Abstract

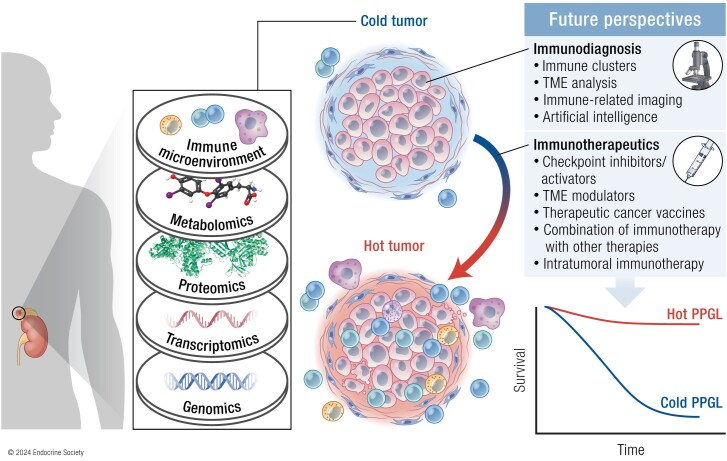

Pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas (PPGLs) are rare neuroendocrine tumors derived from neural crest cells from adrenal medullary chromaffin tissues and extra-adrenal paraganglia, respectively. Although the current treatment for PPGLs is surgery, optimal treatment options for advanced and metastatic cases have been limited. Hence, understanding the role of the immune system in PPGL tumorigenesis can provide essential knowledge for the development of better therapeutic and tumor management strategies, especially for those with advanced and metastatic PPGLs. The first part of this review outlines the fundamental principles of the immune system and tumor microenvironment, and their role in cancer immunoediting, particularly emphasizing PPGLs. We focus on how the unique pathophysiology of PPGLs, such as their high molecular, biochemical, and imaging heterogeneity and production of several oncometabolites, creates a tumor-specific microenvironment and immunologically “cold” tumors. Thereafter, we discuss recently published studies related to the reclustering of PPGLs based on their immune signature. The second part of this review discusses future perspectives in PPGL management, including immunodiagnostic and promising immunotherapeutic approaches for converting “cold” tumors into immunologically active or “hot” tumors known for their better immunotherapy response and patient outcomes. Special emphasis is placed on potent immune-related imaging strategies and immune signatures that could be used for the reclassification, prognostication, and management of these tumors to improve patient care and prognosis. Furthermore, we introduce currently available immunotherapies and their possible combinations with other available therapies as an emerging treatment for PPGLs that targets hostile tumor environments.

Keywords: pheochromocytoma, paraganglioma, neuroendocrine tumors, cancer immunotherapy, perspectives, immune system

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

Essential Points.

Pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas (PPGLs) have been previously considered as immunologically “cold” tumors due to their overall low mutational burden, their lack of tumor antigens, and, therefore, the decreased presence of immune cells in their microenvironment

The recent genetic reclustering of these tumors and advancements in techniques and bioinformatics tools focusing on the assessment of the tumor microenvironment have led to the uncovering of immunogenomic signatures as new promising avenues for the reclassification, prognostication, and management of PPGLs in the near future

According to the newest trends in cancer immunotherapies, research, and clinical studies/trials related to immunotherapy for PPGLs should focus on approaches activating both adaptive and innate immune systems to efficiently attract immune cells in these tumors and convert them from “cold” to “hot,” effectively making them highly vulnerable to subsequent immunotherapies

Combining various immunotherapeutic approaches with other supporting and therapeutic modalities, which further enhances immune system targeting of PPGLs and promotes long-term immunological memory, are promising approaches to targeting metastatic or advanced PPGLs or even preventing their development

Background and Relevance

Pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas (PPGLs) are neural crest tumors that arise from chromaffin cells of the adrenal gland or extra-adrenal tissues, respectively (1). Metastatic variants of these tumors are notoriously difficult to treat and often only stabilize (without regression) upon treatment with various agents. In a small fraction of patients, these tumors can be very aggressive and associated with rapid growth of organ metastatic lesions that ultimately cause either organ failure or severe catecholamine-related cardiovascular and other events, leading to morbidity and mortality (2). Thus, identifying new therapeutic options for treating metastatic or advanced PPGLs is urgently needed.

Over the last few years, considerable interest has been placed on systemic radiotherapies based on the concept of theranostics, a “treat what has been imaged approach” (3, 4). Although promising and valuable for many patients with metastatic PPGLs, these treatments most often promote disease stabilization. Thus, the majority of the guidelines recommend avoiding such therapies in patients with rapidly progressive tumors who are often preferably treated with chemotherapies (eg, a combination of cyclophosphamide/vincristine/dacarbazine, tyrosine-kinase inhibitors, and temozolomide) (2, 5, 6). Furthermore, less common therapeutic models that may be conceptually efficacious are practically nonexistent. These would include neoadjuvant therapies, combined therapies (eg, combining chemotherapy with radiotherapy or immunotherapy with radiotherapy), or the use of dual targeted radionuclide therapies (7, 8). Currently, most clinical trials still solely focus on discrete/solitary approaches, such as chemotherapies, radiotherapies, or treatments altering signaling pathways rather than combined management strategies.

By extension, these suboptimal therapeutic options for PPGLs are a natural consequence of the inherent (and remarkable) developmental, molecular, biochemical, and imaging heterogeneity of these tumors, consequently hindering a “one size fits all” approach.

Currently, PPGLs are classified into 3 consensus genomic subtypes, which are strongly linked with 3 different classes of known driver genes (9, 10). Specifically, the pseudohypoxic subtype, classically known as Clusters C1A and C1B, includes tumors carrying pathogenic variants in Krebs cycle genes (SDHB, SDHA, SDHC, SDHD, SDHAF2, FH, MDH2, and IDH1) and pathogenic variants in genes involved in the regulation of hypoxia transcription factors hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1α and/or HIF-2α (VHL, EPAS1, EGLN1/2, and DLST). This subtype shows a transcriptomic profile that reflects the cellular response to hypoxia (“pseudohypoxic” signature) and predominantly the noradrenergic phenotype (11). The kinase-signaling subtype, classically defined as Cluster C2, comprises pathogenic variants in RET, NF1, TMEM127, HRAS, MAX, and FGFR1-mutated tumors and exhibits an activated kinase receptor profile and increased protein translation, in addition to producing epinephrine and norepinephrine. The third group comprises tumors with activated Wnt signaling that contain a MAML3 fusion gene or CSDE1 pathogenic variants, with The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) study having been the first to report the presence of both alterations in PPGLs (9, 12).

Besides the transcriptomic subtypes, different “omics” profiling techniques, such as copy number alteration profiling, miRNomics, DNA methylomics, metabolomics, and reverse-phase protein arrays, have provided additional information that could facilitate the clear classification of PPGLs according to their genetic background (13, 14). Nevertheless, despite the significant and continuous progress and countless important discoveries in the genomics of these tumors, current therapeutic options for PPGLs have remained relatively stagnant, with only select strategies having been implemented thus far.

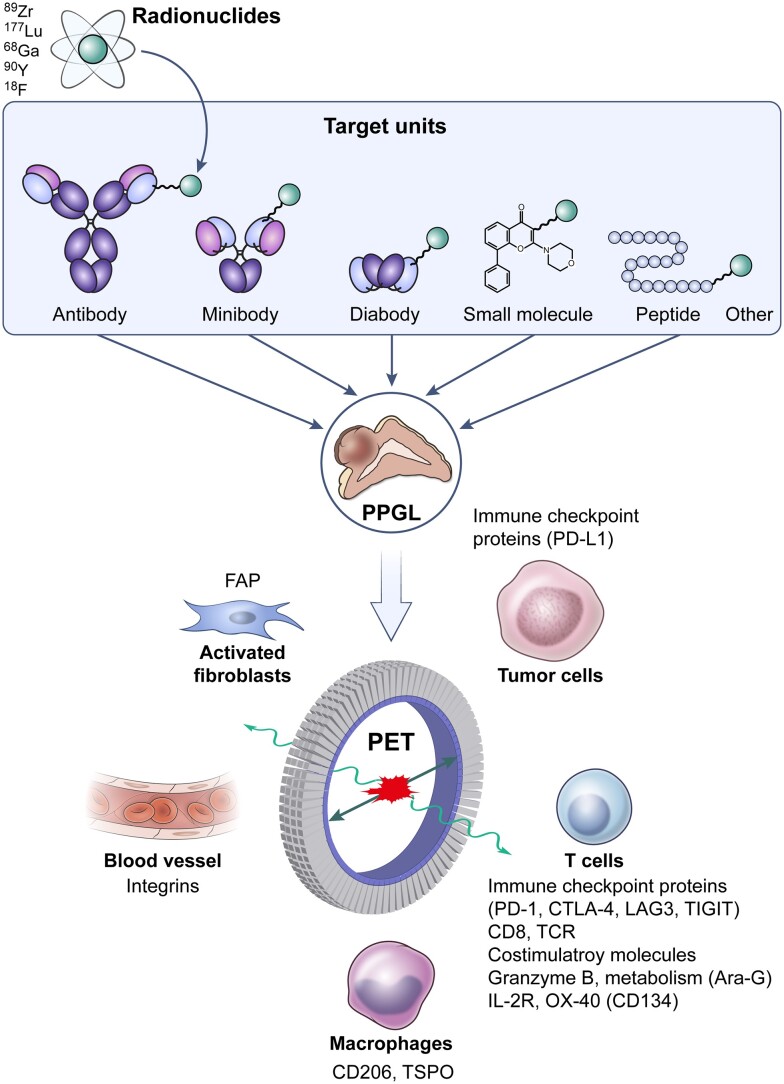

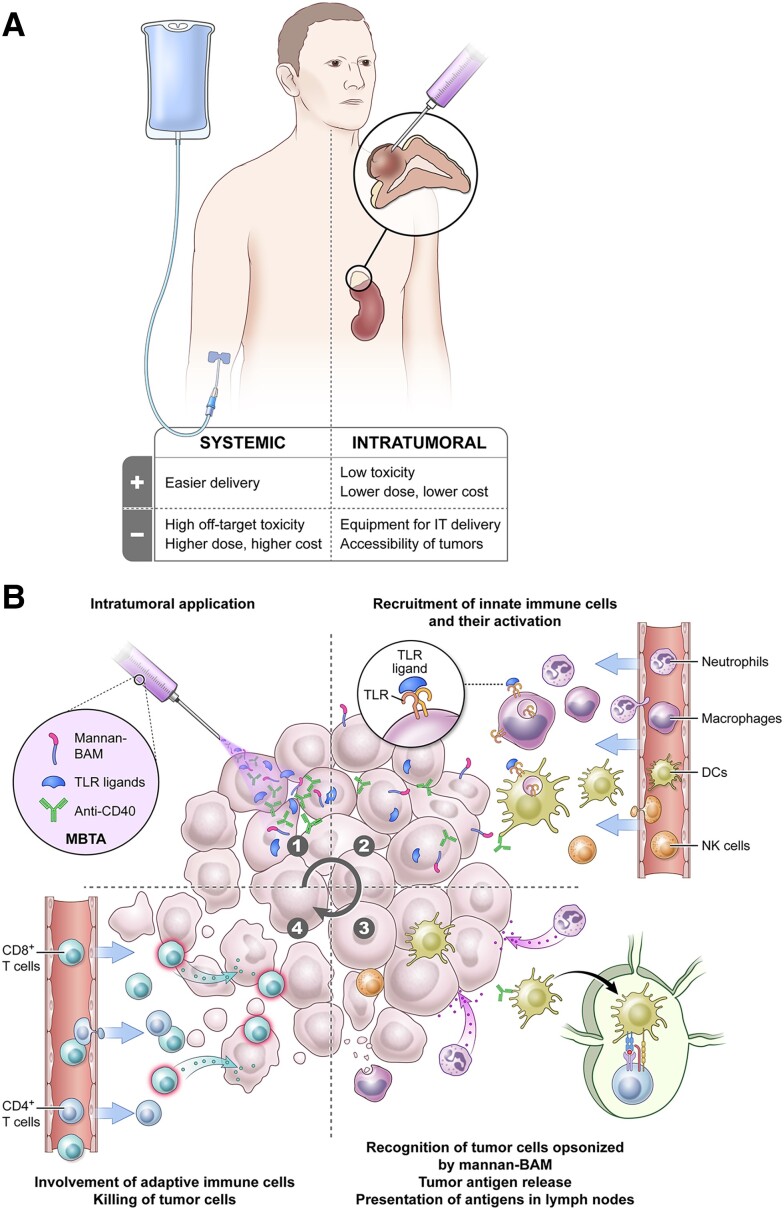

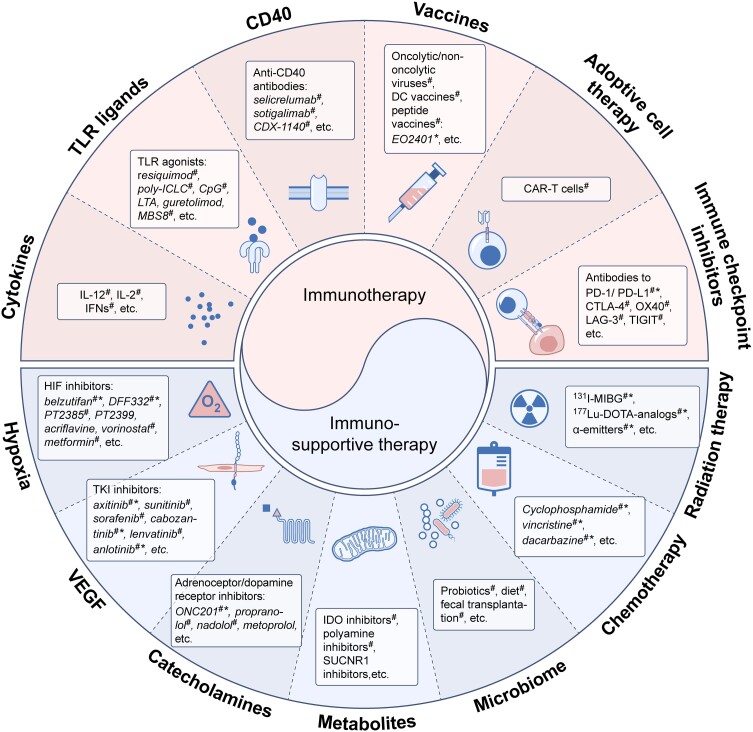

New trends in promising therapies, however, have recently emerged with pioneering discoveries in the role of the tumor microenvironment (TME), particularly the immune system and its inhibitory and stimulatory checkpoint mechanisms (15). The inclusion of the immune system in the revised hallmarks of cancer, increased use of immunomics, launch of a consensus guideline (ie, iRECIST) and expert recommendations for human intratumoral immunotherapy, machine learning (ML), and other methods for identifying the role of the immune system in the metastatic behavior of cancer (including PPGLs) represent a few new frontiers in the therapeutic modification of the immune system to fight cancer (16-21). PPGLs, although rare, have not been overlooked, as evident from the various studies and a recent review describing how the components of the PPGL microenvironment could be used to better understand their pathogenesis, progression, and therapies (22). A few original studies have focused on programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) and programmed cell death ligand (PD-L)1/2 (receptor–ligand) expression, with their findings suggesting that some PPGLs could benefit from PD-L1/2-targeted therapies more than others (21, 23-25), although this has yet to be verified in clinical studies. Recently, a phase 2 clinical trial using pembrolizumab in patients with metastatic PPGL showed that around 40% of patients exhibited no disease progression, with an overall response rate of 9% (26). This clearly shows that the presence of immune checkpoint mechanisms may not sufficiently predict responses to immunotherapy. Indeed, a recent commentary related to the immune landscape of PPGLs and some experimental studies from Hong et al (27, 28) have revealed that some metastatic cancers may require treatment that involves both arms of the immune system, namely innate and adaptive immunity. This is even more important for tumors that lack immune cells, otherwise known as “cold” tumors, which include PPGLs. Thus, aside from the previously described new initiatives, which introduce and assess the role of the immune system in cancer, current studies have shown that an immunoscore or immune-based classification of tumors is tightly linked to cancer behavior and patient outcomes (29, 30). In fact, much effort has been invested toward converting PPGLs into immunologically active lesions (otherwise known as “hot” tumors), thereby ushering in an era of new and potentially promising treatment options.

This review outlines the fundamental principles of the immune system and its consequent role in cancer pathogenesis, progression, and metastasis, with a particular emphasis on PPGLs. Additionally, we highlight recently published studies related to the immune signatures of PPGLs and how these signatures could be used for the reclassification, prognostication, and management of these tumors in near future. Given that PPGLs are inherently heterogenous tumors, isolated conventional treatments (systemic radiotherapy or a particular chemotherapy regimen) may have limited impact and success. In contrast, immunotherapies engender a unique response from each specific tumor, thereby facilitating a personalized approach to the treatment of PPGLs and other rare tumors in this burgeoning era of personalized medicine.

Cancer Immunoediting: The Role of the Immune System in Tumor Development

Understanding the relationship between cancer development and the immune system has been one of the most challenging undertakings in immunology. Although the initial concept had been proposed by Paul Ehrlich in the early 1900s (31), this hypothesis had ultimately been abandoned given the limited knowledge of the immune system at that time. However, progress in the understanding of the composition and function of the immune system, together with conformation of the existence of tumor antigens over following 50 years, had culminated in the postulation of the main hypothesis called cancer immunosurveillance by Lewis Thomas and Frank Macfarlane Burnet (32). They speculated that adaptive immunity could prevent cancer development before disease manifestation. Key findings, such as the importance of interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) in tumor cell rejection or the increased susceptibility of immunodeficient murine models to tumor development (33, 34), had driven the subsequent extension of this hypothesis into 3 phases, “Elimination,” “Equilibrium,” and “Escape,” collectively called cancer immunoediting (35, 36). Each phase describes the role of the immune system in the entire process, from the successful eradication of tumor cells and selective immune pressure to the final tumor progression and associated clinical manifestations. The key principle of the cancer immunoediting process is the ability to recognize tumor antigens (37, 38). Tumor antigens stimulate or activate the immune system. Once activated, the immune system recognizes these antigens as foreign or abnormal and initiates an immune response aimed at damaged or tumor cells carrying these antigens.

The immune system comprises 2 main parts, the innate and adaptive immune systems that work synergistically. The innate system acts nonspecifically, using various cells and proteins like the complement system to mark and eliminate pathogens, damaged, and abnormal cells. Innate immune cells, such as macrophages, dendritic cells (DCs), granulocytes, mast cells, and natural killer (NK) cells, recognize these opsonized pathogens and abnormal cells and eliminate them. Additionally, the innate immune system produces cytokines and chemokines involved in direct cytotoxicity or trafficking other immune cells into site of inflammation, crucial for shaping the adaptive response and maintaining immune balance. The adaptive immune system, composed of B and T cells, generates specific responses against antigens. B cells mainly produce specific antibodies whereas T cells play a critical role in cell-mediated immunity by recognizing and killing infected or abnormal cells. The adaptive immune system is also capable of immune memory, which allows for a more rapid and effective response to repeated antigen exposure. The coordinated actions between the innate and adaptive immune systems are essential for effective immune responses and maintaining immune homeostasis.

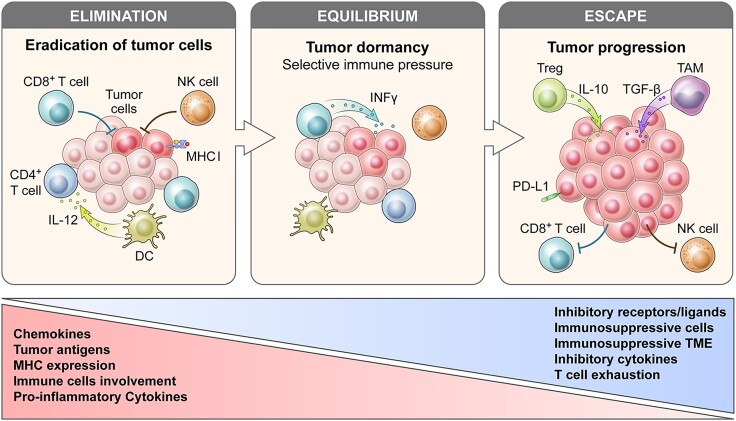

In the first phase of cancer immunoediting (Fig. 1), called the elimination phase, newly arising and immunogenic tumor cells can be recognized and controlled by the immune system and subsequently eliminated from the organism before tumors become clinically detectable. Tumor-infiltrating effector immune cells, such as NK, NKT, and T cells, can recognize tumor neoantigens and other surface molecules on tumor cells, such as cell stress ligands and apoptosis-inducing molecules, and eliminate the tumor cells. Effector cells produce interleukin (IL)-12, interferons, tumor necrosis factor, perforins, and other cytokines to eliminate tumor cells. Stressed and dying cells, including apoptotic and necrotic cells, release alarmins, which are also called damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) (39). Examples of well-studied DAMPs include high mobility group box 1 protein, heat shock proteins, adenosine triphosphate, uracil acid, or DNA (comprehensively reviewed in (35, 36)). These molecules are recognized by pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) expressed mainly on innate immune cells, such as DCs and macrophages (37, 38). The ligation of PRRs by DAMPs may contribute to the immune-mediated eradication of tumor cells via the promotion of DC activation and subsequent increase in antigen presentation to T cells.

Figure 1.

Simplified cancer immunoediting process. Cancer immunoediting proceeds through the phases of elimination, equilibrium, and escape. During the elimination phase the innate and adaptive immune system can recognize MHC expression and antigens of tumor cells and eliminate them. If cancer cells survive the elimination phase, they progress into equilibrium phase where immune pressure select low-immunogenic tumor cell clones. Subsequently, the edited tumor cells can escape from immune surveillance. In this escape phase, tumors are clinically detectable. Tumor cells promote an immunosuppressive microenvironment by recruiting immune regulatory cells, altering immune cell trafficking, dysregulating the secretion of signaling molecules and metabolites, and upregulating surface molecules. Abbreviations: DC, dendritic cell; IL, interleukin; INF, interferon; MHC, major histocompatibility complex; NK cells, natural killer cells; PD-L1, programmed death-ligand 1; TAM, tumor-associated macrophage; TME, tumor microenvironment; TGF, tumor growth factor; Treg, T regulatory cells.

In the second phase, called the equilibrium phase, the immune system and tumor cells are in balance and the immune system recognizes and eliminates immunogenic tumor cells through the aforementioned mechanism. This selective immune pressure may promote the production of resistant and often nonimmunogenic clones of tumor cells, resulting in the escape phase.

During the last phase, called the escape phase, tumor cells accumulate additional immunosuppressive changes that allow them to escape from immunosurveillance. One of the main immune escape mechanisms common for many tumor types is the loss of tumor antigens. Tumor cells may either decrease antigenicity or lose major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules required for the presentation of neoantigens to T cells and their subsequent activation, leading to reduced immune recognition.

Other escape mechanisms may result from the development of an immunosuppressive TME unique to each tumor. Tumor cells often promote an immunosuppressive microenvironment by recruiting immune regulatory cells, altering immune-cell trafficking, dysregulating the secretion of signaling molecules and metabolites, and upregulating surface molecules. Immunosuppressive cytokines, such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β), or IL-10 may dysregulate immune-cell function and recruit regulatory immune cells (40). In response to the immunosuppressive cytokines, 3 main immunosuppressive subpopulation of leukocytes, namely regulatory T cells (Tregs), myeloid-delivered suppressor cells (MDSCs), and tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), infiltrate the tumor and further dysregulate antitumor responses via different mechanisms (reviewed in (41)). Tumor cells can also regulate the production of metabolites, such as adenosine, tryptophan, or lactate that further impair leukocyte functions (42-44). The last immune escape mechanism is the upregulation of surface molecules called checkpoint ligands on tumor cells, such as PD-L1/PD-L2, CD47 (which acts as a “do not eat me” signal), and others (45, 46).

A better understanding of each phase throughout the cancer immunoediting process, especially in development of PPGLs, may provide new insights into improving the immunotherapy of these rare tumors.

Evidence for the Immune Escape of PPGLs

The TME is a complex ecosystem consisting of tumor cells, stromal cells, and other cellular and noncellular components that may have an impact on immune-cell presence in TME. The diversity of the tumor-infiltrating immune cells may be associated with tumor growth, prognosis, prediction, and response to various immunotherapies. Tumors can be divided into 3 groups according to their TME: “cold,” “altered,” and “hot” tumors (29). “Cold” (noninflamed) tumors have no tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) and low mutation burden. “Altered” tumors are characterized by the upregulation of inhibitory mediators and presence of immunosuppressive cells, resulting in T cell infiltration impairment. “Hot” (inflamed) tumors are characterized by TIL infiltration and accumulation of proinflammatory cytokines and genomic instability. Several studies have shown that “hot” tumors exhibit higher response rates to immunotherapy than do “cold” tumors. PPGLs can be considered as “cold” or “altered” tumors given their low mutational burden and absence of TILs, suggesting immune escape. Next, we comprehensively discuss current evidence for the immune escape of PPGLs.

Lack of Tumor Antigens

Tumor mutational burden (TMB) represents the number of genetic mutations in tumor cells. Such mutations may lead to neoantigen peptides and subsequently be presented by antigen presenting cells (APCs) to T cells in the MHC complex. Previous reports have shown that tumors with a high TMB had greater TIL presence than did those with a low TMB (47). With the increasing number of neoantigens, TILs have better chances to recognize and successfully eliminate tumor cells. Data also show that TMB can serve as a biomarker of beneficial clinical response to immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) in various cancers (reviewed in (48)).

Unlike other cancers, such as melanomas or lung squamous cell carcinomas, which have a high TMB, PPGLs have a low TMB (9, 13, 21, 25, 49-52). In fact, PPGLs have one of the lowest median neoantigen burden among all other cancers across TCGA (21), which may reduce and prevent TIL infiltration. Indeed, most PPGLs are lymphocyte-depleted tumors, the details of which will be discussed later. Focusing on the PPGL genetic landscape, a recent study by Calsina et al showed that primary metastatic PPGLs and metastases have a higher TMB than do nonmetastatic primary tumors (21). The same authors also observed that increased TMB and microsatellite instability scores were associated with decreased time to progression. Significant differences in TMB were also observed between genomic subtypes, with the Wnt-altered subtype having the highest values, regardless of tumor behavior. Among all other PPGL genotypes, MAML3 tumors (Wnt signaling cluster) showed the highest neoantigen load (21). However, Tamborero et al described that the TMB of PPGLs were not correlated with their cytotoxic immunophenotypes that represent immune infiltration in tumors and clustering of cytotoxic cell based on gene signature (53).

Taken together, current evidence indicates that TMB by itself may not be a reliable predictive marker for the cytotoxic immune-cell composition of PPGLs and, in turn, their responses to ICIs. Indeed, another group previously reported that TMB should not be used in isolation but should rather be considered along with multiple other factors, such as neoantigen clonality and host immunological environment, which impact the balance of protumor and antitumor cytokines and TIL infiltration (54).

Absence of Tumor-Infiltrating T Cells

Tumor-infiltrating T cells, which include naïve, effector, memory, and Tregs, play a key role in tumor development and progression. Upon initial stimulation of naïve helper CD4+ or cytotoxic CD8+ T cells by an antigen, a cell-intrinsic program guides the differentiation of the cells into their effector phenotypes. CD4+ effector T cells differentiate into 2 major subtypes based on their response to several cytokines: (1) type 1 T helper (Th1) cells generated in response to IFN-γ and increase the cell-mediated response through macrophage and cytotoxic CD8+ T cell activation and (2) type 2 T helper (Th2) cells associated with IL-4, IL-5, and IL-10, which inhibit macrophage activation and promote humoral immune response through B cells. After the expansion of effector CD4+ or CD8+ T cells and clearance of specific antigens, most T cells die, except for a small subpopulation of memory T cells that provide long-term memory and protection against a second exposure to the same antigen. However, chronic exposure of T cells to the same antigen may deregulate their cell activation and differentiation, resulting in their dysfunction and exhaustion, which is one of the main escape mechanisms during cancer immunosurveillance. Tregs are a subpopulation of T cells that act as suppressor cells and therefore maintain immune homeostasis and self-tolerance within the body. However, some tumor cells can hijack Tregs in TME, giving them increased protection against the antitumor mechanisms of the immune system.

As stated earlier, TIL infiltration indicates the immunosurveillance status of the tumors and serves as a marker of their response to ICIs. Based on TCGA data on 29 tumor types, PPGLs have been listed under the category of tumors with the lowest expression of CD45, a cell surface marker of all nucleated hematopoietic cells (10, 55), indicating the limited presence of immune cells in the PPGL microenvironment. Despite exhibiting higher lymphocyte infiltration than the non-neoplastic adrenal medulla, PPGLs have still been considered to be strongly lymphocyte-depleted tumors compared with other cancer types (53). The amount of T cells present within the PPGL microenvironment usually represents only a small fraction of immune cells, with a higher proportion of CD4+ than CD8+ T cells (10, 56). Immunohistochemical studies focusing on the localization of PPGL T cells showed that these cells were homogenously distributed within the TME, without T cell–excluded areas (57). However, each cohort and method showed different results regarding T cell subpopulation infiltration, especially in metastatic PPGLs (summarized in Table 1). An immunohistochemistry (IHC) study by Gao et al showed that samples with a Pheochromocytoma of the Adrenal Gland Scaled Score (PASS) of <4 exhibited a greater presence of CD8+ T cells than did those with a PASS of ≥4 and that well differentiated PPGLs (based on the Grading System for Adrenal Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma) had a greater presence of CD8+ T cells than did moderately differentiated ones (58). Another IHC study by Jin et al showed no difference in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells between primary and metastatic tumors (25). Notably, an IHC study by Celada et al showed no difference in CD8+ T cells between nonmetastatic and metastatic PPGLs but did find higher CD8+ T cell infiltration in metastatic primary PPGLs than in metastases (59). Calsina et al revealed that metastatic primary tumors had a lower proportion of CD8+ (RNA-Seq study) than did nonmetastatic tumors (validated by IHC) (21). Yu et al showed that tumors expressing PD-L1 had a lower proportion of CD8+ and CD4+ T cells among CD3+ TILs than did those not expressing PD-L1 (60). Two other studies showed that Treg infiltration was associated with PPGL progression (20, 21) but not with any somatic pathogenic variant of tested tumor samples (61). Focusing on PPGL clusters, studies have shown that SDHB-negative tumors have fewer CD8+ T cells than do SDHB-positive tumors (56, 59), with MAML3 tumors having the highest number CD8+ T cells among all other genotypes. Within the pseudohypoxia cluster, evidence suggests that CD4+ but not CD8+ T cell infiltration was higher in VHL-mutated tumors than in SDHB-mutated tumors.

Table 1.

Studies focused on tumor-infiltrating T cells in PPGLs

| Marker | Method and number of samples | Results | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Identification of immune cell subsets | RNA-Seq: n = 179 (TCGA) | PPGLs in lymphocyte depleted subtype. | Thorsson et al (55) |

| ↓Th1 response. | |||

| CD45 | IHC: n = 17 | Tumor-infiltrating T cells. | Guadagno et al (57) |

| CD3 | No correlation with any clinic-pathological variables. | ||

| ↓immunoscore in metastatic cases. | |||

| CD4 | IHC: n = 39 | ↑CD8+ T cells in PASS < 4 than PASS ≥ 4. | Gao et al (58) |

| CD8 | ↑CD8+ T cells in well differentiated than moderately differentiated PPGL (based on GAPP score). | ||

| CD8+ T cells inversely correlated with tumor size. | |||

| Identification of immune cell subsets | RNA-Seq: n = 179 (TCGA) | ↑CD4+ memory T cells in older patients (>45 year). | Batchu (61) |

| Proportion of CD4+ memory T cells and Tregs did not associate with any somatic mutations. | |||

| Identification of immune cell subsets | (sn)RNA-Seq: n = 30 + 2 NAM | Lymphocytes in smaller fraction of all immune cells with predominant subpopulation of CD4+ T cells and minor subpopulations of CD8+ T cells, Tregs, and NK cells. | Zethoven et al (10) |

| bulk-tissue RNA-Seq: n = 735 | |||

| CD3 | IHC: n = 65 + 20 NAM | ↑proportion of immune cells in tumors compared with NAM. | Tufton et al (56) |

| CD4 | ↑proportion of CD4+ T cells than CD8+ T cells. | ||

| CD8 | ↑proportion of CD4+ T cells in aggressive tumors. | ||

| ↑level of CD4+ T cells in VHL- compared with SDHB-related tumors. | |||

| ↓CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in SDHB-negative tumors. | |||

| ↓ratio of CD8+/CD4+ T cell compared with NAM. | |||

| CD4 | IHC: n = 63 | 49.2% of samples positive for intratumoral and 22.2% for stromal CD8+ T cells (61.3% of these samples had percentage of intratumoral CD8+ T cells around 1%). | Jin et al (25) |

| CD8 | 2.7% of samples positive for intratumoral and 3.1% for stromal CD4+ T cells. | ||

| No difference between CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and primary and metastatic tumors. | |||

| Identification of immune cell subsets | RNA-Seq: n = 177 (TCGA) | Five immune cluster introduced: 1, M2 macrophages; 2, monocytes; 3, activated NK cells; 4, Tregs and M0 macrophages; 5, CD8+ and CD4+ T cells. | Ghosal et al (20) |

| RT-PCR + NanoString: n = 48 (validation cohort) | ↑proportion of resting CD4+ T cells and resting NK cells had a negative effect on better clinical outcomes. | ||

| CD8 | IHC: n = 102 | CD8+ T cells detected in 19.7% samples. | Celada et al (59) |

| 60% of tumors with levels of infiltrating CD8+ T cells also displayed ↑levels of tumor cells with PD-L1. | |||

| ↑CD8+ T cells in metastatic primary PPGLs than metastases. | |||

| No difference in CD8+ T cells between nonmetastatic and metastatic PPGLs. | |||

| ↑CD8+ T cells more frequent in SDHB-positive than negative tumors. | |||

| ↑CD8+ T cells higher among tumors with negative HIF2alfa IHC. | |||

| No associations were found between CD8+ T cells and overall survival. | |||

| Identification of immune cell subsets | WES: n = 261 | ↑resting, ↓activated CD4+ T cells, ↓proportion of CD8+ and ↑resting and ↓activated NK cells in metastatic primary compared with nonmetastatic tumors (CD8+ T cell proportions validated by IHC). | Calsina et al (21) |

| RNA-Seq: n = 265 | ↓Th1 gene signature in primary metastatic tumors compared with nonmetastatic primary tumors. | ||

| IHC: n = 39 | ↑Tregs associated with shorter time to progression. | ||

| (CNIO, TCGA) | ↑number of CD8+ T cells in MAML3 tumors compared with other genotypes. | ||

| Tumor-infiltrating T cells | FACS: n = 7 | Proportion of CD8+ and CD4+ T cells among CD3+ TILs of PD-L1+ tumors was ↓ than PD-L1− tumors. | Yu et al (60) |

| qPCR: n = 16 | Expression of perforin and granzyme-B was ↓ in the PD-L1+ tumors. | ||

| mIF: n = 6 | Proportion of effector memory T cells in the PD-L1+ tumors was significantly ↑than that in the PD-L1− tumors. |

Abbreviations: CD3, cluster of differentiation—T cells; CD4, cluster of differentiation—helper T cells; CD8, cluster of differentiation—cytotoxic T cells; CD45, cluster of differentiation—leukocytes; CNIO, Centro Nacional de Investigaciones Oncológicas; FACS, fluorescence-activated cell sorting; GAPP, Grading System for Adrenal Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma; IHC, immunohistochemistry; mIF, multiplex immunofluorescence; NAM, normal adrenal medulla; NK, natural killer; PASS, Pheochromocytoma of the Adrenal Gland Scaled Score; PPGL, pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma; qPCR, quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction; RNA-seq, RNA sequencing; (sn)RNA-seq, single nucleus RNA sequencing; SDHB, succinate dehydrogenase subunit B; TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas database; Tregs, regulatory T cells; WES, whole exome sequencing; PD-L1, programmed cell death ligand 1.

In summary, PPGLs are mostly T cell-depleted tumors in which the proportion of helper CD4+ cells usually exceed that of cytotoxic CD8+ T cells, suggesting strong immune escape mechanisms preventing sufficient T cell infiltration. Clinically unfavorable outcomes have been observed in PPGLs infiltrated with Tregs, confirming their suppressive roles.

Higher Presence of Tumor-Associated Macrophages

Macrophages, typically derived from monocytes, are professional phagocytes with a broad spectrum of functions, including digestion of pathogens and cellular debris, presentation of digested antigens, shaping of immune response through cytokine production, presentation of digested antigens, and facilitation of wound healing (62). Cells of the monocyte–macrophage lineage are widely present throughout all bodily tissues and polarized according to the tissue microenvironment in their respective subpopulations. TAMs are usually divided into the binary M1–M2 macrophage polarization system. M1 macrophages are defined as proinflammatory cells capable of producing major inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, or IL-12, whereas M2 macrophages are anti-inflammatory cells known for their production of IL-10 or TGF-β (63). The increased presence of TAMs in many solid cancers, such as glioblastomas or breast, bladder, and prostate cancers, has been associated with tumor progression and invasive behavior due to their immunosuppressive abilities (64).

Several studies have reported the increased presence of monocytes (precursors of macrophages) and macrophages in PPGLs (summarized in Table 2). Thorsson et al, who focused on the immune subtypes in TCGA samples, revealed that PPGLs, together with adrenocortical carcinomas, hepatocellular carcinomas, and gliomas, displayed a more prominent macrophage signature with a high anti-inflammatory M2 response and the least favorable outcome compared with other tumors (55). Farhat et al also described the population of cells immunohistochemically positive for monocyte–macrophage lineage markers CD163 and CD68 (65). A recent publication based on single-nuclei RNA-seq (snRNA-seq) and bulk-tissue gene expression analysis showed that myeloid cells were the predominant leukocytes in PPGLs, confirming previous results (10). These myeloid cells mostly consisted of macrophages (94%), with a few monocytes (4.4%), dendritic (2.9%), and mast cells (3%) (10). A study by Calsina et al showed a higher presence of M2 macrophages in metastatic than in nonmetastatic PPGLs (21). Another study also found an increased presence of M2 macrophages in aggressive PPGLs (56). The bulk-tissue gene expression data revealed that the pseudohypoxia cluster, specifically SDHx head and neck and VHL PPGLs, had a higher expression of macrophage markers (ie, CD68, CD86, CD163, and MRC1) than did the other subtypes. The same authors also showed that the number of CD163+ and CD206+ (M2 macrophage marker) cells was higher in VHL-mutated PPGLs than in the other subtypes (10). After immunoprofiling PPGLs, Ghosal et al identified 5 immune clusters, 3 of which were related to macrophages (specifically M2 macrophages), monocytes, and M0 macrophages (20). Notably, the same study showed that tumors within immune clusters that exhibited increased M0 and M2 macrophage infiltration were associated with aggressive, metastatic, or advanced-stage disease, supporting previous results from Thorsson et al (55). Interestingly, SDHx-mutated pseudohypoxic tumors, which often display metastatic behavior, had an increased proportion of immune cluster associated with M2 macrophages, which also supports previous results (55).

Table 2.

Studies focused on tumor associated macrophages in PPGLs

| Marker | Method and number of samples | Results | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Identification of immune cell subsets | RNA-Seq: n = 179 (TCGA) | More prominent macrophage signature with ↑M2 response and the least favorable outcome (together with adrenocortical carcinoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, glioma) compared with other tumors. | Thorsson et al (55) |

| CD68 | IHC: n = 62 | Dense population of CD68+, CD163+ cells in PPGLs. | Farhat et al (65) |

| CD163 | No significant differences detectable in relation to patients’ gender, age, or mutational status. | ||

| CD68 | IHC: n = 39 | ↑CD68+ cells in PPGL with regular and normal histological pattern compared with those with abnormal patterns: inversely correlate with tumor size (based on GAPP score). | Gao et al (58) |

| CD163 | CD163+ cells correlated with CD8+ T cells. | ||

| Identification of immune cell subsets | RNA-Seq: n = 179 (TCGA) | ↓M2 in tumors from older patient (>45 years). | Batchu (61) |

| Missense mutational burden in genes FRG1B and RET positively correlated with M2 macrophages. | |||

| Identification of immune cell subsets | (sn)RNA-Seq: n = 30 + 2 NAM | Myeloid cells as dominant leukocyte subpopulation, consisting mostly of macrophages (94%) with a minor population of monocytes (4.4%). | Zethoven et al (10) |

| CD68, CD163, and CD206 markers | bulk-tissue RNA-Seq: n = 735 | ↑expression of the macrophage markers in SDHx-head and neck and VHL subtypes compared with other subtypes. | |

| IHC n = 12 (validation cohort) | ↑CD163+ and CD206+ cells in VHL PPGLs compared with other subtypes. | ||

| CD68 | IHC: n = 65 + 20 NAM | ↑proportion of M2:M1 in aggressive tumors (together with CD4+ T cells). | Tufton et al (56) |

| CD163 | ↑higher proportion of M2 infiltration with higher M2:M1 in aggressive SDHB-mutated PPGLs. | ||

| Identification of immune cell subsets | RNA-Seq: n = 177 (TCGA) | Five immune clusters introduced 1, M2 macrophages; 2, monocytes; 3, activated NK cells, 4, Tregs and M0 macrophages; 5, CD8+ and CD4+ T cells. | Ghosal et al (20) |

| RT-PCR + NanoString: n = 48 (validation cohort) | Immune clusters consisted of higher proportion of M0 and M2 macrophages were associated with aggressive, metastatic, or advanced-stage tumors. | ||

| ↑proportion of the immune cluster associated with M2 macrophages in SDHx-mutated pseudohypoxic tumors. | |||

| Identification of immune cell subsets | WES: n = 261 | ↑M2 macrophages in metastatic primary tumors compared with nonmetastatic. | Calsina et al (21) |

| RNA-Seq: n = 265 (CNIO, TCGA) |

Abbreviations: CD68, cluster of differentiation—marker of monocyte/macrophage lineage; CD163, cluster of differentiation—marker of monocyte/macrophage lineage; CD206, cluster of differentiation—M2 macrophages; CNIO, Centro Nacional de Investigaciones Oncológicas; FRG1B, FSHD Region Gene 1 Family Member B, Pseudogene; IHC, immunohistochemistry; NAM, normal adrenal medulla; PPGL, pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma; qPCR, quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction; RET, proto-oncogene, receptor tyrosine kinase; RNA-seq, RNA sequencing; (sn)RNA-seq, single nucleus RNA sequencing; SDHB, succinate dehydrogenase subunit B; TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas database; WES, whole exome sequencing.

Overall, macrophages are the dominant leukocyte subpopulation in PPGLs, with an increased proportion of M2 macrophages being associated with immunosuppressive and aggressive/metastatic behavior. This suggests that targeting of these cells could lead to better outcomes in PPGLs.

Immune Checkpoint Molecules

Immune checkpoint proteins are regulatory receptors that can be found, along with their ligands, in various cell types. Under physiological conditions, immune checkpoint molecules regulate the immune system, diminishing the immune response after the mitigation of an infection. However, immune checkpoint interactions may also be involved in cancer development and growth, representing a particularly major mechanism underlying tumor immune escape (66-69). Among the most studied checkpoint molecules, cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) and PD-1 and its ligands (PD-L1 and PD-L2) are currently considered the most relevant immune system inhibitory molecules, interrupting the costimulatory signals or interfering with TCR signaling, respectively (70). Although CTLA-4 (CD152) is expressed almost exclusively on T cells, limited expression had also been found on B cells. PD-1 (CD279) is expressed on the surface of T cells, B cells, professional APCs, NK cells, and some tumor cells. The signal is activated through 2 specific ligands, namely PD-L1 (CD274) and PD-L2 (CD273). PD-L1 is expressed on T and B cells, DCs, macrophages, endothelial cells, and some tumor cells. PD-L2 is restricted to activated DCs, macrophages, bone marrow–derived mast cells, and tumor cells (71-74). Recently, other inhibitory receptors/mechanisms limiting immune-cell function in cancer have been described, such as T cell immunoglobulin and mucin-domain containing-3 (TIM-3), lymphocyte activation gene 3 (LAG-3), and T cell immunoreceptor with Ig and ITIM domains (TIGIT), and further research and clinical studies related to this inhibitory signaling are underway (70, 75-77). Apart from T cells, other immune cells also express immune checkpoints, but the function of these checkpoints and their manipulation have been much less explored (78).

In the first study on PD-L1/2 and PPGLs published in 2017, Pinato et al detected tumor PD-L1 immunopositivity in 40% (4/10) and 15% (14/90) of metastatic and nonmetastatic cases, respectively, with such immunopositivity not being correlated with germline pathogenic variants, tumor location, tumor size, and patient survival (23). Meanwhile, PD-L2 immunopositivity was found in 50% of metastatic cases (5/10) but in only 12% of nonmetastatic specimens (11/90). The proportion of PD-L2 positivity was higher in PPGLs with vascular invasion and was also correlated with a high expression of genes associated with hypoxia and immune-cell exhaustion (23). A subsequent study that included 77 PPGLs showed PD-L1 positivity in 59.7% of the tumors but found no correlation between PD-L1 presence and relapse/distant metastasis, tumor size, capsular invasion, tumor necrosis, and specific catecholamine production/secretion (79). Nevertheless, a significant correlation was observed between Ki-67, a proliferation marker for tumor cells, and hypertension (79). Although these preliminary studies showed that a considerable number of PPGLs had high PD-L1 expression, later studies revealed much lower positivity in the cohorts. For all clinically advanced PPGLs, PD-L1 immunostaining of tumor cells revealed a positivity rate of less than 10% (52). In fact, a recent study showed a PD-L1 positivity rate of only 7.9% measured in primary and metastatic tumors, in a cohort of 53 patients with PPGL (25). After IHC staining of whole-tumor sections, Hsu et al found that 26.1% of cases expressed PD-L1 in ≥1% of tumor cells, but only 8.7% of the cases expressed PD-L1 in approximately 10% of tumor cells (80). The proportion of PD-L1-positive cells is important information given its association with different therapeutic outcomes in various cancers (81-83). Batchu et al, who analyzed TCGA mRNA expression data, showed that the increased expression of PD-L1 and PD-L2 in the pseudohypoxic cluster was located in the stromal compartments, suggesting that the expression originated from non-PPGL cells in TME and that further studies on the TME of PPGLs are necessary to evaluate immune checkpoint therapies (84). Furthermore, sympathetic PPGLs exhibited higher PD-L1 expression than did parasympathetic PPGLs (59). All studies are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Studies focused on immune checkpoint proteins in PPGLs

| Marker | Method and number of samples | Results | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| PD-L1 | IHC: n = 10 metastatic, n = 90 nonmetastatic | PD-L1 positive 40% metastatic and 15% nonmetastatic—no correlation with germline mutations, tumor location, tumor size, or survival. | Pinato et al (23) |

| PD-L2 | PD-L2 positive 50% metastatic and 12% nonmetastatic—correlation with hypoxia and immune-exhaustion. | ||

| PD-L1 | IHC: n = 77 | PD-L1 positivity 59.7%. | Guo et al (79) |

| qPCR: n = 20 | No correlation to age, sex, tumor size, capsular invasion, tumor necrosis, relapse/distant metastasis, and secretion of catecholamines. | ||

| Correlation to Ki-67 and hypertension. | |||

| PD-L1 | IHC: n = 24 | PD-L1 positivity ≥10% of tumor cells in 8.7% tumors. | Hsu et al (80) |

| PD-L1 positivity in ≥1% of tumor cells in 26.1% tumors. | |||

| PD-L1 | IHC: n = 128 | PD-L1 positivity <10%. | Bratslavsky et al (52) |

| Gene amplification: n = 128 | No CD274 gene amplification. | ||

| PD-L1 | IHC: n = 53 | PD-L1 positivity 7.9%. | Jin et al (25) |

| No correlation to metastatic disease. | |||

| PD-L1 | qPCR: n = 48 | PD-L1 mRNA ↑in PPGL vs NAM, ↓in pseudohypoxic cluster vs sporadic cases and kinase signaling cluster. | Hadrava Vanova et al (24) |

| PD-L2 | validation: n = 72 (TCGA) | PD-L2 mRNA no difference. | |

| No correlation to metastatic status and Ki-67. | |||

| PD-L1 | RNA-Seq—gene expression deconvolution: n = 175 (TCGA) | ↑PD-L1, PD-L2 mRNA in the stromal compartments in pseudohypoxic and Wnt-altered cluster. | Batchu et al (84) |

| PD-L2 | |||

| CTLA-4 | IHC: n = 48 | Higher CTLA-4 positive cells compared with other tumors. | Dum et al (85) |

| PD-L1 | IHC: n = 94 primary, n = 8 metastases | PD-L1 positivity 16.7%, 12.7% in primary samples and 62.5% metastatic samples, ↑metastatic, ↓SDHB-negative tumors. | Celada et al (59) |

| qPCR: n = 184 (TCGA) | ↓pseudohypoxic cluster from the TCGA. | ||

| PD-L1 | IHC: n = 44 | PD-L1 positivity 34%, ↓pseudohypoxic tumors, ↑Wnt-altered subtype. Highly expressed in MAML3-related tumors; <25% of kinase/pseudohypoxic tumors positive. | Calsina et al (21) |

| TIGIT | RNA-Seq: n = 264 (CNIO + TCGA) | No association to clinical behavior. | |

| LAG-3 | No significant changes in TIGIT and LAG-3 expression between metastatic and nonmetastatic or between clusters. | ||

| PD-L1 | IHC: n = 60 | PD-L1 positivity 33.3%. ↑PD-L1 mRNA to NAM. | Yu et al (60) |

| PD-1 | RNA-Seq: n = 7 | ↑PD-L1, PD-1, TIM3, LAG-3 mRNA in IHC PD-L1+ samples; no significant change in TIGIT between IHC PD-L1+ and IHC PD-L1- samples. | |

| TIM3 | qPCR: n = 16 | ↑PD-1, TIM3, LAG-3, TIGIT protein in T cells, correlation with PD-L1 expression. | |

| LAG-3 | FACS: n = 7 | ||

| TIGIT |

Abbreviations: IHC, immunohistochemistry; NAM, normal adrenal medulla; PPGL, pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma; qPCR, quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction; RNA-seq, RNA sequencing; SDHB, succinate dehydrogenase subunit B; TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas database; WES, whole exome sequencing; PD-1, programmed cell death protein 1; PD-L1/2, programmed cell death ligand 1/2; CTLA-4, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated protein 4; TIGIT, T-Cell immunoreceptor with Ig And ITIM domains; LAG-3, lymphocyte-activation gene 3; TIM3, T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin-domain containing-3; FACS, fluorescence-activated cell sorting.

Some studies have suggested that metastatic PPGLs more frequently express PD-L1 than do nonmetastatic PPGLs (23, 59), whereas no correlation had been found in other studies (24, 25). The variety of results from different cohorts currently prevents researchers from definitively concluding whether metastatic PPGLs express more checkpoint molecules than do nonmetastatic PPGLs.

Several recent studies with varying cohorts and analysis of TCGA data have shown that PD-L1 expression was significantly lower in pseudohypoxic PPGLs, which are often metastatic except from VHL and EPAS1 ones, than in sporadic cases and PPGLs from the kinase-signaling subtype cluster (21, 24, 59). This suggests that PD-1/PD-L1-targeted immunotherapy may have limited outcomes in the pseudohypoxic cluster. Recently, the Wnt-altered subtype had been shown to have the highest PD-L1 expression among the other subtypes, including all metastatic MAML3-tumors in this cohort. However, no association was observed between these tumors and clinical behavior (21).

To date, most studies have focused exclusively on PD-L1/PD-L2 and that of other immune checkpoints's expression, and their relevance to tumor behavior is now being explored (eg, CTLA-4 (85)). A recent study by Yu et al found that the increased PD-L1 expression in PPGL samples was correlated with T cell exhaustion markers, including T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin-domain containing-3, LAG-3, and TIGIT, suggesting that TILs in PPGLs showed the function–failure phenotype and may be a potential target for some patients with PPGL (60). Nevertheless, studies with heterogeneous cohorts and possibly different methodologies, and those focusing mainly on PD-1 and its ligands expression, are still limited. Hence, it is difficult to conclude whether immune checkpoint proteins’ expression in PPGLs has predictive significance in therapy. Given the rarity of these tumors, multi-institutional collaborative efforts could help increase the number of patients and provide more robust and clinically relevant studies.

Dysregulation of Signaling Pathways and Metabolites

Besides immune system components, the TME contains many nonimmune elements that can affect immune signaling and immune-cell invasion. Specifically, the secretion and presence of various growth factors and (onco)metabolites have protumorigenic effects that play important roles in tumor maintenance and progression with subsequent metastasis occurrence. Here, we focus on TME elements that potentially contribute to the immune escape of PPGLs.

Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor

VEGF is one of the most well-described angiogenic factors involved in new blood vessel development, tumor growth, tumor cell invasiveness, and immune-cell regulation. Studies have shown that VEGF can mediate macrophages and T cell chemotaxis, inhibit dendritic and T cell differentiation and function, and promote the accumulation of Tregs in various tumors, thereby having profound protumorigenic effects (86-88).

PPGLs are considered to be highly vascularized tumors (1). Notably, studies have shown that metastatic PPGLs had higher VEGF transcripts than did nonmetastatic PPGLs (89-92), suggesting an association between VEGF-mediated angiogenesis and tumor progression. Vascularization and expression of key angiogenic molecules have also been shown to be upregulated in pseudohypoxic PPGLs, regardless of their metastatic status, possibly due to activation of hypoxia-driven angiogenic pathways in this PPGL cluster (93, 94). Focusing on the connection between VEGF and the immune system in PPGLs, 1 study found that VEGF-A overexpression was correlated with microvessel density, which further correlated with the number of intratumoral macrophages (95). This reflects 1 of the known effects of VEGF on the immune system; however, no further studies have been conducted on the role of VEGF on the immune microenvironment in well-defined PPGL molecular clusters.

Currently, several completed and ongoing clinical trials have focused on VEGF inhibitors/tyrosine-kinase inhibitors (TKIs) in patients with PPGL (Anlotinib: NCT05133349, NCT05883085, NCT04860700; Axitinib: NCT03839498, NCT01967576; Sunitinib: NCT00843037, NCT01371201; Lenvatinib: NCT03008369; Cabozantinib: NCT02302833, NCT04400474; Fostamatinib: NCT00923481; Dovitinib: NCT01635907; Temsirolimus: NCT01155258; Vatalanib: NCT00655655). Given the rarity of these tumors, the number of clinical trials indicates the expected efficacy in patients with PPGLs, especially those with advanced/metastatic cases. Sunitinib has shown therapeutic efficacy in patients with pheochromocytomas, resulting in partial or near-complete tumor regression (96). Furthermore, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis including 7 studies demonstrated that metastatic PPGLs can benefit from TKI therapy. According to this meta-analysis, more than 30% patients can achieve partial response, whereas more than 80% of patients can achieve disease control (97).

Unfortunately, no study has focused on the impact of these inhibitors on the function and recruitment of immune cells in PPGLs. Given the higher expression of VEGF in metastatic and pseudohypoxic PPGLs, targeting the VEGF pathway to modulate the TME for concurrent immunotherapy may be promising.

Catecholamines

Catecholamines, namely epinephrine, norepinephrine (NE), and dopamine (DA), are hormones that are synthesized and secreted by chromaffin cells in the medulla of the adrenal gland. Additionally, NE is synthesized and released locally by postganglionic sympathetic neurons (98), whereas DA further originates from dopaminergic neurons (99). Owing to the variety of receptor isoforms for catecholamine binding, they can trigger different and even opposite effects, such as vasoconstriction, vasodilatation, increased heart rate, and smooth muscle relaxation (98, 100). Adrenoceptors were found to be present on both cancer cells and immune cells (101, 102). Thus, catecholamines may play a role in cancer development and progression by either directly affecting cancer cell proliferation and genomic instability or affecting the immune cells in the TME (98, 99). Catecholamine release under chronic stress has been shown to suppress different aspects of immune function, such as antigen presentation, T cell proliferation, and humoral and cellular immunity (103, 104). Catecholamines have been shown to inhibit the generation of antitumor cytotoxic T cells through β-adrenoceptor signaling in vivo (105-107) and NK cell cytotoxicity and cytokine production through β-adrenoceptors and dopamine receptors (108-110). In a preclinical models of several cancers, β-adrenoceptor signaling decreased the efficacy of CD8+ T cell-targeting immunotherapies (107, 111), whereas β-adrenoceptor antagonists increased the sensitivity of tumors to immunotherapy (107, 112, 113).

PPGLs can be characterized by their high production rates of catecholamines and metanephrine (114). Although several clinical trials have investigated the use of α-adrenoceptor blockade to prevent catecholamine crisis during surgery for PPGLs, they generally do not focus on the potential of therapy to delay tumor growth. Moreover, the potential of concurrent targeting of adrenoceptors to increase immune-cell infiltration into PPGLs has not been studied. Recent study has suggested that epinephrine levels were correlated with neutrophil infiltration and that NE levels were correlated with macrophage infiltration in PPGLs, possibly suggesting that catecholamines had differing effects and that immune infiltration could be correlated with the functional status of tumors (56). Yet, this has to be validated in bigger PPGL cohort. Estrada et al showed that NE treatment of human CD8+ T cells decreased IFN-γ and TNF-α secretion and suppressed CD8+ T cell cytolytic capacity in response to TCR activation, which could be specifically reversed by β2-adrenoceptor antagonists (115). Moreover, preclinical model of aggressive renal carcinoma suggested that faulty IFN signaling could possibly increase the risk of metastatic and aggressive tumor behavior (116). Decreased IFN-γ levels have already been shown in SDH-deficient tumors, which generally have a higher risk for metastasis (117). Blocking catecholamine synthesis through metyrosine (α-methyl-paratyrosine), which has been shown to reduce catecholamine biosynthesis by 35% to 80%, in patients with catecholamine-secreting PPGLs (118) had been found to be effective in reducing pulmonary metastasis (119). Furthermore, DA in plasma, or specifically its metabolite 3-methoxytyramine, is a validated prognostic marker for metastatic PPGLs (120). DA has been shown to suppress proliferation of isolated NK cells and subsequent IFN-γ synthesis (109), which could suggest specific targeting for NK- and IFN-depleted tumors, such as SDHx-mutated PPGLs. A small molecule antagonist of dopamine receptor DRD2, ONC201, has already been shown effective in phase II for PPGLs (NCT03034200) (121). ONC201 can initiate intratumoral NK cell infiltration as confirmed in preclinical studies on colorectal and breast human tumor xenografts and patient biopsies (122, 123).

In conclusion, the effects of catecholamines on immune system response and tumorigenic pathways have already been described in preclinical models of some cancers and high concentrations of catecholamines in PPGLs could contribute to the immunologically “cold” behavior of PPGLs.

Succinate

Succinate, a Krebs cycle metabolite, is considered an oncometabolite that can accumulate in the TME and initiate or promote tumor growth through several pathways, such as DNA hypermethylation, HIF stabilization, and succinate receptor 1 (SUCNR1) activation (124-128). Besides these well-documented pro-oncogenic effects of succinate, several studies have focused on its role in the immune system. While mitochondrial succinate accumulation in macrophages acts as an inflammatory modulator (129), extracellular succinate has been shown to induce macrophage polarization into M2 and promote tumorigenic signaling (127, 130, 131). Tumor-associated succinate concentrations have been shown to exert a direct suppressive effect on human T cells in vitro, resulting in lower IFN-γ and TNF-α secretion (117).

Succinate accumulation is mainly characteristic of SDH- and FH-mutated PPGLs (132, 133). A recent study revealed that SDH-deficient tumors had decreased expression of IFN-γ-induced genes, suggesting suppressed T cell function as described above (117). In individuals with SDHB pathogenic variant, isolated neutrophils showed increased succinate accumulation and enhanced survival (134), suggesting the possible mechanism of neutrophil elevation in SDHB carriers. Reports have shown that elevated circulating neutrophils are involved in the immunosuppressive response, thereby supporting tumor cell growth and metastasis (135). Indeed, increased neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio has recently been linked to decreased overall survival among patients with PPGL (136). Apart from the mentioned studies, no other research has investigated the direct outcomes of succinate accumulation in PPGLs and on the immune response, despite the described role of succinate in immune signaling and tumorigenesis. Given the immunosuppressive environment highlighted recently for pseudohypoxic PPGLs, especially SDHB-mutated PPGLs (21, 59), and the possible effects of succinate on T cell function and cytokine secretion in SDH-deficient tumors (117), one can hypothesize that succinate modulates the immune microenvironment in PPGLs to favor tumor growth.

Kynurenine

Abnormal activation of the kynurenine pathway has been repeatedly observed in numerous cancer types. Its functions are hijacked to promote tumor growth and cancer cell dissemination through multiple mechanisms (137, 138). Kynurenine is produced from tryptophan by indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO), the rate-limiting enzyme of tryptophan metabolism, which can help create tolerogenic TME (139). IDO exerted immunosuppressive effects by directly inhibiting CD8+ T cell activity and inducing Treg cell differentiation in preclinical models (reviewed in (139, 140)). Moreover, its pathway metabolites can polarize APCs to exhibit an immunotolerant phenotype in mice (138, 141).

Research has shown that PPGLs exhibit increased expression of IDO2 (142), IDO1, and of transporters for tryptophan uptake (143). Moreover, kynurenine metabolic pathway enzymes, such as kynurenine 3-monooxygenase and kynureninase, are significantly downregulated, suggesting the possibility of kynurenine accumulation in PPGLs (143). Indeed, evidence has shown that pseudohypoxic PPGLs had fewer kynurenine pathway metabolites than did the kinase-signaling PPGL cluster, which could be associated with the shorter metastasis-free survival of patients with pseudohypoxic PPGLs (144).

Taken together, these results suggest that the kynurenine pathway may be affected in PPGLs, especially the pseudohypoxic PPGL cluster, and that IDO inhibitors may serve as an immunometabolic adjuvant to enhance systemic immune responses.

Polyamines

Polyamines, such as putrescine, spermine, and spermidine, are organic polycationic alkylamines synthesized from L-ornithine, an intermediate generated from L-arginine (145). They play essential roles in several fundamental processes including protein and nucleic acid metabolism, cell signaling, functioning of cytoskeleton, and cell death regulation (145, 146). Moreover, studies have documented its role in the immune response. In the TME, excessive L-arginine catabolism (leading to polyamine production) by suppressive myeloid and tumor cells dampens cytotoxic T cell function, suggesting a link between polyamines and T cell suppression (145, 147, 148). Indeed, polyamine blockade therapy relieved polyamine-mediated immunosuppression in TME and allowed for T cell activation in preclinical melanoma model (149). One study found that polyamines and their metabolites were elevated in various tumors, such as breast, lung, colorectal, ovarian, prostate, and pancreatic cancers (150). Several polyamine pathway inhibitors have been evaluated in preclinical and clinical studies with some encouraging outcomes (150).

Rai et al found that SDHx-mutated PPGLs associated with more aggressive or metastatic behavior had increased expression of several polyamines (146), suggesting another immunometabolic target in SDHx-mutated PPGLs that could help “cold” tumors into “hot” tumors.

Hypoxia Signaling

Hypoxia is a common feature of most solid tumors. The low oxygen concentration and consequent metabolic outcomes promote metabolic stress and tumor metastases, favor tumor immune evasion, and affect immune-cell infiltration through the production of chemokines and cytokines (151-153). Hypoxia triggers several pathways that induce immunosuppression; reduction in CD8+ T cells, NK cells, and M1 macrophages; and enhanced tumor-tolerant populations, such as M2 macrophages, MDSCs, and Treg cells (154-157).

Endocrine cancers frequently exhibit major hypoxic areas, and high expression of hypoxia signaling genes has been associated with endocrine tumor development (158). The role of (pseudo)hypoxia in the development of PPGLs, particularly pseudohypoxic PPGLs (159, 160), as well as its effects on the immune system of patients with PPGL (20, 21, 56, 59, 60), has been documented. Moreover, hypoxia has been shown to further promote catecholamine production in mice (161, 162), whose role in immunosuppression we had already been discussed earlier. In PPGLs, HIF-2α was suggested to drive mesenchymal transition that promotes a pro-metastatic phenotype (163-165). In general, hypoxia is believed to contribute to immunotherapy resistance (154, 156, 157). Thus, targeting of hypoxia alongside immunotherapy and other therapies for PPGLs may increase treatment efficacy.

Telomerase

A striking characteristic feature of metastatic PPGLs is its frequent association with telomerase activation either by gene fusion (166) or TERT promoter hotspot mutation (167). Indeed, telomerase activation is an independent adverse prognostic characteristic for overall survival (167), which has been recognized in many cancers (168). Several clinical studies with telomerase inhibitors or vaccines to target TERT peptides have been accomplished with promising results in pancreatic cancer (169), squamous anal cell carcinoma (170), and prostate and renal cancer (171).

Recently, a study demonstrated an association between TERT and immunosuppressive signatures (eg, Th2 cell, Tregs, NK CD56dim cells, MDSCs) across 24 cancer types derived from TCGA; in experimental models, TERT activation was shown to activate endogenous retroviruses and trigger interferon signaling leading to infiltration of suppressive T cells (Th2 cells and Tregs) in tumors (172). Whether or not this action of TERT is relevant to the “cold” immune state of PPGLs requires further study.

Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts in the PPGL Microenvironment

The TME consists of not only tumor and immune cells but also endothelial cells and fibroblasts (58). Endothelial cells play a crucial role in angiogenesis and nutrient delivery. Cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) are a major component of tumor stroma involved in tumor proliferation, aggressiveness, angiogenesis, and immunosuppression through the recruitment and function of various immune cells (173). CAFs usually arise from tumor resident fibroblasts under the influence of cytokines released from cancer cells and are often associated with poor prognosis in many cancer types (173). Several studies have confirmed the connection between fibroblasts and human or murine PPGL cells in vitro (174-176). One in vitro study showed mutual metabolic changes between the primary fibroblast and SDHB-silenced neuroblastoma cells and their increased proliferation compared with their monoculture counterparts (174). Other in vitro studies have shown that SDHB-silenced murine pheochromocytoma cell (MTT cells) spheroids cocultured with CAFs had increased migration/invasion (177, 178) and that CAF metabolism directly affects the invasion process of tumor cells (179). Recent studies have reported that fibroblasts mediate angiogenesis of pheochromocytomas by increasing mitochondrial cytochrome C oxidase subunit 4 subtype 2 (177, 178). Furthermore, insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1) and its receptor (IGF1R) have been associated with murine pheochromocytoma development. Specifically, IGF1R-deficient murine fibroblasts exhibited a negative impact on tumors, promoting a lower incidence and slower tumor proliferation rate (180).

In humans, pericytes, fibroblast-like cells known for their role in vessel formation, are the dominant fibroblasts in PPGLs and account for up to 24% of all cells (10). Myofibroblasts, fibroblasts with a matrix-producing contractile phenotype associated with α-smooth muscle actin expression (181), are detected in up to 1.5% of cells in PPGLs, but are absent in normal adrenal medulla (10). Pericytes are also emerging regulators of cancer progression and development: as in tumor angiogenesis, premetastatic niche formation, sustained tumor growth, and evasion of immune response (182). Myofibroblasts contribute to an immunosuppressive TME in several ways, including paracrine and extracellular matrix remodeling. For instance, in pancreatic cancer, myofibroblasts suppress immune surveillance by increasing Tregs in the tumors (183).

While current studies have mainly focused on the metabolic role of fibroblast and/or CAFs in preclinical models of PPGLs, future research may reveal their immunosuppressive potential in murine and human PPGLs.

Immune Signature Classifications: The Current Status and Road to Consensus

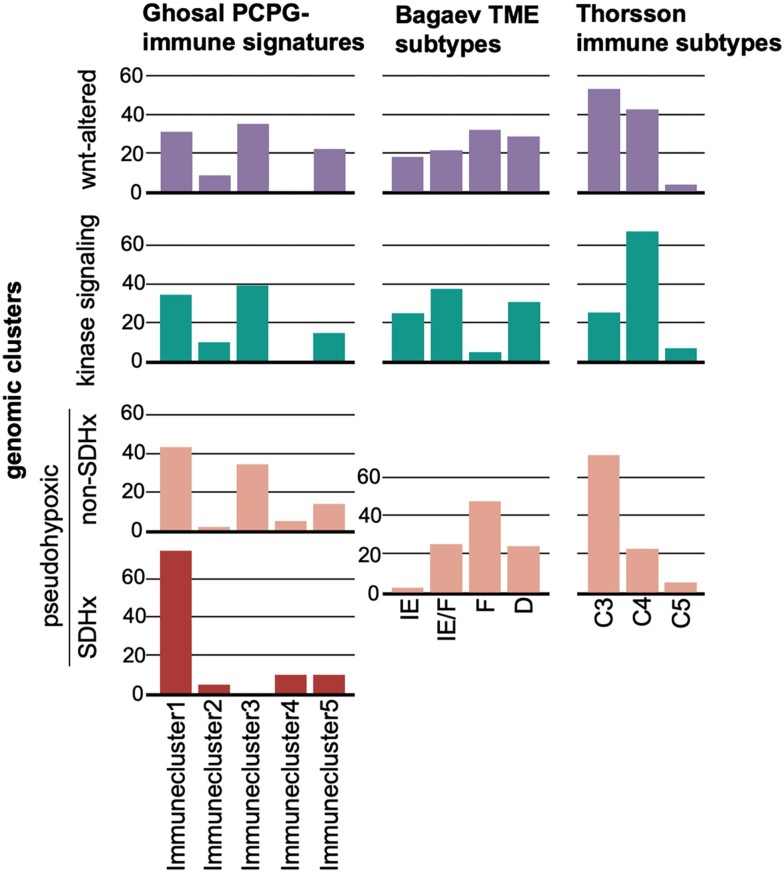

As technology advances, so has the understanding of the complexity and diversity of the immune context of the TME. In fact, recent advancements have allowed for the identification of different subclasses within the immune environment that may influence patient prognosis and potential response to therapy. To date, some reports have partially defined the PPGL TME based on low-resolution methodologies, such as immunohistochemistry. Additionally, other studies have used bulk RNA-Seq and applied techniques such as CIBERSORT to estimate the abundance of the immune infiltrate (20, 21) or more complex gene expression signatures that help characterize other stromal compartments, such as fibroblasts or blood vessels (21, 55, 184). Ghosal et al defined 5 PPGL-specific immune signatures based on the abundance of immune-cell types with high variance in their infiltration scores (immune clusters 1-5: 1, M2 macrophages; 2, monocytes; 3, activated NK cells; 4, Tregs and M0 macrophages; 5, CD8+ and CD4+ T cells (Fig. 2)) (20). Meanwhile, Thorsson et al defined 6 immune subtypes (C1-C6) based on scores obtained from 5 immune expression signatures (macrophages/monocytes, total lymphocyte infiltration, TGF-β response, IFN-γ response, and wound healing) (55). Bagaev et al established 4 additional subtypes (immune-enriched, fibrotic [IE/F], immune-enriched, nonfibrotic [IE], fibrotic [F], and immune-depleted [D]) from 29 knowledge-based functional gene expression signatures representing the major functional components of the TME (184). Both classification methodologies were developed using pancancer data obtained from TCGA project. Recently, Calsina et al applied both methodologies to a large PPGL data set (21) and classified PPGLs into Thorsson's C3 to C5 subtypes and Bagaev's 4 subtypes.

Figure 2.

Classification of immune subtypes within genomic cluster. The proportion (%) of samples of each immune subtype per genomic cluster is shown (x-axis). Data have been extracted from Ghosal et al (20) (first graphs column: Immunecluster1, M2 macrophages; Immunecluster2, monocytes; Immunecluster3, activated NK cells; Immunecluster4, Tregs and M0 macrophages; Immunecluster5, CD8+ and CD4+ T cells) and Calsina et al (21) (second and third graph column: D, depleted; F, fibrotic; IE, immune-enriched, nonfibrotic; IE/F, immune-enriched, fibrotic; C3, inflammatory; C4, lymphocyte depleted; C5, immunologically quiet).

Although the patient cohorts are not large enough to set robust assumptions, some conclusions related to PPGLs and TME can still be established. Pseudohypoxic PPGL tumors are most represented in immune cluster 4 (20) and subtype F (184), which are characterized by their lack of leukocyte/lymphocyte infiltration and TGF-β-driven immune suppression, high M0 macrophage infiltration, low cell proliferation, low levels of overall somatic copy number alterations and tumor mutational burden, and high vascularity and fibrosis (presence of more CAFs). These TME/immune subtypes have been associated with worse prognosis, with TME subtype F being particularly correlated with low response rates to immunotherapy in patients with skin cutaneous melanoma, bladder, lung, or gastric cancer (184). Moreover, the authors compared not only response to the immune checkpoint inhibitors, but other immune-based therapies such as therapeutic vaccination and adoptive cell transfer, suggesting that this classification can be applied to other immunotherapies as a biomarker of response. On the other hand, PPGLs within the kinase-signaling subtype are more represented in immune cluster 3 from Ghosal et al (20) and TME subtype IE and IE/F from Bagaev et al (184), which have been described as having high levels of immune infiltrate, significantly increased cytolytic score, and high T cell activity and T and B cell diversity. They have been associated with a better prognosis, with the TME subtypes IE and IE/F exhibiting the highest percentage of responders to immunotherapies in cohorts of patients with skin cutaneous melanoma, bladder, lung, or gastric cancer. However, the immune infiltrate in some of the cases broadly included in this group could be associated with the increased presence of Th2 cells and Tregs (184). Moreover, the Wnt-altered subtype, described by Fishbein et al in 2017, had been less represented in the PPGL cohorts whose TME had been attempted to be characterized (9). Nevertheless, the recent study from Calsina et al described positivity for PD-L1, which had the highest tumor mutational and neoantigen load, and CD8+ T cell infiltration specifically for MAML3-related tumors, which are part of the Wnt-related subtype, making them the most popular PPGLs in terms of future immunotherapeutic approaches (21). Even though PPGLs are considered to be tumors with the limited presence of immune cells in the microenvironment compared with other tumors and, therefore, response to immunotherapy may be limited, based on the TME clustering and response to immunotherapy in 4 above-described cancer types, we may assume that some PPGL subtypes such as kinase signaling may response better to immunotherapy than other subtypes.

Current Immunotherapy in PPGLs

Cancer immunotherapy research has experienced rapid progress in recent years, resulting in diverse immunotherapy approaches for treating various cancer types. The very first widely known immunotherapy used in humans involved direct stimulation of the immune system within the TME via intratumoral injection of whole bacteria, known as Coley's toxin. William Coley, an American surgeon, reported that 80% of patients with malignant tumors, which at that time had no treatment, survived for more than 5 years (185, 186). However, limited understanding of the immune system and better-defined radiology repressed the use of this approach in clinical practice. With the growing interest in immunology in the 20th century, cancer immunotherapy has become more focused on individual mechanisms and pathways of the immune system. For instance, we have witnessed the approval of tumor-specific monoclonal antibodies, interferons, IL-2, and checkpoint inhibitors for the treatment of specific types of tumors. Blocking immune system regulators, such as PD-1, its ligands, and CTLA-4 have improved outcomes for a broad spectrum of cancers (187-190).

Although specific antibodies against CTLA-4 and PD-1/PD-L1 have shown to be beneficial for the treatment of several types of cancers, including neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) (191-196), data focusing on PPGLs have still been very limited. For instance, 11 patients with metastatic PPGLs were included in a clinical trial (NCT02721732) with pembrolizumab (anti-PD-1). One patient experienced toxicity before week 27 and was therefore excluded from the primary outcome analysis. Among the remaining 10 patients, 4 survived, with no evidence of progression, at 27 weeks. The clinical benefit rate and nonprogression rate at 27 weeks were 72% (95% CI 39-94%) and 40% (95% CI 12-74%), respectively (26). Interestingly, this fascinating and pioneering clinical study also uncovered that IHC staining of tumor PD-L1 did not predict therapy response (26). In 2020, Economides et al published a case of a patient with metastatic disease that did not respond to cabozantinib (tyrosine-kinase inhibitor) and nivolumab (anti-PD-1 antibody) when administered separately but exhibited major tumor response for at least 22 months when administered in combination (197). Similarly, the treatment approach involving the combination of nivolumab and ipilimumab (anti-CTLA-4 antibody) showed benefit in another case of metastatic pheochromocytoma (198). However, the 2 patients with metastatic PGL recruited for a clinical trial (NCT03333616) on ipilimumab/nivolumab exhibited no response, although these numbers are too small to make any useful conclusions regarding efficacy of this therapeutic approach (199). To date, most of the clinical studies on PPGLs are focusing on ICIs (summarized in Table 4). On top of ICIs, a phase I/II study (NCT04187404) is evaluating the effects of vaccine EO2401, which is based on 3 microbiome-derived CD8+ epitopes mimicking parts of tumor-associated antigens, in combination with checkpoint blockade (nivolumab) in patients with metastatic PPGL. Moreover, a recently completed phase I study with VSV-IFNβ-NIS (NCT02923466) virally encoded IFN-β for oncolytic virotherapy. In conclusion, clinical studies for PPGL immunotherapy are still limited and better understanding of immune signatures of PPGL clusters may help to define further development of clinical trials.

Table 4.

Registered clinical trials for immunotherapy of PPGLs

| Clinical trial # | Study phase | Trial name | Condition/Disease | Treatment | Statusa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT05885399 | Phase II | The efficacy and safety of Penpulimab in the treatment of metastatic patients with PPGL who fail to other systemic treatment | Metastatic PPGL | Penpulimab | Recruiting |

| NCT04895748 | Phase I | DFF332 as a single agent and in combination with Everolimus and immuno-oncology agents in advanced/relapsed renal cancer and other malignancies | Renal cell carcinoma | DFF332 | Recruiting |

| Hereditary PPGL | RAD001 | ||||

| PDR001 (Spartalizumab) | |||||

| NIR178 | |||||

| NCT03333616 | Phase II | Nivolumab combined with Ipilimumab for patients with advanced rare genitourinary tumors | Rare genitourinary malignancies | Ipilimumab | Active, not recruiting |

| Adrenal tumors including paraganglioma | Nivolumab | ||||

| NCT04187404 | Phase I/Phase II | A novel therapeutic vaccine (EO2401) in metastatic adrenocortical carcinoma, or malignant pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma | Adrenocortical carcinomaPPGL | EO2401Nivolumab | Recruiting |

| NCT02332668 | Phase I/Phase II | A study of Pembrolizumab (MK-3475) in pediatric participants with an advanced solid tumor or lymphoma | Lymphoma | Pembrolizumab | Recruitingb |

| Advanced solid tumors including paraganglioma | |||||

| NCT02721732 | Phase II | Pembrolizumab in treating patients with rare tumors that cannot be removed by surgery or ere metastatic | Several neoplasms including metastatic PPGL, unresectable PPGL | Pembrolizumab | Active, not recruitingc |

| NCT02834013 | Phase II | Nivolumab and Ipilimumab in treating patients with rare tumors | Several solid tumors including PPGL | Ipilimumab Nivolumab | Active, not recruiting |

| NCT04400474 | Phase II | Trial of Cabozantinib plus Atezolizumab in advanced and progressive neoplasms of the endocrine system. | Neuroendocrine tumorAnaplastic thyroid cancer | CabozantinibAtezolizumab | Active, not recruiting |

| Adenocarcinoma | |||||

| PPGL | |||||

| NCT02923466 | Phase I | Ph1 Administration of VSV-IFNβ-NIS monotherapy and in combination with Avelumab in patients with refractory solid tumors | Solid tumors including PPGL | VSV-IFNβ-NISAvelumab | Completed (April, 2022) |

| NCT05944237 | Phase I/II | HTL0039732 in participants with advanced solid tumors | Solid tumors including PPGL | HTL0039732atezolizumab | Recruiting |

Perspectives

Beyond Conservative Treatments

PPGLs are considered rare neoplasms with significant heterogeneity in their molecular features, clinical behavior, and treatment response. They are one of the most hereditary human neoplasms and are associated with more than 20 susceptible genes described so far (9, 12, 200-209). The genetic landscape of PPGLs undoubtedly affects their TME, responses to various treatment options, and prognosis. While we can now well stratify these tumors into molecular clusters based on their transcriptional profiles, their vast heterogeneity, further supported by their different catecholamine phenotypes, origin, and location, has so far hindered efforts to uncover near optimal and somewhat general treatments, especially for metastatic, locally aggressive, and inoperable PPGLs. According to the World Health Organization classification, all PPGLs are considered to have metastatic potential, replacing the previous term “malignant” (1, 210-212). Thus, there is a continuous need for identifying novel potential treatments beyond surgery, which is currently the only option for cure in some patients. Given the high number of germline pathogenic variants, presence of activation or inhibition of many metabolic pathways with various oncometabolite levels, adrenal and extra-adrenal (including head and neck) locations, and unique molecular signatures, establishing a universal treatment that could target most of these tumors seems impossible, especially when they present with metastatic lesions. While some individual treatments are costly and time-consuming, the main focus in the era of precision medicine is to tailor therapies to specific molecular and metabolic features of tumors (213, 214). Thus, we hypothesize that aside from the current or evolving treatment options, targeting the immune system, along with other therapeutic options further boosted with outcome data from ML modeling approaches that will also include immune signatures (27, 215), will open a new era for the successful treatment of PPGLs.

Prediction of Tumor Behavior and Prognosis