Abstract

Objectives

MDR and XDR Neisseria gonorrhoeae strains remain major public health concerns internationally, and quality-assured global gonococcal antimicrobial resistance (AMR) surveillance is imperative. The WHO global Gonococcal Antimicrobial Surveillance Programme (GASP) and WHO Enhanced GASP (EGASP), including metadata and WGS, are expanding internationally. We present the phenotypic, genetic and reference genome characteristics of the 2024 WHO gonococcal reference strains (n = 15) for quality assurance worldwide. All superseded WHO gonococcal reference strains (n = 14) were identically characterized.

Material and Methods

The 2024 WHO reference strains include 11 of the 2016 WHO reference strains, which were further characterized, and four novel strains. The superseded WHO reference strains include 11 WHO reference strains previously unpublished. All strains were characterized phenotypically and genomically (single-molecule PacBio or Oxford Nanopore and Illumina sequencing).

Results

The 2024 WHO reference strains represent all available susceptible and resistant phenotypes and genotypes for antimicrobials currently and previously used (n = 22), or considered for future use (n = 3) in gonorrhoea treatment. The novel WHO strains include internationally spreading ceftriaxone resistance, ceftriaxone resistance due to new penA mutations, ceftriaxone plus high-level azithromycin resistance and azithromycin resistance due to mosaic MtrRCDE efflux pump. AMR, serogroup, prolyliminopeptidase, genetic AMR determinants, plasmid types, molecular epidemiological types and reference genome characteristics are presented for all strains.

Conclusions

The 2024 WHO gonococcal reference strains are recommended for internal and external quality assurance in laboratory examinations, especially in the WHO GASP, EGASP and other GASPs, but also in phenotypic and molecular diagnostics, AMR prediction, pharmacodynamics, epidemiology, research and as complete reference genomes in WGS analysis.

Introduction

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in Neisseria gonorrhoeae is compromising the treatment of gonorrhoea globally.1–8 Internationally, the extended-spectrum cephalosporin (ESC) ceftriaxone is the only remaining option for first-line empirical gonorrhoea therapy, i.e. given as a high-dose monotherapy or with azithromycin.1,2,8–18 However, gonococcal strains with resistance to ceftriaxone and especially azithromycin have been described globally.2,5–10 Furthermore, since 2015 international spread of the ceftriaxone-resistant MDR strain FC428 has been reported5,10,19–22 and since 2018 gonococcal XDR strains with ceftriaxone resistance combined with high-level azithromycin resistance have been described.23–27 Most of the currently identified ceftriaxone-resistant strains contain a mosaic penA-60.001 allele, which result in a mosaic penicillin-binding protein 2 (PBP2).5,10,19–28 The international spread of ceftriaxone-resistant MDR and XDR gonococcal strains and sporadic treatment failures with ceftriaxone (mainly of pharyngeal gonorrhoea) necessitate enhanced, quality-assured global gonococcal AMR surveillance.1–3,6–8

The WHO3 and ECDC29,30 have developed global and regional action plans, respectively, to control the transmission and impact of AMR gonococcal strains. One key component is to expand, improve and quality-assure the gonococcal AMR surveillance at local, national and global levels. The WHO global Gonococcal Antimicrobial Surveillance Programme (GASP) was relaunched in 2009 (www.who.int/initiatives/gonococcal-antimicrobial-surveillance-programme).3,6–8 Furthermore, the WHO Enhanced GASP (EGASP)26,31–33 is currently being expanded internationally (www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240021341). WHO EGASP includes isolate AMR data linked to patient metadata and WGS, which is already implemented in some regional GASPs.9,10 To fulfil all the aims of WHO GASP and EGASP, valid, internationally comparable and quality-assured AMR data are imperative. This is enabled through the use of WHO reference strains.34,35 In 2016, the latest WHO gonococcal reference strain panel was published.35

Herein, the 2024 WHO gonococcal reference strain panel is presented and characterized in detail. This panel includes 11 of the 2016 WHO reference strains (n = 14),35 which were further characterized, and four novel WHO reference strains. These novel WHO strains represent highly relevant AMR phenotypes and/or genotypes that were not available for inclusion in the previous WHO reference strain panels.34,35 The novel WHO strains include the internationally spreading ceftriaxone-resistant, mosaic penA-60.001-containing FC428 strain (associated with several ceftriaxone treatment failures),5,10,19–22 one strain expressing ceftriaxone resistance due to a new penA mutation (associated with cefixime treatment failure),36 the first cultured strain with ceftriaxone resistance plus high-level azithromycin resistance (mosaic penA-60.001-containing and with 23S rRNA gene A2059G mutations, associated with ceftriaxone 1 g plus doxycycline treatment failure)24 and one internationally spreading azithromycin-resistant strain with a mosaic MtrRCDE efflux pump, i.e. with Neisseria lactamica-like mosaic 2 mtrR promoter and mtrD sequence.10,37,38 The 2024 WHO gonococcal reference strains were characterized in detail phenotypically {e.g. antibiograms [25 antimicrobials] and genetically [e.g. AMR determinants, multi-locus sequence typing (MLST),39,40N. gonorrhoeae multiantigen sequence typing (NG-MAST),40,41N. gonorrhoeae sequence typing for AMR (NG-STAR)42 and NG-STAR clonal complexes (CCs)43]}. Complete and characterized reference genomes are also described. These 2024 WHO gonococcal reference strains are recommended for internal and external quality assurance in all types of laboratory investigation, especially in the GASPs, e.g. the WHO global GASP,6–8 WHO EGASP26,31–33 and other international or national GASPs but also for phenotypic and molecular diagnostics, AMR prediction, pharmacodynamics, epidemiology, research and genomics. All superseded WHO gonococcal reference strains (n = 14), including 11 not previously published WHO reference strains that have been used internationally, were characterized similarly.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains

The 2024 WHO gonococcal reference strains include 11 of the 2016 WHO gonococcal reference strains (n = 14)35 and four additional gonococcal strains. The novel strains are WHO H (Austria, 2011; ceftriaxone resistant due to a new penA mutation),36 WHO Q (UK, 2018; ceftriaxone resistant combined with high-level azithromycin resistance),24 WHO R (Japan, 2015; FC428, internationally spreading ceftriaxone resistant)5,10,19–22 and WHO S2 (Sweden, 2020; internationally spreading azithromycin-resistant strain due to a mosaic MtrRCDE efflux pump).38 Furthermore, all the superseded WHO reference strains (n = 14) were characterized. All strains were cultivated as described.44

Detection of prolyliminopeptidase (PIP)

PIP45 production was detected using API NH (bioMérieux, Marcy l'Etoile, France) and genetically.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

MIC values (mg/L) for 22 antimicrobials were determined using the Etest (bioMérieux) on GCRAP agar plates [3.6% Difco GC Medium Base agar (BD, Diagnostics, Sparks, MD, USA) with 1% haemoglobin (BD) and 1% IsoVitalex (BD)]. MICs of zoliflodacin,46–54 gepotidacin55–57 and lefamulin,58,59 were determined using agar dilution methodology. Clinical breakpoints or the epidemiological cut off (ECOFF, for azithromycin) from the EUCAST (v.14.0, https://www.eucast.org/clinical_breakpoints) were used, where available. For additional antimicrobials, only the consensus MIC values are presented. For all strains and antimicrobials, each determination was performed ≥3 times using new bacterial suspensions on separate batches of agar plates. β-lactamase production was detected using nitrocefin solution (Oxoid, Basingstoke, UK).

Isolation of bacterial DNA

Genomic DNA for short-read and long-read sequencing was isolated using the QIAsymphony instrument (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and Nanobind CBB kit (PacBio, Menlo Park, CA, USA), respectively. Purified DNA was stored at 4°C before WGS.

Whole-genome sequencing

Multiplexed PacBio Single-Molecule, Real-Time (SMRT) DNA genome sequencing was performed from post-shearing DNA fragment sizes (10.8–17 kb) using the Sequel System (PacBio), v.3.0 sequencing chemistry. The average length of the reads was 4120 bp and the sequencing depth averaged 335× (range 224–834×). Paired-end short-read sequencing was performed using Illumina NextSeq 550 with an average sequencing depth of 410× (range 198–597×).

Pacbio SMRT Tools v.7.0.1 indexed the long-read raw sequencing data in bam format using pbindex and convert it to fastq with bam2fastq. Genome assembly of these long reads were performed using both HGAP v.4.060 and Canu v.1.9.61 Complete chromosomes were circularized starting on the dnaA using Circlator v1.5.5.62 Illumina short reads were mapped against the circularized chromosome with BWA-MEM v.0.7.1763 and the output filtered with samtools v.1.1164 to only keep proper-paired reads that map with a mapping quality of ≥25. These mappings were used to detect and fix base errors, small insertions/deletions (indels), local misassemblies and fill gaps in the initial long-read assembly using Pilon v.1.23.65 A minimum base and mapping qualities of 20 were required, and ≥25% of the reads mapping had to support a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) or indel. HGAP and Canu assemblies were compared using ACT v.18.1.66 To resolve discrepancies, we ran Trycycler v.0.4.167 using the raw long-read data and both chromosome sequences from each strain. No changes were needed by Pilon on the Trycycler consensus assemblies. When required, a hybrid assembly approach with Unicycler v.0.4.9b68 was performed using the long- and short-read data. Depth of coverage was obtained by mapping to the final chromosome assemblies using pbmm2 (https://github.com/PacificBiosciences/pbmm2, based on minimap269), and BWA-MEM, respectively, followed by the samtools depth command.

A short-read-only assembly was performed using SPAdes v.3.1270 with k-mer sizes of 21, 33, 55, 63, 77, 99, 111 and the –careful option to minimize mismatches and short indels. Both the long- and short-read assemblies were screened for the three known gonococcal plasmids, pCryptic, pBla and pConj,35 using blastn v.2.10.1+.71 The plasmids pCryptic, pBla and pConj were circularized starting on replication initiator protein, repA and TrfA gene using Circlator v.1.5.5, respectively.

Finalized circular chromosomes and plasmids were annotated using the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Prokaryotic Genome Annotation Pipeline v.6.6,72 which also re-annotated the 2016 WHO gonococcal reference strains.35 Mapping of Illumina reads over the final assemblies was visually inspected using Artemis and sequencing depth across the genomes was obtained with samtools v.1.11. The core genome among the 29 strains was inferred using Panaroo v.1.2.673 with default parameters and strict mode, polymorphic sites were obtained using SNP-sites74 and a maximum-likelihood tree was reconstructed from them using IQ-TREE v.2.0.375 with automatic detection of the best substitution model76 (best-fit model TVM + F + ASC + R7) and 1000 ultrafast bootstrap replicates.77 Long-read sequencing data for WHO S2 was generated on a MinION Mk1C device (Oxford Nanopore Technologies) using a v.R10 flow cell (FLO-MIN114). The sequencing library was prepared without DNA fragmentation, and selection of long fragments (>3 kb) using duplex Nanopore chemistry (SQK-LSK114). Sequence data were deposited at the NCBI under BioProject PRJNA1067895.

Molecular sequence types (NG-MAST, NG-STAR and MLST)39–42 and AMR determinants were obtained from the N. gonorrhoeae scheme at Pathogenwatch.10,78 NG-STAR CCs were assigned using eBURST clustering on the NG-STAR ST database downloaded on 29 February 2024 (https://ngstar.canada.ca/).43 The number of copies of the 23S rRNA gene mutations, pip gene mutants and the presence of the cppB gene in the pCryptic plasmid were inspected manually in Artemis using the finalized assemblies. Individual genome characteristics were also obtained using Artemis. DNA uptake sequences (DUSs) were located in each chromosome using the EMBOSS application fuzznuc.79

Results

Phenotypic characterization

One (6.7%; WHO F) and 14 (93.3%) of the 2024 WHO reference strains belonged to serogroup PorB1a (WI) and PorB1b (WII/III), respectively (Table 1). One strain (6.7%; WHO U) was PIP-negative, and four (26.7%) strains (WHO M, O, R, and V) produced β-lactamase. The antimicrobial susceptibility testing results are described in Table 1. The strains represent all relevant, available resistant; susceptible, increased exposure; and susceptible phenotypes observed for most antimicrobials currently or previously recommended in national and international gonorrhoea treatment guidelines or antimicrobials in advanced clinical development for future treatment. These included strains with clinical resistance to ceftriaxone (n = 7), cefixime (n = 7), azithromycin (n = 5), spectinomycin (n = 1), ciprofloxacin (n = 10), penicillin G (n = 9) and tetracycline (n = 13), and high MICs of cefuroxime, cefepime, ceftaroline, ampicillin, temocillin, aztreonam, erythromycin, moxifloxacin, chloramphenicol, rifampicin and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. No clinical strains with high MICs of ertapenem, gentamicin, kanamycin, fosfomycin, zoliflodacin, gepotidacin and lefamulin were available (Table 1).

Table 1.

Serogroup, PIP production and antimicrobial susceptibility/resistance phenotypes displayed by the 2024 WHO Neisseria gonorrhoeae reference strains (n = 15), which are relevant for susceptibility testing of current, previous and novel therapeutic antimicrobials

| Characteristics | WHO Fa | WHO H | WHO Ka | WHO La |

WHO Ma | WHO Oa | WHO Pa | WHO Q | WHO R | WHO S2 | WHO Ua | WHO Va | WHO Xa | WHO Ya | WHO Za |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCTC number | 13 477 | 15 081 | 13 479 | 13 480 | 13 481 | 13 483 | 13 484 | 14 208 | 15 082 | 15 083 | 13 817 | 13 818 | 13 820 | 13 821 | 13 822 |

| Isolated (country, year) | Canada, 1991 | Austria, 2011 | Japan, 2003 | Asia, 1996 | Philippines, 1992 | Canada, 1991 | USA, Unknown | UK, 2018 | Japan, 2015 | Sweden, 2020 | Sweden, 2011 | Sweden, 2012 | Japan, 2009 | France, 2010 | Australia, 2013 |

| Serogroup | PorB1a | PorB1b | PorB1b | PorB1b | PorB1b | PorB1b | PorB1b | PorB1b | PorB1b | PorB1b | PorB1b | PorB1b | PorB1b | PorB1b | PorB1b |

| PIP production | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | −b | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos |

| β−lactamase (PPNG)c | — | — | — | — | Posc | Posc | — | — | Posc | — | — | Posc | — | — | — |

| Ampicillind,e | 0.032 | 2 | 2 | 2 | PPNGc (8) | PPNGc(32) | 0.064 | 2 | PPNGc (>256) |

0.25 | 0.125 | PPNGc (>256) |

2 | 0.5 | 2 |

| Azithromycind | S (0.25) | S (0.25) | S (0.5) | S (1) | S (0.5) | S (0.5) | R (4) | HLR (>256) | S (0.5) | R (2) | R (4) | HLR (>256) | S (0.5) | S (1) | S (1) |

| Aztreonamd,e | 0.016 | 8 | 4 | 2 | 0.125 | 0.5 | 0.125 | 64 | 32 | 0.064 | 0.064 | 0.25 | ≥256 | 64 | 32 |

| Cefepimed,e | <0.016 | 8 | 4 | 1 | 0.064 | 0.125 | 0.032 | 4 | 8 | 0.064 | 0.016 | 0.25 | 16 | 32 | 4 |

| Cefiximed | S (<0.016) | R (0.5) | LLR (0.25) | S (0.125) | S (<0.016) | S (0.016) | S (<0.016) | HLR (2) | HLR (1) | S (<0.016) | S (<0.016) | S (<0.016) | HLR (4) | HLR (2) | HLR (2) |

| Ceftarolined,e | 0.004 | 0.5 | 0.125 | 0.5 | 0.064 | 0.25 | 0.064 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.064 | 0.016 | 0.25 | 2 | 4 | 0.5 |

| Ceftriaxoned | S (<0.002) | LLR (0.25) | S (0.064) | LLR (0.25) | S (0.016) | S (0.032) | S (0.004) | R (0.5) | R (0.5) | S (0.008) | S (0.002) | S (0.064) | HLR (2) | HLR (1) | R (0.5) |

| Cefuroximed,e | 0.032 | 32 | 16 | 8 | 0.25 | 1 | 0.125 | 16 | 16 | 0.25 | 0.064 | 2 | 16 | 16 | 16 |

| Chloramphenicold,e | 0.5 | 8 | 4 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 8 | 1 | 4 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 8 |

| Ciprofloxacind | S (0.004) | HLR (>32) | HLR (>32) | HLR (>32) | R (2) | S (0.008) | S (0.004) | HLR (>32) | HLR (>32) | S (0.032) | S (0.004) | HLR (>32) | HLR (>32) | HLR (>32) | HLR (>32) |

| Ertapenemd,e | <0.002 | 0.064 | 0.064 | 0.032 | 0.016 | 0.016 | 0.004 | 0.032 | 0.016 | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.008 | 0.064 | 0.008 | 0.016 |

| Erythromycind,e | 0.5 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 | >256 | 2 | 8 | >256 | >256 | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Fosfomycind,e | 32 | 32 | 16 | 8 | 32 | 32 | 32 | 16 | 32 | 8 | 32 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 |

| Gentamicind,e | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 4 | 8 | 4 | 8 | 4 |

| Gepotidacind,e | 0.125 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 4 | 2 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.25 | 1 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Kanamycind,e | 16 | 16 | 16 | 32 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 8 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 8 |

| Lefamulind,e | 0.125 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 2 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 2 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Moxifloxacind,e | 0.004 | 4 | 8 | >32 | 1 | 0.016 | 0.032 | 2 | 8 | 0.064 | 0.008 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 8 |

| Penicillin Gd | S (0.032) |

R (2) |

R (2) |

R (2) |

PPNGc (≥32) | PPNGc (>32) | I (0.25) |

I (1) |

PPNGc (>32) |

I (0.5) |

I (0.125) |

PPNGc (>32) |

R (4) |

I (1) |

R (2) |

| Rifampicind,e | 0.125 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | >32 | 0.25 | >32 | 0.5 | >32 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Spectinomycind | S (16) | S (8) | S (16) | S (16) | S (16) | R (>1024) | S (8) | S (8) | S (8) | S (16) | S (8) | S (16) | S (16) | S (16) | S (16) |

| Temocillind,e | 0.064 | 8 | 16 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 8 | 8 | 1 | 0.5 | 4 | 32 | 8 | 8 |

| Tetracyclined | S (0.25) | R (4) | R (2) | R (2) | R (2) | R (2) | R (1) | TRNG (128) | R (4) | R (2) | R (1) | R (4) | R (2) | R (4) | R (4) |

| Trimethoprim-Sulfamethoxazoled,e | 1 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| Zoliflodacind,e | 0.064 | 0.064 | 0.125 | 0.125 | 0.064 | 0.125 | 0.25 | 0.032 | 0.064 | 0.25 | 0.064 | 0.125 | 0.064 | 0.125 | 0.125 |

National Collection of Type Cultures (NCTC) susceptible; I, susceptible, increased exposure; R, resistant; PPNG, penicillinase-producing N. gonorrhoeae; LLR, low-level resistant; HLR, high-level resistant; TRNG, plasmid-mediated high-level tetracycline resistant N. gonorrhoeae.

aInclude some previously published results.35 However, additional antimicrobials have been examined and some consensus MICs have slightly changed when additional MIC determinations using different MIC-determining methodologies have been performed.

bDo not produce the enzyme prolyliminopeptidase (PIP), which can result in doubtful and/or false-negative species identification of N. gonorrhoeae using biochemical or enzyme-substrate test. Global transmission of PIP-negative N. gonorrhoeae strains has been documented.45

cPPNG, penicillinase-producing N. gonorrhoeae (always considered resistant to all penicillins independent on identified MIC value, which might slightly vary).

dResistance phenotypes based on MIC (mg/L) using Etest and agar dilution (zoliflodacin, gepotidacin, lefamulin), and clinical susceptibility/resistance breakpoints stated by the EUCAST (v.14.0; https://www.eucast.org/clinical_breakpoints), where available. The reported MIC values are mean MICs (rounded to whole MIC doubling dilution) and the acceptable range of the MICs for each antimicrobial and the different strains is ±1 MIC doubling dilution. Note: the consensus MICs shown should be used and interpreted with caution because these were derived using one Etest method only and, consequently, may slightly differ using other methods.

eNo susceptibility/resistance breakpoints stated by the EUCAST (v.14.0; https://www.eucast.org/clinical_breakpoints).

The phenotypic characteristics of the superseded WHO reference strains (n = 14) are described in Table S1 (available as Supplementary data at JAC Online).

Genetic characterization

WHO F harboured a wild-type penA allele, seven strains (WHO H, K, Q, R, X, Y, Z) contained six different mosaic penA alleles (main ESC resistance determinant)1,2,9,10,19–28,42,80 and seven strains displayed the D345 insertion in the β-lactam main target PBP2, which is frequently found in chromosomally mediated penicillin resistance (Tables 1 and 2).1,2,42,80 WHO Q and R contained the mosaic penA-60.001 allele that causes ceftriaxone resistance in most currently-spreading ceftriaxone-resistant strains.5,10,19–28 WHO H contained a PBP2 T534A mutation, which causes ceftriaxone and cefixime resistance.36 WHO L and Y harboured a PBP2 A501 V and A501P alteration, respectively, which can also increase the MICs of ESCs.1,2,42,80,86,87 WHO L, O and V contained PBP2 G542S or P551S, which also may increase the ESC MICs.1,2,42,80,86,88 None of the isolates carried any other known potential ceftriaxone-resistance mutations (e.g. rpoB P157L, G158 V or R201H or rpoD D92–95 deletion or E98K).78,117 Eleven strains contained a deletion of a single nucleotide (A; n = 9) or an A→C substitution (n = 2) in the 13 bp inverted repeat of the mtrR promoter sequence, resulting in an increased MtrCDE efflux of substrate antimicrobials, e.g. macrolides and β-lactam antimicrobials.1,2,86,89–91 Also WHO L has an over-expressed MtrCDE efflux pump, however, this is caused by its mtr120 mutation, resulting in an additional promoter for mtrCDE.92 WHO S2 has a N. lactamica-like mosaic 2 mtrR promoter and mtrD sequence,10,37,38,78 while WHO P has a N. meningitidis-like mosaic 1 mtrR promoter and mtrD sequence.10,78 These mosaics increase the activity of the MtrCDE efflux pump and increase the MICs of antimicrobials such as macrolides.10,78,93–97 By contrast, a two base pair deletion in a GC dinucleotide repeat in mtrC decreases the MICs of antimicrobials, especially macrolides.120 However, this two base pair deletion was not found in any of the strains. Among the PorB1b strains (n = 14), all except WHO U displayed mutations in A102 [A102D (n = 10) and A102N (n = 3)] and 12 also a G101K alteration, which cause a decreased influx of target antimicrobials through the porin PorB1b.1,2,86,99,100 Twelve strains contained the L421P alteration in the second β-lactam target PBP1, which is found in high-level chromosomally mediated penicillin resistance.101 Of the β-lactamase-producing strains (n = 4), two (WHO M, O) contained African-type plasmid and two (WHO R, V) Asian-type plasmid, which harboured blaTEM-1 (WHO M, O, V) or blaTEM-135 (WHO R) resulting in high-level penicillin resistance (Tables 1 and 2).1,86,111–113 Ten strains contained GyrA S91F plus GyrA D95G (n = 4), D95N (n = 4) or D95A (n = 2) alterations, and nine of these strains additionally had 1–2 amino acid alterations in ParC D86, S87 or S88, which cause resistance to ciprofloxacin and other fluoroquinolones.1,2,42,78,102 One strain (WHO O) contained a C1192T spectinomycin target mutation in all four alleles of the 16S rRNA gene (spectinomycin MIC > 1024 mg/L104). One strain (WHO U) comprised the 23S rRNA C2611T gene mutation and two strains (WHO Q, V) harboured the 23S rRNA A2059G gene mutation that cause low- and high-level resistance to azithromycin, respectively.1,2,42,106,107 No azithromycin-resistance mutations were found in the rplD or rplV gene (encoding ribosomal protein L4 and L22, respectively)78 and none of the macrolide resistance-associated genes mefA/E (encoding Mef efflux pump),118ereA and ereB (encoding erythromycin esterase) or ermA-C and ermF (encoding RNA methylases that block macrolides from binding to the 23S subunit target)119 were identified. Three strains (WHO M, P, R) contained the H552N target mutation in RpoB (RNA polymerase subunit B), causing high-level rifampicin resistance.109 A tet(M)-carrying conjugative plasmid (Dutch type) causing high-level tetracycline resistance was detected in WHO Q (Tables 1 and 2).86,114,115 All strains except WHO F contained the V57M mutation in rpsJ, encoding ribosomal protein S10, contributing to chromosomally mediated tetracycline resistance.86,108 All strains except WHO F and WHO L contained the R228S mutation in the sulfonamide target dihydropteroate synthase (DHPS), encoded by folP, associated with sulfonamide resistance.110 Finally, no strain had any transcription-modulating mutations in the promoter sequence for the macAB operon (encoding the MacA-MacB efflux pump)121 or in the putative –35 promoter hexamer sequence (CTGACG) of the promoter sequence for the norM gene (encoding the NorM efflux pump) or in its ribosome binding site (TGAA).122

Table 2.

Genetic characteristics of relevance for epidemiology, diagnostics and AMR in the 2024 WHO Neisseria gonorrhoeae reference strains (n = 15), which are relevant for susceptibility testing of current, previous and novel therapeutic antimicrobials

| Characteristics | WHO Fa | WHO H | WHO Ka | WHO La | WHO Ma | WHO Oa | WHO Pa | WHO Q | WHO R | WHO S2 | WHO Ua | WHO Va | WHO Xa | WHO Ya | WHO Za |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MLST sequence type (ST)39,40 | ST10934 | ST1901 | ST7363 | ST1590 | ST7367 | ST1902 | ST8127 | ST12039 | ST1903 | ST11422 | ST7367 | ST10314 | ST7363 | ST1901 | ST7363 |

| NG-MAST ST40,41 | ST3303 | ST1407 | ST1424 | ST1422 | ST3304 | ST495 | ST3305 | ST16848 | ST3435 | ST3935 | ST2382 | ST8927 | ST4220 | ST1407 | ST4015 |

| NG-STAR ST42 | ST2 | ST1582 | ST4 | ST5 | ST6 | ST8 | ST9 | ST996 | ST233 | ST193 | ST224 | ST225 | ST226 | ST16 | ST227 |

| NG-STAR clonal complex (CC)43 | CC1401 | CC90 | CC348 | CC1229 | Ungroupable | CC26 | CC63 | CC73 | CC199 | CC63 | CC2047 | CC127 | CC348 | CC90 | CC348 |

| porA pseudogene mutant81 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | Yes | — | — | — | — |

| cppB gene82–84 | — | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| pip gene mutant45 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | Yes | — | — | — | — |

| penA mosaic allele2,4,9,10,19–28,42,80 | — | Yes | Yes | — | — | — | — | Yes | Yes | — | — | — | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| NG-STAR penA allele42 | 15.001 | 34.009 | 10.001 | 7.001 | 2.001 | 12.001 | 2.001 | 60.001 | 60.001 | 2.001 | 2.001 | 5.002 | 37.001 | 42.001 | 64.001 |

| PBP2 A3112,4,9,10,42,78,80,85,86 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | A311V | A311V | — | — | — | A311V | — | A311V |

| PBP2 I312, G5452,4,9,10,42,78,80,86,87 | — | I312M, G545S | I312M, G545S | — | — | — | — | I312M, G545S | I312M, G545S | — | — | — | I312M, G545S | I312M, G545S | I312M, G545S |

| PBP2 V3162,4,9,10,42,78,80,85–87 | — | V316T | V316T | — | — | — | — | V316T | V316T | — | — | — | V316P | V316T | V316T |

| PBP2 D345 insertion2,4,42,80 | — | — | — | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | — | — | Yes | Yes | Yes | — | — | — |

| PBP2 T4832,4,85,86 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | T483S | T483S | — | — | — | T483S | — | T483S |

| PBP2 A5012,4,42,80,86,87 | — | — | — | A501V | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | A501P | — |

| PBP2 N5122,4,85,86 | — | N512Y | N512Y | — | — | — | — | N512Y | N512Y | — | — | — | N512Y | N512Y | N512Y |

| PBP2 T53436 | — | T534A | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| PBP2 G5424,42,80,86,88 | — | — | — | G542S | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | G542S | — | — | — |

| PBP2 P5514,42,80,86,88 | — | — | — | — | — | P551S | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| mtrR promoter; 13 bp inverted repeat4,42,86,89–91 | — | A-del | A-del | — | A-del | A-del | A→C SNP | A-del | A-del | — | — | A-del | A-del | A-del | A→C SNP |

| mtr120 92 | — | — | — | Yes | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| MtrR promoter mosaic10,38,93–97 | — | — | — | — | — | — | Yes (99.4% Type 1)10,79 |

— | — | Yes (Type 2)10,79 |

— | — | — | — | — |

| MtrD mosaic10,38,93–97 | — | — | — | — | — | — | Yes (Type 1)10,79 |

— | — | Yes (Type 2)10,79 |

— | — | — | — | — |

| MtrD R714, S821, K82338,94–97 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | S821A, K823E | — | — | — | — | — |

| MtrR A39, G454,89–91,98 | — | — | G45D | G45D | G45D | — | N/Ab | G45D | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| mtrR coding region frame-shift mutation4,35 | — | — | — | — | — | — | T-insert 60b | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| PorB1b G1014,86,99,100 | N/Ac | G101K | G101K | G101K | G101K | G101K | — | G101K | G101K | G101K | — | G101K | G101K | G101K | G101K |

| PorB1b A1024,86,99,100 | N/Ac | A102N | A102D | A102D | A102D | A102D | A102D | A102D | A102D | A102N | — | A102D | A102D | A102N | A102D |

| ponA1; PBP1 L421101 | — | L421P | L421P | L421P | L421P | L421P | — | L421P | L421P | — | L421P | L421P | L421P | L421P | L421P |

| GyrA S91, D951,2,4,42,86,102 | — | S91F, D95G | S91F, D95N | S91F, D95N | S91F, D95G | — | — | S91F, D95A | S91F, D95A | — | — | S91F, D95G | S91F, D95N | S91F, D95G | S91F, D95N |

| GyrA A9255,56 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| GyrB D429, K450, S46749–53 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| ParC D86, S87 or S8886,102 | — | S87R | S87R, S88P | D86N, S88P | — | — | — | S87R | S87R | — | — | S87R | S87R, S88P | S87R | S87R, S88P |

| ParE G410103 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 16S rRNA (C1192)d,4,104 | — | — | — | — | — | C→T (4/) | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| RpsE T24105 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 23S rRNA (A2059, C2611)d,1,2,4,42,106,107 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | A→G (4/4) | — | — | C→T (4/4) | A→G (4/4) | — | — | — |

| rpsJ V5786,108 | — | V57M | V57M | V57M | V57M | V57M | V57M | V57M | V57M | V57M | V57M | V57M | V57M | V57M | V57M |

| RpoB H552109 | — | — | — | — | H552N | — | H552N | — | H552N | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| FolP R228110 | — | R228S | R228S | — | R228S | R228S | R228S | R228S | R228S | R228S | R228S | R228S | R228S | R228S | R228S |

| ß-lactamase plasmid type86,111–113 | — | — | — | — | African | African | — | — | Asian | — | — | Asian | — | — | — |

| blaTEM allele112 | — | — | — | — | TEM-1 | TEM-1 | — | — | TEM-135 | — | — | TEM-1 | — | — | — |

| tet(M) plasmid type86,114,115 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | Dutch | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

Note: none of the 23S rRNA A2058,116rplD,78rplV,78rpoB,78,117rpoD,78,117mef,118ereA,119ereB,119ermC119 and ermF119 mutations associated with increased MICs of macrolides or cephalosporins were present.

ST, sequence type; PBP2, Penicillin-binding protein 2; rRNA, ribosomal RNA.

aInclude some previously published results,35 however, many additional genes and mutations, and reference genomes have been characterized in the present paper.

bN/A, not applicable due to frame-shift mutation that causes a premature stop codon and truncated peptide.

cN/A, not applicable because these strains were of serogroup WI (PorB1a).

d Escherichia coli numbering (A2045 and C2597, respectively, in N. gonorrhoeae). Number of the four alleles of the 23S rRNA gene with mutations is shown in parenthesis.

Regarding novel antimicrobials for gonorrhoea treatment, no strain contained any gyrB mutations associated with increased MICs of zoliflodacin (in GyrB D429 and K450) or predisposition for emergence of zoliflodacin resistance (GyrB S467N).49–53 Furthermore, no alterations in GyrA A92, i.e. one of the two targets for the new antimicrobial gepotidacin, was observed. However, one strain (WHO L) contained the ParC D86N alteration in the other gepotidacin target, i.e. which can predispose for emergence of gepotidacin resistance.55,56

Of importance for molecular (and/or phenotypic) detection of gonococci, cppB81–83 (WHO F), pip45 (WHO U) and porA pseudogene84 (WHO U) mutant strains were included. Finally, the strains represented 11, 14, 15 and 10 MLST STs, NG-MAST STs, NG-STAR STs and NG-STAR CCs (including one ungroupable strain), respectively (Table 2).

The genetic characteristics of the superseded WHO reference strains (n = 14) are described in Table S2.

Reference genome characterization

The general characteristics of the reference genomes of the 2024 WHO gonococcal reference strains (n = 15) as well as the superseded WHO gonococcal reference strains (n = 14) are summarized in Table 3 and Table S3. The genome size ranged from 2 163 258 bp (WHO-β) to 2 308 468 bp (WHO A). The GC content, number of coding sequences (CDS) and average CDS size varied between 52.1%–52.7%, 1945–2125 and 836–856 bp. The number of core genes was 1791 and accessory genes varied from 248 to 402 (Table 3 and Table S3).

Table 3.

General characteristics of the reference genomes of the 2024 WHO Neisseria gonorrhoeae reference strains (n = 15)

| Characteristics | WHO F | WHO H | WHO K | WHO L | WHO M | WHO O | WHO P | WHO Q | WHO R | WHO S2 | WHO U | WHO V | WHO X | WHO Y | WHO Z |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accession number | CP145052 | CP145050-CP145051 | CP145048-CP145049 | CP145045-CP145047 | CP145041-CP145044 | CP145037-CP145040 | CP145035-CP145036 | CP145032-CP145034 | CP145028-CP145031 | CP145026-CP145027 | CP145024-CP145025 | CP145021-CP145023 | CP145019-CP145020 | CP145017-CP145018 | CP145015-CP145016 |

| Genome size (bp) | 2 292 467 | 2 233 100 | 2 169 846 | 2 168 633 | 2 178 344 | 2 169 062 | 2 173 861 | 2 177 981 | 2 218 559 | 2 172 077 | 2 234 269 | 2 221 284 | 2 171 112 | 2 228 980 | 2 229 351 |

| No. of CDS (without/with pseudogenes) | 2125/2370 | 2036/2289 | 1952/2204 | 1955/2216 | 1982/2225 | 1971/2215 | 1961/2222 | 1963/2223 | 2020/2264 | 1964/2214 | 2036/2286 | 2039/2285 | 1961/2210 | 2028/2287 | 2033/2286 |

| Coding density (%) | 77.4 | 77.3 | 76.9 | 76.3 | 77.4 | 77.3 | 76.8 | 76.6 | 77.2 | 77.1 | 77.2 | 77.2 | 76.8 | 77.0 | 77.1 |

| Average gene size (bp; without/with pseudogenes) | 836/822 | 848/829 | 855/836 | 846/832 | 850/832 | 850/832 | 852/832 | 850/832 | 848/835 | 853/834 | 847/832 | 841/827 | 851/833 | 847/829 | 846/828 |

| GC content (%) | 52.1 | 52.3 | 52.6 | 52.6 | 52.6 | 52.6 | 52.6 | 52.6 | 52.4 | 52.6 | 52.4 | 52.4 | 52.6 | 52.4 | 52.4 |

| 5S rRNA | 4 | ||||||||||||||

| 16S rRNA | 4 | ||||||||||||||

| 23S rRNA | 4 | ||||||||||||||

| tRNAs | 55 | 55 | 56 | 55 | 55 | 55 | 55 | 55 | 55 | 55 | 55 | 55 | 56 | 55 | 56 |

| ncRNAs | 3 | ||||||||||||||

| tmRNAs | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| No. genes in pangenome | 2471 | ||||||||||||||

| No. core genesa | 1791 | ||||||||||||||

| Accessory genes (%) | 402 (18.3) | 333 (15.7) | 258 (12.6) | 262 (12.8) | 268 (13.0) | 265 (12.9) | 271 (13.1) | 266 (12.9) | 314 (14.9) | 268 (13.0) | 328 (15.5) | 331 (15.6) | 263 (12.8) | 328 (15.5) | 325 (15.4) |

| No. 10-mer DUS (12-mer DUS)b | 1981 (1533) | 1977 (1526) |

1950 (1510) |

1956 (1518) |

1955 (1516) |

1950 (1519) |

1959 (1517) |

1958 (1521) |

1961 (1518) |

1960 (1521) |

1963 (1512) |

1968 (1518) |

1949 (1510) |

1973 (1522) |

1959 (1512) |

| Number of plasmids | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

bp, base pairs; CDS, coding sequence; GC, guanine-cytosine; rRNA, ribosomal RNA; tRNA, transfer RNA; ncRNA, non-coding RNA; tmRNA, transfer-messenger RNA.

aPresent in 99%–100% of strains.

bNumber of the 10-mer DUS sequence GCCGTCTGAA (no. of the 12-mer ATGCCGTCTGAA). Note: the 10-mer sequence is included in the 12-mer.

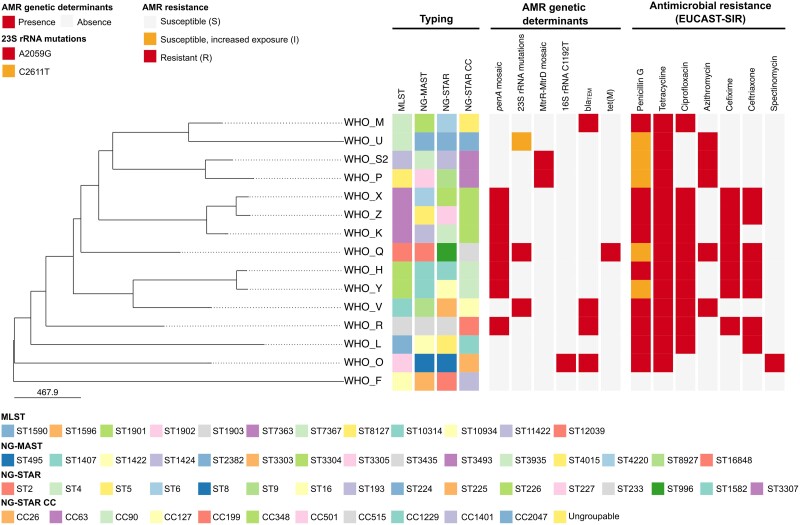

Figure 1 describes the phylogenomic relationship among all the 2024 WHO reference strain core genomes (n = 15, 1791 loci), including their molecular epidemiological types, key AMR determinants and phenotypic AMR patterns.

Figure 1.

Phylogenomic tree of the 2024 WHO Neisseria gonorrhoeae reference core genomes (n = 15). Typing, key genetic determinants of AMR and phenotypic AMR patterns of the 2024 WHO gonococcal reference strains are shown alongside the tree. Only antimicrobials with EUCAST breakpoints (v.14.0, https://www.eucast.org/clinical_breakpoints) are displayed. This figure appears in colour in the online version of JAC and in black and white in the print version of JAC.

Discussion

Herein, the 2024 WHO N. gonorrhoeae reference strains (and superseded WHO gonococcal reference strains) and their detailed phenotypic, genetic and reference genome characteristics are described. The utility of these strains includes internal and external quality assurance in all types of laboratory investigation, especially in the AMR testing (phenotypic and genetic) in GASPs, such as the WHO global GASP6–8 and WHO EGASP,26,31–33 but also for phenotypic (e.g. culture, species verification) and molecular (e.g. NAATs) diagnostics, AMR prediction, pharmacodynamics, epidemiology, research and genomics. The strains include all important global susceptible; susceptible, increased exposure; and resistant phenotypes and the ranges of resistances seen for most antimicrobials currently or previously recommended in national and international gonorrhoea treatment guidelines or antimicrobials in advanced clinical development for future treatment of gonorrhoea. However, the consensus MIC values (Table 1 and Table S1) were determined using one MIC-based method only (Etest). Accordingly, these MIC values may vary slightly using other MIC-based methods, however, the resistance phenotypes should be consistent. The 2024 WHO gonococcal reference strains are available through WHO sources and from the National Collection of Type Cultures (https://www.culturecollections.org.uk).

In many countries, NAATs have more or less replaced culture for gonococcal detection and, consequently, genetic detection of AMR determinants to predict resistance or susceptibility to antimicrobials has become increasingly important for AMR surveillance and, ideally, to also guide individually tailored treatment.123–125 The genetic AMR determinants that result in the different AMR phenotypes in the 2024 WHO gonococcal reference strains were characterized in detail and included most known gonococcal AMR determinants. Accordingly, the 2024 WHO reference strains can be used for internal and external quality assurance and quality controls of both conventional phenotypic AMR surveillance and surveillance using molecular AMR prediction. Molecular AMR methods can never entirely replace phenotypic culture-based AMR testing because they only detect known AMR determinants and new ones will continue to evolve. However, molecular prediction of AMR or susceptibility can supplement the phenotypic AMR surveillance, i.e. with varying sensitivity and specificity for different antimicrobials.123–125 The accuracy of the AMR prediction will also vary across geographic settings and time, due to the dynamics of the gonococcal population, regional variations in AMR and drug use, and evolution as well as importation of gonococcal strains in the settings. Finally, several challenges for direct testing of clinical, especially oropharyngeal, NAAT specimens and for accurate prediction of resistance to the currently recommended ceftriaxone and azithromycin remain.123 Nevertheless, WGS has revolutionized the molecular prediction of AMR or antimicrobial susceptibility, AMR surveillance and in general molecular epidemiological surveillance of N. gonorrhoeae strains nationally and internationally.9,10,23,24,27,28,35,37,38,43,52,78,93,95,97,120,123 However, to fully use the power of WGS joint analyses of quality-assured WGS, AMR and clinical and epidemiological data should be performed. This will substantially enhance the understanding of the spread, introduction, replacement, evolution and biofitness of AMR, and antimicrobial susceptible, clades/clones in risk groups nationally and internationally,9,10 which can inform gonorrhoea epidemiology, preventative measures, prediction of AMR or antimicrobial susceptibility, diagnostics and development of new antimicrobials and gonococcal vaccines. To support this development, we present the fully characterized and annotated chromosomes and plasmids of the 2024 WHO gonococcal reference strains, representing genomes that cover mainly the whole gonococcal species phylogeny (Figure S1), to enable quality assurance of N. gonorrhoeae WGS and its analysis. Ultimately, point-of-care genetic AMR methods, combined with gonococcal detection, should be used to guide individually tailored treatment of gonorrhoea, which can ensure rational use of antimicrobials (including sparing last-line antimicrobials) and affect the control of both gonorrhoea and gonococcal AMR.

The 2024 WHO N. gonorrhoeae reference strain panel includes 11 of the 2016 WHO reference strains (n = 14),35 which were further characterized, and four novel WHO reference strains. The four novel 2024 WHO strains (WHO H, Q, R and S2) represent phenotypes and/or genotypes that were not available when the 2016 WHO reference strains35 were published. Accordingly, WHO R is the first internationally spreading ceftriaxone-resistant strain FC428 (ceftriaxone caused by the mosaic penA-60.001 allele), associated with ceftriaxone treatment failures5,10,19–22; WHO Q is the first identified strain with ceftriaxone resistance (mosaic penA-60.001 allele) plus high-level azithromycin resistance (23S rRNA gene A2059G in all four alleles), associated with ceftriaxone 1 g plus doxycycline treatment failure24; WHO H is also expressing ceftriaxone resistance (mosaic penA-34.009, i.e. penA-34.001 plus the unique PBP2 T534A mutation), associated with cefixime treatment failure36 and WHO S2 is representing the main internationally spreading azithromycin-resistant clade (mosaic MtrRCDE efflux pump, i.e. with Neisseria lactamica-like mosaic 2 mtrR promoter and mtrD sequence10,37,38,78), which account for most of the mainly low-level azithromycin resistance in many countries.10,37,38,78,93–95 Furthermore, internationally spreading multidrug-resistant clones that have accounted for most of the ESC resistance globally such as MLST ST7363, ST1901 and ST1903, as well as NG-MAST ST1407, CC90 and CC199 are represented (Table 2).4–6,9,10,19–22,38,43 Notably, for the previously published WHO reference strains additional antimicrobial phenotypes and genotypes have been described and some consensus MICs have slightly changed when additional MIC determinations using different MIC-determining methodologies have been performed. Finally, all superseded WHO gonococcal reference strains (n = 14), including 11 not previously published WHO reference strains, were characterized in identical manners. It is important to provide quality-assured genetic and phenotypic characteristics for also these strains as they are still in use in some settings. Considering any historical data, the full characterization of the strains provides additional quality assurance to already published data. However, the use of the more relevant and updated 2024 WHO panel is strongly encouraged.

In conclusion, the 2024 WHO N. gonorrhoeae reference strains were extensively characterized both phenotypically and genetically, including characterizing the reference genomes, and are intended for internal and external quality assurance and quality control purposes in laboratory investigations. This is particularly in WHO GASP, WHO EGASP and other GASPs (to allow valid intra- and inter-laboratory comparisons of AMR data derived by different methods in various countries), but also in phenotypic (e.g. culture, species determination) and molecular diagnostics, genetic AMR detection, AMR prediction, pharmacodynamics, molecular epidemiology, research (including pre-clinical drug development) and as fully characterized, annotated and finished reference genomes in WGS analysis, transcriptomics, proteomics and other molecular technologies and data analysis. When additional resistant phenotypes and/or genotypes emerge, novel WHO gonococcal reference strains will be selected, characterized and added to the WHO gonococcal strain panel.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Magnus Unemo, Department of Laboratory Medicine, Faculty of Medicine and Health, WHO Collaborating Centre for Gonorrhoea and Other STIs, National Reference Laboratory for STIs, Microbiology, Örebro University, Örebro, Sweden; Institute for Global Health, University College London (UCL), London, UK.

Leonor Sánchez-Busó, Joint Research Unit ‘Infection and Public Health’, FISABIO-University of Valencia, Institute for Integrative Systems Biology (I2SysBio), Valencia, Spain; CIBERESP, ISCIII, Madrid, Spain.

Daniel Golparian, Department of Laboratory Medicine, Faculty of Medicine and Health, WHO Collaborating Centre for Gonorrhoea and Other STIs, National Reference Laboratory for STIs, Microbiology, Örebro University, Örebro, Sweden.

Susanne Jacobsson, Department of Laboratory Medicine, Faculty of Medicine and Health, WHO Collaborating Centre for Gonorrhoea and Other STIs, National Reference Laboratory for STIs, Microbiology, Örebro University, Örebro, Sweden.

Ken Shimuta, Department of Bacteriology I, National Institute of Infectious Diseases, Tokyo, Japan.

Pham Thi Lan, Hanoi Medical University, National Hospital of Dermatology and Venereology, Hanoi, Vietnam.

David W Eyre, Big Data Institute, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK; Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Oxford, UK.

Michelle Cole, UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA), London, UK.

Ismael Maatouk, Department of the Global HIV, Hepatitis and STI Programmes, WHO, Geneva, Switzerland.

Teodora Wi, Department of the Global HIV, Hepatitis and STI Programmes, WHO, Geneva, Switzerland.

Monica M Lahra, WHO Collaborating Centre for Sexually Transmitted Infections and Antimicrobial Resistance, New South Wales Health Pathology, Microbiology, Randwick, NSW, Australia; Faculty of Medicine, The University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the Department of the Global HIV, Hepatitis and STI programmes, WHO, Geneva, Switzerland; Örebro County Council Research Committee, Örebro, Sweden and Foundation for Medical Research at Örebro University Hospital, Sweden. L.S.B. was supported by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (PID2020-120113RA-I00/AEI/10.13039/501100011033) and Generalitat Valenciana (CDEI-06/20-B, Conselleria de Sanitat Universal i Salut Pública; and CISEJI/2022/66, Conselleria d’Innovació, Universitats, Ciència i Societat Digital), Valencia, Spain.

Transparency declarations

None to declare.

Supplementary data

Figure S1 and Tables S1 to S3 are available as Supplementary data at JAC Online.

References

- 1. Unemo M, Seifert HS, Hook EW IIIet al. Gonorrhoea. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2019; 5: 79. 10.1038/s41572-019-0128-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jensen JS, Unemo M. Antimicrobial treatment and resistance in sexually transmitted bacterial infections. Nat Rev Microbiol 2024. 10.1038/s41579-024-01023-3. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. WHO . Global Action Plan to Control the Spread and Impact of Antimicrobial Resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. WHO, 2012. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241503501. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Unemo M, Shafer WM. Antimicrobial resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae in the 21st century: past, evolution, and future. Clin Microbiol Rev 2014; 27: 587–613. 10.1128/CMR.00010-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. van der Veen S. Global transmission of the penA allele 60.001–containing high-level ceftriaxone-resistant gonococcal FC428 clone and antimicrobial therapy of associated cases: a review. Infect Microb Dis 2023; 5: 13–20. 10.1097/IM9.0000000000000113 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Unemo M, Lahra MM, Cole Met al. World Health Organization global gonococcal antimicrobial surveillance program (WHO GASP): review of new data and evidence to inform international collaborative actions and research efforts. Sex Health 2019; 16: 412–25. 10.1071/SH19023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wi T, Lahra MM, Ndowa Fet al. Antimicrobial resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae: global surveillance and a call for international collaborative action. PLoS Med 2017; 14: e1002344. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Unemo M, Lahra MM, Escher Met al. WHO global antimicrobial resistance surveillance for Neisseria gonorrhoeae 2017–2018: a retrospective observational study. Lancet Microbe 2021; 2: e627–36. 10.1016/S2666-5247(21)00171-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Harris SR, Cole MJ, Spiteri Get al. Public health surveillance of multidrug-resistant clones of Neisseria gonorrhoeae in Europe: a genomic survey. Lancet Infect Dis 2018; 18: 758–68. 10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30225-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sánchez-Busó L, Cole MJ, Spiteri Get al. Europe-wide expansion and eradication of multidrug-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae lineages: a genomic surveillance study. Lancet Microbe 2022; 3: e452–63. 10.1016/S2666-5247(22)00044-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Workowski KA, Bachmann LH, Chan PAet al. Sexually transmitted infections treatment guidelines, 2021. MMWR Recomm Rep 2021; 70: 1–187. 10.15585/mmwr.rr7004a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fifer H, Saunders J, Soni Set al. 2018 UK national guideline for the management of infection with Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Int J STD AIDS 2020; 31: 4–15. 10.1177/0956462419886775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Unemo M, Ross J, Serwin ABet al. 2020 European guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of gonorrhoea in adults. Int J STD AIDS 2020. [Online ahead of print] 10.1177/0956462420949126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hamasuna R, Yasuda M, Takahashi Set al. The JAID/JSC guidelines to clinical management of infectious disease 2017 concerning male urethritis and related disorders. J Infect Chemother 2021; 27: 546–54. 10.1016/j.jiac.2019.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wang QQ, Liu QZ, Xu JHet al. Guidelines of Clinical Management of Sexually Transmitted Diseases. Shanghai Science and Technology Press, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 16. WHO . WHO Guidelines for the Treatment of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. WHO, 2016. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/246114/9789241549691-eng.pdf;jsessionid=7B95502B9A64B5FCDF3E7AE5F88087D6?sequence=1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Australasian Sexual Health Alliance (ASHA) . Gonorrhoea. In: Australian STI management guidelines for use in primary care.www.sti.guidelines.org.au/sexually-transmissible-infections/gonorrhoea#management.

- 18. Romanowski B, Robinson J, Wong T.. Gonococcal infections chapter . In: Canadian Guidelines on Sexually Transmitted Infections. Public Health Agency of Canada, 2022. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/infectious-diseases/sexual-health-sexually-transmitted-infections/canadian-guidelines/gonorrhea/treatment-follow-up.html#a2. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nakayama SI, Shimuta K, Furubayashi KIet al. New ceftriaxone- and multidrug-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae strain with a novel mosaic penA gene isolated in Japan. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2016; 60: 4339–41. 10.1128/AAC.00504-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chen SC, Yuan LF, Zhu XYet al. Sustained transmission of the ceftriaxone-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae FC428 clone in China. J Antimicrob Chemother 2020; 75: 2499–502. 10.1093/jac/dkaa196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lee K, Nakayama SI, Osawa Ket al. Clonal expansion and spread of the ceftriaxone-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae strain FC428, identified in Japan in 2015, and closely related isolates. J Antimicrob Chemother 2019; 74: 1812–9. 10.1093/jac/dkz129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wang D, Li Y, Zhang Cet al. Genomic epidemiology of Neisseria gonorrhoeae in Shenzhen, China, during 2019–2020: increased spread of ceftriaxone-resistant isolates brings insights for strengthening public health responses. Microbiol Spectr 2023; 11: e0172823. 10.1128/spectrum.01728-23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pleininger S, Indra A, Golparian Det al. Extensively drug-resistant (XDR) Neisseria gonorrhoeae causing possible gonorrhoea treatment failure with ceftriaxone plus azithromycin in Austria, April 2022. Euro Surveill 2022; 27: 2200455. 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2022.27.24.2200455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Eyre DW, Sanderson ND, Lord Eet al. Gonorrhoea treatment failure caused by a Neisseria gonorrhoeae strain with combined ceftriaxone and high-level azithromycin resistance, England, February 2018. Euro Surveill 2018; 23: 1800323. 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2018.23.27.1800323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Whiley DM, Jennison A, Pearson Jet al. Genetic characterisation of Neisseria gonorrhoeae resistant to both ceftriaxone and azithromycin. Lancet Infect Dis 2018; 18: 717–8. 10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30340-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ouk V, Heng LS, Virak Met al. High prevalence of ceftriaxone-resistant and XDR Neisseria gonorrhoeae in several cities of Cambodia, 2022–23: WHO enhanced gonococcal antimicrobial surveillance programme (EGASP). JAC Antimicrob Resist 2024; 6: dlae053. 10.1093/jacamr/dlae053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Maubaret C, Caméléna F, Mérimèche Met al. Two cases of extensively drug-resistant (XDR) Neisseria gonorrhoeae infection combining ceftriaxone-resistance and high-level azithromycin resistance, France, November 2022 and May 2023. Euro Surveill 2023; 28: 2300456. 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2023.28.37.2300456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Golparian D, Vestberg N, Södersten Wet al. Multidrug-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolate SE690: mosaic penA-60.001 gene causing ceftriaxone resistance internationally has spread to the more antimicrobial-susceptible genomic lineage, Sweden, September 2022. Euro Surveill 2023; 28: 2300125. 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2023.28.10.2300125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) . Response Plan to Control and Manage the Threat of Multidrug-Resistant Gonorrhoea in Europe. 2012. www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications/Publications/1206-ECDC-MDR-gonorrhoea-response-plan.pdf.

- 30. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) . Response Plan to Control and Manage the Threat of Multi- and Extensively Drug-Resistant Gonorrhoea in Europe—Indicator Monitoring 2019. 2019. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/response-plan-control-and-manage-threat-multi-and-extensively-drug-resistant-0.

- 31. Weston EJ, Wi T, Papp J. Strengthening global surveillance for antimicrobial drug-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae through the enhanced gonococcal antimicrobial surveillance program. Emerg Infect Dis 2017; 23: S47–52. 10.3201/eid2313.170443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sirivongrangson P, Girdthep N, Sukwicha Wet al. The first year of the global enhanced gonococcal antimicrobial surveillance programme (EGASP) in Bangkok, Thailand, 2015–2016. PLoS ONE 2018; 13: e0206419. 10.1371/journal.pone.0206419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kittiyaowamarn R, Girdthep N, Cherdtrakulkiat Tet al. Neisseria gonorrhoeae antimicrobial susceptibility trends in Bangkok, Thailand, 2015–21: enhanced gonococcal antimicrobial surveillance programme (EGASP). JAC Antimicrob Resist 2023; 5: dlad139. 10.1093/jacamr/dlad139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Unemo M, Fasth O, Fredlund Het al. Phenotypic and genetic characterization of the 2008 WHO Neisseria gonorrhoeae reference strain panel intended for global quality assurance and quality control of gonococcal antimicrobial resistance surveillance for public health purposes. J Antimicrob Chemother 2009; 63: 1142–51. 10.1093/jac/dkp098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Unemo M, Golparian D, Sánchez-Busó Let al. The novel 2016 WHO Neisseria gonorrhoeae reference strains for global quality assurance of laboratory investigations: phenotypic, genetic and reference genome characterization. J Antimicrob Chemother 2016; 71: 3096–108. 10.1093/jac/dkw288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Unemo M, Golparian D, Stary Aet al. First Neisseria gonorrhoeae strain with resistance to cefixime causing gonorrhoea treatment failure in Austria, 2011. Euro Surveill 2011; 16: 19998. 10.2807/ese.16.43.19998-en [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gianecini RA, Poklepovich T, Golparian Det al. Genomic epidemiology of azithromycin-nonsusceptible Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Argentina, 2005–2019. Emerg Infect Dis 2021; 27: 2369–78. 10.3201/eid2709.204843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Golparian D, Cole MJ, Sánchez-Busó Let al. Antimicrobial-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae in Europe in 2020 compared with in 2013 and 2018: a retrospective genomic surveillance study. Lancet Microbe 2024; 5: e478–88. 10.1016/S2666-5247(23)00370-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Jolley KA. Multi-locus sequence typing. In: Pollard AJ, Maiden MC (eds), Meningococcal Disease: Methods and Protocols. Humana Press, 2001; 173–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Unemo M, Dillon JA. Review and international recommendation of methods for typing Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates and their implications for improved knowledge of gonococcal epidemiology, treatment, and biology. Clin Microbiol Rev 2011; 24: 447–58. 10.1128/CMR.00040-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Martin IM, Ison CA, Aanensen DMet al. Rapid sequence-based identification of gonococcal transmission clusters in a large metropolitan area. J Infect Dis 2004; 189: 1497–505. 10.1086/383047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Demczuk W, Sidhu S, Unemo Met al. Neisseria gonorrhoeae sequence typing for antimicrobial resistance, a novel antimicrobial resistance multilocus typing scheme for tracking global dissemination of N. gonorrhoeae strains. J Clin Microbiol 2017; 55: 1454–68. 10.1128/JCM.00100-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Golparian D, Sánchez-Busó L, Cole Met al. Neisseria gonorrhoeae sequence typing for antimicrobial resistance (NG-STAR) clonal complexes are consistent with genomic phylogeny and provide simple nomenclature, rapid visualization and antimicrobial resistance (AMR) lineage predictions. J Antimicrob Chemother 2021; 76: 940–4. 10.1093/jac/dkaa552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Unemo M, Olcén P, Berglund Tet al. Molecular epidemiology of Neisseria gonorrhoeae: sequence analysis of the porB gene confirms presence of two circulating strains. J Clin Microbiol 2002; 40: 3741–9. 10.1128/JCM.40.10.3741-3749.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Unemo M, Palmer HM, Blackmore Tet al. Global transmission of prolyliminopeptidase-negative Neisseria gonorrhoeae strains: implications for changes in diagnostic strategies. Sex Transm Infect 2007; 83: 47–51. 10.1136/sti.2006.021733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Jacobsson S, Golparian D, Alm RAet al. High in vitro activity of the novel spiropyrimidinetrione AZD0914, a DNA gyrase inhibitor, against multidrug-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates suggests a new effective option for oral treatment of gonorrhea. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2014; 58: 5585–8. 10.1128/AAC.03090-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Unemo M, Ringlander J, Wiggins Cet al. High in vitro susceptibility to the novel spiropyrimidinetrione ETX0914 (AZD0914) among 873 contemporary clinical Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates from 21 European countries from 2012 to 2014. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2015; 59: 5220–5. 10.1128/AAC.00786-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Jacobsson S, Kularatne R, Kittiyaowamarn Ret al. High in vitro susceptibility to the first-in-class spiropyrimidinetrione zoliflodacin among consecutive clinical Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates from Thailand (2018) and South Africa (2015–2017). Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2019; 63: e01479-19. 10.1128/AAC.01479-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Unemo M, Ahlstrand J, Sánchez-Busó Let al. High susceptibility to zoliflodacin and conserved target (GyrB) for zoliflodacin among 1209 consecutive clinical Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates from 25 European countries, 2018. J Antimicrob Chemother 2021; 76: 1221–8. 10.1093/jac/dkab024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Jacobsson S, Golparian D, Oxelbark Jet al. Pharmacodynamic evaluation of dosing, bacterial kill, and resistance suppression for zoliflodacin against Neisseria gonorrhoeae in a dynamic hollow fiber infection model. Front Pharmacol 2021; 12: 682135. 10.3389/fphar.2021.682135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Jacobsson S, Golparian D, Oxelbark Jet al. Pharmacodynamic evaluation of zoliflodacin treatment of Neisseria gonorrhoeae strains with amino acid substitutions in the zoliflodacin target GyrB using a dynamic hollow fiber infection model. Front Pharmacol 2022; 13: 874176. 10.3389/fphar.2022.874176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Golparian D, Jacobsson S, Sánchez-Busó Let al. Gyrb in silico mining in 27151 global gonococcal genomes from 1928–2021 combined with zoliflodacin in vitro testing of 71 international gonococcal isolates with different GyrB, ParC and ParE substitutions confirms high susceptibility. J Antimicrob Chemother 2022; 78: 150–4. 10.1093/jac/dkac366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Jacobsson S, Golparian D, Oxelbark Jet al. Pharmacodynamics of zoliflodacin plus doxycycline combination therapy against Neisseria gonorrhoeae in a gonococcal hollow-fiber infection model. Front Pharmacol 2023; 14: 1291885. 10.3389/fphar.2023.1291885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Taylor SN, Marrazzo J, Batteiger BEet al. Single-dose zoliflodacin (ETX0914) for treatment of urogenital gonorrhea. N Engl J Med 2018; 379: 1835–45. 10.1056/NEJMoa1706988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Jacobsson S, Golparian D, Scangarella-Oman Net al. In vitro activity of the novel triazaacenaphthylene gepotidacin (GSK2140944) against MDR Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J Antimicrob Chemother 2018; 73: 2072–7. 10.1093/jac/dky162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Scangarella-Oman NE, Hossain M, Dixon PBet al. Microbiological analysis from a phase 2 randomized study in adults evaluating single oral doses of gepotidacin in the treatment of uncomplicated urogenital gonorrhea caused by Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2018; 62: e01221-18. 10.1128/AAC.01221-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Taylor SN, Morris DH, Avery AKet al. Gepotidacin for the treatment of uncomplicated urogenital gonorrhea: a phase 2, randomized, dose-ranging, single-oral dose evaluation. Clin Infect Dis 2018; 67: 504–12. 10.1093/cid/ciy145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Jacobsson S, Paukner S, Golparian Det al. In vitro activity of the novel pleuromutilin lefamulin (BC-3781) and effect of efflux pump inactivation on multidrug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2017; 61: e01497-17. 10.1128/AAC.01497-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Jacobsson S, Golparian D, Oxelbark Jet al. Pharmacodynamic evaluation of lefamulin in the treatment of gonorrhea using a hollow fiber infection model simulating Neisseria gonorrhoeae infections. Front Pharmacol 2022; 13: 1035841. 10.3389/fphar.2022.1035841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Chin C-S, Alexander DH, Marks Pet al. Nonhybrid, finished microbial genome assemblies from long-read SMRT sequencing data. Nat Methods 2013; 10: 563–9. 10.1038/nmeth.2474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Koren S, Walenz BP, Berlin Ket al. Canu: scalable and accurate long-read assembly via adaptive k-mer weighting and repeat separation. Genome Res 2017; 27: 722–36. 10.1101/gr.215087.116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Hunt M, Silva ND, Otto TDet al. Circlator: automated circularization of genome assemblies using long sequencing reads. Genome Biol 2015; 16: 294. 10.1186/s13059-015-0849-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Li H. Aligning sequence reads, clone sequences and assembly contigs with BWA-MEM. arXiv:1303.3997v1 [q-bio.GN] 2013. 10.48550/arXiv.1303.3997 [DOI]

- 64. Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker Aet al. The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 2009; 25: 2078–9. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Walker BJ, Abeel T, Shea Tet al. Pilon: an integrated tool for comprehensive microbial variant detection and genome assembly improvement. PLoS ONE 2014; 9: e112963. 10.1371/journal.pone.0112963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Carver TJ, Rutherford KM, Berriman Met al. ACT: the Artemis comparison tool. Bioinformatics 2005; 21: 3422–3. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Wick RR. Trycycler (v0.5.5). Zenodo. 2024 10.5281/zenodo.3965017 [DOI]

- 68. Wick RR, Judd LM, Gorrie CLet al. Unicycler: resolving bacterial genome assemblies from short and long sequencing reads. PLoS Comput Biol 2017; 13: e1005595. 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Li H. Minimap2: pairwise alignment for nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics 2018; 34: 3094–100. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Bankevich A, Nurk S, Antipov Det al. SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J Comput Biol 2012; 19: 455–77. 10.1089/cmb.2012.0021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Camacho C, Coulouris G, Avagyan Vet al. BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinformatics 2009; 10: 421. 10.1186/1471-2105-10-421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Tatusova T, DiCuccio M, Badretdin Aet al. NCBI prokaryotic genome annotation pipeline. Nucleic Acids Res 2016; 44: 6614–624. 10.1093/nar/gkw569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Tonkin-Hill G, MacAlasdair N, Ruis Cet al. Producing polished prokaryotic pangenomes with the Panaroo pipeline. Genome Biol 2020; 21: 180. 10.1186/s13059-020-02090-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Page AJ, Taylor B, Delaney AJet al. SNP-sites: rapid efficient extraction of SNPs from multi-FASTA alignments. Microb Genom 2016; 2: e000056. 10.1099/mgen.0.000056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Nguyen LT, Schmidt HA, Von Haeseler A et al. IQ-TREE: a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol Biol Evol 2015; 32: 268–74. 10.1093/molbev/msu300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Kalyaanamoorthy S, Minh BQ, Wong TKFet al. ModelFinder: fast model selection for accurate phylogenetic estimates. Nat Methods 2017; 14: 587–9. 10.1038/nmeth.4285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Hoang DT, Chernomor O, Von Haeseler Aet al. UFBoot2: improving the ultrafast bootstrap approximation. Mol Biol Evol 2018; 35: 518–22. 10.1093/molbev/msx281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Sánchez-Busó L, Yeats CA, Taylor Bet al. A community-driven resource for genomic epidemiology and AMR prediction of Neisseria gonorrhoeae at Pathogenwatch. Genome Med 2021; 13: 61. 10.1186/s13073-021-00858-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Rice P, Longden L, Bleasby A. EMBOSS: the European molecular biology open software suite. Trends Genet 2000; 16: 276–7. 10.1016/S0168-9525(00)02024-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Ohnishi M, Golparian D, Shimuta Ket al. Is Neisseria gonorrhoeae initiating a future era of untreatable gonorrhea? detailed characterization of the first strain with high-level resistance to ceftriaxone. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2011; 55: 3538–45. 10.1128/AAC.00325-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Ison C, Golparian D, Saunders Pet al. Evolution of Neisseria gonorrhoeae is a continuing challenge for molecular detection of gonorrhoea—false negative gonococcal porA mutants are spreading internationally. Sex Transm Infect 2013; 89: 197–201. 10.1136/sextrans-2012-050829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Korch C, Hagblom P, Ohman Het al. Cryptic plasmid of Neisseria gonorrhoeae: complete nucleotide sequence and genetic organization. J Bacteriol 1985; 163: 430–8. 10.1128/jb.163.2.430-438.1985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Ho BS, Feng WG, Wong BKet al. Polymerase chain reaction for the detection of Neisseria gonorrhoeae in clinical samples. J Clin Pathol 1992; 45: 439–42. 10.1136/jcp.45.5.439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Lum G, Freeman K, Nguyen NLet al. A cluster of culture positive gonococcal infections but with false negative cppB gene based PCR. Sex Transm Infect 2005; 81: 400–2. 10.1136/sti.2004.013805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Tomberg J, Unemo M, Ohnishi Met al. Identification of amino acids conferring high-level resistance to expanded-spectrum cephalosporins in the penA gene from Neisseria gonorrhoeae strain H041. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2013; 57: 3029–36. 10.1128/AAC.00093-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Unemo M, Nicholas RA, Jerse AEet al. Molecular mechanisms of antibiotic resistance expressed by the pathogenic Neisseria. In: Davies JK, Kahler CM, eds. Pathogenic Neisseria: Genomics, Molecular Biology and Disease Intervention. Caister Academic Press, 2014; 161–92. [Google Scholar]

- 87. Tomberg J, Unemo M, Davies Cet al. Molecular and structural analysis of mosaic variants of penicillin-binding protein 2 conferring decreased susceptibility to expanded-spectrum cephalosporins in Neisseria gonorrhoeae: role of epistatic mutations. Biochemistry 2010; 49: 8062–70. 10.1021/bi101167x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Whiley DM, Goire N, Lambert SBet al. Reduced susceptibility to ceftriaxone in Neisseria gonorrhoeae is associated with mutations G542S, P551S and P551L in the gonococcal penicillin-binding protein 2. J Antimicrob Chemother 2010; 65: 1615–8. 10.1093/jac/dkq187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Folster JP, Johnson PJ, Jackson Let al. MtrR modulates rpoH expression and levels of AMR in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J Bacteriol 2009; 191: 287–97. 10.1128/JB.01165-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Veal WL, Nicholas RA, Shafer WM. Overexpression of the MtrC-MtrD-MtrE efflux pump due to an mtrR mutation is required for chromosomally mediated penicillin resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J Bacteriol 2002; 184: 5619–24. 10.1128/JB.184.20.5619-5624.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Zarantonelli L, Borthagaray G, Lee EHet al. Decreased azithromycin susceptibility of Neisseria gonorrhoeae due to mtrR mutations. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1999; 43: 2468–72. 10.1128/AAC.43.10.2468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Ohneck EA, Zalucki YM, Johnson PJet al. A novel mechanism of high-level, broad-spectrum antibiotic resistance caused by a single base pair change in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. MBio 2011; 2: e00187-11. 10.1128/mBio.00187-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Wadsworth CB, Arnold BJ, Sater MRAet al. Azithromycin resistance through interspecific acquisition of an epistasis-dependent efflux pump component and transcriptional regulator in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. MBio 2018; 9: e01419-18. 10.1128/mBio.01419-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Rouquette-Loughlin CE, Reimche JL, Balthazar JTet al. Mechanistic basis for decreased antimicrobial susceptibility in a clinical isolate of Neisseria gonorrhoeae possessing a mosaic-like mtr efflux pump locus. mBio 2018; 9: e02281-18. 10.1128/mBio.02281-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Golparian D, Bazzo ML, Golfetto Let al. Genomic epidemiology of Neisseria gonorrhoeae elucidating the gonococcal antimicrobial resistance and lineages/sublineages across Brazil, 2015–16. J Antimicrob Chemother 2020; 75: 3163–72. 10.1093/jac/dkaa318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Lyu M, Moseng MA, Reimche JLet al. Cryo-EM structures of a gonococcal multidrug efflux pump illuminate a mechanism of drug recognition and resistance. mBio 2020; 11: e00996-20. 10.1128/mBio.00996-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Ma KC, Mortimer TD, Grad YH. Efflux pump antibiotic binding site mutations are associated with azithromycin nonsusceptibility in clinical Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates. mBio 2020; 11: e01509-20. 10.1128/mBio.01509-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Hagman KE, Pan W, Spratt BGet al. Resistance of Neisseria gonorrhoeae to antimicrobial hydrophobic agents is modulated by the mtrRCDE efflux system. Microbiology 1995; 141: 611–22. 10.1099/13500872-141-3-611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Olesky M, Hobbs M, Nicholas RA. Identification and analysis of amino acid mutations in porin IB that mediate intermediate-level resistance to penicillin and tetracycline in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2002; 46: 2811–20. 10.1128/AAC.46.9.2811-2820.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Olesky M, Zhao S, Rosenberg RLet al. Porin-mediated antibiotic resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae: ion, solute, and antibiotic permeation through PIB proteins with penB mutations. J Bacteriol 2006; 188: 2300–8. 10.1128/JB.188.7.2300-2308.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Ropp PA, Hu M, Olesky Met al. Mutations in ponA, the gene encoding penicillin-binding protein 1, and a novel locus, penC, are required for high-level chromosomally mediated penicillin resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2002; 46: 769–77. 10.1128/AAC.46.3.769-777.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Trees DL, Sandul AL, Peto-Mesola Vet al. Alterations within the quinolone resistance-determining regions of GyrA and ParC of Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolated in the far east and the United States. Int J Antimicrob Agents 1999; 12: 325–32. 10.1016/S0924-8579(99)00081-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Lindbäck E, Rahman M, Jalal Set al. Mutations in gyrA, gyrB, parC, and parE in quinolone-resistant strains of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. APMIS 2002; 110: 651–7. 10.1034/j.1600-0463.2002.1100909.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Galimand M, Gerbaud G, Courvalin P. Spectinomycin resistance in Neisseria spp. due to mutations in 16S rRNA. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2000; 44: 1365–6. 10.1128/AAC.44.5.1365-1366.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Unemo M, Golparian D, Skogen Vet al. Neisseria gonorrhoeae strain with high-level resistance to spectinomycin due to a novel resistance mechanism (mutated ribosomal protein S5) verified in Norway. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2013; 57: 1057–61. 10.1128/AAC.01775-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Chisholm SA, Dave J, Ison CA. High-level azithromycin resistance occurs in Neisseria gonorrhoeae as a result of a single point mutation in the 23S rRNA genes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2010; 54: 3812–6. 10.1128/AAC.00309-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Ng L-K, Martin I, Liu Get al. Mutation in 23S rRNA associated with macrolide resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2002; 46: 3020–5. 10.1128/AAC.46.9.3020-3025.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Hu M, Nandi S, Davies Cet al. High-level chromosomally mediated tetracycline resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae results from a point mutation in the rpsJ gene encoding ribosomal protein S10 in combination with the mtrR and penB resistance determinants. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2005; 49: 4327–34. 10.1128/AAC.49.10.4327-4334.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Nolte O, Müller M, Reitz Set al. Description of new mutations in the rpoB gene in rifampicin-resistant Neisseria meningitidis selected in vitro in a stepwise manner. J Med Microbiol 2003; 52: 1077–81. 10.1099/jmm.0.05371-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Fiebelkorn KR, Crawford SA, Jorgensen JH. Mutations in folP associated with elevated sulfonamide MICs for Neisseria meningitidis clinical isolates from five continents. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2005; 49: 536–40. 10.1128/AAC.49.2.536-540.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Palmer HM, Leeming JP, Turner A. A multiplex polymerase chain reaction to differentiate β-lactamase plasmids of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J Antimicrob Chemother 2000; 45: 777–82. 10.1093/jac/45.6.777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Muhammad I, Golparian D, Dillon JAet al. Characterisation of blaTEM genes and types of beta-lactamase plasmids in Neisseria gonorrhoeae—the prevalent and conserved blaTEM-135 has not recently evolved and existed in the Toronto plasmid from the origin. BMC Infect Dis 2014; 14: 454. 10.1186/1471-2334-14-454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Pagotto F, Aman AT, Ng LKet al. Sequence analysis of the family of penicillinase-producing plasmids of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Plasmid 2000; 43: 24–34. 10.1006/plas.1999.1431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Turner A, Gough KR, Leeming JP. Molecular epidemiology of tetM genes in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Sex Transm Infect 1999; 75: 60–6. 10.1136/sti.75.1.60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Pachulec E, van der Does C. Conjugative plasmids of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. PLoS ONE 2010; 5: e9962. 10.1371/journal.pone.0009962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Pham CD, Nash E, Liu Het al. Atypical mutation in Neisseria gonorrhoeae 23S rRNA associated with high-level azithromycin resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2021; 65: e00885-20. 10.1128/AAC.00885-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]