Abstract

The Escherichia coli K-12 genome (ECO) was compared with the sampled genomes of the sibling species Salmonella enterica serovars Typhimurium, Typhi and Paratyphi A (collectively referred to as SAL) and the genome of the close outgroup Klebsiella pneumoniae (KPN). There are at least 160 locations where sequences of >400 bp are absent from ECO but present in the genomes of all three SAL and 394 locations where sequences are present in ECO but close homologs are absent in all SAL genomes. The 394 sequences in ECO that do not occur in SAL contain 1350 (30.6%) of the 4405 ECO genes. Of these, 1165 are missing from both SAL and KPN. Most of the 1165 genes are concentrated within 28 regions of 10–40 kb, which consist almost exclusively of such genes. Among these regions were six that included previously identified cryptic phage. A hypothetical ancestral state of genomic regions that differ between ECO and SAL can be inferred in some cases by reference to the genome structure in KPN and the more distant relative Yersinia pestis. However, many changes between ECO and SAL are concentrated in regions where all four genera have a different structure. The rate of gene insertion and deletion is sufficiently high in these regions that the ancestral state of the ECO/SAL lineage cannot be inferred from the present data. The sequencing of other closely related genomes, such as S.bongori or Citrobacter, may help in this regard.

INTRODUCTION

Escherichia coli K-12 has been the primary model in bacterial genetics for decades. While E.coli K-12 is not pathogenic, a number of other E.coli strains are pathogens and other closely related species are major pathogens of humans and animals (1, and references therein). Many of the differences between these organisms have been located on ‘pathogenicity islands’. The E.coli K-12 genome sequence has been completed (2) and a series of related pathogen genomes are in the process of being sequenced to completion or have been extensively sample sequenced by our group. Those that are publicly available are listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Divergence of the sampled genomes, relative to E.coli K-12.

| Organism | Abbreviation | Completion | Homologs of E.coli K-12 genesa | DNA homology of orthologous ORFsa | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E.coli K-12 | ECO | 100% | 4405 (100%) | 100% | (2) |

| K.pneumoniae | KPN | ∼95% sample | 2423 (55%) | 82% | WUSTL |

| Y.pestis | YPE | >99% | 992 (23%) | 73% | Sanger Centre |

| S.enterica serovars | |||||

| Typhimurium LT2 | STM | >99% | 2986 (68%) | 84% | WUSTL |

| Typhi CT18 | STY | >99% | 2955 (67%) | 84% | Sanger Centre |

| Paratyphi A | SPA | ∼95% sample | 2872 (65%) | 84% | WUSTL |

aSee Materials and Methods.

We have developed methods to visually portray DNA sequence information in a form that allows one completed genome, in this case E.coli K-12 (ECO), to be compared simultaneously with several sampled or completed genomes from related organisms (3). These tools are available for public use at http://globin.cse.psu.edu/ or via the Salmonella genome sequencing project at http://genome.wustl.edu/gsc/bacterial/newlistdisplay.pl.

Comparison of ECO with the other genomes allows the identification of all of the major differences between ECO and these organisms. We present a preliminary comparison of the E.coli K-12 genome with sample sequences of the genomes of Klebsiella pneumoniae (KPN) and the Salmonella enterica serovars Typhimurium, Typhi and Paratyphi A, collectively referred to as SAL. Genes that are present in ECO but absent in Salmonella or Klebsiella have been determined, clusters of ECO-specific genes have been located and the gross features of genetic reorganization have been examined.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The E.coli K-12 sequence used is that reported by Blattner et al. (2). Sequence data for S.enterica serovars Typhimurium (STM) and Paratyphi A (SPA) and K.pneumoniae (KPN) were obtained from our sequencing project at ftp://genome.wustl.edu/pub/gsc1/sequence/st.louis/bacterial/Salmonella/, those for S.enterica serovar Typhi (STY) from ftp://ftp.sanger.ac.uk/pub/pathogens/st/ and Yersinia pestis (YPE) from ftp://ftp.sanger.ac.uk/pub/pathogens/yp/. Although they are not discussed further in this paper, the genomes for Vibrio cholerae (VCH) (www.tigr.org) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PAE) (www.pseudomonas.com) are also included in our comparative views. At the time of analysis two of the genomes, ECO and VCH, were complete, while the other genomes had been sequenced to varying extents. The numbers of melded contigs were: STM, 518; STY, 133; SPA, 887; YPE, 112; VCH, 2; PAE, 1.

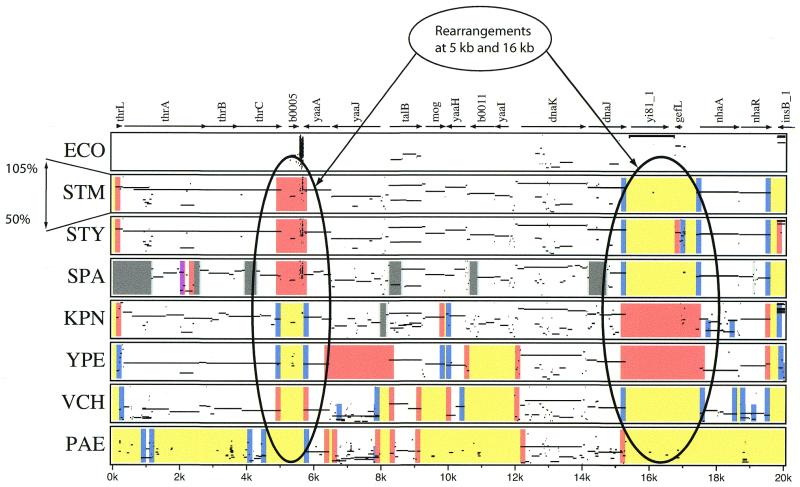

Alignments of ECO with each of the other genomes were inspected with a web-based tool Enteric (3). For a user-supplied address in ECO the Enteric server scans pre-computed sets of pairwise alignments between ECO and each of the bacterial genomes and extracts those in the 20 kb region centered at the specified address. The alignments are computed by the program blastz (4). The Enteric server then produces a PDF document containing a hyperlinked, graphical representation of the selected alignments together with annotations that describe insertion, deletion and gene rearrangement events between the compared genomes. This consists of a set of percent identity plots (PIPs), as in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Enteric alignments of E.coli K-12 with six other genomes. PIP alignments of E.coli with genomes of six other bacteria, in the 20 kb region at the beginning of the E.coli sequence. See Materials and Methods and Florea et al. (3) for a description of how to interpret PIP alignments.

In a PIP, a sequence match is shown as a line parallel to the horizontal axis at its relative position in the first (reference) sequence, positioned along the vertical axis at the coordinate corresponding to the percent identity of the match. Thus, a strongly conserved feature is represented as a horizontal line near the top of the PIP. Enteric produces a stacked array of PIPs, one for each of the comparisons between ECO and another bacterial genome, which show only alignments with 50–100% nucleotide identity.

Annotations of ECO genes are displayed above the PIPs, together with arrows indicating their orientations and with embedded hyperlinks to the corresponding entries in the WIT database (http://wit.IntegratedGenomics.com/IGwit/; 5). Other graphical features include colored rectangles or vertical bars, which denote discontinuities in the PIP alignments. When the cursor is placed over a particular region of the PIP, additional information is disclosed, such as the name of the aligning contig, the size of an inserted region or the ECO position of the adjacent gene in the other organism. More detailed instructions for how to read a PIP are presented in another paper (3). Users can generate their own PIPs using http://genome.wustl.edu/gsc/bacterial/newlistdisplay.pl or http://globin.cse.psu.edu/enterix/.

To measure the proportion of ECO genes present in each of the other genomes we proceed as follows. Each nucleotide in an ECO gene is assigned the highest percentage nucleotide identity found among all the alignments between ECO and the other genomes that include the nucleotide. This number is specified as 0% if no alignments contain that nucleotide. The average of these numbers over all nucleotides in an ECO gene provides a numerical value that assesses the strengths of those alignments for the whole gene. This value is adjusted where an unaligned ECO region is unsequenced in the other species. These gaps are identified as regions where the ends of sequenced contigs in the other species align with ECO (3). A 70% cut-off in this measurment of similarity was used to calculate the proportion of open reading frames (ORFs) shared between ECO and the other genomes in Table 1.

The percent sequence similarity among putative orthologous ORFs was calculated by first identifying ECO ORFs that appeared to have homologs (defined as at least 50% similar) in the SAL, KPN and YPE genomes. Then known transposons and repetitive elements were excluded from this list. Among the 1388 ORFs that remained the percent similarity was determined for the 1000 with the highest overall similiarity to ECO in each genome. This measurement of similarity between the orthologous parts of ECO and the other genomes is given in Table 1.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The genomes will be referred to using the three letter abbreviations described in Table 1. In addition, the abbreviation SAL will be used to indicate features in common among all three Salmonella genomes, STM, STY and SPA. Note that ECO refers to the E.coli K-12 MG1655 genome only and does not include other E.coli genomes.

Over 1000 genes in E.coli K-12 are absent from Salmonella and Klebsiella

The ECO and SAL genetic maps are generally co-linear and quite similar (6). However, evidence of substantial differences in their genomes has mounted (see for example 7). With the completion of the ECO genome and the near completion of some of its relatives, we can now quantify these differences.

The alignment of ECO with the SAL genomes contains many rearrangements or insertion/deletion events. To partially quantify these phenomena, genes that appear to have no close counterpart in the SAL lineage, when compared to ECO, were determined. Only genes that are absent in all three members of subspecies 1 of S.enterica (STM, STY and SPA) were considered. A threshold of 70% DNA sequence identity was used. This cut-off was chosen because these genomes share >80% DNA identity in their closest 1000 putative orthologs (Table 1). Thus, most orthologs should have sequence similarities of >70%. To minimize the chance that an unsequenced portion of a gene would result in an artificially low percent identity, the unsequenced portions of genes were excluded from the calculations (see Materials and Methods). The extent of completion of the sampled genomes (>95%) results in a <100 bp average gap size. If one assumes that particular sequences are not being excluded from the libraries, then, on average, fewer than one gene >500 bp in length would fail to be sampled per genome. However, there are many documented cases where genes are excluded from shotgun libraries. Thus, although it is extremely unlikely that a gene present in all three SAL would be unsampled by chance in all three genomes, it is possible that some genes have been missed due to selection against them in the libraries.

The list of 1350 genes (30.6%) that are present in ECO but lack a homolog with >70% sequence similarity in SAL is available at our web site (http://globin.cse.psu.edu/ftp/dist/Enterix/sim_pct.p70/missing_SAL.p70). The proportion of genes in ECO that appear not to have a close homolog in the three SAL is very similar to our previous estimate of 32%, which was made using a sample of only 7% of the sequence of STY (8). Others predicted 755 genes (18%) as most likely to have been acquired from distant foreign hosts (9). This discrepancy will require further analysis.

1165 ORFs were found in ECO but not in any SAL or in KPN (http://globin.cse.psu.edu/ftp/dist/Enterix/sim_pct.p70/ missing_SAL_KPN.p70). KPN is a very close outgroup, only slightly more divergent from ECO than the three SAL genomes (see the number of shared genes and the DNA similarity of the best conserved ORFs in Table 1). Only 138 (19%) of the 1165 ORFs have assigned gene names. In contrast, 2155 of 4405 genes (49%) are named in ECO. This difference may indicate that some of the genes found only in ECO have phenotypes in a narrow range of conditions that have not yet been found. For example, many genes in cryptic phage presumably contribute to fitness of ECO only indirectly, if at all. Table 2 lists the subset of ORFs found in ECO, but absent or divergent in SAL or KPN, for which a function has been attributed. Their locations in the ECO genome and brief explanations of their known or putative biological role are also given. Genes with attributed functions that are absent or divergent in all three SAL but are present in KPN are listed in Table 3. These tables are further annotated to show genes that have homologs with 50–70% DNA sequence identities. In some cases these genes with weaker homologies may be paralogs, but in other cases they probably represent genes that have experienced accelerated divergence or gene conversion events. Examples of the latter may include genes associated with proteins expressed on the surface (10), such as the flagella, pilin, fimbrial and lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis genes. These include the fli operon, flgA (2), ecpD (11), the rfa operon (13–15), rfbCX (16) and the fim operon (12). There is a fim operon in at least some Salmonella sp. that is not orthologous to the ECO fim operon. However, the Salmonella operon does occur, unannotated, in the ECO genome (12; J.Parkhill, unpublished results). This observation highlights the fact that genes that are unannotated in the reference genome, in this case ECO, will automatically be missed using the strategy we employed here.

Table 2. Escherichia coli K-12 genes with no close homologs in the K.pneumoniae and three Salmonella genomesa.

| Genesb | Startc | Endc | Putative functiond | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| agaRZeVeWASYeBCDI | 3 275 497 | 3 284 666 | N-acetylgalactosaimine (PTS) | (20) |

| aise | 2 363 038 | 2 363 640 | Induced by aluminium | (2) |

| alpA | 2 756 665 | 2 756 877 | Prophage CP4-57 regulatory protein | (32) |

| ampC | 4 375 389 | 4 376 522 | β-Lactamase | (39,40) |

| appA | 1 039 840 | 1 041 138 | Periplasmic phosphoanhydride phosphohydrolase precursor | (41) |

| appY | 582 904 | 583 653 | Transcriptional activator. DLP12 prophage | (42) |

| aqpZ | 914 575 | 915 270 | Water channel gene, aquaporin Z | (43) |

| aroLe | 405 629 | 406 153 | Shikimate kinase II | (2) |

| arp | 4 217 880 | 4 220 066 | Ankyrin-like regulatory protein; regulates acetyl-CoA synthetase | (2) |

| aslABe | 3 980 571 | 3 983 620 | Aryl-sulphate sulphohydrolase | (2) |

| asr | 1 669 373 | 1 669 708 | Acid-inducible RNA | (44) |

| atoSCeDAEBe | 2 318 063 | 2 325 310 | Acetyl coenzyme A:acetoacetyl coenzyme A transferase and thiolase II; required for growth on short chain fatty acids | (21) |

| b2854 | 2 992 021 | Similar to Salmonella invasion protein iagB | (2) | |

| bglJe | 4 601 729 | 4 602 406 | Activator transport operon: aromatic β-glucosides | (45) |

| bioDe | 811 493 | 812 170 | Dethiobiotin synthetase | (46) |

| bisZe | 1 952 602 | 1 955 049 | Biotin sulfoxide reduction | (47) |

| cadCe | 4 357 974 | 4 359 512 | Activator for lysine to cadaverine operon | (48) |

| cble | 2 057 986 | 2 058 936 | Regulatory protein | (49) |

| chpAR | 2 908 778 | 2 909 361 | Homologs of the pem locus; stable maintenance of plasmid R100 | (50) |

| chpBS | 4 446 018 | 4 446 619 | Homologs of the pem locus; stable maintenance of plasmid R100 | (50) |

| cmtAeB | 3 075 490 | 3 077 349 | PTS; mannitol (cryptic) permease iia components | (51) |

| cobTe | 2 061 410 | 2 062 489 | Nicotinate nucleotide dimethylbenzimidazole phosphoribosyltransferase | (52) |

| dicCAFeB | 1 645 958 | 1 647 821 | Cell division; Qin prophage | (53) |

| dive | 2 435 970 | 2 436 965 | Cell division | (2) |

| eaeH | 313 581 | 314 468 | Attaching and effacing protein homolog | (2) |

| ebgRAC | 3 219 107 | 3 223 812 | β-Galactosidase operon | (2) |

| ecpDe | 155 461 | 156 201 | Pilin chaperone | (11) |

| elaD | 2 380 733 | 2 381 944 | Putative sulfatase/phosphatase | (2) |

| emrE | 567 538 | 567 870 | DLP12 prophage; multidrug transporter | (25) |

| emrYeKe | 2 478 658 | 2 481 359 | Multidrug resistance emrAB homologs | (2) |

| entD | 608 682 | 609 311 | Enterochelin synthetase, component D (phoshpantetheinyltransferase) | (54) |

| envRe | 3 410 440 | 3 411 102 | Putative regulator, envCD | (2) |

| envYe | 585 370 | 586 131 | Porin thermoregulatory gene | (55) |

| erfKe | 2 060 413 | 2 061 345 | Cobalamin (coenzyme B12) biosynthetic gene? | (2) |

| farR | 764 376 | 765 098 | Fatty acid and fatty acyl-CoA-responsive DNA-binding protein | (56) |

| fecIRABCDeEe | 4 508 261 | 4 515 803 | Ferric citrate transport | (22) |

| fes | 612 038 | 613 162 | Enterochelin esterase | (57) |

| fhiAe | 248 358 | 250 097 | Putative transport protein, flagellar biosynthesis | (2) |

| fimZe | 563 071 | 563 703 | Type 1 pilin gene | (12) |

| flgAe | 1 129 427 | 1 130 086 | Flagellar basal body P-ring protein | (2) |

| fliCeDeSeTKeOe | 2 000 133 | 2 019 891 | Flagellar biosynthesis | (2) |

| flu | 2 069 405 | 2 072 680 | CP4-44 prophage; antigen 43; controls colony form variation and autoaggregation | (58) |

| flxA | 1 644 429 | 1 644 761 | Unknown | (59) |

| focBe | 2 611 954 | 2 612 802 | Putative formate transporter | (60) |

| frvRXBA | 4 085 688 | 4 090 404 | Sugar-specific PTS; fructose-like | (61) |

| gadA | 3 663 810 | 3 665 210 | Part of glutamate decarboxylasesystem; counteracts acidification during fermentative growth | (17,18) |

| gadB | 1 568 669 | 1 570 069 | Glutamate decarboxylasesystem | (17,18) |

| gatR_2eDeAeZeYe | 2 169 417 | 2 175 230 | Galactitol metabolism | (62) |

| glcCDFGB | 3 119 650 | 3 127 051 | Glycolate utilization | (19) |

| glf | 2 105 248 | 2 106 351 | Galactofuranose biosynthesis | (63) |

| gltF | 3 358 811 | 3 359 575 | Putative periplasmic protein in glutamate biosynthesis | (64) |

| gntPe | 4 547 522 | 4 548 865 | Gluconate permease | (65) |

| goaG | 1 363 574 | 1 364 839 | 4-Aminobutyrate transaminase | (2) |

| hcaR,A1,A2,C,B,D | 2 666 026 | 2 671 266 | Catabolism of 3-phenylpropionic acid and cinnamic acid | (23) |

| hdeABD | 3 654 038 | 3 655 197 | Stress response proteins | (24) |

| hdhA | 1 695 297 | 1 696 064 | α-Hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase gene | (66) |

| hofBeCe | 114 522 | 117 099 | Putative protein transport, pili biogenesis? | (2) |

| hofD | 3 463 180 | 3 463 857 | Leader peptidase, integral membrane protein | (2) |

| hofFeGeH | 3 457 454 | 3 459 614 | Putative general secretion pathway proteins | (2) |

| hrsAe | 765 207 | 767 183 | Thermoinduction of ompC | (67) |

| hsdSe | 4 577 638 | 4 579 032 | Type I restriction system | (68) |

| hslJe | 1 439 345 | 1 439 767 | Heat shock protein | (2) |

| htrC | 4 187 364 | 4 187 903 | Heat shock response | (69) |

| htrEe | 152 829 | 155 426 | Type II pilin porin? | (11) |

| htrL | 3 790 453 | 3 791 325 | Lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis | (2) |

| hyaEeFe | 1 035 577 | 1 036 829 | Hydrogenase-1 operon | (70) |

| hyfABCeDEFGeHeIeRe-focB | 2 599 182 | 2 612 799 | Putative nine subunit hydrogenase complex | (60) |

| inaA | 2 346 842 | 2 347 492 | Weak-acid-inducible | (71) |

| intAe | 2 754 180 | 2 755 421 | Prophage CP-457 integrase | (2) |

| intBe | 4 494 318 | 4 495 508 | Prophage P4 integrase | (2) |

| intE | 1 198 902 | 1 200 029 | Similar to bacteriophage P21 integrase | (2) |

| intF | 294 920 | 296 320 | Probable phage integrase | (2) |

| kch | 1 307 040 | 1 308 293 | Putative potassium channel protein | (2) |

| kdgTe | 4 099 262 | 4 100 254 | 2-Keto-3-deoxygluconate permease | (2) |

| lacA | 360 473 | 361 084 | Galactoside acetyltransferase | (2) |

| lhr | 1 727 111 | 1 731 727 | Probable ATP-dependent helicase | (72) |

| lit | 1 197 918 | 1 198 811 | Similar to phage T4 late gene expression blocking protein (GPLIT); prophage e14 | (2) |

| marB | 1 618 013 | 1 618 231 | Multiple antibiotic resistance | (73) |

| mbhAe | 250 042 | 250 827 | Putative chemotaxis protein | (2) |

| mcrA | 1 209 569 | 1 210 402 | Restriction of methylated DNA; prophage e14 | (74) |

| mcrB | 4 575 528 | 4 576 925 | Restriction of methylated DNA | (75) |

| mcrC | 4 574 482 | 4 575 528 | Restriction of methylated DNA | (75) |

| mcrDe | 4 573 163 | 4 574 425 | Restriction of methylated DNA | (2) |

| mipBe | 862 793 | 863 527 | Transaldolase-like protein | (2) |

| molR_1,R_2,R_2 | 2 194 494 | 2 195 318 | Molybdate metabolism regulator | (76) |

| mrre | 4 584 519 | 4 585 433 | Restriction of methylated DNA | (2) |

| nfrAB | 587 205 | 592 401 | Membrane proteins required for bacteriophage N4 adsorption | (77) |

| nikCeDEe | 3 613 813 | 3 616 213 | Nickel transport | (78) |

| ninE | 572 144 | 572 314 | Cryptic lambdoid prophage DLP12 | (79) |

| nrfGe | 4 291 122 | 4 291 718 | Formate-dependent nitrite reduction | (80) |

| ogrKe | 2 165 324 | 2 165 542 | Phage related | (2) |

| ompFe | 985 117 | 986 205 | Outer membrane protein | (81) |

| ompG | 1 379 971 | 1 380 876 | Porin; large channels; cryptic | (28) |

| ompT | 583 903 | 584 856 | Porin; large channels; cryptic; DLP12 prophage | (28) |

| pdxKe | 2 534 406 | 2 535 257 | Pyridoxine (vitamin B6) kinase | (82) |

| perR | 268 513 | 269 406 | CP4-6 prophage; peroxide resistance protein | (2) |

| phnCeDENeQ | 4 311 389 | 4 320 914 | Phosphonate uptake and degradation | (83) |

| phpB | 668 519 | 669 130 | Cobalamin synthesis (putative) | (2) |

| pinO | 3 451 145 | 3 451 564 | Calcium-binding protein required for initiation of chromosome replication | (2) |

| pmrDe | 2 371 292 | 2 371 588 | polymyxin B resistance protein | (2) |

| ppdAeBe | 2 961 175 | 2 962 199 | Prepilin peptidase-dependent protein A | (2) |

| pphA | 1 920 337 | 1 920 996 | Protein phosphatase 1; signals protein misfolding | (2) |

| pphB | 2 857 783 | 2 858 439 | Ser/Thr protein phosphatase 2 | (2) |

| pqqL | 1 570 431 | 1 573 226 | Redox cofactor for pyrroloquinoline quinone synthesis (cryptic in K-12) | (2) |

| pshM | 3 462 695 | 3 463 180 | Putative general secretion pathway protein M | (84) |

| pspEe | 1 367 713 | 1 368 027 | Phage shock protein | (85) |

| recEe | 1 412 813 | 1 415 410 | Exonuclease VIII; Rac prophage; part is present in S.typhi | (86) |

| recT | 1 412 008 | 1 412 817 | DNA-pairing protein; RecA-independent recombination | (86) |

| relEeBe | 1 643 370 | 1 643 896 | Toxin-antitoxin | (87) |

| rem | 1 642 675 | 1 642 926 | Hypothetical rem protein | (2) |

| rfaBeIeJeKLSYeZe | 3 794 575 | 3 802 743 | Lipopolysaccharide core biosynthesis | (13–15) |

| rfbCeX | 2 106 359 | 2 107 606 | O-antigen synthesis | (16) |

| rhsA | 3 759 810 | 3 763 943 | Rhs multigene family | (26,27) |

| rhsB | 3 616 823 | 3 621 058 | Rhs multigene family | (26,27) |

| rhsC | 728 806 | 732 999 | Rhs multigene family | (26,27) |

| rhsD | 522 485 | 526 765 | Rhs multigene family | (26,27) |

| rhsE | 1 525 914 | 1 527 962 | Rhs multigene family | (26,27) |

| rimLe | 1 496 962 | 1 497 501 | Acetylation of ribosomal protein L12, converting it into L7 | (88) |

| rnae | 643 420 | 644 226 | Ribonuclease I | (89) |

| rpiRB | 4 309 680 | 4 311 378 | Ribose catabolism | (90) |

| rtne | 2 268 746 | 2 270 302 | Resistance to phage N4 and lambda | (2) |

| ruse | 572 594 | 572 956 | Crossover junction endodeoxyribonuclease; cryptic lambdoid prophage DLP12 | (91) |

| sbcCe | 411 831 | 414 977 | ATPase involved in DNA repair | (92) |

| sbm | 3 058 870 | 3 061 014 | Methylmalonly-coA mutase α-subunit | (2) |

| sbmC | 2 078 811 | 2 079 284 | Stationary phase induced SOS gene; gyrase inhibitor | (93) |

| sfa | 1 051 070 | 1 051 300 | Suppressor of the unsaturated fatty acid locus fabA6(Ts) | (94) |

| sfmAeCeDeHeFe | 557 402 | 563 068 | SFM fimbrial proteins | (2) |

| sgcEe | 4 524 473 | 4 525 105 | Putative epimerase | (2) |

| sieB | 1 416 572 | 1 417 183 | Superinfection exclusion protein B | (95) |

| slp | 3 651 558 | 3 652 157 | Outer membrane lipoprotein; carbon starvation-inducible and stationary phase inducible | (96) |

| smf_1e | 3 430 436 | 3 431 197 | Unknown | (2) |

| sohA | 3 274 643 | 3 274 978 | HtrA suppressor protein (protein prlf) | (97) |

| sugEe | 4 374 303 | 4 374 770 | Chaparone; small multidrug resistance family | (2) |

| t150e | 3 718 827 | 3 719 678 | IS150 putative transposase | (2) |

| tap | 1 967 407 | 1 969 008 | Taxis toward peptides | (98) |

| tdcRe | 3 264 895 | 3 265 239 | Threonine dehydratase regulatory protein | (99) |

| thiMe | 2 182 533 | 2 183 321 | Hydoxyethylthiazole kinase | (100) |

| tnaLABe | 3 886 064 | 3 887 774 | Tryptophanase operon | (101) |

| tolAe | 775 565 | 776 830 | Tolerance to phage and colicins | (102) |

| torDe | 1 061 022 | 1 061 621 | Trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) operon | (103) |

| torSe | 1 052 657 | 1 055 371 | TorS-TorR two component system | (103) |

| trge | 1 490 494 | 1 492 134 | Methyl-accepting chemotaxis protein III; ribose and galactose sensor receptor | (104) |

| trkG | 1 421 806 | 1 423 263 | Uptake of K+; Rac prophage | (105) |

| ttdAeBe | 3 204 104 | 3 205 617 | Tartrate dehydratase | (106) |

| uidRABC | 1 689 610 | 1 694 486 | Glucuronide operon (gus) | (2) |

| umuDe | 1 229 990 | 1 230 409 | Translesion DNA synthesis | (2) |

| wbbHIJK | 2 101 413 | 2 105 248 | O-antigen production | (107,108) |

| wzzBe | 2 095 343 | 2 096 359 | Regulator of length of O-antigen component of lipopolysaccharide chains | (2) |

| xasA(gadC)B | 1 566 978 | 1 570 069 | Glutamate decarboxylase and permease; protects from cytoplasmic acidification | (17,18) |

| xylEe | 4 238 358 | 4 239 833 | Xylose transport protein | (109) |

| ygeG | 2 989 290 | 2 989 781 | Similar to Shigella and Yersinia plasmids IPPI and LCRH | (2) |

| ygeH | 2 990 116 | 2 991 492 | Similar to Salmonella invasion protein iagA | (2) |

| ygeK | 2 992 482 | 2 992 928 | Similar to luxR/uhpA family of transcriptional regulators | (2) |

| ygeV | 3 002 030 | 3 003 808 | Hypothetical σ54-dependent transcriptional regulator | (2) |

| ybiL/b0805 | 838 472 | 840 754 | Outer membrane protein; putative ferrisiderophore receptor | (2) |

| ygeW | 3 004 356 | 3 005 447 | Similar to ornithine carbamoyltransferase | (2) |

| ygeY | 3 006 785 | 3 007 996 | Putative dacetylase | (2) |

| yqeI | 2 986 524 | 2 987 333 | Similar to V.cholerae toxR | (2) |

Table 3. Escherichia coli K-12 genes with close homologs in K.pneumoniae but absent in the three Salmonella genomesd.

| Geneb | Startc | Endc | Putative functiond | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| afuC | 276 980 | 278 038 | Putative ferric transport ATP-binding protein | (2) |

| aldA | 1 486 256 | 1 487 695 | Aldehyde dehydrogenase | (2) |

| aldH | 1 360 767 | 1 362 254 | Putative aldehyde dehydrogenase | (2) |

| araFGeH | 1 980 581 | 1 984 151 | l-Arabinose transport system | (110) |

| arsRBCe | 3 646 158 | 3 648 289 | Arsenical resistance operon | (111) |

| ascFBG | 2 837 547 | 2 839 004 | PTS; arbutin, salicin and cellobiose | (112) |

| b1145 | 1 201 482 | 1 202 156 | Putative phage repressor | (2) |

| b2442 | 2 556 791 | 2 558 086 | Putative prophage integrase | (2) |

| betTIBeA | 324 801 | 330 720 | Osmoprotectant glycine betaine from choline | (113) |

| bglBeFeGe | 3 899 920 | 3 904 195 | Transport and phosphorylation of β-glucosides and antiterminator; cryptic operon | (114) |

| chaC | 1 271 709 | 1 272 425 | Cation transport protein | (2) |

| cynReTeSXe | 357 015 | 360 370 | Cyanase and carbonic anhydrase | (115) |

| ddpX/b1488 | 1 560 519 | 1 561 100 | d-Ala-d-Ala dipeptidase, Zn-dependent | (2) |

| dinDe | 3 815 375 | 3 816 211 | DNA damage inducible, regulated by the LexA-RecA | (116) |

| evgAeS | 2 481 775 | 2 485 987 | Two component signal transduction system | (117) |

| exuReT | 3 242 744 | 3 245 065 | Negatively controls uxuAB operon | (118) |

| feaReB | 1 444 402 | 1 447 042 | Regulates expression of tynA and padA; phenylacetaldehyde dehydrogenase | (2) |

| fimBEAeIeCeDeFeGH | 4 538 525 | 4 547 279 | Type 1 pilin; mannose-sensitive hemagglutination; role in pathogenesis | (12) |

| folX | 2 419 345 | 2 419 707 | Dihydroneopterin-triphosphate epimerase | (119) |

| fruLe | 87 860 | 87 946 | fruR leader peptide | (2) |

| GapC_1e,C_2 | 1 487 737 | 1 488 389 | Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase | (2) |

| glvGeBC | 3 858 976 | 3 861 491 | Probable 6-phospho-β-glucosidase and PTS system; arbutin-like components | (2) |

| hipAeBe | 1 588 878 | 1 590 466 | Replication or cell division? | (120) |

| hypAe | 2 848 670 | 2 849 020 | Hydrogenase 3 subunit | (121) |

| idi/b2889e | 3 031 085 | 3 031 633 | Isopentenyl diphosphate isomerase | (2) |

| intC | 2 464 565 | 2 465 722 | Putative prophage sf6-like integrase | (2) |

| lacIZY | 361 150 | 366 734 | Lactose operon | (2) |

| malIeXYe | 1 696 176 | 1 700 153 | Maltose regulon | (122) |

| maoC | 1 449 621 | 1 451 666 | NADH-dependent dehydrogenases | (123) |

| mhpRABCDEFTe | 366 811 | 375 894 | 3,3-(Hydroxyphenyl) propionate catabolism | (124) |

| nac | 2 059 038 | 2 059 955 | Nitrogen assimilation regulatory protein | (125) |

| nikAB | 3 611 298 | 3 613 816 | Nickel transport | (78) |

| nlpAe | 3 836 802 | 3 837 620 | Lipoprotein-28 | (2) |

| ordL | 1 362 256 | 1 363 536 | Probable oxidoreductase | (2) |

| phnFGHIJKLMP | 4 311 389 | 4 320 914 | Phosphonate uptake and degradation | (83) |

| phoA | 400 902 | 402 386 | Alkaline phosphatase precursor | (2) |

| pppA/b2972 | 3 111 560 | 3 112 492 | Bifunctional prepilin peptidase | (2) |

| shiAe | 2 051 665 | 2 052 981 | Shikimate transport system | (126) |

| tam/b1519 | 1 605 370 | 1 606 128 | Trans-aconitate methyltransferase | (2) |

| tauABeCD | 384 399 | 387 870 | Taurine operon | (127) |

| tesAe | 518 363 | 518 989 | Thioesterase I | (128) |

| tynA | 1 447 100 | 1 449 373 | Copper amine oxidase precursor (tyramine oxidase) (maoA) | (2) |

| uxaACe | 3 239 467 | 3 242 381 | Hexuronate degradation | (118,129) |

| uxaB | 1 607 253 | 1 608 704 | Hexuronate degradation | (118,129) |

| Wzy/rfc | 2 104 085 | 2 105 248 | O-antigen polymerase | (130) |

| xylFGeH | 3 728 760 | 3 732 527 | Xylose transport operon | (131,132) |

| yaiP | 381 963 | 383 159 | Polysaccharide metabolism | |

| ybcS | 576 836 | 577 333 | Bacteriophage λ lysozyme homolog | (2) |

| ybcU | 577 823 | 578 116 | Bacteriophage λ Bor protein homolog | (2) |

| ydeP/b1501 | 1 582 231 | 1 584 510 | Efflux of cysteine biosynthetic pathway | (2) |

| ygfG | 3 061 971 | 3 062 798 | Methylmalonyl-CoA decarboxylase, biotin-independent | (2) |

| ygfH | 3 062 822 | 3 064 300 | Propionyl-CoA:succinate-CoA transferase | (2) |

| ygfP | 3 023 787 | 3 025 106 | Guanine deaminase | (2) |

aNote that genes may have been excluded from the sample by negative selection in the library, so this data does not guarantee their absence. Furthermore, genes that appear to be present by our criteria may be recently inactivated pseudogenes or close paralogs with a different function.

bAn E.coli gene is identified as ‘absent’ in a given genome if the best DNA sequence identity for the portion of a gene that appeared to be sequenced in the other genome is <70% (see Materials and Methods). 1350 E.coli genes are absent from all three Salmonella species and 1165 genes are absent from both SAL and KPN. Only named genes and some unnamed genes with assigned putative functions are listed here. A complete list can be found at http://globin.cse.psu.edu/ftp/dist/Enterix/sim_pct.p70/missing_SAL.p70 and http://globin.cse.psu.edu/ftp/dist/Enterix/sim_pct. p7 0/missing_SAL_KPN.p70, respectively.

cStart and stop positions for ECO. When the sequence consists of a set of genes, the span includes all of these genes.

dPutative functions are from the reference paper, GenBank (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov:80/entrez/query.fcgi?db=Protein), WIT (http://wit.mcs.anl.gov/WIT2/) or KEGG (http://www.genome.ad.jp/kegg/).

eGenes with weak homologs in at least one SAL or KPN, defined as 50–70% DNA sequence identity. These are possible paralogous comparisons, gene conversion or accelerated evolution.

Among the genes and operons confirmed to be absent in SAL and KPN are those involved in glutamate metabolism (gadABC/xasAB) (17,18), glycolate utilization (glcCDFGB) (19), the glucuronide operon (uidRABC, gus) (2), the aga operon (20), the ato operon (21), the fec (ferric citrate transport) operon (22), the hca operon (23), the hde operon (24), emrE (a multidrug transporter) (25) and the entire dispersed family of ORFs of unknown function (rhsABCDE) (26,27). However, a set of distant family members does occur (J.Parkhill, unpubished results). The absence of certain other genes was less expected. OmpG is a cryptic phage gene in ECO that is expressed only after a mutation in the gene. Gene expression was reported at low levels in SAL (28), but we found that this gene and its close homologs are absent from SAL, indicating that the reported expression may be of a different gene.

Some genes are absent from only one SAL or KPN. These genes are not reported in Tables 2 and 3 but some are of particular interest, such as rffH, which is explored further elsewhere (3). It is likely that at least a few of the genes that are absent in our SAL and KPN genomes will prove to be present in the genomes of other strains of S.enterica or K.pneumoniae. Nevertheless, we can extrapolate from the very few genes that appear to be shared by ECO and only one out of three SAL (less than 30 such genes) that the lack of a homolog in our data analysis will usually mean lack of a homolog in virtually all the genomes in a species.

There are 394 events where one or more adjacent genes are absent in all three SAL relative to ECO (Table 4). 199 of these events involve more than one gene. Similarly, there were 216 cases where SPA has a sequence of >400 bases that is not found in ECO, 261 in STM and 257 in STY. There are at least 160 cases where the three SAL share sequences of >400 bases that are not found in ECO (Table 4). This number is in line with our previous estimate of a few hundred insertion/deletion events that distinguish these genomes, which was extrapolated from small samples of the genomes (8,29) and estimates based on the codon adaptation index (9).

Table 4. Genome differences between E.coli K-12 and the three Salmonella spp.

| No. of adjacent genes present in E.coli K-12 and absent from Salmonellaa | Frequency |

|---|---|

| 1 | 195 |

| 2 | 67 |

| 3 | 27 |

| 4 | 25 |

| 5 | 13 |

| 6 | 8 |

| 7 | 7 |

| 8 | 15 |

| 9 | 6 |

| 11 | 3 |

| 12 | 6 |

| 13 | 5 |

| 14 | 3 |

| 15 | 2 |

| 17 | 2 |

| 18 | 2 |

| 19 | 2 |

| 20 | 1 |

| 22 | 1 |

| 23 | 1 |

| 28 | 1 |

| 30 | 2 |

| Total | 394 |

| Sequences present in Salmonella and absent in E.coli K-12b | 160 |

aAt a threshold of 70% DNA sequence similarity.

bInsertions in the three Salmonella genomes of >400 bp in length within 200 bp of each other in the E.coli K-12 sequence.

If one discounts phage and transposable elements, both of which are probably not found in all ECO strains, and accepts that the SAL and ECO genomes diverged ∼150 million years ago (30), then the rate at which ECO has acquired a sequence not found in SAL (through an insertion in ECO or deletion in SAL) approaches 2 per million years. On average, each event resulted in the insertion or deletion of about three ORFs. These are conservative estimates, as they do not take into account sequences gained and then lost during the past 150 million years.

Most of the genes unique to E.coli K-12 are in large clusters

It seemed likely that some of the 199 clusters of ECO-specific genes might be associated with known cryptic phage (see for example 31). These genes would presumably be absent from KPN as well as from the three SAL. The list of 1165 such genes (at a 70% DNA identity threshold) was examined for regions in which genes unique to ECO were separated by no more than 3 kb, to account for occasional close paralogs and recent insertions that might disrupt contiguous regions of sequence unique to ECO. This examination revealed 28 regions over 10 kb that consisted primarily of genes unique to ECO (Table 5). Four known cryptic lambdoid phage were identified within these largest clusters: Qin (within a 20 kb region), Rac (21 kb), e14 (27 kb) and DLP12/qsr′ (20 kb). A P4-like phage (32) may reside within a 32 kb cluster. Another cluster of 26 kb may include the CP4-6 prophage (33). The largest cluster, 46 kb, encodes genes with amino acid homology to Salmonella invasion genes and Vibrio toxR, though below the 70% DNA sequence similarity cut-off we have used to distinguish probable orthologs from other homologs. Many other very large clusters have no known association with phage. Perhaps some of these are plasmid integrations (34).

Table 5. Escherichia coli K-12 gene clusters not found in the three Salmonella or the K.pneumoniae genomesa.

| First gene in cluster | Start | End | Size | Named genes in cluster | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b0245 | 262 552 | 273 216 | 10 664 | ? | |

| afuC | 276 980 | 303 406 | 26 426 | Phage CP4-6, intF | (33) |

| ykgL | 311 336 | 324 588 | 13 252 | eaeH | |

| yahA | 331 595 | 344 873 | 13 278 | ? | |

| sfmA | 565 195 | 573 562 | 16 160 | sfmACDHF, fimZ, emrE, ninE, rus | (31) |

| ybcR | 576 621 | 596 686 | 20 065 | Phage DLP12, qsr′, appY, ompT, envY, nfrA, nfrB | (79) |

| ycbE | 992 500 | 1 003 880 | 11 380 | ? | |

| appA | 1 039 840 | 1 055 371 | 15 531 | appA, sfa, torS | |

| ymfD | 1 196 090 | 1 223 130 | 27 040 | Phage e14 | (31) |

| b1345 | 1 410 024 | 1 431 698 | 21 674 | Phage Rac | (31) |

| ydbA_1 | 1 463 416 | 1 480 225 | 16 809 | ? | |

| b1483 | 1 555 136 | 1 596 110 | 40 974 | xasA, gadB, pqqL | |

| ydfK | 1 631 063 | 1 650 732 | 19 669 | Phage Qin | (31) |

| molR_1 | 2 194 494 | 2 208 964 | 14 470 | ||

| atoS | 2 318 063 | 2 334 712 | 16 649 | atoSCDAEB, inaA | |

| emrY | 2 478 658 | 2 493 312 | 14 654 | emrYK, evgAS | |

| hyfA | 2 599 182 | 2 612 802 | 13 620 | hyfABCDEFGHIR, focB | |

| hcaR | 2 666 026 | 2 682 076 | 16 050 | hcaR, A1, A2, CBD | |

| intA | 2 754 180 | 2 786 670 | 32 490 | P4-like phage | (32) |

| ygcN | 2 890 650 | 2 901 396 | 10 746 | ? | |

| yqeH | 2 985 498 | 3 031 633 | 46 135 | Similar to iagAB, toxR | |

| yghK | 3 117 613 | 3 132 838 | 15 225 | glcBGFDC | |

| ygjH | 3 218 556 | 3 228 880 | 10 324 | ebgRAC | |

| sohA | 3 274 643 | 3 290 073 | 15 430 | agaRWASBCDI | |

| pinO | 3 451 145 | 3 467 490 | 16 345 | hofFGD, pshM | |

| slp | 3 651 558 | 3 665 210 | 13 652 | hdeBAD, gadA | |

| yjcP | 4 297 143 | 4 311 796 | 14 653 | rpiRB, phnQ | |

| intB | 4 494 318 | 4 525 105 | 30 787 | fecIRABC |

aAt a threshold of 70% DNA sequence similarity. Clusters may include segments of up to 2.7 kb shared with any of the other genomes. Twenty-eight clusters >10 kb are shown.

Many differences involve insertion/deletion of single genes

Studies of the differences between E.coli and Salmonella have often focused on large groups of genes found in one species or the other (see for example 35–37). However, even at a relaxed threshold of 50% sequence identity there are almost 100 sites where a single gene is absent in SAL but present in ECO and flanked by genes found in both genomes. None of these are known transposable elements nor do they have significant homologies to such elements. These observations add to the growing indications that it will not be sufficient to study a few large ‘pathogenicity islands’ in order to understand the myriad of genetic differences between Salmonella and E.coli. Deletions can also be associated with increased pathogenesis (38). It will be interesting to explore whether any of the 394 sequences that are missing in all three SAL have this effect.

Most of the genome is stable while the rest has sustained multiple changes

The ECO, KPN and SAL genomes are approximately equally divergent, with KPN appearing as a very close outgroup and Yersinia as a distant outgroup to these three genera, as indicated by the numbers of shared genes (Table 1) and the divergence from ECO exhibited by presumptive orthologs (84.5, 84.1, 84.2, 82.1 and 72.9% for STM, STY, SPA, KPN and YPE, respectively) (Table 1). Thus, it should be possible to predict the most parsimonious ancestral state when an ECO sequence is not present in at least one of the other lineages. This is important because the structure of the common ancestors of ECO and SAL and their common ancestor with KPN could help determine what functions were acquired on each lineage as it became specialized to its particular niche over a period that may be in excess of 150 million years (30). We inspected the PIPs for deletions shared by all three Salmonella genomes that were unchanged in the ECO–KPN comparison. Such deletions would be suspected to have occurred in the SAL lineage. Sequences missing from both SAL and KPN would most likely indicate insertions in the ECO lineage. However, with the exception of some of the very large insertions attributable to prophage in ECO, there were relatively few simple insertion/deletion events that occurred in only one of the lineages. In many cases (20 of the first 50 we inspected) all three genomes appeared to have undergone insertions, deletions and rearrangements in the same or overlapping regions.

Two examples can be seen in Figure 1, located at 5 and 16 kb on the ECO genome. A simple absence of a gene occurs in the SAL genomes at 5 kb in the ECO genome, symbolized by the red box. [See Florea et al. (3) for details about PIPs.] However, the absence of this gene in KPN is accompanied by the insertion of an additional sequence of >400 bp (symbolized by the two blue stripes). An insertion also occurs at the same position in the distant outgroup YPE. However, analysis of the insertion in KPN and YPE shows that they are different from each other and not similar to any sequences yet found in any genome (not shown). Thus, there have been different events at this location in all of the genomes, making the ancestor impossible to determine without further comparisons with other related genomes, and perhaps not even then.

At 16 kb on the ECO map is another example where the SAL, KPN and ECO genomes all differ. The ECO sequence at this position includes a suspected insertion sequence and hence the ancestral state may be suspected to be absence of the genes. This hypothesis is supported by referral to the structure of YPE, a very distant enterobacteria, where this segment is missing. However, the SAL have a different sequence inserted at this site, leading to no prediction about the state of this region in the ECO–SAL ancestor.

The ability to determine the ancestral state of the progenitor of these genera will presumably be aided by sample sequencing of other Enterobacteria, especially those other putative Escherichia and Salmonella, such as Escherichia blattae, Escherichia fergusonii, Escherichia hermannii, Escherichia vulneris and Salmonella bongori, as well as other closely related genera, particularly Citrobacter. However, it is likely that the state of the most recent common ancestor of ECO and SAL will remain unresolved at many positions even then.

It is biologically illuminating that so many insertion/deletion events cannot be explained by a single event. If these insertion/deletion events were randomly distributed over the genome one would expect two different insertions/deletions to occur only rarely in the same place in multiple lineages. The observation that the rearrangement events are concentrated in the same place in multiple lineages strongly implies that they are, at a minimum, excluded from large parts of the genome or perhaps in some cases targeted to a subset of the genome. It is these ‘hot-spots’ that appear to have sustained rearrangement events in separate lineages since the divergence of SAL, ECO and KPN.

In summary, an initial comparison of the ECO genome with the SAL and KPN genomes reveals the set of ECO genes that have no close homolog in SAL or KPN. Many genes found in ECO, but not in SAL or KPN, occur in very large clusters, some of which contain cryptic phage but some of which consist primarily of genes of unknown function. Nevertheless, a surprising number of differences involve single genes. Rearrangements appear to be concentrated in areas of the genome where the rate of rearrangement is rapid, relative to the divergence times of these organisms, so that many sites of rearrangement have sustained changes in more than one lineage. The data presented here comprise only the first of a number of possible genome comparisons. It will be interesting to use each of the other genomes in turn as the reference genome, in order to determine the sequences unique to each of the other lineages.

An additional feature of the data is that the genomes of K.pneumoniae (KPN) and S.enterica serovar Paratyphi A are samples with about 4× coverage and no immediate plans for completion. The data we were able to extract from these and the other incomplete genomes helps to demonstrate the utility of the relatively inexpensive sampled genome sequences for comparative genomics. However, one must bear in mind the caveats that some genes may be under-represented due to negative selection in the shotgun libraries and sequencing errors in samples means that one often cannot distinguish genes from pseudogenes. Nevertheless, with these caveats, the utility of sampled genomes, such as the KPN and SPA genomes that we have generated, and of the analysis of partial sequences of genomes undergoing completion, such as STM, STY and YPE, becomes increasingly evident as tools that can exploit these resources are developed.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the members of the Salmonella sequencing consortium, in particular Monica Riley (Woods Hole), Michael Nhan and John Spieth (WUSTL), and Aaron McKay and Bill Pearson (University of Virginia) for their cooperation and many helpful discussions. We particularly thank the members of the Sanger sequencing efforts on S.typhi and Y.pestis for giving us permission to use their data prior to publication. We thank Steffen Porwollik, David Boyle and John Welsh for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by grants AI 34829-09 AI (R.K.W.), AI 34829 (M.M.) and LM05110 (W.M.). Sequencing of S.typhi and Y.pestis at The Sanger Centre was funded by the Wellcome Trust through its Beowulf Genomics initiative.

REFERENCES

- 1.Falkow S. (1996) The evolution of pathogenicity in Escherichia, Shigella and Salmonella. In Neidhardt F.C. (ed.), Escherichia coli and Salmonella. ASM Press, Washington, DC, pp. 2723–2729.

- 2.Blattner F.R., Plunkett,G., Bloch,C.A., Perna,N.T., Burland,V., Riley,M., Collado-Vides,J., Glasner,J.D., Rode,C.K., Mayhew,G.F., Gregor,J., Davis,N.W., Kirkpatrick,H.A., Goeden,M.A., Rose,D.J., Mau,B. and Shao,Y. (1997) Science, 277, 1453–1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Florea L., Riemer,C., Schwartz,S., Zhang,Z., Stojanovic,N., Miller,W. and McClelland,M. (2000) Nucleic Acids Res., 28, 3486–3496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schwartz S., Zhang,Z., Frazer,K.A., Smit,A., Riemer,C., Bouck,J., Gibbs,R., Hardison,R. and Miller,W. (2000) Genome Res., 10, 577–586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Overbeek R., Larsen,N., Pusch,G.D., d’Souza,M., Selkov,E.,Jr, Kyrpides,N., Fonstein,M., Maltsev,N. and Selkov,E. (2000) Nucleic Acids Res., 28, 123–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sanderson K.E. (1976) Annu. Rev. Microbiol., 30, 327–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krawiec S. and Riley,M. (1990) Microbiol. Rev., 54, 502–539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McClelland M. and Wilson,R.K. (1998) Infect. Immun., 66, 4305–4312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lawrence J.G. and Ochman,H. (1998) Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 95, 9413–9417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boyd E.F., Li,J., Ochman,H. and Selander,R.K. (1997) J. Bacteriol., 179, 1985–1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raina S., Missiakas,D., Baird,L., Kumar,S. and Georgopoulos,C. (1993) J. Bacteriol., 175, 5009–5021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boyd E.F. and Hartl,D.L. (1999) J. Bacteriol., 181, 1301–1308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klena J.D., Pradel,E. and Schnaitman,C.A. (1992) J. Bacteriol., 174, 4746–4752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pradel E., Parker,C.T. and Schnaitman,C.A. (1992) J. Bacteriol., 174, 4736–4745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heinrichs D.E., Monteiro,M.A., Perry,M.B. and Whitfield,C. (1998) J. Biol. Chem., 273, 8849–8859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bastin D.A. and Reeves,P.R. (1995) Gene, 164, 17–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hersh B.M., Farooq,F.T., Barstad,D.N., Blankenhorn,D.L. and Slonczewski,J.L. (1996) J. Bacteriol., 178, 3978–3981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Biase D., Tramonti,A., Bossa,F. and Visca,P. (1999) Mol. Microbiol., 32, 1198–1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pellicer M.T., Fernandez,C., Badia,J., Aguilar,J., Lin,E.C. and Baldom,L. (1999) J. Biol. Chem., 274, 1745–1752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Charbit A. and Autret,N. (1998) Microbial Comp. Genomics, 3, 119–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jenkins L.S. and Nunn,W.D. (1987) J. Bacteriol., 169, 2096–2102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Enz S., Mahren,S., Stroeher,U.H. and Braun,V. (2000) J. Bacteriol., 182, 637–646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Diaz E., Ferrandez,A. and Garcia,J.L. (1998) J. Bacteriol., 180, 2915–2923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gajiwala K.S. and Burley,S.K. (2000) J. Mol. Biol., 295, 605–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schuldiner S., Lebendiker,M. and Yerushalmi,H. (1997) J. Exp. Biol., 200, 335–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Feulner G., Gray,J.A., Kirschman,J.A., Lehner,A.F., Sadosky,A.B., Vlazny,D.A., Zhang,J., Zhao,S. and Hill,C.W. (1990) J. Bacteriol., 172, 446–456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang Y.D., Zhao,S. and Hill,C.W. (1998) J. Bacteriol., 180, 4102–4110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fajardo D.A., Cheung,J., Ito,C., Sugawara,E., Nikaido,H. and Misra,R. (1998) J. Bacteriol., 180, 4452–4459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wong R.M., Wong,K.K., Benson,N.R. and McClelland,M. (1999) FEMS Microbiol. Lett., 173, 411–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ochman H. and Wilson,A.C. (1987) J. Mol. Evol., 26, 74–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Campbell A.M. (1996) Cryptic prophage. In Neidhardt,F.C. (ed.), Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium. ASM Press, Washington, DC, pp. 2041–2046.

- 32.Kirby J.E., Trempy,J.E. and Gottesman,S. (1994) J. Bacteriol., 176, 2068–2081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Garcia-Vallve S., Palau,J. and Romeu,A. (1999) Mol. Biol. Evol., 16, 1125–1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hacker J., Blum-Oehler,G., Muhldorfer,I. and Tschape,H. (1997) Mol. Microbiol., 23, 1089–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wong K.K., McClelland,M., Stillwell,L.C., Sisk,E.C., Thurston,S.J. and Saffer,J.D. (1998) Infect. Immun., 66, 3365–3371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Groisman E.A. and Ochman,H. (1996) Cell, 87, 791–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marcus S.L., Brumell,J.H., Pfeifer,C.G. and Finlay,B.B. (2000) Microbes Infect., 2, 145–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maurelli A.T., Fernandez,R.E., Bloch,C.A., Rode,C.K. and Fasano,A. (1998) Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 95, 3943–3948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bergstrom S., Lindberg,F.P., Olsson,O. and Normark,S. (1983) J. Bacteriol., 155, 1297–1305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Poirel L., Guibert,M., Girlich,D., Naas,T. and Nordmann,P. (1999) Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., 43, 769–776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Golovan S., Wang,G., Zhang,J. and Forsberg,C.W. (2000) Can. J. Microbiol., 46, 59–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Atlung T., Knudsen,K., Heerfordt,L. and Brondsted,L. (1997) J. Bacteriol., 179, 2141–2146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Calamita G., Kempf,B., Bonhivers,M., Bishai,W.R., Bremer,E. and Agre,P. (1998) Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 95, 3627–3631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Suziedlien E., Suziedlis,K., Garbencit,V. and Normark,S. (1999) J. Bacteriol., 181, 2084–2093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Giel M., Desnoyer,M. and Lopilato,J. (1996) Genetics, 143, 627–635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Otsuka A.J., Buoncristiani,M.R., Howard,P.K., Flamm,J., Johnson,C., Yamamoto,R., Uchida,K., Cook,C., Ruppert,J. and Matsuzaki,J. (1988) J. Biol. Chem., 263, 19577–19585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Del Campillo Campbell A. and Campbell,A. (1996) J. Mol. Evol., 42, 85–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dell C.L., Neely,M.N. and Olson,E.R. (1994) Mol. Microbiol., 14, 7–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Van Der Ploeg J.R., Iwanicka-Nowicka,R., Kertesz,M.A., Leisinger,T. and Hryniewicz,M.M. (1997) J. Bacteriol., 179, 7671–7678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Masuda Y., Miyakawa,K., Nishimura,Y. and Ohtsubo,E. (1993) J. Bacteriol., 175, 6850–6856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sprenger G.A. (1993) Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1158, 103–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lawrence J.G. and Roth,J.R. (1995) J. Bacteriol., 177, 6371–6380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Faubladier M., Cam,K. and Bouche,J.P. (1990) J. Mol. Biol., 212, 461–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Armstrong S.K., Pettis,G.S., Forrester,L.J. and Mcintosh,M.A. (1989) Mol. Microbiol., 3, 757–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lundrigan M.D., Friedrich,M.J. and Kadner,R.J. (1989) Nucleic Acids Res., 17, 800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Quail M.A., Dempsey,C.E. and Guest,J.R. (1994) FEBS Lett., 356, 183–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Oshima T., Aiba,H., Baba,T., Fujita,K., Hayashi,K., Honjo,A., Ikemoto,K., Inada,T., Itoh,T., Kajihara,M., et al. (1996) DNA Res., 3, 137–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Henderson I.R., Meehan,M. and Owen,P. (1997) FEMS Microbiol. Lett., 149, 115–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ide N. and Kutsukake,K. (1997) Gene, 199, 19–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Andrews S.C., Berks,B.C., McClay,J., Ambler,A., Quail,M.A., Golby,P. and Guest,J.R. (1997) Microbiology, 143, 3633–3647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Reizer J., Michotey,V., Reizer,A. and Saier,M.H.,Jr (1994) Protein Sci., 3, 440–450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nobelmann B. and Lengeler,J.W. (1996) J. Bacteriol., 178, 6790–6795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nassau P.M., Martin,S.L., Brown,R.E., Weston,A., Monsey,D., McNeil,M.R. and Duncan,K. (1996) J. Bacteriol., 178, 1047–1052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Grassl G., Bufe,B., Muller,B., Rosel,M. and Kleiner,D. (1999) FEMS Microbiol. Lett., 179, 79–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Peekhaus N., Tong,S., Reizer,J., Saier,M.H.,Jr, Murray,E. and Conway,T. (1997) FEMS Microbiol. Lett., 147, 233–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yoshimoto T., Nagai,H., Ito,K. and Tsuru,D. (1993) J. Bacteriol., 175, 5730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Utsumi R., Horie,T., Katoh,A., Kaino,Y., Tanabe,H. and Noda,M. (1996) Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem., 60, 309–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gough J.A. and Murray,N.E. (1983) J. Mol. Biol., 166, 1–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Karow M., Raina,S., Georgopoulos,C. and Fayet,O. (1991) Res. Microbiol., 142, 289–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Menon N.K., Robbins,J., Peck,H.D.,Jr, Chatelus,C.Y., Choi,E.S. and Przybyla,A.E. (1990) J. Bacteriol., 172, 1969–1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.White S., Tuttle,F.E., Blankenhorn,D., Dosch,D.C. and Slonczewski,J.L. (1992) J. Bacteriol., 174, 1537–1543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Reuven N.B., Koonin,E.V., Rudd,K.E. and Deutscher,M.P. (1995) J. Bacteriol., 177, 5393–5400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cohen S.P., Hachler,H. and Levy,S.B. (1993) J. Bacteriol., 175, 1484–1492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hiom K. and Sedgwick,S.G. (1991) J. Bacteriol., 173, 7368–7373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kruger T., Grund,C., Wild,C. and Noyer-Weidner,M. (1992) Gene, 114, 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lee J.H., Wendt,J.C. and Shanmugam,K.T. (1990) J. Bacteriol., 172, 2079–2087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kiino D.R., Singer,M.S. and Rothman-Denes,L.B. (1993) J. Bacteriol., 175, 7081–7085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Navarro C., Wu,L.F. and Mandrand-Berthelot,M.A. (1993) Mol. Microbiol., 9, 1181–1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mahdi A.A., Sharples,G.J., Mandal,T.N. and Lloyd,R.G. (1996) J. Mol. Biol., 257, 561–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Grovc J., Busby,S. and Cole,J. (1996) Mol. Gen. Genet., 252, 332–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Inokuchi K., Mutoh,N., Matsuyama,S. and Mizushima,S. (1982) Nucleic Acids Res., 10, 6957–6968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Yang Y., Zhao,G. and Winkler,M.E. (1996) FEMS Microbiol. Lett., 141, 89–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yakovleva G.M., Kim,S.K. and Wanner,B.L. (1998) Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol., 49, 573–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Whitchurch C.B. and Mattick,J.S. (1994) Gene, 150, 9–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Brissette J.L., Weiner,L., Ripmaster,T.L. and Model,P. (1991) J. Mol. Biol., 220, 35–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Noirot P. and Kolodner,R.D. (1998) J. Biol. Chem., 273, 12274–12280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Gotfredsen M. and Gerdes,K. (1998) Mol. Microbiol., 29, 1065–1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Tanaka S., Matsushita,Y., Yoshikawa,A. and Isono,K. (1989) Mol. Gen. Genet., 217, 289–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Meador J.D. and Kennell,D. (1990) Gene, 95, 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sorensen K.I. and Hove-Jensen,B. (1996) J. Bacteriol., 178, 1003–1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sharples G.J., Chan,S.N., Mahdi,A.A., Whitby,M.C. and Lloyd,R.G. (1994) EMBO J., 13, 6133–6142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Leach D.R., Lloyd,R.G. and Coulson,A.F. (1992) Genetica, 87, 95–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Baquero M.R., Bouzon,M., Varea,J. and Moreno,F. (1995) Mol. Microbiol., 18, 301–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Rock C.O., Tsay,J.T., Heath,R. and Jackowski,S. (1996) J. Bacteriol., 178, 5382–5387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Faubladier M. and Bouche,J.P. (1994) J. Bacteriol., 176, 1150–1156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Alexander D.M. and St John,A.C. (1994) Mol. Microbiol., 11, 1059–1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Baird L. and Georgopoulos,C. (1990) J. Bacteriol., 172, 1587–1594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Weerasuriya S., Schneider,B.M. and Manson,M.D. (1998) J. Bacteriol., 180, 914–920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Schweizer H.P. and Datta,P. (1989) Mol. Gen. Genet., 218, 516–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Mizote T., Tsuda,M., Smith,D.D., Nakayama,H. and Nakazawa,T. (1999) Microbiology, 145, 495–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Deeley M.C. and Yanofsky,C. (1981) J. Bacteriol., 147, 787–796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Levengood S.K. and Webster,R.E. (1989) J. Bacteriol., 171, 6600–6609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ansaldi M., Simon,G., Lepelletier,M. and Mejean,V. (2000) J. Bacteriol., 182, 961–966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Bollinger J., Park,C., Harayama,S. and Hazelbauer,G.L. (1984) Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 81, 3287–3291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Schlosser A., Meldorf,M., Stumpe,S., Bakker,E.P. and Epstein,W. (1995) J. Bacteriol., 177, 1908–1910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Reaney S.K., Begg,C., Bungard,S.J. and Guest,J.R. (1993) J. Gen. Microbiol., 139, 1523–1530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Reeves P.R., Hobbs,M., Valvano,M.A., Skurnik,M., Whitfield,C., Coplin,D., Kido,N., Klena,J., Maskell,D., Raetz,C.R. and Rick,P.D. (1996) Trends Microbiol., 4, 495–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Yao Z. and Valvano,M.A. (1994) J. Bacteriol., 176, 4133–4143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Davis E.O. and Henderson,P.J. (1987) J. Biol. Chem., 262, 13928–13932. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Horazdovsky B.F. and Hogg,R.W. (1989) J. Bacteriol., 171, 3053–3059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Diorio C., Cai,J., Marmor,J., Shinder,R. and Dubow,M.S. (1995) J. Bacteriol., 177, 2050–2056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Hall B.G. and Xu,L. (1992) Mol. Biol. Evol., 9, 688–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Lamark T., Rokenes,T.P., Mcdougall,J. and Strom,A.R. (1996) J. Bacteriol., 178, 1655–1662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Chen Q., Postma,P.W. and Amster-Choder,O. (2000) J. Bacteriol., 182, 2033–2036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Kozliak E.I., Fuchs,J.A., Guilloton,M.B. and Anderson,P.M. (1995) J. Bacteriol., 177, 3213–3219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Oh T.J., Lee,C.W. and Kim,I.G. (1999) Microbiol. Res., 154, 179–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Tanabe H., Yamasaki,K., Katoh,A., Yoshioka,S. and Utsumi,R. (1998) Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem., 62, 286–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Blanco C., Ritzenthaler,P. and Kolb,A. (1986) Mol. Gen. Genet., 202, 112–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Haussmann C., Rohdich,F., Schmidt,E., Bacher,A. and Richter,G. (1998) J. Biol. Chem., 273, 17418–17424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Falla T.J. and Chopra,I. (1998) Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., 42, 3282–3284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Lutz S., Jacobi,A., Schlensog,V., Bohm,R., Sawers,G. and Bock,A. (1991) Mol. Microbiol., 5, 123–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Reidl J. and Boos,W. (1991) J. Bacteriol., 173, 4862–4876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Steinebach V., Benen,J.A., Bader,R., Postma,P.W., De Vries,S. and Duine,J.A. (1996) Eur. J. Biochem., 237, 584–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Ferrandez A., Garcia,J.L. and Diaz,E. (1997) J. Bacteriol., 179, 2573–2581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Muse W.B. and Bender,R.A. (1999) J. Bacteriol., 181, 934–940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Whipp M.J., Camakaris,H. and Pittard,A.J. (1998) Gene, 209, 185–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Van Der Ploeg J.R., Weiss,M.A., Saller,E., Nashimoto,H., Saito,N., Kertesz,M.A. and Leisinger,T. (1996) J. Bacteriol., 178, 5438–5446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Karasawa K., Yokoyama,K., Setaka,M. and Nojima,S. (1999) J. Biochem. (Tokyo), 126, 445–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Ritzenthaler P., Mata-Gilsinger,M. and Stoeber,F. (1981) J. Bacteriol., 145, 181–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Marolda C.L., Feldman,M.F. and Valvano,M.A. (1999) Microbiology, 145, 2485–2495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Rosenfeld S.A., Stevis,P.E. and Ho,N.W. (1984) Mol. Gen. Genet., 194, 410–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Song S. and Park,C. (1997) J. Bacteriol., 179, 7025–7032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]