Abstract

Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases (AARS) and tRNAs translate the genetic code in all living cells. Little is known about how their molecular ancestors began to enforce the coding rules for the expression of their own genes. Schimmel et al. proposed in 1993 that AARS catalytic domains began by reading an ‘operational’ code in the acceptor stems of tRNA minihelices. We show here that the enzymology of an AARS urzyme•TΨC-minihelix cognate pair is a rich in vitro realization of that idea. The TΨC-minihelixLeu is a very poor substrate for full-length Leucyl-tRNA synthetase. It is a superior RNA substrate for the corresponding urzyme, LeuAC. LeuAC active-site mutations shift the choice of both amino acid and RNA substrates. AARS urzyme•minihelix cognate pairs are thus small, pliant models for the ancestral decoding hardware. They are thus an ideal platform for detailed experimental study of the operational RNA code.

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

Introduction

Two classes of aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase (AARS)•tRNA cognate pairs (1) accomplish translation of all genetic codes. AARS act as AND gates, forming a covalent bond between the appropriate amino acid and a tRNA with an appropriate codon if and only if both amino acid and tRNA are correct. The codon, in turn, is the amino acid's symbolic representation on the ribosome. The resulting covalent bond in aminoacylated tRNA thus represents the essential symbolic assignment that translates the code. In this way, the earliest AARS also created molecular computation. Many of these ideas became well-established soon after AARS (2,3) and tRNAs (4–6) were first characterized in the middle of the last century.

The role of ancient proteins in enabling Nature to exploit the bar-coding function of nucleic acids remains quite obscure. The many reasons for this include the relative ease of experimental studies of DNA and RNA. Further, the far-reaching implications of base-pairing are much more evident even to lay persons than any aspect of the study of proteins. RNAs can also modestly speed up various hydrolytic reactions. These factors create the pervasive idea that RNA catalysts self-replicated first and produced variants with crude abilities needed to launch genetic coding. Indeed, ribozymes have been described that activate amino acids (7–9) and that acylate tRNA with activated amino acids (10,11), but not both reactions. However, even if this picture were valid, there are strong arguments why there is no viable path from such an RNA world to the way translation occurs in biology (12).

The central role of the AARS implies that an intermediate level of molecular coding arises from details of AARS–tRNA recognition. That problem was highlighted by de Duve (13), who suggested the term ‘paracodon’ for the bases that determine AARS recognition of cognate tRNAs. None of the attempts to pursue how Nature built the coding table (14–17) take that recognition into account.

Little is known of the ancestry of AARS•tRNA cognate pairs. We cannot reconstruct events exactly as they occurred four billion years ago. We can, however, use what is known about contemporary systems to make testable guesses. Experimental tests then raise or lower the posterior probability of such hypotheses. That approach helps build an approximate understanding of such remote events. An attractive proposal was advanced by Schimmel, Giegé and others (18). The dual domain structures of AARS and tRNAs suggested to them that primordial translation systems need not have recognized the tRNA anticodon stem–loop by the AARS anticodon-binding domain (Figure 1A). AARS catalytic domains might, instead, have recognized the paracodon using an ‘operational RNA code’. That proposal built on early work by Zachau (19) who studied aminoacylation of tRNAPhe fragments by phenylalanyl-tRNA synthetase (PheRS). It gained support from successful aminoacylations by full-length AARS of minihelices lacking the dihydrouridine, variable, and anticodon loops and consisting only of the tRNA acceptor stem and TΨC loop (20–24).

Figure 1.

The operational code hypothesis and a molecular system for experimental studies. (A) A Class I molecular system for experimental study of the operational code. The LeuAC urzyme (dark teal) is adapted from the crystal structure of P. horikoshii LeuRS complexed to its cognate tRNALeu (PDB ID 1WC2). The TψC tRNALeu minihelix is a hybrid constructed from the 3′-terminal seven residues of tRNALeu from 1WC2 and the tRNAArg minihelix from PDB ID 4X4T. The scale is enhanced to allow identification of residues that contain the operational code, highlighted in B and by the ellipse in (C). (B) Schematic diagram of the top of the acceptor stem, showing the numbers of each base contributing to the operational code. Base 73, D, is known as the Discriminator base. (C) AARS and tRNA components of contemporary AARS•tRNA cognate pairs. Both molecules have two domains that interact in a bidentate fashion—the AARS catalytic domain and tRNA acceptor-TψC stem (blue) and the AARS anticodon-binding domain and tRNA anticodon-D-stem biloop (green). The enzyme structure is from 1WC2, oriented approximately as in (A). The surface (deep teal) surrounds the LeuAC urzyme and spheres mark leucyl-5′sulfamoyl AMP.

No one attempted to formulate elements of the operational code at the time. Much more recently, we found relationships between amino acid physical chemistry (25–28) and bases in the tRNA acceptor stem (29,30) that correctly identified the groove chosen by the cognate AARS. These nested predictors were the β-coefficients for a regression model. Predictors were derived by assigning two bits, each, to bases −1 (tRNAHis only), 1, 2, 72 and 73 in the acceptor stem. They are digital, in the sense that their regression coefficients are not continuous but are either 1 versus 0 or −0.5 versus 0.5 (31). As an example, bits assigned to bases 2 and 73 suffice to identify the groove recognized by tRNAs for 13 amino acids (C, E, L, M, Q, R W, Y in Class I; A, D, G, S, F in Class II). That work was based on an early database (30) that has been extensively updated (32). The updated database reveals limited variation in the acceptor stem bases, without materially altering the consensus bases originally chosen.

These simple rules clarified how Class I and II AARS probably recognize exclusive sets of tRNA substrates by selecting either the minor (Class I except TrpRS, TyrRS) and/or major (Class II except PheRS) acceptor stem groove (31,33). The rules also suggested why Class I tRNA 3′-DCCA termini form a hairpin but Class II acceptor stems do not (31,33). Together with previous work (25,26) the groove-selection rules completed a detailed elaboration of an operational code. Acceptor-stem bases also mimic codon-anticodon base pairing (31). Thus, the paracodon was indeed a likely ancestor to the anticodon, which today is ∼75 Å away from the CCA 3′ terminus (24,34).

The resulting challenge was then how to test these ideas experimentally. The chief barrier to experimental study of how the paracodon might have functioned in the early evolution of the genetic coding table is the lack of model AARS•tRNA cognate pairs. AARS urzymes are minimal excerpts of AARS catalytic domains that retain the full range of their catalytic properties, albeit at diminished rates and with considerable substrate promiscuity. Urzymes studied so far all catalyze acylation of full-length tRNA (35–37). But do they also catalyze minihelix acylation? The combination of an AARS urzyme and its cognate tRNA minihelix (Figure 1A) approximate the minimal elements of both full-length AARS and tRNA (Figure 1B). They thus seem an ideal system for studies of how amino acid and tRNA specificities evolved as Nature assembled the coding table.

Leucyl-tRNA synthetases (LeuRSs) are not generally among those that can aminoacylate TΨC-minihelices (38). The recently characterized LeuRS urzyme, LeuAC (35,39), represents roughly 13% of the full-length LeuRS. Its cognate minihelix represents 40% of full-length tRNALeu. We demonstrate here that LeuAC can acylate the cognate minihelix consisting of the acceptor stem and TψC stem-loop of Pyrococcus horikoshii tRNALeu. Full-length P. horikoshii LeuRS strongly prefers its proper substrates, tRNALeu and leucine. Further, we recently found significant coupling in full-length (FL) LeuRS between the two active-site signatures that define Class I, HVGH and KMSKS. We therefore compare here amino acid activation and RNA acylation by active-site variants (AVGA, AMSAS, and AVGA*AMSAS). These combinatorial variants eliminate some, or all of the modern catalytic residues, histidine and lysine. The corresponding thermodynamic cycles showed that the two signatures potentiate each other in FL LeuRS, but are antagonistic in LeuAC (39). MinihelixLeu and isoleucine are actually both better substrates for LeuAC than are tRNALeu and leucine. The LeuAC AVGA mutant outperforms other variants with both substrates. These aspects of the LeuAC•minihelixLeu cognate pair thus reveal much about the origins of genetic coding. Such pairs clear the way for experimental study of how reconstructed ancestral cognate pairs implemented the operational RNA code.

Materials and methods

Experimental design

To the extent possible, we used a full 25 factorial design to characterize all possible binary combinations of each experimental variable. Factorial designs afford optimally balanced access to main effects and higher-order interactions between variables. With few exceptions (i.e. the single turnover measurements summarized in Supplementary §D and Supplementary Tables S2 and S3) assays involved at least three replicates, often repeated on multiple occasions as the work proceeded, to detect and correct for decayed activities of both enzymes and RNA substrates.

tRNALeu and TΨC-minihelixLeu preparation

A plasmid encoding the P. horikoshii tRNALeu (UAG anticodon) was synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies and used as template for PCR amplification of the tRNA and upstream T7 promoter and downstream Hepatitis Delta Virus (HDV) ribozyme. The PCR product was used directly as template for T7 transcription. Following a 4-hour transcription at 37°C the RNA was cycled five times (90°C for 1 min, 60°C for 2 min, 25°C for 2 min) to increase the cleavage by HDV. The tRNA was purified by urea PAGE and crush and soak extraction. The tRNA 2′-3′ cyclic phosphate was removed by treatment with T4 PNK (New England Biolabs) following the manufacturer's protocol. The tRNA was then phenol chloroform isoamyl alcohol extracted, filter concentrated, aliquoted, and stored at −20°C.

The original sequence information for composing and designing Pyrococcus horikoshii TΨC-minihelix-Leu was based on the mature P. horikoshii tRNA-Leu, the tRNA sequence was collected from the complement strand of the genomic sequence of P. horikoshii (OT3, GB# BA000001.2, between nucleotides 1448081 and 1448168). The designated minihelix sequence was obtained by combining the acceptor stem sequence including DCCA with the TΨC -stem-loop according to Schimmel (40). A plasmid harboring the minihelix, an upstream T7 promoter, and downstream Hepatitis Delta Virus (HDV) ribozyme was acquired from previous co-worker Jessica Elder. To reduce challenges posed by the high GC content in the stem portion of minihelix during the preparation, we implemented the Phi29 DNA polymerase-mediated isothermal amplification approach according to the manufacture's protocol (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA). After the purification of the product from isothermal amplification, T7 transcription was carried out. Following a 4–6-hour transcription at 37°C, the reaction mixture was subjected to urea PAGE fractionation, crush, and soak extraction. After 2′-3′ cyclic phosphate removal by T4 PNK, the minihelix RNA was then phenol chloroform isoamyl alcohol extracted, filter-concentrated, quantitated and aliquoted, and stored at −80°C.

Expression and purification of LeuAC and is variants

We expressed LeuAC and its AVGA, AMSAS, and AVGA*AMSAS double mutant variants as MBP fusions from pMAL-c2x in BL21Star (DE3) (Invitrogen). Cells were grown, induced, harvested, and lysed after resuspension in buffer (20 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 1 mM EDTA, 5 mM β-ME, 17.5% glycerol, 0.1% NP40, 33 mM (NH4)2SO4, 1.25% glycine, 300 mM guanidine hydrochloride) plus cOmplete protease inhibitor (Roche). Crude extracts were pelleted at 4°C 30 min 15k rpm to remove insoluble material. The extract was then diluted 1:4 with Optimal Buffer and loaded onto equilibrated Amylose FF resin (Cytiva). The resin was washed with five column volumes of buffer and the protein was eluted with 10 mM maltose in Optimal Buffer. Fractions containing protein were concentrated and mixed to 50% glycerol and stored at −20°C. All protein concentrations were determined using the Pierce™ Detergent-Compatible Bradford Assay Kit (Thermo Scientific). Active-site titration was used as described (39) to determine active fractions. Experimental assays were performed with samples cleaved by tobacco etch virus (TEV) protease, purified as described (41). Purity and cleavage efficiency were determined by running samples on PROTEAN®ฏ TGX (Bio-RAD) gels and active fractions for all variants were measured as described in the next section.

Single turnover active-site titration assays

Active-site titration assays were performed as described (42,43) with the exception that 32P-ATP was labeled in the α position in order to follow the time-dependence of all three adenine nucleotides. 3 μM of protein was added to 1× reaction mix (50 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 10 mM MgCl2, 5 μM ATP, 50 mM amino acid, 1 mM DTT, inorganic pyrophosphatase, and α-labeled [32P] ATP) to start the reaction. Timepoints were quenched in 0.4 M sodium acetate 0.1% SDS and kept on ice until all points had been collected. Quenched samples were spotted on TLC plates, developed in 850 mM Tris, pH 8.0, dried and then exposed for varying amounts of time to a phosphor image screen and visualized with a Typhoon Scanner (Cytiva). The ImageJ measure function was used to quantitate intensities of each nucleotide. The time-dependent of loss (ATP) or de novo appearance (ADP, AMP) of the three adenine nucleotide phosphates were fitted using the nonlinear regression module of JMP16PRO™ to equation (1):

|

(1) |

where kchem is the first-order rate constant, kcat is the rate of turnover, A is the amplitude of the first-order process, and C is an offset.

For [ATP] decay curves, the fitted A value estimates the burst size, n, directly as n = A*[ATP]/[Enzyme]. C gives n = (1 – C) * [ATP]/[Enzyme]. For exponentially increasing concentrations of product, the situation reverses, and n = (1 – A) * [ATP]/[Enzyme] and n = C*[ATP]/[Enzyme]. These approximations are justified by the very small variance of multiple estimates.

Aminoacylation assays

We determined the active fraction of tRNALeu by following extended acylation assays using the AVGA mutant LeuAC until they reached a plateau. That plateau value was 0.43, which we used to compute tRNALeu concentrations in assays with all variants.

Aminoacylations of tRNALeu and its minihelix were performed in 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 10 mM MgCl2, 20 mM KCl, 5 mM DTT with indicated amounts of ATP and amino acids. Desired amounts of unlabeled tRNA—mixed with [α32P] A76-labeled tRNA for assays by LeuAC— were heated in 30 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 30 mM KCl to 90°C for 2 min. The tRNA was then cooled linearly (drop 1°C/30 s) until it reached 80°C when MgCl2 was added to a final concentration of 10 mM. The tRNA continued to cool linearly until it reached 20°C. Michaelis–Menten experiments were performed by repeating these assays at the indicated RNA concentrations. Concentration-dependence fitted to kcat/KM and kcat according to the modified formula introduced by Johnson (44) (Eq. 2) gave improved values in several cases, as reflected in the reduction in both the estimated standard error of the fit and the reduced correlation between the two Michaelis–Menten parameters. Fitting to the modified model also facilitated the elimination of experimental outliers through examining studentized residuals.

|

(2) |

Data processing and statistical analysis

Phosphor imaging screens of TLC plates were densitometered using ImageJ. Data were transferred to JMP16PRO™ Pro 16 via Microsoft Excel (version 16.49), after intermediate calculations. We fitted active-site titration curves to Eqn. (1) using the JMP16PRO™ nonlinear fitting module. R2 values were all >0.97 and most were >0.99. Michaelis–Menten assays were fitted using the nonlinear regression module of JMP16PRO.

Factorial design matrices were processed using the Fit Model multiple regression analysis module of JMP16PRO™, using an appropriate form of equation (3) (45).

|

(3) |

where Yobs is a dependent variable, usually an experimental observation such as a free energy, ΔG‡. β0 is a constant derived from the average value of Yobs, βi and βij are coefficients to be fitted, Pi,j are independent predictor variables from the design matrix, and ϵ is a residual to be minimized. All rates and apparent binding constants, KM, were converted to free energies of activation, ΔG‡(k) = – RTln(k), before regression analysis because free energies are additive, whereas rates are multiplicative. For example, the activation free energy for the first-order decay rate in single-turnover experiments is ΔG‡(kchem).

Multiple regression analyses of factorial designs exploit the replication inherent in the full collection of experiments to estimate experimental variances on the basis of t-test P-values, in contrast to the presenting error bars showing the variance of individual datapoints. Multiple regression analyses reported here also entail triplet experimental replicates, which also enhance the associated analysis of variance.

Results

We describe single-turnover and Michaelis–Menten data for the LeuAC•TΨC-minihelixLeu cognate pair. That evidence shows the LeuAC urzyme to be an excellent partner with the minihelix. We compare all LeuAC active-site variants with both amino acid (Leu, Ile) and RNA (tRNALeu, minihelixLeu) substrates. Kinetic data and burst sizes are given in Supplementary Tables S1–S3.

All variants of full-length LeuRS and its urzyme, LeuAC, catalyze acylation of tRNALeu minihelix

The minihelix sequence (Figure 2A) represents the P. horikoshii tRNALeu (UAG) isoacceptor. Expression from a synthetic gene using the φ29 DNA polymerase increased the yield of in vitro transcription (see Materials and methods). Figure 2B shows time courses for aminoacylation of the minihelix with leucine by LeuAC and the more active AVGA active-site mutant of LeuAC. Similar traces, not shown here, confirm that the AMSAS and Double (AVGA*AMSAS) mutant LeuAC also catalyze acylation of the minihelix. These time courses helped us identify a single fixed time point for Michaelis Menten steady-state kinetic assays described further in Figure 3. Acylation of minihelixLeu by full-length LeuRS was barely detectable at a level ∼105 times less than full-length tRNALeu. However, to our surprise, the minihelix is a well-matched substrate of the LeuAC urzyme (Figure 2B), exhibiting more robust acylation activity.

Figure 2.

Minihelix acylation by FL LeuRS, LeuAC and the LeuAC active-site variants. (A) Sequence of the minihelix derived from the acceptor stem and TΨC stem-loop of P. horikoshii tRNALeu(UAG). Note the extended string of G-C base pairs. Bases bounded by bold squares pose significant new questions discussed further in §4. (B) TLC of acylation time courses for the wild-type LeuAC and its AVGA variant.

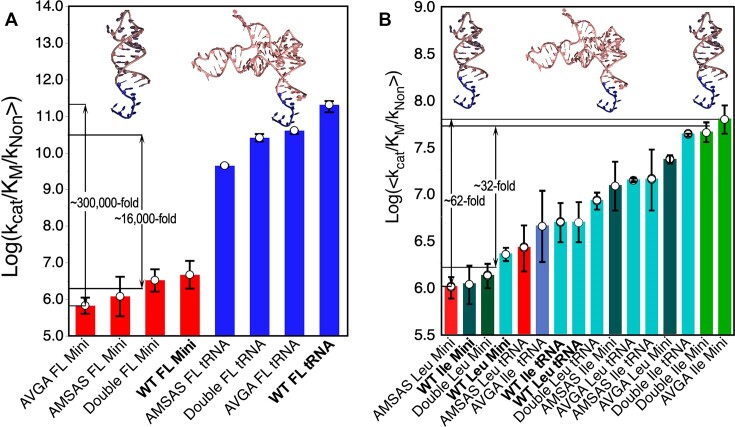

Figure 3.

(A) Histogram of relative rate accelerations for tRNA (blue) and minihelix (red) acylation by FL LeuRS. (B) The corresponding histogram for LeuAC. The vertical axis in (B) spans five orders of magnitude fewer than that in (A). Unlike the sharp distinction in (A), values are evenly spread with respect to active-site mutations, amino acid and RNA substrate. Two distinctive patterns emerge: tRNA substrate values (light teal)) cluster in the middle of the range whereas those for minihelix (dark teal) tend toward the extremes of the range. Within the minihelix values, those containing the AVGA mutation and Ile (green) are ∼60-fold faster than those with HVGH and Leu (red).

We took advantage of a recently prepared set of active-site LeuAC mutants (39) to compare acylation of minihelixLeu and tRNALeu in detail. Previous studies (46,47) suggested that isoleucine was even better than leucine as the amino acid substrate, so we also compared the two amino acids. The comparison between full-length (FL) LeuRS and LeuAC substrate preferences is dramatic (Figure 3). Fully evolved FL LeuRS has an ∼10 000-fold preference for tRNALeu over the minihelix (Figure 3A). In view of the FL LeuRS editing function, we did not measure aminoacylation with isoleucine. The active site variants have a somewhat different pattern from that previously reported (39) because those values were based on initial rates, whereas here we have established saturation with RNA substrate and values are for kcat/KM.

The ancestral LeuAC histogram (Figure 3B) tells a substantially more complex story. It shuffles groups in quite interesting ways. The smaller range of variation along the y-axis (1.8 versus 6 kcal/mol) may be due to the loss of interaction with the tRNALeu D- and variable loops. Curiously, acylation of the minihelix by the four active-site variants is either fastest or slowest. The reason for this is that the minihelix elicits a higher specificity for the amino acid substrate from the different LeuAC variants. Variants with the AMSAS mutation are significantly faster with isoleucine (green bars), and slower with leucine (red bars).

Acylation of tRNALeu with isoleucine by all LeuAC variants tend to cluster in the center of the histogram (Figure 3B; teal bars). For this reason, there is no statistical difference between the minihelix and tRNA substrates. The mean rate enhancements differ by 1.1 ± 2-fold. The rate variations in Figure 3B arise entirely from differences between the four LeuAC active-site mutants and their substrate preferences. We have noted (39) that alanine mutations of the HVGH and KMSKS catalytic signatures contribute in opposite ways to catalysis by LeuAC. Thus, the most active enzyme has the AVGA mutation and the WT KMSKS sequence. These differences impact amino acid substrate selection. The minihelix RNA substrate greatly magnifies these effects.

We dissect the various patterns in the LeuAC histogram further in the following sections.

The TΨC minihelix is a much better RNA substrate for LeuAC than tRNALeu

Isoleucine concentration-dependent aminoacylation assays exhibited saturation behavior for all variants with minihelixLeu. Significant variation in the catalytic proficiencies of the four LeuAC variants makes it hard to simplify the comparison between the two RNA substrates. For that reason, we fitted triplicate assays for both substrates individually to Johnson's modified steady state formula (Eq. (2); (44)) and used plots of the Studentized residuals for regression of the observed to fitted data to identify possible outliers. In this manner, we eliminated 2–3 outliers from the 84 datapoints for each substrate.

Data for aminoacylation of the two RNA substrates by the AVGA LeuAC variant are plotted and fitted in Figure 4. The visual comparison is striking. MinihelixLeu saturates at a higher value of kcat, with a lower KM. The estimate for the apparent second-order rate constant for minihelixLeu is thus 13-fold higher than that for full-length tRNALeu. Although neither RNA substrate shows saturation, thus strongly coupling the values of kcat and KM, the β/σ ratios obtained fitting the Johnson (44) parameters kcat/KM and kcat suggest there is some significance to these values. The estimated standard deviations from the two tables suggest that three of the four fitted parameters are statistically significant. The KM for tRNALeu is so high that saturating concentrations were impractically high.

Figure 4.

Steady-state kinetic analysis of aminoacylation with isoleucine of tRNALeu and its minihelix by the AVGA LeuAC variant. Gray data points (small circles) indicate the experimental noise, which is comparable for the two experiments. Large black circles are calculated using the fitted Michaelis–Menten parameters for each RNA substrate below the plots. KM values were derived from kcat/kcat/KM.

Isoleucine is a better amino acid substrate than leucine for LeuAC

We previously reported that the LeuAC urzyme has a promiscuous amino acid specificity spectrum; specifically, it prefers both isoleucine and methionine to leucine as amino acid substrate (48). In view of the relatively weak catalytic proficiency of AARS urzymes, we wanted to optimize the signal to noise in related work by using the best amino acid for those studies. So, we first verified that earlier observation (Figure 5). Combinatorial mutagenesis of the HVGH and KMSKS active-site signatures had previously provided a valuable experimental system for such a comparison (39). We use it here to demonstrate how much better a substrate Ile is than Leu.

Figure 5.

Isoleucine is a better amino acid substrate for LeuAC than leucine. (A) Combinatorial mutagenesis validates earlier evidence that Ile is a better substrate than Leu by more than 2 kcal/mol (the β coefficient in C is –2.22). Y-coordinates are observed values; X-coordinates are computed using the coefficients in (C) from the multiple regression formula, Eq. (3). Data points are ΔG‡(kcat/KM) for aminoacylation of the TΨC minihelix, so faster values are to the lower left. Empty symbols are for leucine. Colors differentiate the different LeuAC variants. Arrows highlight conclusions drawn from the β coefficients in (C). The difference between the mean values for Leu vs Ile are on the left and between HVGH versus AVGA LeuAC on the right. (B) Studentized residual values are all <4, hence there are no outliers. (C) Table of regression coefficients (β), standard deviations (σ), and Student t-tests and P-values. (D) 3D Plots help in interpreting the three two-way interaction effects in (C). Residuals at each corner accompany the green surfaces and highlight that the AVGA mutation accentuates the preference for isoleucine.

Transformation of the activation free energies of properly chosen combinatorial mutants into a thermodynamic cycle can uncover subtle variations in the catalytic properties of enzymes (39,49). These are especially interesting here, because of the two-way interactions between the amino acid substrate and the active site composition (Figure 5C). It is worth unpacking these here for the benefit of readers who are unfamiliar either with the use of thermodynamic cycles or the use of regression methods to estimate the (β) coefficients.

The first point of note is that the linear model (Figure 5A) reproduces all but 4% of the variation in activation free energies, ΔG‡(kcat/KM). That results from the fact that replicated measurements for each variant exhibit little variation relative to the variation between variants and substrates. Four of the eight possible predictors in the model have Student t-test P-values <0.0001. Thus, as noted previously (39), the Table in Figure 5C is almost exactly a linear transformation of the ensemble of the activation free energies in Figure 3B.

A second point of note is that the horizontal arrows to the left and right of the regression line illustrate the derivation of the β-coefficients for the two most important main effects. Those on the left indicate the ΔG‡(kcat/KM) values for leucine (red) and isoleucine (blue). Those on the right indicate the average values for all variants containing the WT (wild type) HVGH signature and those containing the mutant AVGA signatures. The y-axis differences (vertical arrows) between these average values match the β-coefficients in bold face in Supplementary Figure S1.

Finally, the AVGA*isoleucine interaction term (–0.89) implies a benefit of 0.89 kcal/mol if the AVGA variant uses Ile and a corresponding penalty if the WT LeuAC uses Leucine. Isoleucine is decidedly better for the AVGA variant. The mean activation free energy for the AVGA variant with isoleucine (1.54 kcal/mol) is ∼1.5 kcal/mol smaller than that for the WT LeuAC using leucine (3.05 kcal/mol). This results from the fact that LeuAC does not pay the penalty (+0.89 kcal/mol) with isoleucine and minihelixLeu. That means that AVGA LeuAC•isoleucine•minihelix is ∼13 (= exp(1.5/RT) times faster at tRNA aminoacylation than WTLeuAC•leucine•minihelix. That enhancement is consistent with the β-coefficient of the AVGA*Ile interaction term. This point is clarified in the Supplementary §C and Supplementary Figure S4. Three of the six possible two-way interactions are shown graphically in Figure 5D.

The effects of genetic backgrounds, active-site residues, and substrates are all highly coupled

This work follows a 25 factorial design matrix (Supplementary Table S1). We replicated assays for 24 of the 32 possible combinations of genetic background (FL versus urzyme), active site configuration (AVGA vs HVGH, AMSAS vs KMSKS), RNA substrate (tRNALeu, TΨC minihelix) and amino acid substrate (Ile versus Leu). We omitted the eight combinations involving acylation with Ile by FL LeuRS because FL LeuRS efficiently edits miss-acylated tRNALeu. The design matrix allows us to identify energetic coupling between the independent variables. These are significant for both function and evolution.

As noted in our earlier publication (39), the histograms in Figure 3A and B also tell us about how the independent variables and their synergies effect catalysis. The data in Supplementary Table S1 form a high-dimensional thermodynamic cycle (49). Free energy differences between the 24 different states of that cycle form a vector in a new coordinate system. The y-axis in the new system corresponds to the contributions of the independent variables and their coupling to catalysis. The regression coefficients from fitting the data in Supplementary Table S1 to Eq. (3) correspond to the height in kcal/mole along the new y-axis.

The full regression model (Supplementary Figure S1) has 17 significant coefficients of the possible 24. The remaining coefficients in the table in Supplementary Figure S1C are estimated only as subsets of more significant higher-order terms. Omitting them has a minimal effect on the overall fit, reducing R2 to 0.98. Moreover, coefficients for the two models are almost the same (Supplementary Figure S3; R2 = 0.94). Thus, there is minimal overfitting. See further discussion of this point in the supplementary §B, C.

The narrow bounds of the 95% confidence level show that residuals for the full regression model are quite small. Absolute values of residuals are almost randomly distributed. Those for FL LeuRS measurements are very significantly higher for the experiments with minihelixLeu. LeuAC variants with the AVGA mutation have slightly lower residuals (P = 0.0004). Those with isoleucine have slightly larger values (P = 0.01). The even distribution of errors underscores the validity of all five dimensions in the thermodynamic cycle.

A sample calculation shows how β-coefficients reconstruct the data

An important benefit of thermodynamic cycle analysis is that it provides Student t-test probabilities. These, in turn, allow us to rank order the statistical significance of the main effects and their coupling energies. These are sorted in order of decreasing statistical significance in the table in Supplementary Figure S1C. Interpreting them requires some explanation. Although the main effects have a direct interpretation, the two-way and higher-order coupling energies are somewhat more obscure.

Coefficients for the full-length modern enzyme and its interaction with the RNA substrate (FL; –4.46 kcal/mol and minihelixLeu*FL; 4.38 kcal/mol) are at the top of the sorted list in Supplementary Figure S1C. (Reference to the schematic in Figure 5A may be helpful here.) These two coefficients account for most of the significant rate enhancement of LeuRS (open diamonds at the lower right corner of Supplementary Figure S2A) and for the fact that LeuRS is just barely able to acylate the minihelix substrate (filled diamonds in the upper right of Supplementary Figure S1A). The mean activation free energies, ΔG‡(kcat/KM), are –9.76 and –2.35 kcal/mol, respectively, a difference of –7.4 kcal/mol. The intercept (not shown in the table) is –3.1 kcal/mol. To a first approximation, then, we calculate the mean values as ΔG‡(kcat/KM)tRNALeu = (–3.1 + –4.46) = –7.8 kcal/mol, and ΔG‡(kcat/KM)minihelix = (–3.1 –4.46 + 4.38) = –3.34 kcal/mole. Thus, the two top β-coefficients approximate the observed values quite well. The remaining terms contribute smaller amounts, depending on values of the independent variables in Supplementary Table S1. Those 15 lesser contributions produce the nearly full agreement between observed and calculated values of ΔG‡(kcat/KM).

The variation of the AVGA*AMSAS coupling term reveals a functional role of minihelixLeu

We already have discussed in §2.2 and §2.3 the crucial functions of amino acid and RNA substrate selection. The significance of the other terms of the model also calls for physically plausible implications.

Coefficients for the LeuRS and LeuAC AVGA*AMSAS thermodynamic cycles with leucine and RNALeu (Figure 5A and C) are very close to those determined previously (39). The main differences are that in this case we determined the Michaelis constant for the tRNA substrate at saturating amino acid concentrations. That has the effect of increasing substantially the base-line activation free energy, ΔG‡0, especially for the FL LeuRS.

The Class I active-site signatures apparently assimilated ‘phase 2 amino acids’ histidine and lysine over the course of their evolution to contemporary forms. Because these signatures are so highly conserved across the entire Class I superfamily, it seems likely that their secondary structures likely served catalytic roles even before they acquired their present form. We noted previously (39) that the coupling between HVGH and KMSKS active site segments with tRNALeu (Figure 6C,D) is both small and anti-cooperative. It is especially interesting that the positive values of this interaction (Figure 6E, F) show that the minihelixLeu substrate does coordinate the two active site signatures better than does tRNALeu. That difference is accentuated with the isoleucine amino acid substrate (Figure 6D, F). The significance intervals associated with the coefficients suggest that these observations are highly significant. They provide a satisfying explanation for the superiority of the urzyme•minihelix cognate pair.

Figure 6.

Thermodynamic cycle analysis of energetic coupling within the active site. (A) Schematic for the conversion of variant activation free energies for full-length LeuRS (see Figure 2A) via Eq. (3) into individual contributions to catalysis. (B–G) β coefficients for the six two-way thermodynamic cycles in Supplementary Table S1. (B, C) are full-length LeuRS; (D, E) are LeuAC acylation of tRNALeu; (F, G) are LeuAC acylation of minihelixLeu. Error bars are derived from the standard errors of the respective coefficients to show the 95% confidence range. Yellow background highlights functionally relevant qualitative differences between the way the two active site signatures interact with amino acid and RNA substrates. The most active urzyme variant•amino acid•RNA combination is the AVGA mutant with Ile and minihelix. The reference state here is the LeuAC double mutant. Thus, AVGA and AMSAS replace wild type sequences HVGH and KMSKS along the x-axis and this also affects the signs of the various cross terms AVGA*AMSAS that measure the degree of synergy between the two active-site signatures. Bar colors reflect the relative favorability with respect to the most active urzyme•RNA substrate combination. Red bars indicate unfavorable, anticoupling; green bars indicate favorable coupling between the two most active urzyme catalytic signatures. The net result is that the three of the enzyme•substrate combinations whose active-site cartoons are covered by the prohibition circle cannot coordinate the catalytic contributions of the two signatures. Only the FL LeuRS with tRNALeu and the LeuAC with minihelixLeu can function that way.

RNA substrate binding is the primary source of catalytic rate enhancement by LeuAC

Steady-state parameters in Supplementary Table S1 open a new window on the origins of catalysis. Focusing for the moment on the wild type sequences, it is clear that the 105-fold rate enhancement of LeuRS over that of LeuAC results entirely from increases in kcat (Figure 7). In fact, those increases also compensate for a modest decrease in apparent RNA substrate affinity in the mature enzyme (see differences between the red (<ΔG‡kcat>) and blue (<ΔG‡KM>) dashed lines.

Figure 7.

Catalytic contributions in FL LeuRS and LeuAC from RNA binding and transition-state affinity. LeuAC parameters for aminoacylation of minihelix and tRNALeu with both leucine and isoleucine are shown against a light gray background. FL LeuRS, against a white background, exhibits a very significant reduction (–7.4 ± 0.15 kcal/mol) in the activation free energy for kcat. The corresponding change in the activation free energy for KM (–0.7 ± 0.15 kcal/mol) is both an order of magnitude smaller and in the opposite direction, tending to reduce kcat/KM in FL LeuRS.

The anticodon-binding domain and long connecting-peptide insertion in the urzyme coordinate the catalytic functions of the HVGH and KMSKS signatures in FL LeuRS (39). The present data show that these newer domains are responsible for all the increased transition-state affinity in FL LeuRS. That conclusion puts the independence of urzyme catalysis from specific amino acid side chains in a new light. The apparent second-order rate constant, kcat/KM, also called the specificity constant, is the rate for the second-order reaction of substrate and free enzyme to give product (50). Ground-state affinity must therefore contribute to the overall catalysis (50). Consensus has held that enzyme catalysis requires increased affinity for the transition-state over that for the substrate (50,51). However, the entries in the table in Figure 7 confirm that at the earliest stages of catalysis that contribution (0.17) is minimal and substrate binding in the ground state (0.83) was the dominant contributor.

Discussion

The origin of genetic coding poses this quintessential puzzle: ‘Could AARS•minihelix cognate pairs have self-organized into a reflexive set?’ That question implies others, summarized in Figure 8. Could AARS genes written with a minimal alphabet fold into 3D structures whose amino acid and RNA substrate recognition could then impose the coding rules that governed the expression of their own gene sequences? We can try to answer these key questions if and only if we develop the appropriate experimental tools. Our data show that urzyme•minihelix cognate pairs are the first such tools.

Figure 8.

The reflexivity of AARS genes and the challenges of understanding its origin. The figure illustrates three main challenges. (I) We need to construct a bidirectional gene (salmon background) that uses a minimal amino acid alphabet to encode ancestral AARS from Classes I and II on opposite strands. Polypeptide and nucleic acid sequences have directions indicated by (N,C) and (5′,3′).The genes are sequences of codons (colored ellipses) and use two types of amino acids, A and B. (II) We have to show that both coded proteins (I and II) fold into active assignment catalysts that recognize both amino acid and tRNA (colored letters, ellipses in cavities), producing (mostly) aminoacyl-tRNAs with correct amino acids and anticodons. (III) We have to show that the aminoacylated RNAs can assemble onto messenger RNAs (I) and (II), transcribed from the bidirectional gene (reversed dashed arrows).

MinihelixLeu is the preferred RNA substrate for the LeuAC urzyme. That makes intuitive sense. Both are minimal, highly conserved modules that remain functional outside the context of their full-length descendants. Molecular systems that survived from the origin of coding manifestly must have been functional. The high activity of the urzyme•minihelix pair and the functional pairing of the minimal and full-length components (Figure 3A, B) are key metrics of selective advantage. They are thus almost certainly relevant to the question at hand, and so are an unprecedented searchlight into the early molecular evolution of translation.

§2.4–2.6 also show how active-site mutants and recognition of both amino acid and RNA substrates all depend on one another. This new range of coupling energies between the active site and substrate selectivity transforms our view of the emergence and evolution of genetic coding (Figures 8, 9). The data underscore just how promiscuous—and pliant—the earliest AARSs are likely to have been (52,53). As outlined further below, these interactions provide new details about how both components likely co-evolved.

Figure 9.

Temporal order suggested by this work and other data for events in the evolution of the LeuRS•tRNALeu cognate pair. The top row lists three successive stages. Background arrows suggest time intervals during which the molecules illustrated schematically likely operated. Their heights suggest (on a log scale) the increasing sizes of the coding alphabets (4, 8, 12, 20 letters) that might be achieved with the given molecular components, given the available data. The earliest stage, left, is the AARS urzyme minihelix cognate pair, for which data presented here are most relevant. The editing domain (ED) is almost certainly the final addition to form the modern LeuRS•tRNALeu cognate pair. The order of intermediate accumulations is much less certain, as discussed in the text. The bottom arrow denotes likely biological stages during which the events occurred. Abbreviations: FUCA, first universal common ancestor; LUCA, last universal common ancestor; LECA, last eukaryotic common ancestor.

We previously noted that the coupling between the HVGH and KMKSK loci changed sign with the assimilation of the CP1 insertion and anticodon-binding domain (39). Our interpretation then was that the creation of synergy between the two loci was a consequence of coupling domain motion to catalysis of amino acid activation and implicitly perhaps also RNA aminoacylation. Our observation of a similar inversion induced by minihelixLeu versus tRNALeu in Figure 6D–G raises the possibility that the more effective RNA substrate can induce a similar dynamic change in the active site of LeuAC.

Figure 8 also implies related questions that we cannot address here in detail. One has to do with the base-pairing stability and mechanism of alignment of successive triplet anticodons along a messenger RNA in the absence of a ribosome. Triplet codon-anticodon base pairing by itself is stable for appreciable times only at low temperatures (54). That suggests both a need for and a selective advantage of some type of protoribosome (55,56). A second question is about the evolution of the nucleic acid and protein alphabets (57). We previously commented on this question in our discussion of the interrelatedness of replication and transcription errors (58). That discussion emphasized that as the relative alphabet size of the coding table increased with the introduction of newly differentiated AARS, the lower redundancy of codons per amino acid balances the increased specificity. Thus, the increased specificity brought by introducing new amino acids to the coding alphabet reduces the translation error rate roughly in proportion to the reduction in compensation achieved by the redundancy of codons.

Enzymology is crucial to the experimental study of early genetic coding

Two chemical reactions are necessary and sufficient to translate the genetic code. Amino acids must be activated and then transferred to cognate tRNAs. Both reactions are orders of magnitude slower than peptide bond synthesis from activated amino acids, and must be accelerated (36). Doing so must also discriminate between libraries of two quite different kinds of substrates. Amino acids make up the library of subunits for building polypeptides. Transfer RNAs represent a library of symbols that interpret genetic blueprints. Both theory (12,59–65) and experiment (18,25,26,31,33,35,46,48,66–74) thus imply that AARS•tRNA cognate pairs are the central players. By selecting and catalyzing, AARS serve as assignment catalysts. The central puzzles posed by the origin of translation are thus, fundamentally, problems in enzymology. Many of the answers we seek will be found in studies like this one.

Factorial analysis affords unique insight into higher-order coupling energies

Like most other biological phenomena, enzyme catalysis results from high-order cooperative behavior. Jencks (75) put the analysis of such coupling on a quantitative footing. Early elaborations of the analysis (76–78) represented the coupling between two or more mutations in terms of explicit thermodynamic cycle analyses in which coupling free energies, Δ(ΔG‡), can be represented in two dimensions as free energy differences between parallel mutations in the context of wild-type and single mutant enzymes. Such treatment becomes increasingly cumbersome in higher dimensions. The linearity of free energies means that thermodynamic cycle analysis of high-order coupling is equivalent to fitting the coefficients of Eq. (3) (§2.6). That approach (see also Figure 6A) has the additional benefit of estimating the effects of experimental errors, ϵ, as the difference between calculated and observed values for the activation free energies, Δ(ΔG‡(kcat/KM)) for each variant. We have outlined this equivalence in several previous publications (39,79).

The AVGA LeuAC urzyme strongly prefers TΨC minihelixLeu over tRNALeu as its RNA substrate

Ancestral AARS cannot have functioned without proto-tRNA partners. Minihelices likely co-evolved with AARS urzymes as cognate pairs from pre-existing RNA. Janssen (80) and Di Giulio (81) argued that tRNAs evolved via duplication of ancestral minihelix aminoacylation substrates in which the three nucleotides just prior to the Discriminator base (82) at the 3′ terminus functioned as the anticodon. The acceptor stem alone provides ∼70% of the transition-state (TS) binding free energy for acylation of full-length tRNA by full-length Class II AARS (24). Our work here supports this line of reasoning. The minihelix provides ∼ 60% of the corresponding TS binding free energy for Class I LeuRS (Figure 3A). Surprisingly, the LeuAC urzyme exhibits an even higher percentage (nearly 75%; Figure 3B).

At the outset of this work, the odds seemed stacked against seeing acylation of TΨC minihelixLeu by LeuAC. The small fraction of acylatable tRNALeu made it hard to show acylation by either LeuRS or LeuAC (35). Only full-length LeuRSs from archaea have been demonstrated to acylate minihelices (38). Moreover, absence of evidence for acylation is not evidence against acylation. Authors rarely record the detection limit actually attempted if they cannot demonstrate acylation. Indeed, we initially failed to detect acylation of the minihelix by FL LeuRS. We had to increase the minihelixLeu concentration substantially in order to demonstrate it (Figure 3A).

The AVGA LeuAC•minihelixLeu cognate pair is superior even to the LeuRS•minihelixLeu pair. That inversion—better than both full-length•minihelix and urzyme•tRNA—is interwoven with the other observations. The active-site signatures are coupled to the selection of both substrates (Supplementary Figure S1). MinihelixLeu reinforces the selection of Ile as the preferred substrate (§2.3 and Figure 4). Unlike tRNALeu, it coordinates the AVGA and KMSKS signatures (§2.6 and Figure 5). That mimics the much later impact of acquiring both the CP insertions and the ABD in FL LeuRS. The coupling argues broadly that the adaptor (minihelixLeu) and the decoder (LeuAC) co-evolved from a very early stage.

The LeuAC•minihelixLeu cognate pair is a near ideal experimental platform for study of the operational RNA code

There are plausible reasons to believe that bidirectional coding at the root of the AARS Class division projected into the proteome to differentiate between both Class I and II RNA (31,33,48,83) and amino acid (72) substrates in a single stroke. Even if correct, that proposal begs to be tested experimentally. Nor does it account for subsequent branching of AARS specificites. How subsequent additions to the coding alphabet changed both amino acid and RNA substrate specificity at the same time still poses a major challenge. The LeuAC urzyme•minihelixLeu cognate pair is an ideal paradigm for experimental pursuit of these questions.

Both components are small biomolecules with only one domain. In contrast, full-length AARS and tRNAs are complex, multi-domain macromolecules. Schimmel et al. proposed acylation of minihelices by intact AARS catalytic domains (18). LeuAC (129 residues) approaches a minimal catalytic framework for both activation and acylation. It is actually a better match for the minihelix.

Urzyme catalysis overcomes all kinetic barriers to the synthesis of coded peptides. Uncatalyzed amino acid activation occurs at ∼8 × 10−9 M−1s−1 (84). The best LeuAC variants aminoacylate the minihelix with isoleucine at ∼9 × 101 M−1s−1. That is ∼106-fold faster than peptide bond formation from activated amino acids in the absence of an enzyme or ribosome, (∼3 × 10−5 M−1s−1) (85). The LeuAC•minihelixLeu cognate pair is thus fast enough to be a valid evolutionary intermediate.

Urzymes may have enough amino acid specificity to begin decoding genes. We previously showed that AARS urzymes preferentially activate roughly five of the twenty amino acids, all from the appropriate Class (46,47). Class II urzymes derived from HisRS and GlyRS display similar, minimally overlapping amino acid specificity spectrum (36,37). Thus, AARS urzymes appear able to select ∼four distinct subsets of five amino acids from the correct Class about 80% of the time.

Class I and II AARS•tRNA cognate pairs use different structural features to differentiate between the two kinds of substrates. A unique consequence of having four distinct kinds of binding sites is that modest specificities of each type can reinforce one another, to achieve higher overall fidelity. Thus, four different urzyme•minihelix cognate pairs might have managed a 4-letter coding alphabet (48). We previously suggested such an alphabet as rate-limiting (58).

Both components are closely related to contemporary LeuRS and tRNALeu. Although obvious, one should not overlook that this establishes a direct ancestry. Plausible mechanisms can explain how both components of the cognate pair might have evolved into their contemporary forms (see §3.5).

The LeuAC•minihelix pair now invites us to ask two questions. (i) Can it recognize minihelices as well as it does amino acids? (ii) Can cognate pairs designed with reduced alphabets achieve comparable specificities? We now can answer these questions experimentally.

The operational code cannot fully explain primordial translation.

The operational code concept helps explain how AARS-tRNA recognition led to the present coding table (31,33). If, as we imagine here, minihelixes functioned as tRNAs in ribosomal template-directed protein synthesis, that raises a new problem. Previous work identified the three bases 5′ to the DCCA 3′ terminus as a potential precursor of the anticodon (34,81,86,87). However, the exposed bases of the TΨC loop as shown by bold squares in Figure 2A are more likely to recognize codons in mRNA. These are not obviously related to either of the other sites on modern tRNAs. Thus, either the anticodon-like sequence just prior to the Discriminator base aligned to primordial messages, or the transition to the mature code may have passed through an intermediate stage where readout of mRNA was mediated by something other than the anticodon:codon recognition. We cannot offer any resolution of this puzzle, except to note that the middle base of the putative the leucyl-minihelix, A, is the same as the middle base of the leucine anticodon.

The substantial preference of LeuAC for isoleucine may also have evolutionary significance

Our first study of LeuAC’s amino acid specificity (46,47) showed that isoleucine was a better substrate than leucine for activation. It seemed a curiosity at the time. Both isoleucine and leucine are produced in Miller-Urey spark discharge experiments (88). However, leucine biosynthesis requires nine enzymes, whereas isoleucine requires only five (89). Wong's coevolution theory (90) would thus suggest that isoleucine preceded leucine as a coded amino acid. Further, correlations between amino acid side chain physical properties and the bases that define tRNA identity suggested that one of the earliest distinctions built into the operational code was for amino acids with a β-branched sidechain (26,31). Moreover, such side chains likely enhanced foldability and persistence of early peptides (91). That functionality may have enriched them in preference to unbranched aliphatic side chains. Both isoleucine and valine have β-branched side chains.

In the interim, Farias, Rego and José published phylogenetic analyses of a treatment of tRNA ancestry (92). They updated an earlier proposal (93) that the earliest messenger RNAs derived from ancestral tRNAs that all had RNY anticodons. They constructed a combinatorial library of putative ancestral mRNAs by assembling reconstructed ancestral sequences for the eight tRNAs. They found homologies to several contemporary AARS within that library, none of which corresponded to any of the tRNAs from which their library was built. One intriguing example was that they detected homology to LeuRS instead of IleRS, but tRNAIle was among their founding tRNAs. It may be misleading to assume one-to-one correlations between the ancestral AARS, their amino acid substrates, and tRNAs that functioned as cognate pairs.

Acceleration by the earliest catalysts relied on ground-state substrate binding

The large rate accelerations by protein enzymes have long puzzled enzymologists (94). Fersht (50) concludes that substrate binding can account for some of that rate acceleration. We showed earlier (39) that the two consensus active-site signatures account for little of the overall rate acceleration by LeuAC. This work confirms and extends that conclusion (Figure 7). At least 85% of LeuAC’s transition-state stabilization free energy for aminoacylation arises from KM. Specific transition-state binding contributes less than 15%. That suggestion merits some qualification:

Amino acid activation and aminoacylation are both bi-molecular reactions. They should benefit substantially from the catalytic effect of binding, which orders both substrates in the active site.

The activation step is the rate-limiting step in uncatalyzed protein synthesis. Active-site titration data in Supplementary Table S3 and those described previously for the four LeuAC variants (39) show that the first-order rate constant, kchem, measured by active-site titration can be as high as 0.03 s−1, nearly a million times faster than the uncatalyzed rate. The relative independence of that elevated binding from contributions from specific side chains underscores the special contributions of polypeptide backbone structures.

MinihelixLeu binding-induced coupling between the AVGA and AMSKS signatures increases acylation by LeuAC ∼10-fold (§2.6). That effect is not seen with the tRNALeu substrate. Energetic coupling between domains in LeuRS entails motion of the two signatures relative to the rest of the active site (95–97). So, it remains likely that with the minihelix catalysis does entail some differential stabilization of the transition-state configuration.

Wild type lysine residues in the KMSKS sequence weaken RNA affinity by about 10-fold in specific combination with the isoleucine substrate (Supplementary §E; Supplementary Figure S8). Whatever role the KMSKS sequence may have assumed later in AARS evolution, it does not enhance RNA substrate affinity.

Our data establish a basis for describing events leading to the translation of genes.

The self-organization of genetics must have begun in near chaos (98). We show here that, although no plausible characterization of such remote events can ever be judged the only possible scenario, it likely emerged with a fluid exchange between catalysis and substrate recognition (Figure 9). Recent phylogenetic studies (59) imply that modular acquisition also played a key role in that interchange. The process seems to have evolved relatively rapidly.

The LeuAC•minihelix cognate pair now anchors the left end of the sequence in Figure 9. We suggest broad conclusions about the order of intermediate stages in the figure. High conservation in the ∼80-residue connecting peptide fragment in all Class I AARS implies that that module entered their genes early in their adaptive radiation (59). That work also outlines a much more detailed account of the nested insertions within the full lengths of the connecting peptides within the Class I catalytic domains.

It is unlikely that the anticodon stem-loop became a part of tRNAs until after Class I AARS had acquired at least a minimal connecting peptide (CP). The anticodon stem-loop must have added some selective advantage to the minihelix. That would have been unlikely until their cognate AARSs had acquired sufficient sophistication to overcome the severe functional limitations imposed by the urzyme molecular framework.

Finally, it seems probable that the two components acquired the anticodon binding domain (ABD) and anticodon-stem loop at about the same time. Coupling between the CP insertions and the ABD (39,68,95) enhanced the synergy of the AVGA and AMSAS signatures induced by the minihelix, outlined in §2.4. That likely also played a role in accommodating the anticodon stem-loop of the full-length tRNA substrates.

Coevolution of AARS with their cognate tRNAs has long gripped the field (99,100). Section §2.6 extends the discussion back to a very early stage of molecular evolution. Sloan (101) made a point to note that they could not demonstrate that co-evolutionary effects contribute to rate differences. That conclusion seems to apply only to a small and very recent evolutionary era. The histograms in Figure 6C–F document very significant functional rate changes between minihelixLeu and tRNALeu substrates. Those differences are very likely related to quite elemental interactions between the RNA and enzyme active site (see also supplemental §D). Such interactions could well underlie much of the mechanistic landscape of contemporary AARS. The tRNA dependence for amino acid activation may root deeply in the ancestry of urzyme•minihelix cognate pairs.

Outstanding unanswered questions remain.

Our results have robust statistical support, and we feel they correctly reflect the complex energetic coupling between the LeuRS/LeuAC active sites and their substrate preferences. The close genetic connection between both LeuAC and TΨC-minihelix and their modern, extant forms provide strong support for Schimmel's proposal. That said, we should also add that specific details of this model system do not imply generality. Rather, we view this work as opening a new window on the molecular drama from which genetic coding ultimately emerged. That is, it puts in place a paradigm with an entirely new range of questions and suggests experimental procedures to address them. Key outstanding questions include the following.

Are there significant differences between Class 1 and 2 urzyme•minihelix cognate pairs? The Class 2 Tupanvirus AlaRS (102) suggests that there may be. It specifically acylates both tRNAAla and its TΨC-minihelix almost equally well. Moreover, the Tupanvirus AlaRS is missing the entire C-Ala tRNA binding module. So, it reflects adaptation to a different, presumably more ancient RNA binding mode. The marked contrast of that behavior with the nearly complete loss of minihelix acylation by FL LeuRS suggests there may be important generic differences between the two AARS classes.

How do acceptor stem bases affect the steady-state kinetic parameters of AARS urzymes? Better models for the early genetic codes will require data from acylating different minihelix sequences with LeuAC and other AARS urzymes.

Several Class I AARS—GluRS, GlnRS, LysRS and ArgRS—cannot activate cognate amino acids without their cognate tRNAs (103). Is that behavior a remnant from an ancient energetic coupling between amino acid activation and acylation? The impact of RNA substrates on single-turnover measurements in Supplementary §D and Supplementary Figures S5-S7 suggest that such coupling may also have roots in deeply ancestral forms of AARS.

In what order and with what specificity did amino acids enter the coding table? This remains a most vexing question. The curious preference of isoleucine over leucine is but one example of the likely promiscuity of ancestral codes. We hope to complement experiments like those described here by ancestral sequence reconstructions, along the lines described by Douglas et al. (59). Those will be adapted to use substitution matrices keyed to the successive reduction in the coding alphabet size.

The urzyme•minihelix brings us a comprehensive new experimental platform. Its tools are those necessary to begin to test each of these suppositions. We can vary properties of the cognate pair experimentally. We can readily extend these studies to other urzyme•minihelix cognate pairs. Therefore, it is suitable for comprehensive enzymatic studies of precisely how LeuAC performs as an AND gate. These properties will promote studies of the structure/function relationships that produced the contemporary genetic codes. That lends new intensity to the future of research into the origins of genetic coding.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge helpful discussions about data presentation and interpretation with Peter Wills and Remco Bouckaert throughout the writing of the paper.

Author contributions: G.Q.T. purified all components and performed all assays. C.W.C. and G.Q.T. performed data analysis. H.H. performed QM/MM calculations on structures of LeuAC bound to leucine and isoleucine (these were inconclusive and not used here), and with C.W.C. evaluated the relative contributions of ground-state and transition state binding to RNA substrates from the kinetic data. J.D. contributed critical discussions about data presentation and interpretation. C.W.C. wrote the manuscript, and all authors contributed to and approved the final figures and text.

Contributor Information

Guo Qing Tang, Department of Biochemistry and Biophysics, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-7260, USA.

Hao Hu, Department of Biochemistry and Biophysics, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-7260, USA.

Jordan Douglas, Department of Physics, The University of Auckland, New Zealand; Centre for Computational Evolution, University of Auckland, New Zealand; Department of Computer Science, The University of Auckland, New Zealand.

Charles W Carter, Jr, Department of Biochemistry and Biophysics, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-7260, USA.

Data availability

All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. C.W.C. will provide plasmids pending scientific review and a completed material transfer agreement. Requests for these reagents should be submitted to carter@ med.unc.edu. This work developed no new computer code.

Supplementary data

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

Funding

Alfred P. Sloan Foundation Matter-to-Life program [G-2021-16944]. Funding for open access charge: Alfred P. Sloan Foundation Matter-to-Life Grant [G-2021-16944].

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

References

- 1. Eriani G., Delarue M., Poch O., Gangloff J., Moras D.. Partition of tRNA synthetases into two classes based on mutually exclusive sets of sequence motifs. Nature. 1990; 347:203–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Berg P., Ofengand E.J.. An enzymatic mechanism for linking amino acids to RNA. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1958; 44:78–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hoagland M.B., Keller E.B., Zamecnik. P.C. Enzymatic carboxyl activation of amino acids. J. Biol. Chem. 1956; 21:345–358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Trupin J.S., Rottman F.M., Brimacome R., Leder P., Bernfield M.R., Nirenberg M.. RNA codewords and protein synthesis, VI. On the nucleotide sequences of degenerate codeword sets for isoleucine, tyrosine, asparagine, and lysine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1965; 53:807–811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nirenberg M.W., Mattaei J.H.. The dependence of cell-free protein synthesis in E. coli upon naturally occurring or synthetic polyribonucleotides. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1961; 47:1588–1602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Holley R., Apgar J., Everett G.A., Madison J.T., Marquisee M., Merrill S.H., Penswick J.R., Zamir A.. Structure of a ribonucleic acid. Science. 1965; 147:1462–1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kumar R.K., Yarus M.. RNA-catalyzed amino acid activation. Biochem. 2001; 40:6998–7004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Illangsekhare M., Yarus M.. A tiny RNA that catalyzes both aminoacyl-tRNA and peptidyl-RNA. RNA. 1999; 5:1482–1489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Illangsekhare M., Yarus M.. Specific, rapid synthesis of phe-RNA by RNA. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1999; 96:5470–5475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ishida S., Terasaka N., Katoh T., Suga H.S.. An aminoacylation ribozyme evolved from a natural tRNA-sensing T-box riboswitch. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2020; 702:702–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Niwa N., Yamagishi Y., Murakami H., Suga H.. A flexizyme that selectively charges amino acids activated by a water-friendly leaving group. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2009; 19:3892–3894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wills P.R., Carter C.W. Jr. Insuperable problems of an initial genetic code emerging from an RNA world. Biosystems. 2018; 164:155–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. de Duve C. The second genetic code. Nature. 1988; 333:117–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kondratyeva L.G., Dyachkova M.S., Galchenko A.V.. The origin of genetic code and translation in the framework of current concepts on the origin of life. Biochemistry (Moscow). 2022; 87:45–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Delarue M. An asymmetric underlying rule in the assignment of codons: possible clue to a quick early evolution of the genetic code via successive binary choices. RNA. 2007; 13:161–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nesterov-Mueller A., Popov R.. The combinatorial fusion cascade to generate the standard genetic code. MDPI Life. 2021; 11:975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yarus M. The genetic code assembles via division and fusion, basic cellular events. Life. 2023; 13:2069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Schimmel P., Giegé R., Moras D., Yokoyama S.. An operational RNA code for amino acids and possible relationship to genetic code. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1993; 90:8763–8768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Thiebe R., Harbers K., Zachau H.G.. Aminoacylation of fragment combinations from Yeast tRNAPhe. Euro J. Biochem. 1972; 26:144–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Francklyn C., Schimmel P.. Aminoacylation of RNA minihelices with Alanine. Nature. 1989; 337:478–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Francklyn C., Schimmel P.. Enzymatic aminoacylation of an eight-base-pair microhelix with histidine. Proc. Nati. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1990; 87:8655–8659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Frugier M., Florentz C., Giegé R.. Anticodon-independent valylation of an RNA minihelix. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1992; 89:3900–3904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Francklyn C., Musier-Forsyth K., Schimmel P.. Small RNA helices as substrates for aminoacylation and their relationship to charging of transfer RNAs. Euro J. Biochem. 1992; 206:315–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Musier-Forsyth K., Schimmel P.. Atomic determinants for aminoacylation of RNA minihelices and relationship to genetic code. Acc. Chem. Res. 1999; 32:368–375. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Carter C.W. Jr, Wolfenden R. Acceptor-stem and anticodon bases embed amino acid chemistry into tRNA. RNA Biol. 2016; 13:145–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Carter C.W. Jr, Wolfenden R. tRNA acceptor-stem and anticodon bases form independent codes related to protein folding. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2015; 112:7489–7494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wolfenden R., Lewis C.A., Yuan Y., Carter C.W. Jr. Temperature dependence of amino acid hydrophobicities. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015; 112:7484–7488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wolfenden R., Cullis P.M., Southgate C.C.F.. Water, protein folding, and the genetic code. Science. 1979; 206:575–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Giegé R., Eriani G.. eLS. John Wiley & Sons. 2014; Ltd, Chichester: 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Giegé R., Sissler M., Florentz C.. Universal rules and idiosyncratic features in tRNA identity. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998; 26:5017–5035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Carter C.W., Wills P.R. Hierarchical groove discrimination by class I and II aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases reveals a palimpsest of the operational RNA code in the tRNA acceptor-stem bases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018; 46:9667–9683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jühling F., Mörl M., Hartmann R.K., Sprinzl M., Stadler P.F., Pütz J.. tRNAdb 2009: compilation of tRNA sequences and tRNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009; 37:D159–D162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Carter C.W. Jr, Wills P.R. Class I and II aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase tRNA groove discrimination created the first synthetase•tRNA cognate pairs and was therefore essential to the origin of genetic coding. IUBMB Life. 2019; 71:1088–1098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Di Giulio M. A comparison among the models proposed to explain the origin of the tRNA molecule: a synthesis. J. Mol. Evol. 2009; 69:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hobson J.J., Li Z., Carter C.W. Jr. A leucyl-tRNA synthetase urzyme: authenticity of tRNA synthetase urzyme catalytic activities and production of a non-canonical product. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022; 23:4229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Li L., Francklyn C., Carter C.W. Jr. Aminoacylating urzymes challenge the RNA world hypothesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2013; 288:26856–26863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Patra S.K., Betts L., Tang G.Q., Douglas J., Wills P.R., Bouckeart R., Carter C.W. Jr. Genomic databases furnish a spontaneous example of a functional class II glycyl-tRNA synthetase urzyme. 2024; bioRxiv doi:13 January 2024, preprint: not peer reviewed 10.1101/2024.01.11.575260. [DOI]

- 38. Xu M.-G., Zhao M.-W., Wang E.-D.. Leucyl-tRNA synthetase from the hyperthermophilic bacterium aquifex aeolicus recognizes minihelices. J. Biol. Chem. 2004; 279:32151–32158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Tang G.Q., Elder J.J.H., Douglas J., Carter C.W. Jr. Domain acquisition by class I aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase urzymes coordinated the catalytic functions of HVGH and KMSKS motifs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023; 51:8070–8084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Schimmel P., Alexander R.. Diverse RNA substrates for aminoacylation: clues to origins?. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1998; 95:10351–10353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Parks T.D., Leuther K.K., Howard E.D., Johnston S.A., Dougherty W.. Release of proteins and peptides from fusion proteins using a recombinant plant virus proteinase. Anal. Biochem. 1994; 216:413–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Fersht A.R., Ashford J.S., Bruton C.J., Jakes R., Koch G.L.E., Hartley B.S.. Active site titration and aminoacyl adenylate binding stoichiometry of amionacyl-tRNA synthetases. Biochem. 1975; 14:1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Francklyn C.S., First E.A., Perona J.J., Hou Y.-M.. Methods for kinetic and thermodynamic analysis of aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases. Methods. 2008; 44:100–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Johnson K.A. New standards for collecting and fitting steady state kinetic data. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2019; 15:16–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Box G.E.P., Hunter W.G., Hunter J.S.. Statistics for Experimenters. 1978; NY: Wiley Interscience. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Carter C.W. Jr What RNA world? Why a peptide/RNA partnership merits renewed experimental attention. Life. 2015; 5:294–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Carter C.W. Jr, Li L., Weinreb V., Collier M., Gonzales-Rivera K., Jimenez-Rodriguez M., Erdogan O., Chandrasekharan S.N. The Rodin-Ohno hypothesis that two enzyme superfamilies descended from one ancestral gene: an unlikely scenario for the origins of translation that will not Be dismissed. Biol. Direct. 2014; 9:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Carter C.W. Jr, Wills P.R. The roots of genetic coding in aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase duality. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2021; 90:349–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Horovitz A., Fersht A.R.. Strategy for analysing the co-operativity of intramolecular interactions in peptides and proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 1990; 214:613–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Fersht A.R. Structure and Mechanism in Protein Science. 2017; NY: W. H. Freeman and Company. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wolfenden R. Transition State analog inhibitors and enzyme catalysis. Ann. Rev. Biophys. Bioeng. 1976; 5:271–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Tawfik D.S. Enzyme promiscuity and evolution in light of cellular metabolism. FEBS J. 2020; 287:1260–1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Tawfik D.S., Gruic-Sovulj I.. How evolution shapes enzyme selectivity – lessons from aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases and other amino acid utilizing enzymes. FEBS J. 2020; 287:1284–1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Müller F., Escobar L., Xu F., Węgrzyn E., Nainytė M., Amatov T., Chan C.Y., Pichler A., Carell T.. A prebiotically plausible scenario of an RNA–peptide world. Nature. 2022; 605:279–284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Bose T., Fridkin G., Davidovich C., Krupkin M., Dinger N., Falkovich A.H., Peleg Y., Agmon I., Bashan A., Yonath A.. Origin of life: protoribosome forms peptide bonds and links RNA and protein dominated worlds. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022; 50:1815–1828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Kawabata M., Kawashima K., Mutsuro-Aoki H., Ando T., Umehara T., Tamura K.. Peptide bond formation between Aminoacyl-minihelices by a scaffold derived from the peptidyl transferase center. Life. 2022; 12:573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Strazewski P. Low-digit and high-digit polymers in the origin of life. Life. 2019; 9:17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Wills P.R., Carter C.W. Jr. Impedance matching and the choice between alternative pathways for the origin of genetic coding. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020; 21:7392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Douglas J., Bouckaert R., Carter C.W. Jr, Wills P. Enzymic recognition of amino acids drove the evolution of primordial genetic codes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024; 52:558–571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Shore J., Holland B.R., Sumner J.G., Nieselt K., Wills P.R.. The ancient operational code is embedded in the amino acid substitution matrix and aaRS phylogenies. J. Mol. Evol. 2019; 88:136–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Wills P.R. Reflexivity, coding and quantum biology. Biosystems. 2019; 185:104027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Wills P.R., Nieselt K., McCaskill J.S.. Emergence of coding and its specificity as a physico-informatic problem. Orig. Life Evol. Biosph. 2015; 45:249–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Wills P.R. Genetic information, physical interpreters and thermodynamics; the material-informatic basis of biosemiosis. Biosemiotics. 2014; 7:141–165. [Google Scholar]

- 64. Wills P.R Pollack J., Bedau M., Husbands P., Ikegami T., Watson R.A.. Artificial Life IX. 2004; Cambridge: MIT Press; 51–56. [Google Scholar]

- 65. Nieselt-Struwe K., Wills P.R.. The emergence of genetic coding in physical systems. J. Theor. Biol. 1997; 187:1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Pham Y., Kuhlman B., Butterfoss G.L., Hu H., Weinreb V., Carter C.W. Jr. Tryptophanyl-tRNA synthetase urzyme: a model to recapitulate molecular evolution and investigate intramolecular complementation. J. Biol. Chem. 2010; 285:38590–38601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Li L., Weinreb V., Francklyn C., Carter C.W. Jr. Histidyl-tRNA synthetase urzymes: class I and II aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase urzymes have comparable catalytic activities for cognate amino acid activation. J. Biol. Chem. 2011; 286:10387–10395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Li L., Carter C.W. Jr. Full implementation of the genetic code by tryptophanyl-tRNA synthetase requires intermodular coupling. J. Biol. Chem. 2013; 288:34736–34745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Carter C.W. Jr Urzymology: experimental access to a key transition in the appearance of enzymes. J. Biol. Chem. 2014; 289:30213–30220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Carter C.W. Jr An alternative to the RNA world. Nat. Hist. 2016; 125:28–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]