SUMMARY

Myeloid cells are well-described to suppress antitumor immunity1; however, the molecular drivers of immunosuppressive myeloid cell states are ill-defined. Here, we leveraged single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) of human and murine non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) lesions, and found that in both species the Type 2 cytokine interleukin (IL)-4 was predicted to be the primary driver of tumor infiltrating monocyte-derived macrophage (mo-mac) phenotype. Using a panel of conditional knockout mice, we found that only deletion of IL-4Rα within early myeloid progenitors in bone marrow (BM) reduced tumor burden, while deletion in downstream mature myeloid cells had no effect. Mechanistically, IL-4 derived from BM basophils and eosinophils acted on granulocyte-monocyte progenitors (GMPs) to transcriptionally program the development of immunosuppressive tumor-promoting myeloid cells. Consequentially, depletion of basophils profoundly reduced tumor burden and normalized myelopoiesis. We subsequently initiated the first clinical trial of the IL-4Rα blocking antibody dupilumab2-5 given in conjunction with PD-(L)1 blockade in relapsed/refractory NSCLC patients who had progressed on PD-(L)1 blockade alone (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT05013450). Dupilumab supplementation reduced circulating monocytes, expanded tumor-infiltrating CD8 T cells, and in one out of six patients drove a near-complete clinical response two months post-treatment. Our study defines a central role for IL-4 in controlling immunosuppressive myelopoiesis in cancer, identifies a novel combination therapy for immune checkpoint blockade in humans, and highlights cancer as a systemic malady that requires therapeutic strategies beyond the primary disease site.

MAIN

NSCLC accounts for over 1.6 million annual deaths worldwide6. A key driver of cancer progression is thought to be the tumor microenvironment (TME), which in NSCLC is dominated by macrophages that support tumor growth through diverse mechanisms7,8. We previously used genetic fate mapping to demonstrate that macrophages in lung tumors functionally segregate by their ontogeny: resident tissue macrophages (RTMs) arise during embryonic development, and promote tissue remodeling and tumor invasiveness9. In contrast, mo-macs arise from BM progenitors in response to inflammatory tumor cues and promote tumor growth largely by suppressing the antitumor immune response9,10.

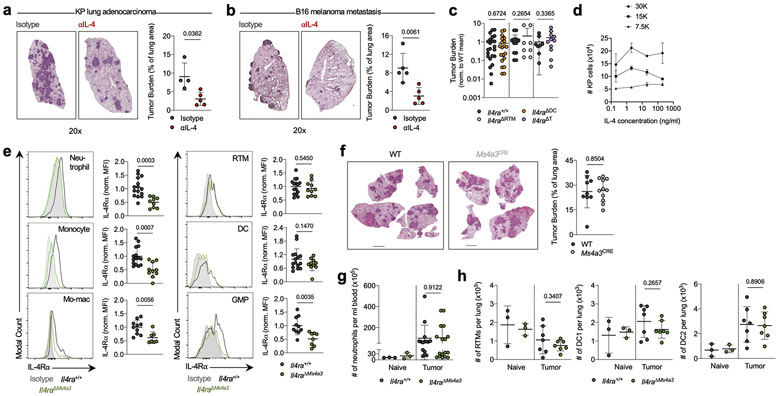

We recently mapped the immune landscape of human and murine NSCLC lesions using scRNA-seq, finding a strong degree of concordance between species. These studies unveiled several insights into myeloid cell diversity within lung tumors, including an essential role for RTMs in early tumor development, the presence of several functionally distinct populations of mo-macs, and a tumor-enriched dendritic cell (DC) program of concomitant activation and immune suppression which we termed “mature DC enriched in regulatory molecules” (mregDC)8,9,11,12. We previously implicated the Type 2 cytokine IL-4 in the control of the immunosuppressive mregDC program, and found that blocking IL-4 strongly reduced lung tumor burden in mice bearing orthotopic KrasG12D Tp53−/− (KP) lung adenocarcinoma lesions11 (Extended Data Fig. 1a) and in the B16 melanoma pulmonary metastasis model (Extended Data Fig. 1b). Surprisingly, however, when we subsequently challenged mice lacking the IL-4Rα on DCs (crossing Zbtb46-Cre13 mice to Il4ra-floxed mice, Il4raΔDC) with KP cells these mice exhibited no difference in lung tumor burden compared to wild-type (WT) littermates (Extended Data Fig. 1c). Similarly, mice specifically lacking IL-4Rα on RTMs (via CD169-Cre14) or T cells (via CD4-Cre15) exhibited no difference in tumor burden compared to control littermates (Extended Data Fig. 1c). As KP cells themselves did not expand in response to IL-4 treatment (Extended Data Fig. 1d), we concluded that another immune cell type must be responding to IL-4 to promote tumor development, and turned to our human and murine NSCLC transcriptional datasets for insight.

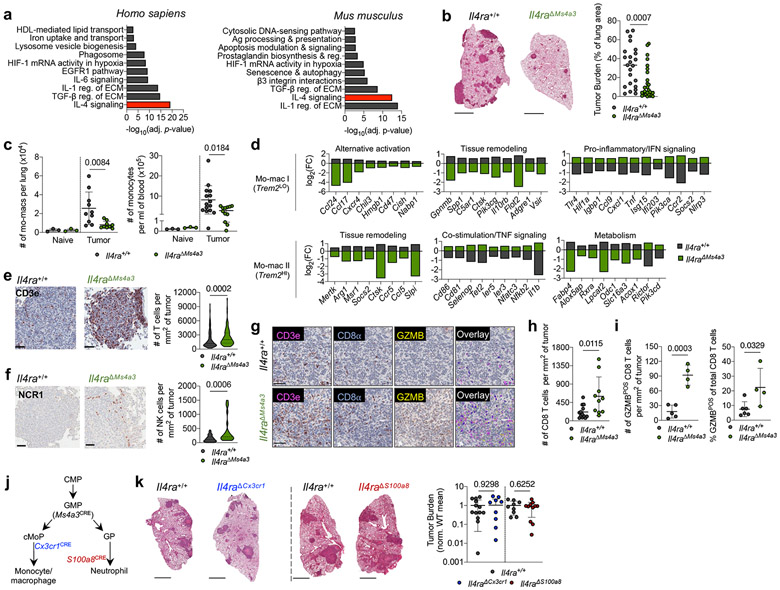

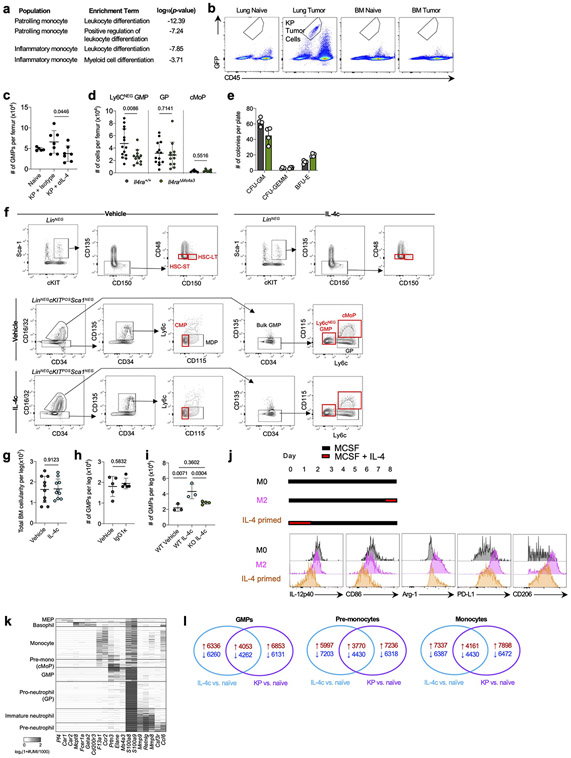

Strikingly, when we performed gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) on differentially-expressed genes (DEGs) between tumor infiltrating mo-macs and RTMs in normal lung we found that “Interleukin-4 signaling pathway” was the most highly enriched term among mo-mac-specific genes in humans and the second most highly enriched term in mice (Fig. 1a; Supplementary Table 1). We therefore crossed Il4ra-floxed mice to newly developed Ms4a3-Cre mice, in which Cre is highly and transiently expressed in GMPs in BM, inducing genetic deletion in all downstream immune lineages, primarily monocytes, mo-macs, and neutrophils, while sparing RTMs16 (Extended Data Fig. 1e). Upon KP tumor challenge, Il4raΔMs4a3 mice exhibited an 85% reduction in tumor burden compared to WT littermates (Fig. 1b), pointing to a central role for IL-4 signaling within the granulocyte-monocyte lineage in tumor development. Of note, no reduction in tumor burden was seen in mice bearing an Ms4a3-Cre allele alone without a floxed allele (Extended Data Fig. 1f), ruling out any off-target effects of Cre expression. Tumor-bearing Il4raΔMs4a3 mice contained half as many lung mo-macs and circulating monocytes as littermate controls (Fig. 1c), although the number of circulating neutrophils (Extended Data Fig. 1g) and other lung myeloid populations (Extended Data Fig. 1h) were unchanged. Given this dramatic reduction in number, our human transcriptional data pointing to a role for IL-4Rα signaling in the mo-mac compartment, and our detailed understanding of monocyte and macrophage molecular programs in NSCLC, we chose to focus our studies primarily on the monocyte / mo-mac lineage.

Figure 1. Targeted deletion of IL-4Rα in early myeloid progenitors restricts lung cancer progression.

(a) Top gene pathways enriched in NSCLC infiltrating mo-macs compared to nLung RTMs from human and mouse datasets. (b) Tumor burden in KP lung tumor-bearing Il4raΔMs4a3 mice (n=27) and littermate controls (n=23). Scale bar=2mm. Pooled from four independent experiments. (c) Number of lung mo-macs and blood monocytes in naïve and tumor-bearing Il4raΔMs4a3 mice and littermate controls (n=3, 3, 10, 9 mice per group for mo-macs and n=3, 3, 15, 12 mice per group for monocytes). Pooled from three independent experiments. (d) Gene expression in lung mo-mac clusters from tumor-bearing Il4ra+/+ and Il4raΔMs4a3 mice. n=3 mice per group. One experiment. (e) Quantification of T cells in lung tumors of Il4ra+/+ (n=140 tumors from 11 mice) and Il4raΔMs4a3 (n=95 tumors from 13 mice) mice. Pooled from three independent experiments. Scale bar=50μm. (f) Quantification of NK cells in lung tumors of Il4ra+/+ (n=59 tumors from 4 mice) and Il4raΔMs4a3 (n=22 tumors from 7 mice) mice. Pooled from 3 out of 4 independent experiments. Scale bar=50μm. (g) IHC co-staining of CD3e, CD8a, and GZMB in lung tumors of Il4ra+/+ and Il4raΔMs4a3 mice. (h) Quantification of CD8 T cells in lung tumors of Il4ra+/+ (n=13) and Il4raΔMs4a3 (n=10) mice. Pooled from three independent experiments. (i) Average number and percentage of GZMBPOS CD8 T cells in lung tumors of Il4ra+/+ (n=7) and Il4raΔMs4a3 (n=4) mice. Representative of three independent experiments. (j) Diagram of myelopoiesis showing activities of indicated Cre drivers. (k) Tumor burden in KP lung tumor-bearing Il4raΔCx3cr1 mice and Il4raΔS100a8 mice compared to littermate controls (n=13, 11, 9, 11 mice per group). Pooled from three independent experiments. Scale bar=2mm. Fisher’s exact test (a), Mann-Whitney test (b,e,f) or Unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test (c,h,i,k). Median (b), median ± first and third quartiles (e,f), mean (d) or mean ± s.d. (c,h,i,k).

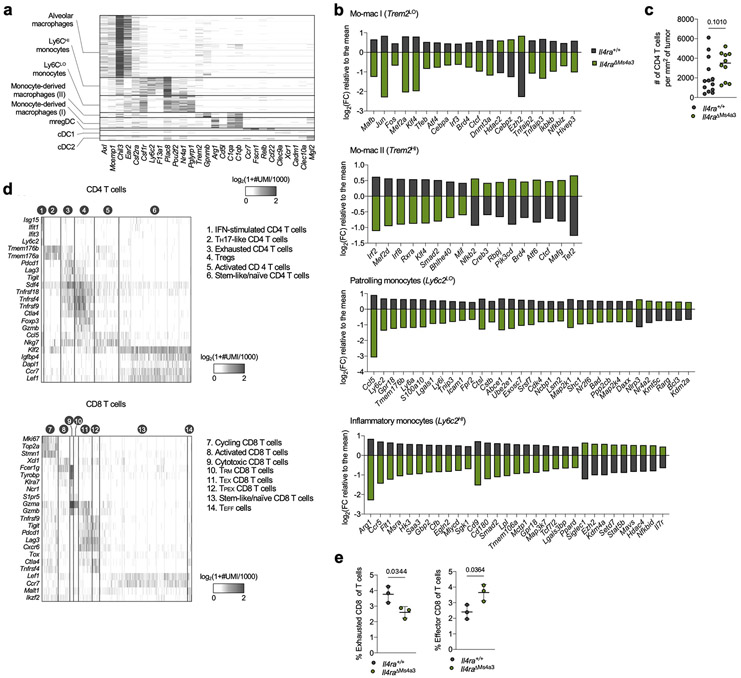

scRNA-seq of myeloid cells in tumor-bearing lungs of both genotypes captured all expected immune populations that we have described in detail elsewhere9,11,12, including two populations of mo-macs (Mo-Mac I and Mo-Mac II) defined by low vs high expression of the Trem2 gene, respectively (Extended Data Fig. 2a). Segregating each mo-mac cluster by genotype revealed dramatic differences in cells from Il4raΔMs4a3 mice compared to those from WT littermates, including a loss of transcripts classically associated with immunosuppression (ie Ccl17, Ccl24, Arg1, Msr1, Chil3, Hmgb1), tissue remodeling (ie Slpi, Gpnmb, Spp1), and lipid metabolism (ie Fabp4, Lpcat2) and an upregulation of transcripts associated with T cell activation and costimulation (ie Il1b, Tnf, Nfatc2, Cd86, Cd81) (Fig. 1d, Extended Data Fig. 2b). Of note, many of these transcriptional changes were also present in developmentally upstream inflammatory (Ly6c2HI) and patrolling (Ly6c2LO) monocytes (Extended Data Fig. 2b).

In line with a central role for mo-macs and monocytes in immune suppression in NSCLC, immunohistochemistry (IHC) revealed that lung tumors in Il4raΔMs4a3 mice contained twice as many T cells (CD3ePOS, Fig. 1e) and natural killer (NK) cells (NCR1POS, Fig. 1f) as WT littermate controls. This was significant to us, as we and others have demonstrated that these two lymphocyte populations are essential for tumoricidal immune control of KP lesions11,12,17,18. Using multiplexed IHC (Fig. 1g), we found that both cytotoxic CD8 T cells (Fig. 1h) and helper CD4 T cells (Extended Data Fig. 2c) were similarly enriched in Il4raΔMs4a3 tumors, with CD8 T cells notably expanding to fourfold their number in WT mice. Concordantly, multiplexed IHC of CD3ePOSCD8aPOS CD8 T cells revealed an increased absolute number and percentage of cells expressing the cytotoxic effector molecule GZMB in tumors of Il4raΔMs4a3 mice (Fig. 1i). ScRNA-seq of total T cells from lung tumors of each genotype followed by fine clustering of CD8 T cells identified clusters in all states of activation (Extended Data Fig. 2d). Notably, Il4raΔMs4a3 lungs contained a reduced proportion of exhausted CD8 T cells (expressing the classical exhaustion genes Tox, Pdcd1, Tigit, and Lag3)19,20 and an increased proportion of effector CD8 T cells (expressing Gzmb, Ikzf2, and Malt1)21-23 (Extended Data Fig. 2e). Thus, loss of Il4ra in all GMP-derived lineages enhanced monocyte and mo-mac immunogenicity and reprogrammed the lung TME toward an inflamed antitumor state.

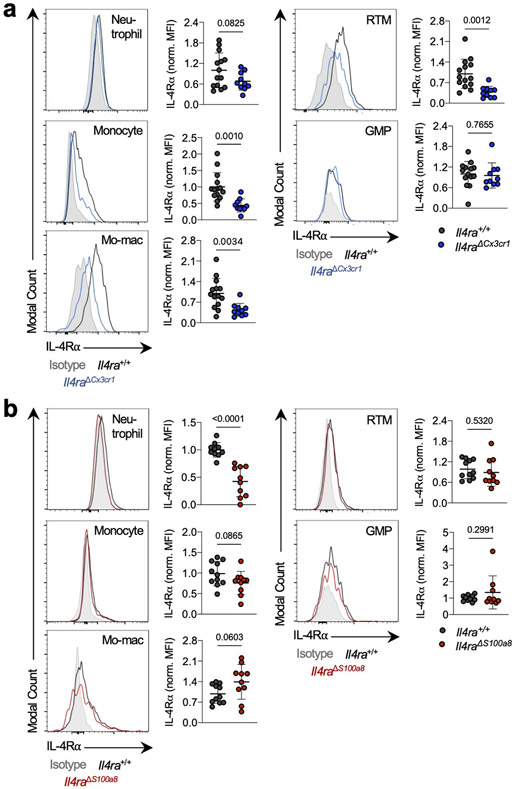

As Ms4a3-Cre targets both the monocyte and neutrophil lineage, we next crossed Il4ra-floxed mice to Cx3cr1-Cre24 or S100a8-Cre25 drivers, which are expressed in more mature myeloid cells downstream of the GMP and are strongly biased towards the monocyte and neutrophil lineages respectively26 (Fig. 1j). Of note, S100a8-Cre deletion was specific to the granulocyte lineage, despite the fact that S100a8 is expressed at low levels in other myeloid cells in settings of inflammation (Extended Data Fig. 3). Unexpectedly, neither Il4raΔCx3cr1 mice nor Il4raΔS100a8 mice exhibited a reduction in lung tumor burden when challenged with KP cells, despite efficient deletion of IL-4Rα in the targeted cell populations (Fig. 1k). Therefore, while deletion of IL-4Rα in early myeloid progenitors in BM drove dramatic remodeling of the lung TME and reduction in lung tumor burden, deletion in mature mo-macs and neutrophils had no effect.

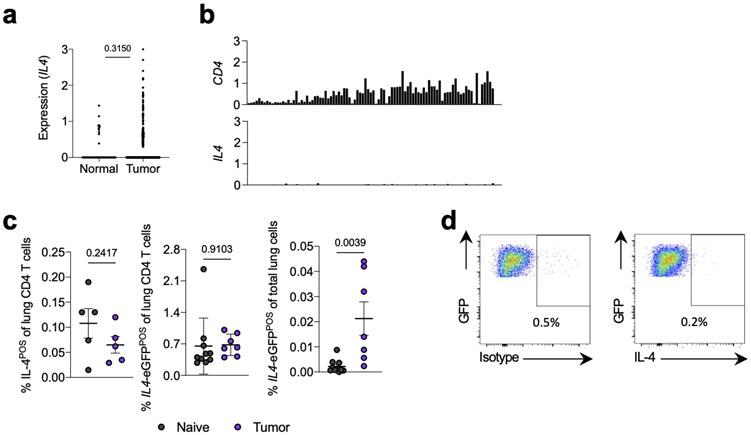

Based on these data, we hypothesized that the relevant IL-4 signaling instructing the immunosuppressive mo-mac state in NSCLC occurred at an upstream stage in the mo-mac developmental pathway, prior to arrival at the tumor site. Indeed, we observed little evidence for a strongly Th2-biased TME in human and murine lung tumors. Upon querying The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) NSCLC database, we observed little expression of IL4 in either tumor tissues or adjacent normal lung (Extended Data Fig. 4a). Consistent with this, IL4 expression was undetectable in all T cell clusters in our human NSCLC scRNA-seq dataset (Extended Data Fig. 4b). Our analysis of mouse tumor-bearing lungs supported this conclusion; we observed essentially no IL-4 producing CD4 T cells of tumor-bearing mice, either by pharmacological stimulation with phorbol myristate acetate and ionomycin (PMA/I) or by using IL4-eGFP (4get) mice, in which a GFP reporter identifies all IL4 producing cells27, though total eGFP-positivity increased marginally to 0.02% of live cells (Extended Data Fig. 4c),. Furthermore, KP tumor cells did not produce IL-4 at the transcript level9 or the protein level (Extended Data. Fig 4d).

Consistent with our hypothesis, pathway analysis of DEGs between Il4ra+/+ and Il4raΔMs4a3 tumor-infiltrating monocytes revealed several pathway hits associated with myeloid development and differentiation (Extended Data Fig. 5a). Indeed Il4raΔMs4a3 monocytes expressed much higher levels of genes associated with monocyte maturation, including the receptors Csf1r and Csf2rb and the transcription factors Nr4a1 and Nr4a228 (Fig. 2a). They concomitantly expressed lower levels of Ly6a (encoding Sca-1, a receptor highly expressed on early hematopoietic progenitors), Bach2, and S100a9, all associated with early stages of myeloid development29,30 (Fig 2a). This was significant to us, as immature myeloid cells induced by emergency myelopoiesis in BM have been widely reported in tumor bearing mice and cancer patients31.

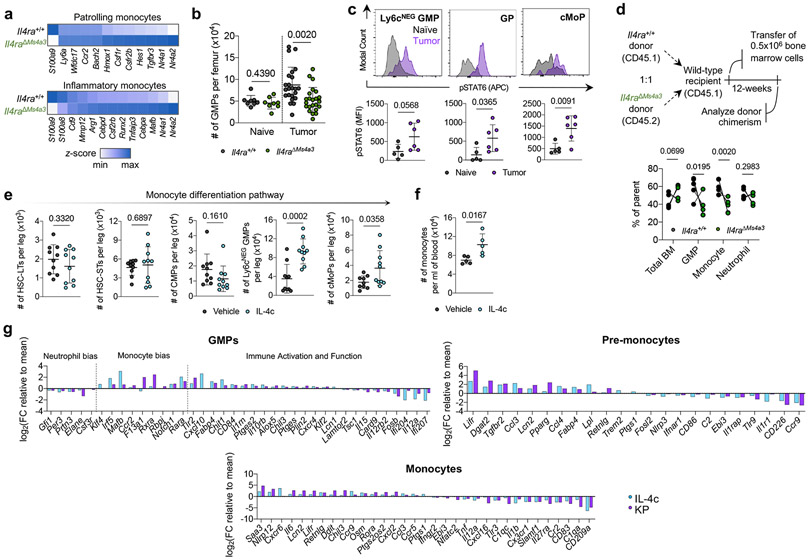

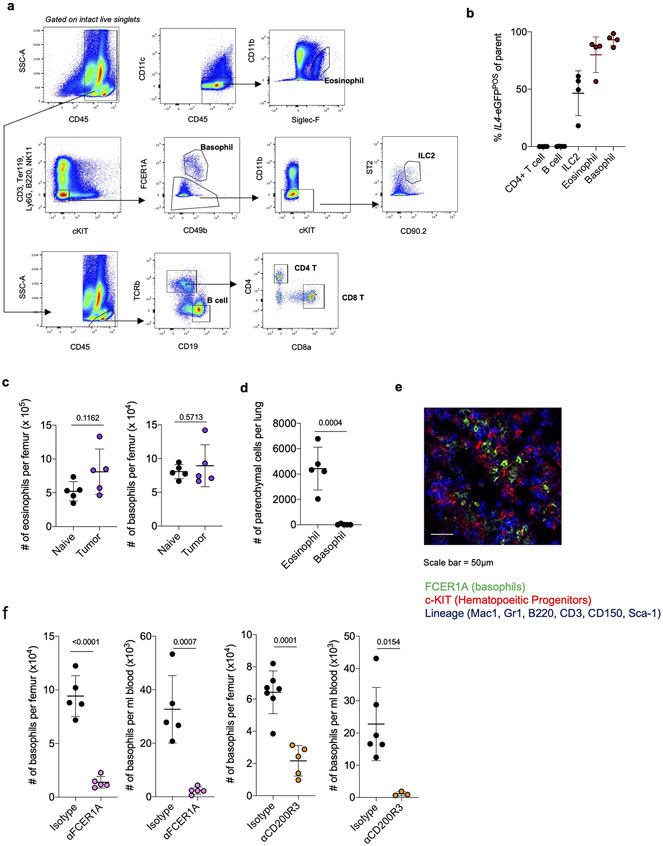

Figure 2. Local IL-4 signaling in bone marrow fuels immunosuppressive myelopoiesis.

(a) Relative expression of statistically significant maturation-associated genes in lung monocyte populations from Il4ra+/+ and Il4raΔMs4a3 tumor-bearing mice (n=3 mice per group). (b) Number of bulk GMPs per femur in naïve and tumor-bearing Il4ra+/+ and Il4raΔMs4a3 mice (n=8, 8, 23, 23 mice per group) Pooled from three independent experiments. (c) pSTAT6 staining in indicated BM myeloid progenitors in naïve (n=5) and KP tumor-bearing (n=6) mice. Representative of two independent experiments. (d) Proportion of WT (CD45.1) and Il4raΔMs4a3 (CD45.2) cells in indicated cell populations in mice reconstituted with 1:1 (WT : Il4raΔMs4a3 ) BM cells 12 weeks post-transplant (n=5 mice per group). One experiment. (e) Number of indicated hematopoietic progenitor populations in BM of vehicle and IL-4c injected mice (n=10 mice per group). Pooled from two independent experiments. (f) Number of monocytes per ml of blood in vehicle and IL-4c injected mice (n=5 mice per group). Representative of two independent experiments. (g) Curated gene lists showing indicate genes in GMP, pre-monocyte, and monocyte clusters of IL-4c and KP-treated mice relative to naïve controls. Unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test. Data are mean ± s.d. HSC-LT, Long term hematopoietic stem cell. HSC-ST, Short term hematopoietic stem cell.

We therefore examined myeloid progenitor populations in the BM of Il4ra+/+ and Il4raΔMs4a3 mice. Importantly, we first confirmed by flow cytometry that tumor cells had not metastasized to the BM in our model (Extended Data Fig. 5b). We used a general, unifying definition for GMPs that have passed the common myeloid progenitor (CMP) stage based on surface markers (LineageNEGSca-1NEGCD135NEGc-KITPOSCD34POSCD16/CD32HI)16,32. We observed no difference in GMP number between genotypes in naïve mice (Fig. 2b). However, while Il4ra+/+ tumor-bearing mice exhibited twofold expansion of GMPs in accordance with enhanced myelopoiesis, this expansion was completely abrogated in Il4raΔMs4a3 mice (Fig. 2b). GMP expansion was also abrogated by treating WT tumor-bearing mice with IL-4 blocking antibodies (Extended Data Fig. 5c). The surface markers Ly6c and CD115 have been proposed to segregate the bulk GMP population into more discrete populations with biased developmental trajectories, such as Ly6cNEG GMPs (Ly6cNEGCD115NEG) with similar monocyte and granulocyte developmental potential, granulocyte progenitors (GPs, Ly6cPOSCD115NEG) which are more biased towards the granulocyte lineage, and common monocyte progenitors (cMoPs, Ly6cPOSCD115POS) biased towards monocyte development16,33,34. Gating on each of these sub populations individually revealed that expansion of the multipotent Ly6cNEG GMP was most strongly abrogated in Il4raΔMs4a3 tumor-bearing mice (Extended Data Fig. 5d). Next, we asked if myeloid progenitors in BM of tumor-bearing mice engage signaling through the IL-4Rα. We employed flow cytometric staining for phosphorylated STAT6 (pSTAT6), a transcription factor that is phosphorylated at Y641 immediately upon binding of the IL-4Rα to IL-4 or IL-1335. While all GMP subpopulations expressed low baseline pSTAT6, staining increased threefold upon tumor challenge (Fig. 2c), demonstrating that the BM is a relevant site of myeloid IL-4Rα signaling in NSCLC.

Next, we asked if IL-4Rα signaling in BM controls monocyte differentiation and, if so, whether it imprints specific molecular programs on downstream macrophages. We first performed competitive BM chimeras, in which lethally irradiated mice were reconstituted with a 1:1 mixture of WT (CD45.1) and Il4raΔMs4a3 (CD45.2) BM cells. Importantly, while total BM cells engrafted equally between the two genotypes, we found that Il4raΔMs4a3 GMPs and downstream blood monocytes expanded significantly less than their WT counterparts within the same animal (Fig. 2d), pointing to a competitive advantage for IL-4Rα signaling in monopoiesis at steady state. Similarly, Il4raΔMs4a3 hematopoietic progenitors were limited in their ability to differentiate towards the granulo-macrophage lineage (Extended Data Fig. 5e). To further establish the role of IL-4 signaling on BM myelopoiesis we treated WT mice with IL-4 complexes (IL-4c), in which IL-4 is stabilized by αIL-4 antibodies to extend its in vivo half-life36, or vehicle control, and quantified BM intermediates in the monocytic developmental pathway from the earliest hematopoietic stem cells (HSC) to blood monocytes. Strikingly, IL-4c treatment had no effect on the earliest HSCs, but induced a sharp and profound expansion of GMPs and all downstream populations, with Ly6cNEG GMPs exhibiting a threefold expansion over four days (Fig. 2e, f; Extended Data Fig. 5f, g). Importantly, injection of the relevant isotype IgG1κ alone did not induce expansion of progenitor populations (Extended Data Fig. 5h). Additionally, GMPs from Il4raΔMs4a3 mice failed to expand upon IL-4c injection (Extended Data Fig. 5i).

To determine if early IL-4 signaling at the myeloid progenitor stage impacts the phenotype of mature macrophages, we first turned to a reductionist in vitro system. Alternatively-activated M2 macrophages are commonly differentiated in vitro by culturing BM in M-CSF to generate “M0” BM-derived macrophages (BMDMs) followed by polarization with IL-412. We modified this protocol to reflect what our data suggests occurs in NSCLC by instead treating BM with IL-4 for the first two days of culture, prior to macrophage differentiation, then removing IL-4 and culturing nonadherent cells in M-CSF for an additional five days to generate “IL-4 primed BMDM”, and compared them to conventional M0 and M2 BMDM. Notably, priming myeloid progenitors with IL-4 was sufficient to fully induce an M2 phenotype in downstream BMDMs- including an upregulation of the canonical M2 markers Arg-1, CD206, and PD-L1 and a downregulation of the T cell activating molecules IL-12p40 and CD86 (Extended Data Fig. 5j).

To extend these observations to a relevant in vivo setting, we performed scRNA-seq of BM myeloid cells and progenitors from naïve, IL-4c-treated, and KP lung tumor-bearing mice. In addition to bona fide monocytes and neutrophils, clustering resolved several myeloid progenitor populations. Using several well-referenced BM transcriptional datasets16,37-39, we annotated these clusters as GMPs (corresponding with Ly6cNEG GMPs by flow cytometry and expressing Mpo, Elane, Prtn3, and the GMP-defining gene Ms4a3) as well as pre-monocytes (corresponding with cMoPs by flow cytometry and expressing GMP genes as well as high levels of Ccr2, F13a1, Klf4, Irf5, Irf8, and Vcan) and pro-neutrophils (corresponding with GPs by flow cytometry and expressing high levels of Ly6g, S100a8, S100a9, Mmp8, Ccl6, Cebpe, Gfi1, and Per3) which had begun to differentiate away from the GMP state (Extended Data Fig. 5k). Within each population along the monocyte differentiation pathway (GMPs, pre-monocytes, and monocytes) we analyzed DEGs in cells from IL-4c-treated and KP-bearing mice compared to those from naïve controls. While IL-4c and KP challenge each induced major transcriptional alterations in these compartments, there was a remarkable degree of overlap, with close to 40% of all up- and downregulated genes being shared between the two conditions (Extended Data Fig. 5l).

We next examined condition-specific DEGs within each of these three populations, focusing on genes that exhibited similar behaviors in IL-4c and KP-treated groups vis-à-vis naïve control (Fig. 2g, Supplementary Table 2). Within the GMP compartment, both IL-4c and KP challenge induced a clear bias towards monocyte differentiation, with a downregulation of granulocytic genes (Elane, Gfi1, Per3) and an upregulation of monocyte-specifying genes (Ccr2, Mafb, Rara). Strikingly, these two treatments also induced several immunosuppressive gene programs in GMPs frequently associated with tumor-promoting myeloid cells, with an upregulation of genes promoting T cell suppression and lipid metabolism (Ccl3, Chit1, Il10rb, Ptges, Ptges2, Alox5) and a downregulation of immunostimulatory genes (Il12a, Il12rb2, Card9, Il15). This archetype was maintained and expanded in pre-monocytes and downstream monocytes, which continued to express higher levels M2 macrophage associated genes such as Retnlg, Ccl3, Ccl4, and Dgat2, and downregulated additional genes that promote cytotoxic immunity such as Nlrp3, CD86, Il1r1, CD226, and Tnf.

Thus, several transcriptional changes that are essential for promoting an immunosuppressive TME are induced in BM myeloid progenitors prior to their arrival at the tumor site, and these changes can be recapitulated by exposing BM to IL-4 in vivo. This, combined with our findings that only deletion of Il4ra in early myeloid progenitors reduces lung tumor burden (Fig. 1) and that myeloid progenitors engage IL-4Rα signaling in tumor-bearing mice (Fig. 2c), points to a central role for a BM-intrinsic IL-4Rα signaling pathway in NSCLC development.

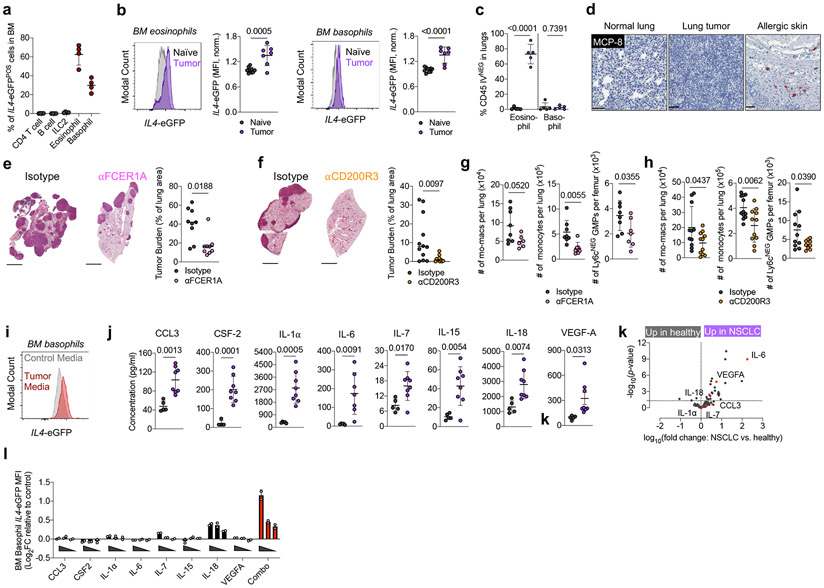

Next, we asked what cell types produce IL-4 to control immunosuppressive myelopoiesis in NSCLC. Consistent with our findings that IL-4 was not highly produced in the lung TME and the fact that IL-4 has an extremely short half-life, we could not detect any IL-4 protein in either lung homogenate or circulating blood of tumor-bearing mice (Limit of Detection = 1pg/ml; Data Not Shown). Therefore, we hypothesized that local cells within BM were the relevant sources of IL-4. Using 4get mice, we found that almost all IL4 produced in BM of tumor-bearing mice was derived from eosinophils and basophils, which collectively constituted roughly 5% of cells in BM (Fig. 3a; Extended Data Fig. 6a, b). These cells, often called Type 2 granulocytes because of their ability to produce several Type 2 effector cytokines, are typically rare to absent in peripheral tissues at steady state, but accumulate rapidly in response to Th2-driven inflammation31. While BM eosinophils and basophils did not increase in number in tumor-bearing mice (Extended Data Fig. 6c), they dramatically upregulated their expression of IL4 compared to naïve controls (Fig. 3b). We therefore hypothesized that BM Type 2 granulocytes are the key cell types driving IL-4 dependent aberrant myelopoiesis in NSCLC.

Figure 3. Type 2 granulocytes in BM upregulate IL-4 and control myeloid output in response to distal tumor cues.

(a) Proportion of indicated cell type among IL4-eGFPPOS cells in BM of tumor-bearing mice (n=4 mice). Representative of two independent experiments. (b) IL4-eGFP expression in BM eosinophils and basophils from naïve (n=10) and tumor-bearing (n=7) mice. Pooled from two independent experiments. (c) Percentage of lung parenchymal eosinophils and basophils in naïve and tumor-bearing mice, (n=5 mice per group). Representative of two independent experiments. (d) IHC for MCP-8 in indicated tissues. Representative of 12 mice. (e) Tumor burden in KP-bearing mice treated with αFCER1A or isotype antibodies (n=9 mice per group). Pooled from two independent experiments. Scale bar=2mm. (f) Tumor burden in KP-bearing mice treated with αCD200R3 (n=11) or isotype (n=12) antibodies. Pooled from two independent experiments. Scale bar=2mm. (g) Immune populations in tumor-bearing mice treated with αFCER1A or isotype antibodies. n=8 isotype and n=7 αFCER1A-treated mice for mo-macs. n=8 isotype and n=7 αFCER1A-treated mice for monocytes and Ly6cNEG GMPs. Representative of two independent experiments. (h) Immune populations in tumor-bearing mice treated with αCD200R3 or isotype antibodies. n=11 mice per group for mo-macs. n=12 isotype and 11 αCD200R3-treated mice for monocytes. n=11 isotype and 9 αCD200R3-treated mice for Ly6cNEG GMPs. Pooled from two independent experiments. (i) IL4-eGFP expression in BM basophils cultured in control or tumor-conditioned media. Representative of two independent experiments. (j) Expression of proteins in lung homogenate of naïve (n=5) and tumor-bearing (n=8) mice. Pooled from two independent experiments. (k) Inflammatory proteins upregulated in plasma of treatment-naïve NSCLC patients (n=29) compared to healthy controls (n=21). Analytes also upregulated in j are indicated in red. One experiment. (l) Expression of IL4-eGFP in BM basophils cultured with indicated cytokines normalized to control media. Two technical replicates per condition, representative of two independent experiments. Unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test (b,c,g,h,j,k) or Mann-Whitney Test (e,f). Data are mean ± s.d. (a,b,c,g,h,j,k) or median (e,f).

We sought to test our hypothesis by deleting an IL-4 source specifically within the BM. Using intravenous (IV) CD45 labeling, which segregates immune cells that have entered the lung parenchyma (CD45-IVNEG) from extra-tissular cells circulating through the blood (CD45-IVPOS)40, we found that eosinophils rapidly entered the lung parenchyma upon tumor challenge (Fig. 3c; Extended Data Fig. 6d); however, 100% of basophils remained in the circulation (CD45-IVPOS) in both naïve and tumor-bearing mice and did not migrate into lung tumors (Fig. 3c, Extended Data Fig. 6d). We confirmed this with IHC staining against the basophil-specific marker mast cell protease 8 (MCP-8)41, and observed no basophil infiltration in lung tumors across 12 mice (Fig. 3d). In contrast, basophils were enriched in BM and made intimate contact with c-KITPOS hematopoietic progenitors in tumor-bearing mice, as measured by immunofluorescence microscopy (Extended Data Fig. 6e). Thus, we reasoned that specific depletion of basophils would eliminate a major source of IL-4 in BM while leaving any IL-4 production in the lung tumor unaltered.

Therefore, we implanted mice with KP tumors and used two orthogonal antibody-mediated strategies to deplete basophils- αFCER1A antibodies, which deplete basophils, but also mast cells and a small population of DC42, and αCD200R3 antibodies, which induce highly specific depletion of the basophil lineage43. We confirmed efficient depletion of peripheral and BM basophils with each of these antibodies (Extended Data Fig. 6f). In both cases, basophil depletion profoundly reduced tumor burden compared to mice receiving control isotype antibodies (Fig. 3d, e). Consistent with our model of basophil IL-4 being a central driver of myelopoiesis in cancer, basophil-depleted mice exhibited a strong reduction in BM GMPs, which translated into reduced lung monocytes and lung mo-macs (Fig. 3f). Thus, basophils are a dominant IL4 source in BM not present in lung tumors and their depletion abrogates immunosuppressive myelopoiesis and reduces tumor burden.

We next aimed to identify the factors that drive BM basophils to produce IL-4 in tumor-bearing animals. Solid tumors are well known to influence hematopoiesis through soluble factors produced both by tumor cells themselves and by stromal components44,45. In line with this, culture of 4get BM basophils with KP cell-conditioned media drove marked IL4-eGFP upregulation (Fig. 3i). We next performed a Luminex multiplex ELISA to survey proteins in lung homogenate of naïve and KP tumor-bearing WT mice. Strikingly, eight proteins reported to induce IL-4 production in basophils46 were upregulated in the lungs of tumor-bearing mice: IL-18, VEGF-A, IL-6, IL-1α, IL-7, CCL3, IL-15, and Csf2 (Fig. 3j). Six of these proteins were also upregulated in the serum of treatment-naïve NSCLC patients compared to healthy controls, as measured by the Olink assay inflammation panel, and three—IL-6, VEGF-A, and IL-18—were statistically significant (Fig. 3k; Supplementary Table 3; Supplementary Table 4). We then directly tested the ability of each of these eight cytokines to induce IL4 in BM basophils upon individual culture. Many of these cytokines induced modest upregulation of IL4-eGFP in 4get basophils when cultured alone; however, there was clear synergy when all cytokines were combined together, with basophils exhibiting a twofold upregulation of GFP mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) when cultured with the eight-cytokine combination cocktail (Fig. 3l). Therefore, multiple cytokines produced in human and mouse NSCLC work collaboratively to induce IL-4 production within the BM compartment. Collectively, these data define a model in which BM Type 2 granulocytes sense distal cues produced by NSCLC tumors and subsequently direct the development of immunosuppressive myeloid cells through production of IL-4.

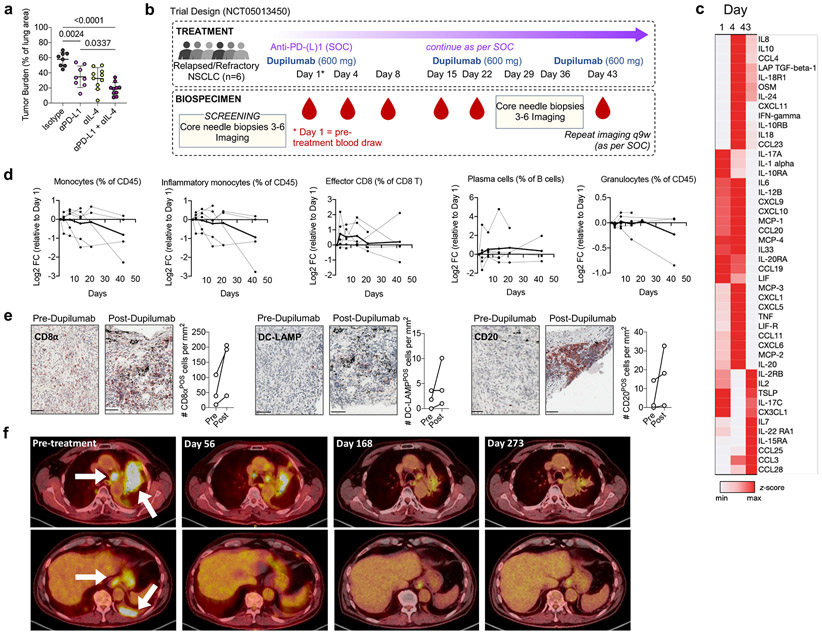

Finally, we asked if this newfound insight could be harnessed for the treatment of human lung cancer. Immune checkpoint blockade directed against the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway has revolutionized treatment for early and late-stage NSCLC; however, fewer than half of patients respond, necessitating the development of novel therapeutic approaches to improve outcomes47-49. We found that in mice bearing orthotopic HKP1 tumors, a variant of KP tumors that are more immunogenic and partially responsive to checkpoint blockade50, αIL-4 treatment enhanced the response to αPD-L1 immunotherapy, suggesting synergistic effects (Fig. 4a). Based on these preclinical data, we designed and opened a Phase 1b trial in which patients with relapsed/refractory NSCLC who had progressed on PD-(L)1 blockade continue αPD-(L)1 while adding IL-4Rα blockade (Dupilumab, Regeneron, Inc.) in an attempt to induce or rescue an antitumor immune response (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT05013450). Dupilumab is a fully humanized monoclonal antibody to the IL-4Rα which disrupts signaling through receptors for both IL-4 and IL-13, and is clinically active and Food and Drug Administration-approved for numerous atopic conditions2-5. The use of dupilumab has yet to be explored specifically in cancer.

Figure 4. IL-4Rα blockade enhances response to immunotherapy in human NSCLC.

(a) Lung tumor burden in mice transplanted with HKP1 cells and treated with αPD-L1 antibodies, αIL-4 antibodies, or a combination of both (n=8, 8, 10, 10 mice per group). Pooled from two independent experiments. (b) Clinical trial design. (c) Averaged heatmap of Olink Inflammation Panel analytes in patients’ plasma at indicated timepoints post dupilumab treatment. (d) Levels of indicated immune cells in patient whole blood at indicated timepoints post dupilumab treatment as assessed by CyTOF, normalized to Day 1 (pre-dupilumab treatment). Dotted lines represent individual patients; solid line represents mean of all patients. (e) Number of CD8, DC-LAMP, and CD20-positve cells in tumor biopsies of relapsed/refractory NSCLC patients prior to and 36 days after initiation of dupilumab treatment, as measured by IHC (n=3 patients). Scale bar=50μm. (f) Chest CT stans of dupilumab responder patient before treatment and 56, 168, and 273 days after treatment. One way ANOVA with post hoc Tukey’s multiple comparison test (a). Panels b-f representative of one clinical cohort.

We recruited six NSCLC patients lacking targetable driver mutations who had radiographic evidence of progressive disease while on treatment with PD-(L)1 blocking antibodies as part of standard of care (SOC) therapy (Supplementary Table 5). PD-(L)1 blockade was continued as per SOC, while patients received dupilumab subcutaneously every three weeks for 3 doses, 600mg loading dose on Day 1 and 300mg for subsequent maintenance doses, administered concomitantly with continuing PD-(L)1 blocking antibodies (Fig. 4b). We observed no dose-limiting toxicities nor treatment-related adverse events. Importantly, we found that dupilumab co-administration drove a rapid (Day 4) upregulation of proinflammatory cytokines well described to promote anti-tumor immune responses, including central drivers of the Th1 immune axis IFNγ and IL-12, and the T cell recruiting chemokines CCL19, CXCL9, CXCL10 (Fig. 4c). Long-term (Day 43), T effector cell expanding cytokines were upregulated, including IL-2, IL-7, CCL25, and IL-15RA (Fig. 4c; Supplementary Table 6). Cytometry by time of flight (CyTOF) on whole blood revealed a steady reduction of inflammatory (CD14POS) monocytes over time in several patients, but minimal effect on circulating granulocytes (Fig 4d), mirroring our results in tumor-bearing Il4raΔMs4a3 mice. Additionally, dupilumab induced an expansion of circulating effector CD8 T cells and antibody-producing plasma cells, both of which are essential for the response to PD-(L)1 blockade51,52 (Fig. 4d). Immunohistochemical analysis of paired tumor biopsies from 3 patients obtained prior to and 36 days post dupilumab initiation revealed a concomitant remodeling of the TME. Dupilumab induced an expansion of CD8 T cells (CD8aPOS), activated DCs (DC-LAMPPOS) and B cells (CD20POS) in all patients analyzed (Fig. 4e), indicating an enhanced capacity for T cell priming and cytotoxic immune function in response to PD-(L)1 blockade.

Notably, one out of these six patients experienced a partial clinical response on imaging as per RECIST criteria53. As per protocol this patient continued to received maintenance checkpoint blockade concurrently with the dupilumab then after the three doses of dupilumab continued maintenance pembrolizumab alone after the first imaging, and has had two subsequent radiographic evaluations demonstrating deepening of the radiographic response and a near complete response on PET scan now over 9 months out (Fig. 4f). Given the small sample size of this Phase 1b trial, we must caution larger conclusions about efficacy of this novel combination, and a larger Phase 2 trial expansion is planned to evaluate the potential benefit of adding dupilumab to checkpoint blockade in patients progressing on standard immunotherapy, and identify biomarkers of patients in whom disrupting the IL-4Rα signaling may be of clinical utility.

DISCUSSION

Tumor-infiltrating monocytes and macrophages have long been considered drivers of immunosuppression and cancer progression; however, to date all therapies targeting these cell types have failed in the clinic54, primarily because we lack a fundamental understanding of the key regulators of myeloid programs in tumors, as well as the heterogeneity within and between patients. Here, we define IL-4 as a central driver controlling monocyte and mo-mac immunosuppression in NSCLC, and make the surprising discovery that the relevant site of IL-4 signaling is not the tumor itself, but the BM, where it acts on GMPs to imprint myeloid cell fate. While our murine models relied on orthotopic transplantation of tumor cells and therefore may mimic some features of lung metastasis, we have previously shown that KP tumors histologically, cellularly, and immunologically resemble primary human NSCLC lesions9,11. Nevertheless, defining how dupilumab administration modulates the antitumor immune response at different stages of human lung cancer remains an important and exciting area for future study.

Though we found IL-4 expression to be relatively low in lung tumors, our study does not preclude a role for local IL-4 signaling in NSCLC. Indeed, low levels of IL-4 competent CD4 T cells (Extended Data Fig. 4b, c) and eosinophils (Fig. 3c) are present in NSCLC tumors and may modulate the TME in ways not addressed in this study. These cell types may be expanded in certain subsets of patients and contribute to inter-patient TME heterogeneity. Additionally, other tumor types such as pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma55 and breast cancer56 are well-described to be highly Th2-biased and may serve as paradigms of IL-4 playing a major signaling role within the TME. However, vis-à-vis the monocyte-mo-mac lineage in NSCLC, our study clearly points to an extratumoral role for IL-4 signaling in determining tumor outcome. Our study also highlights that cancer contributes to a systemic dysregulation of the immune system that requires a deep understanding and therapeutic strategies beyond the primary site of disease. Due to its ability to control immunosuppressive myelopoiesis, a prominent feature of essentially all cancers, we surmise that dupilumab may be an effective combination therapy for many tumor types that should be explored in the future.

METHODS

Mice

C57BL/6 mice were obtained from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA). Zbtb46-Cre (strain#:028538), CD4-Cre (strain # 022071) S100a8-Cre (strain # 021614), Cx3cr1-Cre (strain # 025524), and CD45.1 (strain # 002014) were obtained from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). CD169-Cre mice were a gift from Paul Frenette. IL4-eGFP (4get) mice fully backcrossed to the C57BL/6 background were obtained from Brian S. Kim. Il4rafloxed mice were generated by Cyagen (Santa Clara, CA). Briefly, CRISPR/Cas9 editing was used to generate mice with loxP sites flanking Exon 4 of the Il4ra gene, located on mouse Chromosome 7. Both male and female mice were used, and we observed no differences between sexes in any experiment. Littermate controls were used in all experiments, with the single exception of Extended Data Fig. 1h where sex and age-matched controls were used. All experiments were initiated when mice were between 8-12 weeks of age. Mice were housed in specific-pathogen free conditions at 21-22°C at 39-50% humidity with a 12/12 hour dark/light cycle. Mice were sacrificed by CO2 asphyxiation. All experiments were approved by, and in compliance with, the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

Lung Tumor Models

500,000 KP cells, 150,000 HKP1 cells, or 500,000 B16 cells were injected IV through the tail vein in 300μl of sterile normal saline. In most cases, GFP-expressing KP cells were used. If mice expressed endogenous GFP (ie IL4-eGFP 4get mice), then KP cells lacking GFP were used. Mice were heated with a heat lamp for five minutes prior to IV injection. Mice were sacrificed at 28 days post KP injection, 17 days post HKP1 injection, or 15 days post B16 injection ± 2 days. Mouse cohorts were sacrificed at earlier timepoints (not more than 5 days) if mice showed clinical signs of distress requiring a humane end point (labored breathing, hunched posture, wasting). All cell lines were routinely screened for mycoplasma contamination. All tumor experiments were replicated multiple times on different days using separately thawed vials of cells. After thawing, cells were not passaged more than five times prior to injection and cells were only injected if they were at >90% viability. All cell lines were maintained at 37°C in RPMI (Corning, ref # 10-040-CV) supplemented with 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS, Gibco, ref # A52568-01), and 1% Penicillin / Streptomycin (Pen/Strep, ThermoFisher, ref # 15140163). Cells were injected at 70% confluency after 10 minutes of trypsinization at 37°C (Gibco, ref # 25200-056), washing with sterile PBS, and filtering through 70μm filters.

Antibody and antibody complex treatments

Relevant isotype antibodies were used in control groups for all antibody experiments. Where indicated, mice were treated with 25μg of αIL-4 (BioXcell, clone 11B11, ref # BE0045) intraperitoneally (IP) on Days 21, 23, and 26 post KP injection and analyzed on day 28; 25μg of αIL-4 on Days 8, 10, and 13 and analyzed on day 23. 10μg αFCER1A (ThermoFisher, clone MAR-1, ref# 14-5898-85) IP on days −3, 3, 7, 14, and 21 post KP injection and analyzed on Day 25; 50μg of αCD200R3 (Hajime Karasuyama Lab, clone Ba103) IV on Days 2, 9, 16, and 23 post KP injection and analyzed on Day 25. IL-4c was generated as previously described36. Mice were injected IP with either vehicle control or 5μg IL-4 (Shenandoah, ref# 200-18) complexed to 25μg of αIL-4 on Days 0 and 2 and analyzed on Day 4. For combinatorial PD-L1/IL-4 blockade, two similar experiments using the HKP1 tumor cell line were combined. In Experiment 1, 200μg αPD-L1 (BioXcell, clone 10F.9G2, ref# BE0101) was given on Day 9 and/or 25μg αIL-4 was given on days 7, 9, 11, and 14, and mice were sacrificed on Day 17. In Experiment 2, 200μg αPD-L1 was given on Day 11, and/or 25μg αIL-4 was given on Day 11, 13, and 15, and mice were sacrificed on Day 17.

In vivo labeling of circulating immune cells

To distinguish parenchymal from circulating immune cells, mice were injected IV with 3μg of fluorescently-labeled CD45 antibodies in 100μl of saline. Three minutes later, mice were euthanized and CD45 IV labeling in immune compartments was analyzed by flow cytometry.

Bone marrow transplant

Lethally irradiated (2 x 6.5Gy) 8-12 week-old WT CD45.1 mice were reconstituted with a 1:1 ratio of WT CD45.1 and Il4raΔMs4a3 CD45.2 bone marrow cells (5 x 106 cells of each genotype) retro-orbitally. Mice were kept on sulfamethoxazole–trimethoprim for 3 weeks. Mice were analyzed 12 weeks after reconstitution.

Mouse Lung Histology

One lung lobe per mouse was fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde before being stored in 70% ethanol until further processing. Lungs were sectioned 4μm thick formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue sections, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). All sectioning and staining was performed by the Histopathology Core Facility of the Department of Oncological Sciences at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. Slides were scanned at 20X using a Leica Aperio AT2 Digital Scanner and tumor burden was quantified using Qupath software.

Tissue Processing

Mouse lungs were minced with scissors and digested in 2ml of 0.25mg/ml Collagenase IV (Sigma, ref # C5138-1G) in RPMI for 30 minutes at 37°C before being aspirated through an 18G needle and passaged through 70μm filters. BM was flushed from leg long bones (femur and tibia) and passaged through 70μm filters. Blood was collected from inferior vena cava. Red blood cells from all tissues were lysed with ACK Lysis Buffer (BioLegend, ref # 420301) for 3 minutes at room temperature prior to downstream processing.

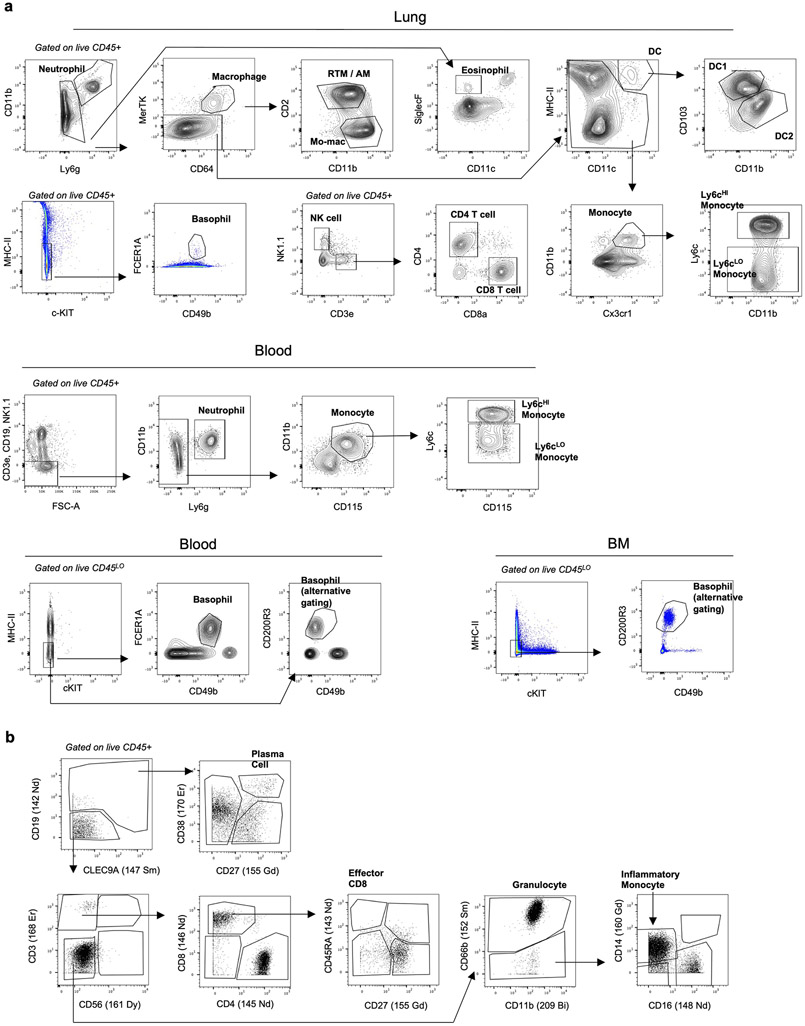

Flow cytometry and fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS)

Single cells were resuspended in FACS buffer (phosphate-buffered saline [PBS, Sigma Aldrich, ref # D8537-6X500ML] supplemented with 2% bovine serum albumin [Equitech-Bio, ref # BAH62-0500] and 5mM EDTA). Cells were surface stained for 15 minutes on ice. For intracellular cytokine staining, cells were fixed with Cytofix/Cytoperm (BD, ref # 554722), and then stained for intracellular antigens in Permeabilization Buffer (BD, ref # 554723). For pSTAT6 staining, surface-stained cells were fixed at room temperature for 10 minutes in 4% paraformaldehyde and then further fixed in methanol at −80°C for 1 hour. Finally, cells were intracellularly stained in PBS containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin and 0.5% Triton X-100. For cytokine staining, cells were first simulated in 10μg/ml Brefeldin A, 0.5μg/ml Ionomycin and 0.2μg/ml PMA for 4 hours at 37°C. Dead cells were excluded by using 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindol (DAPI, ThermoFisher, ref # D1306) or Fixable Blue Live/Dead Dye (Fisher Scientific, ref # L23105). Stained cells were acquired on a BD LSRFortessa Cell Analyzer or sorted on a BD FACSAria. Data was analyzed using FlowJo v10 software. The following anti mouse FACS antibodies were used in this study: CD45 (clone 30-F11, Biolegend, ref# 103138, 1:100), IL-4Rα (clone I015F8, Biolegend, ref# 144805, 1:100), IL-4 (clone 11B11, ThermoFisher, ref# 17-7041-81, 12-7041-82, 1:100), IL-12p40 (clone C17.8, ThermoFisher, ref# 505211, 1:100), CD103 (clone 2E7, Biolegend, ref# 13-1031-82, 1:100), CD11b (clone M1/70, Biolegend ref# 101230, ThermoFisher ref# 47-0112-82, 1:200), CD11c (clone N418, Biolegend, ref# 117336, 1:400), CD127 (clone A7R34, Biolegend, ref# 135019, 1:100), CD4 (clone RM4-5, Biolegend, ref# 100545, 1:200), CD8α (clone 53-6.7, Biolegend, ref# 100714, 1:200), CD3 (clone 17A2, ThermoFisher, ref# 47-0032-82, 1:200), Cx3cr1 (clone SA011F11, Biolegend, ref# 149023, 1:200), Ly6g (clone 1A8, ref# 127624, Biolegend, 1:200), Ly6c (clone HK1.4, Biolegend ref# 128035, Thermofisher ref# 17-5932-82, 1:400), TCRβ (clone H57-597, Biolegend, ref# 109228, 1:400). Siglec F (clone E50-2440, BD Pharmingen, ref# 562680, 565527, 1:100), MHC II I-A/I-E (clone M5/114.15.2, Biolegend, ref# 107643, 1:400), CD115 (clone AFS98, eBioscience, ref# 17-1152-82, 13-1152-85, 1:100), CD2 (clone RM2-4, Biolegend, ref# 100114, 1:200), MerTK (clone DS5MMER, eBioscience, ref# 12-5751-82, 1:100), CD64 (clone X54-5/7.1, ThermoFisher ref# 17-0641-82, Biolegend ref# 139318, 1:100), CD16/CD32 (clone 93, ThermoFisher, ref# 56-0161-82, 1:300), CD34 (clone HM34, Biolegend, ref #128612; clone RAM34, ThermoFisher, ref# 48-0341-82, 1:100), c-kit (clone 2B8, Biolegend ref# 553353, ThermoFisher ref# 25-1171-82, 1:100), ST2 (clone RMST2-2, ThermoFisher, ref# 46-9335-82, 1:100), Sca-1 (clone D7, ThermoFisher, ref# 25-0981-81, Biolegend ref# 108126, 1:100), CD150 (clone mShad150, ThermoFisher, ref# 17-1502-80, 1:100), CD48 (clone HM48-1, ThermoFisher, ref# 46-0481-80, 1:100), CD135 (clone A2F10, Biolegend, ref# 135306, 1:50), NK1.1 (clone PK136, Biolegend ref# 108724, ThermoFisher ref# 45-5941-82, 1:100), CD19 (clone eBio1D3, ThermoFisher, ref# 48-0193-82, 1:200), Ter-119 (clone Ter-119, ThermoFisher, ref# 47-5921-82, 1:200), B220 (clone RAB-632, ThermoFisher, ref# 47-0452-82, 1:200), FCER1A (clone MAR-1, Biolegend, ref# 134308, 1:100), CD49b (clone DX5, eBioscience, ref# 48-5971-82, 1:100), Arg-1 (clone A1exF5, eBioscience, ref# 53-3697-82, 1:100), F4/80 (clone BM8, ThermoFisher, ref# 48-4801-82, 1:200), CD200R3 (Clone Ba13, Biolegend, ref# 142205, 1:100), CD86 (clone GL-1, Biolegend, ref# 105006, 1:100), pSTAT6 (Tyr641) (clone CHI2S4, eBioscience, ref# 17-9013-42, 1:100), CD90.2 (clone 30-H12, ThermoFisher, ref# 25-0902-81, 1:200), CD45.2 (clone 104, Biolegend ref# 109830, ThermoFisher ref# 47-0454-82, 1:200), CD45.1 (clone A20, Biolegend, ref# 110741, 1:200), PD-L1 (clone MIH5, ThermoFisher, ref# 12-5982-82, 1:200), CD206 (clone C068C2, Biolegend, ref# 141703, 1:200). Gating strategies can be found in supplemental data, and all gating strategies not explicitly referenced can be found in Extended Data Fig. 7a.

BMDM Differentiation

WT C57BL/6 BM was plated on non-tissue culture-treated plates at a concentration of 150,000 cells/cm2 in DMEM (Corning, ref # 10-013-CV) containing 10% FBS, 1% Pen/Strep, and 10ng/ml M-CSF (Peprotech, ref # 315–03) or 10ng/ml M-CSF plus 200ng/ml IL-4. After 2 days, nonadherent cells were replated on new plates containing complete DMEM with M-CSF, and media was replenished every 2 days thereafter until day 7, at which time BMDMs were polarized overnight with indicated cytokines. BMDMs were then lifted off plates with cold PBS containing EDTA and analyzed by flow cytometry. BMDMs were identified as live cells co-expressing F4/80 and CD11b, representing over 95% of all cells in each experiment.

Tumor-conditioned Media

Tumor-conditioned media was generated by plating KP cells in 25ml RPMI with 10% FBS and 1% Pen/Strep in a 175cm2 flask (Fisher Scientific, ref # 12-562-000) at 50% confluency. One day later when cells were near 100% confluency media was removed, centrifuged at 1400rpm for 5 minutes to remove cells, and stored at −20°C until further use.

BM Cocultures

3 x 105 RBC-lysed BM cells from 4get mice were cultured for two days 96 well plates in 200μl of control media (RPMI plus 10% FBS and 1% Pen/Strep) or in tumor-conditioned media or in the presence of the following murine cytokines: CCL3 (Peprotech, ref # 250-09), Csf2 (Peprotech, ref # 315-03), IL-1α (R&D Systems, ref # 400-ML-005/CF), IL-6 (Peprotech, ref # 216-16), IL-7 (Peprotech, ref # 217-17), IL-15 (Peprotech, ref # 210-15), IL-18 (R&D Systems, ref # 9139-IL-010/CF), VEGF-A (Peprotech, ref # 450-32) Tumor-conditioned media was used undiluted. Indicated cytokines were cultured at decreasing concentrations- 100ng/ml, 10ng/ml, and 1ng/ml. All cytokines were first resuspended in cell culture grade water at a concentration of 0.1mg/ml and then diluted in RPMI immediately before culture. Basophils were identified per the gating strategy in Extended Data Fig, 6a and IL4-eGFP expression was measured by flow cytometry via the FITC channel. In parallel, all experiments were performed with BM from WT mice to rule out any effect of autofluorescence; these control experiments showed no difference in GFP/FITC MFI between any experimental conditions. No alteration in cell viability was observed in any experiment condition.

Methylcellulose Assay

Total hematopoietic cells were extracted from Il4ra+/+ and Il4raΔMs4a3 BM by flushing one femur and one tibia with PBS, RBC lysed and cells resuspended to a concentration of 3 x 105 cells/ml in IMDM (Cytivia, ref # SH30228.01) containing 1% Pen/Strep and 2% FBS. Cytokines as indicated in figures were added at a 10x concentration (100 ng/ml). 0.4 ml of the resultant cells was added to pre-aliquoted 4 ml StemCell MethoCult M3434 tubes (already containing rmSCF, rmIL3, rmIL6, rhEPO, rhInsulin and transferrin). The methocult was vortexed and dispensed onto 35mm culture dishes in triplicates following manufacturer’s instructions. The dishes were incubated in a humidified incubator at 37°C, 5% CO2. Colonies were manually counted on Day 8 on a Gridded Scoring Dish and averaged across 3 or 4 plates.

CyTOF

Our CyTOF pipeline has been described in detail elsewhere7. Briefly, immune cells from whole blood first were barcoded with antibodies specific to CD45. Then, samples were combined together and stained with a customized panel of metal-conjugated antibodies. Samples were washed, fixed, and stored at 4°C until acquisition. Samples were acquired on a CyTOF2 (Fluidigm), and data were normalized using CyTOF software (bead-based normalization). Samples were debarcoded using the Fluidigm debarcoding software. Immune populations were quantified using FlowJo v10 software. A gating strategy can be found in supplemental data (Extended Data Fig. 7b). A list of CyTOF antibodies and metal conjugates can be found in Supplementary Table 7.

Multiplexed Cytokine Assays

Mouse lung homogenate was analyzed with Multiplex Luminex Assay (Millipore). Plasma from our clinical trial cohort, treatment naïve NSCLC patients, and healthy control donors. analyzed using the Olink proteomic array, and differential protein abundance was calculated using R Studio. Control plasma was obtained from de-identified healthy donors (IRB # 11-00866). NSCLC patient serum was obtained via IRB #10-00472A. Both of these assays were performed by trained staff at the Human Immune Monitoring Center at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

Immunohistochemistry

Our multiplexed immunohistochemical consecutive staining on a single slide (MICSSS) protocol has been described in detail elsewhere57. Briefly, biopsies were fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde and embedded in paraffin, and 4μm sections were cut onto charged glass slides. Slides were baked at 37°C overnight, deparaffinized in xylene, and rehydrated in ethanol. Antigen retrieval occurred for 30 minutes in citrate buffer (pH 6) (Agilent, ref#S236984) or EDTA buffer (pH9) (Agilent, ref # S236784) at 95°C using a water bath. Tissues were blocked in 3% hydrogen peroxide and protein block solution (Dako, X0909), followed by staining with primary antibodies according to their optimized dilutions and secondary antibodies conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Agilent Technologies, K400111-2, K400311-2). Chromogenic revelation was performed with 3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole (AEC) (Vector Laboratories, SK4200). After mounting, slides were scanned at 40X on a Leica Aperio AT2 Digital Scanner. Slides were destained and restained with new antibodies as previously described until the entire antibody panel was completed. Tumor area was identified by a pathologist and cells staining positive for indicated markers were quantified manually using Qupath software. For mouse CD8 T cell quantification in tumors, samples were stained in a similar manner and CD8 positive cells were quantified using automated cell detection with Qupath software. A complete list of antibodies and staining conditions can be found in Supplementary Table 8. As a positive control for MCP-8 basophil staining, we used FFPE sections of ear skin from mice that underwent the classical MC903 model of atopic dermatitis donated by Brian S. Kim58.

For multiplexed imaging, we internally processed our samples to quantitatively analyze localization and coexpression patterns from MICSSS images. For the analysis, we used the svs multi-resolution, pyramidal images obtained per marker after staining. Each image underwent a brief quality control step to ensure tissue masking appropriately captured the tissue area. Both the AEC chromogen stain and the hematoxylin nuclear counterstain were extracted from each image via a dynamically-determined deconvolution matrix. Then, each image was split into smaller tiles to permit computational analysis. Each tile from the first stained image was matched to the respective tile from the sequential stained images and then elastically registered using the extracted hematoxylin nuclear stain and SimpleElastix open-source software. Then, by using an iterative nuclear masking via STARDIST, we produced a composite semantic segmentation for nuclei residing in the series of tiles. Each nucleus was artificially expanded by a number of pixels to simulate a cytoplasm per cell and that was coherent with membrane marker staining. Lastly, cellular-resolution metadata was acquired for all cells in the final cell mask, including AEC and hematoxylin intensity properties (percentiles, dynamic ranges, etc.) and morphological characteristics (circularity, area, etc.) per cell. A final dataframe was appended for each tile processed, producing one dataframe representing all the cellular metadata per sample.

To unbiasedly determine positive and negative cells per marker, we used an unsupervised classification technique to cluster cell populations, followed by a supervised approach where we would evaluate each cluster as positive or negative per marker. First, the metadata aggregated per sample was collected, transformed to z-scores, randomized, and split into subsamples per batch. Each batch was processed in parallel: data for each marker was PCA-UMAP transformed, clustered, and collapsed into multiple groups. Then, we performed the final quality control to manually attribute which clusters were positive or negative. This produced a final cellular-resolution dataframe containing binary marker classification that was used for downstream localization, marker coexpression, tumor annotation and reconciliation, and statistical analyses.

Immunofluorescence on BM sections

Mouse femurs were snap frozen in OCT (Tissue-Tek) and kept at −80°C until sectioning. The sections were prepared in 7μm using a Cryostat with tungsten blades and the Cryojane tape transfer system, dried overnight at room temperature and stored at −80°C until staining. To fix and permeabilize the sections, the slides were incubated in 100% acetone for 10min at −20°C. For basophil staining, anti-FCER1A (MAR-1, ThermoFisher 14-5898-82) was used at 1:200 dilution and followed by goat anti-Armenian hamster IgG conjugated to A488 (Jackson ImmunoResearch, 127-545-160) at 1:500 dilution. For myeloid progenitor staining, anti-CD117 (ACK2, Biolegend 135102) was used at 1:25 dilution and followed by goat anti-rat Cy3 (Jackson Immunoresearch, 112-165-167) at 1:100 dilution. For lineage staining, a combination of anti-Mac1 (M1/70, Biolegend 101218), anti-Gr1 (RB6-8C5, Biolegend 108418), anti-B220 (RA3-6B2, Biolegend 103226), anti-CD3 (17A2, Biolegend 100209), anti-CD150 (TC15-12F12.2, Biolegend 115918), anti-Sca1 (D7, Biolegend 108118) all directly conjugated to A647 and at 1:100 dilution was used. The sections were blocked using 10% goat serum (Gibco 16210064) at room temperature for 1h when goat secondary antibodies were used or 1:50 Rat IgG (Sigma-Aldrich, I8015) at room temperature for 10min when lineage antibodies were used. The sections were then incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. The incubation with secondary antibodies was done at room temperature for 1.5h. Several washing steps were performed after each antibody. The sections were mounted with Prolong Glass Antifade Mountant (ThermoFisher P36980) and imaged with a SP8 inverted confocal microscope (Leica) with 20x objective across z stacks. Images were processed with ImageJ.

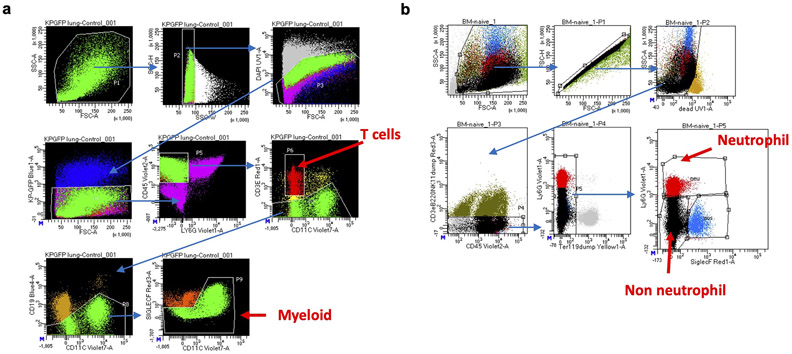

scRNA-seq

For all mouse scRNA-seq analyses, three mice were analyzed per condition. For scRNA-seq of KP tumor bearing Il4ra+/+ and Il4raΔMs4a3 lungs, T cells and myeloid cells were separately sorted and barcoded with 10x Cellplex oligos before being encapsulated using the 10X Chromium 3’ v3 chemistry kit according to manufacturer’s instructions. Cells sorted from the same genotype were barcoded and pooled into individual lanes. A total of 12,000 cells were loaded per lane from each condition. For scRNA-seq of BM of naïve, tumor-bearing and IL-4c treated mice, BM myeloid cells and were sorted for sequencing. Due to their abundance in BM, neutrophils were separately sorted and then recombined back with the above cells at a 1:10 ratio. Sorting strategies for all sequencing experiments can be found in Extended Data Fig. 8a and Extended Data Fig. 8b. Cells sorted from the same genotype were barcoded and pooled into individual lanes. A total of 12,000 cells were loaded per lane from each condition. All sequencing libraries were prepared per manufacturer instructions. After stringent cDNA and sequencing library quality control with the CybrGreen qPCR library quantification assay, samples were sequenced at a depth of 100 million reads per library with a 75-cycle kit on an Illumina Nextseq 550. For human scRNA-seq analysis, our previously published dataset of leukocytes from tumor and adjacent nLung of 35 treatment-naïve NSCLC patients8 was queried.

scRNA-seq Downstream Analysis

Gene expression reads were aligned to the mm10 reference transcriptome followed by count matrix generation using the default CellRanger 2.1 workflow, using the ‘raw’ matrix output. Following alignment, barcodes matching cells that contained > 500 unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) were extracted. From these cells, those with transcripts > 25% mitochondrial genes were filtered from downstream analyses. For lung immune cells sorted for scRNA-seq in Figure 1, a total of 7400 myeloid cells (4171 Il4ra+/+ and 3229 Il4raΔMs4a3) and 9255 T cells (5735 Il4ra+/+ and 3520 Il4raΔMs4a3) passed quality control and were analyzed. For BM myeloid cells and progenitors sorted for scRNA-seq in Figure 2, a total of 22168 cells passed quality control and were analyzed from the following conditions (3 mice per condition): Naïve- 2840, 2574, and 2276 cells per mouse; IL-4c- 3399, 2965, and 2930 cells per mouse; KP- 1963, 1413, 1808 cells per mouse. Matrix scaling, logarithmic normalization, and batch correction via data alignment through canonical correlation analysis, and unsupervised clustering using a K-nn graph partitioning approach were performed as previously described12. Differentially expressed genes were identified using the FindMarkers function (Seurat). Mean UMI were imputed to determine logarithmic fold changes in expression between cell states to further the analysis of markers of interest. Gene set enrichment analysis was performed using the Enrichr database. Other R packages used include: scDissector v.1.0.0; shiny v.1.7.; ShinyTree v.0.2.7; heatmaply v.1.3.0; plotly v.4.10.0; ggvis v.0.4.7; ggplot2 v.3.3.5; dplyr v.1.0.7; Matrix v.0.9.8; seriation v.1.3.5. For bar graphs with curated gene lists in Fig. 1d and Extended Data Fig. 1g, genes which had less than 1UMI in any sample were first excluded. Then the average UMI ratio of Il4ra+/+ over Il4raΔMs4a3 was calculated and filtered to Log2FC >0.7 or <−0.7.

Human Subjects

Informed consent was obtained from all study participants. Patients with NSCLC that had progressed on standard of care PD-1 or PD-L1 agents were enrolled into a clinical trial in which patients received three doses of dupilumab administered subcutaneously (at standard 600mg loading dose, and subsequently 300mg every three weeks, for a total of 3 treatments) in conjunction with continued checkpoint blockade. Patients had to have 1 or fewer intervening lines of therapy between PD-(L)1 blockade, an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 2 or better, adequate organ function, and cannot have received chemotherapy within 14 days prior to the start of therapy. Patients with immunodeficiencies, active autoimmune disease or with active viral or bacterial infections were not permitted to enroll. Patient has to be willing to undergo pre-treatment core needle biopsies of their tumor, and repeat biopsies after 4 weeks on treatment (one week following the second administration of dupilumab). Blood was drawn at routine intervals—on the first day of administration, as well as day 4, Day 8, Day 15, Day 22 and Day 43 following the start of therapy, and plasma and PBMCs were isolated and cryopreserved for batched analysis. In depth immune phenotyping of tumor and blood, at the proteomic and transcriptomic was prespecified within the trial, which was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Mount Sinai Hospital in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The trial was designed as a Phase 1b/2a clinical trial in which Phase 1b constitutes a set-dose open-label run-in cohort of 6 patients with the primary objective of defining safety and tolerability of this novel combination. Secondary endpoints include best overall response (BORR) as per RECIST v1.1 criteria, progression-free survival (PFS) overall survival (OS) and duration of response (DoR). Plasma was collected from patients at indicated timepoints and analyzed by the 96-analyte inflammation panel Olink assay per manufacturer’s instructions. All Olink data are reported as Linearized Normalized Protein Expression (NPX), per manufacturer’s instructions. Olink assay was performed by trained staff at the Human Immune Monitoring Center at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

Study participants

We report analysis of specimens from the first 6 patients that make up the Phase 1b run-in for the clinical trial. The patients were evenly split between adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma, all were male, 5/6 were smokers, all but one patient had received prior chemotherapy with or without radiation, and immunotherapy was the most recent treatment received at the time of enrollment. No patients experienced treatment related adverse events or dose limiting toxicities as described in the protocol. See Supplementary Table 5 for additional clinical meta data.

Statistics

In all cases where we used parametric statistical tests (ie Student’s t-test) we first confirmed that the data were normally distributed using the Anderson-Darling test, D’Agostino and Pearson test, Shapiro-Wilk test, and Klomogorov-Smirnov test, all with an alpha of 0.05. If the data were not normal by any of these tests, then a nonparametric test was used. In cases where more than two groups were compared, an ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey’s test was performed to determine significance. One statistical outlier was removed in Figs. 1c, 1f, 2e, and 4a with a Grubbs test (Graphpad). For Fig. 1a and Supplementary Table 1, DEGs were run through the Enrichr pipeline59 and adjusted P values were determined by Fisher’s Exact Test. For Extended Data Fig. 5a, DEGs were run through the Metascape pipeline60 and adjusted P values were determined by Fisher’s Exact Test.

Extended Data

Extended Data Figure 1. A role for myeloid IL-4Rα expression in NSCLC development.

(a-b) Tumor burden in KP-lung tumor (a) and B16 melanoma metastasis (b) bearing mice treated with isotype or αIL-4 antibodies. Images at 20X. n=4 mice per group in panel a; n=5 mice per group in panel b. Representative of two independent experiments. (c) KP lung tumor burden in Il4raΔDC, Il4raΔRTM, and Il4raΔT mice normalized to WT littermate controls (n=8-24 mice per group). n=24, 22, 16, 9, 8, 11 mice per group. Pooled from three independent experiments. (d) Number of viable KP cells at indicated seeding values after 5 days of culture in complete media with indicated concentrations of IL-4. Two technical replicates per timepoint. Representative of two independent experiments.

(e) IL-4Rα expression in indicated myeloid populations of tumor-bearing Il4ra+/+ and Il4raΔMs4a3 mice, normalized to mean MFI of Il4ra+/+ group. n=15 Il4ra+/+ mice and 9 Il4raΔMs4a3 mice for neutrophils; 15 Il4ra+/+ mice and 10 Il4raΔMs4a3 mice for monocytes, RTMs, and DCs; 10 Il4ra+/+ mice and 7 Il4raΔMs4a3 mice for mo-macs, and 10 Il4ra+/+ mice and 8 Il4raΔMs4a3 mice for GMPs. Pooled from three independent experiments. (f) KP tumor burden in Ms4a3-Cre heterozygous mice bearing no floxed allele (n=11) compared to age-matched WT controls (n=9). Scale bar=2mm. One experiment. (g) Number of circulating blood neutrophils in naïve and KP tumor-bearing Il4ra+/+ and Il4raΔMs4a3 mice. n=3, 3, 15, 17 mice per group. Pooled from 3 independent experiments. (h) Number of lung myeloid populations in naïve and KP tumor-bearing Il4ra+/+ and Il4raΔMs4a3 mice. n=3, 3, 7, 7 mice per group. Representative of two independent experiments. Unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test for all statistical analyses shown. Data are mean ± s.d.

Extended Data Figure 2. Transcriptional and histological analyses of lung tumors in Il4ra+/+ and Il4raΔMs4a3 mice.

(a) Heatmap showing myeloid scRNA-seq clusters (y axis) along with cluster-defining genes (x axis). (b) Gene expression in indicated lung immune clusters of tumor-bearing Il4ra+/+ and Il4raΔMs4a3 mice (n=3 mice per group). One experiment. (c) Average number of CD4 T cells per mm2 of tumor in KP lesions of Il4ra+/+ (n=13) and Il4raΔMs4a3 (n=10) mice. Representative of three independent experiments. (d) Heatmap showing scRNA-seq clusters from sorted T cells (left) and fine-clustered CD4 (middle) and CD8 (right) T cells (y axis) along with cluster-defining genes (x axis). One experiment. (e) Proportion of the “Exhausted CD8” and “Effector CD8” clusters from panel d among all lung T cells in Il4ra+/+ and Il4raΔMs4a3 mice (n=3 mice per group). One experiment. Data are mean (b), median (c), or mean ± s.d (e). Mann-Whitney test (c) or unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test (e).

Extended Data Figure 3. IL-4Rα expression in myeloid populations of tumor-bearing Il4raΔCx3cr1 and Il4raΔS100a8 mice compared to littermate controls.

Representative flow cytometry histograms showing IL-4Rα protein expression in indicated immune populations from tumor-bearing Il4raΔCx3cr1 and Il4raΔS100a8 mice along with WT littermate controls, normalized to mean MFI of WT group. n=14 Il4ra+/+ and 10 Il4raΔCx3cr1 mice; 10 Il4ra+/+ and 10 Il4raΔS100a8 mice for neutrophils; 11 Il4ra+/+ and 10 Il4raΔS100a8 mice for monocytes; mo-macs, and RTMs; 10 Il4ra+/+ and 9 Il4raΔS100a8 mice for GMPs. Pooled from three independent experiments. Grey histogram = Isotype control. Unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test. Data are mean ± s.d.

Extended Data Figure 4. No evidence for Th2-biased immune microenvironment in NSCLC.

(a) Expression of IL4 in matched NSCLC tumors and adjacent normal tissue from TCGA database. (b) Expression of indicated genes (y axis) across T cell clusters (x axis) from Leader et al human NSCLC scRNA-seq dataset. (c) IL-4 production after PMA/I stimulation (left) and IL4-eGFP expression in CD4 T cells (middle) and total live cells (right) from lungs of naïve and tumor-bearing mice. n=5 mice per group for IL-4POS lung CD4 T cells, 10 naïve and 10 tumor-bearing mice for IL4-eGFPPOS CD4 T cells and total IL4-eGFPPOS cells. Representative of two independent experiments. (d) IL-4 production by lung-seeding KP cells in vivo after PMA/I stimulation. One experiment. Unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test. Data are mean ± s.d.

Extended Data Figure 5. IL-4 controls myelopoiesis.

(a) Top pathways enriched among DEGs from indicated lung monocyte populations in tumor-bearing Il4ra+/+ and Il4raΔMs4a3 mice. (b) Flow cytometry plots showing CD45NEGGFPPOS cells in lung and BM of mice bearing GFP-expressing KP tumors. (c) Number of GMPs per femur of naïve mice or KP tumor-bearing mice treated with isotype or αIL-4 antibodies. n=5, 7, 7 mice per group. Representative of two independent experiments. (d) Number of Ly6cNEG GMP, GP, and cMoP progenitors in BM of KP tumor-bearing Il4ra+/+ and Il4raΔMs4a3 mice. n=14 Il4ra+/+ and 12 Il4raΔMs4a3 mice for Ly6cNEG GMPs and GPs and 6 Il4ra+/+ and 7 Il4raΔMs4a3 mice for cMoPs. Pooled from two independent experiments. (e) Methocult differentiation assay of Il4ra+/+ and Il4raΔMs4a3 BM. n=4 technical replicates per condition. Representative of two independent experiments. (f) Representative gating strategy for BM progenitor populations in vehicle and IL-4c treated mice. (g) Total BM cellularity from legs of WT mice treated with vehicle or IL-4c (n=10 mice per group). Pooled from two independent experiments. (h) Number of GMPs per leg of mice treated with vehicle or IgG1κ antibodies. n=5 mice per group. One experiment (i) Number of GMP per leg of Il4ra+/+ (WT) or Il4raΔMs4a3 (KO) mice treated with vehicle or IL-4c. n=3, 3, 4 mice per group. One experiment. (j) Expression of macrophage polarization markers in BMDMs differentiated under indicated conditions. Representative of two independent experiments. (k) scRNA-seq of BM myeloid cells and myeloid progenitors from naïve, IL-4c treated, and KP tumor-bearing mice. Heatmap shows indicated clusters (y axis) and cluster-defining genes (x axis). (l) Total number of genes up or downregulated in each condition relative to naïve in indicated BM scRNA-seq clusters. One experiment. Fisher’s Exact Test (a), Unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test (c,d,g,h), or One-way ANOVA with post hoc Tukey’s test (i). Data are mean ± s.d. Lin = CD3e, B220, Ter-119, CD11b, Ly6g, NK1.1.

Extended Data Figure 6. Dynamics of Type 2 granulocytes in BM.

(a) Flow cytometry strategy for BM populations analyzed in Fig. 3a. (b) Percentage of IL4-eGFPPOS cells among indicated BM populations in WT KP tumor-bearing mice. n=5 mice. Representative of two independent experiments. (c) Number of BM eosinophils and basophils in naïve and tumor-bearing WT mice. n=5 mice per group. Representative of two independent experiments. (d) Number of CD45-IV negative eosinophils and basophils in lungs of tumor-bearing WT mice. n=5 mice per group. Representative of two independent experiments. (e) Representative microscopy of BM of tumor-bearing mice showing colocalization of basophils (green) with hematopoietic progenitors (red) (representative of 3 mice). (f) Basophil depletion efficiency in indicated organs after using αFCER1A (left) or αCD200R3 (right) depletion strategies n=5 isotype and 5 αFCER1A-treated mice; 7 isotype and 5 αCD200R3-treated mice for BM; 6 isotype and 3 αCD200R3-treated mice for blood. Unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test. Data are mean ± s.d.

Extended Data Figure 7. Gating Strategies.

(a) Flow cytometry gating strategy for indicated mouse immune populations. Note “basophil alternative gating” using CD200R3 was used in experiments where mice were treated with αFCER1A antibodies. (b) CyTOF gating strategy for human whole blood.

Extended Data Figure 8. Sorting Strategies.

(a-b) Sorting strategies for scRNA-seq experiments presented in Figure 1 (a) and Figure 2 (b).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank members of the Merad Laboratory for thoughtful feedback on the manuscript, members of the Center for Comparative Medicine and Surgery at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai for animal husbandry, members of the Human Immune Monitoring Center at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai for patient sample processing and scRNA-seq assistance, and all patients who participated in this study and their families.

MM was partially supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants CA257195, CA254104 and CA154947. NML was supported by the Cancer Research Institute / Bristol Myers Squibb Irvington Postdoctoral Research Fellowship to Promote Racial Diversity (Award No. CRI3931). SH was supported by the National Cancer Institute predoctoral-to-postdoctoral fellowship K00 CA223043. RM was supported by the 2021 AACR-AstraZeneca Immuno-oncology Research Fellowship, Grant Number 21-40-12-MATT. OCO was supported by the Cancer Research Institute Irvington Postdoctoral Research Fellowship (Award No. CRI3617). BDB was partially supported by NIH grant U01CA282114. SG was partially supported by NIH grants CA224319, DK124165, CA263705 and CA196521.

Footnotes

DATA AND CODE AVAILABILITY

Code for generating specific figures will be provided by the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Raw RNA-seq data has been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) under accession code GSE245236.

CT images of patients participating in the clinical trial can be downloaded via Amazon Web Services at the following link: https://himc-project-data.s3.amazonaws.com/lamarche_2023/lamarche_image_data.tar.gz?AWSAccessKeyId=AKIAV3HQ5KORNL3V6W43&Signature=N32aM3ouC5FwYvbMvA7eJJd3V4k%3D&Expires=1698691876

COMPETING INTERESTS

MM and TUM have submitted a patent related to the clinical trial described in this study. MM serves on the scientific advisory board and holds stock from Compugen Inc., Myeloid Therapeutics Inc., Morphic Therapeutic Inc., Asher Bio Inc., Dren Bio Inc., Oncoresponse Inc., Owkin Inc., Larkspur Inc., and DEM BIO, Inc. MM serves on the scientific advisory board of Innate Pharma Inc., OSE Inc., and Genenta Inc. MM receives funding for contracted research from Regeneron Inc. and Boerhinger Ingelheim Inc. TUM has served on Advisory and/or Data Safety Monitoring Boards for Rockefeller University, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Abbvie, Bristol-Meyers Squibb, Boehringer Ingelheim, Atara, AstraZeneca, Genentech, Celldex, Chimeric, Glenmark, Simcere, Surface, G1 Therapeutics, NGMbio, DBV Technologies, Arcus, and Astellas, and has research grants from Regeneron, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck, and Boehringer Ingelheim. DBD sits on the advisory boards of Astrazeneca, Mirati Therapeutics, Summit Therapeutics, and G1 Therapeutics. SG reports other research funding from Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Genentech, Regeneron, and Takeda, not related to this study.

References

- 1.Barry ST, Gabrilovich DI, Sansom OJ, Campbell AD & Morton JP Therapeutic targeting of tumour myeloid cells. Nat Rev Cancer 23, 216–237 (2023). 10.1038/s41568-022-00546-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Castro M. et al. Dupilumab Efficacy and Safety in Moderate-to-Severe Uncontrolled Asthma. The New England journal of medicine 378, 2486–2496 (2018). 10.1056/NEJMoa1804092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rabe KF et al. Efficacy and Safety of Dupilumab in Glucocorticoid-Dependent Severe Asthma. The New England journal of medicine 378, 2475–2485 (2018). 10.1056/NEJMoa1804093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Simpson EL et al. Two Phase 3 Trials of Dupilumab versus Placebo in Atopic Dermatitis. The New England journal of medicine 375, 2335–2348 (2016). 10.1056/NEJMoa1610020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beck KM, Yang EJ, Sekhon S, Bhutani T & Liao W Dupilumab treatment for generalized prurigo nodularis. JAMA dermatology 155, 118–120 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herbst RS, Morgensztern D & Boshoff C The biology and management of non-small cell lung cancer. Nature 553, 446–454 (2018). 10.1038/nature25183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lavin Y. et al. Innate Immune Landscape in Early Lung Adenocarcinoma by Paired Single-Cell Analyses. Cell 169, 750–765 e717 (2017). 10.1016/j.cell.2017.04.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leader AM et al. Single-cell analysis of human non-small cell lung cancer lesions refines tumor classification and patient stratification. Cancer Cell 39, 1594–1609 e1512 (2021). 10.1016/j.ccell.2021.10.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Casanova-Acebes M. et al. Tissue-resident macrophages provide a pro-tumorigenic niche to early NSCLC cells. Nature, 1–7 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Loyher PL et al. Macrophages of distinct origins contribute to tumor development in the lung. J Exp Med 215, 2536–2553 (2018). 10.1084/jem.20180534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maier B. et al. A conserved dendritic-cell regulatory program limits antitumour immunity. Nature 580, 257–262 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park MD et al. TREM2 macrophages drive NK cell paucity and dysfunction in lung cancer. Nat Immunol 24, 792–801 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Loschko J. et al. Absence of MHC class II on cDCs results in microbial-dependent intestinal inflammation. J Exp Med 213, 517–534 (2016). 10.1084/jem.20160062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karasawa K. et al. Vascular-resident CD169-positive monocytes and macrophages control neutrophil accumulation in the kidney with ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Am Soc Nephrol 26, 896–906 (2015). 10.1681/ASN.2014020195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee PP et al. A critical role for Dnmt1 and DNA methylation in T cell development, function, and survival. Immunity 15, 763–774 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu Z. et al. Fate Mapping via Ms4a3-Expression History Traces Monocyte-Derived Cells. Cell 178, 1509–1525 e1519 (2019). 10.1016/j.cell.2019.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Horton BL et al. Lack of CD8+ T cell effector differentiation during priming mediates checkpoint blockade resistance in non–small cell lung cancer. Sci Immunol 6 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burger ML et al. Antigen dominance hierarchies shape TCF1(+) progenitor CD8 T cell phenotypes in tumors. Cell 184, 4996–5014 e4926 (2021). 10.1016/j.cell.2021.08.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]