Abstract

The heterotrimeric G-protein alpha subunit has long been considered a bimodal, GTP-hydrolyzing switch controlling the duration of signal transduction by seven-transmembrane domain (7TM) cell-surface receptors. In 1996, we and others identified a superfamily of “regulator of G-protein signaling” (RGS) proteins that accelerate the rate of GTP hydrolysis by Gα subunits (dubbed GTPase-accelerating protein or “GAP” activity). This discovery resolved the paradox between the rapid physiological timing seen for 7TM receptor signal transduction in vivo and the slow rates of GTP hydrolysis exhibited by purified Gα subunits in vitro. Here, we review more recent discoveries that have highlighted newly-appreciated roles for RGS proteins beyond mere negative regulators of 7TM signaling. These new roles include the RGS-box-containing, RhoA-specific guanine nucleotide exchange factors (RGS-RhoGEFs) that serve as Gα effectors to couple 7TM and semaphorin receptor signaling to RhoA activation, the potential for RGS12 to serve as a nexus for signaling from tyrosine kinases and G-proteins of both the Gα and Ras-superfamilies, the potential for R7-subfamily RGS proteins to couple Gα subunits to 7TM receptors in the absence of conventional Gβγ dimers, and the potential for the conjoint 7TM/RGS-box Arabidopsis protein AtRGS1 to serve as a ligand-operated GAP for the plant Gα AtGPA1. Moreover, we review the discovery of novel biochemical activities that also impinge on the guanine nucleotide binding and hydrolysis cycle of Gα subunits: namely, the guanine nucleotide dissociation inhibitor (GDI) activity of the GoLoco motif-containing proteins and the 7TM receptor-independent guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) activity of Ric‑8/synembryn. Discovery of these novel GAP, GDI, and GEF activities have helped to illuminate a new role for Gα subunit GDP/GTP cycling required for microtubule force generation and mitotic spindle function in chromosomal segregation.

Keywords: asymmetric cell division, GoLoco motif, G-protein, RGS proteins, RIC-8

1. Introduction

Heterotrimeric guanine-nucleotide binding proteins (G-proteins) are best known for transducing a wide array of extracellular signals received from heptahelical (7TM) cell-surface receptors, such as those initiated by hormones in the bloodstream, neurotransmitters across the synapse, and photons striking the retina. In the conventional model of heterotrimeric G-protein activation, the ligand/7TM receptor interaction catalyzes guanine nucleotide exchange on the Gβγ-complexed (and GDP-bound) Gα subunit (Fig. 1). The Gα·GTP and Gβγ subunits of the heterotrimer then dissociate and are thus free to propagate the signal forward via separate (and sometimes converging) interactions with adenylyl cyclases, phospholipase‑C isoforms, potassium and calcium ion channels, guanine-nucleotide exchange factors for the GTPase RhoA (“RhoGEFs”), and other “effector” enzymes 1, 2, 3. The intrinsic GTP hydrolysis (GTPase) activity of the Gα subunit resets the cycle by forming Gα·GDP which has low affinity for effectors but high affinity for Gβγ. Thus, the inactive GDP-bound heterotrimer (Gαβγ) is reformed, capable once again of interacting with activated receptor. Based on this cycle, the duration of heterotrimeric G-protein signaling is thought to be controlled by the lifetime of the Gα subunit in its GTP-bound state. In 1996, we and others identified a superfamily of RGS (“regulator of G-protein signaling”) proteins that bind Gα subunits via a hallmark ~120 amino-acid “RGS-box” domain 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, dramatically accelerating their intrinsic GTPase activity 10, 11, 12, and thus attenuating heterotrimer-linked signaling (reviewed in 13, 14, 15). The discovery of the RGS proteins and their GTPase-accelerating (or “GAP”) activity on Gα subunits not only resolved apparent timing paradoxes between known 7TM-receptor-mediated physiological responses and the activity in vitro of the responsible G-proteins (e.g., 16), but in addition, novel functional domains discovered within members of the RGS protein superfamily (Fig. 2) have helped to reveal hitherto unappreciated roles for Gα subunits in cellular processes outside the realm of 7TM receptor signaling.

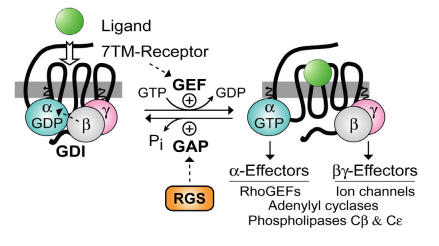

Figure 1.

Standard model of the guanine nucleotide cycle governing 7TM receptor-mediated activation of heterotrimeric G protein-coupled signaling. The Gβγ heterodimer serves to couple Gα to the receptor and also to inhibit its spontaneous release of GDP (i.e., acting as a guanine nucleotide dissociation inhibitor or “GDI” for Gα 17, 18). Ligand-occupied, 7TM cell-surface receptors stimulate signal onset by acting as guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) for Gα subunits, facilitating GDP release, subsequent binding of GTP, and release of the Gβγ dimer. Both the GTP-bound Gα and liberated Gβγ moieties are then able to modulate the activity of various enzymes, ion channels, and other effectors. Regulator of G-protein signaling (RGS) proteins stimulate signal termination by acting as GTPase-accelerating proteins (GAPs) for Gα, dramatically enhancing their intrinsic rate of GTP hydrolysis.

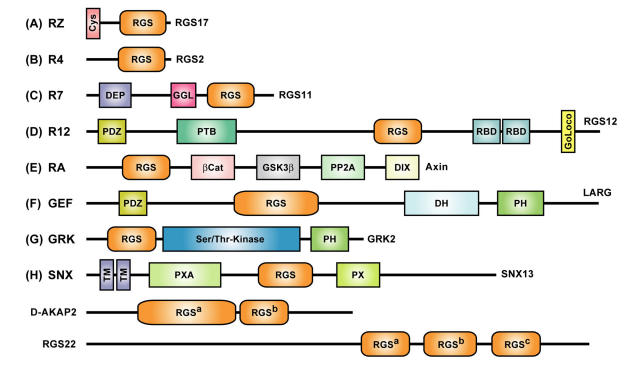

Figure 2.

Multidomain architecture of representative members from all subfamilies of the mammalian RGS protein superfamily. Two alternative nomenclatures have been proposed for several RGS protein subfamilies 23, 24. RZ- or A-subfamily members such as RGS17 25 are characterized by an N-terminal poly-cysteine region (“Cys”) thought to be reversibly palmitoylated 26. R4- or B-subfamily members include RGS2 and RGS21 that are described in the text. RGS11 was the first member of the R7- or C-subfamily to be shown to bind Gβ5 via its Gγ-like or “GGL” domain 27. Of the three members of the R12- or D-subfamily (RGS10, RGS12, RGS14), RGS10 is the smallest and comprises little more than an RGS-box 11, whereas both RGS12 and RGS14 have tandem Ras-binding domains (RBDs) and a C-terminal Gαi/o-Loco interaction (GoLoco) motif 28, and RGS12 additionally has N-terminal PDZ (PSD95/Dlg/ZO-1 homology) and PTB (phosphotyrosine-binding) domains 29. Axin and Axin2 (a.k.a. Axil) are negative regulators of the Wnt signaling pathway and comprise the RA- or E-subfamily; neither protein has been shown to interact with Gα subunits, but rather interact with the tumor suppressor protein adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) using the RGS-box 30. Axin and Axil also contain other domains that interact with β-catenin, the kinase GSK3β, the phosphatase PP2A, and the protein Dishevelled (“DIX” domain) 31. The GEF- or F-subfamily includes three RhoA-specific guanine nucleotide exchange factors (“GEFs”) with canonical Dbl-homology (DH) and pleckstrin-homology (PH) domains: p115-RhoGEF, PDZ-RhoGEF, and leukemia-associated RhoGEF (LARG); the latter two RhoGEFs each possess an N-terminal PDZ domain, as described in the text. In 1996, we were the first group to identify 8 an N-terminal RGS-box within each member of the G protein-coupled receptor kinase family (known as the GRK- or G-subfamily in the context of the RGS protein superfamily). At least three sorting nexins (SNX13, SNX14, SNX25) have RGS-boxes between phosphatidylinositol-binding (PX) and PX-associated (PXA) domains and thus comprise the SNX- or H-subfamily of RGS proteins. Zheng and colleagues reported that SNX13 (a.k.a. “RGS-PX1”) could act as a GAP for the adenylyl-cyclase-stimulatory isoform of Gα (Gαs) 32; however, this report has yet to be confirmed in the literature. TM, putative transmembrane regions. The multiple RGS-box family members D-AKAP2 and RGS22 fall outside the eight established subfamilies; the superscript designations of their RGS-boxes match that used in Figure 3.

2. The spectrum of RGS protein structure and function

Founding members of the RGS protein superfamily were discovered in 1996 in a wide spectrum of species: “supersensitivity to pheromone-2” (Sst2) in the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae 5, 19, 20, FlbA in the aspergillus Emericella nidulans 9, EGL-10 in the nematode worm Caenorhabiditis elegans 7, and RGS1 and RGS2 from human B- and T-lymphocytes, respectively 6, 8. Nearly a decade later, new RGS-box-containing proteins are still being identified in mammalian species (e.g., humans in Fig. 3) and even in plants (Fig. 4C). For example, RGS21 was recently identified as a putative component of taste bud signal transduction that is transacted in lingual epithelium via the T1R2/T1R3 sweet taste and T2R bitter taste 7TM receptors 21. At a mere 152 amino-acids, RGS21 is the shortest RGS protein known to date, with no obvious structural domain N- or C-terminal to the central RGS-box. The singular nature of the RGS21 domain structure is typical of the A/RZ and B/R4 subfamilies (Figs. 2&3) but is unlike other superfamily members that either contain two or more RGS-boxes in tandem (i.e., the PKA regulatory subunit binding partner D‑AKAP2 22 and the testes-specific protein PRTD-NY2 [a.k.a. RGS22; Willard & Siderovski, unpublished observations]) or possess one or more functional modules beyond the defining RGS-box (Fig. 2). Several recent findings as to the functions of these multi-domain RGS proteins are described below.

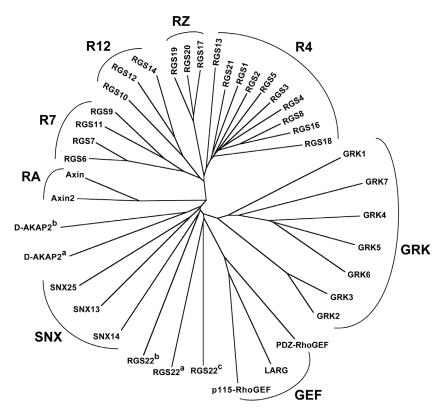

Figure 3.

Relationship between RGS-box sequences of all 37 human RGS proteins identified to date. Unrooted dendrogram was generated by Clustal-W 33 and TreeView 34 using sequences identified by the SMART profile 35 for RGS-boxes as well as those identified by protein-fold recognition algorithms 36. Subfamily designations and identification of isolated RGS-box sequences from multi-RGS-containing proteins D-AKAP2 and RGS22 are as described for Figure 2. Note that there is no RGS15, contrary to an early report 7.

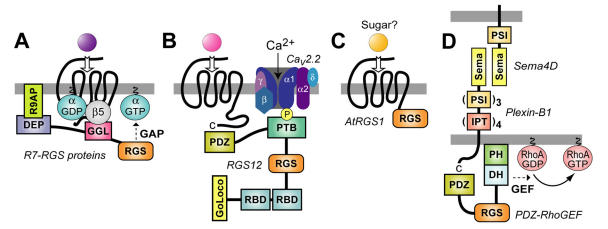

Figure 4.

Membrane targeting strategies employed by multi-domain RGS proteins. (A) The R7 RGS proteins form obligate heterodimers with Gβ5 via a Gγ-like sequence (the “GGL” domain) N-terminal to the RGS-box 37. This GGL/Gβ5 interaction could allow R7 RGS proteins to act as conventional Gβγ subunits in coupling Gα subunits to 7TM receptors, thereby localizing RGS-box-mediated GAP activity to particular receptors 44. The DEP domain of RGS9-1 interacts with a membrane-anchoring protein (R9AP) 47; analogous interactors may exist for the DEP domains of other R7 subfamily members 89. (B) The PDZ domain of RGS12 is able to bind the C-terminus of the IL-8 receptor CXCR2 (at least in vitro) 57. The RGS12 PTB domain binds the synprint (“synaptic protein interaction”) region of the N-type calcium channel (Cav2.2); this interaction is dependent on neurotransmitter-mediated phosphorylation of the channel by Src 29. (C) The AtRGS1 protein of Arabidopsis thaliana (thale cress) has a unique structure for an RGS protein: an N-terminus resembling a 7TM receptor and a C-terminal RGS-box 64. Although a ligand is not known for the 7TM portion of AtRGS1, a simple sugar is most likely 66. (D) The transmembrane receptor Plexin-B1 couples binding of the membrane-bound semaphorin Sema4D to RhoA activation via an interaction with the PDZ domain of PDZ-RhoGEF (and of the related RGS-RhoGEF LARG) 88. Domain abbreviations 35: IPT, immunoglobulin-like fold found in plexins, Met and Ron tyrosine kinase receptors, and intracellular transcription factors; PSI, domain found in plexins, semaphorins, and integrins; Sema, semaphorin domain.

2.a. R7 RGS proteins as novel Gγ subunits

In 1998, we identified a polypeptide sequence, N-terminal to the RGS-box within RGS6, RGS7, and RGS11, with similarity to conventional Gγ subunits 27. This Gγ-like or “GGL” domain was subsequently shown by us 27, 37, 38 and others 39, 40, 41 to bind the neuro-specific outlier Gβ subunit: Gβ5. This constitutive GGL/Gβ5 interaction was also found to hold true for the C. elegans counterparts: the R7 subfamily RGS proteins EGL-10 and EAT-16 each form obligate dimers with the Gβ5-homolog, GPB-2 42, 43. This GGL/Gβ5 pairing presents the possibility that R7 RGS proteins not only serve as GAPs for activated Gα subunits, but also serve to couple inactive Gα subunits to 7TM receptors (Fig. 4A) akin to the function of conventional Gβγ subunits (Fig. 1) (reviewed in 44, 45).

R7 RGS proteins also have an N-terminal DEP (Dishevelled/EGL-10/Pleckstrin homology) domain 46. At least for the retinal-specific R7 RGS protein RGS9-1, a membrane-associated binding partner has been identified for the DEP domain: “RGS9 anchor protein” or R9AP 47, 48, 49, 50. Proper functioning of RGS9-1 as a GAP for the Gα coupled to the retinal photoreceptor (rhodopsin), as well as proper membrane targetting of this GAP activity by R9AP, appear critical to normal vision; Dryja and colleagues have recently reported that loss-of-function mutations to RGS9-1 or R9AP are found in people with abnormalities in photoresponse recovery (“bradyopsia”) that include an inability to see moving objects accurately, especially in low-contrast lighting, and difficulty adjusting to light intensity changes 51. Although this is the first identified human mutation in an RGS protein causing pathological changes to the timing of 7TM signaling, we surmise that it will not be the last. Indeed, one could speculate that a component of essential hypertension might be due to loss-of-function mutation to RGS2; we and others have recently found that Rgs2-deficient mice 52 exhibit constitutive hypertension 53, 54, consistent with an earlier finding that RGS2 establishes an important negative feedback circuit on vasoconstrictive hormone signaling in vascular smooth muscle as mediated by 7TM receptors coupled to Gq heterotrimers 55.

2.b. Membrane targeting of other RGS proteins

With the sheer number of RGS proteins identified (e.g., at least 37 RGS proteins encoded by the human genome; Fig. 3), a central question has arisen as to how (and if) receptor selectivity is engendered for the GAP activity of specific RGS proteins. Similar to the relationship between RGS9‑1 and R9AP, other mechanisms of localizing RGS proteins to membranes and/or specific 7TM receptors are being uncovered. For example, we identified an N-terminal PDZ (PSD-95/Discs-large/ZO-1 homology) domain within the longest isoform of the R12 subfamily member RGS12 (Fig. 2); this PDZ domain is capable of binding peptides derived from the C‑termini of 7TM receptors, including from one of the interleukin-8 receptors (CXCR2) 56, 57. With our colleague Dr. María Diversé-Pierluissi, we have also shown that, in dorsal root ganglion neurons, the phosphotyrosine-binding (PTB) domain of RGS12 mediates its recruitment to the α1B pore-forming subunit of the N‑type calcium channel (Cav2.2) in a neurotransmitter- and phosphorylation-dependent manner (Fig. 4B) 29. We have since mapped the RGS12 PTB docking site to the SNARE-binding or “synprint” region of the Cav2.2 channel (Siderovski & Diversé-Pierluissi; manuscript submitted); the channel/PTB domain interaction, while phosphotyrosine-dependent, does not occur within a canonical Asn-Pro-X-(p)Tyr binding motif common to many PTB docking sites 58. With the ability to interact with a multitude of proteins by virtue of its PDZ, PTB, and Ras-binding domains, along with Gα interactions via its RGS-box and GoLoco motif (described below), RGS12 in particular appears to be a signaling nexus or 'hub' capable of coordinating signal transduction from receptor and/or non-receptor tyrosine-kinases and both monomeric (Ras-superfamily) and heterotrimeric G-protein subunits 13.

An important finding in the RGS field was made by Wilkie and colleagues when they observed receptor selectivity of RGS proteins 59. As an example, RGS1 was observed to be a 1000-fold more potent inhibitor of carbachol- than cholecystokinin-stimulated Ca2+ mobilization in pancreatic acinar cells, despite both agonists having similar coupling profiles (i.e., via Gq/11 family Gα subunits signaling to phospholipase C-β) 60. Strikingly, the closely related RGS2, also a potent GAP for Gαq/11 family members 61 , was equipotent at inhibiting carbachol and cholecystokinin signaling. The molecular determinants of receptor-selective inhibition of G-protein signaling by RGS4 have been delimited to the N-terminal 58 amino acids of this protein 59. Full-length RGS4 and RGS4(ΔN58) are equipotent GAPs in vitro, however RGS4 is a 10,000-fold more potent inhibitor of muscarinic signaling in the context of pancreatic acinar cells 59.

These early findings by Wilkie et al. helped initiate the concept that domains outside the RGS-box may have significant functional effects on signaling specificity and potency. Studies using ribozyme and RNA-interference (RNAi)-mediated knockdown of endogenous RGS proteins have reinforced this notion of complementary selectivity between GPCRs and RGS proteins. For example, in studies employing A-10 rat aortic smooth muscle cells, Neubig and colleagues found that ribozyme-mediated depletion of RGS3 selectively enhances carbachol signaling via the M3 muscarinic receptor, whereas analogous depletion of RGS5 only potentiates angiotensin II signaling via the AT1a receptor; RGS2-directed ribozyme treatment had no effect on either 7TM receptor signaling pathway 62. An obvious molecular mechanism for engendering such receptor selectivity would be direct interaction between a 7TM receptor and an RGS protein. The multidomain architecture of RGS proteins (Fig. 2) provides several potential means by which this could occur. However, to date, there is only limited evidence that 7TM receptors directly interact with RGS proteins. As previously mentioned, we found the RGS12 PDZ domain can bind peptides corresponding to the C-terminal tail of the interleukin-8 (CXCR2) 7TM receptor in vitro 56, 57, but this interaction has not yet been tested with full-length proteins in vivo. A more recent report cites a finding of in vitro binding between an intracellular loop of the M1 muscarinic receptor and RGS2 as evidence for direct coupling between the M1 receptor and RGS2 GAP activity 63. It would be more informative if loss-of-function mutants for the M1-RGS2 interaction (i.e., mutations that do not disrupt G-protein activation or GAP activity) could be created and analyzed in a cell biological context. It must be emphasized that no report has yet demonstrated interaction between a full-length 7TM receptor and a full-length RGS protein in cells.

Our recent discovery of AtRGS1, the first plant RGS protein (from Arabidopsis thaliana), has given the clearest demonstration yet of functional linkage between an RGS-box and a particular 7TM receptor. Indeed, AtRGS1 is an amalgam of the two, with an N-terminal region predicted to have the topology and transmembrane domains of a 7TM receptor, along with a C-terminal intracytosolic RGS-box (Fig. 4C). Genetic evidence is consistent with a model that the action of the AtRGS1 RGS-box opposes that of the activated plant Gα (AtGPA1) in increasing cell elongation in hypocotyls in darkness and increasing cell production in roots grown in light 64. In support of this model, we have shown AtRGS1 to be a potent GAP for AtGPA1 64, 65. The presence of both GEF-like (7TM) and GAP-like (RGS-box) domains within AtRGS1 may seem paradoxical; however, our prevailing hypothesis is that AtRGS1 represents a ligand-operated GAP, given that AtGPA1 exhibits a high rate of spontaneous nucleotide exchange, as well as slow intrinsic GTPase activity, in comparison to mammalian Gα subunits 65. A definitive test of this “ligand-operated GAP” hypothesis awaits the identification of an agonist for the 7TM portion of AtRGS1. Although no ligand has yet been identified, a simple sugar appears the most likely candidate 66.

2.c. RGS-box-containing RhoGEFs as Gα effectors

Most RGS proteins are considered negative regulators of 7TM receptor signaling, either via Gα-directed GAP activity or by “effector antagonism” (i.e., binding activated Gα·GTP in competition with effectors; e.g., 67, 68, 69, 70). In contrast, the three members of the F/GEF subfamily of RGS proteins (Figs. 2&3), p115-RhoGEF, PDZ-RhoGEF, and leukemia-associated RhoGEF (LARG), represent positive regulators of 7TM receptor signaling – specifically, as true effectors that couple Gαq, Gα12, and/or Gα13 subunits to activation of the GTPase RhoA. Thus, these RGS-box effectors link Gq-, G12-, and G13-coupled 7TM receptors to the panoply of cytoskeletal and transcriptional responses mediated by RhoA·GTP-dependent effectors 71, 72. All three proteins possess an RGS-box N-terminal to DH (Dbl-homology) and PH (pleckstrin-homology) domains that, as a tandem, are responsible for catalyzing guanine nucleotide exchange necessary to convert inactive RhoA·GDP into active RhoA·GTP 73. Kozasa et al. first demonstrated in 1998 that the RGS-box of p115-RhoGEF is a potent GAP for both Gα12 and Gα13 subunits 74; more importantly, the same group found that interaction between the RGS-box and Gα13·GTP, but not Gα12·GTP, serves to trigger exchange activity by the C-terminal DH/PH cassette 75. In contrast with p115-RhoGEF, LARG serves as a Gα-responsive RhoGEF not only for Gα13, but also for Gα12 and Gαq 76, 77. The ability of LARG GEF activity to be stimulated by Gα12·GTP appears dependent on tyrosine phosphorylation of LARG (78), ostensibly by Tec-family kinases or focal adhesion kinase (FAK; 79).

Recent work in PC-3 prostate cancer cells by Wang et al. suggests that these three RGS-RhoGEFs each couple distinct receptors to RhoA activation. RNAi-mediated knockdown of LARG specifically inhibited thrombin signaling via the 7TM protease activated receptor-1 (PAR1), whereas RNAi knockdown of PDZ-RhoGEF specifically inhibited lysophosphatidic acid receptor signaling; reduction of p115-RhoGEF levels had no effect on either response 80. Of the three RhoGEFs, two of them possess an N-terminal PDZ domain: LARG and the eponymic PDZ-RhoGEF (Fig. 2). The mechanism whereby RGS-RhoGEF signaling specificity is engendered in PC‑3 cells remains unknown, but might entail direct 7TM receptor tail/PDZ domain interactions. It is known that LARG associates via its PDZ domain with the C-terminal tail of the insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) receptor, providing functional linkage between extracellular IGF-1 and RhoA-mediated cytoskeletal rearrangements 81, 82. Both LARG and PDZ-RhoGEF also use their PDZ domains to bind plexin-B1 (Fig. 4D), a transmembrane receptor for the semaphorin Sema4D (a.k.a. “cluster of differentiation antigen 100” or CD100) 83. Binding of Sema4D to plexin-B1 stimulates RhoA activation via LARG/PDZ-RhoGEF 84, 85, 86, 87, 88. However, the role of the RGS-box in LARG/PDZ-RhoGEF signaling to RhoA activation via these latter, non-7TM receptors remains ill-defined.

3. Discovery of a new family of Gα regulators: The GoLoco motif proteins

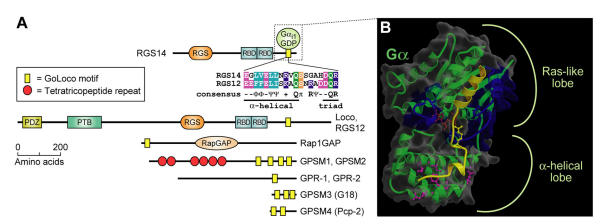

A more recent addition to the pantheon of G-protein regulatory proteins is a diverse family of Gα-interacting proteins, all of which contain one or more conserved GoLoco (“Gαi/o-Loco” interaction) motifs (otherwise known as GPR or “G-protein regulatory” motifs) (Fig. 5A) 28, 90. GoLoco motif-containing proteins generally bind to GDP-bound Gα subunits of the Gi (adenylyl-cyclase inhibitory) class and act as guanine nucleotide dissociation inhibitors (GDIs), slowing spontaneous exchange of GDP for GTP and inhibiting association with Gβγ subunits 91. Our determination of the crystallographic structure of Gαi1·GDP in complex with the 36 amino-acid GoLoco motif of RGS14 92 revealed critical determinants of Gα subunit specificity and GDI activity. The N-terminal alpha-helix of the GoLoco peptide was seen sandwiched between switch II and the α3 helix of the Gαi1 Ras-like lobe (Fig. 5B), grossly deforming the normal site of Gβγ interaction 92. The highly conserved aspartate-glutamine-arginine triad, which defines the final residues of the highly-conserved 19 amino-acid GoLoco signature (Fig. 5A), was found to orient the arginine residue into the guanine nucleotide binding pocket of Gα, allowing contacts to be made between its basic δ-guanido group and the α- and β-phosphates of GDP (Fig. 5B). Loss of GDI activity results from mutation of this arginine 92, 93, or of the preceding aspartate which aids its orientation 94.

Figure 5.

The GoLoco motif, a Gαi/o-interacting polypeptide found singly or in arrays in various proteins, binds across the face of Gα. (A) Alignment of the highly-conserved, 19 amino-acid GoLoco motif signatures from human RGS12 and RGS14 is colored according to side-chain chemistry using Clustal-X defaults 33. Consensus symbols for amino-acid character are hyphen (-), acidic; Φ, hydrophobic; Ψ, large aliphatic; (+), basic; and π, small side chain. Domain abbreviations: RapGAP, Rap-specific GTPase-activating protein domain. (B) Our structure of Gαi1 (green with translucent space-filling shell; switch regions in blue) bound to a 36-amino acid peptide derived from the GoLoco motif-region of RGS14 92. The GoLoco peptide (yellow) binds across both Ras-like and all α-helical lobes within Gαi1, trapping GDP (brown) within its binding site. Note the relative position of the GoLoco triad's arginine “finger” (yellow in ball-and-stick representation) reaching into the GDP binding site. Gαi1-specific contacts from the α-helical lobe to the C-terminal portion of the GoLoco peptide are denoted in magenta.

The family of known GoLoco motif-containing proteins represents a diverse set of signaling regulators, each first discovered and characterized in vastly different contexts; accordingly, their nomenclature is often misleading or uninformative. Here we describe these proteins using their newly-approved Human Genome Organisation (HUGO) nomenclature (http://www.gene.ucl.ac.uk/nomenclature/). One subset of GoLoco proteins includes the R12 subfamily of RGS proteins: RGS12, RGS14, and the Drosophila ortholog Loco. We originally cloned both RGS12 and RGS14 in 1997 from rat C6 glioblastoma cells using degenerate PCR primers directed to sequences conserved within all RGS-box domains 57, 95. In addition to a hallmark RGS-box and tandemly-repeated Ras-binding domains, each of these R12-subfamily members contains a single, C-terminal GoLoco motif that is a GDI for Gαi subunits 96, 97. Concomitant with our discovery of RGS12 and RGS14, the latter protein was also isolated as a putative effector for Rap2·GTP in a yeast two hybrid screen for Rap2-interacting proteins 98. A second subset of GoLoco proteins, consisting of the G-protein signaling modulator protein GPSM1 (formerly AGS3 90), GPSM2 (formerly LGN 99), and the Drosophila ortholog Partner of Inscuteable (Pins/Rapsynoid; 100, 101), all contain a tandem array of three to four GoLoco motifs at their C-terminus, along with an N-terminal region of multiple tetratricopeptide repeats (TPRs; Fig. 5A). The Caenorhabditis elegans proteins GPR-1 and GPR-2 are distantly related (Fig. 6) to GPSM1, GPSM2, and Pins, and have only one easily-identifiable GoLoco motif 102, 103, 104. A third subfamily consists of GPSM3 (formerly G18 94), and Purkinje cell protein-2 (Pcp-2, a.k.a. GPSM4 105); both are small proteins that contain between one and three GoLoco motifs (depending on alternative splicing), but no other identifiable functional domains. The sole member of the fourth and final subset of GoLoco proteins is Rap1GAP. With a few limited exceptions, all the aforementioned GoLoco-containing proteins demonstrate GDP-dependent interaction with Gαi/o subunits and function as GDIs for Gα subunits.

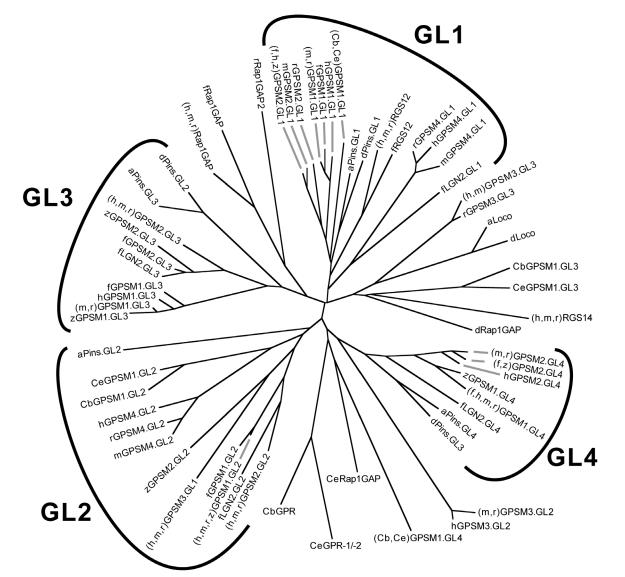

Figure 6.

Relationship between GoLoco motif sequences from all GoLoco proteins identified to date. Unrooted dendrogram was generated by Clustal-W 33 and TreeView 34 using GoLoco motif sequences originally published in our comprehensive review of the GoLoco motif 91. The individual GoLoco motifs from tandem arrays (Fig. 5A) are numbered GL1 to GL4 starting from the first N-terminal motif. Species abbreviations: a, Anopheles gambiae (mosquito); Cb, Caenorhabditis briggsae; Ce, Caenorhabditis elegans; d, Drosophila; f, Fugu rubripes; h, human; m, mouse; r, rat; z, Danio rerio (zebrafish). Note that there are two LGN-like proteins encoded by the genome of Fugu rubripes; we have denoted the one more closely-related to mammalian LGN/GPSM2 as fGPSM2 (Ensembl translation ID SINFRUP00000160450) and the more distantly-related protein as fLGN2 (Ensembl SINFRUP00000146023). Two conclusions can immediately be drawn from this analysis: (i) Drosophila Pins, which has only three GoLoco motifs (Fig. 8) vs the four motifs of GPSM1 and GPSM2 proteins, has lost the second motif, since dPins GL2 is most similar to GL3 of GPSM1/2 proteins, and dPins GL3 is most similar to GL4 of GPSM1/2 proteins; (ii) the triple GoLoco motif protein GPSM3 (a.k.a. G18) is not directly related to the tandem GoLoco arrays of GPSM1/2 proteins (i.e., GPSM3 is not merely missing the N-terminal TPR region of GPSM1/2).

Currently, the only compelling evidence that a GoLoco motif-containing protein acts within the framework of canonical GPCR signaling (outside the R12-subfamily RGS proteins; Fig. 4) has been provided by studies of Rap1GAP as a potential effector for Gαi/o/z subunits. The Rap1GAPII isoform, originally described by Mochizuki and colleagues 106, contains a 31 amino-acid N-terminal extension encoding a full GoLoco motif. In vivo characterization of Rap1GAPII suggested that the GoLoco-containing region specifically interacts with constitutively-activated, GTPase-deficient Gαi(Q205L) 106. In contrast, in vitro studies indicated a strong preference for interaction with GDP-bound Gαi and, consequently, a biochemical function as a GDI 107. Activation of Gi-coupled 7TM receptors can recruit Rap1GAPII to the plasma membrane to accelerate GTP hydrolysis by Rap1. Deactivation of Rap relieves an inhibitory constraint on Ras, thus promoting activation of the MAPK pathway 106. Similarly, Gαz-coupled 7TM receptors also employ Rap1GAPI to attenuate Rap1-mediated ERK activation and PC12 cell differentiation 108, 109. However, some discrepancies exist between these reports describing GTP-dependent Gα/Rap1GAP interactions and a report showing that Gαo-GDP interacts with Rap1GAP to block Rap-directed GAP activity 110. It may be that Gα/Rap1GAP interactions are contextually determined by cell-type and splice-form, and also that multiple Gα-binding sites might exist on Rap1GAP isoforms. Nonetheless, these studies indicate that, at least in the cell transfection paradigm, the GoLoco protein Rap1GAP can modulate 7TM receptor signaling; however, the field requires future studies to further delineate the mechanisms of GoLoco-mediated regulation of 7TM receptor signal transduction.

In sharp contrast to the studies on Rap1GAP, there is a paucity of evidence supporting GoLoco motif-mediated modulation of 7TM receptor signaling in physiologically-relevant systems. Results from our lab and from others indicate that GPSM1-4 proteins do not appear to modulate conventional aspects of 7TM receptor signal transduction. That is, gross overexpression of GPSM1-4 proteins does not alter either the kinetics or magnitude of receptor-induced effector activation. We interpret this to indicate that many GoLoco motif proteins may be spatially segregated from interacting with plasma membrane-delimited 7TM receptor signaling components. Indeed, Graber and colleagues demonstrated this using Sf9 insect-cell membranes overexpressing GPSM1 and the 5-HT1A serotonin receptor 111. Membrane-bound GPSM1 did not affect receptor coupling, but adding soluble GPSM1 protein to the membrane preparation attenuated high affinity agonist binding. A recent report indicates that overexpression of GPSM1 in COS-7 cells may have a modest effect on adenylyl cyclase sensitization and Gαi3 subunit stability 112; however, the physiological relevance of this phenomenon remains to be elucidated. In this light, a recent report indicates that GPSM1 is upregulated in the rat prefrontal cortex following withdrawal from repeated cocaine administration 113. Evidence suggests that GPSM1 modulates cocaine-induced plasticity in 7TM receptor signaling, as increased GPSM1 expression correlates with attenuated Gi-coupled receptor signal transduction 113. Thus, rather than having a role as acute elements of G-protein signal modulation, the GPSM proteins may function as Gα 'sinks' to regulate the overall availability and stability of the Gα component of the heterotrimeric G-protein cycle.

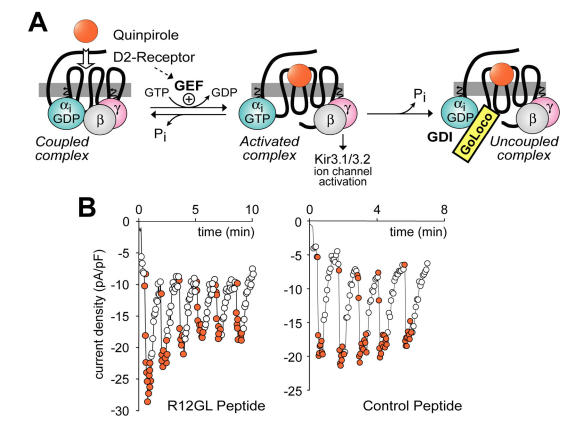

With a view to placing GoLoco motif-containing proteins within the classical paradigm of 7TM receptor signal transduction, it has been suggested that GoLoco motifs may activate heterotrimeric G-protein signaling by actively displacing Gβγ from Gα 90, 100, 114. Indeed, Smrcka and colleagues have demonstrated that a GoLoco consensus peptide can actively displace Gβγ from a preformed heterotrimer, although at a rather high 20,000-fold molar excess in vitro (i.e., 1 μM GPSM1 consensus peptide mixed with 50 pM Gαβγ) 115. However, using similar levels of GoLoco peptides (10 μM) microinjected into cells, it appears that GoLoco proteins only have access to Gα·GDP following a cycle of receptor-mediated GEF activity. In a recent study, Oxford and colleagues measured Gi-coupled activation of Kir3.1/3.2 potassium channels (a Gβγ-mediated process; Fig. 7A) to interrogate the ability of GoLoco peptides to promote Gβγ signaling 116. Electrophysiological recordings of potassium channel currents activated via D2-dopamine receptor stimulation were made in AtT-20 cells. Intracellular application of GoLoco peptides derived from RGS12 and GPSM1 had little effect on single agonist application-induced channel activation (e.g., sample data in Fig. 7B; C.K. Webb, C.R. McCudden, F.S. Willard, R.J. Kimple, D.P. Siderovski, G.S. Oxford; manuscript submitted). However, repeated applications of the D2-receptor agonist quinpirole produced progressive uncoupling of receptor and effector (e.g., Fig. 7B). Repeated activation of potassium current in the same cells using somatostatin, a Go-coupled 7TM receptor-mediated response, was unaffected by GoLoco peptide application, consistent with the Gαi-selective nature of the GoLoco peptides employed. These results indicate that, if GoLoco motifs do have a functional role in modulating 7TM receptor signaling, it may be more subtle to discern than has previously been appreciated.

Figure 7.

Experimental paradigm used to demonstrate that GoLoco motif-derived peptides can uncouple heterotrimeric G-protein signaling, but have no intrinsic ability to directly activate Gβγ-dependent signaling. (A) The dopamine agonist quinpirole, when applied to AtT-20 cells stably or transiently expressing the D2-dopamine receptor 116, activates Gi-heterotrimers and elicits potassium current via the Kir3.1/3.2 channel (as activated by free Gβγ). Upon GTP hydrolysis by Gα, the heterotrimer of Gα·GDP and Gβγ subunits can reform, restoring the “coupled” receptor/G-protein complex. However, in the presence of GoLoco motif-derived peptides, Gα can become trapped in a Gα·GDP/GoLoco complex, preventing Gβγ reassociation and re-coupling to the 7TM receptor. (B) Sample electrophysiological data in support of the model presented in part (A). AtT-20 cells under whole-cell patch-clamp configuration to measure potassium currents were treated with repeated quinpirole pulses (orange circles) or buffer (open circles) after loading with 10 μM RGS12 GoLoco peptide (left panel) or control scrambled peptide (right panel).

4. GoLoco motif proteins and a novel Gα nucleotide cycle involved in cell division

Although the GoLoco motif was first discovered in the context of 7TM receptor signaling, a central role is emerging for GoLoco motif-containing proteins in an unexpected arena: the control of mitotic spindle organization, microtubule (MT) dynamics, and the act of chromosomal segregation during cell division. Early evidence supporting a connection between Gα subunits, GoLoco proteins, and MT dynamics has arisen from studies of asymmetric cell division (ACD) in model organisms.

4.a. Gα and GoLoco protein involvement in Drosophila asymmetric cell division

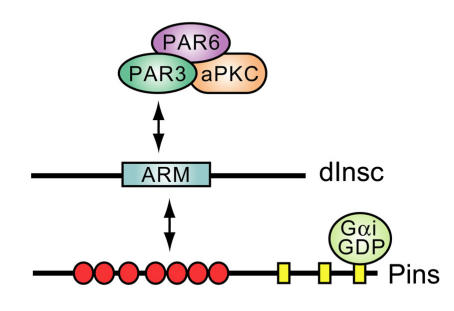

One of the first observations that placed a GoLoco protein within the machinery of cell division was the finding that a complex between Gα and the multi-GoLoco protein Partner of Inscuteable (Fig. 8) is crucial for dictating ACD in Drosophila neuroblasts 100, 101. Upon delamination from ventral neuroectoderm, these neuroblast cells adopt an apical-basal axis of polarity and divide asymmetrically along this axis to produce a large apical neuroblast competent for further ACD and a small ganglion mother cell committed to differentiation (reviewed in 117). In this process, apical determinants Bazooka (PAR3), PAR6, and atypical protein kinase C (aPKC) form a protein complex that recruits the Drosophila protein Inscuteable (dInsc) to the apical cortex 118, 119. Loss of inscuteable expression leads to mislocalization of basal determinants Numb and Prospero, as well as misorientation of the mitotic spindle and, thus, randomization of the plane of cell division with respect to the apical-basal axis 120.

Figure 8.

Known interactions between apical polarity proteins PAR3, PAR6, atypical PKC (aPKC), and Drosophila Inscuteable (dInsc), Partner of Inscuteable (Pins), and Gαi in Drosophila neuroblast asymmetric cell division. ARM, homology to Armadillo repeats. Red circles, TPR motifs; yellow rectangles, GoLoco motifs.

Deletional analysis of dInsc has defined a central Armadillo repeat-containing “asymmetry domain” sufficient to mediate all known functions of the full-length protein 121, 122. In searching for asymmetry domain-interacting proteins as potential dInsc effectors, three groups independently discovered the GoLoco motif-containing Partner of Inscuteable (Pins) protein 100, 101, 123. Pins is the archetypal member of a conserved class of TPR and GoLoco-motif containing proteins involved in cell division processes (GPSM1, GPSM2, Pins; Fig. 5A). dInsc, Pins, and Drosophila Gαi form an apical protein complex essential for neuroblast ACD; ablation of maternal and zygotic Pins results in defective spindle orientation, a failure to segregate determinants asymmetrically, and a limited asymmetry in neuroblast division 100, 101, 123. Similarly, overexpression of wildtype Gαi inhibits polarization of asymmetry determinants and causes mitotic spindle misorientation 124. However, overexpression of constitutively-active (i.e., GTPase-deficient) Gαi(Q205L) has essentially no effect on neuroblast ACD. Thus, in the specific example of Drosophila neuroblast ACD, the functional Gα species appears not to be GTP-bound Gαi (the active form in 7TM receptor signaling; Fig. 1), but rather Gαi·GDP in complex with the GoLoco protein Pins. It is possible that Gβγ sequestration by elevated levels of Gαi·GDP leads to the observed aberrations in neuroblast ACD. However, significant differences are seen in daughter cell size and cell-fate determinant mislocalization upon Gαi overexpression versus loss of Gβ13F (ortholog of the mammalian Gβ subunits Gβ1-4) 124, 125. It is also important to note that the Insc/Pins/Gαi·GDP complex isolated from Drosophila neuroblasts is devoid of Gβ13F 124, consistent with the mutually-exclusive nature of GoLoco- vs Gβγ-binding to Gα·GDP.

4.b. Involvement of Gα and GoLoco proteins GPR-1/-2 in C. elegans asymmetric cell division

The involvement in ACD of many of these polarity proteins is conserved throughout metazoan organisms 91, 126. Early evidence that Gα subunits also function in ACD in the nematode worm C. elegans came from studies in which simultaneous RNA interference (RNAi)-mediated knockdown of two C. elegans Gα subunits, GOA-1 (a Gαo homolog) and GPA-16 (a Gαi homolog), was found to cause a mitotic spindle positioning defect resulting in symmetric division of the nematode zygote 127. Normally, division of the one-cell stage (P0) C. elegans embryo is asymmetric, yielding a large anterior (AB) blastomere and a smaller posterior blastomere (P1). The mitotic spindle at metaphase of this first division is symmetrically positioned along the anterior-posterier axis, but during anaphase the anterior centrosome remains fixed while the posterior centrosome moves toward the posterior cortex with a characteristic rocking motion. These events are believed to originate from asymmetric forces acting through astral MTs that radiate from the mitotic spindle poles to the cell cortex.

Grill et al. recently employed UV laser-induced centrosome disintegration on one-cell C. elegans embryos to study the basis of this net force imbalance 128; calculations based on observed speeds of centrosome fragmentation led Grill et al. to conclude that the force imbalance results from a larger number (~50% more) of force generators in the posterior cortex pulling on astral MTs (relative to the anterior cortex), rather than an increase in the magnitude of force derived from each force generator. In these studies, RNAi-mediated knockdown of GOA‑1 and GPA‑16 was found to greatly reduce aster fragmentation speeds upon laser-induced centrosome disintegration 128, suggesting that some form of Gα signaling during C. elegans ACD is required to mediate posterior astral MT force generation.

A functional genomic screen for genes regulating early C. elegans embryo cell division by Gönczy and colleagues identified the Pins-related GoLoco proteins GPR-1 and GPR-2 (Fig. 5A & 9) 129. GPR-1 and -2 are essential for establishing proper pulling forces during asymmetric P0 division in C. elegans 102. RNAi-mediated reduction in expression levels of these two, near-identical GoLoco proteins leads to a spindle positioning defect indistinguishable from that seen in goa-1/gpa-16 (RNAi) embryos 102, 127. In laser-mediated spindle-severing studies, Colombo et al. established that, during normal asymmetric division, the peak velocity of the posterior spindle pole is ~40% greater than that of the anterior one, presumably reflecting a larger net pulling force by astral MTs 102. In contrast, anterior and posterior spindle pole velocities are both equal and greatly reduced in gpr-1/-2 (RNAi) embryos and in goa-1/gpa-16 (RNAi) embryos 102. Immunofluorescence studies revealed ~50% more GPR-1/-2 protein on the posterior cortex; this asymmetric cortical distribution of GPR‑1/‑2 is dependent on PAR-3 function 102, and nicely correlates with Grill's calculation of ~50% more force generators at the posterior cortex 128 (described above), suggesting that GPR-1/-2 may specify motor localization and/or directly transact a function required for force generation on astral microtubules during chromosomal segregation. These findings by Colombo et al. that the GoLoco proteins GPR-1 and GPR-2 are critical to C. elegans ACD are wholly consistent with independent reports published simultaneously 103, 104.

Figure 9.

Alignment of C. elegans GPR-1 and GPR-2 protein sequences. Although individual tetratricopeptide repeats (TPRs) are not easily identified within the N-termini of GPR-1 and GPR-2 (as they are within mammalian and Drosophila homologs; Figs. 5A & 8), amino-acids 14 to 341 (boxed in grey) are predicted by protein-fold recognition algorithms (e.g., ref. 36) to fold into a right-handed alpha-alpha superhelix (SCOP identifier d1ld8a_; expect value 5 x 10-5) similar to folds exhibited by TPR-containing proteins 130. Also boxed is the conserved GoLoco motif signature (amino-acids 425-442) and its consensus as defined in 91. Consensus symbols for amino-acid character are hyphen (-), acidic; Φ, hydrophobic; Ψ, large aliphatic; (+), basic; and π, small side chain.

4.c. Gα-directed GEF and GAP activities implicated in C. elegans asymmetric cell division

Not only are Gα subunits (GOA-1, GPA-16) and GoLoco proteins (GPR-1, GPR-2) required for asymmetric P0 division in C. elegans, but other novel regulators of the Gα guanine nucleotide cycle have also emerged from genetic studies as being critical to this process. For example, Miller 131, 132 first isolated a novel gene ric-8 (“resistance to inhibitors of cholinesterase”, a.k.a. Synembryn) as an upstream regulator of the C. elegans Gαq-like protein EGL-30. ric-8 reduction-of-function mutants (md303, md1909) were found to have high rates of embryonic lethality, which could be augmented to almost 100% in embryos heterozyous for goa-1 loss-of-function alleles, thus suggesting that RIC-8 and GOA-1 proteins signal in the same pathway during embryogenesis 133. Reduced posterior centrosome rocking during the P0 cleavage was observed in ric-8 mutant embryos, as well as loss of mitotic spindle and daughter blastomere asymmetries. Most compelling is that these ric-8 mutant phenotypes are reminiscent of those seen in goa‑1/gpa‑16 (RNAi) embryos.

It is believed that RIC-8 may represent a novel, receptor-independent guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) for Gα subunits. Tall et al. recently isolated the rat paralogues Ric-8A and Ric-8B in a yeast two-hybrid screen for Gαs- and Gαo-interacting proteins 134; their initial biochemical analyses indicated that rat Ric‑8A can act as a GEF in vitro for several mammalian Gα subunits, including Gαi1, Gαo and Gαq. The GEF activity of rat Ric-8A was found to have characteristics distinct from those of 7TM receptors; specifically, Ric-8A appears to interact preferentially with isolated Gα·GDP subunits to accelerate the release of GDP by Gα, the rate limiting step in the G-protein cycle 135. It is important to stress that, in this initial study, Ric-8A was found to be unable to catalyze the loading of GTP onto “heterotrimeric” Gα (Gα·GDP bound to Gβγ) 134. Irrespective of this initial finding with rat Ric-8A, there are no published reports that the C. elegans RIC-8 protein can act as a GEF for the nematode Gα subunits GOA-1 or GPA-16. More importantly, it has not been determined whether mammalian Ric-8A or C. elegans RIC-8 can act as a GEF for GoLoco-bound Gα·GDP subunits. The Ric-8 gene is highly evolutionarily conserved, but the encoded protein has no obvious domain or motif structure. We have observed Ric-8 orthologues in the Drosophila, mouse, and human genomes (GenBank NP_572550, NP_444424, and NP_068751, respectively). It is tempting to speculate that deletion of (or loss-of-function mutations in) Drosophila Ric-8 will lead to severe phenotypes affecting neuroblast ACD. Similarly, it will be important to examine the physiological roles of Ric-8A and Ric-8B in mammals. The field of mammalian asymmetric cell division is underdeveloped in comparison to C. elegans and Drosophila. Nonetheless there are increasingly powerful approaches being used to study this process in the developing mouse zygote 136 and nervous system 137 that should be employed to investigate the roles of these novel Gα regulators in ACD.

Timely deactivation of Gα·GTP may also be required for proper P0 division in C. elegans. Koelle and Hess have discovered that rgs-7, one of the 13 C. elegans RGS genes (rgs-1 to -11, eat-16, egl-10), is intimately involved in asymmetric P0 division. Loss of rgs-7, encoding a potential GAP for both GOA‑1·GTP and GPA‑16·GTP, results in overly vigorous posterior centrosome rocking (H. Hess & M. Koelle, personal comm.; reviewed in 91). Their finding implies that elevated Gα·GTP levels, presumably by loss of RGS-7 GAP activity, may result in excess force by astral MTs and further implies that, at least in the nematode, Gα·GTP may be the active species for force generation. These genetic and RNAi-based studies have identified Gα subunits and three novel Gα regulatory activities (GDI, GEF, and GAP proteins) as having critical roles in the process of C. elegans ACD, as summarized in Fig. 10A. Thus, initial findings from both Drosophila and C. elegans genetics suggest that Gα subunits and novel regulators of their guanine nucleotide cycle play critical and evolutionarily-conserved roles in establishing appropriate astral MT force on the mitotic spindle for proper chromosomal segregation. Collectively, this initial evidence suggests a preliminary working model in which productive cycling of Gαi subunits between GDP- and GTP-bound states, established through the actions of GoLoco GDI, Ric-8 GEF, and RGS-box GAP activities, is required for mitotic spindle organization and function.

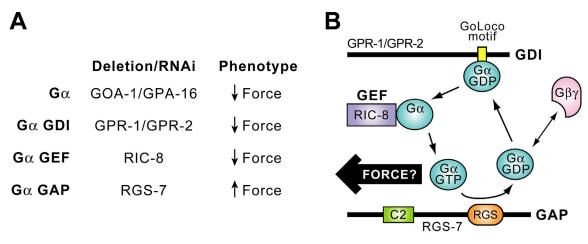

Figure 10.

A. Summary of data implicating Gα and its regulators in generation of asymmetric anterior/posterior forces acting on the mitotic spindle of one-cell C. elegans zygotes during ACD (reviewed in 91). B. Model of a novel Gα nucleotide cycle incorporating the data of part A. RGS-7 contains N-terminal homology to conserved region 2 (“C2”) of protein kinase C and an RGS-box presumed in the model to exert GAP activity. Force arrow denotes speculation that, at least in the nematode, the GTP-bound form of GOA-1/GPA-16 interacts, directly or indirectly, with astral MTs to generate force on the mitotic spindle.

4.d. A novel Gα nucleotide cycle?

In establishing an initial model of Gα nucleotide cycling underlying ACD that explains the genetic evidence (Fig. 10B; 91, 103), several assumptions and accommodations have been made that demand verification by biochemical studies. For example, the biochemical actions on isolated Gα subunits currently assumed for GoLoco proteins and for RIC-8 are actually diametrically opposed: GDI activity preventing nucleotide release vs GEF activity promoting nucleotide release, respectively. Yet these opposing biochemical activities, when individually removed by RNAi or loss-of-function mutation, result in the same nematode zygote phenotype of decreased force and symmetric division (Fig. 10A). To accommodate this apparent enigma, we and others propose that RIC-8 requires interdiction by the GPR-1/-2 GoLoco motif to function on GOA-1 and/or GPA-16 (Fig. 10B). Indeed, this would be consistent with the findings of Tall et al. 134 that rat Ric-8A cannot operate on Gβγ-complexed Gα subunits. Our initial hypothesis, therefore, is that Gβγ is somehow excluded from or removed from GOA‑1/GPA‑16 subunits by the GPR-1/-2 GoLoco motif and, perhaps, GPR‑1/‑2 proteins “present” Gβγ-free Gα·GDP to RIC-8, thus acting cooperatively with RIC-8 to facilitate nucleotide exchange (Fig. 10B). A complication of this theory is that, although GoLoco-derived peptides might be able to disrupt a heterotrimer in vitro 115, 124, this “heterotrimer-splitting” activity appears unlikely to happen under physiological conditions (e.g., Fig. 7) 116. An alternative explanation suggested by the ion channel data of Oxford and Webb is that an initial round of GEF activity is required on the heterotrimer to remove Gα·GTP from the proximity of Gβγ, and then GTP hydrolysis produces Gα·GDP now competent to interact with the GoLoco motif of GPR-1/2 rather than re-associate with Gβγ. RIC-8 cannot provide this initial round of GEF activity if it cannot act on the Gαβγ heterotrimer 134; thus, either 7TM receptor-mediated GEF activity, another (unknown) GEF activity, or a non-GEF “Gβγ releasing factor” would have to operate on the heterotrimer to establish this pathway.

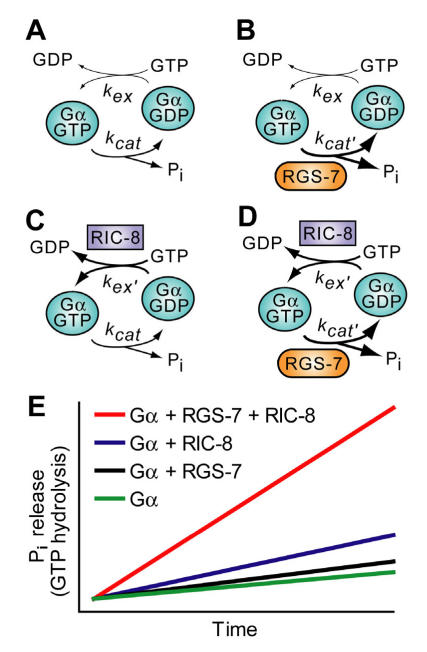

Another possibility to consider is that the crucial parameter determining the output of the system (i.e., astral MT force generation) is the overall rate of the Gα nucleotide cycle, as accelerated by the combined actions of RIC-8 and RGS-7 (Fig. 11). A key observation in this vein is provided by studies from Neubig and colleagues on the effect of RGS proteins on the receptor-catalyzed G-protein cycle. Using reconstituted components, it was observed that, in addition to facilitating steady-state GTP hydrolysis, RGS-box proteins also potently increased receptor-stimulated GTPγS binding 138. This was not due to a physical scaffolding mechanism, rather a kinetic scaffolding or 'spatial focusing' phenomenon 138. This has previously been observed in the context of potassium channel regulation in which RGS proteins accelerate the kinetics of both channel activation and deactivation without altering the steady-state level of channel conductance 139, 140. Thus in asymmetric cell division, it may be that rapid Gα GTPase cycling promoted by RIC-8 and RGS-7 provides a high-efficiency, spatially-localized signaling complex, sufficient for force generation.

Figure 11.

Predicted effects of RIC-8 and RGS-7 on the Gα nucleotide cycle underlying MT force generation in ACD. A. Steady-state GTP hydrolysis of Gα subunits is known to be limited by nucleotide exchange (kex), not by the intrinsic GTPase rate (kcat) 141, 142. B. RGS‑7 GAP activity, while by definition accelerating the intrinsic GTPase rate of Gα (kcat' > kcat), will have no effect on steady-state GTP hydrolysis, as the limiting rate for isolated Gα subunits remains GDP release, a key component of kex 141, 142. C. RIC-8 GEF activity should accelerate nucleotide exchange (kex' > kex) and increase observed rate of steady-state GTP hydrolysis (up to the new limiting rate of kcatif kex' > kcat). D. Addition of both RIC-8 GEF and RGS-7 GAP activities should dramatically accelerate steady-state GTP hydrolysis vs the basal condition in (A), up to whichever component rate is limiting (kex'or kcat'). E. A graphical representation of predicted steady state GTP hydrolysis by Gα in the presence of these two novel G-protein cycle components. The ordinate represents the amount of inorganic phosphate (Pi) released, and the abscissa represents time.

4.e. Direct tubulin/Gα interaction as a model for the mechanism of MT force generation?

Forward genetic studies in Drosophila and, especially, C. elegans (Fig. 10A) have pointed to a critical role in metazoans for Gi-family Gα subunits and their regulators in controlling force generation on astral MTs during chromosomal segregation. One simple model to potentially explain this genetic evidence is that Gαi subunits interact directly with MTs at their stable tubulin·GTP caps to enhance cap stability and MT elongation 143, 144, and that this tubulin/Gαi interaction is dependent on the nucleotide state of Gα. Previous findings from Rasenick and colleagues indicate that mammalian Gα subunits directly interact with tubulin and MTs and modulate their dynamics in vitro. High-affinity binding (KD ≈ 120 nM; ref. 145) between Gαi1 and tubulin·GTP has been shown to result in Gαi1 “transactivation” (i.e., GTP transfer to Gα from the exchangable binding-site on β‑tubulin 146, 147, 148, 149). Moreover, in the absence of GTP or presence of non-hydrolyzable GppNHp, Gαi1 serves as a GAP for tubulin·GTP in vitro 150, activating its GTPase activity and increasing the frequency of MT “catastrophe” (the transition from slow growth to rapid shortening 151); these effects of Gαi1 are inhibited in the presence of GTP and, indeed, MT assembly by tubulin is enhanced by Gαi1 in high GTP levels 150. Goldstein and colleagues have recently developed a live cell imaging technique, “cortical imaging of microtubule stability” (CIMS), to visualize microtubule dynamics in real-time in the C. elegans zygote 152. Using CIMS, it was demonstrated that anterior MTs reside longer at the cell cortex than do posterior MTs. However, in goa‑1/gpa‑16 (RNAi) zygotes, anterior and posterior microtubules have equal stability at the cell cortex. This provides direct evidence that Gα subunits regulate microtubule dynamics in vivo and is consistent with a Gα·GDP/GPR-1/-2 complex regulating cortical force generation. However, it remains to be directly tested whether direct interactions between tubulin and Gα mediate force generation, or whether members of the kinesin and dynein motor protein superfamilies 153, 154 and/or other microtubule-associated proteins at MT ends are the ultimate force generators, with their actions directly modulated by Gα subunits. Future studies in this field should be aimed at delineating the molecular mechanisms by which the novel Gα nucleotide cycle, composed of novel GDI, GEF, and GAP activities, communicates with microtubule machinery.

5. Conclusions

Since the discovery of the RGS proteins and their Gα-directed GAP activity in 1996, there has been a considerable shift in our collective appreciation of RGS protein function in 7TM receptor signal transduction. Far from being mere negative regulators, RGS proteins also serve roles as Gα effectors (e.g., the RGS-RhoGEFs), signaling scaffolds (e.g., RGS12), and (potentially) as novel Gβγ-like dimers coupling Gα to receptors (e.g., the R7/Gβ5 dimers). Moreover, the discovery of the GoLoco motif, first found in RGS12 and RGS14, has illuminated a novel GDI activity for Gα subunits involved in an equally novel interplay between Gα and tubulin controling microtubule force generation critical to chromosomal segregation during cell division. Further exploration of the structural features of RGS protein superfamily members and their functional effects on signal transduction complexes should provide additional surprises.

Biographies

David P. Siderovski received his Ph.D. from the University of Toronto and is currently an Associate Professor of Pharmacology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Siderovski was one of the first scientists to identify the regulators of G‑protein signaling (RGS) protein superfamily. In April 2004, Dr. Siderovski received the John J. Abel Award from the American Society for Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics for his contributions that have helped shape the field of pharmacology and challenged previously established dogmas in the field of G protein-coupled receptor signaling. Dr. Siderovski's current work focuses on elucidating the specific roles of RGS proteins as scaffolds in the coordination of multiple signal transduction pathways, as well as in modulation of microtubule dynamics at the mitotic spindle in dividing cells.

Francis S. Willard obtained a Bachelor's of Science with first-class honours in Physiology at Victoria University, Wellington, New Zealand. He went on to complete his Ph.D. at the Australian National University in 2002, and in 2003 received the prestigious Frank Fenner Medal for his doctoral work on growth factor signal transduction pathways. Dr. Willard is currently working with Dr. Siderovski as a senior postdoctoral fellow in the UNC Department of Pharmacology and is utilizing biochemical and structural approaches to understand the role of G-protein signaling in developmental biology.

References

- 1.Gilman AG. G proteins: transducers of receptor-generated signals. Annu Rev Biochem. 1987;56:615–49. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.56.070187.003151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hamm HE. The many faces of G protein signaling. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(2):669–72. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.2.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Offermanns S. G-proteins as transducers in transmembrane signalling. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2003;83(2):101–30. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6107(03)00052-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Vries L. et al. GAIP, a protein that specifically interacts with the trimeric G protein G alpha i3, is a member of a protein family with a highly conserved core domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92(25):11916–20. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.25.11916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dohlman HG. et al. Sst2, a negative regulator of pheromone signaling in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae: expression, localization, and genetic interaction and physical association with Gpa1 (the G-protein alpha subunit) Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16(9):5194–209. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.9.5194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Druey KM. et al. Inhibition of G-protein-mediated MAP kinase activation by a new mammalian gene family. Nature. 1996;379(6567):742–6. doi: 10.1038/379742a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koelle MR. et al. EGL-10 regulates G protein signaling in the C. elegans nervous system and shares a conserved domain with many mammalian proteins. Cell. 1996;84(1):115–25. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80998-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Siderovski DP. et al. A new family of regulators of G-protein-coupled receptors? Curr Biol. 1996;6(2):211–2. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00454-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yu JH. et al. The Aspergillus FlbA RGS domain protein antagonizes G protein signaling to block proliferation and allow development. Embo J. 1996;15(19):5184–90. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berman DM. et al. GAIP and RGS4 are GTPase-activating proteins for the Gi subfamily of G protein alpha subunits. Cell. 1996;86(3):445–52. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80117-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hunt TW. et al. RGS10 is a selective activator of G alpha i GTPase activity. Nature. 1996;383(6596):175–7. doi: 10.1038/383175a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Watson N. et al. RGS family members: GTPase-activating proteins for heterotrimeric G-protein alpha-subunits. Nature. 1996;383(6596):172–5. doi: 10.1038/383172a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Siderovski DP. et al. Whither goest the RGS proteins? Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 1999;34(4):215–51. doi: 10.1080/10409239991209273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neubig RR. et al. Regulators of G-protein signalling as new central nervous system drug targets. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2002;1(3):187–97. doi: 10.1038/nrd747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kimple RJ. et al. Established and emerging fluorescence-based assays for G-protein function: heterotrimeric G-protein alpha subunits and regulator of G-protein signaling (RGS) proteins. Comb Chem High Throughput Screen. 2003;6(4):399–407. doi: 10.2174/138620703106298491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arshavsky VY. et al. Lifetime regulation of G protein-effector complex: emerging importance of RGS proteins. Neuron. 1998;20(1):11–4. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80430-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brandt DR. et al. GTPase activity of the stimulatory GTP-binding regulatory protein of adenylate cyclase, Gs. Accumulation and turnover of enzyme-nucleotide intermediates. J Biol Chem. 1985;260(1):266–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Higashijima T. et al. Effects of Mg2+ and the beta gamma-subunit complex on the interactions of guanine nucleotides with G proteins. J Biol Chem. 1987;262(2):762–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chan RK. et al. Isolation and genetic analysis of Saccharomyces cerevisiae mutants supersensitive to G1 arrest by a factor and alpha factor pheromones. Mol Cell Biol. 1982;2(1):11–20. doi: 10.1128/mcb.2.1.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chan RK. et al. Physiological characterization of Saccharomyces cerevisiae mutants supersensitive to G1 arrest by a factor and alpha factor pheromones. Mol Cell Biol. 1982;2(1):21–9. doi: 10.1128/mcb.2.1.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.von Buchholtz L. et al. RGS21 is a novel regulator of G protein signalling selectively expressed in subpopulations of taste bud cells. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;19(6):1535–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03257.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang L. et al. Cloning and mitochondrial localization of full-length D-AKAP2, a protein kinase A anchoring protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(6):3220–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051633398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zheng B. et al. Divergence of RGS proteins: evidence for the existence of six mammalian RGS subfamilies. Trends Biochem Sci. 1999;24(11):411–4. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(99)01474-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ross EM. et al. GTPase-activating proteins for heterotrimeric G proteins: regulators of G protein signaling (RGS) and RGS-like proteins. Annu Rev Biochem. 2000;69:795–827. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mao H. et al. RGS17/RGSZ2, a novel regulator of Gi/o, Gz, and Gq signaling. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(25):26314–22. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401800200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jones TLZ. Role of palmitoylation in RGS protein function. Methods Enzymol. 2004;389:33–55. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(04)89003-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Snow BE. et al. A G protein gamma subunit-like domain shared between RGS11 and other RGS proteins specifies binding to Gbeta5 subunits. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(22):13307–12. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.22.13307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Siderovski DP. et al. The GoLoco motif: a Galphai/o binding motif and potential guanine-nucleotide exchange factor. Trends Biochem Sci. 1999;24(9):340–1. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(99)01441-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schiff ML. et al. Tyrosine-kinase-dependent recruitment of RGS12 to the N-type calcium channel. Nature. 2000;408(6813):723–7. doi: 10.1038/35047093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Spink KE. et al. Structural basis of the Axin-adenomatous polyposis coli interaction. Embo J. 2000;19(10):2270–9. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.10.2270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kikuchi A. Modulation of Wnt signaling by Axin and Axil. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 1999;10(3-4):255–65. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(99)00017-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zheng B. et al. RGS-PX1, a GAP for GalphaS and sorting nexin in vesicular trafficking. Science. 2001;294(5548):1939–42. doi: 10.1126/science.1064757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aiyar A. The use of CLUSTAL W and CLUSTAL X for multiple sequence alignment. Methods Mol Biol. 2000;132:221–41. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-192-2:221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Page RD. TreeView: an application to display phylogenetic trees on personal computers. Comput Appl Biosci. 1996;12(4):357–8. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/12.4.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Letunic I. et al. Recent improvements to the SMART domain-based sequence annotation resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30(1):242–4. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kelley LA. et al. Enhanced genome annotation using structural profiles in the program 3D-PSSM. J Mol Biol. 2000;299(2):499–520. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Snow BE. et al. Fidelity of G protein beta-subunit association by the G protein gamma-subunit-like domains of RGS6, RGS7, and RGS11. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96(11):6489–94. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.11.6489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Siderovski DP. et al. Assays of complex formation between RGS protein G gamma subunit-like domains and G beta subunits. Methods Enzymol. 2002;344:702–23. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(02)44750-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Makino ER. et al. The GTPase activating factor for transducin in rod photoreceptors is the complex between RGS9 and type 5 G protein beta subunit. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96(5):1947–52. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.5.1947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Levay K. et al. Gbeta5 prevents the RGS7-Galphao interaction through binding to a distinct Ggamma-like domain found in RGS7 and other RGS proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96(5):2503–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.5.2503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Witherow DS. et al. Complexes of the G protein subunit gbeta 5 with the regulators of G protein signaling RGS7 and RGS9. Characterization in native tissues and in transfected cells. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(32):24872–80. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001535200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.van der Linden AM. et al. The G-protein beta-subunit GPB-2 in Caenorhabditis elegans regulates the G(o)alpha-G(q)alpha signaling network through interactions with the regulator of G-protein signaling proteins EGL-10 and EAT-16. Genetics. 2001;158(1):221–35. doi: 10.1093/genetics/158.1.221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chase DL. et al. Two RGS proteins that inhibit Galpha(o) and Galpha(q) signaling in C. elegans neurons require a Gbeta(5)-like subunit for function. Curr Biol. 2001;11(4):222–31. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00071-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sondek J. et al. Ggamma-like (GGL) domains: new frontiers in G-protein signaling and beta-propeller scaffolding. Biochem Pharmacol. 2001;61(11):1329–37. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(01)00633-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jones MB. et al. The Gbeta/gamma dimer as a novel source of selectivity in G-protein signaling: GGL-ing at convention. Mol Interv. 2004;4:200–14. doi: 10.1124/mi.4.4.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ponting CP. et al. Pleckstrin's repeat performance: a novel domain in G-protein signaling? Trends Biochem Sci. 1996 Jul;21(7):245–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hu G. et al. R9AP, a membrane anchor for the photoreceptor GTPase accelerating protein, RGS9-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(15):9755–60. doi: 10.1073/pnas.152094799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lishko PV. et al. Specific binding of RGS9-Gbeta 5L to protein anchor in photoreceptor membranes greatly enhances its catalytic activity. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(27):24376–81. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203237200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hu G. et al. Activation of RGS9-1GTPase acceleration by its membrane anchor, R9AP. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(16):14550–4. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212046200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Martemyanov KA. et al. The DEP domain determines subcellular targeting of the GTPase activating protein RGS9 in vivo. J Neurosci. 2003;23(32):10175–81. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-32-10175.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nishiguchi KM. et al. Defects in RGS9 or its anchor protein R9AP in patients with slow photoreceptor deactivation. Nature. 2004;427(6969):75–8. doi: 10.1038/nature02170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Oliveira-Dos-Santos AJ. et al. Regulation of T cell activation, anxiety, and male aggression by RGS2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(22):12272–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.220414397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tang MK. et al. Regulator of G-protein signaling-2 mediates vascular smooth muscle relaxation and blood pressure. Nat Med. 2003;9(12):1506–12. doi: 10.1038/nm958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Heximer SP. et al. Hypertension and prolonged vasoconstrictor signaling in RGS2-deficient mice. J Clin Invest. 2003;111(4):445–52. doi: 10.1172/JCI15598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Grant SL. et al. Specific regulation of RGS2 messenger RNA by angiotensin II in cultured vascular smooth muscle cells. Mol Pharmacol. 2000;57(3):460–7. doi: 10.1124/mol.57.3.460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Snow BE. et al. GTPase activating specificity of RGS12 and binding specificity of an alternatively spliced PDZ (PSD-95/Dlg/ZO-1) domain. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(28):17749–55. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.28.17749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Snow BE. et al. Molecular cloning of regulators of G-protein signaling family members and characterization of binding specificity of RGS12 PDZ domain. Methods Enzymol. 2002;344:740–61. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(02)44752-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Forman-Kay JD. et al. Diversity in protein recognition by PTB domains. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1999;9(6):690–5. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(99)00031-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zeng W. et al. The N-terminal domain of RGS4 confers receptor-selective inhibition of G protein signaling. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(52):34687–90. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.52.34687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Xu X. et al. RGS proteins determine signaling specificity of Gq-coupled receptors. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(6):3549–56. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.6.3549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ingi T. et al. Dynamic regulation of RGS2 suggests a novel mechanism in G-protein signaling and neuronal plasticity. J Neurosci. 1998;18(18):7178–88. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-18-07178.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang Q. et al. Receptor-selective effects of endogenous RGS3 and RGS5 regulate mitogen-activated protein kinase activation in rat vascular smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(28):24949–58. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203802200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bernstein LS. et al. RGS2 binds directly and selectively to the M1 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor third intracellular loop to modulate Gq/11alpha signaling. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(20):21248–56. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312407200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chen JG. et al. A seven-transmembrane RGS protein that modulates plant cell proliferation. Science. 2003;301(5640):1728–31. doi: 10.1126/science.1087790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Willard FS. et al. Purification and in vitro functional analysis of the Arabidopsis thaliana Regulator of G-Protein Signaling-1. Methods Enzymol. 2004;389:320–37. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(04)89019-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chen J-G. et al. AtRGS1 function in Arabidopsis thaliana. Methods Enzymol. 2004;389:338–50. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(04)89020-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hepler JR. et al. RGS4 and GAIP are GTPase-activating proteins for Gq alpha and block activation of phospholipase C beta by gamma-thio-GTP-Gq alpha. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94(2):428–32. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.2.428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Carman CV. et al. Selective regulation of Galpha(q/11) by an RGS domain in the G protein-coupled receptor kinase, GRK2. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(48):34483–92. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.48.34483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sallese M. et al. Selective regulation of Gq signaling by G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2: direct interaction of kinase N terminus with activated galphaq. Mol Pharmacol. 2000;57(4):826–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Anger T. et al. Differential contribution of GTPase activation and effector antagonism to the inhibitory effect of RGS proteins on Gq-mediated signaling in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(6):3906–15. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309496200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kaibuchi K. et al. Regulation of the cytoskeleton and cell adhesion by the Rho family GTPases in mammalian cells. Annu Rev Biochem. 1999;68:459–86. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sah VP. et al. The role of Rho in G protein-coupled receptor signal transduction. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2000;40:459–89. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.40.1.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Snyder JT. et al. Structural basis for the selective activation of Rho GTPases by Dbl exchange factors. Nat Struct Biol. 2002;9(6):468–75. doi: 10.1038/nsb796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kozasa T. et al. p115 RhoGEF, a GTPase activating protein for Galpha12 and Galpha13. Science. 1998;280(5372):2109–11. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5372.2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hart MJ. et al. Direct stimulation of the guanine nucleotide exchange activity of p115 RhoGEF by Galpha13. Science. 1998;280(5372):2112–4. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5372.2112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Booden MA. et al. Leukemia-associated Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factor promotes G alpha q-coupled activation of RhoA. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22(12):4053–61. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.12.4053-4061.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Vogt S. et al. Receptor-dependent RhoA activation in G12/G13-deficient cells: genetic evidence for an involvement of Gq/G11. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(31):28743–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304570200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Suzuki N. et al. Galpha 12 activates Rho GTPase through tyrosine-phosphorylated leukemia-associated RhoGEF. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(2):733–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0234057100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chikumi H. et al. Regulation of G protein-linked guanine nucleotide exchange factors for Rho, PDZ-RhoGEF, and LARG by tyrosine phosphorylation: evidence of a role for focal adhesion kinase. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(14):12463–73. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108504200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wang Q. et al. Thrombin and Lysophosphatidic Acid Receptors Utilize Distinct rhoGEFs in Prostate Cancer Cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(28):28831–4. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C400105200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Taya S. et al. Direct interaction of insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor with leukemia-associated RhoGEF. J Cell Biol. 2001;155(5):809–20. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200106139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Becknell B. et al. Characterization of leukemia-associated Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factor (LARG) expression during murine development. Cell Tissue Res. 2003;314(3):361–6. doi: 10.1007/s00441-003-0802-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kumanogoh A. et al. Biological functions and signaling of a transmembrane semaphorin, CD100/Sema4D. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2004;61(3):292–300. doi: 10.1007/s00018-003-3257-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Aurandt J. et al. The semaphorin receptor plexin-B1 signals through a direct interaction with the Rho-specific nucleotide exchange factor, LARG. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(19):12085–90. doi: 10.1073/pnas.142433199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Driessens MH. et al. B plexins activate Rho through PDZ-RhoGEF. FEBS Lett. 2002;529(2-3):168–72. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03323-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hirotani M. et al. Interaction of plexin-B1 with PDZ domain-containing Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factors. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;297(1):32–7. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02122-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Perrot V. et al. Plexin B regulates Rho through the guanine nucleotide exchange factors leukemia-associated Rho GEF (LARG) and PDZ-RhoGEF. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(45):43115–20. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206005200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Swiercz JM. et al. Plexin-B1 directly interacts with PDZ-RhoGEF/LARG to regulate RhoA and growth cone morphology. Neuron. 2002;35(1):51–63. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00750-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hunt RA. et al. Snapin interacts with the N-terminus of regulator of G protein signaling 7. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;303(2):594–9. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00400-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Takesono A. et al. Receptor-independent activators of heterotrimeric G-protein signaling pathways. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(47):33202–5. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.47.33202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Willard FS. et al. Return of the GDI: The GoLoco motif in cell division. Annu Rev Biochem. 2004;73:925–51. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.073756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kimple RJ. et al. Structural determinants for GoLoco-induced inhibition of nucleotide release by Galpha subunits. Nature. 2002;416(6883):878–81. doi: 10.1038/416878a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]