countries with public health-oriented postpartum guidelines that met inclusion criteria (Supplementary Fig. 1). The countries were from 6 continents: Africa (n = 1; Kenya34), Asia (n = 5; Brunei,35 Malaysia,36 Qatar,37 Singapore,38 and Sri Lanka39), Europe (n = 12; Austria,40 Belgium,41 Estonia,42 Finland,43 France,44 Greece,45 Iceland,46 Norway,47 Spain,48 Sweden,49 Switzerland,50 and UK51), North America (n = 1; USA52,53), Oceania (n = 2; Australia5,54 and Fiji55), and South America (n = 1; Brazil56, 57, 58). Herein, we will refer to the guidelines by their country of origin.

Publication dates ranged from 2015 to 2022 and were authored by a Department, Institute, or Ministry of Health; a Health Organization; or a Medical Foundation. Twelve languages were represented (Table 1). Most of the postpartum PA and SB guidance was embedded in population-wide PA guidelines (n = 15/22). However, postpartum guidelines were also included in documents specific to PA during pregnancy/postpartum (n = 4/22), PA and nutrition guidance for pregnancy/postpartum (n = 2/22), and nutrition guidance for pregnancy/postpartum (n = 1/22). Target audiences for the guidelines included stakeholders (n = 9/22), both stakeholders and pregnant/postpartum women (n = 4/22), pregnant/postpartum women only (n = 3/22), or were not specified (n = 6/22). All guidelines addressed PA during postpartum (specifically “exercise” for Belgium, Estonia, Iceland, and Qatar), while 11 guidelines addressed SB during postpartum (Australia, Austria, Belgium, Brazil, Brunei, Finland, France, Norway, Singapore, Spain, and Sweden).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the postpartum PA and SB guidelines (n = 22).

| Characteristic | n | Country |

|---|---|---|

| Continent | ||

| Africa | 1 | Kenya |

| Asia | 5 | Brunei, Malaysia, Qatar, Singapore, Sri Lanka |

| Europe | 12 | Austria, Belgium, Estonia, Finland, France, Greece, Iceland, Norway, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, UK |

| North America | 1 | USA |

| Oceania | 2 | Australia, Fiji |

| South America | 1 | Brazil |

| Year | ||

| 2015 | 1 | Estonia |

| 2016 | 1 | France |

| 2017 | 2 | Kenya, Malaysia |

| 2018 | 3 | Sri Lanka, Switzerland, USA |

| 2019 | 2 | Fiji, UK |

| 2020 | 3 | Australia, Austria, Iceland |

| 2021 | 4 | Belgium, Brazil, Qatar, Sweden |

| 2022 | 5 | Brunei, Finland, Norway, Singapore, Spain |

| Not known | 1 | Greece |

| Language of source documents | ||

| Dutch and English | 1 | Belgium |

| English | 11 | Australia, Austria, Brunei, Fiji, Iceland, Kenya, Qatar, Singapore, Sri Lanka, UK, USA |

| Estonian | 1 | Estonia |

| Finnish, Swedish, and English | 1 | Finland |

| French | 1 | France |

| German | 1 | Switzerland |

| Greek | 1 | Greece |

| Malay | 1 | Malaysia |

| Norwegian and English | 1 | Norway |

| Portuguese | 1 | Brazil |

| Spanish | 1 | Spain |

| Swedish | 1 | Sweden |

| PA guideline type | ||

| PA, population-based inclusive of pregnancy and postpartum | 15 | Austria, Belgium, Brazil, Brunei, Finland, France, Greece, Malaysia, Qatar, Singapore, Spain, Sri Lanka, Sweden, UK, USA |

| PA, specific for pregnancy and postpartum | 4 | Australia, Iceland, Norway, Switzerland |

| PA and nutrition, population-based inclusive of pregnancy and postpartum | 2 | Estonia, Kenya |

| Nutrition specific to pregnancy, inclusive of PA | 1 | Fiji |

| Target audiencea | ||

| Stakeholdersb and pregnant and/or postpartum women | 4 | Australia, Qatar, Singapore, Switzerland |

| Stakeholdersb | 9 | Belgium, Brunei, Fiji, Kenya, Norway, Sri Lanka, Sweden, UK, USA |

| Pregnant and/or postpartum women | 3 | Brazil, Finland, Greece |

| Not specified, written as “women should” or “you should” | 6 | Austria, Estonia, France, Iceland, Malaysia, Spain |

| Evidence process used | ||

| Literature review and consultationc | 8 | Australia, Brazil, France, Qatar, Sweden, Switzerland, UK, USA |

| Literature review | 2 | Singapore, Sri Lanka |

| Consultation,c steering committee,d and/or expert opinion | 5 | Belgium, Brunei, Estonia, Kenya, Spain |

| Not described | 7 | Austria, Fiji, Finland, Greece, Iceland, Malaysia, Norway |

If the “target audience” was not specified, we recorded whether the guideline was written in the second person (“you should”) or the third person (“women should”).

“Stakeholders” included policymakers, health professionals (inclusive of medical practitioners, midwives, nurses, physiotherapists, exercise physiologists, and others who are accredited to work in the health sector and provide care and advice for women), and any others invested in provision of evidence-based guidelines.

“Consultation” involved seeking input from groups including pregnant/postpartum women, exercise trainers, and health professionals.

“Steering committee” was a group of people that developed the guidelines internally.

Abbreviations: PA = physical activity; SB = sedentary behavior.

The evidence process used to create the guidelines included a literature review (n = 2/22); consultation with experts, a steering committee, and/or expert opinion (n = 5/22); both review and consultation (n = 8/22); or the process was not reported (n = 7/22) (Table 1). Among the 10 countries that conducted literature reviews, most conducted primary literature reviews, while the USA conducted an umbrella review. Only Australia and the UK applied a quality assessment tool using the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluations.59

3.1. Benefits of PA and less SB

The most common benefits recorded for PA included weight control/management (n = 10/22), reducing the risk of postpartum depression/depressive symptoms (n = 9/22), and improving mood/well-being (n = 8/22). Other benefits identified in the guidelines are listed in Table 2. Only Finland documented benefits for reducing SB during postpartum, which included improved blood circulation, reduced strain on the body, and activation of muscles.

Table 2.

Benefits of physical activity documented in the postpartum guidelines (reported by 14 of 22 countries).

| Benefits of physical activity | n | Country |

|---|---|---|

| Improves | ||

| Ability to do everyday activities | 1 | Brazil |

| Birth recovery | 1 | Kenya |

| Cardiovascular function | 2 | Spain, UK |

| Energy levels (lower fatigue) | 3 | Finland, Iceland, Malaysia |

| Fitness, cardiorespiratory | 5 | Finland, Iceland, Malaysia, UK, USA |

| Health and well-being, overall | 2 | Brunei, Iceland |

| Mood, mental health, well-being | 8 | Brazil, Fiji, Finland, Iceland, Malaysia, Spain, UK, USA |

| Physical conditioning | 1 | UK |

| Posture | 1 | Iceland |

| Self-esteem | 1 | Qatar |

| Sleep | 1 | UK |

| Social inclusion, strengthening social ties and bonds | 1 | Brazil |

| Strength, including muscles and bones | 1 | UK |

| Tummy muscle tone | 1 | UK |

| Weight including control, management, or loss | 10 | Brazil, Brunei, Fiji, Finland, Iceland, Kenya, Malaysia, Spain, UK, USA |

| Reduces | ||

| Anxiety, worry, or stress | 3 | Brunei, Iceland, UK |

| Back pain | 1 | Brazil |

| Cardiovascular disorder | 1 | Qatar |

| Depression or depressive symptoms, postpartum | 9 | Australia, Brazil, Brunei, Iceland, Qatar, Singapore,a Spain, UK, USA |

| Diabetes, metabolic syndrome | 1 | Qatar |

| Hypertension | 2 | Brazil, Qatar |

| Length of postpartum recovery | 2 | Singapore, USA |

| Obesity | 1 | Qatar |

| Urinary incontinence if pelvic floor exercises are done | 7 | Australia, Belgium, Brunei, Finland, Norway, Singapore, Spain |

| Weight gain | 2 | Singapore, UK |

| Weight retention | 2 | Australia, USA |

Notes: Brazil listed benefits for “pregnant and postpartum women”. We included all of them except when the benefit was clearly only pregnancy-related (i.e., gestational diabetes).

Singapore's guideline stated, “Evidence demonstrates that physical activity during pregnancy may reduce postpartum depression”.

3.2. PA recommendations

The transition back to PA and exercise prescription components (e.g., frequency, duration, intensity, mode/type) were abstracted from the postpartum guidelines, with key quotes provided in Supplementary Table 3.

3.2.1 Transition

A gradual transition or progression back to PA following delivery was recommended in most guidelines. Postpartum women were encouraged to start slowly (Greece) and to gradually resume PA (Iceland, Qatar, Spain, and Sweden). Belgium recommended a gradual build-up after “a long period of physical inactivity”. Australia specified to gradually increase PA until the postpartum check-up at 6 weeks. Austria advised gradually increasing PA starting at 4–6 weeks postpartum, the UK recommended gradual resumption after the 6- to 8-week postnatal visit, and France recommended continuation of PA following the postpartum consultation if no medical contraindications exist.

During the postpartum period, several countries recommended gradually progressing intensity from light to vigorous (Brazil) or from moderate to vigorous (Australia and UK). Specifically, Greece recommended starting with “gentle activities such as walking”, while the USA recommended “light- to moderate-intensity aerobic and muscle-strengthening PA”. Fiji recommended beginning with light intensity activity. Brazil, Brunei, Finland, Greece, and Singapore recommended increasing intensity and duration; Brunei and Singapore also considered gradually increasing frequency. Notably, in their guidelines, Singapore provided 2 case studies as examples of how PA changes over the course of pregnancy and into postpartum.

3.2.2. Duration

Most guidelines included a recommendation on the total weekly or daily duration of PA during postpartum. Many countries recommended moderate intensity PA at 150– 300 min/week (Australia and Austria) or at ≥150 min/week (Belgium, Brunei, Finland, Kenya, Malaysia, Singapore, Spain, Sri Lanka, Sweden, UK, and USA). Sri Lanka specified that this guidance was for healthy women who were “not already highly active”. Finland provided an alternative for vigorous activity of at least 75 min/week; Australia added that 75–150 min/week of vigorous intensity or an equivalent combination of moderate and vigorous intensity was acceptable among postpartum women without contraindications. Brazil and Greece recommended starting with a shorter duration and gradually building to a longer duration. Switzerland specified working towards their adult recommendations (at least 2.5 h/week of moderate intensity or 1.25 h/week of vigorous intensity or some combination of both). If previously inactive or fatigued, Qatar recommended a progression of moderate activity from 45 min/week to 150 min/week. France combined duration and frequency, starting at 15 min/day for 3–5 sessions/week and, following the medical exam at 6 months postpartum, progress to ≥30 min/day ≥3 times/week.

3.2.3. Frequency

Four countries specified that time spent in PA should be spread over the week (Belgium, Brunei, Sri Lanka, and USA). Qatar included a postpartum recommendation on aerobic PA frequency recommending a gradual increase from 2 to 3 times/week during the first few weeks postpartum to ≥5 days/week. Australia encouraged PA on most, preferably all, days/week, and Brazil stated that PA every day is safe. Brunei stated that aerobic PA should be done throughout the week. Several countries specified frequency for certain activities: for example, balance activities 2 times/week (Finland), and muscle strengthening 2 days/week (Australia, Austria, Finland, Sweden, and UK) or 2–3 days/week (Qatar).

3.2.4. Intensity

Focusing on the descriptors of intensity, 4/22 countries included “light” (Brazil, Fiji, Finland, and USA), 17/22 countries prescribed “moderate” (Australia, Austria, Belgium, Brazil, Brunei, Finland, France, Kenya, Malaysia, Qatar, Singapore, Spain, Sri Lanka, Sweden, Switzerland, UK, and USA), and 10/22 countries prescribed “vigorous” or “high/highly active” (Australia, Belgium, Brazil, Brunei, Finland, Singapore, Sri Lanka, Switzerland, UK, and USA) intensity in their recommendations. Apart from intensity, 3 countries (Australia, Brunei, and Singapore) stated that doing some PA is better than none.

3.2.5. Modes/types

Almost all postpartum guidelines recommended aerobic activity, either in general or with suggestions for specific types (Table 3). France specifically indicated 3000 steps/day in 30 min as an option following the 6-month postpartum examination. Thirteen countries specified general muscle strengthening, resistance exercise, or weight training (Australia, Austria, Belgium, Brazil, Brunei, Finland, France, Kenya, Qatar, Singapore, Sweden, UK, and USA). Resistance bands were mentioned by Australia and Malaysia. Seventeen countries specified pelvic floor exercises (Australia, Austria, Belgium, Brazil, Brunei, Estonia, Finland, France, Iceland, Malaysia, Norway, Qatar, Singapore, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and UK).

Table 3.

Modes and types of physical activities documented in the postpartum guidelines (n = 22).

| Modes and types of physical activity | n | Country |

|---|---|---|

| Aerobic physical activities | ||

| Aerobics/general aerobic activities | 13 | Australia, Austria, Belgium, Brunei, France, Iceland,a Kenya, Malaysia, Qatar,b Singapore, Sri Lanka, UK, USA |

| Basketball, netball, floorball | 1 | Singapore |

| Cycling (leisure or transport) | 9 | Australia, Brazil,c Iceland, Kenya, Malaysia, Norway, Qatar, Singapore, UK |

| Dancing | 4 | Australia, Brazil, Malaysia, UK |

| Elliptical | 1 | Singapore |

| Exercise classes | 1 | Australia |

| Pram walking | 1 | Finland |

| Running, jogging | 4 | Brazil, Finland,d Singapore, UK |

| Swimming | 9 | Australia, Brazil, Fiji, France, Iceland,e Kenya, Malaysia, Qatar,f Singapore |

| Walking (leisure or transport) | 11 | Australia, Brazil,g Fiji, France, Greece,h Kenya, Iceland, Malaysia, Norway, Qatar, Singapore |

| Water aerobics | 3 | Brazil, Malaysia, Qatarf |

| Muscle strengthening exercises | ||

| General muscle strengthening, resistance exercise, weight training | 13 | Australia, Austria, Belgium, Brazil, Brunei, Finland, France, Kenya,i Qatar,j Singapore, Sweden, UK, USA |

| Pelvic floor exercises | 17 | Australia,k Austria,l Belgium, Brazil, Brunei,m Estonia, Finland,n France,o Iceland,p Malaysia, Norway,q Qatar, Singapore,r Spain,s Sweden, Switzerland, UKt |

| Resistance bands | 2 | Australia, Malaysia |

| Holistic/stretching activities | ||

| Balance activities | 1 | Finland |

| Gymnastics | 1 | Brazil |

| Meditating | 1 | Malaysia |

| Pilates | 2 | Malaysia, Qatar |

| Posture exercise | 1 | Iceland |

| Stretching, flexibility | 6 | Belgium, Brazil, Brunei, France, Malaysia, Singapore |

| Yoga | 3 | Malaysia, Qatar, Singapore |

| Other behaviors | ||

| Active commuting, by foot or bicycle | 3 | Brazil,c Norway, Singapore |

| Gardening | 1 | Norway |

| Household chores | 5 | Brazil, Finland, Malaysia, Norway, Singapore |

| Outdoor exercise | 1 | Finland |

| Playing with children or your baby, workout with your baby | 4 | Brazil, Finland, Malaysia, UK |

| Shopping trips | 1 | Finland |

| Sitting | 1 | Malaysia |

| Stairs, stair climbing | 3 | Brazil, Finland, Norway |

| Standing | 1 | Malaysia |

Note: For the UK, coded activities came from the infographic on Page 38.51

Iceland's guideline indicated gentle aerobics.

Qatar's guideline indicated low-impact aerobics.

Brazil's guideline indicated that “The use of a bicycle in your free time or commuting is not contraindicated. Just be aware of risk of falling and try to transit through safe places, if possible”.

Finland's guideline stated that “You may return to running 3 months after delivery at the earliest. Before graded return, you should not have any symptoms of pelvic floor weakness in everyday activities or running attempts”.

Iceland's guideline indicated swimming is permissible if vaginal discharge has stopped for at least 7 days and all stitches and wounds are fully healing.

Qatar's guideline indicated swimming and aqua aerobics were permissible once the bleeding has stopped.

Brazil's guideline provided examples of walking, including taking your baby for a walk, pushing the stroller, or walking the dog.

Greece's guideline identified “stroller walking” as an example.

Kenya's guideline listed “light weight training” as an “aerobic activity”. However, in this table we categorized it under “muscle strengthening”.

Qatar's guideline indicated “light” weight training exercises.

Australia's guideline indicated pelvic floor exercises could start as soon as comfortable following the birth (for several times each day) and continue for life.

Austria's guideline indicated that guided, targeted pelvic floor training should be started by all women immediately after childbirth and continued for up to 6 months.

Brunei's guideline stated that “pelvic floor muscle training may be performed on a daily basis”.

Finland's guideline indicated to “start pelvic floor muscle training right after delivery”.

France's guideline indicates that perineal rehabilitation exercises can begin immediately postpartum.

Iceland's guideline stated that until “your pelvic floor muscles have strengthened through exercise, avoid running, jumping, and lifting heavy weights. If you do high intensity exercise with a weak pelvic floor, you could cause damage you cannot reverse”.

Norway's guideline stated that “many women may have problems “finding” the pelvic floor muscles when exercising. After the birth, this can be even more difficult. It is therefore an advantage to have learned how to train the pelvic floor muscles already in pregnancy”.

Singapore's guideline stated that “core strengthening activities and pelvic muscle training may be performed regularly to strengthen the trunk and reduce the risk of urinary incontinence”. “Start pelvic floor exercises early to strengthen your muscles”.

Spain's guideline stated that “it is advisable to continue exercising the pelvic floor muscles on a daily basis to prevent urinary incontinence”.

The UK's guideline indicated that pelvic floor exercises “could start as soon as you can and continue daily” (from the infographic on Page 38).

Holistic and stretching examples included stretching (n = 6/22), yoga (n = 3/22), and Pilates (n = 2/22) (Table 3). Examples of other activities in the guidelines included household chores (n = 5/22), playing with children or baby (n = 4/22), active commuting (n = 3/22), and stairs/stair climbing (n = 3/22) (Table 3). Kenya specified certain activities (e.g., activities requiring sudden starts or stops, jumping, rapid changes in direction, or any that increase the risk of falling or abdominal injury) to be avoided for lactating women. Brazil noted the risk of falling from a bicycle, and Singapore more generally recommended avoiding activities that involved a higher risk of falling or physical contact.

3.3. Guidance for previously inactive women

For inactive women, Australia and Sweden recommended starting slowly and increasing amounts of PA or exercise gradually, while Kenya specified starting with a few minutes each day and gradually increasing the frequency and intensity (Supplementary Table 3). Qatar more specifically recommended that previously inactive or fatigued women start at 45 min/week and progress to 150 min/week of moderate intensity aerobic activity. Sri Lanka recommended that postpartum women not already engaging in vigorous activity should focus on accumulating at least 150 min/week of moderate intensity aerobic activity. The UK discouraged vigorous activity for previously inactive women until after the 6- to 8-week postpartum check-up and further urged them to “start gradually”.

3.4. Guidance for previously active women

Those who previously engaged in light (Singapore), moderate (Malaysia and Singapore), or vigorous (Belgium, Brunei, Singapore, Sri Lanka, and USA) intensity aerobic activity can continue these specific activities in the postpartum period (Supplementary Table 3). Brunei and Sri Lanka further stipulated that the postpartum women remain healthy and discuss their behaviors with their healthcare provider. Sweden indicated that postpartum women can continue their PA as usual as long as they have no complications. The UK specified that “PA choices should reflect activity levels pre-pregnancy” while recommending that women “restart gradually”.

3.5. Delivery type

Guidelines from Australia, Brunei, and Spain suggested that return to PA is variable and dependent on delivery mode (Supplementary Table 4). Several guidelines indicated important considerations regarding PA, including the impact of perineal damage (Australia and France), blood loss (Australia), hemorrhaging (Iceland), and wound infections (Iceland). Following caesarean sections, Greece suggested that recovery may take longer while Belgium advised gradually resuming PA after delivery Qatar recommended resuming PA 8–12 weeks following a caesarean section (in contrast to 4–8 weeks for vaginal delivery) and excluded abdominal exercise until 4 months postpartum. Iceland's guidance specified to “be careful” for at least 6 weeks following a caesarean section, including not lifting anything heavier than the baby and not pulling up into a sitting position from lying down. The guidelines from Qatar further recommended that women who had a caesarean section wait 3–4 months postpartum to resume high-impact exercise.

3.6. Breastfeeding and PA

Eleven guidelines included at least 1 statement on breastfeeding and PA (Table 4 and Supplementary Table 5). Guidelines concluded that PA had no impact on milk volume or quantity (n = 7/22), milk composition or quality (n = 6/22), or infant growth (n = 3/22). When considering PA, adequate hydration (Australia, Finland, and Qatar) and nutrients/calories (Australia and Qatar) should be considered. Greece and Qatar stated that lactic acid resulting from vigorous PA may change the taste of the milk immediately following the session. Qatar recommended breastfeeding before exercise or 1 h after exercise due to the lactic acid.

Table 4.

Summary from postpartum guidelines regarding the interaction of PA with breastfeeding (reported by 11 of 22 countries).

| Country | No PA restriction | PA on milk volume (quantity) | PA on milk composition (quality) | PA on infant growth | No negative impact of PA on lactation | Ensure adequate hydration | Ensure adequate nutrients/calories | Lactic acid from PA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | No impact | No impact | √ | √ | ||||

| Brazil | No impact | No impact | ||||||

| Brunei | No impact | No impact | ||||||

| Estonia | √ | |||||||

| Finland | √ | No impact | No impact | No impact | √ | |||

| Greece | No impact | √ | ||||||

| Qatar | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| Singapore | √ | |||||||

| Spain | No impact | No impact | No impact | |||||

| UK | √ | |||||||

| USA | No impact | No impact | No impact | |||||

| Total | 3 | 7 | 6 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

Note: √ means it is mentioned in the guideline

Abbreviation: PA = physical activity.

3.7. SB recommendations

Eleven of the 22 guidelines provided or made some statement regarding SB recommendations for the postpartum period, such as limiting long-term sitting and interrupting sitting with PA (Table 5). Belgium specified taking breaks every 20–30 min to perform an activity such as walking, while Brazil suggested taking 5-min breaks each hour. France indicated avoiding successive days with less than 5000 steps/day. Sweden recommended more research.

Table 5.

Quotes from postpartum guidelines on sedentary behavior (reported by 11 of 22 countries).

| Country | Quote |

|---|---|

| Australia | “Minimise the amount of time spent in prolonged sitting” “Break up long periods of sitting as often as possible” |

| Austria | “Long-term sitting should be avoided or repeatedly interrupted by physical activity” |

| Belgium | “A healthy mix of sitting, standing, and moving is important for a healthy life” “Limit long periods of sitting still. Interrupt them ideally every 20–30 min. This can be done by standing up and walking or fetching a glass of water” “Replacing sitting still for a long time with exercise of any intensity (including light intensive exercise) provides health benefits” |

| Brazila | “Avoid spending too much time in sedentary behavior. Whenever possible, reduce the time where you sit or lie down watching television or using your cell phone, computer, tablet, or video game” “For example, every hour, move for at least 5 min and enjoy. Change position and stand up, go to the bathroom, drink water and stretch the body. Are small behaviors that can help reduce your sedentary behavior and improve your quality of life” “If you spend a lot of time sitting during the day, try to compensate for this behavior by including more physical activity time in your day-to-day” |

| Brunei | “Pregnant and postpartum women should limit the amount of time spent being sedentary. Replacing sedentary time with physical activity of any intensity (including light intensity) provides health benefits. A sensible approach would be to avoid prolonged periods of sitting and to break up sedentary time” |

| Finland | “Breaks to sedentary behavior were recommended whenever possible” “Set yourself screen time limits and decide which TV programs you wish to watch” |

| Francea | “Periods spent in a sitting or immobile position should be limited as much as possible. Stay less than 2 consecutive hours in a seated or semi-reclined position (excluding periods of sleep) and avoid successions of days with less than 5000 steps taken” |

| Norway | “Activity breaks that interrupt sitting still and physical activity through daily chores are beneficial both during pregnancy and after birth” |

| Singapore | “Limit the amount of time spent being sedentary, particularly recreational screen time, by engaging in activities of any intensity” |

| Spain | “Reduce the periods dedicated to sedentary activities, replacing it with physical activity of any intensity (even mild)” |

| Sweden | “More knowledge is needed about how prolonged sitting affects women's health during and after pregnancy, and pending more specific research, pregnant women are recommended to limit their sitting, just like other adults” |

For both Brazil and France, the guideline section on sedentary behavior was not specified for pregnant and/or postpartum women, so we assumed it was for both.

4. Discussion

This review identified 22 public health country-specific guidelines on either PA or SB during postpartum reviewed since 2010 and published from 2015 to 2022. This is a large increase from the prior review, which summarized postpartum PA guidelines from 5 countries published up to 2009.30 In the past decade, much new scientific evidence has been published on the benefits and risks of postpartum PA and SB,60 so the increase is not surprising. In the current review, all postpartum guidance provided recommendations on PA, and half provided brief recommendations or statements on SB. However, we found the guidance for postpartum was more cursory than the pregnancy guidance related to PA.33

While 22 postpartum guidelines were identified, 172 countries were without postpartum guidelines. Europe had the highest number of guidelines (12 countries), while Africa, North America, and South America each had only 1 country with guidance. This finding is consistent with the Global Observatory for Physical Activity Country Cards and Almanac, which documented the unequal distribution of research productivity by region,61,62 and more generally with research showing that women's health is understudied,63 particularly during postpartum.20,64 While countries without specific postpartum guidelines might instead rely on the WHO guidance,16 country-specific guidelines could potentially offer more detailed advice using culturally appropriate framing. We found that “culture” was expressed by using examples of common activities and graphics depicting postpartum women from a specific country, such as swimming in Australia.

4.1. Benefits of PA and less SB

A wide range of benefits resulting from postpartum PA were identified in most guidelines. The inclusion of these benefits within the guidelines is important, as knowledge of benefits is an enabler of postpartum PA.65, 66, 67, 68 The review conducted to inform Australia's guidelines assigned grades to the quality of evidence.5 In their review, raters determined the quality of evidence on postpartum weight loss was “moderate”, the quality of evidence on mild-to-moderate depressive symptoms and depression was “moderate”, and the quality of evidence on anxiety was “very low”. The results indicated “high” quality evidence for the association of pelvic floor muscle training during and following pregnancy with a reduction of the risk of urinary incontinence postpartum. For the USA guidelines, an umbrella review with evidence ratings was conducted on the relationship between PA and health outcomes during pregnancy and postpartum.6,69 The experts rated the evidence on the association of PA with postpartum affect and anxiety as “not assignable” but with depression as “strong”. Also “not assignable” were the dose and dose–response relationships as well as whether there was effect modification by sociodemographic factors or weight status. Only Finland included the benefits of limiting SB during postpartum.43 While the benefits of reducing SB for several health outcomes are established in the adult population,70 research is needed to clarify the unique benefits of reducing SB during the postpartum period. Research on relevant intervention strategies targeting SB during postpartum is also needed.

4.2. PA components

In terms of exercise-specific characteristics, most postpartum guidelines provided frequency and/or duration as well as examples of the types of recommended PA. Only 4 countries included statements about “light intensity activity”, although several countries indicated that any PA is better than none. Light PA provides health benefits among adults71 and, by extension, could provide benefits to postpartum women. Omitting light activity, particularly as a replacement for SB, may be a missed opportunity. In contrast, 17 countries discussed “moderate intensity” and 10 countries discussed “vigorous intensity” PA.

4.3. Breastfeeding and PA

Half the guidelines provided information on breastfeeding and PA, with some stating PA had no impact on breast milk quantity or quality, or infant growth. The evidence that “PA does not impact the quantity or quality of breast milk” was graded “very low” by Australia.5 The benefits of breastfeeding are widely recognized,72 and conveying to postpartum women that they can continue breastfeeding successfully while also being physically active is an important topic for public health guidance. For example, in an observational study of postpartum women, breastfeeding women were more likely to engage in PA if they received advice about the topic.68

4.4. Delivery type

Another important area that deserves attention in postpartum guidance is how PA types might differ by birth delivery mode. Women who deliver vaginally or by caesarean section may experience different medical or surgical complications, which could impact their ability and motivation to engage in various PA modes.73,74 Eight guidelines remarked about the delivery type as it related to PA. For reference, the WHO guideline advised women to “return to PA gradually after delivery and in consultation with a healthcare provider in the case of delivery by caesarean section”.16 However, the intricacies of childbirth recovery extend beyond a simplistic dichotomy of vaginal vs. caesarean delivery. A vaginal delivery does not guarantee an uncomplicated recuperation. Notably, instances involving episiotomy or extensive perineal laceration tend to entail prolonged recovery periods. Furthermore, even in cases where a vaginal delivery is devoid of such complications, the physiological transformations occurring during pregnancy (e.g., abdominal separation; leading to core destabilization; and the weakening of pelvic floor muscles, which may result in urinary and fecal incontinence) warrant additional consideration in the context of a safe postpartum return to PA. Despite the well-documented nature of these physiological changes and their potential implications for postpartum PA, it is worth noting that only France identified the need for additional considerations beyond the mere categorization of delivery modes; specifically, they recognized the difference between a vaginal delivery with and without episiotomy, and how these scenarios are likely to require distinct approaches to return to activity.44 A comprehensive review on delivery type and their associations with PA would be beneficial for clarifying the current evidence, identifying research gaps, and assisting countries in creating more specific recommendations.

4.5. Gaps in the guidelines

Based on our review of the postpartum guidelines, we identified at least 6 notable gaps that reflect a lack of available research. First, only a few of the guidelines explicitly defined the postpartum period, the time course associated with it, and when certain guidelines should be implemented. For example, the postpartum period was defined as “6 to 8 weeks after the birth” (Australia) or “the period just after delivery” (Brunei). The postpartum period should be explicitly defined when providing guidance, as it can last a year or more (Fig. 1). Second, we found a general lack of advice tailored to the phases of postpartum, even though PA and SB might differ by phase. For example, mother–infant pairs spend more time breastfeeding earlier in postpartum, which may result in higher levels of SB.75 This may be because at least in some countries, postpartum women often receive only 1 follow-up visit around 1–2 months postpartum. More frequent postpartum visits are recommended76 because they provide more opportunity for guidance, support, and greater specificity regarding PA and SB. Importantly, others have shown that receiving PA advice during postpartum was associated with a higher agreement (i.e., knowledge) that it was acceptable to “increase PA during postpartum”.67 Third, some guidelines addressed previously inactive women and others addressed previously active or highly active women. Few guidelines addressed each group separately, which is recommended so as to facilitate distinct guidance for each group.

Fourth, while many guidelines recommended strengthening exercises, few provided advice on frequency, intensity, and progression. This vagueness carried over to pelvic floor exercises and general holistic or stretching activities as well. Other types of activities that include the baby (i.e., carriers, stroller walking) often were not mentioned but seem particularly relevant because of the time the mother spends with the baby. Fifth, few guidelines made specific connections to their general adult recommendations on PA and SB. As the general aim should be to transition postpartum women towards these guidelines, making specific reference to those recommendations would aid in bridging to them. Sixth, while postpartum guidelines addressed frequency, duration, type, and intensity, other important components tended to go unaddressed, including consideration of the physical environment (e.g., where), social environment (e.g., with whom, support system), and instructional mode of delivery (e.g., supervised or not, individual or group based).77

4.6. Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this review include its comprehensive approach, which involved conducting separate searches of both the academic and grey literature of each country in the WHO. Without including the grey literature, many guidelines would have been missed and our results would not accurately represent the evidence base. Another strength is its inclusivity, such that if the document contained any guidance on PA or SB during postpartum, regardless of language, we included it.

There are several limitations to this review as well. We only included public health guidelines or guidelines endorsed by public health practitioners. Sometimes the publication did not identify the organizations endorsing the guidance, so despite extensive searching, we may have missed some guidelines. For example, internet content is censored and/or not readily available in some countries. We acknowledge that additional clinical guidelines exist, but those were not our focus. Rather, we focused only on public health-oriented guidelines to make equivalent comparisons. Additionally, all guidelines contained recommendations for PA during pregnancy, in addition to postpartum guidance.33 At times, the recommendations were not clear as to which statements focused on pregnancy, postpartum, or both, which may have impacted our abstraction. We tried to extract only points specifically targeted to postpartum women.

5. Conclusion

The postpartum period offers a window of opportunity to shape new health behaviors, such as increased PA and reduced SB. We identified 22 countries with public health-oriented PA guidelines and 11 countries with SB guidelines or statements specifically addressing the postpartum period. While many guidelines acknowledged the benefits of PA during postpartum, fewer guidelines provided specific recommendations for transitioning to PA following delivery for both active and inactive women. Guidance on the timing and nature of transitioning to PA was variable and based on sparse research evidence. Moreover, while many guidelines addressed components of exercise prescription (e.g., frequency, duration, type, intensity), other components could also be considered (e.g., where, with whom, and best practices for delivering instruction and programs).

A small but growing research agenda in this field will provide the evidence to develop more specific recommendations for both PA and SB postpartum, which will be helpful for revising or developing new guidelines. This review could also aid public health practitioners and healthcare providers in their important role of supporting postpartum women in their efforts to be physically active and to reduce SB during this critical time. Nevertheless, this review identified several gaps around postpartum PA and SB that future researchers could aim to address in their efforts to develop more informed, evidence-based guidelines.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Tracy Bruce (Senior Research Librarian, University of Southern Queensland) for her expertise in the search process as well as our colleagues who helped translate the non-English guidelines for the project. AKB was provided support by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, award number T32 HD091058. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Authors' contributions

KRE designed the review, conducted the searches, decided on inclusion or exclusion of guidelines, checked the abstractions, and drafted the paper; WJB and MH helped to design the review, conducted the searches, decided on inclusion or exclusion of guidelines, and revised the paper for important content; AKB and EBS extracted information from the guidelines. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript, and agree with the order of presentation of the authors.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Shanghai University of Sport.

Supplementary materials associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.jshs.2023.12.004.

Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Lane-Cordova AD, Jerome GJ, Paluch AE, et al. Supporting physical activity in patients and populations during life events and transitions: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2022;145:e117–e128. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berens P. Overview of the postpartum period: Normal physiology and routine medical care. Available at: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/overview-of-the-postpartum-period-normal-physiology-and-routine-maternal-care. [accessed 27.08.2023].

- 3.Romano M, Cacciatore A, Giordano R, La Rosa B. Postpartum period: Three distinct but continuous phases. J Prenat Med. 2010;4:22–25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pivarnik JM, Hayman M, Haakstad LA, et al. Impact of physical activity during pregnancy and postpartum on chronic disease risk. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2006;38:989–1006. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000218147.51025.8a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown WJ, Hayman M, Haakstad LA, et al. Australian guidelines for physical activity in pregnancy and postpartum. J Sci Med Sport. 2022;25:511–519. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2022.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DiPietro L, Evenson KR, Bloodgood B, et al. Benefits of physical activity during pregnancy and postpartum: An umbrella review. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2019;51:1292–1302. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000001941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu P, Park K, Gulati M. The fourth trimester: Pregnancy as a predictor of cardiovascular disease. Eur Cardiol. 2021;16:e31. doi: 10.15420/ecr.2021.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harrison CL, Brown WJ, Hayman M, Moran LJ, Redman LM. The role of physical activity in preconception, pregnancy and postpartum health. Sem Reprod Med. 2016;34:e28–e37. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1583530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vladutiu CJ, Evenson KR, Borodulin K, Deng Y, Dole N. The association between physical activity and maternal sleep during the postpartum period. Matern Child Health J. 2014;18:2106–2114. doi: 10.1007/s10995-014-1458-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bahadoran P, Tirkesh F, Oreizi HR. Association between physical activity 3–12 months after delivery and postpartum well-being. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2014;19:82–87. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DE Larson-Meyer. Effect of postpartum exercise on mothers and their offspring: A review of the literature. Obes Res. 2002;10:841–853. doi: 10.1038/oby.2002.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Acosta-Manzano P, Acosta FM, Coll-Risco I., et al. The influence of exercise, lifestyle behavior components, and physical fitness on maternal weight gain, postpartum weight retention, and excessive gestational weight gain. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2022;32:425–438. doi: 10.1123/ijsnem.2021-0201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Woodley SJ, Lawrenson P, Boyle R, et al. Pelvic floor muscle training for preventing and treating urinary and faecal incontinence in antenatal and postnatal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;5 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Artal R. Exercise during pregnancy and the postpartum period. Available at: https://www.uptodate.com.[accessed 27.08.2023].

- 15.Network Sedentary Behaviour Research. Letter to the editor: Standardized use of the terms ” “sedentary” and “sedentary behaviours”. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2012;37:540–542. doi: 10.1139/h2012-024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bull FC, Al-Ansari SS, Biddle S, et al. World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Br J Sports Med. 2020;54:1451–1462. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2020-102955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; Geneva: 2020. WHO Guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behavior. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Donnelly GM, Moore IS, Brockwell E, Rankin A, Cooke R. Reframing return-to-sport postpartum: The 6 Rs framework. Br J Sports Med. 2022;56:244–245. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2021-104877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goom T, Donnelly G, Brockwell E. Returning to running postnatal–Guidelines for medical, health and fitness professionals managing this population. Available at:https://absolute.physio/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/returning-to-running-postnatal-guidelines.pdf. [accessed 09.01.2023].

- 20.Bo K, Artal R, Barakat R, et al. Exercise and pregnancy in recreational and elite athletes: 2016/17 evidence summary from the IOC Expert Group Meeting, Lausanne. Part 3-exercise in the postpartum period. Br J Sports Med. 2017;51:1516–1525. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2017-097964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bo K, Artal R, Barakat R, et al. Exercise and pregnancy in recreational and elite athletes: 2016/2017 evidence summary from the IOC expert group meeting, Lausanne. Part 5. Recommendations for health professionals and active women. Br J Sports Med. 2018;52:1080–1085. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2018-099351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Evenson KR, Brouwer RJ, Østbye T. Changes in physical activity among postpartum overweight and obese women: Results from the KAN-DO Study. Women Health. 2013;53:317–334. doi: 10.1080/03630242.2013.769482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Evenson KR, Herring AH, Wen F. Self-reported and objectively measured physical activity among a cohort of postpartum women: The PIN Postpartum Study. J Phys Act Health. 2012;9:5–20. doi: 10.1123/jpah.9.1.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Borodulin K, Evenson KR, Herring AH. Physical activity patterns during pregnancy through postpartum. BMC Womens Health. 2009;9:32. doi: 10.1186/1472-6874-9-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coll C, Domingues M, Santos I, et al. Changes in leisure-time physical activity from the prepregnancy to the postpartum period: 2004 Pelotas (Brazil) Birth Cohort Study. J Phys Act Health. 2016;13:361–365. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2015-0324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hesketh KR, Evenson KR, Ma Stroo, Clancy SM, Østbye T, Benjamin-Neelon SE. Physical activity and sedentary behavior during pregnancy and postpartum, measured using hip and wrist-worn accelerometers. Prev Med Rep. 2018;10:337–345. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2018.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mielke GI, Crochemore-Silva I, Domingues MR, Silveira MF, Bertoldi AD, Brown WJ. Physical activity and sitting time from 16 to 24 weeks of pregnancy to 12, 24, and 48 months postpartum: Findings from the 2015 Pelotas (Brazil) Birth Cohort Study. J Phys Act Health. 2021;18:587–593. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2020-0351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Richardsen KR, Mdala I, Berntsen S, et al. Objectively recorded physical activity in pregnancy and postpartum in a multi-ethnic cohort: Association with access to recreational areas in the neighbourhood. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2016;13:78. doi: 10.1186/s12966-016-0401-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barone Gibbs B, Jones MA, Jakicic JM, Jeyabalan A, Whitaker KM, Catov JM. Objectively measured sedentary behavior and physical activity across 3 trimesters of pregnancy: The Monitoring Movement and Health Study. J Phys Act Health. 2021;18:254–261. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2020-0398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Evenson KR, Mottola MF, Owe KM, Rousham EK, Brown WJ. Summary of international guidelines for physical activity after pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2014;69:407–414. doi: 10.1097/OGX.0000000000000077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:467–473. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodologic framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8:19–32. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hayman M, Brown WJ, Brinson A, Budzynski-Seymour E, Bruce T, Evenson KR. Public health guidelines for physical activity during pregnancy from around the world: A scoping review. Br J Sports Med. 2023;57:940–947. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2022-105777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Republic of Kenya - Ministry of Health. National guidelines for healthy diets and physical activity 2017. Available at: https://www.fao.org/nutrition/education/food-dietary-guidelines/regions/countries/kenya/en/. [accessed 04.08.2023].

- 35.National Physical Activity Guidelines Expert Committee Ministry of Health in Brunei Darussalam. National Physical Activity Guidelines for Brunei Darussalam. 2nd ed. Available at:https://www.moh.gov.bn/Shared%20Documents/DOWNLOADS/NATIONAL%20PHYSICAL%20ACTIVITY%20FIN.pdf. [accessed 04.08.2023].

- 36.Bahagian Pendidikan Kesihatan Kementerian Kesihatan Malaysia. Garis Panduan Aktiviti Fizikal Malaysia. Available at: http://www.moh.gov.my/english.php/pages/view/536. [accessed 04.08.2023].

- 37.Research and Scientific Support Department Aspetar Orthopaedic and Sports Medicine Hospital. Qatar National Physical Activity Guidelines - Second edition. Available at:https://www.aspetar.com/AspetarFILEUPLOAD/UploadCenter/637736948034432931_QATAR%20NATIONAL%20PHYSICAL%20ACTIVITY%20GUIDELINES_ENGLISH.pdf. [accessed 04.08.2023].

- 38.Sport Singapore, Health Promotion Board. Singapore Physical Activity Guidelines (SPAG). Available at:https://www.healthhub.sg/sites/assets/Assets/Programs/pa-lit/pdfs/Singapore_Physical_Activity_Guidelines.pdf2022. [accessed 04.08.2023].

- 39.Institute of Sports Exercise Medicine, Ministry of Sports - Sri Lanka. Technical report on physical activity and sedentary behavior guidelines for public discussion - Sri Lanka. Available at:http://www.health.gov.lk/moh_final/english/public/elfinder/files/publications/publicNotices/GeneralNotice/2017/Physical%20Activity%20Guidelines%20for%20Sri%20Lankans.pdf. [accessed 04.08.2023].

- 40.Austrian Health Promotion Fund. Austrian physical activity recommendations – Key messages (Volume17(1) of scientific reports), Vienna. Available at:https://fgoe.org/sites/fgoe.org/files/2020-09/fgoe_wb17_bewegungsempfehlungen_E_bfrei.pdf. [accessed 04.08.2023].

- 41.Vlaams Instituut Gezond Leven. Vlaamse gezondheidsaanbevelingen 2021 sedentair gedrag (lang stilzitten), beweging en slaap. Available at: https://www.gezondleven.be/meer-beweging. [accessed 04.08.2023] [in Dutch].

- 42.Pitsi T, Zilmer M, Vaask S, et al. Eesti toitumis- ja liikumissoovitused. Available at:https://intra.tai.ee/images/prints/documents/149019033869_eesti%20toitumis-%20ja%20liikumissoovitused.pdf. [accessed 04.08.2023] [in Estonian].

- 43.UKK Institute of Finland. Weekly physical activity recommendation after delivery. Available at: https://www.slideshare.net/UKK-instituutti/physical-activity-recommendation-after-delivery. [accessed 04.08.2023].

- 44.l'Agence Nationale de Sécurité Sanitaire de l'alimentation de l'environnement et du travail. Actualisation des repèresdu PNNS - Révisions des repères relatifs à l'activité physique et à la sédentarité: Avis de l'Anses Rapport d'expertise collective. Available at: https://www.anses.fr/fr/system/files/NUT2012SA0155Ra.pdf. [accessed 04.08.2023] [in French].

- 45.Ινστιτούτο Προληπτικής ΠκΕΙ, Prolepsis. Εθνικός Διατροφικός Οδηγός για Γυναίκες, Εγκύους και Θηλάζουσες. Available at: http://www.diatrofikoiodigoi.gr/?Page=systaseis. [accessed 04.08.2023] [in Greek].

- 46.Iceland Health Service Executive. Exercise after pregnancy. Available at: https://www2.hse.ie/pregnancy-birth/birth/health-after-birth/exercise-after-pregnancy/. https://www2.hse.ie/wellbeing/pregnancy-and-birth/keeping-well/exercise/. [accessed 04.08.2023].

- 47.Norwegian Directorate of Health. Physical activity in prevention and treatment. 3. pregnant women (Fysisk aktivitet i forebygging og behandling 3. gravide). Available at: https://www.helsedirektoratet.no/faglige-rad/fysisk-aktivitet-i-forebygging-og-behandling. [accessed 04.08.2023].

- 48.Gobierno de Espana, Ministerio de Sanidad. Physical Activity for Health Reduction of Sedentary Lifestyle: Recommendations for the population. Available at: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/areas/promocionPrevencion/actividadFisica/recomendaciones.htm. [accessed 04.08.2023].

- 49.Swedish Public Health Authority. Guidelines for Physical Activity and Sedentary Life. Available at: https://www.folkhalsomyndigheten.se/contentassets/106a679e1f6047eca88262bfdcbeb145/riktlinjer-fysisk-aktivitet-stillasittande.pdf. [accessed 04.08.2023].

- 50.Kahlmeier S, Hartmann F, Martin-Diener E, Quack Lötscher K, Schläppy-Muntwyler F. Schweizer bewegungsempfehlungen für schwangere und postnatale frauen. Available at: https://www.rosenfluh.ch/media/ernaehrungsmedizin/2018/04/Schweizer-Bewegungsempfehlungen-fuer-schwangere-und-postnatale-Frauen.pdf. [accessed 04.08.2023] [in German].

- 51.Department of Health and Social Care. UK Chief Medical Officers' physical activity guidelines. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/physical-activity-guidelines-uk-chief-medical-officers-report. [accessed 04.08.2023].

- 52.US Department of Health and Human Services . 2nd ed. 2018. Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans.https://health.gov/paguidelines/second-edition/ Available at: [accessed 04.08.2023] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Piercy KL, Troiano RP, Ballard RM, et al. The Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. JAMA. 2018;320:2020–2028. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.14854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Department of Health Australian Government. Evidence-based physical activity guidelines for pregnant women: Report for the Australian Government Department of Health. Available at: https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/evidence-based-physical-activity-guidelines-for-pregnant-women. [accessed 04.08.2023].

- 55.Public Health Division of the Pacific Community. Pacific guidelines for healthy eating during pregnancy: A handbook for health professionals and educators. Available at: https://www.spc.int/updates/blog/2018/07/pacific-guidelines-for-healthy-living. [accessed 04.08.2023].

- 56.Ministerio da Saude, Secretaria de Atencao Primaria a Saude, Departamento de Promocao da Saude. Guia de Atividade Fisica: Para A Populacao Brasileira. Available at: https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/guia_atividade_fisica_populacao_brasileira.pdf. [accessed 04.08.2023] [in Portuguese].

- 57.Umpierre D, Coelho-Ravagnani C, Marinho Tenorio MC, et al. Physical Activity Guidelines for the Brazilian Population: Recommendations Report. J Phys Act Health. 2022;19:374–381. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2021-0757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Marinho Tenorio MC, Coelho-Ravagnani C, Umpierre D, et al. Physical Activity Guidelines for the Brazilian Population: Development and Methods. J Phys Act Health. 2022;19:367–373. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2021-0756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Guyatt G, Oxman AD, Akl EA, et al. GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction-GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64:383–394. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhou Y, Guo X, Mu J, Liu J, Yang H, Cai C. Current research trends, hotspots, and frontiers of physical activity during pregnancy: A bibliometric analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:14516. doi: 10.3390/ijerph192114516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ramirez Varela A, Cruz GIN, Hallal P, et al. Global, regional, and national trends and patterns in physical activity research since 1950: A systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2021;18:5. doi: 10.1186/s12966-020-01071-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ramirez Varela A, Pratt M. The GoPA! Second set of country cards informing decision making for a silent pandemic. J Phys Act Health. 2021;18:245–246. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2020-0873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Temkin SM, Noursi S, Regensteiner JG, Stratton P, Clayton JA. Perspectives from advancing national institutes of health research to inform and improve the health of women: A conference summary. Obstet Gynecol. 2022;140:10–19. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bo K, Artal R, Barakat R, et al. Exercise and pregnancy in recreational and elite athletes: 2016/17 evidence summary from the IOC expert group meeting, Lausanne. Part 4-Recommendations for future research. Br J Sports Med. 2017;51:1724–1726. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2017-098387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Symons Downs D, Hausenblas H. Women's exercise beliefs and behaviors during their pregnancy and postpartum. J Midwifery Women Health. 2004;49:138–144. doi: 10.1016/j.jmwh.2003.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Symons Downs D. Understanding exercise intention in an ethnically diverse sample of postpartum women. J Sport Exerc Psych. 2006;28:159–170. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Evenson KR, Aytur SA, Borodulin K. Physical activity beliefs, barriers, and enablers among postpartum women. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2009;18:1925–1934. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2008.1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vladutiu CJ, Evenson KR, Jukic AM, Herring AH. Correlates of self-reported physical activity at 3 and 12 months postpartum. J Phys Act Health. 2015;12:814–822. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2014-0147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee. 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee Scientific Report. Available at: https://health.gov/paguidelines/second-edition/report.aspx. [accessed 04.08.2023].

- 70.Katzmarzyk PT, Powell KE, Jakicic JM, et al. Sedentary Behavior and Health: Update from the 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2019;51:1227–1241. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000001935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Füzéki E, Engeroff T, Banzer W. Health benefits of light-intensity physical activity: A systematic review of accelerometer data of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) Sports Med. 2017;47:1769–1793. doi: 10.1007/s40279-017-0724-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Meek JY, Noble L. Section on Breastfeeding. Policy Statement: Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics. 2022;150 doi: 10.1542/peds.2022-057988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Nygaard IE, Wolpern A, Bardsley T, Egger MJ, Shaw JM. Early postpartum physical activity and pelvic floor support and symptoms 1 year postpartum. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;224:193.e1–193.e19. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.08.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Physical activity and exercise during pregnancy and the postpartum period: ACOG Committee Opinion, Number 804. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135:e178–e188. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Saki A, Eshraghian MR, Tabesh H. Patterns of daily duration and frequency of breastfeeding among exclusively breastfed infants in Shirza, Iran, a 6-month follow-up study using Bayesian generalized linear mixed models. Glob J Health Sci. 2013;5:123–133. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v5n2p123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists ACOG Committee Opinion No. 736: Optimizing postpartum care. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131:e140–e150. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Vella SA, Aidman E, Teychenne M, et al. Optimising the effects of physical activity on mental health and wellbeing: A joint consensus statement from Sports Medicine Australia and the Australian Psychological Society. J Sci Med Sport. 2023;26:132–139. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2023.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.